Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 12/189/06. The contractual start date was in April 2014. The draft report began editorial review in October 2016 and was accepted for publication in September 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Rob Anderson contributes to the work of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR) programme as an unpaid member of their funding advisory panel (a researcher-led funding stream). Rod S Taylor is the chairperson of the NIHR HSDR researcher-led panel, a member of the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Efficient Study Designs Board, the NIHR Priority Research Advisory Methodology Group, the HTA General Board, the HTA Themed Call, the Core Group of Methodological Experts for the NIHR Programme Grants for Applied Research programme and the HSDR Commissioning Board (commissioned and researcher led). Willem Kuyken receives royalties from the publication of Kuyken W, Padesky CA, Dudley R, Collaborative Case Conceptualization, New York, NY: Guildford Press; 2011, outside the submitted work.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Richards et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Coronary heart disease

Globally, coronary heart disease (CHD) is the single leading cause of death. The World Health Organization estimated that ischaemic heart disease accounted for 7.4 million deaths in 2012, which is around one-third of all deaths globally. 1 In the UK, 1 in 10 women and 1 in 7 men died from CHD in 2015 (around 70,000 deaths per annum), with most deaths caused by myocardial infarctions (MIs). 2 However, the UK mortality rate from CHD is falling, largely through the introduction of evidence-based treatments and lifestyle changes leading to reductions in major cardiac risk factors (mostly smoking). The successful fall in mortality rate means that many more people are living with heart disease and may need support to manage their symptoms and prognosis. In 2015, around 2.3 million people in the UK were living with CHD, over 60% of whom were male.

As a consequence, the need to address stress, psychosocial factors (e.g. lack of social support) and other underlying mood disorders (such as depression or anxiety), has long been recognised as important within conventional cardiac care in the UK,3 Europe4 and the USA. 5

Depression and coronary heart disease

Among people who have experienced acute coronary syndromes [ACSs including ST elevation MI (STEMI), non-STEMI (NSTEMI) and unstable angina], prevalence rates for major depression are estimated to be around 20% in studies using structured clinical interview schedules. 6 The rate of depression has also been shown to be raised in individuals following coronary artery bypass grafting,7 people with unstable angina8 and those experiencing chronic heart failure. 9 Irrespective of the underlying coronary condition, the rates of depression greatly exceed the UK general population rate of 2.6%. 10

Depression is important among people with CHD, as it predicts a range of negative medical outcomes, including greater morbidity and mortality,11–15 poorer health-related quality of life (HRQoL),16–18 higher use of routine and unscheduled health care19,20 and, therefore, increased health-care costs. 21 The nature of the association between depression and CHD is complex and the mechanisms underpinning this association are unclear, but may include biological and behavioural processes (e.g. poorer adherence to cardiac risk factor management), or may be confounded by shared genetic vulnerability, environmental stresses or perseverative negative cognitive processes. 22 New-onset depression is associated with an approximate doubling of the risk of subsequent incident ACS,23,24 the worsening of associated heart failure25 and increased rates of cardiac mortality. 18 It remains unclear, however, whether new-onset depression is particularly ‘cardio-toxic’22 or whether its apparent associations with poor cardiac outcomes is confounded by, for example, the severity of the underlying cardiac disease. 18

Depression that predates an ACS, on the other hand, differs from new-onset depression in that it is predicted by risk factors that are similar to depression in the general population, including being of young age, lacking social support, experiencing ongoing life difficulties and a past history of psychiatric disorder. 22 Although such depression is associated with poorer medical outcomes, compared with people who are not depressed, the association with adverse medical outcomes appears to be less strong than that for new-onset depression. 14

In light of the high prevalence of depression among people with CHD and its association with poor medical outcomes, there is widespread national and international recognition that detection and treatment of such depression is important. 3–5

Usual health care for people with cardiac heart disease and depression

Cardiac rehabilitation service provision

In the UK, the NHS routinely offers multidisciplinary cardiac rehabilitation to people who experience an acute cardiac event. These are patients with CHD referred following admission with an ACS. The majority will have had coronary revascularisation, usually percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) for STEMI, or coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery. Many patients with heart failure may also be admitted with an ACS, and are also eligible for cardiac rehabilitation. Some patients have concomitant valve surgery with CABG, and others may have had a pacemaker or defibrillator in the context of CHD. Some patient groups, such as people with heart failure, who might benefit from cardiac rehabilitation have historically been excluded from cardiac rehabilitation. However, recent national audit data suggest that such exclusions are diminishing and that the diversity of case mix is increasing. In the UK in 2014–15, an estimated 82,127 patients commenced cardiac rehabilitation, including individuals with a primary indication of MI (19.6%), MI and PCI (28.1%), PCI (14.1%), CABG (14.8%), heart failure (4.4%), angina (3.6%), valve surgery (5.9%) and other or unknown conditions (e.g. having a pacemaker, implantable cardioverter defibrillator; 9.6%). 26

Guidance on the recommended content of usual cardiac rehabilitation care has been published by the British Association for Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation (BACPR),3 the contents of which are broadly comparable with that which is recommended across Europe4 and the USA. 5 Core components include education; exercise and physical activity; diet and weight management; medical management and psychological support. Cardiac rehabilitation follows a seven-stage care pathway (stages 0–6), as illustrated in Figure 1 and Box 1. 27

FIGURE 1.

Cardiac rehabilitation standard patient care pathway. CR, cardiac rehabilitation.

The pathway commences when a patient presents after an acute coronary event, and is identified and referred to a cardiac rehabilitation team by the hospital staff.

Stage 1After the initial referral is received, it is managed by a cardiac nurse specialist who approaches the patient, often on the hospital ward, to begin the rehabilitation process through the provision of clinical advice and educational materials. Where appropriate, the individual is also offered a clinic appointment at a community-based service after their discharge from hospital.

Stages 2 and 3Individuals who elect to attend the clinic appointment with a cardiac nurse receive a multidimensional assessment, covering both physical and mental health status (stage 2), and a care plan is developed to support their rehabilitation needs (stage 3). Individuals deemed medically suitable for a cardiac rehabilitation are then invited to attend the next available structured programme in their locality.

Stage 4Structured cardiac rehabilitation programmes offer participants the opportunity to receive further education and support in relation to cardiac risk factor modification and psychosocial health, as well as undertake a supervised exercise programme. Current guidance recommends that programmes are delivered twice weekly over a period of 8 to 12 weeks. 27

Stages 5 and 6On completion of the structured cardiac rehabilitation programme (or at the point the patient chooses to withdraw from the care pathway), when possible, the cardiac nurse specialist conducts a final assessment of the individual’s physical and mental health status (stage 5), before organising the discharge into existing community services, making any referrals that are deemed appropriate (stage 6).

The organisation and delivery of cardiac rehabilitation services are currently in a state of flux. In 2011–12, in the UK, The National Audit of Cardiac Rehabilitation: Annual Statistical Report 201328 identified 290 operationally distinct, comprehensive cardiac rehabilitation programmes (stages 2–5); by 2014–15, 308 core programmes were identified. 26 While working towards nationally agreed standards and a standardised patient care pathway, there remains considerable regional variation in the staffing and skill mix of individual services.

Patient attrition across the cardiac rehabilitation pathway also remains an area of significant challenge. It has been estimated that, for people with one of the four most prevalent indicated conditions (MI, MI and PCI, PCI or CABG) referred to cardiac rehabilitation in the UK, uptake is around 47% and varies considerably by condition (38%, 54%, 40% and 59%, respectively). 26 The number of individuals who go on to attend a structured rehabilitation programme is strongly influenced by gender. It has been estimated that around two-thirds of potentially eligible men start structured rehabilitation, compared with less than one-third of women, and the reasons underlying these differences are not well understood.

