Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 07/37/64. The contractual start date was in April 2009. The draft report began editorial review in April 2017 and was accepted for publication in November 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Matthew T Thompson reports grants and personal fees from Endologix Inc. and Medtronic Ltd (Watford, UK) and personal fees from Gore Medical (Neward, DE, USA) outside the submitted work. Richard J Grieve is a member of the Health Technology Assessment Commissioning Board. Roger M Greenhalgh serves as a salaried director of Biba Medical Ltd (London, UK) and has an equity interest in the company and serves as an expert witness on behalf of patients with vascular disease.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Ulug et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is a common degenerative disease, with a current prevalence of ≈2% in men aged 65 years; the prevalence increases with age. AAA is about fourfold less common in women. Small AAAs are rarely associated with symptoms but their natural history is progressive enlargement until rupture occurs. Following several randomised trials, a screening programme for 65-year-old men was rolled out, between 2009 and 2013, to cover the UK. Elective aneurysm repair is recommended when the diameter is > 5.5 cm (about three times the normal aortic diameter); the operative mortality for elective procedures for screen-detected aneurysms is low. 1–3 Without intervention, a ruptured AAA is fatal and the overall mortality is > 80%. About half of patients with ruptured aneurysms die in the community. More than one-third of patients who arrive in accident and emergency departments do not reach the operating theatre alive. Among the patients who reach the operating theatre (for open surgical repair under general anaesthesia), only half will leave hospital alive. These stark figures changed little over the 50 years between 1960 and 2010. 4 Ruptured aneurysm is a common vascular emergency, involving various symptoms that are not specific to AAA rupture, usually back or abdominal pain and collapse. It tends to occur in elderly patients who often have comorbidities that may preclude a successful repair, especially if the diagnosis is not made promptly.

Ruptured aortic aneurysms are a common cause of death in the UK and, in the last century, infrarenal AAAs caused ≈8000 deaths per annum in England and Wales. The incidence of both AAAs and ruptured AAAs continued to increase year on year until about 2000 in both men and women. 5,6 More recently, the number of deaths from ruptured AAAs has declined rapidly because of the reducing prevalence of smoking in the population and the increasing number of elective aneurysm repairs in the population aged > 75 years, using the minimally invasive endovascular repair. 7 Nevertheless, when this trial started in 2009, there were still 2581 deaths from AAA ruptures (285 of these in women) in England and Wales. Until about 2004, routine practice was to direct patients with a suspected ruptured AAA directly to the operating theatre for open repair, without preoperative computerised tomography (CT). In England, there were about 1300 open surgical repairs for ruptured aneurysms each year, with 30-day and in-hospital mortality being similar at 47–48%. 4,8,9

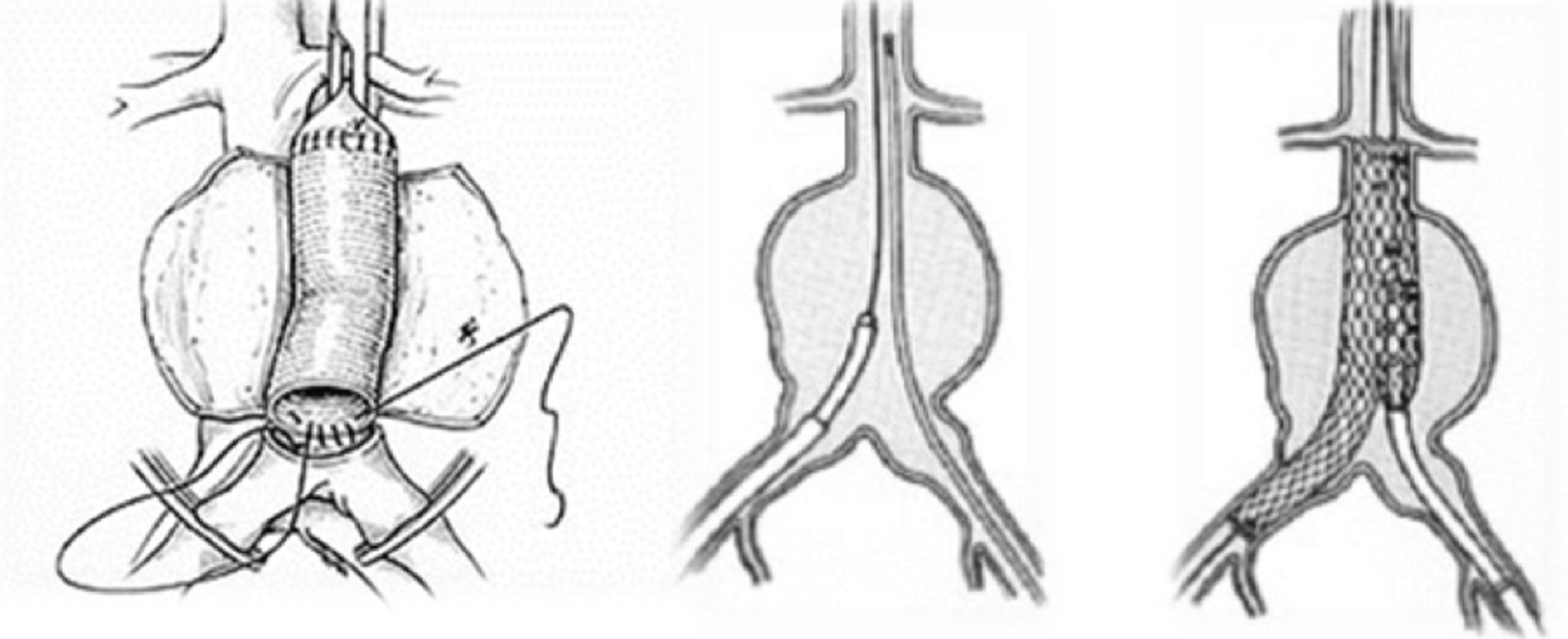

For open AAA repair, the aneurysm is usually approached by a midline laparotomy, carefully moving aside the colonic viscera and cross-clamping the aorta, below the renal arteries wherever possible, and inserting a prosthetic inlay graft, using a tube configuration with sutured anastomoses to the aorta both proximally and distally to exclude the aneurysm wherever possible (Figure 1). When the aneurysm extends beyond the aorta into the common iliac arteries, the use of a bifurcated graft becomes necessary. These procedures are conducted under general anaesthesia and the patients require a critical care bed postoperatively. The in-hospital care of those patients undergoing open surgical repair of a ruptured aneurysm is costly, as many days are spent in the intensive care unit (a mean of 3.5 days for uncomplicated cases and 9.5 days for complicated cases) and the average hospital stay is long. Recuperation after discharge following open surgery for a ruptured aneurysm can take up to 6 months, having a further impact on the resources of the family, social care and general practice. Although the recovery may be slow, the evidence shows that the results of elective open repair are durable and there is no need for longer-term follow-up. Interestingly, the operative mortality of open surgery appears to be independent of hospital volume, although this may be influenced by case selection. 10

FIGURE 1.

Schematics of aneurysm repair, showing (left) open repair, (centre) endograft insertion for endovascular repair and (right) endovascular repair in progress.

Urgent CT angiography is necessary to confirm the diagnosis of ruptured aneurysm and plan the feasibility of endovascular repair. In general, aneurysm neck diameter, length and angulation should be ≤ 3.4 cm, ≥ 10 mm and < 60°, respectively. Catheters are used to deliver the endograft through the femoral arteries, so that tortuous, very narrow or calcified femoral arteries are additional contraindications to endovascular repair. The femoral arteries are accessed via small incisions in the groin and, under imaging control, the endograft is delivered, positioned and secured in place (see Figure 1). This procedure requires specialist imaging equipment and the presence of a CT radiographer as part of the endovascular team. The configuration of the endograft is either bifurcated or aorto-uni-iliac. When the latter endografts are used, the contralateral iliac artery is occluded and a femoro-femoral crossover graft is used to supply blood to the contralateral limb. Endovascular repair can be conducted under local or regional anaesthesia, although general anaesthesia often is used and becomes necessary for most femoro-femoral crossover grafts. Some patients may not need to be transferred to a critical care bed and, in general, recovery is faster after endovascular repair than after open surgical repair. However, in contrast with open repair, continued surveillance of the endograft is necessary and reinterventions for endoleaks and other problems are not uncommon. This is likely to require at least two additional CT scans in the year following endovascular repair.

When this trial was first discussed, observational studies (synthesised in systematic reviews11–14) were reporting much lower 30-day mortality for endovascular repair of ruptured AAAs and some such studies11 have suggested that this should become the new gold standard treatment of ruptured aneurysms without the need for a randomised trial. In addition, the in-hospital and 1-year costs of treating ruptured aneurysms by endovascular repair may be up to 40% lower than for treatment by open repair. 15 However, a single centre pilot randomised trial16 with 32 participants, carried out in Nottingham, UK, showed a 30-day mortality of > 50% for participants treated with either endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) or open repair.

By 2004, randomised trials had shown the advantage of EVAR for elective repairs through reducing 30-day operative mortality threefold compared with open repair,3,17 and endovascular technology, no longer confined to academic centres, was widely available and preferred by patients. It remained an open question whether or not endovascular repair would have the same impact on reducing mortality from ruptured AAAs. Importantly, it was considered that only ≈55% of patients with a ruptured AAA would be anatomically suitable for endovascular repair, so that, for many patients, endovascular repair would not be an option. 14

Therefore, the design of any randomised trials was a question of considerable debate. In the Netherlands, a small randomised trial18 in the Amsterdam region started in 2007. This trial considered only patients with a ruptured AAA of relative haemodynamic stability after CT had demonstrated the anatomical feasibility of EVAR and then randomised these participants to either EVAR or open repair. 18 The primary outcome measure of this trial was combined mortality and morbidity at 30 days and, with optimistic power calculations, it was planned to randomise just 80 participants. Later, in 2010, the trial was extended to include 120 participants; the results were finally reported in late 2013. 19 A trial20 with a similar design started in France in 2008, with the aim of recruiting 160 participants, but it used the rather weak methodology of randomising participants by week of the year. The French trial recruited 107 participants and reported the early outcomes in late 2014. Both the Dutch trial and the French trial had a selective recruitment policy. In contrast, the Immediate Management of the Patient with Rupture: Open Versus Endovascular repair (IMPROVE) trial,21 the last European trial to start, larger than all of the other trials combined, had a non-selective recruitment policy for participants with the clinical diagnosis of ruptured aneurysm, so that health policy implications could be addressed.

Objectives of the IMPROVE trial

In participants with a clinical diagnosis of ruptured AAA who were randomised to either a strategy of endovascular repair (if feasible, with open repair when not feasible) or to a strategy of open repair:

-

Assess whether or not the endovascular strategy was associated with a lower 30-day and mid-term mortality (the primary outcome measure).

-

Determine the proportion of participants in each group who were discharged directly to home (disposal).

-

Assess whether or not the endovascular strategy was associated with lower 30-day costs.

-

Determine the proportion of participants who were suitable for endovascular repair and operational barriers to endovascular repair.

-

Assess whether or not an endovascular strategy was associated with improved 1-year survival and quality of life (QoL) and was cost-effective.

-

Identify subgroups of participants who derived greater benefit from endovascular repair.

The trial was initially funded by a Health Technology Assessment Emergency and Trauma Care initiative. As the trial progressed, it was extended to include three further objectives:

-

Assess whether or not an endovascular strategy was associated with improved 3-year survival and QoL and was cost-effective.

-

Conduct an individual patient meta-analysis of participants randomised in all of the European randomised trials [Amsterdam Acute Aneurysm trial (AJAX),19 Endovasculaire versus Chirurgie dans les Anévrysmes Rompus (ECAR)22 and IMPROVE23], with respect to common 30-day and 1-year outcomes.

-

Develop a risk score for 48-hour mortality for patients with a ruptured AAA.

In addition, the resources and information gathered during the trial have stimulated associated projects including the development of best practice guidelines24 for the transfer of patients and the influence of aortic morphology on mortality and reinterventions, as well as several collaborative projects.

Chapter 2 Methods

The methods for the IMPROVE trial, given in this chapter, are reproduced, in part, from published work. 23 © The Author 2015. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the European Society of Cardiology. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits non-commercial re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. For commercial re-use, please contact journals.permissions@oup.com.

Trial design

The IMPROVE trial was a multicentre randomised trial that randomised patients with a clinical diagnosis of ruptured AAA to either an endovascular strategy of immediate CT and emergency EVAR, with open repair for those who were anatomically unsuitable for EVAR (endovascular strategy group), or to the standard treatment of emergency open repair (open repair group). This trial was conducted in 30 eligible centres (29 in the UK and one in Canada). The eligibility of each centre to participate in the trial was determined by its clinical credentials, including audited volumes of elective EVAR of > 20 cases per year out of ≥ 50 cases of aortic surgery, evidence of good interdisciplinary teamworking, team availability for ≥ 66% of the week, rapid access to emergency CT (target of 20 minutes) and audited experience of emergency EVAR (five or more cases). The trial protocol and the guidelines for fluid management, anaesthesia and management of abdominal compartment syndrome as well as statistical analysis plans are available at www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/073764/#/ (accessed 16 November 2017).

All patients aged > 50 years with a clinical diagnosis of ruptured AAA or ruptured aortoiliac aneurysm, diagnosed by a senior trial hospital clinician (either in emergency medicine or vascular surgery), were recorded and were eligible for inclusion. The first brief consent process could be written, verbal or from a relative and, if necessary, in England only, from a non-treating physician, using the Mental Capacity Act 2005. 25 Participants were re-consented for continued participation in the trial during the recovery period.

Patients were excluded if they had had a previous aneurysm repair or a current rupture of an isolated internal iliac aneurysm, aorto-caval or aorto-enteric fistulae, a recent anatomical assessment of the aorta (e.g. awaiting elective EVAR), a connective tissue disorder or if intervention was considered futile (patient moribund).

Randomisation

An independent contractor (Sealed Envelope Ltd, London, UK) provided telephone randomisation, with computer-generated assignation of participants in a 1 : 1 ratio, using variable block size and stratified by centre. The date and time of randomisation, together with type of initial consent (written/verbal/other), were recorded automatically. The randomisation was communicated by e-mail to the trial manager, site principal investigator and trial co-ordinator. Participants were randomised either to an endovascular strategy (immediate CT followed by EVAR if locally determined as anatomically suitable and open repair when not suitable) or to immediate open repair, with CT being optional. Because this was a surgical trial, neither investigators nor participants could be masked to the treatment allocation. Adherence to the allocated treatment group, wherever possible, was reinforced by on-site training and newsletters.

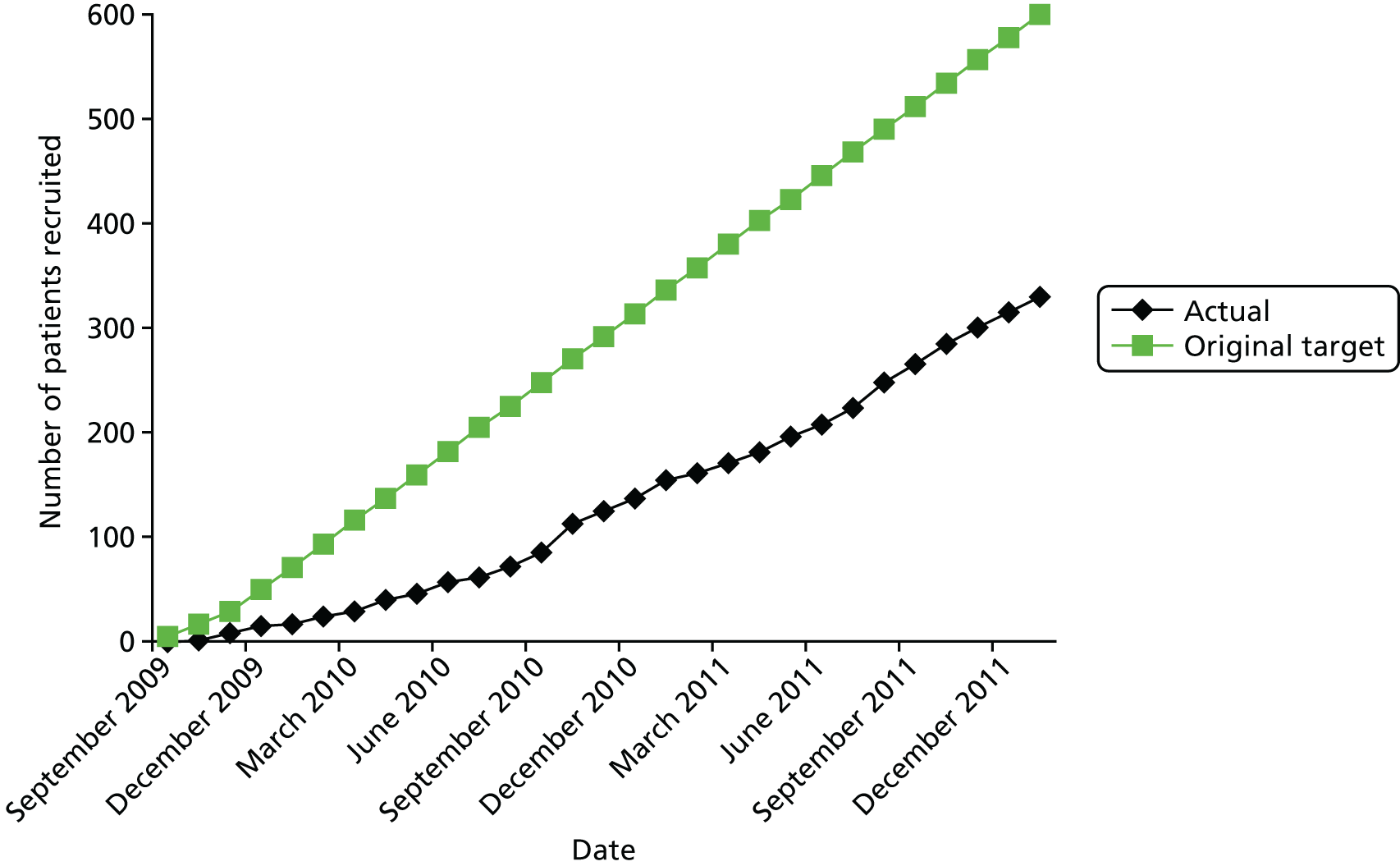

Recruitment and progress

The first participant was randomised into the trial in September 2009; recruitment was initially slow because of the regulatory difficulties in opening centres. By the end of the recruitment phase, 29 centres had been opened in the UK and one had been opened in Canada, but some of the UK sites were subsequently closed by mergers and the creation of larger vascular centres. Recruitment closed in July 2013 after 613 eligible participants had been randomised, 316 to the endovascular strategy and 297 to open repair. Full details of the progress of the trial are given in Appendix 1.

