Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 98/04/501. The contractual start date was in September 2013. The draft report began editorial review in April 2017 and was accepted for publication in November 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Henry Kitchener reports grants from the University of Manchester during the conduct of the study. He is chairperson of the Advisory Committee for Cervical Screening (Public Health England) as well as of the National HPV Pilot Steering Group. Any views expressed in this report are those of the authors and not of Public Health England.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Gilham et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

The NHS Cervical Screening Programme is already one of the most successful in the world in preventing cervical cancer,1,2 but unnecessary referral and treatment should be minimised to reduce NHS costs, inconvenience to women and unnecessary treatment for low-grade cervical dysplasia, which can compromise later birth outcomes. Human papillomavirus (HPV) testing is already used in the UK to triage borderline and mild cervical cytology and as a test of cure following excision of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN). National roll-out of primary HPV testing, scheduled to be complete by December 2019, will further increase sensitivity; however, referrals and, hence, costs will also increase without longer screening intervals and more efficient triage methods for human papillomavirus-positive (HPV+) women. Primary HPV testing with cytology triage of HPV+ women is being piloted at several sites in England following publication of ARTISTIC trial (A Randomised Trial In Screening To Improve Cytology) results over three rounds of HPV screening3–5 and pooled data from ARTISTIC and other randomised trials showing a reduction in long-term cervical cancer risk. 6 The aim of primary HPV screening is to reduce cervical cancer risk by identifying women with high-grade CIN early enough to prevent progression to invasive cancer. The introduction of primary HPV testing in the NHS Cervical Screening Programme will require practical decisions on screening intervals for different age ranges as well as the triage protocol for HPV+ women. The results up to 2009 from the initial screening rounds in ARTISTIC contributed to the decision to pilot HPV primary screening,7 and this extension to 2015 gave a 10-year follow-up from entry, providing further evidence to optimise screening protocols.

The CIN grade 3 or cervical cancer (CIN3+) rate in the second round of ARTISTIC was less than half the rate at entry, as the majority of cases diagnosed at entry reflected a long-term accumulation missed by previous screening. 5 Virtually all prevalent cases will be detected when HPV screening is first introduced. Therefore, follow-up from round 1 represents what will be seen when primary HPV screening is introduced, while follow-up from round 2 represents what will be seen at the second and subsequent rounds of HPV screening. For the purpose of modelling an established HPV screening programme, an important group are the 85% of women who were human papillomavirus negative (HPV–) at entry (round 1), as long follow-up of those with new infections detected at round 2 represents the time course of HPV persistence and CIN3+ risk following first infection. Extending follow-up to 2015 has increased the median follow-up beyond round 2 in ARTISTIC from 4 to 10 years.

Follow-up of the cohort to 2009 showed that the subsequent CIN3+ rate is substantially lower following a single negative HPV test than for negative cytology,4 and this was influential in the National Screening Committee’s (NSC’s) recommendation that HPV testing should replace cytology as the primary screening test. This further follow-up beginning at round 2 will show whether or not the screening interval can safely be increased from the current routine (3 years for those aged < 50 years and 5 years for those aged ≥ 50 years) to up to 10 years for HPV– women, irrespective of previous test results.

Chapter 2 Objectives

The objective of this extended follow-up of the ARTISTIC cohort was to obtain the data required to evaluate the long-term benefits of alternative screening strategies using primary HPV testing, including the following:

-

The long-term cumulative CIN3+ risk following a negative HPV test, and, hence, the safe screening interval at different ages.

-

The effect of HPV type on CIN3+ risk following a positive HPV test, and, hence, the role of HPV genotyping in routine screening.

-

The difference in CIN3+ risks following round 2 between women with type-specific HPV persistence since round 1 and those with a newly acquired HPV type. This is relevant to the triage protocol for HPV+ women: the interval to retesting, and either referral for colposcopic examination or further testing in women who remain HPV+ based on HPV typing and cytology.

-

The effects on CIN3+ risk of different ages at starting and stopping screening. The high prevalence of CIN2+ at age 20–24 years (6.3%) in round 1 of ARTISTIC4 showed that many cases detected when women are first screened at age 25 years developed more than 5 years earlier. The long-term CIN3 risk in HPV– women who are aged ≥ 50 years is very low, but if they are never screened again their lifetime then cancer risk may not be negligible.

Chapter 3 Methods

Data collection during the trial (2001–9)

ARTISTIC compared cytology with and without HPV testing among 24,510 women attending routine cervical screening in 2001–3. Over 60,000 HPV tests [hybrid capture 2 (HC2) with full HPV typing of those testing positive] were performed on routinely collected liquid-based cytology (LBC) cervical samples until September 2009. Methods are described elsewhere3,5 reporting that women were randomly allocated in a ratio of 1 : 3 between having their HPV results concealed (concealed arm, n = 6124) or revealed (revealed arm, n = 18,386). All women with abnormal cytology were recalled for retesting or referred to colposcopy according to national guidelines. 3 After March 2008, the laboratory became part of the Sentinel Sites project in which low-grade cytological abnormalities were triaged using HPV. Women were referred with borderline or mild cytology only if they tested positive for HPV; otherwise, they were returned to routine recall. In addition, women in the revealed arm with normal cytology who were hybrid capture 2 positive (HC2+) were recalled for repeat HPV testing, and those whose HPV infection persisted were referred to colposcopy.

Liquid-based cytology was carried out using ThinPrep® (Hologic, Crawley, UK) and HPV testing using HC2 (Qiagen, Crawley, UK). A cut-off point of 1 relative light unit/mean control (RLU/Co) pg/µl was used to identify positive HPV samples, which were genotyped using at least one of three HPV typing assays. All HC2+ samples during rounds 1 and 2 were genotyped using the prototype Roche Line Blot Assay (Roche Molecular Diagnostics, Pleasanton, CA, USA). 3 This was replaced by the commercially available Linear Array assay and the PapilloCheck® assay (Greiner Bio-one GmbH, Frickenhausen, Germany) during round 3. In addition, approximately two-thirds of archived HC2+ round 1 samples were also tested by the PapilloCheck assay and one-third of archived HC2+ round 2 samples were tested by the Roche Linear Array®. In all three rounds, any of the 13 high-risk human papillomavirus (HRHPV) types detected by HC2 (HPV types 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 68) that was detected by any of the assays was included in the analysis. All other HPV types were ignored in all analyses.

After the trial ended in 2009, all women returned to routine cytology every 3 years if they were aged < 50 years, and every 5 years if they were aged 50–64 years. We have published reports on baseline data,8,9 follow-up through two further screening rounds3–5,10 and various other HPV-related issues. 6,11–13 These analyses were based on follow-up to 2009 through two cytology laboratories in the Manchester area. Any women moving out of the area were lost, and only 60% of the ARTISTIC cohort had a cytology record between 2006 and 2009.

Further data collection (2010–16)

NHS Central Register for cancer incidence and mortality

The cohort was flagged through NHS Central Register (NHSCR), giving notification of deaths and cancer diagnoses, including carcinoma in situ of the cervix (CIN3), until December 2015.

National screening programme call–recall cytology and human papillomavirus records

The cohort was linked to the NHS Cervical Screening Programme call–recall database to obtain lifetime cervical screening records for the entire ARTISTIC cohort. This included any recorded HPV results taken after triaging of borderline or mild dyskaryosis cytology or as part of primary HPV screening (in pilot areas). The reasons for ceasing screening, including hysterectomy, were also recorded.

Testing stored samples for human papillomavirus deoxyribonucleic acid

All samples taken during the trial have been tested using HC2 with HPV typing for HC2+ samples. Women who consented to their HPV samples being retained for future research are now stored at Professor Lorincz’s laboratory at QMUL. Sensitive polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based assays [Roche Line Blot assay and PapType® assay (Genera Biosystems, Scoresby, VA, Australia)] were carried out on hybrid capture 2-negative (HC2–) samples from women who have developed invasive cervical cancer since 2009.

Chapter 4 Definitions and statistical methods

Definition of round 2 follow-up

In previous reports, round 2 was defined as the first adequate cytology between 26 and 54 months after entry, which included 10% with no adequate HPV test on their round 2 sample. In this report, round 2 is defined as the first adequate HPV test between 30 and 48 months after entry. Under this definition, 13,591 women had a round 2 test, on average, 3 years and 7 months after entry. In analyses beginning at round 2, 185 women with CIN3+ registration/histology before this date and six women whose flagging data indicated that they had cancelled from the NHSCR before this date were excluded.

Human papillomavirus clearance

To estimate and compare clearance rates of recently acquired and long-standing HPV infections (i.e. those already present at entry), clearance from the second HPV test in ARTISTIC (regardless of time since entry) was assessed. Women with any histology, regardless of result, between the second and third HPV tests were excluded in case the action of taking a biopsy affected the clearance rate. In addition, women with CIN3+ histology before the second HPV test were excluded. A total of 1026 women with at least three HPV tests whose second test was positive for HRHPV were included in the analysis. Each infection with a HPV type was considered independently, so women with more than one HPV type were counted more than once in the analysis. Clearance of each infection was calculated by time between the second and third HPV test and stratified by whether or not the same HPV type was present at entry (i.e. whether the infection developed since entry or was prevalent at entry).

Human papillomavirus recurrence

The recurrence of type-specific HPV infections was counted in women who had HRHPV infections at round 1 and subsequently tested HC2–. The time to ‘clearance’ (defined as testing HC2–) was stratified into ‘short term’, defined as clearance of < 24 months after round 1, and ‘long term’, defined as clearance 24–54 months after round 1. Recurrence in these two groups of women was defined as any subsequent HRHPV+ result with one or more genotype identified that was also present at entry. Under the protocol, genotyping was not carried out on HC2– samples, which implies that ‘clearance’ means that the HPV infection had become undetectable by HC2.

Type-specific human papillomavirus persistence

The HPV types found in round 2 (30–48 months after entry) were compared with those identified in round 1 so that round 2 infections could be classified as new or persistent. Women with a type-specific persistent infection with or without a new infection of a different genotype were classified as persistent.

Human papillomavirus status

In most other analyses, women were classified hierarchically into mutually exclusive groups: HPV 16 or HPV 18, any of HPV types 31, 33, 45, 52 or 58 (without 16 or 18), any other HRHPV, HC2+ with no HRHPV, or HC2–.

Calculation of cumulative risk for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia or cervical cancer

Cumulative CIN3+ risks were estimated by Kaplan–Meier methods. Subgroups were compared using the log-rank test. Cumulative risks were calculated from entry (round 1) and also from round 2 when incident and persistent infections could be distinguished. Women were censored at date of last cytology prior to hysterectomy according to call–recall data. All analyses were censored on 30 April 2015 to allow for late registration of CIN3 and cancer.

Kaplan–Meier analysis of interval-censored data

The aim of the cumulative risk analyses is to estimate the probability that CIN3+ would be detected by a test at a given time after entry to follow-up, beginning either at entry to the trial or at round 2. This raises several issues.

-

We ignore the possibility that CIN3 occasionally regresses, so cumulative risks may overestimate the prevalence that would be observed if the next test were 5 or 10 years later.

-

CIN3+ histology is backdated to the beginning of follow-up if the histology/registration occurred within a year of the beginning of follow-up. These cases are shown at time zero giving an initial step in the Kaplan–Meier curve. Some of these cases were not present at the time of the initial abnormal cytology or positive HPV test but developed during the period of repeat testing.

-

Later CIN3+ histology/registration dates are backdated to the first test in the preceding year, then further backdated to the mid-point of the interval between that test and the preceding test. For three cancers and a single CIN3 lesion with no recorded cytology within a year, the histology date is taken as the end of the interval. One further cancer was censored on ceasing screening and thus excluded.

This modified Kaplan–Meier treatment of interval-censored data, in which lesions are assigned to the mid-point of the screening interval where they became detectable, gives results similar to a parametric analysis (Professor Peter Sasieni, Queen Mary University of London, 2017, personal communication). The second-order error is that the interval mid-point is not the expected value of the time when the CIN3 would be detectable, which may be slightly earlier or later depending on the assumed model of HPV acquisition and CIN3 development.

Chapter 5 Results

Section 1: description of data

Eligible data

The cohort that participated in ARTISTIC consisted of 24,510 women aged between 20 and 64 years and provided an adequate cytology and HPV test at enrolment. Fourteen women did not have a valid NHS number and so 24,496 women were flagged with NHS Digital for cancer registration and death. These women were then linked to the National Screening Programme call–recall system, which yielded a final cohort of 23,888 after excluding three non-matches and 605 type-2 opt-outs (those opting out of their data being accessed for medical research) (Figure 1). The call–recall data were linked by NHS number to ensure correct linkage. At least one cytology date and result from the laboratory database matched the call–recall data in all but 53 women (99.8%). These 53 women were individually examined and most had only one or two tests identified through the laboratory. We assumed that these cytology dates had not been recorded correctly on the call–recall system. For those whose call–recall screening records matched the Manchester laboratory data during the trial (2001–9), it was not uncommon for some records to be inconsistent between the systems.

FIGURE 1.

The CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) flow of diagram showing women followed up for cancer registration and mortality through national registration, and for cytology through call–recall cervical screening records.

