Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 10/57/20. The contractual start date was in April 2012. The draft report began editorial review in April 2017 and was accepted for publication in July 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Matthew L Costa is a member of the general board for the Health Technology Funding stream. Keith Willett received royalty payments from Zimmer for implant design outside the submitted work. Sarah E Lamb is a member of the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Additional Capacity Funding Board, HTA End of Life Care and Add-on Studies, HTA Prioritisation Group and HTA Trauma Board.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Costa et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Fractures of the lower limb are extremely common injuries in both the civilian and military populations. The majority of these injuries are ‘closed’, that is, the skin around the fracture is intact. In such cases, the risk of infection is low; however, if the fracture is ‘open’, such that the barrier provided by the skin is breached, then the broken bone is exposed to contamination from the environment. In open fractures, the risk of infection is greatly increased. 1

Wounds associated with open fractures of the lower limb are graded by severity, as part of routine clinical practice, using the classification of Gustilo and Anderson2 (G&A). Grade 1 injuries are small clean wounds (< 1 cm in length), grade 2 injuries involve larger wounds (> 1 cm in length) but without extensive soft-tissue damage, and grade 3 injuries are wounds of > 1 cm in length with extensive soft-tissue damage (Table 1). In addition, Gustilo and Anderson2 described a special type of grade 3 injury that involved damage to a major blood vessel that required surgical repair. The greater the extent of the injury to the soft tissues around the broken bone, the greater the risk of infection. In severe, high-energy fractures of the lower limb, infection rates of 27% have been reported,3 even in specialist trauma centres.

| Fracture type | Description |

|---|---|

| Grade 1 | An open fracture with a wound of < 1 cm in length and clean |

| Grade 2 | An open fracture with a laceration of > 1 cm in length without extensive soft-tissue damage, flaps or avulsions |

| Grade 3 | An open segmental fracture, an open fracture with extensive soft-tissue damage or a traumatic amputation. Special categories in grade 3 are gunshot injuries, any open fracture caused by a farm injury and any open fracture with accompanying vascular injury requiring repair |

If complications, such as deep surgical site infection (SSI) occur, treatment frequently continues for years after the open fracture. There is a huge health-care cost associated with such injuries (US study:4 US$163,000 if the limb can be salvaged and > US$500,000 if amputation is required) and this is a fraction of the subsequent personal and societal cost. In the UK civilian population, the risk of an open long-bone fracture is approximately 11.5 per 100,000 per year,5 but this is much higher in the military population and the severity of the injuries is frequently greater. 6

The initial management of open fractures of the lower limb in an emergency department involves the removal of gross contamination, the application of a sealed dressing and the administration of antibiotics, as described in the joint British Orthopaedic Association and British Association of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgeons ‘BOAST’ publication The Management of Severe Open Lower Limb Fractures (www.boa.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/BOAST-4.pdf; accessed 9 October 2017)7 and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) complex fracture guidelines 2016 (www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng37; accessed 9 October 2017). 8 Many patients admitted to local hospitals are transferred immediately to specialist facilities, such as a major trauma centre (MTC). However, the key component of the management pathway is the surgical ‘debridement’ (removal of all contaminated tissue and washout of the open fracture under anaesthetic). Once the wound is clean, the fracture is usually immobilised with some form of internal or external fixation and a dressing is applied at the end of surgery.

Traditionally, if the wound cannot be closed primarily, a sealed, non-adhesive layer is applied to the surface of the wound to protect the open fracture from further contamination. The wound is covered in this way until a reassessment and further debridement is performed in the operating theatre, usually within 48–72 hours after the initial injury. This method has been used throughout the NHS and in military practice for many years.

This study concerns the type of dressing that is applied to the wound at the end of the operation.

Negative-pressure wound therapy (NPWT) is an alternative form of dressing that may be applied to open fractures. In this treatment, an ‘open-cell’ foam or gauze is cut to size and laid onto the wound, followed by a sealed dressing. A hole is made in the dressing overlying the foam or gauze and a sealed tube is used to connect the dressing to a pump, which creates a partial vacuum over the wound. This NPWT removes blood and exudate from the area of the wound, and may also remove any residual bacteria, encouraging ‘granulation’ (healing) tissue. 9 Recent laboratory studies have also suggested that NPWT may stimulate the release of ’cytokines’ that encourage new blood vessel formation. 10 These NPWT dressings are widely used for other surgical wounds after elective surgery and are increasingly used throughout the NHS. However, NPWT is considerably more expensive than traditional wound dressings for the dressing and the associated machinery that generates the partial vacuum.

Negative-pressure wound therapy has shown encouraging results in clinical trials related to diabetic foot wounds11 and abdominal wounds. 12 A systematic review13 of the literature before the Wound management of Open Lower Limb Fractures (WOLLF) study showed only one randomised controlled trial14 (RCT) comparing standard wound dressing with NPWT for patients with open fractures of the lower limb. This trial14 demonstrated a reduction in the rate of wound infection in the group of patients treated with NPWT [5.4% vs. 20%; relative risk (RR) 0.199, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.87]. However, this was a small trial (59 patients, 63 fractures) at a single centre and was funded by a commercial company which produces a NPWT system. There were no similar trials registered on the international trials database.

Relevance of project

Despite the limited supporting evidence, the 2009 UK BOAST7 and 2016 NICE guidelines8 for the management of open fractures of the lower limb included a recommendation for the use of NPWT. A consensus paper, published by the International Expert Panel on NPWT,13 also recommended that, when the use of primary closure is not possible, NPWT needs to be considered in the management of wounds associated with open fractures, but acknowledged that the evidence base to support this statement was very limited.

There was a pressing need to evaluate this relatively expensive technology given the increasing use in clinical practice without a strong supporting evidence base. This multicentre, pragmatic RCT was conducted to compare NPWT with standard dressings for patients with wounds associated with open fractures of the lower limb.

Objectives

The study was conducted in two phases with objectives for each.

Feasibility study

-

To conduct a qualitative assessment of (a) patients’ experience of sustaining fracture of the lower limb; (b) patients’ experience of being enrolled into a clinical trial, giving or declining consent for the trial; and (c) the acceptability of the trial procedures to patients and staff.

-

To determine the number of eligible, recruited and withdrawn patients in five trauma centres over the course of 6 months. In addition, to determine whether or not any trial participants lacked capacity to give consent 6 weeks post injury.

Main study

The primary objective for the main RCT was to:

-

estimate differences between the treatment groups in the Disability Rating Index (DRI) at 12 months after open fracture.

The secondary objectives were to:

-

estimate the rate of ‘deep infection’ (deep SSI) of the limb at 30 days after open fracture

-

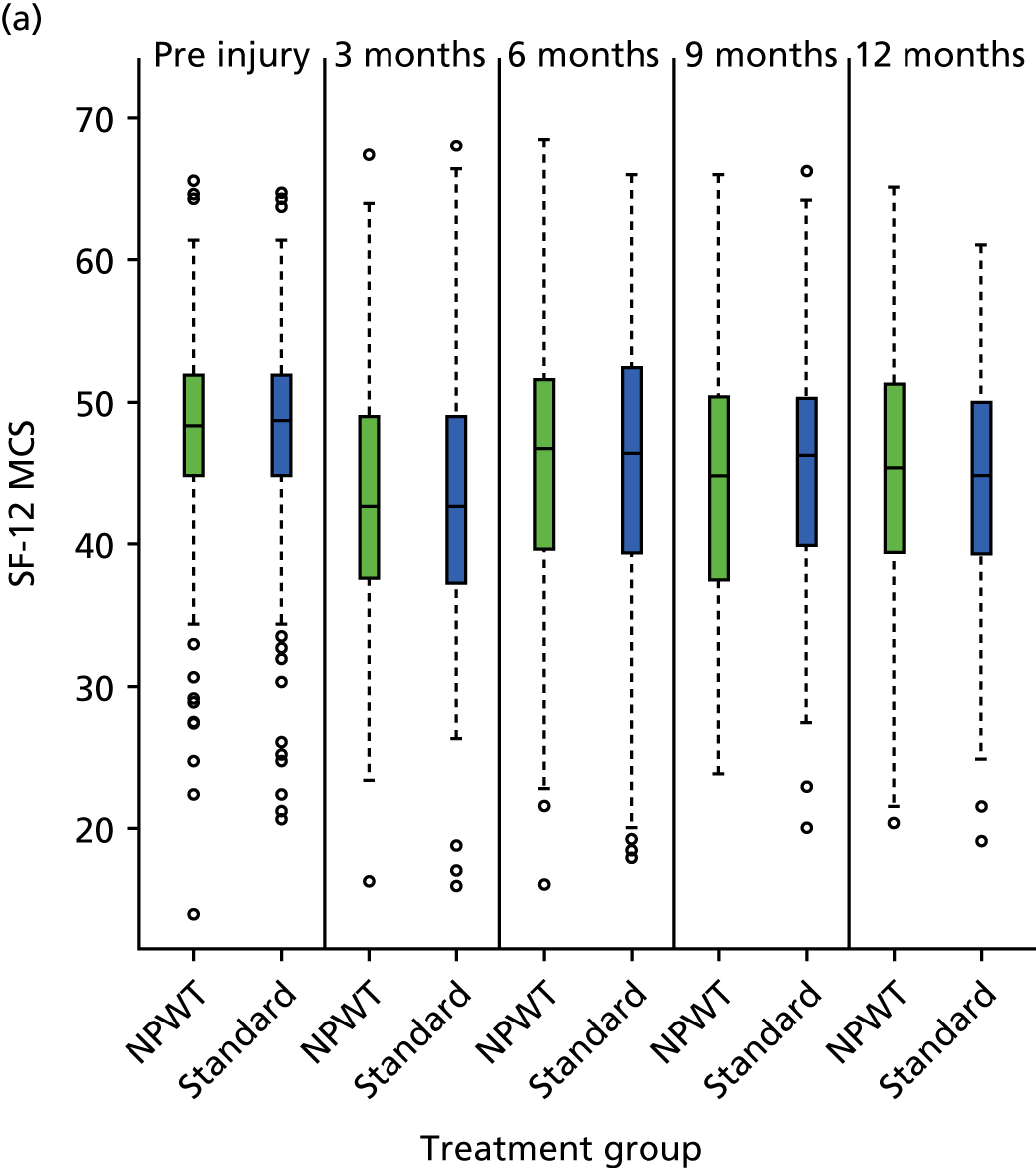

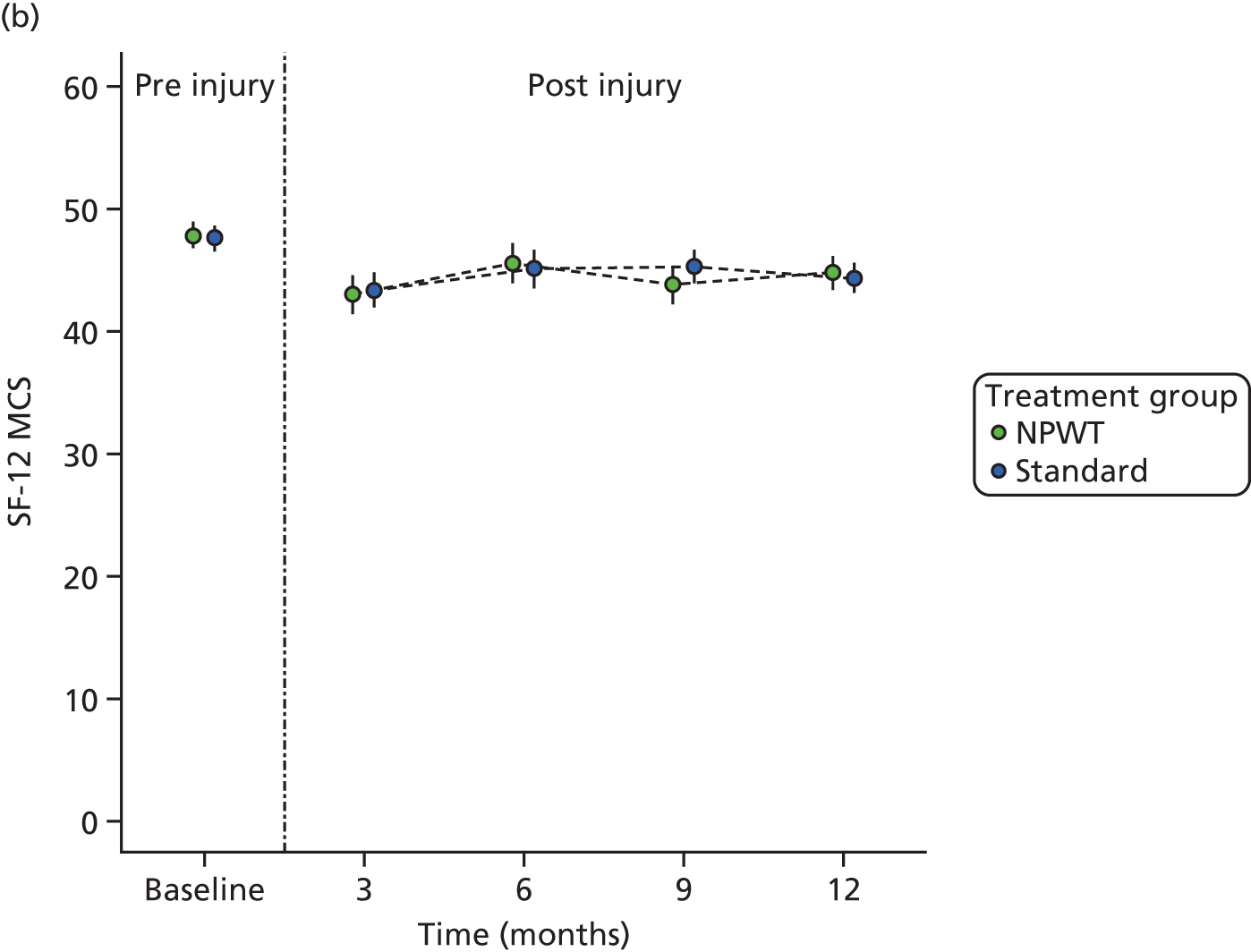

estimate differences in health-related quality of life (HRQoL) [Short Form questionnaire-12 items (SF-12) and EuroQol-5 Dimensions, three-level version (EQ-5D-3L)] up to 12 months after open fracture

-

determine the number and nature of complications and further surgical interventions related to the injury during the first 12 months after open fracture

-

investigate, using appropriate statistical and economic analysis methods, health-care resource use and thereby the cost-effectiveness of NPWT versus standard dressing for wounds associated with open fractures of the lower limb.

