Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 14/160/01. The contractual start date was in January 2016. The draft report began editorial review in June 2018 and was accepted for publication in October 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Nigel Arden has received honoraria from, held advisory board positions (which involved receipt of fees) in and received consortium research grants from Merck & Co. (Kenilworth, NJ, USA) (honorarium), Roche Holding AG (Basel, Switzerland), Novartis (Basel, Switzerland) and Bioiberica S.A. (Barcelona, Spain) (grants), Smith & Nephew plc (London, UK), NicOx S.A. (Valbonne, France), Flexion Bioventus (Bioventus LLC, Durham, NC, USA) and Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer LLP (London, UK) (personal fees) outside the submitted work. Amar Rangan reports grants from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme, Orthopaedic Research UK (London, UK), DePuy Synthes UK (Leeds, UK) and JRI Orthopaedics (Sheffield, UK) outside the submitted work. Andrew Judge is a subpanel member of the NIHR Programme Grants for Applied Research (PGfAR) programme, has received consultancy fees from Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer LLP and has held advisory board positions (which involved receipt of fees) from Anthera Pharmaceuticals Inc. (Hayward, CA, USA). Daniel Prieto Alhambra has received grants and other support from Amgen Inc. (Thousand Oaks, CA, USA) and UCB Biopharmal Srl (Brussels, Belgium); grants from Laboratories Servier (Neuilly-sur-Seine, France), Novartis International AG (Basel, Switzerland), Astellas Pharma Inc. (Tokyo, Japan), the NIHR HTA programme and from NIHR Research for Patient Benefit (RfPB), outside the submitted work. He is also a member of the NIHR HTA Clinical Evaluation and Trials panel (from November 2017 to present) and the NIHR RfPB South-Central Regional Advisory Committee panel (from 2013 to 2017). Tim Holt is a general practitioner (GP) in London and is a GP advisor for, but not employed by, the Clinical Practice Research Datalink. Gary S Collins is a member of the HTA Commissioning Board and has received grants from the NIHR HTA programme, NIHR RfPB, NIHR Biomedical Research Centre (BRC) and British Heart Foundation outside the submitted work. Sarah E Lamb was on the HTA Additional Capacity Funding Board (2012–15), HTA End of Life Care and Add-on Studies Board (2012–15), HTA Prioritisation Group Board (2010–15), HTA Trauma Board (2013–15), HTA Clinical Trials Board (2010–15) and the HTA Funding Boards Policy Group (2010–15) within 36 months of the start of the study. Andrew Carr has received other grants from the NIHR HTA programme, the Medical Research Council and the Wellcome Trust during the conduct of this study. He is a panel member on the Medical Research Council Developmental Pathway Funding Scheme (2016–present), a theme leader for the NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre (2017–present) and was the Director of the NIHR Oxford Musculoskeletal Biomedical Research Unit (2008–17). Jonathan L Rees has received other grants from the NIHR HTA and NIHR PGfAR programmes. He works within a NIHR BRC and currently holds other grants from the Royal College of Surgeons of England, the Dinwoodie Charitable Company (Macclesfield, UK), McLaren Applied Technologies (Woking, UK) and the National Joint Register (NJR). He sits on committees at the NJR, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence and the Orthopaedic Data Evaluation Panel (ODEP), advises the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency and is a council member of the British Elbow and Shoulder Society.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Rees et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background and study introduction

This study is in response to a research commission from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme and, as such, this avenue of research has already been deemed necessary. Since the commissioned call, no systematic reviews or randomised clinical trials that answer the brief have been published.

The most common joint dislocations seen in hospital accident and emergency departments affect the shoulder (8.2–17 cases per 100,000 people per year). 1 Around 95% of traumatic dislocations of the shoulder occur anteriorly, where the top end of the arm bone (humerus) is forced frontwards out of the shoulder socket. 1 The mobility of the shoulder joint renders it particularly unstable and susceptible to re-dislocation. Traumatic anterior shoulder dislocation (TASD) is particularly common in younger patients and often occurs as a result of injury during contact sports. 2 When it occurs, it is very painful and the shoulder often stays dislocated until it is repositioned. The condition is associated with significant morbidity as, following a first-time dislocation, there will probably be damage to the soft tissue and ligaments that are responsible for stabilising the joint, rendering it susceptible to re-dislocation. The literature reports that recurrent dislocation can occur in 85–92% of cases. 3 However, the most effective treatment for the management of first-time traumatic shoulder dislocation in preventing further dislocations remains uncertain.

Surgery versus conservative treatment

Current options for the management of TASD include surgical or conservative treatment (usually physiotherapy) that aims to restore the stability and function of the shoulder joint. 4 However, there is a lack of consensus and a lack of good-quality evidence in support of a particular treatment regime. 2 Prior to both surgical and non-surgical intervention, closed reduction techniques tend to be used to restore the correct position of the shoulder joint. 4 Subsequent surgical management tends to include either soft-tissue reconstruction (e.g. Bankart labral repair) or bony procedures (e.g. coracoid process transfer). 5 Alternatively, non-surgical treatments involve immobilisation of the arm using slings or splints, followed by physical rehabilitation. 2 It is currently unclear from the literature which treatment approach to use following a first-time TASD to restore the stability and function of the shoulder and to help prevent recurrent dislocations.

The use of traditional conservative management approaches after initial reduction and joint immobilisation has been challenged because of high rates of recurrent dislocation among some population groups. In younger patients, rates of recurrence as high as 92–96% have been reported. 6 An incidence study of shoulder instability among athletes at a US military academy showed that 85% of athletes experienced a recurrent event within a 9-month period. 7 A systematic review showed that there were some limited data to support primary surgery following a first-time TASD among young adults engaged in demanding physical activities (military personnel and athletes). 5 A later systematic review also showed that among younger patients, a significantly lower rate of recurrent instability was identified in a 2-year period following a first-time TASD for those having surgery than for those having no surgery (7% vs. 46%). 8 Consequently, there appears to be some limited evidence for surgical intervention following a first-time TASD among younger and/or highly active patients; however, the literature emphasises that there is no evidence to challenge the use of non-surgical techniques for other patient groups. 5

Concerning non-operative treatment approaches in the management of first-time TASD, not only is there a lack of evidence for non-surgical over surgical treatment, but there are also uncertainties regarding the type of non-operative treatment used. For example, there is debate over the length of time the arm should be immobilised and the position (i.e. internal or external rotation) in which it should be immobilised. 6 Some studies have found a lower recurrence rate in patients treated using external rotation (26% recurrence) than in those treated using internal rotation (42% recurrence) methods, and that this technique was also more effective for the younger, < 30 years age group. 9 However, an earlier systematic review did not identify any statistically significant results in re-dislocation rates among patients treated using internal or external rotation methods. 2 The literature has highlighted the absence of and the usefulness of future trials looking at these aspects of non-operative management for TASD. 2

The use of surgical intervention for the management of TASD goes back to 1923, when Bankart described an anterior labral avulsion of the glenoid during shoulder dislocation. 10 Current approaches involve stabilising the joint using open or arthroscopic (keyhole) surgery; however, the literature is unclear as to which strategy is most effective. No significant differences have been identified between open and arthroscopic approaches in terms of recurrent instability or re-injury. 8,11,12

Incidence studies

Studies of the incidence of traumatic shoulder dislocation have been conducted outside the UK. An early, highly cited study of the incidence of shoulder dislocation was carried out in Sweden in 1982 by Hovelius. 13 In a random sample of 2092 people aged 18–70 years, it was shown that 1.7% of participants had a history of dislocation, with re-dislocation more common in young adults and with a male-to-female ratio of 3 : 1 overall (although varying with age). 13 In a 10-year follow-up study of 247 Swedish patients aged 12–22 years at the time of their dislocation, 66% of patients had one or more re-dislocations but only 24% had a recurrence between 30 and 40 years of age. 14

The incidence of shoulder dislocation was again examined in a later (2010) study based on a US population. 15 This study utilised data from the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System (NEISS) and was based on patients of all ages who experienced a shoulder dislocation from 2002 to 2006. Their findings showed an overall adjusted incidence rate of 23.9 per 100,000 person-years [95% confidence interval (CI) 20.8 to 27.0 per 100,000 person-years], a rate that was more than double that originally thought. The majority of dislocations occurred in men (72%), with the highest incidence observed in those aged 20–29 years (47.8 per 100,000 person-years, 95% CI 41.0 to 54.4 per 100,000 person-years). In males, the overall incidence rate was 34.9 per 100,000 person-years (95% CI 30.1 to 39.7 per 100,000 person-years), whereas in females this was 13.3 per 100,000 person-years (95% CI 11.6 to 15.0 per 100,000 person-years).

A further study, by Leroux et al. 16 in 2014, also looked at the incidence rate of primary anterior shoulder dislocation in a Canadian population of 16- to 70-year-olds who were diagnosed between April 2002 and September 2010. Compared with the US study, the Canadian data showed a similar rate of dislocations in men (74%), with an incidence rate highest for 16- to 20-year-olds (98.3 per 100,000 person-years). Similar figures for the overall adjusted incidence rate were observed, which in males was 34.3 per 100,000 person-years and in females was 11.8 per 100,000 person-years.

It is unclear in the current literature as to the most effective treatment pathway (i.e. surgery vs. no surgery) in the management of first-time TASD. Regarding conservative treatment, the optimum position for arm immobilisation and the duration of time are still in question. Concerning surgery, it is debated what technique (i.e. open or arthroscopic, soft tissue or bony) is more effective, and when or if surgery is needed following a first-time TASD. The main problem is an absence of data on the natural history of shoulder dislocation, including in the UK where age and sex incidence data have not been published. The literature also highlights the lack of good-quality evidence and supports the need for further research and randomised trials to address these issues.

Aims

The commissioned aims were:

-

to study the association between surgical treatment and recurrence rates following a first-time TASD in young adults who had surgery compared with those who had not had surgery

-

to identify clinical predictors of recurrent dislocation in young adults with a TASD for surgical and non-surgical patients.

Objectives

To use routinely collected data from two NHS computerised databases [i.e. the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) and Hospital Episode Statistics (HES)] to study the association between surgical treatment and rates of re-dislocation, compared with no surgery in young adults with a first-time TASD. Potential predictors of re-dislocation in patients from each treatment group were further investigated.

The research questions were addressed by implementing a two-stage approach using two work packages.

Work package 1

Work package 1 consists of an internal and external validation study to test the quality and completeness of coding in the CPRD for identifying patients aged 16–35 years diagnosed with and treated for a first-time TASD. From these data, age and sex prevalence rates for first-time TASD in the UK were produced and these were externally validated against reported rates published in other settings.

Work package 2

A propensity-score-matched cohort analysis was conducted using CPRD and HES data. The cohort of participants used in the analysis comprised young adults (aged 16–35 years) with a TASD, who had at least 2 years of coding in the CPRD prior to a first-time entry Read code for shoulder dislocation (washout period) and at least 2 years of follow-up coding. The association between treatment strategy (i.e. surgery compared with no surgery) and rates of re-dislocation were then studied. Propensity matching ensured that patients undergoing surgery were matched and compared with a non-surgical control patient. Risk factors that may play an important role in re-dislocation in both the surgical and the non-surgical groups were further investigated.

Methods

Work package 1

The first phase of this project involved conducting an internal and external validation study to test the suitability of using the CPRD data set for identifying patients with a first-time TASD, and then externally validating the findings against published results from other settings. Relevant risk factors that were identifiable in the CPRD were recorded and used to inform the formal analysis regarding future predictors.

Internal validation

An internal validation study was conducted to check the quality of the coding for shoulder dislocations and treatments in the CPRD. A cohort of patients aged 16–70 years who were diagnosed with a shoulder dislocation in the UK between 1995 and 2015 were initially identified from the CPRD, to use as UK incidence data for all age groups. The included patients all had at least 2 years of coding in the CPRD prior to a first-time entry Read code for shoulder dislocation and at least another 2 years of subsequent coding. The internal validation exercise then focused on the planned study cohort of patients identified from the CPRD who were aged 16–35 years and had the same washout period.

A general practitioner (GP) questionnaire was designed with the help of GPs to internally validate the coding of shoulder dislocations and treatments in the CPRD. A random sample of 172 patients was then selected from those identified as meeting the above selection criteria. A questionnaire was sent to the general practice of each patient using the CPRD GP questionnaire service. A clinician at the practice completed the questionnaire by comparing the records on the CPRD with the clinical records of the patient. Written reminders to complete the questionnaire were sent to the general practice by the CPRD every 2 weeks (up to a total of four reminders). The data from returned questionnaire responses were double-entered into a database, and an academic orthopaedic shoulder surgeon was consulted to resolve data input queries.

The following criteria were established a priori to ensure that shoulder dislocation coding in the CPRD was of high quality prior to moving forwards with the main analysis:

-

The coding of shoulder dislocation within the CPRD needed to have a positive predictive value of ≥ 75%.

-

The coding of ‘primary’ or ‘first-time’ shoulder dislocation coding in the CPRD also had to have a positive predictive value of ≥ 75%.

External validation

The external validation exercise compared the age and sex incidence rates for TASD produced for the UK with those reported in other settings. For this analysis, the original cohort of patients aged 16–70 years who were identified from the CPRD with a shoulder dislocation between 1995 and 2015 were used. The CPRD has a representative coverage of around 6.9% of the UK and includes 11.3 million patients, making it broadly generalisable in terms of age, sex and ethnicity for the UK population as a whole. The external validation study itself produced population-based age- and sex-specific incidence rates for TASD for the UK. Comparing these with the published rates reported from other settings allows for external validation of the UK data.

Work package 2

Propensity-score-matched cohort analysis

The main study is a population-based propensity-score-matched cohort study comparing the association between surgery (vs. no surgery) and rates of re-dislocation in patients diagnosed with a TASD. The cohort of patients used for this analysis consisted of young adults aged 16–35 years with a TASD, with 2 years of coding in the CPRD prior to a first-time entry Read code for shoulder dislocation, and at least another 2 years of follow-up coding after the initial event. A pre-agreed list of Read codes (CPRD) and HES Office of Population Censuses and Surveys (OPCS) 4.7 codes for shoulder dislocation and treatments was used to collect all related outcomes and events; these were further informed by the earlier validation work (work package 1) (see Appendix 1). A ‘primary’ or ‘first-time’ TASD is defined here as a first-time entry Read code for shoulder dislocation.

Identified patients were allocated to the intervention (surgical) or control (non-surgical) groups. Patients in the intervention group were those who underwent shoulder stabilisation surgery following a first-time episode of TASD (early surgical repair is defined here as a ‘decision to treat surgically after a first-time TASD’). Patients in the control group were those who did not receive a surgical intervention following a first-time episode of TASD.

