Notes

Article history

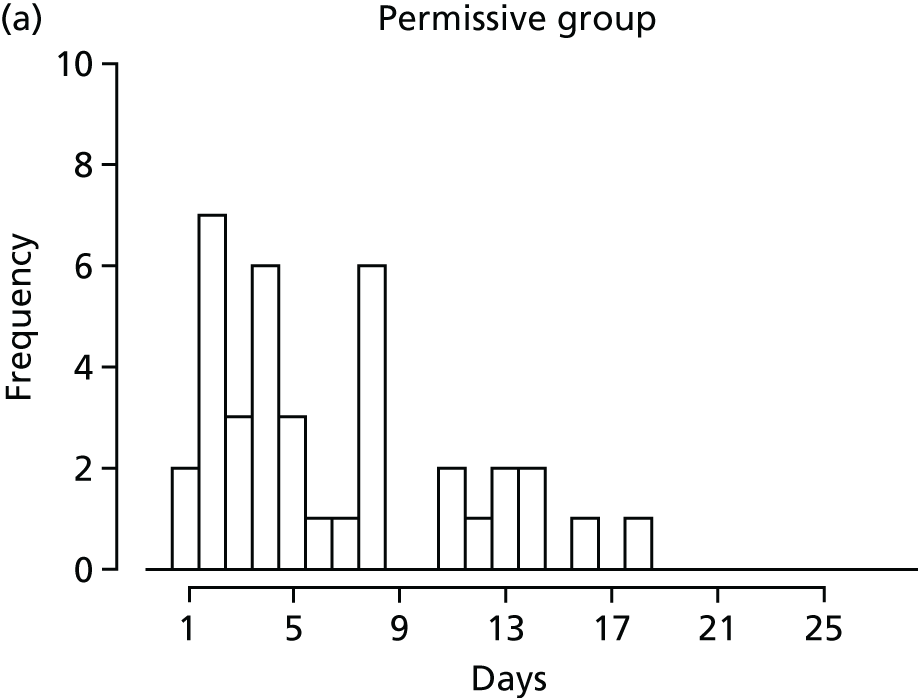

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 15/44/01. The contractual start date was in November 2016. The draft report began editorial review in May 2018 and was accepted for publication in September 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Mark J Peters is a member of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment General Board. Kathryn M Rowan is a member of the NIHR Health Services and Delivery Research Board.

Permissions

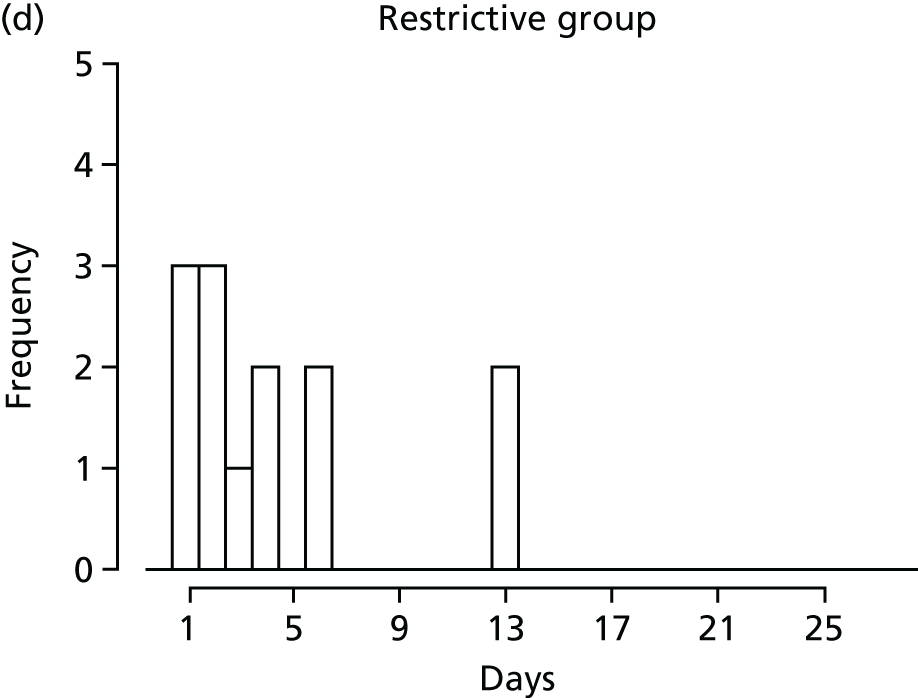

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Peters et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background and rationale

Fever is a host response that helps to control infections with a very wide range of pathogens. 1 Fever has been very highly conserved throughout evolution for at least 580 million years,1 and is seen across many species including reptiles, birds and mammals. 2 Recently, even plants have been shown to raise core temperatures to control fungal infections. 3 In humans, fever is known to increase numerous basic immunological processes including neutrophil production, recruitment and killing; monocyte/macrophage/dendritic cell phagocytosis; and antigen presentation, T-cell maturation and lymphocyte recruitment. 1

Studies in non-critically ill patients with chickenpox,4 malaria5 and rhinovirus6 infections have led to a rediscovery of the potential beneficial effects of fever. This is recognised by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in guidance for the management of feverish illness in children,7 which recommends:

Do not use antipyretic agents with the sole aim of reducing body temperature in children with fever.

However, this advice is not aimed at the management of critically ill children.

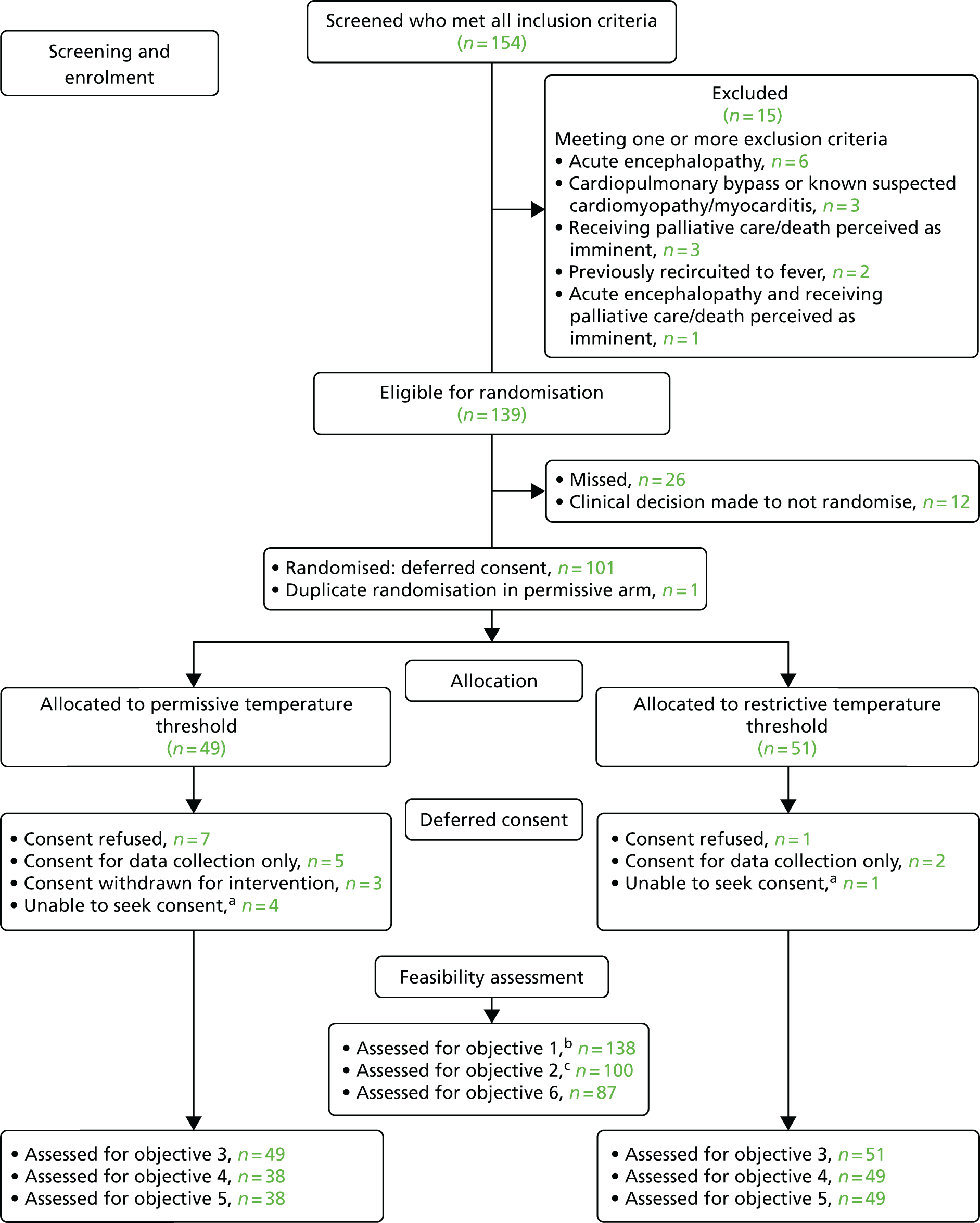

Observational studies demonstrate that treatment of fever in critically ill children is inconsistent. 8 In this population, there is a lack of robust data to guide antipyretic intervention. This frequently leaves the decision of if and when to treat fever at the discretion of the bedside nurse. There is genuine uncertainty as to whether or not the immunological advantages of a fever in defending the body against viruses and bacteria during critical illness outweigh the metabolic costs and cardiorespiratory consequences of a high fever. 2 In cases with underlying neurological pathology (e.g. traumatic brain injury, hypoxic–ischaemic encephalopathy and encephalomyelitis), practice is to avoid fever because of consistent associations with worse outcomes, but in the much larger proportion of emergency admissions in whom other organ failures predominate (most commonly respiratory) the optimal approach is unknown. With emerging evidence that fever may be beneficial in critically ill adults, but also cognisant of the physiological differences between adults and children, there is an important need to evaluate whether or not a more permissive approach to fever management in critically ill children improves outcomes.

A recent systematic review9 identified five, small, completed randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of antipyretic interventions in critically ill adults. These trials were small (ranging from 26 to 200 participants) and the results of a meta-analysis on intensive care unit mortality were inconclusive [relative risk for fever control compared with no fever control or a more permissive threshold 0.97, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.58 to 1.63]. One larger RCT among adults, the HEAT trial10 in Australia and New Zealand, examined the effect of acetaminophen (Perfalgan, Bristol-Myers Squibb) (paracetamol) versus placebo to treat fever in 700 critically ill adults with known or suspected infection. No differences were seen in the primary outcome of the number of paediatric intensive care unit (PICU)-free days to day 28 or in mortality. The CASS trial (NCT01455116)11 found a non-significant increase in 30-day mortality in mechanically ventilated adult patients with septic shock who were actively cooled to hypothermia when compared with normal thermal management. Analysis of the trial’s secondary outcomes revealed that induced hypothermia worsened respiratory failure, circulatory collapse and delayed reduction in serum c-reactive protein. We are not aware of any completed or ongoing RCTs comparing antipyretics or fever thresholds in critically ill children.

A systematic review of observational studies of the association between fever and mortality in critically ill adults found wide variation in the definitions of fever and its association with mortality. 12 Two further observational studies in adults, not included in the systematic review, found different relationships between fever and mortality for patients with and without infection, with fever associated with lower mortality among admissions with infection unless the temperature exceeded 40 °C. 13,14 Similar results have been found in small cohorts of critically ill children with infection. 15

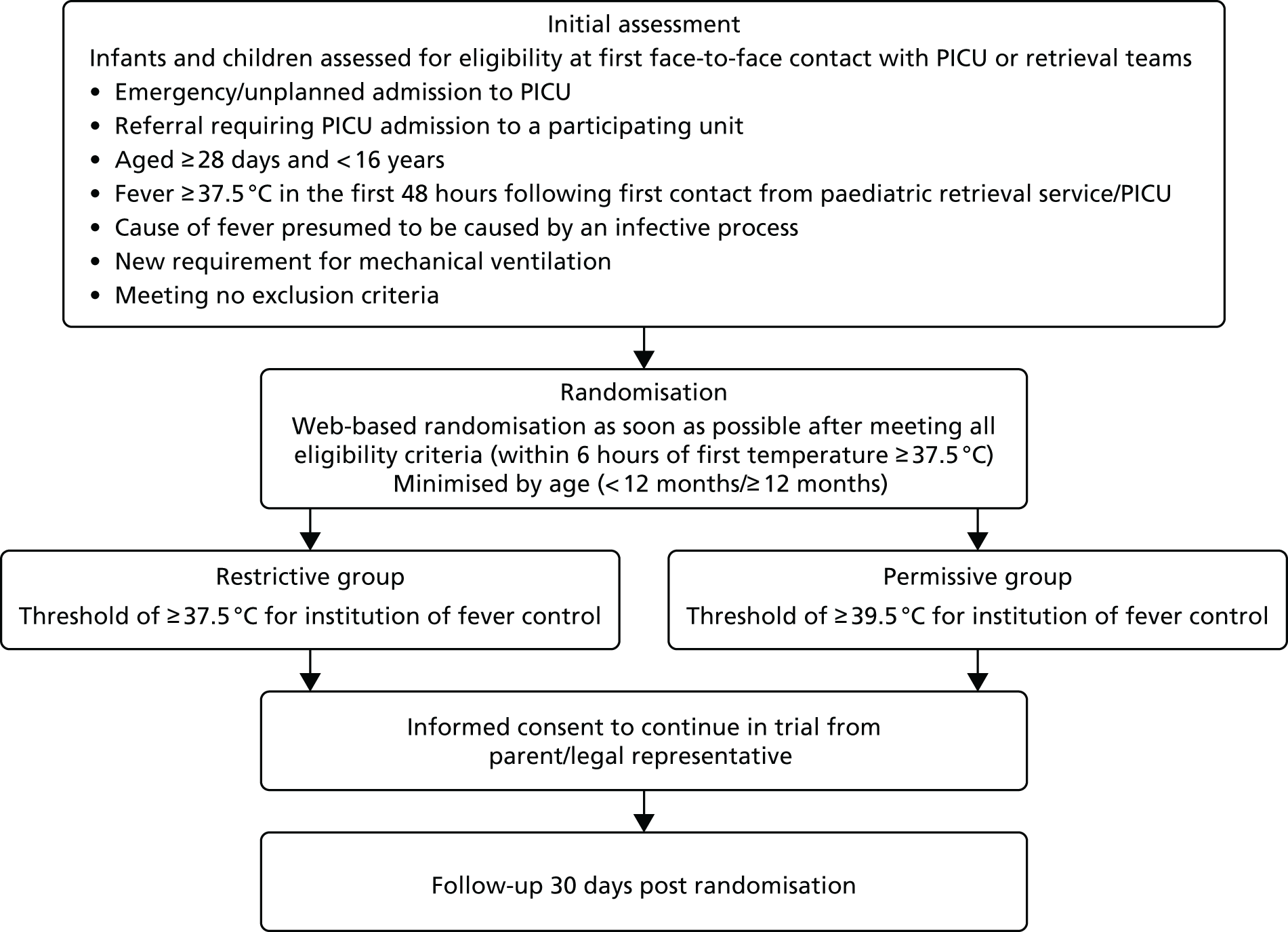

The FEVER feasibility study aimed to establish whether or not it is feasible to conduct a clinical trial to evaluate different temperature thresholds at which clinicians deliver antipyretic intervention in critically ill children with fever owing to infection [i.e. comparing a permissive approach to fever (e.g. treat at ≥ 39.5 °C) with a standard restrictive approach (e.g. treat at ≥ 37.5 °C)].

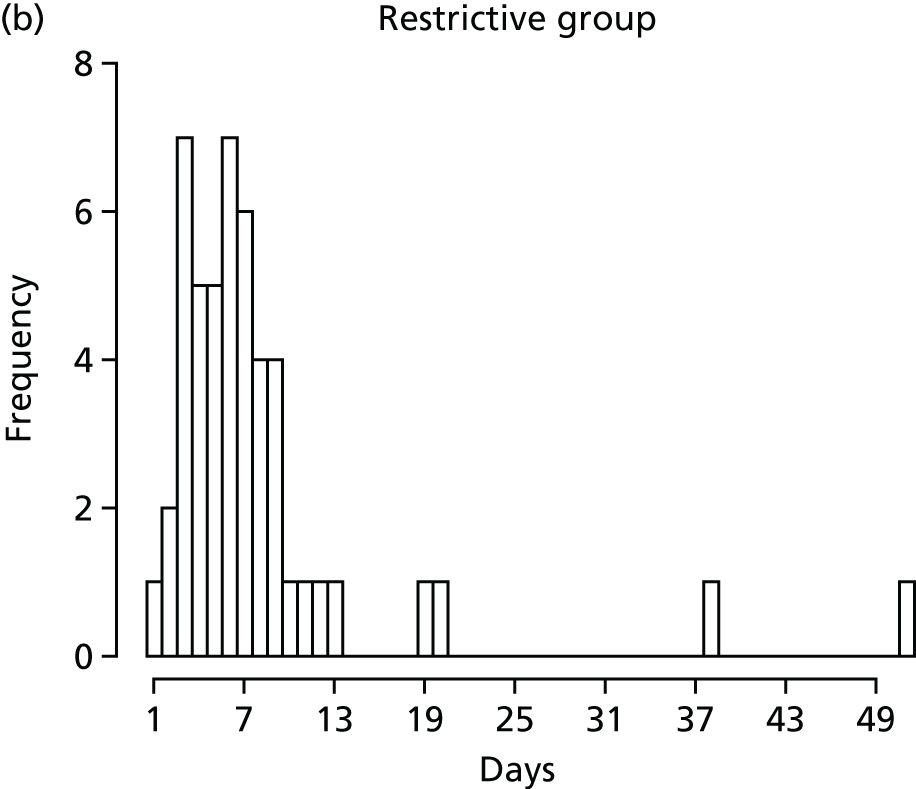

Clinical trials, such as the proposed FEVER RCT, are expensive and the chances of successful completion are improved if both the feasibility and pilot testing of certain key parameters can be clearly demonstrated. Using a mixed-methods approach comprising three separate studies, the FEVER feasibility study included the FEVER qualitative study, the FEVER observational study and the FEVER pilot RCT with integrated-perspectives study.

Aim

The overarching aim for the FEVER feasibility study was to explore and test important key parameters needed to inform the design and ensure the successful conduct of a definitive FEVER RCT, and to report a clear recommendation for continuation or not to a full trial. Each of the three studies had specific objectives.

Objectives

The FEVER qualitative study

To review, with input from parents/legal representatives:

-

the acceptability of the selection of temperature thresholds and options for analgesia for a definitive FEVER RCT

-

potential barriers to recruitment, the proposed process of decision-making and deferred consenting, and co-develop information and documentation for a definitive FEVER RCT

-

the selection of important, relevant, patient-centred, primary and secondary outcomes for a definitive FEVER RCT.

To review and explore, with input from clinicians:

-

the acceptability of temperature thresholds and options for analgesia for a definitive FEVER RCT

-

potential barriers to recruitment, deferred consenting and associated training needs for a definitive FEVER RCT.

The FEVER observational study

-

Estimate the size of the potentially eligible population for the definitive FEVER RCT.

-

Confirm, using empirical data, the temperature threshold(s) currently employed for a standard approach for antipyretic intervention in NHS PICUs.

-

Estimate the characteristics [e.g. mean and standard deviation (SD)] of selected important, relevant, patient-centred primary outcome measure(s).

The FEVER pilot randomised control trial with integrated-perspectives study

-

Test the willingness of clinicians to screen, recruit and randomise eligible critically ill children.

-

Estimate the recruitment rate of critically ill children.

-

Test the acceptability of the deferred consenting procedure and participant information.

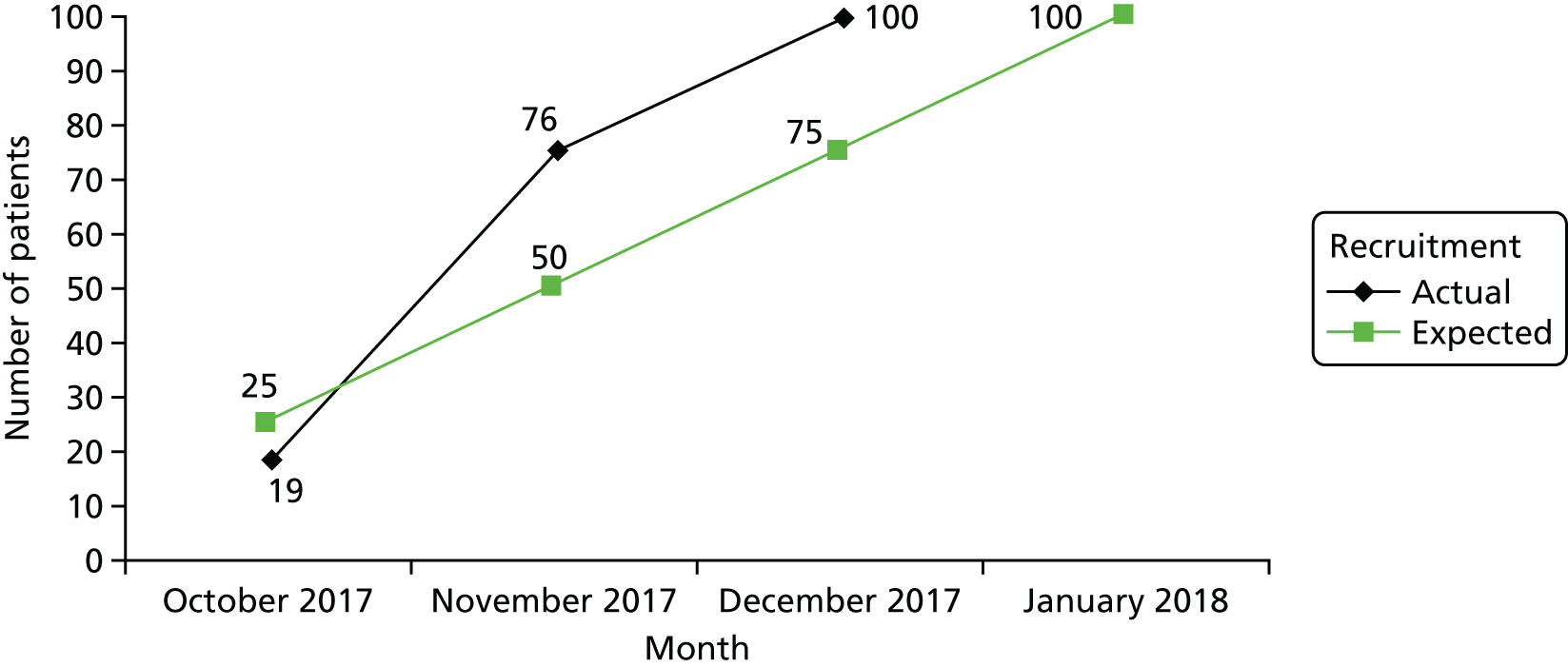

-

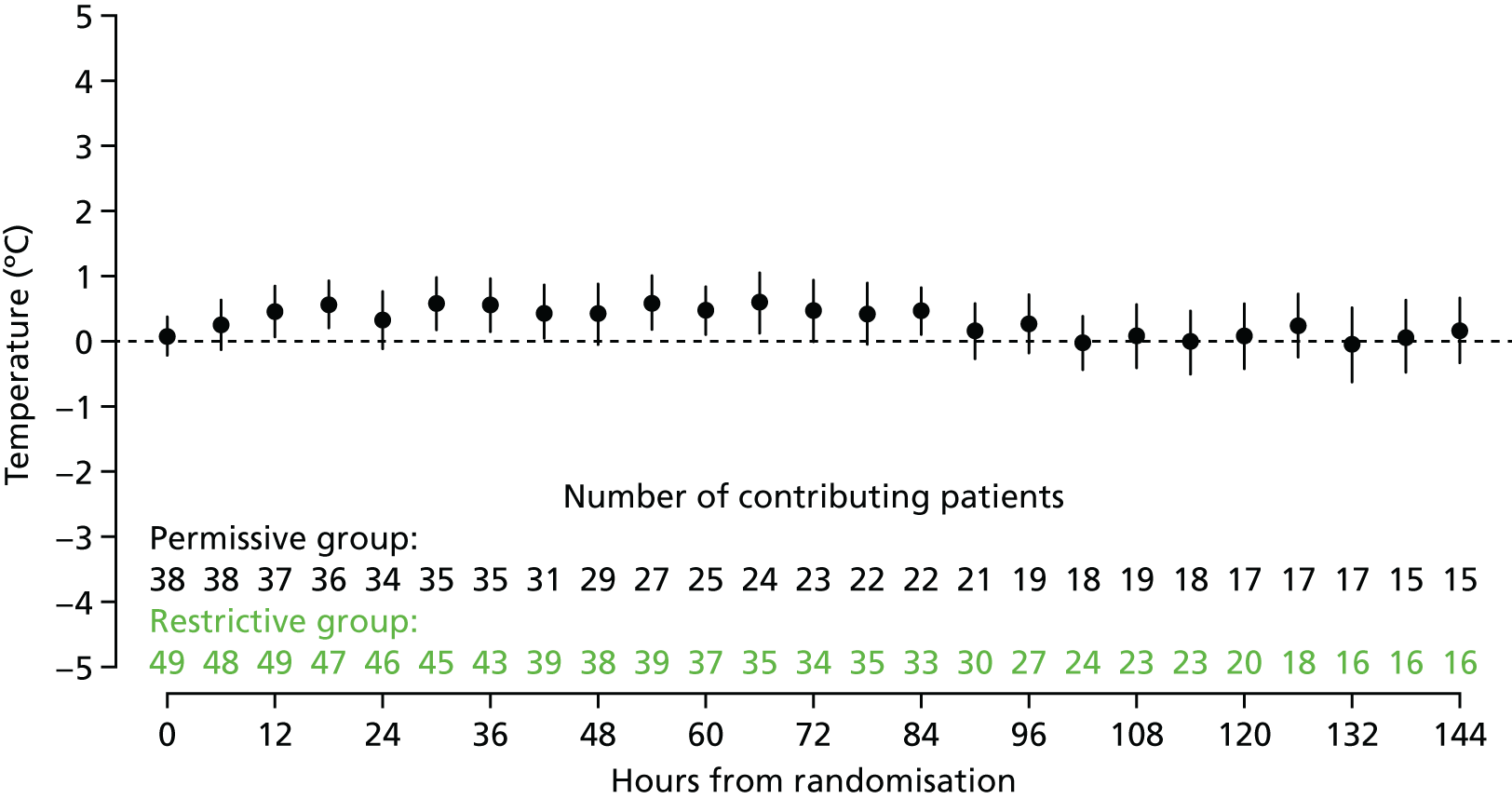

Test, following randomisation, the delivery of and adherence to the selected temperature thresholds (intervention and control) for antipyretic intervention and to demonstrate separation between the randomised groups in peak temperature measurement over the first 48 hours following randomisation.

-

Test follow-up for the identified, potential, patient-centred primary and other important secondary outcome measures and for adverse event (AE) reporting.

-

Inform the final selection of a patient-centred primary outcome measure.

The FEVER feasibility study management

The FEVER feasibility study was sponsored and co-ordinated by the Intensive Care National Audit and Research Centre (ICNARC) Clinical Trials Unit (CTU) (UK Clinical Research Collaboration ID number 42). A Study Management Group (SMG) was convened, comprising the chief investigator (MJP) and co-investigators (RA, ESD, BF, DAH, NK, PRM, PR, KMR, ST, LT, JW and KW), and was responsible for overseeing day-to-day management of the entire FEVER feasibility study. The SMG met regularly throughout the duration of the study to monitor its conduct and progress. Two parents (CF and JW) and one young adult (BF) (all co-investigators) with experience of a critical illness caused by a severe infection were members of the SMG and provided valuable input into the design and conduct of the FEVER feasibility study, including reviewing documents for parent interviews (e.g. draft FEVER pilot trial participant documentation) and informing study recruitment approaches (i.e. identification of social media groups and charities), in addition to being involved in reviewing study progress and findings.

Chapter 2 The FEVER qualitative study

Study design

The FEVER qualitative study was a mixed-methods study involving semistructured interviews with parents/legal representatives of children with relevant experience, and focus groups (including quantitative data collected with a voting system) with staff in pilot RCT sites.

Research governance

An ethics application was made to the North West – Liverpool East Research Ethics Committee on 16 October 2015 and received a favourable opinion on 21 December 2016 (reference number 16/NW/0826). The protocol is available at www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/154401/#/ (accessed 16 November 2018). Local NHS permissions were obtained for the NHS trusts for recruitment routes 2 and 3 (see Recruitment and sampling procedures).

Study management

The FEVER qualitative study was led by a co-investigator (KW). An experienced research associate (ED) was employed to organise, conduct and analyse the interviews and focus groups. The SMG was responsible for overseeing day-to-day management of the entire FEVER feasibility study, including the FEVER qualitative study.

Network support

To maintain the profile of the FEVER feasibility study, updates were provided at national meetings, such as the biannual Paediatric Intensive Care Society Study Group meetings.

Patient and public involvement

Two parents (CF and JW) and one young adult (BF) with experience of severe infection and admission to hospital were co-investigators and members of the SMG. They provided valuable input into the design and conduct of the study, including reviewing documents for parent interviews (e.g. the draft pilot trial participant information sheets) and informing study recruitment approaches (i.e. identification of social media groups and charities). They were also involved in the review of study progress and findings.

Design and development of the protocol

The design and development of the protocol, including sample estimation, recruitment strategy and interview topic guide, were informed by previous trials conducted in paediatric emergency and critical care in the NHS and earlier research. 16–20 Relevant research was used to develop a parent interview topic guide (see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/154401/#/; accessed 23 January 2019), two participant information sheets for the pilot trial (bereaved and non-bereaved) (see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/154401/#/; accessed 16 November 2018),17,18,20,21 a list of potential outcome measures17 to inform discussions with parents/legal representatives during interviews (see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/154401/#/; accessed 23 January 2019) and a staff focus group topic guide (see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/154401/#/; accessed 23 January 2019).

The interview and focus group topic guides contained open-ended questions and prompts to help explore parent/legal representative and staff views on the acceptability of a definitive FEVER RCT, including the draft FEVER pilot RCT participant information sheets and approach to consent. A separate section of questions was developed for bereaved parents/legal representatives.

Amendments to the study protocol

Minor amendments to the protocol, patient information sheet, schedule of events and statement of activities were approved by the Health Research Authority (HRA) on 10 January 2017.

A substantial amendment to the qualitative study protocol was submitted to the North West – Liverpool East Research Ethics Committee. The amendment requested the inclusion of an incentive description in the study recruitment advertisements and placement of the study advertisements in newspapers. A favourable opinion was received on 1 March 2017.

Recruitment

Participants

Based on previous studies,17,20 it was anticipated that 15–25 parents/legal representatives would be recruited to reach data saturation (i.e. the point at which no new major themes are discovered in analysis). We aimed to conduct a focus group with site staff (nurses and doctors) working in the four PICUs and associated retrieval services involved in the subsequent pilot RCT. We anticipated that a minimum of 4 and a maximum of 10 clinicians would attend each of the four focus groups (16–40 in total).

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

Parents/legal representatives who have experienced their child being admitted to an intensive care unit with a fever and suspected infection in the preceding 3 years and clinicians (nurses and doctors) working in the four PICUs/retrieval services planned to be included in the pilot RCT (study 3).

Exclusion criteria

Parents/legal representatives who do not speak English.

Recruitment and sampling procedure

For the focus groups, an e-mail invitation and participant information sheet was sent to lead clinicians (FEVER feasibility study co-investigators) in paediatric emergency and paediatric critical care medicine at the four NHS hospitals taking part in the pilot RCT. Co-investigators disseminated focus group invitations to all relevant staff and arranged a location and time for the focus group.

Parents were recruited through four routes (described in the following sections) to maximise the potential sample within the 6-month active recruitment period and to encourage diversity within the sample.

Recruitment route 1: existing database

Eligible parents were identified from an existing database held by Kerry Woolfall at the University of Liverpool, which contained contact details of parents who participated in the Fluids in Shock (FiSh) feasibility study17 and provided consent to be contacted for future related studies.

Recruitment route 2: postal recruitment

Staff used hospital medical records to identify the 15 most recent parents/legal representatives (including up to five bereaved) of children who met the inclusion criteria. Those identified were sent a postal invitation, including a covering letter and participant information sheet describing how to register interest in taking part.

Recruitment route 3: advertising in paediatric intensive care units

Copies of the FEVER qualitative study participant information leaflet and participant information poster were placed in family/relative waiting rooms and notice boards near the PICUs.

Recruitment route 4: media advertising

An advertisement was posted on Twitter (Twitter, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA; www.twitter.com) and Facebook (Facebook, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA; www.facebook.com), which invited parents/legal representatives to register interest in participating in the study. Relevant charities and parent support groups were asked to place the advertisement on their website and social media. Data saturation was reached before an advertisement was placed in a newspaper.

Screening and conduct of interviews and focus groups

Interviews

Screening

Parents’ expressions of interest to participate were responded to in sequential order. Once eligibility was confirmed, an interview date and time were scheduled. The draft pilot RCT participant information sheet (see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/154401/#/; accessed 16 November 2018) and list of potential outcomes (see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/154401/#/; accessed 23 January 2019) were e-mailed to parents to read prior to the interview. Screening and interview conduct stopped when data saturation and sample variation (recruitment of parents via multiple recruitment routes) were achieved.

Informed consent

Audio-recorded verbal consent was sought over the telephone before the interview. This involved reading each aspect of the consent form to parents, including consent for audio-recording and to receive a copy of the findings when the study is complete. Each box was initialled on the consent form when verbal consent was provided. Informed consent discussions were audio-recorded for auditing purposes.

Conduct of the interviews

Interviews began with a discussion about the aims of the study, an opportunity for questions and a check that the parent had sufficient time to read the draft pilot trial participant information sheet and list of potential outcomes (see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/154401/#/; accessed 23 January 2019).

The interview then commenced using the interview topic guide to explore:

-

the experience of having a child admitted to the PICU with a fever and suspected infection

-

previous experience of participation in clinical trials

-

length and content of the draft pilot RCT participant information sheet

-

the acceptability of restrictive (e.g. ≥ 37.5 °C) and permissive (e.g. ≥ 40 °C) temperature thresholds

-

the acceptability of research without prior consent (RWPC) in paediatric research and in the proposed FEVER RCT

-

the identification of potential barriers to participation in the trial and how these could be addressed

-

the identification of potential facilitators of trial participation

-

trial design, including the selection of outcome measures

-

whether or not parents would (hypothetically) consent to the use of their child’s data in the proposed FEVER RCT.

Example questions can be found on the project web page (www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/154401/#/; accessed 23 January 2019). Respondent validation was used to add unanticipated topics to the topic guide as interviewing and analysis progressed. After the interview, participants were sent a copy of the consent form and a thank you letter, including a £30 Amazon (Amazon.com, Inc., Bellvue, WA, USA) voucher to thank them for their time. A copy of the consent form was retained by the University of Liverpool.

Focus groups

Informed consent

At the start of the focus group, Kerry Woolfall or Elizabeth Deja checked that all participants had read the participant information sheet and understood the purpose of the focus group. The focus group/interview aims and topics to be covered were discussed, followed by an opportunity for questions. Participants were asked to provide written consent using the consent form before the focus group and audio-recording began.

Conduct of the focus groups

A voting system, using TurningPoint software (Turning Technologies, Youngstown, OH, USA), was used alongside verbally administered questions. This involved some of the key questions being presented to the group via a laptop presentation and each participant using a wireless handset to select their answer from those shown on the screen. A test question was used at the beginning of the focus group to help demonstrate how the voting system would work alongside verbally administered questions. This method was used to enable the collection of data from all participants, as well as a means of generating statistical data from all sites alongside qualitative data from group discussions. Once it was established that the handsets were working with the test question, staff were asked to introduce themselves, their role within the PICU and past experience of recruiting to clinical trials.

The focus groups explored site staff views and experiences on:

-

current temperature thresholds for treating pyrexia

-

the acceptability of the proposed FEVER RCT including the selection of temperature thresholds and options for analgesia

-

perceptions of the use of RWPC in the RCT

-

potential barriers to recruitment and consent in the trial and how these might be addressed

-

potential difficulties in adhering to the trial protocol

-

training needs.

Respondent validation22 was used to add unanticipated questions to the topic guide as data collection and analysis progressed; for example, queries raised by staff about the pilot RCT inclusion criteria (e.g. would children need to be on a ventilator to be included in the study?) were added to the topic guide to explore in subsequent focus groups. Once a focus group was completed, staff were thanked for their time and participation in the study.

Transcription

Digital audio-recordings were transcribed verbatim by a professional transcription company (Voicescript Ltd, Bristol, UK) in accordance with the Data Protection Act 1998. 23 Transcripts were anonymised and checked for accuracy. All identifiable information, such as names (e.g. of patients, family members or hospital their child was admitted to), were removed.

Data analysis

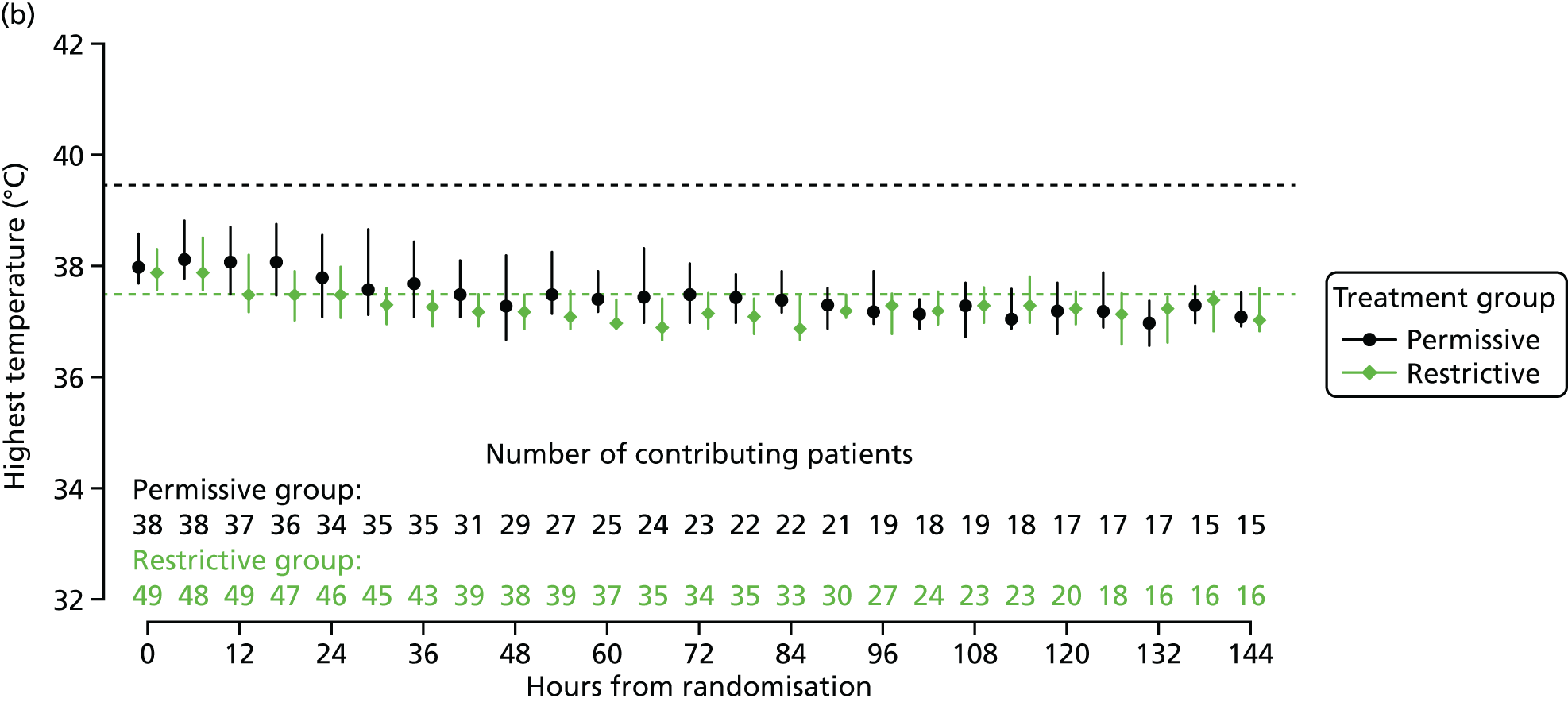

Qualitative data analysis of the interviews and focus groups was interpretive and iterative (Table 1). Utilising a thematic analysis approach, the aim was to provide accurate representation of parental views on trial design and acceptability. Thematic analysis is a method for identifying, analysing and reporting patterns (or themes) within data. Analysis was informed by the work of Braun and Clarke24 and their guide to thematic analysis. This approach allows for themes to be identified at a semantic level (i.e. surface meanings or summaries) or at a latent level (i.e. interpretive – theorising the significance of the patterns and their broader meanings and implications). 28 NVivo 10 (QSR International, Warrington, UK) software was used to assist in the organisation and coding of data. Elizabeth Deja (a psychologist) led the analysis with assistance from Kerry Woolfall (a sociologist).

| Phase | Description |

|---|---|

| 1. Familiarising with data | Elizabeth Deja read and re-read transcripts, noting down initial ideas |

| 2. Generating initial codes | Initially, a data-coding framework was developed using a priori codes identified from the project proposal and the interview topic guide. During the familiarisation stage, Elizabeth Deja identified additional data-driven codes and concepts not previously captured in the initial coding frame |

| 3. Developing the coding framework | Kerry Woolfall coded 10% of the transcripts using the initial coding frame and made notes on any new themes identified and how the framework could be refined |

| 4. Defining and naming themes | Following review and reconciliation by Elizabeth Deja and Kerry Woolfall, a revised coding frame was subsequently developed and ordered into themes (nodes) within the NVivo (QSR International, Warrington, UK) database |

| 5. Completing coding of transcripts | Kerry Woolfall and Elizabeth Deja met regularly to discuss developing themes, sample variance and potential data saturation by looking at the data and referring back to the study aims. When saturation was achieved, data collection stopped. Elizabeth Deja completed coding of all transcripts in preparation for write-up |

| 6. Producing the report | Elizabeth Deja and Kerry Woolfall developed the manuscript using themes to relate back to the study aims, ensuring that key findings and recommendations were relevant to the FEVER RCT design and site staff training (i.e. catalytic validity).24–27 Final discussion and development of selected themes took place during the write-up phase |

Results

Participants

Parents/legal representatives

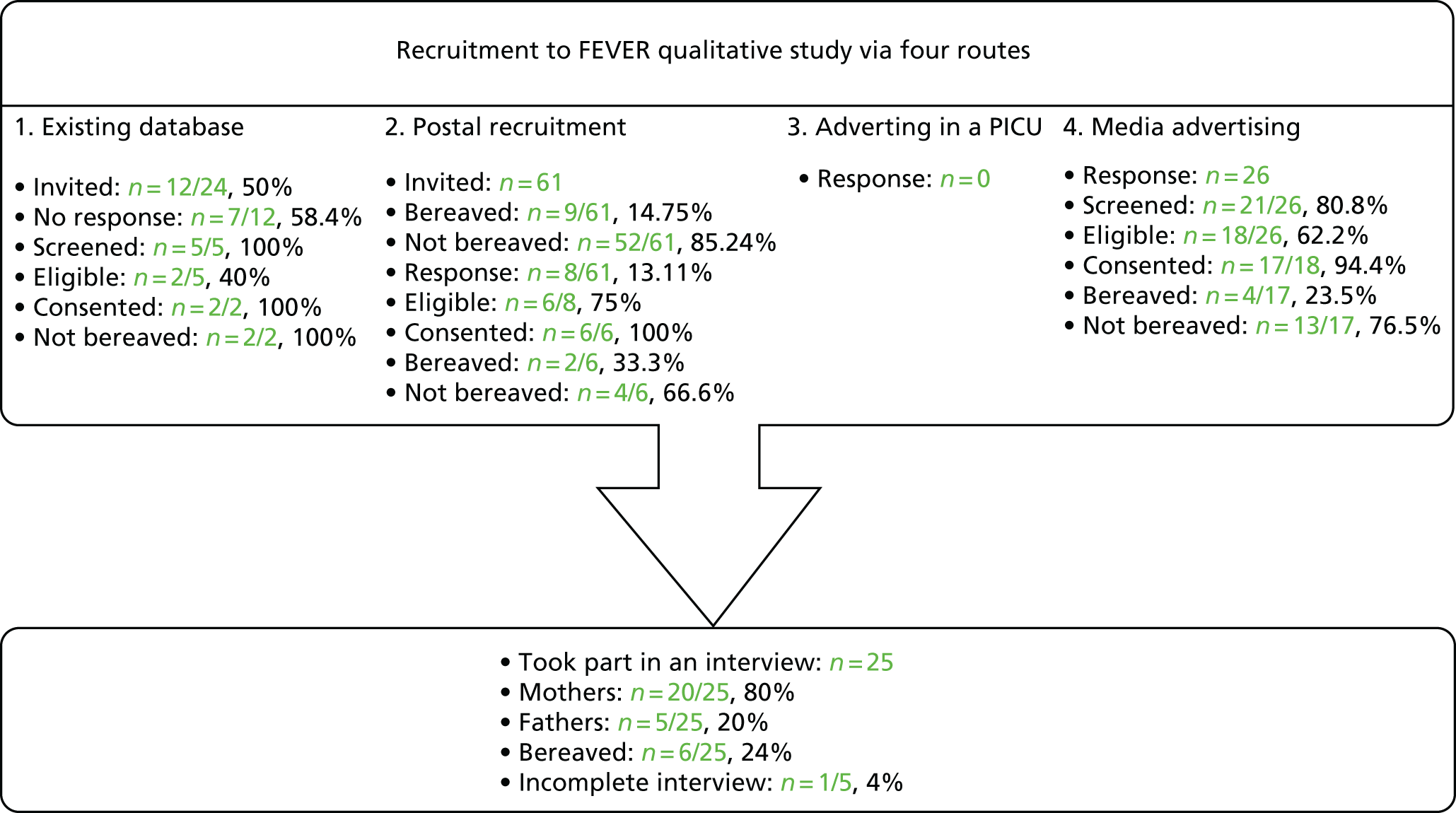

A total of 46 parents registered interest, of whom 34 were screened (Figure 1). Eight were deemed ineligible and one did not confirm a date for interview. No individuals identified themselves as legal representatives; therefore, this term is not used in the remainder of this chapter.

FIGURE 1.

Recruitment to the FEVER qualitative study.

Parent characteristics

The sample included 25 parents: 20 mothers (4 bereaved) and 5 fathers (2 bereaved). Bereaved parents were interviewed at a mean of 19 months (SD 9.8 months) since their child’s admission (range 12–38 months). Children were a median age of 1.96 [interquartile range (IQR) 4.21] years (range 0.0–15.58 years) and had a median hospital length of stay of 12.5 (IQR 33.25) days (range 0.5–140 days) owing to streptococcus (n = 2), meningitis (n = 2), pneumonia (n = 1) and sepsis (n = 2). One bereaved father stopped the interview before diagnosis information was collected. Non-bereaved parents were interviewed a mean of 15.63 months (SD 6.5 months) since admission (range 6–29 months). The children had a median age of 1.5 years (IQR 3.87 years) (range 0.0–15.58 years) and a median hospital stay of 30.67 days (IQR 37.35 days) (range 7–140 days) for streptococcus (n = 2), meningitis (n = 4), sepsis (n = 6), chest infections (pneumonia, n = 5, and bronchitis, n = 2), toxic shock (n = 1), varicella (n = 2) and unknown infection (n = 2).

A total of 9 out of 24 parents (36%) had previous experience of trial participation either directly (themselves) or indirectly (through their child’s participation). Five parents (20%) had previous knowledge of RWPC. Ten out of 24 parents (41.7%) could not recall what temperature their child reached during their admission to hospital with a fever and severe infection. Of those who could recall, 7 out of 24 (29%) stated that their child’s temperature had exceeded 38.0 °C, whereas 5 out of 24 (21%) stated that their child’s temperature had exceeded 40 °C. A total of 15 out of 24 parents (63%) reported giving their child paracetamol at home, whereas the children of 13 out of the 24 parents (54%) were known to have been administered paracetamol by staff in hospital. Interviews took, on average (median), 47.59 minutes (SD 19.26 minutes) (range 15–105 minutes).

Site staff perspectives

A total of 56 staff took part in six focus groups across the four sites, with a median of 49.72 minutes (SD 11.14 minutes) in length (range 30.59–59.48 minutes). Staff mainly self-identified as nurses [20 junior nurses (36%) and 25 senior nurses (45%)]; there were also eight senior doctors (14%) and three junior doctors (5%). All were involved in the clinical care of children.

Parent perspectives

Support for the proposed FEVER randomised controlled trial but some concerns

Prior to the interviews, participants were sent copies of the draft participant information sheet and a list of outcome measures to read through. At the start of the interview, parents were asked questions about their experiences of their child’s hospital admission and the interview then moved on to discussions about the proposed FEVER RCT.

Overall, parents supported the FEVER RCT and all stated that they would give consent for the use of their child’s information in the trial. This acceptability was based on a number of factors, including the child still being treated for the infection; the intervention not being invasive; trust of medical staff; how trial findings might help other children in the future; and the trial question being viewed as important, including whether or not the question being tested ‘makes sense’ in that not treating fever might be beneficial:

Because I think you know from your own kind of anecdotal experience your child’s at home, when they spike a fever, when they’re getting, when they’re ill with something, quite often they feel a lot better afterwards.

P25, mother, non-bereaved

Yeah. Yeah. Because I think erm ‘cause fever is meant to be like part of a fighting off, healing process isn’t it? A natural one. So I can, I can understand exactly why it would be interesting to see what happens.

P07, mother, non-bereaved

No, not if it’s helping other kids. Obviously that’s what they’re there for do you know what I mean, it’s what they’d, I’d expect them to do that, to use it for other kids and stuff.

P09, mother, non-bereaved

Despite parents describing their support for the study, many voiced specific concerns about the acceptability of the higher temperature threshold. Most commonly, parents described their concerns about the negative impact of the higher temperature threshold and if not treating a child’s temperature would increase the likelihood of them having seizures:

I would worry about seizures and I’d worry, that’s what I would worry about, and are we making her more ill by not medicating early?

P03, mother, non-bereaved

Parents were also concerned that children randomised to the higher temperature threshold, may suffer unnecessary discomfort, pain or other detrimental side effects, such as ‘organs shutting down’ (P07, mother, non-bereaved), ‘riggers’ (P06, mother, bereaved) or ‘death’ (P18, father, non-bereaved):

Other problems can arise with a temperature being too high, that, that could have adverse effects on the child or baby regardless of the infection because there’s different problems that it could cause.

P02, mother, bereaved

However, parents stipulated that these concerns were largely addressed by their trust in staff to monitor the children and do what is best for their child:

I think I would trust that my child was being monitored, it’s not like they’re waiting for her condition to get worse before they do something, it’s deciding on a different course of treatment. That wouldn’t concern me, the difference between 39.5 and 40 [°C] . . . I think you’re in that environment where when you are having one-on-one care from, um, a nurse by your bedside at all times, I just had complete trust. And I know that the parents from the beds around us felt the same.

P25, mother, non-bereaved

When a parent spoke of their concern about a high temperature causing seizures, the interviewer explained that that current evidence suggests that fever does not cause a seizure, but rather a seizure is a symptom of an infection. This information was valued by parents, all stating that this explanation needs to be included in trial discussions and information materials, as it would change their views on how acceptable they found the higher temperature threshold in the proposed trial:

Yeah, it’s the infection itself causing the seizure rather than the temperature.

Oh, OK. Could you put that in (trial materials) somewhere?

That’s interesting. OK, OK, so then if that could be explained, I think that’s important to really reiterate to parents.

P03 mother, non-bereaved

Acceptable temperature thresholds

While considering the acceptability of the two proposed temperature thresholds, many parents noted that their opinions on the study were influenced by their understanding of what is ‘normal’ paracetamol use. In their experience, if a child is unwell, has a temperature or is in pain, the first course of action would be to administer an antipyretic such as paracetamol. This was evidenced by parents (15/24, 63%) who said they had given paracetamol to their child prior to taking them to hospital. As shown in the following quotations, parents were concerned that children would be uncomfortable and feel ‘unwell’ if paracetamol was not administered until a high temperature:

It’s normal of a parent if your child, or you know, yourself, if you have a temperature you take paracetamol or Calpol® [Johnson & Johnson Limited], um, and I understand that there’s compelling evidence that, you know having a temperature is the sort of normal response, and therefore actually are we, should we not be treating it. But I suppose at the point where your child has got a temperature, you know generally they’re really not very well, and you just want to make them feel better. And you know what you feel like with a temperature, you know you feel so much better when you’ve had something like paracetamol. So I think I would just feel uncomfortable that my child perhaps was, you know, left to be uncomfortable without having something to cool them down. Um, I think that was what was worrying me about it – I guess it’s just that sort of we’re very used to thinking that you have a temperature and therefore you take something like Calpol or paracetamol.

P01, mother, non-bereaved

When you’re at home with your bottle of paracetamol, as soon as it goes above [laugh] you know, 37 [°C], you start dosing them up don’t you, to try and make them feel better. But these are, these are seriously ill children aren’t they, they’re not going to be feeling great anyway.

P07, mother, non-bereaved

When explicitly asked about the acceptability of waiting until 39.5 °C or 40 °C to treat a child’s fever, many stated that waiting to treat at 40 °C was acceptable. However, parents did state that it is ‘a really frightening temperature, isn’t it? I mean they’re boiling at 40 [°C]’ (P01, mother, non-bereaved). Parents stated that they would give consent for their child’s participation in a trial that did not treat a fever with antipyretics until 40 °C as they trusted staff to act in their child’s best interests. However, owing to concerns about 40 °C being a high and ‘scary number’, the majority suggested that the FEVER RCT would be more acceptable if the higher threshold was set at a lower threshold such as 39.9 °C or 39.5 °C:

I think that, that’s a scary number again when you see you’re little one, err, up at 40 [°C]-odd, you know. It’s, it’s all numbers that you kind of take in, ‘cause they were just staring, that’s all you’re looking at for 24 hours a day, is, is his numbers and hoping they’re taking a turn for the better. So, um, yeah, perhaps I think 39.5 [°C]. But again you guys know best and I think, as I say, you do, do what you need to do, but I’m just saying that is a . . . I think that’s very hot. That would concern me, err, as I say, err, if it’s gone, gone too high before you, before you treat it, if that makes sense?

P17, father, non-bereaved

I would probably go with 39.9 [°C] . . . Yeah. It does sound slightly more agreeable, doesn’t it? 40 [°C] does sound a lot.

P07, mother, non-bereaved

Parents were less concerned about the lower temperature threshold, although a few parents did state that 37.5 °C might be too low a temperature to administer an antipyretic. Some expressed concern that a child may not have a fever at this temperature and may therefore be treated unnecessarily, or the antipyretic might mask how poorly they are:

I remember one night on the ward he, he wasn’t sleeping and one of the nurses said, ‘do you think he wants paracetamol?’. I remember another nurse remember saying, ‘No, I don’t, I think he’s, he’s not in pain. Don’t say yes to paracetamol unless you really do think he needs it because you could be masking something then.’ And I always remember thinking that like, ‘Yeah, what if he like . . . What if his temperature goes up but we’ve given paracetamol and then we don’t realise something’s up with him?’. You know what I mean?

P22, mother, non-bereaved

Research without prior consent

Research without prior consent is acceptable but parents held concerns about the emotive situation.

A definition of RWPC was first read to parents (Box 1). All parents responded positively to the use of RWPC in critical care research and described how, although they would prefer to be asked before their child was entered into a trial, they understood that in time-limited situations this would not be appropriate or possible without delaying emergency treatments:

I think I would feel like I would want to know about it but at the same time I understand why they couldn’t always ask you about it because of how quick, because as we know how quickly things can change and they have to make decisions.

P21, mother, bereaved

I understand why it would have to be done, I understand that it’s important obviously not to delay treatment of the child, I mean I was hysterical at the point that he was admitted to ITU [intensive care unit], so I appreciate it wouldn’t be a time to start having to sit down and decide if you want your child to take part in a study.

P01, mother, non-bereaved

Owing to the need to treat a patient in an emergency without delay, or because parents may not always be present when a child needs treatment, it is not always appropriate or possible to obtain consent before a child is entered into a trial. To enable research to be conducted in the emergency setting, many countries (including the UK) allow consent to be sought as soon as possible afterwards. This is for permission to use the data already collected and to continue in the trial. This is research without prior consent (sometimes called deferred consent). Research without prior consent is a relatively new approach to seeking consent in the UK.

When asked specifically about the acceptability of RWPC in the proposed FEVER RCT, parents made similar comments, such as ‘I understand there’s not really another way you can do it’ (P01, mother, non-bereaved). Many described how they would not be in a position to give informed consent at that point in time as ‘there was panic at that point, so definitely can’t be when it’s all going on. I wouldn’t have been listening’ (P18, father, non-bereaved). One mother commented that she found RWPC reassuring as ‘it’s good because well they’d be treating the child first and prioritising them’ (P16, mother, non-bereaved).

Although the majority supported the use of RWPC, a few were concerned that in such an emotive situation they, or other parents, might be angry or upset at finding out that their child had been placed in the study without their knowledge or consent:

I’d just feel really cross actually, I think, if I found out that this had been done to my child without my consent. Um, even though I understand that you can’t really take consent at the point that the child is that unwell, I think I would just feel that someone else had made that decision. And even though I know that you know it’s not me making the decision about my child’s care anyway, you know if they say that he needs antibiotics, if they say he needs a lumbar puncture, and if actually I don’t like it of course he’s going to have it. I don’t know what it is about this that I would feel uncomfortable about.

P01, mother, non-bereaved

It feels like an experiment. And, as I say, you already feel pretty powerless so I think it’s, it is worth thinking about how people would react to it. ‘Cause I think you would get some bad reactions in some cases.

P12, father, non-bereaved

Parents suggested that the consent process should be carefully managed in order to limit the potential negative impact of RWPC on recruitment and clinician–parent trust. They recommended that clinicians should use their judgement about when it is appropriate to approach families for consent. They also recommended that parents should be informed at the earliest possible time, ‘as long as your child is stable’ (P01, mother, non-bereaved), when the emergency situation has past and ‘people have stopped rushing about and everything’s a bit calmer’ (P03 mother, non-bereaved). All emphasised the importance of a clear explanation of the reasons why their child had been entered into a clinical trial without parental informed consent:

I think you need to communicate why it’s been done in a very clear, very simple way.

P21, mother, bereaved

Interestingly, most parents felt that they would be unlikely to notice that their child’s temperature had not been treated with an antipyretic owing to their emotional distress before their child was stable, as well as all the other medical procedures happening at that point in time. This view is supported by the fact that just under half of parents interviewed (10/24, 41.7%) were unable to recall what temperature their child had reached during their time in the PICU.

Nevertheless, some did suggest that parents of children randomised to the higher threshold ‘would notice’ (P17, father, non-bereaved) that their child’s temperature was not being treated and would therefore broach the subject with the bedside clinician. When it was explained that in this situation clinicians would provide parents with a brief outline of the study, including details of how ‘their child’s treatment was a priority and they would be spoken to in more depth later’, parents felt that this was an acceptable and appropriate response and overall ‘it sounds OK’ (P17, father, non-bereaved).

One father articulated the complexities of information provision in this stressful situation, highlighting the need for site staff to tailor the level of detail provided to meet individual needs:

I think I’d have asked the question, why he’s 38 [°C] and a half, 39 [°C]? Why haven’t you given him any paracetamol? I think I’d have probably asked that question myself, if you weren’t treating him until he was 40 [°C], for example? So I think I would have naturally asked the question anyway. But, err, I don’t suppose everybody else, everybody would. I don’t suppose my wife would’ve because she was just in complete shock . . . You’d want to know more about it then, I think, I don’t think that would sat . . . If you told me that little snippet of information, I’d want to know everything about it. I think. I’d rather, again I think I’d go back to the point just, I think just yeah, just do, do what you think is best at this moment in time. And then if it is a research thereafter, then talk to me about that thereafter.

P17, father, non-bereaved

The FEVER pilot randomised controlled trial participant information sheet

All parents considered the participant information sheet (see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/154401/#/; accessed 16 November 2018) to be ‘fairly clear’ (P10, mother, non-bereaved), ‘make sense’ (P02, mother, bereaved) and written in comprehensible language:

I think they would understand it. It’s not been put in medical jargon, it’s simple for them to read.

P06, mother, bereaved

Parents identified parts of the participant information sheet that required clarification, including if not treating a temperature could cause a seizure, the importance of explaining RWPC at an early point in the recruitment discussion, that all other treatments would be given and some formatting suggestions (Box 2).

-

Does not treating temperature increase the chance of seizure?

-

How long will they be in the trial for?

-

What if my child has already had paracetamol?

-

It needs to be clear from the start that the child has already been entered in the study.

-

Needs highlighting that the child is receiving all other treatment.

-

Would prefer it if the headings were not in red.

Given the emotive situation in which the participant information sheet was going to be read, many suggested that the draft participant information sheet was too long and would benefit from all key information being summarised on the first page. Parents said that this format would provide them with the essential information needed at the time of the consent discussion with the option to read the rest of the information sheet at a later time. Consequently, during later interviews, we explored views on preferred information for the ‘important things you need to know’ section on the first page of the participant information sheet. As a result, the FEVER pilot RCT participant information sheet summary section was revised using information parents prioritised when considering FEVER information (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Important things that you need to know: revised participant information sheet.

Consenting bereaved parents

The researcher asked bereaved parents to consider a scenario in which their child had been entered into the trial before death and a practitioner approached them after death to discuss the trial. All stated that it was important to approach bereaved parents for consent after a child’s death because they would want their child’s information to be used if it could help other children in the future:

If people feel anything like me then they’d want to do anything to save other children and help other children really. Um, and any data that can be taken from the loss of a child will, could help another.

P19, mother, bereaved

Despite this, as P15 (mother, bereaved) noted, although ‘I think I’d be OK about it’ others ‘might feel angry’ and not give consent for the use of their child’s data. In addition to anger, many anticipated that bereaved parents would question practitioners about whether or not involvement in the study had affected their child’s survival: ‘they’re gonna then ask, aren’t they, could it have been the case that ‘cause he was in the study, that’s why he died?’ (P21, mother, bereaved).

Bereaved parents’ views were then sought on the most appropriate way of contacting families to discuss the trial following the death of a child (Box 3). As shown in other studies,17,20 there was disparity in views about the most appropriate timing and method of approach. Indeed, the mother and father who were jointly interviewed had conflicting views on how and when they should be approached:

. . . but 4 weeks struck me as too soon actually, just thinking that, you know, I just wasn’t really in a space to think about anything really, um.

No. But then, I’d also, my gut instinct was like I’d rather have known kind of right at the time, like almost straight away.

The research associate presented several options to consider:

-

Face-to-face discussion with a nurse or doctor.

-

Telephone call by a nurse or doctor.

-

Personalised letter 4 weeks after randomisation, followed by a second letter 8 weeks after randomisation (i.e. if no response is received after sending the initial letter). Letters would explain how to opt out of the study and that there would be no need to respond if they wanted their child’s data to be used in the trial.

The above quotations suggest that it is difficult to make general recommendations on how best to approach parents in this situation and that an individualised approach to consent may be most appropriate. Bereaved parents described how they trusted hospital staff to make an appropriate case-by-case assessment of the best way to approach bereaved families about the study. They recommended that regardless of how parents would be approached (e.g. face-to-face or postal contact) or timing, the communication needed to be honest, personalised and delivered with compassion. It was also accepted that if a letter was sent, that the proposed time frame of 4 weeks then 8 weeks after death with a ‘opt-out’ option was acceptable:

‘Cause I think parents have a lot on their mind and they could be organising funerals and things and could forget to reply.

P15, mother, bereaved

Outcomes of importance to parents

The list of outcomes and accompanying descriptive text sent to parents prior to the interview can be found on the project web page (see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/154401/#/; accessed 23 January 2019). In this section of the interview, a definition of an outcome was first read to parents, including an explanation about why it is important to explore parents’ perspectives about important outcomes (Box 4). Parents were then asked:

-

Thinking about your experience of your child being admitted for a fever and suspected infection, what would you hope the treatment (e.g. paracetamol and/or cooling) would do to help your child? (Prompt: what effect would the treatment have to be useful?) What would you be looking for as an indicator that your child was getting better?

As we have discussed, in the FEVER RCT we want to find out whether or not critically ill children with symptoms of severe infection should be given treatments for fever at a higher temperature (up to 40.0 °C) than usual (up to 37.5 °C).

To do this, we will collect information on (read through outcome measures list).

By collecting information on these main things, we hope to find out which treatment for fever should be used in the future. These are called outcome measures.

However, these outcomes have come from research papers and don’t really give us much information on how children or families feel, or what is important to them. It is important that we include outcome measures that matter to children and their families.

Parents found outcomes listed as ‘reasonable’ (P01, mother, non-bereaved) and comprehensive ‘I think everything’s sort of covered really’ (P24, mother, non-bereaved). The majority of outcomes identified coincided with the predefined short-term (measured during a child’s hospital stay) and longer-term (measured at the end of care or following hospital discharge) categories. Many of the outcomes identified and prioritised by parents were included in the list provided. Three additional outcomes were identified:

-

looking and/or behaving like their normal self (examples included improved mood, communication, more like themselves and more alert, sitting up and start to eat and drink)

-

number of visits to general practitioners and other health professionals as a result of illness

-

infection levels coming down.

The following list presents outcomes identified in the analysis of parent descriptions. Outcomes are listed in order of importance (i.e. defined as how many parents mentioned a particular outcome when directly asked which indicators were most important to them or inferred significance from wider interview discussion). Parents prioritised the following outcomes:

-

long-term morbidity (e.g. kidney function, amputation, skin grafts, teeth pushed back, bowel sections removed affect nutrition absorption, difficulties in school, effect on memory, development or learning and post-sepsis syndrome

-

looking and behaving more normally

-

length of time on breathing support

-

time in PICU and hospital

-

how quickly vital statistics are back to normal.

Interestingly, only two parents explicitly stated that survival should be an outcome measure in the proposed FEVER RCT.

Site staff perspectives

Perceived current practice

At the beginning of the focus groups, site staff were asked to use TurningPoint handsets to identify the temperature threshold they use for administering antipyretic interventions in a child with a fever and suspected infection. As shown in Table 2, the majority of site staff indicated that they would administer antipyretic interventions between 38.1 °C and 38.5 °C. Those who indicated that they would administer at a higher threshold (38.6–39.6 °C) were senior doctors or nurses. Only one junior doctor indicated that they administer antipyretic interventions at 39.1–39.5 °C.

| Temperature threshold (°C) | Participants, n (% within threshold) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All site staff (N = 53a) | Junior doctors (N = 3) | Senior doctors (N = 7) | Junior nurses (N = 19) | Senior nurses (N = 24) | |

| 37.5–38.0 | 4 (7.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (75.0) | 1 (25.0) |

| 38.1–38.5 | 34 (64.2) | 1 (2.9) | 1 (2.9) | 15 (44.1) | 17 (50.0) |

| 38.6–39.0 | 14 (26.4) | 1 (7.1) | 6 (42.9) | 1 (7.1) | 6 (42.9) |

| 39.1–39.5 | 1 (1.9) | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

Although staff in two sites referred to defined thresholds at which they would administer an antipyretic on their unit (38.5 °C in one unit and 38.1–38.5 °C in the other), the majority described how they made individual decisions about temperature thresholds on a case-by-case basis. Many stated that they would lower the threshold at which to administer an antipyretic if they were concerned about a child’s clinical condition and/or the child was showing visible signs that they were in discomfort or were unhappy. Specific conditions or injuries, such as head injuries, tachycardia or febrile seizures or neutropenia, were viewed as requiring a more aggressive temperature management:

Or a child that let’s say is neutropenic, and we don’t get that often . . . but we do get children, then I might be more aggressive and lower my threshold. At least with some kind of consultation with the medical team about actually I’m worried that this child is, um, more compromised than other and therefore is their temperature telling me something that I need to act quicker about.

P01, FG5

Child is miserable, grumpy, and he’s tachycardic of 180 [beats per minute] I would treat that pyrexia.

P04, FG3

Some staff described how they would administer an antipyretic at a lower threshold than they would normally use if parents made a specific request. As the following quotations illustrate, parents’ views on what was a high temperature for their child or a direct request from parents to give their child paracetamol even at a relatively low temperature of 37 °C were acted on, if a child was also showing signs of being in discomfort:

Like I had a patient the other day, the temperature went up as high as 37 [°C], so it’s hardly a temperature but the parent said ‘can we give paracetamol’ and the child was a bit unsettled, so I said ‘yeah’.

P06, FG2

So even families might say to me, oh, but, you know, 37 [°C] is really high for him.

P01, FG5

Acceptable temperature thresholds for the FEVER randomised controlled trial

The researcher sought staff views on acceptable temperature thresholds for the two treatment groups in the proposed FEVER RCT through the use of voting handsets and group discussion.

Site staff views on an acceptable restrictive temperature threshold

The majority (80%, 43/54, two missing) indicated that 38.0 °C should be the lower, restrictive temperature threshold. There were no differences (p = 0.816) in views by staff role, with only 11 members of staff [9/44 (20%) nurses, and 2/10 (20%) doctors] selecting 37.5 °C as the acceptable restrictive threshold for the definitive FEVER RCT.

Concerns about the restrictive threshold in the FEVER randomised controlled trial

Many described how 37.5 °C would be too low a threshold for the trial as it was a ‘normal’ (P01, FG4) temperature and could result in administering an intervention unnecessarily. A few members of staff highlighted the potential impact of the environment and how a temperature of 37.5 °C could be attributable to a hot PICU, which can be controlled without the need for medication:

I’ll tell you what I’ll be more, much more happier with 38 and 39.5 [°C] rather than . . . What I will not be happy is 37.5 and 39.5 [°C] because I don’t want to treat unnecessarily.

P02, FG3

Some children have a temperature 37.5 [°C] is normal.

P01, FG1

We try and give the minimum amount of drugs . . . on this unit, and you would just think why am I giving this . . . at this temperature. Why am I giving this drug for a temperature?

P02, FG5

I think for me it’s about, um, the impact of the, um, environment, and actually as a bedside nurse you’ve got quite a lot of control upon your environment, and bringing the temperature down in that way. And I’ve been in many situations where maybe the baby therm [thermometer] is a bit too warm, or that the unit’s warm and actually when the temperature is 37.5 [°C] and you change it environmentally.

P05, FG5

One focus group participant described how treating a fever at 38 °C was lower than the threshold used in their unit, so they would be personally concerned that the use of an even lower restrictive threshold of 37.5 °C in the FEVER RCT would be changing the standard of clinical care for children presenting with fever and suspected infection:

Well my reasoning was if we don’t normally treat at 38 [°C] why would we then lower the standards of what we’re normally doing in order to do a study?

P05, FG4

There was some discussion about the implications of agreed temperature thresholds on the success of the trial. As the following quotations illustrate, one doctor stated that asking clinicians to treat children differently to their ‘normal’ practice in both the control group and the intervention group may cause concern and have a negative impact on trial success. In contrast, one nurse stated that she had selected 37.5 °C as the acceptable restrictive group threshold for FEVER, as this lower threshold would help ensure sufficient separation between the two trial groups:

I guess I’d have some concerns for a trial if you have a control arm which is not your usual practice, then you might have a problem because then you’re asking people to do something in the control arm and in the intervention arm which is, both of which are different to your current practice.

P03, FG1

I just think, er, I put 37.5 [°C] because I thought would you not get, kind of, a better differentiation of the results. Because, er, if there’s going to be an upper arm as well is it not best to have the lower arm at the lower level so then there might be bigger differences as the results come in.

P07, FG4

Site staff views on an acceptable permissive temperature threshold

Using voting handsets, 82% of staff (45/55, one missing) selected 39.5 °C as an acceptable temperature threshold for the permissive group of the FEVER RCT, whereas only 10 members of staff (18%, five doctors and five nurses) selected 40 °C.

Importantly, the majority of staff were in agreement that that a permissive threshold of 40 °C would not be acceptable:

I think again, if you really want a true answer in your trial you should try for 40 [°C], but realistically I think we will struggle to convince people to let that child wait till 40 [°C].

P08, FG6

A few members of staff described how a permissive threshold of 40 °C may provide a more definitive answer to the trial question. These staff appeared to be more supportive of the study than other participants; they also tended to give examples of personal clinical experience in which it was normal to wait until a higher temperature threshold to treat a fever.

Concerns about the permissive threshold in the FEVER randomised controlled trial

Concerns about not treating a child’s fever until it reached a permissive threshold (e.g. 39–40 °C) included an increased risk of febrile seizures or rigors, discomfort, tachycardia or hallucinations:

Seizures, you’re running the risk I would say of them getting to, er, febrile convulsions.

P08, FG4

I’ve seen kids hallucinate at 39 [°C] so . . .

P01, FG1

An 11-year-old boy who was 39.5 [°C] and he was just on another planet, like he was just so uncomfortable and, you know, you just, as a nurse, to leave that would just, again, that word uncomfortable.

P05, FG5

But also every, every degree above normal you go you increase cardiac workload by, by, by about 15% so, and [inaudible 0:10:08] the child with a temperature of 39 [°C] and a heart rate of 200 [beats per minute], I can’t leave that so I, I have to intervene.

P02, FG1

Some staff described how it would be ‘incredibly difficult to wait and watch’ (P05, FG5) and not administer an antipyretic intervention to a child who was visibly uncomfortable or unsettled with a high temperature. Others discussed the lack of evidence for current practice and the need to conduct the FEVER RCT, yet it seemed that many lacked confidence in waiting to treat in the permissive threshold group as inaction goes against their clinical training or ‘gut instinct’ (P05, FG2):

I think is just a hangover, this is the way, these are the sort of numbers that have triggered your response for decades and there ain’t no science.

P02, FG3

You, [staff name] absolutely right. Well there is, there is a bit of science which suggests we should let the temperature get higher.

P01, FG3

With this it’s more like it’s a gut instinct, isn’t it, ‘cause it’s been drummed into you from the day you start your training and all the pain days, you have to give the paracetamol as well for morphine uptake to improve. And that’s going to be, it’s going to be one of those oh the kid’s temperature 38.5 [°C], it’s going to be an automatic reaction so it’s sort of breaking that as well as . . . it doesn’t matter how much you educate, there’s always going to be that gut reaction first of all.

P05, FG2

One nurse spoke of how it was it was her responsibility to assist children’s recovery by providing treatments that reduce a body’s workload. The need to be proactive and control a child’s temperature was viewed as an important part of a nurse’s role:

That as nurses I think that’s our job, is to maximise their output, I suppose, by reducing the demands. And temperature is one of the things that we can control, we can’t control some of the other stuff, um, but we can control, um, temperature. And I think, and actually it’s probably almost our job, you know, it’s not the medics that come along and administer paracetamol, or strip the child off or cool them, so I think there probably is a very active role that the nurses deliver that intervention. So actually I think even 39.5 [°C] feels quite uncomfortable to me, that, um . . .

P03, FG5

Site staff drew on their own personal experiences, or their child’s experiences, of having a high temperature when describing how they would have concerns about the permissive threshold in FEVER:

I wouldn’t want to have a temperature of 39.5 [°C] and not to give myself some paracetamol, so I just think for the child it will be more comfortable.

P08, FG4

In terms of looking at a ch- in the case of a child, they’d have to get up to 40 [°C] but having personally had um quite regularly get temperatures of 39 [°C] plus, they’re bloody uncomfortable. You’re tachycardic, you, you feel horrible.

P01, FG1

My son rigors at 38.4 [°C] every time . . . He just starts shaking with temperature, so I get it at home, so I’m wary about letting temperatures go up too high.

P02, FG2

As the following quotations illustrate, a few members of staff discussed their concerns about not knowing if the permissive threshold was in the best interests of the child and whether or not waiting to treat the fever could cause harm:

I think it’s just not knowing are you doing the right thing or not. Yeah, I suppose you could be concerned about the other obs [observations], like say tachycardia, high blood pressure, um, and I suppose you’re thinking if I gave paracetamol . . . It’s hard to, to tell whether they’re, I don’t know, whether it’s alright either way or what damage or what good you’re doing.

P02, FG2

Because potentially you could be maybe putting their life at risk and making it worse.

P09, FG4

After considering their own acceptability of the permissive threshold, some considered how acceptable parents would find the permissive threshold group of the trial. A few staff were concerned about how to explain to parents why they were not treating a high temperature:

[H]ow can I justify that to a parent that, yeah, yeah, yeah you can see it rising but we’re not doing anything about it?

P03, FG6

I think they would, you know, feel very uncomfortable about their child being left with a temperature.

P05, FG1

As the following quotations from one focus group illustrate, staff felt that a permissive temperature of 40 °C would seem more frightening and therefore less acceptable than 39 °C to parents:

I think parents would be more concerned as well. If, you know, if you told a parent that their temperature was 40 [°C], I don’t know, maybe it’s just me, that they’d be more con- . . .

. . . Yes, it sounds more scary yeah.

It sounds worse than 39.5 [°C], to them . . .

What if it was 39.9 [°C]? Is it the 40 [°C] that’s scary or that um . . .

For the parents.

Yes, for the parents.

Yeah, their understanding.

Staff concerns about not using paracetamol for analgesia

Seventy-six per cent of staff (42/55, one missing) indicated that they would have concerns about not using paracetamol for analgesia. However, the acceptability of not administering an antipyretic appeared to be influenced by how unwell a child was; for example, staff described how the trial would be more acceptable if it was limited to children who were very poorly and receiving other drugs for pain or discomfort. In contrast, many described how it would not be appropriate to administer alternative analgesic drugs, such as morphine, to treat a discomfort in a spontaneously breathing patient who was not seriously unwell:

I’m more comfortable that they’re sicker because you’ve got the other drugs on board that we could give, and we’re happy we’ve got like back-up vents and . . . whatever we can deal with. Kids who are self-ventilating it feels a bit extreme to jump to an NCA [nurse-controlled analgesia] pump when she’s just a bit grizzly and you could’ve given her paracetamol or something.

P06, FG5

Because when you’re using these drugs, we’re all aware that they have side effects, so if we were going to opioids when we didn’t need to necessarily, then I think that’s what would make me a bit more uncomfortable. But if they already required those then I think that that would be more acceptable.

P04, FG6

When staff views were sought on amending inclusion criteria to include children on ventilators, it was apparent that such a change would help address concerns about not using medication for analgesia. In addition, staff confirmed that limiting the sample to children who were more clinically unwell would also address their concerns about children being uncomfortable or upset, or using alternative painkillers unnecessarily, as ventilated children would already be receiving opioids, such as morphine, for pain:

Maybe if they are intubated and ventilated, they’re having a bit of roc [rocuronium] and a bit more morphine, then actually you wouldn’t feel as guilty or uncomfortable because they’re not crying, and parents aren’t saying ‘what can I do with them ‘cause they’re crying all the time’.

P01, FG6

Approach to consent in the FEVER randomised controlled trial

As shown in Figure 3, 22% (11/49, seven missing) of staff used their handsets to indicate that the use of RWPC was very acceptable or acceptable (25/49, 51%) in the proposed FEVER RCT. Although 14% (7/49) did not have any strong feelings (selected neutral), 12% (6/49) indicated that RWPC was unacceptable in the proposed FEVER RCT.

FIGURE 3.

Staff views on the acceptability of RWPC in the FEVER RCT.

Some members of staff discussed their support for the study and its use of RWPC, saying that there is a need for scientific evidence to address this research question and that they did not view informed consent as feasible owing to parental incapacity in an emergency situation:

. . . by giving paracetamol early, it might be actually prolonging their hospital stay and making them sicker for longer with consequences of actually getting other illnesses in the intensive care . . .

They can’t give consent . . . can they?

. . . they can’t actually give informed consent, they can barely say their name.

Others found it reassuring that although they would not be seeking informed consent, it’s not ‘cloak and dagger stuff’ (R12, FG4), as they anticipated that parents would be informed about trial participation and consent sought fairly shortly after randomisation:

I would anticipate that people do consent quite quickly, I don’t think it would need to be 4 days before you did consent, it would be able to be done within a reasonable . . . I don’t know exactly what time frame but I don’t think the parents would be in the dark about it for very long, so I think that it would be acceptable.

P01, FG6

As the following quotation shows, some staff supported RWPC in this trial, as they stated that the most effective temperature threshold to use in children presenting with a fever and suspected infection is not known, therefore children would not knowingly be denied an effective treatment:

Because we’re not denying a treatment that has a proven benefit, I would find that less acceptable, but because we don’t know whether it helps or not I think it’s acceptable to try and find out.

P02, FG6

Those who used their handsets to indicate a ‘neutral’ response or indicated that RWPC was unacceptable in the FEVER RCT went on to describe a range of reasons for their views. Most commonly, staff were concerned about RWPC in a trial that would require them to not to treat a child’s high temperature, therefore being ‘inactive’ in a potentially life-threatening situation. As the following quotation illustrates, some staff with previous experience of RWPC in paediatric RCTs viewed ‘withholding’ an emergency intervention without prior consent as less acceptable than administering a ‘needed’ intervention:

When you have to do something that’s an emergency, you know, it’s needed, it’s an emergency, you have to intervene and you have to do that without consent, that’s very different to withholding something.

P02, FG4

Staff were also concerned that parents may notice their child’s temperature and respond negatively to finding out that they were not being treated with an antipyretic owing to participation in a trial without their prior consent:

The thing is what won’t it [trial participation] be really obvious to the parents watching.

P03, FG4

I just wonder whether not treating people, which is what this says, is so completely contradictory to parents . . . that it just won’t sit well.

P05, FG3

But if we’re now saying, ‘oh we, we’re not ignoring it but we’re just not treating it,’ I don’t know whether you’d get a good response in an already very highly emotive environment.

P05, FG1

Staff concerns about the impact of research without prior consent on parent–clinician relationships

Many members of staff spoke of how RWPC in the FEVER RCT could negatively impact on rapport, relationship building and communication with parents: ‘You know, potential barrier to communication or, you know, working relationship’ (M3, FG1). One nurse spoke of how the ‘whole ethos of paediatric nursing is you’re meant to do it in partnership with the, you know, child and family’ (P05, FG1), and how RWPC goes against this ethos.

Others were uncomfortable about changing their usual practice of administrating antipyretics for a fever, as they were unsure of the clinical impact that would have on a child. Some stated that they would not give consent for their own child to be in the study, so they were not willing to put someone else’s in the FEVER RCT without prior consent. Nevertheless, they noted their conflicting desire for the study to be conducted to inform future clinical practice:

I think for me it’s a personal thing, I wouldn’t put my daughter into that trial to start off with, so I wouldn’t get, er, uninformed consent from another parent, simple as. There’s no way I would let my daughter’s temperature go that high before giving them paracetamol.

P09, FG4

I suppose the thing is it’s a bit rich isn’t it that, because we’re all happy to benefit from research. But we’re not all . . . that happy to perhaps participate.

P02, FG4

Towards the end of one focus group, provisional findings from the parent interviews were described to staff, including details of how parents viewed the use of RWPC and the higher threshold as acceptable. Although a few queried the representativeness of the interview sample, this information appeared to appease staff concerns, stating that if parents are happy with the study then staff would find taking part in FEVER more acceptable:

If that’s what parents are saying then, how can you dispute what the parents are saying.

P09, FG4

Informing the pilot randomised controlled trial design and training, including inclusion and exclusion criteria

Staff had key questions that were important to consider in the pilot RCT design and site training package development stage. As shown in Box 5, these were often practical questions that required clarification about what would be included the trial protocol, as well as questions related to qualitative study findings about parents’ perceptions of the proposed FEVER RCT. Some queries were prioritised by staff, appearing to influence views on trial acceptability, including concerns about whether a pyretic child would be distressed or combative, the use of environmental cooling methods and the inclusion of children with high heart rates or tachycardia.

-

What if the patient has a high heart rate/tachycardia?

-

What if the patient is combative?

-

What if they have already been given paracetamol or been stripped off?

-

What if they never reach 40 °C?

-

Can we remove blankets if we think the environment has caused the fever?

-

What environmental cooling will we be able to do?

-

How do parents feel about waiting until 40 °C?

-

What do parents think about RWPC in FEVER?

-

How are we measuring temperature?

When specifically asked about what staff thought should be listed as exclusion criteria, suggestions included ‘post op cardiac patient who end up septic’ (P06, FG3), ‘due to cardiovascular instability’ (P01, FG3), ‘oncology patients’ (P01, FG6) and patients admitted with ‘febrile neutropenia’ (P01, FG6). Staff agreed with the researcher’s description of proposed exclusion criteria, including ‘traumatic brain injuries’, ‘seizures’ and ‘children who have a cardiac arrest and need to be kept normothermic’ (researcher descriptions). As described earlier, staff proposed limiting inclusion criteria to only include children who are on ventilators.

Many emphasised the importance of ensuring bedside nurses were supportive of the study, as it is nurses who administer antipyretic interventions, often as a first-line response to an indication of infection:

I think like [name] said, the nurses have to be completely on board with this because they do have their own – I can’t tell you how many times you go into the bed space and they’re like – ‘no, but seriously – oh well temperature was 37.2 [°C] so I’ve given paracetamol’. And you’re like ‘what?’. ‘Well I didn’t want him to get too hot.’ How are you going to know if they’re brewing something anyway?

P06, FG3

Recommendations included the need for further information to help staff feel confident about taking part and explaining the study to families. This included a summary of the clinical evidence, which demonstrates the scientific rationale behind the trial question, as well as previous literature and qualitative research findings on parents’ views on RWPC to help facilitate staff ‘buy-in’ and help staff answer parents’ questions about the study and its approach to consent:

I think arming all staff with the key points from current literature is really helpful . . . we’ll all be in positions where we might have to answer parents’ questions, so it’s really important that everybody’s on the same page with it, because actually it’s not just the people doing the research or the consenting and everything, the bedside nurse is going to be fielding questions and needs to believe in the study. I think that people do really invest and get behind it if they can see what the benefit would be of it, if it has an answer to it . . . I think that needs to be summarised and everybody has to have the same points from it and understand what we’re comparing and why, and why we think it’s safe.

P01, FG6

I had more knowledge and understanding of the benefits to this, as well as the child targets and the thresholds I felt a bit more comfortable with, then I probably would be able to then confidently say to family, yes, actually I know that their temperature is X, and I’m not treating it because there’s this is a study.

P03, FG3

Key findings to inform the FEVER pilot randomised controlled trial

This qualitative study provides insight into the acceptability of the FEVER RCT by exploring the views of parents with relevant experience and site staff at the four pilot RCT sites.