As part of the initial cardiac rehabilitation assessment with a nurse specialist (stage 2), individuals are usually asked to complete the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)29 to assess mood. In 2014–15, it was estimated that 12% of patients exhibited borderline depressive symptoms (i.e. a HADS-D score of 8–10) and 7% were depressed (i.e. a HADS-D score of ≥ 11) during this initial assessment. Of the individuals who completed the final assessment of a structured cardiac rehabilitation programme (stage 5), 8% exhibited borderline depressive symptoms and 4% were depressed during this final assessment. There was considerable regional variation observed in the change scores between localities. 26 These findings indicate that there is considerable scope to improve and standardise treatment for depression among people undergoing cardiac rehabilitation.

Despite the burden of depression, in 2013, only 25 out of 260 cardiac rehabilitation services (10%) reported receiving direct psychologist input. 30 However there is recent evidence that psychologist input is increasing, with 48 out of 261 programmes (18%) reporting such input in 2014. 26 Notwithstanding this progress, the evidence still suggests that patients’ depression usually remains untreated. 31 Locally agreed referral protocols providing for access to psychological care at either the tertiary (stage 1) or community (stages 2–5) levels may be agreed. However, the precise content of such protocols, and the consistency of their implementation, is not clear from audit data.

Although it would appear that structured management of depression is not routinely provided within the majority of cardiac rehabilitation programmes, individuals may access mental health care through existing care pathways for depression provided by other mainstream NHS services. 32–34 Notwithstanding this, there is a need to deliver models of care to increase access to evidence-based depression treatments for people undergoing cardiac rehabilitation.

Effectiveness of psychological care for people with depression

Effective care for people with depressive symptoms includes the provision of psychological and/or pharmacological interventions, as well as the effective co-ordination of mental health-care services. 32–34

Effectiveness of psychological therapies in the general population

Psychological treatments, such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), interpersonal therapy and antidepressant medication, are the mainstay evidence-based treatments for acute depression. Both are recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) as first-line treatments. 33,34 However, there are problems with antidepressant medications, which include side effects, poor patient adherence and relapse risk on cessation of prescribing. Service user organisations and mental health policy advisors advocate greater availability of a range of psychological therapies, which many people prefer, in part because of the problems with antidepressant medications, but also because patients can learn skills to help manage depression. 35

Cognitive behavioural therapy has been shown to be of similar efficacy to antidepressant medication. 36 However, CBT offers two major advantages: (1) it is consistent with many service users’ preferences for non-pharmacological treatment; and, (2) it modifies the illness trajectory, as its benefits continue post treatment, by teaching skills to prevent depressive relapse in the long term. However, CBT may not suit everyone, as not all individuals engage or adhere to it because of a combination of factors (e.g. the investment of time, the burden of homework and the need to make cognitive and behavioural changes). 37 In addition, CBT is typically offered only by specialist CBT therapists, because of the significant training required; the high costs of training and employing sufficient therapists may therefore limit attempts to access CBT. The Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT)38–40 programme in England has done much to enhance access to psychological treatments (recovery rates are at approximately 50%), and recently has extended its scope to people with depression and long-term conditions, including CHD. However, the capacity of the IAPT programme to reach this patient group and its acceptability are as yet untested.

Another psychological therapy that is a potential alternative to CBT is that of behavioural activation (BA). BA alleviates depression by focusing directly on changing behaviour. 41 Behavioural theory postulates that depression is sustained by avoiding many usual activities, and as individuals withdraw and disrupt their basic routines, they become isolated from positive reinforcement opportunities in their environment. Thus, individuals may end up stuck in a cycle of depressed mood, decreased activity and avoidance of activities. 41 BA systematically disrupts this cycle through encouraging individuals to initiate action despite the presence of negative mood, counteracting their natural tendency to withdraw or avoid activities. 42 Although CBT also incorporates behavioural elements and may also increase activities, its primary techniques focus on changing maladaptive beliefs43 by initiating behavioural experiments to test specific beliefs. BA also explicitly prioritises the treatment of negatively reinforced avoidance and rumination. The rationale for BA is simpler to understand and operationalise for both patients and mental health workers. The focus of BA on context and functioning is also closely aligned to the ethos of cardiac rehabilitation services. The relative simplicity of BA makes it more straightforward to train non-mental health nurses in its application. 44–46

Evidence regarding the clinical effectiveness of BA for the treatment of depression in general populations is available from two recent systematic reviews. 47,48

Ekers et al. 47 synthesised evidence from randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of BA for depression with either control patients [waiting list, usual care (UC) or placebo] or participants taking antidepressant medication. Data from 25 trials (1088 participants) were pooled in a meta-analysis, which reported post-treatment depressive symptom levels to be significantly reduced with BA compared with controls [25 studies, n = 1088; standardised mean difference (SMD) –0.74, 95% confidence interval (CI) –0.91 to –0.56]. Although far fewer trials compared post-treatment outcomes for BA with those for antidepressant medication, the effect size estimate favoured BA (four studies, 283 participants; SMD –0.42, 95% CI –0.83 to 0.00). However, these data should be interpreted with some caution, as the upper boundary of the 95% CI bordered the value of no effect.

A second review, by Shinohara et al. ,48 compared the effectiveness of behavioural therapies for the management of depression with other psychological therapies within five major categories (cognitive–behavioural, third-wave cognitive–behavioural, psychodynamic, humanistic and integrative therapies). Synthesising data from 18 trials (690 participants), the authors concluded that the treatment response rates of behavioural therapies were comparable to other psychological therapies [risk ratio (RR) 0.97, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.09] and were broadly acceptable to participants.

It is noteworthy that both review teams noted that the methodological quality of selected studies was low and that there remains some uncertainty regarding the effectiveness of BA,47,48 particularly with regard to the longer-term outcomes. 47 However, a very recent National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme-funded non-inferiority RCT [the Cost and Outcome of Behavioural Activation versus Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for Depression (COBRA) trial]49 comparing BA with CBT has shown that BA is not inferior to CBT for the treatment of depression. 50 In this trial, which randomised 440 participants to BA or CBT, 66% of participants receiving BA or CBT were recovered from depression at 12 months post randomisation, with benefits extending to the same degree at the long-term 18-month follow-up point. The COBRA trial also reported the costs of BA to be lower than CBT (an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of –£6865), with this difference largely attributable to BA being delivered by people with less expertise in psychological therapies. This finding is consistent with data reported from a small RCT of BA (n = 24) versus treatment as usual (n = 23), which reported an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of –£5756 in favour of BA. 51 The evidence, therefore, is now much clearer that BA is an effective, and less costly, front-line treatment for depression in general populations.

Clinical effectiveness of collaborative care approaches in the general population

Despite the proven clinical effectiveness of depression treatments, a number of studies have shown that individuals often have difficulty accessing or maintaining contact with high-quality mental health care. Under these circumstances, effective care for people with depression may require a system-level intervention aimed at overcoming barriers to accessing services and increasing co-ordination of mental health care. Such system-level interventions can be managed in primary care as part of a stepped-care algorithm to ensure optimal access to, and co-ordination of, psychological or pharmacological interventions of proven clinical effectiveness. 32–34

Collaborative care is one example of such a system-level intervention aimed at overcoming barriers to mental health care for people with depression. Collaborative care is a complex intervention52,53 in which a number of health professionals work together to ensure the individual accesses appropriate, evidence-based care to suit their mental health-care needs. In this model, a case manager trained in mental health-care co-ordination works closely with a medical doctor [often the person’s general practitioner (GP)] and mental health specialist services. The case manager is responsible for generating a structured management plan to support the patient’s access to evidence-based treatment based on best-practice guidelines. The case manager will then implement the care plan, providing the patient with scheduled follow-ups to monitor their progress (in person or over the telephone/internet), provide specific interventions (or make the appropriate referrals), encourage treatment adherence and monitor symptoms. Another core goal of such a model is to enhance interprofessional communication across the wider care team.

