Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 14/151/08. The contractual start date was in June 2016. The draft report began editorial review in August 2017 and was accepted for publication in February 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

John Stevens is a shareholder of GlaxoSmithKline plc (GSK House, Middlesex, UK), AstraZeneca plc (Cambridge, UK) and Shire Pharmaceuticals Group plc (Shire plc, Dublin, Republic of Ireland).

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Archer et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Description of the health problem

Clinical features of rheumatoid arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic disease characterised by progressive, irreversible joint damage, impaired joint function, pain, swelling and tenderness of joints. 1 RA is associated with increasing disability and reduced quality of life. 1 Symptoms of RA include pain, morning stiffness, joint swelling, joint tenderness, loss of movement, warmth of the peripheral joints and fatigue. 2,3 RA is associated with substantial costs, both directly (in terms of drug acquisition and hospitalisation) and indirectly, because of reduced productivity. 4 RA has long been linked with increased mortality,5,6 in particular because of cardiovascular events. 7

Epidemiology

It has been estimated that there are approximately 400,000 people in the UK with RA. 8 RA has been reported to have a greater incidence in females (3.6 per 100,000 per year) than in males (1.5 per 100,000 per year). 9 Although the peak age of incidence in the UK is in the eighth decade of life, people of all ages may develop RA. 9

Aetiology

A range of contributing factors, such as genetic and environmental influences, have been implicated as potential causes of RA. The heritability of RA is estimated to be between 53% and 65%,10 with a family history of RA carrying a corresponding risk ratio of 1.6 compared with the general population. 11 Many genes linked with RA susceptibility are concerned with immune regulation. Although infectious agents have been suspected, no consistent relationship with an infective agent has been demonstrated. Sex hormones have also been implicated because of the higher prevalence of RA in women and a tendency for RA to improve during pregnancy. There is no proof of any causal link with lifestyle factors, such as diet, smoking or occupation (but lifestyle factors may increase the risk of developing RA).

Management of rheumatoid arthritis

There are a range of treatment options available for the management of RA, with the aim of alleviating symptoms and of minimising irreversible joint damage that may occur as a result of the disease process. 8

Traditionally, patients have been treated with conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs [(cDMARDs) also known as conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs], including methotrexate (MTX), sulfasalazine (SSZ), hydroxychloroquine (HCQ), leflunomide (LEF) and gold injections, as well as corticosteroids, analgesics and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). However, more recently, a group of biologic immunosuppressant drugs have been developed that specifically modify the disease process by blocking key protein messenger molecules (such as cytokines) or cells (such as B-lymphocytes). 8 These treatments have been termed as biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (bDMARDs); of these, certolizumab pegol, adalimumab (ADA), etanercept (ETN), golimumab and infliximab (IFX) are tumour necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors (or antagonists). Of the remaining bDMARDs, tocilizumab is a cytokine interleukin-6 inhibitor, abatacept (ABT) is a selective modulator of the T-lymphocyte activation pathway and rituximab is a monoclonal anti-body against the cluster of differentiation 20 (CD20) protein. For patients who have exhausted all National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)-recommended treatments, non-biologic final treatment options may be used.

Prompt diagnosis of RA is important in ensuring the appropriate clinical management of patients early in the course of the disease. The 2013 European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) recommendations for the management of RA state that treatment with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) should begin as soon as RA is diagnosed. 12 The lack of sensitivity of the 1987 American College of Rheumatology [(ACR) previously known as the American Rheumatism Association] classification criteria in early disease has been acknowledged and led to the development of the 2010 RA classification criteria. 13 The 2010 criteria for RA require (for classification as definite RA) the confirmed presence of synovitis in at least one joint, the absence of an alternative diagnosis to better explain the synovitis and scoring ≥ 6 (of a maximum of 10) from individual scores across four domains: (1) number and site of affected joints (score range 0–5), (2) serological abnormality (score range 0–3), (3) elevated acute-phase response (score range 0–1) and (4) symptom duration (range 0–1). 13

The EULAR recommended that, if a treatment target is not reached, the use of a bDMARD should be considered in the presence of poor prognostic factors [e.g. high disease activity, positivity to rheumatoid factor (RF) and/or anti-bodies to citrullinated proteins and the early presence of joint damage]. 14

Rheumatoid arthritis is a heterogeneous disease and the disease course can vary considerably between patients. The guideline development group for the NICE guidance on RA [i.e. Clinical Guidance number 79 (CG79)] suggested that it would be useful to clinicians if they could identify at an early stage those RA patients who are most likely to suffer a worse course of disease (or prognosis). 8 These patients could then be closely monitored to ensure that they can receive appropriate treatment to minimise the health problems and joint damage caused by RA. Patients who are considered to be less likely to experience a poor prognosis may require a less intensive follow-up and treatment strategy. The provision of clearer information on the prognosis and prediction of treatment response would be useful to inform the optimal clinical management of patients and to avoid pharmacological overtreatment of patients.

The NICE guidance on RA (i.e. CG79) indicated the potential role of a range of factors in determining the prognosis of patients with early RA. 8 These included RF, anticyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP) positivity, baseline radiological damage, nodules, acute-phase markers, Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) score, grip strength and swollen joint counts (SJCs).

Although there is a large amount of evidence available on the use of tests and assessment tools in determining the prognosis and prediction of treatment response, a recent good-quality evidence synthesis was considered to be lacking. Therefore, there is no clear consensus on which of the available tests and assessment tools used for RA could allow the best assessment of prognosis in people newly diagnosed with RA and whether or not variables, if identified, also predict how well patients respond to different drug treatments.

Measurement of key outcomes in rheumatoid arthritis

Major outcomes in RA include measures of joint destruction (e.g. radiographic progression), disease activity [as assessed via, for example, Disease Activity Score-28 (DAS28)] and disability (as assessed via, for example, HAQ scores).

Radiographic progression is frequently measured in clinical trials and observational research. 15 The two main scoring systems available for measuring radiographic progression are the Larsen et al. 16 system and the Sharp et al. 17 system. The van der Heijde18 modification of the Sharp system includes both hands and feet, erosions, joint-space narrowing and a range of joints.

In the UK, monitoring the progression of RA is often undertaken using the DAS28 in terms of swelling (SW28) and of tenderness to the touch (TEN28). The DAS28 also incorporates erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and a subjective assessment on a scale of 0–100 made by the patient regarding disease activity in the previous week.

The equation for calculating DAS28 is as follows:19

A second version of the DAS28 using C-reactive protein (CRP) levels instead of ESR exists. The DAS28 can be used to classify both the disease activity of the patient and the level of improvement. Patients with a DAS28 of ≤ 3.2 are classed as having inactive disease, patients with a DAS28 of > 3.2 and ≤ 5.1 are regarded as having moderate disease and those with a DAS28 of > 5.1 are regarded as having very active disease. 19

The HAQ is a key measure of patient functional disability. 20 It is a patient-completed assessment resulting in scores ranging from 0 to 3 (with higher scores indicating greater disability).

Background to prognosis research

Key concepts in prognosis research

Prognosis research describes the investigation of the relationship between future outcomes among people with a given baseline health state in order to improve health. 21,22

The PROGnosis RESearch Strategy (PROGRESS) partnership outlined a framework for prognostic research, with the aim of enhancing the quality and translational impact of prognosis research findings. The framework has four key elements, as outlined below:

-

Fundamental prognosis research – examining the average prognosis of patients (natural course of a disease or condition) with current clinical practice. 21,22

-

Prognostic factor research – studying individual factors that, for patients with a given disease or condition, are associated with the clinical outcome of interest. 21,22

-

Prognostic model research – the use of multiple prognostic factors in combination to provide a clinical prediction model, from which the probability of the outcome can be predicted for individuals. This research theme includes model development, validation and assessing the clinical impact of these models. 23

-

Stratified medicine research – the use of prognostic information to predict an individual’s response to treatment, and hence make treatment decisions that are tailored to individuals. 24

The current assessment focuses on prognostic model research (theme 3) and stratified medicine (theme 4). Briefly, prognostic model research seeks to estimate the absolute response of an outcome for an individual, whereas stratified medicine seeks to target therapy and make the best decisions for groups of similar patients. 23 One approach to stratifying the use of treatments is to consider the absolute response of each individual (as estimated using a prognostic model). Those people with the most severe prognosis are likely to derive the largest absolute benefit from a treatment and may be targeted for intervention. For example, lipid-lowering therapy may be recommended to individuals above a certain threshold for the risk of developing cardiovascular disease. 25 The results from prognostic model research are therefore relevant for guiding stratified medicine research, and the two themes are related.

Clinicians may also stratify medicine because the relative treatment effect is inconsistent across patients. In statistical terms, this means that the patient or disease characteristic is a treatment effect modifier (i.e. there is an interaction between the patient or disease characteristic and the effect of treatment on the outcome). Assessing the presence of these differential treatment effects is important in predicting individual treatment response. Examples include the use of trastuzumab for the treatment of breast cancer in individuals with a positive human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 status. The prediction of treatment response is considered in review 2, and further background on the development of treatment-specific clinical prediction models is given in Background to stratified medicine research. Further examples of stratified treatment decisions in clinical practice, based on the prediction of absolute risks, or differential treatment effects across different subgroups of the population are provided by Hingorani et al. 24

Definition of a prognostic model

Prognostic models are developed to aid health-care providers in their decision-making by estimating the probability that a specific event will occur in the future. 23,26

Moons et al. 27 stated that, because of the complexities in patients and diseases, prognostic studies require a multivariable approach. Indeed, Collins et al. 26 noted that, in practice, the prediction of an individual’s response is not typically based on a single predictor and that clinicians integrate a range of patient characteristics and symptoms in their own estimation of prognosis. 26 We further acknowledge that clinical prediction models would simplify to only one variable if this were the only significant predictor of prognosis.

A prognostic model is a formal combination of multiple predictors from which the probability of a specific outcome can be estimated for individual patients. 23,27 For an individual with a given set of baseline characteristics and assuming that the outcome is binary (e.g. progression/no progression), a prognostic model provides an estimate of the probability of experiencing the outcome within a specific period of time (i.e. an estimate of absolute risk). Measures of relative risk [e.g. odds ratios (ORs), relative risks, hazard ratios] are not relevant when evaluating the performance of prognostic models, other than to obtain an estimate of the absolute risk in conjunction with a baseline response. 28

Clinical prediction model development

Prediction model studies may be classed as model development,29 model validation30 or comprise a combination of both. There are many important statistical considerations to the development process, which we summarise here briefly to aid interpretation of the results. More comprehensive descriptions of model development and validation procedures are given in the provided references.

Clinical prediction models are developed using data from cohorts of patients or clinical trials. The development procedure starts with a preselected set of candidate predictors, and suitable procedures should be used to identify the most important predictors and assign relative weights to the predictors to form the combined clinical prediction model. 31 Important considerations include the following:

-

The selection of candidate predictors. Candidate predictors are variables that are chosen to be studied for their prognostic performance. 31 They should be selected based on subject knowledge and availability in practice, with consideration to the size of the data set. 32 Selection based on univariable analyses could lead to the omission of important predictors and so should be avoided. 33

-

The handling of missing values. It is generally recommended that some form of imputation should be used to account for missing data, because an analysis including only the individuals with completely observed data may lead to biased results. 34 A complete-case analysis may be appropriate, provided that the proportion of missing values is small (i.e. typically < 5%). 33

-

Continuous predictors. Simple transformations of continuous variables to account for non-linearity may be appropriate. 31 The creation of artificial categories leads to a loss of information and power and should therefore be avoided. 35,36

-

Final variable selection. Clinical prediction models are usually developed using multivariable regression. If a full-model approach (containing all candidate variables) is not appropriate, then backwards selection is the preferred method for statistical selection. Selection based purely on statistical significance in univariable analysis should not be used. 31,37,38

-

Interactions between variables should also be considered. Interactions between variables and treatment (treatment effect modification) are considered in review 2.

After a model has been developed, validation is conducted to quantify the performance of the model in the population used to develop the model (internal validation). This is described as apparent validation if the validation is conducted in exactly the same sample as that used for model development. This usually produces the best-possible estimate of model performance, because the model was optimally designed to fit the development data set (described as overfitting) and performs less favourably when applied generally to similar samples of patients. 31 Overfitting is of particular concern when the development data set is small and/or the number of candidate predictors is high. 31

Alternatives to apparent validation should ideally be used. Data splitting involves dividing the development sample into a training data set (used to derive the model) and a validation data set that is used to evaluate model performance. However, this approach is considered to be statistically inefficient, as not all available data are used to formulate the model. 31 Therefore, either bootstrapping or cross-validation is recommended as the preferred method of internal validation. 26 Cross-validation extends the simple data-splitting approach by iterating the procedure over several partitions of the data set. The performance results are averaged to provide an overall measure.

