Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 08/106/02. The contractual start date was in March 2011. The draft report began editorial review in May 2016 and was accepted for publication in September 2016. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Ajit Lalvani is the named inventor for several patents underpinning T-cell-based diagnosis including interferon gamma, enzyme-linked immunospot assay, ESAT-6, CFP-10, Rv3615c, Rv3873 and Rv3879c. He has royalty entitlements from the University of Oxford spin-out company (Oxford Immunotec plc), in which he has held a minority share of equity and he is a member of the Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation Board. Jonathan J Deeks is a member of the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Commissioning Board and the HTA Efficient Study Designs Board. Onn Min Kon is chairperson of the UK Joint Tuberculosis Committee. Peter White has received research funding from Otsuka SA for a retrospective study of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis treatment in several eastern European countries outside the submitted work. He received grants from the Medical Research Council during the conduct of the study.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Takwoingi et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

In 2014, globally, an estimated 9.6 million cases of tuberculosis (TB) and 1.5 million deaths caused by the disease were reported to the World Health Organization. 1 Co-infection with TB and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) accounts for a significant proportion of cases globally (12%) and together these infections are the biggest infectious causes of death. Health inequalities are exacerbated by the burden that TB places on the most vulnerable and poor around the world. Over the past 20 years, worldwide TB incidence and mortality have declined. However, despite this, the prevalence of TB still remains unacceptably high. Furthermore, there is not yet evidence of a reduction in the number of cases in England, particularly in major cities such as London and Birmingham.

In England, 6520 cases of TB were reported in 2014, with an incidence rate of 12.0 per 100,000. 2 Of these, 2572 cases were in London, where the incidence rate was 30.1 per 100,000. 2 Other urban high-incidence areas include Leicester, Birmingham, Luton, Manchester and Coventry. The majority of cases in England (72%) occurred in new entrants who were born outside the UK. 2

Tuberculosis is caused by active infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb). Upon initial infection with Mtb, a state of asymptomatic dormancy typically occurs. In most infected individuals this results in a prolonged and perhaps lifelong latent TB infection (LTBI). In others, however, a breakdown of immune control and activation of infection results in symptomatic disease, which can be fatal without treatment. Co-infection with HIV dramatically increases the likelihood of progression from latent to active disease.

Active TB can manifest with pulmonary or extrapulmonary phenotypes. In its active pulmonary form, TB is highly contagious. The diagnosis of active TB is central to preventing the spread of disease and thus controlling the TB epidemic. 3 However, the slow speed and poor sensitivity of existing diagnostic tools often lead to delays diagnosis and treatment of the disease. 4

Diagnosis of tuberculosis

Conventional methods of diagnosing active TB rely primarily on the identification of Mtb bacilli, as well as imaging affected areas. Smear microscopy is quick and inexpensive, but typically lacks sensitivity. Although cell culture is considered the ‘gold standard’ for diagnosis of active TB because of its higher sensitivity, it is often slow, taking up to 6 or 8 weeks to give a result. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based tests for Mtb, such as the new GeneXpert Mtb/RIF® (Sunnyvale, Cepheid, CA, USA), can be quick and sensitive, but they are typically expensive and require a high standard of infrastructure. Imaging techniques such as chest radiography and computed tomography (CT) are quick and usually sensitive, but are not specific. Furthermore, they can be expensive, and, again, require a high standard of infrastructure (for example in the case of CT). All of these tests tend to be less accurate in cases of active TB with HIV co-infection, and also in cases of extrapulmonary TB.

Currently available tests for LTBI include the tuberculin skin test (TST) and interferon gamma release assays (IGRAs). The TST measures the in vivo delayed-type hypersensitivity response to intradermal inoculation of a crude mixture of mycobacterial antigens. Because this mixture contains antigens also present in bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG), the test can be confounded by prior BCG vaccination. IGRAs, on the other hand, detect ex vivo interferon gamma (IFN-γ) release from T cells (lymphocytes that play a key role in cell-mediated immunity) in response to Mtb-specific antigens, early secretory antigenic 6 kDa (ESAT-6) and culture filtrate protein 10 (CFP-10). These antigens are absent from the BCG vaccine and most environmental mycobacteria, and thus IGRAs tend to be more specific than the TST. 5 The two types of commercially available IGRAs are QuantiFERON GOLD In-Tube (QFT-GIT; Cellestis, Carnegie, VIC, Australia), a whole-blood enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), and T-SPOT. TB® (Oxford Immunotec, Abingdon, UK), an enzyme-linked immunospot assay (ELISpot); both IGRAs utilise peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). These tests have been recommended by the UK, European and North American guidelines for diagnosis of LTBI. 6

Although typically used in the diagnosis of LTBI, TSTs and IGRAs actually detect Mtb infection in its entirety (i.e. active or latent). The role of the tests within published guidelines for diagnostic evaluation of suspected active TB to date has been limited because of their low specificity for the disease: they could never confirm a diagnosis of active TB because they cannot differentiate latent and active infection. However, because Mtb infection is a pre-requisite for TB disease, reliable determination of infection status could accelerate diagnostic assessment by enabling rapid exclusion of TB (within 24 hours) when the result is negative.

In order for the IGRA or TST to reliably rule out a diagnosis of Mtb infection and thus TB disease, the sensitivity of the test must be very high (> 95%). The sensitivity and specificity of IGRAs compared with the TST in active TB have been examined in a number of studies, varying in size and quality. 7 IGRAs are typically more specific than the TST for diagnosing Mtb infection and T-SPOT. TB is more sensitive than the TST for diagnosing TB. However, the diagnostic accuracy of T-SPOT. TB and QFT-GIT has not been compared directly head to head in suspected active TB in the UK, nor comprehensively assessed in immunosuppressed patients. Therefore, there is uncertainty in the role and clinical utility of IGRAs in the diagnostic workup of suspected TB, as well as their cost-effectiveness in UK NHS practice.

Aim and study objectives

Aim

To evaluate and compare the diagnostic accuracy and cost-effectiveness of IGRAs with conventional testing for diagnosis of active TB. Specifically, the study aimed to determine the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive values (PPVs) and negative predictive values (NPVs), and likelihood ratios of T-SPOT. TB and QFT-GIT for diagnosis of active TB in routine NHS clinical practice. Second-generation IGRAs were also evaluated.

Study objectives

Primary objectives

-

To compare the diagnostic accuracy of T-SPOT. TB and QFT-GIT for the diagnosis of active pulmonary and extrapulmonary TB in routine clinical practice.

-

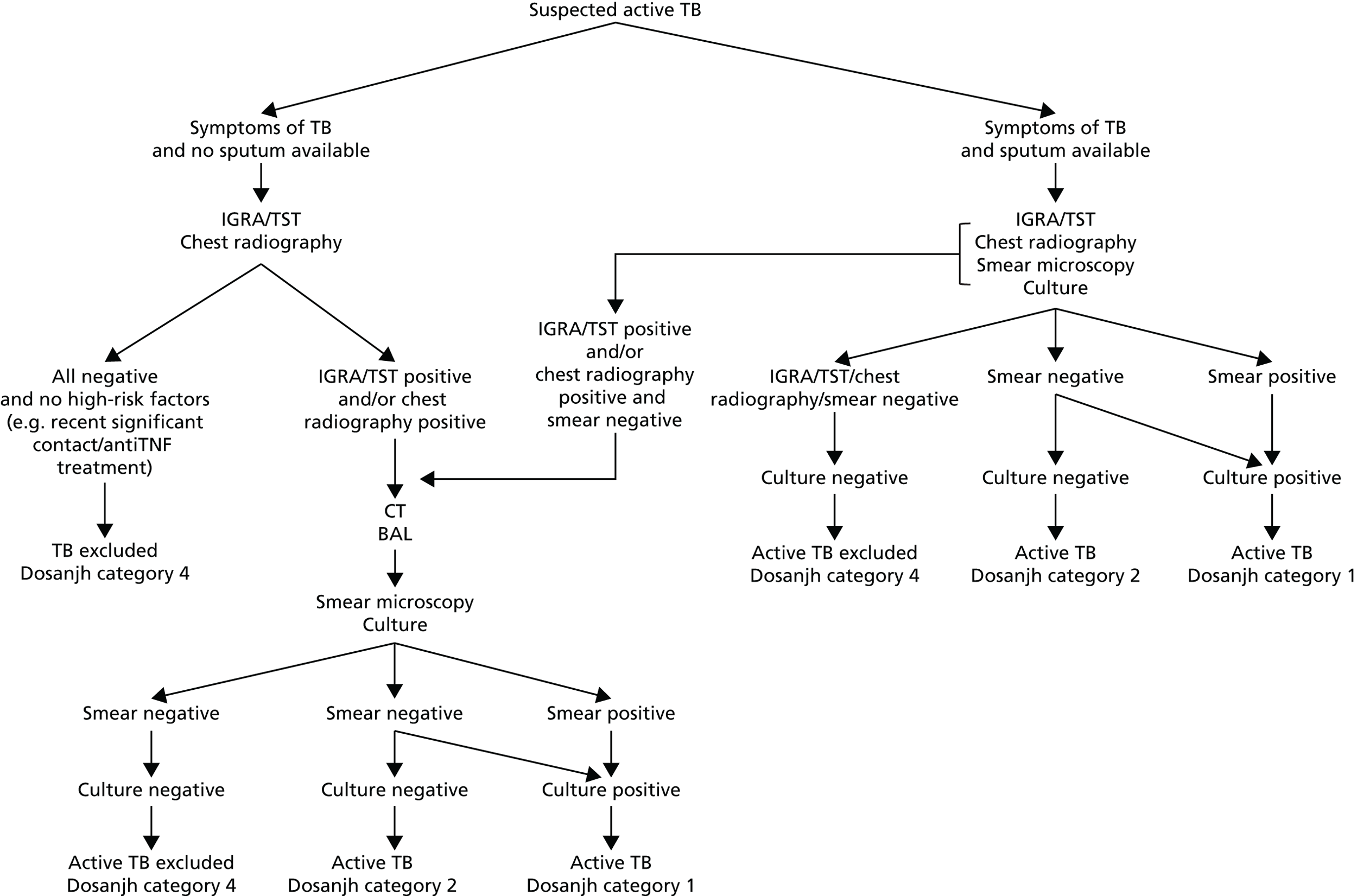

To develop an evidence-based optimal testing algorithm that defines the role of IGRAs in the diagnostic workup of suspected active TB.

-

To deliver the objectives above for a key subgroup: HIV co-infected patients (the highest-risk subgroup of TB).

-

To quantify and compare the cost-effectiveness of a range of possible testing strategies against the present testing regime.

Secondary objectives

-

To quantify the sensitivity, specificity, and positive and NPVs of T-SPOT. TB and QFT-GIT in a number of key patient subgroups, such as patients with pre-existing diabetes mellitus, end-stage renal failure and iatrogenic immunosuppression.

-

To quantify the use of second-generation IGRAs compared with existing commercially available assays.

Chapter 2 Methods

This chapter describes the study design and methods for the evaluation of the diagnostic accuracy of IGRAs in active TB. Our report adheres to the Standards for the Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (STARD) guideline,8 as shown in Appendix 1. Methods for the health economic evaluation are described separately in Chapter 6.

Overview of the study design

This prospective multicentre study comparing the accuracy of IGRAs was conducted in routine clinical practice in the UK. Adults presenting with suspected active TB at NHS outpatient or inpatient services to participating hospitals in London, Slough, Oxford, Leicester and Birmingham were recruited. We used a within-patient design to compare test accuracy by performing all IGRAs on blood samples from each patient with the presence or absence of active TB verified using the reference standard. This design minimises between-patient variability while also allowing estimation of the accuracy of combinations of IGRAs. Blood samples for IGRA testing were collected from patients at baseline and follow-up (2 and 6 months). If necessary, and when available, TST results were used as part of the composite reference standard for verifying the final diagnosis of patients. The TST results were obtained from routine clinical care and so the availability of TST results reflects local practice in participating hospitals.

Participants

Inclusion criteria

Adults (aged ≥ 16 years) presenting with suspected (pulmonary or extrapulmonary) active TB to NHS outpatient or inpatient services were included. To replicate clinical practice, patients with a previous diagnosis of TB and/or history of TB treatment were recruited. However, they were excluded from the analyses on the basis that, when evaluating patients with suspected active TB, the clinician should not perform an IGRA because any immunological biomarker would remain positive and thus affect test accuracy. The study population was expected to be representative of the national TB burden in terms of ethnic mix and range of comorbidities. A key subgroup was HIV-positive patients.

Exclusion criteria

Participants aged < 16 years or those unable to give informed consent were excluded.

Setting

Patients were recruited at the point of diagnostic workup from 14 hospitals in 10 NHS trusts in the UK.

