Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 10/57/21. The contractual start date was in May 2013. The draft report began editorial review in November 2017 and was accepted for publication in September 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Lynn Rochester reports grants from Newcastle University during the conduct of the study and grants from Parkinson’s UK, the European Union Marie Curie Training Network, the Medical Research Council, the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, the Wellcome Trust and the Stroke Association, outside the submitted work. Claire Ballinger is a member of the Primary Care Community and Preventive Interventions Health Technology Assessment (HTA) group and the associated Methods group. Victoria A Goodwin reports grants from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) during the conduct of the study (as a co-applicant), that is the NIHR HTA-funded trial (15/43/07) home-based exercise intervention for older people with frailty as extended rehabilitation following acute illness or injury, (ISRCTN13927531). Sarah E Lamb reports grants from the NIHR HTA programme during the conduct of this study. Furthermore, she was a member of the HTA Additional Capacity Funding Board, HTA End of Life Care and Add-on Studies, HTA Prioritisation Group and HTA Trauma Board during this study.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Ashburn et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease

Parkinson’s disease (hereafter referred to as Parkinson’s) is a progressive neurological condition characterised by impairments of movement and postural control (balance) and non-motor deficits. 1 There are estimated to be around 127,000 people with Parkinson’s in the UK. 2 The prevalence of Parkinson’s increases steadily with age. 2

Falls in Parkinson’s

Falls among people with Parkinson’s are both common and disabling. 3,4 Approximately 40–70% of people with Parkinson’s fall each year, and one-third fall repeatedly. 5 Overall, people with Parkinson’s are twice as likely to experience falls as a healthy elderly population. 6 There is evidence to show that falls have a major impact on the lives of people with Parkinson’s, including debilitating effects on confidence,7 decreased activities levels8,9 and reduced quality of life. 10 Such falls are financially costly for individuals and health-care systems. Repeat falls are a risk factor for further falls and carry devastating consequences, such as fractures, immobility and fear of falling leading to dependency and social isolation. 4 Although the incidence of falling increases with disease severity, falls are common even in the early stages of the condition. 11

Falling among those with Parkinson’s is associated with a host of risk factors, including disease severity, duration of disease,12,13 self-reported disability12 and impaired mobility,11 as confirmed by Canning et al. 6 The strongest predictor of falling, identified from meta-analysis, is having had a previous fall. 4,6 Loss of motor control [e.g. anticipatory and reactive postural control, reduced leg muscle strength, proprioception and gait speed, increased gait variability and freezing of gait (FoG)] have also been shown to be associated with, and predictors of, falls. 14,15 In addition to the motor symptoms, impaired cognition and orientation,14 as well as misjudgement and distraction,16 have also shown significant association with falling.

Falls prevention

Drugs are the main treatment used to manage the symptoms of Parkinson’s, while research into finding a cure continues. However, reduced postural control and falls do not respond to medication. 3 It has long been accepted that exercise is a fundamental component of treatment for people with Parkinson’s, alongside medical and surgical management, and its positive effects on symptoms are well supported in the literature. There is substantial evidence showing that regular exercise can be particularly beneficial for people with Parkinson’s to maintain postural control, mobility, daily living activities and general symptom management. 17,18 At the conception of this trial, there was no definitive evidence that an exercise programme would be as effective in the population of people with Parkinson’s as it is in the general population. Research has also shown that selecting and targeting each of the symptoms independently may not be enough to influence the falls rate. Instead, a multidimensional model that combines functional exercises with behavioural strategies is likely to provide a greater influence on reducing falls. 19

PDSAFE is an example of a multidimensional programme. 19 It is an individualised, home-based, physiotherapist-delivered, personalised treatment programme of exercises and strategies to help prevent falls in Parkinson’s. The novelty lies in both the content (i.e. disease-specific exercises and strategies for instability, use of motor relearning and cognitive awareness) and delivery [i.e. personalised feedback using a digital versatile disc (DVD) for adherence and self-management]. The programme comprises (1) exercises for postural control, gait and muscle weakness; (2) strategies for reducing freezing and encouraging stability and gait efficacy; and (3) a feedback model to promote learning and adherence. Frequency of intervention sessions is faded over time, 1 hour twice a week for 1 month, then once a week for a further 2 months, then once a month for another 3 months.

Primary aim of the PDSAFE trial

The primary aim of this trial was to determine the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a novel personalised exercise and strategy intervention (PDSAFE) as a supplement to usual health-care management in people with Parkinson’s.

Research questions

-

Do fallers with Parkinson’s who undertake PDSAFE with usual care have fewer falls than those who do not undertake the treatment programme during months 0–6 after randomisation?

-

Do fallers with Parkinson’s who undertake PDSAFE with usual care have fewer falls than those who do not undertake the treatment programme during months 6–12 after randomisation?

-

Do fallers with Parkinson’s who undertake PDSAFE have better balance, mobility and quality of life than those who do not undertake the treatment programme?

-

Is the PDSAFE intervention cost-effective, compared with usual care for people with Parkinson’s, from an NHS perspective?

-

What are the personal insights of those who participate in the intervention?

Pilot study

Aims and objectives

Prior to the main trial, a small pilot study was conducted as part of the protocol development work. The aims of the PDSAFE pilot study were to confirm the:

-

content and delivery of the novel intervention

-

implementation of procedures for recording and checking treatment fidelity

-

battery of assessments to be administered at the baseline and follow-up visits.

The objectives of the PDSAFE pilot study were to:

-

recruit a sample of up to 20 people with Parkinson’s: up to 10 in Southampton and up to 10 in Newcastle

-

take informed consent from up to 20 people with Parkinson’s

-

complete screening measures on up to 20 people with Parkinson’s

-

test the collection of falls data through the use of diaries with up to 20 people with Parkinson’s

-

complete baseline assessments with up to 20 people with Parkinson’s

-

assess the time taken to complete assessments

-

determine the feasibility of assessments

-

determine the acceptability to participants of assessments

-

deliver the PDSAFE intervention to up to 20 people with Parkinson’s.

Procedure

Ethics approval was given by the South Central – Hampshire B National Research Ethics Service (reference number 13/SC/0538). Sixteen participants were recruited [six from Newcastle and 10 from Southampton, including one patient and public involvement (PPI) representative]. All participants completed all screening measures [i.e. Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), Hoehn and Yahr (H&Y) scale and falls characteristics]. Six participants from each site completed baseline assessments, participated in the intervention for 1 month and completed the battery of assessments post intervention. The remaining four participants in Southampton provided falls diaries only, to test the diary completion required prior to randomisation in the main trial.

Two patterns of treatment delivery were tested to establish the most appropriate way of providing the intensity of treatment in the early stages. In Newcastle, participants had the intervention for two sessions a week for 3 weeks, then once a week for 1 week. In Southampton, participants had treatment for two sessions a week for 2 weeks and then once a week for 2 weeks.

Outcome

Overall, the participants enjoyed the treatment. Participants’ comments included ‘very pleased he participated – he has found it very beneficial and continues to use several strategies’, ‘Doing all home exercises and feels his balance is getting better’ and ‘have enjoyed the exercises and have learned a lot about keeping active’.

The therapists were enthusiastic about the programme and recognised the importance of mapping the house for problem mobility areas and integrating the exercises with video strategies appropriate for each individual. They commented that there was a lot to do in the initial stages around planning the strategies and fitting the weighted vests, so the pattern of treatment of two sessions a week for 3 weeks may be more valuable than two sessions a week for 2 weeks. However, it was agreed that this may not be appropriate for each person and that some flexibility in the way the sessions are delivered should remain. Training was recognised as very important. Some people found the weighted vests difficult to put on and required help from their partner; most people could tolerate only a small percentage of body weight in the vests, yet most people viewed them positively.

The outcomes of the pilot study were discussed at a face-to-face meeting of the grant holders, which was also attended by three PPI members; adjustments to the protocol were suggested and implemented. The pilot study confirmed the content and delivery of the novel intervention for the main trial (including printed versions of the exercises and strategies, video vignettes for play on a tablet or DVD and the use of weighted vests for strengthening exercises). Procedures for recording and checking treatment fidelity were also established, including weekly telephone and Skype™ (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) consultations with the physiotherapists. As a result of the pilot, the assessment time was shortened and procedures tightened. For example, the handgrip strength measurement test20 was dropped from the main study, but retained as a substudy in the Portsmouth area; and the shorter (15- instead of 30-question) version of Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) was used.

Chapter 2 Methods

Material in this chapter has been adapted from the trial protocol by Goodwin et al. 21 © Goodwin et al. ;21 licensee BioMed Central. 2015. This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Trial design

