Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 14/220/06. The contractual start date was in February 2016. The draft report began editorial review in November 2017 and was accepted for publication in June 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Gill Livingston is on the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) postdoctoral fellowship board. Gill Livingston and Penny Rapaport have grants from NIHR/Economic and Social Research Council, NIHR Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme and the Alzheimer’s Society and are supported by North Thames NIHR Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC). Simon D Kyle reports grant funding from NIHR HTA, NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre, Arthritis Research UK and the Dr Mortimer & Theresa Sackler Foundation. Claudia Cooper and Gill Livingston are supported by the University College London NIHR Biomedical Research Unit. James A Pickett is an employee of the Alzheimer’s Society. Colin A Espie reports grants from the NIHR HTA programme, NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre, the Wellcome Trust, Education Endowment Foundation and the Dr Mortimer & Theresa Sackler Foundation. In addition, he has a patent US Patent Application Serial No. 14/172,347 INTERACTIVE SYSTEM FOR SLEEP IMPROVEMENT: Docket No. HAME-001 issued and is co-founder and Chief Medical Officer of Big Health Ltd (London, UK), which has developed Sleepio, an online digital cognitive–behavioural therapy intervention for insomnia. He is also a shareholder in Big Health Ltd.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Kinnunen et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Scientific background

The prevalence of dementia and its impact, on both an individual level and a societal level, continue to increase. In 2015, there were 47 million people living with dementia worldwide. 1 It is estimated to cost US$818B and projected to become a trillion-dollar disease in 2018. 2 In the UK specifically, 850,000 people are living with dementia, a figure expected to rise to 1 million by 2021, and to double to 1.7 million over the next 30 years. 3 Currently, dementia care costs in the UK amount to approximately £26B, with the majority (£17.4B) falling on the people with dementia and their families. 3,4 Two-thirds of people with dementia live at home, where family members and informal carers provide most of the care. 3

Sleep disturbances are common in older people without dementia, as sleep may be adversely affected by physical health state and pain. In dementia, there are additional factors that cause poor sleep. The prevalence of sleep disturbances in those with neurodegenerative dementias is estimated to be 25–40%,5,6 with one meta-analysis of the prevalence of sleep disturbances in people with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) finding a pooled prevalence of 39%. 7

Sleep disturbances include reduced night-time sleep, fragmented sleep and wandering,8,9 and are correlated with excessive daytime sleepiness and depression. 10 They may be both caused by and worsen AD and other dementias. Recent research has suggested a correlation between sleep disturbances and amyloid beta (Aβ) deposits. 11 Dementia may also lead to impaired production of the hormone melatonin through structural and functional alterations to the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN). 12,13 The circadian rhythm of melatonin production, high levels at night and low levels during the day, helps control the sleep–wake cycle. 14 People with dementia may wake during the night and not be aware of the time, or be frightened because they do not know what is happening. Dementia can therefore lead to decreased regularity of sleep, impaired sleep initiation and difficulty maintaining sleep at night, and wakefulness during daylight hours. 15

Sleep acts as a restorative process for the brain and supports all aspects of mental and physical life, being a major determinant of day-to-day function and quality of life. 16 In turn, sleep disturbances reduce quality of life and are distressing for family members, whose sleep is often affected. Sleep disturbances in dementia increase family carer burden, predict their depressive symptoms and lead to care home admissions, elevating the individual, societal and economic costs associated with dementia. 10,17,18 Importantly, paid night-time care can be unaffordable or unfeasible for people who wish to continue caring at home.

Explanation of rationale

The causes of sleep disruption in individuals with dementia are multifactorial, and include physiological dementia-related changes, pain, environmental and behavioural factors, and medication side effects. There are currently no known effective treatments. Health teams use a mixture of sleep hygiene measures and psychotropic medication, extrapolated from other conditions. These confer limited benefit, and sedative medications may cause harm. A Cochrane review19 of studies examining the effects on actigraphy sleep measures of drugs found no definitive effectiveness evidence. These conclusions are supported by recent investigations20–23 (mostly in people with AD) that similarly found no efficacy evidence for any drugs or melatonin. Cholinesterase inhibitors and glutamate receptor antagonists, given particularly to people with AD or dementia with Lewy bodies, may increase wakefulness, but may hypothetically also support sleep through improved cognition. 24,25 However, there is no evidence of their efficacy. Overall, there is no conclusive evidence to suggest efficacy for any of these pharmacological options in the treatment of sleep disturbances in dementia.

In addition, people with dementia are often frail with multiple comorbidities, and non-pharmacological treatment options should therefore be the first line for sleep management. However, most evidence about non-pharmacological treatments comes from small-scale studies often lacking in methodological rigour, leading to insufficient, conflicting evidence. 26 The need for better research into such treatments for sleep disorders is mentioned specifically in the National Dementia Strategy,27 and the outputs of the 2010 Ministerial Dementia Research Summit and 2011 National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Dementia Research Workshop, summarised in the Ministerial Advisory Group for Dementia Research (MAGDR) final report28 Priority Topics in Dementia Research in February 2011. As with many other problems, studies consistently indicate that patients and their doctors would prefer non-drug approaches for sleep problems. 29

One approach with suggested potential to improve sleep disturbances is bright light therapy. A systematic review and meta-analysis30 and a separate case series31 found that light therapy had small to medium effects on sleep disturbances in the general population.

There have also been recent small pilots of non-pharmacological interventions aiming to reduce sleep disturbances in people living with dementia. In one study, 7 out of 14 (50%) people with dementia and carer dyads completed a sleep education programme, which was delivered to the carers in a group setting. 32 In another pilot study, by Gibson et al. ,33 9 out of 15 (60%) dyads completed a programme incorporating light therapy, exercise and sleep education. Both studies were methodologically limited, with unsatisfactory completion rates, but the interventions showed some promise in alleviating sleep disturbances.

Neurodegenerative dementias are commonly characterised by circadian rhythm disruption attributable to progressive loss of SCN neurons. 34 Thus, strengthening circadian rhythmicity through bright light therapy is theoretically appealing. However, light therapy administered in a non-individualised way, for example on the wrong side of the phase–response curve, may exacerbate sleep disruption.

In the current study, the vision was to build on this contradictory, and as yet incomplete, evidence by bringing together expertise in clinical interventions in dementia and sleep, statistics and input from family carers, and to deliver the intervention individually to fit the specific problems of each participant in the study. The aim was to develop and test a manual to improve sleep and, therefore, quality of life for those with dementia and their families. Through our previous work with STrAtegies for RelaTives (START), a coping strategy-based manual for family carers of people with dementia, short-term and long-term clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness have successfully been demonstrated. 35,36 This provided an ideal platform on which to build our new manual: Dementia RElAted Manual for Sleep; STrAtegies for RelaTives (DREAMS START). It was planned that DREAMS START would be a manualised multicomponent intervention, delivered to carers by clinically supervised psychology graduates, comprising a cognitive–behavioural component, light therapy, behavioural activation, relaxation and coping skills for families. Details of its development and content are below.

Sleep disturbances are complex and their causes and best management strategies differ between individuals. It can also be difficult for family carers to attend a group at a specific or fixed time. Thus, our intervention was individually tailored. It used natural dusk and daylight (whenever feasible) as well as other light sources to manage endogenous melatonin production. In addition to bright light therapy and strategies to increase daytime activity, we planned the intervention to include cognitive–behavioural techniques for sleep management, which a Cochrane review had found effective in older adults without dementia and in family carers of people with dementia. 37,38 A collaborative, non-prescriptive model was central when this intervention was delivered. Family carers were encouraged to try different strategies and note in their manual what worked for them. Psychology graduates were trained as sleep therapists. The therapists had a similar skillset to Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) practitioners, and psychology assistants in memory and mental health services. The intervention was designed to be delivered by therapists with this skill level so that it could be delivered by IAPT-based psychological well-being practitioners and secondary care psychology practitioners in the future. This research has the potential to improve sleep and quality of life of people with dementia and their family carers, in a feasible and scalable intervention without the side effects of medication. If found to be clinically effective in a future full-scale trial, this intervention should also be cost-effective: it is cheap and may delay care home admission.

