Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 12/35/54. The contractual start date was in January 2015. The draft report began editorial review in May 2017 and was accepted for publication in November 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Ray Fitzpatrick is a member of the Health Technology Assessment Priority Research Advisory Methods Group. Richard Hindley has received payments for lecturing and proctoring for SonaCare Medical (Charlotte, NC, USA; high-intensity focused ultrasound treatment). Hashim U Ahmed reports grants and personal fees from SonaCare Medical and grants from Trod Medical (Heverlee, Belgium) and Sophiris Bio Inc. (La Jolla, CA, USA) outside the submitted work.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Hamdy et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Research objectives

-

To assess the feasibility of a randomised controlled trial (RCT) comparing high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) with radical prostatectomy (RP) for intermediate-risk clinically localised prostate cancer (PCa) by recruiting and randomising 80 participants.

-

To undertake a QuinteT Recruitment Intervention (QRI) to understand recruitment challenges for this trial and inform optimal recruitment strategies for a main RCT.

-

To collect data on quality of life and resource use to inform power calculations for the proposed main trial.

-

To explore data capture methods and the feasibility of such methods to inform power calculations and a health economic evaluation for a main RCT.

Scientific background

Prostate cancer prevalence and incidence in the UK

In the UK, PCa is the most common cancer in men and the second most common cause of cancer deaths in males (accounting for 13% of such deaths) after lung cancer. 1 In 2014, 46,690 new cases of PCa were diagnosed, and 11,287 men died from the disease. 1 The lifetime risk of being diagnosed with PCa is one in eight. 1 Incidence is increasing with wider use of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing in asymptomatic men in the community setting and an ageing UK population.

Diagnosis of prostate cancer

Prostate cancer is currently diagnosed following serum PSA testing, imaging in the form of multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging (mpMRI) scans and prostate biopsies.

Although PCa can be lethal, most men who are diagnosed with PCa will not suffer clinically significant consequences from the disease during their lifetime. Currently, opportunistic PSA testing leads to overdetection and overtreatment and places an increasing burden on the NHS.

The risk of progression to metastases in intermediate-risk, clinically localised PCa and the need for accurate targeting and imaging modalities to direct minimally invasive interventions have precluded RCTs from being undertaken; however, mpMRI technology and dissemination is reaching a level at which accurate assessment of the location and grade of PCa using imaging and biopsies is possible, as demonstrated in the recently published National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) PROstate MRI Imaging Study (PROMIS),2 a definitive validating cohort study evaluating mpMRI as a triage test. PROMIS demonstrated higher levels of accuracy in detection of clinically important disease, and found that transrectal ultrasound (TRUS)-guided biopsy performs poorly as a diagnostic test for clinically significant prostate cancer. mpMRI, used as a triage test before first prostate biopsy, could identify one-quarter of men who might safely avoid an unnecessary biopsy and might improve the detection of clinically significant cancer. mpMRI is being increasingly adopted by many centres in the pre-biopsy diagnostic pathway.

Treatment options for localised prostate cancer

Conventional treatment options for men with clinically localised PCa include active monitoring (AM) (also known as active surveillance); radical prostatectomy (RP), now most commonly performed as robot-assisted laparoscopic procedures; intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT); and brachytherapy. These treatment options appear to have similar short- to medium-term oncological outcomes in non-randomised studies.

Active monitoring

Active monitoring protocols involve regular clinical examination, PSA measurements, mpMRI and repeat biopsies. If these parameters suggest the risk of progression, men are offered radical treatment. A number of Phase II studies have shown that signs of progression lead to intervention within 5 years of diagnosis in approximately one-third of patients undergoing AM. 3,4 For those with intermediate-risk disease, AM has been reported as conferring an 84% 5-year metastasis-free survival rate. 5 However, observational strategies can lead to significant anxiety. 6

Active monitoring has been tested in clinically localised PCa in the ProtecT (Prostate testing for cancer and Treatment) trial,7 which reported that, although RP and radiotherapy were associated with lower rates of disease progression, 44% of men assigned to AM did not receive radical treatment and avoided side effects. Men with newly diagnosed, localised PCa therefore need to consider the critical trade-off between the short- and long-term effects of radical treatments on urinary, bowel and sexual function and the higher risks of disease progression with AM, as well as the effects of each of these options on quality of life (QoL).

Radical prostatectomy

Radical prostatectomy involves total open, laparoscopic or robot-assisted surgery to remove the entire prostate gland and seminal vesicles. The proportion of PCa patients receiving surgery varies with age; 8% of PCa patients receive a major surgical resection as part of their cancer treatment, with fewer resections in the oldest age group (0% in those aged ≥ 85 years) than in the youngest group (29% in those aged 15–54 years). 8

Radical radiotherapy

Radical radiotherapy in the form of external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) is a common treatment in the UK for men diagnosed with localised PCa. It is usually preceded by 3–6 months of neoadjuvant androgen suppression, and is given in daily fractions over 4–8 weeks on an outpatient basis. In large reported series, EBRT conferred a 5-year disease-free survival of between 78% and 80%, or 88% and 94% in combination with hormone therapy. 9–12 IMRT, an optimised form of EBRT, is delivered in some centres. 13

Brachytherapy

Brachytherapy can be given either as permanent radioactive seed implantation or as high-dose brachytherapy using a temporary source. For localised PCa, the 5-year biochemical failure rates are similar for permanent seed implantation, high-dose (> 72 Gy) external radiation, combination seed/external beam irradiation and RP. 14

Radical, extensive treatments carry the potential for significant short-, medium- and long-term morbidity such as urinary leakage, erectile dysfunction and radiotherapy toxicity. At present, there is little difference between RP and radical radiotherapy in terms of cancer control in the short to medium term; much of the decision-making process that governs treatment allocation is based on the differences in the side-effect profiles associated with the various interventions. 13

The recently published clinical- and patient-reported outcomes from the ProtecT trial7 demonstrate that each treatment option has a particular pattern of adverse effects on QoL in the short term: urinary incontinence and sexual dysfunction are worst after surgery, followed by recovery by a number of men but persistent difficulties for some, and bowel problems are worst after radiation, with sexual dysfunction mostly related to neoadjuvant androgen deprivation therapy. Although adverse effects of interventions can be avoided initially with AM, there is a natural decline in urinary and sexual function symptoms over time, and the adverse impacts of radical treatments will be experienced when such treatments are received. 15,16 These side-effect profiles have been described consistently, even with more modern and contemporary radical treatment options, such as robot-assisted surgery and different forms of radiation, including brachytherapy. It is, therefore, true that contemporaneous men who are treated with current forms of radical therapy will continue to suffer from the now well-described and well-documented side-effect profile patterns related to these treatments.

Alternatives to conventional therapies

Alternative, targeted focal ablative therapies are being developed in an attempt to reduce treatment burden, improve QoL and reduce adverse events (AEs) associated with radical treatment, while retaining at least equivalent cancer control. Focal therapies should minimise morbidity by lowering the chance of damage to the neurovascular bundles responsible for erectile function and the urinary continence mechanism, and may help to avoid the psychological morbidity associated with surveillance, but their long-term oncological effectiveness remains untested.

These alternative technologies are being used as primary ablative therapies in a number of centres worldwide, but have been introduced without robust Phase III RCT validation. Examples include HIFU, cryotherapy, vascular-targeted photodynamic therapy (VTP), radiofrequency interstitial tumour ablation (RITA), laser photocoagulation and irreversible electroporation. Each one is at a different stage in its evaluation and application to clinical practice. The current evidence for focal therapy for PCa is mainly from non-randomised Phase I and II trials in single centres and from case series with small numbers of patients. A previous Phase I/II study demonstrated that as few as 5% of men suffer from genitourinary side effects after focal therapy and also demonstrated no detectable clinically significant cancer in all treated patients. 17–19 A manufacturer-sponsored Phase III RCT of VTP versus AM in 413 men with very low-risk disease has been published recently with 2-year follow-up data. 20 This is discussed below.

High-intensity focused ultrasound

High-intensity focused ultrasound uses ultrasound energy focused by an acoustic lens to cause tissue damage as a result of thermal coagulative necrosis and acoustic cavitation. The procedure is performed using a transrectal approach and may be performed under general or spinal anaesthesia as a day-case procedure.

Four systematic reviews of HIFU in the treatment of prostate cancer have been published. 21–24 Warmuth et al. 21 identified 20 uncontrolled prospective case series, totalling 3021 patients (2794 primary therapy and 227 salvage therapies). They concluded that, for all HIFU procedures, the biochemical disease-free rate at 1, 5 and 7 years was 78–84%, 45–84% and 69%, respectively. The negative biopsy rate was 86% at 3 months and 80% at 15 months. Overall survival rates and PCa-specific survival rates were 90% and 100% at 5 years and 83% and 98% at 8 years, respectively. AEs included complications of the urinary tract (1–58%), erectile function (1–77%) and the rectum (0–15%), and pain (1–6%). Lukka et al. 22 found that there were no adequate RCTs or meta-analyses. They concluded that the current evidence on HIFU use in PCa patients is of low quality, rendering it difficult to draw conclusions about its efficacy. Veereman et al. 23 found very low-quality evidence in case series of patients who received HIFU treatment with no comparison with AM or radical treatment. These suggested an overall survival rate of ≤ 89% and a PCa survival rate of ≤ 99% after 5 years, but these numbers vary depending on the patient’s risk category. Longer-term effects on QoL are unknown. Kuru et al. 24 conclude that HIFU treatment, and especially focal ablation of tumour foci, seems to be a safe alternative to standard treatment, with fewer side effects. The oncological results seem satisfactory but need further follow-up to validate this practice of PCa control. 24

Cryotherapy

Cryotherapy is the localised destruction of tissue by extremely cold temperatures followed by thawing, and may be performed under general or regional anaesthesia. Cryoneedles or probes are inserted into the prostate via the perineum, using image guidance. Argon gas is circulated through needles or probes, generating very low temperatures and causing the formation of ice around the prostate with profound tissue destruction. Newer cryotherapy techniques allow these needles to be removed or repositioned so that the frozen zone conforms to the exact size and shape of the target tissue.

In 2008, a Cochrane systematic review25 of prostate cryotherapy as a primary treatment was published, and recommended that RCTs comparing cryotherapy with established treatments for early PCa be conducted. All eight studies identified were case series (two of which were retrospective), with a total of 1483 patients. At 5 years, overall survival was reported as 89–92% in two studies and disease-specific survival was 94% in one study. The major complications observed in all studies included impotence (47–100%), incontinence (1.3–19.0%) and urethral sloughing (3.9–85.0%), with less common complications of fistula (0–2%), bladder neck obstruction (2–55%), stricture (2.2–17.0%) and pain (0.4–3.1%). Most patients were discharged the following day (range 1–4 days). Since 2008, one Canadian RCT,26 comparing cryotherapy with EBRT as primary therapy for localised PCa in > 200 men, has been reported. With a median follow-up period of 100 months, no significant difference in disease progression was observed between the two arms. 26 However, because of recruitment difficulties, the study was closed before the target accrual was reached.

Vascular-targeted photodynamic therapy

Vascular-targeted photodynamic therapy uses light to activate a photosensitising drug, administered intravenously, to produce instantaneous vessel occlusion and subsequent tissue necrosis. The light is delivered by optical fibres placed transperineally under transrectal ultrasound guidance. VTP is given under general anaesthesia and can be carried out on a day-case basis.

Small case series of VTP have been reported in groups receiving primary therapy and those receiving salvage therapy. The initial drug-dose escalation studies, followed by a light-dose escalation study, were performed in men who progressed following EBRT. 27–30 These studies showed that around 60% of men receiving whole-gland treatment at the maximal and light drug doses had a complete response to treatment. Side effects included two rectourethral fistulae, one of which required surgical intervention. Urinary side effects tended to last for ≤ 6 months. In a study of 40 men with no previous treatment for PCa, early results showed no significant side effects. 31 Recently, a manufacturer-sponsored Phase III RCT comparing VTP with AM in 413 men with very low-risk disease has been published with 2-year follow-up data. 20 It found VTP to be safe and effective, with a 66% reduced risk of treatment failure (adjusted hazard ratio 0.34, 95% confidence interval 0.24 to 0.46) compared with AM; however, the VTP group experienced more frequent and severe side effects, although these were mostly mild and of short duration. The most common side effect was difficulty passing urine, and in all cases this resolved within 2 months of treatment. Outcomes for 5- and 10-year progression and survival are not known. The major limitation of this study20 is that the cohort of men investigated had low-risk disease; active treatment is currently not recommended for low-risk PCa by most international guidelines, including the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommendations, which advocate that such men are offered primarily AM because of the insignificant risk of disease progression.

