Notes

Article history

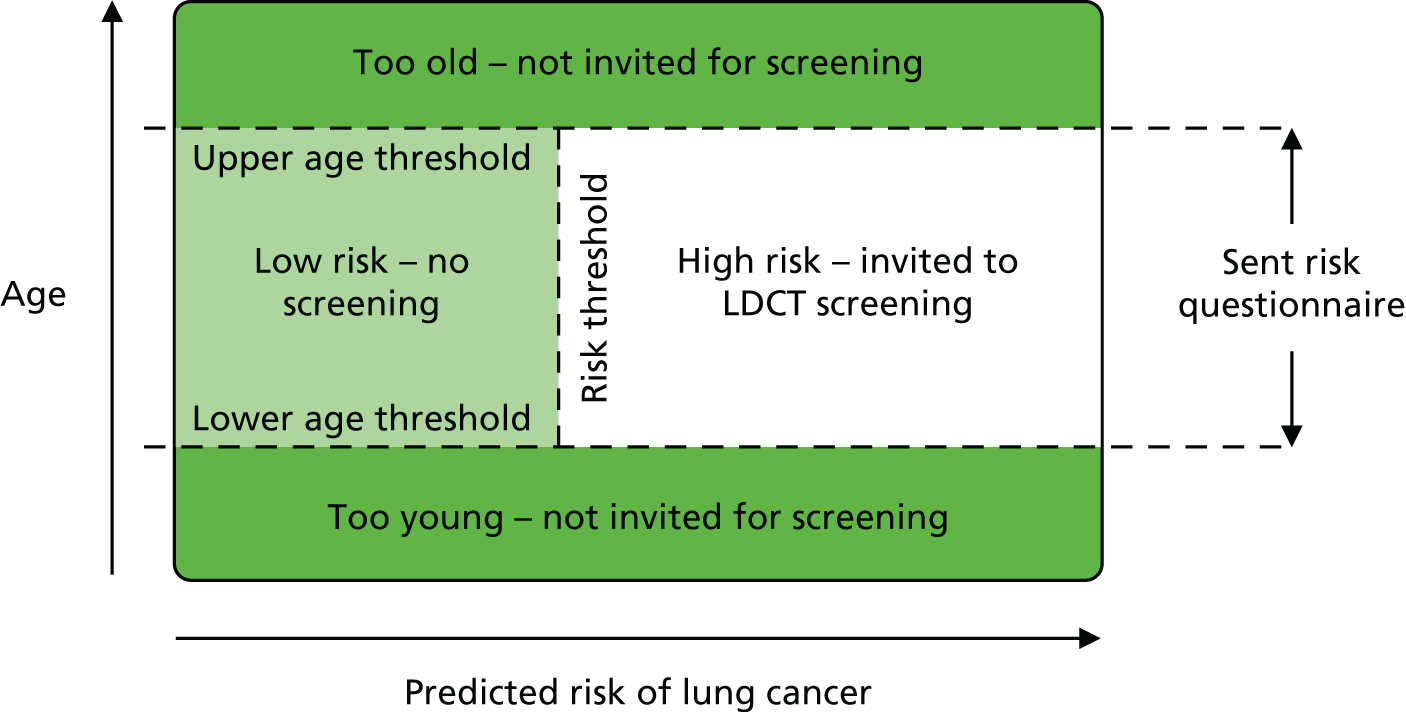

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 14/151/07. The contractual start date was in June 2016. The draft report began editorial review in August 2017 and was accepted for publication in February 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Snowsill et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Description of the health problem

Lung cancer is malignant growth of cells in the lung. It typically affects older people1 who smoke or smoked in the past. Men are more likely than women to get lung cancer and are more likely to die from lung cancer. 1 Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death in men and women and is responsible for 22% of deaths from cancer. 1

Risk factors

Smoking

The main cause of lung cancer is smoking (mainly cigarettes). It is estimated that 85% of lung cancer is attributable to smoking. 2 Smoking cigars, pipes or waterpipes is also associated with lung cancer, as well as other health problems. 3,4

Smoking cessation leads to reduced risk of lung cancer, but the risk still remains higher than for those who have never smoked if there is a significant smoking history. 5 Generally, the risk of lung cancer increases with the number of cigarettes smoked and the duration of smoking, with the pack-year a commonly used measure for smoking history. One pack-year is the equivalent of smoking one pack (20 cigarettes) per day for 1 year (around 7300 cigarettes). Duration of smoking appears to be a more important factor than smoking intensity (the number of cigarettes per day), such that it is worse to smoke one pack per day for 40 years than two packs per day for 20 years. 6

Smoking rates have declined substantially and steadily over the previous 40 years, but there remains a significant proportion of adults who continue to smoke and who have quit smoking but remain at high risk of lung cancer. Since 2005, at least half of the people who were ever regular cigarette smokers have quit. 7

Cigarette smoking rates vary geographically within the UK. 8 Compared with other European Union (EU) countries in 2014, the UK had the second lowest rate of current smokers (17.3%), higher only than Sweden (16.7%). The UK also had a gender gap in the smoking rate of 3.1%, which was significantly below the EU average (9.2%). 9

Smoking is also strongly correlated with income and socioeconomic status (SES). Individuals with a gross personal income of < £20,000 are twice as likely to be current smokers compared with individuals with a gross personal income of ≥ £40,000 (22% vs. 11%). Employment is also significant: 36% of unemployed adults smoke compared with 20% of employed adults, and 15% of economically inactive adults (e.g. pensioners and students). 7

Efforts in the UK to reduce smoking include direct taxation of smoking (tobacco duty),10 smoking cessation services and campaigns (e.g. Smokefree,11 Stoptober12), standardised (plain) packaging (compulsory from May 2017)13 and restrictions on advertising. 14

Passive smoking

Passive smoking is when a person does not smoke themselves, but spends time in an environment where smoking occurs. Passive smoking causes lung cancer and other diseases, including respiratory infections and asthma. For example, women who never smoked but were exposed to second-hand smoke from their spouse face a 27% higher risk of lung cancer than similar women not exposed to second-hand spousal smoke. 15

Environmental risk factors

In addition to smoking, there are other environmental risk factors that, following exposure, have demonstrated an increased risk of lung cancer. These risk factors include asbestos, radon gas and air pollution. When these environmental risk factors are combined with smoking, the overall risk of lung cancer is exacerbated. 16

Pathology

Lung cancer is the term for a malignant neoplasm originating in the lung, typically developing from cells of the respiratory epithelium. 17

Lung cancer cell type

Lung cancer can be divided into two broad categories: (1) small cell lung cancer (SCLC) and (2) non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). SCLC is a highly malignant tumour accounting for 11% of all lung cancer cases in the UK, and is derived from cells exhibiting neuroendocrine characteristics. 18 NSCLC accounts for 88% of all lung cancer cases in the UK. NSCLC can further be divided into three major pathologic subtypes: (1) adenocarcinoma, (2) squamous cell carcinoma and (3) large cell carcinoma. Statistics from the National Lung Cancer Audit Annual Report 201618 report the distribution of NSCLC in the UK as follows: adenocarcinoma 36%, squamous 22%, other 11% and no pathology 31%. 18

Neuroendocrine tumours account for around one-quarter of primary lung neoplasms, including SCLC (20%), large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (LCNEC) (a subtype of large cell carcinoma; 3%) and carcinoid tumours (typical and atypical carcinoid; 2%). 19 Lung neuroendocrine tumours arise from cells of the diffuse neuroendocrine system in the bronchial mucosa. 20

The World Health Organization (WHO) classification of lung tumours21 now recommends (2015 classification) greater restriction on the diagnosis of large cell carcinoma (former subtypes now reclassified), reclassification of adenocarcinoma subtypes, reclassification of squamous cell carcinoma subtypes and a number of smaller changes. 21

Grade

Grading of lung cancer for NSCLC distinguishes lung cancer cells into groups based on the cell’s appearance:22

-

Grade 1 – cells look normal, will grow slowly and are less likely to spread (may also be called ‘low grade’ or ‘well differentiated’).

-

Grade 2 – cells look abnormal and are more likely to spread (may also be called ‘moderate grade’ or ‘moderately well differentiated’).

-

Grades 3 and 4 – cells look very abnormal, will grow quickly and are more likely to spread (may also be called ‘high grade’ or ‘poorly differentiated’).

Neuroendocrine tumours are also graded:19

-

low grade (typical carcinoid)

-

intermediate grade (atypical carcinoid)

-

high grade (SCLC and LCNEC).

Stage

The stage of the lung cancer relates to the extent of the cancer and is currently classified by the NHS in the UK according to the international tumour, node, metastasis (TNM) system (Seventh Edition). 23,24 The Eighth Edition of the TNM system has been recently published25 and is due to be adopted in the UK. There are three components that are combined to make up the overall staging of lung cancer: (1) the size of the tumour (diameter in greatest dimension; TX, T0–T4), (2) whether or not it has spread to the lymph nodes (NX, N0–N3) and (3) whether or not it has distant metastasis (MX, M0, M1). 26 In the UK, the following percentages of cases recorded postoperatively by stage were reported by the National Lung Cancer Audit Annual Report 2016:18

-

stage IA, 11%

-

stage IB, 7%

-

stage IIA, 4%

-

stage IIB, 4%

-

stage IIIA, 12%

-

stage IIIB, 9%

-

stage IV, 53%.

Note that, at present, there is no national lung cancer screening programme, so the vast majority of these cases are either clinically presenting or incidental findings.

Diagnosis

Presentation

Diagnosis of lung cancer generally follows symptomatic presentation of (typically late-stage) lung cancer, but it can also be an incidental finding during other investigations.

Of the 73,063 lung cancer cases diagnosed in England (2012–13), 25,668 presented as an emergency, 20,420 were referred by a general practitioner (GP) through the 2-week wait pathway and 15,525 were otherwise referred by a GP. 27 The remaining cases presented through some other route or were identified only through a death certificate. Stages I–III were most often diagnosed following GP referral, whereas stage IV and unstaged cancers were most often diagnosed following emergency presentation. 27

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines on suspected cancer referral28 identify a number of key symptoms and findings that should prompt an urgent referral or chest X-ray (CXR), which include (not an exhaustive list):

-

unexplained haemoptysis (coughing blood or blood-stained mucus)

-

respiratory symptoms (cough, shortness of breath)

-

chest symptoms and signs (chest pain, persistent or recurring chest infection)

-

general symptoms and signs (fatigue, weight loss, appetite loss)

-

finger clubbing.

In addition, there are decision aids for GPs that can help to identify the significance of combinations of symptoms. 29

Investigation

The 2011 NICE guidelines on lung cancer diagnosis and management30 recommend an investigative pathway for suspected lung cancer that includes contrast-enhanced chest computed tomography (CT) to further the diagnosis and contribute to staging the disease. Positron emission tomography–computerised tomography (PET-CT) is recommended for patients who are potentially suitable for treatment with curative intent. Other investigations are recommended according to the location and spread of the disease; many of these are invasive and involve endoscopy (including bronchoscopy) and biopsy.