Recruitment process

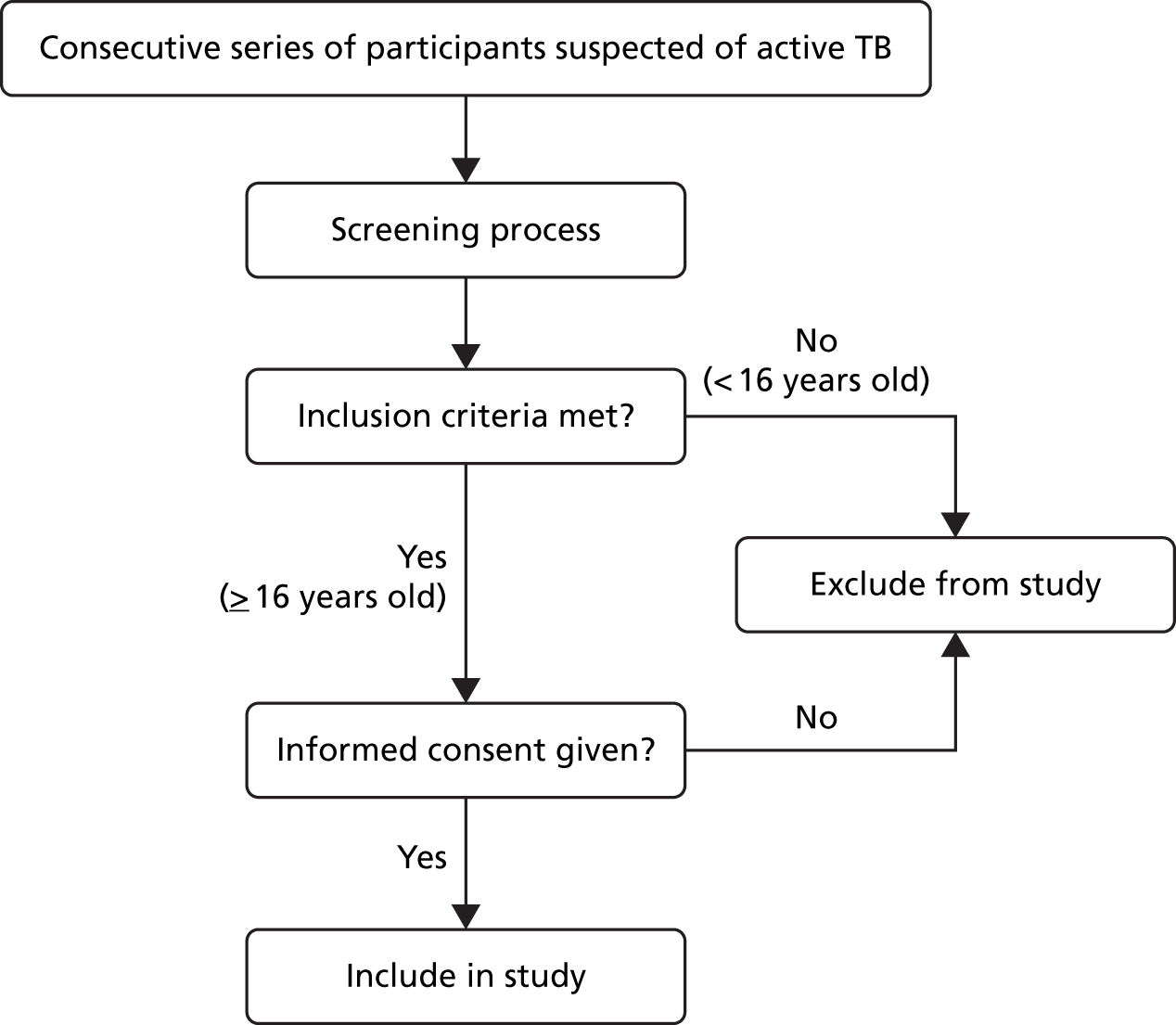

An overview of the recruitment process is shown in Figure 1. Potential participants presenting to participating NHS centres were referred to a TB research nurse by the attending clinician. The nurse then screened participants to ensure that they were eligible for the study according to the inclusion/exclusion criteria stated above. Each potential participant was provided with an information sheet and a verbal description of the study. Participants were included in the study if they were willing and informed consent was obtained.

FIGURE 1.

Overview of recruitment process.

Data collection and management

Follow-up

Participants were seen by research nurses for follow-up visits at 2 and 6 months after recruitment. Follow-up visits were scheduled to be carried out at the same time as the patient’s routine clinic appointments. At these visits blood was collected for IGRA testing and data on patient diagnosis were obtained. If patients were no longer being seen as part of their routine NHS care, they were not required to attend study follow-up visits. In such cases, information about a patient’s diagnosis was obtained from their medical notes. In addition to following up patients at 2 and 6 months, a review of patient records was performed up to 1 year post recruitment, if required, in order to obtain a final diagnosis.

Data management

A case report form (CRF) was used to collect patient data at each recruiting hospital after a patient consented to participate in the IGRAs for Diagnostic Evaluation of Active tuberculosis (IDEA) study. Following receipt of the CRFs, data were entered into an electronic password-protected database. The results of study IGRAs and all other study laboratory tests were entered into a separate secure database. This laboratory database was accessible only to specific laboratory staff. Thus, the Study Management Group (SMG) responsible for day-to-day management of the IDEA study was blinded to the IGRA results. Furthermore, NHS clinicians responsible for routine care and diagnosis of patients involved in the study were also blinded to study IGRA results. To enable preparation of study reports for meetings of the independent oversight committee [Study Steering Committee (SSC)], the study statistician was granted access to the clinical database and excerpts of the laboratory database at specific periods during the study.

Sample collection

Blood samples

Blood sampling was done at three time points: at baseline and at follow-up at 2 and 6 months. Only blood samples collected at baseline were used in the assessment of the index tests and for the reference standard. Samples taken at follow-up were used for further IGRA testing (but not analysed as part of the IDEA study) and also stored for future research as consented by patients. Blood-taking (venepuncture) procedures were carried out in accordance with local trust venepuncture guidelines. The baseline sample was obtained no later than 14 days after the start of treatment for TB or within 7 days of consent, whichever was earlier, depending on the patient’s diagnosis. For patients with a diagnosis of active TB, sarcoidosis or other non-TB diagnosis, follow-up study blood samples were taken 2 and 6 months after the start of treatment. For patients with a diagnosis of latent TB, when possible and if the patient returned to the same clinical team, blood samples were taken 3 and 6 months after the initiation of treatment (if treatment was indicated and given).

A 35-ml blood sample was taken at each time point. Blood was collected into heparinised collection tubes and QFT-GIT collection tubes for T-SPOT. TB and QFT-GIT assays, respectively. Furthermore, heparinised blood was collected for performance of second-generation IGRAs and to store plasma and PBMCs for future research. In addition, blood was collected into uncoated collection tubes in order to store serum for future research.

Blood samples were transported on the same day as sample collection either by a member of the research team or by courier in the appropriate United Nations-type approved packaging to the TB Research Centre for testing. All samples were processed within 6 hours of blood collection for London-based sites and within 8 hours for outer London sites. Excess PBMCs were stored in a liquid nitrogen tank, and serum and plasma were stored in a –80 °C freezer at the TB Research Centre (led by Professor Ajit Lalvani) at Imperial College London (St. Mary’s Hospital).

Diagnostic bronchoscopy samples

In patients with sputum smear-negative pulmonary TB, diagnostic bronchoscopies were performed and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was obtained as part of routine clinical care. When surplus BAL samples were available and not required for diagnostic procedures, aliquots were cryopreserved and stored in the research biorepository for subsequent testing by IGRA. The bronchoscopic procedure, along with collection of surplus BAL samples, were applicable only for patients recruited at St. Mary’s Hospital, Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust, in accordance with set clinical practice guidelines. The BAL sample consent was covered under the consent form as ‘tissue samples’. However, patients were informed if a surplus BAL sample was kept for the IDEA study.

Index tests

Interferon gamma release assays

Two types of commercially available IGRAs, QFT-GIT and T-SPOT. TB, were evaluated. In addition, a new ELISpot-based assay utilising novel antigens (Rv3615c, Rv2654, Rv3879c and Rv3873) was evaluated. The performance of each antigen was evaluated individually and in combinations that included either ESAT-6 and CFP-10, the two antigens that constitute T-SPOT. TB, or both. IGRA testing is not standard practice for HIV-negative patients suspected of having TB in the hospitals of our consortium and is not currently recommended for HIV-positive patients suspected of having TB. However, if IGRAs were used locally at participating hospitals as part of the routine diagnostic workup of patients, we recorded the tests done but we did not analyse the test results as study results for the IDEA study. Thus, only from IGRAs performed in our research laboratory specifically for this study were recorded and assessed. Laboratory staff performing the IGRAs and recording the test results were blinded to clinical information and reference standard results.

Analysis of T-SPOT.TB and novel antigens

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated from heparinised whole blood using the Ficoll-Paque™ density centrifugation method (GE Healthcare Bio-Science, Uppsala, Sweden), as described by Whitworth et al. 6 In brief, whole blood was diluted in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 medium (Sigma-Aldrich, Dorset, UK) and layered onto Ficoll-Paque™ Plus at a ratio of 2 : 1 in 50-ml Falcon® centrifuge tubes (Corning Science Mexico S.A. de C.V., Reynosa, USA). The tubes were centrifuged for 20 minutes at 18–25 °C and the cloudy PBMC layer was aspirated into fresh RPMI 1640 medium. Cells were washed with fresh RPMI 1640 medium and counted using trypan blue stain for use with the Countess® Automated Cell counter (Life Technologies, Eugene, OR, USA). T-SPOT. TB was applied to the freshly isolated PBMCs as per the manufacturer’s instructions9 and as described by Whitworth et al. 6

Cells were resuspended in AIM-V® Serum-Free Medium (Gibco by Life Technologies, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) at a concentration of 2.5 million cells/ml and 250,000 cells per well were incubated overnight (18 hours) at 37 °C with Mtb-specific antigens (ESAT-6, CFP-10, Rv3615c, Rv2654, Rv3879c and Rv3873) individually, and positive (phytohaemagglutinin) and negative (RPMI 1640 medium) controls in a 96-well plate, pre-coated with IFN-γ-specific monoclonal capture antibodies (included in T-SPOT. TB kit). Thus, a total of eight wells were used per patient and samples from 12 patients were included on a plate. Overnight incubation of the cells with antigens allows for IFN-γ secretion from activated Mtb-specific effector T cells present in the culture. Secreted IFN-γ binded to the pre-coated IFN-γ-specific monoclonal capture antibodies on the membrane of each well. After incubation, wells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline and an alkaline phosphatase-conjugated secondary IFN-γ-specific monoclonal antibody was added to bind to any captured IFN-γ. For a visible representation of the spots on the membrane, an alkaline phosphatase chromogen substrate was added.

Each spot formed on the membrane signifies IFN-γ release by a single activated Mtb antigen-specific T cell. Spot-forming cells (SFCs) are expected to be detected in positive control wells and absent in negative control wells. SFCs in TB antigen-stimulated wells indicate infection.

Spot-forming cells were counted using an automated ELISpot plate reader (AID ELISpot read system ELRIFL04; Advanced Imaging Devices GmbH, Strasbourg, Germany), with saturation level set at 60%. For individual antigens, test results were classified as negative, positive, borderline (equivocal) or indeterminate (invalid) by subtracting the spot count in the negative control well from the spot count in each panel, according to the algorithm illustrated in Figure 2 (based on the package insert for T-SPOT. TB). 9 Panels A, B, C, D, E and F correspond to ESAT-6, CFP-10, Rv3615c, Rv2654c, Rv3879c and Rv3873, respectively.

FIGURE 2.

Algorithm for defining test positivity of antigens. Panel X indicates one of the six panels, A to F, which correspond to the following antigens: A, ESAT-6; B, CFP-10; C, Rv3615c; D, Rv2654; E, Rv3879c; and F, Rv3873. TNTC, too numerous to count.

For T-SPOT. TB as well as other antigen combinations, if the positive control spot count was < 20, the result was deemed indeterminate, unless the response to one of the Mtb antigens was positive (or borderline), in which case the test result for the combination was deemed positive (or borderline). Thus, we applied an ‘OR’ rule (at least one antigen spot count deemed positive) for antigen combinations. For example, for T-SPOT. TB, a result was positive if the negative-control spot count was ≤ 10 and either ‘panel A minus negative control’ or ‘panel B minus negative control’ was ≥ 8 spots. This implies the T-SPOT. TB result was negative if both ‘panel A minus negative control’ and ‘panel B minus negative control’ were negative (≤ 4 spots). In the IDEA study, borderline test results (5–7 spots) were considered as positives.

Analysis of QuantiFERON GOLD In-Tube

The QFT-GIT assay was performed in two stages as per the manufacturer’s instructions10 and as described in Whitworth et al. 6 First, whole blood was collected from each participant into three QFT-GIT tubes containing a negative control, mitogen-positive control and Mtb antigens [ESAT-6, CFP-10 and TB7.7 (also known as Rv2654c, a possible PhiRv2 prophage protein) combined], as provided by the manufacturer. 10 The tubes were incubated at 37 °C for 16–24 hours to allow IFN-γ secretion from antigen-specific effector T cells into the extracellular fluid (plasma). After incubation, tubes were centrifuged and 150 µl of plasma was collected and stored in a 96-well plate for up to 4 weeks at 2–8 °C prior to performing the remainder of the assay.

To perform the ELISA step, 50 µl of plasma from each of the QFT-GIT tubes (i.e. containing a mitogen control, negative control and Mtb antigens) was transferred to wells of another 96-well plate pre-coated with IFN-γ-specific monoclonal capture antibodies and incubated with a conjugate [an IFN-γ-specific antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (included in T-SPOT. TB kit)] for 2 hours at room temperature (22 °C). Plasma samples in each well were mixed thoroughly using a microplate shaker (PMS-1000i Microplate Shaker; Grant Instruments Ltd, Shepreth, UK) for 1 minute to ensure that any IFN-γ was evenly distributed throughout the sample. Secreted IFN-γ in the plasma will be sandwiched between the two antibodies.

After incubation and thorough washing with detergent, a photosensitive chromogen substrate solution (3,3’,5,5’-tetramethylbenzidine; included in QFT-GIT kit) was added, which converted the sample to a detectable form (blue colour signal). The reaction was stopped with a substrate stopping solution (sulphuric acid; included in QFT-GIT kit). The intensity of the colour is directly proportional to the levels of IFN-γ present in the plasma after activation of TB-specific T cells by Mtb antigens. Colour should develop in the positive control well and not in the negative control well. Colour in the TB antigen well indicates infection.

The optical density of each well was measured using a microplate reader (Elx800 Absorbance Reader; BioTek, Carnegie, VIC, Australia) with a 450-nm filter and a 620- to 650-nm reference filter. The concentration (IU/ml) of IFN-γ for the plasma sample from each of the three tubes (negative, mitogen and Mtb antigen) was determined against a series of standard concentrations (the standard curve). The test result (negative, positive or indeterminate) was calculated from the concentration values using a US Food and Drug Administration-approved algorithm (Figure 3) run on QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube Analysis Software version 2.62 (Cellestis) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. 10

FIGURE 3.

Determination of the test results for QFT-GIT. Reprinted from Methods, Vol. 61, Whitworth HS, Scott M, Connell DW, Dongés B, Lalvani A. IGRAs – the gateway to T cell based TB diagnosis, pp. 52–62. © 2013, with permission from Elsevier. 6

Tuberculin skin test

A TST was performed as part of routine clinical care. Each recruiting centre has its own policy for TST use based on National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance. 11 Patients eligible for the TST, as defined by local or NICE guidance, received a single intradermal injection of two tuberculin units or 0.1 ml of unlicensed tuberculin Mantoux test [Tuberculin PPD RT23 SSI (Statens Serum Institut, Copenhagen, Denmark); this purified protein derivative (PPD) was used for the main site; however, other sites may have used other PPDs]. The test was administered by trained specialist TB nurses who were entitled to administer medicines within the trust under a Patient Group Directive. The degree of skin induration was measured 48–96 hours later. Test results were obtained from centres and we determined test positivity using three thresholds: ≥ 5 mm, ≥ 10 mm3,12 and a stratified threshold based on BCG vaccination status (≥ 6 mm for unvaccinated and ≥ 15 mm for vaccinated participants). 11 Patients were considered BCG vaccinated if they reported they had been vaccinated and/or had a BCG scar.

