Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 09/01/45. The contractual start date was in April 2011. The draft report began editorial review in February 2017 and was accepted for publication in September 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Jan E Clarkson reports grants from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme during the conduct of the study. Alison M McDonald reports grants from the NIHR HTA programme during the conduct of the study. John DT Norrie reports grants from the University of Aberdeen and grants from the University of Glasgow outside the submitted work. He was a member of the NIHR HTA Commissioning Board (2010–16), is currently a member of the NIHR Editorial Board (2015–present) and is currently the deputy chairperson of the NIHR HTA General Board (2016–present). Marjon van der Pol reports grants from the NIHR HTA programme during the conduct of the study.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Ramsay et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

The subsequent chapters of this monograph describe Improving the Quality of Dentistry (IQuaD), a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme-funded trial testing the relative effectiveness of different types of oral hygiene advice (OHA) and the optimal frequency of periodontal instrumentation (PI). The trial protocol has been published. 1

The reason for the trial

Background

Epidemiology

Periodontal disease is an inflammatory disease that affects the soft and hard tissues supporting teeth. This disease is largely preventable, yet it remains the major cause of poor oral health worldwide and is the primary cause of tooth loss in older adults. 2,3 Severe periodontitis is the sixth most prevalent human disease, with a standardised prevalence of 11.2%. 4

The categorisation of periodontal disease is based on which of the tissues surrounding and supporting the teeth are affected and is classified into two broad categories: (1) gingivitis and (2) periodontitis. Gingivitis is a reversible condition characterised by inflammation and bleeding at the gingival margin. The gum becomes swollen and red because of the inflammation and will bleed easily on probing. It is a prerequisite for periodontitis and is also a risk indicator for caries progression. Periodontitis is the irreversible destruction and loss of the supporting periodontal structures (periodontal ligament, cementum and alveolar bone). 5 The result can be unsightly gingival recession, sensitivity of the exposed root surface, root caries (decay), mobility and drifting of teeth and, ultimately, tooth loss.

Gingivitis and periodontitis are a continuum of the same inflammatory disease6 but it is currently not possible to predict if and/or when an individual will progress from the reversible gingivitis to irreversible periodontitis. Accumulation of microbial dental plaque is the primary aetiological factor for gingivitis and periodontitis, as well as dental caries. However, progression of the disease is known to be affected by other factors including genetics (host’s defence mechanisms to bacterial infection), calculus, smoking and systemic comorbidities including type 2 diabetes mellitus. 7–10 Although several risk factors have been identified, the lack of certainty as to whether or not, and when, they may cause progression to irreversible periodontitis in an individual causes a challenge for the profession.

The 2009 UK Adult Dental Health Survey (ADHS)11 provides evidence that the majority of UK adults might be at risk of developing periodontal disease: 66% of dentate adults had visible plaque, indicating that tooth brushing was ineffective, and 68% had calculus in at least one sextant of the mouth. Gingival bleeding was demonstrated in 54% of dentate adults and 45% of dentate adults had periodontitis (defined by at least one site with a clinical probing depth of ≥ 4 mm), increasing with age from 19% in those aged 16–24 years to 61% in those aged 75–84 years. Indicators of severe disease (at least one site with a clinical probing depth of ≥ 6 mm) also increased with age, affecting 14% of those aged ≥ 65 years. Only 17% of dentate adults had excellent periodontal health, which was defined by the ADHS 200911 as ‘no bleeding, no calculus, no periodontal probing depths of 4 mm or more and in the case of adults aged 55 or above, no loss of periodontal attachment over 4 mm or more anywhere in their mouth’.

As microbial dental plaque accumulation is considered the most important risk factor for periodontitis, its disruption or removal is a key component of prevention, combined with the control/management of other risk factors (e.g. smoking). 12,13

Prevention strategies aim to prevent the inflammatory process from destroying the periodontal attachment as well as prevent the recurrence of inflammation in successfully treated patients. 14

Individuals and dental care professionals have different roles to play in prevention. Effective individual self-care (tooth brushing and interdental aids) for plaque control is considered the foundation stone of successful periodontal prevention and therapy of disease. 13 The current annual public spend on oral care products in the UK alone is £950M. 15 The dental care professionals’ role in prevention and periodontal treatment involves providing patients with OHA (self-care) and PI. There is no agreed published content of OHA, but the overall aim of this intervention is to encourage effective self-care. PI (or ‘scale and polish’) comprises removal of plaque and plaque retentive factors [e.g. calculus (tartar) deposits] which, together with the removal of overhanging restorations (poorly adapted dental fillings), facilitate adequate patient-performed oral self-care. In the UK, almost all of this treatment is provided by general dental practitioners and dental hygienists/therapists in the primary care setting. The British Society of Periodontology16 advises that consideration be given to referral to a specialist periodontist of patients exhibiting severe or aggressive forms of periodontal diseases.

Periodontal instrumentation is one of the most frequently provided treatments in general dental practices. In the year 2014/15, there were 2.2 million claims for this simple periodontal treatment in Scotland, costing £31.5M. 17 This represents 8% of the total NHS budget spend of general and public dental services and 25% of the monetary value of all fee-per-item treatments provided in these settings. There were also 2910 claims for intensive scaling, at a cost of £200,000. During this time frame in England, it was estimated that 12.9 million courses of treatment involved PI for adults and approximately 0.9 million courses for children. 18

Dental reimbursement in Scotland is a retrospective ‘fee-per-item’ service for which dentists are primarily reimbursed for the number of individual treatments provided following completion of a course of treatment. In 2006, England’s dental health service moved from a similar model to a prospective ‘Unit of Dental Activity’ (UDA) system. Dentists agree contracts in advance with health boards to provide a prespecified number of UDAs. In both health-care systems, non-exempt patients face a patient copayment. In Scotland, the copayment equals 80% of the fee-per-item payment up to a prespecified upper limit. In England, there is a fixed copayment according to the band of treatment provided.

Evidence base

Despite evidence of an association between sustained good oral hygiene and a low incidence of periodontal disease and caries in adults,19 there is a lack of strong and reliable evidence to inform clinicians of the relative clinical effectiveness (if any) of different types of OHA that can be delivered in a dental setting.

Prior to the start of the IQuaD trial, a number of relevant systematic reviews20–22 evaluating OHA had been conducted, with some inconsistency in their findings. A recent systematic review23 of psychological approaches to behaviour change for improved plaque control in periodontal management reported benefits of using goal-setting, self-monitoring and planning for improving oral hygiene. Patient understanding of the benefits of behaviour change and the seriousness of periodontal disease were also considered important by the authors of the review. 23 A number of the included trials were of short duration, had non-experimental designs and were rated as being at high risk of bias. A meta-analysis of the available trials was not possible and the results and recommendations should be interpreted with caution.

The evidence to inform clinicians of the clinical effectiveness and optimal frequency of PI is mixed. A Cochrane systematic review24 of routine scale and polish (PI) for periodontal health in adults found insufficient evidence to determine the effects of routine PI treatments, providing little guidance for policy-makers, dental professionals or patients. Only three trials25–27 were eligible for inclusion and all were rated as being at an unclear risk of bias. Given that PI is routinely provided in general dental practice, it is noteworthy that only one of the eligible trials25 was conducted in primary care. Following baseline PI, Jones et al. 25 compared no PI delivery with 6-monthly PI or 12-monthly PI, with a 24-month clinical follow-up. The trial25 recruited only periodontally healthy participants. The Cochrane systematic review24 assessed the body of evidence for PI as being of low quality. The need for further well-conducted trials of sufficient duration, including research investigating patients’ willingness to pay (WTP), was highlighted. 28

The relative effectiveness of OHA and PI was assessed in the IQuaD trial, a robust, adequately powered randomised controlled trial (RCT) in primary dental care.

The questions the IQuaD trial addressed

Aim

The aim of this study was to compare the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of theory-based, personalised OHA or PI at different time intervals (no PI, 12-monthly PI or 6-monthly PI), or their combination, with routine care in improving periodontal health in dentate adults attending general dental practice.

Objectives

The primary objectives were to test the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the following dental management strategies:

-

personalised OHA versus routine OHA

-

6-monthly PI versus 12-monthly PI

-

6-monthly PI versus no PI.

The secondary objectives were to:

-

test the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a combination of personalised OHA and PI at different time intervals

-

measure dentist/hygienist beliefs relating to giving OHA, PI and maintenance of periodontal health.

Chapter 2 Methods of the study

Study design

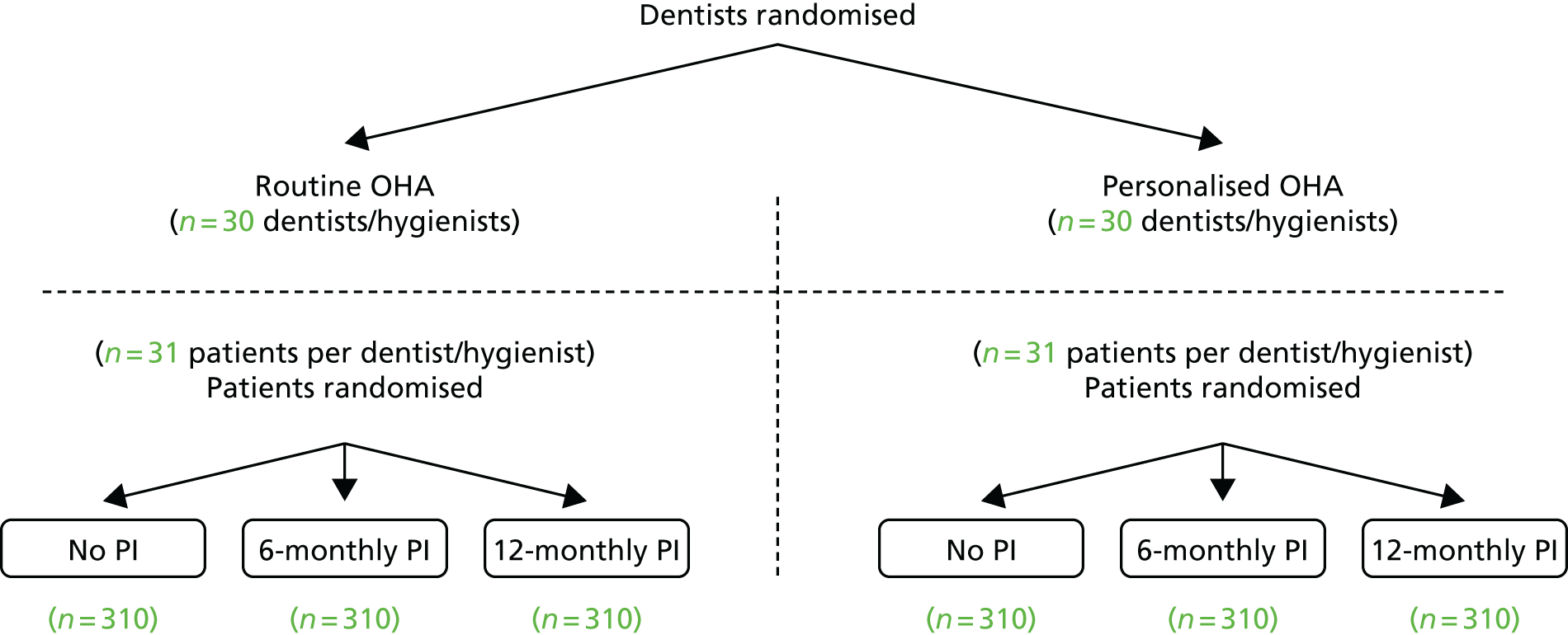

This study was a multicentre, cluster randomised controlled, open trial with blinded outcome evaluations and 3-year follow-ups. The comparisons were made within a factorial design using a combination of cluster and individual participant randomisation. Dental practices were randomised to either a routine or personalised OHA group. All participants were seen in the same dental practice by a dentist or hygienist (a ‘cluster’) and received either routine (current practice) or personalised OHA depending on their dental practice’s allocation. This was the optimal design to address the concern that contamination could happen if each dentist delivered routine OHA to some participants and personalised OHA to others. To test the effects of PI, each individual participant was randomised to one of three groups: (1) no PI, (2) 6-monthly PI (current practice) or (3) 12-monthly PI (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Study design.

Ethics approval and consent

Favourable ethics opinion for the IQuaD trial was confirmed by the East of Scotland Research Ethics Service on 24 March 2011 [Research Ethics Committee (REC) reference number 10/S0501/65].

Participants and procedure

Recruitment and consent of dental practices

Recruitment of dental practices was achieved by a variety of methods. The IQuaD trial was presented at a number of national conferences and promoted within dental professional publications to raise awareness of the trial within the dental profession. In addition, the Scottish Dental Practice Based Research Network and the Faculty of General Dental Practitioners provided trial information to their members. A series of trial information and recruitment evenings were organised across Scotland and north-east England. Potential dentist participants were sent personalised invitation letters to these events in which the reasons for the trial, design of the trial and practice involvement were described, and dental professionals were given the opportunity to discuss participation with the trial team. Information packs about the trial were posted to dentists who were unable to attend a meeting.

Trial team members telephoned dental practices to follow up the trial information letters and noted interest of involvement. Principal dentists (usually the owner of the practice) who were interested in the trial were asked to provide written consent for the dental practice (cluster) to participate. All participating dentists and hygienists within a dental practice were individually invited to complete a consent form and the clinician belief questionnaire (CBQ) prior to cluster randomisation. Participating dental practices were asked to identify dates in advance for training in trial processes and at least three dates for the screening and recruitment of potentially eligible participants.

Recruitment and consent of participants

The identification of potential participants in each dental practice was supported by the Scottish Primary Care Research Network in Scotland and the UK Clinical Research Network in England. A variety of patient appointment management strategies are utilised within dental practices across the UK. Therefore, the IQuaD trial developed a flexible and pragmatic participant recruitment strategy that aimed to adapt to each dental practice’s usual appointment management system. Some dental practices arrange routine check-up appointments for their patients up to 6 months or 1 year in advance, while other practices send letters or mobile phone text message reminders to their patients when their routine dental examinations are due, asking them to contact the dental practice to make an appointment. Dental practices were asked to send an invitation letter to attend a trial screening session, along with a patient information sheet and baseline questionnaire to potentially eligible participants who were due to attend for a routine dental examination and who were regular attenders and did not have severe periodontitis [Basic Periodontal Examination (BPE) score of 4]. This was sent, at most, 6 weeks in advance of the patient’s routine dental examination appointment. Patients who were not interested in taking part were asked to contact their practice for an alternative appointment.