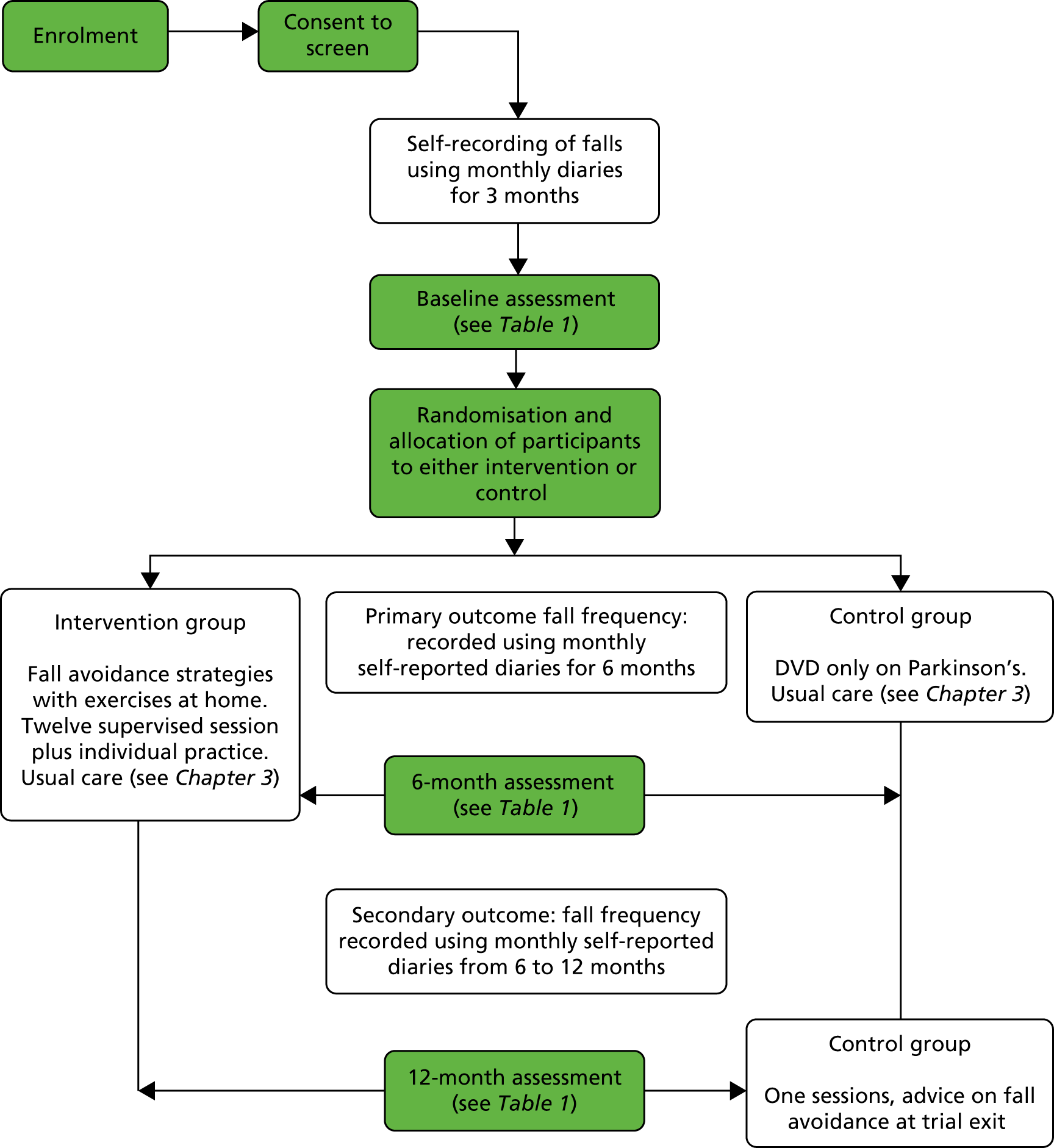

The PDSAFE trial was a UK, multicentre, community-based, single-blind, randomised controlled trial (RCT) with a 12-month follow-up, with nested economic evaluation and qualitative studies. Ethics approval was given by the South Central – Hampshire B National Research Ethics Service (reference number 14/SC/0039). Local research and development approval was obtained at each participating centre. Figure 1 shows how people with Parkinson’s progressed through the trial.

FIGURE 1.

Diagram showing trial plan.

Initially, four recruitment centres were identified: Southampton, Portsmouth, Bournemouth and Poole, and Exeter. The aim was for each of these to recruit 150 people with Parkinson’s to the trial over a 16-month period. Unfortunately, there were several delays in site set-up, and several sites found that they did not have as many people with Parkinson’s as anticipated. Four additional sites were opened: Newcastle, Winchester and Basingstoke, Plymouth and Truro. These centres represent a range of socioeconomic environments. Unfortunately, it was not possible to secure additional funding to follow up participants recruited in these new centres beyond the primary outcome measure at 6 months. Therefore, only participants randomised before 1 May 2016 had a final 12-month assessment.

Participants

Inclusion criteria were broad to allow inclusion of a wide spectrum of Parkinson’s patients in order to provide a generalisable result. Participants were eligible to be included to the trial if they met the following criteria:

-

had a confirmed consultant’s diagnosis of Parkinson’s

-

lived at home

-

had experienced at least one fall in the previous 12 months

-

were able to give informed consent

-

were able to understand and follow commands

-

were able to complete a programme of exercises

-

scored ≥ 24 on the MMSE

-

were willing to participate.

Participants were not eligible to be included in the trial if they:

-

lived in a care home with or without nursing

-

required assistance from another person to walk indoors

-

were wheelchair bound or bedridden unless aided, as defined by H&Y scale stage 5.

Recruitment and selection

Recruitment ran from July 2014 to August 2016. Trial participants were recruited through hospital clinics and Parkinson’s services, through local Parkinson’s UK groups and websites and through word of mouth/the trial website. Research packs comprising an invitation (see Appendix 1), the participant information sheet (see Appendix 2), a response slip (see Appendix 3) and a Freepost pre-addressed envelope were distributed. Once response slips were received by the trial office, trained trial assessors visited potential participants in their own homes to complete consent and screening assessments. The screening assessments included MoCA,22 the MMSE, 23 the H&Y scale,24 demographic information and medical history. Participants were asked to retrospectively recall the number of falls that they had experienced in the previous 12 months. The screening visit was followed by a prospective falls monitoring period of at least 13 weeks.

Three months after a screening visit, the assessor returned to carry out the baseline assessment (October 2014 to November 2016). The assessor checked that the participant was willing to participate in the trial and that they met the criteria to enable them to proceed to the next stage of the trial; the assessor then conducted the baseline assessments with people with Parkinson’s and initiated the randomisation procedure but was blinded to the group allocation. Blinded assessments were repeated 3, 6 and 12 months following randomisation (up to November 2016). Participants recruited during the extension period (those randomised after 1 May 2016) were followed to the primary outcome (6 months) only because of restricted funding.

Randomisation and therapy allocation

Patients were randomised (50 : 50) to receive PDSAFE (intervention group) or usual care plus provision of a Parkinson’s information DVD (control group), using an online randomisation service at the Oxford Clinical Trials Research Unit, University of Oxford. Random allocations were computer-generated, stratified by centre and allocated in blocks with a random size of two, four, six or eight participants. This ensured that the allocated groups within centres were as evenly distributed as possible, while maintaining a system in which allocations were unlikely to be deduced by those needing to remain blinded. The randomisation outcome was e-mailed to the trial co-ordinating centre via the PDSAFE e-mail address and forwarded to the therapy team. The assigned therapist contacted participants within 2 days to inform them of the randomisation outcome and arrange the first visit with them (within 2 weeks for those in the intervention group and within 4 weeks for those in the control group). The same therapist at each site saw control and intervention participants.

Participants in the control group continued to receive their usual care. In addition, they were given a DVD, produced by Parkinson’s UK, containing information about living with Parkinson’s (this was not falls-specific information). A physiotherapist visited the control group participants after randomisation to explain their allocation and the importance of the control group; at the end of the trial, once their final follow-up assessments had been completed, control group participants received guidance on physical activities and strategies for postural control and safety in accordance with their profile of fall events.

For a full description of the PDSAFE intervention refer to Chapter 3.

Outcome measures

The outcome measures are summarised in Table 1. The primary outcome was risk of repeat falling in the first 6 months after randomisation. A fall was defined as an event that resulted in a person coming to rest on the ground or other lower level not as a result of a major intrinsic event or overwhelming hazard. 25 A near-fall was deemed to have occurred when an individual felt that they were going to fall but managed to prevent themselves from doing so. 26 Fall events (falls and near-falls) were recorded using monthly self-completed diaries, which have been used successfully in other studies. 16 Diaries were given to participants by assessors during the visits to conduct screening, baseline and follow-up assessments. The assessors explained to participants how the diaries should be completed and left writing instructions. Participants were asked to return diaries by post each month in a Freepost envelope provided. See Appendix 4 for copies of falls diaries and instructions.

| Screening measure | Source | Time point |

|---|---|---|

| MoCA | Assessor | Screening visit |

| Retrospective recall of falls over the previous 12 months | ||

| MMSE | ||

| H&Y scale | ||

| Demographic information and medical history | ||

| Primary measure | ||

| Fall events 0–6 months (falls) | Monthly self-report diaries | Completed from screening visit to end of participation in trial (maximum of 15 months) |

| Measures | ||

| Fall events 0–6 months (near-falls and fractures) | Monthly self-report diaries | Completed from screening visit to end of participation in trial (maximum of 15 months) |

| Fall events 6–12 months (falls, near-falls and fractures) | Monthly self-report diaries | |

| Mini-BESTest (a test of postural control/balance control) | Assessor | Completed at baseline and at each follow-up assessment (at 3, 6 and 12 months) |

| Timed CST | ||

| Handgrip strength test (substudy in one area only) | ||

| PASE | ||

| PDQ-39 (a quality-of-life measure designed specifically for people with Parkinson’s) | ||

| GDS – 15-question version | Self-report | |

| FES-I | ||

| NFoG test [a questionnaire on FoG (freezing is closely linked to falling)] | ||

| Medication use | ||

| MDS-UPDRS – motor section | ||

| Health professionals and exercise | ||

| Economic measures (people with Parkinson’s) | ||

| Health and social care resource use sheet | Assessor | Completed at baseline and at each follow-up assessment (at 3, 6 and 12 months) |

| EQ-5D | Self-report | |

| Economic Measures (carer) | ||

| Carer demographic information and caring role | Self-report | Completed at baseline and at each follow-up assessment (at 3, 6 and 12 months) |

| CES | Self-report | |

| CSI | Self-report | |

Secondary analysis of the primary outcome measure included rates of falling between 0 and 6 months. Secondary outcomes included risk of repeat falling between 6 and 12 months; rates of falling between 6 and 12 months post randomisation; the Mini-Balance Evaluation Systems Test (Mini-BESTest), a test of balance control;27 the Chair Stand Test (CST); the new freezing of gait test, a questionnaire on FoG;28 the 39-item Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire (PDQ-39), a quality-of-life measure designed specifically for people with Parkinson’s;29 the short, generic quality-of-life measure known as EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) for economic evaluation;30 the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS), 15-question version;31 the Falls Efficacy Scale – International (FES-I);32 and the Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE). 33 The International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society – Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS) – motor section,34 MoCA,22 data on medications, use of professionals and exercise activity outside the trial were not regarded as outcome measures, but were measured at all time points for characterisation of the population. The Carer Experience Scale35 and the Caregiver Strain Index36 were administered to carers at baseline and follow-up time points to capture some broader effects of the intervention.

Power and sample size

Primary outcome: risk of repeat falling between 0 and 6 months

The power and sample size calculations were based on the findings of a previous trial by Ashburn et al. 37 This was a rehabilitation trial similar to PDSAFE in design. In the EXSART trial,37 the risk of repeat falling in a 6-month period was 68% in the control group and 56% in the exercise group. However, falls risk was anticipated to be lower in PDSAFE because EXSART was restricted to people who had fallen twice or more often in the previous year. Therefore, it was assumed that the risk of repeat falling between 0 and 6 months would be 63% for the control group and 50% for the intervention group. This required 228 participants per group, with data for analysis of 456 participants in total. Allowing for a 5% drop-out rate between randomisation and 6 months meant that 480 participants needed to be randomised. Furthermore, allowing for a 10% drop-out rate between agreeing to the 3 months pre-randomisation falls collection and randomisation meant that 534 participants needed to be recruited to the pre-randomisation falls collection period. In total, 541 participants were recruited to the pre-randomisation falls collection period. Power calculation scenarios are summarised in Appendix 6, Tables 26 and 27.

Power calculations (see Appendix 6) for rates of falling were based on Tango38 and related to the number of falls during a fixed follow-up period, analysed using negative binomial regression conditioned on baseline counts: specifically, formula 23 in the paper38 was used, assuming equal rates in the baseline and follow-up periods in the control group and a follow-up period of twice the length of the baseline. Anticipating a falls rate ratio (FRR) of 0.8 between 0 and 6 months post randomisation, that is a 20% reduction in the rate of falling in the intervention group compared with the control group, and based on a rate of 2.5 falls in the 3-month baseline period, 197 participants per group were required at analysis, which led to 488 participants being recruited to the pre-randomisation falls collection period.

