Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 11/69/02. The contractual start date was in September 2013. The draft report began editorial review in January 2018 and was accepted for publication in June 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Paul Little was Programme Director of the Programme Grants for Applied Research (PGfAR) programme, Editor-in-Chief for the PGfAR journal and a member of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Journals Library Editorial Group and the NIHR PGfAR expressions of interest – Health Technology Assessment Projects Remit Meeting. Trudie Chalder reports grants from Guy’s and St Thomas’ Charity. She was a faculty member at the Third International Conference on Functional (Psychogenic) Neurological Disorders, September 2017, Edinburgh, UK; a member of the Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) Education and Training Evidence Review Group (2016); a member of the IAPT Outcomes and Informatics Meeting (2016–present); and the president of the British Association for Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapies (2012–15), for which she did not receive payment. She delivered workshops on medically unexplained symptoms during the conduct of the study (money paid into King’s College London for future research). Trudie Chalder has a patent for the background intellectual property (IP) of the manuals that were developed prior to the trial starting. The Trial Steering Committee Chairperson, Peter White, was a colleague of Trudie Chalder in the past but he has recently retired. Rona Moss-Morris reports personal fees from training in irritable bowel syndrome interventions for Central and North West London NHS Foundation Trust and the University of East Anglia outside the submitted work. The patient manual is background IP developed by Rona Moss-Morris and Trudie Chalder in previous work. The therapist manual was developed for the Assessing Cognitive–behavioural Therapy in Irritable Bowel (ACTIB) trial. These manuals were made available only once the 12-month ACTIB follow-up was complete. Sabine Landau reports support via the Biomedical Research Centre for Mental Health at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Everitt et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Randomised controlled trial

Patient and public involvement

People with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) have been involved in the Assessing Cognitive–behavioural Therapy in Irritable Bowel (ACTIB) trial throughout, from the time of application for the Health Technology Assessment (HTA)-commissioned call through to discussion of the results and dissemination of the findings, including the development of this patient and public involvement (PPI) section of the report.

We were very fortunate to identify two PPI representatives, Jill Durnell and Kate Riley, who had participated in the Management of Irritable Bowel Syndrome (MIBS) feasibility study1 and who were willing to act as PPI representatives for ACTIB. They helped to develop the grant application to HTA for the ACTIB trial. They were positive about the idea of taking the website from MIBS forward to a full trial and commented on drafts of the outline application and full applications for feedback. In particular, our PPI representatives assisted with highlighting areas important to patients to include, with consideration of outcome measures and by helping to develop the Plain English summary and ensuring that it was clear and accessible for a non-specialist audience.

During the early development phase of the ACTIB study materials, our PPI representatives were involved in commenting on paperwork, questionnaires and the updated website to ensure that these were as accessible and user friendly as possible.

Our PPI representatives were part of our trial management team and received communications and updates on all trial management issues. One of our PPI representatives was happy to focus on participation in the Trial Management Group and our other PPI representative on the TSC.

Our PPI representatives have also been involved in the development of this HTA report (in particular the Plain English summary and this PPI section) and have agreed to continue in their PPI roles during our funded extension to complete a 24-month follow-up and process evaluation.

Some specific examples of our PPI representative activities and input are as follows:

-

Jill Durnell has presented to the local Clinical Research Network on being a PPI representative and participating in research.

-

Our PPI provided input and views on potential ways to improve follow-up rates. We instituted multiple methods of contacting participants to remind them to complete their questionnaires and offered them a Love2shop voucher (www.love2shop.co.uk; accessed 4 December 2018) for taking part in the study.

-

Our PPI representatives recently provided quotations for the Southampton primary care website to highlight the benefits/realities of PPI involvement:

Having benefited from participating in the ACTIB pilot study, I felt that I wanted to play a part in ensuring other IBS sufferers had the same opportunity. Being a PPI [representative] provides the opportunity to contribute to expressing the science into what it means to patients. Recruitment and retention of participants in studies is often a challenge. PPI input can enhance any literature provided to patients, by ensuring the information is not bewildering. Hopefully, this helps to keep them involved and the research to achieve its objectives.

Introduction

Irritable bowel syndrome is a common chronic gastrointestinal (GI) disorder, affecting 10–22% of the UK population, with NHS costs of > £200M per year. 2,3 Abdominal pain, bloating and altered bowel habits affect quality of life (QoL) and social functioning and can lead to time off work. 4,5 Treatment relies on a positive diagnosis, reassurance, lifestyle advice and drug therapies. However, many patients suffer ongoing symptoms.

Face-to-face cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) has been shown to help IBS, reducing symptom scores and improving QoL measures,6–8 but NHS availability is poor and cost-effectiveness is uncertain. 8 However, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance9 recommends CBT for patients with refractory IBS symptoms (i.e. ongoing symptoms after 12 months despite being offered appropriate medications and lifestyle advice).

Web-based CBT has shown promise in other long-term conditions, for example depression,10 tinnitus11 and fatigue in multiple sclerosis,12 and is recommended in guidelines13 for the management of depression. It has advantages, for example being accessible at a time, place and rate of completion convenient to the participant, without extra travel time and costs, but some research studies14 have found low levels of uptake and limited benefits. Small pilot trials have shown promise for web-based CBT in IBS15–17 but indicate that some therapist input is needed.

We previously developed a CBT self-management website to support patients with IBS (Regul8) and trialled it among 135 patients in the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Research for Patient Benefit-funded MIBS feasibility study. 1,15

This NIHR HTA ACTIB trial was in response to a commissioned call to assess the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of psychological interventions for patients with refractory IBS.

Aims and objectives

The primary aim of ACTIB was to determine the clinical effectiveness of therapist telephone-delivered CBT (TCBT) and web-based CBT (WCBT) compared with treatment as usual (TAU) for reducing the severity and impact of symptoms in IBS at 12 months from randomisation.

The secondary aims were to:

-

determine the cost-effectiveness of TCBT and WCBT compared with TAU for reducing severity and impact of symptoms in IBS at 12 months

-

determine the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of TCBT and WCBT compared with TAU for reducing severity and impact of symptoms in IBS at 3 and 6 months

-

assess the effect of TCBT and WCBT on relief of IBS symptoms, QoL, enablement, anxiety and depression compared with TAU at 3, 6 and 12 months’ follow-up, and acceptability of the treatment.

Methods

The trial protocol for this trial has been published in Everitt et al. 18

Study design

We conducted an open, pragmatic randomised controlled trial (RCT) in primary and secondary care to determine the clinical effectiveness of TCBT and WCBT in patients with refractory IBS.

Setting

Patients were recruited from general practices from Wessex and South London Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs), and from one Southampton and two London secondary care sites [Southampton University Hospital Trust (SUHT), King’s College Hospital (KCH) and Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust (GSTT)] between May 2014 and March 2016. Research was co-ordinated by two academic centres: the University of Southampton and the Institute of Psychiatry, King’s College London. Treatment took place at participants’ homes via telephone and the internet. Therapists were based at the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust (SLAM).

Ethics approval and research governance

Ethics approval was awarded by the National Research Ethics Service (NRES) Committee South Central – Berkshire on 11 June 2013 (reference number 13/SC/0206) and local research governance approval was obtained from all participating CCGs.

The trial was registered with the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) under the reference number 44427879.

Summary of any changes to the protocol

A total of four substantial amendments were approved by the ethics committee and included a change to the primary outcome, the addition of a 24-month outcome time point and an increase in the recruitment target. Two minor amendments were submitted and acknowledged (Table 1).

| Amendment | Date | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Initial application conditions | Approved 11 June 2013 | |

| Modified amendment V1.0 | Approved 4 February 2014 | Primary outcome changed from SGA of Relief to WSAS |

| Added SAE and withdrawal forms | ||

| Minor changes to study documentation | ||

| Minor amendment 1 | Acknowledged 27 March 2014 | Amended questionnaire instruction |

| Substantial amendment V2.0 | Unfavourable opinion 30 April 2014 | SAE form to include self-harm |

| Substantial amendment V3.0 | Approved 4 April 2014 | Reimbursement for participant travel |

| Substantial amendment V4.0 | Approved 23 May 2015 | Increase recruitment from 495 to 570 participants |

| Substantial amendment V5.0 | Approved 3 December 2015 | Add 24-month follow-up measure |

| Therapist qualitative study documents added | ||

| Vouchers to patients to incentivise completion of questionnaires | ||

| Minor amendment 2 | Acknowledged 7 March 2016 | Comorbidities added to note review form |

| Substantial amendment V6.0 | Approved 26 June 2017 | Protocol title changed to funder’s contractual title |

| Timetable updated to reflect extra recruitment and follow-up time |

Training of co-ordinating centres

Research teams from the co-ordinating centres in Southampton and London were trained in January 2014 at the University of Southampton. The processes covered included telephone screening of patients accepting the invitation and the information required for fully informed consent, therapist procedures, setting up sites (site files, logs and packs), completing the research team database and record-keeping, communication with sites and patients (texts for e-mails and letters) and monitoring LifeGuide (https://lifeguidehealth.org/; accessed 27 January 2019) queries and patient e-mails.

