Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 12/33/28. The contractual start date was in May 2017. The draft report began editorial review in December 2017 and was accepted for publication in August 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Claire Roberts reports grants, in addition to non-financial support, from Novartis Pharmaceuticals UK Ltd (Frimley, UK), outside the submitted work. Peter Howarth reports part-time employment with GlaxoSmithKline plc (London, UK) as a global medical expert.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Kapoor et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background and rationale

The burden of severe asthma

Epidemiology

Asthma affects > 5.4 million people in the UK, with nearly 500,000 experiencing severe symptoms and frequent exacerbations that are inadequately controlled with available treatments. 1,2 The burden of severe asthma on the NHS is enormous, accounting for 80% of the total asthma cost (£1B3), with frequent exacerbations and expensive medications generating much of this cost. 4 In 2009, there were 1131 deaths caused by asthma,5 with those whose asthma remains poorly controlled facing the greatest risk. 6,7 Patients with severe asthma bear the greatest burden of asthma morbidity. They experience more frequent and severe exacerbations,8 which reduce their quality of life, impair their ability to work and place an enormous burden of anxiety on them and their families. 9 There is also an increased risk of significant depression. 10 One in five asthmatics in the UK report serious concerns that their next asthma attack will be fatal. 1 As highlighted in the 2010 Asthma UK report Fighting for Breath,11 these patients also face discrimination from employers, health-care professionals and society as a whole as a result of their asthma.

The unmet need in severe asthma

Current treatments, including oral corticosteroids (OCSs), ‘steroid-sparing’ immunosuppressants and monoclonal antibody therapies, often have limited efficacy and potentially serious side effects (steroids, immunosuppressive agents) or are prohibitively expensive (monoclonal antibodies). The adverse effects of long-term oral steroids include adrenal suppression, decreased bone mineral density, diabetes mellitus and increased cardiovascular mortality. 12 The anti-immunoglobulin E (IgE) treatment omalizumab (Xolair®; Novartis Pharmaceuticals UK Ltd, Frimley, UK) has been shown to reduce exacerbations by up to 50%13 and improve quality of life in severe allergic asthma, but costs up to £26,640 per year. 14 The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)14 reappraised the use of omalizumab in 2012 and, although recognising the grave effects of severe uncontrolled asthma on quality of life for patients and their families, concluded that it is cost-effective within the NHS only when its use is limited to those with severe persistent confirmed allergic IgE-mediated asthma experiencing four or more severe exacerbations in the preceding 12 months. A large number of patients are therefore left with a significant unmet clinical need and a specific requirement for therapies that reduce systemic steroid exposure.

It is also important to acknowledge the often unrecognised role that carers play in looking after patients with poorly controlled severe asthma. The Fighting for Breath11 document highlighted the strain that this can place on the physical and mental health of this vital informal workforce. In addition, having to take time off work, having to work part-time or not being able to work at all as a result of a patient’s care needs places a significant financial burden on carers.

National/international strategies to improve asthma care

The 2011 Department of Health and Social Care report An Outcomes Strategy for COPD and Asthma in England15 recognises the huge burden that poorly controlled asthma places on people’s lives and the NHS. It also describes the political commitment to improve asthma control and reduce asthma-related emergency health-care needs and deaths. 15 The 2011 British Thoracic Society (BTS) and Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) national asthma guideline16 and the 2010 World Health Organization (WHO) consultation on severe asthma8 have highlighted an urgent need for research in severe asthma, acknowledging the limitations of available treatments and the dearth of clinical trials on which to base management recommendations. In its research strategy for 2016–21, Asthma UK17 identified the development of new treatments as a priority for improving clinical outcomes and patient well-being and reducing the cost of treating severe asthma within the NHS. It also identified the need to gain a better understanding of the impact of exposure to substances known to trigger asthma and the impact of strategies that regulate and control this exposure as a key priority.

The significance of allergen exposure and environmental interventions

More than 70% of people with severe asthma are sensitised to common aeroallergens and/or moulds,18 with the level of allergen exposure determining symptom severity; those exposed to high allergen levels are at increased risk of exacerbations and hospital admissions. 19–22 Domestic exposure to allergens is also known to act synergistically with viruses in sensitised patients to increase the risk and severity of exacerbations. 23 Allergen avoidance has been widely recognised as a logical way to treat these patients. 24 In controlled conditions, long-term allergen avoidance in sensitised asthmatics reduces airway inflammation with consequent symptomatic improvement, which is further supported by high-altitude, clean-air studies. 25–27 Unfortunately, effective methods of allergen reduction have proved elusive,28,29 with current measures unable to reduce allergen load sufficiently to yield a consistent clinical improvement, thus leaving a significant gap in the potential strategies for reducing asthma severity through allergen reduction.

Rationale for temperature-controlled laminar airflow therapy

At night, airborne particles are carried by a persistent convection current established by the warm body, transporting allergens from the bedding area to the breathing zone. 30 Proof-of-concept studies have shown that the temperature-controlled laminar airflow (TLA) device reduces the total number of airborne particles of > 0.5 µm in the breathing zone by 3000-fold (p < 0.001) and cat allergen exposure by 30-fold (p = 0.043) and significantly reduces the increase in the number of particles generated when turning in bed for all particle sizes. 31 Compared with a best-in-class traditional air cleaner, TLA is able to reduce exposure to potential allergens by a further 99%. 32 We postulate that this highly significant reduction in nocturnal exposure, targeted to the breathing zone, explains why TLA may succeed when so many other measures, including traditional air cleaners, have failed.

Evidence of benefit with temperature-controlled laminar airflow therapy

Compared with placebo, the TLA device has proven efficacy for asthma-related quality of life and bronchial inflammation (measured by exhaled nitric oxide) in a pan-European, multicentre, 12-month Phase III study33 (n = 282, age range 7–70 years). The greatest benefit was seen in the more severe asthma patients requiring higher intensity treatment [Global INitiative for Asthma (GINA) step 4] and with poorly controlled asthma [7-point Asthma Control Questionnaire (ACQ) score of < 19]. GINA step 4 is consistent with American Thoracic Society (ATS)/European Respiratory Society (ERS) severe asthma guideline definitions34 and BTS/SIGN guideline treatment step 4 [inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) dose of ≥ 1000 µg/day beclomethasone dipropionate (BDP) equivalent plus an additional controller medication such as a long-acting β2-agonist, leukotriene receptor antagonist or sustained-release theophylline]. Although not powered to ascertain an effect on exacerbations, a post hoc analysis of the Phase III study data showed a decreased exacerbation rate in more severe patients treated with TLA compared with placebo, with a trend towards significance (mean TLA 0.23 exacerbations/year, placebo 0.57 exacerbations/year; p = 0.07). 33 Although a cost-effectiveness analysis based on the results from this trial found no significant differences in emergency department (ED) visits, hospitalisation days, medication usage and, therefore, overall costs between the two study groups,35 this may have reflected the fact that the trial was powered to detect a difference in asthma-related quality of life and did not specifically include patients at risk of exacerbations (average annual rate was 0.2 exacerbations per year), a predictor of increased asthma health-care resource use and costs. 36 Despite the lack of a significant reduction in health-care resource use and associated costs, subsequent economic modelling showed that TLA would be cost-effective in Sweden at the current monthly rental price (SEK2000, ≈£167), mainly because of increases in quality of life. 34

