Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 16/30/02. The contractual start date was in December 2016. The draft report began editorial review in May 2017 and was accepted for publication in October 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Westwood et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Objective

The overall objective of this assessment was to summarise the evidence on the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of using alternative risk scores, which includes measuring the levels of cancer antigen 125 (CA125) and human epididymis protein 4 (HE4) or morphological features seen on ultrasound (detailed in Chapter 2, Intervention technologies), to guide referral decisions for people with suspected ovarian cancer in secondary care. The current National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance (CG122)1 recommends that the levels of serum CA125 should be measured in secondary care, in all people with suspected ovarian cancer for whom serum CA125 levels have not already been measured in primary care. CA125 levels are a component of secondary care investigation and are not used in isolation; the CG122 specifically recommends the calculation of a Risk of Malignancy Index 1 (RMI 1) score, which includes the measurement of CA125 levels, and referral to a specialist gynaecological oncology multidisciplinary team (MDT) for people with a RMI 1 score of ≥ 250. The CG122 does not currently include any recommendations on HE4 testing or alternative methods of risk-scoring. An evaluation of current evidence was needed to assess the clinical utility and cost-effectiveness of alternative methods of risk-scoring. The following research questions were defined to address the objectives of this assessment:

-

What are the performance characteristics of alternative risk scores (including alternative RMI 1 score thresholds), which include HE4 or CA125 levels or morphological features seen on ultrasound, compared with the RMI 1 score with a referral threshold of ≥ 250 (current practice), for which the target condition is histologically confirmed ovarian cancer?

-

What are the effects of using alternative risk scores (including alternative RMI 1 score thresholds), which include measuring HE4 or CA125 levels or morphological features seen on ultrasound, compared with the RMI 1 score with a referral threshold of ≥ 250 (current practice), on clinical management decisions and clinical outcomes?

-

What is the cost-effectiveness [incremental cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY)] of alternative risk scores (including alternative RMI 1 score thresholds), which include HE4 or CA125 levels or morphological features seen on ultrasound, compared with the RMI 1 score with a referral threshold of ≥ 250 (current practice), when routinely used, in secondary care, to guide decisions about referral to a specialist multidisciplinary team (SMDT), for women with suspected ovarian cancer?

Chapter 2 Background and definition of the decision problem(s)

Population

The primary indication for this assessment was optimisation of the routine secondary care assessment of women with suspected ovarian cancer, to decide whether or not a patient should be referred to a SMDT. The assessment was conducted in the context of an update to the current guidance (CG122). 1 The relevant population was women of any age, including premenopausal and postmenopausal women, who had been referred to secondary care for the investigation of suspected ovarian cancer. This assessment includes data from women of any age, but no cost-effectiveness modelling was undertaken for the population aged < 18 years owing to a lack of data on the performance of risk scores in this age group. Women with a previous history of ovarian cancer who were being monitored for possible recurrence, and those referred directly from primary care to a SMDT, were outside the scope of this assessment.

Target condition

The target condition for this assessment was ovarian cancer. Ovarian cancer is a term describing a group of cancers arising from cells in or near the ovaries. Ovarian cancers can be classified based on tissue type (epithelial ovarian tumours, sex cord–stromal tumours and germ cell tumours), with epithelial carcinomas being the most common type (90%) of primary ovarian cancers; non-epithelial ovarian cancers are more common in premenopausal women. 2 The target conditions covered by the CG122 were epithelial ovarian cancer, fallopian tube carcinoma, primary peritoneal carcinoma and borderline ovarian cancer;1 excluded target conditions were pseudomyxoma peritonei, relapsed ovarian, fallopian tube or peritoneal cancer, germ cell tumour of the ovary and sex cord–stromal tumours of the ovary. This assessment was not limited to any particular type of ovarian cancer.

Ovarian cancers are staged using the four-stage International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) system:3

-

stage I – confined to the organ of origin (ovaries or fallopian tubes)

-

stage II – invasion of the surrounding organs or tissues [pelvic extension or primary peritoneal cancer (below the pelvic brim)]

-

stage III – spread to the peritoneum outside the pelvis and/or metastasis to the retroperitoneal lymph nodes

-

stage IV – distant metastases, excluding peritoneal (e.g. lungs, liver, spleen).

Ovarian cancer can also be graded based on how differentiated cells appear:

-

grade 1 – well differentiated

-

grade 2 – moderately differentiated

-

grade 3 – poorly differentiated/undifferentiated.

Ovarian cancer is the sixth most common cancer in women in the UK (as of 2013), accounting for 4% of all new cases of cancer in females. 4,5 In 2013, there were 7284 new cases of ovarian cancer in women in the UK, giving an age-standardised incidence rate of 23.3 per 100,000. 4,5 Ovarian cancer accounts for around 5% of cancer deaths in women in the UK; 2014 statistics recorded 4100 ovarian cancer deaths. 6 The incidence of ovarian cancer is strongly related to age, with 2011–13 data indicating that approximately half (53%) of new cases of ovarian cancer were diagnosed in women > 65 years of age. 4,5 Ovarian cancer mortality is also strongly related to age at diagnosis. 6

Data from the Office for National Statistics, published by Cancer Research UK,7 indicate that, although ovarian cancer incidence rates have increased overall since the 1970s, the UK age-standardised incidence rates decreased by 6% in the decade between 2002–4 and 2011–13. However, it remains the case that a high proportion of women (58%) are diagnosed at an advanced stage (stage III or IV), and 21% have metastases at diagnosis. 8 Ovarian cancer survival is strongly related to stage at diagnosis; 2012 data6 showed that the 1-year and 5-year survival rates for women diagnosed at stage I were 97% and 90%, respectively, versus 53% and 4%, respectively, for women diagnosed at stage IV. Improving early diagnosis is therefore a priority, and variation in the performance of testing strategies for the detection of different stages of ovarian cancer should be considered. The majority of studies about ovarian cancer diagnosis concern epithelial carcinomas; however, there is some evidence to indicate that the diagnostic performance of tumour markers and risk scores may vary between tumours of different tissue types;9 the possible effects of tumour tissue type on estimates of test performance should also be considered.

It has been suggested that CA125 results should be interpreted cautiously in premenopausal women because of the high rate of false-positive (FP) diagnoses resulting from various non-malignant conditions (e.g. fibroids, endometriosis, adenomyosis, pelvic infection). 10 It is therefore important to consider the effects of the menopausal status of women on the performance of testing strategies, either by stratification of data from test accuracy studies or by including menopausal status in risk models (as in the RMI 1).

Intervention technologies

Serum tumour markers are used in the secondary care investigation of people with suspected ovarian cancer; these are not considered to be ‘stand-alone’ diagnostic tests, but are used in conjunction with other tests, signs and symptoms to assess the risk of malignancy. An estimate of an individual’s risk of malignancy can inform decisions about specialist referral, further testing and treatment. It is anticipated that these risk assessment tools will be used in secondary care, for people in whom ultrasound imaging suggests confined disease or a low volume of disease outside the pelvis (stages I–IIIb).

An optimised risk assessment that reduces the number of women with ovarian cancer who are not referred for further specialist care [i.e. those with a ‘false-negative’ (FN) risk assessment] has the potential to improve prognosis, be cost-saving in terms of unnecessary further investigations and reduce associated anxiety. Prognosis may be adversely affected by a failure to refer women to a SMDT and specialist surgery. In particular, it is likely that women who are believed to have a benign explanation for any pelvic mass will be operated on in secondary care. If they actually have ovarian cancer, then the prognosis might be worse than if they had been operated on by a specialist gynaecological oncology surgeon. Indeed, there is evidence of up to a 45% difference in the median overall survival between a set of regional centres in the UK and the UK as a whole. 11

The current standard assessment (RMI 1) has been reported as having poor sensitivity – approximately 63% at an operating threshold of 200. 12 If referral decisions are based on the RMI 1 score at this threshold, there remains the potential for significant numbers of people with ovarian cancer to remain unreferred, and to experience consequential delays in diagnosis and detrimental effects on prognosis. A systematic review of studies comparing HE4, CA125 and the Risk of Ovarian Malignancy Algorithm (ROMA) score reported similar overall sensitivity estimates for HE4 and CA125 (76% and 79%, respectively) and a higher sensitivity (85%) for the ROMA score. 9 Sensitivity estimates were lower for early-stage cancer (55% for both HE4 and CA125 levels, and 74% for the ROMA score). 9 Risk scores with higher sensitivity are needed to facilitate prompt referral of the appropriate patient group.

The Risk of Ovarian Malignancy Algorithm score

The ROMA score uses serum HE4 and serum CA125 levels, along with menopausal status, to generate an individualised estimate of the risk that a person has ovarian cancer. Initially, a predictive index (PI) value is calculated using a formula that differs depending on whether the woman is premenopausal or postmenopausal (Equations 1 and 2 in Box 1). This PI value can then be used to calculate the ROMA score (Equation 3 in Box 1). 13 The ROMA score is intended for use in women who present with an adnexal mass (i.e. following ultrasound examination). Manufacturers of HE4 assays recommend the use of these assays, in the context of a ROMA score, in combination with a specific CA125 assay or assays; if a CA125 level has been obtained in primary care, using a different assay, this will need to be repeated in secondary care before a ROMA score can be calculated.

Cut-off values for the ROMA scores are used to classify individuals as having a low or high risk of developing epithelial ovarian cancer. Recommended thresholds can differ depending on the tumour marker assays used, as described below.