Other scenarios were considered for the differences in risk of repeat falling or for the FRR (see Appendix 6, Tables 26 and 27) and generally led to recruiting fewer than 600 participants to the pre-randomisation falls collection period. All the calculations aimed for 80% power in 5% two-sided tests between the intervention and control groups.

Embedded substudies

Once people with Parkinson’s were consented to take part in the main trial, participants were asked if they would be willing to take part in the qualitative substudy that ran alongside the main trial. The qualitative researcher contacted suitable participants on the basis of a theoretical sampling strategy (see Chapter 5). Forty–two selected participants from the intervention group agreed to partake in qualitative interviews, before and after receiving treatment (see Chapter 5).

At the point of recruitment, participants were asked if they had a carer. An information sheet was provided for the carer, along with an invitation letter, response slip and pre-paid Freepost envelope; the substudy explored carers’ quality of life. If a carer expressed a wish to take part, they were invited to attend the participant’s (people with Parkinson’s) baseline visit and informed consent was taken from them at that time. There were 463 participants with a carer; 189 carers agreed to take part.

Statistical analysis

A statistical analysis plan was finalised before the data set was unblinded. An intention-to-treat (ITT) approach was used for the main analyses with data analysed on the basis of group allocation. When there were incomplete diaries, a participant was coded as a repeat faller if they reported two or more falls in their incomplete diaries or if there was a report of two or more falls from a retrospective recall at the end of the trial; otherwise, they were included as a non-repeat faller if they had completed ≥ 50% diary days for the period in question. Participants not reporting two or more falls, completing < 50% of diary days and with no other indication of repeat falling during a follow-up period were excluded.

Repeat faller status during 0–6 months (primary outcome) and 6–12 months post randomisation was analysed in logistic regression controlling for site, age, gender, H&Y scale stage as a regressor, the logarithm of retrospectively collected number of falls in the year prior to screening, repeat fall status prior to screening and the logarithm of the prospectively collected rate of falling during the 3-month period prior to randomisation. A small quantity, 0.5, was added to numerators of the rates of falling so that participants with zero falls during the period were included; the results are not sensitive to the quantity added. 39 These controlling variables were finalised in a blind analysis without access to the group indicator, as specified in the analysis plan, and were included in all regression models. Rates of falling during the periods 0–6 months and 6–12 months post randomisation were examined in negative binomial models fitted with command nbreg in Stata® version 11 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). The logarithm of a participant’s days of diary follow-up was included in nbreg modelling as an offset.

Odds ratios (ORs) and FRRs are presented with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The geometric means of individual participant rates (with 0.5 added to the numerator, as before) of falling during 6-month follow-up periods are presented as rates per 6 months to accommodate the skewed distribution across participants. Prespecified subgroup analyses for falling between 0 and 6 months post randomisation were undertaken to identify the differential impact of the intervention according to MoCA status (≤ 25 and ≥ 26) and freezing status, and removing participants with most severe disease by virtue of the MDS-UPDRS (≥ 58) and H&Y scale stage (1–3). Differential effects were further explored on the basis of MoCA, MDS-UPDRS and number of falls in the year prior to screening by creating subgroups defined by tertiles at baseline. All the subgroup analyses involving tertiles were exploratory, that is they were not pre-stated. Both MoCA and MDS-UPDRS had been pre-stated but with different cut-off points and had shown some indication of differential effects.

Retrospective falls recall was examined by Canning et al. 40 as pre-stated subgroups but with different cut-off points; we wished to check the statistically significant interactions that they reported. Therefore, the decision was taken to examine subgroups defined by tertiles, not selected cut-off points. Subgroup analysis started with likelihood ratio tests for interaction in logistic models and Wald tests for interaction in the negative binomial models. Within-subgroup intervention effects are presented with 95% CIs. A secondary per-protocol analysis was carried out, as prespecified, by excluding participants from the PDSAFE group who received fewer than seven of the planned 12 sessions. A similar approach to analysis was followed for continuous secondary outcomes, additionally controlling for the outcome assessed at baseline. Analysis was conducted in SPSS version 24 [(Statistical Product and Service Solutions) SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA] and Stata.

Safety reporting

Following a full risk assessment, PDSAFE was classified as a low-risk trial and, as such, in agreement with the ethics committee and sponsors, proportional safety reporting was implemented. Incidents of hospitalisation and disability, falls or incapacity are expected among this patient population. Therefore, only death, life-threatening events or new disability leading to prolonged hospitalisation attributed to the trial intervention were considered to be serious adverse events (SAEs). Similarly, any hospitalisation that was planned prior to randomisation or that could not be attributed to the PDSAFE intervention or assessments was not recorded as a SAE. Adverse events, such as hospitalisations, changes in health status and falls, were collected routinely as part of follow-up assessments and were monitored for potential SAEs. Falls diaries were also reviewed: if a fall resulting in hospitalisation had happened while someone was participating in the PDSAFE intervention and trial assessments, it would have been recorded as a SAE, but no one had such an event. All suspected SAEs were reviewed by Professor Helen Roberts, a medical physician, who adjudicated whether or not they were related to the trial activity.

An independent Data Monitoring Committee was established. The group met regularly throughout the trial to undertake interim reviews of the trial’s progress, including the review of updated figures on recruitment, data quality, adherence to protocol and follow-up, and main outcomes and safety data. Falls rates in particular were monitored.

Patient and public involvement

Patient and carer involvement was incorporated at all levels of the PDSAFE trial. Several PPI representatives were involved in the design of the study, including the development of participant information sheets, consent forms and intervention resources. Mr John Wood acted as PPI representative on the Trial Steering Committee. The trial was presented to several local Parkinson’s support groups; representatives were invited to the results launch event in September 2017 and contributed to discussion on the interpretation of results and key messages. PPI representatives will also be involved with the dissemination of the findings through existing patient networks, mainly through Parkinson’s UK and its newsletter service.

Chapter 3 The PDSAFE intervention and its delivery

This chapter details the PDSAFE intervention and its delivery. Background information is provided to support the conceptual development of the intervention, the protocol is presented using the TIDieR (Template for Intervention Description and Replication)41 and descriptive statistics demonstrate the content of the intervention delivered over the intervention period.

Background for intervention design

A role for exercise in the treatment of both the physical and cognitive/behavioural symptoms of Parkinson’s has been advocated and is supported by the European Physiotherapy Guidelines for Parkinson’s Disease. 42 In reviewing 70 clinical trials, the guidelines suggest that there is strong evidence that specific physiotherapy interventions help to improve transfers, balance, gait, physical capacity and movement functions,42 all isolated falls risk factors. A recent Cochrane review43 stated that the overall aim of physiotherapy intervention is to optimise independence, safety and well-being, thereby enhancing quality of life; however, the intervention that is most effective at achieving this remains unclear.

Evidence suggests that a multidimensional intervention to reduce falls, incorporating balance, functional strength and strategy training, and thus appreciating the need for motor, cognitive and behavioural training, may be more effective than interventions focusing on independent risk factors such as postural control and/or functional strength alone. 19

The PDSAFE intervention is delivered in the home, tailored to an individual’s specific falls mechanism and functional presentation and personalised to rehabilitate the primary strategy or strategies that contributed to the fall(s) (Figure 2). Not only does this allow the protocol to align with all components of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF)44 as a person-centred approach, it also follows the consensus-based clinical practice recommendations for falls management in Parkinson’s. 45 From this, personalised exercise prescription, within a menu of exercises, allows an individualised programme to be designed specific to the falls-related risk factors (impairments) that contribute to the primary ‘problematic’ strategy (as recommended by the European Physiotherapy Guidelines for Parkinson’s Disease42). The specific ‘impairment’ training enables physiological improvements in Parkinson’s symptoms and deficits, which allow functional training and strategy task practice in everyday life (see Figure 2). In this way, the rehabilitation of the falls-related strategy and its contributing falls risk factors not only works towards reducing the risk of similar falls again, but also embeds the training in everyday function and, therefore, is more likely to have a greater overall effect across all components of a participant’s life (and, thus, full ICF model).

FIGURE 2.

Conceptual model of the PDSAFE falls prevention protocol intervention.

Intensity is maintained across all aspects of the frequency, intensity, time and type (FITT) principle (as published in the American College of Sports Medicine guidelines)46 to drive physiological adaptation. ‘Frequency’ is regulated to a minimum of three times per week, ‘intensity’ must be perceived as ‘moderately hard/hard’ for all activities of the programme, ‘time’ is set to a maximum of 60 minutes and ‘type’ of exercise is tailored and specific to each individual’s falls mechanism. With the consideration of all factors, it is therefore possible to design a multidimensional programme that does not lose intensity as a result of its many components. In addition, the high intensity, continuous progression and titrated support from intensive to independent practice maintains focus and adherence and encourages personal commitment and investment, as well as fostering an understanding and empowerment of the rehabilitation process for the individual. The addition of visual feedback both in therapy time and as a review through personalised DVDs also aids accurate independent practice and continuation of therapy. Thus, continuous progress and adaption to the neurodegenerative properties of the condition can be made to maintain safety.

In appreciation of the mechanisms of neurorehabilitation and exercise prescription, the PDSAFE intervention protocol is structured in a way that enables intensive, repetitive practice that is salient to an individual and their specific falls profile, thus meeting their needs for effective neuroplastic change. In addition, the embedding of the training in strategy task-related practice across all functional activities enables rehabilitation to take place across all levels of life participation and not just in relation to a specific task, goal or previous fall behaviour.

As a result of its unique structure and delivery, the PDSAFE intervention (see Figure 2) reflects the evidence base for falls prevention in Parkinson’s, meets the holistic recommendations of the ICF framework for practice and facilitates onward progression and independent self-management of the condition by the individual. The novelty lies in both the content (disease-specific exercises and strategies for instability, use of motor relearning and cognitive awareness) and delivery (personalised feedback using a DVD for adherence and self-management).

Intervention protocol

In line with the recommended methods of reporting intervention design, TIDieR41 is detailed in Table 2. The 12 items detailed in the checklist are an extension of the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) 2010 statement – item 547 and the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT) 2013 statement – item 1148 and are intended to improve the reporting of interventions.

| TIDieR | Checklist requirement | Protocol description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Protocol name | PDSAFE: a personalised falls prevention programme of home exercises for postural control training, muscle strengthening and task-orientated movement strategy training |

| 2 | Protocol rationale and theory of main elements |

|

| 3 | Protocol materials | For the participant:

|

| 4 | Procedures of protocol delivery |

|

| 5 | Protocol providers |

|

| 6 | Mode of protocol delivery |

|

| 7 | Location of protocol delivery |

|

| 8 | Protocol duration, intensity and dose |

Intervention Supervised sessions comprise:Independent practice: |

|

Comparison group Supervised sessions comprise: |

||

| 9 | Protocol personalisation |

|

For a visual representation of the intervention, please refer to the film available at: www.youtube.com/watch?v=emNr0REIm4A&list=PLT3AipgP4l_x7OVNryanVgtcvPZXVJyX1 (accessed 21 February 2019).