Reference standard

Participating hospitals followed the minimum set of tests defined within the NICE guideline11 for diagnosing active TB and in accordance with local routine practice. However, the final diagnosis of participants was verified using the composite reference standard defined in Appendix 2. The reference standard was applied by a panel of clinicians blinded to local (routine) and study IGRA results. The role of the clinical panel was to assess anonymised patient clinical data without knowledge of the IGRA results in order to confirm the diagnostic category of all study participants. The composition of the panel and the assessment process is described in Composition of the clinical panel and Assessment of final diagnosis.

Composition of the clinical panel

Clinical panel members were appointed from among the principal investigators (PIs) and co-investigators by the chief investigators. The panel included:

-

an independent chairperson

-

a chest physician

-

a HIV physician with knowledge of HIV/TB infection

-

an infectious disease physician.

All physicians had extensive TB expertise.

Structure of case panel meetings

Meetings were arranged and minutes were recorded by the study co-ordinator or a designated member of the study team. The panel meetings were held quarterly and the schedule was decided by the SMG depending on the number of data available for review. At each meeting, priority was given to assessment of indeterminate (category 3) cases. Additional meetings were arranged to ensure that all patients in categories 2 and 3, and some in category 4, were reviewed (see Assessment of final diagnosis). All panel members had to attend the meeting in person.

Assessment of final diagnosis

Diagnosis data (based on the Dosanjh categorisation3 outlined in Appendix 2) received from recruiting centres were reviewed as follows:

-

Category 1: all culture-confirmed cases were not reviewed, but were signed off at the end of the clinical panel meeting by the chief or co-investigators.

-

Category 2: all probable cases were reviewed.

-

Category 3: all indeterminate cases were reviewed.

-

Category 4: non-active TB cases with a confirmed alternative diagnosis were not reviewed by the panel. Complicated category 4 patients were reviewed by the panel.

Reviewing cases in this way ensured consistent final diagnosis categorisation.

Data available to the panel

For each patient who was reviewed, the following information was presented to the panel:

-

patient demographics

-

TB symptoms, previous TB information, TB exposure history, current medication, patient medical history, follow-up data, HIV infection status and relevant clinical information and travel data

-

relevant clinical correspondence and test results during diagnosis and follow-up (excluding results of routine and study IGRAs) such as culture, smear, PCR, TST, bronchoscopy, biopsy and/or radiological reports.

Documentation

Each panel member reviewed a patient’s documents and completed a form with the following information:

-

diagnosis category (based on the Dosanjh criteria)

-

body site of disease (only if final diagnosis was active TB)

-

method of diagnosis: included culture, PCR, imaging, smear microscopy, histology, clinical features, response to treatment, multiple and other. For multiple and other, details were to be specified.

Confirmation of diagnosis

Final diagnosis decisions were made by a majority vote, with the chairperson having a casting vote, if necessary. Final diagnoses were recorded by the study co-ordinator. If necessary, when a panel member had treated a patient being reviewed, the member was asked to provide information (without disclosing local or study IGRA results) and the member was excluded from final decision-making (their vote was replaced with a vote from the chairperson) for the patient.

Outcomes

Sensitivity, specificity, PPVs and NPVs and likelihood ratios for each test and combinations of tests were calculated to determine their diagnostic accuracy and clinical utility. The likely primary clinical utility of immune-based testing is to exclude TB. Thus, when interpreting the analyses and drawing conclusions, the focus was primarily on the sensitivities and NPVs. For test comparisons, relative test performance was assessed by comparing the sensitivity and specificity of one test with those of another test. These results were presented as relative sensitivities and relative specificities.

Statistical analyses

Sample size calculation

As stated in Outcomes, the primary clinical utility of IGRA results in the assessment of suspected active TB is likely to be in their NPV, which may enable clinicians to reliably rule out TB from the differential diagnoses. This, in turn, depends on the sensitivity of the test and the prevalence of active TB in the tested population. In a meta-analysis, the average sensitivity of T-SPOT. TB and QFT-GIT was 90% [95% confidence interval (CI) 86% to 93%] and 70% (95% CI 63% to 78%), respectively. 7 However, the estimates were mainly based on small studies and most studies included only patients without HIV infection. Furthermore, the estimates were not based on head-to-head comparative accuracy studies. Two large studies (n = 194 active TB cases diagnosed from n = 389 TB suspects;3 n = 216 active TB cases diagnosed from n = 413 TB suspects13) gave more robust estimates for T-SPOT. TB of 85.1% (95% CI 79.2% to 89.9%) and 85.2% (95% CI 76.1% to 91.9%), respectively. The latter study compared T-SPOT. TB and QFT-GIT, and gave an estimate of 78.1% (95% CI 70.7% to 84.3%) for QFT-GIT. 13

Given the available evidence, we powered the IDEA study to detect a conservatively estimated 10% difference in sensitivity between T-SPOT. TB and QFT-GIT, assuming a sensitivity of 85% for T-SPOT. TB and of 75% for QFT-GIT. To detect this difference at the 5% significance level (two-tailed) with 90% power, 855 patients were required (each receiving both tests), assuming a 40% prevalence of active TB in the study population. This calculation was done using a method that accounts for the paired nature of the data (based on McNemar’s test). 14 The method requires knowledge of the probability of positive T-SPOT. TB and positive QFT-GIT results among cases of active TB (concordance probability). A positive correlation, such as may be expected between both blood tests, would give a lower sample size than assuming independence or a negative correlation of test errors. However, as no pilot data were available to inform the choice of the concordance probability, we chose to be conservative and so assumed independence. To allow for missing data, indeterminate index test and reference standard results, withdrawal of consent and possible logistical errors, we aimed to recruit 1012 participants.

According to published evidence, the sensitivity of QFT-GIT decreases in HIV-positive subgroups, whereas that of T-SPOT. TB is unaffected in some studies and decreased in others. 15 Therefore, we computed sample size for the HIV-positive subgroup based on sensitivities of 85% and 65% for T-SPOT. TB and QFT-GIT, respectively. Assuming a 50% prevalence of active TB among these participants, we thus required 156 patients to detect a 20% difference between the IGRAs at the 5% significance level with 80% power. We aimed to recruit 200 patients for similar reasons to those outlined above.

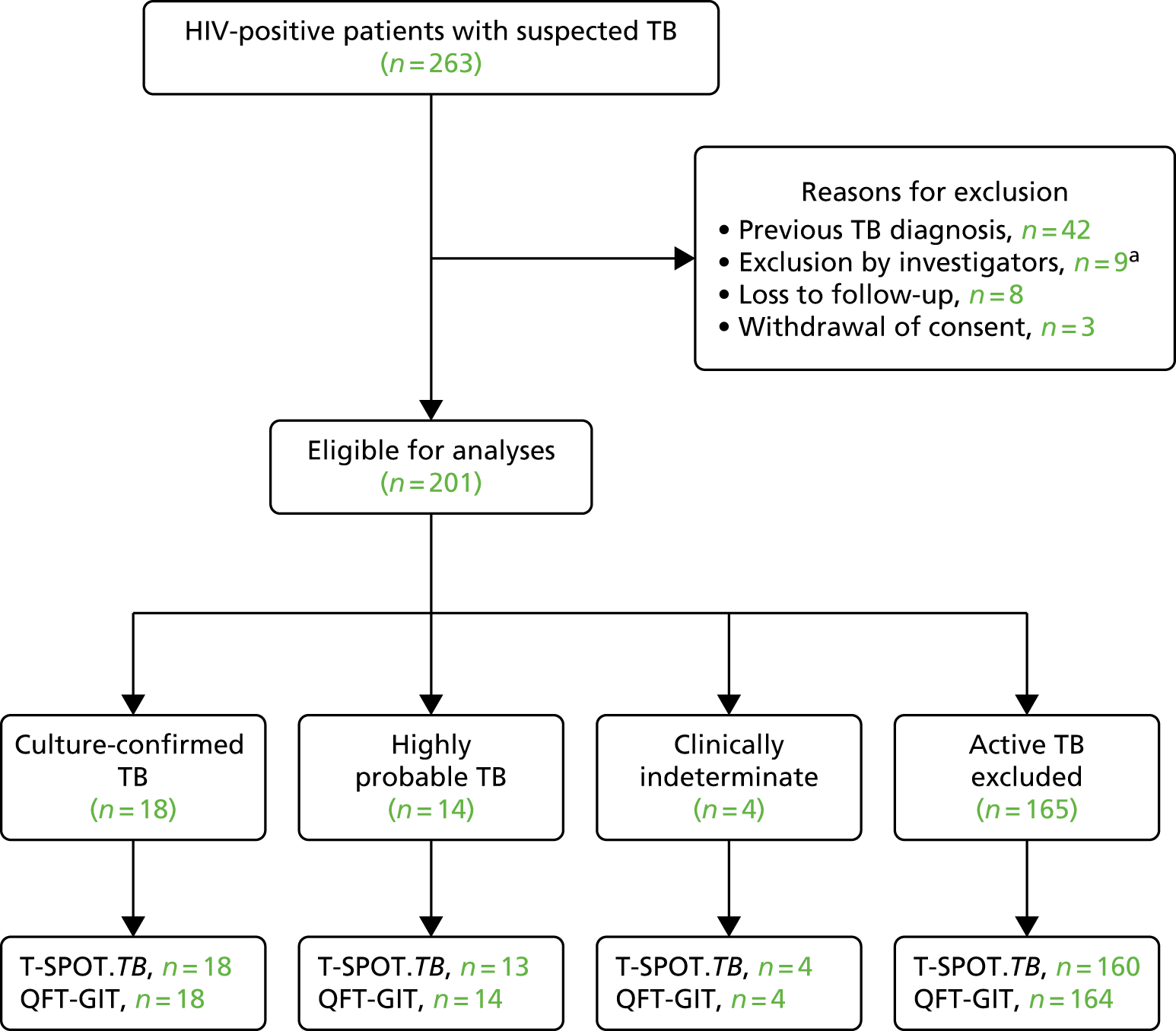

Revision of sample size calculation and study extension for recruitment of HIV-positive participants

During the study recruitment period, the proportion of HIV-positive patients with a final diagnosis of active TB was found to be substantially lower (20% rather than 50%) than originally anticipated when the study was designed. This was attributed to a decrease in TB incidence in this population in recent years. 16 In order to answer a key objective regarding the utility of IGRAs in HIV-positive patients, the SSC and funder supported an extension of recruitment of HIV-positive participants to ensure that the study was adequately powered.

The sample size calculation was revised to take into account the reduced prevalence of active TB in this population. Given a prevalence of 20%, 390 HIV-positive participants will be required to detect a 20% difference between the sensitivity of T-SPOT. TB and QFT-GIT with 80% power at the 5% significance level. Thus, the sample size was increased from 156 to 390. Ethics approval was sought and an extension of 12 months was granted on 5 November 2014 to recruit and follow up only HIV-positive participants. Given the purposive recruitment of additional HIV-positive participants, the results are presented separately for the main cohort (including HIV-positive participants recruited during the first phase of the IDEA study prior to the extension period) in Chapters 3 and 4, and for the entire HIV-positive cohort in Chapter 5.

Data analysis

Sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV and likelihood ratios for each test and combination of tests were calculated to determine their diagnostic accuracy and clinical utility in the main cohort and within the key subgroups outlined in the study objectives. For all proportions, 95% CIs were calculated using the Wilson method. 17,18 CIs for positive and negative likelihood ratios were calculated using the method by Simel et al. 19 Separate analyses of the complete cohort of HIV-positive participants were also performed.

Patients classified as having culture-confirmed (category 1) or highly probable (category 2) active TB and those without active TB (category 4) were included in analyses of diagnostic accuracy (see definition of categories in Appendix 2). However, despite not being included in the analysis, the proportion of patients classified as clinically indeterminate (category 3) was reported. While borderline T-SPOT. TB results were included as test positives in primary analyses of the main study cohort, we examined the impact of this by excluding borderline test results in sensitivity analyses. For the primary analyses, patients with indeterminate IGRA results were excluded from the analyses. In clinical practice, if an IGRA was used as a rule-out test for active TB, then an indeterminate result would have the same implications as a positive result, that is, it could not rule out a diagnosis of the disease (and thus TB would remain a differential diagnosis). The impact of including indeterminate IGRA results as test positives (i.e. true positives and false positives depending on final diagnosis of active TB or no active TB) was assessed in sensitivity analyses. Sensitivity analyses were also conducted to investigate the impact of excluding category 2 patients on the sensitivity of IGRAs.

Comparisons between different IGRAs were performed using generalised estimating equation (GEE) models to exploit the paired nature of the data. Our analysis was based on all available data (i.e. it included patients who did not have a complete set of index test results). Separate GEE models were fitted for those with active TB (Dosanjh categories 1 and 2) and those with no active TB (category 4) to determine differences in sensitivity and specificity, respectively. The outcome variable in the GEE model was IGRA result (positive vs. negative) and the explanatory variable was type of IGRA, for example T-SPOT. TB versus QFT-GIT. The natural outputs from these models are odds ratios. For example, comparing the sensitivity of T-SPOT. TB to that of QFT-GIT, the odds ratio is the odds of a positive T-SPOT. TB result compared with the odds of a positive QFT-GIT result in patients with active TB. For the comparison of specificities, the odds ratio is the odds of a negative T-SPOT. TB result compared with the odds of a negative QFT-GIT result in non-TB patients. As odds ratios do not have an intuitive interpretation, we computed ratios of sensitivities (relative sensitivity) and ratios of specificities (relative specificity) using a function (nlcom) that computes point estimates and CIs for non-linear combinations of parameter estimates post estimation of the models. The CIs are computed using the delta method.