A 2012 Cochrane review synthesised evidence from 79 RCTs (24,308 participants) comparing collaborative care with either UC or alternative treatments for people with depression and anxiety. 53 Although the evidence was of variable quality, the primary analysis found collaborative care to be superior to the comparator condition for reducing depressive symptoms in the short term (0–6 months, 30 studies, 5984 participants; SMD –0.34, 95% CI –0.41 to –0.27) and medium term (7–12 months, 13 studies, 4092 participants; SMD –0.28, 95% CI –0.41 to –0.15). Although one study observed long-term effects (13–24 months) in favour of collaborative care, as these data were derived from only one study (1379 participants; SMD –0.35, 95% CI –0.46 to –0.24), the generalisability of this finding should be treated with caution. There was also some evidence of benefits in other outcomes including medication use, mental HRQoL and participant satisfaction, although benefits in terms of physical quality of life remained uncertain. Although many of the published trials are not from the UK, a recent large Medical Research Council (MRC)/NIHR-funded two-arm cluster RCT (n = 581) found collaborative care to be clinically effective (and cost-effective) for people with depression in UK primary care, and of particular note is that two-thirds of this trial sample also had comorbid physical health problems. 54 A second recent cluster RCT found similar results when testing collaborative care exclusively in a UK primary care-based population with depression and a comorbid physical health problem (diabetes mellitus or CHD). 55

Clinical effectiveness of psychological care for people with coronary heart disease

In the previous section, Effectiveness of psychological therapies in the general population, we reviewed the evidence of clinical effectiveness of psychological therapies and mental health collaborative care models tested in the general population samples of people with depressive symptoms. There is also a considerable body of evidence regarding the clinical effectiveness of psychological therapies designed specifically for use for people with CHD. Similar psychological techniques (e.g. CBT, BA) may be applied in isolation or combined with other psychological interventions (e.g. stress management or problem-solving skills training) as part of multifaceted treatment packages. The target population and setting can vary. Some interventions target people with coronary disease irrespective of their baseline psychological health, whereas others adopt a more selective approach, offering interventions only to those individuals screening positive for an existing psychological condition.

Two systematic reviews56,57 have used meta-analytic techniques to synthesise evidence on the clinical effectiveness of psychological interventions for people with CHD. Direct comparisons between these reviews are problematic because of the important differences in the application of methods and definitions. Both reviews selected studies in which the direct effects of psychological interventions were compared with a comparator group (mostly usual medical care with or without cardiac rehabilitation) on measures of depressive symptoms. However, Dickens et al. 56 selected studies with any length of follow-up (ranging from 5 days to 12 months), and reported only psychological outcomes. In contrast, Richards et al. 57 selected studies that followed up participants for a minimum of 6 months (range 6 months to 10.7 years) and reported evidence for clinical events (e.g. mortality, cardiac morbidity), as well as the psychological outcomes of depressive symptoms and anxiety and stress levels. Both reviews also undertook metaregression analyses, seeking to explore whether or not intervention effectiveness was mediated by their use in unselected populations, as opposed to targeting people with existing psychological conditions. Although the studies applied different taxonomies, both reviews also sought to identify potential explanatory components of psychological interventions. Notwithstanding differences in study methods, there was some consistency in the findings from these reviews.

Analysing data from 62 studies (17,397 participants), Dickens et al. 56 observed a small but statistically significant improvement in depression for psychological interventions compared with UC (SMD 0.18, 95% CI 0.12 to 0.24). Subgroup analysis identified certain treatment components with small beneficial effects on depressive symptoms, including general education, problem-solving, skills training, exercise, CBT and relaxation. In a subgroup analysis, there was also a small effect observed in favour of psychologically based interventions (SMD 0.21; 12 trial arms), when targeted at people with coronary disease and clinical depression, as compared with untargeted populations.

In the second review, Richards et al. 57 synthesised data from 35 studies (10,703 participants), including 12 studies that recruited patients with an established psychopathology (eight studies selected people with depression), and from 19 studies reporting some levels of psychopathology within their participant samples. The interventions tested were mostly multifactorial in nature, designed to address a number of different treatment goals (e.g. reducing stress levels, improving mood states, improving coping strategies, emotional support), through combining psychological techniques (e.g. stress management, CBT or behavioural therapies).

Richards et al. 57 found no significant differences in the effects of psychological interventions versus the comparator group in terms of total mortality (23 trials, 7776 participants; RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.05) and the risk of subsequent revascularisation (13 trials, 6822 participants; RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.81 to 1.11) or of a non-fatal infarction (13 trials, 7845 participants; 0.82, 0.64 to 1.05). However, there was some evidence that cardiac mortality was reduced (11 trials, 4792 participants; 0.79, 95% CI 0.63 to 0.98). When considering psychological outcomes, interventions based on psychological therapies resulted in significant improvements in the participant-reported levels of depressive symptoms (19 trials, 5825 participants; SMD –0.27, 95% CI –0.39 to –0.15), anxiety levels (12 trials, 3161 participants; SMD –0.24, 95% CI –0.38 to –0.09) and stress levels (eight trials, 1251 participants; SMD –0.56, 95% CI –0.88 to –0.24). Metaregression exploring a limited number of intervention characteristics found no significant predictors of intervention effects for the outcome of cardiac mortality. Unlike Dickens et al. ,56 psychological therapies combined with adjunct pharmacology (when deemed appropriate) prescribed for an underlying psychological disorder were found to be more effective than interventions that did not combine psychological and pharmacological therapies (difference in effect size β = –0.51; p = 0.003). For anxiety, interventions recruiting participants with an underlying psychological disorder appeared to be more effective than those delivered to unselected populations (β = –0.28; p = 0.03), although this finding was not replicated for the outcome of depressive symptoms.

Although somewhat different in focus and methodology, both reviews consistently demonstrated that providing psychological interventions for people with established CHD yields small, but statistically significant, improvements in participant-reported levels of depressive symptoms. However, given the multicomponent nature of the interventions tested, combined with the diverse patient groups and settings in which such interventions were tested, it is not possible to ascertain which psychological treatment components may be most effective and for whom.

Clinical effectiveness of collaborative care approaches for people with heart disease

More recently, rather than evaluating the clinical effectiveness of psychological interventions, research is focusing on the clinical effectiveness of collaborative care for people with coronary disease and depression. Consistent with the care models developed in general populations, the focus is not to evaluate the clinical effectiveness of individual psychological therapies per se. Rather, the aim of collaborative care is to ensure that individuals with heart disease and depressive symptoms receive best-practice psychological care through appropriate assessment, symptom monitoring, referral to psychological therapists and, where appropriate, the provision of pharmacological therapy. Psychological care is delivered by a care manager and the wider clinical care team members, who work with the individual over a period of time to tailor their preferences for care with recommendations based on their symptoms and previous experiences. In some models, the care manager also provides elements of psychological therapy.

A recent systematic review by Tully and Baumiester58 synthesised data from six RCTs (1284 participants), which randomised participants to either collaborative care or a UC comparator group. Although there was no evidence of a sustained reduction in major adverse cardiac events (including mortality or morbidity) arising from collaborative care, small reductions favouring collaborative care were found in the short term (3–12 months) for depressive symptoms (six studies, 1277 participants; SMD –0.31, 95% CI –0.43 to –0.19; p < 0.00001) and anxiety symptoms (four studies; SMD –0.36, CI –0.54 to –0.17; p < 0.0001), and mental HRQoL improved (five studies; SMD 0.24, 95% CI 0.08 to 0.38; p = 0.003), although no differences were observed for physical HRQoL.