Recruitment of general practices

Expressions of interest from general practices were gathered by Wessex and South London Clinical Research Networks (CRNs) and passed on to the research teams, who then contacted the practices to provide further information on the trial. The number of general practice sites required was estimated based on information from the MIBS feasibility study. 1,15 An assumption of 30–80 patients with a computer diagnosis of IBS per general practitioner (GP) was made (2–5% prevalence and 1600 registered patients per GP). In addition, it was estimated that 5–10% of those would fulfil the inclusion criteria and be willing to participate in the trial (three to eight per GP). Thus, we initially anticipated recruiting approximately 30 general practices.

Recruitment of secondary care sites

Secondary care sites were identified for participation in ACTIB by expert contacts of the research team and comprised SUHT, KCH and GSTT. It was estimated that over 500 patients with IBS attend Southampton hospital GI clinics each year and over 1000 attend the London GI clinics, providing a large population of patients attending secondary care to invite to the study.

Training of sites

Training was undertaken by providing a written training manual and a training log was signed by all site personnel with a delegated role. The training manual included a list of study materials to be supplied by the co-ordinating centre. It covered procedures for identifying patients from the practice records using Read codes to identify adult patients with an IBS diagnosis and preparation of the invitation letters using a Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) spreadsheet pre-populated with identification (ID) numbers, recruitment of patients from an opportunistic consultation using a pre-numbered pack, recruitment of patients using a poster (see Report Supplementary Material 1) in receptions, instructions for the blood test including postage of the blood samples and completing paperwork for the co-ordinators and pathology and instructions for completing a serious adverse event (SAE) form if needed. Prior to starting the search, all personnel were added to a delegation log and signed off by the principal investigator at the site. All sites received a site file and a copy of the NICE guidelines for IBS. Sites were kept up to date with trial progress and their individual performance by monthly e-mail updates from the co-ordinating centres.

Patient recruitment

Participating sites were asked to recruit patients by sending invitation letters, by opportunistically recruiting during consultations and by displaying posters in receptions. Because of the limited availability of therapy sessions, site initiation was staggered and the response rate monitored to ensure adequate recruitment and a steady workload for the therapists.

Primary care patients were identified by searching GPs’ lists for those with a diagnosis of IBS, by opportunistically recruiting patients presenting with symptoms consistent with IBS and by displaying posters in receptions. General practice administration staff ran searches for eligible patients using appropriate clinical diagnosis and symptom codes. GPs checked the lists of patients to be invited prior to the invitation letters being sent out to ensure that it was appropriate to contact them.

Secondary care patients were identified from gastroenterology clinics at SUHT, KCH and GSTT. When possible, clinic administration staff searched clinic lists for patients with a diagnosis of IBS. Potential participants were contacted by letter (sent from the clinic), which informed them about the trial and invited them to take part. When clinics needed more support, researcher administration staff were available to hand out packs and answer patient queries. The consultants checked the lists of patients to be contacted prior to the invitation letters being sent out to ensure that it was appropriate to contact them. Invitation letters were sent in batches.

Patients received an invitation letter (see Report Supplementary Material 2) and a patient information sheet (PIS) (see Report Supplementary Material 3) by post from the site, or from the GP/consultant, or from the research team following interest from the poster. Patients were asked to return the reply slip in a pre-paid envelope with contact details to the researchers either indicating that they were interested in being contacted or stating that they were not interested by ticking a list of potential reasons (and with an option for free-text responses). The researchers attempted to contact the patients who indicated that they were interested in participating for screening, either by telephone (including attempts during the evening and at weekends) or via text/e-mail, to arrange a convenient day and time to telephone.

Patient screening

Screening was conducted to ensure that potential participants met the inclusion criteria (Box 1), including being aged ≥ 18 years with refractory IBS [clinically significant symptoms defined by an Irritable Bowel Syndrome Symptom Severity Score (IBS SSS) of > 75], fulfilling Rome III criteria19 and having already been offered first-line therapies (e.g. antispasmodics, antidepressants or fibre-based medications) but still had continuing IBS symptoms for ≥ 12 months. Potential participants aged > 60 years were included only if they had undertaken a consultant review in the previous 2 years to confirm that their symptoms were related to IBS and that other serious bowel conditions had been excluded. This was because NICE guidelines9 advise that a new change in bowel habit in those aged > 60 years should be investigated further, as there is an increased risk of bowel cancer in this age group.

-

Patient is aged ≥ 18 years.

-

Patient has refractory IBS (clinically significant symptoms defined by an IBS SSS of > 75).

-

Patient fulfils Rome III criteria.

-

Patient has been offered first-line therapies (e.g. antispasmodics, antidepressants or fibre-based medications) but still has continuing IBS symptoms for ≥ 12 months.

-

If > 60 years old, patient has had a consultant review in the previous 2 years to confirm that their symptoms are related to IBS and that other serious bowel conditions have been excluded.

During the telephone screening, researchers followed a script and completed a paper screening questionnaire (see Appendix 1). Screening was conducted to assess the patient’s full eligibility for the study, check their understanding of the study procedures (including the need for a blood test), answer any questions to ensure that informed consent could be undertaken online and discuss the time commitment and the constraints around availability for therapy; it included the validating measures IBS SSS and Rome III. Screening also checked participants’ access to the internet.

Potential participants were excluded if they had unexplained rectal bleeding or weight loss; had a diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), coeliac disease, peptic ulcer disease or colorectal carcinoma; were unable to participate in CBT because of speech or language difficulties; had no access to an internet-enabled computer to be able to undertake the WCBT; had received CBT for IBS in the past 2 years; had had previous access to the MIBS website; or were currently participating in an IBS/intervention trial (Box 2).

-

Patient has unexplained rectal bleeding or weight loss.

-

Patient has a diagnosis of IBD.

-

Patient has coeliac disease.

-

Patient has peptic ulcer disease.

-

Patient has colorectal carcinoma.

-

Patient is unable to participate in CBT because of speech or language difficulties.

-

Patient has no access to an internet-enabled computer to be able to undertake the WCBT.

-

Patient has received CBT for IBS in the past 2 years.

-

Patient has had previous access to the MIBS website.

-

Patient is currently participating in an IBS/intervention trial.

General practitioners were notified of any of their patients who failed screening for unexplained weight loss or rectal bleeding so that the symptoms could be followed up.

Patient consent

Patients meeting the screening criteria were e-mailed instructions for the website address/uniform resource locator (URL) to log in to the LifeGuide online consent form (see Report Supplementary Material 4). The research team received an automated e-mail once the form was completed, which prompted the researchers to send another e-mail to the patient, customised for each general practice or secondary care site, with an instruction to make a blood test appointment for the next stage of screening.

Blood test

Patients telephoned their general practice surgery or gastrointestinal (GI) clinic to make an appointment for the blood test. When patients already had recent (within the previous 3 months) blood test results, these were requested from the site so that patients were not required to undergo another set of tests. The function of the blood tests was to exclude alternative diagnoses to IBS, as recommended for IBS diagnosis in the NICE guidelines. 9 The blood tests undertaken were full blood count (FBC) for anaemia, tissue transglutaminase antibodies (TTG) as screening for coeliac disease and C-reactive protein (CRP) for inflammation (marker for IBD). The blood tests were undertaken by practice nurses, by GPs within the surgeries or by phlebotomists or research nurses at the secondary care sites. Sites were pre-supplied with vacutainers, a form to fax back to the research team and a form to post with the sample. Patients were instructed to arrive with their ID number so that all forms could be identified by ID number only. Samples were sent to the SUHT pathology laboratory for testing and were then destroyed. The results were posted to the research team and the GP and were checked by the chief investigator. Blood sample results were stored in a locked filing cabinet.

Abnormal blood test results

A patient with abnormal blood test results (e.g. indicating anaemia or a positive TTG) was excluded from the study and referred back to his or her GP for further assessment and the GP was informed of the abnormal results by post. Patients with a CRP level above the normal laboratory range were phoned by the team and given the option to have a second test after 4 weeks (as CRP can be raised temporarily because of a minor intercurrent illness). A second high CRP result excluded them from the trial and their GP was informed of the test result.

Baseline questionnaire

Patients with acceptable blood test results were e-mailed instructions to log on to LifeGuide to complete their baseline questionnaire (see Appendix 3) and, on completion, the team received an automated e-mail that prompted them to initiate patient randomisation.

Randomisation

Randomisation was provided by the randomisation service at the UK Clinical Research Collaboration-registered King’s College London Clinical Trials Unit (CTU) and accessed by the research team via a web-based system. Randomisation was at the level of the individual, using block randomisation with randomly varying block sizes stratified by centre (Southampton general practices, Southampton secondary care, London general practices, London secondary care). The CTU procedure was as follows: on completion of the baseline questionnaire, the trial manager or research assistant electronically submitted details of each participant to the CTU. This included participant ID number, site, initials and date of birth. The system immediately notified the unblinded researchers and recorded the randomisation outcome. Research staff were allocating patients to therapists so could not be kept blinded.

Once a patient was randomised to the study, a letter was sent to their GP (see Report Supplementary Material 5) to inform them of the patient’s participation, their allocated group and their blood test results. Patients were e-mailed instructions to receive their group by logging on to LifeGuide as promptly as possible to enter one of three codes. This directed them to one of three alternative web pages within LifeGuide, allowing them access to the relevant intervention. Patients were asked to register, which triggered future automated reminder e-mails to them at each of the follow-up collection points and directed them to further instructions for each arm of the trial. Having separate sites ensured non-contamination of treatments. Patients in the TCBT arm were asked not to share their therapy manual with others to avoid cross-contamination.