Trial outcome assessor (OA) teams, consisting of qualified dental hygienists/dental therapists and dental nurses employed by the trial, attended the screening and recruitment sessions in participating dental practices to obtain consent from potentially eligible participants and collect the baseline clinical measurements and questionnaires of consented participants.

At the screening appointment, the dentist was available to discuss the trial with potential participants and answer any questions. The OA was present at this appointment and answered any questions specifically related to the trial. Patients who did not wish to take part were seen by their dentist/hygienist, who provided an examination, OHA and/or PI as normal. Potentially eligible participants provided written informed consent to the trial before the baseline clinical outcomes were measured by the OA to confirm a patient’s eligibility for the trial. Reasons for ineligibility or declining to participate were recorded at this session. Participants excluded from the trial solely because of a BPE score of 4 or * (furcation involvement) were not randomised to a PI allocation and were given the opportunity to consent to follow-up by annual postal questionnaires and clinical follow-up in a separate cohort group (see study documentation, available at www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/090145/#/; accessed October 2017). All participants received a baseline PI and OHA from their own dentist or hygienist after the baseline outcome measures and questionnaires were collected by the OA team prior to participants being informed of their randomised PI allocation.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Dental practices

Inclusion criteria

-

NHS provider for adult patients.

-

Primary care provider.

-

Willing to follow protocol.

Exclusion criteria

-

Providing only private dental care to adults.

-

Unwilling to follow protocol.

Participants

Inclusion criteria

Adult patients (aged ≥ 18 years) with periodontal health, gingivitis or moderate periodontitis (BPE score of 0, 1, 2 or 3) who:

-

were dentate

-

had attended for a check-up at least twice in the previous 2 years

-

received their dental care in part or in full as a NHS patient.

Exclusion criteria

-

Patients with periodontal disease with a BPE score of 4 (clinical probing depth of > 6 mm and/or furcation involvements or attachment loss of ≥ 7 mm) in any sextant on the basis that more extensive periodontal care was indicated.

-

Patients with an uncontrolled chronic medical condition (e.g. diabetes mellitus, immunocompromised).

Trial outcome assessor training

Before participant recruitment and 3 years’ clinical follow-up, the OA teams were trained in the recording of the trial clinical outcomes. The training was delivered by trial collaborators who have extensive experience of clinical periodontal research (PH, GM). The emphasis of the training was on the consistency of the scoring, both intra- and interassessor, to achieve assessor alignment.

The practical steps of clinical outcome assessment were agreed on in advance, including sequence of outcome assessment; time allocation; sequence around the mouth; isolation as well as the angulation, positioning and pressure of the University of North Carolina (UNC)-15 probe to ensure a standardised approach across the OA teams.

It is widely accepted that methods of assessing gingival inflammation that provoke gingival bleeding do not allow for repeated assessment. 29 The training for the primary outcome of gingival inflammation as bleeding therefore involved OA group discussion of the technique of assessment, scoring definition, as well as demonstrated photograph and clinical examples. This was repeated for the outcome of calculus.

Periodontal probing depths were recorded at six sites on all erupted teeth using a probing force of approximately 25 g on an independent, but similar, cohort of patients to those recruited to the study at the Newcastle upon Tyne and Dundee dental schools. Assessments by an experienced clinical periodontal researcher (LH) were used the reference standard. Intra- and interoutcome assessor scores were recorded and kappa scores of ≥ 0.60 achieved, with over 95% of scores within 1 mm.

Trial interventions

Both cluster-level intervention (OHA) and individual participant-level intervention (PI) were delivered by the dental practice dentist or dental hygienist in line with each individual dental practice’s usual practice.

Oral hygiene advice

Routine oral hygiene advice

Routine OHA was defined as the OHA currently being provided by the dental practices. There is no published information describing ‘routine’ OHA, but anecdotal evidence suggests that it is often minimal (e.g. ‘you need to brush your teeth more frequently’) or not provided at all.

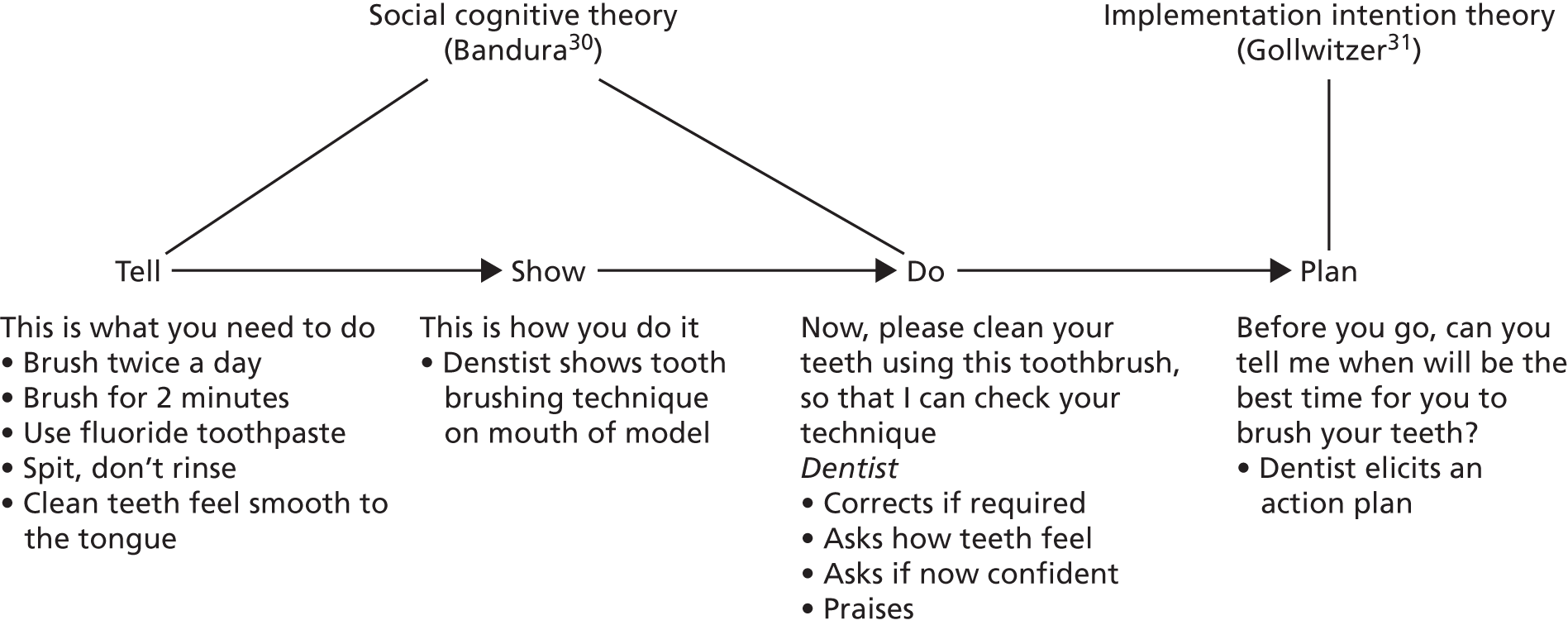

Personalised oral hygiene advice

The personalised OHA intervention used two well-established psychological models for explaining and influencing behaviour (Figure 2). The first was a pre-motivational model, social cognitive theory. 30 This theory proposes that a key variable influencing motivation and behaviour is self-efficacy, assessed as a person’s confidence in their ability to perform behaviour. According to this model, the sources of self-efficacy are doing the behaviour (performance: cleaning their teeth), seeing someone else do it (vicarious example/modelling: the dentist demonstrated to patients how to use the oral health-care tools to clean their teeth on a model of the mouth), being encouraged to perform it (verbal persuasion: the dentist helped the patient make oral hygiene a habit with the right plan) and how we feel afterwards (physical state: the dentist discussed biofeedback, highlighting what clean teeth would feel like). Based on this model, an intervention to influence oral hygiene behaviour should target oral hygiene self-efficacy via these sources. The second model was implementation intention theory,31 a post-motivational model designed to help people put their intentions into practice, bridging the gap between motivation and behaviour. This theory proposes that making an explicit action plan about where and when a behaviour will be performed increases the likelihood of performing it. Action plans work by setting up a cue to remind the individual to perform the behaviour. Therefore, oral hygiene behaviours are likely to be very sensitive to action planning, as they can easily be linked to other behaviours most people do every day, for example tooth brushing after the cue of eating a meal or before going to bed.

FIGURE 2.

The OHA intervention behavioural framework.

The intervention was tested in a study32 consisting of 84 dental practices and 799 patients. The results of this pilot study32 supported the theoretically framed intervention as an effective method of influencing oral hygiene beliefs and behaviour. Participants who received the intervention had significantly better behavioural (timing, duration, method), cognitive (confidence, planning) and clinical (plaque, gingival bleeding) outcomes than the participants in the control group receiving routine care.

Training in the delivery of the personalised oral hygiene advice

Training in the delivery of the personalised OHA intervention was provided by a clinical member of the trial team to all dentists/hygienists within a dental practice randomised to this allocation. The content and the delivery of the intervention were standardised as a series of steps (see study documentation, available at www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/090145/#/; accessed October 2017) designed to take place within an average primary care consultation, taking approximately 5 minutes in total.

A training DVD demonstrating a consultation using the steps was also developed and provided on a memory stick to all practices assigned to personalised OHA intervention (available at http://dentistry.dundee.ac.uk/nihr-hta-iquad-trial; accessed October 2017). The practices were also provided with laminated instruction sheets for use in the dental surgery. Dentists/hygienists retained these training resources in order to be able to undertake self-directed training as required throughout the trial. New clinicians appointed to any of the IQuaD trial dental practices (clusters) throughout the trial were invited to take part and provide consent to IQuaD if they had taken over the care of any IQuaD trial participants. Full training in trial methodology and intervention delivery was provided, as detailed above.

Frequency of oral hygiene advice

At baseline, all participants received OHA in accordance with the cluster-level randomisation allocation. Reinforcement of OHA was provided at the discretion of the dentist/hygienist during the trial.

Periodontal instrumentation

The definition of PI was as used in standard practice and would include the removal of plaque and calculus from the crown and root surfaces using manual or ultrasonic scalers, with no adjunctive subgingival therapy (e.g. antibiotics)33 and the appropriate management of plaque retention factors.

Baseline periodontal instrumentation

A full mouth supra- and subgingival PI was carried out by the practice dentist/hygienist on all participants prior to the participant or dental clinician being aware of the trial allocation. No time limit was set on this treatment and dentists/hygienists were instructed to scale the teeth and root surfaces until they were free of all deposits and were smooth to probing.

Experimental periodontal instrumentation

Experimental groups received a PI at 6- or 12-monthly intervals in accordance with the individual participant-level randomisation. Participants allocated to the no-PI groups attended their dentist at time intervals determined by current practice. However, participants and dental practices were advised that every trial participant should be invited to attend their dentist for a routine examination appointment at least every 12 months.

Randomisation

Practice allocation to oral hygiene advice group

Recruited dental practices were allocated to routine or personalised OHA by minimisation on two factors: (1) practice employed a dental hygienist (yes/no) and (2) practice size (one or two dentists in practice/three or more dentists). This cluster-level randomisation was conducted using the automated, central randomisation service at the Centre for Healthcare Randomised Trials (CHaRT), University of Aberdeen, after the dental practice consent form was received at the Trial Coordinating Office in Dundee (TCOD) and before any potential participant had been approached.

Participant allocation to periodontal instrumentation group

Participants were allocated to the PI trial arms using the automated, central randomisation service at the CHaRT, University of Aberdeen, with access by both telephone and web. Allocation took place once the OA had completed the baseline outcome assessment and was minimised on (1) absence of gingival bleeding on probing (yes/no), (2) highest sextant BPE score (BPE score of < 3/BPE score of 3) and (3) currently smoking (yes/no).

The OAs were informed that allocation had taken place but were blinded to allocation, with the actual allocation transmitted to the TCOD. A letter was sent to all participants to inform them of their PI allocation and all participants received a £25 gift voucher in recognition of their contribution to the study. The TCOD provided each individual recruited dental practice with a list of projected dates for PI and review (no-PI group), according to the individual participant-level allocation, to be delivered throughout the trial for all their trial participants. The list was updated and re-sent by TCOD on an annual basis to each practice.

