Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 14/16/01. The contractual start date was in January 2015. The draft report began editorial review in April 2016 and was accepted for publication in August 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Richard Wakefield has provided consulting advice and spoken for General Electric with regard to ultrasound technologies and has also received speaker fees from AbbVie Inc. for ultrasound-related projects. Cristina Estrach has been a member of advisory boards for and/or received speaker fees from AbbVie Inc., Chugai Pharma (UK) Ltd and General Electric Co. Her institution has received educational grants from Pfizer Inc.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Simpson et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Description of the health problem

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic inflammatory disease characterised by progressive, irreversible joint damage, impaired joint function, pain and tenderness caused by swelling of the synovial lining of the joints (synovitis) and is manifested with increasing disability and reduced quality of life. 1 The primary symptoms are pain, morning stiffness, swelling, tenderness, loss of movement, fatigue and redness of the peripheral joints. 2,3 RA is associated with substantial costs both directly (associated with drug acquisition and hospitalisation) and indirectly, because of reduced productivity. 4 RA has long been reported as being associated with increased mortality,5,6 particularly as a result of cardiovascular events. 7

Diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis

The initial classification criteria for RA were produced in 1987 by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR). 8 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) clinical guideline 799 provides a summary of the ACR criteria, with patients needing to have at least four of the seven criteria to be given a diagnosis of RA: morning stiffness lasting at least 1 hour, swelling in three or more joints, swelling in the hand joints, symmetric joint swelling, erosions or decalcification on radiography of the hand, rheumatoid nodules and abnormal serum rheumatoid factor. For the first four criteria these must have been present for at least a period of 6 weeks. However, in the clinical guideline9 the guideline development group preferred a clinical diagnosis of RA rather than the ACR criteria to permit early treatment, as consistent with European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) recommendations. 10

In 2010, the ACR and EULAR jointly published RA classification criteria, which focused on features present at earlier stages of the disease that are associated with persistent and/or erosive disease rather than defining the disease by its late-stage features. 11 The classification criteria allocate scores to the characteristics of joint involvement, serology, acute-phase reactants and duration of symptoms to produce a total score between 0 and 10, with those scoring ≥ 6 and with obvious clinical synovitis being defined as having ‘definite RA’ in the absence of an alternative diagnosis that better explains the synovitis. 11 The growing recognition of the accuracy of modern imaging [such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and ultrasound (US)] over clinical examination (CE) in detecting synovitis was highlighted in these new classification criteria, which allow the extent of joint involvement to be determined by imaging. 11

Epidemiology

There are an estimated 400,000 people in England and Wales with RA,12 with approximately 10,000 incident cases per year. 13 The disease is more prevalent in females (1.16%) than in males (0.44%),13 with the majority of cases being diagnosed when patients are aged between 40 and 80 years14 and a peak incidence in those in their 70s. 13

Measurement of disease activity and damage progression

Synovitis can be detected by CE. Monitoring may involve taking swollen joint counts (SJCs) or tender joint counts (TJCs). Biomarkers may be used to detect evidence of systemic inflammation, for example anaemia in chronic disease or elevated levels of C-reactive protein (CRP) or an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). 9,15 Common measures of disease activity, disability and response to treatment are presented in Table 1. ACR response19 and EULAR response20 measures have dominated the measurement of improvement in RA symptoms. The ACR response has been widely adopted in randomised controlled trials (RCTs) although studies have shown that the value can vary between trials because of the timing of the response. 21 The EULAR response criteria and the ACR20 improvement criteria (see Table 1) were found to have reasonable agreement in the same set of clinical trials, although van Gestel et al. 22 stated that the EULAR response criteria showed better construct and discriminant validity than the ACR20 criteria. The Disease Activity Score 28 joints (DAS28; see Table 1) can be used to classify both the disease activity of the patient and the level of improvement estimated. The EULAR response has been reported less frequently in RCTs than the ACR response, although the EULAR criteria are much more closely aligned to the treatment continuation rules stipulated by NICE,9 which require a DAS28 improvement of > 1.2 to continue treatment. 22

| Measure | Description |

|---|---|

| Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ)16 | A patient-completed disability assessment with established reliability and validity. Scores range from 0 to 3, with higher scores indicating greater disability. The HAQ scale is a discrete scale with step values of 0.125, resulting in 25 points on the scale |

| Visual analogue scale (VAS) | A global assessment of the extent of disease, which may be assessed by the patient or the physician. This method may also be used for patient-reported pain. The VAS usually consists of a 100-mm line that represents the total range of the disease extent/pain levels experienced. Patients/physicians mark a point on the line |

| DAS28-ESR17 | This assesses 28 joints (shoulder, knee, elbow, wrist, MCP joints one to five, PIP joints one to five, bilaterally) in terms of swelling (SW28) and of tenderness to the touch (TEN28). It also incorporates measures of the ESR and a subjective assessment (SA) on a scale of 0–100 made by the patient regarding disease activity in the previous week. The DAS28-ESR score is calculated using the following equation: 0.56 × TEN280.5 + 28 × SW280.5 + 0.70 × ln(ESR) + 0.014 × SA. A DAS28-ESR of ≤ 3.2 indicates inactive disease; a DAS28-ESR of > 3.2 and ≤ 5.1 indicates moderate disease; a DAS28-ESR of > 5.1 indicates very active disease |

| DAS28-CRP17 | Similar to the DAS28-ESR but uses the CRP value instead of the ESR. The DAS28-CRP is calculated using the following equation: [0.56 × sqrt(TEN28) + 0.28 × sqrt(SW28) + 0.36 × ln(CRP + 1)] × 1.10 + 1.15 |

| Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI)18 | A composite index based on SJCs (0–28), TJCs (0–28), CRP, patient global assessment of disease activity VAS (0–10 cm) and physician global assessment of disease activity VAS (0–10 cm) |

| Simplified Disease Activity Index (SDAI)18 | A simplified version of the CDAI based on SJCs (0–28), TJCs (0–28), patient global assessment of disease activity VAS (0–10 cm) and physician global assessment of disease activity VAS (0–10 cm) |

| ACR response19 | An ACR20 response requires a 20% improvement in TJCs; a 20% improvement in SJCs; and a 20% improvement in at least three of the following five ‘core set items’: physician global assessment, patient global assessment, patient pain, self-reported disability (using a validated instrument) and ESR or CRP. ACR50 and ACR70 responses require 50% and 70% improvements, respectively |

| EULAR response20 | Participants are classified as good, moderate or non-responders based on the individual change in DAS28 and the DAS28 reached.20 The relationship between change in DAS28 and DAS28 reached and EULAR response is shown in Table 2 |

The relationship between change in DAS28 and DAS28 reached and EULAR response is shown in Table 2. Depending on the initial DAS28 of the patient, this change in DAS28 would equate to either a good or moderate EULAR response, as shown in the second column of Table 2.

| DAS28 at end point | Improvement in DAS2823 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| > 1.2 | > 0.6 and ≤ 1.2 | ≤ 0.6 | |

| ≤ 3.2 | Good | Moderate | None |

| > 3.2 and ≤ 5.1 | Moderate | Moderate | None |

| > 5.1 | Moderate | None | None |

Both the ACR criteria and the DAS28-based EULAR criteria rely on subjective measurements and can be influenced by patients’ pain threshold and comorbidities. 24 The DAS28 has been criticised as patients achieving DAS remission can still have synovitis as evidenced by imaging. 25,26 Alternatively, chronic pain experienced by patients or deformity and residual fibrous tissue leading to the detection of swelling by manual examination of joints can raise the DAS, thus overestimating disease activity. 24 If DAS measurement is based on CRP levels, it can be influenced by therapies; for example, tocilizumab (TCZ; RoActemra®, Roche Products Ltd, Welwyn Garden City, UK) has a direct effect on CRP through interleukin-6 and can therefore artificially lower the DAS28. 27 Unlike these subjective measurements, imaging could provide an objective measurement of synovitis.

The role of imaging

Imaging techniques used in the diagnosis and monitoring of RA include US, conventional radiography, MRI and computerised axial tomography (CT). Initial diagnosis of RA, or differential diagnosis of forms of arthritis, may be aided by imaging. There is a EULAR recommendation that US, MRI and conventional radiography can improve the certainty of a RA diagnosis if there is diagnostic doubt. 28

In terms of detecting inflammation, there is evidence to demonstrate that both US and MRI detect more cases of synovitis than CE. 9,28 The benefit of US as an addition to CE will be influenced by the ability of this subclinical synovitis to predict disease progression. Prognostic studies of US-detected synovitis were sought in this report (see Chapter 3). Because of their three-dimensional acquisition, both US and MRI are also more sensitive than conventional radiography at detecting erosion damage and early signs of erosion. 9 MRI can detect bone oedema, which may be a predictor of radiographic progression. 28

Although MRI may be more sensitive than US for detecting erosions,29 US and MRI have comparable abilities to detect synovitis. 28–30 Arthritis Research UK30 suggests that US has an advantage over other imaging techniques as it can be used immediately after CE to assess symptomatic areas or clinical abnormalities and this has the added advantage of improving clinical skills. 30

There is no conclusive gold standard (sometimes referred to as a reference standard) for assessing synovitis. When compiling their 2009 guidelines, NICE9 recognised that many clinicians had limited access to US and so it considered clinician examination as the gold standard for the detection of synovitis in practice. It is possible that US has become more widespread since then. To address this issue, a survey was conducted to determine the usage of US in UK clinical practice (see Appendix 1).