Chapter 2 Methods

Trial design

This was a multicentre pragmatic RCT, recruiting patients with an open lower limb fracture. Patients were randomly assigned to receive either a standard wound dressing or NPWT after lower limb surgery.

Setting

The trial was conducted in 24 NHS hospitals across the UK. Eighteen were designated MTCs and six were large trauma units.

Participants

Inclusion criteria

Patients were eligible for the trial if they:

-

were aged ≥ 16 years

-

presented (or were transferred) to a trial hospital within 72 hours of injury

-

had sustained an open fracture of the lower limb assessed as G&A grade 2 or 3. The treating surgeon determined the G&A grade at the end of surgical debridement as per routine operative practice.

We anticipated that only a very small number of patients would present after 72 hours, but that, in such cases, it was likely that open-fracture wounds would already be infected.

Exclusion criteria

Patients were excluded from the trial if:

-

there were any contraindications to anaesthesia such that the patient was unfit for surgery

-

there was evidence that the patient was unable to adhere to trial procedures or complete questionnaires, such as permanent cognitive impairment. In a small proportion of patients, this exclusion criterion could be determined only after randomisation and emergency surgery had taken place. These patients were withdrawn from the study and no patient-identifiable data were retained.

Screening procedures

Patients with an open fracture of the lower limb are admitted to the hospital from the emergency department. All patients were screened in the emergency department or the trauma wards for eligibility by a trained research associate. Screening logs from each centre were used to determine the number of eligible patients and reasons for exclusions. Patients who declined to take part were offered the opportunity to discuss reasons for this with a member of the research team.

Recruitment challenges

The key challenge to recruitment was the procedure for obtaining the patients’ informed consent. The nature of these injuries meant that the majority of patients were operated on immediately or were allocated to the next available trauma operating list. Some patients were unconscious or had reduced levels of consciousness, and the great majority were given strong opiate-based analgesia. Therefore, many of the patients lacked capacity to provide informed consent before their surgery. The feasibility phase of the WOLLF study was designed to address this issue, as well as to estimate the rate of recruitment.

Consent

Conducting research in the emergency setting is regulated by the Mental Capacity Act (MCA) 2005. 15 As patients were likely to lack capacity, as described above, and because of the urgent nature of the treatment limiting access to, and appropriate discussion with, personal consultees, we acted in accordance with section 32, subsection 9b of the MCA for following a process approved by the Research Ethics Committee (REC).

Patients consented preoperatively

Patients who were able to give informed consent preoperatively were approached and recruited by a member of the research team.

Patients consented postoperatively

Patients who were unconscious or lacking ability to process information were recruited to the study under consultee agreement. Patient consent was not obtained prior to surgery, but a consultee was approached to provide agreement for entry to the trial. The consultee was a next of kin, when available, or a medically trained clinician independent of the trial. At the first appropriate time when the patient had regained capacity, the research associate provided all the study information. The patients were given the opportunity to ask questions and discuss the study with their family and friends. They were then asked to provide written consent for continuation in the study. Participants recruited and randomised under consultee agreement were withdrawn from the trial if they were unable to give informed consent within 6 weeks of randomisation. Any other participant randomised to treatment could withdraw at any time.

Randomisation

A computer-generated random allocation sequence was generated and controlled by York Clinical Trials Unit. The unit of randomisation was the individual patient on a 1 : 1 basis, stratified by trial centre and G&A grade. When a patient entered the trial, non-identifiable details were logged on the secure, encrypted, web-based randomisation system and then the allocation was generated. Information included patient initials, date of birth, gender and eligibility checks. The trial and clinical teams were informed of the unique trial number (TNO) for each participant; this TNO was used on all subsequent trial documentation.

Allocation of treatment

Trial participants were assigned to their treatment allocation intraoperatively at the end of initial surgery, but before a wound dressing was applied. All operating theatres included a computer with internet access. Therefore, a secure, 24-hour, web-based randomisation system was used to generate treatment allocation.

Blinding

As the wound dressings were clearly identifiable, it was not possible to blind trial participants or clinical teams to treatment allocation. However, outcome assessment was undertaken by trained research associates (nurses or research physiotherapists) independent of the clinical care team. For patient-reported outcomes [disability, pain, quality of life (QoL), resource use, other complications], trial participants completed follow-up questionnaires themselves and these were returned directly to the central trial office.

Interventions

Usual-care group

Participants allocated to usual care had a standard dressing applied to the open wound. This comprised a non-adhesive layer applied directly to the wound covered by a sealed dressing or bandage. The standard dressing did not use ‘negative pressure’. The exact details of the materials used were left to the discretion of the treating surgeon as per routine care. Details of each dressing applied in the trial were recorded and classified according to British National Formulary (BNF) classification.

Negative-pressure wound therapy

The NPWT dressing used an ‘open-cell’ solid foam or gauze which was laid onto the wound followed by an adherent dressing. A sealed tube was connected from the dressing to a pump which created a partial vacuum over the wound. The basic features of the NPWT are universal, but the exact details of the dressing and pressure (mmHg) were left to the discretion of the treating health-care team as per routine care. Details of dressings used were recorded in trial documentation.

Post-randomisation withdrawals

Lack of consent

Participants recruited and randomised under consultee agreement were withdrawn from the trial within 6 weeks of randomisation if they were unable to give informed consent by that time.

Participant withdrawal

Participants could decline to take part in the trial at any time. There were different levels of withdrawal:

-

withdrawal from the trial with approval for use of all trial data

-

withdrawal from the trial with approval for use of partial trial data (e.g. clinical records, radiographs only or questionnaires only)

-

withdrawal from the trial rescinding approval for access to trial and clinical data.

Participant care pathway

All of the participants followed routine clinical pathways, other than the allocation of the wound dressing at the end of the initial surgical debridement of the open-fracture wound.

All patients received a general or regional anaesthetic. Antibiotic prophylaxis and prophylaxis for venous thromboembolism was used as per routine protocol at each centre. The wound associated with the fracture was ‘debrided’ (surgically decontaminated and cleaned) in the operating theatre and the fracture was treated with either internal or external fixation. At the end of the initial operation, if the open-fracture wound could not be closed primarily, patients were randomised and allocated to either standard dressing or NPWT.

Both groups of patients then followed the normal postoperative management of patients with an open fracture of the lower limb. This usually involved a ‘second-look’ operation between 48 and 72 hours, at which time a further debridement was performed and the wound closed with sutures or a soft-tissue reconstruction as necessary. Depending on the specific injury and depending on the treating surgeon’s normal practice, the wound may have been redressed again pending further surgery. Any further wound dressing followed the allocated treatment until definitive closure/cover of the wound was achieved.

Postoperative rehabilitation was left to the discretion of the treating surgeon and clinical team, depending on the patient’s injuries and usual clinical practice at that centre.

Primary outcome

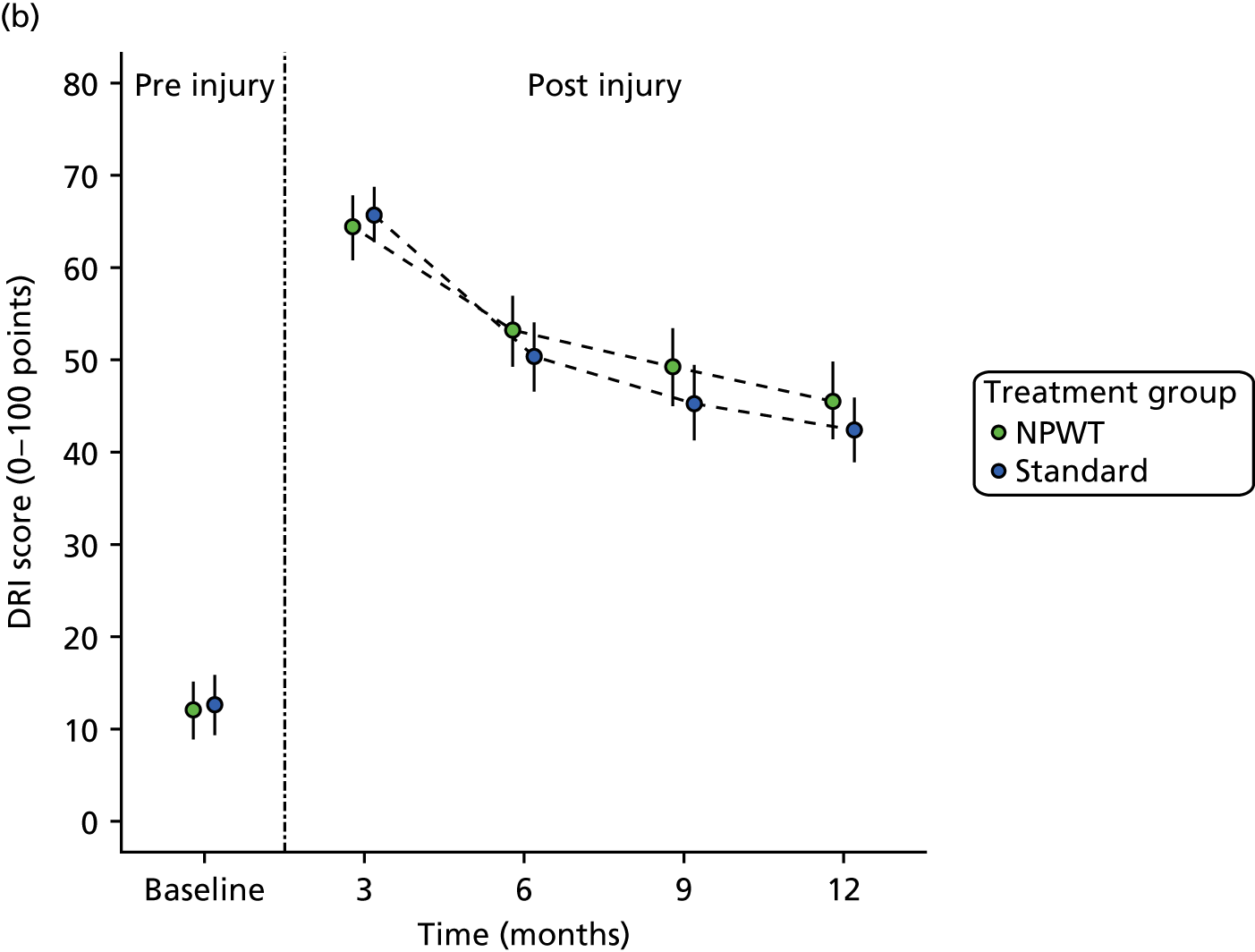

The primary outcome for the trial was the DRI at 12 months after randomisation. The DRI is a self-administered, 12-item visual analogue disability scale questionnaire that is transformed to a 100-point score, where 0 represents normal function and 100 represents complete disability. 16

If more than six items were missing, the DRI was considered to be invalid and was marked as missing; 3 out of the 377 participants (0.8%) with a DRI at 12 months did not provide responses to sufficient items to enable a valid score to be calculated. This outcome measure was chosen because it addressed gross function in the lower limbs, rather than specific joints or body segments. Therefore, it allowed for the different fractures and different injury patterns sustained by the trial participants.

The default method of data capture at baseline (pre injury) was a face-to-face meeting. On later occasions, the default method of data capture was via postal correspondence.

Secondary outcomes

The secondary outcomes were HRQoL, deep SSI, other postoperative complications and resource use. Patient-reported outcomes, including the DRI, HRQoL measures, criteria for SSI and other complications, and health-care resource use, were collected by questionnaire at baseline, 3, 6, 9 and 12 months after randomisation. Baseline assessments were made primarily to allow study participants to retrospectively assess their pre-injury status. Definitions for outcomes and procedures for data collection are described below.

Health-related quality of life

Health-related QoL was captured using the following measures.

-

EuroQoL-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D): a validated measure of HRQoL, consisting of a five-dimension health status classification system and a separate visual analogue scale (VAS). 17 Responses to the health status classification system were converted into multiattribute utility (MAU) scores using a published utility algorithm, anchored at 1 (perfect health) and 0 (death). 18 These MAU scores were combined with survival data to generate quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) profiles for the economic evaluation. In addition, health status was also assessed using the EQ-5D VAS, which required participants to assess their own health from the worst imaginable (0) to the best imaginable (100). These assessments were made by study participants pre injury (retrospectively),19 immediately post injury and at 3, 6, 9 and 12 months post injury.