Descriptive measures

Participant descriptive measures were collected at baseline and annually by self-administered postal questionnaire. They included the time since the last visit at the dental practice, the type of attendee (regular vs. non-regular), the self-reported number of PIs and OHA received in the last 12 months and by whom, smoking status and the type of toothbrush (manual vs. electric). Descriptive measures are presented in Table 1 by year and randomised group, using either mean, standard deviation (SD) or n (%), as appropriate.

| Participant dental characteristics | Randomised group, n (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PI | OHA | ||||

| No (N = 623) | 12-monthly (N = 625) | 6-monthly (N = 626) | Personalised (N = 1008) | Routine (N = 866) | |

| Age (years), mean (SD), n | 47.8 (15.8), 623 | 47.9 (15.7), 625 | 47.8 (15.8), 626 | 47.4 (16.1), 1008 | 48.3 (15.3), 866 |

| Male | 223 (36) | 229 (37) | 225 (36) | 387 (38) | 290 (33) |

| Date of last visit to the dental practice | |||||

| < 1 year ago | 569 (91) | 547 (88) | 553 (88) | 893 (89) | 776 (90) |

| 1–2 years ago | 38 (6) | 57 (9) | 49 (8) | 79 (8) | 65 (8) |

| > 2 years ago | 5 (1) | 4 (1) | 6 (1) | 9 (1) | 6 (1) |

| Missing | 11 (2) | 17 (3) | 18 (3) | 27 (3) | 19 (2) |

| Last course of treatment was | |||||

| NHS | 557 (89) | 573 (92) | 575 (92) | 918 (91) | 787 (91) |

| Private | 10 (2) | 9 (1) | 8 (1) | 15 (1) | 12 (1) |

| Combination | 40 (6) | 23 (4) | 24 (4) | 41 (4) | 46 (5) |

| Missing | 16 (3) | 20 (3) | 19 (3) | 34 (3) | 21 (2) |

| Do you think of yourself as | |||||

| A regular attendee | 565 (91) | 561 (90) | 574 (92) | 903 (90) | 797 (92) |

| Someone who sees a dentist when in pain or trouble | 43 (7) | 47 (8) | 31 (5) | 76 (8) | 45 (5) |

| Missing | 15 (2) | 17 (3) | 21 (3) | 29 (3) | 24 (3) |

| Last time you went to the dental practice were you given OHA? | |||||

| Yes | 410 (66) | 411 (66) | 420 (67) | 688 (68) | 553 (64) |

| No | 192 (31) | 187 (30) | 179 (29) | 275 (27) | 283 (33) |

| Missing | 21 (3) | 27 (4) | 27 (4) | 45 (4) | 30 (3) |

| By whom? | |||||

| Dentist | 298 (48) | 293 (47) | 291 (46) | 484 (48) | 398 (46) |

| Hygienist | 81 (13) | 85 (14) | 97 (15) | 141 (14) | 122 (14) |

| Both | 29 (5) | 27 (4) | 27 (4) | 53 (5) | 30 (3) |

| Missing | 215 (35) | 220 (35) | 211 (34) | 330 (33) | 316 (36) |

| Last time you went to the dental practice were you given a scale and polish? | |||||

| Yes | 371 (60) | 364 (58) | 381 (61) | 619 (61) | 497 (57) |

| No | 230 (37) | 236 (38) | 217 (35) | 341 (34) | 342 (39) |

| Missing | 22 (4) | 25 (4) | 28 (4) | 48 (5) | 27 (3) |

| By whom? | |||||

| Hygienist | 106 (17) | 108 (17) | 114 (18) | 182 (18) | 146 (17) |

| Dentist | 247 (40) | 236 (38) | 244 (39) | 394 (39) | 333 (38) |

| Missing | 270 (43) | 281 (45) | 268 (43) | 432 (43) | 387 (45) |

| What type of toothbrush do you normally use? | |||||

| Manual | 413 (66) | 397 (64) | 382 (61) | 647 (64) | 545 (63) |

| Electric | 180 (29) | 192 (31) | 205 (33) | 300 (30) | 277 (32) |

| Do not use toothbrush | 14 (2) | 18 (3) | 16 (3) | 28 (3) | 20 (2) |

| Missing | 16 (3) | 18 (3) | 23 (4) | 33 (3) | 24 (3) |

| Do you normally pay for dental treatments? | |||||

| Yes | 453 (73) | 436 (70) | 452 (72) | 716 (71) | 625 (72) |

| No | 155 (25) | 170 (27) | 150 (24) | 260 (26) | 215 (25) |

| Missing | 15 (2) | 19 (3) | 24 (4) | 32 (3) | 26 (3) |

| Do you have dental insurance? | |||||

| Yes | 19 (3) | 20 (3) | 24 (4) | 32 (3) | 31 (4) |

| No | 581 (93) | 583 (93) | 573 (92) | 932 (92) | 805 (93) |

| Missing | 23 (4) | 22 (4) | 29 (5) | 44 (4) | 30 (3) |

| How often do you prefer to have a scale and polish? | |||||

| Never | 13 (2) | 13 (2) | 8 (1) | 21 (2) | 13 (2) |

| Once every 2 years | 25 (4) | 20 (3) | 13 (2) | 38 (4) | 20 (2) |

| Once a year | 117 (19) | 122 (20) | 121 (19) | 193 (19) | 167 (19) |

| Twice a year | 269 (43) | 268 (43) | 289 (46) | 451 (45) | 375 (43) |

| Three times a year | 65 (10) | 65 (10) | 59 (9) | 89 (9) | 100 (12) |

| Four times a year | 67 (11) | 71 (11) | 56 (9) | 103 (10) | 91 (11) |

| More often | 26 (4) | 19 (3) | 25 (4) | 32 (3) | 38 (4) |

| Missing | 41 (7) | 47 (8) | 55 (9) | 81 (8) | 62 (7) |

Outcome measures

Primary outcomes

-

Clinical: gingival inflammation/bleeding on probing at the gingival margin at the 3-year follow-up.

-

Patient centred: oral hygiene self-efficacy at the 3-year follow-up.

-

Economic: net benefits (mean WTP minus mean costs).

Secondary outcomes

-

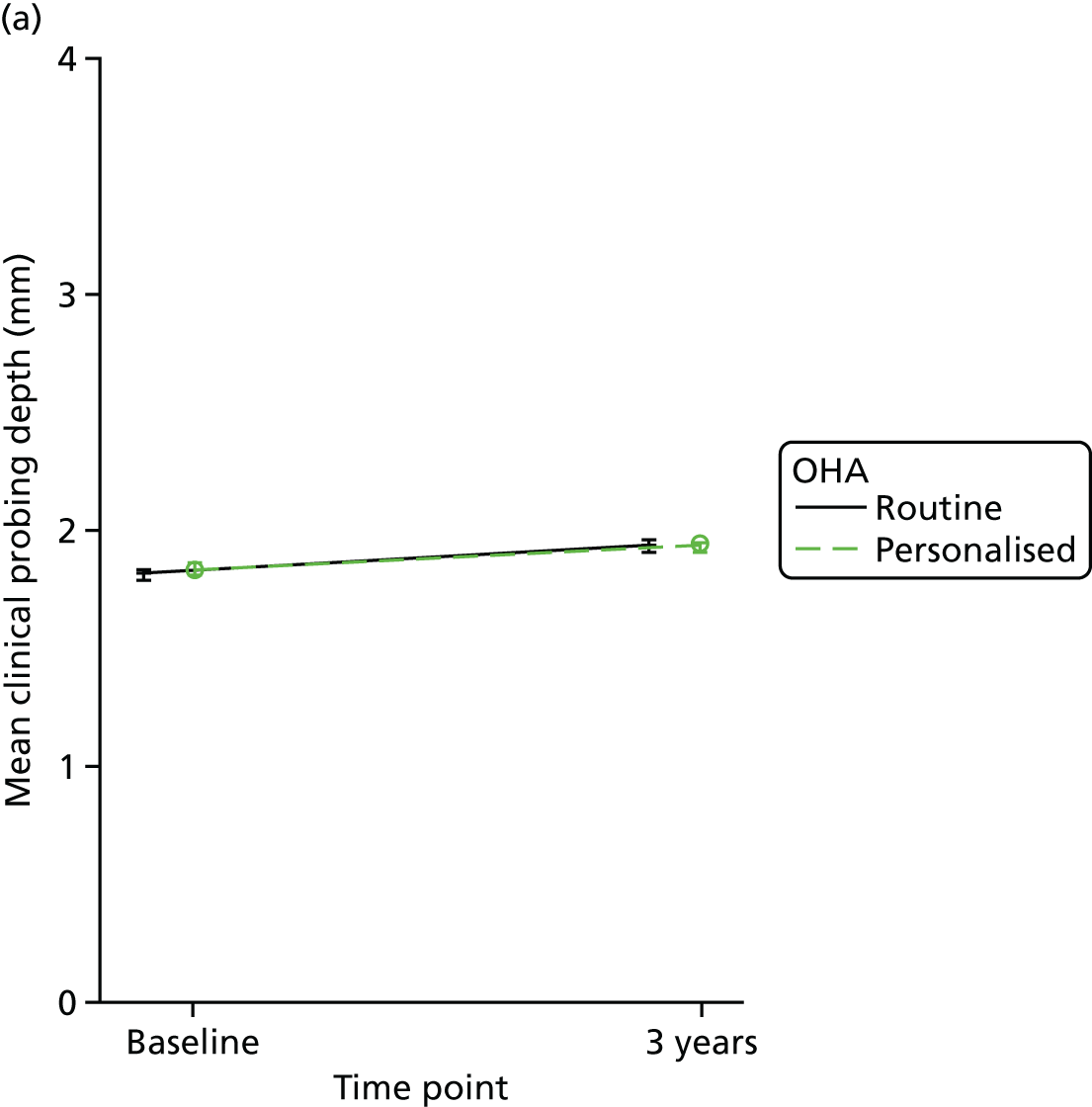

Clinical: (1) calculus, (2) clinical probing depth, (3) additional PI and (4) referral. (All of which were collected at 3-year follow-up.)

-

Patient-centred: (1) dental quality of life (QoL), (2) oral health behaviour and (3) knowledge. (All of which were collected during 3 years’ annual follow-up.)

-

Economic: costs to the NHS and patients; WTP.

-

Providers: beliefs relating to giving OHA and maintenance of periodontal health.

Note: the Periodontal Advisory Group considered that clinical attachment loss and plaque cannot be measured reliably; therefore, neither was included as outcomes.

Collection of clinical outcome measures

Gingival inflammation was measured according to the Gingival Index of Löe34 by running the UNC probe circumferentially around each tooth just within the gingival sulcus or pocket. After 30 seconds, bleeding was recorded as being present or absent on the buccal and lingual surfaces. The primary outcome (gingival inflammation/bleeding) was calculated by adding all the sites at which bleeding was observed and dividing these sites by the number of sites (twice the number of teeth) and presented as a percentage.

The colour-coded UNC periodontal probe was used to measure clinical probing depth and presence of calculus. Clinical probing depths were measured for all teeth (excluding third molars) at six sites per tooth: (1) mesiobuccal, (2) midbuccal, (3) distobuccal, (4) mesiolingual/palatal, (5) mid-lingual/palatal and (6) distolingual/palatal. Clinical probing depth was calculated as the mean of the six different sites measured per tooth and it is presented in mm.

