Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 11/111/02. The contractual start date was in January 2014. The draft report began editorial review in July 2017 and was accepted for publication in August 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Gessler et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background and objectives

Prevalence of sexual difficulties after cancer treatment

Many cancer patients are reported to have sexual difficulties. 1,2 Gynaecological oncology patients are particularly vulnerable to changes in sexual activity and lack of sexual desire,3–5 with sexual difficulty rates estimated between 40% and 100%. 6 Women undergo a range of treatments for ovarian, cervical, womb and vulval cancer, with different combinations of surgery, chemotherapy and radiation. Some of these treatments have a detrimental effect on women’s internal and external sex organs, surrounding tissues and nerves, and render some menopausal. Following such treatments women report a wide range of difficulties including loss of libido, dyspareunia, vaginal dryness and orgasmic difficulty. In addition, the symptom burden of gynaecological cancers is heavy, with many women reporting pain, fatigue, changes in bowel function, urinary symptoms including leakage, and depression and anxiety,7 which interact with menopausal and sexual difficulties. 8 Hazewinkel et al. 9 and Carpenter et al. 10 both note the major effect of physical well-being on sexual function, as well as the lack of relationship between extent of treatment and formal scores of sexual function.

Other factors contributing to sexual problems

It is unsurprising that women treated for a gynaecological cancer are at high risk of emotional distress. One prevalence study11 found that 23% satisfied criteria for major depressive disorder, and Parker et al. 12 found greater depressive symptoms in gynaelogical oncology patients than in those with breast, urology or gastrointestinal cancers.

Carpenter et al. 10 suggest that some of this greater distress is related to the very high levels of sexual difficulty experienced after treatment. They argue that sexual self-schema is an important moderator of response. Self-schema is the set of beliefs and ideas that people have about themselves based on their life experiences and, when this relates to the sexual domain, positive sexual self-schema (belief in and expectation of themselves to be pleasurably sexual) is associated with more frequent sexual activity, better sexual responsiveness and higher global sexual satisfaction across all disease sites,13,14 suggesting that it makes women more resilient to the adverse sexual impacts of gynaecological cancer. Despite their sexual difficulties, many gynaecological cancer survivors resume intercourse. 13,15 Andersen et al. 16 found that frequency of intercourse in their sample was comparable with available norms for similarly aged women, but these and other longitudinal data have shown sexual satisfaction17,18 and responsiveness16–20 to be significantly impaired following treatment.

Professionals’ response to sexual difficulties

Patients report that sexuality is rarely addressed by physicians. 3 Lindau et al. 18 found that conversation with a physician about the sexual effects of cancer was associated with significantly lower likelihood of complex sexual morbidity among very long-term survivors; however, 62% of 221 participants reported that their physician had never initiated a discussion about sexuality after cancer. In their study of sexuality in a palliative care setting, Vitrano et al. 21 found that patients considered it important to talk about sexuality and to face such an issue with an experienced professional, even though their life expectancy was short. Patients in their study had not had this opportunity. Moreover, some patients were still able to maintain a sufficient sexual activity, in terms of quality and quantity. Faithfull and White22 found that cancer nurses were more likely to focus on the technical aspects of sexual recovery post treatment, for example vaginal dilatation, and offered minimal advice or opportunities for disclosure of sexual dysfunctions, dissatisfaction with partner relationships or mood and other psychological difficulties. Clinical nurse specialists (CNSs) in gynaecological cancer acknowledge that they have an important role in this aspect of care but do not always feel confident or competent to assess or manage patients’ psychosexual needs, and appropriate referral is then problematic. 23,24 Recently, a national psychosexual group of expert nurse ‘champions’ has been formed, and its work to date includes a psychosexual assessment guideline document for nurses.

Diagnosing and treating sexual dysfunction in this setting

Sexual dysfunctions are recognised as difficulties affecting both sexual desire and sexual response25 and six apply to women, as defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders:25–27

-

sexual desire disorder or decreased libido – hypoactive sexual desire (low interest in sex)

-

sexual aversion disorder – objections to having the genitals touched

-

sexual arousal disorder

-

orgasmic disorder – premature, delayed or absent orgasm following a normal sexual excitement phase

-

sexual pain disorder of vaginismus – involuntary spasms of the muscles of the outer third of the vagina that interfere with intercourse

-

sexual pain disorder of dyspareunia – pain during intercourse.

A recent review28 of specific complaints of all cancer patients referred to the sexual health programme of the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center found that the most common complaints for which patients sought help were painful intercourse (65%), vaginal dryness (63%), low sexual desire (46%) and orgasmic disorder (7%). The first two of these are partially managed through current best treatment, that is, topical oestrogen, vaginal dilators and lubricants. 2,29 Tsai et al. ,30 using the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI), found that 66.7% of a Taiwanese sample of women with cervical cancer experienced sexual difficulties. Many other studies report high rates of sexual difficulties, from 83% for overall general sexual difficulty,31 to 66% significant and 46% moderate sexual difficulties. 32 Serati et al. ,33 in a study of women with early-stage cervix cancer treated with radical hysterectomy, reported that 65.8% of patients suffered sexual dysfunction.

Interventions for sexual dysfunction after treatment for cancer

In contrast to the majority of sexual therapy interventions in which anxiety reduction is often key, management of low sexual desire in the context of gynaecological cancer requires an intervention that additionally addresses the wider range of mediating factors, including loss, life-threat, trauma, change of body image, pre-existing psychological outlook, mood, depression and anxiety symptoms, as well as the relationship in which the woman finds herself. 34–37 Twenty-seven studies of sexual therapy interventions after any cancer are reported in a systematic review by Brotto et al. ,34 and Abbot-Anderson and Kwekkeboom35 found only three interventions specific to gynaecological cancer. These studies across a range of interventions only show small effect sizes, despite patient satisfaction with the interventions. Flynn et al. ,29 in their Cochrane Review of randomised control interventions for psychosexual dysfunction in women treated for gynaecological cancer, concluded that, ‘there is insufficient evidence to support or refute the use of any interventions for psychosexual dysfunction after gynaecological cancer’. Furthermore, they suggested that future investigations required multicentre randomised controlled trials (RCTs) with outcome measures validated in gynaecological cancer patients. They added specifically that ‘investigators should focus on interventions that can be delivered by existing members of the multidisciplinary team treating women with gynaecological cancers. It is more likely that such measures, if found effective, will be affordable and capable of being integrated into standard care’.

Conclusions and need for the research

The evidence presented above shows that it is often the case that women affected by gynaecological cancer are not aware of basic information about the sexual consequences of their gynaecological cancer and its treatment, and do not receive appropriate advice or help to recover sexual function and to adapt to their changed body and relationships. It is recognised by two Cochrane Reviews2,29 that new interventions are needed for sexual dysfunction in gynaecological cancer, and these need to be examined in multicentre RCTs with agreed outcome measures. There is a sizeable population with these problems to be addressed, for there are currently 2 million people in England living with and beyond cancer of all types, and 2.5 million across the UK as a whole. 38 This number is likely to grow by > 3% per year, reflecting the increasing incidence of cancer and better survival rates. By 2030, there are likely to be around 3 million cancer survivors in England,39 of whom a proportion will be survivors of gynaecological cancers. As we have the ability to develop suitable treatments, we have a duty to explore them. 39,40 The current acceptance of the worth of well-being and, conversely, the cost of depression, anxiety or unwillingness to engage with the health-care system – all potential long-term effects for the patient group concerned – are drivers of this research. 41 Better awareness of mental health issues and depression in general42 and in cancer patients,43 plus greater acceptance that these symptoms have causes that can be treated or addressed, is also relevant. In addition, our work was planned at a time when there was more awareness of sexual health, and evidence from cancer user groups,44 policy-makers45 and research46 of more openness to discuss these matters as a medical need. The potential of CNSs to deliver interventions to help with the consequences of cancer treatment has been recognised by the Department of Health and Social Care,47 yet little is known about CNSs’ training or supervisory needs to provide interventions for psychosexual dysfunction to work alongside psychologists. If care pathways exist for addressing sexual dysfunction in cancer, they are currently unique to individual units; providing the evidence for pathways that better meet the requirements of the population will facilitate clinical application of more appropriate and consistent practice. What is currently missing from the literature is a phased proposal that develops an intervention and tests this to facilitate best practice in the treatment of sexual dysfunction for all relevant women in gynaecological cancer centres. This study was planned to answer this question for the NHS by developing a stepped care intervention to be delivered within existing NHS gynaelogical oncology services. A gynaelogical oncology CNS or radiographer was to deliver interventions at step 1 and step 2 as the major treatment delivery, and only a small minority of more complex psychological issues were to be treated at step 3 by a level 4 practitioner (a clinical psychologist or a psychiatrist), to whom all patients should have access according to NHS guidance for psychological support in cancer. 47,48