Conventional radiography is commonly used to measure disease progression. 9 In clinical trials this may be carried out using the total Sharp score (TSS), the van der Heijde-modified total Sharp score (vdHSS)31 or the modified Genant et al. 32 scoring method, which measure erosions and joint space narrowing, although systematic scoring of radiographs in routine clinical care is very uncommon.

Treatment strategies based on a therapeutic outcome target (known as ‘treat to target’; TTT) are becoming more widely used within rheumatology. 33–35 Typically, targets are either remission or low disease activity (when remission is not attainable). These are usually clinically defined [e.g. DAS of < 2.6, Simplified Disease Activity Index (SDAI) score of ≤ 3.3]. 34,36 However, as a previous review has reported that US has been shown to be superior to CE for detecting synovitis, providing that this is linked to later outcomes,28 US-defined remission may be a more appropriate target for TTT strategies. This previous review thoroughly examined the use of US to detect synovitis;28 however, it was published prior to the publication of the treatment studies, including RCTs, in this report. Research is starting to examine the effectiveness of US compared with clinical treatment targets within TTT strategies in RA. 36,37

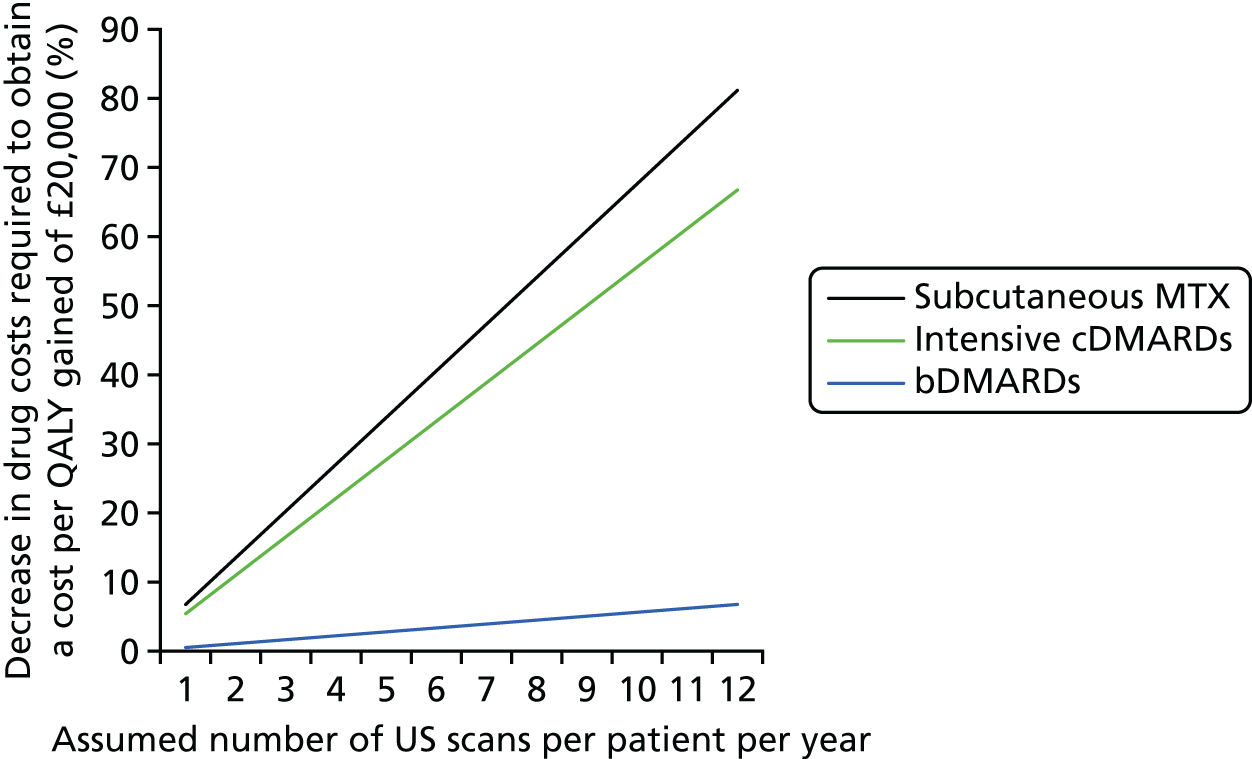

Significance for the NHS

Because previous NICE technology appraisals have recommended a number of biological disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (bDMARDs) (see Current service provision), with a potential sequence of three bDMARDs, there has been a considerable increase in expenditure on RA interventions as bDMARDs are markedly more expensive than conventional disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (cDMARDs). Any imaging technology that could inform decisions on when to start, or to taper or discontinue, treatments has the potential to benefit the NHS. The frequency of monitoring would influence cost-effectiveness.

Further detailed information on RA can be found in NICE clinical guideline 79. 9 Additional information can also be located in the British Society for Rheumatology (BSR) guidelines. 38

Current service provision

Traditionally, patients have been treated with cDMARDs, which include methotrexate (MTX), sulfasalazine (SSZ), hydroxychloroquine (HCQ), leflunomide, ciclosporin and gold injections as well as corticosteroids, analgesics and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). However, more recently, a group of drugs has been developed consisting of monoclonal antibodies and soluble receptors that specifically modify the disease process by blocking key protein messenger molecules (such as cytokines) or cells (such as B-lymphocytes). 9 Such drugs have been labelled as bDMARDs.

A simplified model of the RA clinical pathway has been provided by NICE,39 with the use of US falling into the monitoring and review box. For the purposes of this report, modelling assumes that US would be used only at points in the pathway where a change of treatment is being considered, specifically for those patients for whom a clinician is considering tapering treatment to assess the current level of synovitis and for those patients for whom a clinician is contemplating escalating treatment to rule out non-synovitis-related reasons.

Clinical guidelines

For people with newly diagnosed RA, NICE clinical guideline 799 recommends a combination of cDMARDs [including MTX and at least one other disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug (DMARD) plus short-term glucocorticoids] as first-line treatment, ideally beginning within 3 months of the onset of persistent symptoms. When combination therapies are not appropriate (e.g. when there are comorbidities or the patient is pregnant), DMARD monotherapy is recommended. When DMARD monotherapy is used, emphasis should be on increasing the dose quickly to obtain the best disease control. For the purposes of this report, the term ‘intensive DMARDs’ has been used to denote treatment with multiple cDMARDs simultaneously.

Current National Institute for Health and Care Excellence technology appraisal guidance

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidance [technology appraisal (TA) 375]40 recommends the use of the tumour necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFis) etanercept (ETN; Enbrel®, Pfizer Ltd, Sandwich, UK), infliximab (IFX; Remicade®, Merck Sharp & Dohme Ltd, Hoddesdon, UK), adalimumab (ADA; Humira®, AbbVie Ltd, maidenhead, UK), certolizumab pegol (CTZ; Cimzia®, UCB Pharma, Slough, UK) and golimumab (GOL; Simponi®, Merck Sharp & Dohme Ltd), in combination with MTX, in people with RA after the failure of two cDMARDs, including MTX, and who have a DAS28 of > 5.1 and when bDMARDs have not been tried previously. TA375 also recommends the use of TCZ and abatacept (ABT; Orencia®, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Uxbridge, UK) as alternatives to TNFis in the same circumstances.

Technology appraisal 375 did not recommend the use of bDMARDs in patients with a DAS of ≤ 5.1 nor in patients in whom cDMARDs have failed. 40

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence has also issued guidance on the treatment of RA after the failure of a TNFi (TA195,41 TA22542 and TA24743).

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence clinical guideline 799 recommends the use of intensive cDMARDs – two cDMARDs used in combination, rather than two cDMARDs used sequentially – although this latter option is acceptable.

A simplified summary of the typical pathway recommended by NICE would be the use of intensive cDMARDs followed by a bDMARD, followed by rituximab (RTX; MabTheraR, Roche Products Ltd, Welwyn Garden City, UK) plus MTX and then TCZ before returning to cDMARDs. If RTX or MTX is contraindicated then ADA, ETN, IFX or ABT in combination with MTX or ADA or ETN monotherapy can be used instead (TA19541), as can TCZ in combination with MTX (TA24743) and GOL in combination with MTX (TA22542). A NICE single technology appraisal recommended the use of CTZ after an inadequate response to a TNFi for patients with a DAS28 of > 5.1 for whom RTX is contraindicated or not tolerated. 44

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence criteria for continuing treatment

Each of the NICE TAs state that for patients to continue treatment with a bDMARD there must have been an improvement in DAS28 of at least 1.2 points at 6 months. If this criterion has not been met, treatment should be stopped and the next intervention in the sequence initiated.