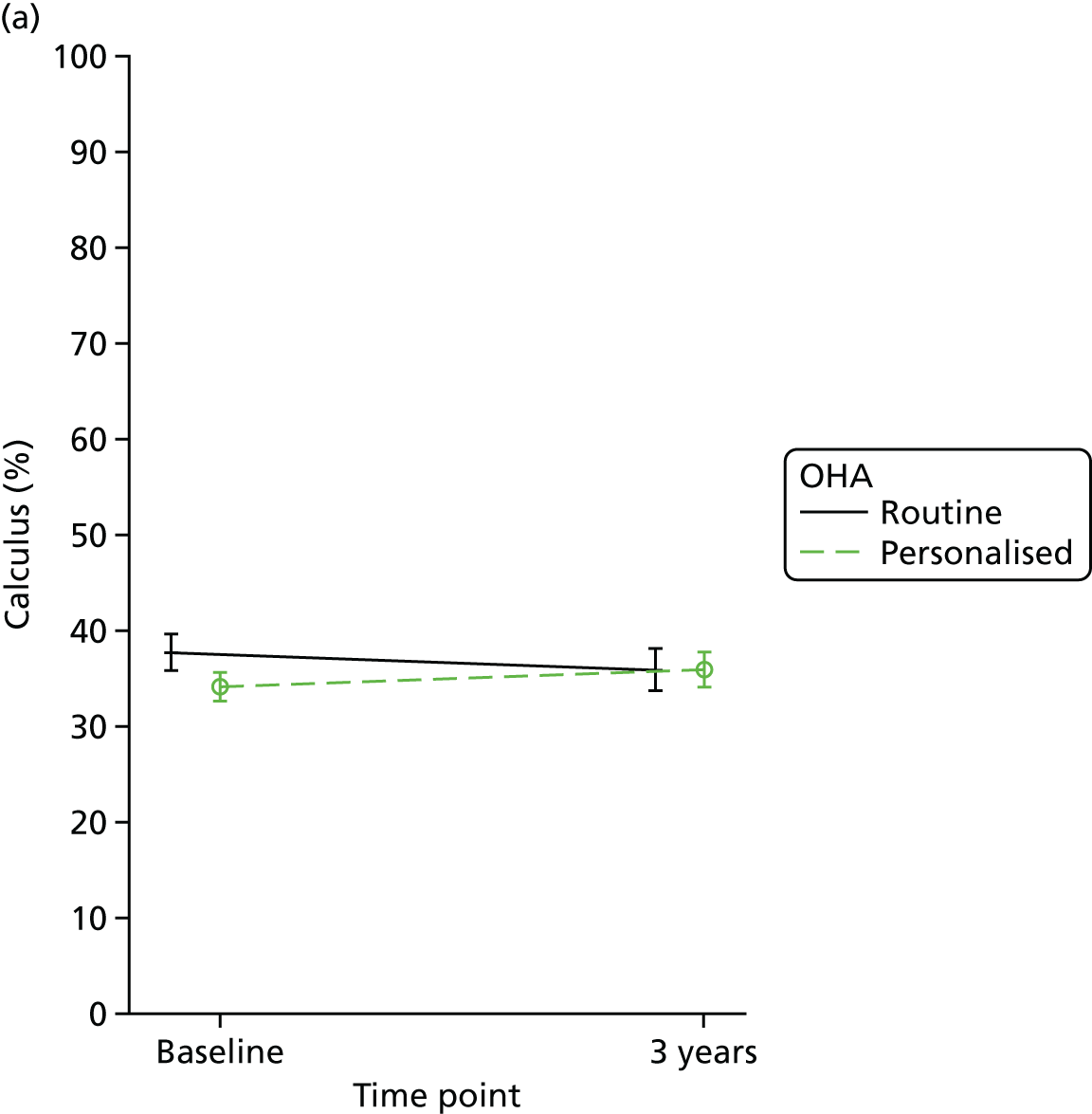

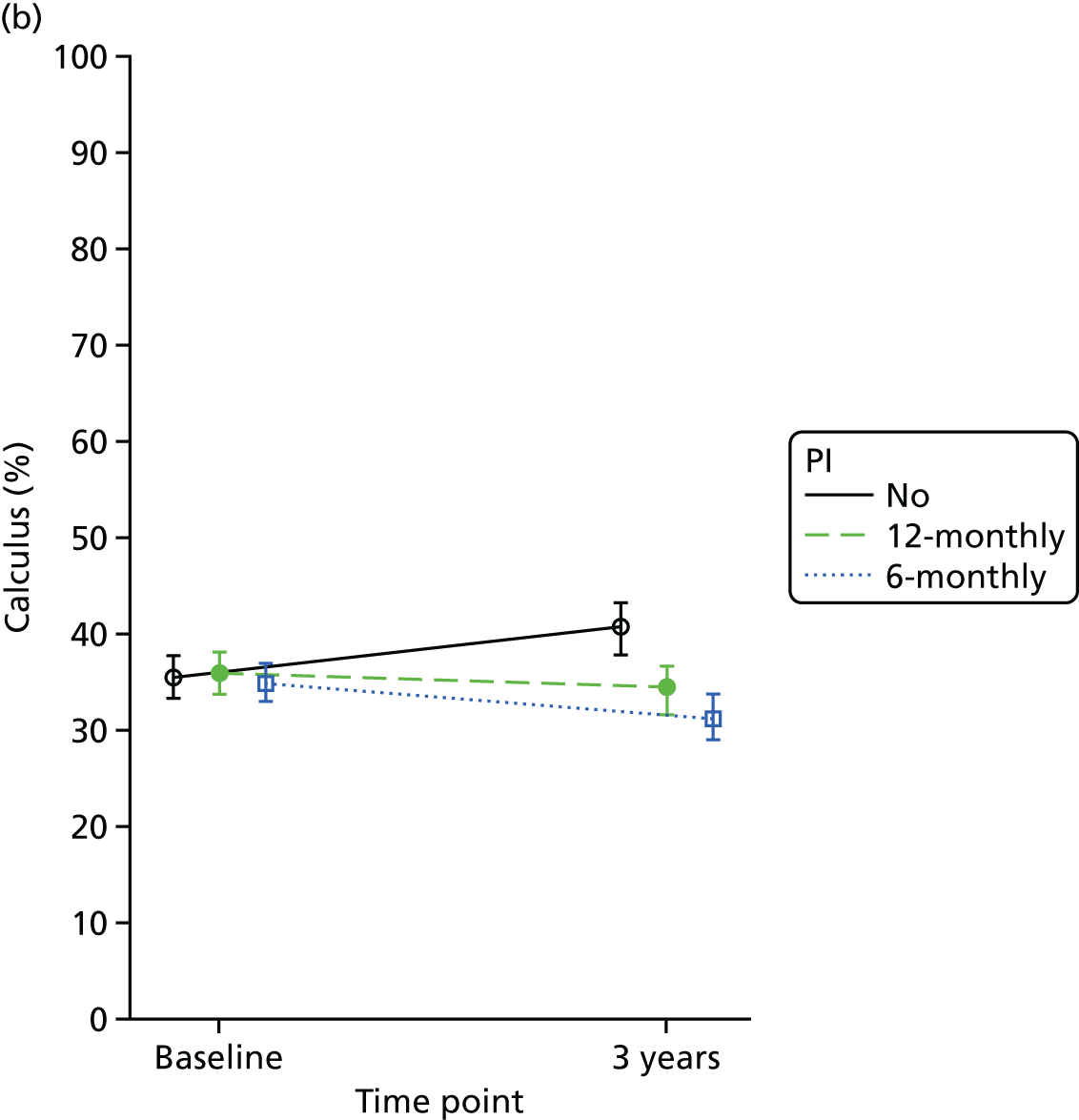

Calculus was calculated by adding all the sites where calculus was observed and dividing it by the number of teeth and presented as a percentage.

The sequence of scoring was gingival inflammation/bleeding, clinical probing depths and calculus.

Collection of patient-centred outcome measures

Patient-centred outcomes were measured at baseline and annually by self-administered postal questionnaire.

The full details of the calculations used to generate each patient-reported outcome are available in Appendix 1, Section 1: methods for computing patient-reported outcomes.

Oral health belief outcomes

The questions for measuring patient-centred oral health belief outcomes were derived from social cognitive theory30 and the theory of planned behaviour. 31

The primary patient-centred outcome was self-efficacy, assessed as a person’s confidence in their ability to perform several different oral health behaviours. Each behaviour was measured using a 7-point scale scored from 1 (not at all confident) to 7 (extremely confident), with 7 being the best outcome.

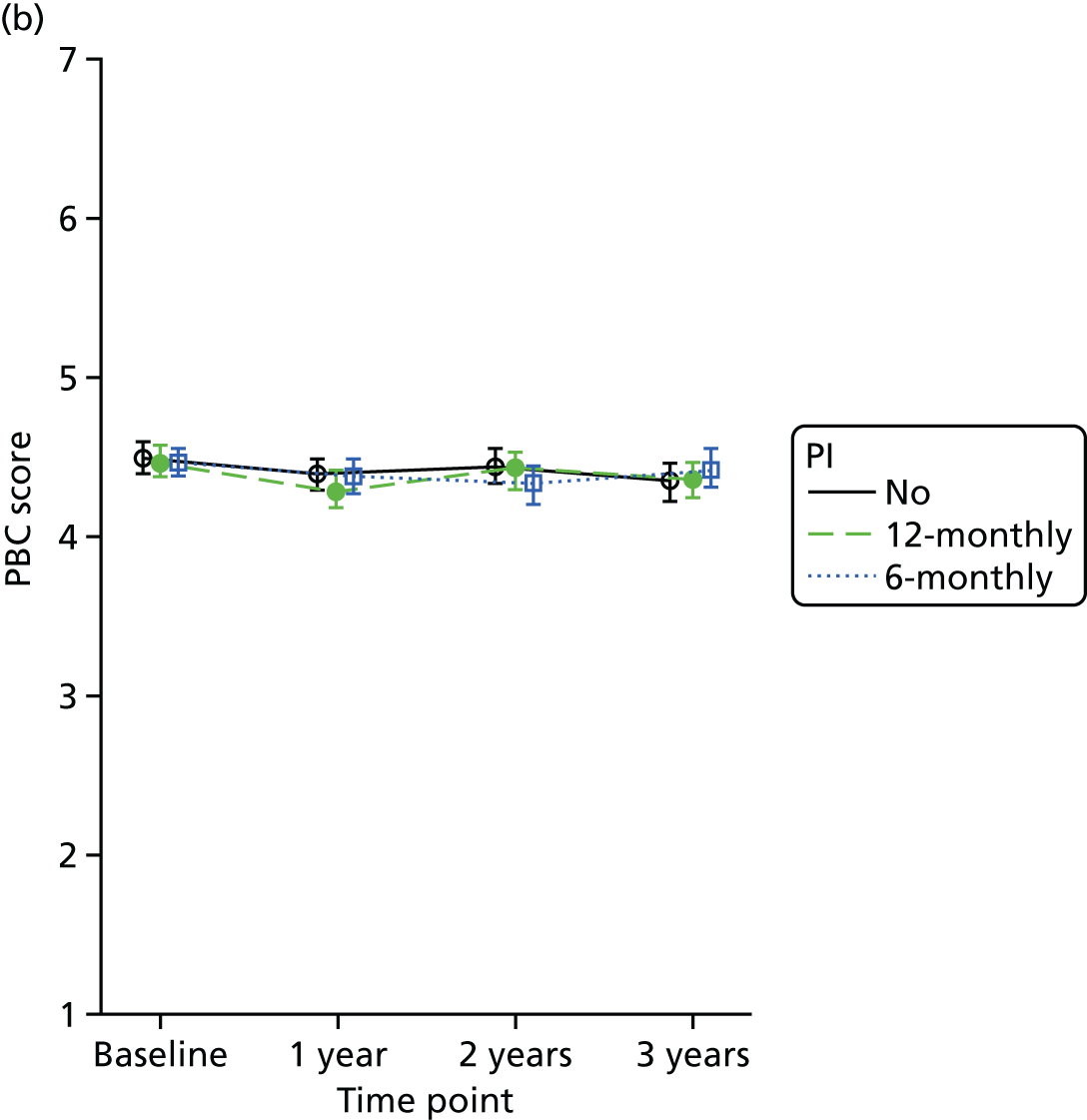

Perceived behaviour control (PBC) outcome, assessed in terms of perceived ease or difficulty of performing several different oral health behaviours, was measured using a 7-point scale varying from 1 (strongly agree) to 7 (strongly disagree), with 7 being the best outcome.

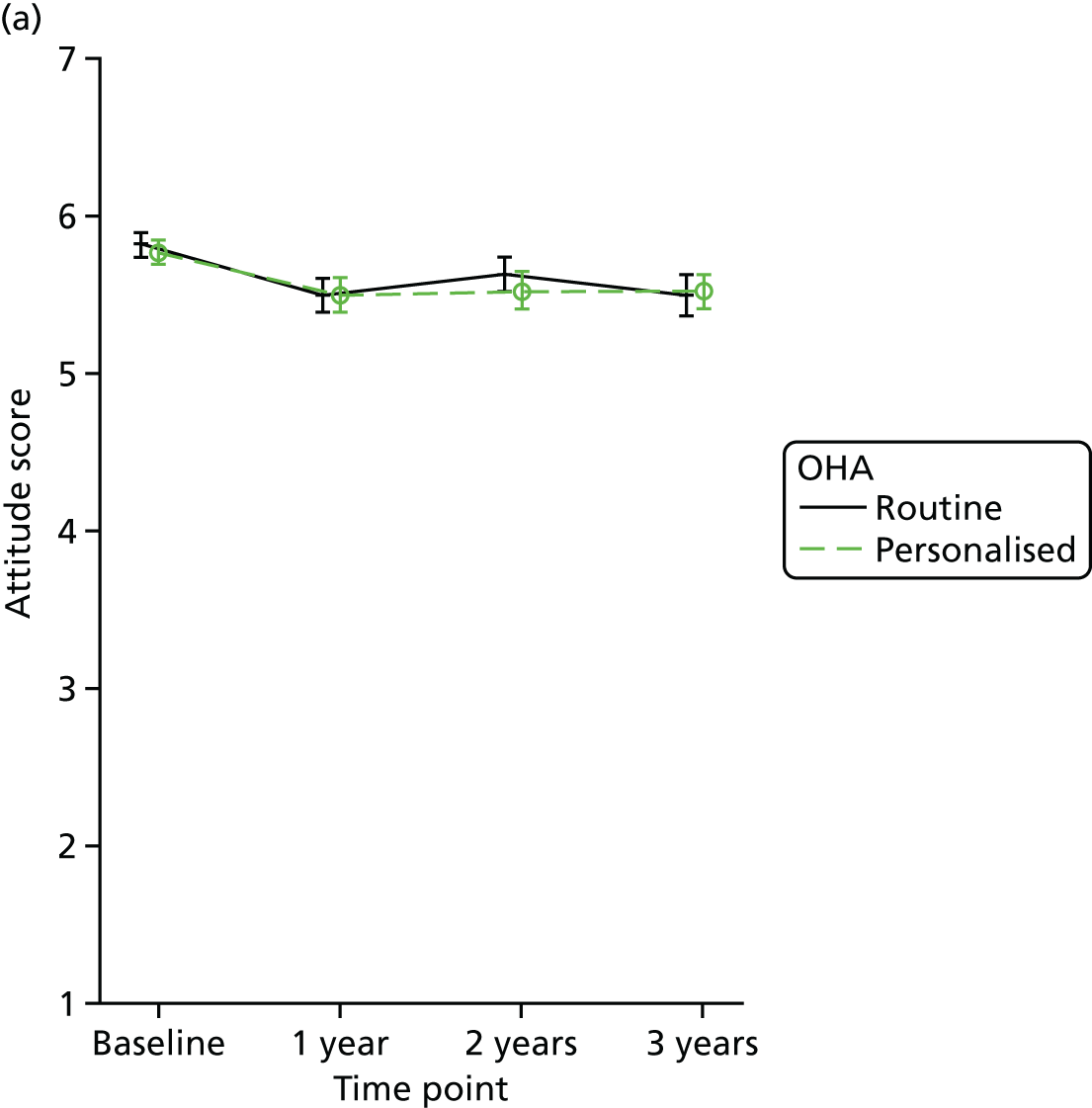

Attitude outcome (perceived consequences of the behaviour) was measured using a 7-point scale varying from 1 to 7 (strongly agree to strongly disagree), with 7 being the best outcome.