Objectives

Aims

-

To develop a stepped care psychosexual intervention [a Stepped Approach Intervention to Improve Sexual Function after Gynaecological Cancer (SAFFRON)] on the Increasing Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) model together with a treatment algorithm for assigning women to levels of intervention.

-

To establish whether or not women treated for gynaecological cancer with moderate to severe sexual dysfunction are willing to participate in a randomised trial and adhere to treatment.

-

To indicate likely rates of recruitment to a future evaluation of the SAFFRON intervention.

-

To pilot a stepped care psychosexual intervention (SAFFRON) on the IAPT model. 49

-

To establish whether or not the SAFFRON intervention is acceptable to patients.

-

To establish whether or not SAFFRON is deliverable by a gynaelogical oncology cancer centre multidisciplinary team.

-

To indicate the most appropriate outcome measures for use in a larger trial.

-

To inform estimates of the likely effect size, which will assist sample size calculations for a larger trial.

Research questions

-

Are women treated for gynaecological cancer who develop moderate to severe sexual dysfunction willing to participate in a randomised trial of treatment and adhere to that treatment?

-

Will women agree to be randomised to an intervention to treat sexual dysfunction?

-

Are different tumour sites, treatments and cancer stages at approach associated with different rates of participation in the trial and uptake of the treatment?

-

Is the stepped care system operable within the NHS system as it stands?

-

What is the likely effect of the three levels of intervention on sexual function, mood and self-esteem as measured by standard measures?

-

What is the rate of attrition from each treatment modality?

Purpose of research

-

Is it possible to design and pilot a RCT that can potentially answer the question ‘Is SAFFRON a clinically and cost-effective treatment for sexual dysfunction after treatment for gynaecological cancer in the NHS?’?

-

Can the SAFFRON intervention be evaluated in a feasibility randomised trial?

-

Is a stepped approach acceptable and practical?

-

Can it be done within NHS settings?

Study design

The call from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme asked for a feasibility study. The study was in the form of a two-arm, parallel-group RCT to gain appropriate information to inform a decision about progressing to a full RCT.

Primary end points: measures of feasibility

-

Recruitment rate in terms of number of women screened.

-

Proportion of women stepping up from level 1 to level 2, and from level 2 to level 3.

-

Proportion of women dropping out of therapy.

-

Number of usable data points from all measures at all time points.

-

Proportion of women lost to follow-up on trial measures.

Secondary end points

-

Female Sexual Function Index score and Sexual Quality of Life (SQOL) Female score at 8 months (accounting for baseline).

-

Change in mood on Patient Health Questionnaire-9 items (PHQ-9) and Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7).

-

Change in quality of life on EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L).

Process measures

-

Satisfaction with interventions and preference for enrolment in one group over another, as measured by bespoke questionnaires.

-

Qualitative feedback from patients about their experience of participating in the trial, from interviews.

-

Qualitative feedback from staff about implementation of study within clinics, from interviews.

Embedded qualitative study

The embedded qualitative study was to explore the attitudes towards participating in the study of both staff and patient participants, and to examine potential barriers to and concerns about participation.

Interviews were planned with:

-

trial participants in the intervention arm

-

trial participants in the control arm

-

participants who withdrew from the study

-

staff who delivered the intervention

-

staff in the clinics who were not involved in delivering the intervention.

Patient and public involvement

Our study involved two patient advocates. Mrs Susan Dunning was a coapplicant and was involved from the very beginning of conceiving the study. Mrs Val Madden joined once the study began and was, together with Mrs Dunning, actively and energetically involved in project meetings and in feedback on the development of the interventions. They gave the Trial Management Group valuable insight and direction throughout the design of the trial and the development of the interventions and were supportive of the entire endeavour.

Participating site selection

To assess the feasibility of recruiting sufficient numbers across the UK to inform a full RCT, two recruitment settings were chosen. Both sites were gynaecological cancer centres with full CNS teams, and access to a clinical psychologist who was embedded in the clinical team as opposed to being part of a generic psychology department. This was to maximise recruitment to the feasibility trial and enable integration of a psychological intervention study in the clinical teams.

University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (UCLH) Gynaecological Cancer Centre had 1839 women attending for a new diagnosis or follow-up in 2010.

Bristol Gynaecological Cancer Centre had an estimated pool of 1639 women attending in 2010.

These numbers were considered sufficient to support the required recruitment levels for the RCT.

Chapter 2 Development of the SAFFRON intervention

Methods

A key part of the conception of this study intervention was developing an intervention using the skills of psychological therapy developers, together with patient involvement, from the start. Therefore, a team was convened of psychological therapy professionals together with initially one patient advocate to the project, Mrs Susan Dunning, who was a named coinvestigator as a result of her expression of interest, and later a second patient advocate to the project, Mrs Val Madden. The involvement of patients was instrumental in changing the character of the intervention, which moved from a close modelling on the IAPT stepped care model to a more sequential one. Patient input was also key in changing language from a mental health vocabulary to one recognising both the physical and the emotional causes of sexual dysfunction in this population, and the interplay between them.

Mrs Susan Dunning was present at all project meetings, and she and Mrs Val Madden commented on all aspects of the level 1 and 2 interventions. Professor Michael King and Dr Sue Gessler met with them both to discuss in detail their views and input to the interventions at levels 1 and 2. Mrs Susan Dunning also met with Professor Alessandra Lemma and Dr Sue Gessler to help inform the development of Interpersonal Psychotherapy for Sexual Adjustment post Gynaecological Cancer (IPT-GO), and she and Mrs Val Madden responded to and commented on early drafts of the IPT-GO manual.

Level 1

Members of the team took account of a Cochrane review of available literature,50 viewed pre publication, and examined a wide range of publicly available material on sexuality after cancer written in English from anglophone countries, and decided by consensus on two basic texts to work from. 51,52 These were commented on by project members, and reviewed in detail by Mrs Susan Dunning and Mrs Val Madden from their experience and that of co-patients. The material was rewritten by Dr Sue Gessler, Professor Michael King and Ms Karen Summerville and submitted to the project team, specifically Mrs Susan Dunning and Mrs Val Madden, for further comments. The project team endorsed the final edited version.

Level 2

The level 2 intervention was derived from an evidence-based intervention aimed at early-stage cervix and endometrial cancers with good prognosis, and was written for clinical psychologists to deliver. 53 With permission from Dr Lori Brotto, the copyright holder, the unpublished manual and worksheets (Brotto LA, Heiman, JR. Sexual Health and Gynaecologic Cancer: Psychoeducation (PED) Treatment Manual. 2003) were adapted by Dr Sue Gessler for this patient group, taking into account the full range of gynaecological cancers and including all points of disease trajectory from initial follow-up through to receipt of palliative input. 1 The manual was also rewritten with greater explicitness to allow a CNS therapist without a clinical psychology training to deliver the intervention. Both sections were submitted to the project team, specifically Mrs Susan Dunning and Mrs Val Madden, for further comments. The project team endorsed the final edited version.

Following the unexpected inability of both sites to allow a CNS to take part in the study, the team reviewed possible staff in both sites. At UCLH a senior CNS from the Macmillan Support Centre was willing to be involved, and at Bristol a senior radiographer who worked with post-treatment gynaecological cancer women on dilator use agreed to take part. This change of personnel required rewriting the manual to take account of the disciplinary change. Training took into account this change of personnel. Dr Sue Gessler presented a full day’s training at one site (Bristol) to both level 2 practitioners together, and with both research assistants (RAs) present, to promote equality of training and fidelity to the model. Training slides were written for the full day, giving background to the study, and the practitioners were taken through the sessions of the intervention using didactic teaching, role play and discussion. Feedback on their training was gathered by the RAs to inform supervision and further skills development over the life of the study. Both requested further direct training before beginning to see patients, reflecting on the difficulty of working to a manualised intervention rather than using their generic patient skills. They also found some elements of the psychological intervention challenging, such as taking a behavioural history of a sexual encounter. Skype™ (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) group supervision sessions were planned to allow both level 2 therapists to be supervised together, to learn from each other and to maintain fidelity to the model. Owing to the halting of the study, this did not take place.

Level 3

The full manual of IPT-GO was completed by Professor Alessandra Lemma with input from Dr Sue Gessler as a specialist clinical psychologist in this area, and Mrs Susan Dunning and Mrs Val Madden as patient advocates. The adaptation of interpersonal therapy (IPT) for a specific purpose followed the principles used by Professor Alessandra Lemma in development of dynamic IPT. 54 It fulfilled the basic elements of IPT but was reconceived to take into account the physical changes and threats within a cancer diagnosis and its treatment. In particular, the requirement of IPT to take on a ‘sick role’ was transmuted in this version to acknowledge the cancer rather than a mental health diagnosis such as depression.

A full day’s training was given by Professor Alessandra Lemma to three clinical psychologists who specialised in gynaecological oncology. The IPT core elements were taught in line with the national training programme for IPT, and IPT-GO adaptations were then reviewed. Each clinical session was specifically covered. At the end of training, all three gave feedback of feeling confident in delivering IPT-GO and all were assessed as competent to deliver IPT-GO within the context of the trial. Trial conditions specified ongoing supervision from Professor Alessandra Lemma, which was to be more frequent at the beginning of the trial and lessening in frequency over time as competence increased and fidelity to the model was more assured.

Quality assurance and fidelity to model

Adherence to the model of intervention and protocol for delivery was planned to be monitored at all steps. CNS and clinical psychologist sessions were to be taped and rated for adherence to the model using standard techniques as used in the IAPT programme. 55 We intended to seek consent from patients and staff for anonymised versions of these to be available for subsequent analysis. The intervention team were to receive regular supervision from seniors involving case discussions and reflection on specific difficulties and challenges. The team were to be encouraged to feed back on gaps in their training and knowledge so that these could be addressed. Field notes were to be taken so that detailed knowledge of training and support needs could be developed; these could then be considered when developing the protocol for a definitive trial. Supervision was to be based on a supervision to competency model, with more and closer supervision at the beginning of the study, and supervisor observation, or auditing of tapes, of full sessions at the early stages.

Fidelity was to be further measured by random tapes selected at the end of interventions that were to be monitored by an independent rater.

Status of intervention materials

Location and access

All intervention documents are archived at University College London (UCL). Level 1 contains elements derived from a document for which the American Cancer Society holds copyright, and these are unable to be reproduced in any form outside the study, including in this report and online.

Level 2 manual and worksheets can be obtained from either Dr Sue Gessler or Dr Lori Brotto on application (this permission level is set by Dr Lori Brotto as the copyright holder).

Level 3, following the opinions of the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and the project team, is not available outside the prospect of an IPT training setting on ethical and intellectual property grounds and a prospective study for its use in the gynaelogical oncology setting by appropriately trained individuals. Any such approach should be made to Dr Sue Gessler or Professor Alessandra Lemma.

Chapter 3 The SAFFRON feasibility two-arm, parallel-group randomised controlled pilot trial

Introduction and background

The SAFFRON study was halted before recruitment began. However, the trial was set up with supporting documentation and the planned methods and analysis are described in Methods and Analysis. The methods also describe changes from the original protocol in response to ethics and the views of the TSC.

Methods

Inclusion criteria

-

Women aged > 18 years (with partners at their choice) treated for any gynaecological malignancy with surgery and/or chemotherapy and/or radiation at UCLH Gynaecological Cancer Centre or University Hospitals Bristol Gynaecological Cancer Centre.

-

≥ 3 months post end of treatment.

-

Any sexual orientation.

-

With sexual function difficulties identified by initial screen (three clinical questions within clinical interview posed by doctor or nurse).

Exclusion criteria

-

Poor English.

-

Current drug or alcohol abuse.

-

Current sexual therapy or psychotherapy.

Justification for not limiting the study to one gynaecological cancer site

The HTA programme call asked for all gynaecological cancer types.

A recent systematic review35 advocated comprehensive and systematic assessment of sexual concerns using reliable and valid measures in large representative samples that include all gynaecological cancer diagnoses, stages of illness and types of treatment. Rees56 suggests a broader definition of sexual satisfaction to be included in our level 2 and 3 interventions.

We used a person-centred, problem-based approach, as there is evidence that extent of treatment does not necessarily correlate with sexual dysfunction. 9,10

Participant recruitment

Accrual and attrition estimates

There were 365 new cancers diagnosed within UCLH in 2010, and 1474 follow-up patients were discussed in the UCLH gynaelogical oncology multidisciplinary meeting that year (peer review report57), giving approximately 100 attendances per week. Using published figures, over the 9-month recruitment period in this study, approximately 550 eligible women were expected to be seen at UCLH [numbers are from UCLH figures that show that 1839 women were treated or in follow-up for a gynaecological cancer in 2010 (UCLH annual review 2010–11)]. 58 Following the literature,4,31,32 we estimated that 80% of these women who were aged ≤ 75 years were likely to be sexually active, and previous publications indicate that a minimum of 50% of these were likely to have sexual dysfunction (see Chapter 1). We therefore expected that the sample size for this feasibility study would be achievable in the 9-month period allowed for recruitment. The addition of Bristol, whose throughput is broadly similar, should have aided effective recruitment. In 2011–12, 469 new diagnoses, 23 recurrences and 14 metastases were discussed in the Bristol multidisciplinary meeting. Follow-up consultations for Bristol were estimated at an additional 1000, thus offering an estimated pool of 1506 eligible women.

The length of the recruitment period was to ensure recruitment in the context of a busy clinic, bearing in mind that asking all clinicians, both doctors and nurses, in two separate medical clinics to ask every woman whether or not she had a sexual difficulty would require a major culture change. 59

Justification of assumptions

Prevalence of sexual dysfunction in this population varies. Tsai et al. 30 reported a prevalence of sexual difficulties, according to the FSFI, of 66.67% in Asian women with cervical cancer. Other studies have reported 83%31 to 66% for significant32 and 46% for moderate difficulties. 32 Serati et al. 33 reported a prevalence of 65.8% among women with early-stage cervical cancer treated with radical hysterectomy. We did not have figures for our population for those who were unpartnered and not in a sexual relationship. We therefore assumed conservatively that an age-standardised rate of sexual difficulty in this population would be 50% (i.e. would answer ‘yes’ to the three opt-in questions; see Opt-in questions), and, of those women, 50% would agree to enter the trial (based on the uptake of depression therapy trials in primary care). El et al. 60 found an 80% acceptance rate of a treatment intervention for depression in cancer.

Attrition rate

In the IAPT programme, Richards et al. 49 reported an attrition rate of < 30% in psychological intervention trials. We drew on this as a direct parallel; however, one of the outcomes of this feasibility work was to assess how well we could minimise attrition.

Recruitment rate

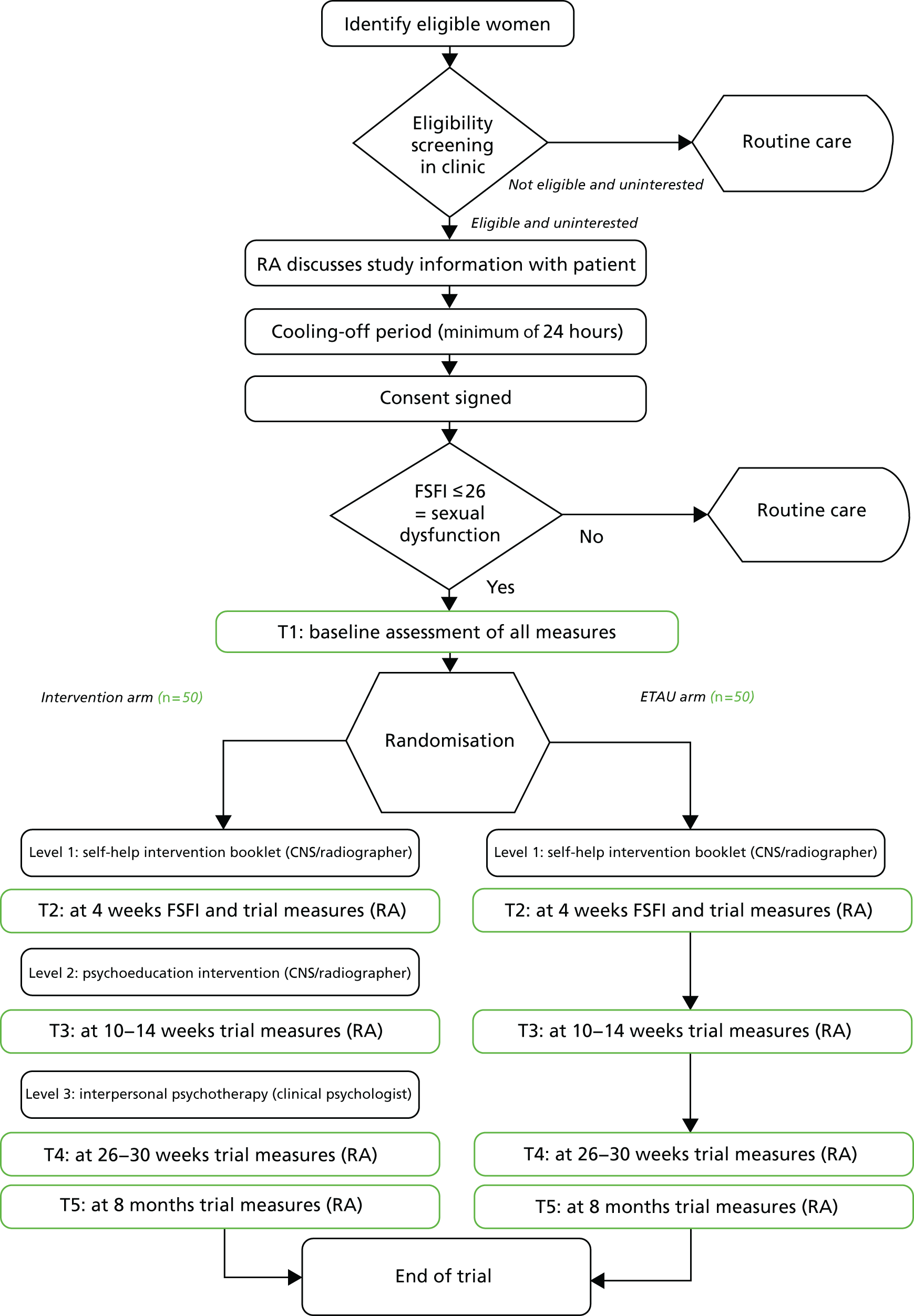

We aimed to recruit two or three participants per week for 9 months across both sites (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart for intended study. ETAU, enhanced treatment as usual.

All women attending a gynaecological oncology clinic following primary treatment for cancer in UCLH or Bristol were potentially eligible.

Providing information on the trial was to take place during the clinical follow-up visit and to form an integral part of the consultation.

Opt-in questions

Three clinical questions were to be asked by all clinicians (doctor or nurse) seeing a post-treatment patient:

-

Are you having any sexual difficulties/problems in your intimate relationships?

-

Is this a problem for you?

-

Would you like some help with this?

Clinicians were able to choose how to word the opening question to suit their relationship with the patient.

If women responded affirmatively to all three questions, they were to be offered screening to the trial. If they answered negatively to at least one question, or did not wish to answer, they were to continue with treatment as usual (TAU).

If women consented to being informed about the trial with a view to screening for it, they were to see a psychologically skilled RA, who would attend all clinics. The RA was to provide the patient information leaflet [see Section 2 PDF; URL: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/1111102/#/ (accessed December 2018)] and explain the nature of the trial.

Once informed, they were to wait a minimum of 24 hours for a cooling-off period before the RA approached them for consent. The maximum period for consent was set as the length of the recruitment period of the trial; that is, women were to be told that they could contact the RAs to discuss entry to the study at any point up to the closure of recruitment, on the grounds that deciding to seek help for sexual difficulties often requires thought, and associated anxiety might lead to avoidance for some time.

The initial screening of patients for entry to the trial was to be carried out by the RA using a paper questionnaire, the FSFI,61 as well as questions on self-attributed reasons for any difficulties. Baser et al. 62 recommend that studies with cancer patients establish self-attributed reasons, as the FSFI cannot distinguish physical reasons from a concern regarding life-threatening illness as cause of low or absent sexual activity. A cut-off score on the FSFI of 26 signifies sexual dysfunction (lower scores signify worse sexual function). 61,62

If patients scored ≤ 26 on the FSFI, they were eligible to enter the trial. If they scored > 26, they were to be referred to a CNS for continued treatment.

Baseline assessment for the study was to be carried out by the RA at T1 (see Table 1).

Maximising recruitment

We identified clinical champions within the team and intended to consult them weekly to monitor and explore concerns that might have arisen. Miss Adeola Olaitan (gynaecological oncologist) was a co-applicant and former Tumour Board chairperson, Miss Jo Bailey (gynaecological oncologist) was the clinical lead for Bristol, Miss Nicola Macdonald (gynaecological oncologist) was the clinical lead for UCLH and Miss Karen Summerville was the lead CNS for UCLH and a co-applicant. 63,64

Randomisation

Based on a randomisation specification document drawn up by the trial statisticians, a suitable web-based randomisation system was organised by the PRIMENT Clinical Trials Unit, a UCL-based clinical trials unit specialising in clinical trials in primary care and mental health. Randomisation was to be blocked (using varying block size) to ensure equal numbers in each arm, and stratified by clinic site (UCLH and Bristol) to ensure equal numbers of patients from these sites randomised to the intervention and control arms. After a patient provided informed consent, the RA was to collect data and enter them into the randomisation system to obtain the allocation for that patient. The patient would be informed of their allocation by the RA, who would also inform the clinical team to mobilise either stepped care or enhanced routine care. Breaking randomisation codes was not relevant here as patients and their clinical professionals would not have been blinded to trial arm allocation.

Trial interventions

Treatment arm

The trial offered three interventions within a stepped care model to be compared with TAU. The three interventions are described in detail in Chapter 2. The assessment is an integral part of the intervention and is described below.

Following submission to the Research Ethics Committee (REC), the REC requested the addition of level 1 (self-help booklet) to the TAU arm, given the low level of information and input generally available. The control arm then became enhanced treatment as usual (ETAU).

The stepped care intervention was developed for this project based on previous evidence-based interventions. Stepped care is widely used within psychological therapies and the IAPT programme,49 and this approach was adapted for the gynaecological cancer setting to produce a three-step model including a clinical assessment. Following the development of the interventions, it became necessary to convert to a sequential progress through levels of intervention, owing to the essentially different content of each level.

-

Level 1: self-help booklet written for the trial.

-

Level 2: three- to five-session intervention based on the work of Brotto et al. 53 This is an evidence-based psychoeducational intervention previously delivered by clinical psychologists, adapted for a wider patient group and to be delivered fortnightly by study-trained CNSs or brachytherapy radiographers with experience in working with women post treatment, with taping and supervision for adherence to protocol and manual. Patients are given worksheets and homework as an integral part of the intervention. There are at least three sessions, with two possible follow-up consolidation sessions depending on specific areas of difficulty to be decided by trial CNS/radiographer in collaboration with the woman.

-

Level 3: 16 weekly sessions of manualised brief psychotherapy intervention, adapted from the high-intensity National Institute for Health and Care Excellence-recommended therapy for depression IPT65 to be delivered by a study-trained clinical psychologist. The new intervention (IPT-GO) was adapted to take account of specific issues concerning the body image and self-image and esteem of women, and was written with input from the two patient advocates on the study.

Enhanced treatment as usual arm

Justification for enhanced treatment as usual versus treatment as usual

Level 1 consists of written material (newly combined and edited for the study) currently available on the internet, but which most women do not access. 51,52 It was to be given to women in both arms for the following reasons:

-

For ethics reasons, women who agreed to the study, and who were disclosing difficult and delicate material, should receive some input that may be helpful.

-

For recruitment reasons, every woman who entered the study should receive something not currently widely available.

Enhanced treatment as usual

-

Any woman who identified herself as having a sexual difficulty was to be referred to the CNS team, in which she would be assigned to a gynaelogical oncology CNS who had not received specialist psychosexual training.

-

The CNS input was defined with both teams as including assessment of the difficulty, normalising the experience, offering supportive counselling, helping her in discussing her relationship and advising on topical lubricants and oestrogen.

-

Women treated with radiation were to be seen in post-treatment nurse-led clinics at UCLH by CNSs, in which they would be physically examined and taught to use dilators to keep their vaginal access patent. The content of the point immediately above would occur at this point. At Bristol, trained radiotherapists (not CNSs) were to follow up all women treated with radiotherapy, introduce dilators and cover the same material as the above points.

Women assigned to ETAU would only be seen by a naive CNS/radiographer (i.e. not trained in the intervention). CNSs/radiographers trained in the intervention would be asked not to share the content of the new interventions with their clinical colleagues, or include study interventions in the delivery of care to non-trial patients. Materials were to be stored separately in locked cabinets and sessions were to be conducted either in clinic rooms or, in the case of telephone sessions, in private rooms where colleague CNSs/radiographers could not overhear the session.

All treatments in the ETAU arm were to be recorded from case notes and CNS/radiographer/psychologist treatment files to characterise the interventions received. All participating women were to receive a patient-held treatment diary in which they could log all treatment contact.

Assessment at intake prior to randomisation

-

Female Sexual Function Index.

-

Patient Health Questionnaire-9 items.

-

Self-assessment of level of sexual activity and self-attributed reasons for difficulties.

Blinding and other measures taken to avoid bias

As is common in trials of complex health-care interventions, it was not possible for clinicians and patients to be blinded to their assignment to treatment group. RAs on the trial would have needed to input group-specific data into the online database, as well as informing participants of their allocation, so they could not be blinded. The trial statistician was to remain masked until all data were collected and the final analysis plan was agreed by the research team. To assess the possible leakage of any aspect of the new intervention into ETAU (as both the intervention and the control arms were to be treated within a single centre), all participants in both arms were to be asked at follow-up to describe any treatments or information they had accessed, as some, by having the possibility of an intervention raised, may have been seeking treatment elsewhere. They were to be assigned a treatment diary (similar to a chemotherapy diary) in which to record all health-care contacts. This was to be cross-checked against clinical process data (outpatient clinic records, CNS databases and records in both centres) by the researchers.

An important element of this trial, which could be avoided, was that there were likely to be women made aware of the issue of sexual difficulty after treatment by doctors and nurses discussing the trial with them within the two centres. Women made aware but randomised to usual care might well have decided to seek out extra information and resources, or make more demands within usual care. This informed the REC decision to request the introduction of the level 1 materials to the control arm, TAU, making the control arm receive ETAU.

Process through levels of intervention

Figure 2 shows the flow chart for the intended study.

-

All women who consented to be part of the study were to be assessed on the entry criteria.

-

Entry to study required a FSFI score of ≤ 26 and self-rated sexual difficulty.

-

All eligible women received level 1 booklet from RA (ETAU: justified in Description and justification of the duration of treatment, subject participation and trial follow-up).

-

All women were to be assessed at 4 weeks by RA following receipt of level 1 booklet.

-

If the FSFI score was ≤ 26 after level 1, then intervention arm women progressed to level 2 (CNS/radiographer intervention).

-

At completion of level 2 (three sessions attended), reassess. If the FSFI score was ≤ 26, offer level 3 intervention. If women failed to attend, RAs were to follow up if women had agreed during the consent process.

FIGURE 2.

Intervention flow chart for intended study.

Data

Measures

Sexual function

The primary outcome measure was the FSFI,61 an internationally recognised rating scale that allows women to describe their sexual experience in a range of domains: desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, pain and satisfaction. This was to be measured at T1, T4 and T5.

At all five time points the following were to be recorded by the RA:

-

Economics – EQ-5D-5L of severity measures an individual’s generic health status and allows the computation of quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) for the cost-effectiveness analysis. SQOL66 is a series of statements about thoughts and feelings around sex life as a measure of sexual-related quality of life. The SQOL also functioned as part of the treatment algorithm during the interventions, as the FSFI score was the primary outcome measure for sexual function.

-

Depression – PHQ-9 is a brief measure of depression severity. 67 PHQ-9 scores of 5–9, 10–14, 15–19 and 20–27 represent mild, moderate, moderately severe and severe depression, respectively.

-

Anxiety – GAD-7 is a brief self-report scale to identify probable cases of general anxiety disorder. 68 Scores of 5–9, 10–14 and 15–21 represent mild, moderate and severe anxiety, respectively.

At other time points additional measures were to be completed:

-

Client Services Receipt Inventory (CSRI) – our in-house adaptation of the CSRI to assess use of health and social services. 69 Data were to be collected at T1, T3 and T5.

-

Preference measure – a one-item, bespoke questionnaire that asks participants to rate their preference for intervention or ETAU groups on a seven-point Likert scale. Data were to be collected at T1, T3, T4 and T5 (see Description and justification of the duration of treatment, subject participation and trial follow-up).

-

Evaluation and Satisfaction Measure – a bespoke questionnaire that asks participants who have completed the level 2 intervention to answer questions on satisfaction and adherence.

-

At baseline (randomisation) the following additional demographic and clinical information was to be recorded on a case report form by the RA –

-

Demographics: ethnicity, current relationship status, occupation, education.

-

Personal history: within a relationship; gender of partner; self-rated quality of relationship measure.

-

Disease information: cancer diagnosis (cervix, ovarian, endometrial, other), stage of disease at diagnosis, time since end of primary treatment in months, stage of disease at last appointment (relapse or first-line treatment), treatment modality.

-

Eastern Co-operative Oncology Group/World Health Organization: performance status (0–5) assessed by clinician, for which 0 = fully active and able to carry on all pre-disease performance without restriction and 5 = dead. 70

-

All cancer disease information was to be gathered by the RA on each site from electronic records and cross-checked against the hospital database on all gynaelogical oncology patients (Table 1).

| Name of outcome measure | Time point | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (T1) | 4 weeks (T2) | 10 weeks (T3) | 25 weeks (T4) | 8 months (T5) | |

| Demographics, personal history | ✗ | ||||

| Diagnosis, stage, treatment | ✗ | ||||

| FSFI | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| SQOL | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| EQ-5D-5L | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| CSRI – to cover use of services in the previous . . . | ✗ 3 months | ✗ 6 months | ✗ 2 months | ||

| PHQ-9 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| GAD-7 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Preference for treatment measure | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| Satisfaction measure (intervention arm only) | ✗ | ✗ | |||

Description and justification of the duration of treatment, subject participation and trial follow-up

Outcome measure collection time points were set independent of the intervention delivery to ensure standardised collection of data and consistency between the intervention group and controls:

-

T1 – baseline assessment and level 1 booklet given.

-

T2 – 4 weeks (to allow use of the booklet and reassessment).

-

T3 – 10 weeks from baseline. All women in intervention group should have completed level 2 by this time. Two to five fortnightly sessions. Length of treatment derived from existing manual and evidence.

-

T4 – 25 weeks from baseline (primary end point).

-

T5 – Follow-up data collected 8 months after baseline (follow-up).

The willingness of women to participate at each level was to be measured by counting the uptake of each intervention when offered and attendance at sessions offered. Their preference for any particular therapy was to be measured at baseline with the preference for treatment measure.

Trial follow-up was planned to be 8 months from baseline to evaluate whether or not any advantage of treatment endured over time, and to allow for, and to compare against, natural recovery rates in the ETAU group.

The follow-up time of 8 months, as opposed to 12 months as originally planned in the protocol submitted to NIHR, was proposed by the TSC when it first met the project team in August 2015. It was suggested that this would be a meaningful follow-up period while extending the time period available to recruit participants who could (theoretically) progress sequentially through all three interventions within the time period of the study. Unfortunately, this was not discussed with the funders at the time and was held to be a breach of contract as well as being considered an inappropriately short follow-up period.

Qualitative investigation

Semistructured interviews were to be conducted at 9 months with a purposive sample of 18 patients randomised to the stepped care arm of the trial to explore their experience of the process of recruitment to the trial and of receiving the interventions. Good and poor responders were to be chosen, as were those who did not take up the offer of interventions. Women were to be asked about their experience of the ‘stepped care’ model, and whether or not they liked the interventions that were offered to them. Women who dropped out or withdrew were to be asked for their reasons at point of leaving (if women had previously consented to do this at randomisation). We also intended to interview clinical staff to understand their experiences of recruiting participants to the trial, and senior clinicians and managers about the operation of the SAFFRON intervention and stepped care model. These data were to be analysed thematically using the framework approach71,72 with the aid of QSR NVivo qualitative data analysis software (QSR International, Warrington, UK) to provide important information on acceptability and potential for harm, as well as potential obstacles to and facilitating elements of the intervention.

At follow-up, the RA was to establish and record any additional treatments or information women had accessed, and record timing of drop-out from treatment or follow-up and reasons for drop-out, when ascertainable. They could telephone the women, e-mail them (with permission from women if given in the initial consent form) or visit them in their homes if they were too ill or fatigued to attend clinic.

Analysis

Statistical plan

The aim of the study was to establish the feasibility of a larger trial of the proposed stepped care intervention.

The critical parameters that were to be used to quantitatively assess feasibility were the:

-

consent rate

-

proportion in the intervention group who moved up at least one step on the intervention

-

proportion of all randomised subjects who had a useable (non-missing) score for total FSFI (the proposed primary outcome for any subsequent study) at 8 months.

To inform whether or not a main trial might be viable, the study planned to examine whether or not it is possible to achieve:

-

a consent rate of ≥ 40%

-

≥ 70% of randomised subjects having a useable (non-missing) score for total FSFI (our primary outcome) at 8-month follow-up.

We also intended to use the feasibility data to provide an estimate of standard deviation of the FSFI score that would be required for the sample size calculation of the main trial.

A sample size of 100 patients, randomised equally to the two treatment groups, was chosen for this feasibility work. This sample size is shown below to be adequate to ensure sufficient precision to exclude the minimum acceptable values for the three critical parameters based on exact, one-sided 95% confidence intervals around assumed values for each parameter:

-

Consent rate. We expected that 50% of women would consent to randomisation. With a sample size of 100 women, this consent rate could have been estimated with a lower 95% confidence interval of 44%.

-

Proportion in the intervention group who move up at least one step on the intervention. We expected that 80% of the 50 women allocated to the intervention group would step up at least one level on the intervention during their treatment period. We planned to estimate our expected proportion of 80% with a lower 95% confidence bound of 68%.

-

Proportion of all randomised subjects who had a useable score for total FSFI at 8 months. We estimated that 80% of the 100 women randomised in the trial would provide useable data to score the FSFI at 8 months. With 100 women we would have been able to estimate 80% with a lower 95% confidence bound of 72%.

Data from 100 patients would also be adequate to provide a precise estimate of the standard deviation of the primary outcome (FSFI) score to inform the sample size calculation for the main trial. 73

Economic evaluation plan

The aim of the economic evaluation was to optimise the methods of conducting an economic evaluation of the stepped care system compared with ETAU as part of a full trial. This would have included an estimate of the cost of stepped care and an evaluation of using a gynaelogical oncology-specific version of the CSRI to collect resource use data. A preliminary cost–utility analysis would have been conducted, reporting the incremental cost per QALY gained of the stepped care system compared with ETAU. The key aim of this would have been to evaluate the effect of using the EQ-5D-5L to calculate QALYs in this patient group versus a sexual function measure (the SQOL questionnaire) to calculate QALYs.

Recruitment rate required by the study

We aimed to recruit two or three women per week for 9 months between both sites.

Changes to methods before planned study commencement

-

The REC review changed the original study design. Concerns about women in the control arm being identified as having clinically significant sexual difficulties, and the awareness that there is no consistently available TAU for this, led the REC to ask for the level 1 booklet to be given to participants in both arms of the study. This point had been raised by patient advocates during the intervention development and was accepted by the research team.

-

When the TSC was convened in August 2015, its members were concerned that the full study would not be achievable with 1 full year of follow-up. The research team had hoped that there could be a no-cost extension to the study but this was not possible. To make the study more achievable, they proposed (1) reducing the follow-up period to 8 months and (2) introducing the SQOL as a within-treatment measure allowing the FSFI to be the outcome measure for sexual function. This required a substantial amendment and resubmission to the REC and engendered further delay. Convening the TSC earlier would have helped mitigate this delay.

Results

Closure of study

The study was closed by the funder, NIHR, in November 2015 because of slow progression to recruitment as well as changes to the protocol made after its original filing with NIHR, which led to a substantial REC amendment. There are, therefore, no results of the stepped care intervention with patients and the questions posed in the objectives cannot be answered here.

Set-up and site opening delay

Administrative delay in the legal and financial set-up of the study, and hence funding of access to clinicians’ time to contribute to the intervention development, posed severe challenges to the timely progress of the study in the first instance. The set-up of the study was hindered by the chief investigator (CI) being a clinician without previous experience of running a trial. Administrative support from within the NHS was a secondment from an inexperienced, albeit enthusiastic, staff member who was unaware of mechanisms to raise the profile of the study locally within the local bureaucracy.

Working across a range of hospitals and a university proved difficult for set-up, and some hospitals asked to release a clinical staff member to write the intervention. Professor Alessandra Lemma had never undertaken such a financial or legal arrangement before. It seemed very clear that setting up a psychosocial study within a medical setting was very complex and unfamiliar to those who were highly competent at setting up a drug study.

The development of the interventions took substantially longer than the time estimated in the application. The lack of prepared interventions had been signalled as a risk by one reviewer in response to the original response to the commissioned call from the HTA programme.

The study was initially suspended by NIHR in October 2014 for financial reasons, with the assumption that it would be at least 1 year before it was restarted, and many involved assumed that it was permanently halted. Momentum was lost at this point, which was, in retrospect, key. Once funding restarted in February 2015, it was problematic to re-engage clinicians and the services, as they had made plans that excluded the study. Employment processes within the university for RAs needed to be started from scratch.

Once the interventions were ready and the study was able to progress, nursing teams felt unable to participate as trainees and deliverers of a new psychoeducational intervention, causing the need to seek other staff to deliver level 2. This was because of maternity leave at one site, a prospective hospital merger at the other and the need to have two CNSs at each site, one study trained and the other not. By contrast, clinical psychologists at both sites were fully trained in the level 3 intervention and were piloting it without difficulty. They were unconcerned about delivering the level 3 intervention, largely because it offered new resources in terms of skills, and the intervention fell within the professional demands of their role.

A substantial ethics amendment was required after the meeting of the TSC in August 2015, in which the committee recommended the addition of two further measures and, in addition, suggested that in order to keep the study within its time limits, the follow-up period should be shortened. All three changes formed part of the amendment.

There were differences between the two sites with respect to trust research and development approval. One was flexible and responsive. The other had still not approved research and development at the point of the study closure despite the application being over 2 months in the system.

Achievements of study and responses to obstacles

This section describes that which was completed and changes that occurred in the pre-recruitment phase to address obstacles that arose.

The development of the stepped intervention was completed. The study adapted to input from the REC that asked it to change the TAU arm to give participating women a better clinical experience.

Training of CNSs (as originally envisaged) at both sites was delayed by issues of:

-

maternity leave of one study CNS, with locum cover inappropriate for the study in terms of both training and in length of contract

-

lack of funding for backfill of CNS time while delivering level 2 intervention

-

work demands at one site changing substantially after the project commenced because of a projected merger of hospitals within the time frame of the study.

Teams in both sites were keen that the study should proceed but neither team of CNSs was able, at the time the study went live, to offer CNSs for training and participation. The study therefore approached supernumerary staff at each site to train in, and deliver, the level 2 intervention. At UCLH this staff member was a former nurse consultant, currently running the UCLH Cancer Centre Macmillan Support and Information Service, and at University Hospitals Bristol the staff member was a consultant specialist radiographer who had academic time in her job plan that enabled her to participate.

Training

Initial training of level 2 therapists for Bristol and UCLH was written and delivered using a Microsoft PowerPoint® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) summary of the background of the study [see section 4 PDF; URL: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/1111102/#/ (accessed December 2018)], and by working through each of the required sessions. Teaching involved some didactic elements and substantial role play and group discussions. Although highly experienced in general counselling techniques, feedback from both therapists revealed that they were not yet confident about carrying out specific psychological techniques, such as taking a behavioural history, or ‘gently challenging beliefs’ as required in one session. It appeared that each session required about 3 hours’ teaching time. At the point the study was halted, both had requested, in addition to supervision on pilot cases, top-up training. This was arranged but could not occur as the study was halted. This suggests that cross-disciplinary training with psychological interventions requires more time than was envisaged in this study.

Training of three clinical psychologists in IPT-GO was delivered by Professor Lemma in a full day. This used the national IPT training as its foundation, and additional material was included to show how IPT-GO differed from usual IPT for depression. All three psychologists felt confident to deliver IPT-GO and initial pilot cases completed before formal opening of recruitment. Professor Lemma judged them capable of carrying out IPT-GO within the confines of the study (i.e. with follow-up supervision on the first cases). The difference in confidence and capacity may derive from the fact that Professor Lemma is highly experienced in training for IPT. It may also be related to the fact that clinical psychologists are, by definition, used to delivering a range of different therapies. Although newly formulated, IPT-GO was closely related to their core skills and discipline, and they were able to develop quickly variations on their technique as required.

Other outcomes

Preparation of the full range of study documents was completed [see Section 2, 3 and 4 PDFs; URL: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/1111102/#/ (accessed December 2018)].

Interview schedules for the qualitative study were prepared (see Appendices 10 and 11).

All intervention documents are archived at UCL. Level 1 contains elements derived from a document for which the American Cancer Society holds copyright, and these are unable to be reproduced in any form outside the study, including in this report and online.

Level 2 manual and worksheets can be obtained from either Dr Sue Gessler or Dr Lori Brotto on application for use by qualified psychologists in the setting of a study (this permission level is set by Dr Lori Brotto as the copyright holder).

Level 3 is incompletely developed and has not been tested in a study. Following opinions of the TSC and the project team, on ethical and intellectual property grounds, it is not available outside the prospect of an IPT training setting and a prospective study for its use in the gynaelogical oncology setting by appropriately trained individuals. Any such approach should be made to Dr Gessler or Professor Lemma. Access requires IPT-qualified clinicians with a capacity to train in its application to gynaelogical oncology and a prospective study to complete the appropriate development stages for a new psychological therapy.

Learning for the future

Closure of the study was regretted by the clinical teams at both project sites as they had welcomed the prospect of new interventions for their patients. The TSC considered the interventions to be worthwhile and well developed.

Causes of delay

Development of the intervention took substantially longer than initially envisaged. The research team delayed key parts of the study in the attempt to get the interventions right. In particular it was important to acknowledge the patient input, which changed the team’s initial assumptions, in particular interpretation of the commissioned call as attending to mood. Major input adapting mental health materials on mood in the stepped intervention was found pathologising and inappropriate by the patient advocates. The project team found this highly valuable, leading to a more robust and patient-appropriate set of interventions. The research team considered that it was better to delay while getting the interventions right, drawing on wide experience in psychological intervention research. However, these changes led to delays in advertising for RAs and in progress, which contributed to the initial suspension of the study.

The structure of the intervention itself changed during this time. The original design envisaged direct access via the treatment algorithm to levels 2 and 3, as successfully used in IAPT. The REC was concerned for the well-being of women in the control arm, in that they had been identified as being in need of, and wanting, help for sexual difficulties and would be offered nothing. They asked whether we could offer both arms the level 1 booklet, changing the TAU arm to an ETAU arm. This change in design had the advantage of dealing with any prospective contamination between arms by widespread distribution of the booklet within clinics. It also addressed a concern of the patient advocates, who had pointed out as the interventions were developed that much of the level 1 and level 2 materials were unknown to them, and would be a necessary basis for any more psychologically intense intervention. The learning from this element was that mapping directly from psycho-oncology to mainstream clinical psychology interventions is often perceived as unhelpful by both patients and RECs, and such differences should be considered at an early stage.

Administrative delay in the legal and financial set-up of the study, and hence funding of access to clinicians’ time to contribute to the intervention development, posed severe challenges to the timely progress of the study. This appeared to be rooted in institutional barriers to setting up a psychosocial study in cancer services within the NHS; for example, some involved institutions had never participated in this way before and did not understand the processes involved or required. Formal structures between the NHS division and UCL did not work as well as would be expected. Many processes had to be repeated across organisations. The release of clinical time by a full-time clinician to develop the level 3 intervention (AL) required advance agreement, which led to further delay.

Major issues arose as a result of the intention to conduct the trial within the existing clinical teams, including using clinical staff to deliver the interventions. This intention was in line with the recommendation of the 2009 Cochrane review29 aimed at speeding subsequent integration into clinical practice. However, implementation of the study was therefore subject to real-life fluctuations in staff and in the clinical demands on teams the trial necessarily involved.

The study had proposed one CNS to be trained and the other to offer TAU at each site. At one site, the maternity leave of the CNS intended to be trained for the study, together with delays and concerns about locum cover, left the site without a CNS to be trained, and the lead CNS was no longer able to support the study. At the second site, despite initial enthusiasm, at the point of training, the CNS team was unable to offer a staff member, owing to concerns about existing clinical load and a prospective enlargement of their catchment area with a consonant rise in referrals to the centre. Hence searches were made for alternative staff with links to the clinical teams but who were able, owing to the structure of their jobs, to take on an extra task both of training and of clinical input. Although ultimately successful, this also led to delay.

The nursing teams at both sites stated that they were under clinical pressure, and the inability of the study to offer direct backfill for their time was a further obstacle. The original proposal to the HTA programme for this study proposed a trial CNS for 18 months with clerical support to address issues of clinical demand on existing teams, and to examine the effect of the intervention as delivered by CNSs. The team was advised that under the terms of a HTA award, this could not be funded as it would appear as a NHS excess treatment cost. Although the CI secured limited charitable funding to support the CNS teams, terms of the charity prevented direct payment for staff time, and hence this did not fully allay the concerns of the nursing teams. Other psychosocial studies funded differently have tended to establish the intervention with research staff initially, and then proceed with the roll-out into clinical practice. With hindsight, this might have been a preferable approach to the development and testing of the SAFFRON interventions.

Attempting to launch in both sites simultaneously added delay. A pilot phase at UCLH before moving to Bristol could have given opportunities for ironing out logistical issues and service delivery problems.

Positive outcomes

Patient involvement was present from the inception of the study, contributing at all points and forming a particularly valuable part of the study process for all the participating clinicians and academics.

The interventions are now adapted for the UK and for the gynaelogical oncology patient group. A subsequent study may be able to establish whether or not they are effective as an intervention over TAU. They are available through contact with the CI, subject to copyright agreements.

The development of the interventions and the discussion at the two sites has raised the profile of psychosexual difficulties after gynaecological cancer within both centres and the need for patients to be asked about their psychosexual well-being in follow-up clinics. It is not known if this has led to any change in practice.

Conclusions and recommendations for further research

Given the stated views of the TSC, the patient advocates on the project and the clinical teams at both sites, the SAFFRON interventions appeared appropriate for managing sexual difficulties after treatment for gynaecological cancer. These interventions should be tested within a formal research study in the future. Delivery of these interventions within and in parallel to usual care would require careful planning and resource and time allocation.

This study showed that it was not feasible to deliver the SAFFRON stepped care approach within the structure of the trial and with the resources available within the usual clinical setting. Given the difficulties of maintaining continuity of staff within busy clinical settings, it would be helpful if the designated deliverers of new face-to-face interventions were formally research funded, and were supernumerary to the existing clinical team.

It is essential that any further study in this area continues to have strong patient involvement in the model of that which has formed a key part of SAFFRON.

The experience of the team showed that, other than institutional delays, there were two main problems with the study itself:

-

slowness in finalising the intervention and accompanying materials

-

finding staff with the time and commitment to deliver the interventions.

This suggests that future research should explicitly focus on the intervention development phase. SAFFRON attempted to design an intervention and test it in a feasibility trial in two separate clinical settings. It was a complex intervention requiring a range of changes within an existing clinical system, and future studies should follow the Medical Research Council’s complex intervention guidance. 74 This means moving away from using the model of phases of drug development and separating out intervention development from implementation.

Interventions should be evidence and theory based and well formulated before proceeding to a full trial. Such processes tend to allow grassroots service providers to be fully involved in the development process and hence better skilled and more motivated to deliver the interventions.

This could lead to difficulties in providing that ‘clear water’ between two groups in a RCT, but different trial designs can be used to accommodate such difficulties. A cluster trial, in which one whole service delivers the intervention to everyone and one whole service delivers usual care, would be one way of working within a single clinical service to bring about change, rather than attempting to randomise two groups within one service, with its attendant problems of contamination.

Implementation studies should occur in advance of a full trial to cost the intervention and iron out any implementation barriers. These should take account of the range of factors involved in improving health care. Ferlie and Shortell75 conceive of four levels of change: individual, group or team, organisation and the environment in which the organisation is embedded. They suggest that, to maximise chances of successful change, all four levels must be considered.

Grol et al. 76 point out the need to recognise the interaction between an intervention and the complex setting in which it is used, and suggest the need for a process theory to cover both the ‘organisational plan’ and the ‘utilisation plan’. This would include working closely with the target group (in this case, doctors, nurses and psychologists working in gynaelogical oncology clinics) and involving them in the development of the innovation and the implementation plan.

A sequential approach to implementation would require, before proceeding to a full trial, an implementation study with analysis of reasons for departure from the desired change, looking at characteristics of the target group and setting, influential individuals and factors that promote, or inhibit, the change. Interventions regarding sexuality can be particularly sensitive to resistance at professional and patient levels, so even more development may be required.

Stepped care as a model is itself sophisticated and was similarly examined in its implementation phase within mental health in routine care. 49

The main trial questions of efficacy or effectiveness remain to be answered in any future study, but the current study focused on feasibility. Our conclusions are that it was not feasible to deliver our stepped care approach within the structure of the trial and the resources (mainly clinical researchers) that were available.

The areas to be worked on in future studies should focus on acceptability, involvement and structures.

Acknowledgements

Contributions of authors

Dr Sue Gessler (Consultant Clinical Psychologist, Gynaelogical oncology Centre) was CI, conceived the initial study, contributed to the study design with the project team, convened project meetings, cowrote new materials at levels 1 and 2, and wrote and delivered the training for level 2. She drafted this report.

Professor Michael King (Psychiatrist and the then Co-director of the PRIMENT Clinical Trials Unit) contributed to the study design, was involved in the development of the interventions, advised on trial methods, attended project meetings and cowrote new intervention materials.

Professor Alessandra Lemma (Co-chairperson, Psychological Therapies Development Unit, UCL) contributed to the study design, wrote the IPT-GO manual, and devised and delivered the IPT-GO training.

Dr Julie Barber (Senior Statistician, PRIMENT) contributed to the study design, conducted the statistical analysis for numbers required for accrual and advised on the study at all points.

Dr Louise Jones (Palliative Care Senior Lecturer, UCL) contributed to the study design and the development of the interventions.

Mrs Susan Dunning (Patient Advocate) contributed to the study design, attended project meetings and commented on and coedited the patient materials at level 1 and commented on materials at levels 2 and 3.

Mrs Val Madden (Patient Advocate) attended project meetings and commented on and coedited the patient materials at level 1 and commented on materials at levels 2 and 3.

Professor Stephen Pilling (Co-chairperson, Psychological Therapies Development Unit, UCL) contributed to the study design and helped design the stepped care model.

Ms Rachael Hunter (Senior Health Economist, PRIMENT) contributed to the study design and prepared the study-specific health economics metrics.

Professor Peter Fonagy (Chairperson, Department of Psychology and Psychoanalysis, UCL) contributed to study design and intervention development.

Miss Karen Summerville (Lead Clinical Nurse Specialist) contributed to project meetings, clinical implementation and reviewing all patient intervention materials at level 1.

Miss Nicola MacDonald (current Clinical Lead, Gynaecological Oncology Centre, UCLH and Consultant Gynaecological Oncologist) contributed to clinical implementation planning.

Miss Adeola Olaitan (former Clinical Lead, Gynaecological Oncology Centre, UCLH, and Consultant Gynaecological Oncologist) contributed to the study design and was the local principal investigator for the UCLH treatment site.

Dr Anne Lanceley (Senior Lecturer, Department of Women’s Cancer, Institute for Women’s Health, UCL) contributed to the study design, attended project meetings, prepared the REC application, contributed to the development of study materials and managed the RAs who were employed through UCL.

Data-sharing statement

No new data were generated during this study, and, therefore, there is nothing available for access and further sharing. All materials created are available; however, some conditions apply to the intervention materials. All queries should be submitted to the corresponding author.

Disclaimers