Follow-up via local histology laboratories to 2009 when the trial ended and via cancer registrations to April 2015 identified 509 cases of CIN3+, including 23 invasive cancers. Three cases of CIN3 were excluded owing to censoring at last cytology as no link was made to call–recall data. In addition, one invasive cancer was excluded as the woman’s screening record indicated that she had ceased screening after reaching the age of 65 years. Therefore, 505 cases of CIN3+ were included in the analysis (Table 1).

| Histology only (2001–9), n (%) | Registration only (2001–15), n (%) | Both histology and registration, n (%) | Total number | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CIN3 | 99 (20.4) | 94a (19.3) | 293 (60.3) | 486 |

| Invasive cancer | 11b (47.8) | 12 (52.2) | 23 | |

| Year of diagnosis | ||||

| 2001–3 | 61 (21.2) | 7 (2.4) | 220 (76.4) | 288 |

| 2004–6 | 21 (22.8) | 11 (12.0) | 60 (65.2) | 92 |

| 2007–9 | 17 (23.6) | 30 (41.7) | 25 (34.7) | 72 |

| 2010–15 | 0 (0.0) | 57 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 57 |

| Total | 99 (19.4) | 105 (20.6) | 305 (59.9) | 509 |

Among women who had not ceased screening due to age by 2016 (n = 17,602), 642 women aged 30–64 years were recorded as ceased on the call–recall system due to hysterectomy: 0.3% aged 30–39 years, 2.5% aged 40–49 years, 5.3% aged 50–59 years and 6.9% aged 60–64 years.

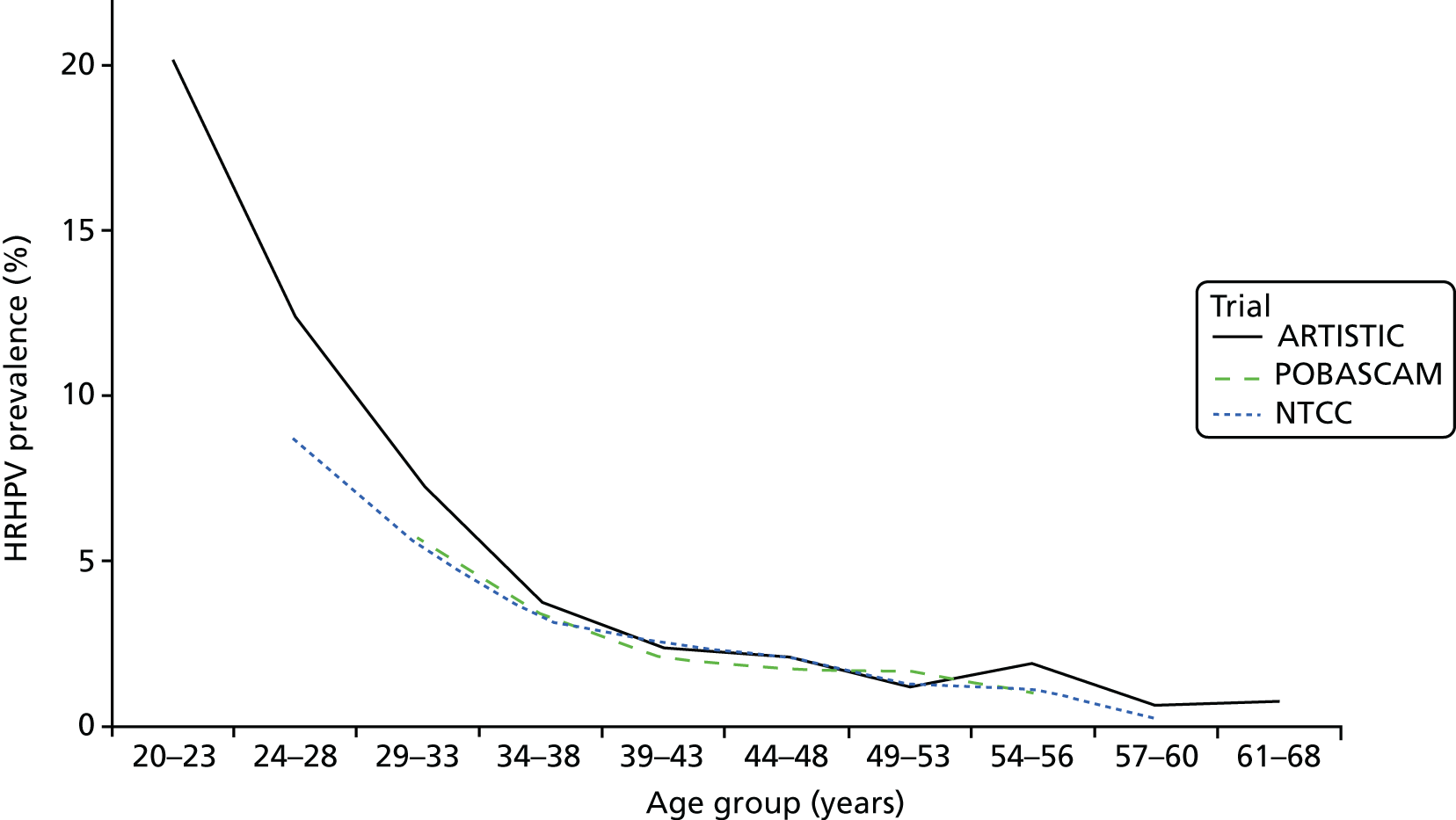

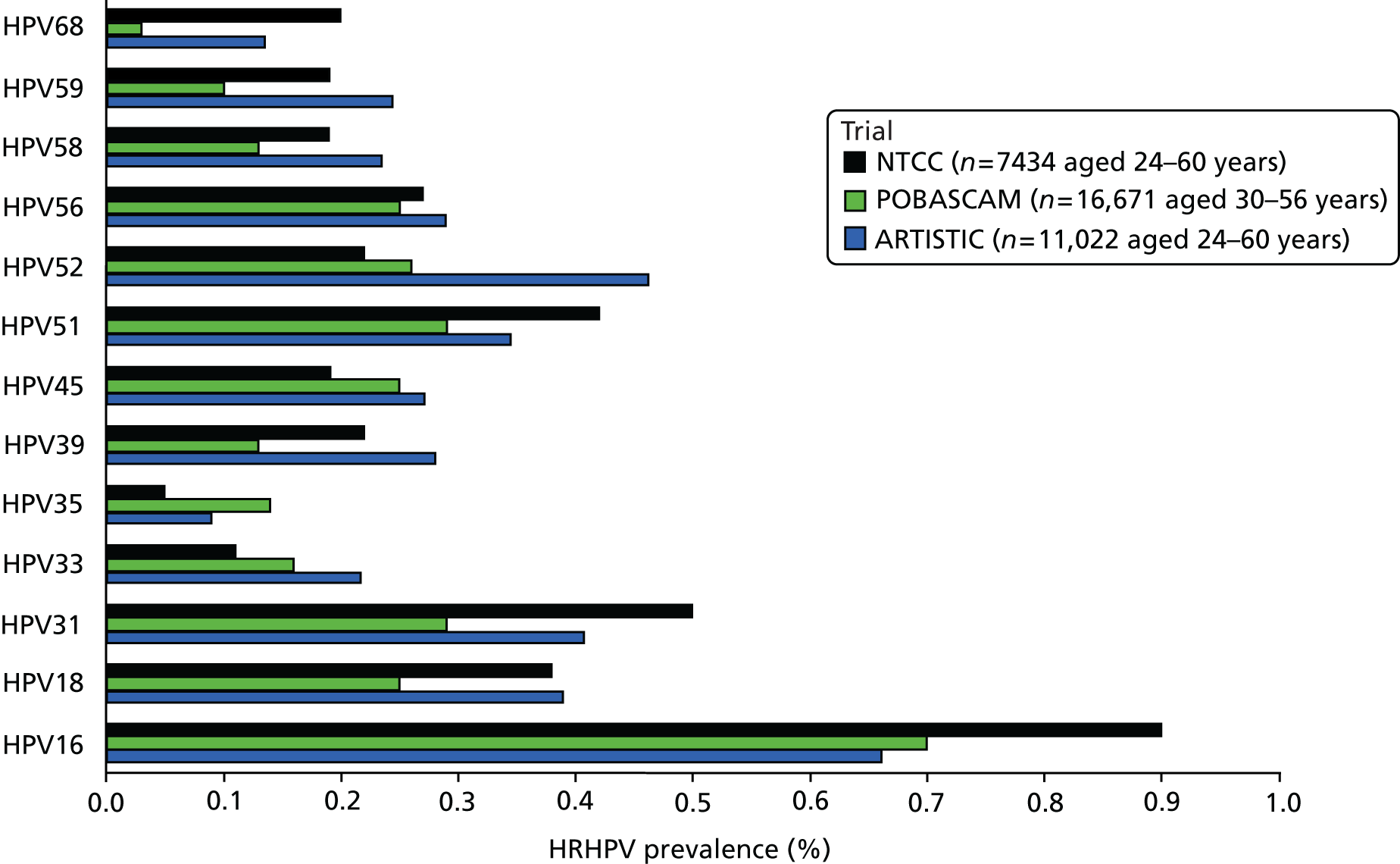

Natural history of human papillomavirus infection

Table 2 shows the prevalence of HPV infection at rounds 1 and 2 by age. HC2 was the primary assay used and only HC2+ samples were further genotyped. Overall, 4% of samples tested positive by HC2 but no HRHPV was detected. These have been assumed to be HRHPV– in the analysis shown in Table 3, which shows prevalence of HRHPV by age at round 2 among women who were HPV– at round 1, and prevalence rates of type-specific persistence and new infection among those who were HPV+ at round 1. The prevalence of new infection falls steeply with age in those women who were HPV– at round 1, from 19.7% at 20–24 years to 1.0% at 55–64 years. In contrast, among women who were HPV+ at round 1, the proportion with persistence at round 2 (17.9%) shows little or no age trend. Round 2 HPV prevalence in women who were HPV– at entry in ARTISTIC and in the POBASCAM (the Netherlands)14 and NTCC (Italy) trials14 are shown by age in Figure 2 and by HPV type in Figure 3, in which ARTISTIC data are restricted to the age range of the NTCC trial. The screening interval was 3 years in ARTISTIC and NTCC and 5 years in the POBASCAM trial. Figure 2 shows remarkably similar HRHPV rates in England, Italy and the Netherlands above the age of 33 years, but higher rates in ARTISTIC for younger women. Figure 3 shows the data by HPV genotype.

| Age (years) | Prevalence, n (%) | Total HRHPV+, n (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPV 16/18 | HPV 31/33/45/52/58 | Other HRHPV | No HRHPV detected (HC2+) | HC2– | ||

| Round 1 (entry) | ||||||

| 20–24 | 408 (15.7) | 254 (9.8) | 204 (7.9) | 167 (6.4) | 1560 (60.2) | 2593 (33.4) |

| 25–29 | 264 (10.2) | 200 (7.7) | 145 (5.6) | 106 (4.1) | 1874 (72.4) | 2589 (23.5) |

| 30–34 | 190 (5.2) | 200 (5.4) | 131 (3.6) | 164 (4.5) | 2998 (81.4) | 3683 (14.2) |

| 35–39 | 103 (2.6) | 104 (2.6) | 120 (3.1) | 150 (3.8) | 3462 (87.9) | 3939 (8.3) |

| 40–44 | 58 (1.7) | 56 (1.7) | 70 (2.1) | 128 (3.8) | 3069 (90.8) | 3381 (5.4) |

| 45–49 | 26 (1.0) | 42 (1.6) | 43 (1.6) | 110 (4.1) | 2496 (91.9) | 2717 (4.1) |

| 50–54 | 25 (1.1) | 29 (1.2) | 28 (1.2) | 90 (3.8) | 2210 (92.8) | 2382 (3.4) |

| 55–59 | 19 (1.0) | 10 (0.5) | 22 (1.1) | 67 (3.4) | 1853 (94.0) | 1971 (2.6) |

| 60–64 | 11 (0.9) | 7 (0.6) | 11 (0.9) | 47 (3.8) | 1165 (93.9) | 1241 (2.3) |

| Total | 1104 (4.5) | 902 (3.7) | 774 (3.2) | 1029 (4.2) | 20,687 (84.5) | 24,496 (11.4) |

| Round 2 (30–48 months) | ||||||

| 20–24 | 36 (9.4) | 37 (9.6) | 22 (5.7) | 29 (7.6) | 260 (67.7) | 384 (24.7) |

| 25–29 | 73 (8.1) | 57 (6.3) | 33 (3.7) | 69 (7.6) | 673 (74.4) | 905 (18.0) |

| 30–34 | 66 (4.7) | 45 (3.2) | 30 (2.2) | 65 (4.7) | 1187 (85.2) | 1393 (10.1) |

| 35–39 | 25 (1.3) | 51 (2.5) | 40 (2.0) | 73 (3.6) | 1819 (90.6) | 2008 (5.8) |

| 40–44 | 14 (0.6) | 39 (1.7) | 19 (0.8) | 72 (3.2) | 2129 (93.7) | 2273 (3.2) |

| 45–49 | 19 (1.0) | 23 (1.2) | 11 (0.6) | 48 (2.5) | 1846 (94.8) | 1947 (2.7) |

| 50–54 | 8 (0.5) | 14 (0.8) | 13 (0.8) | 48 (2.9) | 1574 (95.0) | 1657 (2.1) |

| 55–59 | 9 (0.6) | 6 (0.4) | 8 (0.5) | 32 (2.1) | 1464 (96.4) | 1519 (1.5) |

| 60–64 | 6 (0.6) | 5 (0.5) | 7 (0.6) | 29 (2.6) | 1053 (95.7) | 1100 (1.6) |

| 65–69 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.7) | 8 (2.0) | 394 (97.3) | 405 (0.7) |

| Total | 256 (1.9) | 277 (2.0) | 186 (1.4) | 473 (3.5) | 12,399 (91.2) | 13,591 (5.3) |

| Age (years) at round 2 | Infection status at entry | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HRHPV– | HRHPV+ | ||||

| Number of women | New HRHPV at round 2, n (%) | Number of women | New HRHPV at round 2, n (%) | Persisting HRHPV type at round 2, n (%) | |

| 20–24 | 239 | 47 (19.7) | 145 | 20 (13.8) | 28 (19.3) |

| 25–29 | 648 | 77 (11.9) | 257 | 37 (14.4) | 49 (19.1) |

| 30–34 | 1119 | 60 (5.4) | 274 | 21 (7.7) | 60 (21.9) |

| 35–39 | 1814 | 68 (3.8) | 194 | 16 (8.2) | 32 (16.5) |

| 40–44 | 2138 | 48 (2.3) | 135 | 7 (5.2) | 17 (12.6) |

| 45–49 | 1869 | 37 (2.0) | 78 | 8 (10.3) | 8 (10.3) |

| 50–54 | 1602 | 24 (1.5) | 55 | 0 (0.0) | 11 (20.0) |

| 55–59 | 1482 | 14 (0.9) | 37 | 3 (8.1) | 6 (16.2) |

| 60–64 | 1079 | 12 (1.1) | 21 | 3 (14.3) | 3 (14.3) |

| 65–69 | 396 | 1 (0.3) | 9 | 0 (0) | 2 (22.2) |

| All women | 12,386 | 388 (3.1) | 1205 | 115 (9.5) | 216 (17.9) |

FIGURE 2.