Current service cost

The decision problem compares the use of US for the monitoring of synovitis in addition to CE compared with CE alone, assuming that there are US facilities within the hospital. As such, no attempt has been made to estimate the costs of providing a rheumatology service without US monitoring, as it is presumed that these costs, such as maintenance costs, consumable costs and receptionist costs, will be the same regardless of whether or not US monitoring is undertaken for RA patients. No analyses have been undertaken assuming that the machinery required to perform US would be bought primarily for the use of RA patients, although it is expected that in such circumstances the costs per US scan would be markedly higher.

Description of the technology under assessment

In US, reflected pulses of high-frequency sound are used to assess soft tissue, cartilage and bone surfaces. 30

Grey-scale ultrasound (GSUS) (also known as B-mode ultrasound) displays different intensities of echoes, denoting different densities of tissue, in black, white and shades of grey. 30 GSUS can measure synovial hypertrophy and effusion. 45 Doppler US is based on the principle that sound waves increase or decrease in frequency when objects (such as blood cells) move towards or away from the transducer, respectively. 30 Thus, power Doppler ultrasound (PDUS) can be used to detect the volume of blood flow. 30

Musculoskeletal US can be used for evaluating joint and soft tissue pathology. 30 Within the field of rheumatology, US can be used for the initial diagnosis of arthritis and for US-guided injections or aspirations (which fall outside the scope of this report). 30 It can also be used to assess the extent of inflammatory disease and determine the response to therapy. 30 A significant advantage of US over other imaging technologies such as MRI and CT is the ability to focus on the area of symptoms or clinical abnormality with the US probe immediately after CE. 30

The ACR has published guidelines on the use of US in rheumatology. 46 This included several recommendations across a range of disorders and various stages of the clinical pathway, including that it is reasonable to use US to evaluate inflammatory disease activity. 46

The EULAR recommendations on imaging for RA, published in 2013, covered several imaging technologies and pathologies across stages of the clinical pathway. 28 Recommendations included that US be used to detect and monitor inflammation and that imaging be used to predict the response to therapy.

Ultrasound is useful for distinguishing inflammatory from non-inflammatory joint disease. Effusion may indicate synovial inflammation; however, abnormally thickened hypoechoic intra-articular tissue may indicate synovitis in the absence of effusion. 30 PDUS can be used to assess synovitis as it can detect minimal increases in perfusion in the synovium. 30 US can detect subclinical synovitis. 28,30 Subclinical synovitis may predict structural deterioration in RA patients; thus, prognostic studies were sought (see Chapter 3) as progression can occur in RA patients in remission. 47,48 The benefit of US as an addition to CE will be influenced by the ability of this subclinical synovitis to predict disease progression.

Interpreting US scans is a skill. In the past, there have been concerns about inter-rater reliability; however, a review published in 201049 found that both intra-rater and inter-rater reliability for still-image interpretation was high for both GSUS and PDUS. Limited evidence is available for assessing image acquisition reliability. 50 The Outcome Measures in Rheumatoid Arthritis Clinical Trials (OMERACT) US task force has addressed many issues involved in measuring RA and has looked specifically at the variability of US. 30,51 In the past, GSUS was used to assess the presence or absence of synovitis, but this was followed by the creation of semiquantitative scoring systems (Table 3). 45 PDUS used to detect vascularity may be quantified30 (see Table 3). Concerns had also been voiced regarding intermachine variability, but with current high-end systems this is now less of a concern. 30,45 D’Agostino et al. ,60 as reported by Arthritis Research UK,30 showed that there is good reliability between experts using different types of US machine. There may be some variability in synovitis throughout the day; response to cDMARDs may be detected within 6–8 weeks and response to bDMARDS may be seen as early as 1 week. 61,62 The optimal frequency of testing will depend on the frequency of treatment decisions. It is envisaged that the number of US tests conducted per year would be aligned to the frequency at which clinical decisions regarding changing the treatment for a patient would be undertaken.

| Reference | Scoring system |

|---|---|

| Szkudlarek et al. 200352 | Joint effusion (compressible anechoic intracapsular area):

|

| Scheel et al. 200553 | Synovitis and effusion included in a combined scoring method (the larger the anechoic structure or extent of synovial hypertrophy seen on US images, the higher the assigned score):

|

| Naredo et al. 2005,54 Naredo et al. 2007,55 Naredo et al. 200856 | Subjective grading of joint effusion and synovitis from 0 to 3:

|

| Karim et al. 200457 | Semiquantitative assessment for degree of synovitis:

|

| Schmidt et al. 200058 | Subjective grading of echogenity of effusion on a 0–3 scale:

|

| Klauser et al. 200459 | Criteria for grading intra-articular vascularisation with colour Doppler US/PDUS:

|

At the OMERACT 7 meeting in 2004 an international panel of experts agreed on the first definitions of sonographic pathology. 51 This meeting achieved consensus in US definitions of joint effusion, bursal effusion and synovitis. Studies following on from that meeting, undertaken within the EULAR/OMERACT network, were reported at the OMERACT 8 meeting in 2006. 63 The international panel of experts concluded that the standardised definitions produced by OMERACT had improved inter-rater and intra-rater reliability for detecting and grading synovitis of the hand joints. 63 The OMERACT US special interest group defined a Global Synovitis Score, which combines synovial hypertrophy and the PDUS signal in a composite score and has acceptable reliability. 64,65

Although the 28-joint count is well established for CE, the optimal joint count for US is currently unclear. Joint counts featuring smaller numbers of joints are more feasible for a clinical encounter. 45 Several studies have compared various different joint counts;45,66–70 however, there is no clear consensus on the optimal joint count at present and joint counts vary between studies, rendering comparison across studies difficult. Research is ongoing.

Patient experience of ultrasound

Ultrasound is relatively inexpensive and safe, avoiding the exposure to radiation that is necessary for conventional radiography and CT. US is a painless and harmless procedure, being non-invasive and not radioactive. As confirmed by this study’s patient advisor (see Appendix 2), US is comfortable for the patient, unlike MRI, which can be noisy, can make the patient feel claustrophobic and requires lying still for a prolonged period of time. It should be noted that only one patient advisor contributed to this report.

The advent of portable US machines means that scans can be carried out at the bedside or in the outpatient clinic without the need for a second appointment in the radiology department. Most scans for RA involve the hand or wrist joints or focus on the most affected joint and take < 20 minutes.

Current usage in the NHS

Few published data were identified on the current usage of US for RA in the NHS. Therefore, a survey was conducted to address this issue (see Appendix 1).

A published survey conducted in 200571 analysed data from 126 UK rheumatologists. It found that 93% (117/126) of the surveyed rheumatologists used US results in patient management, with 33% (41/126) conducting the US examination themselves. Of the 60% (76/126) who referred patients to other departments for US, the majority referred patients to the radiology department (56%, 71/126). Synovitis was the second most common indication (estimate from graph: 87%, 110/126) for investigation by US, after tenosynovitis. The authors acknowledge the possibility that US use was overestimated because of the sample of rheumatologists being targeted at imaging events and because of response bias (126 questionnaires returned out of 250 circulated).

Another survey of 100 rheumatologists, conducted in 2009 (Richard Wakefield, University of Leeds, 22 March 2016, personal communication), found that most used US results to detect inflammatory arthritis (84%), but fewer used US for prognostic assessment (44%) or disease monitoring (32%). In total, 28% had conducted the US examination themselves and 81% had referred patients to the radiology department. Of those surveyed, 40% reported that US frequently influenced patient management (Richard Wakefield, personal communication).

The Targeted Ultrasound Initiative,72 founded in 2012, provides training and resources regarding US. A survey of its international users suggests that > 90% use US for diagnosis and the assessment of remission and approximately 80% use US for routine monitoring (Richard Wakefield, personal communication).

Anticipated costs associated with the intervention

The cost of monitoring synovitis using US was estimated using data provided by our clinical experts (Professor Philip Conaghan, University of Leeds; Dr Cristina Estrach, Aintree University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust; Professor Christopher Edwards, University of Southampton; and Dr Richard Wakefield, University of Leeds) and a survey (see Appendix 1) sent to members of the BSR. Our clinical advisors stated that US used for monitoring synovitis would be undertaken as an outpatient appointment and that contrast would not be required. A broad consensus was reached that two-thirds of scans would take < 20 minutes with one-third taking ≥ 20 minutes. Based on this advice, it was assumed that two-thirds of scans would be costed as NHS reference cost RD40Z (£55.03) and the remainder would be costed as NHS reference cost RD42Z (£59.90), resulting in a weighted cost per scan of £56.66. 73 Therefore, if it is assumed that, on average, four USs are performed on a patient every year, this would equate to a yearly cost of US monitoring of £226.62. No distinction has been made between different types of US for two reasons. First, detailed data on the differential costs have not been identified. Second, there was no clear evidence of a distinction between different US modes regarding the association with synovitis levels detected and in the successful tapering of treatment. Four US scans were chosen as the base case as it was assumed that clinicians may actively monitor patients in whom they had tapered treatment. This assumption was tested in sensitivity analyses.