Delivery outcomes

Delivery of the PDSAFE intervention was over 2 years and 4 months. The intervention was delivered in a total of eight clinical sites across nine NHS trusts.

Therapists

Physiotherapists were recruited by each site. Trial requirements stated that each therapist should have experience in Parkinson’s or falls rehabilitation. It was initially designed that each site would have one treating therapist and a trained cover for periods of absence. However, owing to clinical workload and logistical delivery, a total of 18 therapists were trained over the study period. One lead therapist co-ordinated the team, delivered the training and development activities, and monitored the fidelity of intervention delivery.

Training, facilitated by the lead therapist, included attendance at one of the compulsory 2-day training events held on three separate occasions. In addition, therapists were asked to attend a virtual weekly meeting by telephone to discuss clinical cases and problem-solve within the boundaries of the intervention protocol. These sessions were chaired by the lead therapist, with a total of 122 telephone contacts made available over the intervention period. To maintain a high standard of clinical reasoning throughout the intervention period, therapists were also asked to attend (either physically or virtually) monthly ‘masterclasses’ on key clinical topics such as cognition and dual tasking, turning, FoG and balance. Alternating with masterclasses, therapists were asked to present case studies on key topics for team discussion. Twelve ‘masterclass’ topics (some were repeated for new therapists) and seven case study reviews were held over the intervention period.

Fidelity of the intervention was a priority to encourage uniformity of practice. The lead therapist observed each therapist in a treatment session with a participant, once a month for the first 3 months of delivery and then once every 3 months for the delivery period. Following the observation, a clinical reasoning discussion was completed and a report written. Therapists could also request additional joint sessions with the lead therapist if they had concerns or queries regarding a particular participant. This ensured that the PDSAFE intervention was uniformly delivered across all sites and by all therapists. A total of 75 fidelity sessions were held over the intervention period, with all therapists being assessed.

Intervention sessions

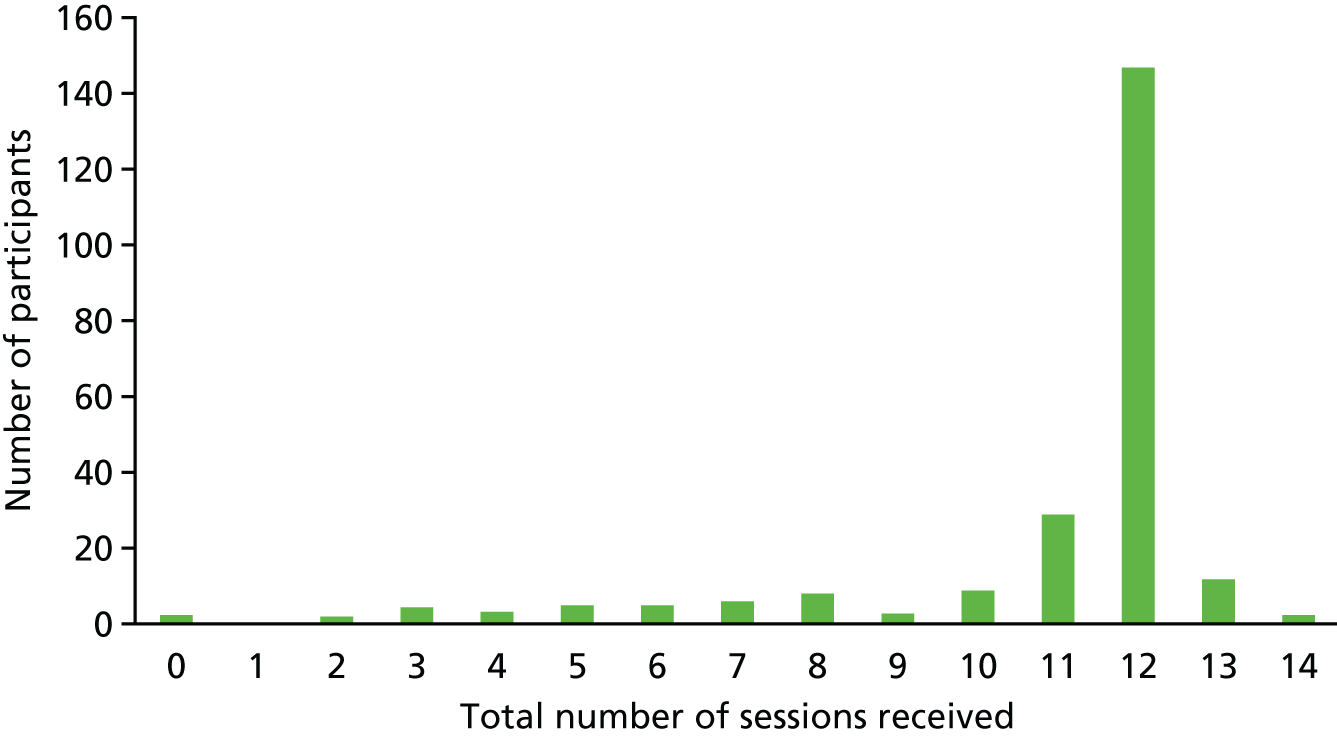

A total of 2587 sessions were delivered to the 291 intervention participants, with the majority of participants receiving the anticipated 12 sessions (mode = 12).

Figure 3 presents the total number of sessions received by participants allocated to the intervention arm of the trial. The majority of participants, 236 out of 238, received the exercise assessment and at least one supervised session. Two participants did not start because they had changed their mind and 19 received fewer than seven sessions; reasons for not fully engaging included admission to a nursing home, deteriorating health, commitment was too much and caring for others; in some cases, no reason was given.

FIGURE 3.

Total number of intervention sessions received by participants.

All interventions sessions included a brief review of falls; warm-up exercises; review, practice and progression of a participant’s individual exercise programme; and strategy training in functional scenarios as a basic structure. Each therapist tailored the strategies treated, exercises prescribed and functional tasks practised from a menu for each participant.

Selection of strategies

Evidence from the literature and from previous studies of falls among patients with Parkinson’s, as well as expert opinion, were used to determine the most frequent falls mechanisms in Parkinson’s. 19 Eight strategies were defined: avoiding tripping, dual tasking, freezing cues, moving in tight spaces, picking up an object, reaching, stepping backwards and turning. As described above, through the process of taking a detailed falls history, clinical assessment and advanced clinical reasoning, therapists determined the most likely ‘fall mechanism’ for each participant (levels 1 and 2 in Figure 2). For example, in the case of a participant who repeatedly reported catching their foot and falling, regardless of the task being undertaken or location, would be most likely to have a falls mechanism of tripping; thus, the strategy ‘avoiding tripping’ would be selected by the therapist.

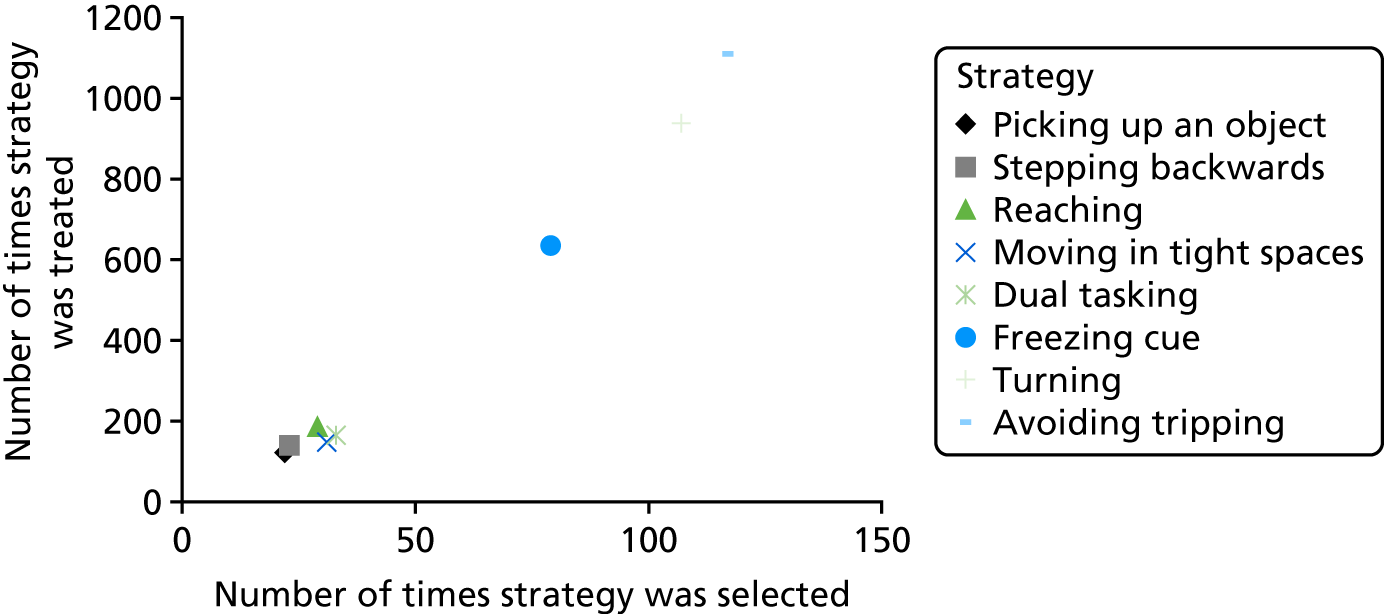

Over the 291 participants who received the PDSAFE intervention, strategies were selected a total of 440 times, with a strategy being used in treatment a total of 3447 times over the period. This provides a large sample to consider the clinical reasoning process of the therapists selecting the strategies. Figure 4 demonstrates the number of times each strategy was selected as a potential falls mechanism corresponding to the number of times that strategy was used in a treatment session.

FIGURE 4.

Stratification of strategies used in delivery of PDSAFE intervention.

Importantly, this allows description of the strategies selected as primary falls mechanisms and thus treated for the majority of the intervention period versus strategies that may have been selected as a secondary or subsequent strategy and thus treated less frequently or for a shorter period of time.

It is apparent that ‘avoiding tripping’ was the most widely used strategy. It was selected following assessment a total of 116 times, used 1110 times during treatment sessions and accounted for 26% of all strategies selected. The figures for ‘turning’ are similar [selected 107 times and used 938 times during treatment (26% of the total)]. ‘Freezing cues’ was also frequently selected as a strategy [selected 79 times and used 365 times (24% of the total)]. It is clear from Figure 4 that all other strategies were selected and used in treatment with similar frequencies to each other.

