Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 09/22/67. The contractual start date was in April 2016. The draft report began editorial review in November 2016 and was accepted for publication in July 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Hashim U Ahmed reports grants and personal fees from SonaCare Medical, Sophiris Bio Inc. and Galil Medical and grants from TROD Medical outside the submitted work. He conducts private practice in London for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with potential prostate cancer through insurance schemes and self-paying patients in addition to his NHS practice. Ahmed El-Shater Bosaily reports grants and non-financial support from University College London Hospitals/University College London Biomedical Research Centre, grants and non-financial support from The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust and the Institute for Cancer Research Biomedical Research Centre and non-financial support from the Medical Research Council’s Clinical Trials Unit during the conduct of the study. Mark Emberton reports grants from Sophiris Bio Inc., grants from TROD Medical, other support from STEBA Biotech, grants and other support from SonaCare Medical and other support from Nuada Medical and London Urology Associates, outside the submitted work. Rita Faria reports grants from the National Institute for Health Research during the conduct of the study. Richard Graham Hindley reports payment as a Clinical Director from Nuada Medical during the period of recruitment. Alexander Kirkham reports other support from Nuada Medical outside the submitted work. Derek J Rosario reports personal fees from Ferring Pharmaceuticals Ltd and grants from Bayer Pharmaceuticals Division, outside the submitted work. Iqbal Shergill reports grants from Ipsen and Astellas Pharma Inc. and non-financial support from Boston Scientific and Olympus, outside the submitted work. Eldon Spackman reports personal fees from Astellas Pharma Canada, Inc., outside the submitted work. Mathias Winkler reports grants and personal fees from Zicom-Biobot (Singapore), outside the submitted work.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Brown et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Rationale

There are approximately 40,000 new cases of prostate cancer annually in the UK. The reported incidence has doubled in the last 15 years, mainly as a result of the increased use of serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing in healthy men. As a result, prostate cancer has become the most commonly diagnosed cancer in men. 1 Many, if not most, prostate cancers that are currently detected are clinically non-significant (CNS) (i.e. would have no clinical impact during the man’s remaining life expectancy). Although the UK has no formal population-based PSA screening programme, the rising numbers of cases in the UK are primarily the result of increased awareness and incidental PSA testing. The existing diagnostic pathway will, if left unchecked, result in a further rise in the number of CNS cases identified and in the associated costs and harms of treatment, without necessarily reducing the risk of dying from the disease.

This position is exemplified in two large randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of population-based prostate cancer screening using serum PSA testing compared with standard practice. First, a large RCT of prostate cancer screening in the USA2 showed no evidence of a survival benefit when comparing an annual screening strategy (with an approximately 85% rate of screening) with usual care, which included quite considerable rates of PSA testing (approximately 46–52%). Second, the European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer3 showed a modest reduction in the risk of death from prostate cancer in men who were screened every 4 years, from 8.2% to 4.8% [risk ratio 0.8, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.65 to 0.98] at 9 years’ follow-up. The number of participants needed to screen was 1410 and the number needed to treat was 48 to prevent one death from prostate cancer over a 10-year period. 4 This benefit was maintained up to 13 years’ follow-up. 5

Once diagnosed, the lack of benefit for radical treatment of CNS cancer compared with a strategy of monitoring has been exemplified in three RCTs. First, the Scandinavian Prostate Cancer Group – 4 (SPCG-4) trial6 randomised men who were clinically diagnosed (not from screening). Most of these men had clinically significant (CS) medium- to high-risk cancers and radical prostatectomy (RP) showed a survival benefit at long-term follow-up compared with watchful waiting (a less active form of surveillance than that used in the modern era). 6 Treatment conferred significant harms for patients. 7 Second, the Prostate Cancer Intervention versus Observation Trial (PIVOT)8 randomised men diagnosed early through PSA screening in the USA between watchful waiting and RP and found no cancer-specific survival benefit, although subgroup analyses showed that men with high-risk disease did survive longer with treatment and there was a possible benefit, albeit marginal, for those with intermediate-risk cancers. Most recently, the Prostate Testing for Cancer and Treatment (ProtecT) trial in the UK9 found that, in 1643 men with localised prostate cancer detected as a result of PSA-based screening, there was no statistically significant difference in prostate-specific or all-cause mortality at 10 years in men assigned to active surveillance, surgery or radiotherapy; however, rates of disease progression and metastasis were higher with active surveillance. Commentators were quick to voice their concern that overdiagnosis, and hence overtreatment and associated morbidity, would increase further if PSA screening was adopted more widely. 10,11 However, if a diagnostic method was available that was more specific to clinically significant prostate cancer, the beneficial effect of screening and subsequent treatment on mortality could be retained, but overdiagnosis and overtreatment would be minimised.

Current clinical pathway

At present, a man is judged to be at risk of harbouring prostate cancer if he has any of the following: a raised serum PSA level (present in the majority of cases), an abnormal digital rectal examination (DRE), a positive family history of prostate cancer or a specific ethnic risk profile. 12 The diagnostic pathway of interest to this work relates to men with signs and symptoms that are suspicious of prostate cancer who have been referred for confirmatory diagnostic testing. In these men, prostate cancer, if present, is typically localised. Men with signs and symptoms of locally advanced cancer or metastatic cancer are often managed in a different manner with staging whole-body scans and the institution of systemic therapy with or without confirmatory prostate biopsy.

Men in whom there is diagnostic uncertainty are currently advised to have a transrectal ultrasound (TRUS)-guided prostate biopsy. 13 Men with a negative TRUS-guided biopsy result are advised to consider multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging (mpMRI) (using T2- and diffusion-weighted imaging) to determine whether or not another biopsy is needed. Between 59,000 and 80,000 men have a TRUS-guided biopsy in the UK each year,14 although this is likely to be an underestimate considering that three to four TRUS-guided biopsies are usually carried out to diagnose one man with cancer.

Men diagnosed with localised prostate cancer in England are managed according to their risk of progression (Table 1). The risk of progression is assessed on the basis of their serum PSA concentration, Gleason score and clinical stage. PSA is a protein produced by the prostate gland; an elevated PSA level is a sign that cancer may be present. The Gleason pattern classifies prostate cells obtained in the TRUS-guided biopsy by level of differentiation, which is related to the degree of aggressiveness of prostate cancer. Cancer cells can be classified from Gleason grade 1 (well differentiated and lower risk) to Gleason grade 5 (poorly differentiated and higher risk). 13 The Gleason score is the sum of the grades of the two most common types of cells. For example, if the man’s most common cells are Gleason grade 3 and Gleason grade 4, the Gleason pattern is 3 + 4 = 7. The clinical stage is assessed by the urologist by DRE with or without imaging scans, although the majority of men diagnosed with prostate cancer also undergo pelvic and prostate magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) after the biopsy.

| Risk | PSA level (ng/ml) | Gleason score | Stage | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | < 10 | AND | ≤ 6 | AND | T1–T2a |

| Intermediate | 10–20 | OR | 7 | OR | T2b |

| High | > 20 | OR | 8–10 | OR | ≥ T2c |

The 2014 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) clinical guideline13 recommends that men with low-risk prostate cancer are offered active surveillance, as described in Table 2. Men with intermediate- or high-risk cancer should be offered active treatment. In men with intermediate-risk cancer, the 2014 NICE clinical guideline recommends RP or radical radiotherapy but considers active surveillance or high-dose-rate brachytherapy with external-beam radiotherapy as possible options. Men with high-risk cancer should be offered RP, radical radiotherapy or high-dose-rate brachytherapy with external-beam radiotherapy. Interestingly, the NICE guidance also recommends prostate MRI as a baseline test at the commencement of active surveillance. Under the current NICE guidance and clinical practice, therefore, almost all men who have a TRUS-guided biopsy are recommended to undergo MRI after biopsy.

| Timing | Testsa | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Enrolment in active surveillance | mpMRI if not previously carried out | Not applicable |

| Year 1 | PSA level | Every 3–4 monthsb |

| PSA kinetics | Throughout active surveillancec | |

| DRE | Every 6–12 monthsd | |

| Prostate rebiopsy | At 12 months | |

| Year 2 and beyond | PSA level | Every 3–6 monthsb |

| PSA kinetics | Throughout active surveillancec | |

| DRE | Every 6–12 monthsd |

The current clinical pathway and potential for imaging

Men undergo prostate biopsy in the absence of accurate imaging that can visualise a suspicious lesion, as ultrasonography is used to identify the prostate, not the suspect lesion. The result is that biopsies are taken ‘blindly’ from areas of the gland. Although protocols stipulate that the biopsies should sample certain regions in a fanlike manner, studies have shown that this is often not the case and that the biopsies are clustered. 15 This results in a random, rather than systematic, deployment of the needle. This approach (Figure 1) contrasts markedly with that used for other cancers, in which the physician either visualises (e.g. using endoscopy) or images (e.g. using mammography) a suspect lesion in order to guide a biopsy needle to it.

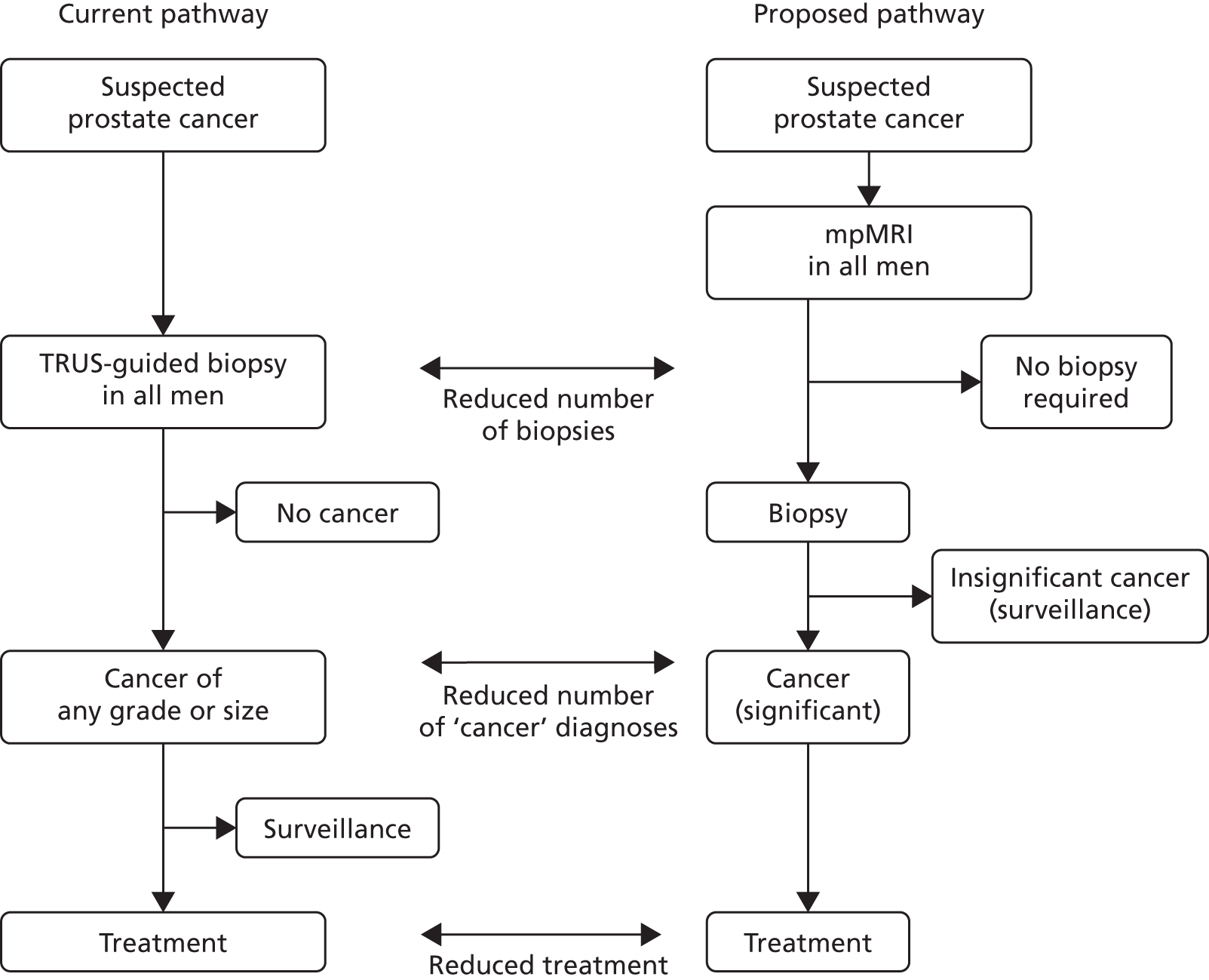

FIGURE 1.

Current and proposed diagnostic pathway for prostate cancer. Note that the proposed future pathway is not the pathway taken by patients in the Prostate Magnetic Resonance Imaging Study. Reproduced from El-Shater Bosaily et al. 16 © 2015 The Authors. Published by Elsevier Inc. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

The use of mpMRI prior to TRUS-guided biopsy could offer several important advantages:

-

less overdiagnosis – in that fewer CNS prostate cancers are detected by avoiding unnecessary biopsy of men who do not have CS cancer

-

less overtreatment – as fewer CNS prostate cancers are detected

-

increased detection of CS prostate cancers – by directing biopsies to areas of the prostate that appear abnormal on mpMRI

-

improved characterisation of individual cancers – as a result of more representative biopsy sampling

-

reduced complications (including sepsis and bleeding) – as fewer men are biopsied and fewer biopsies are taken in men who are biopsied.

In addition, a revised diagnostic pathway based on the findings of the PROstate Magnetic resonance Imaging Study (PROMIS) also has the potential to offer a more cost-effective use of NHS resources. This is explored in the accompanying economic evaluation.

Limitations of transrectal ultrasound-guided biopsy

-

Overdetection of CNS prostate cancer: men who undergo TRUS-guided biopsy have a 25% chance of being diagnosed with prostate cancer. 17 This compares with a lifetime risk of 6–8% for symptomatic prostate cancer, illustrating the overdiagnosis of harmless cancers in men who undergo TRUS-guided biopsies (Figure 2). 18

-

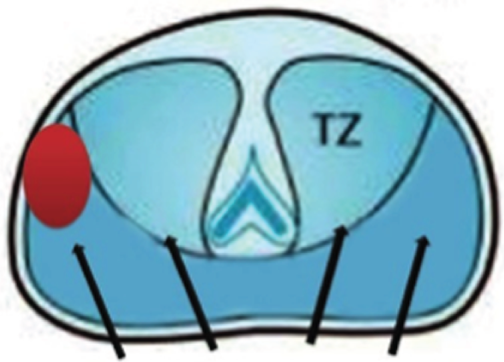

Underdetection of CS prostate cancer: TRUS-guided biopsies have an estimated false-negative rate of 30–45%, although the true false-negative rate is unknown as few studies have applied a detailed reference test to those men who have a negative TRUS-guided biopsy. 19,20 Although the clinician takes 10–12 biopsies in a manner that attempts to obtain representative tissue within the peripheral zone (Figure 3, left-hand image), several parts of the gland are not well sampled (a systematic error). The anterior part of the gland may be missed as a result of its greater distance from the rectum (Figure 3, middle and right-hand image). Tissue in the midline is missed as a result of efforts to avoid the urethra, whereas the apex of the prostate is often difficult to access by the transrectal route.

-

Inaccurate risk stratification: TRUS-guided biopsies can be unrepresentative of the true burden of cancer as a result of random sampling error (Figure 4). Either the size or the grade of cancer may be underestimated if the cancer tissue obtained in a TRUS-guided biopsy is not representative. 21 Figure 4 illustrates how accurate estimation of tumour size will depend on hitting the centre of a lesion. At present, because these lesions are not visualised, this relies purely on chance. However, improved risk stratification is likely if MRI results can be used to guide deployment of needles in biopsies.

Equally, the pathological status derived from TRUS-guided biopsies can be unreliable if the test is reapplied, for instance in active surveillance, not only in discriminating clinically important cancer from clinically unimportant prostate cancer but also in attributing a non-cancer status from a cancer status, in approximately one-quarter of men subject to serial testing. 22

-

Side effects: TRUS-guided biopsy is associated with a number of complications, the most important being urinary tract infection (in 1–8% of cases), which can result in life-threatening sepsis (in 1–4% of cases). Haematuria (in 50% of cases), haematospermia (in 30% of cases), pain/discomfort (in most cases), dysuria (in most cases) and urinary retention (in 1% of cases) can also be expected. 23–27

FIGURE 2.

Overdetection of CNS prostate cancer.

FIGURE 3.

Underdetection of CS prostate cancer.

FIGURE 4.

Inaccurate risk stratification.

Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging in diagnosing prostate cancer

The available evidence suggests that MRI can achieve both sensitivity and specificity of between 70% and 90% for the detection of CS prostate cancer. 28 However, a systematic review of the literature29 found the quality of the initial studies evaluating MRI to be disappointing. 30 They repeatedly showed low sensitivity and specificity as well as high interobserver variability, even when using high-resolution endorectal MRI. 31–37 Much has changed since these early reports, including an appreciation of the impact of post-biopsy changes on MRI; technological improvements such as increasing magnetic field strength (from 0.5 T to 1.5 T and 3.0 T); shorter pulse sequences enabling faster image acquisition; and the introduction of functional imaging in the form of diffusion weighting (DW) and dynamic contrast enhancement (DCE).

The main types of magnetic resonance images available are those produced by T2 weighting, DW and DCE. Multiparametric approaches (mpMRI, combining these three sequences together) have also been investigated. 38–48 Although their samples are small, single-centre case series have found an advantage of using two or three magnetic resonance sequences rather than just one. A recent systematic review49 incorporating studies that reported after PROMIS started has demonstrated the following ranges in accuracy metrics in studies using mapping biopsies and radical whole-mount prostatectomy specimens (often in retrospective case series): sensitivity, 73–95%; specificity, 28–87%; positive predictive value (PPV), 34–93%; and negative predictive value (NPV), 3–98%. However, no studies prior to PROMIS have prospectively evaluated the clinical validity of mpMRI in the population of interest (men at risk of harbouring prostate cancer who have not had a prior prostate biopsy) against an accurate and appropriate reference standard within a multicentre study in a double-blinded fashion.

Limitations of the magnetic resonance imaging literature

There are important limitations of previous studies investigating the diagnostic accuracy of MRI for prostate cancer:

-

Biopsy artefact: studies mostly evaluate MRI after biopsy; however, the biopsy procedure can affect what is seen on MRI, which can result in an increase in false-positive or false-negative results.

-

Limited application: studies mostly evaluate only the peripheral zone of the prostate, ignoring up to one-third of prostate cancers.

-

Segmentation: when each region of interest is segmented to achieve a sufficient number of data sets, increasing the power of the analysis and accuracy by incorrectly treating each region of interest as independent.

-

Poor reference standard: most studies use RP, leading to selection bias as those undergoing surgery tend to have burdens of cancer that are distinct from men with an abnormal PSA level, and patients choosing other treatments can never be evaluated. 50 Co-registration of a magnetic resonance image to a RP specimen is challenging because of shrinkage (10–20%), distortion, tissue loss as a result of ‘trimming’ (10%), orientation and absent perfusion.

These deficiencies, which mean that there is a discernible lack of level 1 evidence on the accuracy of mpMRI, probably account for the limited acceptance of MRI in contemporary prostate cancer diagnostic pathways. 51

The optimal reference standard: template prostate mapping

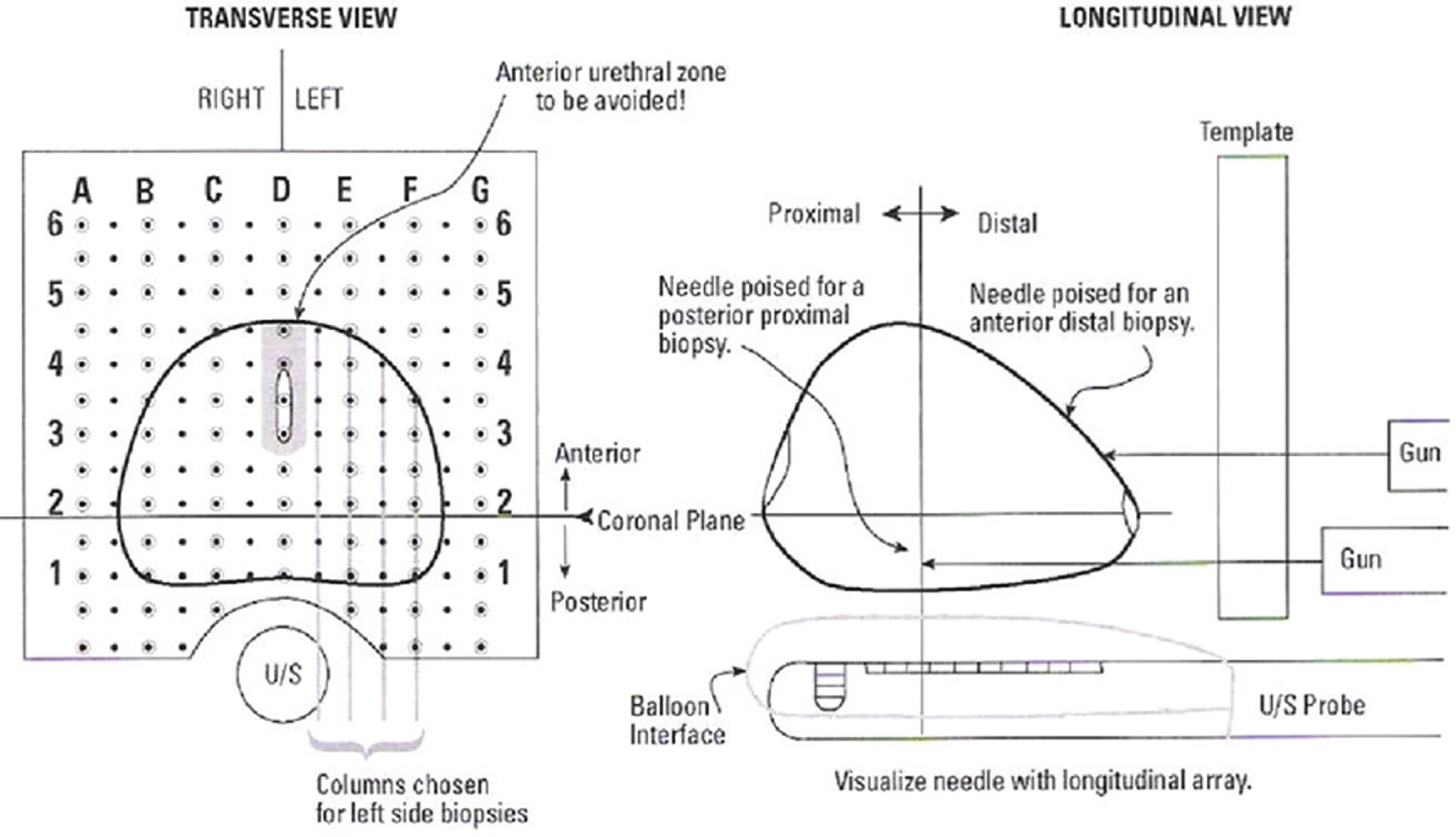

Template prostate mapping (TPM) biopsy was selected as the reference test for this study as it meets the required specification for our defined population when using 5-mm sampling52 (Figure 5). TPM-biopsy:

-

Produces a histological map of the entire prostate in three dimensions. 52–55

-

Has an estimated sensitivity and a NPV in the order of 95% for CS cancers when assessed against RP. 56–58

-

Avoids selection bias because all men exposed to the index test can be exposed to the reference standard.

-

Has a similar side-effect profile to that of TRUS-guided biopsy, with three important differences. TPM-biopsy:

-

carries a significantly lower risk of urosepsis (< 0.5%), as the needles do not traverse the rectal mucosa23 (urosepsis is the most serious complication of TRUS-guided biopsy)

-

confers a higher risk of self-limiting failure to void urine (5%) as a result of greater gland swelling; the risk is 5% compared with 1–2% associated with TRUS-guided biopsy55,59,60

-

requires general or spinal anaesthesia.

-

FIGURE 5.

Illustration of a TPM-biopsy procedure. Reproduced from El-Shater Bosaily et al. 16 © 2015 The Authors. Published by Elsevier Inc. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Although the accuracy of TPM-biopsy is high in the diagnosis of prostate cancer, it is not currently recommended as standard practice as it requires general anaesthesia and theatre time and so cannot be used routinely in the tens of thousands of men undergoing TRUS-guided biopsy. 61

Template prostate mapping biopsy is carried out in accordance with a set protocol and so can be conducted blind to any clinical or imaging data. Mapping using 5-mm sampling is obtained using core needles inserted via a brachytherapy grid fixed on a stepper placed against the perineum with the patient under general anaesthesia in the lithotomy position. In most prostates, two biopsies at each grid point are required to sample the full craniocaudal gland length.

Aims and objectives

The purpose of PROMIS was to assess the clinical validity (sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV) of mpMRI for the detection of CS prostate cancer and compare these accuracy metrics with those of TRUS-guided biopsy.