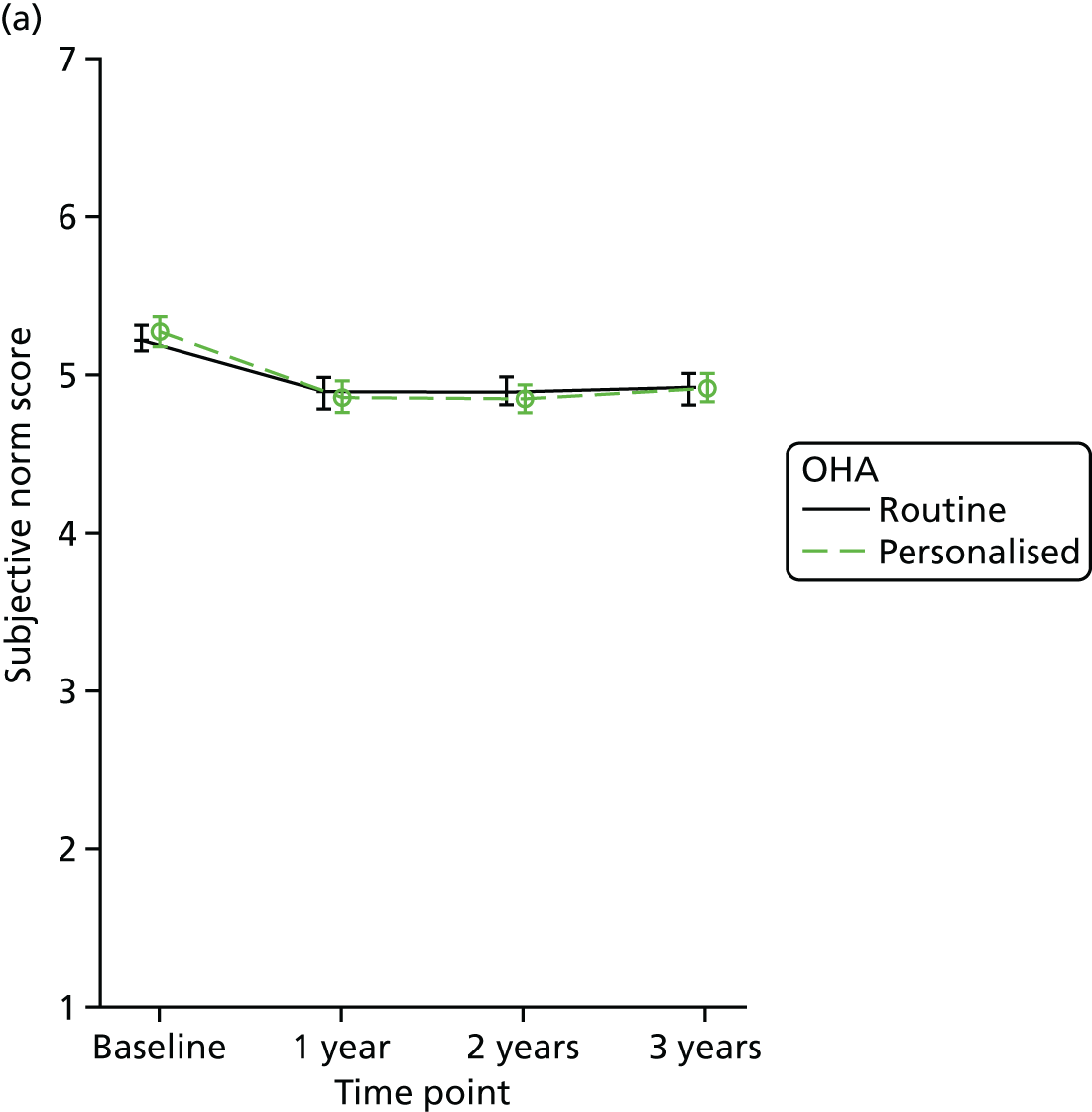

Subjective norm outcome (perceptions of social pressure to perform the behaviour) was measured using three questions with points varying from 1 (strongly agree) to 7 (strongly disagree), with 7 being the best outcome.

Oral health behaviour outcome

Patient-reported oral health behaviour outcome was measured using four questions (about duration and frequency of brushing, frequency of flossing and frequency of interdental brushes use). Each response varied from 0 to 3, with a score of 3 being the best possible behaviour. The best value between flossing and interdental brushes was used as a measure of interdental cleaning behaviour. The responses for each question were summed to produce a summary score ranging from 0 to 9, with 9 being the best outcome.

Intention outcome

Intention (motivation to perform a behaviour) was measured using three questions (about duration and frequency of brushing and frequency of flossing). Each response varied from 0 to 3, with a score of 3 being the best possible intention. The responses were summed to produce a summary score ranging from 0 to 9, with 9 being the best outcome.

Quality of life

Quality of life was measured using the Oral Health Impact Profile-14 (OHIP-14). 35 The OHIP-14 is a 14-question, oral health-specific, patient-centred measure of symptoms experienced in the previous 12 months. The questions are scored from 0 (never) to 4 (very often) and summed to produce a summary score ranging from 0 to 56, with 56 being the worst outcome.

Additional periodontal instrumentation outcome

The additional PI outcome assessed at the 3-year follow-up was the number of participants self-reporting in their annual questionnaire that they had received any private PI at any time during the trial. It was based on the question, ‘In the last 12 months have you received a private scale and polish?’.

Having a plan to floss or brush

Participants were asked in all questionnaires if they had a plan to brush better and if they had a plan to floss better. If they answered ‘yes’ to either question, they were considered to have a plan. This outcome was also used as a measure of fidelity of the personalised OHA intervention.

Dentist beliefs

Clinician belief questionnaires were collected at baseline and at the 3-year follow-up. At baseline, the following variables were measured: self-efficacy, attitude, PBC, intention, subjective norm and action planning. All of the variables are measured on a scale of 1 to 7, except subjective norm (measured from 1 to 49) and intention (measured from 0 to 100). At follow-up, the variables measured were the same. Again, all variables varied from 1 to 7, except for subjective norm (varies from 1 to 49). The full details of the calculations used to generate each dentist belief outcome are available in Appendix 1, Section 1: methods for computing patient-reported outcomes.

Post hoc outcomes

Self-reported bleeding was assessed using one question with the scale varying from 1 (never) to 5 (very often) at the 3-year follow-up in the annual questionnaire.

Tertiary measures

Dental appearance was measured using four different questions (e.g. ’How clean and pleasant do your teeth look and feel after you brush and after a scale and polish’?). Each scale varied from 1 (not at all clean/not at all pleasant) to 7 (could not get any cleaner/extremely pleasant) and were summarised separately using the mean responses, with 7 being the best outcome.

Sensitivity was measured using four different questions. First, it was measured through a binary (yes/no) question: ‘Do you experience sensitivity in your teeth?’. Second, it was measured through three different scales, the first varying from rarely sensitive to always sensitive and the other two scales varying from 1 to 7 (never to all the time, and no pain to worst imaginable pain). These tertiary outcomes were self-reported at the 3-year follow-up.

Fidelity measures

Fidelity measures were collected at baseline and annually by self-administered postal questionnaire. These included whether or not participants had a plan to start brushing and/or flossing better and whether or not, after brushing, the patients did, or intended to, ‘spit, but not rinse’.

Dental practice compliance with the protocol was monitored in two ways: (1) through annual face-to-face visits by a member of the trial office team and (2) through an annual audit of six participants. All practices received at least one face-to-face visit between baseline and follow-up. This was to ensure practice compliance with the protocol and an understanding of their role, to answer any queries the practice staff had and to build and maintain a rapport with the practices to ensure a smooth transition into the follow-up phase of the trial. The annual audit of six participants (two from each PI allocation) was conducted with each practice to check if participants had been contacted to attend an appointment according to their allocated treatment group. If ≥ 50% of these six random participants had not been contacted or invited to attend, this triggered a telephone call to the practice to check the trial processes and, if required, a visit to review protocol was arranged.

Number of periodontal instrumentations received (routine data and self-report)

The self-reported number of PIs received in the previous 12 months was collected annually by postal questionnaire. If participants replied that they had not received any PI in the previous 12 months, this response was recorded as a zero for those 12 months. If participants replied that they received PI in the previous 12 months but did not indicate how many times, these responses were set as missing. The total number of received PIs over the 3 years was calculated by summing the number of times the participant self-reported receiving PI over the course of the trial.

Routine treatment data were obtained from Information Services Division (ISD) Scotland and the NHS Business Services Authority (BSA) in England for the time period of 2010 to 2016. The routine data informed on the number of PI received throughout the trial, by counting the number of claims for PIs made by dentists for each participant. Further details regarding how these variables were calculated can be found in Chapter 3.

Data collection

Assessment for eligibility and informed consent was achieved at the screening stage. Clinical outcome assessment was carried out at baseline and the 3-year follow-up. Participants were sent a trial questionnaire at baseline, 12 months, 24 months and 36 months following recruitment. Clinicians were asked to complete a belief questionnaire at baseline and at the 3-year follow-up.

Baseline

Dentists and/or hygienists were asked to complete the CBQ at baseline, after each individual dental practice had consented to take part in the IQuaD trial.

Patient-centred outcomes were collected at baseline by self-administered questionnaire.

Arrangement of clinical assessment appointments has been outlined in the recruitment section above.

Clinical outcomes were measured at baseline by trained OAs who were blinded to allocation. Gingival inflammation/bleeding scores, calculus, clinical probing depth and BPE scores were measured by the OA and recorded on the baseline clinical chart by the dental research nurse who was a member of the trial team.

At the baseline appointment, the OAs also collected personal details from participants, including preferred contact method (telephone, e-mail) and contact details.

Annual follow-up

Patient-centred outcomes were collected annually by self-administered postal questionnaires.

Like the baseline questionnaire, the annual follow-up questionnaire contained questions on self-efficacy, PBC, attitude, subjective norm, behaviour, OHIP-14, dental appearance and sensitivity. Questions designed to collect the descriptive measures were also included in this questionnaire, as were questions on dental costs for the health economic outcomes. Annual follow-up questionnaires at year 1 and year 2 post randomisation were posted from the CHaRT trial office to participants’ home addresses, along with a covering letter and reply-paid envelope for return of the completed questionnaire. Those participants who failed to return their questionnaire within 3 weeks were sent a reminder letter, a further copy of the questionnaire and a reply-paid envelope. If questionnaires were returned to the trial office marked ‘return to sender’, every effort was made to obtain updated contact details from the participant’s dental practice.

Three-year follow-up

As at baseline, dentists and hygienists were asked to complete the clinician CBQ. These were collected by the OAs when they visited the dental practices to collect participant clinical outcomes.

Patient-centred outcomes were collected at the 3-year follow-up using the annual follow-up questionnaire, with an additional question on self-reported bleeding. The questionnaire was sent to participants at least 3 weeks before the date of the first 3-year follow-up appointment made at the dental practice where they were recruited. Participants who had not returned a questionnaire by the time of their follow-up appointment were asked to complete a shortened one-page version of the follow-up questionnaire containing questions on the primary patient-centred outcome (self-efficacy) at that appointment. Participants who did not attend the follow-up appointment and who had not returned a questionnaire were sent a reminder letter, a further copy of the questionnaire and a reply-paid envelope to return the completed questionnaire to the CHaRT trial office.

All trial participants were invited to attend a trial follow-up assessment appointment by their dental practice either at the time of their routine check-up or at a separate trial assessment appointment at which the clinical outcomes were measured by trained OAs who were blinded to allocation. As at baseline, gingival inflammation/bleeding scores, clinical probing depths and calculus were measured by the OAs and recorded on the follow-up clinical chart by the dental research nurse who was a member of the trial team.

Participants who could not attend were contacted and given the option of attending on at least one other day or time.

All participants who attended the follow-up assessment received a certificate of appreciation for their participation in the trial, details of when the trial results would be published and a £25 gift voucher in recognition of their contribution.

Sample size

The study was powered to detect a difference of 7.5% in the number of gingival sites showing bleeding on probing at 3 years’ follow-up between routine and personalised OHA and for each pairwise comparison across both routine and personalised OHA groups. An OHA exploratory trial32 in the same population demonstrated that, at baseline, 35% of gingival sites were bleeding on probing with a SD of 25%.The PI Cochrane review24 suggested that a reduction of 15% of sites with bleeding was a plausible reduction for 6-monthly PI. If the effect is assumed to be linear, halving the number of PIs should half the expected difference of 15% of sites. If the effect is non-linear and the difference is > 7.5%, the trial would be adequately powered. A smaller effect would be of questionable clinical significance. There is some evidence that personalised OHA can reduce the number of gingival sites that bleed on probing by approximately 7.5%. 32

Oral hygiene advice

Assuming a conservative estimate of the intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.05, a cluster RCT of 50 dentists collecting information from 25 patient participants each (25 × 25 = 625 patient participants per arm) was expected to have 90% power to detect a difference of 7.5%. Should the ICC be 0.1, the trial would still have approximately 80% power to detect a difference of 7.5%.

Periodontal instrumentation

Given that the comparison of routine versus personalised OHA required 625 participants in each arm, equal randomisation 1 : 1 : 1 (no PI, 12-monthly PI, 6-monthly PI) of participants implied 208 in each of the six groups. Assuming no interaction effect, the corresponding PI groups could be combined across both routine and personalised OHA groups, requiring 416 patients allocated to each PI group. Based on a sample size of 416 in each group, the trial has in excess of 95% power for each pairwise comparison to detect a difference of 7.5% in the percentage of gingival sites that bleed on probing.

Interaction

A substantive interaction effect between the PI interventions and the personalised OHA was not expected. Assuming an ICC of 0.05, the trial had 80% power to detect an interaction effect of 7.5%. Should the ICC be 0.1, the trial had approximately 80% power to detect an interaction effect of 10%.