Data verification, role of the computerised tomography core laboratory in the diagnosis of aneurysm rupture, symptomatic unruptured aneurysm or other cause of admission

All consent forms were audited, and source data for a minimum of 15% of participants at each centre were verified. Admission CT scans were sent for analysis in the trial core laboratory (St George’s Hospital, London) and were subject to expert review for the presence of rupture. Aneurysm rupture was defined in accordance with the protocol. Briefly, evidence on CT scans of the presence of blood or haematoma outside the aneurysm wall (abdominal aorta and/or common iliac artery) constituted a diagnosis of aneurysm rupture. If no CT scan was available, the diagnosis of rupture was made intraoperatively. In those participants who had not undergone CT or laparotomy, diagnosis was deduced from the underlying cause of death. All participants who were randomised in the UK were registered to obtain automatic reporting of the date and cause of death from the Office for National Statistics (via NHS Digital).

Participants who were admitted with symptoms attributable to an AAA but in whom there was no robust evidence of aortoiliac rupture (core laboratory diagnosis or laparotomy findings), and who underwent repair semielectively during the same admission, were categorised as having ‘symptomatic, non-ruptured aneurysm’. Other participants had primary hospital discharge diagnoses that were unrelated to AAAs.

The core laboratory also measured detailed aneurysm morphology in accordance with the method previously described. 26 The repeatability of the key variables of maximum aortic diameter, neck diameter, neck length, neck conicality, proximal and distal neck angles and maximum common iliac diameter was assessed using Bland–Altman methods. 27

Participant follow-up

Participants were followed up closely through their primary hospital admission, and the following were reported: stays in intensive therapy units and other high-dependency units and readmissions to theatre with types of complications and adverse events. Participants also were followed up at 3, 12 and 36 months with questionnaires for QoL [EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D)] and use of health resources, in addition to clinical follow-up for aneurysm-related complications and reinterventions. Between the primary hospital discharge and 3 years, participants were followed up for aneurysm-related reinterventions both prospectively and by annual audit of hospital notes, with a final QoL questionnaire on trial exit at 36 months. Mortality reporting, including the cause, for all UK participants was from the Office for National Statistics (via NHS Digital) and was from local state sources for Canadian participants. All of the case report forms (CRFs) are provided at www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/073764/#/, accessed 16 November 2017. In addition, because > 90% of participants were recruited from England, Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) data were used to cross-check reinterventions and identify those taking place at non-trial centres for the 12- and 36-month analyses.

The IMPROVE trial approvals

Ethics approval for the participation of patients in England and Wales was from the South Central Berkshire Research Ethics Committee (08/H0505/173), in Scotland from the Scotland A Research Ethics Committee 08/MRE00/90 and in Canada from the University of Western Ontario Health Sciences Research Ethics Board (17698). Approval for the use of routine NHS data for participants lost to follow-up in England and Wales was obtained from the National Information Governance Board [Ethics and Confidentiality Committee (ECC) 4-03 (f) 2012].

Trial outcomes

The primary outcome measure was survival at 30 days after randomisation. The trial, comparing the groups as randomised, had 94% power to detect (as significant at 5%) a difference in 30-day mortality of 14% with 600 participants enrolled. This was based on estimated 30-day mortalities of 47% and 21% for participants receiving open repair and EVAR, respectively,4,14 an estimate of 55% of participants being anatomically suitable for EVAR after CT and an estimate that 5% of both randomised groups would not have a proven diagnosis of ruptured AAA and no 30-day mortality. 16 Hence, the estimated 30-day mortality was 44.7% in the open repair group [(0.95 × 47) + (0.05 × 0)] and 30.4% in the endovascular strategy group [(0.55 × 21) + (0.4 × 47) + (0.05 × 0)].

Early secondary outcome measures included 24-hour mortality, in-hospital mortality, costs of primary admission, number of reinterventions, time of discharge and the place to which the participant was discharged from the trial hospital after the primary admission. Details of specialist care bed-days, organ support and reinterventions were recorded primarily to inform costs. In the first 30 days, reinterventions were categorised as rebleeding, limb ischaemia, mesenteric ischaemia, abdominal compartment syndrome or other, with details of others being provided as free text. Complications such as strokes or myocardial infarction were not recorded separately from the need for specialist stroke or coronary care unit bed-days.

The unit costs of the stents and consumables used for rupture repair were taken from manufacturers’ list prices and published sources (see Appendix 2, Table 28). Salary costs for rupture repair were calculated by combining staffing levels reported from a survey of 10 IMPROVE trial centres (see Appendix 2, Table 29) with published staffing costs. The costs per critical care bed-day by Healthcare Resource Group were taken from the Payment by Results database. 28 Unit costs for outpatient visits and community service use were obtained from a recommended source for health and social care costs. 29

In addition, the impact of aortic morphology on reinterventions and mortality has been assessed. To optimise generalisability, most of these listed outcomes have also been assessed in an individual patient data meta-analysis that was conducted across all three recent European trials (see Individual patient data meta-analysis of three European ruptured aneurysm trials).

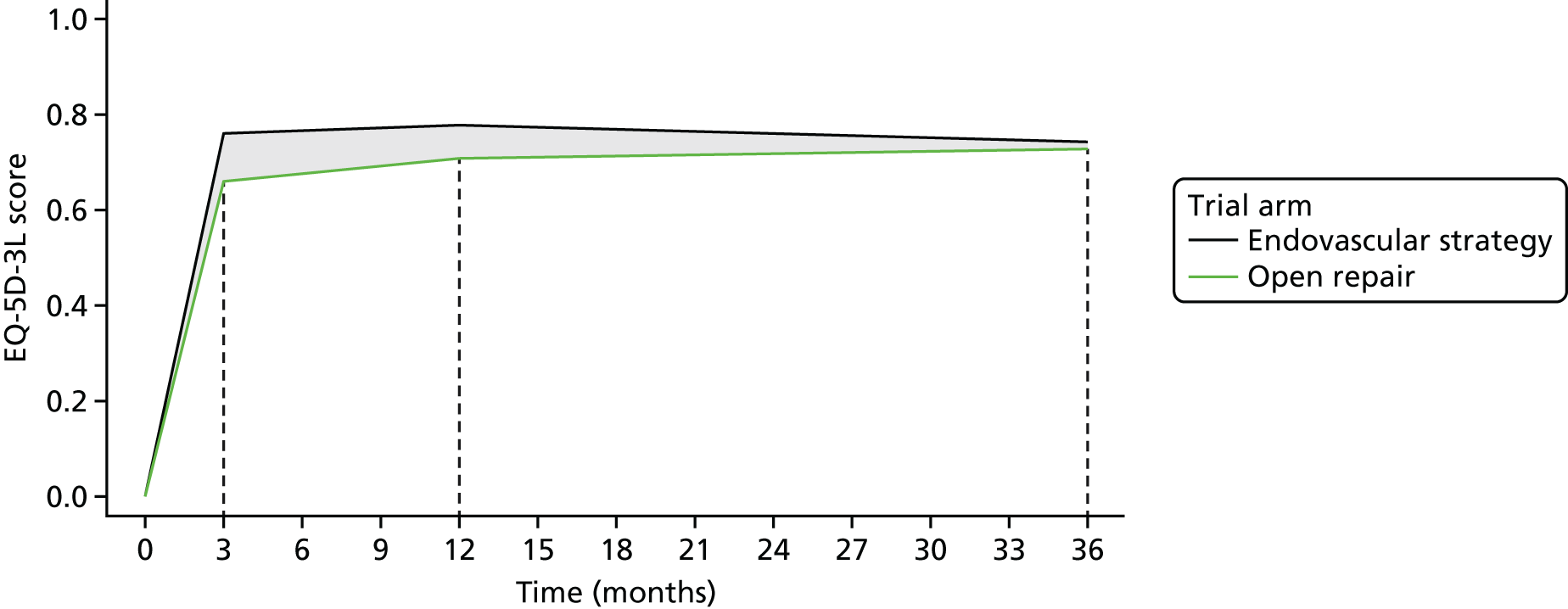

Longer-term outcomes measures (at 1 and 3 years) took a health economic perspective, in addition to measuring mortality and reinterventions. QoL, using the EQ-5D, was reported at 3, 12 and 36 months after randomisation, and the costs of aneurysm-related care were evaluated to 3 years. This enabled cost-effectiveness evaluations at 1 and 3 years. The detailed methods for the health economic and other analyses are encompassed within their statistical analysis plans (www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/073764/#/; accessed 16 November 2017) and are detailed in Chapter 5.

Oversight of the trial

The Trial Steering Committee, chaired by Professor Ian Roberts (members listed in Appendix 1), was responsible for ensuring that adequate recruitment strategies were in place and that the ethics framework for conducting this emergency surgery trial was adhered to.

An independent Data Monitoring Committee, chaired by Professor Charles Warlow (members listed in Appendix 1), reviewed the data, with interim analyses carried out after the enrolment of 50, 200 and 400 participants, and agreed that it was safe to continue the trial. The statistician on this committee was the responsible statistician for the Dutch ruptured aneurysm trial (AJAX). 19

The Trial Management Committee, chaired by Professor Janet T Powell (members listed in Appendix 1), took responsibility for the day-to-day running and timely reporting of the trial. The progress of the trial and recruitment information are detailed in Appendix 1.

Patient and public involvement in the trial

Before the trial was designed, a group of seven patients was consulted. Their viewpoints were incorporated into the trial design (e.g. place of discharge from primary admission) and can be found in the published supplement to the 1-year outcomes paper. 23

The Trial Steering Committee included Anne Cheetham, the wife of a patient who survived an open repair of a ruptured AAA after a stormy course. She also is active in the Circulation Foundation (a peripheral arterial disease charity).

At the end of the trial, a small group of patients and members of the public (associated with the Circulation Foundation) were consulted about their views on the seriousness and fear of reinterventions that may become necessary after the original aneurysm repair. Their view of the severity of reinterventions (detailed at www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/073764/#/; accessed 16 November 2017) was different from that of clinicians. These views of the patients and members of the public have been incorporated into the 3-year analysis results, in which reinterventions are also reported according to the views about the most severe reinterventions. Further research on the development and use of metrics that are important to patients is suggested in Chapter 9.

A patient focus group (run by Professor Matt Bown in Leicester) and Anne Cheetham provided input for the plain English summary of the trial.

Timelines for reporting of IMPROVE trial outcomes

The reporting of IMPROVE trial outcomes took place in three phases: (1) 30-day outcomes, (2) 1-year outcomes and (3) 3-year outcomes. The 3-year outcomes analysis was delayed by 4/5 months because of changes in application procedures at NHS Digital (the provider of both mortality reporting and HES data).

Prespecified statistical analysis plans

For each analysis conducted, a prespecified analysis plan was prepared and approved by the Trial Management Committee and by the Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee for the main 30-day, 1- and 3-year analyses. The analysis plans were then placed on the trial websites (www.Improvetrial.org and www.imperial.ac.uk/medicine/improvetrial). These analysis plans, together with full details of the different analyses, are provided at www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/073764/#/ (accessed 16 November 2017).

All analyses, except the causal analyses, were intention-to-treat analyses. The primary outcome measures assessed the proportion of participants surviving for 30 days in each of the randomised groups, following an intention-to-treat policy using a Pearson’s chi-squared test without continuity correction. The primary outcome measure was then adjusted for age, sex and Hardman index using logistic regression (with the age and Hardman index considered as continuous), providing an adjusted odds ratio (OR) (Hardman index is a validated risk scoring system for ruptured aneurysms). 30,31 Missing baseline data were multiply imputed using chained equations to increase the precision of the estimates:32 the variables used for imputation are provided at www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/073764/#/ (accessed 16 November 2017). Sensitivity analyses were undertaken: (1) including centre as a random effect in a generalised linear mixed model and (2) restricting analysis to participants with a confirmed diagnosis of rupture only. A complier average causal effects model was also fitted to obtain an unbiased estimate of the potential policy effect if participants had adhered to trial allocation. 33 Specifically, participants who were randomised to the endovascular strategy but who were subsequently found to be not anatomically suitable and thus were treated by open repair were considered to have adhered to trial allocation. Otherwise, reasons for crossover were classified as non-adherence (see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/073764/#/, accessed 16 November 2017, for further details). Prespecified subgroup analyses were conducted for all outcomes (age, sex and Hardman index).

Secondary end-point analyses were undertaken to assess time to in-hospital mortality and time to discharge using competing risks methodology, with in-hospital mortality and discharge as the two competing risks. Gray’s non-parametric test was used to compare cumulative incidence curves. 34 Hospital costs were also evaluated, with full details of the methods provided at www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/073764/#/ (accessed 16 November 2017).

A causal analysis in the ruptured AAA population only was conducted to determine the effect of an endovascular strategy compared with open repair in this population if all participants had adhered to the IMPROVE trial policy design (i.e. a CT scan plus EVAR if found anatomically suitable compared with open repair). The causal analysis estimates the effect of the interventions in participants, as randomised, on the primary outcome (30-day mortality) in a complier population. 33 This provides an unbiased estimate of the true treatment effect, subject to certain modelling assumptions,35 which would not be possible with a per-protocol analysis.

For the causal analyses, participants who were randomised to the endovascular strategy who were found to be not anatomically suitable and underwent open repair were classified as having adhered to randomisation. Failure to receive the allocated treatment for any other reason was classified as non-adherence. Participants who had no operation (died before repair) were excluded from the analysis under the assumption that their outcome would be the same no matter what group they were randomised to. Participants who had a converted operation (EVAR converted to open repair) in the group randomised to the endovascular strategy, and who were anatomically suitable, were considered to have adhered to randomisation. Participants who had a converted operation after randomisation to open repair were classified as non-adherent.

Subsequent analyses of mortality and reinterventions at 1 and 3 years followed a similar pattern but included analysis of AAA-related mortality, reporting of other causes of death and full health economic evaluations. The reinterventions at these later time points were categorised as arterial, laparotomy related or other and according to their severity as perceived by (1) clinicians and (2) patients and members of the public (details of the coding of 30-day reinterventions and later reinterventions are provided at www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/073764/#/; accessed 16 November 2017).

The cost analysis took a UK NHS and Personal Social Services perspective36 and included costs up to 1 or 3 years after randomisation, for all randomised participants. Resource use measures were taken from the IMPROVE trial CRFs for the initial hospital admission, readmissions and outpatient visits to the study hospitals that were related to ruptured AAAs. Other outpatient visits and community service use (visits to the family doctor and home nursing) were taken from responses to a health services questionnaire administered to surviving ruptured AAA participants at 3 and 12 months after randomisation. The specific resource use categories included were (1) medical devices and consumables for each intervention (see Appendix 2, Table 28), (2) length of hospital stay during the primary admission, including critical and specialist unit bed-days and extent of organ support, (3) all reinterventions during the primary admission, whether or not directly associated with the ruptured aneurysm (including time in the operating theatre or endovascular suite), and use of devices and consumables, (4) readmissions related to the ruptured aneurysm (a sensitivity analysis was undertaken including all readmissions) and (5) outpatient and community services whether their use was related to the ruptured aneurysm or other conditions. The unit costs of the stents and consumables used for rupture repair were taken from manufacturers’ list prices and published sources (see Appendix 2, Table 28). Salary costs for rupture repair were calculated by combining staffing levels reported from a survey of 10 IMPROVE trial centres (see Appendix 2, Table 29) with published staffing costs.