There are currently three commercial HE4 assays for use with automated immunoassay analysers that are available for use in the UK NHS; a summary of the key technical characteristics of these assays is provided below (Table 1).

| Name of assay (manufacturers’ details) | Company | Detection | Assay time | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Limit | Range | |||

| ARCHITECT HE4 (Abbott Diagnostics, Abbott Park, IL, USA) | Abbott Diagnostics | 15 pmol/l | 20–1500 pmol/l | 28 minutesa |

| LUMIPULSE® G HE4 (Fujirebio Diagnostics, Gothenburg, Sweden) | Fujirebio Diagnostics | 3.5 pmol/l | 20–1500 pmol/l | 35 minutesb |

| Elecsys® HE4 (Roche Diagnostics, Rotkreuz, Switzerland) | Roche Diagnostics | 15 pmol/l | 15–1500 pmol/l | 18 minutesc |

The ARCHITECT human epididymis protein 4 assay (Abbott Diagnostics)

The ARCHITECT HE4 assay (Abbott Diagnostics, Abbott Park, IL, USA) is a chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay for the quantitative determination of HE4 levels in human serum. The assay is designed for use on an immunoassay analyser, specifically the ARCHITECT i2000SR or the ARCHITECT i1000SR analysers. Additional materials required to run the assay are the ARCHITECT HE4 assay software file, ARCHITECT HE4 calibrators, ARCHITECT HE4 controls, ARCHITECT multiassay manual diluent, ARCHITECT pre-trigger solution, ARCHITECT trigger solution, ARCHITECT wash buffer, ARCHITECT reaction vessels, ARCHITECT sample cups, ARCHITECT septum and ARCHITECT replacement caps.

The results of the assay are intended to be used in conjunction with the ARCHITECT CA125 II assay, as an aid in estimating the risk of epithelial ovarian cancer in women presenting with a pelvic mass who will undergo surgical intervention. The company recommends that the HE4 assay results are used in the calculation of the ROMA scores, using the following cut-off values for ROMA scores, based on obtaining a specificity of 75%:

-

in premenopausal patients, a ROMA value of ≥ 7.4% indicates a high risk of finding epithelial ovarian cancer

-

in premenopausal patients, a ROMA value of < 7.4% indicates a low risk of finding epithelial ovarian cancer

-

in postmenopausal patients, a ROMA value of ≥ 25.3% indicates a high risk of finding epithelial ovarian cancer

-

in postmenopausal patients, a ROMA value of < 25.3% indicates a low risk of finding epithelial ovarian cancer.

These results must be interpreted in conjunction with other methods and clinical data (e.g. symptoms and medical history), in accordance with standard clinical management guidelines. The company states that additional testing should be done if the HE4 results are inconsistent with the clinical evidence.

LUMIPULSE G human epididymis protein 4 (Fujirebio Diagnostics)

The LUMIPULSE G HE4 (Fujirebio Diagnostics, Gothenburg, Sweden) is a chemiluminescent enzyme immunoassay (CEIA) for the quantitative measurement of HE4 levels in human serum. The assay is designed for use on the LUMIPULSE G system (either the LUMIPULSE G1200 or the LUMIPULSE G600 immunoassay analysers). Samples are run using immunoreaction cartridges, which contain reagents and into which samples are added. Further materials required for the assay are LUMIPULSE G HE4 calibrators, LUMIPULSE G substrate solution, LUMIPULSE G wash solution, LUMIPULSE G specimen diluent I, sampling tips for the LUMIPULSE system, soda lime for the LUMIPULSE system and LUMIPULSE G dilution cartridges.

The assay is intended for use in conjunction with CA125 levels (measured using the LUMIPULSE G CA125 II assay) as an aid in estimating the risk of epithelial ovarian cancer in premenopausal and postmenopausal women presenting with a pelvic mass who will undergo surgical intervention.

The company recommends that the HE4 results are used in the calculation of the ROMA scores, and suggests the following cut-off values for the ROMA scores, based on obtaining a specificity of 75%:

-

in premenopausal patients, a ROMA value of ≥ 13.1% indicates a high risk of finding epithelial ovarian cancer

-

in premenopausal patients, a ROMA value of < 13.1% indicates a low risk of finding epithelial ovarian cancer

-

in postmenopausal patients, a ROMA value of ≥ 27.7% indicates a high risk of finding epithelial ovarian cancer

-

in postmenopausal patients, a ROMA value of < 27.7% indicates a low risk of finding epithelial ovarian cancer.

Results should be interpreted in conjunction with further methods and clinical data (e.g. clinical findings, age, family history and imaging results), in accordance with standard clinical management guidelines.

A further HE4 assay is also available from Fujirebio Diagnostics: the HE4 enzyme immunoassay (EIA), a manual, enzyme immunometric assay for the quantitative determination of HE4 in human serum. Clinical experts commented that manual kits would be unlikely to be used in routine practice in the NHS; therefore, this assay has not been included in the scope of this assessment.

Elecsys human epididymis protein 4 immunoassay (Roche Diagnostics)

The Elecsys HE4 (Roche Diagnostics, Rotkreuz, Switzerland) is an immunoassay that uses Roche Diagnostics’ electrochemiluminescence detection technology to quantify HE4 levels. The assay uses anti-HE4 mouse monoclonal antibodies to capture HE4 in a serum sample and label it with a ruthenium complex. The application of a voltage to the samples then induces chemiluminescent emissions, which are measured by a photomultiplier.

The assay is designed for use on an immunoassay analyser, specifically the following analysers: modular analytics E170, cobas e 411, cobas e 601/e 602 and cobas e 801. Additional materials required for the HE4 assay are the HE4 CalSet (Roche Diagnostics, Rotkreuz, Switzerland), PreciControl HE4 (Roche Diagnostics, Rotkreuz, Switzerland) and Diluent MultiAssay (Roche Diagnostics, Rotkreuz, Switzerland). Further materials are also required for the general running of analysers, such as wash and cleaning solutions and disposable consumables.

The assay is intended to be used in conjunction with the Elecsys CA125 II assay as an aid in estimating the risk of epithelial ovarian cancer in premenopausal and postmenopausal people with a pelvic mass. The company recommends that the HE4 and CA125 assay results are used in the calculation of the ROMA scores. The company suggests the following cut-off values for the ROMA scores, based on obtaining a specificity of 75%:

-

in premenopausal patients, a ROMA value of ≥ 11.4% indicates a high risk of finding epithelial ovarian cancer

-

in premenopausal patients, a ROMA value of < 11.4% indicates a low risk of finding epithelial ovarian cancer

-

in postmenopausal patients, a ROMA value of ≥ 29.9% indicates a high risk of finding epithelial ovarian cancer

-

in postmenopausal patients, a ROMA value of < 29.9% indicates a low risk of finding epithelial ovarian cancer.

The company states that additional testing should be done if the HE4 results are inconsistent with the clinical evidence.

Simple Rules ultrasound classification system (International Ovarian Tumour Analysis group)

Simple Rules is a morphological scoring system based on the presence of ultrasound features (described as rules) to characterise an ovarian mass as benign or malignant, and was developed by the International Ovarian Tumour Analysis (IOTA) group. The system uses a morphological scoring system based on the presence of ultrasound features to characterise an ovarian mass as benign or malignant, and requires the use of transvaginal sonography (TVS), which may be supplemented with abdominal ultrasound for larger masses. There are five ‘rules’ describing the features of malignant tumours (M-rules) and five rules that describe benign tumours [B-rules (see Table 2)]. 14,15 Because the use of the Simple Rules system requires specialist training in interpreting real-time ultrasound images in relation to these rules, it is assumed that using the Simple Rules system in the specified population will require a secondary care ultrasound examination (i.e. a repeat examination in which the ultrasound has been conducted in primary care).

| M-rules (rules for predicting a malignant tumour) | B-rules (rules for predicting a benign tumour) |

|---|---|

|

|

The M-rules and B-rules can be combined to aid classification:

-

If any M-rules (and no B-rules) apply, the mass is classified as malignant.

-

If any B-rules (and no M-rules) apply, the mass is classified as benign.

-

If both M-rule and B-rule (or neither) apply, the mass is unclassifiable, and the IOTA group states that there are then a number of options:

-

classify the mass as malignant

-

refer the patient to an expert ultrasound operator for a second opinion

-

use alternative imaging techniques

-

use the Simple Rules risk model16 to calculate risk of malignancy using the morphological features seen on ultrasound described in the Simple Rules model.

-

No specific make or model of ultrasound device is required for the model inputs. A transvaginal probe is required, and the image must be of sufficient quality to allow the ultrasound features specified by the model to be seen. The IOTA group states that the approach to evaluating masses required by the classification system is not more time-consuming than a standard ultrasound scan.

The IOTA group organises 1-day courses that teach the techniques for classifying masses required by the system, with participants assessed by a multiple-choice test. An online training tool, which will be freely accessible to NHS practitioners, is also being developed. In addition to this training, the IOTA group also recommends that practitioners should have completed 300 gynaecological scans. Software is not required to run the Simple Rules model.

The Simple Rules model is not recommended for use with women who are pregnant. Physiological changes during pregnancy can alter the appearance of ovarian masses, which can affect the classification made using the Simple Rules model, and the model has not been validated in this group.

The Assessment of Different NEoplasias in the adneXa model (International Ovarian Tumour Analysis group)

The Assessment of Different NEoplasias in the adneXa (ADNEX) model was developed by the IOTA group to aid preoperative discrimination between benign, borderline, stage I invasive, stages II–IV invasive and secondary metastatic ovarian tumours in women with an ovarian (including paraovarian and tubal) mass. 17 The model uses nine predictors, three clinical variables [age, serum CA125 level and type of referral centre (oncology or other)] and six ultrasound variables (maximal lesion diameter, proportion of solid tissue, > 10 cyst locules, number of papillary projections, acoustic shadows and ascites). The IOTA group have produced iPhone, Android and web applications for calculating the ADNEX risk score (www.iotagroup.org/adnexmodel/). Guidance has also been published on the application of the ADNEX model in clinical practice, and the selection of risk cut-off values for risk stratification and choice of clinical management. 18 The IOTA group notes that, as with other diagnostic prediction models (other IOTA group models, ROMA scores, the RMI 1), the ADNEX model cannot be applied to women with conservatively treated adnexal tumours.

Overa (multivariate index assay, second generation)

The Overa [multivariate index assay, second generation (MIA2G); Vermillion, Inc., Austin, TX, USA] assay is a Conformité Européenne (CE)-marked qualitative serum test that combines the results of five immunoassays into a single numeric result [i.e. the Overa (MIA2G) risk score]. The five biomarkers included in the test are:

-

follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH)

-

HE4

-

apolipoprotein A-1 (apo A-1)

-

transferrin (TRF)

-

CA125.