Prognosis

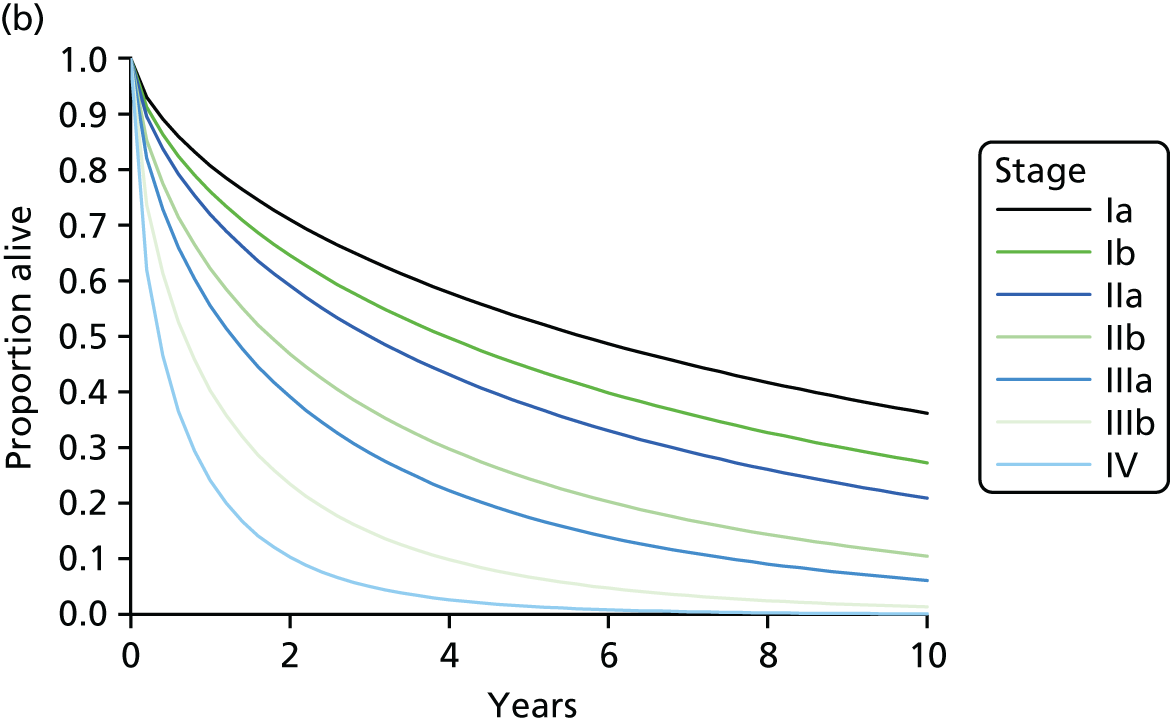

Overall, the prognosis for long-term survival with lung cancer is poor. Net survival for adults (aged 15–99 years) in England and Wales in 2010–11 was predicted as follows: 1-year survival, 32.1%; 5-year survival, 9.5%; and 10-year survival, 4.9%. 31 The 10-year survival for lung cancer ranks second lowest out of 20 common cancers in England and Wales. 31 However, prognosis is variable depending on a multitude of factors including:

-

type of lung cancer – survival is lower for those with SCLC than for those with NSCLC32

-

age – the prognosis for long-term survival with lung-cancer deteriorates with age32

-

stage – the higher the stage, the poorer the prognosis (e.g. the 1-year survival rate is > 80% when lung cancer is diagnosed in stage I, but < 20% when diagnosed in stage IV32)

-

sex – the prognosis for women is better than for men32

-

route of diagnosis – those presenting through the 2-week wait referral route have a better prognosis than those with emergency presentation33

-

geographical location. 34

Epidemiology

Incidence

Lung cancer is the most common cancer in the world, with 1.8 million new cases diagnosed in 2012. 35

In the UK in 2014, 46,400 new cases of lung cancer were diagnosed (130 new cases per day on average). Lung cancer is the third most common cancer in the UK and, in 2014, it accounted for 13% of all new cases of cancer in the UK. The directly age-standardised rates of lung cancer incidence in England (2014) were 91.6 and 65.2 per 100,000 person-years for men and women, respectively, but the incidence rate climbs with age. 1

The incidence of lung cancer has declined for men compared with historical levels, but has climbed for women. 1 Men continue to be at a higher risk of lung cancer than women. Across the UK, the age-standardised rate of lung cancer decreased from 2012 to 2014, to approximately 2006 levels.

Mortality

Lung cancer is the most common cause of deaths from cancer in the EU (20.8% of all cancer-related deaths). 36 Lung cancer accounted for 5.4% of the total number of deaths in the EU (2013), equating to more than one-quarter of a million people (268,744 people) or 55.2 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants. 36

There were 35,895 lung cancer deaths in the UK in 2014,37–39 accounting for 22% of all cancer deaths; lung cancer is the most common cause of cancer death. Crude mortality rates indicate that there are 62 lung cancer deaths for every 100,000 males and 50 for every 100,000 females. 37–40 In England in 2014, 15,856 men and 12,993 women died from lung cancer (19,563 and 16,332, respectively, for the UK). 37–39

Prevalence

The prevalence of lung cancer (i.e. the proportion of people previously diagnosed with lung cancer who are still alive at a given time) is relatively low because survival is generally poor. Worldwide, the overall ratio of mortality to incidence is 0.87, because of the high fatality rate associated with lung cancer.

In 2006, it was estimated that 38,141 people were alive in the UK who had been diagnosed with lung cancer within the previous 10 years, 15,802 of whom had been diagnosed within the previous year. 41

Impact of health problem

Significance for lung cancer patients

The prognosis for those diagnosed with lung cancer is disappointing despite recent advances in oncology and surgery. This is because lung cancer is typically diagnosed when the cancer is in the later stages, and in older people, who often have concomitant diseases that subsequently limit therapeutic options.

For individuals with NSCLC, the primary symptoms (or most frequent) are appetite loss (98%), fatigue (98%), shortness of breath (94%), cough (93%), pain (90%) and blood in sputum (70%). From the literature, it appears that fatigue is the primary symptom that has an impact on daily living for those with lung cancer, followed by pain (chest pain/pain swallowing). 42 Quality-of-life (QoL) scores deteriorate as the number of chemotherapy cycles increases (i.e. the longer the treatment lasts, the lower the QoL). 42 Being treated for lung cancer also has a detrimental impact on an individual’s social life, family life and ability to work. 42

Significance for the NHS

Luengo-Fernandez et al. 43 estimated that lung cancer had the highest economic cost of any cancer in the UK, but health-care costs are greater for colorectal cancer and breast cancer (lung cancer leads to significantly more productivity losses).

Measurement of disease

Treatment for lung cancer depends on where the cancer is within the lung, the tumour size, whether or not, and how far, it has spread, and the general health and fitness of the individual presenting. The main treatment options are chemotherapy, radiotherapy, surgery, chemoradiotherapy, control of symptoms and palliative care. These treatments may be offered in combination or in sequence. Typically, if the stage is low (I or II) and a patient is fit for surgery, this will generally be the treatment option. This may be followed by chemotherapy and radiotherapy depending on whether or not the patient has lymph node metastases. The intent will usually be curative. If the stage is high (III or IV), the intent of further treatment is typically palliative although it may be, in some cases, long-term survival.

Whether or not treatment is effective is measured by the following means:

-

Long-term survival (particularly for early-stage lung cancer in which treatment is with curative intent).

-

The size of the tumour (diameter, volume). With the intention of slowing progression of growth of the tumour, reducing it in size or removing it entirely. Typically, the RECIST 1.1 treatment response criteria44 can be used to assess this outcome.

-

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL). This can be measured using a variety of condition-specific tools including –

-

European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) QLQ (Quality of Life Questionnaire)-C3045 (a 30-item patient questionnaire for use in cancer trials, including multi-item scales such as physical and role function, a global HRQoL scale and a number of single items) and QLQ-LC1346 (a 13-item patient module primarily consisting of symptoms of lung cancer and lung cancer treatments)

-

Lung Cancer Symptom Scale (LCSS)47 [a nine-item patient questionnaire using visual analogue scales (VASs), focusing particularly on physical and functional QoL]

-

Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – General (FACT-G)48 (a 27-item patient questionnaire for patients receiving cancer therapy covering physical, social/family, emotional and functional well-being) and Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – Lung (FACT-L)49 (a nine-item patient module primarily consisting of symptoms of lung cancer and lung cancer treatments).

-

In addition, generic, preference-based measures were used to measure treatment effectiveness, such as the EuroQoL 5-Dimensions (EQ-5D).

Current service provision

Management of disease

The normal clinical pathway in the absence of screening is that people will present with symptoms such as persistent cough, haemoptysis or persistent breathlessness that will then be investigated with CXR, CT, bronchoscopy and biopsy. The investigations not only potentially confirm lung cancer, but are also used for staging. Occasionally individuals will have a CXR or CT scan for another clinical investigation in which lung cancer is noted as an unexpected finding without any symptoms.

The National Lung Cancer Audit Annual Report 201618 reported that, in the UK, the following treatments were given for 20,323 males and 17,946 females: any anticancer treatment in 60% of males and 60% of females, surgery in 15% of males and 18% of females, chemotherapy in 32% of males and 31% of females and radiotherapy in 35% of males and 32% of females.

Current service cost

In 2009, it was estimated that cancer costs the EU €126B, of which €18.8B (or 15%) was specifically for lung cancer. 43 The total costs for lung cancer in the EU were made up from €4.23B for health-care costs, €9.92B from mortality losses, €8M from morbidity losses and €3.82B in informal care costs. 43 The same study reported that the proportion of health-care costs in 2009 for the EU were 12% on medicine, 68% on inpatient care, 1% on accident and emergency services, 13% on outpatient care and 6% on primary care. 43

Costs are generally concentrated around the time of diagnosis (when treatment is likely to be initiated) and the time of death (when significant palliative care and medical management costs accrue). The following estimates were obtained for the health economic model, and details of sources are given in Chapter 6, Resources and costs:

-

Costs in the first year following diagnosis range from approximately £8000 to £13,000 (depending on the stage).

-

Costs in subsequent years range from around £1000 to £1600.

-

The estimated cost at the end of life is approximately £4600.

Variation in services and/or uncertainty about best practice

It is evident that there is a variation in service across the UK. The National Lung Cancer Audit Annual Report 201618 reports the following ranges for different treatments: percentage of people who received any anticancer treatment ranged from 54% on the south-east coast to 64% in the London Cancer Alliance, surgery ranged from 13% on the south-east coast to 21% in the London Cancer Alliance, chemotherapy for NSCLC ranged from 58% in Cheshire and Merseyside to 78% in the London Cancer Alliance, and chemotherapy for SCLC ranged from 57% on the south-east coast to 78% in Wessex.

Relevant national guidelines, including National Service Frameworks

There are many potential relevant guidelines for the diagnosis, treatment and management of lung cancer. NICE has produced a significant amount of guidance through various programmes. The British Thoracic Society has also produced two relevant guidelines. 50,51

Description of technology under assessment

Over several decades, a number of potential screening tests for lung cancer have been investigated, including CXRs and sputum cytology. Neither of these has been found to be effective in randomised controlled trials (RCTs). As CT scanning has developed and offered progressively improved images at lower radiation dosage, so it has become the test offering the greatest potential for clinically effective and cost-effective screening for lung cancer, with much research devoted to investigating whether or not this is the case. 52

Summary of intervention

Computed tomography scanning makes use of computer-processed combinations of many X-ray images taken from different angles to produce cross-sectional (tomographic) images (virtual ‘slices’) of specific areas of a scanned object, allowing the user to see inside without cutting. CT scanning has developed in a number of ways, notably the number of detectors, the speed with which data can be acquired and the sophistication of the computer reconstruction techniques. The amount of radiation required to provide an acceptable image for initial diagnostic purposes has also reduced, so that a low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) scan requires an effective radiation dose of ≤ 1.6 mSv. In the UK, the average annual exposure, including background and medical applications, is about 2.7 mSv of radiation per year. 53 Training and quality control are critical in achieving high-quality images while minimising X-ray exposure.

Lung CT scans detect discrete pulmonary nodules as the most common abnormality that may be suggestive of malignancy, but abnormal scarring and ground glass opacities may also be seen as worrying features and potentially recognised as malignant changes. Nodules suspicious of malignancy are often referred to as non-calcified nodules, but calcification is not a guarantee that the nodule is not cancerous. Size is also important in determining the likelihood that a non-calcified nodule is malignant, and large lesions are more likely to be malignant than small ones. 54

An important issue is that LDCT screening for lung cancer is not a homogenous technology, so careful attention needs to be paid to the exact nature of the device being used, the protocol being used and precise criteria being employed to define an abnormality as potentially malignant, benign or indeterminate. In a screening programme, this needs to take into account the possibility that screening scans may be repeated and stability of abnormalities over time may be part of the criteria indicating a possible cancer. The further management of each category, particularly further investigation, also needs to be specified as part of the definition of the technology.

A major challenge in all screening is that virtually no test is completely accurate. As a consequence, the benefits flowing from earlier identification and treatment of disease in some individuals will need to be offset by the likelihood that there will be some who may be falsely reassured by false-negative results and a number found to be false positives who will require further investigations and possibly experience additional anxiety relative to the situation in which no screening takes place. The problem of false positives is frequently magnified in screening because the incidence of the cancer being detected is often still low in the screened population, so apparently accurate tests, particularly in terms of their specificity, generate large absolute numbers of false positives.