Selection of exercise prescription

Once the strategy or strategies most appropriate for addressing a participant’s falls mechanism had been selected, therapists used advanced clinical reasoning and assessment skills to determine the physical impairments and deficits in physical falls risk factors that were most likely to contribute to the fall mechanism (see Figure 2). For example, the participant described above, who frequently caught their foot and subsequently fell, was allocated the ‘avoiding tripping’ strategy. The therapist must consider a number of reasons why the participant has a tendency to catch their foot, such as weakness of the muscles used to lift the toes, failure to transfer weight onto the supporting leg appropriately because of hip weakness or reduced limits of postural control stability, or failure to achieve enough clearance from the ground because of weakness in the hip flexors. Through assessment, the therapist determines the most likely impairment and designs a functional strength and postural control exercise programme from the available menu that treats this impairment.

Evidence from the literature and from previous studies of falls among patients with Parkinson’s, as well as expert opinion, were used to determine what exercises were available on the menu for therapists to select from. 19

Table 3 shows the menu of exercises available for the therapist to select from when putting together an individual participant’s PDSAFE intervention.

| Function | Exercise |

|---|---|

| Balance/postural control | |

| Standing | Standing balance |

| Tandem stand | |

| Reaching | |

| Compensatory step and lunge | |

| Walking | Heel/toe walking |

| Toe/heel walking backwards | |

| Tandem walking | |

| ‘Figure of 8’ walking | |

| Picking up an object | |

| Stepping over an object | |

| Strengthening | Sit to stand |

| Standing toe and heel raises | |

| Forward stepping up and down | |

| Side stepping up and down | |

Exercises were available on six levels; working through the levels enabled progression (level 4 in Figure 2) and maintenance of intensity for each exercise. All programmes had to include at least one balance and one strengthening exercise. A total of 1693 exercises were selected by all therapists over the intervention period with an average of six (range one to eight) exercises prescribed per participant across the period. Figure 5 shows a spread of all exercises being used over the intervention period.

FIGURE 5.

Exercise use frequency across all of the intervention, in all participants.

Figure 5 demonstrates the predominance of the more dynamic postural control (compensatory step and lunge and heel/toe walking) and strengthening exercises over other exercises from the menu. The complex nature of the compensatory step and lunge exercise makes it suitable for the treatment of many of the falls risk factors associated with Parkinson’s; for example, high dynamic stepping actions help with motor control, compensatory stepping helps with the regain of an appropriate base of support from a loss of postural control or a trip by increasing stepping amplitude for those who freeze and expanding limits of stability for those who fall when reaching. The practice of stepping backwards with appropriate postural control and weight distribution will assist those who fall stepping backwards. A common symptom of the Parkinsonian gait is loss of foot clearance, heel strike and step length45 (hence the predominance of tripping as a falls mechanism); thus, the high frequency of the use of heel/toe walking to improve these impairments is also unsurprising. As each exercise programme had to include both strengthening and postural control exercises, the high frequency of selection of strengthening exercises can be attributed to the fact that the postural control menu contained fewer exercises that could be selected. This is less of a clinical reasoning observation and more related to the ratio of exercises in the menu.

Summary

The PDSAFE intervention was deeply rooted in evidence from both rehabilitation after falls and exercise prescription literature. The protocol was a holistic model encompassing all aspects of the ICF and its design allowed a personalised, sophisticated, complex intervention to be prescribed for each participant. ‘Personalised’, ‘intensive’ and ‘progressive’ were key parameters of the intervention, demanding a high level of commitment and collaboration between the therapist and the participant. The intervention was delivered to a high standard. All requirements of fidelity were met and the intervention was comparable across all sites. Delivery was significantly enhanced by the level of training and support provided to the delivery team and a high standard of clinical reasoning and protocol delivery was maintained. The majority of participants received the planned number of sessions. There was a slight rise in the number of participants receiving only seven or eight sessions as this is the point at which the therapists visited less frequently and participants were required to complete longer periods of independent practice. It is likely that this led to some participants withdrawing at this point because of the reduced support/motivation from the therapist. There was a clear predominance of some strategies, which is likely to reflect the demographic of the intervention group (i.e. more frequent fallers and people with Parkinson’s who freeze, plus those who have more advanced disease and thus are more likely to have difficulty turning: with axial rigidity, poor stepping and impaired cognition). The predominance of ‘avoiding tripping’, ‘turning’ and ‘freezing cues’ is in line with the reasons for falling provided by participants most frequently in the previous literature. 26 The design of strategy selection leading to supported exercises to treat falls risk factors provided a protocol design that was deliverable, with all participants receiving both strategies and exercises as planned. Owing to the complexity of the exercises, some exercises are better able to be adapted for multiple impairments and thus are used more frequently. Previous studies19 have provided the same intervention for all participants, regardless of fall mechanism. The use of all the strategies and exercises demonstrates the need for a complex intervention and variability as ‘one size, clearly does not fit all’.

Chapter 4 Statistical trial results

Participants

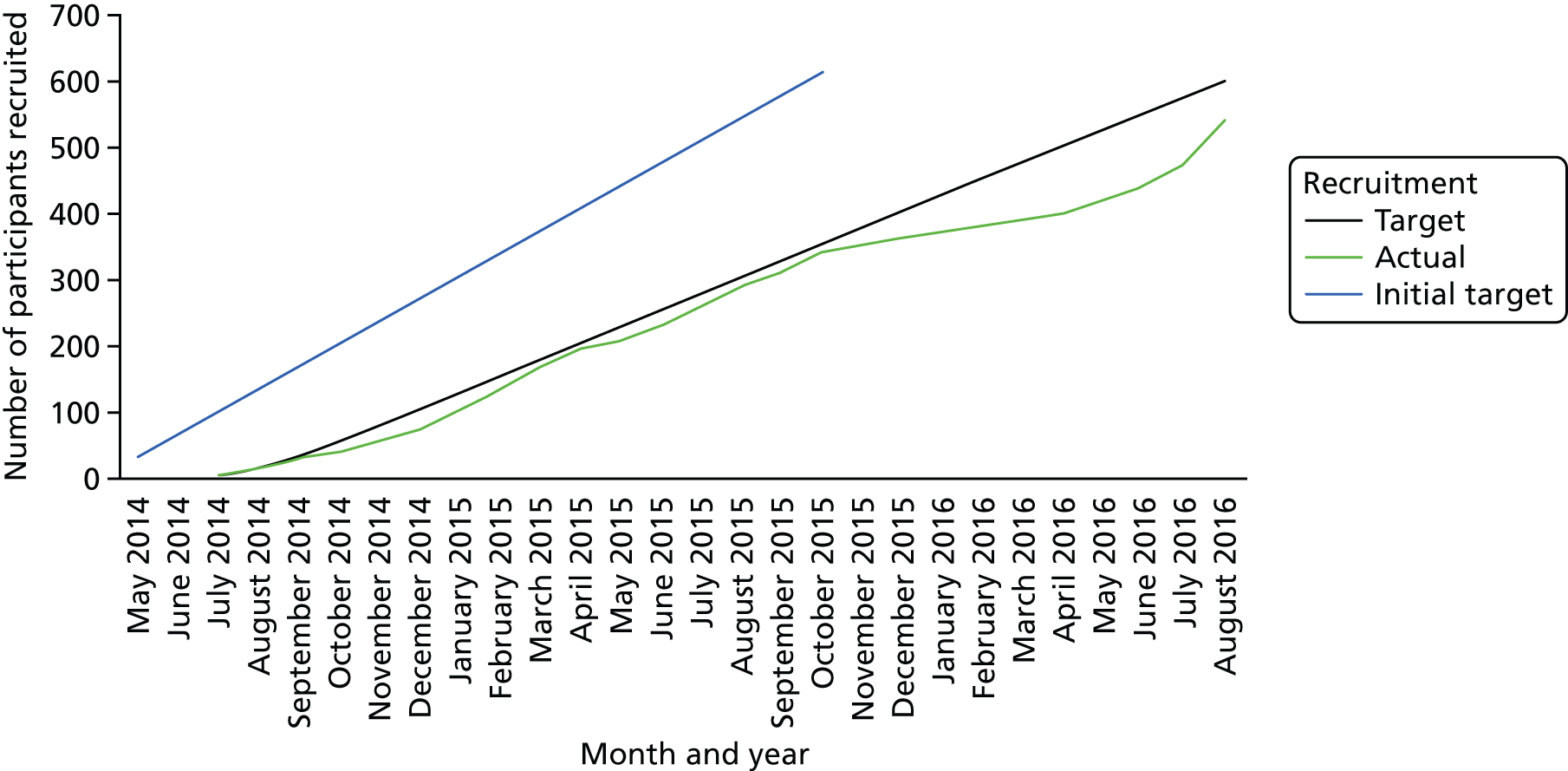

Recruitment of participants ran from July 2014 to August 2016 (see Appendix 5, Figure 14).