Specific objectives

Our research question was: how feasible is a pragmatic, randomised study to investigate the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a manualised intervention (DREAMS START) to manage NHS patients with dementia and significant sleep disturbance living in their own homes?

Aims

The aims were to develop a manualised behavioural intervention for sleep disturbances in dementia and examine the feasibility of a full-scale trial.

Objectives

The objectives were to:

-

obtain estimates of acceptability and feasibility that will inform continuation to the main trial, specifically to estimate [with 95% confidence intervals (CIs)] the proportion of eligible participants who agreed to participate in the trial and the proportion of participants offered the intervention that adhered to it

-

obtain estimates required for the main trial’s sample size calculation in relation to potential primary outcomes [standard deviations (SD); correlation between baseline and follow-up measurements and drop-out rate]

-

use qualitative interviews to assess acceptability of the intervention and to detail any required refinements.

Chapter 2 Methods

Ethics

The trial was approved by the London – Queen Square Research Ethics Committee (reference number 16/LO/0670; see Appendix 1).

Trial design

This was a cluster-randomised, parallel-group superiority trial, with blinded outcome assessment. Participants were allocated 2 : 1 to the intervention or treatment-as-usual (TAU) arm.

Participants: eligibility criteria

People with dementia and their family carer were included, and the inclusion criteria for such dyads are laid out in the feasibility study below. To help determine feasibility for a full trial, people with a range of types of dementia and living situations were included. We wanted to find out if there were obstacles in such wide inclusion criteria, to enable us to consider criteria for a full trial. In particular, people who had an alcohol-related dementia or lived alone or were looked after by paid carer were not excluded, although it was uncertain how this would affect delivery of the therapy.

People with dementia

Adults with dementia (any type and severity) and clinically significant sleep difficulties [Sleep Disorders Inventory (SDI)39 item score of ≥ 4 on screening] that were judged a problem by the person with dementia or their family were included. If the person with dementia did not have capacity to give consent, a consultee’s declaration was sought. Patients living in a care home were excluded. Those with a primary sleep disorder diagnosis (e.g. sleep apnoea), rather than dementia-related sleep problems, were also excluded.

Carers

Primary family carers of the person with dementia were included for quantitative assessment interviews and intervention delivery. When the carer who spent most time with the person with dementia was not a family carer, then the paid carer was able to participate in the intervention. The family carer, however, completed the carer assessment measures. All carers provided emotional or practical support to the person with dementia at least weekly. Carers who were unable to give informed consent, or with probable dementia, were excluded.

Study settings

NHS trusts

Participants were primarily recruited from two NHS trusts in London: Camden and Islington NHS Foundation Trust (site 1) and Barnet, Enfield and Haringey Mental Health NHS Trust (site 2). Both trusts provided funding to cover the excess costs resulting from training, intervention delivery and clinical supervision. Clinicians approached people with dementia and their family carers who were attending one of the five memory services: (1) Camden, (2) Islington, (3) Barnet, (4) Enfield or (5) Haringey. Those interested in the study were asked to give permission for the research team to approach them, and were given an information sheet. Following contact by our team, an appointment was arranged to obtain informed consent in the potential participants’ homes (or in the research team’s office if preferred). A baseline assessment was carried out after this. Intervention delivery and follow-up assessments also took place in the participants’ homes.

Join Dementia Research

In addition, the research team approached potential ‘matches’ through Join Dementia Research (JDR). This is an online and telephone service developed and launched in 2014/15 by the NIHR. It aims to make it easier for people with dementia and other interested members of the public to participate in dementia studies. People register their interest, providing basic or more detailed demographic and clinical information and their contact details (including their preferred means of contact). The registrant or a named representative can then be contacted by researchers to discuss the potential suitability of studies. To recruit from this site [site 3, University College London (UCL)/JDR], potential matches with any dementia diagnosis listed on JDR were identified. We ticked ‘yes’ to ‘Has next of kin?’, chose ‘Include empty or NULL values’, ticked ‘yes’ to ‘Has a carer?’, ticked ‘no’ to ‘Volunteer is a carer?’, ticked ‘no’ to ‘Volunteer cares/supports a person with dementia?’, and selected ‘More than 3 times per week’ for ‘Contact with carer’ (‘Include empty or NULL values’), and selected ‘Private Residence’ and ‘Assisted Living Accommodation’ for ‘Accommodation Type’ (‘Include empty or NULL values’). Owing to limited resources, we defined our search area based on proximity to UCL.

Data collection

Family carers were interviewed at screening/baseline (pre randomisation) and at the 3-month follow-up to collect data on the person with dementia and the carer. For around one-third of the participant dyads (22/62 randomised), each value entered into the participant database was double-checked; no systematic errors were found.

Patient measures

Demographic and clinical characteristics

-

Sociodemographic details (i.e. sex, date of birth, type of dementia diagnosed, age when left education, last occupation, current marital status, ethnicity) were collected at baseline. We had information on all potential participants’ sex, including those who did not provide consent to be screened, those who were not eligible and those who were not randomised.

-

Type of dementia was recorded from clinical information.

-

Severity of dementia was measured using Clinical Dementia Rating™ (CDR)40,41 through informant information at baseline. This is a reliable and valid instrument for rating the severity of dementia. 42 It is used to rate performance in memory, orientation, judgement and problem-solving, community affairs, home and hobbies, and personal care. This information was used to classify dementia severity of clinically diagnosed patients or those on JDR into very mild (0.5), mild (1), moderate (2) or severe (3).

-

Rescue medication’s role: all prescribed psychotropic medication and melatonin was measured at baseline and 3 months by completing the Client Service Receipt Inventory (CSRI),43 which incorporates a list of all medications in the previous 3 months. Use of the following was recorded:

-

anxiolytics and hypnotics

-

antipsychotics

-

antidepressants

-

other psychotropics.

-

-

Reported side effects: side effects were measured using a study-specific Safety and Tolerability Assessment (see Appendix 2) to record the occurrence of falls, dizziness, headaches and gastrointestinal symptoms (appetite or bowel symptoms) and any other side effects at baseline and 3 months.

Potential outcomes for the main trial

-

Sleep disturbance in the person with dementia was measured using the SDI39 at screening and 3 months. The SDI is a standalone tool for assessing sleep disorder symptoms in people with dementia, developed for use to measure outcomes in original melatonin trials. It has been used in pharmacological and non-pharmacological studies and validated against actigraphy and clinical variables. The SDI consists of the seven sleep subquestions of the sleep and night-time domain of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI). 44 These are: (1) difficulty falling asleep, (2) getting up at night, (3) wandering, pacing or conducting inappropriate activities at night, (4) awakening the carer at night, (5) awakening at night, dressing, planning to go out, thinking that it is morning, (6) awakening too early in the morning and (7) excessive daytime sleepiness. SDI item scores are based on the carer’s ratings on each of the seven symptoms separately. Each item is rated according to frequency (scale 0–4) and severity (scale 0–3) of sleep-disturbed behaviours and, when frequency and severity are multiplied, possible item scores range from 0–12. Those who scored ≥ 4 on any individual item were judged to have clinically significant sleep disturbance and were eligible for the study. The SDI mean global score, which is often reported, is the total frequency multiplied by severity, divided by 7.