In particular, PROMIS aimed to evaluate whether or not mpMRI improves the ability to detect, as well as rule out, CS prostate cancer in a group of men at risk of harbouring prostate cancer, who have not had a previous biopsy and who would normally be advised to undergo a prostate biopsy as part of standard care. PROMIS was designed to determine whether or not it is appropriate for men with a risk factor for harbouring CS cancer to first undergo mpMRI to select who should have a prostate biopsy and who might safely forgo a first prostate biopsy. In other words, we sought to determine whether or not mpMRI could be used as a triage test prior to a first biopsy (see Figure 1). 62

The main objectives of the trial were to:

-

Assess the ability of mpMRI to identify men who can safely avoid unnecessary biopsy.

-

Assess the ability of the mpMRI-based pathway to improve the rate of detection of CS cancers compared with TRUS-guided biopsy, by evaluating the diagnostic accuracy of both mpMRI (the index test) and TRUS-guided biopsy (standard test) against an accurate reference standard, TPM-biopsy.

-

Estimate the cost-effectiveness of a mpMRI-based diagnostic pathway. Using data from the main study and the wider literature, the study considered the implications of alternative diagnostic strategies for NHS costs and men’s quality-adjusted survival duration.

Chapter 2 Methods

Study design

This chapter is partially reproduced from El-Shater Bosaily et al. 16 © 2015 The Authors. Published by Elsevier Inc. This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The protocol is also available at www.ctu.mrc.ac.uk/research/documents/cancer_protocols/promis_protocol_v4 (accessed 12 December 2017).

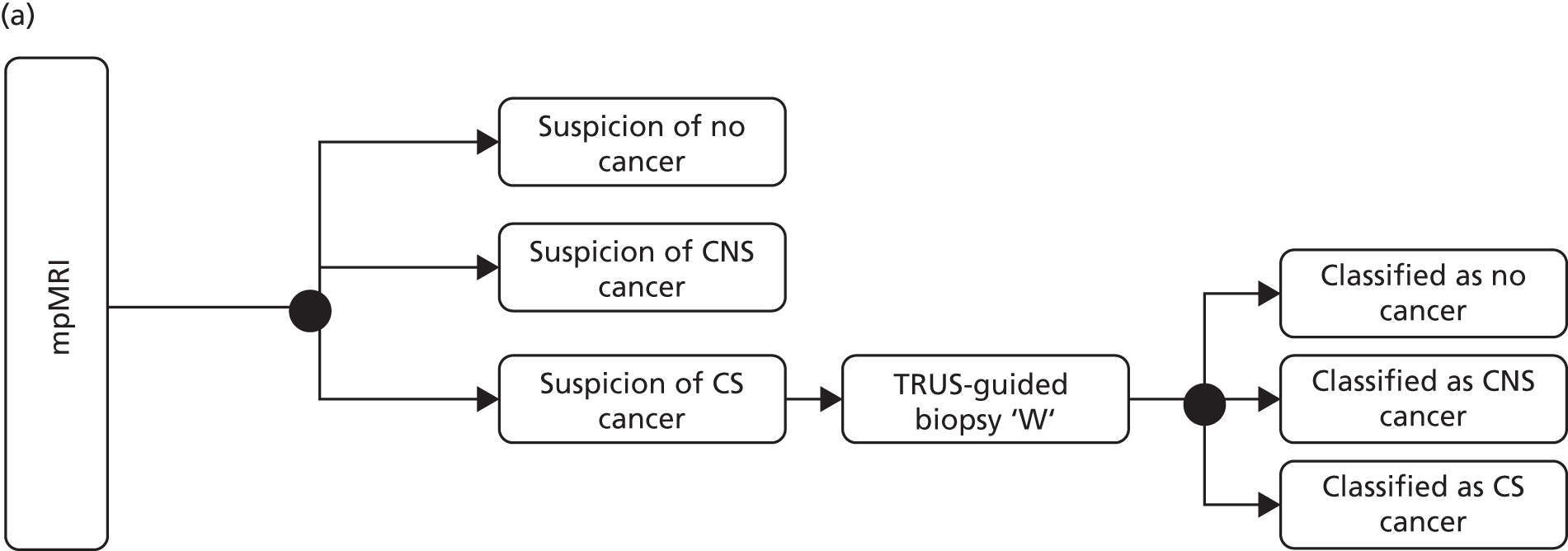

The PROMIS study was a prospective validating paired-cohort study representing level 1b evidence for diagnostic studies. 63 The population of interest was men at risk of prostate cancer who are usually recommended to undergo a first prostate biopsy within standard care. The study was conducted at 11 NHS hospitals in England. To compare the diagnostic accuracy of mpMRI (the index test) and TRUS-guided biopsy (the current standard), both must be individually compared with a reference standard, TPM-biopsy. Therefore, all participants in the study underwent all three tests (mpMRI, TPM-biopsy and TRUS-guided biopsy), with TPM-biopsy followed by TRUS-guided biopsy carried out as a combined biopsy procedure (CBP). The trial schema is shown in Figure 6. Each test was conducted blind to all of the other test results and reported independently of the other tests.

FIGURE 6.

Trial schema. Reproduced from El-Shater Bosaily et al. 16 © 2015 The Authors. Published by Elsevier Inc. This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

A patient and public representative (Robert Oldroyd) was involved in the study, in all aspects relating to the design, the writing of the patient information and consent process, the conduct throughout the study as a member of the Trial Management Group, the critical review of the results and the dissemination of the results to both clinician and patient audiences. He contributed to the Trial Management Group deliberations on the study concept and design for the duration of the trial, at both face-to-face meetings and during teleconferences. As a lay member of the Nottingham 1 Research Ethics Committee (REC) from 2006 until 2015, he contributed expertise on ethics issues, including elements of the project proposal presented to the London–Hampstead REC, which he attended with Mark Emberton in March 2011. As a former prostate cancer patient, he voiced initial concerns about the patient volunteer burden in the study. He rewrote the patient information sheet (reducing the initial 28 pages to 14 pages) to make it more acceptable to the REC and revised the consent form. He commented fully on aspects of the study report, clarifying some sections to make them more accessible to lay readers. He spoke about PROMIS at the Nottingham Prostate Cancer UK conference in March 2017.

PROMIS was designed to overcome several shortcomings that are associated with other studies reported in the literature. These shortcomings prompted the following decisions to be made around the design of PROMIS:

-

All patients were biopsy naive and underwent mpMRI prior to any biopsy, so there was no biopsy artefact.

-

mpMRI was evaluated for all anatomical zones of the prostate including peripheral and transition zones.

-

The study was powered so that the primary outcome was derived using the whole prostate as the sector of analysis rather than segmented sectors of the prostate.

-

The study used an accurate reference test that can be applied to all men at risk.

The study was also designed to avoid or minimise a number of biases that are inherent in the current literature:

-

Spectrum and selection biases were avoided by recruiting men at risk of prostate cancer and applying all tests to all of the men.

-

Work-up bias was eliminated by ensuring that patients and clinicians remained blinded to all imaging test results until the biopsies were carried out and reported.

-

Reviewer/reporter bias was avoided by ensuring that the radiologist was blinded to the reference test and the pathologist was blinded to the imaging. The radiology report was submitted prior to the biopsies.

-

Incorporation bias was minimised by ensuring that TPM-biopsies and TRUS-guided biopsies followed a standard accepted protocol.

Patient eligibility

Patients were eligible for registration into the study if they fulfilled all of the inclusion criteria and none of the exclusion criteria (Box 1). Men with a PSA level of > 15 ng/ml were excluded as the higher prevalence of prostate cancer in this subgroup means that mpMRI is unlikely to be used as a triage test in these men. Men whose prostate volume on mpMRI was found to be > 100 ml were withdrawn from the study. Men were required to give written informed consent before participating.

-

Men aged ≥ 18 years who are at risk of prostate cancer and have been advised to have a prostate biopsy.

-

Serum PSA level of ≤ 15 ng/ml within the previous 3 months.

-

Suspected stage ≤ T2 on rectal examination (organ confined).

-

Fit for general/spinal anaesthesia.

-

Fit to undergo all protocol procedures including a TRUS-guided biopsy.

-

Signed informed consent.

-

Treated using 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors at time of registration or during the prior 6 months.

-

Previous history of prostate biopsy, prostate surgery or treatment for prostate cancer (interventions for benign prostatic hyperplasia/bladder outflow obstruction are acceptable).

-

Evidence of a urinary tract infection or history of acute prostatitis within the last 3 months.

-

Contraindication to MRI (e.g. claustrophobia, a pacemaker, an estimated glomerular filtration rate of ≤ 50 ml/minute).

-

Any other medical condition precluding procedures described in the protocol.

-

Contraindications for MRI (history of hip replacement surgery, metallic hip replacement or extensive pelvic orthopaedic metal work).

Reproduced from El-Shater Bosaily et al. 16 © 2015 The Authors. Published by Elsevier Inc. This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Ethics considerations

The study was carried out in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki64 and the UK Research Governance Framework version 265 and received UK REC approval on 16 March 2011 from the London–Hampstead REC. PROMIS has been registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01292291).

Test procedures

The index test: multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging

In PROMIS, mpMRI was standardised to the minimal requirements advised by a European consensus meeting,66 the European Society of Urogenital Radiology67 and the British Society of Urogenital Radiology guidelines. 68 T1-weighted, T2-weighted, diffusion-weighted [apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) maps and long-b scan] and dynamic gadolinium contrast-enhanced imaging was acquired using a 1.5-T scanner and a pelvic phased array (Table 3).

| TR | TE | Flip angle, ° | Plane | Slice thickness [mm (gap)] | Matrix size | Field of view (mm) | Time from scan | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T2 TSE | 5170 | 92 | 180 | Axial, coronal, sagittal | 3 (10%) | 256 × 256 | 180 × 180 | 3 minutes 54 seconds (ax) |

| VIBE at multiple flip angles for T1 calculation (optional) | ||||||||

| VIBE fat sat | 5.61 | 2.52 | 15 | Axial | 3 | 192 × 192 | 260 × 260 | Continue for ≥ 5 minutes 30 seconds after contrast |

| Diffusion (b = 0, 150, 500, 1000) | 2200 | Minimum (< 98) | Axial | 5 | 172 × 172 | 260 × 260 | 5 minutes 44 seconds (16 averages) | |

| Diffusion (b = 1400) | 2200 | Minimum (< 98) | Axial | 5 | 172 × 172 | 320 × 320 | 3 minutes 39 seconds (32 averages) |

Endorectal coils were not used as there is no consensus on their role in minimal scanning requirements. 66 Magnetic resonance spectroscopy was not included because evidence from a large prospective multicentre study at the time showed no benefit of spectroscopy for localisation of prostate cancer compared with T2-weighted imaging alone. 69 We decided to use only 1.5-T scanners as these were more widely available in the UK health-care setting and most studies in the literature had reported the accuracy of mpMRI results based on 1.5-T scanners alone.

Quality assurance and reporting

A robust quality control process was used to maintain the quality of scans and ensure uniformity across all centres. All MRI scanners and individual mpMRI scans underwent quality control checks by an independent commercial imaging clinical research organisation appointed through open tender (IXICO plc, London, UK). Prior to site initiation, the lead radiologist (Alexander Kirkham) reviewed a number of prostate MRI scans from each centre and gave iterative feedback on improving scan quality.

During the study, scans deemed to be of insufficient quality were repeated prior to biopsy. In addition, a standardised operating procedure for mpMRI reporting was adopted in line with the recommendations of the European consensus meeting66 and the European Society of Urogenital-Radiology prostate MRI guidelines. 67 This was convened before publication of the more recent Prostate Imaging Reporting and Data System (PI-RADS) mpMRI reporting consensus. 67 Subsequent comparisons of the Likert and PI-RADS reporting schemes have yielded similar results. 70,71

At each centre, mpMRI scans were reported by dedicated urological radiologists who had undergone centralised training provided by the lead centre [University College London Hospital (UCLH)]. Radiologists were provided with clinical details including PSA levels, DRE findings and any other risk factors such as a family history of prostate cancer.

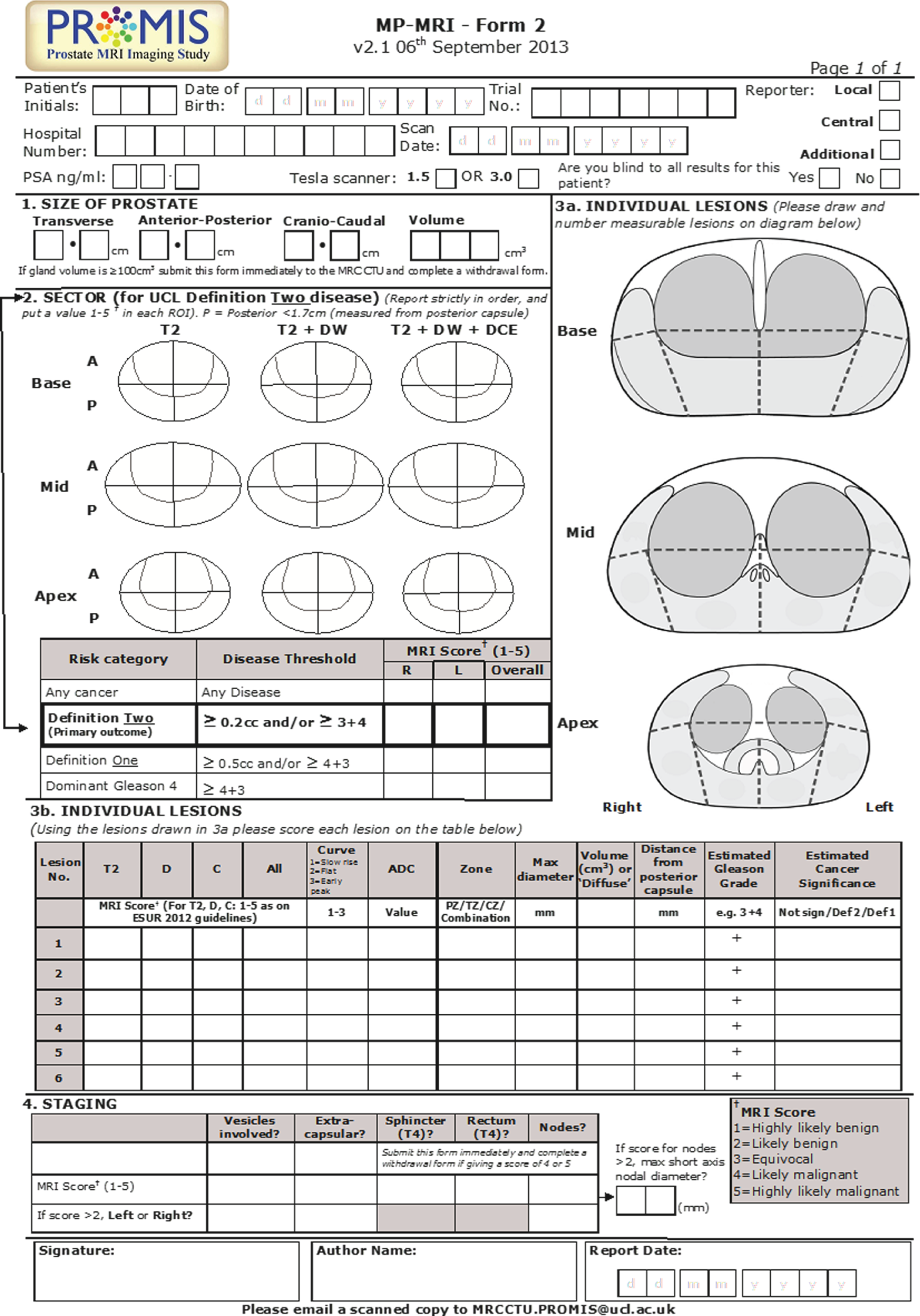

Images were reported in sequence, with T2-weighted images reported first, T2-weighted and diffusion-weighted images reported together and then a third report issued for T2-weighted with diffusion-weighted and dynamic contrast-enhanced scans together. The reporting form is shown in Figure 7. Future analyses will investigate whether or not both diffusion-weighted and dynamic contrast-enhanced images are required. As DCE requires a contrast agent (with its need for intravenous access, medical supervision and contrast-related risks) and an additional 10–15 minutes of scan time, it will be useful to determine whether or not this additional resource use and cost is necessary.

FIGURE 7.

Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging reporting form.

A five-point Likert scoring system66,67,72 was used to indicate the probability of cancer (1, highly likely to be benign; 2, likely to be benign; 3, equivocal; 4, likely to be malignant; 5, highly likely to be malignant). The prostate was divided into 12 regions of interest and each region was scored from 1 to 5. In addition, each lesion was identified and scored separately and the longest axial diameter, lesion volume, ADC value and contrast enhancement curve type were recorded. 73–76 From these observations, an overall score of 1–5 (using the same definitions) was assigned to the whole prostate. This was carried out for ‘any cancer’ and for definitions 1 and 2 of CS cancer (see Definitions of clinically significant prostate cancer).

For the primary outcome, an overall score of ≥ 3 was used to indicate a suspicious scan in relation to CS cancer (i.e. a positive mpMRI score). This reflects the level at which further tests (e.g. biopsy) would be considered if mpMRI were to be introduced into the diagnostic pathway in the future. To assess interobserver agreement, 132 scans from the lead site were rereported by a blinded second radiologist based at that site. The values used in the analyses were those from the original reporter.

The results of the mpMRI could be unblinded by the radiologist if the mpMRI revealed an enlarged prostate volume of > 100 ml, which would be impossible to sample every 5 mm because of the interference of the bony pelvic arch. This might have reduced the number of ‘negative’ prostate results in the final analyses. The mpMRI could also be unblinded if there was evidence of stage T4 prostate cancer or involved lymph nodes or colorectal/bladder invasion. This might have had a detrimental impact on the performance characteristic of mpMRI, as such tumours were more likely to be detected. The presence of other cancers such as bladder or colorectal cancers was also a criterion for withdrawal. Withdrawal was deemed appropriate in these men as expedited referral for biopsy and treatment was required. These withdrawals were unlikely to have an impact on the primary or secondary outcomes.

The standard test: transrectal ultrasound-guided biopsy

Transrectal ultrasound-guided biopsy of the prostate was carried out after the TPM-biopsy (see The reference test: transperineal template prostate mapping biopsy), under the same general/spinal anaesthesia. This was to ensure that the results for the reference test (i.e. TPM-biopsy) were obtained in an optimal fashion in a biopsy-naive gland that had not undergone swelling and distortion. It also theoretically minimised the risk of infection as the potential for faecal contamination was restricted to the end of the procedure. The surgeon carrying out the biopsy procedure was blind to the mpMRI results so that suspicious areas would not be targeted during the TRUS-guided biopsy and the fidelity of the TPM-biopsy reference test was maintained. TRUS-guided biopsies were taken as per international guidelines77 and incorporated 10–12 core biopsies. Each core was identified and potted separately. The TPM-biopsies and TRUS-guided biopsy sets from individual patients were sent to different pathologists to minimise review bias and work-up bias.

The reference test: transperineal template prostate mapping biopsy

Centres were selected for their prior experience in carrying out TPM-biopsies and training was provided to all centres to enable them to conduct TPM-biopsies in accordance with the PROMIS protocol.

Definitions of clinically significant prostate cancer

Disease significance was defined using criteria that have been previously developed and validated for use with TPM-biopsy for the detection of primary Gleason grades of ≥ 478 and of a cancer core length that is predictive of the presence of lesions of ≥ 0.5 ml. 79–82 Gleason scoring was based on the most frequent pattern and not on the highest grade detected on histological analysis.

The primary definition of CS prostate cancer used a histological target condition on TPM-biopsy that incorporated the presence of a Gleason score of ≥ 4 + 3 and/or a cancer core length of ≥ 6 mm of any Gleason score, in any location (definition 1). This was chosen as the primary outcome on the basis that few physicians would disagree that any man with this burden of cancer would require treatment. A secondary definition of CS disease was also used (a cancer core length of ≥ 4 mm and/or a Gleason score of ≥ 3 + 4; definition 2). A further definition of clinical significance (any Gleason pattern of ≥ 7) was added at the request of reviewers at The Lancet and this was treated as an exploratory definition (definition 3).

Monitoring of adverse events

The expected side effects of combining the TPM-biopsy and TRUS-guided biopsy procedures were discussed with patients before registration. The rate of serious adverse events (SAEs) was monitored weekly by an independent Trial Steering Committee.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measures were the diagnostic accuracy of mpMRI, TRUS-guided biopsy and TPM-biopsy using the primary mpMRI and histology definitions, as measured by sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV. The same parameters using combinations of alternative definitions of disease for each test were investigated as secondary outcomes. The other outcomes reported were inter-rater agreement between tests and adverse events (AEs).

Magnetic resonance imaging outcome measures

For the primary outcomes, a MRI score of ≥ 3 to indicate a positive MRI result (primary analysis) was used. MRI scores of 1 or 2 were used to identify a group of men who might be able to avoid biopsy. Other reporting thresholds and radiological criteria were recorded and will form exploratory tertiary analyses in subsequent reports.

Translational research objectives

PROMIS was an ideal setting for assessing the utility of biomarkers (from urine and blood) to identify men with CS prostate cancer. It was, to our knowledge, the first time that a broad spectrum of men at risk have been evaluated using an optimal biopsy technique that accurately characterises the presence, size and grade of prostate cancer. A comprehensive bank of tissue samples (serum, plasma, germline DNA, urine) was collected from men prior to biopsy, to enable urinary and serum biomarkers to be analysed with respect to the detection of CS prostate cancer on TPM-biopsy. The results of these analyses will be reported at a later date.

Sample size

Power calculations were performed in relation to (1) the precision of the estimates for the accuracy of mpMRI relative to TPM-biopsy in terms of the primary definition of CS cancer, (2) a head-to-head comparison of mpMRI with TRUS-guided biopsy and (3) an assumed underlying prevalence of CS cancer of 15% according to the primary definition. 19,20,83,84 For the less stringent definition (definition 2), it was assumed that 25% of participants would have CS prostate cancer as detected by the reference standard.

The largest sample size obtained from the power calculations around (1) and (2) in the previous paragraph was 714 (see protocol16); this was considered to be the maximum number of men required to have all three tests (mpMRI, TPM-biopsy and TRUS-guided biopsy), based on the assumption that mpMRI and TRUS-guided biopsy are uncorrelated.

Assuming a specificity of 77%, in order to demonstrate that the lower 95% CI is ≥ 70%, we would require 407 cases of CNS prostate cancer. This is equivalent to a total of 479 men for definition 1 and 543 men for definition 2. Assuming a sensitivity of 75%, in order to demonstrate that the lower 95% CI for sensitivity is ≥ 60%, we would require 97 cases of CS prostate cancer. This is equivalent to a total of 647 men for definition 1 and 388 for definition 2. These estimates of sensitivity and specificity were considered realistic based on current unpublished and published literature. 85,86

It was assumed that TRUS-guided biopsy detects 48% of CS prostate cancers83,87 and that mpMRI would detect ≥ 70%; these were conservative estimates. Using McNemar’s test for paired binary observations,88 in order to show an absolute increase in the proportion of CS cancers detected of ≥ 22% (from 48% to 70%) with a power of 90% and a two-sided alpha of 5%, a total of 107 cases are required. This is equivalent to a total study population of 714 men for definition 1 and 428 men for definition 2. Table 4 shows the required sample size for McNemar’s test for different levels of agreement between mpMRI and TRUS-guided biopsy. The shaded regions reflect the scenario in which virtually all cancers are detected by either mpMRI or TRUS-guided biopsy, in which there is extremely low agreement between mpMRI and TRUS-guided biopsy. This is very unlikely but is included for completeness.

| mpMRI results | TRUS-guided biopsy result (for true cases)a | Required number of casesb | Required sample size | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | Positive | ||||||

| –ve | +ve | –ve | +ve | Prevalence of 15% (definition 1) | Prevalence of 25% (definition 2) | ||

| Sensitivity = 70% | 0.29 | 0.23 | 0.01 | 0.47 | 48 | 321 | 192 |

| 0.25 | 0.27 | 0.05 | 0.43 | 66 | 441 | 264 | |

| Independence assumptionc | 0.156 | 0.364 | 0.144 | 0.336 | 107 | 714 | 428 |

| 0.05 | 0.47 | 0.25 | 0.23 | 153 | 1021 | 612 | |

| 0.01 | 0.51 | 0.29 | 0.19 | 170 | 1134 | 680 | |

The independent Trial Steering Committee carried out an a priori interim review after 50 participants had received all three tests. Although a higher than anticipated prevalence of any cancer was observed, no changes to the target sample size were recommended.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were carried out in accordance with a statistical analysis plan agreed before the data were inspected. Stata® version 13.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) was used to carry out the analyses. The primary analysis was based on all evaluable data, excluding men without all three test results and any data that were rejected as part of the external mpMRI quality control/quality assurance process.

For each comparison, 2 × 2 contingency tables were used to present the results and calculate the diagnostic accuracy estimates with 95% CIs. Given the paired nature of the test results, McNemar’s tests were used for the head-to-head comparisons of sensitivity and specificity between mpMRI and TRUS-guided biopsy. Because the PPV and NPV are dependent on disease prevalence, a generalised estimating equation (GEE) logistic regression model was used to compare the PPV and NPV for mpMRI and TRUS-guided biopsy against those for TPM-biopsy. 89,90

The sensitivities, specificities and predictive values were calculated for mpMRI based on the overall radiological score for mpMRI [assigned to definition 2 on the mpMRI case report form (CRF)] and definition 1 for CS cancer on TPM-guided biopsy.