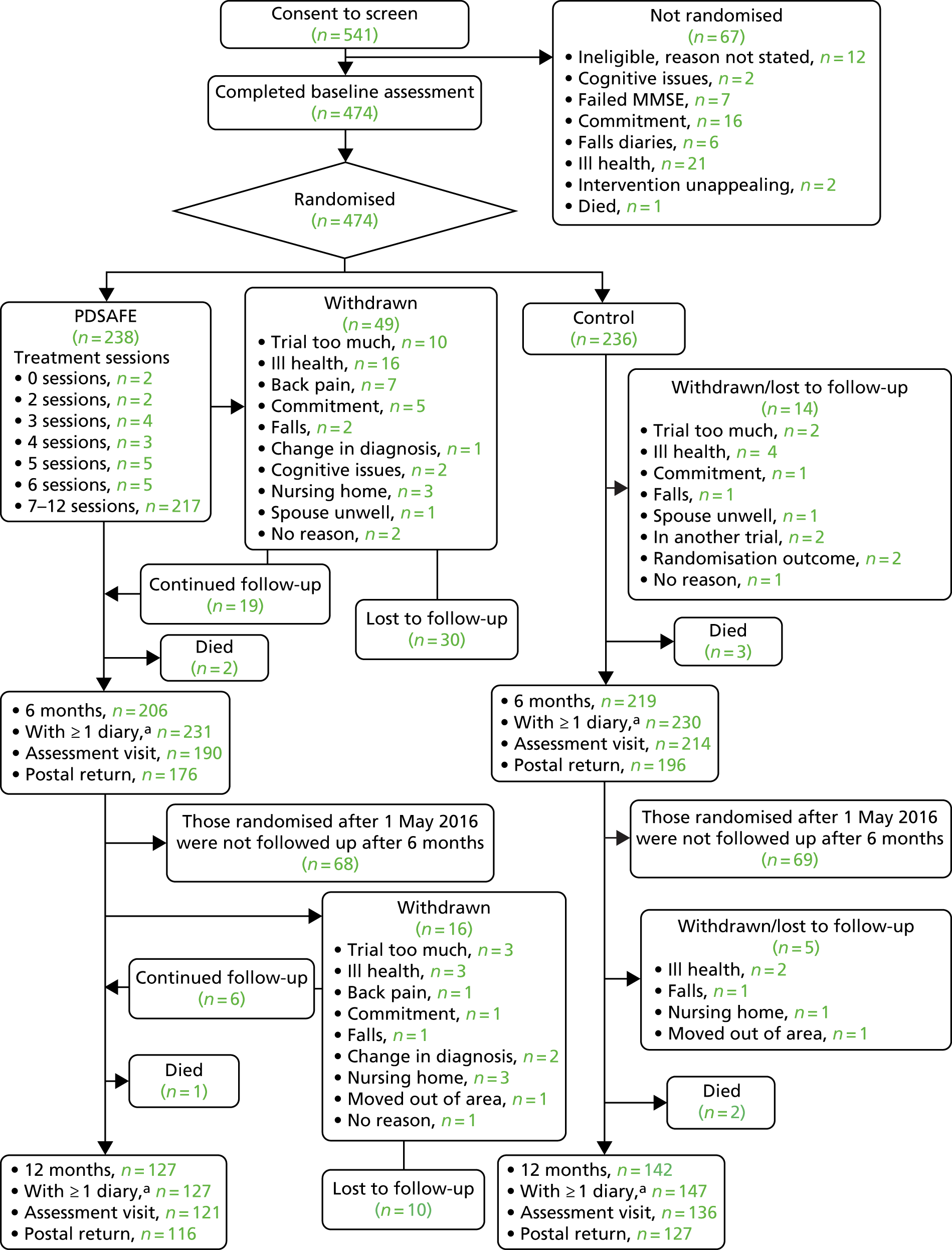

Figure 6 provides the CONSORT flow diagram of participants’ assessments. A total of 640 people with Parkinson’s were invited to participate, but 99 either did not respond or did not meet the eligibility criteria, which left 541 people for consent and completion of a screening visit with a trial assessor in their own home. Of these 541 people, seven did not score the minimum score on the MMSE and were excluded. The remainder went on to complete prospective falls diaries for 3 months (i.e. a minimum of 13 weeks). A further 60 people were excluded during this time [reasons for not being randomised were as follows: medically unfit (n = 21), dislike of completing falls diaries (n = 6), no longer met eligibility criteria (n = 12), reported cognitive issues (n = 2), died (n = 1) or decided not to participate in the trial (n = 18)]. The remaining 474 (88%) people completed a baseline assessment and were randomised into one of two groups: control (n = 236) or the PDSAFE intervention (n = 238). Recruitment and randomisation graphs can be found in the appendices. The groups allocated to PDSAFE and control were similar at baseline (Table 4) in terms of age, gender, disease severity, disease duration, cognitive ability, freezing, medication and coexisting conditions and living status. Retrospective recall of falls was also similar between the groups, but the rate of falling in the 3 months prior to randomisation was greater in those subsequently randomised to the intervention group.

FIGURE 6.

Flow diagram of participants’ progression through the trial. a, Number with any diaries during the preceding 6 months. Adapted from Chivers Seymour et al. 49 © Author(s) [or their employer(s)] 2019. Re-use permitted under CC BY-NC. No commercial re-use. See rights and permissions. Published by the BMJ Publishing Group Ltd. This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited, appropriate credit is given, any changes made indicated, and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

| Characteristic | Trial group | |

|---|---|---|

| PDSAFE (n = 238)a | Control (n = 236)b | |

| Gender, n (%) | ||

| Male | 147 (62) | 119 (50) |

| Female | 91 (38) | 117 (50) |

| Age (years) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 71 (7.7) | 73 (7.7) |

| Minimum, maximum | 51, 91 | 46, 88 |

| Disease duration (years) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 8 (6.6) | 8 (5.8) |

| Minimum, maximum | 0, 36 | 0, 29 |

| MMSE score | ||

| Mean (SD) | 28 (1.7) | 29 (1.6) |

| Minimum, maximum | 24, 30 | 24, 30 |

| MoCA score | ||

| Mean (SD) | 26 (2.9) | 26 (3.2) |

| Minimum, maximum | 15, 30 | 9, 30 |

| ≤ 25 (cognitively impaired), n (%) | 91 (38) | 93 (39) |

| Living status, n (%) | ||

| Lived alone | 48 (20) | 59 (25) |

| With a spouse/partner | 174 (73) | 166 (70) |

| With a friend/family | 15 (6) | 10 (4) |

| H&Y scale stage, n (%) | ||

| 1 | 26 (11) | 30 (13) |

| 2 | 78 (33) | 56 (24) |

| 3 | 102 (43) | 112 (48) |

| 4 | 32 (13) | 38 (16) |

| MDS-UPDRS | ||

| Mean (SD) | 32 (15.2) | 33 (17.3) |

| Minimum, maximum | 2, 77 | 4, 92 |

| Phenotype | ||

| TD, n (%) | 21 (9) | 19 (8) |

| PIGD, n (%) | 194 (83) | 206 (88) |

| Indeterminate, n (%) | 20 (8) | 10 (4) |

| FoG in the past month, n (%) | 152 (64) | 139 (59) |

| Number of falls in the 12 months prior to screening | ||

| Median (minimum, maximum) | 3 (1, 1460) | 3 (1, 1095) |

| Mean (SD) | 26 (132.7) | 19 (105.4) |

| Repeat falling in 12 months prior to screening, n (%) | 186 (78) | 189 (80) |

| Rate of falls/person/3 months prior to randomisation | ||

| Median (minimum, maximum) | 1.98 (0, 319) | 0.99 (0, 73) |

| Mean (SD) | 5.9 (22.8) | 3.0 (7.3) |

| Rate of near-falls/person/3 months prior to randomisation | ||

| Median (minimum, maximum) | 4.4 (0 to 440) | 4.3 (0 to 601) |

| Mean (SD) | 13.8 (35.8) | 15.6 (51.4) |

| Medications, n (%) | ||

| Levodopa | 208 (88) | 216 (92) |

| Dopamine agonist | 108 (46) | 106 (45) |

| Monoamine oxidase inhibitor | 52 (22) | 46 (20) |

| Catechol-O-methyltransferase inhibitors | 59 (25) | 41 (17) |

| Other Parkinson’s medication | 19 (8) | 23 (10) |

| GDS score at baseline, n (%) | ||

| > 5 (suggestive of depression) | 147/235 (63) | 164/236 (70) |

| ≥ 10 (indicative of depression) | 50/235 (21) | 49/236 (21) |

| Coexisting conditions, n (%) | ||

| Orthopaedic | 109 (46) | 129 (54) |

| Cardiovascular/respiratory | 85 (36) | 96 (41) |

Delivery of intervention

In the PDSAFE group, 66 participants did not engage with the intervention for a number of reasons, including admission to a care home, deteriorating health, changing their mind about participation, feeling the commitment to be too great, or death; in some cases, no reason was given. The therapy aim was to provide 12 supervised sessions for each participant and, on average, participants had a median of 12 sessions [interquartile range (IQR) 11–12 sessions] or a mean of 11 sessions [standard deviation (SD) 2.4 sessions]. A total of 21 participants received fewer than seven sessions and, along with a further four participants for whom the number of sessions was not available, were excluded from per-protocol analyses.

Falling outcomes

In Table 5, the prospective completion of diaries is described during the period of baseline diary completion prior to randomisation, and in the 12-month period of post-randomisation follow-up. The percentage who returned no diaries was generally low (2–4%) during the period 0 to 6 months; during the final 6 months the percentage who returned no diaries was higher (1–12%). These percentages exclude the number who withdrew or died during the respective periods. Among those returning any diaries for the period in question, the IQR of the numbers of days completed was 90–92 (within target). The target number of days varied between 89 and 92 days across participants, depending on the calendar months covered by their 3-month baseline period.

| Characteristic | Trial group | |

|---|---|---|

| PDSAFE | Control | |

| Randomisation, n | 238 | 236 |

| Baseline | ||

| Number with no diaries | 1/238 | 0/236 |

| Number of diary days among those with diaries | (n = 237) | (n = 236) |

| Median | 92 | 92 |

| IQR | 90–92 | 90–92 |

| Minimum, maximum | 12, 92 | 26, 92 |

| n/N with complete diaries (%) | 196/238 (82) | 198/236 (84) |

| n/N with ≥ 50% diary days (%) | 229/238 (96) | 226/236 (96) |

| 0–6 months post randomisation | ||

| Number entering 0–6 months period | 238 | 236 |

| n/N with no diaries (%) | 7/238 (3) | 6/236 (3) |

| n/N in falls rate ratio analysis (%) | 231/238 (97) | 230/236 (98) |

| n/N exiting (died or withdrawn from follow-up during 0–6 months) (%) | 32/238 (13) | 17/236 (7) |

| n/N exiting with no diaries | 2/206 (1) | 3/219 (1) |

| Number of diary days among those not exiting with diary days | (n = 204) | (n = 216) |

| Median | 182 | 182 |

| IQR | 153–183 | 174–183 |

| Minimum, maximum | 3184 | 29,184 |

| n/N with complete diaries (%) | 130/238 (55) | 158/236 (67) |

| n/N with ≥ 50% diary days (%) | 203/238 (85) | 211/236 (89) |

| Number in follow-up at 6 months | 206 | 219 |

| Number in trial follow-up randomised after 1 May 2016 | ||

| Southampton | 5 | 4 |

| Portsmouth | 7 | 6 |

| Bournemouth | 2 | 2 |

| Newcastle | 15 | 13 |

| Hampshire | 13 | 18 |

| Plymouth | 10 | 11 |

| Cornwall | 16 | 15 |

| Total | 68 | 69 |

| 6–12 months post randomisation | ||

| Number entering 6–12 months period | 138 | 150 |

| n/N with no diaries (%) | 11/138 (8) | 3/150 (2) |

| n/N in falls rate ratio analysis (%) | 127/138 (92) | 147/150 (98) |

| n/N exiting (died or withdrawn from follow-up during 6–12 months) (%) | 11/138 (8) | 7/150 (5) |

| n/N exiting with no diaries (%) | 5/127 (4) | 2/143 (1) |

| Number of diary days among those not exiting with diary days | (n = 122) | (n = 141) |

| Median | 180 | 180 |

| IQR | 151–183 | 153–183 |

| Minimum, maximum | 4184 | 30,184 |

| n/N with complete diaries (%) | 94/138 (68) | 112/150 (75) |

| n/N with ≥ 50% diary days (%) | 114/138 (83) | 132/150 (8) |

There was a trend towards increased repeat falling during the 6 months following randomisation in the PDSAFE group compared with the control group (OR 1.21, 95% CI 0.74 to 1.98; p = 0.447). During the final 6 months of follow-up, there was a trend towards decreased repeat falling (OR 0.86, 95% CI 0.45 to 1.65; p = 0.657). No statistically significant differences between the groups were found (Table 6). These analyses followed the planned treatment for participants with incomplete diaries during a follow-up period, that is participants were classified as a repeat faller if they reported two or more falls in their incomplete diaries or if a check of all PDSAFE records indicated two or more falls in that period. They were classified as a non-repeat faller if fewer than two falls were reported in the incomplete diaries, there was no indication of repeat falling in the period in the PDSAFE records and ≥ 50% of diary days for the period had been completed. Otherwise they were excluded. Two sensitivity analyses are shown in Appendix 7, Table 28, where analysis of repeat falling is also reported, restricted to participants with complete diaries and including all participants with any diaries during the follow-up period in question. Although there were no changes in the statistical significance or otherwise depending on these treatments of missing diaries, there were changes in the magnitude of ORs.