Interventions

Two active interventions were assessed in the study: TCBT with a detailed patient manual; and low-intensity WCBT (the Regul8 programme developed in the MIBS trial20), with some therapist support.

Those in the control arm received TAU. Patients in the two active intervention arms also received TAU.

The CBT content of the two treatments was the same. The CBT was based on an empirical cognitive–behavioural model of IBS,20,21 which specifies that factors such as stress and gastric infection trigger the symptoms of IBS, which are then maintained by patients’ cognitive, behavioural and emotional responses to the symptoms. For instance, if a patient becomes anxious (emotion) about the symptoms, believes that he or she has no control over them (cognitions) and responds by avoiding social situations (behaviour), this can increase anxiety and maintain symptoms through the link between a heightened autonomic nervous system and the enteric nervous system. This model was used to structure the content of the therapy sessions.

The therapy consisted of education, behavioural and cognitive techniques, aimed at improving bowel habits, developing stable healthy eating patterns, addressing unhelpful thoughts, managing stress, reducing symptom focusing and preventing relapse (Table 2).

| Session | Summary |

|---|---|

| 1. Understanding your IBS | Rationale for self-management, which includes the following explanations:

|

| 2. Assessing your symptoms | Self-assessment of the interaction between thoughts, feeling and behaviours and how these can impact on stress levels and gut symptoms |

| Development of a personal model of IBS that incorporates these elements | |

| Homework: daily diaries of the severity and experience of IBS symptoms in conjunction with stress levels and eating routines/behaviours | |

| 3. Managing symptoms and eating | Review of the symptom diary |

| Behavioural management of the symptoms of diarrhoea and constipation, and common myths in this area are discussed. Goal-setting is explained | |

| The importance of healthy, regular eating and not being overly focused on elimination is covered | |

| Homework: goal-setting for managing symptoms and regular/healthy eating. Goal-setting, monitoring and evaluation continue weekly throughout the programme | |

| 4. Exercise and activity | The importance of exercise in symptom management is covered |

| Identifying activity patterns such as resting too much in response to symptoms or an all-or-nothing style of activity is addressed | |

| Homework: goal-setting for regular exercise and managing unhelpful activity patterns, if relevant | |

| 5. Identifying your thought patterns | Identifying unhelpful thoughts (negative automatic thoughts) in relation to high personal expectations and IBS symptoms is introduced |

| The link between these thoughts, feelings, behaviours and symptoms is reinforced | |

| Homework: goal-setting plus daily thought records of unhelpful thoughts related to personal expectations and patterns of overactivity | |

| 6. Alternative thoughts | The steps for coming up with alternatives to unhelpful thoughts are covered together with personal examples |

| Homework: goal-setting plus daily thought records including coming up with realistic alternative thoughts | |

| 7. Learning to relax, improving sleep, managing stress and emotions | Basic stress management and sleep hygiene are discussed |

| Diaphragmatic breathing, progressive muscle relaxation and guided imagery relaxation are presented in video and audio formats | |

| Identifying common positive and negative emotions and the participant’s current ways of dealing with these | |

| New strategies to facilitate expression of emotion as well as coping with negative or difficult emotions are discussed | |

| Homework: goal-setting for stress management, good sleep habits and emotional processing | |

| 8. Managing flare-ups and the future | The probability of flare-ups is discussed and patients are encouraged to develop achievable long-term goals and to continue to employ the skills they have learned throughout the manual to manage flare-ups and ongoing symptoms |

The two main differences between the therapy trial arms were:

-

The amount of therapy contact was predetermined (TCBT participants received 8 hours and WCBT participants received 2.5 hours of therapy). Those in the TCBT arm had six 1-hour telephone sessions with a CBT therapist at weeks 1, 2, 3, 5, 7 and 9 and homework tasks. They also received two 1-hour booster sessions at 4 and 8 months. WCBT participants received three 30-minute telephone therapy support calls at weeks 1, 3 and 5 and two 30-minute booster sessions at 4 and 8 months.

-

The TCBT patients used a self-management CBT manual and the WCBT patients had access to an interactive website.

Development of therapy manuals

Telephone-delivered cognitive–behavioural therapy patient manual

The patient manual was an updated version of the manual used in a pilot RCT of CBT-based self-management for IBS,20 which drew on some content from a nurse-delivered CBT trial. 7 Minor updates were made to ensure that the content of the manual closely mirrored the content of the Regul8 website, including incorporating the most recent NICE guidance regarding issues such as diet. 9 Content was written to be user friendly, with minimal technical jargon and easy-to-read text broken up by imagery and diagrams. Chapters included example scenarios and educational diagrams regarding the digestive system, the fight-or-flight stress response and links between the enteric and autonomic nervous system. Homework tasks were linked to the content in each chapter and included sheets to allow participants to record activities (see Table 2).

Telephone-delivered cognitive–behavioural therapy therapist manual

The therapist manual was developed by drawing on the IBS patient manual and the therapist manual used in the PACE (Pacing, graded Activity, and Cognitive behaviour therapy; a randomised Evaluation) trial for chronic fatigue,22 adapting the content to IBS rather than fatigue. For TCBT, the manual was designed to be used flexibly by therapists for formulation-driven sessions. The manual also provided guidelines for therapists to use alongside the more structured WCBT-guided self-help sessions. This included instructions for the optimum setting for the telephone calls (i.e. ensuring that patients were in a quiet environment without interruptions). Sessions were less formulation driven than in the TCBT arm and related more closely to the sequence of the Regul8 sessions. However, therapists were encouraged to be responsive to the issues patients raised. The first two support sessions focused on clarifying and reviewing material such as the personal model, eliciting updates on clients’ progress with the programme, helping to set realistic behavioural goals and monitoring progress on goals. Later sessions focused more on eliciting and challenging unhelpful thoughts, managing stress and sleep, and possible setbacks.

Standard operating procedures for adverse event (AE) and SAE reporting, assessing low mood and suicide risk, scheduling of sessions and the non-attendance of sessions, were detailed in the manual, with additional forms provided to therapists to fill out when necessary.

Allocation to therapists

Once participants were randomised to a treatment condition, they were allocated to therapists based on therapist availability in terms of client caseload and ability to arrange sessions at times that suited the participant.

Participants randomised to TCBT were immediately sent a CBT manual, including homework sessions, in the post. A digital copy was also sent via e-mail alongside three additional documents: (1) a standard information sheet on lifestyle and diet in IBS based on the NICE guidance (see Report Supplementary Material 6), (2) a participant information sheet about the allocated treatment and (3) a brief profile of their therapist including a picture. The allocated therapist contacted participants within 1 week of allocation to arrange the first session. Participants randomised to the WCBT arm were e-mailed a login with access to the Regul8 website. 15 E-mails included the same attachments as for TCBT (excluding the CBT manual).

Therapist scheduling

Ten CBT-trained therapists undertook the therapy sessions for both the TCBT arm and the WCBT arm of the study (see Therapy summary for more details of therapist characteristics). The therapists had different work schedules (some worked full time and some part time) and there was some changeover in therapists as a result of scheduled maternity leave and therapists leaving the service. Prior to therapist allocation, participants were asked by the research assistants to detail any times that they would be unavailable for sessions. Two therapists could take calls in the evenings with participants who were unavailable during the day. A few patients were unable to participate in the trial because of the low availability of evening sessions.

For both TCBT and WCBT, therapists sought to schedule all non-booster sessions within the 9-week period following randomisation. When possible, booster sessions were arranged around the 4- and 8-month post-randomisation points. However, ability to do this was variable dependent on the availability of the patient, finding mutually agreed times for sessions and session non-attendance without prior notice. Trial research assistants provided some limited practical support to the therapists during the process of scheduling sessions for some participants (approximately 20% of the participants who were allocated to the CBT arms). This was because of repeated non-attendance or lack of reciprocal contact from participants.

Intervention fidelity and supervision

The therapists received a 1-day training session in the two CBT interventions before recruitment started, which was delivered by co-applicants (RMM and TC). During the first 3 hours of the training, the research assistants delivered oral presentations focused on the aetiology and pathophysiology of IBS, the diagnostic criteria, the financial and humanistic burden of IBS, the treatment evidence, the cognitive–behavioural interventions for managing symptoms and impact in IBS and the main processes involved with the trial. Rona Moss-Morris and Trudie Chalder contributed to these presentations by sharing their clinical experience and knowledge. The second half of the training was led by Rona Moss-Morris and Trudie Chalder. It focused on the model of understanding IBS and interventions that therapists could potentially discuss with patients using guided discovery.

Telephone therapy sessions were audio-recorded for the purpose of providing regular supervision, assessing treatment fidelity and recording the length and number of telephone sessions. Therapists completed a protocol deviation form when they were unable to record a session.

The therapists attended one 90-minute group supervision session every fortnight in the first half of the trial, which reduced to monthly in the second half of the trial. Supervision was led by Rona Moss-Morris and Trudie Chalder. Regular supervision is part of good clinical practice in CBT. Rona Moss-Morris focused on supervising the WCBT and Trudie Chalder on the TCBT. Rona Moss-Morris and Trudie Chalder listened to an audio-recording of one session from each therapist chosen by one of the research assistants. The selection of sessions sent was aimed to provide a variety of sessions across the progression of therapy for the different therapists. Therapists were also encouraged to ask supervisors to listen to recordings of sessions for which they felt that feedback might be particularly helpful. Feedback was provided on the session by the supervisors in a collaborative manner, with all therapists providing suggestions and input.

