Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 10/57/14. The contractual start date was in March 2013. The draft report began editorial review in July 2018 and was accepted for publication in August 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Since November 2013, Edmund Juszczak has been a member of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) General Funding Committee and HTA Commissioning Funding Committee. William McGuire is a member of the NIHR HTA Commissioning Board and the NIHR HTA and Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation Editorial Board. Jon Dorling is a member of the NIHR HTA General Board (from 2017) and the Maternal, Neonatal and Child Health Panel (from 2013). Nicholas Embleton reports grants from Prolacta Biosciences Inc. (Duarte, CA, USA), grants from Danone Nutricia Early Life Nutrition (Paris, France), personal fees from Nestlé Nutrition Institute (Vevey, Switzerland) and personal fees from Baxter Healthcare Ltd (Newbury, UK) outside the submitted work.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Griffiths et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Late-onset infection in very preterm infants

Late-onset invasive infection (occurring > 72 hours after birth) is the most common serious complication associated with hospital care for preterm infants. The UK James Lind Alliance Preterm Birth Priority Setting Partnership has identified the development and assessment of better methods to prevent infection in preterm infants as a research priority. 1

The incidence of late-onset infection is typically estimated to be > 20% in very preterm infants, reflecting the level and duration of exposure to invasive procedures and intensive care. 2,3 Very preterm infants who acquire a late-onset bloodstream or deep-seated infection are at higher risk of mortality and a range of acute morbidities including necrotising enterocolitis (NEC), retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) and bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) than comparable infants without infection. 4–6 Over the long term, late-onset infection is associated with higher rates of adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes, including visual, hearing and cognitive impairment, and cerebral palsy. 5

Mortality and morbidity are usually associated with Gram-negative bacterial, Staphylococcus aureus or fungal bloodstream infections or meningitis. 7–9 Coagulase-negative staphylococcal infection, despite accounting for about half of all infections, is generally associated with a more benign clinical course. 10 Meningitis and other deep-seated infections are rare and the mortality rate is lower than that attributed to Gram-negative or other Gram-positive bacterial infections. However, even low-grade coagulase-negative staphylococcal bloodstream infections may generate inflammatory cascades that are associated with both acute morbidity (metabolic, respiratory or thermal instability, thrombocytopenia) and long-term white matter and other brain damage that may result in adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes. 11

As a consequence of associated morbidities, very preterm infants with late-onset infection may spend about 20 more days in hospital than gestation-comparable infants without infection. 12 Late-onset infection and associated morbidities therefore have major consequences for perinatal health-care service management, delivery and costs.

Diagnosis, treatment and prevention of late-onset invasive infection

Clinical signs and laboratory markers may be unreliable predictors of true late-onset infection, especially in very preterm infants. 13,14 A policy of early empirical treatment of suspected infection is usually implemented. Most neonates who are treated as a result of ‘sepsis evaluation’, however, do not have infection confirmed subsequently. 15 This results in unnecessary exposure to antibiotics, which not only subjects very preterm infants to more interventions but may drive the emergence of antibiotic-resistant pathogens in the neonatal unit. 16,17 Although generic infection control measures, such as hand-washing and intravascular catheter ‘care bundles’, have helped to prevent some episodes of late-onset invasive infection in very preterm infants, benchmarking and quality improvement studies in neonatal networks have indicated that there is a need for measures to further reduce the incidence. 18

Given this burden of mortality, acute and long-term morbidity, and costs to families and health services, there is a need to develop innovative strategies to prevent late-onset invasive infection in very preterm infants. 19

Lactoferrin

Lactoferrin, a member of the transferrin family of iron-binding glycoproteins, is a key component of the mammalian innate response to infection. 20–22 It is the major whey protein in human colostrum, present at a concentration of about 6 mg/ml and is present in mature breast milk at a concentration of about 1 mg/ml. 23 Lactoferrin is also present in mammalian tears, saliva, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and other secretions. 22

Lactoferrin has broad microbiocidal activity by mechanisms, such as cell membrane disruption, iron sequestration, the inhibition of microbial adhesion to host cells and the prevention of biofilm formation (Box 1). 20,21 Development of resistance to lactoferrin is improbable as it would require multiple simultaneous mutations. Lactoferrin remains a potent inhibitor of viruses, bacteria, fungi and protozoa after millions of years of mammalian evolution. 24,25

-

Antimicrobial effects:

-

cell membrane disruption

-

iron sequestration

-

inhibition of microbial adhesion to host cells

-

prevention of biofilm formation.

-

-

Prebiotic effects:

-

promote intestinal growth of beneficial bacteria (probiotics)

-

reduce colonisation with pathogenic species.

-

-

Immune-modulatory and anti-inflammatory actions:

-

modulate cytokine expression

-

mobilise leucocytes into the circulation

-

activate T-lymphocytes

-

suppress free-radical activity.

-

-

Intestinal integrity effects:

-

stimulate differentiation and proliferation of enterocytes

-

promote closure of enteric gap junctions

-

increase expression of intestinal digestive enzymes.

-

Lactoferrin has prebiotic properties, creating an enteric environment that promotes the growth of beneficial bacteria and reducing colonisation with pathogenic species. 26,27 It has direct intestinal immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory actions mediated by modulating cytokine expression, mobilising leucocytes into the circulation and activating T-lymphocytes. 28,29 At high concentrations, as in colostrum, lactoferrin enhances the proliferation of enterocytes and the closure of enteric gap junctions. 30 At lower concentrations, lactoferrin stimulates the differentiation of enterocytes and the expression of intestinal digestive enzymes. 31 Lactoferrin suppresses free-radical activity when iron is added to milk, suggesting that it may have further anti-inflammatory actions that could modulate the pathogenesis of diseases linked with free-radical generation, such as NEC, ROP and BPD. 32

Bovine lactoferrin

Bovine lactoferrin (The Tatua Cooperative Dairy Company Ltd, Morrinsville, New Zealand) is > 70% homologous with human lactoferrin but has higher antimicrobial activity. It is inexpensive compared with human or recombinant lactoferrin and is available commercially as a food supplement in a stable powder form. 33 The affinity of bovine lactoferrin for the human small intestine lactoferrin receptor is low and intact lactoferrin and digested fragments (lactoferricins), which also have high microbiocidal activity, are excreted enterally. 34,35 Bovine lactoferrin has been a component of the human infant diet for thousands of years and is registered as ‘Generally Recognised As Safe’ by the US Federal Drug Administration with no reports of human toxicity. 36 The ‘no observed adverse effect level’ is > 2 g/kg/day in rodents. 37 Given the absence of adverse effects, the European Food Safety Authority Panel concluded that bovine lactoferrin for infants is safe at the standard supplementation levels (up to about 210 mg/kg of body weight per day). 38

Lactoferrin supplementation

Very preterm infants typically ingest little or no milk during the early neonatal period and thus have low lactoferrin intake. This deficiency may be further exacerbated by delays in establishing enteral feeding. Enteral lactoferrin supplementation has been proposed and assessed as a simple strategy to compensate for this gestational immunodeficiency. 39

Existing evidence

The Cochrane review by Pammi and Suresh40 identified six completed randomised controlled trials (RCTs), involving 1071 participants in total. 41–46 Meta-analyses suggest that enteral supplementation with lactoferrin reduces the incidence of late-onset invasive infection by about 40%; the effect size is similar whether infants are fed predominantly human milk or formula milk. The incidence of NEC is decreased by about 60%. No evidence of an effect on all-cause mortality was found and no adverse effects or intolerance were reported (Box 2). However, because the trials were generally small and contained various methodological weaknesses that increased the risk of selection and performance bias, and because meta-analyses were limited by data availability and heterogeneity, the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) working group assessment of the quality of this evidence was ‘low’, meaning that further research was likely to have an important impact on the confidence in the estimates of effect and is likely to change these estimates. The Cochrane review concluded that additional data from large, good-quality RCTs of lactoferrin supplementation in very preterm infants were needed to enhance the validity and applicability of the evidence-base sufficiently to inform policy and practice. 40

-

Late-onset infection: typical RR 0.59, 95% CI 0.40 to 0.87; typical RD –0.06, 95% CI –0.10 to –0.02; number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome was 17, 95% CI 10 to 50; six trials, 886 participants.

-

Necrotising enterocolitis (Bell’s stage II or III): typical RR 0.40, 95% CI 0.18 to 0.86; typical RD –0.04, 95% CI –0.06 to –0.01; number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome was 25, 95% CI 17 to 100; four trials, 750 participants.

-

All-cause mortality: typical RR 0.65, 95% CI 0.37 to 1.11; typical RD –0.02, 95% CI –0.05 to 0; six trials, 1071 participants.

CI, confidence interval; RD, risk difference; RR, risk ratio.

Objective

The study aimed to assess the effect of enteral administration of bovine lactoferrin on the incidence of late-onset infection, other morbidity and mortality in very preterm infants.

Chapter 2 Methods

Design

The Enteral Lactoferrin In Neonates (ELFIN) trial was a UK, multicentre, parallel-group, placebo-controlled RCT (see www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/elfin). 47

Ethics approval and research governance

The ELFIN trial protocol was approved by the National Research Ethics Service Committee East Midlands – Nottingham 2 on 2 April 2013 (reference number 13/EM/0118).

Local approval and site-specific assessments were obtained from the NHS trusts for trial sites.

The trial was registered with the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Register (https://doi.org/10.1186/ISRCTN88261002).

Patient and public involvement

During the development and delivery of the ELFIN trial, we engaged with infant and family representatives experienced in voicing service users’ views (principally via Bliss, a UK national charity supporting preterm or sick newborn infants and their families: www.bliss.org.uk/). Parents with children who had received neonatal intensive care contributed via Bliss and directly to the development of trial materials (e.g. parent information and resources) and research staff training (e.g. in simulated sessions on ‘seeking consent’). We adhered to INVOLVE good practice guidelines to ensure service-user leadership in the delivery of the trial and dissemination of the findings (www.invo.org.uk/).

Participants

Inclusion criteria

-

Gestational age at birth of < 32 weeks.

-

< 72 hours old at randomisation.

-

Written informed parental consent.

Exclusion criteria

-

Severe congenital anomaly.

-

Anticipated enteral fasting for > 14 days.

-

No realistic prospect of survival.

Infants receiving antibiotic treatment at randomisation were eligible to participate.

Setting

Neonatal units in the UK caring for very preterm infants:

-

recruiting sites where parents’ consent was obtained and infants could be recruited and randomised to commence participation in the trial (n = 37; see Appendix 1)

-

continuing care sites where clinicians continued to administer the intervention and collect routine data if a participating infant of < 34 weeks’ postmenstrual age was transferred from a recruiting site (n = 97; see Appendix 2).

Depending on the interventions being given, it was possible for an infant to participate in other clinical trials at the same time as participating in the ELFIN trial. The Speed of Increasing Milk Feeds Trial (SIFT) was designed to allow infants to be enrolled in both trials. 48 The ELFIN trial and SIFT shared procedures and, in some cases, joint data collection forms and other documentation. Other trials being run simultaneously in any units were discussed by the chief investigators or their delegated representative to agree whether or not joint recruitment was appropriate and likely to be acceptable.

Screening and eligibility assessment

Potential participants meeting the eligibility criteria were identified by the local health-care team. As the eligibility criteria did not require specific medical assessment, assessment of eligibility was accepted to be within the scope of competency of appropriately trained and experienced neonatal nurses, if so delegated by the principal investigator (PI).

Informed consent and recruitment

Consent was sought from parents of potential participants only after they had received a full verbal and written explanation of the trial [parent information leaflet (PIL); see www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/elfin/parent-resources (accessed 29 June 2018)]. Parents who did not speak English were approached only if an adult interpreter was available.

Informing potential participants’ parents of possible benefits and risks occurred as a staged process. 49 If it was likely that the expected infant was eligible to participate in the trial, the PIL and preliminary verbal information was offered prior to birth. Further verbal information was provided after birth as it was to the parents of infants who were not identified antenatally.

Written informed parental consent was obtained by means of dated parental signature and the signature of the person who obtained informed consent: the PI or health-care professional with delegated authority (see www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/elfin/neonatal-staff). A copy of the signed informed consent form was given to the parents. A copy was retained in the infant’s medical notes, a copy was retained by the PI and the original was sent to the Clinical Trials Unit.

Participants or parents were not given any financial or material incentive or compensation to take part. It was made clear that parents remained free to withdraw their infant from the trial at any time without the need to provide any reason or explanation. Parents were aware that this decision would have no impact on any aspects of their infant’s continuing care.

The trial entry form was completed after informed consent had been given. The recorded information was entered on to the National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit Clinical Trials Unit (NPEU CTU) randomisation website [see https://rct.npeu.ox.ac.uk/ (accessed 29 June 2018)]. Infants were considered to have been enrolled once they have been given a study number and have been allocated a treatment pack number by the randomisation facility.

Intervention

Trial participants were allocated randomly to receive either:

-

bovine lactoferrin or

-

sucrose (British Sugar, Peterborough, UK).

The UK Medicines and Healthcare Regulatory Agency (MHRA) indicated that, for the purposes of the trial, the intervention and sucrose placebo were considered to be Investigational Medicinal Products (IMPs) and subject to good manufacturing practice (GMP) regulations. After discussion with MHRA, the IMP was considered to be ‘category B’ (risk slightly above routine practice because bovine lactoferrin is not a licensed product).

Bulk lactoferrin was imported from The Tatua Cooperative Dairy Company Ltd, a New Zealand-based company that manufactures highly purified powder (see www.tatua.com/specialty-nutritionals-ingredients/lactoferrin/).

Bulk sucrose was obtained in the UK from British Sugar (see www.britishsugar.co.uk/).

The IMP was packaged into individual doses in sealed opaque containers and assembled into participant packs to GMP in the MHRA-approved NHS clinical trials pharmacy unit at the Royal Victoria Hospital, Newcastle upon Tyne (www.newcastle-hospitals.org.uk/services/Pharmacy_services_newcastle-specials-pharmacy-production-unit.aspx).

Investigational Medicinal Product management

-

Bovine lactoferrin was packaged into 25-ml opaque pharmacy pots (fill equivalent to 375 mg per pot) at the trials pharmacy in Newcastle Royal Infirmary, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK. Boxes containing 24 identically numbered pots were labelled with the same pack identification (ID) number to indicate that they all belonged to the same treatment course. At randomisation, infants were allocated a study number and a pack ID number; the study number was added to the label of the allocated pack with the infant’s name and date of birth for checking before each administration of the IMP. Lactoferrin powder was stable within unopened pots and could be stored at room temperature. When the infant completed the course of treatment, any unused IMP pots were retained for accounting and destruction by the site pharmacist.

-

Sucrose was processed, packaged and distributed as for bovine lactoferrin.

Investigational Medicinal Product prescription and preparation

Lactoferrin and sucrose were prescribed at a dose of 150 mg/kg body weight per day (up to a maximum of 300 mg/day). The IMP was prepared by neonatal nurses or clinicians on the neonatal unit in the unit milk kitchen or other appropriate area determined locally. The IMP powder was prepared for administration by mixing in sterile water plus expressed breast or formula (see Appendix 3).

The IMP was administered once daily by nasogastric or orogastric tube or orally once the enteral feed volume was > 12 ml/kg/day and continued until 34 weeks’ postmenstrual age. Some small infants may have had the dose split at the discretion of the responsible clinical team. A maximum of 70 days of treatment was given.

All other aspects of care, including the timing of the commencement of enteral feeds and the type of milk feed used, were as per local policy, practice and discretion.

Randomisation

Randomisation of participants to receive either lactoferrin or sucrose was managed via a secure web-based randomisation facility hosted by the NPEU CTU, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK. Telephone assistance and randomisation back-up was available at all times.

To confirm eligibility, investigators needed to supply gestational age, sex and time of birth. To proceed to randomisation, investigators needed to confirm that signed informed consent was available. Infants were allocated to the lactoferrin versus sucrose groups in the ratio of 1 : 1 using a minimisation algorithm to ensure balance between the groups with respect to the recruiting site (neonatal unit), sex, single versus multiple births and gestational age in completed weeks. Twins or higher order multiple births were randomised individually.

Allocation concealment and blinding

Participating infants were randomly allocated a numbered pack containing either the lactoferrin or the placebo and allocated a unique study number. Parents, clinicians, investigators and outcomes assessors were unaware of the allocated treatment groups.

Stopping Investigational Medicinal Product

Administration of the trial IMP may have been stopped temporarily. Missed doses did not necessitate the removal of an infant from the trial. Data continued to be collected as per protocol if the trial medication was stopped temporarily or permanently in order to facilitate an unbiased treatment comparison via an intention-to-treat analysis.

Masking

Bovine lactoferrin has a pale pink/brown tinge, whereas sucrose was very light brown. The opaque containers did not allow the dry IMP to be seen unless the sealed stopper was removed intentionally. The lactoferrin powder had similar granularity to sucrose so that when the dry IMP was shaken within the opaque, sealed pots it was not possible to distinguish lactoferrin from sucrose by the sound generated. Mixing the IMP with sterile water plus breast milk or formula generated foam that settled within 30 minutes after shaking. When the mixed IMP was removed in a syringe with a purple plunger, the pink tinge to the lactoferrin was disguised by the colour of the breast milk or formula, which often resulted in a light brown colour (and this varied markedly between batches of milk). As lactoferrin was more likely than sucrose to retain a light pink tinge, all sites were supplied with a laminated picture of a range of possible colours for the IMP mixture in syringes, and it was stressed that this applied to both lactoferrin and sucrose.

Clinicians were able to request knowledge of the treatment allocation to guide the clinical management of the participant if it was deemed to be an emergency situation. In such instances, a single-use access code was provided in a sealed envelope and the participant’s allocation was unmasked via the randomisation website.

Internal pilot

An internal pilot study was conducted in six neonatal centres within the Northern Region and Yorkshire Neonatal Networks (‘operational delivery networks’) to test whether or not the components and processes of the study worked together and ran smoothly. The main aims of the pilot were to:

-

confirm that regulatory processes were in order

-

ensure that the randomisation process was acceptable and effective

-

demonstrate efficient intervention and placebo preparation and distribution

-

determine that the anticipated acceptance rate (40% of eligible infants) was achievable

-

determine whether or not the projected recruitment rate was realistic – we set a target of a total of 4, 6 and 8 infants recruited in months 1, 2 and 3, respectively, expecting to reach a ‘steady state’ of a total of 10 infants (two per month per centre) by month 4 of the pilot phase

-

evaluate the delivery, management and acceptability (to families and staff) and ease of preparation and administration

-

assess the processes for collecting clinical outcomes and event rates and to determine that the predicted retention rate (> 95% of recruited infants) was attainable.

The decision to progress with the main trial was made in consultation with the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and the funder.

The internal pilot phase was followed by a 3-year main recruitment phase in 37 recruiting centres (see Appendix 1).

Outcomes

Primary outcome

The number of infants who experience at least one episode of microbiologically confirmed (Box 3) or clinically suspected (Box 4) late-onset infection from trial entry until hospital discharge.

Microbiological culture from blood or CSF sampled aseptically > 72 hours after birth of any of the following:

-

potentially pathogenic bacteria (including coagulase-negative Staphylococcus species but excluding probable skin contaminants, such as diphtheroids, micrococci, propionibacteria or a mixed flora)

-

fungi.

AND treatment, or clinician intention to treat, for ≥ 5 days with intravenous antibiotics (excluding antimicrobial prophylaxis) after investigation was undertaken. If the infant died or was discharged or transferred prior to the completion of 5 days of antibiotics this condition would still be met if the intention was to treat for ≥ 5 days.

Adapted from the UK Neonatal Infection Surveillance Network case definition. 2,3

Absence of positive microbiological culture, or culture of a mixed microbial flora or of likely skin contaminants (diphtheroids, micrococci, propionibacteria) only

AND treatment, or clinician intention to treat, for ≥ 5 days with intravenous antibiotics (excluding antimicrobial prophylaxis) after the above investigation was undertaken for an infant who demonstrates three or more of the following clinical or laboratory features of invasive infection:

-

increase in oxygen requirement or ventilatory support

-

increase in frequency of episodes of bradycardia or apnoea

-

temperature instability

-

ileus or enteral feeds intolerance or abdominal distension

-

reduced urine output to < 1 ml/kg/hour

-

impaired peripheral perfusion (capillary refill time of > 3 seconds, skin mottling or core–peripheral temperature gap > 2 °C)

-

hypotension (clinician defined as needing volume or inotrope support)

-

‘irritability or lethargy or hypotonia’ (clinician defined)

-

increase in serum C-reactive protein levels to > 15 mg/l or procalcitonin level of ≥ 2 ng/ml

-

white blood cells count of < 4 × 109/l or > 20 × 109/l

-

cells/l or platelet count of < 100 × 109/l

-

glucose intolerance (blood glucose levels of < 40 mg/dl or > 180 mg/dl)

-

metabolic acidosis (base excess of < –10 mmol/l or lactate level of > 2 mmol/l).

Adapted from the European Medicines Agency consensus criteria and predictive model. 50,51

Secondary outcomes

-

Microbiologically confirmed infection (see Box 3).

-

All-cause mortality prior to hospital discharge.

-

Necrotising enterocolitis: Bell’s stage II or III (see Appendix 4). 52

-

Severe ROP treated medically or surgically. 53

-

Bronchopulmonary dysplasia: when the infant is still receiving mechanical ventilator support or supplemental oxygen at 36 weeks’ postmenstrual age. 54

-

A composite of invasive infection, major morbidity (NEC, ROP or BPD) and mortality.

-

Total number of days of administration of antimicrobials per infant from trial entry until 34 weeks’ postmenstrual age.

-

Total length of stay until discharge home.

-

Length of stay in (1) intensive care, (2) high-dependency and (3) special-care settings (see Appendix 5).

Sample size

The sample size estimate was informed by a range of plausible primary outcome control event rates (CERs) from 18% to 24%, based on surveillance reports from Europe, North America and Australasia (Table 1). 2,7,8,10,12 In summary, with 90% power and a two-sided 5% significance level, to detect an absolute risk reduction (ARR) of 5–5.8% (relative risk reduction of between 24% and 28%) would require a total of up to 2200 participants if the CER was 18%, 2070 if the CER was 21% and 2076 if the CER was 24%. This target sample size of 2200 allowed for an anticipated loss to follow-up of up to 5%. This sample size was sufficient to exclude important effects on secondary outcomes with 90% power [e.g. a 7% ARR in antibiotic exposure (from 45% to 38%)].

| Control event rate (%) | Treatment group event rate (%) | Absolute risk reduction (%) | Relative risk reduction (%) | Number required per arm | Total sample size required |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 | 18.2 | 5.8 | 24 | 1038 | 2076 |

| 21 | 15.5 | 5.5 | 26 | 1035 | 2070 |

| 18 | 13.0 | 5.0 | 28 | 1099 | 2200 |

The participating recruiting neonatal units were estimated to admit 60 very preterm infants per annum on average. Based on 40% recruitment, 30 units were estimated to be able to recruit a total sample size of up to 2160 infants over 3 years (an average of two infants per unit per month).

Statistical analyses

Demographic factors and clinical characteristics at randomisation were summarised with counts (percentages) for categorical variables, mean [standard deviation (SD)] for normally distributed continuous variables or median [interquartile range (IQR)] for other continuous variables.

Outcomes for participants were analysed in the groups to which they were assigned regardless of deviation from the protocol or treatment received. Comparative analyses calculated the relative risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) for the primary outcome (99% CIs for all other dichotomous outcomes), the mean difference (99% CI) for normally distributed continuous outcomes or the median difference (99% CI) for skewed continuous variables.

The groups were compared using regression analysis adjusting for the minimisation factors (recruiting centre, sex, weeks’ gestation at birth and single vs. multiple births) to account for the correlation between treatment groups introduced by balancing the randomisation. We used random-effects models with centre fitted as a random effect and mother’s ID number nested within this to take account of clustering within centre and within multiples. The other minimisation factors were fitted as fixed effects, with sex and multiplicity of birth included as binary variables and gestational age modelled as a continuous variable. The crude unadjusted and adjusted estimates were calculated with the primary inference to be based on the adjusted analysis.

The consistency of the effect of lactoferrin supplementation on the primary outcome across specific subgroups of infants was assessed using the statistical test of interaction. Prespecified subgroups were (1) completed weeks of gestation at birth and (2) infants given maternal or donated expressed breast milk versus formula versus both human milk and formula during the trial period (received on > 50% of days on which infant is fed enterally until developing late-onset infection or NEC, dying or reaching 34 weeks’ postmenstrual age).

Data collection

All of the outcome data for this trial were routinely recorded clinical items that could be obtained from the clinical notes or local microbiology laboratory records. Information was collected using the data collection forms (see Appendix 6).

A ‘blinded end-point review committee’, masked to participant allocation, reviewed all case report forms (CRFs) reporting episodes of late-onset infection or necrotising enterocolitis or other gastrointestinal pathology. Two members independently assessed adherence to case definitions and resolved any disagreements or discrepancies by discussion or referral to a third committee member or both. Persisting uncertainties were discussed with the site PI or research nurse or both until resolved.

Adverse event reporting

Some adverse events were foreseeable (expected) because of the nature of the participant population, and their routine care and treatment. No adverse drug reactions were expected from bovine lactoferrin. Consequently, only those adverse events (or reactions) identified as serious were recorded for this trial (see Appendix 7).

Expected serious adverse events (SAEs) were recorded on the CRFs. All other SAEs were reported by trial sites to the NPEU CTU within 24 hours of the event being recognised. Information was recorded on a SAE reporting form and faxed to the NPEU CTU. Additional information (follow-up of or corrections to the original case) needed to be detailed on a new SAE form and faxed to the NPEU CTU. A standard operating procedure (SOP) outlining the reporting procedure for clinicians was provided with the SAE form and in the trial handbook. The NPEU CTU processed and reported the event as specified in its own SOPs. All SAEs were reviewed by the Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) at regular intervals throughout the trial. The CI informed all investigators of information that could affect the safety of participants.

Suspected unexpected serious adverse reactions

Suspected unexpected serious adverse reactions (SUSARs) were reported to the MHRA and the approving Research Ethics Committee (REC) within 7 days, if life-threatening, and within 15 days for other SUSARs. In addition, a copy of the SUSAR form was forwarded to the chairperson of the DMC. The chairperson was provided with details of all previous SUSARs with their unmasked allocation. The chief investigator informed all investigators of any issues raised in a SUSAR that could affect the safety of participants.

Development safety update report

In addition to the expedited reporting above, the chief investigator submitted, once a year throughout the clinical trial, or on request, a development safety update report to the Competent Authority, the Ethics Committee and the sponsor.