The levels of these biomarkers present in serum are determined using immunoassays run on the Roche Diagnostics’ cobas® 6000 system (Roche Diagnostics, Rotkreuz, Switzerland). The Overa (MIA2G) risk score is generated by the company’s OvaCalc software, with the results ranging between 0.0 and 10.0. A risk score of < 5.0 is indicative of a low probability of malignancy and a score of ≥ 5.0 indicates a high probability of malignancy.

The assay is indicated for use in people > 18 years with a pelvic mass in whom surgery may be considered. It is intended for use as part of a preoperative assessment to help decide if a person presenting with a pelvic mass has a high risk or a low risk of ovarian malignancy.

The company states that the test results must be interpreted in conjunction with an independent clinical and imaging evaluation, and that the test is not intended for use in screening or as a stand-alone assay.

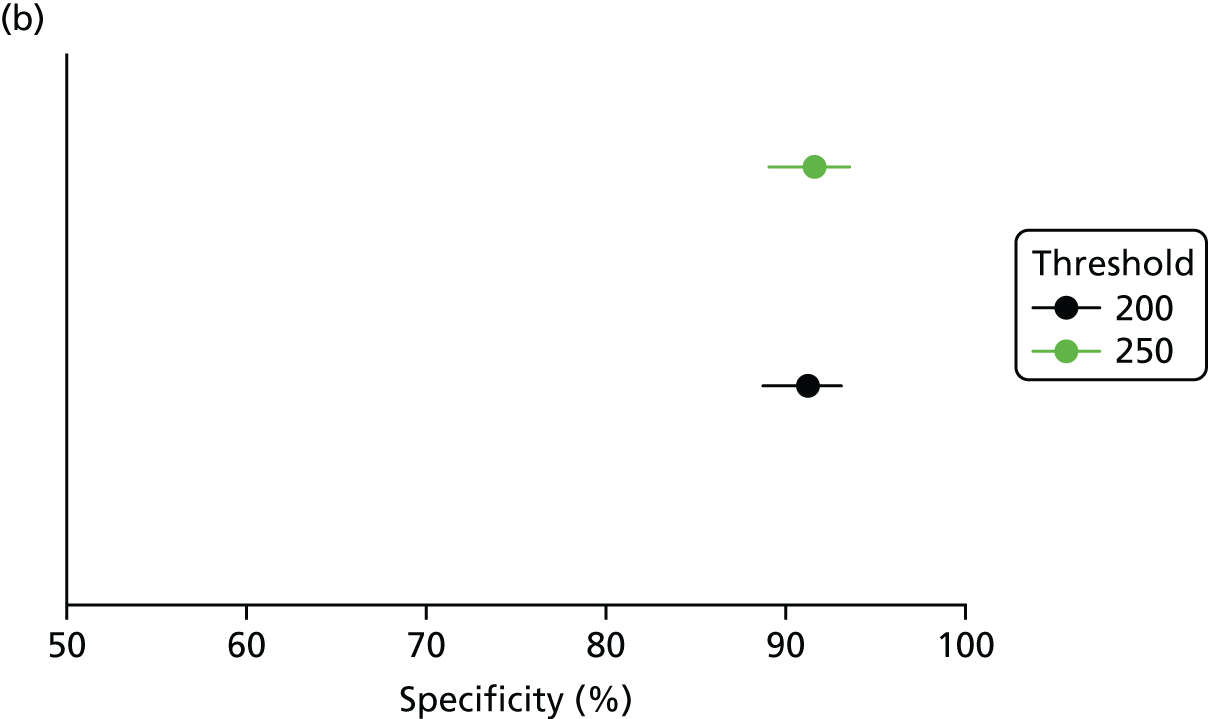

The Risk of Malignancy Index 1

The RMI 1, used at thresholds other than those currently recommended in the NICE clinical guidelines (see Comparator), was considered as an alternative intervention technology.

Comparator

The comparator for this assessment is the RMI 1, using the referral thresholds that best reflect current UK clinical practice (≥ 250), recommended in NICE clinical guideline CG122. 1 The RMI 1 score uses three components (measured serum CA125 levels, ultrasound imaging and menopausal status) to calculate a risk score:

where:

-

U is the ultrasound score – 1 point scored for the presence of each of the following features: multilocular cysts, solid areas, metastases, ascites, bilateral lesions. U = 0 (0 points), U = 1 (1 point) or U = 3 (2–5 points)

-

M is the menopause score – M = 1 (premenopausal) or M = 3 (postmenopausal); a ‘postmenopausal’ woman is one who has had no period for more than 1 year or a woman aged > 50 years who has had a hysterectomy

-

CA125 is the serum CA125 concentration – measured in international units (IU)/ml.

Notably, because the ultrasound score component of this equation is zero, if none of the specified features is present on an ultrasound scan, RMI 1 scores above zero are possible only if ultrasound scans identify features indicative of ovarian cancer.

The NICE clinical guideline CG1221 recommends that people with a RMI 1 score of ≥ 250 should be referred to a specialist gynaecological oncology MDT. However, this guideline also includes a research recommendation that states that further research should be undertaken to determine the optimum RMI 1 threshold that should be applied in secondary care to guide the management of people with suspected ovarian cancer. The guideline notes that there was variation in the evidence base at that time with regard to the optimum RMI 1 threshold to use in secondary care, and that the value used will have implications for the management options considered, and the number of women who will be referred for specialist treatment.

The Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN)’s guideline on the management of epithelial ovarian cancer (SIGN 135)19 recommends referring women with a RMI 1 score of > 200 to a gynaecological oncology MDT. In addition, the Royal College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology (RCOG)’s guideline on ovarian cysts in postmenopausal women recommends the use of 200 as a threshold to predict the likelihood of ovarian cancer, although it notes that the threshold of 250 is also acceptable; in the current literature,10 a score of 200 is often used as a cut-off value.

Reference standard

Histopathology is the reference standard for assessing the accuracy of tests to identify people at a high risk of developing epithelial ovarian cancer. In addition to distinguishing between malignant and benign tumours, this testing can also determine the type of ovarian cancer present. Tissue samples used to confirm diagnosis can be obtained by biopsy or during surgery; however, for the population of interest (people in whom imaging suggests a confined disease or a low volume of disease outside the pelvis), it is expected that pre-surgery biopsy would not routinely occur. When tissue samples are not taken, clinical follow-up (ideally for a minimum of 12 months) may be required to determine the presence, or absence, of ovarian cancer.

Care pathway

Primary care assessment and criteria for referral to secondary care

The 2011 NICE clinical guideline CG1221 provides recommendations about the assessment of people with suspected ovarian cancer in primary care.

These recommendations include information about signs and symptoms (e.g. abdominal bloating, feelings of satiety or loss of appetite, pelvic or abdominal pain, changes in bowel habit and urinary frequency/urge) as well as information about the use of CA125 testing.

More recent guidance about cancer diagnoses, the NICE guidance NG12,20 published in 2015, reproduces the recommendations from the CG1221 with no update.

The more recent (2013) guidance, from SIGN19 provided recommendations covering similar topic areas.

Establishing a diagnosis in secondary care

The 2011 NICE clinical guideline CG1221 also includes recommendations about testing following referral to secondary care. These recommendations cover the use of various blood tests [alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), beta-human chorionic gonadotrophin (beta-hCG) and CA125], risk scoring using the RMI 1 score, imaging (ultrasound and CT) and the role of the MDT.

Those secondary care recommendations that refer to CA125 consider its use in a clinical context, particularly in relation to the calculation of the RMI 1 score. 1

The SIGN guideline (SIGN 135)19 includes similar recommendations about the RMI 1 score and further imaging investigations.

The RCOG and the British Society for Gynaecological Endoscopy have produced a joint guideline about the management of suspected ovarian masses in premenopausal women. This guideline aimed to clarify when ovarian masses can be managed in a ‘benign’ gynaecological service and when referral to a gynaecological oncological service is needed. 10 The guideline notes the importance of thorough history-taking, including risk factors, and careful physical examination, including abdominal and vaginal examination and the determination of the presence or absence of local lymphadenopathy.

The Royal College of Radiologists iRefer radiological investigation guidelines tool21 recommends that CT of the abdomen and pelvis has a role in identifying women who may benefit from chemotherapy or cytoreductive surgery. MRI of the abdomen and pelvis is recommended for specialised investigation when enhanced CT is contraindicated, or for problem-solving. PET-CT is indicated as a specialised investigation for difficult management situations.

Management of early (stage I) ovarian cancer

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guideline CG1221 includes recommendations about the overall management of women with suspected early (stage I) ovarian cancer, and NICE Technology Appraisal (TA) guidance TA5522 provides recommendations about first-line chemotherapy regimens.

Management of advanced (stage II to IV) ovarian cancer

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guideline CG1221 includes recommendations about the management of women with advanced (stages II–IV) ovarian cancer, and NICE TA guidance (TA55 and TA284)22,23 provides recommendations about first-line chemotherapy regimens.

Further recommendations about chemotherapy regimens for women with recurrent ovarian cancer can be found in NICE TA guidance documents TA389, TA381 and TA285. 24–26

Summary of the decision problem

The current guidance, NICE clinical guideline CG122,1 recommends that serum CA125 levels should be measured in secondary care in all women with suspected ovarian cancer in whom serum CA125 levels have not already been measured in primary care. CA125 levels can inform clinical decision-making in secondary care and are not used in isolation; CG1221 specifically recommends the calculation of a RMI 1 score, which includes CA125 level. CG122 does not currently include any recommendations on HE4 levels, risk scores or testing algorithms (other than RMI 1 score). An update to the section of CG1221 that deals with establishing a diagnosis in secondary care is planned in order to assess the potential role of alternative risk scores in assessing women with suspected ovarian cancer for possible referral to a SMDT and to consider the best way to incorporate tumour markers and other tests in the decision-making process.

This assessment systematically reviews the evidence about the comparative performance of alternative risk scores that include CA125 levels, HE4 levels or ultrasound (detailed in Intervention technologies) to guide referral decisions for women with suspected ovarian cancer in secondary care. The assessment focuses on direct comparisons between the interventions described and the RMI 1 score, using the referral threshold of ≥ 250 (current practice as indicated in CG1221). However, assessments of the accuracy of individual risk scores have also been included. Data were collected on the accuracy and comparative accuracy of different risk scores, alternative cut-off values and risk scores used in combination in order to determine the best way to incorporate tumour markers and ultrasound findings in the diagnostic process. Prediction-modelling studies have also been included, which report the development and validation of multivariable prediction models intended to be used to guide individual patient care.