Treatment integrity and competence were assessed at the end of the trial by two independent clinical psychologists who were experienced in using CBT for medically unexplained syndromes. A random selection of 20% of session 2 for WCBT and session 3 for TCBT was rated. Randomisation was carried out by the trial statistician and stratified so that at least two sessions for every therapist and for each therapy type were available. These were rated in terms of adherence to the TCBT manual or WCBT approach. A scale used in a large RCT of treatments for chronic fatigue syndrome23 was modified and simplified for these ratings in the ACTIB trial. There were three key areas to rate on a seven-point Likert scale: (1) overall therapeutic alliance (single item), (2) CBT skills (five items) and (3) overall therapist adherence to the manual (single item). Therapy manuals covered each session in both arms.

The independent clinical psychology raters received an initial training in the fidelity ratings delivered by Rona Moss-Morris and Trudie Chalder. The training was conducted face to face and lasted approximately 2.5 hours. Tapes were rated using the scale and ratings were cross-checked and discussed. Approximately 10% of the tapes were double rated to check for inter-rater reliability and cross-checked for consistency by Rona Moss-Morris and Trudie Chalder.

Three further telephone calls were scheduled to be checked for consistency after double ratings were completed. This training ensured that the clinical psychologists worked in a similar way and that there was adequate inter-rater reliability. Raters were blind to the identity of the patient. Ratings were made independently after listening to an entire session of therapy.

Treatment as usual

Patients in all three arms received TAU, with the control arm being TAU alone. TAU was defined as continuation of current medications and usual GP or consultant follow-up with no psychological therapy. All general practice sites or secondary care sites involved in the study received a copy of the NICE guidance for IBS9 at the start to ensure that all clinicians had the standard best practice information on IBS management. They also received a deskside reminder (see Report Supplementary Material 7) to remind them of the guidelines, protocol guidance on prescribing psychological therapies and inclusion criteria. All participants received a standard information sheet on lifestyle and diet in IBS based on the NICE guidance (see Report Supplementary Material 6). Information was collected on any changes in IBS treatment/management during the study, and numbers of GP and consultant consultations were recorded for all three arms. The TAU-alone participants had access to the WCBT website (but with no therapy support) at the end of the 12-month follow-up period.

Treatment adherence for intervention arms

Treatment adherence was defined separately for the two active treatment arms. Participants allocated to TCBT who completed at least four of the initial telephone CBT sessions were deemed as having adhered to treatment. Those who were offered WCBT and completed four or more website sessions and at least one telephone support session were considered treatment adherent.

Withdrawal from treatment and/or follow-up

In accordance with good clinical practice, patients were free to withdraw from the treatment and/or follow-up at any time without this affecting their medical care. Therapists made two attempts to contact non-attenders of the therapy sessions before withdrawing patients. All information on the event was collected in the drop-out report form (see Report Supplementary Material 8) and added to the CTU commercial data entry system [InferMed MACRO (InferMed, London, UK)].

Blinding

As with any therapy trial, blinding was not possible for participants or therapists. It was also impractical for the research assistants, who liaised with the participants and therapists regarding administration tasks. However, blinding was pre-planned for the outcome assessors and the trial statisticians, as described below.

After the database was locked, a decision was taken to use multiple imputation (MI) to deal with missing data in the formal statistical analysis (see Statistical methods), which meant that the trial statistician would become aware of treatment allocation when carrying out these analyses. However, these analyses were undertaken at the end so that any that could be carried out without revealing treatment allocations were carried out by a blinded statistician.

Outcome measures were collected via the web (when possible) and were patient reported. The researcher who contacted patients by telephone to capture primary outcome data in a short questionnaire (see Appendix 4), for those patients who did not complete follow-up questionnaires after reminders, was kept blinded to the participant’s treatment group to avoid bias. Statisticians, the principal investigators and all oversight committee members were also kept blinded to treatment group.

Baseline data

The baseline data included sociodemographic details, current medication, past medical history and medications, duration of IBS symptoms, previous or current psychiatric diagnoses, Rome III, IBS SSS, Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS) , EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D), Client Service Receipt Inventory (CSRI), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), Cognitive scale for Functional Bowel Disorders (CG-FBD), Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire for IBS (IPQ), Irritable Bowel Syndrome Behavioural Responses Questionnaire, Beliefs about Emotions Scale (BES), impoverished emotional experience (IEE) factor of the Emotional Processing Scale-25 and Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS).

Primary outcome measures

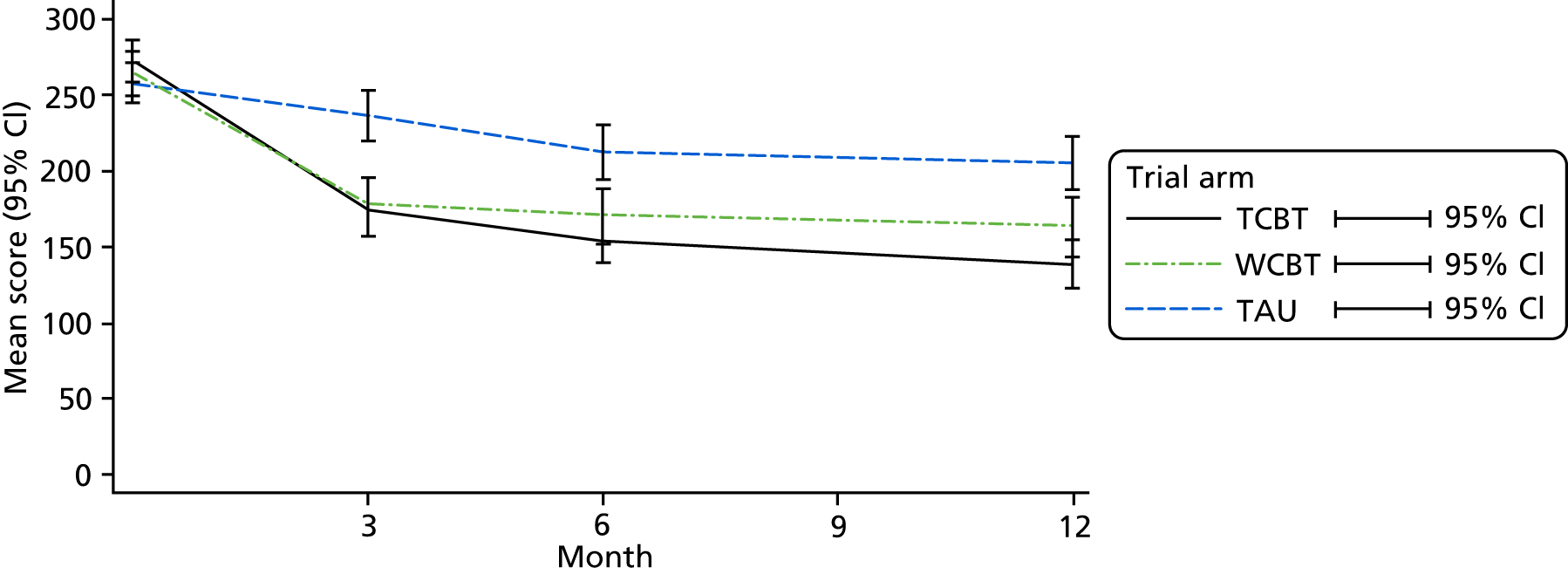

The clinical effectiveness of the intervention was assessed by two co-primary measures: IBS SSS24 and WSAS. 25

The IBS SSS is widely used in IBS studies (a 50-point within-participant change from baseline is regarded as clinically significant). 24 We powered this trial to detect a 35-point difference between groups at 12 months for the sample size calculations. This was to account for a 15-point placebo response in the TAU arm (the placebo response is known to be important in IBS, and the MIBS trial1,15 showed a 24-point difference in the no-website group from baseline to 12-week follow-up; thus, allowing for a 15-point placebo response at 12 months was prudent). The IBS SSS24 is a five-item, self-administered questionnaire measuring severity of abdominal pain, duration of abdominal pain, abdominal distension/tightness, bowel habit and QoL. It has a maximum score of 500: a score of < 75 indicates normal bowel function, 75–174 indicates mild IBS, 175–299 indicates moderate IBS and 300–500 indicates severe IBS.

