Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 08/116/75. The contractual start date was in April 2011. The draft report began editorial review in September 2016 and was accepted for publication in February 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Maya H Buch reports grants from Pfizer and Chugai Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd (Roche), and personal fees from AstraZeneca, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Chugai Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd (Roche), Sandoz and R-Pharm, during the conduct of the study. Claire Hulme reports grants from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme, during the conduct of the study, and was a member of the NIHR HTA Commissioning Board during the conduct of the study. Paul Emery reports grants and personal fees from Pfizer, Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, UCB Pharma Ltd, Roche, Novartis, Samsung, Sandoz, and Eli Lilly and Company, during the conduct of the study. Sue Pavitt is a member of the Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation Board and NIHR Clinical Trials Unit Board and has been a recipient of NIHR Clinical Trials Unit Support funding. Linda Sharples, Sarah Brown and Claire Davies report grants from NIHR HTA programme during the conduct of the study. Christopher McCabe reports that historically he worked as a paid consultant for a number of pharmaceutical companies. He has also done paid extensive work for the NHS.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Brown et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA), the most common autoimmune disease in the Western world,1 is a chronic and systemic inflammatory arthritis that affects 0.8% of the UK population. 2 RA is the largest cause of treatable disability in the Western world. 3,4 Patients with RA suffer considerable pain, stiffness and swelling and, if not adequately controlled, sustain various degrees of joint destruction, deformity and significant functional decline. RA has a considerable health and socioeconomic impact, as a result of both hospitalisation and loss of employment, with over 50% of patients work-disabled within 10 years of diagnosis. 5–7

Rheumatoid arthritis is associated with significant comorbidity and increased mortality compared with the general population,8 largely because the prevalence of premature cardiovascular disease9 is as high as that seen in patients with other major cardiovascular disease risk factors, such as type 2 diabetes,10 and, in fact, is the cause of death of 48% of patients with RA. RA-related inflammation and disease activity over time are associated with increased cardiovascular disease risk in patients with RA,11–14 which further emphasises the importance of ensuring optimal and effective disease control.

As compared with other chronic diseases, such as hypertension and type 2 diabetes, treatment of RA previously employed a gradual ‘step-up’ strategy with the use of conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (csDMARDs). 15 The concept of the ability to modify disease course started to be realised in the 1990s,16 with key studies demonstrating the importance of early diagnosis and expedient implementation of csDMARD therapy,17–19 which remain the cornerstones of management of RA. These paradigms have been consolidated by strategy trials and meta-analysis on the radiographic benefit. 20–24

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence’s rheumatoid arthritis management guidance

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)’s clinical guidance for the management of RA25 recommends, in people with newly diagnosed active RA, a combination of csDMARDs [including methotrexate (MTX) and at least one other csDMARD, plus short-term glucocorticoids] as first-line treatment as soon as possible, ideally within 3 months of the onset of persistent symptoms (and within 6 weeks of diagnosis by a rheumatologist).

Methotrexate is thus recommended as the optimal first-line treatment strategy25,26 either as monotherapy or in combination. Nevertheless, it had become clear that poor response (even if initially effective) remained a feature with most csDMARDs over time, with progression of joint damage and functional decline. In addition, a high incidence of toxicity has been observed with these drugs. 27 Such obstacles to therapy, combined with data suggesting limited alteration in long-term outcome, even in those patients showing a response, are an argument for more effective therapy. 28

Biological therapies

This unmet clinical need fuelled continued research into our understanding of RA, which led to significant advances by the 1990s. Inflammation was recognised to be a result of imbalance between pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumour necrosis factor (TNF) alpha [as well as interleukin 1(IL-1), IL-6 and others] and anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-4 and IL-10. In RA, an excess of pro-inflammatory cytokines, in particular TNF and IL-1, has been shown to be responsible for disrupting this balance towards continued inflammation and cartilage and bone damage, and thus critical in driving RA pathogenesis. 29 This understanding was complemented with significant advances in biotechnology. Following in vitro and in vivo work, the most compelling evidence for a key role for TNF stemmed from studies in which marked clinical benefit was observed in patients with RA treated with a chimeric anti-TNF monoclonal antibody. 30 The subsequent introduction of several costly, but highly effective, tumour necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi) therapies marked the start of a new era in biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (bDMARD) development for RA. 31–33

Tumour necrosis factor inhibitors

Tumour necrosis factor inhibitor drugs [etanercept (Enbrel®; Pfizer, New York City, NT, USA), infliximab (REMICADE®, Janssen Pharmaceutical, Beerse, Belgium), adalimumab (HUMIRA®; Abbott, now AbbVie, North Chicago, IL, USA), certolizumab pegol (CZP) (CIMZIA®; UCB, Brussels, Belgium) and golimumab (Simponi®; Janssen Pharmaceutical)] in combination with MTX produce better outcomes in RA than in placebo or treatment with MTX alone. 31–37 TNFi drugs, however, differ in several respects:

-

molecule type [chimeric (mouse–human) monoclonal antibody (infliximab), fully human monoclonal antibody (adalimumab, golimumab), pegylated Fab fragment of a humanised monoclonal antibody (CZP) and a TNF receptor fusion protein (etanercept)]38

-

target (etanercept binds both TNF and another cytokine, lymphotoxin alpha)39

-

binding affinity to TNF

-

clinical administration (intravenous vs. subcutaneous).

Non-tumour necrosis factor inhibitors

Following the development of TNFis, recognition of other key cytokines and immune cells in RA pathogenesis43 led to the development of additional bDMARDs: rituximab (MabThera; Roche, Basel, Switzerland), a chimeric anti-CD20-depleting monoclonal antibody,44 tocilizumab (Actemra®; Roche), an IL-6 receptor monoclonal antibody45 and abatacept (Orencia®; Bristol-Myers Squibb, New York City, NY, USA), a recombinant fusion protein T-cell co-stimulation blocking agent. 46 All of these bDMARDs demonstrated significant benefits compared with placebo and MTX in MTX-inadequate response44,47,48 and TNFi-inadequate response49–51 groups, respectively.

The clinical unmet need

Tumour necrosis factor inhibitor is the most frequently used first-line bDMARD. Despite the extensive benefits of TNF-directed bDMARDs, a significant proportion, 20–40%, of patients with RA who have MTX-inadequate response and treated with TNFi52 fail to achieve sufficient response (primary non-response) or lose responsiveness over time (secondary non-response). 36,52

Thus, following initial TNFi-inadequate response, two broad approaches could theoretically be employed to manage patients: switching to alternative TNFi therapy or switching to a bDMARD with another mode of action. 26

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence’s technology appraisal for biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs

At the time of the SWITCH study, a NICE technology appraisal recommended TNFi use if disease is severe, that is, a Disease Activity Score of 28 joints (DAS28) of > 5.1 units and disease has not responded to at least two conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), including MTX. Initially, adalimumab, etanercept and infliximab53 (and later on CZP54 and golimumab55) were recommended by NICE as first-line bDMARD therapy for the treatment of patients with RA who had failed to respond to, or had been intolerant of, at least two csDMARDs including MTX. 56

The current NICE technology appraisal 37556 has updated possible first-line bDMARD options and now recommends use not only of one of the five TNFi, but also of tocilizumab57 and abatacept,58 which are also approved by NICE for first-line bDMARD therapy following MTX-inadequate response. 58 Nevertheless, TNFi remains the most frequently used first-line bDMARD (both in the UK and worldwide).

Non-response to tumour necrosis factor inhibitor

In the context of first-line bDMARD TNFi failure, NICE guidance recommends using rituximab as second-line bDMARD. 59 Switching to alternative TNFi, abatacept or tocilizumab, is permitted only if patients have had an inadequate response to rituximab57 or are intolerant of rituximab57,59 or if rituximab is contraindicated. 57,59 This is in the absence of any trial data demonstrating that rituximab is more appropriate than the alternative bDMARDs. Of note is the fact that this technology appraisal guidance applies to bDMARD use with background MTX. For individuals who are unable to take MTX, TNFi switching is permitted. This guidance has not been comprehensively updated following approval of tocilizumab and abatacept as first-line bDMARDs.

It is the absence of robust trial data to support NICE’s guidance regarding the process to follow in the event of failure of initial TNFi treatment (discussed below), effectively limiting the treatment choice to rituximab, which we recognise is not effective for all individuals, that is the basis for the SWITCH study.

Switching between tumour necrosis factor inhibitors

Observational studies

Several early-phase uncontrolled studies and an initial small randomised study suggested benefit in switching between TNFi agents. 60–70 A report of extremely high responses on alternative TNFi agent in specific subgroups of patients62 also indicated the potential value and the need to explore this approach further. A literature review71 documented 29 reports on switching from one TNFi to another in RA, with the data largely indicating benefit of switching from a first TNFi to a second, with switching for secondary non-response likely to be more effective. A systematic review reported similar findings. 72

Randomised controlled trials

No randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of switching between adalimumab, etanercept and infliximab have been conducted in patients in whom these three established TNFi have failed. The rationale and argument for switching between different TNFi drugs, however, were further strengthened by a large, international, multicentre, randomised, Phase II study73 that investigated 461 patients who had previously received and either failed or were intolerant of one or more TNFis. Patients were randomised to either golimumab (50 mg or 100 mg every 4 weeks) or placebo. American College of Rheumatology 20 (ACR20) response rates at week 14 were significantly higher in the golimumab groups than in the placebo group (35% and 38% vs. 18%, respectively). More recently, two RCT studies,74,75 one with open-label evaluation,74 have demonstrated significant efficacy of CZP in prior TNFi treatment failures. In a small but first prospective RCT,74 patients in whom an initial TNFi was stopped because of secondary non-response (i.e. the initial response to the TNFi was lost) were randomised to 12 weeks of either CZP (n = 27) or placebo (n = 10), followed by an open-label CZP 12-week period. The primary end point was the proportion of patients reaching an ACR20 response by week 12, observed in 61.5% of patients in the CZP group, compared with 0% of patients in the placebo group. Placebo patients who were switched blindly to CZP attained similar results seen with CZP in weeks 0–12. As this result was highly significant, study inclusion was terminated after entry of 33.6% of the originally planned 102 patients. The REALISTIC study, a 28-week Phase IIIb study, assessed safety and maintenance of response to CZP in a diverse population of RA patients, stratified by prior TNFi exposure, concomitant MTX use and disease duration.

Switching to non-tumour necrosis factor inhibitor biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug therapies

Randomised controlled trials

Randomised controlled trials49–51 and their long-term extension studies (LTEs)76–78 have demonstrated the benefits of non-TNFi bDMARDs over placebo/MTX following TNFi-inadequate response.

The randomised evaluation of long-term efficacy of rituximab in RA (REFLEX) study evaluated the efficacy of rituximab versus placebo in patients receiving MTX who had failed at least one TNFi. 49 Significantly more rituximab-treated patients than placebo-treated patients achieved ACR20, American College of Rheumatology 50 (ACR50), American College of Rheumatology 70 (ACR70) and moderate to good European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) responses at week 24. Of note, despite a significant reduction in Disease Activity Score in the rituximab group, the mean DAS28 at week 24 was still high, at 5.1 units (a reduction of 1.83 from 6.9 at baseline). 49 In the LTE study (and thus a selected subgroup), rituximab showed sustained effects on joint damage progression. 76 The ATTAIN (A Therapeutic Trial of Afatinib In the Neoadjuvant Setting) study51 compared the efficacy of abatacept and placebo/MTX in patients with TNFi-inadequate response and found that significantly more patients in the abatacept group achieved ACR20, ACR50 and ACR70 responses, impressive quality-of-life results and improvement in DAS28 (a reduction in Disease Activity Score of > 1.2 in 70% in the abatacept group vs. 18.2% in the placebo group)51 and patients continued to maintain these improvements throughout the 2-year LTE study. 77 The RA study in anti-TNF failures (RADIATE) study compared the efficacy of tocilizumab (8 mg/kg or 4 mg/kg) plus MTX to placebo plus MTX in patients with one or more TNFi-inadequate responses. 50 At week 24, more patients in the tocilizumab groups than in the placebo group achieved ACR20, ACR50 and ACR70 responses and good or moderate EULAR responses. 50 The efficacy of tocilizumab was maintained for up to 4.2 years during the LTE study. 78

Switching to a second tumour necrosis factor inhibitor or alternative class biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug

Observational studies

A number of observational studies have compared clinical response after switching to either rituximab or alternative TNFi in patients who failed initial TNFi treatment. 79–82 As summarised below, most have suggested better efficacy on switching to rituximab, although there are also reports of equivalent clinical responses in patients who switched to either alternative TNFi or rituximab following failure of one or more TNFi therapies. 83,84 These observational studies, however, had several design limitations, such as small sample sizes,79 selection bias,79–82 pooling all causes of TNFi failure81 and missing data,79–82 although they tried to address these issues by calculating propensity scores and using multivariable analysis techniques. 79–82

Analysis of patients with RA in the Swiss Clinical Quality Management in Rheumatic Diseases RA registry (SCQM-RA),79,80 who had treatment failure with at least one TNFi and were switched either to alternative TNFi or to one cycle of rituximab, showed that switching to rituximab may be more effective than switching to another TNFi. Furthermore, when the motive for switching was ineffectiveness of the TNFi, patients who received rituximab achieved a significantly better improvement in DAS28 at 6 months than patients who received alternative TNFi. 80 However, when the reason for switching was other causes, the improvement in DAS28 was similar in the two groups. 80 The same registry also reported that rituximab was as effective as alternative TNFi in preventing joint erosions in patients who had previous treatment failure with a TNFi. 83 A study of 1300 patients with RA on the British Society of Rheumatology (BSR)’s Biologics Register who had a failed response to their first TNFi treatment and were switched to a single cycle of either rituximab or alternative TNFi found that patients who switched to rituximab had better EULAR responses and were more likely to achieve improvement in their Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) scores. 81 More recently, a global observational real-life study (SWITCH-RA)82 also showed that among patients with RA who failed to respond to, or were intolerant of, a single previous TNFi, those who were switched to rituximab achieved significantly better clinical responses at 6 months than those patients who were switched to a second TNFi. However, further subgroup analysis showed that these differences were observed only in seropositive [to either or both of rheumatoid factor (RF) and anti-citrullinated peptide antibody (ACPA)] patients who switched because of lack of efficacy of the first TNFi. 82

An observational study from the US Consortium of Rheumatology Researchers of North America (CORRONA) cohort85 reported clinical effectiveness of abatacept versus subsequent TNFi in patients with RA following one or more TNFi drug failures, using propensity scoring to reduce bias attributable to systematic prescribing practices. Six- and/or 12-month response outcomes with change in disease activity, remission rates based on the Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI) and modified DAS28 (mDAS28) and American College of Rheumatology (ACR) response rates were evaluated. The main analysis included all patients regardless of the reason for switching in the main analysis, with inadequate response to prior TNFi addressed in a sensitivity analysis. For the primary outcome (minimum clinically important difference in the change in CDAI score of 4.3) and the secondary outcomes, no differences between the two treatments were recorded.