Health-related QoL (HRQoL) was measured using a generic measure, the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, three-level version (EQ-5D-3L), which requires patients to describe their health on five dimensions: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression. Each dimension requires patients to state whether they have ‘no problems’ ‘some problems’ or ‘severe problems’. A participant’s described health at each time point was valued in accordance with health state preferences from the general population to calculate EQ-5D-3L utility scores, which are anchored on a scale from 0 (death) to 1 (perfect health). 37 Quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) were assessed at 3 months, 1 year and 3 years. For survivors at 3 months, QALYs were calculated using the EQ-5D-3L scores at 3 months, assuming a EQ-5D score of 0 at randomisation and a linear interpolation between randomisation and 3 months. This implies that, at day 30, the EQ-5D utility score is approximately one-third of that at 3 months. For decedents between randomisation and 3 months, we assumed zero QALYs. For those surviving up to 12 months, we assumed a linear interpolation, using the EQ-5D-3L scores at 3 months and 12 months. For decedents between 3 months and 12 months for which a EQ-5D-3L score at 3 months was available, a linear interpolation was applied between EQ-5D-3L at 3 months and the date of death, at which point a EQ-5D-3L score of 0 was applied. A similar approach was used for decedents between 1 and 3 years.

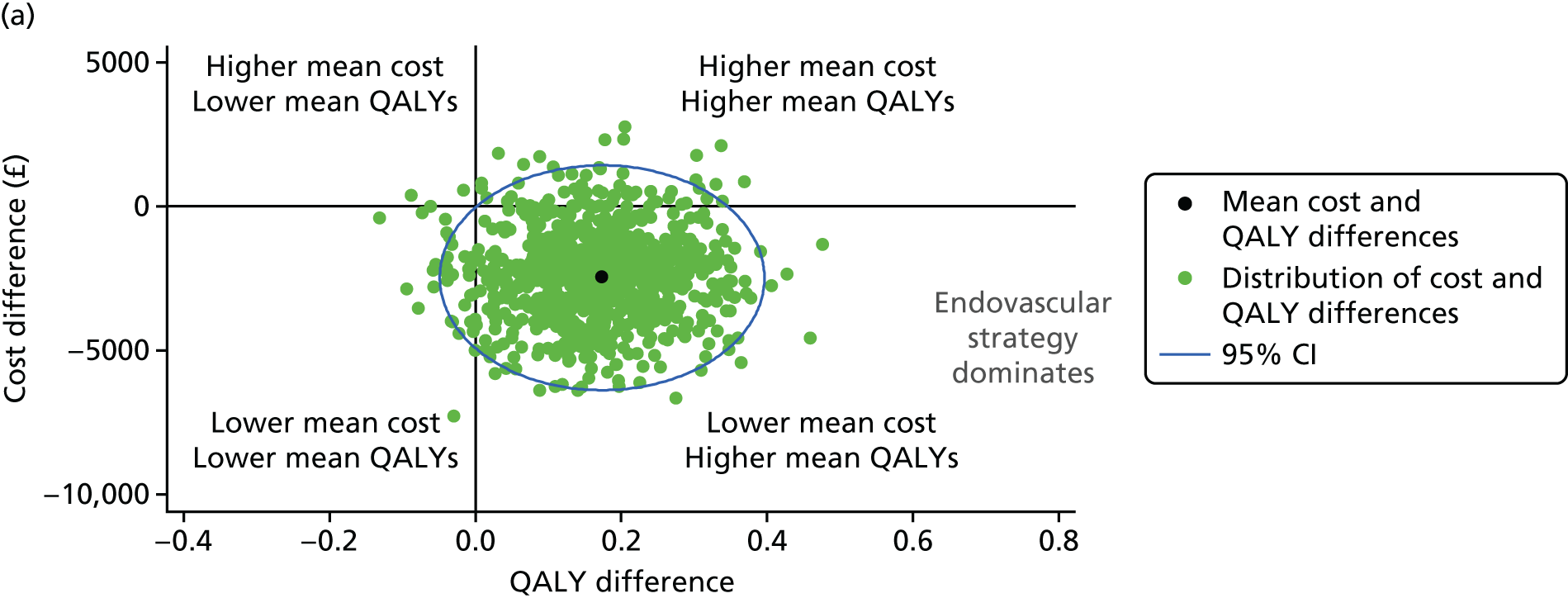

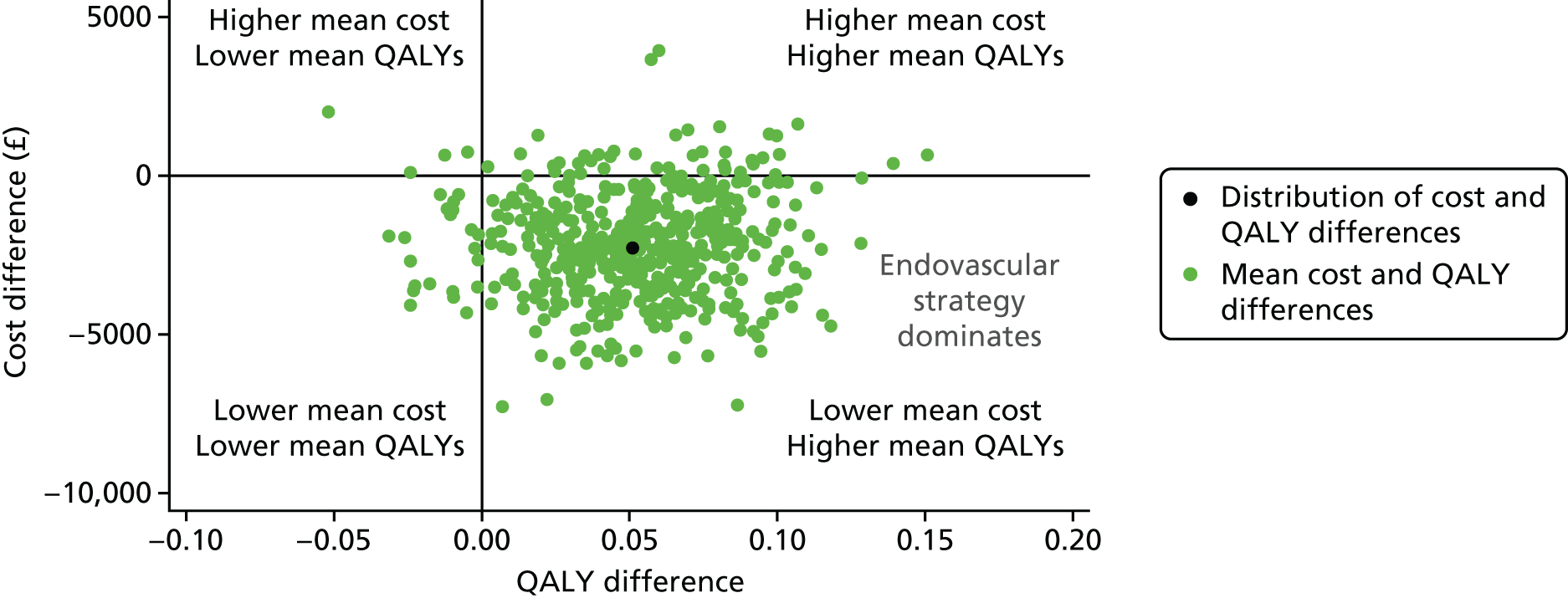

The mean differences in 1- or 3-year QALYs and costs [measured in Great British pounds (GBP) and converted into US dollars (USD)]38 between the endovascular strategy and the open repair strategy were reported. The differences in mean costs and QALYs were plotted on the cost-effectiveness plane and were used to calculate incremental net benefits (INBs) by valuing the incremental (difference in mean) QALYs at recommended thresholds of willingness to pay for a QALY gain36 and subtracting from this the incremental costs.

Cost-effectiveness results were also reported for the prespecified subgroups (according to age, sex and Hardman index). Missing data on baseline covariates (Hardman index), QoL and costs were addressed with multiple imputation, using the same variables as the clinical analyses32 (full details at www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/073764/#/; accessed 16 November 2017). Sensitivity analyses were undertaken to assess whether or not the cost-effectiveness results were robust to alternative assumptions (rationale and details in Chapter 5). Additional work concerning methods and assumptions for missing QoL data is discussed in Chapter 8.

Total costs at 1 year and 3 years were calculated by combining the resource use with unit costs at 2012 and 2016 prices, respectively (in GBP), and then converting them to USD. 38 This conversion rate was based on purchasing power parities, which avoided the impact of short-term currency fluctuations, and recognised the relative purchasing power of the USA compared with the UK in 2012 and 2016. In the base case, incremental costs were reported as unadjusted mean differences between randomised groups, together with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

The differences in average costs and QALYs between the randomised groups were used to calculate the incremental net monetary benefits (INMBs). We valued the incremental QALYs according to threshold of willingness to pay for a QALY gain recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (between £20,000 and £30,000 per QALY),36 and subtracted from this the incremental cost. INBs were reported overall, and for the same prespecified subgroups as for the clinical end points.

The uncertainty around the differences in average costs and QALYs between the randomised groups is illustrated in the cost-effectiveness plane. We estimated the incremental costs and QALYs with a seemingly unrelated regression model. 39 To express the uncertainty in the estimation of the incremental costs and QALYs, we used the estimates of the means, variances and the covariance from the regression model to generate 500 estimates of incremental costs and QALYs from the joint distribution of these end points, assuming asymptotic normality. We then plotted these incremental costs and QALYs in the cost-effectiveness plane. We also reported cost-effectiveness acceptability curves, by calculating the probability that, compared with open repair, the endovascular strategy is cost-effective at alternative levels of willingness to pay for a QALY gain. Sensitivity analyses were conducted, varying the base-case assumptions, including costs of the devices, use of additional theatre staff, for participants with a proven ruptured AAA only and including hospital readmissions for all causes taken from the Health Resources Questionnaire (available at www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/073764/#/; accessed 16 November 2017).

The rationale for the sensitivity analyses and details of resource use, multiple imputation and handling of missing data are described in Chapter 5.

Individual patient data meta-analysis of three European ruptured aneurysm trials

The three recent European trials20,40,41 for the management of ruptured AAAs have published their methods and results. AJAX19 included only participants in whom CT revealed both probable rupture and aortic anatomy suitable for endovascular repair using aorto-uni-iliac stent grafts and all participants had to be eligible for both open and endovascular repair. AJAX randomised 116 participants in three centres between 2004 and 2011, using sealed envelopes for randomisation to either open or endovascular repair. The ECAR trial22 had a similar selection methodology and design but used the additional criterion for haemodynamic stability of a systolic blood pressure of > 80 mmHg and used both aorto-uni-iliac and bifurcated stent grafts. The ECAR trial randomised 107 participants, with treatment allocation by weekly rotation to either open or endovascular repair, in 14 centres between 2008 and 2012. In contrast, the IMPROVE trial randomised participants with an in-hospital clinical diagnosis of ruptured aneurysm, before CT, either to an endovascular strategy (with open repair if endovascular repair was not anatomically feasible) or to open repair. The IMPROVE trial randomised 613 participants in 30 centres between 2009 and 2013.

The three data sets were merged, based on the largest trial (IMPROVE), enabling estimation of Hardman index scores for all participants.

Statistical analysis

The primary analyses considered mortality according to the groups, as randomised, within each trial, irrespective of the different trial designs. The timing of death was assessed from randomisation (for the IMPROVE trial) and from hospital admission (for the AJAX19 and ECAR22 trials). Logistic regression analysis was used to estimate the OR of both 30- and 90-day mortality for endovascular repair (or endovascular strategy) compared with open repair, adjusting for trial to obtain a one-stage fixed-effect pooled estimate. Further analysis was conducted by estimating the OR separately for each trial and then pooling using random-effects meta-analysis, estimating between-study heterogeneity using a method of moments. 42 The proportion of between-trial variability beyond that expected by chance was quantified using the I2 statistic. 43 Analyses were then adjusted for age, sex and Hardman index score. 30,31 Multiple imputation using chained equations was used to account for missing baseline covariates in adjusted analyses. 32

Secondary analyses were conducted on a restricted subgroup of more homogeneous participants from the three trials. The restrictions imposed were (1) a confirmed diagnosis of rupture and (2) anatomical suitability for EVAR. EVAR suitability was an entry criterion for inclusion in both the AJAX19 and ECAR22 trials. For the IMPROVE trial, suitability for EVAR was defined as local CT assessment of suitability; if not assessed locally, a ‘within liberal instructions for use’ definition from a core laboratory CT analysis was used.

Kaplan–Meier survival plots and cumulative incidence of time to primary hospital discharge, by randomised group, were produced within each trial separately and were accompanied by a log-rank test. A Cox proportional hazards model was used to assess whether or not the randomised groups differed in terms of the cause-specific hazard of primary hospital discharge (competing in-hospital mortality notwithstanding).

The age, sex and Hardman index scores of the subgroups were assessed for differences in the effect of the endovascular and open strategies by including an interaction term between the subgroup and randomised group in a logistic regression model.

The reporting of reinterventions was very different across the three trials; all trials reported on the use of occlusion balloons and the incidence of the abdominal hypoperfusion syndromes (abdominal compartment syndrome and mesenteric and colonic ischaemia),44 although the abdominal compartment syndrome data for AJAX were collected retrospectively. The largest trial, IMPROVE, did not report complications such as myocardial infarction, whereas complications were reported for both the AJAX and ECAR trials.

In addition, AAA diameter, aortic neck diameter, aortic neck length and proximal neck α angulation (aortic morphology) were assessed within each trial for their effect on 30-day mortality. These analyses are not a comparison between randomised groups and, therefore, were adjusted for the following potential confounding factors: age, sex (the AJAX and IMPROVE trials), Hardman index, admission systolic blood pressure, mean arterial pressure, treatment commenced and randomised group (the IMPROVE trial only). Each of the other four morphological variables was analysed, both adjusted and unadjusted for the other three variables.