New infections: prevalence of HRHPV at round 2 in the ARTISTIC, NTCC (Italy) and POBASCAM (the Netherlands) trials in women who were HRHPV– at entry.

FIGURE 3.

New infections: prevalence (%) at round 2 of each HRHPV type in the ARTISTIC, NTCC and POBASCAM trials in women who were HRHPV– at entry.

The proportion of HPV infections clearing increased by time interval to testing (Table 4). Clearance of new HPV infections (i.e. infections that had developed in the preceding screening interval) was higher than persisting HPV infections (i.e. those that were present at the previous screening round). Clearance of HPV 16 infection was lower than other infections and approximately 40% of new HPV 16 infections were still persisting in women tested over 3 years.

| Infections | Proportion of infections clearing by time to next HPV test, n/N (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 1 year | 1–2 years | 2–3 years | ≥ 3 years | |

| New HPV 16 infections | 20/51 (39.2) | 18/26 (69.2) | 7/13 (53.9) | 7/12 (58.3) |

| Other new infections | 142/249 (57.0) | 107/144 (74.3) | 53/65 (81.5) | 66/74 (89.2) |

| All new infectionsa | 162/300 (54.0) | 125/170 (73.5) | 60/78 (76.9) | 73/86 (84.9) |

| HPV 16: present at entry | 20/94 (21.3) | 12/22 (54.6) | 9/21 (42.9) | 7/12 (58.3) |

| Other infections: present at entry | 91/243 (37.5) | 52/104 (50.0) | 44/65 (67.7) | 36/48 (75.0) |

| All infections present at entryb | 111/337 (32.9) | 64/126 (50.8) | 53/86 (61.6) | 43/60 (71.7) |

Short-term recurrence was assessed among 405 women who were HRHPV+ at entry and who tested HC2– less than 2 years after entry (Table 5). Of these, 27 (6.7%) women had a recurrent infection of the same HPV type present at entry. Long-term recurrence was assessed among 415 women who were HRHPV+ at entry and tested HC2– at least 2 years later. Of these, only five (1.2%) women had a later recurrence or reinfection of the HPV type present at entry.

| Recurrence | Months from HC2– test to next HPV test | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 6 | 12 | 24 | 36 | ≥ 48 | |

| Short-term recurrence (following a HC2– test < 24 months after entry) | ||||||

| Number of women | 26 | 81 | 122 | 118 | 29 | 29 |

| Cumulative number of women | 26 | 107 | 229 | 347 | 376 | 405 |

| Cumulative recurrent infections (%) | 2 (7.69) | 7 (6.54) | 14 (6.11) | 21 (6.05) | 22 (5.85) | 27 (6.67) |

| Long-term recurrence (following a HC2– test 24–54 months after entry) | ||||||

| Number of women | 11 | 54 | 81 | 77 | 175 | 17 |

| Cumulative number of women | 11 | 65 | 146 | 223 | 398 | 415 |

| Cumulative recurrent infections (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.68) | 1 (0.45) | 5 (1.26) | 5 (1.20) |

Comparison with data from the UK primary human papillomavirus screening pilot

A UK pilot study is trialling primary HPV screening in six sites in England. Women who are HPV+ and have borderline or worse cytology are referred to colposcopy and those with negative cytology are recalled after 12 months for repeat HPV testing and cytology. 15 An immediate effect of introducing primary HPV testing is diagnosis of prevalent CIN3+ which had been missed by previous cytology. This was seen in ARTISTIC,10 the NTCC trial16 and in a German study,17 and a much lower CIN3 rate than at entry will presumably be seen in later screening rounds in the UK pilot study. 15 Table 6 shows that the prevalence of moderate/severe cytology among HPV+ women in ARTISTIC was similar at each age in round 1 of ARTISTIC and in the pilot study, but in round 2 it was about three times lower and referral rates were halved. This reflects prevalent disease that had been missed by previous cytology but was reliably detected by HPV testing. When primary HPV testing has been rolled out nationally it may be safe to introduce a longer recall interval for HPV+ women with borderline/mild cytology in round 2 whose previous HPV test was negative.

| Age (years) at test | HPV+,a n (%) | Cytology result among HPV+ women, n (%) | Referral rate,b % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | Borderline/mild | Moderate+ | |||

| Pilot sites | |||||

| 25–29 | 8231 (28.3) | 5108 (62.1) | 2019 (24.5) | 1104 (13.4) | 11.0 |

| 30–39 | 6127 (13.6) | 4170 (68.1) | 1330 (21.7) | 627 (10.2) | 4.5 |

| 40–49 | 4024 (8.0) | 2951 (73.3) | 822 (20.4) | 251 (6.2) | 2.2 |

| 50–59 | 1937 (6.0) | 1453 (75.0) | 365 (18.8) | 119 (6.1) | 1.5 |

| 60–64 | 333 (4.7) | 273 (82.0) | 42 (12.6) | 18 (5.4) | 0.9 |

| All women | 20,652 (12.6) | 13,955 (67.6) | 4578 (22.2) | 2119 (10.3) | 4.2 |

| Round 1 ARTISTIC | |||||

| 25–29 | 716 (27.7) | 374 (52.2) | 245 (34.4) | 96 (13.4) | 13.2 |

| 30–39 | 1161 (15.2) | 679 (58.5) | 339 (29.1) | 144 (12.4) | 6.3 |

| 40–49 | 533 (8.7) | 343 (64.4) | 137 (25.7) | 53 (9.9) | 3.1 |

| 50–59 | 290 (6.7) | 238 (82.1) | 40 (13.8) | 12 (4.1) | 1.2 |

| 60–64 | 76 (6.1) | 68 (89.5) | 3 (3.9) | 5 (6.6) | 0.6 |

| All women | 2776 (12.7) | 1702 (61.3) | 764 (27.5) | 310 (11.2) | 4.9 |

| Round 2 ARTISTIC | |||||

| 25–29 | 230 (25.6) | 160 (69.6) | 63 (27.4) | 7 (3.0) | 7.8 |

| 30–39 | 393 (11.6) | 267 (67.9) | 107 (27.2) | 19 (4.8) | 3.7 |

| 40–49 | 239 (5.7) | 193 (80.8) | 40 (16.7) | 6 (2.5) | 1.1 |

| 50–59 | 137 (4.3) | 113 (82.5) | 23 (16.8) | 1 (0.7) | 0.8 |

| 60–64 | 46 (4.2) | 43 (93.5) | 3 (6.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0.3 |

| All women | 1045 (8.2) | 776 (74.3) | 236 (22.6) | 33 (3.2) | 2.1 |

Invasive cervical cancer

Table 7 shows the 23 invasive cancers identified within the cohort between 2001 and 2015 by HPV result and cytology at entry. The six HC2– samples were further tested using PCR-based assays and five were found to contain HRHPV deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) (HPV 16 in four women, HPV 51 in one woman). Low levels of HPV 52 DNA were detected in a later sample (3 years after entry but 3 years before cancer registration) taken from the sixth woman. The 10 prevalent cancers diagnosed within 7 months of entry were all PCR+ with moderate or worse cytology, and nine were HC2+. Test positivity at entry for the remaining 13 women whose cancers were diagnosed between 4 and 13 years later was 15% (2/13) for cytology, 62% (8/13) for HC2 and 92% (12/13) for PCR. Table 8 shows that cancer is almost as common as CIN3 in those women aged ≥ 55 years, indicating the need to focus on sensitivity for cancer as well as CIN3 detection in a woman’s final (exit) screen. With up to 14 years of follow-up since trial entry in 2001–3, there have so far been no cervical cancer deaths in the cohort.

| Time from entry to cancer registration | Cytology | HC2+ | HC2– | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal n (%) | Abnormal n (%) | PCR+ n (%) | PCR– n (%) | PCR+ n (%) | PCR– n (%) | ||

| 0–7 months | 0 | 10 (0.3) | 9a (0.3) | 0 | 1 (0.6) | 0 | 10 |

| 8–47 months | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4–13 years | 11 (0.05) | 2 (0.06) | 8 (0.3) | 0 | 4 (2.5) | 1b (0.005) | 13 |

| Number of women | 21,369 | 3127 | 2780 | 1029 | 157c | 20,530 | 24,496 |

| Age at registration (years) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20–29 | 30–39 | 40–49 | 50–59 | 60–69 | |

| ARTISTIC | |||||

| Cervical cancer | 0 | 7 | 10 | 4 | 2 |

| CIN3 | 158 | 163 | 55 | 10 | 2 |

| CIN3-to-cancer ratio | ∞ | 23.3 | 5.5 | 2.5 | 1.0 |

| England | |||||

| Cervical cancer | 483 | 643 | 521 | 330 | 230 |

| CIN3 | 14,458 | 7752 | 2692 | 848 | 206 |

| CIN3-to-cancer ratio | 29.9 | 12.1 | 5.2 | 2.6 | 0.9 |

Section 2: the long-term protection of a negative human papillomavirus test and, hence, the safe screening interval at different ages

