Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 11/66/02. The contractual start date was in March 2013. The draft report began editorial review in February 2017 and was accepted for publication in September 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Jain Holmes received consultancy fees as an employee of Obair Associates to train and mentor FRESH therapists and was subsequently granted PhD Studentship funding from the University of Nottingham and UK Occupational Therapy Research Foundation to work on this study. She was a paid employee of Obair Associates Ltd during the conduct of the study. Tracey Sach was a member of the Health Technology Assessment Efficient Study Designs Board during the conduct of the trial.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Radford et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

In 2011, the UK’s National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme identified the need to evaluate the feasibility of conducting a definitive randomised controlled trial (RCT) into the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of vocational rehabilitation (VR) interventions to support a return to work (RTW) for people with traumatic brain injury (TBI). The RCT should use interventions likely to be feasible for routine NHS delivery and compare these with usual NHS rehabilitation [i.e. usual care (UC)], which does not typically include interventions to support a RTW. This report describes the work commissioned to address these issues and a mixed-methods process evaluation which sought to understand factors likely to affect the conduct and outcomes of the definitive RCT.

Traumatic brain injury

Traumatic brain injury is defined as an injury to the brain caused by a trauma to the head. 1 It is a leading cause of death and a major cause of long-term disability in working-age adults. 2–4 More than 1 million people attend UK emergency departments for head injuries annually, with over 160,000 admitted to hospital. 5,6 Approximately 1.3 million people in the UK live with the consequences of TBI. 6 The economic and societal impact is considerable,7–9 costing the economy an estimated £15B per year. 10 This includes premature death, health and social care costs and lost productivity. TBI is also a known cause of personal bankruptcy. 11 However, the human cost far outweighs the economic impact. People who survive TBI are more likely to suffer from depression12 and have poor quality of life (QoL). 13,14 Even those without prior history of mental illness are twice as likely to suffer from mental health problems later in life. 10

Traumatic brain injury resulting from a blow to the head, blast waves from an explosion, swift acceleration or deceleration, or a foreign object penetrating the brain2,15 causes damage to brain tissues. In closed head injuries, it is the shearing movement and swelling of the brain within the skull following impact that causes damage. Open head injuries are caused by an object penetrating the skull and entering the brain16 or by skull fractures resulting from road traffic accidents (RTAs), falls and sports injuries. Although closed head injuries are more common than open head injuries, they are often more difficult to treat17 as they tend to result in diffuse damage affecting different areas of the brain.

The severity of TBI ranges from mild to severe and is usually determined by measures such as the duration of coma or post-traumatic amnesia (PTA), Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) scores and the nature and extent of functional impairments following the injury. 18 A minor or mild TBI is usually defined by a GCS score of 13–15. Moderate TBI is usually defined as resulting in PTA lasting < 24 hours, a GCS score of 9–12 or a loss of consciousness lasting between 15 minutes and 6 hours. Severe TBI is usually diagnosed if the patient has a GCS score of 3–8, has been unconscious for ≥ 6 hours or has been in PTA ≥ 24 hours. 19,20 However, definitions of TBI severity vary widely across studies.

Traumatic brain injury symptoms may be physical, cognitive, perceptual, behavioural or emotional21,22 and include movement problems, seizures, impaired speech, fatigue, memory loss, decision-making difficulties, inattention, difficulty in planning or initiating tasks, inability to express thoughts, and visual and sensory problems. 22 It is often the hidden cognitive, psychological and emotional sequelae that present some of the greatest problems for people with TBI. They include reduced awareness, anxiety, anger, depression and apathy,21 and may affect social participation, independence and self-confidence, which, ultimately, have an impact on QoL.

The long-term outcomes of TBI depend on a number of factors, such as the location and severity of the injury,22 and are difficult to predict as they do not necessarily correlate with the amount of observable damage to the brain. 18,23,24 Restricted activity and social participation are common consequences. Although 70% of people who incur moderate or severe TBI are likely to sustain permanent neurological damage, resulting in long-term physical, cognitive, emotional and behavioural problems that interfere with work,25–27 many people who incur milder injuries also experience long-term impairments that limit participation in daily life activities, including work. 28,29 Doctor et al. 30 studied all consecutive patients with TBI at a level I trauma centre in the USA. Participants had to have positive evidence of TBI [e.g. any period of loss of consciousness, PTA of at least 1 hour and computerised tomography (CT) evidence of a brain lesion]. They stratified mild TBI from other severity levels using the GCS and found that workers with mild TBI were almost 3.5 times more likely to be unemployed at 1 year post injury than the general population, after controlling for age, sex and education [relative risk 3.46; confidence interval (CI) 2.87 to 4.28]. 30 Whatever the extent of the damage, TBI may be further complicated by the distressing nature of the injury and the survivor’s and family’s psychological response to it.

Return to work following traumatic brain injury

Returning to work is a primary rehabilitation goal following a TBI. Data on the reported employment rates of people with TBI vary widely between studies. Methodological differences such as sampling methods, definitions of work, length of follow-up and loss to follow-up make drawing comparison between studies difficult. 3 A systematic review31 identified that only 41% (range 30–65%) of people who were in work prior to their TBI were working at 1 and 2 years post injury. Those who do not return to work within 2 years post injury are unlikely to ever return. 31,32 For those who do, retaining work is also problematic. Many TBI survivors return prematurely but drop out once the impact of the brain injury on their job is realised. 33 Longer-term follow-up studies suggest a downwards trend in job type and earning potential as TBI survivors return to, but fail to retain, work, spiralling into more menial and poorly paid employment. 34 Although some people with mild TBI may successfully return to work without external support,35 a significant proportion (24%, range 5–56%) encounter difficulties,28,36,37 and approximately 35% are able to find only part-time work. 38 The challenge is in identifying who needs help. 35

Traumatic brain injury sequelae, including physical, sensory, communication, cognitive, behavioural, emotional, financial and social difficulties, can all have an impact on a person’s ability to work. 2,39,40 Cognitive problems especially may present considerable problems in the workplace40 and, unless the TBI survivor and employer are aware of them, they can be misinterpreted. For example, reduced ability to initiate activities may be misconstrued as laziness, yawning when losing attention as a sign of boredom and increased irritability due to fatigue as rudeness. In addition, reduced insight, which affects the ability to accurately self-monitor and adjust performance, is regarded as a poor indicator for RTW success even in people who are otherwise independent in activities of daily living (ADL). 41–44

Emotional difficulties such as anxiety and depression, which are common following TBI,44,45 have also been associated with lower levels of post-injury employment. 41,46–48 Even in those with mild TBI, post-concussive symptoms, fatigue and mild balance problems may be predictive of employment outcomes. 44,49–52 Moreover, the increased risk of seizures can preclude people from driving and doing certain jobs. 44,53–55 Ensuring that timely mechanisms are in place to identify and address these problems, irrespective of TBI severity, would seem important.

Therefore, although study heterogeneity and the known difficulty in following up people with TBI over time56 may explain some of the difference in reported outcomes, inadequate VR is also a plausible explanation for poor rates of return and job retention difficulties.

Vocational rehabilitation

Vocational rehabilitation is defined as whatever helps someone with a health problem to return to, or remain in, work. 57 It involves helping people find work, helping those who are in work but having difficulty, and supporting career progression in spite of illness or disability. The primary aim is to optimise work participation. 58

Early Specialist Traumatic brain injury Vocational Rehabilitation (ESTVR) is an adaptive form of rehabilitation that depends on identifying problems that the person with TBI has. ESTVR therapists then advise that person and their employer on how to adapt their behaviour and activities so that the problems can be managed by the patient and accommodated in the workplace. The person with TBI can then continue to be involved in work. The need for such an intervention was based on the reported prevalence of employment difficulties for people with TBI38 and findings from our previous pilot study,59 which suggested that for people with more moderate and severe injuries, continued involvement in work was unlikely to happen without support beyond 3 months, and that 10% fewer people with mild injuries would be in work at 12 months post injury without VR.

Vocational rehabilitation targets not only the brain-injured person but also their family, the work environment and the employer; crossing boundaries between health, employment, social care and welfare services. Therefore, it is a complex intervention,60 and one that needs to be individually tailored to the person and the local context, which makes it difficult to standardise.