| Period | Trial group | OR (95% CI)a | p-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDSAFE | Control | |||

| Repeat falling restricted to ≥ 50% diaries, n (%) | ||||

| Baseline | 127/231 (55) | 92/230 (40) | ||

| Baselineb | 112/203 (55) | 80/211 (38) | ||

| 0–6 months | 125/203 (62) | 116/211 (55) | 1.21 (0.74 to 1.98) | 0.447 |

| Baselineb | 55/114 (48) | 47/132 (36) | ||

| 6–12 months | 57/114 (50) | 71/132 (54) | 0.86 (0.45 to 1.65) | 0.657 |

| Fall rates | Falls/person/6 monthsc | FRR (95% CI) | ||

| Baseline | 4.5 | 3.3 | ||

| 0–6 months | 3.4 | 2.7 | 0.98 (0.80 to 1.19) | 0.824 |

| 6–12 months | 2.7 | 2.8 | 0.83 (0.62 to 1.11) | 0.200 |

| Near-fall rates | Near-falls/person/6 monthsc | NFRR (95% CI) | ||

| Baseline | 8.0 | 8.1 | ||

| 0–6 months | 4.7 | 5.6 | 0.67 (0.53 to 0.86) | 0.001 |

| 6–12 months | 3.9 | 3.7 | 1.01 (0.67 to 1.52) | 0.968 |

Participants typically reported rates of falling, expressed per 6 months, of between three and five falls (see Table 6). There was little difference in the rate of falling between the two groups in the first 6 months of follow-up, indicated by the FRR, and a slightly greater difference, with FRR of 0.83 (95% CI 0.62 to 1.11; p = 0.200), during the following 6 months. The analysis of rates of falling is based on participants with any amount of diary completion for the follow-up period in question, with only participants returning no diaries excluded.

Rates of near-falling are also shown in Table 6, expressed per 6-month period. Near-falling was greater in the period prior to randomisation than subsequently. During the 6 months post randomisation, the ratio of near-falling rates between the PDSAFE and control groups was significantly reduced (p = 0.001), with a rate of near-falling in the PDSAFE group of 0.67 (95% CI 0.53 to 0.86) that of the control group. This reduction in near-falling was not maintained during the following 6 months. Like the analysis of falling rates, the analysis of near-falling rates also includes participants irrespective of the amount of diary completion for the period of follow-up in question (as long as any diaries were returned for the period).

In Table 7 a comparison is made between the overall falling (and near-falling) results following the ITT analysis and a per-protocol analysis (excluding participants in the PDSAFE groups receiving fewer than seven sessions). This shows the findings to be similar, there being no suggestion of reduced falling in the PDSAFE group when the analysis is restricted to those receiving seven or more sessions.

| Period | Analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITT | Per protocol | |||

| OR (95% CI)a | p-valuea | OR (95% CI)a | p-valuea | |

| Repeat falling restricted to ≥ 50% diaries | ||||

| 0–6 months | 1.21 (0.74 to 1.98) | 0.447 | 1.16 (0.71 to 1.92) | 0.538 |

| 6–12 months | 0.86 (0.45 to 1.65) | 0.657 | 0.92 (0.47 to 1.77) | 0.793 |

| Fall rates | FRR (95% CI) | p-valuea | FRR (95% CI) | p-valuea |

| 0–6 months | 0.98 (0.80 to 1.19) | 0.824 | 0.99 (0.81 to 1.22) | 0.982 |

| 6–12 months | 0.83 (0.62 to 1.11) | 0.200 | 0.84 (0.63 to 1.13) | 0.268 |

| Near-fall rates | NFRR (95% CI) | p-valuea | NFRR (95% CI) | p-valuea |

| 0–6 months | 0.67 (0.53 to 0.86) | 0.001 | 0.67 (0.53 to 0.86) | 0.001 |

| 6–12 months | 1.01 (0.67 to 1.52) | 0.968 | 1.01 (0.67 to 1.52) | 0.963 |

Secondary outcomes

Analysis of the secondary outcomes collected by the assessing therapist during home visits (Mini-BESTest, FES-I, FoG and MDS-UPDRS) is reported in Table 8, with CST results reported in Tables 9 and 10. At the 6-month visit, the PDSAFE group had improved mean Mini-BESTest score of 0.95 points (95% CI 0.24 to 1.67 points; p = 0.009), controlled for baseline Mini-BESTest score and other covariates (see Table 7); better falls confidence as assessed by a lower mean FES-I score of 1.60 points (95% CI 3.00 to 0.19 points; p = 0.026), controlled for similar covariates; and improved balance as assessed by the CST (p = 0.041). There were no significant differences at 12 months.

| Outcome measure | Visit | Trial group, mean (SD), n | Mean difference (95% CI)a | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDSAFE (N = 238) | Control (N = 236) | ||||

| Mini-BESTest (0–28, lower values worse) | Baselineb | 18.3 (5.7), 183 | 17.3 (6.1), 211 | ||

| 6 months | 19.4 (5.9), 183 | 17.5 (6.4), 211 | |||

| 6 months – baseline | 1.1 (3.8), 183 | 0.2 (3.8), 211 | 0.95 (0.24 to 1.67) | 0.009 | |

| Baselineb | 18.5 (5.8), 115 | 17.5 (6.1), 126 | |||

| 12 months | 17.9 (6.5), 115 | 17.4 (6.7), 126 | |||

| 12 months – baseline | –0.7 (4.5), 115 | –0.2 (3.8), 126 | –0.41 (–1.48 to 0.66) | 0.449 | |

| FES-I (16–64, higher values worse) | Baselineb | 34.1 (11.0), 189 | 35.1 (11.5), 211 | ||

| 6 months | 33.4 (10.6), 189 | 36.2 (11.4), 211 | |||

| 6 months – baseline | –0.7 (7.9), 189 | 1.1 (7.2), 211 | –1.6 (–3.0 to –0.19) | 0.026 | |

| Baselineb | 33.4 (10.7), 119 | 33.7 (11.3), 135 | |||

| 12 months | 34.8 (11.2), 119 | 37.2 (11.6), 135 | |||

| 12 months – baseline | 1.3 (8.2), 119 | 3.5 (9.3), 135 | –1.4 (–3.41 to 0.66) | 0.184 | |

| PASE (0–4, lower values worse) | Baselineb | 107.8 (73.5), 153 | 100.1 (67.1), 177 | ||

| 6 months | 110.2 (70.4), 153 | 100.6 (68.0), 177 | |||

| 6 months – baseline | 2.4 (50.8), 153 | 0.5 (49.5), 177 | –1.05 (–11.3 to 9.21) | 0.841 | |

| Baselineb | 108.1 (71.9), 98 | 98.6 (61.1), 115 | |||

| 12 months | 99.4 (72.8), 98 | 87.6 (62.3), 115 | |||

| 12 months – baseline | –8.7 (53.0), 98 | –11.0 (48.5), 115 | –0.55 (–13.9 to 12.8) | 0.935 | |

| PDQ-39 (0–100, higher values worse) | Baselineb | 27.4 (14.3), 126 | 28.7 (15.9), 153 | ||

| 6 months | 28.3 (15.0), 126 | 29.5 (16.5), 153 | |||

| 6 months – baseline | 0.8 (8.3), 126 | 0.9 (9.0), 153 | 0.12 (–2.0 to 2.28) | 0.911 | |

| Baselineb | 27.2 (13.6), 77 | 28.9 (15.9), 100 | |||

| 12 months | 29.1 (15.4), 77 | 31.7 (15.5), 100 | |||

| 12 months – baseline | 1.9 (8.6), 77 | 2.8 (11.2), 100 | 0.48 (–2.53 to 3.49) | 0.754 | |

| GDS (0–15, higher values worse) | Baselineb | 7.7 (2.3), 154 | 7.7 (2.1), 183 | ||

| 6 months | 7.8 (2.5), 154 | 8.0 (2.5), 183 | |||

| 6 months – baseline | 0.3 (1.8), 154 | 0.2 (1.9), 183 | –0.02 (–0.42 to 0.39) | 0.942 | |

| Baselineb | 7.7 (2.1), 96 | 8.0 (2.2), 118 | |||

| 12 months | 7.8 (2.5), 96 | 8.5 (2.4), 118 | |||

| 12 months – baseline | 0.2 (2.0), 96 | 0.4 (1.7), 118 | –0.21 (–0.72 to 0.31) | 0.421 | |

| Period | Trial group, n/N (%) | PDSAFE/control OR (95% CI) | p-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDSAFE | Control | |||

| Baseline | 45/236 (19) | 45/235 (19) | ||

| Baseline among participants with a 6-month assessment | 29/188 (15) | 35/213 (16) | ||

| 6 months | 27/188 (14) | 47/213 (22) | 0.61 (0.37 to 1.02) | 0.076 |

| Baseline among participants with a 12-month assessment | 15/119 (13) | 21/134 (16) | ||

| 12 months | 23/119 (19) | 38/134 (28) | 0.66 (0.37 to 1.17) | 0.208 |

| Period | Trial group, median (IQR); n | p-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PDSAFE | Control | ||

| Baseline among participants with 6-month assessment | 14 (11–18); 159 | 14 (11–18); 178 | |

| 6-month assessment | 12 (10–15); 161 | 13 (10–16); 166 | 0.041 (n = 401) |

| Baseline among participants with 12-month assessment | 14 (11–17); 104 | 14 (12–18); 113 | |

| 12-month assessment | 12 (9–14); 96 | 13 (11–15); 96 | 0.163 (n = 253) |

Analysis is shown in Table 11 of the secondary outcomes self-reported by participants after the 6- and 12-month home visits and returned by post. No statistically significant differences between the groups overall were found for these outcomes.

