Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 09/165/01. The contractual start date was in June 2013. The draft report began editorial review in April 2017 and was accepted for publication in August 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Leone Ridsdale secured funding from the Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London. Laura H Goldstein reports that her independent research also receives support from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Maudsley Biomedical Research Unit at the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London. She receives royalties from Goldstein LH and McNeil JE (editors) Clinical Neuropsychology. A Practical Guide to Assessment and Management for Clinicians. 2nd edn. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2013; and from Cull C and Goldstein LH (editors) The Clinical Psychologist’s Handbook of Epilepsy: Assessment and Management. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge; 1997. Sabine Landau reports grants from NIHR Maudsley Biomedical Research Unit at the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London during the conduct of the study and received a grant from NIHR Health Technology Assessment. Stephanie JC Taylor is on the Health Technology Assessment Clinical Trials Board and reports grants from the NIHR Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care North Thames at Barts Health NHS Trust. The authors received a contribution from Sanofi UK to enable printing of the patient workbooks.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Ridsdale et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

The original funding application referred to the study intervention as SMILE. Over time, we have found that SMILE is a common acronym for other interventions (including other interventions for epilepsy). For this reason, we used SMILE (UK) in our publications. To remain consistent, we will use SMILE (UK) in our report.

Background

In 2010, the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) issued a call for a randomised controlled trial (RCT) on a self-management education programme for people with epilepsy (PWE) (see Appendix 1). The call specified that the trial was to include people with poorly controlled epilepsy who were aged ≥ 16 years. It was specified that effectiveness should be evaluated based on quality of life (QoL) measures and that participants should be followed up 1 year post intervention. Two existing studies were cited, one based in Germany1 and one in North America. 2 Both featured 2-day self-management education programmes. The investigators of this study responded to the NIHR call by offering to adapt the intervention developed in German-speaking countries for the UK. Funding was agreed for the current RCT.

The trial was named Self-Management education for adults with poorly controlled epILEpsy [SMILE (UK)]. 3 This study was a pragmatic, parallel design, multicentre RCT in the UK. 4 The broad objective of the research was to evaluate the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a group self-management programme for people aged ≥ 16 years who were experiencing ‘poorly controlled’ epilepsy. This was defined as epilepsy resulting in two or more seizures per year.

Epilepsy in the UK: causes, challenges and consequences

Epilepsy is a common neurological condition defined as the occurrence of two or more seizures more than a day apart. 5 Prevalence rates range from 4.2 to 9 per 1000 people6 and currently up to 1% of the UK population live with the condition. 7

The aetiology of epilepsy is variable. It can arise as a result of cerebrovascular disease (i.e. stroke), head trauma, congenital abnormalities and neurodegenerative disease (i.e. Alzheimer’s disease) or it can be idiopathic. 8 Mortality risk varies for PWE and is higher than in the general population. 9

The NHS recommends that epilepsy care should consist of a combination of regular general practitioner (GP) consultations, adherent medication use, patients’ knowledge of seizure triggers and adequate self-management. 10 Pharmacological intervention is currently the mainstay of treatment. Most PWE are able to eliminate seizure occurrence through use of antiepileptic drugs (AEDs). However, up to 40% are considered to have drug-resistant epilepsy. 11 The present research focuses on patients who experience epilepsy with two or more seizures per year, despite medical intervention, which, following the wording of NIHR guidelines, is defined as ‘poorly controlled epilepsy’.

Epilepsy is costly to UK health-care services. Recurrent seizures are a significant cost for the NHS,4 particularly when services are used on an emergency basis. 12 From 2014 to 2015, almost 130,000 people were admitted to UK hospitals for epilepsy and around 83,000 used emergency services. 13 Indirect costs of epilepsy are also likely to be high as a result of missed days of employment14 and early retirement because of illness. 15 Given the direct and indirect financial consequences of epilepsy (i.e. emergency service use, time off work), better ambulatory care management strategies offer a potential for secondary prevention and could be cost-effective for health-care service providers. 16

Epilepsy diagnosis is associated with significant psychological and social costs. Being labelled negatively as ‘epileptic’ can be accompanied by discrimination. 17,18 This further undermines well-being and QoL. 19,20 Educators and health-care service providers are mindful of the complex psychosocial nature of epilepsy,21 particularly as poor QoL and psychosocial well-being has a bidirectional relationship with seizure frequency and severity. 22 Structured education programmes that target psychosocial and biological aspects of seizure management may result in better outcomes for people with poorly controlled epilepsy and could improve QoL.

Improving quality of life of people with epilepsy

In the planning stages of an intervention designed to improve the lives of PWE, and using QoL as a primary outcome measure, the factors that could affect QoL were considered. The factors that were identified will be presented in the following sections.

Seizures

Seizure frequency and QoL are linked. PWE are likely to have similar QoL to the general population when seizures are controlled. 23 QoL is inversely associated with the amount of time since last seizure (i.e. ‘seizure recency’). 24 Given this association, even a minor improvement in seizure frequency may have a beneficial effect on health-related quality of life (HRQoL)25 and vice versa.

Seizures are associated with physical consequences that can negatively affect QoL. For instance, sustaining a serious injury during a seizure can be associated with long-lasting repercussions. Thus, minimising seizure frequency is also likely to reduce the ongoing consequences of seizure-related injury.

Antiepileptic drugs

The primary means of treating epilepsy is with AEDs; however, patients may also experience debilitating side effects from their medication. Adverse effects of medication significantly reduce QoL. 26 Apart from seizure frequency, adverse side effects from AEDs may be the biggest predictor of poor QoL in PWE. 24

Failure to comply with treatment regimens (i.e. ‘non-adherence’) also has serious implications for PWE. Non-adherence may result in increased seizure frequency, decreased QoL and missed employment. 27 Results of one AED adherence study showed that depression is associated with medication non-adherence. 28 This suggests a complex association between medication use, QoL and psychosocial well-being. These factors could be targeted by self-management intervention.

Psychological comorbidity

Psychosocial consequences may be as important as the physical consequences of epilepsy. Although treatment success is often reliant on biomedical factors, there are also important psychosocial issues to consider when managing the condition. 21 There is an elevated risk of poor mental health following epilepsy diagnosis. 29 PWE are more likely to experience higher rates of depression,30 anxiety31 and suicidal ideation. 32 Depressive symptoms can diminish QoL33,34 and influence seizure frequency. 35,36 Moreover, some forms of psychological conditions frequently co-occur,36 such as anxiety and depression, having a further impact on seizure frequency. Given the complex relationship between seizure frequency and psychological well-being, interventions that address both treatment targets seem worthwhile.

Stigma and resilience

Stigma is a major factor that influences QoL in PWE. 37,38 Although public perceptions about epilepsy have changed,38 negative beliefs and lack of knowledge continue to perpetuate stigma and discrimination. 39 In a survey of attitudes of the UK general public, participants felt epilepsy was embarrassing, frightening and meant being unable to drive or participate in employment. 40 Participants attributed seizures to stress, intoxication and mental health problems. These findings illustrate some of the prevalent, general attitudes and misconceptions about epilepsy. Despite epilepsy being a neurological condition, psychological and social factors are often attributed to its development,41 which may exacerbate feelings of ‘differentness’ and isolation in PWE.

Scambler and Hopkins42 divided stigma into felt versus enacted. Enacted stigma is discrimination against PWE based on a belief that the attributes of PWE are undesirable or unacceptable. Low employment rates among PWE may partly be a manifestation of enacted stigma. 38 Felt stigma is linked with the fear and shame tied to being ‘epileptic’. 42 Felt stigma is associated with low self-esteem, anxiety and depression. 38 Dilorio et al. 43 suggest that people with frequent seizures may internalise felt stigma and have unhelpful perceptions about their treatment. On the other hand, resilience can help to combat the diminished QoL associated with epilepsy diagnosis. 24 Those involved with epilepsy care can help PWE to combat stigma by giving them information and support strategies for overcoming stigma and discrimination. 38

Mastery and control

The term mastery is used to describe a state of confidence in which a person feels able to independently overcome the challenges with which they are faced. 44 Mastery is used in combination with self-efficacy to reduce stress and develop positive new behaviours. 45 In the literature, the term ‘self-mastery’ has been used interchangeably with self-efficacy. Evidence suggests when a person feels more confident in their ability to cope and manage their illness effectively, they are more likely to put self-management behaviours into practice. 46 Therefore, a sense of mastery and control is important for PWE as they have the potential to have an impact on seizure control and QoL. 47

Age and socioeconomic factors

The effect of epilepsy-related challenges on QoL can be related to the person’s life stage. 48 In a focus group study of UK adolescents, epilepsy diagnosis had an effect on QoL and identity formation. 49 In a study from the USA, seizure frequency was less concerning for older adults and their QoL than maintaining ‘normalcy’ in social and emotional function. 50 Other lifestyle variables such as socioeconomic status are also important for QoL in PWE. For instance, low socioeconomic status is related to an elevated risk of developing epilepsy,51,52 frequent hospital visits53 and attrition from epilepsy care,54 all of which can be associated with QoL. In interpreting the results of an intervention aiming to improve QoL and reduce seizure frequency, consideration of these factors will be important.

Summary of quality of life research

Living with epilepsy can influence QoL in PWE. In the present study, we aim to test the effect of an intervention designed to improve psychological, physical and social consequences of epilepsy. In considering the complexity of the above factors in managing this condition, the benefits of ‘self-management’ have been proposed in the literature. This addition to epilepsy treatment will be discussed in the remainder of this chapter.

Self-management education

What is self-management?

There is no widely accepted description of what self-management means, but the Department of Health has used the 2002 definition from Barlow et al. :55

Self-management refers to the individual’s ability to manage the symptoms, treatment, physical and psychosocial consequences and lifestyle changes inherent in living with a chronic condition.