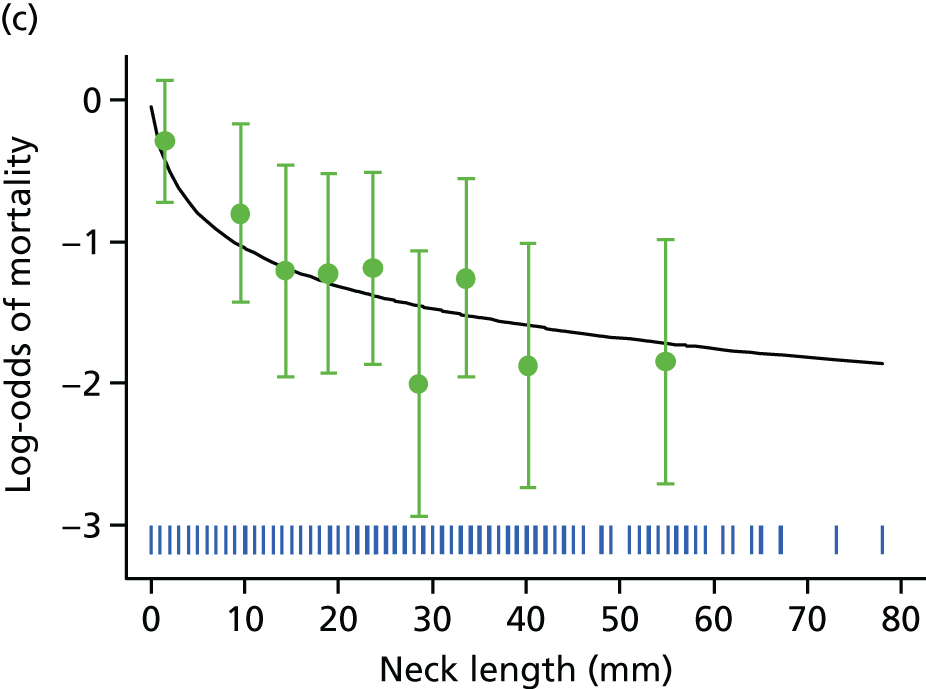

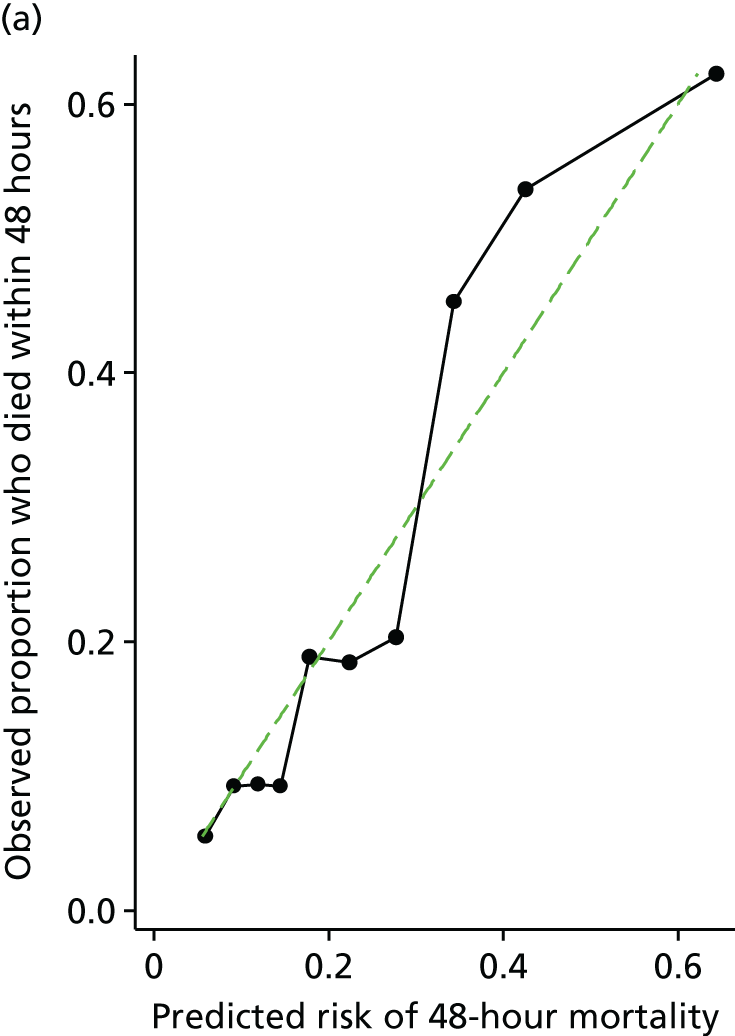

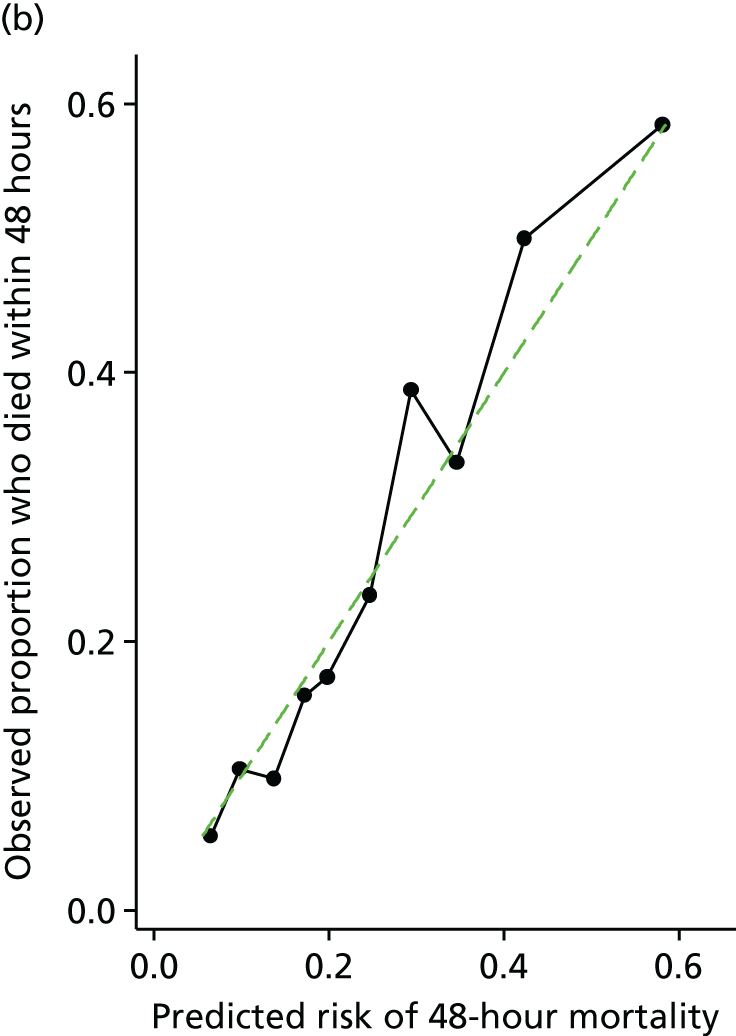

Development of a new risk score

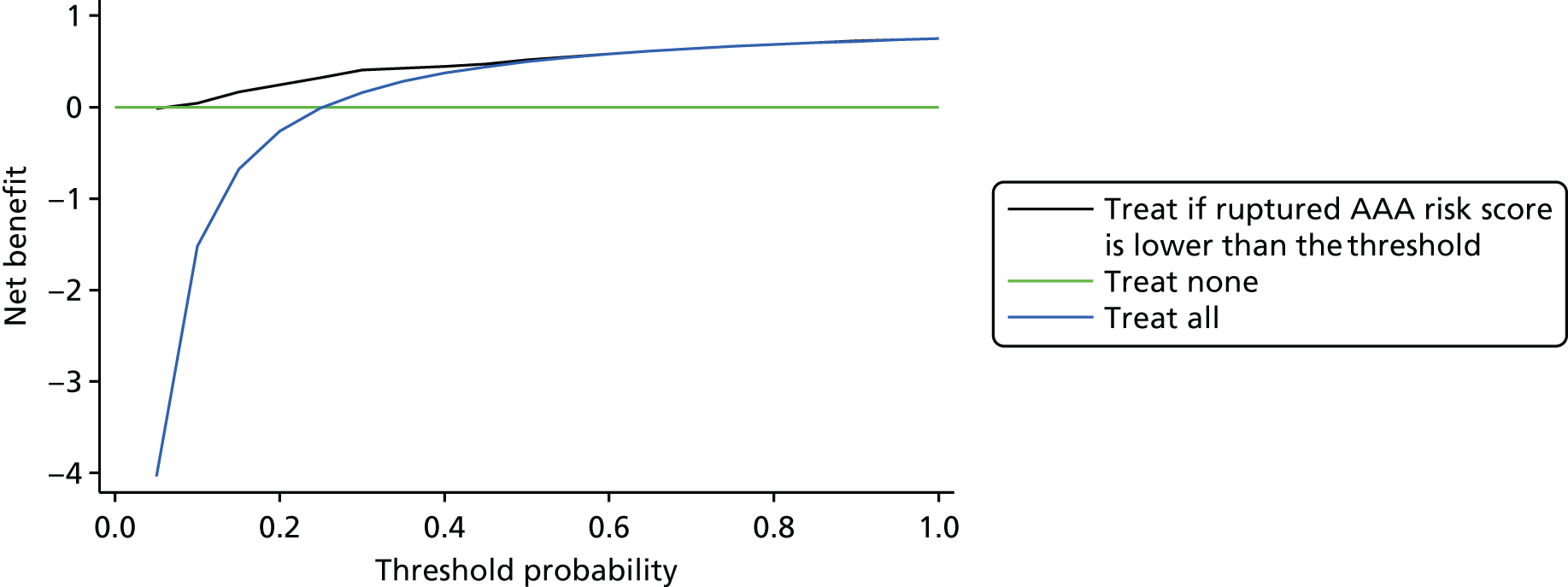

The purpose of this work was to develop a novel, point-of-care, risk score based on both physiological and imaging data that are immediately available in the emergency department to identify patients with ruptured AAAs in whom aneurysm repair or transfer to a specialist centre for repair is futile. The definition of futile is death within 48 hours of presentation, either with or without aneurysm repair.

The principal outcome measure is mortality within 48 hours of randomisation. The secondary outcome measure is death within 30 days of randomisation.

Participants from the IMPROVE trial were used to develop the score, excluding participants with a final diagnosis other than ruptured AAA (incidental or symptomatic AAA) but including participants with aortoiliac ruptures. All participants with ruptured AAA or aortoiliac rupture were considered in the risk score regardless of whether or not an operation was carried out. These criteria resulted in 536 participants, before the exclusion of those with missing risk factor data (e.g. CT results were not available).

External validation of the risk score will be conducted in participants from the AJAX19 and ECAR22 randomised controlled trials (RCTs), the wider Amsterdam cohort for AJAX, which included those unsuitable for randomisation in AJAX, and data from Stockholm. There also will be internal validation of derived risk scores using 10-fold cross-validation.

Full details of the statistical analysis are provided at www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/073764/#/ (accessed 16 November 2017).

Other risk scores for ruptured AAAs have been proposed. From the available information in the IMPROVE, AJAX and ECAR trials, it may be possible to calculate these other risk scores. We will compare the discrimination (c-statistic) of the published risk scores, calculated in the IMPROVE, AJAX and ECAR trials, with the derived risk score. This will initially be done using 48-hour mortality as the outcome measure. However, as the published risk scores were derived from longer-term (in-hospital or 30-day) mortality, we will also compare the discrimination of these risk scores against our derived risk score using 30-day mortality as the outcome measure.

Chapter 3 Mortality and other 30-day outcomes in the IMPROVE trial and the other ruptured aneurysm trials

The first pilot randomised trial of endovascular repair compared with open repair of ruptured AAAs was conducted in Nottingham and randomised 32 unselected patients between September 2002 and December 2004. 45 The 30-day mortality was 53% in each group. This contrasted with results from observational studies, which indicated that the 30-day mortality following emergency EVAR for ruptured AAAs was much lower, at about 25%. 46,47 Since the time of this initial trial, experience with EVAR, devices and imaging have all improved. Moreover, observational studies continued to report similarly low 30-day mortality for EVAR and reported a 30-day mortality of closer to 50% for open repair. 14,48 Therefore, there was a clear need for larger multicentre randomised trials.

Design of the recent randomised trials

The first of the later randomised trials (AJAX)19 started in the Netherlands in 2004 and had a selective recruitment design. Participants with a suspected rupture underwent CT. Next, if rupture was observed and the aortic morphology was suitable for EVAR, relatively haemodynamically stable patients were approached for consent for randomisation (using sealed envelopes) to either EVAR or open repair. Just 116 out of a target of 120 participants were randomised between 2004 and 2011 at three centres. A French trial (ECAR)22 started in 2008, with even more selective patient recruitment: only haemodynamically stable patients (systolic blood pressure of > 80 mmHg) with aortic morphology suitable for EVAR were included and the randomisation was based on a weekly rotation of treatment (EVAR one week, open repair the next). This trial recruited 107 participants at 14 centres between 2008 and 2012. The IMPROVE trial was much larger, with a total target recruitment of 600 unselected patients (all-comers), randomised at the point of in-hospital clinical diagnosis, before CT, to confirm either the diagnosis or morphological suitability for EVAR. This trial randomised 613 participants between 2009 and 2013. The different trial designs are shown in Figure 2. The first results of 30-day mortality came from the Dutch trial (AJAX) in August 2013,14,19 after recruitment to the IMPROVE trial had closed on 21 July 2013. AJAX reported a low 30-day mortality for both randomised groups (21% for the EVAR group and 25% for the open repair group; p = 0.66); however, this was a secondary outcome measure. The primary outcome measure was 30-day mortality and major complications, which also did not differ significantly between the randomised groups. 19

FIGURE 2.

Comparison of designs for three European trials comparing endovascular and open repair for a ruptured AAA.

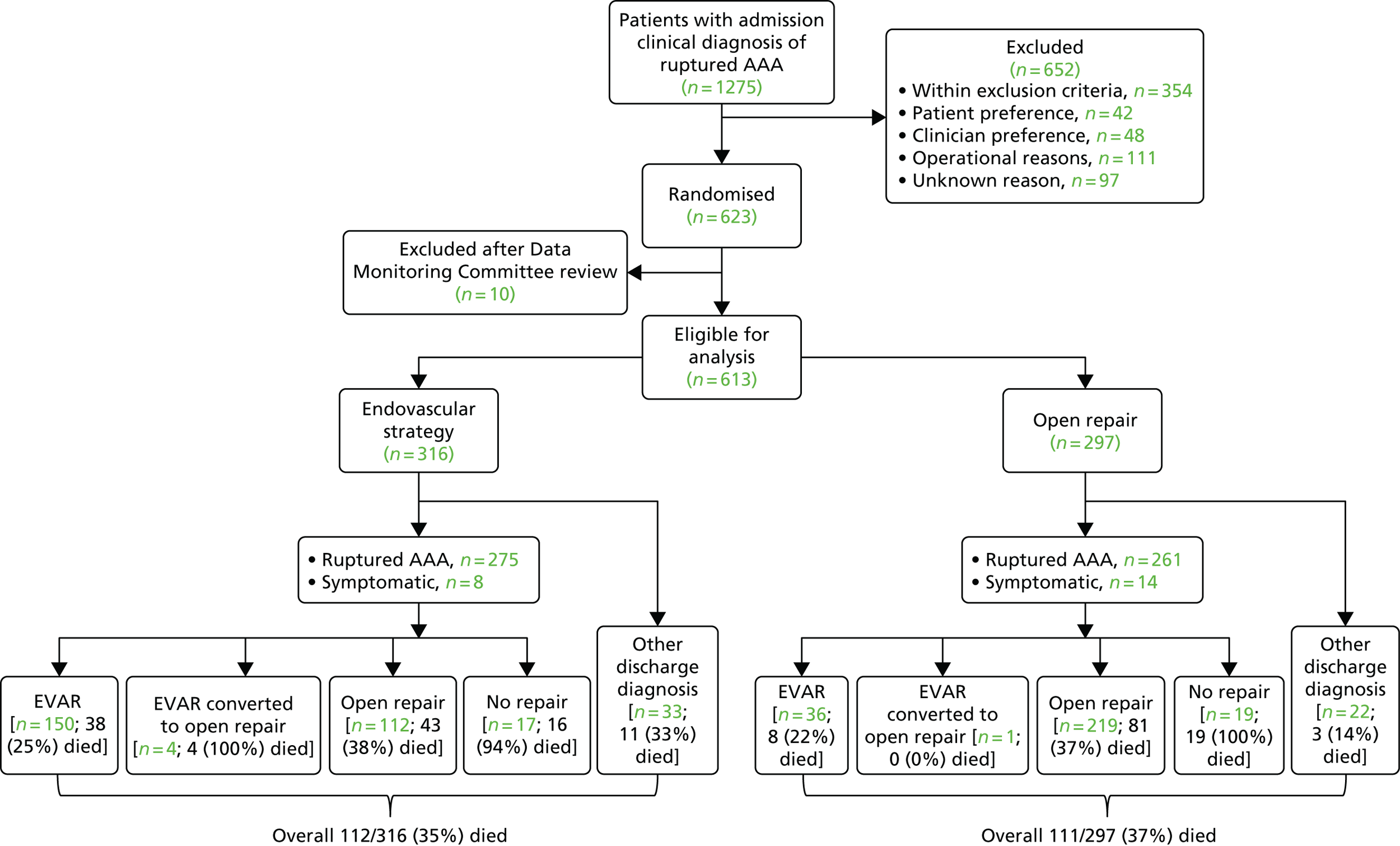

The IMPROVE trial

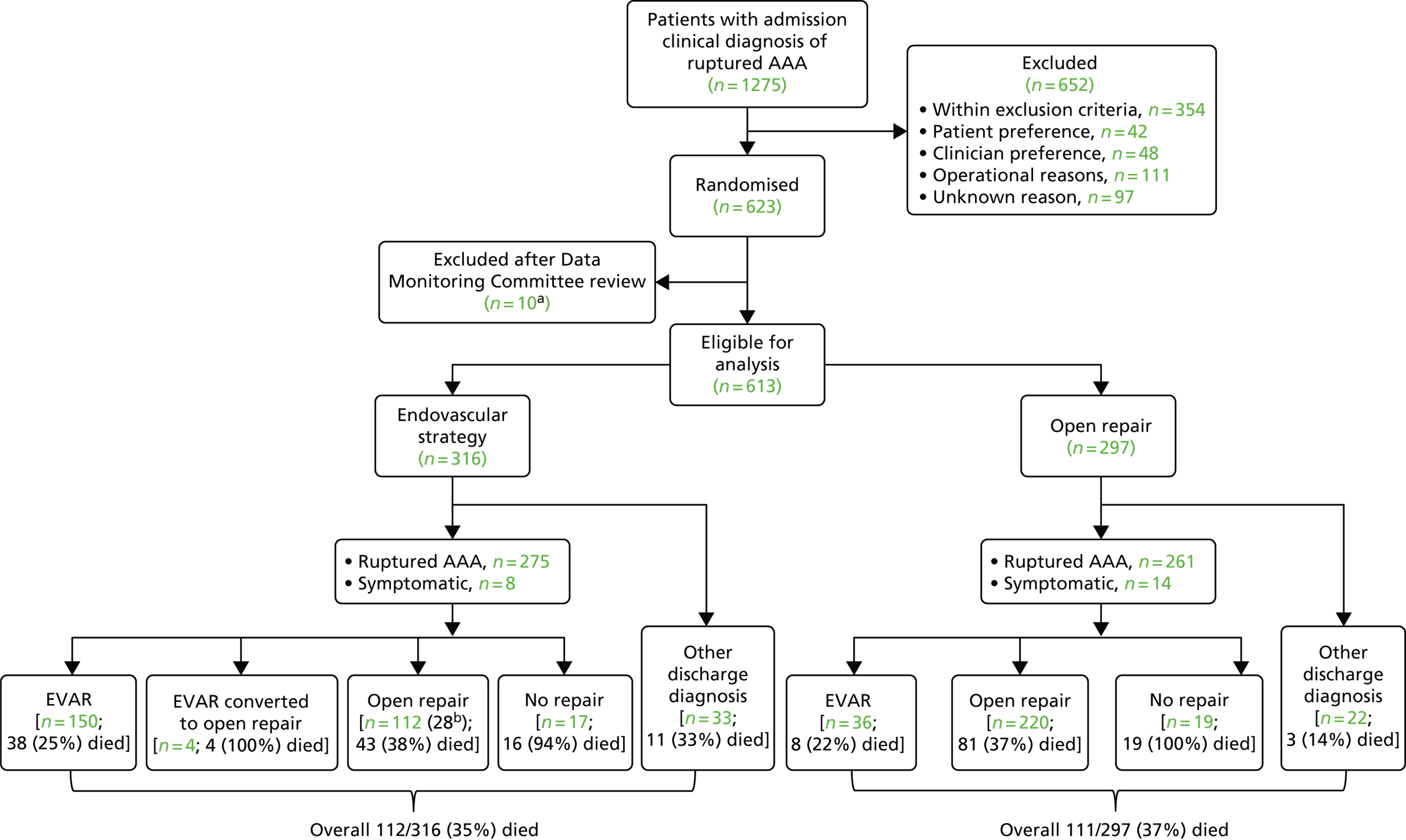

The 30-day outcomes for the IMPROVE trial were first presented at the Annual Scientific Meeting of the Vascular Society of Great Britain and Ireland at the end of November 2013, followed by publication by the IMPROVE trial investigators. 21 in January 2014. Between September 2009 and July 2013, 613 participants with an in-hospital diagnosis of ruptured AAA, made by a senior hospital clinician, were randomised either to EVAR (with the default of open repair when EVAR was not anatomically feasible; n = 316) or to open repair (n = 297). Randomisation, which was computer based, was carried out by an independent contractor with the assignation of participants in a 1 : 1 ratio using variable block sizes. These 613 participants constitute 48% of 1275 patients admitted at the trial hospitals with a diagnosis of ruptured AAA during the trial recruitment period. The recruitment rate and list of participating centres are shown in Appendix 1 and at www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/073764/#/, accessed 16 November 2017, respectively. A Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram and the baseline characteristics of the randomised participants are given in Figure 3 and Table 1, respectively.