Rationale for current research

This study was undertaken in response to a NIHR commissioning brief in 2013, which invited research addressing the question: What is the clinical and cost-effectiveness of enhanced care for new onset depression post cardiac event? The brief envisaged that the intervention would involve enhanced, non-pharmacological care for depression tailored to adults with new-onset depression after an acute cardiac event. The intervention was required to be easily deliverable in the NHS, and integrated within existing NHS cardiac rehabilitation during the recovery phase.

In responding to this brief, our review of the literature regarding the clinical effectiveness of psychological treatments was inconclusive. Recent systematic reviews56–58 report modest, but statistically significant, reductions in depressive symptoms for patients with coronary disease receiving psychological treatments, although the methodological quality of studies selected is such that it precludes firm conclusions regarding which treatment components are most effective and who should be targeted for intervention.

Most intervention studies have recruited participants immediately following an acute cardiac event, and the complexity of depression in that period may have contributed to the lack of conclusive evidence regarding the treatment response. The reasons for the limited benefits of conventional depression treatments in patients with CHD are not clear, although three factors are noteworthy.

First, depression that starts after an ACS is different from depression in the general population. 22 Post-ACS depression does not have the usual risk factor profile as that observed for the general population; instead, it is associated with ongoing cardiac symptoms and increased concerns about health,59,60 which may act to reduce the response to conventional treatment. 61 Second, established psychological treatments, such as CBT, that encourage recall of past experience and challenge maladaptive thoughts may be too traumatic for people who have suffered a recent life-threatening event. Finally, the psychological therapies available through IAPT may not be widely available to people with CHD. Indeed, in 2013 a qualitative study of people undergoing cardiac rehabilitation62 concluded that management of depression should be embedded within cardiac rehabilitation teams, rather than as another source of onward referral. As UK cardiac rehabilitation services experience significant patient attrition at each stage of the rehabilitation pathway (53% attrition prior to commencing a structured programme), and 19%26 of individuals are found to have depressive symptoms upon initial assessment, another outward referral for psychological care may be a barrier to accessing timely care.

If a relatively simple psychological treatment of proven benefit in general populations of people with depression, such as BA,47,50 has the potential to be safely and effectively embedded within the cardiac rehabilitation service, this could holistically tackle the depressive symptoms at the same time as physical rehabilitation, as part of patient case management. Similarly, acknowledging that attrition from rehabilitation is high, we also believe that any attempt to enhance psychological care should include training cardiac rehabilitation nurses (who routinely screen for depressive symptoms) to apply evidence-based mental health referrals. Such a mental health collaborative care approach should also be in place for patients completing structured cardiac rehabilitation programmes, but whose depressive symptoms do not respond to psychological treatment.

Chapter 2 Aims and objectives

Feasibility study aims

The overarching aim of the feasibility study was to design an enhanced psychological care (EPC) intervention for the management of patients with new-onset depressive symptoms, composed of care co-ordination and BA, and to test its implementation within routine cardiac rehabilitation settings. We also sought to specify the psychological components within UC for patients with depressive symptoms using cardiac rehabilitation services (NHS care pathway stages 2–5; see Figure 1) following an acute cardiac event. There were five objectives:

-

(1a) To describe the content of psychological support routinely offered by cardiac rehabilitation services, including active treatments offered by rehabilitation teams, or referral practices to existing NHS mental health services.

-

(1b) To develop, and refine, the underlying intervention theory of a standardised EPC intervention (including a supporting intervention manual and training package) for implementation by cardiac rehabilitation nurses.

-

(1c) To determine the feasibility, and acceptability, of implementing/experiencing EPC from the perspectives of cardiac rehabilitation staff and patients.

-

(1d) To describe process measures, including: (1) the number of patients with new-onset depressive symptoms identified during the initial cardiac rehabilitation assessment (NHS care pathway stages 2–3); (2) participant attendance at, and adherence with, the comprehensive cardiac rehabilitation programme with an embedded EPC aimed at treating depression, and the time elapsed to the start of treatment; and (3) the psychological care co-ordination activities provided to participants when exiting from the cardiac rehabilitation care pathway.

-

(1e) To develop and undertake preliminary testing of study methods (cardiac rehabilitation team and participant recruitment, data collection procedures) required to implement a pilot trial.

To address these objectives, a multimethod feasibility study was undertaken, including a qualitative study involving cardiac rehabilitation staff and patient participants (addressing objectives 1a, 1b and 1c) and a before-and-after observational study (addressing objectives 1b, 1d and 1e).

External pilot trial aims

The main aim of the pilot trial that followed the feasibility study was to test the methods and procedures required to undertake a fully powered evaluation of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of cardiac rehabilitation teams implementing EPC for individuals with new-onset depressive symptoms using cardiac rehabilitation services compared with cardiac rehabilitation delivering UC. There were four objectives:

-

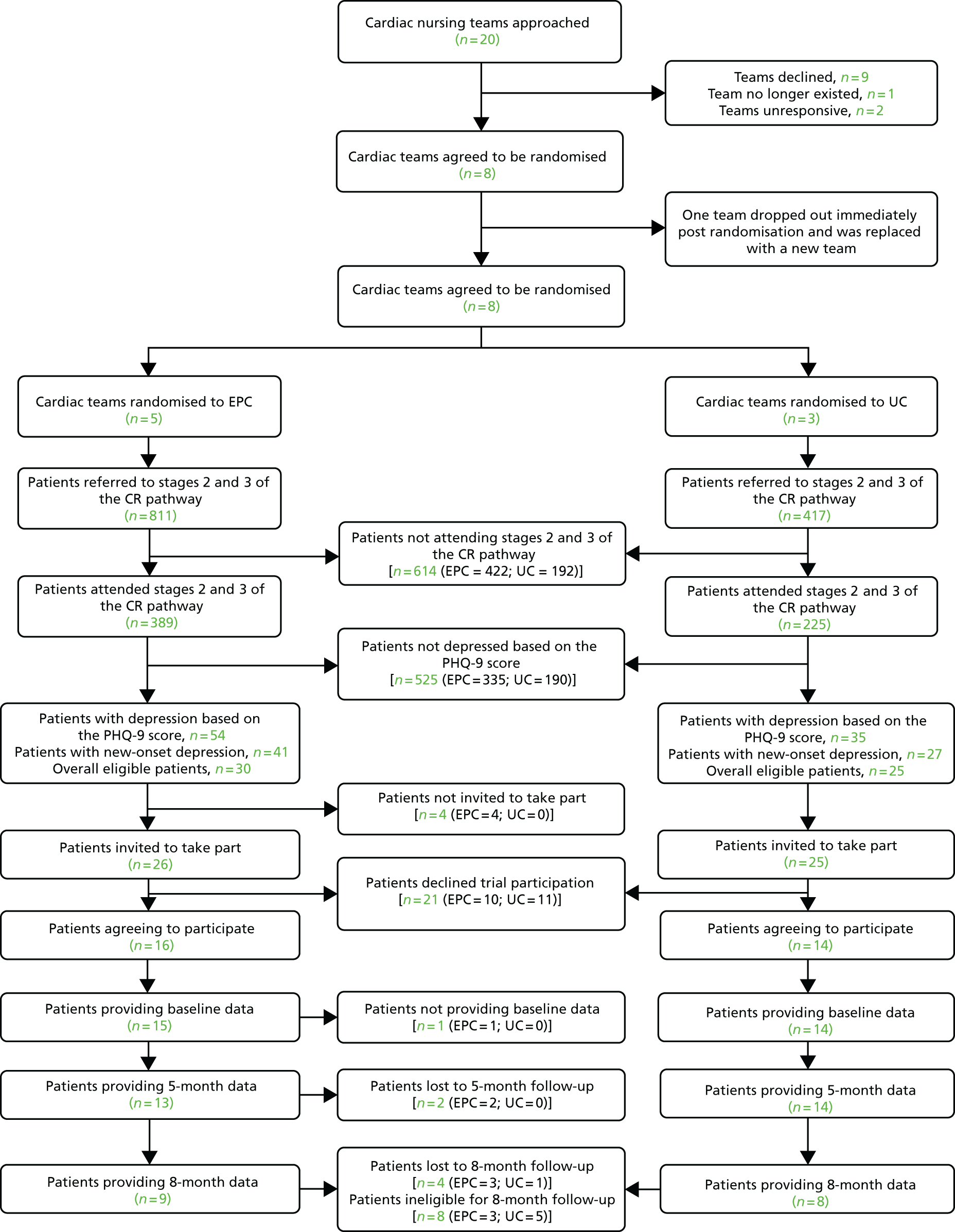

(2a) To quantify the flow of patients from the cardiac event to the 8-month follow-up for patients entering into the cardiac rehabilitation care pathway, and to document the flow of those participants who agreed to take part in the pilot trial (i.e. eligibility, recruitment and attrition).