Variation in the relative performance of T-SPOT. TB and QFT-GIT with HIV infection status and other clinical characteristics was investigated by including one covariate at a time in the GEE models. 20 To assess the effect of a covariate on relative test performance, an interaction term for test type and the covariate was included in the model. In addition to these characteristics pre-specified in the protocol, we also investigated the effect of smoking, because this has been associated with a twofold increase in the risk of developing active TB. 21 We included both inpatients and outpatients in all our analyses of diagnostic accuracy to allow for generalisability of these tests as an initial test in any case of possible active TB. However, because disease severity and spectrum can influence the diagnostic performance of a test, we also investigated the effect of clinical setting (inpatients vs. outpatients) to determine if our approach was tenable. We were interested in exploring the effect of vitamin D, as it is an important cofactor for the intracellular killing of TB. It is associated with an increased resistance to TB infection, and with the phenotype of active TB. The value of vitamin D supplementation in active TB to improve disease outcome is unclear. However, we were unable to evaluate the effect of vitamin D status on IGRA performance because of variation between centres in the definition of vitamin D status.

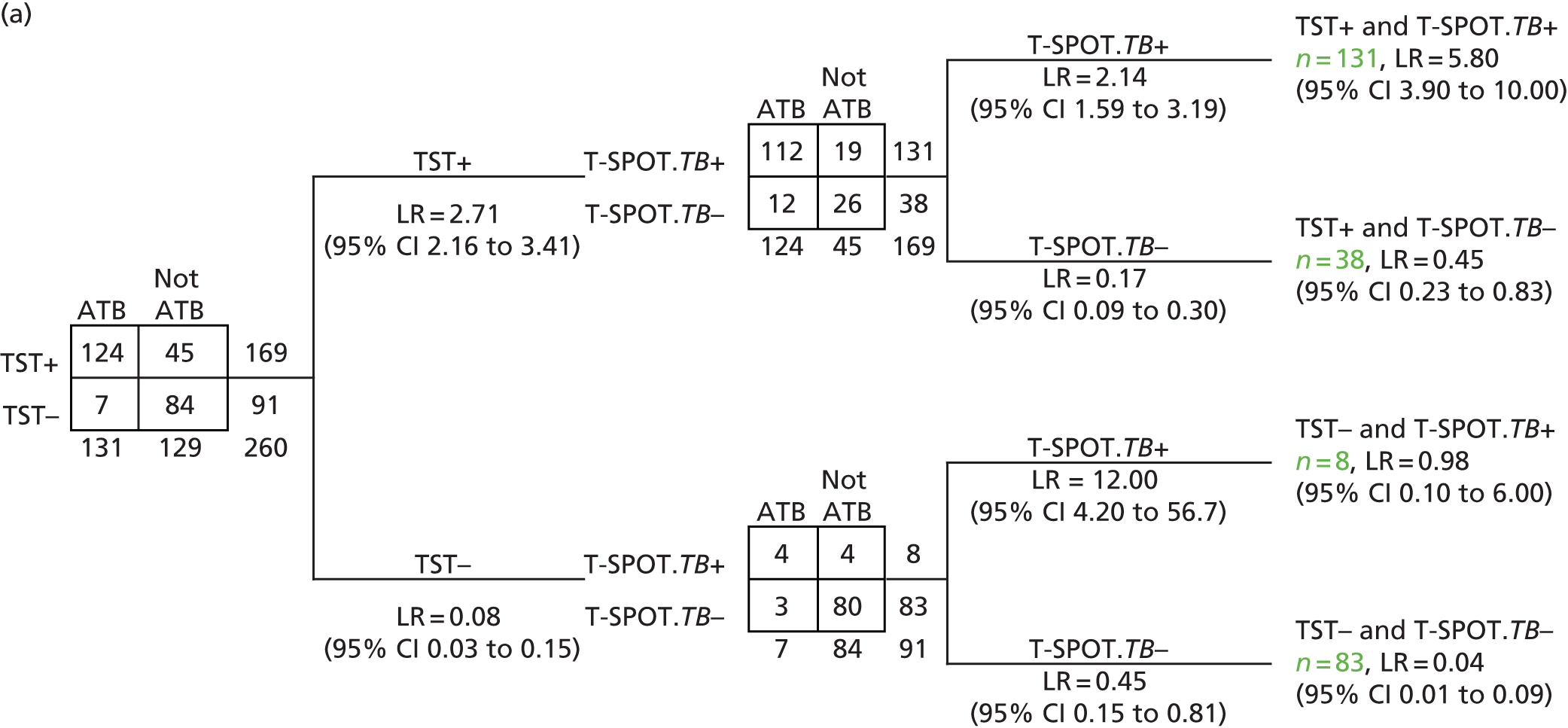

In the subset of patients presenting with a TST result as part of their clinical diagnostic workup, the performance of the TST used in sequence with IGRAs was evaluated. The performance of this combination was assessed using logistic regression models constructed in the same form as Bayesian updating (post-test odds = pre-test odds × likelihood ratio) by including the log of the pre-test odds of prevalence (a constant term of known value) as an offset in the model. A linear predictor was then used to estimate log-likelihood ratios, rather than log-odds ratios, and bootstrap methods were used to obtain valid CIs. 22 Model parameterisations from Knottnerus23 were used to compute likelihood ratios for the additional diagnostic value of each test in a testing sequence. Non-parametric, bias-adjusted CIs for parameter estimates from 1000 bootstrap samples were computed.

We performed all analyses using Stata®, version 13.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Patient and public involvement

Ms Nisha Karnani was our patient and public representative for the duration of the study. She was consulted at key points during the study and was invited to SSC meetings and the IDEA study presentation at the end of the study.

Study oversight and management arrangements

Study Management Group

The SMG included the chief investigators, study co-ordinator, lead research nurse and a post-doctoral research associate. The day-to-day management of the study was carried out by the study co-ordinator, with close support provided by the chief investigators and other members of the SMG. The SMG met monthly to discuss study progress and oversight.

Data Management Group

The Data Management Group (DMG) consisted of members of the statistical team and members of the SMG. The group met regularly to review data on recruitment and the prevalence of TB and HIV in the study cohort. The DMG reported to the SSC (see Study Steering Committee).

Study Steering Committee

Independent oversight was provided by the SSC. The committee included an independent chairperson (Professor Khalid Khan), three other independent members (Dr Stephen Gordon, Dr James Grey and Dr Johannes B Reitsma) and a patient and public involvement (PPI) representative (Ms Nisha Karnani).

Ethics arrangements and regulatory approvals

Ethics approval for this study

This study received ethics approval from the London – Camden Kings Cross Research Ethics Committee (REC) (reference number 11/H0722/8). The research study was submitted for site-specific assessment at each participating NHS trust. The chief investigators required a copy of the research and development (R&D) approval letter before accepting participants into the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the recommendations for physicians involved in research on human subjects adopted by the 18th World Medical Assembly, Declaration of Helsinki (1964) and later revisions. 24

Consent and study withdrawal

Consent to enter the study was sought from each participant only after a full explanation had been given, an information sheet offered and time allowed for consideration. Signed participant consent was then obtained. The right of the participant to refuse to participate without giving reasons was respected. After a participant was entered into the study the clinician remained free to give any treatment that he or she considered necessary, or to refer onto an appropriate health-care professional, at any stage if it was judged to be in the best interest of the participant. Reasons for such decisions were recorded. In such cases, participants remained in the study for the purposes of follow-up and data analysis. All participants were free to withdraw at any time from the study without giving reasons. Assurance was provided by the person taking consent that withdrawal will not affect the patient’s care. In accordance with good clinical practice guidance, participants who withdrew were not required to give a reason for withdrawal. Data were collected on participant’s final diagnosis unless consent was withdrawn for any data to be used.

Confidentiality

The chief investigator and all members of the research team abided by the Data Protection Act25 and preserved the confidentiality of participants involved in the study. Participants were allocated a unique identifying code (anonymised) on recruitment, with no personal identifiers recorded on any sample or data.

Indemnity

The Imperial College London, as sponsor of this study, holds negligent and non-negligent harm insurance policies that applied to this study. These were arranged through the Joint Research Office.

Protocol amendments

Between April 2011 and February 2015, the protocol underwent seven amendments as detailed in Appendix 3, Table 53. Six of the seven amendments were deemed substantial amendments that required ethics approval, whereas one was a minor amendment.

Chapter 3 Participant characteristics

The results presented in this chapter are based on all participants recruited prior to the study extension, including those with HIV infection. Thus, the chapter excludes HIV-positive patients recruited during the study extension period.

Recruitment of participants into main study cohort

A total of 1074 participants, including 177 (16.5%) who were HIV positive, were recruited from 10 NHS trusts into the main study between 25 November 2011 and 31 August 2013. The number of patients recruited at each centre is shown in Table 1. Over half of the study participants were recruited from two trusts: Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust (26.4%) and London North West Healthcare NHS Trust (27.8%).

| Hospital trust | Patients recruited, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust | 283 (26.4) |

| Heart of England NHS Foundation Trust | 106 (9.9) |

| Chelsea and Westminster Hospital NHS Foundation Trust | 52 (4.8) |

| Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust | 59 (5.5) |

| St George’s Healthcare NHS Trust | 61 (5.7) |

| Frimley Health NHS Foundation Trust | 44 (4.1) |

| University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust | 116 (10.8) |