Head-to-head comparisons

Gottenberg et al. 86 reported a 52-week pragmatic open-label RCT that randomised 300 patients who did not respond to a first TNFi to receive either alternative TNFi or an alternative-mechanism bDMARD (abatacept, rituximab or tocilizumab). This was a superiority trial, with the primary outcome of a good or moderate EULAR response at 6 months. Primary outcome was achieved in a significantly greater proportion of patients in the non-TNFi group, with 70% achieving a good or moderate EULAR response, compared with 52% in the second TNFi group. Similar differences were observed from week 12 and persisted at week 52, with, in addition, significantly better low disease activity and remission rates. Although an instructive and randomised study, the multiple treatment options included within the non-TNFi group limit the extent to which these data can inform on which specific targeted agent should be considered.

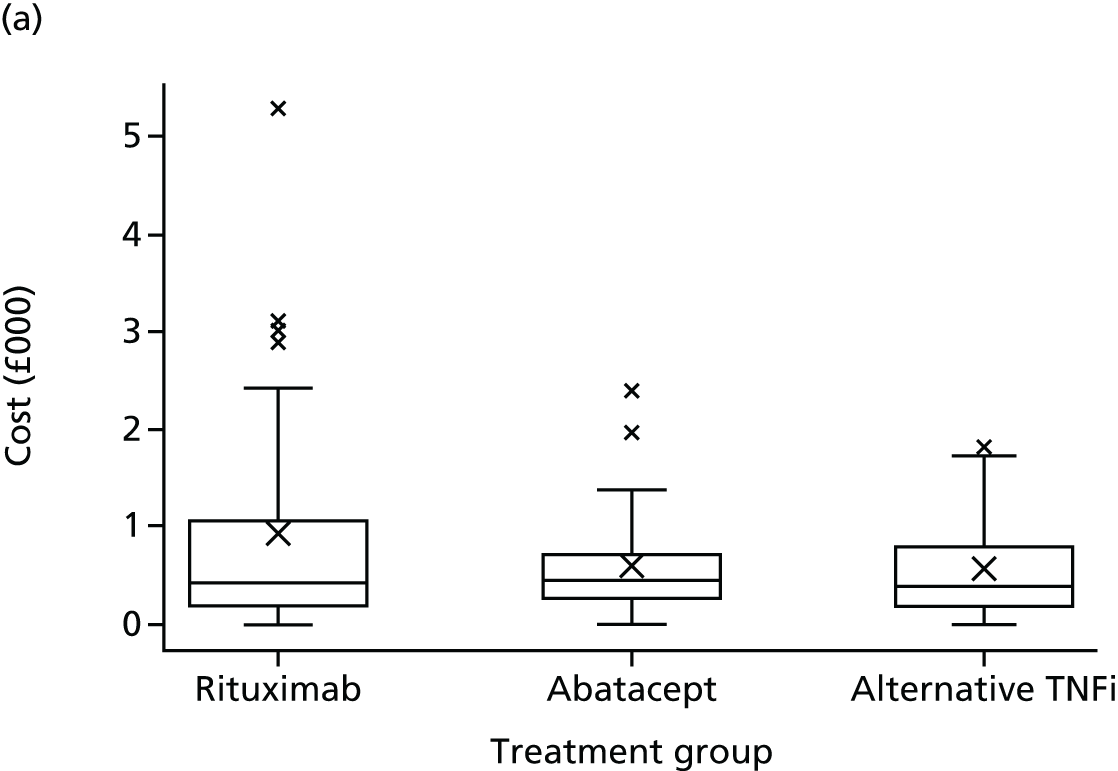

In contrast, a recent preliminary report from a Dutch randomised trial of 144 patients with RA who had failed a first TNFi and were randomised (1 : 1 : 1) to receive alternative TNFi, abatacept or rituximab, showed that there was comparable improvement in the DAS28, HAQ scores and Short Form questionnaire-36 items (SF-36) outcome measures over a 12-month period. 87 Rituximab therapy was the most cost-effective of the three (although this finding may not be true in other countries with different health-care provision and pricing structures). 87 Further studies with larger sample sizes and inclusion of tocilizumab in the treatment options are needed to confirm these results.

Serology and response

Compared with rituximab, and potentially the other two non-TNFi bDMARDs, a key benefit of the TNFi appears to be its suitability in both seropositive (either or both of RF and ACPA positive) and particularly seronegative disease. 82 Seronegative antibody status (seen in up to 25–30% of patients with RA) is associated with a poorer response to rituximab84,88,89 and better response rates have been demonstrated in antibody-positive patients treated with rituximab, which was most evident in the TNFi failure group;84 perhaps intuitive in the light of its target and rationale for use. Recent studies have also demonstrated that abatacept may be more effective in seropositive (ACPA-positive) patients. 90–93 Furthermore, a Japanese study of 58 patients with RA treated with tocilizumab (including 22 patients who previously received a TNFi) reported that a high titre of immunoglobulin M RFs at baseline was the only variable to be associated with CDAI remission at 24 weeks. 94 However, a larger French cohort study95 of 208 patients with RA did not find an association between seropositivity at baseline and a EULAR response after 24 weeks of tocilizumab therapy.

Additional clinical factors for consideration

Apart from antibody status, certain patients will not be appropriate for rituximab therapy, and coexisting pathologies, such as inflammatory bowel disease and psoriasis, that are also treated with TNFi may make other agents less appropriate. Rituximab, for example, has been associated with the development of psoriasis in patients with no previous history of the disease,96 although it is recognised that bDMARDs, including TNFi therapy, can induce paradoxical clinical manifestations such as pustular psoriasis. 97,98

Summary comments

Despite the benefits of recent advances in the management of RA, no universally effective treatment exists. It remains unclear how best to utilise the alternative bDMARDs following an initial TNFi-inadequate response. Although large observational studies have been performed, the need for more direct comparisons to provide sufficiently robust evidence to inform clinicians is necessary. Results from recent trials are emerging. Nevertheless, data suggesting that subgroups are more responsive to a particular targeted therapy (seronegativity and TNFi99) highlight the importance of including such factors in study design to avoid prematurely discounting alternative TNFi drug as an effective therapeutic option, particularly in the context of resistant and aggressive disease cohorts. In addition, optimal bDMARD choice based on the nature of prior inefficacy (primary or secondary) has not been addressed to date. Despite several treatment options now available, no large-scale head-to-head comparisons investigating the efficacy of sequential biologic treatments have been conducted to date.

The SWITCH trial100 was a well-designed randomised trial in this therapeutic area, which also aimed to explore the more refined clinical questions that would thus provide clear guidance to clinicians. This study aimed to evaluate whether or not alternative class bDMARDs compared with rituximab (the NICE-preferred second-line option) were comparable in efficacy and safety outcomes. The results of this study were expected to contribute to the development of a rational treatment algorithm and more judicious and cost-effective management, in particular to allow individualised treatment regimens rather than switching all patients to a single (and potentially unsuccessful and toxic) therapy. The trial was stopped early by the funding committee because of unforeseen interruptions and lengthy site set-up, which, thus, impacted on the inability to recruit to target on time. Although the results presented in this report are not sufficiently powerful to address these aims, we expect that the controlled data will inform the emerging evidence base and can be included in meta-analyses.

Chapter 2 Clinical trial methods

Objectives

In patients with RA who had failed treatment to an initial TNFi (according to NICE guidance), the objectives of this study were as follows.

Primary objective

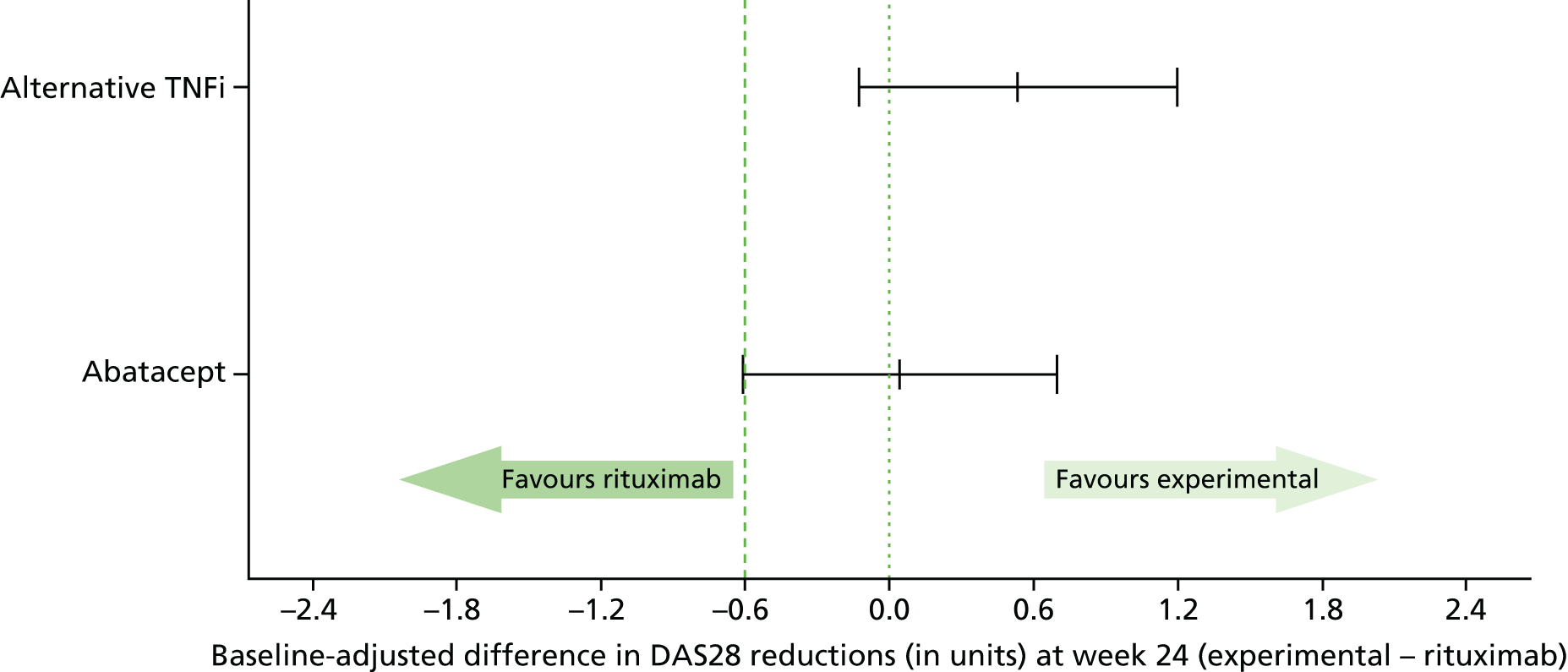

The primary objective was to determine whether or not an alternative-mechanism TNFi or abatacept is non-inferior to rituximab in disease response at 24 weeks post randomisation.

Secondary objectives

The secondary objectives were:

-

to compare alternative TNFis and abatacept with rituximab for disease response, quality of life, toxicity and safety over 48 weeks

-

to undertake an evaluation of the cost-effectiveness of switching patients to alternative TNFi, abatacept or rituximab

-

to compare structural and bone density outcomes for abatacept and alternative TNFis with those for rituximab over 48 weeks using plain radiography and bone densitometry score.

Exploratory objectives

The exploratory objectives were:

-

to determine the optimal sequence of treatments by assessing whether or not the response to the second treatment in patients with RA is affected by which initial TNFi the patients failed treatment on (TNFi monoclonal or TNFi receptor fusion protein)

-

to evaluate whether or not the response to the second treatment (alternative TNFi, abatacept or rituximab) is affected by whether or not the patient was a primary (no initial response) or secondary (loss of an initial response) response failure to their initial TNFi therapy

-

to ascertain whether or not seropositive (to either or both of RF and ACPA) and seronegative patients with RA behave differently in their response and disease outcome measures across the three treatment arms, particularly with respect to rituximab.

Design

The study was a multicentre, Phase III, open-label, non-inferiority, parallel-group, three-arm RCT comparing the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of alternative TNFi and abatacept (separately) with that of rituximab in patients with RA who have failed an initial TNFi treatment.

Patients were randomised on a 1 : 1 : 1 basis to receive one of the following:

-

alternative TNFi:

-

etanercept if patient had initial failure of a monoclonal antibody: infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab or golimumab

-

OR

-

monoclonal antibody: infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab or golimumab if patient had initial failure of etanercept (choice of monoclonal TNFi at investigator’s discretion)

-

abatacept

-

rituximab.

Patients received randomised treatment during the interventional phase to a maximum of 48 weeks and were subsequently followed up to a maximum of 96 weeks in the observational phase.

The study was reviewed and approved by the National Research Ethics Service, Research Ethics Committee Leeds (West) (reference number 11/H1307/6) and was registered as an International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial number 89222125 and with ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01295151. The trial protocol100 can be accessed at http://bmcmusculoskeletdisord.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2474-15-452.

Patient and public involvement

Ailsa Bosworth, Chief Executive and Founder of the National Rheumatoid Arthritis Society, was the patient and public involvement (PPI) member on the Trial Management Group and provided valuable PPI input to the development of the SWITCH trial proposal and on key decisions throughout the trial.