Some recent lung cancer screening trials [the UK Lung Cancer Screening Trial (UKLS)55 and the Dutch–Belgian Lung Cancer Screening trial, NEderlands Leuvens Longkanker Screenings ONderzoek (NELSON)56,57] have discriminated between positive and indeterminate findings, whereby positive findings require follow-up with technology other than LDCT, while indeterminate findings can be managed purely by LDCT follow-up. From an intention-to-diagnose perspective (for calculating measures of diagnostic accuracy), these are both counted as positive findings (and false positive if lung cancer is not actually present), although it is likely that management purely by LDCT follow-up will be less invasive and lead to less radiation exposure, [although other harms (e.g. anxiety) may not be lessened by an indeterminate classification].

Identification of important subgroups

The following subgroups present with variable risk profiles associated with the incidence of lung cancer:

-

smoking history

-

age

-

exposure to asbestos

-

history of respiratory disease

-

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) link

-

socioeconomic group/income

-

urban or rural living.

Consideration as to how these subgroup risk profiles affect lung cancer risk will need to be considered for any screening programme.

Current usage in the NHS

In the UK, population-level lung cancer screening is currently not implemented by the NHS. This was based on the findings of the UK National Screening Committee (NSC) in July 2006 when they last assessed whether or not lung cancer screening should be recommended for adult cigarette smokers. They concluded that it should not be recommended but should be reviewed in 2015/16, which prompted the commissioning of this review.

Some screening pilots have gone ahead at local levels (without control arms), such as the Macmillan Cancer Improvement Partnership pilot in Manchester. 58

Anticipated costs associated with intervention

If a lung cancer screening programme is to be implemented, there are a multitude of costs that will need to be considered. These can be broadly categorised in accordance with the phase of implementation (setup, running, evaluation) and dependency on volume (fixed and variable costs). It is also likely that implementation would proceed initially with pilots before rollout, with pilots having their own evaluation costs. Furthermore, there would likely be societal costs and benefits of a screening programme, and impacts on other areas of government spending, though these would often not be considered by NHS policy-makers, such as NICE.

If lung cancer screening significantly has an impact on smoking behaviour, or if it is implemented with attached smoking cessation interventions, there could be significant impacts on the NHS, the government and society more widely.

Challenges of screening programmes

Implementation

When implementing a screening programme, of any nature, there will always be challenges in executing its delivery effectively. Predominantly all of these challenges fall around communication. First, how to identify and communicate with the target population so that they are eligible for the screening programme. Identification could be through GP records, questionnaires or self-referral, and they all come with their own limitations. For example, how accurate the GP records are, how honest will individuals be at responding to a questionnaire, would self-referral predominantly identify only the worried-well. Once the target population has been identified, the response to invitation needs to be considered. Again, will it disproportionately be the worried-well who respond and attend screening. Whether SES or income factors affect attendance and also whether or not the invitation itself causes a detrimental increase in anxiety for the individual invited need consideration. Communication regarding making and rescheduling appointments along with follow-up of missed appointments will all require careful administration along with the communication of results and any follow-up appointments required.

Value

Understanding the added value that a screening programme can offer will also be a challenge. Ensuring that public attitudes are acceptable and amenable to the implementation and value of the screening programme will be paramount. Also of importance will be ensuring that the value of the screening programme is understood by those selected for participation (individuals to be screened) and placating concerns surrounding whether or not accepting screening has an impact on health insurance. Beyond the added value of reducing costs of treating lung cancer early and improving outcomes for an individual, a screening programme can furthermore benefit individuals by prompting/motivating smoking cessation, give individuals with a lung cancer diagnosis more time with their loved ones and also give them time to put their affairs in order.

Assessment

Finally, when implementing a screening programme, there will be challenges in assessing whether or not the screening programme is clinically effective. Primarily these challenges hinge on the lack of an appropriate gold standard to compare against, particularly for negative results but also accounting for overdiagnosis, lead-time bias, length bias and other forms of bias such as differential efforts to achieve smoking cessation.

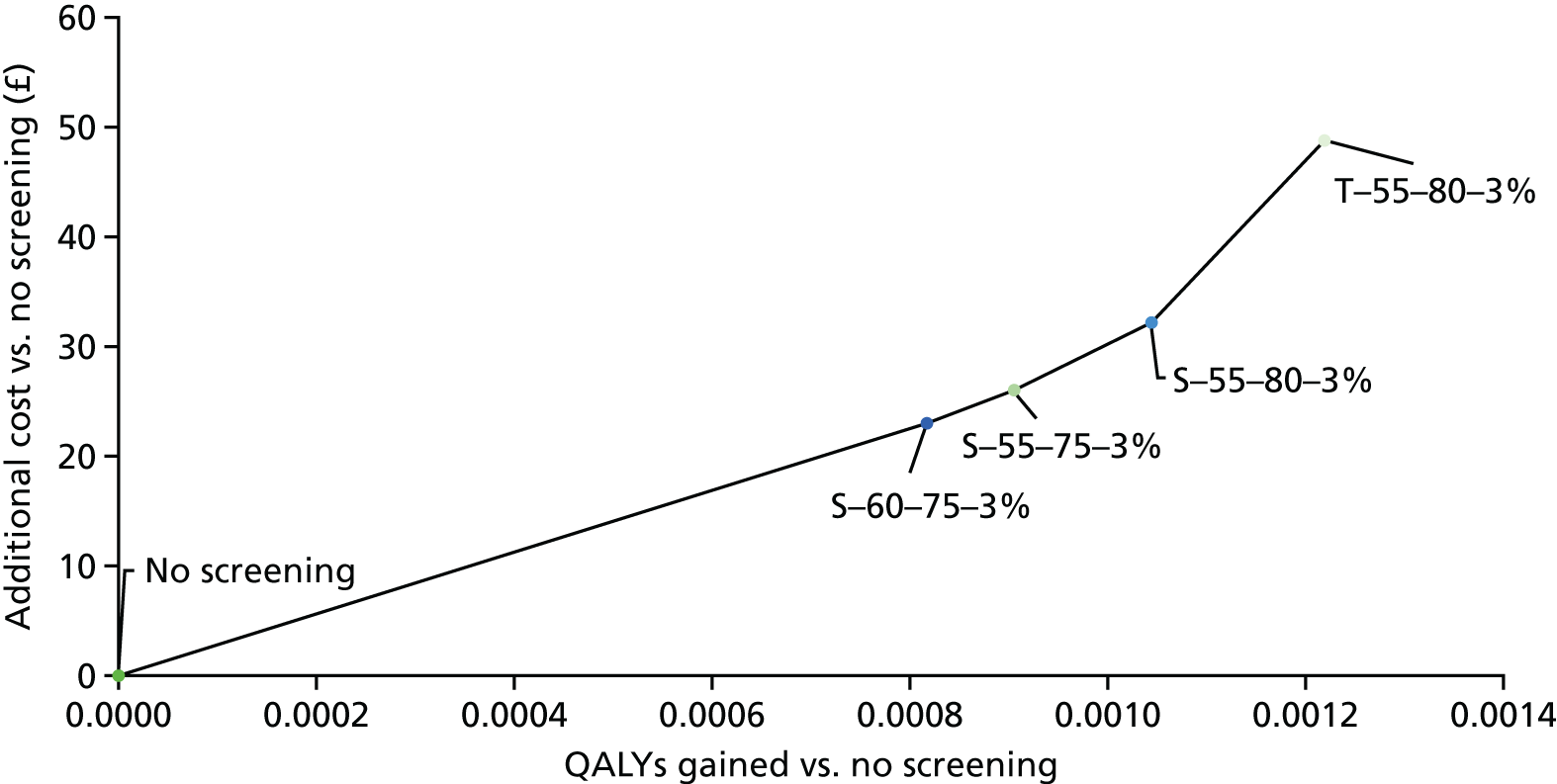

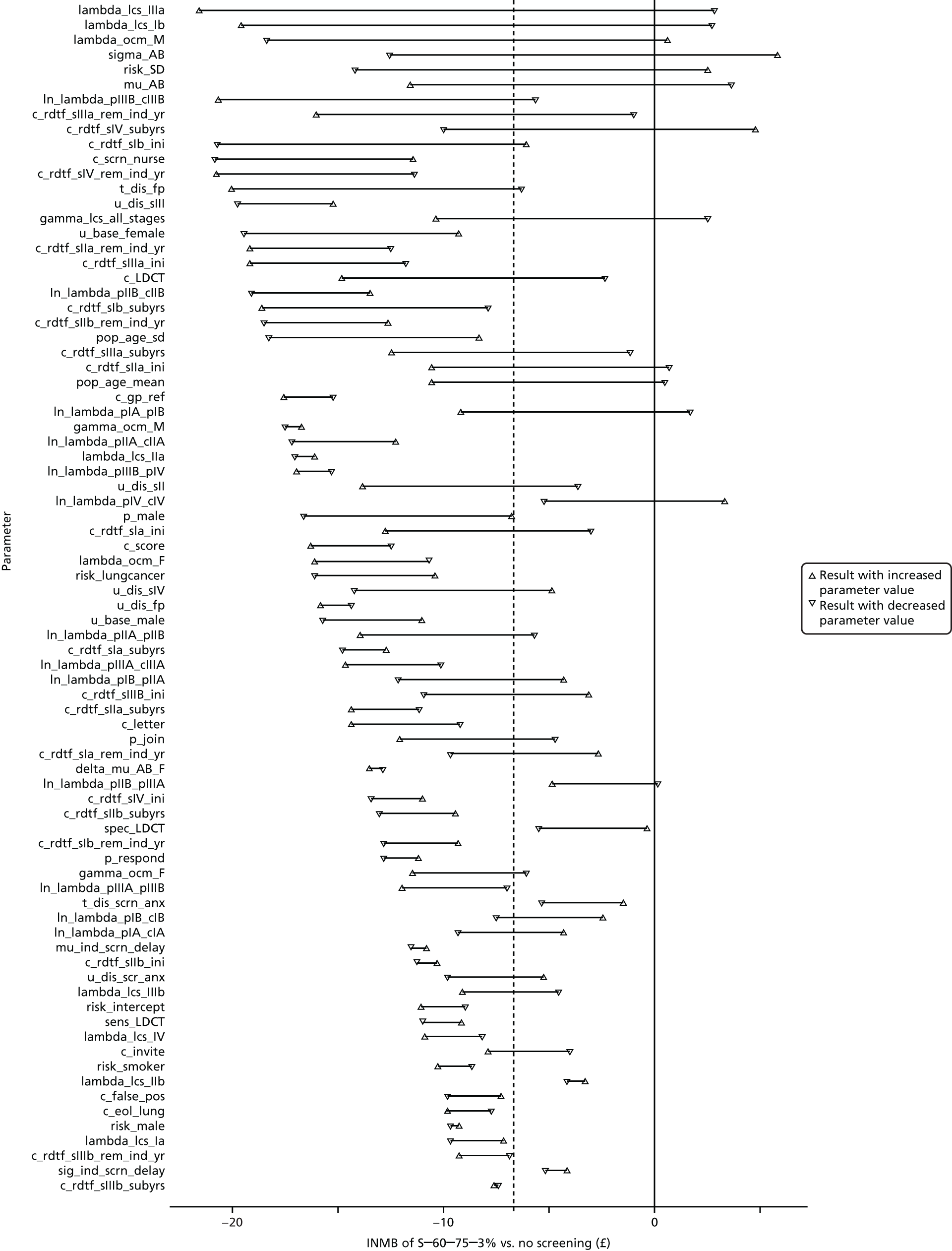

Chapter 2 Definition of the decision problem

The purpose of this work was to provide the NSC with the most up-to-date clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness evidence for the screening of lung cancer in the UK by LDCT.

Decision problem

Population

People identified as being at ‘high’ risk of lung cancer.

Intervention

Low-dose CT screening.