-

Neuropsychiatric symptoms were measured using the NPI44 at baseline and 3 months. This is a validated instrument with 12 domains of neuropsychiatric symptoms. A single frequency and severity rating is given for all behaviour subquestions within a domain, with each domain scoring between 0 and 12; higher scores mean increasing severity. A summed score out of 144 captures total neuropsychiatric symptoms.

-

Daytime sleepiness was measured from the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS)45 at baseline and 3 months. This is an eight-item measure assessing the tendency to sleep/doze in specific daily situations (possible score range 0–24; a score of > 10 indicates excessive sleepiness).

-

Quality of life was measured using the Dementia Quality of Life – Proxy (DEMQoL-Proxy)46 at baseline and 3 months. It is a 31-item interviewer-administered questionnaire answered by a carer. It is a responsive, valid and reliable measure of quality of life in people with dementia with satisfactory psychometric properties. 47

-

Services use was measured using the CSRI at baseline and 3 months. It is widely used for dementia trials and will delineate treatment as usual (TAU) as well as treatment for those in the active arm of the study.

Wrist-worn Actiwatches, worn 24 hours a day for 2 weeks at baseline pre randomisation and again 3 months after randomisation, provided estimates of rest–activity rhythms, light exposure and sleep. Actigraphy has theoretical advantages for patients who may not be able to remember well enough to accurately fill in questionnaires or sleep diaries. It has been validated against polysomnography (PSG) in populations including older adults without dementia (one study48 of 77 people, with a mean age of 35 years) for its accuracy at correctly detecting sleep, wakefulness and wakefulness after sleep onset. The Actiwatch detected sleep in the whole population with 96.5% accuracy, but was not as good at detecting wakefulness (32.9% accuracy), and this became worse with increasing age. Another study of older women without dementia (with a mean age of 69 years) found that wrist actigraphy detected sleep less accurately in this age group and was unacceptable for those with low measures of sleep efficiency. 49 However, it has been used in 10 nursing home residents with severe dementia to estimate sleep during night-time, and the measures significantly correlated with total sleep time from electroencephalographic recordings. 50 We used the MotionWatch 8 (herein referred to as ‘the Actiwatch’), a Conformité Européenne (CE)-marked class 1 (low-risk) medical device (CamNtech Ltd, Cambridge, UK). Such non-intrusive, reusable Actiwatches have been used successfully in previous trials of people with dementia and sleep disturbance. 51 The aim was to use a minimum of 1 week’s worth of data. The participants were given written instructions (see Appendix 3). It was ensured that that the person with dementia and their carer between them understood the instructions and had the opportunity to ask questions. Whenever possible, the watch was placed on the wrist of the participant’s non-dominant hand, and variability was controlled among the watches by ensuring that the participants wore the same watch at baseline and follow-up. The data were recorded in MotionWatch Mode 1, which uses a single-axis algorithm and peak detection, sampled at 50 Hz, and processed into 60-second epochs. Each recording was started in the evening on the day of the baseline or follow-up assessment (preferably at 17:00) and continued for a minimum of 14 days, after which the watch was collected. Carers were asked to use a sleep diary (see Appendix 3) to keep a record of the bedtimes and rise times of the person with dementia, or, as an alternative, to indicate these times by pressing the Actiwatch’s ‘event marker’ button. These were used to define each participant’s sleep analysis window. We also asked the carers to write down (e.g. in the sleep diary) any occurrences when the watch was not worn for > 1 hour. Participants were encouraged to contact the research team if they had any further questions about the watch.

-

Sleep measures:

-

Sleep efficiency – sleep time expressed as a percentage of time in bed. This captures both initiation and maintenance of sleep, reflecting the proportion of time in bed spent asleep, and has been found to be reliably impaired in actigraphy studies of people with dementia and sleep problems.

-

Sleep time (minutes) – the total time spent in sleep according to the epoch-by-epoch wake/sleep categorisation. As the Actiwatch infers, time asleep is not ‘actual sleep time’.

-

Wake time (minutes) – the total time spent awake according to the epoch-by-epoch wake/sleep categorisation. As the Actiwatch infers, time awake is not ‘actual wake time’ but it is the label used.

-

Time of ‘lights out’ or going to bed.

-

Time of falling asleep.

-

Time of waking up.

-

Time of getting up.

-

Time in bed (hours) – the total time between ‘lights out’ and getting up.

-

Fragmentation index – the degree of fragmentation of the sleep period, calculated by summing mobile time (%) and immobile bouts of ≤ 1 minute (%).

-

-

Circadian rest–activity rhythm metrics/non-parametric circadian rhythm analysis (NPCRA) measures to assess the timing, amplitude and stability of rest–activity rhythms:

-

Relative amplitude – the amplitude of circadian rhythm (range 0–1), calculated by dividing the difference between average activity in the most active (M10) and most restful (L5) periods by the sum of M10 and L5.

-

Interdaily stability – the degree of regularity in the activity–rest pattern, ranging from a total lack of rhythm (0) to a perfectly stable rhythm (1).

-

Intradaily variability – the degree of fragmentation of activity–rest periods (range 0–2), from prolonged periods of activity and rest over 24 hours to multiple short periods.

-

L5 – activity count for the 5 most restful hours.

-

L5 – start hour (of the 5 most restful hours).

-

M10 – activity count for the 10 most active hours.

-

M10 – start hour (of the 10 most active hours).

-

-

Core night-time analysis sleep measures:

-

Core night-time (00.00 to 06.00) sleep efficiency.

-

Core night-time (00.00 to 06.00) sleep time (minutes).

-

Core night-time (00.00 to 06.00) wake time (minutes).

-

Carer measures

Demographic characteristics

Sociodemographic details [sex, date of birth, current or last occupation, carer relationship to person with dementia, co-resident carer (yes/no), average number of visits per month (non-resident carer) and ethnicity] were collected at baseline. The details of a carer’s sex and relationship to the person with dementia were available for all potential participants referred to the study, including those who did not provide consent to be screened, those who were not eligible and those not randomised.

Potential outcomes for the main trial

-

Carer sleep quality was measured using the following:

-

The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI)52 at baseline and 3 months. It is a validated, reliable instrument to measure the carer’s sleep (since it is commonly disrupted by sleep–wake patterns of the person with dementia).

-

The Sleep Condition Indicator (SCI)53 at baseline and 3 months (a new eight-item scale developed in the UK with data on tens of thousands of people of all ages). It characterises sleep both dimensionally (like PSQI) and against insomnia disorder criteria (which PSQI does not).

-

-

Mood disturbance was measured using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) at baseline and 3 months. 54,55 It is a validated, reliable measure of mood in carers throughout the age groups.

-

Subjective burden for carers was measured using the Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI) at baseline and 3 months. 56 It is the most commonly used and well-validated measure of burden for carers of people with dementia and was used in this report to indicate whether or not burden may be changed by the intervention.

-

A carer’s health-related quality of life was measured using the Health Status Questionnaire-12 (HSQ-12) at baseline and 3 months. 57 It is a 12-item quality-of-life scale validated throughout the age group.

Interventions

DREAMS START intervention development

Conceptualisation of manual elements

The DREAMS START intervention was developed using an iterative and collaborative coproduction process with the team that developed the START and Managing Agitation and Raising Quality of Life (MARQUE) manualised interventions for carers of people with dementia (GL, PR, CC), experts in manualised cognitive–behavioural interventions for sleep disorders (CAE, SDK), our collaborators from the Alzheimer’s Society (JAP, RH) and carers of people with dementia who have experienced sleep disturbances, and through practice sessions as part of therapist training. Figure 1 summarises the manual development process.

FIGURE 1.

Development process of the DREAMS START manual.