Chapter 2 Definition of the decision problem

Decision problem

Purpose of the decision to be made

The aim of this assessment was to systematically review the evidence on the use of US examination in addition to clinical assessment, compared with CE only, in relation to how synovitis in patients with RA can be used to predict prognosis or response to treatment and to investigate the cost-effectiveness of US joint examination for monitoring synovitis in terms of guiding decisions about when treatment can be tapered or which patients should be progressed to more intensive treatment.

Intervention

The included intervention was US examination of joints in patients with RA used in addition to CE to detect synovitis. US technologies included were GSUS and PDUS.

Population/setting

The population was adult patients with a confirmed diagnosis of RA at any point in the disease pathway. The setting was secondary care.

Relevant comparators

The comparator was assessment of synovitis by CE, without the use of US technology. This included assessment of inflammatory biomarkers68 such as ESR or CRP15 and the use of disease activity scoring tools68 such as the DAS28,17 Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ),16 SDAI18 and Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI)18 (see Table 1).

Outside the scope of the decision problem

Ultrasound used in the initial diagnosis of arthritis or to determine the type of arthritis or US to guide injections.

Key factors to be addressed

The review aimed to address the clinical value of US in addition to CE for detecting synovitis at different joints and at different points in the disease pathway, compared with CE alone. The review aimed to investigate the economic costs and benefits associated with the use of US to monitor synovitis in RA.

Overall aims and objectives of the assessment

The review aimed to:

-

investigate reported data on the detection of synovitis in RA patients by US and CE and the ability of US and clinically detected synovitis to predict clinical outcome or response to RA treatment

-

investigate the economic costs and benefits associated with the use of US to monitor synovitis in RA

-

suggest key areas for primary research.

Chapter 3 Assessment of ultrasound studies

Methods for reviewing ultrasound studies

The search for evidence on US for monitoring synovitis in RA was undertaken systematically following the general principles recommended in the PRISMA statement. 74 The search strategies used are provided in Appendix 3.

Identification of studies

The following electronic databases were searched:

-

MEDLINE and MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations (via Ovid) (1946 to October 2015)

-

EMBASE (via Ovid) (1974 to October 2015)

-

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR) (via Wiley Online Library) (1996–2015)

-

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (via Wiley Online Library) (1898–2015)

-

Health Technology Assessment (HTA) database (via Wiley Online Library) (1989–2015)

-

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) (via Wiley Online Library) (1946–2014)

-

NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED) (via Wiley Online Library) (1968–2014)

-

Science Citation Index Expanded (via Web of Science) (1900 to October 2015)

-

Science Citation Index and Conference Proceedings Index (via Web of Science) (1900 to October 2015)

-

ClinicalTrials.gov (US National Institutes of Health) (October 2015)

-

European League Against Rheumatism Abstract Archive (via Web of Science) (October 2015)

-

American College of Rheumatology and Association of Rheumatology Health Professionals (via Web of Science) (October 2015)

-

OMERACT conference proceedings (via Web of Science) (October 2015).

In addition to electronic database searching, bibliographies of systematic reviews and included studies were checked for studies meeting the review inclusion criteria.

Initial scoping searches identified eight relevant guidelines. 9,24,28,30,46,75–77 Bibliographies of these guidelines were also checked.

Following the submission of the report for peer review, the full results of one of the included studies [Targeting Synovitis in Early Rheumatoid Arthritis (TaSER)] were published. 78 On the request of a peer reviewer, the results from this publication have been included. The searches were not updated. However, as this was a publication of an already included study, with data relevant to the treatment strategies, it was decided that the publication would be included. Additionally, the Aiming for Remission in Rheumatoid Arthritis (ARCTIC) trial, although not published in full at the time of peer review, was published in a preliminary conference abstract in November 2015. 79 It was decided that this publication would also be discussed.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Population

Adult patients diagnosed with RA. 11

Intervention

The intervention was US of joints in patients with RA, as used to assess synovitis. Studies were not excluded on the basis of type of US technology used. US technologies included were GSUS and PDUS.

Comparators

The comparator was assessment of synovitis by CE without the use of US technology (in the same patients). This included assessment of inflammatory biomarkers such as ESR or CRP15 and the use of disease activity scoring tools such as the DAS2817 and HAQ. 16

Outcomes

Outcomes were diagnostic accuracy measured by sensitivity and specificity (CE with reference US, or reported US with reference CE, or sufficient data reported to calculate sensitivity or specificity); responsiveness to change in inflammation as measured by standardised response mean (SRM);80 synovitis detection rate; prognostic sensitivity or prognosis associated with baseline measures; prediction of response to treatment; or the use of US in clinical decision-making.

For diagnostic accuracy data, studies were accepted if they reported sensitivity or specificity or if they provided sufficient data to calculate sensitivity or specificity.

Study design

Diagnostic studies, prognostic studies and studies investigating prediction of response to treatment, or the influence of US on treatment decisions, whether as a one-off US test or as serial US testing, were included. Studies were not excluded based on quality alone; however, for prognostic studies, the method and setting of outcome measurement had to be the same for all study participants. 81

Additionally, systematic reviews were sought and were used to identify studies meeting the inclusion criteria for the review.

Exclusion criteria

The exclusion criteria were as follows:

-

US used for RA diagnosis only (for initial diagnosis of arthritis or for differentiating between types of arthritis)

-

US used to guide injections

-

US used for inflammatory conditions other than RA

-

studies with healthy control subjects unless outcome data were reported separately for the RA subgroup

-

studies of US compared with another imaging technology (or other diagnostic method) for which clinical comparator data were not available or for which data did not allow comparison of US with CE

-

studies with a low proportion (< 80%) of patients diagnosed with RA, unless outcome data were reported separately for the RA subgroup

-

studies of US reporting inter-rater or intra-rater reliability only

-

studies of tenosynovitis not reporting data about synovitis

-

animal models

-

preclinical and biological studies

-

narrative reviews, editorials and opinions

-

non-English-language papers

-

abstracts reporting insufficient details to allow inclusion.

This review concentrated on US as the intervention. There is no conclusive gold standard/reference standard for assessing synovitis related to disease progression. This review investigated the association of US-detected synovitis with later outcomes in prognostic studies (see Assessment of prognostic studies). This can be considered as validating the test results. 28 For detection of synovitis, it may be considered that surgery is the gold standard/reference standard, allowing direct visualisation of the synovial membrane. 57 In clinical practice, this would not be used for monitoring synovitis, and limiting studies to those including surgery would limit the amount of studies eligible for the review. In terms of other imaging techniques that have a potential role in monitoring, it has been suggested that MRI may be used as a gold standard/reference standard. However, it has been reported that US and MRI detect similar rates of inflammation. 28 Scintigraphy and positron emission tomography (PET) have been reported to detect similar rates of inflammation to CE. 28 Other imaging techniques with a potential for use in RA patients are conventional radiography and CT scans. US is more likely to be practical than other imaging techniques in assessing synovitis. US is more comfortable for the patient than MRI, is less expensive and has an advantage over other imaging techniques as it can be used immediately after CE to assess symptomatic areas. 30 Limiting studies to those including an additional imaging technique would have limited the number of studies eligible for the review. As this review concentrated on US as the intervention, the decision was taken not to compare US-detected synovitis with synovitis detected by other imaging techniques.

Study selection

Titles and abstracts were examined by one reviewer. Study selection based on full texts was carried out by two reviewers, with discrepancies resolved by discussion.

Data extraction strategy

Data relevant to the decision problem were extracted from all studies by one reviewer using a standardised data extraction form. All data extracted were checked thoroughly by a second reviewer. Data were extracted without blinding to authors or journal. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion.

Quality assessment strategy

The methodological quality of each included study was assessed by one reviewer and checked by a second reviewer. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion. Diagnostic studies were assessed using criteria based on the QUADAS (Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies) tool. 82 The QUADAS tool was selected as it is a validated, evidence-based tool that has been widely used in diagnostic review. Prognostic studies were assessed using criteria taken from the Generic Appraisal Tool for Epidemiology (GATE)83 and the Quality in Prognosis Studies (QUIPS)81 tool. These are both validated tools that have been used for reviewing prognostic studies. Two items of particular relevance to RA studies were adapted from recommendations on inclusion criteria and study design for RA studies by Karsh et al. 84

Methods of analysis/synthesis

For calculations of diagnostic accuracy, US was counted as the reference standard and the accuracy of the clinical comparator was assessed using sensitivity, that is, the proportion of true positives (TPs), and specificity, that is, the proportion of true negatives (TNs), calculated as follows: sensitivity is the number of TPs divided by the sum of the TPs and the false negatives (FNs); specificity is the number of TNs divided by the sum of the TNs and the false positives (FPs).

Data were tabulated and discussed. Evidence synthesis would be attempted unless precluded by heterogeneity (of population, intervention, comparator or outcomes).

Survey

In addition to the systematic review, a survey was conducted to investigate current usage of US in treatment decisions for RA patients. The survey was publicised by the BSR through newsletters. The questions used in the survey are provided in Appendix 1. The survey was available to clinicians from December 2015 to February 2016.