There was also involvement from a PPI representative on the Trial Steering Committee, Sandra Purdy, who provided input into the patient information sheet and other trial documentation intended for use by patients. Through membership of the Trial Steering Committee, the PPI representative also provided input into the design and conduct of the trial through annual meetings.

Participants

Patients attending hospital-based rheumatology outpatient departments throughout the UK, who had been diagnosed with RA, were receiving MTX, had not responded to (at least two) csDMARD therapy (including MTX) and had experienced an inadequate response to treatment with one TNFi were invited to be screened for eligibility in the trial if they:

-

were male or female and aged ≥ 18 years

-

had a diagnosis of RA as per the ACR/EULAR 2010 classification criteria confirmed at least 24 weeks prior to the screening visit

-

failed csDMARD therapy according to NICE/BSR guidelines,101 that is failure of at least two csDMARDs including MTX

-

had persistent RA disease activity despite having been treated with a current initial TNFi agent for at least 12 weeks. Active RA was defined as:

-

primary non-response defined as failing to improve DAS28 by > 1.2 units or failing to achieve a DAS28 of ≤ 3.2 units within the first 12–24 weeks of starting the initial TNFi treatment (this may include patients who have shown a reduction in DAS28 of > 1.2 units but still demonstrate an unacceptably high disease activity in the physician’s judgement with evidence of an overall DAS28 of ≥ 3.2 units)

-

OR

-

secondary non-response defined as lack of efficacy of the first TNFi treatment (having demonstrated prior satisfactory response) as per clinician judgement, with the reason for cessation of the first TNFi treatment other than intolerance

-

were MTX dose stable for 4 weeks prior to the screening visit and to be continued for the duration of the study

-

were on non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and/or corticosteroids (oral prednisolone not exceeding 10 mg daily), on an unchanged regimen for at least 4 weeks prior to the screening visit and were expected to remain on a stable dose until the baseline assessments have been completed

-

provided written informed consent prior to any trial-specific procedures.

Patients were excluded if they met any one of the following criteria.

-

They had had major surgery (including joint surgery) within 8 weeks prior to the screening visit or planned major surgery within 52 weeks following randomisation.

-

They had inflammatory joint disease of different origin, mixed connective tissue disease, Reiter’s syndrome, psoriatic arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, or any arthritis with onset prior to 16 years of age.

-

They had received doses of prednisolone of > 10 mg/day within the 4 weeks prior to the screening visit.

-

They had received intra-articular or intramuscular steroid injections within 4 weeks prior to the screening visit.

-

They had previously received more than one TNFi drug OR any other bDMARD for the treatment of RA.

-

They were unable or unwilling to stop treatment with a prohibited DMARD (i.e. synthetic DMARD aside from MTX, e.g. oral or injectable gold, chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, ciclosporin, azathioprine, leflunomide, sulfasalazine) prior to the start of protocol treatment.

-

They had been treated with any investigational drug in the last 12 weeks prior to the start of protocol treatment.

-

They had other comorbidities including acute, severe infections, uncontrolled diabetes, uncontrolled hypertension, unstable ischaemic heart disease, moderate/severe heart failure (class III/IV of the New York Heart Association functional classification system102), active bowel disease, active peptic ulcer disease, recent stroke (within 12 weeks before the screening visit), or any other condition which, in the opinion of the investigator, would put them at risk if they participated in the study or would make implementation of the protocol difficult.

-

They had experienced any major episode of infection requiring hospitalisation or treatment with intravenous antibiotics within 12 weeks of start of the treatment protocol or oral antibiotics within 4 weeks of start of the protocol treatment.

-

They were at significant risk of infection that, in the opinion of the investigator, would put them at risk if they participated in the study [e.g. leg ulceration, indwelling urinary catheter, septic joint within 52 weeks (or ever if a prosthetic joint is still in situ)].

-

They had known active current or a history of recurrent bacterial, viral, fungal, mycobacterial or other infections including herpes zoster [for tuberculosis (TB) and hepatitis B and C, see below], but excluding fungal infections of nail beds as per clinical judgement.

-

They had untreated active current or latent TB. Patients should have been screened for latent TB (as per BSR’s guidelines) within 24 weeks prior to the screening visit and, if positive, treated following local practice guidelines prior to the start of protocol treatment.

-

They had active current hepatitis B and/or C infection. Patients should have been screened for hepatitis B and C within 24 weeks prior to the screening visit and, if positive, excluded from the study.

-

The had primary or secondary immunodeficiency (history of or currently active) unless related to primary disease under investigation.

-

In the case of women, they were pregnant or lactating or were women of child-bearing potential (WCBP) who were unwilling to use an effective birth control measure while receiving treatment and after the last dose of protocol treatment, as indicated in the relevant summary of product characteristics (SmPC) or investigator’s brochure (IB).

-

In the case of men, their partners were WCPB who were unwilling to use an effective birth control measure while receiving treatment and after the last dose of protocol treatment as indicated in the relevant SmPC/IB.

-

They were known to have significantly impaired bone marrow function as a result of, for example, significant anaemia, leucopenia, neutropenia or thrombocytopenia, defined by the following laboratory values at the time of the screening visit:

-

haemoglobin level of < 8.5 g/dl

-

platelet count of < 100 × 109/l

-

white blood cell count of < 2.0 × 109/l

-

neutrophil count of < 1 × 109/l

-

-

They were known to have severe hypoproteinaemia at the time of the screening visit as a result of, for example, nephrotic syndrome or impaired renal function, defined by:

-

a serum creatinine concentration of > 150 µmol/l.

-

The eligibility criteria were based on BSR’s guidelines on the use of TNFi. 101 Important exclusion criteria that are adhered to in clinical practice were applied in this study.

Recruitment

Patients were approached during standard clinic visits for the management of their RA, or were identified by waiting lists, registries or reviews of case records, and sent a personalised letter inviting them to participate. Patients were provided with verbal and written details about the trial and had as long as they required to consider participation. Assenting patients provided written consent before being registered into the trial and formally assessed for eligibility. Patients at Chapel Allerton Hospital also had the option of giving informed consent for blood and tissue samples to be taken for the SWITCH trial biobank for future scientific research. The participant information sheet and consent forms are provided in Appendix 1.

Interventions

Abatacept

Abatacept is a selective T-cell co-stimulation blocking agent that is a fusion protein composed of the Fc region of the immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) fused to the extracellular domain of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4).

Alternative tumour necrosis factor inhibitors

Etanercept

Etanercept is a human TNF receptor p75Fc fusion protein produced by recombinant deoxyribonucleic acid (rDNA) technology. Patients randomised to receive alternative TNFis whose initial TNFi was a monoclonal antibody received etanercept as their intervention.

Monoclonal antibodies

For patients randomised to receive alternative TNFi whose initial TNFi was etanercept, the allocation was to one of four anti-TNF monoclonal antibodies. Within this group of interventions, allocation was at the discretion of the treating clinician.

-

Adalimumab: a recombinant fully human IgG1 monoclonal antibody specific for TNF produced in a mammalian cell expression system.

-

CZP: a recombinant (Fc-free) humanised antibody Fab fragment against TNF and conjugated to polyethylene glycol.

-

Infliximab: a chimeric (human–murine) IgG1 monoclonal antibody produced by rDNA technology.

-

Golimumab: a fully human IgG1 monoclonal antibody to TNF.

Rituximab (control)

A genetically engineered chimeric (human–murine) monoclonal antibody against the B-cell protein marker CD20 (clusters of differentiation 20).

Efficacy of rituximab to placebo was established in a similar patient population in the REFLEX study. 49

Table 1 illustrates the treatment regimen including mode of administration and dose, for each of the three treatment arms. The intervention period was 48 weeks, achieved via treatment regimens administered for a minimum of 24 weeks.

| Treatment arm | Treatment description |

|---|---|

| Rituximab | A single dose of 1 g as an intravenous infusion administered at days 0 (week 0) and 15 (week 2). In line with standard practice, a patient who lost an initial 6-month (week 24) response, as per NICE’s guidance, could receive a further cycle of rituximab after a minimum of 6 months following the first dose. The second cycle of rituximab was, again, given at a dose of 1 g; two intravenous infusions administered at a 2-week interval, for example week 24 and 26. Prior to receiving rituximab, 100 mg of intravenous methylprednisolone was given as a premedication |

| Abatacept | Solution for subcutaneous injection: 125 mg per syringe (125 mg/ml). Administered at a dose of 125 mg at week 0 and once weekly thereafter for a minimum of 24 weeks |

| Alternative TNFi | |

| Etanercept | A single dose of 50 mg by subcutaneous injection weekly for a minimum of 24 weeks (unless not tolerated) |

| Adalimumab | A single dose of 40 mg by subcutaneous injection every 2 weeks for a minimum of 24 weeks (unless not tolerated) |

| Infliximab | A dose of 3 mg/kg per intravenous infusion, administered on a day-case unit or equivalent at weeks 0, 2 and 6 and then every 8 weeks thereafter for a minimum of 24 weeks |

| CZP | Single dose of 400 mg by subcutaneous injection at weeks 0, 2 and 4 and then at a dose of 200 mg every 2 weeks thereafter for a minimum of 24 weeks |

| Golimumab | Dose of 50 mg by subcutaneous injection every 4 weeks for a minimum of 24 weeks. Available as IMP within the SWITCH trial following approval in November 2013 |

Study procedures

Screening and baseline assessments

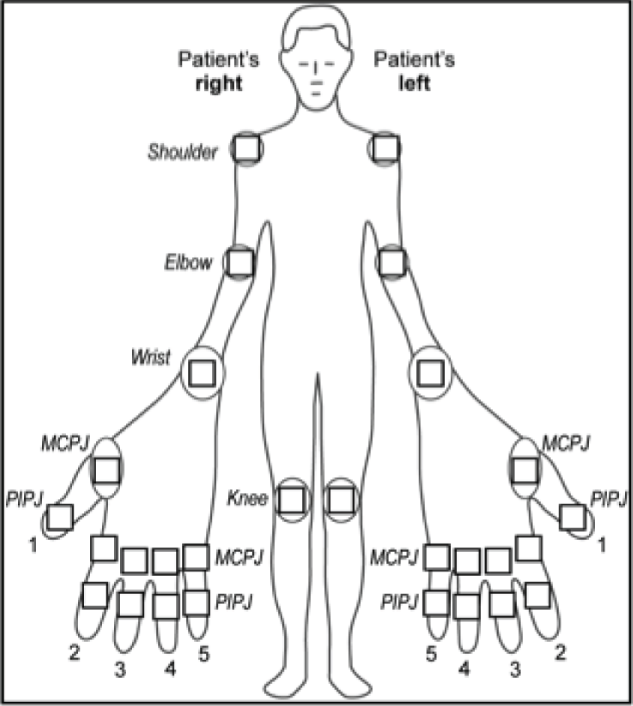

Following written informed consent and prior to any trial-related procedures, patients were registered into the study. All patients had a screening assessment within 4 weeks prior to the baseline assessment (and, when applicable, the assessment was repeated at the baseline assessment) to establish eligibility. The clinical assessment included a medical history, a physical examination, which included measurements of height, weight and vital signs, electrocardiography (ECG), chest radiography and a screen for TB (if not performed within specified time window prior to the screening visit). In addition, a 28 swollen joint count (SJC) and tender joint count (TJC) were performed (Figure 1), and blood and urine tests [haematology, blood chemistry, C-reactive protein (CRP) level test, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), serological tests, hepatitis B and C screen, a pregnancy test and urinalysis] were undertaken. At the baseline assessment, a further blood test was undertaken to assess glucose levels and lipid profiles.

FIGURE 1.

Manikin showing joints to be included in the SJC and TJC. MCPJ, metacarpophalangeal joint; PIPJ, proximal interphalangeal joint.

At screening and baseline assessments, patients completed a Global Assessment of Arthritis using a visual analogue scale (VAS) and reported the extent of their early-morning stiffness. The clinician assessed the Global Disease Activity using a VAS. At the baseline assessment, patients completed a Global Assessment of Pain VAS and an assessment of their general health using a VAS.

Intervention and observational phase assessments

Randomised patients attended clinic assessment visits at weeks 12, 24, 36 and 48 in the interventional phase and at weeks 60, 72, 84 and 96 in the observational phase. Patients allocated to the subcutaneous TNFi or abatacept therapies had additional standard assessment for safety purposes (usually week 4) in line with local practice. At the Leeds Chapel Allerton Hospital site, biological samples from patients consenting to the SWITCH trial biobank substudy were collected prior to commencement of the trial treatment and at weeks 2, 4, 12, 24 and 48 or at the time of early discontinuation, and stored for future research. See Appendix 5, Tables 33–35, for the schedule of events for rituximab, infliximab and subcutaneous bDMARDs.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome measure

The primary outcome measure was the absolute reduction from baseline in DAS28 at 24 weeks post randomisation. DAS28 is a measure of disease activity in RA. 103,104 The composite score is calculated as a function of the number of tender and swollen joints (total 28 joints), the ESR and the patient’s global assessment of their arthritis measured using a VAS (see Appendix 6, Box 1).

Secondary outcome measures

The following outcomes were measured over 48 weeks (at each of the visit time points).

Clinical measures

-

DAS28.

-

Reduction in DAS28 of ≥ 1.2 units.

-

Low disease activity rate and remission rate: low disease activity is defined as 2.6 < DAS28 ≤ 3.2 units and remission as DAS28 of ≤ 2.6 units (see Appendix 6, Table 36).

-

EULAR response scores: EULAR response criteria are applied to the DAS28 and classify patients as good, moderate or non-responders using the DAS28 and the absolute reduction in the DAS28 from baseline (see Appendix 6, Table 37).