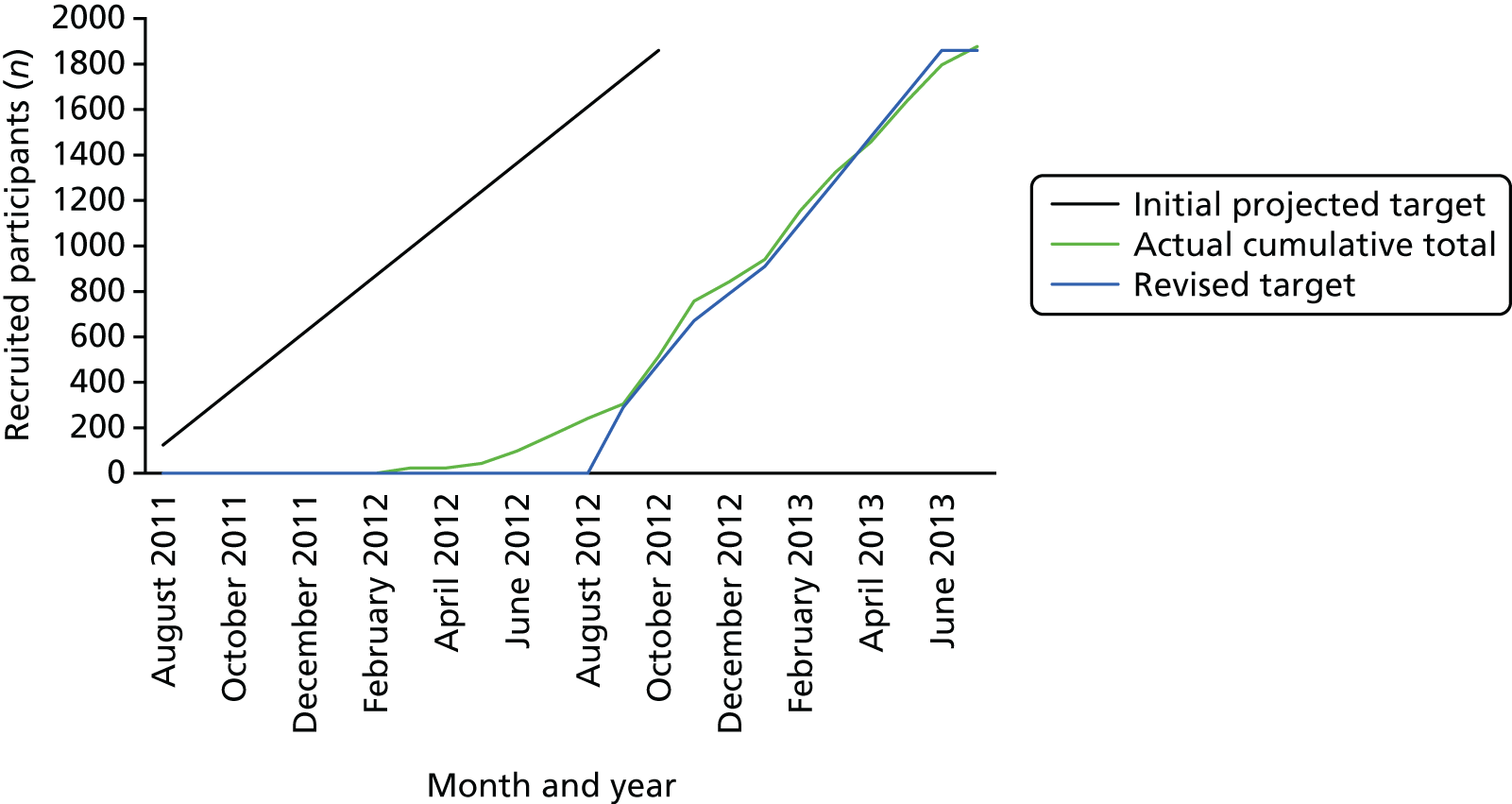

The total number of dentists required was 50, and the total number of participants was 1248 (6 × 208). A previous trial36 in general dental practice suggests that we should expect to lose a small number of dental practices from the trial for reasons such as practices amalgamating with other practices or restricting NHS patients; a conservative assumption of 17% attrition for dentists and 20% for participants was anticipated, requiring a minimum of 60 dentists and 1860 participants. Each dentist was required to recruit, on average, 31 participants to ensure 25 at follow-up.

Collection of providers outcomes

Differences in the frequency of PI visits would have an impact on clinicians’ costs and benefits. The effect on incomes, job satisfaction and changes to the level of fees on the provision of PI were assessed using self-reported questionnaires administered to clinicians over the duration of the trial.

Statistical analyses of outcomes

Statistical analyses were based on all participants randomised. Three principal comparisons and their interactions were tested in the factorial design. The principal comparisons were between (1) all those allocated to routine OHA and all those allocated to personalised OHA, (2) all those allocated to no PI and those allocated to 6-monthly PI and (3) all those allocated to 12-monthly PI and those allocated to 6-monthly PI.

Reflecting the clustered nature of the data, the clinical outcomes were compared using mixed models with dental practice as a random effect, and with adjustment for minimisation variables [practice employs dental hygienist (yes/no) and practice size (one or two dentists in practice/three or more dentists) for the cluster-level randomisation and absence of gingival bleeding on probing (yes/no), highest sextant BPE score (BPE score of < 3/BPE score of 3) and currently smoking (yes/no) for the patient-level randomisation] and participant baseline values (when available) as fixed effects. Patient-centred outcomes were compared using a mixed model with a random effect for the participant (to take into account the three-level nested and correlated data structure: a variable number of observations nested within participants and participants grouped in dental practices) and another for the centre and adjusting for the same variables as before. Statistical significance was at the 5% level, with corresponding confidence intervals (CIs) derived.

Pre-planned subgroup analyses on the primary outcome included exploration of participant age (< 45 years, 45–64 years or ≥ 65 years), smoking status (non-smoker or smoker), periodontal disease severity (no clinical signs or presence of gingival bleeding on probing) and intervention provider (dentist or practice hygienist). Post hoc subgroup analyses were undertaken by region (Scotland or England) and clinical pocket depth (four or more sites with clinical pocket depth of ≥ 4 mm, or fewer than four sites). These analyses were conducted by including a subgroup by treatment interaction term in the primary outcome model described above. Conservative levels of statistical significance (p < 0.01) were sought, reflecting the exploratory nature of these pre-planned and post hoc subgroup analyses.

Non-response analysis

Descriptive data are presented, comparing the baseline characteristics of participants who did and who did not attend the 3-year follow-up clinical appointment. The t-test (continuous outcomes) and chi-squared test (dichotomous outcomes) were used to estimate the statistical significance of the differences between responders and non-responders.

Missing items

Missing items were dealt with according to the relevant published recommendations for the specific instruments. 35 For missing items with no published recommendation, self-efficacy, PBC, attitude and subjective norm were calculated as a mean of the items available. Behaviour and intention were calculated using complete cases.

Sensitivity analysis

To assess the possible effect of outliers, treatment effects by individual dental practices were explored to assess the influence of between-centre differences in the primary clinical outcome: bleeding. Any practices where the treatment effect excluded zero from the 99% CI and had at least twice the target difference estimate (either –15% or 15%) were excluded from the analysis comparing no PI with 6-monthly PI, as well as from the subgroup analysis.

Trial oversight

The University of Dundee acted as sponsor for the study. The trial was co-ordinated from the TCOD in the Dental Health Services Research Unit, University of Dundee, which provided day-to-day support for the dental practices and OAs/research nurses. The TCOD was responsible for transacting the randomisation of dental practices, collecting trial data (including baseline questionnaires) and co-ordination of participant follow-up. CHaRT, in the Health Services Research Unit, University of Aberdeen, provided the database applications and information technology (IT) programming for the trial, hosted the randomisation system, co-ordinated the participant follow-up questionnaires, provided experienced trial management guidance and took responsibility for all statistical aspects of the trial [including interim reports to the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and the Data Monitoring Committee (DMC)]. A Project Management Committee (PMG) met monthly, chaired by the chief investigator, comprising co-investigators in Newcastle upon Tyne and key members of the TCOD and CHaRT. A Trial Management Committee (TMC) met biannually, chaired by the chief investigator, comprising co-investigators and key members of the TCOD and CHaRT. A Periodontal Advisory Group was convened to provide expert clinical advice to the TMC.

Independent TSCs and DMCs were also established. The TSC comprised an independent chairperson (a professor and honorary consultant of dental public health) and two further independent members (both members of the public acting as patient representatives). The TSC met approximately annually over the course of the trial. The DMC comprised an independent chairperson (a professor of restorative dentistry) and two further independent members (a professor of dental public health and a statistician). The DMC met approximately annually.

Patient and public involvement

Prior to the start of the IQuaD trial, patients were involved with the trial design and provided invaluable feedback on trial recruitment and communication strategies. Patients also contributed to the content and layout of the trial invitation, trial newsletters and the design of patient participant questionnaires. This ensured that trial participants could understand and easily complete these materials. Members of the public also contributed to trial oversight through membership of the TSC, including helping to interpret the trial findings and the preparation of the monograph.

Protocol amendments after trial initiation

A number of protocol revisions were made after trial initiation. These included:

-

an amended start date, list of grant holders, TSC members and DMC members

-

clarification of the measurement of gingival bleeding and the list of grant holders was updated

-

an amended timescale for sending patient information to ‘at most 6 weeks’, in line with routine practice for scheduling check-up appointments

-

an amended end date, in line with approved contract variation.

Adaptations of study administrative processes (e.g. the use of additional letters, revisions to letters) were also implemented.

Chapter 3 Health economic methods

The health economics analysis assessed the cost–benefit of theory-based, personalised OHA or PI at different time intervals (no PI, 12-monthly PI or 6-monthly PI), or their combination for improving periodontal health in dentate adults attending general dental practice. A cost–benefit analysis (CBA) reporting incremental net benefit, relative to standard care (routine OHA with 6-monthly PI), was conducted alongside the cluster RCT. Costs were assessed from a NHS perspective and a wider societal perspective including both NHS and participant costs. Benefits were assessed using a general population’s WTP for personalised OHA and PI, estimated from a discrete choice experiment (DCE). All analyses were based on the intention-to-treat (ITT) principle.

Cost–benefit analysis is based on the concept of maximising societal welfare including a wider, more holistic measure of value, going beyond narrow measures, such as quality-adjusted life-years, which are not appropriate in the context of dentistry. In CBA, both costs and benefits are measured in monetary terms and net benefits (benefits – costs) can be directly interpreted as either welfare increasing or welfare decreasing. The CBA conducted here is an incremental analysis of alternative policies of OHA with/without PI in terms of costs and benefits (WTP). The analysis focuses on whether moving from standard care to an alternative policy increases or decreases welfare.

Resource use and costs

Health service costs and Participant costs describe the methods for generating NHS and participant perspective costs, respectively.

Health services costs

Use of NHS dental services

Resource utilisation data for NHS treatments at dental practices over the trial follow-up period were collected using routine sources held by the ISD of the Scottish Government and the NHS BSA in England. Dentists are paid on the basis of claims and, therefore, relatively rich and reliable routine data on NHS dental care provided are available. Dental claims data were linked to the trial data set on an individual level to each trial participant.

Different remuneration systems are in place across the UK, which has implications for the level of detail that is available on resource use.

In Scotland, NHS payments are based on fee-for-service contracts. There is a high level of detail, as fees are attached to each individual item of service. This includes a separate fee for PI. Although there is a separate fee for intensive hygiene instruction, this cannot be claimed if a PI was claimed within the same course of treatment or within the previous 5 months.

In England, dentists are reimbursed according to contracts negotiated at (1) national level [General Dental Service (GDS) contracts negotiated through the British Dental Association] or (2) local level (personal dental contracts). The former accounts for 85% of dental contracts in England and forms the basis for the trial costing analysis. 37 Under the GDS contracts, each dental practice is contracted to provide an agreed amount of dental treatment, described in terms of UDAs. Treatments provided to participants are grouped into four bands based on the complexity of the treatment. Each band carries a set number of UDAs,38 as follows:

-

Band 1 (check-up, radiography, advice, PI) = 1 UDA.

-

Band 2 (band 1 treatments plus fillings, extractions, root canal treatments) = 3 UDAs.

-

Band 3 (band 1 and band 2 work plus crowns, dentures, bridges) = 12 UDAs.

-

Urgent band = 1.2 UDAs.

A number of services do not fall into any of the patient charge bands in their own right, but are awarded UDAs when provided outside other banded treatments. The number of UDAs for such treatments is as follows:

-

Arrest of bleeding = 1.2 UDAs.

-

Bridge repair = 1.2 UDAs.

-

Denture repair = 1.2 UDAs.

-

Issue of prescriptions = 0 UDAs.

-

Removal of sutures = 1 UDA.

As dentists in England are reimbursed on the basis of UDAs, the level of detail on resource use is clearly much lower than in Scotland. The claim form (FP17) in England collects some further information on treatments provided, including PI, but these are not associated with additional payments. Given the structure of the contract, it is less likely that there will be a difference in costs across the different policies in England as PIs and personalised OHA are not associated with any additional UDAs if they are provided alongside other treatments such as a dental check-up.

Costs were attached directly to items of service (Scotland) and treatment course bands (England) using the appropriate NHS unit cost. Unlike other NHS services, patients contribute to the cost of their dental care. The cost to the NHS is therefore equal to the unit cost minus the appropriate patient charge. The Scottish Statement of Dental Remuneration – Amendment No 130 Letter39 was used to attach unit costs to the treatment items in Scotland. In England, the cost of a UDA delivered under the GDS contracts can vary widely by practice. Determining an average cost per UDA across England is not straightforward. The 2009 Steele report40 suggested that the value of a UDA was approximately £25, but that actual practice-specific values ranged widely from £17 to £40. Work informing National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) public health guidance on oral health promotion41 assumed a mean cost of £25 (95% CI £15 to £35). We conducted a descriptive analysis of published data for contract payments in England in 2014/1537 and found that the median gross value (prior to deduction of participant charges) of a UDA (after removal of payments for units of orthodontic activity) is still approximately £25, ranging from £20 to £33 (5th to 95th percentile). Therefore, we use a unit value of £25 per UDA for the analysis. The NHS cost per UDA is varied in the sensitivity analysis to explore the impact of practice-level variation on results.

Some patients do not pay a co-charge (e.g. those in receipt of income support, pension credit, universal credit or tax credit, as well as those aged < 18 years, in full-time education or who are pregnant or who have given birth in the last 12 months). Table 2 summarises the most common breakdown of costs in England and Scotland. When participants were exempt from treatment charges, the full cost was attributed to the NHS budget. We tested for any cross-group differences in the proportion of participants exempt from charges, as any differences could bias predictions of incremental NHS costs. We also repeated the cost analysis assuming that all participants were exempt, that is, the NHS bears the full cost.

| Region | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| England | Scotland | |||||

| Treatment category | Total UDA cost (£) | aPatient charge (£)38 | NHS cost (if charge is paid) (£) | Treatment category | Patient chargea | NHS cost |

| Band 1 | 25.00 | 18.50 | 6.50 | Check-ups and case assessments | 0% of full cost | 100% of full cost |

| Band 2 | 75.00 | 50.50 | 24.50 | Other treatments | 80% of full cost | 20% of full cost |

| Band 3 | 300.00 | 219.00 | 81.00 | Maximum charge per course of treatment | £384.00 | Unlimited |

| Urgent | 30.00 | 18.50 | 11.50 | |||

Data are in the form of courses of treatment that have a commencement date and a claim payment date (Scotland) or a completion date (England). The base-case analysis excludes the baseline and final study visits, as treatments provided at these visits are not part of routine care nor the trial intervention. The exception is the provision of personalised OHA at the baseline visit. However, as explained above, these are typically not associated with additional payments in either region. A sensitivity analysis was conducted to explore the impact of including an additional fee for personalised OHA.