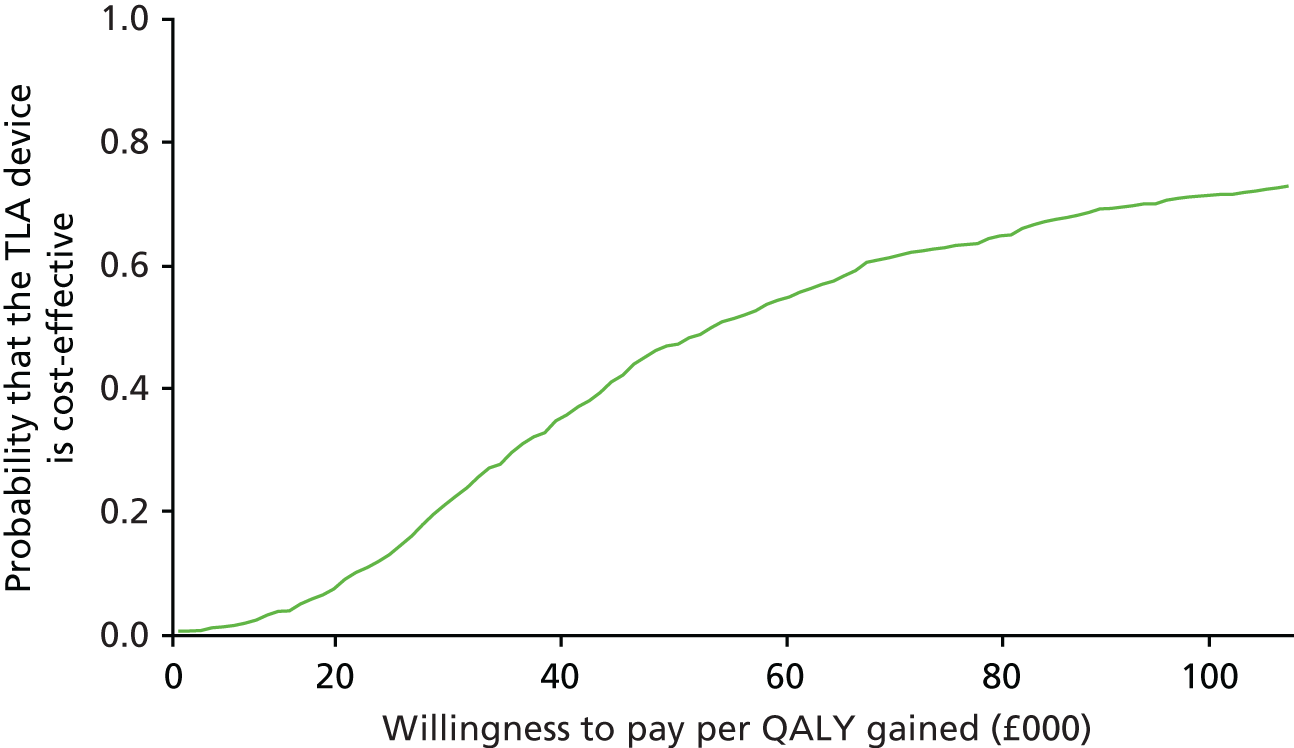

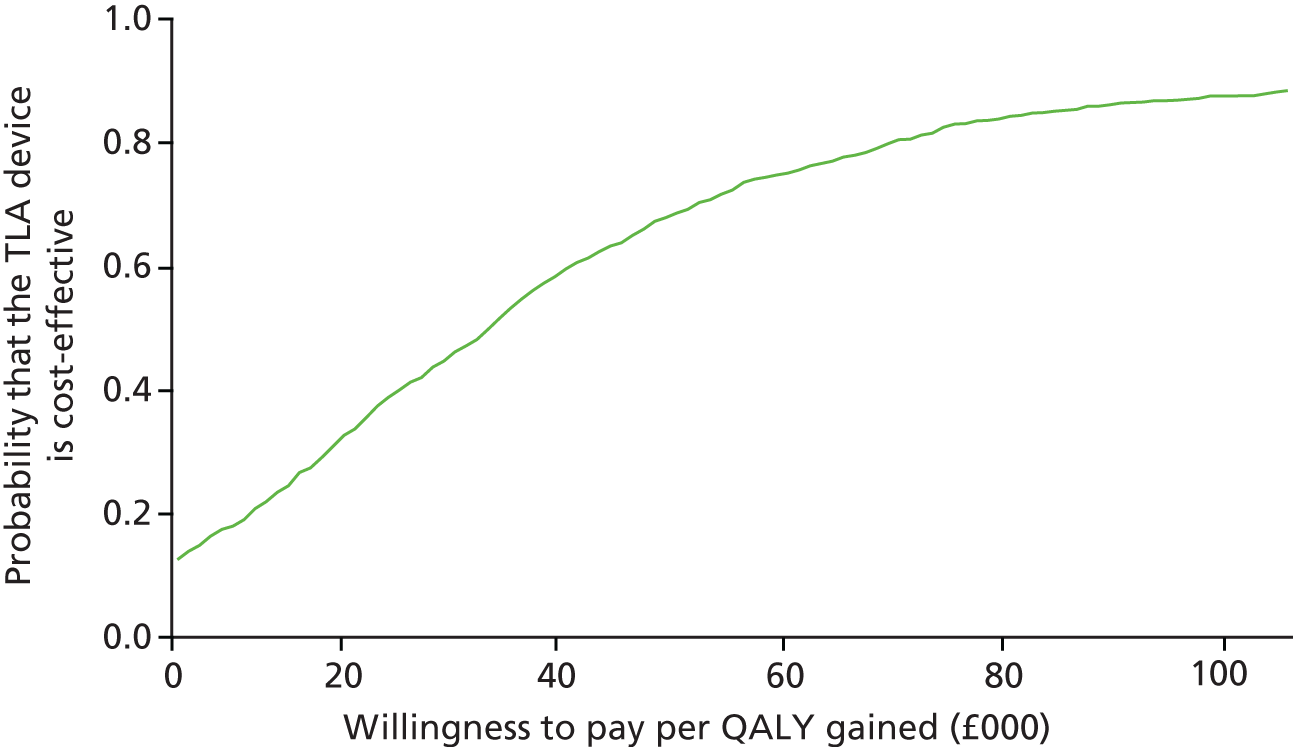

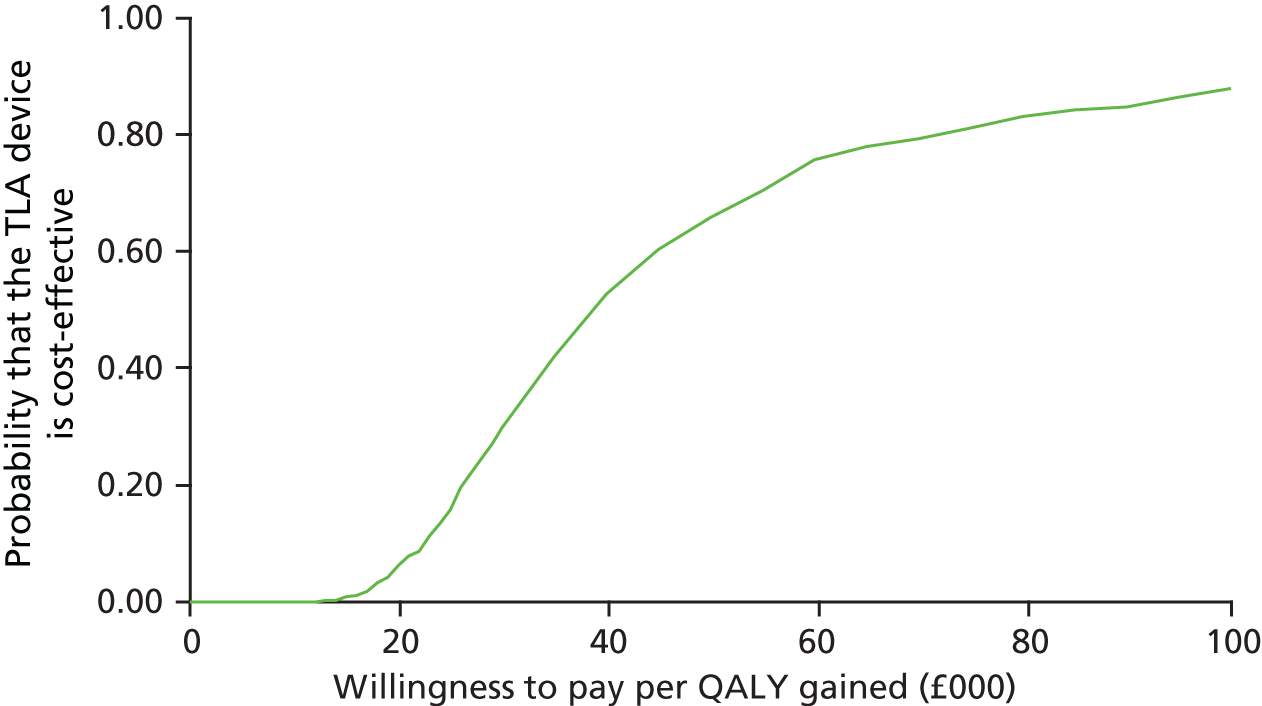

Using the results from a very small, 10 + 10-week randomised controlled crossover trial in Sweden,37 a modelling study addressed the potential cost-effectiveness of TLA therapy over a projected 5-year period. 38 Assuming no impact of TLA on health-care resource use, TLA was cost-effective compared with placebo at a device cost of €8200 (≈£6890), at a willingness-to-pay threshold of €35,000 (≈£30,000) per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained. We considered that the greatest potential for cost-effectiveness could occur in severe asthma through reducing exacerbations, which was not addressed in the Swedish trial because of the short observation period and less severe patient population included.

A further pragmatic, patient-centred randomised controlled trial (RCT) of this novel non-pharmacological treatment in severe allergic asthma was thus warranted.

Objectives

The aim of the Laminar Airflow in Severe asthma for Exacerbation Reduction (LASER) trial was to assess whether or not home-based nocturnal TLA treatment can effectively reduce asthma-related morbidity over a 1-year period in a real-life group of patients in the UK with poorly controlled, severe allergic asthma.

Primary objective

The primary objective was to determine whether or not nocturnal TLA treatment reduces the frequency of severe asthma exacerbations (defined as an acute deterioration in asthma requiring treatment with systemic corticosteroids).

Secondary objectives

The secondary objectives were to:

-

assess the impact of nocturnal TLA treatment on asthma control, including:

-

current clinical asthma control, which is the extent to which the clinical manifestations of asthma (i.e. symptoms, reliever use and airway obstruction) have been reduced or removed by treatment

-

the risk of future adverse asthma outcomes, which includes loss of control, exacerbations, accelerated decline in lung function and side effects of treatment

-

-

ascertain the effect of TLA treatment on quality of life in participants with poorly controlled, severe allergic asthma and their carers

-

qualitatively evaluate participants’ perceptions, values and opinions of the device to identify potential modifications to improve participant acceptance and to inform future use of the device within the NHS setting

-

evaluate the impact of TLA treatment on health-care utilisation and related costs and its impact on education/work days lost

-

fully assess the cost-effectiveness, both at 1 year and over the lifetime of the participant, of nocturnal TLA treatment using a cost–utility analysis to determine the incremental cost per QALY gained.

Chapter 2 Methods

The objective of the LASER trial was to assess whether or not home-based nocturnal TLA treatment can effectively reduce asthma-related morbidity over a 1-year period in a real-life group of patients with poorly controlled, severe allergic asthma. The trial was sponsored by Portsmouth Hospitals NHS Trust and funded by the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme. The first participant was recruited to the trial in May 2014 and the final participant completed participation during January 2017.

Patient and public involvement

The design of the methods for this trial was supported by patient and public involvement (PPI) members in several ways. First, Mrs Wilsher and Mr Boughton worked with the investigators and co-applicants during the grant submission stage to inform the outcomes and objectives, for example by including carers inthe study design. During the trial, they assisted with the design and participated in the delivery of patient information events and designed study advertisements for use on social media platforms. They also assisted with writing the plain English summary for the ethics application and the patient information sheet and consent form. Further support was provided by Mr Supple, an expert patient member from Asthma UK, who sat on the Trial Management Group (TMG). Representatives from Allergy UK also assisted with the organisation and delivery of patient-facing events and the design and posting of recruitment materials on the Allergy UK website. Mrs Wilsher is further involved in the interpretation of data from the qualitative analyses and is currently contributing to a publication on the importance of the use of social media in recruitment to clinical trials.

Trial design

The LASER trial was designed exclusively to meet the objective previously described. The trial design determined to best meet this objective was a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo comparator, parallel-group trial design, with each individual participant trialling the active or placebo device for 12 months.