Results

Quantity and quality of research available

A total of 2724 records were identified from the electronic databases following deletion of duplicate records.

Eight guidelines were identified through grey literature searching. 9,24,28,30,46,75–77 Eight systematic reviews of relevance to the decision problem were also identified. 25,29,45,50,85–88 Guidelines were published on US in rheumatology by the ACR,46 Arthritis Research UK30 and EULAR,75 which also published guidelines on imaging in RA. 28 Guidelines on the management of RA were published by NICE9,77 and the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. 76 Reviews were published on the use of US in inflammatory arthritis29,85–87 or US for use in RA including the detection of synovitis and defining remission. 24,25,45,50,88 The bibliographies of these guidelines and reviews were searched to identify studies meeting the review inclusion criteria, identifying an additional 26 records. This led to a total of 2750 records being screened.

The study selection process is provided in Figure 1. At title and abstract sift, 2596 records were excluded. The 63 records excluded at full paper sift are presented with reasons for exclusion in Appendix 4.

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of study inclusion.

A total of 75 articles53,55,68,69,89–158 describing 58 studies were included in the review; following the searches but prior to publication of this report, one of the studies identified as ongoing by the searches (ARCTIC) was published as an abstract. 79 Data extraction forms for these included studies are provided in Appendix 5.

Study quality assessment forms for the included studies are provided in Appendix 6.

Ten89–98 of the 58 included studies were reported as abstracts only and so limited details were available.

Of the 58 studies included, diagnosis of RA was reported as being confirmed using the ACR or EULAR classification criteria for RA, either the 2010 criteria11 or an earlier version,8 in all except nine studies. 89,90,92–96,98,99

An established US scoring system was referenced in all but nine89,91,94,95,100–104 of the 58 included studies. According to the hierarchy of evidence published by Merlin et al. ,159 diagnostic accuracy studies are of higher quality if they are blinded and recruit consecutive patients and prospective cohort studies are of higher quality than other forms of prognostic studies. Of 33 studies53,92,96,102–116,118–132 reporting diagnostic accuracy or detection rates of synovitis, 13102–104,107,109–111,113–115,118,119,124 were blinded comparisons of consecutive patients. Of 15 studies of prognosis,55,69,97,98,113,134,135,137–144 all but one,138 an ancillary study to a RCT, were prospective cohort studies.

Studies reporting the detection of synovitis are described in Appendix 7 (see Tables 138–140). Diagnostic data were extracted from 37 publications53,68,92,96,99,102–132,146 reporting on 33 studies. One of these studies113,146 also provided prognostic data.

For most of the studies providing diagnostic data (see Appendix 7, Table 138), CE had a high specificity and low sensitivity when using PDUS or GSUS as the reference standard. This indicates some agreement between CE and US, with US detecting synovitis in some joints that CE did not detect and only a few cases in which CE detected synovitis and US did not. This agrees with the higher detected rates of synovitis for US over CE (see Appendix 7, Table 139) reported in the majority of studies.

However, five studies found lower rates of detection of synovitis with US than with CE. 106,115,123,125,130 Also, there were mixed results in three studies, with higher detection rates for GSUS than for CE but lower detection rates for PDUS than for CE in two studies108,119 and lower detection rates for PDUS than for CE for metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints but higher detection rates for PDUS than for CE for proximal interphalangeal (PIP) and wrist joints in one study. 131

The five studies106,115,123,125,130 that found lower rates of detection with US than with CE were some of the older trials; however, there were other trials from the early 2000s that did not report this finding and so this cannot explain the difference between these trials and trials finding a higher rate of detection with US than with CE. Study quality did not explain the differences between the study results, although one of the studies reporting a lower rate of detection with US than with CE had a small sample size (n = 6), and the differences did not appear to be caused by the US scoring system used (0–1 vs. 0–3 or 0–4; see Table 3).

It may be that the types of joint examined could explain the differences between the study results. Of the studies finding lower rates of detection with US than with CE, three studies106,115,130 investigated ankle and/or foot joints and one study123 included metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joints; however, this study also assessed PIP and MCP joints, which have been shown to have higher rates of detection of synovitis using US than using CE. 125 This agrees with one within-study comparison of joints, which reported that CE had a lower sensitivity for MTP joints than for MCP or PIP joints. 160 However, heterogeneity between other studies, suggesting that US is less useful for foot and ankle joints than for wrist and hand joints, means that there is uncertainty in the findings.

The detection of subclinical synovitis would be useful only if clinically relevant, as investigated using prognostic studies.

Prognostic data were extracted from 23 publications55,56,69,97,98,100,113,134–139,141–148,150,151 reporting on 15 studies. One of these studies was an ancillary study to a RCT. 138 The other studies were prospective cohort studies in which a cohort of patients was assessed at baseline with US and with CE and was then followed up to assess the association of these baseline measures with a given outcome. Prognostic data are provided in Tables 6–8.

Treatment data were extracted from 16 publications89–91,93–95,100,101,139,152–157 reporting on 13 studies. Following the searches but prior to publication of this report, one of the studies identified as ongoing (ARCTIC) was published as an abstract. 79 This abstract was included to provide treatment data, meaning that 14 studies in total provided data relating to treatment. Six of these were prospective cohort studies that measured the association of an outcome at follow-up with the US and CE variables measured at baseline93,101 or US and CE variables measured after 4 months of treatment139 or at the time of treatment discontinuation or tapering. 95,155,156 One study reported data from a prospective cohort in which baseline US and CE variables were tested for association with an outcome taken from a RCT of RA treatment. 95,132 Two studies were RCTs comparing treatment strategies with or without US. 79,154 One of these RCTs154 also provided data on treatment decisions. Treatment decisions were also investigated using observational data. 89–91,94,152 Treatment data are provided in Tables 9–14.

Meta-analyses were not performed because of heterogeneity in the type of US used, US scoring systems used (see Table 3), joints assessed, clinical comparators (type of examination; use of composite clinical scoring), outcome measures and follow-up times.

Assessment of prognostic studies

Heterogeneity of trials precluded meta-analysis. Therefore, no summary estimates of effect were available, which is a limitation of the review. Significance values refer to the association of baseline US and CE measures with later outcome measures. Radiographic progression measures are of importance to patients as they reflect structural damage, which is associated with loss of function over time. Other outcomes assessed are of importance to patients as they reflect disease activity and function. Studies investigated whether or not baseline measures could be predictive of later outcomes, rather than directly comparing different baseline measures. As well as heterogeneity of outcome measures, studies differed in the statistics reported to assess the association of baseline US and CE measures with clinical outcome at follow-up, including Spearman correlations (R) and odds ratios (ORs) (univariate analysis unless otherwise stated).

Two studies113,134 reported the sensitivity of US and CE measures to predict progression (Table 4). These were prospective cohort studies in which patients were tested with US and underwent CE at baseline and were then followed up and evaluated for the outcome measures of progression. Boyesen and Haavardsholm134 used a measure of GSUS inflammation based on synovitis and tenosynovitis and found that this US measure had a similar sensitivity for predicting erosive progression as MRI at 12 months, indicating that the majority of patients with a high US score, or high DAS, relapsed. This measure of GSUS inflammation134 had a higher specificity than DAS28 (although neither US nor DAS28 had high specificity) for predicting erosive progression as measured by MRI at 12 months, indicating that more patients with a low GSUS score than a low DAS did not progress. Ikeda et al. 113 found that GSUS, PDUS and Disease Activity Score 28 joints using C-reactive protein (DAS28-CRP; see Table 1) had similar sensitivities for predicting radiographic progression at 24 weeks (see Table 4). GSUS had a lower specificity than PDUS and DAS28 for predicting radiographic progression. 113 This study subgrouped patients by recently retrieved treatment and found that in MTX-treated patients (n = 16) and TCZ-treated patients (n = 17) PDUS had higher specificity than DAS28-CRP, but that specificities were similar in TNFi-treated patients (n = 24) (see Appendix 5). Both of these studies were prospective cohort studies, at level II in the study quality hierarchy, although the study by Ikeda et al. 113 was a better-quality and more rigorous study given that blinding was unclear in the study by Boyesen and Haavardsholm134 (see Appendix 8).

| Study | Population | Outcome | Patients with outcome, n (%) | US measure | Sensitivity (95% CI), % | Specificity (95% CI), % | Clinical measure | Sensitivity, % | Specificity, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boyesen 2011134 | 79 patients, dominant wrist | MRI erosive progression at 12 months (≥ 1-unit increase in RAMRIS) | 53 (67.1) | GSUS inflammation score cut-off values < 0.5 vs. ≥ 0.5a | 79 (NR) | 55 (NR) | DAS28 remission/low vs. moderate/highb | 74 (NR) | 21 (NR) |

| Ikeda 2013113 | 57 patients, 28 joints of DAS28 | Radiographic progression (mTSS) at 24 weeksc | 21 (36.8) | Total GSUS score cut-off values of < 62 | 56 (NR) | 57 (NR) | DAS28-CRP cut-off of < 9.0 | 64 (NR) | 81 (NR) |

| Total PDUS score cut-off values of < 21 | 69 (NR) | 76 (NR) |

Eleven studies (with 14 publications55,69,97,113,134–136,138–141,144,148,150) reported an association of US and CE prognostic factors with radiographic progression/erosion (Table 5). These were prospective cohort studies in which patients were tested with US and underwent CE at baseline and were then followed up and evaluated for the outcome measures of progression.