The format of the 2 × 2 table is shown in Table 5. Specificity = d/(c + d), where d = the number of men testing negative on mpMRI and negative for CS cancer on TPM-biopsy and c = the number of men testing positive on mpMRI and negative for CS cancer on TPM-biopsy. The NPV = d/(b + d), where d = the number of men testing negative on mpMRI and negative for CS cancer on TPM-biopsy and b = the number of men testing negative on mpMRI who test positive for CS cancer on TPM-biopsy. Sensitivity = a/(a + b), where a = the number of men testing positive on mpMRI and positive for CS on TPM-biopsy and b = the number of men testing negative on mpMRI who have CS cancer on TPM-biopsy. The PPV = a/(a + c), where a = the number of men testing positive on mpMRI and positive for CS on TPM-biopsy and c = the number of men testing positive on mpMRI who do not have CS cancer on TPM-biopsy.

| TPM-biopsy | mpMRI | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| +ve | –ve | Total | |

| +ve | a | b | a + b |

| –ve | c | d | c + d |

| Total | a + c | b + d | |

For the comparison of TRUS-guided biopsy and mpMRI, McNemar’s test was used to compare the agreement between mpMRI (radiological score of ≥ 3 assigned to definition 2 on the mpMRI CRF) and TRUS-guided biopsy (definition 1) in the subset of men found to have CS prostate cancer on TPM-biopsy according to definition 1. For the secondary analysis, all analyses that were carried out for definition 1 were repeated for definition 2 and, at the request of The Lancet reviewers, for any Gleason score of ≥ 7.

Exploratory analyses will be performed in the future to evaluate the impact on the sensitivity, specificity and predictive values of mpMRI when each of the 12 regions of interest are correlated between mpMRI and TPM-biopsy. Agreement between mpMRI and TPM-biopsy in identifying CS cancer in the same region will be based on a nearest neighbourhood approach. 91 Sensitivity to this approach will be tested by also presenting results according to complete match (the most stringent rule) and using a left/right rule (the less stringent rule). The sensitivity, specificity and predictive values of each of the individual MRI reporting sequence combinations, namely T2, T2 + DW and T2 + DW + DCE, will inform additional important tertiary analyses in subsequent publications.

Odds ratios (ORs) represent the odds of each test correctly detecting the presence or absence of disease. For specificity and NPV, the coding logic was reversed as the correct test result is a negative test result. Ratios are presented for TRUS-guided biopsy relative to mpMRI, so ratios of > 1 favour TRUS-guided biopsy and ratios of < 1 favour mpMRI.

Chapter 3 Results

The main results of PROMIS have been published by Ahmed et al. 92 Sections of this chapter have been reproduced from Ahmed et al. 92 © 2015 The Authors. Published by Elsevier Inc. This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Recruitment and screening

A total of 740 participants were registered to the trial from 11 NHS hospitals in England. Recruitment took place between May 2012 and November 2015. Details of the screening and participating centres are given in Appendix 1.

Flow of participants through the study

Figure 8 shows the flow of participants through the study. Of the 740 men registered, 164 subsequently withdrew from the study before completing all three tests. Reasons for withdrawal are presented in Table 6. Most withdrawals took place before the combined biopsy was carried out; the most common reason for withdrawal was the discovery of a large prostate volume (> 100 ml), which was a mandatory withdrawal criterion. A total of 576 men were included in the final analysis. For the analysis set, the median (range) time between mpMRI and the combined biopsy was 38 days (1–190 days). The median (range) time between registration and the end-of-study visit was 111 days (31–421 days).

FIGURE 8.

Participant flow through the study. Reproduced from Ahmed et al. 92 © 2015 The Authors. Published by Elsevier Inc. This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

| Reason | Timing of withdrawal | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before MRI | Before CBP | During CBP | After CBP | Total | |

| Ineligible | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| Unblinded | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Large prostate | 1 | 46 | 21 | 1 | 69 |

| Stage T4 or nodal disease | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Clinical reasonsa | 5 | 15 | 0 | 1 | 21 |

| Did not want biopsy | 4 | 17 | 0 | 0 | 21 |

| Did not want to wait: sought private medical treatment | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| No longer wished to participate | 5 | 21 | 0 | 0 | 26 |

| Other | 0 | 10 | 0 | 1 | 11 |

| Total | 17 | 122 | 21 | 4 | 164 |

Baseline characteristics

Table 7 summarises the baseline characteristics for the 576 men who were included in the final analysis and the 164 men who withdrew after registration. The group of participants who withdrew had a similar age and PSA level to the included group, but were slightly less likely to report a family history of prostate cancer.

| Characteristic [missing data, n] | Men included in the final analysis (N = 576) | Withdrawals (N = 164) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) age, years [0] | 63.4 (7.6) | 64.5 (7.5) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) [1] | ||

| White | 502 (87) | 136 (83) |

| Mixed | 6 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Asian or Asian British | 16 (3) | 5 (3) |

| Black or black British | 39 (7) | 16 (10) |

| Other | 12 (2) | 4 (3) |

| Family history of prostate cancer, n (%) [7] | ||

| Yes | 127 (22) | 27 (17) |

| No | 442 (78) | 130 (83) |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) [62] | 27.8 (4.4) | 28.6 (5.2) |

| PSA level (ng/ml), mean (SD) [range] [0] | 7.1 (2.9) [0.5–15.0] | 7.1 (2.7) [1.0–14.7] |

Cancer prevalence by template prostate mapping biopsy

The prevalence of any cancer as assessed by the reference test, TPM-biopsy, was 71% (95% CI 67% to 75%). The prevalence of CS cancer according to the primary definition (a Gleason score of ≥ 4 + 3 and/or a cancer core length of ≥ 6 mm) was 40% (95% CI 36% to 44%). The prevalence of CS cancer according to the secondary definition (a Gleason score of ≥ 3 + 4 and/or a cancer core length of ≥ 4 mm) was 57% (95% CI 53% to 62%). Using the exploratory definition of any Gleason pattern of ≥ 7, the prevalence of CS cancer was 53% (308/576).

Cancer prevalence according to each definition as detected by TPM-biopsy is summarised in Table 8, together with the number of cancers that were identified to have perineural or lymphovascular involvement. A summary of the cancer grades according to TPM-biopsy pathology results is given in Appendix 1.

| Prevalence | TPM-biopsy (N = 576), n (%) [95% CI] |

|---|---|

| Any cancer | 408 (71) [67 to 75] |

| PNI | 156 |

| LVI | 3 |

| CS cancer, primary definition (Gleason score of ≥ 4 + 3 and/or cancer core length of ≥ 6 mm) | 230 (40) [36 to 44] |

| PNI | 133 |

| LVI | 3 |

| CS cancer, secondary definition (Gleason score of ≥ 3 + 4 and/or cancer core length of ≥ 4 mm) | 331 (57) [53 to 62] |

| PNI | 155 |

| LVI | 3 |

| CS cancer, exploratory definition (Gleason score of ≥ 7) | 308 (53) [49 to 58] |

| PNI | 152 |

| LVI | 3 |

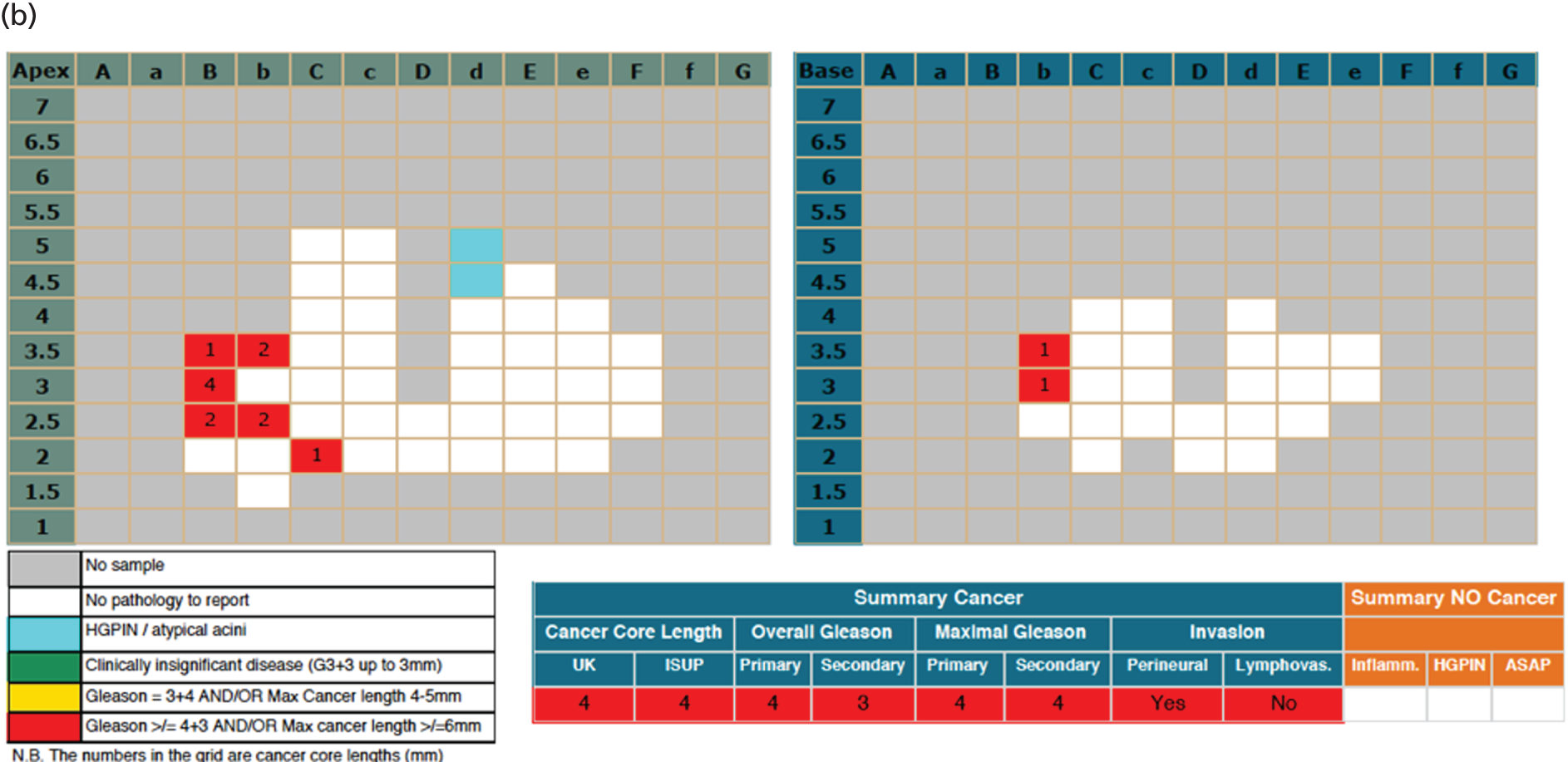

Diagnostic accuracy of transrectal ultrasound-guided biopsy compared with template prostate mapping biopsy (primary outcome)

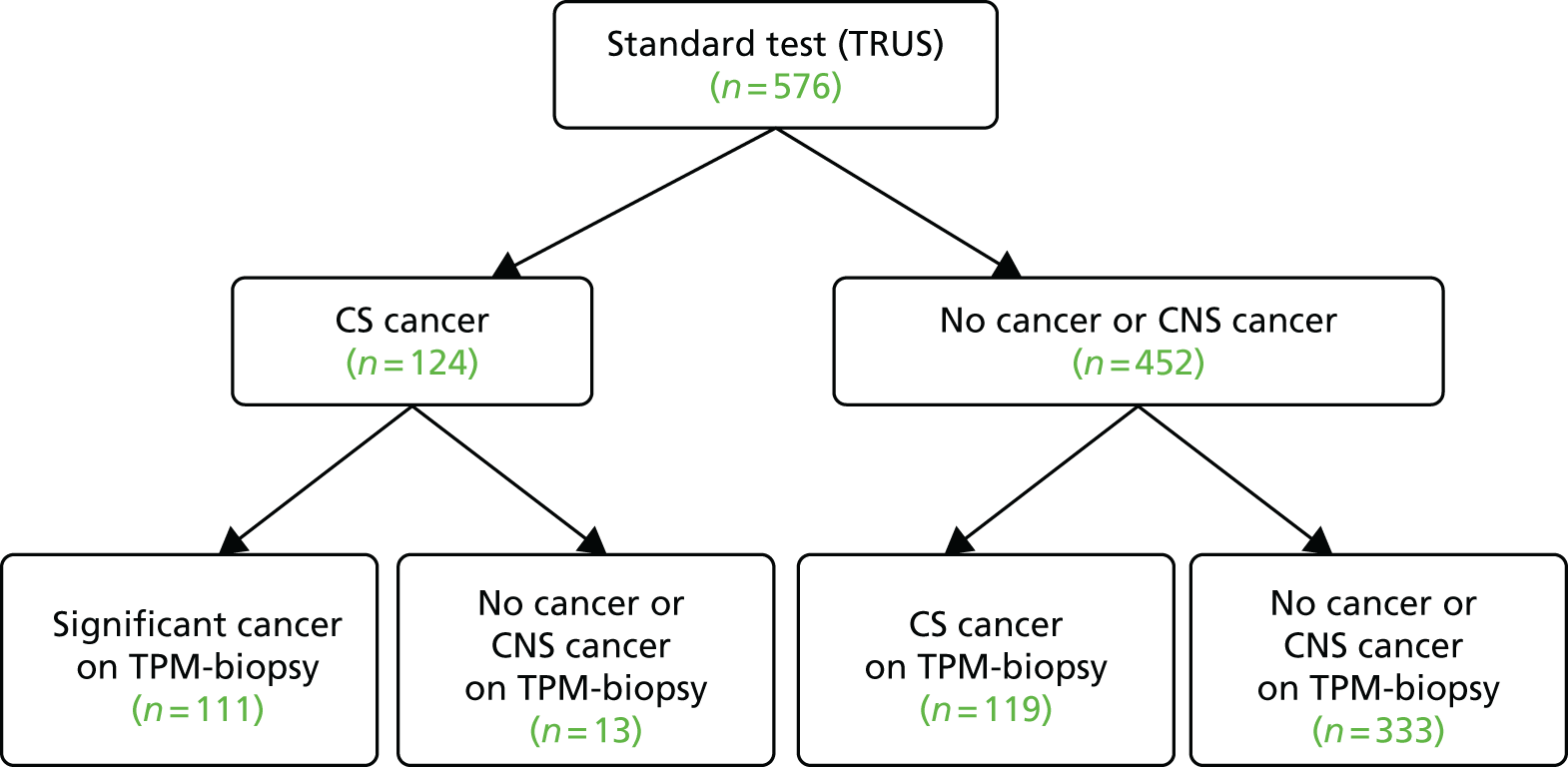

The diagnostic accuracy results for TRUS-guided biopsy compared with TPM-biopsy are shown in Table 9 and Figure 9. Cancer was detected in 286 out of 576 men (50%, 95% CI 45% to 54%), of whom 65 had perineural invasion and one had lymphovascular invasion. CS cancer according to the primary definition was detected in 124 out of 576 men (22%, 95% CI 18% to 25%), of whom 48 had perineural invasion and one had lymphovascular invasion.

| TRUS-guided biopsy | TPM-biopsy, n | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| CS cancer (+) | NC or CNS cancer (–) | Total | |

| CS cancer (+) | 111 | 13 | 124 |

| NC or CNS cancer (–) | 119 | 333 | 452 |

| Total | 230 | 346 | 576 |

FIGURE 9.

Diagnostic accuracy of the detection of CS cancer for TRUS-guided biopsy compared with TPM-biopsy.

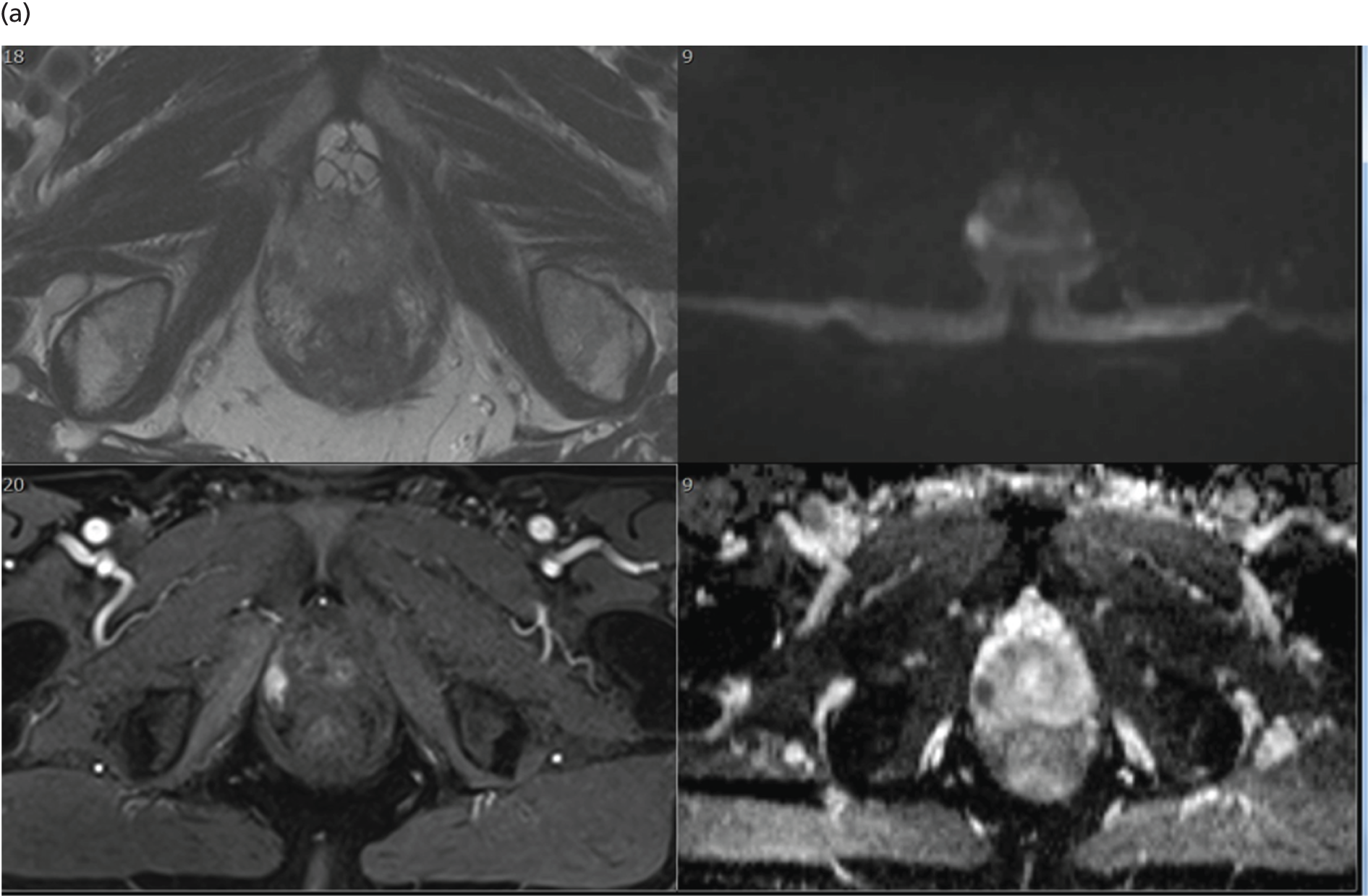

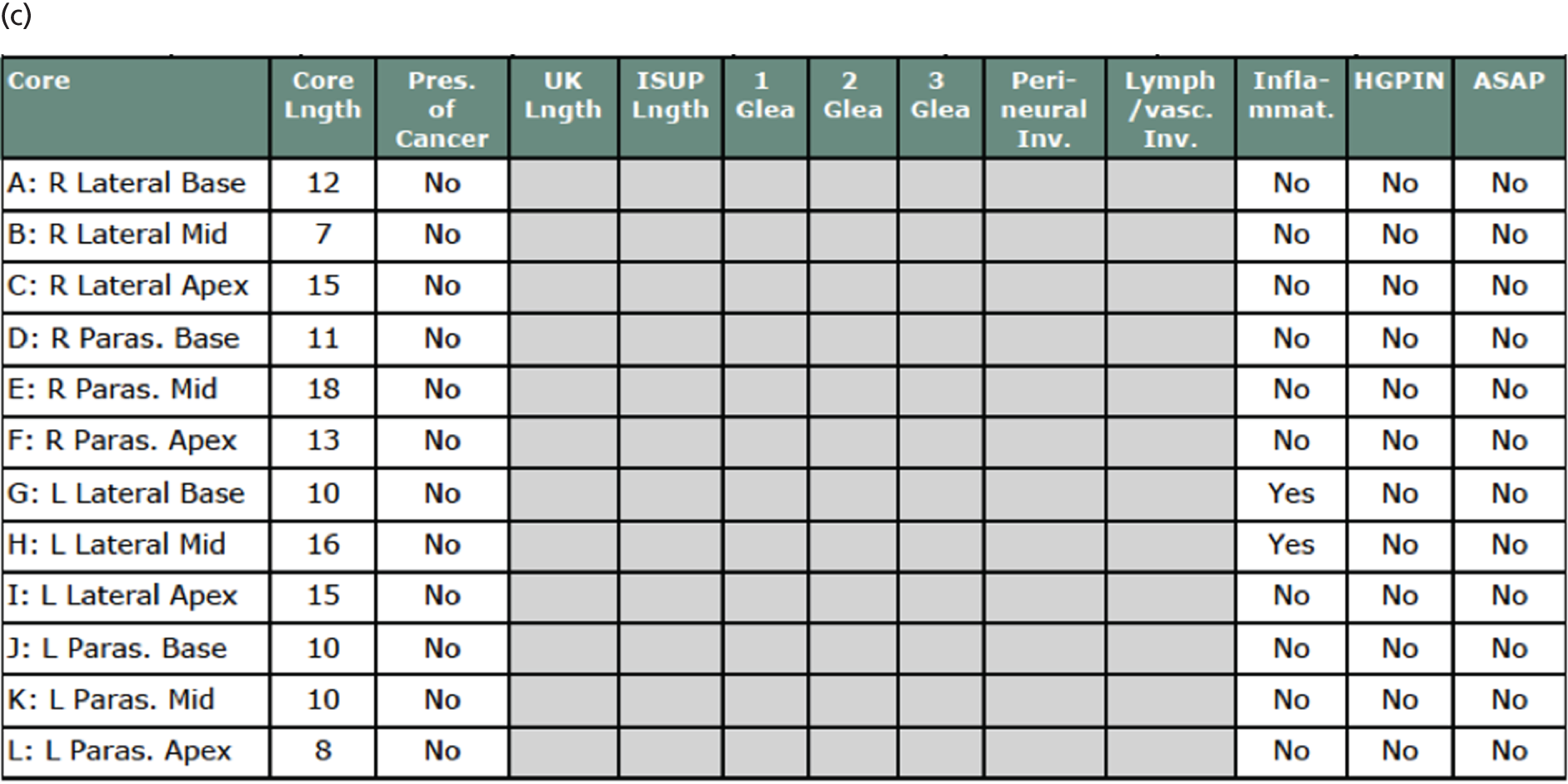

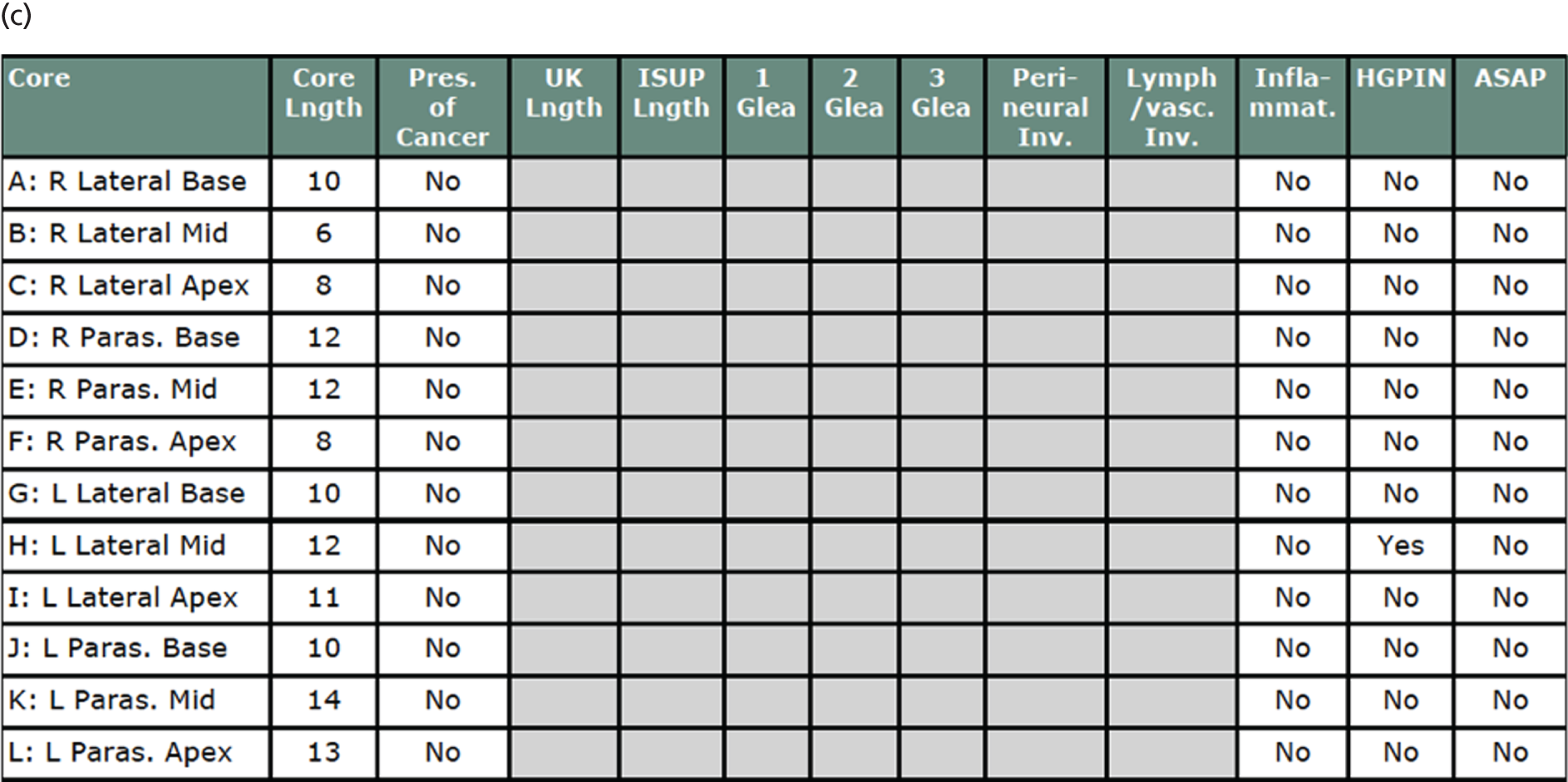

A summary of the cancer grades according to TRUS-guided biopsy pathology results is given in Appendix 1. Appendix 1 also provides two case illustrations showing the correlation of TRUS-guided biopsy and mpMRI with TPM-biopsy, one for a man harbouring CS cancer and one for a man with no cancer.

