Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned and funded by the HTA programme on behalf of NICE as project number 15/69/19. The protocol was agreed in June 2016. The assessment report began editorial review in June 2017 and was accepted for publication in January 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

John Ramage reports research grants to King’s College Hospital from Novartis Pharmaceuticals UK Ltd (Frimley, UK) and Imaging Equipment Ltd (Radstock, UK) and a research grant to Hampshire Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust from Pfizer UK (Tadworth, UK), outside the submitted work.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Mujica-Mota et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Description of the health problem

‘Neuroendocrine tumours’ (NETs) is the overarching term for the group of heterogeneous cancers that develop in cells in the diffuse neuroendocrine system. The diffuse neuroendocrine system is made up of neuroendocrine cells found in the respiratory and digestive tracts. As these cancers share common clinical features, they are considered under the same group of neoplasms. 1 Most commonly, NETs are found in the lungs, pancreas or gastrointestinal (GI) system. NETs also encompass carcinoids and may be referred to as neuroendocrine carcinoids, which leads to substantial confusion over their name. 2

Aetiology, pathology and prognosis

The aetiology of NETs is poorly understood. 1 Predominantly, NETs are sporadic in nature (i.e. they arise from de novo changes); however, there is a small genetic risk associated with familial endocrine cancer syndromes. Neuroendocrine cells are present throughout the gut and are the largest group of hormone-producing cells in the body. 2 NETs develop slowly and may remain undetected over a number of years. Therefore, it is common for NETs to be diagnosed when they have already metastasised (i.e. spread to other organs or tissues in the body).

Characteristics of neuroendocrine tumours

The characteristics of a NET will determine the methods of treatment and the impact on prognosis. Important characteristics include the tumour location, tumour grade and differentiation, tumour stage and secretory profile of the tumour. There are, however, inconsistencies in the reproducibility of diagnoses between pathologists and institutions, which has been suggested to be caused by the use of a variety of different classification systems and a lack of adherence to them. 2

Location

Most NETs have been generally classified as foregut (including those in the lungs), midgut or hindgut, as it was thought that they were derived from embryonic neural crest cells. However, this theory is not now accepted and classification should be based on the site of origin of the tumour, that is, pancreas, lung, stomach, small bowel or large bowel (colon). The term ‘carcinoid’ is outdated but colloquially refers to NETs of the small bowel that secrete 5-hydroxytryptamine; the term ‘carcinoid’ is also still in common usage for NETs of the lung. ‘NET’ is the preferred term for all of these tumours. NET tumours may be grouped together as gastroenteropancreatic (GEP) NETs. Typically, the locations of these tumours are as follows:1

-

foregut tumours: develop in the bronchi, stomach, gallbladder, duodenum and pancreas

-

midgut tumours: develop in the jejunum, ileum, appendix and right colon

-

hindgut tumours: develop in the left colon and rectum.

Prognosis can be dependent on where a tumour is located. An analysis of 13,715 carcinoid tumours over a 5-decade period in the USA found that the best 5-year survival rates were found in patients with rectal (88.3%), bronchopulmonary (73.5%) and appendicle (71.0%) NETs. 3 The lowest 5-year survival rates were found in patients with pancreatic NETs (pNETs) (37.5%). 3

Neuroendocrine tumours from the pancreas may also be called endocrine tumours of the pancreas and include insulinomas (which produce the hormone insulin), gastrinomas (which produce the hormone gastrin), glucagonomas (which produce the hormone glucagon), VIPomas (which produce the hormone vasoactive intestinal peptide) and somatostatinomas (which produce the hormone somatostatin). However, the majority of pNETs are non-functioning and do not produce measurable levels of hormones that give symptoms.

Other, rarer locations for NETs include the thyroid gland (medullary thyroid tumours), skin (Merkel cell cancer), pituitary gland, parathyroid gland and adrenal gland.

This assessment report focuses on the tumours of the pancreas, GI tract and lung as these are locations for which the interventions of interest are licensed.

Tumour grade/degree of differentiation

A NET can be defined as grade 1, 2 or 3. The grade relates to an estimation of how fast the cells are dividing to form new cells and is based on the histological assessment and the mitotic count of the tumour. The grade of a tumour is also related to its differentiation. Differentiation relates to how well/little the tumour looks like the normal tissue/tissue of origin. Well-differentiated and low-grade cancer cells look more like normal cells and tend to grow and spread more slowly than poorly differentiated cells. High-grade tumours have cells that look very abnormal and are likely to grow and spread rapidly.

In 2010, the World Health Organization (WHO) introduced a new system for grading cancer tumours. 4 This grading system is also endorsed by the European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society (ENETS) grading schemes. 5,6 The grading scheme is as follows:

-

NET grade 1 (low grade)

-

well-differentiated tumour with a low number of cells actively dividing

-

Ki-67 index of ≤ 2%

-

mitotic count of < 2 per 10 high-power field (HPF)

-

-

NET grade 2 (intermediate grade)

-

well-differentiated tumour, but with a higher number of cells actively dividing

-

Ki-67 index of 3–20%

-

mitotic count of 2–20 per 10 HPF

-

-

neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC) grade 3 (high grade)

-

poorly differentiated, malignant carcinoma (most aggressive form of NET)

-

Ki-67 index of > 20%

-

mitotic count of > 20 per 10 HPF.

-

Stage of tumour (see Appendix 20)

Determination of the size of a tumour and whether or not it has spread beyond its original site is known as staging of the tumour. Tumour staging is performed according to a system of site-specific criteria. There are two main systems for staging NETs: the Union for International Cancer Control’s (UICC’s) TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours, Seventh Edition7 (see Appendix 19, Table 133) and the ENETS staging system5,6 (see Appendix 20, Table 134). The Royal College of Pathologists8 recommended both the WHO and the ENETS systems for assessing the grade/stage of a NET. In current practice, both systems are used together with the UICC grading system above. The difference between the UICC grading system and the ENETS grading systems is not great and would not affect outcomes relating to this report.

Secretory profile

A tumour that is releasing above-typical levels of hormones is known as a functioning tumour. The increase in hormone release will often cause symptoms that may themselves need treating in addition to treating the cancer. For example, hormones released by a pNET include insulin, glucagon and pancreatic polypeptide, whereas hormones released by an appendix NET include serotonin and somatostatin. Tumours that are not releasing hormones, and, therefore, that have no hormone-related clinical features, are known as non-functioning tumours.

Epidemiology

Incidence and prevalence

In October 2016, Public Health England (PHE)9 published the first data briefing on the incidence and survival in NETs and NECs in England. In 2013 and 2014, 8726 neoplasms were diagnosed, equating to 4000 per year or an approximate rate of 8 per 100,000 people per year (not age standardised). Although the annual incidence of NETs is low, because of the long survival of individuals with NETs, the prevalence is much greater and has been calculated as 35 per 100,000 people. 10

Incidence trends for NETs were compared between a Norwegian registry and an American registry. 11 From the time period 1993–7 to 2000–4, there was an incidence rate increase of 72% for NETs in Norway (from 2.35 to 4.06 per 100,000 people). Over the same time period in America, the increase was 37% (from 4.22 to 5.79 per 100,000 people) for the white population and 40% (from 5.48 to 7.67 per 100,000 people) for the black population. In a Canadian population, between 1994 and 2009, the incidence rates for NETs at all locations increased by 138% (from 2.46 to 5.86 per 100,000 people). 12

More specifically, for the subgroup of GI NETs, Ellis et al. 13 reviewed incidence rates in the UK between 1971 and 2006. In this time period, 10,324 cases of GI NETs were identified from the national population-based cancer registry. They report an overall increase per 100,000 people from 0.27 in men and 0.35 in women (1971–8) to 1.32 in men and 1.33 in women (2000–6). This is equivalent to an increase in incidence rates for GI NETs from 1971 to 2006 of 392% for men and 282% for women. 13

However, these incidence rates for the diagnosis of NETs do not account for the overall prevalence of NETs. As the delay in diagnosis is typically 5–7 years after the appearance of the first symptoms, many cases of NETs are undiagnosed. 1

Public Health England9 produced a diagram depicting the morphology (form of the neuroendocrine neoplasms) and topography (location of the neuroendocrine neoplasms) of 8726 individuals diagnosed with NETs and NECs in 2013 and 2014. Low-grade (grade 1) NETs and not-otherwise-specified NECs make up the predominant morphology of neuroendocrine neoplasms in England. PHE went on to describe some characteristics of the cohort:

-

almost an exact 50 : 50 male-to-female ratio

-

no obvious variation with geographical region

-

no obvious variation by ethnicity

-

distribution of age similar to that of other malignant cancers combined

-

higher incidence of patients from the most affluent population quintile (20.2%) than from the most deprived population quintile (18.6%; p = 0.011).

Risk factors

As NETs are sporadic in nature; there are very few factors known to determine susceptibility to developing a NET.

In the USA, African American males have a higher overall incidence rate of NETs than other demographic groups. 3 Following an epidemiological review of NETs in Japan, the authors compared the distribution of the origin of NETs between European and US populations and Asian populations. 14 In the former countries, a midgut origin represented 30–60% of new NETs, whereas in Asian populations the midgut was the origin of < 10% of new NETs. In a parallel way, the hindgut was the origin of a higher proportion of new NETs in Asian populations. 14 A case–control study of risk factors for NETs of the small intestine, stomach, lung, pancreas and rectum in 740 individuals with NETs and 924 healthy control subjects in the USA indicated an increased risk for women with a family history of cancer and diabetes mellitus. 15 In contrast, in the UK, PHE9 found no association of ethnicity and sex with NET prevalence.

There are some suggestions that individuals suffering from rare family syndromes may have a higher risk of developing NETs. These family syndromes include multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1), neurofibromatosis type 1 and von Hippel–Lindau (VHL) syndrome.

Survival

Although prognosis is generally better with an early diagnosis, the majority of NETs are diagnosed at a later stage when the tumour has already metastasised.

In data collected between 1986 and 1999 for 4104 cases of malignant digestive endocrine tumours in England and Wales, overall 5-year and 10-year survival was reported to be 45.9% and 38.4% respectively. 16 Well-differentiated tumours had a higher 5-year survival rate (56.8%), whereas small-cell tumours had the lowest 5-year survival rate (5.2%). Survival rates were higher for women and young people (15–54 years vs. 55–74 years and 75–99 years) and the overall prognosis was dependent on the features (e.g. tumour differentiation, anatomical site, histological type) of the NET. 16

Although it is impossible to compare accurately different countries with the data available, median 5-year survival varied from 38% to 61% across Europe,17 Taiwan18 and Canada. 12 Whether or not survival has improved over time remains debated. Korse et al. 19 reported in the Netherlands an ongoing improvement in survival for well-differentiated NETs and suggested that the introduction of somatostatin analogues (SSAs) and their long-acting forms may explain this change in survival over time. However, other research groups in the USA and France have not confirmed this trend. 20,21

Impact of the health problem

Significance for patients in terms of ill health (burden of disease)

Although prognosis is better with an early diagnosis, NETs are generally diagnosed at a late stage when the tumour has already metastasised. In such cases, treatment is rarely curative, although individuals can live and maintain a good quality of life for a number of years (e.g. 68–77% of people diagnosed with a carcinoid tumour will survive for ≥ 5 years22). The primary management strategy for NETs is managing symptoms originating from the tumour. The onset of symptoms, however, may take between 3 and 5 years from the development of the tumour. Symptoms can vary widely and some patients may have no symptoms or non-specific and vague symptoms (often leading to a delay in diagnosis).

Most individuals with NETs will experience non-specific symptoms such as pain, nausea and vomiting and, in some cases, anaemia, because of intestinal blood loss. Most GEP NETs are non-functioning and present predominantly with mass effects of the primary tumour or metastases (usually liver). 1 Symptoms are more common with functioning pNETs, in which hormones are significantly elevated.

In total, 20% of well-differentiated endocrine tumours of the jejunum or ileum (midgut NETs) will have carcinoid syndrome. Carcinoid syndrome consists of (usually) dry flushing (without sweating; 70% of cases) with or without palpitations, diarrhoea (50% of cases) and intermittent abdominal pain (40% of cases). 1 The metastases in the liver release vasoactive compounds, including biogenic amines (e.g. serotonin and tachykinins), into the systemic circulation, which cause the carcinoid syndrome. Direct retroperitoneal involvement with venous drainage bypassing the liver may also cause carcinoid syndrome (i.e. it is not dependent on liver metastases). 1

Carcinoid crisis may also occur in individuals with NETs. Symptoms include profound flushing, bronchospasm, tachycardia and widely and rapidly fluctuating blood pressure. It is usually linked to an anaesthetic induction for an operation or other invasive therapeutic procedure and is thought to be linked to the release of mediators leading to high levels of serotonin and other vasoactive peptides. 1

Measurement of disease

A number of outcomes can be measured in clinical trials or as part of the management of disease:

-

Overall survival (OS), defined as the time from randomisation to death from any cause.

-

Progression-free survival (PFS), defined as the time from randomisation until disease progression or death.

-

Objective response rate (ORR), defined as either a partial response or a complete response:

-

Complete response – all detectable tumour has disappeared.

-

Partial response – roughly corresponds to a ≥ 50% decrease in the total tumour volume but with evidence of some residual disease still remaining.

-

Stable disease – includes either a small amount of growth (typically < 20% or < 25%) or a small amount of shrinkage.

-

Progressive disease – means that the tumour has grown significantly or that new tumours have appeared. The appearance of new tumours is always defined as progressive disease regardless of the response of other tumours. Progressive disease normally means that the treatment has failed.

-

-

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL): how a person’s well-being is affected by treatment. HRQoL is a key measure for the treatment of NETs as this captures changes in symptom control. It is the control of the symptoms that has the most impact on a patient’s day-to-day life.

Current service provision

Management of disease

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of NETs can be difficult as they are often small tumours (some may be < 1 cm in size), they can occur almost anywhere in the body and they can result in a vast array of symptoms or no symptoms at all. NETs are slow-growing tumours and may be present for many years without recognisable symptoms. Therefore, diagnosis often occurs at quite a late stage in the disease.

Typical symptoms in the early stages include vague abdominal pain and potential changes in bowel habits, which primarily are diagnosed as irritable bowel syndrome. 23 More progressive symptoms include shortness of breath, loss of appetite and weight loss. 24 Diagnosis primarily occurs following detailed histology. Other tests may include urine tests, blood tests, ultrasound scans, computed tomography (CT) scans, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans, radioactive scans and positron emission tomography (PET)/CT scans. Diagnosis is also dependent on the clinical manifestations, peptide and amine secretions and specialised radiological and nuclear imaging of the NETs. 1 Being able to determine the secretory products of a NET is helpful for diagnosis, to assess the efficacy of subsequent treatment and to assess changes in prognosis. 1 Similarly, imaging is used not only for detecting the primary tumour, but also for screening at-risk populations, assessing the extent of the disease and assessing the response to treatment at follow-up. 1

Treatment

The aim of treatment, when realistically possible, should always be curative. However, in the majority of cases it is most likely to be palliative (i.e. aimed at symptom control). As metastatic disease is common for individuals with NETs, often improving quality of life is the primary aim of treatment (as opposed to curing the disease). 1 Individuals with NETs can maintain a good quality of life for a long period of time. 1 Quality of life is therefore assessed regularly throughout treatment.

There is a vast array of treatment options for treating NETs. The initial treatment often starts with surgery and symptom management. Surgery is the only curative treatment for NETs. Symptom treatment, particularly with hormonal hypersecretion in functional NETs, can have a significant impact on an individual’s quality of life as the symptoms themselves, as opposed to the cancer, may be life-threatening (e.g. severe diarrhoea and hypokalaemia). 1 Symptom control is often manged with a SSA, for example octreotide (Sandostatin®; Novartis International AG, Basel, Switzerland) or lanreotide (Somatuline Autogel®; Ipsen, Paris, France). Available treatments that follow surgery and initial symptom control include:

-

liver transplant

-

interferon alpha (Roferon-A, Roche Products Ltd)

-

chemotherapy

-

ablation therapies

-

targeted radionuclide therapy, including one of the interventions of interest in this assessment report: lutetium-177 DOTATATE [(177Lu-DOTATATE) Lutathera®; Imaging Equipment Ltd, Radstock, UK]

-

transhepatic artery embolisation/chemoembolisation

-

external-beam radiotherapy

-

emerging therapies, including two of the interventions of interest in this assessment report: everolimus (Afinitor®; Novartis) and sunitinib (Sutent®; Pfizer Inc., New York, NY, USA).

Describing an overarching treatment pathway for NETs is challenging as there are many different options depending on the characteristics of the NET (e.g. location, grade, differentiation, secretory profile).

Current service cost

The economic burden to the NHS of health-care provision for people with NETs is not well documented. This may be partly because of the rarity and heterogeneity of the disease, but also because significant new therapeutic options have only recently been introduced.

