Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 08/14/39. The contractual start date was in August 2010. The draft report began editorial review in May 2017 and was accepted for publication in September 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Joanne Blair undertakes paid advisory work for, and has received funding for research, to attend academic meetings and to support a nursing salary from, Novo Nordisk Ltd (Gatwick, UK), a pharmaceutical company that manufactures some of the insulins used in the SubCutaneous Insulin: Pumps or Injections? (SCIPI) study. The work undertaken by Joanne Blair for Novo Nordisk Ltd relates to growth hormone therapy and not diabetes. Mohammed Didi has received payment for advisory work and funding to attend academic meetings and to support a nursing salary from Novo Nordisk Ltd. The work undertaken by Mohammed Didi for Novo Nordisk Ltd relates to growth hormone therapy and not diabetes. Mohammed Didi has received expenses from Merck Serono Ltd (Feltham, UK) to attend educational meetings. Carrol Gamble is a member of the Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation Programme Board of the National Institute for Health Research. Dyfrig Hughes is a member of the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Clinical Trials Board (2010–16), the HTA Funding Teleconference (2015–16) and the Pharmaceuticals Panel (2008–12). John W Gregory reports grants from Cardiff University during the conduct of the study, and membership of the HTA Commissioning Board (2010–14). John W Gregory received speaker fees from Pfizer Inc. and Eli Lilly and Company (Basingstoke, UK), fees for attending an advisory board for Eli Lilly and Company and financial assistance to attend annual meetings of the European Society for Paediatric Endocrinology from Sanofi Genzyme (Guildford, UK), Merck Serono Ltd, Ipsen and Novo Nordisk Ltd.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Blair et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Type 1 diabetes (T1D) is one of the most common chronic diseases of childhood, affecting > 28,000 children and young people in the UK. 1 In Europe, the incidence of childhood T1D is rising, and it is estimated that between 2005 and 2020 the number of children diagnosed per year will increase from 15,000 to 24,400 and will double in children aged < 5 years. 2

The treatment of T1D and its complications presents a considerable burden to patients, the NHS and society, and, as the number of affected patients increases, so do the projected costs. Currently, there is no cure for T1D, and so it is essential that insulin therapies are optimised to enable the best possible quality of life (QoL) for patients and effective use of NHS resources, while minimising the risk of acute and long-term complications.

The use of intensive insulin treatment regimens, in the form of multiple daily injections (MDI) (≥ 4) and continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII; or ‘insulin pumps’), is associated with a reduction in the risk of developing long-term vascular complications of T1D3 and both treatments are used widely in the NHS.

Treatment with MDI utilises insulin analogues with different pharmacokinetic properties. Once or twice a day, a long-acting insulin is administered using a pen injection device, which delivers insulin just beneath the skin into the subcutaneous tissues. This gives a relatively stable concentration of insulin throughout a 24-hour period. Additional injections of a short-acting insulin analogue are given every time ≥ 10 g of carbohydrates is consumed or when blood glucose concentrations rise above an acceptable level.

The term ‘CSII’ refers to the use of a small pump that infuses insulin, via a fine catheter and needle, to the subcutaneous tissues just under the skin. Using this technology, there is the potential to deliver insulin with a more physiological profile than can be achieved by treatment with MDI. Background insulin infusion rates can be increased and decreased to mimic the normal diurnal patterns of insulin secretion and physiological responses to exercise, illness, fasting, etc. Insulin boluses are infused by patients when > 5 g of carbohydrates is consumed or when blood glucose concentrations increase above an acceptable level. It seems logical to assume that the more physiological profile of insulin that can be achieved from CSII, together with a markedly reduced need to self-inject, would result in improved glycaemic control, reduced frequency and severity of hypoglycaemic events and improved QoL.

In 2008, a National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guideline4 recommended that children aged ≥ 12 years who cannot achieve glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c) concentrations of < 8.5% without disabling low blood glucose concentrations (hypoglycaemia), despite a high level of care, should be offered a trial of CSII. Children aged < 12 years should be offered CSII therapy from diagnosis of T1D if MDI is considered impractical or inappropriate. Data from 28,400 paediatric patients were submitted to the 2015/16 National Paediatric Diabetes Audit (NPDA),1 of whom 30% were treated with CSII, compared with 23% in the previous year. Of the 18,500 patients aged < 14 years, most would fulfil the age criteria for CSII therapy, and data reporting HbA1c concentrations suggest that many of the older children would also qualify for treatment on the basis of poor glycaemic control.

Glycaemic control, intensive insulin therapy and complications of diabetes

In the short term, failure to manage T1D adequately may result in episodes of hypoglycaemia that may result in seizures in the most extreme circumstances or high blood glucose concentrations (hyperglycaemia), which may result in life-threatening episodes of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) if left untreated. However, it is the long-term vascular complications of T1D that have the greatest impact on morbidity, mortality and well-being. These can be broadly classified as macrovascular complications (coronary artery disease, peripheral arterial disease and stroke) and microvascular complications (diabetic nephropathy, neuropathy and retinopathy).

The risk of acquiring these complications of T1D is directly related to glycaemic control, duration of T1D, insulin sensitivity and weight. By the time patients enter adult health-care services, many will have lived with T1D for ≥ 10 years, including a period of pubertal growth and development when changes in lifestyle, relationships within families and with peers, normal risk-taking behaviour and physiological insulin resistance make glycaemic control particularly challenging.

In 1993, The Diabetes Control and Complications Research Group3 published conclusive evidence that both the degree and duration of hyperglycaemia are critical determinants of the risk of both microvascular complications and macrovascular complications. The median HbA1c concentration was lower in patients treated intensively with either MDI or CSII (7.3%) than in patients treated using conventional insulin regimes (9.1%). In patients with established T1D who were observed over a period of 6.5 years, the risk of acquiring retinopathy or nephropathy was reduced by 76% and 39%, respectively, and of having a cardiovascular event was reduced by 41% in those treated with CSII or MDI. Glycaemic control exerted greatest influence on acquisition or progression of complications; however, following correction for the HbA1c concentration, those patients who were treated with intensive regimes demonstrated a persistent benefit.

Data from historical paediatric cohorts have confirmed that the link between glycaemic control and microvascular complications is established in childhood. 5 Furthermore, there is a strong relationship between improved glycaemic control in children and young people and a fall over time in the prevalence of childhood-onset retinopathy and nephropathy. 6

Glycaemic control in the first year after diagnosis has a long-lasting effect on glycaemic control in later life and, independently of glycaemic control, on the prevalence of complications. Two British, single-centre, retrospective studies, together reporting data from > 300 patients, reported that HbA1c concentration at 6 months following diagnosis of T1D was an independent predictor of long-term glycaemic control up to 10 years later. 7,8 In a larger Swedish cohort of > 1550 children, HbA1c concentrations at 3–15 months following diagnosis was related to poorer glycaemic control and increased risk of microalbuminaemia and retinopathy in young adult life. 9 These data highlight the importance of researching interventions that may influence glycaemic control during the critical first year of diagnosis.

Data relating to glycaemic control in childhood and macrovascular complications in adult life are sparse because of the long natural history of the disease. However, markers of an increased risk of cardiovascular complications have been validated and used to identify modifiable risk factors in childhood and adolescence. The SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth (SEARCH) study10 has produced evidence that T1D affects (increases) arterial stiffness, a validated measure of risk for cardiovascular events and mortality in adult life, by late adolescence and early adult life. When data from a mixed cohort of patients with T1D and healthy control participants were analysed using multivariate analyses, other correlates of increased arterial stiffness included adiposity, blood pressure, lipid profile, ethnicity (black and hispanic ethnicities), blood pressure and microalbuminuria. In addition to the long-term vascular complications of poor glycaemic control, patients are subject to a number of health and social disadvantages during childhood. Hospital admission rates are nearly five times higher for children with T1D than for the background population, with the poorest children and those in the youngest age group being most likely to require admission. 11 Frequent episodes of severe hypoglycaemia and sustained hyperglycaemia have been associated with changes on functional brain magnetic resonance imaging, impaired memory and poorer cognitive outcomes. 12,13 Patients with poor glycaemic control may experience poor growth, particularly during puberty,14 and poor glycaemic control has also been associated with an increased risk of childhood depression and use of antidepressants. 15

Prevalence of vascular complications of type 1 diabetes

In the UK, data describing patient demographics, insulin treatment regimes, compliance with NICE guidelines and clinical outcomes are collected in the NPDA. In the 2015/16 NPDA report,1 9.7% of patients had microalbuminuria, an early marker of evolving diabetic nephropathy, and 13.8% had an abnormality on screening for retinopathy. Nearly one-third of patients were hypertensive, 20% had elevated blood cholesterol and 21% of those aged ≥ 12 years were obese. In a quantitative epidemiological systematic review of data from young adults (aged 18–30 years),16 there was some evidence of diabetic retinopathy in 50% of patients, with more severe features presenting in 10% of patients. In the same population, one in six patients had evidence of evolving diabetic nephropathy and half were hypertensive. 16

The data for adult patients for 2014/15 have yet to be reported in the National Diabetes Audit. However, the 2012/13 audit17 reported that, compared with the background population, adults with T1D are 139% more likely to be admitted to hospital with angina, 94% more likely to be admitted to hospital with myocardial infarction, 126% more likely to be admitted to hospital with heart failure, 63% more likely to be admitted to hospital with a stroke, 400% more likely to be admitted to hospital for a major amputation, 817% more likely to be admitted to hospital for a minor amputation and 272% more likely to be admitted to hospital for renal replacement therapy.

There can be little doubt that the burden of T1D complications has a profound impact on the QoL and career prospects of patients. In a study of 91 young adults in their mid-thirties who had lived with T1D for nearly 30 years,18 the mortality rate was 10 times higher than in a control population, owing to diabetic nephropathy and trauma, including suicide. People with T1D were less likely to be employed and more likely to need social welfare. Long-term complications of T1D were the primary predictor of an adverse outcome, with patients with T1D and no complications showing no significant differences from the control population. 18

Treatment of childhood type 1 diabetes and glycaemic control in the NHS

In 2015/16, the NPDA reported data from approximately 28,400 patients aged < 19 years. 1 Intensive insulin regimes were used by 82% of patients: 54% were treated with MDI, having four or more insulin injections a day, and 28% were treated with CSII, an increase from 14% in 2011.

The NPDA also reports trends of improving glycaemic control over time, with the number of patients achieving the target HbA1c concentration of < 58 mmol/mol, rising from 15.8% in 2012/13 to 27.0% in 2015/16. In the current NICE guideline for the treatment of childhood T1D, the target HbA1c concentration has been reduced to 6.5% (48 mmol/mol). 19

The Paediatric Diabetes Best Practice Tariff Criteria20 were introduced in the UK in 2012. These allow for a payment of £3189 per patient per year, linked to the provision of core clinical services for paediatric T1D care. For most children’s diabetes services, the additional funding made available by the Paediatric Diabetes Best Practice Tariff Criteria20 enabled the recruitment of more specialist staff and the relative impact of this increase in resources compared with the introduction of CSII therapy on the improvement in glycaemic control reported in the NPDA is unknown.

National databases of children and young people with T1D are maintained in a number of other countries worldwide, enabling clinical outcomes to be compared between countries. In general, data from the UK compare poorly with those from other countries: a publication reported data from 201221 that were held in the NPDA data set, the Prospective Diabetes Follow-up Registry (DPV) from Germany and Austria, and the T1D Exchange database (T1D Exchange) from the USA. The data showed that glycaemic control was the poorest in the NPDA, which also had the lowest rate of CSII usage. In Britain, the disadvantage of poor glycaemic control during childhood appears to persist into adult life. When HbA1c concentrations were compared between national registries, reporting data from all age groups, from the UK, Germany, Denmark, Latvia and Austria, only Latvian patients had poorer glycaemic control. 22

Evidence for the use of continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion in childhood

Evidence for CSII therapy comes from three areas: single-centre observational studies, national database reports and randomised controlled trials (RCTs).

Single-centre observational studies

A number of observational studies examining the effect of CSII therapy on glycaemic control have been published. 23–33 In these studies, authors report longitudinal data examining within-patient change in HbA1c concentrations following the introduction of CSII or cross-sectional data comparing glycaemic control in patients treated with MDI with those treated with CSII. In general, the introduction of CSII therapy is associated with an improvement in glycaemic control in longitudinal observational studies,23–27,34 coupled with a reduction in the number of severe hypoglycaemic episodes23–25 and, in some studies, weight loss,25,26 a reduction in insulin requirements26,27 and an improvement in QoL. 23,24 Other authors have reported a transient improvement in glycaemic control, with a return to baseline values 6 months after the start of CSII therapy. 28 Transient improvements in markers of vascular function, blood pressure, HbA1c concentration and glycaemic variability have also been reported 3 weeks after the introduction of CSII; however, at 12 months these measurements returned to baseline values and HbA1c concentrations deteriorated. 29

Cross-sectional studies report a less favourable effect of CSII on glycaemic control and QoL. 30,31,35 This difference may be explained by the fact that longitudinal studies followed patients who were changing from MDI to CSII, presumably because treatment outcomes with MDI were unsatisfactory, whereas those who were treated with MDI in cross-sectional studies are more likely to be satisfied with their treatment and to have acceptable glycaemic control.

Reduced glycaemic variability, but not HbA1c concentration was reported in a cross-sectional study of 22 children treated with CSII compared with 26 children treated with MDI. 32 Insulin requirements and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels were also lower in those treated with CSII. Adolescents with established T1D treated with CSII for > 12 months have been reported to have reduced glycaemic variability and a reduction in the prevalence of microvascular disease compared with those treated with MDI. 33

National database reports

An association between superior glycaemic control and CSII treatment has been reported in the DPV, T1D Exchange and NPDA data sets. 36 Higher rates of CSII use are reported in girls, whereas those from ethnic minorities and the most deprived patients are least likely to use CSII, even in health-care settings with universal funding. 37–39 In these studies, lower socioeconomic status and ethnicity were also predictors of poorer glycaemic control, even when the effect of CSII use was accounted for. This demonstrated that the characteristics of those who use CSII are the same as the characteristics that facilitate good glycaemic control, raising important issues of bias.