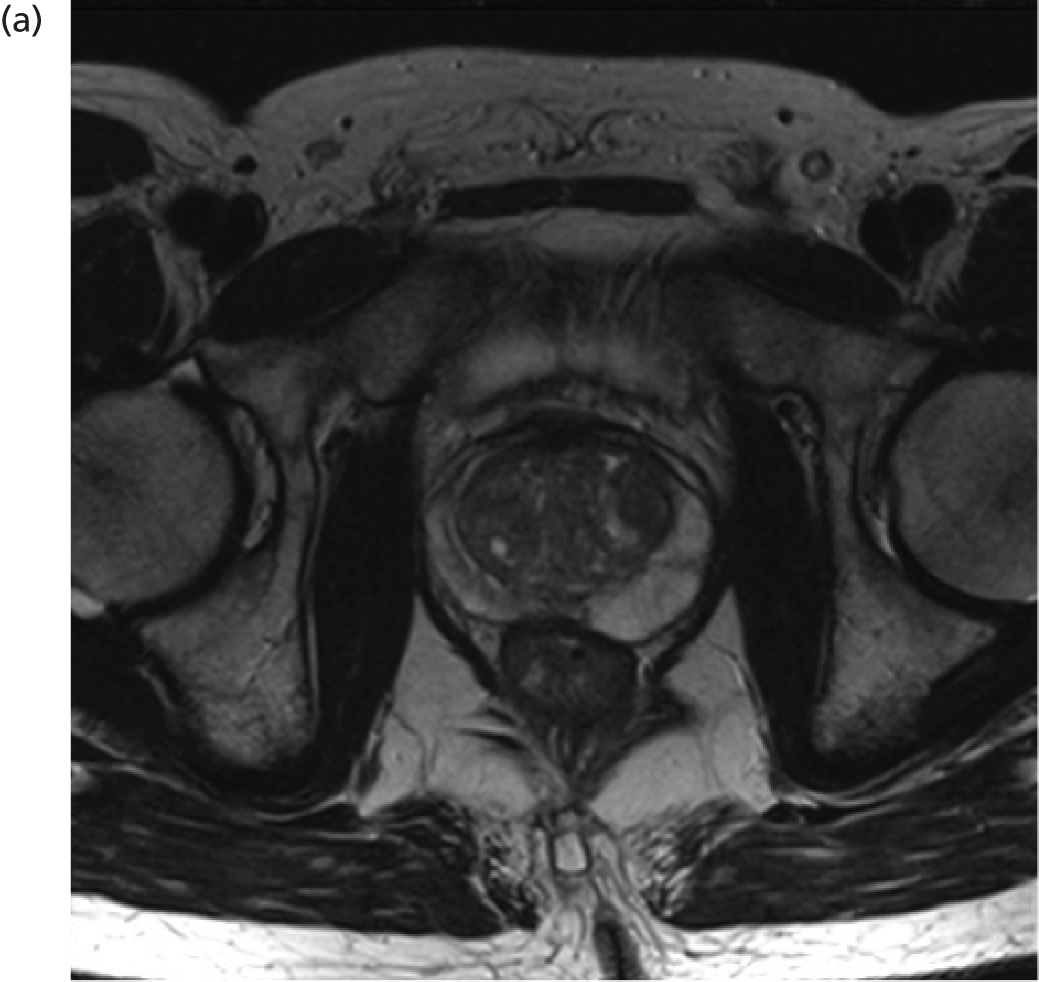

Diagnostic accuracy of multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging compared with template prostate mapping biopsy (primary outcome)

Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging results

In the group of 576 men included in the final analysis, the mean volume of the prostate was 48 ml [standard deviation (SD) 20 ml]. Six men had a prostate volume of > 100 ml as they had been entered into the trial before this threshold was adopted as an exclusion criterion mid-way through the study. The Trial Management Group decided that these six men should remain in the study as they had been fully sampled using TPM-biopsy.

The distribution of mpMRI scores is presented in Table 10. Agreement between mpMRI and TRUS-guided biopsy for the detection of CS cancer is shown in Appendix 1.

| Primary MRI score | Participants, n (%) |

|---|---|

| 1: highly likely benign | 23 (4) |

| 2: likely benign | 135 (23) |

| 3: equivocal | 163 (29) |

| 4: likely malignant | 120 (21) |

| 5: highly likely malignant | 135 (23) |

| Total | 576 (100) |

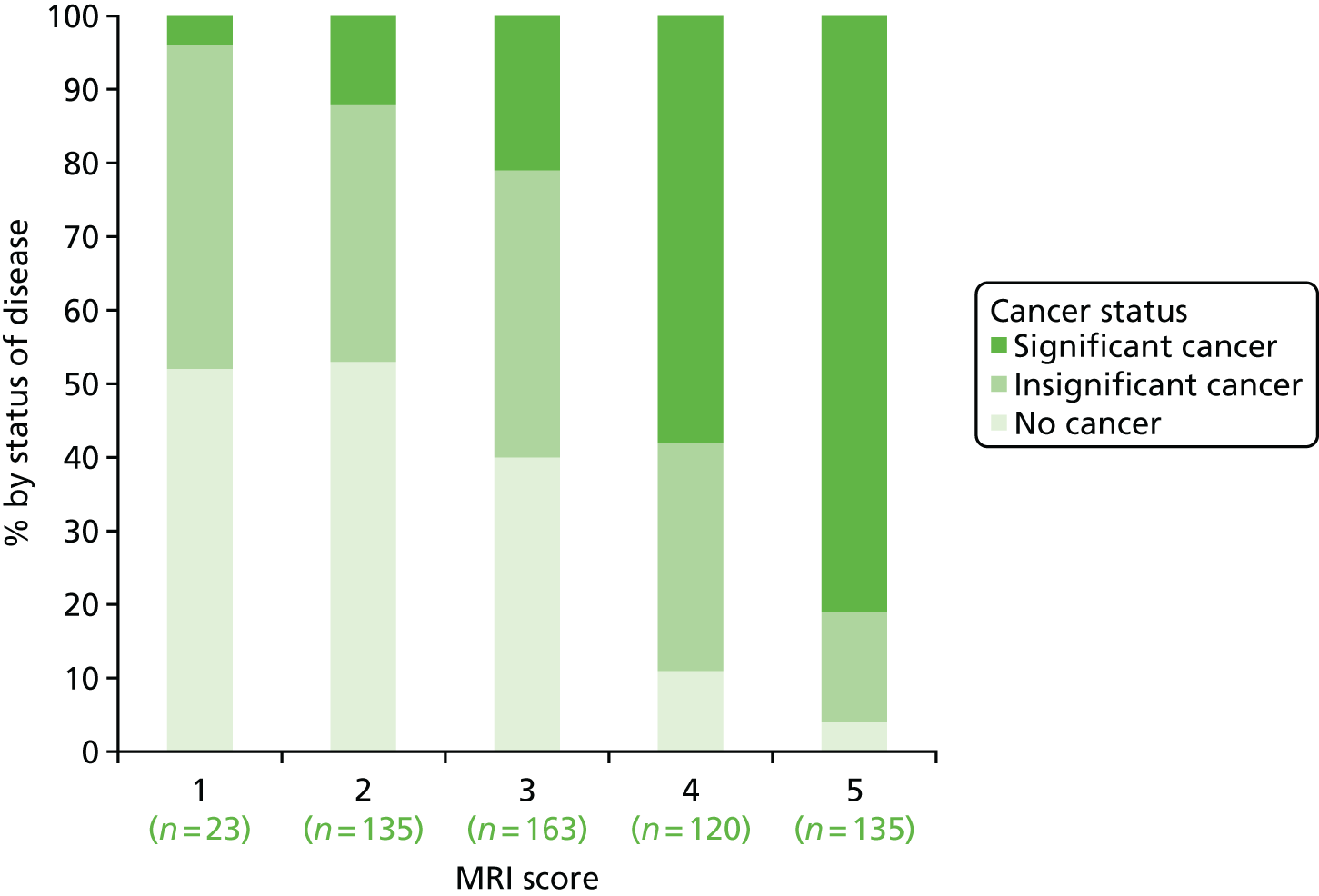

The diagnostic results for mpMRI compared with TPM-biopsy are shown in Table 11 and Figure 10. The sensitivity of mpMRI for CS cancer was 93% (95% CI 88% to 96%) and the NPV was 89% (95% CI 83% to 94%). The specificity of mpMRI was 41% (95% CI 36% to 46%), with PPV being 51% (95% CI 46% to 56%). The proportion of CS disease by mpMRI score is shown in Figure 11.

| mpMRI | TPM-biopsy, n | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| CS cancer (+) | NC or CNS cancer (–) | Total | |

| CS cancer (+) | 213 | 205 | 418 |

| NC or CNS cancer (–) | 17 | 141 | 158 |

| Total | 230 | 346 | 576 |

FIGURE 10.

Diagnostic accuracy of the detection of CS cancer for mpMRI compared with TPM-biopsy. Pie charts represent actual mpMRI scores from 1 to 5. Reproduced from Ahmed et al. 92 © The Authors. Published by Elsevier Inc. This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

FIGURE 11.

Proportion of men with no cancer, insignificant cancer and significant cancer based on TPM-biopsy by mpMRI score. Reproduced from Ahmed et al. 92 © 2015 The Authors. Published by Elsevier Inc. This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

A negative mpMRI result was recorded for 158 men (27%). Of these, 17 were found to have CS cancer on TPM-biopsy (see Table 15 and Figure 10). All 17 had Gleason grade 3 + ≤ 4, and core lengths of between 6 mm and 12 mm (Table 12). Of the 119 significant cancers missed by TRUS-guided biopsy, 13 had a Gleason score of 4 + 3, 99 had a Gleason score of 3 + 4 and 7 had a Gleason score of 3 + 3 (see Table 12).

| Gleason grade | Number of cases missed (range of maximum cancer core length, mm), by trial arm | |

|---|---|---|

| mpMRI (N = 17) | TRUS-guided biopsy (N = 119) | |

| 3 + 3 | 1 (8) | 7 (6–11) |

| 3 + 4 | 16 (6–12) | 99 (6–14) |

| 4 + 3 | 0 | 13 (3–16) |

Head-to-head comparison of the diagnostic accuracy of multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging and transrectal ultrasound-guided biopsy compared with template prostate mapping biopsy (primary outcome)

Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging was more accurate than TRUS-guided biopsy in terms of both sensitivity (93% compared with 48%, respectively; McNemar’s test ratio 0.52, 95% CI 0.45 to 0.60) and NPV (89% compared with 74%, respectively; GEE model estimate for OR 0.34, 95% CI 0.21 to 0.5; p < 0.0001). A total of 119 significant cancers were missed by TRUS-guided biopsy, of which 13 had a Gleason score of 4 + 3, 99 had a Gleason score of 3 + 4 and 7 had a Gleason score of 3 + 3 (see Table 12). However, compared with mpMRI, TRUS-guided biopsy showed better specificity (41% compared with 96%, respectively; McNemar’s test ratio 2.34, 95% CI 2.08 to 2.68; p < 0.0001) and a better PPV (51% compared with 90%; GEE model estimate for OR 8.2, 95% CI 4.7 to 14.3; p < 0.0001].

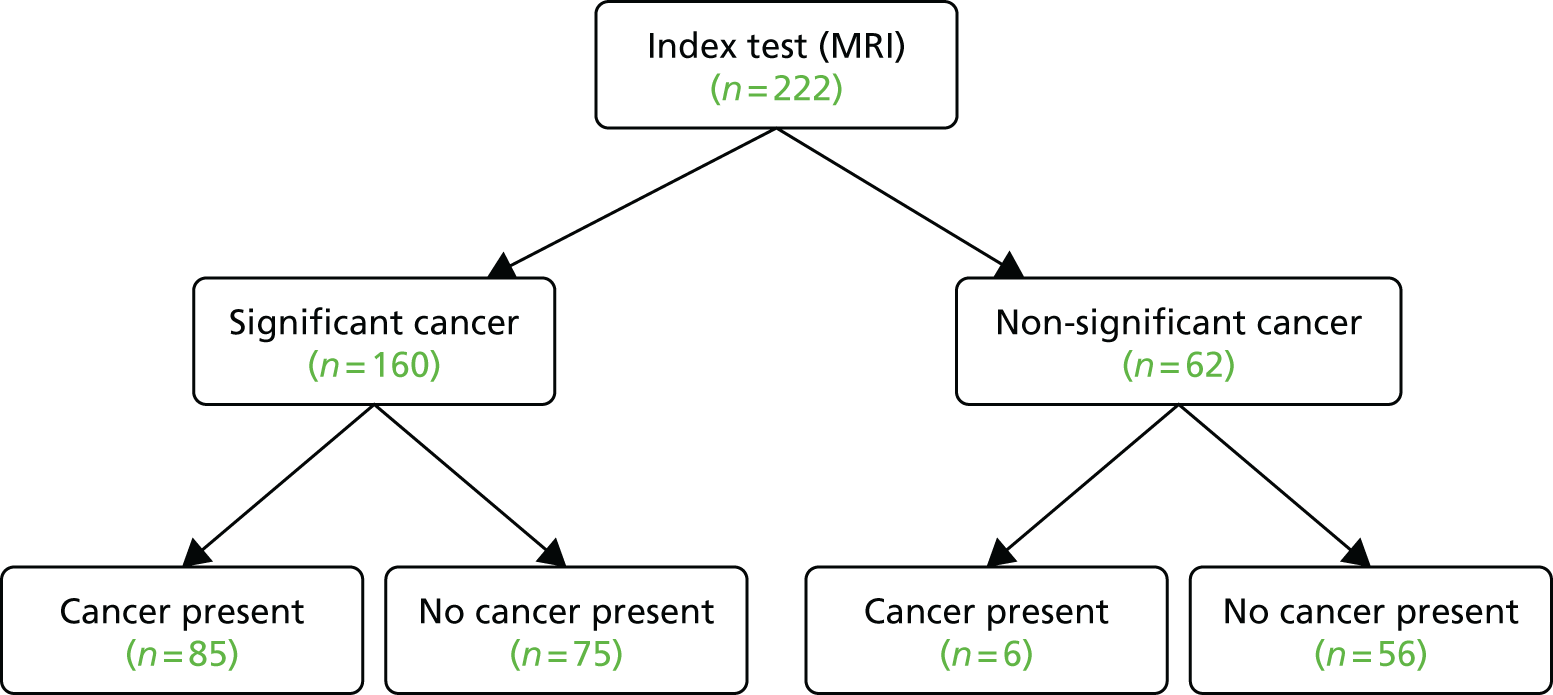

Clinical implications of introducing multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging into the diagnostic pathway

We considered the implications of using mpMRI in clinical practice by comparing a strategy of an initial TRUS-guided biopsy for all men (standard care) with two alternative strategies. In both alternative strategies, mpMRI would be used as a triage test and only men with a suspicious mpMRI result (i.e. a Likert score of ≥ 3) would go on to have a biopsy (Table 13), with the remainder receiving active surveillance or being discharged. In the first alternative strategy – the worst-case scenario – a standard TRUS-guided biopsy would be carried out but mpMRI would not be used to direct needle deployment. The TRUS-guided biopsy results for each patient have been used to calculate overdiagnosis. In the second alternative strategy – the best-case scenario – the TRUS-guided biopsy needle deployment would be guided by the mpMRI findings and the results presented assume that such targeted biopsies would achieve similar diagnostic accuracy to that of TPM-biopsy. 93,94 We expect the actual scenario to lie somewhere between these best- and worst-case scenarios.

| Outcome | Strategy | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| TRUS-guided biopsy-only pathway | mpMRI triage followed by non-directed TRUS-guided biopsy (worst-case scenario)a | mpMRI triage followed by MRI-directed TRUS-guided biopsy (best-case scenario)b | |

| Primary biopsy carried out, n (%) [95% CI] | 576 (100) [99 to 100] | 418 (73) [69 to 76] | 418 (73) [69 to 76] |

| Overdiagnosis (CNS cancer detected), n (%) [95% CI] | 90 (16) [13 to 19] | 62 (11) [8 to 14] | 121 (21) [18 to 25] |

| Significant cancer correctly detected, n (%) [95% CI] | 111 (19) [16 to 23] | 105 (18) [15 to 22] | 213 (37) [33 to 41] |

For both of these scenarios, 158 out of 576 men (27%) might avoid a primary biopsy because they would have a non-suspicious mpMRI result with a low (1 in 10) probability of harbouring significant cancer. For the worst-case scenario, an absolute reduction in the overdiagnosis of CNS cancers might be seen, with 28 out of 576 (5%) fewer cases (relative reduction of 31%, 95% CI 22% to 42%) than with the current standard. However, in this worst-case scenario, important information on tumour location would not be used, resulting in the number of CS cancers that are detected being 1% lower than in standard care.

Under the best-case scenario, overdiagnosis might increase to 21% [i.e. there would be 31/576 (5%) more cases]. However, this figure is based on the probability of detecting CNS cancers on TPM-biopsy and, therefore, is an overestimation. Nonetheless, if the mpMRI information was used for biopsy deployment in this scenario, it might also lead to 102 out of 576 (18%) more cases of CS cancer being detected than in the standard pathway of TRUS-guided biopsy for all (see Table 13). We envisage that, in practice, the actual impact of including mpMRI in the pathway would lie somewhere between the best- and worst-case scenarios.

Diagnostic accuracy of transrectal ultrasound-guided biopsy and multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging for other definitions of clinically significant cancer

In total, 203 out of 576 cases (35%, 95% CI 31% to 39%) had CS cancer on TRUS-guided biopsy according to the secondary definition [University College London (UCL) definition 2: Gleason grade of ≥ 3 + 4 and/or any grade of cancer length of ≥ 4 mm]. Table 14 presents the definitions and prevalence according to TPM-biopsy. Of these 203 cases with UCL definition 2 disease, 63 had perineural invasion and one had lymphovascular invasion. For the exploratory definition (any Gleason pattern of ≥ 7), 151 out of 576 cases (26%, 95% CI 23% to 30%) had CS disease. Of these 151 cases with disease with a Gleason grade of ≥ 7, 54 had perineural invasion and one had lymphovascular invasion.

| TPM-biopsy definition of clinical significance | Prevalence of disease on TPM-biopsy, n (%) [95% CI] | Test attribute | mpMRI, % (95% CI) | TRUS-guided biopsy, % (95% CI) | Test ratioa (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Secondary (Gleason score of ≥ 3 + 4 and/or cancer score lenght of ≥ 4 mm) | 331 (57) [53 to 62] | Sensitivity | 87 (83 to 90) | 60 (55 to 65) | 0.69 (0.64 to 0.76) | < 0.0001 |

| Specificity | 47 (40 to 53) | 98 (96 to 100) | 2.11 (1.85 to 2.41) | < 0.0001 | ||

| PPV | 69 (64 to 73) | 98 (95 to 100) | 22.7 (8.6 to 59.9) | < 0.0001 | ||

| NPV | 72 (65 to 79) | 65 (60 to 70) | 0.70 (0.52 to 0.96) | 0.025 | ||

| Exploratory [any Gleason pattern of ≥ 7 (≥ 3 + 4)] | 308 (53) [49 to 58] | Sensitivity | 88 (84 to 91) | 48 (43 to 54) | 0.55 (0.49 to 0.62) | < 0.0001 |

| Specificity | 45 (39 to 51) | 99 (97 to 100) | 2.22 (1.94 to 2.53) | < 0.0001 | ||

| PPV | 65 (60 to 69) | 99 (95 to 100) | 40.8 (10.2 to 162.8) | < 0.0001 | ||

| NPV | 76 (69 to 82) | 63 (58 to 67) | 0.53 (0.38 to 0.73) | < 0.0001 |

Diagnostic accuracy results for the secondary and exploratory definitions of CS cancer are shown in Table 14. Table 15 shows the histological characteristics of cancers missed by TRUS-guided biopsy and mpMRI for all histological definitions.

| Definition of clinical significance | Missed cases, n | |

|---|---|---|

| mpMRI | TRUS-guided biopsy | |

| Primary (N = 230) | 17

|

119

|

| Secondary (N = 331) | 44

|

132

|

| Exploratory (Gleason score of ≥ 7) (N = 308) | 38

|

159

|

Interobserver and intraobserver variability in the reporting of multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging scores

Blinded, double reporting was available for the mpMRI scans of 132 men. For this group, agreement between radiologists in the detection of CS cancer according to the primary definition was 80% (Table 16). This corresponded to a Cohen’s kappa statistic of 0.5 [moderate agreement according to the Landis and Koch classification,95 in which agreement is graded as excellent (κ ≥ 0.80), good (κ = 0.60–0.79), moderate (κ = 0.40–0.59), poor (κ = 0.20–0.39) or very poor (κ < 0.20)]. Cohen’s kappa statistics indicate how much better the agreement is over the agreement that would have occurred by chance (the expected agreement). We propose to carry out further analyses on interobserver and intraobserver variability and all of the mpMRI scans have been archived for future training and quality assurance purposes.

| Radiologist 1 | Number of cases by mpMRI score | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radiologist 2 | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Total | |

| 1 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| 2 | 0 | 19 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 34 |

| 3 | 0 | 9 | 33 | 5 | 0 | 47 |

| 4 | 0 | 1 | 10 | 7 | 5 | 23 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 22 | 23 |

| Total | 0 | 33 | 59 | 13 | 27 | 132 |

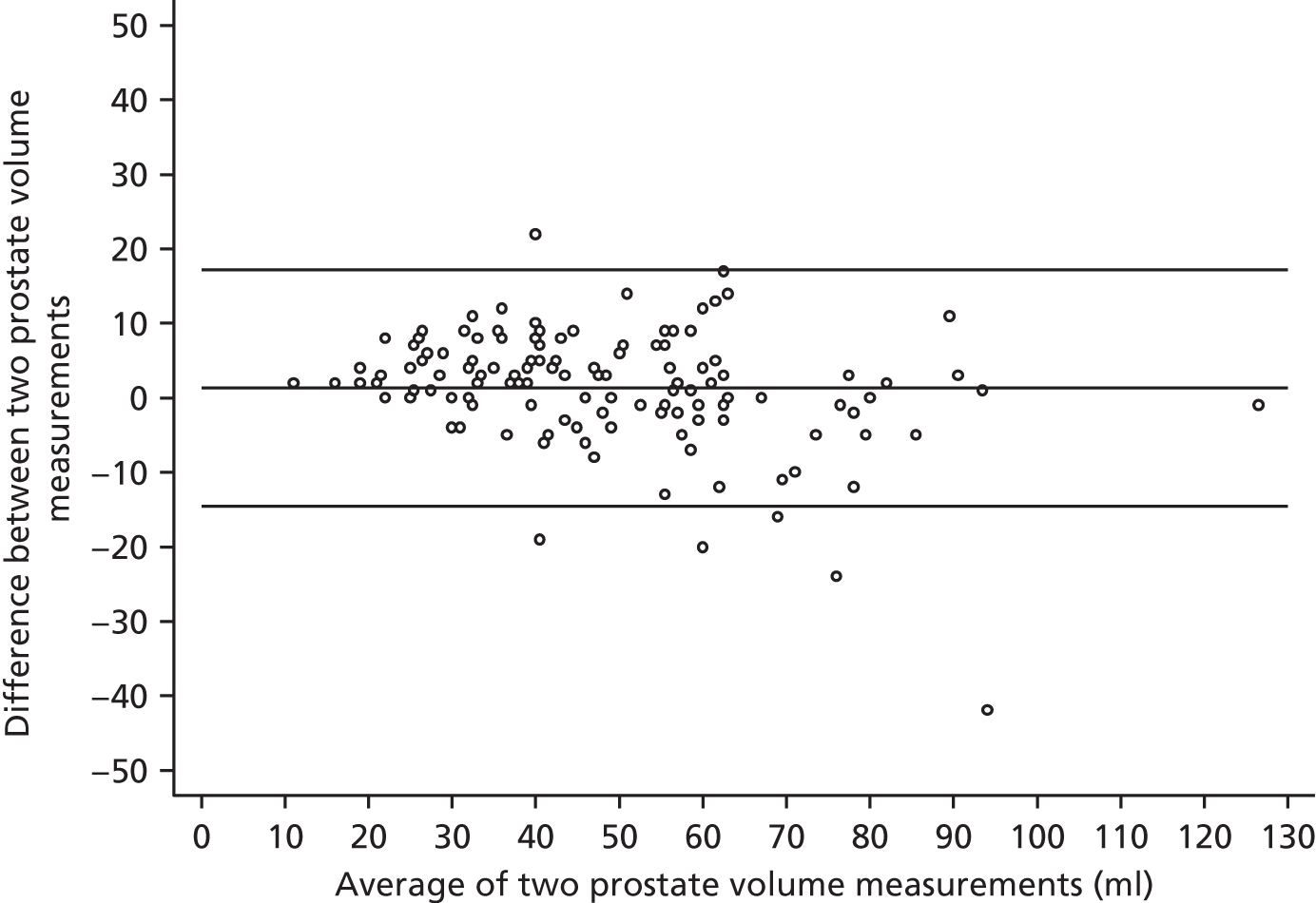

Agreement between radiologists for prostate volume measurements by mpMRI is shown in Figure 12, using the Bland–Altman method, which plots the difference between measurements against the average of the measurements. The average prostate volume was 48 ml. Overall, the mean difference between volumes was +1.3 ml (95% CI –0.04 ml to +2.69 ml]. The plot indicates that the interobserver reproducibility between radiologists for prostate volume measurement was approximately ±15 ml. There was a tendency for poorer agreement with larger volumes and this association was significant according to Pitman’s test, as well as simple linear regression.

FIGURE 12.

Bland–Altman plot for volume measurements between two radiologists.

There was no difference in diagnostic accuracy between the lead radiology site (UCLH, responsible for training all other sites) and the other sites (see Appendix 1 for comparison).

Health-related quality of life

Participants filled in EuroQol-5 Dimensions, three-level version (EQ-5D-3L) questionnaires at enrolment, after undergoing mpMRI, after undergoing the CBP and at the end of the study, which was, on average, 42 days after the CBP. As part of the economic evaluation, the EQ-5D-3L profiles were converted into preference-based index scores using the UK tariff. 96 The index scores after each test were compared with the values at enrolment. There was no evidence of a change in index score between post mpMRI and baseline (change = 0.008, 95% CI –0.002 to 0.018). However, there was a large and statistically significant negative impact after the CBP, with a change of –0.176 (95% CI –0.203 to –0.149). The health-related quality of life (HRQoL) implications of the various diagnostic strategies are explored further in the economic evaluation (see Chapters 4–8).

Safety

This section summarises the safety information for the CBP, which involved TPM-biopsy followed by TRUS-guided biopsy under the same anaesthesia. The CBP was carried out for the purposes of the study only; it is important to note that the CBP would not be required in routine clinical practice under any protocols developed as a result of PROMIS.

Risk of sepsis

There were nine cases of sepsis after the CBP during the study. There was one case of sepsis prior to the CBP. This equates to a post-CBP risk of sepsis of 9 out of 601 (1.5%, 95% CI 0.7% to 2.8%).

Risk of serious adverse events and side effects

A SAE is defined as any event that leads to death, a life-threatening situation, inpatient hospitalisation, persistent or significant disability, a congenital anomaly/birth defect or another important medical condition. 97 There were 44 reports of SAEs during the study. This equates to a risk of 44 out of 740 (5.9%, 95% CI 4.4% to 7.9%). Twenty-eight of the events (64%) involved the urogenital system, with the most common events being urinary retention and urinary tract infections or urosepsis. As reported in Risk of sepsis, there were 10 cases of sepsis. There were no deaths up to the time limit for reporting SAEs (30 days after the last study visit). All SAEs, including sepsis cases, were independently reviewed by the independent Data Monitoring Committee to ensure that the rate of sepsis was no higher than that reported for TRUS-guided biopsy on its own. No safety concerns were raised during these reviews.

Most men (88%) experienced at least one side effect. Table 17 summarises the numbers of any side effects documented at the patients’ last study visit.

| Side effect (n with missing data) | n (%) |

|---|---|

| mpMRI | |

| Pain/discomfort (15) | 11 (2) |

| Allergic reaction to contrast medium (16) | 1 (< 1) |

| Other | 3 (< 1) |

| CBP | |

| Pain/discomfort (13) | 362 (64) |

| Dysuria (17) | 256 (46) |

| Haematuria (11) | 380 (67) |

| Haematospermia (51) | 291 (55) |

| Erectile dysfunction (requiring medication, injection therapy or devices) (48) | 76 (14) |

| Urinary tract infection (only if confirmed by a laboratory test) (11) | 32 (6) |

| Systemic urosepsis (9) | 8 (1) |

| Acute urinary retention (12) | 58 (10) |

| Symptoms associated with general/spinal anaesthesia (43) | 19 (4) |

| Other | 65 (11) |

| Total patients with any side effect (8) | 501 (88) |

Chapter 4 Economic evaluation approach

Overview

The economic evaluation conducted for PROMIS is presented in four chapters. Chapter 4 states the aims and objectives of the economic evaluation and describes the approach used. Chapter 5 describes the evaluation of the short-term outcomes associated with using the different diagnostic tests to detect CS cancer. Chapter 6 describes the evaluation of the long-term outcomes associated with treatment compared with monitoring of men with prostate cancer. Chapter 7 combines the results of Chapters 5 and 6 and presents conclusions on the cost-effectiveness of the diagnostic strategies.

Introduction

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer in men, with approximately 47,000 new cases diagnosed in the UK in 2013. It is the second most common cause of death for men in the UK, with approximately 11,000 deaths per year. 1 As discussed in Chapter 1, prostate cancer is divided into risk groups based on a combination of PSA level, Gleason score (i.e. cancer grade) and stage (see Table 1). Low-risk cancer is considered to be CNS because it is unlikely to have a clinical impact during the man’s remaining lifetime. The term ‘clinically insignificant’ is also commonly used. Intermediate-risk cancer and high-risk cancer have a greater risk of progression and are considered to be CS.

Currently in the UK, all men considered to be at risk of having prostate cancer are invited to undergo a biopsy, usually of the TRUS-guided type, to identify and classify the cancer. The biopsy procedure has adverse health consequences, albeit mostly temporary, and misses a considerable proportion of CS cancers.

There are two possible ways of improving the current practice of TRUS-guided biopsy for all men considered to be at risk: (1) choose another test that is better at detecting CS cancer (better sensitivity) or (2) incorporate additional tests prior to biopsy that might inform the decision to proceed to biopsy (triage test) and/or might improve the sensitivity of biopsy. The mpMRI is in the latter category, because it may enable the selection of patients who should have a biopsy and also provide information to enable targeted biopsies of suspicious areas within the prostate. The mpMRI can be used in combination with TRUS-guided biopsy or other biopsy types to better detect CS cancer and avoid unnecessary biopsies.

The different ways of combining mpMRI and biopsy form a range of diagnostic strategies for prostate cancer. These diagnostic strategies have different costs and health outcomes, in both the short term and the long term. The short-term costs and health outcomes depend on the prices of the tests and their direct health effects and detection rates in men with and without CS cancer. The long-term costs and health outcomes relate to the downstream consequences of treatment decisions, which in turn depend on the detection rates of each test. The short- and long-term costs and health outcomes together determine the most cost-effective way in which to use mpMRI and biopsy (i.e. the cost-effective diagnostic strategy).

To inform decisions on how best to use the tests in combination, decision modelling is required to combine the data generated in PROMIS with external information. The clinical data generated in PROMIS provide information on how accurate mpMRI and biopsy are at detecting CS and CNS prostate cancer. However, the data do not provide information on the effect of using mpMRI and biopsy in combination (e.g. the proportion of CS cancers detected when using mpMRI to direct the TRUS-guided biopsy to suspicious lesions). External information is also required to predict the long-term costs and health outcomes of the alternative strategies, based on the proportions who are correctly diagnosed with CS prostate cancer, that is, the quality-adjusted survival and lifetime costs of men according to their cancer status and diagnostic classification. Decision modelling structures the available evidence using a mathematical model, combining the different pieces of information to produce an estimate of the costs and health outcomes of the different diagnostic strategies. Health outcomes are typically expressed as quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs), a measure that weights life expectancy with its HRQoL.

An evaluation of the effectiveness of the alternative strategies can rely on the health outcomes associated with each, the most effective strategy being the one conferring the most health to the potential population of users. To ascertain cost-effectiveness, however, the consequences of the additional costs that some of the strategies impose on the NHS also need to be considered. This requires information on the health opportunity cost of diverting resources to more costly interventions. The health opportunity cost is the health benefit forgone by other patients if their interventions are no longer funded in order to release resources for other more costly diagnostic strategies. The cost-effective diagnostic strategy is the strategy that achieves the greatest health gain net of the health opportunity cost.

Previous research98 has estimated that £13,000 in additional costs displaces 1 QALY. This is the health opportunity cost for the NHS of offering a more costly intervention and is often referred to as the cost-effectiveness threshold. Therefore, the most cost-effective diagnostic strategy is the one that achieves the most QALYs net of its costs, converted into QALYs forgone using the health opportunity cost of £13,000. NICE uses a higher value, of between £20,000 and £30,000 per QALY, to make recommendations to the NHS on the cost-effectiveness of new interventions. 99 This means that an additional £20,000–30,000 is assumed to impose on the NHS a loss of 1 QALY.

Aims and objectives of the economic evaluation

The aim of the economic evaluation was to identify the most cost-effective diagnostic strategy in men with suspected localised prostate cancer from the perspective of the UK NHS, using information on TRUS-guided biopsy, mpMRI and TPM-biopsy. The evaluation makes use of information generated in PROMIS, supplemented by external evidence as appropriate, and compares the various ways that these diagnostic tests can be used to diagnose prostate cancer.

The specific objectives of the economic evaluation were to:

-

define potential diagnostic strategies involving combinations of TRUS-guided biopsy, mpMRI and TPM-biopsy that could reasonably be used in clinical practice

-

estimate the proportions of men correctly identified with prostate cancer, both CNS and CS, and men with cancer who have been missed, for each diagnostic strategy

-

estimate the direct HRQoL and NHS costs associated with each diagnostic strategy

-

evaluate the expected quality-adjusted survival and NHS costs of men depending on their diagnostic classifications, treatment decisions and true disease status

-

compare the quality-adjusted survival and NHS costs of all diagnostic strategies incrementally to identify the most cost-effective strategy for a given cost-effectiveness threshold range

-

identify the main drivers of cost-effectiveness and explore how they affect the results

-

characterise the uncertainty around the results and identify the key areas of uncertainty, which should be prioritised for future research.

