Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 12/138/02. The contractual start date was in June 2014. The draft report began editorial review in October 2016 and was accepted for publication in June 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Fiona Burns reports grants from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) for other projects during the conduct of the study, and personal fees and other from Gilead Sciences Ltd (London, UK), outside the submitted work. Rachael Hunter reports grants from the NIHR Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme for other projects, during the conduct of the study. Ibidun Fakoya reports a grant from NIHR for another project, during the conduct of the study. Eleni Nastouli reports personal fees from Roche (Burgess Hill, UK), grants from Viiv Healthcare (London, UK), grants from the European Union (H2020) and personal fees from NIHR, outside the submitted work. Lisa McDaid reports grants from the NIHR HTA programme for other projects, during the conduct of the study. Jane Anderson reports grants and personal fees from Gilead Sciences Ltd, and personal fees from ViiV Healthcare, Merck Sharp & Dohme Limited (Hoddesdon, UK), Bristol-Myers Squibb (Uxbridge, UK), Jansen-Cilag Limited (High Wycombe, UK) and AbbVie (Maidenhead, UK), outside the submitted work.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Seguin et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

HIV in the UK

Since 2003, more people have been living with heterosexually acquired human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in the UK than those with HIV acquired via sex between men. Black Africans account for 55% of people with heterosexually acquired HIV and 2% of new HIV diagnoses in men who have sex with men (MSM); thus, people of black African ethnicity account for almost one-third of the 103,000 (95% credible interval 97,500 to 112,700) adults estimated to have HIV in the UK. 1 This equates to nearly four out of every 100 black African people being HIV positive. 2

Effective antiviral therapy means that HIV incidence is likely to be driven by the fraction of undiagnosed people living with HIV, and most HIV-related morbidity and mortality is increasingly associated with diagnosis at a late stage of infection [as defined by a cluster of differentiation 4 (CD4) white cell count of < 350 cells/mm3]. 2–4 Black African people in the UK are more likely to present to HIV services with an advanced infection than people in other ethnic groups. 5,6

Late diagnosis is associated with a 10-fold increased risk of death in the first year post diagnosis, when compared with people who are diagnosed with less advanced infection. 2 Late diagnosis also implies that a person has been living with undiagnosed HIV for a substantial period of time, which increases the risk of HIV transmission to other people. Reducing the incidence of late presentation to HIV services is the single most useful way of decreasing the ill health and death associated with HIV, and reducing late diagnosis is the only HIV-specific indicator within the 2013–16 Department of Health Public Health Outcomes Framework. 7 HIV prevention efforts have increasingly focused on increasing opportunities for people to have a HIV test, which reduces both the incidence of late presentation and undiagnosed HIV infection. The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV and AIDS (UNAIDS) has set a global target of 90% of people living with HIV to be aware of their diagnosis by 2020; increasing the uptake of HIV testing is the only means by which this can be achieved. 8

HIV testing among black African communities in the UK

HIV testing in the UK is predominantly offered at sexual health clinics. Black African people are less likely to use these services than other higher-risk communities. 1 General practice (GP) is accessed by this population, but opportunities for earlier HIV diagnosis are often missed. 9 Black African men in particular have high rates of undiagnosed infection and late presentation,10 in part because they have less contact with health services than women. In addition, concerns regarding confidentiality,11,12 stigma and discrimination11–13 and fear of a HIV-positive status14 present barriers to effective testing initiatives. These obstacles are compounded by structural issues that discourage access to HIV prevention, diagnostic and treatment services, such as poverty, unemployment and lack of child care,11 the reticence of non-specialist health staff to offer HIV testing,15 a lack of political will to recognise the pervasive health inequalities faced by many migrants16 and a lack of African representatives in decision-making processes. 14 Despite these obstacles, there is evidence to suggest that many black African people will test for HIV if provided the opportunity. 10,17

At a population level, no single intervention is likely to control HIV. However, HIV testing is the starting point from which to build effective strategies. A negative test result can support individual vigilance to remain uninfected. For those who test positive for HIV, the test result opens treatment and prevention options. Timely diagnosis and treatment means that those affected can expect near-normal life expectancy. 18

Owing to the challenges associated with traditional HIV testing options for black African people, innovative methods to increase the uptake and opportunities for testing among this population are required. Interventions should extend testing opportunities and directly address the barriers that foster late and undiagnosed infection. Such interventions could incorporate developments in testing technology that reduce the need to attend specialist services [e.g. use of self-sampling or self-testing kits (STKs)] or target testing interventions to specific populations (e.g. considering the psychosocial and sociocultural contexts of target populations, such as black African communities, rather than the general population). These interventions must also address the barriers that exist at a service provider level. Interventions need to be time and cost efficient, easy to use and deliver, and supported by robust clinical pathways.

Self-sampling kits

The range of HIV testing options continues to expand, with community-based point-of-care testing (POCT) and blood and oral self-sampling kits (SSKs) increasingly available. 19 In addition, HIV STKs are now licensed for use in the UK. Self-sampling negates the need for dedicated staff or special infrastructure for specimen collection, and can be used at a time and in a setting of the user’s choice. SSKs, accessed via clinical settings and online, have been shown to be an acceptable and feasible alternative to clinic attendance for HIV testing, and may increase the uptake of testing among hard-to-reach MSM. 20–22 Testers have shown an overall preference for oral-based sampling rather than blood-based sampling, especially among first-time testers. 23 Research among young men in the UK has also demonstrated the acceptability of SSKs for HIV testing, with health-care settings being the preferred venue for accessing kits. 24

Despite the burgeoning research base focused on SSKs, there is little evidence to support the acceptability or feasibility of using SSKs to increase the uptake of HIV testing among black African people in the UK. A pilot study, initiated by the Terrence Higgins Trust/HIV Prevention England and Dean Street at Home, has documented success in reaching black African people through internet-based SSK distribution. 25 Though the study had greater success in uptake among MSM than black African people of all sexualities, it found that 9.8% of the 7761 kits were requested by black African people and 7.3% of those were returned, with a positivity rate of 2.6%.

Embedding SSKs within existing health services (including health promotion initiatives and NHS screening) may facilitate the uptake of HIV testing. A cross-sectional study undertaken among black African people in England revealed that nearly one-third of participants without diagnosed HIV said that they would prefer to have a future HIV test at their GP surgery. 26 This may indicate the acceptability of offering SSKs via existing primary care venues. However, a lack of evidence persists regarding testing preferences by ethnicity, gender and age.

In 2012, the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme released a commissioned call (12/138) driven by the following research question: ‘what is the feasibility and acceptability of interventions to overcome individual and health-care professional barriers to the provision and uptake of HIV testing in black African adults in the UK?’.

The hypothesis behind the following research was that embedding SSKs for HIV testing in existing services is an acceptable and feasible means to increase the provision and uptake of HIV testing among black African people residing in the UK.

Aims

The overall aims of our research were to:

-

develop a SSK-based intervention to increase the provision and uptake of HIV testing among black African people using existing community and health-care provision (stage 1 of the project)

-

conduct an evaluation of selected SSK distribution models to assess feasibility and optimal trial design for a future Phase III evaluation (stage 2 of the project).

To answer the research question, the following objectives and outcomes were established.

Objectives

Stage 1

-

Examine/evaluate barriers to, and facilitators of, provision, access and use of HIV SSKs by black African people, in primary care, pharmacies and community outreach settings.

-

Determine appropriate SSK-based intervention models for different settings.

-

Determine robust HIV result management pathways.

-

Develop an intervention manual to enable intervention delivery.

Stage 2

-

Determine the feasibility and acceptability of a provider-initiated, HIV SSK distribution intervention targeted at black African people in two settings:

-

GP surgeries

-

community-based organisations (CBOs).

-

Secondary objectives

-

Establish the acceptability of interventions for service providers and service users.

-

Evaluate the clinical effectiveness of self-sampling for HIV in increasing the uptake of HIV testing by black African people.

-

Determine the cost-effectiveness of distributing SSKs among black African people compared with other screening methods.

-

Monitor the ability to trace participants with reactive results, confirmatory testing and linkage into specialist care.

-

Determine the cost per kit distributed and cost per HIV diagnosis per setting.

-

Assess the feasibility of collecting data for a lifetime cost-effectiveness model.

-

Assess the feasibility and, if appropriate, the optimal trial design (including sample size parameters) for a future Phase III evaluation.

Outcomes

Primary outcome

HIV SSK return rate.

Secondary outcomes

Point-of-delivery outcomes:

-

acceptability of the targeted HIV SSK distribution

-

acceptability and feasibility of the targeted SSK distribution among specified service providers.

Data collection outcomes:

-

ability to record the number of people offered SSKs, accepting SSKs and returning SSKs

-

feasibility of collecting correct contact details enabling follow-up, reminders and communication of results.

Pathway-to-care outcomes:

-

proportion of those whose samples are reactive, who –

-

are informed of the results in person

-

attend for confirmatory testing at a NHS setting of their choice.

-

Overarching outcomes:

-

cost per kit distributed and cost per HIV diagnosis per setting

-

attrition rates

-

confirmatory testing, proportion of those receiving a HIV-positive diagnosis and clinical stage at diagnosis

-

feasibility and sensitivity of outcome measures (testing, behavioural and economic) for a definitive trial.

Structure of the report

The report is structured in accordance with the aims and objectives of stages 1 and 2 of the study. Chapters 2–5 address the objectives of stage 1, and Chapters 6–10 address the objectives for stage 2, with the discussion and conclusions in Chapter 11.