-

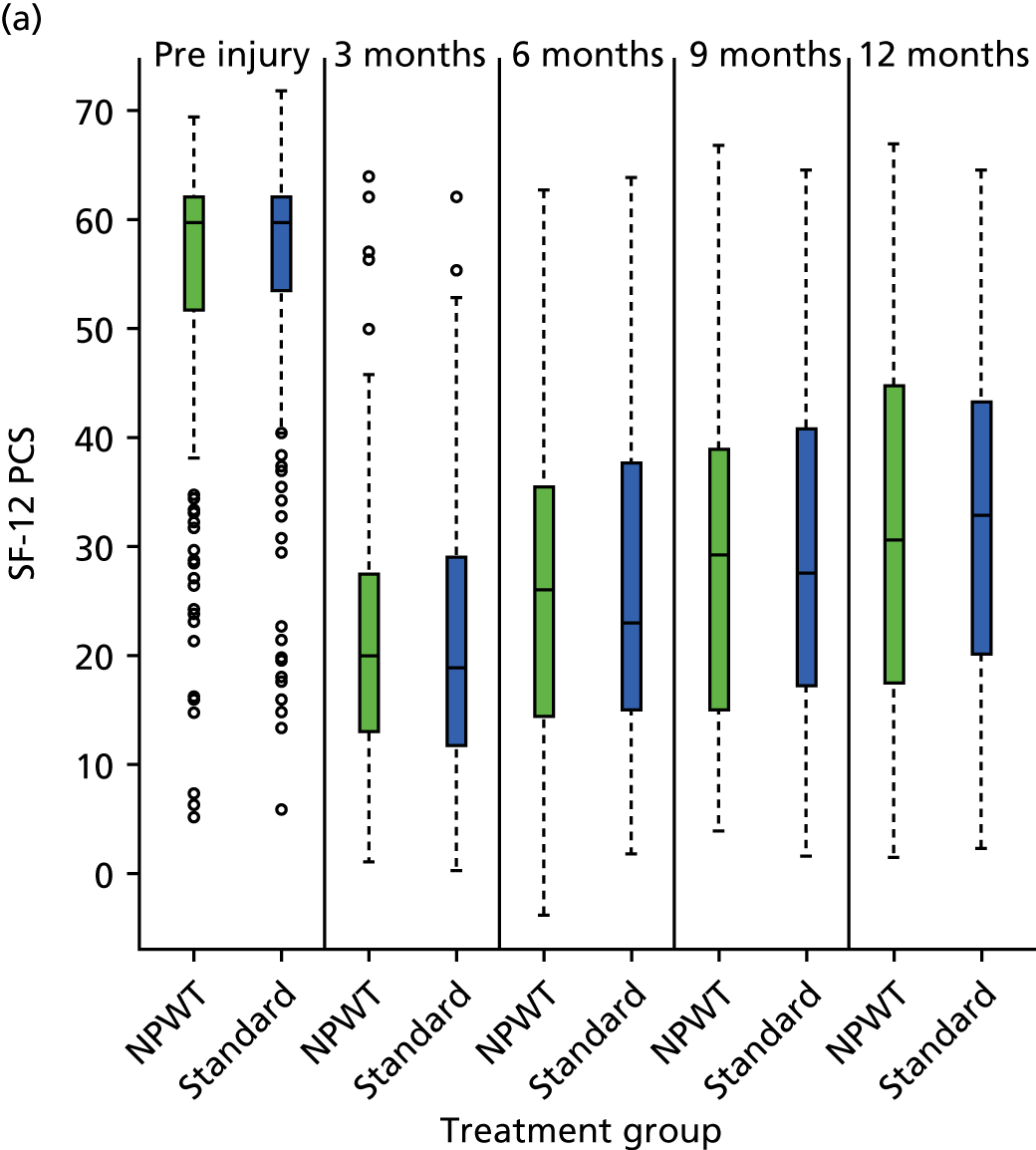

SF-12: a validated and widely used health-related QoL measure. 17 The UK factor score coefficients20 were used to give physical component scores (PCSs) and mental component scores (MCSs). Each permutation of response to the SF-12 was converted into a Short Form questionnaire 6-Dimensions (SF-6D) health utility score using a published utility algorithm. 21 These data were also combined with survival data to generate QALY profiles for a sensitivity analysis within the economic evaluation. HRQoL using the SF-12 was assessed at pre-injury baseline (retrospectively recalled) and at 3, 6, 9 and 12 months post injury.

Surgical site infection and wound healing

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) definitions of SSIs were used (Box 1 and see Appendices 10 and 11). The CDC definition for superficial and deep SSIs is at 30 days following surgery (randomisation). Wounds were assessed and medical records reviewed at discharge, or at the first outpatient appointment after discharge from hospital if the patient was discharged before 30 days. Patients discharged before 30 days had their first follow-up appointment between 30 days and 6 weeks after surgery as part of normal clinical practice in the UK. Wounds were directly observed and infection characteristics were recorded by research staff. The CDC criteria23 for deep SSI also include any deep infection occurring within 1 year if an implant has been left in place. Therefore, we also recorded deep infection presenting within 12 months of the injury: any wound infection that required continuing medical or surgical intervention after 30 days, including infections leading to amputation, was considered a deep SSI.

Must meet the following criteria:

Infection occurs within 30 days after the operative procedure if no implant is left in place or within 1 year if an implant is in place and the infection appears to be related to the operative procedure.

AND

Involves deep soft tissues of the incision (e.g. fascial and muscle layers).

AND

Patient has at least one of the following:

-

Purulent drainage from the deep incision but not organ/space component of surgical site.

-

A deep incision that spontaneously dehisces or is deliberately opened by a surgeon and is culture-positive or not cultured when the patient has at least one of the following signs or symptoms: fever (> 38 °C), or localised pain or tenderness. A culture-negative finding does not meet this criterion.

-

An abscess or other evidence of infection involving the deep incision is found on direct examination, during reoperation or by histopathologic or radiological examination.

-

Diagnosis of a deep incisional SSI by a surgeon or attending physician.

Wound photographs

Wound photographs were taken at 6 weeks. A Samsung ES9 digital camera with flash (Samsung Electronics Limited, Surrey, UK) was given to each centre. Staff were trained to adhere to a standard wound protocol to ensure that images were of adequate quality (e.g. instructions for lighting). Nurses were instructed to remove wound dressings from the open-fracture wound and place a 15-cm paper ruler next to the wound for scaling. This paper ruler included the participant TNO. All images were password protected and returned to the trial co-ordinating centre. Photographs were reviewed blind to treatment allocation by two experienced wound healing specialists. Disagreement was resolved by a third reviewer.

Other postoperative complications

All complications and further surgical interventions related to the open-fracture wound or treatment of the wound were recorded using multiple approaches. Complications were documented at routine follow-up appointments, were self-reported by patients or were notified as adverse events (AEs) or serious adverse events (SAEs) (see Approval for main trial).

All participants were invited for clinical review and a radiograph at 12 months, as per routine practice after this type of injury. If a participant had not returned a 12-month postal questionnaire, this was completed in clinic.

Radiographic images (radiographs)

Radiographic images were taken at 6 weeks and 12 months post surgery as part of routine follow-up for this group of patients. Standard anteroposterior and lateral radiographs were taken at each centre. Copies of original radiographs were stored on a secure compact disc and returned to the central trial office. The radiographs were reviewed by an independent surgeon who was blinded to the treatment allocation. As part of the assessment of complications, each set of radiographic images was assessed for failure of fixation (yes or no). For long-bone fractures, the sagittal and coronal angulation were measured for the index fixation; sagittal angulation > 10° and coronal angulation > 5° were considered to be clinically important. At 12 months, each set of radiographs was also assessed for bony union (bridging cortical bone across three cortices).

Health-care and social care resource use

Resource use was measured for the purposes of the health economic evaluation. Unit cost data were obtained from national databases such as the BNF24 and Personal Social Services Research Unit (PSSRU)’s Unit Costs of Health and Social Care 2012. 25 When these were not available, the unit cost was estimated in consultation with the University Hospitals Coventry and Warwickshire (UHCW) NHS Trust finance department. The cost–consequences following hospital discharge, including NHS costs and patients’ out-of-pocket expenses, were estimated using questions included within a questionnaire sent to participants at 3, 6, 9 and 12 months post randomisation. Patient self-reported information on service use has previously been shown to be accurate in terms of the intensity of use of different services. 26

Data management: postal questionnaires

All questionnaires were sent from and returned to the Warwick Clinical Trials Unit (WCTU), managed by data clerks. If no questionnaire was received within 2 weeks, a reminder questionnaire was sent. When there was no response to reminders, participants were contacted by telephone and invited to answer questions on core outcomes (DRI and EQ-5D). A small proportion of participants were invited to complete the 12-month questionnaire during their routine clinic follow-up appointment 1 year post surgery.

We used techniques common in long-term cohort studies to ensure minimum loss to follow-up such as collection of multiple contact addresses, telephone numbers, mobile telephone numbers and e-mail addresses. Considerable efforts were made by the trial team to maintain contact with participants throughout the trial, including regular participant newsletters.

Approval for main trial

On completion of the 6-month feasibility study, results were reviewed by the Trial Steering Committee (TSC). The target recruitment rate was achieved across five trauma centres (one patient per month per centre) indicating that it was feasible to proceed. In brief, findings from the qualitative interviews suggested that patients were willing to consent and they understood the rationale for the study. Therefore, no changes to the protocol or recruitment targets were made. Following the TSC report, the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme granted approval for progression to the main phase of the trial.

Adverse event management

An AE is defined as any untoward medical occurrence in a clinical trial participant that does not necessarily have a causal relationship with the treatment. All AEs were listed on the appropriate case report form for routine return to the central trial office.

A SAE is defined as any untoward and unexpected medical occurrence that:

-

results in death

-

is life-threatening

-

requires hospitalisation or prolongation of existing inpatient hospitalisation

-

results in persistent or significant disability or incapacity

-

is a congenital anomaly or birth defect

or any other important medical condition that, although not included in the above, may require medical or surgical intervention to prevent one of the outcomes listed.

All SAEs were entered onto a SAE reporting form and faxed to the dedicated fax system at WCTU within 24 hours of the investigator becoming aware of them. Once received, causality and expectedness were confirmed by the chief investigator. SAEs that were deemed to be unexpected and related to the trial were notified to the REC within 15 days. All such events were reported to the TSC and Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) at regular meetings.

Serious adverse events that were expected as part of the surgical interventions and that did not require reporting to the main REC were complications of anaesthesia or surgery (wound infection, bleeding or damage to adjacent structures such as nerves, tendons and blood vessels; delayed unions/non-unions; delayed wound healing; further surgery to remove/replace metal work; and thromboembolic events). All participants experiencing SAEs were followed up as per protocol (PP) until the end of the trial.

Risks and benefits

The risks associated with this trial were predominantly those related to the injury and surgery, for example postoperative infection and bleeding and damage to adjacent structures such as nerves, blood vessels and tendons. Participants in both groups underwent surgery and were potentially at risk from any/all of these complications. Allocation of the trial intervention took place at the end of the initial surgery so that there was no difference between the groups in terms of surgical or anaesthetic risk. Both standard dressings and NPWT have been used widely in the civilian and military settings, and there were no specific risks anticipated with the use of either type of wound management, which was the focus of this trial.

Statistical analysis

Sample size

The minimal clinically important difference (MCID) for the primary outcome measure (DRI) is 8 points. At an individual patient level, a difference of 8 points represented the ability to climb stairs or run with ‘some difficulty’ versus with ‘great difficulty’. At a population level, 8 points represented the difference between a ‘healthy patient’ and a ‘patient with a minor disability’.

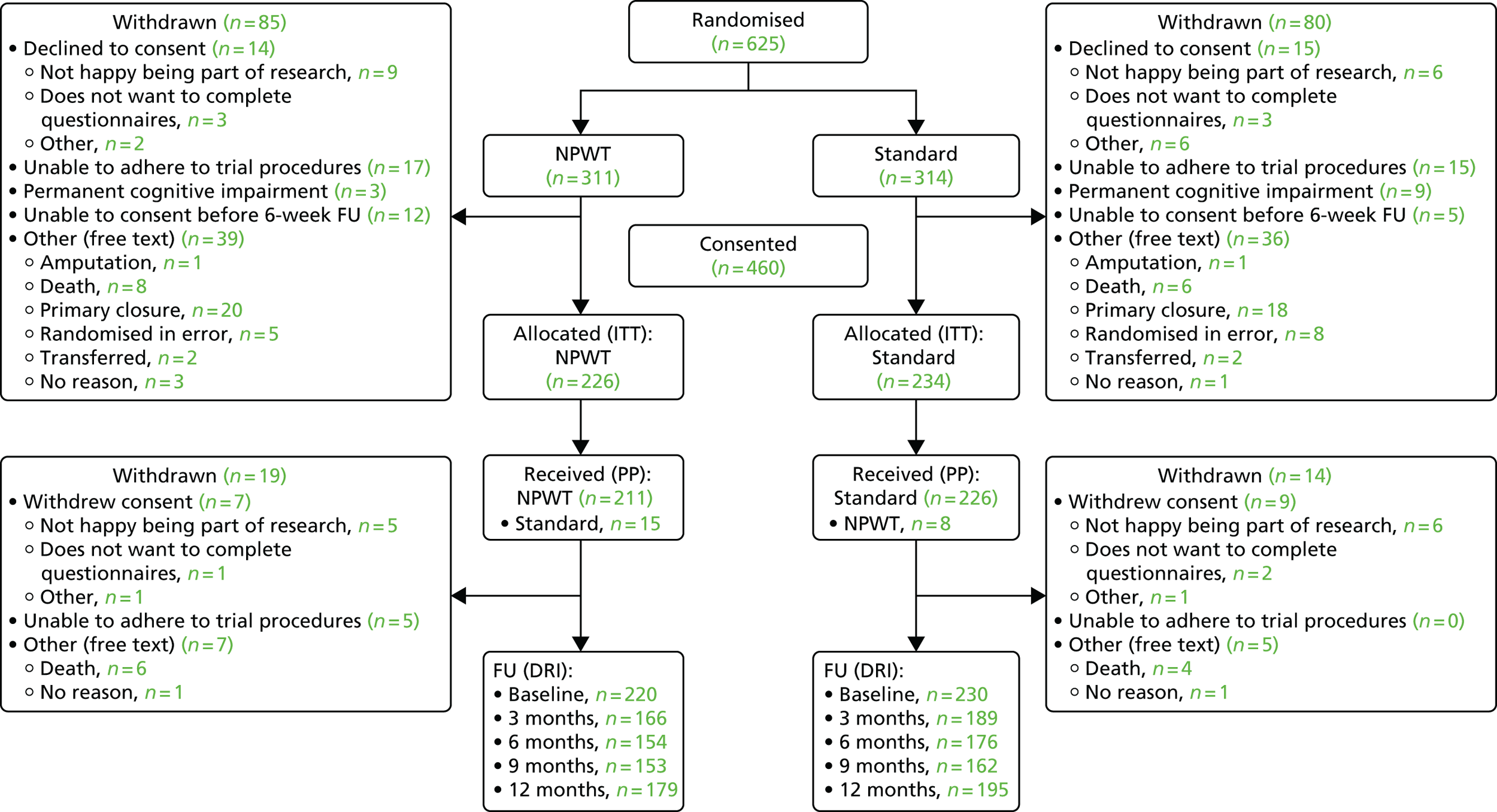

In Table 2, the figure of 412 participants represents a conservative scenario, based on a standard deviation (SD) of 25 participants and 90% power to detect the selected MCID. Allowing a margin of 10% loss during follow-up, including the small number of patients who die in the first year following their injury, gave a total sample size of 460 patients. Therefore, 230 patients consented to each intervention arm would provide 90% power to detect a difference of 8 points in DRI at 12 months at the 5% significance level.