-

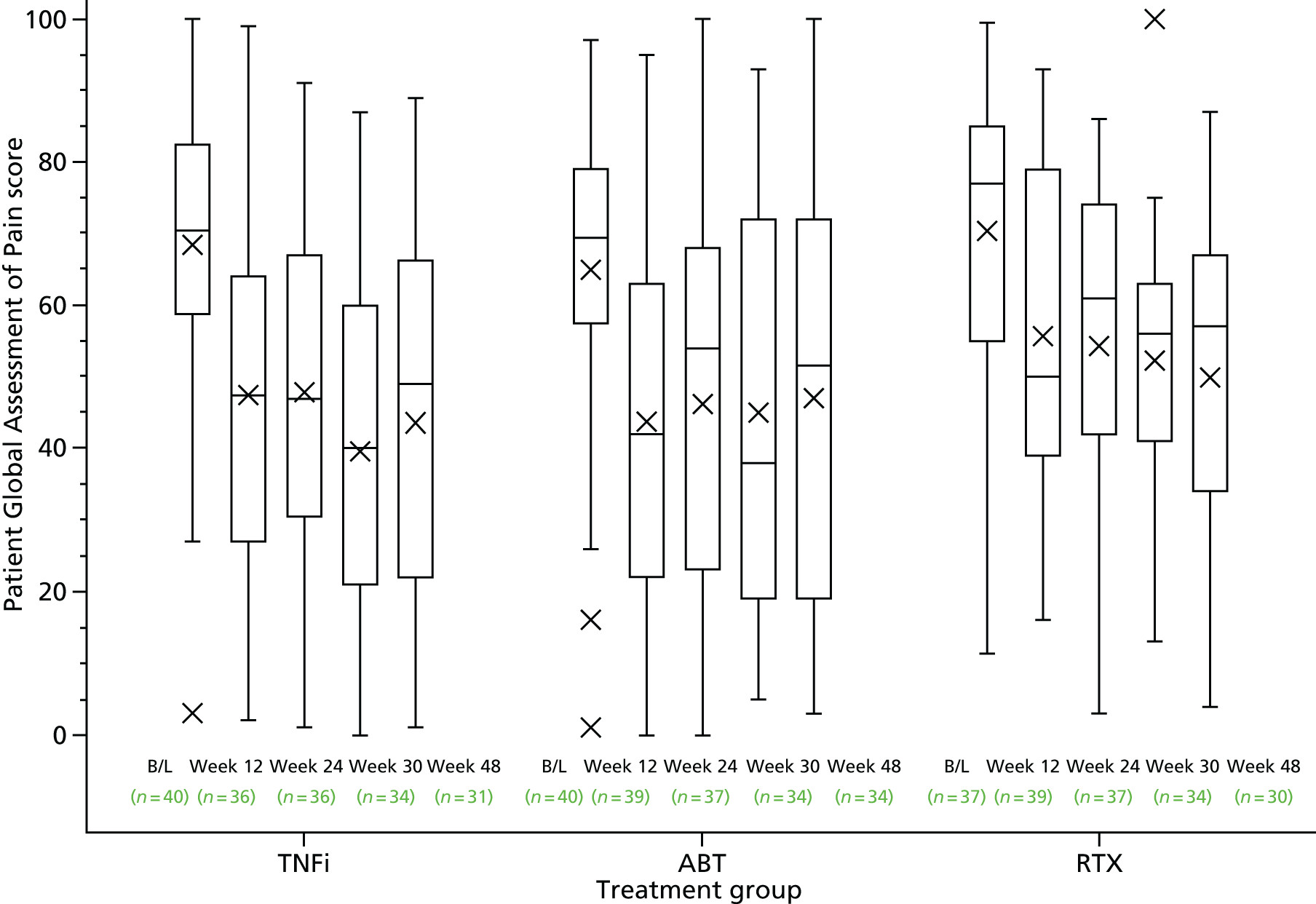

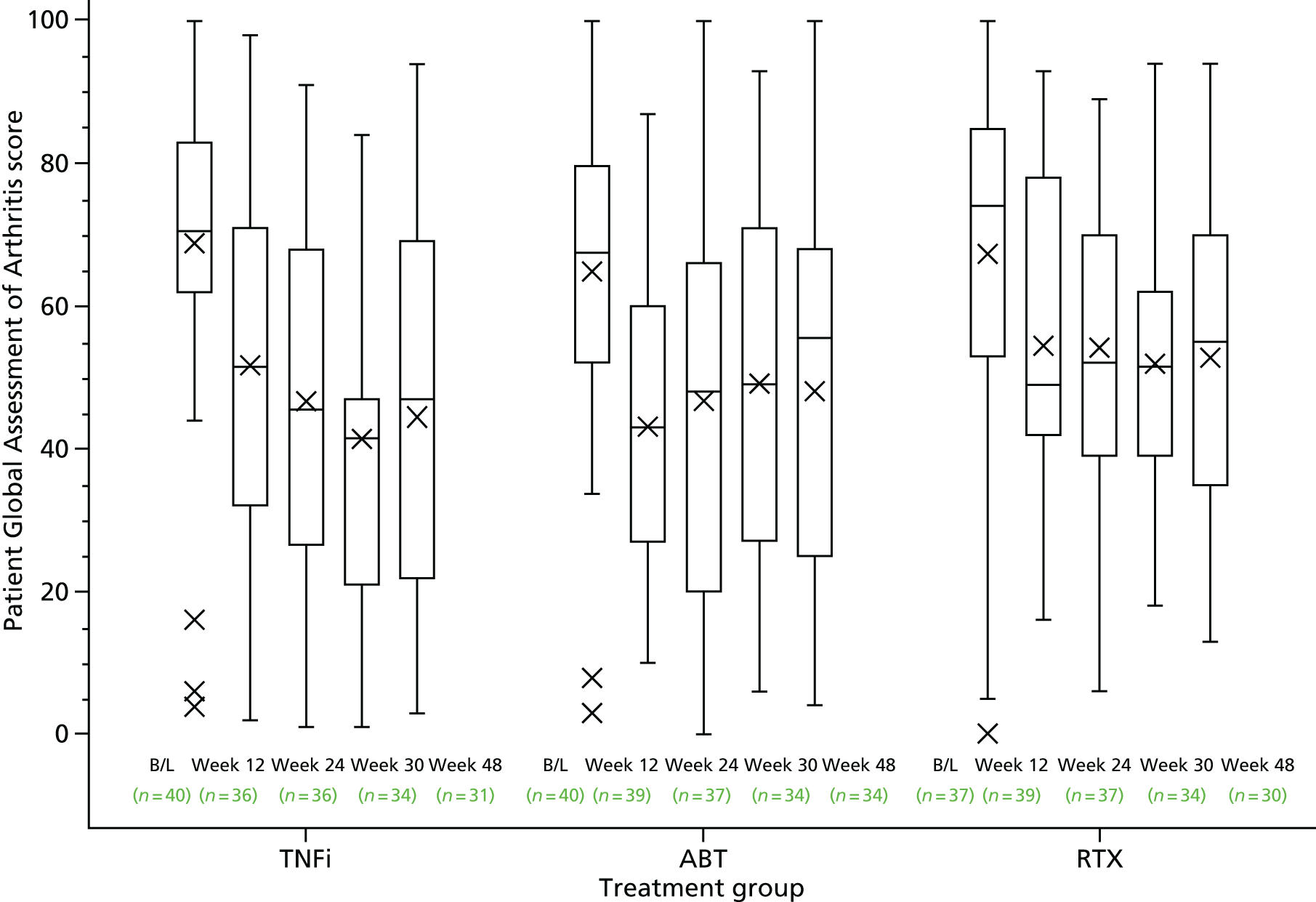

ACR20, ACR50 and ACR70:105 composite measures developed for RA. These are defined as a relative improvement (reduction) from baseline of at least 20% (or 50% or 70% for ACR50 and ACR70, respectively) in TJCs and SJCs and a relative 20% (or 50% or 70% for ACR50 and ACR70, respectively) improvement in three out of the five following criteria:

-

Patient Global Assessment of Arthritis (VAS)

-

Physician Global Assessment of Disease Activity (VAS)

-

Patient Global Assessment of Pain (VAS)

-

Patient assessment of physical function as measured by the Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index (HAQ-DI) questionnaire

-

Results of laboratory test for inflammatory markers (either ESR or CRP level).

-

-

CDAI:104,106 a composite outcome measure consisting of the number of tender joints (i.e. 28-joint count), the number of swollen joints (i.e. 28-joint count), a patient global assessment of disease activity (measured via a 100-mm VAS) and Physician Global Assessment of Disease Activity (measured via a 100-mm VAS). Appendix 6,Table 38, provides the response categories for CDAI.

-

Simplified Disease Activity Index (SDAI):104,107 a composite outcome measure consisting of the number of tender joints (28-joint count), the number of swollen joints (28-joint count), the Patient Global Assessment of Disease Activity (measured via a 100-mm VAS), the Physician Global Assessment of Disease Activity (measured via a 100-mm VAS) and CRP level (mg/dl). Appendix 6,Table 39 provides the response categories for SDAI.

-

In-remission rates according to the ACR/EULAR Boolean criteria: this is defined as SJC, TJC, patient global assessment and CRP level scores all ≤ 1. 108

The use of 28-joint count-based outcome measures is well accepted and established in RA trials. This is based on prior evaluation of the performance between 28- and 66-joint count assessments. 109–111 However, we acknowledge on an individual patient level, RA activity outside the 28 joints may be missed and thus influence individual disease activity and response assessments.

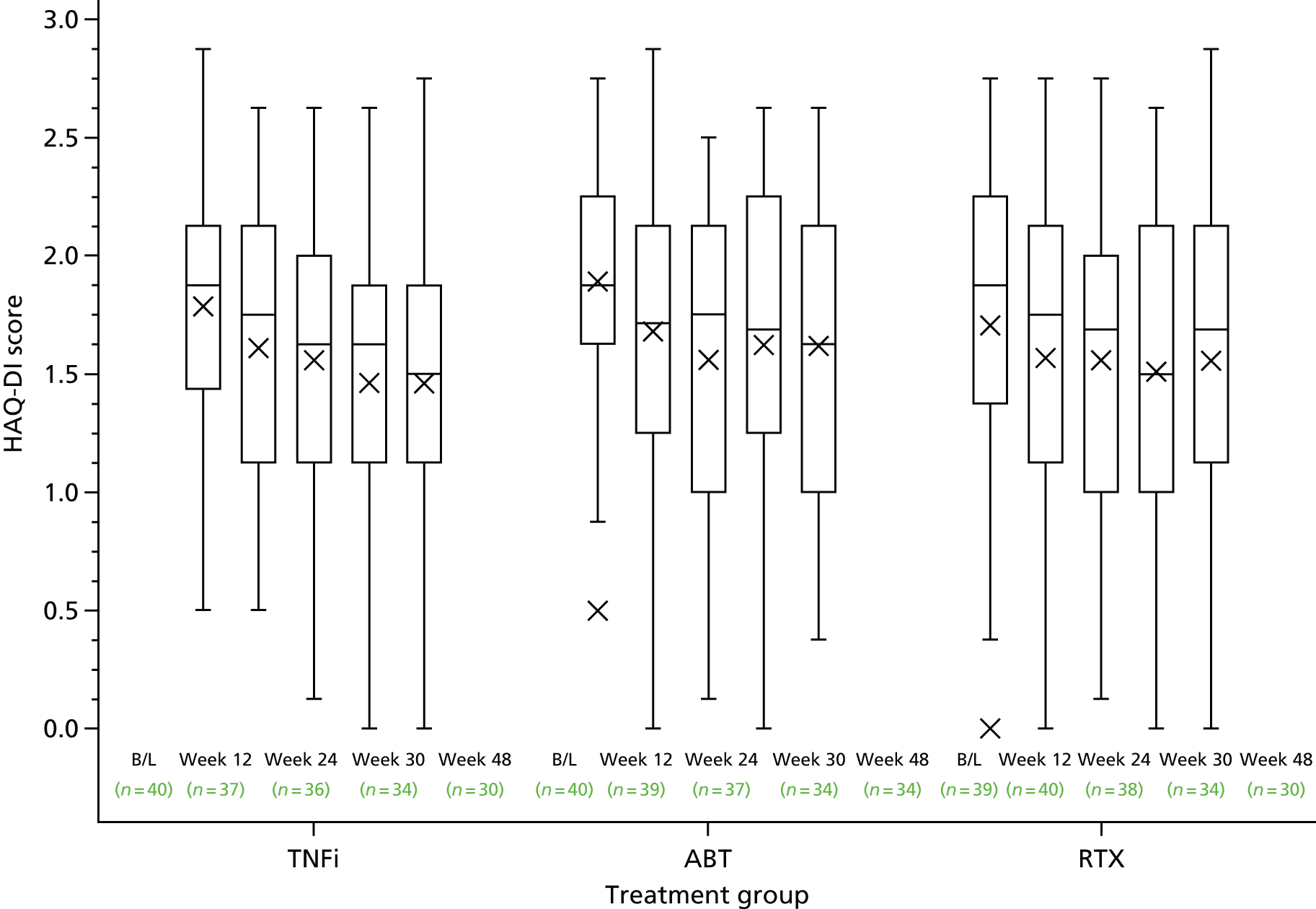

Quality of life

-

The Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index112 includes 20 questions across eight domains relating to physical function and the need for any help or aids to undertake daily activities. The extent of disability is scored on a scale from 0 (no disability) to 3 (severe disability) for each item relating to rising, dressing, walking and other activities; patients are then asked to list any aids or devices required to undertake such activities. The use of help or aids increases the category score from 0 or 1 to 2 if it has been indicated that aids/help are required in that category. If the category score is already a 2 or 3, no adjustment is made. The total score is derived by taking the maximum score across all domains (0–24) and dividing by 8 to provide an average score (0–3), with higher scores representing greater disability.

-

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)113 describes the degree to which patients feel anxious and/or depressed. It comprises 14 questions for each symptom, and each question has four possible responses, ranging from 0, representing no anxiety/depression, to 3, representing high anxiety/depression. Responses are totalled to provide two scales, one for each domain, with a measurement range from 0 to 21.

-

The Rheumatoid Arthritis Quality of Life (RAQoL)114 questionnaire is a specific disease activity measure for RA. It is a 30-item questionnaire, the response to each item being yes (score as 1) or no (score as 0), that ascertains the extent of RA symptoms experienced. The maximum RAQoL score is 30.

