Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 11/72/01. The contractual start date was in September 2013. The draft report began editorial review in August 2017 and was accepted for publication in January 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Robert Pickard reports grants from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) during the conduct of the study. Thomas Chadwick reports grants from the NIHR Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme during the conduct of the study and outside the submitted work. Katherine Walton reports grants from NIHR during the conduct of the study. Elaine McColl reports grants from the NIHR HTA programme during the conduct of the study and from the NIHR Journals Library outside the submitted work. From 2013 to 2016 she was an editor for the NIHR Programme Grants for Applied Research (PGfAR) series, with a fee paid to her employing organisation. Luke Vale reports that he is a member of the NIHR HTA Clinical Evaluation and Trials panel and is co-director of NIHR Research Design Service North East. Mohamed Abdel-Fattah reports grants from Bard Medical UK (Crawley, UK), Astellas Pharma Inc. (Tokyo, Japan), Coloplast (Humlebæk, Denmark), Pfizer Inc. (New York, NY, USA), Advanced Medical Solutions [(AMS) Winsford, UK] and Ethicon Inc. (Somerville, NJ, USA) outside the submitted work and is a member of the HTA Interventional Procedures panel. Paul Hilton reports a grant from the NIHR HTA programme during the conduct of the study and grants from the William Harker Foundation and Wellbeing of Women outside the submitted work. He was a member of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Interventional Procedures Advisory Committee (2002–7), NIHR Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre (NETSCC)-HTA Therapeutic Procedures Panel (2007–8) and NETSCC-HTA Clinical Evaluations and Trials Prioritisation Group (2008–10). He chaired the NICE development group for clinical guideline on urinary incontinence in women (2004–7). Mandy Fader reports grants from NIHR (reference number RP-PG-0610-10078) and from the Small Business Research Initiative grant outside the submitted work. Simon Harrison reports grants from the NIHR HTA programme (reference number 11/72/01) during the conduct of the study. James Larcombe reports grants from the NIHR HTA programme during the conduct of the study and is a member of the HTA Elective and Emergency Specialist Care panel. Paul Little reports that he is director of PGfAR and editor-in-chief of the PGfAR publication in the NIHR Journals Library. James N’Dow is a member of the HTA General Board. Nikesh Thiruchelvam reports grants from Astellas, non-financial support from Astellas and personal fees from Coloplast outside the submitted work.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Pickard et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction (background and objectives)

Material from Brennand et al. 1 has been used within this chapter. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Scientific background

Clean intermittent self-catheterisation

Clean intermittent self-catheterisation (CISC) is an important management option for people who cannot empty their bladder naturally owing to bladder outlet obstruction or to failure or inco-ordination of bladder muscle contraction, most frequently associated with neurological disease. 2,3 Patients needing CISC insert a thin (typically 4.5 mm diameter) catheter up through the urethra, drain the bladder and then remove the catheter. 4 This is then repeated at set time intervals or as dictated by sensation of bladder fullness. Single-use, sterile-packed disposable catheters, typically with a hydrophilic coating, appear to be the most commonly used option in the UK, although there is no robust evidence of benefit over reusable or uncoated catheters. 5

Prevalence of use of clean intermittent self-catheterisation in the UK

There are no specific incidence or prevalence data for CISC use in the UK. The NHS England prescription database shows that approximately 66 million CISC catheters were prescribed in 2015, at a cost of £103M. 6 This estimate ties in with calculations using data from catheter manufacturers from 2013, which showed 54 million catheters dispensed at a cost of £81M (unpublished data courtesy of Doreen McClurg, Glasgow Caledonian University, February 2017). Assuming that each individual uses an average of three catheters per day,7 there are about 60,000 CISC users in England and perhaps 72,000 in the UK as a whole.

Recurrent urinary tract infection among people using intermittent catheterisation

Recurrent urinary tract infection (UTI) is the commonest adverse event (AE) experienced by CISC users, affecting between 12% and 88% of cohorts. 8 Separation of rates of asymptomatic bacteriuria, which would not normally be treated, and symptomatic UTI in these studies is often not possible. From the available literature, we estimate that 50% of users have persistent bacteriuria and about 25% suffer two or more symptomatic UTI episodes per year. 9 Neurological disease, female sex, young age and high bladder volumes have been associated with higher prevalence of UTI. 2 Rates will also vary according to the definition of symptomatic UTI used, in particular whether or not microbiological proof is required. 10 The most frequently isolated organism is Escherichia coli, accounting for 60–70% of isolates. 9 Most episodes are associated with transient symptoms such as lower abdominal pain, urethral pain and flu-like symptoms (occasionally systemic upset can occur with fever and loin pain). Rarely, bloodstream infection requiring hospital treatment ensues. Those with reduced bladder sensation may complain of cloudy urine, increased odour and worse incontinence. 11 Recurrent UTI is distressing and an additional burden for patients on top of their underlying disease and functional disability. 8 In one study,2 a cohort of 407 CISC users self-rated UTI symptoms over the previous 12 months. The findings were that 24% had no symptoms, 59% had mild symptoms, 14% had moderate symptoms and 3% had major symptoms;2 the rate of bacteriuria was 60%, with symptomatic UTI occurring in 12–18% of the 407 participants. Conservatively, using the lower rate, this suggests that 8640 CISC users in the UK suffer recurrent UTI. This is the target population for this trial.

A number of simple interventions have been trialled to reduce UTI risk for CISC users, including single-use hydrophilic catheters and antiseptics, but a Cochrane review5 and meta-analysis12 found no robust evidence for their efficacy. More recent randomised controlled trials (RCTs) reported reduced UTI risk with single-use hydrophilic catheters for patients with spinal cord injury during initial hospitalisation but increased risk of UTI in children compared with reusable, uncoated catheters. 13 A further two trials14,15 showed no benefit of cranberry extract in the prevention of UTI in CISC users. 16 The need for strategies to reduce prevalence of UTI in this population has been emphasised by recent reports from the James Lind Alliance and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). 17

Evidence for use of antibiotic prophylaxis

Once-daily low-dose antibiotic prophylaxis is effective for women without bladder emptying problems who suffer recurrent UTI. A systematic review and meta-analysis18 of 10 RCTs involving 403 participants showed a relative risk of UTI of 0.15 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.08 to 0.28] in favour of antibiotic prophylaxis. AEs in trials using nitrofurantoin, trimethoprim (Kent Pharmaceuticals, Ashford, UK) or cefalexin (Sandoz Ltd, Holzkirchen, Germany) were mild and rarely associated with withdrawal, but were more frequent in the antibiotic group, with a relative risk of 1.78 (95% CI 1.06 to 3.0); gastrointestinal upset, skin rash and vaginal candidiasis predominated. Nitrofurantoin appeared to be more effective than trimethoprim but resulted in more withdrawals. These two drugs, together with cefalexin, are recommended and licensed for this indication in the UK. 19 There were no reports of serious adverse events (SAEs), such as neuropathy or pulmonary fibrosis, in the nitrofurantoin groups in randomised studies included in the Cochrane review,18 but an observation study20 of prophylactic nitrofurantoin noted one episode of possible neuropathy in 219 patients over 12 months’ use. Awareness of these conditions, together with the possibility of liver inflammation and higher risk of side effects in people with renal impairment, is advised on the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) licence for nitrofurantoin. 21

Evidence for the use of antibiotic prophylaxis for CISC users suffering recurrent UTI, the focus for this trial, has been summarised in a Cochrane review updated to September 2011. 22 The review found five small, low-quality RCTs23–27 relevant to the present trial with a total of 363 participants. For the outcome of clinical UTI, two crossover trials involving children showed no difference, while one-third involving children in an unblinded, parallel-group design found an incidence density ratio of 0.69 (95% CI 0.55 to 0.87) in favour of prophylaxis using a variety of agents. For the outcome of antibiotic-treated, microbiologically proven UTI, one trial24 showed no difference, whereas a second parallel-group placebo-controlled trial23 involving 131 adults hospitalised by recent spinal injury found a risk ratio of 0.78 (95% CI 0.62 to 0.97) in favour of prophylaxis with co-trimoxazole. The review authors concluded that, although results were promising, there was inadequate evidence for the clinical effectiveness of antibiotic prophylaxis for CISC users, agreeing with a previous review. 28 None of these trials found any excess harms in the prophylaxis groups, but changes in bacterial pathogens were recorded in only one study. 23 This looked at change in bacterial sensitivity and found that 75% of participants had at least one occurrence of isolation of a resistant pathogen with no difference between prophylaxis and placebo groups. 23 Recommendations for future trials were to:

-

use incidence of symptomatic UTI as the primary outcome

-

measure antibiotic resistance

-

control for factors increasing UTI risk – sex, frequency of catheterisation, neurological cause, frequency of previous UTI and prior use of antibiotic prophylaxis.

These results and the need for further research have been highlighted in a further narrative review. 29 The most recent trial included in the Cochrane review was published in 2011;26 we updated the Cochrane search to November 2016, using the same strategy and literature database sources, and found no additional reports.

Antibiotic stewardship

The impact of prophylactic antibiotic therapy for UTI on bacterial ecology particularly of gut flora (faecal microbiome) was explored in only one of the trials23 included in the Cochrane reviews, which found no difference between prophylaxis and no-prophylaxis groups. An observational study20 of prophylaxis with nitrofurantoin in a general population with recurrent UTI found no evidence of development of faecal organisms resistant to nitrofurantoin or loss of sensitive organisms in the gut, suggesting that this drug does not have potentially harmful effects on gut commensals. In a large RCT of antibiotic prophylaxis of recurrent UTI in women with normal voiding, it was found that use of once-daily co-trimoxazole markedly increased faecal and urinary carriage of resistant E. coli but that this returned to baseline 3 months after discontinuing the antibiotic prophylactic therapy. 30 There remains a high level of public health concern regarding the empiric continuous use of antibiotics as preventative or suppressive therapy for people who suffer repeated infection given the rapid emergence of resistant strains of a number of pathogenic bacteria. 31,32

Summary with implications for trial design

This background led the UK National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) to commission a trial to determine the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the use of once-daily antibiotic prophylaxis for UTI in users of CISC (NIHR reference number 11/72/01). The call required a trial design to determine whether or not the apparent benefit of antibiotic prophylaxis seen in a small trial23 among a specific group of CISC users could be translated to a wider population in a routine care setting and whether or not any benefits are worth the costs, both financially and in terms of harms. To fulfil this brief, we designed the Antibiotic Treatment for Intermittent Catheterisation (AnTIC) trial. We specified an experimental UTI prevention strategy using continuous once-daily low-dose prophylactic antibiotic therapy against the control strategy of no prophylaxis in adults carrying out intermittent bladder catheterisation and suffering recurrent UTI. The aim was to determine the relative clinical effectiveness in terms of reduction in rate of UTI over 12 months and cost-effectiveness in terms of incremental cost of UTI avoided. The estimates of prevalence, clinical effectiveness, cost effectiveness and harms of prophylaxis from the literature allowed us to power a trial conservatively based on what was considered to be a minimum important difference from clinician, patient and economic perspectives.

Aims and objectives

The hypothesis addressed in the trial is that a strategy of antibiotic prophylaxis reduces the rate of symptomatic antibiotic-treated UTI by ≥ 20% compared with a strategy of no prophylaxis. To investigate this hypothesis, we aimed to achieve the following objectives.

Primary objectives

-

Determine the relative impact of prophylaxis on incidence of symptomatic, antibiotic-treated UTI over 12 months.

-

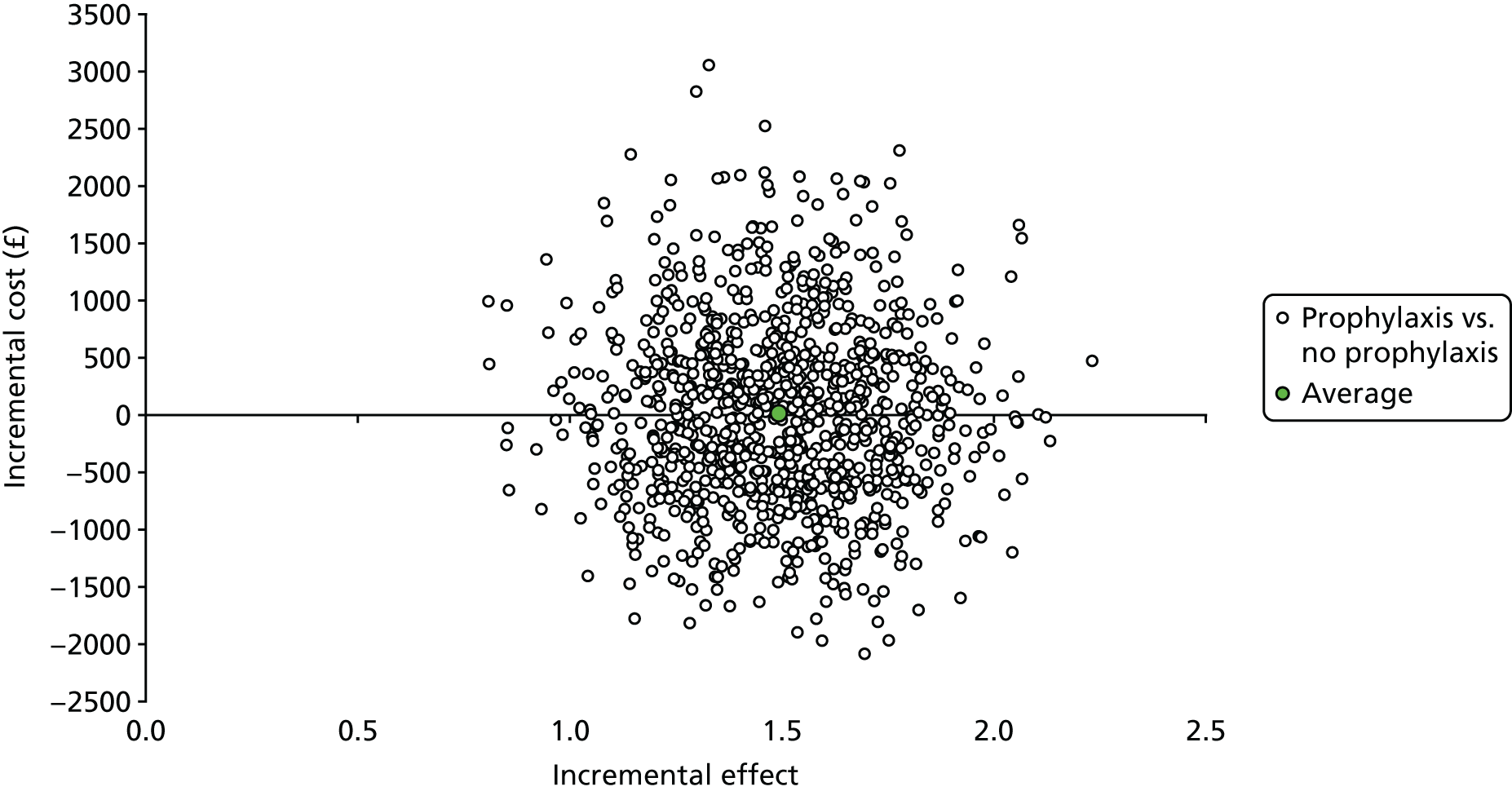

Determine the incremental cost per symptomatic UTI avoided.