| SD | Power | |

|---|---|---|

| 80% | 90% | |

| 15 | 112 | 150 participants |

| 20 | 198 | 264 participants |

| 25 | 308 | 412 participants |

Analysis plan

Feasibility study

At the end of the feasibility phase, the overall mean recruitment at the five selected centres for this phase of the study was estimated (with a 95% CI) and compared with the target rate of one patient per month per centre. The estimated recruitment rate and the overall rate of withdrawn patients in the feasibility phase informed the design and the decision to proceed to the main RCT.

Main randomised controlled trial

Standard statistical summaries (e.g. medians and ranges or means and variances dependent on the distribution of the outcome) and graphical plots showing correlations were presented for the primary outcome measure and all secondary outcome measures. Baseline data were summarised to check comparability between treatment arms and to highlight any characteristic differences between those individuals in the study, those ineligible and those eligible but withholding consent.

The main analysis investigated differences in the primary outcome measure, the DRI score at 1 year after injury, between the two treatment groups (standard dressings and NPWT) on an intention-to-treat (ITT) basis. In addition, early functional status was assessed and reported at 3, 6 and 9 months. Differences between groups were assessed based on a normal approximation for the DRI score at 12 months post injury and at interim occasions. Tests were two-sided and considered to provide evidence for a significant difference if p-values were < 0.05 (5% significance level).

Although generally we had no reason to expect that clustering effects would be important for this study, in reality the data were hierarchical in nature, with patients naturally clustered into groups by the recruiting centre. Therefore, we accounted for this by generalising the conventional linear (fixed-effects) regression approach to a mixed-effects modelling approach, in which patients were naturally grouped by recruiting centres (random effects). This model formally incorporated terms that allowed for possible heterogeneity in responses for patients owing to the recruiting centre, in addition to the fixed effects of the treatment groups, G&A grade and other patient characteristics that proved to be important moderators of the treatment effect, such as age and gender.

It seemed likely that some data would not be available owing to voluntary withdrawal of patients, lack of completion of individual data items or general loss to follow-up. When possible, the reasons for data ‘missingness’ were ascertained and reported. Although missing data were not expected to be a problem for this study, the nature and pattern of the missingness were carefully considered including, in particular, whether or not data were treated as missing completely at random. If judged appropriate, missing data were imputed, using the multiple imputation facilities available in R (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). The resulting imputed data sets were analysed and reported, together with appropriate sensitivity analyses. Any imputation methods used for scores and other derived variables were carefully considered and justified. Reasons for ineligibility, non-compliance, withdrawal or other protocol violations were stated and any pattern observed was summarised. More formal analysis, for example using logistic regression with ’protocol violation’ as a response, was also considered, when appropriate, to aid interpretation. About 1–2% of patients were expected to die during follow-up; therefore, this is unlikely to be a serious cause of bias. However, we conducted a secondary analysis taking account of the competing risk of death, using methods described by Varadhan et al. 27

A detailed statistical analysis plan (SAP) was agreed with the DMC. Any subsequent amendments to this initial SAP were clearly stated and justified. Interim analyses were performed only when directed by the DMC. The routine statistical analysis was carried out using R.

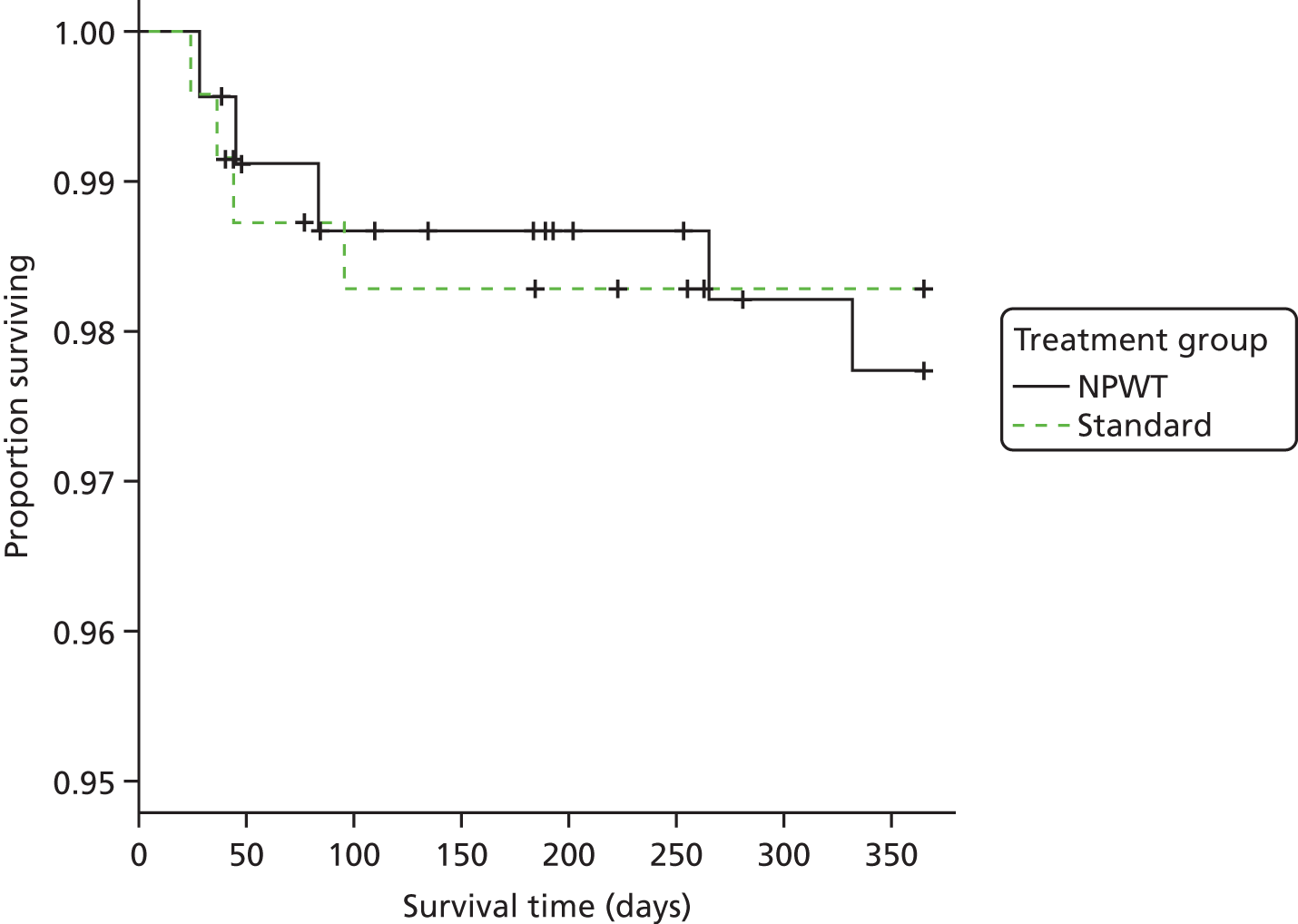

Secondary analyses were undertaken using the above strategy for approximately normally distributed outcome measures SF-12 and EQ-5D. For dichotomous outcome variables, such as indicators of deep infection and other complications related to the trial interventions, mixed-effects logistic regression analysis was undertaken with results presented as odds ratios (ORs) [and 95% confidence intervals (CIs)] between the trial groups. In addition, temporal patterns of any complications were presented graphically and, if appropriate, a time-to-event analysis (Kaplan–Meier survival analysis) was used to assess the overall risk and risk within individual classes of complications.

Health economic analysis plan

An economic evaluation was integrated into the trial design. The economic evaluation was conducted from the recommended NHS and Personal Social Services (PSS) perspective. 28 Data were collected on the health and social service resources used in the treatment of each trial participant during the period between randomisation and 12 months post randomisation. Trial data collection forms recorded the duration of each form of hospital care, surgical procedures, adjunctive interventions, medication profiles, and tests and procedures. Observational research was required to detail additional staff and material inputs associated with clinical complications. At 3, 6, 9 and 12 months post randomisation, trial participants were asked to complete economic questionnaires profiling hospital (inpatient and outpatient) and community health and social care resource use and, for the purposes of sensitivity analysis, out-of-pocket expenditures and costs associated with lost productivity. Current UK unit costs were applied to each resource item to value total resource use in each arm of the trial. Per diem costs for hospital care, delineated by level or intensity of care, were largely derived from national reference cost schedules. The unit costs of clinical events that were unique to this trial were derived from the hospital accounts of the trial participating centres, although primary research that used established accounting methods was also required. 29 The unit costs of community health and social services were largely derived from national sources. Trial participants were asked to complete the EQ-5D-3L17 and SF-1230 measures at baseline and at 3, 6, 9 and 12 months post randomisation. Responses to the EQ-5D-3L and SF-12 were converted into health utility scores using established algorithms. 18,21