Overfitting can also be avoided or minimised using a procedure called shrinkage. This is a statistical estimation method that preshrinks the model regression coefficients towards zero. 33

Measures of predictive model performance (binary outcomes)

There are several summary measures used to quantify the predictive performance of clinical prediction models in internal and external validation. The following key measures of predictive model performance are considered in the assessment.

Overall model performance statistics

Overall model performance statistics include R2 and the mean-squared error/Brier score. R2 ranges from zero to one and describes the proportion of explained variation in the data. There are several methods for calculating R2, with Nagelkerke’s39 R2 commonly being reported for logistic regression models. The mean-squared error is defined as the average-squared difference between the observed outcome (0 or 1) and the predicted probability of the outcome.

Calibration

Calibration indicates the extent to which expected outcomes (predicted from the clinical prediction model) and observed outcomes agree. Summarising the estimates of calibration performance is challenging, because studies may quantify calibration using different summary statistics. 40 In a recently published guide to systematic review and meta-analysis of prediction model performance, Debray et al. 40 based their assessment of calibration on the total number of observed (O) events compared with the expected number of events (E) predicted by the model. The observed-to-expected (O : E) ratio provides a rough indication of the overall model calibration across the entire range of predicted probabilities. An O : E ratio of close to one would indicate good calibration, whereas values that are < 1 or > 1 indicate a model that either overestimates or underestimates the number of events.

Discrimination

Discrimination refers to the ability of a prediction model to distinguish between patients who do and those who do not experience the outcome of interest. For binary outcomes, discrimination is frequently quantified using the concordance statistic (c-statistic), and it is also known as the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve. For categorical outcomes, Harrell’s c-statistic for ordinal data37 can be used. The c-statistic is also relevant for other outcome measures (e.g. time to event) and is sometimes termed the c-index. A c-statistic of 0.5 indicates no discriminative ability over that that would be expected because of chance, whereas a c-statistic of 1 indicates perfect discriminative ability.

External validation

Demonstrating that a clinical prediction model can successfully predict the outcome of interest in the sample used to derive the model is not, by itself, sufficient to confirm its value. 23,28 A more objective measure of model performance is obtained using external validation, in which the model performance is assessed in a sample of patients who are external to those who were used for the model development.

Model updating or recalibration can be considered if a particular model does not calibrate well in external populations. This is considered to be a better alternative to redeveloping new models in each patient sample as a result of poor performance of existing models. 31 Despite this recommendation, a recent systematic review shows that recalibration is not commonly undertaken. 41

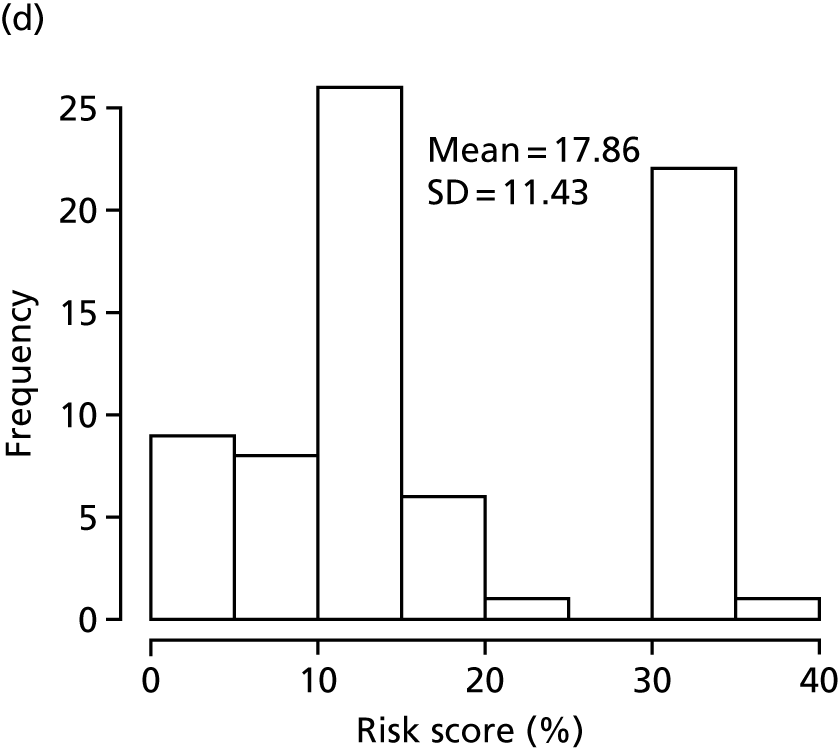

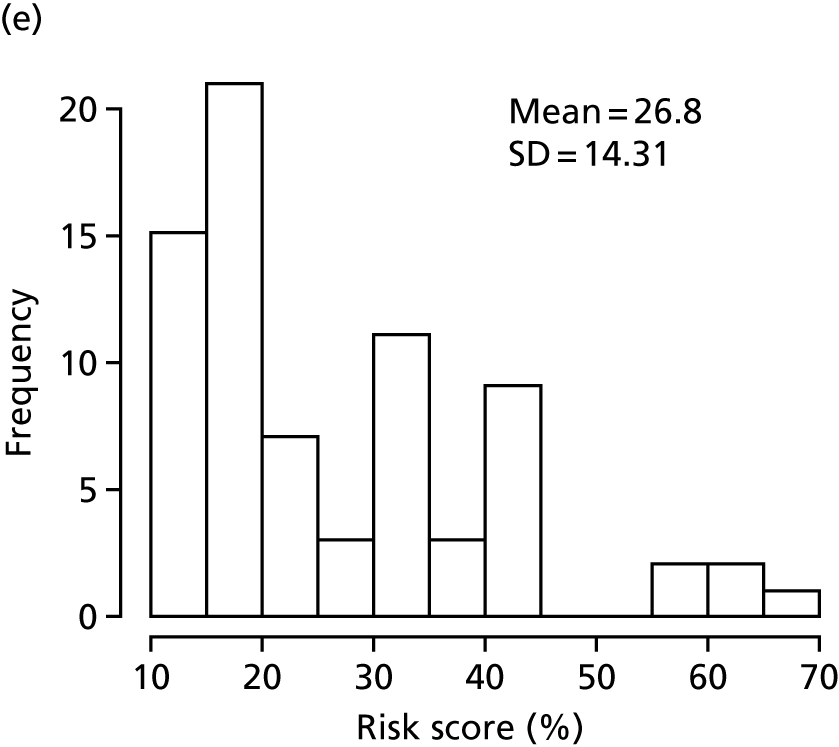

The c-statistic of a clinical prediction model may vary substantially between different validation studies, and a common cause for this heterogeneity is because of differences in the distribution of patient characteristcs. 40 Vergouwe et al. 42 demonstrated in a simulation study that a more heterogeneous sample was related to a higher discriminative ability. It is therefore important to consider the distribution of patient characteristics (case mix) of the included validation studies. This could be done by considering the standard deviation (SD) of key variables or of the combined linear predictor (the weighted sum of regression weights and covariate values in the validation sample).

Background to stratified medicine research

Developing treatment-specific clinical prediction models

Stratified medicine research is concerned with the use of prognostic information to predict an individual’s response (i.e. clinical benefit or adverse events) according to different treatments. The prediction of absolute treatment effects according to different patient and/or disease characteristics for different treatments is based on an analysis of relative treatment effects. The development of treatment-specific clinical prediction models should follow the same process as described in Clinical prediction model development; an assessment of differential treatment effects should be conducted formally, including the use of interaction tests, and not through subgroup analyses.

Issues associated with subgroup analyses

Although it is common for an assessment of differential treatment effects to be based on a series of subgroup analyses, this is not generally recommended. Constructing subgroups based on patient and/or disease characteristics that are continuous (e.g. ESRs of < 25 mm/hour, 25–50 mm/hour and > 50 mm/hour) assumes that treatment effects are constant within categories and have a discontinuity according to each category; in practice, such categorisation is often subjective and not supported by evidence. Some subgroups, including definitions such as early disease, involve other patient and/or disease characteristics that are correlated with such definitions of subgroup, and the resulting estimates of treatment effects may have a more complex interpretation. Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence, and a statistically significant treatment effect in one subgroup but not in another should not be interpreted as there being a true effect in one subgroup but not in another; the result may reflect different degrees of uncertainty or different magnitudes of treatment effect in the subgroups. Assessing the statistical significance of treatment effects in different subgroups does not incorporate an adjustment for other covariates that may be important and assumes that there is no residual differential treatment effect within the subgroup. Treatment effects may be misleading when treatments interact with covariates that were not used to form subgroups, and when the subgrouping variable interacts with a patient and/or disease characteristic that was ignored. 43

Assessing treatment by covariate interactions

Ideally, patient and/or disease characteristics that may affect relative treatment effects should be prespecified. All covariates believed to be prognostic or treatment effect modifiers should be included in the analysis and should be used consistently across data sets irrespective of the statistical significance of the covariates. The main effects should be modelled flexibly and should not assume linearity of response with a change in the value of a covariate; interaction effects should be modelled using the same approach. The statistical significance of all interaction effects included in a model should be assessed using a single test; this controls for multiplicity and will not be affected by potential treatment effect modifiers that are colinear with each other. The absence of a statistically significant interaction effect should not necessarily be interpreted to mean that this is evidence of the absence of an interaction effect. Studies are not typically designed to assess interaction effects, and a lack of statistical significance may simply reflect a lack of power of the test. Similarly, some interaction tests may be statistically significant by chance. Furthermore, it is important when interpreting interaction effects to distinguish between qualitative interactions, whereby the effect of treatment is reversed for some value(s) of the covariate, and quantitative interactions, whereby the treatment effect is in the same direction for different values of the covariate, but the magnitude of the treatment effect is different and may be clinically irrelevant. Finally, in non-linear models, such as the use of logistic regression for binary outcomes, any omitted covariates will result in biased estimates of treatment effect.

Assessing treatment by covariate interactions in this review

Studies used in this assessment to evaluate whether or not different patient and/or disease characteristics are prognostic according to different treatments will include those used in the development of treatment-specific clinical prediction models, as well as randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and observational studies that include patients with differential treatment use at entry. The use of RCTs and observational studies is to acknowledge the evidence that these studies provide about differential treatment effects in the absence of treatment-specific clinical prediction models. Studies that provide information only about the prognostic effect of patient and/or disease characteristics are excluded; nevertheless, studies meeting the inclusion criteria do provide some, albeit selective, information about the prognostic effect of covariates according to treatment. However, the results should be treated with caution for the reasons given above.

The primary parameter of interest is that representing the interaction between treatment and baseline covariate; it is this parameter that quantifies whether or not the response to treatment varies according to the value of the covariate. In practice, such interactions should be assessed in a single regression model incorporating main effects and interaction terms.

As discussed previously, studies may lack sufficient power to detect interaction terms as being statistically significant [i.e. 95% confidence intervals (CIs) not including the null value] and it should not be assumed that absence of evidence is equivalent to evidence of absence. Similarly, in the event that a statistically significant treatment effect modifier is identified, it may not be clinically relevant. In addition, the results should be considered as hypothesis-generating, because studies were generally not designed to detect interaction effects; the potential treatment effect modifiers are assessed univariately in this review, although their relevance may be different when the correlation between multiple covariates is taken into consideration in clinical prediction models, and spurious results may occur by chance given the number of multiple comparisons being performed.

Interpretation of the evidence regarding patient and/or disease characteristics

There are four scenarios that may arise depending on whether a covariate is (or is not) prognostic for at least one treatment and whether a covariate is (or is not) a treatment effect modifier: these are illustrated below for a comparison of two treatments with respect to a single covariate, which may be discrete or continuous.

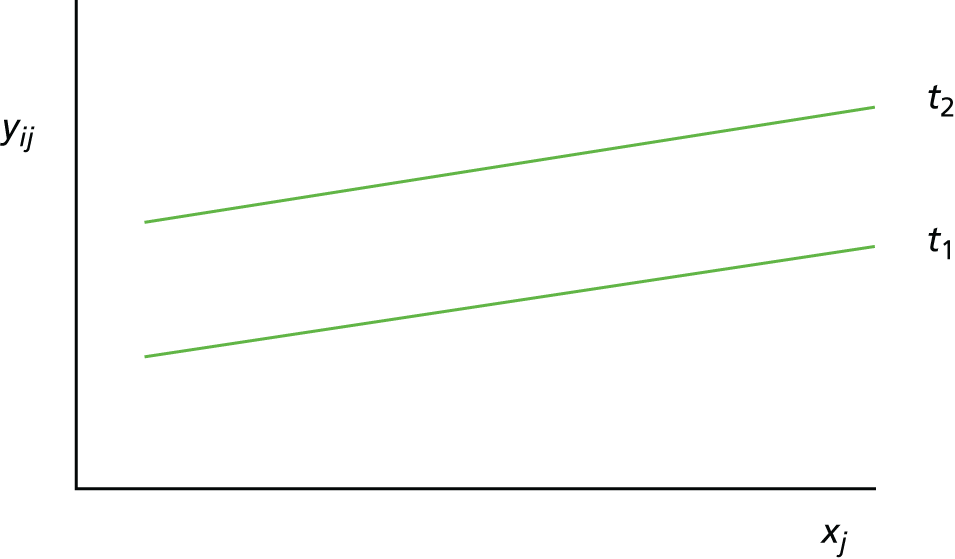

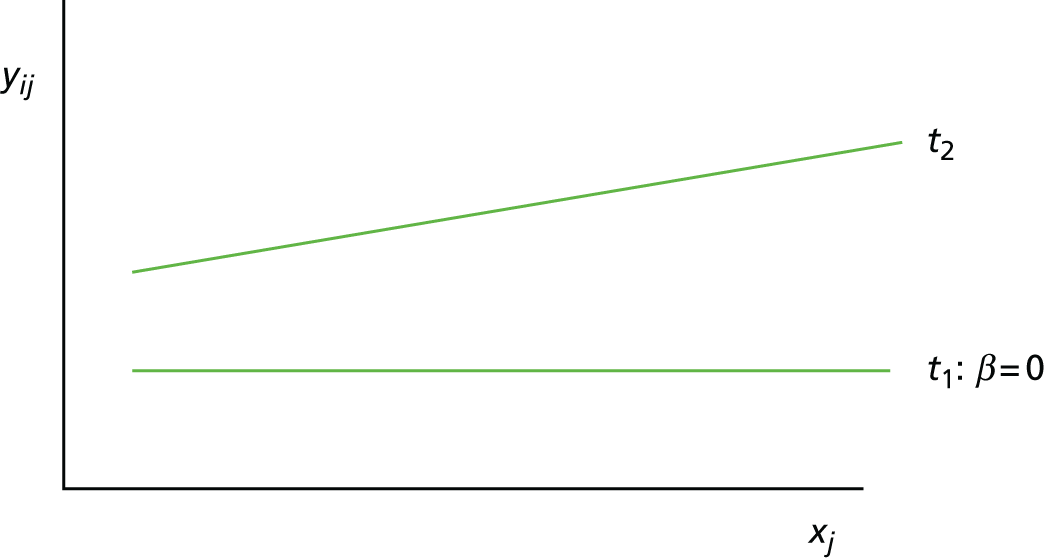

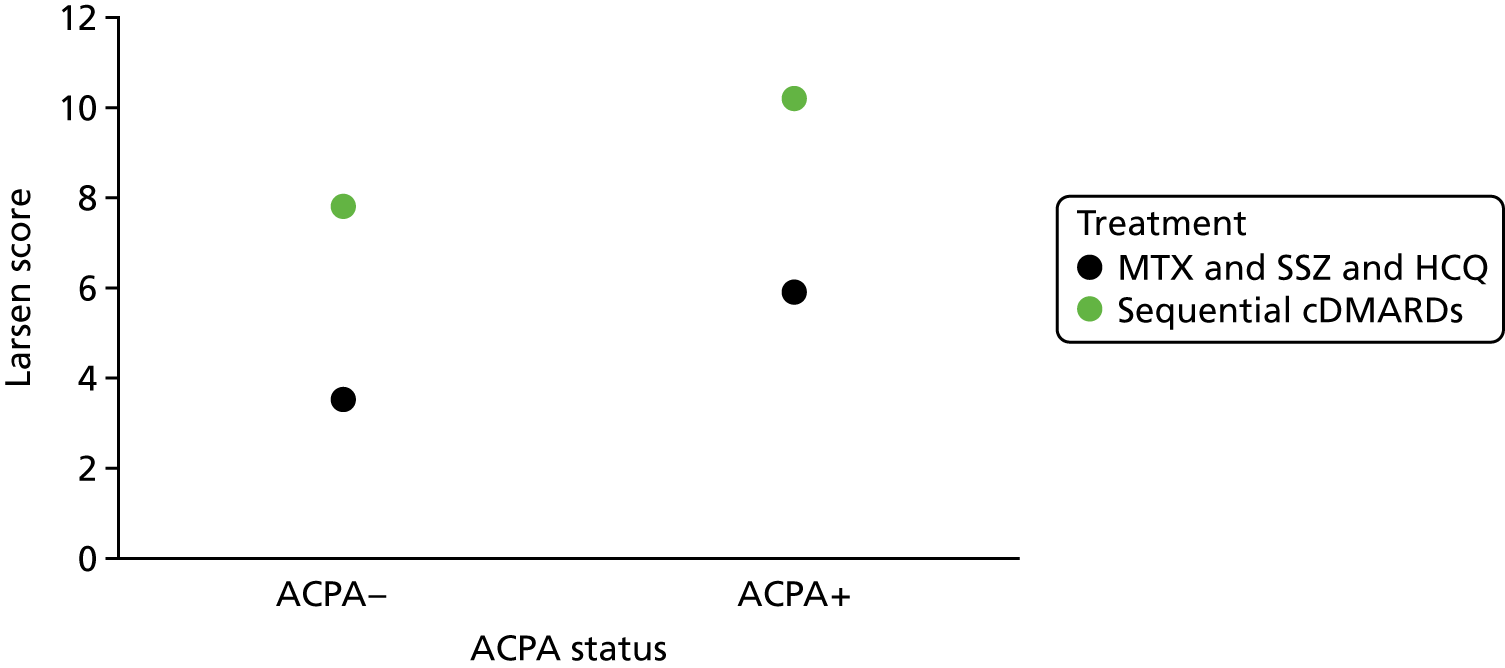

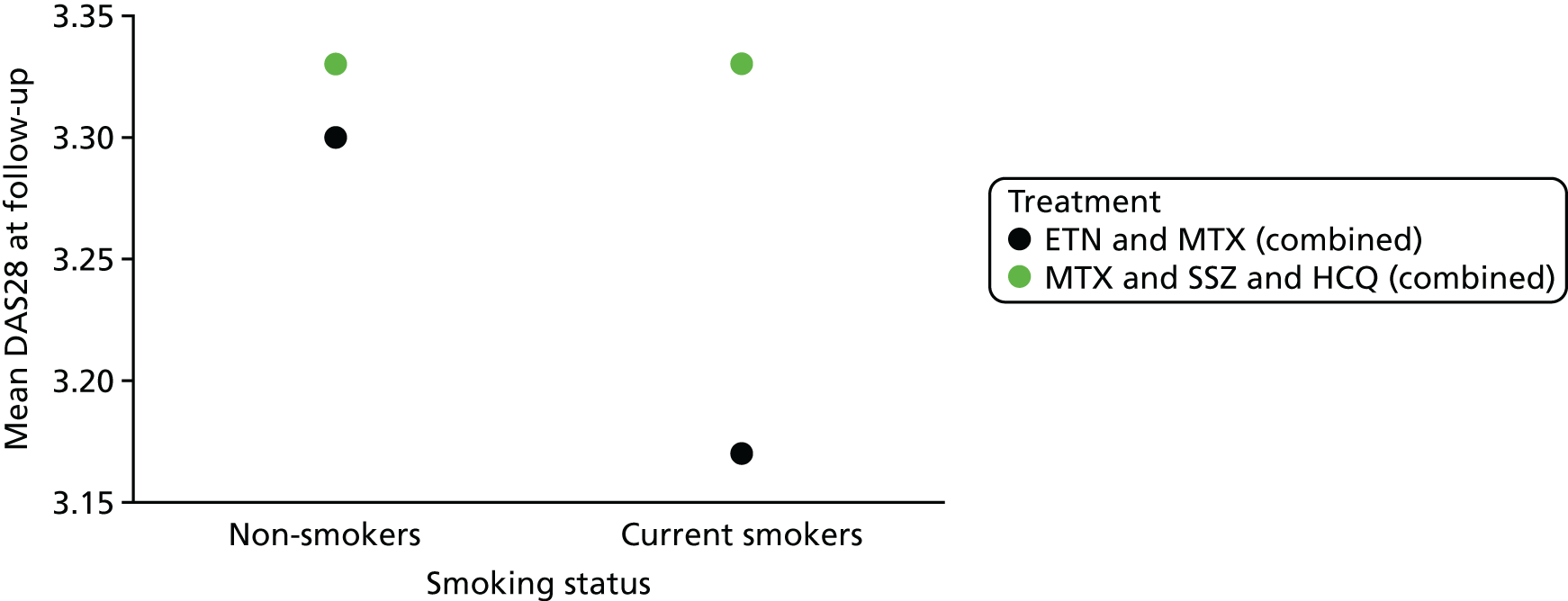

Scenario 1: prognostic variable for both treatments, but not a treatment effect modifier (Figure 1)

Given two treatments coded such that t1 = 0 and t2 = 1, the mean response (i.e. expected value) for a person with a baseline value of xj who receives treatment t1 is:

For treatment t1 this is:

and for treatment t2 this is:

FIGURE 1.

Scenario 1: prognostic variable for both treatments but not a treatment effect modifier.

In this scenario, the treatment effect is β2, which is constant at each value of the predictor; it is also possible for a baseline variable to be a prognostic and for there to be no treatment effect (in which case, the two regression lines would be superimposed).

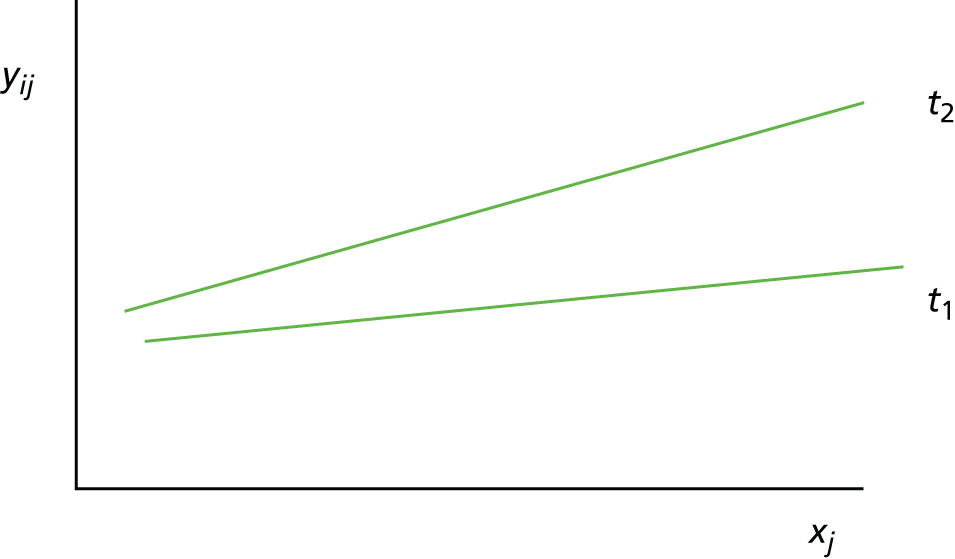

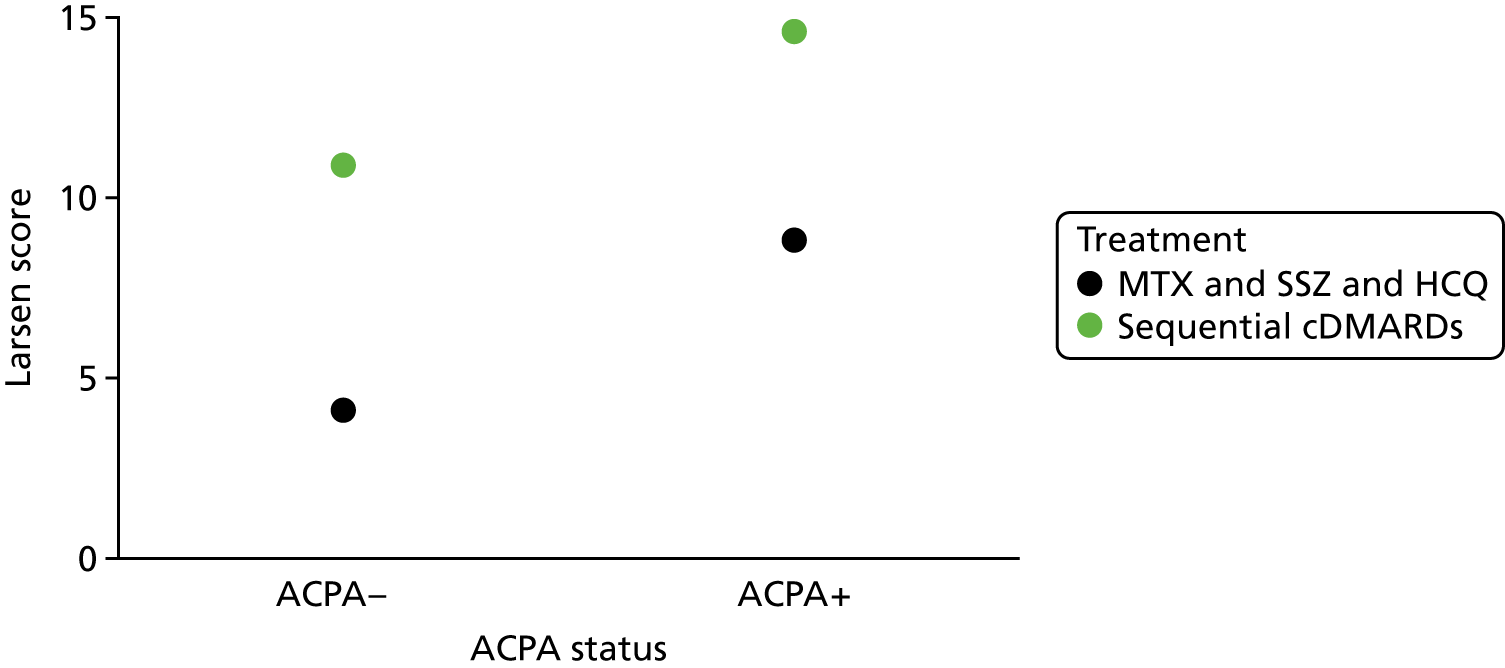

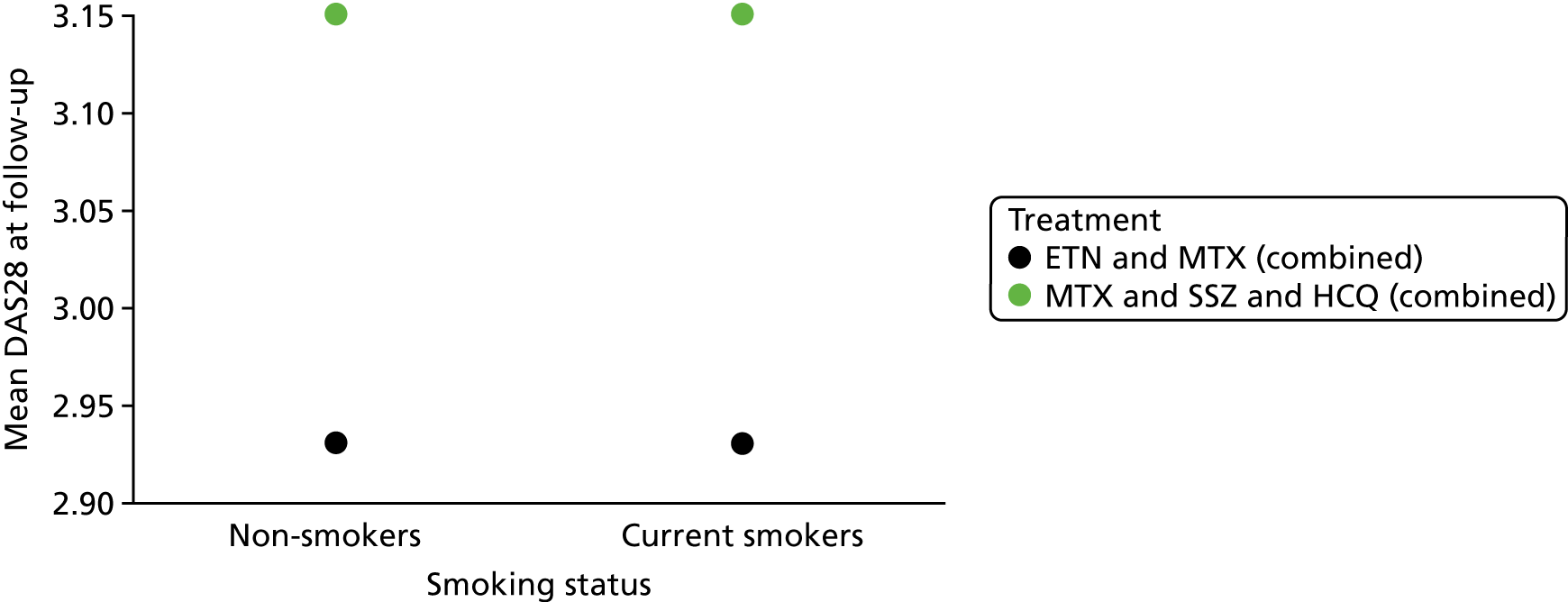

Scenario 2: prognostic variable for both treatments and a treatment effect modifier (Figure 2)

Given two treatments coded such that t1 = 0 and t2 = 1, the mean response (i.e. expected value) for a person with a baseline value of xj who receives treatment t1 is:

For treatment t1 this is:

and for treatment t2 this is:

FIGURE 2.

Scenario 2: prognostic variable for both treatments and a treatment effect modifier.

In this scenario, the treatment effect at xj is β2 + β12xj, which depends on the value of the baseline variable; it is also possible that β2 = 0.

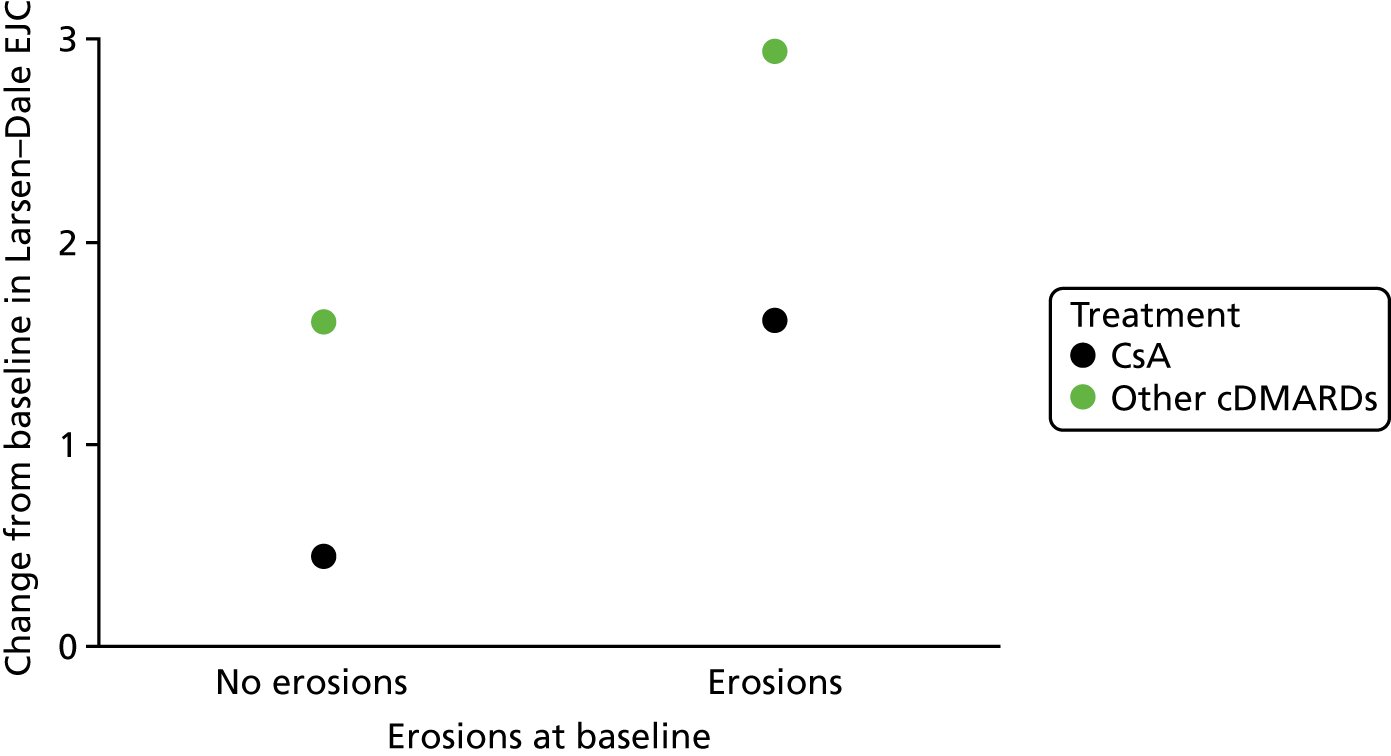

Scenario 3: not a prognostic variable for one treatment, but a treatment effect modifier (Figure 3)

Given two treatments coded such that t1 = 0 and t2 = 1, the mean response (i.e. expected value) for a person with a baseline value of xj who receives treatment t1 is:

For treatment t1 this is:

and for treatment t2 this is:

FIGURE 3.

Scenario 3: not a prognostic variable for one treatment, but a treatment effect modifier.

In this scenario, the treatment effect at xj is β2 + β2xj, which depends on the value of the baseline variable; it is also possible that β2 = 0.

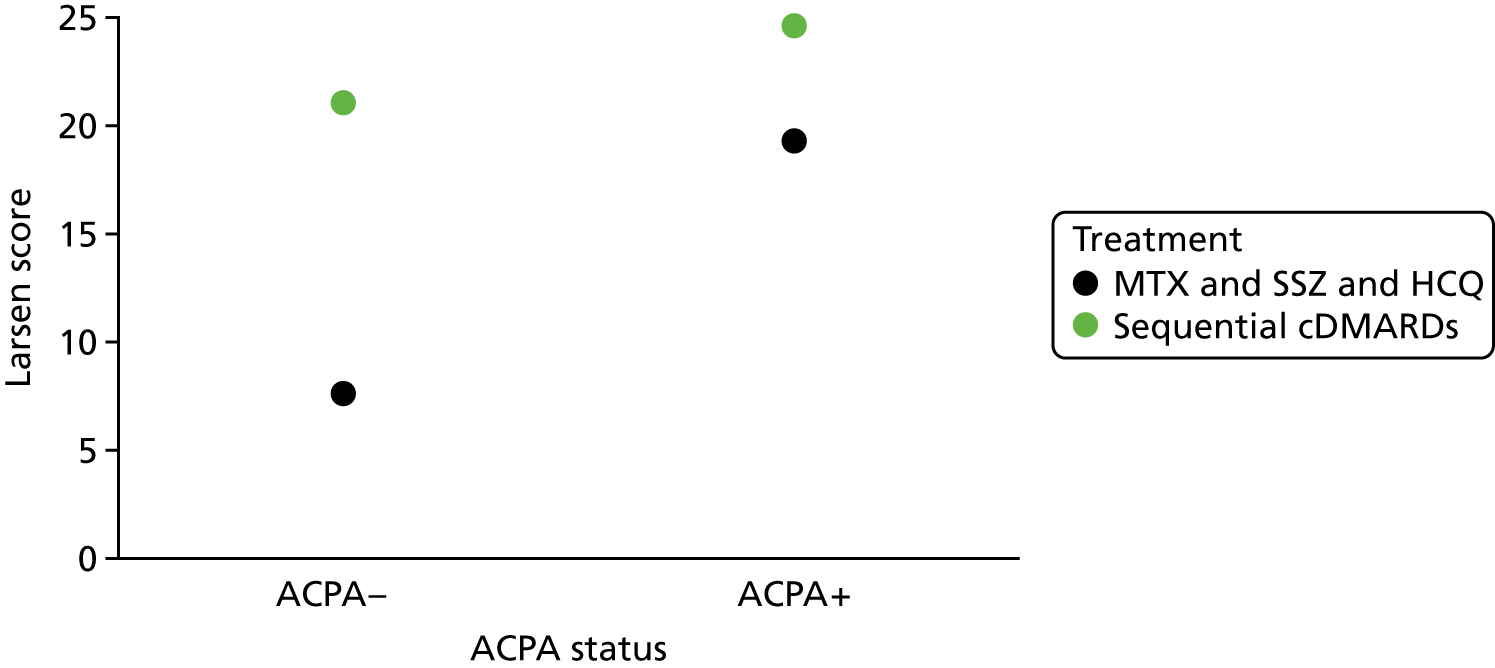

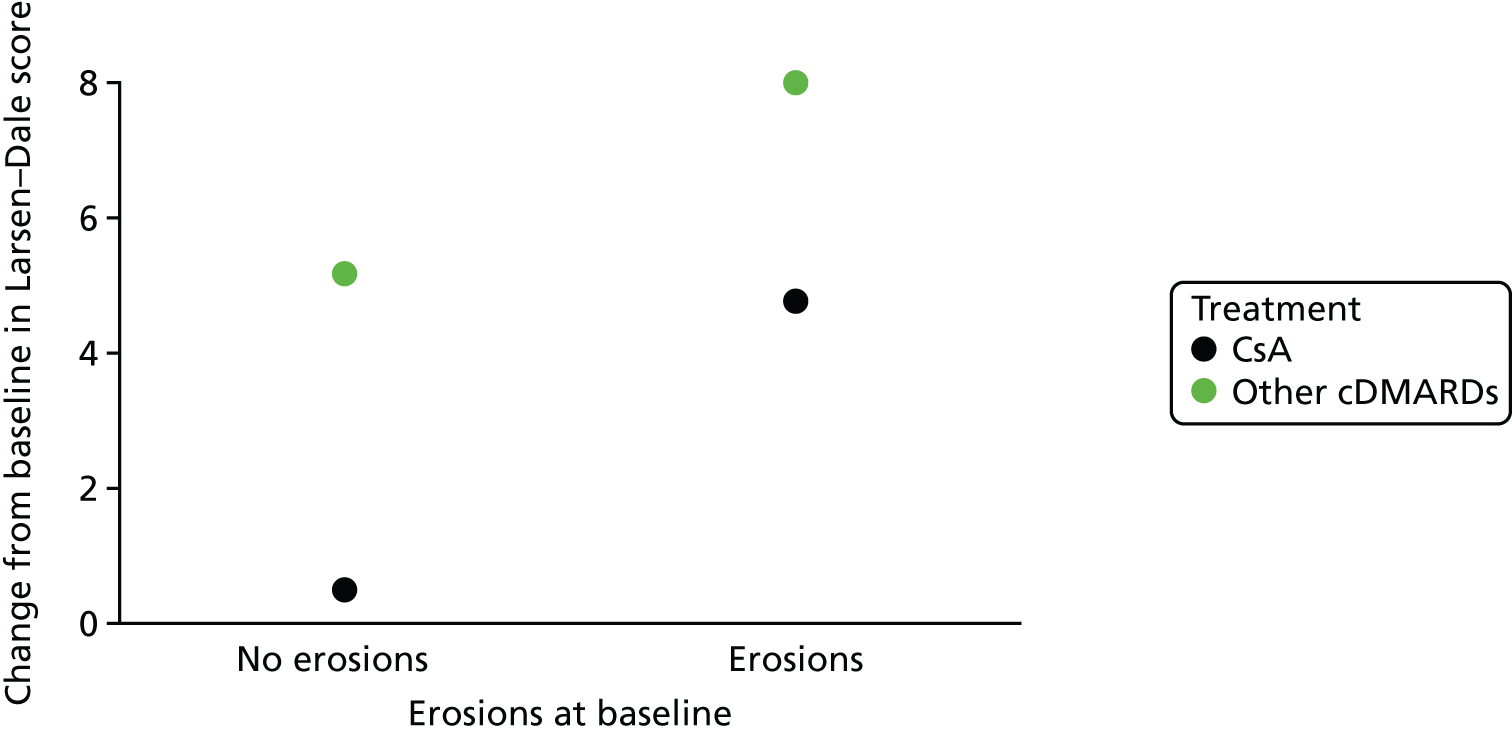

Scenario 4: not a prognostic variable for either treatment and not a treatment effect modifier (Figure 4)

Given two treatments coded such that t1 = 0 and t2 = 1, the mean response (i.e. expected value) for a person with a baseline value of xj who receives treatment t1 is:

For treatment t1 this is:

and for treatment t2 this is:

FIGURE 4.

Scenario 4: not a prognostic variable for either treatment and not a treatment effect modifier.

In this scenario, the treatment effect at xj is β2, which is independent of the baseline variable; it is also possible for there to be no treatment effect (in which case, the two regression lines would be superimposed).

Stratified medicine research is concerned with identifying treatment effect modifiers, as illustrated by scenarios 2 and 3.

Chapter 2 Review question and objectives

Review question

The review question as outlined in the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) commissioning brief and final protocol was as follows: what test or combination of clinical, laboratory and imaging tests gives the best assessment of prognosis in RA, and how well do they predict response to treatment?

Assessment structure

The assessment structure consisted of systematic reviews with appropriate predefined subgroup analyses.

It was anticipated in the final protocol that the factors most likely to be of use for prognosis and prediction of treatment response would be assessed through meta-analysis of available aggregate-level data. The de novo development of a specific prediction model and the use of individual participant data (IPD) were outside the remit of this assessment.

Overall objectives of the assessment

The objectives of this work were to undertake systematic reviews to determine the:

-

use of selected tests and assessment tools in the evaluation of prognosis in patients with early RA

-

potential of selected tests and assessment tools as predictive markers of treatment response in patients with early RA.

Chapter 3 Methods for the assessment of prognosis and prediction of treatment response in early rheumatoid arthritis

Assessment structure

This assessment consisted of two related systematic reviews. The first systematic review (review 1, clinical prediction models) investigated the use of assessment tools and tests in the evaluation of prognosis in early RA patients. The second systematic review (review 2, prediction of treatment response) determined the ability of selected assessment tools and tests to predict the response to specific treatments.

The systematic reviews were informed by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (www.prisma-statement.org/) and current good practice in prognostic reviews, as advocated by the Cochrane Prognosis Methods Group (http://methods.cochrane.org/prognosis/).

A final protocol for this assessment was registered on PROSPERO (as record CRD42016042402).

Scoping of the assessment

The searches for reviews in this assessment were structured in two phases. The phase 1 scoping searches were performed to determine the approximate extent of the evidence base relevant to the assessment and to inform the discussion of prognostic and predictive variables for inclusion in conjunction with clinical advisors (full details are provided in Appendix 1).

Following discussions with two expert clinical advisors who manage patients with early RA in the UK (as described in Acknowledgements), the review team selected variables for inclusion. The selection of prognostic and predictive variables was based on:

-

tests and assessment tools (e.g. selected laboratory tests, imaging tests and clinical assessment measures) the variables being readily available and used in UK clinical practice (and, therefore, genetic markers were not included by the review team)

-

the clinical experience of advisors in evaluating prognosis/treatment response in patients

-

the initial scoping of literature in the area by the review team.

The selected prognostic and predictive variables were used in the development of the full searches for reviews 1 and 2.

Justification of review approach

In view of the anticipated large number of search results, it was necessary for the review team to revise the intended review approach in order to maintain the feasibility of the assessment within the available resources and time scales. Additional details of protocol deviations are provided in Appendix 2.

Therefore, the two related systematic reviews were planned as detailed in the following sections.

Review 1: clinical prediction models

A systematic review of studies that describe the development, external validation or impact of eligible clinical prediction models in early RA was performed. As outlined in Background to prognosis research, prediction model research requires a multivariable analysis approach and, therefore, it was considered methodologically appropriate to restrict review 1 to the study of prognostic variables analysed in combination.

Review 2: prediction of treatment response

A systematic review of primary studies that describe the development, external validation or impact of eligible outcome models to predict treatment response in early RA patients was undertaken. Given that it was anticipated (based on earlier scoping searches) that the availability of outcome models and external validation studies relevant to review 2 would be limited, it was decided that review 2 would also include a review of studies to predict treatment response in patients with early RA. This approach would provide information for researchers who wish to develop outcome models for the prediction of treatment response based on a summary of the key evidence for the variables/tests and assessment tools selected following discussions with our clinical experts.

Methods for review 1 (clinical prediction models)

Identification of studies

Electronic databases

Studies were identified by searching the following electronic databases and research registers:

-

MEDLINE, MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations and Epub ahead of print (via Ovid; 1947 to September 2016)

-

EMBASE (via Ovid; 1974 to September 2016)

-

The Cochrane Library (via Wiley Online Library), including Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) and Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE), NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED), HTA databases (inception to September 2016, or 2015 in the case of DARE/NHS EED, which are no longer being updated)

-

Web of Science Conference Proceedings (1990 to September 2016).

Sensitive keyword strategies using free text and, where available, thesaurus terms using Boolean operators and database-specific syntax were developed to search the electronic databases. Synonyms relating to disease (e.g. Arthritis, Rheumatoid/) and prognostic variables were combined with a highly sensitive search filter aimed at restricting results to prognostic studies. 44

No date restrictions were used on any database. However, all searches were restricted to the English language because of time and resource constraints for translation services.

All resources were initially searched from inception to 27 September 2016. An example of the MEDLINE search strategy is provided in Appendix 3.

Research registers and other websites

The following resources were also searched for relevant evidence:

-

The World Health Organization’s trial search portal (http://apps.who.int/trialsearch) and ClinicalTrials.gov [(https://clinicaltrials.gov) records added since 2010 up to the date of the search on 27 September 2016].

-

Arthritis Research UK; British Society for Rheumatology; National Rheumatoid Arthritis Society; Outcome Measures in Rheumatology (OMERACT) Task Force; Royal College of Pathologists; Royal College of Physicians; Royal College of Surgeons; EULAR, American College of Rheumatology; the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA); and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) (no date restrictions).

Results were manually added to EndNote Version X7 [Clarivate Analytics (formerly Thomson Reuters), Philadelphia, PA, USA] for sifting.

Other resources

To identify additional studies, the reference lists of all included studies and key systematic reviews were checked. In addition, key experts in the field were contacted.

Results from the phase 2 full searches were imported into reference management software EndNote and duplicates were removed.

Study selection

Studies were assessed for eligibility for review based on the following criteria.

Inclusion criteria

Population

Adult patients (aged ≥ 18 years) diagnosed with early RA. The final protocol stated that patients would be diagnosed with RA according to established criteria. Patients with early RA were defined in consultation with clinical advisors as being within 2 years of the onset of symptoms. It was noted that studies may report the duration of symptoms or the duration of disease at baseline and so the definitions applied in included studies were noted and tabulated. In the absence of any further information, disease duration at baseline was considered to be equivalent to symptom duration.

Studies investigating mixed populations were included only if ≥ 80% of the study population were early RA patients or if subgroup data were presented for this population.

Externally validated clinical prediction models were included if the external validation population met the inclusion criteria, even if the original development population did not meet the inclusion criteria. The rationale for this was that a clinical prediction model might perform well for the decision problem and it is not important that it was originally developed in a different population. In this case, the study that developed the original clinical prediction model was included even if it did not meet the criteria stated above. In addition, studies proposing clinical prediction models that did not present internal validation were included if they had been externally validated in another study. External validations in populations outside the scope of the assessment were not included in the review, but were referred to in the discussion as appropriate.

Technology

Blood tests, imaging modalities and clinical assessment scores used in the evaluation of prognosis in patients with early RA were included. Specific tests and assessment tools to be included were determined following the phase 1 scoping searches and agreed with clinical advisors. Tests and assessment tools were for the measurement of prognostic variables as described below.

Prognostic variables

Prognostic variables considered in the assessment were informed by the phase 1 scoping searches and agreed following discussion between the review team and clinical advisors. The prognostic variables selected for inclusion for review 1 were:

-

anticitrullinated protein/peptide anti-bodies (ACPAs) status; RF status

-

erosions/joint damage as assessed on radiographs

-

C-reactive protein levels

-

erythrocyte sedimentation rate

-

SJC

-

DAS28

-

early RA untreated for ≥ 12 weeks following the onset of symptoms

-

smoking

-

HAQ scores.

Genetic markers were discussed in the assessment only when these were included in a final clinical prediction model alongside other eligible prognostic factors as selected by the review team in collaboration with the clinical advisors. This was decided on the basis that genetic testing is not currently used in routine UK clinical practice.

Included clinical prediction models contained at least one eligible prognostic variable. Results were presented based on all prognostic variables included in each multivariable model (including those not included in this review).

Outcomes

The selected outcomes considered in this assessment were agreed following discussions between the review team and the clinical advisors. The outcomes below were considered by the review team and the clinical advisors to have clinical relevance and to be important to patients, and are widely reported in RA research. The outcomes selected for inclusion in review 1 were:

-

disease activity as measured by the DAS28

-

physical function as measured by the HAQ

-

joint damage as assessed on radiographs.

Study types

It was anticipated in the final protocol that the study types included in review 1 would be likely to include published reports of cohort studies (and potentially case–control studies), which report the associations between individual prognostic variables and outcomes. However, as described above, in order to maintain the feasibility of the assessment, review 1 was restricted to the inclusion of studies that describe the development, external validation or the impact of eligible clinical prediction models in early RA.

Included studies were categorised in accordance with the Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis Or Diagnosis (TRIPOD) classification, which groups studies according to their methods of determination of performance.

Studies developing clinical prediction models that had not been validated in one of the included external validation studies were included if they presented some form of internal validation to quantify predictive performance [e.g. calibration and discrimination measures, such as the c-statistic or area under the curve (AUC)]. For clinical prediction models that were not externally validated and did not report the c-statistic or AUC or calibration, a study reporting at least two alternative measures of predictive performance [e.g. sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), accuracy] was considered to be eligible on the basis of being sufficiently informative to the review. When a study reported only R2 (a measure of the model goodness-of-fit), this was not considered to provide sufficient information regarding predictive performance, and the study was not included (but recorded in the table of excluded full-text studies in Appendix 4).

Exclusion criteria

The following criteria were applied to exclude studies:

-

non-English-language papers

-

reports published as meeting abstracts only, in which insufficient methodological/results details are reported

-

animal models

-

preclinical and biological studies

-

narrative reviews, editorials and opinions.

It was necessary, because of resource and time constraints, to deviate from the final protocol in the applied screening approach (see Appendix 1). An iterative approach to the screening of evidence was undertaken (adapted from Archer et al. 45). Titles and abstracts of search records were examined by one reviewer. Titles and abstracts were searched for terms relating to clinical prediction models. Key terms were identified by consulting publications relating to prediction model research (e.g. Moons et al. ,31 Debray et al. 40). Terms used were risk model*, prognostic model*, prediction model*, predictive model*, risk assessment model*, prediction score*, algorithm*, matrix/matrices, assessment tool*, prediction rule*, decision rule*, and risk score* in order to identify potentially relevant studies for screening at the full-text stage. As described previously, this method was supplemented by the hand-searching of reference lists of included studies, existing key systematic reviews (e.g. Bombardier et al. ,46 Navarro-Compán et al. 47), contact with clinical experts and the searching of grey literature.

Full texts of remaining articles were screened for eligibility before inclusion. Study inclusion based on full-text articles was performed by one reviewer and queries were discussed with a second reviewer. Any discrepancies were resolved by discussion, with the involvement of a third team member when required.

Data extraction

A data extraction form was designed and piloted before use on a minimum of two studies.

Data were extracted by one reviewer. Extracted data were checked for accuracy by a second reviewer. Any discrepancies were discussed and resolved, with reference to a third team member when required.

The CHecklist for critical Appraisal and data extraction for systematic Reviews of prediction Modelling Studies (CHARMS)48 includes guidance on the relevant items for extraction from reports of prediction modelling studies. Data extraction was guided by CHARMS. 48 Predictive performance measures relating to each clinical prediction model’s overall performance, calibration and discriminative ability were extracted from each clinical prediction model development and external validation study. Following advice in Debray et al. ,40 the c-statistic was used as the primary measure of discrimination and the O : E ratio used as the primary measure of calibration. If these measures or the associated variance estimates were not reported for a particular study, they were computed from other information when possible. The results of the Hosmer–Lemeshow test (a measure of model calibration) were also extracted, along with measures of model overall goodness of fit (such as R2). Information regarding the case mix of the development/validation population, which may help to explain the heterogeneity in the results, was also summarised from the available information when possible. Further details relating to the data extraction and associated calculations are provided in Appendix 5.

Quality assessment strategy

The assessment of the study quality characteristics of clinical prediction modelling studies was informed by criteria included in an unpublished draft version of the Prediction model study Risk Of Bias Assessment Tool (PROBAST). 49 The risks of bias for participant selection, predictors and outcomes were discussed narratively and tabulated. Potential key sources of bias in the model development and validation were discussed narratively.

The methodological quality of each included study was assessed by one reviewer and checked with a second reviewer. Disagreements were resolved by discussion between the two reviewers and if agreement could not be reached, a third reviewer was consulted.

Synthesis methods

Data relating to clinical prediction model performance were described in a narrative synthesis, presented separately for internal and external validation studies. An evidence synthesis using meta-analysis was considered for external validation studies.

Variation in predictive performance is expected because of differences in the design and execution of alternative external validation studies and, hence, a random-effects (RE) model that accounts for between-study heterogeneity was used. 40 Results using a fixed-effects (FE) model (i.e. a condition inference given the observed studies) are also presented for comparison.

Results are presented in terms of the summary c-statistic (and 95% CIs) that quantifies the average performance across the included studies. For RE models, it was anticipated that an estimate of the between-study SD (that quantifies the extent of heterogeneity between studies), as well as the 95% prediction intervals (which provide a range for the potential model performance in a new study), would also be provided. However, this was not possible on account of the limited number of studies that validated each prediction model, thereby providing limited information with which to estimate the between-study heterogeneity.

All analyses were conducted in R50 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) using the metafor package. 51 A restricted maximum likelihood estimation was used with the Hartung–Knapp–Sidik–Jonkman method (which accounts for uncertainty in the estimated between-study heterogeneity) to estimate the CIs for the pooled estimate and the 95% prediction intervals. 40,52 Analysis was conducted on the logit scale as previously recommended and back-transformed to the original scale for the presentation of results. 40,52

It was stated in the review protocol that meta-analyses would be conducted using a Bayesian RE model. However, this was modified for the final analysis, because there were very few studies that validated each clinical prediction model, thereby providing limited information with which to estimate the between-study heterogeneity. Although it would be possible to implement a Bayesian RE analysis using a weakly informative prior, this was not implemented, because there was a lack of empirical evidence to inform the prior distribution for the heterogeneity parameter and eliciting experts’ beliefs was beyond the scope of this project. Although the analysis deviated slightly from the protocol, the implemented RE model accounts for uncertainty in the between-study heterogeneity and is consistent with methodological recommendations. 40

Given the limited number of studies available, it was not possible to explore heterogeneity in prognostic/predictive effects using metaregression. However, subgroup analyses based on baseline DAS28 were considered in the narrative synthesis of evidence for review 1 and review 2.

Methods for review 2 (prediction of treatment response)

Identification of studies

Electronic databases

Electronic databases, research registers and other websites searched were identical to those for review 1 (see Identification of studies). Sensitive keyword strategies using free text and, when available, thesaurus terms using Boolean operators and database-specific syntax were developed to search the electronic databases. The disease and candidate variable terms used in review 1 were combined with the appropriate search filter for review 2. 53

Research registers and other websites

The resources searched were identical to those used in review 1. The results were manually added to EndNote for sifting.

Other resources

To identify additional studies, the reference lists of all included studies were checked. Hand-searching of key systematic reviews and narrative reviews was also performed. A citation search of included articles [using Google Scholar (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA)] was undertaken. In addition, key experts in the field were contacted.

Results from the phase 2 full searches were imported into reference management software EndNote (version X8) and duplicates were removed.

Study selection

Studies were assessed for eligibility for review 2 based on the following criteria.

Inclusion criteria

Population

Adult RA patients (aged ≥ 18 years) who have:

-

received treatment with cDMARDs/bDMARDs for RA

-

baseline/early disease and follow-up data for selected variables (as defined below).

For the review for the prediction of treatment response (review 2), response to cDMARDs and bDMARDs was studied. It was planned in the final protocol for review 2 that, if data allowed, treatment would be subdivided into cDMARDs and bDMARDs. Response to any other treatments (e.g. steroids) was not assessed for reasons of feasibility. Predictors of treatment response to individual drugs (e.g. specific biologics) would be explored if feasible and if sufficient evidence was available.

Studies were eligible for inclusion in review 2 if they involved at least 6 months’ treatment duration (with the exception of certolizumab pegol, for which the response is largely known at 12 weeks and, therefore, a 12-week treatment duration was considered to be more acceptable by clinical advisors and was applied for this drug).

Technology

The tests and assessment tools for the measurement of predictive variables are as described below.

Predictive variables

The predictive variables considered in the assessment were also informed by phase 1 scoping searches and selected following discussion between the review team and clinical advisors. The predictive variables selected for inclusion in review 2 were the same as those for review 1, with the addition of two variables:

-

body mass index (BMI)

-

vascularity of synovium assessed using power Doppler ultrasound (PDUS).

Outcomes

The outcomes selected for inclusion were the same as for review 1, with the addition of:

-

definitions of response/remission selected in conjunction with clinical advisors (EULAR response; remission: a DAS28 of < 2.6, a Disease Activity Score (DAS) of < 1.6 or ACR/EULAR remission).

Study types

It was anticipated in the protocol that the included study types in review 2 would be cohort studies and RCTs. Following a protocol amendment, in order to maintain the feasibility of the assessment within the available time and resources, review 2 consisted of:

-

a systematic review of studies that describe the development, external validation or impact of eligible clinical prediction models to predict the response to individual treatments in patients with early RA (developed/validated in observational cohorts or experimental data sets)

-

a review of primary studies (experimental or observational) to identify patient characteristics that affect the response to individual treatments in patients with early RA.

The exclusion criteria were as described for review 1.

The titles and abstracts of search records were examined by one reviewer and irrelevant evidence was excluded. The full texts of remaining articles were screened for eligibility before inclusion. Study inclusion based on full-text articles was performed by one reviewer and queries were discussed with a second reviewer. Any discrepancies were resolved by discussion, with the involvement of a third team member when required.

Data extraction

A data extraction form was designed and piloted before use on a minimum of two studies.

Data were extracted by one reviewer. Extracted data were checked for accuracy by a second reviewer. Any discrepancies were discussed and resolved, with reference to a third team member when required.

Quality assessment strategy

Any identified clinical prediction model studies were to be critically appraised, guided by the items included in the PROBAST. 49 Studies of prognostic variables were assessed by criteria informed by the Quality in Prognosis Studies (QUIPS) tool (see Hayden et al. 54), as stated in the final protocol.

Critical appraisal was performed by one reviewer and double-checked by a second reviewer. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion, with the involvement of a third team member if necessary.

Synthesis methods

In the protocol, it was envisaged that a formal meta-analysis comparing all treatments across all studies would be performed with respect to the predictive ability of treatments. However, for specific outcome measures and potential treatment effect modifiers, there were no studies that shared any treatments in common. Consequently, a formal meta-analysis was not performed and the results are presented assessing the predictive ability of treatments by study.

Some authors fitted single regression models to the data from all treatment groups and included only the main effects of treatment and baseline covariates; these models do not allow an assessment of the interaction between treatments and baseline covariates. Other authors fitted separate regression models to the data from each treatment group and presented estimates of treatment effects by covariate; it is these estimates that are used to quantify the extent to which the treatment effect varies by covariate.

For continuous outcomes, the interaction effect is estimated by calculating the difference (and 95% CI for the difference, when possible) in the mean between treatments; departures from zero are indicative of the covariate being a treatment effect modifier. For binary outcomes, the interaction is estimated by calculating the ratio (and 95% CI for the ratio when possible) of the ORs between treatments; departures from one are indicative of the covariate being a treatment effect modifier.

Results indicating that a covariate is not a treatment effect modifier should not be interpreted to mean that a covariate is prognostic, only that the relationship between covariate and response may be the same for both treatments subject to a treatment effect (i.e. the covariate may be prognostic for both treatments or not prognostic for both treatments).

Chapter 4 Results: review 1

Quantity of research available

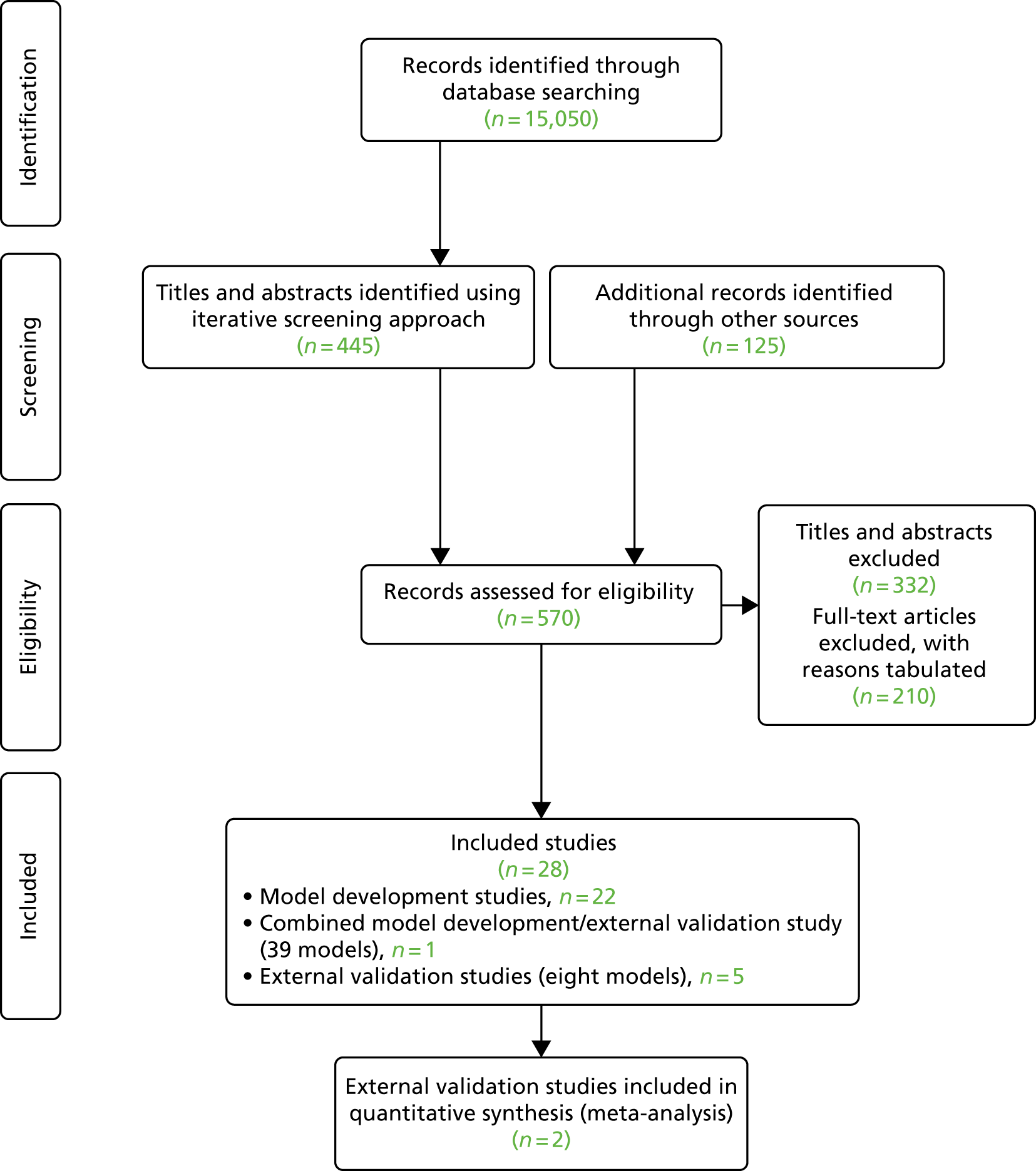

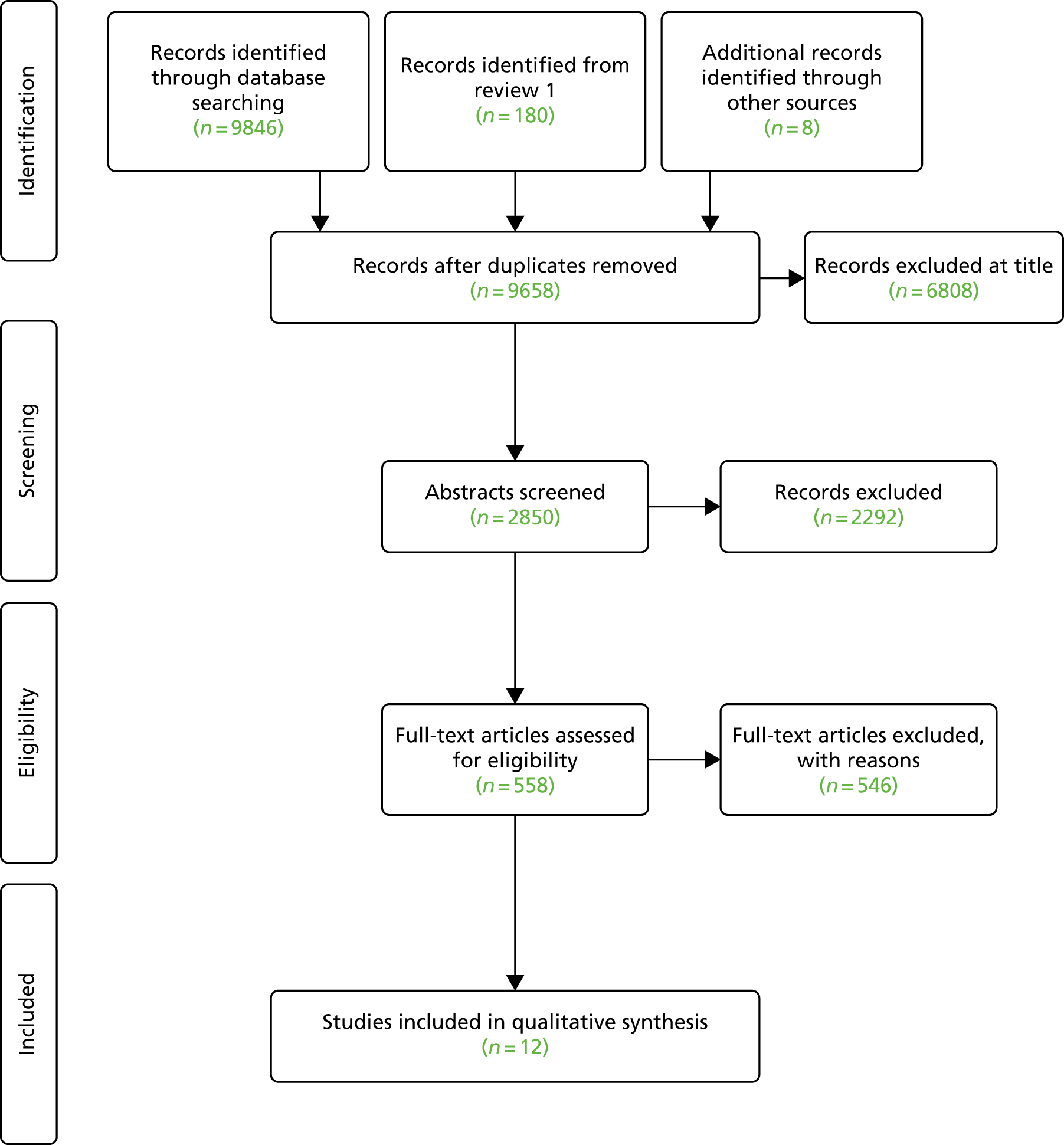

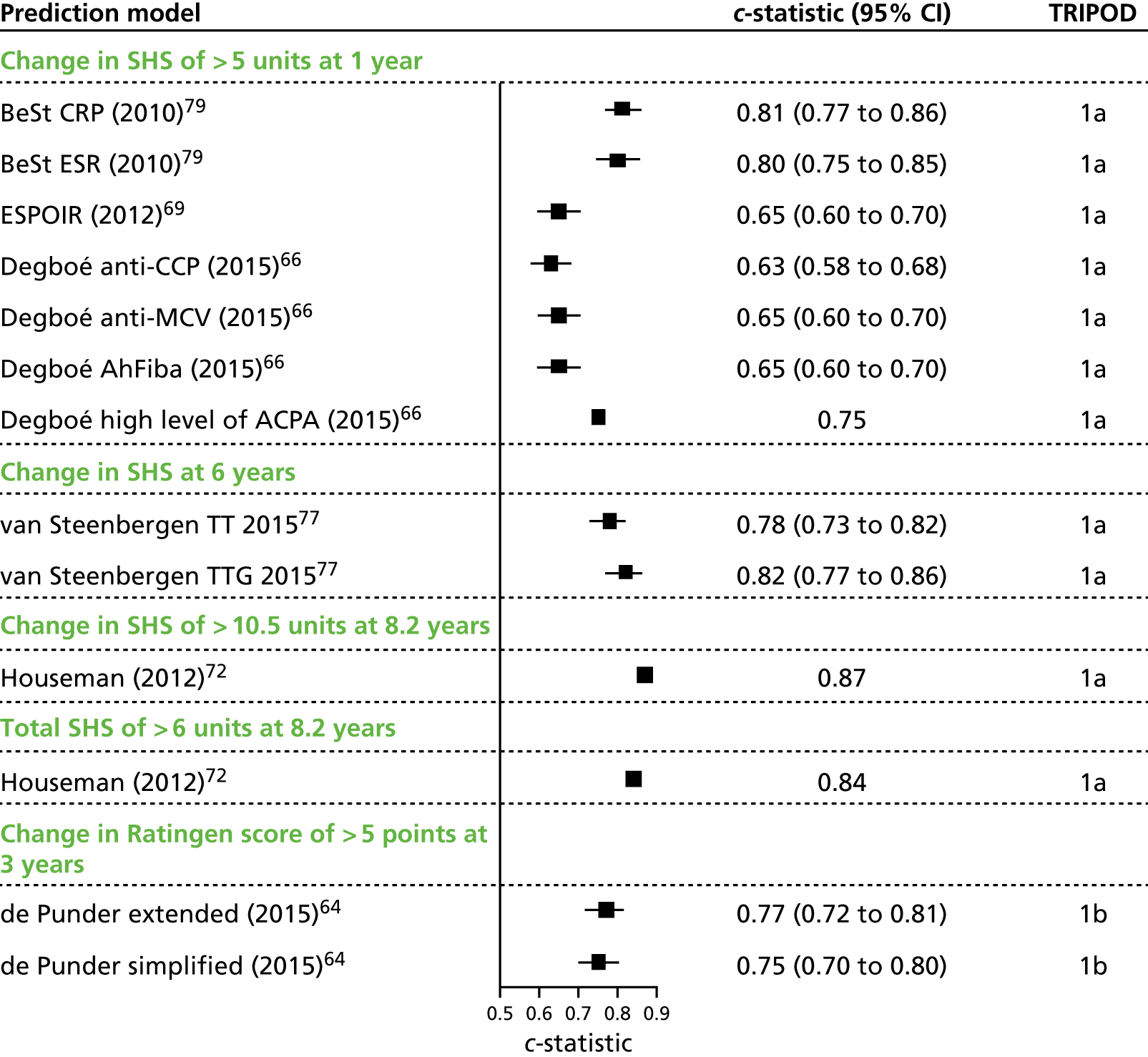

Searches for evidence (Figure 5) identified 22 model development studies and one combined model development/external validation study, reporting a total of 39 clinical prediction models for the prediction of major outcomes, including radiographically assessed joint damage, the HAQ score and the DAS28 (note that one publication56 considered the development of models for multiple outcomes; however, because of unclear reporting, the individual models could not be summarised and so have been counted as a single entry for the purposes of the assessment). The study by Bombardier et al. 57 was available as a conference abstract only and a full-text publication was not available. Six external validation studies (including the combined model development/external validation study) of eight previously proposed clinical prediction models for radiographically assessed joint damage outcomes were identified. No studies assessing the impact of the use of clinical prediction models in the clinical management of early RA were identified.

Quality of the research available

Potential sources of bias in participant selection, predictors, outcomes, model development and validation are discussed in the following sections and tabulated in Appendix 6.

Types of included prediction model studies

The TRIPOD statement26 was developed with the aim of improving the quality of reporting of prediction model studies. Collins et al. 26 described six categories (listed below) that can be used to classify studies according to their aim (development or/and validation) and the methodology used.

The inclusion criteria for review 1 required that studies developing clinical prediction models apply some form of internal validation to quantify the predictive performance of the developed model (e.g. calibration and discrimination), with the exception of cases in which the clinical prediction model had been subsequently externally validated. In these cases, the external validation results may be considered to be more informative than the omitted internal validation results and it was deemed necessary to include the original development paper for completeness. These studies did not have a category according to the TRIPOD statement, and it was therefore necessary to introduce a new TRIPOD category (Type 0) to allow the description of these studies.

The tailored TRIPOD classification categories used in this review (based on Collins et al. 26) are as follows:

-

Type 0 – development of a clinical prediction model in which the predictive performance is not evaluated in the development paper, but an evaluation of the predictive performance has been considered in a separate publication.

-

Type 1a – development of a clinical prediction model with an evaluation of the predictive performance using the same data set (apparent performance).

-

Type 1b – development of a clinical prediction model using the whole data set and an evaluation of the predictive performance using resampling (e.g. bootstrapping or cross-validation).

-

Type 2a – random splitting of data into two groups, the first for clinical prediction model development and the second for the testing of its predictive performance.

-

Type 2 – non-random splitting of data into two groups, the first for clinical prediction model development and the second for the testing of its predictive performance.

-

Type 3 – development of a clinical prediction model in one data set and an evaluation of the predictive performance on separate data (e.g. from a different study).

-

Type 4 – the evaluation of the predictive performance of an existing clinical prediction model using separate data (external validation).