Safety

Toxicity is defined as any symptom or event requiring permanent cessation of treatment.

Imaging

Plain radiographs of hands and feet were requested (for later scoring to calculate the modified Genant score) and bone densitometry scans for T-scores of unilateral neck of femur and lumbar spine were obtained at baseline and week 48 in a subgroup of patients recruited at centres with the facilities to do the imaging. Note that the plain radiographs were not scored because of the inability to secure additional resource centrally to conduct the analysis (compounded by the early termination/underpowered study).

Safety monitoring

Adverse events (AEs) and adverse reactions (ARs) were monitored throughout the trial and recorded at each treatment visit. An AE was defined as any untoward medical occurrence in a trial patient that does not necessarily have a causal relationship with the treatment. An AR was defined as any untoward and unexpected responses to an investigational medicinal product (IMP) related to any dose administered.

A serious adverse event (SAE) or a suspected serious adverse reaction (SSAR) was defined as any untoward medical occurrence or effect that resulted in death, persistent or significant disability or incapacity or a congenital anomaly or birth defect, or was life-threatening, or required inpatient hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation or may have jeopardised the patient necessitating medical or surgical intervention to prevent one of the outcomes stated in Outcome measures.

Expected common SAEs related to RA were the development of major extra-articular manifestations of disease, for example vasculitis, and blood dyscrasia associated with disease activity. Expected serious ARs common to all treatments were allergic reactions, injection site/infusion reaction, blood dyscrasias, serious infections, diarrhoea, new infections, toxic epidermal necrolysis, Stevens–Johnson syndrome or severe rash, pulmonary fibrosis, renal failure, neurological impairment, new autoimmunity and cardiovascular abnormalities.

All SAEs, regardless of the suspected relationship to the trial treatment, were reported to the Clinical Trials Research Unit within 24 hours of the research staff becoming aware of the event. SAEs were followed up until the event had resolved or a trial outcome had been reached. All AEs/ARs and SAEs were monitored from randomisation until a maximum of 30 days (later revised to 32 days) after the last dose of randomised treatment during the interventional phase (week 48 maximum). Beyond this, only SAEs considered to be related to the randomised treatment administered during the interventional phase were reported.

Patient withdrawal

Patients could withdraw from the trial at any time without explanation, and continue to receive treatment as per standard clinical practice. Patient withdrawal was categorised as withdrawal of consent for: further trial treatment only, further trial treatment and visits but willing to have follow-up data collected or further trial treatment and follow-up information.

Sample size and power calculation

A total of 429 evaluable patients were required to have 80% power to demonstrate non-inferiority of either abatacept or alternative TNFi to rituximab at the 5% significance level. A total of 143 evaluable patients in each treatment group provided 80% power for the lower limit of the two-sided 95% confidence interval (CI) for the true difference in the reduction in the DAS28 (abatacept/alternative TNFi – rituximab) to lay above –0.6 units, assuming no difference between treatment groups and a standard deviation (SD) between patients of 1.8 units (the REFLEX study49). Allowing for a loss to follow-up of 10%, a total of 477 patients were to be recruited. No adjustment for multiplicity of the comparisons of each treatment group to rituximab was made. 115,116

The proposed non-inferiority margin of –0.6 units in the reduction in the DAS28 at 24 weeks post randomisation corresponds to the maximum difference in a reduction in the DAS28 that is considered to be of no clinical relevance and is the threshold for the clinical distinction of ‘inferiority’ (corresponds to the maximum change in the DAS28 within patients with a low or moderate disease activity that is classified as ‘no response’ by the EULAR criteria). A DAS28 of 0.6 units is also the reported measurement error. 117

For the analysis of the secondary outcome measures to compare quality of life, toxicity and safety at 24 weeks between treatment arms the sample size of 143 evaluable patients per group would detect a standardised effect size of 0.33 (small to medium by the definition of Cohen118), with 80% power and two-sided 5% significance level.

After opening, the trial underwent a major redesign. The original target sample size was 870, based on 80% power to determine whether or not abatacept or alternative TNFi are non-inferior to rituximab at 24 weeks post randomisation in the proportion of patients achieving a DAS28 reduction of ≥ 1.2 units without toxicity. The corresponding non-inferiority margin was set at 12% (as an absolute difference) and assumed a response rate of 65% in the rituximab arm. The original trial design was also powered for a definitive subgroup analysis to determine if there was a differential treatment response between seropositive and seronegative patients. Owing to the challenges in trial setup and associated poor initial patient recruitment, and reassessment of important end points, the primary outcome measure was changed from a binary to a continuous outcome that (following consensus discussion with the principal investigators) was still considered clinically relevant. This allowed a reduction in sample size to 477 patients while still ensuring a trial of clinical relevance. The previous planned definitive subgroup analysis was relegated to an exploratory analysis. The trial redesign was unanimously supported by the Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee and the Trial Steering Committee, was approved by the funder and received ethics approval.

Randomisation

Randomisation took place once eligibility was confirmed and baseline assessments and questionnaires were complete. Patients were randomised in a 1 : 1 : 1 allocation ratio to receive alternative TNFi, abatacept or rituximab. Treatment group allocation used a computer-generated minimisation program incorporating a random element of 0.8, to ensure that treatment groups were well balanced for the following minimisation factors: centre, disease duration (< 5 years or ≥ 5 years), non-response (primary or secondary) and RF/ACPA status (either of RF or ACPA positive, or both RF and ACPA negative).

Both registration and randomisation were performed centrally using an automated 24-hour telephone system based at the Clinical Trials Research Unit. Centres completed a log of all patients aged > 18 years with RA whose treatment had failed for an initial TNFi agent and were considered for the trial but who were not registered for screening or randomised, either because of ineligibility or because of refusal to participate.

Blinding

Blinding of patients and the treating clinicians to treatment allocation was not possible in the trial because of the nature and mode of administration of the different treatment regimens.

Analysis

Formal analyses were conducted using a two-sided 5% level of significance, with exception of the primary analysis, which used a one-sided 2.5% level of significance. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). The statistical analysis plan is provided in Appendix 7.

The trial planned for one interim analysis to allow for early stopping of either abatacept or alternative TNFi if inferiority compared with rituximab was demonstrated. This analysis would have taken place once 50% of patients (i.e. 239) had reached 24 weeks of follow-up. Following the early termination of the trial, there was no basis for an interim analysis.

Patient populations

All patients recruited into the trial were included in the analysis using ‘intention to treat’ (ITT) and analysed according to the randomised allocation.

A per protocol (PP) population analysis was also undertaken; patients who deviated from the protocol or failed to comply with the required treatment regimen were excluded (see Appendix 7 for further details of exclusions). For the analysis of the primary outcome measure, non-inferiority needed to be demonstrated in both the ITT and PP populations in order to infer non-inferiority.

The complete-case population included all patients with complete data for the relevant outcome measure summarised.

The safety population included all patients who received at least one dose of treatment and is summarised by treatment received.

Missing data

Multiple imputation by chained equations was used to impute missing values at the component level for the DAS28 and ACR20,119 under the assumption that the data were ‘missing at random’. The minimisation factors of disease duration, RF/ACPA status and non-response category and the values of the component end points at all visits from baseline to week 48 (for DAS28 components) and to week 24 (for ACR components) were included in the imputation models. Centre was not included because of the small number of patients recruited in each centre.

Imputations were performed separately for each of the three treatment groups; 27 imputed data sets were created for each treatment group for the primary end point DAS28 and 22 for the secondary end-point ACR20, corresponding to the maximum percentage of missing data across all end points and time points. Predictive mean matching was used to select a value to impute from the three observed values closest to the fitted value in each imputation. 120 The composite end points were then derived in each of the fully imputed data sets (see Appendix 7 for further detail).

Primary outcome measure

A mixed-effects linear regression model was fitted to the primary end point, absolute reduction in the DAS28 at 24 weeks, with covariates corresponding to the minimisation factors and treatment group; centre was fitted as a random effect.

Algebraic representation for the mixed-effects linear regression model is:

Parameter estimates from the mixed-effects models across each of the fully imputed data sets were combined using Rubin’s rules. 119,121 Estimates of each treatment effect and corresponding 95% CIs and p-values were reported in relation to the predefined non-inferiority margin of –0.6 units on the reduction in the DAS28 at 24 weeks post randomisation.

The primary analysis model was fitted to the ITT, PP and complete-case populations. Non-inferiority in both the ITT and PP patient populations was required in order to conclude non-inferiority. A sensitivity analysis was completed on the ITT population with an additional covariate, baseline DAS28, fitted to the primary analysis model.

Key secondary outcome measures

Disease Activity Score of 28-joint scores over 48 weeks

Initially a random coefficient linear regression model was fitted to the DAS28 over time, with covariates entered for the minimisation factors, baseline DAS28, treatment group, time and time-by-treatment interaction; centre, patient and patient-by-time interaction random effects were fitted. However, as there was evidence of non-constant residual error variance, a multivariable covariance pattern model was fitted to the scores over time (at weeks 12, 24, 36 and 48), with the same covariates entered for the minimisation factors (excluding centre), baseline DAS28, treatment group, time and time-by-treatment interaction, and an unstructured covariance pattern was specified. Centre was not fitted as a random effect, as there was no centre component of variation in 24 of the 27 imputed data sets.

Algebraic representation for the random coefficient linear regression model is:

Algebraic representation for the covariance pattern model is:

where m and n denote two (arbitrary) different visit time points.

Disease Activity Score of 28 joints response over 48 weeks (reduction in Disease Activity Score of 28 joints of ≥ 1.2)

A multivariable covariance pattern logistic model was fitted to the response variable, achieving a reduction in the DAS28 of ≥ 1.2 units over time (at weeks 12, 24, 36 and 48), with covariates entered for the minimisation factors (excluding centre), baseline DAS28, treatment group, time and time-by-treatment interaction. An unstructured covariance pattern was specified. Centre was not fitted as a random effect because the model failed to converge.

where m and n denote two (arbitrary) different visit time points.

American College of Rheumatology 20 at week 24

A multivariable logistic regression model was fitted to ACR20 at 24 weeks post randomisation, with covariates entered for the minimisation factors (excluding centre) and treatment group. Centre was not fitted as a random effect, as there was no centre component of variation.

Algebraic representation of the analysis model:

In all analyses estimation of the treatment effects was of primary interest, but hypothesis testing was also performed. Treatment group effects were tested and the significance level is presented based on the Wald test (because of limitations of the likelihood ratio test for imputed data sets119). Model fit was assessed informally by examination of standardised residuals.

Additional secondary outcome measures

All additional secondary outcome measures, including further measures of disease activity and quality of life were summarised by treatment group and compared informally using descriptive statistics. The predefined subgroup analyses to evaluate the treatment modification effect of RF/ACPA status, initial TNFi group failed on and non-response category on the DAS28 were summarised by treatment group. In addition, treatment compliance, toxicity and safety were summarised.

Summary of protocol amendments

Appendix 8 provides a summary of the key protocol amendments throughout the trial.

Chapter 3 Clinical trial results

Patient recruitment

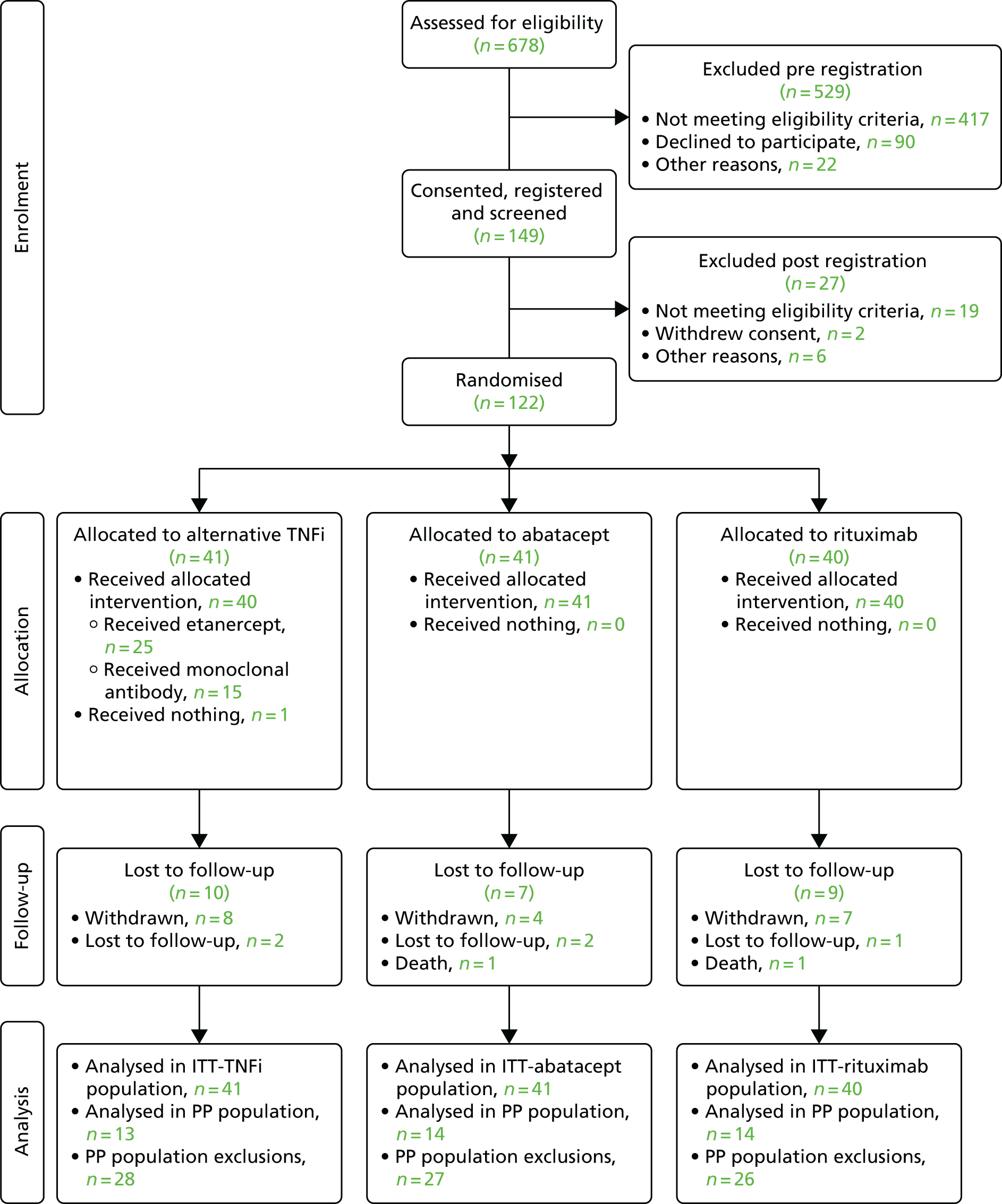

Between July 2012 and December 2014, 678 patients were screened for the trial across 35 centres. A total of 529 patients were excluded at screening (pre-registration), 417 of whom failed to meet the eligibility criteria. The main reasons for failing to meet the eligibility criteria were that they had not failed an initial TNFi agent (n = 95), were not on a stable dose of MTX over the previous 28 days (n = 92) and had received more than one TNFi drug or other biological agent (n = 72). A total of 149 patients gave written informed consent and were registered onto the trial.