FIGURE 3.

A CONSORT diagram showing the flow of participants through the trial, with 30-day mortality for each group. Details of the post-randomisation exclusions (n = 10) are given in Appendix 1.

| Variable | Missing data (n) | Trial group | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Endovascular strategy (N = 316) | Open repair (N = 297) | ||

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 0 | 76.7 (7.4) | 76.7 (7.8) |

| Male sex, n/N (%) | 0 | 246/316 (78) | 234/297 (79) |

| Admission blood pressure (mmHg), mean (SD) | 12 | N = 306 | N = 295 |

| Systolic | 110.3 (32.9) | 110.4 (31.2) | |

| Diastolic | 65.3 (21.4) | 66.8 (22.5) | |

| Admission haemoglobin (g/dl), mean (SD) | 6 | 11.2 (2.5); N = 312 | 11.1 (2.3); N = 295 |

| Admission creatinine (µmol/l), median (IQR) | 13 | 117 (94–152); N = 312 | 115 (93–151); N = 288 |

| Acute myocardial ischaemia ECG, n/N (%) | 52 | 22/291 (8) | 23/270 (8) |

| Loss of consciousness, n/N (%) | 27 | 29/305 (10) | 21/281 (7) |

| Hardman index score,a n (%) | 74 | N = 282 | N = 257 |

| 0 | 93 (33) | 69 (27) | |

| 1 | 130 (46) | 126 (49) | |

| 2 | 46 (16) | 48 (19) | |

| 3 | 11 (4) | 12 (5) | |

| 4 | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | |

| 5 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| CT carried out, n/N (%) | 0 | 305/316 (97) | 266/297 (90) |

| Maximum aortic diameter (mm), mean (SD) | 86 | 84 (19); N = 263 | 81 (18); N = 264 |

| Time from randomisation to theatre admission | |||

| Ruptures (minutes), median (IQR) | 6 | 47 (28–73) | 37 (22–62) |

| Symptomatic aneurysms (hours), median (IQR) | 2 | 3.6 (3.1–15.6) | 3.0 (1.5–17.6) |

The diagnosis of ruptured aneurysm was confirmed either by CT or in surgery in 275 out of 316 participants (87%) in the endovascular strategy group and in 261 out of 297 participants (88%) in the open repair group. In the endovascular strategy group, 64% of participants (174/272) were considered suitable for EVAR after CT. A further eight participants (3%) in the endovascular strategy group and 14 participants (5%) in the open repair group had a repair of a symptomatic intact aneurysm in the same admission. The 55 participants (33 in the endovascular strategy group and 22 in the open repair group) with a final diagnosis unrelated to an AAA had a wide range of other primary diagnoses, varying from ruptured thoracic aortic aneurysm to urinary tract infection, but 45 of these participants (82%) had an asymptomatic AAA. One further participant had a thoracoabdominal aneurysm, and only 9 out of 613 participants (1.5%) did not have an aortic aneurysm.

The primary outcome measure was 30-day mortality. The overall 30-day mortality was 35.4% (112/316 participants) in the endovascular strategy group and 37.4% (111/297 participants) in the open repair group (OR 0.92, 95% CI 0.66 to 1.28; p = 0.62). However, in each group, some participants died before aneurysm repair or breached the randomisation allocation. In the endovascular repair group, 28 participants who were morphologically suitable for EVAR (26 with rupture and 2 without rupture) received emergency open repair for operational reasons (e.g. staff or endovascular suite not available or not yet available when the patient was deteriorating). In the open repair group, 33 participants with a rupture had emergency EVAR, mainly because the anaesthetist deemed them unsuitable for general anaesthesia, and a further three participants had delayed elective repair with EVAR. The detailed results are presented in Figure 3. Overall, 548 out of 613 participants (89%) adhered to the trial protocol. Among 502 participants with a ruptured aneurysm who received repair, the 30-day mortality was 32% (84/259 participants) in the endovascular strategy group and 36% (87/242 participants) in the open repair group (OR 0.86, 95% CI 0.59 to 1.24).

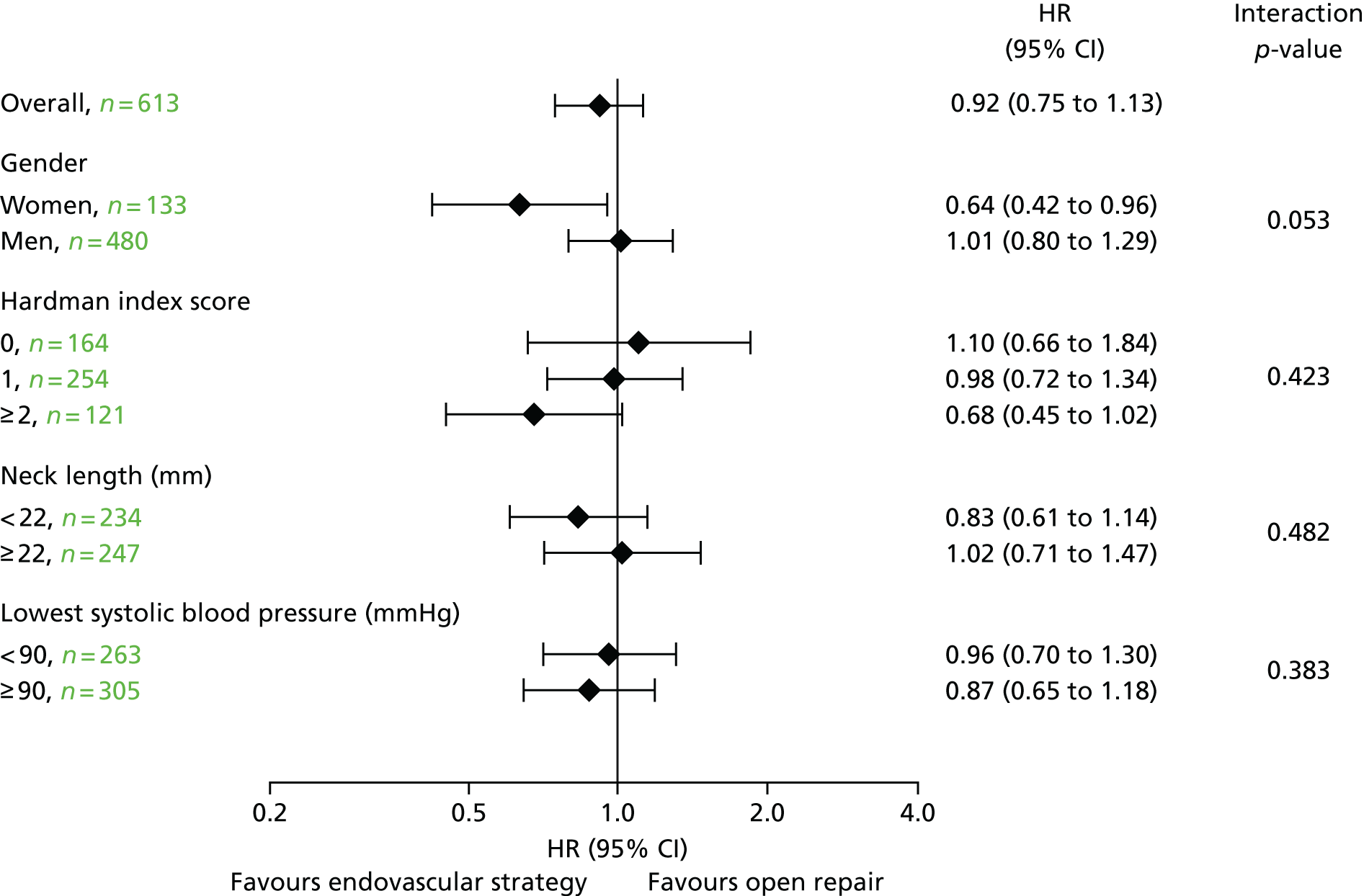

Limited subgroup analyses (age, sex and Hardman index) were also conducted for the primary outcome measure (30-day mortality by randomised group). There were no clear differences between the randomised groups according to age (above or below 77 years) or Hardman index (0, 1 or ≥ 2). However, there was weak evidence that the endovascular strategy was more effective in women than in men (p = 0.02). Among women, 30-day mortality was 37% (26/70 participants) in the endovascular strategy group and 57% (36/63 participants) in the open repair group, compared with 35% (86/246 participants) and 32% (75/234 participants), respectively, among men.

The secondary outcome measures at 30 days included 24-hour mortality, in-hospital mortality (Table 2), number of reinterventions, time and place of discharge, and costs. The first three of these outcomes were similar between the randomised groups and are reported in full by Powell et al. 21 In the endovascular strategy group, nearly all of the patients discharged (94%) within 30 days were discharged home, compared with only 77% in the open repair group (p < 0.001) (see Table 2). The mean resource use costs to 30 days was £13,433 [standard deviation (SD) £10,354] in the endovascular strategy group and £14,619 (SD £12,353) in the open repair group (mean difference –£1186, 95% CI –£2997 to £625) (see Appendix 2, Table 30).

| Discharge status | Trial group, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Endovascular strategy (N = 316) | Open repair (N = 297) | |

| Discharged alive from trial hospital | ||

| Yes | 201 (64) | 183 (62) |

| No | 115 (36) | 114 (38) |

| Place of discharge | ||

| Home | 189 (94) | 141 (77) |

| Another hospital: routine bed | 7 (3) | 28 (15) |

| Another hospital: intensive care | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Nursing home | 0 (0) | 3 (2) |

| Residential home | 1 (1) | 3 (2) |

| Sheltered accommodation | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Other | 3 (1) | 7 (4) |

The mean use of critical care was 4.5 bed-days (SD 5.9 bed-days) in the endovascular strategy group, compared with 6.3 bed-days (SD 7.7 bed-days) in the open repair group. Postoperatively, renal replacement therapy was used in 78 participants: 32 in the endovascular strategy group and 46 in the open repair group, but only one participant, in the open repair group, was discharged on dialysis. Specialist coronary care was used in 11 participants (total of 38 bed-days), nine in the endovascular strategy group and two in the open repair group (total of 4 bed-days) within 30 days of randomisation; there was no additional coronary care between 30 and 90 days. A total of 28 participants in the endovascular strategy group and 47 participants in the open repair group were still in hospital 30 days after randomisation.

Individual patient meta-analysis of the three recent European trials

By 2015, four European trials had reported results, and searching the published literature and clinical trial databases did not reveal any further trials. The ECAR trial22 was presented to the European Society for Vascular Surgery in September 2014 and published results in 2015, with 30-day mortality rates (the primary outcome measure) similar to those reported in AJAX:19 19% for the EVAR trial group and 24% for the open repair group. Unfortunately, half of the data for the Nottingham trial16 had been lost, but the other three trials agreed to pool their data for an individual patient meta-analysis.

The baseline descriptions of the participants in the three trials are compared in Table 3. The IMPROVE trial had recruited older patients, less haemodynamically stable patients (lower admission blood pressure) and a higher proportion of women than the other two trials. There were other important differences too, with the AJAX and ECAR trials using predominantly aorto-uni-iliac configurations of endografts so that the procedure could not be completed under local anaesthesia, and the ECAR trial aggressively monitoring for abdominal hypoperfusion syndromes postoperatively (abdominal compartment syndrome and colonic and mesenteric ischaemia).

| Numbers, clinical details and baseline variables | Trial | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| AJAX (N = 116) | ECAR (N = 107) | IMPROVE (N = 613) | |

| Randomised group, n (%) | |||

| EVAR/endovascular strategy | 57 (49.1) | 56 (52.3) | 316 (51.5) |

| Open repair | 59 (50.9) | 51 (47.7) | 297 (48.5) |

| Ruptured AAA suitable for EVAR,a n (%) | N = 113 | N = 104 | N = 310 |

| EVAR/endovascular strategy | 57 (50.4) | 54 (51.9) | 168 (54.2) |

| Open repair | 56 (49.6) | 50 (48.1) | 142 (45.8) |

| Procedure started, n (%) | |||

| EVAR | 57 (49.1) | 56 (52.3) | 192 (31.3) |

| Aorto-uni-iliac | 49 (86) | 43 (77) | 39 (20) |

| Open repair | 59 (50.9) | 50 (46.7) | 331 (54.0) |

| Tube | 50 (88) | 26 (54) | 268 (81) |

| No aneurysm repair | 0 (0) | 1 (0.9) | 90 (14.7) |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 74.2 (9.4) | 74.4 (10.6) | 76.7 (7.6) |

| Male sex, n (%) | 99 (85) | 97 (91) | 480 (78) |

| Maximum AAA diameter (cm), mean (SD) | 7.6 (1.6) | 7.7 (2.0) | 8.4 (1.9) |

| Aneurysm neck length (mm), median (IQR) | 25 (19–34) | 22 (16–32) | 22 (10–34) |

| Admission blood pressure (mmHg),b mean (SD) | 87 (27); N = 113 | 108 (30); N = 104 | 81 (24); N = 601 |