Enabling people who have capacity to work to do so is a UK Government priority. 61 Clinical guidelines and professional recommendations62–64 state that VR should be provided for people with TBI. Ensuring people who develop long-term health conditions can return to, and remain in, work is both a government health outcome priority65 and a recognised role for health-care professionals (HCPs). 66 Despite this, NHS provision does not typically extend to VR for TBI survivors. 67 Health-based services supporting people with TBI in returning to work are rare in the UK and estimated to meet < 10% of the need. 68

Evidence for vocational rehabilitation for people with traumatic brain injury

There is a lack of evidence to support the clinical effectiveness or cost-effectiveness of VR for people with TBI. Two systematic reviews3,69 of RTW following TBI have concluded that there is a need for well-conducted experimental and observational studies. Saltychev et al. ,3 in a systematic review of pre- and post-injury predictors of vocational outcome, identified 80 studies, comprising 12 controlled (eight RCTs, two controlled clinical trials and two observational reports) and 68 uncontrolled observational reports. They found no strong evidence that vocational outcomes after TBI could be predicted or improved. However, most of the studies included in the review were generic studies of neurorehabilitation rather than trials evaluating the effectiveness of a VR intervention.

In a systematic review examining the effectiveness of VR in TBI, Graham et al. 69 identified three small RCTs: two of military populations in the USA37,70 and one of civilians in Hong Kong. 71

Salazar et al. 70 compared an intensive in-hospital cognitive rehabilitation intervention and integrated work programmes delivered by a neuropsychologist, occupational therapist (OT) and speech pathologist (n = 67) with an in-home rehabilitation programme including TBI education and individual counselling from a psychiatric nurse (n = 53). Participants were active US military personnel with moderate to severe TBI within 90 days of injury. At 1 year, there were no significant differences between groups in fitness for military duty, RTW rate, cognition, physical or verbal aggression, or QoL. However, among those who were unconscious for > 1 hour (n = 75), the proportion who returned to work was 7% higher in the cognitive rehabilitation and VR group, although the difference was not significant (95% CI –10% to 24%; p = 0.43).

Twamley et al. 37 compared a 1-year supported employment programme with the same programme plus CogSMART (for the first 3 months). Participants were US military veterans with mild to moderate TBI (n = 50). The authors hypothesised that augmenting work rehabilitation with compensatory cognitive training may improve functional outcomes because compensatory interventions can be individually tailored to each person’s job search process and job duties. CogSMART sessions were delivered by an employment specialist and included strategies to improve sleep, fatigue, headaches and tension, and compensatory cognitive strategies for prospective memory, attention, learning and memory, and executive functioning. At 12 months, there was no difference in employment between the groups. However, those also receiving CogSMART had significant reductions in post-concussive symptoms, improvements in prospective memory functioning, less severe post-traumatic stress disorder and less depression, which suggested that adding CogSMART to supported employment might improve post-concussive symptoms and prospective memory.

Man et al. 71 compared 12 sessions of three-dimensional artificial intelligence (AI), virtual reality-based VR with 12 sessions of psychoeducational VR with a vocational trainer. People with mild to moderate TBI were recruited from rehabilitation facilities in Hong Kong (n = 50). The programmes included similar problem-solving tasks, instructions and provided time to practise skills. Of the 40 participants self-reporting employment outcomes at 6 months, 8 out of 20 in the AI-VR group were employed compared with only 4 out of 20 in the psychoeducational VR group [odds ratio (OR) 2.20, 95% CI 0.46 to 10.57].

Graham et al. 69 concluded that VR for people with TBI may improve employment status but no programme was more effective than its comparator. No studies compared VR with UC or a non-VR attention control group, or reported secondary employment outcomes such as hours worked, wages earned, absenteeism, presenteeism or self-efficacy.

Since this review,69 two further VR in TBI trials72,73 have been published. O’Connor et al. 72 compared VR enhanced by cognitive rehabilitation and a computer-based homework programme with supportive client-centred therapy in a small pilot trial in US veterans with mild TBI and mental illness (n = 18). At 12 months, they identified small to moderate effects in the VR group on employment outcomes (more people competitively employed and more days worked). The 12-session VR programme, led by therapists and psychologists, included strategies to manage cognitive difficulties in the workplace, enhance skills to recognise and control unhelpful behaviours at work, deal with negative emotions, and foster positive relationships among coworkers and employers. There was also a computer-based homework programme, in addition to support, from a VR specialist. This feasibility study was small and hampered by poor adherence with therapeutic strategies in both groups, although programme attendance was similar, and high withdrawal rates. Of the 25 participants randomised, six withdrew or were withdrawn in the first two study sessions owing to mental health destabilisation (n = 3), an unexpected move out of the area (n = 2) and dissatisfaction with the control group assignment (n = 1).

Trexler et al. 73 examined the effectiveness of resource facilitation (RF) (i.e. a partnership that supports people to make informed choices and achieve rehabilitation goals, involving active engagement with a previous employer) in 44 people with mild to moderate acquired brain injury (ABI) who were working pre injury (n = 22, 13 with TBI) and a UC control group (n = 22, 10 with TBI). At 15 months, 17 out of 22 participants in the RF group with a goal of returning to work, volunteering or returning to education were successful (11 had returned to paid employment, three became volunteers and three returned to education), compared with 12 out of 22 participants in the UC control group meeting return-to-work/volunteering/education goals (10 remained employed and two returned to education). RF participants with a work-related goal had seven times higher odds of returning to productive activity than the control participants (95% CI 1.25 to 39.15).

However, although this case-co-ordinated approach in ABI seems positive, the trial73 took place in a single centre, numbers were small and there were only 23 participants with TBI (mostly mild). The intervention was staff resource intensive, requiring three more staff than UC, and lasting for 15 months. Both intervention and UC participants had access to acute and outpatient rehabilitation services, neuropsychological services and specialised day treatment programmes. However, the total amount of RF and outpatient therapies provided to the VR and UC groups was not reported, meaning that it is difficult to identify if both groups received similar levels of outpatient therapy and if differences are attributable to RF VR. Data specific to people with TBI were not reported. Interestingly, more participants in the RF group than in the UC group were employed in professional and executive positions to which they returned, which may also have contributed to the favourable outcome. Therefore, this study requires replication on a larger scale elsewhere.

Overall, current evidence for effectiveness of VR in TBI is limited and inconclusive. Of the five VR trials37,70–73 published to date, three37,70,72 have been with US military personnel or veterans. Military studies differ from those in civilian populations as participants present with different challenges (e.g. post-traumatic stress disorder) but also opportunities (e.g. better motivation, adherence and greater opportunities for redeployment within the military).

The effectiveness of neurological rehabilitation in traumatic brain injury on work outcomes

Other trials have compared various neurological rehabilitation interventions (e.g. cognitive rehabilitation,74,75 multidisciplinary rehabilitation programmes,76,77 individually tailored intervention78 and telephone-based motivational interviewing79) for people with TBI and reported work outcomes. These interventions did not include VR and no significant differences in work outcomes were identified.

In the only two large trials35,36 of early intervention following head injury, Wade et al. 36 offered intervention following routine review of all patients (n = 314) presenting to accident and emergency (A&E) with TBI. Eligible patients were prospectively randomised to a TBI specialist rehabilitation team (n = 184) or a group receiving existing standard services (n = 130). Intervention group participants were assessed 7–10 days post TBI to identify their rehabilitation needs and offered interventions as appropriate, for example information, signposting, telephone support or further outpatient intervention (46%) from different TBI specialist HCPs, including, but not specific to, advice and support with aspects of work. 80 At 6 months post TBI, 132 trial and 86 control participants were followed up (attrition: 32% intervention, 34% control) and assessed on a social disability measure. Severity of TBI was estimated from duration of PTA as mild (n = 79, 40%), moderate (n = 62, 32%) or severe (n = 55, 28%). Intervention group participants had significantly less social disability (p = 0.01) than the control group, suggesting that early intervention by a TBI specialist service can significantly reduce social morbidity post TBI. The amount of intervention increased with length of PTA. However, most participants receiving extensive services had mild to moderate TBI, suggesting that persistent TBI problems may not be severity related. In a similar trial35 (n = 1156), 71% of the 478 participants followed up at 6 months (41% response rate) had returned to some form of work or education, with no differences in work outcomes between groups (i.e. both 71%). However, in a subgroup analysis of participants with PTA lasting > 1 hour and admitted to hospital (n = 71), those in the intervention group were significantly less likely to report problems in work, relationships and social and leisure activities as measured by the Rivermead Head Injury Follow-up questionnaire (p = 0.04), suggesting that this could be a group that might benefit most from this support.

Limitations of previous studies

There are very few RCTs of VR in TBI and no cost-effectiveness evaluations of VR.

Previous trials of VR in TBI are typically small, military-based and of low methodological quality, with limitations in blinding, incomplete data, high attrition and selective outcome reporting. The definitions used for employment are wide-ranging (e.g. from homemaker to competitive employment) and time points at which employment outcomes are measured (3, 6 or 12 months) vary between studies, making trial comparisons difficult. Studies included mixed samples including TBI, stroke and other cerebral pathologies, or a range of different TBI severities.