A placebo comparator was chosen as other add-on treatments in severe asthma (e.g. omalizumab and bronchial thermoplasty) vary greatly in indication, use and delivery, are not suitable for every patient and would therefore not be able to be used consistently or safely in an ‘active’ control group. Participants were randomised in a 1 : 1 ratio to receive either an active treatment device or a placebo device. Throughout the trial, participants in both treatment arms received standard asthma care in accordance with the national BTS/SIGN guidelines for the management of asthma in adults. 16

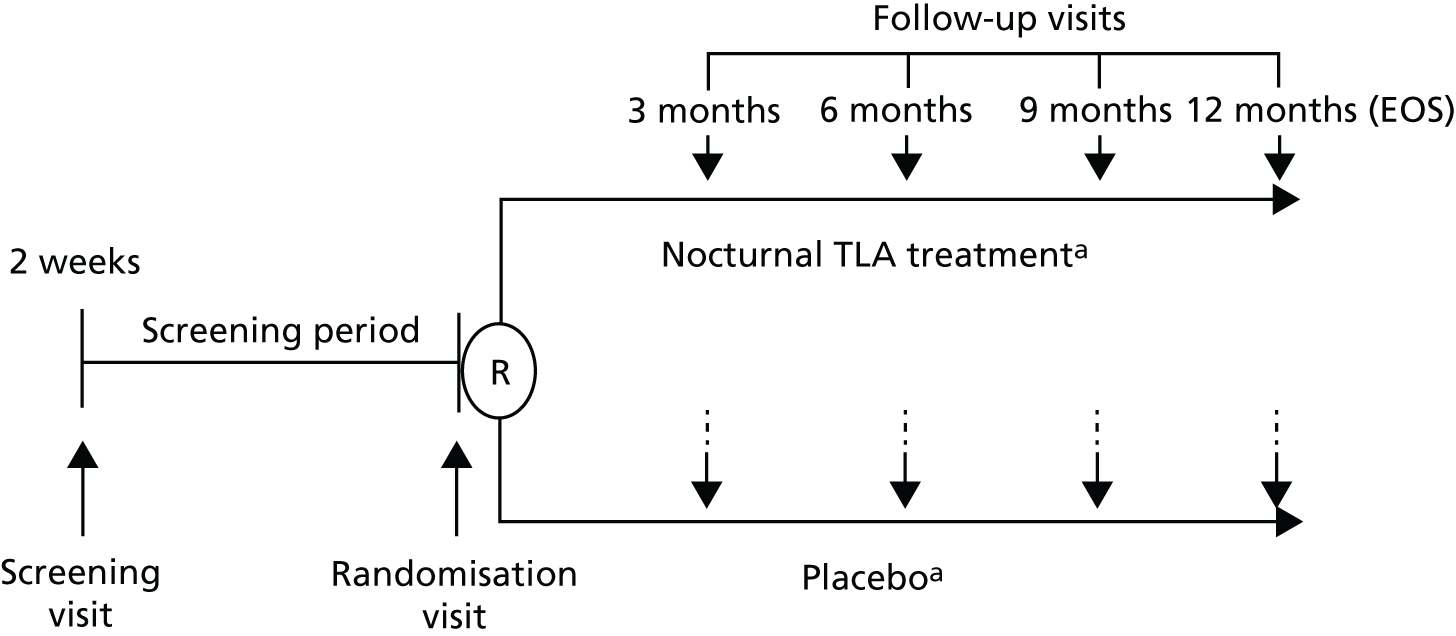

Figure 1 presents a simple overview of the trial design, highlighting the six study visits (1, screening visit; 2, randomisation visit; 3–6, follow-up visits at months 3, 6, 9 and 12 months, respectively). The full trial flow chart and data collected at each of these study visits are summarised in Table 1, presented in full in Table 27 and explained throughout this chapter.

FIGURE 1.

Simple overview of trial design. EOS, end of study; R, randomisation. a, In addition to existing asthma treatments that will not be adjusted during the trial.

| Visit | Data collected |

|---|---|

| Scheduled data | |

| Visit 1: screening | Lung function (spirometry + bronchodilator reversibility) (FeNO) |

| Allergy testing (skin prick tests) (total IgE) (serum-specific IgE) | |

| Questionnaires (ACQ) | |

| Visit 2: baseline | Lung function (spirometry + bronchodilator reversibility) |

| Questionnaires (ACQ, AQLQ, EQ-5D-5L, SNOT-22, AC-QoL) | |

| 2-week diary submissiona | |

| Visits 3–6: treatment period | Lung function (spirometry) (FeNO) |

| Questionnaires (ACQ, AQLQ, ED-5D-5L, SNOT-22, WPAI) | |

| 2-week diary submissiona | |

| TLA diary review of device adherence/health-care usage | |

| Visit 6 only (end of study) | Lung function (bronchodilator reversibility) |

| Additional questionnaires (GETE, AC-QoL) | |

| Telephone call: 1-month telephone call | Telephone review – participant-reported adherence |

| Unscheduled data | |

| Exacerbation history collected throughout study at ‘exacerbation reviews’ | |

Trial protocol

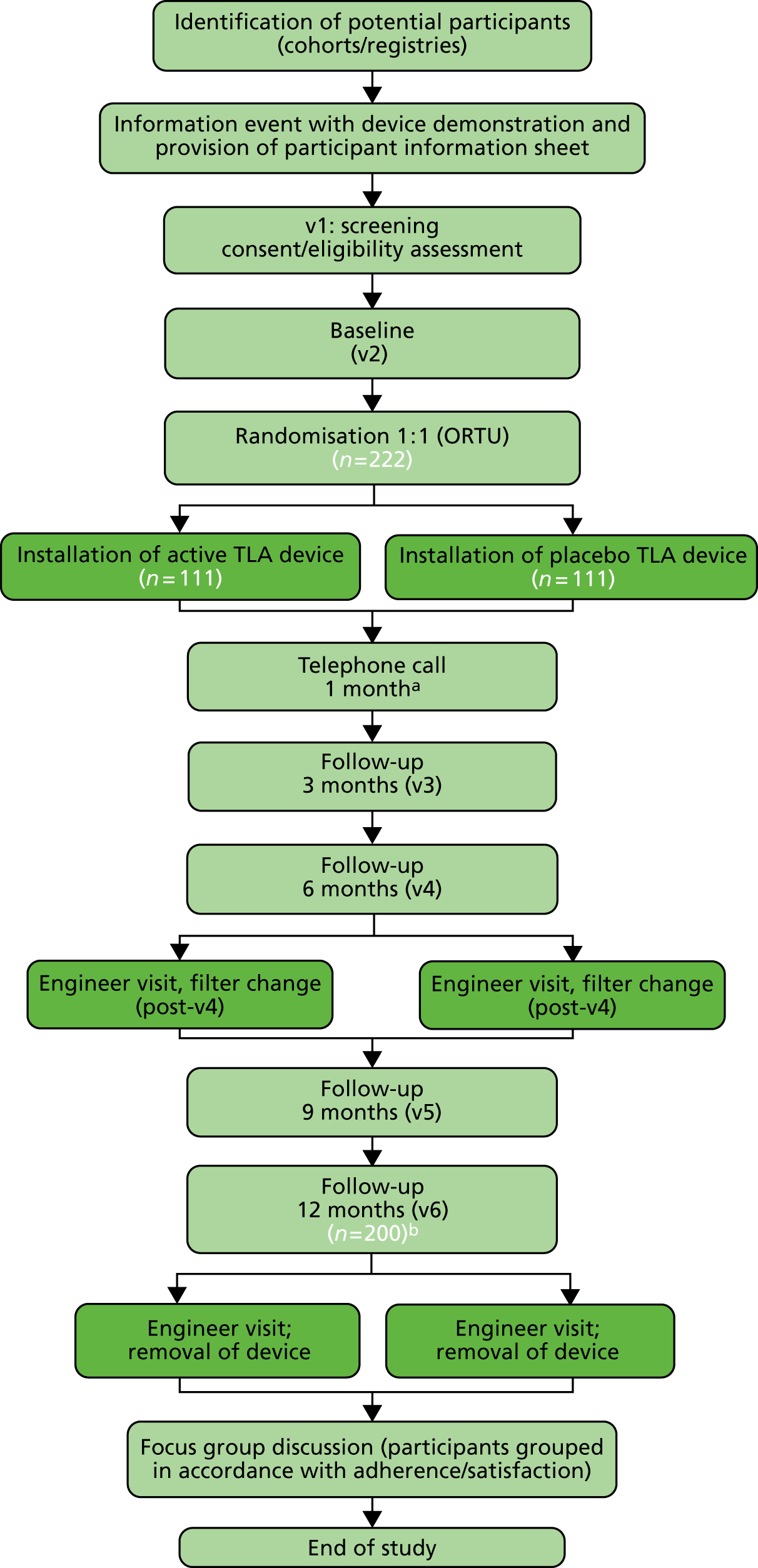

Figure 2 consolidates and summarises the major content of the trial protocol into a simple flow chart. The major activities in the trial are described below, linked to the corresponding sections of this report for full details, for the reader’s convenience. The data collected at these visits are listed in Table 1.

-

Participant recruitment (see Recruitment).

-

Study visits: participants were required to attend the following six study visits to collect the scheduled data –

-

screening visit [see Screening visit (–2 weeks)]: purpose of data collection = screen participant against trial inclusion and exclusion criteria (see Participants)

-

randomisation visit [see Randomisation visit 2 (0 months)]: purpose = assign participant to active or placebo device treatment arm (see Participants and minimisation criteria)

-

3-month follow-up visit

-

6-month follow-up visit

-

9-month follow-up visit

-

12-month follow-up visit: common purpose of study visits 3–6 = secondary outcome data collection (see Secondary outcomes).

-

-

Unscheduled data collection: purpose of data collection = primary outcome data collection (see Primary outcome).

-

Optional focus group sessions: purpose of data collection = capture individuals’ perceptions, expectations and meanings to explore acceptance, level of personal control, motivation and usefulness of the TLA device (see Focus groups).

FIGURE 2.