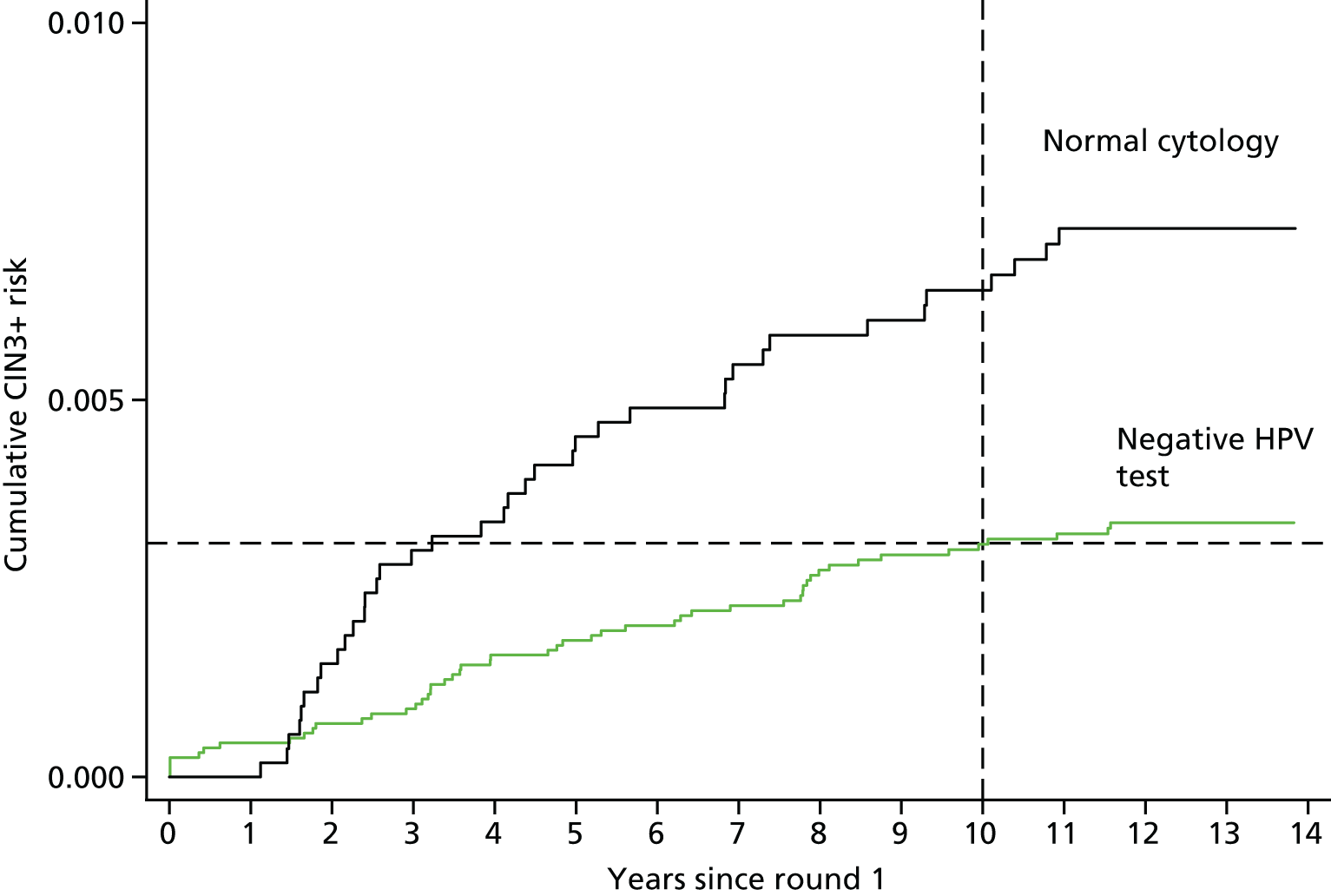

Table 9 shows cumulative CIN3+ risks in women testing HC2– at rounds 1 and 2 by age. The 10-year risks decrease from 1.10% [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.69% to 1.77%] in women aged 20 –25 years at entry to 0.08% (95% CI 0.03% to 0.20%) in women aged ≥ 50 years at entry. The 10-year CIN3+ risk in all HPV– women aged 25–39 years was 0.40% (95% CI 0.28% to 0.56%) and significantly higher than the risk in women aged ≥ 40 years at entry (0.11%, 95% CI 0.06% to 0.20%; p < 0.0001). Table 10 shows cumulative risks from round 2 in those HC2– at both time points compared with those women who had cleared an infection present at entry. Risks were based on very small numbers, but were approximately three times higher among those women who cleared an infection at entry. Presumably this is confounded with sexual activity and, hence, risk of acquiring a new HPV infection. Figure 4 and the bottom panel of Table 9 show a similar CIN3+ risk 10 years after a negative HPV test (0.31%, 95% CI 0.18% to 0.49% in the revealed arm) and 3 years after a negative cytology test (0.30%, 95% CI 0.23% to 0.41% in the concealed arm). These data support a much longer screening interval after a negative HPV test than after a negative cytology test.

| Women who were HC2– at round 1 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) at round 1 | Number (%) of women at baseline | Number of CIN3+ womena | Risk from round 1 | |||||

| 2.5-year | 5-year | 10-year | ||||||

| Number of CIN3+ women (%) | 95% CI | Number of CIN3+ women (%) | 95% CI | Number of CIN3+ women (%) | 95% CI | |||

| 20–24 | 1563 | 19 | 3 | 0.19 (0.06 to 0.59) | 6 | 0.39 (0.17 to 0.86) | 17 | 1.10 (0.69 to 1.77) |

| 25–29 | 1870 | 16 | 5 | 0.27 (0.11 to 0.64) | 8 | 0.43 (0.22 to 0.86) | 14 | 0.76 (0.45 to 1.28) |

| 30–39 | 6466 | 20 | 7 | 0.11 (0.05 to 0.23) | 12 | 0.19 (0.11 to 0.33) | 19 | 0.30 (0.19 to 0.46) |

| 40–49 | 5562 | 9 | 4 | 0.07 (0.03 to 0.19) | 7 | 0.13 (0.06 to 0.26) | 8 | 0.14 (0.07 to 0.29) |

| 50–64 | 5226 | 4 | 2 | 0.04 (0.01 to 0.15) | 4 | 0.08 (0.03 to 0.20) | 4 | 0.08 (0.03 to 0.20) |

| All women (HC2–) | 20,687 (84.5) | 68 | 21 | 0.10 (0.07 to 0.16) | 37 | 0.18 (0.13 to 0.25) | 62 | 0.31 (0.24 to 0.39) |

| Women who were HC2– at round 2 | ||||||||

| Age (years) at round 2 | Number (%) of women at round 2 | Number of CIN3+ women | Risk from round 1 | |||||

| 2.5-year | 5-year | 10-year | ||||||

| Number of CIN3+ women (%) | 95% CI | Number of CIN3+ women (%) | 95% CI | Number of CIN3+ women (%) | 95% CI | |||

| 23–24 | 304 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.33 (0.05 to 2.35) | 1 | 0.33 (0.05 to 2.35) | |

| 25–29 | 701 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 30–39 | 3131 | 9 | 4 | 0.13 (0.05 to 0.34) | 5 | 0.16 (0.07 to 0.38) | 9 | 0.29 (0.15 to 0.56) |

| 40–49 | 3949 | 2 | 1 | 0.03 (0.00 to 0.18) | 1 | 0.03 (0.00 to 0.18) | 2 | 0.05 (0.01 to 0.20) |

| 50–68 | 4314 | 1 | 1 | 0.02 (0.00 to 0.16) | 1 | 0.02 (0.00 to 0.16) | 1 | 0.02 (0.00 to 0.16) |

| All women (HC2–) | 12,399 (91.2) | 13 | 6 | 0.05 (0.02 to 0.11) | 8 | 0.07 (0.03 to 0.13) | 13 | 0.11 (0.06 to 0.2) |

| Women who were cytology negative at round 1 (concealed arm only) | ||||||||

| Age (years) at round 1 | Number (%) of women at baseline | Number of CIN3+ womena | Risk from round 1 | |||||

| 2.5-year | 5-year | 10-year | ||||||

| Number of CIN3+ women (%) | 95% CI | Number of CIN3+ women (%) | 95% CI | Number of CIN3+ women (%) | 95% CI | |||

| 20–24 | 489 | 11 | 4 | 0.82 (0.31 to 2.17) | 9 | 1.85 (0.97 to 3.53) | 11 | 2.27 (1.26 to 4.06) |

| 25–29 | 523 | 9 | 2 | 0.38 (0.10 to 1.52) | 4 | 0.77 (0.29 to 2.03) | 8 | 1.55 (0.78 to 3.08) |

| 30–39 | 1642 | 13 | 6 | 0.37 (0.16 to 0.81) | 8 | 0.49 (0.25 to 0.98) | 11 | 0.68 (0.37 to 1.22) |

| 40–49 | 1340 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0.07 (0.01 to 0.53) | 2 | 0.15 (0.04 to 0.60) | |

| 50–64 | 1341 | 2 | 1 | 0.07 (0.01 to 0.53) | 2 | 0.15 (0.04 to 0.60) | 2 | 0.15 (0.04 to 0.60) |

| All women (cytology negative) | 5335 | 38 | 13 | 0.24 (0.14 to 0.42) | 24 | 0.45 (0.30 to 0.67) | 34 | 0.65 (0.46 to 0.90) |

| HPV status at rounds 1 and 2 | Number of women at round 2 | Number of CIN3+ women | Risk from round 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.5-year | 5-year | 10-year | ||||||

| Number of CIN3+ women (%) | 95% CI | Number of CIN3+ women (%) | 95% CI | Number of CIN3+ women (%) | 95% CI | |||

| HC2 results (aged 20–64 years at entry) | ||||||||

| HC2 double positive | 510 | 54 | 45 | 8.8 (6.7 to 11.6) | 49 | 9.6 (7.4 to 12.5) | 54 | 10.6 (8.2 to 13.6) |

| HC2 negative positive | 682 | 15 | 12 | 1.8 (1.0 to 3.1) | 14 | 2.1 (1.2 to 3.5) | 15 | 2.2 (1.3 to 3.6) |

| HC2 positive negative | 1249 | 3 | 1 | 0.08 (0.01 to 0.57) | 2 | 0.16 (0.04 to 0.65) | 3 | 0.25 (0.08 to 0.76) |

| HC2 double negative | 11,150 | 10 | 5 | 0.04 (0.02 to 0.11) | 6 | 0.05 (0.02 to 0.112) | 10 | 0.09 (0.05 to 0.17) |

| Aged 25–39 years at entry | ||||||||

| HC2 positive negative | 615 | 3 | 1 | 0.16 (0.02 to 1.15) | 2 | 0.33 (0.08 to 1.30) | 3 | 0.49 (0.16 to 1.52) |

| HC2 double negative | 4019 | 6 | 3 | 0.07 (0.02 to 0.23) | 3 | 0.07 (0.02 to 0.23) | 6 | 0.15 (0.07 to 0.33) |

| Aged 40–64 years at entry | ||||||||

| HC2 positive negative | 410 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| HC2 double negative | 6673 | 3 | 2 | 0.03 (0.01 to 0.12) | 2 | 0.03 (0.01 to 0.12) | 3 | 0.05 (0.02 to 0.15) |

FIGURE 4.

Cumulative CIN3+ risk (%) following a negative HPV test or normal cytology at entry.

Section 3: the role of human papillomavirus typing

The increasing availability of partial genotyping allows risk-based stratification in an organised screening programme. Four of the six sites are utilising partial typing HPV tests (Roche COBAS and Abbott Realtime assays) in the English pilot study, which both allow identification of HPV 16 and HPV 18 infections. Table 11 and Figure 5 show that the cumulative risk for women with HPV 16 is much higher than for any other genotype. Women with HPV 16 constituted 22% of all HC2+ infections, but 57% of CIN3+ occurred among this group of women, giving a 10-year cumulative CIN3+ risk of 29.8% (95% CI 26.8% to 33.0%). HPV 18 was a much less common type among ARTISTIC women, constituting 9% of all HC2+ infections (including 2% who also had HPV 16) and the 10-year cumulative risk did not differ from the group of types including 31, 33, 45, 52 and 58. It is clear that assays that could identify these five types in addition to HPV 16 and 18 would be beneficial for a risk-based referral strategy.

| Single HPV test at round 1 | Number (%) of women at baseline | Number of CIN3+ womena | Risk from round 1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.5-year | 5-year | 10-year | ||||||

| Number of CIN3+ women (%) | 95% CI | Number of CIN3+ women (%) | 95% CI | Number of CIN3+ women (%) | 95% CI | |||

| HPV 16 | 831 (3.4) | 249 | 219 | 26.4 (23.5 to 29.5) | 238 | 28.7 (25.7 to 31.9) | 247 | 29.8 (26.8 to 33.0) |

| HPV 18 | 273 (1.1) | 36 | 23 | 8.4 (5.7 to 12.4) | 32 | 11.7 (8.4 to 16.2) | 36 | 13.2 (9.7 to 17.9) |

| HPV 31/33/45/52/58 | 902 (3.7) | 104 | 75 | 8.3 (6.7 to 10.3) | 89 | 9.9 (8.1 to 12.0) | 101 | 11.3 (9.4 to 13.5) |

| Other HRHPV | 774 (3.2) | 30 | 20 | 2.6 (1.7 to 4.0) | 26 | 3.4 (2.3 to 4.9) | 29 | 3.8 (2.6 to 5.4) |

| HC2+ non-high riskb | 1029 (4.2) | 18 | 8 | 0.8 (0.4 to 1.6) | 13 | 1.3 (0.7 to 2.2) | 18 | 1.8 (1.1 to 2.8) |

| All HC2+ | 3809 (15.5) | 437 | 345 | 9.1 (8.2 to 10.0) | 398 | 10.5 (9.5 to 11.5) | 431 | 11.4 (10.4 to 12.4) |

| HC2– | 20,687 (84.5) | 68 | 21 | 0.10 (0.07 to 0.16) | 37 | 0.18 (0.13 to 0.25) | 62 | 0.31 (0.24 to 0.39) |

| Total women | 24,496 (100) | 505 | 366 | 435 | 493 | |||

FIGURE 5.

Cumulative CIN3+ risks by HPV detection from entry (483 CIN3, 23 invasive cervical cancers in 24,500 women).