Barlow et al. 55

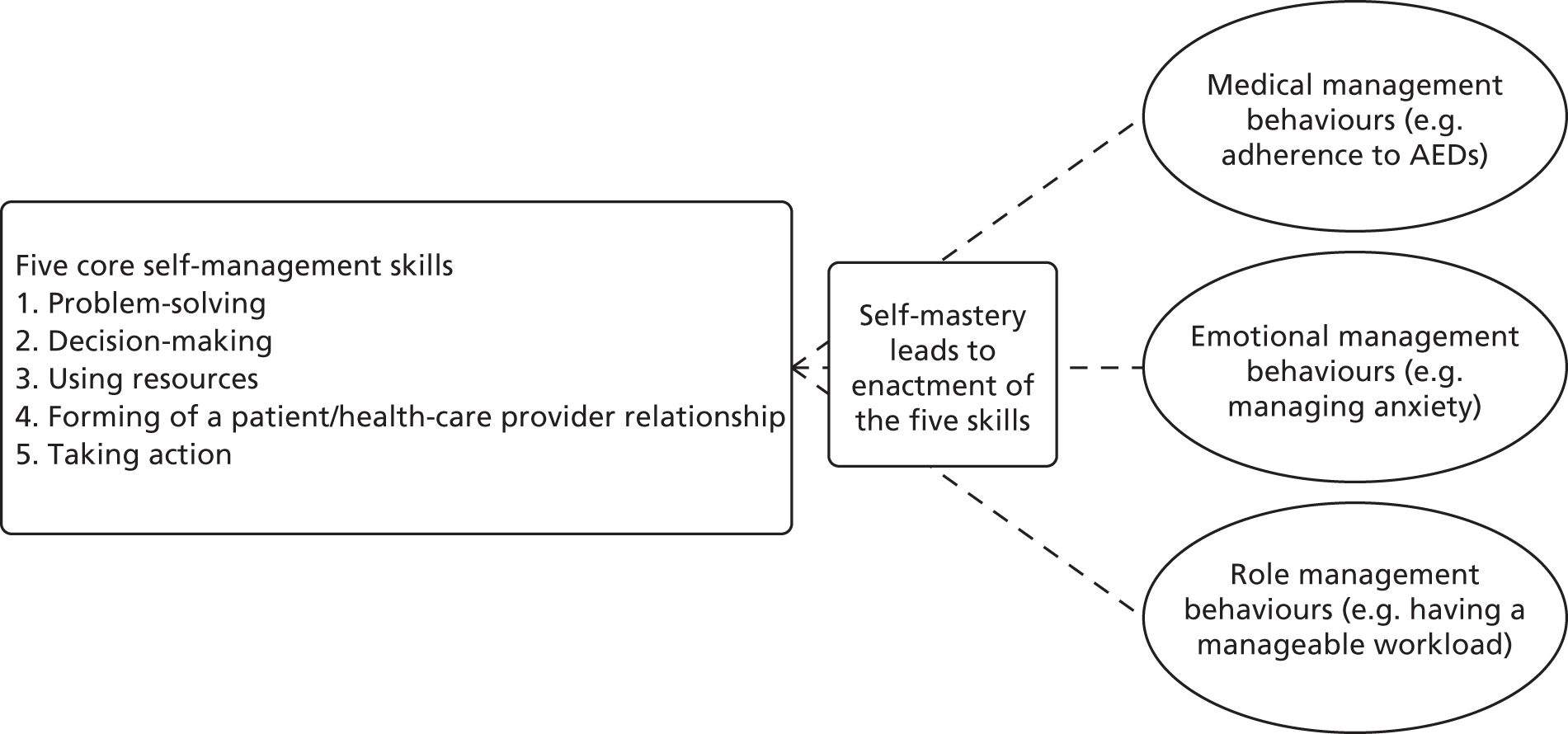

The notion that self-management encompasses all of the aspects of living with a chronic condition is summarised in the following:

Self-management is defined as the tasks that individuals must undertake to live with one or more chronic conditions. These tasks include having the confidence to deal with medical management, role management and emotional management of their conditions.

Adams and Corrigan. p. 5756

Corbin and Strauss identified these tasks (i.e. medical, role and emotional management) as the key aspects of disease self-management. 57 It is axiomatic that those living with a long-term condition (LTC) must be self-managing their condition. Thus, interventions that focus on self-management are really directed at supporting people to manage their LTC optimally (i.e. supported self-management interventions).

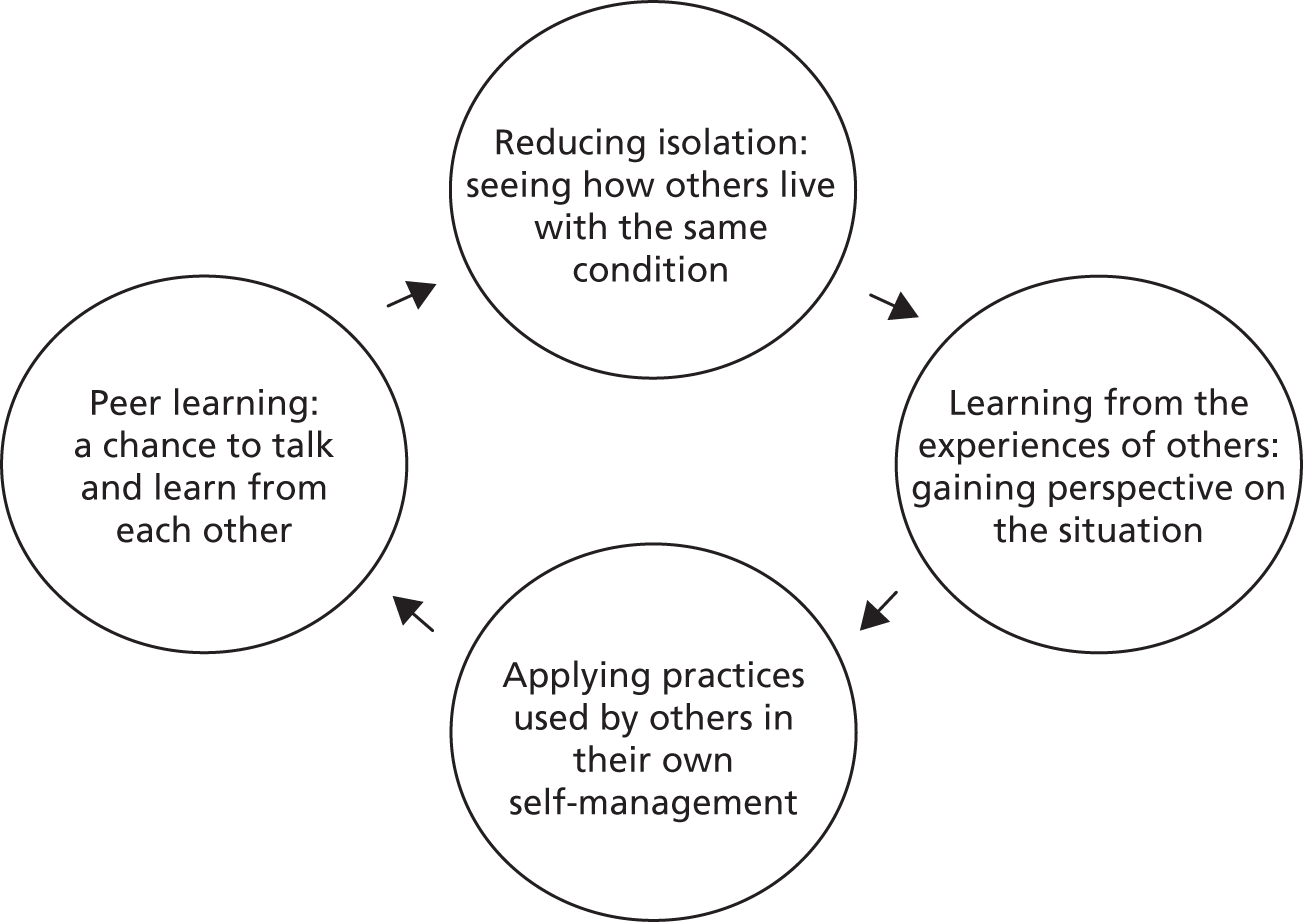

To facilitate the core tasks of self-management described above, Lorig and Holman58 proposed the acquisition of five core self-management skills including ‘problem-solving, decision-making, appropriate resource utilisation, forming a partnership with a health care provider, and taking necessary actions’. For a schematic representation of how this might be incorporated into an intervention, refer to Appendix 2.

Extensive qualitative research has identified a number of common themes relating to self-management support among individuals living with a wide range of LTCs. These common themes include:

-

the need for collaborative relationships with health-care professionals (HCPs)

-

the need for support from HCPs regarding information and education

-

medication adherence issues

-

the need for emotional and peer support

-

the need for carers to balance support and independence

-

the individuality of each person’s experience of illness

-

the importance of psychological support to help with adjustment for some people with LTCs. 59

The first two items on this list are reported in most studies looking at the experience of people living with any LTC. 57

What are self-management interventions?

Self-management interventions teach behaviours that seek to alleviate the consequences of a chronic illness. 60 The objectives are to facilitate patients taking an active role in their own health care by encouraging autonomy and providing accurate information on symptom management. 61

Recent work has attempted to identify the different activities that could be involved in supporting self-management (Box 1). 62 This taxonomy, derived from an expert advisory workshop and a systematic overview of the literature, describes only the potential components of self-management interventions as described in the literature. 59 Efficacy of these components in different LTCs has not been established. How, for example, does self-management support work?

-

Information about the LTC and/or its management.

-

Information about available resources.

-

Establishing specific clinical safety plans and/or rescue medication.

-

Regular assessment and evaluation.

-

Offering the patient feedback and monitoring.

-

Practical support regarding treatment.

-

Provision of equipment.

-

Providing opportunities to practise practical self-management.

-

Providing opportunities to practise everyday activities.

-

Providing opportunities to communicate with a HCP.

-

Providing training on psychological approaches.

-

Provision of easy access to advice or support when needed.

-

Peer support.

-

Lifestyle advice and support.

Note that not all of these components are appropriate for self-management support of all LTCs and the effectiveness of the individual components in self-management support for different LTCs is often unknown.

Self-management courses have been successfully implemented in the UK for other LTCs such as diabetes mellitus and arthritis [e.g. Dose Adjustment For Normal Eating (DAFNE),63 Diabetes Education for Self-Management for Ongoing and Newly Diagnosed (DESMOND),64 X-PERT65]. 55 DESMOND, for instance, is a group education programme based on psychosocial theories of learning and self-mastery as a basis for behaviour change. 66 The diabetes mellitus course is generally 1 or 2 days long and consists of non-didactic teaching methods. 66 Increased self-confidence and empowerment have been reported following these targeted self-management education courses. 64,65,67 Thus, previous research suggests that short-term self-management programmes can be of benefit in UK health-care settings and diabetes mellitus courses are now offered to all people with diabetes mellitus in the UK free of charge.

Why self-management for people with epilepsy?

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends that PWE are given adequate, structured information, and empowered to be successful in managing their condition. 68 Past studies indicate that PWE want to know more about how to effectively manage their condition. 69,70

Although PWE might wish to speak with someone other than their doctors about managing their epilepsy;70 many do not know who to ask or lack the confidence to do so. 21 The level of information needed to enhance seizure control and facilitate patient empowerment may require more detail than can be delivered through traditional outpatient consultation. 71 Interventions that aim to improve knowledge, confidence and empowerment may encourage PWE to seek support from a wider range of services to help manage their condition. At present, there are no standardised group education programmes available for PWE in the UK.

A Cochrane review of epilepsy interventions found that there is a potential benefit of self-management groups, although it is essential that further empirical evidence is generated. 72 The review was later updated, indicating that evidence exists to support the benefit of self-management and epilepsy nurse specialist (ENS) involvement in interventions. 73 However, the review stressed the limitations of findings to particular settings and called for improved service models for widespread intervention delivery. In order to test the usefulness of self-management interventions in helping improve QoL for PWE across the UK, further research is needed. 74,75

What evidence exists on self-management for people with epilepsy?

Epilepsy is a condition that requires targeted behaviour and management (such as medication adherence and avoidance of seizure triggers) to alleviate epilepsy-related consequences. For PWE, self-management strategies are defined as the behaviours that minimise frequency and severity of seizures76 and improve overall QoL. 77 Good self-management strategies may also help PWE to potentially feel more confident about health-care decisions and overcome psychosocial consequences of living with epilepsy. 76

At the time of developing the research protocol for this project, there was little evidence on the efficacy of group self-management programmes for PWE. Two key studies on group-based interventions were highlighted during trial design. The interventions that informed development of the SMILE (UK) trial are described below.