-

(2b) To collect participant outcome data in order to estimate the standard deviation (SD) for various continuous outcomes to inform sample size calculations (number of cardiac rehabilitation teams and participants) for a definitive trial.

-

(2c) To establish the data collection methods required to support a definitive economic evaluation.

-

(2d) To gather qualitative evidence from patient participants (including participants who did or did not adhere to the EPC, and from those patients who declined to take part in the trial) and from nurses on the acceptability of receiving/implementing EPC, on the appropriateness of study methods and procedures, and on the content of usual psychological care within cardiac rehabilitation services.

Chapter 3 Study methods

Consistent with MRC’s guidance for the development and evaluation of complex interventions,63 a two-phase study was undertaken. The first phase included a multimethod feasibility study composed of qualitative and observational methods, and the second phase entailed a pilot cluster RCT, which also tested the methods for economic data collection and included a nested qualitative study.

Feasibility study design

The feasibility study was designed to support the development and preliminary testing of the EPC intervention, and to undertake an early evaluation of study methods and procedures before undertaking the pilot RCT. A before-and-after observational study was combined with observations of UC and qualitative interviews with cardiac nurses and patient participants.

Observational study

Feasibility study intervention

Enhanced psychological care was a complex intervention, comprising nurse-led BA therapy and mental health-care co-ordination. The intervention was developed and delivered by experts within the research team who had used BA in other clinical trials conducted in general populations of patients with depression. 44,50,54 Current UK NICE guidance33 was used as the basis for the mental health-care co-ordination component of EPC. This guidance recommends the regular review of participants’ symptoms, including them in decisions about their treatment and, when necessary, referring them to their GP and/or existing community or primary care mental health services, either during or on their point of discharge from EPC.

Before taking part in the study, nurses from participating cardiac rehabilitation teams underwent a 2-day training course covering the topics of BA, mental health-care co-ordination, managing mental health risk issues (e.g. suicide ideation) and delivery of the intervention. Each nurse was given a manual (version 2, 20 August 2014; available on request from the study team) providing detailed information to support their delivery of EPC. Once trained, nurses were asked to start consecutively screening all patients for depressive symptoms during their initial cardiac rehabilitation assessment and to offer study entry to eligible participants. Nurses delivering EPC to one or more patients received weekly supervision from a clinical supervisor with mental health expertise working within the study team. Supervision was conducted by telephone, with nurses receiving individual supervision.

In the UK, the NHS routinely offers multidisciplinary cardiac rehabilitation following a seven-stage standard patient care pathway (see Figure 1). 3,27 Cardiac rehabilitation programmes usually consist of an initial assessment, with a structured 6- to 8-week programme with up to two sessions each week. However, the precise content of a cardiac rehabilitation session can vary across sites, and could include a clinic appointment during which the patient’s underlying cardiac condition would be monitored/discussed, a rehabilitation fitness session would be overseen by a nurse or there would be a group education session. It was recommended that nurses provide EPC once per week to participants, at a point in a rehabilitation session that was deemed to be appropriate based on local circumstances.

At the start of rehabilitation, the nurse provided the participant with a CADENCE (enhanced psychological CAre in carDiac rEhabilitatioN serviCEs for patients with new-onset depression compared with usual care) participant handbook (version 2, 20 August 2014), and asked that they read it before the next session. The nurse then provided an individually tailored treatment programme of BA and care co-ordination (as appropriate) across the course of the rehabilitation programme. Although there was some flexibility in how EPC was delivered, some elements of the intervention were deemed to be central. The intervention protocol advised that each EPC session should comprise:

-

The monitoring of depressive symptoms, using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9),64,65 and of anxiety, using the Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7)66 instrument; these tools replaced the HADS, which cardiac nurses had previously used to monitor symptoms of anxiety and depression; this change was implemented because both GPs and community mental health services routinely use the PHQ-9 and the GAD-7 to make treatment decisions/referrals; unlike the HADS, the PHQ-9 also asks individuals to report any suicidal ideation, the identification of which is core to the safe and effective management of depression. Thus, the change from the HADS to the PHQ-9 was intended to facilitate seamless mental health-care co-ordination by ensuring that clinicians communicated the symptoms burden and risk safely and effectively.

-

Monitoring of suicide and self-harm risk at every nurse–participant contact, and procedures to manage such risks should they arise.

-

Participant self-monitoring through the completion of a mood–activity diary between rehabilitation sessions; at each session, the participant and nurse undertook a functional analysis of the diary, aiming to identify patterns of behaviour linked to high mood. Participants were encouraged to identify valued activities, and triggers to ‘depressed behaviours’; after identifying different coping strategies, over the following week, participants were encouraged to schedule other routine, pleasurable and necessary activities to replace those behaviours associated with low mood.

-

Application of mental health-care co-ordination algorithms targeted at those individuals whose low mood had not resolved during EPC (a PHQ-9 score of ≥ 10), or participants who elected not to continue with BA as part of their rehabilitation programme. On completion of cardiac rehabilitation, the participant’s GP was routinely informed of the psychological care provided, and of the last PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scores recorded during symptom monitoring.

Nurses were asked to record patient participation with EPC in their nursing notes during the course of cardiac rehabilitation attendance.

Settings and participants

The observational study aimed to recruit up to 20 eligible participants from three locality-based comprehensive cardiac rehabilitation teams in Devon, south-west England. Early discussions with cardiac rehabilitation specialists suggested that the study intervention would be delivered by cardiac nurse(s) from locality-based teams that were operationally distinct (i.e. there was no crossover of staff) from neighbouring teams. Thus, in some teams it might be necessary to train more than one nurse, particularly if two nurses work interchangeably to provide continuity of care for individual patients within their locality.

Sample size

Consistent with the feasibility design, no formal sample size calculation was undertaken; rather, a target sample (three teams, 20 participants) was deemed sufficient to provide the preliminary data required to test our feasibility study aims; that is, ensuring that nurses had sufficient experience of delivering EPC (circa eight or nine patients per team) to comment meaningfully on the intervention design.

Participant inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria

Adult patients (aged ≥ 18 years) referred for cardiac rehabilitation based on local clinical referral protocols were eligible to take part in the observational study. The inclusion criteria included patients admitted with an ACS (i.e. STEMI or NSTEMI and unstable angina), and/or following a coronary revascularisation procedure (i.e. CABG or PCI). At the time this study commenced, this constituted the majority of patients referred for cardiac rehabilitation services in the UK [the 2012 National Audit of Cardiac Rehabilitation (NACR)28]. Patients with a new episode of depressive symptoms were identified through nurse screening during their initial cardiac rehabilitation appointment. Those patients scoring ≥ 10 using the PHQ-9 were eligible for inclusion (note that this meant that participating teams changed their usual practice of monitoring mood using the HADS29 to monitoring mood using the PHQ-9 and the GAD-7). This cut-off point was chosen to aid identification of people with at least moderate depression,67 but also to maintain alignment with primary care psychological services (IAPT), which offer treatment for people with PHQ-9 scores of ≥ 10 upon referral from GP-based services.