Secondary objectives

-

Determine the relative effect of prophylaxis on the incidence of microbiologically proven UTI.

-

Determine relative rates of fever or hospitalisation because of UTI.

-

Determine relative rates of asymptomatic bacteriuria over 12 months.

-

Record AEs related to use of prophylactic or treatment antibiotics.

-

Assess change in resistance of pathogens isolated from urine and E. coli from perianal swabs.

-

Measure overall satisfaction with prophylactic antibiotic treatment.

-

Determine the relative effect on health status among trial participants.

-

Measure difference in kidney and liver function at 12 months.

-

Measure incremental cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained.

-

Assess participants’ willingness to pay (WTP) to avoid a UTI by contingent valuation.

-

Assess participants’ perception of benefit using qualitative methods.

Chapter 2 Methods

Material from Brennand et al. 1 has been used within this chapter. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

This chapter covers general study methods, statistical analysis and governance; details of health economic and qualitative analyses are provided in Chapters 4 and 5, respectively.

Summary of trial design

We designed an open-label, patient-randomised parallel-group superiority trial comparing an experimental strategy of once-daily low-dose antibiotic prophylaxis with a control strategy of no prophylaxis in adults undertaking CISC who suffer recurrent UTI. Because both strategies are in routine use and the choice of antibiotic agent used for prophylaxis is governed by a number of clinical and microbiological factors, we chose a pragmatic design without blinding of clinicians or participants. Central trial staff entering and managing trial data, trial staff adjudicating outcomes and laboratory staff analysing microbiological samples were blinded to participant allocation. Both groups otherwise received usual care, including on-demand, discrete treatment courses of antibiotic treatment for UTI. Inclusion criteria were broad and the trial was set in the UK community recruiting participants from both primary and secondary care UK NHS organisations to ensure that trial results could be applied to all people using CISC who suffer recurrent UTI.

Sites

From November 2013 to October 2015, we progressively established 51 research sites comprising NHS organisations affiliated to the NIHR Clinical Research Networks (CRNs) in England and equivalent organisations in Scotland that agreed to host the trial locally. The sites were grouped around seven UK secondary care centres: (1) Newcastle upon Tyne, (2) Wakefield, (3) Bristol, (4) Cambridge, (5) Southampton, (6) Glasgow and (7) Aberdeen. All seven centres had a recruitment co-ordinator funded by the trial. The central trial office was established at the Newcastle Clinical Trials Unit (NCTU), Newcastle University. The central microbiological laboratory at Freeman Hospital, Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Newcastle upon Tyne, received all urine and perianal swab specimens for culture and storage. These results were used for the microbiological outcomes of the trial but were not used for local clinical decisions. Central trial staff liaised with NIHR CRNs to identify further sites. These sites consisted of 26 hospitals (secondary care) and 19 general practices (primary care). We also established a further six participant identification centres (PICs) that identified potential participants and referred them to nearby recruitment sites. The PICs were one secondary care, three primary care and two NHS community care provider sites (Table 1).

| Site/PIC | Number of participants | |

|---|---|---|

| Randomised | Hub total | |

| Hubs | ||

| Newcastle upon Tyne | ||

| Freeman Hospital, Newcastle upon Tyne | 70 | 78 |

| Royal Victoria Infirmary, Newcastle upon Tyne | 2 | |

| Sunderland Royal Infirmary (PIC) | 2 | |

| Harbinson House, Sedgefield (primary care site) | 2 | |

| Jubilee Practice, Newton Aycliffe (primary care site) | 2 | |

| Cambridge | ||

| Addenbrooke’s Hospital | 17 | 17 |

| Bristol | ||

| Southmead Hospital | 14 | 25 |

| Bristol, Somerset and South Gloucestershire Community Care Groups (PIC) | 2 | |

| Sirona Care and Health (PIC) | 7 | |

| Weston Area Health (PIC) | 2 | |

| Glasgow | ||

| Southern General Hospital, Glasgow | 25 | 52 |

| University Hospital, Ayr | 12 | |

| Western General Hospital, Edinburgh | 15 | |

| Aberdeen | ||

| Aberdeen Royal Infirmary | 34 | 46 |

| Aberdeen primary care (PIC) | 12 | |

| Wakefield | ||

| Pinderfields Hospital, Wakefield | 25 | 32 |

| Leeds Community Healthcare (PIC) | 7 | |

| Southampton primary care sites | ||

| Portsdown Group Practice, Portsmouth | 3 | 30 |

| Adam Practice, Poole | 2 | |

| Wareham Health Centre, Wareham | 3 | |

| Bridges Medical Centre, Weymouth | 1 | |

| Ramilies Surgery, Southsea | 1 | |

| Liphook & Liss Surgery, Liphook | 1 | |

| Old Fire Station Surgery, Woolston, Southampton | 2 | |

| Forest End Surgery, Waterlooville | 5 | |

| Chawton Park Surgery, Alton | 1 | |

| Cowplain Practice, Cowplain | 2 | |

| Bermuda & Marlowe Practice, Basingstoke | 1 | |

| Swanage Medical Centre, Swanage | 1 | |

| Wellbridge Practice, Wool, Dorset | 1 | |

| Three Swans Surgery, Salisbury | 3 | |

| Swan Surgery, Petersfield | 1 | |

| Grove House, Isle of Wight | 1 | |

| Friarsgate Practice, Winchester | 1 | |

| Total hubs | 280 | |

| Other hospital sites | ||

| Coventry and Warwickshire University Hospital | 12 | |

| Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Birmingham | 5 | |

| Cheltenham General Hospital | 11 | |

| Ninewells Hospital, Dundee | 9 | |

| Southport and Formby District General Hospital | 7 | |

| Ipswich Hospital | 19 | |

| James Cook University Hospital, Middlesbrough | 11 | |

| Royal Bolton Hospital | 5 | |

| St James’ University Hospital, Leeds | 1 | |

| Kent and Canterbury Hospital | 3 | |

| New Cross Hospital, Wolverhampton | 5 | |

| Royal National Orthopaedic Hospital, Stanmore | 10 | |

| Raigmore Hospital, Inverness | 16 | |

| North Devon District Hospital | 6 | |

| Charing Cross Hospital, London | 1 | |

| Bedford Hospital | 1 | |

| Guy’s Hospital, London | 2 | |

| Total additional sites | 124 | |

Participants

Adults carrying out CISC were identified at the time of clinic reviews and from health-care records at each site. In addition, the trial was promoted to patients through the Multiple Sclerosis (MS) Society, Bladder Health UK, local patient groups and catheter delivery companies. Clinicians were encouraged, through the NIHR CRN, local and national primary and secondary care meetings and relevant professional organisations (including British Association of Urological Surgeons, British Society of Urogynaecology and the Association for Continence Advice), to introduce the trial to patients.

Patients were approached and introduced to the trial by clinical staff at the sites. If they were interested, an eligibility check was carried out in accordance with the following inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria

-

Adult aged ≥ 18 years.

-

Established user of CISC who was predicted to continue using for ≥ 12 months.

-

Able to give informed consent for participation in the trial.

-

Able and willing to adhere to a 12-month follow-up period.

-

Had suffered either at least two episodes of symptomatic UTI related to CISC within the previous 12 months or at least one episode of UTI requiring hospitalisation. Or, for those currently prescribed prophylactic antibiotic for UTI, has completed a 3-month washout period without antibiotic prophylaxis. Any symptomatic UTI was treated prior to randomisation.

-

Able to take a once-daily oral dose of at least one of 50 mg of nitrofurantoin, 100 mg of trimethoprim or 250 mg of cefalexin.

Exclusion criteria

-

Aged < 18 years.

-

In a learning phase of CISC.

-

Already taking prophylactic antibiotic against UTI and declining or unable to tolerate a 3-month washout period without antibiotic prophylaxis.

-

Inability to tolerate all three of the prophylactic antimicrobial agents.

-

Women who were pregnant, breastfeeding or who intended to become pregnant during the planned period of trial participation.

-

Previous participation in this study.

-

Inability to give informed consent or complete study documents in English (the outcome measures had not been validated in other languages).

Potentially eligible patients were given or sent brief trial information. Those interested and eligible were approached by research staff and provided with full trial information. We welcomed participation of otherwise eligible patients who were already taking antibiotic prophylaxis against recurrent UTI, provided that they agreed to have a 3-month washout period without taking prophylaxis.

Consent procedures

The trial was carried out according to the principles of Good Clinical Practice33 (GCP) and the Declaration of Helsinki. 34 All participants provided written informed consent prior to randomisation and to any trial-specific procedures by signing and dating the trial consent form, which was witnessed and dated by a member of the local research team. If participants were experiencing symptomatic UTI at the time of consent, they were treated with standard antibiotic therapy and not randomised until they were symptom free. Those currently using antibiotic prophylaxis who agreed to stop for a 3-month washout period were consented to take part, but baseline data were collected, and randomisation carried out, only when the 3-month washout period was completed.

Randomisation

Participant allocation

Randomisation was administered centrally by the NCTU secure web-based system. Permuted random blocks of variable length were used to allocate participants 1 : 1 to the control and experimental groups. A statistician not otherwise involved with the trial produced the final randomisation schedule. Stratification by three variables [(1) prior frequency of UTI (fewer than four episodes per year and four or more episodes per year), (2) diagnosis of neurological lower urinary tract dysfunction (yes or no) and (3) sex (female or male)] was performed to ensure a balanced allocation within these known UTI risk factors. For those allocated to prophylaxis, an appointment was arranged with the prescribing clinician to commence an individually suitable trial drug: 50 mg of nitrofurantoin (or 100 mg according to clinician preference and local guidance), 100 mg of trimethoprim or 250 mg of cefalexin.

Progress in trial

Once in the trial, participants were encouraged through verbal, written and electronic information to contact their local site team or the central trial team if they had any concerns or questions related to the trial. Trial duration for each participant was 12 months, with an additional optional 18-month follow-up outside the trial under separate consent to provide longer-term data on treatment choice and pathogen resistance patterns. Local research staff were instructed to interview each participant, either face to face or by telephone, at 1, 3, 6, 9 and 12 months following randomisation, focusing on ensuring that there was adherence to the allocated group and that any occurrence of symptomatic antibiotic-treated UTI was documented.

Participant expenses

Expenses incurred by participants as a result of taking part, including any NHS prescription charges for trial medication, were reimbursed. Participants were also given a gift of £20 when they started the trial.

Withdrawal of participants

Participants remained in the trial unless they withdrew consent or the local principal investigator (PI), chief investigator or trial office felt that, because of serious issues, it was no longer appropriate for the participant to continue. If a participant chose to withdraw, permission was sought for the research team to continue to collect outcome data from their health-care records. Participants who withdrew later than 6 months after randomisation were included in the primary analysis. If participants withdrew completely (i.e. from intervention and follow-up), data already collected were retained up to the point of withdrawal. The reason for withdrawal was recorded if the participant agreed.

Patient and public Involvement

During protocol development, we sought the advice of a CISC user (co-investigator) on trial design, focusing on important outcomes and their definition, recruitment policies and phrasing of patient-facing documents such as the participant information sheet, consent form and further information on other measures to prevent UTI. We also consulted with patient organisations including Bladder Health UK and the MS Society. During the trial, two people who are CISC users and who responded to an advert on the MS Society website were recruited and appointed to the Trial Steering Committee (TSC). They provided continuing advice on outcome measurement and recruitment strategies, including adjustment of patient literature. In addition, they reviewed the final report and advised on dissemination of findings to a lay audience.

Outcome measurement

Primary clinical outcome

The primary clinical objective was to determine the relative clinical effectiveness of an experimental UTI prevention strategy of continuous once-daily prophylactic antibiotic therapy against the control strategy of no prophylaxis in people carrying out CISC who suffer recurrent UTI. This was assessed by comparing the incidence of patient-reported UTI over 12 months.

Participants were asked to report all episodes of symptomatic UTI for which they took a treatment course of antibiotic. This was done on a UTI record form that was returned to the central trials office [see Questionnaire (10 Jan 2018), Participant UTI Record available at www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/117201/#/documentation (accessed 3 April 2018)]. The participant recorded symptoms from a predefined list, encompassing the recommendations of the British Infection Association (BIA), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and spinal cord injury UTI consensus statement. 11,35,36 The type and duration of treatment antibiotics was also recorded. In addition, at each 3-monthly review by local research staff, participants were asked about occurrence of symptomatic UTI and associated use of treatment courses of antibiotic. Details were recorded on the case report form (CRF) [see Interview Material (10 Jan 2018) available at www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/117201/#/documentation (accessed 3 April 2018)] and 3-monthly participant-completed questionnaire [see Questionnaire (10 Jan 2018), Participant 3 Monthly Questionnaire available at www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/117201/#/documentation (accessed 3 April 2018)].

Occurrence of a UTI was defined as the presence of at least one symptom together with taking a discrete treatment course of antibiotics prescribed by a clinician or as part of a patient-initiated self-start therapy.

To ensure consistent attribution, we set a hierarchy of evidence on which to base the primary outcome [see Study Documentation (10 Jan 2018), AnTIC Primary Outcome Assessment Procedure available at www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/117201/#/documentation (accessed 3 April 2018)]. First, we reviewed all UTI record forms returned by the participants. For each, we checked the information on symptoms, the identity of the antibiotic used and the duration of use. If a UTI was reported by the participant but details were missing, we then checked the 3-monthly review CRF and participant questionnaire corresponding to the time period in which the UTI occurred. Finally, if necessary, the research team at the trial site and/or the participant were contacted to confirm missing details. Only episodes in which trial documentation from UTI record forms, regular review CRFs or participant 3-monthly postal questionnaires showed symptomatic antibiotic-treated UTI were counted as fulfilling the primary outcome.

