Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 13/144/01. The contractual start date was in October 2015. The draft report began editorial review in November 2017 and was accepted for publication in March 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Understanding Frames is independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under its Health Technology Assessment programme (13/144/01). Anna Basu and Niina Kolehmainen report grants from NIHR outside the submitted work. Anna Basu reports employment as consultant paediatric neurologist in the Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and an educational grant from Ipsen outside the submitted work. Sarah Crombie is employed by Sussex Community NHS Foundation Trust and works at Chailey Clinical Services, which supply standing frames. From 2013 to 2016, Elaine McColl was an editor for the NIHR Programme Grants for Applied Research programme and her employer received a fee for her work. Andrew Roberts and Keith Miller are employed by the Robert Jones and Agnes Hunt Orthopaedic Hospital, which designs, builds and supplies standing frames within the NHS. Jill Cadwgan reports honoraria from Ipsen for delivery of a lecture and support for the development of training materials for botulinum toxin treatment outside the submitted work.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Goodwin et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background and aims

Context

Cerebral palsy (CP) affects 1 in 400 children and young people. CP is associated with spasticity and secondary musculoskeletal complications. Twenty-five per cent of young people with CP are non-ambulant [Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS) levels IV or V]. 1,2 These young people frequently experience joint contractures, loss of bone mineral density (BMD), fractures and hip dislocation, leading to pain and progressive disability. 3 Postural management, including standing frame use, is recommended4 and widely used in clinical practice for young people with CP. A standing frame has a rigid frame with a wide base. A child is positioned in the standing frame with variable support that may enable movement of the head, upper body and upper limbs, thus potentially improving their function and participation. For the lower limbs, standing is usually passive (i.e. continuous and stationary loading) but can be dynamic (i.e. simulating the forces applied during natural walking). Standing frames are predominantly used in non-ambulant young people (GMFCS III–V), but in the younger age range it may also be used in those with some independent mobility (GMFCS III).

Research objectives

The overall purpose was to answer the question: what is the likely acceptability of a trial to determine the clinical effectiveness of standing frames? To do this, we undertook two surveys as well as focus groups and in-depth interviews to assess the feasibility and potential design of a trial (or trials) of standing frame use for young people with CP.

Aims and objectives

Aim 1. To determine current standing frame use in UK practice for the postural management of young people with CP aged 1–18 years with severe movement impairment (GMFCS IV and V).

This aim was addressed by:

-

Objective 1: conduct a survey (survey 1) of parents, health-care providers and education staff to determine current standing frame use for young people with CP. The questions comprised treatment indications, treatment goals, types of frame, duration of intended and actual use, and perceptions and practicalities of standing frame use.

Aim 2. To assess the willingness of parents to have their child randomised in a potential trial, including the acceptability of different treatment regimens, and to assess the preparedness of health-care providers to recruit to a potential randomised controlled trial (RCT).

This aim was addressed by:

-

Objective 2: undertake qualitative research to explore attitudes to standing frame use and acceptability of evaluating their benefit through a trial or trials. This comprised (1) focus groups with parents, health-care providers and education staff and (2) in-depth interviews with young people.

-

Objective 3: propose a small number of potential trial designs, structured around a population, intervention, comparison, outcome, timing, setting (PICOTS) framework and informed by the results of survey 1 and the qualitative research.

-

Objective 4: conduct a second survey (survey 2) of parents, health-care providers and education staff regarding the acceptability and feasibility of these potential trial designs.

Aim 3. To propose a substantive trial design (or designs) that is informed by, and acceptable to, parents and health-care providers.

This aim was addressed by:

-

Objective 5: combine the results from survey 1, focus groups, interviews and survey 2 to develop a substantive trial design or designs.

Literature review

A consensus statement4 recommended the use of standing frames as part of a postural management programme for young people with CP (GMFCS IV and V) from the age of 12 months, but acknowledged the lack of an evidence base for this intervention; the evidence that there was came from small case series, which were not blinded or randomised.

Reviews of standing frames5–7 and this Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme-commissioned call concurred that the evidence base was limited. The most recent review7 claimed a positive effect on BMD, hip stability and joint range of movement at the hip, knee and ankle with variable duration of standing frame use, but Fehlings et al. 6 found the evidence unconvincing. Frames may also be disadvantageous. Young people have reported pain and discomfort, and families have reported increased demands on their time. 5 Furthermore, standing frames are expensive (they cost around £800–2500 each), require adaptation with the young person’s growth and use therapist time to prescribe and monitor their use. We are aware of a UK group currently conducting a systematic review of supported standing in CP, although we were advised that it will not be published until 2018 (Rachel Rapson, Bidwell Brook School, 2017, personal communication).

Gibson et al. 8 conducted a small case series that examined the effect of standing frame use for 1 hour every day for 6 weeks in five non-ambulant young people with CP, aged 6–9 years. Two 6-week intervals of standing frame use were alternated with two 6-week periods of no standing frame use. There was a suggestion of an improvement regarding hamstring stretches with standing frame use.

Caulton et al. 9 reported a RCT of a standing frame programme on BMD in 26 prepubertal young people (aged 4–11 years) with CP. This was a heterogeneous group, paired according to vertebral and tibial BMD scores and then randomised to either their usual standing duration or 50% increased duration of standing. There was, on average, an increase of 6% in vertebral BMD in the intervention group but no significant change in proximal tibial BMD in either group. The authors concluded that by increasing vertebral BMD through increased duration of standing there might be a potential to reduce risk of vertebral fractures. However, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance10 recommends that standing frames should not be used for the sole purpose of preventing low BMD.

There is variability in the amount of weight bearing in different standing frames, which may affect BMD outcomes. 11 Dynamic standing interventions may have more potential to improve bone health than passive standing frames. 12

How did the literature inform this study?

Synthesis of the literature revealed evidential equipoise (i.e. conflicting results from a weak evidence base). This justifies the need for further study, particularly to better understand the impact of standing frames at different stages in the lives of individuals with CP, with respect to their participation and subjective well-being rather than simply changes in their body structure and body function.

Current practice in the use of standing frames

Little is known about current UK practice with respect to the prescribing or actual use of standing frames, at home or in the community. Clinical experience from co-applicants suggests that most young people with CP have a physiotherapy programme that includes standing frame use, but prescription, timing, and dosage of intervention may be varied. To our knowledge, there is no previously published description of current UK practice.

Why this research is needed

There is a large population for whom obtaining clarity on the benefits of standing frame use is important. The birth prevalence of CP is about 2.5 per 1000 live births, so approximately 1740 CP births annually in England and Wales. 13 Approximately 25% of young people with CP are GMFCS level IV or V, and are therefore likely to have standing frames considered as part of their postural management.

The potential impact of standing frame use extends beyond childhood. Life expectancy in those with GMFCS level IV or V cannot be precisely estimated because published studies use different classifications of severity; however, 89% of those with only motor impairment and who need a self-propelled wheelchair lived to age 30 years, and 42% of those who could not self-propel lived to age 30 years. 14

For a young person, a standing frame may reduce risks of joint contractures, hip dysplasia and scoliosis. It may improve BMD and increase the likelihood, as a non-ambulant adult, that they will be able to assist a caregiver in a standing or weight-bearing transfer. It may reduce pain and make daily care easier. By enabling the young person to be vertical, a standing frame may improve head and trunk control; fine motor skills; gastrointestinal, bladder and respiratory function; self-esteem; and social, communicative and exploratory participation. 7

However, these are only potential benefits. The NHS needs to know if these benefits are real, given that there are significant cost implications of use and also reported negative effects: some young people experience discomfort in standing frames, and families and education staff describe practical difficulties in their use. 15

If there is clinical benefit in the use of standing frames, then the costs need to be balanced against the cost of long-term health-care needs (including quality of life), and secondary musculoskeletal complications of spasticity in CP, such as management of hip migration and dislocation, neuromuscular scoliosis, pathological fractures, pain and respiratory compromise that might have been prevented.

The NICE guideline16 for spasticity highlighted the limited evidence base for all interventions for young people with spasticity and specifically for postural management programmes. NICE proposed a trial of standing frame use for young people aged 1–3 years with GMFCS level IV or V. Our study was designed in the light of the 2013 National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) HTA commissioning brief, which widened the question to include young people < 18 years. We agreed that this was appropriate because of clinical indications for frames and changing neurodevelopmental profiles of young people at different ages.

A future trial of standing frame use would also fit with the CMO’s 2012 annual report17 which highlighted the need for research into effective intervention for long-term conditions in childhood, particularly in neurodevelopmental disorders where the health needs may be great but for which the evidence base for interventions is weak. A standing frames trial also aligns with the top research question identified for young people with neurodisability:18 does the timing and intensity of therapies alter the clinical effectiveness of therapies for infants and young children with a neurodisability? This includes strategies, dosage and direction of therapeutic interventions.

Co-applicant clinical experience shows that some parents and professionals have strong preformed views about standing frame use. Some professionals may have opinions that have been informed by their training or subsequent clinical experience, and this may lead them to making persuasive arguments to parents despite the weak evidence base. Parents in turn may have invested time, effort and faith in standing frames. Thus, although the current paucity of evidence demonstrates a clear need for evaluative research, a substantive trial will be difficult to design. The challenges for trial design arise from the heterogeneity of current practice regarding the purpose and delivery of standing frame intervention, and the many variables in each of the PICOTS frameworks that need to be considered. Depending on the young person’s neurodevelopmental profile and the goal of standing frame use, a variety of different comparators in a trial may be appropriate.

Furthermore, parents, professionals and young people report benefits of standing frames with respect to activity and participation that is not included in the current literature and has not been explored. Research needs to consider further aspects of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: Children and Youth version (ICF-CY),19 such as participation factors, along with body structure. The ICF-CY is a useful framework for examining the impact of the surrounding environment (including therapeutic interventions such as standing frames) and individual characteristics on a young person’s health-related functioning; it encompasses functions and structures of the body, activity, participation, personal factors and environmental factors.

This study was designed to address these issues and consider how a trial could be designed by determining current UK practice in the use of standing frames for young people with CP and by consultation with young people, parents and professionals who use standing frames.

Chapter 2 Methodology

During the conduct of this study we adopted a view of health as conceptualised by the ICF-CY. 19

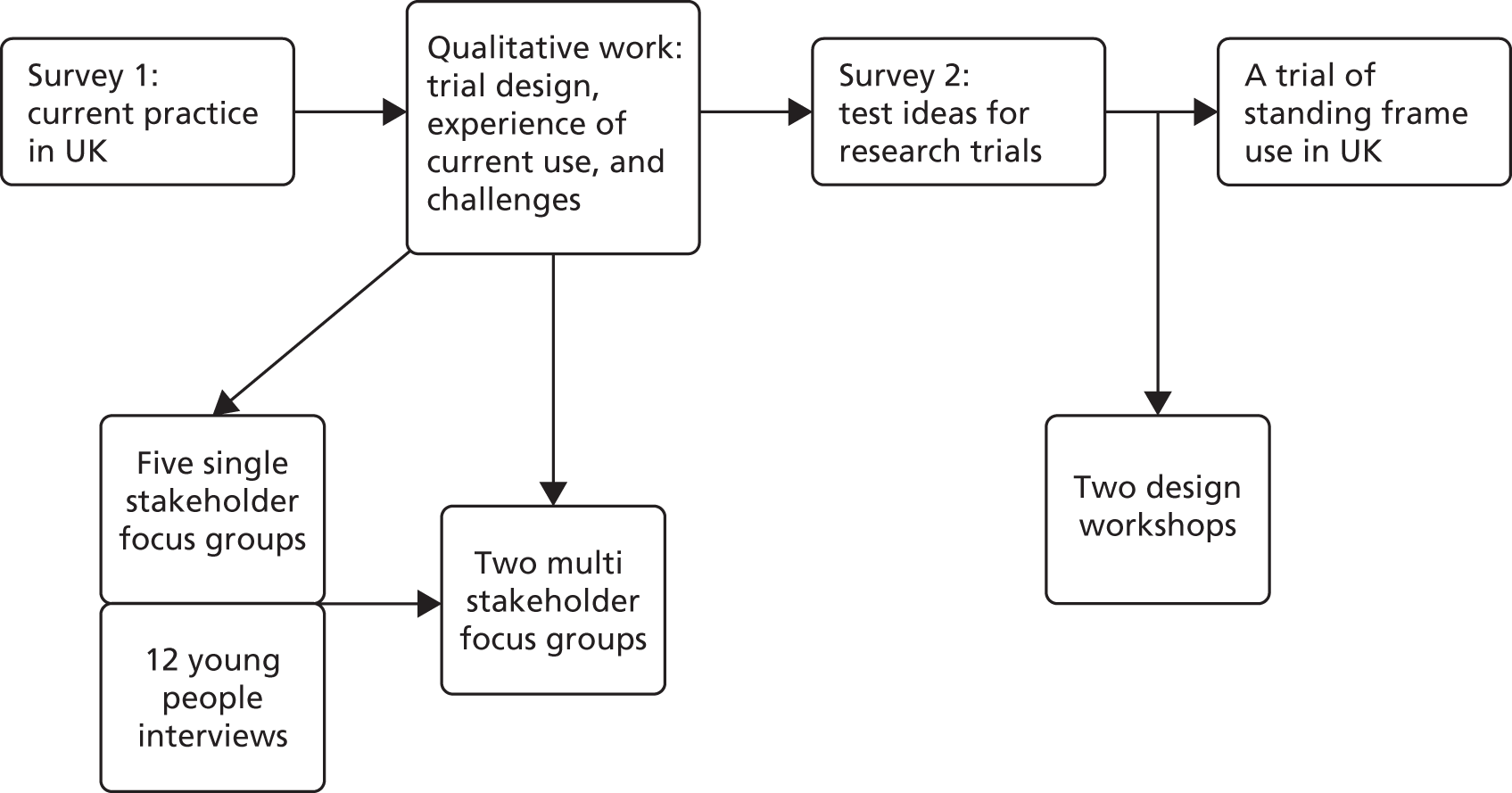

We used a sequential mixed-methods design, as outlined in Figure 1, whereby the findings from each stage informed the subsequent stage. The quantitative and qualitative findings are synthesised in Chapters 9 and 10. This process involved accounting for convergence (i.e. providing research recommendations) and divergence (i.e. highlighting potential challenges) between the data sources. People could take part in all stages if eligible, with the exception of the multistakeholder focus groups. Single stakeholder focus group participants could not participate in the multistakeholder focus groups.

FIGURE 1.

Flow of sequential mixed-methods design.

There were multiple study populations: prescribing professionals, professionals who work with standing frame users, parents of young people who currently use or have previously used a standing frame and young people who currently use or have previously used a standing frame.

Analysis

Quantitative data analysis was descriptive, largely reporting percentages of respondents in each category for each question. For survey 2, if there was a large spread of responses for particular items, the related open-ended responses were examined and then grouped into themes to explore the reasons behind participants’ closed-answer choices.

The qualitative analysis was informed by the framework method,20 which is not aligned with a particular epistemological or philosophical approach. 21 The framework method was chosen because it allowed for systematic data analysis that was accessible for our multidisciplinary research team. Table 1 outlines the stages of analysis. We used a deductive–inductive approach; although certain themes and codes were preselected based on the ICF-CY or the PICOTS, any new themes that were elicited were added to the framework and codes were then created. NVivo qualitative data analysis software version 11 (QSR International, Warrington, UK) was used to manage the data.

| Stage | Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | Verbatim transcription |

| 2 | Familiarisation with the interview (e.g. reading and rereading transcripts, relistening to the audio-recording) |

| 3 | Coding as per the ICF-CY. Although deductive coding was used, some open coding took place at this stage to ensure that important aspects of the data were not missed |

| 4 | Developing a working analytical framework through discussion and definition of labels after coding the first three interviews |

| 5 | Applying the analytical framework by indexing subsequent transcripts using existing codes |

| 6 | Charting data into the framework matrix (i.e. data were summarised by category for each transcript, with illustrative quotations) |

| 7 | Interpreting the data through discussion, reflection and writing up |

Reflexivity

All of the research team were active in disability research. Anna Basu, Jill Cadwgan, Sarah Crombie, Andrew Roberts, Jeremy R Parr, Keith Miller and Niina Kolehmainen work clinically with young people with CP who use standing frames. Johanna Smith is a parent of a young person with CP who uses a standing frame.

Mixed-methods design

A mixed-methods (qualitative and quantitative) design was chosen to provide a comprehensive means of researching this topic. Mixed-methods research has many benefits such as the ability to have an exploratory approach (rather than needing clear hypotheses), richer data from a variety of stakeholders and greater confidence in research findings through a holistic examination. Using only quantitative methods can produce results that may not reflect stakeholders’ experiences accurately because the researchers’ own agendas are driving the study. Using only qualitative methods can produce findings that are not generalisable to the understanding or prediction of issues affecting the wider population. Using both allows for weight to be given to the meanings, experiences and views of a variety of stakeholders. 22 Another advantage is that paradoxes between the data sources can open up new ways of thinking about a particular topic and enable further theory conceptualisation and the creation of recommendations for future research. 23

Trustworthiness in qualitative research

Each focus group was facilitated by Jane Goodwin and Jan Lecouturier, with the exception of the physiotherapist focus group (JG and SC) and the medical professional focus group (JG and JC). Sarah Crombie (Physiotherapist) and Jill Cadwgan (Consultant Paediatrician In Neurodisability) were chosen as secondary facilitators in the focus groups related to their discipline because it was anticipated that their specialist knowledge would be necessary to facilitate an in-depth discussion, including answering any clinical questions. Jane Goodwin conducted all of the interviews.

We approached clinicians who completed survey 1, personal contacts and professional networks (including via social media); however, it was difficult gathering a group of clinicians at the same time in the same place for a research focus group owing to their clinical commitments and other responsibilities. Two members of the research team (KM and AR) participated in the clinician single stakeholder focus group as we experienced trouble with recruitment (including having two clinicians recruited to the focus group who did not show up on the day due to urgent clinical commitments), and because they met eligibility criteria for the target population.

All qualitative data were analysed by Jan Lecouturier and Jane Goodwin. Although they had experience in disability research, they were naive about standing frames in research and clinical practice. This meant that they were fully in equipoise at the point of data collection. They had a greater awareness of stakeholders’ views about standing frames at the end of the focus groups and interviews, but, as these views were mixed, it is unlikely that they would have had any influence on the interpretation of the data at the analysis stage. They also independently coded all transcripts. A robust discussion followed to resolve any discrepancies, of which there were few. The coding was discussed and clarified with the co-applicants as a means of quality control and rigour check. Clinical members of the co-applicant team (e.g. JC, SC and AB) and the parent co-applicant (JS) were available to sense check the meaning of the transcripts and advise on the interpretation. Each researcher remained conscious of their biases to avoid them negatively influencing the analysis and write up. However, it is important to note that the researchers’ relevant knowledge and experience was also a strength because it allowed for in-depth engagement with the data, including unexpected themes. The transcripts and recordings were referred to continuously to ensure that the analysis and interpretation were staying true to the data. Quotations from participants are provided as supporting evidence for the themes. The transparent audit trail in NVivo 11 accounted for the systematic examination at each level of analysis.

Patient and public involvement

Patient and public involvement (PPI) was vital to this study from the outset; we outline PPI contributions at each stage. PPI was important for piloting surveys, creating topic guides and providing advice on interviewing young people with CP. A nominated Research Advisory Group (RAG) with six parents of young people with CP was convened. The parents were approached through the parent co-applicant’s (JS’s) contacts. A flexible approach to PPI was taken; as a result of the nature of parents’ caring roles and the complexity of CP, it was difficult at times for our nominated RAG to engage as outlined in the study timelines. Therefore, informal discussions with families known to the co-applicant team were held throughout, as well as two design workshops after all the data had been collected. In addition, the North East Young Persons Advisory Group was approached, with co-applicant Johanna Smith presenting and receiving feedback on study content at two of its meetings. This group comprises teenagers in the local area who are interested in medical research. Although at the time of our contact there were no members with CP, some had siblings or friends affected by disability. The young people provided invaluable input on how to engage young people in research and PPI. They also contributed extensively to a booklet of interview findings, which was then sent to the young people who participated in the interviews.

We learnt valuable lessons about the involvement of parents in PPI. We found that an online RAG allowed parents to engage in the study on their own terms [six parents joined a private Facebook (Facebook, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA; www.facebook.com) group for this purpose]. For example, they could provide feedback on documents in their own home after their children had gone to bed. Furthermore, the parent co-applicant (JS) ensured that the study was grounded in what was accessible (e.g. language used in documents), acceptable and reasonable (e.g. appropriate times to approach for consent), and feasible (e.g. which trial designs would be possible pragmatically) for families at all times. For example, from a research design perspective, a trial could (in theory) have recruited families to a ‘delayed start’ research study at the time of standing frame prescription because many families have a lengthy waiting period before receiving the prescribed standing frame anyway. Although acceptable to other participant groups, parent participants had commented that this would be unacceptable because it would be around the same time as the child’s CP diagnosis. Given the amount of complex information being processed by families during this time it would be difficult to ascertain informed consent to participate in a research trial. The appropriate weight may not have been given to the parents’ voices if Johanna Smith had not continued to speak on their behalf in research team meetings.

Research Ethics Committee approval and study governance

The study sponsor was Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. The research was approved by the Health Research Authority East Midlands – Nottingham 1 Research Ethics Committee (15/EM/0495, 9 December 2015).

Changes to the protocol

Originally, the protocol stated that four of the focus groups would be single stakeholder, one each for parents, therapists, medical staff (orthopaedic surgeons and paediatricians) and educational professionals. However, the parent co-applicant (JS), PPI advisors and other parents highlighted that it would be difficult for parents to travel long distances to attend a focus group, and that there may be important differences in opinion that are associated with where the parents live. After discussion, we decided to convene two parent focus groups, one in the north of England and one in the south. This was a substantial amendment and, therefore, required review and approval from the Research Ethics Committee. These were the only changes to the protocol (version 4, May 2016).

Initially, participants in the multistakeholder focus groups were going to be selected from those who had previously taken part in the single stakeholder focus groups. After co-applicant discussion, we decided to recruit new participants for the multistakeholder groups. This was because our knowledge about the acceptability and feasibility of a research trial had evolved, and we did not want to replicate the discussion in the single stakeholder focus groups.

Chapter 3 Survey 1: UK standing frame practice

Objectives

A survey was conducted from March to May 2016 to determine current UK standing frame practice, as well as the perceived benefits and challenges of standing frame use.

Methods

Population

Three populations in the UK were sampled:

-

professionals, such as physiotherapists, who prescribe standing frames for young people with CP

-

professionals, such as paediatricians, orthopaedic surgeons, physiotherapists, and education staff, who do not prescribe standing frames but work with young people with CP who use them

-

parents of young people (aged < 18 years) with CP who currently use or have used a standing frame.

Questionnaire development: UK standing frame practice

A questionnaire was developed to explore current standing frame practice. Following a literature review, parents and paediatric health professionals were consulted regarding ideas for appropriate questionnaire content. Based on this information, the co-applicant study group devised the content of the questionnaires, drawing on their clinical expertise and background experience of survey design for similar studies. Multiple drafts were circulated via e-mail and discussed prior to production of the three final drafts, that is, separate versions for the three populations sampled for this study (prescribers, professionals and parents). These drafts were then piloted with a small number of people known to the researchers (i.e. three prescribers, six professionals and five parents. Prescribers and professionals who worked across both private practice and the public sector were asked to respond in relation to their public sector work). Based on PPI advice, piloting using cognitive interviews was considered but rejected. The individuals provided feedback regarding the comprehensibility and acceptability of the questions and associated instructions, as well as the usability and technical functionality of the electronic questionnaire. Minor changes, such as wording and question logic, were made at this time. The authors then reviewed the questionnaires again in a co-applicant meeting prior to dissemination.

The final survey questions comprised: (1) demographic characteristics of respondents, (2) experience and use of standing frames as part of a postural management programme for young people with CP, (3) factors influencing standing frame choice and prescribing practice, (4) challenges of standing frame use, (5) indications for prescribing standing frames and (6) perceived benefits of standing frame use. The survey also identified any differences between recommended or prescribed use versus actual use. Most questions offered fixed-choice responses, though there were some brief free-text responses. Participants could use a ‘back’ button to review or change their answers as required (see Appendices 1–3).

Procedure

A convenience sample of prescribing clinicians and non-prescribing professionals were approached through relevant national royal colleges, professional bodies and their national newsletters, and child development teams via the British Academy of Childhood Disability. Parents were approached via clinical services located in the North, South, and West Midlands of England, and through the following national organisations: the National Network of Parent Carer Forums, Contact a Family and the Peninsula Cerebra Research Unit for Childhood Disability Research. In addition, we approached parents directly through school newsletters and peer-to-peer support groups. Facebook pages (e.g. Cerebra) and the study’s Twitter (Twitter, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA; www.twitter.com) feed (@UnderstandFrame) were used to allow those interested to link to the study website (https://research.ncl.ac.uk/understandingframes/) and access the questionnaire. A £10 voucher was offered to all who completed the questionnaire.

Recruitment was UK-wide and took place between March and May 2016. The survey questionnaires were hosted on SurveyMonkey® (Palo Alto, CA, USA), with paper versions available on request. E-mail and web-based flyers were sent to potential participants with a link to the appropriate version of the questionnaire.

Results

Participants

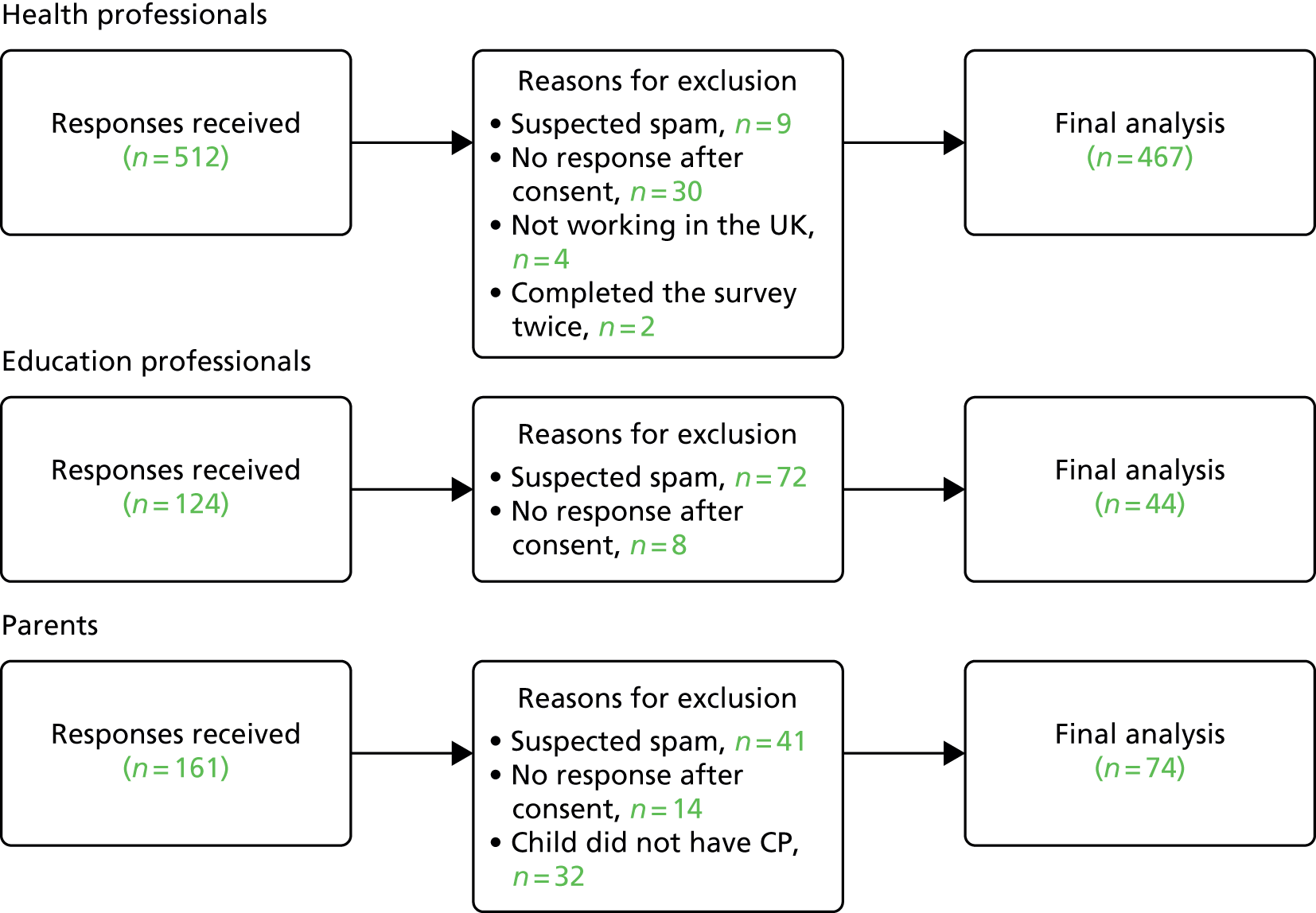

Numbers included in the final analysis are presented here. Figure 2 indicates participant flow through the study from responses received to responses included in the final analysis.

-

Prescribing clinicians: professionals, such as physiotherapists, who prescribe standing frames for young people with CP, n = 305.

-

Non-prescribing professionals: professionals, such as paediatricians, orthopaedic surgeons, physiotherapists and education staff, who do not prescribe standing frames but work with young people with CP who use them, n = 155.

-

Parents: parents of young people with CP who currently use or have used a standing frame, n = 91.

FIGURE 2.

Survey 1: participant flow through the study from responses received to responses included in the final analysis.

Tables 2 and 3 outline the respondent characteristics. Most prescribing clinicians and a large number of non-prescribing professionals were physiotherapists working in community settings. The majority had > 10 years’ experience and used a variety of standing frame types.

| Characteristics | Prescribing clinicians, n (%) | Non-prescribing professionals, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Occupation | ||

| Physiotherapist | 302 (99) | 49 (31.6) |

| Occupational therapist | 1 (0.3) | 39 (25.2) |

| Paediatrician | 0 | 29 (18.7) |

| Classroom teacher or support teacher | 0 | 15 (9.6) |

| Therapy assistant or technical instructor | 1 (0.3) | 11 (7.1) |

| Other health professional | 0 | 7 (4.5) |

| Technician – engineering background | 0 | 3 (1.9) |

| Orthopaedic surgeon | 0 | 2 (1.3) |

| Missing | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Current working environmenta | ||

| Inpatients | 34 (11.1) | 32 (20.6) |

| Outpatients | 153 (50.2) | 77 (49.7) |

| Community – home | 263 (86.2) | 79 (51) |

| Community – education centre (school/preschool) | 279 (91.5) | 107 (69) |

| Other | 1 (0.3) | 6 (3.9) |

| Missing | 4 (1.3) | 2 (1.3) |

| Number of children on current case load who are prescribed standing frames | ||

| < 10 children | 126 (41.3) | 66 (42.6) |

| 11–20 children | 123 (40.3) | 35 (22.6) |

| 21–30 children | 23 (7.5) | 12 (7.7) |

| > 30 children | 21 (6.9) | 20 (12.9) |

| Missing | 12 (3.9) | 8 (5.2) |

| Did not know | – | 14 (9) |

| Years working with children who use standing frames | ||

| < 2 | 25 (8.2) | 14 (9) |

| 2–5 | 44 (14.4) | 24 (15.5) |

| 6–10 | 59 (19.3) | 32 (20.6) |

| > 10 | 173 (56.7) | 83 (53.5) |

| Missing | 4 (1.3) | 2 (1.3) |

| Groups of children with whom the clinicians worka | ||

| GMFCS I | 15 (4.9) | 9 (5.8) |

| GMFCS II | 79 (25.9) | 33 (21.3) |

| GMFCS III | 244 (80) | 74 (47.7) |

| GMFCS IV | 289 (94.8) | 105 (67.7) |

| GMFCS V | 277 (90.8) | 95 (61.3) |

| Would rely on prescriber | – | 25 (16.1) |

| Reported not familiar with GMFCS | 5 (1.6) | 12 (7.7) |

| Missing | 12 (3.9) | 9 (5.8) |

| Experience with types of standing framea | ||

| Fixed prone standing frame | 282 (92.5) | 116 (74.8) |

| Upright standing frame | 282 (92.5) | 136 (87.7) |

| Supine standing frame | 281 (92.1) | 111 (71.6) |

| Dynamic frame | 162 (53.1) | 53 (34.2) |

| Sit-to-stand frame | 116 (34.8) | 33 (21.3) |

| Missing | 13 (4.3) | 12 (7.7) |

| Children whose parents responded | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Child’s distribution of CP | |

| Whole body | 72 (79.1) |

| Both sides of the body but legs more than arms | 14 (15.4) |

| One side of the body only | 5 (5.5) |

| Missing | 0 |

| Child’s school typea | |

| Specialist school | 68 (74.7) |

| Mainstream | 29 (31.9) |

| College (post 16 years of age, with additional or special provision) | 5 (5.5) |

| Other | 11 (12.1) |

| Missing | 4 (4.4) |

| Child’s age (years) | |

| > 10 | 46 (50.5) |

| 6–10 | 25 (27.5) |

| 2–5 | 14 (15.4) |

| < 2 | 1 (1.1) |

| Missing | 5 (5.5) |

| Child’s estimated GMFCS level | |

| GMFCS I or II | 8 (8.8) |

| GMFCS III | 20 (22) |

| GMFCS III or IV | 10 (11) |

| GMFCS IV | 36 (39.6) |

| GMFCS V | 17 (18.7) |

| Missing | 0 |

| Experience with types of standing framea | |

| Fixed prone standing frame | 34 (37.4) |

| Upright standing frame | 43 (47.3) |

| Supine standing frame | 32 (35.2) |

| Dynamic frame | 10 (11) |

| Sit-to-stand frame | 6 (6.6) |

| Missing | 0 |

| Funding source for standing framea | |

| Statutory services (health, social care or education) | 76 (83.5) |

| Charity funding | 7 (7.7) |

| Private or self-funding | 7 (7.7) |

| Did not know | 3 (3.3) |

| Missing | 8 (8.8) |

| Professional who assessed and fitted the standing framea | |

| Physiotherapist | 78 (85.7) |

| Occupational therapist | 23 (25.3) |

| Frame manufacturer or representative | 21 (23.1) |

| Paediatrician | 2 (2.2) |

| Therapy assistant or technical instructor | 5 (5.5) |

| Did not know | 3 (3.3) |

| Missing | 8 (8.8) |

| Professional who monitors the use of the standing framea | |

| Physiotherapist | 74 (81.3) |

| Occupational therapist | 25 (27.5) |

| Frame manufacturer or representative | 6 (6.6) |

| Therapy assistant or technical instructor | 8 (8.8) |

| Paediatrician | 1 (1.1) |

| Did not know | 2 (2.2) |

| Missing | 14 (15.4) |

Sixty-five per cent of parents had children who used or had used only one type of standing frame that was assessed, fitted and monitored by a physiotherapist. The standing frames were generally funded by statutory services (see Table 3).

Children of the parent respondents were aged 1–18 years (median 10 years and 6 months). They began standing frame use at 1–11 years (median 3 years) and stopped use at 3–16 years (median 9 years and 7 months). Waiting times to receive a standing frame after it had been recommended ranged between the response options ‘less than 4 weeks’ and ‘more than 26 weeks’ (see Table 8).

Patient and public involvement work had indicated that asking parents to categorise their child based on their GMFCS level was inappropriate. Therefore, we estimated the GMFCS level from reported information about independent walking, use of mobility aids, weight bearing and maintenance of head position. However, for ten young people, it was not possible to determine whether they were GMFCS III or GMFCS IV based on the information provided. We therefore categorised them as ‘GMFCS III or IV’ (see Table 3).

Prescribing practice and actual use of standing frames

Standing frame recommendations and prescriptions for use were primarily based on clinical experience rather than national or local guidance, as reported by both non-prescribing professionals and prescribing clinicians (81% and 89%, respectively).

Of prescribing clinicians, 82% suggested that standing frames should be used daily; however, only 21% of parents reported that this was achieved. Furthermore, 76% of prescribers recommended that the duration of standing should be 30–60 minutes, yet only 39% of parents reported this duration of use (Tables 4–6). In terms of frequency of standing frame use, 59% of parents reported at least as much use as prescribed, and 91% reported a duration at least as much as described (see Tables 5 and 6).

| Frequency and duration of use | Prescription of prescribing clinicians, n (%) | Views of non-prescribing professionals, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Frequency of use | ||

| Every day | 251 (82.3) | 93 (60) |

| More than three times each week | 38 (12.5) | 15 (9.7) |

| More than once each week | 0 | 0 |

| Once each week | 0 | 0 |

| Less than once each week | 0 | 0 |

| Did not know | – | 27 (17.4) |

| Missing | 16 (5.2) | 20 (12.9) |

| Duration of standing | ||

| < 30 minutes | 9 (3) | 4 (2.6) |

| 30–60 minutes | 233 (76.4) | 66 (42.6) |

| 1–2 hours | 46 (15.1) | 18 (11.6) |

| > 2 hours | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.6) |

| Did not know | – | 46 (29.7) |

| Missing | 16 (5.2) | 20 (12.9) |

| Prescribed usea | Actual usea | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Every day | More than three times each week | More than once each week | Once each week | Less than once each week | Did not know | |

| Every day | 13 | 5 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| More than three times each week | 1 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| More than once each week | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Once each week | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Less than once each week | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| I do not know | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Prescribed usea | Actual usea | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| > 2 hours | 1–2 hours | 30–60 minutes | Less than 30 minutes | Not recommended in this location (home or school) | Did not know | |

| > 2 hours | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1–2 hours | 0 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 30–60 minutes | 0 | 1 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| < 30 minutes | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 1 |

| Not recommended in this locationb (home or school) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Did not know | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

Professionals considered a variety of factors, including physical space and cost, when choosing standing frames. They generally considered starting standing frame use by 18 months of age (Table 7).

| Factors | Prescribing clinicians, n (%) | Non-prescribing professionals, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| External factors influencing choice of standing frame | ||

| Physical space | 225 (73.8) | 88 (56.8) |

| Cost of standing frames or funding pathways | 214 (70.2) | 96 (61.9) |

| Availability of standing frames | 206 (67.5) | 87 (56.1) |

| Parent or young person choice of standing frame | 163 (53.4) | 63 (40.6) |

| Other | 45 (14.7) | 22 (14.2) |

| Missing | 19 (6.2) | 20 (12.9) |

| Age at which they would first consider starting standing frame use | ||

| < 6 months | 1 (0.3) | 4 (2.6) |

| 7–12 months | 75 (24.6) | 29 (18.7) |

| 13–18 months | 171 (56.1) | 57 (36.8) |

| 19–24 months | 34 (11.1) | 29 (18.7) |

| 25–30 months | 4 (1.3) | 9 (5.8) |

| > 30 months | 5 (1.6) | 10 (6.5) |

| Missing | 15 (4.9) | 17 (11) |

Most professionals and parents reported waiting times for standing frames to be up to 13 weeks from identification of need to commencing a standing frame programme (Table 8).

| Average waiting time | Prescribing clinicians, n (%) | Non-prescribing professionals, n (%) | Parents, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| < 4 weeks | 23 (7.5) | 3 (1.9) | 16 (17.6) |

| 4–8 weeks | 106 (34.8) | 25 (16.1) | 25 (27.5) |

| 9–13 weeks | 86 (28.2) | 18 (11.6) | 12 (13.2) |

| 14–20 weeks | 29 (9.5) | 10 (6.5) | 5 (5.5) |

| 21–25 weeks | 5 (1.6) | 1 (0.6) | 2 (2.2) |

| > 26 weeks | 2 (0.7) | 0 | 5 (5.5) |

| Did not know | 38 (12.5) | 82 (52.9) | 15 (16.5) |

| Missing | 16 (5.2) | 16 (10.3) | 11 (12.1) |

Tables 9 and 10 show that most prescribing clinicians suggested that standing frame use should be monitored (for suitability of the standing frame) and reviewed (for the suitability of the standing frame programme) every 3 months or more often.

| Monitoring: ideal | Monitoring: in practice | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| More than once per week | Weekly | Fortnightly | Monthly | Every 3 months (or termly) | Less than termly | When requested | |

| More than once per week | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Weekly | 1 | 7 | 2 | 13 | 8 | 0 | 1 |

| Fortnightly | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 9 | 0 | 0 |

| Monthly | 0 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 68 | 3 | 9 |

| Every 3 months (or termly) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 65 | 30 | 20 |

| Less than termly | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 0 |

| When requested | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Reviewing: ideal | Reviewing: in practice | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| More than once per week | Weekly | Fortnightly | Monthly | Every 3 months (or termly) | Less than termly | When requested | |

| More than once per week | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Weekly | 1 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| Fortnightly | 0 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 3 | 0 | 1 |

| Monthly | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 62 | 6 | 5 |

| Every 3 months (or termly) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 86 | 31 | 19 |

| Less than termly | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 2 |

| When requested | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 8 |

Reasons for use, and perceived benefits and difficulties associated with standing frames

Parents reported all the benefits they observed for their child, including opportunities for a change of position, participation and enjoyment in activities, and interaction with peers (Table 11). Eighty-nine per cent of parents reported more than one benefit. When parents were asked to indicate the three most important benefits of standing frames, the most frequently selected choice was the opportunity for a change of position, second was a reduced risk of hip dislocation or damage, and equal third were improvement of bladder and bowel function and a reduced risk of joint contractures (see Table 15).

| Benefits of standing frame use | Parent-reported benefits for their child, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Enjoy activities | 39 (42.9) |

| Help child communicate | 12 (13.2) |

| Help child stand independently in future | 29 (31.9) |

| Help child use their vision | 21 (23.1) |

| Help child walk in future | 17 (18.7) |

| Improve bladder and bowel functions | 52 (57.1) |

| Improve bone density/strength | 56 (61.5) |

| Improve breathing | 25 (27.5) |

| Improve motor abilities (head control) | 34 (37.4) |

| Improve motor abilities (trunk control) | 45 (49.5) |

| Improve motor abilities (upper limbs) | 40 (44) |

| Interact with peers | 42 (46.2) |

| Opportunity for a change of position | 72 (79.1) |

| Participate in activities | 52 (57.1) |

| Reduce risk of fractures | 23 (25.3) |

| Reduce risk of hip dislocation or damage | 47 (51.6) |

| Reduce risk of joint contractures | 52 (57.1) |

Prescribing clinicians and non-prescribing professionals consistently reported that they used the frames to offer the young person a change of position; improve BMD, breathing, bladder and bowel functions; reduce the risk of fractures and joint contractures; reduce the risk of hip dislocation or damage; and improve motor abilities, communication, vision, activity enjoyment, participation in activities and peer interaction (Table 12).

| Benefits | Patient age (years), n (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 5 | 5–11 | 12–18 | ||||

| Prescribing cliniciansa | Non-prescribing professionals | Prescribing cliniciansa | Non-prescribing professionals | Prescribing cliniciansa | Non-prescribing professionals | |

| Enjoy activities | 231 (75.7) | 77 (49.7) | 230 (75.4) | 79 (51) | 222 (72.8) | 77 (49.7) |

| Help child communicate | 217 (71.1) | 68 (43.9) | 217 (71.1) | 67 (43.2) | 212 (69.5) | 67 (43.2) |

| Help child stand independently in future | 59 (19.3) | 46 (29.7) | 96 (31.5) | 36 (23.2) | 55 (18) | 23 (14.8) |

| Help child to use their vision | 173 (56.7) | 58 (37.4) | 170 (55.7) | 56 (36.1) | 169 (55.4) | 54 (34.8) |

| Help child walk in future | 120 (39.3) | 29 (18.7) | 77 (25.2) | 22 (14.2) | 38 (12.5) | 15 (9.7) |

| Improve bladder and bowel function | 225 (73.8) | 66 (42.6) | 231 (75.7) | 69 (44.59) | 229 (75.1) | 65 (41.9) |

| Improve bone density/strength | 217 (71.1) | 70 (45.2) | 224 (73.4) | 71 (45.8) | 208 (68.2) | 64 (41.3) |

| Improve breathing | 205 (67.2) | 59 (38.1) | 207 (67.9) | 61 (39.4) | 208 (68.2) | 60 (38.7) |

| Improve motor abilities (head control) | 243 (79.7) | 74 (47.7) | 234 (76.7) | 75 (48.4) | 196 (64.3) | 64 (41.3) |

| Improve motor abilities (trunk control) | 221 (72.5) | 60 (38.7) | 217 (71.1) | 62 (40) | 176 (57.7) | 54 (34.8) |

| Improve motor abilities (upper limbs) | 226 (74.1) | 70 (45.2) | 222 (72.8) | 72 (46.5) | 201 (65.9) | 62 (40) |

| Interact with peers | 238 (78) | 75 (48.4) | 239 (78.4) | 76 (49) | 233 (76.4) | 73 (47.1) |

| Opportunity for a change of position | 245 (80.3) | 81 (52.3) | 246 (80.7) | 82 (51.6) | 244 (80) | 81 (52.3) |

| Participate in activities | 243 (79.7) | 79 (51) | 242 (79.3) | 81 (52.3) | 238 (78) | 79 (51) |

| Reduce risk of fractures | 175 (57.4) | 47 (30.3) | 175 (57.4) | 51 (32.9) | 172 (56.4) | 52 (33.5) |

| Reduce risk of hip dislocation or damage | 225 (73.8) | 60 (38.7) | 219 (71.8) | 63 (40.6) | 195 (63.9) | 56 (36.1) |

| Reduce risk of joint contractures | 234 (76.7) | 67 (43.2) | 237 (77.7) | 72 (46.5) | 232 (76.1) | 69 (44.5) |

Both prescribing clinicians and non-prescribing professionals reported that as well as child-specific factors, environmental and personal factors, such as cost, space for use and storage, availability of frames and parent/young person’s choice of frame also determined the most appropriate standing frame to use.

Tables 13 and 14 outline the difficulties that prescribing clinicians, non-prescribing professionals and parents experienced with the prescription and use of standing frames. Resourcing and environmental factors included funding for frames (87% of non-prescribing professionals), physical space in the home (78% of prescribing clinicians) and a child having a standing frame at nursery/school but not at home (55% of parents). Child-specific factors as identified by the respondents included needing a rest from using a frame (25.3%), dislike of using a standing frame (19.8%) and experiencing pain (14.3%). These were more frequently reported by parents of children who no longer used frames (31.6% of parents of previous users reported pain compared with 10.4% of parents of current users).

| Difficulties identified by professionals | Prescribing clinicians, n (%) | Non-prescribing professionals, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Resources | ||

| Allocation of resources or funding for frame | 183 (60) | 89 (87.4) |

| Allocation of resources for staff to prescribe/monitor use | 64 (21) | 42 (27.1) |

| Availability of parents/carers at home to help position the child | 166 (54.4) | 74 (47.7) |

| Availability of staff/carers in school to help position the child | 176 (57.7) | 72 (46.5) |

| Environment | ||

| Physical space at home | 238 (78) | 96 (61.9) |

| Physical space at school | 124 (40.7) | 53 (34.2) |

| Transportation of equipment | 106 (34.8) | 55 (35.5) |

| Other | 62 (20.3) | 26 (16.8) |

| Difficulties identified by parents | Parents (previous users and current users at home only),a n (%) | Parents (current users but not at home),b n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Resources | ||

| Time | 25 (48.1) | 4 (12.1) |

| Do not have a standing frame at home | – | 18 (54.6) |

| Using a standing frame at home was not recommended | – | 2 (6.1) |

| Availability of parents/carers to help position the child | 14 (26.9) | 9 (27.3) |

| Environment | ||

| Physical space | 19 (36.5) | 16 (48.5) |

| Sometimes moving and handling difficulties at home for child | 14 (26.9) | 6 (18.2) |

| Difficulty with access to other equipment used to position child in the frame | 10 (19.2) | 3 (9.1) |

| Child factors | ||

| Child dislikes standing in their frame | 14 (26.9) | 4 (12.1) |

| Child sometimes wants a rest from using the frame | 19 (36.5) | 4 (12.1) |

| Child experiences pain when standing in their frame | 12 (23.1) | 1 (3) |

| Other | 7 (13.5) | 6 (18.2) |

What did survey 1 add?

Survey 1 provided insight into current standing frame use. Standing frames were widely used as part of postural management for young people with CP, despite limited evidence of clinical effectiveness. Prescribing practice was generally consistent across the UK, but achieving the prescribed use was not always possible because of resources or environment/child factors. Professionals and parents of young people with CP were invested in using standing frames. They reported a variety of benefits, although they also recognised many challenges associated with standing frame use.

How did survey 1 inform the next step?

Survey 1 was primarily used to inform the content in the next stages of the Understanding Frames study; that is, single stakeholder focus groups, interviews and multistakeholder focus groups. For example, survey 1 gave the research team insight into the perceived benefits of standing frames. However, it was unclear which benefits were research priorities for different stakeholder groups. There were also specific topics and/or issues raised in survey 1 that were necessary to explore with particular stakeholder groups, and these are outlined here.

The large number of physiotherapist respondents in survey 1 demonstrated that they are a key stakeholder group with an interest and investment in standing frames. This led to the following topics for exploration: whether or not physiotherapists are prepared to recruit to a trial, their anticipated barriers to trial recruitment and what kind of outcomes that they believe would be appropriate to use to examine the clinical effectiveness of standing frames. In terms of education professionals, we wanted to explore which of the challenges identified in survey 1 were specific to the classroom. We also asked for their opinions on adherence to a standing frame prescription, and how they would feel if they could not meet such requirements for the purposes of a trial. For parents, survey 1 revealed that many older young people were not using a standing frame, particularly during the school holidays. We needed to explore whether or not suspending standing frame use for this amount of time for the purposes of a trial (or switching standing frame use for an appropriate comparator) would be acceptable to parents. We explored all of these issues in the qualitative stages of the study.

Finally, participants in survey 1 provided contact details if they wished to participate in further stages of the Understanding Frames study (e.g. focus groups). Parents also provided contact details if their child was interested in being interviewed. Therefore, survey 1 was vital for participant recruitment for the later stages of the study.

Chapter 4 First stage focus groups: single stakeholder

Objectives

Five single stakeholder focus groups were held to explore views on the design and challenges of a trial to determine the clinical effectiveness of standing frame use in young people with CP.

Methods

Population

Single stakeholder focus groups were conducted with the same populations as survey 1; that is, clinicians, physiotherapists, education staff and parents. Respondents to survey 1 provided their contact details if they were willing to take part in other stages of the research. From this, a shortlist of potential participants was created for each group to ensure a representative sample. Potential participants were contacted via telephone or e-mail (depending on the contact details they provided in survey 1); the study was explained, and if the person was interested an information sheet and invitation to attend the appropriate focus group were posted or e-mailed to them, depending on preference.

Topic guide development and conduct of focus groups

A meeting was held with co-applicants Jill Cadwgan, Jan Lecouturier, Johanna Smith and research associate Jane Goodwin to discuss how the survey 1 results should inform the topic guide, and which topics should be explored. It was agreed that information on the context (e.g. purpose of study, findings from our study so far) would be helpful. Rather than rely on attendees reading materials sent beforehand, it was decided to give a presentation [Microsoft PowerPoint® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) Presentation Manager 2013] about the study, the current evidence base and the results from our study so far. In addition, it was deemed important to explain levels of evidence and elements of trial design (i.e. PICOTS framework). Furthermore, it was suggested that we give participants time to introduce themselves, especially parents, so that there would be an informal, friendly start to the conversation with everyone given equal status. We chose a few topics to explore in detail with the aim of stimulating rich, thoughtful discussion. The topics were chosen to clarify the findings from survey 1 (e.g. why was an opportunity for change of position a benefit of standing frames?) and increase our understanding of research feasibility (e.g. would school or home be a better setting for a research trial?).

Following the meeting, there was an e-mail conversation with the wider team, and informal discussions with PPI members, as well as parents and health professionals known to the co-applicant team, were conducted. Minor adjustments were made as a result of these conversations, such as reducing the amount of information on the PowerPoint slides. We were also mindful that participants may have invested in standing frames and may not be aware that there is limited evidence for their use, and sought to handle this sensitively. The facilitators for each focus group were also decided at this stage. Each focus group had a lead facilitator and co-facilitator, at least one of whom was a qualitative researcher (JL or JG). The second facilitator was selected depending on background and logistics.

The final topic guide included (1) opinions on survey 1 results, (2) perceived benefits of standing frames, (3) challenges associated with standing frame use and (4) feasibility aspect of a future trial (see Appendix 4). Minor amendments were made to the topic guide for each group, which evolved iteratively. For example, we asked education staff about their experiences of how young people ‘perform’ in a standing frame at school, and we asked parents how they felt on learning that there is limited evidence for standing frame use. The brief PowerPoint presentation given at the beginning of the focus group, which informed the participants and framed the discussion around pertinent issues, is provided in Appendix 5.

Procedure

Five single stakeholder focus groups were conducted, with one each for physiotherapists, medical professionals and education professionals, and two for parents. One group was held for parents residing in the north and one in the south of England to ensure that we captured any geographical variation while minimising travel burden for parents.

The process of contacting and recruiting participants was identical for each of the focus groups. Potential participants were contacted via telephone or e-mail to explain the study, then an information sheet was e-mailed or posted out to them if they expressed an interest. Written consent was obtained on the day of the focus groups, before discussion commenced. Focus groups were digitally recorded with the permission of the participants. Sound files were transcribed verbatim and anonymised.

Findings

Participants

Five focus groups were convened in June and July 2016: two with parents of young people with CP (one in the North and one in the South), one with physiotherapists from around the UK (including London, Newcastle, Leeds, Leicester and Liverpool) who worked in a variety of services, one with clinicians (in the West Midlands) and one with education staff from a specialist school (in the North East). The numbers attending the groups ranged from three to nine. The numbers in one of the parent groups and the clinician group were lower than anticipated, three and five respectively, but the data were rich and all attendees participated fully in the discussion. It is important to note that because of difficulty in recruiting non-prescribing clinicians, two members of the research team (AR and KM) participated in the clinician focus group. Therefore, caution must be taken when interpreting the results, and we have indicated which quotes were from members of the research team.

Focus group format

Focus groups were scheduled for two hours including breaks. Refreshments were provided at each group. As a gesture of goodwill, attendees were offered a £10 Amazon voucher (Amazon.com, Inc., Bellevue, WA, USA). At the beginning, the study information sheet was provided to each attendee and they were given time to read through it. Written consent was obtained and ground rules agreed. Before the discussion, and to set the scene, a member of the research team gave a 10-minute PowerPoint® presentation. This presentation covered background information around the levels of evidence on which clinical decisions are made and the evidence base for standing frame use, results from the Understanding Frames survey 124 (see Chapter 3), the purpose of the focus groups and the topic questions.

Perceived benefits of standing frame use and potential outcomes for a trial

Participants in survey 1 had been asked to identify the three most important benefits of standing frame use. We then ranked these based on frequency (Table 15) and presented them on the screen, and a member of the research team summarised these verbally. The aims were to generate discussion, elicit attendees’ views on these perceived benefits and ascertain what would be useful and meaningful to measure to determine the outcome of standing frame use.

| Rank | Benefit |

|---|---|

| 1 | Opportunity for a change of position |

| 2 | Reduce risk of hip dislocation or damage |

| = 3 | Reduce risk of joint contractures |

| = 3 | Improve bladder and bowel function |

| 5 | Improve bone density/strength |

| 6 | Enjoy activities |

| 7 | Interact with peers |

| 8 | Participate in activities |

| 9 | Help child stand independently in future |

| 10 | Improve motor abilities (trunk control) |

| 11 | Improve motor abilities (upper limbs) |

| 12 | Help child walk in future |

| 13 | Improve motor abilities (head control) |

| 14 | Improve breathing |

| 15 | Help child use their vision |

| 16 | Help child communicate |

| 17 | Reduce risk of fractures |

Opportunity for a change of position

As illustrated in Chapter 3, ‘change of position’ was one of the most commonly mentioned benefits of standing frame use cited in survey 1. As there was no opportunity in the survey to elicit why a change of position was a benefit, this was explored in the groups. Two main reasons were given by parents, physiotherapists and education staff. The first was that it supports social interactions and enables the child to be able to see what is happening at a different level:

It was a social thing . . . he had a lot of young friends in the community who used to come in and I think being able to stand when they were standing as well, it was good for him to be at a similar height.

Parent group

From the educational point of view what is often forgotten about is if you find a different position your perspective on the world and how you feel about the world and what you see . . . is totally different . . . as soon as you put them in a standing frame you’ve changed that so they are going to get a totally different feedback . . . about their environment, about everything.

Education staff group

In the clinician group there was recognition of the importance of standing frames in facilitating social interaction but also that, depending on the situation, this could be isolating for children:

Because the point about social interaction, I think it’s all very well if you’re in a standing frame but if you’re static in the classroom with all the other kids running around, you’re not socially interacting.

Clinician group

This was also raised in the physiotherapist group, and one attendee said they had overcome this problem by having a number of children using standing frames at the same time to form a group. However, the education staff group, which was from one specialist school, commented that in their school there were too few standing frames to have one per child, limiting the number who could be standing at the same time.

The physiotherapist group recognised the importance of participation and commented that there sometimes had to be a trade-off between participation and maintaining body structure and body function. They commented that standing can improve participation in the classroom for some children, particularly those who use assistive technology such as switches. An example was given of one child who communicated to the physiotherapist that she felt more alert in the classroom when standing. Education staff were of the same opinion, and talked of children who were more involved in group discussions when standing, and could participate in classroom activities such as arts and crafts. The physiotherapist group thought that some children had better head control when standing, which could facilitate participation in certain classroom tasks or subjects.

On a less positive note, education staff were also aware of children whose participation was restricted when standing. For example, when using a communication aid, such as a voice output communication aid (VOCA), there were problems situating the device at the child’s eye level. They also believed that some children are not comfortable when standing, either because it is painful or unfamiliar to them:

If you put them in a stander you know they’re not going to perform because they are so concerned over how they feel because they are not used to being in those positions . . . it overrides everything and they can’t actually focus on anything else.

Education staff group

The second reason for the importance in a change of position was to give the young person the opportunity to stretch out after being in a sitting position for sometimes up to 10 hours a day; standing was thought to combat stiffness. Parents considered how they themselves would feel being restricted to a sitting position for hours on end and that ‘most people wouldn’t be able to tolerate it at all’. For one parent, the standing frame achieved both perceived benefits of a change of position:

We usually have the choice of either his wheelchair or his bed. So to keep him in the living room and keep him with everybody else where everything is going on, transfer him to a standing frame and allow him to have a bit of a stretch out and still be with everybody.

Parent group

For those in the education staff group, standing fulfilled the need for the children to stretch their muscles, particularly the hamstrings, and reduce the risk of contractures. They commented that, with some children, they could see a deterioration in skills (e.g. posture, joint range of movement) and an increase in stiffness when they had not been using a standing frame.

Parents said a change of position led to something tangible where they could ‘see the relief in a change of position’ whereas other ‘clinical’ effects were not easy for them to recognise. For this and the other reasons mentioned, a change of position was considered very important for the majority of parents.

Improve bladder and bowel function

Most parents also supported the survey result of standing frames being beneficial to digestion and bowel function, and reported that not using a frame had an impact on bowel movement. This was evidenced by parents who noticed a difference in the school breaks or following surgery when their child did not use a standing frame:

I know for a fact if he doesn’t stand his bowels do block up.

Parent group

The use of a standing frame to encourage bowel movements was also mentioned in the physiotherapist and education staff focus groups. The latter said some children stand during or following lunch to aid digestion. The physiotherapist group commented that, for the older children in particular, this was the main purpose of using a standing frame:

We have children who remain medication free and better managed by their families because of that reason. And they say if the child doesn’t stand then they have to use medication and that makes it very difficult to manage the bowels and makes it harder for them to go out.

Physiotherapist group

Improve bone mineral density and reduce risk of contractures

In the clinician group there was a discussion about the potential of standing frames in improving bone strength and reducing the risk of contractures. BMD was considered to be a surrogate measure of benefit but if the child ‘does not have an increased rate of fractures, what does it matter?’. One parent attributed improved bone density to using a standing frame but another parent commented that a trial where this was the main measure of effect may not be appealing to parents:

When my son had his hip operation, they said that his bone density was really good therefore the operation was a lot . . . there was a good fix with the pins and stuff. I think had he not used the standing frame, they wouldn’t have been as strong.

Parent group

I think you’d need a list . . . rather than just one specific thing. Because I think if it was just bone density . . . I don’t know how eager I would have been to put him in it and go through that every day when he was younger I think you need to have all the potential benefits to weigh up.

Parent group

Physiotherapists commented that measuring bone density would not be appropriate in children who use supine boards rather than standing frames, as they are not weight bearing. Another raised the issue of which bone to measure, and referred to a study where time in a standing frame was doubled but the team did not measure bone density in the femur: ‘I’m sure if they’d have got different results if they’d measured the femur instead’. In the clinician group it was thought that a longitudinal study would be needed to measure the impact of standing on BMD; to date only short-term studies have been conducted using this as an outcome.

In terms of reducing the risk of contractures, there were mixed feelings in the clinician group about whether or not this was important in determining the impact of standing frames. One person thought that if a child uses a wheelchair all of the time, then reducing the risk of contractures was not as important. There was an alternative view from another in the group which said that pain from contractures was an important issue; interestingly, pain reduction was not included as a benefit of standing frames in the responses to survey 1. As well as stressing the importance of reducing pain, the group also concurred with what was said by physiotherapists, namely that there should be a consideration of what happens to children in later life:

Standing is a physiological need of the body, it’s not a luxury – long-term pain and contractures do have . . . a knock-on effect on the rest of the joint . . . long term they may have the effect in their adulthood as an result of not doing the physiotherapy and the stretching early on.

Clinician group

This person went on to say that if a child is compliant with standing frame use ‘the outcomes that we see are completely different in terms of contractures and pain’. It was felt in the clinician group that it could be possible to measure a change in contractures in a 12-month period.

Improve motor abilities – trunk, head and upper limbs

The physiotherapist group raised the issue of maintaining movement and mobility of the joints because of the ‘unknowns’ for these children as they grow. They commented on pain, which was also mentioned as an important factor by the clinician group:

I think it’s a pain factor and I wonder whether it’s important to maintain a range of movement and some sort of mobility for all the joints because as they transition into adulthood . . . the debilitating factor is the pain.

Physiotherapist group

Physiotherapists also believed that maintaining alignment of the trunk and pelvis was important for respiratory function and preventing scoliosis. Parents and education staff mentioned the benefits of standing frames in relation to posture:

His core stability is really bad so he leans all the time which I think is making his scoliosis worse as well. Whereas he hasn’t got as much pressure through his back if he’s in a stander.

Parent group

Education staff gave an example of the difference a standing frame was making for one child by enabling her to achieve and maintain a straight position while in her wheelchair:

We have one [child] who only recently started going in [standing frame] every morning . . . we’re at 45 minutes of standing, to keep the head up and straighten up and you can’t half see the difference. . . . It’s working for her.

Education staff group

Prevention or delay of surgical intervention

The potential for standing frames to prevent or delay surgical intervention was a perceived benefit mentioned by physiotherapists and parents that had not been reported as a finding from survey 1. For physiotherapists, using a standing frame to prevent surgery would depend on the child’s gross motor function:

We use standing frames a lot with GMFCS V to maintain and prevent surgery and try and give them that prolonged stretch that we can’t necessarily do in other positions, whereas then we have GMFCS II who we would use to try and increase lower limb strength or try to build up the function.

Physiotherapist group

Another commented that they use standing frames primarily to provide a change of position but perhaps in the back of their mind to prevent surgery:

And I kind of think, well I’m not sure but I’d use it to kind of help prevent hip surgery but I don’t know whether it does long term or not because I’ve had a few kids who have refused to use standing frames and use their walkers instead and they’re still doing okay without needing surgery.

Physiotherapist group

A number of parents said their child had undergone surgery despite using a standing frame. There was a discussion and a belief that their children would have needed surgery regardless, but that use of the standing frame had delayed it. Despite the fact that the standing frame did not prevent surgery, one parent said there had been other benefits. Another parent, whose child used a walker and needed hip surgery, said, ‘I do not know if that’s down to me not having a standing frame at home’. A suggestion was made by the parent group for a study to determine the impact of surgery:

So if you can get X-rays [radiographs] from young babies who are likely to have cerebral palsy or mobility issues, then you’ll be able to watch the hip X-rays [radiographs] and see whether that’s making any difference and whether it changes the outcome of them having to have major hip surgery or not.

Parent group

This reflects the point made by the clinician group that hip dislocation would be difficult as an outcome measure because of the length of time in which children would have to be followed up. Clinicians also added that the pathology was little understood and there were a number of confounding variables.

Reduce risk of pressure sores

One parent commented that as children with CP tend to be very thin there is an increased risk of pressure sores from sitting, and standing reduces that risk. The education staff focus group also mentioned that a long time spent in a wheelchair can become uncomfortable for children and the opportunity to stand is a relief for them and ‘takes the pressure off their bottoms’.

Other benefits

Other benefits of standing frames mentioned were improved respiratory function (particularly an improvement in breathing), helping the child to relax (as they have more support in a standing frame than in a wheelchair), and reduced spasms. Parent participants also felt emotional seeing their non-ambulant child in a standing position. These feelings were still very strong, even years later, with participants becoming teary while discussing it.

What should the trial intervention and comparator be?

In the presentation to the groups the following examples were given of interventions and comparators: delayed or suspended use of a standing frame, a comparison of other devices, or therapies.

Current standing frame versus no standing frame use

Delayed start

The question was posed, would parents have taken part in a trial in which the introduction of a standing frame was delayed by 6 months? Clinicians had reservations about the ability to recruit to such a study and commented that most parents would feel that their child was missing out on a potentially beneficial therapy. One of the physiotherapists thought that a waiting list control of delayed standing frame introduction would be an acceptable study design, but then added that they were unsure whether or not this was ethical. When broached with parents, this option was not popular, despite accounts of delays of months in obtaining a standing frame when their child was first prescribed one, and the lack of evidence for their clinical effectiveness:

I can see why it would be useful in a study, but I wouldn’t want to be in the group that didn’t [get it].

Parent group

You’d go out of your way to get it if you thought it was going to make any difference at all and I don’t think I’d want to be a parent in the ‘wait and see group’ if I thought there was something there that could help.

Parent group

The reason for this parental stance was that, even in the face of a lack of evidence of clinical effectiveness, parents want to ensure that they have tried everything that may benefit their child; they would feel that they were missing out in a ‘delayed use’ trial design. Parents mentioned they would feel guilty if they delayed the introduction of anything that may help:

. . . it would always be in the back of your head that if they had been in it sooner would it have made any difference.

Parent group

Some commented that it would be unlikely that parents would be happy to participate if they had to delay the intervention onset, particularly as it would be around the same time as receiving their child’s diagnosis of CP. Only one parent disagreed:

You see I would have done. My daughter, she was 9 months old before she was diagnosed and . . . I saw the standing frames in a line and they looked like pieces of torture equipment . . . so if they’d given me a choice I’d have said no.

Parent group

This parent said she had not been aware of the lack of evidence of the benefits of standing frames at that time. One parent in the other group felt that an awareness of the rationale for, and the benefits of, standing frame use would ‘give the parent more of an understanding of whether they would want to take part in something like that or not’.

Even when an alternative therapy was suggested for the delayed standing frame group, opposition to the idea remained in the parent group. However, one parent said that it would depend on the alternative therapy and mentioned their experience of having physiotherapy ‘with a lot of standing’ when her child was younger. In the other parent group, hydrotherapy was mentioned as an alternative and this appeared to have the approval of the other parents.

Suspended standing frame use