| Study | Population | Joints | Follow-up | Outcome | Type of US | Correlation of US synovitis with outcome | Type of CE | Correlation of CE with outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Backhaus 201369 | 453 patients | US7 score | 12 months | Bone erosion (US7 erosion sum score) | US7 synovitis sum score in GSUS | R ± SD: 0.140 ± 0.038 (95% CI 0.066 to 0.215; p < 0.001) | DAS28, ESR, CRP | R ± SD: DAS28 of 0.621 ± 0.141 (95% CI 0.345 to 0.898; p < 0.001); ESR 0.008 ± 0.010 (95% CI −0.011 to 0.027; p = 0.399); CRP 0.001 ± 0.009 (95% CI −0.017 to 0.018; p = 0.945) |

| US7 synovitis score in PDUS | R ± SD: 0.099 ± 0.051 (95% CI −0.001 to 0.200; p = 0.053) | |||||||

| Boyesen 2011134 | 84 patients | Dominant wrist | 1 year | MRI erosive progressiona | GSUS (univariate analysis)b | OR 2.15 (95% CI 1.23 to 3.75; p = 0.01) | DAS28 (univariate analysis) | OR 1.15 [95% CI 0.80 to 1.64; p = 0.46 (NS)] |

| GSUS (multivariate analysis)b,c | OR 2.01 (95% CI 1.14 to 3.53; p = 0.02) | ESR (univariate analysis) | OR 1.02 [95% CI 0.98 to 1.06; p = 0.29 (NS)] | |||||

| GSUS synovitis (radiocarpal joint assessed in the dorsal midline) | OR 7.2 (95% CI 0.9 to 61.0; p = NS) | CRP (univariate analysis) | OR 1.04 [95% CI 0.98 to 1.10; p = 0.16 (NS)] | |||||

| Brown 2008135 (same study as Ikeda 2007136) | 90 patients in clinical remission | Dominant hand MCP joint and wrist | 12 months | Progressive radiographic damage (both hands and feet)d | PDUS signal | OR 12.21 (95% CI 3.34 to 44.73; p < 0.001) | Painful joint count | OR 3.32 (95% CI 0.39 to 28.30; p = 0.273) |

| GSUS synovial hypertrophy | OR 1.92 (95% CI 0.49 to 7.54; p = 0.350) | TJC | OR 2.17 (95% CI 0.26 to 18.10; p = 0.473) | |||||

| SJC | OR 1.69 (95% CI 0.43 to 6.67; p = 0.457) | |||||||

| Ikeda 2007136 (same study as Brown 2008135) | 107 patients in remission (clinician assessed) on DMARDs | Dominant hand MCP and wrist | 12 months | Radiographic progression (direct assessment of individual joints) | GSUS synovial hypertrophy score | Mann–Whitney U-test p = 0.027 | Painful joints | Chi-squared test p = 0.284 |

| PDUS score | p < 0.001 (in asymptomatic joints only p = 0.002) | Tender joints | p = 0.389 | |||||

| Increased PDUS signal | Likelihood ratio 7.02, chi-squared test p = 0.037 | Swollen joints | p = 0.417 | |||||

| Cavet 2009138 | 24 patients | 10 MCP joints100 | 110 weeks | Radiographic progressione | GSUS synovial thickening | R = 0.59 (p-value NR) | Biomarkers (93 serum proteins) at 6 weeks (multivariate model) | Significant correlation R = 0.79 (p-value NR) |

| Power Doppler area) | R = 0.77 (p-value NR) | |||||||

| Dougados 2013139,149 | 59 patients | MCP (×10), PIP (×10), wrist (×2) and MTP (×10) joints | 2 years | Radiological progressionf | GSUS (0 vs. 1–3) | OR 1.64 (95% CI 1.08 to 2.47) | Clinical synovitisg | 0 vs. 1–3: OR 2.08 (95% CI 1.39 to 3.11; p < 0.001); 0–1 vs. 2–3: OR 1.64 (95% CI 1.14 to 2.36; p = 0.008) |

| GSUS (0–1 vs. 2–3) | OR 1.91 (95% CI 1.18 to 3.10) | Tender joints | OR 1.53 (95% CI 1.02 to 2.29; p = 0.04) | |||||

| PDUS 0 vs. 1–3 | OR 1.80 (95% CI 1.20 to 2.71; p = 0.005) | Tender joints with clinical synovitis | OR 1.89 (95% CI 1.25 to 2.85; p = 0.002) | |||||

| PDUS 0–1 vs. 2–3 | OR 1.36 (95% CI 0.78 to 2.38; p = 0.278) | |||||||

| Ikeda 2013113 | 57 patients (MTX, n = 16; TNFi, n = 24; TCZ, n = 17) | Finger, wrist, elbow, shoulder and knee | 24 weeks | Radiographic damagee | GSUS (cumulative total GSUS score) | R = 0.062; p = 0.649 (MTX, r = 0.210, p = 0.436; TNFi, r = 0.027, p = 0.900; TCZ, r = 0.492, p = 0.179) | Cumulative DAS28-CRP | R = 0.342, p = 0.009 (MTX, r = 0.487, p = 0.056; TNFi, r = 0.308, p = 0.144; TCZ, r = 0.369, p = 0.145) |

| PDUS (cumulative total PDUS score) | R = 0.357; p = 0.006 (MTX, r = 0.679, p = 0.004; TNFi, r = 0.153, p = 0.476; TCZ, r = 0.353, p = 0.165) | |||||||

| Naredo 200755 | 42 RA patients starting DMARDs (38 patients followed up to 1 year) | 28 joints | 1 year | Total radiographic score progression (radiographic erosion score and JSN score)e | Joint count for GSUSh | GSUS r = 0.61; p < 0.001 | SJC, TJC, DAS28, HAQ, ESR, CRP | SJC, r = 0.46, p < 0.01; TJC, r = 0.36, p < 0.05; DAS28, r = 0.40, p < 0.05; HAQ, r = 0.36, p < 0.05; ESR/CRP, NS |

| Joint count for PDUS signali | PDUS r = 0.59; p < 0.001 | |||||||

| Naredo 2008140 | 278 patients with complete data (of 367 RA patients starting TNFis) | 86 intra-articular and periarticular sites in 28 joints | 1 year | Total radiographic score progression (radiographic erosion score and JSN score);e multivariate analysisj | Time integrated values of US joint count for PDUS signal | Total radiographic score (R = 0.59) significant; erosion score (R = 0.64) significant; JSN score NS | ESR, CRP | Total radiographic score: ESR (R = 0.59) significant; ESR for erosion or JSN score NS; baseline CRP level weak predictive value for JSN score progression (R = 0.2); CRP NS for erosion and total scores |

| Osipyants 201397,150 | 35 patients | Wrists | 1 year | Radiographic progression (mTSS)e | PDUS signals of residual inflammation of the wrists at 6 months | Significantly correlated (r = 0.696; p = 0.011); mTSS at 1 year significantly higher [93 (range 56–131) vs. 32.5 (range 19.5–83) units; p < 0.04] in patients with middle- or high-active PDUS signals (n = 27) (SJC > 1, PDUS > 1) than in cases with lower imaging activity or the absence of the PD signals (n = 8) at 6 months | SJC | Non-significantly lower radiographic progression over 1 year in those with SJC ≤ 1 [55 (range 31–116) vs. 88.5 (range 55–130); p < 0.205] than in those with SJC > 1 (n = 25) |

| Reynolds 2009141 | 25 patients (providing data at the 2-year follow-up of 40 patients recruited) | MCP and PIP joints | 2 years | Erosion progressionk | GSUS and PDUS | Mann–Whitney U-test synovial score (0–3) NS; mean synovial thickness (cm) NS; pre-contrast PDUS score (0–3) NS; post-contrast PDUS score (0–3) NS | ESR | NS |

| Yoshimi 2013144 | 22 RA patients in clinical remission (of 31 recruited) | Bilateral wrists and all of the MCP and PIP joints | 2 years | Radiographic progressione | Total PDUS score | Total PDUS score significantly higher in patients with radiographic progression than in patients without (6.00 ± 6.44 vs. 0.87 ± 1.15; p = 0.0011) | SJC, DAS28, gVAS and the serum levels of ESR, CRP and MMP-3 | Significant differences in SJC (0.33 ± 0.79 vs. 1.29 ± 0.70; p = 0.0040) and DAS28-ESR (p = 0.0010) and DAS28-CRP (p = 0.041) between the radiographic progression group and the non-progression group. Borderline significance for TJC (p = 0.054). No significant difference in other clinical parameters (gVAS and the serum levels of ESR, CRP and MMP-3) between the radiographic progression group and the non-progression group |

| Total GSUS score | No significant difference in the total GSUS score, (12.6 ± 12.4 vs. 8.80 ± 5.78; p = 0.57), between the radiographic progression group and the non-progression group |

Of the 11 studies, seven55,69,113,138–140,144 found that US and at least one of the clinical measures investigated could significantly predict radiographic progression, most of which were of high quality (with the exception of two studies69,138 in which blinding was unclear). Three studies found that US could significantly predict radiographic progression whereas the clinical comparator could not (DAS28-ESR/ESR/CRP;134 joint counts;135 SJC97), two97,134 of which were less rigorous in terms of study quality, with blinding being unclear. One study141 found that neither US nor the clinical comparator (ESR) was significantly associated with later progression; this study was more rigorous in terms of study quality. All of the studies were prospective cohort studies, at level II in the study quality hierarchy, with the exception of one study,138 which was an ancillary study to a RCT (see Appendix 8).