Secondary outcomes

The following secondary patient-reported and clinical outcomes were measured.

Severity of urinary tract infection

During review of each UTI record form and associated CRF, severity was classified as non-febrile or febrile, and whether or not hospitalisation was required. Febrile UTI was defined as the primary outcome plus presence of a recorded fever of > 38 °C. Hospitalisation due to UTI was defined as an unplanned visit to hospital for treatment of a UTI, which required at least one overnight hospital stay. We also asked participants to self-rate the severity of each UTI as mild, moderate or severe.

Adverse events related to both prophylaxis and treatment antibiotic use

Any AEs possibly related to the trial intervention suffered during the trial participation were recorded as free text by local research staff at 1-, 3-, 6-, 9- and 12-month trial visits on CRFs. Those occurring during treatment courses of antibiotic for UTI (adverse reactions) were recorded on the participant UTI record form [see Questionnaire (10 Jan 2018), Participant UTI Record available at www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/117201/#/documentation (accessed 3 April 2018)]. During episodes of antibiotic-treated UTI and by review of health-care records by local research staff [see Interview Material (10 Jan 2018), Participant 3-Month review interview and Health care records 3-month review available at www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/117201/#/documentation (accessed 3 April 2018)], AEs were categorised as mild (discomfort is noticed, but there is no disruption of normal daily activities), moderate (discomfort is sufficient to reduce or affect normal daily activities) or severe (discomfort is incapacitating, with inability to work or to perform normal daily activities). The investigator at the relevant site assessed the relationship of the AE to the trial treatment by checking against the Reference Safety Information (RSI) in the Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPCs) specific to the prescribed antibiotic, which was included in the protocol.

Overall satisfaction with prophylactic antibiotic treatment

This was measured by the participant completion of the Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medication37 (TSQM) at the end of the trial. Separate scores from the four subscales were reported: (1) effectiveness, (2) side effects, (3) convenience and (4) global satisfaction.

The relative effect on health status among trial participants

This was measured by participant completion of the Short Form questionnaire-36 items version 2 (SF-36v2; 1-week acute recall version) at baseline, after 6 and 12 months of participation and at the time of each UTI. The SF-36v2 includes 36 different questions, each of which contributes to the score that can be calculated for eight different dimensions: (1) physical functioning, (2) role limitations due to physical health, (3) bodily pain, (4) general health perceptions, (5) vitality, (6) social functioning, (7) role limitations due to emotional problems and (8) general mental health caused by either physical or emotional problems. From the scores attached to each of these dimensions, two additional summary scores were derived. These are the physical component summary (PCS) score and the mental component summary (MCS) score. The higher the value of the summary scores, the higher the level of functionality of the patient. 38

Change in kidney and liver function at 12 months

Change in kidney function was determined by comparison of the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) derived from measurement of serum creatinine and accounting for race and sex, at baseline and 12 months for each individual and each group using an online calculator [available at www.kidney.org/professionals/kdoqi/gfr_calculator (accessed 27 October 2017)]. At baseline, research staff were asked to calculate creatinine clearance using an online calculator [available at www.nuh.nhs.uk/staff-area/antibiotics/creatinine-clearance-calculator (accessed 27 October 2017)] to detect participants allocated to prophylaxis with clearance values of < 45 ml/minute who would not be able to use nitrofurantoin. Change in liver function was assessed using the measured value of the liver enzyme alanine transaminase (ALT) at baseline and 12 months, compared within individuals and according to trial group and the agent used for prophylaxis.

Microbiological outcomes

For trial purposes, the standard definition of microbiologically confirmed UTI in a symptomatic participant was the laboratory report of one or two isolates at > 104 colony-forming unit (CFU)/ml. 39 The results of culture of urine specimens sent to the central trial laboratory were preferentially used for this outcome. If a central laboratory specimen was missing and a local laboratory report was available, then this was used. For evaluation of antimicrobial resistance and assessment of asymptomatic bacteriuria, only culture and sensitivity results from specimens received by the central laboratory were used. Asymptomatic bacteriuria was defined as a positive urine culture in the absence of symptoms. Bacterial ecological change was assessed by comparing changes in resistance patterns of all pathogens isolated from urine specimens received at the central laboratory both at the time of UTI and during asymptomatic periods at baseline and at the time of 3-, 6-, 9- and 12-month reviews. Perianal swabs taken and submitted at baseline and at the 6- and 12-month visits were cultured for E. coli only.

Data collection

Summary

Outcome data from the CRFs were entered by local research staff at each site into a trial-specific database set-up using the MACRO clinical data management system (Elsevier B.V., Amsterdam, the Netherlands). Participant-completed questionnaires were collated at the central trial office and data entry outsourced to a commercial company (Ndata, North Shields, UK) for conversion to an electronic format. We made concerted efforts to obtain any missing data through contact with the sites and by direct checking with participants using their preferred means of communication (telephone, text message, e-mail or during the clinic appointment).

Trial events

Screening

General demographics and eligibility were checked. Trial Information was provided [see Patient Information Sheet (10 Jan 2018) available at www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/117201/#/documentation (accessed 3 April 2018)] to the participant and consent taken prior to randomisation. Participants experiencing symptomatic UTI were treated with standard antibiotic therapy and not randomised until symptom free.

Randomisation

Randomisation was performed as close as possible to the date of consent (normally immediately after). The continued eligibility of those consented participants who had completed a 3-month washout period was checked prior to their randomisation.

Follow-up

Participants were contacted by local trial staff 1 month after randomisation by telephone regarding general concerns, understanding of trial documentation and their tolerance of the prophylactic antibiotic agent (if allocated).

At 3, 6, 9 and 12 months after randomisation, telephone or face-to-face contact (according to local circumstance and participant preference) took place. Details of UTI occurrence, UTI symptoms, adverse reactions to antibiotics taken for UTI and other infections requiring treatment with antibiotics during the previous 3 months were recorded in the electronic CRF (e-CRF). Participants were asked to return a urine specimen during an asymptomatic period at 3, 6, 9 and 12 months, and a perianal swab at 6 and 12 months, to the central laboratory in postage pre-paid, safety-compliant sample packaging provided to them.

During episodes of symptomatic antibiotic-treated UTI, participants completed a UTI record form [see Questionnaire (10 Jan 2018) available at www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/117201/#/documentation (accessed 3 April 2018)] recording symptoms, antibiotic use, adverse reactions to treatment for UTI, participant rating of severity of UTI and details if hospitalised. They were also asked to post a urine specimen to the central laboratory prior to commencing a treatment course of antibiotics, for analysis and subsequent storage. This was in addition to urine specimens requested by the local treating clinician required for diagnosis and management of the episode locally in line with routine local diagnostic practice.

Other outcome data were collected by participant postal questionnaire sent by the central trial office at 3, 6, 9 and 12 months and completed by participant. This was then returned to the central trial office. Follow-up data were supplemented by regular inspection of health records by local trial site staff for documented visits to clinicians because of UTI, episodes of fever recorded as > 38 °C associated with UTI, antibiotic prescriptions for UTI, hospitalisations and results of local laboratory urine cultures. The schedule of events for the trial are summarised in Table 2.

| Intervention | Time point | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visit 1 (initial screen) | Visit 2 | Visit 3 (3 months) | Visit 4 (6 months) | Visit 5 (9 months) | Visit 6 (12 months) | At time of UTI | |||

| Consent | Baseline | Randomisation | |||||||

| Eligibility checklist | ✗ | ||||||||

| Trial discussed and patient information sheet given | ✗ | ||||||||

| Informed consent | ✗ | ||||||||

| Trial outcome UTI report form and questionnaire | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| AEs | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||

| SF-36v2 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| Health resource use questionnaire | ✗ | ✗ | |||||||

| Patient costs (time and travel) questionnaire | ✗ | ||||||||

| TSQM | ✗ | ||||||||

| Contingent valuation questionnaire (sent at 13 months) | ✗ | ||||||||

| Urine specimen to central laboratory | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| Perianal swab to central laboratory | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||

| Blood test for creatinine eGFR and liver enzyme (ALT) | ✗ | ✗ | |||||||

Data handling and record keeping

Data were recorded by site staff on e-CRFs in a clinical data management software package. Patient questionnaires were returned by post to the trial management office in Newcastle upon Tyne. They were checked by NCTU staff and sent to a commercial data entry organisation (Ndata), which then returned the electronic data files and paper questionnaires to the trial office for transfer to the trial database and archiving. Two reminders with a second and third copy of questionnaires were sent to participants to prompt return. Patients were allocated an individual specific trial number to allow anonymised versions of the secure database to be available to the trial team and subsequently more widely under open data access arrangements. Essential data will be retained for a period of at least 10 years following close of the trial in line with sponsor policy and the latest European Directive on GCP (2005/28/EC). 40 Data were handled, digitalised and stored in accordance with the Data Protection Act 1998. 41

Details of trial medication

Planned interventions

Both experimental and control strategies are in routine NHS use and these strategies were specified clearly in the trial information literature.

Antibiotic prophylaxis (experimental)

The agent used was selected from the alternatives of nitrofurantoin, trimethoprim and cefalexin by the responsible clinician depending on patient characteristics such as previous use, allergy, kidney function, prior urine cultures and local guidance. There is no universally agreed national guidance on appropriate agents but available evidence suggests use of 50 mg of nitrofurantoin (or 100 mg dependent on clinician preference and local guidance), 100 mg of trimethoprim or 250 mg of cefalexin, in that order of preference. 21,42,43 Kidney function was determined by creatinine clearance at baseline; if this was < 45 ml/minute, nitrofurantoin was not used. Otherwise, participants and their clinicians were asked to review the prescribing information for each drug given in the trial documentation to guide selection of the individually most appropriate initial agent. At the planned 1-month telephone review, local trial staff asked about tolerability of the prescribed medication. If there were specific and intolerable AEs, then switching to an alternative agent was advised in consultation with the relevant clinician, with the reasons for the change recorded. This process was repeated at planned 3-monthly reviews and a third agent advised, if necessary. More frequent telephone follow-up was undertaken if needed to help the participants become established on a suitable agent. The aim was to maintain participants allocated to the prophylaxis group on any one of the three prophylactic agents for as long as possible over the 12-month trial period within tolerance and safety constraints. Participants were asked to take the once-daily antibiotic prophylaxis as a single dose at bedtime. If a participant in the prophylaxis group developed symptoms and signs suggestive of breakthrough UTI, they were advised to seek treatment in their usual way, predominantly by contacting their general practitioner (GP) and starting a discrete treatment course of antibiotics. In this scenario, they were instructed to stop the prophylactic antibiotic while they were taking a treatment course and restart it again the day after the last dose of the treatment course. Clinicians and participants were advised to use a different agent for treatment to the one they were taking for prophylaxis.

No prophylaxis

The strategy applied to the control group was that of no prophylaxis. Participants self-monitored their symptoms as usual and reported to their GP or other clinician if they developed symptoms and signs suggestive of a UTI requiring treatment.

Standard care for both groups

Apart from the randomised allocation to prophylaxis and the avoidance of the prophylactic agent as treatment for symptomatic UTI, there were no differences in care between the groups. We ensured as far as possible that participants in both groups received their usual care in terms of identification and treatment of UTI, health surveillance and support related to use of CISC, and monitoring and treatment of the underlying cause of their lower urinary tract dysfunction. We recorded all health-care episodes for each participant. We considered standard care for CISC users who suffer recurrent UTI to be the use of discrete treatment courses of antibiotics as indicated by symptoms or signs of UTI. Treatment typically involved a 3- or 7-day course of an antibiotic active against urinary pathogens, depending on severity of symptoms and response to treatment. In accordance with local protocols, a urine specimen was sent for microbiological examination at the local laboratory at the time of starting antibiotic treatment. If therapy was successful, no further action would be required, whereas if symptoms did not resolve, the choice and duration of antibiotic would be reconsidered in the light of any urine culture result and, if necessary, a further urine sample submitted for analysis. 35 This suggested standard of care was emphasised in trial documentation given to participants and clinicians. Regular surveillance of kidney function using serum creatinine was also expected. Guidance was provided to participants in both groups and to their clinicians regarding use of urine testing and antibiotic options in terms of agents used and their duration of use. Participants in both groups continued their regular care with primary and secondary care clinic visits, access to continence advice and relevant patient support groups according to local practice and individual preference. All participants were given information detailing simple non-antibiotic measures that may help prevent UTI and provide symptom relief [see Study Documentation (10 Jan 2018) available at www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/117201/#/documentation (accessed 3 April 2018)].

Delivery of interventions

Local NHS clinicians at the site of randomisation were responsible for initiating trial medication for those participants allocated to prophylaxis, whether in secondary or primary care, with a 3-month supply of the relevant medication. The participants’ GPs were then asked to prescribe further supplies until the end of the 12-month trial treatment period. If this was not possible then the clinician at the NHS site of randomisation continued to supply the medication. If the participant wished, and if the clinician responsible for their routine care agreed, antibiotic prophylaxis was continued beyond the 12-month trial participation period but without further active monitoring from the trial research team.

Funding of trial intervention

The interventions were funded by standard NHS contracting mechanisms, having been sanctioned by local commissioning groups through local study approval mechanisms. The NHS excess treatment costs were approved by the sponsor and, for primary care, the local Clinical Commissioning Group. Any prescription charges for trial drugs incurred by participants were reimbursed from research costs. The trial intervention was low cost.

Sample size calculation

We planned to recruit 372 participants to the trial. Based on systematic reviews and expert opinion, we considered that an overall 20% reduction in symptomatic UTI rate from an average of 3 to 2.4 episodes per year represents the minimum clinically important difference. 18,22 Using the Poisson rate test, completion of the trial by 158 participants in each group, 316 in total, would give 90% power to detect this difference at the 5% level. A total of 372 would allow for a 15% attrition rate that was estimated from previous trials included in the systematic review. This gives a 92% power to detect a 25% difference in the high-frequency subgroup (from four to three episodes per year) and > 99% power for a 50% reduction in the low-frequency group (from two episodes to one episode per year) without allowance for multiple testing. At the start of the trial, we aimed to approach at least 750 eligible patients, anticipating a 50% recruitment rate.