Randomised controlled trials of general neurological rehabilitation in TBI including work outcomes and VR as part of a neurorehabilitation programme have not described the VR provided in sufficient detail for replication or implementation into clinical services. None of the trials included economic evaluation. Observational studies contribute to the evidence base but cannot provide robust, reliable evidence of clinical effectiveness that generalises to the target clinical population.

Justification for the current study

A single-centre cohort comparison study of ESTVR developed in the NHS and delivered by an OT supported by a TBI case manager (CM) was compared with usual NHS rehabilitation in people with TBI of all severities (n = 94). 59 The primary focus of the ESTVR was to prevent job loss by identifying people early after injury and optimising the opportunity to return to work with an existing employer. The findings suggested that better work outcomes (job retention at 12 months post TBI) may be achieved through early occupational therapy targeted at job retention,59 particularly for those with moderate or severe injury, although a clinically meaningful 10% difference was also observed in people with mild TBI at 12 months post injury.

However, as ESTVR was already part of a specialist TBI service and it was delivered by one therapist in a single centre, it is unclear whether or not the successful outcomes were attributable to ESTVR and whether or not it is deliverable by OTs elsewhere.

The lack of RCTs of VR and of rehabilitation in people with TBI and the known difficulty in conducting RCTs of complex health interventions,81 mean that a feasibility study is needed prior to a definitive RCT. The aims are to test the feasibility of conducting a multicentre RCT comparing ESTVR delivered by NHS OTs in addition to usual NHS rehabilitation (i.e. UC) with UC alone on work outcomes at 12 months post TBI. The feasibility study should also explore factors related to the trial process and outcomes, intervention delivery, training provided and factors likely to affect its clinical implementation in the NHS.

Structure of the Health Technology Assessment monograph

The FRESH (Facilitating Return to work through Early Specialist Health-based interventions) study consisted of a feasibility RCT, a feasibility health economic evaluation and an embedded mixed-methods process evaluation. Chapter 2 describes the design of ESTVR, the development and delivery of ESTVR training package for OTs (training, manual and mentoring) and its evaluation. Chapter 3 reports the aims, methods and findings of the feasibility RCT. Chapter 4 describes the feasibility economic evaluation and Chapter 5 summarises the aims, methods and findings of the process evaluation. The study’s key findings are discussed in Chapter 6 and the study conclusion is in Chapter 7. The appendix and supplementary material files contain details of the study components.

Chapter 2 Intervention and training package development

Aims and objectives

The aim of this chapter is to describe the ESTVR intervention and the development of the ESTVR training package.

The development of a programme theory and logic model

The starting point for the trial and subsequent process evaluation was a clear description of the intervention and its underlying theory (i.e. assumptions about how it would work in context). These assumptions included theories based on evidence from the literature and those based on experience or ‘common sense’ (see Appendix 1 for a summary of ESTVR).

The ‘theory of change’ underpinning ESTVR

For people who survive TBI and who are employed or studying at the time of injury, advice not to return to work too soon or make a premature decision about the ability to return to work is an important pre-discharge need. However, hospitals do not routinely identify and record whether or not people who have a TBI are employed pre injury. Information and advice about work is not routinely provided by HCPs for people who survive TBI, and work ability is rarely assessed early after injury. When advice is given, it can sometimes be unhelpful. For example, HCPs sometimes advise a person that they will be unable to return to work, based on an assumption that this involves returning to the same job with the same roles and responsibilities and the same working hours. However, a RTW can involve returning to the same employer but doing a modified or entirely different job. Or it might mean returning to work for a new employer, or doing the same, doing a modified or doing a different job than pre injury. Moreover, disability discrimination law requires employers to make reasonable adjustments to accommodate the injured person in the workplace. Adjustments can include more breaks, reductions in working hours, reduced responsibilities, increased supervision, flexitime working, working from home and receiving help from other people or agencies, including rehabilitation. They can also include modifications to the work environment.

Therefore, health-based support for returning to work after TBI has typically been deficient in meeting TBI survivors’ work needs. ESTVR was designed to bridge the gap between existing TBI rehabilitation services and employers and the voluntary sector in supporting survivors in a RTW. Tested in a single-centre cohort comparison, we found that the intervention may be effective in supporting job retention at 12 months post TBI.

The implicit theory of change on which ESTVR is based can be expressed as follows:

Traumatic brain injury results in physical, psychological, behavioural and emotional changes that are likely to have an impact on the capacity to return to, and remain in, work. The ability to early identify work needs after TBI is missing from TBI rehabilitation services and there is a VR knowledge and skills gap.

Implementing mechanisms for identifying TBI survivors who are employed at the time of injury, educating TBI care teams about ‘return to work’, and teaching OTs with TBI knowledge, basic skills in VR, disability discrimination, how to evaluate jobs and assess work capability, and how to match TBI survivor’s abilities to job demand, engage with employers and other employment sector stakeholders, go into the workplace and how to negotiate reasonable adjustments and a phased RTW, will enable TBI rehabilitation services to support stroke survivors in a RTW. This should result in a higher proportion of TBI survivors returning to, and remaining in, work in the first 12 months post TBI.

Logic model

A logic model was generated based on the programme theory and the intervention manual to visually depict how the intervention works and describe the resources needed, the intended activities, the hypothesised mechanisms underpinning the intervention and intended outcomes82 (Table 1).

| Resources | Core process inputs from TBI/VR OT | Short-term impacts | Impacts | Health outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Facilitating legal framework and policies Skilled, knowledgeable TBI/VR therapist and patient with a job Colocation: crossing boundaries between health, employment, charities Multistakeholder engagement |

Intervenes within 4 weeks of injury, advises on impact of injury and RTW | Patient does not make rapid RTW decisions | Patient and employer satisfaction | Prevent job loss |

| Provides ongoing education, advice and emotional support to patient and family | Patient aware of available support and how to access | Patient confident and able to self-manage | Improved physical and mental health | |

| Co-ordinates patient’s VR across all sectors | Vocational case co-ordinator has early and regular contact with the trauma survivor, family and other stakeholders (e.g. employer, GP, DWP, OH) |

Stakeholders report to one key contact, all aware of stakeholders involved and work towards RTW Conflicting RTW advice prevented |

Personal and financial well-being | |

| Communicates openly in writing with stakeholders regarding work performance | Patient and stakeholders aware of residual problems and coping strategies | Everyone is heard, no confusing communications | ||

| Assesses impact of TBI on person and job, analyses impact on work ability | Patient and employer aware of impact of TBI on work |

Considered decisions made re RTW Patient and employer satisfaction |

||

|

Delivers individually tailored VR in the community Explores alternatives to pre-injury employment when existing employment not feasible or sustainable |

Patient and stakeholders aware of residual TBI problems |

Employment environment optimised Workplace accommodations in place |

||

| Adapts workplace, negotiates phased RTW, provides feedback on performance | Coping strategies in place |

Phased RTW facilitated Patient able to cope with work |

Reduced sickness absence Reduced health resource use |

|

| Monitors RTW to ensure work stability | Referrals made for relevant support | Contributes to economy | Patient in sustainable employment |

Logic models provide stakeholders with a road map describing a sequence of events that connect the health intervention with its desired results and impact (improvement in patient outcomes and retaining work). 83 The process of mapping the intervention helped identify the resources and activities (core inputs) required to achieve the goals (outputs and outcomes) and overall sustained improvements (impact).

The logic model was informed by the meaningfulness (personal opinions, values, thoughts, beliefs, positive or negative experiences and perceptions of TBI service users) and the appropriateness of the intervention (i.e. how ESTVR meets expectations and the extent to which ESTVR fits with what is considered state of the art) from the perspective of researchers and TBI service users. 82

To develop the model, three of the authors (KR, JP, JH) experienced in delivering VR for people with an ABI analysed the component parts of the ESTVR intervention described in the training manual to identify:

-

core activities/processes leading to the desired outcomes

-

necessary resources (considered essential to intervention delivery and outcome success, e.g. the knowledge and expertise of the therapist, supportive policies and legal frameworks that facilitate workplace accommodations and prevent disability discrimination)

-

immediate impacts (influence on patient and stakeholder decisions and awareness that facilitate longer-term outcomes, e.g. patient’s increased awareness of problems, employer awareness of injury impact)

-

longer-term impacts (resulting from immediate outcomes, e.g. RTW, sustained work)

-

health outcomes (benefits of the intervention at a person, employer, health organisation and societal level, e.g. prevention of long-term work disability, cost savings).

The logic model was then used to design and develop an intervention fidelity checklist for use during monitoring visits (see Report Supplementary Material 1), an intervention content pro forma for recording the intervention delivered (see Report Supplementary Material 2) and to inform the interview topic guides (see Report Supplementary Material 3).