Development of the intervention began in February 2016 when the project management team met and agreed that DREAMS START would be a six-session, multicomponent intervention, based on the best existing evidence at the time,26,35,37,38,58–61 comprising a cognitive–behavioural component (including psychoeducation, coping skills for families, and activities for people living with dementia) and light therapy. Figure 1 provides an overview of this process.

The first stage of intervention development was to share the existing StrAtegies for RelaTives (START)35 and Oxford’s manuals on cognitive–behavioural therapy for insomnia62 within the team and to consider which elements to build into the DREAMS manual. One month later, Gill Livingston, Simon D Kyle and Penny Rapaport met face to face and, joined by Colin A Espie on the telephone, agreed the main initial structure and content of the six sessions. At this stage, it was agreed that the intervention would be both interactive and individualised, using the actigraphy data collected at baseline to inform a shared understanding of the person with dementia’s night-time settling and waking problems, and their daytime sleepiness/fatigue and to help generate an optimal ‘sleep window’. As in the team’s previous work, a collaborative, non-prescriptive model was adopted, explicitly encouraging family carers to build on their own experience of what they have found works and to develop and use new techniques and behavioural strategies, recording what works in their manual, and continuing to use successful strategies. A specific focus was incorporated within sessions on identifying and overcoming barriers to changing behaviours and routines of people with dementia and considering how to minimise the risk of harm when people with dementia are awake at night. In line with the form of the START intervention, each session included a stress reduction exercise, a between-session practice task, a recapitulation on the previous session and troubleshooting around putting strategies into practice. Five of the same stress reduction techniques from the START intervention were used in the DREAMS START manuals (sessions 1–5). All manuals from the START intervention are available freely online. 36,60

Session structure

Penny Rapaport and Simon D Kyle developed initial drafts of the six manual sessions (for further details, see Intervention content). These were as follows:

-

understanding sleep and dementia

-

making a plan

-

daytime activity and routine

-

difficult night-time behaviours

-

taking care of your own sleep

-

what works? Using strategies in the future.

Each session, after the first one, followed a similar structure. It began with a recapitulation of the previous week’s session and a discussion about what the carer had achieved since then. The new topic was then introduced, and the carer and therapist generated relevant, individually tailored, plans that the carer could implement in the coming week. At the end of the session, the therapist talked the carer through a new relaxation exercise.

Drafts of the manuals were initially circulated within the project management team and revised based on feedback on both form and content. The goal was for the manuals to present comprehensive information succinctly and in plain English, without jargon, in an interactive format that encouraged carers to actively engage in sessions. This was done by including both theoretical components and practical exercises that called on the carers’ own experiences and were discussed during the session. In addition, vignettes were used to involve the carer and to illustrate points, and to display diagrams and graphical information simply and clearly. We tried to maintain a balance between information provision and interactive exercises, to ensure that the carer participated in, rather than was lectured about, the manual. Large chunks of overly technical information were avoided and information was presented in a clear and engaging manner.

Patient and public involvement in the intervention development

After making initial revisions, family carers were invited, via the Alzheimer’s Society Research Network (ASRN), to attend a focus group (in May 2016) to provide feedback on the drafts and to share their experiences of what strategies they did and did not find useful in caring for a relative with sleep difficulties. The group was facilitated by Penny Rapaport and Kirsi M Kinnunen, based on a semistructured topic guide (see Appendix 4). All carers consented to the discussion being audio-recorded, and discussions were then externally transcribed and the data were entered into NVivo 11 software (QSR International, Warrington, UK) and analysed using thematic analysis. 63,64 Two researchers (BH and LW) independently coded the transcript for the main themes that occurred and each labelled the themes and generated a thematic framework. They then met with Penny Rapaport to discuss and agree a consensus on their coding and generate the final framework, according to which the data were organised. Two current and two former carers of people with dementia attended the focus group and, having further revised the manual based on this initial feedback, a virtual reference group of family carers and people living with dementia was consulted by e-mail to obtain further feedback on the draft manuals. The virtual reference group included the four focus group participants and three additional members of the ASRN, including one person living with dementia, one current carer and one former carer.

The key themes elicited from the focus group related to the sleep disturbances that people with dementia experienced and the explanations carers had for these difficulties, the effects that sleep disturbances had on the carers, what they found helpful, and suggestions that they had for the DREAMS START intervention.

The main difficulty that the carers described was their relative waking repeatedly in the night and getting out of bed. This often increased the risk of coming to harm, for example by falling down the stairs or by using electrical appliances unsafely. Carers attributed this night-time waking to a number of causes, mainly confusion, worrying about their symptoms, and dementia type and severity. Confusion meant their relative with dementia mixing up night and day, which one carer felt was exacerbated by being indoors and inactive during the day.

All four of the carers in the focus group spoke of the emotional, physical and practical effects that their relative’s sleep disturbance had on themselves, their relatives and other family members. The main effect on carers was that they themselves became sleep deprived. This happened because they were woken up directly by their relative, and also because they were kept awake by the worry that their relative might awaken, get up and come to harm. Carers described how the lack of sleep over time had negative physical effects on their health and affected their ability to work and function during the day. Carers highlighted various successful and unsuccessful strategies that they had used. Gentle touch and physical comfort had a relaxing effect on their relatives at bedtime and during the night, and keeping the evenings calm and winding down before bed was helpful. They also highlighted the importance of carers finding ways to manage their own stress and sleep problems. There was a common consensus between the carers that using medication to manage sleep problems in their relatives was not helpful. Some also found that there sometimes did not seem to be any pattern to the sleep problems and no helpful strategies.

These findings were used to further refine the manual, ensuring that the emergent themes were included and, in particular, that there was a greater focus on carers finding ways to minimise the impact of sleep disturbances on their own well-being and ensure that the person with dementia was physically and emotionally comfortable. At this point, direct quotations from the carers about their experiences were added to the manual to situate the content and privilege the experiences of family carers. In addition, both the focus group participants and the virtual reference group participants gave feedback and made suggestions about different aspects of the manual sessions. These are summarised in Table 1.

| Topic | Suggestions |

|---|---|

| Content | To include more on the impact of different dementia types on sleep |

| To make session 1 less didactic | |

| To explain the actigraphy data very simply | |

| To include a discussion of becoming more agitated or confused in the evening | |

| To include more on the physical causes of sleep problems, including medication | |

| To focus on increasing activities at times that the person is most likely to nap | |

| To mention the impact of nutrition on sleep | |

| Design | To reduce the number of words per page and overall |

| To include more pictures to make the manual more readable | |

| To ensure that any instruction to carers is very detailed and clear | |

| To simplify the diagrams delineating sleep processes | |

| To change specific pictures that were not felt to fit | |

| Formatting and typographical errors were identified | |

| Session delivery | To emphasise potential benefits of the intervention and how the intervention could help and make life easier |

| To ensure that the tone of this was as a partnership, working together with the carer rather than teaching them | |

| To respect the carer’s existing knowledge and experience | |

| To allocate more time for session 1 or reduce the content |

Finalising the intervention

Having further revised the manual based on feedback from family carers, Penny Rapaport drafted a therapist version of the manual that included additional prompts and guidance for the therapists. At this point, the team also checked the manuals for readability using the Flesch Reading Ease test,65 and all sessions were rated to be within the categories of ‘fairly easy’ or ‘easy’ to read. The research assistants who were going to be delivering the intervention then spent time practising each session in pairs, with Gill Livingston, Penny Rapaport, Claudia Cooper and Kirsi M Kinnunen making further revisions to timing, content and structure whenever it did not flow or was unclear, too long or repetitive. The research assistants also met in groups, practised delivering the sessions and provided oral and written feedback on how to improve the sessions and increase the accessibility and clarity of the session content. This process was repeated until it was agreed by the researchers and therapists that the sessions were ready for use. Box 1 shows the derivation of the final manual, including where each element of the intervention came from. Final versions of both the therapist and carer versions of the manual were then produced for use within the study (see Appendix 5).

Sleep and dementia – material provided by Simon D Kyle.

What is sleep? – material provided by Simon D Kyle.

What causes sleep problems in dementia? – written by Penny Rapaport, Simon D Kyle and Gill Livingston for DREAMS.

Making changes to improve sleep (lifestyle and bedroom factors) – adapted from CBT work by Colin A Espie.

Managing the stress that sleep problems can bring – adapted from START.

Managing stress: the signal breath – adapted from START.

Summary – adapted from START.

Putting it into practice – adapted from START.

Session 2Recapitulation on understanding sleep and dementia.

Light and sleep – material provided by Simon D Kyle.

Light, dementia and the body clock – material provided by Simon D Kyle.

Making a light therapy plan – developed for DREAMS.

Your relative’s sleep pattern – developed for DREAMS.

Making a new sleep routine: your relative’s plan – developed for DREAMS based on work on sleep efficiency by Colin A Espie and Simon D Kyle.

Managing stress 2: focused breathing – adapted from START.

Summary – adapted from START.

Putting it into practice – adapted from START.

Session 3Recapitulation on making a plan.

The importance of daytime activity and routine – adapted from START.

Planning daytime activity – adapted from START.

Sleep, exercise and physical activity – developed for DREAMS by Penny Rapaport, Gill Livingston and Simon D Kyle.

Establishing a good day and night routine – adapted from CBT work by Colin A Espie.

Managing stress 3: guided imagery – adapted from START.

Summary – adapted from START.

Putting it into practice – adapted from START.

Seated exercises visual guide – from NHS Choices website. 66

Session 4Recapitulation on daytime activity and routine.

Troubleshooting: putting plans into action – developed for DREAMS.

Managing night-time behaviour problems – adapted from MARQUE/START.

Describing and investigating behaviours – adapted from MARQUE/START.

Managing stress 4: stretching – adapted from START.

Summary – adapted from START.

Putting it into practice – adapted from START.

Session 5Recapitulation on night-time behaviour problems.

Creating strategies for managing behaviours – adapted from MARQUE.

Managing your own sleep – developed for DREAMS.

Managing thoughts and feelings – adapted from CBT work by Colin A Espie.

Challenging unhelpful thoughts and feelings – adapted from START.

Managing stress 5: guided imagery – ocean escape – adapted from START.

Summary – adapted from START.

Putting it into practice – adapted from START.

Session 6Overall structure based on that developed in START and refined in MARQUE.

Putting it all together.

What works? Light, sleep and dementia – written by Simon D Kyle for DREAMS.

What works? The importance of daytime activity – from START.

What works? Making a new sleep routine – based on the sleep manual by Colin A Espie and Simon D Kyle.

What works? Making changes to improve sleep – based on the sleep manual by Colin A Espie and Simon D Kyle.

What works? Managing night-time behaviours – based on MARQUE/START.

What works? Challenging unhelpful thoughts and feelings – based on START and CBT work by Colin A Espie.

What works? Relaxation – based on START.

Keeping it going – developing an action plan – developed for DREAMS.

Action plan for you and your relative – developed for DREAMS.

Summary – developed for DREAMS.

CBT, cognitive–behavioural therapy.

Adherence to the manual

To inform the calculation of adherence to the intervention, the number of sessions that would count as adherence was discussed in a project management meeting. It was agreed that this was a matter of clinical judgement. Penny Rapaport (psychologist) and Gill Livingston (psychiatrist) judged that, as this was a group of people who often had comorbidities, those who attended most of the sessions, that is four or more, could be judged as adhering to the manual. This was specified in the analytical plan before analysis.

Intervention delivery

The six-session DREAMS START intervention is manual based and was delivered by trained and clinically supervised psychology graduates to carers. They were sometimes accompanied by people with dementia who were able to participate or whom chose to be there. Each carer was given part of the manual specific to each session at the beginning of each meeting, for them to write in and keep. Generally, the sessions took place in the home of the carer or the home of the person with dementia for whom they were caring. Occasionally, carers chose to have sessions elsewhere (the team base, the premises of the memory service from which the participant had been referred to the trial) because it was easier for them to attend. Each session lasted ≈1 hour and took place approximately weekly, at a time convenient to the carer, including evenings. The intervention sessions were generally delivered to the family carer who had been recruited to the study. However, sometimes paid carers participated in the sessions if, for example, they were with the person around the clock who would be most likely to implement strategies. Generally, the carers were encouraged to have the sessions without the person with dementia in the room, so that they could talk freely about any difficulties and to reduce any potential distress to the person with dementia. If the person with dementia wanted to participate in the sessions, either alone or with their main carer, they were included in the sessions. However, carers were encouraged to also participate in the sessions to maximise the potential for new strategies to be developed and used.

Intervention content

The DREAMS START manual used in the trial was designed to optimise both the individual’s sleep at night and his/her wakefulness during the day. To optimise night-time sleep pressure and the circadian regulation of sleep, the intervention focused on supporting carers to use practical zeitgebers (cues that influence a person’s biological rhythms, e.g. regular timing of bed and rising, morning wake-up light, standardised mealtimes) and to establish adaptive stimulus control (e.g. pre-bed settling routine, management of wakeful episodes). The intervention introduces strategies to promote de-arousal at night (e.g. relaxation, bedroom comfort, no caffeine or alcohol intake before bed, no activities in bedroom) and behavioural activation during the day to maintain alertness, reduce daytime naps and increase engagement to strengthen both central and peripheral clock timing. The intervention also focuses on helping carers to develop coping strategies to manage concerns about their own sleep health.

Sessions 1–5 all included one or two key topics for discussion, a specific plan or goal to try out between sessions, a stress reduction exercise with an accompanying compact disc (CD)/MPEG-1 Audio Layer III (MP3) file and a sleep diary for the carer to fill in for monitoring progress between sessions. Although manualised, during each session the participants would develop specific goals, which were combined to make an individualised plan.

The six intervention sessions covered the following:

-

Understanding sleep and dementia – psychoeducation on the importance of sleep, sleep process, the impact of dementia on sleep and what causes sleep problems in people with dementia. This session also discussed lifestyle and bedroom environment factors that can affect sleep, and carers were encouraged to identify potential changes that they could try out before the next session. In addition, the impact that sleep problems can have on the person with dementia and their relative was discussed.

-

Making a plan – psychoeducation on the importance of light for sleep and the relationship between light, sleep and dementia. This session was built around the light and activity data collected by actigraphy at baseline, with the individual’s data inserted into the manual in advance of the session and an explanation given. The carers were given a ‘light box’ (Lumie Arabica SAD Light, Lumie, Cambridge, UK) to keep and it was switched on and left on during the sessions to encourage people to understand that they habituated to the bright light (10,000 lux at 25 cm). A time switch was provided if carers wanted it, so that it could be switched on when they were otherwise engaged. It was recommended that the light box be used for 30 minutes at the same time every morning. During the session, the participants made an individual plan for increasing natural and artificial light for the person with dementia. Based on the individual’s sleep data, a ‘sleep efficiency’ score (time asleep/time in bed) was calculated, and any suggested changes to an individual’s time to bed and rise and for reducing daytime naps was integrated into their individual action plan.

-

Daytime activity and routine – this session highlighted the importance of daytime activity and routine and focused on building pleasant activities and exercise/physical activity into the day. This session included a seated exercise video for less physically able individuals. It also included the importance of establishing a good day and night routine and ways to strengthen the link between bed and sleep. In addition, an exercise and activity plan were built into the individual plan.