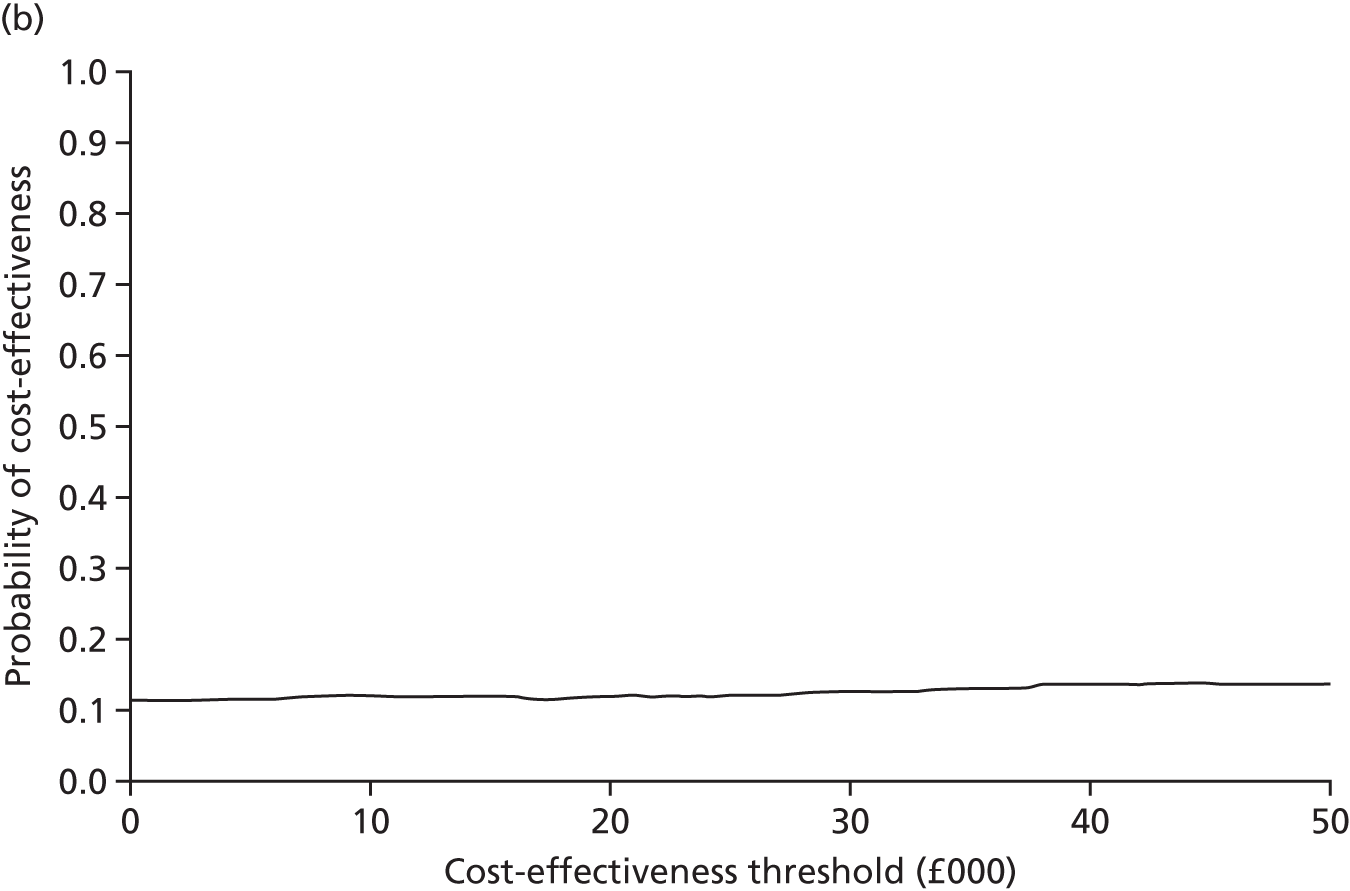

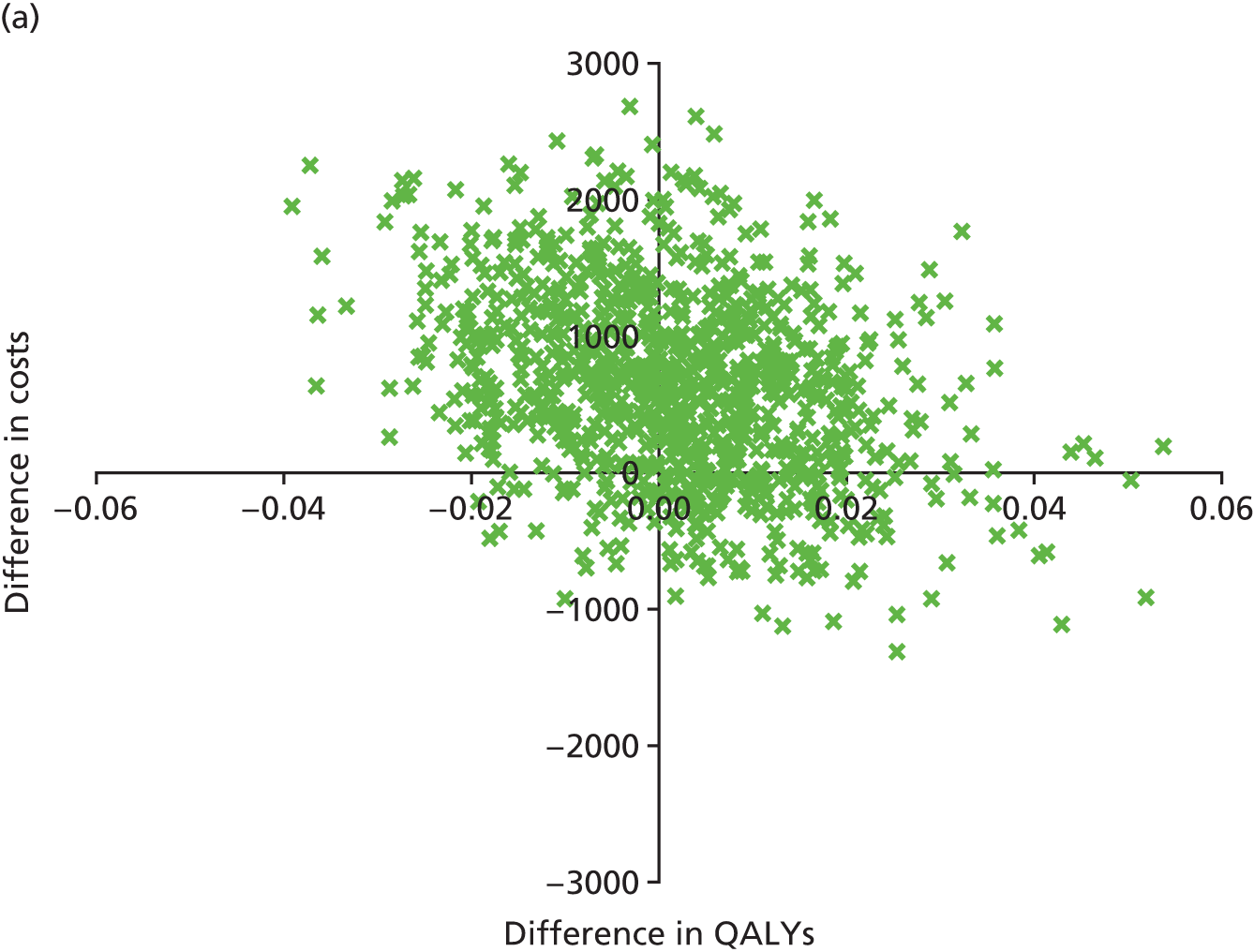

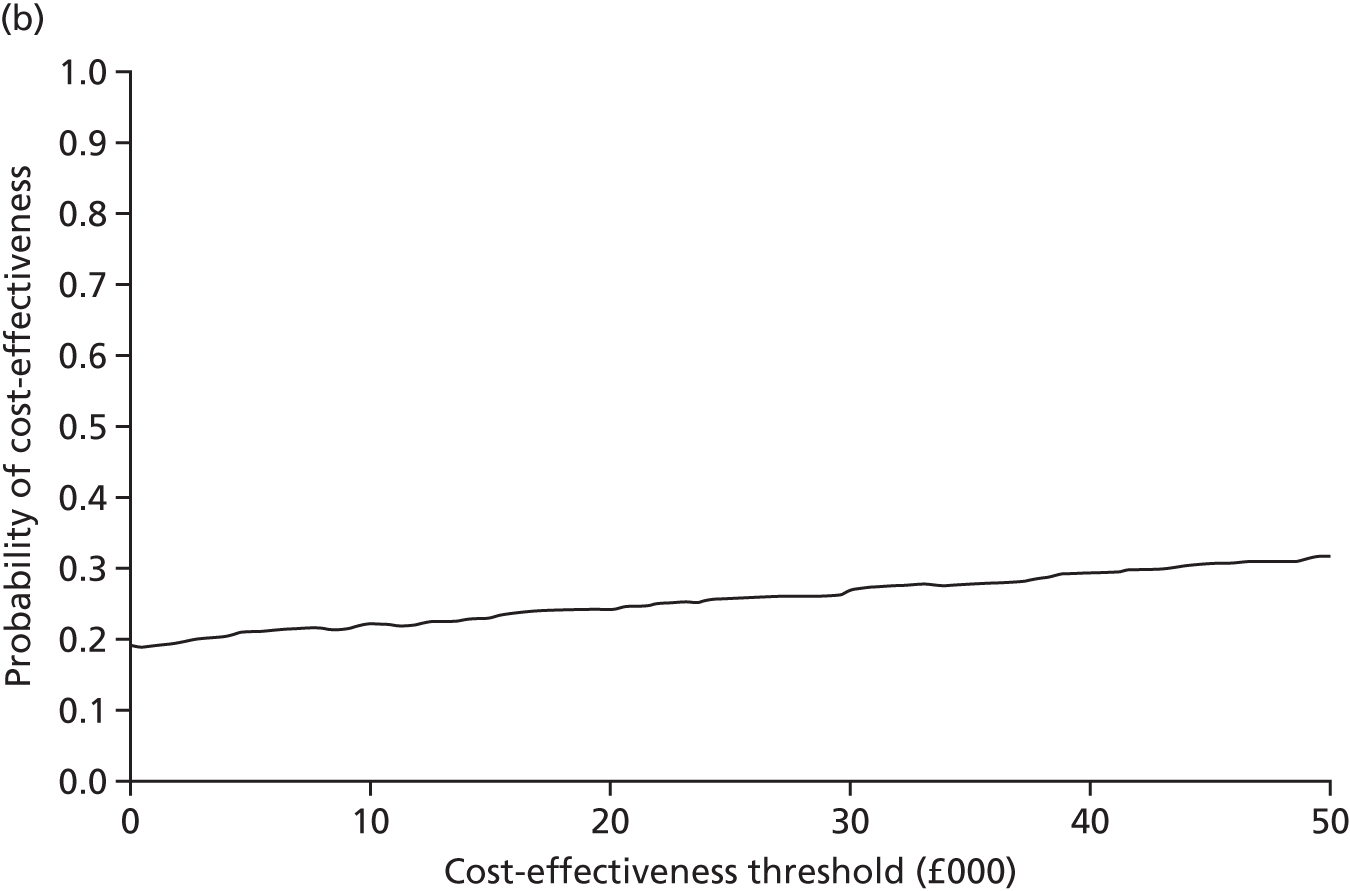

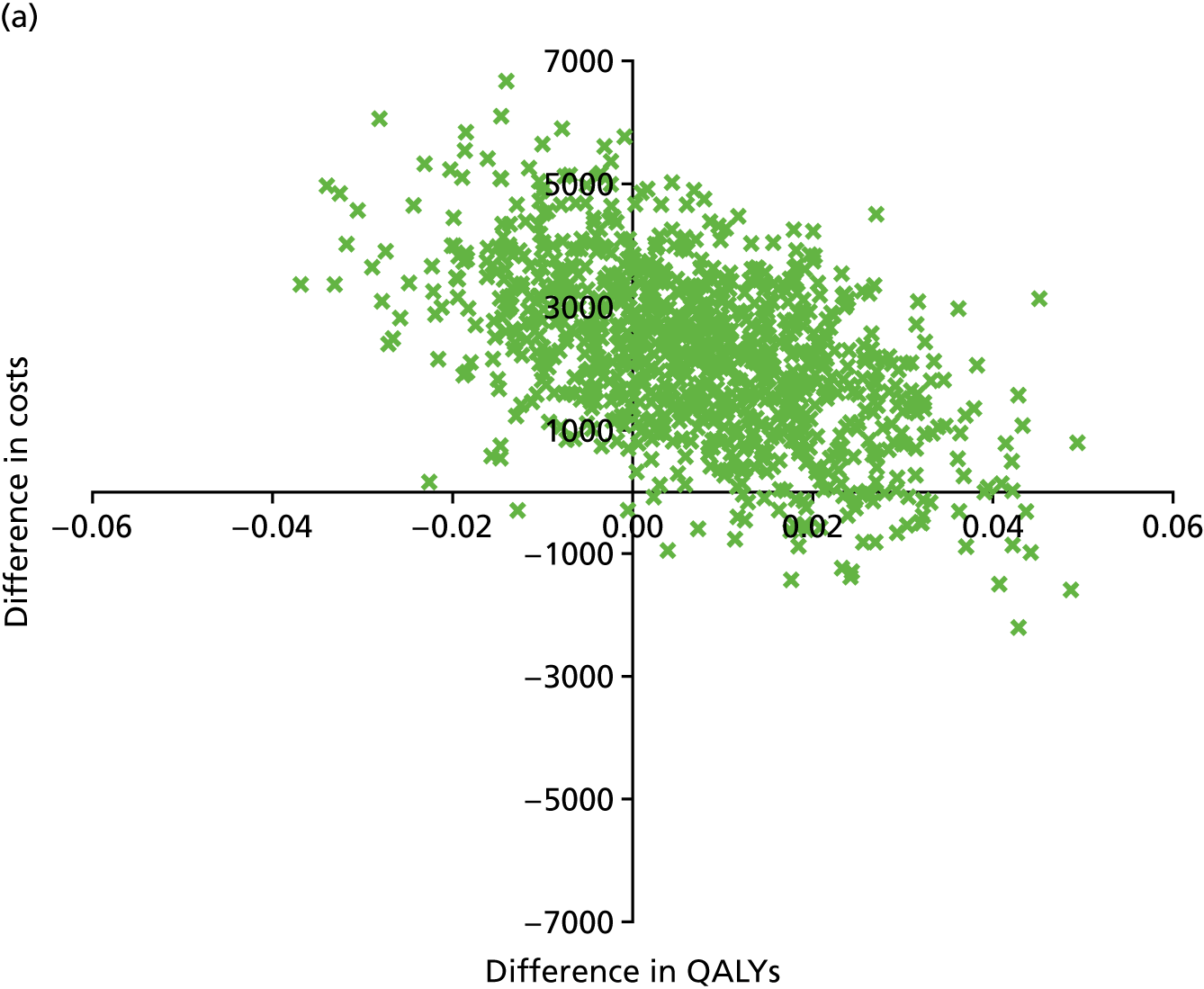

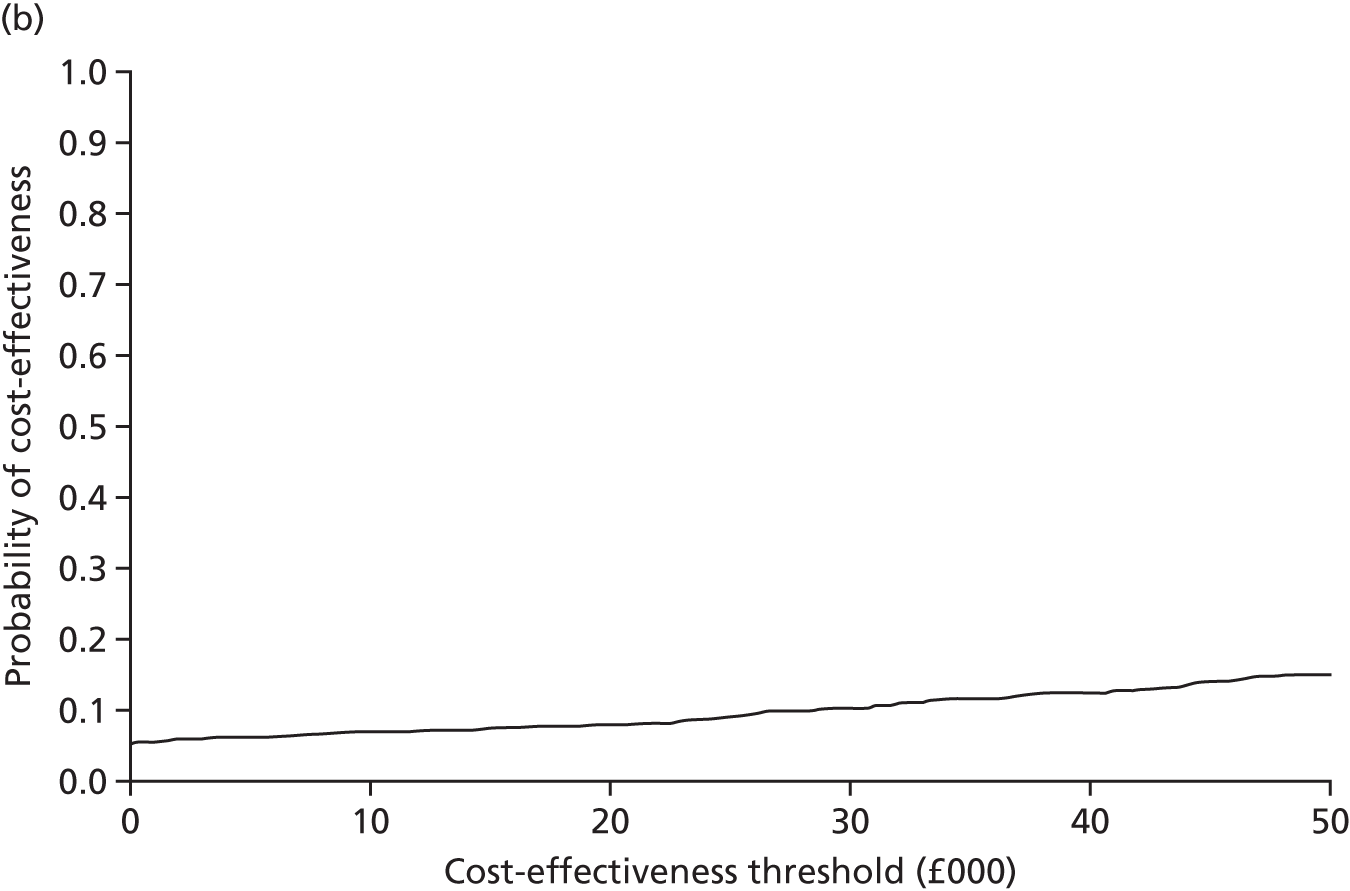

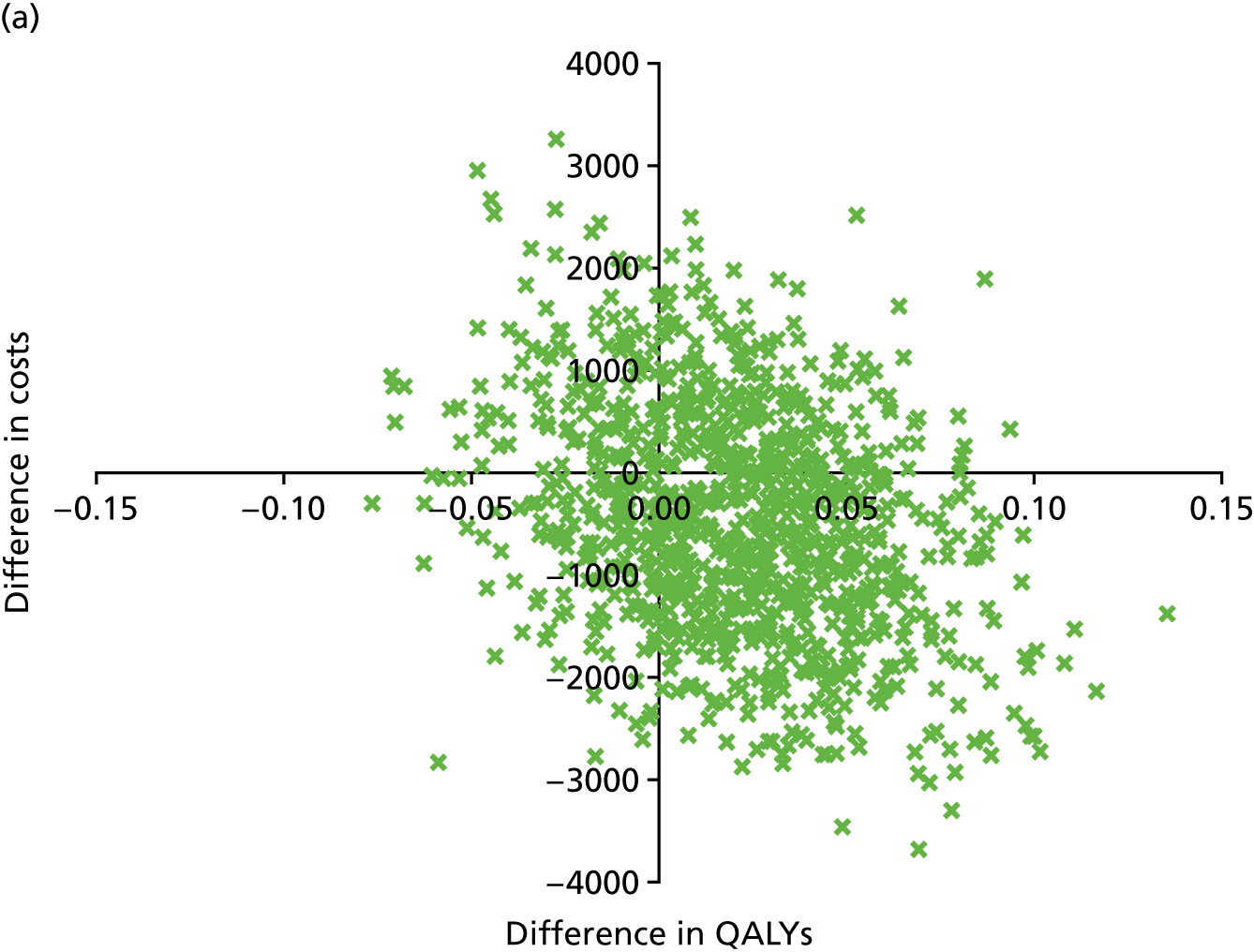

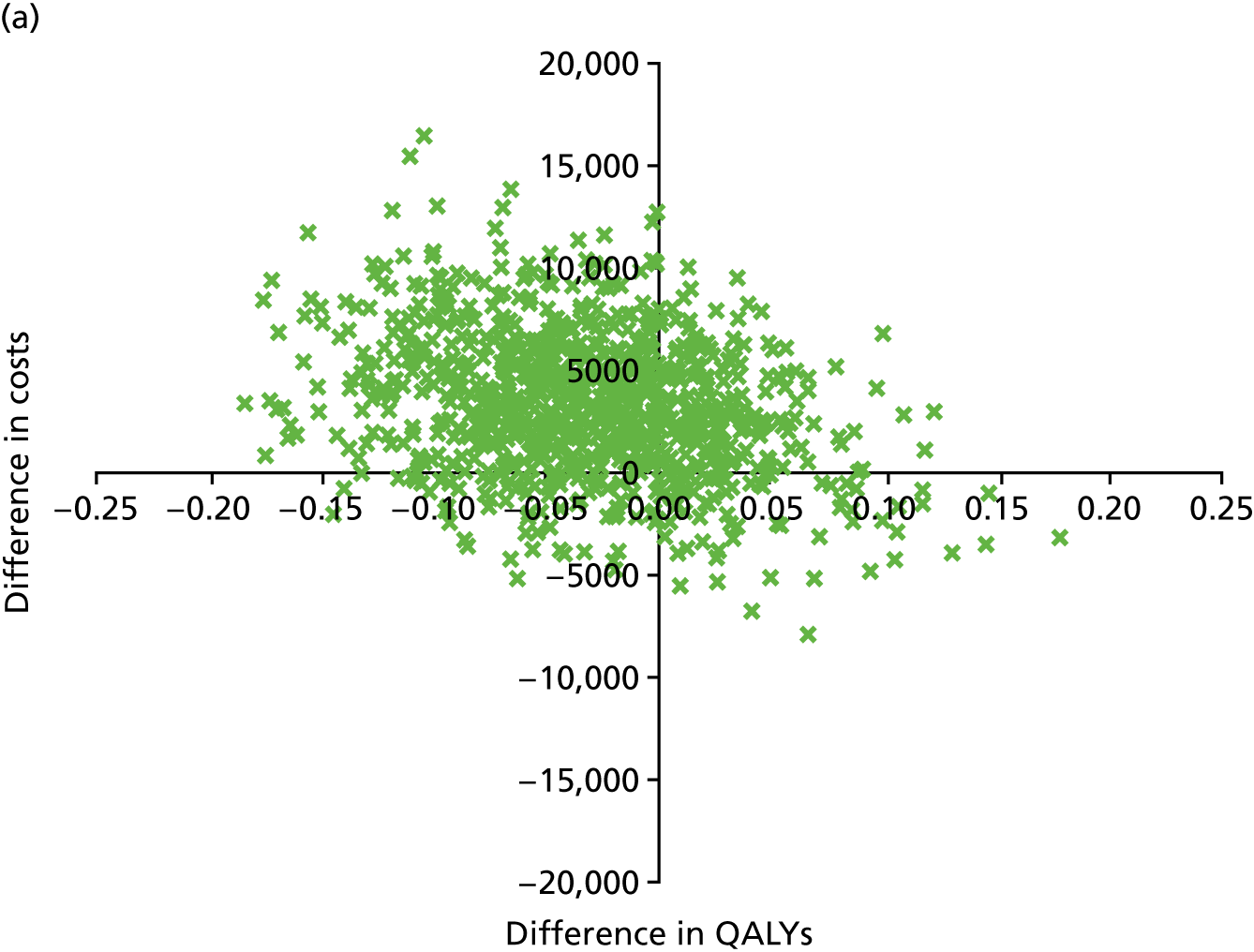

An incremental cost-effectiveness analysis, expressed in terms of incremental cost per QALY gained, was performed. Results were presented using incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) and cost-effectiveness acceptability curves (CEACs) generated via non-parametric bootstrapping. This accommodated sampling (or stochastic) uncertainty and varying levels of willingness to pay for an additional QALY. A series of sensitivity analyses were undertaken to explore the implications of parameter uncertainty on the ICERs. In addition, CEACs were constructed using the net benefits approach.

Ethics approval and monitoring

Standard NHS cover for negligent harm was in place. There was no cover for non-negligent harm.

Ethics committee approval

The WOLLF study was approved by the Coventry REC on 6 February 2012 (REC reference 10/57/20) and by the research and development department of each participating centre. The trial protocol31 was published in the BMJ Open.

Trial Management Group

The day-to-day trial management was the responsibility of the trial co-ordinator, based at WCTU, and supported by administrative staff. The Trial Management Group (TMG) met monthly to assess overall trial progress. It was also the responsibility of the trial co-ordinator to train the research associates at each of the trial centres.

Trial Steering Committee

A TSC was appointed by the NIHR HTA programme and was responsible for oversight, monitoring and supervising trial progress. The TSC consisted of four independent experts, a lay member and the chief investigator. Members of the TSC are listed in Acknowledgements.

Data Monitoring Committee

The DMC was also appointed by the NIHR HTA programme and was tasked with monitoring ethics, safety and data integrity. The trial statistician provided data and analyses requested by the DMC at each meeting. Members of the DMC are listed in Acknowledgements.

Patient and public involvement