Twenty-seven patients were excluded post registration, of whom 19 did not meet the eligibility criteria, two withdrew consent and six were excluded for other reasons (rescreening required, previous hepatitis infection, raised alkaline phosphatase levels, awaiting cancer diagnosis/treatment, patient not contactable, unknown reason). The remaining 122 patients were randomised to treatment. Following early trial termination because of the withdrawal of funding, the last patient was randomised on 18 December 2014.

A summary of the number of patients considered, registered and randomised by centre is provided in Appendix 9,Table 40. The flow of patients from initial assessment through to the end of follow-up is shown in Figure 2 (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials diagram). Full reasons for ineligibility and non-consent are provided in Appendix 9, Tables 41–43.

FIGURE 2.

The flow of patients through the SWITCH trial (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials diagram).

Recruitment target

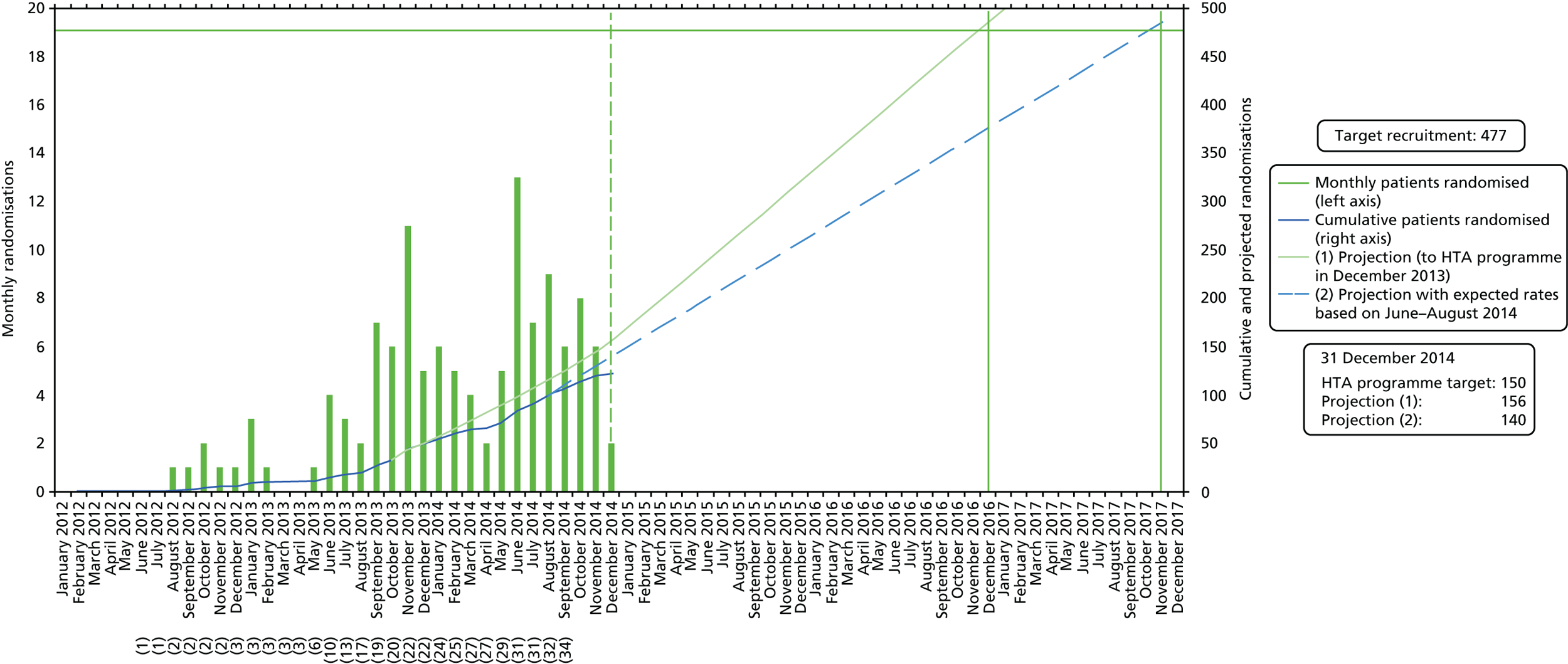

Figure 3 displays the projected recruitment against the actual recruitment across all centres during the trial recruitment period. Although the target for recruitment of 16 centres was reached by September 2013, the number of eligible patients identified by centres was much lower than expected (see Appendix 9, Table 40). Barriers to reaching the target included a 9-month halt to recruitment because of unforeseen contractual issues with a home health-care company, longer times for centre set-up, primarily because of the commissioning environment with significant geographical variability in receptiveness of Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) to approve RCTs that included non-NICE-approved therapies and delays to approval.

FIGURE 3.

Graph showing actual recruitment and projected recruitment when the trial was terminated. Projection 1 assumes 35 centres opened. Projection 2 assumes 31 centres opened. (XX), number of centres open.

Although the patient recruitment rate improved as new centres were initiated, overturning the deficit accrued from the above delays was not feasible within the planned recruitment period. Based on the number of centres opened and observed recruitment rates, recruitment to November 2017 would have been required to reach the target of 477 patients, at an additional cost of £450,000. Consequently, the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme monitoring panel withdrew funding in November 2014; the trial closed to recruitment in December 2014.

The study closure patient information sheet and article for the National Rheumatoid Arthritis Society web page (and other relevant electronic forums) are in Appendices 3 and 4, respectively.

Randomisation

The overall mean randomisation rate was 0.26 patients per month, that is, 3.12 patients per centre per year, across 35 centres. Twenty-eight centres randomised at least one patient and only seven centres randomised more than five patients, with the co-ordinating hospital (Chapel Allerton) providing 32 (26%) of all the randomised patients.

Of the 122 patients randomised to the treatment group, 41 were allocated to alternative TNFi, 41 were allocated to abatacept and 40 were allocated to rituximab.

The median time from the centre opening to randomisation of the first patient was 3.8 months (95% CI 2.5 to 7 months). Two centres did not randomise their first patient until more than 12 months after opening, and two further centres recruited no patients despite being open for more than 12 months.

Generalisability of the patient population randomised

Summaries of the clinical and demographic variables collected on the non-registration logs for patients considered for enrolment, registered but not randomised, and for patients randomised are provided in Appendix 9, Table 44. Age distribution and sex of registered, consented and non-randomised patients were similar. The proportion of patients who were RF seropositive or ACPA positive was also similar between patients registered but not randomised and those patients who were randomised; however, there was a large proportion of patients for whom RF and ACPA status was unknown among non-registered patients, making an assessment of generalisability on RF/ACPA status difficult.

Withdrawals

A summary of follow-up attendance up to the end of the 48-week intervention phase is provided in Figure 4.

FIGURE 4.

Summary of follow-up attendance up to the end of the 48-week intervention phase. DNA, did not attend.

Six patients withdrew consent to continue with randomised treatment and follow-up, two patients on alternative TNFi, one on abatacept and three on rituximab. Two further patients, one on alternative TNFi and one on abatacept, withdrew from follow-up during the observational period after week 48. An additional patient (2.4%) on abatacept withdrew from treatment but continued to have follow-up assessments and a further patient, also on abatacept (2.4%), was withdrawn from the study because of an AE (chest infection).

Appendix 9, Table 45 provides a full list of the reasons for withdrawal.

Two patients on alternative TNFi were lost to follow-up by 48 weeks: one patient (2.4%) on abatacept and one on rituximab.

Protocol deviations

Two patients were eligibility violations, one randomised to alternative TNFi and one to rituximab, both of whom continued to receive their allocated treatment and were followed up. One patient had juvenile-onset RA and one received sulfasalazine and hydroxychloroquine prior to the start of protocol treatment, had not received MTX and had started taking NSAIDs (naproxen) within 4 weeks prior to the screening visit.

A further patient randomised to alternative TNFi had a susceptibility to myeloma if given a monoclonal antibody and a clinical judgement was made to withdraw this patient before the allocated treatment and follow-up.

Eighty-one patients (66.4%) deviated from the protocol in some way, which resulted in exclusion from the PP population, corresponding to 28 (68.3%) patients on alternative TNFi, 27 (65.9%) on abatacept and 26 (65.0%) on rituximab. The most common protocol deviation was receiving steroid treatment within 6 weeks of an end-point assessment (35 patients; 28.7%), followed by not being compliant with treatment up to week 24 (based on information obtained via direct questioning) (27 patients; 22.1%), and receiving additional contraindicated treatment (23 patients; 18.9%). Appendix 10, Table 46, provides a further summary of reasons for protocol deviations resulting in exclusion from the PP population.

Treatment compliance

All except one patient received their allocated treatment. One patient was randomised to receive alternative TNFi (monoclonal antibody) but before treatment commenced the treating clinician withdrew the patient because of the presence of a comorbidity that precluded treatment with a monoclonal antibody TNFi.

Rituximab

All 40 patients randomised to rituximab received at least one infusion of rituximab. By week 12, all infusions had been given in line with the protocol, although infusions for four patients had been delayed (because of patient choice, clinician examination delaying first dose, AE and out-of-range pre-treatment tests). A total of 35 (87.5%) patients were known to be at least 80% compliant with treatment up to week 24.

Abatacept

All 41 patients randomised to receive abatacept received at least one injection of abatacept. A total of 29 patients (70.7%) were known to be at least 80% compliant with treatment up to week 24.

Alternative tumour necrosis factor inhibitor

Forty out of 41 patients (97.6%) randomised to the alternative TNFi treatment arm received their allocated treatment. A total of 31 patients (75.6%) were known to be at least 80% compliant with their randomised treatment up to week 24.

Etanercept

Twenty-five patients were assigned to receive etanercept as a result of being randomised to alternative TNFi. All 25 received at least one injection of etanercept.

Monoclonal antibody

The remaining 16 patients randomised to an TNFi were assigned to receive a monoclonal antibody, the choice of which was at the clinician’s discretion.

Adalimumab

Ten patients received adalimumab as a result of allocation to a monoclonal antibody and all 10 received at least one injection.

Certolizumab pegol

Only one patient received CZP as a result of allocation to a monoclonal antibody. With the exception of one missed injection between baseline and week 12, this patient received all injections in line with the protocol up to week 36.

Golimumab

Three patients received golimumab as a result of allocation to a monoclonal antibody. All three patients received all injections to at least week 24.

Infliximab

One patient received infliximab as a result of allocation to alternative TNFi. Up to week 24, infusions were delivered in line with the protocol.

Baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics are presented in Tables 2–6. The mean age was 56.7 years (SD 12.2 years; range 24–81 years). A total of 102 patients (83.6%) were female.

| Minimisation factor | Treatment arm | Total (n = 122) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alternative TNFi (n = 41) | Abatacept (n = 41) | Rituximab (n = 40) | ||

| Disease duration category, n (%) | ||||

| < 5 years | 16 (39.0) | 15 (36.6) | 14 (35.0) | 45 (36.9) |

| ≥ 5 years | 25 (61.0) | 26 (63.4) | 26 (65.0) | 77 (63.1) |

| Disease duration (years) | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 5.9 (3.9–12.3) | 6.9 (4.0–15.4) | 7.0 (3.9–15.6) | 6.7 (3.9–14.2) |

| Range | 0.4–35.2 | 0.6–43.5 | 1.3–33.7 | 0.4–43.5 |

| Missing | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| RA/ACPA seropositivity, n (%) | ||||

| RF seropositive or ACPA positive | 36 (87.8) | 31 (75.6) | 33 (82.5) | 100 (82.0) |

| Both RF seronegative and ACPA negative | 5 (12.2) | 10 (24.4) | 7 (17.5) | 22 (18.0) |

| Non-response category, n (%) | ||||

| Primary | 15 (36.6) | 15 (36.6) | 15 (37.5) | 45 (36.9) |

| Secondary | 26 (63.4) | 26 (63.4) | 25 (62.5) | 77 (63.1) |

| Patient characteristic | Treatment arm | Total (n = 122) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alternative TNFi (n = 41) | Abatacept (n = 41) | Rituximab (n = 40) | ||