The baseline visit is excluded from the analysis by removing all treatment claims with an acceptance date < 90 days following the baseline examination date. Owing to practice-specific approaches to calling participants for their final study visit, some had their final study visit prior to randomisation and others after 3 years post randomisation. To remove all final visits from the claims data, we excluded all treatment acceptance dates at > 2.5 years following the baseline study visit. This implies that, after exclusion of all baseline and final study visits, the follow-up period for the CBA is 2.25 years. Sensitivity analysis explores the impact on net benefits of including all the baseline and final clinic visits in the analysis.

Routine data downloads were taken in August 2016 (ISD, Scotland) and November 2016 (NHS BSA, England). For Scotland, data are a complete and accurate reflection of resource use up to 3 months prior to data download (i.e. May 2016). For England, the data are likely to be an accurate reflection of resource use up to April 2016, reflecting the end of the financial year, by which time dental practices are required to have submitted all relevant information. The final clinic examinations took place in July 2016. Given that the base-case analysis excludes claims with treatment acceptance dates beyond 2.5 years post randomisation, the latest treatment claims in the data set have acceptance dates in February 2016 and, therefore, all data are assumed to provide an accurate and complete reflection of resource use for both regions.

All costs are presented in 2014/15 GBP values and discounted at a rate of 3.5% per annum. 42 A sensitivity analysis varying the discount rate was conducted.

Costs of other NHS services during follow-up

Annual questionnaires collected data on use of other NHS services for problems related to participants’ teeth. These included secondary care resource use [hospital inpatient data, outpatient consultations, day-case procedures and accident and emergency (A&E) attendances] together with general practitioner (GP) appointments and contact with NHS 24 (Scotland) or NHS Direct (England). As is common with participant-reported resource use, a number of conservative assumptions were made to address issues of discrepancy in the reported data:

-

When respondents reported that they did not attend a service but entered a number of visits, it was assumed that no resource use was incurred.

-

When respondents stated that they attended hospital as an inpatient for problems related to their teeth but provided no further information, it was conservatively assumed that such responses should be treated as day-case admissions. National data43,44 show that the majority of hospital admissions in the UK for dental problems are day-case procedures.

Rates of secondary care visits, including outpatient, day-case and hospital admissions, were checked against practice records and average rates in the general population to assess their validity. The outcomes of the validation exercise are reported in Chapter 5.

Participant costs

Three sources of participant cost were considered for the analysis: (1) charges for NHS dental care, (2) privately purchased dental care products and treatments and (3) time and travel costs (for participants and companions) associated with visits to the dental practice.

Charges for NHS dental care

Participant charges were sourced directly from the routine data sets described in Health services costs. Participant charges were based on the co-charge that should have been collected at the dental practice, as opposed to the actual value paid by the participant. This reflects the way in which dental practices are paid.

Self-purchased dental care products and private dental care

Participants reported how often they used interdental brushes, electric toothbrushes and manual toothbrushes in the annual questionnaires, as well as how often they replaced electric toothbrush heads. These resource use data were combined with an assumed average market price for four commonly available products, including a range of high- and low-cost items. Details of unit costs applied are provided in Appendix 2, Section 1: additional detailed methods for costing, the discrete choice experiment and mapping discrete choice experiment valuations to the trial outcomes. Resource use was multiplied by the average unit cost to generate a cost per participant.

Furthermore, in each annual questionnaire, participants were asked to recall and report the total cost of private PI and any other privately purchased dental care that they incurred over the previous year. It should be noted that, although participants were asked to report how often they received private PI, it may be difficult in some scenarios to determine whether treatment was private or via the NHS because, for example, many NHS dentists may also offer private PI. For this reason, there may be a risk of double-counting from the participant perspective, but only if NHS co-charges were interpreted as private treatment. All reported data were summed across the questionnaires to generate a cost to each participant of self-purchased dental care products and stated private care costs.

Costs of time and travel

Participants incur costs travelling to, and attending, NHS dental appointments. The number of visits to the dentist was collected from the routine data sets, conservatively assuming that each unique treatment acceptance date (rather than each claimed item) relates to a single dental visit. The true costs may be higher if a course of treatment involved more than one visit to the dentist. The opportunity cost to participants and companions of making a return journey to visit the dental practice was estimated using responses to the participant time and travel cost questions in the baseline questionnaire. It is assumed that the data collected on opportunity cost at baseline are applicable to each subsequent visit to the dental practice. National unit cost sources (Table 3) were used to value time commitment of attendance (including travelling to and from) at a dental appointment, as well as the opportunity cost based on the reported activity forgone through attendance. The calculated opportunity cost for a single visit was multiplied by the number of treatment courses from the routine data to generate a total participant level estimate of the opportunity cost of time and travel.

| Activity | Assumptions made | Unit cost (£) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paid work | Median weekly wage: £528; 39.1 hours per week | 13.50 | Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings: 2015 Provisional Results, ONS45 |

| Self-employed | Average of two reports, 52 weeks, 40 hours per weeka | 15.13 |

The Boox Report 2014, Boox46 Cost Converter, EPPI Centre47 Self-employed Workers in the UK – 2014, ONS48 |

| Transport | Cost per mileb | 0.45 | Expenses and Benefits: Business Travel Mileage for Employees’ Own Vehicles, HMRC (approved millage rate)49 |

| Caring for a relative or friend | Median gross weekly pay: £341; 39.2 hours per weekc | 8.70 | NHS Pay Review Body, p. 17 (2015 values), DHSC50 |

| Leisure activities | Value of non-working time | 6.81 | WebTAG: TAG data book, July 2016, TAG51 |

| Childcare | Assumed as paid work | 13.50 | Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings: 2015 Provisional Results, ONS45 |

| Voluntary work | Assumed as paid work | 13.50 | Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings: 2015 Provisional Results, ONS45 |

| Unemployed | Value of non-working time | 6.81 | WebTAG: TAG data book, July 2016, TAG51 |

| Retired | Value of non-working time | 6.81 | WebTAG: TAG data book, July 2016, TAG51 |

| Parking | Participant’s individual costs | Various | Participant questionnaires |

| Housework | Cost of housework in the NHS, assumed annual salary £21,000 gross, 2012 values inflated to 2015 | 10.56 | NHS Pay Review Body, p. 17 (2015 values), DHSC50 |

Combined participant and NHS perspective costs

Data from Health services costs and Participant costs were combined to generate a wider combined NHS and participant perspective of the costing analysis.

Statistical analysis of cost data

Cost data were analysed according to best practice methodology for cluster randomised trials. 52–54 We used multilevel mixed-effects models that account for clustering of the data through a cluster-level random effect. 52 Models for cost data were estimated using the meglm command in Stata® 14 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) specifying a gamma family and log-link function for cost data to account for skewness of the distribution. The decision to use this model for costs was based on a combination of the results of a modified Park’s test, which identified both an inverse Gaussian and gamma distribution to be acceptable, and software restriction (only gamma family allowed within Stata’s meglm command). The log-link function was decided on as it allowed easier model convergence and had a preferred Akaike information criterion score than an identity link. The models were estimated by maximum likelihood. Incremental costs were estimated as the mean cost difference between randomised policies (relative to the policy most representative of standard care: routine OHA with 6-monthly PI), together with 95% CIs. All models were adjusted for baseline characteristics (age, age-squared and sex) as well as minimisation variables (cluster level: hygienist employed at practice and practice size; individual level: smoker, gingival bleeding at baseline and BPE score band).

Owing to the high level of completeness, descriptive analyses of NHS dental costs and participant co-charges were based on complete cases. Participant costs were presented and analysed using multiple imputation of missing cost data from participant annual questionnaires. For the analysis of total costs within the CBA, the small proportion of missing routine data were also imputed to complete the data set. The imputation process followed best practice guidelines. 55,56 All imputation was completed using Stata’s multiple imputation procedure. Missing cost data were imputed at the level of cost component (e.g. missing data on private PI imputed for each annual questionnaire). Costs were imputed using predictive mean matching accounting for the repeated measures nature of the costs from the annual participant questionnaires. The average of the five closest values was used for each imputed data point. Data were imputed separately for each randomised group to preserve the allocation of participants. Imputation models were adjusted for cluster, age and sex as well as minimisation covariates. Sixty imputed data sets were used to ensure stable results and were combined using Rubin’s rules to generate estimates of costs. 57

Benefits (willingness to pay)

The main outcome measure in the economic evaluation is WTP, estimated using a DCE administered via online survey panels to a representative sample of the UK general population. The DCE was administered to a separate sample from the general population while the trial was ongoing and before the results of the trial were known. A DCE is a survey method for which participants are asked to make hypothetical choices between different goods or, in this case, different packages of dental care provided over 3 years (the follow-up period of the trial). An underlying assumption of all DCEs is that a treatment’s or service’s value depends on its attributes and the levels of those attributes. By including the price proxy within the DCE (i.e. the annual cost of each dental package), we can obtain a monetary valuation for any given dental treatment package. These WTP estimates are used as a measure of benefit within the CBA. Ethics approval for the conduct of the DCE substudy was obtained from the College Ethics Review Board at the University of Aberdeen (REF 2015/12/1278).

Selection of attributes and levels

The relevant attributes were, to a large extent, determined by the trial. Preferences needed to be elicited for the specific interventions (PI and personalised OHA) and for the outcomes that may vary across the arms of the trial (i.e. self-reported bleeding gums and perception of appearance and feel of cleanliness). We followed recommended practice to assess whether or not these attributes were important to individuals and whether or not there were any other important attributes that should be included in the DCE. We conducted a literature review and focus groups (FGs) with the general population to develop the final list of attributes and levels to present in the DCE (see Appendix 2, Section 2: research conducted for questionnaire development). We also engaged with, and sought advice from, a range of stakeholders, including clinical dental experts, practising dentists and hygienists, and patient representatives on our trial advisory group about the DCE content. Table 4 shows the final list of attributes and levels included in the DCE.