Randomised controlled trials

A number of small RCTs have been undertaken in children and young people,2,7,35,40–48 and these are summarised in Table 1. A meta-analysis49 of RCTs investigating the outcomes of children with T1D treated with CSII compared with those treated with MDI assessed six small studies. 34,35,44–47 The largest number of children included in a single study was 32. In total, 165 children and young people were included in these six studies, of which three included pre-school children only, and 78 children in total were aged > 5 years. In general, the period of observation was brief: ≤ 7 months in five studies. A statistically significant difference in HbA1c concentrations between children treated with CSII and MDI was demonstrated at 3 months, but this was modest [–0.24%, 95% confidence interval (CI) –0.41% to –0.07%; p < 0.001]. The insulin dose, reported in three out of the six studies, was significantly lower in children treated with CSII [0.22 international units (IU)/kg/day, 95% CI 0.31 to 0.14 IU/kg/day; p < 0.001], whereas the incidences of ketoacidosis and severe hypoglycaemic events did not differ.

| Study design | Observation period | Baseline characteristics | Between-treatment findings at study completion | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Age (years)a | HbA1c (%)a | Duration of T1D (years)a | |||

| Crossover RCT40 (2003) | 6 months for each arm | 16 | Median: 14.2 (range 14.1–17.5) | CSII: 8.6 ± 0.8 | Not reported |

No difference in HbA1c concentrations or severe hypoglycaemia CSII: greater treatment satisfaction |

| MDI: 8.5 ± 1.4 | ||||||

| Parallel RCT35 (2004) | 16 weeks | 32 | CSII: 12.5 ± 3.2 | CSII: 8.2 ± 1.1 | CSII: 6.8 ± 3.8 |

HbA1c: 7.2% (CSII) vs. 8.1% (MDI); p < 0.05 Insulin doses: 0.9 unit/kg/day (CSII) vs. 1.2 unit/kg/day (MDI); p < 0.003 No difference in QoL |

| MDI: 13.0 ± 2.9 | MDI: 8.1 ± 1.2 | MDI: 5.6 ± 4.0 | ||||

| Parallel RCT41 (1982) | 6 days | 16 | CSII: 13.3 ± 4.0 | CSII: 10.5 ± 2.9 | Not reported |

No significant difference in blood glucose (mean of seven samples/day) or 24-hour glycosuria MDI arm: more frequent morning hypoglycaemia |

| MDI: 12.9 ± 2.4 | MDI: 10.7 ± 1.1 | |||||

| Parallel RCT42 (2008) | CSII: 10.5 months | 38 | CSII: 10.0 ± 3.0 | CSII: 8.3 ± 0.8 | CSII: 5.6 ± 3.3 | No significant difference in QoL or glycaemic control |

| MDI: 3.5 months, then 7 months for CSII | MDI: 10.0 ± 3.7 | MDI: 8.4 ± 1.1 | MDI: 4.7 ± 2.9 | |||

| Parallel RCT43 (2008) | 2 years | 72 | CSII: 11.8 ± 4.9 | CSII: 8.2 ± 0.4 | CSII: 12.2 ± 2.0 (number of days between diagnosis and entering the trial) |

No difference in HbA1c concentrations or severe hypoglycaemia Insulin doses: 0.7 unit/kg/day (CSII) vs. 1.1 unit/kg/day (MDI); p = 0.001 CSII: greater treatment satisfaction |

| MDI: 12.3 ± 4.5 | MDI: 8.4 ± 0.5 | MDI: 10.4 ± 1.7 (between diagnosis and entering the trial) | ||||

| Crossover RCT43 (2004) | 3.5 months for each arm | 23 | Arm A: 11.9 ± 1.4 | Arm A: 8.0 ± 1.1 | Arm A: 5.3 ± 1.9 |

No significant difference in HbA1c concentrations severe hypoglycaemia, DKA or QoL CSII: greater treatment satisfaction |

| Arm B: 11.9 ± 1.5 | Arm B: 8.3 ± 0.7 | Arm B: 6.3 ± 2.6 | ||||

| Parallel RCT44 (2004) | 6 months | 42 | CSII: 3.8 ± 0.8 | CSII: 9.0 ± 0.6 | CSII: 1.8 ± 0.6 | No difference in HbA1c concentrations or severe hypoglycaemia |

| MDI: 3.7 ± 0.7 | MDI: 9.0 ± 0.6 | MDI: 1.8 ± 0.6 | ||||

| Parallel RCT45 (2005) | 24 weeks | 26 | CSII: 3.9 ± 0.4 | CSII: 7.4 ± 0.5 | CSII: 1.2 ± 0.3 | No difference in HbA1c concentrations or severe hypoglycaemia |

| MDI: 3.8 ± 0.4 | MDI: 7.6 ± 0.3 | MDI: 1.6 ± 0.3 | CSII: fathers reported greater improvement in QoL | |||

| Crossover RCT46 (2003) | 3.5 months for each arm | 23 | Median: 11.9 (range 9.3–13.3) | Median: 8.9 (range 6.1–10.1) | Median: 6.0 (range 2.5–11.0) |

No difference in HbA1c concentrations Continuous glucose monitoring during CSII: greater duration target range, less time in hypoglycaemic range, more frequent hyperglycaemic readings |

| Parallel RCT47 (2005) | 12 months | 22 | 3.6 ± 1.0 | 8.0 ± 0.8 | 1.4 ± 0.6 | No difference in HbA1c concentrations QoL, episodes of severe hypoglycaemia or DKA |

| Parallel RCT48 (2009) |

CSII: 12 months MDI: 6 months for then 6 months for CSII |

35 | 3.7 ± 0.8b | 8.9 ± 0.6a | 1.6 ± 0.6a | No difference in HbA1c concentrations neurocognitive or parenting stress parameters |

In summary, there is no conclusive evidence that treatment with CSII is or is not superior to MDI for glycaemic control or other clinical outcomes. This was in part attributable to the small number of patients studied, short observation periods and issues of bias.

Acceptability of continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion and multiple daily injections

The success of treatment with either MDI or CSII is likely to be heavily influenced by patients’ and parents’ views on the acceptability of each treatment modality. Studies examining this aspect of treatment are very limited. Data reporting parental stress and QoL in studies comparing clinical outcomes during treatment with MDI and CSII are summarised in Table 1.

Discontinuation rates for CSII are reported to be < 20%, implying a high level of satisfaction with CSII therapy. 50–52 Older children, girls and those with poor glycaemic control are more likely to revert to MDI. Reasons for discontinuing CSII therapy include greater sense of disease, difficulties in doing sports, poorer sense of well-being during CSII therapy, wearing an insulin pump, embarrassment, pain at the site of needle insertion, poor glycaemic control, fear and dislike of frequent blood glucose monitoring. 53–55

Qualitative work undertaken in a study of 19 parents with children aged < 12 years who had changed from MDI to CSII reported the benefits of CSII therapy to include no longer having to administer painful injections, fewer dietary restrictions, improved quality of family life and improved glycaemic control. 56 When patients and parents were interviewed in another study, they also reported improved glycaemic control, in addition to increased lifestyle flexibility and participation in social activities, during CSII therapy. 57 However, parents also reported increased demands on them during CSII therapy, primarily relating to increased blood glucose monitoring. These data give only a limited insight into the acceptability of either treatment. It is likely that patients who participated in these studies changed from MDI to CSII treatment because MDI treatment was unsatisfactory, and studies of unselected cohorts of patients are required to examine acceptability of both treatments.

Costs of treatment of childhood type 1 diabetes and its complications

The cost of T1D to the NHS in the UK is significant: estimates of expenditure range from £1B to £1.8B per year,58,59 and this is expected to rise further, and is projected to account for 2% of total NHS expenditure over the next two decades. 58 The proportion of this cost that is attributable to paediatric T1D services and the budgetary implications of switching patients to CSII is unknown. The number of children and young people aged < 19 years old in the UK with a diagnosis of diabetes is 31,500;60 however, this may be a conservative estimate as not all children aged > 15 years old are managed in paediatric care settings and the true prevalence could be as high as 42,000. The majority of paediatric patients (95.1%) have T1D60 requiring insulin therapy, which is currently administered by CSII in 24% of 10- to 14-year-olds and by MDI in 67%, with the remainder on mixed-methods treatment (three injections per day or fewer). 61 Based on published estimates of MDI and CSII costs62 and the modelled costs of mixed insulins,19 the current annual treatment costs for children and young people with T1D range from £52M to £70M. This would rise to between £79M and £106M if all were converted to using CSII. Additional costs relating to the management of T1D and its complications may be more than three times higher than treatment costs alone,58 suggesting total current annual costs of between £179M and £241M, rising to between £272M and £366M if all patients used CSII.

In 2011, the year that the SubCutaneous Insulin: Pumps or Injections? (SCIPI) study opened to recruitment, it was also estimated that patients with T1D took 830,000 sickness days from work at a cost of £94M, and additional costs associated with T1D during work were > £91M. Premature death accounted for a further 37,000 lost working years, at an estimated cost of £0.6B. 58

It is clear from these observations that T1D represents a significant threat to the well-being and life expectancy of affected patients, a significant cost to society in loss of productivity and economic output and an increasing threat to the NHS as its prevalence continues to rise, particularly in the youngest patients, who will require NHS treatment for the longest period of time. It is critical, therefore, to identify and manage factors that may influence the natural history of the disease and the risk of complications.

Rationale for research

The role of intensive insulin therapy in optimising glycaemic control and thereby reducing the risk of vascular complications of T1D is unquestioned. The optimal way in which to achieve this and the cost-effectiveness of the tools currently available are unknown. A number of observational studies and small RCTs have compared the outcomes of children and young people treated with CSII with those treated with MDI. However, in studies reported to date, there are concerns relating to bias, small patient numbers and short observation periods, and no RCT is directly applicable to the health-care environment in the UK.

Aims and objectives

The SCIPI study is a pragmatic RCT that compares the outcomes of infants, children and young people treated with CSII with those treated with MDI from the time of diagnosis of T1D. The study protocol was developed during a period in which children’s diabetes care in the UK was changing rapidly with the widespread introduction of CSII.

The aim of the SCIPI study was to provide robust clinical data, together with a careful health economics appraisal, to inform the place of CSII therapy in the treatment of individual patients from diagnosis of T1D, and within national diabetes treatment strategies. This study compared CSII with MDI during infancy, childhood and adolescence to identify which treatment facilitates superior glycaemic control and to examine the impact that treatment modalities have on other predictors of vascular complications of T1D, adverse events (AEs) and QoL.

The study was designed with an internal pilot prior to progression to the full study. The objectives of the pilot and full study are detailed in the following sections.

Internal pilot study

Primary objective

-

To acquire an understanding of the acceptability of randomisation to MDI or CSII at diagnosis of T1D in children and young people.

Secondary objectives

-

To define the characteristics of patients who consent and those who do not consent to randomisation.

-

To generate data to confirm the size of the standard deviation (SD) used in the sample size calculation of the full study.

Full study

Primary objective

-

To compare glycaemic control, assessed by HbA1c concentrations 12 months after diagnosis of T1D in infants, children and adolescents receiving CSII with those receiving MDI.

Secondary objectives

To compare the following outcomes in children and adolescents receiving CSII with those receiving MDI:

-

clinical effectiveness

-

safety

-

growth

-

quality of life

-

cost-effectiveness.

Summary

Type 1 diabetes is a common disease of childhood, associated with complex treatment regimens and lifelong complications that pose a significant burden to individual patients. The cost to society and the NHS is also significant, as patients may not fulfil their potential in the workplace, may be more dependent on state assistance and may need intensive and expensive therapies throughout their lifetime.

There is the potential to modify the disease trajectory of patients by optimising treatment, particularly in children who will live with T1D for many years. Data from national registries suggest that children in the UK have less satisfactory glycaemic control than those in other health economies in which access to health care is also unrestricted. Some researchers have linked improved glycaemic control to higher rates of CSII use; however, the characteristics of those who are treated with CSII are the same as those that favour good glycaemic control, and the relative contribution of these factors is unclear.

Chapter 2 Trial design and methods

In developing the SCIPI study protocol, we aimed to address areas of potential bias identified in previous studies, to recruit a population of patients that was sufficiently large to enable us to be able to report, with confidence, differences in glycaemic control between treatment groups and to study secondary outcome measures that should give some insight into the evolving risk profile for macrovascular complications. A key part of the SCIPI study is the health economics assessment that examines how the additional investment in CSII may be offset against long-term health costs and QoL; this is reported separately in Chapter 4. To ensure acceptability of the study design and protocol across clinics in the UK, the study protocol was written in close collaboration with the Endocrinology and Diabetes Clinical Study Group of the Medicines for Children Research Network (MCRN). While developing the study protocol, we aimed to address three critical issues, discussed in the following sections.

Measures taken to address bias in patient populations

Previous RCTs have recruited patients with established T1D who are treated with MDI and randomised them to continue with treatment with MDI or to change to CSII. This recruitment strategy may introduce bias in favour of CSII, as patients who are satisfied with treatment with MDI and who have good glycaemic control are less likely to be approached or to participate in a study than those in whom treatment is less satisfactory. Furthermore, previous experience of treatment success or failure is likely to have an impact on the use of a treatment in the future. In order to address this potential bias, we recruited patients from the time of diagnosis of T1D.

We continued to address the internal pilot study objectives throughout the full study, by maintaining screening logs documenting patients’ demographic data (age, sex, ethnicity and deprivation score derived from their postcode) and the reasons why patients were ineligible, why eligible patients were not approached to participate and why they declined. This enabled us to identify differences in the characteristics of those who consented to participate and those who declined and also to identify major barriers to recruitment.

Measures taken to address potential bias in treatment arms

There are two key areas of concern that were addressed within the SCIPI study design that could otherwise lead to bias between treatment arms.

Education

At the introduction of CSII therapy, there is a period of intensive education in which patients and their families consolidate their understanding of the relationship between insulin, carbohydrate consumption, exercise and periods of ill health. Intensive blood glucose monitoring is undertaken to determine the distribution of insulin infused across 24 hours, together with planned increases and decreases in infusion rates to account for periods of illness, exercise, etc.

In previous studies, it was not possible to determine whether the beneficial effect of CSII on glycaemic control was because of the method of insulin delivery or because of the period of intensive education and insulin dose titration. To address this educational imbalance, the SCIPI study protocol was designed such that both treatment arms were required to receive core diabetes education, as defined by the International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes. 63 We then defined a minimum set of contacts between members of the diabetes team, patients and families in the period following diagnosis, and documented how long additional episodes of education or advice lasted. This information was included in the health economics assessment and used to detect imbalance in education and support across treatment arms.

Glucometers

The glucometers provided with insulin pumps advise patients of the dose of insulin required for a given quantity of carbohydrate, accounting for the patient’s blood glucose concentration measured at that time. If blood glucose is measured when carbohydrates are not going to be consumed, and the blood glucose reading is high, the glucometer prompts the patient to take an additional dose of insulin, calculated to return the blood glucose to the target range.

At the time that the SCIPI study opened to recruitment, glucometers issued routinely to patients treated with MDI did not advise on insulin doses, placing them at risk of miscalculating doses or failing to recognise when additional doses may be required. In the SCIPI study protocol, we addressed this potential source of bias by ensuring that both treatment arms used the same F. Hoffman-La Roche AG’s Expert glucometer (Basel, Switzerland).

Measures taken to ensure generalisability of study findings

It was important to generate data that could be used to inform local and national treatment strategies. To achieve this, the SCIPI study needed to recruit and retain participants who were representative of children and young people treated in the NHS. This required that the protocol be deliverable in a wide range of clinics and patient populations, including large clinics in university hospitals and smaller clinics in district general hospitals. To ensure a high retention rate, clinic, participant and parent acceptability needed to be high. The trial design aimed to achieve minimal disruption to normal clinic routines and appointments by drawing on clinical information collected routinely, ensuring that study visits coincided with the times of routine clinic appointments and including minimal additional tasks for patients and their carers.

Study design

The SCIPI study was designed as a pragmatic, open-label two-arm multicentre RCT comparing use of CSII with use of MDI in children and young people aged 7 months to 15 years who were newly diagnosed with T1D. The study included an internal pilot with a sample size of 30 participants to estimate the rate of consent to randomisation and to define the characteristics of recruited participants.

Progression from the internal pilot to the full study was based on the following criteria:

-

At least 50% of patients who are eligible and are invited to participate in the pilot study are successfully recruited.

-

Demographic characteristics that are significantly associated with glycaemic control (age, ethnicity, sex, deprivation score) are not significantly different in the group of patients who are recruited compared with those who decline.

The trial protocol has been published previously. 64 A schematic representation of the study design is given in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Study design. HUI2, Health Utilities Index Mark 2; PedsQL, Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory.

Ethics approval and research governance

This trial compared alternative methods of insulin delivery via Conformité Européenne (CE)-marked medical devices employed for their intended purpose; therefore, this trial was not considered to be a clinical investigation under The Medical Devices Regulations 2002. 65 The trial did fall within the remit of the European Union Directive 2001/20/EC,66 transposed into UK law as Medicines for Human Use (Clinical Trials) Regulations 200467 as amended.

The protocol was approved by the Liverpool East Research Ethics Committee (reference number 10/H1002/80) and the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (clinical trial authorisation number 21362/0002/001-0001). The trial was funded by the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment programme (08/14/39) and included on the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number registry (ISRCTN29255275) and the European Union Drug Regulating Authorities Clinical Trials database (EudraCT 2010-023792-25). Site-specific approval was obtained at all recruiting sites.

The study opened on protocol version 1.0 and the final approved version of the protocol was version 7.0. Protocol amendments are summarised in Table 2, and full details are provided in the study protocol (www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/081439; accessed 15 February 2017).

| Protocol version (date) | Key amendments |

|---|---|

| 2.0 (30 March 2011) |

Inclusion criteria amendment to include patients and parents able to complete study material HbA1c samples will be collected, analysed and destroyed according to local clinical practice rather than analysis at a central laboratory Pharmacovigilance: only related SAEs and related AEs will be reported for this trial. RUSAEs related to medical devices will be reported as per user vigilance reporting |

| 3.0 (1 July 2011) |

The time period to start the randomised treatment was changed from within 3–5 days to within 10 days. The study information will be provided and the consent should occur as close to the time of diagnosis as possible, ideally between the time of diagnosis (day 0) and day 5 Timelines for providing information and approaching the patient for consent will be recorded on the screening log Internet randomisation system to be used instead of telephone, with randomisation envelopes as a backup. Up to this point all randomisations were completed using backup envelopes PedsQL (QoL) questionnaire booklets were removed from baseline and will only be administered at 6- and 12-month study visit |

| 4.0 (17 August 2012) |

Revision to the inclusion criteria, change to patients and parents able to comply with the treatment regimen and study visits Additions to exclusion criteria list: g. Known thyroid condition in a non-euthyroid state h. Known coeliac disease and unable to maintain a gluten-free diet Exclusions previously specified within the protocol but not numbered within the exclusion criteria Revision to the exclusion criteria: change to a. have a sibling with existing T1D rather than first degree relative Additional guidance and change to recruitment window period to 14 days and further guidance on patients being approached and consented as soon after diagnosis as possible HbA1c samples to be collected, analysed and destroyed at a central laboratory |

| 5.0 (21 January 2015) |

Removal of the following from the eligibility criteria: patients aged ≥ 8 years are able to comply with the treatment regimen and study visits Addition of Omnipod® (Ypsomed Ltd, Escrick, UK) as a pump that can be supplied in line with normal clinical practice Addition of text permitting use of the insulin detemir (Levemir®, Novo Nordisk Ltd, Gatwick, UK) |

| 6.0 (16 February 2016) | Update of contact members and their details |

| 7.0 (1 August 2016) |

Updated the HbA1c concentration recommendations in line with the recent NICE guidance: change to the secondary objective. HbA1c concentrations reduced from 7.5% to 6.5% and HbA1c concentrations also provided in mmol Change to secondary end point – percentage of participants in each group with HbA1c concentrations reduced from < 7.5% to < 6.5%. Added partial remission and height as end points Outcomes may be presented as mmol/mol or equivalent % |

Selection of study sites

Participants were recruited from 15 centres in England and Wales, which serve demographically diverse populations. To be eligible to participate in the study, centres had to have ≥ 10 participants treated with CSII within their clinic population and have sufficient resources to deliver the clinical aspects of the study protocol.

To inform our selection of recruiting centres, we drew on the experience of the investigators of the Delivering Early Care In Diabetes Evaluation (DECIDE) study,68 another RCT that recruited paediatric patients at diagnosis of T1D. This study was delivered across eight children’s diabetes centres. We invited the principal investigators who had recruited well to the DECIDE study to recruit patients to the SCIPI study.

Participants

The study recruited infants, children and young people who were newly diagnosed with T1D.

Inclusion criteria

Participants were considered for inclusion in the trial if they met the following criteria:

-

they have newly diagnosed T1D using standard diagnostic criteria69

-

they are aged 7 months to 15 years (inclusive)

-

parent/legal representative of the patient is willing to give consent for the study

-

parent/legal representative of the patient is able to comply with the treatment regimen and study visits.

Exclusion criteria

Participants with the following characteristics were excluded from the trial:

-

previous treatment for diabetes

-

haemoglobinopathy

-

co-existing pathology conditions likely to affect glycaemic control (e.g. cystic fibrosis)

-

psychological or psychiatric disorders (e.g. eating disorder)

-

receipt of medication likely to affect glycaemic control (e.g. systemic or high-dose topical corticosteroid) or growth hormone therapy

-

allergy to a component of insulin aspart (Novorapid®, Novo Nordisk Ltd, Gatnick, UK) or insulin glargine (Lantus®, Sanofi, Guildford, UK)

-

sibling with existing T1D

-

known thyroid condition in a non-euthyroid state

-

known coeliac disease and inability to maintain a gluten-free diet.

Recruitment procedure

At the time that the SCIPI study opened, children’s diabetes teams were notified within 72 hours of presentation of all infants, children and young people who were newly diagnosed with T1D. This possible delay in the identification of potential participants was addressed when the Paediatric Diabetes Best Practice Tariff Criteria20 were introduced in 2011/12, shortly after the study opened. It is a requirement for centres receiving this additional payment that newly diagnosed patients are discussed with a senior member of the children’s diabetes team within 24 hours of presentation, and that all new patients are seen by a member of the children’s diabetes team on the next working day. All potentially eligible participants were therefore identified promptly.

Screening

Sites maintained detailed screening logs of all patients with newly diagnosed T1D. The screening logs collected data on the number of patients who:

-

were assessed for eligibility at diagnosis of T1D

-

met the study inclusion criteria

-

were eligible at screening, were invited to consent and, subsequently, gave consent to participate

-

were eligible at screening, were invited to consent but did not consent to participate in the study (with details of the reasons why consent was not given)

-

were eligible at screening but consent was not sought (with details of the reasons for not seeking consent).

Dates and times of consent process milestones were also recorded along with the deprivation score calculated from patients’ postcodes and ethnicity. These data were used to monitor and inform the recruitment process and to fulfil the internal pilot objectives.

Informed consent

Participants and families were given verbal and written information about the study at the time of diagnosis of T1D. Patient information leaflets were developed in collaboration with the MCRN Young Person’s Advisory Group, ‘Stand Up, Speak UP!’ Three age-appropriate information leaflets for children aged < 8 years, 8–12 years and > 12 years were prepared to ensure that study information was accessible to children of all ages. A separate information sheet was prepared for parents or legal guardians.

To support recruitment, and to address issues of patient preference, the SCIPI study team also produced a video. This was aimed at patients and families interested in taking part in the study, and gave a balanced patient’s perspective of treatment with both methods of insulin delivery from some of the children, young people and their parents who had participated in the study. Four children and young people took part in the video; two were treated with MDI and two with CSII. The video was intended to be viewed after the SCIPI study had been introduced to the family by their diabetes team and the SCIPI information leaflet had been read.

The video was approved by the main research ethics committee in December 2013. The video went live on the SCIPI study website on 14 February 2014 (www.scipitrial.org.uk/families.html; accessed 15 February 2017) and was available for use at SCIPI study sites from 17 February 2014.

Consent was obtained by an appropriately trained and experienced member of the research or diabetes staff. The timing of consent was dependent on the needs and wishes of the patient and family. However, consent had to be obtained within a time frame that allowed for the randomised treatment to start within 14 days of diagnosis of T1D.

Randomisation, concealment and blinding

Once eligibility criteria were confirmed and informed consent, and assent when appropriate, had been obtained, participants were randomised to treatment with MDI or CSII, using a secure (24-hour) web-based randomisation programme controlled centrally by the MCRN division of the Clinical Trials Research Centre Clinical Trials Unit (CTU). A personal login (username and password), provided by the MCRN CTU, was required to access the randomisation system.

The randomisation code list was generated by a statistician within the MCRN CTU who was otherwise independent of the study, using random variable block sizes of 2 and 4. Participants were randomised to either MDI or CSII treatment in a ratio of 1 : 1, stratified by recruitment site and age using three bands (7 months to < 5 years, 5 years to < 12 years and ≥ 12 years).

The allocated treatment arm was communicated immediately to the patient and family and the treating health-care professionals, with the randomised treatment to start within 14 days of diagnosis.

Owing to the nature of the interventions, it was not possible to blind either the participants or clinical teams.

Treatment group allocation

Multiple daily injections

Participants randomised to treatment with MDI were treated with two insulin analogues: insulin aspart, a short-acting insulin, and insulin glargine or insulin detemir, long-acting insulin analogues. Insulin was delivered using ‘pen’ injection devices, which contain cartridges of insulin that are administered via a fine needle at the tip of the pen and injected using a plunger at the top of the pen.

Insulin aspart is a short-acting insulin analogue licensed for the treatment of T1D in adults, adolescents and children aged 2–17 years. It should be used in children aged < 2 years only under careful supervision; however, the rapid onset and offset of action of this insulin make it particularly attractive in the management of young children. For this reason, it is widely used in young children with T1D. Insulin aspart was administered every time ≥ 10 g of carbohydrates was consumed.

Insulin glargine is a long-acting insulin analogue, administered once or twice daily. It is not currently licensed for use in children aged < 6 years; however, the use of insulin glargine in this age group has been associated with a reduction in hypoglycaemia and improved metabolic control. 70 For these reasons, it is widely used in MDI treatment regimens in UK paediatric practice.

In protocol version 5.0, the use of detemir was added to the long-acting insulin analogues permitted at the initiation of MDI therapy. This amendment was made in recognition that a number of recruiting sites started treatment with MDI, using insulin detemir at the time of diagnosis, and were reluctant to change to insulin glargine following randomisation to MDI. This insulin has been studied in the age group recruited to the SCIPI study and found to be safe and effective. 71

Continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion

Insulin aspart was administered using CSII insulin pumps. The F. Hoffman-La Roche AG insulin pump (Basel, Switzerland) was selected at the start of the study, following discussion with the participating centres. This pump was used widely at the time the study opened, and participating centres had experience in its use. The use of the F. Hoffman-La Roche AG insulin pump also enabled us to use the same glucometer across both treatment arms. This glucometer includes a ‘bolus wizard’, which calculates insulin doses according to blood glucose readings and carbohydrate consumption. The use of this glucometer ensured consistency in the insulin bolus doses across treatment arms.