| Hardman index score, n (%) | N = 61 | N = 105 | N = 539 |

| 0 | 26 (43) | 41 (39.0) | 164 (30.4) |

| 1 | 19 (31) | 44 (41.9) | 254 (47.1) |

| 2 | 12 (20) | 11 (10.5) | 94 (17.4) |

| ≥ 3 | 4 (7) | 9 (8.6) | 27 (5.0) |

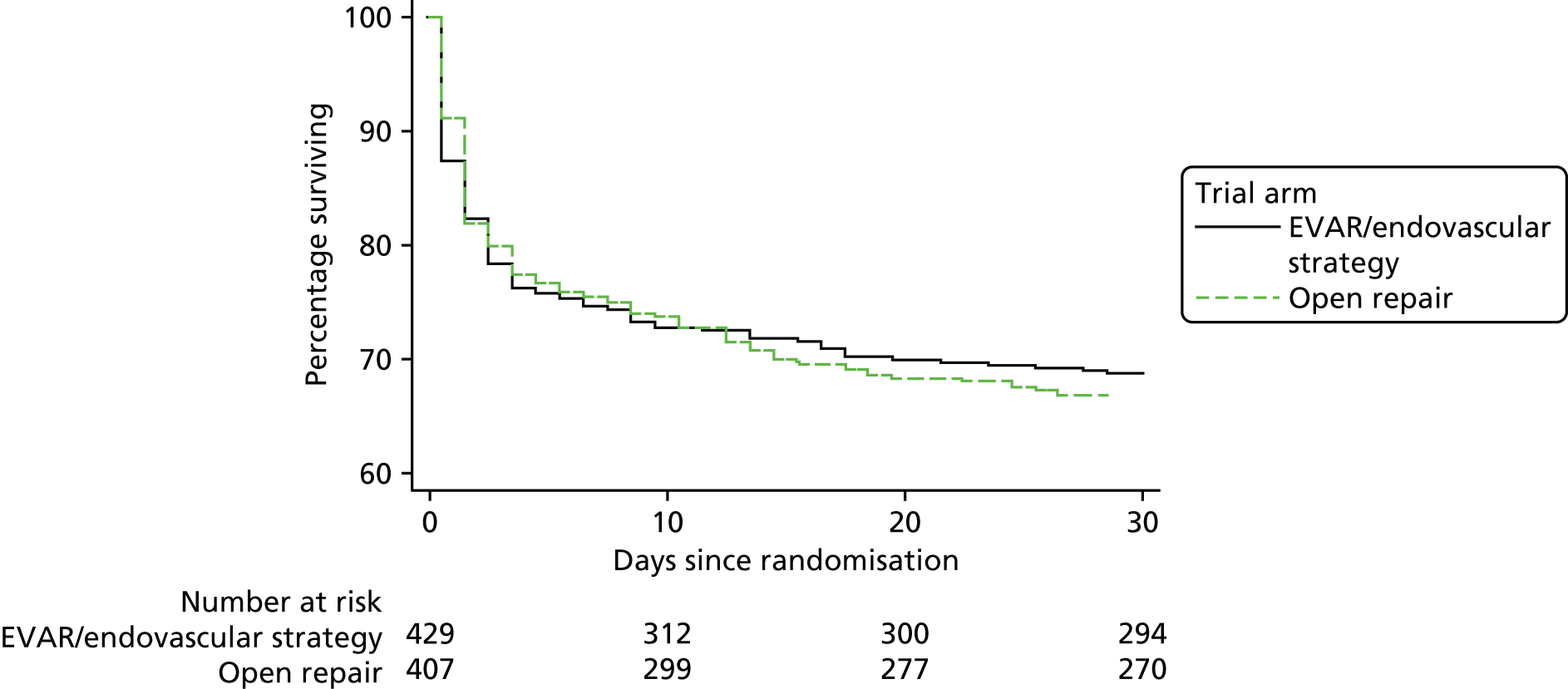

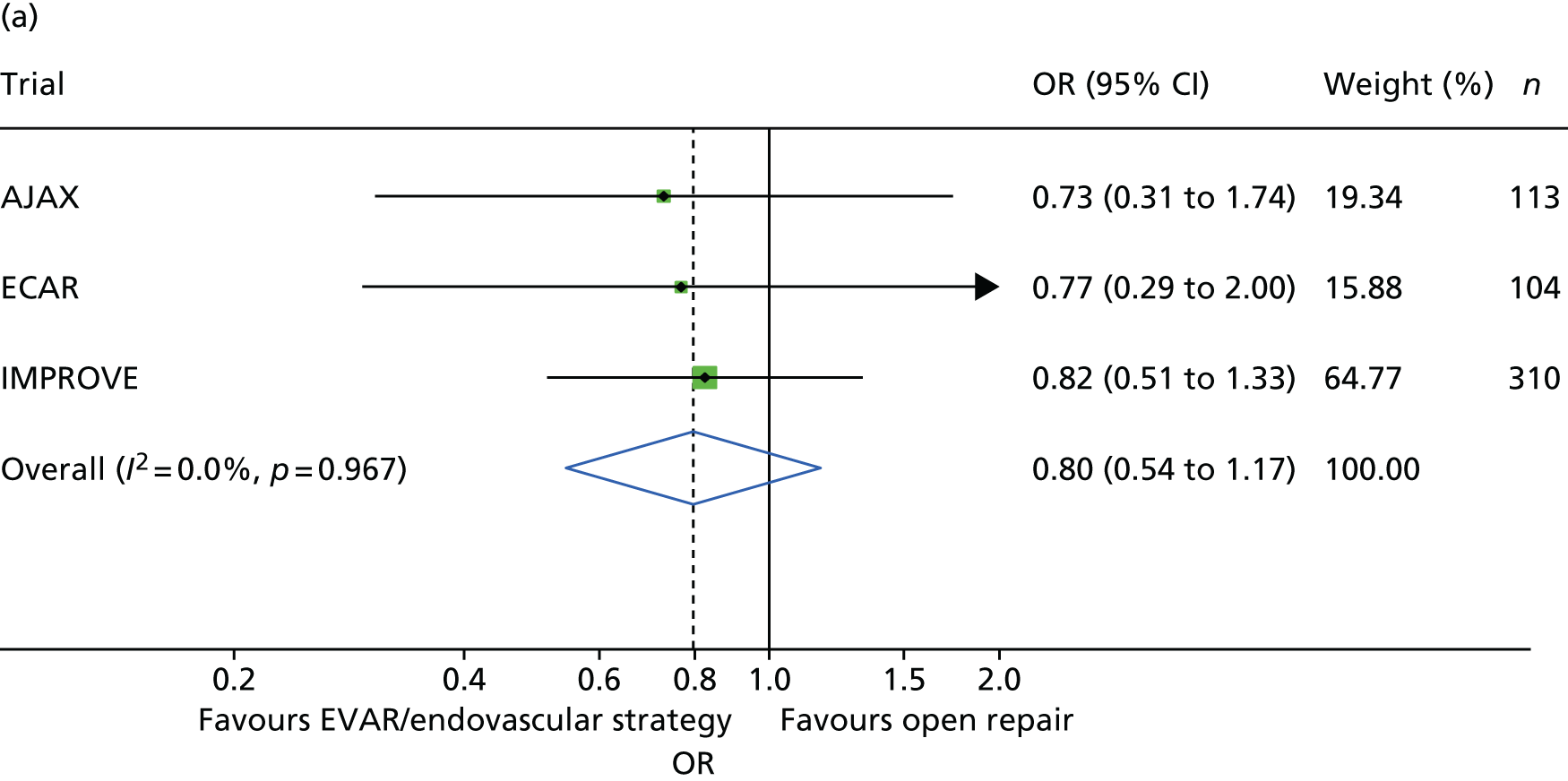

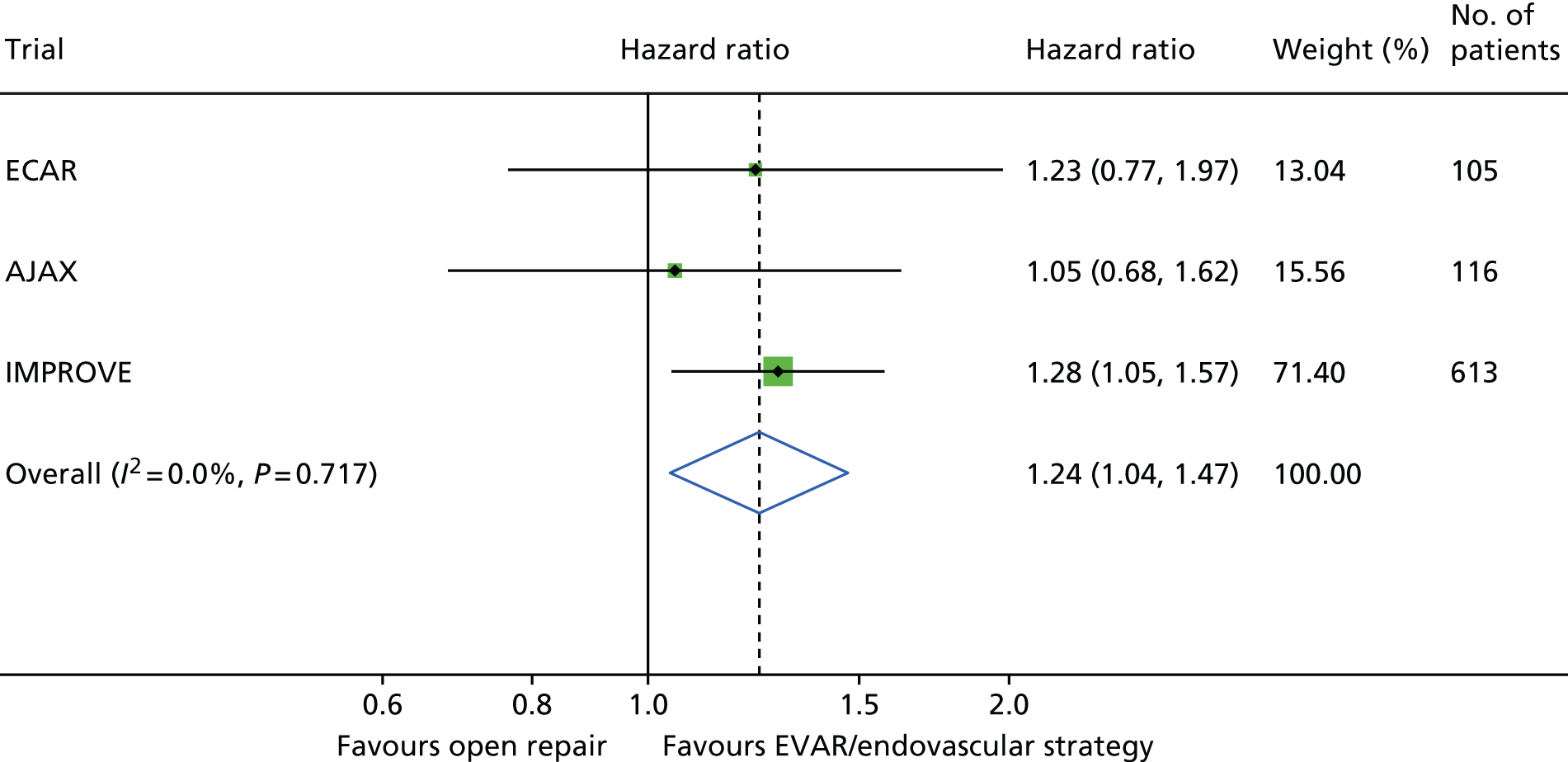

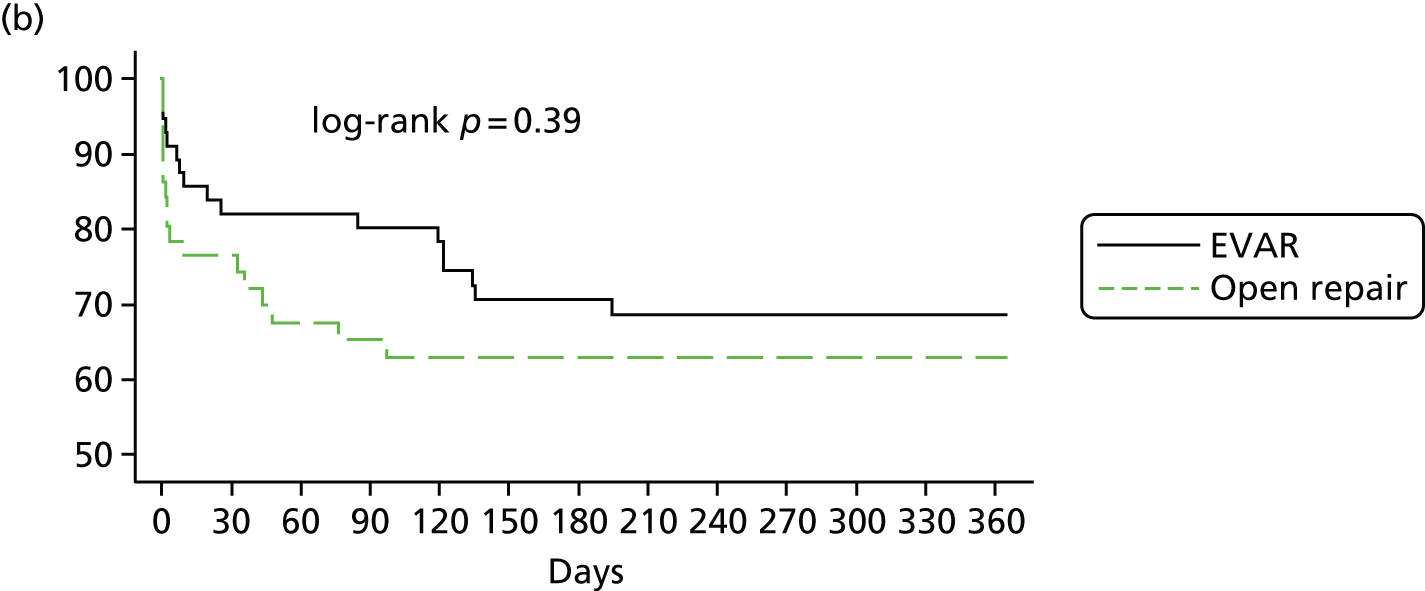

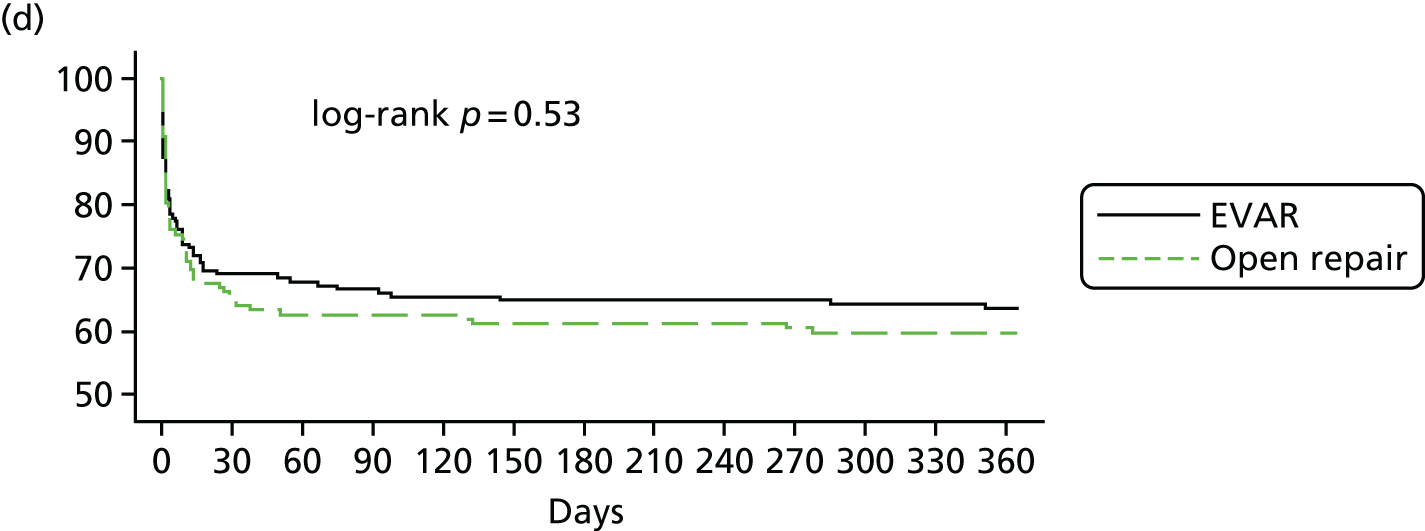

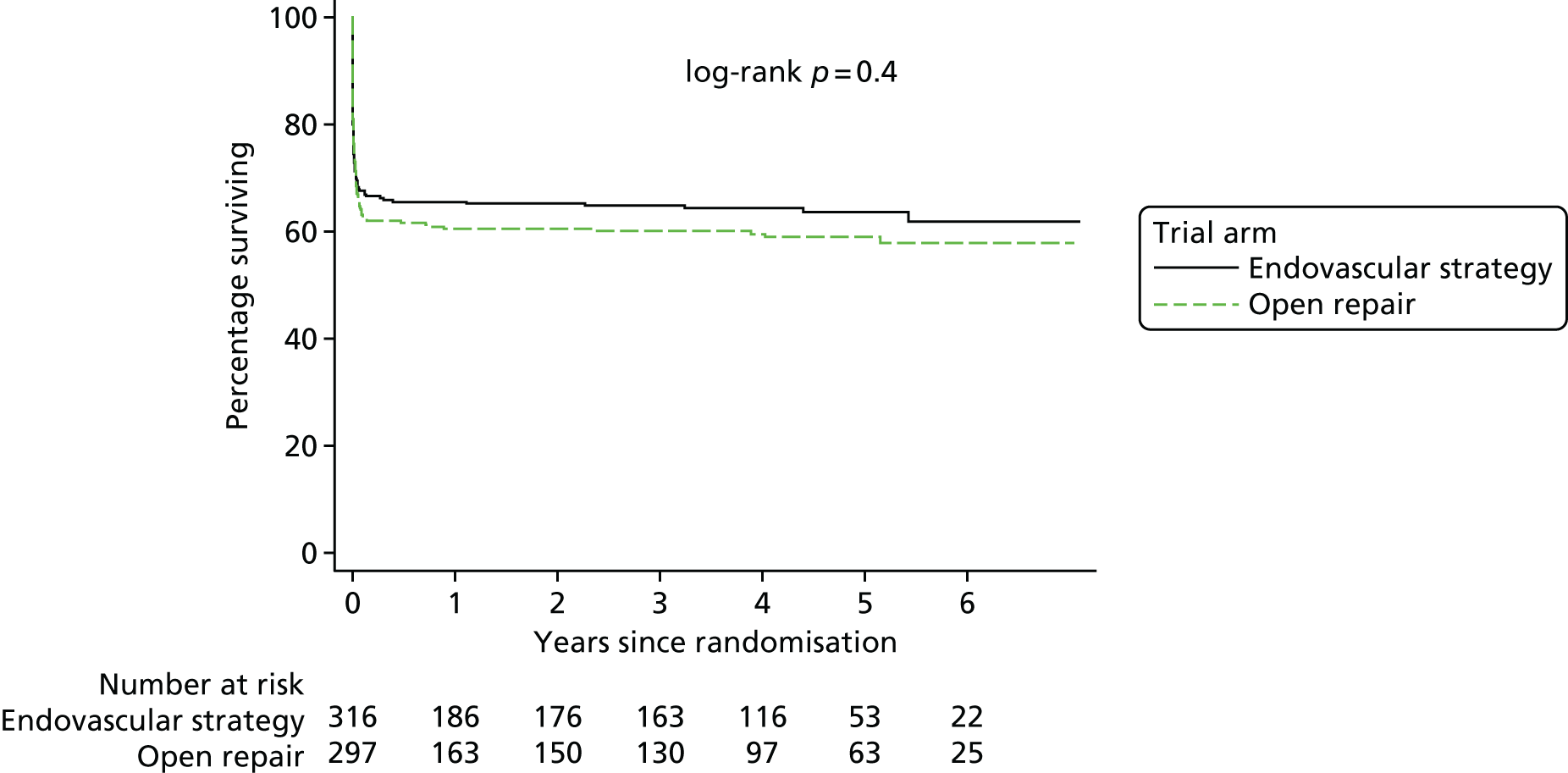

Survival to 30 days by trial and by randomised group is shown in Figure 4. Additionally, the Kaplan–Meier curves for restricted IMPROVE trial participants who were morphologically suitable for endovascular repair (and more similar to the participants in the AJAX and ECAR trials) are shown in Appendix 2, Figure 24. Mortality was higher for both randomised groups in the IMPROVE trial than in either the AJAX or ECAR trials. However, restricting the IMPROVE trial population to those patients who were morphologically suitable for EVAR reduced the mortality in both groups. When the results from the three trials were pooled in a meta-analysis, there was no evidence of heterogeneity (pooled OR 0.88, 95% CI 0.66 to 1.18) (Figure 5). When only patients with a ruptured aneurysm who were eligible for both EVAR and open repair were included (AJAX, n = 113; ECAR, n = 104; and IMPROVE, n = 310), the pooled OR reduced slightly (OR 0.80) but the CI widened (95% CI 0.54 to 1.17) (see Figure 5).