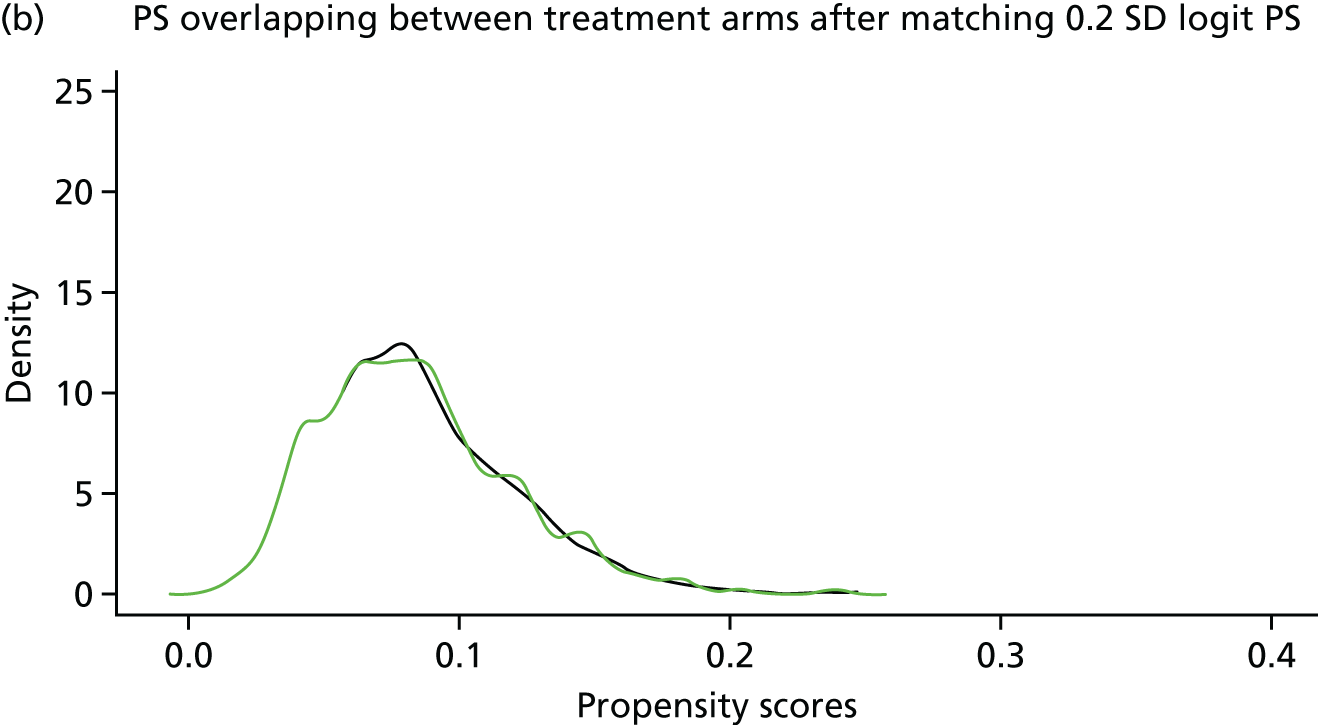

Propensity score matching methods were used to match each patient receiving surgery to a comparable patient in the non-surgical group. Propensity score methods were used because they provide the best approach to handling observational data sets that may be influenced by confounding (e.g. some patients being more likely to have surgery than others). Propensity score methods allow for bias being introduced into the data set through confounding, as the type of treatment received (i.e. surgery or no surgery) was not randomly allocated in this study.

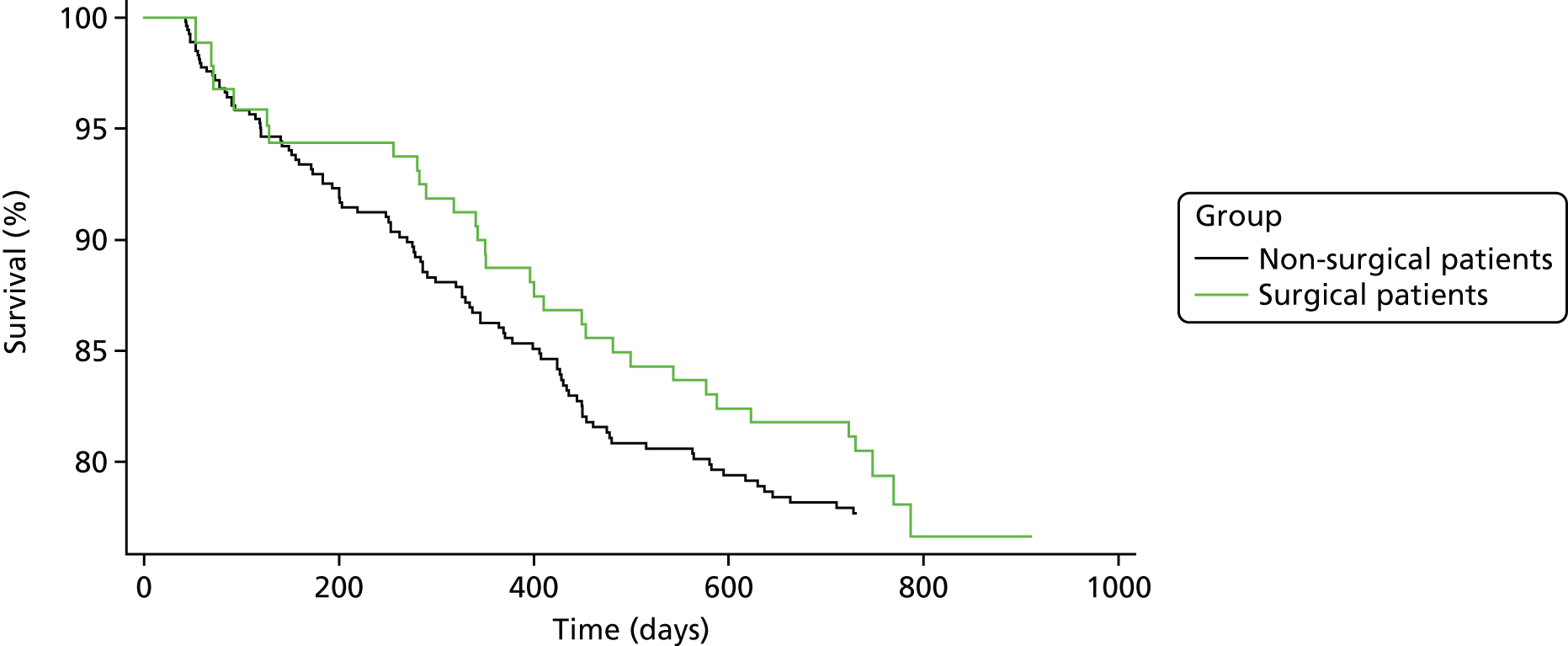

After the process of matching surgical patients to non-surgical control patients, a Cox regression survival model was used to assess the association between surgery and time to re-dislocation over a 2-year period.

Identify clinical predictors of recurrent dislocations by treatment type

In this component, investigated potential risk factors associated with re-dislocation for both the surgical and the non-surgical groups were investigated. Prediction models were developed using linked CPRD and HES data, including any risk factors defined a priori by consensus that were available and those identified through the earlier validation work.

Conclusion

The relevant background information supporting the need for research into the efficacy of management options for patients with first-time traumatic shoulder dislocation has been described. Each of the four key components of the study has been outlined in this chapter and they are described in more detail in Chapters 2–5.

Chapter 2 Internal validation study of shoulder dislocation coding within the Clinical Practice Research Datalink

Results from the validation study have been published in Shah et al. 17 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Introduction

The first phase of this study was to carry out an internal validation of shoulder dislocation coding in routinely collected data from the CPRD to confirm the feasibility of using the CPRD to study shoulder dislocations for the main analyses. It also sought to identify which risk factors were relevant to shoulder dislocation and were readily available in the CPRD for use in the main analyses.

Objectives of Chapter 2

-

Identify patients in the CPRD aged 16–35 years who were diagnosed with a traumatic shoulder dislocation between 1 April 1997 and 31 March 2015 in England.

-

Develop a GP questionnaire using a validation algorithm and with input from GPs.

-

Take a random sample of patients from those identified in the CPRD and use the CPRD GP questionnaire service to send the questionnaire to the respective patient practices for completion.

Methods

Data source

Population-based primary care data from the CPRD were used to identify a cohort of patients diagnosed with a traumatic shoulder dislocation (aged 16–35 years) in the UK from 1 April 1997 to 31 March 2015. The CPRD covers 11.3 million people from 674 UK general practices and provides a representative coverage of around 6.9% of the UK population, which is broadly representative of the population in terms of age, sex and ethnicity. 18 Patient and practice data are anonymised, but patient-level data are available on age, sex, geographic region, body mass index (BMI), smoking status (i.e. current smoker, ex-smoker, non-smoker) and drinking status (i.e. current drinker, ex-drinker, non-drinker). The CPRD data were linked to data from the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) 200419 for English patients and the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) score was calculated using predefined Read codes.

Participants

The Read codes were used to identify patients from the CPRD with a shoulder dislocation. These codes had been established a priori through consensus by specialist shoulder surgeons with clinical experience and experts in epidemiology research (see Appendix 1). To ensure that ‘primary’ or ‘first-time’ shoulder dislocations were captured, patients were required to have no recorded shoulder dislocations in their CPRD clinical data for 2 years prior to first entry of a shoulder dislocation Read code. The 2-year washout period was defined using the date that the general practice was classified as ‘up to standard’ and the date that the patient was first registered at the general practice. This first entry of a shoulder dislocation Read code was defined as the primary dislocation.

The patients had to be registered at ‘active’ CPRD practices. An ‘active’ practice was defined as a practice that had contributed to the CPRD database in the previous 6 months. No general practices were classified as active in the East Midlands, and so it was not possible to include patients from this region. Following the identification of the shoulder dislocation cohort from within the CPRD data set, a predefined set of patient exclusion criteria was applied to facilitate the validation (Table 1).

| Exclusions | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Total number of CPRD shoulder dislocation patients received | 63,324 (100) |

| Unacceptable patients (i.e. CPRD flags that data quality for a patient is insufficient for medical research) | 806 (1) |

| Unacceptable dates (i.e. impossible to find a shoulder dislocation code between the CPRD minimum and maximum acceptable dates as defined by data management standard operating procedures for clinical research)18 | 34,710 (55) |

| Shoulder dislocation date prior to 1 April 1997 | 2507 (4) |

| Shoulder dislocation date after 31 March 2015 | 823 (1) |

| < 2-year minimum washout period (i.e. washout period defined using the date the general practice was classified as ‘up to standard’ and the date the patient first registered at the practice) | 3694 (6) |

| Aged < 16 years | 825 (1) |

| Aged > 35 years | 12,125 (19) |

| Non-resident of England patients | 1788 (3) |

| Patients remaining in cohort | 6046 (10) |

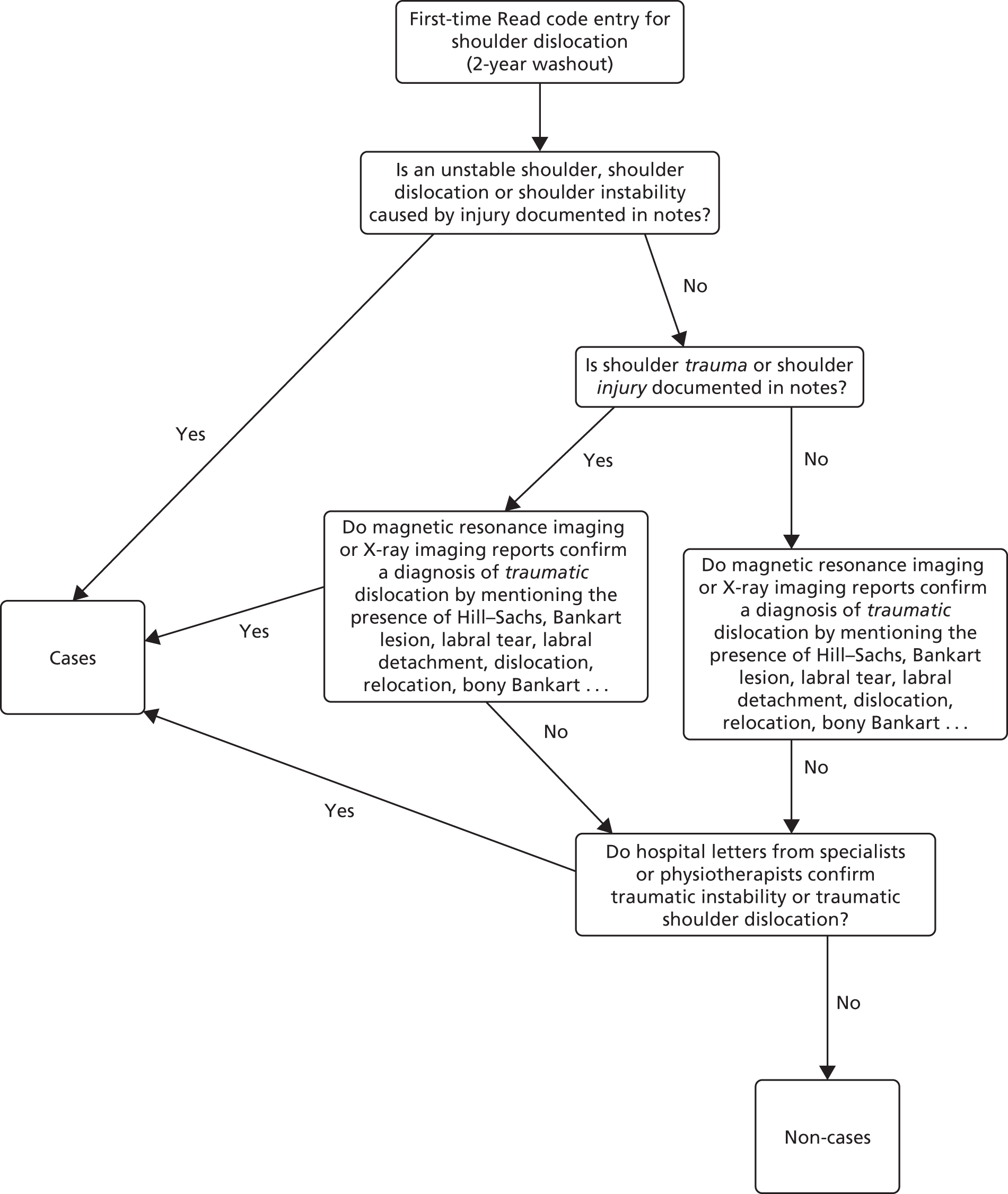

General practitioner questionnaire design and implementation

The GP questionnaire was designed with the assistance of GPs and based on a developed validation algorithm (see Appendices 2 and 3) and a random sample of 172 patients was selected from a list of the 6046 eligible patients. CPRD personnel then sent the questionnaire to each patient’s general practice for a clinician to complete by comparing the records on their CPRD computer system with the patient’s clinical records. The GPs assessed the use of shoulder dislocation codes for traumatic dislocation, confirmation of first-time shoulder dislocation, subsequent codes used for further events, physiotherapy referral codes and confirmation that physiotherapy took place.