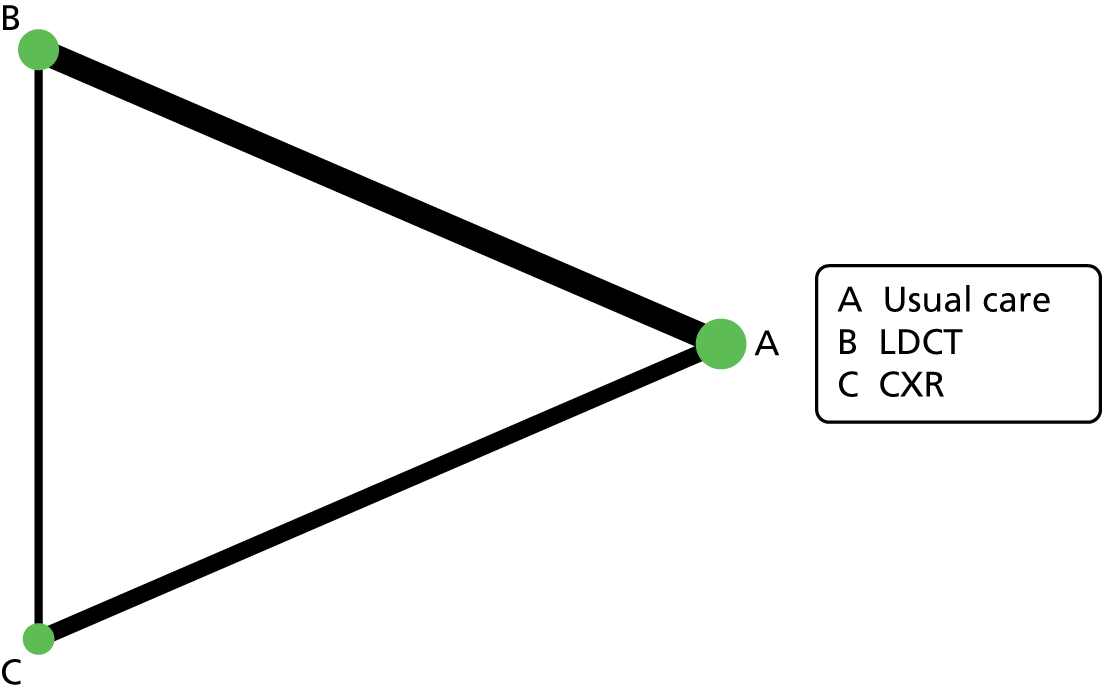

Comparators

No screening was set by the scope as the primary comparator. We have also included alternative screening programmes (e.g. CXR) for comparative purposes.

Outcomes

From the scope, the outcomes suggested were potential effect on mortality, QoL and cost-effectiveness. Additional outcomes that were deemed relevant following consultation with our advisory committee included lung cancer incidence, stage and morphology of lung cancer, follow-up investigations and treatments, smoking cessation, adherence to screening, diagnostic accuracy, radiation dose of screening and adverse psychological impacts.

Overall aims and objectives of assessment

In order to assess the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of lung cancer screening in a high-risk population using LDCT screening, the following key objectives were performed:

-

a systematic review of the clinical effectiveness

-

a systematic review of the cost-effectiveness

-

a de novo cost-effectiveness model.

Chapter 3 Assessment of clinical effectiveness

Methods for reviewing clinical effectiveness

Identification of studies

The literature search aimed to systematically identify studies relating to the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of LDCT screening programmes in high-risk populations. For the identification of studies for clinical effectiveness, the following bibliographic databases were searched:

-

MEDLINE (via Ovid)

-

MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations (via Ovid)

-

EMBASE (via Ovid)

-

Health Management Information Consortium (via Ovid)

-

PsycINFO (via Ovid)

-

Web of Science (via Clarivate Analytics)

-

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) and Health Technology Assessment (HTA) (all via The Cochrane Library)

-

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (via EBSCOhost).

The search strategies were developed by an information specialist (SR) and were carried out in two stages. The first searches, from 2004 to January 2012, were intended to update the HTA by the Aberdeen HTA Group in 200654 and to supplement the Cochrane systematic review of 2013. 52 These comprised population terms for lung cancer and intervention terms for LDCT screening. Filters for diagnostic studies were not used to limit the study designs retrieved as these have not been found to be effective. Search results were limited to RCTs and English-language studies and were run in January 2017.

The second searches, from 2012 to January 2017, were more comprehensive in scope. These searches comprised population terms for lung cancer and intervention terms for CT screening (not restricted to low dose) and for CXR as a comparator. Searches were limited to RCTs and English-language studies. The search results were exported to EndNote X7 [Clarivate Analytics (formerly) Thomson Reuters, Philadelphia, PA, USA] and deduplicated using automatic and manual checking.

Systematic reviews identified by further bibliographic database searches were used to source other relevant studies. Items included after full-text screening were backward-citation chased using Scopus (via Elsevier) in order to identify additional relevant studies. A search for ongoing clinical trials was carried out in February 2017 in clinicaltrials.gov, the WHO registry, the EU clinical trials registry and the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN).

Reference lists of relevant systematic reviews were checked. We defined systematic reviews as those reviews in which systematic and reproducible search strategies were used, a well-defined research question (with clear inclusion and exclusion criteria) was addressed and either a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram or a sufficient description of the flow of studies that allows the construction of the flow diagram was included. A full search strategy for each database can be found in Appendix 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria

Population

The eligible population was individuals at high risk of lung cancer. Any definitions of high-risk populations were eligible in order to facilitate exploration of risk as a particular feature by which clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness might vary.

Intervention(s)

Low-dose CT screening programmes, including both single and multiple rounds, were eligible for inclusion. We carefully investigated variations in the screening programme, not only in the techniques used to do the initial screen, but also the criteria used to define positive tests and how positive and indeterminate tests (when applicable) were followed up.

Comparator(s)

The eligible comparators were usual care (no screening) or other imaging technology screening programmes (such as CXR), including both single and multiple screening rounds.

Study design

The eligible study design was RCTs. The following types of report were excluded: editorials and opinions, case reports and reports focusing on only technical aspects of the CT technology (such as technical descriptions of the CT technology).

Outcomes

The following outcomes were included:

-

lung cancer mortality

-

all-cause mortality

-

stage distributions of lung cancers

-

number of lung cancers detected

-

number and type of follow-up investigations

-

number of patients who were more amenable to surgical treatment

-

surgical resection rate

-

any HRQoL

-

smoking cessation and patients’ smoking behaviour change

-

adherence rate to screening

-

diagnostic accuracy outcomes (including indeterminate results)

-

overdiagnosis

-

complications in those who underwent an invasive procedure

-

radiation dose of screening

-

radiation-related patient outcomes

-

adverse psychological impact.

Exclusion criteria

Studies were excluded if they did not match the inclusion criteria. In addition, certain studies were not considered, particularly:

-

animal models

-

preclinical and biological studies

-

non-systematic reviews, editorials, opinions

-

non-English language papers

-

reports published as meeting abstracts only, as there is unlikely to be sufficient methodological details to allow critical appraisal of study quality.

At least two reviewers independently screened the titles and abstracts (if available) of all reports identified by the search strategy. Full-text copies of all studies deemed to be potentially relevant were obtained and two reviewers independently assessed them for inclusion. Any disagreements were resolved by consensus or by a third reviewer.

Data abstraction strategy

We selected the most recent or most complete report in cases of multiple reports for a given study or when the possibility of overlapping populations could not be excluded.

The data extraction forms were developed and piloted. One reviewer independently extracted details from full-text studies of study design, participants, intervention, comparator and outcome data. The data extraction was checked by another reviewer. Any disagreements were resolved by consensus or by a third reviewer.

For studies reporting clinical outcomes, we extracted data on these as numbers of patients experiencing the specified outcome. Mean differences, relative risks (RRs) or odds ratios (ORs) [with 95% confidence intervals (CIs)] were extracted, when reported.

Critical appraisal strategy

One reviewer independently assessed the quality of all included studies using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool. Other risks of bias include the following two items: (1) underpowered sample size for important outcomes and (2) significant baseline differences between study arms on important characteristics. The quality assessment was checked by another reviewer. Any disagreements were resolved by consensus or by a third reviewer if necessary.

Methods of data synthesis

All data were tabulated and primarily considered in a narrative review. When appropriate, DerSimonian and Laird random-effects models59 were performed to pool the estimates of effect size of clinical effectiveness data from included trials. A random-effects approach was prespecified as part of the protocol development process; a fixed approach was not favoured as it was thought highly unlikely that only random variation would account for differences between the results of included studies.

Statistical heterogeneity was assessed using the I2-statistic: 30–50% was considered as moderate heterogeneity and > 50% as substantial heterogeneity. We performed only statistical pooling of data for both lung cancer mortality and all-cause mortality with ≥ 5 years’ follow-up. The statistical analyses were performed in Stata® 14 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

We closely took into account any heterogeneity observed between studies. Particularly, we considered the following factors for the exploration of heterogeneity:

-

quality of trials (focusing on adequacy of randomisation to define the criteria)

-

characteristics of populations (e.g. different level of risk status of participants at baseline)

-

nature of interventions (e.g. frequency of LDCT screening)

-

characteristics of control groups (such as CXR screening or usual care).

Sensitivity analyses and subgroup analyses based on the above factors were performed to explore the potential sources of heterogeneity.

Changes to protocol

The methods for this review differ from the protocol prospectively registered on PROSPERO as described below.

Decision problem

The set of outcomes was expanded to include the following, after consultation with clinical experts:

-

number of patients who were more amenable to surgical treatment

-

surgical resection rate

-

smoking cessation and patients’ smoking behaviour change

-

adherence rate to screening

-

overdiagnosis

-

complications in those who underwent an invasive procedure

-

radiation dose of screening

-

radiation-related patient outcomes

-

adverse psychological impact.

Search methods

The following resources were not searched:

-

National Research Register

-

Food and Drug Administration website

-

European Medicines Agency website.

In addition, the WHO trial registry was searched.

Subgroups

The prospectively registered protocol indicated that heterogeneity would be explored through consideration of the study populations, methods and interventions. In the review, heterogeneity was specifically explored through consideration of study quality, which relates to study methods, but was not explicitly listed in the protocol.