The F. Hoffman-La Roche AG insulin pumps and consumables were provided at a 25% discounted price for the study participants. However, this is a pragmatic study and treating clinicians were able to use other insulin pumps when this was considered to be in the patient’s best interest. A small number of Medtronic (Medtronic Ltd, Minneapolis, MI, USA) and Omnipod® pumps (Ypsomed Ltd, Escrick, UK) were also used in some study centres. In these instances, patients used the appropriate glucometer for their pump.

Participants were given insulin aspart using basal insulin infusion with bolus doses of insulin aspart when ≥ 5 g of carbohydrate was consumed.

Starting dose calculations: multiple daily injections and continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion

The initial total daily dose of insulin was calculated from body weight. In prepubertal participants, a dose of 0.5 units/kg body weight/day was used, and in pubertal participants 0.7 units/kg body weight/day was used.

For the MDI arm, 50% of the calculated dose was given as a single injection either as insulin glargine or detemir, injected into the anterior-lateral aspect of the thigh, arm, abdomen or the upper outer quadrant of the buttocks.

For the CSII arm, 50% of the calculated dose was given as a continuous 24-hour infusion [0.5 × body weight (kg) ÷ 2 ÷ 24 = hourly rate].

The remaining 50% of the daily dose was given as three divided preprandial doses at mealtimes in both arms. If the doses were not equal, more insulin was given before breakfast and the evening meal than at lunchtime to account for diurnal variation in insulin sensitivity.

It was recommended that blood glucose readings should be undertaken at least four times a day: before breakfast, before the midday meal, before the evening meal and before supper/bed.

Insulin dose modifications

Correction doses were calculated according to the ‘100’ rule. 72 Insulin doses were titrated according to home blood glucose readings, as per local routine clinical advice. The diabetes clinical team supported insulin dose titration according to participant needs. Telephone contact was also used as an opportunity to provide support and education regarding the management of T1D. The frequency and duration of all contact between participants and their local clinical service were logged. All participants and their parents had 24-hour telephone access for support and advice throughout the study, as is standard practice. Participants on CSII treatment also had 24/7 access to the pump manufacturer’s helpline for assistance for technical problems relating to the pump.

Education

At entry to the study, all participants completed a structured educational programme delivered to participants and their families in accordance with the standards of the International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes. 63

Participants and their families were educated in:

-

type 1 diabetes

-

the use and administration of insulin

-

hyperglycaemia and correction doses

-

hypoglycaemia symptoms and treatment

-

exercise

-

sick day rules

-

carbohydrate counting

-

the benefits of maintaining optimal glycaemic control for long-term health

-

blood glucose monitoring.

All the participants were trained in the use of the MDI regimen and the F. Hoffman-La Roche AG Expert glucometer; participants undergoing CSII treatment were also trained in the use of CSII pumps.

Additional diabetic education was organised to suit individual needs of the participant and family. The dietitian met the participant and their family to assess their diet and educate them in carbohydrate counting. All contact was recorded within the participant follow-up.

To support recruiting sites in the initiation of CSII so soon after diagnosis of T1D, treatment guidelines and written patient information were available from the lead site. These resources were used at the discretion of the recruiting sites.

Baseline assessment

At entry to the study, we collected the following routine biochemical data recorded in medical case notes:

-

blood pH at diagnosis

-

blood glucose at diagnosis

-

presentation with DKA

-

glycosylated haemoglobin

-

thyroid function tests

-

tissue transglutaminase antibody titres, or other screening test for coeliac disease

-

titres of anti-glutamic acid decarboxylase and anti-islet cell antibodies.

These baseline tests were not required as part of the SCIPI study protocol, but results were collected if available.

Baseline measurements of height and weight were recorded on the day that the participants commenced randomised treatment to allow for rehydration in participants who were dehydrated at diagnosis of T1D. The Health Utilities Index (HUI) questionnaire was completed and information was collected relating to prescribed concomitant medications. The Health Utilities Index Mark 2 (HUI2) was used for the base-case analysis and the Health Utilities Index Mark 3 (HUI3) (based on a Canadian tariff) was used in the sensitivity analysis.

Follow-up

Study visits were timed to coincide with the times of routine clinic appointments at 3, 6, 9 and 12 months from the date of randomisation. A window of 15 days either side of the appointment time was permitted to allow for holidays, clinic availability and other commitments. A schematic representation of follow-up assessments is given in Table 3. At each visit, permanent and temporary changes in the delivery of insulin were recorded under the heading ‘Review of insulin use’.

| Procedures | Time point | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (randomisation) | Follow-up (months after randomisation) | |||||

| Diagnosis | Prior to start of treatment | 3 | 6 | 9 | 12 | |

| Assessment of eligibility criteria | ✗ | |||||

| Signed consent form | ✗a | |||||

| Randomisation | ✗ | |||||

| Review of concomitant medications | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| Review of insulin use (insulin requirements) | ||||||

| Treatment diaries | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Prescriptions | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| CSII pumps download | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Blood glucose measurement | ✗b | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| Blood pH measurement | ✗ | |||||

| Demographics | ✗ | |||||

| Study intervention | ✗c | |||||

| Physical examination | ||||||

| Height | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| Weight | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| Injection sites | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Symptom-directed | (✗) | (✗) | (✗) | (✗) | ||

| Assessment of related AEs | ||||||

| Incidence of severe hypoglycaemia | (✗) | (✗) | (✗) | (✗) | ||

| Incidence of DKA | (✗) | (✗) | (✗) | (✗) | ||

| Other AEs | (✗) | (✗) | (✗) | (✗) | ||

| Related to diabetes | (✗) | (✗) | (✗) | (✗) | ||

| Clinical laboratory | ||||||

| HbA1c analysisd | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| Other routine testse (e.g. chemistry, haematology, urinalysis) | (✗) | (✗) | (✗) | (✗) | (✗) | |

| Questionnaires | ||||||

| Participant-completed PedsQL | (✗) | (✗) | ||||

| Parent-completed PedsQL | ✗ | ✗ | ||||

| Participant-completed HUI Questionnairef | (✗) | (✗) | (✗) | (✗) | (✗) | |

| Parent-completed HUI Questionnairef | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| Resource use | ||||||

| RN-completed CRF | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

Measures

Primary end point

The primary outcome measure was glycaemic control (HbA1c) concentrations 12 months after diagnosis.

Capillary blood samples were collected from finger-pricks into small capillary tubes and were analysed in two separate locations. At study sites, most samples were analysed using portable instrumentation at outpatient clinics. Samples were also analysed at the clinical pathology laboratory in Alder Hey Children’s NHS Foundation Trust. Samples were transported to the central laboratory through the post or via bespoke courier systems that ensure that the samples are received the next day.

Quality assurance of the measurement of glycosylated haemoglobin levels

Portable instrumentation is calibrated regularly with local laboratories. All laboratories involved in the measurement of HbA1c concentrations are obliged to participate in external quality assurance schemes, ensuring that laboratories with equivalent equipment are able to produce results that are comparable to each other. For almost all HbA1c measurements (local and central), the biochemical methodology employed was immunoassay.

Since June 2009, HbA1c assays have been calibrated against the International Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine standardised values,73 and centralised analysis should no longer be necessary; therefore, costs to support central analysis were not provided within the study budget. However, the preference in the trial design was for central analysis and this was included when funds were identified to support this (changed from local to central analysis in protocol version 4.0, August 2012).

To determine whether or not central analysis was required, a limits of agreement analysis was performed when 590 paired samples were available. Based on the results of this analysis,74 samples continued to be analysed both locally and centrally.

Data from local samples were usually recorded in two units of measurement: mmol/mol and % (percentage of total haemoglobin). The HbA1c concentration measured at the central laboratory was recorded in mmol/mol only. The following formula was used for conversion between the two units of measurement:

Secondary end points

Percentage of participants in each group with a glycosylated haemoglobin level of < 48 mmol/mol at 12 months after diagnosis

At the time the SCIPI study protocol was written, the target HbA1c concentration was < 58 mmol/mol. However, in the most recent NICE guideline, the target has been reduced to 48 mmol/mol. 19 This lower figure was used in our analysis to ensure that the findings are relevant to current clinical practice; however, as sites would have previously worked to the 58-mmol/mol threshold, the results for this are also presented.

Incidence of severe hypoglycaemia

Severe hypoglycaemia was defined according to the criteria of the American Diabetes Association: a hypoglycaemic episode that required the assistance of another person to administer carbohydrate, glucagon or other treatments. 75

Incidence of diabetic ketoacidosis

Diabetic ketoacidosis was defined according to the criteria of the European Society of Paediatric Endocrinology and the Lawson Wilkins Pediatric Endocrine Society:76 blood glucose level of > 11 mmol/l, with a venous pH of < 7.3 and/or bicarbonate concentration of < 15 mmol/l.

Change in body mass index standard deviation score

Height was measured using a fixed stadiometer and weight was measured using electronic scales. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated according to the formula:

Standard deviation scores (SDSs) were derived from 2007 World Health Organization growth data. 77,78

Insulin requirements (unit/kg/day)

Insulin usage was downloaded from F. Hoffman-La Roche AG’s Expert glucometers for participants in both treatment arms. For participants who were treated with CSII, insulin usage was also downloaded from insulin pumps, and for participants who were treated with MDI, data were retrieved from patient-held records. Finally, to guard against significant over-reporting and for the health economics assessment, the general practitioner (GP) of the participant was contacted for details of issued prescriptions.

Percentage of patients in partial remission at 12 months

Rates of partial remission were calculated at each time point, according to insulin dose-adjusted HbA1c (IDAA1c) level. This measure is calculated according to the formula:

Health-related quality of life

Health-related QoL was assessed using version 3 of the diabetes module of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL) questionnaire,79,80 completed at routine clinic appointments at 6 and 12 months. The questionnaire was not completed at baseline because patients and parents are asked to rate their experience of living with T1D in the previous month. Given that patients were recruited at diagnosis of T1D, these questions were not relevant.

The PedsQL has age-specific questionnaires to be completed by children (aged 5–7 years old, 8–12 years old and 13–16 years old). The parent-reported PedsQL includes an additional age band for children aged 2–4 years.

Sample size

A difference in HbA1c concentration of 0.5% is widely recognised as the threshold used by the US Food and Drug Administration and the pharmaceutical industry to determine effectiveness of any new oral hypoglycaemic agents. A meta-analysis of 20 studies comparing CSII with MDI detected an improvement of 0.61% in adults, suggesting that, in addition to this estimate being the minimum clinically important, it is also a realistic difference to detect. 81–100 To achieve 80% power, a sample size of 143 in each group was required to detect a difference in means of 0.50, assuming that the common SD is 1.50 using a two-group t-test with a 0.05 two-sided significance level. Allowing for 10% loss to follow-up increased the sample size to a total of 316 participants (158 per group). The estimate used for the SD in the sample size calculation was taken from an unpublished audit at Alder Hey Children’s NHS Foundation Trust (Joanne Blair, Mohammed Didi, Princy P, Atrayee Ghatak, Alder Hey Children’s NHS Foundation Trust, 2009, personal communication) based on children matching the inclusion criteria for this proposed study.

Statistical methods

The analysis and reporting of the SCIPI study was undertaken in accordance with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT)101 and the International Conference on Harmonisation E9 guidelines. 102 The main features of the statistical analysis plan are included here with a full and detailed statistical analysis plan provided as a separate document [URL: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/081439/# (accessed 26 July 2018)]. All statistical analyses were undertaken using SAS® software (version 9.2; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). SAS and all other SAS Institute Inc. product or service names are registered trademarks or trademarks of SAS Institute Inc. in the USA and other countries. ® indicates US registration.

A two-sided p-value of ≤ 0.05 was used to declare statistical significance for all analyses. Similarly, all CIs were calculated at the 95% level. No adjustment for multiplicity was made to adjust the type 1 error rate for secondary outcomes. Relevant results from other studies already reported in the literature were taken into account in the interpretation of results.

The primary analysis followed the intention-to-treat (ITT) principle as far as practically possible; a secondary analysis using the per-protocol approach was conducted for the primary outcome. The purpose of the per-protocol approach is to consider the robustness of the conclusions reached from the analysis using the ITT principle, which includes protocol deviations.