Exclusion criteria

Patients who reported that they were actively treated for depression (psychological or drug therapy) in the 6 months before their acute cardiac event were excluded. The nurse also excluded patients for whom there was evidence of alcohol or drug dependency, when the participant was acutely suicidal or when there was evidence of poorly controlled bipolar disorder or psychosis/psychotic symptoms based on a clinical review (and having sought external confirmation from the GP or other clinicians as required). Potential participants also needed to have sufficiently good English-language skills to engage with both the mental health-care co-ordination and BA components of the EPC intervention, or to be willing to work with a NHS translator if required, and to provide informed consent to take part.

Participant recruitment procedure

All cardiac rehabilitation nurses were trained to apply a structured checklist to ascertain participant eligibility based on the study’s inclusion/exclusion criteria. Eligible participants were identified by cardiac rehabilitation nurses during their initial clinic appointment (NHS care pathway stage 2/3) before commencing the structured rehabilitation programme (stage 4). Eligible patients were asked by the nurse to take part in the observational study and associated qualitative interview study, and provided with brief study information to take away and review. The nurse asked for patients’ permission to pass their contact details onto a researcher, who was independent of the clinical team.

Within 2 working days of receipt of a completed ‘permission for release of personal details’ form from the cardiac team, the researcher contacted the potential participant to discuss the study. During this initial telephone call, the researcher confirmed that the patient was currently not receiving any form of active treatment for their depressive symptoms. The individual was provided with the opportunity to ask any further questions about the study. For those individuals who were happy to progress, the researcher agreed a date for the face-to-face baseline home visit within 1 week, and sent a confirmation letter, which included a detailed participant information sheet for their review. During the baseline visit, the researcher once again briefly reviewed the study eligibility criteria to ensure that there had been no major changes in their treatment for depression since referral. The researcher then went through the participant information sheet and answered any remaining questions that the individual raised. The participant was reminded that their involvement was entirely voluntary, that their usual health care would not be affected by their decision to take part, and that they could withdraw from the study at any point without giving a reason. If the individual was happy to proceed, written consent was obtained prior to completion of the baseline assessment. The baseline assessment was typically conducted before the participant commenced their comprehensive cardiac rehabilitation programme. Mental health-care co-ordination was implemented for participants who subsequently elected not to attend the rehabilitation.

Data collection and analysis procedures

The aim of this feasibility study was to collect preliminary data regarding process measures relating to the flow of participants in the study and the adequacy of data collection procedures. We therefore restricted data collection to a baseline interview and a single 5-month follow-up, and a subset of process and outcome measures was assessed.

Process measures

Process data were collected in relation to patient throughput and intervention fidelity. To ascertain study eligibility and recruitment, cardiac rehabilitation nurses completed a screening log, recording the numbers of patients attending an initial nurse assessment, the proportion identified with depressive symptoms during this assessment, the prevalence of new-onset (as opposed to existing) depression and the number of patients who were deemed eligible for study participation. The nurse screening log also captured brief, anonymised data on patient sociodemographic characteristics (e.g. age, sex, ethnicity/preferred language) and on the clinical conditions resulting in the cardiac rehabilitation referral, allowing the characteristics of our sampling frame to be described. For eligible patients, the nurse also recorded the number of participants offered study entry and the number who later agreed to be contacted by a researcher. The research team documented the number of individuals who subsequently consented to take part and who underwent a baseline interview. Descriptive statistics documenting the flow of patients through the study procedures are presented.

For this study, intervention fidelity was assessed through a review of cardiac nurse notes conducted by the researcher. We documented the numbers of people recruited to the study who subsequently did not attend the structured rehabilitation programme. For participants who commenced intensive rehabilitation with EPC, we assessed adherence by recording the number of BA sessions offered and the number of sessions attended. We reviewed the nursing notes for all participants, and recorded the number with documentary evidence of mental health-care co-ordination on exiting cardiac rehabilitation and the type of mental health referrals made (if appropriate).

Adequacy of data collection procedures

As this was a feasibility study, we restricted our focus to testing the completeness of data relating to participant-reported outcome measures at baseline and the 5-month follow-up (i.e. excluding cardiac morbidity and mortality, and health-care resource use). A full description of the participant-reported outcome measures collected at both time points is provided under the description of the pilot trial methods (see Data collection procedures). Descriptive statistics were presented on the number of participants completing assessments and the completeness of data recorded therein. Descriptive summaries of the baseline and 5-month outcomes were also calculated.

Qualitative study

Data collection procedures

Although broadly following the NHS cardiac care pathway, discussions with clinical co-applicants and participating teams indicated that there was considerable variation between the cardiac teams on how cardiac rehabilitation was delivered. Thus, before EPC was operationalised by participating teams/nurses, the qualitative researcher conducted observations of UC within each study team to assess what variations existed. These observations indicated that the study teams varied in terms of their patient waiting list times, how cardiac rehabilitation was delivered, what room facilities were available to cardiac nurses and how many cardiac rehabilitation sessions were offered to patients. These insights informed the development of the intervention and the nurse training package prior to nurses being trained and EPC being implemented. During the qualitative study, observations were also made of the nurse training. All observations were recorded by the qualitative researcher using field notes. This researcher also took notes during the early informal discussions held with participating nurse teams about the practicalities of, and barriers to, EPC delivery.

Nurses were interviewed within 4 weeks of completing EPC training, and before they started to deliver EPC, to ascertain their views of the training and to identify any problems they envisaged in delivering EPC within their rehabilitation programme. Nurses were interviewed again towards the end of delivering EPC to study participants to explore their views on the acceptability of the intervention and the study materials, and the extent to which they thought EPC could be embedded within cardiac rehabilitation services.

Nurses’ experiences of delivering the intervention were also gauged through nurse/clinical supervisor sessions being observed and field notes being taken. In addition, the clinical supervisors wrote an anonymised summary of the nurses’ experiences, detailing the issues identified during supervisory sessions relevant to EPC delivery.

Patient participants were interviewed once they had completed their EPC to explore their views and experiences of receiving it. The aim was to interview approximately 15 patients, having purposefully sampled individuals to achieve variation in relation to participant age and gender, the recruiting team and treatment adherence (including patients who refused any cardiac rehabilitation, participants who fully engaged with EPC and individuals who undertook EPC but did not complete treatment).

Nurse and participant interviews were conducted by an experienced qualitative researcher. Topic guides were used to ensure consistency across the interviews (see Appendix 1). The content of the guides was informed by the aims of the study, the research team’s knowledge of the literature and the intervention and the insights gained through observations and discussions held early on in the study with nurses and the intervention developers. The nurse and patient interview topic guides were developed in parallel to ensure that key areas were explored during both sets of interviews, allowing findings from participant and nurse interviews to then be triangulated, increasing the confidence with which conclusions could be drawn. All nurse and participant interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. Prior to analysis, the transcripts were checked against the audio-recordings for accuracy and anonymised, with individual participants being allocated a numerical identification code.

Protocol changes when implementing the qualitative feasibility study

A number of methodological changes were made to the protocol for the qualitative elements for the feasibility study. These were made during the course of the feasibility study in response to insights gained as the work progressed.

-

The original protocol stated that a focus group would be conducted with nurses directly following their training in EPC. Once the training package had been developed, it was clear that nurses would be expected to attend a 2-day training course and that there would be little time at the end of the second day to complete a focus group with those attending. To reduce the burden on nurses, a decision was made to replace the focus group with a brief one-to-one telephone interview conducted within 4 weeks of the training.

-

We had originally planned to interview patients who were eligible for the study but who declined to take up cardiac rehabilitation to ascertain the reasons behind their decision. However, it became apparent that patients who refused cardiac rehabilitation usually did not attend the initial appointment with the nurse. As this meant that we could not determine which of these patients would be eligible for study participation (i.e. those who had low mood), these interviews were not conducted.