Chapter 3 Assessment of clinical effectiveness

A systematic review was conducted to summarise the evidence on the clinical effectiveness of different risk scores, used as a triage step to guide referral decisions for women with suspected ovarian cancer in secondary care, compared with the RMI 1 score, as recommended in CG122. 1 Systematic review methods followed the principles outlined in the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination’s (CRD’s) guidance27 for undertaking reviews in health care and NICE’s diagnostics assessment programme manual. 28

This report contains reference to confidential information provided as part of the NICE appraisal process. This information has been removed from the report and the results, discussions and conclusions of the report do not include the confidential information. These sections are clearly marked in the report.

Systematic review methods

Search strategies

Search strategies were based on the specified risk scores [the ROMA score, the IOTA group’s simple ultrasound rules, the ADNEX score, Overa (MIA2G) score and the RMI 1 score] and the target condition (ovarian cancer), as recommended in the CRD’s guidance27 for undertaking reviews in health care and the Cochrane’s handbook for diagnostic test accuracy reviews. 29,30

Candidate search terms were identified from target references, browsing database thesauri (e.g. MEDLINE MeSH and EMBASE Emtree), and from existing reviews identified during the initial scoping searches. These scoping searches were used to generate test sets of target references, which informed the text-mining analysis of high-frequency subject indexing terms, using EndNote X6 [Clarivate Analytics (formerly Thomson Reuters), Philadelphia, PA, USA] reference management software. Strategy development involved an iterative approach, testing candidate text and indexing terms across a sample of bibliographic databases and aiming to reach a satisfactory balance of sensitivity and specificity. Search strategies were developed specifically for each database.

No restrictions on language, publication status or date of publication were applied. Searches took into account generic and other product names for the intervention. The main EMBASE strategy for each search was independently peer reviewed by a second information specialist, using the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health’s peer review checklist. 31 Identified references were downloaded in EndNote X6 software for further assessment and handling. References in retrieved articles were checked for additional studies. The final list of included papers were also checked on PubMed for retractions, errata and related citations. 32–35

The following databases were searched for relevant studies:

-

MEDLINE (via Ovid) – 1946 to week 2 November 2016

-

MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations (via Ovid) – to 22 November 2016

-

MEDLINE Daily Update (via Ovid) – to 22 November 2016

-

MEDLINE Epub Ahead of Print (via Ovid) – to 22 November 2016

-

EMBASE (via Ovid) – 1974 to 23 November 2016

-

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (via Wiley Online Library) – to issue 11 of 12, November 2016

-

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (via Wiley Online Library) – to issue 10 of 12, October 2016

-

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (via Wiley Online Library) – to issue 2 of 4, April 2015

-

Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Database (via Wiley Online Library) – to issue 4 of 4, October 2016

-

International Network of Agencies for HTA publications (via the internet: www.inahta.org/publications/) – to 25 November 2016

-

National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) HTA programme (via the internet: www.nets.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta) – to 25 November 2016

-

Aggressive Research Intelligence Facility database (via the internet: www.birmingham.ac.uk/research/activity/mds/projects/HaPS/PHEB/ARIF/index.aspx) – to 25 November 2016

-

PROSPERO (international prospective register of systematic reviews; via the internet: www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/) – to 25 November 2016.

Completed and ongoing trials were identified by searches of the following resources:

-

National Institutes of Health ClinicalTrials.gov (via the internet: www.clinicaltrials.gov/) – to 24 November 2016

-

European Union Clinical Trials Register (via the internet: www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu/ctr-search/search) – to 25 November 2016

-

World Health Organization’s International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (via the internet: www.who.int/ictrp/en/) – 24 November 2016.

The following key conference proceedings were identified in consultation with clinical experts and were screened for the last 3 years:

-

Radiological Society of North America

-

American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Conference

-

Society of Gynecologic Oncology

-

The National Cancer Research Institute

-

European Society of Radiology.

Full search strategies are presented in Appendix 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria for each of the clinical effectiveness questions are summarised in Table 3. Studies that fulfilled these criteria were eligible for inclusion in the review.

| Criteria | Question | |

|---|---|---|

| What are the performance characteristics of alternative risk scores (including alternative RMI 1 score thresholds), which include HE4 levels, CA125 levels or morphological features seen on ultrasound, compared with the RMI 1 score with a referral threshold of ≥ 250 (current practice1), for which the target condition is histologically confirmed ovarian cancer? | What are the effects of using alternative risk scores (including alternative RMI 1 score thresholds), which include HE4 levels, CA125 levels or morphological features seen on ultrasound, compared with the RMI 1 score with a referral threshold of ≥ 250 (current practice1), on clinical management decisions and clinical outcomes? | |

| Participants | Women of any age with suspected ovarian cancer, who have not previously been treated for ovarian cancer and are not currently receiving chemotherapy | |

| Setting | Secondary carea | |

| Interventions (index test) | Alternative methods of risk-scoring or RMI 1 used at thresholds other than 250, as described in Chapter 2, Intervention technologiesb | |

| Comparators | RMI 1 scorec | |

| Reference standard | Histological examination of surgically resected tissue sampled | NA |

| Outcomes | Diagnostic accuracy (the numbers of TP, FN, FP and TN test results), whereby the target condition is histologically confirmed ovarian cancer | Diagnosis of ovarian cancer confirmed by pathological examination of a biopsy, or prognostic outcomes for ovarian cancer (e.g. stage at diagnosis, differentiation status, suitability for surgical intervention/curative treatment, overall survival, progression-free survival) |

| Study designc | Diagnostic cohort studies directly comparing one or more interventions (index tests) with the comparatore | Prediction-modelling studies, randomised and non-RCTs |

Inclusion screening and data extraction

Two reviewers (MW and SL or SD) independently screened the titles and abstracts of all reports identified by searches, and any discrepancies were discussed and resolved by consensus. Full copies of all studies deemed potentially relevant were obtained, and the same reviewers independently assessed these for inclusion; any disagreements were resolved by consensus. Details of the studies excluded at the full-paper screening stage are presented in Appendix 2.

When studies reported insufficient information (e.g. tumour marker assay details not specified, incomplete accuracy data), the authors were contacted by e-mail to request additional information.

Studies cited in materials provided by the manufacturers of HE4 assays, the manufacturer of the Overa (MIA2G) multiple-marker test and the IOTA group were first checked against the project reference database in EndNote X6; any studies not already identified by our searches were screened for inclusion, following the aforementioned process.

Data were extracted on the following: study design/details; participant characteristics (age, pre- or post-menopause, presenting symptoms, tumour marker levels and other risk factors, when these were reported); details of the risk score and its component tests [manufacturer, antibody, detection method (including analyser used), ultrasound method and definition of a positive risk score]; details of the reference standard (details of the methods used, when these were reported, definition of disease positive and details of the final histopathological diagnoses of study participants, when these were reported); and test performance outcome measures. Data were extracted by one reviewer, using a piloted, standard data extraction form, and checked by a second reviewer (MW and SL or SD); any disagreements were resolved by consensus.

Quality assessment

The methodological quality of included test accuracy studies was assessed using the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies 2 (QUADAS-2) tool,36 and the methodological quality of prediction model studies was assessed using the PROBAST (Prediction model study Risk Of Bias Assessment Tool). 37 Quality assessment was undertaken by one reviewer and checked by a second reviewer (MW and SL or SD); any disagreements were resolved by consensus or discussion with a third reviewer.

The results of the quality assessments are summarised in tables and graphs in the results of the systematic review (see Study quality) and examples of full quality assessments (QUADAS-2 and PROBAST) are provided in Appendix 3; full quality assessments for all included studies can be obtained from the authors.

Methods of analysis/synthesis

Sensitivity and specificity were calculated for each set of 2 × 2 data. All meta-analyses estimated separate pooled estimates of sensitivity and specificity using random-effects logistic regression. 24 The bivariate/hierarchical summary receiver operating characteristic model38–40 could not be applied because the data sets were too small and/or homogeneous. Heterogeneity was assessed visually, using summary receiver operating characteristic plots or receiver operating characteristic space plots. Analyses were performed in MetaDisc (Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal, Madrid, Spain). 41

The differences between the sensitivity and specificity estimates for different risk scores were described as statistically significant when the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) did not overlap.

Studies were grouped by risk score, manufacturer of the tumour marker assays (when appropriate), definition of disease positive (target condition) and menopausal status. Stratified results tables and forest plots were used to illustrate the variation of test performance by threshold.