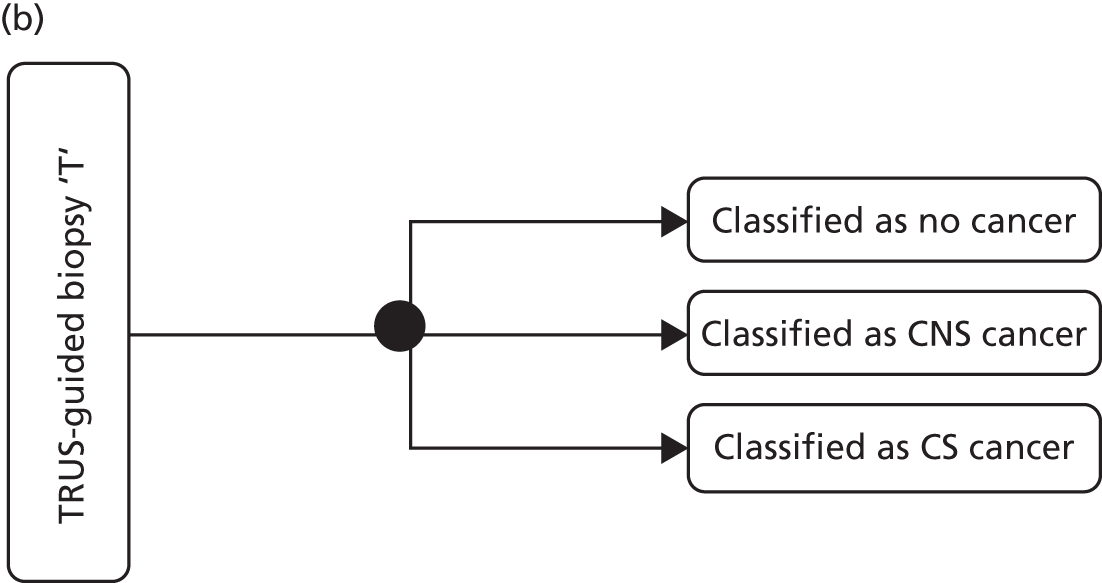

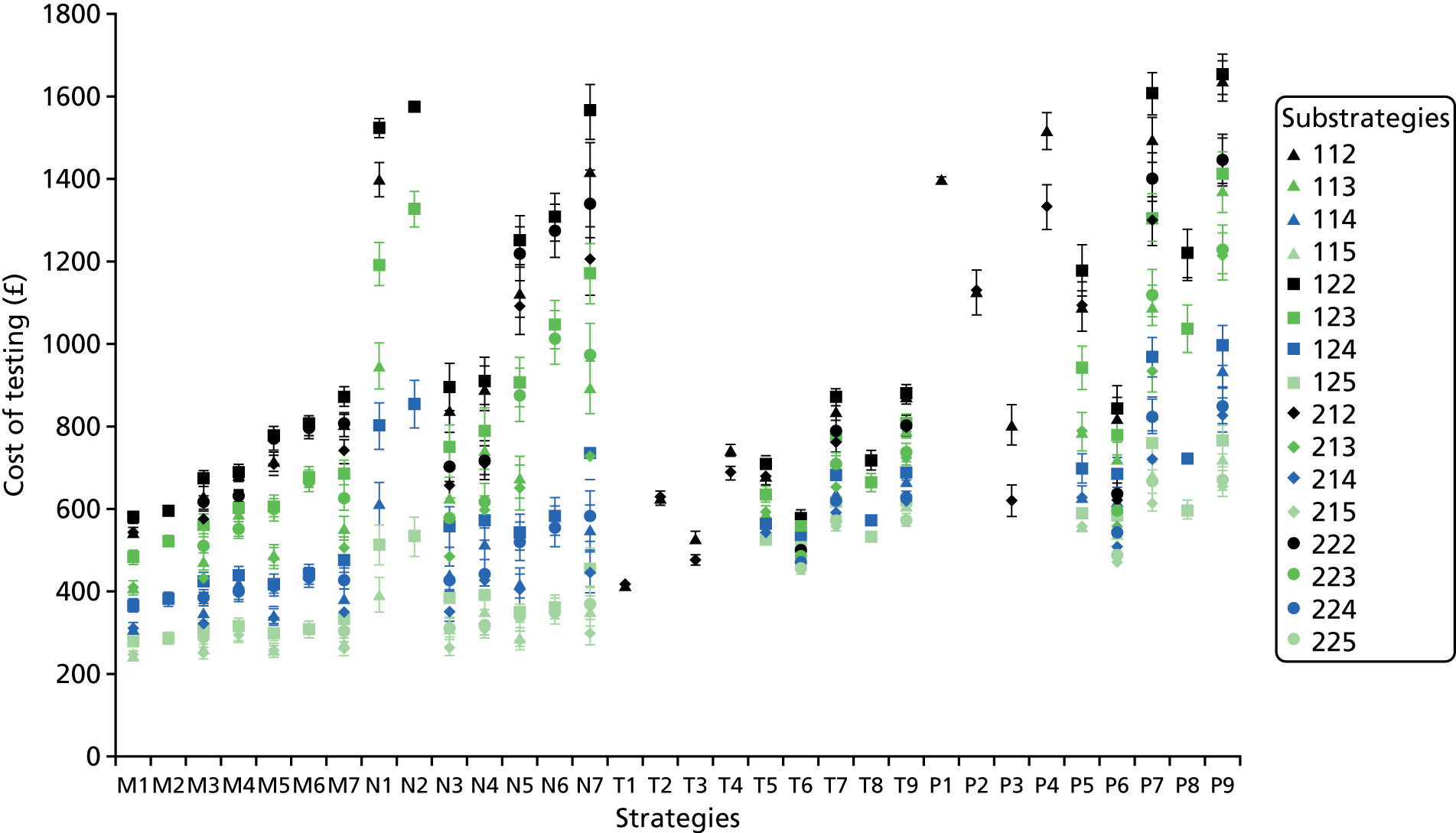

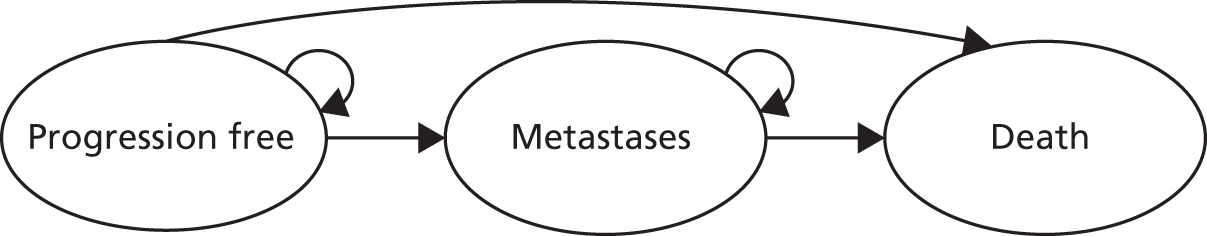

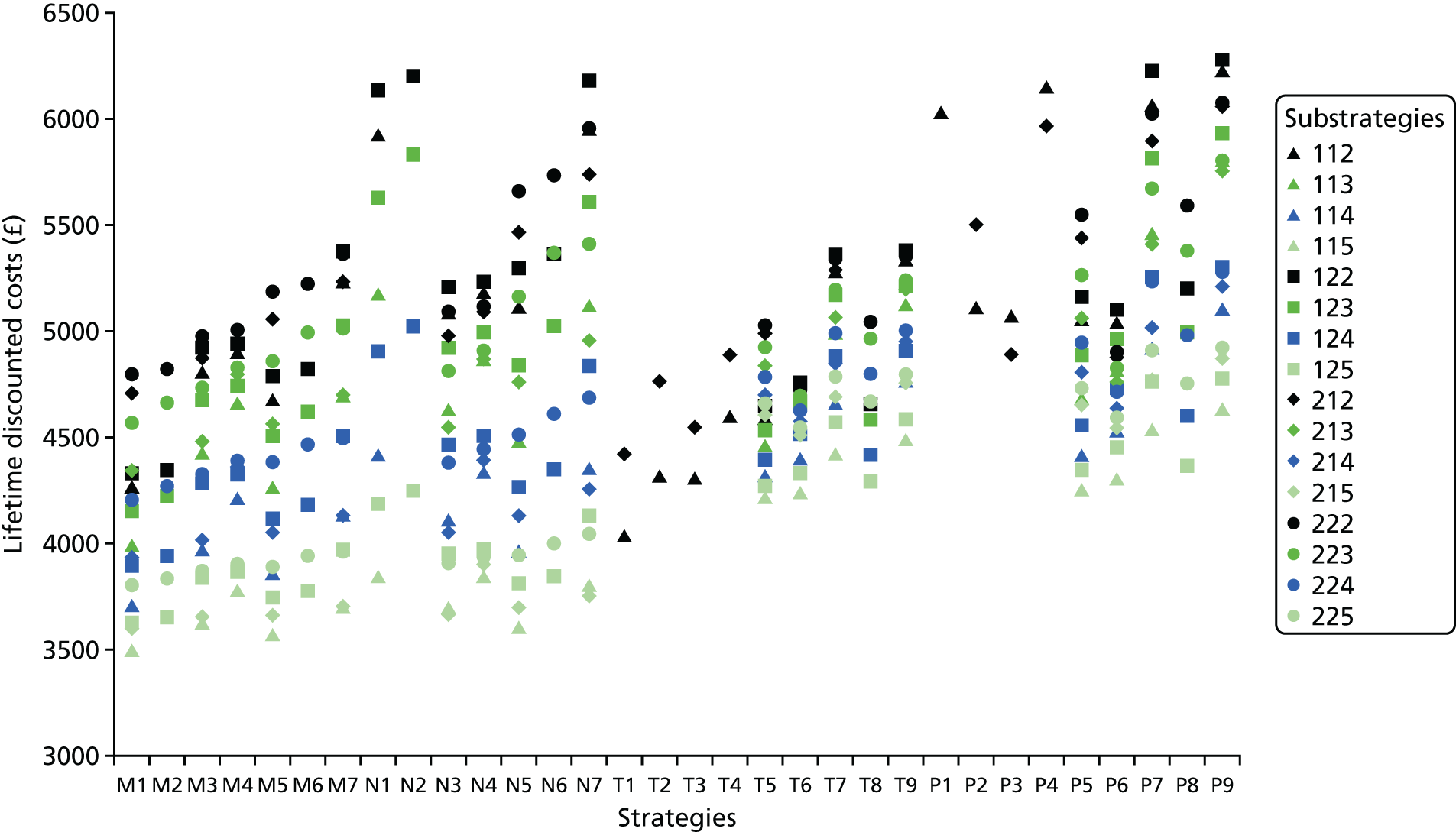

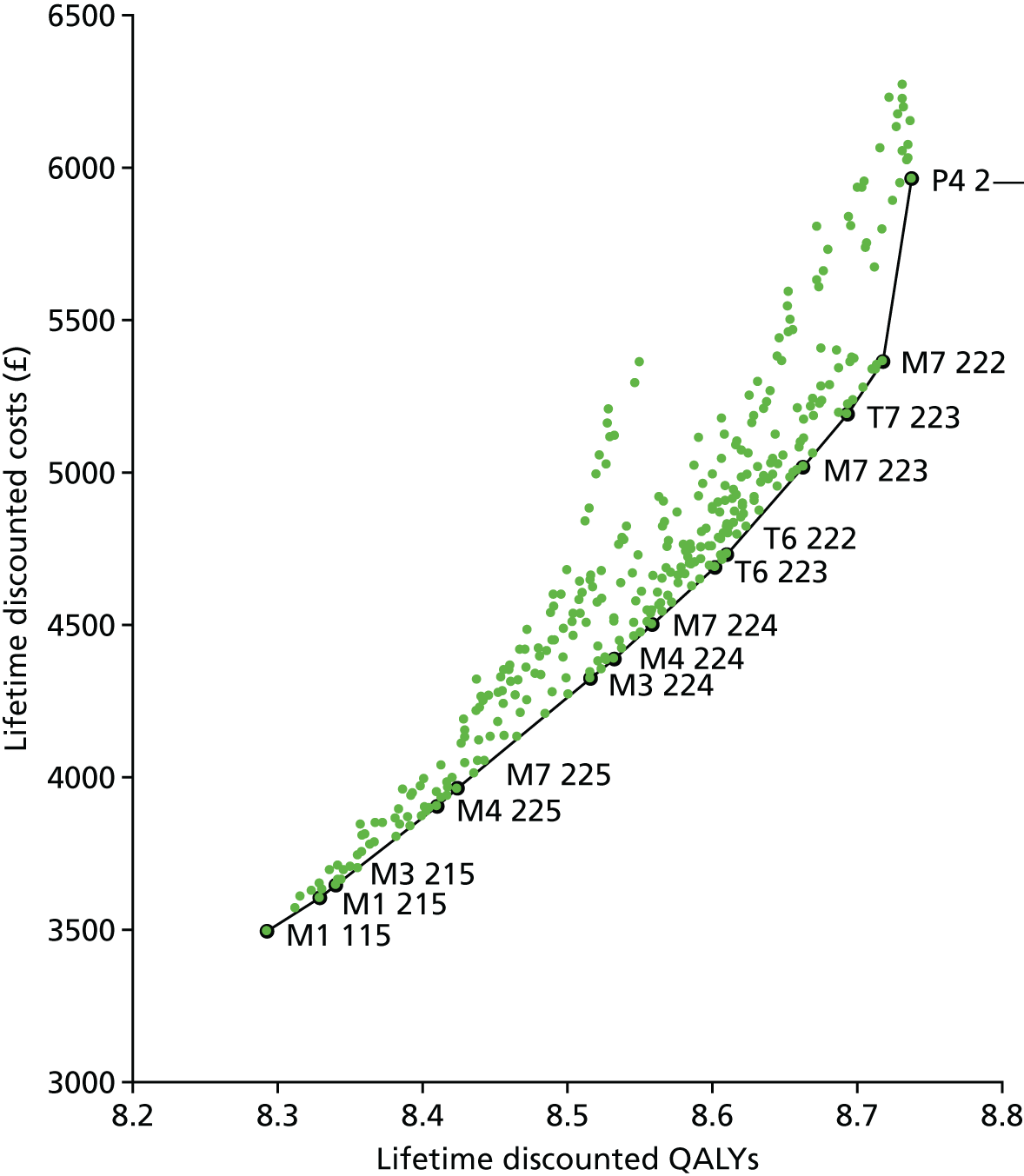

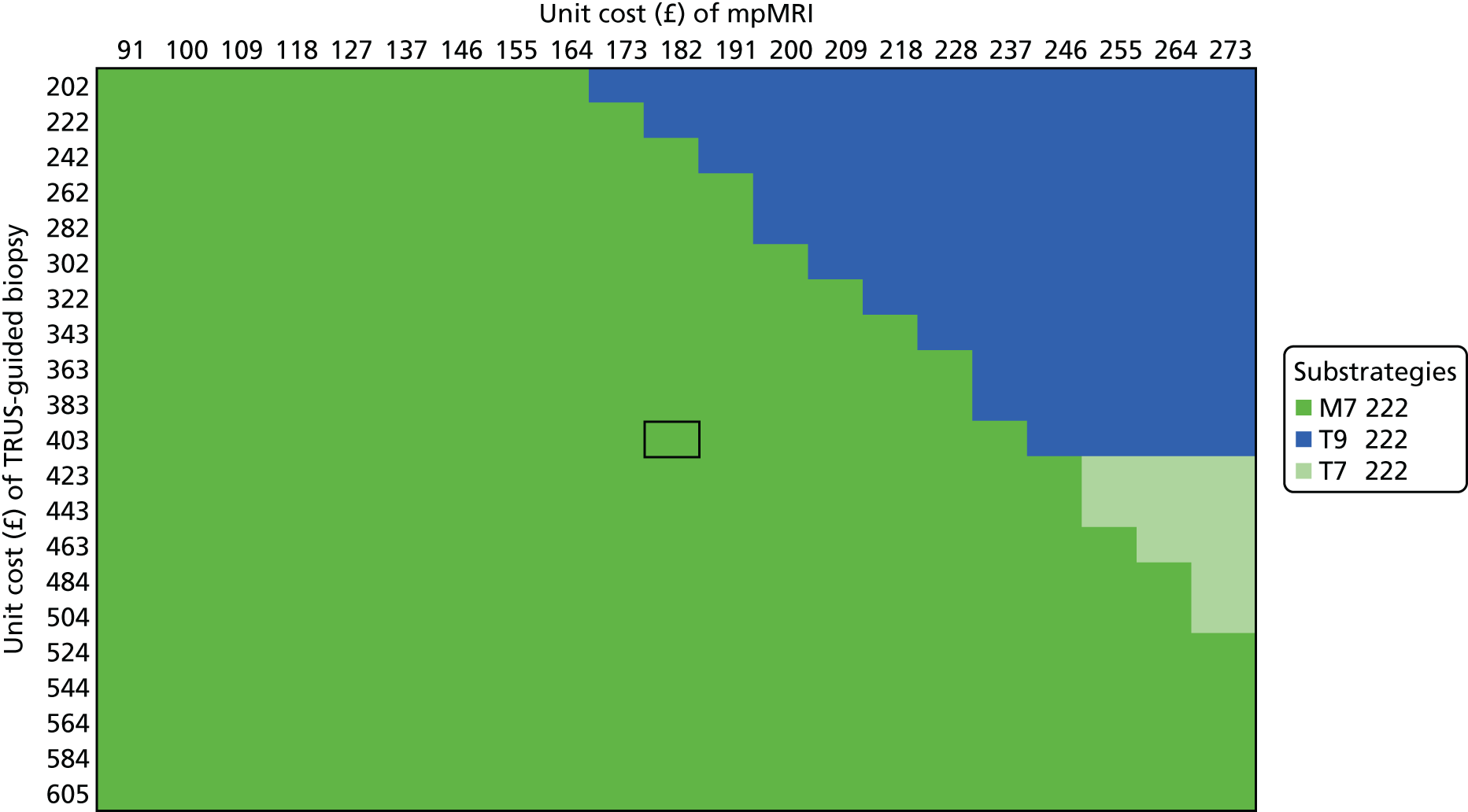

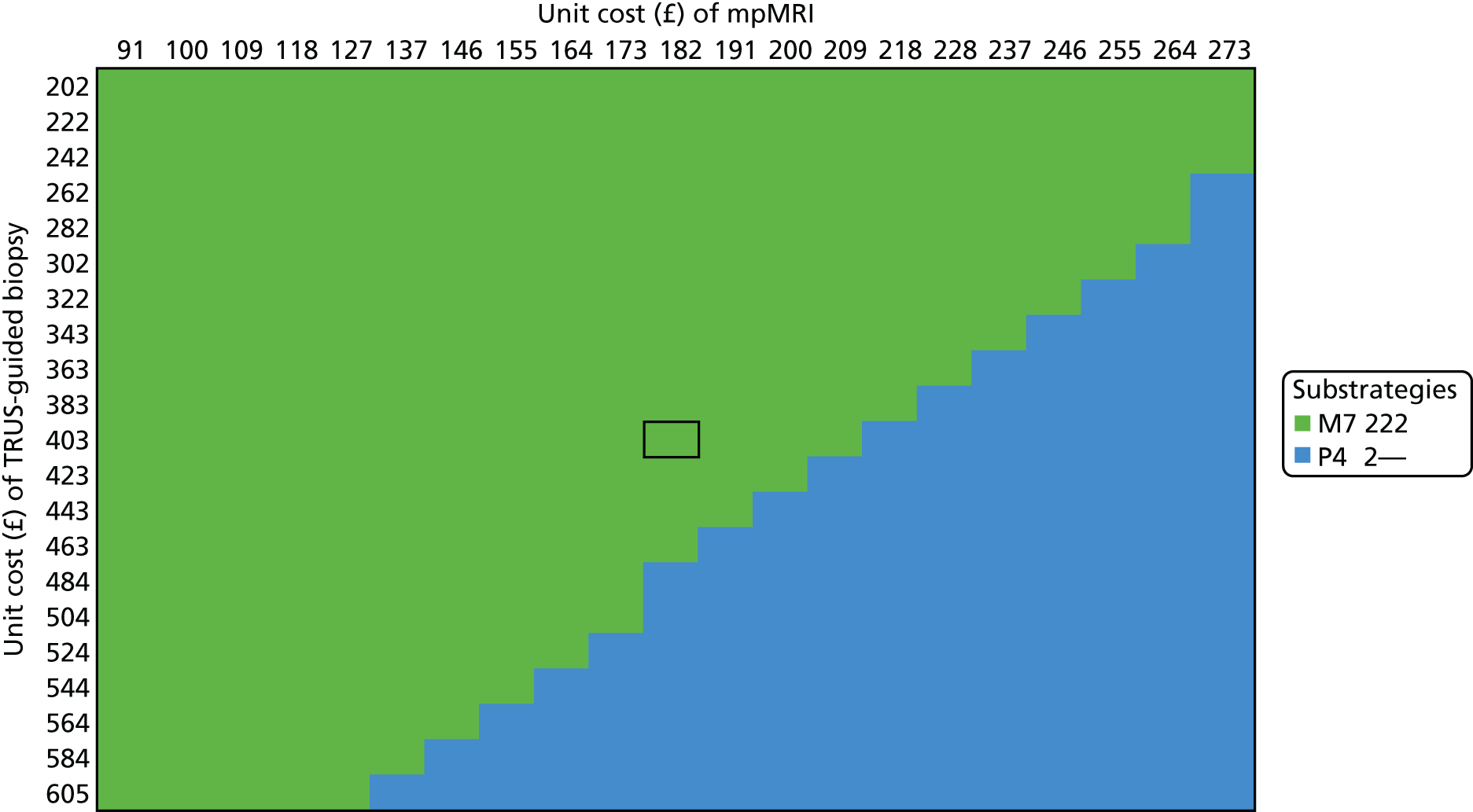

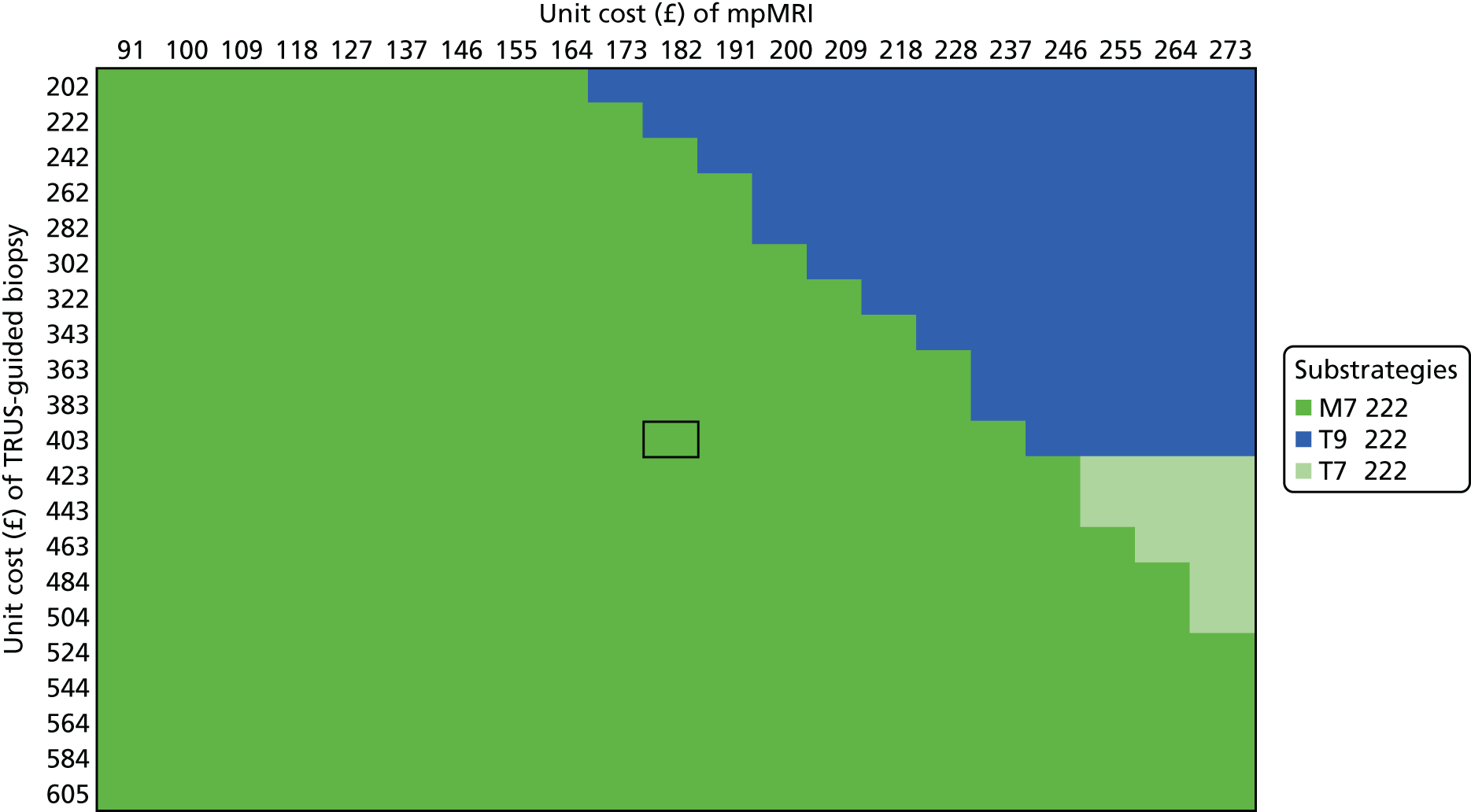