Four written reminders were sent every 2 weeks to the general practices. Data from the returned questionnaires were double-entered into a data set by a statistician and a project manager. Any queries were resolved by an academic orthopaedic shoulder surgeon. In the instance that two questionnaires were received for the same patient with differing answers (on three occasions two questionnaires were sent back for one patient, i.e. three patients and six questionnaires; differing responses were only received for questions 6 and 7), clarification was sought from the general practice via CPRD personnel (clarification was received for one patient).

The following validation criteria were defined a priori to reflect that the coding of shoulder dislocations in the CPRD was of a sufficiently high quality to proceed with the main analyses planned in work package 2:

-

a positive predictive value of ≥ 75% accuracy for shoulder dislocation coding in the CPRD

-

a positive predictive value of ≥ 75% accuracy in coding ‘primary’ or ‘first-time’ traumatic shoulder dislocation within the CPRD.

Results

Cohort

An initial cohort of 63,324 patients with codes for shoulder dislocation was identified from the CPRD database. A database manager and statistician assessed the cohort against clear predefined and important exclusion criteria (see Table 1). Unacceptable patients were defined as those whose records had not met quality standards and had been flagged by the CPRD as ‘unacceptable’. Unacceptable dates were defined as when it was impossible to find a shoulder dislocation code between the CPRD minimum and maximum acceptable dates, as defined by data management standard operating procedures for clinical research. 18 During this process, the majority of patients were excluded, either because they had a shoulder dislocation diagnosis outside the study time period (55%) or because they were outside the study age limits (16–35 years) (20%). The final cohort included 6046 patients aged 16–35 years who were diagnosed with a shoulder dislocation between 1 April 1997 and 31 March 2015 in England.

Internal validation

Of the 172 patients whose GP received a copy of the validation questionnaire, a response for 95 (55%) patients was received. For two patients, their GPs confirmed that they had transferred out of the practice and that no further information was available for them on the CPRD system.

Table 2 presents demographic characteristics for the following patient groups:

-

the cohort of 6046 patients from the CPRD aged 16–35 years and diagnosed with a shoulder dislocation between 1 April 1997 and 31 March 2015 in England

-

the 172 patients randomly selected to have their GPs receive a questionnaire

-

the 97 patients for whom completed questionnaires were returned by their general practice

-

the 75 patients for whom questionnaires were not returned by their general practice.

| Demographic characteristic | Patient group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole cohort | All GP questionnaires | Responders | Non-responders | |

| Cohort size, (n) | 6046 | 172 | 97 | 75 |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 4991 (83) | 137 (80) | 81 (84) | 56 (75) |

| Female | 1055 (17) | 35 (20) | 16 (16) | 19 (25) |

| Median age (years) (IQR) | 24 (20–34) | 24 (20–29) | 24 (20–29) | 24 (19–29) |

| Median BMI (kg/m2) (IQR) | 24 (22–27) | 24 (21–27) | 25 (22–28) | 23 (21–26) |

| Median CCI score (IQR) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) |

| Region, n (%) | ||||

| East Midlands | 263 (4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| East of England | 673 (11) | 21 (12) | 17 (18) | 4 (5) |

| London | 695 (12) | 23 (13) | 11 (11) | 12 (16) |

| North East | 133 (2) | 4 (2) | 3 (3) | 1 (1) |

| North West | 951 (16) | 29 (17) | 13 (13) | 16 (21) |

| South Central | 965 (16) | 32 (19) | 17 (18) | 15 (20) |

| South East Coast | 702 (12) | 25 (15) | 12 (12) | 13 (17) |

| South West | 743 (12) | 17 (10) | 17 (18) | 0 (0) |

| West Midlands | 667 (11) | 15 (9) | 7 (7) | 8 (11) |

| Yorkshire and the Humber | 254 (4) | 6 (3) | 0 (0) | 6 (8) |

| IMD 2004 quintile, n (%) | ||||

| 1 (affluent) | 1279 (21) | 53 (31) | 28 (29) | 26 (35) |

| 2 | 1077 (18) | 35 (20) | 20 (21) | 15 (20) |

| 3 | 958 (16) | 24 (14) | 16 (16) | 8 (11) |

| 4 | 876 (14) | 38 (22) | 19 (20) | 18 (24) |

| 5 (deprived) | 624 (10) | 22 (13) | 14 (14) | 8 (11) |

| Missing | 1232 (20) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

All four groups were similar with respect to demographic characteristics, including age, BMI and CCI score. The highest response rate (100%) was received from general practices in the South West of England, but otherwise the proportion of responses received reflected the regional distribution of patients included in the cohort. Data on the IMD 200419 were obtained and linked after the selection of the 172 records to be validated. There were no missing data on deprivation, as all practices sampled were ‘active practices’. A higher proportion of patients had been sampled from category 1 (affluent) and category 4 (somewhat deprived) than in the initial cohort of 6046 patients, but otherwise response rates were similar from all deprivation groups.

The distribution of CPRD Read codes used by GPs to code shoulder dislocations is given in Table 3. Codes S41..00, S41z.00 and 14G5.00 for dislocation of shoulder accounted for 82% of all shoulder dislocation coding in the data. Recurrent shoulder dislocation codes only identified another 10% of patients, indicating that the 2-year washout period was a successful approach to identifying primary or first-time shoulder dislocations. Of the seven patients who had a recurrent shoulder dislocation code and for whom a GP questionnaire response was obtained, four were confirmed as having had a primary shoulder dislocation and one was confirmed as not having had a shoulder dislocation at all.

| CPRD description (Read code) | Patient group (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole cohort | All GP questionnaires | Responders | Non-responders | |

| Total number of patients | 6046 | 172 | 97 | 75 |

| CPRD description (Read code) | ||||

| Dislocation or subluxation of shoulder (S41..00) | 55 | 55 | 52 | 60 |

| Dislocation of shoulder NOSa (S41z.00) | 10 | 10 | 9 | 11 |

| H/O:a dislocated shoulder (14G5.00) | 17 | 19 | 20 | 17 |

| Closed reduction of dislocation of shoulder (7K6G300) | 3 | 3 | 5 | 1 |

| Closed traumatic dislocation of shoulder (S410.00) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Recurrent dislocation of shoulder, anterior (N083A00) | 6 | 6 | 5 | 7 |

| Anterior dislocation of shoulder (S410111) | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Recurrent joint dislocation, of shoulder region (N083100) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Recurrent subluxation of shoulder, anterior (N083C00) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| Closed traumatic dislocation shoulder joint, anterior (subcoracoid) (S410100) | < 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Closed traumatic dislocation shoulder joint, unspecified (S410000) | < 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Closed traumatic subluxation, shoulder (S412.00) | < 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

Shoulder dislocation was confirmed as having been coded correctly in 89% (95% CI 83% to 95%) of all patients (Table 4). The remaining 11% (10 patients) had been miscoded and the patient had suffered other shoulder trauma or injuries, such as strains or dislocations of the acromioclavicular joint, as confirmed by their GP. Of all patients, a first-time or primary shoulder dislocation was confirmed in 76% (95% CI 67% to 85%) of cases. Subsequent dislocations occurring up to 2 years after the primary dislocation were recorded in the CPRD for 32% of patients. From the GP responses, an additional 11% of patients experienced a re-dislocation during this time that was not recorded in the CPRD.

| Validation of shoulder dislocations | n (%) |

|---|---|

| GP confirmation of shoulder dislocation | 85 (89) |

| Patients who had a confirmed ‘primary’ shoulder dislocation | 72 (76) |

| Patients who had a further dislocation within 2 years of the primary dislocationa | 27 (32) |

| Confirmation that this was a further dislocation episode and not a review of the problem | 21 (78) |

| Patients with further dislocations that have not been noted in the CPRD | 9 (11) |

| Patients who have CPRD Read codes for physiotherapy in the 2 years following the first dislocation code | 24 (28) |

| It is clear that this physiotherapy code indicates that the patient received physiotherapy for their shoulder | 15 (63) |

| Patients who did not have a CPRD Read code for physiotherapy, but for whom documentation exists confirming that they received physiotherapy for their shoulder | 17 (21) |

Twenty-eight per cent of patients had been coded as having received physiotherapy within the CPRD, and GPs confirmed that physiotherapy had been given to 63% of these. However, a further 17 patients had received physiotherapy for their shoulder dislocation that was not recorded within the CPRD. Thus, 41% of patients known to be receiving physiotherapy were not recorded within the CPRD.

Conclusion

This validation exercise, carried out, to our knowledge, for the first time for this condition in the CPRD, has demonstrated that the CPRD is an acceptable data set to identify and study shoulder dislocation patients. The validity of GP coding of shoulder dislocations within the CPRD in a subset of patients proved very high, at 89%. Of all patients, 76% were confirmed to have primary shoulder dislocations. All of the CPRD Read codes used to identify shoulder dislocation patients were useful for identifying patients who had a primary shoulder dislocation, including the three codes that are specific to re-dislocations (i.e. N083A00, N083100 and N083C00). There was a small amount of under-reporting of subsequent shoulder dislocations. Physiotherapy treatment coding was of a poorer quality given that it is under-reported, at 41%, and, as such, the effectiveness of physiotherapy cannot be evaluated using the CPRD in any subsequent analyses of shoulder dislocations. Although not all general practices responded to the questionnaire, those that did and those that did not respond to the questionnaire survey were similar by deprivation level, geography and other demographic characteristics.

The strength of the CPRD is that it is a large, population-based primary care cohort that is representative of the UK general population. The positive internal validation result achieved on the correct coding of shoulder dislocations in the CPRD now provides the opportunity to use these codes and study definitions in the main study analysis.

Chapter 3 External validation study of shoulder dislocation data within the Clinical Practice Research Datalink

Results from the external validation study have been published in Shah et al. 17 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Introduction

The second phase of this study was to produce, for the first time, the age- and sex-specific incidence rates for shoulder dislocations in the UK. These would then allow the comparison of numbers and incidence rates of shoulder dislocations in the UK with those published from the USA and Canada. The comparison will facilitate an external validation of the data contained within the CPRD on shoulder dislocations.

Objectives of Chapter 3

The objectives of this chapter are to produce age- and sex-specific incidence rates for shoulder dislocation for the UK population and to validate UK data by comparing age- and sex-specific incidence rates of first-time TASD with those of similar studies from the USA and Canada. 15,16

Methods

Data source

The CPRD of population-based primary care data was used to identify a cohort of patients diagnosed with a traumatic shoulder dislocation aged 16–70 years during 1995–2015 in the UK. A description of the CPRD and the potential risk factors available within it was presented in Chapter 2.

Participants

The cohort of 16,763 CPRD patients aged 16–70 years with a TASD during 1995–2015 in the UK was used. The patients were identified using predefined Read codes as described in Chapter 2 (see also Appendix 1).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarise the epidemiology of primary shoulder dislocations by demographic factors. The incidence rates by age and sex per 100,000 person-years and incidence rate ratios with 95% CIs and p-values were calculated for all age and sex groups using Stata® software version 14.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Incidence rate denominators were constructed using the patient-level data from the CPRD. Observation time per patient was calculated between 1995 and 2015 as the sum of total year-time contributed by all subjects, wherein person-years start as the latest of first registration date, practice up-to-standard date and 1 January 1995, and end as the earliest from patient transfer out date, practice last collection date, death date and 31 December 2015.

Results

An initial cohort of 63,324 patients with codes for shoulder dislocation was identified. A predefined set of exclusion criteria was applied (Table 5). During this process, many patients were excluded either because they had a shoulder dislocation diagnosis outside the study time period (55%) or because they were outside the study age limits (16–70 years) (8%).

| Exclusion | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Total number of CPRD shoulder dislocation patients received | 63,324 (100) |

| Unacceptable patients (i.e. CPRD flags that data quality for a patient is insufficient for medical research) | 806 (1) |

| Unacceptable dates (i.e. impossible to find a shoulder dislocation code between the CPRD minimum and maximum acceptable dates, as defined by data management standard operating procedures for clinical research) | 34,710 (55) |

| Shoulder dislocation date prior to 1 January 1995 | 1446 (2) |

| Shoulder dislocation date after 31 December 2015 | 75 (< 1) |

| < 2-year minimum washout period (i.e. washout period defined using the date the GP was classified as ‘up to standard’ and the date the patient first registered at the general practice) | 4008 (6) |

| Aged < 16 years | 878 (1) |

| Aged > 70 years | 4638 (7) |

| Patients remaining in cohort | 16,763 (26) |

The final cohort produced included 16,763 patients aged 16–70 years who were diagnosed with a shoulder dislocation between 1995 and 2015 in the UK. The numbers of patients identified by CPRD Read codes are given in Table 6. Table 7 highlights the baseline characteristics of the cohort. Most (72%) of the shoulder dislocations occurred in men and the median age for the whole cohort was 36 years [interquartile range (IQR) 24–52 years]. Most patients had a ‘normal’ BMI (18.5–24.9 kg/m2) and 88% of patients had no comorbidities.