Chapter 2 Study design and methodology of stage 1

To develop a SSK-based intervention to increase the provision and uptake of HIV testing among black African people, using existing community and health-care provisions, we first needed to address the following objectives:

-

examine/evaluate barriers to, and facilitators of, provision, access and use of HIV SSKs by black African people in primary care, pharmacies and community outreach

-

determine appropriate SSK-based intervention models for different settings

-

determine robust HIV result management pathways

-

develop an intervention manual to enable intervention delivery.

The objectives were met via the following three main research activities:

-

Conducting a systematic literature and policy review exploring the feasibility and acceptability of self-sampling for HIV testing, and the clinical effectiveness of self-sampling for HIV in increasing the uptake of HIV testing (see Chapter 3).

-

Conducting focus group discussions (FGDs) with non-specialists and service providers, and one-to-one interviews with the latter to gain stakeholder input into the development of an acceptable SSK distribution pathway and protocol via community-based health and HIV prevention services already accessed by black African people (see Chapter 4).

-

Developing an intervention manual for the feasibility trial in stage 2, drawing on theoretical frameworks and findings from the first two research activities (see Chapter 5).

The remainder of this chapter focuses on the methodological and analytical approaches to the literature review; qualitative data collected through FGDs and one-to-one interviews; and the intervention manual development.

Methodology of the systematic literature review

Search strategy and identification of studies

Ten electronic databases were searched using detailed search strategies:

-

OvidSP MEDLINE

-

OvidSP EMBASE Classic and EMBASE

-

OvidSP Global Health

-

OvidSP Social Policy and Practice

-

OvidSP PsycINFO

-

OvidSP Health Management Information Consortium

-

EBSCOhost Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature Plus with Full Text

-

The Cochrane Library

-

Web of Science Core Collection

-

Scopus.

The search strategy used for OvidSP MEDLINE is provided in Appendix 1.

Only studies written in English were included. The results were downloaded into a deduplicated database in EndNote 7 [Clarivate Analytics (formerly Thomson Reuters), Philadelphia, PA, USA]. The initial search was undertaken on 26 September 2014. Two further searches to update the database were undertaken on 17 April 2015 and 3 May 2016. Additional grey literature was retrieved from websites operated by the following organisations:

-

Avert (www.avert.org)

-

Terrence Higgins Trust (www.tht.org.uk)

-

National AIDS Trust (www.nat.org.uk)

-

Lambeth Council (www.lambeth.gov.uk/consultations/lambeth-southwark-lewisham-sexual-health-strategy-consultation)

-

Naz Project London (http://naz.org.uk)

-

Sexual Health Sheffield (www.sexualhealthsheffield.nhs.uk).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Only studies published since 1 January 2000 were included, as studies published earlier would be unlikely to reflect current technology or attitudes to HIV testing. Only studies conducted in the European Union/European Free Trade Agreement countries, North America, New Zealand or Australia were included, as studies conducted in other locations (particularly resource-poor settings) would probably have markedly different contexts and, thus, their results would not be applicable to the UK. Study populations that included lay groups, as well as health professionals, were included. Only studies that examined home/self-sampling tests for HIV were included as intervention studies. Studies without comparators were also included, as well as studies that compared home/self-sampling tests for HIV with routine service provision or other HIV testing interventions. Studies were included if they reported on any of the following outcomes:

-

increase/decrease in the number of HIV tests

-

proportion/number of confirmatory tests

-

proportion/number of participants linked into care

-

adverse events associated with HIV self-sampling

-

proportion/number of false positives or failed tests

-

increase/decrease in the reported history and frequency of taking HIV tests

-

increase/decrease in the number and types of venue where HIV testing is offered.

Qualitative studies were included only if they reported one or both of the following:

-

barriers to, or facilitators of, self-sampling reported by the general population

-

barriers to, or facilitators of, self-sampling reported by service providers.

The following study designs were considered for inclusion:

-

randomised or non-randomised controlled trials

-

prospective or retrospective cohorts

-

cross-sectional studies/prevalence studies

-

pilot or feasibility studies

-

qualitative studies (using in-depth interviews, FGDs and document analysis).

Studies that examined the use of, or views about, self-sampling for HIV in health-care workers were excluded, because the review focus was on uptake among testers, not service providers, as were all conference communications, because of insufficient detail and lack of peer review. Studies that focused solely on, or the outcomes of which were predominantly about, self-testing for HIV were also excluded at the study selection stage.

Study selection

Studies were selected using a two-stage screening approach. Reviewers Ibidun Fakoya and Esther Mugweni devised a checklist to independently screen titles and abstracts (see Appendix 1). When a consensus could not be reached about study inclusion, a third reviewer (FB) was consulted. Full-paper copies of the selected studies were screened and assessed independently by Ibidun Fakoya and Esther Mugweni, using a screening tool (see Appendix 1). Updated searches were screened using the same approach by Caroline Park, Thomas Hartney and Lisa McDaid. Inter-reviewer reliability scores of the different stages of the review were calculated using kappa in Microsoft Excel® 2010 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). The full-paper screening achieved a kappa score of 1.0, which indicates a high level of agreement between reviewers.

Data extraction, analysis and synthesis

Structured data extraction tools were developed to capture the required information from the included papers on study types, populations, SSK interventions and acceptability, feasibility and efficacy outcomes. Data were extracted by Caroline Park and checked by Thomas Hartney.

A meta-analysis was not conducted, as a result of the heterogeneity of the designs, methods, samples and outcomes of the included studies. There are a number of narrative approaches to data synthesis, including integrative synthesis, to primarily combine and summarise data, and interpretative synthesis that aims to generate new concepts and theory. 27 An integrative approach to summarising and presenting the data was appropriate to this review. The narrative synthesis is supported by tables in Results of the systematic literature review, which outline the key characteristics and findings of each included study, as relevant to the research questions. To reduce the risk of bias, the extracted data were first summarised by Lisa McDaid and then reviewed by Thomas Hartney. Disagreements in interpretation were resolved through discussion between the two authors.

Quality appraisal

The quality of the eligible papers was appraised by Thomas Hartney using the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) quality appraisal checklist for quantitative papers. 28 Each quantitative paper was assigned a score for internal and external validity, from ++ (high quality) to – (poor quality). Each qualitative paper was assigned a single overall score. The appraisal process was validated by a second researcher (Lisa McDaid) assessing a sample of papers with a high level of agreement reached. Any papers that did not present self-sampling data separately from other forms of testing were excluded, but papers were not excluded on the basis of quality.

Methodology of focus group discussions and one-to-one interviews

Qualitative research methods were used to collect data using FGDs and one-to-one interviews in late 2014. Ethics approval was obtained from the University College London (UCL) Research Ethics Committee [REC; project identification (ID) number 3321/001].

The study team conducted 12 FGDs, a method which was selected to maximise the extent of interaction between research participants in order to establish group similarities, as well as differences, by encouraging discussion, exchange and justification of divergent viewpoints. 29 Six of these groups were conducted with non-specialist members of the public who identified as black African and six were conducted with professionally, culturally and ethnically diverse people who provide HIV and other social services to black African people. From the latter group, nine participants also participated in one-to-one interviews, a choice that was made primarily to enable interviewers to tailor the topic guide in ways that would help to best capture the specific world view of these expert interviewees. 30

Topic guides for the non-specialist and service provider FGDs (see Appendices 1 and 2, respectively) were developed in consultation with members of the steering group and study team. The topic guide for the one-to-one interviews was adapted from that for service provider FGDs. These guides structured flexible discussions about participant views towards SSKs, community trust of SSKs, the practicalities and rationales for selecting potential community settings outside sexual health clinics, mechanisms for returning the sample, and communicating and confirming results to users, and the content of SSK packs. Group facilitators and interviewers sought to create a balance between the a priori issues outlined above, while also harnessing participant-led articulation of perspectives, social norms and discourses.

During the FGDs, participants were shown a video made by the producers of the TINY vial SSK (www.tdlpathology.com/test-information/test-service-updates/tdl-tinies). In a number of groups, participants were also shown an instructional video developed by a community organisation (www.youtube.com/watch?v=FSm0zP1TGUo) on self-use of dried blood spot sampling kits. TINY vial SSKs were displayed, distributed and discussed in all groups. As it was known that the use of an oral fluid kit was not possible within the context of the HAUS study, no oral-based kit was demonstrated during the groups. However, these kits were discussed by participants.

Participatory methods, such as ranking activities, were used to enhance data collection and participant engagement during FGDs. 29 The study team members who collected qualitative data in this stage were Catherine Dodds, Esther Mugweni, Sonali Wayal, Caroline Park, Gemma Philips and Ingrid Young. Catherine Dodds, Sonali Wayal and Ingrid Young already possessed extensive training and experience in this format of data collection in the HIV field among specialist service providers and non-specialists alike, and Catherine Dodds and Ingrid Young in particular were responsible for training and overseeing the research development of Esther Mugweni, Gemma Philips and Caroline Park. All FGDs were initially led by those with the greatest experience and ‘seconded’ by Esther Mugweni, Gemma Philips and Caroline Park, and, over time, these roles started to switch as the last group gained familiarity and experience with the method and the research tools being used. Two researchers attended every group to better enable data capture (including observation). All those involved in data collection had considerable opportunity to discuss challenges, successes and possible improvements to data collection during fortnightly core team meetings, designed to assist such exchange. Esther Mugweni and Gemma Philips undertook all one-to-one interviews, and each had considerable experience and training in this method.