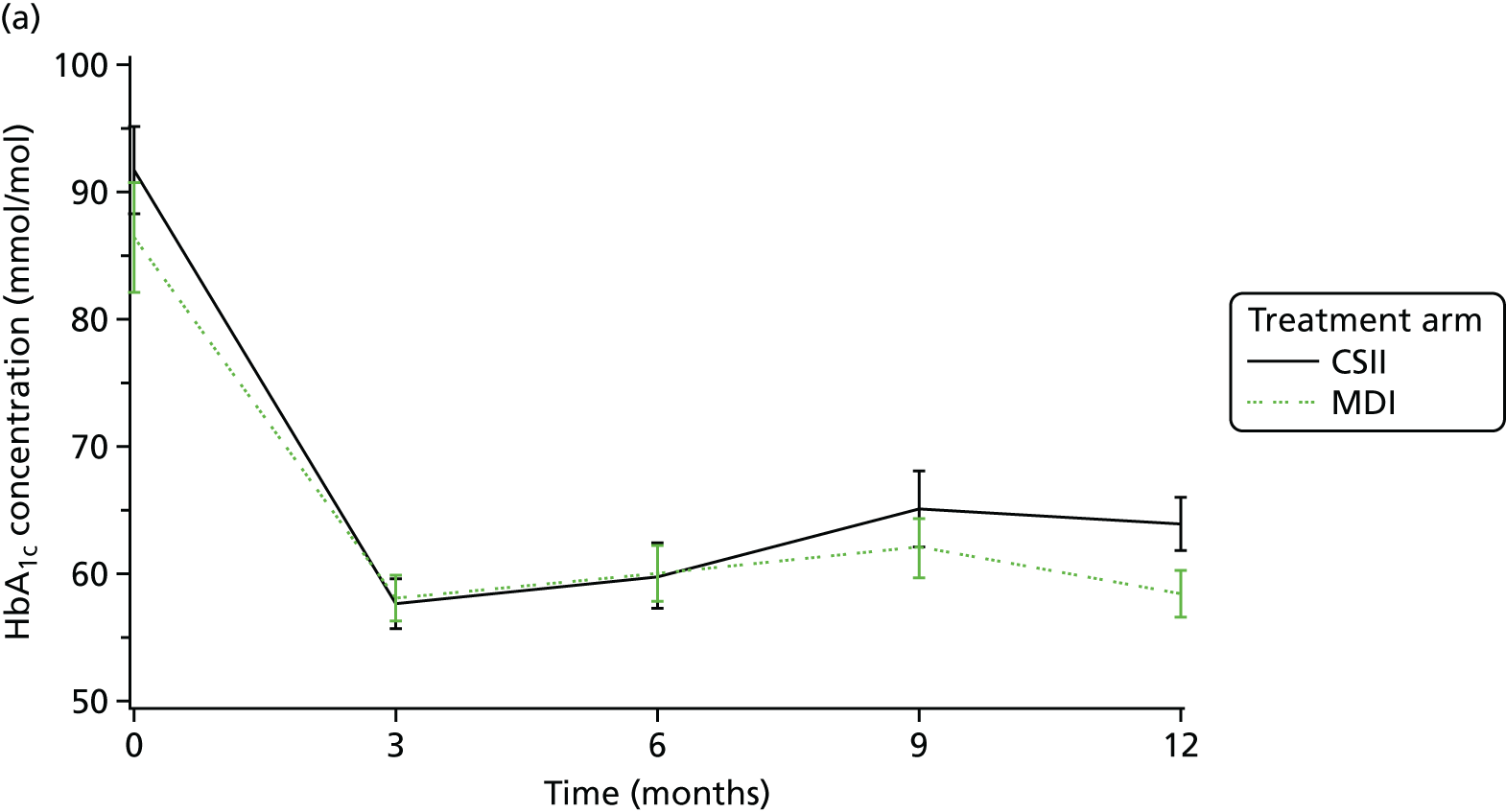

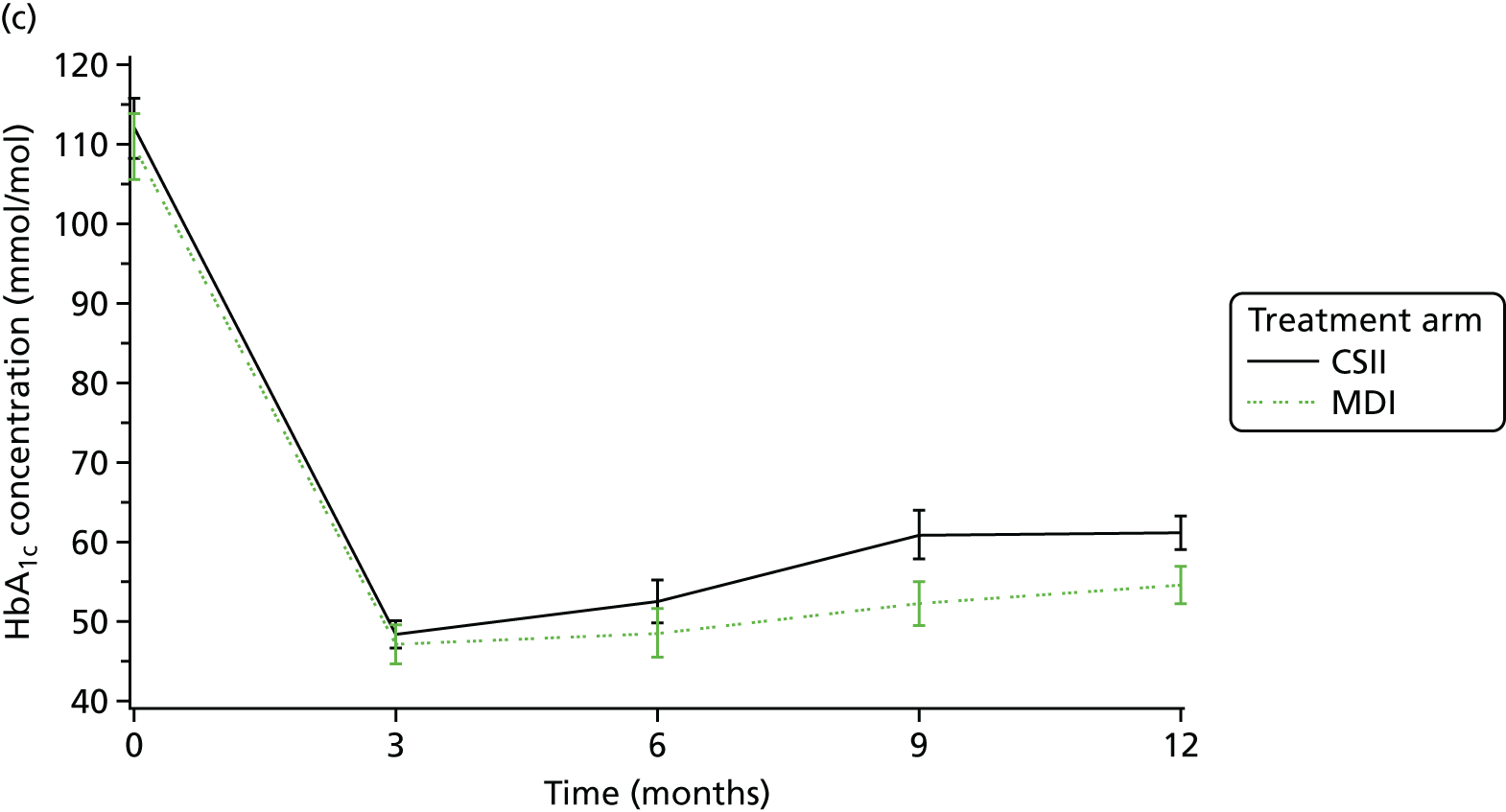

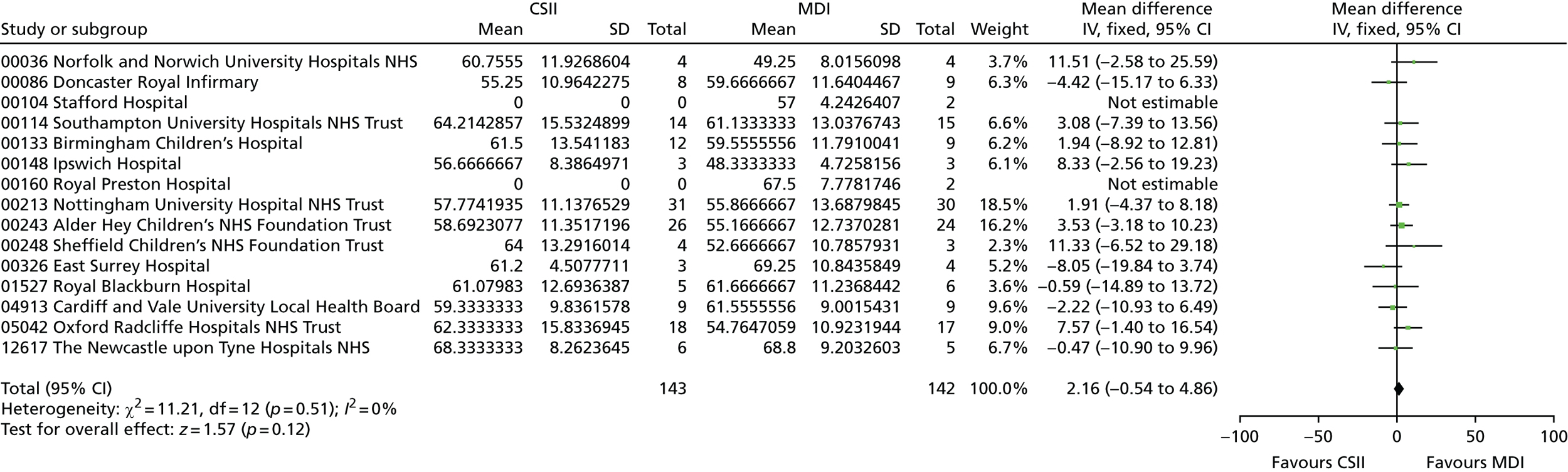

Glycosylated haemoglobin, a continuous outcome, was compared between the trial groups using mixed-model regression with 12-month HbA1c as the dependent variable, treatment group as an explanatory factor and the randomisation stratification variables (age group and centre) as covariates; centre was fitted as a random effect. The mean and SD of HbA1c concentrations were reported for each age group and treatment group. The mean difference in HbA1c concentrations and 95% CI between treatment groups was given as the estimated age group- and centre-adjusted treatment effect calculated by the fitted mixed-model regression. Central measures of HbA1c concentration were used in preference to local measurements; local measurements were used if central ones were not available.

Secondary continuous outcomes were analysed as per the primary outcome methods. For binary outcomes, the number and percentage of participants with the outcome are reported overall and for each treatment group. The difference between groups is tested using the chi-squared test. Relative risks with 95% CI are presented.

The safety analysis data set contains all participants who were randomised and received at least one dose of insulin via the randomised treatment. Participants’ AEs/serious adverse events (SAEs) were included in the treatment group the participant was actually receiving at the time of AE/SAE onset to take into account any participants who permanently changed their mode of insulin delivery at any point during the trial. The number of related AEs occurring and the number and percentage of participants involved were reported by treatment arm. The incidence rates of total numbers of AEs/SAEs were calculated for each treatment group in person-days using the incidence density ratio (IDR). The IDR is the number of patients with at least one new AE per population at risk in a given time period. The denominator is the sum of the person-time in years for each treatment group (accounting for treatment switches) of the at-risk population.

The statistical analysis of the data follows the standard operating procedures of the Clinical Trials Research Centre, which requires independent programming of the primary outcome and safety analyses by an independent statistician.

Study oversight and role of funders

The Trial Management Group (TMG), comprising the chief investigator, other lead investigators (clinical and non-clinical), members of the MCRN CTU and three parent contributors, was responsible for the day-to-day running and management of the trial. The membership of the oversight committees was suggested by members of the TMG to the trial funders and appointed by the funders with their constitution following funder requirements.

The Trial Steering Committee (TSC) consisted of an independent chairperson, Dr Peter E Clayton, two independent experts in the fields of diabetes and endocrinology, Dr Christine P Burren and Dr Ian Craigie, an expert in medical statistics, Professor Gordon D Murray, and a parent contributor, Mrs Christina McRoe. The role of the TSC was as the executive decision-making committee considering the recommendations of the Independent Data and Safety Monitoring Committee (IDSMC). Monitoring reports viewed by the TSC were not split by treatment group.

The IDSMC consisted of an independent chairperson, Professor Stephen Greene, plus two independent members, Professor John Wilding, an expert in the field of endocrinology, and Dr Arne Ring, an expert in medical statistics. The IDSMC was responsible for reviewing and assessing recruitment, interim monitoring of safety and effectiveness, trial conduct and external data. The IDSMC provided recommendations to the TSC concerning the continuation of the trial and viewed accumulating data split by treatment group.

Chapter 3 Results

Recruitment

The study opened to recruitment on 16 May 2011 and was closed on 30 January 2017.

At the outset of the study, we planned to recruit 316 patients within 30 months across eight study sites. The recruitment rate had been informed by the DECIDE trial68 and the study sites were selected to build on the experience and expertise acquired by local researchers during the DECIDE trial.