Prior to the submission of the grant application for the WOLLF study, an informal survey was conducted at a large university hospital trust to establish the opinion of patients and their carers with regard to research in orthopaedic trauma. We established that patients place great importance on research comparing different types of interventions in the area of trauma surgery. Furthermore, they have demonstrated that they are willing to take part in such trials.

Throughout the trial, a patient with direct experience of sustaining an open lower limb fracture and the subsequent recovery path reviewed all patient documents prior to submission to the sponsor and the ethics committee. Furthermore, advice was sought from this lay collaborator during management meetings when issues were discussed directly related to patient engagement and commitment.

Independent lay representation was present on the TSC. Members of the Trauma Patient and Public Involvement Group also reviewed the progress of the WOLLF study at the annual NIHR Trauma Trials Meetings.

Chapter 3 Qualitative study

Background

This study explores the experiences of patients in acute care who have an open fracture of the lower limb and their experience of being in a trial. Research that examines the experience of having an open fracture of the lower limb is limited, particularly in the acute phase of recovery. Some studies explore recovery at a variety of time points post hospitalisation. For example, in order to develop an outcome tool, Trickett et al. 32 interviewed nine participants 1.2–2.8 years post injury. They identified the serious impact of injury on participants’ daily life as they struggled to recover in terms of a range of different types of pain including stiffness and discomfort, reduced mobility and flexibility, the impact of temperature on their body, frustration and fear, anxiety around their appearance, concerns about getting back to work, a fear of falling, reduced finances and the impact of injury on family and friends. Using a grounded theory approach, Shauver et al. 33 sought to explore the relationship between high satisfaction levels and poor outcomes. Semistructured interviews (n = 20) were undertaken 2.3–12 years post injury. Satisfaction despite poor outcomes was explained by approaches to coping, problem-solving practical difficulties and using cognitive restructuring to identify positive aspects of experience. Personal growth was present as participants developed alternative careers to accommodate their injury.