-

Difficult night-time behaviours – this session began with troubleshooting around putting the individual plan into action and identifying potential solutions to any barriers. The rest of the session focused on describing and investigating difficult night-time behaviours that were specific to the individual with dementia.

-

Taking care of your own sleep – this session included using the information collected on difficult night-time behaviours to create strategies for managing these difficulties. The rest of the session focused on the carer managing their own sleep, including ways to challenge unhelpful thoughts and feelings and make time for themselves.

-

What works? Using strategies in the future – this session recapitulated on earlier sessions and focused on what carers found useful and what worked. From this, an individualised sleep action plan was finalised, which included strategies for both the person with dementia and the carer.

Treatment as usual

Participants received TAU for 6 weeks, delineated by the CSRI. This was expected to vary between trusts, and also according to individual patient needs, but was expected to be in line with the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) pathways guidelines for dementia. 67 TAU varies according to the practices of the trust in which the person with dementia is treated and the person’s individual needs, but incorporates the NICE pathways guidelines67 for dementia and consists of assessment, diagnosis, symptomatic interventions, risk assessment and management and information.

The volunteers from JDR may not have been currently receiving professional care, but details of any services they were receiving were gathered. Services are based around the person with dementia. Treatment is medical, psychological and social. Thus, TAU consisted of assessment, diagnosis, risk assessment and information. These included referral to dementia navigators; medication; cognitive stimulation therapy; START (in some trusts); practical support (social services provided); risk plans, for example telecare, treatment of neuropsychiatric symptoms, driving information to the Driver and Vehicle Registry Agency, medical identification (ID) bracelets and advice regarding power of attorney and capacity assessment; and social services referral for personal care, day centre and financial advice, and carer support.

After the follow-up data had been collected (including the 2 weeks of follow-up actigraphy), the participants in the control group received a summary of the baseline Actiwatch data, with advice on improving sleep (see Appendix 6). To maintain the follow-up assessor’s blinding until the follow-up Actiwatch data had been analysed, the unblinded team posted this information to the participants once the follow-up actigraphy was complete (of which the assessor informed the unblinded team).

Both groups

After the follow-up assessor’s unblinding, the assessor sent the participants an end-of-involvement letter (see Appendix 7), enclosing a summary of the follow-up Actiwatch data. The referring clinician was sent a copy of the letter.

Details of how the interventions were standardised

The intervention was standardised primarily through being manualised. This allowed the research team to maintain tight control over how the intervention was delivered, and provided a clear and detailed structure for the graduate psychologist therapists to adhere to. It also meant that the carers could keep the manual and refer back to notes, plans and information between and after the sessions. Variation came with the introduction of personalised goals and strategies, and the use of individual actigraphy data. Delivery of the interventions as intended and in a standardised way was assured by training the therapists and ensuring that they were ‘signed off’ as individually competent in each session, and by offering regular and structured clinical supervision, as detailed in the following section.

Training the therapists

Four research assistants who were psychology graduates with no clinical training were employed to deliver the intervention and received in-depth training prior to delivering the intervention. The research assistants participated in five knowledge and skills-based sessions on the following topics:

-

Dementia (CC)

-

Sleep (SK)

-

Introducing DREAMS START (GL)

-

Clinical skills for delivering the intervention part 1 (PR)

-

Clinical skills for delivering the intervention part 2 (PR).

Training was delivered through a combination of seminars, discussion, reflective learning and guided reading. Skills-based competencies were learnt through role-play, small-group exercises and clinical simulation in pairs. Training drew on the curriculum for psychological therapists devised by the Department of Health and Social Care for its IAPT programme, and the successful training programme developed for the START intervention. There was a strong practical focus in the training programme on how to deliver the therapy, potential clinical dilemmas, collaborative goal-setting, managing sessions with more than one participant, working with interpreters, empathic listening skills, effective use of supervision, safe working practice, and when to ask for help. Throughout the training, an emphasis was placed on the researchers facilitating carers to develop and practise using their own strategies and finding their own solutions rather than feeling the need to instruct carers and provide solutions within the session. In addition to the knowledge and skills-based training, therapists were trained to adhere to the manual by practising repeatedly in pairs, and required to demonstrate, by role playing the entire intervention for one of the clinical members of the research team, competence in delivering each session of the intervention to an agreed standard.

Supervising the therapists

The process of formal clinical supervision of the therapists began at the start of the intervention delivery period and continued until the final sessions had been delivered. The clinical psychologist, Penny Rapaport, met with each of the two teams (two therapists in each team) for 1.5 hours of group supervision per fortnight. In addition to this group supervision, she was available for individual supervision, which was either requested by the psychology graduates on an ad hoc basis, or (on occasion) was initiated by the investigators. If they had any urgent clinical or procedural concerns or questions relating to their clients, the therapists could approach Penny Rapaport, Claudia Cooper or Gill Livingston at any time, for example if risk issues arose during a session.

The group supervision format was seen as the most effective use of available resources, with psychology graduates benefiting from both the professional expertise of their supervisor and the clinical experiences of their peers; it was successfully applied in the START randomised controlled trial (RCT). It was expected that the supervision format would also maximise peer support within and outside the supervision sessions, and facilitate effective teamworking. The format was tailored to reflect the specific needs of the present research study. During the course of the project, supervision performed a number of functions including case management, clinical skills development, ensuring safe practice with clients, and staff support. Each of these functions is explored in turn in the following sections.

Case management

An important function of supervision was to ensure that all of these interventions were being managed consistently, effectively and appropriately. Therefore, in every group supervision session, each therapist provided a brief overview of their caseload, ensuring that clients and any related issues or concerns did not get overlooked. This encouraged the therapists to be transparent about their work and to recognise when apparently simple or straightforward cases were more complex than initially perceived. As the cases for intervention were allocated and managed within the team, it was useful for the therapists to be aware of who their colleagues were seeing and who had space to take on new clients, developing a sense of shared responsibility. 61

Clinical skills development

Group and individual supervision sessions provided the therapist with the opportunity to develop their clinical skills via a range of approaches. In addition to giving a brief summary of their caseloads at the start of every supervision session, the therapists would identify a clinical challenge or dilemma that they wished to explore in more detail. 61 Although the intervention was manualised and psychology graduates were expected to adhere strictly to the manual, there was great variety in the dilemmas that they encountered in delivering the intervention. Various issues tended to emerge within supervision, for example how to keep carers focused on the manual and engaged in the process, and how to manage sessions when the person with dementia and the carer were both contributing. Using a combination of role play and reflection on extracts of the fidelity recordings, the therapists were able to enhance their skills in delivering the intervention in a safe environment.

Ensuring safe practice with clients

There was a written policy about lone working and safeguarding, to which the therapists were trained to adhere. The clinical team provided the therapists with specific training in how to respond to any risks either disclosed by carers or witnessed in interactions, in relation to harm to either themselves or the person for whom they were caring. If concerns were raised, a plan was made with one of the lead investigators about how to manage the risk, and information was shared with the local clinical teams. By ensuring that there was an opportunity for individual supervision on request, and that a senior member of the team was always available, a culture of transparency developed whereby the therapists felt comfortable raising concerns about clients with the clinical academics in the team. Time was also taken within supervision to highlight the importance of behaving ethically and safely in all aspects of clinical work, for example how to practise safely when working alone in people’s homes.

Staff support

Many of those receiving the intervention were experiencing high levels of emotional distress, often in the context of challenging social situations and physical environments. An important dimension of clinical supervision was to give the therapists an opportunity for self-reflection, making sense of their own responses to the people with whom, and situations in which, they were working. The combination of group and individual supervision meant that the psychology graduates benefited from the support of their peers and felt that their experiences were validated by their shared experiences.

Details of how adherence of care providers to the protocol was assessed or enhanced

Monitoring fidelity to the intervention

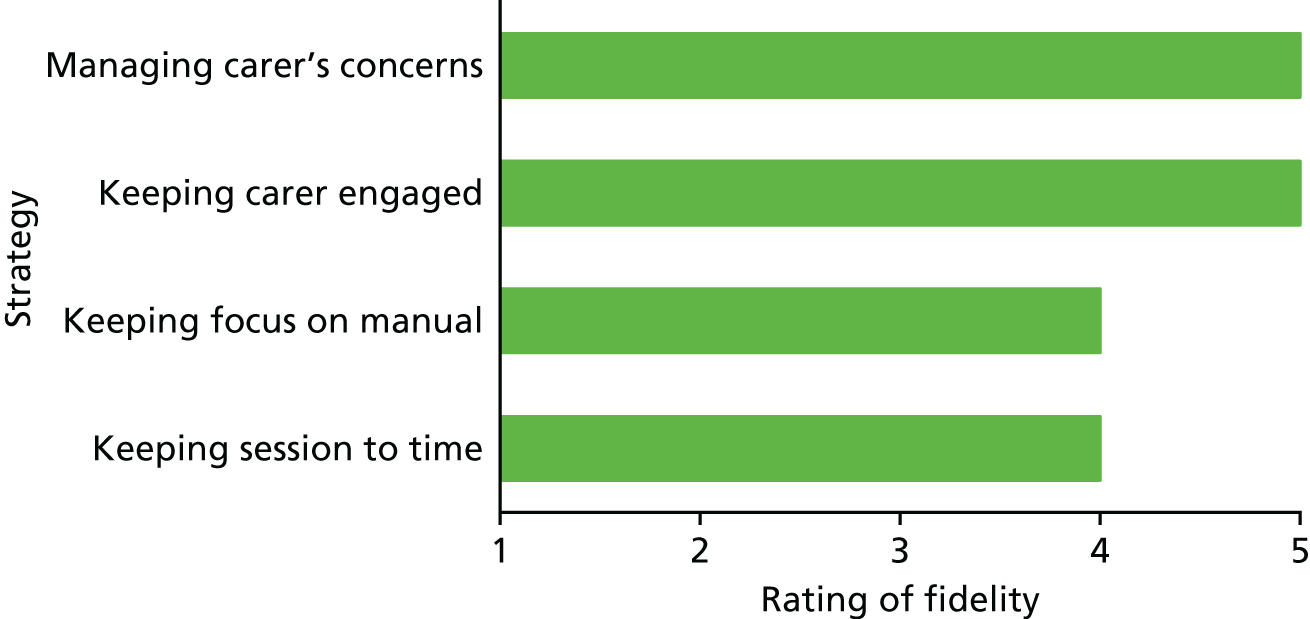

In addition to the close supervision and training identified in the previous section, a formal process for monitoring the fidelity of the therapists to the manualised intervention was instigated. Following a similar process to that used in the START RCT,35,61 therapists audio-recorded one session per participant. The session to be recorded was selected at random by the trial manager using a Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) formula, before any interventions were carried out. Penny Rapaport devised a fidelity checklist for each session by considering the most important components of each session (see Appendix 8). To maintain the follow-up assessor’s blinding, this session was rated for fidelity to the manual by the other therapist in the same team (who was not involved in that participant’s intervention), using the checklist. For each recorded session, a fidelity score for four process factors was given by the rater, considering whether the therapist was (1) keeping the session to time, (2) keeping the carer focused on the manual, (3) keeping the carer engaged in the session and (4) managing the concerns of the carer. Possible scores ranged from 1, meaning ‘not at all’, to 5, meaning ‘very focused’, for each item. Ratings were out of a possible 5 points.

Outcomes

Primary outcomes

-

Feasibility of recruitment: this was assessed by (1) the proportion of participants consented out of those meeting the eligibility criteria at screening and (2) the proportion randomised after baseline assessment.

-

Feasibility of the intervention: this was assessed by recording the proportion of participants randomised into the intervention group who by the end of the trial had attended four or more of the six sessions.

-

Acceptability of the intervention: this was assessed through qualitative interviews with up to 20 intervention group participants after follow-up, post unblinding.

Therapist

Secondary outcomes

-

Referral rates from the recruitment period were measured from records about all and eligible referrals at the end of the recruitment period.

-

Follow-up rates were measured after the last follow-up visit, from records indicating which participants completed follow-up assessments at 3 months.

-

Reported side effects (patient falls and comorbid physical illnesses) were recorded using a study-specific DREAMS side-effects questionnaire at baseline and 3 months.

Acceptability of outcome measures for a future trial of clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness was assessed through recording the completion rates of instruments (see below) at baseline and 3 months, the acceptability of tools from the qualitative interviews post unblinding, and calculating the sample size that would be required to detect a clinically important difference in outcome.

Qualitative interviews

Sample recruitment and procedure

A purposive sample of carers who had received the intervention for qualitative interviews was recruited in order to assess acceptability of the intervention and whether or not there were groups that the intervention was unsuitable for, and to detail any required refinements in the intervention or the assessment procedure. They were invited to participate in the interview after follow-up assessment and unblinding.

Purposive sampling was used to ensure that people from a range of sociodemographic backgrounds were interviewed. 68 Included were people of differing ages and relationships to the person with dementia, family and paid carers, those living with the person with dementia and those living separately, people from varying ethnic backgrounds, those who had finished the intervention and one carer who had not finished the intervention. Carers were recruited until theoretical saturation was reached.

After this, Penny Rapaport and Lucy Webster met with the ASRN members who had been part of the development of the manual for a focus group to consider any changes post trial.

Qualitative interview content

A semistructured interview guide was developed for the carers who had been participants in the trial (see Appendix 9) of open-ended questions based on our study objectives. These explored the acceptability and practicality of both the intervention and the assessment measures, to gain suggestions for refining the trial. The interview guide was revised iteratively during the interview phase, adding themes as they were brought up by interviewees. All interviews were audio-recorded and recordings were destroyed after analysis.

After completing the trial and gaining qualitative feedback from the participants, the family carers that had contributed to the intervention development were invited to attend a focus group at the Alzheimer’s Society premises in September 2017. The aim of this focus group was to hear group members’ thoughts on the qualitative findings, the final version of the manual used in the trial and the materials being presented, and any suggestions for further refinement of the intervention.

Analysing actigraphy data

The actigraphy data were analysed using MotionWare Software 1.1.25 (CamNtech Ltd, Cambridge, UK), in accordance with a standard operating procedure (see Appendix 10). The analyses were performed as described below; baseline and follow-up measures were produced in the same way.

Sleep and non-parametric circadian rhythm analysis measures

The sleep analysis function of MotionWare was used to produce sleep measures from overnight actigraphy data. The NPCRA analysis in MotionWare is based on an approach that does not assume that the data fit any predefined distribution. 69 First, the whole recording period was highlighted, and the editing tool was used to remove recordings exceeding 14 days and periods of missing data (when the watch was off the wrist based on notes in the sleep diary or the carer’s verbal report on Actiwatch data collection, or the recording indicated no data). The maximum recording period used for the analysis was 14 days (in the majority of cases from 17.00 on the first day to 17.00 on day 14, but in some from 18.00/19.00 on the first day to 18.00/19.00 on day 14). Second, using the edited data, each sleep period was defined, choosing as the start and end points the bedtimes and rise times recorded in the sleep diary or by using event markers (showing as blue lines in the data). If the carer did not complete the sleep diary or use the event maker button, the bedtimes and rise times were defined based on the carer’s verbal report on Actiwatch data collection. In addition, the activity and light data were used as guidance for editing the sleep periods. When unsure, two researchers edited a sleep period and reached a consensus. Each sleep period was saved. The edited recording period was also saved to derive the NPCRA measures, and the summary option used to record average light (lux) over the same period. Finally, a report was produced, including all the sleep analyses and NPCRA measures evaluated in the feasibility trial as possible outcomes for the main trial. In the statistical analysis, sleep data based on fewer than seven nights were excluded. To produce NPCRA measures used in the statistical analysis, copies were made of each previously saved edited recording. The length of each missing data period was then checked, and any 24-hour periods with ≥ 3 hours of missing data were excluded. 70 Having saved the NPCRA period, a new report was produced containing the non-parametric measures only.