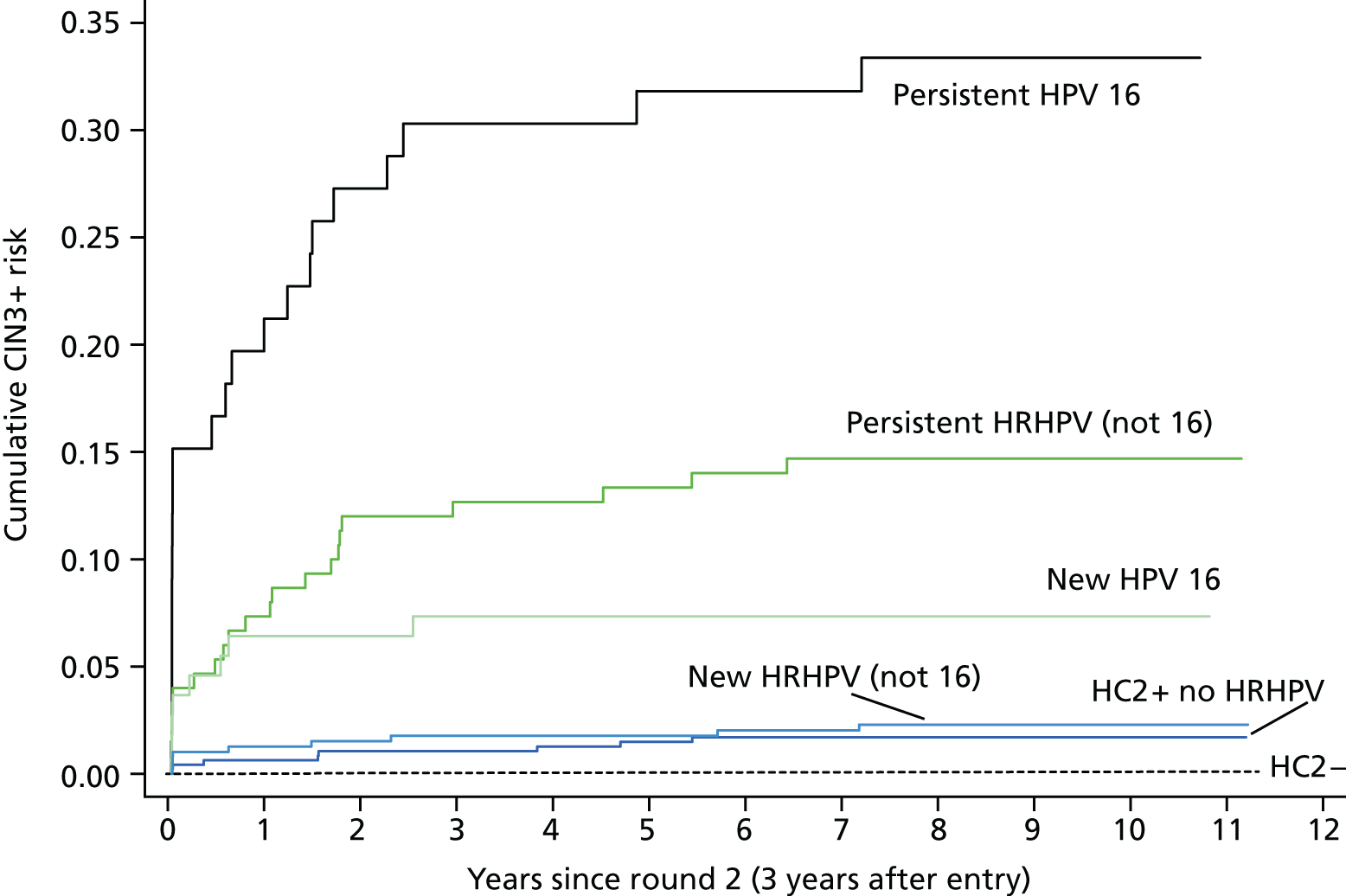

Table 12 and Figure 6 show the risks following two tests approximately 3 years apart. The 10-year cumulative CIN3+ risk following a new HPV infection is low at 3.4% (95% CI 2.1% to 5.4%). The 10-year CIN3 risk from round 2 was no higher in those women who were HPV+ with another type at round 1 (2.7%, 95% CI 0.9% to 8.0%) than in those women who were HPV– at round 1 (3.6%, 95% CI 2.2% to 6.0%).

| HPV status at round 2 | Number of women at round 2 | n CIN3+ | Risk from round 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.5-year | 5-year | 10-year | ||||||

| n CIN3+ (%) | 95% CI | n CIN3+ (%) | 95% CI | n CIN3+ (%) | 95% CI | |||

| Women with type-specific persistence | ||||||||

| Persistent HPV 16 | 66 | 22 | 20 | 30.3 (20.7 to 42.9) | 21 | 31.8 (22.1 to 44.5) | 22 | 33.4 (23.4 to 46.1) |

| Persistent HPV 18 | 23 | 3 | 3 | 13.0 (4.4 to 35.2) | 3 | 13.0 (4.4 to 35.2) | 3 | 13.0 (4.4 to 35.2) |

| Persistent 31/33/45/52/58 | 83 | 15 | 12 | 14.5 (8.5 to 24.1) | 13 | 15.7 (9.4 to 25.4) | 15 | 18.1 (11.3 to 28.2) |

| Persistent other HRHPV | 44 | 4 | 3 | 6.8 (2.3 to 19.7) | 4 | 9.1 (3.5 to 22.4) | 4 | 9.1 (3.5 to 22.4) |

| Any HRHPV type specific persistence | 216 | 44 | 38 | 17.6 (13.1 to 23.4) | 41 | 19.0 (14.4 to 24.9) | 44 | 20.4 (15.6 to 26.4) |

| Women without type-specific persistence | ||||||||

| New HPV 16 | 109 | 8 | 7 | 6.4 (3.1 to 13.0) | 8 | 7.3 (3.7 to 14.1) | 8 | 7.3 (3.7 to 14.1) |

| New HPV 18 | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| New 31/33/45/52/58 | 193 | 8 | 7 | 3.6 (1.8 to 7.5) | 7 | 3.6 (1.8 to 7.5) | 8 | 4.2 (2.1 to 8.1) |

| New other HRHPV | 151 | 1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.7 (0.1 to 4.8) |

| Any new HRHPV | 503a | 17 | 14 | 2.8 (1.7 to 4.7) | 15 | 3.0 (1.8 to 4.9) | 17 | 3.4 (2.1 to 5.4) |

| HC2+ but no HRHPV | 473 | 8 | 5 | 1.1 (0.4 to 2.5) | 7 | 1.5 (0.7 to 3.1) | 8 | 1.7 (0.9 to 3.4) |

| HC2– | 12,399 | 13 | 6 | 0.05 (0.02 to 0.11) | 8 | 0.07 (0.03 to 0.13) | 13 | 0.11 (0.06 to 0.19) |

| HC2 results ignoring genotyping | ||||||||

| HC2 double positive | 510 | 54 | 45 | 8.8 (6.7 to 11.6) | 49 | 9.6 (7.4 to 12.5) | 54 | 10.6 (8.2 to 13.6) |

| HC2 negative positive | 682 | 15 | 12 | 1.8 (1.0 to 3.1) | 14 | 2.1 (1.2 to 3.5) | 15 | 2.2 (1.3 to 3.6) |

| HC2 positive negative | 1249 | 3 | 1 | 0.08 (0.01 to 0.57) | 2 | 0.16 (0.04 to 0.65) | 3 | 0.25 (0.08 to 0.76) |

| HC2 double negative | 11,150 | 10 | 5 | 0.04 (0.02 to 0.11) | 6 | 0.05 (0.02 to 0.112) | 10 | 0.09 (0.05 to 0.17) |

| All women | 13,591 | 82 | 63 | 71 | 82 | |||

FIGURE 6.

Cumulative CIN3+ risks following round 2 for persistent and newly acquired HPV infection (82 CIN3+ in 13,591 women).

The highest risks were associated with type-specific persistent infections that, overall, conferred a 10-year cumulative risk of 20.4% (95% CI 15.65% to 26.45%). HPV 16 again showed the highest risks and the 10-year risk following a new infection reached 7.3% (95% CI 3.7% to 14.1%), suggesting that any women with HPV 16 detected could be referred immediately. Of the 331 women with double-positive HRHPV tests (see Table 3), 115 (35%) were positive with a new HPV type at the second test and 216 (65%) was type-specific persistent. The proportion of new infections was highest in younger women (43% in women in their 20s) and decreased to just 23% of double-positive infections in women aged ≥ 50 years.

Section 4: triage of human papillomavirus-positive women, particularly the interval to retesting for human papillomavirus-positive women

Table 13 shows cumulative CIN3+ risks by HPV type and cytology at entry. Referring moderate or worse cytology to immediate colposcopy is clearly a highly effective strategy for identifying those women at highest risk of disease (52% by 5 years). Among HC2+ women, the 10-year cumulative CIN3+ risks in those with negative and borderline/mild cytology were estimated to be 4.1% (95% CI 3.3% to 5.0%) and 10.3% (95% CI 8.7% to 12.2%), respectively. These risks vary by HPV genotype, and, hence, a partial genotyping assay could identify those at highest risk (e.g. HPV 16 or 18). Table 14 is restricted to the 1116 women who were HC2+ and cytology negative and had a follow-up sample taken 30–48 months later (round 2). The current UK protocol for HC2+ cytology-negative women is to repeat HPV and cytology testing at 12 and 24 months and refer all those still HPV+ at 24 months. Table 14 shows these women under a protocol of repeat testing after a 3-year recall interval. This excludes 10 CIN3+ that were diagnosed in cytology-negative HPV+ women in the revealed arm who were diagnosed before the round 2 test, but under a 3-year recall protocol would probably have been diagnosed at round 2. Analysis restricted to the concealed arm would avoid this bias. Only 277 out of the 1120 women in Table 14 were in the concealed arm and the results were consistent between the arms; therefore, they were pooled to maximise numbers. The majority of women cleared their infection by round 2, with 72% testing HC2– and a further 7% who remained HC2+ in whom no HRHPV was detected. A small proportion (1.3%) of women developed moderate or worse cytology by round 2, most (9 out of 15) of whom had CIN3+ immediately diagnosed. Out of 220 women who remained HPV+ with normal, borderline or mild cytology, 38% were infected with a new HPV type and 62% were type-specific persistent. Among the new infections, the 10-year cumulative CIN3+ risk remained low (3.7%, 95% CI 1.2% to 11.0%). The risks were slightly higher for those women with borderline or mild cytology, but there was insufficient power to detect a significant difference. Further genotyping of these samples to determine type-specific persistence would refer only those women at highest risk of developing CIN3+ to colposcopy.

| Negative cytology at round 1 | Number (%) of women at baseline | Number of CIN3+ womena | Risk from round 1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.5-year | 5-year | 10-year | ||||||

| Number of CIN3+ women (%) | 95% CI | Number of CIN3+ women (%) | 95% CI | Number of CIN3+ women (%) | 95% CI | |||

| HPV 16 | 332 (1.6) | 41 | 22 | 6.6 (4.4 to 9.9) | 36 | 10.9 (8.0 to 14.7) | 41 | 12.4 (9.3 to 16.5) |

| HPV 18 | 146 (0.7) | 10 | 1 | 0.7 (0.1 to 4.8) | 6 | 4.1 (1.9 to 8.9) | 10 | 6.9 (3.8 to 12.4) |

| HPV 31/33/45/52/58 | 482 (2.3) | 25 | 6 | 1.3 (0.6 to 2.8) | 14 | 2.9 (1.7 to 4.9) | 22 | 4.6 (3.1 to 7.0) |

| Other HRHPV | 479 (2.2) | 9 | 3 | 0.6 (0.2 to 1.9) | 7 | 1.5 (0.7 to 3.1) | 8 | 1.7 (0.8 to 3.3) |

| HC2+ non-high riskb | 784 (3.7) | 9 | 1 | 0.1 (0.02 to 0.90) | 5 | 0.6 (0.3 to 1.5) | 9 | 1.2 (0.6 to 2.2) |

| All HC2+ | 2223 (10.4) | 94 | 33 | 1.5 (1.1 to 2.1) | 68 | 3.1 (2.4 to 3.9) | 90 | 4.1 (3.3 to 5.0) |

| HC2– | 19,146 (89.6) | 53 | 11 | 0.06 (0.03 to 0.10) | 25 | 0.13 (0.09 to 0.19) | 48 | 0.26 (0.19 to 0.34) |

| All women with negative cytology | 21,369 (100) | 147 | 44 | 93 | 138 | |||

| Borderline/mild cytology at round 1 | Number (%) of women at baseline | Number of CIN3+ womena | Risk from round 1 | |||||

| 2.5-year | 5-year | 10-year | ||||||

| Number of CIN3+ women (%) | 95% CI | Number of CIN3+ women (%) | 95% CI | Number of CIN3+ women (%) | 95% CI | |||

| HPV 16 | 283 (10.6) | 65 | 54 | 19.1 (15.0 to 24.0) | 59 | 20.9 (16.6 to 26.1) | 63 | 22.3 (17.9 to 27.6) |

| HPV 18 | 93 (3.5) | 10 | 7 | 7.5 (3.7 to 15.1) | 10 | 10.8 (5.9 to 19.1) | 10 | 10.8 (6.0 to 19.1) |

| HPV 31/33/45/52/58 | 309 (11.6) | 31 | 24 | 7.8 (5.3 to 11.4) | 29 | 9.4 (6.6 to 13.2) | 31 | 10.1 (7.2 to 14.0) |

| Other HRHPV | 259 (9.7) | 10 | 7 | 2.7 (1.3 to 5.6) | 9 | 3.5 (1.8 to 6.6) | 10 | 3.9 (2.1 to 7.1) |

| HC2+ non-high riskb | 226 (8.5) | 6 | 4 | 1.8 (0.7 to 4.7) | 5 | 2.2 (0.1 to 5.2) | 6 | 2.7 (1.2 to 5.8) |

| All HC2+ | 1170 (43.9) | 122 | 96 | 8.2 (6.8 to 9.9) | 112 | 9.6 (8.0 to 11.4) | 120 | 10.3 (8.7 to 12.2) |

| HC2– | 1495 (56.1) | 10 | 6 | 0.4 (0.2 to 0.9) | 7 | 0.5 (0.2 to 1.0) | 9 | 0.6 (0.3 to 1.2) |

| All women with borderline/mild cytology | 2665 (100) | 132 | 102 | 119 | 129 | |||

| Moderate/severe cytology at round 1 | Number (%) of women at baseline | Number of CIN3+ womena | Risk from round 1 | |||||

| 2.5-year | 5-year | 10-year | ||||||

| Number of CIN3+ women (%) | 95% CI | Number of CIN3+ women (%) | 95% CI | Number of CIN3+ women (%) | 95% CI | |||