Trial flow chart. ORTU, Oxford Respiratory Trials Unit; v, visit. a, Telephone review only; b, expected 10% dropout. Light green shading represents the study team with participant. Dark green shading represents the TLA engineer.

Further quantitative data are detailed in the subsections of Study assessments.

The internal pilot study

A 4-month internal pilot study was used to validate the feasibility of the trial for achieving its objectives. Specifically, the internal pilot study evaluated the following indicators of trial feasibility at the five initial recruiting centres during the first 4 months of recruitment. Amendments were made to the original trial protocol based on the resulting insights, including practical modifications to trial processes that could be implemented to enhance participant and partner experience during the remainder of the trial.

-

Recruitment and retention of participants:

-

participant numbers emerging from the screening, consent and randomisation processes

-

participant experiences of the recruitment process

-

time from randomisation to device installation

-

adherence to follow-up (including the 1-month telephone review).

-

-

Data collection methods and quality: quality and completeness of the following trial outputs –

-

clinical exacerbation reports

-

participant diaries

-

participant case report forms (CRFs)

-

participant questionnaires.

-

-

Participant and partner experiences:

-

potential barriers to trial recruitment

-

challenges to trial adherence, including device acceptability.

-

A trained qualitative researcher elicited the participant and partner experience feedback through semistructured one-to-one telephone interviews during study month 9 (recruitment month 3). Ten trial participants and two participant partners (aged ≥ 18 years) living within the same home and sharing the same bedroom environment were invited to take part in the qualitative interviews. Although it was intended to recruit participants from different study sites, this was not possible within the 3-month deadline because of the initial slow recruitment rate. All telephone interviews were therefore conducted at the main study site, Portsmouth. Participants and their partners shared their views in separate telephone interviews.

Amendments to the trial protocol

Three amendments were made to the trial protocol following trial initiation. Each of these amendments was deemed necessary to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the trial for meeting its objectives. The amendments were as follows:

-

7 August 2014 (minor): Vitalograph Asma-1 USB device removed. Reason: the international stock levels of the original device were low; switching to similarly licensed devices minimised delays.

-

23 October 2014 (minor): removal of 12-month limit on historical bronchial challenge test results. Reason: several participants failed screening as their bronchial challenge test had fallen just outside the 12-month window. Removing this criterion ensured that more participants with asthma were able to be recruited.

-

28 May 2015 (major): three amendments to the trial inclusion criteria: (i) reduction in the lower age for participation from 18 years to 16 years, (ii) reduction in the length of the pre-screening stability period from 4 weeks to 2 weeks and (iii) reduction in the required ICS dose from > 1000 µg/day of BDP or equivalent to ≥ 1000 µg/day of BDP or equivalent. Reason: all amendments were based on examination of the reasons why participants failed screening. Working with patient advisors, amendments to the protocol were made to ensure that more participants were able to be screened as well as randomised.

All material in this report refers to the version of the protocol in place after these three amendments were made.

Eligibility and inclusion/exclusion criteria

Participants

The selected eligibility criteria reflected a population of participants with severe exacerbation-prone allergic asthma, which was also consistent with previous similar trials in this population (see Table 28).

Inclusion criteria

Potential participants had to meet all of the following inclusion criteria by randomisation visit 2 to be considered eligible for the study:

-

Adults (aged 16–75 years inclusive).

-

A clinical diagnosis of asthma for ≥ 6 months supported by evidence of any one of the following –

-

Airflow variability with a mean diurnal peak expiratory flow (PEF) variability {calculated by [PEF(highest) – PEF(lowest)]/[PEF(mean)]} of > 15% during the baseline 2-week period or a variability in forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) of > 20% across clinic visits within the preceding 12 months, with concomitant evidence of airflow obstruction (FEV1/FVC ratio < 70%, where FVC is forced vital capacity).

-

Airway reversibility with an improvement in FEV1 of ≥ 12% or 200 ml after inhalation of 400 µg of salbutamol (Ventolin® GlaxoSmithKline UK) via a metered dose inhaler and spacer at the first study visit or within the preceding 12 months.

-

Airway hyper-responsiveness demonstrated by methacholine challenge testing, with a provocative concentration of methacholine (Nova Laboratories, Leicester, UK) causing at least a 20% reduction in FEV1 (PC20) of ≤ 8 mg/ml, or an equivalent test (see Table 29).

-

-

Severe asthma –

-

Requirement for high-dose ICSs (≥ 1000 µg/day of BDP or equivalent; see Table 30) plus a second controller (long-acting β2-agonist or antimuscarinic, theophylline or leukotriene antagonist) and/or systemic corticosteroids.

-

If on maintenance corticosteroids, the maintenance dose must have been stable for 3 months; this excluded any interim need for short-term steroid bursts to treat exacerbations.

-

-

Poorly controlled asthma demonstrated by both –

-

Two or more severe asthma exacerbations requiring systemic corticosteroids of ≥ 30 mg of prednisolone or equivalent daily (or ≥ 50% increase in dose if maintenance dose of ≥ 30 mg prednisolone) for ≥ 3 days during the previous 12 months, despite the use of high-dose ICSs and additional controller medication.

-

ACQ (7-point scale) score of > 1 at screening visit 1 and randomisation visit 2.

-

-

Atopic status –

-

Sensitisation to one or more perennial indoor aeroallergens (including house dust mites, domestic pets or fungi) to which participants are likely to be exposed during the study, demonstrated by a positive skin prick test against Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus (Der p 1) or Dermatophagoides farinae (Der f 1), Aspergillus fumigatus (Asp f 1), Alternaria alternata (Alt a 1) or Cladosporium herbarum (Cla h 1), cat – Felis domesticus (Fel d 1) – or dog – Canis familiaris (Can f 1) (wheal diameter of ≥ 3 mm more than a negative control test) or specific IgE of ≥ 0.35 IU/l determined by blood test.

-

-

Recent medical stability –

-

Exacerbation free and taking stable maintenance asthma medications (not including short-acting bronchodilator or other reliever therapies) for at least 2 weeks prior to screening visit 1 and in the period between screening visit 1 and randomisation visit 2 (the screening period). Participants suffering a severe exacerbation during the screening period were rescreened 2 weeks after returning to their maintenance asthma medications.

-

-

Adherence –

-

Able to use the TLA device during sleep on at least five nights per week (excluding holidays).

-

Able to understand and give written informed consent prior to participation in the trial and able to comply with the trial requirements.

-

Exclusion criteria

Potential participants who met any of the following exclusion criteria were excluded from participating in the study:

-

Current smokers or ex-smokers abstinent for < 6 months.

-

Ex-smokers with a ≥ 15 pack-year smoking history.

-

Partner who is a current smoker and smokes within the bedroom where the TLA device is installed.

-

TLA device cannot be safely installed within the bedroom.

-

Intending to move out of study area within the follow-up period. (Participants moving out of the study area after randomisation were not automatically withdrawn. Every effort was made to continue treatment and trial follow-up.)

-

Documented poor treatment adherence.

-

Occupational asthma with continued exposure to known sensitising agents in the workplace.

-

Previous bronchial thermoplasty within 12 months of randomisation.

-

Treatment with omalizumab (Xolair®, Novartis Pharmaceuticals UK Ltd, Grimley, UK) (anti-IgE) within 120 days of randomisation.

-

Using long-term oxygen, continuous positive airway pressure or non-invasive ventilation routinely overnight, as it is known that this impairs the effect of the TLA device.

-

Uncontrolled symptomatic gastro-oesophageal reflux that may act as a persistent asthma trigger.

-

Presence of clinically significant lung disease other than asthma, including smoking-related chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), bronchiectasis associated with recurrent bacterial infection, allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (mycosis), pulmonary fibrosis, sleep apnoea, pulmonary hypertension or lung cancer, that, in the opinion of the principal investigator (PI), is likely to be contributing significantly to a participant’s symptoms.

-

Clinically significant comorbidity (including cardiovascular, endocrine, metabolic, gastrointestinal, hepatic, neurological, renal, haematological and malignant conditions) that remains uncontrolled with standard treatment.

-

Currently taking part in other interventional respiratory clinical trials.

Centres and care providers

The feasibility was considered of 25 secondary care providers as recruiting centres for the LASER trial. The 14 sites listed in Table 2 were selected, all with trial teams embedded within respiratory departments. Each of these recruiting centres activated the trial at different dates during the study period and these activation dates are also shown in Table 2.

| Site | Date of activation | Number randomised, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Portsmouth (trial lead site) | 7 May 2014 | 74 (31) |

| Liverpool (Aintree) | 17 June 2014 | 13 (5) |

| Birmingham (Heartlands) | 26 June 2014 | 28 (12) |

| Leicester | 09 July 2014 | 14 (6) |

| Southampton | 09 July 2014 | 25 (10) |

| Bradford | 09 September 2014 | 9 (4) |

| Royal Liverpool | 20 January 2015 | 18 (8) |

| London (St George’s) | 22 January 2015 | 11 (5) |

| Chester | 03 February 2015 | 6 (3) |

| Oxford | 26 February 2015 | 7 (3) |

| Hull | 02 April 2015 | 10 (4) |

| Maidstone | 07 July 2015 | 17 (7) |

| Birmingham (Queen Elizabeth) | 30 July 2015 | 5 (2) |

| Belfast | 26 August 2015 | 3 (1) |

The trial was very well supported by the lead site’s local Clinical Research Network (Wessex) as well as by the 13 other recruiting sites. This enabled the trial to facilitate the support of general practice surgeries in the Portsmouth area as participant identification centres (PICs). To ensure swift recruitment at the sites and to avoid protracted contractual negotiations between sites, commissioners and the supplier, in particular with regard to excess treatment costs (ETCs), it was agreed that the lead site and sponsor (Portsmouth Hospitals NHS Trust) would assume responsibility for receipt and distribution of all TLA devices and arrange separate research contracts with the sites. This prevented other sites from having separate contracts with the supplier with the risk that they may not be able to recover the ETCs associated with the active intervention. This risk was particularly acute because the sites and participants would be blinded to the treatment allocation and so any costs recovered for the active intervention could be based on only retrospective invoicing, often carried over into subsequent financial years, which would further complicate financial contracts.