Core night-time measures

To produce sleep measures for what the research team defined as core night-time (0.00 to 06.00), a copy was created of the edited recordings previously saved. The existing sleep periods were removed and then the sleep summary table option was used to limit each new sleep period to start at 0.00 and end at 06.00. Having saved these periods, a report was produced containing the new sleep measures.

Sensitivity analysis

In a sensitivity analysis, only participants who lived with a family carer at baseline were included on the sleep and NPCRA measures. The sleep data that were based on seven or more nights and the NPCRA data without ≥ 3 hours of missing data for each 24-hour period were used.

Quantitative analysis

The flow of participants through the trial is described using a Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram (see Figure 3). A patient’s recruitment site, sex of the person with dementia, sex of the carer and a carer’s relationship to the person with dementia were summarised as counts and proportions. Eligible patients and carers who consented were compared with those who were screened and did not consent. The following, with 95% CIs, were calculated:

-

proportion of screened patients who were eligible for the trial

-

proportion of eligible patients referred who consented to the trial

-

proportion of participants in each randomised group who dropped out or were lost to follow-up by 3 months (when available, reasons for losses will be summarised)

-

proportion of participants in the intervention group who adhered to the intervention (i.e. attended at least four of the six sessions)

-

median number of sessions attended by those in the intervention group.

Summary of baseline data

Baseline data (sociodemographic characteristics, actigraphy measures and other scores) for participants and carers were summarised by treatment group using means (with SDs), medians [with interquartile ranges (IQRs)], counts and proportions, as appropriate, to gauge the balance in characteristics between the randomised groups.

Three-month follow-up

Follow-up scores, actigraphy measures and other scores at 3 months were summarised using means (with SDs), medians (IQRs) and counts (%) as appropriate. For continuous measures, correlations between baseline and follow-up measurements were calculated. The number of participants with completed values was summarised for each outcome.

Measurements were compared between randomised groups using appropriate regression models to provide estimates of the effect of the intervention with 95% CIs (e.g. difference in means), adjusted for baseline score and site. For actigraphy data analyses, the following were focused on: sleep efficiency, relative amplitude, sleep fragmentation index, start hour of most restful hours, activity count for most restful hours, start hour of most active hours and activity count for most active hours for those with ≥ 7 days of data. Core sleep data between 0.00 and 06.00 were measured and a sensitivity analysis excluding participants who did not live with a carer at baseline was carried out.

Use of psychotropic medication

The frequency (%) of participants in each randomised group who had taken each type of medication (anxiolytics and hypnotics, antipsychotics, antidepressants, other psychotropics and melatonin) during the 3-month period prior to both the baseline and follow-up assessment was calculated.

Side effects

The frequencies (%) of comorbid physical illnesses and participant falls were summarised by randomised group at baseline and 3 months.

Qualitative analysis

Each interview with a carer who had participated in the trial was transcribed verbatim, with the transcription checked for accuracy by listening to the recording, and then anonymised. The transcribed interviews were entered into a software package for qualitative data analysis (NVivo 11). A thematic framework for analysis64 was created by displaying coding in matrices and diagrams until a comprehensive picture of all the phenomena was obtained, a standard, recommended method to ensure rigour. 71 This constant comparison method was used to identify similarities and differences in the data. To create the initial coding framework, trial manager Kirsi M Kinnunen and research assistants Brendan Hallam and Lucy Webster independently coded the first three interviews, identifying the main themes that occurred in line with the study’s objectives. They then met with investigators Gill Livingston and Penny Rapaport to discuss the themes and decide on a coding framework. If any discrepancies were identified, they met with Penny Rapaport and reached a consensus.

Using the initial framework, different pairs of researchers then independently coded all of the interviews and, as emerging themes and subthemes were identified, iteratively revised the framework. Each pair of researchers met to discuss discrepancies and agreed a consensus.

Similarly, in the focus groups of ASRN members, the carers consented to the discussion being audio-recorded. The recording was then externally transcribed and the data entered into NVivo 11 software and analysed using thematic analysis. 63,64

Sample size

It was estimated that with 40 intervention participants (a larger group than the control group, to allow a more precise estimate of the proportion adhering to the intervention) and 20 control participants, the following 95% CIs would be achieved for the expected adherence and participation estimates:

-

proportion of participants adhering to intervention – expected value 75%, 95% CI 59% to 87%

-

proportion of appropriate referrals consenting to the trial – expected value 50%, 95% CI 41% to 59%.

This sample size was also judged sufficient for estimating the SD required for the sample size calculation in the main trial. 72,73 The estimated recruitment referral rate was approximately six potential participants per week. Two out of these were expected to be suitable and agree to participate. The expected follow-up rate was approximately 80%.

It was anticipated that the 95% CI for the expected adherence and participation estimates would provide acceptable ranges to inform continuation to the main trial. Overall, it was expected that the ‘stop–go’ measures would be related to the proportion adhering:

-

≥ 70% – go to main trial

-

60–69% – consider a modified trial design to increase adherence

-

< 60% do not progress to main trial using this model.

Randomisation

Computer-generated randomisation lists were produced in Stata® Version 14 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) by an independent statistician (not involved in data analysis). Randomisation was stratified by site and based on random permuted blocks of sizes three and six to allow 2 : 1 allocation to the intervention and TAU groups. The three site-specific lists produced were password protected, and could be accessed only by two members of a separate study team (randomisation allocator, as seen in Figure 2).

Blinding

Figure 2 shows the process from screening/baseline assessments (pre randomisation) through intervention delivery to blinded follow-up assessments. Three researchers [Assessors (A) 1 to 3 in Figure 2] screened the participants and carried out baseline assessments. The two researchers who were also therapists [Therapist (T) 1/A1 and T2/A2] asked for allocations from the randomisation allocators. They worked in two separate teams of two therapists each (Team A: T2 and T4; Team B: T1 and T3), and assessed outcomes only for those participants to whom the opposite team had delivered the intervention. The teams had their clinical supervision separately. Researcher A3 did not deliver any interventions and was kept blind to all participants’ allocations. The follow-up assessments were arranged by T1/A1 and T2/A2, for those participants they were unblinded to. Owing to the nature of the intervention, it was not possible to blind the trial participants. When arranging the appointment, participants were reminded that they should not disclose their allocation group to the assessor, and should hide anything related to the intervention from view (e.g. light box, manual). On arrival for the outcome assessment, the assessor also asked participants not to disclose their group. Two baseline assessments and one follow-up assessment took place in our team base at UCL; all others took place in the homes of the participants.

FIGURE 2.

Assessments, randomisation and intervention delivery. A, assessor; T, therapist.

Statistical methods

The co-applicant statistician led and supervised the analysis, planned and conducted according to International Conference on Harmonisation (ICH) E974 and following the standard operating procedures of the PRIMENT Clinical Trials Unit. A predefined statistical analysis plan described the analysis fully; the following sections are a summary of the methods used to assess the primary and secondary outcomes.

Primary outcomes

Feasibility of recruitment