Other ablative technologies

Other ablative technologies are currently under evaluation, but there is not sufficient evidence to be used within the context of a RCT. Examples include radiofrequency ablation, which acts by converting radiofrequency waves to heat, resulting in thermal damage. RITA has recently been proposed as a treatment for PCa. 32–35 Interstitial laser photocoagulation was reported by Amin et al. ,36 who described a percutaneous technique for local ablation. Irreversible electroporation is a new non-thermal ablation method that uses short pulses of direct current (DC) to create irreversible pores in the cell membrane, thus causing cell death. 37,38 This technology is in the early clinical phases of development, and a RCT is currently under way. 39

These newer techniques have been evaluated in a systematic review by Ramsay et al. ,40 who conclude that they have not been evaluated with sufficient reliability to inform their utilisation within the NHS. There is, however, some evidence that cancer-specific outcomes in the short term are either better than or equivalent to either EBRT or RP, with comparable adverse effect profiles; however, there is a possible increased risk of dysuria and urinary retention. Valerio et al. 41 undertook a more recent systematic review and concluded that there is evidence that focal therapy is safe and has low detrimental impact on continence and potency, but they note that the oncological outcome has yet to be evaluated against the standard of care. Combined with the increasing incidence of clinically localised PCa, demand for these less aggressive, organ-sparing treatments is expected to increase. 40 A further important consideration is the rapid evolution of the technologies over time, with constant new developments to improve energy delivery, targeting, safety and imaging. Focal therapy relies on accurately assessing the status of the disease in the prostate, using imaging and biopsies for which the technology is improving and becoming more widely disseminated. Transperineal prostate mapping (TPM) biopsies provide the optimal biopsy strategy for accurately mapping disease within the prostate with sensitivity of > 90% for 0.2-cc and 0.5-cc lesions. 42

Ongoing and recently completed studies clearly indicate that the evidence base for partial ablation (PA) therapies – in particular, focal ablative therapies – is increasing. However, the quality of the evidence base will not improve substantially given that the majority of these studies are case series. Research efforts in the use of ablative therapies in the management of PCa should focus on conducting more rigorous, high-quality studies. Ramsay et al. 40 identify HIFU and brachytherapy as the most promising newer interventions, but these lack high-quality evaluation. They recommended evaluation by multicentre RCTs, with long-term follow-up, to include predefined assessment of cancer-specific, dysfunction and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) measures, as well as economic evaluations to inform economic modelling.

Implications for research

The lack of RCT-based evidence means that the true clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of focal treatment have not been established; this lack of evidence highlights the need for robust primary research.

An important strategy, which remains untested, is to use novel technologies to target and treat all clinically significant cancers in the gland focally, with careful follow-up and repeat treatments as necessary, particularly for emerging new lesions detected by biopsy. The strategy may obviate the need for any radical therapies.

The current NIHR HTA feasibility study was therefore developed and conducted in order to inform a main, definitive RCT. RP was selected in the radical treatment arm to reflect true pathological staging and grading of the randomised cohort, and ease of determination of treatment failure. HIFU was selected as the partial ablation comparator in the feasibility stage. At the time of the design of this study, a HTA systematic review40 suggested that HIFU was the most likely treatment to be considered cost-effective when assessed against threshold values for a cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) that society might be willing to pay.

Recruitment to RCTs is often slower or more difficult than expected,43 and recruiting to surgical RCTs is particularly challenging. 44 Although the communication style of a doctor or nurse explaining the study is one of the key factors that exerts a considerable influence on patients’ preparedness to accept or decline participation,45 research has shown that recruiters can experience emotional and intellectual challenges related to their roles as researchers and clinicians. 46,47 Many recruiters find it difficult to accept the possibility that their usual preferred treatment is no more effective than the comparator. 48 In particular, surgeons often have to take decisive action during operations (often with incomplete information), which can make it difficult to be certain which treatment is best for patients. 44 In addition, research has shown that recruiters can find concepts such as randomisation challenging to explain to patients. 49 Taken together, these factors highlight the need for training and support for recruiters.

Systematic reviews have identified only a few programmes that provided training to those recruiting patients into RCTs. 50,51 The majority of these workshops provide general information about the key principles of RCTs without covering issues specific to a particular trial. Few interventions to improve recruitment have been shown to be effective;52 the most successful have been studies that used qualitative research to identify key issues and then developed interventions based on these issues to improve recruitment. 50

A feasibility trial was conducted to assess rates of recruitment and randomisation, identify barriers to recruitment and devise strategies to overcome them, and test the trial processes and data collection methods to inform the design and conduct of a main RCT.

Chapter 2 Methods

Study design

This study aimed to evaluate the feasibility of a prospective, multicentre, parallel-group (1 : 1) RCT to assess the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of PA (using HIFU) or RP in patients with intermediate-risk, unilateral clinically localised PCa. The study flow chart and visit schedule are shown in Appendices 1 and 2, respectively.

The full trial protocol can be accessed in the NIHR Journals Library: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/123554/#/ (accessed 13 November 2017).

QuinteT Recruitment Intervention methods

A QRI was embedded into the feasibility study with the aim of understanding the recruitment process and to identify clear obstacles and hidden challenges to recruitment. 46,47,53 The methods were developed initially in the ProtecT trial by the applicants involved in the Partial prostate Ablation versus Radical prosTatectomy (PART) trial,54 and have subsequently been used and refined in other RCTs. 55

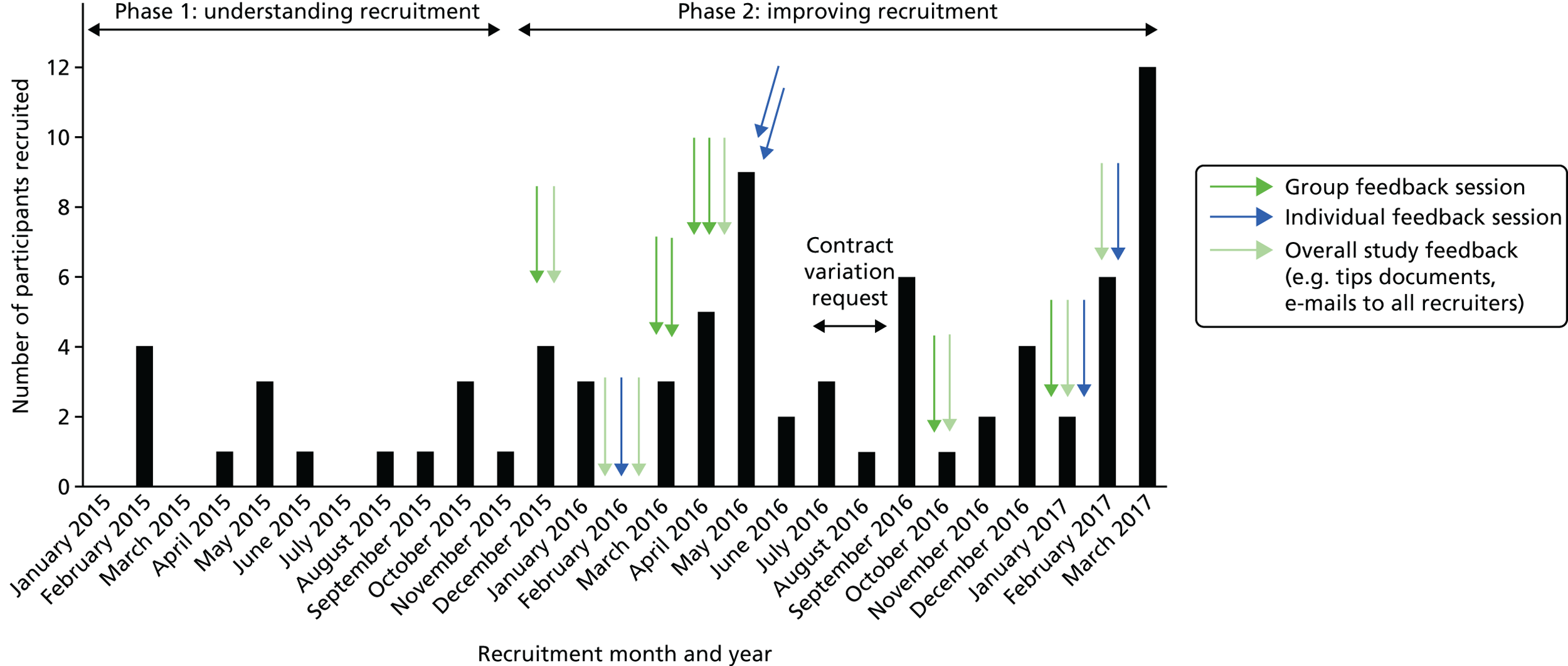

The QRI involved two iterative phases: phase I (January to November 2015) sought to identify and understand recruitment difficulties through the use of multiple qualitative methods, and phase II (December 2015 to March 2017) developed and implemented strategies to optimise recruitment and informed consent.

Phase I: understanding recruitment issues

Phase I of the QRI sought to understand recruitment in each clinical centre, with the intention of subsequently developing interventions to improve recruitment and informed consent. The approaches used to identify recruitment difficulties followed principles of ethnography: data collection and analysis were supplemented by observations of recruitment appointments and meetings, monitoring screening log data and examining study documentation.

Sampling and recruitment

In-depth interviews

Scene-setting interviews were conducted with members of the Trial Management Group (TMG) [including the chief investigator (CI) and those most closely involved in the design, management, leadership and co-ordination of the PART trial overall and in each of the clinical centres]. Snowball sampling was subsequently used, in which TMG members provided the names of colleagues whom they considered it would beneficial for the QRI researcher to talk to. These informants were invited via e-mail to take part in an interview with the QRI researcher at a mutually convenient time and date. E-mail reminders were sent 1 week after dispatch of the original invitation. Informants were purposefully selected, so as to build a sample of maximum variation on the basis of professional role (e.g. surgeons, research nurses) and recruitment centre. Characteristics were assessed as the study progressed and some individuals were subsequently selected on the basis of emerging issues that warranted further investigation (i.e. the evidence for HIFU) or were approached as new centres opened throughout the course of the study (i.e. Southampton and Basingstoke).

Recorded recruitment consultations

All health-care professionals recruiting to the trial were requested to audio-record all appointments in which they provided information to eligible patients about the study and treatment options, until a decision was reached. To facilitate this, the QRI team provided each participating centre with a ‘Recruiter Pack’ with detailed guidance on the process of obtaining informed consent, the operation of digital recorders and how to record, name and transfer audio-files and documents to ensure that information from the QRI remained secure and confidential. In addition, site visits were conducted to ensure that each recruiter had the appropriate equipment and felt comfortable with recording consultations.

Data collection

In-depth interviews

Written consent for the QRI component of the PART trial was obtained at the start of the interview. A digital voice-recorder was used to record the discussions. Interviews followed topic guides that had been designed and piloted in several other trials. Separate topic guides were developed for members of the TMG and those recruiting to the study to ensure that discussions covered the same basic issues but with sufficient flexibility to allow new issues, of importance to the informants, to emerge (see Report Supplementary Material 1). Key topics included perspectives on the trial design and protocol, views about the evidence on which the trial was based, perceptions of uncertainty/equipoise in relation to the treatment arms, views about how the arms/protocol were delivered in the relevant clinical centre, methods for identifying eligible patients, views on eligibility and examples of actual recruitment successes and difficulties. The interview schedule was adapted as analysis progressed to enable exploration of emerging themes, such as how clinicians interpreted the impact of the publication of the ProtecT trial findings.

Recorded recruitment consultations

Eligible patients were sent information about the QRI before their surgical consultation. This allowed the patient sufficient time to carefully read the information sheet and decide whether or not they were comfortable with their initial consultation being recorded. Written consent was obtained from each patient before the start of the consultation. If consent was provided, the recruitment consultation – and any subsequent discussions – were recorded on an encrypted audio-recorder. A research nurse at each centre regularly uploaded all recordings from the device on to an encrypted memory stick and securely posted them to the QRI researcher.

Patient pathway through eligibility and recruitment

All study centres were asked to maintain detailed screening logs, capturing details of patients who were screened for the PART trial, reasons for ineligibility and details of eligible patients who did not consent to trial participation. These logs were returned to the trial manager on a monthly basis. Unclear or absent information was checked and queried. The QRI researcher also conducted regular site visits to understand patient pathways and to discuss and observe how the PART trial was integrated into clinical practice.

Observation of study meetings

In addition to these data collection methods, the QRI researcher attended as many study meetings as possible to gain an overview of trial conduct and overarching challenges, including ‘core’ TMG meetings that took place every few months (consisting of the CI and those with the greatest responsibility for trial oversight), wider monthly study meetings (for the core TMG and those recruiting to the study), and collaborators’ meetings (attended by all involved in the management of and recruitment to the study).

Data analysis

In-depth interviews

Interview recordings were transcribed verbatim or in selected parts, whichever was necessary to conduct a sufficiently detailed analysis. Transcripts were imported into NVivo version 10 (QSR International, Warrington, UK), in which data were analysed sentence by sentence and similarities and differences were coded. Data were analysed using techniques of constant comparison56 and emerging themes and codes within transcripts and across the data set were then compared with each other, to look for shared or disparate views among patients. Emerging themes were discussed within the QRI team with reference to the raw data. Data collection and analysis continued until the point of data saturation, that is, the point at which no new themes emerged.

Recorded recruitment consultations

Recordings of consultations were also transcribed verbatim or in selected parts, whichever was necessary to conduct a sufficiently detailed analysis. These were analysed as described above for interviews, with the addition of some of the techniques of focused conversation analysis. The delivery of information during the recruitment appointments was investigated, with a particular interest in the interaction between the recruiter and the patient to identify and document aspects of informed consent and information provision that were unclear, or disrupted or hindered recruitment.

Patient pathway through eligibility and recruitment

Detailed eligibility and recruitment pathways were compiled for each clinical centre, noting the point at which patients received information about the trial, which members of the clinical team they met and the timing and frequency of appointments. Recruitment pathways were compared with details specified in the trial protocol and pathways from other centres to identify practices that were more efficient and those that were less efficient. Logs of eligible and recruited patients were collated using simple flow charts and counts to display the numbers and percentages of patients at each stage of the eligibility and recruitment processes. These insights were considered alongside data emerging from interviews and audio-recorded consultations.

Sample size

The sample size for the feasibility study was determined pragmatically, based on the number of patients that it was considered feasible to recruit within the given time frame. In the grant application, we proposed to randomise between 80 and 100 men, to assess willingness to participate in and be randomised to the PART trial. The sample size was set at 100 participants in the trial protocol; this was revised to 80 participants, as discussed and agreed with the NIHR HTA Monitoring Committee following a monitoring hub meeting on 26 November 2015 and formalised in the PART trial contract variation, which was approved by the NIHR HTA programme in September 2016.

Outcomes

-

Recruitment and randomisation of men to RP or HIFU (the target was set at 80 randomised participants).

-

Findings of the QRI.

-

Assessment of data capture methods including, collection and completeness of case report forms (CRFs), Patient Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) and resource use diaries.

Patients were asked to complete the following PROMs:

-

International Index of Erectile Function – 15 items (IIEF-15)57

-

International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS)58

-

EuroQoL-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L)59

-

Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – Prostate (FACT-P)60

-

University of California, Los Angeles – Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC)61

-

Memorial Anxiety Scale for Prostate Cancer (MAX-PC). 62

They were also asked to complete a self-reported resource use diary (see Report Supplementary Material 2), in which they were asked to identify and record items relating to utilisation of the health-care resources mentioned and any other relevant health-care resources. These were completed at baseline and at 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, 24, 30 and 36 months, in line with routine clinical follow-up schedules.

Patient selection and recruitment

Patients must have been diagnosed with intermediate-risk, unilateral, clinically localised PCa and be fit for either RP or PA of the prostate.

Inclusion criteria

Men were eligible if they had unilateral, clinically significant intermediate-risk PCa or dominant unilateral clinically significant intermediate-risk and small contralateral low-risk disease and met all of the following criteria:

-

Gleason score of 7(3+4 or 4+3) or

-

a high-volume Gleason score of 6 (a cancer core length of > 4 mm)

-

a PSA level of ≤ 20 ng/ml

-

a clinical stage ≤ T2b disease

-

a life expectancy of ≥ 10 years

-

be fit, eligible and normally destined for radical surgery

-

have no concomitant cancer

-

have no previous treatment of their PCa

-

have sufficient proficiency in the English language to understand written and verbal information about the trial, its consent process and the study questionnaires.

Exclusion criteria

-

Unfit for radical surgery.

-

Significant bilateral disease.

-

Low-risk disease (i.e. a Gleason score of ≤ 6, PSA level of 10 ng/ml).

-

High-risk disease (i.e. a Gleason score of ≥ 8, PSA level of > 20 ng/ml).

-

Clinical T3 disease (extracapsular locally advanced).

-

Men who have received previous active therapy for PCa.

-

Men with evidence of extraprostatic disease.

-

Men with an inability to tolerate a TRUS.

-

Men with a latex allergy.

-

Men who had undergone a transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) for symptomatic lower urinary tract symptoms in the previous 6 months.

-

Metal implants/stents in the urethra.

-

Prostatic calcification and cysts that interfere with effective delivery of HIFU.

-

Men with renal impairment and a glomerular filtration rate (GFR) of < 35 ml/minute/1.73 m2.

-

Unable to give consent to participate in the trial, as judged by the attending clinicians.

Appropriate patients were identified by the dedicated research nurse or clinician. Potential patients were identified at the multidisciplinary team (MDT) meeting, during which histopathological data were discussed. Men with a histological diagnosis of intermediate-risk PCa following a biopsy (see Trial management processes) and mpMRI (see Safety), and evidence of unilateral, clinically localised disease, were assessed for the PART trial. Some patients required a targeted or template biopsy to confirm unilateral disease. Patients who were ineligible for the PART trial were informed by their doctor, who discussed their treatment options with them.

Once confirmed as eligible for the study, patients were approached at urology/oncology clinics in the centres and provided with a patient information leaflet (PIL) (see Report Supplementary Material 3), detailing the exact nature of the trial, what it would involve for the participant, the implications and constraints of the protocol and the known side effects and any risks involved in taking part. Patients who fulfilled all the entry criteria for the trial were invited to attend an information appointment. Patients were given ample time to discuss the trial with family, friends and their general practitioner (GP) (there were typically around 6 weeks between MDT discussion, counselling and then randomisation). If the patient agreed to take part, they were asked to sign an informed consent form (ICF) (see Report Supplementary Material 4).

It was clearly stated that the participant was free to withdraw from the trial at any time for any reason, without prejudice to future care and with no obligation to give the reason for withdrawal. In the event of withdrawal, the choice of treatment was decided on by the patient and his clinical team.

Randomisation

Participants were randomised on a 1 : 1 basis to receive either RP or HIFU. A secure web-based system [Registration/Randomisation and Management of Product (RRAMP)] was provided by the Oxford Clinical Trials Research Unit (OCTRU). Randomisation was undertaken using the method of minimisation by a member of the research team or the PART trial office and participants were notified immediately of their treatment allocation. Participants were stratified by the following factors: age (< 60, 60–64, 65–70 or > 70 years), PSA level (< 3.0, 3.0–4.9 , 5.0–9.9 or 10.0–20.0 ng/ml), Gleason score (3 + 4, 4 + 3 or high-volume score of 6) and whether participants were considered to have unilateral clinically localised intermediate-risk disease or dominant unilateral clinically significant intermediate-risk and small contralateral low-risk disease. Owing to the nature of the interventions, it was not possible to blind participants, clinical staff or outcome assessors to treatment allocation.

Trial interventions

Once participants accepted their allocation, treatment was delivered within 8 weeks of randomisation, when possible. Participants randomised to RP were listed for surgery, optimally within 2 weeks of randomisation. This was co-ordinated by local investigators and study research nurses.

Conventional open, laparoscopic or robot-assisted RP is carried out under general anaesthesia in accordance with local centre expertise and clinical judgement, to remove the entire prostate gland and seminal vesicles. Lymphadenectomy was performed at the discretion of the operating surgeon in discussion with the participant, and conducted as standard (obturator nodes), or extended (to the bifurcation of the common iliac vessels), based on disease extent, PSA level and Gleason grade. Nerve-sparing surgery was usually carried out on the contralateral side of the existing tumour, and bilaterally if judged to be appropriate by the operating surgeon. Full operative and postoperative details were recorded for each participant.

Partial ablation is performed using HIFU (defined in Chapter 1). Patients randomised to PA underwent a mandatory rest period of 4–6 weeks following biopsies to allow swelling and inflammation to settle in the prostate, thereby lowering the risk of side effects such as rectal damage. Patients were admitted on the day of the procedure or the evening before, as appropriate. A phosphate enema was administered on the morning of surgery to ensure an empty rectum. The type of anaesthesia (regional/general) was discussed with the participant and depended on the opinion of the anaesthetist. A catheter is inserted before the proposed HIFU treatment. This can either be a urethral or suprapubic catheter depending on surgeon preference.

The HIFU probe is introduced into the rectum with as little trauma as possible. The treatment is then planned using the pre-operative imaging and biopsy data. The area of cancer is targeted and treated with a safe margin; this usually constituted a hemiablation, that is, treating approximately the 50% of the prostate containing the significant disease. Other treatment protocols include a quadrant ablation and true focal ablation of the tumour. There is an additional trial-specific instruction (TSI) relating to the HIFU treatment/re-treatment strategy and training of HIFU clinicians (see Report Supplementary Material 5).

The patients go home on the day of the procedure with the catheter remaining in situ.

Follow-up

Patients randomised to radical prostatectomy

-

Routine removal of catheter at 10–14 days.

-

Follow-up in the clinic at approximately 6 weeks post surgery as per routine NHS care. Patients will have had a PSA test prior to their follow-up appointment, the result of which should be available.

-

Follow-up in the clinic approximately every 3 months post surgery in the first year and then approximately every 6 months, as per routine NHS care, for 3 years (see Appendix 2). Patients will have had a PSA test prior to their follow-up appointment, the result of which should be available. If at any point disease progression is suspected (i.e. a PSA level rising to ≥ 0.2 µg/ml) the patient will be restaged.

Patients randomised to partial ablation

-

Routine removal of catheter at 7 days.

-

For centres new to performing HIFU, a study-specific mpMRI was performed on the first five patients at 2 weeks post HIFU.

-

Followed up routinely at approximately 6 weeks post surgery as per routine NHS care. Patients will have had a PSA test prior to their follow-up appointment, the result of which should be available.

-

Followed up in the clinic approximately every 3 months post surgery for the first year and then approximately every 6 months, as per routine NHS care, for 3 years. Patients will have had a PSA test prior to their follow-up appointment, the result of which should be available.

-

Standard care included a mpMRI at 12 months.

-

Standard care included transrectal biopsies at 12 months.

-

Standard care included a mpMRI at 3 years.

-

Standard care included transrectal biopsy at 3 years.

Trial completion and exit

The end of the trial would be when the last patient was contacted to arrange their final follow-up visit, whether or not the visit took place at 3 years from receiving their treatment.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses are mostly descriptive because this was a feasibility study. The number and percentage of patients screened, consented and randomised are summarised in a Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram (see Figure 2). Baseline and outcome variables are described by treatment arm, continuous variables are described using mean and standard deviation or median and interquartile range (IQR), and categorical variables are summarised as percentages. The percentage of missing data is summarised but imputation was not performed.

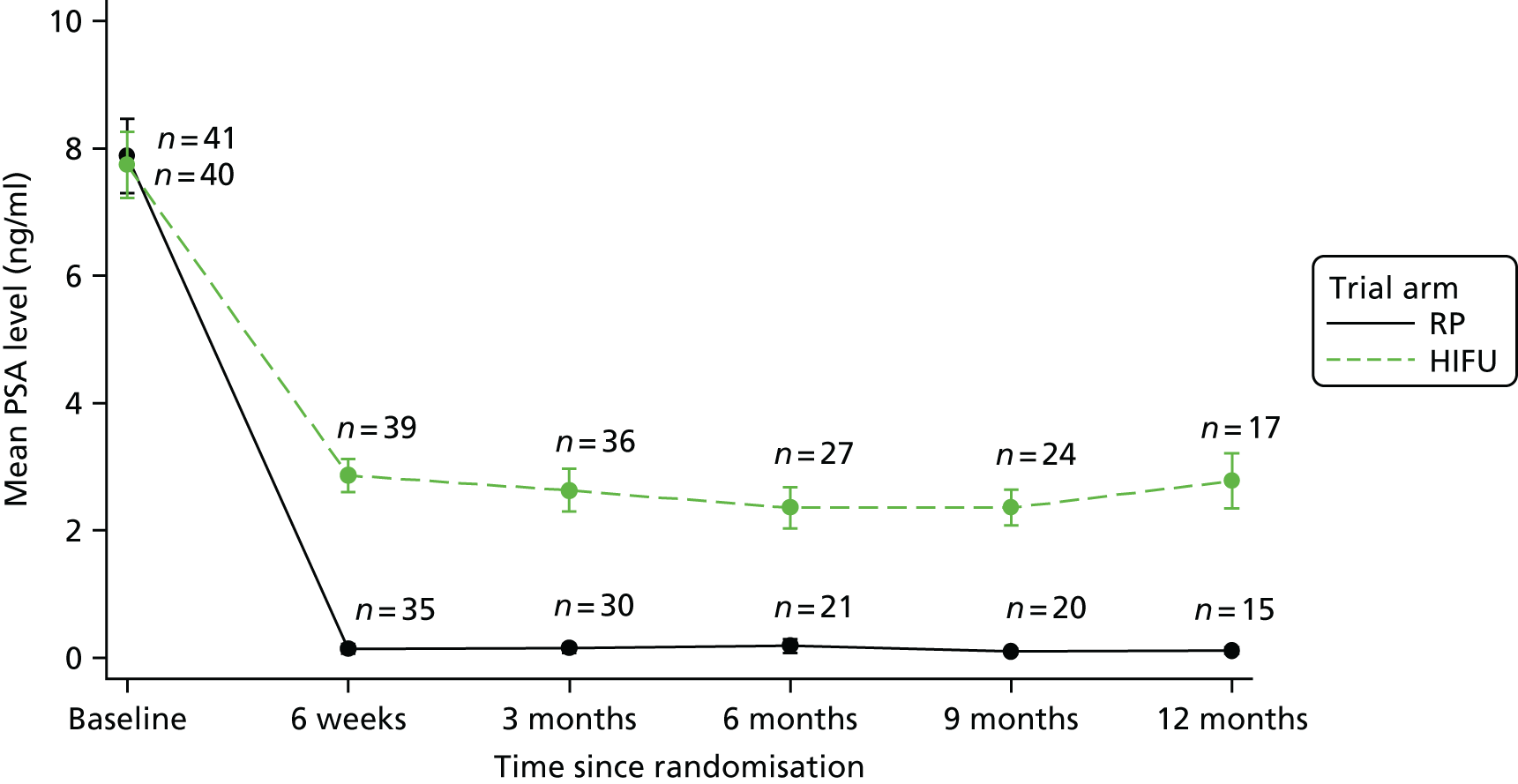

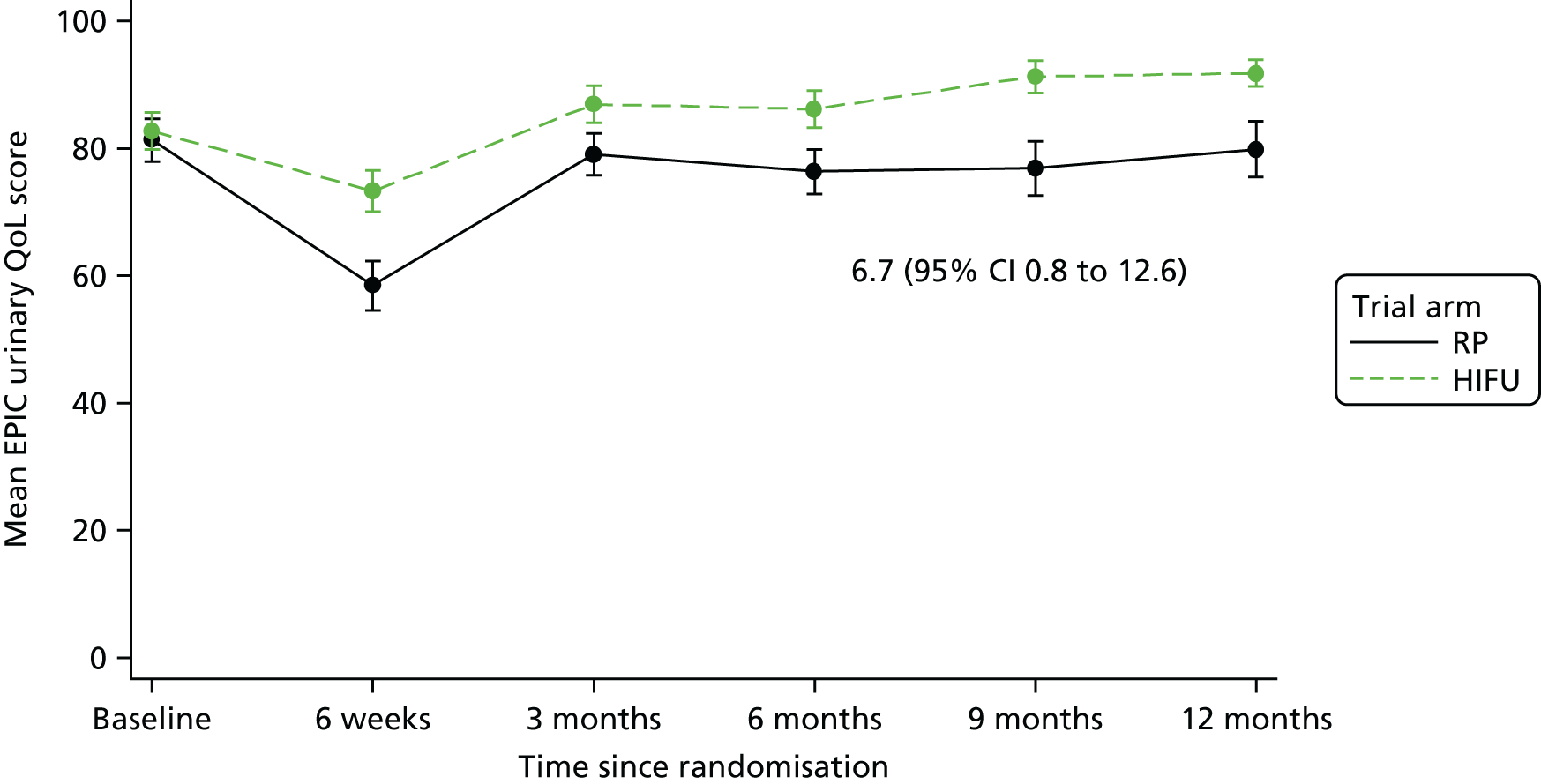

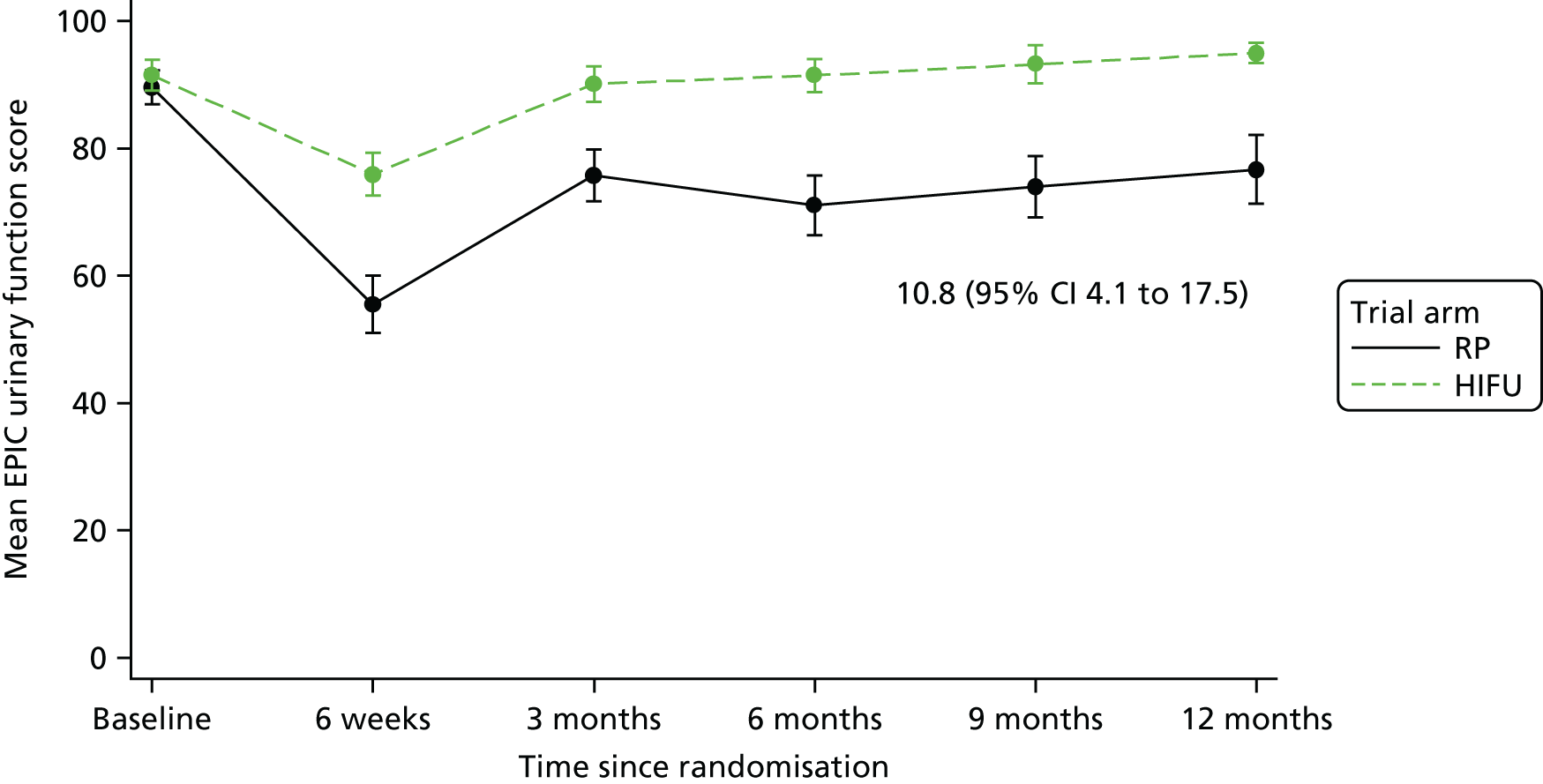

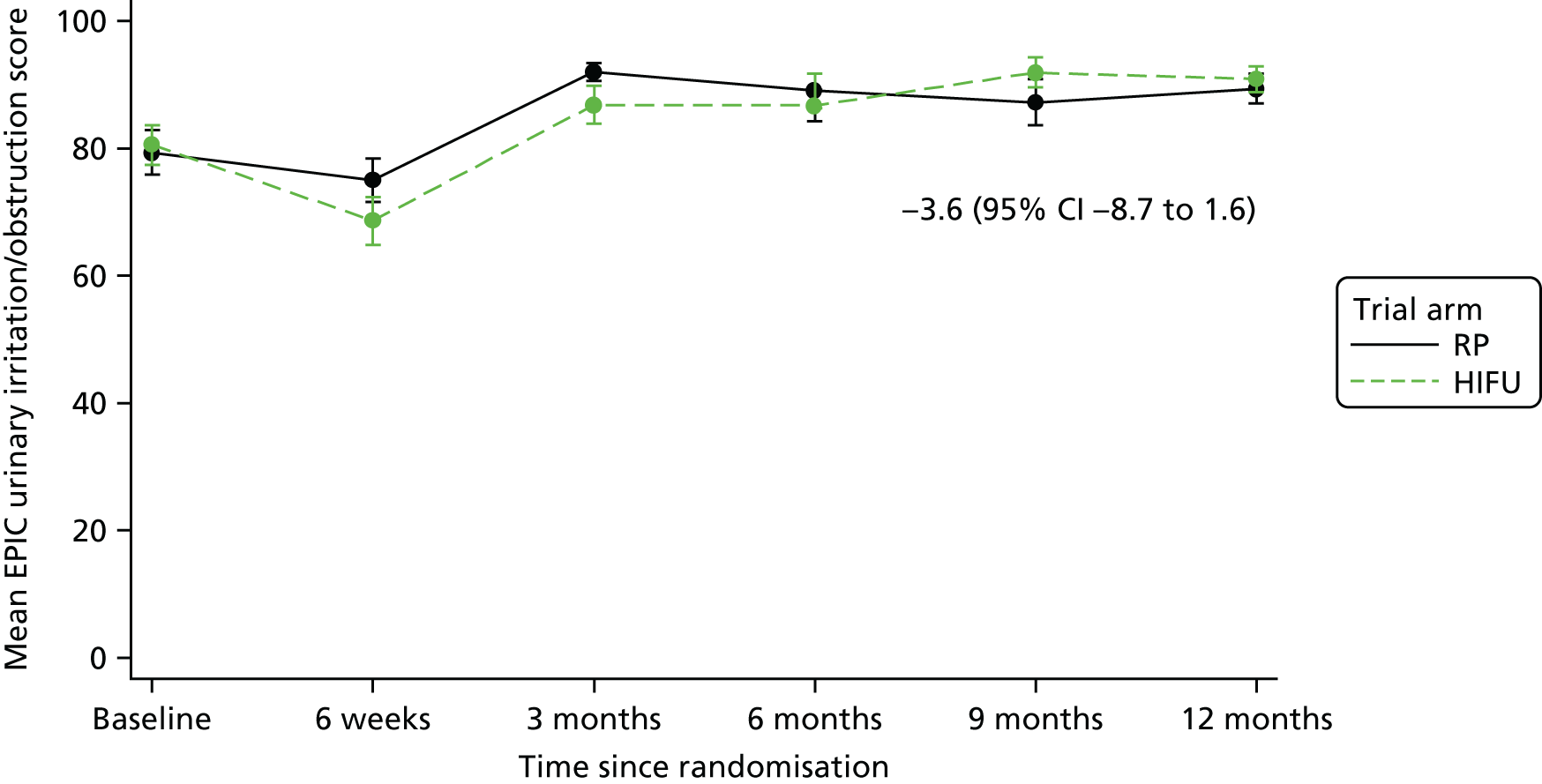

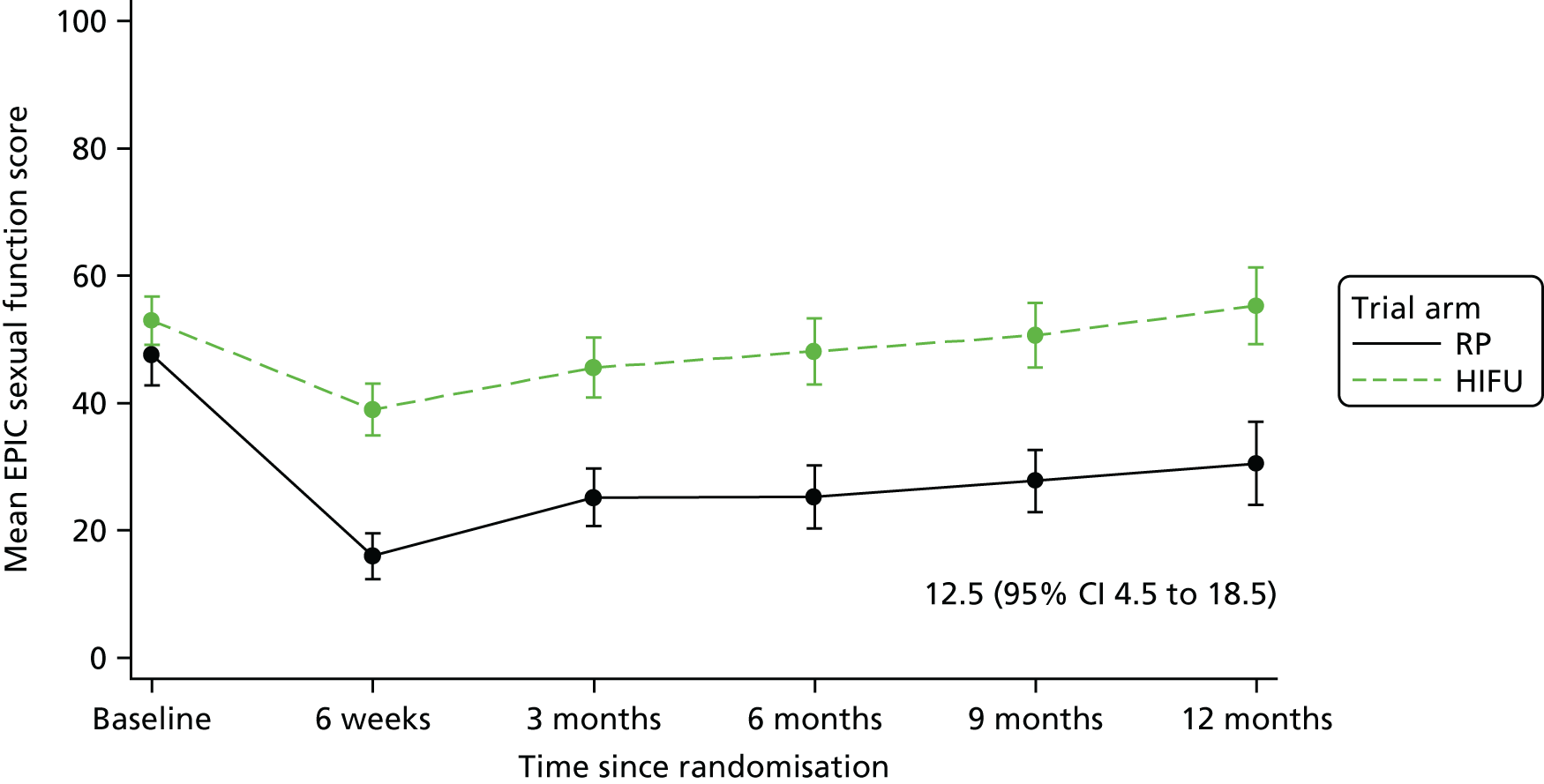

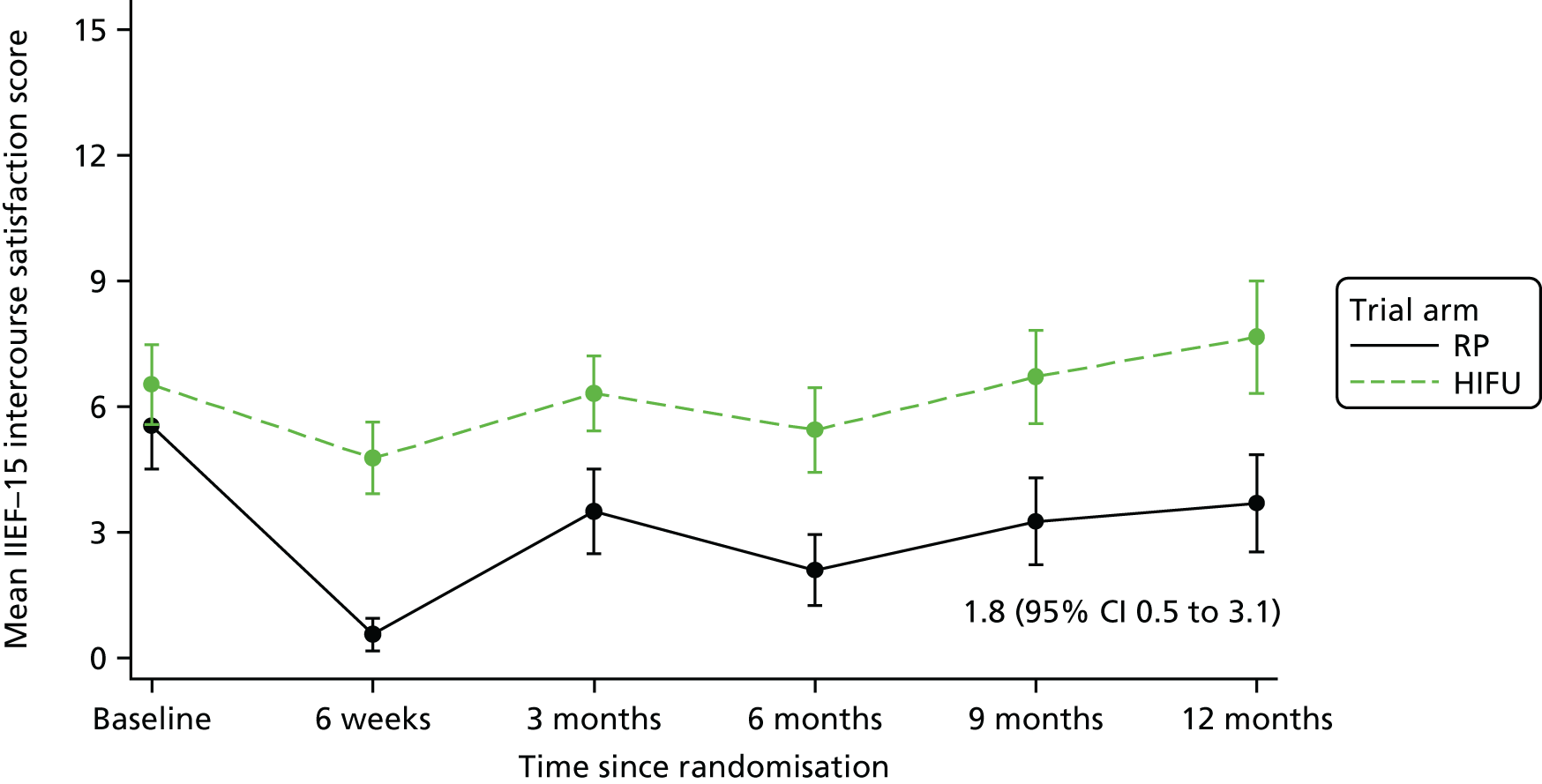

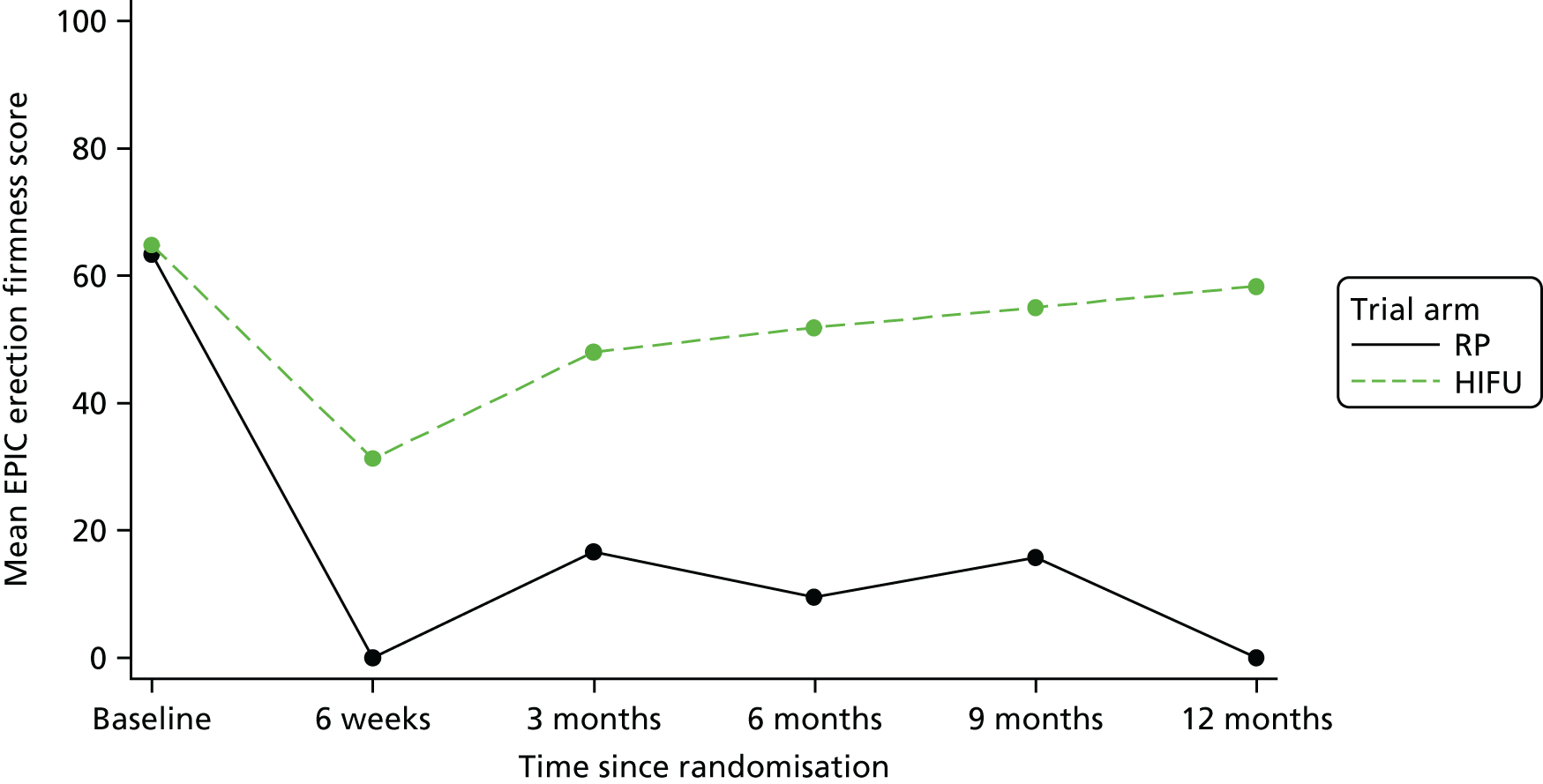

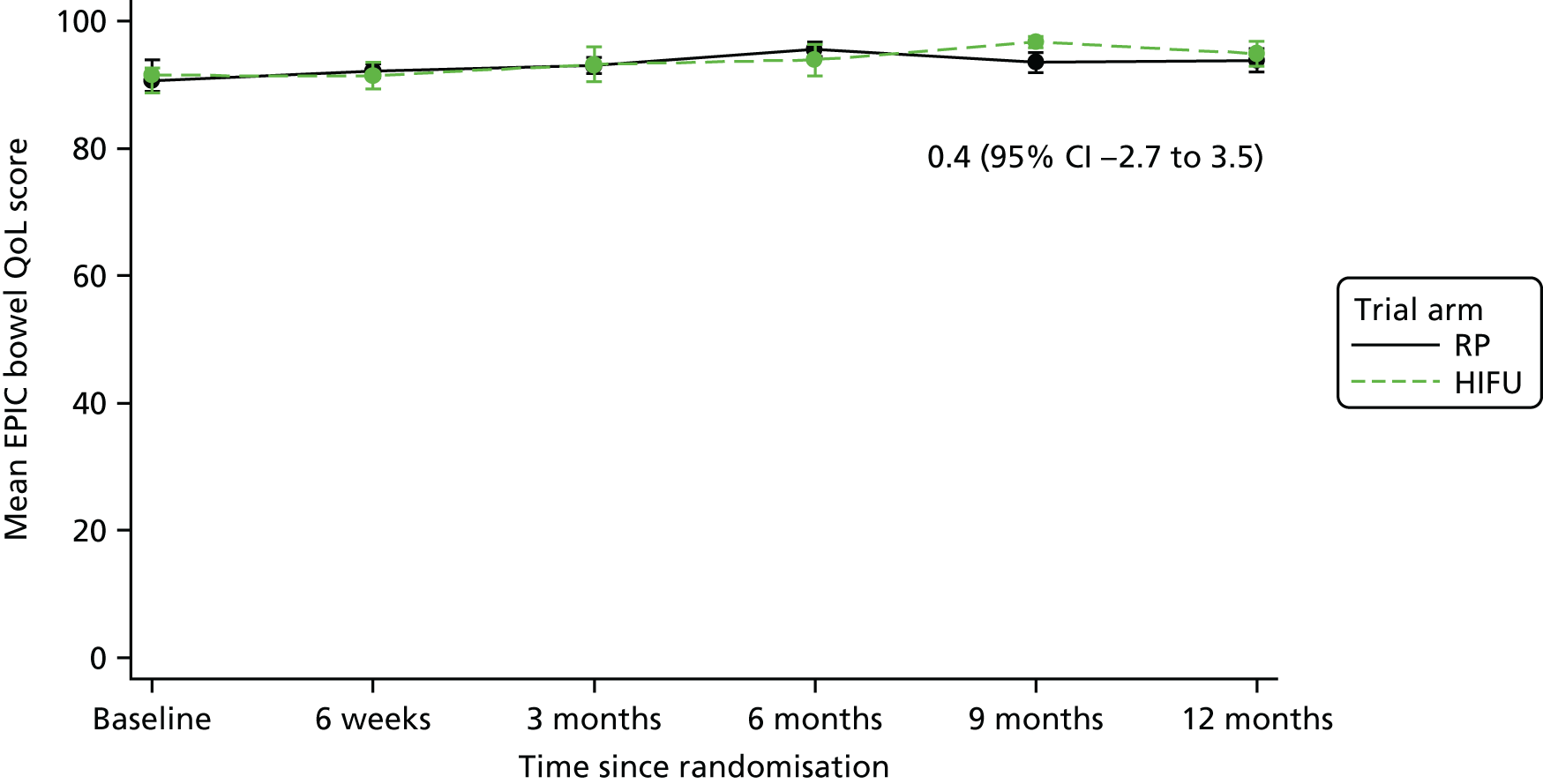

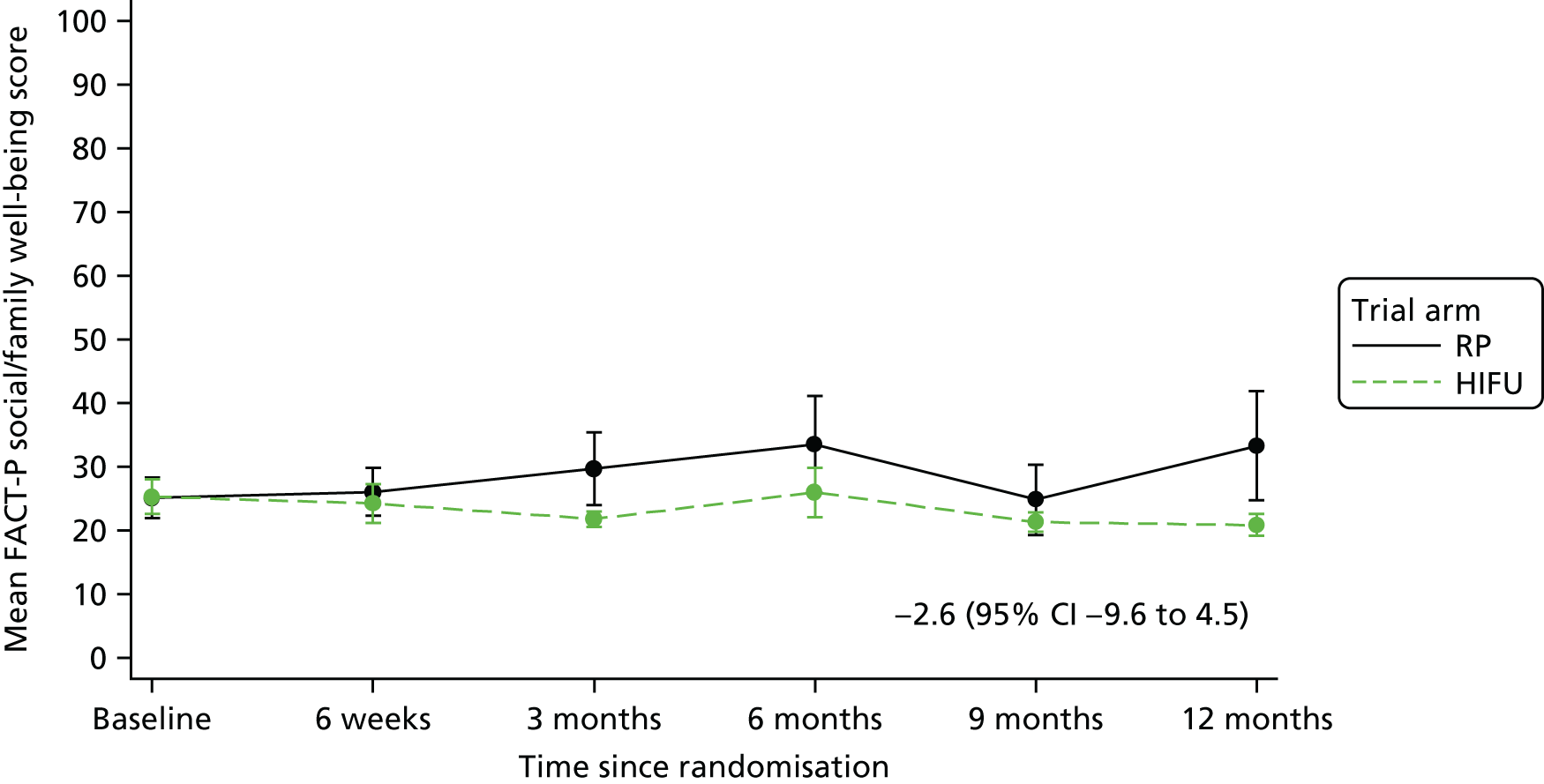

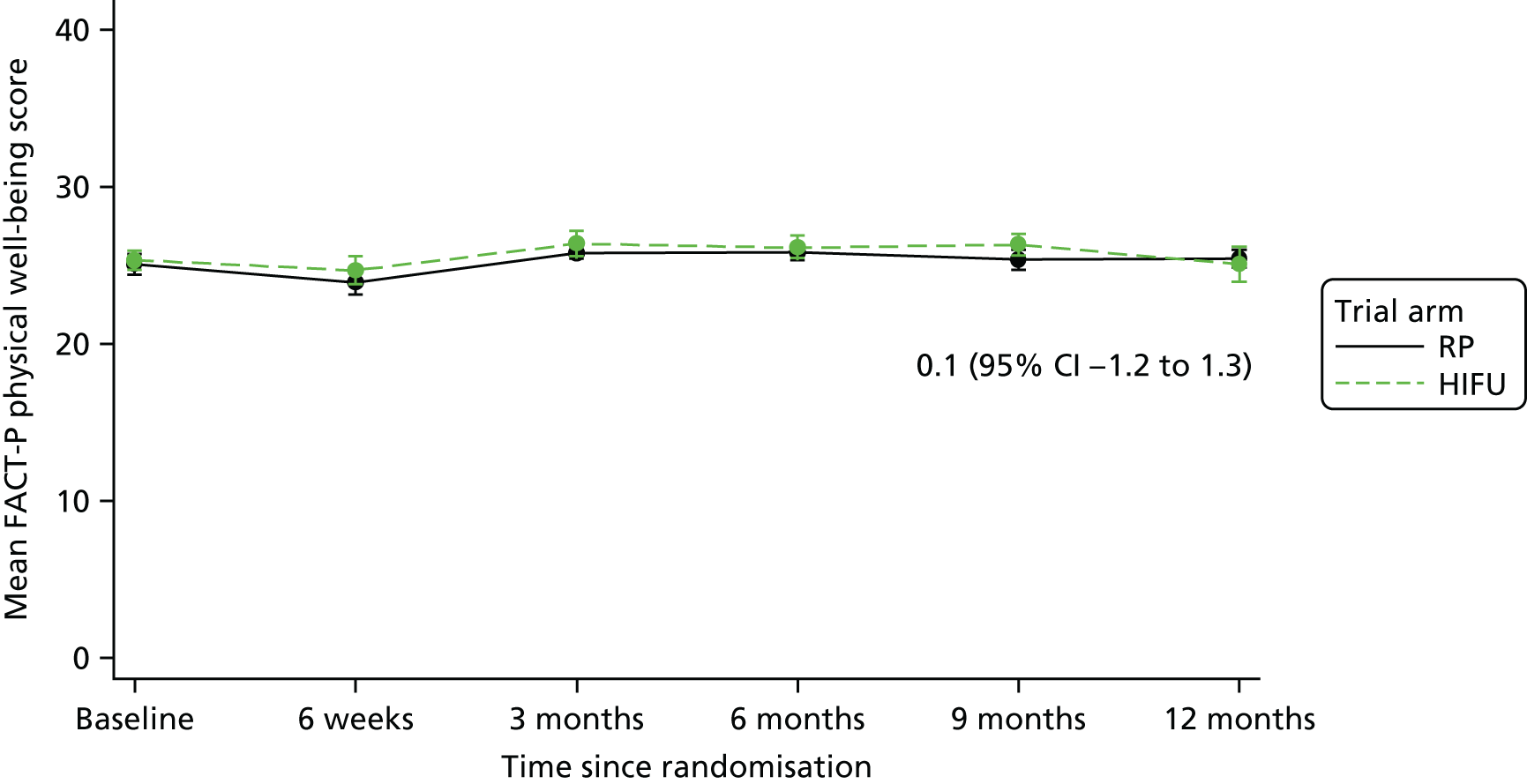

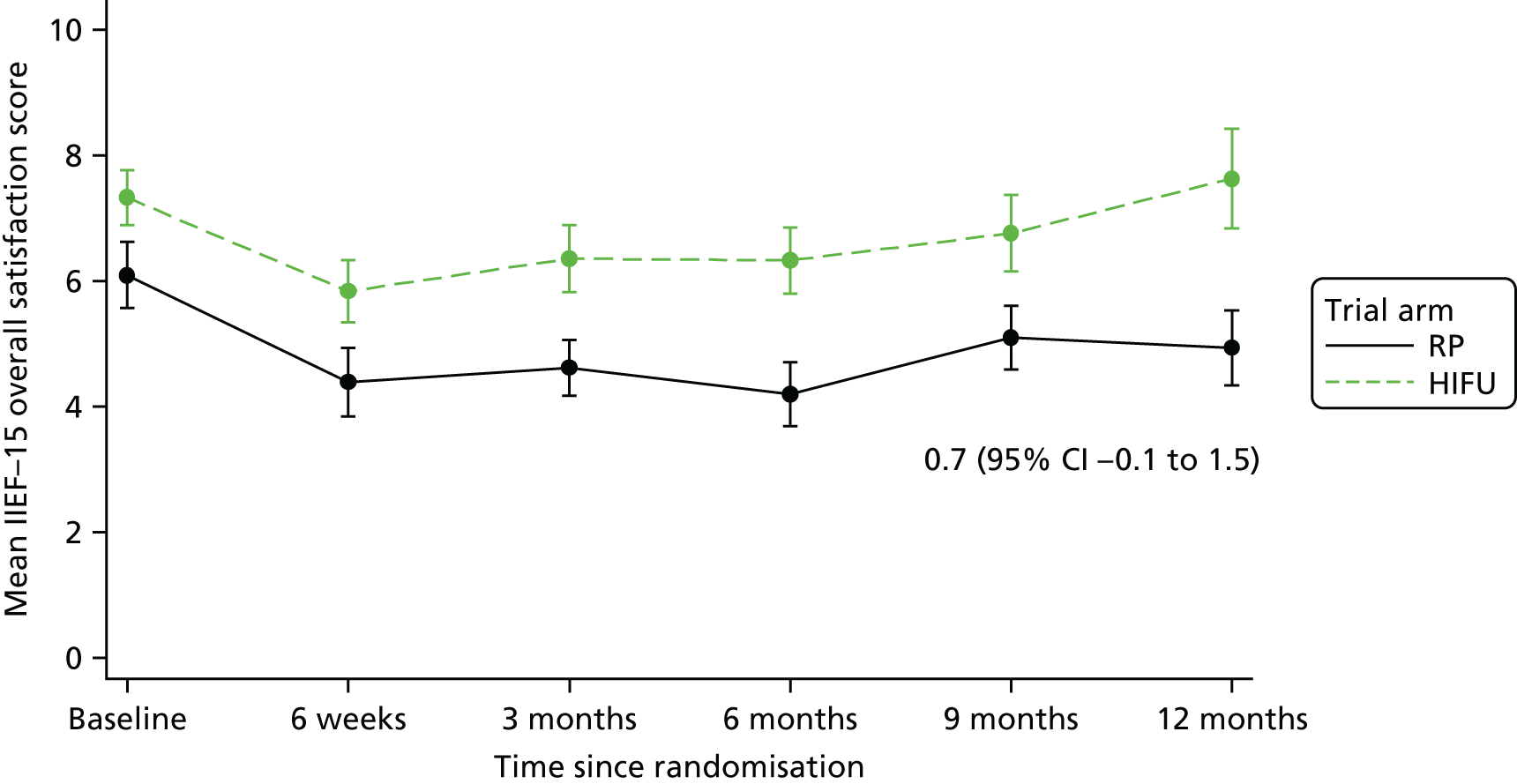

For disease-specific HRQoL outcomes, mixed models for repeated measures (MMRMs) were used to evaluate differences over time by treatment arm. MMRMs were adjusted for treatment, baseline score, visit and a treatment-by-visit interaction as fixed-effect terms with patient included as a random effect and reported as mean difference with 95% confidence intervals. All HRQoL outcomes were analysed up to the 12-month postprocedure assessment, because most patients in the study had not reached further than this visit at the time of analysis. HRQoL forms returned partially complete were analysed in accordance with the scoring instructions for each questionnaire.

All statistical analyses are in accordance with the intention-to-treat (ITT) principle, apart from procedural and postprocedural complication rates, serious adverse events (SAEs) and treatment-related details, which are summarised according to the treatment the patient received. Analyses were performed using SAS® version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and Stata® version 13.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Health economic methods

The objectives of the exploratory health economics data collection alongside the PART feasibility study were to:

-

evaluate the response and completion rates of the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L) instrument for assessing generic QoL, as well as the response and completion rates of the trial-specific patient resource use diary

-

conduct a preliminary exploration of reported generic HRQoL using the EQ-5D-5L utility scores and EuroQol Visual Analogue Scale (EQ-VAS) scores and reported resource use across trial arms, which may inform the design of a main RCT.

At the randomisation visit, generic and disease-specific HRQoL were assessed in the format of a PROMs survey pack that was given to each participant to fill out at each follow-up appointment. The EQ-5D-5L instrument (included in the PROMs survey pack), used to inform the health economic analysis, was completed at baseline, 6 weeks and 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, 24, 30 and 36 months post procedure. The completed survey pack was expected to be returned to the trial nurse prior to the participant attending the follow-up visit with the consultant.

A trial-specific patient resource use diary was developed using feedback from clinicians and nurses. This assessed the following four types of resource use.

-

Section 1: how many times the participant had to see or talk to a doctor or nurse or other health-care professional in relation to PCa, and what for. This included hospital admissions.

-

Section 2: what special medications, aids and adaptations the participant bought or had prescribed to help them with PCa and treatment-related symptoms.

-

Section 3: how many days the participant felt too unwell to engage in normal activities because of PCa-related symptoms.

-

Section 4: details of any travel made for the participant’s health-care appointments.

The diary was given to each participant by the trial nurse after the initial treatment and at each follow-up visit (i.e. at 6 weeks and 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, 24, 30 and 36 months). The participant was reminded to keep track of all health-care resources used and any time off work or usual activities between visits.

The completeness assessment for the exploratory health economics data collection differed from the ITT cohort used in the statistical analysis, and comprised patients meeting the following criteria: those who were randomised and received treatment by 16 March 2017 as per their initial treatment allocation (per-protocol analysis). The generic HRQoL instrument, EQ-5D-5L, was evaluated at the individual domain level [the five domains captured in the EQ-5D-5L are (1) mobility, (2) self-care, (3) usual activities, (4) pain/discomfort and (5) anxiety/depression, with five possible response levels, 1 being no problems and 5 being severe problems] and these were summarised along with the EQ-VAS scores. 63 Completeness levels are presented and patient/environment factors, including age and trial centre, were assessed to identify any drivers of incomplete data. For complete cases, EQ-5D-5L profiles were constructed for each time point and transformed into utility scores using the EQ-5D-5L UK population-based preference weights. 64 The baseline differences for the utility and EQ-VAS scores were assessed, along with changes from baseline for the follow-up period. These are presented by trial arm. Similar to the statistical analysis of disease-specific HRQoL, differences in utility were analysed up to 12 months post procedure, because most patients in the study had not reached further than this visit at the time of analysis.

Self-reported resource use from the patient diary was assessed by section and subsection for completeness levels and descriptive statistics were presented by trial arm across all follow-up time points up to the 12-month assessment. Units of resource use were aggregated across the follow-up period and presented by trial arm.

Resource use following treatment, including inpatient length of stay, intensive care unit (ICU) bed-days and high-dependency unit bed-days, was collected in the trial CRFs and is reported in the statistical analysis (see Table 7). Resource use associated with SAEs and complications was also analysed in the statistical analysis (see Tables 13 and 14). The resource use diary also collected self-reported data on accident and emergency (A&E) visits and inpatient days in the follow-up period. For this feasibility stage, the cost implications of trial procedures (i.e. HIFU and RP), inpatient bed-days and SAEs are informed by the literature and NHS reference costs;65,66 costs are expressed in 2015 Great British pounds.

The exploratory analysis was performed in Microsoft Excel® 2010 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and Stata.

Although not undertaken within this feasibility trial, a full costing and cost-effectiveness analysis would be required in a main RCT. A full RCT would include a complete cost-effectiveness analysis and a budget impact model with the cost of all trial procedures estimated using a microcosting approach.

Safety

Adverse event reporting was undertaken in accordance with the National Research Ethics Service (NRES) guidelines for reporting in non-CTIMPs (Clinical Trial of an Investigational Medicinal Product).

Details of recurrence and any subsequent re-treatment were captured on a ‘Treatment Failure’ and a ‘For cause HIFU treatment’ worksheet as appropriate, and entered remotely to the trial database, or returned to the trial office for central data entry.

Treatment failure

Radical prostatectomy

In patients receiving RP, primary treatment failure was defined as a rising serum PSA level reaching ≥ 0.2 ng/ml following initial reduction to < 0.1 ng/ml after surgery; or a failure of serum PSA to reach the level of < 0.1 ng/ml after surgery; or clinical progression to local recurrence/systemic disease.

Partial ablation

In patients receiving PA, primary treatment failure was determined by a combination of repeat prostate biopsies, serum PSA level and clinical appearance of symptoms/signs suggesting disease progression. Prostate biopsies following PA would determine one of five defined scenarios:

-

negative biopsies, in which case the patient would continue to be followed up as described

-

positive biopsy in the originally treated area, in which case the patient would be allowed one additional HIFU treatment before the treatment is classed as having failed

-

positive biopsy in the untreated area demonstrating a new focus of intermediate-risk disease, in which case the patient would be offered additional PA in this area

-

positive biopsies in any area of the prostate demonstrating low-risk, low-volume disease, in which case the patient will not require additional treatment and follow-up will continue as described

-

positive biopsy following two consecutive treatments in any area of the prostate, in which case the treatment will be deemed as having failed.

If follow-up biopsies demonstrate high-risk disease at any point, this will be considered as primary treatment failure and patients will be offered whole-gland treatment in accordance with standard of care.

In the presence of primary treatment failure as described above, the patient would be re staged using pelvic cross-sectional imaging and bone imaging. Patients would be fully informed of their disease status, grade, clinical stage and the treatment options, such as salvage EBRT. Regardless of decisions about additional interventions, patients would continue to be followed up and analysed within the trial in accordance with ITT, with full documentation of subsequent treatments.

Trial management processes

The PART trial was run within the Surgical Intervention Trials Unit (SITU) and the OCTRU, which is registered with the UK Clinical Research Collaboration (UKCRC). This trial was given ethics approval for conduct in the NHS by the South Central – Berkshire Ethics Committee (see Report Supplementary Material 6).

The PART trial was conducted in accordance with OCTRU standard operating procedures (SOPs) and a number of complementary TSIs on performing HIFU procedures, proctoring of HIFU cases and histopathology reporting. The aim of these documents was to ensure quality assurance (QA) and quality control (QC) among participating clinicians. Clinicians new to performing HIFU were proctored by a HIFU expert and a competency form was required after each proctoring session. All documentation was saved on a secure Oxford University drive in the e-Trial Master File.

The PART trial management team were all trained in Good Clinical Practice (GCP) and an in-depth risk assessment was carried out. Central Monitoring and Data Management plans were finalised. PART trial data were entered into the OCTRU in-house OpenClinica (OpenClinica, Waltham, MA, USA) database system. Central monitoring activities were conducted by the trial manager; no on-site monitoring took place.

The trial manager conducted site initiation visits at all participating centres, and each centre received an investigator site file. The trial manager trained the local research teams in OpenClinica, Registration/Randomisation and Management of Product (RRAMP; the in-house randomisation system) and all study documentation. Ad hoc training was delivered both face to face and by telephone throughout the duration of the study. Screening logs were requested and collated on a monthly basis. To aid centres, the PART trial office pre-printed all CRFs, PROM questionnaire packs and resource use diaries and produced individual participant packs.

The CI, trial manager and core study staff met regularly to discuss the progress at all centres, and the following oversight meetings took place:

-

monthly minuted TMG and recruiter teleconferences

-

two full face-to-face TMG meetings, on 9 December 2015 and 28 March 2016

-

two Trial Steering Committee (TSC) meetings, on 9 June 2015 and 24 January 2017

-

four independent safety data reviewer meetings, on 20 May 2015, 25 September 2015, 13 April 2016 and 14 December 2016

-

one investigator’s meeting (open to all PART trial collaborators), on 9 December 2015.

Quality assurance and quality control

Radiology

All the mpMRI was performed in accordance with European Society of Urogenital Radiology (ESUR) guidelines, using both 1.5- and 3-tesla magnetic field strengths and a pelvic phased-array coil. Standard T1, T2, diffusion-weighted and dynamic contrast-enhanced mpMRI sequences were performed.

The pre-treatment scans were reported using the standardised reporting Prostate Imaging and Data Reporting System (PI-RADS) scoring system approved by ESUR, with a local T stage also reported. Additionally, it was agreed that the degree of capsular abutment of identified tumour would be recorded to the nearest millimetre, and patients with abutment of > 15 mm were regarded as ineligible for the study.

The post-HIFU treatment scans were performed at three time points: within the first month post HIFU for centres new to performing HIFU, and at 12 and 36 months. The early scans focused on assessing technical treatment success and complications, whereas the later scans focused on identification of disease, particularly the position of the tumour on the initial scan.

We aimed to establish the ability of early post-HIFU mpMRI to determine whether or not treatment has been adequate and the likelihood of local relapse, by reviewing the non-enhancing volume on initial scans against appearances at 12 and 36 months.

The reports were provided on a standard template across all centres, with the prostate divided into anterior and posterior, right and left, and three sectors: base, mid and apex.

Pathology

Biopsies and RP specimens were reported at the local trial centres to the requirements set in Dataset for Histopathology Reports for Prostatic Carcinoma. 67 Gleason grading was undertaken using the 2005 International Society of Urological Pathology’s modified Gleason grading system. 68 Pathological tumour, node, metastasis (TNM) staging was undertaken using TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours. 69

Biopsy reporting

Biopsies were reported at the centres by local pathologists. Biopsies were not routinely double reported or reviewed before completion of the CRF.

These were not double reported or centrally reviewed for the feasibility study.

Postprocedure biopsies can often be difficult, and immunohistochemistry may be required to distinguish posttreatment glands from residual adenocarcinoma. Cases are reported as negative for tumour, prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN), atypical small acinar proliferation (ASAP) or residual invasive adenocarcinoma. Data on histopathological features of post-HIFU changes are limited, but some guidance is provided by Ryan et al. 70 Difficult cases can be reviewed by the pathology group. Stromal fibrosis is the commonest finding post HIFU, with necrosis in a smaller number of cases. Treatment effects that preclude the ability to identify or Gleason grade post HIFU prostatic adenocarcinoma have not been identified. 70

All study pathologists were required to report histology specimens as detailed in the PART trial histopathology TSIs (see Report Supplementary Material 7). There was a lead pathologist at each recruiting centre; these pathologists formed the PART trial pathology group and were invited to participate in the PART trial monthly teleconferences. Members of the PART trial pathology group attended the update meeting on 9 December 2015 in Oxford, at which the lead PART trial pathologist gave a pathology update talk.

Radical prostatectomy reporting

Radical prostatectomy specimens were reported in each centre by the local pathologists. Oxford cases were centrally reviewed in Oxford by the PART trial lead pathologist, to record additional parameters that would not otherwise have been routinely reported and to allow future correlation of tumour topography with the mpMRI. Additional parameters recorded on central review were the diagnosis within each of the 12 PI-RADS zones A–L (benign, malignant, atypical), Gleason grade grouping71 and whether or not there was inflammation or fibrosis present.

Tumour location on the RP was summarised as follows:

-

unilateral clinically significant intermediate-risk disease – defined as a Gleason score of 7 (3 + 4 or 4 + 3) or a high-volume Gleason score of 6 (any tumour dimension of ≥ 4 mm)

-

dominant (defined as the largest tumour, which is usually the tumour with the highest stage and grade)68 unilateral clinically significant intermediate-risk disease and small contralateral low-risk disease – defined as a Gleason score of 7 in the dominant tumour (3 + 4 or 4 + 3) with a Gleason score of ≤ 3 + 3 on the contralateral side (any tumour dimension of ≤ 4 mm)

-

bilateral/high-risk disease – bilateral disease is defined as a Gleason score of 7 (3 + 4 or 4 + 3) on the dominant side and a Gleason score of 7 (3 + 4 or 4 + 3) or a high-volume Gleason score of 6 on the contralateral side (any tumour dimension of > 4 mm); high-risk disease is defined as a Gleason score of ≥ 8.

Partial ablation

As HIFU is a relatively new technology, proctoring of clinicians new to performing the procedure is important. A PA working group was established, chaired by a HIFU expert, and two TSIs were written detailing the training and delivery of HIFU (see Report Supplementary Material 5). Proctoring was performed by HIFU experts, and training and competency forms were completed for each proctored case. mpMRI scans at 2 weeks post HIFU were also requested for the first five patients in centres new to performing HIFU, to be centrally reviewed by the chairperson of the PA working group.

Patient and public involvement

Strong links with the Oxfordshire Prostate Cancer Support Group (OPCSG) were maintained throughout the feasibility study. The previous OPCSG chairperson and secretary were involved in the development of the original HTA funding application. The NIHR Research Design Service South Central patient and public involvement (PPI) officer facilitated a meeting to discuss the research idea, the proposed design and opportunities for involvement throughout the duration of the study, as well as in the dissemination process. This was attended by an independent patient representative, who had recently been treated with HIFU for localised PCa in a clinical trial. A lay summary was produced for Cancer Research UK’s website and permission was granted by Cancer Research UK to use its logo on our website.

The lead PART trial research nurse in Oxford presented the PART trial to the OPCSG in January 2016. The PART trial was well received by the committee, and all members of the committee agreed on the importance of the study and the need for a larger RCT.

The new OPCSG chairperson continued PPI involvement as a lay member on the TSC, in addition to another patient representative, who had previously received RP. The OPCSG chairperson acted as a link to the OPCSG members and attended the PART trial investigator’s meeting, at which he participated in the discussion about how QoL is being measured in the PART trial, a question that had previously been raised by the OPCSG members. OPCSG members reviewed the PIL to ensure that it was a clear and understandable document from a patient’s perspective. Two queries arose regarding the risk of leaking urine and the risk of problems with sexual activity; these were addressed in the PIL, which was amended and approved by the Research Ethics Committee (REC) in February 2016.

Protocol and study documentation changes

Research Ethics Committee approval was obtained on 22 December 2014 for all PART study documentation. The protocol and PIL underwent substantial amendments and approvals were obtained on 18 January 2016 and 10 February 2016, respectively.

Protocol version 3.0, dated 2 November 2015

Further detail/clarification was included on:

-

the pre-randomisation diagnostic (imaging/biopsy) pathway for PCa patients

-

QA and QC information (for HIFU delivery, radiology and pathology)

-

the definition of treatment failure in patients receiving HIFU.

Consent process

There were no changes to the consent process.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

‘Clinical T3 disease’ was added as an exclusion criterion.

Participant documentation

Following on from the PPI review of the PIL (now version 4.0 dated 21 January 2016), the ‘Possible disadvantages following RP’ column in table 2 was amended to read:

-

The risk of severe urine leaking is about 1%. The risk of moderate urine leaking is about 10%.

-

The risk of problems with sexual activity is around 50%.

Two clinic posters received Research Ethics Committee approval

-

One for clinicians, itemising the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

-

One promoting the study to patients [with a Quick Response (QR) code added so that patients could navigate directly to the PART trial website].

New centre recruitment

Originally, four recruiting centres were planned, including North Bristol, which was never opened because of unforeseen circumstances. Southampton General Hospital was opened to replace North Bristol. Basingstoke and North Hampshire Hospital opened as a fifth recruiting centre.

Project timetable and milestones

The recruitment period was originally projected to end on 30 June 2016 but was extended until 31 March 2017.

Chapter 3 Trial results

Recruitment and screening

Five UK NHS centres were opened in the PART study and recruitment took place in four of these five centres: (1) Churchill Hospital (Oxford), (2) Royal Hallamshire Hospital (Sheffield), (3) Southampton General Hospital, (4) Basingstoke and North Hampshire Hospital and (5) University College Hospital (UCH), London (no patient recruitment). The first patient was consented on 27 January 2015 and randomised on 3 February 2015. Quarterly randomisation by centre is shown in Table 1 for both the initial recruitment period (up to 30 June 2016) and the period of extension (up to 31 March 2017).

| Centre | Recruitment period | Grand total | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | ||||||||

| January–March | April–June | July–September | October–December | January–March | April–June | July–September | October–December | January–March | ||

| Churchill Hospital, Oxford | 4 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 9a | 37 |

| Royal Hallamshire Hospital, Sheffield | R&D 16 November 2015 | 2 | 0 | 7 | 4 | 2 | 10b | 25 | ||

| Basingstoke and North Hampshire Hospital | R&D 1 June 2015 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 10 | |

| Southampton General Hospital | R&D 7 October 2015 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 10 | ||

| UCH, London | R&D 29 May 2015 | No patients recruited | 0 | |||||||

| Quarterly total | 4 | 5 | 2 | 8 | 6 | 16 | 10 | 7 | 24 | 82 |

The cumulative consent and randomisation rate is shown in Figure 1. The rate of recruitment was slower than expected, with one centre (UCH, London) unable to recruit any patients. The number of patients recruited per month ranged between 1 and 12, with an average of three per month throughout the 27-month period.

FIGURE 1.

Cumulative recruitment rate (consented and randomised patients).

Eligibility and randomisation

A total of 329 patients were screened across the five centres. The CONSORT flow diagram is presented in Figure 2, summarising the overall number of patients screened, considered eligible, consented and randomised. Of the patients screened, 93 were found to be ineligible and 149 declined consent. As the study had only just completed recruitment at the time of writing this report, data were pending for a number of patients. To allow for analysis to be undertaken on the available data, a database lock and extraction took place on 10 October 2017 (to include all data received up to and including 10 October 2017) when 82 participants had been randomised. See Table 5 for a summary of the data received by this time point.

FIGURE 2.

The CONSORT flow diagram. a, Incomplete screening data received on 72 patients. b, Consent data included up to and including 31 March 2017. c, Randomisation data included up to and including 4 May 2017. d, Data included up to and including October 2017.

Of the 87 patients who consented by 31 March 2017, 82 were randomised by 4 May 2017. Five patients were not randomised after giving consent: three patients failed imaging assessment post consent and two patients preferred not to be randomised. Of the 82 participants randomised, 41 were allocated to RP and 41 to HIFU. One participant randomised to RP withdrew from the study before receiving treatment. Within the RP group, eight participants rejected their treatment allocation: four participants crossed treatment groups to receive HIFU, one participant chose brachytherapy, two participants chose radiotherapy and one participant chose AM. One participant in the RP group was deemed unfit to receive surgery on clinical grounds, and crossed over to receive HIFU. In the HIFU group, two participants received brachytherapy treatment as a result of clinical judgement and one participant crossed over to receive RP. All randomised participants were included in analyses apart from the health economic evaluation, for which patient selection is described in Chapter 2, Study design.

QuinteT Recruitment Intervention results

In the presentation of the findings in the following sections, quotations are provided to support the results, and distinctions are made between data from interviews and those from recorded consultations. Quotations are anonymised to ensure confidentiality.

Data

Interviews

The QRI researcher approached 23 staff members to take part, and a total of 13 one-to-one interviews were conducted between July and November 2015. Interviews were conducted by the QRI researcher. Eight interviews were conducted face to face and five were conducted by telephone. The final sample of interviewees consisted of the trial manager, 11 recruiting clinicians (four of whom were members of the TMG) and one research nurse. At least one representative from each of the recruiting centres was interviewed. Interviews lasted an average of 43 minutes (range 31–53 minutes).

Recorded consultations

A total of 64 recruitment appointments, with 54 different patients, were obtained (in the case of five patients, two consultations were recorded). The first recording was received in September 2015. A total of 22 recordings were made before any QRI feedback had been provided and 45 were made after QRI feedback had been provided. Consultations lasted an average of 27 minutes (range 10–42 minutes). Twelve different recruiters (11 consultant urologists and one research nurse) led the consultations. Audio-recordings were obtained from four recruiting centres. One centre did not any provide recordings, another provided two recorded consultations (although both of these patients were ineligible), two centres provided 14 recordings and one centre provided 34 recordings.

Phase I: understanding recruitment challenges

The aim of phase I of the QRI was to understand recruitment difficulties as quickly as possible, so that they could be promptly addressed in phase II. The difficulties tended to be related to organisational arrangements or more complex issues about aspects of the design of the trial and intervention – so-called hidden challenges associated with perceptions of evidence, aspects of patient eligibility and the existence (or not) of equipoise.

Support for the study

Those involved in the study were asked about the existing evidence and the rationale for the study. HIFU was described as an ‘exciting’ and ‘promising’ alternative to radical procedures. Most of the recruiters described findings from observational studies, which suggested that HIFU had a lower side-effect profile in terms of erectile dysfunction or incontinence and acceptable outcomes in terms of cancer control. Recruiters described how much of the research had been conducted within UCH, and several commented that Oxford running the study was a strength as it was considered an ‘impartial’ centre:

I think this trial is needed because there has been a lot of hype or buzz about HIFU and focal therapy for some years now.

Interview, recruiter

I think having a study that is being led by a sort of equivocal centre is probably going to be very good for the study.

Interview, recruiter

Overall, there was strong commitment to a randomised study comparing RP with HIFU:

It’s an important study, I think everyone would like it to succeed.

Interview, recruiter

We don’t have any high-quality, randomised, comparative trial results, so it’s crying out really for a randomised trial and a good comparator would be radical prostatectomy.

Interview, recruiter

However, the QRI identified a number of issues that affected recruitment. These are outlined in the following section.

Organisational challenges

Several logistical obstacles disrupted the anticipated recruitment timelines, including the delivery of HIFU equipment in two centres (Sheffield and Bristol). In January 2015, it became evident that if the centre did not own a HIFU machine, the cost of hiring one was not covered in the original costing tariff. The TMG approached the manufacturers of the HIFU device to determine if the machine could be rented for free, which was not possible. The TMG then approached both Basingstoke and Southampton centres that were offering HIFU routinely, in May 2016. In Sheffield, an excess treatment cost (ETC) bid was submitted and successfully awarded so that part of the shortfall was covered by the Clinical Commissioning Group. However, ensuring the ETC took nearly 10 months and, as a result, recruitment in Sheffield (a high-yielding recruitment centre) was severely delayed:

HIFU is a new technology and costings in the NHS in terms of R&D [research and development] finance and the way they are costing it is quite difficult. What it meant was that the cost of hiring a HIFU machine if the site didn’t own it wouldn’t have been covered in the original tariff, so there would be a shortfall to the trust essentially. This had quite a severe knock-on effect in two of the original sites, Sheffield and Bristol, because they don’t own a HIFU machine and HIFU wasn’t routinely offered there. I think that might have been the biggest delay.

Interview, TMG

Obtaining research and development (R&D) approval in all centres, apart from Oxford, took significantly longer than hoped. In some institutions, it took as long as 6 months from submitting the site-specific information (SSI) form to centre R&D approval being issued. Many staff involved in recruitment to the study left their roles. This included the proposed PI for Bristol, and, in December 2015, the TMG made the decision not to pursue activating this centre. Research nurses from two active centres also left their roles (November 2015 in Basingstoke, April 2016 in Southampton and December 2016 again in Basingstoke), meaning that all new staff had to be recruited and subsequently trained:

We’re 6 months in and we’ve not even hit the start button for our R&D approval. That’s the biggest problem.

Interview, recruiter

Table 2 provides an overview of the organisational issues encountered. Although it was anticipated that all five centres would begin recruitment in January 2015, delays in activating the centres meant that, combined, a total of 30 recruiting months were lost.

| Issue | Impact on recruitment |

|---|---|

| Delay getting centres active | Obtaining R&D approval in all centres meant that four centres began recruitment significantly later than anticipated:

|

| Availability of HIFU machine | Not all centres owned a HIFU machine and this had not been covered in the original costing tariff. An ETC was awarded to Sheffield, although this meant that there was an 11-month delay in getting the centre activated |

| High staff turnover | Many staff involved in recruitment left their roles, including the PI for Bristol, and several research nurses in Basingstoke and Southampton. Consequently, new staff had to be identified and trained |

Hidden challenges

The organisational issues meant that data collection for the QRI was also delayed in most centres. For instance, the first recording of a consultation was only obtained in September 2015. Once the centres began recruiting and sufficient QRI data became available, analyses demonstrated that there were a number of intellectual and emotional challenges to recruiting to the PART trial. These are outlined in the following sections.

Previous randomised controlled trial experience

Before the PART trial, many of those interviewed had not been involved in recruiting to randomised studies and had therefore not received any support or training for their role as recruiters. The exception to this was several recruiters from Oxford and Sheffield, who had received recruitment training for the ProtecT trial. Analysis of the data showed that, overall, these recruiters appeared more comfortable with the concept of uncertainty, with the need for pragmatic inclusion criteria and with explaining trial concepts to patients. This is further discussed throughout this chapter, but is exemplified by the following quotations:

I have seen patients that have been recruited to different trials through my training, but I haven’t, personally, been responsible for recruiting to trials [. . .] I have no idea whether HIFU’s going to work or not, so it makes it very difficult to know how much of that information to tell patients. The problem with HIFU is that I have no idea whether, in a year’s time or whatever it is, 20% of all the people that are having HIFU need a further treatment, or whether it’s 2% or whether it’s 50%. Therefore, it’s very difficult to then talk to patients about it. Whereas, if they opt for surgery, I can say to them, based on their disease parameters, that their chance of having a recurrence is something like 5% to 10% in 10 years.

Interview, recruiter

I think we need to be confident on our uncertainty, and you know, I’ve learned a lot by being involved in ProtecT [. . .] We have a national reputation for being good with prostate cancer, and we acknowledge that there are uncertainties in the decision-making, which is why we run clinical trials.

Interview, recruiter

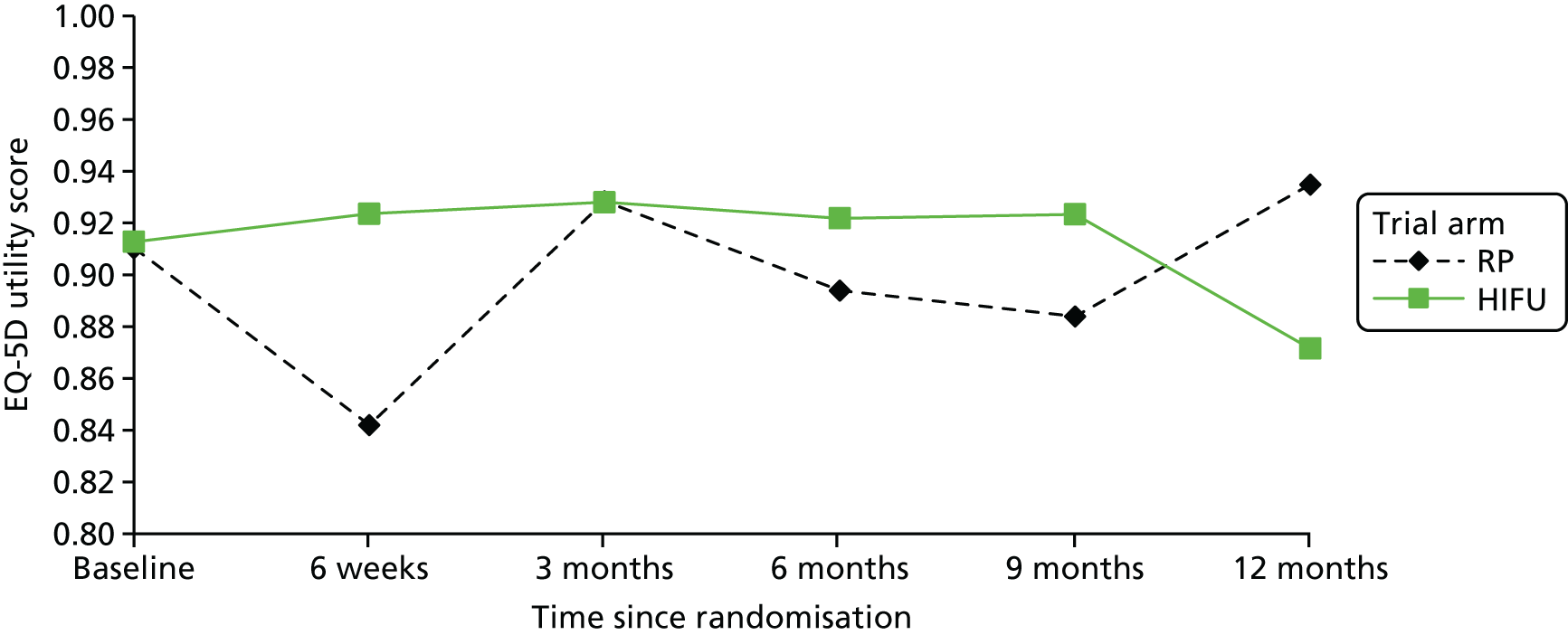

Discomfort regarding the inclusion criteria