FIGURE 4.

The 30-day mortality by randomised group across the three recent European ruptured aneurysm trials.

FIGURE 5.

The 30-day mortality by randomised group. (a) Restricted to 527 participants with a ruptured AAA who were eligible for both EVAR and open repair; and (b) 834 participants (two ECAR trial participants lost to follow-up before 30 days).

There was little evidence of treatment effect changing according to age or Hardman index. There were no early deaths among women who had EVAR in the ECAR trial. However, in the pooled analyses, women benefited more than men from an endovascular strategy (OR 0.47, 95% CI 0.23 to 0.97). For abdominal compartment syndrome, the highest rate was reported from the ECAR trial. Over the three trials, there was no significant difference in the incidence of abdominal compartment syndrome between the randomised groups, although the AJAX team is currently conducting per-protocol analyses. However, there was an indication that the incidence of colonic and mesenteric ischaemia was lower after EVAR or an endovascular strategy than after open repair (pooled ORs 0.57, 95% CI 0.32 to 1.01) (Table 4). A higher rate of ischaemic colitis after open repair than after endovascular repair has recently been reported in the analysis of a large US database. 49

| Trial | Trial group, n/N (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| EVAR/endovascular strategy | Open repair | |

| AJAX | ||

| ACS | 5/57 (9) | 2/59 (3) |

| CMI | 2/57 (4) | 5/59 (8) |

| ECAR | ||

| ACS | 8/56 (14) | 1/51 (2) |

| CMI | 4/56 (7) | 8/51 (16) |

| IMPROVEa | ||

| ACS | 14/259 (5.4) | 13/243 (5.3) |

| CMI | 14/259 (5.4) | 19/243 (7.8) |

The three trials were set in different health-care systems, leading to differences in discharge policies, including the use of ‘step-down’ care. For instance, many of the French ECAR trial participants were discharged to other facilities for convalescent care, whereas more participants in the IMPROVE trial were discharged directly to home. Over the three trials, for those participants discharged alive from the main trial hospital, the primary hospital stay was shorter for participants in the EVAR or endovascular strategy groups [pooled hazard ratio (HR) for discharge 1.24, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.47] (see Appendix 2, Figure 22).

The individual patient data meta-analyses have been reported with 90-day mortality50 as the primary outcome measure;51 again, there was no difference in mortality between the randomised groups, but EVAR appeared to be more effective in women than in men.

Discussion

The best evidence comes from the synthesis of evidence from randomised trials, and 30-day mortality is the standard surgical outcome measure. This best evidence, from the 836 participants from the three recent trials, shows that there is no significant difference in 30-day mortality between EVAR or an endovascular strategy and open repair (pooled OR 0.88, 95% CI 0.66 to 1.18), with no evidence of heterogeneity. The absolute differences between the trials, lowest mortality in the ECAR trial and highest mortality in the IMPROVE trial, probably relate to the selection criteria for participants in the three trials, AJAX and ECAR being highly selective and IMPROVE being unselective and ‘real world’. The influence of some of these selection criteria on 30-day mortality is explored and discussed in Chapter 4. The flexibility of individual patient meta-analysis also allowed only specific participant subsets to be included in the analysis. All trials included some participants in whom rupture was not confirmed, at laparotomy in the AJAX and ECAR trial and either at CT scan or at laparotomy in the IMPROVE trials. At 30 days, there was no evidence that EVAR offered a survival advantage in participants with a confirmed rupture who were eligible for both endovascular and open repair, although the pooled OR had reduced to 0.80.

One of the surprising findings from the IMPROVE trial was that there was weak evidence that an endovascular strategy was more effective in women than in men, partly attributable to the very high mortality after open repair in women. Despite the scant number of women in the other two trials, this finding was maintained on meta-analysis. This could suggest that EVAR should be a more common treatment option for women, although further research is needed. There was no clear effect of age.

These main findings from the trials have not been universally welcomed. The AJAX and ECAR trials have been dismissed as being too small and criticised for their use of aorto-uni-iliac endografts; certainly both trials took a long time to recruit not very many patients. The IMPROVE trial was more ‘real world’ but has been criticised for including participants who did not have a ruptured aneurysm or who died before repair could be accomplished. This serves to highlight the difference in time taken to start definitive repair with either EVAR or open repair. In each trial, the time taken to bring a participant to endovascular repair was significantly longer than for a participant to have open repair started; this difference was 0.48 hours, 1.6 hours and 0.16 hours for the AJAX, ECAR and IMPROVE trials, respectively. There is weak evidence showing that time to treatment influences survival adversely. 52,53 This might be have been a contributor to mortality in the EVAR groups of the AJAX and ECAR trials but, for the IMPROVE trial, the time difference was much shorter. Misdiagnosis might also contribute to the mortality rate in the EVAR group because diagnosis, even after CT, can be in doubt. 27 In both the AJAX and IMPROVE trials, other bleeding diagnoses were shown to be the cause of admission in a few participants at laparotomy, whereas, at endovascular repair, such diagnoses would have been missed. Since the inception of the trials and since publication of the trial results, there have been several observational studies to show how team training and protocols can enhance performance and reduce mortality. 54,55 This could include improved reading of CT scans and a reduction in the time to start EVAR. Team training could also limit misjudgement about attempting EVAR because, in the randomised trials, conversion to open repair was associated with 100% mortality. However, part of the reported reduction in mortality from team training might also have been achieved by different selection of patients for repair; few other studies report the number of untreated patients.

The appropriate time to subject new technologies to a randomised trial is controversial. The IDEAL (Idea, Development, Exploration, Assessment and Long-term follow-up) recommendations56 suggest that a trial should be considered when an intervention is sufficiently well evolved to warrant evaluation, but without the expectation that the intervention will continue to develop. Before the start of the IMPROVE trial, the uptake of EVAR for ruptured aneurysms was low and patchy and NICE recommended emergency EVAR for evaluation purposes only. 57 Therefore, the IMPROVE trial might have started when experience and team training for emergency EVAR was rather limited in some centres. However, with its widespread coverage of experienced EVAR centres that participated across the UK, the trial has acted as stimulus to evaluate the new technology. Data taken from HES for 2014/15 show that, in England, 36.4% of emergency aneurysm repairs in men and 31.7% in women were conducted using EVAR (Professor Jonathon Michaels, University of Sheffield, 2016, personal communication).

Other criticisms of the IMPROVE trial include the fact that we did not highlight the relatively low mortality in the participants who actually received EVAR58 and that, partly because of the improvements in intensive care medicine, there may be many ‘long-stayers’ and, therefore, 90-day outcome measures are more relevant than 30-day outcome measures. 59 Even after 90 days, there was no difference in mortality between the randomised groups in any of the three trials considered. 51 Surprisingly, few sources in the literature have highlighted another important outcome measure for patients: time to discharge and place of discharge. Regarding this outcome, there is a clear benefit from the EVAR/endovascular strategy, with times to discharge being much shorter than after open repair, which was observed in all three trials. These trials were set in different health-care systems and only the IMPROVE trial specifically reported discharge to home, which was much more common after the endovascular strategy (94%) than after open repair (77%).

Summary

Neither IMPROVE, the largest of the three recent trials, nor pooled data from the three trials identified that an endovascular strategy or EVAR led to lower 30-day mortality. At the time of rupture, the main clinical concern is to stop the bleeding and it is recognised that the initial repair, either endovascular or open, may need to be supported by further reinterventions beyond 30 days. For these reasons, longer-term follow-up is needed for all principal outcome measures, as well as patient QoL and cost-effectiveness, which were not assessed at 30 days, and to advise whether or not the benefits of an endovascular strategy for subgroups or secondary outcomes, observed in IMPROVE and the other trials, are maintained in the longer term.

Chapter 4 Factors other than the type of repair that influence 30-day survival of patients with a ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm

The type of aneurysm repair, endovascular or open surgery, is not the only factor that influences the outcome for patients with a ruptured AAA. First, the patient may present at the emergency department of a hospital that does not offer emergency vascular surgery and a decision will be made as to whether or not the patient should be transferred to a specialist vascular centre. Then, the time taken for patients to be transferred to a vascular centre could be influential. 53,60 Next, there is evidence that operative mortality after rupture is lower in the larger-volume vascular centres10 and that, at least in England, operative mortality for all types of emergency surgery is lower if patients present within working hours. 61 Even larger-volume centres cannot usually offer sufficiently sized prospective case series in which to investigate other hospital, patient and clinical factors that may be associated with better or worse patient outcomes. To date, the largest patient series focused on endovascular repair reported on 473 patients who were treated between 1998 and 2011 from centres in two countries. 10 The IMPROVE trial recruited 613 eligible patients with a clinical diagnosis of abdominal aortic rupture between late 2009 and the summer of 2013. Some 536 participants had a confirmed aneurysm rupture, together with 22 urgent symptomatic aneurysms, making this the largest contemporary prospective cohort in which to investigate both the factors used for primary adjustment of 30-day mortality results (age, sex, Hardman index) and the role of factors, such as hospital presentation, time to surgery, fluid replacement therapy, aortic morphology and type of anaesthesia, on the outcomes of emergency surgery. As expected, Hardman index score was highly predictive of 30-day mortality, but mortality also increased with age; for each 5-year increase in age, the OR was 1.37 (95% CI 1.21 to 1.56) (Table 5).

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | p-value (z-test) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (per 5-year increase)a | 1.20 | 1.04 to 1.38 | 0.015 |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 1.00 | 0.45 to 1.14 | 0.162 |

| Male | 0.72 | ||

| Hardman index score (per 1-unit increase) | 1.62 | 1.26 to 2.08 | < 0.001 |

| Randomised group | |||

| Open repair | 1.00 | 0.62 to 1.28 | 0.535 |

| Endovascular strategy | 0.89 | ||

Transfer guidelines

At the beginning of the IMPROVE trial, we conducted a survey of the participating centres about the type of patient with a ruptured AAA who would accept for transfer from another hospital that did not offer emergency vascular surgery. It was clear that there was a wide disparity of opinion about suitable patients for transfer. This stimulated a Delphi consensus approach, working with the vascular surgeons, emergency medicine physicians and anaesthetists from the IMPROVE trial centres, as well as emergency medicine physicians and senior trainees across the NHS Wessex Clinical Strategic Network. Eventually, this generated best practice guidelines,24 endorsed by the Royal College of Emergency Medicine, the Vascular Society of Great Britain and Ireland and the Royal College of Radiologists. 62 These guidelines emphasise that there is no upper age limit for transferring patients and that all patients aged < 85 years, alert or with fluctuating consciousness, with moderate or minimal systemic disease and who need no or some help with daily living should be transferred, whereas those with cardiac arrest in current episode should not. Speed is accepted as important, and specialty trainees should be allowed to arrange transfer (target of ≤ 20 minutes of clinical diagnosis) if consultants are not on-site. CT confirmation of diagnosis is not necessary before transfer (although ultrasound assessment is desirable) and transfers should not be delayed by waiting for specific tests. A systolic blood pressure of ≥ 70 mmHg is sufficient for transfer without the need for intravenous fluids, unless deterioration occurs, in which case any fluids should be administered in small boluses only.

Use of the IMPROVE trial as a large observational series of patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm rupture

Before the IMPROVE trial had closed to randomisation, the possibility of using the patient series to investigate a number of hypotheses relating to other factors that might influence 30-day survival had been discussed and analysis plans had been formulated to address the following hypotheses:

-

Thirty-day mortality is lower in patients randomised during routine working hours than at other times.

-

Patients transferred from other hospitals to trial centres have lower Hardman index scores and better outcomes than those arriving primarily at the trial centre.

-

Lowest blood pressure is not associated with 30-day survival because overadministration of fluid and/or blood products is associated with higher mortality.

-

General anaesthesia for endovascular repair is associated with higher operative mortality than local anaesthesia.

-

Aortic morphology, particularly increasing aneurysm diameter and hostile aneurysm necks, is associated with high 30-day mortality.

All of these analyses focused on the 558 participants who had a confirmed diagnosis of either ruptured AAA or acute symptomatic AAA.

Time of presentation

Those participants who were randomised out of hours had higher 30-day mortality (144/362) than those randomised within routine working hours (65/196) (primary adjusted OR 1.47, 95% CI 1.00 to 2.17; p = 0.048). 63 However, there was little evidence that the efficacy of the endovascular strategy compared with open repair in those participants who were randomised out of hours was different from that in those randomised during routine working hours (test of interaction p = 0.100). This suggestion that mortality is higher among patients who are admitted out of hours is supported by data from the National Inpatient Sample in the USA. Among 5800 ruptured AAA participants, the in-hospital mortality was significantly higher among those participants admitted at weekends than among those admitted during the week (OR 1.32, 95% CI 1.13 to 1.55; p = 0.0004), and only 77% of those admitted at weekends underwent same-day repair, compared with 80% admitted during the week (p = 0.004). 52 Given the large sample size, Groves et al. 52 tried to identify factors contributing to the increased (32% higher) mortality at the weekend. It was not related to differential use of EVAR but, at weekends, participants received blood transfusion more often than during the week. Higher mortality among patients admitted at weekends may be a widespread phenomenon – it also has been reported in Italy64 and in Canada,65 where in-hospital mortality was 42% at weekends compared with 36% during the week – and might be attributable to the lower availability of specialised teams for treating patients or to staffing levels more generally.

Patient transfers: primary presentation compared with secondary presentation

The characteristics of participants with direct and secondary presentation to trial centres, including Hardman index scores, were similar, although a higher proportion of secondary presentation patients (221/335, 70%) were randomised out of hours. After adjustment for this, there was no difference in the 30-day mortality of those participants who were admitted directly to the trial centre and those (233 out of 335) transferred from other hospitals (adjusted OR 0.76, 95% CI 0.52 to 1.12). There are several potential explanations for this result, including the possibility that only lower-risk patients were transferred or that the highest-risk patients died during transfer. One recent study from the USA has suggested that 17% of patients die during transfer. 60

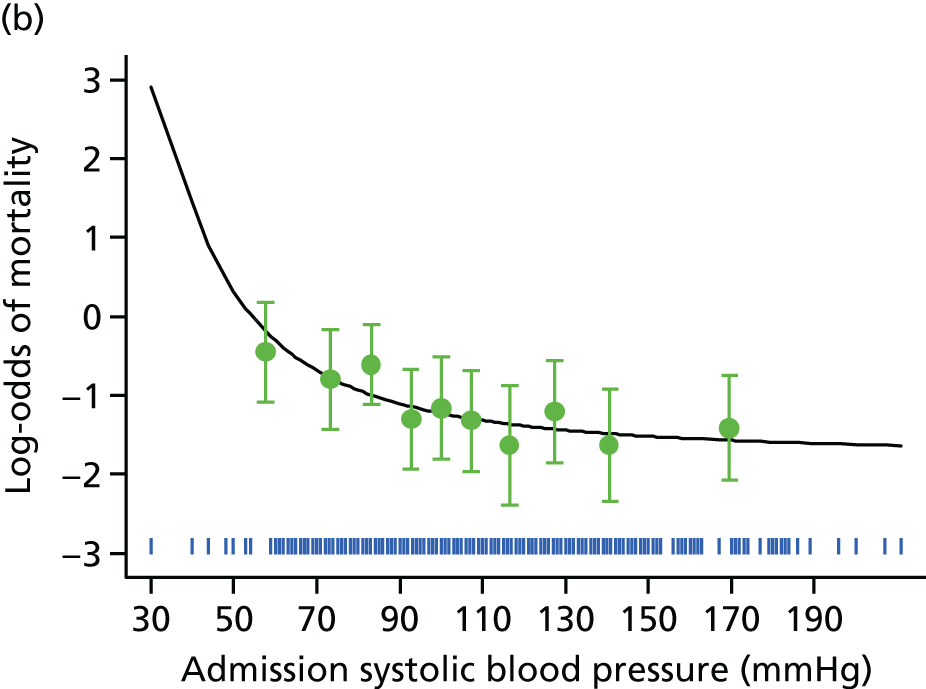

Preoperative variables: fluid administration and blood pressure

There was no evidence from IMPROVE trial participants that the volume of fluids administered before arrival in the operating theatre had a significant effect on postoperative mortality in a multivariable model. However, the volume of fluids given was recorded in only 302 participants. In contrast, there was a strong inverse association between the lowest in-hospital preoperative measured systolic blood pressure and mortality, with no significant association between this blood pressure measurement and the fluid volume administered. The association between the lowest systolic blood pressure and 30-day mortality showed no evidence of non-linearity [adjusted OR per 10-mmHg increase in blood pressure of 0.88 (95% CI 0.82 to 0.94)] (see Appendix 2, Figure 23). The 30-day mortality among participants whose blood pressure was above and below the threshold value of 70 mmHg was 34% and 51%, respectively.