| HPV 16 | 216 (46.8) | 143 | 143 | 66.2 (59.9 to 72.4) | 143 | 66.2 (59.9 to 72.4) | 143 | 66.2 (59.9 to 72.4) |

| HPV 18 | 34 (7.4) | 16 | 15 | 44.1 (29.4 to 62.2) | 16 | 47.1 (32.1 to 64.9) | 16 | 47.1 (32.1 to 64.9) |

| HPV 31/33/45/52/58 | 111 (24.0) | 48 | 45 | 40.5 (32.1 to 58.3) | 46 | 41.4 (32.9 to 51.2) | 48 | 43.2 (34.6 to 53.0) |

| Other HRHPV | 36 (7.8) | 11 | 10 | 27.8 (16.0 to 45.5) | 10 | 27.8 (16.0 to 45.5) | 11 | 30.8 (18.4 to 48.7) |

| HC2+ non-high riskb | 19 (4.1) | 3 | 3 | 15.8 (5.4 to 41.4) | 3 | 15.8 (5.4 to 41.4) | 3 | 15.8 (5.4 to 41.4) |

| All HC2+ | 416 (90.0) | 221 | 216 | 51.9 (47.2 to 56.8) | 218 | 52.4 (47.7 to 57.3) | 221 | 53.2 (48.4 to 58.0) |

| HC2– | 46 (10.0) | 5 | 4 | 8.7 (3.4 to 21.5) | 5 | 10.9 (4.7 to 24.2) | 5 | 10.9 (4.7 to 24.2) |

| All women with moderate/severe cytology | 462 (100) | 226 | 220 | 223 | 226 | |||

| Women who were HC2+ and cytology negative entry | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPV status and cytology at round 2 | Number (%) of women at round 2 | Number of CIN3+ women | Risk from round 2 | |||||

| 2.5-year | 5-year | 10-year | ||||||

| Number of CIN3+ women (%) | 95% CI | Number of CIN3+ women (%) | 95% CI | Number of CIN3+ women (%) | 95% CI | |||

| HC2– | 806 (72.0) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.13 (0.02 to 0.90) | 2 | 0.26 (0.06 to 1.03) |

| HC2+ but no high risk detected | 79 (7.1) | 5 | 4 | 5.1 (1.9 to 12.9) | 5 | 6.3 (2.7 to 14.5) | 5 | 6.3 (2.7 to 14.5) |

| HRHPV+ normal cytology | 158 (14.1) | 14 | 9 | 5.7 (3.0 to 10.7) | 11 | 7.0 (3.9 to 12.2) | 14 | 8.9 (5.4 to 14.5) |

| Persistent HRHPV | 97 | 13 | 9 | 9.3 (4.9 to 17.1) | 11 | 11.3 (6.5 to 19.5) | 13 | 13.4 (8.0 to 22.0) |

| New HRHPV | 61 | 1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.7 (0.2 to 11.3) |

| HRHPV+ borderline/mild cytology | 62 (5.5) | 10 | 8 | 12.9 (6.7 to 24.2) | 9 | 14.5 (7.8 to 26.0) | 10 | 16.2 (9.0 to 28.0) |

| Persistent HRHPV | 40 | 8 | 7 | 17.5 (8.8 to 33.2) | 8 | 20.0 (10.5 to 36.0) | 8 | 20.0 (10.5 to 36.0) |

| New HRHPV | 22 | 2 | 1 | 4.6 (0.7 to 28.1) | 1 | 4.6 (0.7 to 28.1) | 2 | 9.1 (2.4 to 31.7) |

| HRHPV+ normal/borderline/mild cytology | 220 | 24 | ||||||

| Persistent HRHPV | 137 | 21 | 16 | 11.7 (7.3 to 18.4) | 19 | 13.9 (9.1 to 20.9) | 21 | 15.3 (10.3 to 22.6) |

| New HRHPV | 83 | 3 | 1 | 1.2 (0.2 to 8.3) | 1 | 1.2 (0.2 to 8.3) | 3 | 3.7 (1.2 to 11.0) |

| HRHPV+ moderate/severe cytology | 15 (1.3) | 9 | 9 | 60.0 (37.2 to 83.5) | 9 | 60.0 (37.2 to 83.5) | ||

| Totala | 1120 (100) | 40 | 30 | 34 | 40 | |||

Tables 15 and 16 show cumulative CIN3+ risks following new and persisting HPV infections at round 2 in women with negative and borderline/mild cytology, respectively. Similar patterns are seen, with the highest risks in women with persisting infections and in those with HPV 16 infections.

| HPV status at round 2 (negative cytology) | Number of women at round 2 | Number of CIN3+ women | Risk from round 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.5-year | 5-year | 10-year | ||||||

| Number of CIN3+ women (%) | 95% CI | Number of CIN3+ women (%) | 95% CI | Number of CIN3+ women (%) | 95% CI | |||

| Women with type-specific persistence | ||||||||

| Persistent HPV 16 | 41 | 9 | 7 | 17.1 (8.5 to 32.5) | 8 | 19.5 (10.3 to 35.3) | 9 | 22.0 (12.1 to 38.1) |

| Persistent HPV 18 | 13 | 1 | 1 | 7.7 (1.1 to 43.4) | 1 | 7.7 (1.1 to 43.4) | 1 | 7.7 (1.1 to 43.4) |

| Persistent 31/33/45/52/58 | 54 | 7 | 4 | 7.4 (2.9 to 18.5) | 5 | 9.3 (4.0 to 20.8) | 7 | 13.0 (6.4 to 25.3) |

| Persistent other HRHPV | 26 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Any HRHPV type specific persistence | 134 | 17 | 12 | 9.0 (5.2 to 15.2) | 14 | 10.5 (6.3 to 17.0) | 17 | 12.7 (8.1 to 19.7) |

| Women without type-specific persistence | ||||||||

| New HPV 16 | 61 | 2 | 1 | 1.6 (0.2 to 11.1) | 2 | 3.3 (0.8 to 12.5) | 2 | 3.3 (0.8 to 12.5) |

| New HPV 18 | 32 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| New 31/33/45/52/58 | 143 | 3 | 2 | 1.4 (0.4 to 5.5) | 2 | 1.4 (0.4 to 5.5) | 3 | 2.1 (0.7 to 6.4) |

| New other HRHPV | 114 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Any new HRHPV | 350a | 5 | 3 | 0.9 (0.3 to 2.6) | 4 | 1.1 (0.4 to 3.0) | 5 | 1.4 (0.6 to 3.4) |

| HC2+ but no HRHPV | 383 | 5 | 3 | 0.8 (0.3 to 2.4) | 4 | 1.1 (0.4 to 2.8) | 5 | 1.3 (0.6 to 3.2) |

| HC2– | 12,028 | 12 | 5 | 0.04 (0.02 to 0.10) | 7 | 0.06 (0.03 to 0.12) | 12 | 0.10 (0.06 to 0.18) |

| HC2 results ignoring genotyping | ||||||||

| HC2 double positive | 331 | 21 | 15 | 4.5 (2.8 to 7.4) | 17 | 5.1 (3.2 to 8.1) | 21 | 6.4 (4.2 to 9.6) |

| HC2 negative positive | 536 | 6 | 3 | 0.6 (0.2 to 1.7) | 5 | 0.9 (0.4 to 2.2) | 6 | 1.1 (0.5 to 2.5) |

| HC2 positive negative | 1166 | 2 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.09 (0.01 to 0.62) | 2 | 0.18 (0.04 to 0.71) |

| HC2 double negative | 10,862 | 10 | 5 | 0.05 (0.02 to 0.11) | 6 | 0.06 (0.02 to 0.12) | 10 | 0.09 (0.05 to 0.18) |

| All women | 12,895 | 39 | 23 | 29 | 39 | |||

| HPV status at round 2 (negative cytology) | Number of women at round 2 | Number of CIN3+ women | Risk from round 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.5-year | 5-year | 10-year | ||||||

| Number of CIN3+ women (%) | 95% CI | Number of CIN3+ women (%) | 95% CI | Number of CIN3+ women (%) | 95% CI | |||

| Women with type-specific persistence | ||||||||

| Persistent HPV 16 | 13 | 7 | 7 | 53.9 (30.4 to 80.8) | 7 | 53.9 (30.4 to 80.8) | 7 | 53.9 (30.4 to 80.8) |

| Persistent HPV 18 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 25.0 (6.9 to 68.5) | 2 | 25.0 (6.9 to 68.5) | 2 | 25.0 (6.9 to 68.5) |

| Persistent 31/33/45/52/58 | 22 | 3 | 3 | 13.6 (4.6 to 36.6) | 3 | 13.6 (4.6 to 36.6) | 3 | 13.6 (4.6 to 36.6) |

| Persistent other HRHPV | 16 | 2 | 1 | 6.3 (0.9 to 36.8) | 2 | 12.5 (3.3 to 41.4) | 2 | 12.5 (3.3 to 41.4) |

| Any HRHPV type specific persistence | 59 | 14 | 13 | 22.0 (13.4 to 34.9) | 14 | 23.7 (14.8 to 36.8) | 14 | 23.7 (14.8 to 36.8) |

| Women without type-specific persistence | ||||||||

| New HPV 16 | 42 | 4 | 4 | 9.5 (3.7 to 23.4) | 4 | 9.5 (3.7 to 23.4) | 4 | 9.5 (3.7 to 23.4) |

| New HPV 18 | 17 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| New 31/33/45/52/58 | 43 | 3 | 3 | 7.0 (2.3 to 20.1) | 3 | 7.0 (2.3 to 20.1) | 3 | 7.0 (2.3 to 20.1) |

| New other HRHPV | 35 | 1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 2.9 (0.4 to 18.6) |

| Any new HRHPV | 137a | 8 | 7 | 5.1 (2.5 to 10.4) | 7 | 5.1 (2.5 to 10.4) | 8 | 5.9 (3.0 to 11.4) |

| HC2+ but no HRHPV | 79 | 2 | 1 | 1.3 (0.2 to 8.7) | 2 | 2.6 (0.6 to 9.8) | 2 | 2.6 (0.6 to 9.8) |

| HC2– | 304 | 1 | 1 | 0.3 (0.05 to 2.3) | 1 | 0.3 (0.05 to 2.3) | 1 | 0.3 (0.05 to 2.3) |

| HC2 results ignoring genotyping | ||||||||

| HC2 double positive | 140 | 18 | 15 | 10.7 (6.6 to 17.1) | 17 | 12.1 (7.7 to 18.8) | 18 | 12.9 (8.3 to 19.7) |

| HC2 negative positive | 135 | 6 | 6 | 4.5 (2.3 to 10.7) | 6 | 4.5 (2.3 to 10.7) | 6 | 4.5 (2.3 to 10.7) |

| HC2 positive negative | 63 | 1 | 1 | 1.6 (0.2 to 10.7) | 1 | 1.6 (0.2 to 10.7) | 1 | 1.6 (0.2 to 10.7) |

| HC2 double negative | 241 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| All women | 579 | 25 | 22 | 24 | 25 | |||

Section 5: optimal ages at starting and stopping screening

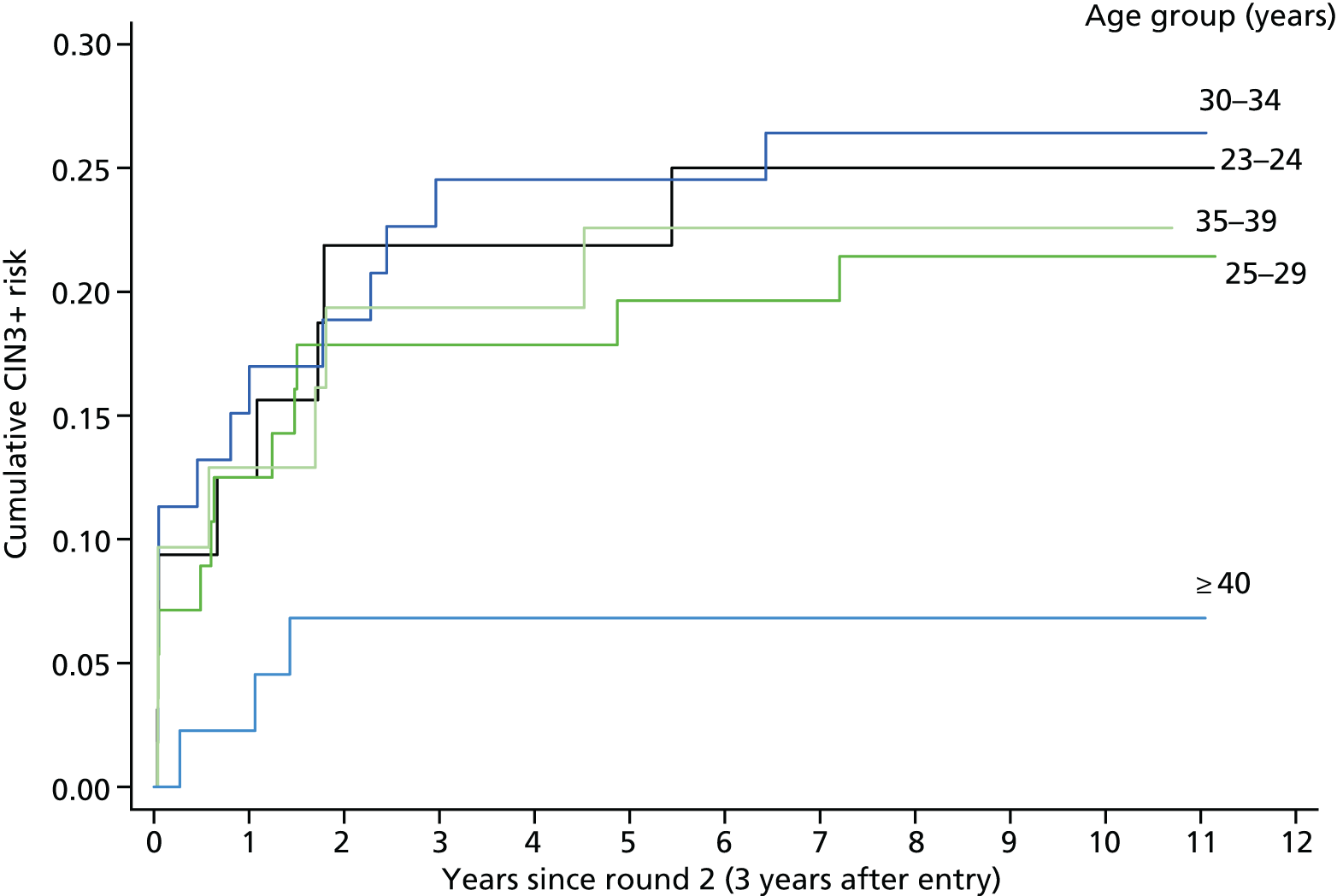

Table 17 and Figure 7 show that the cumulative CIN3+ risk 5 years after round 2 in women with type-specific persisting infection is similar regardless of age before the age of 40 years (23.8%, 95% CI 18.2% to 30.9%), but significantly lower in women aged ≥ 40 years (6.8%, 95% CI 2.3% to 19.7%; p = 0.02). Persistent HPV 16 infections account for 44% of the type-specific infections in those women aged < 30 years, but only 11% among women aged ≥ 40 years.