The majority of the studies reported a significant correlation between US and radiographic progression, using GSUS55,69,134–136,138,139,148 or PDUS;55,69,97,113,134–136,138–140,144,148 most of these studies were rigorous in terms of study quality, with four less rigorous studies in which blinding was unclear. 69,97,134,138

In some cases, GSUS was not significantly correlated with radiographic progression whereas PDUS was (see Table 5). There was no significant correlation with radiological progression for GSUS in the study by Ikeda et al. ,113 which did not find improved sensitivity or specificity above those for DAS28-CRP at 24 weeks (see Table 4). This study also found that PDUS was significantly correlated with radiological progression in the MTX-treated subgroup but not in bDMARD-treated patients.

Grey-scale ultrasound was not significantly correlated with radiographic progression in a study of 22 patients in clinical remission whereas there was a significant correlation between PDUS and radiographic progression. 144 One study135,136 found that PDUS was significantly associated with later radiographic outcomes. Another study of 25 patients found that neither GSUS nor PDUS was significantly correlated with erosion progression at 2 years’ follow-up. 141

Some studies reported a significant association of CE with radiographic progression (see Table 5). DAS28 was significantly correlated with radiographic progression in four studies,55,69,113,144 although not in the study by Boyesen and Haavardsholm134 nor in the bDMARD subsets in the study by Ikeda et al. 113 HAQ score was significantly correlated with radiographic progression in the only study reporting this outcome. 55 ESR and CRP did not significantly correlate with radiographic progression,55,69,134,141,144 with the exception of the study by Naredo et al. ,140 which found that ESR and total radiographic score progression were significantly associated. Biomarkers (serum proteins) were significantly correlated with modified total Sharp score (mTSS) in the only study reporting this comparator. 138

Swollen joint count and TJC were significantly correlated with radiographic progression in three studies55,139,144 but not in two studies97,135,136 and painful joint count was not significantly correlated with radiographic progression in one study. 135,136

Power Doppler ultrasound was significantly associated with radiographic progression in 10 studies in which it was measured. Associations reported as ORs were as follows: OR 12.21 [95% confidence interval (CI) 3.34 to 44.73; p < 0.001]135 and OR 1.80 (95% CI 1.20 to 2.71; p = 0.005). 139 Associations reported at correlation coefficients were as follows: r = 0.099 (p = 0.05);69 r = 0.357 (p = 0.006);113 r = 0.59 (p < 0.001);55 r = 0.696 (p = 0.011);97 r = 0.59 (p-value not reported);140 and r = 0.77 (p-value not reported). 138 Mann–Whitney U-test results reported were p < 0.001136 and p = 0.0011. 144

One study141 reported a non-significant association of baseline PDUS with the outcome measure. This different result could not be explained by study quality or the joints assessed and, although the authors suggested that the scoring system used was not as sensitive as that used in other studies, other studies that used semiquantitative scores found significant associations. This study did differ from most in that the outcome of erosion was measured by US. The other study that used US to measure the end point was the study reporting borderline significance for association. 69

Grey-scale ultrasound was significantly associated with radiographic progression in six studies. Significant associations reported were as follows: Mann–Whitney U-test p = 0.027,136 r = 0.140 (p < 0.001),69 r = 0.61 (p < 0.001),55 OR 2.15 (95% CI 1.23 to 3.75; p = 0.01)134 and OR 2.08 (95% CI 1.39 to 3.11). 139 A moderate correlation was found between GSUS and radiographic progression in one study. 138 GSUS was not significantly associated with radiographic progression in three studies: OR 1.92 (95% CI 0.49 to 7.54; p = 0.350);135 R = 0.062 (p = 0.649);113 and Mann–Whitney U-test non-significant. 141 One of these studies113 had a shorter follow-up time (24 weeks) than the others, but the other two studies135,141 with non-significant associations had similar follow-up times to the studies finding significant associations. These two studies135,141 were two of the older studies included in the review, which may indicate a difference in the US machines used; however, because of the heterogeneity between studies, it is uncertain why these studies differed from those reporting a significant association. The difference between studies reporting significant associations and studies reporting non-significant associations could not be explained by study quality, joints assessed or how the end point was measured.

The DAS28 joints was significantly correlated with radiographic progression in one study measuring progression using the ultrasound 7 score (US7) score (r = 0.621, p < 0.001)69 and three studies measuring progression using the mTSS [r = 0.342, p = 0.009;113 r = 0.40, p < 0.05;55 and p = 0.0010 (DAS28-ESR) and p = 0.041 (DAS28-CRP) (only p-values reported)144]. DAS28 was not significantly correlated in one study measuring MRI erosive progression. 134 Given heterogeneity between trials, it is uncertain whether outcome measure was the factor explaining the difference between trials finding a significant association, or not, between DAS28 and later radiographic progression.

Other outcomes

Studies reporting outcomes other than radiographic progression (measures of disease activity) are shown in Table 6. These were prospective cohort studies in which patients were tested with US and underwent CE at baseline and were then followed up and evaluated for outcome measures of disease activity. All studies used measures in the baseline CE that were not the same as the outcome measure at follow-up (although some studies additionally reported assessment of the outcome measure at baseline (DAS28 and HAQ score;55 components of the composite outcome measure145).

| Study | Population | Joints | Follow-up | Outcome | Type of US | Correlation of US synovitis with outcome | Type of CE | Correlation of CE with outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scirè 2009137 (same study as Bugatti 2012147) | 43 patients achieving clinical remission | Bilateral shoulder, elbow, wrist, MCP, PIP, sternoclavicular, acromioclavicular, knee, ankle and MTP joints | 6 months | Clinical relapse | US joint count > 2 (multivariable)a | OR 4.6 (95% CI 0.4 to 49.5; NS) | SJC > 1 | OR 0.6 (95% CI 0.1 to 5.5) |

| PDUS > 0 | OR 12.8 (95% CI 1.6, 103.5; p < 0.05) | DAS28 of > 1.1 | OR 9 (95% CI 0.7 to 110.3) | |||||

| Bugatti 2012147 (same study as Scirè 2009137) | 161 patients with early RA | Hands | 12 months | Low disease activity (i.e. a DAS of < 2.4) | PDUS synovitis scored (0–3) | OR 0.94 [0.31 to 2.83; p = 0.91 (NS)] | Serum levels of the chemokine CXCL13 | NS |

| Naredo 200755 | 42 patients with RA starting DMARDs (38 followed up for 1 year) | 28 joints | 1 year | DAS28 | Joint count for GSUSb | GSUS r = 0.63; p < 0.001 | SJC, TJC, DAS28, HAQ, ESR, CRP | DAS28, r = 0.75, p < 0.001; HAQ; r = 0.66, p < 0.001; TJC, r = 0.50, p < 0.01; SJC; r = 0.45, p < 0.01; ESR/CRP, r = 0.49, p < 0.01 |

| Joint count for PDUS signalc | PDUS r = 0.63; p < 0.001 | |||||||

| HAQ | Joint count for GSUSb | GSUS NS | SJC, TJC, DAS28, HAQ, ESR, CRP | HAQ, r = 0.82, p < 0.001; DAS28; r = 0.49, p < 0.01; TJC, r = 0.50, p < 0.01; SJC NS; ESR NS | ||||

| Joint count for PDUS signalc | PDUS NS | |||||||

| Osipyants 201397,150 | 35 | Wrists | 6 months | HAQ | PDUS | Significant (r = –0.821; p = 0.003) | DAS28-CRP, SDAI | Association with baseline DAS28 or SDAI NS. Subgroup [disease duration < 2 years (n = 9)]: HAQ score at 6 months correlated with baseline DAS28-CRP (r = 0.705, p = 0.02) and SDAI (r = 0.678, p = 0.03) |

| Ramirez García 201498 | 28 | Knees and hands (wrists, MCP, PIP flexor and extensor tendons of the hand) | 12 months | Relapse from clinical remission (i.e. a DAS28 of < 2.6) | PDUS | p = 0.034; logistic regression model OR 6.18d | ESR, TGFβ1 | ESR, p = 0.046; TGFβ1, p = 0.082 |