General anaesthesia compared with local anaesthesia

Overall, among participants undergoing EVAR (n = 186), the 30-day mortality associated with procedures conducted under local anaesthesia only appeared to be substantially lower. After adjustment for age, sex, Hardman index, lowest systolic blood pressure and randomised group, local anaesthesia was associated with a fourfold reduction in 30-day mortality (adjusted OR 0.27, 95% CI 0.10 to 0.70; p = 0.007). Local anaesthesia was more commonly used with bifurcated graft configurations whereas general anaesthesia was more commonly used with aorto-uni-iliac configurations because of the requirement for a femoro-femoral crossover graft, which causes considerable ischaemic leg pain that cannot be tolerated under local anaesthesia. Even after adjustment for graft configuration, the benefits of local anaesthesia remained highly significant. By 2016, there was increasing recognition that endovascular repair of ruptured AAA should be conducted under local anaesthesia whenever possible. 63,66,67

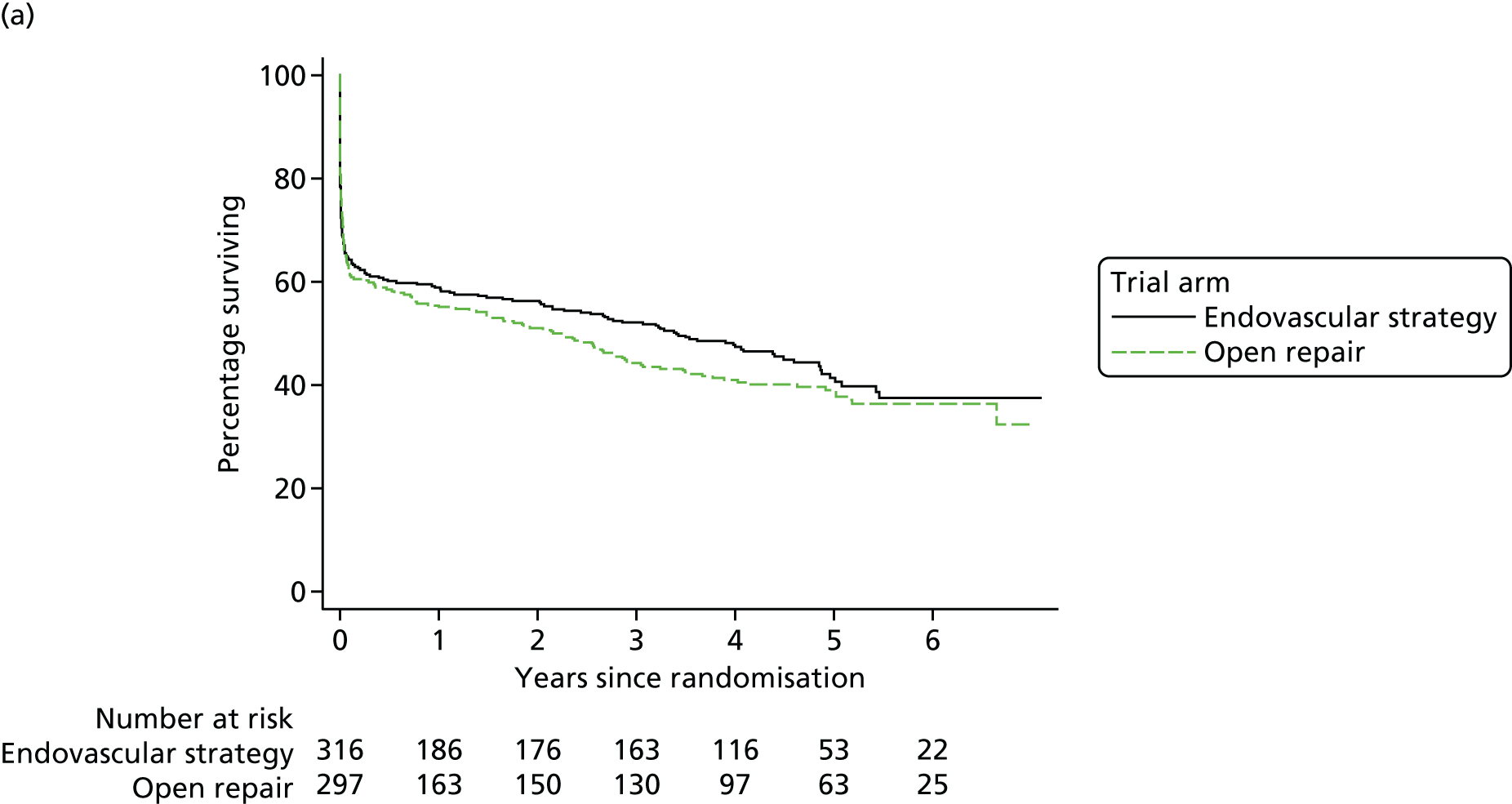

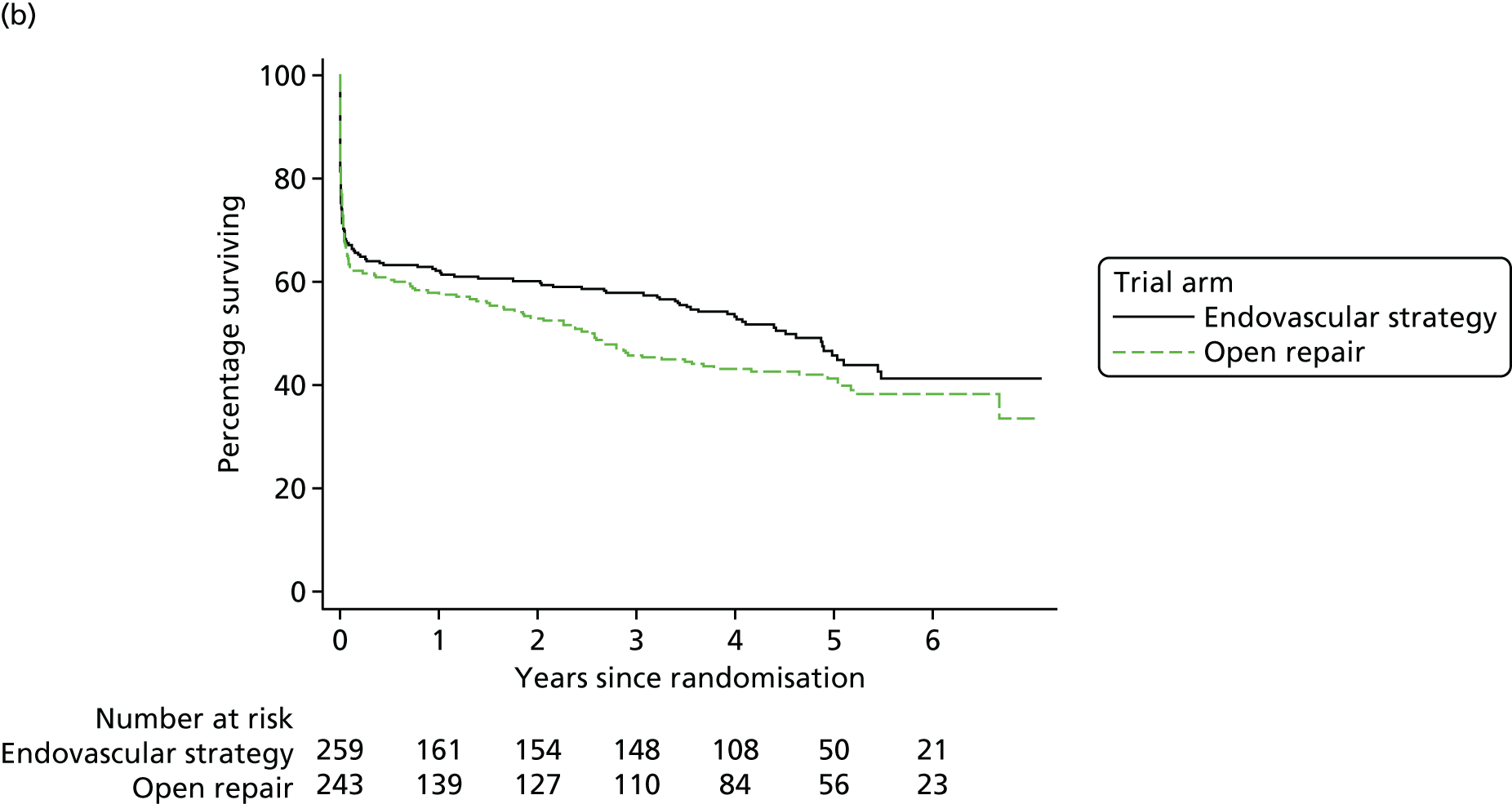

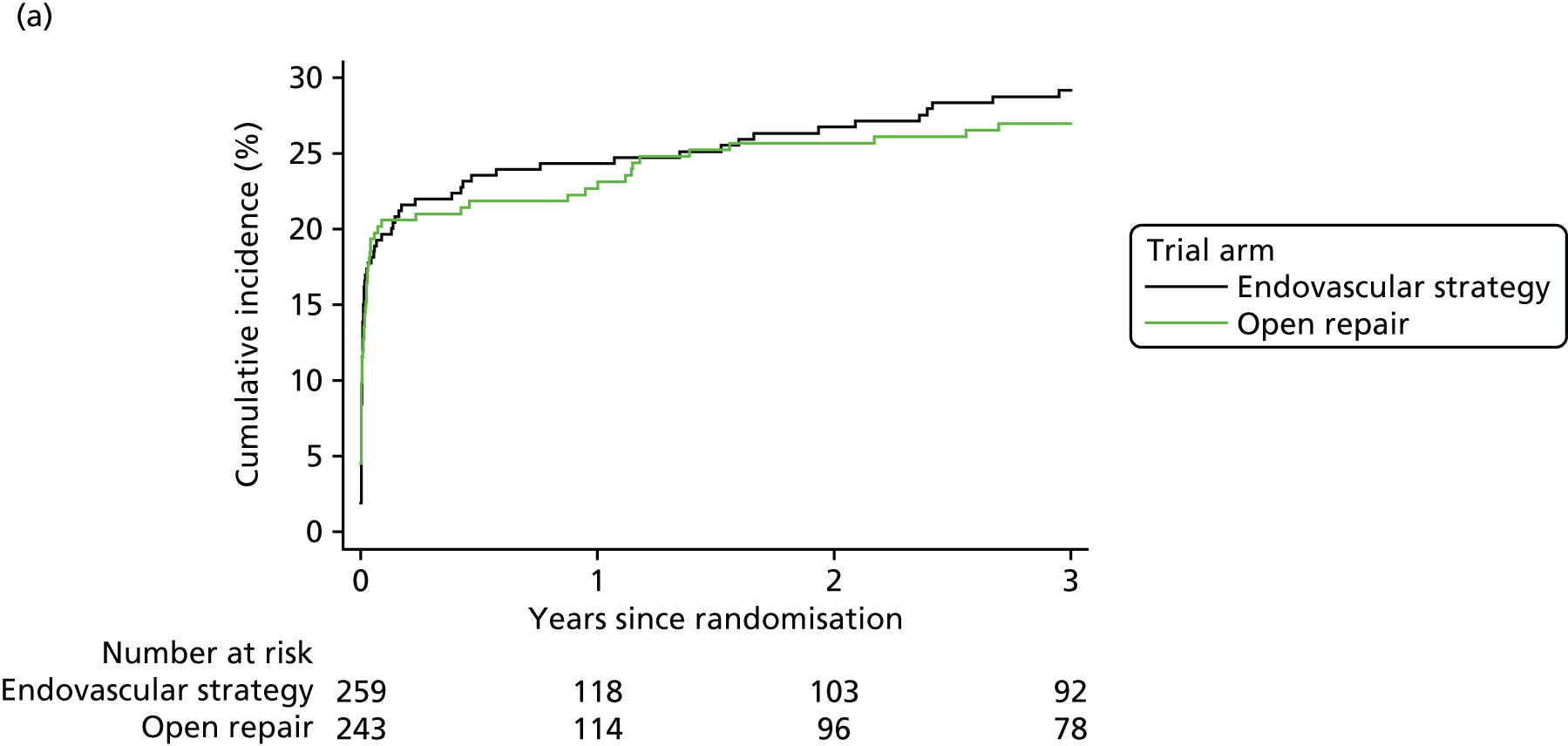

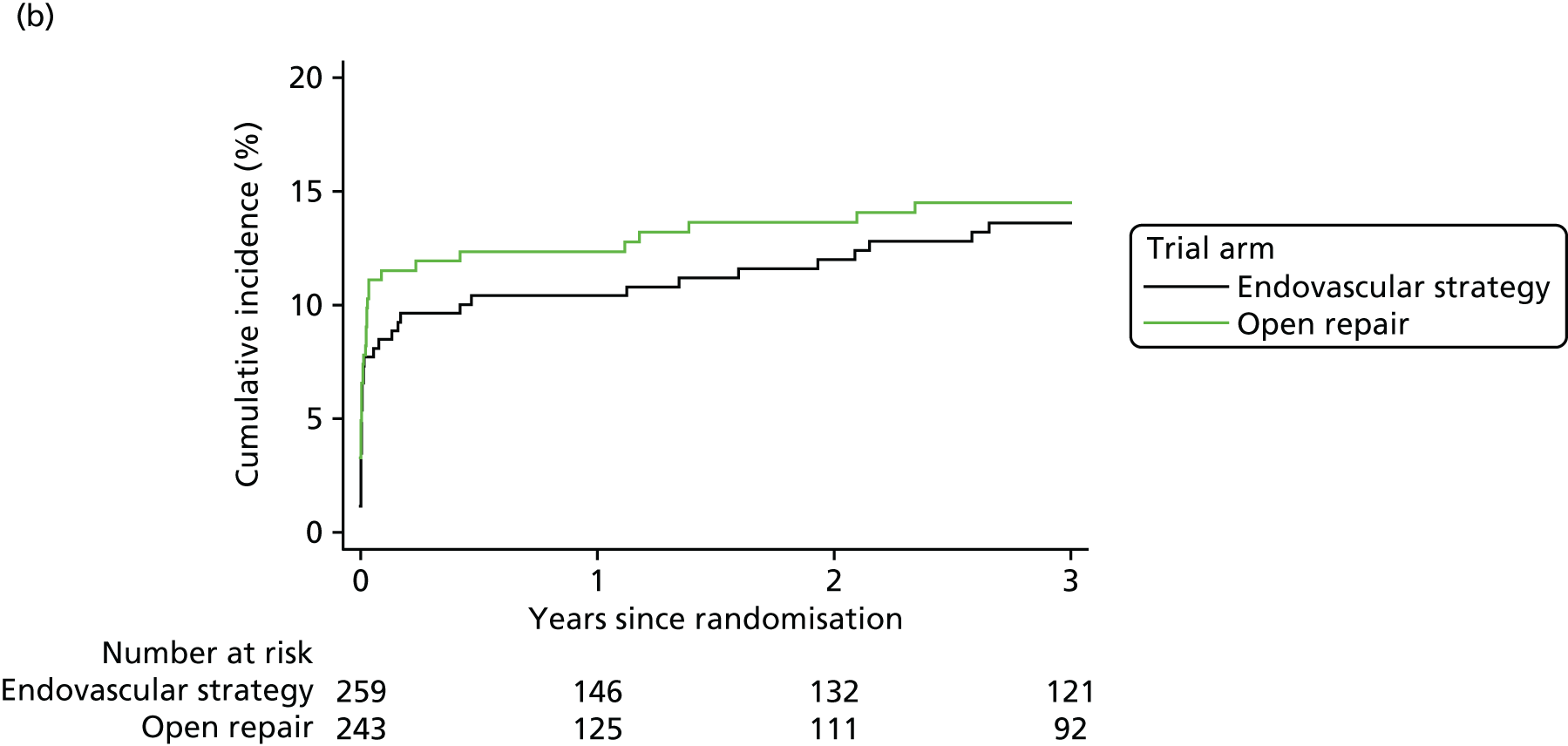

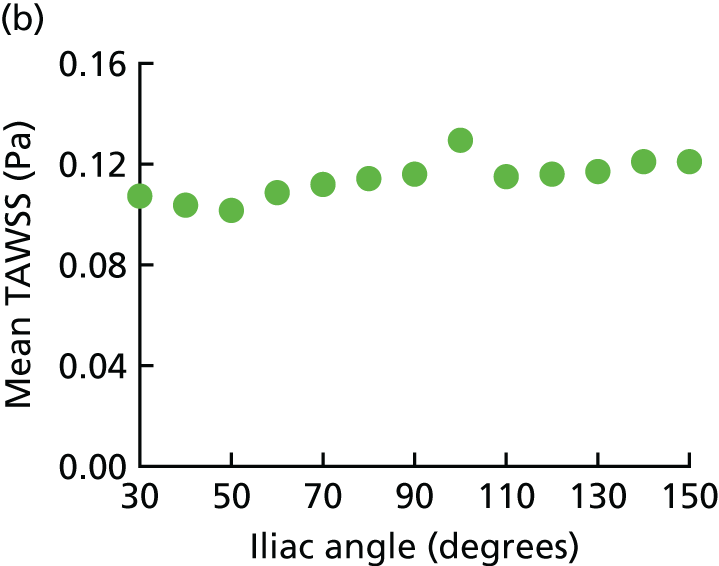

Aortic morphology and the hostile aneurysm neck