The TRIPOD classification categories of the 28 included studies are presented in Table 1. The PROBAST49 study-type classifications of the included studies are also presented in Table 1.

| First author (year of publication) | Name of clinical prediction modela | Externally validated? (Y/N) | Model presented in useable format? | Category | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PROBAST | TRIPODb | ||||

| Clinical prediction model development studies | |||||

| Bansback (2006)58 | Bansback | N | Y | Development only | 1b |

| Berglin (2006)59 | Berglin | N | N | Development only | 1a |

| Bombardier (2009)57 | SONORA | Y | N | Development only | 0 |

| Brennan (1996)60 | Brennan | N | Y | Development only | 2a |

| Centola (2013)61 | Centola | Y | Y | Development only | 0 |

| Combe (2001)62 | Combe (A) | N | Y | Development only | 1a |

| Combe (2003)63 | Combe (B) | N | N | Development only | 1a |

| de Punder (2015)64 | de Punder | N | Y | Development/external validation | 1b/4 |

| de Vries-Bouwstra (2006)65 | de Vries-Bouwstra | N | N | Development only | 1a |

| Degboé (2015)66 | Degboé | N | N | Development only | 1a |

| Dirven (2012)67 | Dirven | N | Y | Development only | 1a |

| Dixey (2004)68 | Dixey | N | N | Development only | 2a |

| Drossaers-Bakker (2002)56 | Drossaers-Bakker | N | N | Development only | 1a |

| Fautrel (2012)69 | ESPOIR | Y | Y | Development only | 1a |

| Forslind (2004)70 | Forslind | N | Y | Development only | 1a |

| Graell (2009)71 | Graell | N | Y | Development only | 1a |

| Houseman (2012)72 | Houseman | N | N | Development only | 1a |

| Saevarsdottir (2015)73,74 | SWEFOT | Y | N | Development/external validation | 1a/4 |

| Sanmartí (2007)75 | Sanmartí | N | Y | Development only | 1a |

| Syversen (2008)76 | Syversen | Y | Y | Development only | 1a |

| van Steenbergen (2015)77 | van Steenbergen | N | N | Development only | 1a |

| Vastesaeger (2009)78 | ASPIRE | Y | Y | Development and external validation | 3c |

| Visser (2010)79 | BeSt | Y | Y | Development only | 1a |

| External validation studies | |||||

| De Cock (2014)80 | External validation only | 4 | |||

| Granger (2016)82 | External validation only | 4 | |||

| Hambardzumyan (2015)83 | External validation only | 4 | |||

| Heimans (2015)84 | External validation only | 4 | |||

| Markusse (2014)85 | External validation only | 4 | |||

Of the 23 clinical prediction model development studies, the vast majority (n = 16) were TRIPOD type 1a {i.e. Berglin et al. ,59 Visser et al. 79 [Behandelings Strategie (BeSt)], Combe et al. 62 (Combe A), Combe et al. 63 (Combe B), de Vries-Bouwstra et al. ,65 Degboé et al. ,66 Dirven et al. ,67 Drossaers-Bakker et al. ,56 Fautrel et al. 69 [Études et suivi des polyarthrites indifférenciées récentes (ESPOIR)], Forslind et al. ,70 Graell et al. ,71 Houseman et al. ,72 Saevarsdottir et al. 73,74 [Swedish Farmacotherapy (SWEFOT)], Sanmartí et al. ,75 Syversen et al. 76 and van Steenbergen et al. 77}, with validation conducted in exactly the same data as those used for clinical prediction model development. Fewer studies were categorised as type 1b (n = 1; i.e. Bansback et al. 58), using techniques to evaluate performance and optimism of the developed model, type 2a (n = 2; i.e. Brennan et al. 60 and Dixey et al. 68), using a data-splitting approach for development and validation, or type 0 {n = 2; i.e. Bombardier et al. 57 [Study Of New-Onset Rheumatoid Arthritis (SONORA)] and Centola et al. 61}, with no internal validation presented for Bombardier et al. 57 Although internal validation was conducted for Centola et al. ,61 it was developed for a different outcome measure and so the study is categorised as type 0 for the purpose of the current review. One study {n = 1; i.e. Vastesaeger et al. 78 [Active controlled Study of Patients receiving Infliximab for the treatment of Rheumatoid arthritis of Early onset (ASPIRE)]} considered validation in an external population in addition to model development (type 3); however, the external validation population comprised patients with established RA and, therefore, was outside the scope of this assessment. The methods of internal validation and reporting of models in the included development studies are described in greater detail in Model development.

Five additional included studies were external validations of clinical prediction models (TRIPOD class 4). Three of these studies (i.e. De Cock et al. ,80 Granger et al. 82 and Heimans et al. 84) externally validated a total of seven clinical prediction models (i.e. ASPIRE CRP,78 ASPIRE ESR,78 BeSt,79 ESPOIR,69 SONORA,57 SWEFOT73 and Syversen76). The remaining two external validation studies (Hambardzumyan et al. 83 and Markusse et al. 85) evaluated the use of a multibiomarker disease activity (MBDA) test61 (developed as a measure of disease activity) in the prediction of eligible clinical outcomes. In addition to the seven purely external validation studies, the de Punder model development paper64 (TRIPOD category 1b/4) also externally validated the BeSt79 and ESPOIR69 models.

Two additional external validation studies were identified but not included. 73,86 The study reported by Durnez et al. 86 is considered to be a precursor study to the work by De Cock et al. ,80 and so the work by De Cock et al. 80 is utilised in this assessment as being more recent and comprehensive in the coverage of validated models. The application of the BeSt model79 was considered by Saevarsdottir et al. 73 (TRIPOD category 1a/4) using the SWEFOT data set. However, the presented results did not provide sufficient data to be considered as informative to the current review, as no summary statistic of overall performance (e.g. c-statistic) was reported. Saevarsdottir et al. 73 presented the allocation of individuals to risk matrix categories, combined for the whole validation sample rather than separately by treatment group.

Description of data sources for the development of clinical prediction models and external validation

Moons et al. 31 advocated the use of cohort study data in the development of clinical prediction models, which are preferably prospective in design to allow for the greater completeness of data collection. 31 Trial data are also an appropriate data source, although it has been noted that trial eligibility criteria may result in more restricted and less generalisable data than registry cohort studies. 31 All identified clinical prediction models for review 1 were developed in either observational cohort or registry data or in existing cohorts from intervention trials in early RA populations and, therefore, can be considered to have been developed in appropriate data sources. Studies were longitudinal in design, with potential predictors measured in an early RA population at baseline or in an early disease stage before the measurement of a specified outcome at a subsequent time point. There was one main exception to this, Houseman et al.,72 which is discussed further in Description of predictors. The characteristics of the data sources used in the development and external validation of the included clinical prediction models are tabulated in Table 2.

| Name of clinical prediction model/external validation | Name and study design of data source | Setting (number of centres) and period of data collection | Key eligibility criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical prediction model development studies | |||

| ASPIRE78 |

Active-controlled study of patients receiving infliximab for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis of early onset (ASPIRE) RCT87 Internally validated in the anti-TNF trial in rheumatoid arthritis with concomitant therapy (ATTRACT)88 [median disease duration, 8.4 years (IQR 4.3–14.7 years); established RA outside scope of assessment] |

Multicentre, multinational study (122 sites in North America and Europe) Patients recruited between 2000 and 2002 |

Aged 18–75 years, met the 1987 revised ACR criteria, persistent synovitis for 3 months to 3 years, ≥ 10 swollen joints and ≥ 12 tender joints. Plus one or more of positive serum RF, radiographically detected erosions of hands/feet or CRP level of ≥ 2.0 mg/dl. Patients excluded if any prior MTX (three or fewer pre-study doses permitted), received other DMARDs within 4 weeks of entry (or LEF within past 6 months) or treated with IFX, ETN, ADA or other anti-TNF Subjects were excluded if they were infected with HIV, hepatitis B or hepatitis C, they had a history of active or past TB, congestive heart failure, lymphoma or other malignancy within the past 5 years (excluding excised skin cancers) |

| Bansback58 | Early Rheumatoid Arthritis Study (ERAS) inception cohort |

Unspecified regions of England (nine centres) Cohort established in 1986 |

All consecutive RA patients seen within 2 years of initial symptoms and before second-line drug use. Patients completing 5 years of follow-up included in the analysis |

| Berglin59 | Cohort data | Department of Rheumatology, University Hospital, Umeå, Sweden, co-analysed with Northern Sweden Health and Disease Study (NSHDS) cohort and maternity cohort of northern Sweden (Medical Biobank), Umeå, Sweden (number of centres and period of data collection NR) | Department of Rheumatology, University Hospital, Umeå register: early RA (duration of < 1 year) meeting the 1987 revised ACR criteria for RA, with a known date of the onset of symptoms |

| BeSt79 | Behandelings Strategie (BeSt) RCT89 |

18 peripheral and two university hospitals in the western Netherlands Patients recruited between 2000 and 2002 |

Early RA defined by the 1987 revised ACR criteria, disease duration of ≤ 2 years, aged ≥ 18 years, active disease with ≥ 6 of 66 swollen joints, ≥ 6 of 68 tender joints and either an ESR of ≥ 28 mm/hour or a global health score of ≥ 20 mm on a 0- to 100-mm VAS (0 = best, 100 = worst) Subjects were excluded if they had previous DMARD treatment other than antimalarials, concomitant treatment with an experimental drug, malignancy within the past 5 years, bone marrow hypoplasia, serum aspartate aminotransferase or alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels of > 3 times the upper limit of normal level, serum creatinine levels of > 150 µm/l or estimated creatinine clearance of < 75 ml/minute, diabetes mellitus, alcohol or drug abuse, concurrent pregnancy, wish to conceive during study period or inadequate contraception |

| Brennan60 | Prospective cohort |

All primary care general practices in Norwich Health Authority, Norfolk, UK (number of centres NR) Recruited between 1990 and 1993 |

Satisfied any subset of the revised 1987 ACR RA criteria and were recruited within 180 days of the onset of symptoms, with complete baseline and 1-year follow-up measurements (and having provided blood for RF testing at baseline) |

| Centola61 |

Feasibility studies (stage 2): Oklahoma City cohort and Brigham and Women’s Rheumatoid Arthritis Sequential Study (BRASS) cohort Algorithm training study (stage 3): Brigham and Women’s Rheumatoid Arthritis Sequential Study (BRASS) cohort and Index for Rheumatoid Arthritis Measurement (InFoRM) study |

NR | All patients met ≥ 4 of 7 of the 1987 revised ACR criteria for RA |

| Combe (A)62 | Prospective cohort |

France (four centres: Montpellier, Paris-Cochin, Toulouse and Tours) Included March 1993 to October 1994 |

All consecutive outpatients referred from primary care, disease duration of < 1 year, met ACR criteria for RA, DMARD-naive |

| Combe (B)63 | Prospective cohort |

France (four centres: Montpellier, Paris-Cochin, Toulouse, Tours) Included March 1993 to October 1994 |

All consecutive outpatients referred from primary care, disease duration of < 1 year, met ACR criteria for RA and were DMARD naive |

| de Punder64 | Nijmegen early RA inception cohort |

Radboud University Medical Centre, Nijmegen, the Netherlands Included from 1985 to 2008 |

Satisfied the 1987 ACR criteria for RA, disease duration of ≤ 1 year, no previous DMARD use and aged ≥ 18 years. Patients with radiographs available at inclusion and after 2 or 3 years’ follow-up included in analysis Patients treated with biologic DMARDs within first 3 years were excluded from analysis |

| de Vries-Bouwstra65 | Leiden Early Arthritis Clinic cohort |

Early Arthritis Clinic (EAC), Department of Rheumatology, Leiden University Medical Centre, the Netherlands Sample from patients included from 1993 to 1999 |

Arthritis confirmed by rheumatologist, duration of symptoms of < 2 years and patient had not seen another rheumatologist for the same symptoms. All patients presenting with RA/probable RA and in whom a diagnosis of RA was confirmed at 3 months after presentation. Follow-up of ≥ 1-year and radiographs of hands and feet at baseline and after 1 year included in analysis. Definite RA according to the 1987 revised ACR criteria but without the criterion that symptoms must be of 6 weeks’ duration and observed by a physician |

| Degboé66 | ESPOIR cohort |

14 regional centres, France Period of data collection NR |

Suspected or confirmed RA diagnosis, aged 18–70 years, ≥ 2 swollen joints for > 6 weeks and < 6 months, no receipt of DMARDs or steroids except for < 2 weeks prior to entry. Included in analysis if satisfied the 2010 ACR/EULAR criteria and with complete radiographs at baseline and year 1 and complete ACPA measurements |

| Dirven67 | Behandelings Strategie (BeSt) RCT89 |

The Netherlands Number of centres and period of data collection NR |

DMARD-naive patients, with RA as defined by the 1987 revised ACR criteria |

| Dixey68 | Inception cohort |

Rheumatology departments of nine hospitals, country NR, but assumed to be the UK Recruitment of patients from 1986 |

Patients with RA according to the 1987 revised ACR criteria, duration of symptoms of ≤ 2 years, no use of second-line medication. Patients completing 3 years’ follow-up with adequate-quality radiographs for scoring were included in the analysis |

| Drossaers-Bakker56 |

Prospective inception cohort Leiden Early Arthritis Clinic cohort |

Rheumatology outpatient clinic of Leiden University Medical Centre, the Netherlands Patients attending from 1982 to 1986 |

All consecutive female RA patients, with symptoms of < 5 years’ duration, aged 20–50 years at first visit |

| ESPOIR69 | ESPOIR cohort |

14 regional centres in France (16 university hospital rheumatology departments) Patients referred and included from December 2002 to March 2005 |