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 8 (19.5) | 2 (4.9) | 10 (25.0) | 20 (16.4) |

| Female | 33 (80.5) | 39 (95.1) | 30 (75.0) | 102 (83.6) |

| Patient age (years) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 54.2 (9.98) | 58.1 (13.89) | 57.8 (12.37) | 56.7 (12.21) |

| Median (IQR) | 56.9 (45.5–59.8) | 60.5 (45.2–66.9) | 57.0 (52.4–67.4) | 57.3 (46.7–65.4) |

| Range | 34.2–73.6 | 28.8–81.7 | 24.5–81.1 | 24.5–81.7 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 30.1 (7.25) | 29.2 (5.74) | 30.4 (6.80) | 29.9 (6.60) |

| Median (IQR) | 28.7 (25.0–34.0) | 28.4 (24.3–34.5) | 29.0 (25.4–33.5) | 29.0 (24.9–34.1) |

| Missing | 1 | 2 | 2 | 5 |

| Smoking status, n (%) | ||||

| Non-smoking (never smoked) | 12 (29.3) | 17 (41.5) | 21 (52.5) | 50 (41.0) |

| Past smoker | 18 (43.9) | 13 (31.7) | 11 (27.5) | 42 (34.4) |

| Current smoker | 11 (26.8) | 11 (26.8) | 8 (20.0) | 30 (24.6) |

| Prior comorbidities, n (%) | ||||

| Hypertension | 15 (36.6) | 13 (31.7) | 14 (35.0) | 42 (34.4) |

| Osteoarthritis | 11 (26.8) | 14 (34.1) | 8 (20.0) | 33 (27.0) |

| Hyperchloesterolaemia | 7 (17.1) | 8 (19.5) | 10 (25.0) | 25 (20.5) |

| Depression | 7 (17.1) | 7 (17.1) | 4 (10.0) | 18 (14.8) |

| Thyroid dysfunction | 8 (19.5) | 5 (12.2) | 2 (5.0) | 15 (12.3) |

| Asthma | 6 (14.6) | 3 (7.3) | 4 (10.0) | 13 (10.7) |

| Diabetes | 4 (9.8) | 1 (2.4) | 5 (12.5) | 10 (8.2) |

| Cancer | 3 (7.3) | 1 (2.4) | 1 (2.5) | 5 (4.1) |

| Bowel disease | – | 2 (4.9) | 1 (2.5) | 3 (2.5) |

| Ischaemic heart disease | 1 (2.4) | – | 2 (5.0) | 3 (2.5) |

| Emphysema/chronic bronchitis | 1 (2.4) | 1 (2.4) | – | 2 (1.6) |

| Myocardial infarction | – | – | 2 (5.0) | 2 (1.6) |

| Peptic ulcer disease | – | 1 (2.4) | 1 (2.5) | 2 (1.6) |

| Stroke | – | 1 (2.4) | 1 (2.5) | 2 (1.6) |

| Chronic liver disease | 1 (2.4) | – | – | 1 (0.8) |

| Epilepsy | 1 (2.4) | – | – | 1 (0.8) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | – | – | 1 (2.5) | 1 (0.8) |

| Renal disease | – | 1 (2.4) | – | 1 (0.8) |

| Treatment history | Treatment arm, n (%) | Total (n = 122), n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alternative TNFi (n = 41) | Abatacept (n = 41) | Rituximab (n = 40) | ||

| Type of initial TNFi that failed | ||||

| Monoclonal antibody | 25 (61.0) | 23 (56.1) | 22 (55.0) | 70 (57.4) |

| Etanercept | 16 (39.0) | 18 (43.9) | 18 (45.0) | 52 (42.6) |

| Previous TNFi agent | ||||

| Adalimumab | 10 (24.4) | 10 (24.4) | 8 (20.0) | 28 (23.0) |

| CZP | 11 (26.8) | 9 (22.0) | 5 (12.5) | 25 (20.5) |

| Etanercept | 16 (39.0) | 18 (43.9) | 18 (45.0) | 52 (42.6) |

| Golimumab | 2 (4.9) | – | 4 (10.0) | 6 (4.9) |

| Infliximab | 2 (4.9) | 4 (9.8) | 5 (12.5) | 11 (9.0) |

| Measure of disease activity | Treatment arm | Total (n = 122) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alternative TNFi (n = 41) | Abatacept (n = 41) | Rituximab (n = 40) | ||

| Experience early-morning stiffness?, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 39 (95.1) | 39 (95.1) | 40 (100.0) | 118 (96.7) |

| No | 2 (4.9) | 2 (4.9) | – | 4 (3.3) |

| TJC | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 15.3 (6.40) | 15.1 (7.39) | 17.4 (8.13) | 15.9 (7.33) |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| SJC | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 9.9 (6.43) | 8.8 (5.54) | 10.0 (6.64) | 9.5 (6.19) |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| ESR (mm/hour) | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 19.0 (8.0–27.0) | 34.0 (17.0–54.0) | 27.0 (9.0–44.0) | 26.0 (11.0–43.0) |

| Missing | 0 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| CRP level (mg/l) | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 5.0 (4.0–15.5) | 9.0 (5.0–27.0) | 6.0 (5.0–15.0) | 6.0 (5.0–18.0) |

| Missing | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 |

| DAS28 | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 5.9 (1.05) | 6.2 (1.08) | 6.2 (1.28) | 6.1 (1.13) |

| Missing | 1 | 3 | 5 | 9 |

| CDAI score | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 38.6 (13.12) | 36.6 (13.34) | 39.6 (13.68) | 38.3 (13.31) |

| Missing | 1 | 3 | 4 | 8 |

| SDAI score | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 39.8 (13.98) | 38.8 (13.87) | 41.9 (14.49) | 40.2 (14.04) |

| Missing | 2 | 5 | 5 | 12 |

| Physician Global Assessment of Disease Activity VAS (mm) | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 67.0 (56.0–75.0) | 66.0 (58.0–84.0) | 65.0 (53.0–84.2) | 66.0 (57.0–79.0) |

| Missing | 0 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Patient-reported outcome measure | Treatment arm | Total (n = 122) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alternative TNFi (n = 41) | Abatacept (n = 41) | Rituximab (n = 40) | ||

| Patient Global Assessment of Arthritis VAS (mm) | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 70.5 (62.0–83.0) | 67.5 (52.0–79.5) | 74.0 (53.0–85.0) | 71.0 (56.0–83.0) |

| Missing | 1 | 1 | 3 | 5 |

| Patient Assessment of General Health VAS (mm) | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 56.5 (45.5–72.0) | 62.0 (47.8–68.5) | 61.0 (46.0–74.0) | 59.0 (47.0–70.0) |

| Missing | 1 | 1 | 3 | 5 |

| Patient Global Assessment of Pain VAS (mm) | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 70.5 (59.0–82.5) | 69.5 (57.5–79.0) | 77.0 (55.0–85.0) | 71.0 (58.0–81.0) |

| Missing | 1 | 1 | 3 | 5 |

| HAQ-DI score | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 1.9 (1.4–2.1) | 1.9 (1.6–2.3) | 1.9 (1.4–2.3) | 1.9 (1.5–2.1) |

| Missing | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| RAQoL score | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 21.6 (15.0–24.5) | 22.0 (14.0–25.5) | 22.0 (15.0–25.0) | 22.0 (15.0–25.0) |

| Missing | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 |

| HADS score | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 13.5 (8.0–20.0) | 17.0 (10.0–22.0) | 14.0 (11.0–19.0) | 15.0 (10.0–21.0) |

| Missing | 1 | 1 | 3 | 5 |

Minimisation factors

The median disease duration was 6.7 years (range 0.4–43.5 years) (see Table 2). Seventy-seven patients (63.1%) were secondary non-responders and 100 patients (82.0%) were RF seropositive or ACPA positive.

Demographics

Ninety patients (73.8%) had a current comorbidity, with the most frequently reported being hypertension (42 patients; 34.4%), osteoarthritis (33 patients; 27.0%) and hypercholesterolaemia (25 patients; 20.5%) (see Table 3).