Results

Quantity and quality of research available

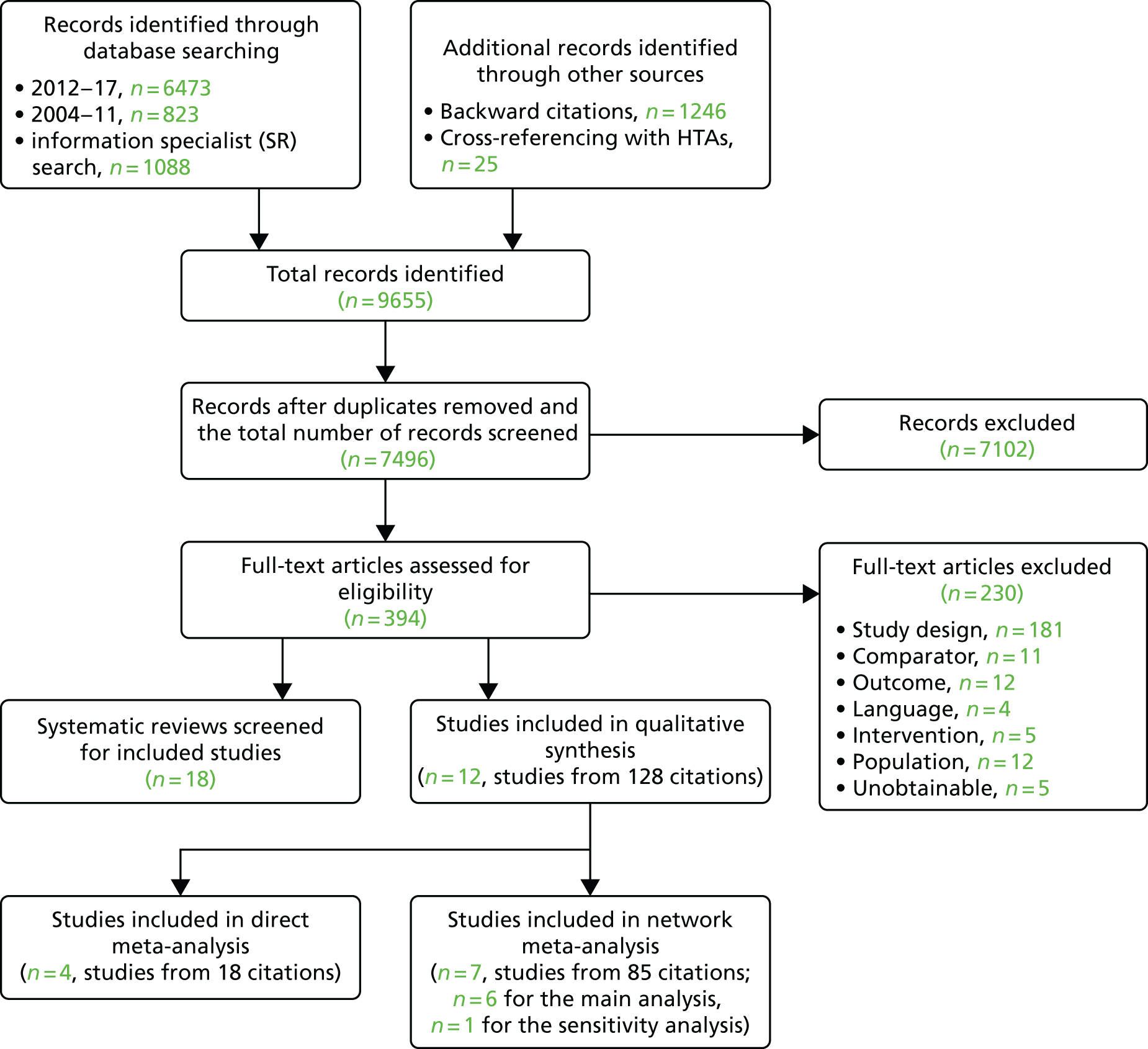

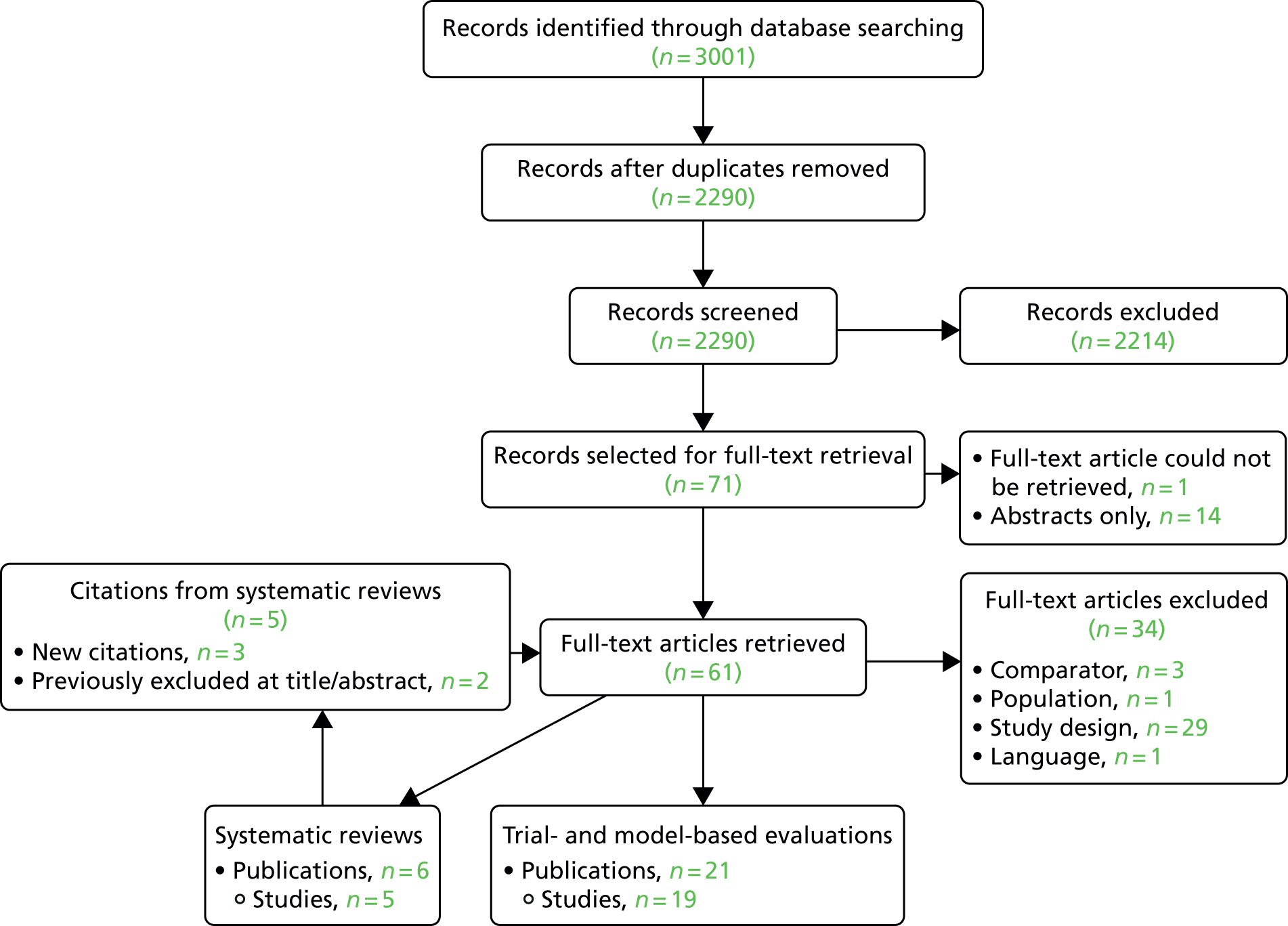

The literature searches of bibliographic databases identified 7496 references. After initial screening of titles and abstracts, 380 were considered to be potentially relevant and were ordered for full-paper screening. In total, 12 RCTs were included for the systematic review of clinical effectiveness of lung cancer screening by LDCT scanning. All the included trials with linked citations are presented in Appendix 2. Figure 1 shows a flow diagram outlining the screening process with reasons for exclusion of full-text papers.

FIGURE 1.

The PRISMA flow diagram for systematic review of clinical effectiveness. SR, systematic review. Adapted from Moher et al. 60 © 2009 Moher et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Most trials were reported in multiple papers and abstracts, with considerable overlaps in data and reporting. We selected the paper with the most up-to-date and complete data for the data extraction.

A list of full-text papers that were excluded along with the reasons for their exclusions is given in Appendix 3. These papers were excluded because they failed to meet one or more of the inclusion criteria in terms of the type of study design, participants, interventions or outcomes reported.

Assessment of clinical effectiveness

Characteristics of included studies

Table 1 presents the summary information of characteristics of included trials for the systematic review of clinical effectiveness. All of the included studies were RCTs. Nine studies were conducted in European countries and three studies were conducted in the USA. Two trials (one of which was a pilot trial) were conducted in the UK. Only a minority of included trials contributed to important comparative outcomes.

| Study identifier | Country | Recruitment time | Screening programme | Comparator | Sample size (n) | Age range, years (recruitment protocol) | Number of screening rounds | Screening times and interval (years) | Duration of follow-up (mean/median) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DANTE61 | Italy | March 2001 to February 2006 | LDCT, medical examination and one CXR | No screening, medical examination and one CXR | 2811 (2400 planned) | 60–74 | 5 | T0, T1, T2, T3, T4 (1-year interval) | At December 2012, median 6 years 3.5 months |

| Depiscan62 | France | NR | LDCT | CXR | 830 | 47–76 (protocol 50–75) | 3 | T0, T1, T2 (1-year interval) | NR |

| DLCST63 | Denmark | October 2004 to March 2006 | LDCT | No screening | 4104 | 50–70 | 5 | T0, T1, T2, T3, T4 (1-year interval) | Median: 9.47 years vs. 9.53 years (planned 10 years) |

| Garg et al.64 | USA | January 2001 to October 2001 | LDCT | No screening | 190 (400 planned) | 50–80 | 2 | T0, T1 (1-year interval) | NR (planned 2 years) |

| ITALUNG65 | Italy | NR | LDCT, smoking cessation programme | No screening, smoking cessation programme | 3206 | 55 –59 | 4 | T0, T1, T2, T3 (1-year interval) | NR |

| LSS-PLCO66 | USA | Randomisation from September 2000 to November 2000 or January 2001 (depending on source) | LDCT | CXR | 3318 (3000 planned) | 55–74 | 1 | T0, T1 (1-year interval) | NR |

| LungSEARCH67 | UK | August 2007 to March 2011 | Sputum surveillance, if abnormal sputum, LDCT and AFB | CXR at 5 years | 1568 (1300 planned) | Mean 63 | 5 | T0, T1, T2, T3, T4 (1-year interval) | NR (planned 5 years) |

| LUSI68 | Germany | September 2007 to April 2011 | LDCT, smoking counselling | No screening, smoking counselling | 4052 (4000 planned) | 50–69 | 5 | T0, T1, T2, T3, T4 (1-year interval) | NR |

| MILD69 | Italy | September 2005 to September 2011 | LDCT (annual and biannual), smoking cessation, pulmonary function test, blood sample | No screening, smoking cessation, pulmonary function test, blood sample | 4099 (10,000 planned) | > 49 | 10 | T0, T1, T2, T3, T4, T5, T6, T7, T8, T9, (1-year interval) vs. T0, T2, T4, T6, T8 (2-year interval) | Median 7.3 years |

| NELSON56,57 | The Netherlands/Belgium | Second half of 2003 to December 2006 | LDCT | No screening | 15,822 | 50–75 | 4 |

T0, T1, T2, T3, T0 to T1, 1 year; T0 to T2, 3 years; T0 to T3, 5.5 years |

NR (planned 10 years) |

| NLST70,71 | USA | August 2002 to April 2004 | LDCT | CXR | 53,454 | 55–74 | 3 | T0, T1, T2 (1-year interval) | Median 6.5 years |

| UKLS55 | UK | August 2011 to August 2012 | LDCT | No screening | 4061 (4000 planned) | 50–75 | 1 | T0 | NR (planned 10 years) |

Low-dose CT screening was a key component of the screening programmes. Most of the included trials used usual care as a comparator, whereas three trials used CXR as a comparator. The sample size of included trials ranged from 190 to 53,434. The included trials recruited participants with age ranging from 47 to 80 years. The number of screening rounds ranged from 1 to 10. Most trials adopted 1-year interval screening. However, one trial [Multicentric Italian Lung Detection (MILD)]69 used both annual and biennial screening and the NELSON trial56 performed screening at baseline, 1 year, 3 years and 5.5 years of follow-up. When reported, the duration of follow-up ranged from 2 to 9.53 years.

All included trials recruited high-risk populations. The characteristics of study populations are shown in Appendix 4. The percentage of male participants ranged from 32% to 100%. All the studies recruited current smokers and former smokers. Most trials recruited participants through targeted mailings of questionnaires via GPs and family doctors, media, internet and newspaper advertisements. The characteristics of recruitment methods are shown in Appendix 4.

As seen from this table, there were wide variations in definitions of high risk between trials. For example, the National Lung Screening Trial (NLST)71 (which was conducted in the USA) used two variables (age and smoking history) to define high risk:

-

aged 55–74 years

-

current smokers with at least a 30 pack-year smoking history

-

former smokers (who had quit within the previous 15 years) with at least a 30 pack-year smoking history.

However, UKLS55 used the Liverpool Lung Project lung cancer risk prediction algorithm to predict high risk. This risk prediction rule has been validated in three independent studies from Europe and North America and demonstrated its predictive benefit. The following variables were included in this risk prediction model:

-

age

-

sex

-

prior diagnosis of pneumonia

-

family history of lung cancer

-

smoking duration

-

prior diagnosis of malignant tumour

-

personal history of other cancer and non-malignant lung diseases

-

early onset (< 60 years of age) family history of lung cancer.

In this trial,55 participants were selected based on the prediction result (i.e. ≥ 5% risk of developing lung cancer in the next 5 years). It should be noted that such variations in the definition of ‘high-risk’ participants can lead to different prevalences of lung cancer being detected at baseline between different trials.

Furthermore, the Detection and Screening of Early Lung Cancer with Novel Imaging Technology and Molecular Essays (DANTE) trial61 defined high-risk participants as those smokers or former smokers (aged 60–74 years) of at least 20 pack-years who had quit < 10 years before recruitment. Similar criteria were adopted by the Italian lung cancer screening (ITALUNG) trial. 72 The Despiscan trial62 defined high-risk patients as those aged 50–75 years who were current or former smokers (having quit < 15 years from enrolment) with cigarette consumption of ≥ 15 cigarettes per day for ≥ 20 years. The Danish Lung Cancer Screening Trial (DLCST)63 defined high-risk participants as those current or previous smokers (aged 50–70 years) with ≥ 20 pack-years of smoking. Previous smokers had to have quit after the age of 50 years and < 10 years prior to the start of the study. Patients had to be able to climb 36 steps without pause. In this trial, forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) had to be at least 30% of predicted normal at baseline. It should be noted that the MILD trial69 recruited younger participants (≥ 49 years) who were current or former smokers (having quit smoking within 10 years of recruitment) with ≥ 20 pack-years of smoking. 69

The DANTE trial61 recruited only male participants, whereas most trials recruited both male and female participants. The NELSON trial57 recruited at first only men, and later also women (aged 50–75 years), who were current and former smokers with ≤ 10 years of cessation, who smoked > 15 cigarettes per day for > 25 years or > 10 cigarettes per day for > 30 years.

The characteristics of screening programmes are shown in Appendix 4. Most studies compared LDCT screening with usual care (no screening), whereas three studies compared LDCT screening with CXR screening. As seen in Appendix 4, Table 43, the definitions of a positive scan varied across studies in terms of nodule sizes. For example, the NELSON trial57 defined positive CT scans as those non-calcified nodules that had a solid component of > 500 mm3 (> 9.8-mm diameter) or volume-doubling time of < 400 days. If the volume of largest solid nodule or the solid component of a partially solid nodule was 50–500 mm3 (4.6–9.8 mm in diameter) or > 8 mm in diameter for non-solid nodules or volume-doubling time was 400–600 days, these results were treated as indeterminate test results. In NLST,71 any non-calcified nodule measuring ≥ 4 mm in any diameter and radiographic images were classified as positive, suspicious for lung cancer. Other abnormalities (e.g. adenopathy or effusion) could be positive or suspicious. As per the protocol, abnormal findings suspicious for lung cancer that were stable across the three screening rounds were classified as minor abnormalities rather than positive findings.

There were variations in imaging evaluation and interpretation strategy across included trials. When reported, two radiologists independently interpreted and reported the results in most trials. If there was disagreement, final interpretation was based on joint consensus.

The diagnostic follow-up strategies for suspicious abnormality findings varied between studies. When reported, most studies used further diagnostic imaging {e.g. high-resolution CT or chest fludeoxyglucose (18F) positron emission tomography ([18F] FDG-PET)} and/or invasive biopsy with rapid on-site examination.

Computed tomography parameters

The key CT technical specifications of the included studies are presented in Tables 2 and 3 (see the Glossary for definitions of CT parameters). Given the selective reporting of CT vendors, the available information suggests that the trials transition from single (single bank of detectors) to multislice (multiple banks of detectors) technology during a time of rapid CT development. The DANTE,61 Garg et al. ,64 ITALUNG72 and German Lung Cancer Screening Intervention (LUSI)68 trials have incorporated single-slice technology. The advantages of multislice over single-slice technology mainly include the same acquisition in shorter time, better z-axis resolution and the capacity to scan larger volumes in the same time. Specific to CT of the thorax, multislice technology allows for quicker scanning, resulting in reduced breathing artefact and better quantification of thoracic lesions where present.

| Study identifier | CT technology (vendor CT scanner) | Multi or single detector | Voltage (kV) | Tube current-time product (mAs) | Slice thickness (mm) | Volumetric analysis | Pitch | Estimated average effective dose (mSv) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DANTE61 | NR | Multi after 2003 and single before 2003 | 140 | 40 | 5 | NR | 1.25 | NR |

| DLCST63 | Philips Mx 8000 (Philips Medical Systems, Eindhoven, the Netherlands) | Multi (16 slice) | 120 | 40 | 1–1.5 | Philips evaluation semiautomated software | 1.5 | 1 |

| Garg et al.64 | NR | Single | 120 | 50 | NR | NR | 2 : 1 | NR |

| ITALUNG65 | NR | 1 × single and 4 × multi | 120–140 | 20–43 | 1–1.25 for multislice | NR | 1–2 | NR |

| LungSEARCH67 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| LUSI68 | Unspecified Toshiba and Siemens scanners, (switch of technology at 2010) | Multi (16 and 128 slice) after 2010 and single before 2010 | NR | NR | 1 | Computer-aided detection (MEDIAN Technologies, Valbonne, France) with volumetric software | NR | 1.6–2 |

| MILD69 | Somatom Sensation 16, Siemens (Siemens Medical Solutions, Forchheim, Germany) | Multi (16 slice) | 120 | 30 | 1 | LungCare, Siemens, semi-automated software (Siemens Healthcare, Forchheim, Germany) | 1.5 | NR |

| NELSON56,57 | M×8000 IDT (Philips Medical Systems, Cleveland, OH, USA) or Brilliance 16P, Philips (Philips Medical Systems, Cleveland, OH, USA), or Sensation-16, Siemens (Siemens Medical Solutions, Forchheim, Germany) | Multi (16 slice) | 80–90 (< 50 kg) 100 (< 60 kg) 120 (60–80 kg) 140 (> 80 kg) | 20 | 1 | LungCare, Siemens, semi-automated software | 1.5 | < 0.4 (< 60 kg) < 0.8 (60–80 kg) < 1.6 (> 80 kg) |

| UKLS55 | Unspecified Siemens and Philips Brilliance 64 (Philips Medical Systems, Cleveland, OH, USA) | Multi (128 and 64 slice) | Automated based on BMI | Automated based on BMI | 1 | Siemens syngo LungCare, version Somaris/5 VB 10A, (Siemens Medical Solutions, Forchheim, Germany) | 0.9–1.1 | NR |

| Study | CT technology (vendor CT scanner) | Multi or single detector | Voltage (kV) | Tube current-time product (mAs) | Slice thickness (mm) | Volumetric analysis | Pitch | Estimated average effective dose (mSv) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depiscan62 | NR | Multi | 100–140 automated based on BMI | 20–100 automated based on BMI | 1.25–3 | NR | NR | NR |

| LSS-PLCO66 | Variable and not specified | Multi (inclusion criteria said must have a history of a spiral/helical CT scan) | 120–140 | 60 | NR | NR | 2 | NR |

| NLST70,71 | 97 different scanners | Multi > 4 slices | 120–140 | 40–80 automated based on BMI | 1–2.5 | NR | 1.25–2 (typically 1.5) | 1.5 |

In general, the slice thickness ranges between 1 and 3 mm. These are generally considered ‘thin’ slices and were considered superior to ‘thick’ slices. Reconstructed slice thickness (which includes the consideration of pitch and collimation) is complicated in helical multidetector compared with single-detector scanning. In helical scanning, reducing slice thickness increases z-axis resolution but this results in a trade-off with increased image noise and possibly dose. The DANTE trial61 adopted a slice thickness of 5 mm, which is at odds with the other trials.

In the last decade, the development of multislice technology expanded the applications of CT, leading to the increased number of examinations and radiation exposure. Given the concern about the rise of medical radiation, automatic tube current modulation was designed to achieve the same image quality for individuals with different biological make-up/patient attenuation characteristics, reducing radiation exposure. In the setting of LDCT screening, there are two broad strategies in performing CT thorax, either (1) tube current modulation (as described) or (2) a fixed-tube current approach. In this report, three main strategies of dose reduction have been identified:

-

fixed-tube current and voltage regardless of the body mass index (BMI)

-

fixed-tube current and voltage depending on the BMI

-

automatic tube current and voltage depending on the BMI.

Considering the selective reporting, each LDCT thorax strategy results in different radiation output but the reported doses are generally lower than the doses of standard CT thorax in the literature.

Some trials conducted volumetric analysis using software mostly developed by the CT vendors. DLCST63 used semiautomated software designed by Philips, whereas MILD,69 NELSON56,57 and UKLS55 used semiautomated software made by Siemens. LUSI68 used computer-aided detection software made by MEDIAN. The comparability of volumetric measurements using different software is not known.

Estimation of radiation dose is achieved by multiplying the dose length product by a conversion factor; none of the studies reported whether or not the commonly used conversion factor (0.014) was used in estimating the average radiation dose. However, all studies used radiation doses that would be considered low by CT standards and are less than annual background radiation exposure. Image quality has not been considered as an outcome in the trials, which is influenced by patient demographics.

Ongoing studies

A total of 125 ongoing trials were identified in the search and investigated further. Of these, only two were considered relevant to this review. One is the MILD trial69 (NCT02837809), which is already included, and the second is a RCT based in China (NCT02898441), which is due for completion by December 2018. This study compares LDCT screening for lung cancer with usual care. The anticipated recruitment is 6000 participants and the primary outcome is lung cancer incidence. The 5-year follow-up is planned for lung cancer incidence, lung cancer mortality and all-cause mortality.

Outcome measures in included trials

In order to demonstrate the variability of reporting in the included trials, Table 4 displays which outcome is measured and whether or not it includes ≥ 5 years of follow-up. Additional information, when available, is given on whether or not the outcome was predefined in a protocol and, if so, whether it was categorised as a primary or secondary outcome.

| Study identifier (recruitment period) | Number of randomised participants | Mortality | Cancer incidence | Stage distribution | Complete resection | HRQoL | Smoking cessation | Additional information | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lung cancer | All-cause | ||||||||

| DANTE61,73 (March 2001 to February 2006) | 2450 | ≥ 5 years | ≥ 5 years | ≥ 5 years | ≥ 5 years | ≥ 5 years | NR | ≥ 5 years | NCT00420862

|

| Depiscan62 (October 2002 to December 2004) | 830 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Pilot

|

| DLCST63 (October 2004 to March 2006) | 4104 | ≥ 5 years, 1°, 10 years | ≥ 5 years | ≥ 5 years, 2°, 5 years | ≥ 5 years, 2°, 5 years | NR | COS-LC 1–5 years | Annual smoking status 1–5 years | NCT00496977

|

| Garg et al.64 (January 2001 to October 2001) | 190 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Feasibility study

|

| ITALUNG65 [March 2004 to September 2010 (end of last intervention scan at year 4)] | 3206 | NR, 1°, 8 years | NR, 2°, 8 years | NR, 2°, 8 yearsa | NR | NR | NR | NR | NCT02777996

|

| LSS-PLCO66 (September 2000 to November 2000 or January 2001)b | 3318 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NCT00006382

|

| LungSEARCH67 (August 2007 to March 2011) | 1568 | NR, 1°, 15 years | NR | NR | NR, 2°, 5 years | NR | NR | NR | NCT00512746

|

| LUSI68 (September 2007 to April 2011) | 4052 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

|

| MILD69 (September 2005 to September 2011) | 4099 | ≥ 5 years, 1°, 10 years | ≥ 5 years | ≥ 5 years | NR | NR | NR | NR, 2°, 10 years | NCT02837809

|

| NELSON56,57 (January 2004 to December 2006) | 15,822 | NR, 10 | NR | NR | NR | NR | < 5 yearsc 2° | < 5 yearsc | ISRCTN63545820

|

| NLST70,71,74 (August 2002 to April 2004) | 53,454 | ≥ 5 years,d 1° | ≥ 5 years,d 2° | ≥ 5 years,d 2° | ≥ 5 years | ≥ 5 years | < 1 years | NR | NCT00047385

|

| UKLS55 (August 2011 to August 2012) | 4061 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | < 5 years | NR | ISRCTN78513845

|

Of the 12 included studies, predefined outcomes could not be verified for five studies. 61,62,64,66,68 Only the ITALUNG trial65 had a full protocol published,65 whereas the remaining trials listed outcomes in relevant clinical trials registries. 55,57,63,67,69,70 Five studies62,64,66–68 have no data on the outcomes of interest. A sixth trial (ITALUNG65) has recently reported results for several outcomes; however, as they were published after the inclusion date for the current review, these results were not incorporated in the analyses.