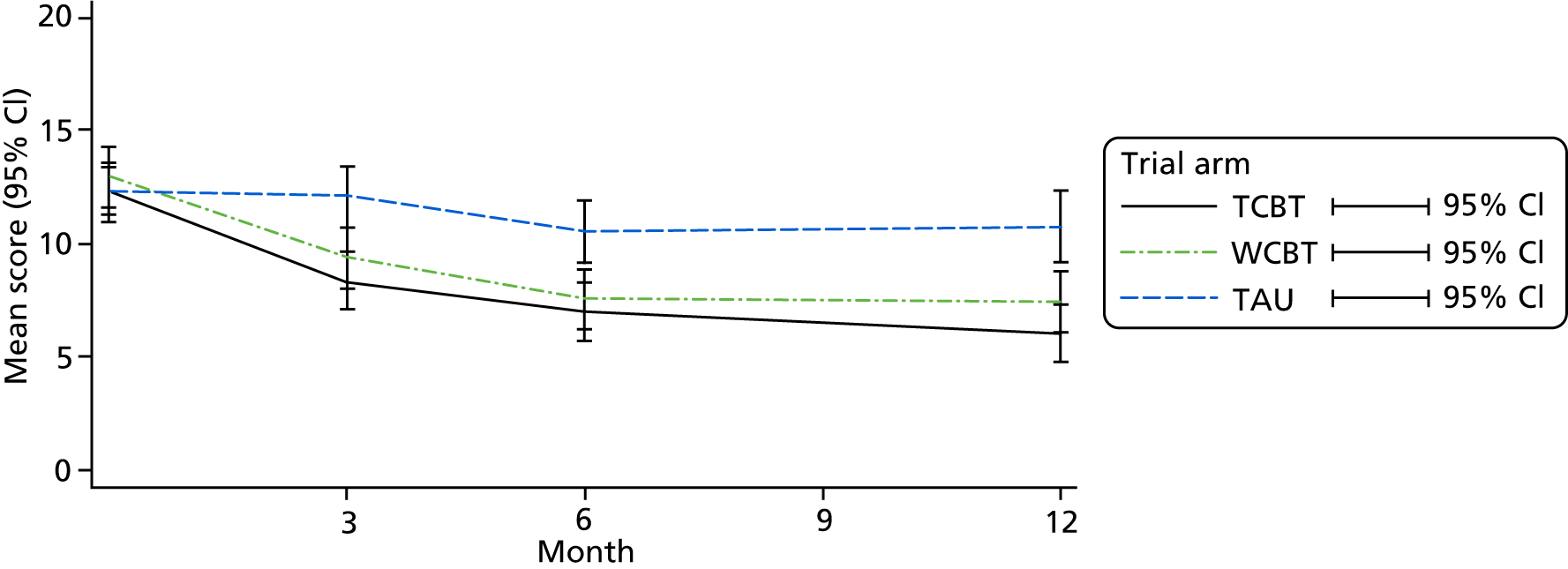

The WSAS measures the effect of the IBS on people’s ability to work and manage at home and to participate in social and private leisure activities and relationships. 25 WSAS has been shown to be sensitive to change in IBS trials. 7,20 It has five aspects, each scored from 0 (not affected) to 8 (severely affected), with a possible total score of 40.

Secondary outcome measures

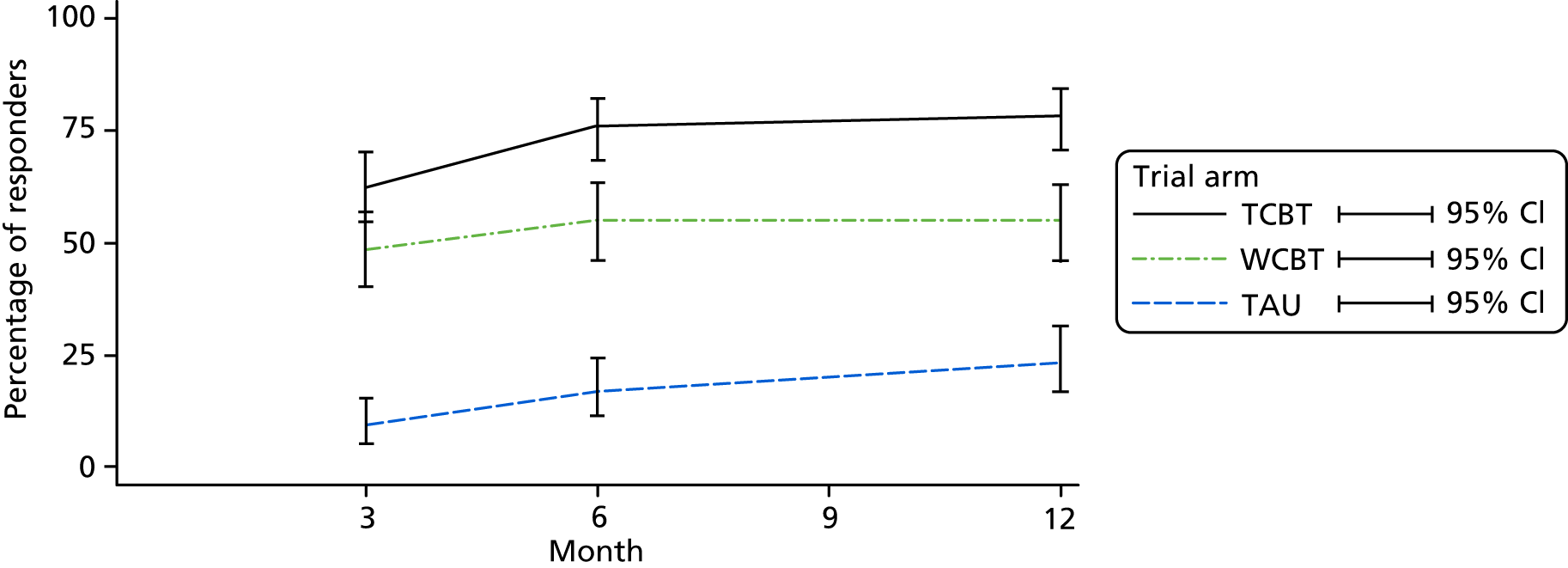

The Subject’s Global Assessment (SGA) of Relief26 is frequently used in treatment trials to identify IBS responders for therapy. 26 Participants rate their relief from IBS symptoms on a scale of 1 to 5, ranging from ‘completely relieved’ to ‘worse’. Scores are dichotomised so that patients scoring 1–3 are considered responders and those scoring 4–5 are considered non-responders.

The HADS27 is a well-validated, commonly used self-report instrument for detecting depression and anxiety in patients with medical illnesses.

The Patient Enablement Questionnaire (PEQ)21 assesses participants’ ability to cope with their illness and life.

The CSRI28 and EQ-5D29 were used to gather information on use of health services and QoL.

Patients’ GP notes were reviewed at 12 months to assess GP and other consultations in the year prior to entering the study and in the 12 months since entry into the study. Other studies20,30 have shown an impact on GP contacts from patient self-management programmes.

Patients’ adherence to the CBT treatments was measured by recording the number of telephone sessions and an automated count of web sessions accessed. A patient completing four or more sessions of the website and one or more of the telephone support calls was deemed compliant with the WCBT arms. In the TCBT arm, a patient completing four or more of the initial telephone CBT sessions was deemed compliant. Patients kept a simple log of homework tasks to complete.

Process/mediator variables

Process and mediator variables were collected in this trial and will be used to inform a process evaluation that will be undertaken in a funded extension agreed by the HTA programme, and will be reported separately from this HTA report.

The measures collected were:

-

The CG-FBD,31 a 31-item scale assessing unhelpful cognitions related to IBS.

-

The IPQ,32 an 8-point scale to assess participants’ perceptions of their illness.

-

The Irritable Bowel Syndrome-Behavioural Responses Questionnaire,33 a 26-item scale that measures changes in behaviour specific to managing IBS symptoms.

-

The BES,34 a 12-item questionnaire that measures beliefs about the unacceptability of experiencing and expressing negative emotions. These beliefs are likely to have implications for emotion regulation and processing. Principal components analysis identified one factor and the scale had high internal consistency (0.91). 34

-

The IEE factor of the Emotional Processing Scale,35 composed of five items and related to the labelling and awareness of emotional events, which influence the way people process their emotions. The subscale has high internal consistency (0.82). 35

-

The PANAS36 measures both positive and negative affect. The reliabilities of the PANAS, as measured by Cronbach’s alpha, were 0.89 for positive affect and 0.85 for negative affect. 37 Participants completed only the positive affect subscale because the HADS measures negative affect.

Adverse event reporting

An AE was defined as any clinical change, disease or disorder experienced by the participant during their participation in the trial, whether or not it was considered related to the intervention. A SAE was defined as an AE that was life-threatening or that resulted in inpatient hospitalisation, a disability/incapacity, a congenital anomaly/birth defect in the offspring of a subject, or another medical event requiring intervention to prevent one of these outcomes. All sites and therapists were supplied with SAE forms (see Report Supplementary Material 9) to complete and a SAE standard operating procedure (SOP).

In addition, patients were asked to self-report any medical events at each assessment.

Patients were asked the following online questions at the 3-, 6- and 12-month follow-up points:

-

Since you started the study have you had any of the following events – a life-threatening event, admission to hospital where you had to stay overnight, permanent disability/incapacity, a congenital anomaly/birth defect in a child of yours, or other medical events requiring medical attention to prevent one of the above? If yes, please give details.

-

Has your health been adversely affected since the start of the study? If yes, please give details.

The chief investigator, on behalf of the sponsor, assessed each completed SAE form for relatedness to the intervention and expectedness, to identify serious adverse reactions (SARs) and suspected unexpected serious adverse reactions. The co-ordinating centres’ SOPs were followed with respect to reporting to the sponsor, Research Ethics Committee (REC), Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC), Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and local governance offices. Annual safety reports were submitted to the REC. All AEs and SAEs were entered onto MACRO.

Economic evaluation measures

These are discussed in Chapter 3.

Follow-up procedures

Participants completed follow-up measures online at 3, 6 and 12 months after baseline using the LifeGuide website (see Appendix 5). Those who were unable to complete the outcome measures online received a paper copy of the questionnaires. If this was not completed, then they received a telephone call from a blinded researcher, who took the participant through a limited selection of the main outcome measures. These were the IBS SSS, WSAS, SGA, PEQ and HADS.