-

Initially, we had planned to interview nurses on two occasions during the period in which they were delivering EPC. The first interview was scheduled to be conducted early on in the delivery of EPC to explore nurses’ initial experiences of delivering BA. The second interview was to be conducted once they had finished providing EPC. The first interview was dropped, as issues relating to the early EPC implementation formed the basis of clinical supervision sessions and, with the nurses’ consent, the supervisors were willing to let the qualitative researcher sit in on the supervision sessions.

-

The protocol stated that the qualitative researcher was to conduct observations of the nurses’ provision of the intervention to assess implementation and integration of EPC into existing care. However, as participant recruitment was much lower than anticipated (only one of the four nurses provided care to more than one patient), we elected not to conduct these observations, as we anticipated that the nurses would be uncomfortable with being observed at this early stage of delivering a new intervention.

-

Finally, we aimed to invite staff from the wider cardiac rehabilitation teams to contribute to a focus group discussion on whether or not the provision of EPC had affected them. However, it became clear that the cardiac rehabilitation nurses were working in isolation, and thus it was unlikely that the provision of EPC would impact upon other team members. Instead, a question was added to the nurse topic guide to enquire as to whether or not the nurses were aware of anyone else from the immediate clinical teams being affected by the intervention.

Our sponsors and funders were notified of all of these protocol changes.

Qualitative data analysis

Notes taken during the observations were read and re-read by the qualitative researcher, who then fed back key points that were relevant to the design and delivery of the intervention to the rest of the research team.

Interview data were analysed thematically, focusing on how study materials and nurse training could be improved in terms of making them more acceptable for nurses, and the intervention could be improved in terms of its effective implementation in practice and its acceptability to nurses and participants.

Transcripts from the nurse and participant interviews were read and re-read by two members of the research team to gain an overall understanding of the accounts given, to ascertain emerging themes and to develop an initial coding frame. The two researchers then independently coded a sample of transcripts and discussed their preliminary coding and interpretation of the data. The coding frame was then revised, with new codes being developed and existing codes being defined more clearly or deleted. Once both researchers had agreed the coding frame, transcripts were manually coded and data under each code were summarised in a table, using an approach based on framework analysis. 68 Having done this, comparisons were then made within and across the data. When coding the nurse and patient interviews, similar codes were used, when possible, to allow for triangulation of findings between data sets. Nurse and patient data sets were analysed separately to ensure that a thorough understanding of each group’s account was established before comparisons were made between the views held by patients and nurses.

The findings from the observations and interviews were fed back and discussed within the wider research team throughout the feasibility study, so that changes could be made to the intervention and study materials prior to undertaking the pilot trial.

Design of the pilot randomised controlled trial

The second phase of research included a pilot RCT, the testing of economic data collection procedures and a nested qualitative study.

An external pilot cluster RCT69,70 was undertaken. We recruited eight comprehensive cardiac rehabilitation teams (clusters) and randomised five of these to EPC plus UC embedded within cardiac rehabilitation (intervention), and the other three to usual cardiac rehabilitation care (control). The decision to allocate more clusters to the intervention arm was informed by data emerging from our feasibility study (see Chapter 4, The transition between feasibility study and pilot study), which suggested that participant recruitment would be slower than anticipated. We therefore sought to ensure that a sufficient number of nurses and patient participants had exposure to EPC to support the aims of the qualitative study interviews (i.e. recruiting enough participants with experience of EPC).

Randomisation and allocation concealment

A cluster randomised design was adopted in preference to individual randomisation to ameliorate concerns around potential contamination between the intervention and control arms (i.e. intervention participants coming into direct contact with control participants and sharing aspects of their treatment). Our EPC intervention included training for cardiac rehabilitation nurses to provide mental health-care co-ordination to participants with depressive symptoms. Once trained, we judged that it would be very difficult operationally for the nurse to apply care co-ordination to only the subset of their patients randomised to receive EPC (as would be required with individual randomisation).

Randomisation was carried out by the trial statistician (FCW), who was independent of the recruitment of rehabilitation teams or patient participants. The allocation sequence was generated using computer-generated random numbers. Cluster randomisation was balanced (to the extent possible) by team type (community, hospital or mixed community and hospital teams) and patient throughput at the initial cardiac rehabilitation assessment (NHS care pathway stage 2/3; categorised as low/high). The latter cut-off point between low/high throughputs was determined post hoc after scrutinising the mean monthly throughput across cardiac rehabilitation teams, with ‘low’ being equivalent to ≤ 22 patients per month, and ‘high’ being equivalent to > 22 patients per month (these cut-off points were based on a natural break in the distribution of team throughput assessed during a preparatory audit collecting data for a 2-month period in January and February 2015). The throughput of new patients assessed by cardiac rehabilitation teams was selected as a stratifying variable, as this appeared to be a better predictor of team workload than staffing levels, and would ensure that a sufficient number of patient participants were recruited into each trial arm. Team setting was selected as a stratifying variable, as our feasibility study suggested that teams working in hospital or community settings, or in a combination of both, may encounter different resource issues that could affect the delivery of EPC.

Randomisation took place after all eight cardiac teams had been recruited. Each team was informed of its allocation by the trial researcher.

Trial interventions

Usual care

Usual care is defined here as the standard NHS care pathway, commencing at the point of assessment undertaken by a cardiac rehabilitation specialist nurse from a locality-based cardiac rehabilitation team (see Figure 1). 3,27 Of the people invited to attend an initial cardiac rehabilitation assessment, it is estimated that less than half will attend a comprehensive rehabilitation programme offered within 2–10 weeks of assessment (stage 4). 28 Treatment as usual typically includes intensive rehabilitation for one or two sessions per week for approximately 8 weeks. Sessions generally last around 2 hours, and include structured exercise, education (e.g. managing lifestyle and cardiac risk) and some psychological input (e.g. relaxation, stress management) in order to meet the core standards of care described by the BACPR. 3 On exiting a comprehensive rehabilitation programme, patients receive a final assessment (stage 5), and discharge arrangements are made to community services (stage 6).

There is considerable debate as to what constitutes standard psychological care within cardiac rehabilitation. Although most nurses will assess the patient’s mood using the HADS during the initial assessment, and on completion of the rehabilitation programme, little is known about how this information is used as part of care planning. National audit data found that psychological expertise within locality-based cardiac rehabilitation teams is uncommon (< 10%),28 although some teams may refer patients onto specialist mental health services if they have specific concerns regarding an individual’s mental well-being.

Enhanced psychological care

Based on our feasibility findings (see Chapter 4, Refinements to the enhanced psychological care intervention prior to the pilot study), we made some important modifications to the EPC intervention before starting the pilot study. The most fundamental changes in the delivery of EPC between the feasibility and pilot phases were (1) an increased emphasis on the mental health-care co-ordination component of EPC and (2) a shift from a ‘nurse-delivered’ to a ‘participant-led’ programme of self-help BA embedded within cardiac rehabilitation, reflecting the need to reduce the impact of EPC on nurse time. The EPC training programme and supporting materials, including the participant handbook (version 5, 4 June 2015) and nurse handbook (version 5, 29 May 2015; available from the NIHR project website), were amended based on feasibility findings (see Chapter 4, The transition between feasibility study and pilot study). Nurses were trained to implement mental health-care co-ordination,33,34 including an embedded participant-led BA programme42,44–46,71,72 using the restructured materials and training package. New materials were also provided to support nurses in delivering EPC, including a structured form to insert in the participant’s clinical record for nurses to capture core data on what aspects of EPC were offered at each session (see the EPC session planner in Appendix 2).