Results of the assessment of clinical effectiveness

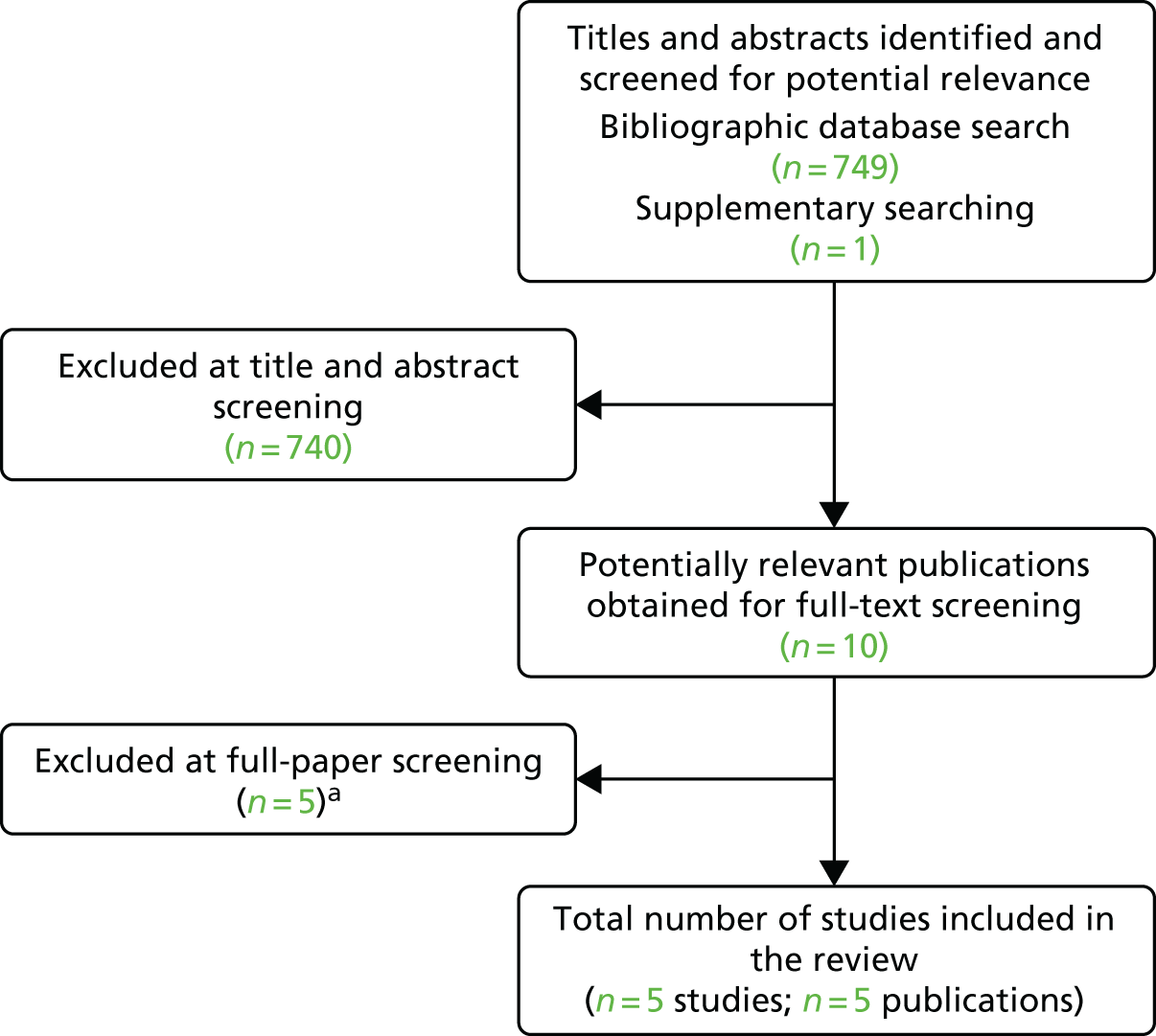

The searches of bibliographic databases identified 2456 records after deduplication. Following the initial screening of titles and abstracts, 241 publications were considered to be potentially relevant and ordered for full-paper screening; of these, 64 were included in the review. 17,42–103

In addition, one set of slides from a conference presentation was provided, through NICE, by the manufacturer of Overa (MIA2G),104 and an unpublished interim report of phase 5 of the IOTA study was provided (confidential information has been removed) personal communication: e-mail via Frances Nixon, Technical Advisor, NICE Diagnostic Assessment Programme to Marie Westwood, Project Lead, Kleijnen Systematic Reviews Ltd, 1 March 2017. All potentially relevant studies cited in other documents supplied by the test manufacturers had already been identified through other sources. Figure 1 shows the flow of studies through the review process, and Appendix 2 provides details, with reasons for exclusions, of all publications excluded at the full-paper screening stage. In total, there were 51 included studies, reported in 65 publications, and one unpublished interim report.

FIGURE 1.

Flow of studies through the review process. a, One study reported data for both the ROMA score using Roche Diagnostics’ Elecsys tumour marker assays and Overa (MIA2G); and b, two studies reported data for both the ADNEX model and IOTA group’s simple ultrasound rules.

A total of 165 publications were excluded after full-text screening. Six articles could not be obtained,105–110 and a further three ongoing studies, reported in four references, were identified as potentially relevant to future updates of this assessment. 111–114 Of particular note is Refining Ovarian Cancer Test accuracy Scores (ROCkeTS),112,113 a large prospective Phase III study, which was funded by NIHR and which is due to report in 2019/2020. The ROCkeTS study is evaluating the clinical utility, as well as the accuracy, of the RMI 1, ROMA scores, IOTA group’s simple ultrasound rules and other models and novel models not included in the scope of this assessment, and will consider the delivery of tests in the NHS (in which an imaging service is predominantly delivered by sonographers, rather than expert gynaecologists or radiologists). Trial registry entries for two additional diagnostic test accuracy studies were identified: one ongoing study is comparing the diagnostic performance or IOTA group’s simple ultrasound rules with that of ultrasound pattern recognition in women undergoing surgery for adnexal mass (the reference standard is the histopathological diagnosis) and the estimated completion date is September 2017;111 the second trial registry entry referred to a study assessing the diagnostic performance of a two-step triage process involving RMI 1 (threshold of 200) and IOTA group’s simple ultrasound rules, which has been terminated without publication. 114

The authors of 11 studies that were reported as conference abstracts with insufficient detail were contacted to determine whether or not the studies met our inclusion criteria, or when the outcomes were unclearly reported in the full paper;45,53,60,83,84,90,94,115–118 four authors provided additional information that allowed the study to be included in this review. 83,84,90,94

Overview of included studies

Details of the 51 included studies and their associated references are provided in Table 4. The following sections of this report cite studies using the primary publication and, when this is different, the publication (shown in bold in Table 5) in which the referenced data were reported.

| Details | Country | n | Main target condition reported |

|---|---|---|---|

| ROMA score | |||

| Abbott Diagnostics | |||

| ARCHITECT | |||

| Karlsen et al. (2012)83 | Denmark | 579 | All ovarian malignancies, excluding borderline |

| Al Musalhi et al. (2016)103 | Oman | 213 | All malignant tumours, including borderline |

| Chan et al. (2013)82 | Multinational (Asia) | 387 | All epithelial ovarian malignancies, including borderline |

| Clemente et al. (2015)90 | The Philippines | 62 | Ovarian malignancies (undefined – not clear whether or not borderline tumours were included) |

| Li et al. (2016)96 | China | 917 | Ovarian malignancies (undefined – not clear whether or not borderline tumours were included) |

| USA | 450 | All epithelial ovarian malignancies, including borderline | |

| Novotny et al. (2012)86 | Czech Republic | 277 | All malignant tumours, including borderline |

| Presl et al. (2012)81 | Czech Republic | 552 | Ovarian malignancies (undefined – not clear whether or not borderline tumours were included) |

| Winarto et al. (2014)99 | Indonesia | 128 | All epithelial ovarian malignancies, including borderline |

| Fujirebio Diagnostics | |||

| Langhe et al. (2013)94 | NR | 377 | All malignant tumours, including borderline |

| Belgium | 374 | All malignant tumours, including borderline | |

| Roche Diagnostics | |||

| Janas et al. (2015)97 | Poland | 259 | All malignant tumours, including borderline |

| Shulman et al. (2016)104 | USA | 993 | All malignant tumours, including borderline |

| Xu et al. (2016)95 | China | 521 | All epithelial ovarian malignancies, excluding borderline |

| Yanaranop et al. (2016)89 | Thailand | 260 | All malignant tumours – borderline tumours classified as disease negative |

| China | 612 | All epithelial ovarian malignancies | |

| Simple ultrasound rules (IOTA group) | |||

| Poland | 87 | All malignant tumours, including borderline | |

| Alcázar et al. (2013)52 | Spain | 340 | All malignant tumours, including borderline |

| Baker et al. (2013)66 | UK | 28 | All ovarian malignancies |

| Multinational (worldwide) | 2445 | All malignant tumours, including borderline | |

| Fathallah et al. (2011)63 | France | 109 | All malignant tumours, including borderline |

| IOTAa | Confidential information has been removed | Confidential information has been removed | Confidential information has been removed |

| Poland | 226 | All malignant tumours, including borderline | |

| Meys et al. (2016)44 | The Netherlands | 326 | All malignant tumours, including borderline |

| Murala et al. (2014)60 | UK | 51 | All malignant tumours (undefined – not clear whether or not borderline tumours were included) |

| Italy | 391 | All malignant tumours, including borderline | |

| Ruiz de Gauna et al. (2015)64 | Spain | 154 | All malignant tumours, including borderline |

| Sayasneh et al. (2013)62 | UK | 255 | All malignant tumours, including borderline |

| Silvestre et al. (2015)55 | Brazil | 75 | All malignant tumours, including borderline |

| Tantipalakorn et al. (2014)51 | Thailand | 319 (masses) | All malignant tumours, including borderline |

| Testa et al. (2014)50 | Multinational (Europe) | 2403 | All malignant tumours, including borderline |

| Multinational (worldwide) | 1938 | All malignant tumours, including borderline | |

|

Tinnangwattana et al. (2015)47 Tongsong et al. (2016)59 |

Thailand | 94 | All malignant tumours, including borderline |

| Weinberger et al. (2013)53 | NR | 347 | All ovarian malignancies, including borderline |

| ADNEX model | |||

| IOTAa | Confidential information has been removed | Confidential information has been removed | Confidential information has been removed |

| Joyeux et al. (2016)43 | France | 284 | Ovarian malignancies, including borderline |

| Meys et al. (2016)44 | The Netherlands | 326 | All malignant tumours, including borderline |

| Moffatt et al. (2016)45 | UK | 81 | Ovarian malignancies (undefined – not clear whether or not borderline tumours were included) |

| Sayasneh et al. (2016)46 | UK and Italy | 610 | All malignant tumours, including borderline |

| Szubert et al. (2016)42 | Poland and Spain | 327 | All ovarian malignancies, including borderline |

| Van Calster et al. (2014)17 | Multinational (Europe) | 2403 | All malignant tumours, including borderline |

| Overa (MIA2G) | |||

|

Coleman et al. (2016)70 Wolf et al. (2015)69 |

USA | 493 | All malignant tumours, including borderline |

| Shulman et al. (2016)104 | USA | 993 | All malignant tumours, including borderline |

| Zhang et al. (2015)68 | USA | 305 | All malignant tumours, including borderline |

| RMI 1 threshold variation | |||

| Aktürk et al. (2011)71 | Turkey | 100 | All ovarian malignancies, excluding borderline |

| Asif et al. (2004)77 | Pakistan | 100 | All malignant tumours (undefined – not clear whether or not borderline tumours were included) |

| Davies et al. (1993)79 | UK | 124 | All malignant tumours, including borderline |

| Jacobs et al. (1990)78 | UK | 139 | All malignant tumours, including borderline |

| Lou et al. (2010)73 | China | 223 | All malignant tumours, including borderline |

| Manjunath et al. (2001)75 | India | 148 | All malignant tumours, excluding borderline |

| Morgante et al. (1999)80 | Italy | 124 | All malignant tumours, including borderline |

| Tingulstad et al. (1996)76 | Norway | 173 | All malignant tumours, including borderline |

| Ulusoy et al. (2007)74 | Turkey | 296 | All malignant tumours, including borderline |

| Yamamoto et al. (2009)72 | Japan | 253 | All ovarian malignancies, including borderline |