| Description | Read code | Number of patients |

|---|---|---|

| Dislocation or subluxation of shoulder | S41..00 | 9600 |

| Dislocation of shoulder NOSa | S41z.00 | 2066 |

| H/O: dislocated shouldera | 14G5.00 | 2331 |

| Closed reduction of dislocation of shoulder | 7K6G300 | 739 |

| Closed traumatic dislocation of shoulder | S410.00 | 410 |

| Recurrent dislocation of shoulder, anterior | N083A00 | 646 |

| Anterior dislocation of shoulder | S410111 | 424 |

| Recurrent joint dislocation, of shoulder region | N083100 | 176 |

| Recurrent subluxation of shoulder, anterior | N083C00 | 168 |

| Closed traumatic dislocation shoulder joint, anterior (subcoracoid) | S410100 | 64 |

| Closed traumatic dislocation shoulder joint, unspecified | S410000 | 78 |

| Closed traumatic subluxation, shoulder | S412.00 | 61 |

| Total | 16,763 | |

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Total | 16,763 (100) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 12,148 (72) |

| Female | 4615 (28) |

| Age at shoulder dislocation (years) | |

| 16–20 | 2561 (15) |

| 21–30 | 4266 (25) |

| 31–40 | 3021 (18) |

| 41–70 | 6915 (41) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |

| < 18.5 | 180 (1) |

| 18.5–24.9 | 3392 (20) |

| 25.0–29.9 | 3020 (18) |

| 30.0–34.9 | 1292 (8) |

| ≥ 35.0 | 768 (5) |

| Missing | 8111 (48) |

| Smoking | |

| Non-smoker | 6674 (40) |

| Current smoker | 3388 (20) |

| Ex-smoker | 2014 (12) |

| Missing | 4687 (28) |

| Drinking | |

| Current drinker | 6854 (41) |

| Non-drinker | 1113 (7) |

| Ex-drinker | 188 (1) |

| Missing | 8608 (51) |

| CCI score | |

| 0 | 14,834 (88) |

| 1 | 950 (6) |

| 2 | 523 (3) |

| ≥ 3 | 456 (3) |

| Region | |

| East Midlands | 600 (4) |

| East of England | 1444 (9) |

| London | 1484 (9) |

| North East | 279 (2) |

| North West | 2071 (12) |

| Northern Ireland | 602 (4) |

| Scotland | 1626 (10) |

| South Central | 2005 (12) |

| South East Coast | 1572 (9) |

| South West | 1462 (9) |

| Wales | 1591 (9) |

| West Midlands | 1470 (9) |

| Yorkshire and the Humber | 557 (3) |

| IMD 2004 (quintile of deprivation) | |

| 1 (affluent) | 2790 (17) |

| 2 | 2345 (14) |

| 3 | 2001 (12) |

| 4 | 1793 (11) |

| 5 (deprived) | 1309 (8) |

| Missing | 6525 (39) |

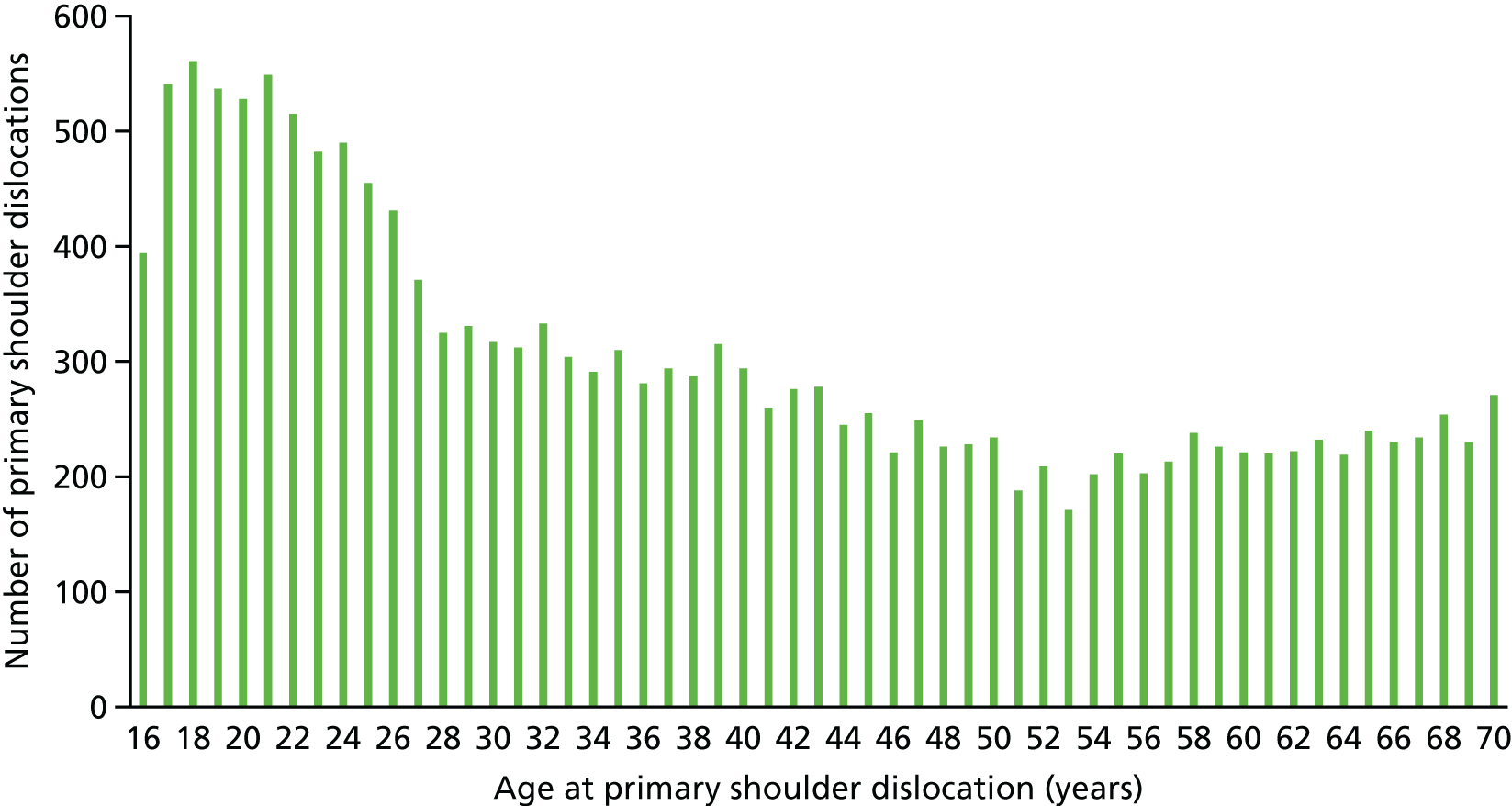

The age distribution of primary shoulder dislocation patients during 1995–2015 in the UK within the CPRD is given in Figure 1. A peak of > 500 patients per year of age occurs in patients aged 17–21 years, which then decreases until the age of 53 years. Between 55 years and 70 years, there is a gradual increase in the number of patients with a primary shoulder dislocation.

FIGURE 1.

Distribution of primary shoulder dislocation patients by age (years), demonstrating the overall distribution within CPRD during 1995–2015 in the UK.

UK incidence rates

The incidence rates and incidence rate ratios by age and sex for primary shoulder dislocation patients in the UK are presented in Table 8. The overall incidence rate in males was seen to be 40.39 per 100,000 person-years (95% CI 40.38 to 40.41 per 100,000 person-years) and in females was 15.52 per 100,000 person-years (95% CI 15.51 to 15.52 per 100,000 person-years). The highest incidence observed was in 16- to 20-year-old males (80.55 per 100,000 person-years, 95% CI 80.45 to 80.65 per 100,000 person-years). The incidence in men decreased with an increase in age. A U-shaped pattern of incidence was observed in women. The incidence was 16.36 per 100,000 person-years in those aged 16–20 years. This decreased in women aged 21–50 years and then increased to 28.64 per 100,000 person-years in women aged 61–70 years. Overall, the incidence was significantly higher in men than in women in almost all age groups, with an overall incidence rate ratio of 2.60 (95% CI 2.52 to 2.69). The exception was found in men and women aged 61–70 years, in whom no significant difference in incidence was observed (p = 0.334).

| Demographic category | Number of patients | Person-yearsa | Incidence rateb | 95% CI | Demographic comparison | Incidence rate ratio | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 12,148 | 30,074,078 | 40.39 | 40.38 to 40.1 | Male vs. female | 2.60 | 2.52 to 2.69 | < 0.001 |

| Female | 4615 | 29,741,559 | 15.52 | 15.51 to 15.52 | ||||

| Age (years) | ||||||||

| 16–20 | 2561 | 5,245,428 | 48.82 | 48.78 to 48.87 | ||||

| 21–30 | 4266 | 11,006,586 | 38.76 | 38.74 to 38.78 | 16–20 vs. 21–30 | 1.26 | 1.20 to 1.32 | < 0.001 |

| 31–40 | 3021 | 12,362,061 | 24.44 | 24.42 to 24.45 | 16–20 vs. 31–40 | 2.00 | 1.90 to 2.11 | < 0.001 |

| 41–50 | 2472 | 12,244,890 | 20.19 | 20.18 to 20.20 | 16–20 vs. 41–50 | 2.42 | 2.29 to 2.56 | < 0.001 |

| 51–60 | 2091 | 10,583,309 | 19.76 | 19.75 to 19.77 | 16–20 vs. 51–60 | 2.47 | 2.33 to 2.62 | < 0.001 |

| 61–70 | 2352 | 8,373,363 | 28.09 | 28.07 to 28.11 | 16–20 vs. 61–70 | 1.74 | 1.64 to 1.84 | < 0.001 |

| Age (years), sex (male) | ||||||||

| 16–20 | 2137 | 2,653,062 | 80.55 | 80.45 to 80.65 | ||||

| 21–30 | 3588 | 5,463,830 | 65.67 | 65.61 to 65.72 | 16–20 vs. 21–30 | 1.23 | 1.16 to 1.29 | < 0.001 |

| 31–40 | 2316 | 6,265,348 | 36.97 | 36.94 to 36.99 | 16–20 vs. 31–40 | 2.18 | 2.05 to 2.31 | < 0.001 |

| 41–50 | 1733 | 6,243,377 | 27.76 | 27.74 to 27.78 | 16–20 vs. 41–50 | 2.90 | 2.72 to 3.094 | < 0.001 |

| 51–60 | 1244 | 5,342,095 | 23.29 | 23.27 to 23.31 | 16–20 vs. 51–60 | 3.46 | 3.22 to 3.71 | < 0.001 |

| 61–70 | 1130 | 4,106,366 | 27.52 | 27.49 to 27.54 | 16–20 vs. 61–70 | 2.93 | 2.72 to 3.15 | < 0.001 |

| Age (years), sex (female) | ||||||||

| 16–20 | 424 | 2,592,366 | 16.36 | 16.34 to 16.38 | ||||

| 21–30 | 678 | 5,542,756 | 12.23 | 12.22 to 12.24 | 16–20 vs. 21–30 | 1.34 | 1.18 to 1.51 | < 0.001 |

| 31–40 | 705 | 6,069,714 | 11.56 | 11.55 to 11.57 | 16–20 vs. 31–40 | 1.41 | 1.25 to 1.60 | < 0.001 |

| 41–50 | 739 | 6,001,514 | 12.31 | 12.30 to 12.32 | 16–20 vs. 41–50 | 1.33 | 1.18 to 1.50 | < 0.001 |

| 51–60 | 847 | 5,241,214 | 16.16 | 16.15 to 16.17 | 16–20 vs. 51–60 | 1.01 | 0.90 to 1.14 | 0.840 |

| 61–70 | 1222 | 4,266,996 | 28.64 | 28.61 to 28.67 | 16–20 vs. 61–70 | 0.57 | 0.51 to 0.64 | < 0.001 |

| Age (years), sex (male vs. female) | ||||||||

| 16–20 | 16–20 vs. 16–20 | 4.92 | 4.44 to 5.47 | < 0.001 | ||||

| 21–30 | 21–30 vs. 21–30 | 5.37 | 4.95 to 5.83 | < 0.001 | ||||

| 31–40 | 31–40 vs. 31–40 | 3.20 | 2.94 to 3.48 | < 0.001 | ||||

| 41–50 | 41–50 vs. 41–50 | 2.25 | 2.07 to 2.46 | < 0.001 | ||||

| 51–60 | 51–60 vs. 51–60 | 1.44 | 1.32 to 1.57 | < 0.001 | ||||

| 61–70 | 61–70 vs. 61–70 | 0.96 | 0.89 to 1.04 | 0.334 | ||||

Comparison of UK incidence data with Canadian incidence data

Incidence rates for TASD in the UK were also compared by age and sex with those reported in Canada. 16 A comparative summary of the characteristics of the UK and Canadian cohorts is shown in Table 9. The UK cohort included in the analysis consisted of 15,666 patients aged 16–70 years with a primary shoulder dislocation in the UK as recorded in the CPRD between 1 April 1997 and 31 March 2015. Denominators for incidence analyses were obtained from the CPRD by individual year, age and sex. Data on urban or rural residence were not available in the CPRD, and thus this comparison could not be made.

| Details | Canadian data (Leroux et al.16) | UK data |

|---|---|---|

| Setting | Hospital records of patients having closed reduction of the shoulder | Primary care records of coded shoulder dislocations |

| Geography | Ontario cohort | UK sample (CPRD) |

| Dates | April 2002–September 2012 | April 1997–March 2015 |

| Patient age (years) | 16–70 | 16–70 |

| Numbers of patients | 20,719 | 15,666 |

The demographic data for the UK cohort (Table 10) were similar in age and sex distribution to those observed in the Canadian cohort. 16 The median age in both cohorts was 35 years, with a similar IQR. In the UK, 72% of primary shoulder dislocations occurred in men; in the Canadian cohort, this was slightly higher, at 74%.

| Demographic variable | UK cohort | Canadian cohort (Leroux et al.16) |

|---|---|---|

| Cohort size (n) | 15,666 | 20,719 |

| Age (years) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 38.29 (16.31) | 37.99 (16.62) |

| Median | 35 | 35 |

| IQR | 24–52 | 22–51 |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Male | 11,357 (72) | 15,399 (74) |

| Female | 4309 (28) | 5320 (26) |

| Deprivation quintile,a n (%) | ||

| 5 (most deprived) | 1224 (8) | 3698 (18) |

| 4 | 1686 (11) | 3862 (19) |

| 3 | 1889 (12) | 4071 (20) |

| 2 | 2188 (14) | 4356 (21) |

| 1 (most affluent) | 2625 (17) | 4732 (23) |

| Missing | 6054 (39) | 0 (0) |

The English IMD 200419 is a composite deprivation index at the small-area level, based on seven domains: income, employment, health and disability, education, barriers to housing and services, living environment, and crime. The Canadian measure of deprivation is solely based on income. These two measures are not directly comparable but a similar pattern of deprivation is observed, with increasing numbers of patients linked to increasing affluence. There was a large number of missing data for the UK cohort because the IMD results were available for English patients only, whereas complete data on deprivation were available for the Canadian patients.