Statistical analysis

A complete statistical analysis plan (SAP), which provides full details of all statistical analyses, variables and outcomes, was finalised and signed before the final database lock and analysis [see Statistical Analysis Plan (10 Jan 2018) available at www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/117201/#/documentation (accessed 3 April 2018)].

All statistical analyses were carried out on a modified intention-to-treat (ITT) basis, retaining participants in their randomised treatment groups and including those in the prophylaxis group who stopped prophylaxis but remained in the trial, those in the no-prophylaxis group who started prophylaxis but remained in the trial and those who withdrew before the end of the trial but who had ≥ 6 months of follow-up recorded.

Primary outcome measure

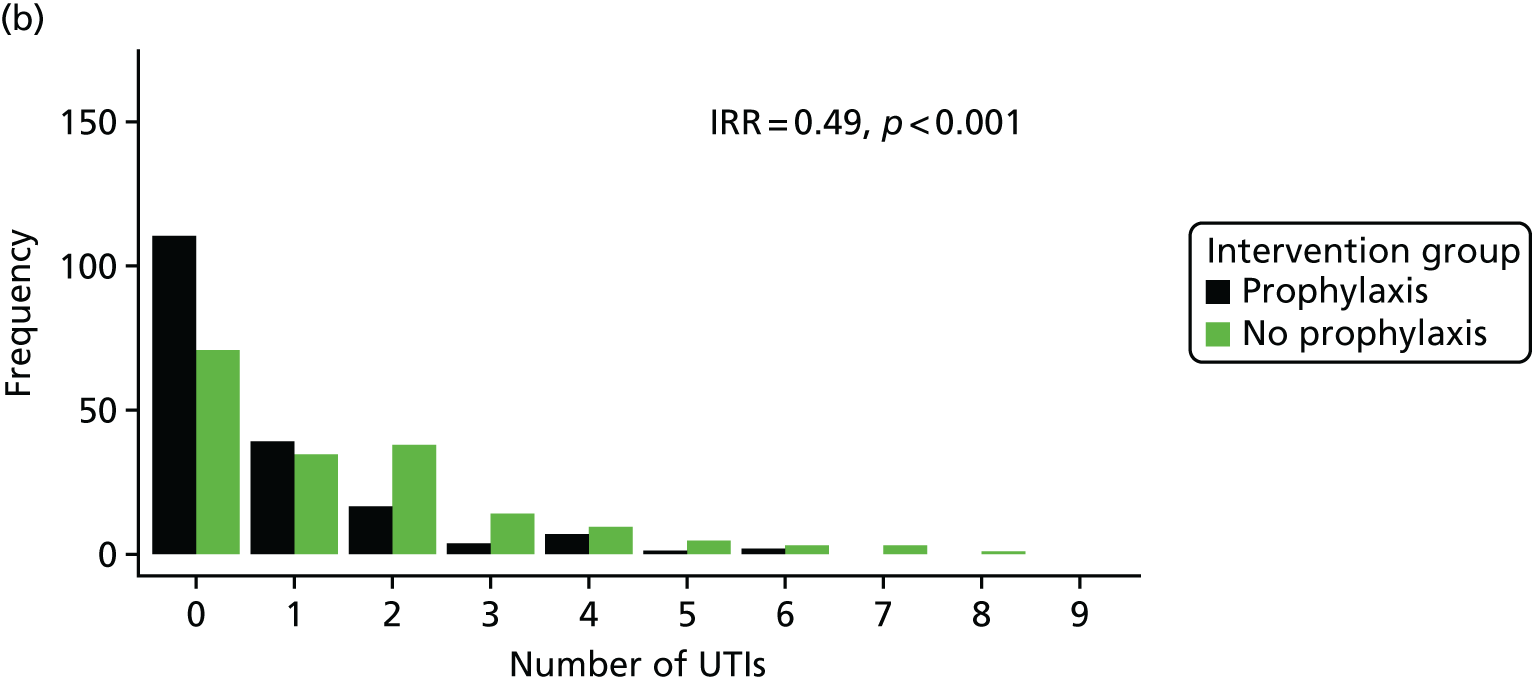

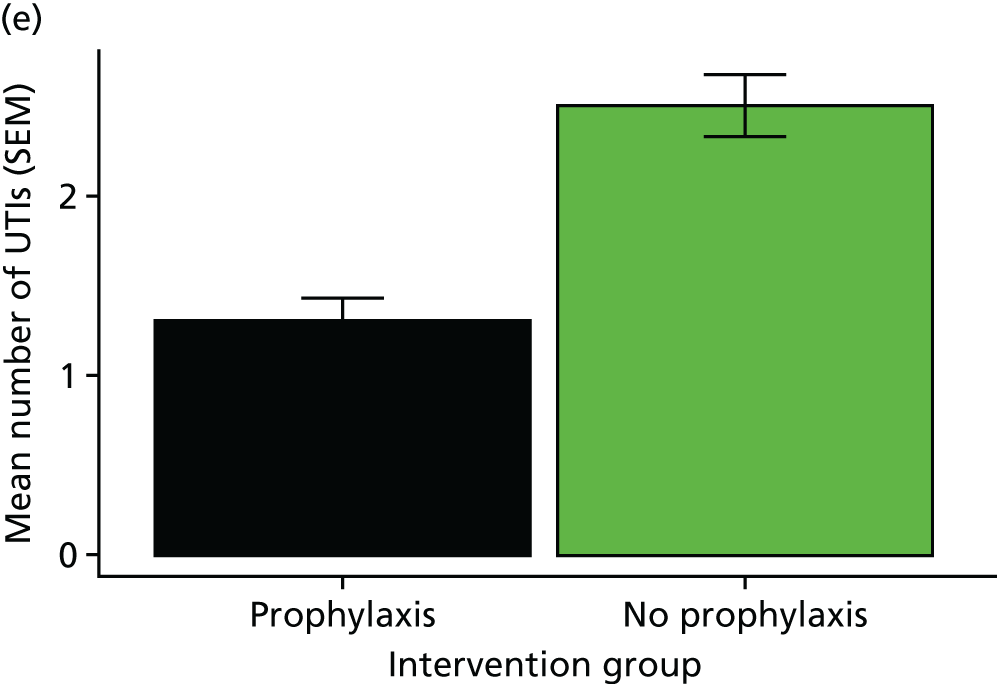

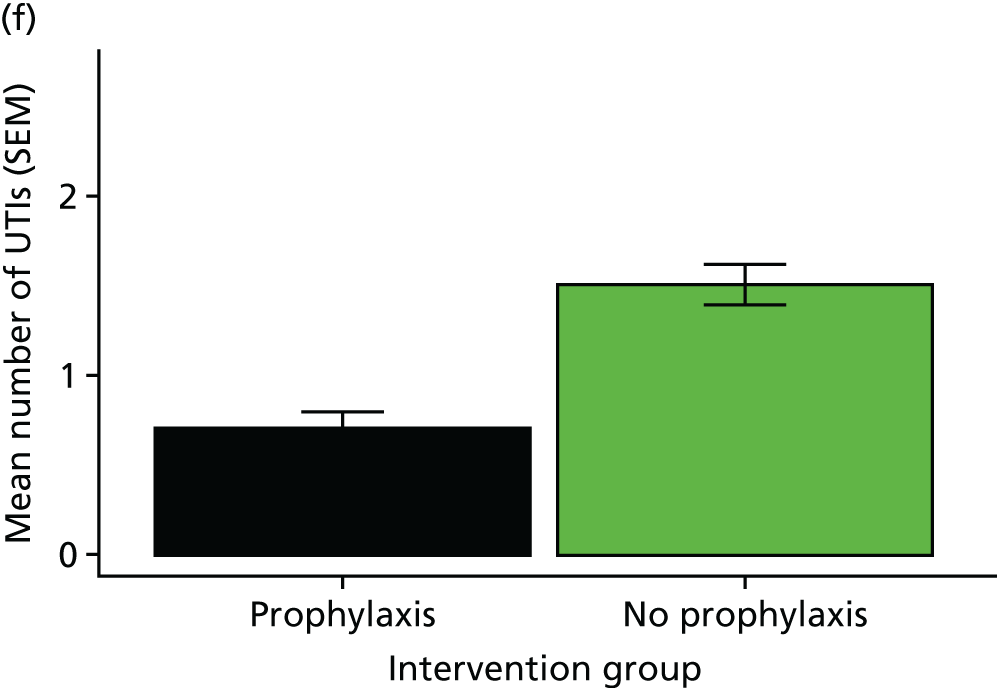

The primary outcome measure was the difference in incidence of symptomatic antibiotic-treated UTI during the 12-month observation period. Symptomatic UTI was defined as the presence of at least one patient-reported or clinician-recorded symptom from a predefined list encompassing the recommendations of the BIA, the CDC and spinal cord injury UTI consensus statement44 together with taking a discrete treatment course of antibiotics prescribed by a clinician or as part of a patient-initiated self-start policy. 11,35,36

The rate of UTI in each group was defined to be the incidence rate ratio (IRR), that is, the total number of UTIs suffered across all patients, allowing for differing durations of follow-up. Analyses of the primary outcome measure were performed using both the Poisson rate test (as a simple univariate approach with consideration of days in follow-up) and an IRR modelling approach to allow for the different durations of treatment for symptomatic UTIs, which reduce the number of days-at-risk for individuals. Days-at-risk was defined as the total observation period minus days spent taking treatment courses of antibiotics active against urinary tract organisms. When no information on the duration of antibiotic treatment course was available, it was assumed to last 7 days. A Poisson regression approach was used to adjust for the effects of covariates. The model selection process included the stratification factors and other baseline variables. Site was also explored as an interaction term. An analysis of the primary outcome measure was performed both for the full data set and for the separate subgroups defined by high and low baseline UTI rate (as specified during stratification for the randomisation process). The simple univariate analysis was considered to be the primary analysis for reporting purposes.

Secondary outcome measures

For the following secondary outcome measures included in the SAP, rates were defined in a similar way to the primary outcome:

-

microbiologically confirmed symptomatic UTI rate

-

febrile UTI rate

-

hospitalisation rate attributable to UTIs during the 12 months of the trial

-

asymptomatic bacteriuria rate

-

antibiotic prescription for asymptomatic UTI rate

-

AE rate (those related to prophylaxis and treatment antibiotics), including antibiotic resistance.

Statistical analyses of these outcome measures generally used the same approach as for the primary outcome.