Public Health England9 has reported that approximately 4000 new cases of neuroendocrine neoplasms are diagnosed each year. From a budgetary perspective this is a small subgroup of the 300,000 new cancer diagnoses registered annually in England,25 but with the arrival of new high-cost targeted therapeutic treatments, the cost-effectiveness of disease management is now a relevant area for scrutiny through secondary research.

The main costs involved in current service provision for people with inoperable progressive NETs can be divided into the cost of diagnosis and monitoring of disease (e.g. measurement of blood markers and CT, MRI and PET), the cost of acquiring and administering active and supportive treatments (in particular long-acting repeat SSA therapy but also chemotherapy), the cost of managing symptoms (if the tumour is functioning), the cost of managing adverse events (AEs) and the cost of human resources for patient consultation, multidisciplinary team meetings and hospitalised care.

Relevant national guidelines, including National Service Frameworks

Guidelines for the management of GEP NETs (including carcinoid tumours) were published in 2012 by a group of authors who are members of the UK and Ireland Neuroendocrine Tumour Society (UKINETS). 1

There is a related guideline from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) from 2010 that focuses on tumours of unknown origin26 that fall under the NETs umbrella. This guideline is distinct from the work in this report, which focuses on pancreatic, lung and GI NETs.

Description of the technology under assessment

Summary of interventions

The scope of this review is to ascertain the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of three interventions for unresectable or metastatic NETs with disease progression. These interventions are everolimus, 177Lu-DOTATATE and sunitinib.

Everolimus27

Everolimus is an orally active agent that is able to slow down the growth and spread of a tumour. It acts by binding to FK506-binding protein-12 (FKBP-12) to form a complex, which is able to block the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) protein. Division of tumour cells and growth of blood vessels require mTOR and it is through the blocking of mTOR that everolimus is able to slow down the growth and spread of the tumour.

Everolimus has a marketing authorisation for tumours of pancreatic origin:

Afinitor is indicated for the treatment of unresectable or metastatic, well- or moderately-differentiated neuroendocrine tumours of pancreatic origin in adults with progressive disease.

It also has a marketing authorisation for NETs of GI or lung origin:

Afinitor is indicated for the treatment of unresectable or metastatic, well-differentiated (Grade 1 or Grade 2) non-functional neuroendocrine tumours.

Everolimus is an oral drug that is typically given at a dose of 10 mg a day. It is recommended that treatment is continued for as long as benefits are observed or an unacceptable level of side effects occur. The dose of everolimus may be reduced or stopped in an effort to minimise side effects. Tablets should be taken every day at the same time of day.

The most common side effects of everolimus (affecting > 1 in 10 people) are rash, pruritus (itching), nausea, decreased appetite, dysgeusia (taste disturbances), headache, decreased weight, peripheral oedema (swelling, especially of the ankles and feet), cough, anaemia (low red blood cell count), fatigue (tiredness), diarrhoea, asthenia (weakness), infections, stomatitis (inflammation of the lining of the mouth), hyperglycaemia (high blood glucose level), hypercholesterolaemia (high blood cholesterol level), pneumonitis (inflammation of the lungs) and epistaxis (nosebleeds). Everolimus is not suitable for people who are hypersensitive to rapamycin derivatives.

Everolimus was removed from the Cancer Drugs Fund (CDF) on 12 March 2015; it was previously available for the treatment of progressive unresectable or metastatic well-differentiated NETs of the pancreas.

177Lu-DOTATATE28

Lutetium-177 DOTATATE is a radiolabelled SSA. It is made up of a radionuclide (177Lu) and the peptide–chelator complex [DOTA0, Tyr3-]-octreotate (DOTATATE). The (Tyr3)-octreotate binds to malignant cells that overexpress somatostatin receptors [specifically the somatostain receptor type 2 (SSTR2)]. Once bound, the 177Lu-DOTATATE accumulates within the tumour cells, delivering cytotoxic radiation that kills them.

As of December 2016, 177Lu-DOTATATE does not have marketing authorisation in the UK for any indication.

Administration of 177Lu-DOTATATE is through an intravenous infusion and involves 3 days of hospital appointments, including an overnight stay. Typically, four cycles are administered over a total of 8 to 10 months.

There are two main types of side effects from 177Lu-DOTATATE: those relating to the therapy and those relating to the radiation dose given. Side effects related to the therapy include nausea, pain, flushing, sweating, palpitations, wheezing, diarrhoea, hair loss and fatigue. Side effects relating to the radiation dose include the effects on bone marrow production and kidney function, which in turn may increase the number of infections experienced by patients.

Lutetium-177 DOTATATE was removed from the CDF on 4 November 2015. It was previously available for the treatment of advanced NETs after sunitinib/chemotherapy, pNETs and midgut carcinoid tumours (after octreotide/somatostatin therapies).

Sunitinib29

Sunitinib is a protein kinase inhibitor that is able to reduce the growth and spread of cancer and cut off the blood supply that enables cancer cell growth. Sunitinib works by blocking enzymes known as protein kinases that are found in some receptors at the surface of cancer cells. The development of new blood vessels and the growth and spread of cancer cells requires protein kinases and it is through the blocking of these enzymes that sunitinib is able to slow the growth and spread of the tumours.

Sunitinib has a marketing authorisation for tumours of pancreatic origin:

SUTENT is indicated for the treatment of unresectable or metastatic, well-differentiated pNETs with disease progression in adults.

Sunitinib is an oral drug and is typically given at a dose of 37.5 mg a day. Treatment is recommended to be continued for as long as benefits are observed or an unacceptable level of side effects occurs. The dose of sunitinib may be reduced or stopped in an effort to minimise side effects.

The most common side effects of sunitinib are fatigue (tiredness), GI disorders (such as diarrhoea, feeling sick, inflammation of the lining of the mouth, indigestion and vomiting), respiratory disorders (such as shortness of breath and cough), skin disorders (such as skin discoloration, dryness of the skin and rash), hair colour changes, dysgeusia (taste disturbances), epistaxis (nosebleeds), loss of appetite, hypertension (high blood pressure), palmar–plantar erythrodysaesthesia syndrome (rash and numbness on the palms and soles), hypothyroidism (an underactive thyroid gland), insomnia (difficulty falling and staying asleep), dizziness, headache, arthralgia (joint pain), neutropenia (low levels of neutrophils, a type of white blood cell), thrombocytopenia (low blood platelet count), anaemia (low red blood cell count) and leukopenia (low white blood cell count).

Sunitinib is available on the CDF for the treatment of pNETs when all of the following criteria are met:

-

application made, and first cycle of systemic anticancer therapy to be prescribed, by a consultant specialist specifically trained and accredited in the use of systemic anticancer therapy

-

biopsy-proven well-differentiated pNET

-

first-line indication or second-line indication or third-line indication

-

no previous vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-targeted therapy.

Identification of important subgroups

From the NICE scope,30 the following subgroups were identified as being important in the treatment of NETs:

-

location of tumour

-

grade/degree of differentiation

-

stage of tumour

-

secretory profile

-

number of previous treatments.

Further information on these subgroups can be found in Characteristics of neuroendocrine tumours.

Current usage in the NHS

It was difficult to ascertain the current usage of everolimus, sunitinib and 177Lu-DOTATATE in the NHS. In its submission, Advanced Accelerator Applications (AAA) Ltd31 (Saint-Genis-Pouilly, France) reported that, although unlicensed, 177Lu-DOTATATE has been used to treat patients in England through the CDF (confidential information has been removed). Likewise, Pfizer32 report that sunitinib is also available through the CDF and is used in the NHS in England for the treatment of patients with pNET (52 requests were made in the 12 months ending March 2015). Novartis33 did not report in its submission the estimated use of everolimus within the NHS in England; however, our clinicians suggest that the rate of use of everolimus is higher than that of sunitinib.

Anticipated costs associated with the interventions

The cost of treating a patient with everolimus or sunitinib varies from one patient to the next because the duration of treatment with these oral preparations is continuous and largely dependent on effectiveness for the individual. The mean duration of treatment with everolimus in the RADIANT-3 (RAD001 in Advanced Neuroendocrine Tumors, Third Trial)34 and RADIANT-4 (RAD001 in Advanced Neuroendocrine Tumors, Fourth Trial)35 trials of NET patients is about 9 months, with a range of 1 week to 2 years. 34 In practice, it is disease stability and drug tolerability that trigger the decision to purchase the next month of therapy. Everolimus and sunitinib are normally self-administered and so the cost of drug delivery is limited to the time needed by hospital pharmacy staff to dispense the drugs. In contrast, the drug acquisition cost of 177Lu-DOTATATE is less variable between patients because its delivery is fixed to a maximum of four treatment cycles. In addition, in comparison to the oral preparations of everolimus and sunitinib, the delivery of 177Lu-DOTATATE is more resource intensive. 177Lu-DOTATATE is a radiolabelled intravenous preparation and so administration involves careful handling, specialist staff and post-administration observation, which for most patients means an overnight hospital stay. Beyond acquisition and administration, the remaining treatment-related costs arise from disease monitoring and the medical management of AEs, which will of course differ across treatments but which are less substantial components of the overall cost.

We expect that all of these cost components will vary between individuals and hence they were subject to modelling, but the acquisition costs of treatments are presented in Table 23 for simple comparative purposes. 36

Chapter 2 Changes to the project scope

During the course of this review, NICE consulted on amendments to the original project scope. The revised scope was agreed on 18 August 201630 and the differences between the original and the revised scope are provided in Table 1.

| Characteristic | Old scope | New scope |

|---|---|---|

| Intervention(s) |

|

|

| Population(s) |

People with progressed unresectable or metastatic NETs According to the specific locations covered by the marketing authorisations of the interventions |

People with progressed unresectable or metastatic NETs According to the specific locations covered by existing and anticipated marketing authorisations of the interventions |

| Comparators |

|

|

| Outcomes | The outcome measures to be considered include:

|

The outcome measures to be considered include:

|

| Other considerations | If the evidence allows the following subgroups will be considered:

|

If the evidence allows the following subgroups will be considered:

|

| Economic analysis |

The reference case stipulates that the cost-effectiveness of treatments should be expressed in terms of incremental cost per quality-adjusted life-year The reference case stipulates that the time horizon for estimating clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness should be sufficiently long to reflect any differences in costs or outcomes between the technologies being compared Costs will be considered from a NHS and Personal Social Services perspective The use of 177Lu-DOTATATE is conditional on the presence of somatostatin receptor-positive GEP NETs. The economic modelling should include the costs associated with diagnostic testing for somatostatin receptor-positive GEP NETs in people who would not otherwise have been tested. A sensitivity analysis should be provided without the cost of the diagnostic test. See section 5.9 of the Guide to the Methods of Technology Appraisals37 |

The reference case stipulates that the cost-effectiveness of treatments should be expressed in terms of incremental cost per quality-adjusted life-year The reference case stipulates that the time horizon for estimating clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness should be sufficiently long to reflect any differences in costs or outcomes between the technologies being compared Costs will be considered from a NHS and Personal Social Services perspective |

What is the impact of the changes in scope?

-

The population and outcomes under review were unchanged from the original scope.

-

The following intervention was removed: lanreotide (NETs of mid-gut, pancreatic or unknown origin).

-

The following comparator was removed: octreotide (long-acting release formulation).

Chapter 3 Definition of the decision problem

Decision problem

Population

The population specified in the final scope issued by NICE30 is people with progressed unresectable or metastatic NETs. In addition, the population must be in accordance with the specific locations covered by the existing and anticipated marketing authorisations of the interventions.

Subgroups of interest based on the NICE scope include:

-

location of the tumour

-

grade/degree of differentiation of the tumour

-

stage of the tumour

-

secretory profile of the tumour

-

number of previous treatments.

Interventions

-

Everolimus – for NETs of GI, pancreatic or lung origin.

-

Lutetium-177 DOTATATE – for NETs of GI or pancreatic origin.

-

Sunitinib – for NETs of pancreatic origin.

Comparators

Interventions should be compared with each other and with:

-

interferon alpha

-

chemotherapy regimes (including but not restricted to combinations of streptozocin, fluorouracil (5-FU), doxorubicin, temozolomide and capecitabine)

-

best supportive care (BSC).

The Assessment Group (AG) noted, following consultation with our clinicians, that interferon alpha was not commonly used within UK clinical practice.

Outcomes

The outcomes of interest based on the NICE scope include:

-

OS

-

PFS

-

response rates (RRs: including complete response, partial response, stable disease, progressive disease, tumour shrinkage and ORR)

-

symptom control

-

AEs

-

HRQoL.

Key issues

The primary factors that may influence the clinical effectiveness of treatment for individuals with NETs are predominantly covered within the population subgroups listed in Population.

In addition to the number of previous treatments, covered as a population subgroup, the use of concomitant treatment (primarily SSA use) while taking part in clinical trials may also be a key issue. This is because the administration of SSAs as a concomitant treatment is not uniform in the treatment of NETs.

Treatment switching from placebo to the active treatment is also another key issue for consideration in terms of how the switching may confound the outcomes reported for the placebo arm.

Overall aims and objectives of the assessment

The aim of this report was to review the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of everolimus, 177Lu-DOTATATE and sunitinib for treating unresectable or metastatic NETs with disease progression in a multiple technology appraisal (MTA). We carried out a systematic review of clinical effectiveness studies to assess the medical benefit and risks associated with these treatments, and compared the treatments against available alternative standard treatments. We also assessed whether or not these drugs are likely to be considered good value for money for the NHS using a model-based economic evaluation.

Note

This report contains reference to confidential information provided as part of the NICE appraisal process. This information has been removed from the report and the results, discussions and conclusions of the report do not include the confidential information. These sections are clearly marked in the report.

Chapter 4 Assessment of clinical effectiveness

Methods for reviewing effectiveness

Evidence for the clinical effectiveness of everolimus, 177Lu-DOTATATE and sunitinib within their marketing authorisations for treating unresectable or metastatic NETs with disease progression was obtained by conducting a systematic review of published and unpublished research evidence. This review was undertaken following the methodological guidance published by the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD). 38

Changes to the protocol

As discussed in Chapter 2, NICE issued a revised scope for this project on 18 August 2016. 30 The revised scope necessitated a change to our published protocol39 as lanreotide was removed as an intervention and octreotide was removed as a comparator. A revised protocol was drafted (PROSPERO CRD42016041303); there were no other changes to the published protocol.

Identification of studies

The literature search aimed to systematically identify studies relating to the clinical effectiveness of everolimus, 177Lu-DOTATATE and sunitinib in the treatment of unresectable or metastatic NETs with disease progression. The search strategy was developed in MEDLINE (Ovid) and then adapted for use in the other resources searched.

The bibliographic literature search was undertaken in May 2016 and the search was further updated in September 2016.

Searching of bibliographic databases and databases of ongoing trials

The following bibliographic databases were searched: MEDLINE (Ovid), MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations (Ovid), MEDLINE Daily (Ovid), MEDLINE Epub Ahead of Print (Ovid), EMBASE (Ovid), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library, Wiley Interface) and Web of Science (including Conference Proceedings Citation Index) (Thomson Reuters).

The search syntax took the following form: (search terms for neuroendocrine tumours) AND (search terms for the interventions under review). The searches were not limited by study design, language or date.

The following trial registries were handsearched: Current Controlled Trials, ClinicalTrials.gov, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) website and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) website40 [including European Public Assessment Reports (EPARs)].

The full search strategies are provided in Appendix 1.

Website searching

The following websites were searched:

-

ENETS [www.enets.org/ (accessed 19 May 2016)]

-

UKINETS [www.ukinets.org/ (accessed 19 May 2016)].

Deduplication

All references were exported into EndNote X7 (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA), where automatic and manual deduplication was performed.

Screening

Title and abstracts were independently double-screened by two reviewers. Studies meeting the inclusion criteria at the title and abstract stage were ordered as full texts, which were independently double-screened by three reviewers.

Citation searching, appraisal of company submissions and identification of systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials

All studies meeting the full-text inclusion criteria were citation chased. Forwards citation searching was conducted in Web of Science (Thomson Reuters) and backwards citation searching was conducted manually through the appraisal of the bibliographies of included studies. Citation searching is reported in Appendix 1.

Included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) from identified systematic reviews were checked against the table of included studies for this review. Studies included in the clinical effectiveness sections of company submissions were also checked against the table of studies included in this review.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for the selection of clinical effectiveness studies were defined exactly as per the decision problem (see Chapter 3). Studies identified prior to the publication of the revised scope30 were rechecked for inclusion against this revised scope.

The inclusion and exclusion criteria for the original and revised scope are summarised in Table 1. Studies were also required to be in the English language.

The systematic review of clinical effectiveness focused only on RCTs. When no RCTs were identified for an intervention of interest, a non-systematic review of non-randomised evidence was conducted (see Appendix 2). Non-randomised evidence included prospective observational cohort studies (both comparative and single-arm studies). Case reports were not included.