All studies included in our systematic review were diagnostic cohort studies that reported data on the diagnostic accuracy of one or more ovarian cancer risk scores [the ROMA score, IOTA group’s simple ultrasound roles, the ADNEX model or Overa (MIA2G)], or that provided data on the accuracy of the RMI 1 at different decision thresholds (including 250, as specified in the current NICE guidelines1). Although 10 studies reported an age range that included women aged < 18 years,42,44,48,51,52,61,64,65,83,103 no study reported separate test performance data for this age group or indicated how many women were aged < 18 years. Sixteen studies reported data on the accuracy of the ROMA score,81–83,86,89,90,94–99,101–104 five of which reported data to support a direct comparison of the ROMA score to the RMI 1 score, using a decision threshold of 200. 83,89,98,99,103 There were no studies that reported comparative accuracy data for the ROMA score versus the RMI 1, using a decision threshold of 250. Seventeen published studies reported data on the accuracy of the IOTA group’s simple ultrasound rules,44,47–53,55,58,60–66 six of which reported data to support a direct comparison of the IOTA group’s simple ultrasound rules with the RMI 1 score, using a decision threshold of 200. 44,48,50,61,62,65 One study compared the IOTA group’s simple ultrasound rules with the RMI 1 score, using a decision threshold of 250, but this study was reported only as a conference abstract and the results were incomplete. 60 Six published studies reported data on the accuracy of the ADNEX model,17,42–46 one of which reported data to support a direct comparison of the ADNEX model with the RMI 1, using a decision threshold of 200. 44 The unpublished interim report (Frances Nixon, personal communication) provided data to support a direct comparison between the IOTA group’s simple ultrasound rules, the ADNEX model and the RMI 1 at both decision thresholds (200 and 250). Three studies reported data on the accuracy of Overa (MIA2G),68,70,104 one of which also provided comparative accuracy data for Overa (MIA2G) versus the ROMA score. 104 There were no studies comparing the accuracy of Overa (MIA2G) with the RMI 1, at any decision threshold. Finally, 10 studies provided data on the accuracy of the RMI 1 at different decision thresholds. 71–80

No randomised controlled trials (RCTs) or controlled clinical trials (CCTs) were identified; no studies provided data on patient-relevant outcomes following different risk assessment strategies.

Approximately half of the included published studies (25/51) were conducted in Europe,17,42–46,48–50,52,58,60,62–64,66,78–81,83,86,97,98,119 six of which were conducted solely in the UK45,60,62,66,78,79 and a further two were multinational studies that included a UK centre. 17,42 The unpublished interim analysis (Frances Nixon, personal communication) (confidential information has been removed). There were two multinational, worldwide studies, both of which included UK centres. 61,65 Four studies were conducted in the USA,68,70,101,104 13 were conducted in Asia,47,51,72,73,75,77,82,89,90,95,96,99,102 two were conducted in Turkey,71,74 one was conducted in Oman103 and one was conducted in Brazil. 55 Two studies, which were published only as conference abstracts, did not report information about geographic location. 53,94

Seventeen published studies,17,44,46,47,50,51,61,62,65,78,81,86,95–98,102 and the unpublished study for which an interim report was provided (confidential information has been removed) (Frances Nixon, personal communication), were publicly funded, and four studies reported receiving some funding from manufacturers (including a supply of test kits, reagents and analysers). 70,82,83,101 The remaining 29 included studies either did not report any information about funding42,43,45,48,49,52,53,55,58,60,63,64,66,68,71–77,79,80,89,90,94,99,104 or stated that they were unfunded. 103

All studies included women with an adnexal/ovarian mass; however, studies frequently reported analyses that excluded some women based on their final histopathological diagnosis (information that could not be known at the point of presentation); hence, only those studies that reported data for the target condition ‘all malignant tumours, including borderline’ could be considered to have evaluated risk scores in a population similar to those in whom these scores would be applied in practice. Full study details [inclusion and exclusion criteria, baseline characteristics of study participants and details of the risk score(s) (index test) evaluated are provided in Appendix 4 (Tables 34 and 35)].

Study quality

All studies included in this systematic review were diagnostic cohort studies. The methodological quality of these studies was assessed using the QUADAS-2 tool (summarised in Table 5 and Figure 2). One of these studies17 reported the development and validation of the ADNEX model, in addition to the test accuracy results. This study was assessed using PROBAST, a tool specifically developed to assess the methodological quality of prediction-modelling studies, (Table 6) as well as the QUADAS-2. Examples of full QUADAS-2 and PROBAST assessments are provided in Appendix 3, and full assessments for each included study are available on request.

| Study (year of publication) | Risk of bias | Applicability | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient selection | Index test | Reference standard | Flow and timing | Patient selection | Index test | Reference standard | |

| Abdalla et al. (2013)48 | ? | + | ? | + | – | – | – |

| Aktürk et al. (2011)71 | ? | + | ? | ? | + | + | + |

| Al Musalhi et al. (2016)103 | ? | + | ? | ? | + | + | – |

| Alcázar et al. (2013)52 | ? | + | ? | + | + | + | + |

| Asif et al. (2004)77 | + | ? | ? | ? | + | + | + |

| Baker et al. (2013)66 | – | ? | ? | – | + | – | ? |

| Chan et al. (2013)82 | + | + | + | – | + | + | + |

| Clemente et al. (2015)90 | ? | ? | + | + | ? | + | + |

| Coleman et al. (2016)70 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Davies et al. (1993)79 | + | + | – | – | + | + | ? |

| Di Legge et al. (2012)61 | + | + | ? | + | – | – | ? |

| Fathallah et al. (2011)63 | + | + | + | – | ? | + | + |

| IOTA5 (2017)a | Confidential information has been removed | Confidential information has been removed | Confidential information has been removed | Confidential information has been removed | Confidential information has been removed | Confidential information has been removed | Confidential information has been removed |

| Jacobs et al. (1990)78 | + | + | – | – | + | + | ? |

| Janas et al. (2015)97 | ? | + | ? | + | ? | + | + |

| Joyeux et al. (2016)43 | ? | ? | ? | + | + | + | + |

| Karlsen et al. (2012)83 | ? | + | ? | – | + | + | + |

| Knafel et al. (2016)49 | + | + | ? | + | ? | – | – |

| Langhe et al. (2013)94 | ? | + | ? | – | ? | – | ? |

| Li et al. (2016)96 | + | + | ? | ? | ? | + | ? |

| Lou et al. (2010)73 | ? | ? | + | ? | + | + | – |

| Manjunath et al. (2001)75 | + | + | + | – | + | + | + |

| Meys et al. (2016)44 | + | – | + | + | ? | – | + |

| Moffatt et al. (2016)45 | ? | ? | + | – | + | – | ? |

| Moore et al. (2011)101 | ? | + | ? | – | – | + | + |

| Morgante et al. (1999)80 | + | ? | ? | ? | + | + | ? |

| Murala et al. (2014)60 | + | – | ? | – | + | ? | ? |

| Novotny et al. (2012)86 | ? | + | ? | ? | + | + | ? |

| Piovano et al. (2016)58 | + | + | + | + | ? | + | – |

| Presl et al. (2012)81 | ? | ? | ? | ? | + | ? | ? |

| Ruiz de Gauna et al. (2015)64 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Sayasneh et al. (2013)62 | + | + | ? | + | – | + | – |

| Sayasneh et al. (2016)46 | + | ? | + | + | + | + | – |

| Shulman et al. (2016)104 | ? | ? | ? | ? | + | + | – |

| Silvestre et al. (2015)55 | + | + | + | + | + | + | – |

| Szubert et al. (2016)42 | ? | + | ? | + | + | – | – |

| Tantipalakorn et al. (2014)51 | ? | + | ? | – | + | + | – |

| Testa et al. (2014)50 | + | + | + | + | – | – | – |

| Timmerman et al. (2010)65 | + | + | + | – | – | – | – |

| Tingulstad et al. (1996)76 | – | + | ? | ? | + | + | – |

| Tinnangwattana et al. (2015)47 | + | + | + | + | + | + | – |

| Ulusoy et al. (2007)74 | + | + | ? | + | – | – | – |

| Van Calster et al. (2014)17 | + | + | + | ? | + | + | – |

| Van Gorp et al. (2012)98 | + | + | ? | – | ? | – | + |

| Weinberger and Minar (2013)53 | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | – | ? |

| Winarto et al. (2014)99 | ? | + | ? | + | ? | + | + |

| Xu et al. (2016)95 | – | + | ? | + | ? | + | + |

| Yamamoto et al. (2009)72 | ? | + | ? | + | + | + | + |

| Yanaranop et al. (2016)89 | ? | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Zhang et al. (2015)68 | ? | ? | ? | ? | + | + | ? |

| Zhang et al. (2015)102 | – | + | ? | – | ? | + | + |

FIGURE 2.

Summary of QUADAS-2 results for accuracy studies of risk scores.

| Study (year of publication) | Risk of bias | Applicability concerns | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant selection | Predictors | Outcome | Analysis | Overall judgement | Participant selection | Predictors | Outcome | Overall judgement | ||||||||

| Development | Validation | Development | Validation | Development | Validation | Development | Validation | Development | Validation | Development | Validation | Development | Validation | |||

| Van Calster et al. (2014)17 | + | + | + | + | ? | ? | ? | + | ? | – | – | + | + | + | + | + |

Eight studies were reported only as conference abstracts or meeting slides, with limited descriptions of the methods used,45,53,60,66,68,90,94,104 and study methods were generally poorly reported. Thirty-seven studies (73%) were rated as having an ‘unclear’ risk of bias on at least one QUADAS-2 domain, and 24 studies (47%) were rated as being ‘unclear’ for applicability on at least one domain.

Two studies64,70 were rated as having a ‘low’ risk of bias and ‘low’ concerns regarding applicability for all domains, and four further studies were rated low for all risk-of-bias domains. 47,50,55,58 In total, 11 studies (22%) were rated as having ‘low’ concerns regarding all applicability domains. 43,52,64,70–72,75,77,82,83,89

Nineteen studies (37%) were rated as having a ‘high’ risk of bias on at least one QUADAS-2 domain, whereas 26 studies (51%) were rated as ‘high’ for applicability on at least one domain.

The main potential sources of bias across the included published studies concerned flow and timing. Fifteen studies (30%) were rated as having a ‘high’ risk of bias on the flow and timing domain. For most of these studies (13/1545,47,51,60,63,65,66,78,82,94,98,101,102), this was because not all included patients were included in the analysis. In five studies51,75,78,79,83 the included patients did not all receive the same reference standard.

The main areas of concern regarding applicability were in relation to how the index test was applied and whether or not this could be considered to be representative of routine practice, and how the reference standard positive (target condition) was defined. Fourteen studies (28%) were rated as having ‘high’ concerns regarding the applicability of the index test; for six studies,48,50,61,65,94,98 this was because all or part of the index test was performed before referral; in three studies,45,53,66 the index test was applied retrospectively to existing patient data; and in seven studies,42,44,49,50,53,65,74 the index test was performed by practitioners whose level of experience was judged to be higher than that likely to be routinely available in secondary care settings. Eighteen studies (35%) were rated as having ‘high’ concerns regarding the applicability of the reference standard because malignancy was defined as ‘any malignant tumour’, which could include non-ovarian cancers and metastases, whereas the scope of this assessment defined the target condition as ovarian cancer. However, it should be noted that, in order for a study to report risk score performance data for the specific target condition of ovarian cancer, study participants found to have non-ovarian cancers and metastases would need to be excluded from the analysis. Studies that excluded patients with non-ovarian cancers and metastases were rated as having a ‘high’ risk of bias on the flow and timing domain, because post hoc exclusion of these patients may result in overestimation of test performance. Appendix 4, Table 36 lists the final histological diagnoses (where reported) of the study participants. These data illustrate the between-study variations in the definitions of disease positive used, which could include borderline, non-ovarian cancers, metastatic cancers and non-ovarian metastatic cancers. To take into account as much of this heterogeneity as possible, the results were analysed according to whether or not disease positive (target condition) was defined as ‘ovarian malignancy’ or ‘any malignant tumour’, and whether or not this definition included borderline tumours.

(Confidential information has been removed.)

Overall, more than half of the included studies were rated as having a high or unclear risk of bias for patient selection, the reference standard and flow and timing. More than half of the studies were rated as having a high level of, or unclear, concern for the applicability of the reference standard.

The PROBAST prediction score (see Table 6) for Van Calster et al. 17 indicated that there was a high risk of bias for the applicability of patient selection. The high risk of bias was attributable to the selection of women from a mixture of secondary and tertiary care centres, which is not a complete match for the scope of this assessment. However, the ADNEX model adjusts for study setting and, therefore, the overall concern regarding applicability is low. The overall risk of bias was judged to be unclear, as not all aspects of the model development were clearly described.

Clinical effectiveness of risk scores

No RCTs or CCTs were identified; no studies provided data on patient-relevant outcomes following different risk assessment strategies.

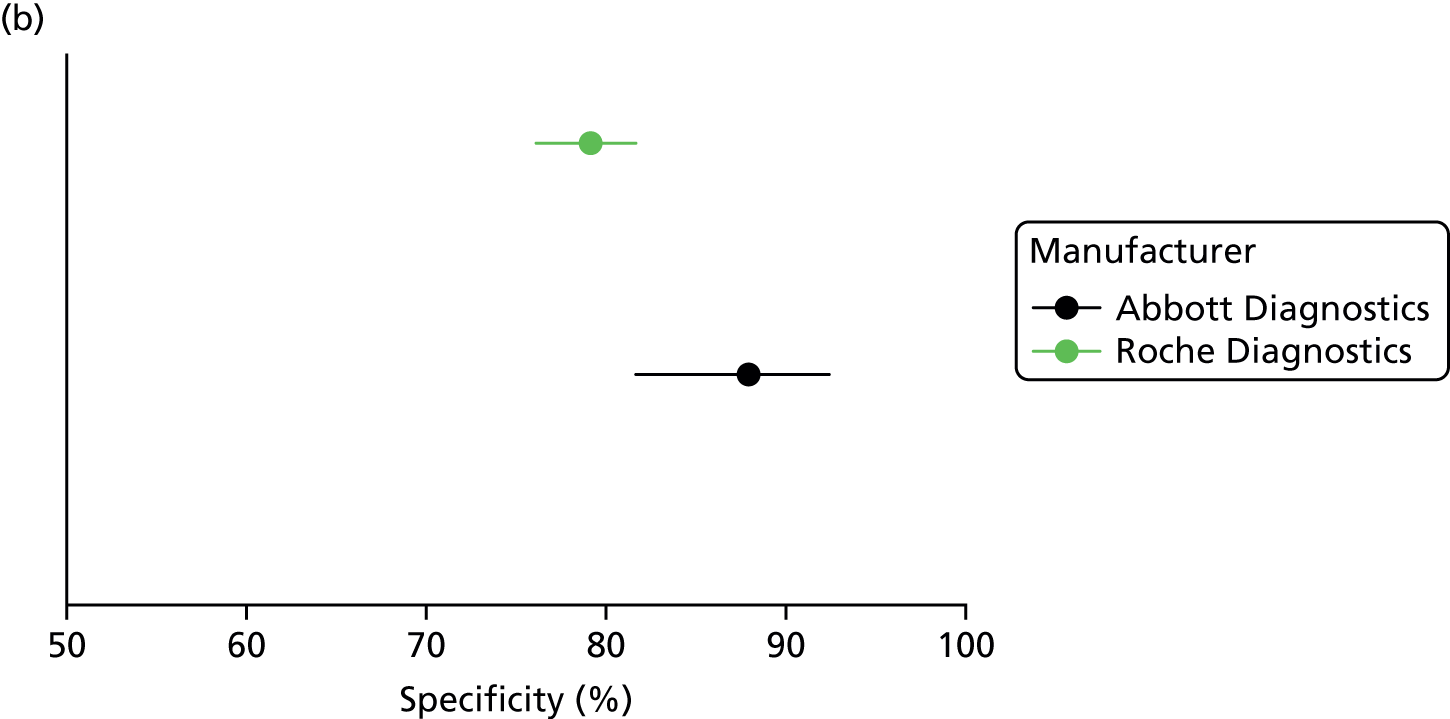

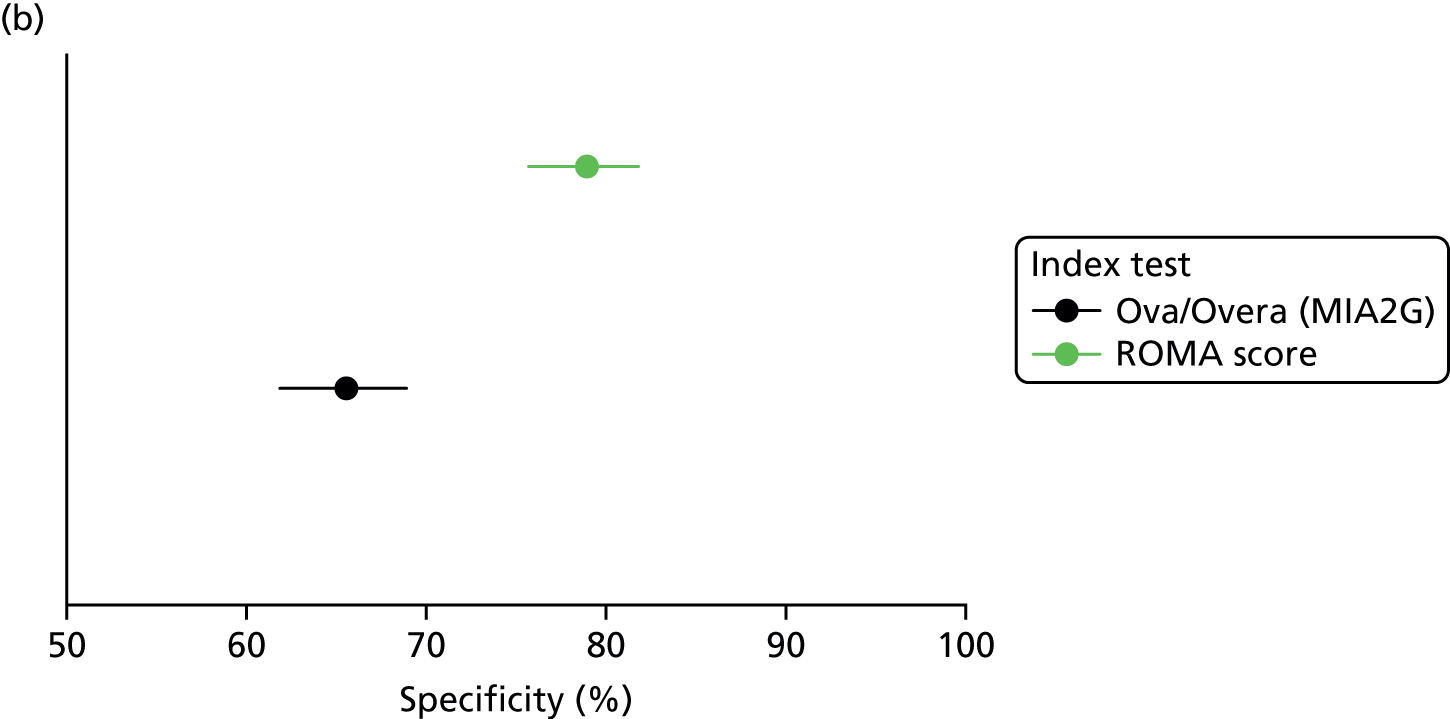

Diagnostic performance of the Risk of Ovarian Malignancy Algorithm score

Details of Risk of Ovarian Malignancy Algorithm studies

Sixteen diagnostic cohort studies,81–83,86,89,90,94–99,101–104 reported in 24 publications,56,81–83,85–104 provided data on the diagnostic performance of the ROMA score for identifying women who have an adnexal mass and are at a high risk of developing ovarian cancer. Nine studies81–83,86,90,96,99,101,103 used a ROMA score based on Abbott Diagnostics’ ARCHITECT tumour marker assays, of which six81,82,86,96,99,103 evaluated a decision threshold for the ROMA score that was consistent with the manufacturer’s recommendations. None of the included studies used the Fujirebio Diagnostics’ LUMIPULSE G automated CEIA system. For information, two studies94,98 that used a ROMA score based on manual Fujirebio Diagnostics’ tumour marker EIAs (see Appendix 5, Tables 41 and 42) were included, both using the manufacturer’s recommended decision threshold for the ROMA score; however, it should be noted that the manual assays are not specified interventions for this assessment. Finally, five studies89,95,97,102,104 used a ROMA score based on Roche Diagnostics’ Elecsys tumour marker assays, all of which used the manufacturer’s recommended decision threshold for the ROMA score.

None of the ROMA score studies that used Abbott Diagnostics’ ARCHITECT tumour marker assays was conducted in the UK; three studies81,83,86 were conducted in European countries, four82,90,96,99 were conducted in Asia, one101 was conducted in the USA and one103 was conducted in Oman. None of the ROMA score studies that used Roche Diagnostics’ Elecsys tumour marker assays was conducted in the UK, and only one97 was conducted in a European country. Three89,93,95 of the remaining studies were conducted in Asia and one104 was conducted in the USA.

This assessment is primarily concerned with providing a comparison between the RMI 1,78 used with a decision threshold of 250 (current standard practice in the NHS1), and the specified alternative risk-scoring methods (see Chapter 2, Intervention technologies). No studies were identified that reported a direct comparison (both tests used to assess the same patient cohort) between the ROMA score and the RMI 1, used with a decision threshold of 250. Five studies reported direct comparisons between the ROMA score and the RMI 1, used with a decision threshold of 200; three studies used Abbott Diagnostics’ ARCHITECT tumour marker assays;83,99,103 one study used Roche Diagnostics’ Elecsys assays;89 and one study used Fujirebio Diagnostics’ manual EIAs. 98 The following sections report all available data from direct comparison studies, as well as non-comparative data on the accuracy of the ROMA score, when decision thresholds that were consistent with the manufacturers’ recommendations were used. Additional accuracy data for alternative decision thresholds are reported in Appendix 5, Table 37.

The target condition for this assessment is ovarian cancer, including conditions covered by the NICE clinical guideline CG1221 (i.e. epithelial ovarian cancer, fallopian tube carcinoma, primary peritoneal carcinoma and borderline ovarian cancer). All studies in this section included women with one or more adnexal mass. The definition of reference standard positive ‘ovarian cancer’ varied between studies, with borderline tumours being most frequently classified as positive or excluded from analyses. In addition, some studies included patients with non-ovarian primary cancers/metastases to the ovary97,98,103 and germ cell tumours. 103 When the target condition was described as ‘all ovarian malignancy’, those women whose postoperative histological diagnosis was identified as non-ovarian primary were excluded from the estimates of test performance. Conversely, when the target condition was described as ‘all malignant tumours’, women with a non-ovarian primary were not excluded and were classified as being disease positive; this could potentially include women with any tumour on the ovaries that has metastasised from another primary [e.g. colorectal cancer (CRC)], and/or women with an adnexal/pelvic mass that turns out to be non-ovarian (not clearly specified by the included studies). Full details of the final histopathological diagnoses of study women who had a malignant mass are reported in Appendix 4, Table 36.

Accuracy of the Risk of Ovarian Malignancy Algorithm score using Abbott Diagnostics’ ARCHITECT tumour marker assays

Three83,99,103 of the nine81–83,86,90,96,99,101,103 ROMA score studies that used Abbott Diagnostics’ ARCHITECT tumour marker assays, reported a direct comparison of the ROMA score with the RMI 1. Only one study included all participants the analysis, regardless of their final histopathological diagnosis (target condition: all malignant tumours, including borderline) and this study used different thresholds from those recommended by the manufacturer (13.1% in premenopausal women and 27.7% in postmenopausal women, as opposed to the manufacturer’s recommendation of 7.4% and 25.3%). 103 One study was a retrospective study, which excluded women with histopathological diagnoses other than epithelial ovarian cancer. 99 A second study excluded from the analysis nine women (1%) with non-epithelial ovarian cancer, 69 women (6%) with non-ovarian cancers and 252 women (21%) with borderline tumours;83 the distribution of positive and negative ROMA score results in these women was not reported.

The sensitivity estimate for the ROMA score was highest (96.4%, 95% CI 93.6% to 98.2%) when the analyses excluded women with borderline tumours and those with malignancies other than epithelial ovarian cancer, and lowest (75.0%, 95% CI 60.4% to 86.4%) when all women were included in the analysis, regardless of their final histopathological diagnosis (Table 7). Conversely, the specificity estimate for the ROMA score was highest (87.9%, 95% CI 81.9% to 92.4%) in the study that included all participants,103 and lowest (53.3%, 95% CI 50.0% to 56.7%) when the analyses excluded women with borderline tumours and those with malignancies other than epithelial ovarian cancer (see Table 7). When women with borderline tumours and/or those with malignancies other than epithelial ovarian cancer were excluded from the analyses, the sensitivity estimates for the ROMA score were not significantly different from those for the RMI 1 (threshold 200), whereas the specificity estimates were significantly lower (see Table 7). In contrast, the study that included all participants in the analysis reported similar sensitivity and specificity estimates for the ROMA score and the RMI 1, with a sensitivity of 75% (95% CI 60.4% to 86.4%) versus 77.1% (95% CI 62.7% to 88.0%), and a specificity of 87.9% (95% CI 81.9% to 92.4%) versus 81.8% (95% CI 75.1% to 87.4%), respectively. 103 This study also reported lower sensitivity and higher specificity estimates, for both the ROMA score and the RMI 1, in premenopausal women than those in postmenopausal women (see Table 7).

| Study (year of publication) | Subgroup | ROMA threshold | TP, n | FN, n | FP, n | TN, n | Total, n | Sensitivity, % (95% CI) | Specificity, % (95% CI) | RMI 1 | TP, n | FN, n | FP, n | TN, n | Total, n | Sensitivity, % (95% CI) | Specificity, % (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target condition: all malignant tumours, including borderline | |||||||||||||||||

| Al Musalhi et al. (2016)103 | All women | 13.1%/27.7% | 36 | 12 | 20 | 145 | 213 | 75.0 (60.4 to 86.4) | 87.9 (81.9 to 92.4) | 200 | 37 | 11 | 30 | 135 | 213 | 77.1 (62.7 to 88.0) | 81.8 (75.1 to 87.4) |

| Premenopausal women | 13.1% | 11 | 10 | 14 | 127 | 162 | 52.4 (29.8 to 74.3) | 90.1 (83.9 to 94.5) | 200 | 12 | 9 | 21 | 120 | 162 | 57.1 (34.0 to 78.2) | 85.1 (78.1 to 90.5) | |

| Postmenopausal women | 27.7% | 25 | 2 | 5 | 19 | 51 | 92.6 (75.7 to 99.1) | 79.2 (57.8 to 92.9) | 200 | 22 | 2 | 9 | 18 | 51 | 91.7 (73.0 to 99.0) | 66.7 (46.0 to 83.5) | |

| Target condition: epithelial ovarian malignancies, including borderline | |||||||||||||||||

| Winarto et al. (2014)99 | All women | 7.4%/25.3% | 61 | 6 | 35 | 26 | 128 | 91.0 (81.5 to 96.6) | 42.6 (30.0 to 55.9) | 200 | 54 | 13 | 21 | 40 | 128 | 80.6 (69.1 to 89.2) | 65.6 (52.3 to 77.3) |

| Target condition: epithelial ovarian malignancies, excluding borderline | |||||||||||||||||

| Karlsen et al. (2012)83 | All women | 7.4%/25.3% | 244 | 8 | 371 | 438 | 1061 | 96.8 (93.8 to 98.6) | 54.1 (50.6 to 57.6) | 200 | 238 | 14 | 150 | 659 | 1061 | 94.4 (90.9 to 96.9) | 81.5 (78.6 to 84.1) |

| Winarto et al. (2014)99 | All women | 7.4%/25.3% | 47 | 3 | 35 | 26 | 111 | 94.0 (83.5 to 98.7) | 42.6 (30.0 to 55.9) | 200 | 44 | 6 | 21 | 40 | 111 | 88.0 (75.7 to 95.5) | 65.6 (52.3 to 77.3) |

| Summary estimates | 96.4 (93.6 to 98.2) | 53.3 (50.0 to 56.7) | 93.4 (90.0 to 95.9) | 80.3 (77.5 to 82.9) | |||||||||||||

| Karlsen et al. (2012)83 | Premenopausal women | 7% | 46 | 3 | 251 | 279 | 579 | 93.9 (83.1 to 98.7) | 52.6 (48.3 to 57.0) | 200 | 41 | 8 | 42 | 488 | 579 | 83.7 (70.3 to 92.7) | 92.1 (89.4 to 94.2) |

| Postmenopausal women | 25.3% | 198 | 5 | 120 | 159 | 482 | 97.5 (94.3 to 99.2) | 57.0 (51.0 to 62.9) | 200 | 196 | 7 | 108 | 171 | 482 | 96.6 (93.0 to 98.6) | 61.3 (55.3 to 67.0) | |