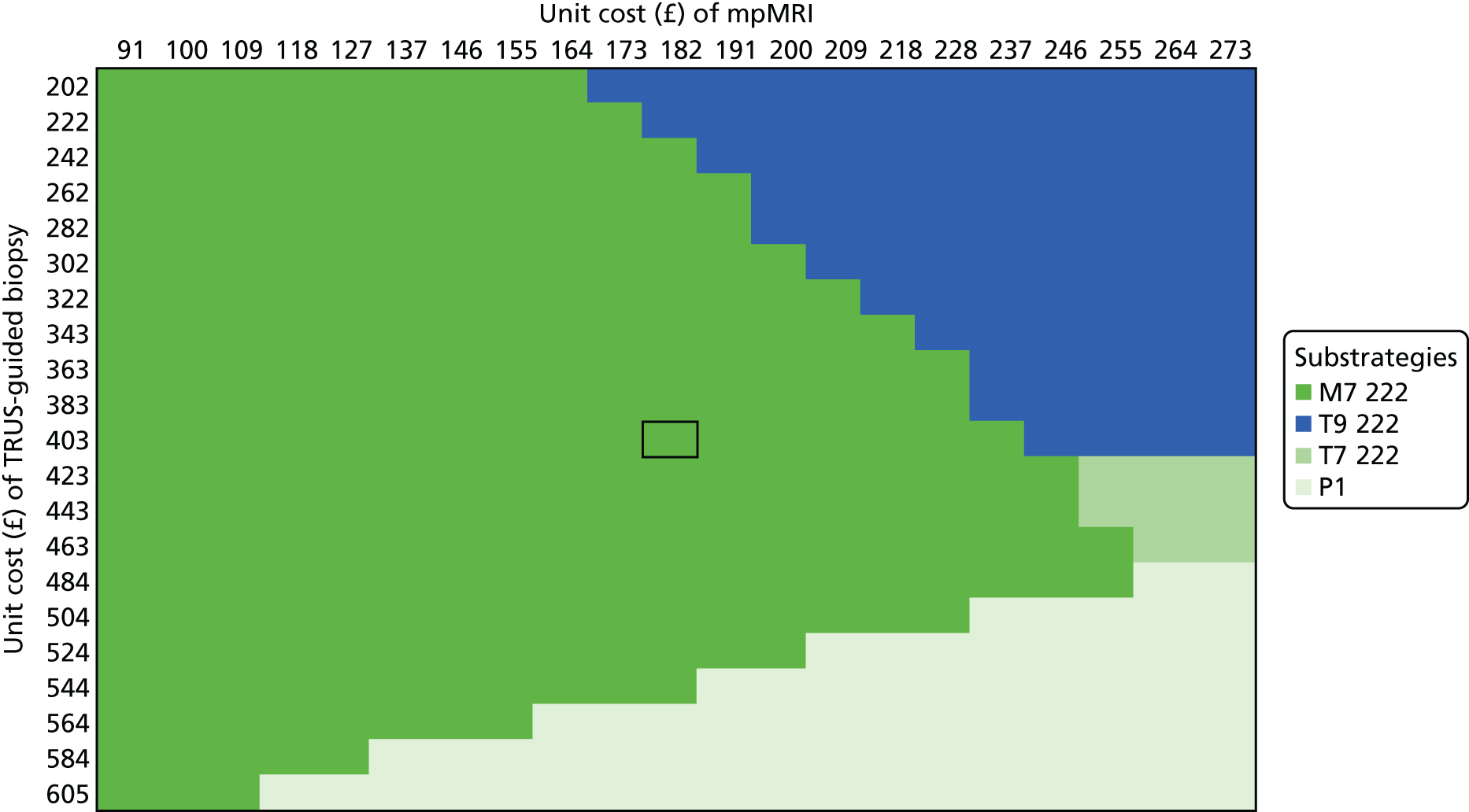

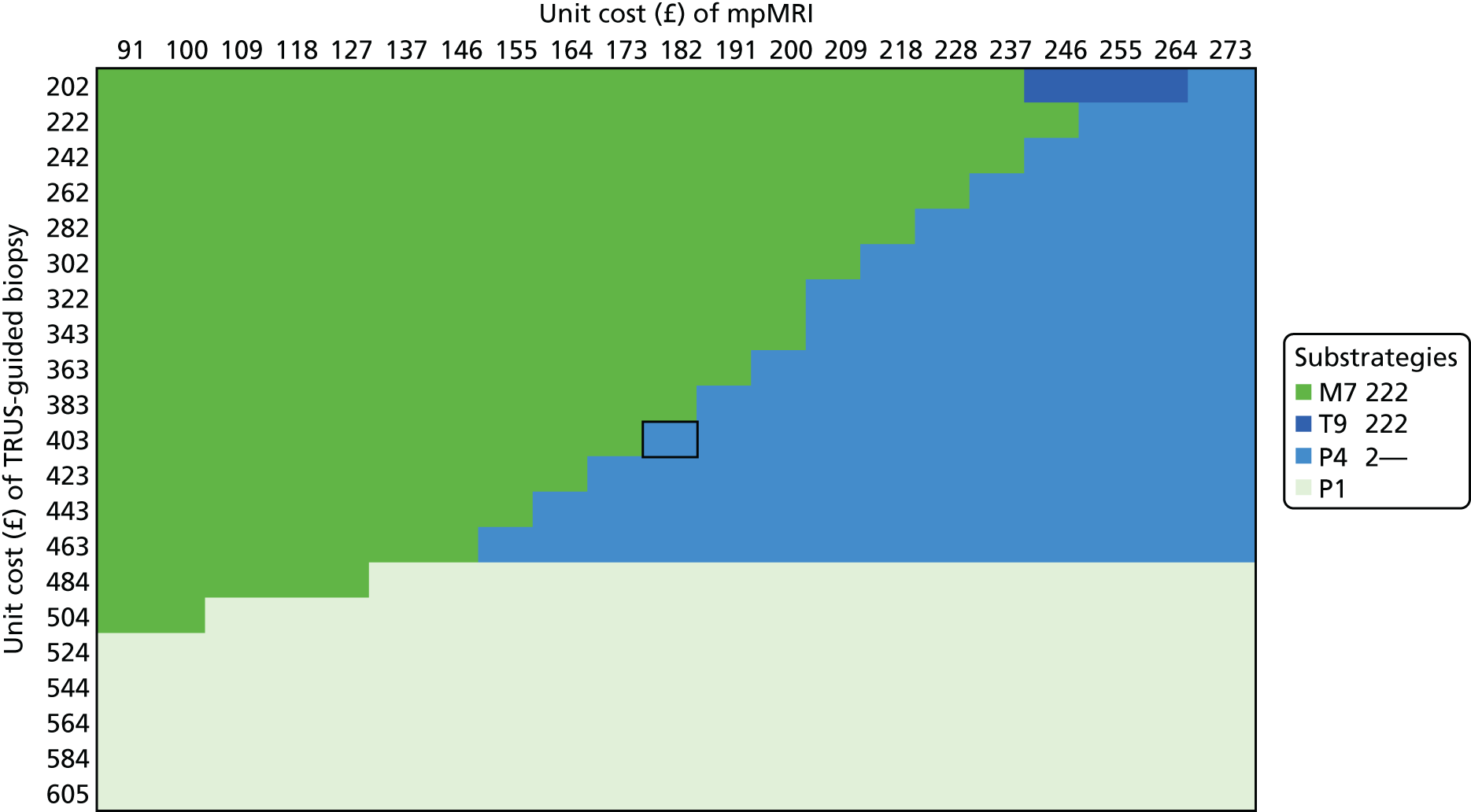

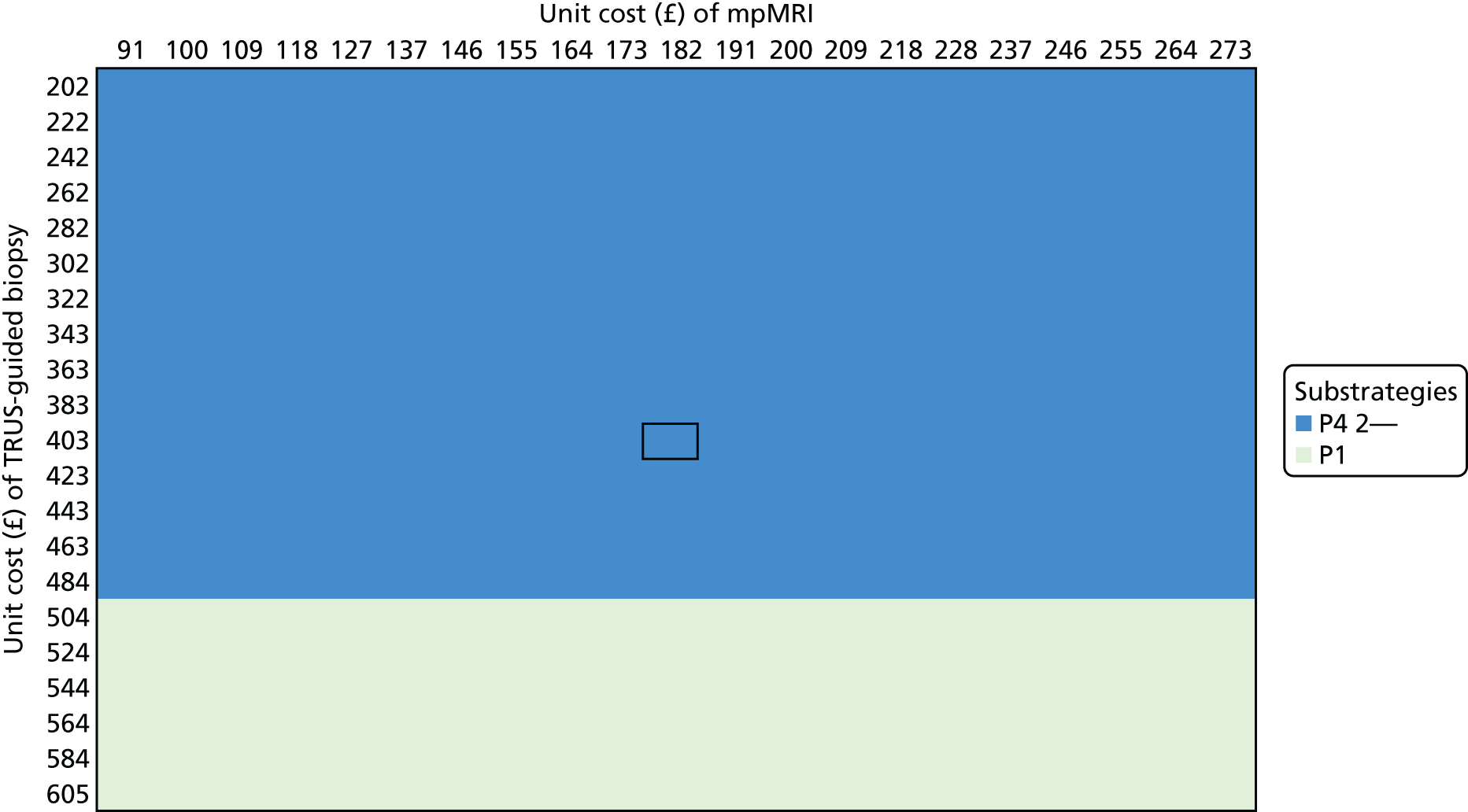

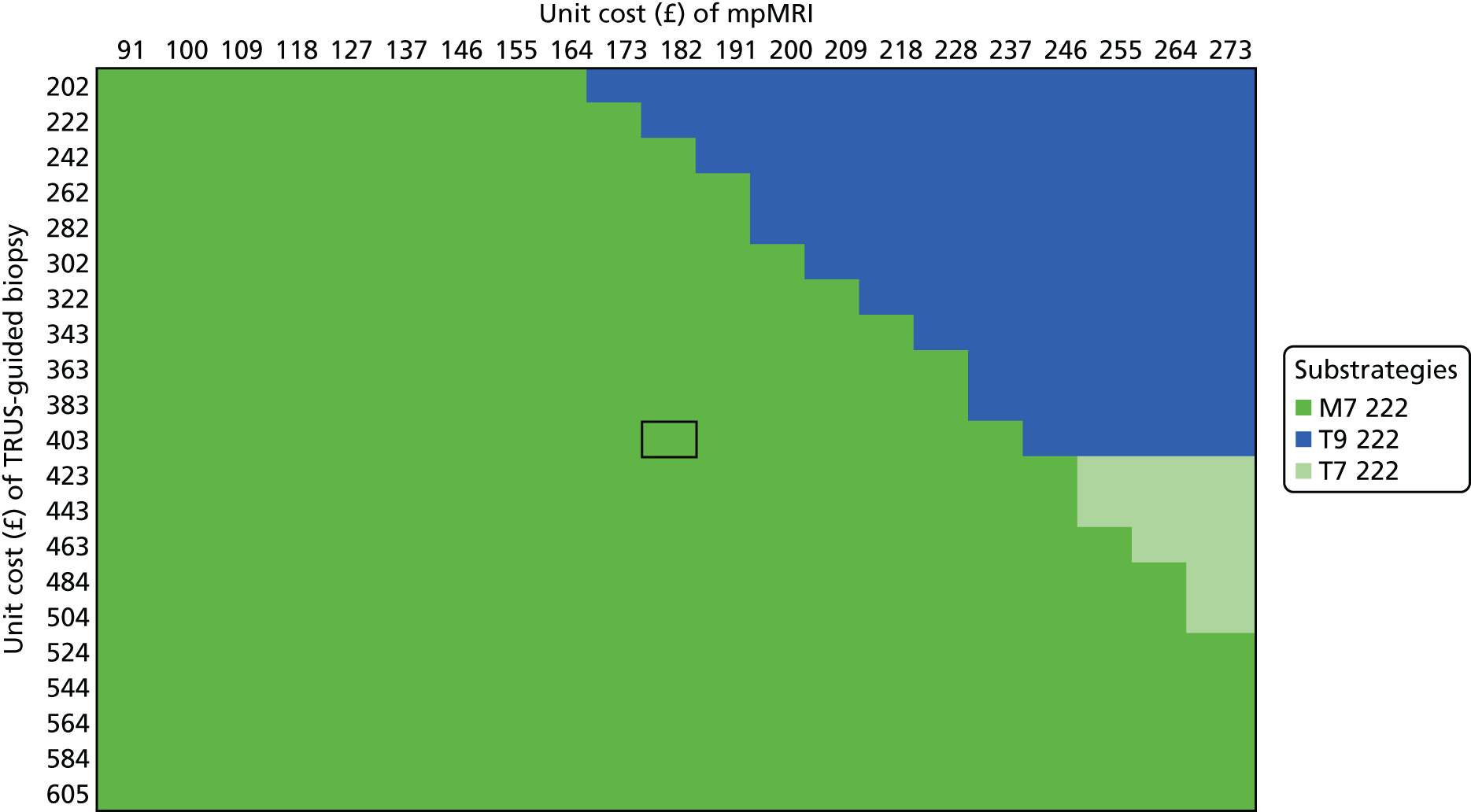

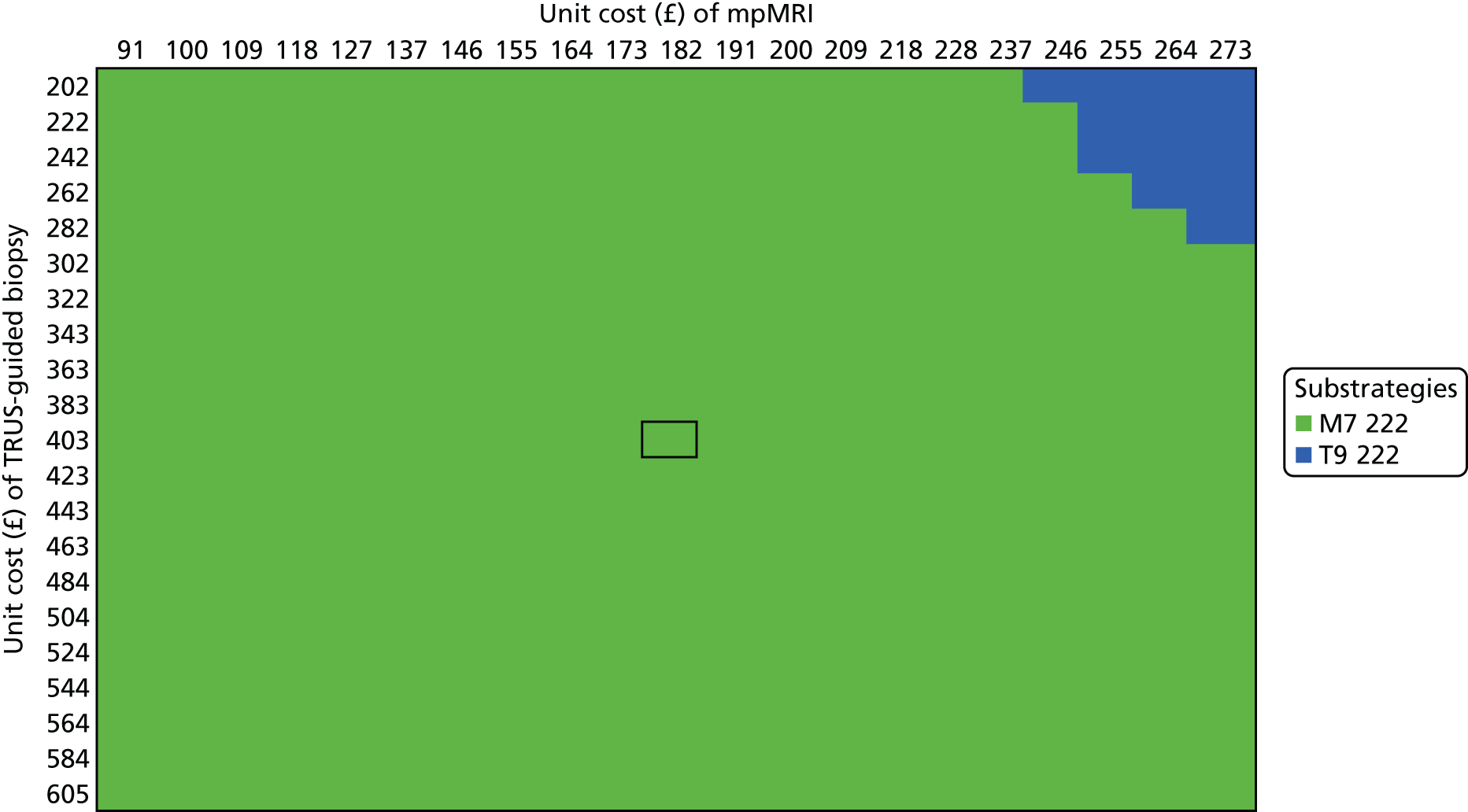

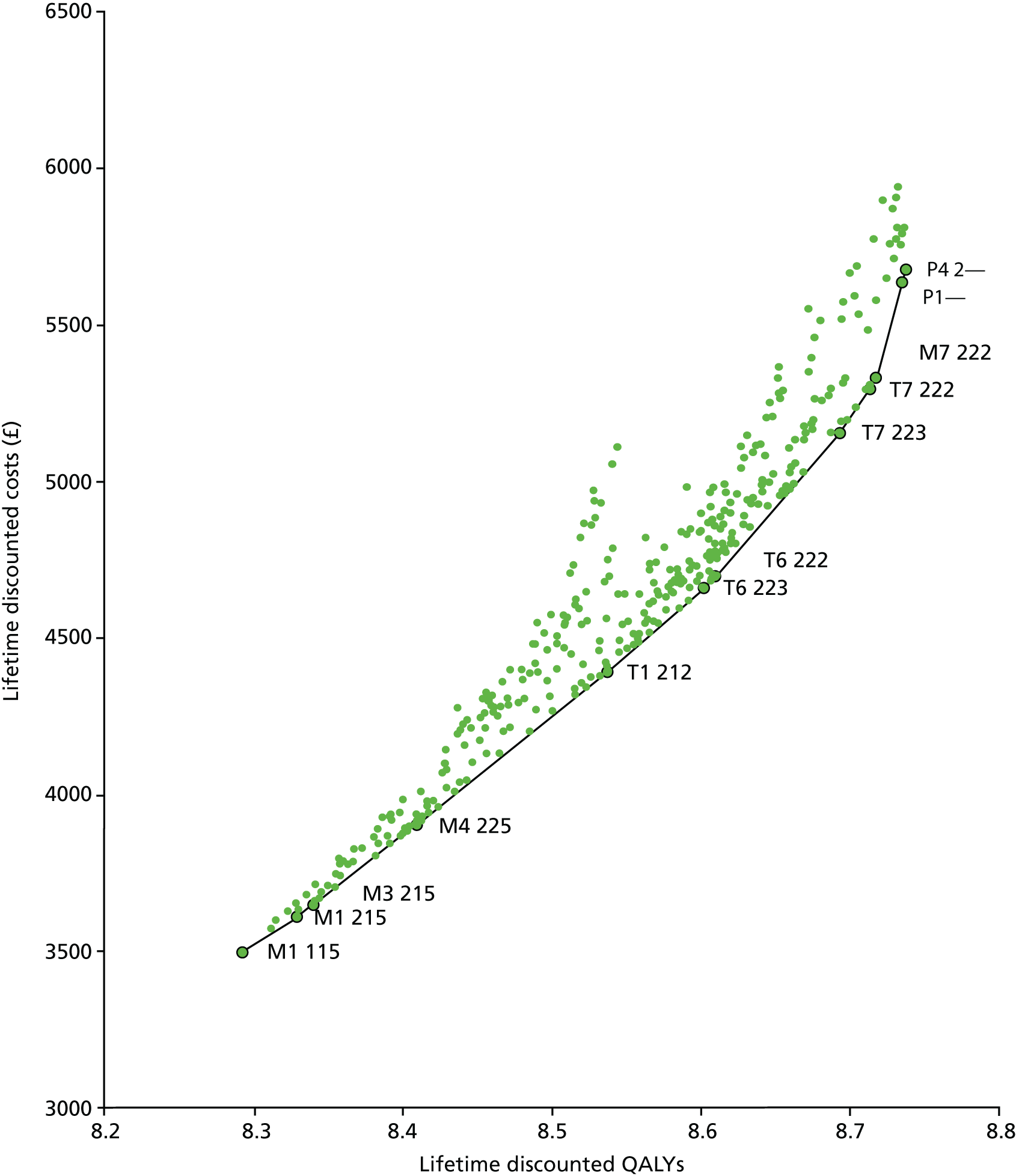

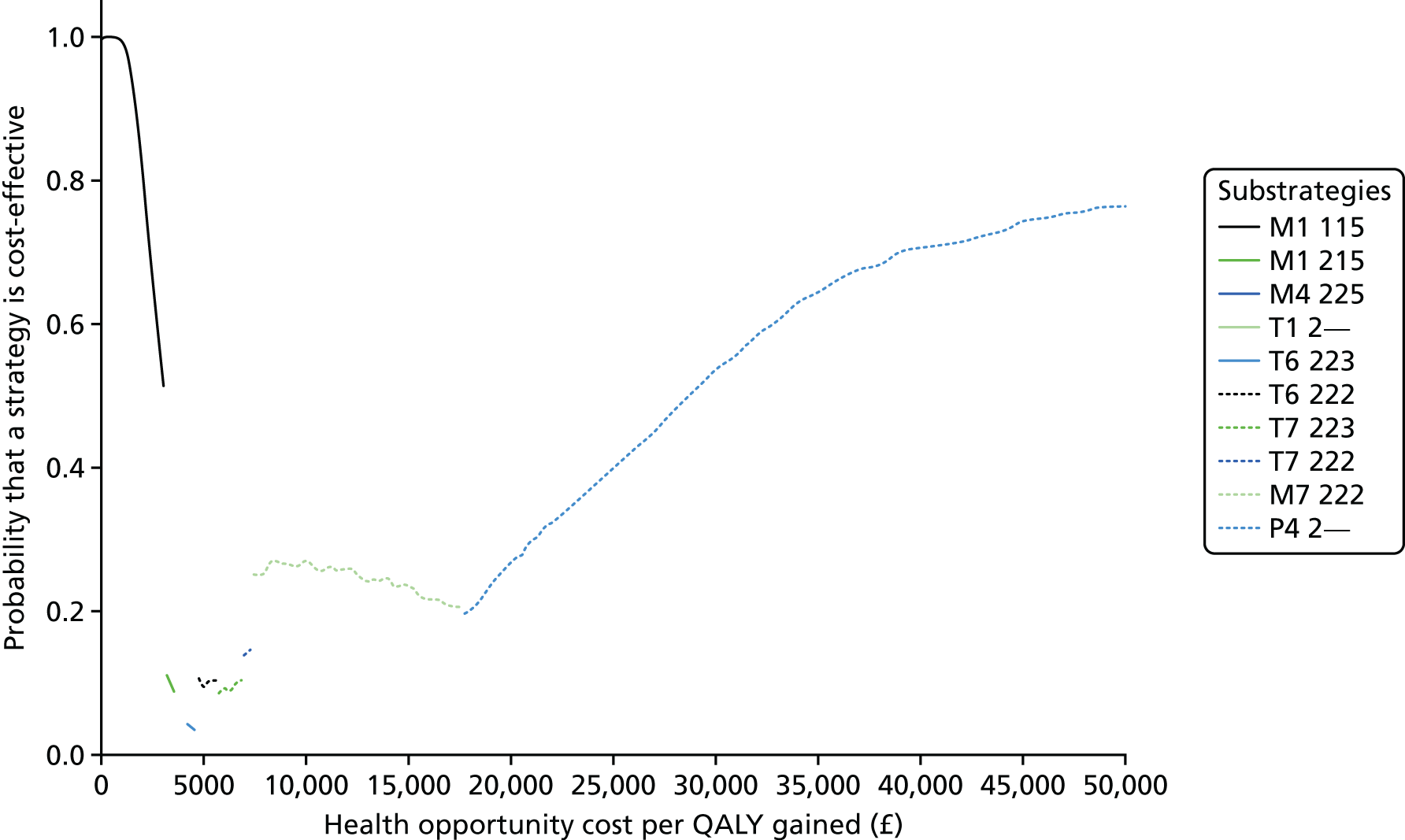

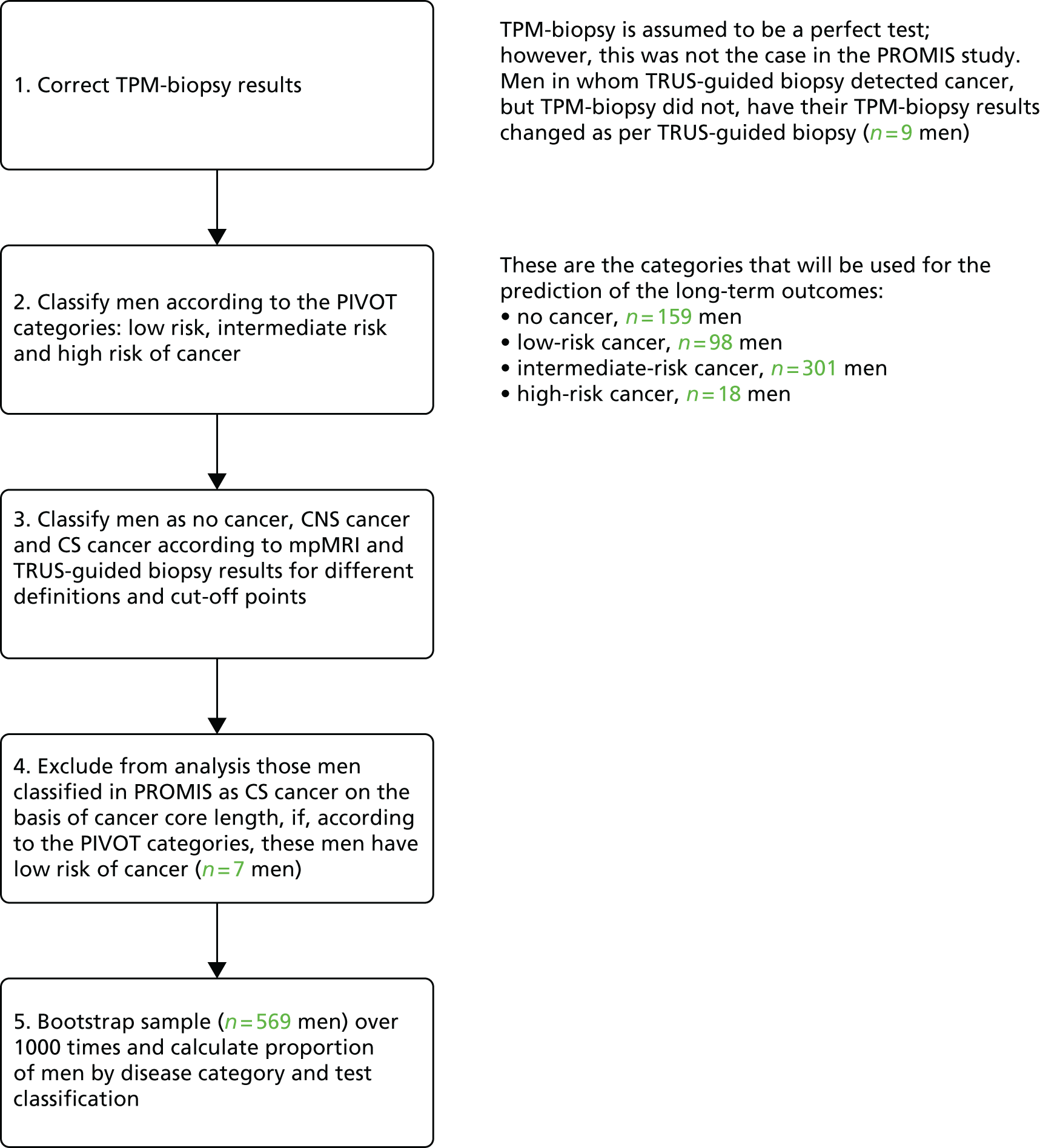

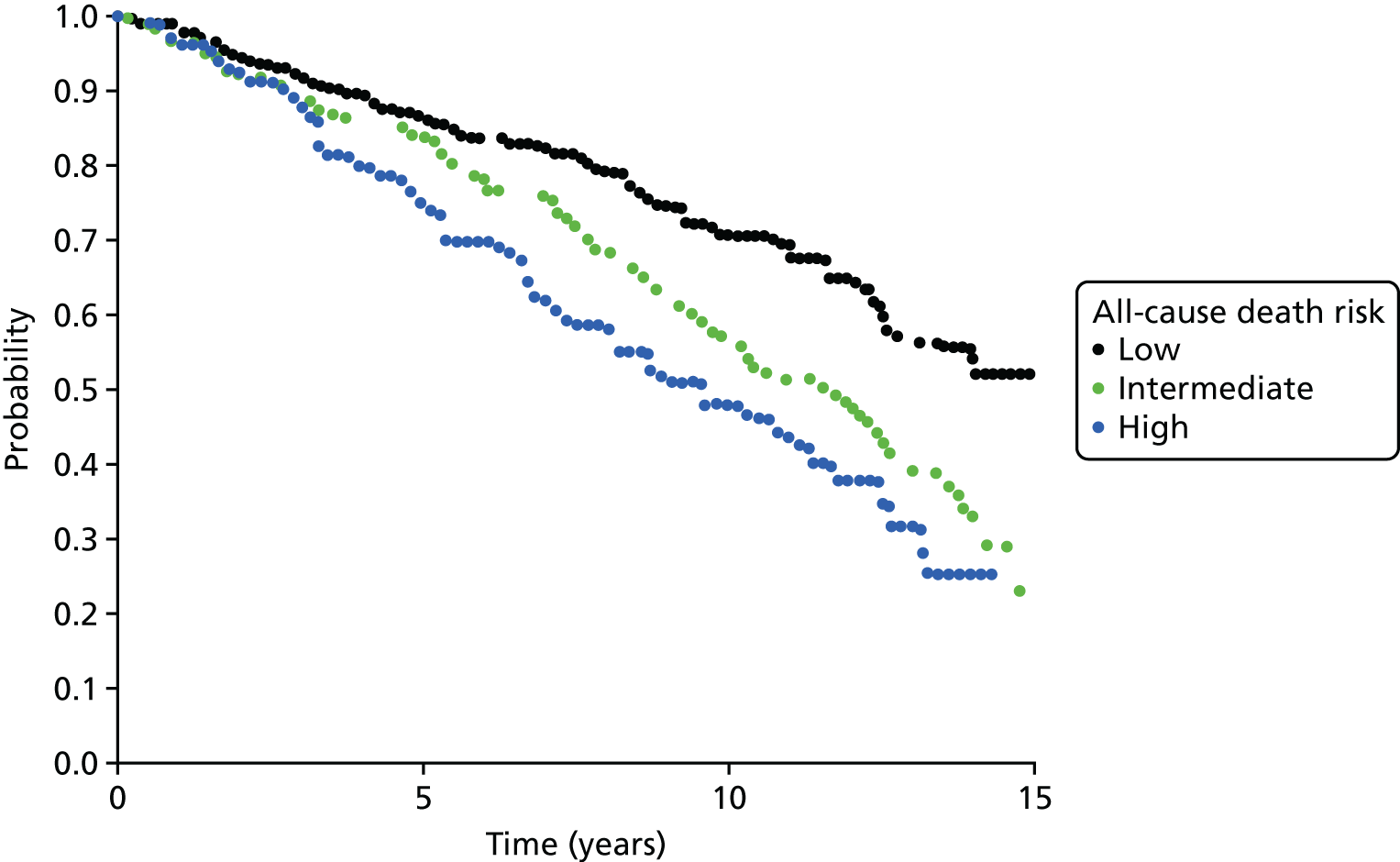