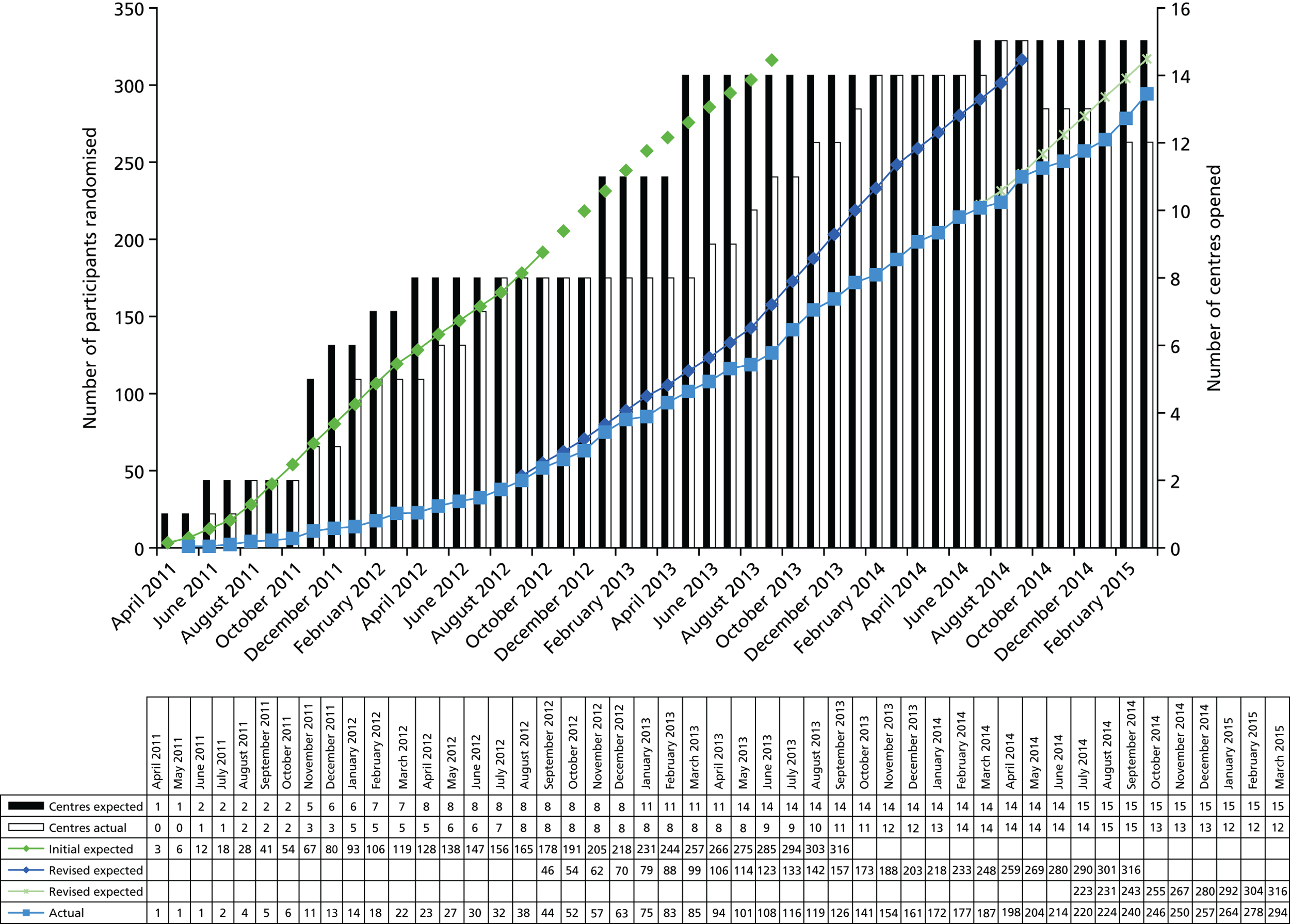

All study sites had to secure funds to meet the excess treatment costs of the study protocol. This process incurred some considerable delays, and in some centres was not possible. Recruitment rates were also slower than expected and, consequently, the recruitment curve was revised in month 18 to allow for an additional 12 months of recruitment and again in month 40 to allow a further 6 months. The number of study sites was increased from 8 to 15. The recruitment graph showing the initial, and revised, predictions and the observed recruitment numbers is displayed in Appendix 1.

To increase recruitment, key protocol amendments were made (protocol version 3.0 to 4.0) that increased the permitted time window for recruitment from diagnosis to 14 days and softened eligibility criteria to place emphasis on ability to comply with treatment regimens rather than complete study questionnaires and to support inclusion of children with parents with T1D but to maintain exclusion of siblings with T1D.

To optimise consent rates, screening log data were used to inform the recruitment strategy. Screening data indicated that patients who consented to participate were approached sooner after diagnosis than those who declined. In the light of these data, clinical teams and research nurses (RNs) were encouraged to share information about the study as soon as possible following diagnosis.

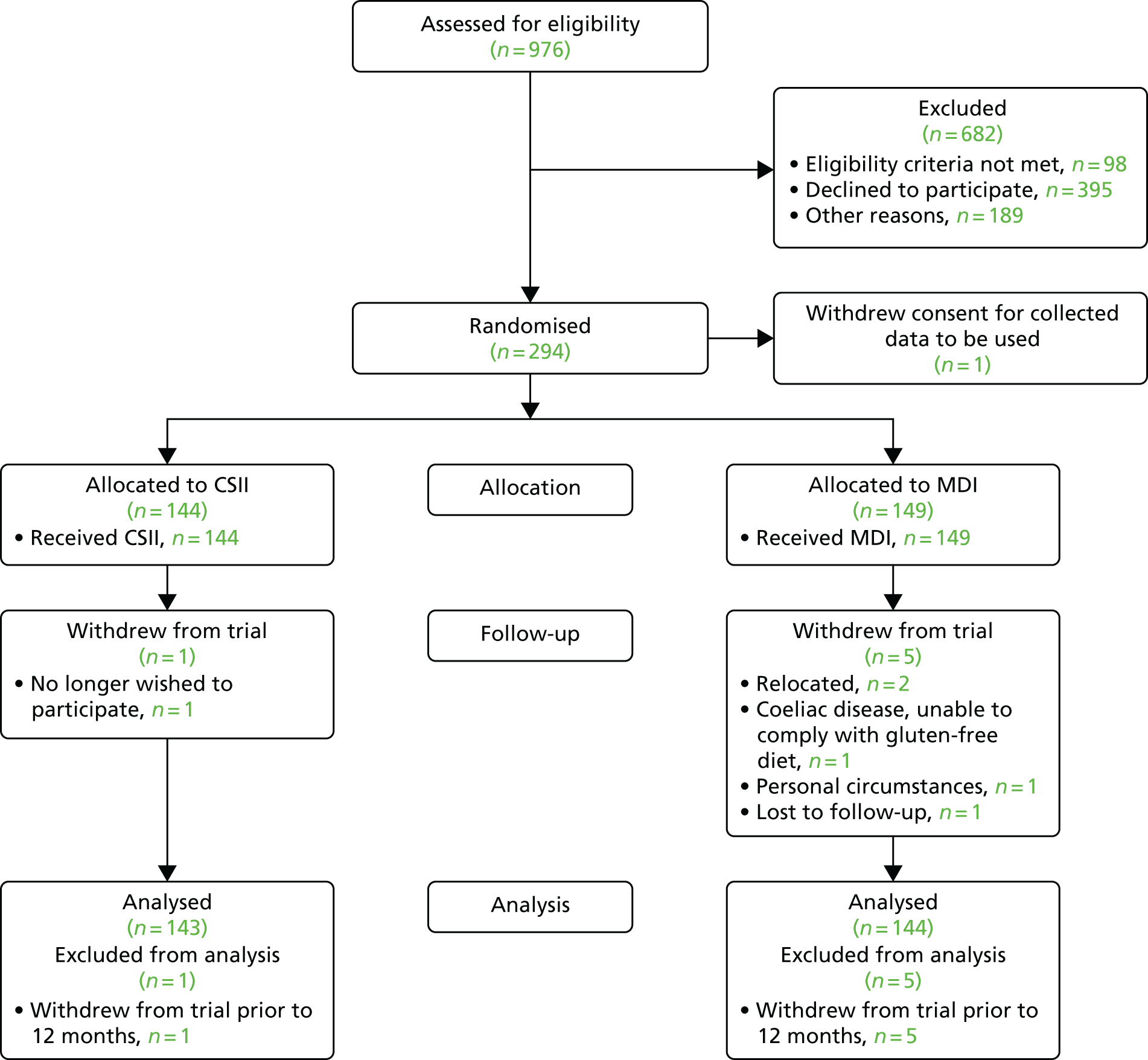

In total, 976 patients were diagnosed with T1D in the 15 study centres in England and Wales during the 48-month recruitment period, of whom 98 (10%) did not meet the study eligibility criteria. One hundred and eighty-nine patients (22%) were not approached about participation. Of these, 115 (61%) were considered to be unsuitable by treating clinicians for reasons other than the study exclusion criteria, 52 patients (28%) were not approached because staffing levels at the site were too low at the time of diagnosis to deliver the study protocol and no reason was recorded for 22 (12%). Of the remaining 689 patients, 294 (42.7%) consented to participate in the study; however, one randomised participant withdrew consent for their data to be used immediately following randomisation, leaving 293 randomised participants.

Patients and families were invited to share their reasons for declining to participate in the study. The main reason given was patient preference for one of the trial arms. Strong patient preference had been expected at the design stage, and of the 395 eligible participants who declined consent, 36 (9%) cited a preference for CSII therapy and 259 (66%) cited a preference for MDI.

In response to this strong patient preference and to support an informed decision, we made a short film in which four SCIPI study participants (two randomised to CSII and two randomised to MDI) and their parents shared their experiences of diagnosis and living with T1D and the treatment in each of the study arms. Although the film was generally well received, we did not observe any increase in recruitment rates following its introduction and the issue of patient preference persisted throughout the trial.

A CONSORT flow diagram illustrating the pathway of patients from diagnosis to consent and randomisation and through the study protocol is given in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

The CONSORT flow chart.

The purpose of the SCIPI study was to generate evidence that could be applied to the population of patients treated in children’s diabetes services in the NHS. For this reason, it was important to demonstrate that patient characteristics, in particular those known to be associated with glycaemic control, did not differ between those who consented and those who declined to participate. The baseline characteristics of patients who were invited to participate in the study are given in Appendix 1, Table 28. There was no difference in age, sex or ethnicity between the group of patients who consented and the group of patients who declined. The median deprivation score for those who declined because they had a strong preference for CSII was 27.7 (range 16.6–63.9), compared with 17.0 (range 1.62–77.23) for those who consented and 17.96 (range 1.18–74.35) for those who stated a strong preference for MDI.

Internal pilot

The internal pilot was planned after 30 patients had been recruited. Of the 89 eligible patients approached for consent, 30 provided consent and 59 declined (33.7% consent rate, 95% CI 23.9% to 43.5% consent rate). The first patient was randomised on 31 May 2011, and 30 patients were randomised by 3 July 2012. A review of the consent rates by recruiting centre identified lower consent rates in one centre that started patients on three daily injections at diagnosis, rather than MDI. Excluding this site, the consent rate increased (26/60 patients; 43.3%, 95% CI 30.8% to 55.9%). Screening data comparing characteristics of eligible consenting participants did not differ from those declining for age, sex, ethnicity or deprivation score. A review of the SD used in the sample size calculation to the accrued data indicated that the study should continue to the planned sample size. The recommendation of the IDSMC was that the SCIPI study should progress to the full study.

Baseline comparability

There was no difference in age, sex, ethnicity or deprivation score between treatment arms (Table 4). Baseline data also showed that auxological and biochemical characteristics did not differ between treatment groups at baseline (Table 5).

| Demographic variable | Treatment arm | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CSII | MDI | ||

| Age at randomisation (years) | |||

| n (missing) | 144 (0) | 149 (0) | 293 (0) |

| Median (IQR) | 9.9 (5.7–12.2) | 9.4 (5.8–12.5) | 9.8 (5.7–12.3) |

| Minimum, maximum | 0.8, 16 | 0.7, 15.4 | 0.7, 16 |

| Age category, n (%) | |||

| n (missing) | 144 (0) | 149 (0) | 293 (0) |

| 7 months to < 5 years | 33 (22.9) | 32 (21.5) | 65 (22.2) |

| 5 years to < 12 years | 71 (49.3) | 76 (51) | 147 (50.2) |

| 12 years to 15 years | 40 (27.8) | 41 (27.5) | 81 (27.6) |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| n (missing) | 144 (0) | 149 (0) | 293 (0) |

| Female | 71 (49.3) | 69 (46.3) | 140 (47.8) |

| Male | 73 (50.7) | 80 (53.7) | 153 (52.2) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| n (missing) | 143 (1) | 146 (3) | 289 (4) |