In addition to identifying RCTs, systematic reviews of RCTs, although not formally included in the systematic review, were used as potential sources of additional references providing efficacy evidence.

Studies published as abstracts or conference presentations were included if they linked to included full-text papers, in which appraisal of the methodology and an assessment of the results could be undertaken.

Data extraction and management

Studies included at the full-text stage were shared between three reviewers for the purposes of data extraction. A standardised data specification form was used and extracted data were double-checked by a second reviewer. When multiple publications of the same study were identified, data were extracted and reported as if a single study.

Information sourced for extraction and tabulation included the study design and methodology, the baseline characteristics of participants and the following outcomes; PFS, OS, RRs, AEs and HRQoL. Definitions of the outcomes are provided in Chapter 1 (see Measurement of disease).

When information on key data was incomplete, we attempted to contact the study author(s). In addition, the companies were approached through NICE and asked to provide missing data and supplementary individual patient data.

Assessment of risk of bias

The methodological quality of each included study was assessed by one reviewer and checked by a second reviewer, using criteria based on those proposed by the CRD for RCTs. 38 An additional question (question 10; see Table 4) was added to assess the applicability of the study to the NHS in England.

Methods of data analysis/synthesis

Data were tabulated and narratively synthesised. If sufficient evidence was available and study designs were homogeneous, meta-analysis would be performed. In addition, when the data allowed, an indirect treatment comparison (ITC) would be performed.

The study design and baseline characteristics for all included studies are presented, followed by the outcome results. Outcomes from the studies are reported by tumour location, first for pNETs and then for GI and lung NETs combined, as this was how the included studies were published. Additional data were subsequently made available so that GI NETs and lung NETs could be assessed as isolated tumour locations.

Indirect treatment comparisons

When data were available, the Bucher et al. 41 method was used for an ITC for the outcomes of PFS, OS, RR and AEs. This method was best suited for this assessment given that the available data were only in summary form and were limited to a handful of studies. More sophisticated methods were explored in the economic analysis described in Chapter 6 using individual patient data, which highlight the limitations of the Bucher et al. 41 method, but resource limitations prevented this evidence being incorporated in the clinical effectiveness review. Further details can be found in Indirect treatment comparison: pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours.

Results

The results of study identification in accordance with the updated NICE scope are discussed first in this section, followed by a description of the quality of the evidence and overview tables of the included trials. When available, outcomes (PFS, OS, RRs, HRQoL and AEs) are then reported by tumour location and by subgroup. The subgroups considered were based on the NICE scope (see ‘Other considerations’ in Table 1).

When non-randomised evidence was sought, details are presented after the RCT evidence. These data are tabulated and narratively discussed in brief.

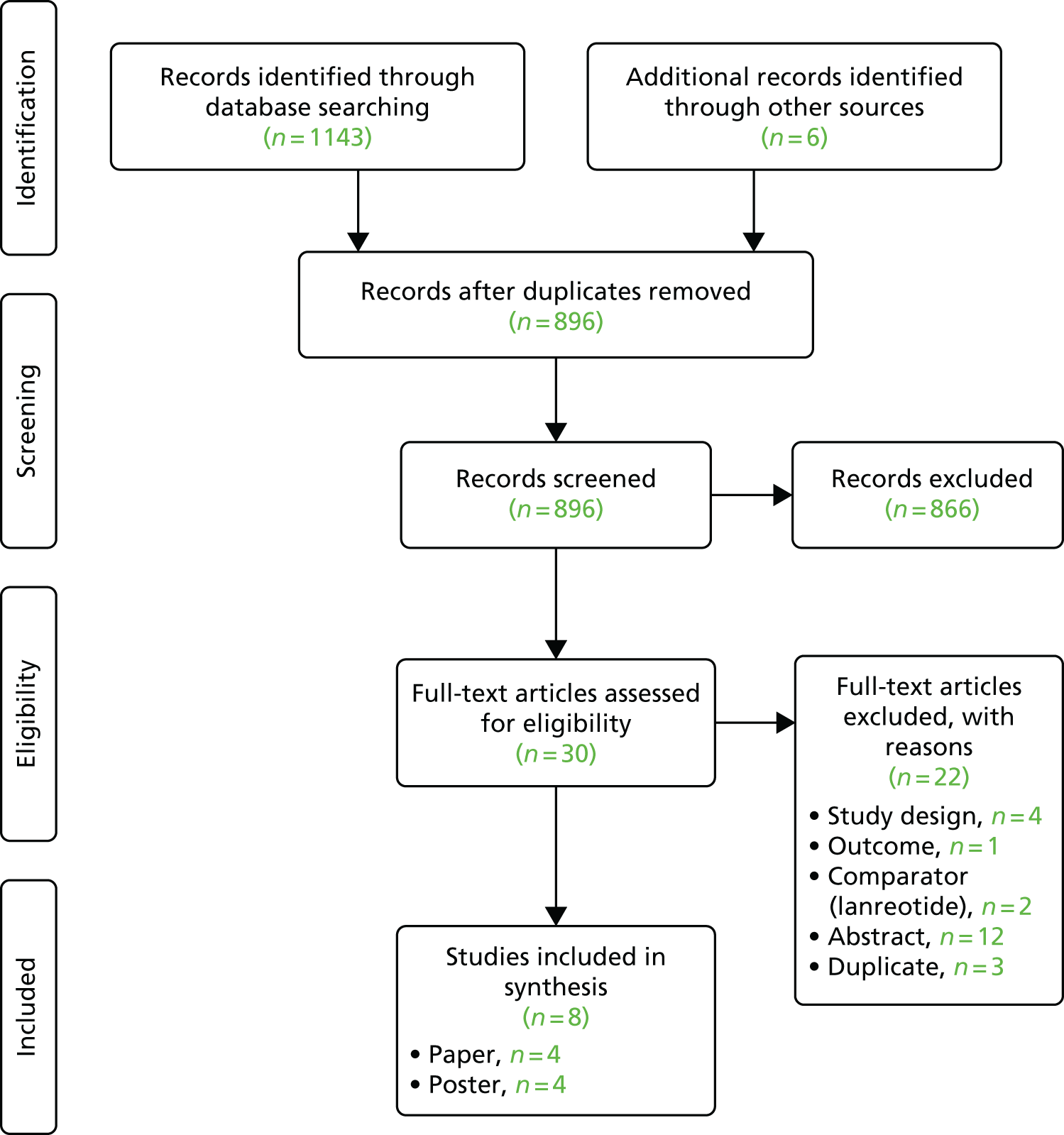

Quantity and quality of research available (randomised controlled trial evidence)

Studies identified

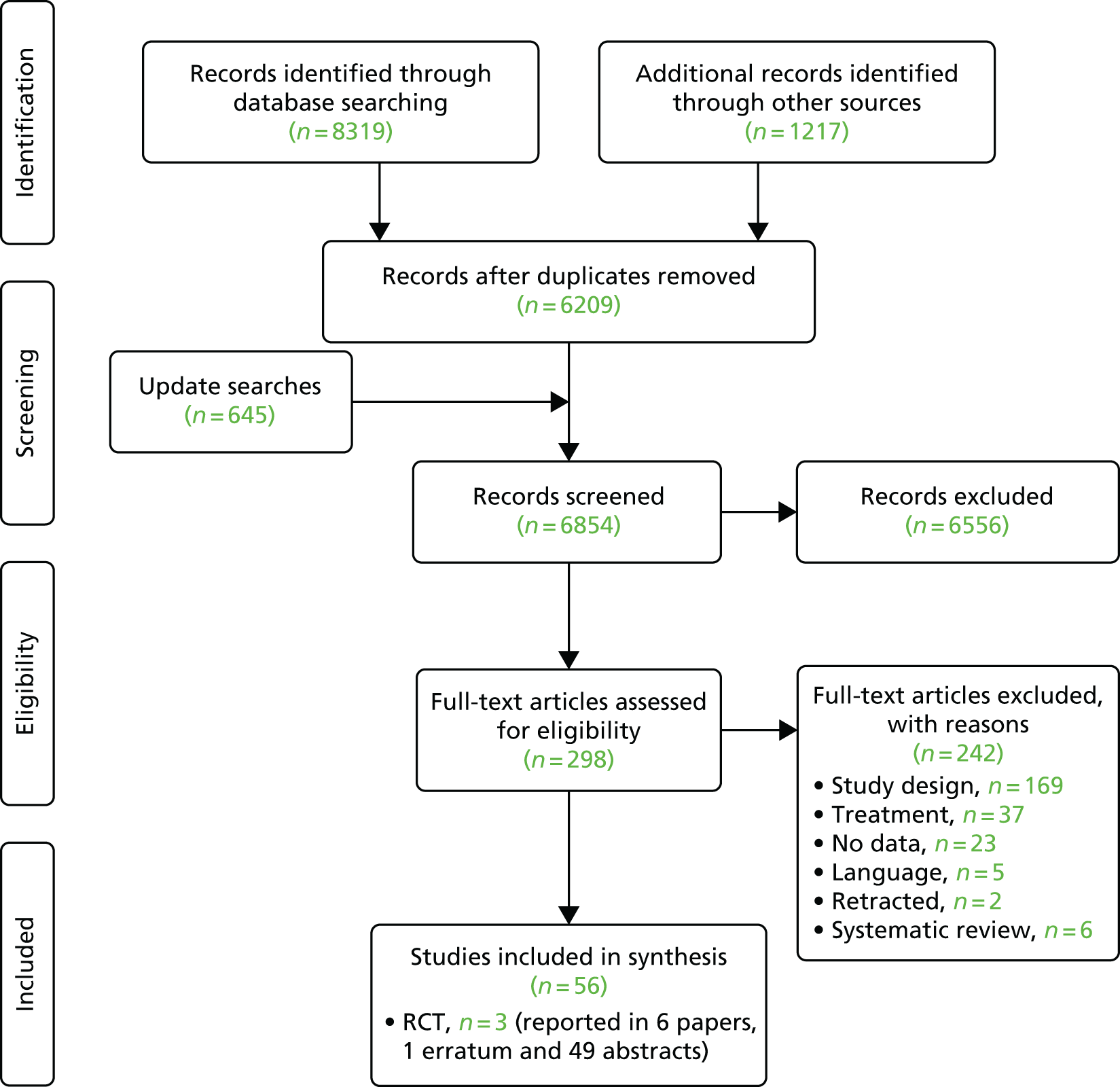

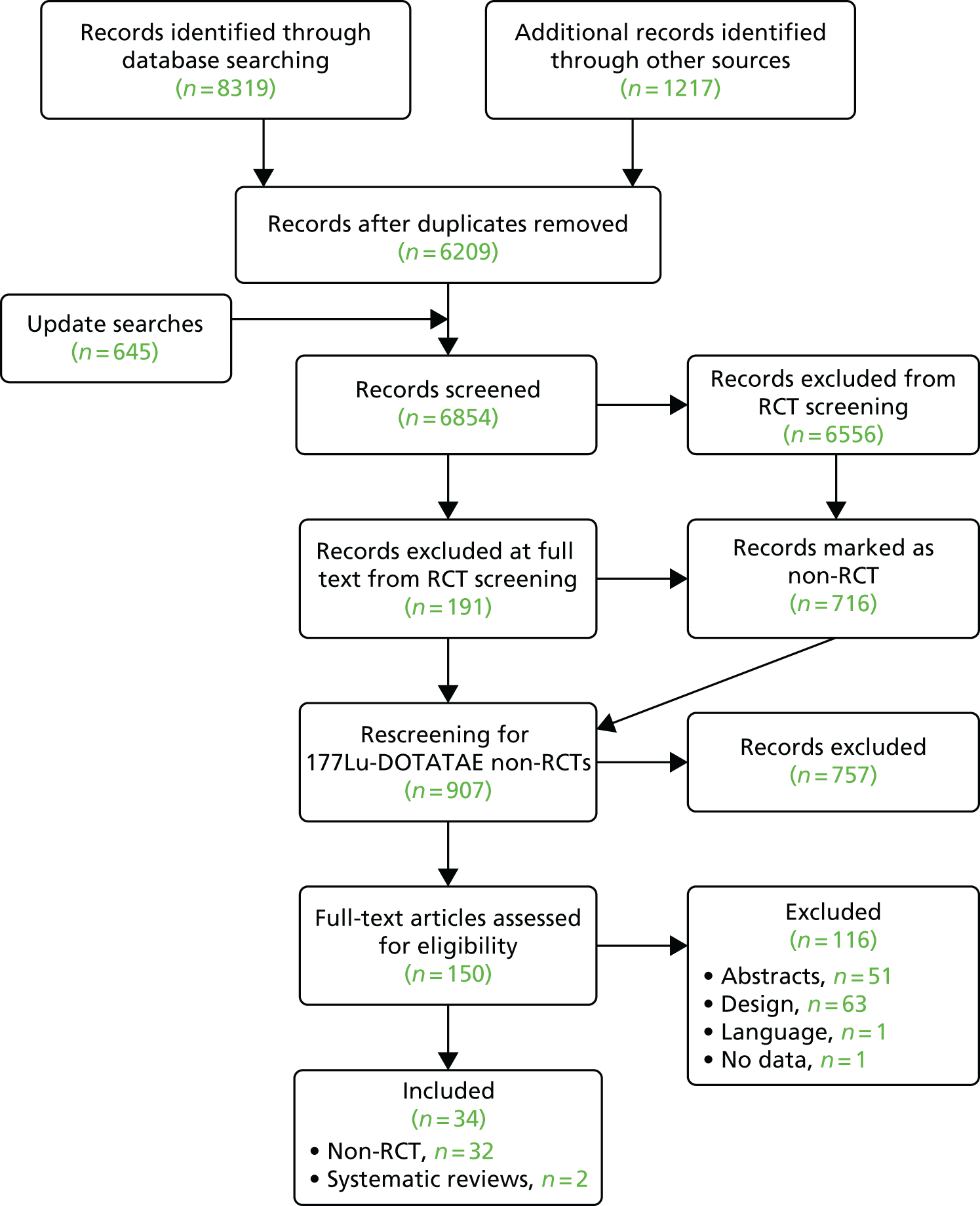

Titles and abstracts were screened for 6209 unique references identified by the searches, after which 273 full-text papers were retrieved for detailed consideration. A total of 217 full texts were excluded (a table of these excluded references, along with the reasons for exclusion can be found in Appendix 3). The Cohen’s kappa for full-text screening was 0.579 [standard error 0.045, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.491 to 0.667].

Update searches were conducted in September 2016. A total of 645 references were identified and 25 were selected for full-text retrieval. Of these, six citations were formally included in the review.