| Saleem 2012142 | 93 RA patients in clinical remission as determined by their treating rheumatologist | Hand and wrist | 12 months | Flare – defined as any increase in disease activity requiring a change in therapy [24/93 (26%)] | PDUS and GSUS | PDUS (unadjusted OR 4.08, 95% CI 1.26 to 13.19; p = 0.014); GSUS score was not significantly associated (p = 0.658) | HAQ-DI, TJC, SJC, RAQoL, CRP, DAS28, SDAI | HAQ-DI per 0.1 unit OR 1.27 (95% CI 1.07 to 1.52; p = 0.006). RAQol OR 1.10 (95% CI 1.01 to 1.20; p = 0.036). Other variables were NS: SJC, p = 0.690; TJC, p = 0.827; CRP, p = 0.308; DAS28 remission, p = 0.499; SDAI remission, p = 0.616 |

| Wakefield 2007143 | 10 | Bilateral glenohumeral, elbow, wrist, MCP, PIP, knee, tibiotalar, midtarsal and MTP joints | 46 weeks | Time to clinical remission | GSUS score | R = –0.221 (NS) | Baseline DAS28 | r = 0.627; p = 0.071 (NS trend) |

| PDUS score | R = –0.289 (NS) | |||||||

| Yoshimi 2014145 | 22 patient with RA in clinical remission (of 31 recruited) | Bilateral wrists and all of the MCP and PIP joints | 2 years | Remission, defined by ACR/EULAR Boolean criteria; score of ≤ 1 for all of TJC, SJC, CRP and PGA components | PDUS total score | p = 0.020 | DAS28-CRP, DAS28-ESR, SJC, TJC, CRP, ESR | NS for all: DAS28-CRP, p = 0.76; DAS28-ESR; p = 0.38; SJC; p = 0.060; TJC, p = 1.00; CRP, p = 0.17; ESR, p = 0.39 |

| GSUS total score | p = 0.020 |

In three cases, US and at least one clinical comparator measure were associated with the later outcome [ESR,98 Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index (HAQ-DI)142 and DAS55]. Three studies found that US was significantly associated with the later outcome but the clinical comparator was not (DAS28-CRP or SDAI;97 DAS28-CRP, DAS28-ESR, SJC, TJC, CRP and ESR;145 and SJC and DAS28137). In the study by Naredo et al. ,55 the clinical comparator DAS28 was associated with the later HAQ outcome, but the US joint count of 28 joints was not. The authors suggested that their results may differ from those of other studies because early RA patients were used in their study and, at this point of disease, functional status is related to inflammatory activity more than residual structural damage.

Low disease activity (i.e. a DAS of < 2.4) at 1 year was not significantly correlated with PDUS or the biomarker chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 13 (CXCL13). 147

The Disease Activity Score 28 joints at 1 year was significantly correlated with GSUS and PDUS and HAQ, SJC, TJC and ESR/CRP. 55 Relapse from clinical remission (i.e. of DAS28 of < 2.6) was significantly correlated with PDUS and ESR but not transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGFβ1). 98 Relapse (i.e. a DAS of ≥ 1.6) at 6 months was significantly correlated with PDUS, SJC and DAS but not GSUS. 137 Time to clinical remission (DAS28 of < 2.6) was not significantly correlated with GSUS, PDUS or DAS28 at baseline in a study of 10 patients. 143

Remission, defined by ACR/EULAR Boolean criteria [score of ≤ 1 for all of the TJC, SJC, CRP and patient global assessment components], at 2 years was significantly correlated with PDUS and GSUS, but not with the clinical comparators DAS28, SJC, TJC, CRP or ESR. 145

Flare, defined as any increase in disease activity requiring a change in therapy, at 12 months was significantly correlated with PDUS, HAQ and Rheumatoid Arthritis Quality of Life (RAQoL), but not with GSUS, SJC, TJC, CRP, DAS28 or SDAI. 142

Two studies investigated HAQ, one of which found that HAQ score at 1 year of follow-up was not significantly correlated with GSUS, PDUS, SJC, or ESR, but was with DAS28 and TJC. 55 One study97 found that HAQ score at 6 months was significantly correlated with PDUS, but not with DAS28 or SDAI (DAS28 and SDAI were significantly correlated in the subgroup with a disease duration of < 2 years but there were only nine patients in this subgroup).

Treatment studies

Treatment response or strategies

Nine studies79,93,95,100,101,139,154–156 reported data relating to treatment response or strategies. RA was reported as being diagnosed by 2010 ACR/EULAR criteria11 in two studies154,155 and by pre-2010 ACR/EULAR criteria8 in four studies;100,101,139,156 the criteria used were not reported in two studies. 93,95 Established semiquantitative scoring systems were used by Dougados et al. ,139 Inanc et al. ,93 Naredo et al. 156 (scoring system published by Wakefield51), Iwamoto et al. 155 (scoring system published by Naredo et al. 140) and Dale et al. 154 (scoring system published by Szkudlarek et al. 52). The heterogeneity of the trials precluded meta-analysis. Therefore, no summary estimates of effect are available, which is a limitation of the review. Significance values referred to the association of baseline US and CE measures with treatment measures (such as treatment persistence or response to treatment tapering). These measures could be of importance to patients in so far as they can be used to refine treatment.

Ultrasound was compared with CE as potential predictors of treatment persistence or response (Table 7). The study by Ellegaard et al. 101 investigated patients starting TNFi treatment to determine whether or not treatment persistence at 1 year of follow-up was associated with US and clinical measures [TJC, SJC, CRP, visual analogue scale (VAS), HAQ and DAS28]. This was a prospective cohort study in which patients were tested with US and underwent CE at baseline and were then followed up and evaluated to investigate the ability of these factors to predict treatment adherence, defined as patients remaining on TNFi therapy at the 1-year follow-up. Among US measures, the square root of the US Doppler colour fraction (USDCF), a measure of hyperaemia, was the only measure that significantly predicted TNFi continuation (p = 0.008). None of the clinical measures assessed, including SJC, TJC, DAS28 and CRP, was significantly associated with treatment persistence. 101 In the study by Inanc et al. 93, when considering EULAR response compared with no response after 3 months, baseline PDUS (p = 0.029) and GSUS (p = 0.020) differed significantly between responders and non-responders. This was a prospective cohort study in which patients were tested with US and underwent CE at baseline and were then followed up and evaluated to investigate the association with EULAR response at 3 months’ follow-up. Two of the clinical measures assessed also significantly differentiated between responders and non-responders [pain VAS (p = 0.009) and SJC (p = 0.05)], whereas other clinical measures (DAS28, TJC, ESR and CRP) did not. 93

| Study | Population | Joints | Follow-up | Outcome | US type | US association with outcome | CE association with outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ellegaard 2011101 | 109 patients starting TNFis (ADA, ETN or IFX) | Wrist (most affected) | 1 year (n = 69 with US follow-up) | Treatment persistence (continued with TNFi) | USDCF square roota | Treatment persistence vs. dropouts because of lack of efficacy, p = 0.024; treatment persistence vs. all dropouts, p = 0.008 | Treatment persistence vs. dropouts because of lack of efficacy (all NS): TJC, p = 0.86; SJC, p = 0.98; CRP, p = 0.86; VAS (patient global), p = 0.08; HAQ, p = 0.416; DAS28, p = 0.943. Treatment persistence vs. all dropouts (all NS): TJC, p = 0.321; SJC, p = 0.486; CRP, p = 0.453; VAS (patient global), p = 0.240; HAQ, p = 0.098; DAS28, p = 0.375 |

| Inanc 201493 | 43 patients starting TNFis (drugs NR) | 28 joints according to EULAR guideline | 3 months | EULAR no response vs. response | PDUS | p = 0.029 | Pain VAS, p = 0.009; SJC, p = 0.05; other clinical measures NS (DAS28, p = 0.90; TJC, p = 0.12; HAQ, p = 0.31; ESR, p = 0.61; CRP, p = 0.98) |

| GSUS | p = 0.020 | ||||||

| EULAR good/moderate response (multivariate analysis)b | PDUS | OR 0.88 (95% CI 0.68 to 0.94; p = 0.04) | NR | ||||

| GSUS | NS |

Patients with persistent synovitis measured by GSUS or PDUS (Table 8), after 4 months of bDMARD treatment, were significantly more likely to have radiological progression at 2 years’ follow-up. 139 The study by Dougados et al. 139 was a prospective cohort study in which 4 months of biological therapy were prescribed, with further follow-up up to 2 years. The association of lack of response to treatment at 4 months, measured by US or CE using a semiquantitative scoring system, with radiological progression at 2 years was assessed. For persistent synovitis as measured by CE, this did not reach significance. 139 Taylor et al. 100 reported prognostic data from a study that was part of a RCT comparing MTX plus IFX with MTX plus placebo in aggressive early RA. Baseline US and CRP were tested for association with radiological progression at 54 weeks. US could significantly predict radiological progression in MTX plus placebo-treated patients (p = 0.020), but not in IFX plus MTX-treated patients (p = 0.479). 100 However, there were only 12 patients in each group in this study. Baseline CRP did not significantly predict progression in either treatment group. 100

| Study | Population | Follow-up duration | Joints | Outcome | Type of US | US association with outcome | Type of CE | CE association with outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|