Non-specialist black African focus group discussions

Participants in the non-specialist FGD included members of the public who self-identified as being black African (n = 48). Three of the FGDs occurred in Greater Glasgow, and three occurred in Greater London. The participants were recruited via social media (n = 1) and African embassies in London (n = 6), as well as university student groups (n = 16), and CBOs (n = 24) in both Glasgow and London (missing data, n = 1). Participants were eligible if they self-identified as being black African and were aged ≥ 18 years. The sample was purposively selected sequentially during recruitment (with some interested individuals being set aside into a ‘pool’ of recruited participants in case they were needed at a latter stage) to ensure diversity of age, region of birth and HIV testing experience. Men were slightly over-represented in the sample, with 28 out of 48 male participants (58%), compared with 20 female participants (42%). The age ranged from 18 to 60 years. Participants were born in various regions of Africa, including East Africa (n = 17), Southern Africa (n = 10), West Africa (n = 10) and Central and North Africa (n = 3), and some were born in the UK, Europe or the USA (n = 7; missing data, n = 1). In order to ensure a balance of voices, one of the FGDs consisted only of people aged < 30 years (in London), another group consisted of men only (in London) and a further group consisted of people living with diagnosed HIV (in Glasgow). The other three FGDs were mixed in terms of participant gender, age and HIV testing experience (London and Glasgow). Nineteen participants had never tested for HIV. The black African non-specialist FGD participants were compensated £25 for participating in the discussion. Each FGD lasted between 1.5 and 2 hours, with an average of nine participants in each group (range of 7–11 participants). The FGDs were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Service provider focus group discussions and interviews

Six FGDs were conducted with service providers: three in Glasgow and three in London. Sequential purposive sampling (undertaken with the support of simple screening questions asked during the recruitment process) ensured the diversity of service providers from a range of professional backgrounds, all of whom provided HIV-related or other social services to black African people. Black African ethnicity was not a criterion for involvement in these FGDs. GPs were recruited via Clinical Research Networks (CRNs) in London and through established working relationships with members of the research team in both Glasgow and London. Community workers in both cities were recruited from organisations with extensive experience of delivering HIV prevention and care, as well as a range of other non-HIV-specific services to black African people. The research team approached pharmacies in areas with high numbers of African residents in Glasgow and London, with support from local pharmacy associations. Almost all specialist FGDs comprised those from diverse working backgrounds, in order to elicit contrasts within working and experiential contexts.

In total, 53 service providers participated in either a FGD or a supplementary interview. Those taking part in FGDs included HIV CBO staff (n = 15), pharmacists and pharmacy assistants (n = 9), general practitioners (n = 7), those who provided services to black African people (non-HIV focused) (n = 5), GP and specialist nurses (n = 3), African faith leaders (n = 3) and a health-care assistant (HCA; n = 1). The service provider FGD participants were offered reimbursement for their travel and their time given to the study. The level of reimbursement varied according to profession. The service provider FGDs lasted between 1.5 and 2 hours, with an average of seven participants in each group (range of 4–10 participants). These sizes fell within the ideal range to prompt discussion, while ensuring the participation of everyone in the group. 30

Following the FGDs, interviews with 10 highly specialised HIV service providers (including HIV clinicians, HIV service managers and service commissioners) in London (n = 3) and Glasgow (n = 7) were conducted to help check the acceptability of the intervention and procedures. This approach was undertaken to include diversity of voice in FGDs, accompanied by highly specialised expertise gained through interviews. Each interview lasted between 30 and 45 minutes. The FGDs and interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Analysis of focus group discussions and interviews

An analysis of the qualitative data was undertaken using a ‘blended’ thematic approach drawing heavily on framework analysis. 31 NVivo version 10 (QSR International, Warrington, UK) was used to synthesise and code data within a thematic matrix to enable elucidation of conceptual associations. Both a priori concepts used in the development of the FGD topic guide, as well as emergent concepts arising from the data, informed the process of identifying the key thematic categories used in data coding. Two researchers devised an agreed coding frame, which was then used to index and chart the findings. The integrated model of behavioural prediction and change was used as the theoretical framework to assess attitudes, willingness and perceived behavioural control to use HIV SSKs. 32

Broad descriptive themes included the feasibility and accessibility of HIV testing, and existing knowledge and uptake of SSKs, and the practicalities of distribution emerged. Cross-cutting themes also surfaced, which influenced our analysis, particularly those concerned with trust and HIV-related stigma. The themes were then refined to devise a more detailed participant-led, inductive, thematic framework. Researcher team discussions and iterative analysis focused on the internal coherence and face validity of the resulting analytic structure.

Methodology and analytic approach of intervention development

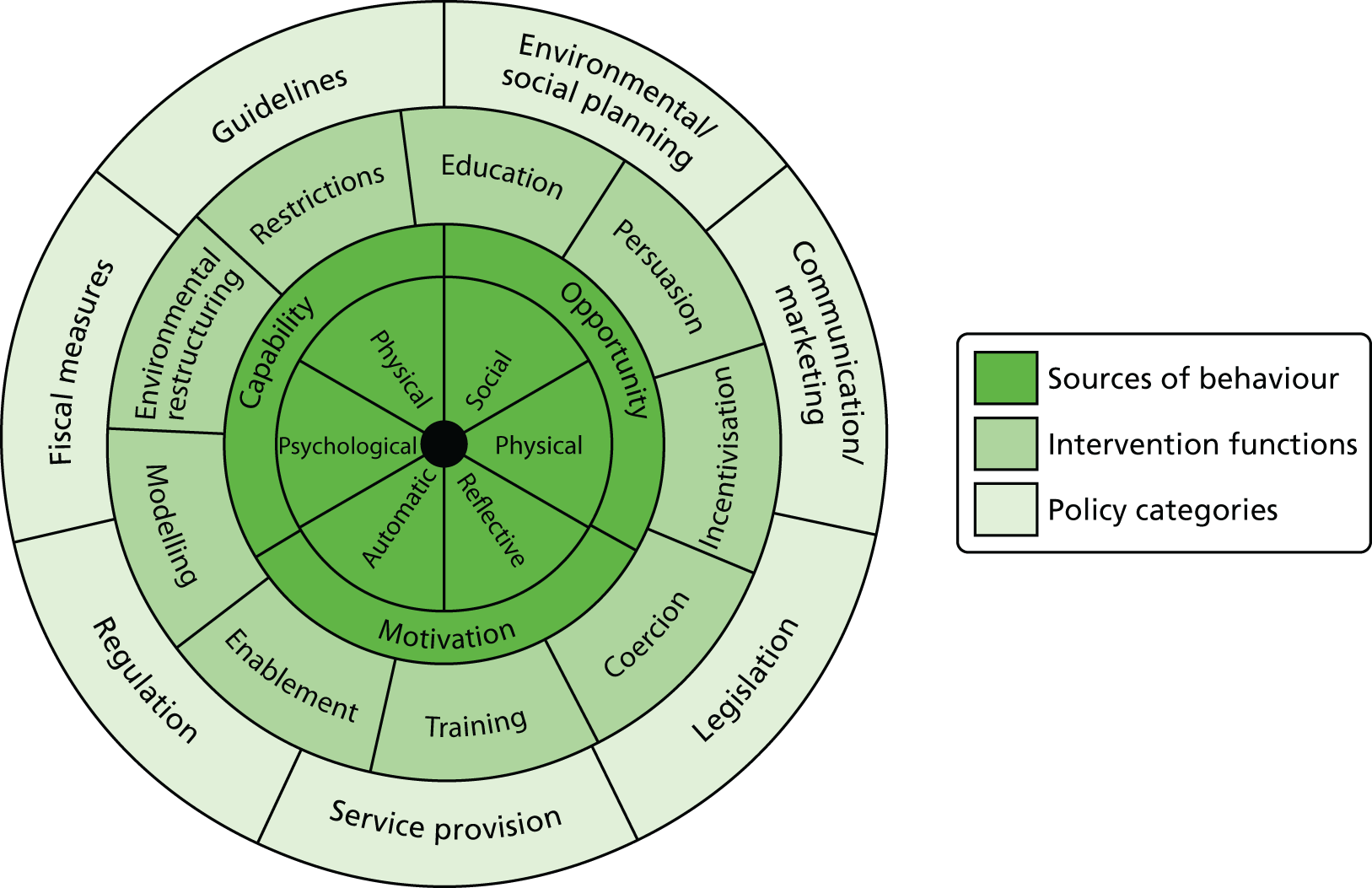

At the outset, it was recognised by the study team that successful interventions to increase the uptake of HIV testing are particularly challenging, as a result of the sexual transmission aspect and stigma associated with HIV, the latter being particularly prevalent among African communities in the UK. To mitigate the complexity inherent in developing and implementing a HIV SSK intervention, a systematic four-step approach to intervention development was adopted, drawing on the behaviour change wheel33 (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

The behaviour change wheel. Reproduced from Michie et al. 33 This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Step 1: delineate key intervention components

The intervention development process began with identifying and conceptualising the diverse intervention components arising from a combination of existing SSK distribution practice and process-oriented data emerging from stage 1. The research team considered the sequential flow across social contexts, health professionals, SSK recipients and clinical governance procedures. In this way, the study team systematically considered the segmentation and flow of the intervention chain. This conceptual work also assisted in informing the topic guides for follow-up interviews with participants who agreed to take a SSK (regardless of whether or not they ultimately used it; see Appendix 4) and the choice of analytical approach for the intervention development work that followed.