| Asian or Asian British | 4 (4.2) | 7 (6.1) | 10 (5.6) |

| Black or British black | 0 (0) | 3 (2.1) | 3 (1) |

| British white | 124 (86.7) | 118 (80.8) | 242 (83.7) |

| Mixed | 4 (2.8) | 6 (4.1) | 10 (3.5) |

| Other white | 9 (6.3) | 10 (6.9) | 19 (6.0) |

| Deprivation scorea | |||

| n (missing) | 137 (7) | 143 (6) | 280 (13) |

| Median (IQR) | 19.4 (8.9–37.9) | 14.7 (7.8–31.8) | 17 (8.4–35.8) |

| Minimum, maximum | 1.8, 77.1 | 1.6, 77.2 | 1.6, 77.2 |

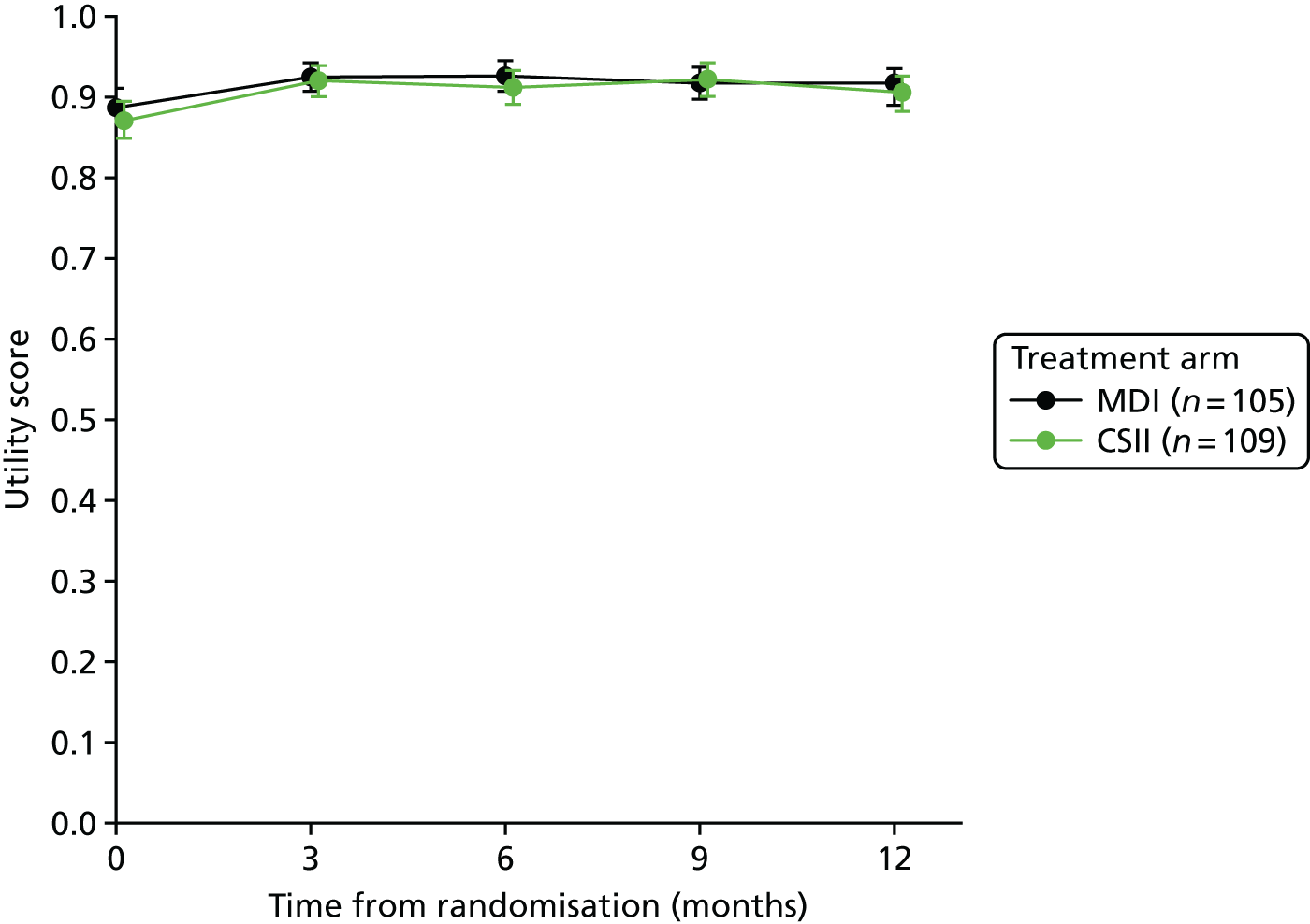

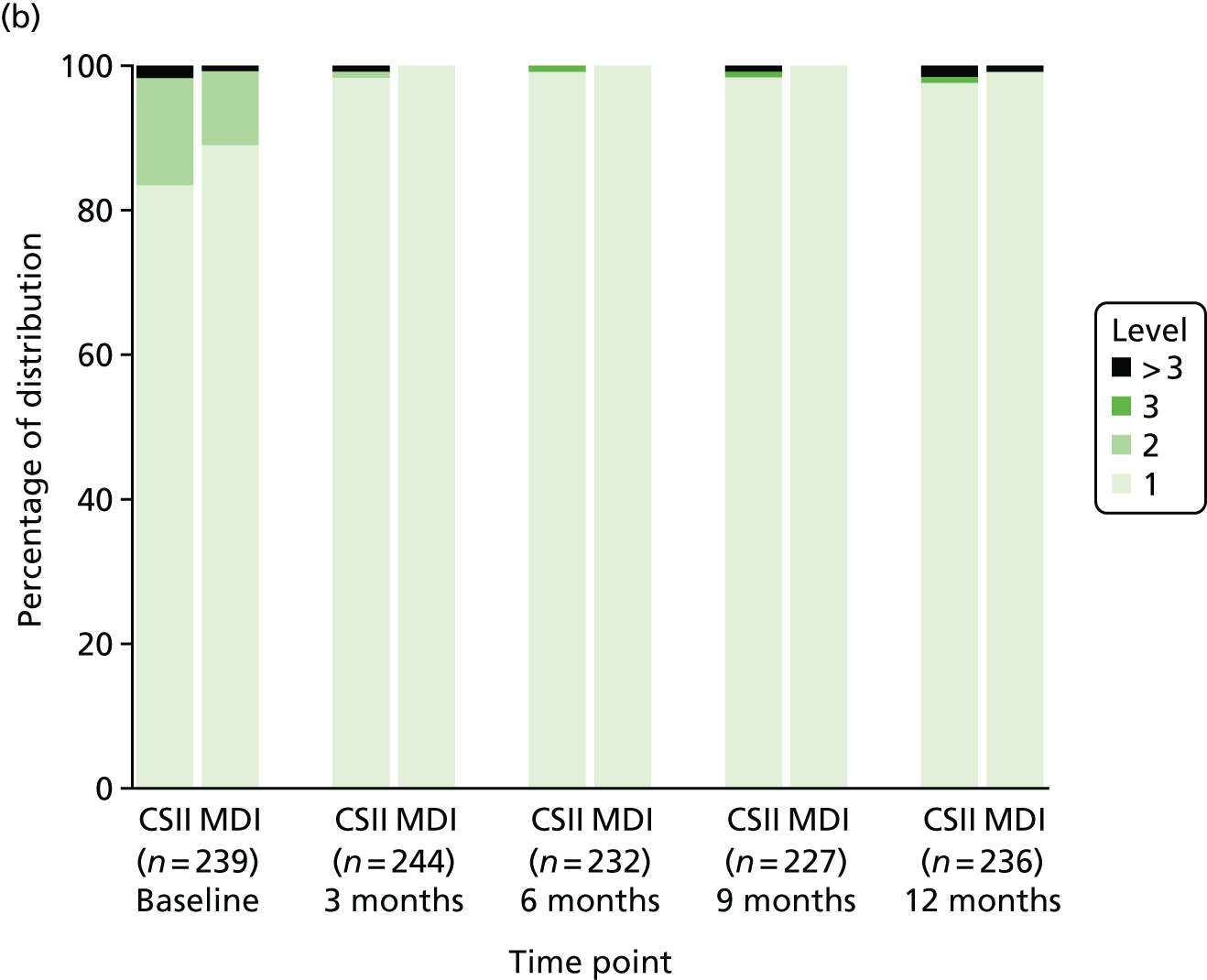

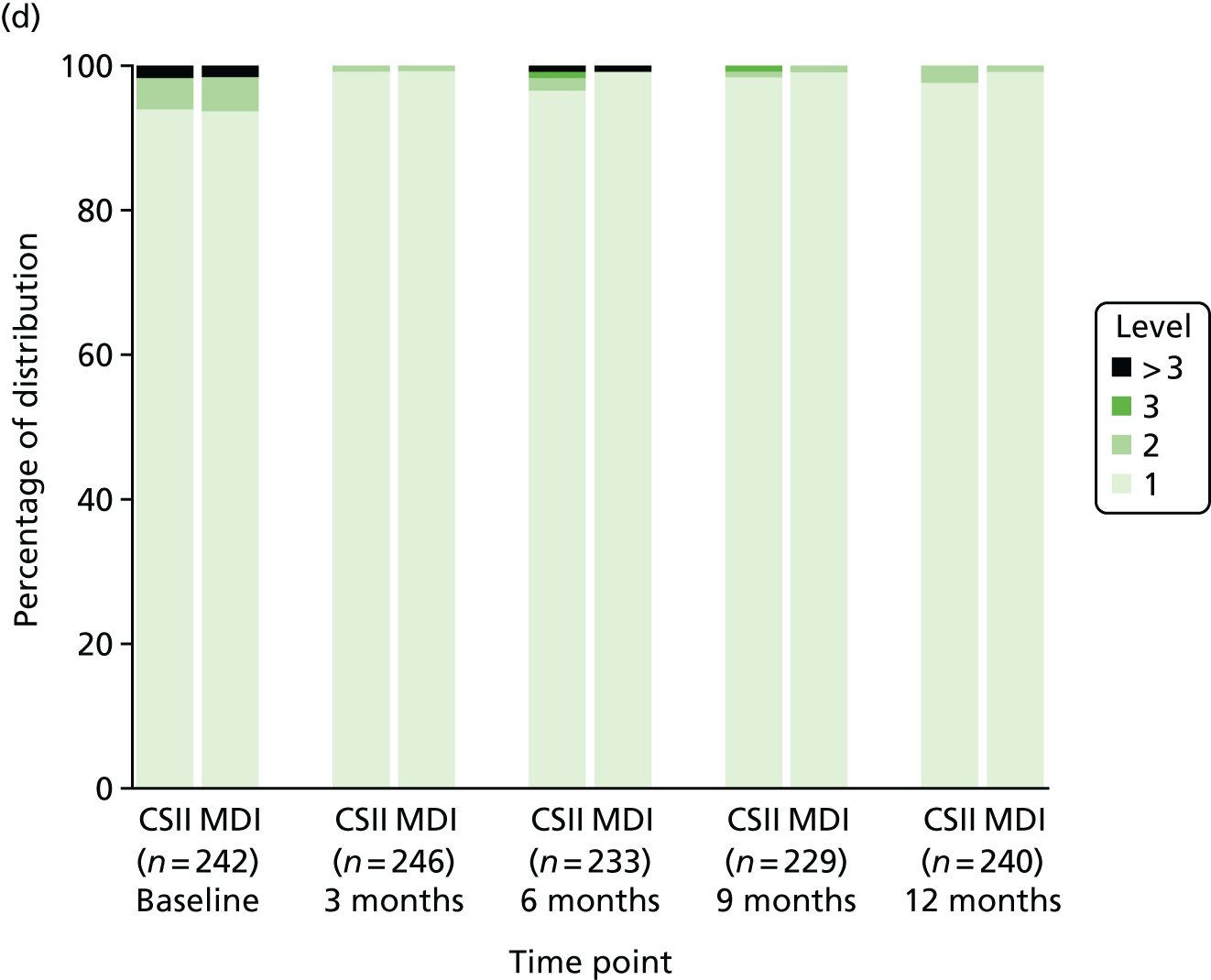

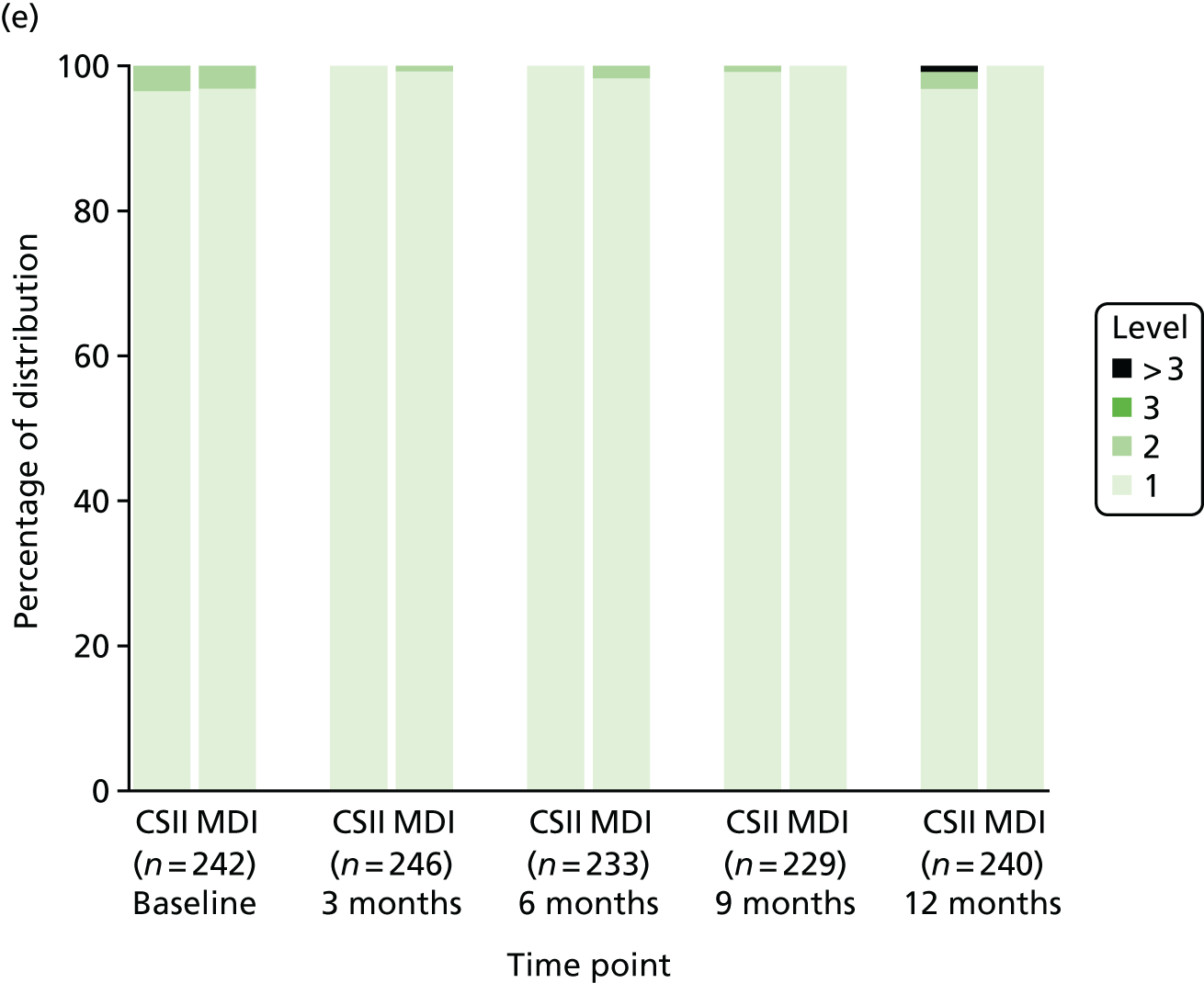

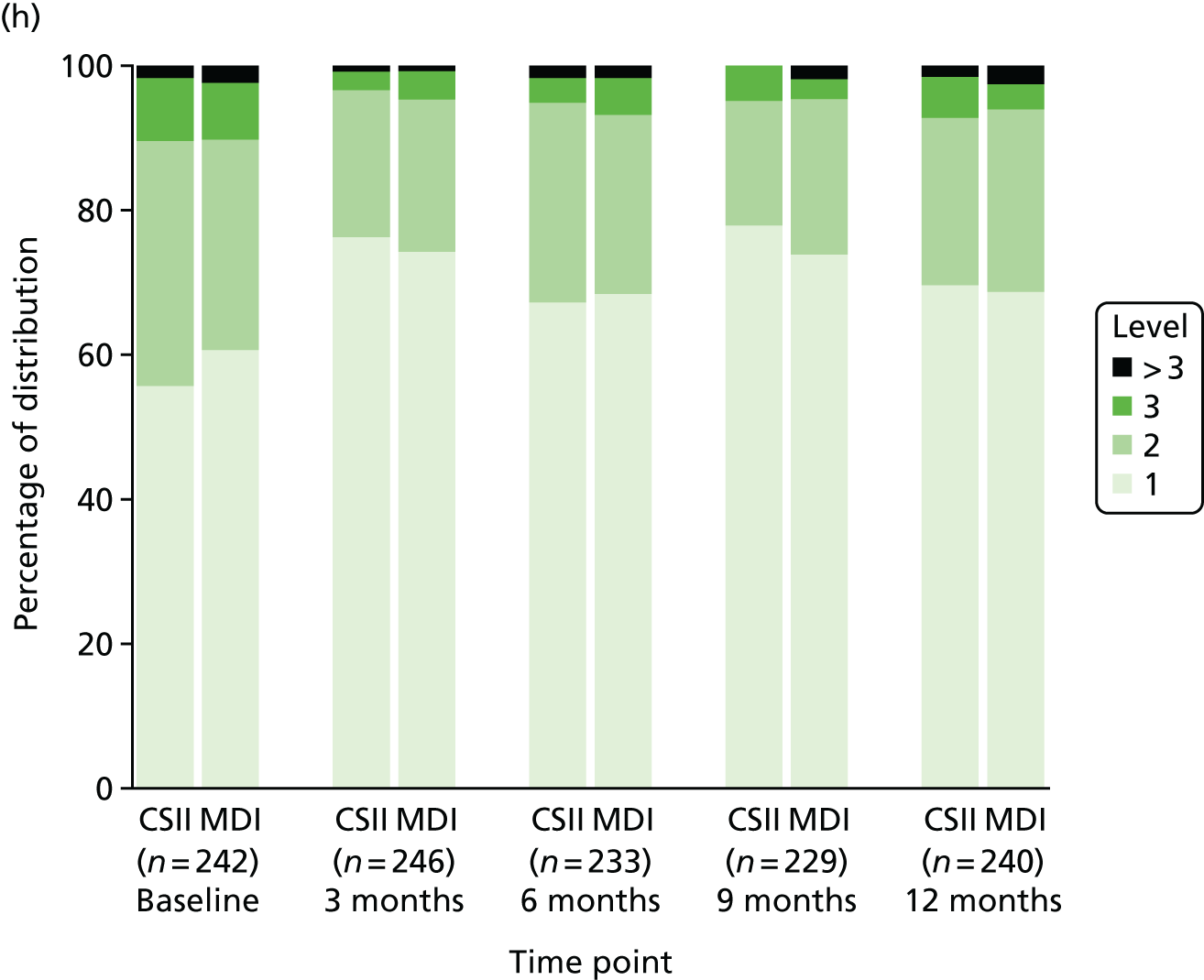

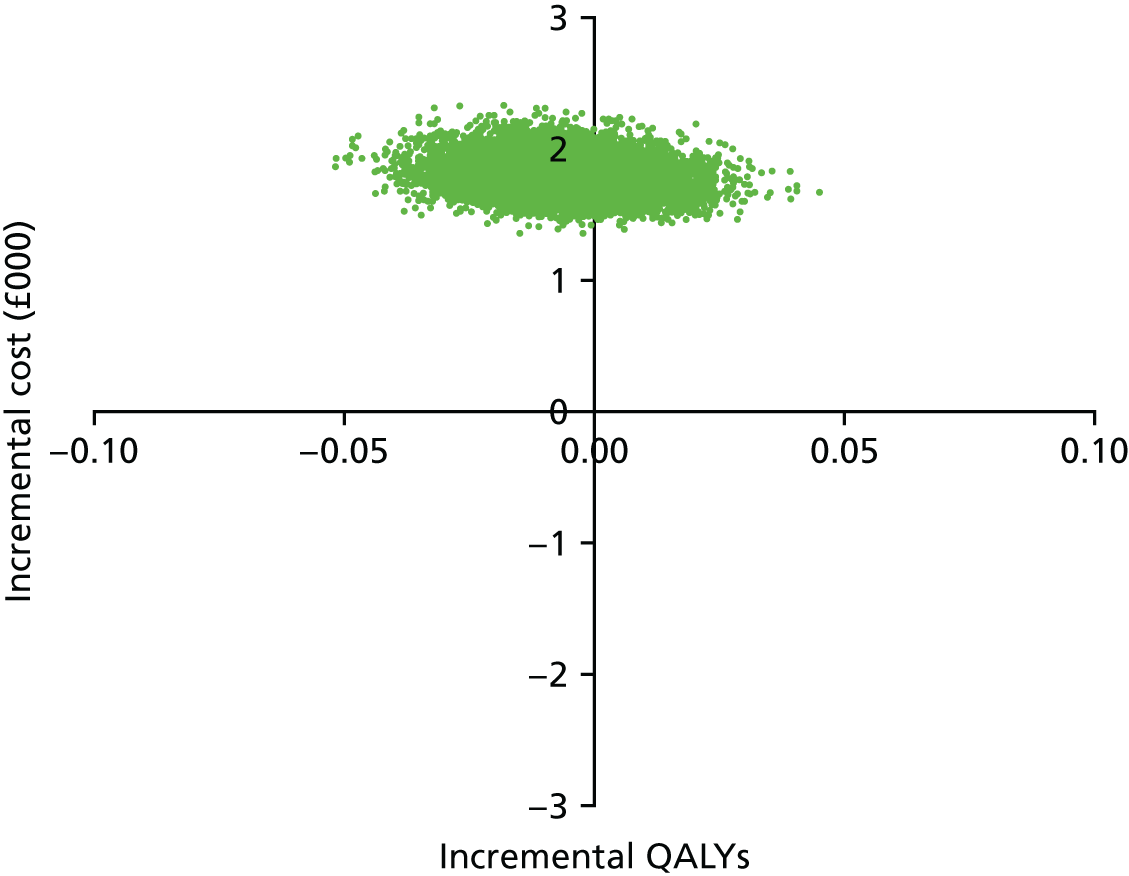

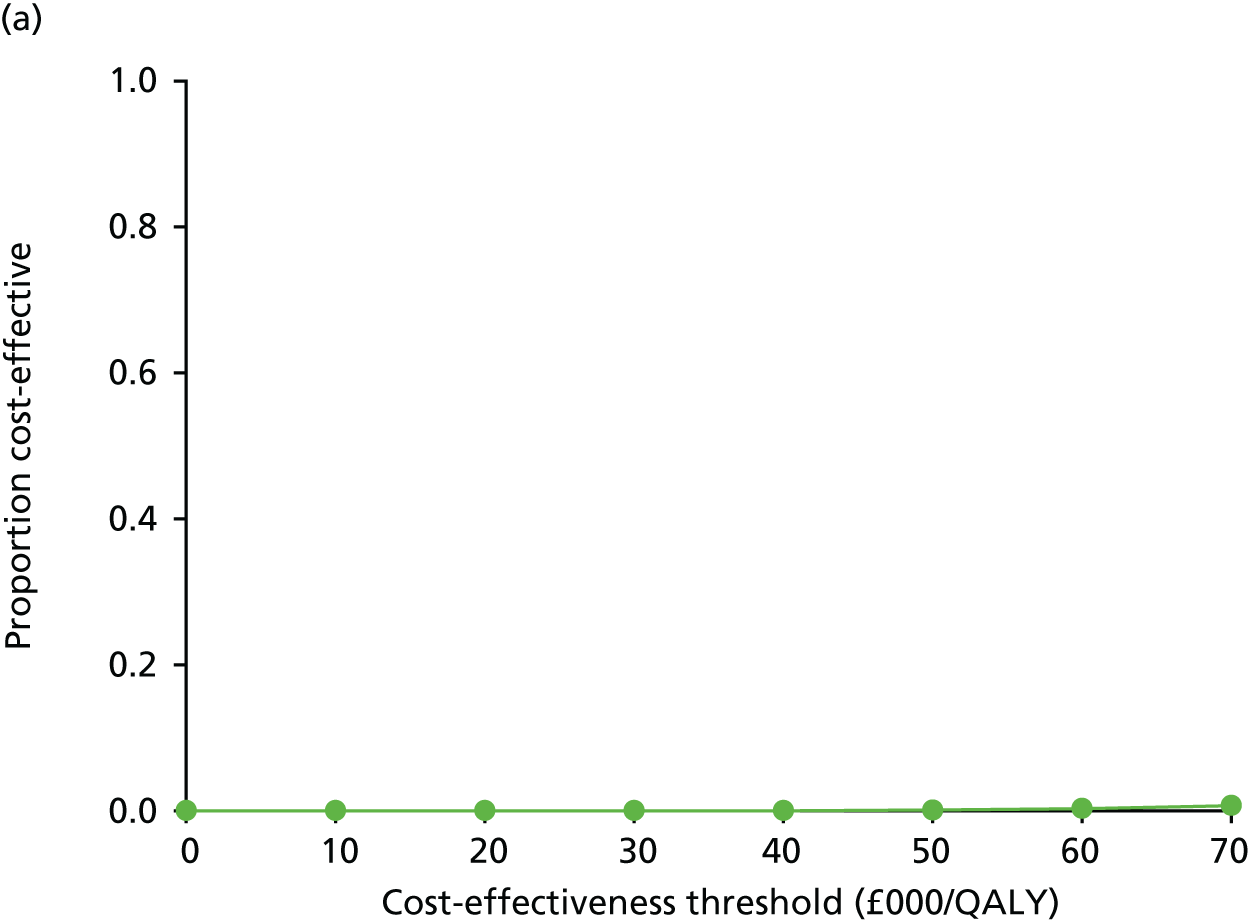

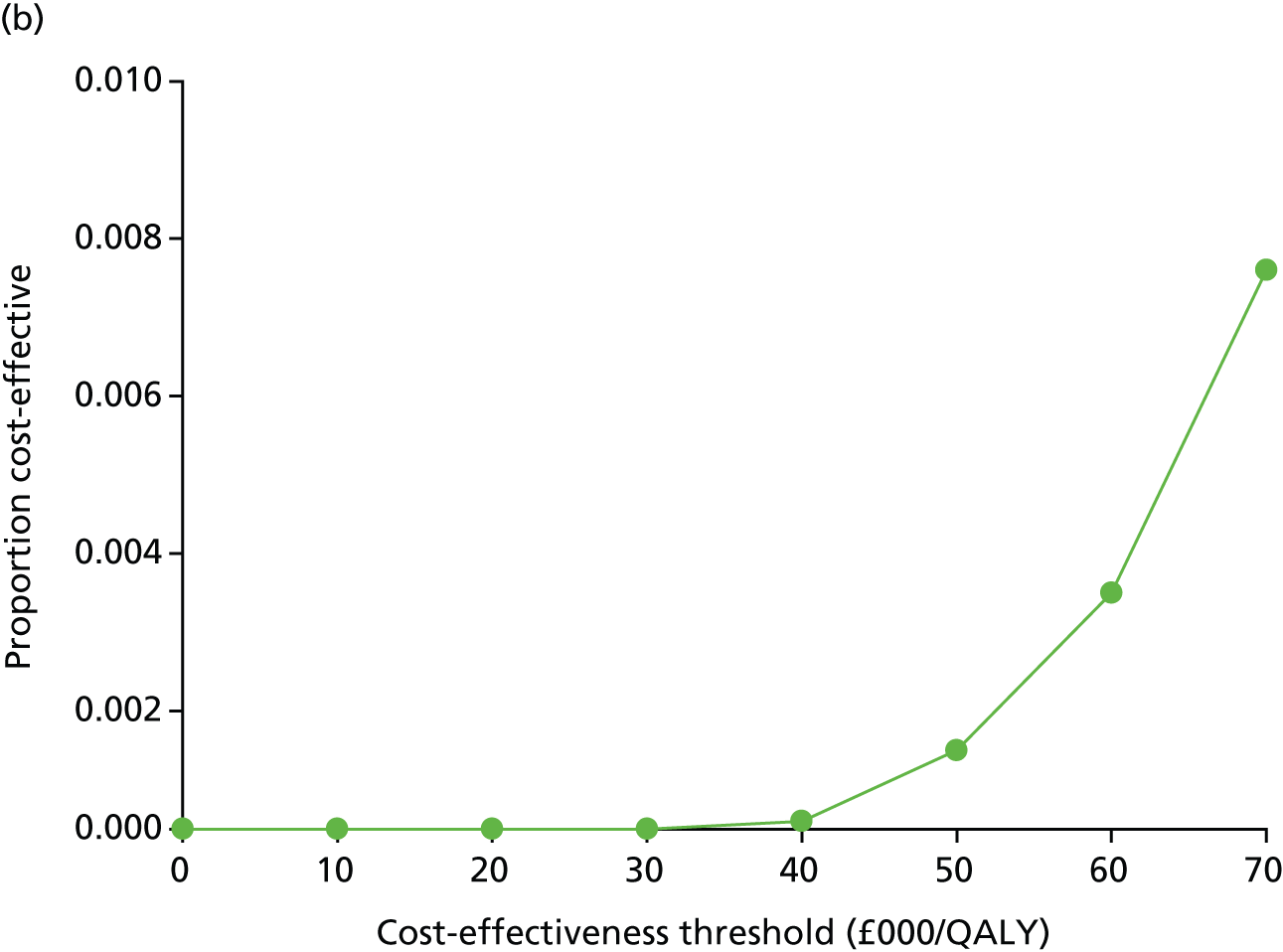

| Demographic variable | Treatment arm | Total | |