Patient-led, nurse-supported behavioural activation therapy

As in the feasibility study, the main psychological intervention consisted of six to eight sessions of BA flexibly delivered face to face or via telephone (the latter was used for the follow-up session only). Sessions focused on the three key components of BA: activity monitoring (recording what people were doing), functional analysis (developing a shared understanding of how activity relates to mood) and activity scheduling (increasing pleasurable, routine and necessary activities that are less likely to maintain depression). Sessions focused on encouraging the participant to follow the participant handbook and review progress, and decreased the emphasis on the nurse leading the intervention. As a result, sessions were shorter, lasting 10–20 minutes, thereby reducing the burden on the nurse’s time.

The participant handbook (version 5, 4 June 2015) consisted of a structured programme aimed at enabling participants to identify and re-engage with sources of positive reinforcement from their environment and develop future strategies for managing their depressive symptoms. The handbook described the nature of the BA intervention and the structure of the treatment patients would receive, and arrangements were made to meet again to discuss the workbook and start the therapy. A functional analytical approach was adopted as part of BA; participants were helped to develop an understanding of behaviours that might interfere with meaningful, goal-oriented behaviours (e.g. negative avoidant behaviours). The handbook also explained how to self-monitor mood, and then how to identify behaviour patterns associated with low mood. Participants were encouraged to develop alternative behaviours that were goal-orientated, targeting routine, pleasurable and necessary activities, and to undertake activity scheduling of these identified behaviours. Although our pilot intervention involved a participant-led self-help BA manual, the cardiac rehabilitation nurses were trained to support participants actively.

As in the feasibility study, each session began by assessing the patient’s symptoms (using the PHQ-9 and the GAD-7) and assessing any identified risks of self-harm, suicide or risks to others. In session 1, the treatment options were briefly discussed (BA with a cardiac nurse, referral to a GP or local IAPT services, or, if appropriate, referral to psychological service provision associated with cardiac service, if available). Participants choosing BA with the rehabilitation nurse were provided with a participant handbook (version 5, 4 June 2015). The content of subsequent sessions remained flexible to accommodate different rates of progress, but also to accommodate issues with physical health that frequently came up and needed to be dealt with immediately. As serious physical problems could arise unpredictably and derail the discussions about BA, to operationalise the treatment and allow calculation of the dose of BA (the number of sessions in which BA was delivered), it was deemed to have occurred only if all of the following had occurred: an assessment of mood and risk, a discussion of progress since last time and an agreement on a plan of activity for the next week.

Early sessions (2 and 3) still focused on encouraging patients to complete a diary of their activity throughout their week, alongside a record of their mood rated on a 10-point scale (0 = lowest, 10 = normal). Mid-range sessions (3–5) focused on encouraging patients to identify the link between mood and activity (functional analysis), although the tools to achieve this were simplified. Patients were encouraged to schedule in achievable tasks (pleasurable, necessary and routine). Late sessions (6–8) continued the monitoring of mood and activity and scheduling of further activities, but with an emphasis on identifying and reinforcing the benefits of scheduled activities on mood, and considering the next steps (onwards referral if necessary, and relapse prevention).

Mental health-care co-ordination

During the feasibility study, care co-ordination was conceived as occurring after BA to ensure that care was handed on to another appropriate clinician when the cardiac rehabilitation nurses ceased to be involved. What became apparent in the feasibility study was that considerably greater flexibility in mental health-care co-ordination was required to accommodate patients with differing needs, that is, when patients refused or discontinued BA or when the nurse did not have the capacity to support BA. Furthermore, in some circumstances, a physical deterioration meant that nurses lost contact with patients (e.g. during readmission), so psychological care could be delayed. Nurses were given the flexibility to co-ordinate care with another clinician at any point during the patient’s journey, as they considered appropriate, and after discussion with their supervisor.

To deliver mental health-care co-ordination, nurses were trained to apply clinical decision-making rules based on current best practice,33,34 matching the intensity of treatment with participant preferences for mental health care. All patients referred to a cardiac rehabilitation team who agreed to undertake an initial assessment (stages 2 and 3) were routinely screened for depressive symptoms using the PHQ-9, with individuals who scored ≥ 10 being deemed eligible for inclusion. On identifying an eligible individual, the nurse explained what evidence-based treatment options were available. This could include BA self-help materials supported by the nurse, GP referral, referral to local IAPT services and/or referral to specific cardiac patient psychological support services where available. Nurses co-ordinated care by monitoring symptoms of depression and anxiety, assessing risk to self or others and agreeing a plan of care with participants that may include BA and/or referral to a GP, IAPT services or other therapeutic agencies, as described previously. As part of this care co-ordination protocol, all participants were offered patient-led, nurse-supported self-help BA, as outlined in Enhanced psychological care.

Nurses’ training in enhanced psychological care

Two cohorts of nurses underwent training. Nurses’ training comprised either 1 or 2 days of face-to-face classroom-based training, supplemented as appropriate by self-directed online teaching materials (including videos of the previous training session), which could be worked through in preparation for taught sessions. The course was delivered by experienced mental health practitioners (a liaison psychiatrist and a mental health nurse with BA accreditation) who provided training on the key techniques of mental health-care co-ordination, managing safety and risks and BA. This training allowed nurses to actively support participants during care co-ordination, and to assist participants as they worked through the BA manual alongside their cardiac rehabilitation programme. Nurses were provided with a session-by-session guide, detailing the types of care co-ordination tasks that might be relevant for participants as they moved through their 6- to 8-week comprehensive rehabilitation programme (see Appendix 3). This guide was flexible to accommodate participant preferences for care. Nurses delivering EPC to study participants also received clinical supervision by a mental health practitioner (an accredited BA therapist). Clinical supervision was obligatory for nurses who delivered EPC to participants while they had one or more EPC participants on their caseload. The sessions were usually delivered fortnightly by telephone, at a time that was convenient to the teams and which met with their clinical demands; they could be arranged either one to one or as a team. Each session lasted no more than 30 minutes.

On completion of cardiac rehabilitation (stage 5), the nurse sent structured details of a participant’s care to their GP. All participants, including those receiving BA and whose depressive symptoms did not respond (based on their PHQ-9 score), were given an opportunity to review their management options with the nurse. Here, treatment response was defined as achieving a minimum clinically important difference (MCID) for the PHQ-9 that was equivalent to a 5-point reduction in score. 73 It is important to note, however, that some people achieving this MCID may remain above the PHQ-9 diagnostic threshold (i.e. a score of ≥ 10). As part of their care co-ordination, these individuals will be referred for continuing mental health management.

Settings and study population

Cardiac rehabilitation programmes

We aimed to recruit and randomise eight locality-based comprehensive cardiac rehabilitation teams from south-west England (the geographical regions of Bristol, Cornwall, Devon, Dorset and Somerset). After excluding the four sites that took part in the feasibility study, a total of 20 teams (sites) were approached to take part between December 2014 and February 2015. In each site, the lead cardiac rehabilitation nurses from each team were invited to take part and provided detailed information about the study. In each geographical region, the recruitment letter was co-signed by the trial chief investigator and, where appropriate, the local co-applicant. In addition, the study recruitment letter was accompanied by a letter of support from a local NHS cardiac rehabilitation lead for each region.

Teams that indicated an interest were visited by the research team, whereby the trial design and methods were explained and staff were given the opportunity to ask questions. To support randomisation, teams were asked to provide some descriptive information on their staffing model and service, as well as reporting some audit data on patient throughput in the previous 2 months. In order for the team to take part, the team leader was required to provide written consent on behalf of the service. In addition, given that nurses would be required to actively contribute to the research, we also requested written consent from individual team members who would be directly involved in participant recruitment and, where appropriate, implementation of EPC. After the last team was recruited (May 2015), the trial statistician (FCW) randomised the teams into the respective allocation groups and teams were informed of their allocation.

Managing a post-randomisation withdrawal