Step 2: intervention barriers and facilitators, and relation to theoretical domains

Step 2 involved further consideration of the key intervention components identified in step 1 by utilising stage 1 data on barriers to, and facilitators of, the intervention. Appendix 5 provides an example of how the study team analysed the relevant data regarding the component ‘appearance and packaging of the HIV SSK’. Key barriers and facilitators were then mapped onto the theoretical domains framework (TDF). 34

The TDF is a metatheoretical framework that integrates key theoretical domains known to be important in understanding behaviour change across a range of populations. It provides a coherent way of organising explanations of why things do or do not happen in relation to either behaviour change or the implementation of particular intervention components. It enables insights into potential mechanisms of action for developing or optimising interventions. Table 1 illustrates the key domains of the TDF and provides a brief explanation of the content to which the particular domain refers.

| Domains | Explanatory statement of the domain |

|---|---|

| Knowledge | An awareness of the existence of something |

| Skills | Ability or proficiency acquired through practice |

| Professional roles/identity | Coherent set of behaviours and personal qualities of an individual in a work setting |

| Beliefs about capabilities | Acceptance of the truth or validity of an ability that a person can put to constructive use |

| Optimism | Confidence that things will happen for the best or that desired goals will be obtained |

| Beliefs about consequences | Acceptance of the truth or validity about the outcomes of a behaviour |

| Reinforcement | Increasing the probability of a response by arranging a dependent relationship between the response and a contingency |

| Intentions | Conscious decisions to perform a behaviour or act in a certain way |

| Motivation and goals | Representation of the outcome that an individual wants to achieve |

| Memory and decision processes | Ability to retain information, focus selectively and choose between two or more alternatives |

| Environmental context and resources | Any circumstances of a situation or environment that discourage/encourage development of skills, abilities and competencies |

| Social influences (norms) | Interpersonal processes that can cause individuals to change their thoughts, feelings or behaviours |

| Emotions | Complex reaction pattern, involving experiential, behavioural and physiological elements |

| Behavioural regulation | Anything aimed at managing or changing objectively observed or measured actions |

Analysis and the mapping of barriers to, and facilitators of, the TDF domains were discussed within a single all-day event attended by the research team. Differences of opinion were resolved through consensus.

Step 3: identifying intervention components that could overcome barriers and enhance facilitators

In step 3, an ideal hypothetical intervention that minimised key barriers and amplified key facilitators was constructed. The behaviour change wheel33 was then used to structure the intended intervention, guided by the ideal intervention.

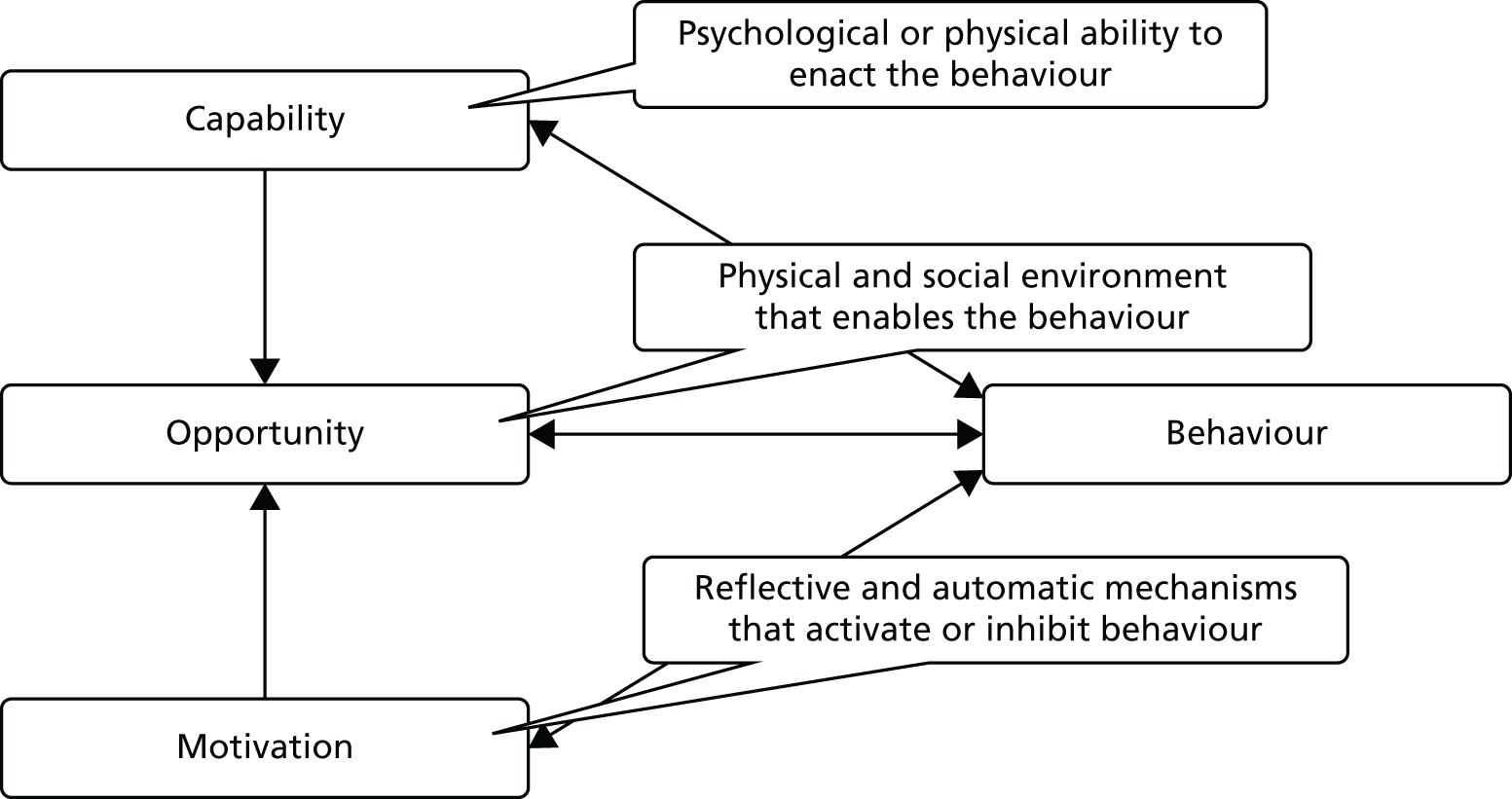

The behaviour change wheel33 links the domains of the TDF to the COM-B (capability, opportunity, motivation and behaviour) model of behaviour change36 (Figure 2). The COM-B model suggests that behaviour change is related to three key factors: (1) capability, (2) opportunity and (3) motivation. These three factors can be broken down into fine-tuned categories and, eventually, the TDF domains. Table 2 shows how the TDF domains relate to each COM-B component.

FIGURE 2.

The COM-B model. Adapted from Michie et al. 33 This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

| COM-B component | TDF domain |

|---|---|

| Capability | |

| Psychological | Knowledge |

| Cognitive and interpersonal skills | |

| Memory, attention and decision processes | |

| Behaviour regulation | |

| Physical | Skills |

| Opportunity | |

| Social | Social influences (norms) |

| Physical | Environmental context and resources |

| Motivation | |

| Reflective | Professional roles/identity |

| Beliefs about capabilities | |

| Optimism | |

| Beliefs about consequences | |

| Motivation and goals | |

| Intentions | |

| Automatic | Reinforcement |

| Emotions | |

Step 4: viability of the intervention

The outcome of step 3 provided a range of potential ways in which the intervention could be structured that would reflect key mechanisms of action and reduce barriers to effective implementation. However, it was important to ensure that the resulting intervention was viable within busy service delivery contexts. Thus, the study team evaluated the intervention content with the APEASE (affordability, practicability, effectiveness and cost-effectiveness, acceptability, site-effects/safety and equity) criteria,32 assessing the viability of intervention function and behaviour change techniques for a real-world intervention implementable within the UK.

Summary of stage 1 methods

This chapter has described and provided a rationale for each of the activities undertaken to meet the key objectives for this stage of the project, namely to:

-

review the available literature on SSKs with regard to the feasibility, acceptability and clinical effectiveness of this technology at increasing the uptake of HIV testing

-

gain insight from experts and non-experts into the best means of targeted distribution of SSKs for the benefit of black African people in the UK, as well as their perspective on kit use and functionality; and

-

convert these insights using a systematic four-step approach to intervention development, drawing on the behaviour change wheel. 33

Strengths and limitations

Although limited in scope and scale, the range of methods used in stage 1 enabled the team to select a mix of data sources and analytical approaches in its systematic, theoretically driven approach to intervention development.

Findings of the formative stage 1 FGDs and interviews with specialist service providers and non-specialist members of the public, and the ensuing intervention development process, are presented in Chapters 4 and 5, respectively. The next chapter presents the methodology and results from the policy and systematic literature review.

Chapter 3 Systematic policy and literature review

A systematic literature and policy review exploring the feasibility and acceptability of self-sampling for HIV testing, and the clinical effectiveness of HIV self-sampling in increasing the uptake of HIV testing, was conducted. The overall purpose of this exercise was to address the first three objectives of stage 1: (1) to clarify barriers to, and facilitators of, provision, access and use of HIV SSKs by black African people, in primary care, pharmacies and community outreach; (2) to determine appropriate SSK-based intervention models for different settings; and (3) to determine robust HIV result management pathways. This review also informs the fourth objective, to develop an intervention manual to enable intervention delivery. This chapter contains the methodology and results of the policy and systematic literature review.