Economic analysis (planned)

We planned to combine the health service resources used during an infant’s hospital admission with clinical effectiveness data to conduct an economic evaluation to assess whether or not the intervention was likely to be cost-effective over the time horizon of the trial period. If appropriate, we intended to synthesise the costs and consequences of the intervention to generate an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio to inform any adoption decision. We planned to use regression models to allow for differences in prognostic variables, principally gestational age bands, and other sources of heterogeneity and to assess differences in the probable cost-effectiveness between the groups.

The primary outcome for an economic analysis was the incidence of late-onset invasive infection. As invasive infection is linked closely to morbidity and mortality, it is likely that the consequences will continue to appear over a longer time frame and may have an impact on both duration and quality of life. Therefore, as a second analysis, we intended to develop an economic model to account for projected longer-term costs and effects and to estimate the additional cost per quality-adjusted life-year gained of lactoferrin compared with placebo.

Governance and monitoring

At least one site initiation visit was conducted at all recruiting sites. The trial research nurse and the chief investigator or a delegated co-investigator provided structured training for site investigators, local research nurses and other clinical staff, including the site pharmacy team responsible for IMP management. Training focused on approaches to consent, protocol processes and governance requirements. These visits were supported with bespoke written and online training material available to all staff via the trial website (www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/elfin/training). Staff in continuing care sites did not have initiation visits unless requested but were directed to online training and access support from the chief investigator and trial research nurse as needed.

Ongoing monitoring included review of investigator site files, delegation logs, staff qualifications and training (good clinical practice certificates, curricula vitae) and pharmacy documentation. Quality assurance was achieved by following data management procedures at the study data centre and data monitoring at trial sites. Further site monitoring or audit was conducted if central monitoring exercises raised concern about patterns of recruitment or data reporting. This monitoring approach was justified by the level of risk associated with the trial and the intervention.

Data management was undertaken in accordance with NPEU CTU SOPs and a prespecified management plan. Data monitoring included the review of consent forms and participant eligibility. Additional data validation checks were carried out periodically, with data queries issued to study sites for resolution. Prior to database lock, final data validation checks were carried out and questions were resolved by discussion with the site PI or local research nurse, when possible.

During the trial, the study statisticians produced reports for the TSC and independent DMC. Issues of data quality identified by study statisticians were reported to study data management staff and queried when appropriate or included in future routing data validation checks, or both. TSC and DMC meetings provided opportunities for the external, independent review of summary data, with additional feedback on potential data quality issues being incorporated into ongoing data quality checks.

Summary of changes to the study protocol

A summary of the changes made to the original protocol is presented in Appendix 8.

Chapter 3 Results

Recruitment and retention

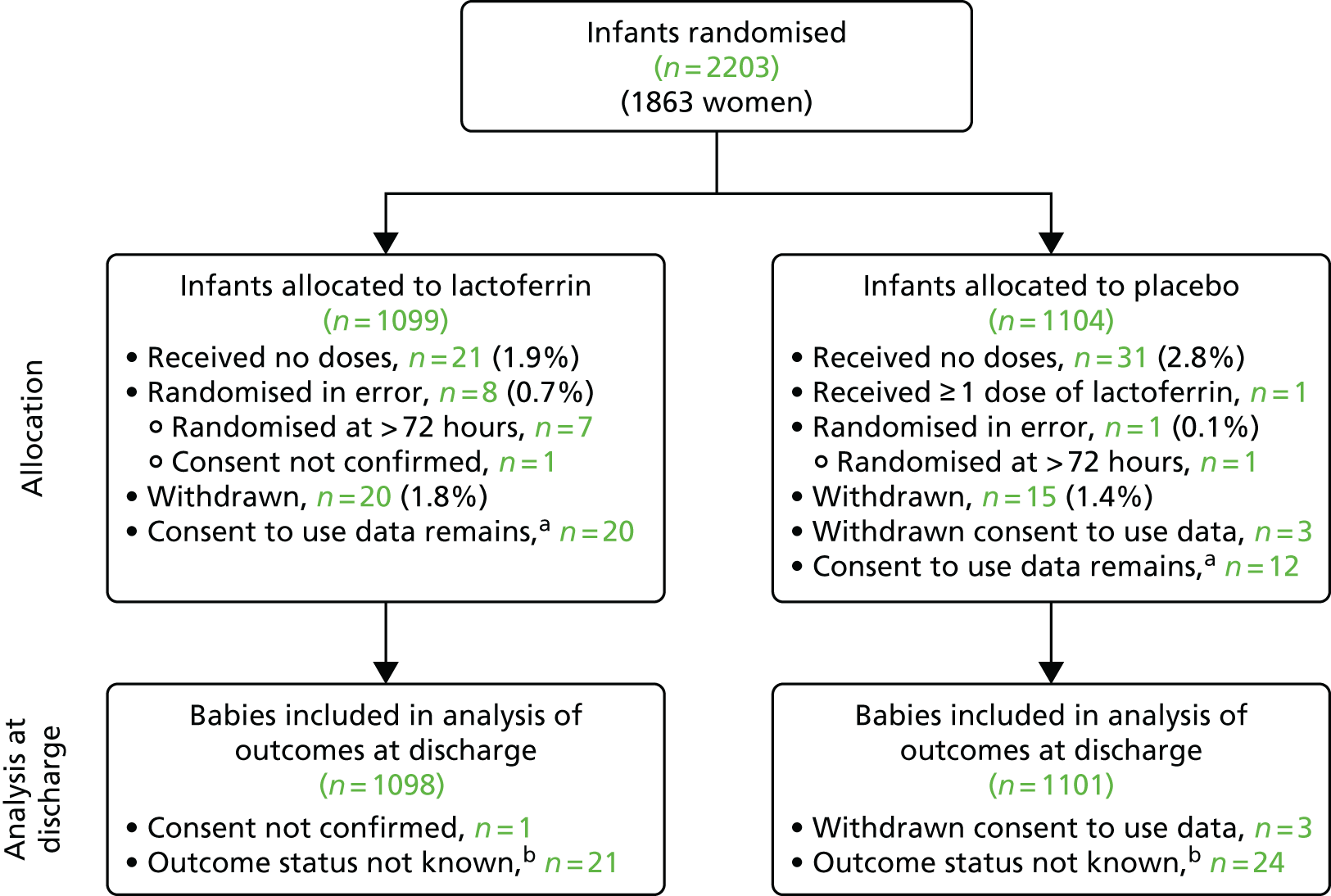

Recruitment and retention to the trial are summarised in the flow chart (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Flow of participants through the trial. a, Included in the analysis when data are available; b, included in analysis except when knowledge of discharge or discharge date is required.

The internal pilot was undertaken in six neonatal units between May 2014 and April 2015. In total, 90 infants were recruited to participate. The main trial recruited infants from 37 neonatal units (including the six pilot sites) from July 2015 to September 2017 (when the recruitment target was reached). The trial randomised 2203 infants in total:

-

1099 infants were allocated to receive bovine lactoferrin

-

1104 infants were allocated to receive the sucrose placebo.

Four infants had consent withdrawn or unconfirmed. In total, 1098 infants in the lactoferrin group and 1101 in the placebo group were included in the intention-to-treat analyses (see Appendix 9).

Demographic and other baseline characteristics

The baseline characteristics and other demographic features of participating infants were well balanced between the two treatment allocation groups (Table 2). The median gestation age was 29 weeks in both groups (37% aged < 28 weeks). The median birthweight was 1126 g in the lactoferrin group and 1143 g in the placebo group. Overall, 91% of infants were exposed to antenatal corticosteroid, 57% were born via caesarean section, 25% were born following rupture of maternal amniotic membranes for > 24 hours, and 12% had evidence of absent or reverse end diastolic flow in the fetal umbilical artery. The allocation arms were well-balanced in individual recruiting sites as per the minimisation algorithm (see Appendix 10).

| Characteristic | Trial group | |

|---|---|---|

| Lactoferrin (n = 1098) | Placebo (n = 1101) | |

| Number of centres, n | 37 | 37 |

| Male sex, n/N (%) | 575/1098 (52.4) | 578/1099 (52.6) |

| Missing, n | 0 | 2 |

| Infant age at randomisation in days | ||

| Median (IQR) | 2 (2–3) | 2 (2–3) |

| Birthweight (g) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 1125.9 (356.2) | 1143.3 (367.1) |

| < 500, n (%) | 8/1098 (0.7) | 7/1101 (0.6) |

| 500 to 749, n (%) | 172/1098 (15.7) | 172/1101 (15.6) |

| 750 to 999, n (%) | 254/1098 (23.1) | 244/1101 (22.2) |

| 1000 to 1249, n (%) | 268/1098 (24.4) | 255/1101 (23.2) |

| 1250 to 1499, n (%) | 199/1098 (18.1) | 199/1101 (18.1) |

| ≥ 1500, n (%) | 197/1098 (17.9) | 224/1101 (20.3) |

| Birthweight < 10th centile for gestational age, n/N (%) | 175/1097 (16.0) | 177/1098 (16.1) |

| Missing, n | 1 | 3 |

| Gestation at delivery (completed weeks) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 29 (27–30) | 29 (27–30) |

| < 23, n/N (%) | 1/1098 (0.1) | 1/1101 (0.1) |

| 23+0 to 23+6, n/N (%) | 33/1098 (3.0) | 31/1101 (2.8) |

| 24+0 to 24+6, n/N (%) | 73/1098 (6.6) | 76/1101 (6.9) |

| 25+0 to 25+6, n/N (%) | 73/1098 (6.6) | 73/1101 (6.6) |

| 26+0 to 27+6, n/N (%) | 227/1098 (20.7) | 221/1101 (20.1) |

| 28+0 to 29+6, n/N (%) | 315/1098 (28.7) | 319/1101 (29.0) |

| 30+0 to 31+6, n/N (%) | 376/1098 (34.2) | 380/1101 (34.5) |

| Mother’s age at randomisation (years) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 30.3 (6.1) | 30.4 (6.0) |

| Multiple birth, n/N (%) | 350/1098 (31.9) | 346/1101 (31.4) |

| Caesarean section delivery, n/N (%) | 635/1098 (57.8) | 616/1101 (55.9) |

| Membranes ruptured before labour, n/N (%) | 422/1093 (38.6) | 428/1097 (39.0) |

| Missing, n | 5 | 4 |

| Membranes ruptured > 24 hours before delivery, n/N (%) | 286/1092 (26.2) | 264/1096 (24.1) |

| Missing, n | 6 | 5 |

| Mother received antenatal corticosteroids, n/N (%) | 998/1093 (91.3) | 997/1099 (90.7) |

| Missing, n | 5 | 2 |

| Infant heart rate of > 100 b.p.m. at 5 minutes, n/N (%) | 995/1090 (91.3) | 1010/1093 (92.4) |

| Missing, n | 8 | 8 |

| Infant temperature on admission (°C) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 36.9 (0.7) | 37 (0.7) |

| Missing, n | 4 | 10 |

| Infant worst base excess within first 24 hours of birth | ||

| Mean (SD) | –6.2 (3.9) | –6.3 (3.8) |

| Missing, n | 9 | 12 |

| Infant ventilated via endotracheal tube at randomisation, n/N (%) | 338/1098 (30.8) | 357/1101 (32.4) |

| Infant had absent or reverse end diastolic flow, n/N (%) | 134/1079 (12.4) | 130/1081 (12.0) |

| Missing, n | 19 | 20 |

Adherence

A total of 35 (1.6%) infants discontinued the intervention early: 20 in the lactoferrin group and 15 in the sucrose group. This includes a small number of infants who in the early stages of the trial discontinued the intervention because they were transferred to a hospital that did not have the regulatory approvals to administer the intervention. Parental consent remained for data collection for intention-to-treat analyses for 32 out of the 35 infants.

Adherence was high for infants who continued to receive the IMP (Table 3). The median percentage of days when an IMP dose was not given or not recorded was 4% in both treatment groups, and 0% of days in both groups for the dose not given or not recorded when those days where feeds were stopped or withheld for > 4 hours (for clinical reasons) were excluded. The median difference between expected dose and actual dose per day was 7 mg/kg/day lower in both groups and was 1 mg/kg/day (lactoferrin) or 2 mg/kg/day (sucrose) lower excluding those days where enteral feeds were stopped or withheld for > 4 hours.

| Measure | Trial group | |

|---|---|---|

| Lactoferrin (n = 1007)a | Placebo (n = 1011)a | |

| Percentage of days dose not given or not recordedb | ||

| Median (IQR) | 4 (0 to 18.18) | 4 (0 to 16.22) |

| Range | 0 to 100 | 0 to 100 |

| Missing, n | 10 | 13 |

| Percentage of days dose not given or not recorded, excluding days where feeds were stopped or withheld for > 4 hoursb | ||

| Median (IQR) | 0 (0 to 5.71) | 0 (0 to 5.56) |

| Range | 0 to 100 | 0 to 100 |

| Missing, n | 11 | 13 |

| Difference between expected dose and actual dose per day (mg/kg/day)c | ||

| Median (IQR) | –7 (–29 to 0) | –7 (–27 to 0) |

| Range | –150 to 253 | –150 to 88 |

| Missing, n | 10 | 13 |

| Difference between expected dose and actual dose per day, excluding days where feeds were stopped or withheld for > 4 hours (mg/kg/day)c | ||

| Median (IQR) | –1 (–11 to 0) | –2 (–11 to 0) |

| Range | –150 to 271 | –150 to 88 |

| Missing, n | 11 | 13 |

Outcomes

The estimates of effect for the primary and secondary outcomes are presented in Table 4.

| Outcome | Trial group | Unadjusted RR (CI)a,b | Adjusted RR (CI)a,b,c | p-valued | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lactoferrin (n = 1098) | Placebo (n = 1101) | ||||

| Microbiologically confirmed or clinically suspected late-onset infection, n/N (%) | 316/1093 (28.9) | 334/1089 (30.7) | 0.94 (0.83 to 1.07) | 0.95 (0.86 to 1.04) | 0.233 |

| Missing, n | 5 | 12 | |||

| Microbiologically confirmed late-onset infection, n/N (%) | 190/1093 (17.4) | 180/1089 (16.5) | 1.05 (0.82 to 1.34) | 1.05 (0.87 to 1.26) | 0.490 |

| Missing, n | 5 | 12 | |||

| All-cause mortality, n/N (%) | 71/1076 (6.6) | 68/1076 (6.3) | 1.04 (0.69 to 1.59) | 1.05 (0.66 to 1.68) | 0.782 |

| Missing, n | 22 | 25 | |||

| NEC (Bell’s stage II or III), n/N (%) | 63/1085 (5.8) | 56/1084 (5.2) | 1.12 (0.71 to 1.77) | 1.13 (0.68 to 1.89) | 0.538 |

| Missing, n | 13 | 17 | |||

| Severe ROP treated medically or surgically, n/N (%) | 64/1080 (5.9) | 72/1080 (6.7) | 0.89 (0.58 to 1.35) | 0.89 (0.62 to 1.28) | 0.420 |

| Missing, n | 18 | 21 | |||

| BPD at 36 weeks’ postmenstrual age, n/N (%) | 358/1023 (35.0) | 355/1027 (34.6) | 1.01 (0.87 to 1.18) | 1.01 (0.90 to 1.13) | 0.867 |

| Died before 36 weeks’ postmenstrual age | 64 | 60 | |||

| Missing, n | 11 | 14 | |||

| Infection, NEC, ROP, BPD or mortality, n/N (%) | 525/1092 (48.1) | 521/1094 (47.6) | 1.01 (0.90 to 1.13) | 1.01 (0.94 to 1.08) | 0.743 |

| Missing, n | 6 | 7 | |||

| Total number of days of administration of antimicrobials from commencement of IMP until 34 weeks’ postmenstrual age | |||||

| Median (IQR) | 2 (0–8) | 3 (0–8) | 0 (0 to 0) | 0 (–1 to 1) | 0.625 |

| Missing, n | 39 | 44 | |||

| Length of hospital stay (days) to discharge | |||||

| Median (IQR) | 59 (40–85) | 58 (40–84) | 1 (–2 to 4) | 1 (–1 to 3) | 0.446 |

| Missing, n | 95 | 97 | |||

| Days in level 1 (intensive) care | |||||

| Median (IQR) | 8 (4–16) | 8 (4–16) | 0 (–1 to 1) | 0 (–1 to 1) | 0.963 |

| Missing, n | 87 | 66 | |||

| Days in level 2 (high-dependency) care | |||||

| Median (IQR) | 10 (3–30) | 9 (3–29) | 0 (–1 to 1) | 1 (–1 to 3) | 0.420 |

| Missing, n | 83 | 60 | |||

| Days in level 3 (special) care | |||||

| Median (IQR) | 29 (21–39) | 30 (22–39) | –1 (–2 to 1) | –1 (–3 to 1) | 0.216 |

| Missing, n | 75 | 55 | |||

Primary outcome

Data were available for 2182 infants (99%). In the lactoferrin group, 316 out of 1093 (28.9%) infants acquired a late-onset infection versus 334 out of 1089 (30.7%) infants in the control (placebo) group (adjusted RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.81 to 1.10).

Secondary outcomes

There were no significant differences in secondary outcomes: microbiologically confirmed infection (RR 1.05, 99% CI 0.80 to 1.37), mortality (RR 1.05, 99% CI 0.68 to 1.63), NEC (RR 1.13, 99% CI 0.70 to 1.82), ROP (RR 0.89, 99% CI 0.57 to 1.40), BPD (RR 1.01, 99% CI 0.83 to 1.22), or a composite of infection, major morbidity and mortality (RR 1.01, 99% CI 0.86 to 1.18). There were no differences in the number of days of administration of antimicrobials until 34 weeks’ postmenstrual age, or in length of stay in hospital, or length of stay in intensive care, high-dependency care or special-care settings.

Subgroup analyses

Subgroup analyses did not show any significant interactions for completed weeks’ gestation at birth or type of enteral milk received (Table 5 and Figure 2).

| Late-onset infection | Trial group | Unadjusted RR (95% CI) | Adjusted RRa (95% CI) | p-valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lactoferrin (n = 1098) | Placebo (n = 1101) | ||||

| Gestational age at delivery (completed weeks), n/N (%) | 0.273 | ||||

| < 24 | 25/34 (73.5) | 27/31 (87.1) | 0.84 (0.66 to 1.07) | 0.91 (0.69 to 1.20) | |

| 24 | 46/73 (63.0) | 56/75 (74.7) | 0.84 (0.68 to 1.05) | 0.84 (0.69 to 1.03) | |

| 25 | 45/73 (61.6) | 44/73 (60.3) | 1.02 (0.78 to 1.34) | 1.03 (0.73 to 1.45) | |

| 26 to 27 | 107/227 (47.1) | 99/220 (45.0) | 1.05 (0.86 to 1.28) | 1.04 (0.85 to 1.28) | |

| 28 to 29 | 69/311 (22.2) | 72/316 (22.8) | 0.97 (0.73 to 1.30) | 0.98 (0.74 to 1.29) | |

| ≥ 30 | 24/375 (6.4) | 36/374 (9.6) | 0.66 (0.40 to 1.10) | 0.66 (0.42 to 1.03) | |

| Type of milk, n/N (%) | 0.400 | ||||

| Breast only | 99/315 (31.4) | 83/291 (28.5) | 1.10 (0.87 to 1.40) | 1.03 (0.88 to 1.21) | |

| Mixed | 199/707 (28.1) | 228/710 (32.1) | 0.88 (0.75 to 1.03) | 0.89 (0.79 to 1.01) | |

| Formula only | 10/53 (18.9) | 12/60 (20.0) | 0.94 (0.45 to 2.00) | 1.06 (0.58 to 1.91) | |

| Missing, n | 18 | 29 | |||

FIGURE 2.

Subgroup analyses for confirmed or suspected late-onset invasive infection.

Economic analysis

Given the absence of any effects on infant- or family-important outcomes (clinical effectiveness), and with the approval of the DMC and TSC, we did not undertake the proposed within-trial economic analyses or modelling (protocol amendment submitted).

Safety and adverse events

Table 6 summarises reported adverse events (definitions of adverse reactions and events are presented in Appendix 7).

| Trial group | SAE | Age (days) | Brief description of event | Severity | Related to trial |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lactoferrin (n = 1098) | 1 | 12 | Meconium ileus following one dose of IMP. Resolved with laparotomy, no bowel removed | Moderate | No |

| 2 | 30 | Two episodes of clinical seizures, resolved with brief course of anticonvulsant | Moderate | No | |

| 3 | 59 | Cluster of seizures, probably related to severe Gram-negative bacteraemia and sepsis (ultimately fatal) | Severe | No | |

| 4 | 12 | Episode of supraventricular tachycardia, resolved with adenosine and propranolol | Mild | No | |

| 5 | 49 | Metabolic acidosis (likely renal tubular acidosis), resolved with sodium bicarbonate | Severe | No | |

| 6 | 20 | Episode of supraventricular tachycardia, resolved with face cooling | Mild | No | |

| 7 | 19 | Suspected NEC | Moderate | No | |

| 8 | 18 | Cluster of clinical seizures, resolved with magnesium sulphate and course of phenobarbital | Mild | No | |

| 9 | 81 | Infective exacerbation of chronic lung disease, resolved with antibiotics and corticosteroids | Severe | No | |

| 10 | 17 | Large inferior vena caval thrombus | Moderate | No | |

| 11 | 68 | Acute airway obstruction, resolved with respiratory support | Severe | No | |

| 12 | 44 | Aspiration pneumonitis resolved with respiratory support | Severe | No | |

| 13 | 21 | Blood in stool, unknown cause, resolved spontaneously | Moderate | Possibly (expected) | |

| 14 | 19 | Haemolytic anaemia, unknown cause, resolved spontaneously | Mild | No | |

| 15 | 10 | Death following intestinal perforation secondary to NEC | Severe | Possibly (SUSAR) | |

| 16 | 27 | Death attributed to Gram-negative bacteraemia | Severe | No | |

| Placebo (n = 1101) | 1 | 61 | Rib fracture secondary to osteopenia of prematurity, resolved with supportive care and nutrient supplementation | Moderate | No |

| 2 | 50 | Superior sagittal sinus non-occlusive thrombus, resolved with heparin (6 weeks of treatment) | Moderate | No | |

| 3 | 48 | Hyperammonaemia, unknown cause, resolved with course of sodium benzoate | Moderate | No | |

| 4 | 36 | Death attributed to infection and sepsis | Severe | No | |

| 5 | 24 | Episode of tachycardia and ectopic beats, resolved with face cooling and reduction in caffeine dose | Mild | No | |

| 6 | 37 | Death secondary to exacerbation of chronic lung disease (severe BPD) | Severe | No | |

| 7 | 26 | Death attributed to severe BPD | Severe | No | |

| 8 | 57 | S. aureus bacteraemia and osteomyelitis, resolved with antibiotics | Moderate | No | |

| 9 | 22 | Episode of supraventricular tachycardia, resolved with adenosine | Moderate | No | |

| 10 | 6 | Episode of supraventricular tachycardia, resolved with carotid massage and adenosine | Mild | No |

There were 16 SAEs reported for infants in the lactoferrin group (six severe) and 10 for infants in the sucrose group (three severe). No infant had more than one reported event. Two SAEs, both in the lactoferrin group, were assessed as being ‘possibly related’ to the trial intervention: one case of blood in stool (expected) and one death following intestinal perforation likely associated with NEC (SUSAR). The remaining 24 SAEs were considered to be unrelated to the trial intervention.

Post hoc analyses

-

Post hoc exploratory analyses did not show any differential effects depending on the infecting micro-organism identified for the outcome ‘microbiologically confirmed late-onset infection’ (Table 7 and Box 5).

-

Post hoc exploratory analyses did not show any between-group differences in the risk of having more than one episodes of infection (Table 8).

-

Post hoc exploratory analyses did not show any differential effects for the primary outcome depending on whether infants had or had not received probiotics as part of their routine care (Table 9).

| Classification of micro-organism | Trial group | |

|---|---|---|

| Lactoferrin (n = 1098) | Placebo (n = 1101) | |

| Microbiologically confirmed late-onset invasive infection from trial entry until hospital discharge, n/N (%) | 190/1093 (17.4) | 180/1089 (16.5) |

| At least one Gram-positive organism confirmed, n/N (%) | 153/1093 (14.0) | 147/1089 (13.5) |

| At least one CoNS group organism, n/N (%) | 122/1093 (11.2) | 111/1089 (10.2) |

| At least one Gram-negative organism confirmed, n/N (%) | 46/1093 (4.2) | 39/1089 (3.6) |

| At least one fungal organism confirmed, n/N (%) | 3/1093 (0.3) | 2/1089 (0.2) |

| At least one other organism confirmed, n/N (%) | 3/1093 (0.3) | 2/1089 (0.2) |

| Missing, n | 5 | 12 |

-

Staphylococcus epidermidis.

-

Staphylococcus capitis.

-

Other coagulase-negative Staphylococci.

-

S. aureus.

-

Enterococcus faecalis.

-

Group B streptococci.

-

Enterococcus sp. (other).

-

Streptococcus sp. (other).

-

Micrococcus sp.

-

Bacillus sp.

-

Diphtheroids.

-

Streptococcus pneumoniae.

-

Propionibacterium acnes.

-

Listeria monocytogenes.

-

Other Gram-positive bacteria.

-

Escherichia coli.

-

Klebsiella sp.

-

Enterobacter sp.

-

Pseudomonas sp.

-

Serratia sp.

-

Coliforms (other).

-

Acinetobacter sp.

-

Citrobacter sp.

-

Burkholderia sp.

-

Haemophilus sp.

-

Other Gram-negative bacteria.

-

Candida albicans.

-

Candida sp. (other).

-

Other fungi.

-

Other organisms.

1–15, Gram positive; 1–3, coagulase-negative Staphylococcus group; 16–26, Gram negative; 27–29, fungi; 30, other.

| Number of episodes | Trial group | |

|---|---|---|

| Lactoferrin (n = 1098) | Placebo (n = 1101) | |

| Microbiologically confirmed or clinically suspected sepsis, n/N (%) | ||

| None | 777/1093 (71.1) | 755/1089 (69.3) |

| 1 | 258/1093 (23.6) | 279/1089 (25.6) |

| 2 | 46/1093 (4.2) | 39/1089 (3.6) |

| 3 | 9/1093 (0.8) | 13/1089 (1.2) |

| 4 | 3/1093 (0.3) | 2/1089 (0.2) |

| 5 | 0/1093 (0.0) | 1/1089 (0.1) |

| Missing, n | 5 | 12 |

| Microbiologically confirmed infection, n/N (%) | ||

| None | 903/1093 (82.6) | 909/1089 (83.5) |

| 1 | 162/1093 (14.8) | 155/1089 (14.2) |

| 2 | 24/1093 (2.2) | 23/1089 (2.1) |

| 3 | 3/1093 (0.3) | 2/1089 (0.2) |

| 4 | 1/1093 (0.1) | 0/1089 (0.0) |

| Trial group | ||

|---|---|---|

| Lactoferrin (n = 1098) | Placebo (n = 1101) | |

| Any record of probiotics being given, n/N (%) | ||

| Yes | 99/354 (28.0) | 97/329 (29.5) |

| No | 208/728 (28.6) | 227/749 (30.3) |

| Missing,a,b n | 16 | 23 |

Chapter 4 Discussion and conclusions

Summary of main findings

The ELFIN trial shows that enteral lactoferrin supplementation (150 mg/kg/day until 34 weeks’ postmenstrual age) does not reduce the risk of late-onset infection, other morbidity or mortality in very preterm infants.

This finding contradicts the existing evidence base and illustrates why high-quality evidence from adequately powered RCTs is needed to inform policy and practice. 55 The current Cochrane review includes six RCTs, and meta-analyses of their data suggest substantial reductions in the risk of late-onset infection and NEC associated with lactoferrin supplementation in very preterm infants. 40 However, the trials included in the Cochrane review were small and some contained other design and methodological weaknesses that may have introduced biases resulting in overestimation of the effect sizes. 41–46 Given these concerns, the Cochrane review authors graded the evidence for key outcomes as being of ‘low quality’ and concluded that data from methodologically rigorous RCTs were needed to generate evidence of sufficient validity to inform policy and practice. 40

The ELFIN trial provides these data. The validity of the findings is enhanced by the quality and power of the trial. We used best practices to limit bias, including central web-based randomisation for allocation concealment, blinding of parents, caregivers and investigators to the group allocation, and complete follow-up and assessment of the trial cohort with intention-to-treat analyses based on a prespecified statistical analysis plan. The trial achieved recruitment of 2203 participants as per protocol, based on the a priori sample size estimation. Demographic and prognostic characteristics were well-balanced between the two groups at randomisation, with a minimisation algorithm ensuring balance for major known or putative prognostic indicators (completed weeks of gestation, sex, single vs. multiple births) or potential confounding influences (recruiting site). Interim analyses by the trial’s independent DMC used strict criteria to minimise the chances of spurious findings attributable to data fluctuations before a sufficient sample size was achieved. 56,57 Adherence to the allocated interventions was high, the incidence of protocol violations was low and outcome data were available for > 99% of the trial cohort. Event rates for the primary and secondary outcomes were broadly similar to those that we anticipated and as have been described in other cohort studies and RCTs involving very preterm infants. 2,3 Consequently, the trial had sufficient power and internal validity to detect reliably modest yet important effects on the risk of late-onset infection and other morbidities.

Given the size of the ELFIN trial, with more than twice as many infants than had participated in all of the existing trials combined, we were able to generate more precise estimates of effect size than were available previously. The 95% CI for the relative risk estimate for the primary outcome excludes a > 14% risk reduction and a ≥ 4% increase in risk. These estimates were consistent across completed weeks of gestation at birth, making it unlikely that bovine lactoferrin has any important benefits for extremely preterm infants who have a higher risk of infection. Similarly, although it is plausible that lactoferrin may have had different effects in infants with lower levels of exposure to the immunoprotective factors present in human milk, we did not show any interaction with the type of enteral milk feeds received during the trial period (human milk, formula or both). 58

The largest previous trial, in which 331 very low birthweight infants in neonatal units in Italy participated, showed a relative risk reduction of 66% for late-onset infection. 41 Although this estimate of effect may have been inflated by methodological weaknesses, such as the absence of predefined criteria for interim analyses, the Italian trial differed from the ELFIN trial in other ways that could have contributed to the divergence of findings. The participants and the intervention were broadly similar, as were enteral feeding practices, including receipt of human breast milk versus formula milk. However, key differences in the epidemiology of late-onset infection, as well as in infection-prevention practices and exposure to other interventions, may have contributed to the difference in effects size estimates shown in the two trials. Notably, the incidence of invasive fungal infection was very high in the Italian trial (7.7% of the control group) and a substantial proportion of the overall effect on reducing late-onset invasive infection was due to the effect on preventing invasive fungal infection. 59 In contrast, the overall incidence of late-onset fungal infection was low in the ELFIN trial cohort (five episodes in total), consistent with that reported in UK surveillance studies. 9,60

Given that a postulated mechanism of action of lactoferrin is to reduce bowel translocation of enteric pathogens, we assessed whether or not invasive infections with particular groups of enteric organisms were reduced. 58,61 In post hoc analyses, we did not show any evidence that lactoferrin supplementation affected the risk of late-onset infection with different groups of infecting micro-organism including Gram-negative bacteria (mainly Escherichia coli and other Enterobacteriaceae). This finding is consistent with the previously largest trial, which did not show an effect of lactoferrin supplementation on the incidence of infection with Gram-negative bacteria. 41

The ELFIN trial did not show any difference in the effect of lactoferrin on the risk of late-onset infection in a post hoc subgroup analysis of infants who had or had not received probiotic supplementation during the trial period. A previous trial and the current Cochrane review had suggested that combining supplementation of lactoferrin with the probiotic micro-organism Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG was associated with a greater reduction in the risk of late-onset infection (> 70%) and NEC (> 90%) than lactoferrin alone. 40,41 This raised the possibility that the immunoprotective and prebiotic properties of lactoferrin might act synergistically with probiotic supplementation. 61 Although the ELFIN trial did not show any evidence of differential effects depending on whether or not infants had received probiotics during the trial period, the data are not sufficient to exclude the possibility that such prebiotic–probiotic synergism exists. A recent large cluster RCT in India has suggested that the prophylactic administration of an oral synbiotic (prebiotic fructo-oligosaccharide combined with probiotic Lactobacillus plantarum) reduces infection and mortality in late preterm or term newborn infants. 62 We are conducting a mechanistic study in a subgroup of ELFIN trial participants to analyse whether or not, and how, lactoferrin supplementation affects the intestinal microbiome and metabolite profile. The study will explore changes in microbiomic and metabolomic patterns preceding disease onset including NEC and late-onset infection. 61

Limitations

The prespecified primary outcome included ‘clinically suspected’ and ‘microbiologically confirmed’ late-onset infection. We took this pragmatic approach because of concerns about the diagnostic accuracy of microbiological culture of blood in this population. 63 Standard microbiological culture may not detect cases of bacteraemia or fungaemia if an insufficient volume of the infant’s blood is incubated (‘false negative’). Conversely, microbiological cultures may also generate ‘false-positive’ results if blood sampling techniques allow entry of contaminating micro-organisms (typically from the infant’s skin). To mitigate these potential sources of bias, we used an established consensus case definition that (1) required additional evidence of infection (clinical signs or biomarkers) and (2) mandated that clinicians indicate an intention to treat the infant with antibiotics or antifungals for at least 5 days. 2,3

Typically, microbiological confirmation was obtained by culture of potentially pathogenic bacteria or fungi from an infant’s blood or CSF sample, or from another normally sterile tissue space. The outcome definition included infection with coagulase-negative Staphylococci, provided that these were not a mixed flora but excluded micro-organisms that were likely to be skin contaminants (diphtheroids, micrococci or propionibacteria). This approach is consistent with standard clinical practice and surveillance protocols in the UK and elsewhere. The case definition of late-onset infection did not include urinary tract infection or radiologically confirmed pneumonia, as these are not accurate and reliable in very preterm infants in the absence of bacteraemia. 64

Secondary outcomes

Estimates for the secondary outcomes indicated consistently that lactoferrin supplementation does not have important effects on the risk of major morbidities. We prespecified an analysis of the effect on a composite of infection, NEC, BPD, ROP and mortality. The adjusted RR point estimate for this secondary outcome was 1.01, with a 99% CI excluding a > 6% reduction and a ≥ 8% increase in risk. We plan to increase the precision of these estimates of effect on rarer secondary outcomes by combining these data in a meta-analysis with other trials, including a recently completed Australasia RCT (n = 1500) of bovine lactoferrin supplementation for very low birthweight infants (Lactoferrin Infant Feeding Trial; see www.anzctr.org.au/ACTRN12611000247976.aspx). 65

Cost analyses

As late-onset infection and NEC are the major reasons for receipt of invasive interventions and higher levels of ‘categories of care’ in very preterm infants, it is not surprising that we did not show any effects on the level of exposure to antimicrobial agents or on the duration of hospitalisation or stay in intensive or special care settings. Given that the ELFIN trial did not show any differences between groups in the risk of morbidity or on levels of care received, we did not undertake detailed analyses of health-care costs as had been proposed in our approved funding application and trial protocol. We did not conduct a within-trial health economic analysis or use these data in a model to explore long-term family and health service costs, as these are driven mainly by the consequences of infection and other morbidity during the initial hospitalisation. Without evidence of clinical effectiveness on these infant-important outcomes, we considered a cost-effectiveness analysis of lactoferrin supplementation to be futile. 66

Qualitative analysis and parent views

A qualitative analysis and exploration of participants’ parents views and expectations has been undertaken in collaboration with the SIFT investigators. 48 Given that this study included SIFT participants predominantly (with few ELFIN trial participants), the findings will be reported within the SIFT report.

Long-term outcomes

We do not plan to apply for permission and additional funding to assess longer-term outcomes of trial participants. We specified in our funding application and protocol that if the trial did not detect statistically significant or clinically important differences in the in-hospital outcomes then follow-up will not be undertaken because any between-group differences in growth and neurodevelopmental outcomes are predicated largely on differences in the incidence of late-onset infections, NEC and associated morbidities. 5,6,11 As these were not shown, there is no longer an impelling rationale for expecting lactoferrin supplementation to have an impact on long-term growth or development.

Applicability

The ELFIN trial findings are likely to be applicable in the UK and internationally. Participants were enrolled in 37 neonatal units across the country, providing broad geographical, social and ethnic representation. Many infants who were enrolled in a recruiting site were transferred subsequently to another neonatal unit, which was typically closer to the family home, for ongoing care. Trial participation continued in another 97 neonatal units and this practice mirrors managed clinical network care pathways for very preterm infants in the UK.

The trial population was representative of very preterm infants cared for within health-care facilities in well-resourced health services and included a substantial proportion of extremely preterm infants (37%) and infants with other putative risk factors for neonatal morbidity, such as prolonged rupture of maternal amniotic membranes (25%) and evidence of absent or reverse end diastolic flow in the umbilical artery (12%). Overall, about 30% of participants acquired a microbiologically confirmed or clinically suspected late-onset infection, and about 17% in total had a microbiologically confirmed infection, consistent with rates reported from cohort studies and other RCTs. Similarly, the incidence of NEC (about 5%) was similar to rates reported in large, population-based surveillance and cohort studies and RCTs. 67

Implications for practice

The ELFIN trial does not support the routine use of enteral bovine lactoferrin supplementation to prevent late-onset infection or other morbidity or mortality in very preterm infants.

Implications for research

Research efforts should continue to investigate the aetiology, epidemiology and pathogenesis of late-onset infection and related morbidities, and to develop, refine and assess other interventions that may prevent or reduce adverse acute and long-term consequences for very preterm infants and their families.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all of the parents of participating infants and to all staff and carers in recruiting and continuing care sites. We thank the members of the independent DMC and TSC, Yan Hunter-Blair and colleagues at the Newcastle Specials Pharmacy team, Tatua Dairy Co-operative, New Zealand, and the administrative and support colleagues at the NPEU CTU.

Independent Trial Steering Committee

Richard Cooke (chairperson), Fan Hutchison (deputy chairperson), Andrew Ewer, Jennifer Hellier and Paul Mannix.

Independent Data Monitoring Committee

Henry Halliday (chairperson), Nim Subhedar, Michael Millar, Alison Baum and Mike Bradburn.

Ethics approval

National Research Ethics Service Committee East Midlands – Nottingham 2 (reference number 13/EM/0118, 02/04/2013).

Contributions of authors

James Griffiths (Trial Manager), Paula Jenkins (Trial Research Nurse), Monika Vargova (Administrator and Data Co-ordinator), Ursula Bowler (Senior Trials Manager), Andrew King (Head of Trials Programming), David Murray (Senior Trials Programmer), Paul T Heath (Co-investigator, chairperson of the blinded end-point review committee) and William McGuire (Chief Investigator) were responsible for the data collection and management.

Edmund Juszczak (NPEU CTU Director), Janet Berrington (Co-investigator), Nicholas Embleton (Co-investigator), Jon Dorling (Co-investigator), Paul T Heath, William McGuire and Sam Oddie (Co-investigator) were responsible for the study design.

Louise Linsell (Trial Statistician), Christopher Partlett (Trial Statistician), Edmund Juszczak, Paul T Heath and William McGuire were responsible for the data analysis.

Mehali Patel (Patient and Public Involvement Representative), Edmund Juszczak, Janet Berrington, Nicholas Embleton, Paul T Heath, William McGuire and Sam Oddie were responsible for the data interpretation.

James Griffiths, Edmund Juszczak, Louise Linsell, Christopher Partlett and William McGuire were responsible for the report writing.

All authors approved the final draft of the manuscript.

Publications

ELFIN Trial Investigators Group. Lactoferrin immunoprophylaxis for very preterm infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2013;98:F2–4.

The ELFIN Trial Investigators Group. Enteral lactoferrin supplementation for very preterm infants: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2018; in press.

Data-sharing statement

All data requests should be submitted to the corresponding author for consideration. Please note that exclusive use will be retained until the publication of major outputs. Access to anonymised data may be granted following review.

Disclaimers

This report presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). The views and opinions expressed by authors in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NHS, the NIHR, NETSCC, the HTA programme or the Department of Health and Social Care. If there are verbatim quotations included in this publication the views and opinions expressed by the interviewees are those of the interviewees and do not necessarily reflect those of the authors, those of the NHS, the NIHR, NETSCC, the HTA programme or the Department of Health and Social Care.

References

- Duley L, Uhm S, Oliver S. Preterm Birth Priority Setting Partnership Steering Group . Top 15 UK research priorities for preterm birth. Lancet 2014;383:2041-2. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60989-2.

- Vergnano S, Menson E, Kennea N, Embleton N, Russell AB, Watts T, et al. Neonatal infections in England: the NeonIN surveillance network. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2011;96:F9-F14. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.2009.178798.

- Cailes B, Kortsalioudaki C, Buttery J, Pattnayak S, Greenough A, Matthes J, et al. Epidemiology of UK neonatal infections: the neonIN infection surveillance network. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2018;103:F547-53. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2017-313203.

- Chapman RL, Faix RG. Persistent bacteremia and outcome in late onset infection among infants in a neonatal intensive care unit. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2003;22:17-21. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.inf.0000042922.10767.10.

- Adams-Chapman I, Stoll BJ. Neonatal infection and long-term neurodevelopmental outcome in the preterm infant. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2006;19:290-7. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.qco.0000224825.57976.87.

- Bassler D, Stoll BJ, Schmidt B, Asztalos EV, Roberts RS, Robertson CM, et al. Trial of Indomethacin Prophylaxis in Preterms Investigators . Using a count of neonatal morbidities to predict poor outcome in extremely low birth weight infants: added role of neonatal infection. Pediatrics 2009;123:313-18. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2008-0377.

- Gordon A, Isaacs D. Late onset neonatal Gram-negative bacillary infection in Australia and New Zealand: 1992–2002. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2006;25:25-9. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.inf.0000195628.35980.2e.

- Isaacs D, Fraser S, Hogg G, Li HY. Staphylococcus aureus infections in Australasian neonatal nurseries. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2004;89:F331-5. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.2002.009480.

- Clerihew L, Lamagni TL, Brocklehurst P, McGuire W. Invasive fungal infection in very low birthweight infants: national prospective surveillance study. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2006;91:F188-92. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.2005.082024.

- Isaacs D. Australasian Study Group for Neonatal Infections . A ten year, multi-centre study of coagulase negative staphylococcal infections in Australasian neonatal units. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2003;88:F89-93. https://doi.org/10.1136/fn.88.2.F89.

- Stoll BJ, Hansen NI, Adams-Chapman I, Fanaroff AA, Hintz SR, Vohr B, et al. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network . Neurodevelopmental and growth impairment among extremely low-birth-weight infants with neonatal infection. JAMA 2004;292:2357-65. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.292.19.2357.

- Stoll BJ, Hansen N. Infections in VLBW infants: studies from the NICHD Neonatal Research Network. Semin Perinatol 2003;27:293-301. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0146-0005(03)00046-6.

- Fowlie PW, Schmidt B. Diagnostic tests for bacterial infection from birth to 90 days – a systematic review. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 1998;78:F92-8. https://doi.org/10.1136/fn.78.2.F92.

- Malik A, Hui CP, Pennie RA, Kirpalani H. Beyond the complete blood cell count and C-reactive protein: a systematic review of modern diagnostic tests for neonatal sepsis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2003;157:511-16. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.157.6.511.

- Buttery JP. Blood cultures in newborns and children: optimising an everyday test. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2002;87:F25-8. https://doi.org/10.1136/fn.87.1.F25.

- Gordon A, Isaacs D. Late-onset infection and the role of antibiotic prescribing policies. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2004;17:231-6. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001432-200406000-00010.

- Isaacs D. Unnatural selection: reducing antibiotic resistance in neonatal units. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2006;91:F72-4. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.2005.074963.

- Murphy BP, Armstrong K, Ryan CA, Jenkins JG. Benchmarking care for very low birthweight infants in Ireland and Northern Ireland. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2010;95:F30-5. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.2009.160002.

- Shane AL, Sánchez PJ, Stoll BJ. Neonatal sepsis. Lancet 2017;390:1770-80. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31002-4.

- Valenti P, Antonini G. Lactoferrin: an important host defence against microbial and viral attack. Cell Mol Life Sci 2005;62:2576-87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-005-5372-0.