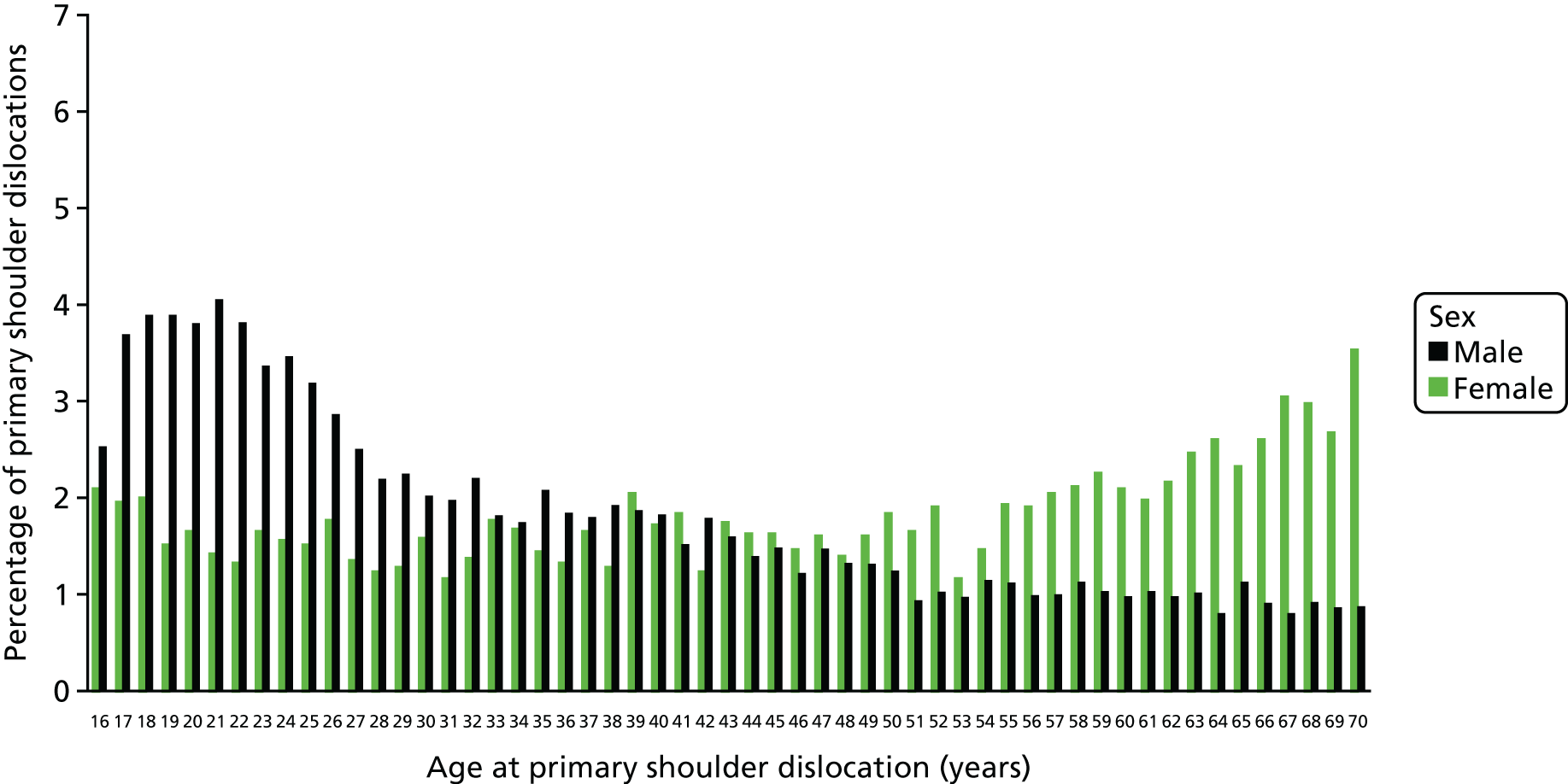

Figures 2 and 3 present the percentage of primary shoulder dislocation patients by age and sex in the UK and Canada, respectively. In the UK, the peak in numbers for men is spread over those aged 17–22 years, whereas there is a distinct peak in men aged 17 years in Canada. The pattern in the number of women with shoulder dislocations is similar in both cohorts, with a high percentage in those aged 16 years, which decreases up to the early 30s and then increases until the age of 70 years.

FIGURE 2.

The percentage of primary shoulder dislocation patients by age (16–70 years) and sex recorded within CPRD (UK) between 1 April 1997 and 31 March 2015. Reproduced from Shah et al. 17 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

FIGURE 3.

The percentage of primary shoulder dislocation patients by age and sex recorded in Canada. Leroux T, Wasserstein D, Veillette C, Khoshbin A, Henry P, Chahal J, et al. , American Journal of Sports Medicine, vol. 42, issue 2, pp. 442–50, copyright © 2014 by American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine, reprinted by Permission of SAGE Publications, Inc. 16

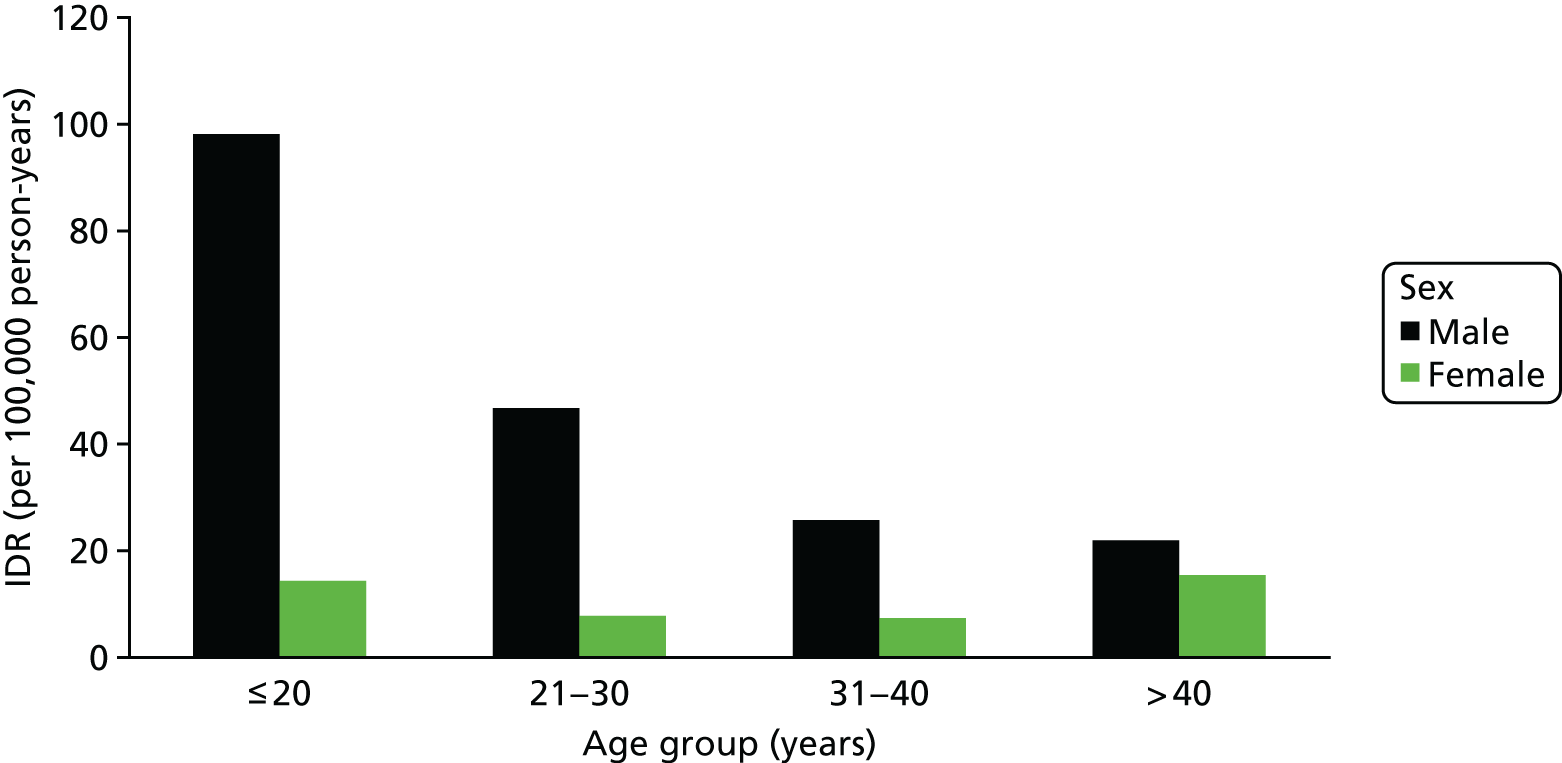

The incidence rates by age and sex for primary shoulder dislocation patients in the UK and an extract of similar Canadian incidence data are presented in Table 11. The patterns of incidence by age and sex were similar and are also represented in Figures 4 and 5. Incidence rates were higher in the UK for all combinations of age groups and sex, except for men aged 16–20 years [UK men (81.6 per 100,000 person-years) vs. Canadian men (98.3 per 100,000 person-years)].

| Demographic category | UK cohort | Canadian cohort (Leroux et al.16) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Incidence ratea | 95% CI | Incidence ratea | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 40.4 | 40.4 to 40.4 | 34.3 |

| Female | 15.5 | 15.5 to 15.5 | 11.8 |

| Age (years) | |||

| 16–20 | 48.8 | 48.8 to 48.9 | 56.6 |

| 21–30 | 38.8 | 38.7 to 38.8 | 27.0 |

| 31–40 | 24.4 | 24.4 to 24.5 | 16.5 |

| 41–70 | 22.2 | 22.2 to 22.2 | 18.8 |

| Age (years), sex (male) | |||

| 16–20 | 80.5 | 80.5 to 80.6 | 98.3 |

| 21–30 | 65.7 | 65.6 to 65.7 | 46.9 |

| 31–40 | 37.0 | 36.9 to 37.0 | 25.9 |

| 41–70 | 26.2 | 26.2 to 26.2 | 22.3 |

| Age (years), sex (female) | |||

| 16–20 | 16.4 | 16.3 to 16.4 | 13.8 |

| 21–30 | 12.2 | 12.2 to 12.2 | 7.5 |

| 31–40 | 11.6 | 11.6 to 11.6 | 7.1 |

| 41–70 | 18.1 | 18.1 to 18.1 | 15.2 |

FIGURE 4.

The incidence rate of primary shoulder dislocation by age and sex among patients aged 16–70 years with a primary shoulder dislocation recorded within CPRD (UK) between 1 April 1997 and 31 March 2015.

FIGURE 5.

The overall IDR of primary anterior shoulder dislocation in Canada requiring closed reduction in accordance with both age and sex. The y-axis depicts the IDR per 100,000 person-years and the x-axis depicts each age category. IDR, incidence density rate. Leroux T, Wasserstein D, Veillette C, Khoshbin A, Henry P, Chahal J, et al. , American Journal of Sports Medicine, vol. 42, issue 2, pp. 442–50, copyright © 2014 by American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine, reprinted by permission of SAGE Publications, Inc. 16

Comparison of UK incidence data with US incidence data

The age and sex incidence rates for primary shoulder dislocation in the UK were also compared with published data from the USA. 15 A comparison of the characteristics between the UK and US cohorts is shown in Table 12. The UK cohort included in the analysis comprised 20,784 patients of all ages with a primary shoulder dislocation between 1 April 1997 and 31 March 2015. Data on ethnicity were not available within the CPRD, thus this comparison could not be made. Denominators for incidence analyses were obtained from the CPRD by individual year, age and sex.

| Details | USA data (Zacchilli and Owens15) | UK data |

|---|---|---|

| Setting | Hospital records of patients presenting to 100 hospital emergency departments with a shoulder dislocation | Primary care records of coded shoulder dislocations |

| Geography | USA sample (NEISS) | UK sample (CPRD) |

| Dates | 2002–2006 | April 1997–March 2015 |

| Patient age (years) | All ages | All ages |

| Numbers of patients | 8940 | 20,784 |

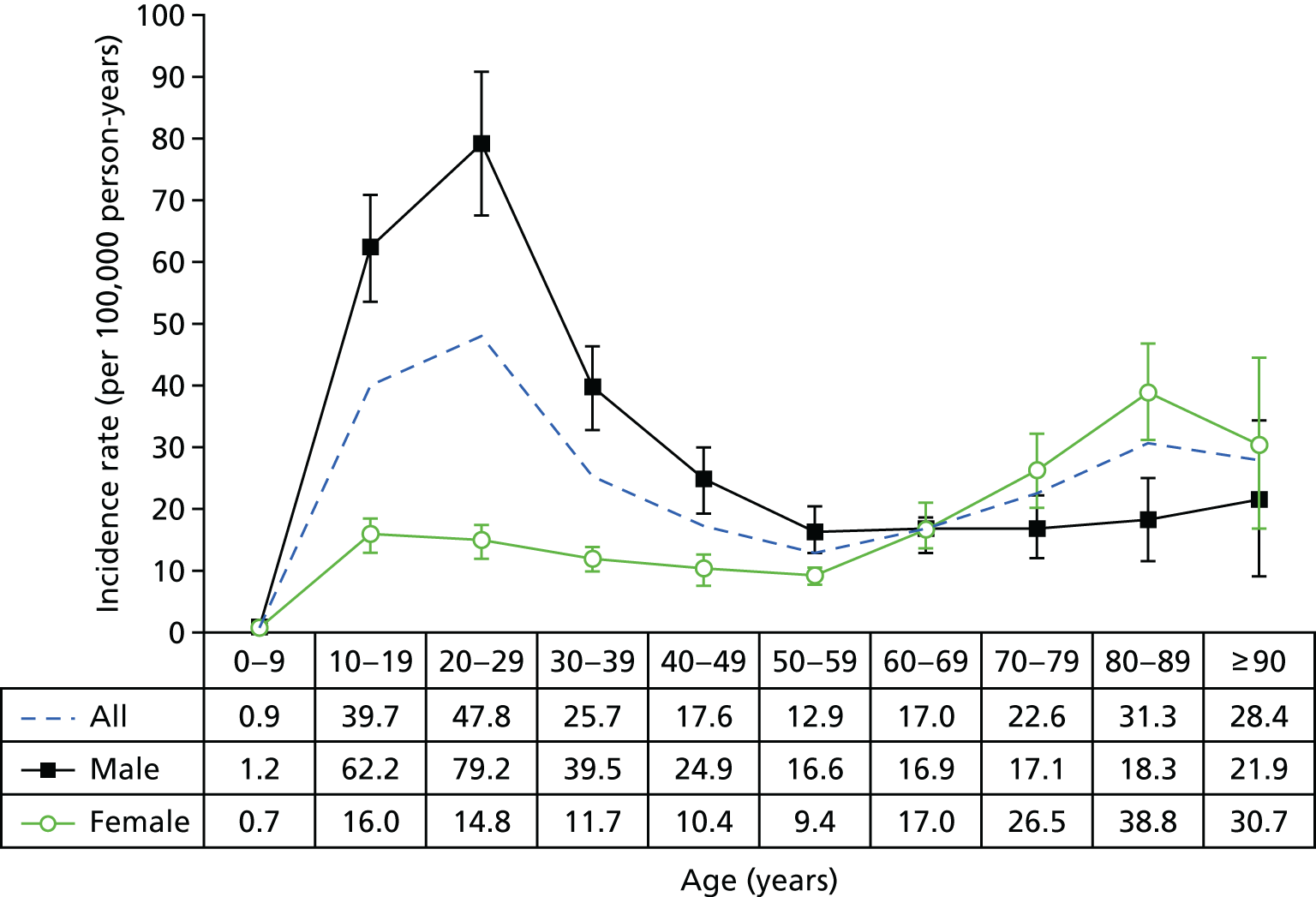

The overall incidence rate in the UK was 26.6 per 100,000 person-years (95% CI 26.2 to 26.9 per 100,000 person-years), which was similar to the incidence rate reported in the USA (23.9 per 100,000 person-years, 95% CI 20.8 to 27.0 per 100,000 person-years). The peak incidence occurred in patients aged 20–29 years in the UK (41.8 per 100,000 person-years, 95% CI 40.6 to 43.1 per 100,000 person-years) (Table 13), which is similar to the peak in 20- to 29-year-olds observed in the USA (47.8 per 100,000 person-years, 95% CI 41.0 to 54.5 per 100,000 person-years). 15 Significantly higher rates of incidence were observed in the UK among patients aged > 50 years in comparison with those in the USA (see Table 13).

| Demographic category | UK cohort data | USA cohort data (Zacchilli and Owens15) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incidence ratea | 95% CI | Incidence rate ratio | 95% CI | p-value | Incidence ratea | 95% CI | Incidence rate ratio | 95% CI | p-value | |

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Female | 19.02 | 18.59 to 19.45 | Referenceb | 13.26 | 11.56 to 14.96 | Referenceb | ||||

| Male | 34.29 | 33.71 to 34.88 | 1.80 | 1.75 to 1.86 | < 0.001 | 34.90 | 30.08 to 39.73 | 2.64 | 2.39 to 2.88 | < 0.05 |

| Age (years) | ||||||||||

| 0–9 | 1.23 | 1.01 to 1.49 | 0.06 | 0.05 to 0.08 | < 0.001 | 0.92 | 0.56 to 1.29 | 0.07 | 0.04 to 0.10 | < 0.05 |

| 10–19 | 27.34 | 26.32 to 28.41 | 1.38 | 1.30 to 1.46 | < 0.001 | 39.71 | 34.05 to 45.37 | 3.07 | 2.62 to 3.53 | < 0.05 |

| 20–29 | 41.80 | 40.55 to 43.08 | 2.11 | 2.00 to 2.23 | < 0.001 | 47.76 | 41.02 to 54.50 | 3.70 | 3.15 to 4.25 | < 0.05 |

| 30–39 | 25.05 | 24.14 to 25.99 | 1.26 | 1.19 to 1.34 | < 0.001 | 25.69 | 21.85 to 29.53 | 1.99 | 1.73 to 2.25 | < 0.05 |

| 40–49 | 20.66 | 19.84 to 21.51 | 1.04 | 0.98 to 1.11 | 0.169 | 17.59 | 14.22 to 20.96 | 1.36 | 0.91 to 1.82 | > 0.05 |

| 50–59 | 19.81 | 18.95 to 20.70 | Referenceb | 12.89 | 10.48 to 15.30 | Referenceb | ||||

| 60–69 | 26.71 | 25.60 to 27.87 | 1.35 | 1.27 to 1.43 | < 0.001 | 16.96 | 14.06 to 19.87 | 1.31 | 0.98 to 1.65 | > 0.05 |

| 70–79 | 41.12 | 39.48 to 42.82 | 2.08 | 1.95 to 2.20 | < 0.001 | 22.56 | 17.51 to 27.61 | 1.74 | 1.45 to 2.03 | < 0.05 |

| 80–89 | 58.03 | 55.40 to 60.79 | 2.93 | 2.75 to 3.12 | < 0.001 | 31.34 | 25.05 to 37.63 | 2.43 | 1.93–2.93 | < 0.05 |

| ≥ 90 | 65.55 | 59.65 to 72.03 | 3.31 | 2.98 to 3.67 | < 0.001 | 28.38 | 17.97 to 38.79 | 2.20 | 1.30–3.10 | < 0.05 |

In the UK, the incidence of primary shoulder dislocation was significantly higher in men (34.3 per 100,000 person-years, 95% CI 33.7 to 34.9 per 100,000 person-years) than in women (19.0 per 100,000 person-years, 95% CI 18.6 to 19.5 per 100,000 person-years) (p < 0.001), which is similar to the pattern observed in the USA (see Table 13). Incidence of shoulder dislocation in men was similar between the UK and US cohorts, but incidence in women in the UK was much higher than incidence in women in the USA. In the UK cohort, 36% of shoulder dislocations occurred in women, in contrast to 28% of shoulder dislocations in the US cohort.

Figure 6 shows the peak of incidence in men aged 20–29 years in the UK (71.5 per 100,000 person-years), which was similar to the peak in men in the same age group in the USA (79.2 per 100,000 person-years) (Figure 7). The peak in women in the UK was observed in those aged > 90 years (71.7 per 100,000 person-years), in contrast with the 38.8 per 100,000 person-years in women aged 80–89 years in the USA. A possible reason for the differences in incidence may be caused by the UK study being based on primary care records and the US study being based on emergency department records.

FIGURE 6.

Shoulder dislocation incidence rates and 95% CIs by age and sex in CPRD (UK) between 1 April 1997 and 31 March 2015.

FIGURE 7.

Total weighted NEISS estimates of all US shoulder dislocations between 2002 and 2006 by age and sex, demonstrating a bimodal distribution with peaks among men (aged 20–29 years) and women (aged 80–89 years). The vertical bars denote the 95% CIs. 15 Zacchilli MA, Owens BD. Epidemiology of shoulder dislocations presenting to emergency departments in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg 1992;3:542–9. https://insights.ovid.com/pubmed?pmid=20194311. Reprinted by permission of Wolters Kluwer.

Conclusion

This chapter describes a large population-based cohort of 16,763 patients aged 16–70 years in the UK during 1995–2015 identified in the CPRD data set in relation to shoulder dislocations. Most shoulder dislocations occurred in males (72%), with an overall incidence rate of 40.4 per 100,000 person-years. In females, the overall incidence rate was 15.5 per 100,000 person-years. The highest incidence was observed in 16- to 20-year-old males (80.5 per 100,000 person-years). An unexpected finding was that incidence in women increased beyond the age of 50 years to 28.1 per 100,000 person-years among those aged 61–70 years; this pattern was not observed in men.

The results from the UK cohort were then compared with other cohorts in other countries. The UK cohort was similar in age, sex distribution and incidence patterns to those observed in the Canadian, US and Norwegian cohorts. 15,16,20 Although the incidence patterns were similar between countries, in the UK the peak in numbers observed for men is spread over those aged 17–22 years, whereas there is a distinct peak in men aged 17–18 years in Canada and the USA. Possible reasons for this difference may be the high numbers of young men playing ice hockey and American football at school, aged 17–18 years, of whom not all continue to play at college. In a smaller study of the causes of shoulder dislocations in Sweden, incidence was high (8%) among ice-hockey players. 13 Other explanations might be the under-reporting of shoulder dislocations among college students or a genuine decrease because of better skeletal maturity and shoulder muscle strength and control.

Incidence rates were higher in the UK than in Canada for all combinations of age groups and sex, except for men aged 16–20 years (UK men, 80.5 per 100,000 person-years; vs. Canadian men, 98.3 per 100,000 person-years). These higher incidence rates may be explained by UK data being based on primary care records in contrast to Canadian data, which are based on accident and emergency hospital records. 16

A study conducted in Denmark identified the same bimodal age distribution of incidence, and also specifically noted that older people most frequently dislocated their shoulders at home by falling on their arm, whereas young people most frequently suffered a shoulder dislocation while playing sports. 21 However, the increasing incidence of shoulder dislocations seen in UK women aged > 50 years is a new finding that is of both interest and concern because the reasons for it are not known. Such injuries in the elderly are usually associated with rotator cuff tears and fractures with subsequent loss of function, as well as instability. However, further work will be required to examine the reasons that may explain this increased risk of shoulder dislocations in ageing women. Possible reasons include biological differences between ageing men and women, including differences in joint proprioception, soft tissue tendon quality and protective muscle bulk. Other possibilities might be a difference in the incidence of falls between men and women. This is of particular importance, given that the population of the UK continues to change to include more elderly people. The increasing population priority needs to be given to increasing the safety of the elderly to reduce falls, dislocations and fractures, as advocated by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE),22 which suggests that this is a finding that needs further investigation and research.

The main strength of this study is its large population-based cohort that uses real-world data from primary care. The CPRD is representative of the UK general population by age and sex and the age- and sex-specific incidence of primary shoulder dislocations observed are similar to those observed in Canada and the USA. Although some differences were observed, the incidence of traumatic shoulder dislocations in these other countries has only been calculated using regional data or hospital data. This is, therefore, the first time, to our knowledge, that the incidence of shoulder dislocations has been studied using population-based primary care data and the first time, to our knowledge, that results for the UK have been produced. The findings in this chapter and Chapter 2 support the use of CPRD for the subsequent study chapters and work package 2 studies.

In summary, in the UK most primary shoulder dislocations during the selected time period occurred in young men. An unexpected finding was that incidence increased in women aged > 50 years but not in men of the same age. The reasons for this are unknown. Priority and attention should be directed towards increasing preventative measures for young people playing contact sports, and to the research of the possible causes of the increase in primary shoulder dislocation incidence for women aged > 50 years.

Chapter 4 The impact of surgical treatment within 6 months or no surgical treatment on the rates of shoulder re-dislocations in young people aged 16–35 years with first-time traumatic anterior shoulder dislocation in England

This chapter begins the main analysis of the commissioned research (work package 2). The previous chapters described the internal and external validation of the data to be used in this and the following chapters.

Objectives of Chapter 4

To study the effect of surgical treatment on the 2-year recurrent shoulder dislocation rates in young adults in England when surgical treatment took place within 6 months of the first episode of TASD.

Methods

Study design

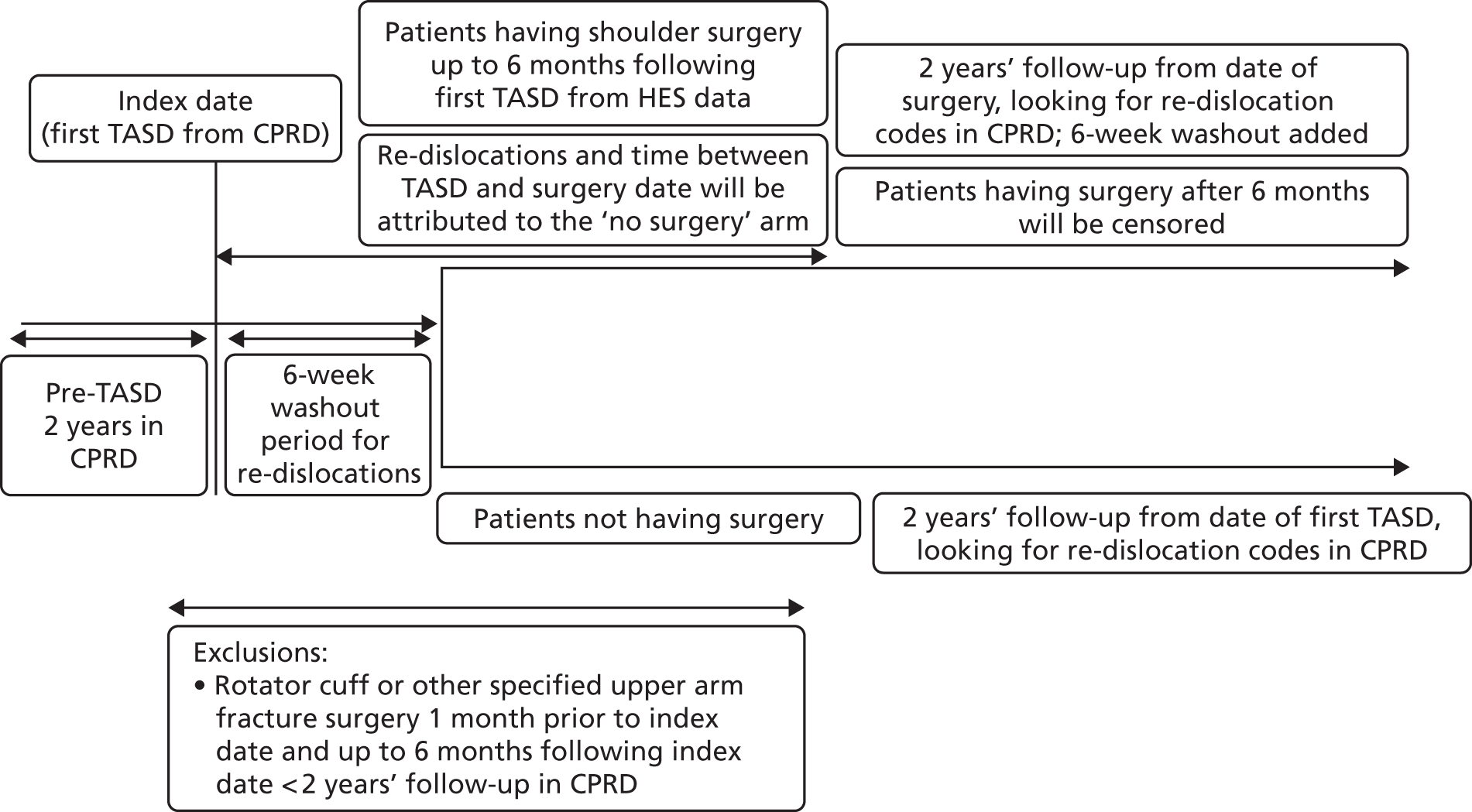

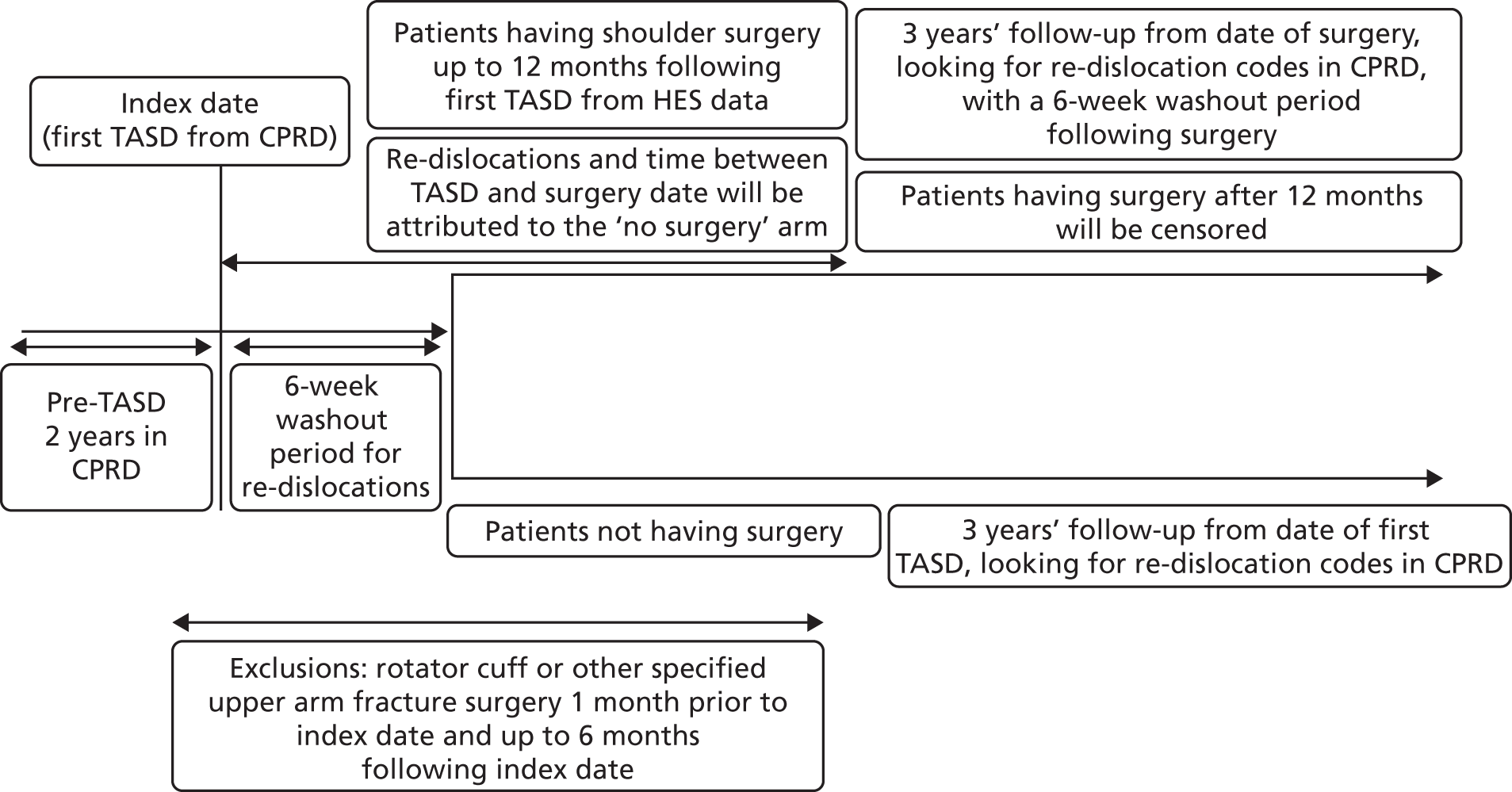

A population-based propensity-score-matched cohort study to control for confounding at baseline has been conducted. Young adults (aged 16–35 years) who presented with a first-time TASD were selected from two computerised NHS databases (CPRD and HES). Figure 8 shows a detailed illustration of the study plan, which is described in more detail in the following paragraphs.

FIGURE 8.

The UK TASH-D phase 2 plan design for patients who received surgery or no surgical treatment within 6 months of a diagnosis of a first-time TASD during 1 April 1997–26 April 2014, in England.

Using methodology identical to the internal validation study described in Chapter 2, to ensure that only primary dislocations had been captured, all participants had to have 2 years of clinical data within CPRD before their first TASD and at least 2 years’ follow-up from the event (re-dislocation). This 2-year washout period is required to ensure that a first dislocation code actually represents a first-time dislocation, as a recurrent dislocation usually occurs within 2 years of the primary event. This period therefore minimises the risk of a code being a second dislocation code. The period was defined using the date that the general practice was classified as ‘up to standard’ and the date that the patient was first registered at the practice. Patients had to be registered at ‘active’ practices, as defined in Chapter 2, Data source. Taking into account this washout period, the first Read code entry in CPRD for shoulder dislocation was then defined as the first dislocation. All events were collected using a pre-agreed validated list of CPRD Read codes (see Appendix 1). Patients experienced their first-time TASD between 1 April 1997 and 26 April 2014, allowing at least 2 years of follow-up for each patient to the end of the study on 26 April 2016.

A 6-week washout period for re-dislocation codes within CPRD was applied to all patients following their TASD to avoid duplicate records. Patients were highly unlikely to re-dislocate their shoulder during this period as their arms would be in slings and they would be following rehabilitation protocols, but would probably return to visit their GP for prescriptions for painkillers or referrals to physiotherapy and secondary care.

Surgical group

The surgical group comprised patients in CPRD with a first-time TASD who underwent shoulder stabilisation surgery after their first dislocation. Early surgical repair in this NHS context means ‘a decision to treat surgically after the first TASD’ (as per the approved study protocol) and receiving surgery within 6 months of injury before any subsequent dislocations. This meant linking HES data to CPRD data in such a way that a HES surgical OPCS 4.7 code was seen to occur after a single first dislocation code in CPRD before that surgical date. The timelines between first dislocation codes and OPCS 4.7 codes were recorded. If a re-dislocation occurred prior to their surgery date, the patient was allocated to the non-surgical arm.

A further 6-week washout period for re-dislocation codes within CPRD was applied to all patients in the surgical group following their surgery date to avoid duplicate records because they would have been asked to immobilise their arm for this period and, thus, a re-dislocation would be highly unlikely to occur. During these 6 weeks, patients would most probably return to visit their GPs for painkillers or referral to physiotherapy. Surgery patients were followed up for at least 2 years from the date of their surgery. Patients who had surgery more than 6 months following their TASD were censored on their date of surgery. The surgery dates for these patients ranged from 25 December 1997 to 18 August 2014.

Non-surgical group

Although the most desirable control group would have been physiotherapy, the internal validation study identified that the referral codes for physiotherapy are lacking and unreliable in CPRD. Thus, conservative care has been defined as ‘non-surgical intervention’, with no linked OPCS 4.7 surgical shoulder codes, producing a control cohort of patients whose first-time shoulder dislocation has been treated non-operatively. Non-surgical patients were followed up for at least 2 years following the date of their first-time TASD, as illustrated in Figure 8.

Outcome

The outcome was time to a shoulder re-dislocation, as defined by the CPRD Read codes given in Appendix 1. For the surgical group, the shoulder re-dislocation can occur between 6 weeks and 2 years following the date of surgery. For the non-surgical group, the shoulder re-dislocation could occur between 6 weeks and 2 years following the date of first-time TASD.

Any patients who died during the study were censored on their date of death.

Data sources

The analysis utilised two computerised NHS databases, one from primary care (the CPRD) and the other from secondary care (the HES). The characteristics of the CPRD have been described in Chapter 2, Data source. For HES data, each time a patient sees a health professional in a hospital, a record or ‘episode’ is created and added to the HES database. The HES record contains patient details, some diagnosis codes, treatments and lengths of hospital stay.

Clinical Practice Research Datalink has been linked with HES data to provide a HES-linked patient identifier. About 60% of CPRD-contributing practices have been linked to HES data. HES data provide a general patient identifier to facilitate linkage of hospital records belonging to the same individual. Management of the CPRD and HES databases was carried out by a senior data manager with expertise in the use of these data sets. The senior data manager developed an ad hoc code using Python (version 3.6, developed by Python Software Foundation, Wilmington, DE, USA) and Structured Query Language (SQL) (version 5.6.12, developed by the International Electrotechnical Commission and the International Organization for Standardisation; Geneva, Switzerland) to produce a final working data set that was analysed using standard statistical software packages Stata® version 14.1 and R (version 3; The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Sample size

The original sample size considerations for this study were based on data from a Cochrane systematic review comparing surgical and non-surgical treatment for an acute TASD. 5 From the pooled results, 3 out of 58 patients in the surgical arm had subsequent further surgery (5.17%) compared with 17 out of 61 patients in the non-surgical arm (27.9%), at a minimum follow-up of 2 years (risk ratio 0.22, 95% CI 0.08 to 0.64). The large effect size is based on the pooled results of three randomised controlled trials with uncertainty around the true size of the effect outside a clinical trial setting in routine general practice. Therefore, values were set to detect a smaller difference in subsequent surgery within 2 years, with a 25% re-dislocation rate in the non-surgical group, compared with a 20% re-dislocation rate in the surgical group (an absolute difference of 5%). A two-sided, log-rank test for equality of survival curves was used, with 90% power at a 5% significance level (alpha) and for which the outcome is time to re-dislocation with an anticipated 25% re-dislocation rate in the non-surgical control group compared with a 20% re-dislocation rate in the surgical group [equivalent to a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.78]. Allowing for a 10% loss to follow-up and assuming equal group sizes meant that the study required a total sample size of 3065 participants, with 656 expected re-dislocations. 5 It was assumed that 35% of the patients would receive surgery within 6 months after one dislocation (n = 1073). 23

Participants

Inclusion criteria

The CPRD records of 6046 patients, aged 16–35 years with 2 years of data in the CPRD before a first-time TASD, identified in the internal validation study (see Table 1) were linked to HES records.

Exclusion criteria

The following patients were excluded:

-

those aged 16–35 years with a first-time TASD who cannot be linked by CPRD-HES

-

those with < 2 years of follow-up in the CPRD

-

those with prior shoulder surgery for a shoulder dislocation

-

those whose instability was treated with rotator cuff repair surgery or fracture surgery prior to or following a TASD.