Excess treatment costs

The Department of Health and Social Care agreed to provide a subvention payment to cover the ETCs for those recruited to the active intervention arm, contributing £2088 per participant. The sponsor was able to access this funding on behalf of all sites only once the study had recruited sufficient participants in a year to reach a threshold of £50,000 costs. At this point, the Department of Health and Social Care would contribute £2088 for each additional participant recruited to the active intervention arm of the study. The first year began on the date that a centre recruited its first participant to the study and the second year began on the first anniversary of that date, the third year on the second anniversary, and so on. The maximum subvention available for this trial was £131,768. The NHS was required to meet all other treatment costs associated with the study through local commissioning arrangements. The sponsor was able to invoice the Department of Health and Social Care 6-monthly in arrears for the ETCs incurred above the £50,000-per-annum threshold on behalf of all of the recruitment sites. Centres in Wessex (Portsmouth and Southampton) had made arrangements for the Wessex Clinical Research Network to fund the ETCs up to the £50,000 threshold and the trial and recruitment were set up to maximise that support, which we gratefully acknowledge.

Interventions

Treatment compared with comparator

Active devices

The active TLA device (Airsonett®; Airsonett AB, Ängelholm, Sweden) significantly reduces nocturnal allergen exposure by filtering ambient air through a high-efficiency particulate air filter, slightly cooling the air (0.5–0.8 °C) and ‘showering’ it over the participant during sleep. The reduced temperature allows the filtered air to descend in a laminar stream, displacing allergen-rich air from the breathing zone and thereby reducing allergen exposure without creating draught or dehydration. 39 The device is installed next to the participant’s bed, as shown in Figure 3, and is easy to use with no identified safety concerns in previous trials. The device is CE (Conformité Européenne) marked and licensed for use in the UK for allergic asthma. The device uses the same amount of electricity as a 60-W light bulb and has an anticipated lifespan of 5 years, with filter changes required every 6 months.

FIGURE 3.

The TLA device manufactured by Airsonett. Reproduced with permission from Airsonett AB (Ängelholm, Sweden).

Placebo devices

The placebo devices were adjusted to deliver isothermal air instead of slightly cooled air and holes in the filter effectively allowed the air to bypass it while still maintaining an equivalent sound and airflow level as with the active device. This allowed the placebo device to deliver a laminar flow of non-filtered, non-descending, isothermal air that, when mixed with the warm body convection current, ascended towards the ceiling and thus had no effect on the normal air flow pattern around the breathing zone. There was no difference in the air delivery rate, perceived air movements or sound level between the active and the placebo device. The human body is not able to detect an absolute temperature difference of 0.75°C and, therefore, there is no perceptible temperature difference sleeping beneath an active or a placebo device. Electricity usage was the same as for the active device and the filter was changed at 6-monthly intervals.

Asthma care during the trial

Treatments when stable

All participants were evaluated during the study follow-up visits (study visits 3–6) by clinicians with expertise in severe asthma. These experts were able to identify and exclude alternative or comorbid pathologies contributing to poor asthma control and confirm treatment adherence.

No adjustment or reduction in asthma medications (excluding antihistamines and nasal corticosteroids) was allowed during the trial (unless required for patient safety reasons) because of the significant risk of precipitating severe asthma exacerbations. Any variation in non-asthma medication usage was recorded at each follow-up visit [including the use of over-the-counter (OTC) medications].

Those participants using variable maintenance and adjustable reliever therapy (MART), which combines ICS and bronchodilator therapy in a single inhaler, were converted to a fixed-dose regimen (preferably without changing inhalers) and an alternative short-acting bronchodilator [e.g. salbutamol, terbutaline (Bricany®, AstraZeneca UK Ltd)] by the site team for the duration of the trial. A LASER ‘BDP equivalent’ dose calculator was developed to allow centres to easily calculate the BDP equivalent of their ICS based on the dose and frequency of use and on known pharmacokinetics of all available inhaled therapy.

Participants using a self-management plan (SMP) prior to the trial were allowed to continue and were asked not to change this during the trial treatment period.

Asthma exacerbations

Asthma exacerbations were managed following best clinical practice in the appropriate setting following the national BTS/SIGN guidelines. 16

If participants required urgent medical attention at any time during the follow-up period, they were instructed to call 999 and/or to attend the ED. Participants who did not require urgent medical attention were instructed to follow their normal process for seeking medical attention from their general practitioner (GP), practice nurse or asthma specialist within working hours and to contact their local primary care out-of-hours service at other times.

Participants who self-managed their OCSs were instructed to contact 999 if they required urgent medical attention or to self-manage in the community as directed by their agreed SMP if they did not require urgent medical attention.

Participants reported severe exacerbations to their local site trial team as soon as possible after exacerbation onset.

Clinicians prescribed the process for reducing and ultimately stopping corticosteroid treatment and returning to a normal maintenance dose after each exacerbation, determined by individual patient need.

Intervention standardisation

Prior to shipping, the manufacturer (Airsonett) ensured that all devices were quality checked to CE standard on air temperature regulation, airflow and breathing-zone particle reduction metrics. It also provided all of the required quality control documentation.

Adherence monitoring

To simplify adherence to the intervention, study devices were programmed at installation to automatically turn on for a minimum of 10 hours to cover the participants’ normal sleeping hours. This could be over-ridden by participants should they wish to start the treatment at a different time or turn off the device. Participants were allowed to increase their use of the device, for example for daytime naps. All episodes of use of the device were documented in the daily participant-completed TLA diary, which was collected at the follow-up visits (see Temperature-controlled laminar airflow diary).

Outcomes

The trial used validated, standardised primary and secondary outcomes for clinical asthma trials recommended by the ATS/ERS40 and endorsed by the Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials (COMET) initiative. 41 Comparison of data at multiple time points was carried out to assess the magnitude and rate of treatment response and variation in level of control.

Primary outcome

There was one primary outcome: severe asthma exacerbations occurring within the 12-month follow-up period.

Severe asthma exacerbations are defined in accordance with ATS/ERS guidelines40 as a worsening of asthma requiring systemic corticosteroids [≥ 30 mg of prednisolone or equivalent daily (or a ≥ 50% increase in dose if maintenance dose is ≥ 30 mg of prednisolone)] for ≥ 3 days. Courses of corticosteroids separated by ≥ 7 days were treated as separate severe exacerbations.

Measurement of primary outcome

Participants were asked to start a participant exacerbation diary (PED) when exceeding the ‘exacerbation dose’ threshold of systemic corticosteroids, individually defined for each participant during randomisation visit 2. The PED included PEF measurements (using the trial electronic PEF device), OCS dose, reliever medication use and nocturnal asthma symptoms. Participants were asked to report severe exacerbations to their local site trial team as soon as possible after onset via a dedicated telephone line or a secure NHS e-mail account. Whenever possible, participants were asked to attend an exacerbation review with their local trial team within 72 hours to corroborate the exacerbation, at which the local trial team completed an exacerbation review form.

If participants were not able to attend an exacerbation review, the PED was collected at the next follow-up visit.

Information about exacerbations was also collected from the participant-completed daily diary in which participants recorded their daily corticosteroid dose (TLA diary) and from follow-up visit forms completed by the clinician delivering each follow-up visit.

Details about how these various sources of exacerbation data were combined to make a useable primary outcome are detailed in Data collection.

Secondary outcomes

Quantitative

The three quantitative secondary outcomes of the LASER trial were:

-

Asthma control – to assess the impact of nocturnal TLA treatment on asthma control.

-

Quality of life – to ascertain the effect of TLA treatment on quality of life in participants with poorly controlled severe allergic asthma and their adult carers.

-

Impact and cost-effectiveness – to evaluate the impact of TLA treatment on health-care utilisation and related costs to fully assess the cost-effectiveness, both at 1 year and over the lifetime of the participant, of nocturnal TLA treatment using a cost–utility analysis to determine the incremental cost per QALY gained, and to evaluate the impact of TLA treatment on education/work days lost.

The data from which these outcomes could be determined were collected as detailed in the following sections. All data collected at the screening or randomisation visit were recorded by the attending clinician on CRFs. All data collected at any of the 3-, 6-, 9- or 12-month follow-up visits were recorded by the attending clinician on follow-up visit forms.

Asthma control

The following indicators of current asthma control were determined and recorded at the randomisation visit (as baseline data) and at each follow-up visit (3, 6, 9 and 12 months during the trial, as intervention data):

-

lung function measures –

-

pre-bronchodilator FEV1

-

mean morning pre-bronchodilator PEF rate over 2 weeks preceding the follow-up visit

-

fraction of exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO)

-

-

ACQ score

-

Asthma Control Diary (ACD) score over 2 weeks preceding the follow-up visits

-

22-outcome Sino-Nasal Outcome Test (SNOT-22) score.

The following indicators of risk of future adverse asthma outcomes were also determined and recorded at these visits:

-

severe exacerbations (see Asthma exacerbations)

-

systemic corticosteroid use over the 12-month follow-up period only

-

post-bronchodilator FEV1 at the 12-month follow-up only.

Quality of life

The following health-related participant quality-of-life scores were determined and recorded at the randomisation visit (as baseline data) and at each follow-up visit (3, 6, 9 and 12 months, as intervention data):

-

Standardised Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire [AQLQ(S)] score

-

EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L) score.

The following health-related adult carer quality-of-life score was determined and recorded at the randomisation visit (as baseline data) and at study visit 6 only (12 months, as intervention data), if the carer consented to this:

-

Adult Carers Quality of Life (AC-QoL) questionnaire score.

Impact and cost-effectiveness

The impact and cost-effectiveness measures that were calculated and recorded at follow-up visits were:

-

Work Productivity and Activity Impairment (Asthma) [WPAI(A)] score at the randomisation visit (as baseline data) and at 3, 6, 9 and 12 months (as intervention data)

-

Work Productivity and Activity Impairment (Caregiver) [WPAI(CG)] score at the randomisation visit (as baseline data) and at 12 months only (as intervention data)

-

health-care resource use and costs at 3, 6, 9 and 12 months.

Device usage

The following measures of device usage were determined and recorded at the follow-up visits to identify participants with persistent or recurrent non-adherence to the device usage requirement of five nights per week, excluding holidays:

-

participant-reported device usage at 3, 6, 9 and 12 months

-

engineer-reported device usage at 6 and 12 months only.

Persistent or recurrent non-adherence could lead to a participant being withdrawn from the trial.

Global Evaluation of Treatment Effect questionnaire

The Global Evaluation of Treatment Effect (GETE) questionnaire was completed at 12 months by both participants and physicians as a simple measure of the perceived treatment effectiveness of the TLA device, using five responses ranging from excellent (complete control of asthma) to worsening (deterioration in asthma).

Qualitative

In addition to the quantitative secondary outcomes described (see Quantitative), there was one qualitative secondary outcome:

-

acceptability – to qualitatively evaluate participant and carer perceptions, values and opinions of the trial process and TLA device to identify potential modifications to improve participant acceptance and to inform future implementation of the device within the NHS setting.

Supplementary variable

Indoor Air Quality Questionnaire

It was decided that the air quality of the indoor home environment should be measured as a supplementary variable in the LASER trial to maximise the impact of the investigation into non-intrusive management of people with severe allergic asthma. The statistical analysis of these measurements is not included in this report.

Sample size calculation

Members of the PPI group felt that a reduction of one severe exacerbation per year with a new treatment would be worthwhile to them and have a meaningful impact on their life. Based on an estimated rate of two severe asthma exacerbations per participant over the 12-month period in the placebo group (informed by previous trials; see Table 28), it was calculated that a minimum of 222 participants (111 per group) were required to provide 80% power (at the 5% two-sided significance level) to detect a clinically meaningful 25% reduction in the average exacerbation rate in the group using the TLA device. This sample size was based on a Poisson regression model with the treatment group as the covariate and a 10% overall dropout rate. 42 A review of comparative interventions of proven efficacy in severe asthma gave effect sizes ranging from 21% to 63%, with a mean of 41% (see Table 28). Given that this was a pragmatic trial in which the intervention was expected to be less effective than in an efficacy trial, a more conservative effect size of 25% was chosen deliberately. This represents, on average, one less severe exacerbation every 2 years.

Termination conditions

The Data and Safety Monitoring Committee (DSMC), a committee independent of the sponsor and with the major aims of safeguarding the interests of trial participants, monitoring the main outcome measures, including safety and efficacy, and monitoring data quality and completeness, was granted authority to be supplied with interim data emerging from the trial during the period of recruitment as frequently as was requested. In the light of interim data and other evidence from relevant studies, the DSMC could inform the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) if, in its view, there was proof beyond reasonable doubt that any part of the protocol under investigation was either clearly indicated or contraindicated, either for all participants or for a particular subgroup of trial participants. A difference of at least 3 standard errors (SEs) in the interim analysis of the major end point was indicated as potential justification for halting or modifying the trial prematurely.

Two post hoc analyses of the primary outcome data were requested by the DSMC: (1) using an alternative definition of severe exacerbation and (2) subgroup analysis by allergy to dust mites.

Recruitment

Participants

The trial opened to recruitment at Portsmouth Hospital on 7 May 2014, with the first participant randomised on 25 May 2014 and the last recruited in January 2016. In total, 545 participants were screened against the inclusion/exclusion criteria for the trial during this period: 56 of these were excluded and 489 were approached for consent. A total of 100 participants either refused consent or were excluded, with 389 being consented. Of these, 149 participants failed the pre-screening phase; 240 participants were entered into the trial and randomised.

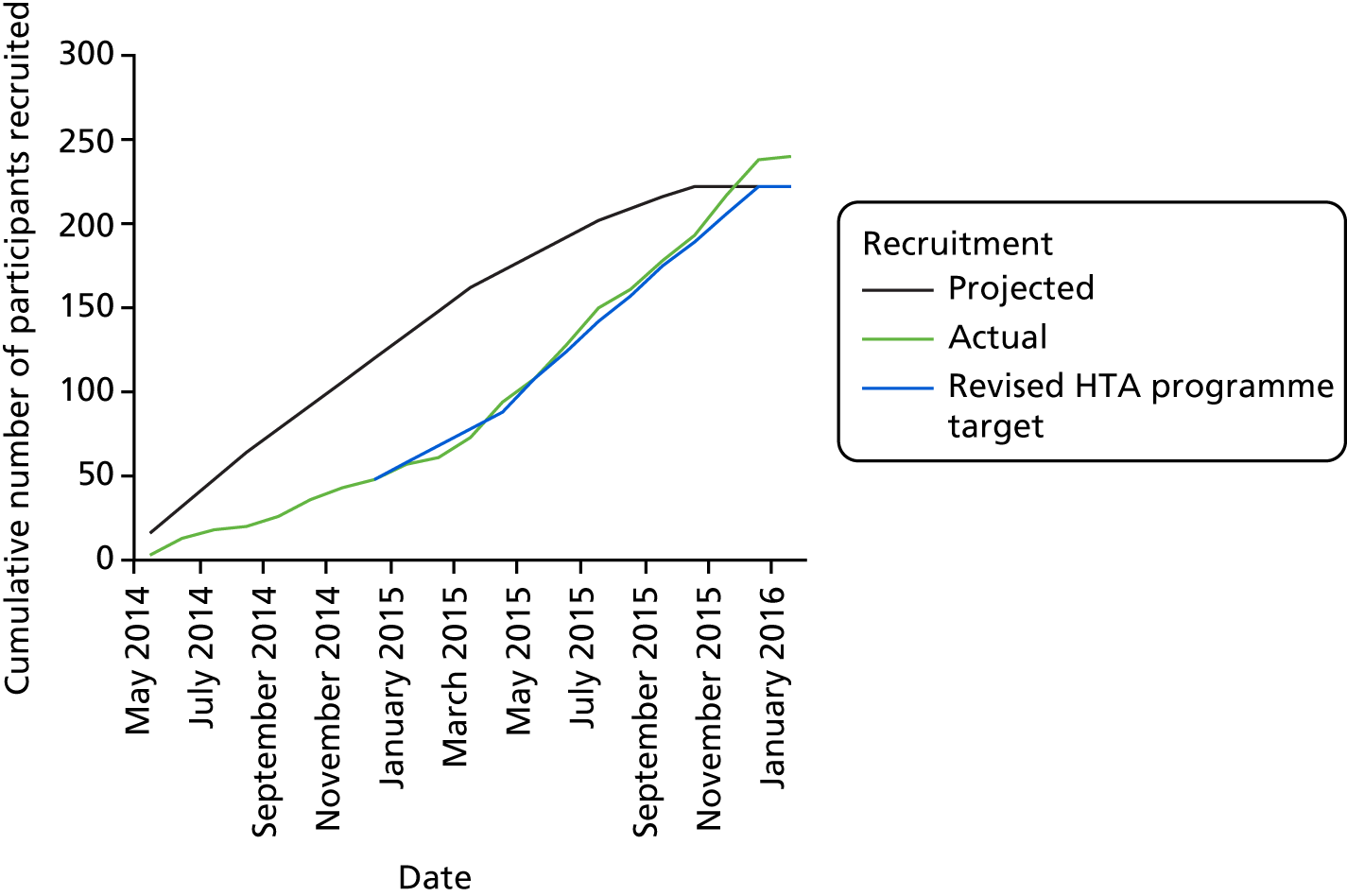

The overall recruitment rate is shown in Figure 4. It can be seen that the target participant recruitment rate was not met during the first 8 months of the trial. This was partly because of multiple recruiting sites activating their trial sites later than anticipated. Nevertheless, the revised recruitment trajectory was met and the recruitment target was ultimately exceeded (240 participants recruited instead of 222) because the 2-week pre-screening phase meant that new participants had already begun the pre-screening phase once the target had been met. It was felt unethical to exclude these participants on the basis of meeting a target.

FIGURE 4.

Participant recruitment rates.

Table 3 lists the sources that referred the 240 recruited participants to the trial. In total, 80% of participants were recruited as existing participants of the 14 health-care provider recruiting sites or PIC general practice surgeries. The majority of the remaining participants were recruited through social media channels, which are described in Social media.

| Referral source | Randomised participants, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Existing clinic patient | 192 (80) |

| Social media (Trialbee) | 27 (11) |

| Social media [Asthma UK/Allergy UK/Tillison Consulting (Waterlooville, UK)] | 13 (5) |

| Newspaper advertisement | 0 |

| Radio advertisement | 1 (< 1) |

| Other | 7 (3) |

| Total | 240 |

Adult carers and partners

Four adult carers consented to participation in the trial for the purposes of collecting quality-of-life and productivity information about these stakeholders; 32 partners gave informed consent for inclusion in the qualitative study.

Website

The trial website (see www.lasertrial.co.uk; accessed 29 November 2018) (see Figure 5 for a screenshot), which was approved by the relevant ethics committee, enabled the public to submit the following screening details if they were interested in participating in the trial: age, postcode, smoking status, allergies, number of exacerbations in the previous 12 months, current asthma treatment and current asthma symptoms. The trial team was notified of those individuals who passed these screening questions. The process was approved by the information governance framework of the sponsor and that of its Caldicott Guardian.

FIGURE 5.

The LASER trial website landing page.

Strategies for increasing trial publicity and channelling more traffic to the LASER website were required to facilitate recruitment to time and target.

Television coverage

In September 2014, Professor Chauhan (Chief Investigator) appeared alongside one of the trial participants in a news feature on British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) South Today. Following the broadcast, BBC South published the video on its Facebook (Facebook, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA; www.facebook.com) and Twitter (Twitter, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA; www.twitter.com) accounts. The Facebook post included a comment displaying the trial website URL so that potential participants could access more information and register for the trial. The Google Analytics tool (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) revealed that this social media interaction led to a significant increase in website traffic on the day of the broadcast, with 160 individual website sessions (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6.

BBC South social media content and result. Reproduced with permission from BBC South (Southampton, UK).

Social media

As more evidence is emerging from both commercially driven and academic trials that social media can be a useful tool in recruitment, a social media strategy for the LASER trial was developed. This strategy was considered to be especially appropriate for the trial population, who tend to be younger patients and are therefore likely to be working and have less time to engage with the traditional advertising and recruitment pathways, but who are likely to explore the availability of new treatments and technologies for their condition via the internet and social media platforms. All social media postings were approved by the ethics committee and moderated by the trial co-ordinator and the trial lead research nurse, who were involved in recruiting for the trial.

National charities

First, we partnered with national charities with an interest in the new treatment, Asthma UK and Allergy UK, which publicised the trial on their websites and posted trial information on both Twitter and Facebook that signposted patients to the LASER trial website; see Figure 7 for example content from Asthma UK, which has 29,000 followers on Twitter and has had > 40,000 likes on Facebook. Allergy UK has 5000 followers and has had > 7000 likes on Facebook.

FIGURE 7.

Asthma UK website, Facebook and Twitter content. Reproduced with permission from Asthma UK (London, UK).

Using Google Analytics, a spike in activity on the website was seen when posts/tweets were published.

Facebook and Twitter

Second, we partnered with Tillison Consulting (see https://tillison.co.uk; accessed 29 November 2018) to develop a LASER trial Facebook page and set up business accounts that facilitated trial advertisements on Facebook and Twitter. This business account permits targeted advertising, enabling us to set demographic parameters based on trial inclusion criteria (aged between 18 and 65 years, both men and women, location up to 50 km from a recruiting centre) and also to target people who have a search or following history that indicates an interest in asthma or asthma awareness. The tweets and posts directed people towards the study website and through the screening questions. Techniques such as ‘Google remarketing’ were also used, in which people who had visited the website would be shown ‘branded adverts’ in the following 30-day period, although these were less successful than the social media campaigns.

On Facebook, > 100,000 individuals were reached, there were 1361 clicks through to the website and a large number of patients engaged with the trial via ‘likes’, ‘shares’ and ‘comments’, which would have further increased the trial’s visibility if it led to patients sharing the information with friends or family with the condition. Similarly, on Twitter, > 150,000 people were reached.

Trialbee

Finally, in March 2015 we partnered with the Swedish company Trialbee (Malmö, Sweden), which specialises in social media solutions for clinical trials. On arriving at the Trialbee LASER trial ‘landing page’ (Figure 8), where there is information about the trial, interested patients answered a series of initial screening questions concerning their eligibility and those that passed screening were passed on to the trial team.

FIGURE 8.

Text from the Trialbee LASER trial landing page.

The Trialbee screening questions were answered 14,059 times, with 910 people passing questions. Of these, and following more in-depth screening by our trial team, 57 were eligible for the trial and 27 of these were consented and randomised to participate in the trial. This represented 16% of people recruited during this time period, demonstrating the power of social media for recruiting patients to clinical trials. In addition to being a cost-effective way to recruit patients, another benefit of social media engagement is that it empowers people to approach the research team of their own volition, thus possibly selecting more motivated, engaged research participants.

Adaptation of the recruitment approach

Many reasons for an initial delay in recruitment were encountered, as described in the following sections.

Delays in opening the first four and subsequent sites

There were a number of delays in opening the initial four recruiting sites because of delays in research and development (R&D) department approvals. We therefore identified a number of potential additional recruiting centres.

Change in National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommendations for omalizumab

After the trial began, NICE reappraised its technology appraisal guidance for omalizumab,14 a drug manufactured by Novartis that is a costly injectable anti-IgE therapy, delivered from centres with asthma specialists, and a treatment option that competes directly with the TLA device tested in this trial. In the 2007 guidance,43 the NICE recommendation included confirmation of IgE-mediated allergy to a perennial allergen by clinical history and allergy skin testing and with either two or more severe exacerbations of asthma requiring hospital admission within the previous year or three or more severe exacerbations of asthma within the previous year, at least one of which required admission to hospital and a further two that required treatment or monitoring in excess of the patient’s usual regimen in an accident and emergency (A&E) unit.

The revised guidance broadened the inclusion criteria to include any patient who needed continuous or frequent treatment with OCSs (defined as at least four courses in the previous year).

This expanded the population of patients who might be eligible for omalizumab (no requirement to attend hospital or EDs and everyone on OCSs for asthma, irrespective of their prior exacerbation history). This had a negative impact on LASER trial recruitment as it dramatically shrunk the anticipated ‘prevalent’ population of severe asthma patients previously identified by recruiting centres when performing the extensive feasibility assessments and recruitment projections.

Omalizumab treatment pathway

This change in the licensed indication for omalizumab led to considerable variation among centres regarding the treatment option offered to patients. Several centres offered omalizumab therapy to patients prior to them being considered for the LASER trial, even though they potentially met the eligibility criteria for both treatments; some specialists were concerned that half of the patients may be randomised to placebo in this trial and therefore could still remain potentially uncontrolled.

The eligibility criteria allowed the recruitment of participants with severe allergic asthma who had failed or responded only partially to omalizumab therapy after a washout period of 120 days. Even then, a ‘trial’ of omalizumab treatment involves 2-weekly injections for 16 weeks before a patient is deemed to have responded or failed treatment. Thus, any potential participant who was first offered omalizumab in preference to the LASER trial device would have received omalizumab for 16 weeks (4 months) and then could not be screened for another 3 months, delaying recruitment to the LASER trial even further.

Competition with other commercial research trials

There has been a plethora of monoclonal antibody treatments for severe asthma in the last 3 years, sponsored by the pharmaceutical industry and facilitated by all local Clinical Research Networks through their commercial portfolio to encourage centres to participate in more commercial trials. The 30-day metrics of the Clinical Research Networks ensures that centres are incentivised and performance managed to recruit patients into all portfolio trials, including those that were competing with the LASER trial. Naturally, nearly all of our centres were approached to participate in such trials, with significant variations between centres in terms of participation; in some cases participants were recruited to other trials in preference to the LASER trial.

NHS England service specifications for severe asthma centres

In 2013, NHS England controversially approved the service specification for a limited number of centres to be designated as specialist asthma centres (SACs) (Birmingham, Brompton, Leicester and Manchester being approved at the time of commencement of the LASER trial). The designation and numbers of SACs were finally confirmed in March 2019. One criterion for specialist status had been the introduction of ‘bronchial thermoplasty’ as a new treatment option in severe asthma, with a requirement that each SAC perform 10 procedures per year to maintain status; those aspiring to become a SAC are required to perform a similar number of procedures over a 12-month period. Given the political incentives, potential participants eligible for the LASER trial were, in some instances, considered for bronchial thermoplasty in preference to the LASER trial in order to meet the politico-clinical targets set by the service specification.

Screen failures prior to randomisation

The number of patients requiring active screening to the point of consenting was not known; consequently, centres had been unaware of the number of potential participants that needed to be screened over any given period of time to ensure a sufficient volume of randomisation. Based on estimates, it was anticipated that two of every three patients screened would progress on to randomisation. Although relatively minor, this guidance allowed centres to manage their recruitment performance.

Resource problems

Despite the trial being on the Clinical Research Network portfolio, there were several instances of Clinical Research Networks not being able to support sites with clinical staff because of lack of funding, which required the transfer of potential participants to other centres. Other centres similarly completed a feasibility assessment but did not open because of staff shortages.

Solutions to boost recruitment

The actions taken to overcome the challenges to recruitment were wide-ranging:

-

increase the number of centres

-

greater engagement and performance management of existing centres

-

website optimisation

-

search engine optimisation

-

use of Google Display

-

Google remarketing

-

use of social media

-

media broadcasts and outputs to facilitate recruitment

-

broaden eligibility criteria (i.e. reduction in ICS dose required, reduction in lower age limit for inclusion and reduction of screening period from 4 to 2 weeks)

-

modification of patient pathway at existing centres to ensure trial visibility (Chief Investigator visited some of the centres)

-

detailed interrogation of primary care for suitable participants.

Participant screening and enrolment

Screening visit (–2 weeks)

At the screening visit, informed consent was sought for participation in the main trial as well as the qualitative focus group sessions. Informed consent preceded any study procedures (including tests to ascertain eligibility for trial inclusion), thus ensuring that individuals had had an opportunity to fully discuss the participant information sheet (PIS) with the research team.

Individuals who met all of the inclusion criteria and did not meet any of the exclusion criteria pertinent to the screening visit (namely the baseline spirometry including the reversibility test, skin prick test, blood test and ACQ score criteria described in Eligibility and inclusion/exclusion criteria) were trained in the use of the electronic PEF meter to measure morning and evening PEF (prior to taking asthma medications) and in completion of the ACD for the 2 weeks prior to randomisation visit 2.

If appropriate, a PIS was given to each participant for his or her adult carer and/or partner to complete, if he or she also wished to participate.

Extension of the screening period

To continue to be deemed potentially eligible for the trial, individuals needed to demonstrate acceptable compliance with the electronic PEF recordings and ACD during the 2-week screening period. However, in the event of electronic PEF device malfunction or if, in the investigator’s opinion, there were significant extenuating circumstances, the screening period was extended by up to a further 2 weeks. Participants experiencing a severe exacerbation during the screening period were no longer eligible but could be rescreened 2 weeks after returning to their maintenance asthma medications.

Randomisation visit 2 (0 months)

The following data collected during the screening period and at the randomisation visit (study visit 2) were used to assess whether or not potential participants fulfilled the following remaining eligibility criteria (see Eligibility and inclusion/exclusion criteria for a full description of the eligibility criteria):

-

demographics, asthma history and asthma review (see Demographics, asthma history and asthma review)

-

review of the ACD, including electronic PEF recordings (see Asthma Control Diary)

-

ACQ score (see Participant questionnaires).

Those individuals who met these remaining eligibility criteria were confirmed as eligible for participation. The data used in the final eligibility assessment were supplemented by the following data from the CRF to act as baseline data (see Secondary outcomes, Quantitative, for descriptions of these measures):

-

SNOT-22, AQLQ(S), EQ-5D-5L, WPAI(A) and Indoor Air Quality Questionnaire scores

-

FeNO

-

baseline spirometry after withholding bronchodilator (pre-bronchodilator FEV1).