| London North West Healthcare NHS Trust | 299 (27.8) |

| Oxford University Hospitals NHS Trust | 4 (0.4) |

| Sandwell and West Birmingham Hospitals NHS Trust | 50 (4.7) |

| Total | 1074 (100) |

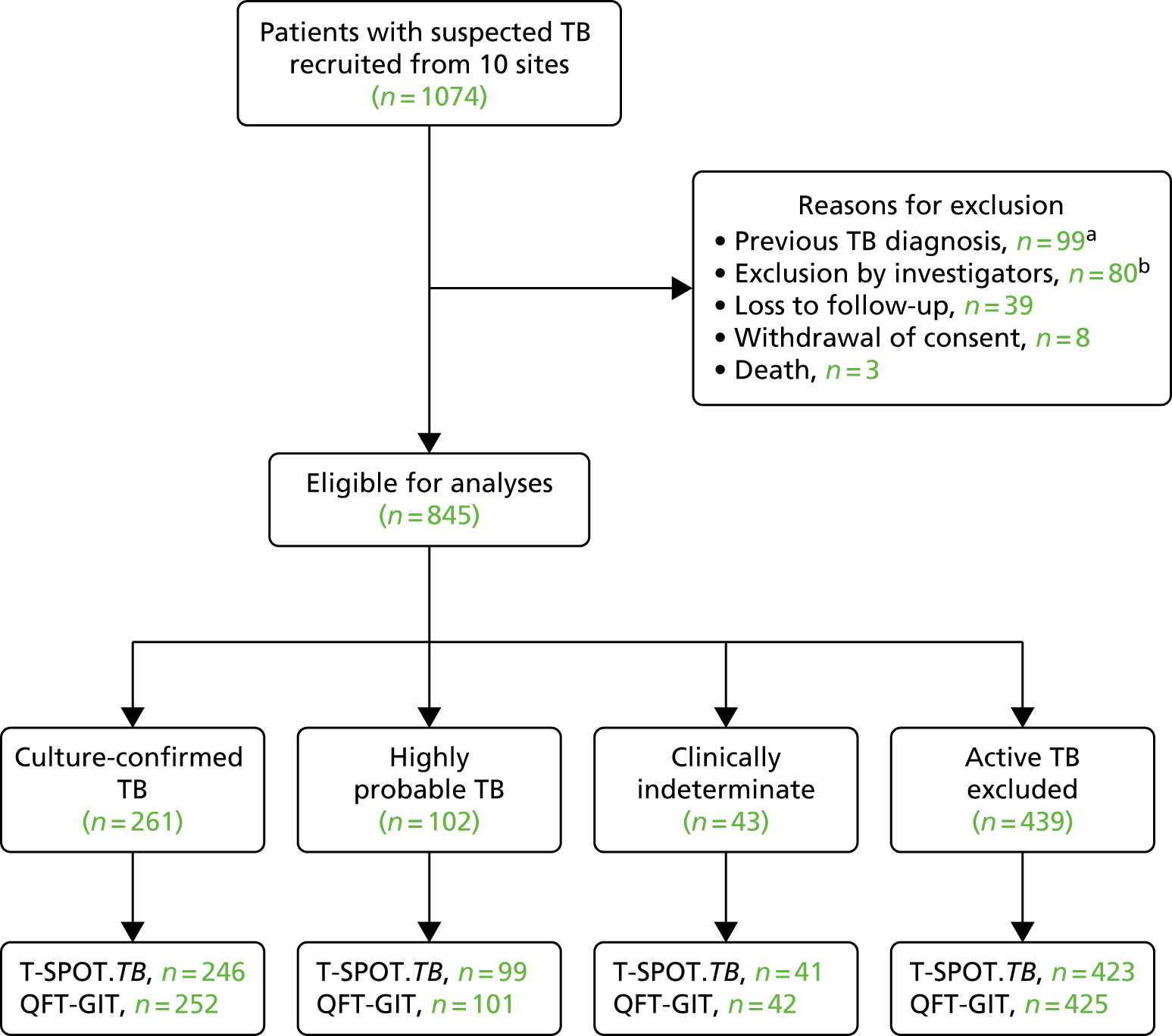

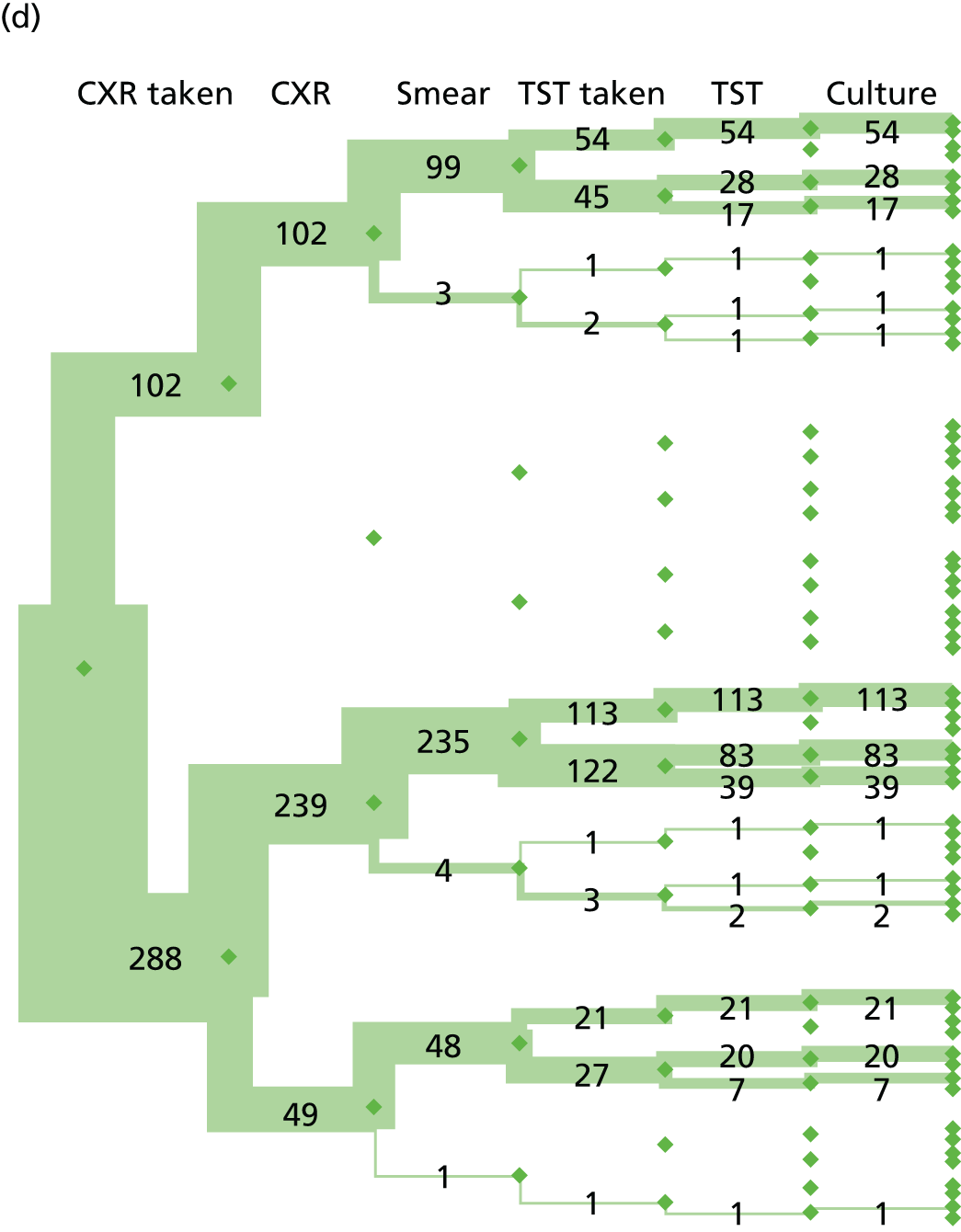

The flow of patients through the study is shown in Figure 4. Of the 1074 patients recruited, 845 were included in the analyses. Reasons for exclusion are shown in Figure 4. Forty patients from Frimley Health NHS Foundation Trust were excluded because patients all had diagnoses of confirmed or highly probable TB (categories 1 and 2) due to an error of implementation of recruitment criteria at this site (i.e. the natural spectrum of patients with suspected TB was not being recruited). The decision to exclude these patients was approved by the SSC following a SSC meeting during which the diagnosis of patients recruited at each centre was reviewed.

FIGURE 4.

Study flow diagram of patients with suspected active TB. The final four boxes show the number of patients with available IGRA results. a, Patients with previously diagnosed TB were excluded from analyses because IGRA results cannot be reliably interpreted in previously treated patients. The decision to exclude was taken by the expert diagnostic panel and study management group in consultation with the independent Study Steering Committee before unblinding of IGRA and next-generation IGRA results. b, On advice from the Study Steering Committee, and following consultation between the study management group and data management groups, 80 patients were excluded from analyses. Patients recruited from Frimley Health NHS Foundation Trust (n = 40) were excluded because they all had diagnoses of confirmed or highly probable TB (categories 1 and 2) due to an error of implementation of the recruitment criteria at this site, i.e. the natural spectrum of patients with suspected TB was not being recruited. A further subset of patients (n = 27) were, on review, considered by the expert diagnostic panel to be ineligible (before unblinding IGRA results) on the basis that they were being investigated for TB (due to an incidental abnormal chest X-ray, known contact with active TB, or screening for anti-TNF treatment), but did not present with symptoms or signs suggestive of TB. An additional 13 patients were excluded due to invalid consent forms. Republished with permission of Elsevier Science and Technology Journals, from Clinical utility of existing and second-generation interferon-γ release assays for diagnostic evaluation of tuberculosis: an observational cohort study, The Lancet Infectious Diseases, Whitworth HS, Badhan A, Boakye AA, Takwoingi Y, Rees-Roberts M, Partlett C, et al. , vol. 19, pp. 193–202, copyright 2019;27 permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc.

Table 2 shows the number of patients assigned to each diagnostic category. There were 43 (5.1%) patients with a clinically indeterminate (category 3) diagnosis. Of the remaining 802 patients, there were 363 (45.3%) cases of active TB [based on those with culture-confirmed (category 1) and highly probable (category 2) TB] and 439 (54.7%) in whom active TB was excluded (categories 4A to 4D). Of the 439 non-active TB cases, 117 (26.7%) were category 4D.

| Diagnostic category | Criteria | Number of patients |

|---|---|---|

| 1: Culture-confirmed TB | Microbiological culture of Mtb AND suggestive clinical and radiological findings | 261 |

| 2: Highly probable TB | Clinical and radiological features highly suggestive of TB and unlikely to be caused by other disease AND a decision to treat made by a clinician AND appropriate response to therapy AND histology supportive (if available) | 102 |

| 3: Clinically indeterminate | Final diagnosis of TB neither highly probable nor reliably excluded | 43 |

| 4: Active TB excluded | ||

| 4A: inactive TB | Stable CXR changes AND TST positivea (if done) AND bacteriologically negative (if done) AND no clinical evidence of active disease | 7 |

| 4B: one or more risk factors for TB exposure,b TST positivea | TST positivea AND bacteriologically negative (if done) AND no clinical evidence of active disease | 48 |

| 4C: one or more risk factors for TB exposure,b TST negative | History of TB exposure AND TST negative (if done) | 267 |

| 4D: no risk factors for TB exposure,b TST negative | No history of TB exposure AND TST negative (if done) | 117 |

| Total | 845 | |

Baseline characteristics of participants

The main demographic characteristics of the 845 patients are given in Table 3. Most patients (64.4%) were recruited from an outpatient setting, and the remaining were recruited from an inpatient setting. The median age of patients was 38 (range 16–86) years and most (59.3%) of the patients were male. Almost half (48.2%) of the study population were of Indian origin. Altogether, 75 countries of birth were represented in the study; 16 of the countries had at least 10 participants, with India (26.7%) and the UK (22.8%) accounting for almost half of the study population. The complete list of countries is given in Appendix 4, Table 54.

| Characteristic | Dosanjh category | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Culture-confirmed TB | Highly probable TB | Clinically indeterminate | Active TB excluded | ||

| Clinical setting, n (%) | |||||

| Inpatient | 90 (34.5) | 30 (29.4) | 11 (25.6) | 170 (38.7) | 301 (35.6) |

| Outpatient | 171 (65.5) | 72 (70.6) | 32 (74.4) | 269 (61.3) | 544 (64.4) |

| Age (years), median (range) | 32 (16–81) | 36 (18–76) | 38 (16–79) | 44 (17–86) | 38 (16–86) |

| Male, n (%) | 177 (67.8) | 53 (52.0) | 21 (48.8) | 250 (56.9) | 501 (59.3) |

| Ethnic origin, n (%) | |||||

| Asian | 16 (6.1) | 6 (5.9) | 5 (11.6) | 14 (3.2) | 41 (4.9) |

| Black | 50 (19.2) | 22 (21.6) | 10 (23.3) | 102 (23.2) | 184 (21.8) |

| Hispanic | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (1.6) | 8 (0.9) |

| Indian subcontinent | 167 (64.0) | 61 (59.8) | 16 (37.2) | 168 (38.3) | 412 (48.8) |

| Middle Eastern | 4 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 12 (2.7) | 16 (1.9) |

| Mixed | 1 (0.4) | 4 (3.9) | 0 (0.0) | 8 (1.8) | 13 (1.5) |

| White | 22 (8.4) | 9 (8.8) | 12 (27.9) | 126 (28.7) | 169 (20.0) |

| Unknown | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.5) | 2 (0.2) |

| Years in the UK, median (range) | 4.9 (0.1–52.9) | 6.1 (0.3–59.7) | 10.5 (0.4–56.9) | 13.2 (0.0–60.3) | 8.3 (0.0–60.3) |

| Profession, n (%)a | |||||

| Paid employment | 130 (49.8) | 52 (51.0) | 21 (48.8) | 214 (48.7) | 417 (49.3) |

| Unpaid employment | 62 (23.8) | 24 (23.5) | 16 (37.2) | 164 (37.4) | 266 (31.5) |

| Student | 50 (19.2) | 13 (12.7) | 3 (7.0) | 26 (5.9) | 92 (10.9) |

| Health-care/laboratory worker | 16 (6.1) | 9 (8.8) | 2 (4.7) | 24 (5.5) | 51 (6.0) |

| Social/prison worker | 1 (0.4) | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.5) | 4 (0.5) |

| Sex worker | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.5) | 3 (0.4) |

| Unknown | 2 (0.8) | 2 (2.0) | 1 (2.3) | 7 (1.6) | 12 (1.4) |

Table 4 shows the clinical characteristics of the patients. Of the 845 patients, 135 (16.0%) were HIV positive. Out of the 135 patients, there were two (1.5%) with a clinically indeterminate diagnosis. Of the remaining 133 patients, 25 (18.8%) were active TB cases and 108 (81.2%) were non-active TB cases.

| Characteristic | Dosanjh category | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Culture-confirmed TB | Highly probable TB | Clinically indeterminate | Active TB excluded | ||

| Height (m), median (range) | 1.7 (1.4–2.0) | 1.7 (1.5–1.9) | 1.6 (1.5–1.8) | 1.7 (1.3–2.0) | 1.7 (1.3–2.0) |

| Weight (kg), median (range) | 63 (35–127) | 64 (40–116) | 71 (37–110) | 68 (38–157) | 65 (35–157) |

| BMI (kg/m2), median (range) | 22 (14–48) | 22 (16–42) | 24 (13–45) | 24 (15–47) | 23 (13–48) |

| BCG vaccinated, n (%) | 194 (74.3) | 79 (77.5) | 36 (83.7) | 340 (77.4) | 649 (76.8) |

| BCG scar visible, n (%) | |||||

| Yes | 172 (65.9) | 72 (70.6) | 29 (67.4) | 283 (64.5) | 556 (65.8) |

| No | 12 (4.6) | 3 (2.9) | 3 (7.0) | 19 (4.3) | 37 (4.4) |

| Unsure | 16 (6.1) | 8 (7.8) | 6 (14.0) | 44 (10.0) | 74 (8.8) |

| Missing | 61 (23.4) | 19 (18.6) | 5 (11.6) | 93 (21.2) | 178 (21.1) |

| Known TB contact, n (%) | 70 (26.8) | 25 (24.5) | 12 (27.9) | 83 (18.9) | 190 (22.5) |

| HIV positive, n (%) | 13 (5.0) | 12 (11.8) | 2 (4.7) | 108 (24.6) | 135 (16.0) |

| Other pre-existing conditions/comorbidities, n (%)a | |||||

| None | 169 (64.8) | 61 (59.8) | 19 (44.2) | 169 (38.5) | 418 (49.5) |

| Diabetes | 22 (8.4) | 5 (4.9) | 8 (18.6) | 53 (12.1) | 88 (10.4) |

| Hepatitis B | 5 (1.9) | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (1.1) | 11 (1.3) |

| Hepatitis C | 1 (0.4) | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 10 (2.3) | 12 (1.4) |

| Chronic/end-stage renal failure | 5 (1.9) | 1 (1.0) | 2 (4.7) | 4 (0.9) | 12 (1.4) |

| Cancer | 1 (0.4) | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 12 (2.7) | 14 (1.7) |

| Organ transplantation | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.5) | 2 (0.2) |

| Asthma | 12 (4.6) | 5 (4.9) | 4 (9.3) | 50 (11.4) | 71 (8.4) |

| Sarcoidosis | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) |

| Other | 74 (28.4) | 37 (36.3) | 20 (46.5) | 228 (51.9) | 359 (42.5) |

| Vitamin D deficiency,b n (%) | |||||

| Deficient | 106 (40.6) | 35 (34.3) | 12 (27.9) | 59 (13.4) | 212 (25.1) |

| Insufficient | 49 (18.8) | 14 (13.7) | 7 (16.3) | 65 (14.8) | 135 (16.0) |

| Normal | 13 (5.0) | 8 (7.8) | 5 (11.6) | 34 (7.7) | 60 (7.1) |

| Not known | 93 (35.6) | 45 (44.1) | 19 (44.2) | 281 (64.0) | 438 (51.8) |

Of the 845 patients, over half had other comorbidities: 300 (35.5%) patients had a single comorbidity, 127 (15.0%) had multiple comorbidities and the remaining 418 (49.5%) had none. There were 88 (10.4%) patients with pre-existing diabetes mellitus, 12 (1.4%) patients with chronic/end-stage renal failure and 105 (12.4%) patients were on immunosuppressive therapy (Table 5). These were the three key subgroups that we had planned to investigate in the subgroup analyses. The thresholds used to categorise vitamin D status varied between hospital trusts, as detailed in Appendix 5, Table 55. Although vitamin D measurements were missing for a large number of patients (49.1%), when the results were available, many patients were categorised as either vitamin D deficient (26.5%) or insufficient (16.9%), with few (7.5%) having normal results (see Table 4).

| Medication | Dosanjh category, n (%)a | Total, n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Culture-confirmed TB | Highly probable TB | Clinically indeterminate | Active TB excluded | ||

| None | 63 (24.1) | 35 (34.3) | 13 (30.2) | 203 (46.2) | 314 (37.2) |

| Chemotherapy | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) |

| Corticosteroids ≥ 15 mg/day | 20 (7.7) | 5 (4.9) | 5 (11.6) | 20 (4.6) | 50 (5.9) |

| Corticosteroids < 15 mg/day | 13 (5.0) | 7 (6.9) | 1 (2.3) | 19 (4.3) | 40 (4.7) |

| Corticosteroids unknown | 1 (0.4) | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.2) |

| Ciclosporin, tacrolimus or everolimus | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) |

| Other immune suppressants | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (1.1) | 5 (0.6) |

| Methotrexate | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (1.1) | 6 (0.7) |

| Other | 191 (73.2) | 64 (62.7) | 30 (69.8) | 233 (53.1) | 518 (61.3) |

| Unknown | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.2) |

The social history of participants is outlined in Table 6. Smoking history was missing for two patients; about two-thirds of the patients had never smoked, and the remaining patients were current or ex-smokers. Most (58.6%) patients also had no history of alcohol use. Almost all patients (97.6%) had no history of homelessness and a few patients (27/845, 3.2%) had a history of imprisonment.

| Characteristic | Dosanjh category | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Culture-confirmed TB | Highly probable TB | Clinically indeterminate | Active TB excluded | ||

| Smoking history, n (%) | |||||

| Never smoked | 181 (69.3) | 81 (79.4) | 26 (60.5) | 248 (56.5) | 536 (63.4) |

| Ex-smoker | 31 (11.9) | 8 (7.8) | 6 (14.0) | 93 (21.2) | 138 (16.3) |

| Current smoker | 49 (18.8) | 13 (12.7) | 11 (25.6) | 96 (21.9) | 169 (20.0) |

| Unknown | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (0.5) | 2 (0.2) |

| Pack years if current smoker, n (%) | |||||

| ≤ 10 | 11 (22.4) | 6 (46.2) | 4 (36.4) | 27 (28.1) | 48 (28.4) |

| 11–20 | 1 (2.0) | 2 (15.4) | 1 (9.1) | 6 (6.3) | 10 (5.9) |

| 21–50 | 1 (2.0) | 1 (7.7) | 0 | 7 (7.3) | 9 (5.3) |

| > 51 | 1 (2.0) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.0) | 2 (1.2) |

| Unknown | 35 (71.4) | 4 (30.8) | 6 (54.5) | 55 (57.3) | 100 (59.2) |

| History of alcohol use, n (%) | |||||

| Non-drinker | 163 (62.5) | 80 (78.4) | 27 (62.8) | 225 (51.3) | 495 (58.6) |

| Ex-drinker | 10 (3.8) | 2 (2.0) | 1 (2.3) | 35 (8.0) | 48 (5.7) |

| Current drinker | 88 (33.7) | 20 (19.6) | 15 (34.9) | 175 (39.9) | 298 (35.3) |

| Unknown | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 (0.9) | 4 (0.5) |

| Units/week if current drinker, median (range) | 4 (0–250) | 5 (1–35) | 2 (0–140) | 5 (0–210) | 4 (0–250) |

| History of alcohol misuse, n (%) | 9 (3.4) | 0 | 1 (2.3) | 20 (4.6) | 30 (3.6) |

| History of recreational drug use, n (%) | |||||

| Non-user | 21 (8.0) | 10 (9.8) | 1 (2.3) | 18 (4.1) | 50 (5.9) |

| Ex-user | 2 (0.8) | 0 | 1 (2.3) | 5 (1.1) | 8 (0.9) |

| Current user | 5 (1.9) | 3 (2.9) | 1 (2.3) | 13 (3.0) | 22 (2.6) |

| Unknown | 233 (89.3) | 89 (87.3) | 40 (93.0) | 403 (91.8) | 765 (90.5) |

| History of homelessness, n (%) | |||||

| None | 256 (98.1) | 101 (99.0) | 43 (100.0) | 425 (96.8) | 825 (97.6) |

| Previously homeless | 2 (0.8) | 1 (1.0) | 0 | 11 (2.5) | 14 (1.7) |

| Currently homeless | 3 (1.1) | 0 | 0 | 3 (0.7) | 6 (0.7) |

| Years homeless if currently or previously homeless, median (range) | 4 (0–6) | 12 | – | 6 (0–24) | 6 (0–24) |

| History of imprisonment, n (%) | 4 (1.5) | 2 (2.0) | 0 | 21 (4.8) | 27 (3.2) |

Table 7 summarises the frequency of presenting symptoms for 827 patients. The main symptoms recorded were cough, fever, night sweats, weight loss, haemoptysis and lethargy. Patients generally presented with multiple symptoms, but a cough was often present (576/827, 69.6%). The median number of symptoms was four (range 1–10).

| Symptom | Diagnosis as per reference standard1 | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Culture-confirmed TB | Highly probable TB | Clinically indeterminate | Active TB excluded | ||

| Cough, n (%) | 174 (68.0) | 53 (53.5) | 23 (53.5) | 326 (76.0) | 576 (69.6) |

| Fever, n (%) | 126 (49.2) | 49 (49.5) | 14 (32.6) | 195 (45.5) | 384 (46.4) |

| Night sweats, n (%) | 129 (50.4) | 53 (53.5) | 20 (46.5) | 215 (50.1) | 417 (50.4) |

| Weight loss, n (%) | 154 (60.2) | 54 (54.5) | 21 (48.8) | 211 (49.2) | 440 (53.2) |

| Haemoptysis, n (%) | 31 (12.1) | 8 (8.0) | 3 (7.0) | 65 (15.2) | 107 (12.9) |

| Lethargy, n (%) | 133 (52.0) | 56 (56.6) | 23 (53.5) | 222 (51.7) | 434 (52.5) |

| Other, n (%) | 163 (63.7) | 59 (59.46) | 25 (58.1) | 202 (47.1) | 449 (54.3) |

| Number of symptoms, median (range) | 4 (1–10) | 4 (1–8) | 3 (1–7) | 3 (1–10) | 4 (1–10) |

Final diagnosis

Table 8 shows the diagnostic tests performed during the diagnostic workup of patients. Chest radiography and culture were often performed (in 89.4% and 86.5% of patients, respectively), but cerebrospinal fluid testing and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were uncommon (in 3.6% and 12.0%, respectively). The number of T-SPOT. TB, QFT-GIT and TST tests performed as part of routine care at each centre is shown in Appendix 6, Table 56. However, for the purpose of the IDEA study, IGRAs were not used in determining the final diagnosis of patients. TSTs were performed in only 336 patients across the nine centres and results were available for 322 patients. Most of these 336 patients were recruited at London North West Healthcare NHS Trust (57%) and Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust (26%).

| Test | Dosanjh category, n (%) | Total, n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Culture-confirmed TB | Highly probable TB | Clinically indeterminate | Active TB excluded | ||

| BAL investigation | 51 (19.5) | 20 (19.6) | 7 (16.3) | 108 (24.6) | 186 (22.0) |

| CXR | 231 (88.5) | 95 (93.1) | 38 (88.4) | 391 (89.1) | 755 (89.3) |

| CSF investigation | 7 (2.7) | 6 (5.9) | 3 (7.0) | 14 (3.2) | 30 (3.6) |

| CT | 142 (54.4) | 69 (67.6) | 26 (60.5) | 273 (62.2) | 510 (60.4) |

| Culture | 261 (100) | 90 (88.2) | 29 (67.4) | 351 (80.0) | 731 (86.5) |

| Histology or biopsy | 72 (27.6) | 42 (41.2) | 15 (34.9) | 101 (23.0) | 230 (27.2) |

| MRI | 29 (11.1) | 17 (16.7) | 8 (18.6) | 47 (10.7) | 101 (12.0) |

| PCR | 85 (32.6) | 20 (19.6) | 6 (14.0) | 66 (15.0) | 177 (20.9) |

| Smear test | 232 (88.9) | 75 (73.5) | 24 (55.8) | 335 (76.3) | 666 (78.8) |

The final diagnosis of active TB patients is detailed in Table 9. Of the 363 patients with active TB, 237 (65.3%) had smear-negative TB. Forty-five (12.4%) active TB cases had both pulmonary and extrapulmonary TB. Approximately half (189/363, 52.1%) had only extrapulmonary TB. This occurred more often among those diagnosed as having highly probable TB (75/102, 73.5%) relative to culture-confirmed cases (114/261, 43.7%). In 129 (35.5%) active TB cases, patients had only pulmonary TB. In contrast to extrapulmonary TB, pulmonary TB was more common among culture-confirmed cases (110/261, 42.15%) than in highly probable TB cases (19/102, 18.6%). The most common sites of TB infection were the lungs (174/363, 47.9%) and lymph nodes (154/363, 42.4%). The drug sensitivity profile shows that of the 351 culture tests performed, 239 (65.8%) were fully sensitive and 22 (6.3%) were drug resistant.

| Characteristic | Category of TB, n (%) | Total, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | ||

| All TB | 261 (71.9) | 102 (28.1) | 363 (100) |

| Smear-positive TB | 67 (25.7) | 3 (2.9) | 70 (19.3) |

| Smear-negative TB | 165 (63.2) | 72 (70.6) | 237 (65.3) |

| Pulmonary TB | 110 (42.1) | 19 (18.6) | 129 (35.5) |

| Extrapulmonary TB | 114 (43.7) | 75 (73.5) | 189 (52.1) |

| Pulmonary and extrapulmonary TB | 37 (14.2) | 8 (7.8) | 45 (12.4) |

| Site of infectiona | |||

| Abdomen | 6 (2.3) | 3 (2.9) | 9 (2.5) |

| Bones | 5 (1.9) | 0 | 5 (1.4) |

| Brain | 2 (0.8) | 4 (3.9) | 6 (1.7) |

| Chest wall | 1 (0.4) | 1 (1.0) | 2 (0.6) |

| Lungs | 147 (56.3) | 27 (26.5) | 174 (47.9) |

| Lymph node | 105 (40.2) | 49 (48.0) | 154 (42.4) |

| Miliary TB (disseminated) | 11 (4.2) | 0 | 11 (3.0) |

| Pericardium | 4 (1.5) | 2 (2.0) | 6 (1.7) |

| Pleura | 15 (5.7) | 11 (10.8) | 26 (7.2) |

| Spine | 10 (3.8) | 6 (5.9) | 16 (4.4) |

| Other | 15 (5.7) | 16 (15.7) | 31 (8.5) |

| Drug sensitivity profileb | |||

| Fully sensitive | 239 (91.6) | 0 | 239 (68.1) |

| Drug resistant | 21 (8.1) | 0 | 21 (6.0) |

| MDR | 1 (0.4) | 0 | 1 (0.3) |

| Not tested | 0 | 90 (100) | 90 (25.6) |

Table 10 shows the final diagnosis of non-active TB patients. A patient may have multiple conditions. Of the seven conditions listed in the table, pneumonia was the most frequent diagnosis, with 104 of 439 (23.7%) patients having the condition. A higher proportion of inpatients were diagnosed with cancer (14.1%) or pneumonia (38.8%) than outpatients (4.5% and 14.1%, respectively). In contrast, a higher proportion of outpatients were diagnosed with chest infections, latent TB infection and sarcoidosis.

| Diagnosis | Non-active TB patients, n (%) | Total, n (%) (N = 439) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inpatients (n = 170) | Outpatients (n = 269) | ||

| Cancer | 24 (14.1) | 12 (4.5) | 36 (8.2) |

| Chest infection | 1 (0.6) | 15 (5.6) | 16 (3.6) |

| Lower respiratory tract infection | 10 (5.9) | 13 (4.8) | 23 (5.2) |

| Pneumonia | 66 (38.8) | 38 (14.1) | 104 (23.7) |

| Sarcoidosis | 5 (2.9) | 33 (12.3) | 38 (8.7) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 0 (0.0) | 13 (3.0) | 13 (3.0) |

| Other | 70 (41.2) | 153 (56.9) | 223 (50.8) |

Chapter 4 Diagnostic accuracy results

Overview

Estimates of the accuracy of IGRAs presented in this chapter are for the main cohort of patients (including HIV-positive patients recruited prior to the extension period). Estimates of the accuracy of T-SPOT. TB and QFT-GIT are presented individually, followed by comparisons of test accuracy (T-SPOT. TB vs. QFT-GIT). The results of subgroup analyses are then presented for T-SPOT. TB and QFT-GIT. Finally, test accuracy estimates are provided for ESAT-6, CFP-10 and second-generation IGRAs (Rv3615c, Rv2654, Rv3879c and Rv3873) individually and in combinations; the diagnostic accuracy of the test combinations were then compared with that of T-SPOT. TB. For completeness, we also briefly address the accuracy of the TST.

Completeness of interferon gamma release assay results

Of the 845 patients, T-SPOT. TB and QFT-GIT results were available for 809 (96%) and 820 (97%) patients, respectively. All 809 patients with T-SPOT. TB results also had results for the second-generation IGRAs (Rv3615c, Rv2654, Rv3879c and Rv3873). Table 11 shows the results for T-SPOT. TB and QFT-GIT by diagnostic category. For 805 patients, results were available for both IGRAs; reasons for missing T-SPOT. TB and QFT-GIT results are shown in Table 12. The cross-classified results of the two tests are given in Appendix 7 (see Table 57) for the 805 patients.

| Index test result | Dosanjh category | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4A | 4B | 4C | 4D | 4A–D | ||

| T-SPOT.TB | |||||||||

| Positive | 185 | 68 | 15 | 0 | 18 | 27 | 6 | 51 | 319 |

| Negative | 33 | 25 | 23 | 6 | 26 | 200 | 87 | 319 | 400 |

| Borderline | 16 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 14 | 1 | 16 | 33 |

| Indeterminate | 12 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 18 | 17 | 37 | 57 |

| Missing | 15 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 6 | 16 | 36 |

| Total | 261 | 102 | 43 | 7 | 48 | 267 | 117 | 439 | 845 |

| Median SFCs ESAT-6 (range) | 13 (0–387) | 13 (0–492) | 0 (0–325) | 0 (0–1) | 2 (0–274) | 0 (0–210) | 0 (0–147) | 0 (0–274) | 1 (0–492) |

| Median SFCs CFP-10 (range) | 17 (0–465) | 13 (0–437) | 1 (0–315) | 0 (0–3) | 1 (0–160) | 0 (0–166) | 0 (0–148) | 0 (0–166) | 1 (0–465) |

| QFT-GIT | |||||||||

| Positive | 163 | 57 | 14 | 0 | 19 | 49 | 6 | 74 | 308 |

| Negative | 68 | 39 | 22 | 7 | 25 | 187 | 85 | 304 | 433 |

| Indeterminate | 21 | 5 | 6 | 0 | 2 | 26 | 19 | 47 | 79 |

| Missing | 9 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 5 | 7 | 14 | 25 |

| Total | 261 | 102 | 43 | 7 | 48 | 267 | 117 | 439 | 845 |

| Median IFN-γ levels (range) | 0.69 (0–10) | 0.64 (0–10) | 0.15 (0–6.69) | 0.02 (0–0.34) | 0.15 (0–10) | 0.03 (0–10) | 0.01 (0–7.58) | 0.03 (0–10) | 0.12 (0–10) |

| Reason | Test, n | |

|---|---|---|

| QFT-GIT | T-SPOT.TB | |

| No sample could be taken | 1 | 0 |

| Sample destroyed for laboratory reasons | 2 | 11 |

| Sample unsuitable for testing | 6 | 8 |

| Unable to obtain sample from patient | 16 | 17 |

| Total | 25 | 36 |

Diagnostic accuracy of T-SPOT.TB and QuantiFERON GOLD In-Tube

Table 13 shows the cross-tabulation of T-SPOT. TB and QFT-GIT results against active TB status (i.e. active TB or not). The proportion of indeterminate test results was 7.0% (57/809) for T-SPOT. TB and 9.6% (79/820) for QFT-GIT. The difference between the two proportions was 2.6% (95% CI –0.1% to 5.3%; p = 0.06). Based on all culture-confirmed and highly probable active TB cases and excluding indeterminate IGRA results, sensitivity was 82.3% (95% CI 77.8% to 86.1%) for T-SPOT. TB and 67.3% (95% CI 62.0% to 72.1%) for QFT-GIT. Among those in whom active TB was excluded, specificity was 82.6% (95% CI 78.6% to 86.1%) for T-SPOT. TB and 80.4% (95% CI 76.1% to 84.1%) for QFT-GIT (Table 14). The PPVs for T-SPOT. TB and QFT-GIT were 80.1% (95% CI 75.5% to 84.0%) and 74.8% (95% CI 69.6% to 79.5%), respectively, and the NPVs were 84.6% (95% CI 80.6% to 87.9%) and 74.0% (95% CI 69.5% to 78.0%), respectively. For T-SPOT. TB, 4.1% (33/809) of the test results were borderline (see Table 13). When these borderline results were excluded from the T-SPOT. TB analysis, sensitivity (95% CI) was 81.4% (76.6% to 85.3%), specificity (95% CI) was 86.2% (82.3% to 89.4%), PPV (95% CI) was 83.2% (78.6% to 87.0%) and NPV (95% CI) was 84.6% (80.6% to 87.9%). The full results of the analysis are shown in Appendix 7, Table 58.

| T-SPOT.TB, n | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active TB positive (categories 1 and 2) | Active TB negative (category 4) | ||||||||||||

| Positive | Negative | Borderline | Indeterminate | Missing | Total | Positive | Negative | Borderline | Indeterminate | Missing | Total | ||

| QFT-GIT | Positive | 187 | 13 | 6 | 9 | 5 | 220 | 37 | 30 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 74 |

| Negative | 49 | 41 | 8 | 7 | 2 | 107 | 12 | 250 | 12 | 26 | 4 | 304 | |

| Indeterminate | 16 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 26 | 2 | 36 | 1 | 8 | 0 | 47 | |

| Missing | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 10 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 14 | |

| Total | 253 | 58 | 17 | 17 | 18 | 363 | 51 | 319 | 16 | 37 | 16 | 439 | |

| Test performance | T-SPOT.TB | QFT-GIT | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n/N | Estimate (95% CI) | n/N | Estimate (95% CI) | |

| Sensitivity for a diagnosis of active TB | ||||

| All TB | 270/328 | 82.3 (77.8 to 86.1) | 220/327 | 67.3 (62.0 to 72.1) |

| Culture-positive TB | 201/234 | 85.9 (80.9 to 89.8) | 163/231 | 70.6 (64.4 to 76.1) |

| Culture-negative TB | 59/83 | 71.1 (60.6 to 79.7) | 48/84 | 57.1 (46.5 to 67.2) |

| Smear-positive TB | 50/60 | 83.3 (72.0 to 90.7) | 42/56 | 75.0 (62.3 to 84.5) |

| Smear-negative TB | 179/216 | 82.9 (77.3 to 87.3) | 148/222 | 67.7 (60.2 to 72.5) |

| Pulmonary TB | 87/113 | 77.0 (68.4 to 83.8) | 78/114 | 68.4 (59.4 to 76.2) |

| Extrapulmonary TB | 147/175 | 84.0 (77.9 to 88.7) | 113/171 | 66.1 (58.7 to 72.8) |

| Specificity for a diagnosis of active TB | ||||

| Active TB excluded | 319/386 | 82.6 (78.6 to 86.1) | 304/378 | 80.4 (76.1 to 84.1) |

| Active TB excluded, TST negative, no risk factors for LTBI | 87/94 | 92.3 (85.4 to 96.4) | 85/91 | 93.4 (86.4 to 96.9) |

| Predictive values | ||||

| PPV | 270/337 | 80.1 (75.5 to 84.0) | 220/294 | 74.8 (69.6 to 79.5) |

| NPV | 319/377 | 84.6 (80.6 to 87.9) | 304/411 | 74.0 (69.5 to 78.0) |

| Likelihood ratios | ||||

| Positive likelihood ratio | – | 4.74 (3.79 to 5.93) | – | 3.44 (2.76 to 4.27) |

| Negative likelihood ratio | – | 0.21 (0.17 to 0.27) | – | 0.41 (0.35 to 0.48) |

Using only culture-confirmed active TB cases, the sensitivities of T-SPOT. TB and QFT-GIT increased slightly to 85.9% (95% CI 80.9% to 89.8%) and 70.6% (95% CI 64.4% to 76.1%), respectively. The sensitivity of T-SPOT. TB was 7.0% lower in patients diagnosed with pulmonary TB than in those with extrapulmonary TB [77.0% (95% CI 68.4% to 83.8%) vs. 84.0% (95% CI 77.9% to 88.7%)]. In contrast, although the difference was small (2.3%), the sensitivity of QFT-GIT was higher in patients who had pulmonary TB (68.4%, 95% CI 59.4% to 76.2%) than in those with extrapulmonary TB (66.1%, 95% CI 58.7% to 72.8%). Using only category 4D patients without active TB gave much higher specificities than using all patients without active TB (see Table 14).

In the sensitivity analyses with indeterminate test results included as test positives, the sensitivity of T-SPOT. TB was 83.2% (95% CI 78.9% to 86.8%) and 69.7% (95% CI 64.7% to 74.2%) for QFT-GIT. The specificity of T-SPOT. TB was 75.4% (95% CI 71.1% to 79.3%) and 71.5% (95% CI 67.1% to 75.6%) for QFT-GIT. Full results are provided in Appendix 7, Table 59.

Sensitivity, specificity and predictive values are presented as percentages. For TSPOT. TB, there were 69 test positives out of 94 highly probable TB cases, with sensitivity (95% CI) of 73.4% (63.7% to 81.3%). For QFT-GIT, there were 57 test positives out of 96 highly probable TB cases, with sensitivity (95% CI) of 59.4% (49.4% to 68.7%). Note that in the primary analyses of T-SPOT. TB, borderline test results were included as test positives. Sensitivity analyses were performed with borderline T-SPOT. TB results excluded and the results are shown in Appendix 7, Table 58. Indeterminate IGRA results were excluded from all analyses. See Appendix 7 for sensitivity analyses using all IGRA results with indeterminates included as test positives.

Comparison of diagnostic accuracy of T-SPOT.TB and QuantiFERON GOLD In-Tube

Excluding indeterminate IGRA results, there were 714 T-SPOT. TB results and 705 QFT-GIT results. Based on analyses using GEE models, the sensitivity of T-SPOT. TB was superior to that of QFT-GIT (relative sensitivity 1.22, 95% CI 1.14 to 1.31; p < 0.001), but there was no statistical evidence of a difference in specificity (relative specificity 1.02, 95% CI 0.97 to 1.08; p = 0.3) (Table 15). Excluding the 33 borderline T-SPOT. TB results (see Appendix 7, Table 60), the results for relative sensitivity were similar to those from the main analysis but there was statistical evidence of a difference in specificity; the relative sensitivity (95% CI) was 1.20 (1.12 to 1.29; p < 0.001) and the relative specificity (95% CI) was 1.07 (1.02 to 1.12; p = 0.004). When all IGRA results were analysed and indeterminate IGRA results were included as test positives in a sensitivity analysis, the analysis included 768 T-SPOT. TB results and 778 QFT-GIT results. Similar to the primary analysis, there was statistical evidence of a difference in sensitivity (relative sensitivity 1.19, 95% CI 1.12 to 1.28; p < 0.001) and no evidence of a difference in specificity (relative specificity 1.05 95% CI 0.98 to 1.13; p = 0.1) (see Appendix 7, Table 61).

| Test | Number of test resultsa | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Number of test resultsb | Specificity (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T-SPOT.TB | 328 | 82.2 (77.7 to 85.9) | 386 | 83.0 (78.9 to 86.4) |

| QFT-GIT | 327 | 67.3 (62.1 to 72.2) | 378 | 81.0 (76.8 to 84.6) |

| Ratio (95% CI);c p-value | – | 1.22 (1.14 to 1.31); < 0.001 | – | 1.02 (0.97 to 1.08); 0.3 |

Subgroup analyses for T-SPOT.TB and QuantiFERON GOLD In-Tube

Human immunodeficiency virus-positive and -negative patients

Human immunodeficiency virus co-infected patients are the highest-risk subgroup for TB. In this section we briefly present results for the 135 HIV-positive patients in the main cohort and address the primary objectives related to this subgroup in Chapter 5 using all HIV-positive patients recruited into the IDEA study. Appendix 8 (see Table 62) shows the results for T-SPOT. TB and QFT-GIT against active TB status. Appendix 8 (see Table 63) shows the cross-tabulation of T-SPOT. TB and QFT-GIT results in HIV-positive patients. For 134 patients, results were available for both T-SPOT. TB and QFT-GIT.

The number of test results for active TB and non-active TB patients who were available for the analyses of test performance in HIV-positive patients was small (see Appendix 8, Table 62). Using culture-confirmed and highly probable active TB cases and excluding indeterminate IGRA results, sensitivity was 63.2% (95% CI 41.0% to 80.9%) for T-SPOT. TB and 56.5% (95% CI 36.8% to 74.4%) for QFT-GIT. Among all non-active TB patients, specificity was 89.9% (95% CI 81.3% to 94.8%) for T-SPOT. TB and 92.0% (95% CI 84.3% to 96.1%) for QFT-GIT (Table 16). For T-SPOT. TB and QFT-GIT, the PPVs were 60.0% (95% CI 38.7% to 78.1%) and 65.0% (95% CI 43.3% to 81.9%), respectively, and the NPVs were 91.0% (95% CI 82.6% to 95.6%) and 88.9% (95% CI 80.7% to 93.9%), respectively.

| Test performance | Test | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

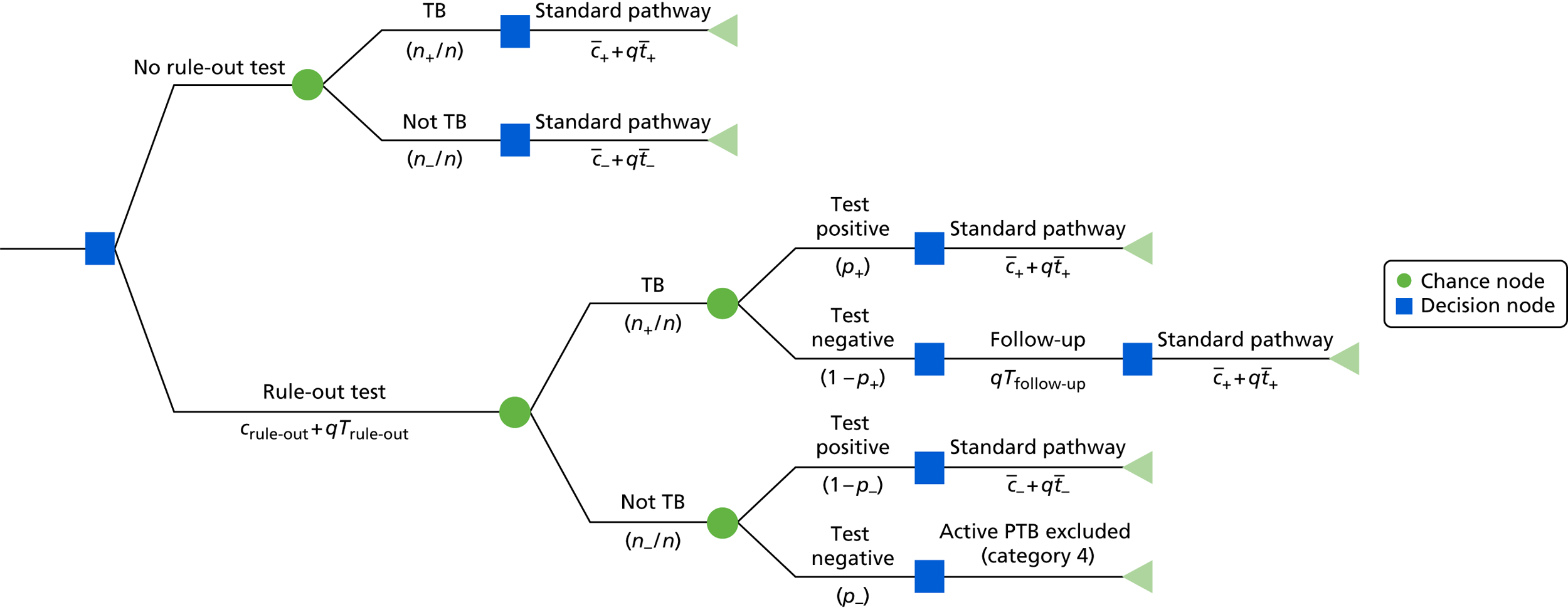

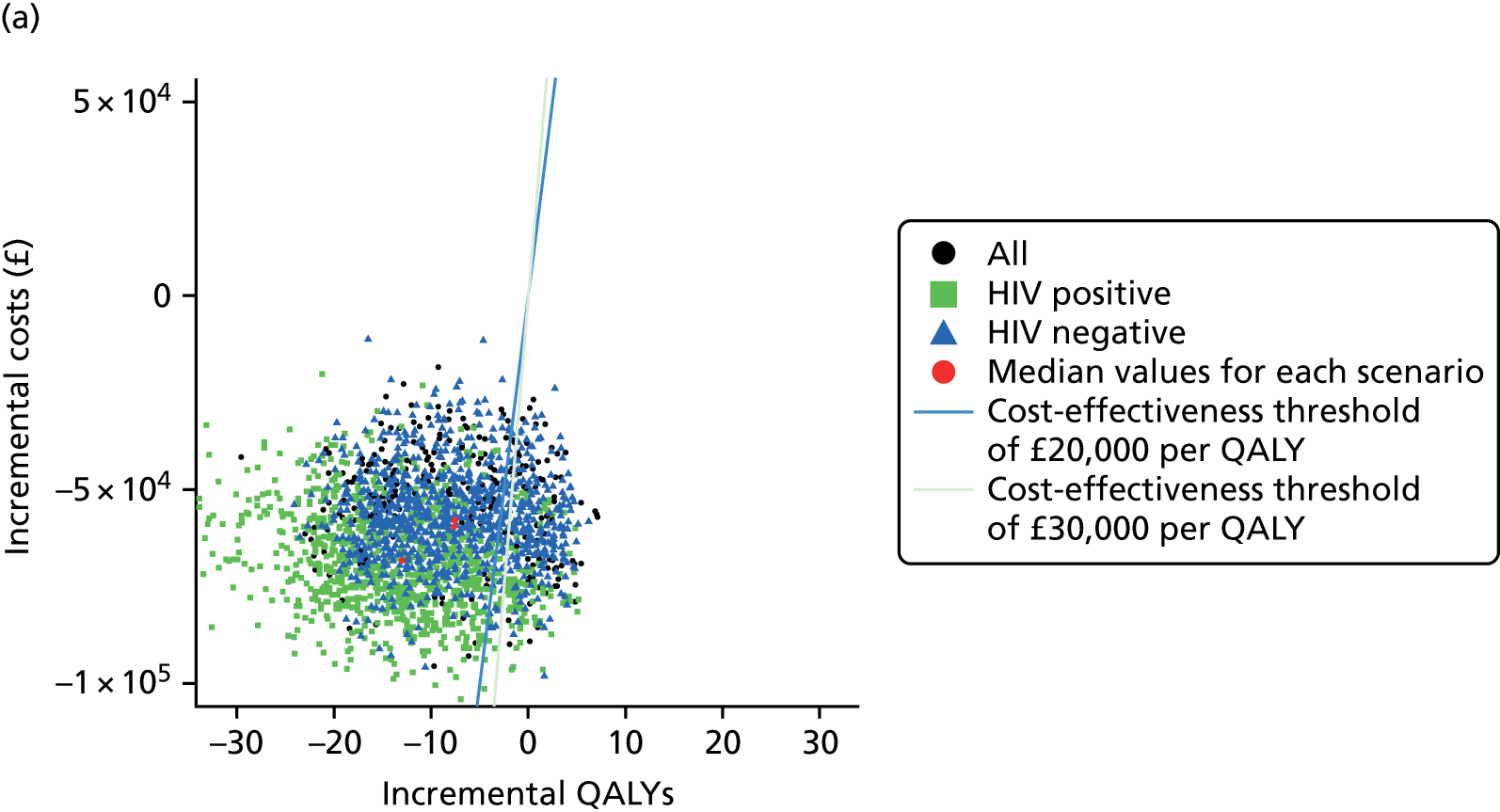

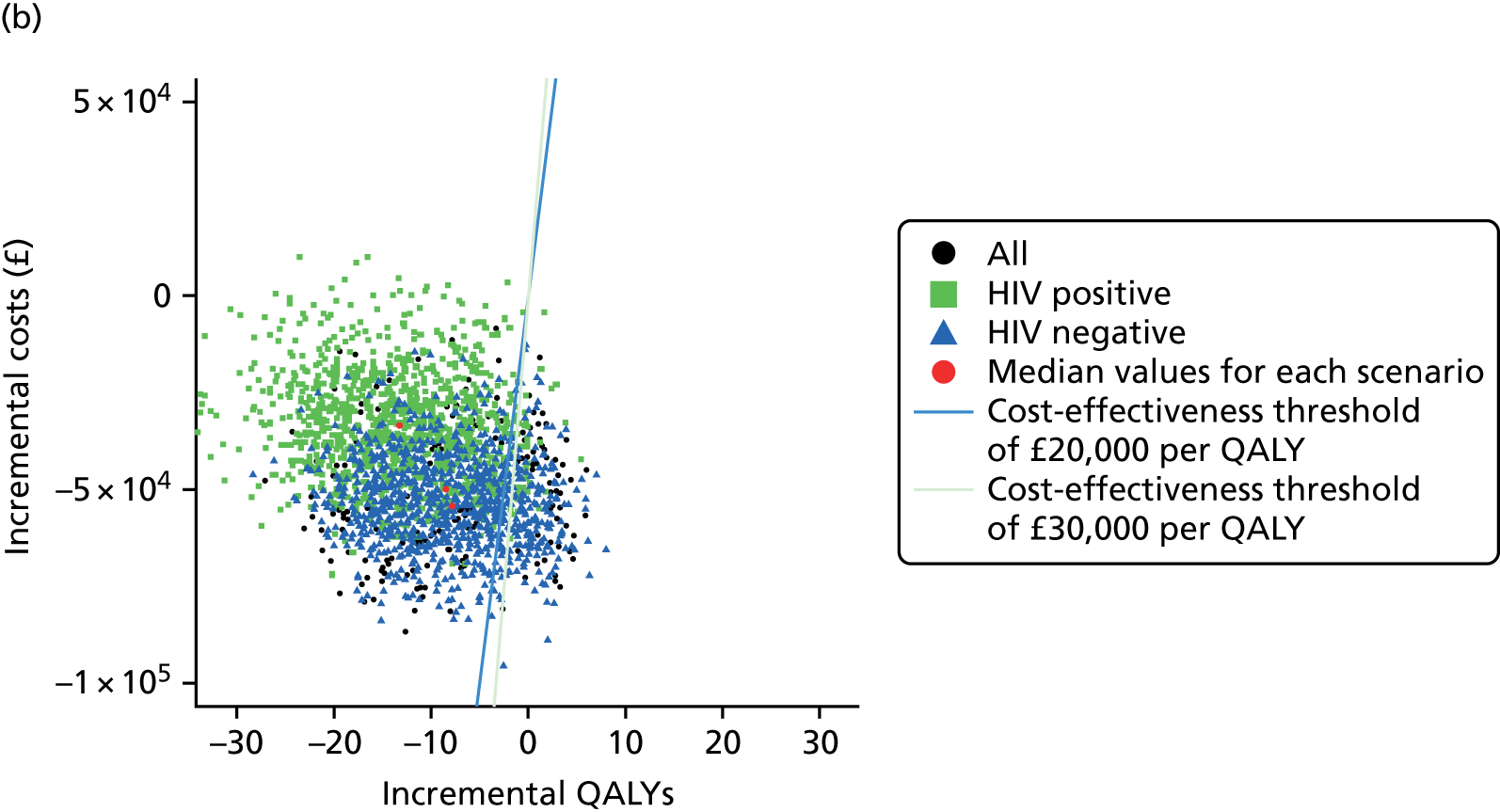

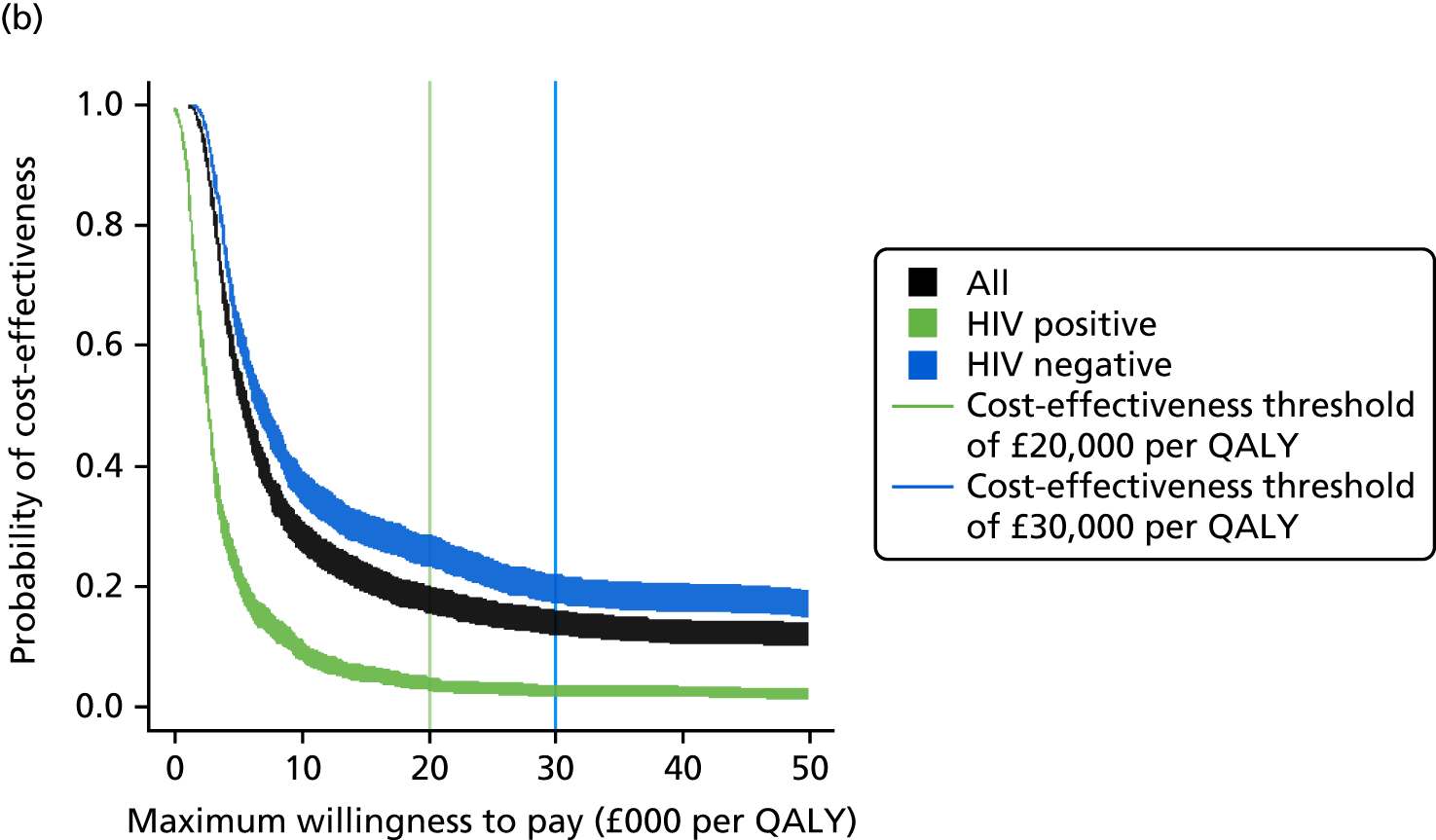

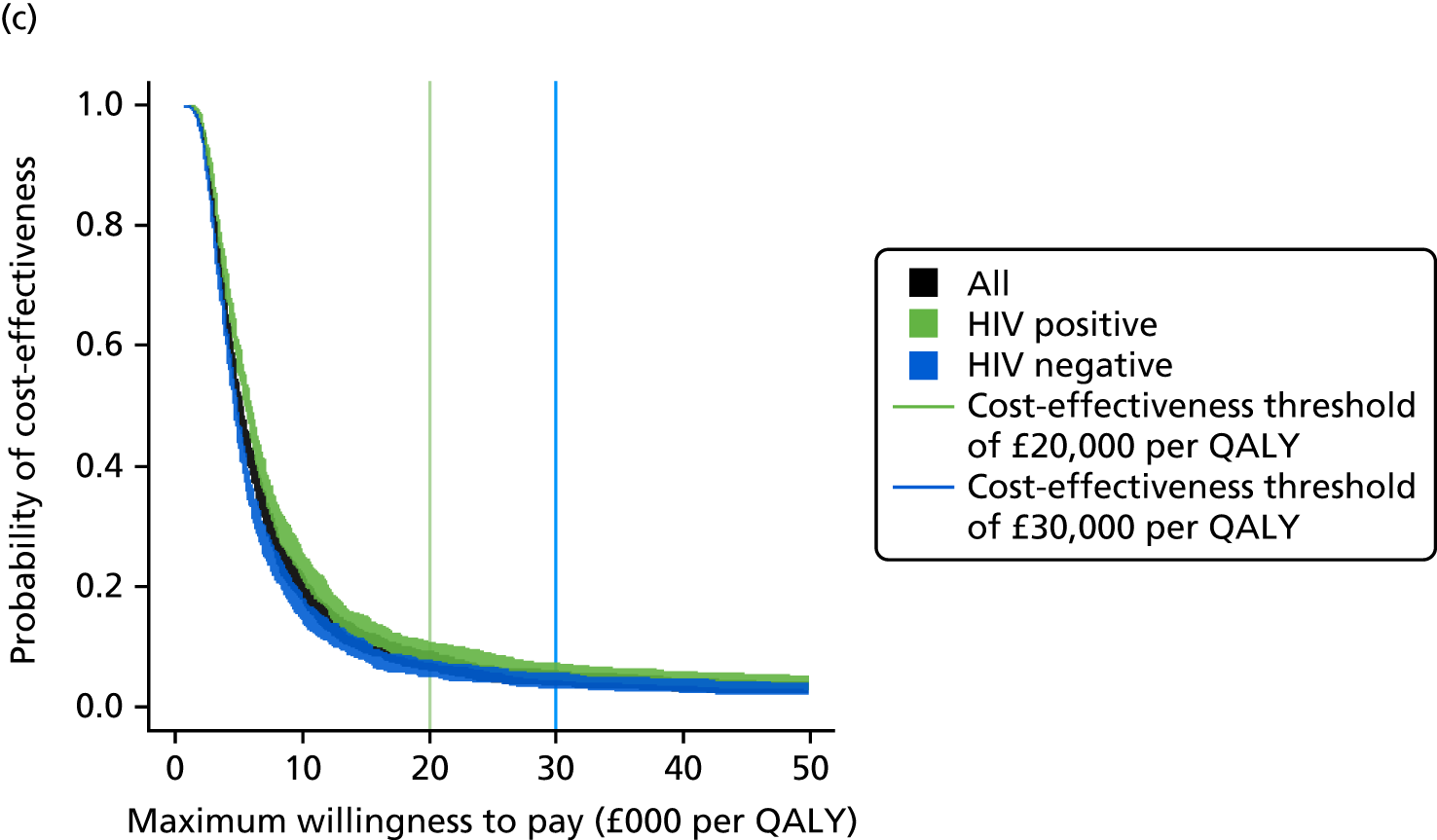

| T-SPOT.TB | QFT-GIT | |||