The systematic review was registered as PROSPERO CRD42014010698.

Policy review

A policy review was conducted with the aim of summarising current approaches to, and policies/protocols around, the use of SSKs for the detection of HIV in the UK to add context to, and inform the development of, the HAUS SSK intervention manual. Eleven policy statements, clinical guidelines, reports and strategies that contained programmatic or clinical guidance on HIV self-sampling or on HIV testing in the UK or specific guidance on HIV testing for black African people in the UK, published between January 2008 and July 2016, were included (see Appendix 6). In the section below, we provide an overview of the policy approaches and recommendations relevant to SSKs.

Policy approaches and recommendations relevant to self-sampling kits

Most of the policy guidance documents yielded by this search were not specific to SSKs. The UK National HIV testing guidelines were produced by the British HIV Association (BHIVA), the British Association of Sexual Health and HIV (BASHH) and the British Infection Society in 2008, against the background of late HIV diagnosis and undiagnosed HIV status in the UK. 37 The guidelines advocated for the expansion of HIV testing services, including routine offering of HIV testing in GPs, in areas where the prevalence is higher than two per 1000 among 16- to 59-year-olds, to patients attending specified services, such as sexual health clinics or pregnancy termination services, and to patients who report practising high-risk behaviour and patients with indicator conditions. 37 Implementation of these guidelines was assessed using eight pilot projects in acute medical settings, emergency departments, primary care and community settings. 38 Findings from the pilot projects showed that the implementation of guidelines to expand HIV testing in the medical and community settings was both feasible and acceptable; HIV SSKs were successfully used in one of the pilot projects. A later review by Public Health England (PHE) on the evidence of the clinical effectiveness of HIV testing in medical and community settings noted that self-sampling could broaden the available testing options. 39 Other strategies have advocated for self-testing as an alternative option. 40 Indeed, the national response to HIV continues to evolve and, in April 2014, HIV STKs became legal in the UK. 41,42

With regard to policy specific to the black African community, NICE published specific guidance on increasing the uptake of HIV testing among black African people in 2011. 43 In 2014, NICE provided detailed recommendations for commissioners, including local authorities, Clinical Commissioning Groups and NHS England, on delivering HIV testing services. 44 NICE recommended that commissioners assess the local need for HIV testing for black African people and then develop a local HIV testing strategy with clear referral pathways, particularly for outreach point-of-care services. To address undiagnosed HIV and late diagnosis of HIV, NICE recommended that commissioners promote HIV testing, including through the use of modern HIV tests, and reduce barriers to HIV testing among black African people. In line with the 2008 guidelines mentioned above,37 NICE recommended that HIV testing should be offered by health professionals in primary and secondary care. Although SSKs were not specifically mentioned in these guidelines, SSKs have been commissioned by some local authorities as part of their HIV testing services. The NICE guidelines were updated in December 2016 and SSKs were considered a potentially innovative way of increasing the uptake of HIV testing among black African people, given that these kits may address known barriers to HIV testing in this risk group. 45 In the draft guidelines issued for consultation earlier this year, SSKs and STKs were endorsed as innovative ways of increasing uptake of HIV testing among black African people, given that they may potentially address the known barriers to HIV testing in this group. 45 Despite support within the policy documents for HIV SSKs as a means of increasing uptake of testing, evidence on the impact of SSKs on uptake compared with clinic-based testing was limited to one study.

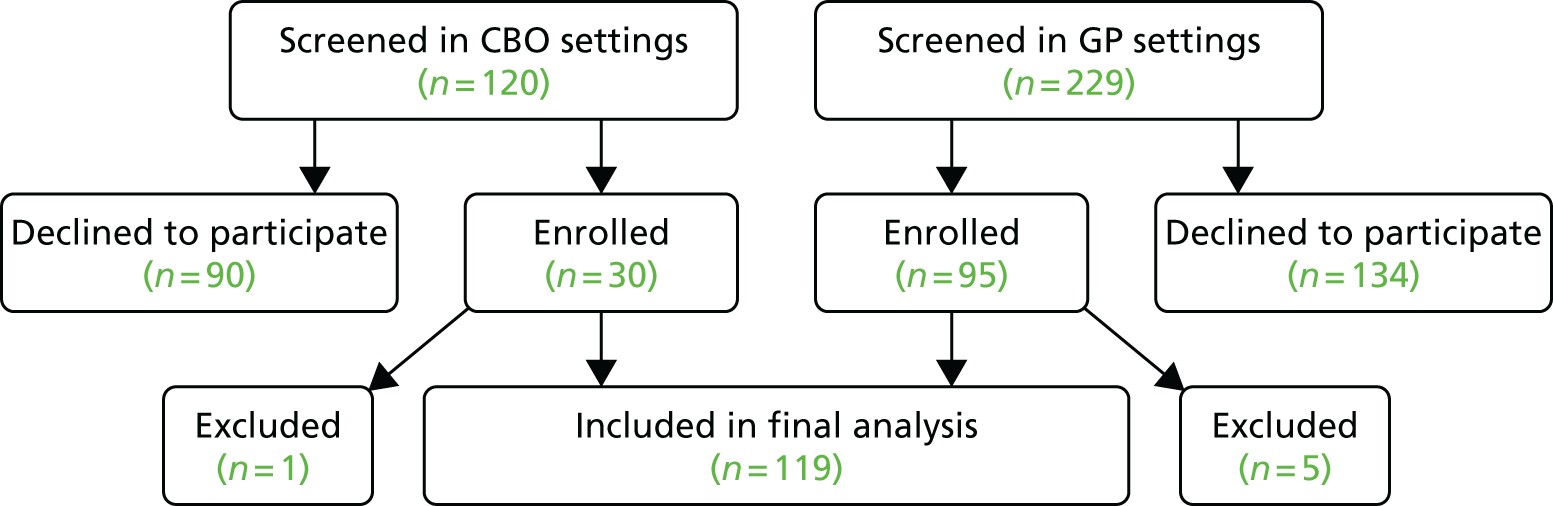

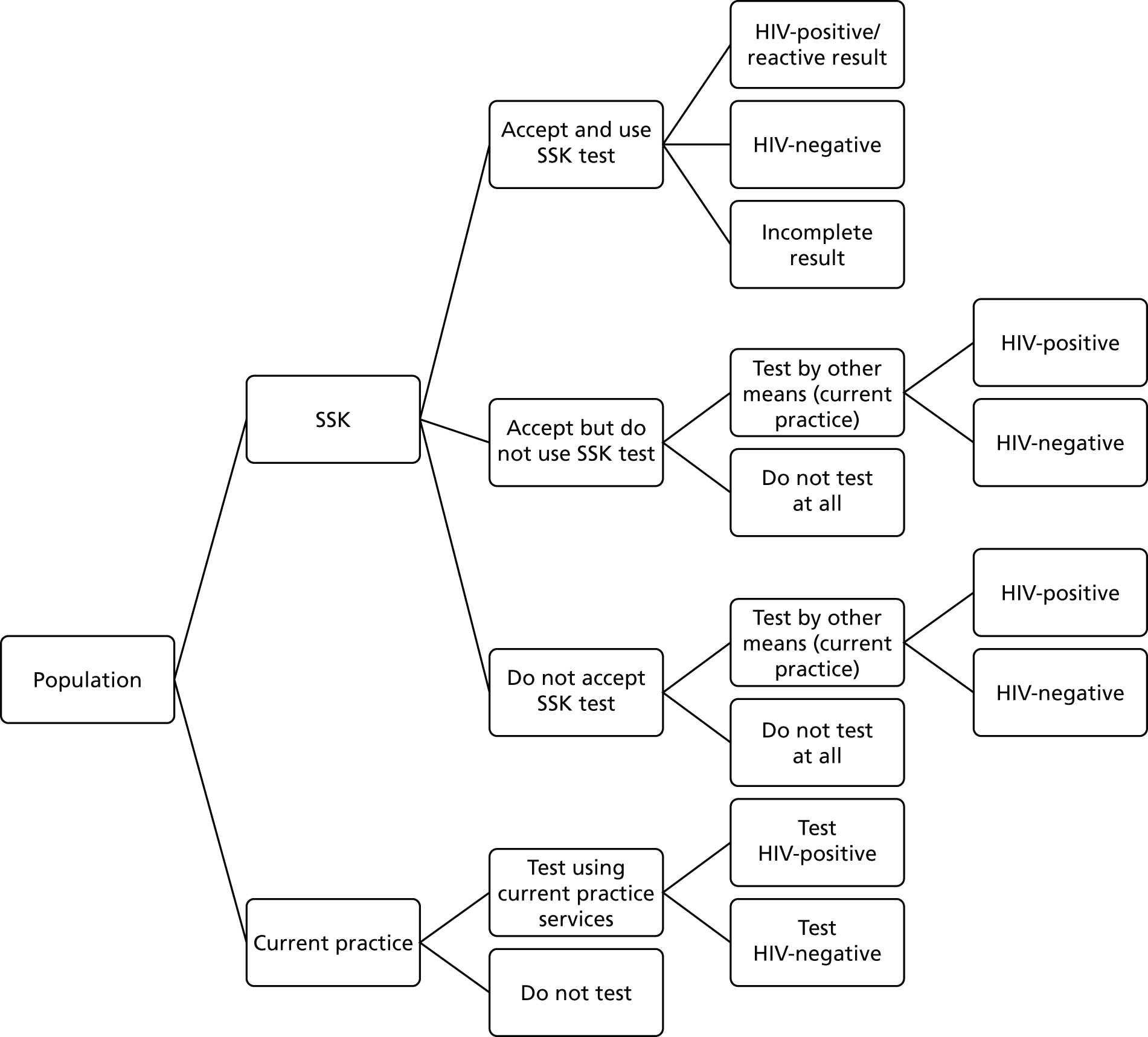

Results of the systematic literature review

A total of 4052 documents were retrieved, of which 1994 were duplicates. Reviewers identified 85 papers eligible for full-paper screening, with 1973 excluded as they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Seventy-two papers were excluded after full-paper screening as a result of not including SSKs for HIV testing or presenting only combined results with other types of testing (n = 38), inappropriate publication type (n = 26), inappropriate study type (n = 6) or irrelevant country setting (n = 2). Figure 3 contains a flow chart of the study search and selection process. Thirteen studies were selected for inclusion in the literature review.

FIGURE 3.

Flow chart of the study search and selection process.

Description of included studies

Table 3 presents the description of the 13 studies included in the review. 21,46–57 Of the included studies, nine were conducted in the USA21,46,47,50–55 and four were conducted in the UK. 48,49,56,57 Eight were cross-sectional surveys,47,49–55 three were prospective cohort studies,21,48,57 one was a qualitative study56 and one was a randomised controlled trial (RCT). 46 The total sample size across the papers was 15,816, with an average response rate of 78% (range 38–100%; information was not provided in two studies47,57). The majority of the studies included communities at high risk of HIV infection. Ten studies included MSM,21,47–53,56,57 three included people who inject drugs (PWID)46,47,50 and three included non-specified individuals or clinic populations who practised high-risk activities. 21,54,55 Only two studies focused on heterosexual populations who practised high-risk activities (both studies were based in the USA);47,50 all of the UK studies included only MSM. The only RCT in the included studies was conducted with PWID. 46 Most studies reported a predominantly white sample, although the sample in the RCT was 48% African American. 46 Among the studies that provided this information, the average age of participants ranged from 18 to 47 years.

| Study number | First author (year of publication) and reference number | Study design | Study aims | Setting | Population (i.e. clinic, MSM, etc.) | Sample size, n | Response rate, % | Sample characteristics (i.e. age, gender, ethnicity) | Type of HIV testing sample | Method of SSK distribution | Method of return | Quality appraisal score (internal/external)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bartholow (2005)46 | RCT | To compare the likelihood of HIV testing and obtaining test results between participants randomised to:

|

USA | PWID | 489 | 92 | Mean age of 40 years; 71% male; and 48% African American | Dried blood spot | Provided in drug clinic | Post | ++/++ |

| 2 | Colfax et al. (2002)47 | Multiple cross-sectional surveys | An examination of intent to use a SSK, actual use and barriers to use among persons at high risk of HIV | USA | MSM, PWID, heterosexuals at high risk of HIV | 3471 | Not reported | 74% male; and 44% white | Dried blood spot | Purchased (presumably from a pharmacy) | Not specified | +/+ |

| 3 | Fisher et al. (2015)48 | Prospective observational cohort | To determine the uptake of SSKs for HIV and STIs compared with conventional clinic-based testing, and to determine whether or not the availability of SSKs would increase the uptake of STI testing among HIV-infected MSM and those attending a community-based HIV testing service compared with historical controls | UK | MSM | 433 (80 for HIV testing) | 75 | Median age of 33 years; and 84% white British | Oral fluid | By post | Post | +/+ |

| 4 | Formby et al. (2010)49 | Cross-sectional survey | To evaluate the ‘Time 2 Test’ pilot study, which was based on the use of SSKs | UK | MSM | 126 | 100 | Median age of 24 years; and 89% white British | Oral fluid | Postal and public sex environments | Post | –/– |

| 5 | Greensides et al. (2003)50 | Cross-sectional survey | To determine the levels of awareness and use of alternative HIV tests (SSKs and rapid tests among people at high risk of HIV) | USA | MSM, PWID, heterosexuals at high risk of HIV | 2836 | 66 | Mode age of 25–34 years; 73% male; and 39% white | Dried blood spot | Not specified | Not specified | +/+ |

| 6 | Osmond et al. (2000)51 | Cross-sectional survey | To test the feasibility of obtaining HIV test results by SSKs from a probability telephone sample of MSM | USA | MSM | 490 | 78 | Urban areas; 67% white; and 71% aged 18–29 years | Oral fluid | Mailed | Post | ++/+ |

| 7 | Sharma (2011)52 | Cross-sectional survey with randomisation | To describe the factors associated with the willingness of internet-using MSM to take a free anonymous home HIV test as part of online prevention activities | USA | MSM | 6163 | 68 | Median age of 18–24 years; 43% white; and 31% Hispanic | Not specified | Not specified | Post | +/+ |

| 8 | Sharma et al. (2014)53 | Cross-sectional survey | To investigate attitudes towards six different HIV testing modalities presented collectively to internet-using MSM and identify which options rank higher than others in terms of intended usage preferences | USA | MSM | 973 | 38 | Median age of 26 years; and 77% white | Dried blood spot | Not specified | Not specified | +/+ |

| 9 | Skolnik et al. (2001)54 | Cross-sectional survey | To examine preferences for specific types of HIV tests (public clinic test, doctor test, SSKs, home self-test), as well as for test attributes, such as cost, counselling and privacy | USA | Public clinics | 354 | 96 | Mean age of 34 years; 77% male; and 63% white | Dried blood spot | Mailed or pharmacy | Post | +/+ |

| 10 | Spielberg et al. (2000)21 | Prospective cohort | To assess the feasibility and acceptability of bimonthly home oral fluid and dried blood spot collection for HIV testing among individuals at high risk of HIV | USA | At-risk individuals enrolled in vaccine study | 241 | 84 | Mainly white males; 58% MSM; and mean age of 36 years | Dried blood spot or oral fluid | Choice of having the test mailed or collecting it from the study site | Post | ++/+ |

| 11 | Spielberg et al. (2001)55 | Cross-sectional survey | To evaluate attitudes about SSKs and telephone counselling among participants, HIV counsellors, community advisory board members and cohort participants | USA | Clinic staff and at-risk individuals | 126 | ≈80 | Mean age of 35 years; 71% male; and 54% white | Dried blood spot or oral fluid | Not specified | Post | –/– |

| 12 | Wayal et al. (2011)56 | Qualitative interviews | To explore the preferred mechanism for offering home sampling kits, perceptions about using SSKs to screen for STIs and HIV and views about STI clinic use and SSKs | UK | MSM | 24 | 80 | Median age of 39 years; and mainly white | Not specified | Range of options assessed | Several options | + (overall) |

| 13 | Wood et al. (2015)57 | Prospective cohort | To compare the results of a pilot outreach STI service using nurse-delivered screening and SSKs at a sex-on-premises venue with screening within a sexual health clinic | UK | MSM | 90 | NA | Median age of 47 years | Dried blood spot | Collected in a sauna | Post | –/+ |

The majority of the studies evaluated a dried blood spot SSK (n = 8),21,46,47,50,53–55,57 whereas five studies assessed an oral fluid test21,48,49,51,55 (two studies assessed both types of sampling21,55 and another two did not specify the type of test52,56).

The methods by which SSKs were distributed varied across the studies, with five studies including the option of kits being mailed out to participants21,48,49,51,54 and six studies requiring participants to pick up a SSK from a study site21 (including a pharmacy,47,54 a drug clinic,46 a public sex environment49 and a sauna;57 the remainder did not specify the method of SSK distribution50,52,53,55). Three studies offered participants a choice of both options21,49,54 and four studies did not specify how kits were distributed. 50,52,53,55 Nine studies required participants to return kits by post (the remainder did not specify the method of return or it was not applicable to the study type). 21,46,48,49,51,52,54,55,57 The qualitative study assessed a range of options with participants. 56

Quality appraisal

In accordance with the criteria used for both qualitative and quantitative studies, only a few high-quality papers were identified that related to the study outcomes. The majority of studies took the form of cross-sectional surveys47,49–55 (eight out of 13 papers), with only one RCT identified. 46

Only the RCT scored ‘++’ for both internal and external validity. 46 Two21,48 of the three prospective cohort studies21,48,57 scored ‘+’ or higher for both categories, as did six47,50–54 of the eight cross-sectional studies. 47,49–55 The qualitative study scored ‘+’ overall. 56 Two of the cross-sectional studies assessed the acceptability of a hypothetical offer of self-sampling and, overall, few of the studies directly compared the efficacy of different forms of testing. Those studies that scored poorly on both categories commonly featured a small sample size and/or deficient level of analysis.

Acceptability, feasibility and clinical effectiveness of self-sampling

All but one of the included studies50 reported on some measure of the acceptability of self-sampling (Table 4). In total, only five studies21,46,48,49,51 (three studies21,46,51 from the USA and two studies48,49 from the UK) reported on the distribution and return of SSKs. Within these, 1652 SSKs were distributed (range 80–716 SSKs) and 1373 participants returned a specimen (range 60–665 participants who returned a specimen). This suggests a median return rate of 77.5% (range 47.6–92.9%). The two UK studies48,49 distributed 80 and 126 HIV SSKs, with 62 (77.5%) and 60 (47.6%) returned, respectively. Both of these studies used oral fluid sampling, and no inadequate samples were reported. Twelve of the included studies did include (self-reported) data on the acceptability of SSKs to participants,21,46–49,51–57 but the measures used were inconsistent. Self-reported acceptability was generally high, with self-sampling reported to be broadly acceptable to participants (see Table 4). For example, Spielberg et al. 21 reported that 98% of participants agreed to take part in either oral fluid or dried blood spot bimonthly sampling in the future. Similarly, Fisher et al. 48 reported that 81% of MSM found (oral fluid) SSKs to be acceptable. However, Colfax et al. ,47 Wood et al. ,57 Skolnik et al. 54 and Sharma et al. 53 reported that few participants took up the offer of testing and/or it was the least preferred option among participants – it is notable that all of these studies used blood sampling. In terms of comparing the different types of tests, Spielberg et al. 21 found no difference in testing rates between dried blood spot and oral fluid testing, but this was the only study to compare the two methods. 21 Acceptability did not vary significantly by distribution method.

| Study number | First author (year of publication) and reference number | Number of SSKs returned/number of SSKs distributed | Completion rate, % | HIV positivity rate, % | Self-reported acceptability | Feasibility | Efficacy (i.e. increases in uptake of HIV testing) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bartholow (2005)46 | 174/240 (self-reported; not clear if all were self-sampled tests) | 72.5 | 3.4 (6/174) | Those in the SSK arm rated their satisfaction as being higher than those in the clinic testing arm | 37 (22%) of those who reported being tested did not report receiving their test results | Those in the SSK arm were twice as likely to have tested in the past month. However, they were not more likely to obtain their results |

| 2 | Colfax et al. (2002)47 | NA | NA | NA | 19% of participants chose SSKs for their next test in the first survey (pre-marketing), but in the second survey only 1% had used them | NA | Availability of SSKs did not increase testing rates among those not tested previously |

| 3 | Fisher et al. (2015)48 | 62/80 | 77.5 | 0 (0/62) | Acceptable to 81% of MSM in a sexual health clinic setting | Two out of 62 participants required a reminder to return the sample | Greater acceptance level than that for clinic-based testing (62.5% vs. 37.5%) |

| 4 | Formby et al. (2010)49 | 60/126 | 47.6 | 0 (0/60) | Pre-study survey showed that 52% of MSM chose SSKs as their preferred method of testing. Anecdotal evidence suggested that there was demand for the pilot to continue | Some samples were delayed in getting to the laboratory, meaning that participants had to be contacted to resend their samples. Seven samples had equivocal results and were retested (all negative). Capacity issues within virology for processing oral samples | Pilot successfully reached those not regularly engaging with HIV testing, including higher than expected numbers of bisexual men, men not otherwise tested in the last year and those not accessing GUM |

| 5 | Greensides et al. (2003)50 | NA | NA | NA | – | NA | High levels of awareness, but low reported usage of SSK use in the past year (4%) |

| 6 | Osmond et al. (2000)51 | 412/490 | 84 | 1.5 (6/412) | Many participants commented on how easy it was to provide oral fluid samples | Two indeterminate test results. Ten insufficient samples. Six new diagnoses made. Only half of participants tested telephoned for their results | SSKs found to be an effective method for estimating population seroprevalence among MSM |

| 7 | Sharma et al. (2011)52 | NA | NA | NA | 62% likely and 20% somewhat likely to take an offered SSK | NA | SSKs are acceptable, and future research and interventions should focus on addressing self-identified barriers faced by MSM to testing using SSKs |

| 8 | Sharma et al. (2014)53 | NA | NA | NA | SSKs were the least likely option among those available: appealed to less than half the participants | NA | Novel approaches are needed to increase HIV testing frequency, including combination packages |

| 9 | Skolnik et al. (2001)54 | NA | NA | NA | 1% preferred the SSK option of clinic or self-testing | NA | Most preferred self-testing and clinic testing to the SSK |

| 10 | Spielberg et al. (2000)21 | 665/716 | 92.9 | 0 (0/665) | 98% agreed to participate in bimonthly testing in the future. 99% said the test was easy to use | Staff concerns raised about the efficacy of telephone counselling. Anxiety reported among 28% of male PWID. 99% test adequacy: no positive diagnoses were made | No detectable difference in testing rates between dried blood spot and oral fluid samples |

| 11 | Spielberg et al. (2001)55 | NA | NA | NA | 92% of participants were willing to enrol in a monthly SSK study | NA | Despite staff concerns, the majority of participants expressed willingness to submit regular SSKs |

| 12 | Wayal et al. (2011)56 | NA | NA | NA | Acceptability of oral specimens examined with different parameters; broadly acceptable to MSM | NA | SSKs could be a viable alternative to meet the increasing demand for sexual health services, but, to improve uptake, the method of service provision must be culturally sensitive and acceptable |

| 13 | Wood et al. (2015)57 | NA | NA | NA | Lower rates of acceptance for SSKs than nurse-delivered testing (33 SSK users compared with 80 nurse-delivered tests) | Three out of 30 tests not processed. Four out of 30 test results not communicated | A combination outreach screening approach, including SSKs, is effective in targeting MSM using sex on premises venues |

In terms of feasibility, only six studies included any documentation of how tests were completed, errors in testing, communication of results or linkage to care. Three of these studies used oral samples, two studies used blood samples and one study used both. There were few reports of errors in testing. Spielberg et al. 21 reported that 99% of both oral fluid and dried blood spot samples were adequate for testing, whereas Osmond et al. 51 reported two indeterminate results and 10 insufficient samples (out of 412 returned oral fluid samples) and Formby et al. 49 reported that seven (out of 126) equivocal oral fluid samples had to be retested (all tests gave negative results). Wood et al. 57 reported that three out of 30 tests of dried blood spot samples were not processed. Spielberg et al. 21 reported that staff members were concerned about the efficacy of telephone counselling and Osmond et al. 51 found that only half of participants tested telephoned for their results. Similarly, Bartholow46 reported that 22% of those tested did not report receiving their test results and Wood et al. 57 reported that 4 out of 30 test results were not communicated to participants. Fisher et al. 48 reported that 2 out of 62 required a reminder to return their sample. Formby et al. 49 also reported that oral fluid samples were delayed in getting to the laboratory, which required participants to be contacted and asked to resend their samples to ensure accuracy of results. Linkage to care was not assessed, because most studies (n = 9) had no reactive results. The studies that did have reactive results were unable to check on outcomes for linkage to care because of the features of their methodology.

Only six studies provided data on the clinical effectiveness of SSKs for HIV in increasing the uptake of HIV testing. In the one RCT included in the review, Bartholow46 reported that those in the self-sampling arm were twice as likely to have tested for HIV in the past month, but were not more likely to obtain their results than those in the clinic-based testing arm. In the USA, Colfax et al. 47 reported that the availability of SSKs had not increased testing rates among those not tested previously, nor had it significantly changed testing behaviour among those who do get tested. In the UK studies, Formby et al. 49 reported that SSKs offered an alternative means of testing, with 35% of participants having never tested for HIV before, while Fisher et al. 48 reported greater uptake of SSKs (62.5%) than clinic-based testing (37.5%). Formby et al. 49 concluded that the pilot successfully reached those not regularly engaging in HIV testing, including higher than expected numbers of bisexual men, men not otherwise tested in the last year and those not accessing existing sexual health services. Other studies provided data in support of this stance as well. For example, the only qualitative study included in the review noted that the use of SSKs could be a viable alternative to meet increasing demand for sexual health services, but to improve uptake, the method of service provision must be culturally sensitive and acceptable. 56 Wood et al. 57 concluded that including self-sampling in outreach settings could be effective in targeting MSM using sex on premises venues. Finally, five studies21,46,48,49,51 reported the HIV positivity rate, which was an average of 0.9% (12/1311). Two studies48,49 (both including MSM in the UK) reported a positivity rate of 0%.

Barriers and motivators to, and facilitators of, self-sampling for HIV

The final section of the review assessed the barriers and motivators to, and facilitators of, HIV self-sampling (Table 5). Key barriers included anxiety, concerns over the accuracy of testing, concerns about confidentiality, privacy and the lack of face-to-face counselling and fears about the difficulty or pain involved in collecting samples. On the other hand, one of the UK studies reported that there was no difference in uptake related to the importance of accuracy of results or willingness to wait for results. 48 Test reliability was reported to be a barrier in the other UK study. 49 In addition, Wayal et al. 56 reported potential barriers to uptake among British MSM, including preference for medical venues (which were perceived as discrete and appropriate, especially if symptomatic), fear that distribution in gay social venues could trivialise testing or promote stigma, concerns about the unreliability of the postal service for delivering samples and anxiety over waiting for the results.

| Study number | First author (year of publication) and reference number | Barriers | Facilitators | Motivators (i.e. factors contributing to the acceptability of SSKs) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bartholow (2005)46 | Difficulty of collecting blood sample. Negative reactions from others if diagnosed | Attendance at syringe exchange | Perceptions of personal risk of HIV. Perceived benefits of regular testing |

| 2 | Colfax et al. (2002)47 | Most common concern was accuracy (56%) | – | – |

| 3 | Fisher et al. (2015)48 | No difference in uptake related to the importance of accuracy of the results or willingness to wait for the results | – | – |

| 4 | Formby et al. (2010)49 | Reliability of test result. Speed of obtaining test results | Ease of use of kit. Ease of following instructions. Lack of embarrassment | Number of partners in previous year |

| 5 | Greensides et al. (2003)50 | Concerns raised about accuracy, privacy and cost by those who had not used self-sampling | Convenience and privacy cited as main advantages. Ease of use also mentioned | Awareness of alternative testing methods |

| 6 | Osmond et al. (2000)51 | 42% of study subjects (241/568) expressed concerns:

|

– | Cash incentive used to recruit to study (resulting in high uptake among those with previous HIV diagnosis) |

| 7 | Sharma et al. (2011)52 | Barriers cited:

|

– | Hypothetical cash incentive was offered for testing |

| 8 | Sharma et al. (2014)53 | – | – | Motivations for HIV test (across all methods):

|

| 9 | Skolnik et al. (2001)54 | 99% of participants selected other test methods; the most important attributes were:

|

Reasons for selecting self-sampling as their first choice (n = 2):

|

– |

| 10 | Spielberg et al. (2000)21 | Reasons for refusal to participate in the study:

|

|

Agreement that early treatment for HIV results in prolonged health |

| 11 | Spielberg et al. (2001)55 | Anxiety over receiving regular test results. Fear of pain of collecting a sample. Concerns over inaccuracy of results. Waiting time for blood spots to dry | Key themes: convenience (51%), ease of use (32%) and time efficiency (29%) | Help with reducing high-risk behaviour |

| 12 | Wayal et al. (2011)56 |

|

|

|

| 13 | Wood et al. (2015)57 | – | Clear supporting information and the opportunity to access health promotion advice | – |

Conversely, reported facilitators of SSKs were the availability of telephone (as opposed to face-to-face) counselling, and perceived anonymity, accuracy, convenience and ease of use. Finally, additional motivating factors that were reported to contribute to the acceptability of self-sampling were awareness of the seriousness of HIV56 and the benefits of regular/early testing,21,46 and agreement or awareness of being at risk of HIV. 21,46,53,56 Two studies also noted that a cash incentive could be a motivating factor to test. 51,52

Summary

Few studies have examined the acceptability or feasibility of self-sampling for HIV testing, and only 13 studies met the inclusion criteria to be included in this review. The majority of the evidence came from cross-sectional surveys or cohort studies, and there was only one qualitative study and one RCT. Most studies were conducted in the USA, with just four conducted in the UK. The majority of the studies, and all of those conducted in the UK, focused on MSM. The overall quality of the studies was mixed and relatively poor.

Few studies assessed acceptability and feasibility in terms of actual uptake and return of tests, with only five studies assessing distribution and return of SSKs. Acceptability varied by sample type. The majority of the studies evaluated a dried blood spot SSK and these appeared somewhat less acceptable to participants than oral fluid sampling. 47,53,54,57 However, the one study that directly compared the two types of test found no difference in testing rates between dried blood spot and oral fluid sampling. 21 Only one UK study (with MSM) included dried blood spot SSKs, and this method proved less acceptable than nurse-led testing. 57 The methods by which SSKs were distributed varied across the studies, but acceptability did not differ substantially by distribution method. It was not possible to assess acceptability by method of return, because all of the studies that specified a return method reported that SSKs were returned by post. Overall, feasibility was mixed and problems were reported with the return of tests and communicating results to participants. Again, there did not appear to be any significant difference by sample type; three of the studies reported on feasibility having used oral samples, two studies having used blood samples and one study having used both. Evidence on linkage to care was particularly lacking and not assessed, because most studies had no reactive results.

Evidence on the clinical effectiveness of self-sampling for HIV in increasing the uptake of HIV testing was also limited. In the one RCT included in the review, Bartholow46 reported that those in the self-sampling arm were twice as likely to have tested for HIV in the past month, but were not more likely to obtain their results. Two of the UK studies reported increased testing among groups never tested before, including higher than expected numbers of bisexual men, men not otherwise tested in the last year and those not accessing existing genitourinary medicine (GUM) services, but neither study included African communities. 48,49 Although other studies reported that using SSKs could be a viable means of reducing pressure on existing sexual health services,56,57 the HIV positivity rate (where reported) was low for the high-risk populations included (two studies48,49 with MSM in the UK reported a positivity rate of 0%), suggesting that those most at risk of contracting HIV were not using this method of testing.

Despite the limitations in assessing acceptability, feasibility and efficacy, all 13 studies in the review included some data to inform understanding of how SSKs could work in practice, with concerns about anxiety over the testing process, the accuracy of testing, confidentiality and privacy being key barriers. The qualitative study also noted that there was a preference among the MSM interviewed for testing to remain in clinical settings. Conversely, key facilitators were the availability of telephone (as opposed to face-to-face) counselling, perceived anonymity, accuracy (although this was also identified as a barrier), convenience and ease of use (again, somewhat in contrast to opposing fears about difficulties in collecting samples). A number of studies also noted that awareness and the perceived personal risk of contracting HIV were motivating factors for testing. 21,46,53,55,56

Strengths and limitations

The studies included in this review were of relatively poor quality, with most data derived from cross-sectional studies and only one RCT included in the review. Most studies were conducted in the USA, which raises questions about the transferability of the findings to a UK context. Most of the studies, and all of the UK studies, were conducted with MSM, which again raises questions about the transferability of the findings to black African people not identifying as MSM in the UK. Furthermore, data on actual uptake and return of tests, the clinical effectiveness of self-sampling to increase the uptake of HIV testing and the clinical effectiveness of processes for linkage to care were largely absent, and this represents key knowledge gaps. The lack of standardised reporting of outcomes also made it difficult to compare findings across studies. Only one qualitative study was yielded by the search, despite the potential for such studies to inform the design and implementation of self-sampling for HIV interventions.

Conclusion

Self-sampling for HIV testing has been suggested as an approach to broaden the available testing options,39 and was successfully used in one pilot project set up to assess implementation of the UK national HIV testing guidelines. 37 In the 2016 NICE guidelines, SSKs were endorsed as a potentially innovative way of increasing the uptake of HIV testing among black African people, given that these kits may address known barriers to HIV testing in this risk group. 45 In the draft guidelines issued for consultation, SSK sand STKs are endorsed as innovative ways of increasing uptake of HIV testing among black African people. However, our review suggests that evidence to support the acceptability, feasibility and clinical effectiveness of this as an approach to increase the uptake of HIV testing is limited, and absent for black African people of all sexualities in the UK. There is a need for well-conducted trials of self-sampling interventions to assess acceptability, feasibility and whether or not the approach can increase the uptake of HIV testing among all high-risk populations, and black African people in particular. It is important that these studies include detailed description of processes for, and the acceptability, feasibility and clinical effectiveness of, the processes for linkage to care, including uptake of confirmatory testing and methods for linking those who test positive for HIV to care and treatment services. This will be particularly important for self-sampling (and self-testing) interventions to be implemented in practice.

The next chapter presents the findings yielded via FGDs with non-specialists and service providers, and one-to-one interviews with the latter regarding the development of an acceptable SSK distribution pathway and protocol via community-based health and HIV prevention services already accessed by black African people.

Chapter 4 Findings from focus group discussions and one-to-one interviews

As stated in Chapter 1, the aim of stage 1 of the HAUS study was to develop a SSK-based intervention that could increase the provision and uptake of HIV testing among black African people using existing community and health-care provisions. In doing so, it was important to understand the barriers to, and facilitators of, HIV testing in general, to consider how participants responded to the SSK itself and to gain their insights into the most feasible distribution, collection and communication of results procedures. This chapter presents qualitative findings drawing on FGDs and interviews, as described in Chapter 2, Methodology of focus group discussions and one-to-one interviews.

Perceptions of HIV testing interventions

Non-specialist black African participants demonstrated awareness of the range of settings in which most HIV testing currently takes place. It was clear among all participants, however, that specialist sexual health and HIV services were regarded as playing a crucial role in recommending and facilitating HIV testing, as well as providing ongoing social support for those who are diagnosed with or affected by HIV. Experience of, and opinions about, community and non-HIV/sexual health clinic offers of HIV testing were varied, with most mentioning HIV testing during antenatal care, new GP registrations in high prevalence areas and POCT in community-based HIV charities. The vast majority of participants regarded HIV testing as an acceptable and effective intervention because of the universal availability of antiretroviral treatment in the UK.

Some service providers highlighted that undocumented African migrants were often isolated from the UK medical system and unaware of free access to HIV treatment, presenting barriers to HIV testing. One non-specialist participant commented that:

I think on a social level, from what I have experienced while working, is that a lot of people who are undocumented in this country don’t understand the fact that the test is free, and the treatment is free.

London non-specialist group 3

Furthermore, there was some concern that a profusion of HIV testing interventions could lead to a disjointed and confusing service landscape. Some felt that unfamiliarity with the NHS could mean that a proportion of black African people may be unaware of the confidentiality provisions, particularly those pertaining to HIV and sexual health.

There was considerable agreement that the stigmatising association of HIV with ‘sexual immorality’ and promiscuity (an association that many FGD participants and interviewees described as being heightened within black African communities) provides an ongoing disincentive to test.

Aligned with findings from previous research,9,58 some service provider and non-specialist participants alike pointed out that testing uptake may continue to be low, because a HIV diagnosis was regarded as having profound health, social, financial, insurance and immigration implications. These views were often based on assumptions or considerably outdated information, even among service providers. One service provider had the following query regarding HIV testing: