Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 08/68/01. The contractual start date was in May 2010. The draft report began editorial review in August 2017 and was accepted for publication in January 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Ibrahim Abubakar is a member of the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Commissioning Board. Ajit Lalvani is a named inventor on several patents underpinning the T-SPOT.TB test assigned by the University of Oxford to Oxford Immunotec Ltd and has royalty entitlements from the University of Oxford. He was the scientific founder of Oxford Immunotec Ltd and ceased to be a director 10 years ago. He is a member of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation Board. Charlotte Jackson was funded by NIHR, during the conduct of the study, and reports personal fees from Otsuka Pharmaceutical, outside the submitted work. Chris Griffiths is involved in NIHR-funded clinical trials units. Jonathan J Deeks is Chairperson of the NIHR HTA Efficient Studies Themed Board, Chairperson of the NIHR HTA Multimorbidities in Older People Themed Board, Deputy Chairperson of the NIHR HTA Commissioning Board, Chairperson of the NIHR HTA Monitoring Strategy Group, a member of the NIHR HTA Methods Group for Diagnostic, Technologies & Screening, a member of the NIHR HTA Methods Group for Elective & Emergency Specialist Care, a member of the NIHR HTA Programme Commissioning Strategy Group and a member of the NIHR HTA Strategy and Oversight Group. The other authors have no competing interests to declare.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Abubakar et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background, aims and objectives

Background

Tuberculosis (TB) is a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. In 2015, an estimated 9 million cases occurred globally and > 1.5 million people died of TB. 1 The UK has seen a resurgence of TB since the late 1980s, and there are currently > 7000 new cases each year. 2 Although there has been a decline over the last few years, levels remain higher than in most Western European countries. Most cases in the UK occur in major cities, particularly London, and two-thirds of TB patients were born abroad. There are also high rates among those with social risk factors such as homelessness and/or drug/alcohol misuse. Control measures have traditionally relied on the prompt diagnosis of active TB and ensuring that patients completed their treatment. More recently, the collaborative TB strategy for England has initiated a programme of latent TB screening of migrants entering the UK from countries with a high TB burden. 3

The majority of TB cases in the UK are a result of reactivation of latent infection. 2 Among migrant groups, the infection is likely to have been acquired abroad whereas, among the elderly UK-born population, the infection is likely to represent acquisition several decades ago when TB was highly prevalent in the UK. The policy of targeting active TB cases for treatment alone will therefore not be sufficient to control and eventually eliminate TB in the UK. The identification and treatment of individuals with latent TB infection (LTBI) who are at high risk of developing active TB may therefore be an essential additional measure provided that (1) true LTBI can be identified [and distinguished from prior bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) vaccination], (2) the probability of developing active TB in people with untreated LTBI can be determined and (3) the intervention strategy available (treatment of latent infection) is effective and can be successfully implemented.

Identification of latent tuberculosis infection

It is estimated that between one-quarter and one-third of the world’s population is latently infected with the tubercle bacterium4,5 and it is widely accepted that, among those with LTBI, there is approximately a 10% lifetime chance of progression to active TB. Until recently, the tuberculin skin test (TST) was the only tool for the diagnosis of LTBI. TST assesses the delayed-type hypersensitivity response to a purified protein derivative, which contains antigens shared by several mycobacteria and Mycobacterium bovis BCG, by measuring the size of the skin induration following the injection of the antigen. Limitations to the validity (sensitivity and specificity) of TST as a measure of latent infection have been recognised for many years. These are partly attributable to variability in the quality of the administration and interpretation of the test, as well as the state of host immunity.

Interferon gamma release assays

Interferon gamma release assays (IGRAs) are based on the detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex specific region of difference 1 (RD1) antigens such as early secretory antigenic target 6 (ESAT-6), culture filtrate protein 10 (CFP-10) and other TB-specific antigens. Two commercial assays have been developed using these M. tuberculosis antigens: (1) QuantiFERON® TB Gold In-Tube (QFT-GIT; Cellestis International Pty Ltd, Chadstone, VIC, Australia), which uses an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) format; and (2) the T-SPOT®.TB test (Oxford Immunotec Ltd, Oxford, UK), which is an enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT)-based assay.

Predictive value studies of interferon gamma release assays

Early systematic reviews6 of the role of IGRAs in the diagnosis of latent infection with M. tuberculosis concluded that they have several advantages over the TST, including higher specificity (less cross-reactivity with BCG vaccine and environmental mycobacteria) and better correlation with exposure to M. tuberculosis. In the absence of a gold standard for the diagnosis of LTBI, all of the studies in these reviews have used other proxy measures to estimate the sensitivity and specificity of IGRAs for latent infection. These measures include ‘degree of contact with a case of TB’ and the use of ‘active TB disease’ as an indicator of a true positive result and ‘low prevalence of infection in the test population’ to estimate true negative results. 4

The majority of the studies included in these reviews were conducted in high-incidence countries, with a limited number conducted in low-incidence countries. Most of the completed studies either had low power7–9 or used routinely collected data. 10 More recent systematic reviews still conclude that the predictive value of IGRAs is comparable to that of TST. 11,12 We have updated these reviews in Diagnostic performance of interferon gamma release assays for development of active tuberculosis: evidence summary.

National and international guidelines and policy context

National policy

The national policy for the control of TB is currently based on the Collaborative Tuberculosis Strategy for England,3 published in January 2015, which outlines 10 action areas including treatment of LTBI in new entrants to the UK from high-burden countries. Based on this strategy, Public Health England (PHE; formerly the Health Protection Agency) recommends screening using IGRA alone. 13 In contrast, the most recently published (January 2016) National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance14 recommended that a TST and, where this is not available, an IGRA for migrants (as this was the most cost-effective strategy based on analysis using predictive value data) and a two-step approach using the TST followed by an IGRA if the TST was positive for contacts.

International policy

The World Health Organization (WHO) has published guidelines for the management of LTBI,12 which is targeted at countries with an incidence of TB of < 100 cases per 100,000 people. These guidelines recommend the use of either IGRAs or TST as alternatives based on very low-quality evidence. Internationally, individual country guidelines differ considerably with five broad approaches: (1) an IGRA and TST as alternatives, (2) a two-step process consisting of a TST followed by an IGRA, (3) an IGRA and TST together, (4) an IGRA alone, replacing the TST, and (5) the TST alone.

Diagnostic performance of interferon gamma release assays for development of active tuberculosis: evidence summary

Because of the known limitations of the TST, there is no gold standard against which to compare IGRAs to estimate their sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV) or negative predictive value (NPV) for the presence of LTBI. However, for clinical and public health purposes, arguably a more important issue is what a positive or negative IGRA result means for the risk of developing active TB. Several studies have estimated PPV and NPV, sensitivity or specificity of IGRAs for the development of active TB, and two recent systematic reviews15,16 have included meta-analyses of these parameters. A further, more up-to-date, review12 concluded that the two tests were not significantly different in terms of their PPV and NPV.

The two recently published reviews15,16 had slightly different objectives, inclusion criteria and analytical approaches and, for this reason, reached different conclusions. One of them15 estimated a pooled PPV of 2.7% [95% confidence interval (CI) 2.3% to 3.2%] from 17 studies and 6.8% (95% CI 5.6% to 8.3%) from 13 studies that were conducted in high-risk groups. The pooled NPV was considerably higher, at 99.7% (95% CI 99.5% to 99.8%). The included studies were heterogeneous for both PPV and NPV. The other review16 compared rates and risks of TB disease in IGRA-positive and IGRA-negative individuals, as well as estimating sensitivity and specificity of IGRAs for the development of active TB. The pooled rate ratio was 2.10 (95% CI 1.42 to 3.08) and the pooled risk ratio was 3.54 (95% CI 2.23 to 5.60). Sensitivity was estimated as 72% (95% CI 58% to 82%) and specificity as 50% (95% CI 41% to 58%) for the ELISPOT assay; for whole-blood ELISA, only two eligible studies estimated sensitivity and specificity, with values of 79% (95% CI 61% to 91%) and 43% (95% CI 18% to 72%) for sensitivity and 34% (95% CI 32% to 36%) and 59% (95% CI 55% to 62%) for specificity. In the subset of studies that assessed both IGRA and TST, Rangaka et al. 16 reported incidence rate ratios (IRRs) of 2.11 (95% CI 1.29 to 3.46) for IGRA, 1.60 (95% CI 0.94 to 2.72) for TST with a 10-mm cut-off point and 1.43 (95% CI 0.75 to 2.72) for TST with a 5-mm cut-off point. In the review by Diel et al. ,15 PPV appeared higher for IGRA (2.1%, 95% CI 1.7% to 2.5%) than for TST (1.4%, 95% CI 1.2% to 1.8%) in studies that assessed both tests.

The review by Rangaka et al. 16 was updated by Pai et al. ,11 who identified an additional five longitudinal studies that compared the incidence of TB between individuals with positive and negative IGRA results. Three of these studies were conducted in immunocompromised populations: human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive patients,17 patients with various immunosuppressive conditions18 and renal transplant recipients19. The remaining two studies assessed the development of active TB among contacts of TB cases in the UK7 and France,20 comparing those with a positive IGRA result at baseline with those with a negative result. In the UK, this generated a rate ratio of 4.9 (95% CI 2.7 to 8.7) over 2 years,7 whereas the French study reported a PPV of 1.96% among contacts who were not given chemoprophylaxis (CPX), over a mean follow-up period of 34 months. 20

PubMed was searched on 19 July 2016 to update the evidence base, using the search strategy of Rangaka et al. 16 (which was itself based on strategies used in previous reviews21) and restricting to publication dates in 2013 or later. We sought to identify primary studies in which individuals underwent IGRA testing at baseline and were followed up for the development of active TB, and which either presented estimates of PPV and NPV or provided sufficient information for these to be estimated. Studies in which no cases of active TB occurred were considered not to be informative for this purpose and were excluded.

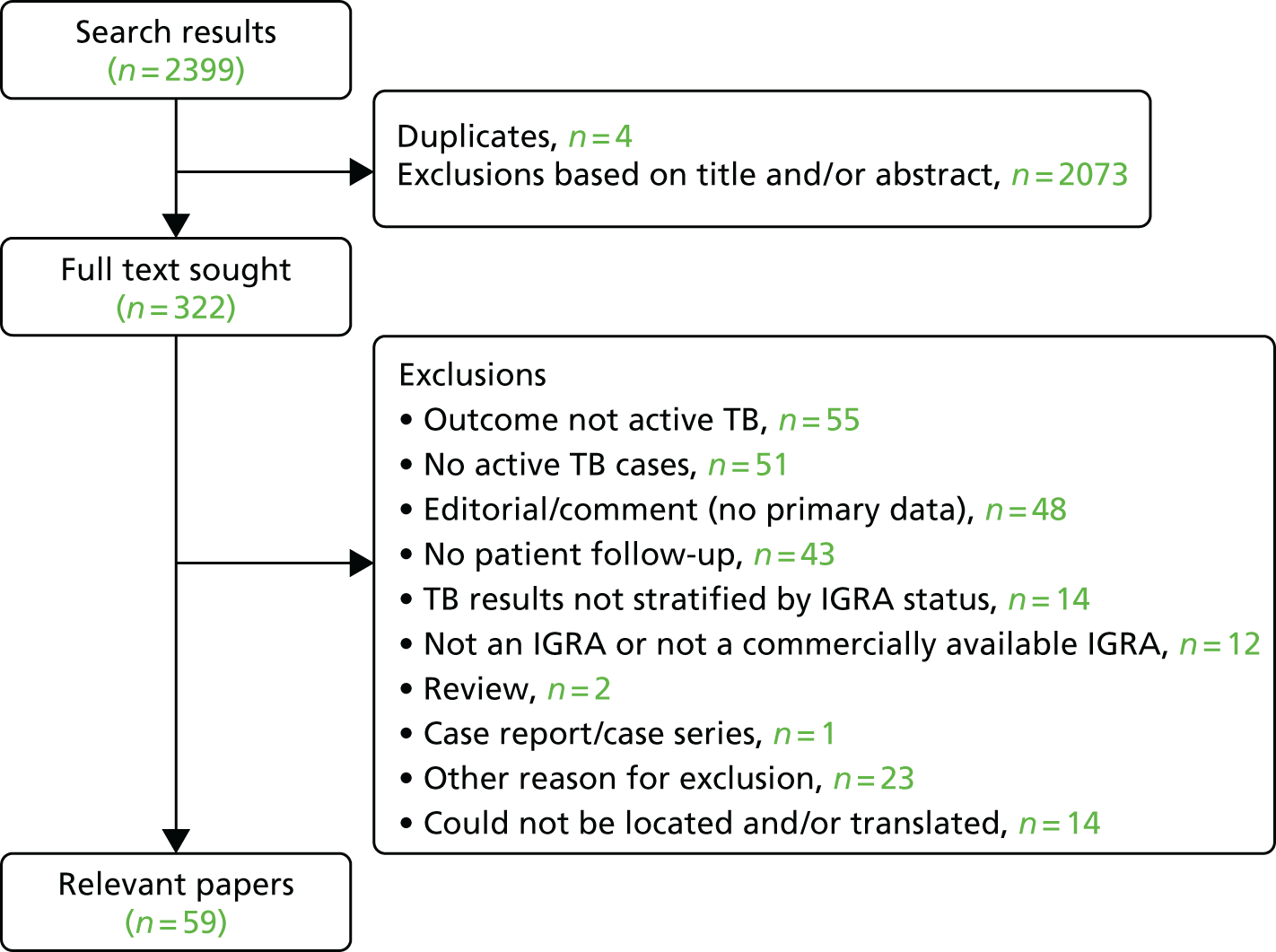

The search of PubMed generated 2399 results (Figure 1), of which 597,9,10,22–77 included the required information on PPV and/or NPV (see Appendix 2, Figure 14). In addition, we are aware of a further relevant study78 that was published after we conducted our review. Many of these 59 studies did not have the primary aim of assessing diagnostic accuracy. Many recorded few cases of active TB (often < 10)22,25–27,29–33,35–38,40,42–45,47,48,50,51,56–59,62–65,67–75,77,78 and/or were restricted to groups such as patients infected with HIV,9,28,29,36,49,51,56,60,65,68,75 recipients of haemodialysis or kidney transplants,35,43,44,62–64 patients taking or initiating treatment with biological agents such as tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) inhibitors,37–40,42,45,47,48,58,71,74 recipients of haematopoietic stem cell transplants,50,57 lung cancer patients30 or patients with combinations of these conditions. 61 Four further studies were conducted among health-care workers. 59,69,73,77 The duration of follow-up ranged from 8 to 10 weeks to 10 years. Consistent with the previous systematic review,15 estimates of PPV were consistently low, ranging from 0% to 24%; NPV was considerably higher (always ≥ 90%).

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram summarising study selection.

Eighteen studies (including the additional study78) did specifically assess the diagnostic accuracy of IGRAs for future development of active TB (Table 1) or otherwise quantify the association between a positive IGRA and subsequent TB. Of these, five assessed both IGRAs and TST. 23,52,56,62,72 Except when noted, these studies did not include treatment for LTBI. In this subset of studies, estimates of the PPVs ranged from < 1% to 17%, whereas the NPV was ≥ 97%. Sensitivity was reported as 37.5–100.0% and specificity as 27.0–86.0%. Even among these studies, case numbers were sometimes low (see Table 1). In addition, several of the studies29,31,32,35,36,52,56,62,72 did not explicitly state that prevalent cases were excluded, although the extent to which this may have affected their estimates was not always clear.

| Study | Population | Participants, n/N (%) | Number of active TB cases | Follow-up duration | PPV (%) (95% CI) | NPV (%) (95% CI) | Sensitivity (%) (95% CI) | Specificity (%) (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IGRA positive at baseline | IGRA negative at baseline | IGRA indeterminate at baseline | IGRA positive at baseline | IGRA negative at baseline | |||||||

| aAltet et al.23 | Contacts (Spain) | 81/453 (18) | 372/453 (82) | 0 | 14 | 0 | 4 years | 17 (9 to 26) | 100 (100 to 100) | 100 (100 to 100) | 85 (81 to 88) |

| bBlount et al.78 | New entrants (USA) | 513/1152 (45) | 639/1152 (55) | 0 (excluded) | 5 | 2 | 10 years | 0.97 (0.32 to 2.3) | 99.7 (98.9 to 100) | 71 (29 to 96) | 56 (53 to 59) |

| cDoyle et al.29 | HIV-positive patients being screened for LTBI at a sexual health centre (Australia) | 29/917 (3) | 884/917 (96) | 4/917 (0.4) | 1 | 1 | Median 26.4 months | 3.4 (0.1 to 17.8) | 99.9 (99.4 to 99.9) | N/A | N/A |

| aGeis et al.31 | IGRA-positive contacts without history of TB disease (Germany) | 207/207 (100) | 0 | 0 | 5 | N/A | ≈1 year | 2.9 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Goebel et al.32 | Contacts (Australia) | 212/643 (33) | 431/643 (67) | 0 | 4 | 2 | Mean 3.7 years | 2 | 99 | N/A | N/A |

| Haldar et al.7 | Contacts not receiving LTBI treatment (UK) | 112/1669 (7) | 1557/1669 (93) | 0 | Unclear | Unclear | 2 years | 13 (7 to 20) | 99 (98 to 100) | 70 (46 to 88) | 86 (83 to 88) |

| Hermansen et al.34 | General population (Denmark) | 1520/15,749 (10) | 13,425/15,749 (85) | 804/15,749 (5) | 20 | 20 | Median 3.36 years | 1.3 | 99.9 | N/A | N/A |

| Jeong et al.35 | Kidney transplant recipients (Republic of Korea) | 42/129 (33) | 87/129 (67) | 0 | 1 | 1 | Median 8.4 months | 2.4 | 98.9 | 50 | 67.7 |

| Jonnalagadda et al.36 | HIV-positive pregnant women tested during pregnancy and followed up for post-partum TB (Kenya) | 125/327 (38) | 157/327 (48) | 45/327 (14) | 7 | 2 | 1 year in primary analysis (2 years in supplementary analysis) | 5.9 (2.4 to 12.2) | N/A | 77.7 (45.7 to 100.0) | 54.6 (49.3 to 60.1) |

| Lee et al.49 | HIV-infected patients (Taiwan) | 90/772 (12) | 651/772 (84) | 31/772 (4) | 6 | 10 | Median 5.2 years | N/A | 98.5 | 37.5 | |

| aLeung et al.52 | Contacts (Hong Kong) | 244/865 (28) | 621/865 (72) | 0 | 15 | 5 | Mean 4.68 years | 6.1 (3.5 to 9.9) | 99.2 (98.1 to 99.9) | 75.0 (50.9 to 91.3) | 72.9 (69.8 to 75.9) |

| Mathad et al.56 | Pregnant women infected with HIV (India) | 71/252 (28) | 173/252 (69) | 8/252 (3) | 5 | 0 | ≈1 year | 7 | N/A | 100 | 27 |

| Seyhan et al.62 | Haemodialysis patients (Turkey) | 39/95 (41) | 56/95 (59) | 0 | 4 | 0 | Mean 4.9 years | 10.3 | 100 | 100 | 62 |

| Shu et al.64 | Haemodialysis patients (Taiwan) | 193/940 (21) | 713/940 (76) | 34/940 (4) | 3 | 1 | Average 3 years | 1.6 | 99.9 | 75.0 | 79.7 |

| Soborg et al.65 | HIV-infected patients (Denmark) | 28/522 (5) | 478/522 (91) | 16/522 (4) | 2 | 0 | 6 years | 7 (1 to 22) | 100 (99 to 100) | ||

| Sun et al.68 | HIV-infected patients (Taiwan) | 64/608 (11) | 534/608 (88) | 10/608 (2) | 1 | 0 | Mean 2.6 years | 1.6 | 100 | ||

| Verhagen et al.72 | Indigenous child contacts (Venezuela) | 56/142 (39) | 76/142 (54) | 10/142 (7) | 2 | 2 | 12 months | 4 (1 to 12) | 97 (91 to 100) | ||

| dZellweger et al.10 (QFT-GIT) | Contacts (multiple European countries) | 1068/3895 (27) | 2803/3895 (72) | 24/3895 (< 1) | 17 | 3 | Median 2.5 years | 1.9 (1.1 to 3.0) | 99.9 (99.7 to 100.0) | 85.0 (62.1 to 96.6) | 74.0 (72.5 to 75.5) |

| dZellweger et al.10 (T-SPOT.TB) | Contacts (multiple European countries) | 299/1125 (27) | 823/1125 (73) | 3/1125 (< 1) | 2 | 2 | Median 2.5 years | 0.7 (0.1 to 2.6) | 99.7 (99.1 to 99.9) | 50.0 (8.3 to 91.7) | 73.6 (70.8 to 76.2) |

Within the subset of 18 studies, several compared the frequency of TB disease between IGRA-positive and IGRA-negative participants, consistently finding that rates, hazards or odds of TB were higher among the former (although CIs sometimes crossed the null value). Unadjusted estimates included a hazard ratio of 4.0 (95% CI 0.8 to 19.3),36 odds ratio of 2.10 (95% CI 0.13 to 34.4)35 and rate ratios of 8.5 (no CI given),34 2.9 (95% CI 2.8 to 21.2)78 and 7.7 (95% CI 2.8 to 21.2). 52 Doyle et al. 29 estimated the hazard ratio as 42.4 (95% CI 2.2 to 827) after adjustment for age, gender, cluster of differentiation 4 (CD4) count, viral load and country of birth. Of the studies that did not specifically aim to assess diagnostic performance, such estimates included unadjusted rate ratios of 2.12,24 3.4650 and 73.9 (95% CI 3.9 to 1397.7);75 odds ratios of 9.26 (95 CI 1.02 to 84.0)30 and 7.9 (95% CI 3.46 to 18.06);66 and hazard ratios were 16.82 (95% CI 5.84 to 48.46), excluding treated individuals, and 2.38 (95% CI 1.15 to 4.91), including treated individuals. 41 Adjusted values included a hazard ratio of 2.0 (95% CI 1.2 to 3.3), after adjustment for BCG vaccination scar, maternal education and current/prior household TB contact,54 and an odds ratio of 14.9 (95% CI 2.77 to 80.3), adjusted for the number of IGRA-positive contacts of the same index case, receipt of treatment and place of contact (household vs. other). 76 These effect estimates varied considerably and were often imprecise. In addition, analyses of data from contacts often did not account for clustering by index case, and logistic regression did not account for differences in time at risk of developing active TB.

Table 2 summarises the studies that compared IGRAs with TST in the same participants and assessed predictive values, combining the results of our literature search with earlier studies identified in previous reviews. 12 Only four of these studies23,79–81 were conducted in low-incidence countries with a PPV range of 3% to 17% for IGRA compared with 2–5% for TST. The estimates of NPV for both IGRA (range 98–100%) and TST (99–100%) were very high. Studies from intermediate- and high-burden settings56,62,72,75,82–84 had a wider range of PPV for both IGRA and TST and, similarly, a high but wider range of NPVs.

| Study | Location | Study population | Follow-up | Mean follow-up duration (months) | Tests done | PPV of (%) | NPV of (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TST | IGRA | TST | IGRA | ||||||

| Altet et al.23 | Spain | Adult and child contacts | Active | 48 | TST (5 mm) and QFT-GIT | 2 | 17 | 100 | 100 |

| Diel et al.79 | Germany | Adult and child contacts | Passive | 43 | TST and QFT-GIT | 5 | 13 | 99 | 100 |

| Harstad et al.80 | Norway | Asylum seekers (adults) | Passive | 23–32 | TST and QFT-GIT | 2 | 3 | 100 | 100 |

| Kik et al.81 | The Netherlands | Adult contacts in migrants | Active | 24 | TST, QFT-GIT and T-SPOT.TB | 3 | 3 | 100 | 98 |

| Lee et al.82 | Taiwan | Adults with end-stage renal disease | Active | 24 | TST and T-SPOT.TB | 5 | 0 | 92 | 88 |

| Leung et al.83 | China | Adult silicosis patients | Passive | 29.9 | TST and T-SPOT.TB | 7 | 8 | 96 | 99 |

| Mahomed et al.84 | South Africa | Adolescents | Active | 27.6 | TST and QFT-GIT | 1 | 1 | 99 | 99 |

| Mathad et al.56 | India | Pregnant women infected with HIV | Active | 12 | TST and QFT-GIT | 7 | 7 | 99 | 100 |

| Seyhan et al.62 | Turkey | Dialysis patients | Unclear | 60 | TST (10 mm/15 mm with BCG) and QFT-IG | 3 | 10 | 95 | 100 |

| Verhagen et al.72 | Venezuela | Child contacts | Active | 12 | TST and QFT-GIT | 3 | 4 | 98 | 97 |

| Yang et al.75 | Taiwan | Adults infected with HIV | Active | 35.6 | TST and T-SPOT.TB | 3 | 5 | 100 | 100 |

Our evidence review, and the previously published systematic reviews and meta-analyses, highlight several important research gaps. There has been relatively little study of the diagnostic performance of IGRAs, compared with TST, for the development of active TB in low-incidence countries and particularly in the UK. The one study in Table 1 that was UK based7 did not include a head-to-head comparison with TST and was focused on contacts of TB cases. Although contacts are an important risk group, current guidance in many low-incidence countries includes testing of new entrants from high-burden countries, in whom there is limited evidence of diagnostic performance. Predictive values, both positive and negative, depend on the prevalence of the condition within the population of interest; consequently, results from high-incidence settings may not be generalisable to the UK. Owing to the low risk of progression from LTBI to active TB disease, the PPV of IGRAs for this outcome will, in general, be low. 11 It is therefore important to identify which individuals, among those with a positive IGRA (or TST) result, are most likely to develop disease and, therefore, benefit from treatment of LTBI. The PREDICT (Prognostic Evaluation of Diagnostic IGRAs ConsorTium) study aimed to address these gaps in the evidence base in order to inform UK and international policy for testing and treating LTBI in contacts of TB cases and in migrants.

Review of cost-effectiveness studies

The NICE guideline on TB, which was published in 2006,85 recommended a two-step testing strategy to diagnose LTBI: TST followed by IGRA for patients with a positive TST result. This recommendation was informed by a cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) based on a simple decision tree model, a systematic review of diagnostic accuracy of TST compared with IGRA, and a series of assumptions about the predictive performance of IGRA in populations at different levels of risk. The impact of transmission was estimated by assuming a fixed number of incident cases in contacts of the modelled cohort. The Guideline Development Group noted the high degree of uncertainty over the estimates of cost-effectiveness of different testing strategies for LTBI.

In 2011, NICE published an updated review86 of diagnostic accuracy of tests for LTBI and economic analysis, reaching rather different conclusions. The revised model suggested that the IGRA-alone strategy (without TST) was optimal, although the estimated differences in costs and quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) were small. Given the high level of uncertainty, the 2011 NICE guideline recommended IGRA-alone or TST-IGRA strategies as options. Owing to limitations in the evidence base, the 200685 and 201186 NICE guidelines did not distinguish between the two types of commercially available IGRAs [QuantiFERON TB Gold (QFT-G) and T-SPOT.TB], and compared only three screening strategies (TST alone, IGRA alone and TST followed by IGRA if TST result was positive). Both the 2006 and 2011 guidelines followed policy at the time, recommending two cut-off points for defining a positive TST result: induration of ≥ 15 mm for patients with a prior BCG vaccination or ≥ 6 mm for patients without a BCG vaccination. More recent NICE guidelines,14 published in 2016, based on a new decision model, led to revised recommendations, described further in the following paragraphs.

A series of cost-effectiveness analyses have also been published in the literature. In 2011, Nienhaus et al. 87 published a review of economic studies evaluating TST and/or IGRA as components of screening strategies for groups at high risk of TB, such as migrants, close contacts and health-care workers, mostly in low-incidence countries. 87 Of the 13 papers that met their inclusion criteria, eight88–95 involved CEA, whereas five96–100 were cost analyses.

The published cost-effectiveness studies reviewed by Nienhaus et al. 87 all used Markov modelling to estimate transition of a cohort through different health states, assuming a fixed rate of infection in the cohort. None modelled the dynamics of transmission within a wider population. One CEA study95 presented results in terms of cost per avoided TB case, whereas the remaining studies88–94 used QALYs or life-years gained as treatment outcomes. The time horizon for analysis after initial testing for LTBI ranged from 2 years to lifetime in the different CEA models. Some populations were stratified, for example health-care workers with/without BCG vaccination. Although the CEA studies generally supported the IGRA-alone or IGRA-based strategies, Nienhaus et al. 87 noted that comparison of the different models was hindered by a wide range of assumptions. The models were most sensitive to assumptions about specificity of TST, which varied among non-BCG-vaccinated individuals from as low as 34% in one study to 98% in another. There was also significant uncertainty surrounding the rates of progression to active TB following a positive test, as well as overassumptions for IGRA and TST sensitivities.

In 2011, after the Nienhaus et al. 87 review, Pareek et al. 101 published a UK-based prospective assessment and an economic analysis. They sought to address the limitations of the existing models and to examine how LTBI prevalence varied by TB-incidence thresholds in migrants’ regions of origin. They found that single-step QFT-GIT without port-of-arrival chest radiography could be cost-effective at certain incidence thresholds. The results are, however, limited by the small number of participants and the fact that not all of the participants received all three tests.

The NICE TB clinical guideline was updated again in 2016,14 making the following recommendations for LTBI testing in contacts and new entrants to the UK.

-

Offer TST to diagnose LTBI in adults aged 18–65 years who are close contacts of a person with pulmonary or laryngeal TB:

-

If the TST is inconclusive, refer the person to a TB specialist.

-

If the TST is positive (an induration of ≥ 5 mm, regardless of BCG vaccination history), assess for active TB.

-

If the TST is positive but a diagnosis of active TB is excluded, consider an IGRA if more evidence of infection is needed to decide treatment.

-

If the TST is positive, and if an IGRA was carried out and that is also positive, offer treatment for LTBI.

-

-

Offer TST as the initial diagnostic test for LTBI in people who have recently arrived from high-incidence countries and who present to health-care services. If the TST is positive (an induration of ≥ 5 mm, regardless of BCG vaccination history):

-

assess for active TB

-

and if this assessment is negative, offer treatment for LTBI

-

if TST is unavailable, offer IGRA.

-

These recommendations differ from the previous NICE guidelines85,86 in two key respects. First, they downplay the role of IGRA, recommending it as an option following TST when more evidence is needed before treating contacts, or when TST is not available for new entrants to the UK. Second, they recommend a single cut-off point for a positive TST (an induration of ≥ 5 mm) regardless of BCG vaccination status, rather than two cut-off points, as recommended in previous guidelines (an induration of ≥ 6 mm without prior BCG vaccination or an induration of ≥ 15 mm with prior BCG vaccination).

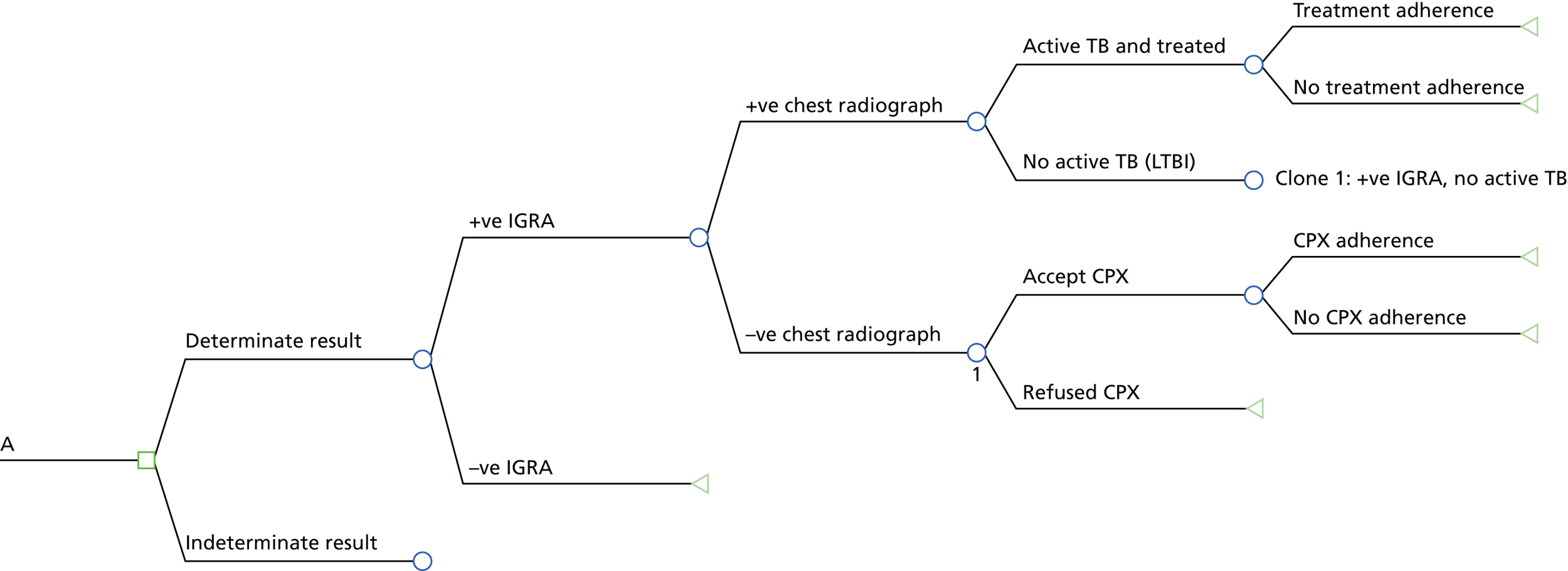

The 2016 NICE recommendations14 were informed by an evidence review and new economic analysis by Auguste et al. 102 (henceforth referred to as the Warwick Evidence report). Auguste et al.'s model consisted of two stages. In the first stage (illustrated in Figures 2 and 3), a decision tree was used to represent LTBI screening, active TB diagnosis and treatment adherence. They examined four diagnostic strategies:

-

IGRA alone

-

TST alone

-

combined strategies – TST followed by IGRA if TST is positive

-

simultaneous testing – both TST and IGRA are carried out.

FIGURE 2.

Starting decision tree of the Warwick Evidence analysis for new entrants from high-incidence countries. Reproduced from Auguste et al. 102 Contains information licensed under the Non-Commercial Government Licence v2.0.

FIGURE 3.

Example decision tree extension from Figure 2, showing only strategy A (i.e. IGRA alone). +ve, positive; –ve, negative. Reproduced from Auguste et al. 102 Contains information licensed under the Non-Commercial Government Licence v2.0.

Only the pathway for the IGRA-alone strategy (A) is presented here (see Figure 3). A do-nothing (no test) strategy was not explored. The IGRA strategies A, C and D were evaluated for three types of commercially available IGRAs: QTF-G, QFT-GIT and T-SPOT.TB.

The decision tree was used to estimate the proportion of patients emerging from the initial assessment, diagnosis and treatment stages with different risks of disease progression in the second stage of the model. Three populations were considered: (1) children, (2) immunocompromised individuals and (3) recently arrived individuals from high-incidence countries.

The second stage of the Warwick Evidence model102 (Figure 4) was a transmission model, operationalised using discrete event simulation (DES), programmed using R (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Individuals arriving from the decision tree were grouped as (1) having active TB, (2) already successfully treated for LTBI and, hence, free of LTBI/TB or (3) untreated for LTBI. The model then tracked disease progression, deaths and cases of new secondary infection. Secondary infection in other individuals was modelled as a proportion of the initial cohort (sampled from a Poisson distribution) who progressed or relapsed to active TB. The analysis assumed that individuals who entered the transmission model with LTBI would ultimately develop active TB if they did not receive treatment, although they might die of other causes before developing TB. In the initial population, as well as in secondary cases, people with LTBI who do not progress to active TB were not simulated in the second part of the model. The risk of an event in the transmission model, such as death or onset of active TB, was dependent on an individual’s age, TB status and current treatment, and was updated when any of these factors changed. Time to activation of TB for individuals entering stage two of the model with LTBI (untreated or unsuccessfully treated LTBI cases) was simulated assuming a constant activation rate over time.

FIGURE 4.

Warwick Evidence analysis (Tuberculosis Clinical Guidance) transition model. Reproduced from Auguste et al. 102 Contains information licensed under the Non-Commercial Government Licence v2.0.

The Warwick Evidence analysis102 presented per-patient costs as well as a breakdown of total costs (including costs of diagnosis, LTBI treatment, active TB and treatment-related hepatitis) for all of the strategies, based on the mean values of all parameters after 250,000 individual patient simulations. The incidence rates (IRs) of active TB in the initial cohort, the number of secondary infections and the mean life-years and QALYs per strategy were also presented. In addition, based on 2000 Monte Carlo simulations, probabilistic estimates of the total cost, incremental costs, diagnostic errors (false-positive results plus false-negative results), incremental diagnostic error, mean QALYs, incremental QALYs and incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) were also presented.

The analysis suggested that, for new entrants from high-incidence countries, simultaneous testing strategies were dominated by the equivalent sequential strategies. The QFT-GIT-alone strategy was least costly, but the TST-positive (an induration of ≥ 5 mm) followed by QFT-GIT strategy had the fewest errors. At a willingness-to-pay threshold of £20,000 per QALY gained, the TST-alone (≥ 5 mm) strategy was optimal, with an ICER of £1524 per QALY gained compared with the QFT-GIT strategy. The TST-negative (an induration of < 5 mm) followed by QFT-GIT strategy was ranked as the next most cost-effective strategy, with an ICER of £58,720 per QALY gained compared with TST (an induration of ≥ 5 mm). The other strategies were dominated. Univariate sensitivity analysis suggested that the TST-alone strategy remained cost-effective in most scenarios. However, results were sensitive to LTBI prevalence, sensitivity of QFT-GIT and sensitivity of TST.

A major common limitation of all current CEA of screening strategies for LTBI relates to assumptions surrounding the predictive value of IGRAs and TST, because there is no gold standard against which to establish the sensitivity or specificity of the different tests. Previous CEA studies have based their estimates of LTBI predictive values on various, and often conflicting, sources and assumptions. This leaves considerable uncertainty over the cost-effectiveness of LTBI screening strategies.

We adopted a different approach, basing our economic analysis on the ability of the three tests (TST, QFT-GIT and T-SPOT.TB), individually and in combination, to predict progression to active TB in the PREDICT cohort. This represents a much stronger evidence base for modelling the predictive performance of LTBI test strategies than was available for previous economic evaluations, with three main advantages. First, the cohort provides a coherent source of baseline data, including risk factors and TST, QFT-GIT and T-SPOT.TB test results for large samples of new entrants and contacts being tested for LTBI in the UK. Second, the long-term follow-up and predictive modelling of TB incidence bypasses the problems of conventional diagnostic accuracy in the absence of a reliable reference standard test. Third, this evidence source enables the comparison of two commercially available IGRAs (T-SPOT.TB and QFT-GIT) with TST strategies with a single cut-off point (an induration of ≥ 5 mm) or with different cut-off points for BCG-naive and BCG-experienced patients (indurations of ≥ 5 mm and ≥ 15 mm, respectively).

Objectives

Primary objectives

-

To assess the prognostic value of the two current IGRAs compared with the standard Mantoux test for predicting the development of active TB among untreated individuals at increased risk of LTBI, specifically:

-

contacts of active TB cases

-

new entrants to the UK from high-TB-burden countries.

-

-

To assess the cost-effectiveness of various screening strategies (including the NICE-recommended two-step approach86) using IGRAs and/or TST in defined patient groups (contacts and new entrants to the UK stratified by age and risk).

Secondary objectives

-

To quantify and compare the predictive value of a whole-blood ELISA and an ELISPOT-based assay independently.

-

To develop a collection of specimens (serum and white blood cells), with linked clinical and epidemiological information, to investigate the prognostic value of new biomarkers for TB infection and disease progression.

Structure of the report

In this chapter of the report, we have included a description of the background of the project as well as the primary and secondary objectives. Chapter 2 describes the methods used in the research. In Chapter 3, we present the results of the epidemiological study by describing the cohort and the development of active TB in the cohort. We present the results of the economic analysis examining multiple screening scenarios in Chapter 4 and, in Chapter 5, we discuss the findings, implications for TB testing and treatment guidelines and recommended future research areas.

Chapter 2 Methods

Design

Setting, population and disease burden

This prospective cohort study recruited individuals aged ≥ 16 years who were (1) close contacts of patients with active TB or (2) new entrants to the UK arriving in the last 5 years from high-incidence countries, defined as exceeding 40 cases per 100,000 people, and operationalised by focusing on those from sub-Saharan Africa or Asia.

Participants were recruited in TB clinics from a network of hospitals in London, Leicester and Birmingham, general practices (GPs) in London and several community settings in London (see Appendix 1). All study sites were co-ordinated from the tuberculosis section of PHE.

Recruitment and inclusion criteria

Participants were recruited between May 2010 and July 2015. Contacts of active TB (pulmonary and extrapulmonary) patients and new entrants arriving in the UK in the last 5 years from high-incidence countries (as defined in Setting, population and disease burden) and attending participating TB clinics or primary care centres for screening were invited to take part. Those born in high-incidence countries who entered the UK > 5 years ago, but who had spent > 1 year (cumulative) in the past 5 years in a high-incidence country, as per the study’s defined list, were also invited to participate. Contacts included all individuals with a cumulative duration of exposure of > 8 hours to the relevant index case in a confined space during the period of infectiousness (prior to initiation of treatment).

Eligible persons were identified by study TB specialists or practice nurses, and written informed consent was obtained following the provision of information sheets (translated as appropriate). Baseline assessment questionnaires, including demographic and clinical information, were completed by the research nurse.

In addition, recruitment was undertaken en masse using two methods.

-

New entrants to the UK were recruited from non-NHS community settings, such as places of worship and community centres.

-

Contacts of active cases were recruited through mass screening events organised as part of the public health response to a case of active TB in some situations. For example, clinical teams may attend workplaces or colleges where an exposure had taken place, to facilitate screening of large numbers of contacts.

For recruitment through primary care, study flyers and the contact details of the co-ordinating centre were displayed in general practices so that interested people could contact the study team to book an appiontment. At the appointment, as with all recruitment meetings, a study nurse went through the full patient information leaflet before taking written informed consent to undertake study procedures. We also utilised the primary care trust (PCT)-held Flag 4 data (records held by the local primary care group about international migrants who register with a NHS GP) to invite newly registered patients, recently arrived from the countries of interest, to take part in the study.

At the time of the study, treatment of LTBI was recommended only for individuals aged < 35 years. We therefore prioritised the recruitment of patients aged > 35 years (who were not eligible for CPX) in order to estimate and compare the ability of the TST and IGRAs to predict natural progression to active disease in the absence of treatment. Individuals aged 16–35 years were also eligible, as they may not be offered, or may not accept, CPX.

The general practioners of all participants were informed of their patients’ participation by letter.

Health technologies being assessed

Participants were tested by the Mantoux test and two IGRAs: ELISA (QFT-GIT) and ELISPOT assay (T-SPOT.TB). All tests were conducted using standardised protocols. 17–19 Tests for LTBI were undertaken among contacts at about 6 weeks after last known exposure (consistent with NICE guidelines14), and at ≥ 6 weeks for new entrants after arrival in the UK.

The QFT-GIT and T-SPOT.TB assay samples were transported to a study testing centre (see Statistical analysis).

After IGRA testing, samples were used for repetition of indeterminate assays. Paxgene tubes, plasma and peripheral blood mononuclear cells were stored for future research.

Test results and further action

All test results were obtained by clinicians who were blind to other results. Clinicians were informed of all test results by the testing laboratory for tests conducted at the National Mycobacterial Reference Laboratory (NMRL), whereas those results from the Imperial College London laboratory were not reported. Subsequent action after testing followed the version of NICE guidance that was applicable at the time of screening and took place after discussion with participants. Further action followed one of three options:86

-

If the participant had a negative result in the TST and IGRA, follow-up only was conducted.

-

If the participant had a positive result in either the TST or IGRA, and active TB was excluded, follow-up was conducted irrespective of age.

-

If the participant had a positive result in the TST and either one or both IGRA(s), follow-up only was conducted for those aged ≥ 35 years, and, for those aged 16–35 years, CPX was offered within the routine care setting after excluding active TB, with balanced advice about potential benefits and risks.

Follow-up

Participants were followed prospectively after IGRA/TST testing. Follow-up utilised multiple data sources to enable the comprehensive national identification of participants and to minimise loss attributable to transfer of care to other centres by physicians. Data were sourced from (1) telephone calls to the participants at 12 months and at 24 months or at the end of follow-up, (2) a search of national mandatory enhanced TB surveillance (ETS) reports, (3) a search of the national database of culture-proven TB and (4) a search of clinical records. Individuals found to have active TB were excluded from the analysis if they had evidence of active disease at the time of recruitment (see Primary outcome). Follow-up continued until the development of active TB, death or May 2016.

Data collection

Baseline data were collected by trained research nurses using paper questionnaires. Outcome data were collected using the four approaches outlined in Follow-up. Questionnaire data were entered into a purpose-built database [using Microsoft Access® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA)] that was maintained at the TB section at PHE and linked, as necessary, to data from the other sources. IGRA results were received from laboratories in Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) spreadsheets and imported into the database.

Data collected from participants included age; gender; country of birth and date of entry to the UK for non-UK-born persons; ethnicity; current employment; the nature and duration (in hours) of contact with the index case (for contacts); the time interval between the most recent suspected exposure date and the date of diagnosis in the index case; details of any previous contact tracing; history of previous TB, including treatment, results of previous TST and chest radiographic findings; BCG vaccination status (assessed based on criteria in the Green Book:103 a scar or reliable recall or vaccination record); associated medical diagnoses; and use of immunosuppressive agents. Self-reported HIV infection status was collected, and further work through record linkage with the national HIV surveillance system will be used to improve the completeness of HIV data. Quality-of-life data were collected using the EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) questionnaire. During follow-up, information on the drugs used for the treatment of LTBI and adverse effects of CPX was collected and validated through a review of clinical records.

Index cases (identified through clinical records) of contacts were identified through a web-based ETS system using data provided by the contact and/or clinicians. The characteristics of index cases were summarised descriptively. For contacts who progressed to active TB disease during follow-up, deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) fingerprinting data [24-locus mycobacterial interspersed repetitive unit – variable number tandem repeats (MIRU-VNTR)] from the UK national TB strain typing database, hosted by PHE, were utilised to compare strain types between index cases and subsequent diagnoses among contacts. This enabled the assessment of whether any TB disease in secondary cases was likely to have arisen from the initial infection (i.e. that the test result related to the outcome) and not as a result of subsequent exposure to another case.

Sample size

The study size (and associated power) was determined by simulating the study and its analysis 1000 times and observing the proportion of simulations yielding significant results across various scenarios. Conventional methods for sample size calculation would not account for the Poisson nature of the data and the within-patient comparisons of the tests; therefore, simulation was necessary. The simulated data on the disease progression of study participants were created, presuming a LTBI prevalence of 30% and presuming that 5% of participants with LTBI would progress to active TB in 2 years if untreated, as observed in previous studies. 81,104 Test results were simulated for each participant using sensitivities and specificities of IGRA in the range of 65–95%.

The simulations indicated that a cohort of 5000 participants, among whom 90 incident events were observed, would have around 85% power to detect significant (p < 0.05) differences in predictive performance that would arise from differences in sensitivity and specificity of 10% between tests. These differences correspond to increases in predictive performance (expressed as a ratio of relative rates between patients with a positive test result) of 30%, which would be clinically useful.

It was assumed that 50% of TB contacts and new entrants would be aged ≥ 35 years, so a cohort of 10,000 would initially yield at least 5000 participants for the primary analysis of progression without treatment, among whom 90 evaluable events would occur. Given the probable loss to follow-up (which, based on clinic data, was likely to be around 20%) and the possibility that progression to disease may be < 5%, the power of the study would be maintained by including in the cohort all participants aged 16–35 years who did not take CPX (estimated to be an additional 2500 participants). A total of 90 incident events would still be observed should 7500 participants be recruited, 20% be lost to follow-up and the rate of progression to disease be only 4.2%.

Primary outcome

The primary outcome of interest was the development of active TB, with the prognostic values of tests quantified as IRRs, comparing those with positive results and those with negative results, among contacts and new entrants to the UK. Individuals were considered to have progressed to active TB if they had culture-confirmed TB or were clinically diagnosed with radiological or histological evidence of TB and a clinician had decided to treat the individual with a full course of anti-TB disease treatment, the definition used for the TB register. In addition, participants were considered to have progressed to active TB only if:

-

The participant had no evidence of active TB at the time of enrolment, determined through the review of clinical records.

-

The clinical diagnosis of active TB was at least 3 weeks after recruitment/enrolment to the PREDICT study, based on the date of diagnosis (or treatment start date if date of diagnosis was not available).

In the absence of laboratory confirmation of TB, awareness by the clinician of a prior positive IGRA/TST result should not influence the clinical diagnosis of active TB.

Any case that was subsequently denotified was excluded from analyses (i.e. when the clinician reported that the patient did not have TB).

For any cases in which participants were reported to have TB in a follow-up telephone call at 12 or 24 months, the record was searched in the national data set of clinical reports and through the review of case notes at the hospital where the participant was treated. Only cases in which the participant was confirmed to have active TB, meeting the criteria outlined above, were included as a case of TB. The central team ascertaining the diagnosis were blinded to the IGRA and TST status of participants.

Statistical analysis

Primary analysis

The analysis estimated the ability of the tests (TST, T-SPOT.TB and QFT-GIT), individually and in combination, to predict progression to active TB in latently infected individuals, and made comparisons between tests. Estimated rates of progression to active TB were calculated, accounting for the follow-up period for each individual.

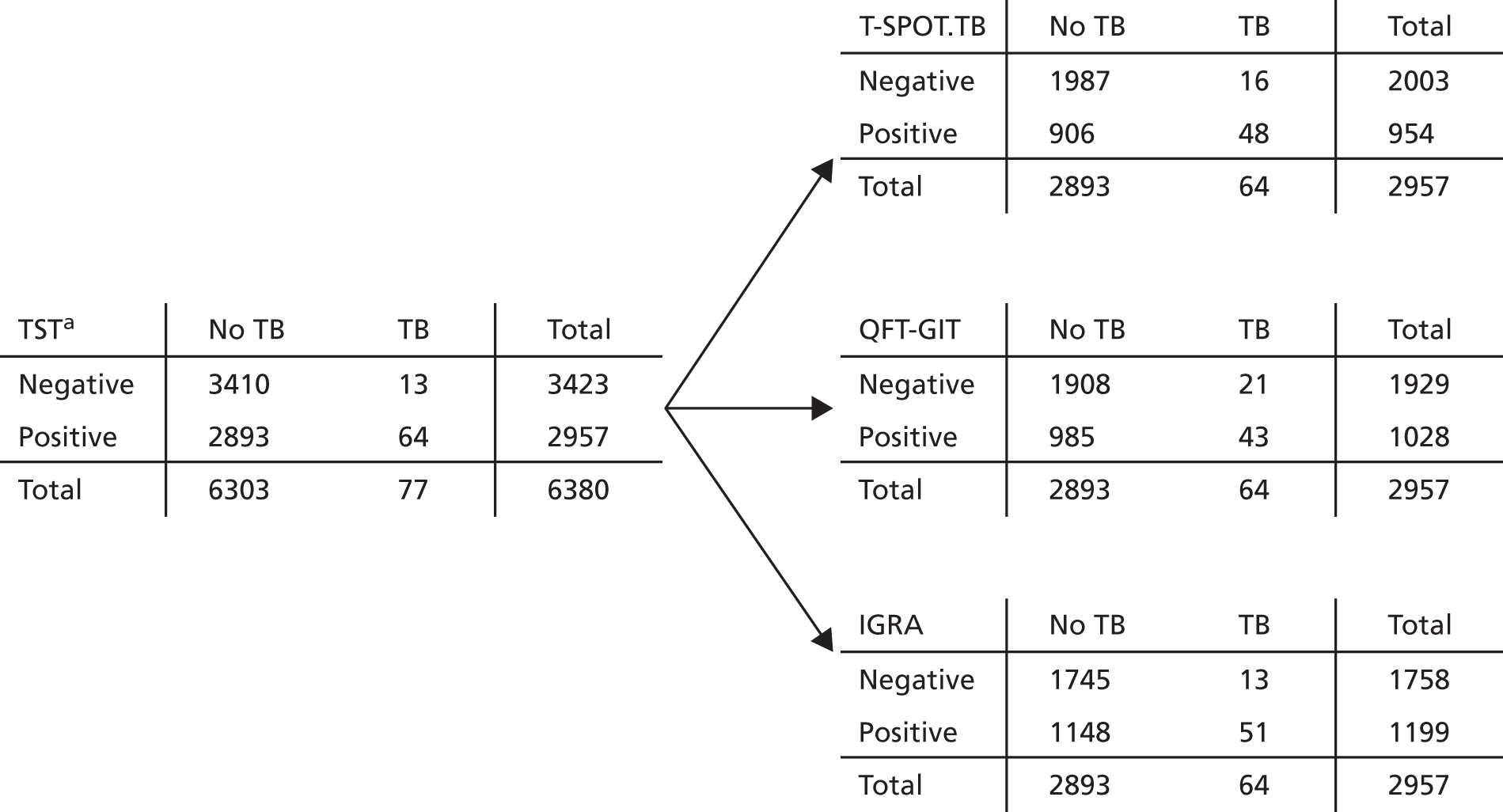

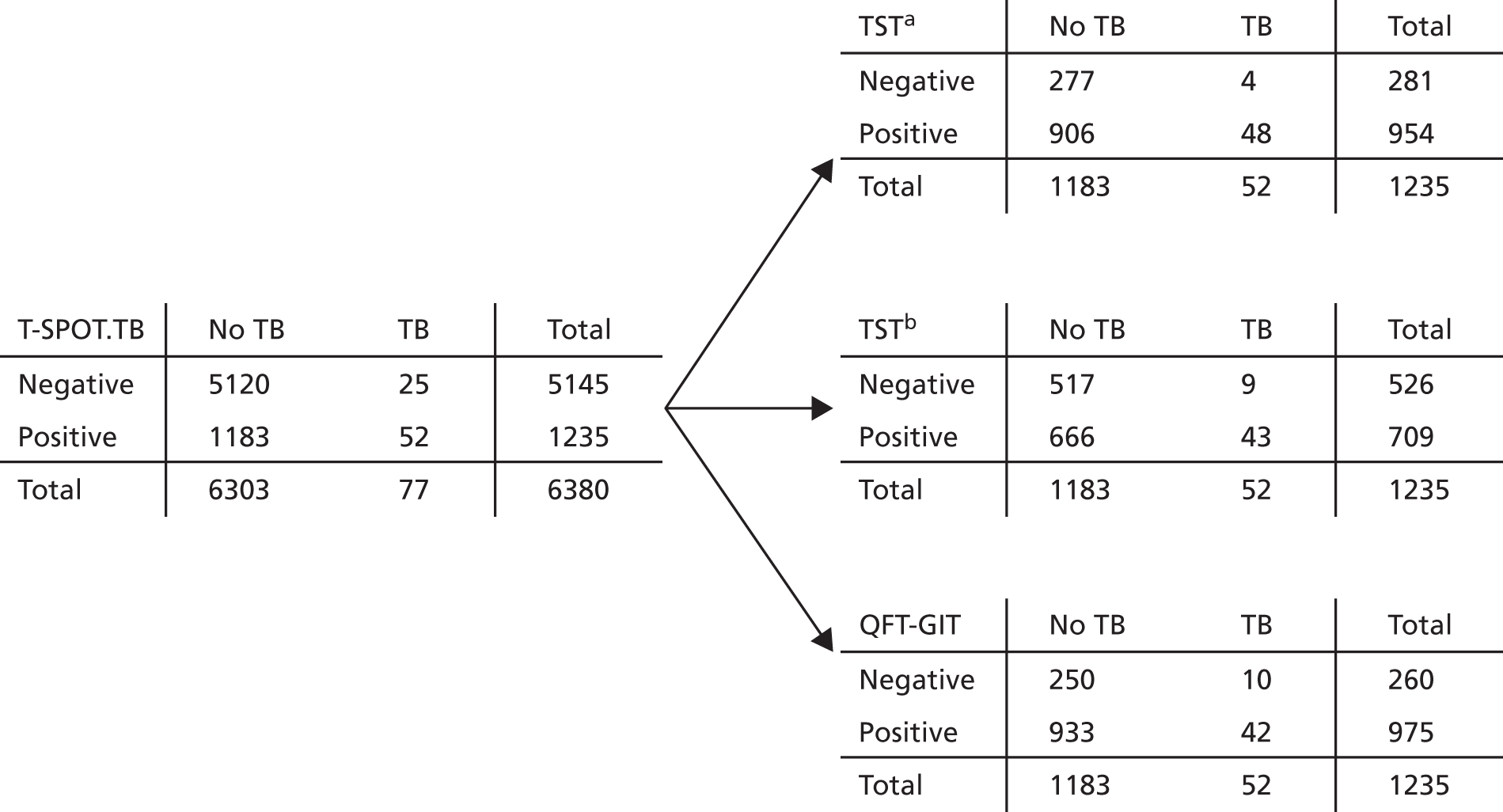

The predictive performance of each test (TST, T-SPOT.TB and QFT-GIT) and of each two-step test strategy [using combinations of TST + T-SPOT.TB, TST + QFT-GIT and IGRA (T-SPOT.TB or QFT-GIT) + TST] was summarised by the calculation of IRs of developing active TB in the ‘test-positive’ and ‘test-negative’ groups, expressed with 95% CIs computed using Poisson exact methods. In each combination strategy, the second test result was used if the first was positive, meaning that both tests must be positive for a participant to be positive for the strategy. IRs were calculated using all available follow-up data and also at 1 year and 2 years after study entry. The discriminatory predictive value of the test was based on the relative comparison of these rates (the relative IRs comparing those with positive test results and negative test results), together with the prevalence of positive test results (indicating the number of patients who would be treated should the test be used for recommending CPX).

The primary analyses of the performance of tests used only participants with test result data for all three tests. Participants who were treated for LTBI were excluded.

We made pairwise comparisons of the ability of tests and strategies to identify (1) those participants who progress and (2) those participants who do not progress using generalised estimating equation (GEE) marginal regression models. 105 These models estimate (1) ratios of positive test results and (2) ratios of negative test results in those participants who progress compared with those participants who do not, which are comparable to positive and negative likelihood ratios for diagnostic studies. We compute ratios of these ratios to make pairwise comparisons between tests, accounting for the paired data. A marginal regression GEE model was fitted, with the two test results as outcomes (with a positive test result coded as the event) and with test type and progression status as predictors, and an interaction term between test type and progression. The interaction term assessed whether or not the relationship between progression and test positivity was stronger for one test than the other. A similar second model was fitted with test negative as the outcome, such that the interaction term assessed whether or not the relationship between non-progression and test negativity was stronger for one test than the other. The model accounted for the intra-individual correlation between tests using an unstructured correlation matrix and was configured to give population average estimates. The primary analysis fitted models with a binomial error structure and a log link (as described by Pepe105). In a sensitivity analysis, we adapted the Poisson model to include follow-up using an offset and obtained identical point estimates to two decimal places and confidence limits to one decimal place. We report the binomial model results.

Regression models were fitted in Stata® version 15.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Positive predictive values and NPVs were also calculated as the percentage of people with a positive result developing TB across all follow-up (PPV) and as the percentage of people with a negative result who did not develop TB (NPV).

Owing to testing processes, a small number of participants had two T-SPOT.TB and/or QFT-GIT tests performed (T-SPOT.TB, n = 21; QFT-GIT, n = 33). For participants with multiple results for a single test, results from the primary research laboratories were used (Imperial College London and NMRL), with results from Imperial College London being used if the test was carried out at both Imperial College London and NMRL. For some participants, neither T-SPOT.TB result was obtained from Imperial College London or NMRL and, therefore, the result from Oxford Immunotec or SYNLAB (London, UK) was used.

The QuantiFERON TB Gold In-Tube test

The QuantiFERON test results were classified as positive, negative or indeterminate according to the manufacturer’s algorithm. 106 For analysis purposes, indeterminate results were treated as missing.

The T-SPOT.TB test

The T-SPOT.TB test can have positive, borderline positive, negative, borderline negative or indeterminate results. All categories of test results were reported. For the majority of participants, the required test information (spot count) was available and T-SPOT.TB test result classifications were calculated by the study team in accordance with the manufacturer’s algorithm (Figure 5)107 For 660 tests (7.9% of the 8387 participants, or of the 8366 participants with a duplicate test for 21 participants) in which the necessary information (T-SPOT.TB counts and positive and negative control values) was not provided, the classification of results reported from the laboratory was used in all subsequent analyses.

FIGURE 5.

T-SPOT.TB result classification algorithm.

Indeterminate results were treated as missing, borderline positive results were treated as positive and borderline negative results were treated as negative, in line with the interpretation of results in clinical practice. 1

The Mantoux test

The TST was administered in accordance with national guidelines. Different thresholds for TST positivity were considered. In the primary analysis, participants were considered to have a positive result if they had a skin induration of ≥ 5 mm (this will be referred to as TSTa), consistent with the 2016 NICE guidelines. 14 Alternatively considered was the strategy varying with BCG status, in which a skin induration measuring ≥ 6 mm following the standard TST test was considered a positive result if the participant was not known to have had a BCG vaccination, and in which a skin induration of ≥ 15 mm following the standard TST test indicated a positive result for those known to have had a BCG vaccination, the strategy previously recommended by NICE. 86 When BCG vaccination status was unknown, BCG vaccination was assumed for those participants who were born outside the UK and, for UK-born participants with unknown BCG vaccination status, a positive or negative TST result could not be obtained. The secondary definition will be referred to as TSTb.

Sensitivity analyses

Sensitivity analyses were carried out using all available test data rather than using data only from participants with results for all three tests. Analyses were also performed excluding those participants with BCG vaccination status assumed to generate a TSTb result and those participants with an uncertain progression status because of a short period between testing and diagnosis. Additional sensitivity analyses were performed using data from new entrants only and restricted to 2 years of follow-up, and from contacts of pulmonary TB cases only.

Economic analysis

The decision problem

We developed an individual-level DES model to estimate the effect of different test strategies on risk prediction, use of preventative CPX and BCG vaccination, subsequent incidence of TB, and, hence, costs to the health-care system and health outcomes for patients. We considered a DES model to be most suitable as individual simulation and a bootstrapping approach preserved individual patient data and the correlation between baseline risk factors and the test results. The analysis followed the NICE reference case for public health interventions. Health outcomes were quantified using QALYs, including the impact of TB and treatment-related adverse effects on mortality and health-related quality of life (the utility). EuroQol-5 Dimensions, three-level version scores from the PREDICT study were valued using the UK general population tariff. Costs were estimated from a UK public sector perspective, including costs for case finding, prevention (BCG vaccination and CPX) and treatment of active TB and adverse effects. In the base case, we discounted costs and QALYs at 3.5% per annum and simulated outcomes over a lifetime horizon for a cohort of patients undergoing tests for LTBI.

Population

We evaluated the cost-effectiveness of LTBI testing strategies in the PREDICT cohort. The model used an individual patient data set comprising 4162 contacts and 3795 new entrants without active TB at baseline (total of 7957 participants) with sufficient data: age, sex, BCG vaccination status, baseline EQ-5D score (utility) and contact/new entrant status. We excluded participants with active TB at the baseline assessment, but included those with missing values for one or more baseline LTBI tests (TST, QFT-GIT or T-SPOT.TB) in order to model the impact of missing or indeterminate test results.

For our base-case analyses, we evaluated results for the whole cohort, and also for the two subgroups: new entrants to the UK and contacts. We had initially intended to present stratified analysis for other risk factors: age, BCG vaccination status, previous treatment status and baseline risk (defined by level of exposure or duration and nature of contact; or by country or region of birth for new entrants to the UK). However, an analysis of the PREDICT results did not show any important or statistically significant differences in incidence according to these risk factors (see Chapter 4). Instead, we investigated the sensitivity of results for populations at different a priori levels of risk in the absence of preventative treatment (BCG vaccination or CPX). This illustrated the possible effects of changing referral thresholds for LTBI tests, such as the threshold for defining a ‘close’ contact or ‘high-incidence’ country of recent residence.

In our modelling protocol, we stated that we would consider additional exploratory analyses in other subgroups, such as people infected with HIV or who have diabetes mellitus, but the numbers of participants in these groups were too low to support such analysis.

Interventions and comparators

We compare 11 approaches to LTBI testing:

-

0. no test

-

1. T-SPOT.TB

-

2. QFT-GIT

-

3. TSTa: positive if induration is ≥ 5 mm

-

4. TSTb: positive if induration is ≥ 6 mm without prior BCG vaccination or ≥ 15 mm with prior BCG vaccination

-

5. TSTa + T-SPOT.TB: positive if both TSTa and T-SPOT.TB are positive

-

6. TSTa + QFT-GIT: positive if both TSTa and QFT-GIT are positive

-

7. TSTa + IGRA: positive if TSTa is positive and either T-SPOT.TB or QFT-GIT are positive

-

8. TSTb + T-SPOT.TB: positive if both TSTb and T-SPOT.TB are positive

-

9. TSTb + QFT-GIT: positive if both TSTb and QFT-GIT are positive

-

10. TSTb + IGRA: positive if TSTb is positive and either T-SPOT.TB or QFT-GIT are positive.

In the single-test strategies (1–4), participants who tested positive for LTBI were assumed to undergo diagnostic tests to rule out active TB, then to be offered appropriate treatment (CPX if aged ≤ 35 years), whereas those who tested negative for LTBI would be offered BCG vaccination if eligible (no previous BCG vaccination and age ≤ 35 years). Participants with missing test results for a strategy were assumed not to receive any preventative treatment (CPX or BCG vaccination).

In the dual-test strategies (5, 6, 8 and 9), the second test would only be carried out if the first test result was positive. Participants who tested positive in the second test (T-SPOT.TB or QFT-GIT) would be further evaluated to rule out active TB, and offered CPX or BCG vaccination if appropriate. Participants without a TST result, or with a positive TST result but missing T-SPOT.TB or QFT-GIT data, were assumed to not receive any preventative treatment.

In the three-test strategies (7 and 10), we assumed that participants with a positive TST result would have both IGRAs (T-SPOT.TB and QFT-GIT). Then, if either of the IGRAs were positive, they would be tested for active disease and offered treatment or CPX if appropriate. If both IGRAs were negative they would be offered a BCG vaccination if appropriate. Participants with an indeterminate result attributable to one or more missing test results would not receive preventative treatment; this included all participants with a missing TST result, and those with a positive TST result and either both IGRAs missing or one negative IGRA and one missing IGRA.

The ‘no test’ strategy was included as a comparator, which allowed us to investigate changes to the referral thresholds for LTBI testing.

Outcomes

Strategies were evaluated in terms of the health-care costs and health outcomes measured using QALYs. For validation purposes, we also present disaggregated outcomes (numbers of incident TB cases; numbers given a BCG vaccination, CPX and active TB treatment; treatment-related adverse events; deaths from TB; and life-years) and costs [costs of diagnosis, preventative treatment (BCG vaccination and CPX) and active TB treatment (including treatment of adverse effects)].

Modelling methods

Model structure

Figure 6 is a process map of our model. The software used to develop the DES model was SIMUL8 Professional 2017 (SIMUL8 Corporation, Boston, MA, USA).

FIGURE 6.

Model process map. –ve, negative; +ve, positive; AE, adverse event; LTFU, lost to follow-up; Tx, treatment for active TB.

Cohort selection

The model was programmed so that a cohort of patients with chosen initial characteristics could be selected to run through the pathway, to allow flexible subgroup analysis. However, for this report we present results only for the whole cohort, and for the ‘new entrant’ and ‘contact’ subgroups.

Individual participants from the PREDICT cohort were randomly sampled (with replacement) from an individual-level data set from the PREDICT cohort. This data set included individuals’ demographic information and baseline characteristics: age, gender, prior BCG vaccination status, utility (EQ-5D scores) and LTBI test results (TST, T-SPOT.TB and QFT-GIT). For the purposes of this analysis, we excluded patients who were diagnosed with active TB at the beginning of the PREDICT study (n = 175). This left a data set of 7957 individuals for inclusion in the economic analysis.

The size of the sampled population in the model can be changed, but for the analysis presented below we used a bootstrapping approach; for each probabilistic iteration of the model, we sampled a simulation cohort (with replacement) of the same size as the individual patient data set (n = 7957). This scales uncertainty over the distribution of baseline characteristics in our probabilistic sensitivity analysis (PSA) to reflect sampling error in the PREDICT cohort.

Screening, diagnosis and treatment initiation

The model can be set to one of the 11 test strategies, and members of the cohort enter to be offered the chosen strategy. Treatment decisions, such as whether a patient is offered BCG vaccination, CPX or treatment for active TB, depend on the patient’s test results and history or demographic data. For example, under strategy 5 (TSTa + T-SPOT.TB), an individual aged ≤ 35 years with no prior BCG vaccination, no active TB, a TST induration of 7 mm and a negative T-SPOT.TB test result would be offered a BCG vaccination. Or, under the same strategy, a patient aged ≤ 35 years, who has had a BCG vaccination, with no TB, a TST induration of 18 mm and a positive T-SPOT.TB result would be offered CPX.

This first section of the model is treated as timeless; patients cannot experience adverse events and their utility is fixed at their baseline EQ-5D value (as observed in PREDICT), but they accrue costs based on choices that are made within the model as per LTBI testing, active TB diagnosis, BCG vaccination and initiation of CPX and treatment of active disease.

Health status

Having received tests and treatments, or having been lost to follow-up, participants flow into the second part of the model, in which time starts to elapse. At any time, each member of the cohort who is alive is in one, and only one, of the following health states:

-

Active TB and on treatment – participants in this state have been diagnosed with active TB and are being treated. From this state, participants might successfully finish treatment, experience an adverse reaction to treatment and/or drop out of treatment, or they may die from TB or other causes.

-

Active TB and not on treatment – this state includes participants with active TB who have not yet been diagnosed, as well as participants who have been diagnosed but have stopped treatment for some reason. From this state, participants might present clinically with symptoms and be diagnosed, or they might die from TB or other causes. Contacts of people with untreated active TB who are at heightened risk enter the model in the ‘no TB and not on CPX’ state.

-

No TB and on CPX – these participants do not have TB but have tested positive for LTBI (according to the defined test strategy) and are taking prophylactic treatment. Future possibilities for this group are to complete CPX, have an adverse event and/or stop CPX, progress to TB or to die from other causes.

-

No TB and not on CPX – this state includes all participants who do not have TB and are not taking CPX. This is a diverse group including participants who have tested positive for LTBI but did not start CPX or defaulted from CPX, those who have tested negative for LTBI and who may or may not have been vaccinated, as well as those who did not complete the LTBI test(s) or who had indeterminate results. All of these people are at risk of progressing to TB or they might die from other causes.

Note that LTBI is not modelled as a ‘disease state’ as such, but rather it means that each person who does not currently have active TB is at risk of developing active TB. Each person’s risk of an event is estimated using observed IRs in the PREDICT cohort, based on their current status, other characteristics and treatment effects. Then, for each possible event, a time to event is sampled.

Events and outcomes

The possible events are:

-

Adverse events from treatment for active TB or CPX – this may result in death, in which case costs and QALYs are calculated. If the individual survives, the adverse event (drug-induced hepatotoxicity) may resolve with the participant continuing treatment, or symptoms may persist, in which case the participant is withdrawn from treatment.

-

Dropout from CPX or treatment for active TB – for simplicity, we assume that dropout from CPX and treatment for active TB will take place halfway through the treatment period (after 1.5 months for CPX or 3 months for treatment for active TB). Possible events following dropout from CPX are death and progression to active TB. The next event after dropout from active TB treatment is either reinitiation of treatment (as patients with active disease are likely to re-present at some time), death from TB or death from other causes.

-

Complete CPX or treatment for active TB – participants who complete CPX (after 3 months) may still progress to active TB, or die from other causes. Individuals who complete treatment for active TB (after 6 months) may be reinfected but we assume that this would be captured as secondary infection in a new incident cohort and is therefore outside the scope of this model. They may also suffer reactivation. The next event after completing treatment for active TB may therefore be death from other causes or active TB diagnosis if reactivation takes place.

-

Progression to active TB – all individuals without current active TB have a risk of progressing to active TB. Those with positive LTBI test results are at higher risk. Once participants progress, they become undiagnosed cases of TB and the next event may be death or active TB diagnosis.

-

Active TB diagnosis – individuals with active TB who are not on treatment will develop symptoms and are likely to present clinically, leading to diagnosis and an offer of treatment. We assume a fixed time to diagnosis for these individuals based on the average time between onset of symptoms and diagnosis (3 months).

-

Death from active TB or other causes – costs and QALYs are calculated at this point.

Model assumptions

The key modelling assumptions are:

-

Only BCG-naive individuals who are aged ≤ 35 years are offered a BCG vaccination, a proportion of whom accept (94% in the base-case model). Any adverse effects of BCG vaccination are assumed to be negligible.

-

Only those individuals aged ≤ 35 years are offered CPX; this reflects UK practice and guidelines86 during the study period. A proportion of patients who are eligible accept and start CPX (94% in the base case), although they may drop out or suffer an adverse event.

-

Death from a CPX-related adverse event (hepatotoxicity) is possible, and is assumed to take place at the start of treatment. Fatal adverse reactions to CPX are very rare; thus, the timing of adverse events during treatment is unlikely to influence the results.

-

If the patient survives and the adverse event resolves, the patient resumes CPX but may drop out later. We assume that if the patient resumes CPX they will not experience a second adverse event. If the adverse event is not resolved, the patient stops CPX and will either develop active TB or die from other causes.

-

Patients who drop out from CPX are assumed to do so in 1.5 months and incur half of the cost of a complete course (3 months) of CPX. Incomplete CPX provides some protection against progression to active TB, but is less effective than complete CPX.

-

After completing CPX patients may still progress to active TB (despite preventative treatment) or die from other causes.

-

All individuals have a risk of developing active TB with a hazard conditional on their baseline test results (based on IRs estimated and sampled probabilistically from the PREDICT study). Hazards are estimated based on patients’ available test results, using the test or combination of tests with the greatest predictive value.

-

Once an individual progresses to active TB they may be diagnosed, die from active TB or die from other causes. For patients who are diagnosed with active TB, the time from TB onset to diagnosis is assumed to be 3 months.

-

All those diagnosed with active TB are assumed to start treatment, although they may drop out or suffer an adverse event.

-

A treatment-related adverse event can only take place once. Death from an adverse event is possible and is assumed to take place at the start of treatment.

-

If the patient survives, and the adverse event resolves, the patient resumes treatment but may drop out later. A second adverse event is not possible.

-

If the patient survives but the adverse event is not resolved, the patient stops treatment and will either die from active TB or die from other causes. For simplicity, we have not modelled second and subsequent lines of treatment for patients who experience adverse reactions or resistance to the standard regimen.

-

Patients who drop out from treatment for active TB are assumed to do so in 3 months and incur half of the cost of a complete course of 6 months. They do not get any treatment benefits from incomplete treatment for active TB and are still at risk of active TB death, as well as death from other causes. However, patients who have dropped out may be identified through opportunistic testing or clinical presentation, and will be offered a repeat course of treatment.

-

Patients who complete treatment for active TB are assumed to be free of TB and will die only from other causes.

-

Individuals come into the model with a utility estimated from their PREDICT EQ-5D data. For simplicity, we have assumed that an individual’s utility score remains constant as they age. As utility tends to fall with increasing age, QALY differences between strategies will be overestimated.

-

Individuals’ utility scores are adjusted when they have active TB. A pre-treatment utility multiplier is applied as soon as the patient develops active TB to reflect the impact of emerging TB symptoms prior to treatment. A lower utility multiplier is applied during the first 3 months of treatment to reflect continuing symptoms, inconvenience and distress caused by isolation and adverse effects of treatment that are tolerated. The utility multiplier applied during the last 3 months of treatment is then higher as most patients will have less-severe symptoms by this time, and the prevalence of adverse effects is likely to be lower. After completion of treatment, patients are assumed to return to their initial utility value. 108

-

It is assumed that CPX has a negligible impact on utility. 108

-

For simplicity, our base-case model does not include transmission from members of the cohort who develop TB to their contacts. This will tend to underestimate the benefits (QALY gain and health-care cost savings) associated with TB prevention. We conducted a scenario analysis with a ‘cascade’ approach to model the impact of secondary transmission.

Model parameters

Tuberculosis incidence

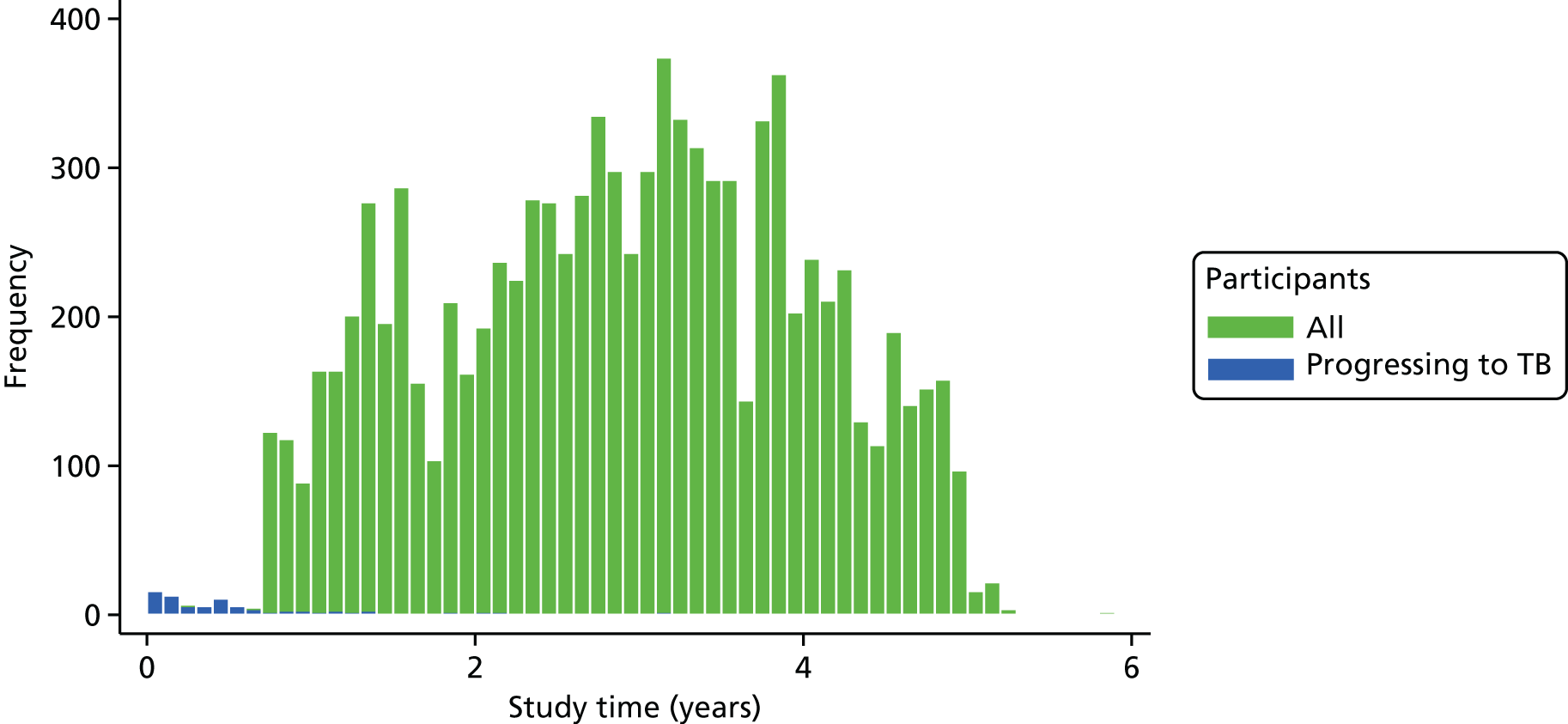

The incidence of TB was modelled using a Weibull distribution to reflect the falling number of cases over time in the PREDICT cohort. This is expected as contacts of people with active TB are most likely to develop TB close to the time of exposure, and, similarly, migrants from high-incidence countries are at most risk shortly after entry to the country they are migrating to. In the PREDICT cohort, 77 participants were diagnosed with active TB over a total of 20,571.4 person-years at risk. This equates to an overall IR of 0.00374 per person-year. We used a calibration approach to fit a Weibull distribution to these data (Table 3). Our best estimate used a scale parameter of 2.5 and a shape parameter of 6. This achieved an IR of 0.00932 in year 1 (matching that in PREDICT), 0.00115 in year 2 (compared with 0.00167 in PREDICT) and 0.00373 averaged over the first 3 years (compared with 0.00375 in PREDICT).

| Parameter | Base-case value | 95% CI | PSA distribution | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IR (TB incidence per person-year) | 0.00374 | 0.00296 to 0.00462 | Beta (77, 20,494.4) | PREDICT |

| Hazard multiplier for year 1 | 2.5 | – | – | Fitted Weibull distribution |

| Shape parameter | 6.0 | – | – |

Test performance

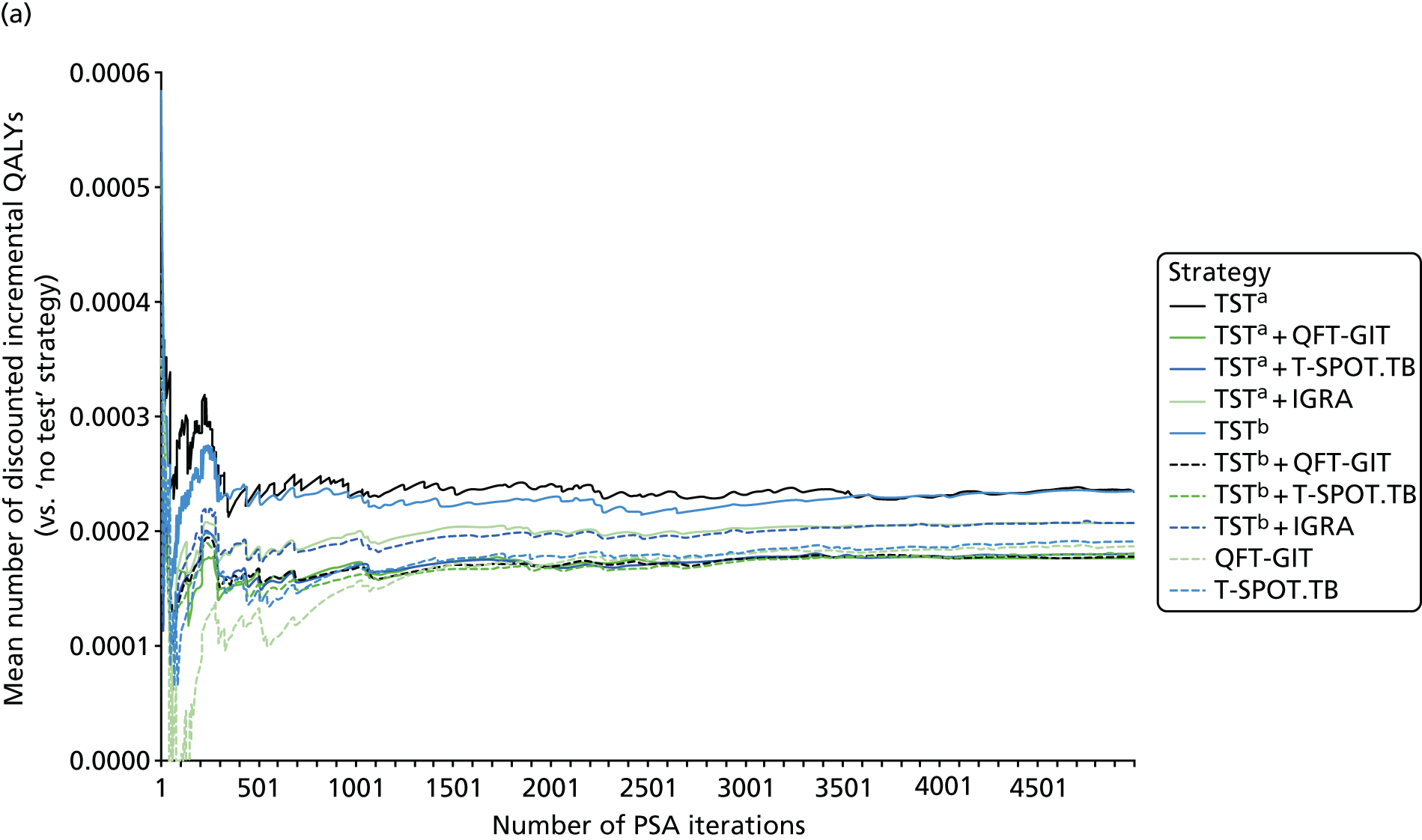

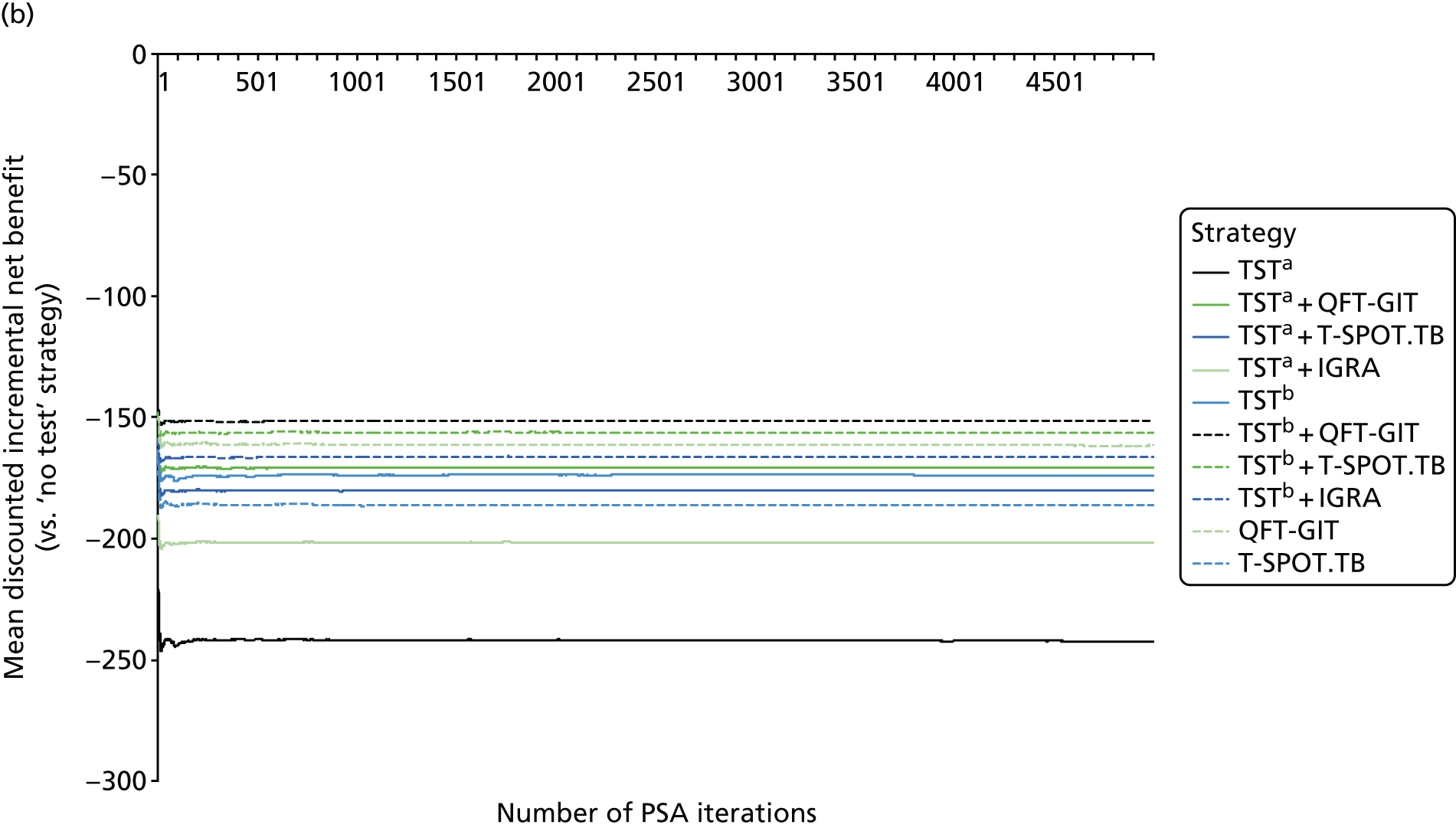

Estimates of the predictive performance of the various test strategies were taken from the analysis of PREDICT data presented in Chapter 3. For the PSA, we used a chained approach to generate correlated estimates of the TB IRs for patients testing positive or negative for each of the modelled strategies.

We started by estimating IRs for patients with a negative TSTa result [IR(TSTa–)] from the overall incidence of TB in the population (R), the proportion of person-years in patients with a positive TSTa result (p) and the IRR for TSTa positive compared with TST negative [IRR(TSTa+ vs. TSTb–)]:

The IR for patients with a positive TSTa result is then: