Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 11/15/04. The contractual start date was in October 2012. The draft report began editorial review in September 2017 and was accepted for publication in January 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Martin Knapp received funding from Lundbeck Limited (St Albans, UK) in relation to work on depression in younger adults and workplace mental health and from Takeda UK Limited (High Wycombe, UK) for advice on measures of the impact on carers of caring for people with dementia. Zoe Hoare is a member of the Health Services and Delivery Research Associate Board. Bob Woods received a grant from the Welsh Government via Health and Care Research Wales (Cardiff, UK).

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Clare et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

There is a greater need than ever before to identify effective and beneficial interventions for people with early-stage dementia. Timely diagnosis of dementia creates an opportunity to equip people with dementia and their carers to manage and live well with the condition. Psychological and social interventions can help to reduce or delay the development or progression of functional disability, depression or behavioural difficulties, maintain independence, support management of comorbid health conditions and, hence, avoid or reduce hospitalisation, maintain quality of life and ultimately delay institutionalisation. 1 At present, however, the chances of accessing psychological or social interventions following a diagnosis of dementia are limited. 2 There is a need to develop relevant and helpful interventions and to provide research evidence regarding the efficacy of these interventions. Research priorities set out by the Ministerial Advisory Group on Dementia Research in 2011 emphasised the need to identify ways of enabling people with dementia and their family members or other supporters (here referred to as ‘carers’) to enjoy a better quality of life and to evaluate the effects of psychological and social interventions for people with dementia living in the community. Nevertheless, there is still a significant ‘psychosocial intervention gap’ that remains to be addressed. 2

What is needed is a range of accessible psychological and social interventions that are effective in supporting or enabling people to live well with dementia and tackling the specific challenges that people face in managing everyday life with the condition. In the early stages of dementia, this includes approaches that can enable people to function as well as possible and remain as independent as possible. 3 Neuropsychological and behavioural studies show that people with early-stage dementia have many retained cognitive and behavioural capacities and are capable of behaviour change and new learning, although this is likely to require extra support. 4–7 It should be possible to harness these retained capabilities to enable people to manage daily activities better and support engagement and participation. Models of disability8–10 make an important distinction between underlying impairment, resulting from pathology, and disability, resulting from limitations on activity and restrictions on social participation. Furthermore, the possibilities for engaging in activity and participating in society are not solely determined by the extent of impairment, but are influenced by a range of other personal, relational, social and environmental factors. Unhelpful, unsupportive or negative influences can contribute to the development and maintenance of excess disability,11 when functional disability is greater than would be predicted by the degree of impairment; an example would be when an unsupportive environment leads to a loss of confidence. This is similar to Kitwood’s12 account of the way in which a negative social context can undermine well-being for people with dementia. In contrast, facilitative and positive influences can enable a person to function optimally. A focus on support and overcoming barriers to activity and participation should therefore produce benefits for people with dementia and their family members.

Traditionally, however, and despite the expressed concerns of clinicians,13 considerable effort has been devoted to using non-pharmacological approaches to attempt to address the underlying impairments in memory and other cognitive functions that are a defining feature of mild dementia, rather than focusing directly on enabling people to function well in everyday life. An example is the use of cognitive (or ‘brain’) training, which involves repeated, structured practice of tasks targeting specific cognitive domains, such as working memory or attention. A Cochrane systematic review14,15 found no evidence for significant benefits in early-stage dementia, and expert consensus endorses this finding. 16 A general issue with cognitive training (CT) that is a concern also in work with healthy older people or those with mild cognitive impairment is the lack of generalisation of benefits. Even in people in whom improvements are observed in trained domains, there is no evidence that these generalise to other areas, improve the ability to undertake everyday activities or have any beneficial impact in real life. 17 There is a need for more directly relevant approaches that can enable better functioning or reduce functional disability for people with dementia.

Interventions that aim to enable functional ability by targeting activity and participation, drawing on retained strengths to support adaptive behaviour, are typically described as forms of rehabilitation. The aim of rehabilitation is to enable people to function at their optimal level in the context of their intrinsic capacity and current health state. 18 The rehabilitation of people with cognitive impairments is termed cognitive (or neuropsychological) rehabilitation. The work described here has applied this approach in the care and support of people with early-stage dementia.

Principles of cognitive rehabilitation

Cognitive rehabilitation (CR) is an individualised behavioural therapy based on a problem-solving approach. 3,19,20 It represents the application of rehabilitation principles to address the effects of cognitive impairment. CR aims to address the impact of cognitive disability by enabling people with cognitive impairments to function at the highest possible level, given the nature and extent of these impairments. Supporting optimal functioning means enabling people to manage their daily lives, engage in worthwhile and meaningful activities and sustain as much independence as possible. This, in turn, allows people to feel more in control of their lives and supports the continuing experience of a coherent sense of identity. CR is person centred, acknowledging that each person’s combination of life experience, motivations, values, preferences, skills and needs is unique, and views the person holistically, taking account of the person’s relationships and environment.

Cognitive rehabilitation does not aim to train cognition or directly improve performance on cognitive tasks. Its goal is the functional rehabilitation of people with cognitive impairment. The focus is on better management of the functional disability that results from cognitive impairment and on reducing any excess or unnecessary disability resulting from secondary consequences, such as a loss of confidence. This is achieved by working with people on the goals that are important to them and that will make a difference in their daily lives.

Concept and terminology

Most people are familiar with the concept of rehabilitation following injury or illness, aiming to return the person to a former state of functioning or, if this is not possible, to enable the person to adjust to altered capacity and function at the best possible level given the residual impairments. 18 In the acute phase during recovery, intensive rehabilitation in specialist settings may be indicated, whereas at later stages, a less intensive community-based approach may be appropriate. Rehabilitation may target physical or cognitive functioning. The concept of rehabilitation is equally relevant for people with progressive impairments, who may benefit from episodes of community-based rehabilitation at various stages or as circumstances change.

In community settings, the term ‘rehabilitation’ is now sometimes replaced by ‘reablement’, which is derived from the same root and essentially shares the same meaning, but is perhaps viewed as a more readily understandable label. Rehabilitation can also be considered as being related to the concept of ‘tertiary prevention’, which is used in public health. We will use the term ‘rehabilitation’ here. The key point is that rehabilitation (or reablement) is grounded in a philosophy of enablement, which reflects a positive approach to finding solutions and encouraging optimal functioning. This philosophy emphasises a collaborative approach in service delivery, which can be summarised as ‘doing with’ rather than ‘doing for’ or ‘doing to’21 and which translates into specific individualised interventions aimed at optimising functioning.

Application to dementia

Living with dementia means living with disability resulting from cognitive impairment. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities sets out a range of rights, including the right to be able to attain and maintain as much independence as possible through the assistance of comprehensive rehabilitation services [Article 26 (1)]. 22 For people with dementia, rehabilitation has been proposed both as an overarching principle of care and service provision, reflecting the aim of enabling optimal functioning,3,20,23,24 and as a specific intervention approach that aims to support the attainment of practical functional goals.

The principles of rehabilitation can be applied flexibly to address different types of need at various stages of dementia. These might include needs resulting from the impact on functioning of cognitive, behavioural, emotional, communication-related, relational, social or physical changes or difficulties. CR for people with dementia focuses primarily on the effects on functioning of the cognitive, behavioural and social communication impairments that form the core symptoms of dementia and the emotional and relational impact of these. A person might have several episodes of rehabilitation over time as needs change or in response to particular circumstances, such as being discharged after a period of hospitalisation. CR is distinct from physical rehabilitation, but it is important to note that people with dementia can benefit from exercise-based interventions and should of course have access to intensive physical rehabilitation when needed following injury or illness. 25

Rehabilitation, with its focus on optimising functioning, provides a highly relevant framework for supporting people with dementia and their carers, and for designing interventions to meet their needs. However, the term ‘cognitive rehabilitation’ (or ‘neuropsychological rehabilitation’), although familiar in areas, such as brain injury research, needs to be better understood in the dementia field. ‘Rehabilitation’ signifies that the intervention aims to enable people to function optimally given any impairments they may have and ‘cognitive’ signifies that the intervention specifically addresses the impact of cognitive impairment on functional ability. This impact may be the direct result of the cognitive impairment (e.g. difficulty remembering) or may reflect secondary effects, such as loss of confidence. CR has a different focus and takes a different approach to other interventions that include the term ‘cognitive’ in their titles. 15 CT and cognitive stimulation focus on cognitive function and target specific domains or global functioning, respectively; the term CR is sometimes incorrectly used to describe these types of interventions, or as an umbrella term for them. Cognitive or cognitive–behavioural therapy targets unhelpful or self-defeating thought patterns that may underlie mental health difficulties or adjustment issues. CR is distinct from all of these other approaches, which include the term ‘cognitive’, and should not be confused with them.

Cognitive rehabilitation in practice

Cognitive rehabilitation is focused on the attainment of realistic personal goals26 that are meaningful to the individual and address relevant needs. Goal-setting is a powerful behavioural strategy,27 and goal-oriented approaches are widely used in rehabilitation interventions, including rehabilitation for people with brain injury,28,29 stroke,30 neurological illness,31 memory difficulties,32 physical disability,33 chronic pain34,35 and age-related frailty. 36 Goals for rehabilitation are expressed in a form that meets the description captured in the acronym SMART (specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, time-bound). The goal-oriented approach has hitherto rarely been used in dementia care, but it is consistent with person-centred principles.

Goals are identified collaboratively and realistic targets are established, leading to the generation and implementation of strategies to support goal attainment. This process is based on a formulation, or understanding, of the individual’s intrinsic capacity, current functioning, strengths and needs, which considers cognitive, behavioural, emotional, relational and environmental factors.

To arrive at a formulation reflecting this global level of understanding, the CR therapist assesses the person’s intrinsic cognitive and functional capacity and current level of functioning. This makes it possible to understand the person’s potential and to pinpoint any areas in which the person is functioning below capacity. Understanding the reasons for this can indicate avenues that need to be addressed before specific rehabilitation goals are tackled. For example, depression or a loss of confidence may lead to reluctance to engage in activities, with a consequent loss of skills, creating an unnecessary burden of excess disability. An early stage of therapy may therefore involve addressing issues of this kind.

The overall formulation provides a framework for identifying specific areas of daily life that the person would like to manage better and establishing which of these may be amenable to change. Through a collaborative process, which can be facilitated by using a structured interview schedule, individual personally meaningful and achievable goals are identified. These relate to particular activities or situations that give rise to concern for the individual. For each of these, the CR therapist assesses the demands of the activity or situation that the person wishes to engage in or manage better, identifies any areas of mismatch between these demands and what the person is able to do, and pinpoints areas in which difficulties are likely to arise and why. This is an important precursor to devising strategies for goal attainment. For example, a person could encounter difficulty with engaging in an activity as a result of not remembering what to do or being unable to concentrate (cognitive), lacking some of the skills needed (behavioural), feeling anxious or fearful (emotional), being in surroundings that are not conducive to carrying out the activity (environmental) or lacking someone to do the activity with (social), or some combination of these. Understanding where the difficulties arise provides a focus for the problem-solving process and for starting to work together to generate possible solutions that can support goal attainment. For example, if the difficulty arises from a lack of necessary skills, the solution may be to teach these skills or to modify the activity; if the difficulty is attributable to memory problems, the solution may be to provide support for remembering; and if the difficultly is due to anxiety, the solution may be to find ways of regulating emotions. The CR therapist can select from a range of methods and strategies, which could involve new learning, relearning, use of compensatory strategies, task modification, environmental modification, application of assistive technology, or some combination of these.

Once a possible solution is chosen, a plan for goal attainment is devised. Specific strategies that can help with implementing the solution are identified collaboratively and tested out in practice. Evidence-based rehabilitative strategies include techniques (such as spaced retrieval) that support new learning or relearning of information or skills, techniques to support the introduction and use of compensatory aids and the introduction of environmental adaptations. Assistive technology may be used to augment the person’s capacity.

Progress towards attaining therapy goals is reviewed continually and strategies are adjusted as needed. Throughout this process, the therapist provides important psychological support and models a positive, problem-solving orientation. Alongside the focus on problem-solving, goal-setting and strategy application, CR incorporates other behavioural therapy methods. First, many people with dementia experience low mood and apathy, and this may need to be addressed at the outset of therapy. Behavioural activation is used to increase engagement in activities that would usually be enjoyable, with the experience of engagement and pleasure providing a source of motivation to make changes and improvements. Secondly, tackling rehabilitation goals can trigger distress, including fear, despondency or frustration, and therapists provide important psychological support in acknowledging these emotions and helping people to develop ways of dealing with them and overcoming the barrier they can present.

Rehabilitation interventions for people with dementia need to offer practical benefits in daily life. When providing behavioural interventions, it is essential to consider first whether or not benefits will transfer from the specific situation to application in real life and second whether or not these benefits generalise, for example to other similar activities. The potential for transfer and generalisation is often limited in the absence of specific efforts, and this is a particular concern in the context of cognitive impairment. For this reason, CR interventions for people with dementia are designed to circumvent the issue by being conducted in the person’s everyday setting in which the skills and strategies learned need to be applied. Whenever possible, carers and other family members are involved to help to implement and maintain changes in daily life.

Supporting carers is an essential part of CR for people with dementia. For family carers, this includes both explaining and demonstrating the strategies and skills employed to promote goal attainment and attending to the carer’s own needs and well-being by providing psychological support, discussing needs and signposting to appropriate sources of help. When the needs and wishes of the person with dementia and those of the family carer differ, resulting in tensions, the therapist has to negotiate a balance between the two perspectives, and this can be one of the most challenging aspects in delivering CR interventions, requiring sensitivity and skill.

Evaluating the outcomes of cognitive rehabilitation

For a behavioural intervention, the first requirement is to demonstrate change in the behaviour or behaviours targeted, and hence progress with therapy goals must be the primary outcome for CR. 19 As CR interventions are based on individual formulations and address personally relevant goals, this has important implications for the assessment of primary outcomes at a group level, for example in clinical trials. In a trial, the overall therapeutic approach and the structure of the intervention (e.g. number and duration of sessions) will be consistent across all participants receiving the intervention, but the content and focus of the intervention and the specific strategies applied will be different for each individual. This is typical for psychological interventions based on individual formulations, for example cognitive–behavioural therapy for depression. However, CR does not address a single defined clinical problem, such as depression, which can be clearly targeted as a common outcome across all participants. Instead, it aims to enable each individual to manage aspects of his or her daily life more effectively and with greater satisfaction. Therefore, the appropriate proximal outcome is the individual’s performance in relation to these selected aspects of daily life.

In single-case designs, the outcome can readily be assessed directly in relation to the therapy goal – for example, whether or not a given activity is completed successfully or a desired behaviour is demonstrated. For effective outcome evaluation in large trials, however, there is a need for a standardised means of capturing individual functioning and changes in functioning. Observational methods can be used in single-case or small-group studies, but are unlikely to be feasible for large trials. Patient-reported outcomes are increasingly understood to be not only valuable but indeed an essential component in evaluating the effectiveness of psychological and social interventions. This is particularly the case in rehabilitative interventions in which the approach is one of collaboration in identifying and solving practical problems, and patient-reported outcome measures are central to researching rehabilitation outcomes. Although goal attainment scaling37 was developed as a means of evaluating the overall effectiveness of multicomponent rehabilitation programmes,26,28,36 client-centred performance measures have been developed that aim to identify outcomes for individuals. The most widely used example of such a measure is the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM),38 which provides a structured format for identifying individual goals and rating current performance in relation to these. Research using this measure has provided evidence for the reliability, validity and sensitivity to change of the rating method. 30,39–42

Patient-reported outcomes may raise questions about the accuracy with which people rate specific aspects of their own experience. However, there is increasing recognition that people in the mild to moderate stages of dementia can provide meaningful accounts of their own experience. 43 This issue of awareness and accuracy in reporting rehabilitation outcomes stimulated our extensive investigations of awareness in people with early-stage dementia. 44–46 Evidence from these studies shows that, although people with early-stage dementia are likely to overestimate their cognitive abilities relative to their objective test score,47 they appear to be relatively accurate in estimating their functional ability in everyday tasks relative to objective test scores based on observation, and indeed may be more accurate than carers. 48 Therefore, patient-reported outcomes in relation to performance of the activities that are the subject of rehabilitation goals can be considered to be an appropriate means of evaluating intervention effectiveness.

Development work undertaken prior to GREAT

Experience with CR for people with cognitive disability resulting from non-progressive acquired brain injury led to the formulation of the research question: ‘Can cognitive rehabilitation be adapted to enable people with dementia and their carers to better manage the effects of cognitive disability?’ Literature searches identified a few examples of interventions for people with dementia consistent with the principles of CR,49–51 and some descriptions of the application of specific learning strategies, mainly using single-case designs. 52 We carried out a Cochrane systematic review,14 which confirmed that there were no relevant randomised controlled trials (RCTs).

A series of feasibility studies conducted by our group demonstrated that it was possible for people with early-stage dementia to identify personal rehabilitation goals and to apply rehabilitation strategies to change behaviour and improve functioning in relation to these goals. These were either single-case experimental designs53–56 or small-group pre/post comparisons. 57 Behavioural change was observed in relation to the identified goals, and sometimes this generalised to other situations. Secondary benefits included maintained social engagement and reduction in carer burden. Gains were maintained for several months, and this was also the case for one participant with long-term follow-up over several years. 58 Additional work extended the evidence for efficacy, relevance and acceptability of specific rehabilitation methods, such as spaced retrieval or errorless learning. 59,60 These findings were supported by reports from other research groups. 61,62

We next conducted a single-site pilot trial of individual, goal-oriented CR in North Wales from 2005 to 2009, funded by the Alzheimer’s Society. 63 This was the first RCT of CR for people with early-stage dementia. We anticipated that the CR intervention would result in improvements in participants’ functioning in the areas targeted in the intervention, but not in cognitive test scores. We included measures of mood and quality of life to explore whether or not the intervention had any effects in these domains, and to allow us to check that the intervention did not have any adverse effects, given the concerns expressed by clinicians that CT interventions could adversely affect mood and well-being. 13

The participants in the pilot trial were 69 people with dementia recruited from NHS memory clinics, of whom 44 had a family carer who also contributed. Participants had an International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition(ICD-10), diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease or mixed Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia, were in the early stages as indicated by a Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) score of ≥ 18 points, and were receiving a stable dose of either donepezil (Aricept®, Eisai Co., Ltd, Tokyo, Japan; Pfizer, New York, NY, USA), galantamine (Reminyl®, Shire Plc, Dublin, Republic of Ireland) or rivastigmine (Exelon®, Novartis, Basel, Switzerland). All participants identified personal rehabilitation goals during the baseline assessment, using the structured interview format of the COPM. 38 Participants were then randomised to one of three trial arms: CR, relaxation therapy or treatment as usual (TAU). The CR intervention involved weekly 1-hour home visits by the therapist for 8 weeks. The main focus of the intervention was addressing the identified personal rehabilitation goals, and this was supported by improving strategies for emotion regulation, retaining information and enhancing concentration and managing everyday activities. Carers were included in part of each session when they were available and willing. Selected goals related primarily to managing the impact of memory, communication or organisational difficulties, improving the performance of practical skills and activities, learning new skills, regaining confidence and motivation to engage in activities and increasing social interaction. 64 The relaxation therapy intervention, delivered by the same therapist, involved eight weekly 1-hour home visits in which participants were taught progressive muscle relaxation and breathing exercises. Participants allocated to receive TAU had no contact with the therapist.

The primary outcome was participant-reported goal performance using the COPM rating system. At the post-intervention follow-up, ratings of goal performance and satisfaction with functioning in relation to goals improved significantly for the CR group and did not change for the other two groups; effect sizes in favour of CR were large. Behavioural changes in the CR group were corroborated by therapist ratings of performance and of the extent to which goals were attained. The average performance ratings made by participants and therapists improved by a magnitude greater than the 2-point change required to indicate clinical significance. 38

For the secondary outcomes, CR produced benefits in quality of life, mood and cognition for the person with dementia and in stress, well-being and quality of life for the carer, relative to relaxation therapy and TAU. Some of these secondary benefits were maintained 6 months later. There were no differences between the relaxation therapy and TAU groups. A subset of participants underwent functional magnetic resonance imaging scanning using a recognition memory task;65 at the post-intervention follow-up, participants from the CR group showed higher, and those from the control groups showed lower, brain activation in relevant areas, although neither group improved performance on the task. This was interpreted as suggesting that CR may have promoted a partial restoration of function in frontal brain areas. 66

The intervention was acceptable to participants and carers. Attrition was low, with 64 out of the 69 randomised participants (93%) completing the post-intervention assessment and 56 participants (81%) completing the 6-month follow-up (19% attrition overall). Reasons for loss to follow-up included death (n = 3), illness (n = 1), moving out of the area (n = 3) and change of diagnosis (n = 1), with elective withdrawal accounting for only five cases.

In summary, the pilot trial provided evidence to show that people with early-stage dementia can identify realistic goals and make significant improvements in functioning with regard to their chosen goals during a brief CR intervention.

Lessons learned from the pilot trial

We used the experience gained during the pilot trial to develop plans for a large, definitive trial. We updated our Cochrane review during the course of the pilot trial in 200767 and continued to monitor the emerging literature, but found no other RCTs to inform our development work.

A key area of learning from the pilot trial related to outcome measurement. In the pilot trial, we used the COPM, which provides a pragmatic rating system based on a simple 0–10 scale. This is accessible for people with cognitive impairments and can be presented visually as well as verbally. There was consistency in the ratings over time for the non-treated groups, and for the CR group, the measure was sensitive to change, corroborated by therapist observation. This reflects similar findings from other clinical groups30,40–42,68,69 and suggests that goal performance ratings made by people with early-stage dementia can be considered to be reliable and valid64 and that changes in ratings are a valid indicator of treatment effectiveness, with improvements of 2 points being considered to be clinically significant.

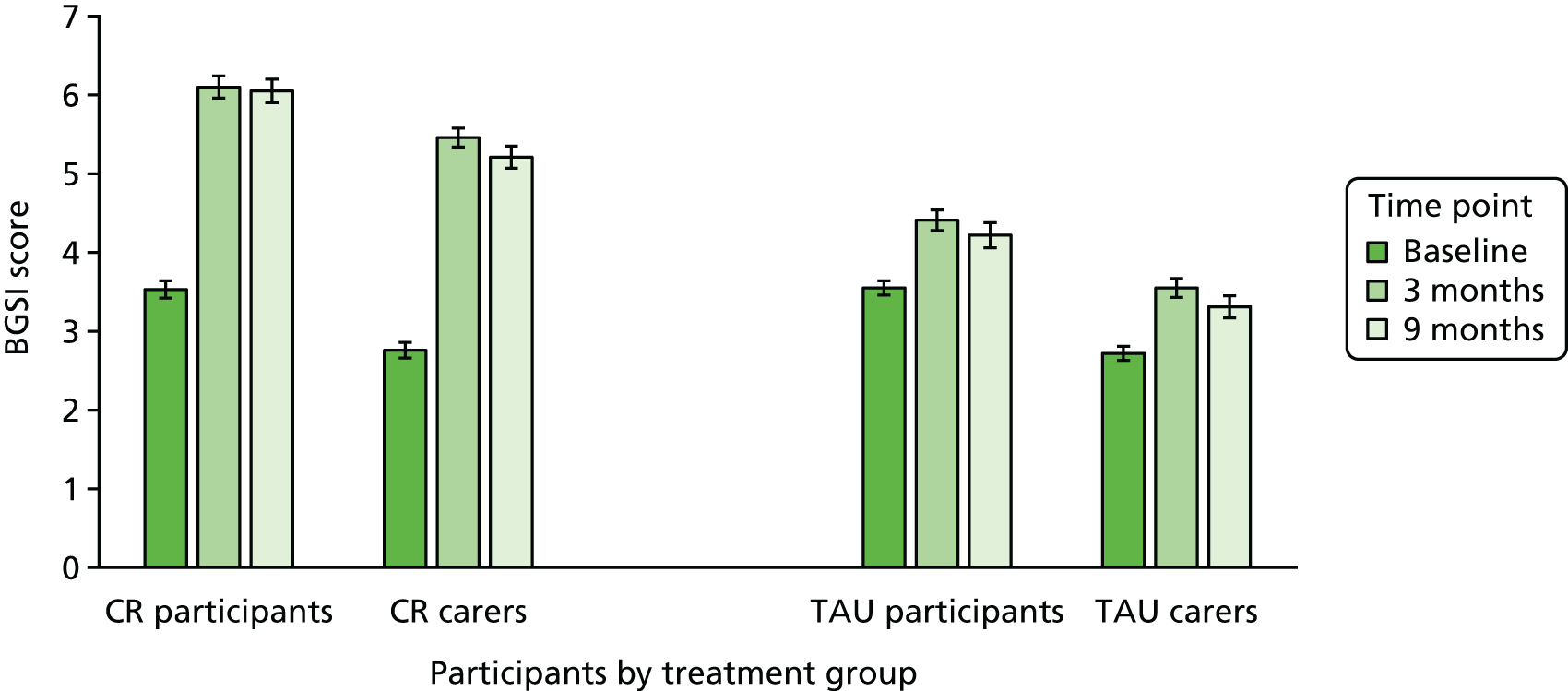

Although the COPM rating system proved to be suitable in the pilot trial, the semistructured interview format specified domains of self-care, leisure and productivity, reflecting its generic nature. These domains do not necessarily cover everything that might be relevant for specific groups, such as people with early-stage dementia, or that might be addressed in individual research projects. We therefore developed a semistructured goal-setting interview that used the same rating method, but placed this within the context of a more directly relevant and targeted discussion and goal-setting process, which could be adapted to the needs of specific groups or projects. The measure we developed, the Bangor Goal-Setting Interview (BGSI), has been used to elicit goals and evaluate progress towards goal attainment in trials with cognitively healthy older people70 and people with mild cognitive impairment,71 and is used in GREAT (Goal-oriented cognitive Rehabilitation in Early-stage Alzheimer’s and related dementias: multicentre single-blind randomised controlled Trial), as described here.

In the pilot trial, we included people who did not have a carer available to participate, as people living alone with dementia may be in particular need of support to manage everyday activities, and therefore carer ratings were not obtained for these participants. However, when conducting CR with people who have cognitive impairments, it is good practice, if possible, to obtain a collateral perspective from a family carer,30,42 and such a perspective is particularly valuable in research trials. For this reason, we concluded that an inclusion criterion for participating in GREAT should be the availability of a carer who is willing to provide collateral information. The BGSI provides for the inclusion of parallel informant ratings. A further limitation in the pilot trial was that ratings were obtained post intervention only and not at the 6-month follow-up. In GREAT, we assessed goal attainment at each follow-up.

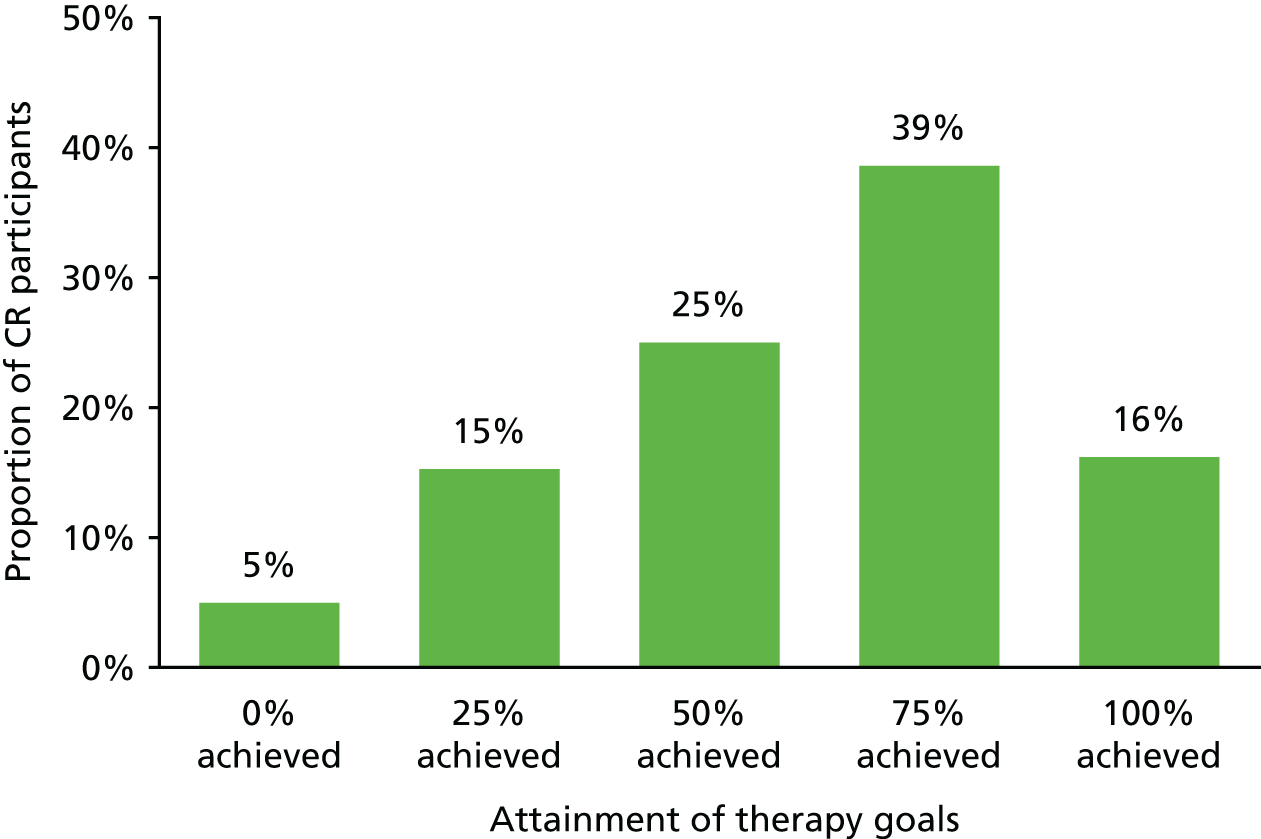

In the pilot trial, 46% of goals were rated as being fully achieved, 50% were rated as being partially achieved and 4% were rated as being not achieved within the 8-week time frame of the intervention. Reviewing the therapy logs kept by the therapist indicated that, in the case most of the ‘partially achieved’ goals, the therapist considered that further improvements could have been achieved with a little more time. The therapist’s view was that a slightly longer intervention was needed in order to optimise and consolidate benefits. For GREAT, we therefore decided on a 10-session intervention with four additional maintenance sessions.

Finally, the lack of observed differences between the relaxation therapy and TAU groups suggested that in a further trial, a two-arm design comparing CR with TAU should be acceptable.

Aims of GREAT

Building on our extensive development work, we aimed to provide definitive evidence about whether or not goal-oriented CR is a clinically effective and cost-effective intervention for people with early-stage Alzheimer’s disease or vascular or mixed dementia and their carers.

We hypothesised that:

-

This personalised intervention would improve functioning in areas directly targeted in the therapy sessions, and this would be reflected in self-ratings and carer ratings.

-

The intervention might have an impact on perceived self-efficacy, reflecting a possible psychological mechanism of action.

-

Carers of participants receiving the intervention, having learned new ways of supporting and enabling their relatives, might report feeling less stressed following the intervention.

In line with our theoretical model of CR, we did not anticipate changes in performance on cognitive tests, as CR does not directly target or train specific underlying cognitive processes. We did not plan to select participants on the basis of having clinical levels of depression or anxiety, poor scores on quality-of-life measures or carers who reported that their quality of life was poor, although we expected that some participants would show these features. This would necessarily limit the potential for demonstrating improvements in these domains. Nevertheless, there were some improvements in these domains in the pilot trial,63 and we therefore planned to include relevant measures in our assessment of secondary outcomes. This would also make it possible to identify any harms arising if the intervention had a negative impact on well-being.

We set the following specific objectives:

-

To compare the effectiveness of goal-oriented CR with that of TAU, with regard to (1) improving self-reported and carer-rated functional performance in areas identified as causing concern by people with early-stage dementia, (2) improving the quality of life, self-efficacy, mood and cognition of people with early-stage dementia and (3) reducing stress levels and ameliorating the quality of life of carers of participants with early-stage dementia.

-

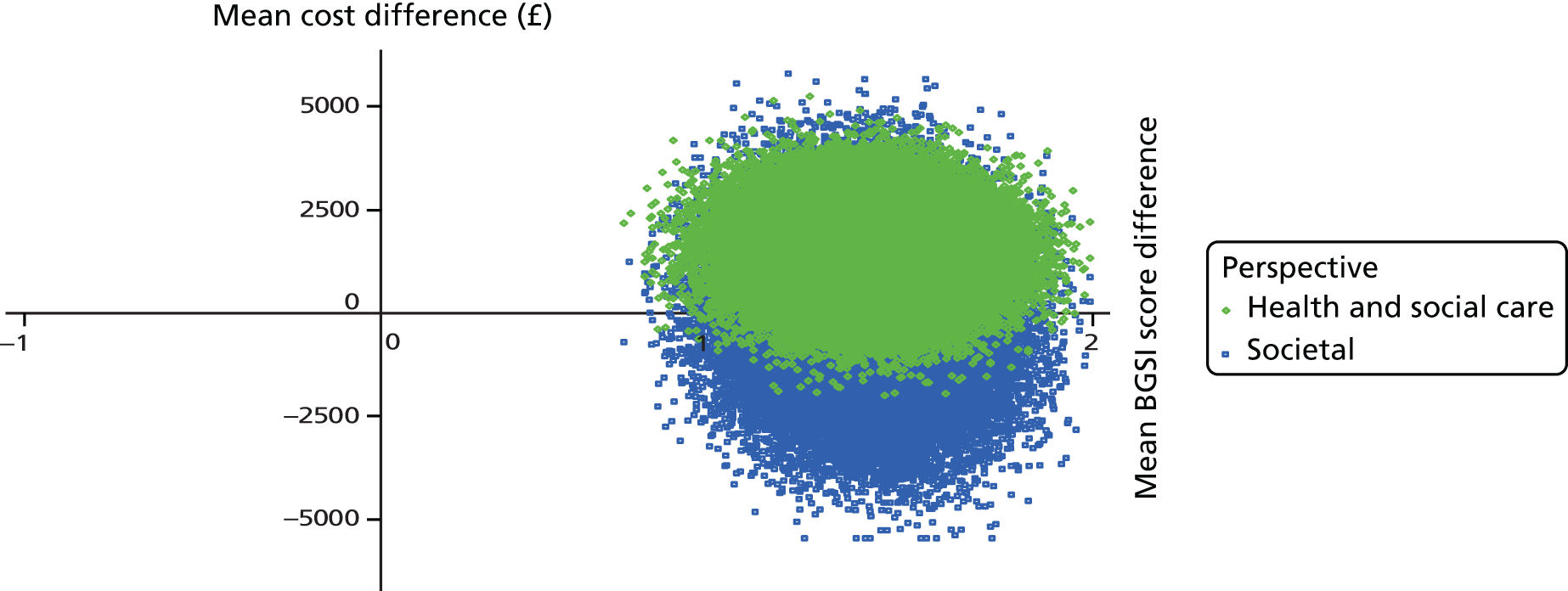

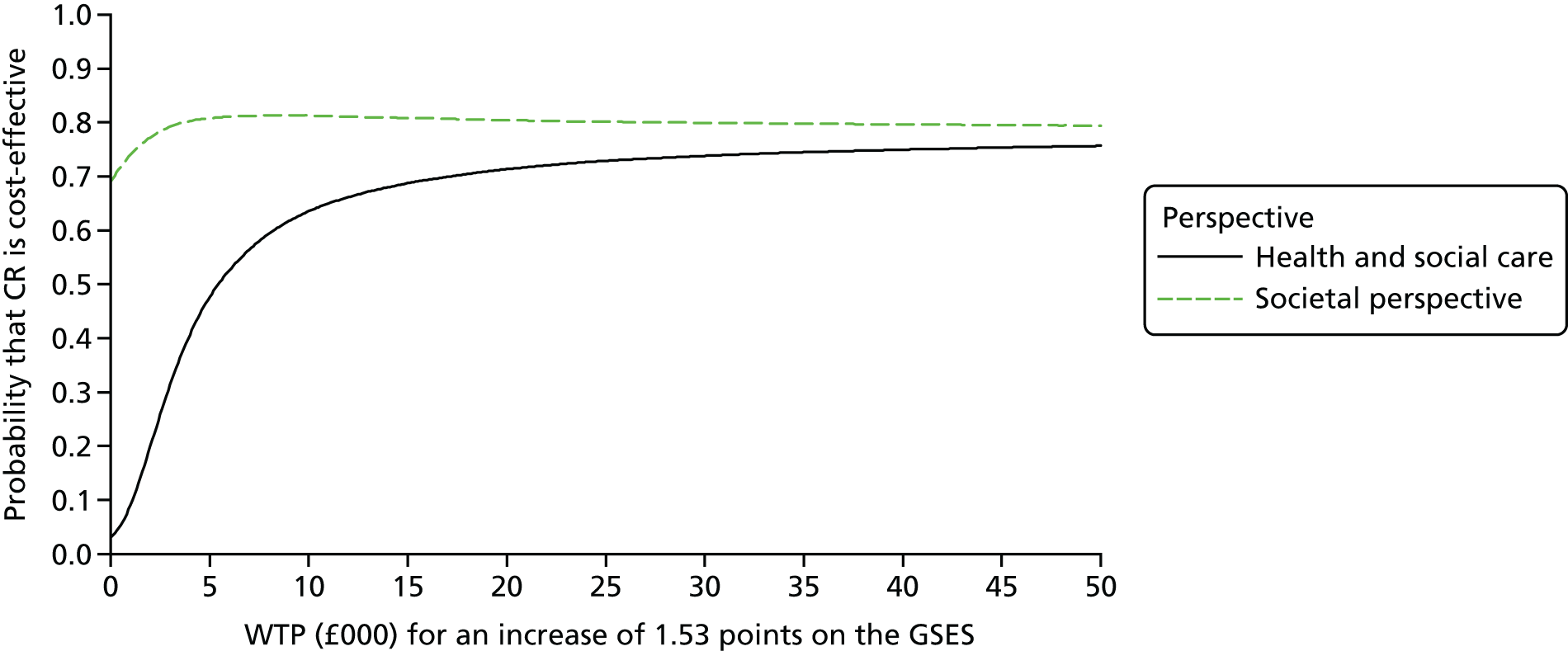

To estimate the incremental cost-effectiveness of goal-oriented CR compared with TAU.

-

To examine how the goal-oriented CR approach could most effectively be integrated into routine NHS provision, to develop a pragmatic approach that could be directly applied within standard NHS services and to develop materials to support the implementation of this approach within the NHS following trial completion.

A short journal article presenting the results of the GREAT trial has been published in the International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 72 The following chapters provide a detailed account of all aspects of the trial.

Chapter 2 Methods

Design

This was a multicentre, two-arm, single-blind randomised (on a 1 : 1 basis) controlled trial comparing CR added to usual treatment with TAU alone. The design and planned flow of participants through the trial are summarised in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Overview of trial design and planned flow of participants through the trial. CLRN, Comprehensive Local Research Network; MHRN, Mental Health Research Network; NISCHR CRC, National Institute of Social Care and Health Research Clinical Research Collaboration; PwD, person/people living with dementia.

Ethics

The study was reviewed by Wales Research Ethics Committee (REC) 5, which issued a favourable opinion on 25 June 2012 (reference number 12/WA/0185), and was approved by the Bangor University School of Psychology REC. Based on findings from the pilot trial, it was expected that participants and carers who were allocated to receive the CR intervention would derive some benefits, whereas people who were allocated to receive TAU would not be harmed by this allocation. As there was no existing large-scale evidence about the effects of CR, it was not considered to be unethical to withhold the treatment from those allocated to receive TAU. In addition, based on existing evidence, there were no known risks associated with CR. However, trial researchers and therapists were trained to be alert to any concerns about participants’ well-being and to refer any serious concerns to the clinician responsible for the person’s care whenever possible, with the knowledge and permission of the person and their carer.

Governance

The trial was sponsored first by Bangor University (from its start on 1 October 2012 to 28 February 2015) and then, following transfer of the co-ordinating centre, by the University of Exeter (from 1 March 2015 until its completion on 31 December 2016). The governance was overseen by a Trial Steering Committee (TSC), which included two Alzheimer’s Society research volunteers who were former carers and a sponsor’s representative, and by a Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee.

Trial registration

The trial was registered with Current Controlled Trials under reference ISRCTN21027481.

Trial protocol

The trial protocol was published in 2013. 73

Participants

Participants were individuals of any age who were diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease or vascular or mixed dementia, and who were in the mild stages of the condition. Each participant was recruited together with a carer.

Eligibility

Inclusion criteria

-

Participants had to have been assigned an ICD-10 diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia or mixed Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia. These conditions are estimated to account for 89% of all dementia diagnoses. 74 Although people with rarer subtypes of dementia could potentially benefit from CR, they might require an intervention that is tailored to take account of the specific profile of their condition, and we considered that this would best be assessed in separate studies.

-

Participants had to be in the relatively early stages of dementia, with mild to moderate cognitive impairment as indicated by a MMSE75 score of ≥ 18 points. Although people with more advanced dementia could potentially benefit from CR, the focus and specific approach would differ, and using a cut-off score in this way provided a basic means of ensuring that the approach was appropriately targeted.

-

It was acknowledged that some, but not all, participants would be receiving dementia-specific medication in accordance with standard practice guidelines. To ensure that the results were not affected by changes in medication use, participants taking dementia-specific medication, such as acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, must have been receiving a stable dose for at least 1 month before entering the trial, with no expectation that the dose would be changed during the course of the trial unless a specific clinical need emerged.

-

Participants had to have a carer who was willing to take part. Having a carer involved is not essential, although it is helpful, for CR; however, for the purposes of the trial, it was important to have collateral information and informant ratings of progress, and it was valuable to be able to determine whether or not CR provided any benefits for carers. By ‘carer’, we mean a family member or close friend who provides unpaid care and support; we acknowledge that some people undertaking this role may not use the term ‘carer’ to describe their role.

-

Participants had to be able to give informed consent to participation. This CR intervention was aimed at people in the earlier stages of dementia and involved engaging the person with dementia in a collaborative process of identifying and addressing meaningful and personally relevant goals. It was therefore essential for participants to understand the process and make a positive choice to engage with it.

Exclusion criteria

-

Potential participants were excluded if they had a prior history of stroke, brain injury or other significant neurological condition. Such conditions would be expected to affect cognitive, behavioural and emotional functioning, and people who have one of these conditions prior to developing dementia could have additional rehabilitation needs. Although such individuals might benefit from CR, their inclusion would have represented a potential confounding factor.

-

Participants were excluded if they were unable to speak English. This criterion was applied for practical reasons, because of the time and costs that would be involved in translating standardised measures and providing interpreters for assessment and therapy sessions. However, when setting this criterion, we expected that no, or only very few, individuals would be excluded from participation owing to an inability to communicate in English.

Any cases of participants for whom eligibility was unclear were referred to an eligibility panel consisting of four clinically qualified co-investigators (two old age psychiatrists, one neuropsychiatrist and one clinical psychologist) for a decision.

Recruitment

Participants were recruited through NHS services, such as memory clinics and old age psychiatry teams, carer and patient support groups, led by NHS staff, support groups and networks run by the Alzheimer’s Society and Join Dementia Research. Recruitment to the trial covered a 36-month period from 1 April 2013 to 31 March 2016.

Potentially eligible individuals were initially identified by either GREAT researchers or National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Clinical Research Network staff in England and Health and Care Research Wales staff in Wales (previously the National Institute of Social Care and Health Research Clinical Research Collaboration). GREAT researchers and research network staff visited clinics to provide information and ascertain interest in participating. Research network staff also identified possible participants through note-screening and wrote to them on behalf of the responsible clinician; they were invited to indicate their interest by sending a reply slip directly to a GREAT researcher, who then made contact by telephone, sent written information and made a further telephone call to ascertain the participant’s willingness to continue.

When a possible interest in participating was identified, a GREAT researcher visited the potential participant and carer to explain the study in detail, answer any questions, recheck eligibility and ensure that the person with dementia had the capacity to consent. Informed consent from both the person with dementia and the carer was taken at this visit or, if either person required more time to decide, at a subsequent visit. As participants were in the early stages of dementia, we expected that they would continue to have the capacity to consent throughout the period of participation. However, on entry to the trial, participants were asked whether or not, in the event that they did lose capacity, they would wish to continue to be included in the trial and to have their data used in the analysis.

Obtaining informed consent at the start of the trial was only the beginning of an ongoing process. This is particularly crucial in an intervention of this kind, which requires the participant’s active engagement. The trial researchers and therapists were trained to monitor ongoing consent and identify and respond to any indication of a possible withdrawal of consent.

Locations

The trial was conducted in eight NHS sites throughout England and Wales. These were:

-

North Wales – Betsi Cadwaladr University Health Board (Bangor site)

-

South Wales – Cardiff and Vale University Health Board (Cardiff site)

-

London – South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust, with recruitment supported by King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, St George’s Healthcare NHS Trust, and Oxleas NHS Foundation Trust (London site)

-

South East England – Kent and Medway NHS and Social Care Partnership Trust (Kent site)

-

South West England – RICE (Research Institute for the Care of Older People), Bath, with recruitment supported by Royal United Hospitals Bath NHS Foundation Trust and by general practitioner (GP) practices within the Wiltshire NHS Clinical Commissioning Group [(CCG) Bath site]

-

West Midlands – Birmingham and Solihull Mental Health NHS Foundation Trust, with recruitment supported by Black Country Partnership NHS Foundation Trust and Heart of England NHS Foundation Trust (Birmingham site)

-

North West England – Manchester Mental Health and Social Care Trust, with recruitment supported by Pennine Care NHS Foundation Trust (Manchester site)

-

North East England – Northumberland, Tyne and Wear NHS Foundation Trust (Newcastle site).

Setting

All assessments and intervention sessions were conducted in participants’ own homes.

Sample size

Power calculations were based on findings from the pilot trial. Improvement in goal performance was assessed in the pilot trial, with the rating scale of the COPM,38 which is equivalent to the rating of goal attainment used as the primary outcome measure in GREAT. The effect size for improvement in goal performance was large, with a standardised effect of > 1 at the post-intervention assessment. However, it was important to be able to detect at least medium effect sizes of 0.3 for both the primary and secondary outcomes. To achieve 80% power to detect a medium effect size of 0.3, with alpha 0.05, in primary and secondary outcomes, 175 people with dementia, together with their carers, were needed to complete the trial in each treatment arm. Attrition in the pilot trial was 19% overall, but as the rate could be higher in a longer multicentre trial, we adopted a more conservative estimate of 27%. Allowing for the potential attrition of 27%, it was necessary to randomise 480 people with dementia, each with a carer.

To meet this target, we calculated that each centre would need to recruit three participants per month over 27 months, a total of 80 participants per site. Experience suggested that one in three of the people with dementia who were identified as eligible and invited to participate would be successfully recruited; thus, each month, nine potentially eligible participants would need to be approached in each centre.

Randomisation

Participants were individually randomised following consent and a baseline assessment. Randomisation was triggered by the trial researchers on completion of the baseline assessment through secure web access to the remote randomisation centre, the North Wales Organisation for Randomised Trials in Health (NWORTH) Clinical Trials Unit (CTU) at Bangor University. In this system, which was maintained and monitored independently of the trial statistician or other trial staff, the randomisation was performed by dynamic allocation76 to protect against subversion while ensuring that the trial maintained good balance to the allocation ratio of 1 : 1, both within each stratification variable and across the trial. Participants were stratified by centre, sex, age (< 75 years vs. ≥ 75 years) and MMSE score (< 24 points vs. ≥ 24 points). For validation purposes, additional information was recorded, including the participant’s trial number, initials and date of birth and the details of the person requesting the randomisation. Group allocation was notified to the trial therapists.

Blinding

The trial researchers were blind to participants’ group allocation. The importance of maintaining blinding was emphasised in the training of both the researchers and the therapists. The potential for unblinding could arise through the researchers’ contact with participants at the 3- and 9-month assessments and through day-to-day contact between the researchers and the therapists at each site.

To address the potential for unblinding through day-to-day contact between researchers and therapists at each site, we ensured that they were based in different offices and did not share telephones or printers. Arrangements for the follow-up assessment visits by the researcher were made by the therapist for all participants. As the participants and carers could not be blinded to their group allocation, they were specifically asked not to comment at post-intervention and follow-up assessments on the nature of their involvement in the study and not to reveal to the researcher whether or not they had been visited by the therapist. This was explained by the researcher during baseline visits and included in the written information given to participants, and it was reiterated by the therapists when they contacted participants to confirm the dates of the 3- and 9-month assessments.

Following each assessment at the 3- and 9-month points, the blinded researcher noted to which condition s/he thought the participant had been allocated and how certain s/he was of the allocation.

Owing to the nature of the intervention, it was not possible to blind participants and carers to group allocation.

Intervention

Participants allocated to the intervention group received CR in addition to usual treatment. CR is an individualised, goal-oriented, problem-solving approach aimed at managing or reducing functional disability and maximising engagement and social participation, in which people with dementia and their carers work together with a health professional over a number of sessions to identify personally relevant goals and devise and implement strategies for achieving these. In this trial, CR was delivered by appropriately qualified therapists with experience of rehabilitative interventions. We set out to recruit therapists with psychology, occupational therapy or nursing backgrounds. In the event, our therapists were from occupational therapy and nursing backgrounds. Ten therapists worked on the trial [nine occupational therapists (OTs) and one nurse]; two sites (West Midlands and North West England) had a change of therapist during the trial.

Cognitive rehabilitation was delivered in 10 individual sessions over 3 months, followed by four maintenance sessions over 6 months. Carers were involved in part of each session whenever possible, and were kept informed when direct involvement was not possible (e.g. because the carer was at work). The involvement of a carer helps to ensure that skills are maintained and applied to novel situations, and it facilitates communication about how current or possible future difficulties might be managed.

Over the course of the 10 weekly sessions, participants with dementia worked collaboratively with the therapist to address personal rehabilitation goals. Alongside the information from the initial assessment with the BGSI, the therapists used the Pool Activity Level (PAL) instrument77 to facilitate their understanding of participants’ current level of functioning and potential for goal attainment and to support the development of a comprehensive formulation. The PAL instrument provides a framework for care-planning with people who have cognitive impairments caused by conditions related to dementia, stroke and intellectual disability. 77,78 The PAL instrument contains a valid and reliable tool for assessing functional ability in nine domains, with ability being graded at one of four levels for each domain. It was recommended in the national clinical practice guideline for dementia79 for activity of daily living skill training and for activity planning. The instrument also contains profiling tools for interpreting the assessment in order to plan and deliver effective enabling care and support. As part of the assessment for each participant, the therapist completed the PAL checklist with the carer, and used the resulting profile in planning and implementing the intervention.

Drawing on the goals identified at the baseline assessment, up to three behavioural goals were operationalised for each participant and strategies for addressing these were devised and implemented. These strategies could include environmental adaptations and prompts, use of compensatory memory aids, procedural learning of relevant skills, supported learning of important new information and restorative learning methods to reactivate prior knowledge. For each goal, a set of strategies was formulated into an individual plan, following discussion of the possible options and selection of the most promising solutions. Following the introduction and modelling of strategies and skills during the therapy sessions, the participant and carer worked on the selected goal between sessions following an agreed schedule of activities. Progress was reviewed and the strategies adopted were adjusted as necessary on a weekly basis. Goals were introduced one at a time, in a flexible manner depending on the rate of progress. Performance for each goal was independently rated at the outset and in week 10 by the participant, carer and therapist.

Work on the identified goals was supplemented by five key therapy components, which were considered at appropriate stages across the 10 sessions:

-

Developing a problem-solving orientation. Introduction of, and practice in applying, a solution-focused problem-solving approach by following a short sequence of steps to specify and test possible solutions. This was emphasised at the start of therapy and provided a continued focus throughout.

-

Addressing motivational and affective issues. Strategies to tackle motivational and affective responses that could affect the progress of therapy were considered at an early stage:

-

Emotion regulation strategies. Encountering problems with functioning in daily life can result in emotional reactions, such as anxiety, distress or frustration. Tackling therapy goals and finding these challenging could potentially trigger similar responses. Therefore, it was important to assess participants’ strengths and needs in this area and, when appropriate, introduce, or enhance, emotion regulation strategies for managing anxiety and other affective reactions, and provide practice in strategy use and application.

-

Behavioural activation strategies. Lack of interest, anhedonia, apathy and withdrawal are common and can lead to further loss of skills and confidence. Therefore, it was important to assess participants’ activity levels and, when appropriate, to identify plans for increasing engagement in meaningful and enjoyable activities and to support the implementation of these plans.

-

-

Addressing cognitive disability. A comprehensive set of skills and strategies was developed to help to manage the effects of cognitive disability, complementing the goal-specific problem-solving work:

-

The participant’s use of compensatory strategies (e.g. calendars, diaries, reminder systems) was reviewed and a plan for improving strategy use was developed and implemented, which might include both increasing the efficiency of existing strategies and introducing new strategies.

-

The participant’s knowledge and use of strategies for retaining new information or improving recall was reviewed, and practice in applying key strategies (mnemonics, semantic association and spaced retrieval) was provided, enabling the participant to identify a preferred strategy that could be used in everyday situations.

-

– Difficulties with attention and concentration can interfere with strategy application. Methods for maintaining or improving attention and concentration were taught and practised.

-

-

Carer support. Specific support for the carer included discussion of the carer’s well-being and sources of stress, and identification of strategies the carer could use, or enhance, to manage stress more effectively.

-

Signposting to other sources of support. For both the carer and the participant, the therapist explored options for further sources of help and support, and encouraged them to take advantage of these.

The four maintenance sessions were focused on supporting the maintenance of gains and encouraging continued goal performance and strategy use.

It was acknowledged that participants’ progress with goals would be variable, and although it was suggested that participants work on three goals, the number of goals tackled was likely to vary. Similarly, participants’ needs with regard to the other therapy components were expected to vary, and hence both the amount of time spent on these and the stage at which they were introduced could also vary for different individuals. The therapists needed to be flexible in structuring the sessions in order to take account of individual differences. An example of a session-by-session protocol for the CR intervention, which assumes that three goals are addressed, is shown in Table 1.

| Session | Participant with dementia | Carer | Between sessions |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Orientation to the intervention and explanation of between-session tasks; goal 1 selection and rating; emotion regulation strategies; activity monitoring exercise | Orientation and explanation; goal 1 rating; emotion regulation; activity monitoring | Monitor current activities using diary sheet; practise emotion regulation strategies |

| 2 | Review of activity monitoring and plans for increasing activities; introduction of solution-focused problem-solving approach; intervention plan for goal 1; emotion regulation | Problem-solving; goal 1 intervention; plans for increasing activities | Agreed tasks for goal 1; practise emotion regulation strategies; develop plans for increasing activities; practise solution-focused approach |

| 3 | Progress review for goal 1; progress review for increasing activities; review of adaptations and compensatory strategy use; emotion regulation | Progress review; review of adaptations and compensatory strategy use; increasing activities | Agreed tasks for goal 1; practise emotion regulation strategies; implement plans for increasing activities |

| 4 | Progress review for goal 1; progress review for increasing activities; goal selection and rating – goal 2; plan to improve compensatory strategy use | Progress review; goal 2a rating; plan to improve compensatory strategy use | Agreed tasks for goal 1; implement changes to compensatory strategies |

| 5 | Progress review for goal 1; progress review for compensatory strategy use; intervention plan for goal 2; strategies for improving attention and concentration | Progress review; goal 2 intervention; strategies for improving attention and concentration | Agreed tasks for goals 1 and 2; changes to compensatory strategies; practise maintaining attention and concentration |

| 6 | Progress review for goals 1 and 2; progress review for compensatory strategy use; goal selection and rating – goal 3; improving attention and concentration | Progress review; goal 3a rating; carer well-being | Agreed tasks for goals 1 and 2; practise in maintaining attention and concentration |

| 7 | Progress review for goals 1 and 2; intervention plan for goal 3; restorative strategies for taking in new information | Progress review; restorative strategies; carer well-being | Agreed tasks for goals 1–3; practise restorative strategies |

| 8 | Progress review for goals 1–3; practise restorative strategies | Progress review; application of restorative strategies | Agreed tasks for goals 1–3; practise restorative strategies |

| 9 | Progress review for goals 1–3; practise restorative strategies; preparation for ending weekly sessions | Progress review; discuss other sources of help and support | Agreed tasks for goals 1–3; practise restorative strategies; investigate other sources of support |

| 10 | Progress review for goals 1–3; review of strategy use for emotion regulation, attention and concentration strategies, compensatory strategies and restorative strategies; re-rating of goal performance | Progress review; re-rating of goal performance; review other sources of help and support | Review written information provided about strategies; monitor progress; when appropriate, access other sources of support |

| M1 | Reorientation to problem-solving approach; review of progress with goals; review of strategy use | Problem-solving approach; progress review | Review information given; monitor progress |

| M2 | Problem-solving; review of progress with goals; review of strategy use | Problem-solving; progress review | Review information given; monitor progress |

| M3 | Problem-solving; review of progress with goals; review of strategy use | Problem-solving; progress review | Review information given; monitor progress |

| M4 | Review of progress; goal ratings; reminder of problem-solving approach and strategies; goodbyes | Progress review; goal ratings; future orientation; goodbyes | N/A |

Intervention fidelity

In line with practice recommendations,80 intervention fidelity was promoted through the provision of initial training, a therapy manual, regular centralised supervision and the recording of information about each session in therapy logs:

-

Training – therapists participated in a 2-day training course to prepare them for delivering the intervention at the start of the trial, and subsequently attended a refresher training day annually. The co-investigator Jackie Pool, an OT, specialist consultant and experienced trainer with expertise in applying rehabilitation in dementia care, delivered initial training to all of the trial therapists and guided them throughout the trial in the effective and consistent application of the therapy protocol.

-

Therapy manual – therapists were provided with a detailed therapists’ manual that included information about the principles and key elements of CR, as well as session-by-session overviews and references to the relevant literature.

-

Supervision – therapists had monthly individual supervision via video-conferencing and 3-monthly face-to-face group supervision meetings with Jackie Pool, with ad hoc advice available between meetings if needed. Supervision meetings offered detailed guidance on the delivery of CR and enabled ongoing monitoring of fidelity to the protocol, with potential concerns discussed and resolved as they were raised. Each supervision session was documented and notes were reviewed annually to ensure the appropriate involvement of all therapists in the supervisory process. The trial manager attended the quarterly supervision meetings to review progress with therapy provision and regular updates were given to the chief investigator and the trial management group. The supervision meetings were focused on reviewing therapists’ plans for achieving individual therapy goals, resolving any specific difficulties relating to individual participants and reviewing overall progress with implementing the therapy protocol for current participants in the CR group. Advice was also given about achieving a positive therapeutic relationship with participants and managing caseloads. Group meetings provided a platform for sharing best practice and ensuring consistency across sites.

-

Therapy logs – supervision was facilitated by the use of therapy logs summarising session content (with participant details anonymised). A therapy log was maintained for each participant receiving CR, with notes on session content added by the therapist after each session. The logs were submitted to the supervisor for review prior to the supervision sessions and formed a basis for discussion during the sessions.

Treatment fidelity was considered in relation to form and function. 81 While the therapy protocol was prescriptive in relation to the number and length of sessions and provided guidelines on the typical content of each session (form), a degree of flexibility was required in order to facilitate individual goal attainment, as this was a key aspect of the intervention (function). Therapists could therefore make adjustments to the content of therapy sessions in order to take account of participants’ preferences, levels of cognitive and functional ability, and social and family context.

Comparator

The comparator was TAU. Participants allocated to the control group received usual treatment only, and had no contact with the research team between assessments. TAU consisted of dementia-specific medication when prescribed and any other services normally provided, apart from specific programmes of CR or other cognition-focused interventions. TAU could include, for example, routine monitoring by the Memory Clinic, information provision and attendance at drop-in groups or support groups, or carer participation in support groups, as well as the receipt of any services provided by voluntary organisations.

Outcomes

The assessment measures are summarised in Table 2, which indicates which measures were administered at each time point by the trial researchers. The assessments were completed by 15 trial researchers, all with backgrounds in psychology, nursing or clinical research. Some sites employed more than one researcher. There were changes of researchers during the trial at three sites (West Midlands, South West England and London).

| Domain | Measure | Time point | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 3 months post baseline | 9 months post baseline | ||

| Person with dementia | ||||

| Goal attainment | BGSI | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Satisfaction with goal attainment | BGSI | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Quality of life | DEMQOL | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Self-efficacy | GSES | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Depression | HADS | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Anxiety | HADS | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Memory | RBMT story recall | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Attention | TEA elevator counting | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Executive function | D-KEFS letter fluency | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Comorbid conditions | Charlson Index | ✗ | ||

| Service utilisation | CSRI | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Carer | ||||

| Participant’s goal attainment | BGSI | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Stress | RSS | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Quality of life | WHOQOL-BREF | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Health status | EQ-5D | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

Demographic details

At the baseline assessment, we collected demographic and background information for the person with dementia and their carer, including sex, age, relationship between the person with dementia and the carer and whether they live together, age at onset of dementia, educational level, social class and comorbid health conditions assessed using the Charlson Comorbidity Index,82 to provide both the number of conditions and the weighted comorbidity score. A weighted score of ≥ 5 is used to indicate people with a particularly high level of comorbidity translating into a high risk of mortality. This was intended to provide a profile of the sample and to allow us to examine the effects of demographic and social variables on treatment efficacy.

Primary outcome measure

The primary outcome for GREAT was participant-reported goal attainment at 3 months post randomisation (the 3-month follow-up). Participant-reported goal attainment was also assessed at 9 months post randomisation (the 9-month follow-up). Parallel carer ratings of goal attainment were obtained at both the 3-month and 9-month assessments. These ratings were obtained using the structured interview protocol of the BGSI. The trial researchers participated in a 2-day initial training course to prepare them for conducting goal-setting using the BGSI, attended annual refresher training days and participated in monthly telephone supervision with two of the investigators (from a rotating panel of four), which was focused specifically on optimising the goal-setting process.

During the initial assessment using the BGSI, participants were asked how memory and other cognitive difficulties affect (1) everyday tasks, activities and routines, (2) the possibility of engaging in pleasurable and meaningful activities and (3) social contacts and relationships. For each of these domains, participants rated how important it was to them and how ready they were to try to make changes, in each case using a scale of 1–10. This provided a basis for identifying areas in which participants would like to make changes or improvements and for setting specific goals. Participants could select up to three goals. Goals were expressed in behavioural terms using SMART principles: specific, measurable, achievable, realistic and attainable within a defined period of time. Participants described what they want to be able to do and what they are currently doing, and made ratings of their current level of goal attainment on a scale of 1–10, whereby 1 was unable to do or not currently doing and 10 was able to do well with no difficulty. Participants also rated their satisfaction with this level of attainment on the same scale of 1–10, where 1 was extremely dissatisfied and 10 was extremely satisfied. The scale was presented in a visual format as well as through verbal explanation. The mean levels of attainment and satisfaction were calculated by summing the ratings across all of the identified goals and dividing by the number of goals identified.

Carers provided their own descriptions of the person’s current functioning and made parallel ratings of attainment on the same scale of 1–10. The mean ratings for attainment were calculated by summing the ratings across all of the identified goals and dividing by the number of goals.

At the 3-month and 9-month follow-ups, participants and carers were shown the goal descriptions and baseline ratings for the originally identified goals and asked to rate the current attainment and satisfaction levels for each goal. The mean attainment and satisfaction ratings were calculated as before.

The key information that the performance and satisfaction ratings provide is an indication of the extent and direction of change. In clinical practice, it is usual for people to remember and consider previous ratings or previously obtained information when making such ratings, and this can make current ratings more informative and the process of completing the ratings more transparent. 83 However, people with dementia may find it difficult to remember their previous ratings as a result of their memory difficulties. Various approaches to obtaining follow-up ratings are used in clinical trials, and one question that arises is whether or not participants should have access to their previous ratings when completing a new set of ratings at follow-up. Evidence shows that participants prefer to be reminded of previous scores and that, in the case of healthy adults, being reminded of previous scores produces no significant differences in ratings compared with not being reminded. 84 People with dementia, because of their difficulties with memory, may benefit more than other groups from being reminded about the rating process and being given access to their earlier ratings. Furthermore, in GREAT, participants in the CR group made in-session ratings of goal attainment in the sessions prior to the 3- and 9-month assessments, and providing a reminder of previous scores to all study participants removed this source of inequity.

Secondary outcome measures for participants with dementia

The secondary outcomes for the person with dementia at the 3- and 9-month follow-ups were self-rated quality of life, self-efficacy and mood, cognitive test scores (memory, attention and executive function) and extent of service utilisation. The following measures were taken at baseline and follow-up.

DEMentia Quality Of Life questionnaire85

The DEMentia Quality Of Life (DEMQOL) questionnaire is a measure of the health-related quality of life (HRQoL) of people with dementia, with good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha 0.87) and test–retest reliability (intraclass correlation coefficient 0.76) in people with mild to moderate dementia. We used the 28-item interviewer-administered questionnaire for the person with dementia to obtain participants’ ratings of their own quality of life. Items are rated on a 4-point scale, with potential scores ranging from 28 to 112. This measure was also used in the economic evaluation, drawing on the algorithm that has been developed to generate quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) scores from DEMQOL questionnaire scores. 86

Generalized Self-Efficacy Scale87

The Generalized Self-Efficacy Scale (GSES) is a 10-item scale that assesses a general sense of perceived self-efficacy, which is the potential to influence one’s situation through one’s own actions. Responses are made on a 4-point scale. Responses to all 10 items are summed to yield the final composite score with a range from 10 to 40. Cronbach’s alphas range from 0.76 to 0.90. 88

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale89

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) contains 14 items that form subscales for anxiety and depression. Each item is rated on a 4-point scale, giving maximum scores of 21 for anxiety and for depression. Scores of ≥ 11 on either subscale are considered to be a significant ‘case’ of psychological morbidity, with scores of 8–10 being classified as ‘borderline’ and scores of 0–7 being classified as ‘normal’. The HADS has been employed and validated in studies of people with dementia and carers. 90,91

Brief cognitive assessment battery

The brief cognitive assessment battery consisted of brief tests of memory, attention and executive function, suitable for people with early-stage dementia, each taking < 5 minutes to administer:

-

Memory – Rivermead Behavioural Memory Test (RBMT),92 a story recall subtest. The RBMT is a well-established, ecologically valid test of everyday memory. In the story recall task, the researcher reads out a short story, similar to a brief report of a newsworthy event in a daily newspaper, and the participant is asked for immediate and, after 20 minutes, delayed recall of the content. Recall is scored following a standard protocol (inter-rater reliability of > 0.9) with a maximum possible score of 21 for the immediate and for the delayed component. Four parallel versions of equivalent difficulty are available to permit reassessment without the risk of practice effects; practice effects are not anticipated with test–retest intervals of 3 and 6 months, but as a precaution we used a different version at each time point. The raw scores were used in the analysis, as they provide a greater range than the condensed standardised profile score that is used in the calculation of the overall RBMT score.

-

Attention – Test of Everyday Attention (TEA),93 elevator counting and elevator counting with distraction subtests. The TEA is a well-established, ecologically valid test of everyday attention, with subtests assessing different components of attention. The elevator counting subtest assesses sustained attention. Participants are required to count a short string of monotonous tones and give the total number. Seven strings are presented, and the total score is the number of strings correctly counted. The elevator counting with distraction subtest assesses auditory selective attention. Ten strings of tones are presented, this time also including distractor (high-pitched) tones that are not to be counted. The total score is the number of strings correctly counted. Three equivalent versions of each subtest are available to permit reassessment without the risk of practice effects; as above, practice effects were not anticipated, but as a precaution we used a different version at each time point.

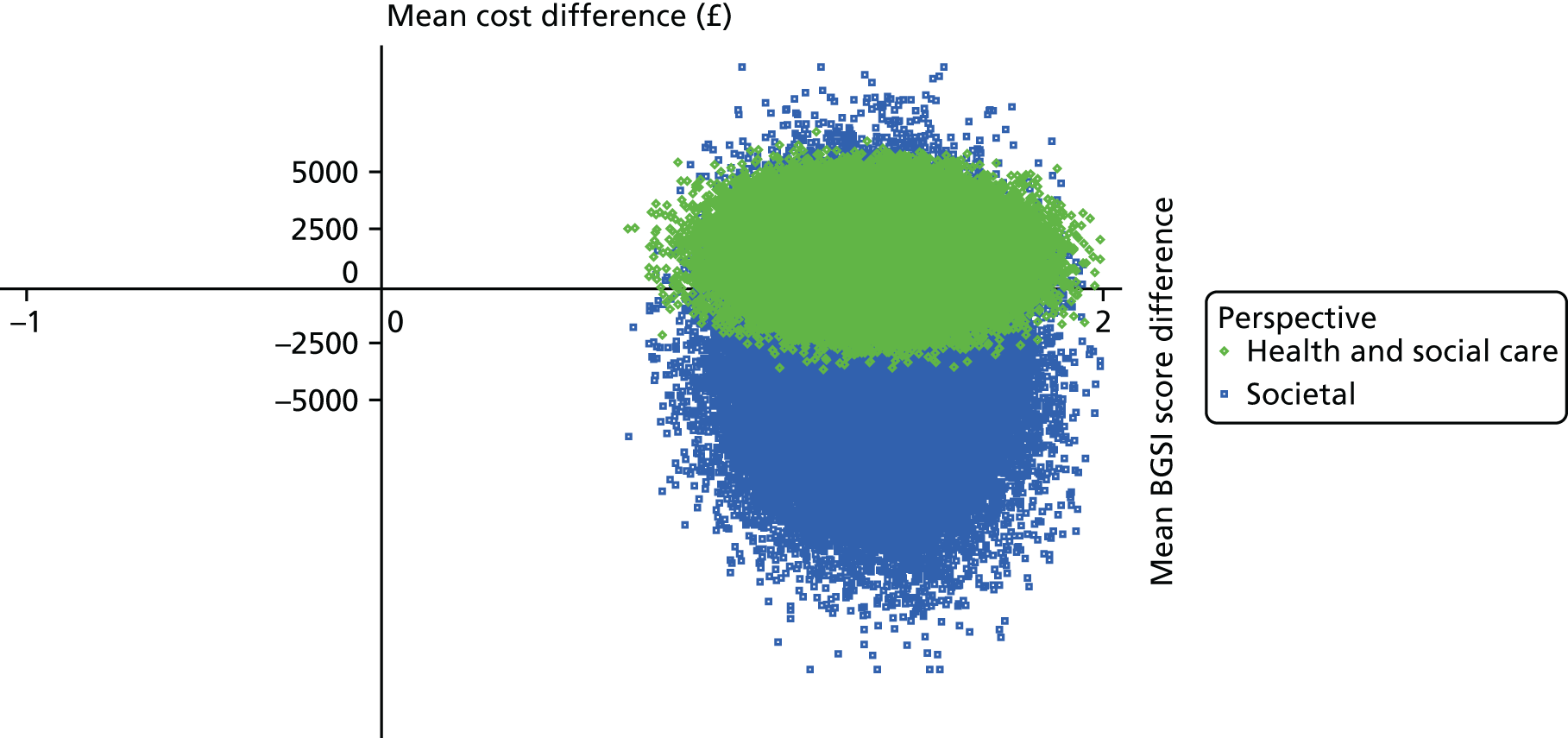

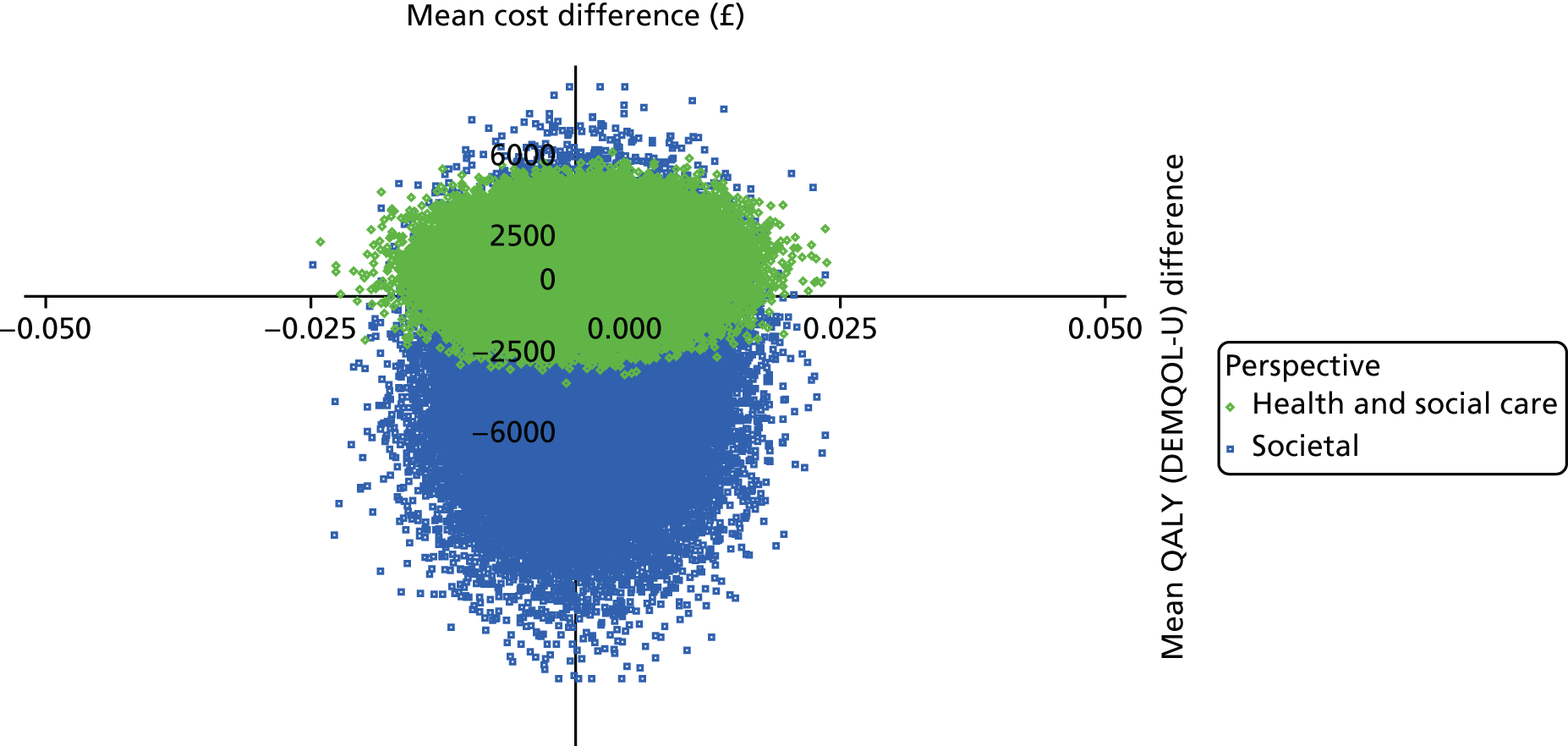

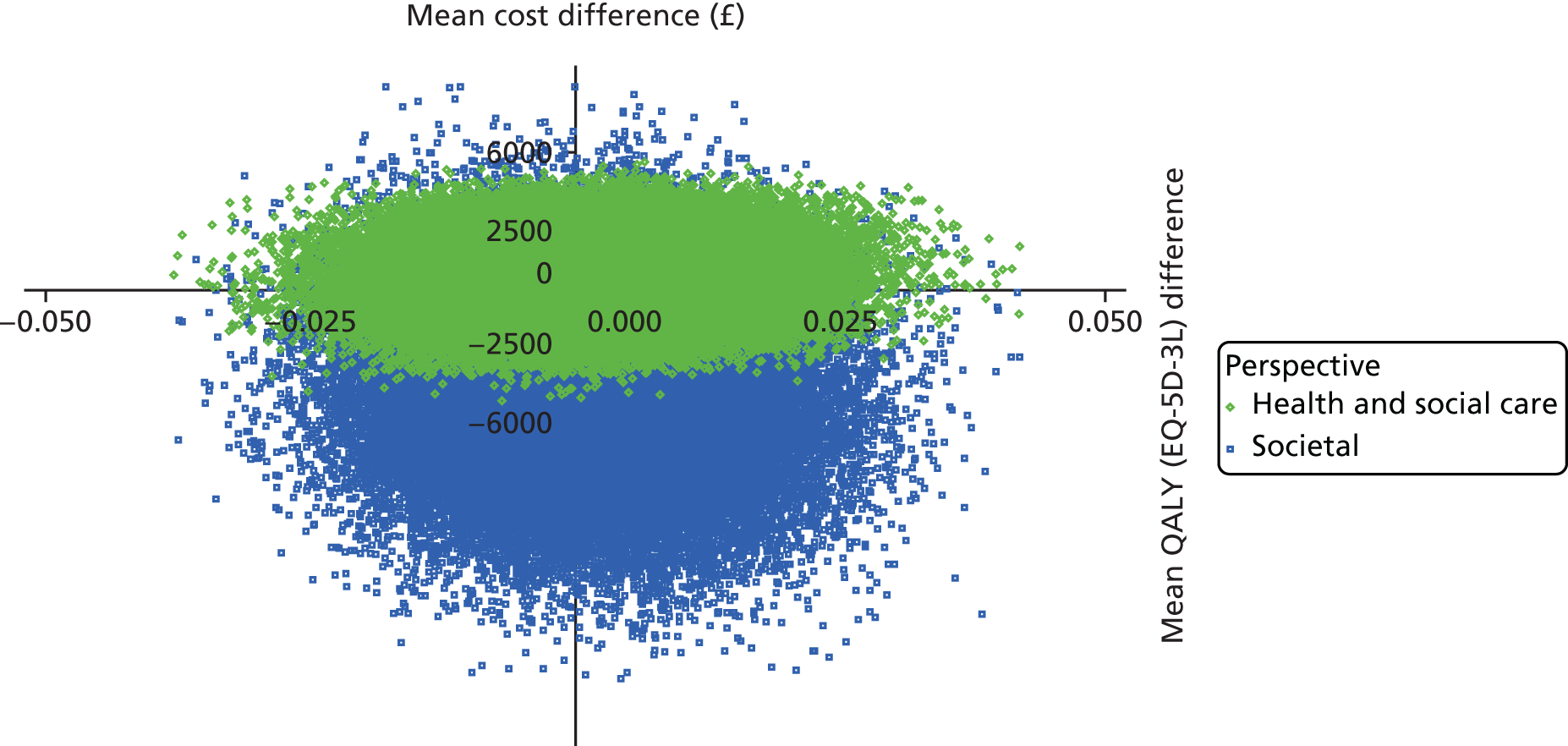

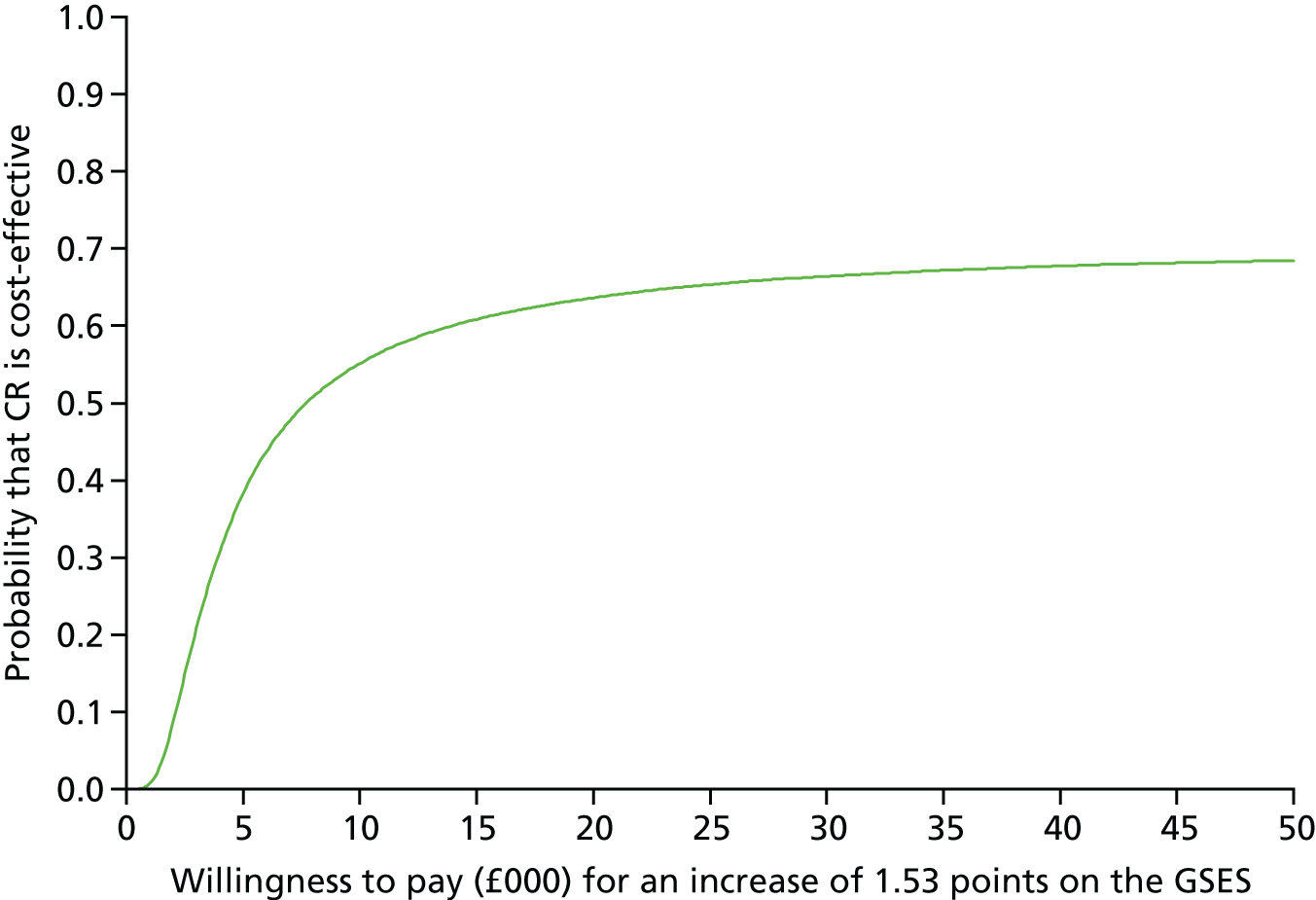

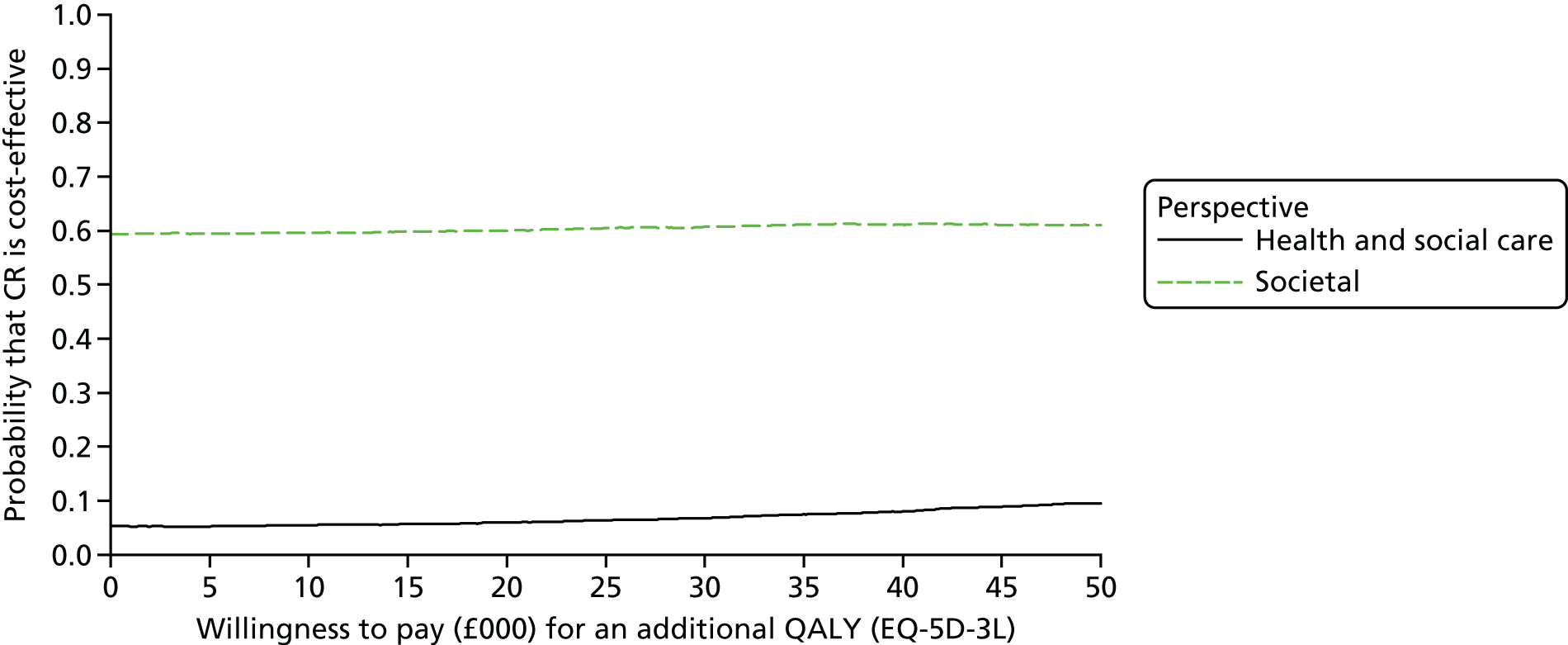

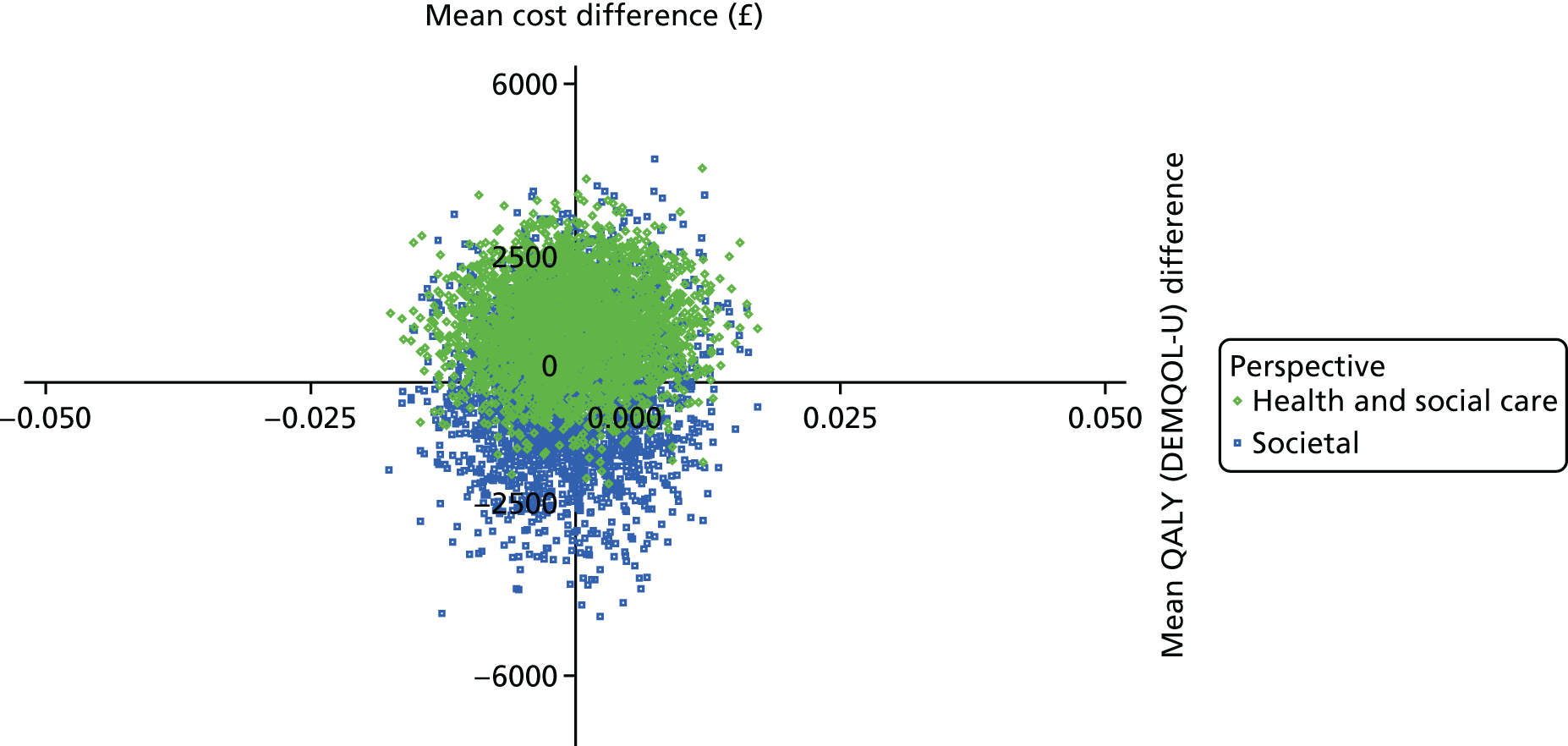

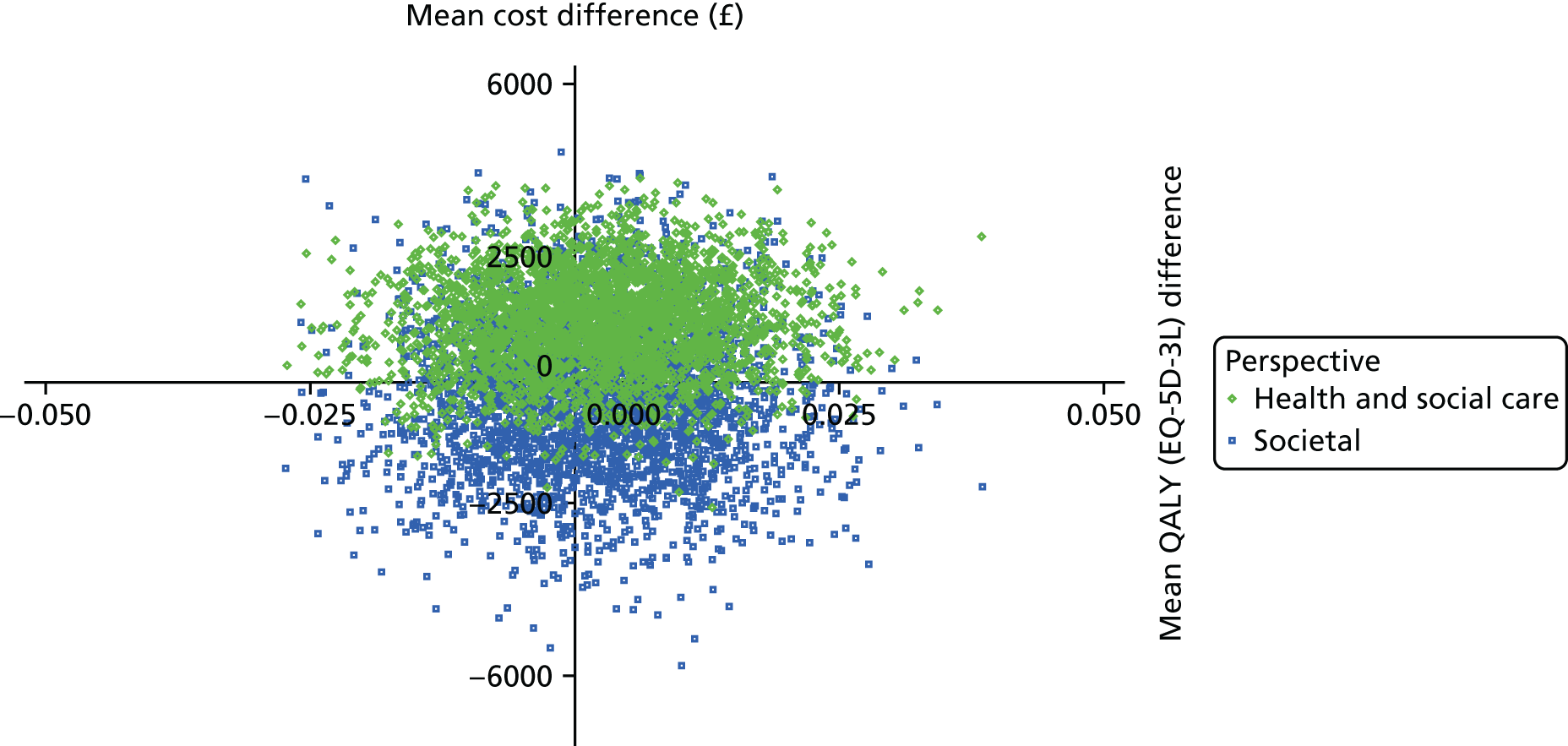

-