Other studies that include lower limb injury provide useful insights into patient experience. Griffiths and Jordan34 used diaries and semistructured interviews (n = 9) 5–8 weeks post surgery. Three themes of (1) dealing with uncertainty, (2) seeking control and (3) returning to normality were identified. The participants experienced high levels of pain, had difficulty controlling pain and found dependency on others problematic in their attempt to return to normality. Participants studied by Forsberg et al. 35 were interviewed (n = 9) from 1 to 12 months after injury and identified feelings of frustration, helplessness and vulnerability as they struggled to feel in control and safe as they regained their autonomy. Like the participants in the Griffiths and Jordan study,34 they sought to control their pain but also felt vulnerable while waiting for, and going to, the operating theatre for surgery; security was gained from supportive staff. Studies of ankle fracture support these aspects of experience. McPhail et al. 36 interviewed 12 participants aged < 60 years at 6 weeks to > 2 years post injury and six staff members. They identified ongoing swelling and pain, frustration and depression, an inability to return to normal activities and to wear usual footwear, and a reduction in social life and reduced finances. The emotional vulnerability of older people (aged > 60 years) with an unstable ankle fracture was identified by Keene et al. 37 Unstructured interviews (n = 36) at 6–10 weeks post treatment identified the emotion work participants undertook as they processed being injured and feeling older and renegotiated interdependency with their partners as they coped with non-weight bearing. Rethinking taken-for-granted activities and finding ways of keeping busy was key for their physical and mental well-being. Struggling to move was hampered by comorbidities, lack of skill in using walking aids, pain, swelling and lack of confidence. Support from family and friends was crucial to the maintenance of well-being during this period.

Understanding how participants make sense of trauma trials in an emergency situation when their ability to make decisions may be impaired by pain, medication and emergency treatments is part of the feasibility phase of the trial. In other research studies,37–39 trust in the clinical team and altruism have been identified as reasons to take part in a trial. Often, understanding of trial methodology, such as randomisation, can be limited, which has led to a belief that staff have provided the best treatment for them, often termed ‘therapeutic misconception’. 38,39 The acceptability of randomisation or equipoise when clinical treatment is required is called into question by trial and lay participants40,41 and can threaten participants’ feelings of trust in the clinician. 40 Patients may also make decisions based on a limited understanding of the risks and disadvantages of being in a trial42 and how the trial benefits them personally. 39,43

Our current understanding of patient experience of taking part in orthopaedic trauma trials is limited. In a study of ankle injury management,37 in which participants often had at least 24 hours to consider entering the study, they developed a strong preference for surgery or the non-surgical intervention and were disappointed when they did not get the treatment they desired. Sometimes the experience of family and friends supported their preference, also found by Canvin and Jacoby. 38 However, when interviewed at 6 weeks, they felt that they had received the right treatment for them. 37 This suggests that a process of acceptance developed over time as participants made sense of their treatment as the best course of action for them. This may be an extension of therapeutic misconception, a term used to describe the inability of patients to distinguish between trial participation and normal clinical care or a way of living with their allocated treatment. This study also identified the importance of experiential knowing at the time of consenting and how participants felt they could not know the interventions as they had no prior experience of them. The timing of consent and assessing individuals’ capacity to make an informed decision is problematic in studies of emergency orthopaedic trauma. From a systematic review of a range of studies, Gobat et al. 44 concluded that researchers face a conflict between providing an opportunity for patients to take part in a trial and being viewed as immoral by causing high levels of patient distress, related to patients’ ability to absorb sufficient information, and the additional distress of family members. Third-party consent was generally considered acceptable but there were concerns in high-risk studies and a suggestion that the burden of consent should be shared between several people. Further evidence is required in relation to this study and in particular the use of presumed consent, using personal and nominated consultees, with informed written consent provided for continuation in the study when the participants were well enough to make a decision.

As outlined above, it is not easy for patients to make a full recovery from open fracture of the lower limb, and psychological, physical and social consequences limit many from returning to a pre-injury state. Research involving patients with a range of lower limb injuries adds depth in relation to the impact of such injuries on patients’ emotions, the need for control over pain management and the effects on daily life and relationships. Studies are variable in the quality of their reporting of methodology and rigour, and in some studies samples are small. The theoretical perspectives and timing of the interviews are also variable, and it is difficult to determine how experiences change over time and what may influence change. There is currently a gap in the literature regarding patient experience in the early phase of injury while in acute care. There is also limited evidence regarding the experience of taking part in an orthopaedic trauma trial during the early phase of treatment and recovery. An understanding of this phase will help lay the foundation for improving care for this group of patients and lead to better outcomes of care in the future. This study intends to add to the body of knowledge on patient experience of injury and being in a trial while in hospital.

Methods

The study is underpinned by phenomenology drawing on the work of Heidegger. 45 This is a philosophical approach that focuses on ‘being in the world’ and what it is like to be in the world or ‘dasein’. Research focuses on the meanings inherent in everyday life, including aspects that may be taken for granted. Madjar and Walton46 suggest using a ‘listening gaze’ to focus on the unknown in order to gain a deeper understanding of the person within his or her life world. The central tenets of phenomenology convey ‘being’ within the social, historical context of the person, and include temporality and a sense of space, both spatially but also in relation to aspects of ‘concern for’ the other. 45 The research process therefore is framed by a focus on what life is like for an individual and the taken for granted meanings inherent in their everyday world. Interviews are often the method of choice; through descriptions of what it is like, notions of being, context, time and space can be examined.

In this study, unstructured interviews were undertaken while participants were in acute care. The interview focused on their experience of being injured. This was followed by prompts such as ‘tell me more about that’, ‘how did you feel?’, ‘what did you think at that time?’ and ‘how did that differ from?’. The intention was to give participants the opportunity to describe what it was like to be injured from their perspective, and to explore the issues, concerns and taken-for-granted aspects that were part of their everyday experience. In addition, one focus group with five clinical and research staff, including doctors and nurses, focused on what it was like to recruit patients to the trial.

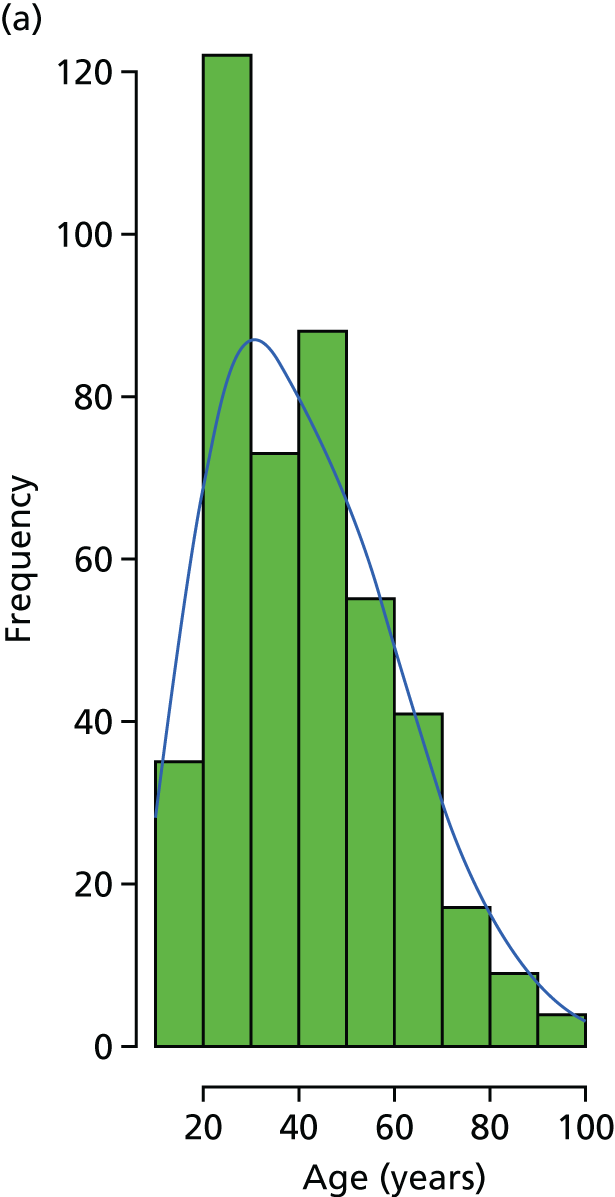

A purposive sample of 20 patients of different ages, genders and breadth of experience was recruited; participants had been hospitalised for treatment for open fracture of the lower limb and had consented to be part of the WOLLF study. 31 All patients had fractures, G&A grade 2 (n = 4) or grade 3 (n = 16), often alongside other injuries; two participants had an extended period in critical care. Injuries had been sustained through motorbike/car collisions and activities at work or in the home. They were aged 20–82 years (mean 40 years, median 38 years). Time since first surgical intervention (within 72 hours of injury) ranged from 5 to 35 days (mean 12 days, median 11 days). Interview length ranged from 25 to 86 minutes (mean 54 minutes, median 58 minutes). In addition, one focus group was undertaken (46 minutes) with five interdisciplinary staff to ascertain their experience of undertaking the study.

Interviews took place between July 2012 and July 2013. The researcher approached those who gave permission and discussed the study with them. They received an information sheet and had at least 24 hours to consider participation before signing a consent form. NHS research ethics approval was granted. Interviews took place in a ward environment because the nature of participants’ injuries necessitated them being confined to the ward area. Interviews in busy clinical environments are problematic as maintaining privacy and dignity can be challenging. This was discussed with participants, who were given control over when to stop the interview; visiting times were avoided and the researcher left the area during clinical visits and mealtimes. The participants were comfortable with the interview environment and not concerned when interruptions occurred.

Interviews were recorded (digital–audio) and transcribed verbatim. Analysis was undertaken by drawing together codes that conveyed inherent meaning within the descriptions to form categories and themes while being aware of similarities and differences within the meanings. 47 For example, descriptions underpinning codes reflecting death, saviours, miracles and being lucky were drawn together within the category ‘being alive’, which best reflected the meaning underlying the codes. This was then drawn into the theme ‘being emotionally fragile,’ as emotions reflected the broader theme underlying each of these categories. Reflection on the process drew on notions of the hermeneutic circle,48 considering each meaning in relation to each other and the emerging whole. NVivo 10 (QSR International, Warrington, UK) was used to help manage the data. The same process was undertaken for the focus group.

Rigour was demonstrated through the notions of trustworthiness. 49 The researcher was immersed in the data for a prolonged period of time and used verbatim quotes. A range of experiences were presented, reflecting the breadth of data to enhance transferability and resonance with the reader. Auditability was demonstrated through identification of the research process. Intersubjectivity of the researcher with the data was examined throughout by reflection on data collection and the process of analysis with peers and in field notes. The previous experience of the researcher (ET) of researching concepts such as comfort, hope and other areas of injury was part of this reflective process.

The findings

The findings identify the overall theme of embodied vulnerability, in which the impact of the injury goes beyond the physical body to have an impact on all aspects of the individual’s self and their life.

Embodied vulnerability in this study was defined as a response to injury in which participants experienced a new way of being in the world expressed through their emotionally fragile, visibly wounded, constrained and painful body. They suffered and endured their recovery in hospital in the context of uncertainty and, when ready, they reimagined how their life would be at home and at work.

In this group of previously generally healthy, independent people with busy lives, there were high levels of emotional and physical distress as a result of sudden injury. The experience was extremely challenging, requiring dependency on others and a high degree of personal resilience. The participants vulnerability was expressed through four themes depicted in Figure 1: (1) being emotionally fragile, with categories of being alive, being close to losing a leg, being a person with strong emotions and being aware of others; (2) being injured, with categories of being a person with wounds, being constrained and being in pain; (3) living with injury, with categories of being at home and being at work; and (4) being compromised, with categories of being dependent on others, being trusting, being grateful, and being without prior experience.

FIGURE 1.

Conceptual framework: embodied vulnerability – relationships between themes.

Theme 1: being emotionally fragile

Being emotionally fragile reflects the feelings required to make sense of the event, live with continued uncertainty and process their own strong emotions and those of others. It was expressed through being alive, being close to losing a leg, being a person with strong emotions and being aware of others.

Category: being alive

Being alive conveyed the dramatic, life-threatening nature of this injury, often caused by high-impact road traffic events, many involving motorbikes, or industrial incidents. Many of the participants felt that they could have died and the last their families would see of them was in a ‘box’ (participant 10). The shocking nature of the near-death event created a sense of being saved and, for some, a sense of spirituality, a ‘sort of a miracle’ (participant 3), with professionals regarded as saviours. Being grateful that they had received such good care went alongside being lucky, which was linked to what could have happened and how the situation could have been so much worse:

I’ve just got to go with what happens really but at the same time I’ve still got to harp back to the fact that in the first place I was lucky. I could easily have died in that incident so you’ve got to think about relative situations really haven’t you and the injury that I eventually sustained . . .

Participant 5

Being alive, being saved and being lucky were notions that participants reflected on when talking about their recovery and planning their life in the future.

Category: being close to losing a leg

Participants were horrified and shocked, when, at some point in their recovery, they felt, or were told, that losing their leg had been, or remained, a possibility. The ease with which this could happen, and the inherent uncertainty about whether or not it would, created a high degree of anxiety:

Emotionally it’s been a real shock and quite a rollercoaster . . . and to be told that if they didn’t get it right I could lose my leg which was a bit of a shock and just to realise how easy it is to do something so serious.

Participant 16

Interviewees felt a mixture of relief and hope in relation to the potential loss of a leg. It was not something they had envisaged before the accident and they hoped it would never happen. Relief that they had kept their leg so far was mixed with apprehension regarding the uncertain progression of their recovery and the potential threat of its loss in the future.