Sepulveda Epilepsy Education

The Sepulveda Epilepsy Education (SEE) programme was developed with an aim of meeting the complex psychosocial and educational needs for a wide range of PWE in the USA. 2 Helgeson et al. 2 evaluated the effect of the 2-day SEE intervention on psychological and physical outcome measures (i.e. self-efficacy, AED adherence). With a sample size of n = 38 (18 treatment, 20 waiting list control), limited statistically significant differences were found between groups at follow-up (Table 1). Nevertheless, compared with controls, the treatment group showed a significant decrease in seizure-related fear, hazardous self-management behaviour and misconceptions about epilepsy. The study also showed a statistically significant decrease in self-rated depression in the treatment group (p < 0.0007) immediately after participating in the course; however, this did not persist at their 4-month follow-up. No other statistically significant differences were observed between groups at the last follow-up, 4 months after enrolment (i.e. seizure frequency, self-efficacy).

| Study | Setting | Sample | Design | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Helgeson et al.2 | Medical care clinic, CA, USA | PWE n = 38 | Pre-/post-test controlled outcome study; 4-month follow-up period | Statistically significant increase in understanding of epilepsy at 4-month follow-up. Statistically significant decrease in seizure-related fear, hazardous self-management behaviour and misconceptions about epilepsy. Statistically significant increase in AED compliance in treatment group at follow-up |

| Limitations: small sample size. Short follow-up period | ||||

| May and Pfäfflin1 | Epilepsy centres in Austria, Germany and Switzerland | PWE n = 242; 16–80 years | Pre-/post-test randomised study; 6-month follow-up period | Statistically significant improvement at follow-up in epilepsy-related knowledge and coping |

| In treatment group, seizure outcomes improved and participants reported feeling more satisfied with AED therapy | ||||

| Limitations: per-protocol analysis may bias the results. No long-term follow-up |

Modular Service Package for Epilepsy

The Modular Service Package for Epilepsy (MOSES) intervention was originally developed in Germany. 78 After programme development, MOSES was tested in three German-speaking countries in a RCT. 1

The programme was adapted for both in- and out-patient contexts, and the course content was covered over 2 consecutive days. Participants were recruited from 22 specialist outpatient clinics and allocated to either the treatment or the waiting list control group receiving treatment as usual (TAU). Their sample contained 242 adults with epilepsy aged > 16 years with no other major comorbidity (see Table 1).

The final follow-up was carried out at 6 months. At this time point, course attendance had a positive effect on epilepsy-related knowledge, overall coping ability, seizure frequency and medication use. Thus, the authors concluded that MOSES is effective and reduces seizure frequency. They did not find, however, any effect of the intervention on a generic measure of QoL, self-esteem and other aspects of coping with epilepsy (i.e. information seeking). 1 They used the Short Form questionnaire-36 items during the trial, which may not have adequately detected the effect of the education programme. An epilepsy-specific measure of QoL [e.g. Quality Of Life In Epilepsy 89 (QOLIE-89) or Quality Of Life In Epilepsy 31 (QOLIE-31)] may be more sensitive in future research. 1

Overall, the effect of the MOSES programme on seizure frequency was encouraging and MOSES has now been routinely offered across Germany for approximately 15 years. Its success in practice led us to hope that it may be appropriate in UK health settings. Thus, MOSES was selected to trial for use in the UK.

These two seminal studies offered important conclusions about the benefits of self-management education in group settings. However, these studies lacked:

-

a sample size adequate to detect significant differences in QoL with enough statistical power while minimising type 1 errors (false positives)

-

a long-term follow-up period (e.g. at least 1 year)

-

a process evaluation of self-management courses using qualitative methods to gain the patient’s perspective

-

a health economics evaluation of the cost-effectiveness of self-management courses

-

an assessment of implementation fidelity to determine whether or not the intervention was delivered according to protocol.

The SMILE (UK) programme was designed to address these topics.

Summary and methodological rationale

Epilepsy is a highly stigmatised condition, associated with multiple potential psychosocial consequences. Past research indicates that many PWE want to know more about their condition,69,70 but may not know where to find information. This suggests that offering guidance and information may be valuable for PWE in the UK.

Self-management education offers an opportunity to address a gap in outpatient or community service provision. Self-management programmes are different to traditional educational offerings as they are designed to educate and empower those living with chronic health-care conditions. 79 No such programme has been evaluated for UK-based health-care services for epilepsy.

Research objectives

The main aim of this research, as required by the NIHR call, was to evaluate the effect of an intervention [the SMILE (UK) course] on patient QoL compared with TAU. The primary outcome was assessed using total QOLIE-31-P (Quality Of Life In Epilepsy 31-P)80 score at 12-month follow-up. Secondary outcomes included seizure frequency and recency, impact of epilepsy, adverse effects of medication, depression, anxiety, stigma and self-efficacy (measured via mastery and control). We also collected health economics data to determine the cost-effectiveness of the intervention.

Objectives of this research were to:

-

refine the content and delivery of the SMILE (UK) course after receiving feedback from Epilepsy Action Information Reviewers, who assessed the content of research materials for PWE

-

recruit and provide training for SMILE (UK) course facilitators

-

conduct a pilot study with volunteers to determine the suitability of outcome measures in terms of ease of completion

-

obtain qualitative feedback on the SMILE (UK) course by conducting an external pilot study with Epilepsy Action volunteers

-

describe the experiences of those who attended the SMILE (UK) course, as well as perceptions of barriers to attendance and benefits of the programme

-

assess the delivery of SMILE (UK) courses by conducting a fidelity analysis

-

test the hypothesis that participants with poorly controlled epilepsy would report improved QoL 12 months after being offered the SMILE (UK) course with TAU compared with those who received TAU alone

-

evaluate changes in secondary outcome measures at 6- and 12-months after randomisation

-

assess the cost-effectiveness of the SMILE (UK) course

-

highlight training requirements for implementing SMILE (UK) in the UK

-

disseminate findings to researchers, service users and commissioners of policy development.

Taking into account Medical Research Council (MRC)81 guidelines, the SMILE (UK) trial was undertaken in a series of stages.

-

The SMILE (UK) intervention was adapted for a UK context based on existing evidence from a similar intervention developed in Germany1 and an early English translation.

-

A complex intervention protocol was developed and published. 3

-

The SMILE (UK) intervention was piloted externally. 82

-

A statistical analysis plan was published. 4

-

A process evaluation of participants’ views of the courses was undertaken. 83

-

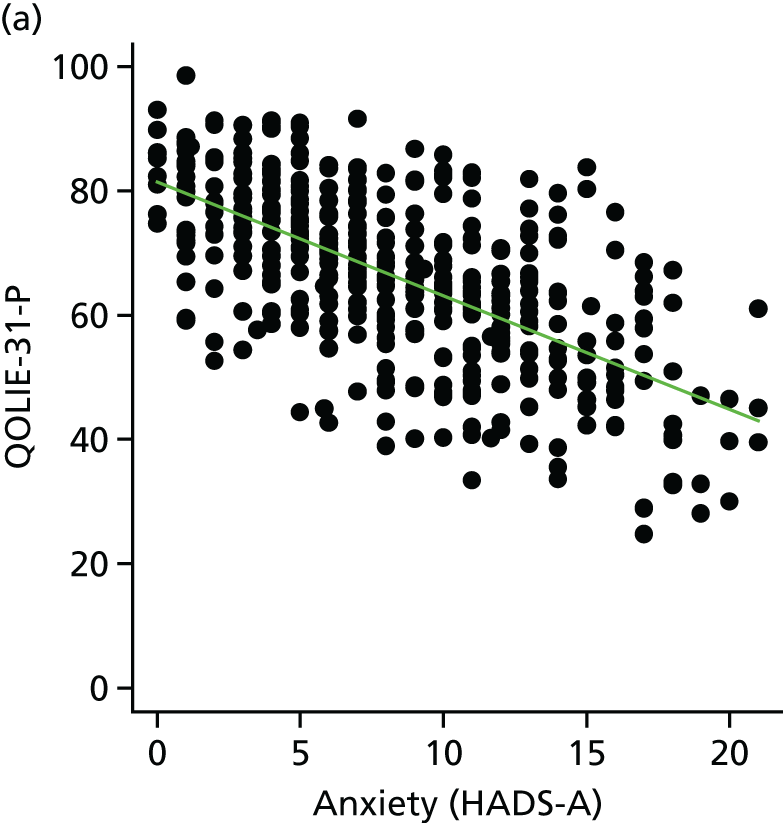

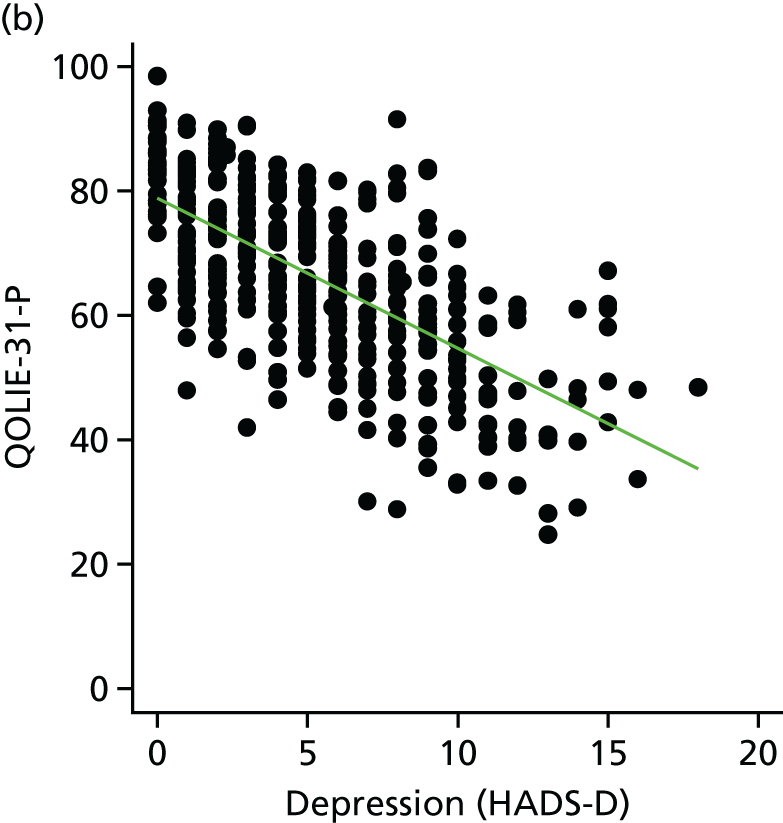

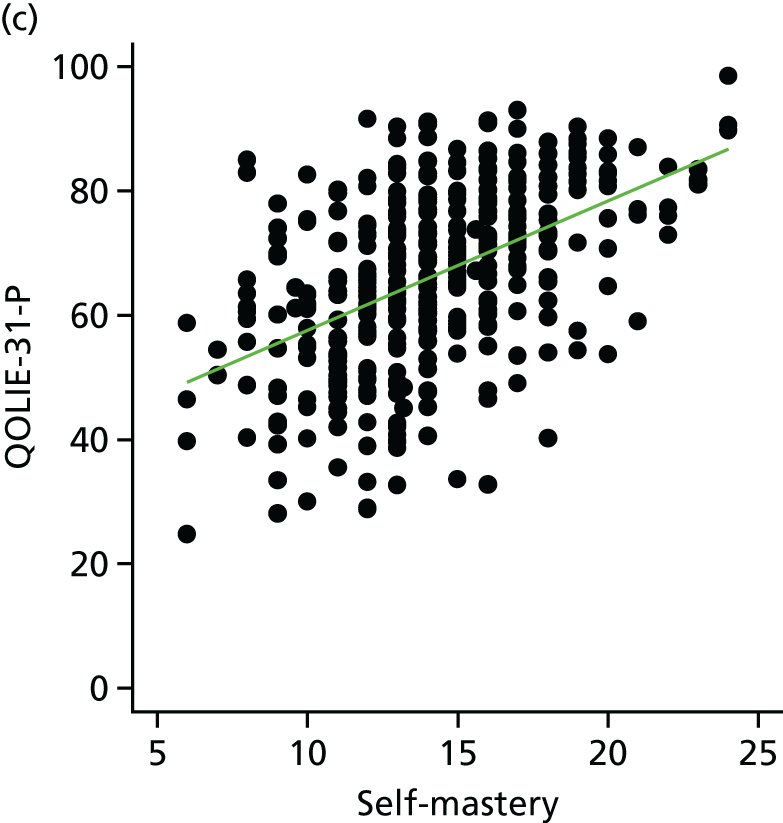

A baseline description of SMILE (UK) participants was combined with an analysis of which outcome measures are related to QoL (measured by QOLIE-31-P). 84

-

A fidelity analysis was undertaken on complex intervention delivery. 85

-

Clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness follow-up data were collected for both trial arms and analysed.

-

Results would be disseminated when the study was complete.

Chapter 2 Intervention development

Introduction

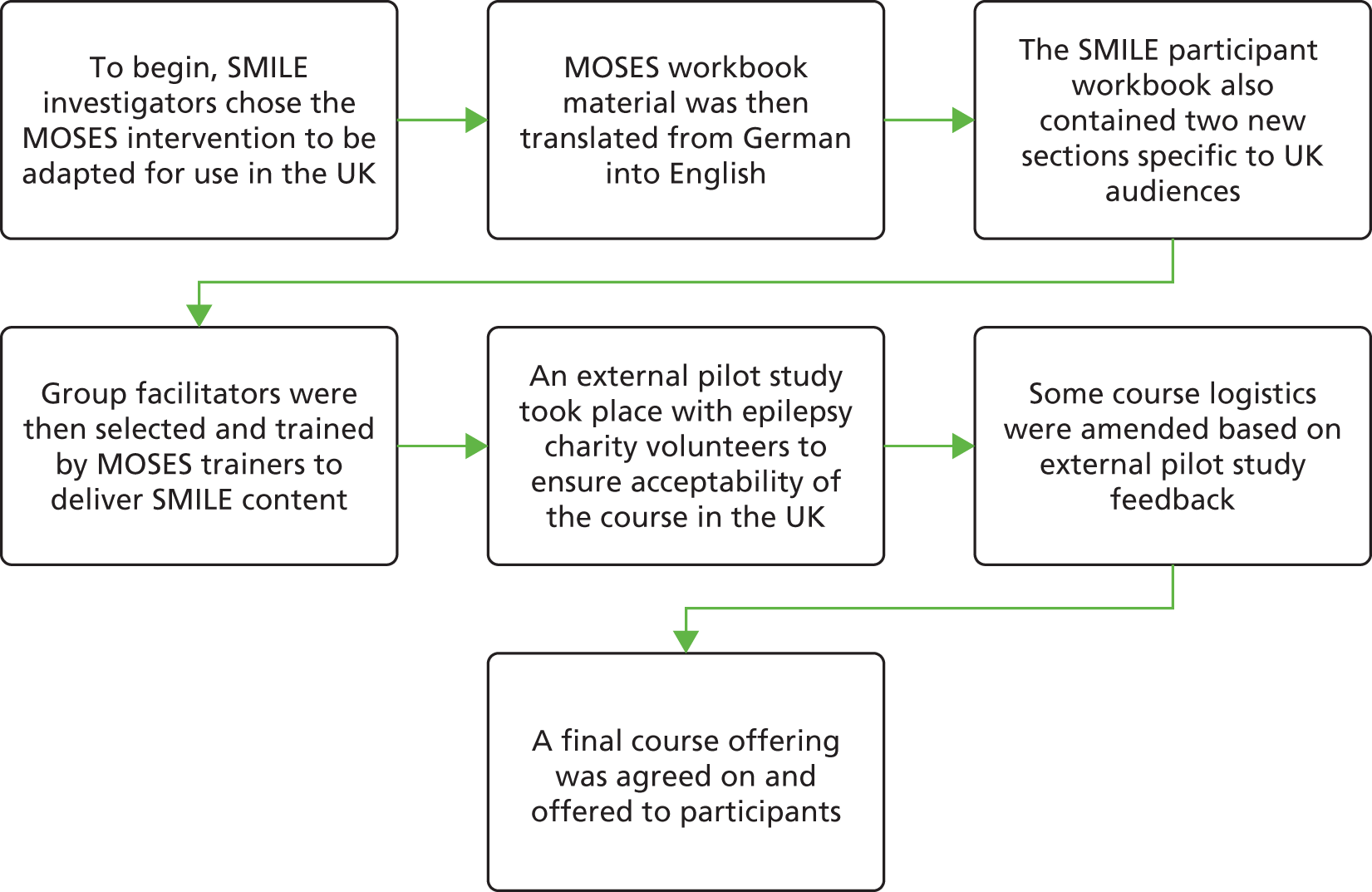

The SMILE (UK) intervention was adapted from MOSES, an educational treatment programme designed in Germany for PWE. It is a group course designed with input from specialists, non-medical professionals and patient groups. The intervention was originally developed by Ried et al. 78 for German-speaking adults aged > 16 years with any severity of epilepsy. The course is also suitable for patients with both epilepsy and mild learning difficulties. This chapter will outline the process by which the intervention was developed for use by PWE in the UK. A schematic of this process can be found in Appendix 3.

Overview of the MOSES intervention

The MOSES programme was designed to promote coping with epilepsy, increase participation in everyday activities and improve general self-esteem. Content is focused on supporting patients to become experts in managing their epilepsy, which is also consistent with NICE guidelines. 68

The MOSES developers did not adopt a specific behavioural change model. 78 Instead, they designed the intervention pragmatically, incorporating three levels of information processing to achieve change:78

-

the cognitive level (providing information)

-

the emotional level (identifying and discussing emotions)

-

the behavioural level (discussing actual activities).

Cognitive, emotional and behavioural aims are included in all nine MOSES modules, which were subsequently adapted for the SMILE (UK) intervention. Ried et al. 78 specified educational aims for PWE taking part in the course, as well as for those teaching the courses. 78 Although not conceptualised as such,78 key evidence-based behavioural change elements include:86

-

education about self-monitoring (of seizures)

-

obtaining support

-

increasing confidence (through identifying previous strengths and successes)

-

exposure to role models, both within the formal teaching material and to others within the group teaching format

-

provision of encouragement from others

-

discussion within the sessions of realistic outcome expectations.

The MOSES programme is intended to improve participants’ self-mastery (i.e. their confidence in being able to perform behaviours)87 to manage their condition. It focuses on a number of lifestyle changes, including obtaining sufficient sleep, avoiding alcohol, reducing stress, obtaining social support, understanding and coping with adverse effects of medication, following their prescribed medication schedule and planning ahead for collecting medicines. 88 Self-mastery may also be increased by exposure to the experiences of other PWE and facilitators during the course. By improving the self-mastery of PWE and their expectations regarding the outcomes of treatment and seizures,89 it was anticipated that MOSES and, therefore, SMILE (UK) would lead to better outcomes for PWE.

The MOSES programme has a flexible timetable arrangement. It can be run over a short period of time (i.e. a weekend) or longer (i.e. weekly sessions for up to 8 weeks) if preferred. 78 Topics covered during the programme include the following. 78

-

Living with epilepsy: identifying and expressing how it feels having epilepsy and how it felt being first diagnosed.

-

Epidemiology: teaching how common epilepsy is and learning about famous people with the condition.

-

Basic knowledge: causes of epilepsy and different types of seizures.

-

Diagnostics: tools and techniques used for epilepsy diagnosis.

-

Therapy: treatments for epilepsy, such as AEDs.

-

Self-control: recognising what can cause seizures and using countermeasures to interrupt auras.

-

Prognosis: discussing seizure control and the possibility of seizure freedom.

-

Psychosocial aspects: discussing the impact that epilepsy has on daily life, relationships, employment and day-to-day functioning.

-

Network epilepsy: talking about help that is available from self-help groups and other institutions.

The content is delivered in a workshop-style environment in which patients are encouraged to share their experiences with group members and engage with structured teaching activities.

The programme’s aims address understanding and coping with epilepsy, how it is diagnosed and treated, how to be more involved with the treatment plan, how it can impact life socially and at work, how to become independent and lead a normal life, and especially how to become expert representatives for one’s own condition. 78

At the conclusion of the course, it was hoped that participants would gain a deeper understanding of epilepsy, have generated ideas within the group about effective coping strategies and learn how to manage their condition autonomously.

Mechanisms whereby MOSES modules may lead to improvement in QoL in PWE are outlined in Table 2. Numbers in the table refer to the specific MOSES modules 1–9, as listed above.

| Factors influencing QoL in PWE | Relevant MOSES modules | Specific content |

|---|---|---|

| Seizures (frequency and recency) |

4. Diagnostics 5. Therapy 6. Self-control 7. Prognosis |

Knowing difference between seizure types; accurate recording of seizures and their semiology to assist better medical management Understanding importance of tests (e.g. blood tests) to monitor treatment; use of aids (e.g. dosette boxes) to assist adherence; encourage use of seizure diary to monitor progress/help medical management achieve better seizure control; being able to explain treatment to others and why one may have to take drugs at certain times; planning medication for holidays etc.; what to do if a dose is omitted; understanding other non-pharmacological treatments (e.g. surgery, vagus nerve stimulation) Learning to identify, record and respond to seizure triggers; learning to identify and respond to seizure auras (using countermeasures) Learning about factors likely to improve prognosis (i.e. to increase chances of becoming seizure free) |

| Seizures (injury) |

5. Therapy 6. Self-control 8. Psychosocial aspects |

Being able to tell others about one’s seizures, what they look like; how others should respond to prevent injury Learning to identify, record and respond to seizure triggers; learning to identify and respond to seizure auras (using countermeasures) Learning how to minimise risks at home/work |

| AEDs | 5. Therapy | Reducing/improving acceptance of AED adverse effects |

| Psychological comorbidity |

1. Living with epilepsy4. Diagnostics 5. Therapy 6. Self-control 8. Psychosocial aspects |

Dealing with anger/anxiety about having epilepsy Understanding the purpose of/reducing anxiety about different investigations Reducing psychiatric comorbidities associated with adverse effects of some AEDs Improving seizure control Improving self-esteem, using problem-solving approaches and seeking psychological support; seeking neuropsychological assessment to identify cognitive difficulties and address these; identifying own positive attributes and weaknesses |

| Stigma |

2. Epidemiology 5. Therapy 7. Prognosis 8. Psychosocial aspects 9. Network epilepsy |

Learning that epilepsy is common and can affect everybody; learning about achievement potential of PWE Provision of advice on family planning; learning that taking medication can be part of everyday life Learning what can still be achieved if PWE do not achieve seizure freedom Learning to reduce unnecessary restrictions on activities; maintaining social contacts; engaging in physical exercise; understanding relevant disability legislation and entitlements Identifying/contacting/joining relevant organisations/support groups |

| Resilience | 1. Living with epilepsy | Helping with reactions to diagnosis and planning future coping strategies |

| Age |

7. Prognosis 9. Network epilepsy |

Learning about what can be achieved at different ages even if PWE do not achieve seizure freedom Identifying age-appropriate sources of support/services |

In order to teach the MOSES programme, course facilitators are required to have experience of facilitating groups and to have completed a MOSES-specific training seminar. 78 Facilitators are nurses, psychologists, clinicians or social workers. Resources for facilitators during programme delivery consist of a ‘trainer manual’ and a workbook for group participants. Various techniques were developed to teach the course material in an interactive way and these were also used for SMILE (UK).

The course modules can be delivered on separate days over a period of weeks. For the MOSES trial, researchers offered the nine course modules over 2 consecutive days. The ideal group size was thought to be between 7 and 10 participants, with a maximum of 12;78 however, the group size in the RCT was not specified. 1

Presently, MOSES is offered to all PWE aged ≥ 16 years, regardless of seizure frequency, who can follow 90-minute teaching sessions. 90 It has been offered for approximately 15 years with great success, with over 20 courses scheduled in the current year. 90

Developing the SMILE (UK) intervention

There were a number of components involved with adapting the intervention for use in the UK. We adapted the patient workbook and teaching manual, liaised with patient user groups and trained UK-based facilitators to deliver the course. The following sections will outline how this was undertaken prior to intervention delivery. A schematic representation of the timeline is presented in Appendix 3.

Adapting the participant workbook and teaching manual for the United Kingdom

The SMILE (UK) research team obtained course material from the MOSES group. Most content had been translated from German except for personal testimonies from PWE. Personal testimonies were translated into English within the research department. Each SMILE (UK) collaborator edited and revised one module of the patient workbook. Some module titles were modified for ease of understanding.

Changes were made to several sections. For example, the section on ‘Famous PWE’ was modified to include celebrities and public figures that would be recognisable to people living in the UK. The section on ‘Networks’ was also changed to reflect local support network information. Epilepsy Action contributed as subeditors during this part of the intervention adaptation. They reviewed the use of English throughout the patient workbook to reduce the required reading age and improve accessibility for a wide range of audiences. Current information on antiepileptic medication was adapted from information available from the Epilepsy Society. Local regulations (e.g. regarding insurance and driving) were changed to reflect UK legislation.

Overview of the SMILE (UK) intervention

The SMILE (UK) course is a group-based, interactive education programme based on MOSES, developed to provide strategies for individuals living with poorly controlled epilepsy in the UK. 3 SMILE (UK) was designed to be delivered in 16 hours over 2 days.

The number of people per group was intended to range from 6 to 12 participants (including carers or family). All participants assigned to the treatment group were given the option to have a carer or significant other accompany them to the course if they wished. This was encouraged to make the participant feel supported, but also to add another perspective to group conversations (i.e. family or carer perspective). The group number was selected based on the original MOSES research78 and because it might have helped allay anxiety about speaking in front of a large audience and would thus be small enough to share personal experiences comfortably.

Two trained HCPs acted as group facilitators during the course, wherein attendees progressed through set modules and participated in group discussions. A workbook was used throughout the course so participants could become familiar enough with it to be able to use it at home. The programme covered the same nine modules offered by MOSES (i.e. living with epilepsy, epidemiology, basic knowledge, diagnostics, therapy, self-control, prognosis, psychosocial aspects, and network epilepsy)78 renamed for SMILE (UK) (see Table 3).

SMILE (UK) teaching materials

The SMILE (UK) course is taught using a number of items, including two sets of workbooks (teaching manual and participant workbook), a flip chart for teaching demonstration, stickers for group exercises (used with flip chart), and Microsoft PowerPoint® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) slides. Each of these teaching resources will be discussed in the following sections.

Teaching manual

A teaching manual was developed based on the MOSES ‘trainer workbook’. 78 For copyright reasons, specific content will not be provided here (please see Acknowledgements for more information). Content can be requested from the MOSES group. The aim of this resource is to guide facilitator teaching of the SMILE (UK) course. In the preface section of the book, it is suggested that course content may be negotiated between participants and facilitators in the future. The teaching manual is divided into two sections.

Section 1

This contains six introductory modules: (1) a preface, (2) SMILE (UK) teaching aims, (3) structure and implementation of SMILE (UK), (4) requirements for teaching SMILE (UK), (5) key terms, and (6) sources for further information. The guide stresses the need to provide participants with accurate information and the importance of adopting an interactive teaching style. Facilitators are encouraged to adapt their teaching methods and speed according to the needs of the group. Overall teaching goals include (1) promotion of active learning, (2) support sympathetic and friendly communication between course participants and (3) fostering a stimulating and varied learning environment.

Section 2

This contains a summary of each module from the participant workbook. Each module contains information on the duration of each session, teaching methods and materials. Teaching advice is given as a guideline that can be used flexibly or supplemented during the course. Throughout each module, suggestions are made to facilitators to indicate where certain teaching materials (i.e. flip chart, stickers) can be used. Throughout the course, facilitators are encouraged to allow time for social interaction and discussion rather than focusing solely on teaching.

Participant workbook

Participants were provided with a workbook at the beginning of the SMILE (UK) course and encouraged to use it as a home reference after the course had finished. Each of the nine modules (Table 3) begins with a summary page (about the topic, aims and contents), and includes note-taking space, interactive questions (e.g. what does my doctor need to know about my seizures?) and a final summary of key points (see Acknowledgements for more information about copyright).

| Module | Topic | Objective | Page |

|---|---|---|---|

| Introduction | 5 | ||

| One | Living with epilepsy | How to recognise and express different emotions that you may experience because of epilepsy. How to develop better ways to cope with epilepsy | 25 |

| Two | PWE | How common is epilepsy in the UK? When are you most likely to develop epilepsy? Famous PWE and what they have achieved | 47 |

| Three | Basic knowledge | The causes of epileptic seizures, how seizures develop and how to identify the different seizure types | 57 |

| Four | Diagnosis | How to observe and describe seizures accurately. How to document seizures, the results of investigations and understand the different diagnostic methods | 67 |

| Five | Treatment | An overview of the most common AEDs and different treatment options. How to actively participate in your treatment | 81 |

| Six | Self-control | How to avoid seizure triggers and become aware of auras/warnings. Working out what might be relevant to developing abilities of self-control | 113 |

| Seven | Prognosis | The chances of achieving seizure freedom and the chances of staying seizure-free after stopping AEDs. Options if seizure freedom is not achieved | 131 |

| Eight | Personal and social life | How to improve self-esteem and social contacts. Support for independent living, sports and professional life, driving regulations and how to explain epilepsy to others | 136 |

| Nine | Network | Addresses and other information related to treatment, psychosocial support and specific information for your epilepsy | 193 |

Not all workbook material is covered during the 2-day programme, so facilitators suggest that participants refer to the book in their own time and share content with family and friends. At the end of each module, there is a series of questions that encourage further consideration of issues raised and further teaching session. Ample time is provided for sharing problems and solutions.

Course slides

Facilitators are provided with a Microsoft PowerPoint file to show slides during the course. In the original MOSES study, course facilitators were encouraged to use overhead transparencies. We opted for PowerPoint slides based on these transparencies adapted for a UK audience. Slides correspond to participant workbook content and provide supplementary information.

Flip chart

A freestanding flip chart with large paper sheets was set up in full view of course participants. Throughout each day, discussion statements were written on the flip chart and participants were asked to respond during a group discussion. For example, participants were given ‘dot’ stickers on the first morning and these were used throughout the course as a method to compare participants’ views on certain topics. Questions were asked about how participants felt regarding certain statements and they were asked to place a sticker on a scale of responses (Figure 1). The array in the placement of stickers along the scale was then used as a way to initiate discussion on the topic.

FIGURE 1.

Example of reflective exercise using stickers on a flip chart. Participants were asked to place a sticker (represented by a green circle) on the scale according to how they felt.

SMILE (UK) course delivery

To balance out emotional and teaching topics, the modules were delivered to participants in a different order than in the workbook. Each day of the course followed set schedules (see Appendix 4) corresponding to the workbook modules described in Table 3. The timing of course activities followed an organised but not prescriptive structure. The SMILE (UK) course was divided into four sessions: day 1 morning session, day 1 afternoon session, day 2 morning session and day 2 afternoon session. Each session lasted 3 hours and contained a tea/coffee break. Lunch was provided between the morning and afternoon sessions.

There were always two facilitators present at the course so that should a seizure occur, one facilitator could continue the course while the other attended to the participant. One facilitator led each module while the other assisted. Who would lead each module was discussed between the two facilitators prior to the start of the course. The course began with individual introductions of course facilitators and participants. One facilitator explained housekeeping rules and building facilities. The first module on ‘living with epilepsy’ had a heavy emotional component and was divided into two parts. The first part focused on discussing experiences and naming emotions experienced following diagnosis. Course participants were reminded that there are no ‘right or wrong feelings’ in response to living with epilepsy. The point of this module was that thoughts and feelings about epilepsy can be shared with others. The second part consisted of a discussion on how group members had coped with their condition in the past. Depending on the size of the groups, there was likely to have been a range of experiences and feelings described regarding diagnosis length, seizure severity and seizure management.

The ‘people with epilepsy’ module contained discussions about famous PWE and risk factors/causes of the condition. Facilitators compared the prevalence of epilepsy with other chronic health conditions to show how common epilepsy is. Module three on ‘basic knowledge’ covered causes of epilepsy, epileptic activity in the nerve cell and where seizures originate from in the brain. Participants were asked if they knew what type of seizures they had and were given a chance to share their experiences with the group.

Module six covered ‘self-control’. During this section, participants were asked to place a sticker on the flip chart with other course participants, to show how preventable they believed seizures were. Course facilitators then shared instances where this may or may not be possible, discussed triggers and how to keep records of seizures. Module nine addressed personal support networks for PWE. Participants were asked to share their own sources of support they used to cope with epilepsy. Local support networks were also discussed and the day closed with an overall summary of the course.

Day 2 began with a brief outline of what would be covered for the day, as well as ‘checking in’ with how participants felt about day 1 (see Appendix 4). Emotional responses to the first day were discussed together as a group. The first module of the day was a discussion on ‘treatment’. The facilitators outlined different treatment options available in the UK. Ideas and strategies were shared on how participants could actively be involved with their treatment plans. Participants were asked to write down personal drug therapy goals in their workbook.

The next module on ‘diagnosis’ listed diagnostic methods during this session and, with time permitting, described means of assessing seizure activity, such as electroencephalogram (EEG) information collected during routine assessment. Module seven focused on ‘prognosis’. Participants were asked when or if they expected to become seizure free. This topic was discussed as a group and the facilitator explained their answers from a medical viewpoint. Factors affecting prognosis were also discussed.

The final topic of day 2 was on ‘personal and social life’, which covered ways of helping people cope and overcome challenges associated with epilepsy in daily life. At the end of the course, participants were thanked for their participation. Those who wished to remain in contact with other attendees were able to give their permission for contact details to be circulated by e-mail at a later date (if not shared by individual group members during the course already).

SMILE (UK) course facilitators

The teaching model for SMILE (UK) required there to always be two course facilitators present during teaching. In international provisions of group education courses for PWE, various clinicians have acted as group facilitators. These have included psychologists,46 researchers,91 social workers and neurologists. 71

The literature is unclear on ‘who is best’ to deliver self-management education programmes. Past research suggests that lay persons might be well placed to deliver self-management groups; however, limited long-term benefits have been demonstrated. 79 Based on national literature92 and staff availability,93 we chose to recruit ENSs and EEG technicians to run the course.

In the UK, ENSs are likely to be part of outpatient epilepsy care. The role of an ENS is to provide specialist outpatient care for PWE and to support primary and secondary care teams. 94 They incorporate social support and counselling in their role, but also focus on consultation and advice for PWE. ENS services may be provided in person or over the telephone on topics ranging from AED side effects, pregnancy queries and overall support. 94

Past UK-based research found that ENSs were important support for PWE, especially those with a recent epilepsy diagnosis and with long term epilepsy. 95 ENSs are well-placed to take group courses with PWE because they possess specialist knowledge of managing epilepsy and experience of managing interpersonal dynamics and psychological issues (such as those that occur in group settings).

The chief investigator who was responsible for recruiting facilitators found that ENSs in London and the South Thames were enthusiastic about the course. Nevertheless, many felt overstretched by their NHS roles and did not have the capacity to volunteer additional time delivering the course. ENSs on the whole choose Monday to Friday work hours and it seemed unlikely that they would undertake courses at the weekends.

The decision to have EEG technicians as facilitators was primarily because of their specialist experience of epilepsy diagnosis and training in medical aspects of epilepsy. EEG technicians collect diagnostic information and have specific experience in assessing PWE. These clinicians were available at King’s College Hospital (KCH) and were willing to be involved with the trial. Many have higher education training (e.g. Master of Science-level education) and an interest in teaching others about epilepsy. Furthermore, the lead neurophysiologist at KCH (Dr F Brunnhuber) had previously trained to deliver MOSES and was able to assist with recruiting of EEG staff at the hospital and also mentored the facilitators during their SMILE (UK) training and delivery of the programme. Although EEG technicians do work out of hours, the reimbursement allowed for locum substitutions is for weekdays only.

Facilitator training

The chief investigator and co-investigators of the study underwent several stages in recruiting and training of SMILE (UK) facilitators. LR was responsible for recruitment of facilitators and staff.

The first step involved the engagement of London- and Kent-based ENSs. Requests to hospitals were generally received well, although were dependent on resource availability. Several centres had staff who expressed enthusiasm to teach, but had workloads that prevented their involvement with the study.

After an initial group of prospective facilitators had applied, the trial chief (LR) and a co-investigator (AJN) held interviews to assess each candidate’s suitability for SMILE (UK) facilitator training. A final group of facilitators was selected (see Appendix 5). In total, there were eight female and three male facilitators; seven were EEG technicians and four were ENSs. Four facilitators had a Bachelor of Science-level degree and seven had a Master of Science in epilepsy or epileptology. The average length of experience in epilepsy care for the group was 20 years (range 5–40 years).

SMILE (UK) facilitator training course

Three clinicians/researchers from the MOSES group came to London to conduct a 2-day facilitator training course held on 10 and 11 June 2013 (for topics covered during training, see Appendix 6). The study chief investigator (LR) and a co-investigator (LHG) attended the training course as well.

The MOSES trainers went through the SMILE (UK) course material, showed a facilitator training digital versatile disc (DVD), and went through group-based exercises with trainee facilitators. Attendees were provided with a ‘teaching manual’, which is organised similarly to the patient’s workbooks, with indications on the techniques to use such as mind maps and writing out participant answers on a flip chart or slides. Attendees were able to ask questions on why activities were undertaken in a certain way and learn from the experiences of the MOSES facilitators who were undertaking the course with patients in Germany. Strategies were shared for enhancing participant engagement and understanding, such as focusing on topics in the workbook relevant or of interest to course participants (e.g. if participants already use a seizure diary, move on to another topic), or asking someone to clarify what they mean (e.g. ‘Can you please elaborate on that?’ or ‘Could you give an example?’). When teaching SMILE (UK), facilitators were encouraged not to follow all workbook content sentence by sentence. All sessions during the 2-day facilitator training were video-recorded so that facilitators could review them. On conclusion of the SMILE (UK) training course, all facilitators received a certificate of completion. Throughout the SMILE (UK) study period, there was attrition of facilitators owing to work commitments in their clinics. New facilitators received training by watching the video of the 2-day training session and sitting in on an active SMILE (UK) course.

Patient and public involvement during SMILE (UK)

Patient and epilepsy care groups were consulted throughout intervention development in order to assure acceptability of the treatment technology. The Epilepsy Action Research Network (EARN) is the largest national user group that supports academic research for PWE and so became user partners in the SMILE (UK) trial. Members of EARN are PWE, carers and members of the public who are familiar with health research.

To verify the content and reading levels were appropriate for PWE in the UK, documents intended for patients such as the patient information sheet and the participant workbook were sent to Epilepsy Action Information Reviewers. Comments received were on the reading difficulty and on the volume and level of information given in the participant workbook. It was decided to give workbooks out at the beginning of the course, in order to go through it selectively during the sessions. With this arrangement, participants could ask questions on content covered in the workbook and choose for themselves if they wanted to read further once they had completed the course, but not be put off by its length and complexity before the course began.

Service user feedback from EARN was sought during the design of the study protocol (see Appendix 1). Information was provided about the study, then PWE were asked, via Epilepsy Action’s website and online forum, if group-based education was something that they would find helpful.

In order to ensure that findings from SMILE (UK) would be communicated to the public on study completion, a dissemination plan was drafted. We actively sought feedback from Epilepsy Action about this plan by discussing it during collaborators’ meetings. Following the completion of the trial, a website would be created with study results and researchers or facilitators would attend meetings to present final results.

Two key individuals represented service user groups and remained in regular contact throughout the trial. We involved Mary-Jane Atkins from the patient/service user group at KCH in the early phases of the research (pre-pilot). Mary-Jane assisted by participating in the external pilot study82 and completing the battery of assessment questionnaires used during the baseline and follow-up assessments. She provided feedback on her experience of completing the questionnaires in order to ensure that they could be answered comfortably (i.e. easy to fill in, ≤ 60 minutes to complete). As the trial was being undertaken, the epilepsy services manager from Epilepsy Action (Angela Pullen) attended and participated in collaborator meetings throughout the study.

External pilot of SMILE (UK)

The external pilot was conducted prior to starting the main RCT. The aims were to identify whether or not any changes would be required to content or delivery and to explore the beliefs and understandings of those attending the SMILE (UK) course. The results from the pilot study were published82 and this section serves as a summary of the study.

Methods

Recruitment

We aimed to test the SMILE (UK) course with two groups of 10 PWE. Volunteers were sought by placing an advertisement in Epilepsy Today96 and via Epilepsy Action’s website. 97 From March to May 2013, 22 participants were recruited. Eleven did not participate as a result of illness, work obligations, being uncontactable or fatigue (and other effects of a recent seizure). A further one participant declined to take part in the research interviews after attending the SMILE (UK) course. In the end, 10 volunteers participated in the external pilot study

SMILE (UK) course delivery

Two pilot courses were given from 9:30 until 17:00, each over 2 days. Two sets of course facilitators gave the course, and this also served as a practice after their training. Each course had an ENS and an EEG technician facilitating. The courses were held at an education facility part of King’s College London (KCL), located next to KCH. The course days followed the schedule described in Appendix 4. All volunteers received the participant workbook. Courses were generally delivered by an ENS and an EEG technician working in tandem. This pairing enabled their knowledge and skills to combine optimally.

Data collection

The groups were then asked to provide feedback on their experience. Data were collected in two ways: three participants completed a focus-group interview and seven completed one-on-one semistructured interviews (two over the telephone, four in person and one by e-mail). Both took place less than 1 month after participants took part in the pilot SMILE (UK) course. The focus group lasted 60 minutes and the semistructured interviews lasted between 20 and 30 minutes.

Interview procedure

Discussion topics were established with input from Epilepsy Action. 82 The resulting topic guide was flexible and served as a prompt during discussions (see Appendix 7). Topics focused on (1) reasons for interest in the SMILE (UK) pilot study, (2) views on content covered during the course, (3) appraisal of group learning processes, (4) appraisal of teaching methods and (5) overall utility of the SMILE (UK) course. To minimise chances of bias, the study interviewer was not involved with facilitating or co-ordinating the SMILE (UK) programme. The topic guide was flexible in that prompts could be revised on the spot and returned to throughout the interview sessions.

Data analysis

Interviews and focus group discussions were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. The transcripts were checked by the interviewer and two co-investigators (MM and LR). Analysis began by manual marking of topics in margins. This process took on an iterative format of going back and forth between notes and emerging themes. Software (NVivo 9, QSR International, Warrington, UK) was used to formally code themes from transcripts and grouping into broader themes.

Results and discussion

Many themes emerging from the pilot study were similar to those from the process evaluation presented in Chapter 9. For these common themes, data will be presented together. In the section that follows, we will present the results relevant to the intervention that helped us to shape the SMILE (UK) course for the RCT. Full characteristics of volunteers from the pilot are also presented in Chapter 9. Briefly, six females and four males participated, aged from 21 to 60 years, having had epilepsy for 8 to 52 years.

Reasons for participating

Most volunteers said they chose to participate in the pilot study for general interest, especially as it offered a chance to meet other PWE. Two saw it as a way to be involved in developing a new intervention and one saw it as a way to help in taking control of her life. These reasons give insight into why PWE may wish to participate in the SMILE (UK) RCT.

SMILE (UK) content

Out of the nine modules, four were found to be especially useful. These were module 3, basic knowledge; module 4, diagnosis; module 6, self-control; and module 8, personal and social life. This was useful to know when we considered how to evaluate implementation fidelity of SMILE (UK) (described in Chapter 7). Importantly, the volunteers did not find any parts of the course to be redundant.

SMILE (UK) duration

The volunteers considered the duration of the course days to be too long and would have preferred to spread the course over 3 days. This was considered by the research team. As the target group was PWE with active seizures, there would be a higher risk of non-completion of the course as a result of seizures if it was spread out over more days. PWE may also not want to participate because of the longer time commitment if the course was longer. As a result of this, the investigators decided to keep the course length to 2 days.

SMILE (UK) materials

All volunteers considered the participant workbook to be a valuable source of information that could be used as a reference for the future. It was also a source of information for their family and friends. One common criticism was not incorporating the participant workbook into the course. Volunteers said they would have like to have time to take notes during sessions and to fill in some of the relevant exercises. Following this, the facilitators were instructed to include the workbook more often by indicating on which page participants could find the relevant information and invite them to complete relevant exercises (e.g. describing what happens to them during a seizure). To ensure course facilitators implemented this, workbook use throughout the course was measured in the implementation fidelity assessment (see Chapter 7).

Two participants had seizures during the course, reinforcing the value of holding SMILE (UK) near hospital emergency department (ED) services. It also confirmed the need to have two facilitators at every course so that one could assist with the seizure while the other continued with the group.

Other topics emerged, such as the positive value of a group setting, using new information to empower their discussions with HCPs and improving their personal lives. Full results from this external pilot will be presented in Chapter 9.

Summary

By incorporating local information on epilepsy care and approaching local epilepsy care networks, we adapted a German-based intervention called MOSES78 for use in the UK. Training was provided to 11 facilitators (ENSs and EEG technicians) in order to be able to deliver the SMILE (UK) intervention. A teaching manual and participant workbook were adapted from the MOSES course materials. Workbooks and course content were largely unchanged from MOSES, with the exception of topics such as local support networks, UK regulations and famous PWE. The SMILE (UK) course contained a mix of teaching modules, largely containing factual topics and others touching on emotional aspects of life with epilepsy. This balance offers a unique opportunity for PWE to gain knowledge about their condition but also to share with people like themselves. The pilot study of two SMILE (UK) courses resulted in positive feedback. The volunteers concluded that there were no major barriers perceived with running this kind of intervention in the UK.

Chapter 3 Methods

Study design

The trial was designed as a multicentre, pragmatic, parallel arm RCT of a complex intervention. Participants were randomised in a 1 : 1 intervention-to-control ratio. The intervention group received TAU and was offered the SMILE (UK) course, while the waiting list control group received TAU until the 12-month follow-up assessment. The intervention was offered to the TAU group once they had completed the final trial assessment. In addition, the study contained two qualitative elements: an external pilot and a nested process evaluation. Prior to the RCT, an external pilot was conducted of SMILE (UK) (see Chapter 2). For the nested process evaluation, 20 participants were recruited after having attended the SMILE (UK) course (see Chapter 9).

Study settings

The chief investigator (LR) visited and arranged for local principal investigators (PIs) to recruit participants from epilepsy clinics in eight hospitals in south London and south-east England: KCH (Lambeth, London); University Hospital Lewisham (Lewisham, London); the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery (NHNN) (Camden, London); St George’s Hospital (Wandsworth, London); Croydon University Hospital (Croydon, Surrey); Princess Royal University Hospital (Bromley, Kent), Darent Valley Hospital (Dartford, Kent); and Guy’s and St Thomas’ Hospital (Southwark and Lambeth, London).

The trial was run from a central location at KCL. Throughout the study, face-to-face meetings between participants and research workers were held at a location convenient to the participant – at KCH (Denmark Hill campus in Southwark, London), a public place or their own homes.

Trial approval and monitoring

The study was approved by the National Research Ethics Service Committee London – Fulham (Research Ethics Committee reference 12/LO/1962; see Appendix 8). The study was approved by the local research and development departments at each recruitment site. The study was monitored regularly by the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and the Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC). Meetings with both groups were held at least once a year with interim reports sent when needed.

Screening and recruitment

Participants were recruited from eight sites in London and south-east England. Local PIs identified patients from having attended neurology clinics within the previous 12 months.

Stage 1

Individuals having attended a neurology clinic were sent a letter from the local clinical PI along with information about the study in a patient information sheet (see Appendix 9). At this stage, patients had the chance to opt out from the next stage of the study. They had a 3-week period to return their opt-out slip in a pre-paid envelope. As this stage did not involve screening medical notes, patients contacted may not have necessarily met the eligibility requirements. The only requirement at this stage was that they had attended the neurology clinic within the past year.

Stage 2

At the second stage of recruitment, medical notes were screened by clinicians at the local hospital and a second invitation was sent to eligible participants along with the patient information sheet. Once again, patients had the opportunity to opt out from further contact from the research team. Again, at this stage, patients had 3 weeks to return their opt-out slip. Patients who did not opt out of either stage were contacted by the research team to invite them to enrol in the study.

Stage 3

At this point of contact, the research team telephoned eligible participants who had not opted out to invite them to join the study. Research workers confirmed eligibility criteria of interested individuals and arranged a face-to-face meeting to explain the study in more detail, obtain informed consent and conduct a baseline assessment. Participants gave written consent themselves. All meetings were arranged at participants’ homes or public locations convenient for them.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria:

-

confirmed epilepsy diagnosis (all epilepsy-related conditions and seizure types included)

-

current AED prescription

-

aged ≥ 16 years

-

ability to give informed consent, contribute during groups and complete questionnaires in English

-

have experienced two or more seizures in past 12 months (self-reported).

Exclusion criteria:

-

only having seizures that are psychogenic or non-epileptic in origin

-

only experiencing seizure related to acute neurological illness or substance misuse

-

diagnosis of a serious psychiatric disorder or terminal illness

-

participation in other epilepsy-related research.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained during a face-to-face meeting between the participant and a research worker, arranged either at their home or somewhere convenient for them. The study was explained in detail and participants were given the opportunity to ask questions. Once the consent form was signed (see Appendix 10), baseline data were collected.

Randomisation

Two to three weeks following enrolment, participants were randomised in batches of 12–24 participants per recruitment site to obtain a sufficient group size for the intervention. For each batch, participants were randomised in a 1 : 1 ratio between the SMILE (UK) group and the TAU group using fixed block sizes of two, to ensure equal number of participants in each group. Thus, the randomisation was stratified by the location of recruitment sites (KCH, University Hospital Lewisham, the NHNN, St George’s Hospital, Croydon University Hospital, Princess Royal University Hospital, Darent Valley Hospital, Guy’s and St Thomas’ Hospital).

To reduce bias, randomisation was carried out by the King’s Clinical Trials Unit at the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience (IoPPN). The trial manager had the only access to the online randomisation request system. For each batch, participant information was entered into the system by the trial manager who then sent the request for randomisation to the Clinical Trials Unit. This ensured that randomisation was performed independently of the research or statistical teams. An e-mail was generated to the trial manager reporting the assigned group for each participant, thus the trial manager remained unblinded. A letter was posted to each participant to advise them of the group to which they had been allocated.

Blinding and protection from bias

Treatment allocation could not be kept from participants. In addition, the trial manager and administrator were unblinded as they were involved in contacting participants to attend the course. Research workers collecting data, the trial statistician and health economist, along with investigators, remained blinded. Participants were asked to not disclose their allocated group during assessments. To ensure that the blinding process worked, research workers completed a ‘Research Worker Treatment Guess’ form after the 12-month follow-up assessment or at point of withdrawal of participants leaving the study early. They stated to which group they thought the participant had been randomised and then whether this was a guess or whether they already knew. If unblinding had occurred during the course of the study, they noted how this happened. Any reporting to oversight boards was also done in a blinded manner, excepting in closed DMEC reports in which data were reported in a semi-blinded manner (i.e. groups were labelled A and B without specifying the treatment allocation).

Intervention delivery

The SMILE (UK) course was held at several locations during the trial. Locations were chosen based on being easily accessible, familiar to the patient and having access to emergency care services, if required. Originally, it was hoped that all courses would be offered at the hospital nearest the patient; however, this was not possible because of challenges with off-site room bookings and staff availability. Therefore, participants were mostly invited to attend a course at KCH. The data for course attendance are given in Chapter 5.

All participants were sent a venue map and room location by post in advance. When possible, and to facilitate group interaction, chairs were arranged in a semicircle. A flip chart was set up for writing notes and discussion points. Workbooks, pens, name badges and stickers were ready for participants on arrival and a sign-in sheet was positioned beside the workbooks.

Completion of follow-ups

Every effort was made to minimise dropouts at follow-ups, including researcher phone calls to ask whether or not the questionnaire was received and whether or not any help was needed at 6-month follow-ups, and mailing questionnaires by post and e-mail for 12-month follow-ups. On completion of the final questionnaire, participants were given a £20 store voucher. We also opted for additional procedures to improve response rates when posting questionnaires,98 such as using colour printing for the participant questionnaires.

Adverse event reporting

Information about adverse events (AEs) was collected at the 6- and 12-month follow-ups by a research worker. An AE was defined as a health-related event that was experienced by a trial participant. The AEs were self-reported by participants and any change in health was recorded. Seizures and any event related to a seizure (including hospitalisations) were not recorded, as these are expected events related to the nature of poorly controlled epilepsy. Any AEs requiring hospitalisation (unrelated to seizures) or prolongation of hospital stay, that were life-threatening, or that resulted in death or in persistent disability were recorded as serious adverse events (SAEs). Status epilepticus was considered as a SAE. SAEs were reported to the site PI and reviewed by the chief investigator. A list of AEs and SAEs was included in the reports to the trial oversight committees and to the ethics committee.