Lung cancer mortality, all-cause mortality and cancer incidence with > 5 years’ follow-up are reported in four studies. 61,63,69,70 When lung cancer mortality is cited as a primary outcome, data for two studies57,65 were not identified. However, one of these is the ITALUNG trial,65 as previously mentioned, and the second is the more recent NELSON trial,57 for which results may be published imminently. As a secondary outcome in the LungSEARCH trial,67 data for lung cancer mortality remain unreported.

Cancer incidence is defined as a secondary outcome for three studies, with results available for two studies63,70 in this review and the third being the ITALUNG trial. 65

Data for stage distribution are provided for three studies61,63,70 with ≥ 5 years’ follow-up. Although the LungSEARCH trial67 has stage distribution defined as a primary outcome, no results were available.

Complete resection is the least reported outcome, with only two studies61,70 providing data for ≥ 5 years.

Smoking cessation was reported in three studies,56,61,63 with a fourth study defining this as a secondary outcome; however, the results have not been published. 69

With regard to HRQoL, this is reported for four studies;55,57,63,70 however, the follow-up is < 5 years and actually < 1 year for the NLST trial. Furthermore, the NELSON trial57 included only a subsample of participants for this outcome.

Risk of bias of included studies

All the studies were assessed for risk of bias using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool. 76 However, as indicated in Table 4, only a minority of the included studies contributed data to the consideration of the main outcome measures assessed through a comparison of the intervention arm with the control. Thus, the reporting of quality focuses on the risk of bias for the studies contributing results of the main outcomes, particularly separating mortality, psychological consequences/HRQoL and smoking cessation, as we noted that not only were there different included studies for these outcomes, but also differing threats to validity depending on the outcome. This stemmed from variation in the objectivity of the outcome and different losses to follow-up between outcomes within a trial.

Risk of bias for lung cancer and overall mortality

There were four contributing included studies to mortality outcomes. As indicated in Table 5, according to the standard criteria for risk of bias, all but one of these trials were well conducted. All performed power calculations and met their sample size targets, but it should be noted that the anticipated effect on mortality was much more modest in NLST71 and, hence, the trial very much larger, with > 10 times the number of participants of DANTE61 and DLCST. 63 The only quality assessment issues identified for DANTE,61 DLCST63 and NLST71 were lack of demonstration of allocation concealment of randomisation and failure to blind study participants to allocation. Although allocation concealment is the most sensitive indicator of trial quality, it should be noted that failure to demonstrate allocation concealment is still common in trials, more so with RCTs designed several years ago. The great practical difficulty of achieving blinding in DANTE,61 DLCST63 and NLST71 was not felt to introduce bias in view of the relative objectivity of the outcome. This would have been reinforced further in the NLST trial because it employed an active control arm.

| Study identifier (country) | Criteria | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random-sequence generation (selection bias) | Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Blinding outcome assessment (detection bias) | Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Other risk of bias | |

| DANTE (Italy)61 | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low and low |

| DLCST (Denmark)63 | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low and low |

| MILD (Italy)69 | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low | Inadequate and inadequate |

| NLST (USA)71 | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low and low |

Relative to the other trials measuring mortality, MILD69 appeared to be considerably more open to bias than DANTE, DLCST or NLST. 61,63,71 Like the other trials it did blind assessment of outcome, achieve complete follow-up and avoid selective reporting. Again, like the other trials, it did not achieve allocation concealment or blind participants. However, there were considerably greater concerns about the randomisation process, which were not true of the other trials. First, there was lack of detail about the process of randomisation. Second, there were marked differences in three of the baseline characteristics (participant sex, current smoking status and FEV1). This greatly challenges the assumption that randomisation achieved equivalence between the CT screening arm and the control arm, which is the fundamental premise of all RCTs. The comparison between the two intervention arms may not have been as badly affected.

An additional table illustrates the size of the imbalance in baseline characteristics between the four trials contributing results on mortality (Table 6).

| Study characteristics | Study (number of participants) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DANTE78 (n = 2450) | DLSCT63 (n = 4104) | MILD69 (n = 4099) | NLST71 (n = 53,456) | ||||||

| Trial arm | LDCT | Control | LDCT | Control | LDCT (biennial) | LDCT (annual) | Control | LDCT | Control |

| n (%) | 1264 (51.6) | 1186 (48.4) | 2052 (50) | 2052 (50) | 1186 (28.9) | 1190 (29.0) | 1723 (42.0) | 26723 (50) | 26733 (50) |

| Sex (% of n male) | NR | NR | 55.9a | 54.6a | 68.5 | 68.4 | 63.3 | 59.0 | 59.0 |

| Age (years), mean | 64.6 | 64.6 | 57.9a | 57.9a | 58.2a | 58.3a | 57.6a | 61.6a | 61.6a |

| Occupational exposure (%) | 31.3 | 34.1 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 27.9 | 28.3 |

| Smoking | |||||||||

| Current smokers (%) | 56.5 | 57.4 | 75.3a | 76.9a | 68.3 | 68.9 | 89.7 | 48.2 | 48.3 |

| Pack-years (mean) | 47.3 | 47.2 | NR | NR | 39b | 39b | 38b | 56.0 | 55.9 |

| Smoking duration (years), mean | NR | NR | 38.5a | 38.6a | 38.4a | 38.3a | 38.5a | 43.1 | 43.1 |

| Cigarettes/day (mean) | NR | NR | 19.2a | 18.6a | 26.3a | 26.8a | 25.2a | 28.5 | 28.4 |

| Duration smoking cessation in former smokers (years), mean | NR | NR | 4.2a | 4.4a | NR | NR | NR | 7.7a | 7.7a |

| Comorbidities, n | |||||||||

| Respiratory | 35.3 | 31.2 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Chronic bronchitis, emphysema or COPD | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 17.5 | 17.4 |

| Hypertension | 36.1 | 37.7 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 35.1 | 35.7 |

| Cardiac | 12.6 | 13.9 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Heart disease or heart attack | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 12.9 | 12.5 |

| Stroke | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 2.8 | 2.8 |

| PVD | 10.3 | 9.0 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Diabetes | 8.3 | 8.4 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 9.7 | 9.7 |

| Malignancies | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 4.0 | 4.5 |

| Lung function | |||||||||

| FEV1 (litres) | NR | NR | 2.9 | 2.9 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| FEV1 < 90% predicted | NR | NR | NR | NR | 27.7 | 28.2 | 19.2 | NR | NR |

| Other data available | Social status | Paper indicates that only ‘selected baseline characteristics’ were reported | Race; education; marital status; BMI categories | ||||||

In the MILD trial,69 percentage of male participants and smoking history were similar at baseline. However, there were more current smokers in the usual-care group (90%) than in the annual (69%) and biennial (68%) screening groups. There were more participants aged < 55 years in the usual-care group (38%) than in the annual (33%) and biennial (32%) screening groups. Furthermore, it should be noted that fewer participants in the usual-care group (19%) had FEV1 per cent predicted that was < 90%, compared with both the annual screening (28%) and biennial screening groups (28%). This indicated that the overall lung functions of patients in both annual and biennial screening groups were worse at baseline compared with the usual-care group, which could threaten the validity of the results.

The baseline imbalances in the other trials, DANTE,61 DLCST63 and NLST71 were much less common and, when they did occur, were much less marked in size.

Risk of bias for psychological consequences and health-related quality of life

Four included trials contributed information on psychological consequences and HRQoL. Two were common to mortality outcomes (DLCST and NLST)63,71 and two were trials which currently did not contribute evidence on mortality but are likely to do so in the future (NELSON and UKLS). 55,57 The risks of bias in the four RCTs, DLCST,63 NELSON,56,57 NLST71 and UKLS,55 contributing evidence on psychological consequences and HRQoL are shown in the Table 7.

| Study identifier (country) | Criteria | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random-sequence generation (selection bias) | Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Blinding outcome assessment (detection bias) | Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Other risk of bias | |

| DLCST (Denmark)63 | Low | Unclear | High | High | High | Low | Unclear and low |

| NELSON (Dutch-Belgian trial)57 | Unclear | Unclear | High | High | High | Low | Unclear and low |

| NLST (USA)71 | Unclear | Unclear | High | High | High | Low | Unclear and unclear |

| UKLS (UK)55 | Low | Low | High | High | High | Low | Unclear and low |

The most important feature is that, relative to mortality, the risk of bias for psychological consequences and HRQoL is much higher. This arises both because the outcomes are more subjective and, hence, susceptible to the lack of blinding that occurs across all the included trials, but also because losses to follow-up were often in excess of 10% and unequal between CT screening arms and the controls.

The UKLS was the only trial that demonstrated both good allocation sequence and allocation concealment. 55

None of the included trials was clear about whether or not it was adequately powered to assess the outcomes in question, which was often further complicated by the fact that samples of the whole-trial population were used to measure the effectiveness of screening on psychological consequences and HRQoL. UKLS was the largest study with respect to these outcomes, even though it was a pilot study. 55

There were no risk-of-bias issues with respect to baseline equivalence as there were for mortality. NLST did not demonstrate baseline equivalence, but it may be reasonable to assume this from the demonstration of baseline equivalence for the whole trial and that the sample of participants used for assessment of psychological consequences and HRQoL appeared to be random. 71

Risk of bias for smoking behaviour

Three included trials contributed information on smoking behaviour. Two were common to mortality outcomes (DLCST and NLST),63,71 and one was a trial that currently does not contribute evidence on mortality but is likely to do so in the future (NELSON). 57 The NLST reported its findings on smoking in two parts: one for each of its two contributing research networks, Lung Screening Study (LSS) and American College of Radiology Imaging Network (ACRIN). The risk of bias for each substudy was the same (Table 8). Evidence on smoking behaviour from the UKLS study was in press at time of writing, but has subsequently been published. 80 The risks of bias for the three RCTs, DLCST,63 NELSON56,57 and NLST71 contributing evidence on smoking behaviour are shown in Table 8.

| Study identifier (country) | Criteria | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random-sequence generation (selection bias) | Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Blinding outcome assessment (detection bias) | Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Other risk of bias | |

| DLCST (Denmark)63 | Low | Unclear | High | High | High | Unclear | Unclear and low |

| NELSON (Dutch-Belgian trial)57 | Unclear | Unclear | High | High | High | Low | Low risk and low |

| NLST – LSS (USA)71 | Low | Unclear | High | High | Low | Unclear | Unclear and low |

| NLST – ACRIN (USA)70 | Low | Unclear | High | High | Low | Unclear | Unclear and low |

As for psychological consequences and HRQoL, the most important feature is that, relative to mortality, the risk of bias for smoking behaviour is much higher. This mainly arises because the outcomes are more subjective and, hence, susceptible to the lack of blinding that occurs across all the included trials, but also because of losses to follow-up, which were often > 10% and unequal between CT screening arms and the control arms. NLST performed best with respect to loss to follow-up, with levels well below 10%, but it did not report whether or not the levels were similar in both the CT screening and CXR screening arms. 71 However, despite this, it was categorised as being at a low risk of bias with respect to attrition bias. The risk of bias for NLST71 arising from lack of blinding may have been less than DLCST63 and NELSON57 because it had an active control arm rather than usual care. Across all trials, smoking behaviour was generally based on participant self-report with little or no confirmation of true smoking status using measurements such as exhaled carbon monoxide.

None of the included trials was clear about whether or not it was adequately powered to assess smoking behaviour. Given the nature and frequency of smoking behaviour, it seems likely that DLCST and NLST were adequately powered to assess it. 63,71 However, the smoking behaviour study for NELSON was undertaken on a very small subsample of the whole trial. 57 A power calculation was done to confirm that the sample size was sufficient to detect a 7% difference in quit rate.

There were no risk-of-bias issues with respect to baseline equivalence as there were for mortality.

Risk of bias for assessments of characteristics based on a single arm of a randomised controlled trial

Many studies provided information on outcomes measured in one arm of the study only, usually the intervention arm. These are not randomised comparisons and are hence open to the same biases as case series, particularly confounding. The data were summarised in the results sections for completeness. However, it should be clearly noted that they do not provide the same robustness of evidence as the randomised comparisons even though they are derived from RCTs, and they are clearly separated from the randomised comparisons in the results section as a consequence. The results from single arms of the RCTs have not been formally quality assessed, beyond noting that they are at very high risk of bias when making comparisons.