The follow-up procedure was as follows: the baseline assessment was conducted within 90 days of screening (to allow time for the blood tests) and randomisation was conducted within 3 days of baseline (to allow for weekends). Patients received two automated reminders from LifeGuide to complete their follow-up assessments at 3, 6 and 12 months. In addition, the researchers received an automated message from LifeGuide after 3 weeks if the questionnaires had not been completed, which prompted the team to send a personalised e-mail to the patient. This was followed by a further text, a paper copy of the full questionnaire sent to the patient’s home address and then, if still not complete, a telephone call from a blinded member of the research team to complete a short questionnaire.

All baseline and most 3-, 6- and 12-month outcome data were self-completed by the patient on a data collection section of the Regul8 programme website (LifeGuide). LifeGuide was maintained and hosted by the University of Southampton. The research team was notified when LifeGuide data were missing, and actions were taken to collect these data via paper questionnaires in the post and by telephone. Primary outcome data and some secondary outcome data that were collected by paper questionnaires or short telephone questionnaires were entered by the research team onto MACRO; these included PEQ, IBS SSS, WSAS, SGA and HADS. Other paper-collected outcome measures, including CSRI, IPQ, Behavioural Responses Questionnaire, IEE-EPS (Emotional Processing Scale), BES, PANAS and EQ-5D, were entered onto a spreadsheet. In addition, all questionnaire completion dates and sources of data were entered onto MACRO, as were economic data, AEs and SAEs and withdrawals.

Error checking was carried out in the full questionnaire database of the ACTIB trial. This was to check that the error rates for the primary outcomes were < 1% and the error rates for the secondary outcomes were < 5%; 20% checks were carried out on all variables for the 3-, 6- and 12-month questionnaires. Data checking was carried out by the London data entry research assistants, with Stephanie Hughes, Alice Sibelli and Sula Windgassen ensuring that the checks were carried out by a different person from the original data entry:

-

3 months – 89 questionnaires, every fifth ID selected = 18 patients

-

6 months – 103 questionnaires, every fifth ID selected = 21 patients

-

12 months – 139 questionnaires, every fifth ID selected = 28 patients.

A spreadsheet of any errors and changes needed was kept, listing variable name, original data entry, change, date, initial and reason.

Patient retention

In late 2014, follow-up monitoring revealed that follow-up rates were not as high as the 80% anticipated in the original sample size calculation. Follow-up procedures were very carefully scrutinised and every effort was made to increase rates using the follow-up methods described in the previous section. In December 2015, the REC approved an increase in the number of participants to be recruited, with a new target of up to 570 participants [as per an updated sample size calculation to allow for the lower follow-up rates (see Sample size)]. The REC also approved sending vouchers to participants, as evidence from the literature38 suggested that non-conditional vouchers could help to incentivise patients to complete follow-up questionnaires. Cards with an enclosed £10 Love2shop voucher were posted to all participants before their 3-month questionnaire date (and immediately for any patients who had passed this date).

Sample size

A 35-point difference between therapy groups and TAU on IBS SSS at 12 months was regarded as the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) (assuming a 15-point placebo response in the TAU arm in the trial). 15,24 Assuming a within-group IBS SSS standard deviation (SD) of 76 (taken from the MIBS pilot study1), this equated to an effect size of 0.46. To achieve 90% power to detect such an effect or larger using a two-sided independent-samples t-test at the 2.5% significance level (adjusting for two primary outcomes), it was estimated that the trial would require 119 subjects per group. Based on each of 10 therapists delivering therapy to 17 patients in the WCBT and TCBT groups, and an intraclass correlation of 0.02, taken from Baldwin et al.,39 this sample size was increased by an inflation factor of 1.32 to take account of therapist effects. We measured IBS SSS at baseline and assumed that baseline values were predictive of post-treatment values (correlation 0.4). Accounting for this in our statistical analysis model allowed us to decrease the sample size by a deflation factor of 0.84. Finally, we applied a further inflation factor of 1.25 on the assumption that attrition would be < 20%. The final sample size requirement was thus calculated as 165 patients per group or 495 patients in total.

In terms of our second primary outcome (WSAS), the initial 495 sample size was calculated to be sufficient to detect a difference between the WCBT (or TCBT) and TAU groups of ≥ 3.7. Specifically, we assumed inflation factors of 1.32 for correlation of outcomes within therapists and of 1.25 for attrition and a deflation factor of 0.84 for correlation between baseline and follow-up measures. Based on this, a moderate effect size of 0.46 could be found with 90% power at the 2.5% significance level, given 119 participants per group. Assuming a SD of 8.0 (as estimated in a study of CBT for IBS7), this would equate to a treatment difference of 3.7 on this scale. This is less than the difference of 5.4 in change of means in WSAS that was found in a trial of a CBT-based self-management intervention for IBS. 20

As the trial progressed, we found that the attrition rate was closer to 30% (November 2014 estimate). The sample size was recalculated using the same group size of 119 subjects, with inflation and deflation factors of 1.32 and 0.84 kept constant. The updated attrition rate of 30% gave a sample size of 189 patients per group and a total of 567 patients. We gained ethics approval to increase recruitment to the trial within the same recruitment time frame to aim for this larger calculated sample size.

Statistical methods

A statistical analysis plan (SAP) (see Appendix 6) was developed by the statisticians (KG, RH and SL), discussed by the trial management team and the DMEC and approved by the chief investigator (HE) and chairperson of the TSC before database lock. The following approach was used to formally compare the primary and secondary outcomes between a CBT arm and TAU: an intention-to-treat (ITT) approach was used for all primary and secondary outcomes, that is, participants were analysed in the groups to which they were randomised. For each outcome and assessment time point (3, 6 or 12 months), we estimated the effect of treatment (TCBT or WCBT) compared with TAU to assess treatment effectiveness. The TCBT and WCBT arms were not formally compared.

As we had two primary outcomes (IBS SSS and WSAS at 12 months), significance testing for these two variables was conducted at the Bonferroni-adjusted significance level of alpha = 0.025 to account for two outcome comparisons. Furthermore, because we carried out two planned comparisons per outcome measure, further adjustments were not necessary.

The primary outcome measures and the secondary outcome measure, HADS score, were continuous variables. Their modelling relied on normal assumptions for error terms and treatment effects were quantified by trial arm differences (and standardised differences). We had planned to analyse PEQ under a normal assumption but found inflated floor and ceiling effects for this variable. To facilitate modelling, the original PEQ was reclassified as a binary responder measure (0 = non-response, 1 = response). SGA measures were also reclassified as binary responders, as originally described in the SAP. A ‘PEQ responder’ was defined as a participant achieving a score of ≥ 6 at the post-randomisation time point. A ‘SGA responder’ was defined as a participant achieving a score of between 1 and 3, as planned in the SAP. Binary outcome variables were analysed within a logistic regression framework and treatment effects quantified by odds ratios (ORs).

Need for multiple imputation

Formal trial arm comparisons were carried out by MI, more specifically by using the flexible multivariate imputation by chained equations (MICE) approach. 40 This was necessary because non-adherence to treatment, defined as completing four of the telephone calls (not including booster sessions) for the TCBT arm and as completing four or more of the website sessions and at least one telephone call (not including booster sessions) for the WCBT arm, was found to be predictive of missing primary outcomes at 12 months in each of the CBT arms. To avoid unblinding the trial statisticians, testing for whether or not adherence to treatment was associated with missing data at the final time point was carried out by an independent statistician. The association between treatment adherence and missing data at the final time point in the TCBT or WCBT arms was tested using Fisher’s exact tests. Adherence was found to be predictive in both CBT arms. Thus, a MI approach was pursued to allow for a missing data-generating mechanism that was missing at random (MAR), with the observed variables allowed to drive missingness including adherence with TCBT or WCBT.

We empirically assessed whether or not baseline variables were predictive of missing data using logistic regression. The following baseline variables were considered: IBS SSS, HADS, WSAS, age at randomisation, Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD), duration of IBS symptoms, duration of IBS symptoms before diagnosis, whether or not the participant was registered with an IBS specialist, who they lived with, their marital status, the type of residence in which they lived, their choice of group at baseline, their highest level of education and their gender. Variables were considered to be potentially important, and later considered for inclusion in the imputation model, if an unadjusted logistic regression of missingness at 12 months on the baseline variable was statistically significant at a liberal 20% test level. The variables found to be potentially important predictors of missingness were then included in a multivariate logistic regression, starting with baseline IBS SSS and IMD. At each stage, the more complex model was tested against the simpler model using a likelihood ratio test, again at the 20% level. The preferred model of baseline predictors of missingness was found to be baseline IBS SSS and IMD only.

The MICE approach was used with regression models for imputation of missing values in continuous variables and logistic regression models for imputation of missing values in binary variables. In addition, predictive mean matching to a randomly chosen value from one of the 10 nearest neighbours was used for continuous outcome variables (IBS SSS, WSAS and HADS) to ensure that all imputed values lay within the observed data range.

Analysis model

The analysis models used to estimate treatment effectiveness included the outcome variable as the dependent variable and the trial arm (two dummy variables indicating the TCBT and WCBT arms), baseline values of the outcome (if available) and randomisation stratifier (dummy variables for four levels) as explanatory variables. As both TCBT and WCBT were delivered by therapists, possible therapist effects were investigated. For this purpose, two therapists who saw only a small number of participants, all of whom were compliers, were merged into a single group that also included those participants in the TCBT and WCBT arms who were not assigned a therapist. This was to avoid the computational instability and perfect prediction issues that were seen when the two therapists with few participants were considered as single therapists. To select appropriate therapist effects, a series of models were fitted for the participants who completed follow-up (completers) and compared using likelihood ratio tests. Model A allowed for therapist-varying random intercepts in each of the CBT arms with the variances of these random effects allowed to differ between TCBT and WCBT. Model B included therapist-varying random intercepts, but only in the TCBT arm. Model C did not include any therapist effects. Model A fitting significantly better than model B at a liberal 10% level was interpreted as evidence for therapist effects in both CBT arms; model B fitting better than model C was evidence for therapist effects in the TCBT arm only. We detected therapist effects in the TCBT arm for some variables (see Table 31) in both continuous and binary outcomes. Hence, the analysis models were extended to also include therapist-varying random intercepts in the TCBT arm. For binary outcomes affected by therapist effects, this meant that estimated ORs were conditioned on the therapist. In such cases, the OR was marginalised across therapists within a stratifier level to ensure that all quoted ORs estimated the same effect size measure (OR of treatment within stratifier level).

Imputation model

For each outcome variable, the imputation model included (1) all of the variables of the analysis model, (2) measures of the outcome variable at other assessment time points including baseline and (3) known predictors of missingness (binary adherence variables for each of TCBT and WCBT, IBS SSS and IMD). (1) is stipulated by MI theory, (2) was carried out to improve the precision of the imputed values and also allow outcome measures at earlier time points to drive dropout at later time points, and (3) accommodates identified predictors of missingness and allowed us to make a more realistic MAR assumption. For analysis models that contained (random) therapist effects, (4) fixed effects for therapists in the TCBT arm were also added to ensure that the imputation model remained more general than the analysis model.

Relevant assumptions were checked. Normality and homogeneity assumptions were checked for modelling of IBS SSS, WSAS and HADS using residual diagnostics. All of these checks were satisfactory. This was also carried out for PEQ and highlighted that PEQ scores could not be treated as normally distributed.

The validity of the imputations was checked using the Stata® version 14.2 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) command midiagplots,41 comparing the cumulative distribution of the imputed data against the fully observed data and the merged completed and imputed data. The differences in distribution across different iterations of the imputation were also investigated.

Sensitivity analyses

Four sets of sensitivity analyses were conducted. The first sensitivity analysis assessed the impact of excluding participants who had IBS SSS values at baseline below the inclusion threshold of 75 from the analysis set. (The IBS SSS eligibility criterion was determined at screening.) For the primary outcomes, non-eligible participants were dropped from the analysis set, the reduced data were reanalysed and the finding was compared with the original results to evaluate sensitivity. The second sensitivity analysis looked at the impact of using only observations that were recorded within the prespecified assessment time windows. Again, those outside the window were dropped from the analyses of the primary outcomes. The third sensitivity analysis evaluated the impact of defining PEQ responders according to an alternative threshold. ‘PEQ responders’ were defined according to another possible threshold and PEQ response was reanalysed at the primary outcome time point (12 months). Finally, the complier-average causal effect (CACE) was estimated in order to estimate efficacy without bias. The original ITT analyses estimate the clinical effectiveness of the interventions, but these estimates are biased for efficacy in the presence of non-compliance. To understand the extent to which the ITT estimates were affected by non-compliance with randomised treatment, we carried out a simple CACE analysis using complete cases. To this end we modelled the effect of the binary endogenous variables ‘receipt of TCBT’ and ‘receipt of WCBT’ on the co-primaries using randomisation to TCBT or WCBT, respectively, as instrumental variables. Further covariates in the models were baseline values of the outcome and dummy variables reflecting the randomisation stratifier. We had also considered a sensitivity analysis to investigate the impact on results of the missingness process being not MAR. However, follow-up rates were reasonably good and there was no information to inform such sensitivity analyses, so this was not carried out.

All analyses were carried out in Stata version 14.2.

Software

Data management

Two online data collection systems were used: LifeGuide and MACRO. The senior research assistant (SH) in charge of LifeGuide extracted the data from the main database and removed unblinding data or any disclosive information if required. MACRO was hosted on a dedicated server at King’s College London and managed by the King’s College London CTU. Its data manager extracted data periodically as needed.

Results

Recruitment

Sites were entered into the study in stages to ensure a continuous and steady feed of patients into the available therapy slots. The first sites to participate were given the instruction to search databases in February 2014 and the first invitation letters were sent in March 2014. The patient recruitment rate was monitored and subsequent sites were started each month over the following 23 months.

A total of 15,065 invitations were given out by 77 sites (74 general practice surgeries and three secondary care centres). There were 14,908 invitation letters (98.96%) delivered by mail-outs following a note search of potential participants. Forty-four invitation letters (0.29%) were sent after potential participants saw displayed posters and contacted the research teams, and 113 invitation letters (0.75%) were handed out by consultants or GPs during GI consultations as opportunistic recruitment (Table 3).

| Centre | Recruitment method (n) | Total (n) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mail-out | Poster | Opportunistic | ||

| GSTT | 203 | 80 | 283 | |

| KCH | 208 | 208 | ||

| LPC sites | 5482 | 2 | 7 | 5491 |

| SPC sites | 8841 | 40 | 25 | 8906 |

| UHS | 174 | 2 | 1 | 177 |

| Total | 14,908 | 44 | 113 | 15,065 |

Characteristics of general practices

Of the 103 (38 South London and 65 Wessex) general practices that initially agreed to participate, 74 (28 South London and 46 Wessex) progressed to carrying out note searches and mail-outs (some general practice sites dropped out, citing that they were too busy, or did not reply to prompts). At each practice, a GP or practice manager acting as site principal investigator was assigned to the study. Practices were reimbursed for activity time by Department of Health and Social Care service support costs. Sites were recruited from both urban and rural settings and had a range of sociodemographic characteristics (Tables 4 and 5).

| CCG | Number of general practices |

|---|---|

| South London | |

| Bexley | 2 |

| Bromley | 4 |

| Croydon | 1 |

| Greenwich | 1 |

| Lambeth | 10 |

| Lewisham | 1 |

| Merton | 2 |

| Southwark | 6 |

| Wandsworth | 1 |

| Total | 28 |

| Wessex | |

| Dorset | 8 |

| Fareham and Gosport | 3 |

| Hampshire | 1 |

| Isle of Wight | 2 |

| North East Hampshire and Farnham | 3 |

| North Hampshire | 2 |

| Portsmouth | 3 |

| South Eastern Hampshire | 9 |

| Southampton City | 4 |

| West Hampshire | 5 |

| Wiltshire | 6 |

| Total | 46 |

| Characteristic | General practice (n) | Total (n) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| London | Wessex | ||

| Practice list size | |||

| 1–4999 | 1 | 5 | 6 |

| 5000–14,999 | 23 | 31 | 54 |

| ≥ 15,000 | 4 | 10 | 14 |

| Number of GP partners | |||

| 0–5 | 11 | 12 | 23 |

| 6–10 | 15 | 28 | 43 |

| 11–15 | 2 | 5 | 7 |

| ≥ 16 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Deprivation score (IMD decile): 1 (most deprived) to 10 (least deprived) | |||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| 3 | 6 | 0 | 6 |

| 4 | 5 | 10 | 15 |

| 5 | 5 | 2 | 7 |

| 6 | 3 | 5 | 8 |

| 7 | 1 | 5 | 6 |

| 8 | 1 | 6 | 7 |

| 9 | 1 | 5 | 6 |

| 10 | 2 | 13 | 15 |

| Total | 28 | 46 | 74 |

An indication of the level of deprivation of the practice setting was calculated using the IMD score 2016 obtained from the Public Health England website (www.gov.uk/government/statistics/english-indices-of-deprivation-2015; accessed 27 January 2019), using practice postcode (8). This website was recommended by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) CRN Wessex for its reliability. The IMD measures the deprivation of small areas using 38 separate indicators in each of the seven domains: (1) income deprivation, (2) employment deprivation, (3) health deprivation and disability, (4) education, skills and training deprivation, (5) barriers to housing and services, (6) living environment deprivation and (7) crime. These indicators are then combined using appropriate weightage to calculate the IMD. IMD scores in deciles are presented as numbers ranging from 1 (most deprived) to 10 (least deprived).

Characteristics of invited participants

Data on the gender and date of birth of invitees were collected by the sites and reported to the research team anonymously. A total of 71.4% of those invited were female and the average age was 47.7 years (Tables 6 and 7).

| Centre | Gender (n) | Total (n) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | Missing | ||

| GSTT | 201 | 82 | 0 | 283 |

| KCH | 140 | 63 | 5 | 208 |

| LPC sites | 3618 | 1791 | 82 | 5491 |

| SPC sites | 6451 | 2228 | 227 | 8906 |

| UHS | 134 | 42 | 1 | 177 |

| Total | 10,544 | 4206 | 315 | 15,065 |

| Variable | Mean | SD | Number of participants | Minimum | Maximum | Median | IQR | Possible range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at invitation (years) | 47.7 | 16.8 | 15,065 | 15.9 | 102.2 | 47 | 34–62 | 16–98 |

Reasons for declining the ACTIB invitation

When sending out the ACTIB invitations, we included an option to return a ‘reason for decline’ slip so that we could gather information on why people chose not to participate in the ACTIB trial.