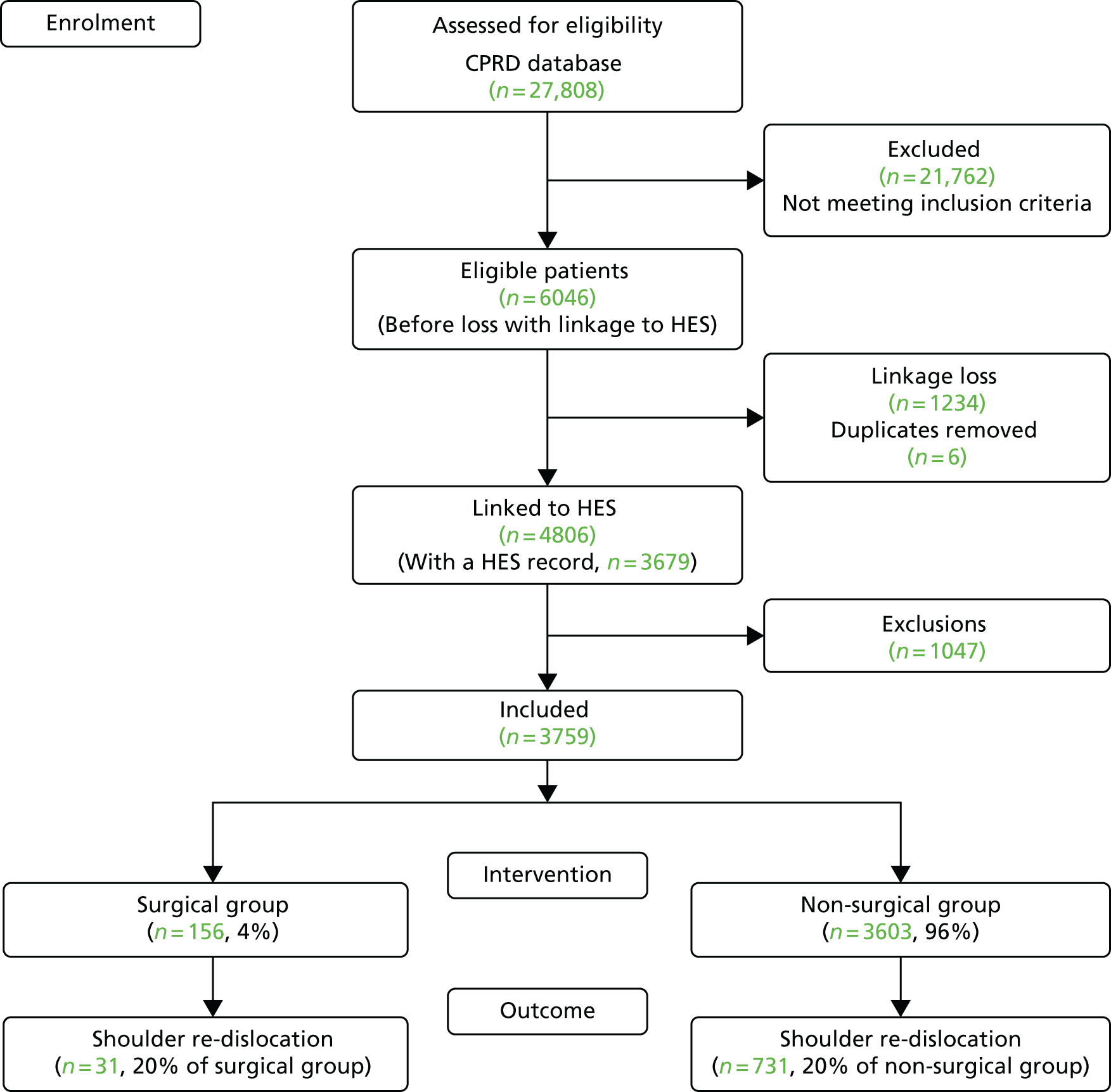

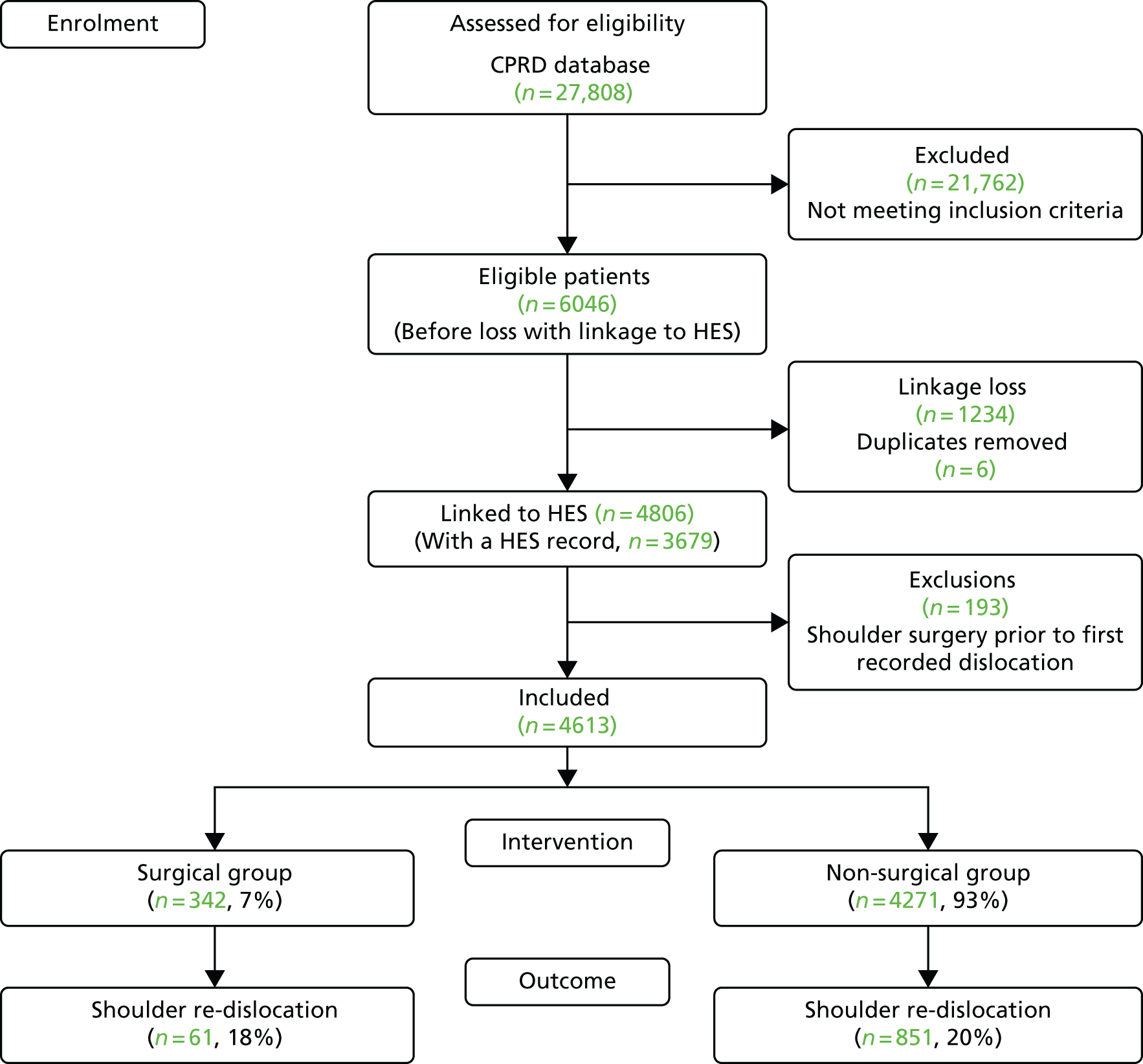

Exclusions were made in accordance with the criteria above and are described in Table 14. Following linkage to HES, there was a linkage loss of 1234 patients and six duplicates were identified and removed. A substantial number of patients had < 2 years of follow-up within the CPRD (n = 854), which may relate to these young people moving away from home to attend university or to start new jobs in new locations, which, in turn, requires a change of GP. A very small proportion of patients (3%) were excluded for having shoulder surgery for rotator cuff tears, fractures or prior dislocations. In total, 3759 patients remained available for analysis, which was greater than the minimum number of patients (n = 3065) required for a sufficient sample size and power (Figure 9).

| Exclusions | Excluded (n) | Total (N) | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eligible patients in the CPRD cohort for the internal validation study, following exclusions made in Table 1 | 6046 | 100 | |

| HES linkage loss | 1234 | 20 | |

| Duplicate removal | 6 | < 1 | |

| < 2 years of follow-up within the CPRD | 854 | 14 | |

| Prior shoulder surgery for a shoulder dislocation | 155 | 3 | |

| Surgery for rotator cuff tear prior to TASD | 1 | < 1 | |

| Surgery for rotator cuff tear in the 6 months following TASD | 4 | < 1 | |

| Surgery for a shoulder fracture prior to TASD | 14 | < 1 | |

| Surgery for a shoulder fracture in the 6 months following TASD | 19 | < 1 | |

| Total exclusions | 2287 | ||

| Patients included in subsequent analyses | 3759 | 62 |

FIGURE 9.

Shoulder dislocation exclusions flow chart for patients aged 16–35 years during 1 April 1997–26 April 2014, within CPRD in England with linkage to HES records.

Statistical analysis

The aim of this study was to investigate the effect of surgical intervention within 6 months compared with non-surgical intervention on the rates of re-dislocation in young patients with a first-time TASD over a 2-year period. In addressing this research question, the exposure is whether or not a patient received surgery, and the primary outcome of interest is the time from date of surgery for surgical patients or date of the first-time TASD for non-surgical patients to having a subsequent re-dislocation within 2 years.

Covariates

Demographic data were available from the CPRD on age, sex, BMI, IMD 2004,19 smoking status (i.e. current smoker, ex-smoker, non-smoker), drinking status (i.e. current drinker, non-drinker), geographic region, epilepsy and prescriptions for painkillers in the 3 months preceding the first-time TASD and 1 month following the first-time TASD. The CCI score was calculated using a list of predefined CPRD Read codes.

A consensus survey was conducted of specialist shoulder surgeons and shoulder physiotherapists who were all members of the British Elbow and Shoulder Society. The saturation point and a list of predictors was reached rapidly and this list is tabulated in Appendix 4. The list highlights the risk factors (and covariates) deemed most important. However, data were only reliably available on the following factors from the list: age, sex, geographic region, deprivation scores, time between first dislocation and surgery.

Missing data

Multiple imputation using chained equations was used to address potential bias and increase precision as a result of missing data on BMI, smoking, drinking and IMD. 24 The imputation equations included all potential factors, including the outcome and length of follow-up time. Fifty imputed data sets were generated and the resulting estimates were combined using Rubin’s rules.

Confounding by indication

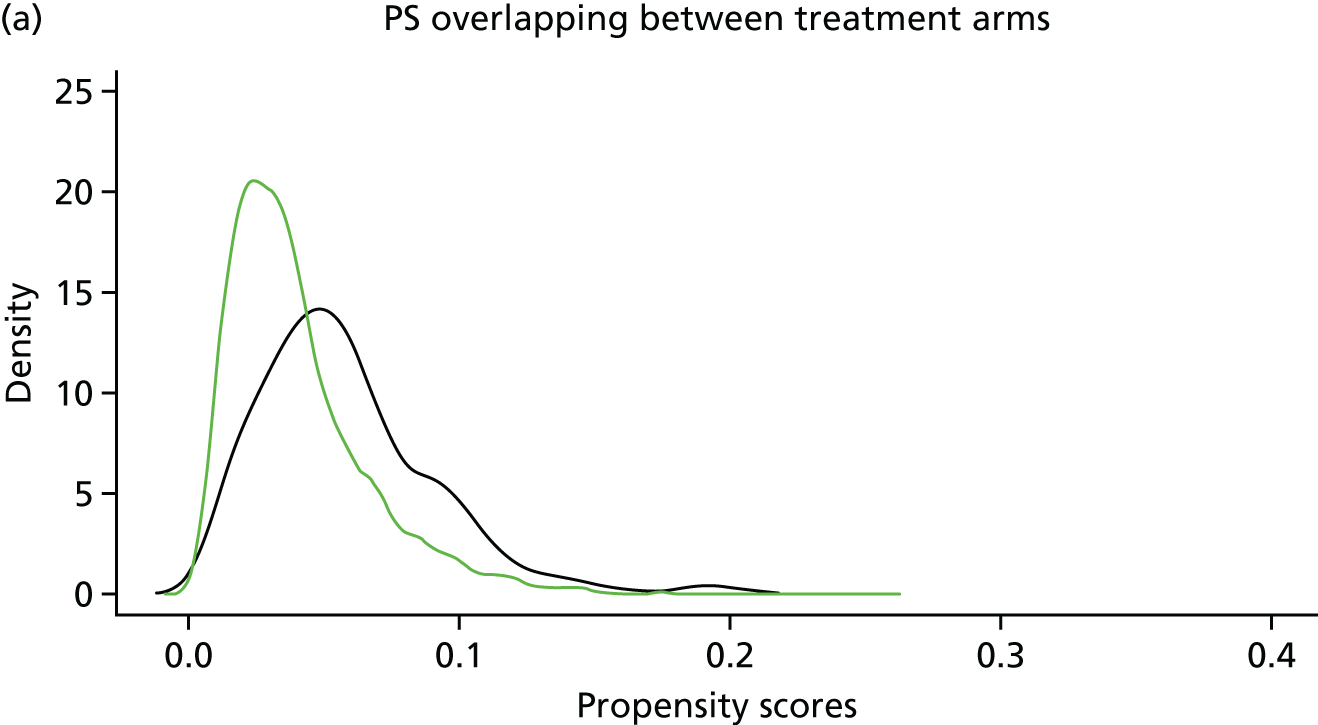

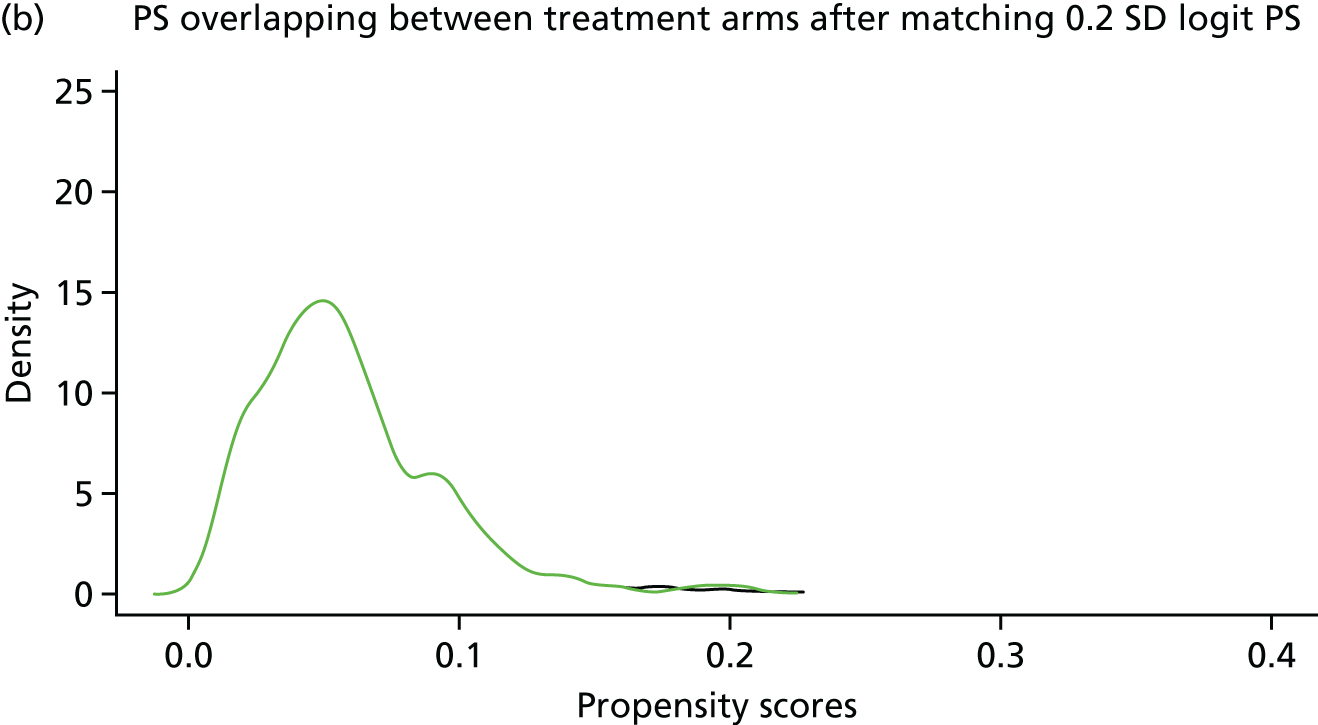

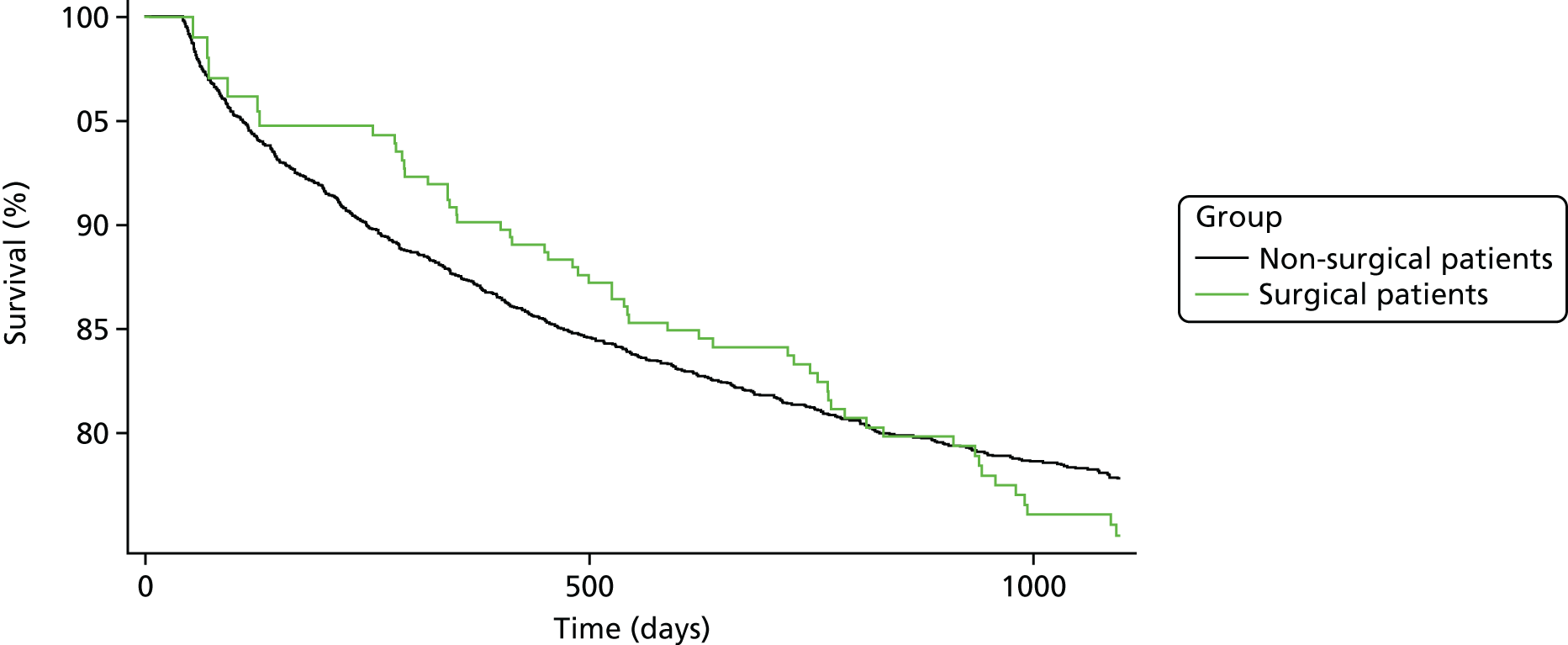

In randomised controlled trials, each person has an equal probability of being in the treatment or the control group. Observational study designs, such as the one used for this study, are limited by an inherent imbalance of both known and unknown confounders, making some patients more likely to receive surgery than others. A surgeon typically uses information and risk factors on the patient at baseline to make a decision about whether or not to operate. Whether or not a patient receives surgery is therefore not random in this population-based setting.