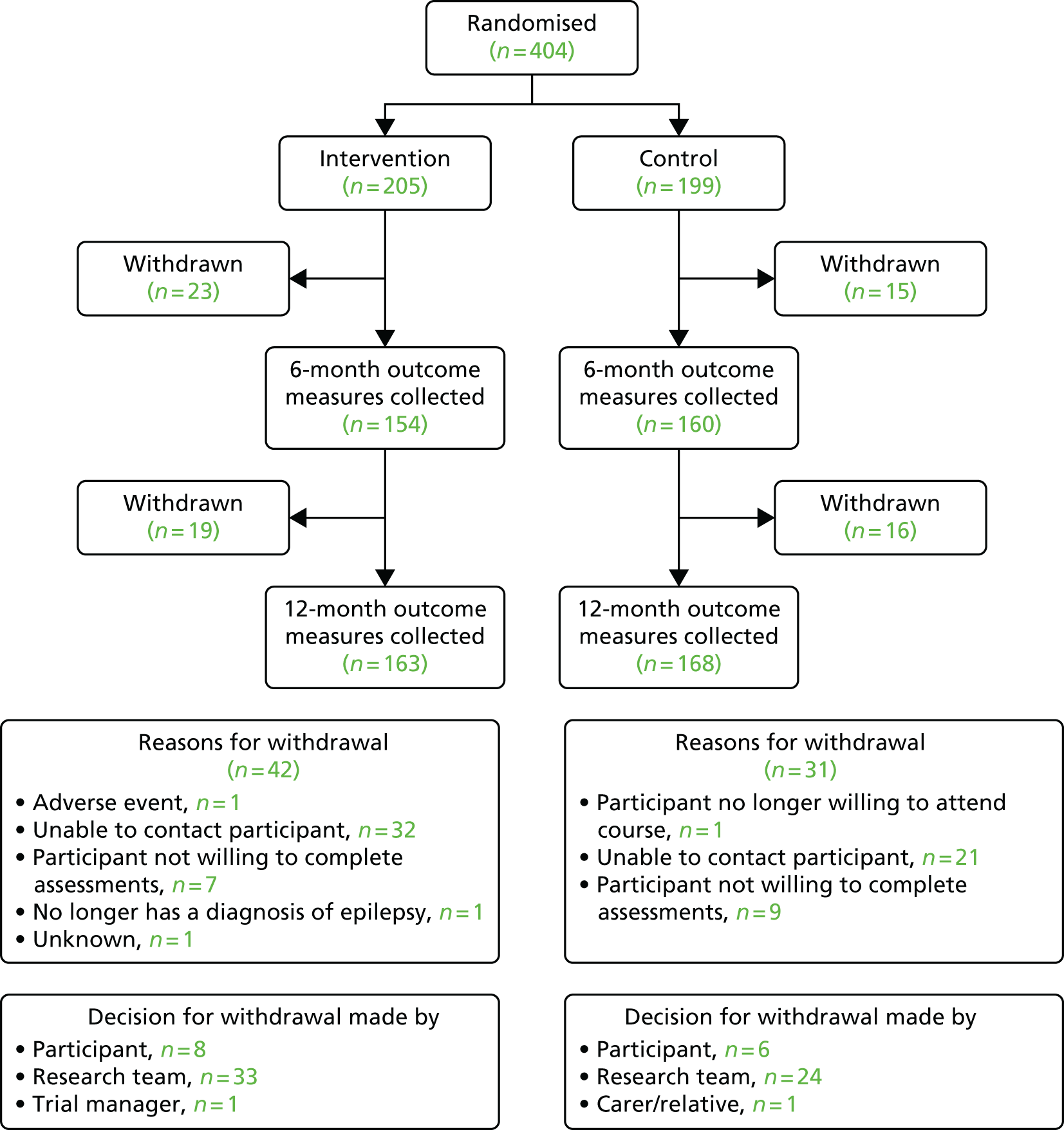

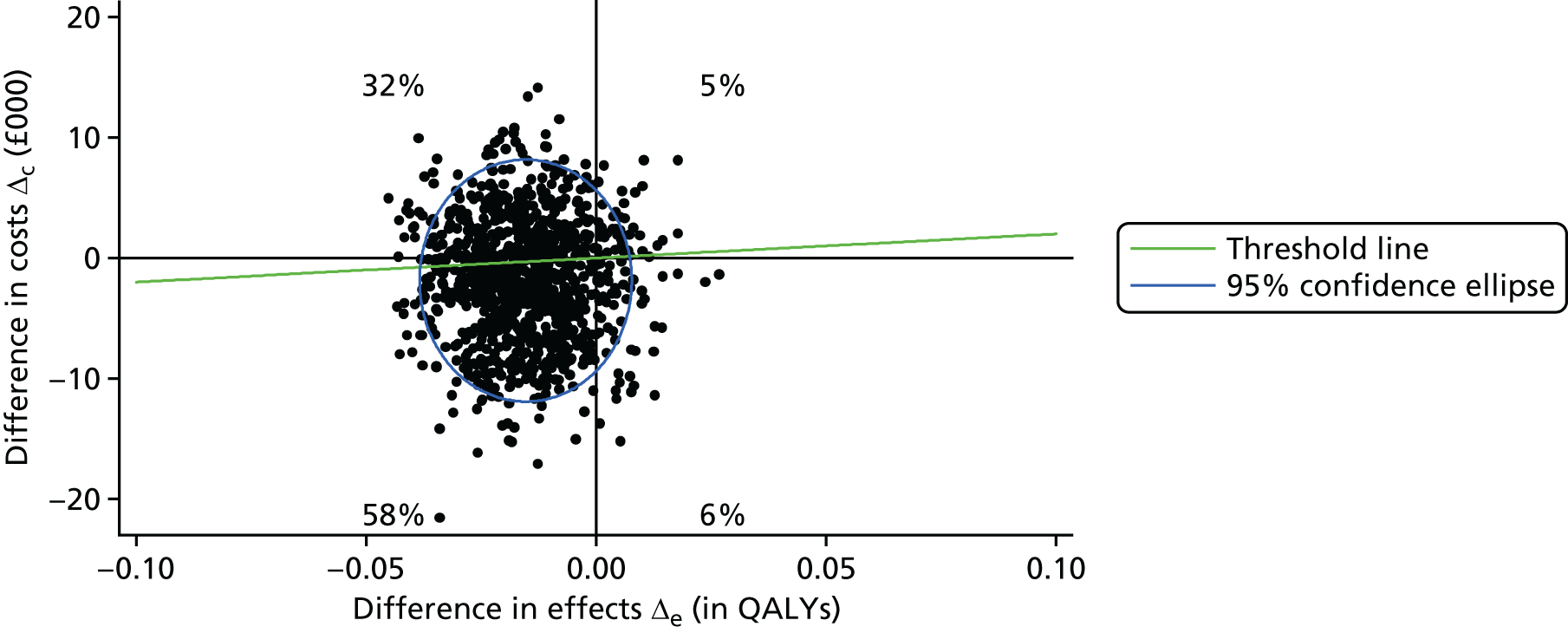

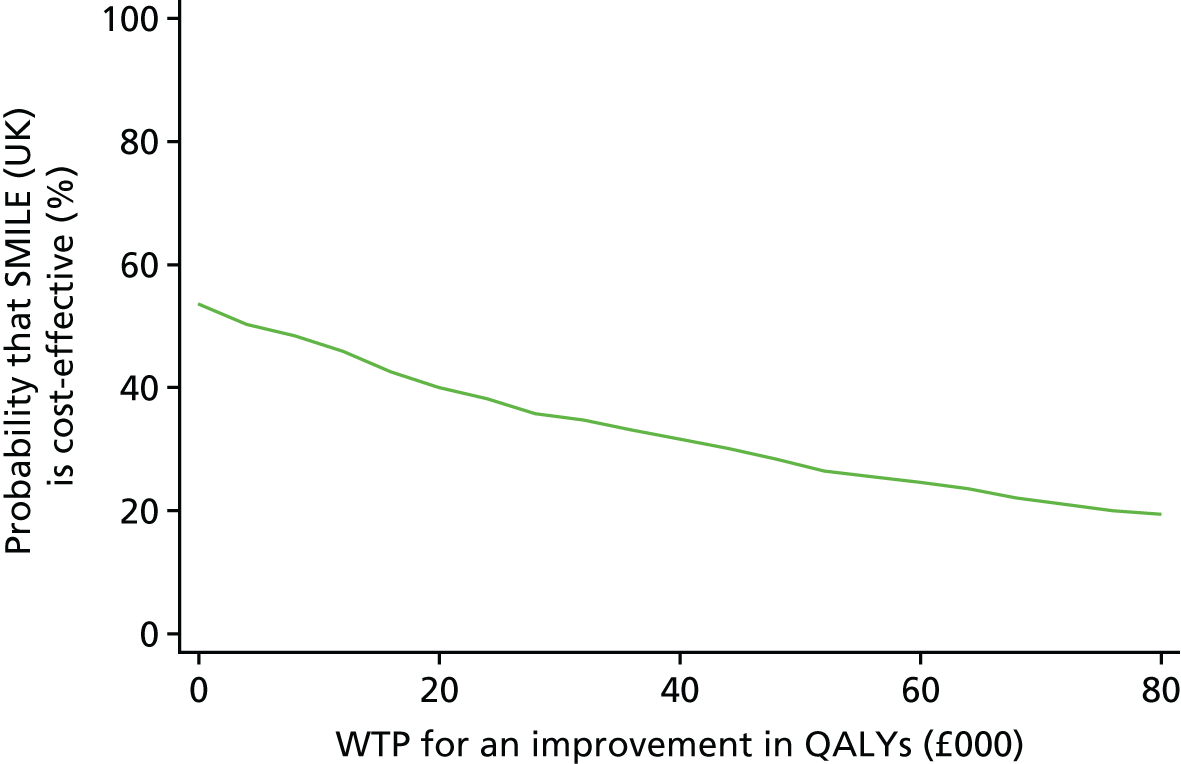

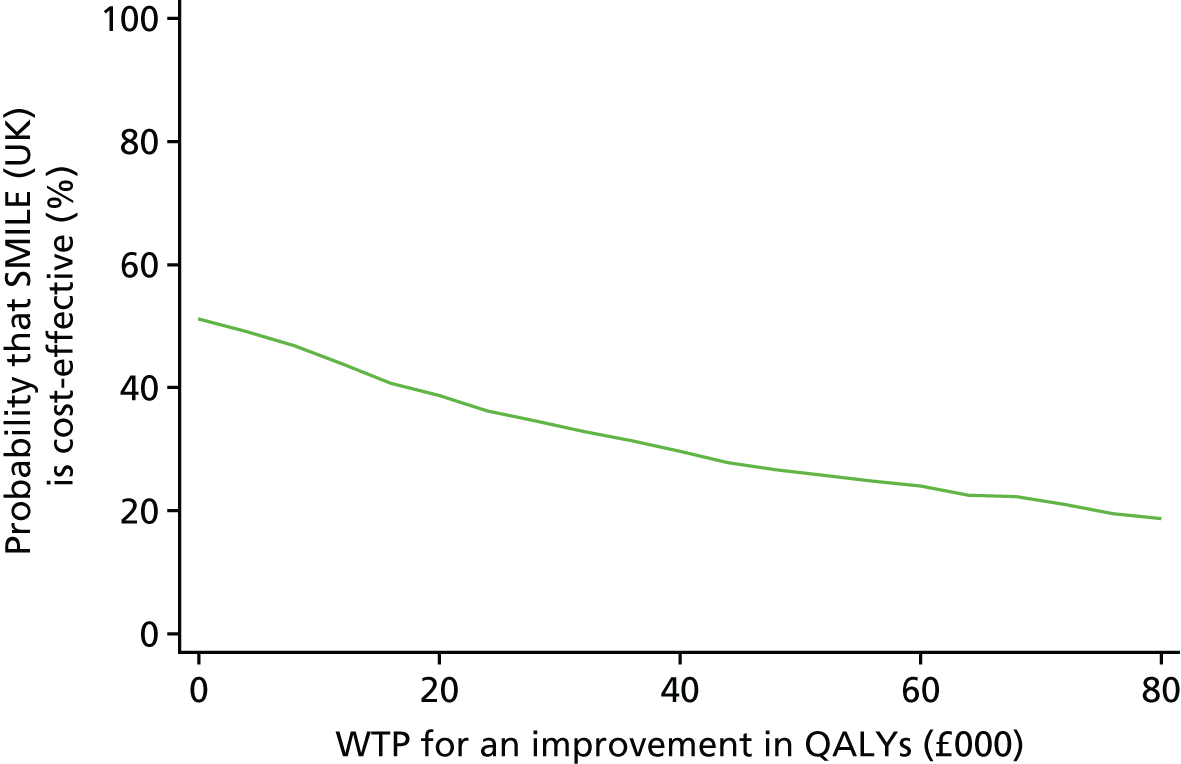

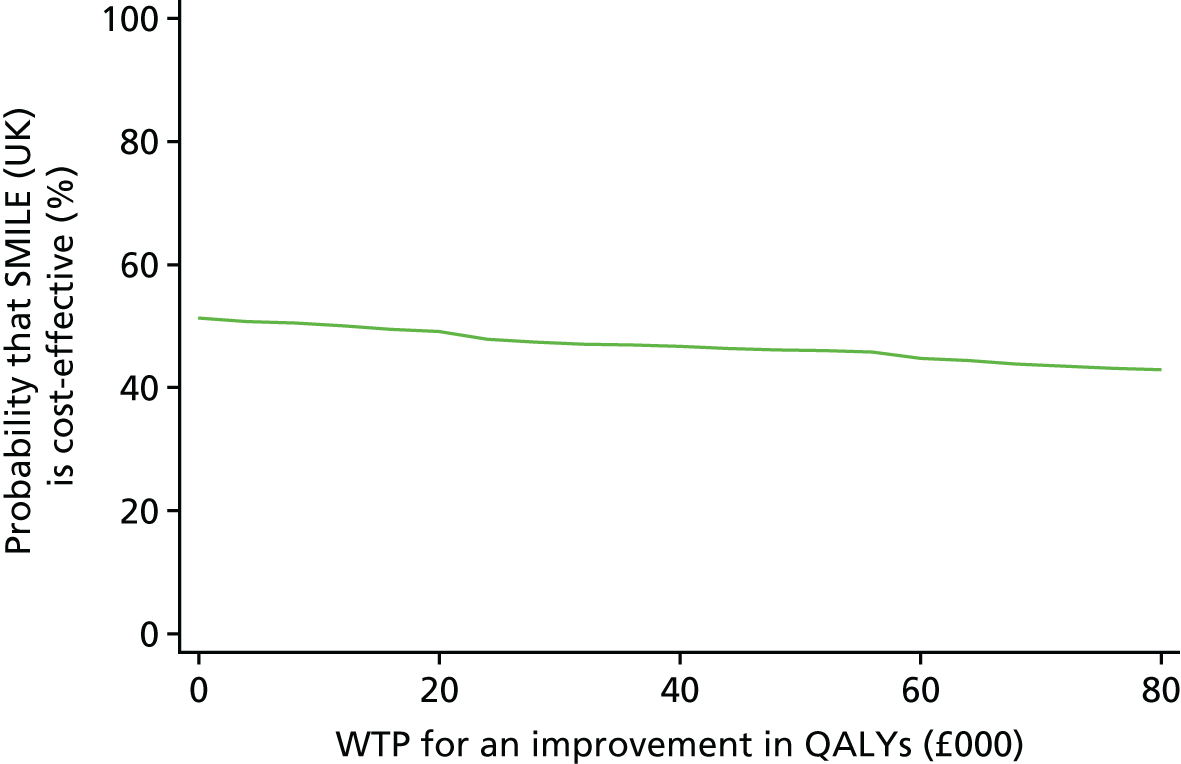

Summary of changes to project protocol