Results of clinical effectiveness

Comparative outcomes

Lung cancer mortality

Four RCTs (DANTE, DLCST, MILD and NLST) assessed the effects of LDCT screening compared with either usual care (no screening) or the best available care (CXR screening), and reported lung cancer mortality at long-term follow-up. 61,63,69,71 Over the long-term follow-up, it was likely that CXR could be an element that constituted usual care for the early detection of lung cancer in a high-risk population. Therefore, usual care in this context was not dissimilar to the best available care when CXR was used in early detection of lung cancer. For this reason, we performed statistical pooling of all the four RCTs on mortality outcomes. All trials were conducted in participants at high risk for lung cancer. We only performed statistical pooling for trials that reported lung cancer mortality data with ≥ 5 years of follow-up, using the random-effects model.

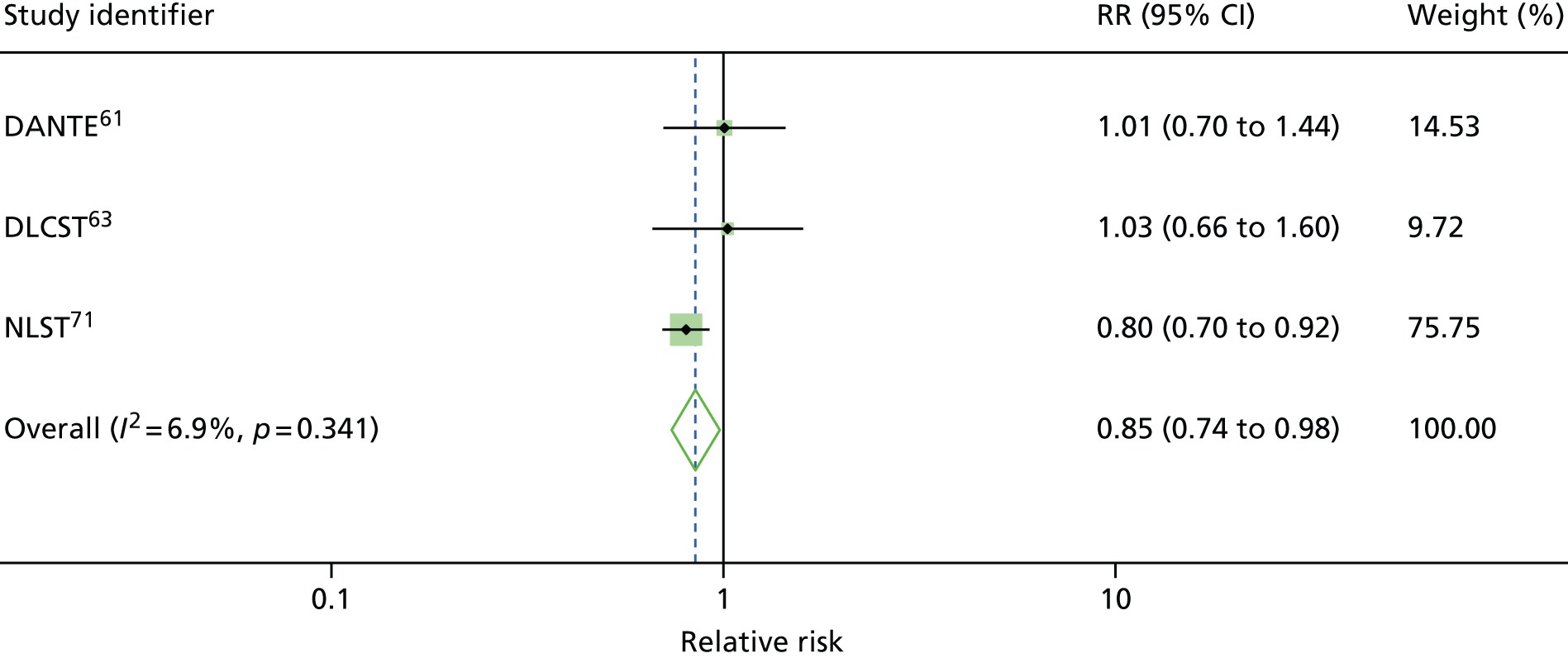

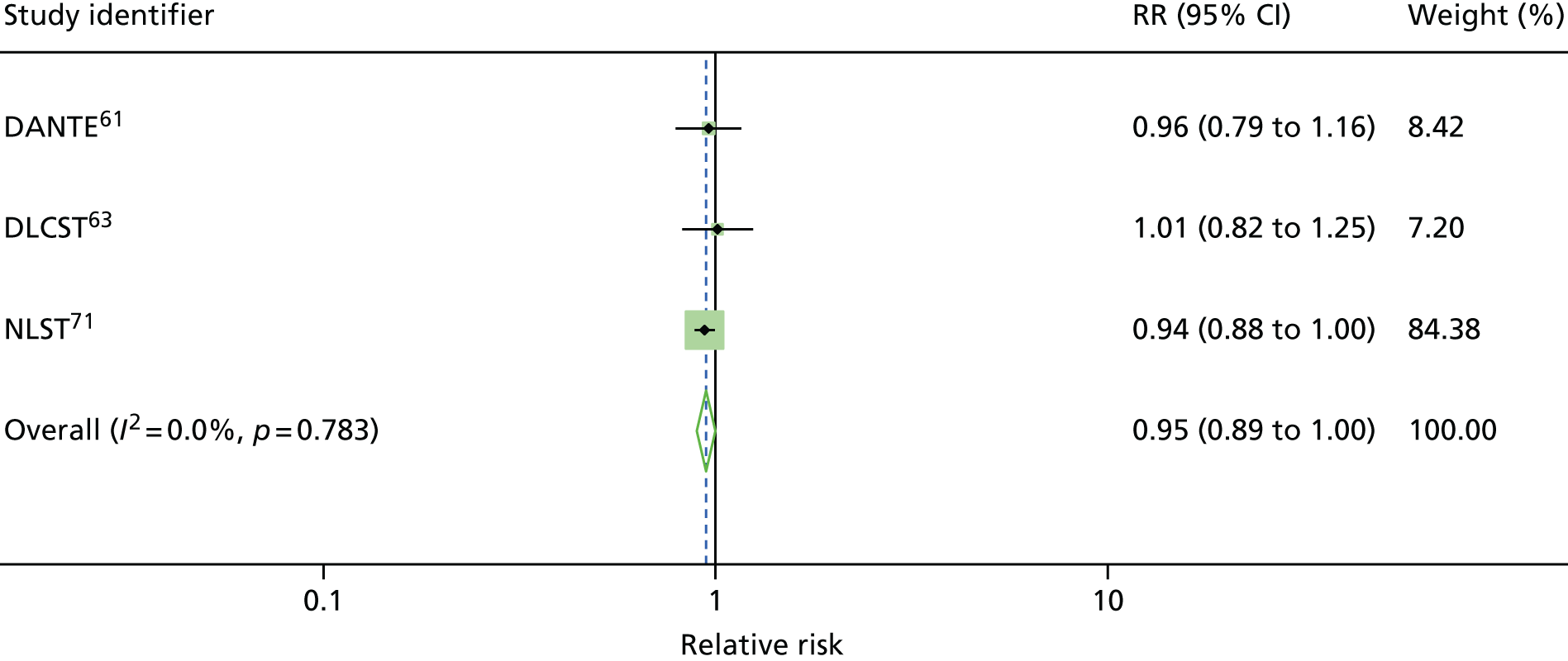

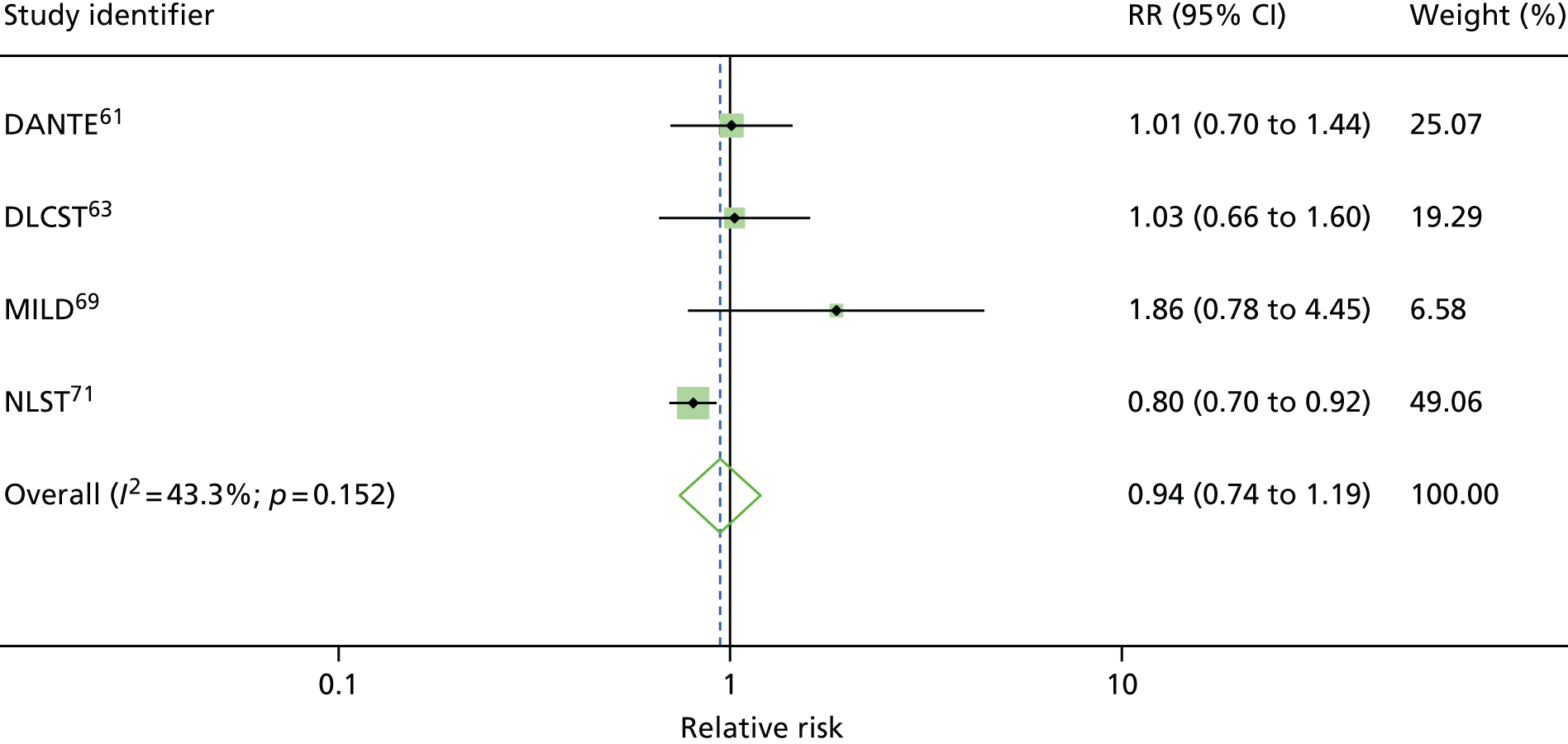

Figure 2 shows the overall pooled result of four RCTs comparing LDCT screening with controls. When compared with controls (usual care/best available care), LDCT screening was associated with a non-statistically significant reduction in lung cancer mortality (pooled RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.74 to 1.19) with up to 9.80 years of follow-up. There was moderate heterogeneity in the magnitude of effects (I2 = 43.3%).

FIGURE 2.

Lung cancer mortality: overall results.

It is important to note that, given the moderate heterogeneity observed with this outcome (I2 = 43.3%), the pooled non-statistically significant decrease in lung cancer mortality (pooled RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.74 to 1.19) should be treated with caution.

Among these four RCTs, the MILD trial69 was judged to be of poor quality, whereas the remaining trials were judged to be of moderate to high quality (see Risk of bias for lung cancer and overall mortality). 55 We explored the impact of trial quality on the robustness of overall results.