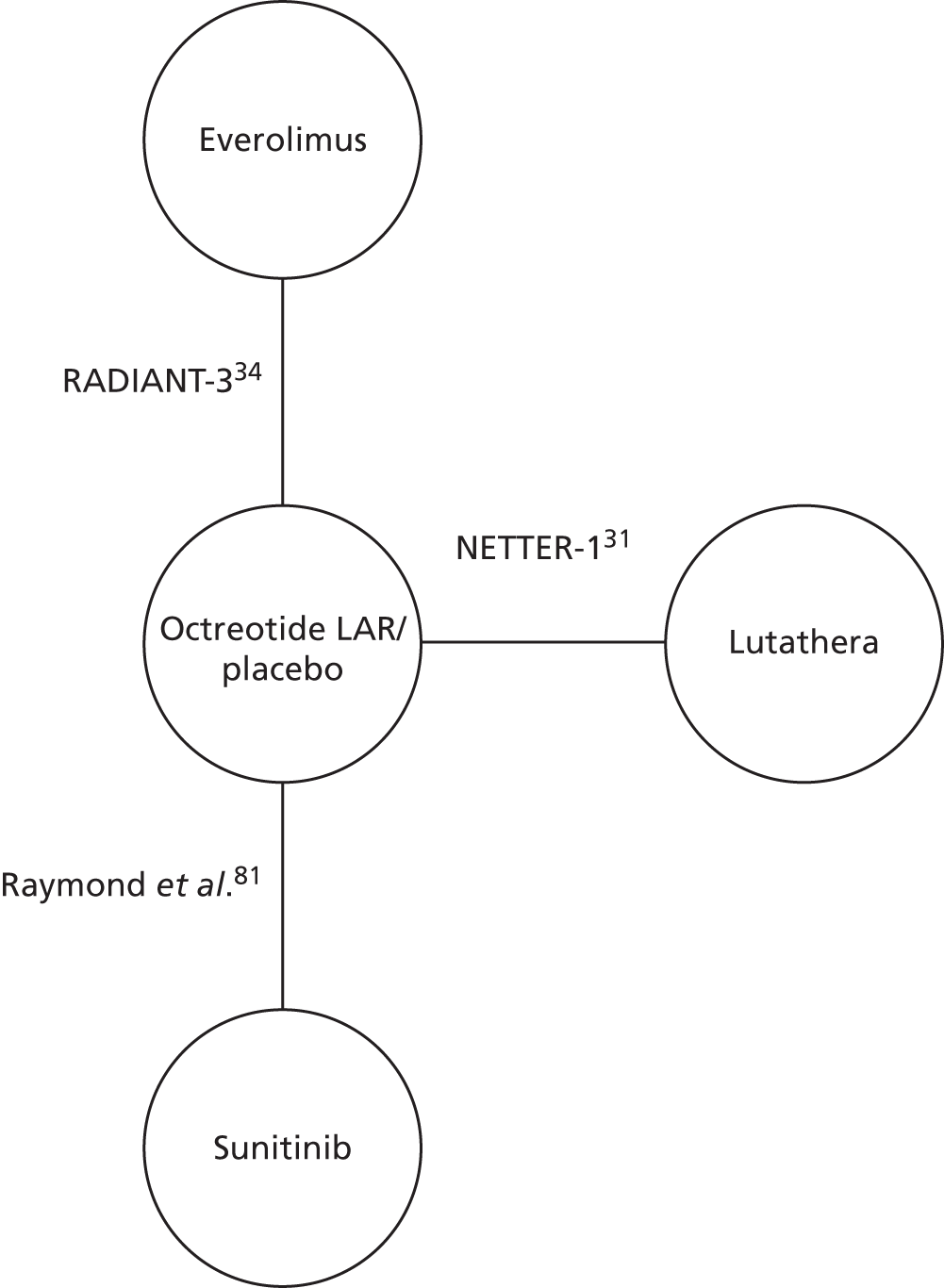

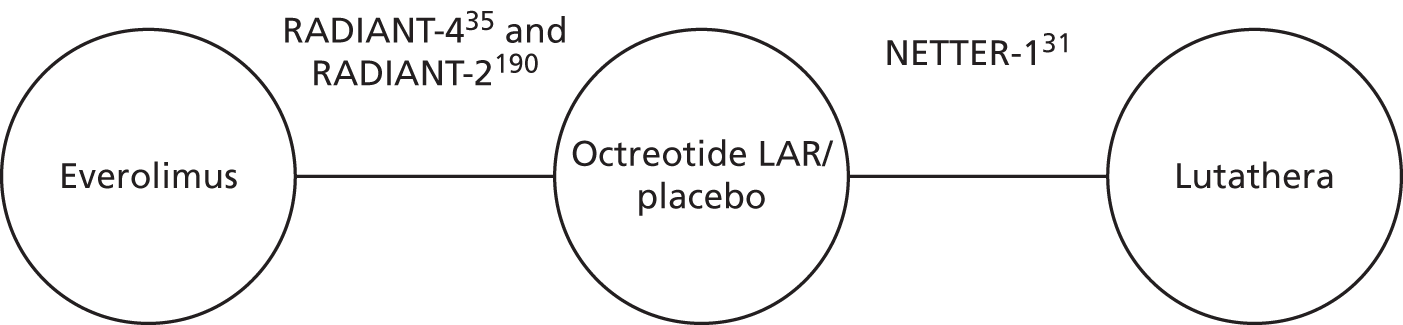

Six systematic reviews42–47 were retained for scrutiny and three trials were included in the review: RADIANT-3 (four full texts34,48–50 and 22 abstracts51–72), RADIANT-4 (one full text35 and eight abstracts73–80) and A6181111 (one full text,81 19 abstracts82–100 and erratum to the full text81). Following scrutiny of the included studies from the six systematic reviews, no further evidence was identified. A table of all of the included citations is provided in Appendix 4.

Of note, two citations related to a study by Yao et al. 101 This study met our inclusion criteria; however, it was excluded as the paper was retracted because ‘the authors discovered statistical errors which need further validation’. The study compared everolimus (n = 44) with placebo (n = 35) in Chinese patients with pNETs.

No randomised studies were identified that met the inclusion criteria of the systematic review for clinical evidence for the following interventions and comparators:

-

177Lu-DOTATATE compared with any of the included comparators

-

everolimus compared with interferon alpha or chemotherapy

-

sunitinib compared with interferon alpha or chemotherapy.

The AG ran an additional search (see Appendix 5 for the search strategy) with the aim of identifying any RCTs that compared chemotherapy with BSC or placebo in the NETs population. Identified studies would help inform discussions around the clinical effectiveness of the interventions in comparison to chemotherapy through an ITC. Following the screening of 850 citations, no studies were identified. The AG, on the advice from our clinicians, did not search for RCTs comparing interferon alpha with BSC or placebo, as interferon alpha is not commonly used in UK clinical practice.

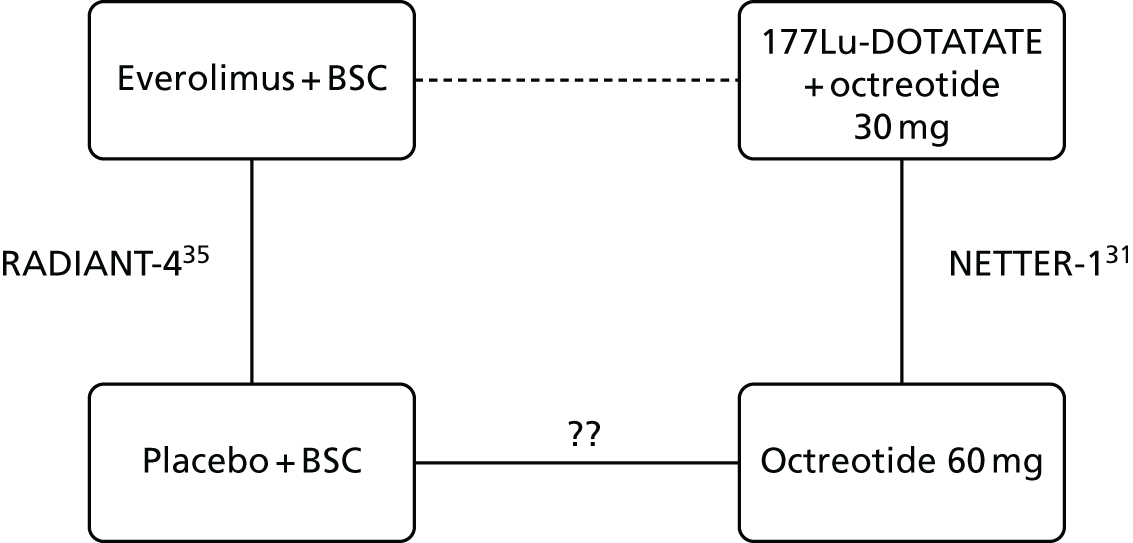

Neuroendocrine Tumors Therapy trial

The NETTER-1 (Neuroendocrine Tumors Therapy) trial102 was identified as an includable trial through four published abstracts103–106 identified in the systematic review in accordance with the original NICE scope. However, it was not included in this systematic review as it did not meet the revised inclusion criteria of the updated scope issued by NICE on 18 August 2016. 30

The NETTER-1 trial is a RCT that compares 177Lu-DOTATATE plus 30 mg of octreotide long-acting release (LAR) with 60 mg of octreotide LAR. Whether or not octreotide LAR could be deemed a concomitant treatment, as the doses were different in each treatment arm, was explored.

The AG sought consultation from our clinicians, who were unable to confirm whether or not the different dosing of octreotide LAR would result in different clinical effectiveness results. Therefore, the AG searched for RCT dosing studies (see Appendix 5 for the search strategy) to ascertain whether or not 30 mg of octreotide LAR had the same clinical effectiveness as 60 mg of octreotide LAR in the NETs population. Following screening of 180 citations, no studies were identified.

As the AG could not verify with any certainty that 30 mg of octreotide LAR had the same clinical effectiveness as 60 mg of octreotide LAR, and octreotide LAR was not a comparator within the scope, this study was excluded from the review.

Taken from the company submission,31 AAA reports that the rationale for treating the comparator arm with a high dose of octreotide (60 mg) was as follows:

A higher dose was required by the regulatory authorities at the time of the parallel scientific advice meeting with the FDA and EMA considering that the patients enrolled in the trial had have progressive disease following 20 or 30 mg octreotide LAR, and it was not ethical to maintain them on the same dose regimen. Consequently, 60 mg octreotide LAR at 4-week intervals dose was agreed for the control arm in the absence of an alternative efficacious treatment approved for this type of tumour.

p. 4431

The AG appreciate that, as the only RCT of 177Lu-DOTATATE identified, this trial may be of interest to the committee and so the main outcomes are presented in Appendix 6 along with the results of an ITC with everolimus from RADIANT-4. 35

The study selection process is outlined in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram.

Ongoing trials

The following trials registries were handsearched for ongoing trials: Current Controlled Trials, ClinicalTrials.gov; the FDA website and the EMA website (including EPARs) (see Appendix 1 for the search strategy). All searches were carried out in May 2016. Three trials were considered relevant to this review:

-

NCT02687958: Study of Everolimus as Maintenance Therapy for Metastatic NEC with Pulmonary or Gastroenteropancreatic Origin. N = 30, currently recruiting, sponsored by the Gruppo Oncologico Italiano di Ricerca Clinica.

-

NCT02358356: Capecitabine ON Temozolomide Radionuclide Therapy Octreotate Lutetium-177 NeuroEndocrine Tumours Study (CONTROL NETs). N = 165, currently not open for recruitment, sponsored by the Australasian Gastro-Intestinal Trials Group.

-

NCT02230176: Antitumor Efficacy of Peptide Receptor Radionuclide Therapy With 177Lutetium -Octreotate Randomized vs Sunitinib in Unresectable Progressive Well-differentiated Neuroendocrine Pancreatic Carcinoma: First Randomized Phase II (OCCLURANDOM). N = 80, currently recruiting, sponsored by Gustave Roussy, Cancer Campus, Grand Paris.

As two of the trials were investigating 177Lu-DOTATATE, the intervention that we were unable to provide relevant RCT evidence for, we contacted the study organisers and received replies from both. The CONTROL NETs trial is in progress and data are not expected until 2018/19. The OCCLURANDOM study has recruited a total of 13 individuals and data are not expected to be ready before submission of this assessment report.

Study design and participant characteristics: pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours

This review includes the two trials that evaluated treatments in pNETs (RADIANT-334 – everolimus; A618111181 – sunitinib). The characteristics of the study designs are summarised in Table 2. In both trials, participants were randomised 1 : 1 to the intervention or placebo and BSC was given in both the intervention arm and the placebo arm. Both trials measured the following outcomes: PFS, OS, RR (to include complete response, partial response, stable disease, progressive disease and ORR) and AEs. A618111181 also reported HRQoL.

| Study ID | ITT population (n) | Intervention | Tumour locations included | Inclusion criteria | Randomisation stratification factor | Primary end point | Secondary end points | Median (range) treatment duration (months) | Median follow-up (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RADIANT-333,34 (NCT00510068) | 207 | Everolimus + BSC | Pancreas | Low or intermediate grade, advanced (unresectable or metastatic), disease progression in previous 12 months | Stratified according to status with respect to previous chemotherapy (receipt vs. no receipt) and according to WHO PS (0 vs. 1 or 2) at baseline | PFS | OS, ORR, duration of response, safety | (Confidential information has been removed | 17 |

| 203 | Placebo + BSC | (Confidential information has been removed | |||||||

| A618111181 (NCT00428597) | 86 | Sunitinib + BSC | Pancreas | Pathologically confirmed, well differentiated, advanced and/or metastatic, disease progression in previous 12 months | NR | PFS | OS, ORR, time to response, duration of response, safety, patient-reported outcomes | 4.6 (0.4–17.5) | 34.1 |

| 85 | Placebo + BSC | 3.7 (0.03–20.2) | |||||||

| RADIANT-435 (NCT01524783) | 205 | Everolimus + BSC | Lung + GI (Ileum, rectum, unknown origin, jejunum, stomach, duodenum, colon, other, caecum, appendix) | Pathologically confirmed, advanced (unresectable or metastatic), non-functional, well differentiated (grade 1 or 2), disease progression in previous 6 months | Stratified by previous SSA treatment, tumour origin and WHO PS (0 vs. 1) | PFS | OS, ORR, disease control rate, HRQoL, WHO PS, safety, pharmacokinetics, changes in chromogranin A and neuron-specific enolase levels | 9.3 (0.1–27.7)a | 21 |

| 97 | Placebo + BSC | 4.5 (0.9–30.0)b | |||||||

| Study ID | ITT (n) | Interventions evaluated (dose) | Mean relative dose intensityc | Dose reductions/interruptions, n/N (%) | Treatment switching, n/N (%) | SSA use during study | |||

| RADIANT-334 (NCT00510068) | 207 | 10 mg of oral everolimus once daily; BSC (confidential information has been removed)a | 0.86 | (59) | NA | Approximately 40% of individuals: everolimus arm 37.7%,d placebo arm 39.9%e | |||

| 203 | Matching placebo; BSC (includes SSAs)a | 0.97 | (28) | 148/203 (73) | |||||

| A618111181 (NCT00428597) | 86 | 37.5 mg of oral sunitinib once daily;f BSC | 0.91 | (30) | NA | n = 23 (n = 22 were already on SSAs; n = 1 started following study enrolment) | |||

| 85 | Matching placebo; BSC | 1.01 | (12) | 59/85 (69)g | n = 25 (n = 20 were already on SSAs; n = 5 started following study enrolment) | ||||

| RADIANT-435 (NCT01524783) | 205 | 10 mg of oral everolimus once daily; BSC | 0.90h | 135/202 (67) | NA | NRi | |||

| 97 | Matching placebo; BSC | 1.00j | 29/98 (30) | Not permitted | |||||

The primary end point was the same (PFS) for both trials. Median treatment duration was 4.6 months in the treatment arm in A618111181 and (confidential information has been removed) in RADIANT-334 for the treatment arm and (confidential information has been removed) for the placebo/BSC arm. Median follow-up was reported to be 17 months for RADIANT-334 and 34.1 months for A6181111. 81

A summary of information relating to drug administration is also provided in Table 2. The mean relative dose intensity (RDI) of the active treatment was slightly lower in the everolimus studies (0.86 in RADIANT-334) than in the sunitinib study (0.91 in A618111181). The use of SSAs was permitted in both treatment arms in both trials. Treatment switching after disease progression (from placebo to active treatment) was allowed in both trials.

The A6181111 trial was discontinued early following a recommendation from the safety monitoring committee:

because of the greater number of deaths and serious adverse events in placebo group and the difference in progression-free survival favouring sunitinib.

Raymond et al. 81

The statistical power of the study was reduced because of the early termination of the trial. Only 171 individuals were randomised rather than the target of 340.

To achieve sufficient statistical power in RADIANT-3,34 it was estimated that 392 individuals would need to be randomised to detect a clinically meaningful improvement in PFS. This target was reached as 410 patients were recruited and randomised to the study.

Population characteristics: pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours

The baseline demographic and disease characteristics for RADIANT-334 and A618111181 are reported in Table 3.

| Study ID | Intervention | Tumour location | n | Age (years), median (range) | Male, n/N (%) | Tumour functioning, n/N (%) | Tumour differentiation, n/N (%) | WHO PS, n/N (%) | Previous treatments, n/N (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Well differentiated | Moderately differentiated | Unknown | ||||||||

| RADIANT-334 | Everolimus + BSC | Pancreas | 207 | 58 (23–87) | 110/207 (53) | NR | NR | 170/207 (82) | 35/207 (17) | 2/207 (1) | 0: 139/207 (67); 1: 62/207 (30); 2: 6/207 (3) | Radiotherapy: 47/207 (23); chemotherapy: 104/207 (50); SSAs: 101/207 (49) |

| Placebo + BSC | 203 | 57 (20–82) | 117/203 (58) | NR | NR | 171/203 (84) | 30/203 (15) | 2/203 (1) | 0: 133/203 (66); 1: 64/203 (32); 2: 6/203 (3) | Radiotherapy: 40/203 (20); chemotherapy: 102/203 (50); SSAs: 102/203 (50) | ||

| A618111181 | Sunitinib + BSC | Pancreas | 86 | 56 (25–84) | 42/86 (49) | 25/86 (29) | 42/86 (49) | 86/86 (100)a | (0) | ECOG PS: 0: 53/86 (62); 1: 33/86 (38); 2: 0/86 (0) | Surgery: 76/86 (88); radiation therapy: 9/86 (10); chemoembolisation: 7/86 (8); radiofrequency ablation: 3/86 (3); percutaneous ethanol injection: 1/86 (1); SSAs: 30/86 (35) | |

| Placebo + BSC | 85 | 57 (26–78) | 40/85 (47) | 21/85 (25) | 44/85 (52) | 85/85 (100)a | (0) | ECOG PS: 0: 41/85 (48); 1: 43/85 (51); 2: 1/85 (1)b | Surgery: 77/85 (91); radiation therapy: 12/85 (14); chemoembolisation: 14/85 (16); radiofrequency ablation: 6/85 (7); percutaneous ethanol injection: 2/85 (2); SSAs: 32/85 (38) | |||

| RADIANT-435 | Everolimus + BSC | Lung, GI | 205 | 65 (22–86) | 89/205 (43) | 0/205 (0) | 205/205 (100) | 205/205 (100)a | (0) | 0: 149/205 (73); 1: 55/205 (27) | Surgery: 121/205 (59); chemotherapy: 54/205 (26); radiotherapy: 44/205 (22); locoregional + ablative therapy: 23/205 (11); SSAs: 109/205 (53) | |

| Placebo + BSC | 97 | 60 (24–83) | 53/97 (55) | 0/97 (0) | 97/97 (100) | 97/97 (100)a | (0) | 0: 73/97 (75); 1: 24/97 (25) | Surgery: 70/97 (72); chemotherapy: 23/97 (24); radiotherapy: 19/97 (20); locoregional + ablative therapy: 10/97 (10); SSAs: 54/97 (56) | |||

RADIANT-334 and A618111181 recruited participants of a similar age (median age ranged from 56 to 58 years). There was a slightly higher proportion of men recruited to RADIANT-334 (53% to the everolimus arm and 58% to the placebo arm) than to A618111181 (49% to the sunitinib arm and 47% to the placebo arm). Both studies recruited individuals with pNETs only.

The functionality of the tumour was not reported in RADIANT-3,34 whereas A618111181 recruited a mixture of functioning (> 30%) and non-functioning (≈50%) individuals (the functionality of the remaining ≈20% was not clarified).

A618111181 recruited individuals with well-defined or moderately defined tumours, whereas RADIANT-334 recruited around 80% of individuals with well-defined tumours, with the remainder having moderately defined tumours.

RADIANT-334 measured performance status (PS) using the WHO PS score system, whereas A618111181 measured PS using the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) PS system. Our clinicians suggested that there is little difference between PS measured by either system. The majority of individuals had a PS score of 0 in RADIANT-334 (66–67%), with the majority of the remaining individuals having a PS score of 1 (30–32%) and the remainder having a PS score of 2 (3%). A618111181 had a lower proportion of individuals with a PS score of 0 (62% in the sunitinib arm and 48% in the placebo arm) and a higher proportion of individuals with a PS score of 1 (38% in the sunitinib arm and 51% in the placebo arm) than RADIANT-3. 34 One individual was recruited with a PS score of 2 in the placebo arm; this was a protocol deviation for A6181111. 81

The proportions of individuals who had received previous treatments were variable between RADIANT-334 and A618111181 (see Table 3). Of particular note, SSA use prior to treatment was around 50% in RADIANT-334 and between 35% and 38% in A6181111. 81

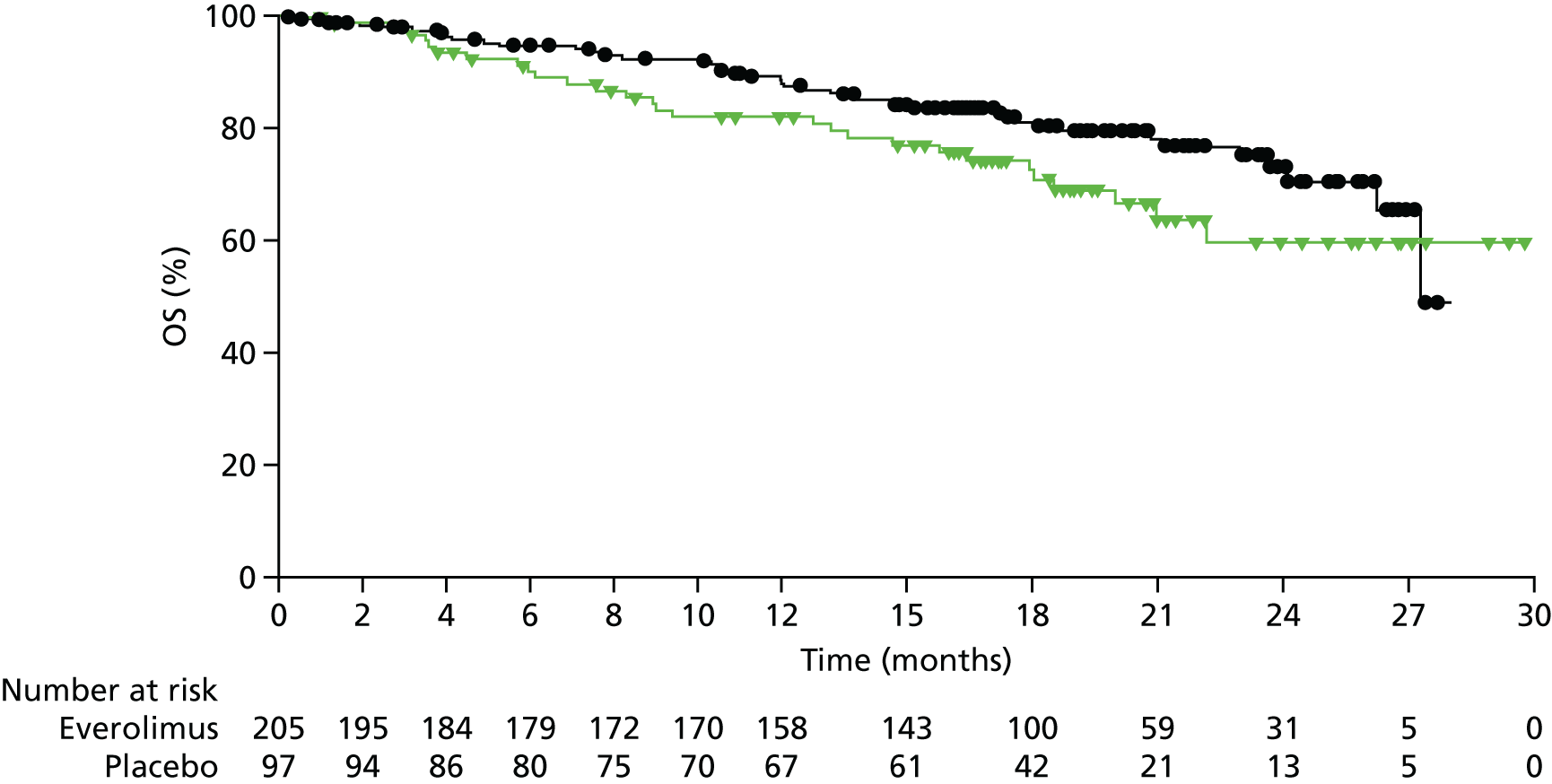

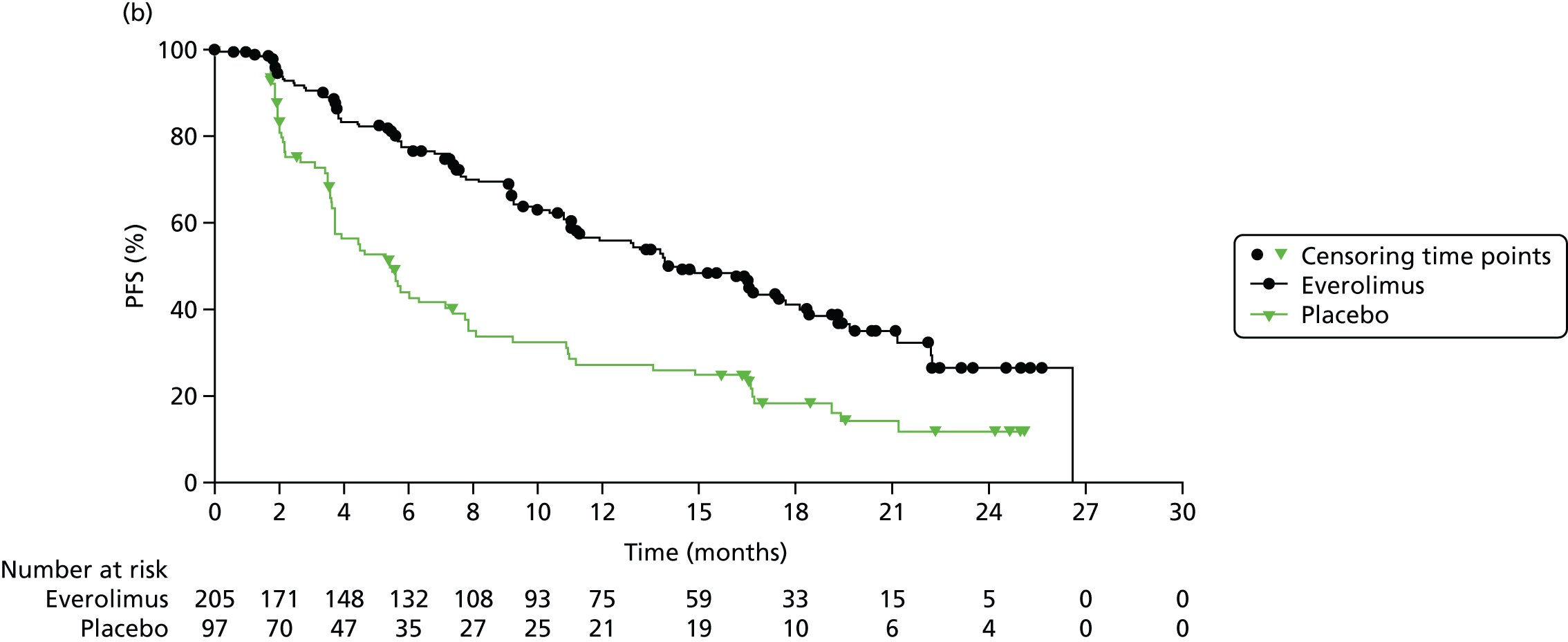

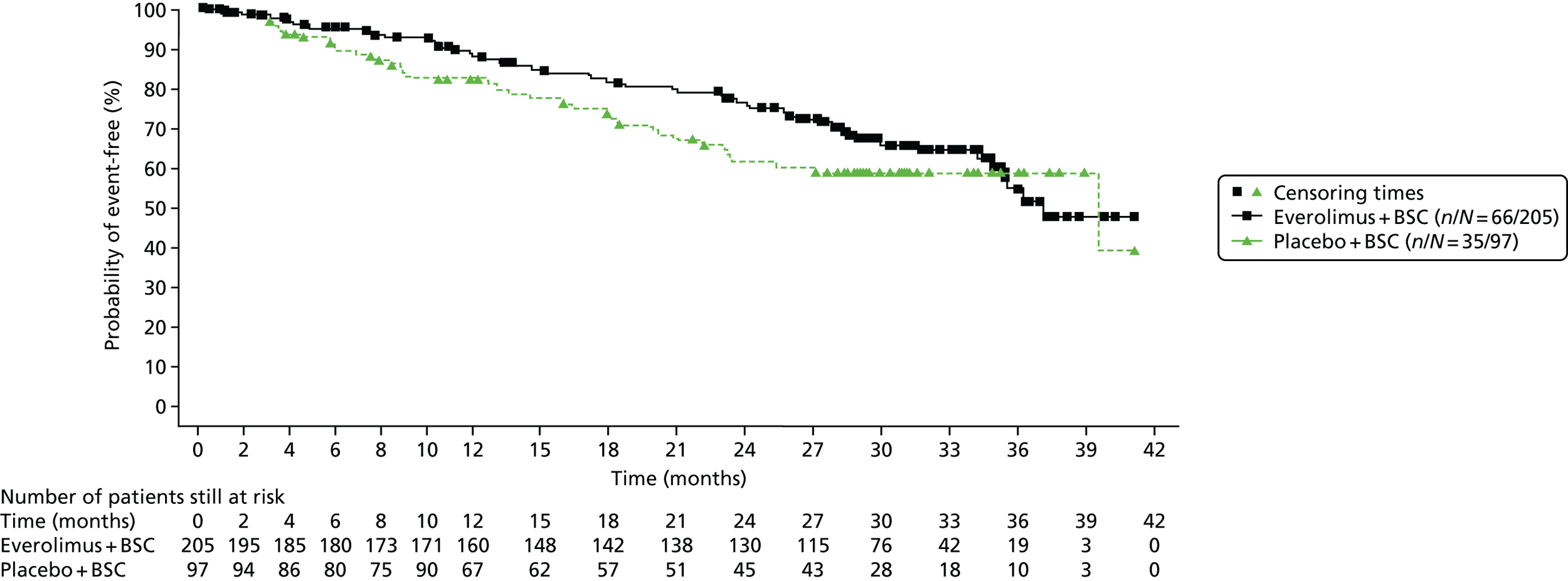

Study design and participant characteristics: gastrointestinal and lung neuroendocrine tumours

This review includes RADIANT-4,35 which evaluated everolimus in individuals with GI and lung NETs. The characteristics of the study design are summarised in Table 2. Participants were randomised 2 : 1 to everolimus or placebo. BSC was given in both the intervention (everolimus) arm and the placebo arm. RADIANT-435 measured the following outcomes: PFS, OS, RR (to include complete response, partial response, stable disease, progressive disease and ORR) and AEs. The primary end point was PFS. Median treatment duration was 9.3 months in the everolimus arm and 4.5 months in the placebo arm. Median follow-up was 21 months.

A summary of information relating to drug administration is provided in Table 2. The use of SSAs was permitted in both treatment arms. Treatment switching (from placebo to active treatment) was not allowed in RADIANT-4. 35

For RADIANT-435 it was estimated that 285 individuals would need to be randomised at a ratio of 2 : 1. This requirement was met as 302 individuals were randomised.

Population characteristics: gastrointestinal and lung neuroendocrine tumours

Baseline demographic and disease characteristics for RADIANT-435 are reported in Table 3.

The median age of participants ranged from 60 to 65 years in RADIANT-4. 35 There was a slightly lower proportion of men recruited to the everolimus arm (43%) than to the placebo arm (55%). Only individuals with non-functioning, well-defined tumours were recruited to RADIANT-4. 35 PS was measured using the WHO PS scoring system. The majority of individuals had a PS score of 0 (73–75%), with the remaining having a PS score of 1 (27–25%). The proportions of individuals who had received previous treatments were variable between the arms (see Table 3).

Quality appraisal

The three identified RCTs were appraised for quality (Table 4). When necessary for clarification purposes, published protocols available as online supplementary material for each of the main citations for the three studies were referred to. For each trial, data from all publications for that trial contributed to the quality appraisal.

| Item | RADIANT-334 | A618111181 | RADIANT-435 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1. Was the assignment to the treatment groups really random? |

Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

|

2. Was treatment allocation concealed? |

Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

|

3. Were the groups similar at baseline in terms of prognostic factors? |

Unclear riska | Unclear riskb | Unclear riskc |

|

4. Were the care providers blinded to the treatment allocation? |

Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

|

5. Were the outcome assessors blinded to the treatment allocation? |

Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

|

6. Were the participants blinded to the treatment allocation? |

Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

|

7. Were all a priori outcomes reported? |

Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

|

8. Were complete data reported [e.g. was attrition and exclusion (including reasons) reported for all outcomes]? |

Low risk | Low riskd | Low risk |

|

9. Did the analyses include an ITT analysis? |

Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

|

10. Are there any specific limitations that might limit the applicability of this study’s findings to the current NHS in England? |

Unclear riske | Unclear riskd | Unclear risk |

Treatment allocation

Overall, the risk of bias was found to be the same in the three trials with regard to selection, performance, detection, attrition and reporting bias. It was assessed that these trials demonstrated a low risk of bias.

RADIANT-3,34 A618111181 and RADIANT-435 all used a centralised internet or telephone registration system for determining treatment allocation. RADIANT-334 and RADIANT-435 based their stratification on prognostic factors (tumour location,35 WHO PS,34,35 previous chemotherapy use34 and previous SSA use35). A618111181 stratified by country/region only.

Similarity of groups

Baseline characteristics were predominantly similar between the two arms for all of the trials. However, there were some differences between arms in the trials:

-

RADIANT-334 – participants in the everolimus arm tended to have a shorter time from initial diagnosis at baseline than participants in the placebo arm (6 months to < 2 years: 31% vs. 21% respectively; 2 years to ≤ 5 years: 26% vs. 40% respectively). The proportion of individuals with two disease sites was higher in the everolimus arm than in the placebo arm (41% vs. 32%).

-

A618111181 – there was a higher proportion of participants with an ECOG PS of 0 in the sunitinib arm than in the placebo arm (62% vs. 48%), whereas the proportion of participants with a PS of 1 was lower in the sunitinib arm than in the placebo arm (38% vs. 51%).

-

RADIANT-435 – there was a higher proportion of women in the everolimus arm than in the placebo arm (57% vs. 45%). In addition, fewer individuals had been treated with surgery prior to entering the study in the everolimus arm than in the placebo arm (59% vs. 72%).

The difference in ECOG PS between arms in A618111181 is the difference most likely to affect the clinical effectiveness results, with those receiving sunitinib having a proportionally better PS than those receiving placebo. Otherwise, it was considered by the clinicians that these baseline differences between the treatment arms were unlikely to affect significantly the clinical effectiveness outcomes reported in the trials.

Implementation of masking

RADIANT-3,34 A618111181 and RADIANT-435 were all double-blind trials and, as such, the participants, investigators, site personnel and trial teams were blinded to the allocated treatment. In addition, central reviews of tumour progression were carried out in both RADIANT-334 and RADIANT-4;35 these outcome assessors were also blinded to treatment allocation. Information obtained from the protocols indicated that both everolimus and placebo had an identical appearance, identical packaging and labelling and an identical scheduling of administration in both RADIANT-334 and RADIANT-4. 35 Information on the appearance of the placebo medication was not provided for A6181111. 81

It was assessed that there was a low risk of bias with regard to the blinding of outcome assessors, participants and care providers.

Completeness of trial data

All a priori outcomes reported in the protocols were reported in the trial publications. 34,35,81 Intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis was carried out in each of the trials. Discrepancies in participant numbers in reports of AEs were poorly explained in all three trials. Both RADIANT-334 and A618111181 included fewer participants in their AE outcomes than the number of participants recruited, whereas RADIANT-435 included an additional participant in the placebo arm who was not accounted for (n = 97 randomised and n = 98 reported for AEs).

It was assessed that there was a low risk of bias for the completeness of trial data from all three trials.

Generalisability

The populations evaluated by RADIANT-3,34 A618111181 and RADIANT-435 were all in line with the licensed indication for each treatment and with the final scope issued by NICE. 30 All of the studies were multicentre studies including centres in both the UK and Europe. In total, 38% of the population in RADIANT-334 were European, whereas 67% of the population in A618111181 were European. It was not reported in RADIANT-435 what proportion of the population was European.

To assess the generalisability of the trials to the UK setting, the AG sought data on the prevalence of NETs in the UK. There is limited information available on the current prevalence of NETs in the UK. In October 2016, PHE9 published the first documentation of the incidences of and survival in NETs, based on a cohort of 8726 neoplasms diagnosed in England in 2013–14. 9

In the UK, NETs were described by PHE as having a 50 : 50 male-to-female ratio, with no obvious variation by geographical region or ethnicity. 9 In the three trials included here there was an average split for male-to-female ratio, with the percentage of males recruited ranging from 43%35 to 58%. 34

Public Health England9 deemed the age at which NETs are most prevalent to be similar to that for all other malignant cancers. The age range of participants in the three trials appears to be younger (median age ranging between 56 and 65 years) than the age range of the typical population with NETs in the UK.

Based on the very limited data available on what the UK demographic for people with NET constitutes, it was assessed that all three trials had an unclear risk for the applicability of their results to the UK.

Assessment of effectiveness: randomised controlled trial evidence

The following outcomes were assessed:

-

PFS

-

OS

-

RRs: complete response, partial response, stable disease, progressive disease, ORR and tumour shrinkage

-

AEs

-

HRQoL.

Outcomes from randomised controlled trial evidence for pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours

Progression-free survival

In RADIANT-334 and A618111181 the primary outcome was PFS. Disease progression was defined by both trials as the time from randomisation to the first evidence of progression or death from any cause. 34,81 Both trials used the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours (RECIST) version 1.0107 to define disease progression. In RADIANT-3,34 PFS was obtained from central radiology review and also local investigator review, whereas in A618111181 PFS was obtained only from local investigator review in the published paper. 81 PFS from the assessment of an independent review was available from the company submission. 33

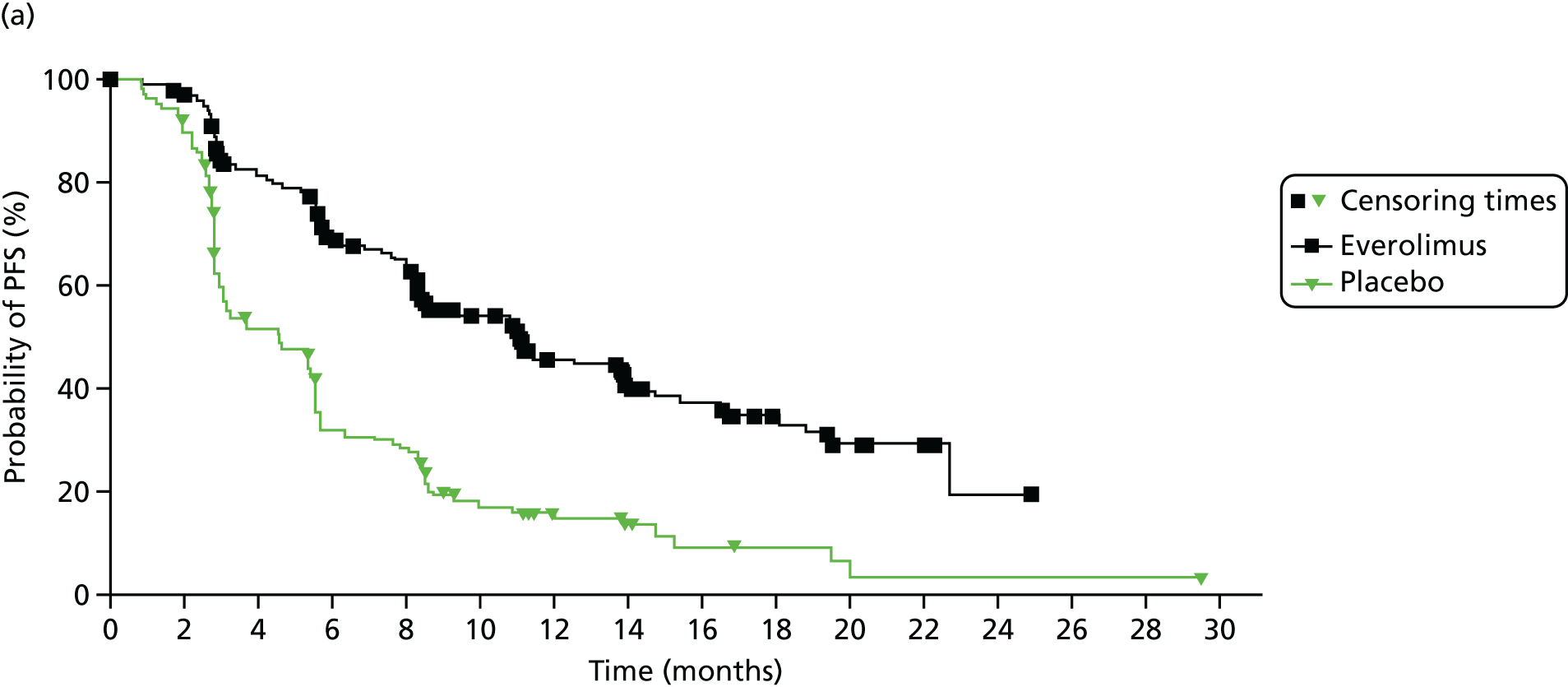

In RADIANT-3,34 median PFS as assessed by central review was 11.4 months (95% CI 10.8 to 14.8 months) in the everolimus plus BSC arm and 5.4 months (95% CI 4.3 to 5.6 months) in the placebo plus BSC arm. Everolimus was associated with a 66% reduction in the risk of disease progression or death for people with pNETs compared with placebo [hazard ratio (HR) 0.34, 95% CI 0.26 to 0.44; Table 5].

| Outcome | RADIANT-334 | A618111181 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Everolimus + BSC (n = 207) | Placebo + BSC (n = 203) | HR (95% CI) | Sunitinib + BSC (n = 86) | Placebo + BSC (n = 85) | HR (95% CI) | |

| Tumour location | Pancreas | Pancreas | ||||

| PFS (central radiology review) (months), median (95% CI) | (n = 95/207) 11.4 (10.8 to 14.8) | (n = 142/203) 5.4 (4.3 to 5.6) | 0.34 (0.26 to 0.44), p < 0.001 | 12.6 (11.1 to 20.6) | 5.8 (3.8 to 7.2) | 0.32 (0.18 to 0.55), p < 0.001 |

| PFS (local review) (months), median (95% CI) | (n = 109/207) 11.0 (8.4 to 13.9) | (n = 165/203) 4.6 (3.1 to 5.4) | 0.35 (0.27 to 0.45), p < 0.001 | (n = 30/86) 11.4 (7.4 to 19.8) | (n = 51/85) 5.5 (3.6 to 7.4) | 0.42 (0.26 to 0.66), p < 0.001 |

| OS (months), median (95% CI) | Not reached | Not reached | 1.05 (0.71 to 1.55),a p = 0.59 | (n = 77/86) 92.6 (86.3 to 98.9)b | (n = 64/85) 85.2 (77.1 to 93.3)b | 0.41 (0.19 to 0.89),c p = 0.02 |

| Final OS (months), median (95% CI) | (n = 81/207)d 44.0 (35.6 to 51.8) | (n = 73/203)d 37.7 (29.1 to 45.8) | 0.94 (0.73 to 1.20), p = 0.30 | (n = 31/86)d 38.6 (range 25.6–56.4) | (n = 27/85)d 29.1 (range 16.4–36.8) | 0.73 (0.50 to 1.06), p = 0.094 |

| Complete response, n/N (%) | 0/207 (0) | 0/203 (0) | 2/86 (2) | 0/85 | ||

| Partial response, n/N (%) | 10/207 (5) | 4/203 (2) | 6/86 (7) | 0/85 | ||

| Stable disease, n/N (%) | 151/207 (73) | 103/203 (51) | 54/86 (63) | 51/85 (60) | ||

| Progressive disease, n/N (%) | 29/207 (14) | 85/203 (42) | 12/86 (14) | 23/85 (27) | ||

| Tumour shrinkage, n/N (%) | 123/191e (64) | 39/189e (21) | 12/86 (14) | 11/85 (13) | ||

| ORR, n/N (%) | 10/207 (5) | 4/203 (2) | 9.3 (3.2 to 15.4), p = 0.007 | 8/86 (9.3)f | 0/85 (0)f | |

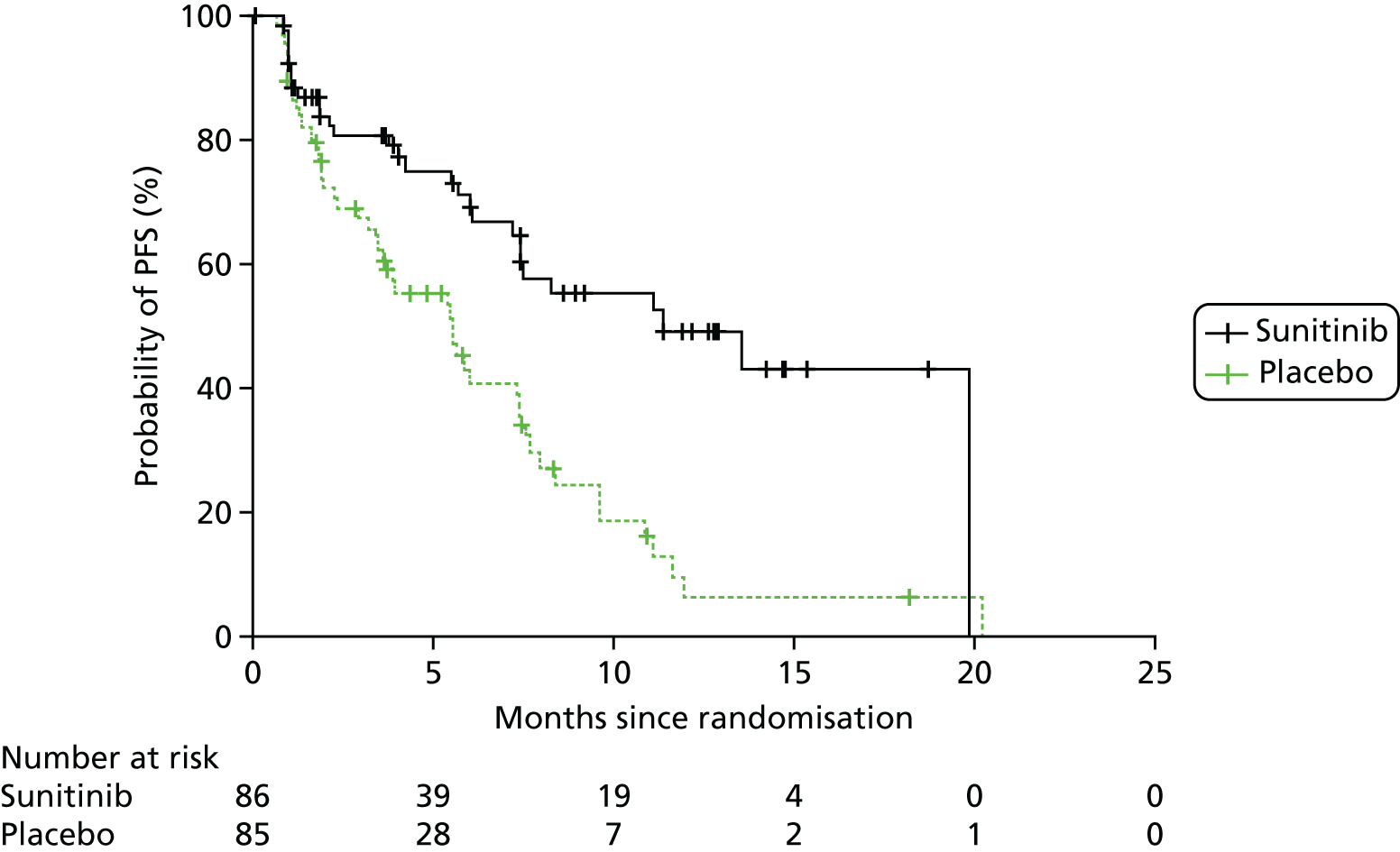

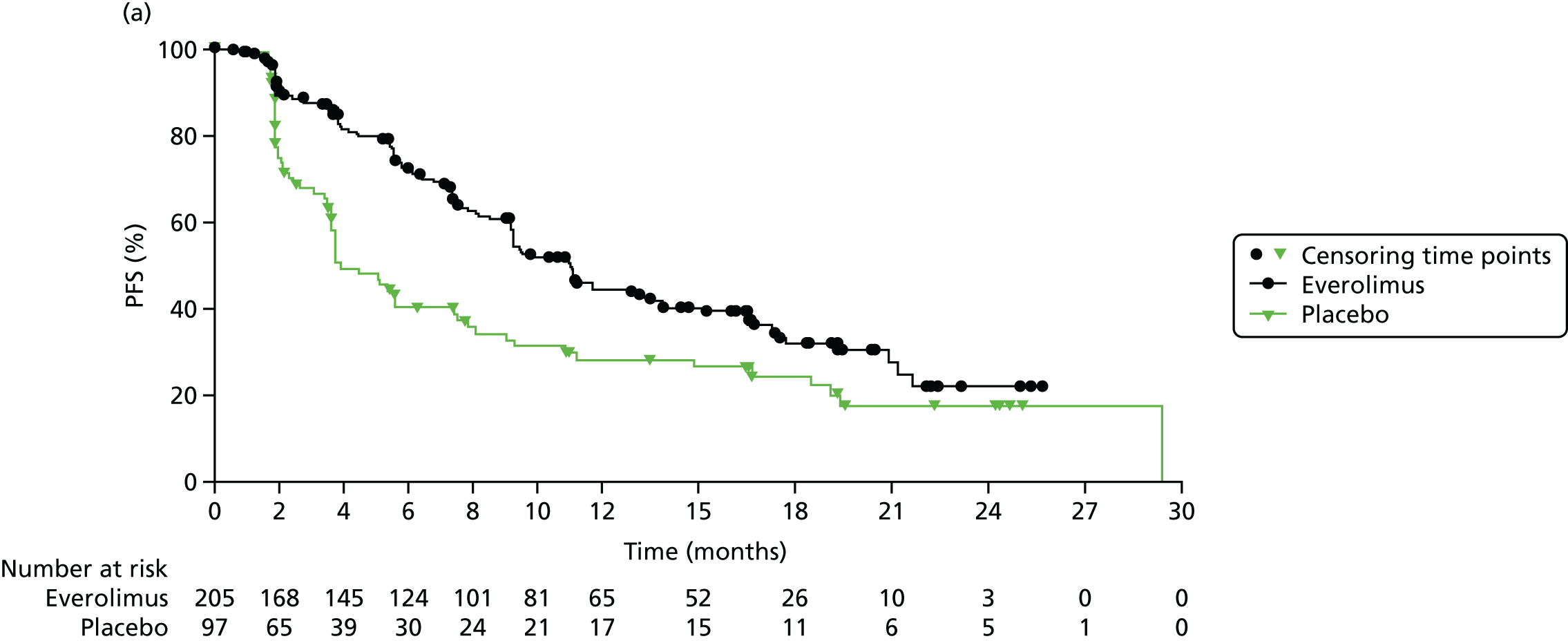

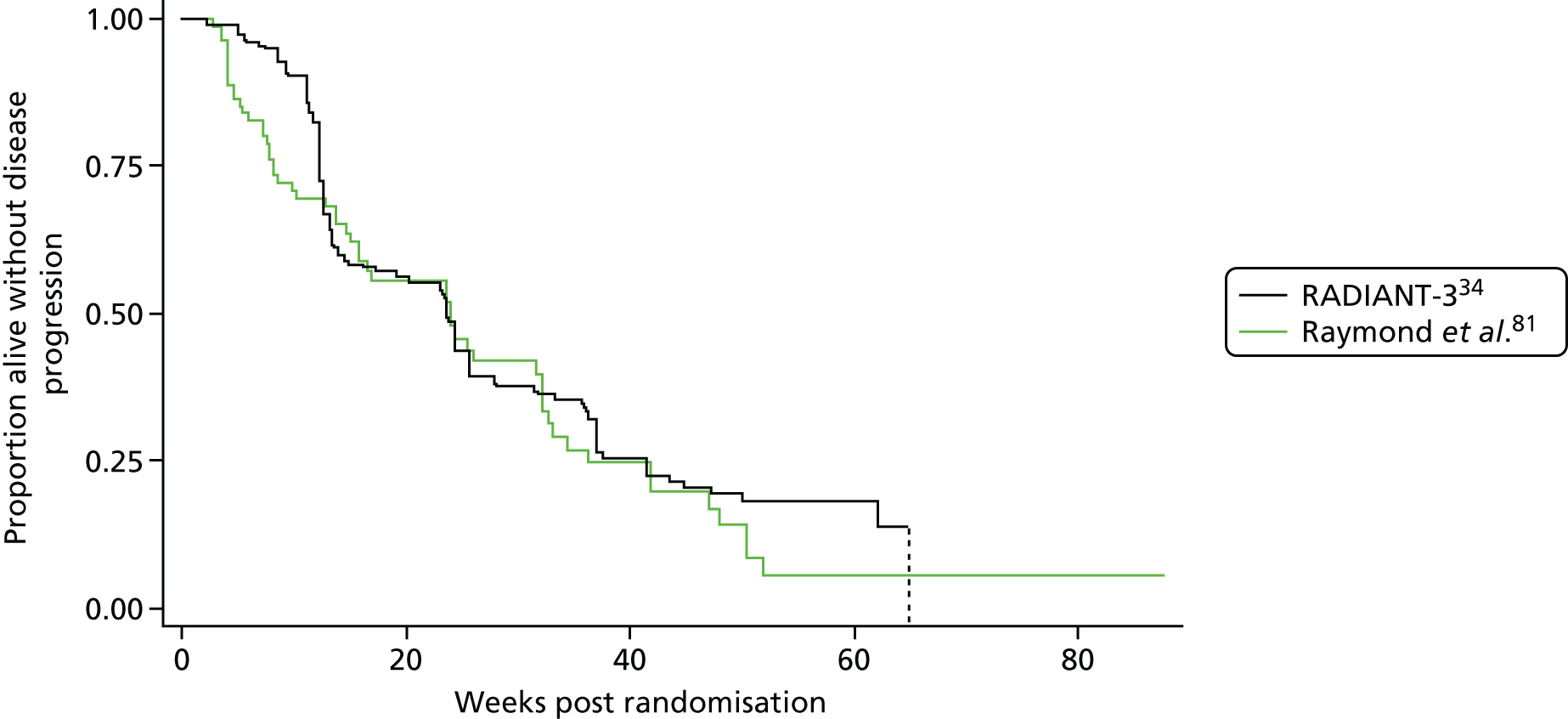

In the submission from Pfizer,32 PFS from the assessment of an independent review was 12.6 months (95% CI 11.1 to 20.6 months) for sunitinib plus BSC and 5.8 months (95% CI 3.8 to 7.2 months) for placebo plus BSC. Sunitinib was associated with a 68% reduction in the risk of disease progression or death for people with pNETs compared with placebo (HR 0.32, 95% CI 0.18 to 0.55; see Table 5).

Locally assessed PFS in RADIANT-334 was 11.0 months (95% CI 8.4 to 13.9 months) in the everolimus plus BSC arm compared with 4.6 months (95% CI 3.1 to 5.4 months) in the placebo plus BSC arm. Everolimus was associated with a reduction (65%) in the risk of disease progression or death for people with pNETs compared with placebo (HR 0.35, 95% CI 0.27 to 0.45; see Table 5). The A618111181 trial reported locally assessed PFS to be 11.4 months (95% CI 7.4 to 19.8 months) in the sunitinib plus BSC arm and 5.5 months (95% CI 3.6 to 7.4 months) in the placebo plus BSC arm. Sunitinib was associated with a 58% reduction in the risk of disease progression or death for people with pNETs compared with placebo (HR 0.42, 95% CI 0.26 to 0.66; see Table 5). Both trials reported a shorter time for PFS in both arms for locally assessed PFS than for central/independent review.

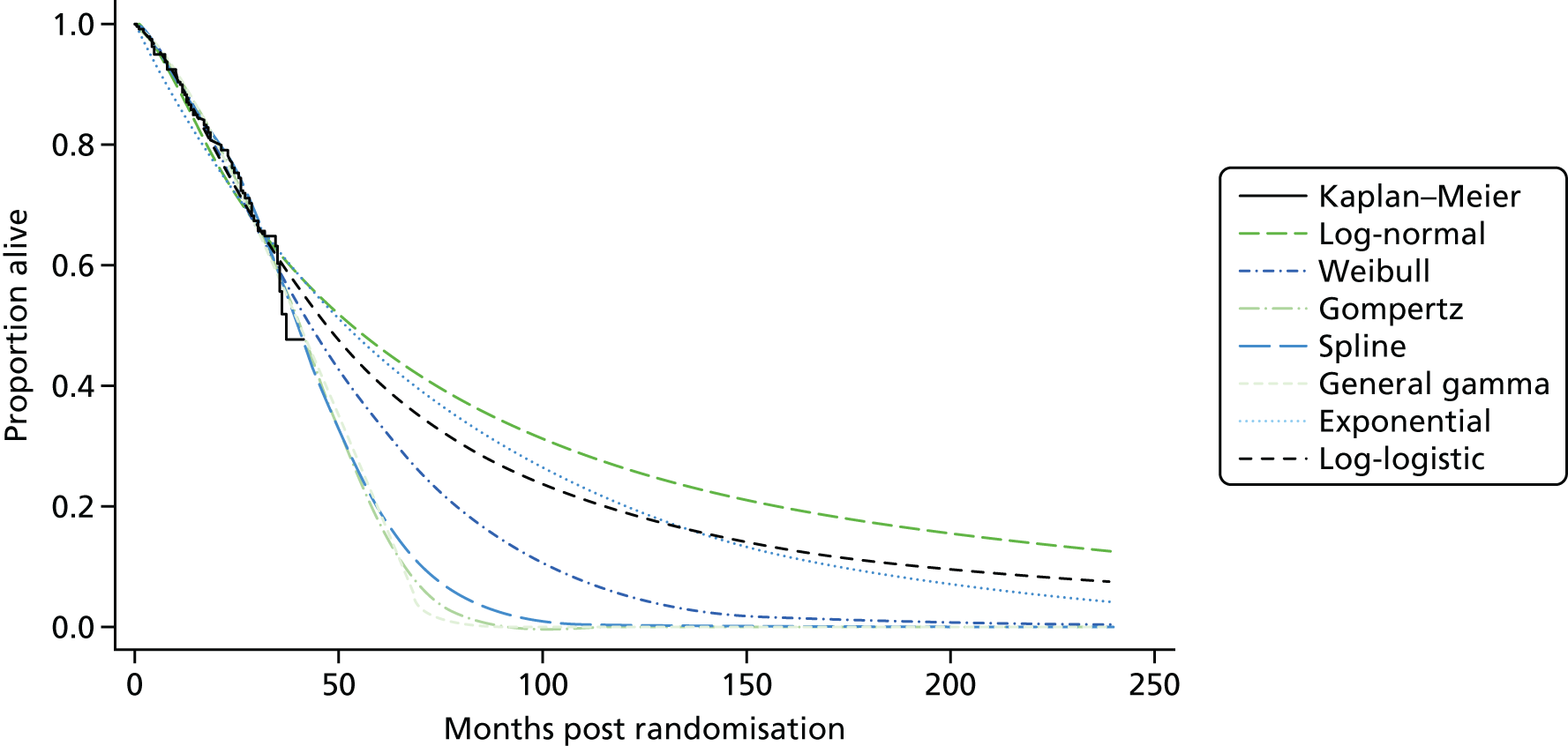

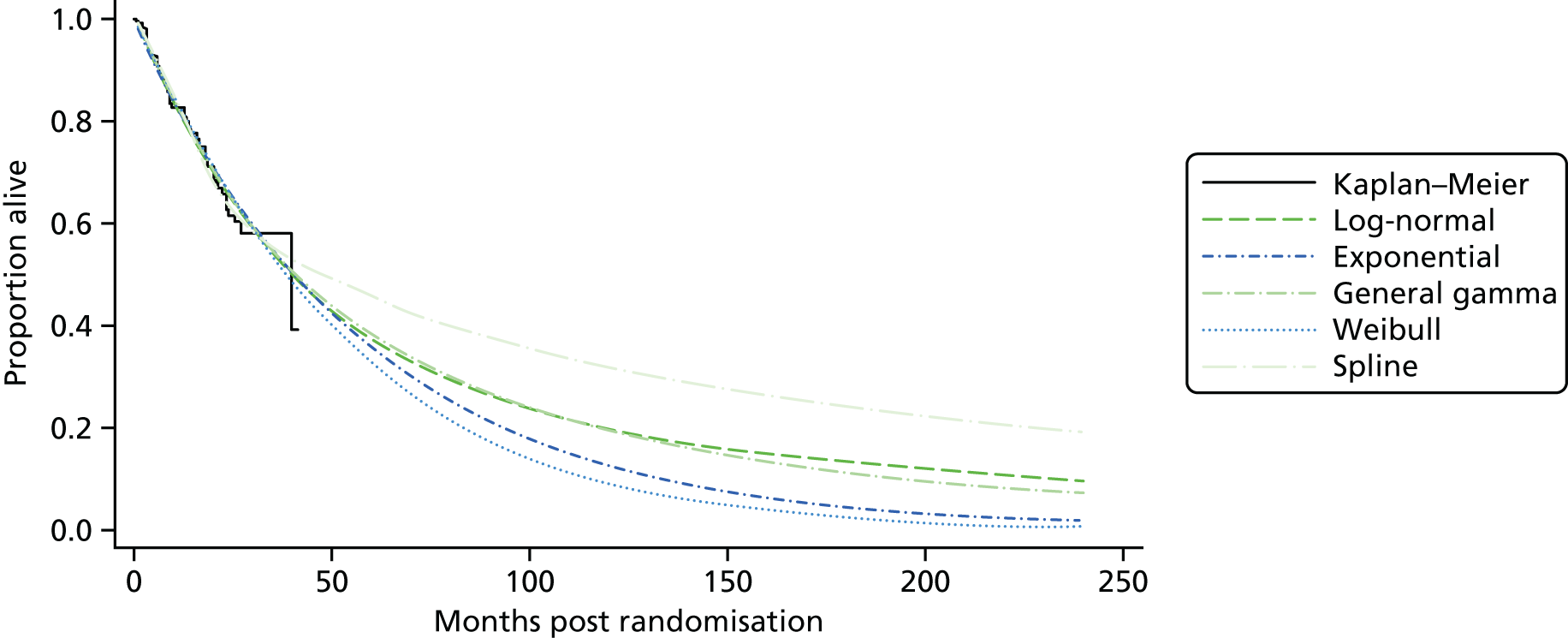

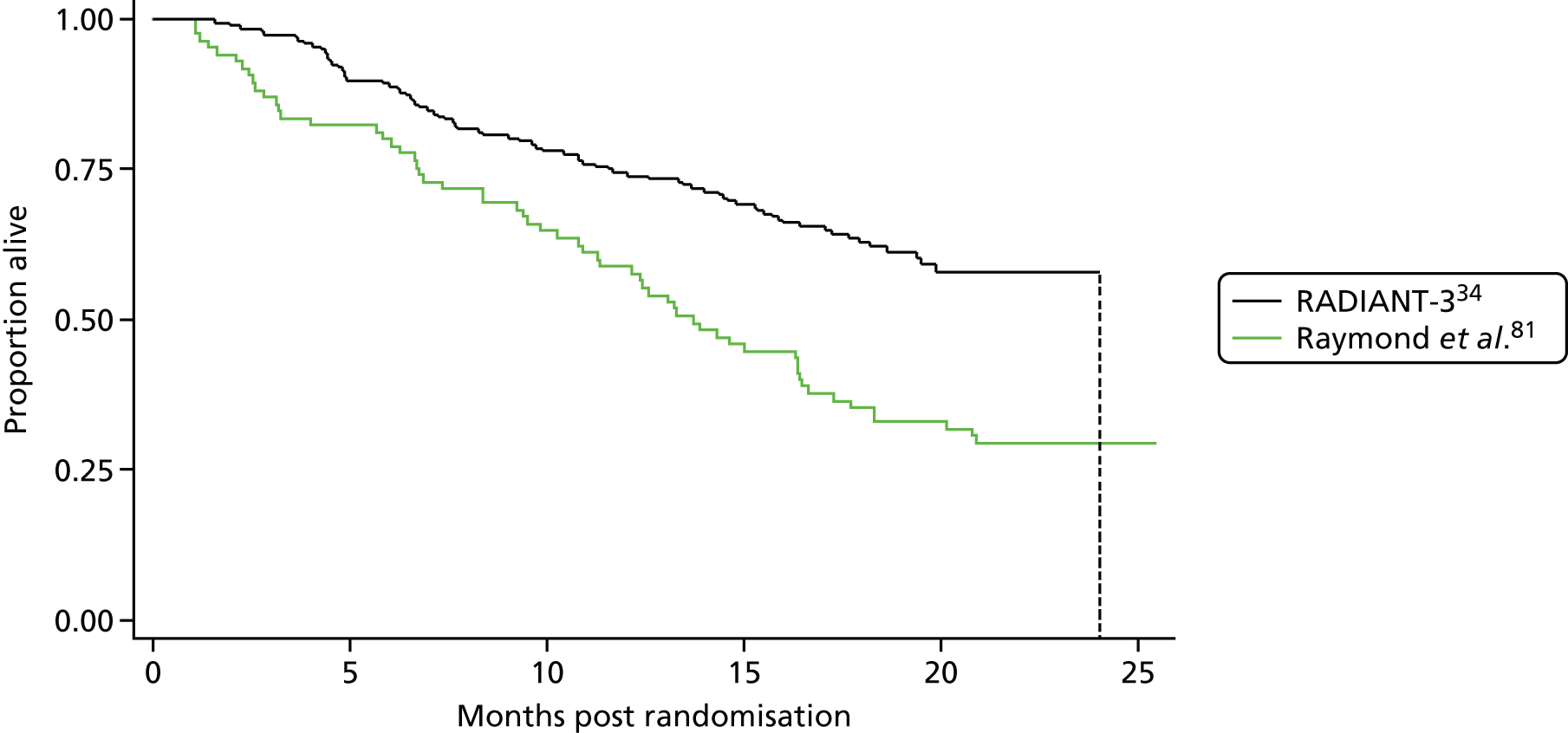

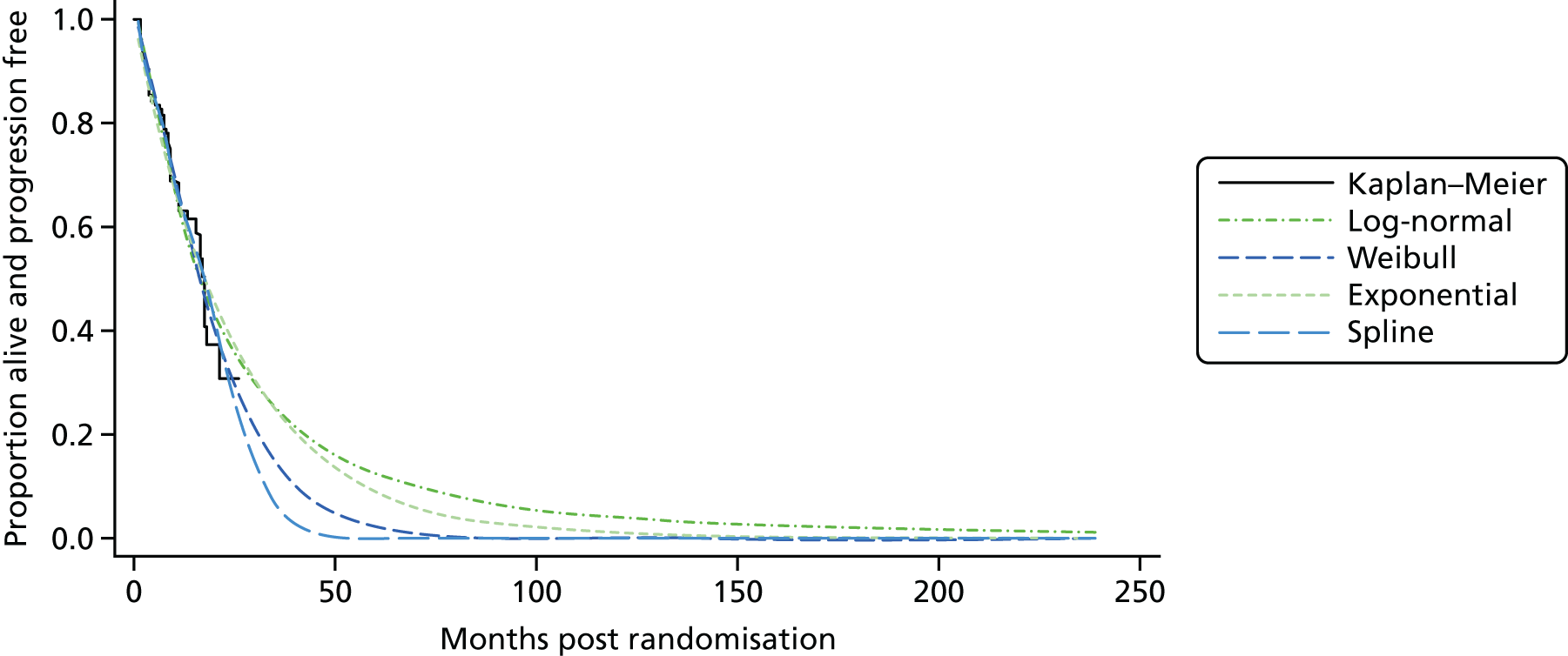

Kaplan–Meier curves are presented for RADIANT-334 (local and central review) and A618111181 (local review) in Figures 2 and 3 respectively.

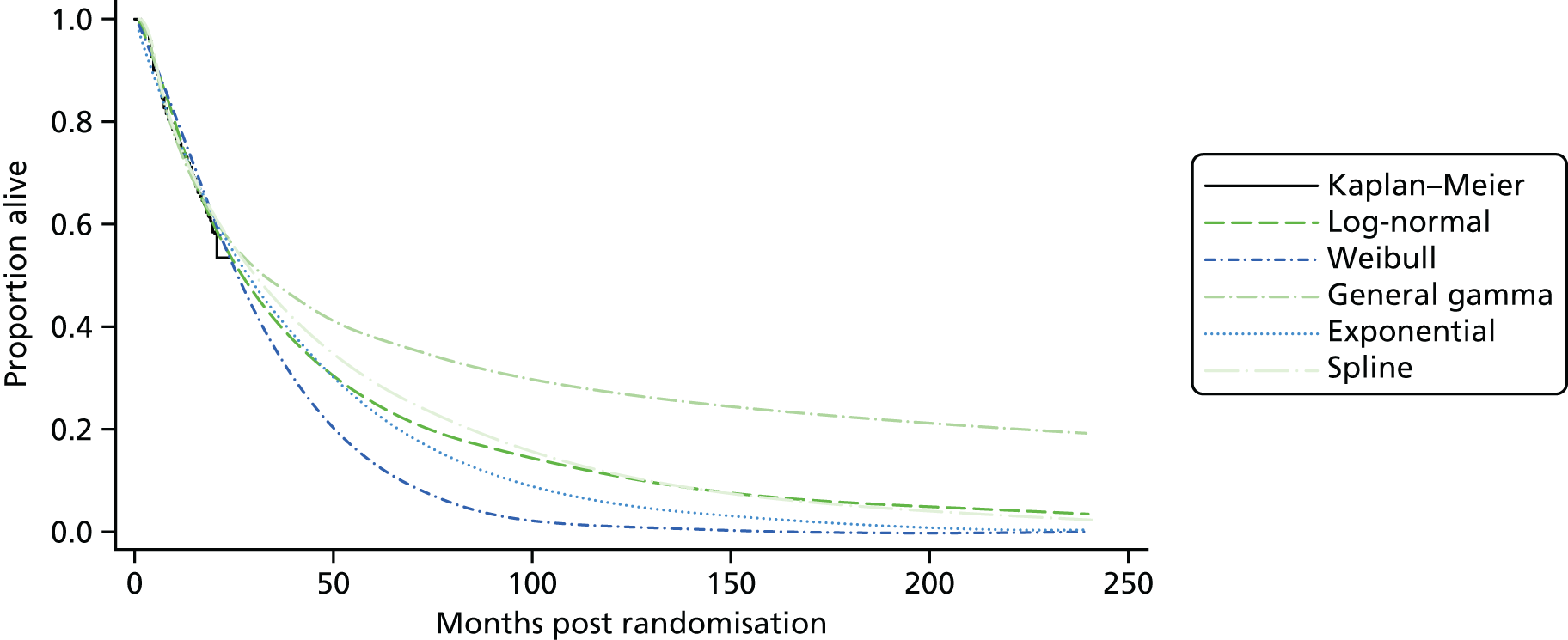

FIGURE 2.

Kaplan–Meier plots for PFS in RADIANT-3. 34 (a) PFS assessed by local review – Kaplan–Meier medians: everolimus 11.0 months, placebo 4.6 months; HR 0.35 (95% CI 0.27 to 0.45; p < 0.001 by one-sided log-rank test); (b) central review – Kaplan–Meier median: everolimus 11.4 months, placebo 5.4 months; HR 0.34 (95% CI 0.26 to 0.44; p < 0.001 by one-sided log-rank test). Source: figure 4.3 (p. 39) of the Novartis submission. 33

Overall survival

Both of the pNET studies (RADIANT-334 and A618111181) reported some data relating to OS.

It was reported for RADIANT-334 that the OS data were immature: ‘median overall survival was not reached at the time of this analysis . . . final analysis of overall survival will be performed once approximately 250 deaths have occurred’. 34 In addition, of the 203 people initially assigned to receive placebo in RADIANT-3,34 172 (85%) received open-label everolimus and 148 (73%) crossed over from placebo to everolimus following disease progression. By individuals crossing over from placebo to everolimus, the detection of a treatment-related survival benefit is confounded in ITT analysis. In RADIANT-334 the HR for OS was 1.05 (95% CI 0.71 to 1.55; see Table 5).

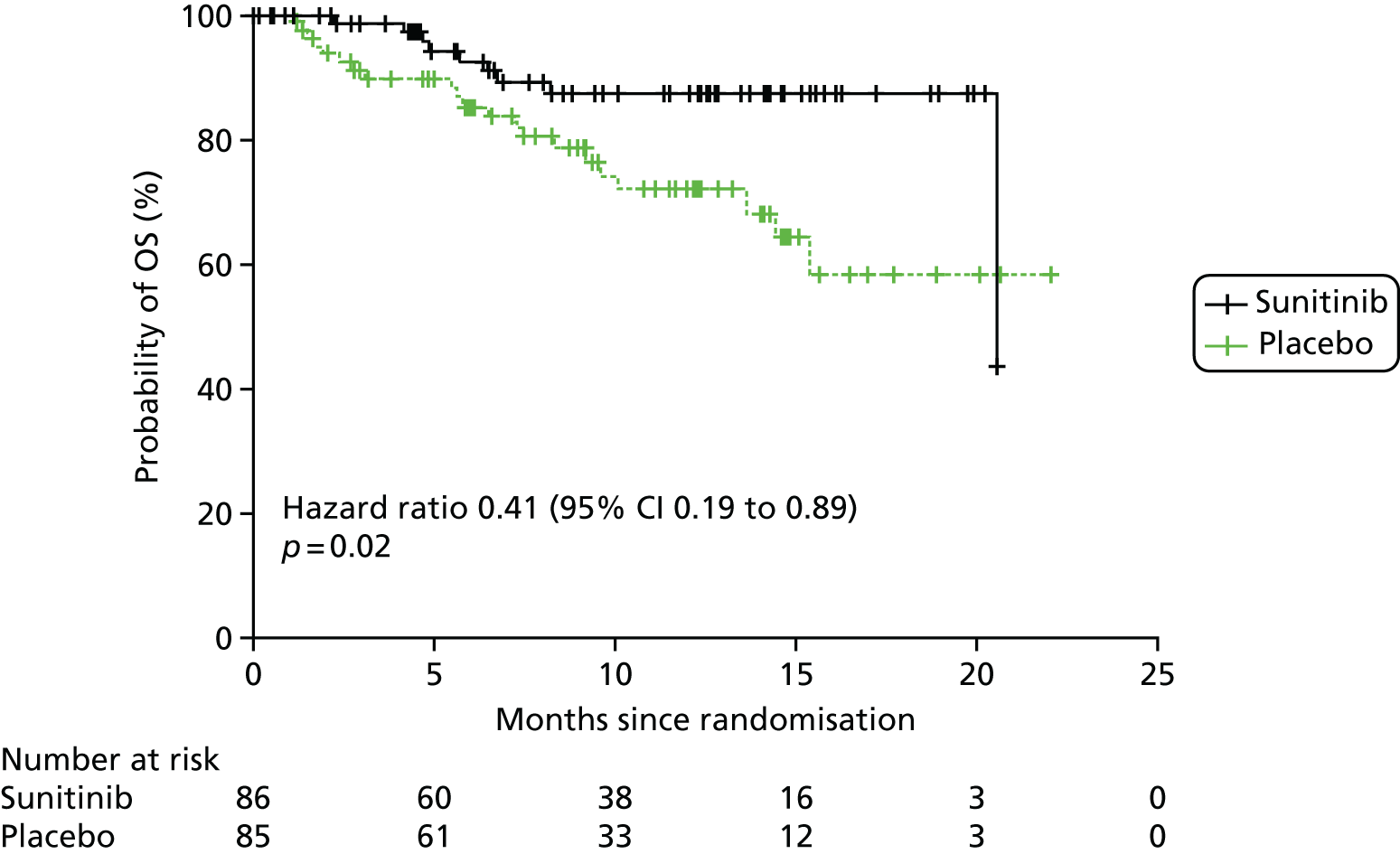

As it had not been reached, median OS was not reported for A6181111;81 instead, survival probability at month 6 was reported. Survival was predicted to be higher in the sunitinib arm (92.6%, 95% CI 86.3% to 98.9%) than in the placebo arm (85.2%, 95% CI 77.1% to 93.3%). Survival was improved by 59% following sunitinib treatment compared with placebo (HR 0.41, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.89; see Table 5).

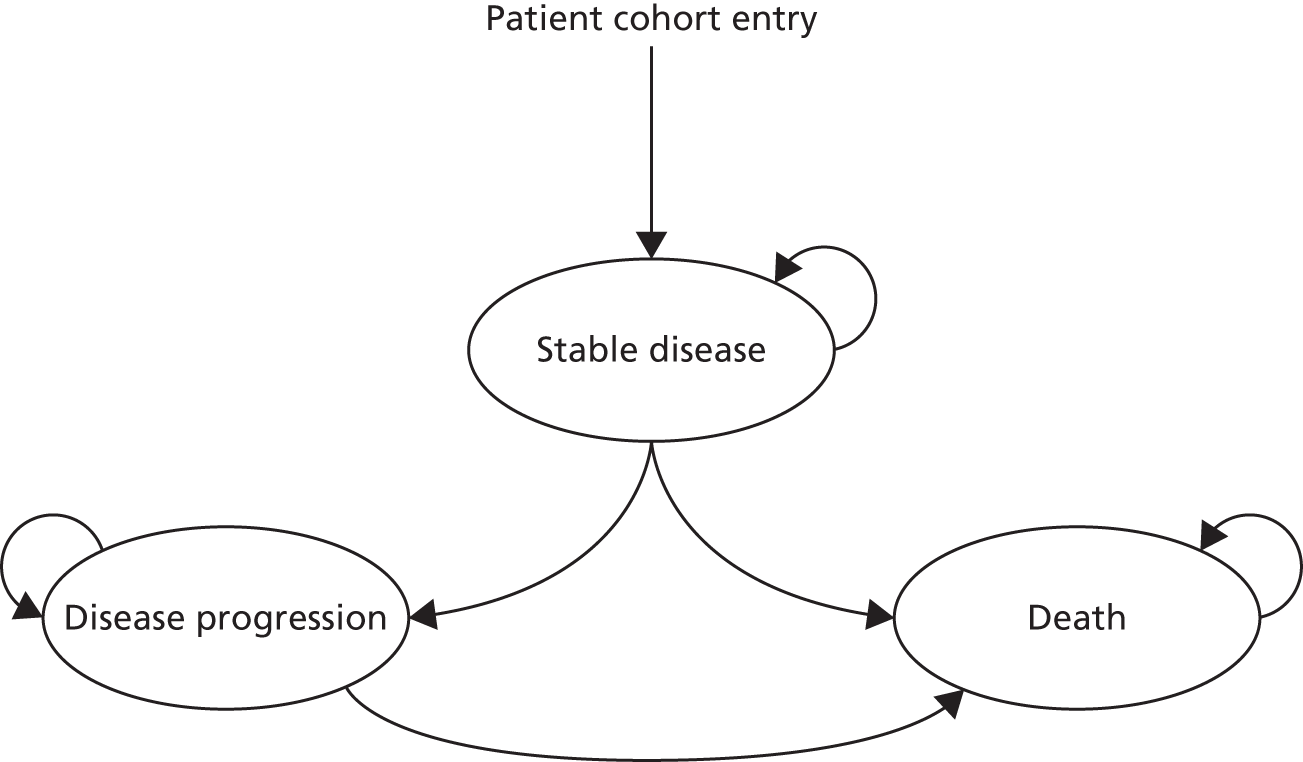

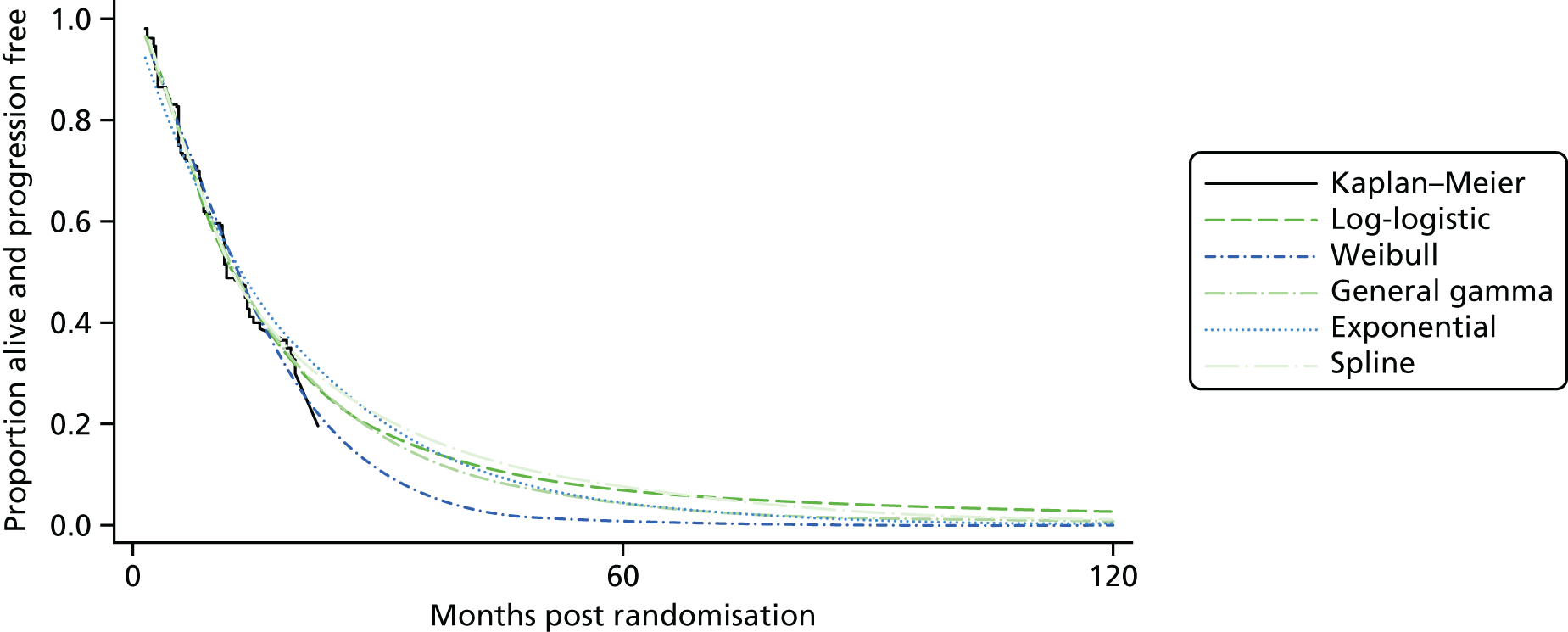

Both companies [Novartis33 for everolimus (RADIANT-334) and Pfizer32 for sunitinib (A618111181)] presented updated OS data in their submission.