ESTVR

ESTVR was based on an intervention initially delivered by the Nottingham Traumatic Brain Injury Service (NTBIS), and described and evaluated by Radford et al.,59 Phillips84 and Phillips et al. 85 It is an early, specialist, health-based, case co-ordination model. People with TBI who are employed or studying full-time are identified early (within 8 weeks) following injury and the intervention is aimed at preventing job loss and optimising employment and education outcomes by ensuring the person can return to work/study. It is delivered by HCPs with specialist knowledge of TBI and VR-specific knowledge working in the NHS. The VR is based on best practice recommendations64 and is either delivered by an OT, supported by a health-based TBI specialist CM, or by an OT adopting a case-co-ordination role. 86 Its aim is to prevent job loss in people who are employed or studying at injury onset.

The intervention is based on the premise that a RTW need not involve a return to the same job with the same roles and responsibilities but could include a return to some form of work or an adapted or modified job with different roles and responsibilities with an existing employer, and that these adaptations could be negotiated as part of the employer’s requirement to make reasonable adjustments to support their employee in a RTW.

The ESTVR intervention seeks to lessen the impact of TBI by assessing the person’s role as a worker and finding acceptable strategies to overcome problems (e.g. assessing and addressing new physical, cognitive or psychological disabilities which might have a direct impact on work activities in relation to job demands). In the ESTVR model, it is intended that the OT provides pre-work training to prepare the person for work by establishing structured routines with gradually increasing activity levels, provides opportunities to practise work skills (e.g. computer use to increase concentration, cooking to practise multitasking), liaises with employers/tutors and disability employment advisors (DEAs) to advise about the effects of the brain injury and to plan and monitor graded work return, conducts worksite visits and job evaluations, identifies the need for workplace or job adaptations and serves as the link between health and Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) services to access additional support.

The TBI CM co-ordinates the overall TBI care package, provides support, education and advice to the person with TBI, family and others (e.g. NHS staff, social services, Headway and solicitors) and remaining in contact while there are achievable rehabilitation goals.

The intervention involves eight core processes as depicted in the logic model:

-

early intervention from a TBI team [i.e. within 8 weeks (ideally 4 weeks) of injury to provide information and advice about the impact of TBI and RTW (e.g. maintaining contact with employer/tutor)] to prevent job loss

-

assessment of the impact of TBI on the individual and the job, and analysis of the impact of TBI on the person’s work ability

-

provision of individually tailored education and rehabilitation to support a RTW

or, when return to the pre-existing employer is not feasible or sustainable, exploration of alternatives to pre-injury employment/learning:

-

optimisation of the employment/learning environment (the OT negotiates a graded RTW and any necessary accommodations to the job role, responsibilities, coworker or supervisory support and environmental adaptations needed for reintegration, and provides feedback on performance)

-

monitoring of the RTW to ensure that the person can maintain employment

The CM/VR therapist:

-

provides ongoing education, advice and emotional support to the person with TBI and their family throughout the VR process

-

co-ordinates the return to work/education rehabilitation across all sectors

-

communicates openly in writing with stakeholders about work performance at all stages of the return to work/education process.

Early intervention

The purpose of intervening early is to ensure advice (1) not to make premature decisions about relinquishing work and (2) to maintain contact with the employer is given to patients, family members and other key NHS service providers involved in the person’s care.

The assessment involves:

-

asking questions about occupational status and vocational aspirations and needs

-

responding to the person with TBI’s questions and concerns about return to work, education or training. It sometimes involves input from other relevant stakeholders who form part of a wider multidisciplinary team co-ordinated by the VR therapist or CM including NHS HCPs such as medical consultant, clinical psychologists and physiotherapists and external agencies (e.g. Jobcentre Plus, occupational health).

The rehabilitation involves:

-

providing interventions (directly related to the person’s work or study) that promote optimal recovery and management of difficulties, including one or more of the following –

-

developing skills or behaviours necessary for work or study

-

restoring work-related routines

-

activities to improve attention, work/study tolerance and stamina

-

extending coping strategies (e.g. fatigue management) for use in the workplace or for study.

-

-

planning a return to work/study with relevant agreed accommodations, such as equipment, graded return, voluntary trial, restricted hours/duties, advice/support in the workplace, job coaching, support from work colleagues, off-site support (e.g. from the OT or other relevant agencies). In the case of study return, these may include adjustments to course, learning-support equipment, individual learning support, examination support and personal support (e.g. personal tutor). These plans take account of family and personal circumstances and the required motor sensory and cognitive–behavioural and emotional skills necessary to a return to work/education.

Education involves:

-

advising the person with TBI not to return to work too soon (i.e. until the impact of the TBI is understood and coping strategies formulated)

-

educating the person, family and employer about difficulties likely to affect work/study (e.g. functional ability, insight and ability to work or return to work/study)

-

developing strategies for the person to explain the effects of their TBI to others

-

providing written information for participants and employers (e.g. about managing fatigue, job accommodations and informing the Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency about driving) (see Report Supplementary Material 4).

Communication and co-ordination includes:

-

establishing which other community services [e.g. ABI team, speech and language therapy (SALT)] are involved and communicating with them

-

supporting the person prior to, and during, meetings with employers and other stakeholders (including clarifying what was said and agreed in meetings)

-

seeking the person’s consent to contact the employer, education provider and/or training provider to discuss needs

-

establishing and maintaining communication with employer and informing them of rehabilitation goals

-

consulting with occupational health, DEA, Jobcentre Plus occupational psychologist or other VR service providers to discuss relevant action if there is doubt about a client’s ability to cope with a supervised and graded RTW

-

providing clear written and verbal advice about appropriate timing, and gradual increases in hours and responsibilities

-

liaison with the relevant occupational health department for advice or, when unavailable, consulting the NHSPlus website

-

agreeing and discussing the disclosure of information to an employer or occupational health provider (providing clients with draft submissions for comment prior to disclosure)

-

agreeing and discussing the RTW plans with the client and a family member (when possible)

-

negotiating and agreeing workplace accommodations, such as equipment, graded return, voluntary trial, restricted hours/duties, advice/support in the workplace, job coaching, support from work colleagues, off-site support (e.g. from the OT or other relevant agencies) with the employer. In the case of study return, these may include adjustments to course, learning-support equipment, individual learning support, examination support and personal support (e.g. personal tutor).

Monitoring involves:

-

reviewing progress with ongoing advice, support and feedback for person and employer (supervisor and work colleagues, as appropriate) and obtaining feedback from family members about the impact of work on personal life, family life and relationships

-

liaising with DEAs when long-term adjustment and support are needed (e.g. major adjustments to work duties, specialist equipment or help with travel to work).

The intervention is individually tailored and delivered in the community, clinic or workplace over weeks or months based on participants’ individual needs. In our earlier cohort comparison,85 participants had a mean of 6.5 sessions of occupational therapy and 4.7 1-hour-long sessions of case management over the 12-month intervention period. Half of the sessions were delivered in person and half by telephone or e-mail. This ‘direct’ contact with the person accounts for about two-thirds of the therapist’s overall time. The rest is spent in administration and travel.

In the single-centre cohort study, ESTVR was delivered by a single experienced OT trained in VR. ESTVR was developed based on best practice recommendations64 over a number of years and evaluated pragmatically in the context in which it was developed. What remained unclear was whether or not OTs in other contexts could be trained to deliver it so that its effectiveness could be tested in a RCT. The intervention needed to be described such that the key intervention components were clear before an intervention training manual could be developed. Therefore, the starting point for this study was to manualise the intervention and train OTs in the three sites to deliver it.

Development, delivery and evaluation of the ESTVR training package

The OTs employed on FRESH needed to learn how to deliver the ESTVR intervention over the 12-month duration.

Development of the manual

A group of experts in VR TBI and training was formed [Julie Phillips (JP), Jain Holmes (JH), Yash Bedekar (YB) and Ruth Tyerman (RT)], including one service user (TJ). Three development meetings were held, supplemented by e-mail and telephone communication. The manual was based on the existing NTBIS manual and a description of the intervention delivered by Phillips et al. 85 in an earlier study. Phillips was interviewed to elicit information about the core activities, process, outcomes, impacts and resources essential to ESTVR delivery. These are illustrated in the logic model (see Report Supplementary Material 5). Manuals developed for other rehabilitation trials were used to inform the content and design. 87–90

The manual was presented in hard copy, accompanied by an electronic copy on a memory stick and was issued to OTs during training.

Manual content

The first five chapters followed a typical patient journey from hospital admission to RTW and covered the aims of ESTVR, examples of core intervention activities, the role of the OT and the CM, information on the frequency of visits and a section on common problems related to RTW following TBI (see Report Supplementary Material 4). To optimise implementation, the OTs were encouraged to adapt the manual to their local context (e.g. by adding local contact details for Jobcentre Plus, Headway groups, etc.).

Development, delivery and evaluation of the training

Training involved didactic teaching, case vignette discussions and role play. This multimodal approach was considered the best way to achieve learning. 91 Training was scheduled to take place within 1 month of trial recruitment to ensure that learning was current. However, trial recruitment was delayed by 3 months in two centres and by 6 months in the third. Refresher training was scheduled 6 months after the initial training to provide a top-up and an opportunity for shared learning once OTs had case experience. Training was delivered over 2 days by training group members. The OTs were taught together to provide peer support.

At the end of day 1, homework (case study problem-solving) was given to embed learning. A video of the training was made available to OTs as an additional resource.

It was assumed that the OTs would already be knowledgeable about TBI but have little understanding of VR. Therefore, pre-training reading materials were VR specific.

A learning needs analysis was used to assess the OTs’ knowledge and confidence on TBI and VR 1 month before, and immediately following, the training on a scale of 1 (not very confident or knowledgeable) to 5 (very confident and knowledgeable) (see Report Supplementary Material 6).

The evaluation of the training is reported in Chapter 5.

Mentoring

Mentoring was used to supplement training and ensure ESTVR was delivered with fidelity, a method found successful in implementing other complex therapy interventions. 92 The FRESH trial OTs received mentoring from one of four mentors assigned to them. Mentors were the same people who delivered the VR training. Mentors were intended to provide approximately 1 hour of support per month consistent with typical clinical supervision practice. Mentoring was delivered flexibly and included meetings, telephone calls, e-mails or text messages as agreed between the OT and mentor.

Mentoring was evaluated in interviews with OTs and the content and quantity was measured. The findings are reported in Chapter 5.

Chapter 3 Feasibility randomised controlled trial

This chapter describes the design, conduct and findings of the feasibility trial according to CONSORT 2010 statement: extension to randomised pilot and feasibility trials. 93,94 This chapter is used to address the study’s primary objective and the first 10 of the 12 secondary objectives listed below, although the process evaluation, presented in Chapter 5, also contributes to the evaluation of the protocol detailed in objective one. The remaining objectives (11 and 12), relating to the acceptability of the intervention to TBI patients, staff and employers, and the views of TBI patients and staff on recruitment and the acceptability of randomisation, are listed here to give an overall picture of the FRESH study but are not addressed until Chapter 5.

Methods

Study design

The FRESH study was a pragmatic, multicentre, individually randomised parallel-group controlled feasibility trial comparing ESTVR plus UC with UC alone, with both a feasibility economic evaluation and an embedded process evaluation.

Aim

To assess the feasibility of conducting a multicentre, two-arm randomised (1 : 1) controlled trial comparing ESTVR delivered by NHS therapists in addition to usual NHS rehabilitation with usual NHS rehabilitation alone (UC), and of measuring its effects and cost-effectiveness on work (work return and job retention) and health outcomes at 12 months post TBI.

Objectives

To:

-

assess the integrity of the study protocol (e.g. inclusion/exclusion criteria, staff training, adherence to intervention, and identify reasons for non-adherence)

-

estimate the proportion of potentially eligible TBI patients recruited and identify reasons for non-recruitment (missed, medical, logistic, other)

-

estimate the recruitment rate (by centre)

-

determine the spectrum of TBI severity among recruits

-

estimate the proportion of participants lost to follow-up and the reasons for loss to follow-up

-

describe the completeness of data collection for potential primary outcome(s) for a definitive trial

-

explore potential gains in using face-to-face data collection rather than postal data collection

-

determine the most appropriate method(s) of measuring key outcomes (RTW, job retention)

-

investigate how RTW is related to mood, well-being, function, work capacity, social participation, QoL and carer strain

-

estimate the parameters necessary to calculate the sample size for a larger trial (e.g. rate of RTW at 12 months in the control group)

-

explore the views of TBI patients and staff on recruitment and the acceptability of randomisation

-

determine whether or not ESTVR can be delivered in a way that is acceptable to TBI patients, staff and employers [views of TBI patients, staff and employers on the interventions (ESTVR vs. UC)].

Summary of design and methods of randomised controlled trial

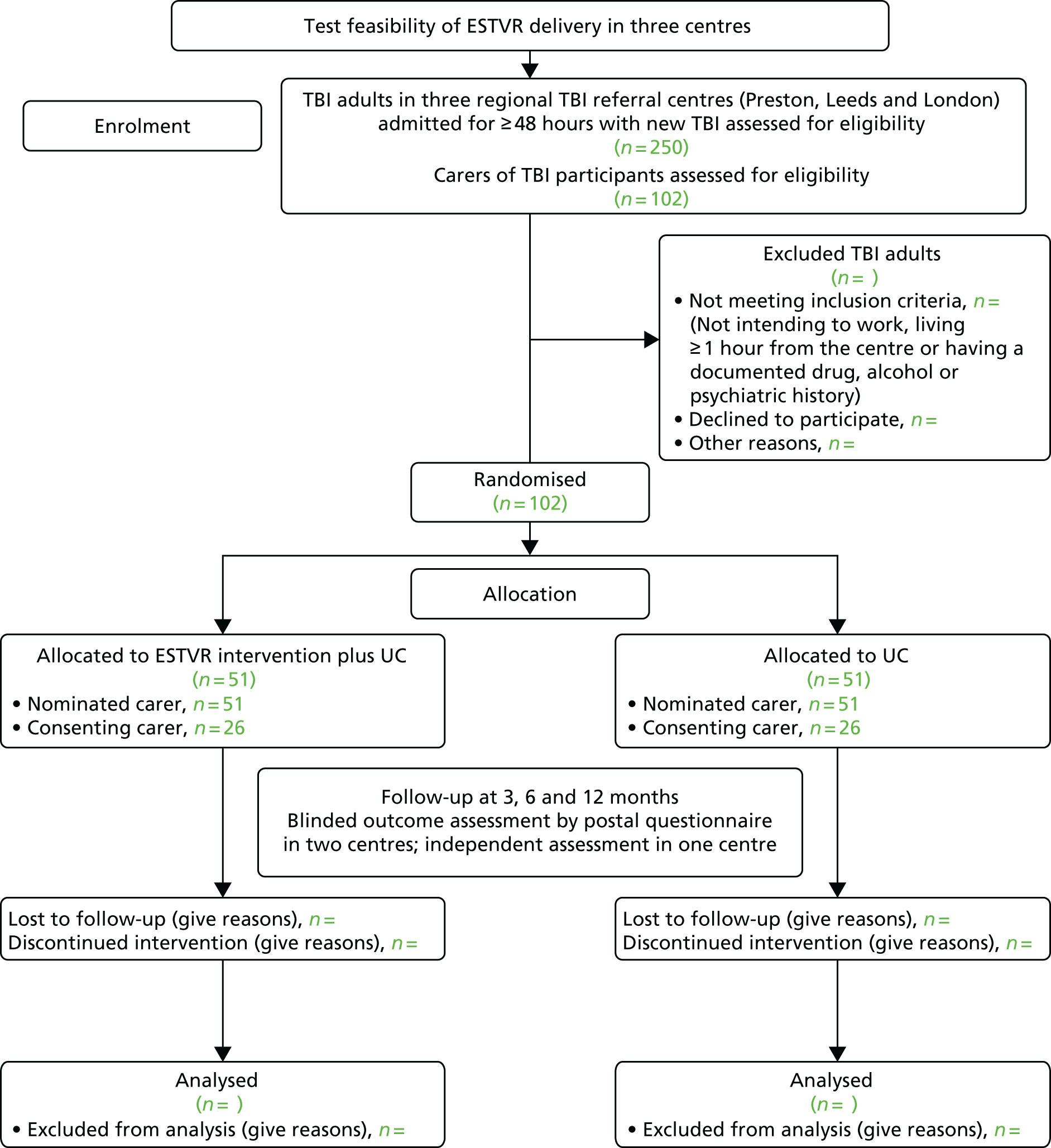

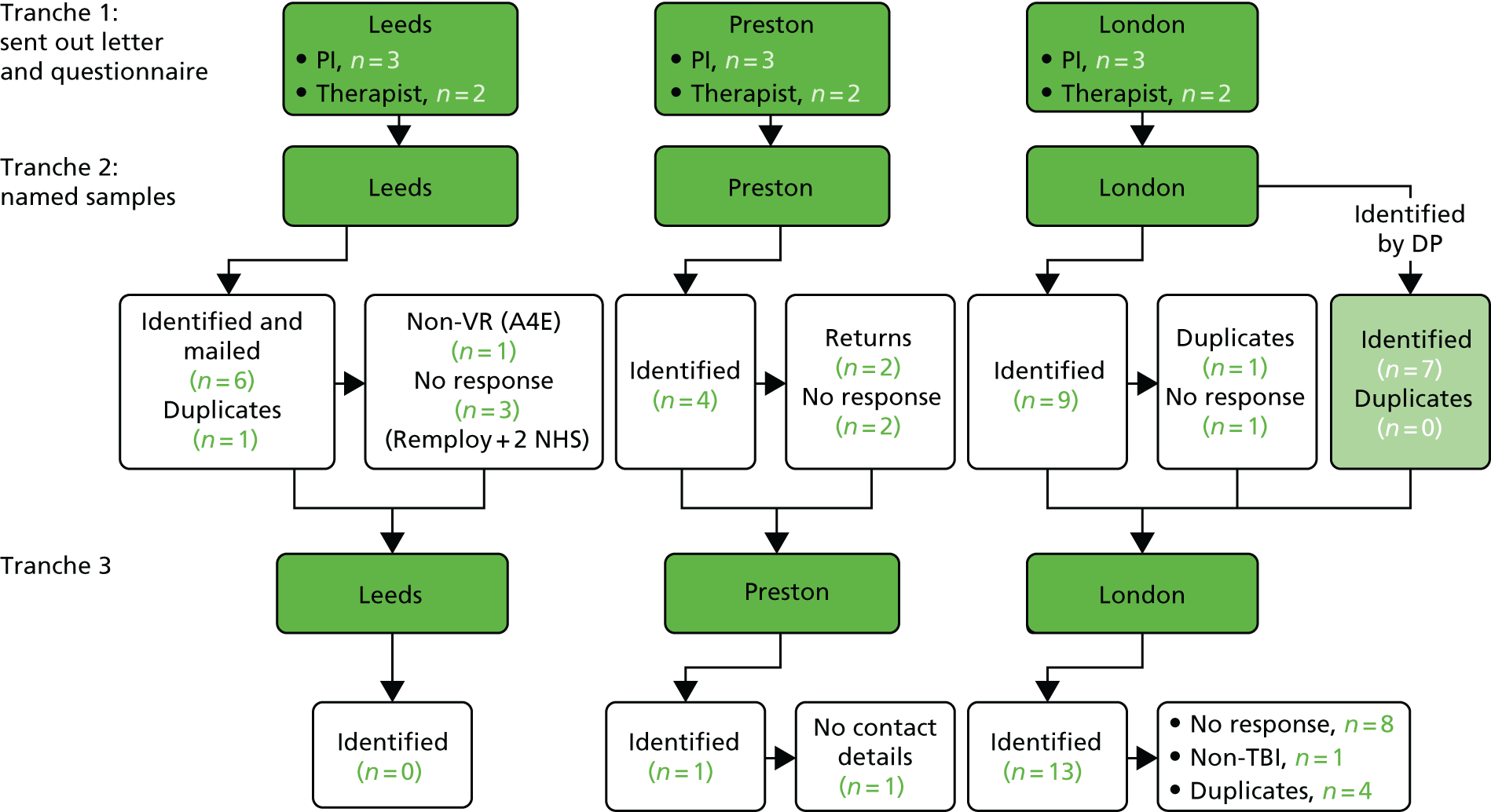

Figure 1 summarises the study method in line with the recommendations93 for individually randomised controlled trials of non-pharmacological interventions.

FIGURE 1.

Study method CONSORT flow chart. CONSORT, Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials.

Setting and locations

The study was sponsored and co-ordinated by the University of Nottingham and the feasibility trial was co-ordinated and managed by the University of Central Lancashire Clinical Trials Unit (CTU). It involved three sites; each a designated major trauma centre (MTC).

Participants were identified initially during an inpatient stay but the intervention was delivered in other settings, for example outpatients, domiciliary visits, the workplace and other community settings.

Three sites were involved in the study.

-

Site 1 was in the North West.

-

Site 2 was in London.

-

Site 3 was in Yorkshire.

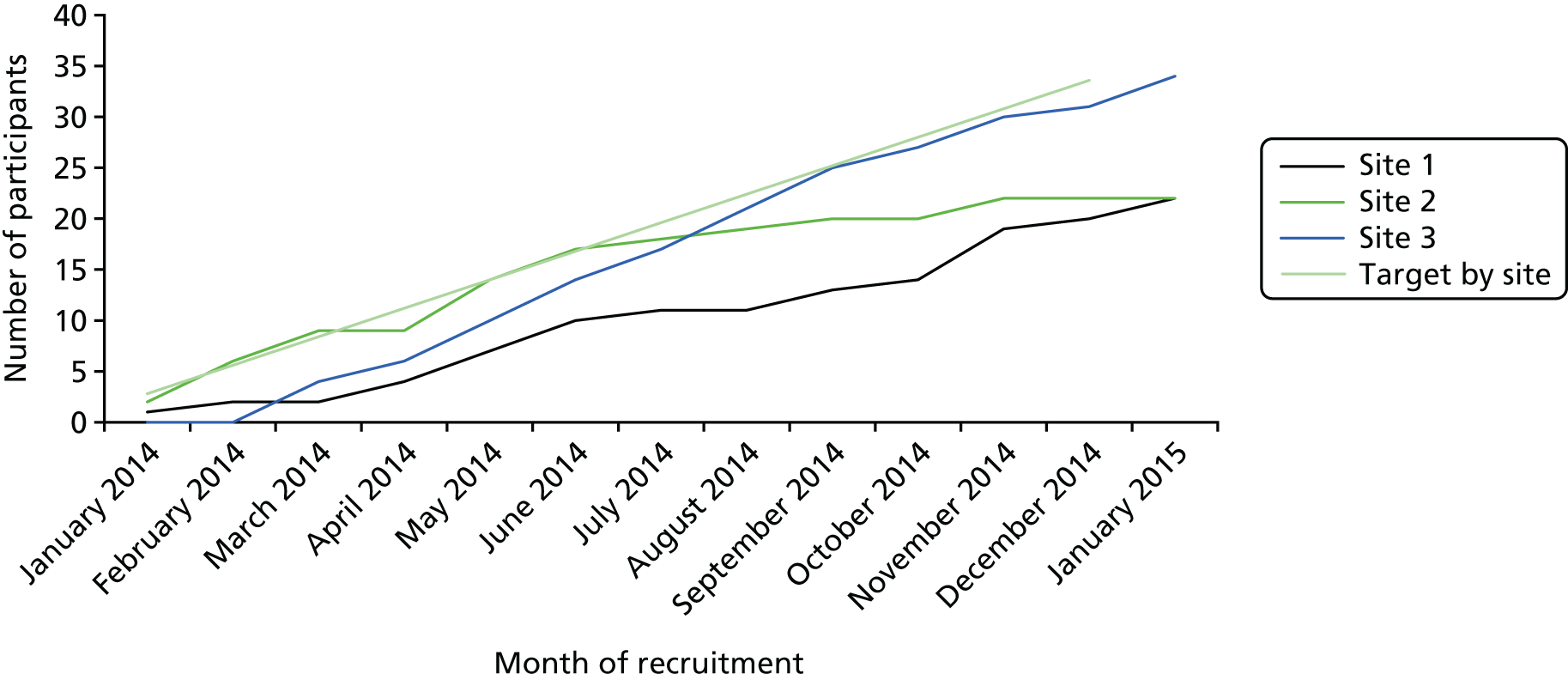

These sites were involved in FRESH from the start of the study in March 2013 until the end (last patients identified January 2015 and completed outcome assessments in January 2016). We planned to open all sites to recruitment for 12 months in September 2013.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion

Patients were eligible for the trial if they were:

-

adults (aged ≥ 16 years)

-

living in the health communities served by the three trial sites

-

admitted for ≥ 48 hours with a new TBI

-

in work (paid or unpaid) or in full-time education prior to their injury

-

within 8 weeks of TBI.

Exclusion

Patients who met the inclusion criteria were excluded from the trial if they:

-

did not intend to return to work/study

-

were unable to provide consent for themselves

-

lived > 1 hour (or reasonable) travelling distance from the recruiting centre.

People with a language barrier resulting from TBI (e.g. aphasia) or for whom English was not their first language were not excluded. We planned to seek help from family members and interpreters to include people who met the inclusion criteria wherever possible.

Changes to eligibility criteria during the trial

No changes to eligibility criteria were made during the trial, although we considered widening the recruitment window from 8 weeks to 12 weeks post TBI. However, following discussion, it was decided not to amend the recruitment window but to collect data about repatriation in two centres (sites 2 and 3) to assess the potential impact on recruitment.

Carers

Carers of TBI participants were eligible if they were nominated during the baseline assessment visit by a consenting TBI participant as the person (spouse, partner, parent or other) with whom they had most contact.

Inclusion criteria

Carers of adults (aged ≥ 16 years) living in health communities surrounding sites 1, 2 and 3 and admitted for ≥ 48 hours with a new TBI who were in work (paid or unpaid) or in full-time education prior to their injury.

Screening, recruitment and baseline assessment

Screening process

Potential TBI participants were identified by members of the usual clinical care team using existing TBI registers. A screening log was used by the research assistant (RA) or research therapist to monitor and identify recruitment against eligibility criteria. Every person with TBI admitted to hospital and who fitted the inclusion criteria during the trial recruitment period was entered onto the screening log by the RA or Clinical Local Research Network (CLRN) research nurse. The minimum data recorded were age, gender, meeting eligibility criteria (yes/no) and consented (date) or reason for non-consent. The status of eligible patients (refused, consented) and reasons for refusal (when given) were recorded on the screening log. In addition, information about employment status was gathered to ascertain fit with inclusion criteria.

Completeness of screening was verified by cross-checking with existing trauma and local TBI registers. This was done by staff deployed to support recruitment by the participating trust and administrative staff from the clinical care team who were familiar with local mechanisms and trust policies and procedures. In two sites, this included RAs (a study-specific RA in one site), and in another this was the local CLRN research nurse, working within the trust.

Recruitment process

The initial approach was made by a member of the patient’s UC team, who provided information sheets and notified the research team. The research team (RA or CLRN research nurse) in each centre informed potential participants of all aspects pertaining to participation in the study. Patients fitting the inclusion criteria but who were discharged before being seen by a member of the research team were sent a participant information sheet with a covering letter from the consultant informing them about the project. This letter also stated that a researcher would contact them to ask if they were interested in taking part. If the patient expressed an interest, then an appointment was made for the researcher to visit, answer any questions and, if applicable, take informed written consent. Patients were given a minimum of 24 hours to consider the information prior to consent being taken. The status of eligible patients (refused, consented) and reasons for refusal (when given) were recorded on the screening log. In addition, the screening log included additional information about the employment status and type of injury (e.g. fall, assault, RTA).

Consenting participants were asked to nominate a carer (spouse, partner, parent or person with whom they had most contact) during the baseline assessment. Carers were sent a carer’s information sheet and covering letter from the consultant informing them about the project, and stating that a researcher would contact them to ascertain their interest in taking part. Interested carers were visited by a member of the research team who took written consent. Only carers nominated by a participant with TBI were approached.

The process for obtaining participant (patient and carer)-informed consent was in accordance with research ethics committee guidance and good clinical practice. The investigator, or their nominee, and the participant both signed and dated the informed consent form before the person could participate.

Baseline assessments

Baseline assessments were completed as soon as possible following consent but prior to randomisation. All baseline measures were collected face to face by the RA or research nurse either in hospital or at the participant’s home if they had been discharged at the time of recruitment.

Traumatic brain injury participants

A minimal amount of basic demographic information required for randomisation was collected from each participant by the RA or research therapist at the baseline visit (see schedule of outcome measures in Table 2).

Carers

Consenting carers in the three sites were sent a brief questionnaire including a measure of carer strain95 and asking about the impact of the TBI participant’s injury on their working hours and income.

Sample size

The sample size was based on an expectation to recruit approximately one-third of patients fitting the eligibility criteria (e.g. 100 participants from 300 patients approached over 12 months). This was intended to enable us to estimate the recruitment rate to within ± 6% (with 95% confidence) and the attrition rate to within ± 7% (with 95% confidence) (assuming an attrition rate of ≤ 15%). We anticipated that not all TBI participants would have, or be willing to pass on, carer details; however, we believed that at least 30% of carers identified by TBI participants would be recruited.

Randomisation and allocation concealment

Once TBI patients had consented to join the trial and completed their baseline assessment, participants were randomised to UC or ESTVR plus UC. The allocation sequence was computer generated via an algorithm which implemented stratified (by site) randomisation using random permuted blocks of randomly varying size. It was created by Nottingham CTU in accordance with its standard operating procedure and held on a secure server.

The randomisation system was accessed via the web by the RA or the CLRN research nurse performing the recruitment in each site and an automatically generated e-mail was sent to the nominated site staff informing them of the allocation; a similar e-mail, but without details of the intervention allocation, was sent to the trial management and data management staff at Lancashire CTU. These e-mails also contained the unique participant identification code, which was generated by the randomisation system and then used on patient questionnaires, on other trial documents and in the electronic database. The documents and database also used participant initials and date of birth for verification purposes.

Carers were not randomised.

Intervention and control conditions

ESTVR

Participants randomised to the intervention group received all usual NHS rehabilitation interventions but, in addition, they received the ESTVR (as required) targeted at job retention.

ESTVR is an early, TBI-specialist, VR, job retention intervention. It was developed in Nottingham by an OT and is routinely delivered as part of usual NHS rehabilitation by the NTBIS. It was evaluated in a single-centre cohort comparison study59 and the results suggested a positive influence on 12-month work outcomes in those who received it. ESTVR is a case co-ordination model85 based on best practice guidelines for VR following ABI. 63 It is delivered by an OT and supported by a health-based CM, both of whom have knowledge and skills in working with people with a TBI and in VR. Most interventions are delivered in the community.

People with TBI are identified early (at point of injury) and the intervention aims to prevent job loss. The VR intervention seeks to lessen the impact of TBI by assessing the patient’s role as a worker and finding acceptable strategies to overcome problems (e.g. assessing and addressing new disabilities which might have a direct impact on work activities). The intervention process follows three stages: (1) assessment, (2) intervention and (3) monitoring and review. Detailed assessment of the person’s occupational status and vocational aspirations and functional capacity for work is followed by intervention to prepare the person with TBI for work by providing pre-work training and establishing structured routines with gradually increasing activity levels and the opportunity to practise work skills (e.g. computer use to increase concentration, cooking to practise multitasking). The OT liaises with employers/tutors and employment services to advise about the effects of TB and to plan and monitor graded work return, conduct worksite visits and job evaluations, identifies the need for workplace or job adaptations, and serves as the link between health and employment services to access additional support. During ‘monitoring and review’, progress is reviewed and ongoing advice, support and feedback is provided for the TBI patient, their family and employer (supervisor and work colleagues, as appropriate) with ongoing liaison with employment services, if needed. TBI CMs co-ordinate the overall TBI care package, provide support, education and advice to patients, family and others (e.g. NHS staff, social services, Headway and solicitors), remaining in contact with patients and families while there are achievable rehabilitation goals.

The intervention was tailored to individual needs according to the following menu of components:

-

assessing people’s functional capacity for work

-

detailed job evaluation and safety assessment

-

liaison with employers regarding necessary accommodations (equipment and adaptations) and graduated RTW programmes

-

individual work-related goal setting and problem-solving sessions

-

partnership working with statutory and voluntary service providers such as disability employment and benefits advisors and Headway

-

negotiating voluntary work placements

-

providing information and advice to TBI patients, their families and employers, and counselling.

A more detailed description of the intervention is provided in Chapter 2 and Appendix 1.

Control: usual NHS rehabilitation

Participants allocated to the control group availed themselves of whatever usual health and social care services were available to them in their area. Usual NHS rehabilitation differed in each area but none of the sites had existing specialist VR services.

Usual care was measured by including resource use questions in the follow-up questionnaires. Additional information about efforts to support people with TBI in a RTW in the control group was gathered in qualitative interviews with UC participants.

Concomitant therapy

Continued use of NHS/social services department/third-sector services alongside the ESTVR intervention was anticipated. There were no known issues with the intervention and concomitant treatments; therefore, no concomitant treatments were excluded. We attempted to capture and describe concomitant therapy by including questions intended to capture the nature and quantity of concomitant therapy and any intervention received by the control group. This included information on participants’ use of other community rehabilitation, social care and third-sector services.

Training programme

A manualised training programme developed in advance of the trial and based on the original Nottingham Pilot study59,86 was delivered centrally by the chief investigator (KR) and VR expert OTs (JP, JH, YB and RT) to the OTs from each of the three centres. Therapists were trained to adopt a vocational case co-ordination/case management role in addition to delivering VR (see Chapter 2).

Therapists were asked to maintain their usual clinical notes and, in addition, to record the intervention content delivered in each intervention session in 10-minute units using an intervention fidelity pro forma (see Report Supplementary Material 2) based on the training manual. Pro formas captured face-to-face activity, travel, non-face-to-face activity [participant-related activity that did not involve direct face-to-face contact (e.g. telephone calls, letter writing)] and administration (e.g. writing clinical notes).

Monitoring and mentoring

Training and intervention delivery was supported by monthly telephone and e-mail mentoring to ensure that the intervention was delivered as intended and that the therapists felt confident in its delivery.

One hour per month of mentoring time was allocated per therapist in accordance with usual clinical practice for NHS supervision. Mentoring was delivered by therapists with expertise in VR for people with TBI (JP, JH, YB and RT). Pairing of mentors with therapists was done geographically.

In addition to the formally agreed 60-minute monthly mentoring sessions, therapists were supported by telephone and via e-mail, ensuring that they always had access to someone who could help with issues/queries as they arose. Mentoring was recorded using a mentoring record form, which also served as a mentoring checklist (see Report Supplementary Material 7). The content of the mentoring sessions is reported in the process evaluation in Chapter 5.

Intervention delivery was also quality monitored and fidelity checks were carried out to assess adherence to the ESTVR therapy process described in the manual. Further detail on the assessment of fidelity can be found in Chapter 5.

Regular, 3-monthly fidelity monitoring visits were conducted in each site by the therapy co-ordinator (JP). Therapists were asked to bring clinical case notes and to supply completed intervention fidelity pro formas for their current caseload of participants in advance of each visit. The intervention fidelity pro formas were collected and returned to the University of Nottingham for data entry and analysis.

During fidelity monitoring visits, review of case notes was used to check that the process of assessment had been completed and goals for therapy were clearly stated, as described in the therapy manual. This meant that impairments and functional limitations had been identified and RTW goals had been articulated by the participant. A discussion with the therapist about the rationale for their treatment plans provided an opportunity to ask questions or seek advice. In addition, checks were made to ensure that information had been provided to participants.

An intervention fidelity checklist (see Report Supplementary Material 1) was used to monitor whether or not the intervention delivered by trial therapists was consistent with the ESTVR core process components described in the training manual and whether or not the content was consistent with that delivered in the Nottingham pilot study. 59

The OT therapy co-ordinator (JP) carried out a minimum of four direct monitoring sessions with each of the four therapists during the intervention delivery period. In total, 16 sessions of direct monitoring were conducted.

Once completed, the fidelity pro formas and fidelity checklist were collected by the therapy co-ordinator and used to ensure intervention fidelity. In addition to these fidelity monitoring processes, therapists were interviewed about factors affecting intervention fidelity as part of the process evaluation reported in Chapter 5.

In addition to the direct monitoring and mentoring, the OTs were invited to present, to their peers, details of two participants with whom they were working at a workshop 3 months after recruitment commenced.

Outcome assessments

All outcomes for TBI participants and carers were assessed at 3, 6 and 12 months post randomisation. Outcome measures from both TBI participants and carers were collected by post in two centres and assessments were collected face to face by a RA masked to treatment allocation in one centre. In the two centres using postal data collection, participants requesting help to complete the measures were offered a home visit by a RA. Similar steps to minimise missing data were taken irrespective of the mode of data collection (postal or face to face) using personal contact by telephone and text messaging to prompt returns when 2 weeks had elapsed since the due date, using an agreed protocol (see Report Supplementary Material 8). Key data, including RTW information, were collected by telephone normally when 60 days had elapsed since the questionnaire due date.

As the likely primary measure of effectiveness for the main trial was work status at 12 months, defined as competitive employment (full- or part-time paid work in an ordinary work setting, paid at the market rate96) at 12 months post randomisation, data were collected on participants who reported having returned to:

-

work in the same role with an existing employer

-

a different role with an existing employer

-

work with a different employer (i.e. new work in the same or a different role)

-

self-employed work.

The proposed secondary outcome measures of effectiveness for a potential effectiveness trial were also collected from TBI participants and were as follows:

-

Perception of mood, using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). 97

-

Perception of functional ability, using the Nottingham Extended Activities of Daily Living (NEADL) scale. 98

-

Perception of participation ability using the Community Integration Questionnaire (CIQ). 99

-

Perception of health-related QoL using the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, three-level version (EQ-5D-3L). 100

-

Perception of productivity at work using the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment (WPAI v2) questionnaire. 101

-

Use of health, social care, and broader resources, using bespoke resource use questions.

-

Perception of work self-efficacy, measured using a single question from the Work Ability Index (WAI) (Ilmarinen et al. ). 102

-

TBI recovery (at 12 months only) for comparison with other TBI studies, measured using the Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS) score. 103 Responses were recorded into one of five categories: (1) death, (2) persistent vegetative state, (3) severe disability, (4) moderate disability and (5) low disability.

Detail of the secondary outcome measures and time points for administration are summarised in the schedule in Table 2. For each TBI participant, the measures described above were collected at recruitment to the study (baseline) and at 3, 6 and 12 months post randomisation.

| Measure | Baseline | Follow-up time points | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 months | 6 months | 12 months | ||

| For TBI participants | ||||

| Demographic information | ✓ | – | – | – |

| Duration PTA | ✓ | – | – | – |

| GCS score | ✓ | – | – | – |

| Duration unconsciousness | ✓ | – | – | – |

| Specific VR-focused questions | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| EQ-5D-3L | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| HADS | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| NEADL | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| CIQ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Resource use of health, social care and broader | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Self-efficacy (single question from the WAI) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| WPAI v2 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| GOS score | ✓ | |||

| For carers | ||||

| CSI | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Questions about specific impact on carer’s work | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

At each time point, consenting carers were asked:

-

to complete the self-reported Caregiver Strain Index (CSI)95

-

to answer questions about the financial impact on the carer of the TBI participant’s injury at 3, 6 and 12 months post randomisation (see Table 2).

The outcome measures were compiled into booklets (see Report Supplementary Material 9 and 10) for ease of completion.

Blinding

Participants were not blinded to the intervention group allocation. The RAs and research nurses conducting recruitment and baseline assessments were not blinded to the intervention group allocation, with the exception of the RA in site 3, who was responsible for collecting postal and face-to-face follow-up outcome measures. Participants were asked not to mention group allocation to the RAs on arrival. However, it was anticipated that the RA could become unblinded (e.g. by reference to the name of the therapist).

Other members of the research team, including the chief investigator, health economist and all Lancashire CTU staff, including the trial statistician, were blinded to group allocation. They remained blinded until all interventions were assigned, recruitment and data collection were completed and the Statistical and Health Economics Analysis Plan (SHEAP) was approved by Lancashire CTU and the chief investigator. When the databases were locked, the intervention arm codes were released by Nottingham CTU; the data analysis was performed using codes for the intervention arms, with the exception of the health economic analysis. The health economic analysis was blinded as much as possible [i.e. the majority of resource use items were valued and utility values scored with estimation of quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs), without knowledge of the intervention group], but unblinded once intervention costs were assigned to participants and the final analysis conducted.

Participant withdrawal criteria

Participants could be withdrawn from the study either at their own request or at the discretion of the principal investigator (PI). The participants were made aware that this would not affect their future care. Participants were also made aware (via the information sheet and consent form) that, should they withdraw, the data already collected could not be erased and might still be used in the final analysis. Participants could also withdraw from the intervention without ceasing participation in the trial.

Safety evaluation

Given the nature of the trial intervention, no serious adverse reactions were anticipated. Therefore, no specific safety investigations were proposed and no additional safeguards were put in place over and above those adhered to by any OT in the delivery of therapy. It was not anticipated that any special conditions needed to be imposed for monitoring safety over and above those for eliciting and recording adverse events. However, as this was feasibility work, it was envisaged that safety factors which may need to be accounted for in a larger trial might be revealed and described.

Adverse events were classified as follows (some were included in more than one of the categories below):

-

deterioration in a participant’s physical or psychological health resulting in inpatient acute admissions, use of emergency, health or social care services.

Safety was assessed by collecting all adverse outcomes considered to be related to the ESTVR intervention. As the side effects of the intervention were unknown, we hoped to identify them in order to inform the design of future trials. Therefore, we collected outcome data potentially related to the intervention, including:

-

accidental injury resulting from non-compliance with equipment or workplace adaptations recommended by the FRESH VR OTs

-

work accidents resulting in injury requiring hospital treatment (hospitalisation due to a work-related injury was classified as a serious adverse outcome)

-

incidents of aggression (defined as excessive verbal aggression, physical aggression against objects, physical aggression against self and physical aggression against others) of the participant towards the researcher, staff or others (e.g. work colleagues)

-

attempted suicide (hospitalisation due to attempted suicide was classified as a serious adverse outcome).

In order to provide formal reassurance that the intervention was of extremely low risk, the Study Steering Committee (SSC) was provided with a report detailing adverse events and safety outcomes. These have also been analysed and details are included in this report.

Identification of adverse events

Questions that helped to identify adverse events were included in the questionnaire booklets at 3, 6 and 12 months. The information was extracted by the RA collecting outcome data in site 3 and the Lancashire CTU trial staff from responses to questions regarding hospital and general practitioner (GP) visits reported in service use questions. These were enhanced by records of any deaths (obtained from hospital records, GP contact and/or reports from carers and VR therapists during the trial).