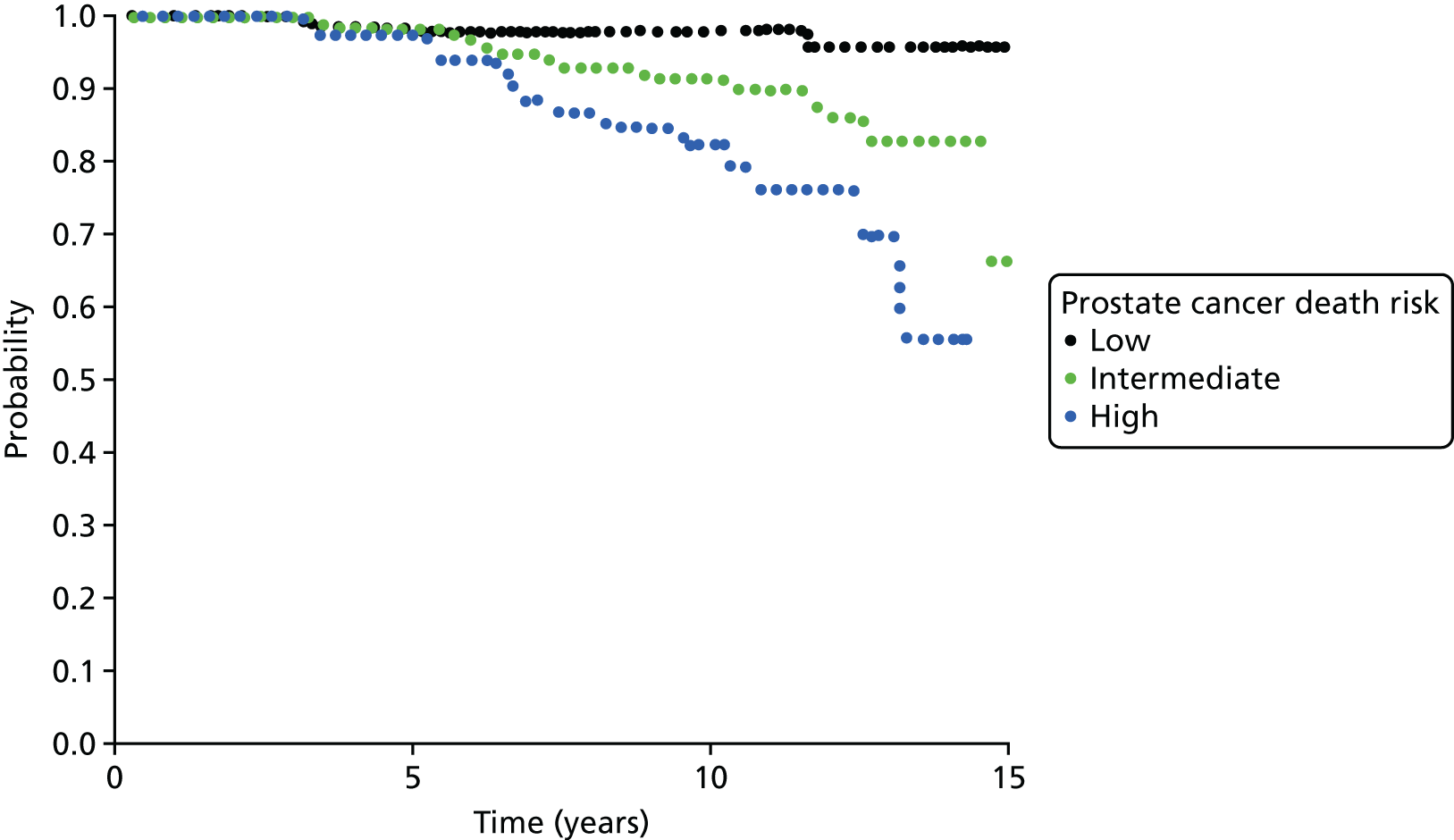

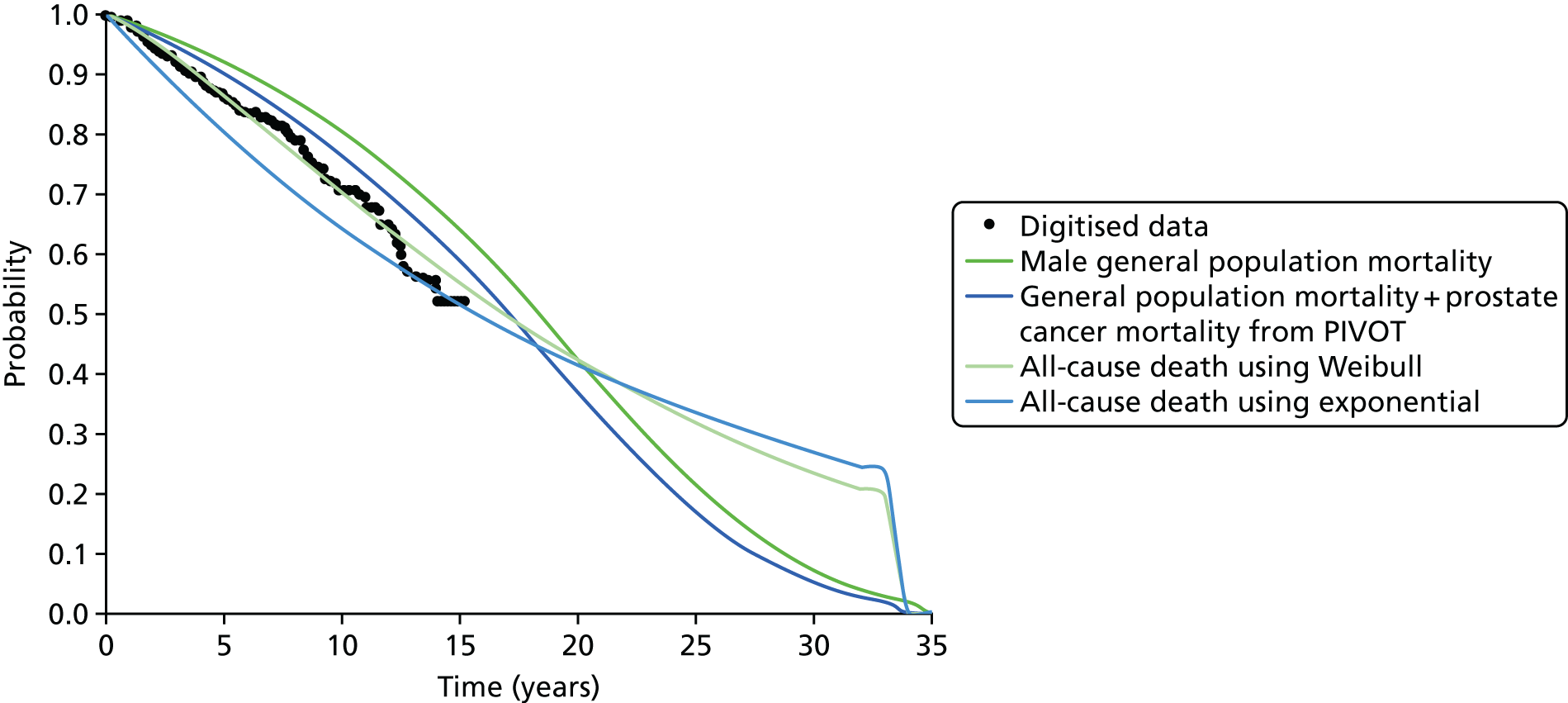

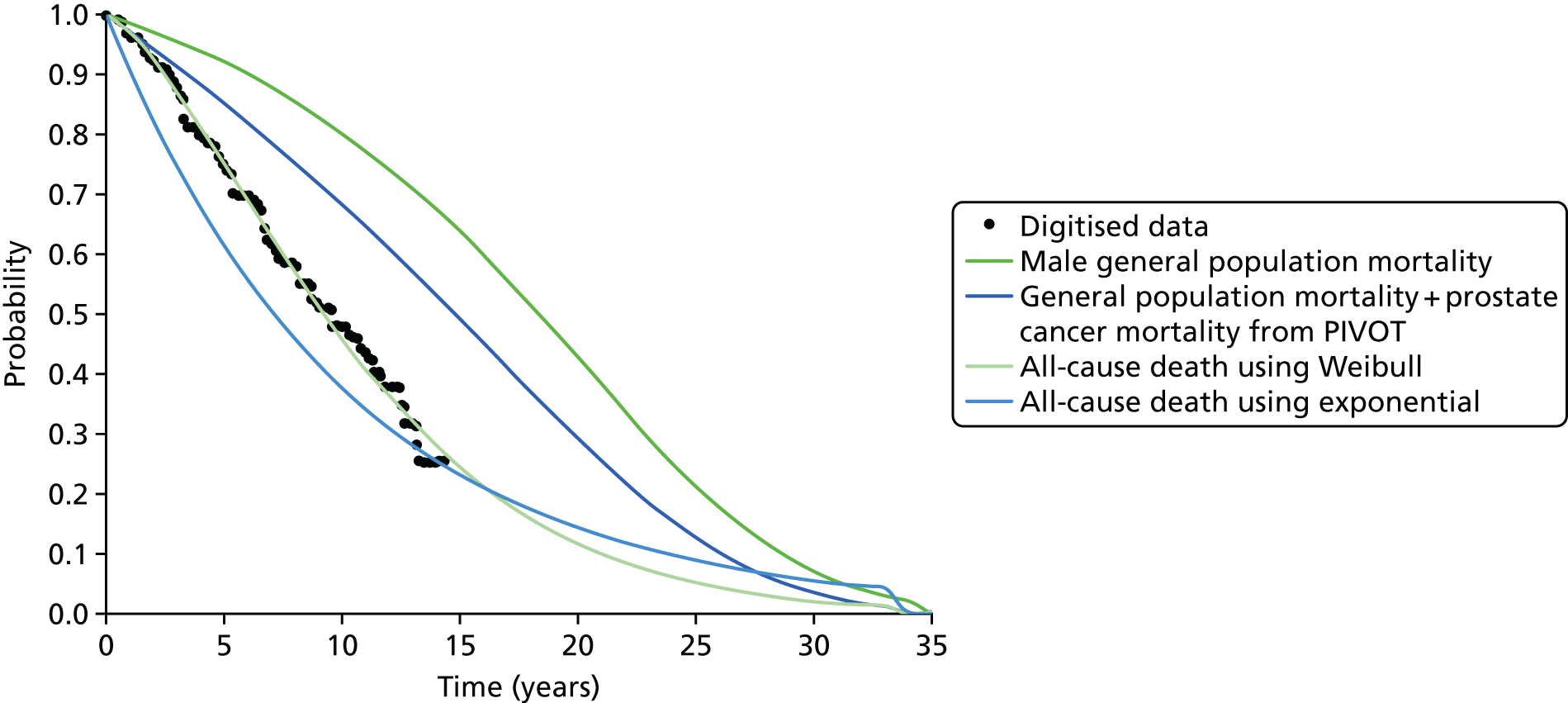

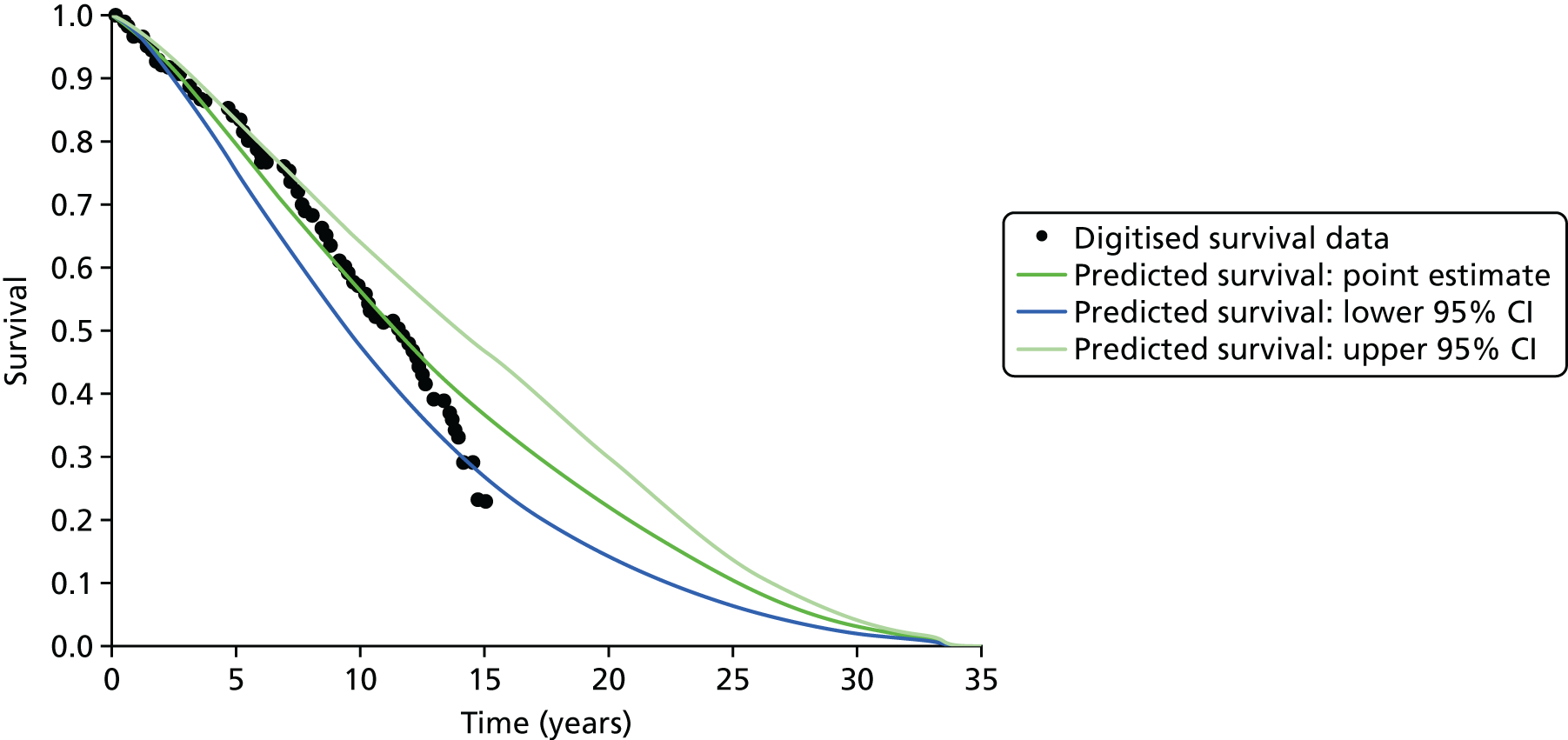

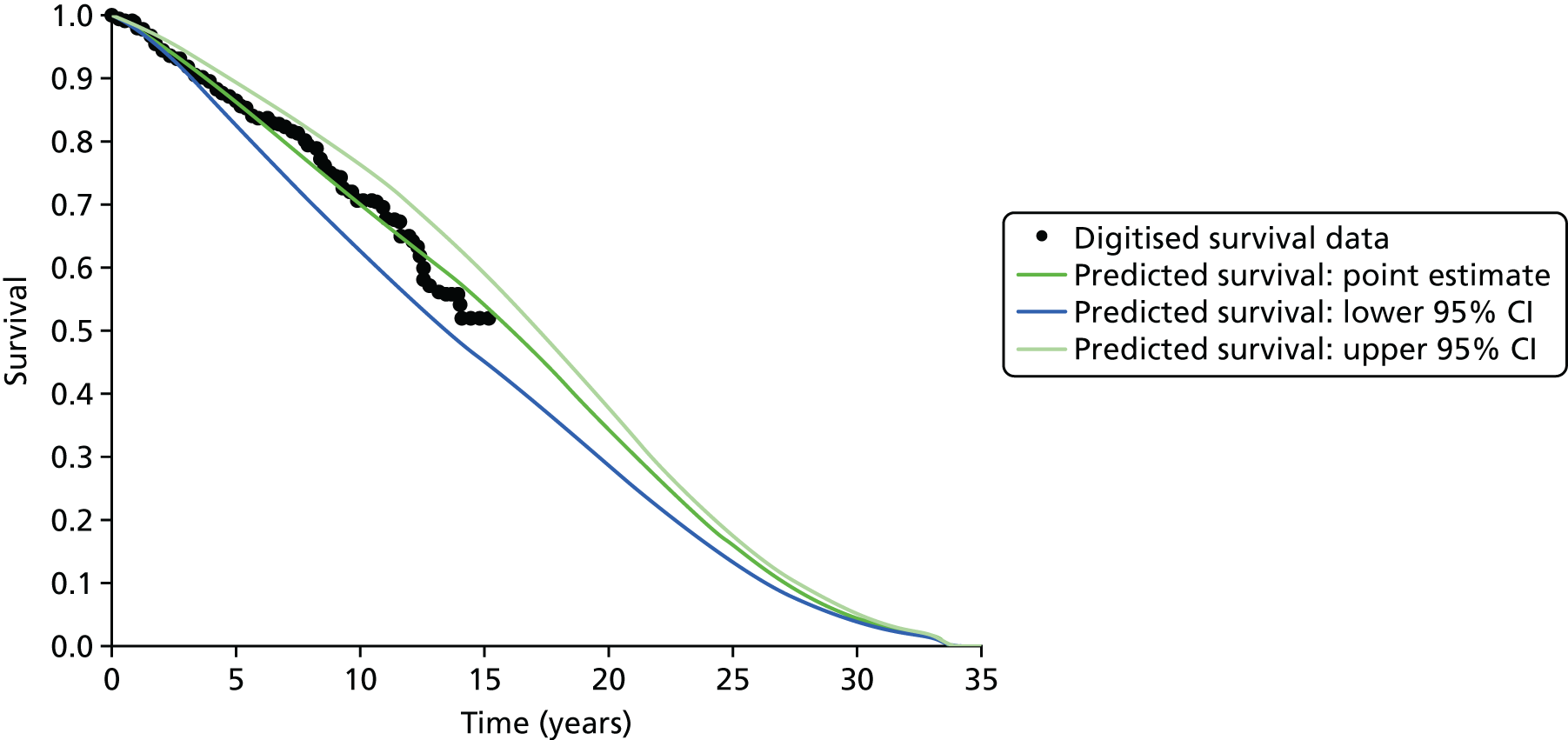

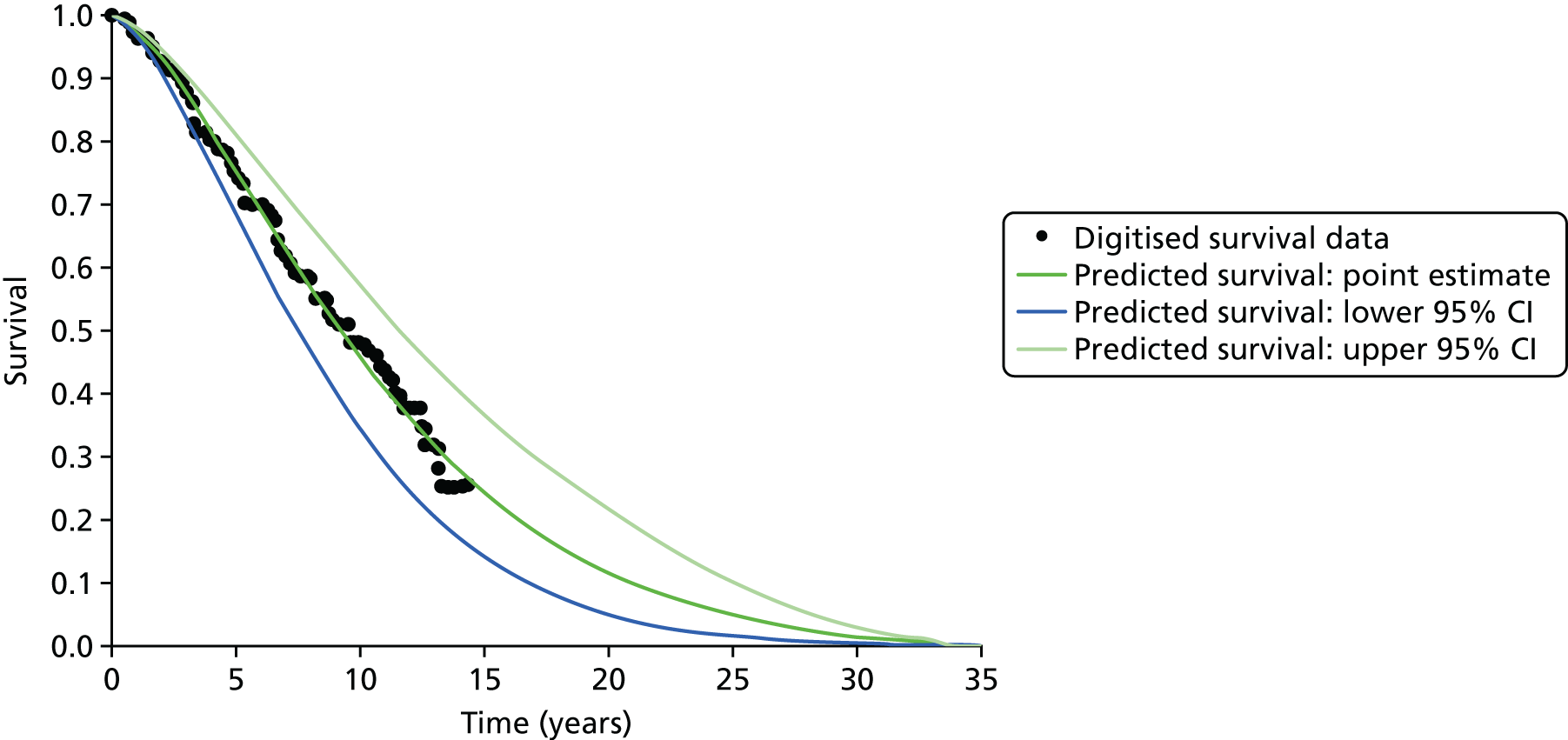

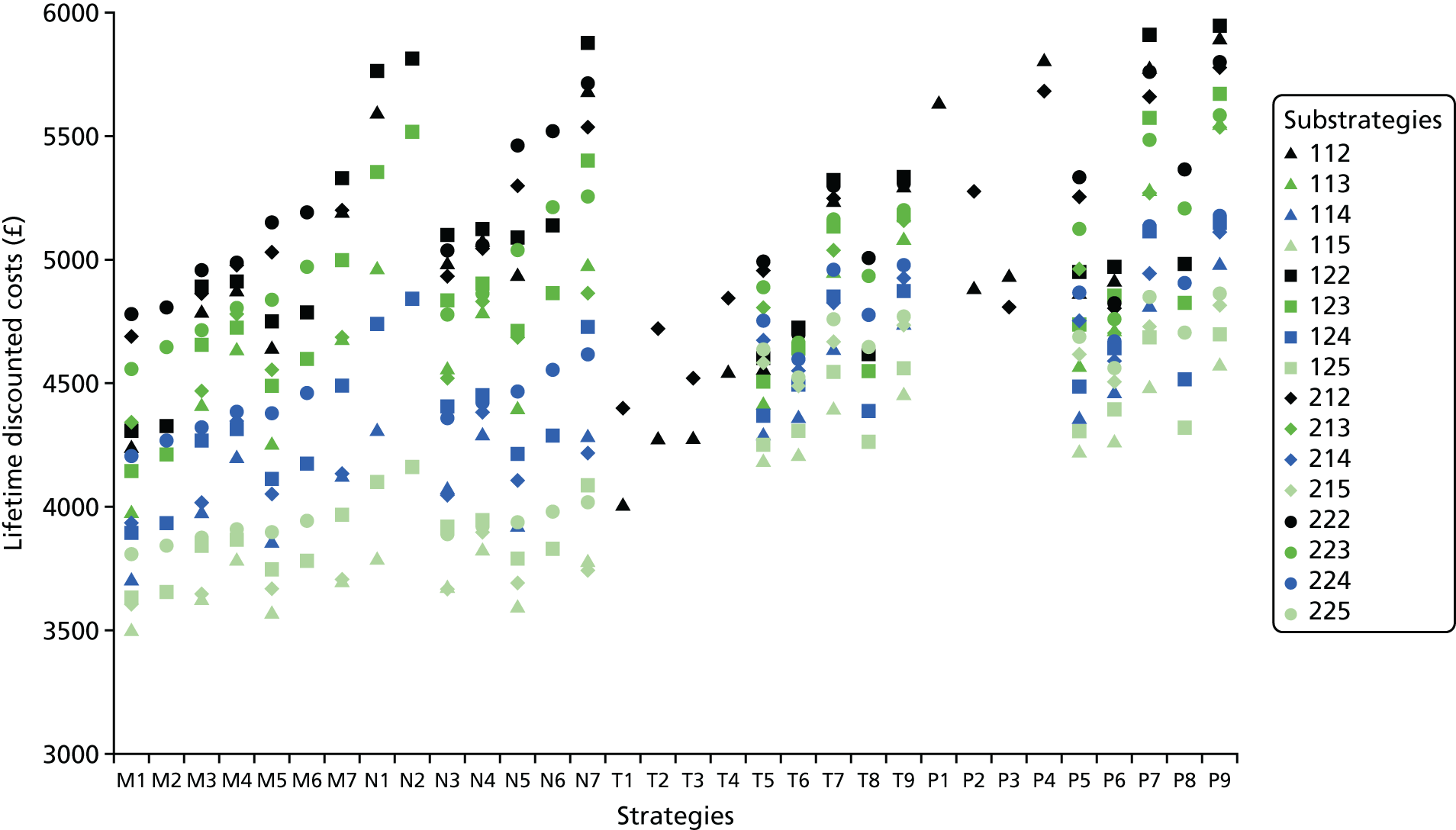

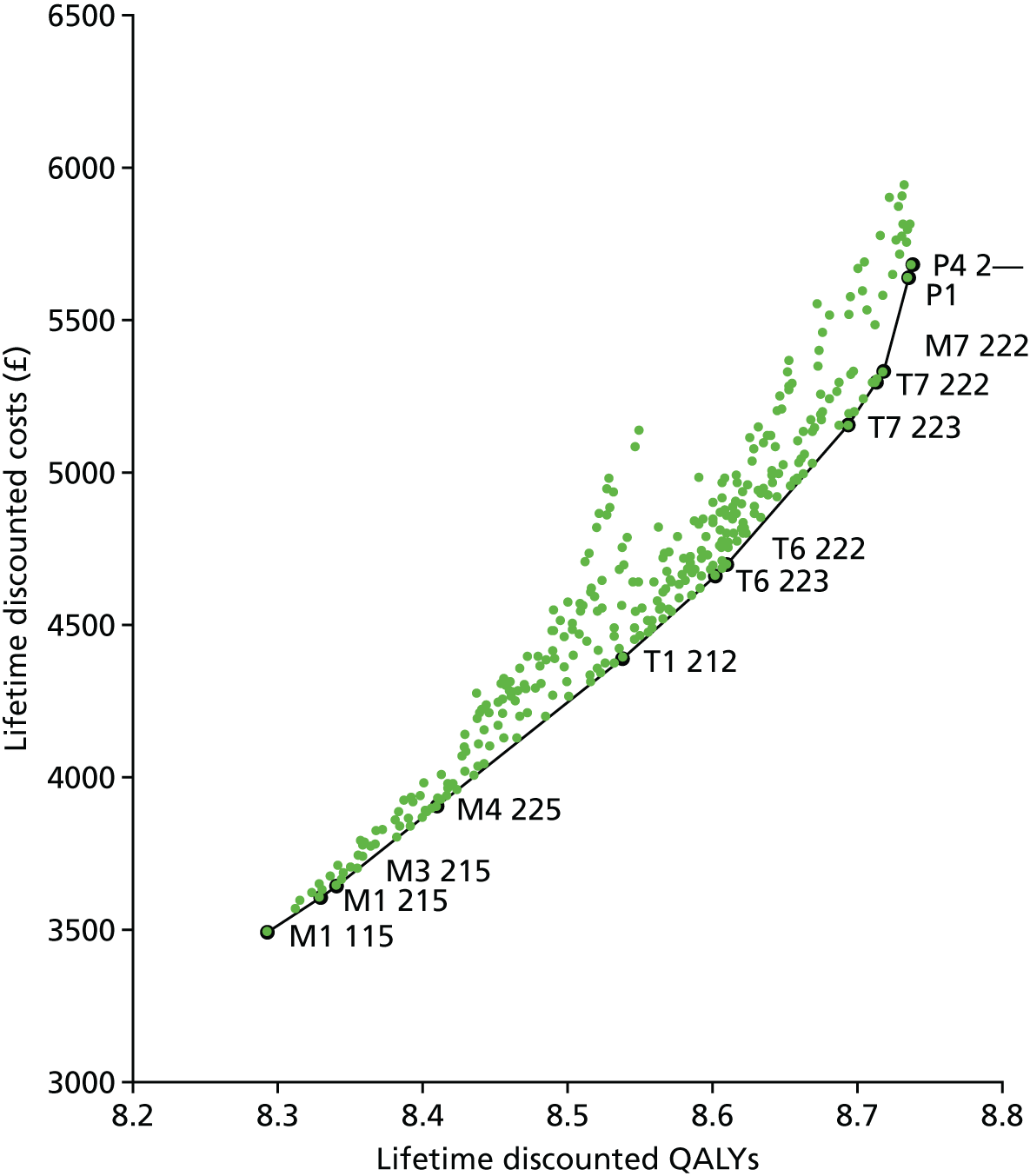

Framework of analyses