| HPV status at round 2 (negative cytology) | n at round 2 | n CIN3+ | Risk from round 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.5-year | 5-year | 10-year | ||||||

| n CIN3+ (%) | 95% CI | n CIN3+ (%) | 95% CI | n CIN3+ (%) | 95% CI | |||

| 23–24 | ||||||||

| Persistent HPV 16 | 14 | 5 | 5 | 35.7 (16.7 to 65.7) | 5 | 35.7 (16.7 to 65.7) | 5 | 35.7 (16.7 to 65.7) |

| Persistent other high-risk type | 18 | 3 | 2 | 11.1 (2.9 to 37.6) | 2 | 11.1 (2.9 to 37.6) | 3 | 16.7 (5.7 to 43.2) |

| 25–29 | ||||||||

| Persistent HPV 16 | 25 | 8 | 6 | 24.0 (11.6 to 45.8) | 7 | 28.0 (14.5 to 49.9) | 8 | 32.0 (17.5 to 53.9) |

| Persistent other high-risk type | 31 | 4 | 4 | 12.9 (5.1 to 30.8) | 4 | 12.9 (5.1 to 30.8) | 4 | 12.9 (5.1 to 30.8) |

| 30–34 | ||||||||

| Persistent HPV 16 | 16 | 8 | 8 | 50.0 (29.0 to 75.5) | 8 | 50.0 (29.0 to 75.5) | 8 | 50.0 (29.0 to 75.5) |

| Persistent other high-risk type | 37 | 6 | 4 | 10.8 (4.2 to 26.3) | 5 | 13.5 (5.9 to 29.5) | 6 | 16.2 (7.6 to 32.6) |

| 35–39 | ||||||||

| Persistent HPV 16 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 16.7 (2.5 to 72.7) | 1 | 16.7 (2.5 to 72.7) | 1 | 16.7 (2.5 to 72.7) |

| Persistent other high-risk type | 25 | 6 | 5 | 20.0 (8.9 to 41.6) | 6 | 24.0 (11.6 to 45.8) | 6 | 24.0 (11.6 to 45.8) |

| ≥ 40 | ||||||||

| Persistent HPV 16 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Persistent other high-risk type | 39 | 3 | 3 | 7.7 (2.6 to 22.0) | 3 | 7.7 (2.6 to 22.0) | 3 | 7.7 (2.6 to 22.0) |

| All women | ||||||||

| Persistent HPV 16 | 66 | 22 | 20 | 30.3 (20.7 to 42.9) | 21 | 31.8 (22.1 to 44.5) | 22 | 33.4 (23.4 to 46.1) |

| Persistent other high-risk type | 150 | 22 | 18 | 12.0 (7.7 to 18.4) | 20 | 13.3 (8.8 to 19.9) | 22 | 14.7 (9.9 to 21.5) |

FIGURE 7.

Cumulative CIN3+ risks following round 2 by age in women with type-specific persistence of any HRHPV.

Chapter 6 Discussion

Risk-based screening and cancer prevention

The UK National Screening Programme will adopt HPV screening and triage protocols that strike an acceptable balance between cancer risk and the cost and patient inconvenience of excessive screening and referral rates and unnecessary treatment. Acknowledging that there is no such thing as zero risk, Castle et al. 18 proposed a risk-based strategy for cervical screening based on widely accepted practice, and suggested that women should be returned to routine screening if they have a < 2% CIN3+ risk, recalled earlier than the routine screening interval if they have a 2–10% risk, and referred to immediate colposcopy if they have a > 10% risk. These specific cut-off points may be considered arbitrary and do not consider the relationship between CIN3 and cancer risk. The aim of screening is to prevent invasive cancer and not CIN3; therefore, the acceptable cumulative CIN3+ risk when a woman is next screened depends on the ratio of cancer risk to CIN3 risk at the next screen. This ratio depends mainly on the delay between time of development of CIN3 during the screening interval and its treatment when it is detected at the next HPV test or after subsequent triage processes.

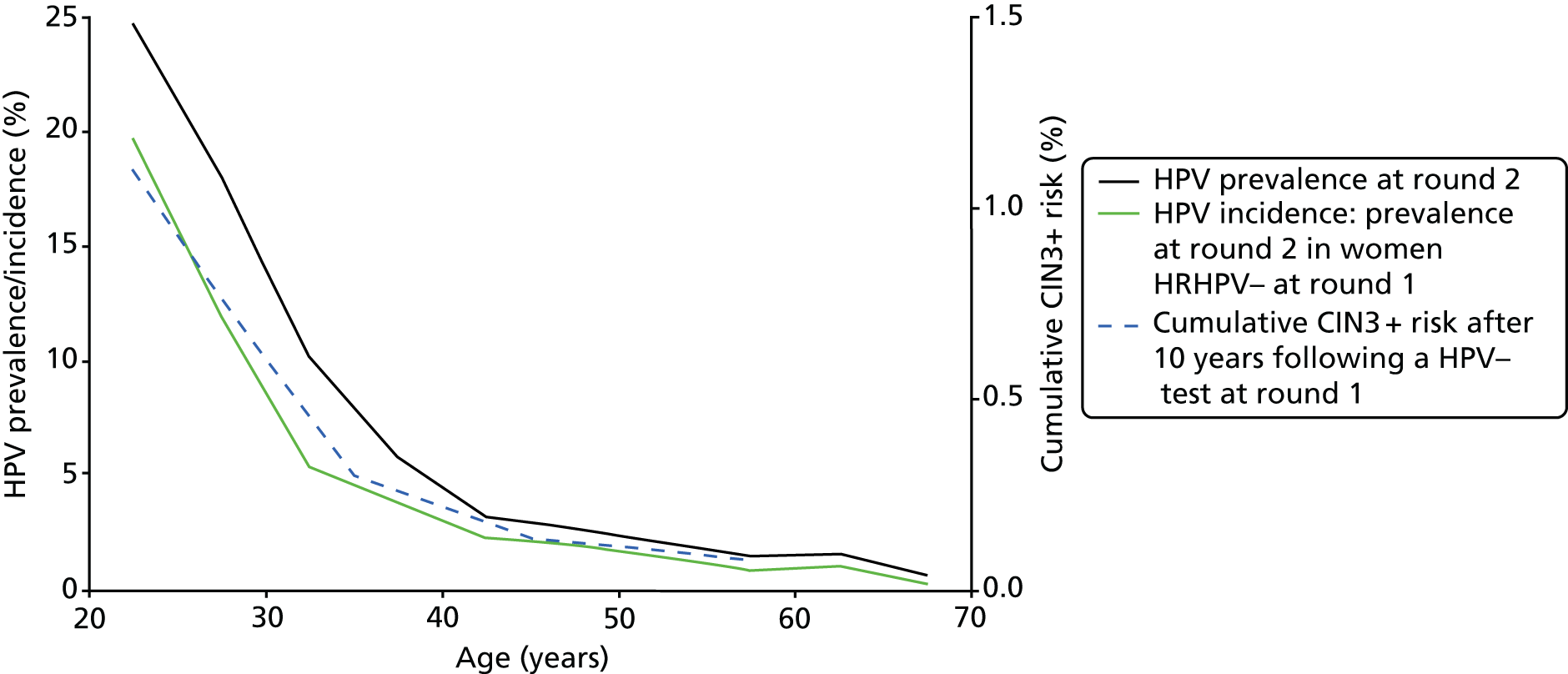

Many CIN3 cases develop soon after HPV acquisition and most develop within a few years. 19 Therefore, the CIN3 incidence rate in women who were HPV– at their last test is approximately proportional to their age-specific incidence rate of new HPV infection (with a lag of a year or two), and, hence, proportional to the overall population HPV prevalence (Figure 8), as most prevalent infections are newly acquired and transient even in older women (see Table 3).

FIGURE 8.

Age-specific HRHPV prevalence at round 2 by age at round 2 overall and in women who were HRHPV– at round 1, and cumulative 10-year CIN3+ risk by age at round 1 in women who were HC2– at round 1. (HRHPV prevalence rates at round 2 by age at round 1 in women who were HRHPV– at round 1 in 5-year age groups from 20–24 years to 55–59 years were 14.7%, 8.1%, 3.6%, 2.9%, 2.2%, 1.5%, 1.5% and 0.8%.)

The cumulative CIN3 risk at next screen is also roughly proportional to the screening interval (Figure 9). The cervical cancer incidence rate in women with untreated CIN3 appears to be fairly constant at about 1% per year, independent of age,1 so the cancer risk at next screen should be roughly proportional to the square of the screening interval. In unscreened populations with fairly constant HPV infection rates up to middle age, cervical cancer incidence should therefore rise linearly from age at first intercourse. From 10 to 30 years after first intercourse, the observed quadratic relationship corresponds closely to a linear increase with a diagnostic lag of 7.5 years. 20 In primary screening, women who test HPV– acquire new infections and develop resulting CIN3 throughout the interval to next test. In contrast, in the further interval before retesting when HPV+ women are being triaged, most CIN3 lesions will have developed long before or soon after their positive HPV test. Therefore, some cancers will be present at the screening visit when HPV is detected, and the cancer risk will further increase at a roughly constant rate throughout the triage process. This simplified and speculative model ignores several relevant factors, including the lag from HPV acquisition to CIN3 development and the rate of progression to detectable cancer, but it illustrates the weakness of screening and triage protocols based only on CIN3+ risk. An undefined model of cancer risk underlies the focus on CIN3 that informs cervical screening and triage protocols. An explicit model based on epidemiological knowledge should perhaps be developed and refined as an alternative basis for cost–benefit evaluation of the details of HPV screening and triage protocols, as it is unlikely that their effects on cancer incidence can be observed directly. Even the simple comparison of HPV testing against cytology required the pooled results of trials with a total of 176,000 randomised women to detect the effect on cancer incidence. 6

FIGURE 9.

Age-standardised prevalence (%) of CIN2+ during ARTISTIC by time since previous normal cytology to entry, and by time since cytologically normal entry to next test. Women whose previous cytology was abnormal or < 2 years before entry are excluded.

The long-term protection of a negative human papillomavirus test and, hence, the safe screening interval at different ages

The 10-year CIN3+ rate among women who were HPV– at entry to ARTISTIC is only 0.1% in those aged ≥ 40 years, suggesting that screening intervals for HPV– women aged 40–49 years might be extended even further than the 6 years previously suggested. 4 Our data are consistent with the long-term risks reported from women participating in the POBASCAM trial in the Netherlands that has led to the recommendation for the Dutch HPV screening programme to adopt a 10-year screening interval in women aged ≥ 40 years. 21 Many HPV– women have had an earlier infection, so this very low long-term risk after a single negative HPV test suggests that a HPV infection that has become undetectable rarely recurs and then progresses to CIN3. Frequent HPV testing, therefore, greatly increases the number of transient infections that are detected without increasing sensitivity for CIN3 detection.

As noted above, if most CIN3 cases (and a large proportion of CIN2 cases) persist, then their prevalence will increase almost linearly with increasing screening interval. This was seen in routinely screened women in Manchester in the 1990s, in whom CIN3 prevalence increased almost linearly with longer intervals since last normal cytology. 22 Age-standardised CIN2+ prevalence in ARTISTIC shows this pattern at round 2 (Figure 9), with an annual increase of about 0.2% per year since entry in women with a cytologically normal entry test. Figure 9 shows that CIN2+ prevalence at entry increased at a similar rate with increasing interval from the previous normal cytology to entry, with the addition of about 1.2% reflecting the CIN2+ prevalence missed by previous screening rounds that was detected at entry to ARTISTIC.