Category: being a person with strong emotions

The participants’ stories conveyed an emotional fragility that pervaded every aspect of their lives. Some had not felt this degree of fragility before; others had, but only in relation to extreme events, such as the death of a loved one. All interviewees expressed strong emotions, and sometimes these spilled out as ‘meltdowns’, when they cried and felt they were unable to cope. A few participants in this study preferred not to talk about their injury as the feelings engendered were too strong. Some struggled with these more than others and, at times, it felt like a rollercoaster as the slow realisation of the seriousness of the impact of injury on themselves, their families and their lives unfolded. They were unprepared for the emotional hit of the accident; in addition, the repeated surgical interventions, despite knowing they were in safe hands, made participants feel vulnerable, a feeling they were not used to in their busy successful lives:

. . . initially I think I found it quite difficult and to be emotional. It’s just not something for me at all. It would take a lot for me to bring my emotion out, it would take a significant thing in my life and I’ve probably only experienced it twice, so yes quite a lot to deal with, I found it quite strange but I think we’re getting there.

Participant 9

The injury event was shocking and overwhelming; many participants relived the event through talking; for others, it was too upsetting. Some processed the fear and anxiety through regular dreams and nightmares:

I have nightmares about not being able to walk ever again or my children will walk in with my leg in their hands and stupid stuff like that.

Participant 19

The long, slow process of repeatedly requiring further surgery and coping with the impact of injury in a hospital setting reduced the participants’ capacity to emotionally cope with their recovery:

. . . it wasn’t until I got right down to the anaesthetics room that the penny dropped and then I was like a big girl’s blouse because I didn’t have the wife there or anybody there just two strangers and I felt lonely and vulnerable and basically my life is in their hands.

Participant 3

Strong emotions, such as anxiety, fear and low mood, were expressed in relation to sleep patterns, the next surgical step, the anaesthetic and being in hospital. As the extent of care required and the impact on their lives came to the fore, emotional resilience was required to endure the interventions, but participants often lacked emotional capacity and felt ‘like flipping, and going absolutely off my head . . . going absolutely schizo’ (participant 14). Psychologically, it was hard work with frustration setting in after the initial relief at being in the right place with the right care. The strength of emotions was a surprise for participants, but something they learnt to manage in a public place. However, on occasions, it was directed at staff or spilled out when insurance personnel or police asked about the accident. They also suppressed the emotional consequences of their injury for the sake of family and friends.

Category: being aware of others

The participants were not only processing their own emotions but were also facilitating family and friends’ responses who were also experiencing strong emotions. For example, a group of friends came in singing with cards and balloons but were stunned when they saw the degree of injury sustained:

I realised they were shocked and that was quite shocking to me, and they realised the grief and looked back and just joked about it.

Participant 2

There was some degree of suppression of their own emotions with the intention of maintaining normality and instilling a sense of hope that recovery was progressing:

Inside I really am as tough as old boots. I was more upset when I saw my wife upset and the effect it had had on her. I don’t think I really realised just how close I did come but as I said, I am still here and it didn’t happen, it’s just part of life . . . I put on a brave face so the wife can start to relax and start being normal again, that’s the most important thing to me for the kids to stop worrying, Dad’s on the mend and it’s all going to be good. There is light at the end of the tunnel.

Participant 3

The younger participants found Facebook (Facebook, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA; www.facebook.com) and the social contact with a wide range of friends incredibly supportive and a good way of maintaining contact with everyday life, family and friends; however, the nature of the interactions and type of support was not explored in this study.

Theme 2: being injured

Being injured was an emotional and physical shock for all participants and they struggled to manage their bodies through the categories of being a person with wounds, being constrained and being in pain.

Category: being a person with wounds

The wound itself and the state of the injured leg created a real sense of panic and shock. Interviewees were reluctant to see the actual wound and had to be ready to do so. They had to prepare: ‘giving it time and psych myself up’ (participant 1). The visual look of the wounds often left participants feeling shocked and sick:

It was off and I looked down and thought oh my God they’ve obviously got to cut my leg off because it just looked horrendous . . .

Participant 2

Participants were concerned about how they would live with the resulting wound. They were surprised by staff responses when they described their wound as brilliant, beautiful or healing well. Preparation of participants for seeing their wound was varied; good preparation was beneficial:

I saw it [the wound] for the first time yesterday, which was a bit weird, but if I hadn’t seen the pictures in the book I wouldn’t have known what to expect at all and it would have been horrible and it probably would have made me feel a bit sick . . . I’m glad again that I was shown the pictures so I knew what to expect . . .

Participant 11

There was a sense of being damaged and concern about what others would think:

I was worried that she wouldn’t find me attractive and she’s so pretty and so perfect and I thought ‘what is she going to think of me now?’.

Participant 2

Some became accustomed to their wounds and, on some level, accepted them and took a cognitive interest in their healing and progression:

Yes, last couple of days, side by side (both legs undressed and visible), a bit overwhelming but also a big sigh of relief because they are on the mend, well definitely very far into the mend. Compared to what they were like. Everything seems to be alright with them, the plastics are happy with them . . . I was just intrigued to be honest. I took photos to send to the family. It’s not pretty to look at but to me looking at it, it makes me feel happy to be honest because my legs are still there. It is not pretty to look at but it is what my legs are like now.

Participant 19

For certain participants, at some point in their recovery, there was a feeling of detachment from their body; they needed time to assimilate what was happening or were unable to cope with the implications and so temporarily disconnected from the situation:

The only time I actually felt detachment was when Jim first mentioned the possibility, the extreme possibility, of amputation. When another surgeon came in and mentioned it again I almost felt like I was in heaven and just detached slightly. I was listening to him and thought blimey I’ve completely disconnected from this, that’s when I feel detachment when that gets raised, I’m not consciously, it’s not a decision to detach, but it just seems to happen because it’s something that even though I’m aware of it I don’t really want to have to consider it right now.

Participant 15

Readiness to see a wound and preparedness are key elements in being a person with wounds; inclusion of family and friends is important in this process where they can offer support for the emotional impact of having a wound with a focus on the natural bodily responses and how they change over time.

Category: being constrained

The participants felt they were constrained by their body’s inability to perform in its normal way. The majority were outdoor, active people who had physically busy lifestyles. Being constrained by their body was boring and frustrating. Instead of being taken for granted, their body now required surveillance and they observed their body, noting the swelling and changes in bruising and watched for signs of healing. They expressed their shock at how limited they were in terms of what they could do. Their bodies were lacking in strength and constrained in their ability to function which affected what they did and how they felt:

Yes, the strength in my legs is so reduced it’s quite incredible and so you can imagine a few more weeks like this and it’s going to take a while to get my strength back, it’s your core strength. If I transfer from this to a wheelchair I’m absolutely exhausted and you’ve just got no trunk strength or virtually none.

Participant 2

Many participants had lost the use of both legs and had other injuries that left them constrained to the bed, resulting in frustration, boredom and stress as they tried to cope with the daily discomforts and waited for their body to heal:

The largest frustration has been the scaphoid fracture in my right wrist which is just another thing to go with the left leg.

Participant 13

Hospital life was frustrating, particularly being on bed rest. Once they could physically move, there was a sense of surprise that they were unable to move naturally, had to plan everything and required help. Participants had to learn how to cope with prolonged periods of bed rest and immobility, deal with the frustrations of limited mobility, accept the pace of recovery dictated by the healing process and move their bodies within the limits of their injuries. There was a heightened sense of surveillance in relation to monitoring their body for signs of recovery but also a mix of frustration and acceptance combined with relief when they could finally move about.

Category: being in pain

Participants experienced extreme pain at some point that they found difficult to control and expressed strong emotions that they would not normally express. Many had support from the pain relief team with some success. Others struggled to find pain relief that suited them, to get timely access to pain relief, to balance activities around pain relief and to control their emotions as a result of pain. Pain was a constant source of concern and was worse early on in the recovery process. Interviewees who had patient-controlled analgesia were fairly happy with their pain control once they had worked out how to use it, but timely access to oral medication was difficult. For some, the pain varied in nature but was persistent, wearing down their ability to cope:

Yes there are days that the pain is bad and there have been days where I can’t bear the pain. I’ve been asking for painkillers and I’ve curled up . . . to try and deal with the pain. It does have its days of coming and going, the pain. I had pain when I woke up just now, and now it’s gone into an ache, which is sometimes worse because obviously an ache you can’t do anything about. It’s aching now and that’s why I keep fidgeting . . . It’s not always just pain, it’s like itching where it’s healing and I can’t itch it, which is annoying. There’s aching, itching, pain, throbbing, there’s a burning pain like when you’ve got sunburn, it feels like that on my legs where they took the skin grafts from.

Participant 19

Trying to be ‘big and strong’ was a difficult facade to maintain in the face of persistent acute pain; resilience was lowered by pain to a point at which participants expressed distress:

Yes, it has made me cry a few times and I’m not really the sort of person to cry but obviously where I’m so stressed out in here and in so much pain it’s bound to come to it.

Participant 14

Overall, pain was a source of concern to all participants at some point in their recovery. This was complicated by the variety of sources of pain, access to medication and a general reluctance of patients to take medication. The group appeared to suffer considerably, which reduced their energy to cope and often led to expression of strong emotions in public that were not normal for them. Thus, being a person in pain was an inherent part of the injury experience and affected their ability to process their emotions and actively manage their recovery.

Theme 3: living with injury

Living with injury evolved as they found mental space to rethink or reimagine how they might live their life at home and at work in the future and was conveyed through the categories of being at home and being at work. This thinking was done within the context of a high level of uncertainty.

Category: being at home

The participants felt that the future was unknown and uncertain but that they were lucky to have a future. The need to get home was overwhelming, but as they progressed through the recovery process it was something they felt was more tangible and they could ‘visualise’ (participant 19) what it would be like to go home. Emotionally, they were anxious and daunted about going home which was sometimes expressed in nightmares. Cognitively working through how it would be at home and how they would manage physically was mixed with concern about how their families would cope. Managing false hope and having realistic expectations of what being at home would be like were of concern. Returning to their hobbies was also a preoccupation, with some planning ways to continue them and others processing the loss of their ability to undertake their hobby:

It’s really hard and it sickens me the thought of losing my bikes but it’s a small sacrifice. If I want to live another 30 years on this planet and I want to walk these beautiful girls down the aisle, then it’s a small price to pay.

Participant 3

Planning a return to home was largely about thinking it through, supporting activities at home to make living at home doable for the family and planning how they might cope. There was sadness at the loss of the life they had before and a degree of uncertainty about how things would work out but also a determination to get home and cope with the changes in their lives.

Category: being at work

Part of getting back to normal was getting back to work. This proved to be a slippery concept that was difficult to visualise owing to the uncertainty of recovery from trauma and degree of functional recovery expected. Any information on this aspect was gratefully received, but participants felt that clarity about timescales was unlikely owing to the complex nature of their injury and individual recovery paths.

Participants with physical jobs had difficulty imagining what they would do. Some had casual contracts with no other skills and were thinking about what they could do to earn a living, some had plans and others were unsure how they would manage. Uncertainty over their ability to function as before was a source of concern:

Yes but I’m not too worried about getting back on a horse or anything like that or the nerves and it’s whether I can physically do it. Mentally I will be fine, there’s no question about that but physically I don’t know . . . we’ll see whether it’s time to pack up and get a new trade. I don’t know but it’s a possibility.

Participant 8

For some interviewees, the accident had provided an opportunity to re-evaluate their lives. Getting back to work was seen as part of a return to normality and necessary for financial security but they were uncertain about their ability to function and make it happen. Those with physical jobs were aware that their ability to work as before was unlikely but could not see an alternative at this stage.

Theme 4: being compromised

The decision to go into the trial was based on being compromised, defined as being dependent on others owing to the acute/emergency nature of the injury and a high degree of trust invested in the clinical team. Being grateful included feelings of altruism and the need to give something back, supported by prior research knowledge and the minimal burden of the research process. Being without prior experience of the two treatments led to a state of not knowing about the interventions; however, experience of the two treatments or information from others clearly identifed a technological preference for NPWT.

Category: being dependent on others

There were challenges in relation to the acute circumstances of the injury, the high degree of trust in the clinical team and the lack of prior experience of the two treatments. The decision to go into the trial was made at a time of great stress, ‘I don’t think I was in any fit state to make any decisions’ (participant 6), and there was acceptance that ‘somebody had to make a decision on your behalf’ (participant 2); however, some were able to make sense of the trial and, based on the fact that both interventions were commonly used and not invasive, were happy to go into the trial:

I was informed about it on the first day and I can half remember being informed about it because I was on gas and air and morphine, tramadol, I was on all sorts of stuff the first day, but yes I can remember being asked about it. I can remember agreeing to it then but not quite with it and then they mentioned it afterwards and yes I can’t really see it having that much effect on me.

Participant 11

Verbal consent before going to the operating theatre sometimes helped them make sense of the trial when they were later asked to provide written consent:

They asked me beforehand and I can remember giving verbal consent so the written consent afterwards didn’t bother me at all.

Participant 11

The nature of the trial was unproblematic for participants but the principle of being asked to take part was important for some participants. Some preferred, if at all possible, to be asked about the trial before the surgery – ‘I would rather that they woke me up and asked me given the choice’ (participant 15) – but, in light of their poor state and lack of concern about the nature of the dressings, were not concerned about the study itself. There was a general acceptance that, in some areas of life, there is no choice. Some participants, despite knowing they were not in a fit state to be asked, considered being a ‘guinea pig’ as a way of making sense of their participation, while others did not mind and still others felt rather ‘shocked’ (participant 8) at being asked to consent after surgical intervention, but balanced this against any potential harm and their ability to get better in the longer term. There was some confusion or lack of memory in relation to the trial, but generally doctors were seen to ‘know best’ (participant 20):