Treatment history

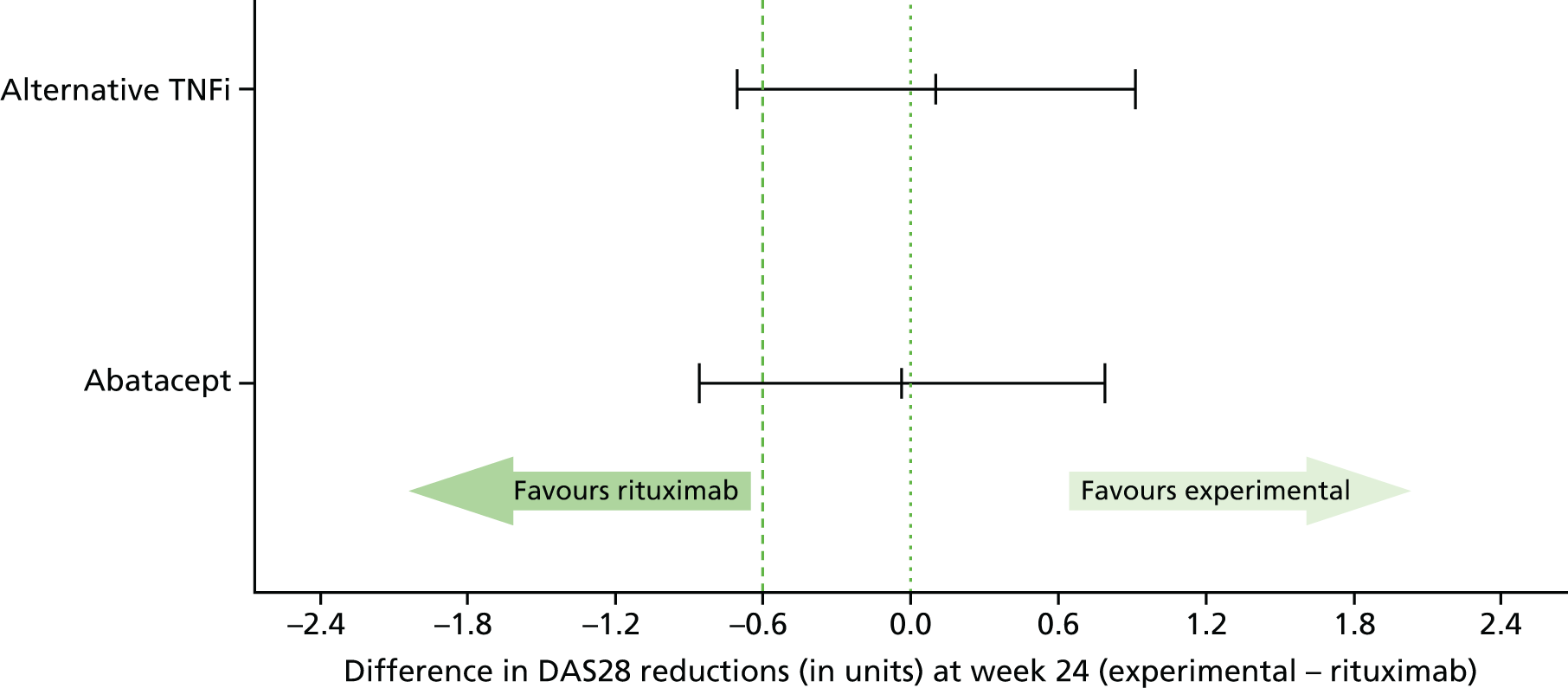

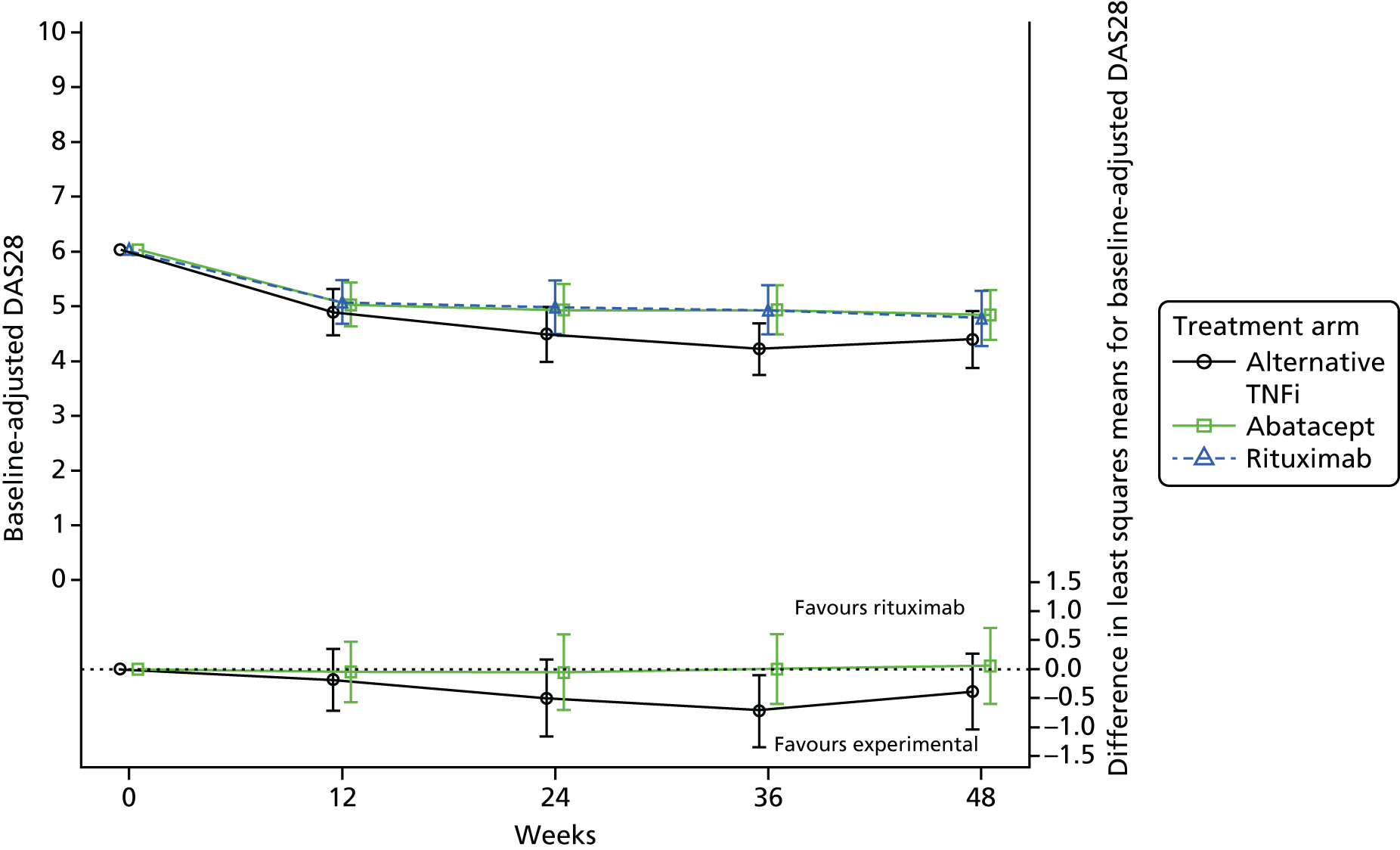

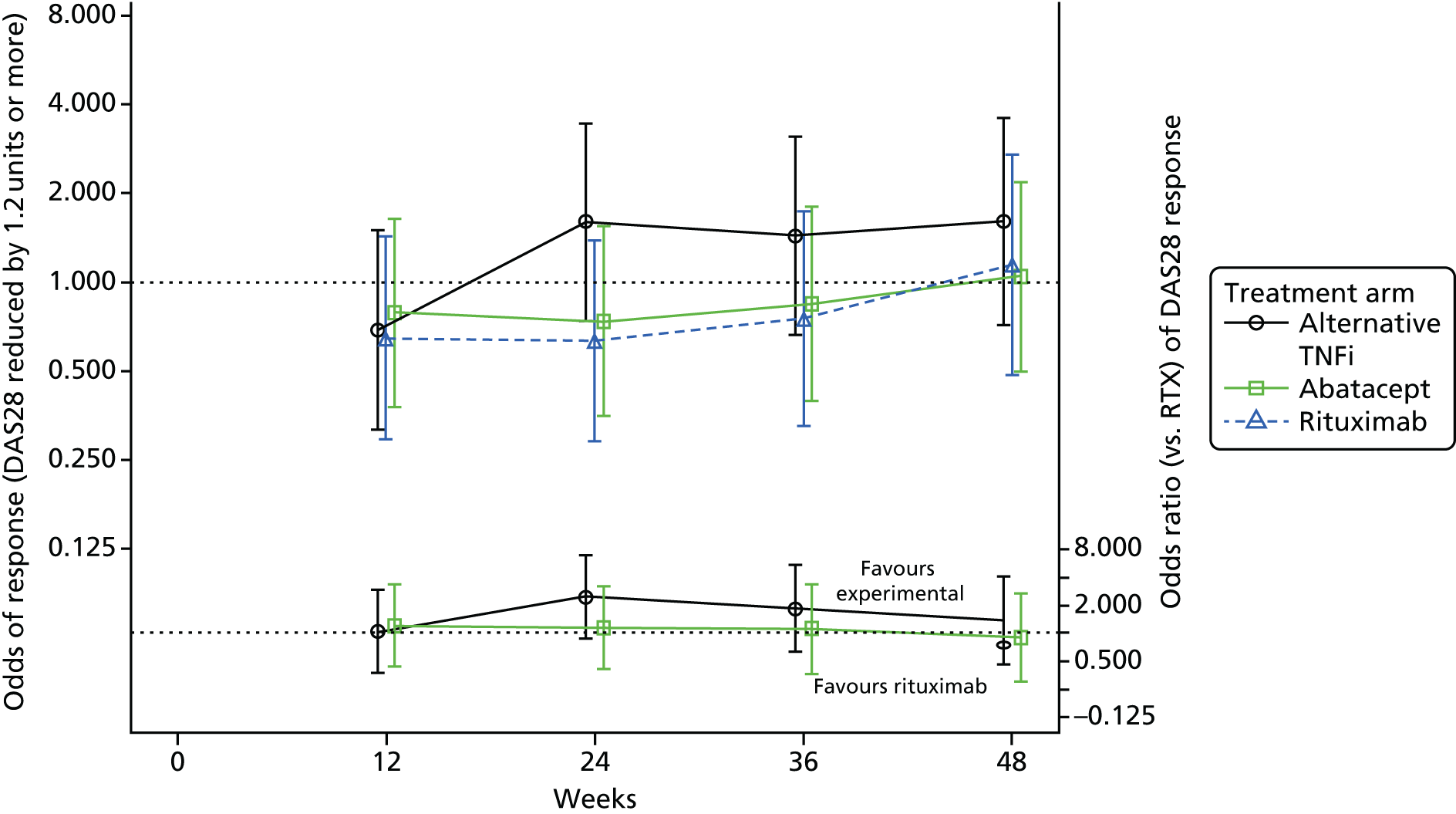

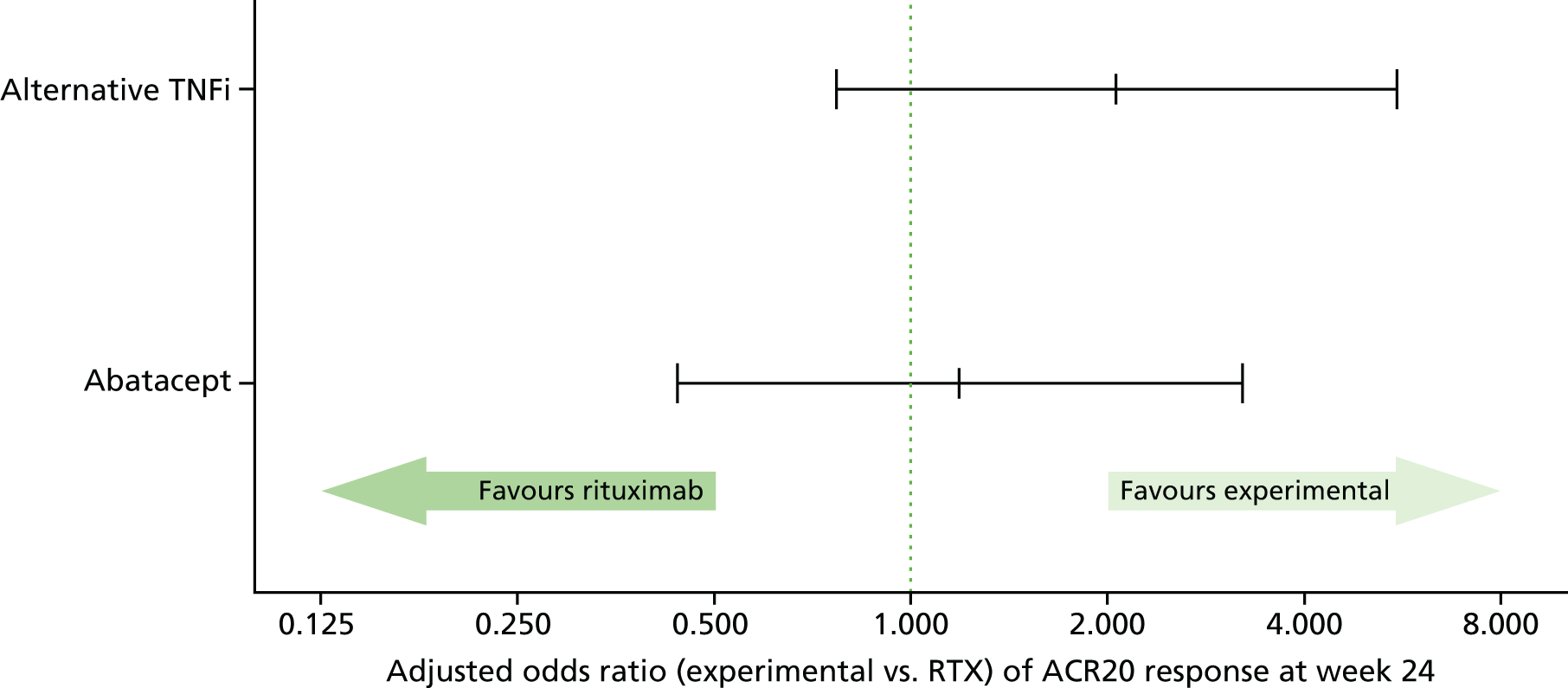

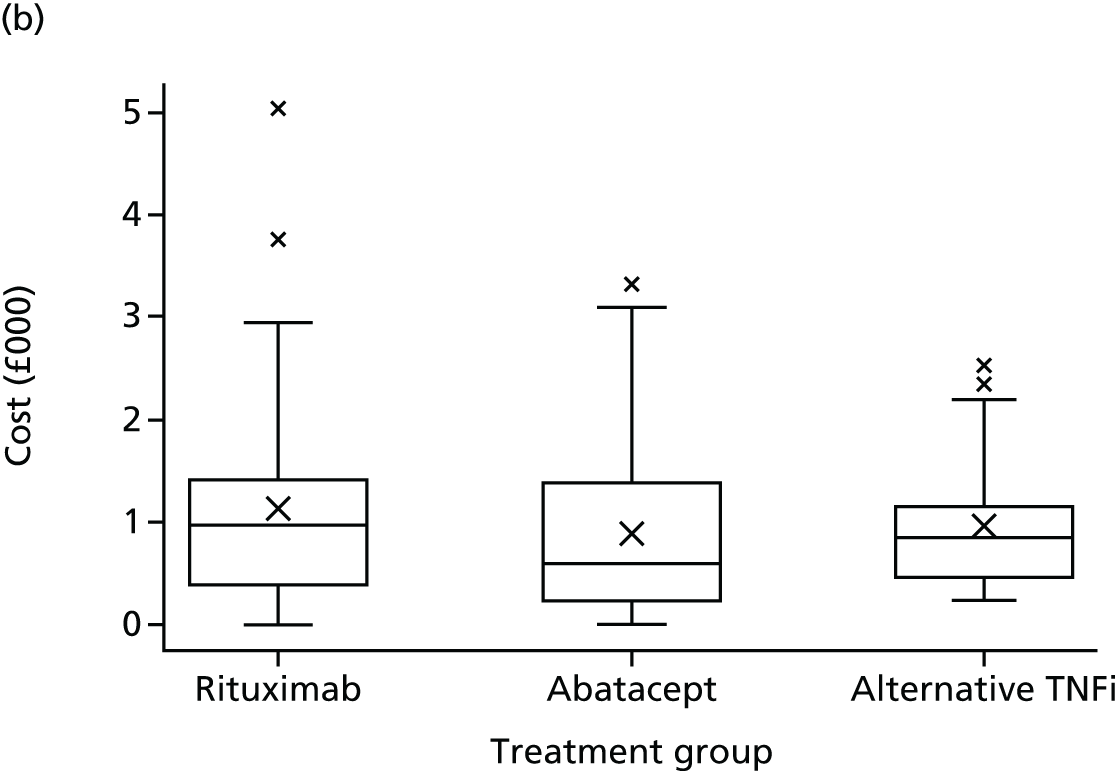

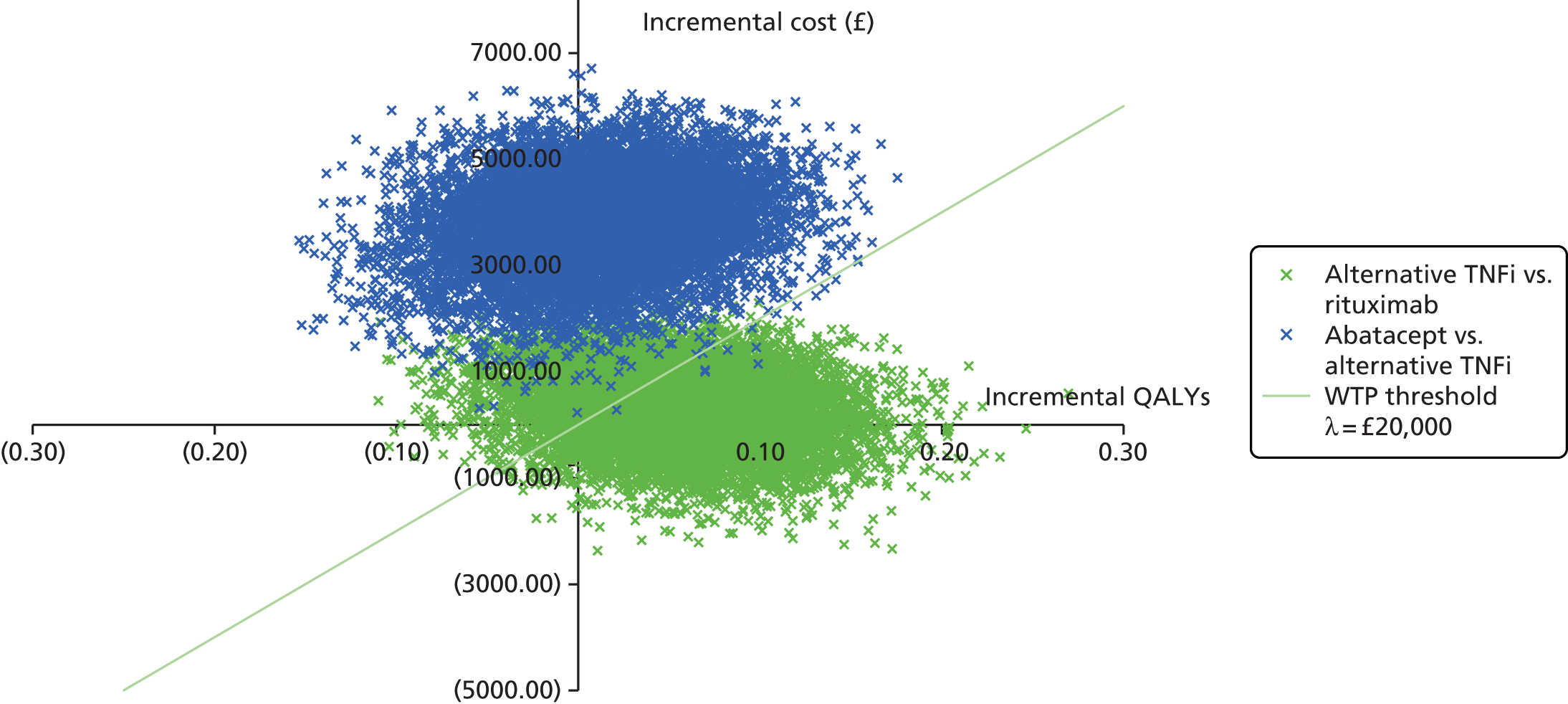

Seventy patients (57.4%) had previously failed to respond to a monoclonal antibody TNFi agent. The most common first TNFi agent used was etanercept (52 patients; 42.6%), followed by adalimumab (28 patients; 23.0%) and then CZP (25 patients; 20.5%) (see Table 4).