The role of human papillomavirus typing

The HPV+ women with borderline/mild cytology as well as those with negative cytology might be further triaged by HPV type to identify those who can be recalled later. A HPV test that identifies HPV types 16, 18 and 31/33/45/52/58 would enable this moderate-risk subgroup, which constitutes 58.4% of HPV+ women with borderline/mild cytology, to be referred immediately or followed up within (say) 1 year. See Table 13, which shows the 5-year CIN3+ risks of 10.9%, 4.1% and 2.9% with negative cytology, and 20.9%, 10.8% and 9.4% with borderline/mild cytology. Borderline/mild cytology with other HRHPV types (35, 39, 51, 59 and 68) has a 5-year CIN3+ risk of 3.5% and might be recalled 3 years later for a repeat HPV test. Immediate referral or early retesting of women with HPV 16 was recently recommended in the Netherlands23 and proposed more than 10 years ago in the USA,24 but the cost–benefit balance of more complex triage protocols based on full HPV typing following cytology triage deserves further consideration, particularly for vaccinated women. Table 13 shows that most of the CIN3+ risk in HPV+ women with abnormal cytology is present at, or soon after, HPV detection and increases by about only 2% from 2.5 to 10 years irrespective of cytology.

Triage and referral policy in relation to primary screening interval

Figure 9 confirms that the marked reduction from round 1 to round 2 in the proportion of HC2+ women aged ≥ 25 years who had moderate+ cytology (11.2% and 3.2%, respectively; see Table 6) reflects the elimination of long-standing high-grade disease that had been missed at previous routine cytology. The round 1 results, thus, represent what might be seen in primary HPV testing with a very long screening interval, whereas round 2 shows results after an interval of about 3 years. However, the overall CIN3 risks in HRHPV+ women were almost the same after stratifying by cytology, with 5-year CIN3 risks for normal, borderline/mild and moderate+ cytology of 3.1%, 9.5% and 52.4%, respectively, in round 1, and 2.5%, 8.4% and 44.7%, respectively, in round 2. This suggests that recall policy following cytology triage of HPV+ women need not depend on the primary screening interval.

Triage and referral policy in relation to type-specific human papillomavirus persistence

Table 12 shows that the 10-year CIN3 risk for women with a new HPV type at round 2 was only 3.4% (95% CI 2.1% to 5.4%). The risk was no higher in those whose HPV infection at round 1 had cleared (2.7%, 95% CI 0.9% to 8.0%) than in those who were HPV– at round 1 (3.6%, 95% CI 2.2% to 6.0%). In contrast, the 10-year CIN3 risk in women with type-specific persistence at round 2 is six times greater than for a new infection of the same type. Among 331 women with HRHPV at both rounds, 58% had the same type (10-year CIN3 risk 20.4%, 95% CI 15.6% to 26.4%). The 10-year CIN3 risk in the remaining 42% who had cleared the original type and acquired a new type was only 2.7%, so these women could safely be recalled 3 years later when most of their infections will have cleared. This large difference in risk (p < 0.0001), and, hence, the potential efficiency of further triage, is diluted with HPV tests that do not identify all 13 high-risk types. The price of different HPV tests and the disadvantages of more complex triage and referral protocols will determine whether or not the advantages of full HPV typing outweigh the costs.

A triage protocol in which women are recalled repeatedly until their CIN3 risk exceeds (say) 10% implies a cycle of repeated testing that ends only in HPV clearance or referral, and some limit must be set to detect and treat occult CIN3 that has regressed cytologically. A HPV infection that has persisted for 5 years should perhaps be referred for random cervical biopsy. In a prospective study in the Netherlands, six out of the eight women with untreated CIN who regressed to normal cytology and colposcopy but remained HRHPV+ over several years had occult CIN3 detected by random biopsy. 25

We excluded women with any recorded histology in calculating HPV clearance rates, as biopsy can induce clearance. 26 This might lead to an overestimate of clearance but, as the clearance rates for new and persistent HRHPV infections shown in Table 4 are similar to those reported by Nobbenhuis et al. 27 in women followed up without intervention, any bias seems to be small.

Triage of human papillomavirus-positive women

If the screening interval is increased, the time between appearance and diagnosis of CIN3 and, hence, the risk of progression to cancer will also increase, so the triage protocol must minimise the delay in referring those at highest risk to colposcopy. Nonetheless, the evidence from round 1 of ARTISTIC (see Table 13) indicates that the triage protocol being piloted in England could be too conservative, at least for HPV+ women with negative cytology. The risk of developing CIN3 within 5 years in HPV+ women is 52.4% for moderate/severe cytology, 9.6% for borderline/mild cytology and only 3.1% for normal cytology (see Table 13). The suggestion that a CIN3+ risk of about 10% is a reasonable threshold for immediate colposcopy18,28 would, therefore, imply rapid referral for HPV+ women with any abnormal cytology except perhaps the minority of women with borderline/mild cytology who have genotypes with the lowest associated risks. The minimal increase in the risk of developing cancer by retesting women with borderline/mild cytology rather than referring them directly to colposcopy has always been accepted, and it is not clear that this risk/benefit balance should be abandoned when they are found to have HPV. In round 1 of ARTISTIC, the proportion of HPV+ women with moderate + cytology was 12% below age 50 years and at age 50 years or older. By round 2 of ARTISTIC, only 5% of HPV+ women aged < 50 years and 1% of women aged ≥ 50 years had moderate/severe cytology. The majority of HPV+ women in a population regularly screened by HPV testing will, thus, have negative or borderline/mild cytology.

Triage: women with normal cytology

Of the women who were HC2+ with normal cytology at entry to ARTISTIC, 72% had cleared their HPV infection within 3 years (see Table 14). Only 1.3% (15 out of 1116) of women had moderate or worse cytology by round 2 (of whom, nine were diagnosed with CIN3). Fourteen per cent of women remained HPV+ with normal cytology, but approximately 60% of these (97 out of 158) had type persistent HPV and approximately 40% (61 out of 158) had new HPV types. The subsequent elevated cumulative risk was among those with type-specific infections. This also applied to those with borderline/mild cytology at the follow-up, but this was based on small numbers. This implies that the current policy in the pilot sites (repeat testing after 1 year and referral to colposcopy after 2 years if women are still HPV+ with normal cytology) is referring a large proportion of women to unnecessary testing and colposcopy. Recall after 2 or 3 years then referring only those developing moderate+ cytology and those with type-specific persistence may be a better strategy.

Triage: women with borderline/mild cytology

Among HPV+ 24- to 64-year-old women presenting with borderline/mild cytology at entry, 29% had cleared their HPV infection within 1 year and an additional 19% remained HPV+ but became cytologically normal. Those with HPV 16 with 5-year CIN3+ risk of 20.5% should clearly be referred immediately, but inviting all HPV+ women with borderline or mild cytology to return for a repeat test at 1 year would substantially reduce immediate referrals and could be a better strategy.

Ages at starting and stopping screening

Stopping screening

The effect on long-term CIN3+ risk of stopping screening in women who are HPV– at various ages can be inferred from Table 10. For example, the 10-year CIN3+ risk in HPV– women aged ≥ 50 years is only 0.1%. Their risk of acquiring HPV is an order of magnitude lower than for women aged 20–24 years (see Table 3), and there is plausible epidemiological evidence that HPV infection in middle age confers little lifetime risk of cervical cancer. 20 Conversely, the case for a further test at least 10 years later is that their lifetime cancer risk could also be of the order of 1 per 1000 and possibly higher. The sharp decline with increasing age in the CIN3-to-cancer ratio in ARTISTIC (see Table 8), and the observation that CIN3 that remains detectable by HPV testing and random biopsy can regress to become cytologically and colposcopically undetectable25 suggests that their CIN3 risk may be underestimated. A quirk of the current screening protocol is that a woman’s age at her final test ranges from 60 to 64 years because the final invitation is 5 years after her previous test unless this was at age 60 years or older. One final test at the age of 65 years could be offered to all women who were HPV– at the age of 50 years. Whatever the age at stopping, the final HPV test might require a more sensitive test than at younger ages. Five out of the six women in ARTISTIC who developed invasive cervical cancer after a negative HC2 entry test were found to be HRHPV+ when the stored entry sample was retested by PCR. Alternatively, HPV and cytology cotesting might be considered at a woman’s final test. The one woman in ARTISTIC and all three in the POBASCAM trial21 who developed invasive cancer within 4 years of a HPV– entry test were cytologically abnormal at entry.

Age at starting screening

The natural history of HPV infection, persistence and progression to CIN3 is similar at all ages from 20 years to about 45 years, after which the CIN3 rate in HPV+ women falls (see Figure 7) and cervical cancer incidence in unscreened populations shows a sharp inflection. 20 Therefore, the age at which screening begins (currently 25 years) might be reconsidered when HPV testing is introduced. Owing to this, we have outlined some of the effects of beginning HPV screening at (say) age 22 years to illustrate the issues involved. Screening after age 25 years reduces cervical cancer incidence, particularly for more advanced disease;2 therefore, earlier screening would presumably achieve some reduction in the rising cancer incidence in young women. The effect on referrals to colposcopy would depend on whether immediate referral was restricted to women with moderate or severe cytology, and on the recall interval for HPV+ women with normal, borderline or mild cytology. Almost 40% of women aged 20–24 years were HC2+ at entry to ARTISTIC, but only 4.2% had moderate or severe cytology. 3 A second test at age 25 years for those who were HPV+ at age 22 years would enable type-specific persistence to be identified and triaged. As discussed above, the CIN3+ risk is much lower in those with a new HPV infection; therefore, they could safely be recalled 3 years later, when most infections will have cleared, except perhaps those with HPV 16 (see Table 12).

Study limitations

The effect of cervical sampling and biopsy on human papillomavirus clearance

A potential bias in the observed 10-year cumulative CIN3+ rates in HPV– women is the possibility that intervening screening, biopsy and treatment could have induced clearance of subsequent HPV infections and prevented progression to CIN3. 26

Variation in cytology practice

ARTISTIC recruited from 127 centres spread throughout the Greater Manchester area and cytology was performed in two laboratories where the staff were retrained ahead of the national roll-out of LBC, which improved the sensitivity of our cytology,10 as this varies between laboratories. The HC2 test used in ARTISTIC has largely been replaced for use in the NHS by modern PCR-based assays. We do not know how these assays would have performed, particularly in detecting HPV among women who tested HC2– at entry but subsequently developed invasive cervical cancer (see Table 7). Despite these potential issues, we have shown similarities between the first round of ARTISTIC and the national pilot study (see Table 6) and believe the results to be generalisable to the British population.

Hybrid capture 2 test sensitivity

Table 2 shows that about 4% of samples from women aged ≥ 25 years who tested positive for HPV by HC2 showed no HRHPV on genotyping. These constituted over half of HC2+ results in women aged ≥ 50 years. A total of 40% of these women had a RLU of between 1 and 2 pg/μl, indicating that most are probably false positives. 11 (The definition of HC2 test positivity is a RLU of ≥ 1 pg/μl.) Our conclusions are unlikely to have been much affected by ignoring these women who were HC2+ but negative for the 13 high-risk target types (4.2% of all women in round 1 and 3.5% in round 2; see Table 2). Their 10-year CIN3 rate was 1.8% (3.0% in those with low-risk HPV types and 0.8% in those negative for all 27 HPV types identified by the linear array), and their inclusion in the HC2– group would increase the 10-year CIN3+ risk in HC2– women from 0.31% to 0.37%. Low-risk HPV types occasionally cause high-grade neoplasia but by definition are not associated with invasive cancer risk, so the proportion of high-grade CIN cases that are missed by HRHPV testing is not an indication of inadequate sensitivity. Modern PCR-based HRHPV tests may have slightly better sensitivity with respect to cancer than the HC2 test.

Human papillomavirus-negative cancers

The small proportion of cervical cancers that do not contain HPV DNA will be missed by any HPV-based primary test. Only 0.3% were HPV– in an international series of cancer biopsies with stringent criteria for diagnosis and PCR adequacy and separate PCR assays for each high-risk type. 29 A more relevant estimate for the practical purpose of improving routine screening is the proportion of cancers in which HPV cannot be detected in recent cervical samples. None of the latest available samples before diagnosis from the 23 cancers in this cohort was HPV– on retesting, but Table 7 shows that the entry sample was HC2 negative but HPV positive by PCR in 5 (22%). Larger numbers tested by standard modern assays will provide a more precise estimate of this important index of sensitivity.

Further research

The National Institute for Health Research has funded a further extension, under which follow-up for CIN2 diagnoses (which are managed clinically in the same way as CIN3 but are not recorded centrally) will be updated through local histology laboratories. The sample bank, augmented by further samples from women in the cohort who are screened between 2018 and 2022, will be used to retest samples from women who develop CIN3 or cancer and matched controls. Interim results for CIN2+ as well as CIN3+ will be provided to the NSC in order to inform its recommendations on screening intervals for HPV– women and triage protocols following HPV detection. The same data would be available in the future from national routine screening records if these were linked to histology records to capture CIN2 diagnoses as well as to national cancer registration. The establishment of a larger national bank of samples from routinely screened women would provide much larger numbers of samples from women who will develop cervical cancer for retesting by more sensitive PCR and with alternative screening or triage assays such as DNA methylation.