The main reasons that those invited gave for declining participation were that their IBS symptoms had improved and they did not need further input, that they did not have the time and that they did not want to take part in CBT or an online programme (Table 8). The number who declined was 2423 (multiple answers were allowed).

| Centre | Reason (n) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIBS accessa | MIBS studyb | No timec | Declined TCBTd | Declined onlinee | IBS OKf | Other reasong | |

| GSTT | 0 | 1 | 11 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 9 |

| KCH | 0 | 1 | 13 | 5 | 7 | 6 | 11 |

| LPC sites | 10 | 12 | 235 | 172 | 158 | 314 | 225 |

| SPC sites | 23 | 13 | 521 | 551 | 504 | 893 | 616 |

| UHS | 0 | 0 | 12 | 7 | 6 | 10 | 8 |

| Total | 33 | 27 | 792 | 740 | 679 | 1227 | 869 |

Telephone screen and consent

Screening commenced 2 months ahead of the first scheduled randomisation to allow time for the screening blood tests. A total of 1525 replies that indicated an interest in participating were returned and 1452 patients were screened, with 558 patients (38.4%) randomised into the study over 23 months. Tables 9 and 10 show the gender and age of those interested in participating. The main reasons for ineligibility at screening were not having been offered first-line therapies (e.g. antispasmodics, antidepressants or fibre-based medications) and/or not having continuing IBS symptoms for ≥ 12 months, being > 60 years of age with no consultant review, failing to meet IBS SSS criteria, failing to meet Rome III criteria, or having no access to the internet (see Table 13).

| Centre | Gender (n) | Total (n) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | Missing | ||

| GSTT | 71 | 29 | 0 | 100 |

| KCH | 0 | 0 | 44 | 44 |

| LPC sites | 99 | 21 | 294 | 414 |

| SPC sites | 733 | 205 | 0 | 938 |

| UHS | 21 | 8 | 0 | 29 |

| Total | 924 | 263 | 338 | 1525 |

| Variable | Mean | SD | Number of participants | Minimum | Maximum | Median | IQR | Possible range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at invitation (years) | 47.87 | 15.77 | 47.87 | 16 | 94 | 48 | 34–60 | 16–94 |

The mean age of potential participants interested in participating was 47.8 years, the mean age of those invited was 47.7 years and the mean age of those randomised was 43.1 years (some potential participants aged > 60 years were excluded on safety grounds at screening because they had not had a consultant review).

The proportion of females was 77.8% among those interested, 71.5% among those invited and 75.8% among those randomised.

Screening blood test results

The reasons for failing the blood test are given in Table 11.

| Blood test failure reason | n |

|---|---|

| Abnormal CRP | 33 |

| Abnormal FBC | 13 |

| Abnormal FBC and CRP | 5 |

| Abnormal TTG | 2 |

| Missing sample/unlabelled blood/haemolysed | 6 |

| Other medical reason | 1 |

| No blood from veins | 1 |

| Total | 61 |

Summary of recruitment

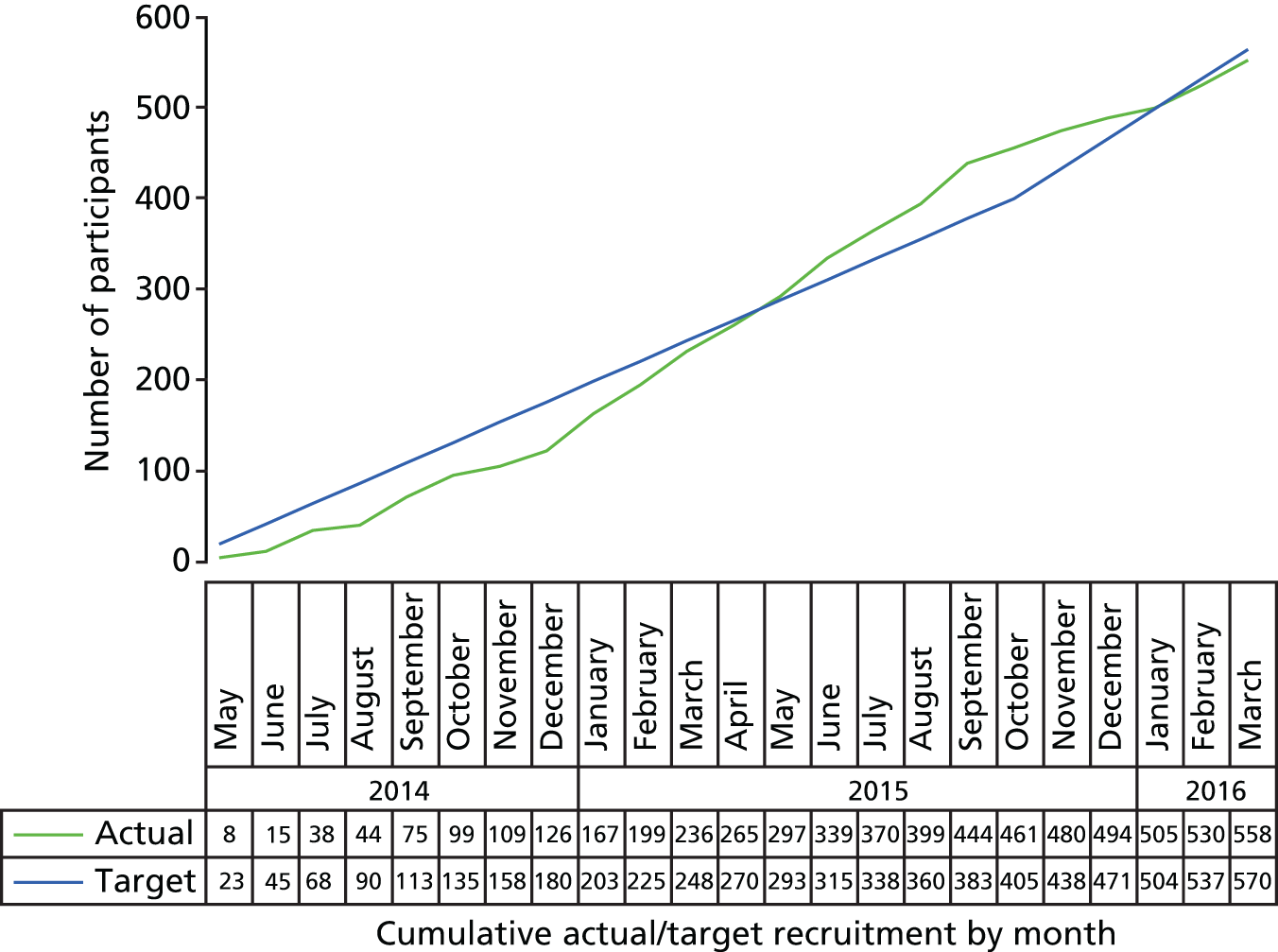

Table 12 and Figure 1 show recruitment by centre and over time.

| Pathway | Site (n) | All centres (n) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GSTT | KCH | LPC sites | SPC sites | UHS | ||

| Sites | 1 | 1 | 28 | 46 | 1 | 77 |

| Mailout | 203 | 208 | 5482 | 8841 | 174 | 14,908 |

| Poster | 0 | 0 | 2 | 40 | 2 | 44 |

| Opportunistic | 80 | 0 | 7 | 25 | 1 | 113 |

| Patient invitations | 283 | 208 | 5491 | 8906 | 177 | 15,065 |

| Invitations | ||||||

| ‘Yes’ | 100 | 44 | 414 | 938 | 29 | 1525 |

| ‘Declined’ | 18 | 28 | 633 | 1719 | 25 | 2423 |

| Screened | 96 | 41 | 370 | 916 | 29 | 1452 |

| Randomised | 59 | 19 | 141 | 324 | 15 | 558 |

FIGURE 1.

Participant recruitment against target.

Consolidating Standards of Reporting Trials

A CONSORT flow chart has been constructed. This includes the number of potential patients contacted and screened, the number of eligible patients, the number of patients agreeing to enter the trial and the number of patients refusing to enter the trial, and then, by treatment arm, the number of patients adherent to treatment, the number of patients continuing through the trial, the number of patients withdrawing, the number of patients lost to follow-up and the number of patients excluded/analysed.

Treatment adherence was defined separately for the two active treatment arms. Participants allocated to TCBT who completed at least four of the initial telephone calls were deemed adherent to treatment. Those who were offered WCBT and completed four or more website sessions and at least one telephone support call were considered as treatment adherent.

Details of the patient pathway through the recruitment process are included in the CONSORT flow diagram (Figure 2), with details of the inclusion and exclusion criteria given in Table 13.

| Ineligibility criteria | Number of participants |

|---|---|

| Failed inclusion criteria | 547 |

| Not aged ≥ 18 years | 2 |

| Does not have refractory IBS (clinically significant symptoms defined by a IBS SSS of > 75) | 54 |

| Does not fulfil Rome III criteria | 43 |

| Has not been offered first-line therapies (e.g. antispasmodics, antidepressants or fibre-based medications) and does not have continuing IBS symptoms for ≥ 12 months | 297 |

| If > 60 years old, patient has not had a consultant review in the in the previous 2 years | 151 |

| Exclusion criteria | 76 |

| Unexplained rectal bleeding or weight loss | 5 |

| Diagnosis of IBD | 8 |

| Diagnosis of coeliac disease | 2 |