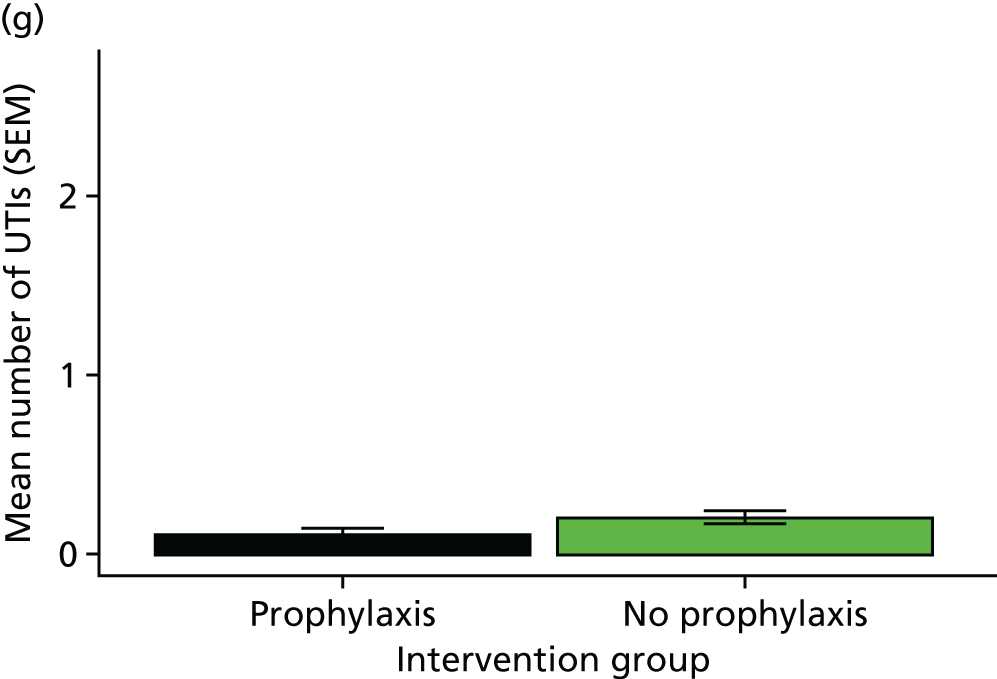

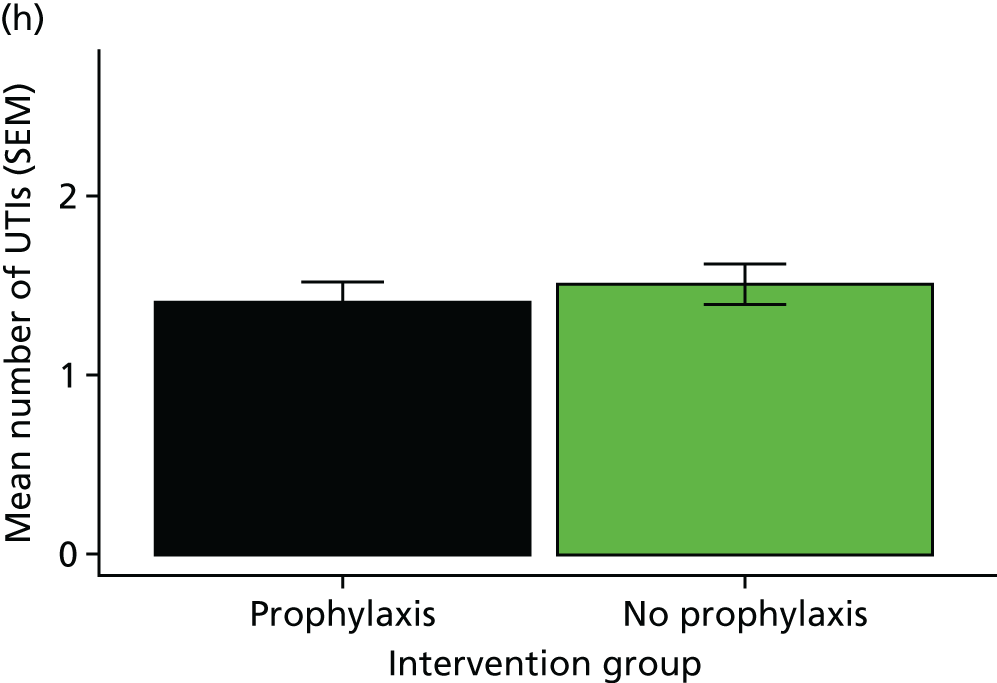

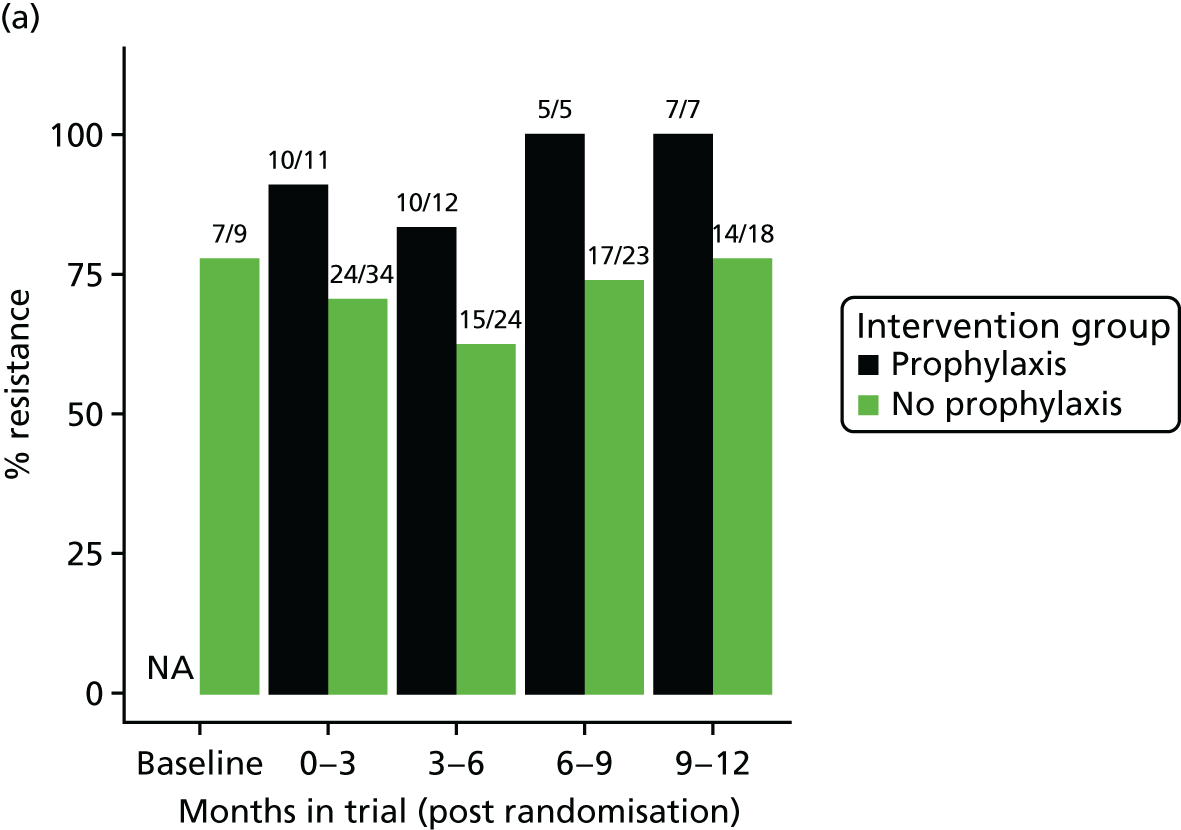

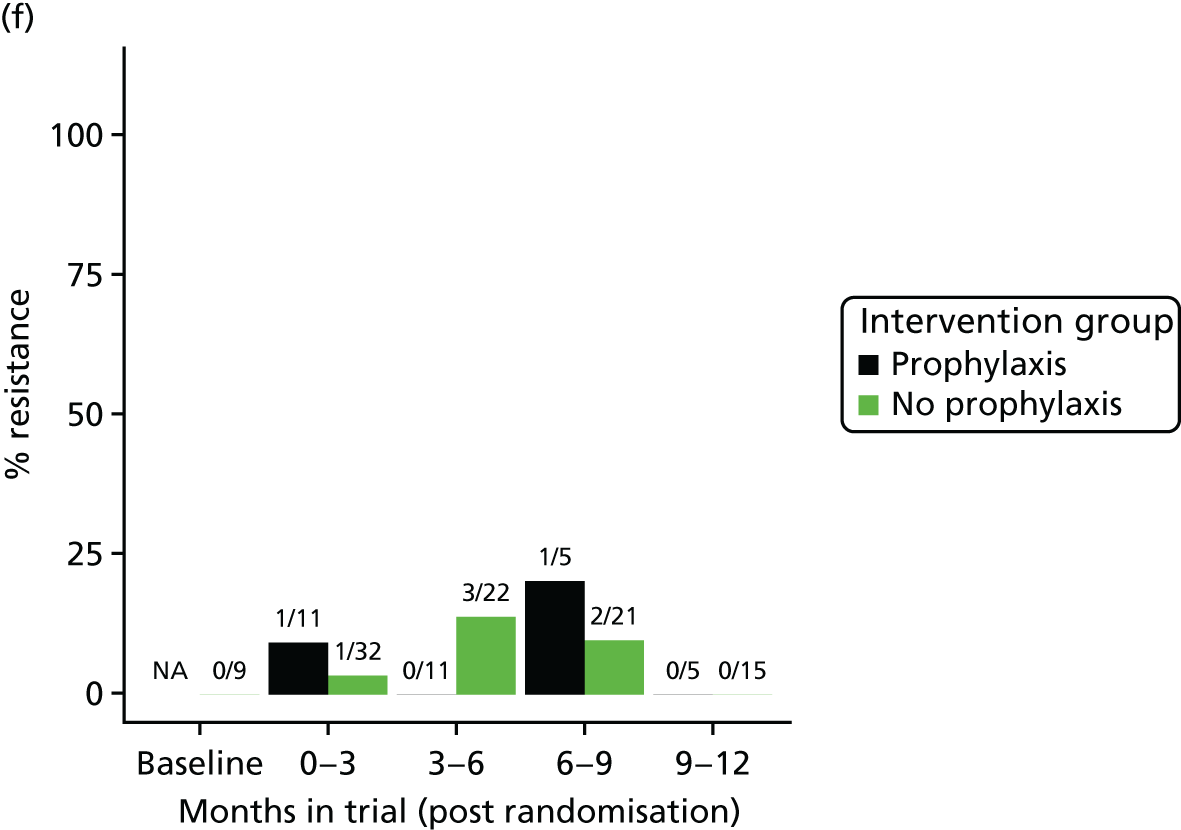

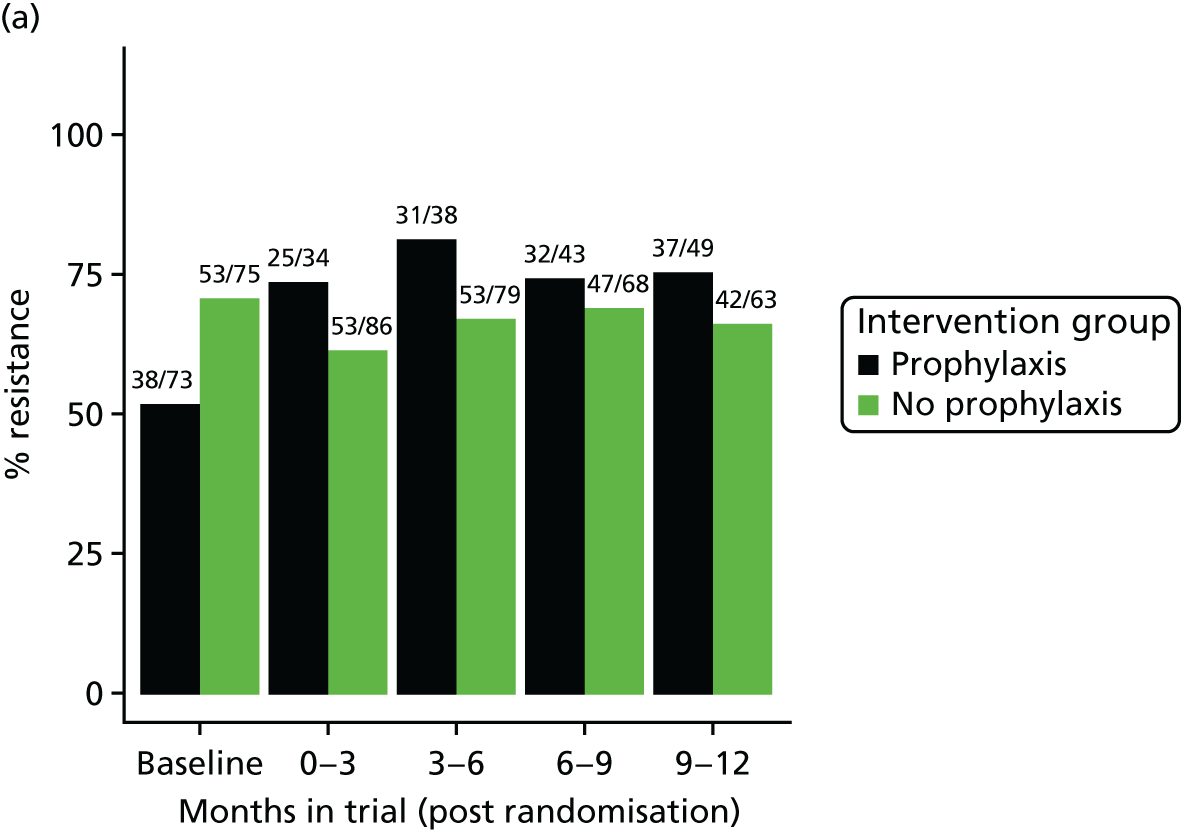

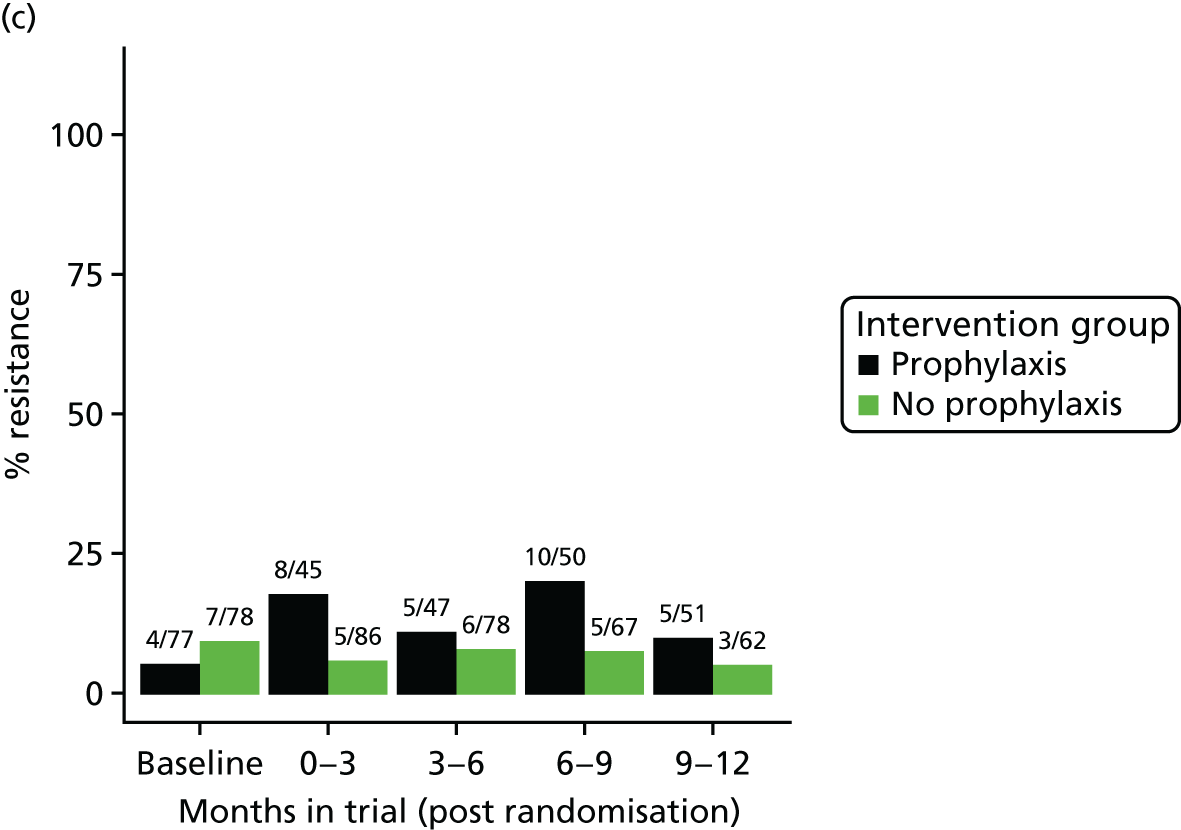

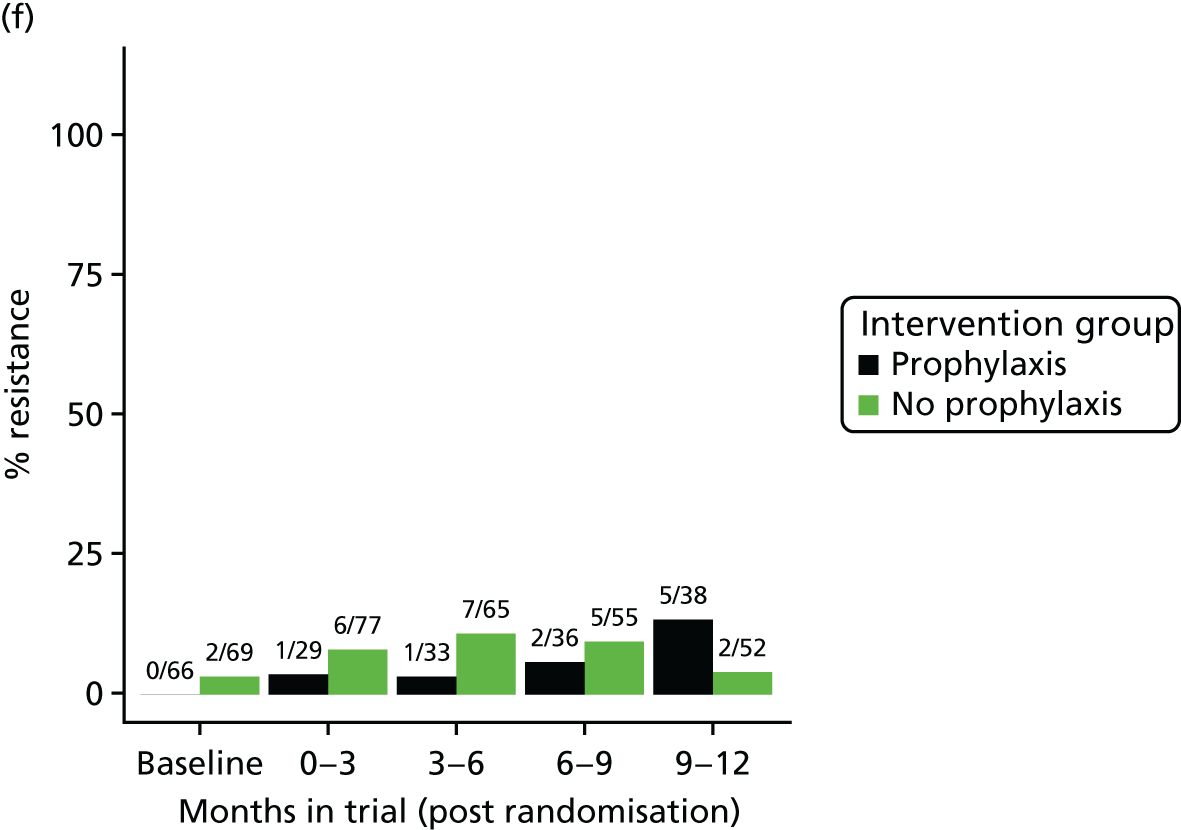

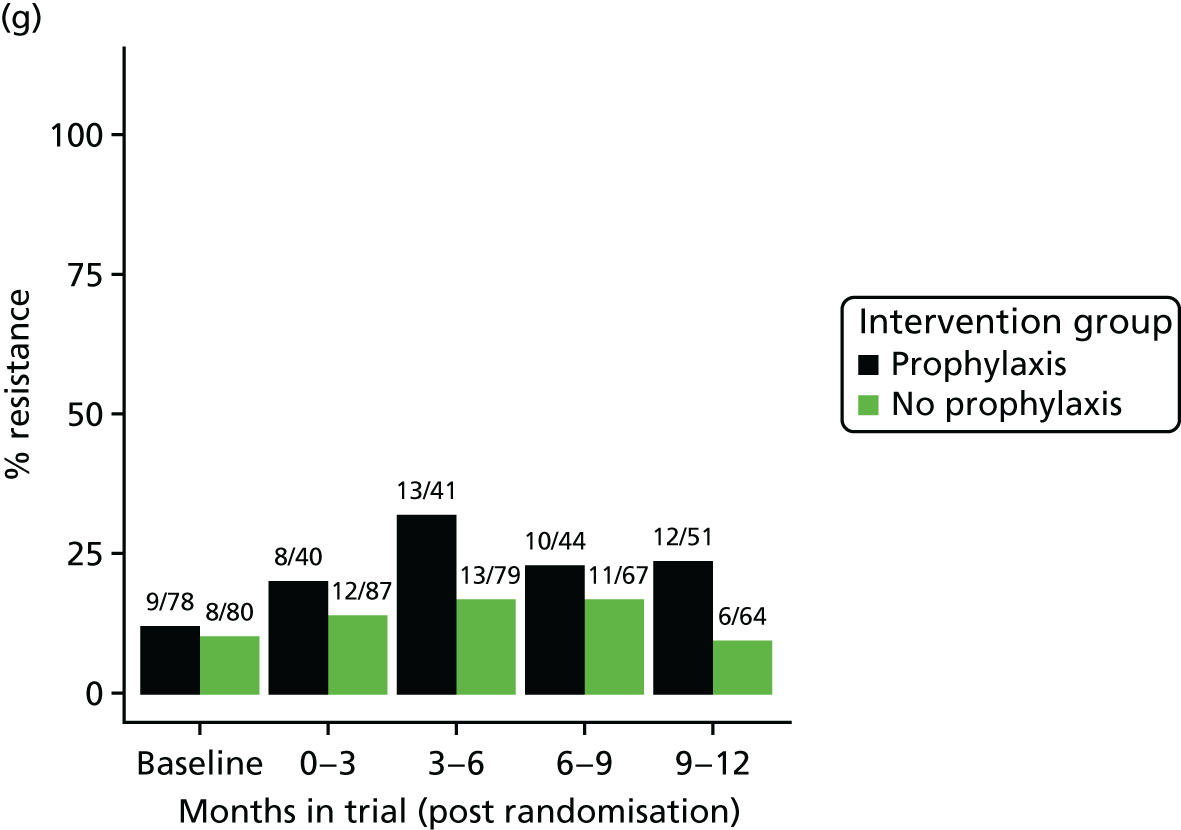

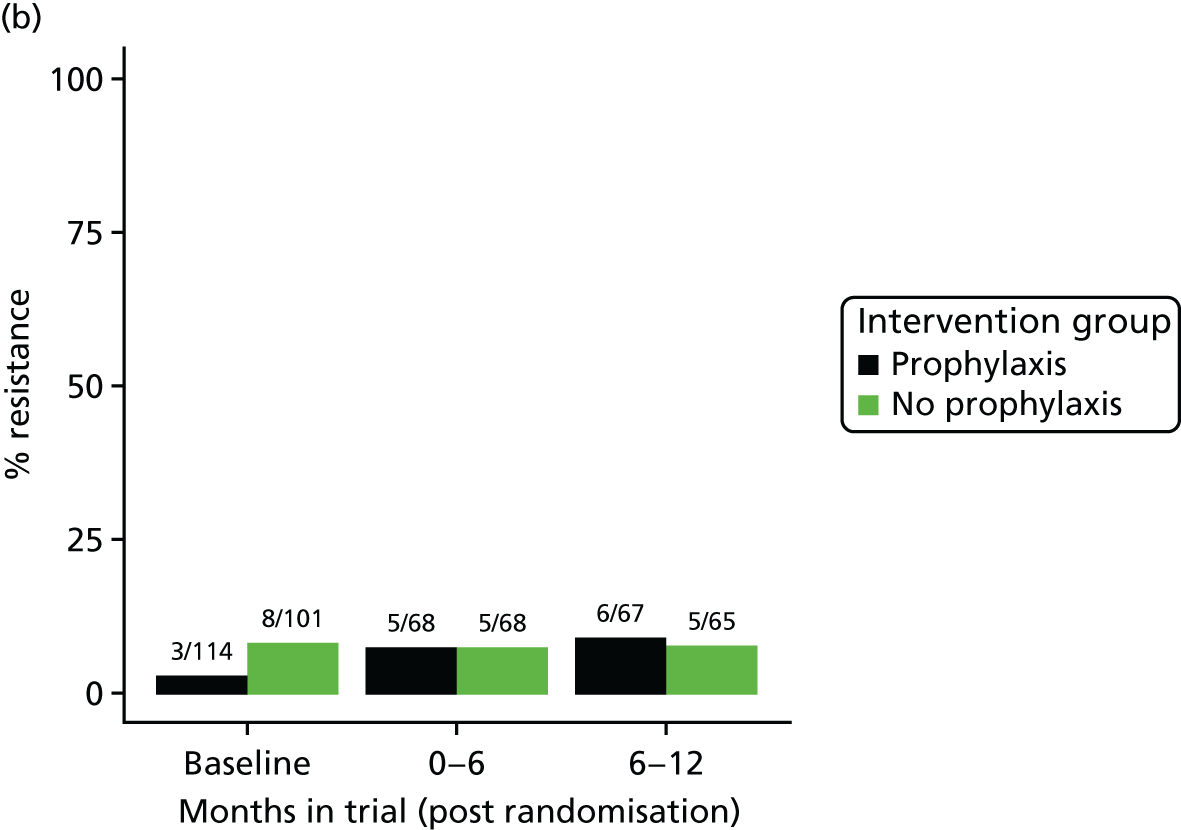

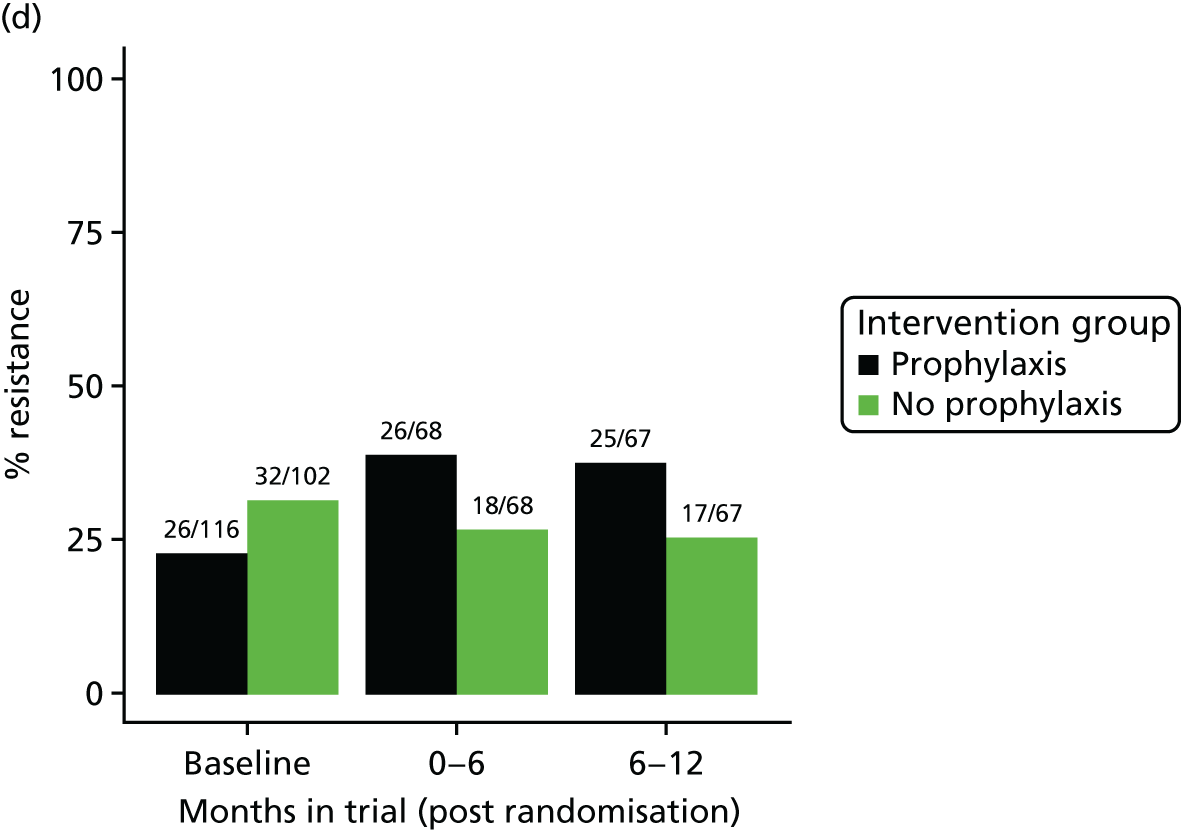

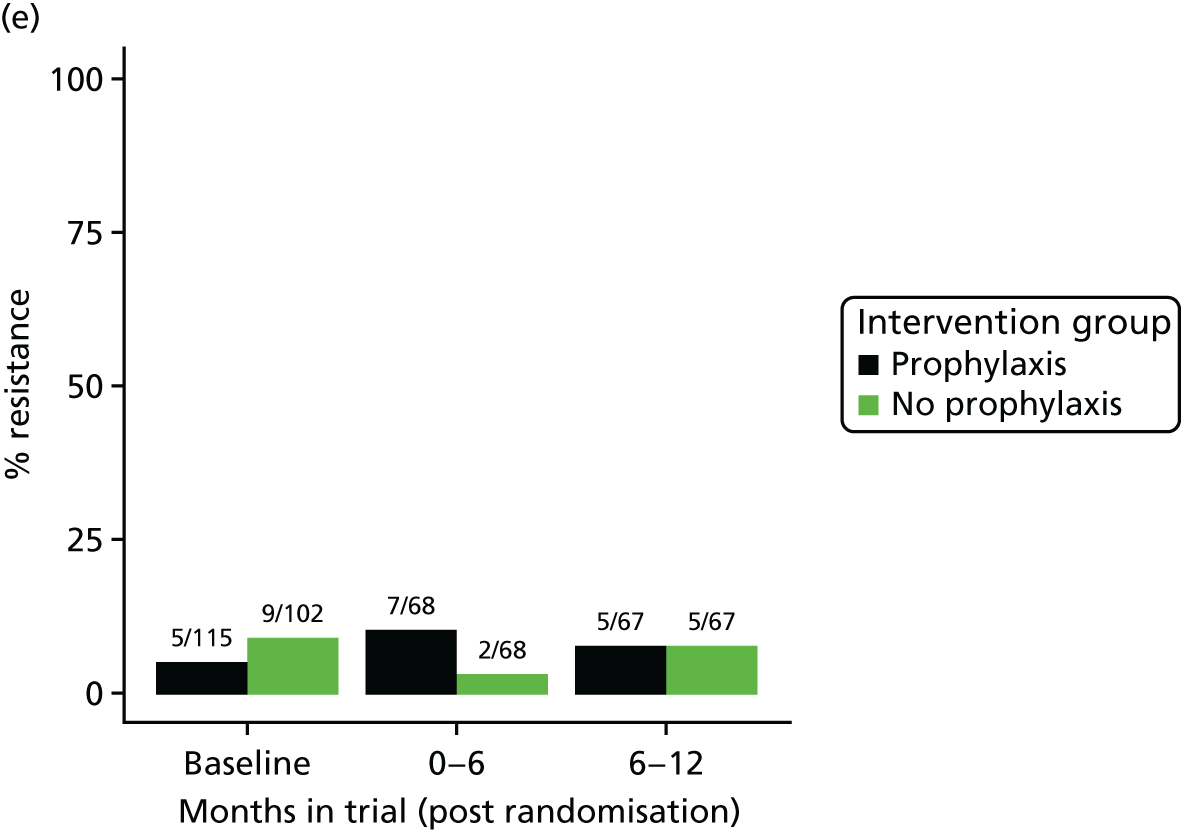

The detection rate for resistance of all pathogens isolated from urine and strains of E. coli from perianal swabs to tested antibiotics at any point during 3-month time periods (0–3, 3–6, 6–9 and 9–12 months) was summarised by trial group. When numbers were sufficient, a chi-squared test for the 9- to 12-month samples from the prophylaxis group versus the no-prophylaxis group and tests for trend including baseline for both groups were used for analysis of the resistance patterns over the 12-month trial period. For perianal swab specimens, 6-month time periods and chi-squared tests for the 6–12 months period were used.

For TSQM scores and change in kidney and liver function at 12 months, the two-sample t-test was used as a simple univariate analysis. Furthermore, an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) approach was employed using the covariates identified during the primary outcome modelling (for the TSQM scores, each subscale was considered separately).

For base-case analysis of the MCS and PCS of the SF-36v2 completed at baseline and 6 and 12 months, a simple Student’s t-test was used. For the adjusted analyses, linear regression was used with the component scores as the dependent variable and with treatment allocation, score at baseline and baseline characteristics as covariates. This analysis allowed assessment of the impact of the interventions after controlling for imbalances at baseline. A two-sample t-test was used as a simple univariate analysis for differences between groups in MCS and PCS. A linear regression was also performed adjusting for the baseline characteristics: age, sex, neurological bladder dysfunction or not, number of UTI episodes in the 12 months before randomisation (fewer than four vs. four or more), renal function (creatinine clearance) and MCS or PCS scores at baseline. Data from completion of the SF-36v2 at the time of UTI were excluded from this analysis but were used in the cost–utility component of the health economic evaluation.

Trial progress and monitoring

The recruitment plan set out to build progressively to a target of 372 participants over 24 months [see Study Documentation (10 Jan 2018) Gantt Chart available at www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/117201/#/documentation (accessed 3 April 2018)]. This included a 12-month feasibility study at which recruitment and patient adherence to the intervention were evaluated.

Feasibility of recruitment was analysed after 9 months of active recruitment (trial month 12) and reported in August 2014 to the TSC and the funder, with an additional safety report reviewed by the Data Monitoring Committee (DMC). Recruitment continued to be monitored by the Trial Management Group (TMG) through returns to the randomisation website. Both the funder and TSC approved continuation of the trial and a subsequent 5-month extension to the planned recruitment period including moderate over-recruitment to ensure completion to target sample size.

Sources of bias

To allow randomisation, both the eligible patient and the responsible clinician needed to be sufficiently uncertain about whether the experimental or control strategy was best for management of recurrent UTI. Given the lack of high-level evidence as to which was the more effective, trial information was provided illustrating the uncertainty and the need for a definitive trial. This aimed to ensure that any selection bias in terms of characteristics of CISC users willing to be randomised compared with those who were eligible but not willing to participate was minimised. As far as possible, we recorded reasons for declining randomisation but patients were free to decline participation and randomisation without giving a reason.

Trial literature was given to all participants and to their clinicians, detailing other measures that may reduce the risk of UTI, such as adequate fluid intake, increased frequency of catheterisation, cranberry products and, if appropriate for post-menopausal women, vaginal oestrogen supplements. To reduce the risk of participants allocated to the control of no prophylaxis being more likely to seek treatment for symptoms suggestive of UTI, and knowing that clinicians may be more likely to prescribe treatment antibiotics to this group, we gave information on use of antibiotic treatment describing indication and choice of agent in trial literature to all participants and their GPs in accordance with established guidance from the BIA and other groups. We also included advice on when to seek help regarding symptoms suggestive of UTI and use of simple measures to avoid or avert symptomatic UTI in the participant information packs.

To ensure uniformity of laboratory processing and culture techniques, we asked participants to post a specimen of urine taken at the onset of symptomatic UTI to the central laboratory at Freeman Hospital, Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, for culture. The use of urine culture at a local microbiology laboratory was at the discretion of the treating clinician. Details of strategies to minimise ascertainment and attribution bias (also known as detection bias) for the primary outcome are given above in Outcome measurement.

Microbiological methods

Participants who were developing symptoms of a UTI and intended to commence a treatment course of antibiotic were instructed to send a sample of urine to the central laboratory at Freeman Hospital, Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, prior to commencing antibiotic treatment. The sample was dispatched in a standard urine specimen container pre-loaded with boric acid at a concentration of 18 g/l (International Scientific Supplies Ltd, Bradford, UK), within secure packaging (Safebox™, Royal Mail Ltd, London, UK) and accompanied by a sample shipment checklist, completed by the participant, identifying the time point and type of sample. Participants were also encouraged to submit diagnostic urine samples as usual in accordance with local protocols through their GP practice or hospital clinic. These were analysed by the participant’s local microbiology laboratory, where they were processed in accordance with the laboratory’s standard operating procedures (SOPs) for the examination of urine specimens. Participants were also instructed to submit urine samples and perianal swabs to the central laboratory during asymptomatic periods as part of their baseline and 3-, 6-, 9- and 12-month assessments scheduled by the trial protocol (perianal swabs at baseline and 6 and 12 months only). Local trial staff assisted participants with this task.

Microscopy and semi-quantitative culture was carried out on all urine samples sent to the central reference laboratory. Automated microscopy was performed using the iQ200 Sprint cytometer (Beckman Coulter, High Wycombe, UK) and specimens were inoculated onto ChromidID® CPS® Elite media using a 1-µl loop and incubated for 18–24 hours in room air at 37 °C. Growth was then enumerated and the presence of up to two isolates at ≥ 1 × 104 CFU/ml was reported, in line with the UK Standards for Microbiology Investigations. 45 Bacterial counts of ≤ 103 CFU/ml and mixed cultures of three isolates or more were regarded as not significant. Presumptive identification was confirmed by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionisation-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF) (Bruker microflex, Coventry, UK). Disc diffusion susceptibility testing against a panel of 16 antimicrobial agents was carried out using Mueller–Hinton agar (Oxoid Limited, Basingstoke, UK) in accordance with the methods outlined by the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST). 46 For E. coli isolates, susceptibility testing was carried out in triplicate. For trial purposes, resistance patterns to the following agents were included in reported analysis: amoxicillin, cefalexin, ciprofloxacin, co-trimoxazole, co-amoxiclav, mecillinam, nitrofurantoin and trimethoprim.

Perianal swabs were inoculated onto ChromID CPS Elite media (bioMérieux, Basingstoke, UK) and examined for the presence of E. coli after overnight incubation in room air at 37 °C. As above, antimicrobial susceptibility testing was carried out in triplicate for E. coli strains using EUCAST’s disc diffusion methodology. 46

The central laboratory was accredited (ISO15189) and analyses were carried out in accordance with current standards set by the UK Health Protection Agency (now Public Health England).

Definition of end of trial

The end of the trial was defined as the last recruited participant’s final study contact at 12 months after their randomisation, which happened on 23 February 2017. Participants were consented separately for the sending of a urine specimen and perianal swab at 6 months after the end of the trial (18 months post randomisation) together with completion of an antibiotic usage questionnaire. As a proportion of these 18-month reassessments took place outside the funded trial period, the results will be communicated separately to this report as an update to the outcome of change in resistance pattern together with a descriptive result of patient choice concerning prophylaxis against UTI.

Compliance and withdrawal

Assessment of adherence

Outcome data were collected remotely, whenever feasible, by participant completion of postal questionnaires. Local research staff made use of planned routine clinical visits to check completion of trial documentation and ensure submission of urine specimen and perianal swab. Adherence to the allocated group (prophylaxis or no prophylaxis) was checked by 3-monthly contact with the participant. If crossover between the groups was reported, local trial staff explored and recorded the reasons for this with the participant and the relevant clinician by telephone or face-to-face contact. Whenever possible, participants remained in the study and continued collection of planned outcome information. The trial literature emphasised the need to adhere to the allocated strategy during the 12-month trial period if possible. Multiple switching between prophylactic agents was allowed. Previous studies47 suggested that this would affect approximately 12% of participants. The trial statistician monitored attrition rate against our anticipated maximum of 15% and reported to the TMG, TSC and DMC as appropriate.

Data monitoring, quality control and assurance

Quality control was maintained through adherence to SOPs governing the work of the sponsor, NCTU and local research teams; adherence to the study protocol and the principles of GCP; research governance; and clinical trial regulations. The MHRA agreed Type A status for the trial. An independent DMC was set up that included one methodologist, one physician not connected to the trial and one statistician (chairperson). The purpose of this committee was to monitor efficacy and safety end points; it operated in accordance with written terms of reference linked to the DMCs: Lessons, Ethics, Statistics charter. 48 Prior to completion of the trial, only the DMC and the statistician preparing reports to the DMC had access to the data separated by allocated group. The DMC met at the start of, completion of, and four times during, the study.

A TSC was established to provide overall supervision of the trial. The TSC consisted of an independent chairperson, two further independent clinicians, an independent statistician, two independent lay representatives and the chief investigator. Other members of the TMG attended as required or requested by the chairperson. The committee met approximately every 6 months during recruitment and annually thereafter for the duration of the trial.

Monitoring of study conduct and data collection was performed by a combination of central review and site monitoring visits to ensure that the study was conducted in accordance with GCP. Study site monitoring was undertaken by members of the TMG. The main areas of focus were consent, SAEs and completeness of the site file.

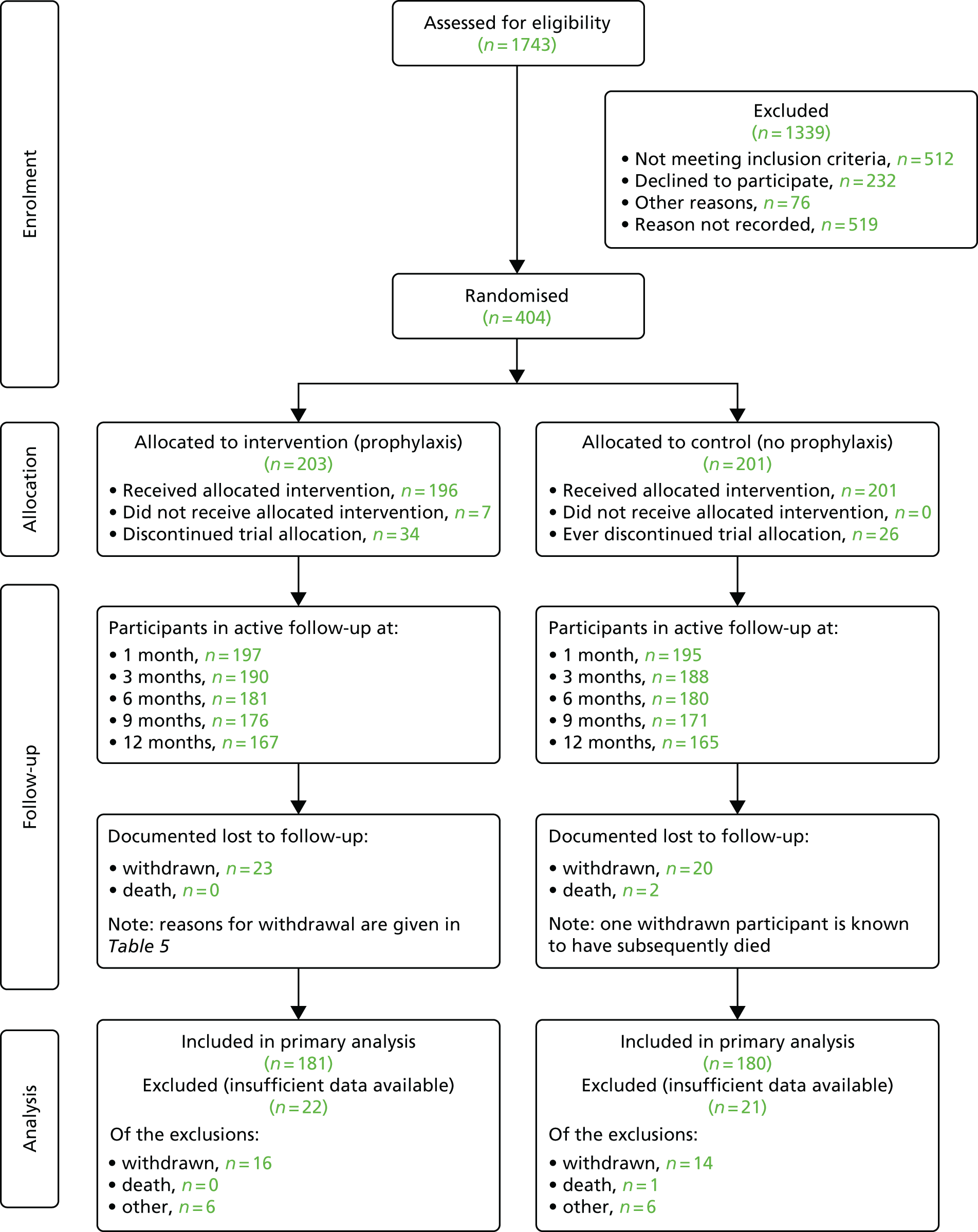

Trial flow chart

The trial flow for participants anticipated at the start of the trial is illustrated in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Diagram showing the planned flow of participants through the trial.

Ethics and governance

The Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust was the sponsor for the trial (reference 6672). Favourable ethics opinion for the trial was obtained on 1 August 2013 from the NHS Research Ethics Service Committee North East – Sunderland [Research Ethics Committee (REC) reference 13/NE/0196] and subsequent research and development and Caldicott approvals were granted by each participating site. A Type A notification submission was made to MHRA and notice of authorisation for the trial was granted with effect from 10 September 2013. Approval was sought and obtained for all substantive protocol amendments.

Trial registration and protocol availability

The trial was registered as ISRCTN67145101 on 25 October 2013. The latest version of the full protocol is available at www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/117201/#/ (accessed 27 October 2017) and a published version is also available. 1

Table 3 summarises key changes to the original AnTIC trial protocol as approved by the REC and MHRA, when required.

| Description | Version | Date |

|---|---|---|

| Widening of inclusion criteria to include those who had had one serious UTI – in line with options that would be offered in standard care | 1.1 | 5 November 2013 |

| More frequent participant contact – to help participants as much as possible to complete UTI log and avoid ascertainment bias | ||

| Payment of any prescription charge to avoid participants being out of pocket | ||

| £20 gift to participants on study entry | ||

| Use of calculated creatinine clearance rather than eGFR – in line with recent NHS guidance for use of nitrofurantoin as UTI prophylaxis | ||

| The protocol was updated to make it clear that washout participants should be consented at the beginning of the washout period, but not randomised until the washout period was complete | 1.2 | 13 May 2014 |

| The protocol was also amended to clarify that an active, symptomatic UTI did not exclude a participant from the trial and that consent to participate could still be taken, but that the UTI should be treated before a participant could be randomised | ||

| Update to the contraindications section of the SmPC for nitrofurantoin concerning patients with kidney dysfunction with an eGFR of < 45 ml/minute. The trial protocol and all trial documentation were amended to reflect this update | 1.3 | 14 November 2014 |

| Change to the protocol to allow sites to send a second invitation letter to participants who had not responded to the initial invitation to the trial | 1.4 | 30 July 2015 |

| Update to clarify the wording around the approved RSI for the trial. The RSI contained in section 4.8 of the SmPC for the three antibiotics used in the trial was submitted to MHRA for approval. The updated SmPC for nitrofurantoin, trimethoprim and cefalexin were included in the appendices of the new protocol | 1.5 | 17 August 2016 |

Serious adverse event reporting

Guidance on AE and SAE reporting, as well as determining the degree of relatedness and assessment of causality for SAEs to study participation, was provided in the protocol. The RSI for assessment of expectedness of related events was contained in the SmPC for each of the three antibiotics and appended to the protocol. SAEs excluded UTI as this was the primary outcome collected and documented throughout the trial. All SAEs were reported for the duration of the trial and for 4 weeks after the trial intervention was stopped.

Chapter 3 Results

Recruitment

The trial was set in the UK NHS (England and Scotland). The first participant was randomised on 26 November 2013 and the last on 29 January 2016. The planned recruitment window was extended by 5 months to 26 months to accommodate the opening of more sites and to achieve the target sample size (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Recruitment by month.

Participants were identified when attending NHS secondary care clinics, by search of primary and secondary care NHS health records and from commercial organisations contracted to provide NHS care (see Table 1). The recruitment strategy involved first establishing seven hubs, each with a funded recruitment co-ordinator, with two (Cambridge and Glasgow) recruiting from secondary care only, four recruiting from both secondary care and primary care/community services (Aberdeen, Bristol, Wakefield and Newcastle upon Tyne) and one from primary care only (Southampton). As the trial progressed, we opened a further 17 secondary care sites and six PICs that referred interested patients to their local hub. Overall, 340 (84%) participants were recruited from secondary care, 50 (13%) from primary care and 14 (3%) from NHS community service providers. We consented 28 patients already on prophylaxis who agreed to start a 3-month washout period, 22 of whom completed washout and were randomised.

Participant flow

The flow of participants enrolled in the trial is shown in Figure 3. A total of 1743 people were identified by study sites (73% of the estimated target of 2400) and screened for eligibility. Of these, 512 (29%) were deemed ineligible to take part by local research staff (Table 4). Of the 1231 deemed eligible and given information about the study, 232 (19%) declined the offer to participate and 76 (6%) gave other reasons for not wanting to participate. Reasons for non-participation for the remaining 519 (42%) were not recorded (an unrecorded number did not respond to postal letters of invitation). Of the 76 who gave other reasons for not wanting to participate, 20 cited age or ill health, 11 did not want to travel to the study site and 10 did not want to take prophylaxis. Following consent and collection of baseline data, 404 participants (109% of the target) were randomised, with 203 allocated to antibiotic prophylaxis and 201 to no prophylaxis. We excluded 43 participants from the primary analysis (11%; see Table 7): 30 who withdrew before completing 6 months of follow-up, one participant who died prior to the 6-month visit and 12 for whom there were insufficient data despite multiple data capture attempts by local and central trial staff (Table 5). A total of 332 participants completed the 12-month trial of allocated intervention and follow-up, surpassing the pre-set target in our sample size calculation (n = 316), with an additional 29 participants having at least 6 months of follow-up data, which allowed their inclusion in the primary analysis.

FIGURE 3.

Trial Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram.

| Reasons for ineligibility | Number of ineligible participants |

|---|---|

| Aged < 18 years | 1 |

| CISC training not completed | 8 |

| Predicted CISC use was < 12 months | 101 |

| Fewer than two episodes of symptomatic UTI or one severe UTI within the previous 12 months | 176 |

| Unable to give consent for randomisation | 10 |

| Already taking prophylactic antibiotic and declining the 3-month washout period | 113 |

| Unable to take any of the three trial drugs (nitrofurantoin, trimethoprim and cephalexin) | 6 |

| Current pregnancy or breastfeeding | 1 |

| Intending to become pregnant in the next 12 months | 3 |

| Inability to adhere to the trial protocol | 4 |

| Competing research study | 2 |

| Unwilling to adhere to the 12-month follow-up period | 10 |

| Does not carryout or no longer carries out CISC | 77 |

| Total not meeting inclusion criteria | 512 |

| Reason for withdrawal | Intervention group, n | Total (N = 43), n | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prophylaxis (N = 23) | No prophylaxis (N = 20) | ||

| Adverse reaction to prophylaxis | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Unable to take any of the prophylactic antibiotics | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Unwilling to continue with the study | 4 | 6 | 10 |

| Unwilling to continue as a result of comorbidities | 4 | 4 | 8 |

| Clinician decision to withdraw as a result of comorbidities | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Study burden too great | 4 | 2 | 6 |

| Withdrawn as a result of ineligibility | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Site unable to contact participant | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Stopped CISC | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Illness of family member | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| No reason recorded | 0 | 2 | 2 |

Baseline data

Key baseline measures are given in Table 6. There was no imbalance between the groups.

| Variable | Intervention group | Total (N = 404) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prophylaxis (N = 203) | No prophylaxis (N = 201) | ||

| Stratification factors | |||

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 115 (56.7) | 114 (56.7) | 229 (56.7) |

| Female | 88 (43.3) | 87 (43.3) | 175 (43.3) |

| Number of UTI episodes in 12 months prior to randomisation, n (%) | |||

| < 4 | 71 (35.0) | 78 (38.8) | 149 (36.9) |

| ≥ 4 | 132 (65.0) | 123 (61.2) | 255 (63.1) |

| Cause of bladder dysfunction, n (%) | |||

| Neurological | 80 (39.4) | 78 (38.8) | 158 (39.1) |

| Non-neurological | 123 (60.6) | 123 (61.2) | 246 (60.9) |

| Clinical measurements | |||

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 59.1 (17.0) | 60.1 (15.6) | 59.6 (16.3) |

| Weight (kg) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 78.9 (17.4) | 81.3 (16.2) | 80.1 (16.8) |

| Creatinine clearance (ml/minute) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 95.7 (40.1) | 100.4 (38.9) | 98.0 (39.5) |

| Median (IQR) | 89.8 (68.6–121.4) | 99.1 (71.9–124.2) | 93.3 (69.8–122.3) |

| Catheterisation details | |||

| Type of intermittent catheterisation, n (%) | |||

| By self | 201 (99.0) | 198 (98.5) | 399 (98.8) |

| By spouse/carer | 1 (0.5) | 2 (1.0) | 3 (0.7) |

| Missing | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 2 (0.5) |

| Planned future duration of need for intermittent catheterisation, n (%) | |||

| Between 1 and 2 years | 0 (0.0) | 4 (2.0) | 4 (1.0) |

| Between 2 and 5 years | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.2) |

| Indefinite | 182 (89.7) | 181 (90.0) | 363 (89.9) |

| Not known | 20 (9.9) | 14 (7.0) | 34 (8.4) |

| Missing | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 2 (0.5) |

| Route of intermittent catheterisation, n (%) | |||

| Urethra | 196 (96.6) | 195 (97.0) | 391 (96.8) |

| Mitrofanoff | 6 (3.0) | 5 (2.5) | 11 (2.7) |

| Missing | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 2 (0.5) |

| Type of catheter used, n (%) | |||

| Single use | 200 (98.5) | 199 (99.0) | 399 (98.8) |

| Reuseable | 2 (1.0) | 2 (1.0) | 4 (1.0) |

| Missing | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) |

| Hydrophilic-coated catheter used?, n (%) | |||

| No | 9 (4.4) | 8 (4.0) | 17 (4.2) |

| Yes | 189 (93.1) | 192 (95.5) | 381 (94.3) |

| Missing | 5 (2.5) | 1 (0.5) | 6 (1.5) |

| Frequency of CISC (per 24 hours), n (%) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 3.8 (2.2) | 4.1 (2.9) | 4.0 (2.6) |

| Median (IQR) | 4.0 (2.0–5.0) | 4.0 (2.0–5.0) | 4.0 (2.0–5.0) |

| Main functional reason for requiring intermittent catheterisation, n (%) | |||

| Bladder outlet obstruction | 49 (24.1) | 56 (27.9) | 105 (26.0) |

| Bladder failure (underactivity) | 139 (68.5) | 128 (63.7) | 267 (66.1) |

| Bladder augmentation/replacement | 13 (6.4) | 16 (8.0) | 29 (7.2) |

| Missing | 2 (1.0) | 1 (0.5) | 3 (0.7) |

| UTI | |||

| Episodes of UTI experienced by participant in previous 12 months, n (%) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 5.2 (3.3) | 5.6 (3.8) | 5.4 (3.6) |

| Median (IQR) | 4.0 (3.0–6.0) | 4.0 (3.0–7.0) | 4.0 (3.0–6.0) |

| Positive urine culture reports in previous 12 months | |||

| Mean (SD) | 2.6 (2.4) | 2.5 (2.4) | 2.5 (2.4) |

| Median (IQR) | 2.0 (1.0–4.0) | 2.0 (1.0–4.0) | 2.0 (1.0–4.0) |

| Approximate months of use of antibiotic prophylaxis for UTI in previous 12 months | |||

| Mean (SD) | 1.1 (2.6) | 1.0 (2.4) | 1.1 (2.5) |

| Median (IQR) | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) |

| Central laboratory culture of urine at baseline, n (%) | |||

| No growth | 93 (45.8) | 84 (41.8) | 177 (43.8) |

| Growth of one or two isolates | 76 (37.4) | 77 (38.3) | 153 (37.9) |

| Missing | 34 (16.8) | 40 (19.9) | 74 (18.3) |

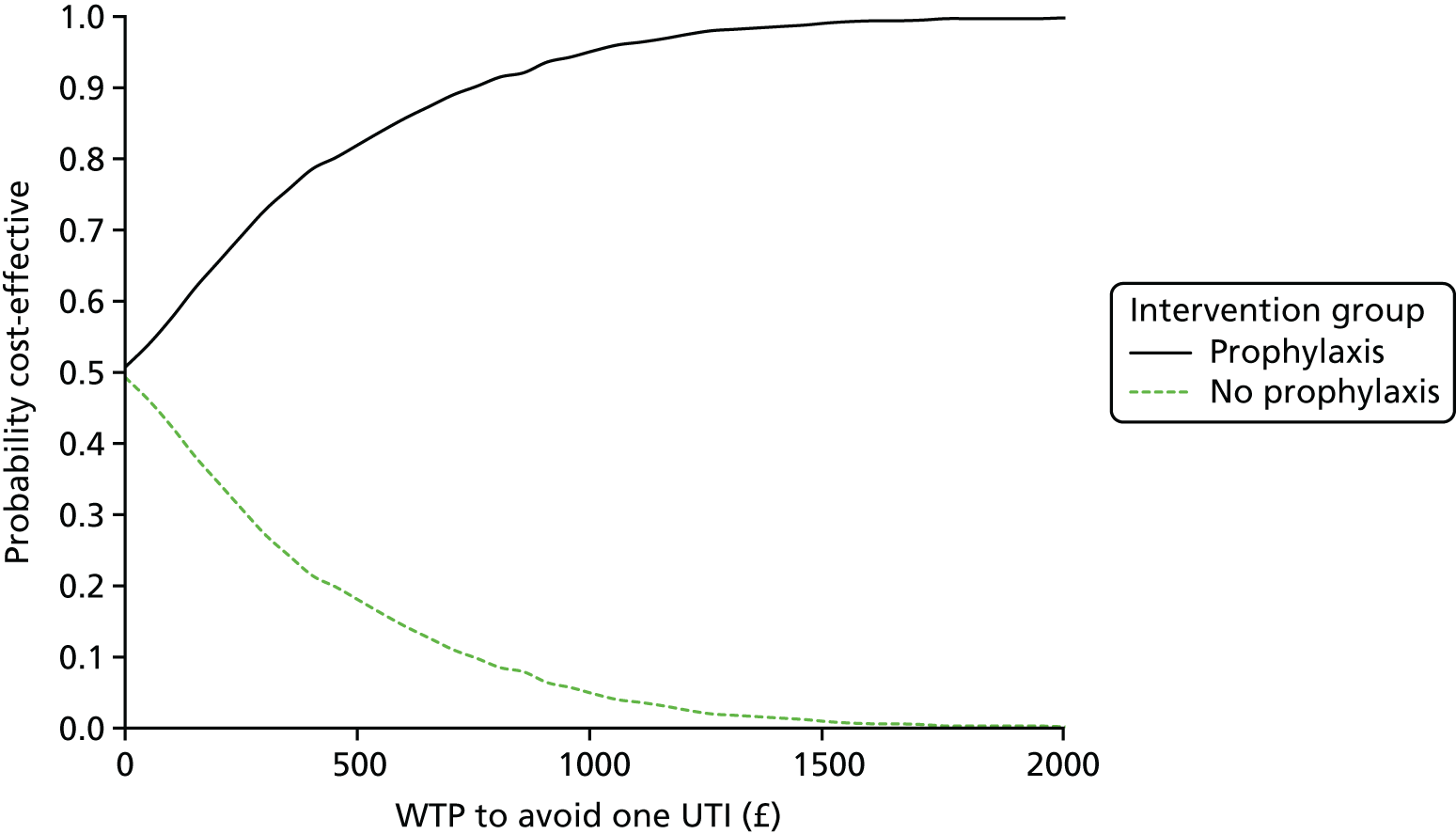

Numbers analysed