If appropriate, informed consent from adult carers of participants to participate in the trial was sought. If a participant’s carer was unable to attend, an additional appointment was arranged. After giving informed consent the carers completed:

-

the AC-QoL questionnaire

-

the WPAI(CG) questionnaire.

If appropriate, informed consent from partners of participants for inclusion in the qualitative study was also sought. Again, if a participant’s partner was unable to attend, an additional appointment was arranged.

Finally, participants were then provided with the materials required to measure and record the primary and secondary trial outcome data (see Outcomes and Secondary outcomes, respectively, for outcome definitions), including a TLA diary for self-reported device usage (see Temperature-controlled laminar airflow diary), a resource use log for health-care utilisation over each 3-month follow-up period (see Resource use log), at least three PEDs (see Participant exacerbation diary and exacerbation review form) and a 2-week ACD (including electronic PEF recordings; see Asthma Control Diary) issued for completion prior to the 3-month follow-up visit.

Randomisation

Devices

The trial statistician generated a list of LASER trial-specific device numbers (L-numbers) coded against a X or a Y (i.e. active or placebo), which they sent in a password-protected electronic file to the following Airsonett personnel only: Chief of Operations, the Director of R&D and the Director of Quality Assurance. This list was generated using the Stata® version 13.1 command RALLOC (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). A total of 400 codes were generated in blocks of 20 (10 active and 10 placebo) in line with Airsonett manufacturing the devices in blocks of 20.

The Airsonett personnel with access to the list oversaw the manufacture of the active and placebo devices according to the L-numbers. Each device was labelled with both L-number and manufacturing serial number.

Participants and minimisation criteria

Once the eligibility of an individual was confirmed at the randomisation visit, the trial team at the recruiting site contacted the Oxford Respiratory Trials Unit (ORTU; part of the Oxford Clinical Trials Research Unit) to arrange randomisation. Participants were randomised in a 1 : 1 ratio to receive either an active TLA device or a placebo device. Randomisation was undertaken centrally by Sealed Envelope™ Ltd (London, UK) using a validated computer randomisation program including a non-deterministic minimisation algorithm to ensure balanced allocation of participants across the two treatment groups for each clinical site, prevalent compared with incident cases and the following prognostic factors at baseline, which are key indicators of future exacerbation risk: exacerbation frequency in the previous 12 months (two, three or more than three), use of OCSs (yes/no) and pre-bronchodilator FEV1 (> 50% predicted yes/no). In essence, this approach accounted for the characteristics of the participants who had been previously randomised when randomising each new participant. By trial end, 119 of the 240 participants were allocated an active device and 121 were allocated a placebo device.

Participants previously known to the recruiting centre were termed prevalent participants, whereas participants not previously known to the recruiting centre but referred from another centre or through a social media channel were termed incident participants.

Once participant randomisation was complete, Sealed Envelope sent a secure e-mail to the local trial team to confirm randomisation and to provide the information required for implementation, described in the following section. It should be noted that the device allocation was embedded into the Sealed Envelope system.

Implementation

After randomisation of each new participant to the active or placebo treatment group, Sealed Envelope selected which device with the appropriate treatment would be received by each randomised participant. It then sent secure e-mail and text messages to the local independent device distributor (Bishopsgate Specialist Logistics & Installation, Swindon, UK), which specialises in medical devices, with the following details: participant trial number, allocated L-number (without X or Y designation so that the allocated treatment arm remained concealed) and an exclusive link for the engineering team to log in to access participants’ contact details.

Device installation

The Bishopsgate engineering team contacted participants within 72 hours of their randomisation visit to arrange device delivery and installation. Members of the engineering team were trained, with certificates of competency based on completion of a Good Clinical Practice (GCP) training course on trial procedures, and they followed a standard device delivery, filter change and removal protocol developed by the trial team. The agreement with Bishopsgate was that devices should be installed within 10 working days, excluding weekends and bank holidays. Members of the engineering team left written instructions on device operation for participants during the installation visit.

Device maintenance

Devices had a filter change 6 months into their use in the trial, automatically calculated from the date of randomisation. The Trial Manager informed Bishopsgate on a monthly basis of which filter renewals were due.

Troubleshooting

One item discussed during the telephone review conducted by the site research team with participants 1 month into their trial period was troubleshooting on any issue related to the trial, including difficulties with using the device.

Blinding

The methods described above for the manufacture of the active and placebo devices, the allocation of participants to the two treatment arms and the implementation of device installation ensured that all participants, trial teams and members of the installation team were blinded to the trial treatments. This ensured that everyone apart from the statistician who generated the codes for the devices and the programmers at Sealed Envelope was blinded to treatment allocation. Airsonett was the only party to know the differences between the real and the placebo devices but it did not have access to any information related to participants recruited to the trial or device usage once in the UK.

Study assessments

This section describes the quantitative and qualitative data collected at the study visits, including those recorded between study visits:

-

quantitative data –

-

demographics, asthma history and asthma review

-

lung function measures:

-

pre-bronchodilator FEV1

-

reversibility testing

-

FeNO

-

-

allergy testing:

-

skin prick test

-

serum-specific IgE testing

-

measurement of serum total IgE and peripheral blood eosinophil count

-

-

participant questionnaires:

-

ACQ

-

AQLQ(S) (disease-specific quality of life)

-

EQ-5D-5L (generic quality of life)

-

SNOT-22 (rhinosinusitis health status)

-

Indoor Air Quality Questionnaire

-

GETE questionnaire

-

WPAI(A) questionnaire

-

-

carer questionnaires:

-

AC-QoL questionnaire

-

WPAI(CG)

-

-

pre-visit data collection:

-

ACD – PEF rate, symptom and reliever medication use

-

TLA diary – device usage, corticosteroid dose, reliever usage, work/study days lost

-

resource use log: health-care usage

-

PED

-

-

-

qualitative data –

-

focus groups.

-

These quantitative and qualitative data were used for one or more of the following six purposes:

-

to inform eligibility of an individual to participate in the trial against the inclusion and exclusion criteria (see Eligibility and inclusion/exclusion criteria, Participants) (P1)

-

to build the primary outcome data set (see Primary outcome for the primary outcome definition) (P2)

-

to build the secondary outcome data sets (see Secondary outcomes for the secondary outcomes definitions) (P3)

-

to create participant factor data sets used to control the primary and secondary outcome data against associations unrelated to the treatment (P4)

-

to contribute to the baseline outcome data sets (P5)

-

to build the supplementary variable data sets that may be used for future analyses, not all of which are mentioned in Supplementary variable (P6).

The purpose of each type of data mentioned in the following section is indicated by the codes P1–P6.

Quantitative data

Demographics, asthma history and asthma reviews

The following data were recorded about each participant on the CRF at the randomisation visit only:

-

demographics –

-

age (P1, P4)

-

sex (P4)

-

socioeconomic class (P4)

-

ethnicity (P4)

-

-

asthma history –

-

date of asthma diagnosis (P1, P4)

-

history of life-threatening and near-fatal asthma exacerbations [intensive treatment unit (ITU) admissions] (P6)

-

number of severe asthma exacerbations in previous 12 months (P1, P5)

-

history of previous asthma treatment (P1)

-

history of atopy (P1)

-

family history of asthma/atopy (P6)

-

asthma triggers (P1)

-

medical or surgical comorbidities (P1)

-

occupational history (P1)

-

smoking history (P1)

-

height (cm)/weight (kg) for measuring predicted lung function (P3).

-

The following data were collected at each follow-up visit as well as at the randomisation visit and recorded by the attending clinician on the follow-up visit form/CRF:

-

asthma review

-

current asthma symptoms and treatment (P1, P3, P5)

-

current medications (P1)

-

history of severe asthma exacerbations since the previous trial visit and current participant-reported clinical status (still in exacerbation or recovered) (P2)

-

unscheduled asthma-related health-care use (P3)

-

work/study days lost as a result of asthma symptoms (P3).

-

Lung function measures

The following indicators of lung function were collected at the study visits:

-

Pre-bronchodilator FEV1 (P1, P3, P5) – spirometry was conducted at the screening visit, the randomisation visit and the 3-, 6-, 9- and 12-month follow-up visits to collect the following variables:

-

FEV1 (l)

-

FVC (l)

-

FEV1/FVC ratio

-

forced expiratory flow at 25–75% of the pulmonary volume (FEF25–75) (%).

FEV1 and FVC were documented both as absolute values and as a percentage of the predicted value. A spirometer conforming to ATS/ERS standards44 was used as specified by the manufacturer’s instructions.

-

-

Reversibility testing (P1, P3, P5) – post-bronchodilator FEV1 (both percentage change and volume change) was measured at the screening visit and 12-month follow-up visit only. Following ATS/ERS standards,44 post-bronchodilator FEV1 was defined as FEV1 recorded 15 minutes after administration of 400 µg of salbutamol via a metered dose inhaler and spacer device. An improvement in FEV1 post-bronchodilator use of ≥ 12% or 200 ml was considered significant.

-

FeNO (P1, P3, P5) – FeNO was measured before spirometry at the randomisation visit and the 3-, 6-, 9- and 12-month follow-up visits. The measurements were made using a NIOX MINO® device (Aerocrine AB®, Solna, Sweden) as specified by the manufacturer’s instructions and outlined in the ATS/ERS standards. 45

Allergy testing

The following allergy tests were made during the screening visit to determine whether the allergy-related trial inclusion criteria were met:

-

Skin prick testing (P1) – a standard skin prick test procedure using common indoor aeroallergen (Der p 1, Der f 1, Asp f 1, Alt a 1, Cla h 1, Fel d 1 and Can f 1) extracts along with negative (saline) and positive (histamine) controls was performed on all subjects. This occurred during the randomisation visit instead of at the screening visit if antihistamine hold was required (see Appendix 1). Skin prick testing was performed in accordance with the practice parameter released by the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. 46 A positive skin prick test reaction was measured as a wheal of at least 3 mm diameter greater than the negative control.

-