| Attributes | Levels |

|---|---|

| Dental advice | No detailed or personalised advice |

| Detailed and personalised advice from the dentist | |

| Detailed and personalised advice from the hygienist | |

| Scale and polish | None |

| One per year from the dentist | |

| One per year from the hygienist | |

| Two per year from the dentist | |

| Two per year from the hygienist | |

| Your teeth will look and feel | Very unclean |

| Unclean | |

| Moderately clean | |

| Clean | |

| Very clean | |

| In 3 years’ time, your gums will bleed | Never |

| Hardly ever | |

| Occasionally | |

| Fairly often | |

| Very often | |

| The cost to you | £10 per year (total cost: £30 over 3 years) |

| £20 per year (total cost: £60 over 3 years) | |

| £50 per year (total cost: £150 over 3 years) | |

| £100 per year (total cost: £300 over 3 years) | |

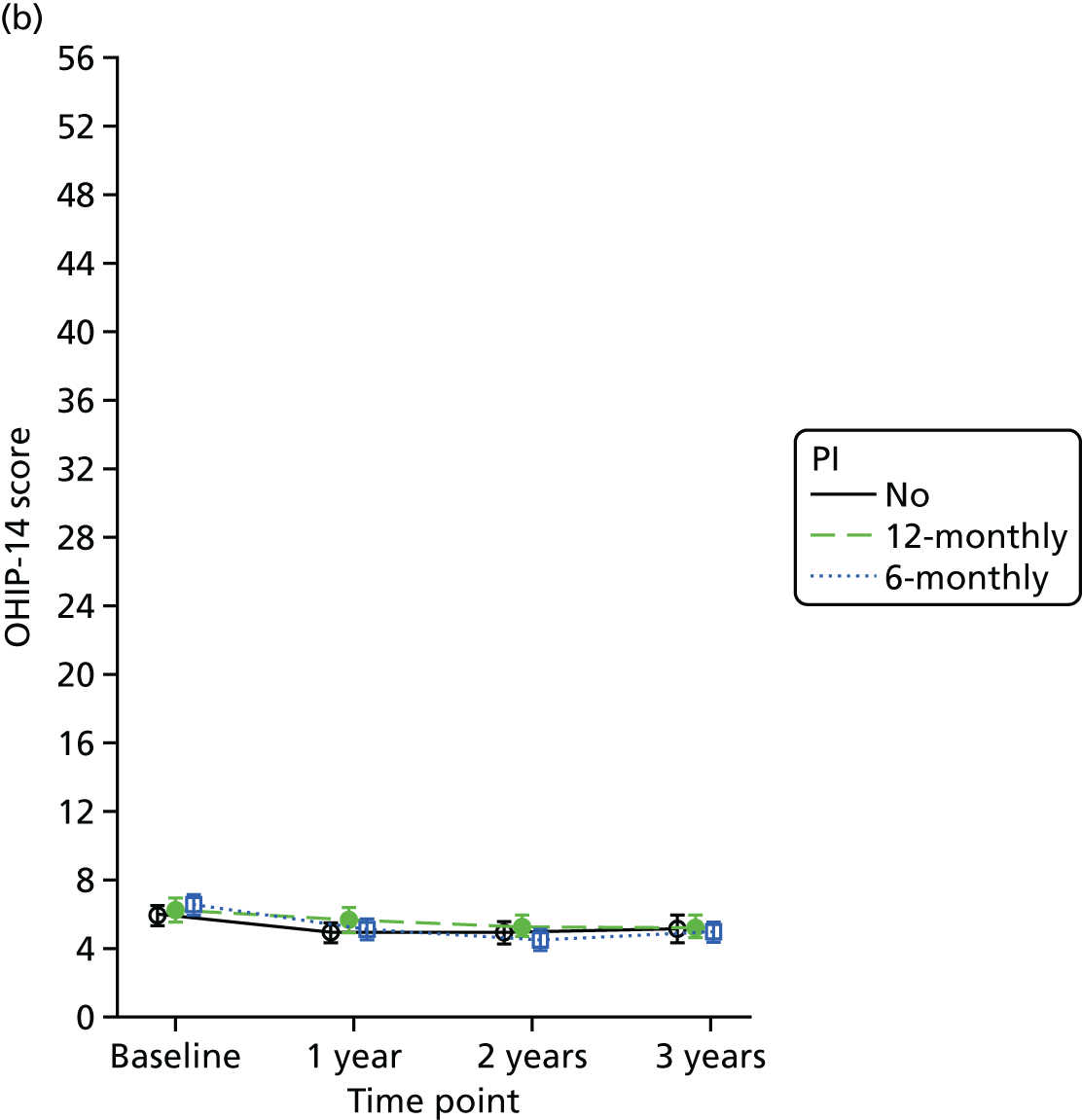

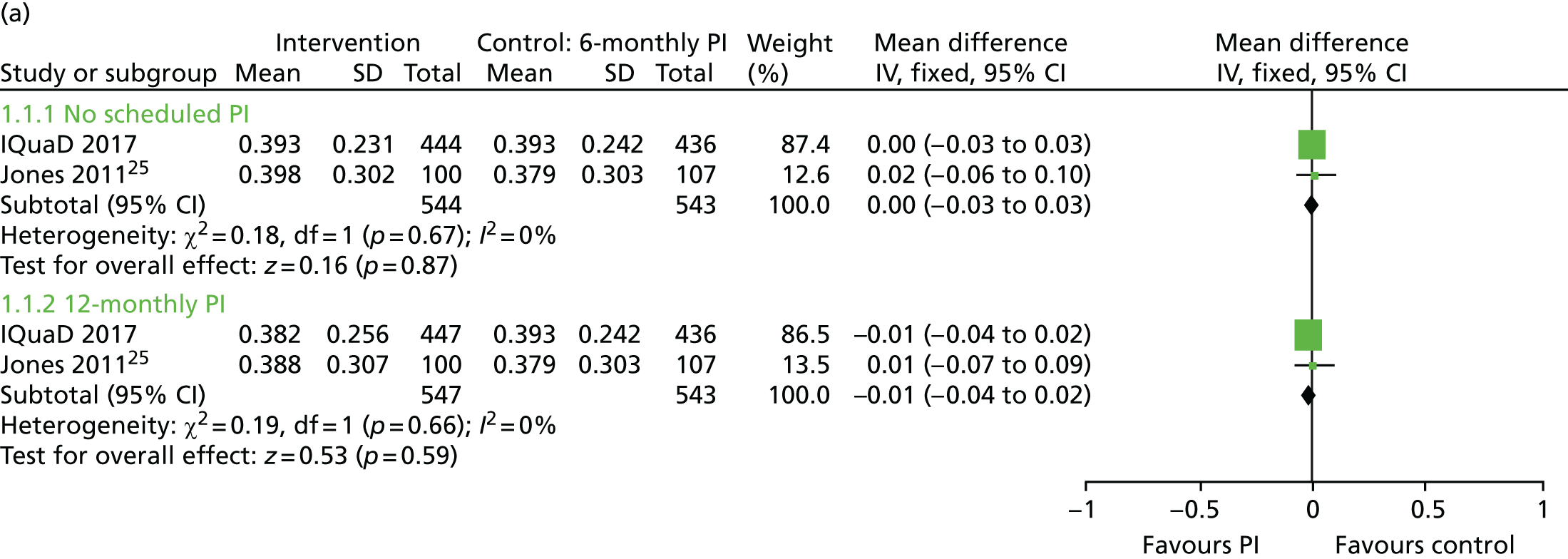

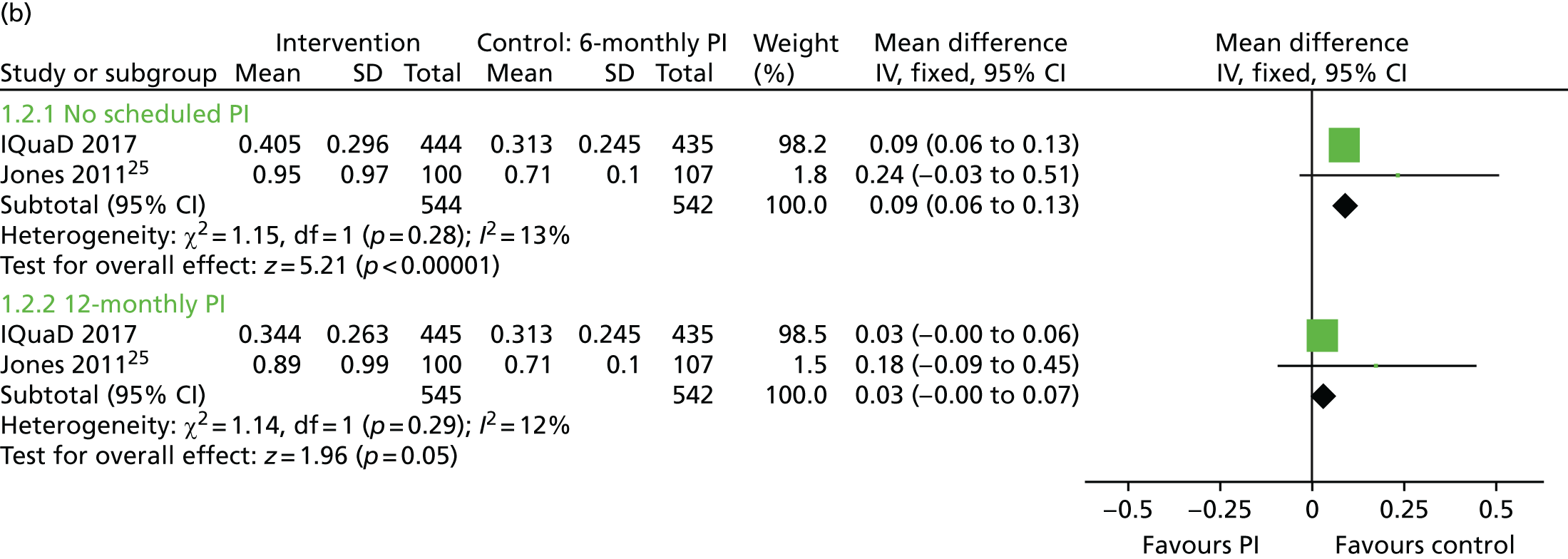

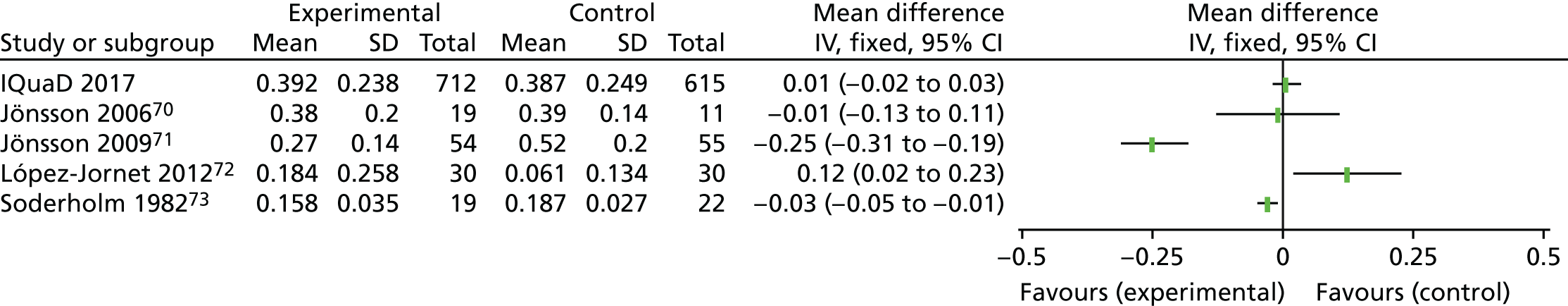

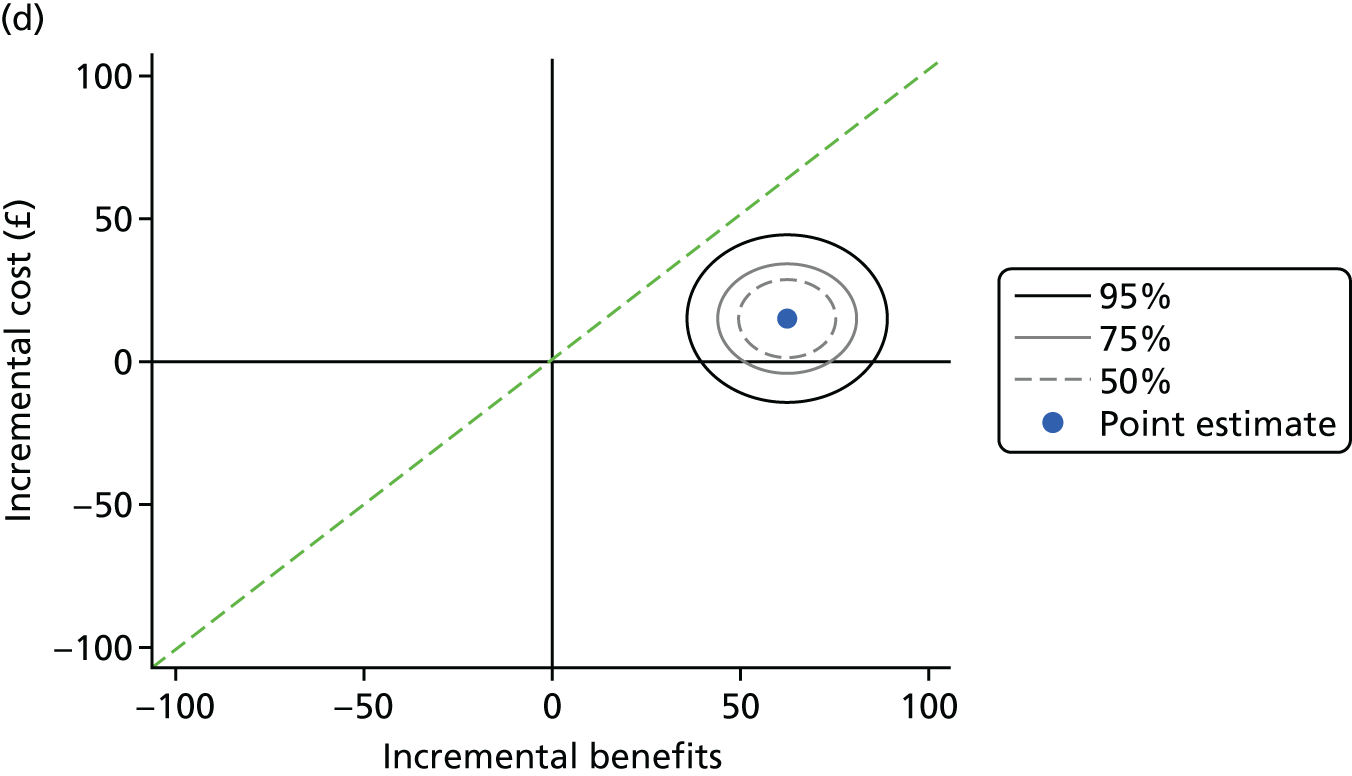

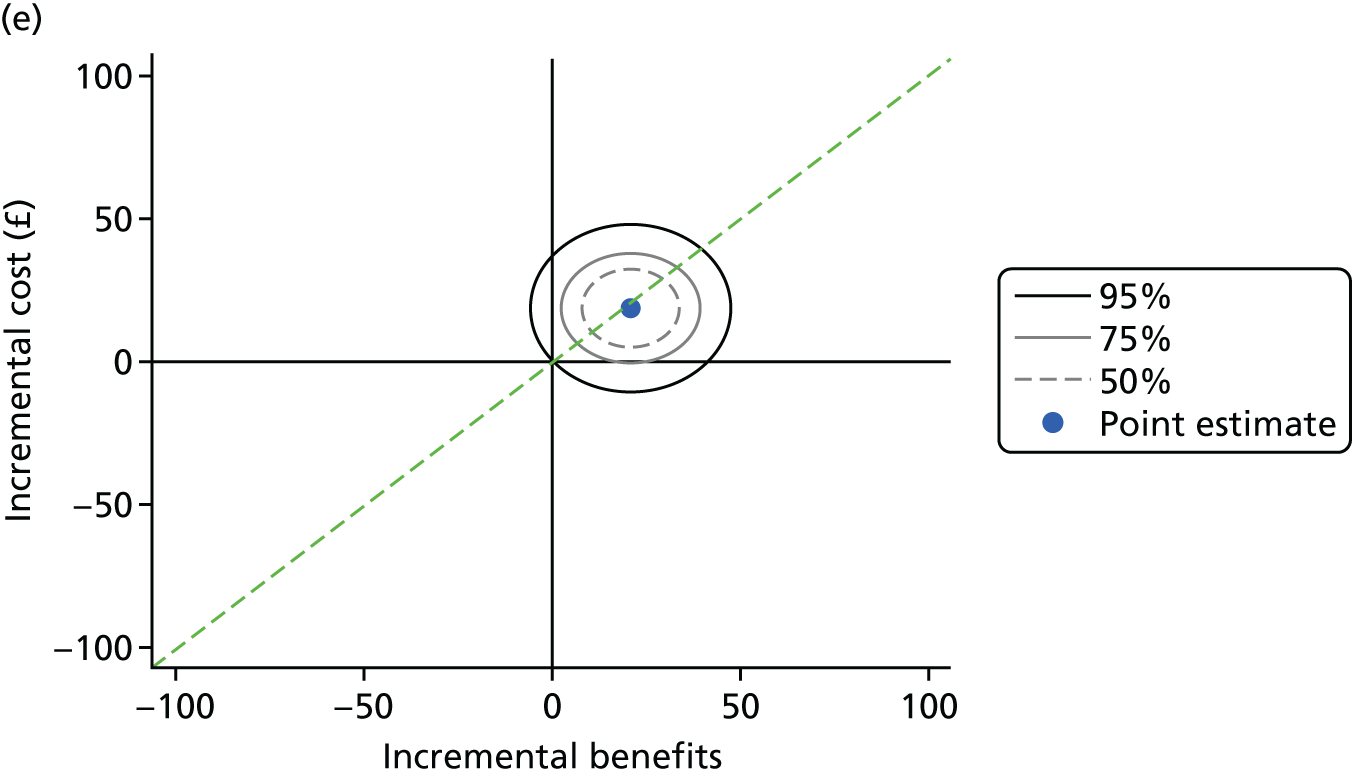

| £200 per year (total cost: £600 over 3 years) |