| Assessment and visit | Trial group, mean (SD) | Mean difference (PDSAFE – control) (95% CI)a | p-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDSAFE (N = 238) | Control (N = 236) | |||

| PASE (0–400, lower values worse) | ||||

| Baselineb | 107.8 (73.5); n = 153 | 100.1 (67.1); n = 177 | ||

| 6 months | 110.2 (70.4); n = 153 | 100.6 (68.0); n = 177 | ||

| 6 months – baseline | 2.4 (50.8); n = 153 | 0.5 (49.5); n = 177 | –1.05 (–11.3 to 9.21) | 0.841 |

| Baselinec | 108.1 (71.9); n = 98 | 98.6 (61.1); n = 115 | ||

| 12 months | 99.4 (72.8); n = 98 | 87.6 (62.3); n = 115 | ||

| 12 months – baseline | –8.7 (53.0); n = 98 | –11.0 (48.5); n = 115 | –0.55 (–13.9 to 12.8) | 0.935 |

| PDQ-39 (0–100, higher values worse) | ||||

| Baselineb | 27.4 (14.3); n = 126 | 28.7 (15.9); n = 153 | ||

| 6 months | 28.3 (15.0); n = 126 | 29.5 (16.5); n = 153 | ||

| 6 months – baseline | 0.8 (8.3); n = 126 | 0.9 (9.0); n = 153 | 0.12 (–2.0 to 2.28) | 0.911 |

| Baselinec | 27.2 (13.6); n = 77 | 28.9 (15.9); n = 100 | ||

| 12 months | 29.1 (15.4); n = 77 | 31.7 (15.5); n = 100 | ||

| 12 months – baseline | 1.9 (8.6); n = 77 | 2.8 (11.2); n = 100 | 0.48 (–2.53 to 3.49) | 0.754 |

| GDS (0–15, higher values worse) | ||||

| Baselineb | 7.7 (2.3); n = 154 | 7.7 (2.1); n = 183 | ||

| 6 months | 7.8 (2.5); n = 154 | 8.0 (2.5); n = 183 | ||

| 6 months – baseline | 0.3 (1.8); n = 154 | 0.2 (1.9); n = 183 | –0.02 (–0.42 to 0.39) | 0.942 |

| Baselinec | 7.7 (2.1); n = 96 | 8.0 (2.2); n = 118 | ||

| 12 months | 7.8 (2.5); n = 96 | 8.5 (2.4); n = 118 | ||

| 12 months – baseline | 0.2 (2.0); n = 96 | 0.4 (1.7); n = 118 | –0.21 (–0.72 to 0.31) | 0.421 |

Subgroup analysis

In the statistical analysis plan, a subgroup analysis excluding participants with severe disease by virtue of a MDS-UPDRS score of ≥ 59 or H&Y stage 4 was prespecified. These analyses yielded very similar results to those shown in Table 6 for the group as a whole.

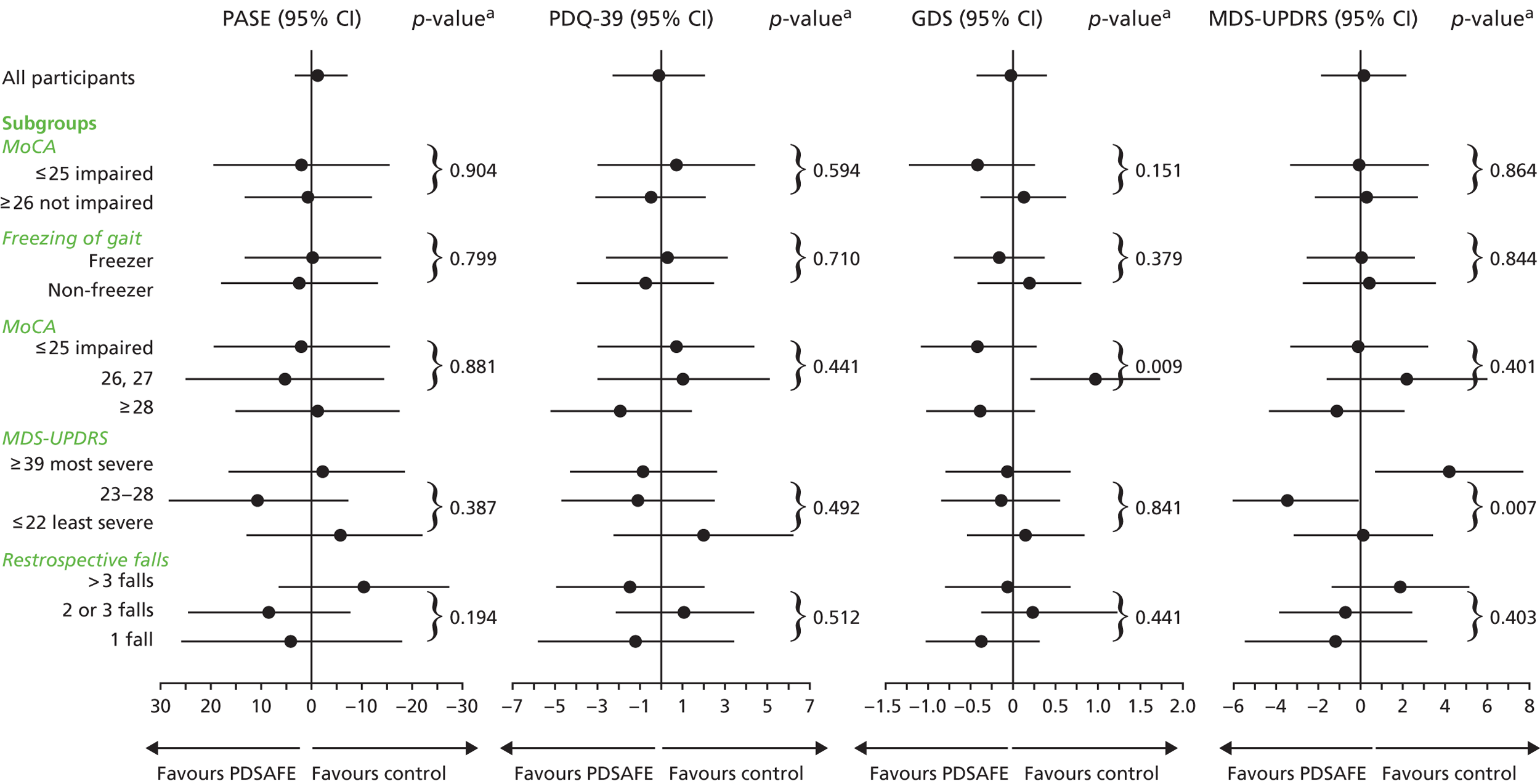

In addition, subgroup analyses were prespecified among those with reported freezing of gait or not and among the cognitively impaired (i.e. MoCA score of ≤ 25) and not impaired (i.e. MoCA score of ≥ 26) at baseline. The results of these analyses, relating to the period 0–6-months following randomisation in the case of the falling outcomes, and to the 6-month home visit in the case of the MINI-BESTest and FES-I, are shown in Figure 7. There was a significant interaction between the PDSAFE intervention effect and freezing status (p = 0.025). Among those with Parkinson’s who experienced freezing, the OR of repeat falling was doubled in the PDSAFE group (2.04, 95% CI 1.03 to 2.70; p = 0.042) compared with the control group. With a p-value for interaction of 0.088, there was a trend of differential PDSAFE effect in relation to the rate of falling according to the prespecified MoCA subgroups, with a FRR of 1.19 (95% CI 0.88 to 1.61; p = 0.255) in the cognitively impaired subgroup (i.e. MoCA score of ≤ 25). Subgroup-specific effect sizes and p-values are given in Appendix 8 (Table 29) and Appendix 9 (Table 30) for the analyses of repeat falling and fall rates, respectively.

FIGURE 7.

Overall and subgroup analyses of falling and near-falling outcomes during 0–6 months and secondary outcomes at 6 months. a, Test for interaction of PDSAFE contrast differing across subgroups, controlled for site, age, gender, repeat falling or not in the year prior to screening, log number of falls in the year prior to screening, log rate of falling in the pre-randomisation falls collection period, H&Y scale stage and the outcome in question assessed at baseline. Adapted from Chivers Seymour et al. 49 © Author(s) [or their employer(s)] 2019. Re-use permitted under CC BY-NC. No commercial re-use. See rights and permissions. Published by the BMJ Publishing Group Ltd. This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited, appropriate credit is given, any changes made indicated, and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. NFRR = near-falls rate ratio.

The results of further subgroup analyses exploring the differential effects of PDSAFE on the basis of tertiles of MDS-UPDRS, MoCA and the retrospective falls question asked at screening are shown in Figure 7. A further prespecified subgroup analysis excluding the most severe participants according to MDS-UPDRS (≈10% were excluded) did not show statistically significant PDSAFE-to-control effects for falling outcomes. In an exploratory subgroup analysis, only the middle tertile showed a PDSAFE reduction in falls, whereas the most severe tertile showed an increase in falls rate. A similar pattern was found across the tertiles according to the retrospectively reported number of falls in the year prior to screening, with p-value for interaction of 0.050 and only the middle tertile showing a PDSAFE reduction in falls. The analysis of subgroups defined by tertiles of MoCA, MDS-UPDRS and the number of falls, retrospectively, reported in the year prior to screening were not specified in the protocol, but were carried out to explore further the prespecified subgroups in relation to MoCA, and, because Canning et al. 40 report prespecifying subgroup analysis in relation to falls history, the MDS-UPDRS and cognition.

The same subgroup analyses were also explored with respect to near-falls and other secondary outcomes, and results for near-falling, Mini-BESTest and the FES-I are also shown in Figure 7. The effect of PDSAFE did not differ significantly across subgroups for any of these three outcomes, with interaction p-values > 0.05; in general, the PDSAFE effect can be seen to be more consistent across the various parts of the participant group. Details of these analyses are shown in Appendices 8–12 (Tables 29–33).

Appendices 13 and 14 (Tables 34 and 35) repeat the subgroups analyses for the repeat falling and falls rate outcomes shown in Tables 6 and 7, but include corresponding analyses carried on a per-protocol basis. Although there are some differences (including changes in p-values around the cut-off point of 0.05), the overall picture remains similar to that of Figure 7. Appendices 15–17 (Tables 36–39) detail subgroup analyses for the MDS-UPDRS, PASE, PDQ-39 and GDS and these are displayed graphically in Appendix 18 (Figure 13).

Serious adverse events

As described in Chapter 2, Safety reporting, for this trial a SAE was defined as a death, a life-threatening event or a new disability leading to prolonged hospitalisation, attributed to the trial intervention. No SAEs were reported in this trial. From the CONSORT flow diagram (see Figure 6), it can be seen that, in total, three participants died in the PDSAFE group and five in the control group, from causes unrelated to the trial protocol.

Information on hospitalisations was self-reported by participants during the baseline, 3-month, 6-month and 12-month home visits. At each visit, participants were asked about any hospitalisation that occurred since the previous visit and its duration. In the first 6 months following randomisation, nine PDSAFE and 20 control group participants reported hospitalisations; of these, one PDSAFE participant reported two stays. During the 6- to 12-month follow-up period, 18 PDSAFE and 21 control group participants reported hospitalisations; of these, two PDSAFE and four control group participants reported two stays.

Information on fractures was obtained from a variety of sources, including fall-specific information associated with the falls diaries and from self-reported hospitalisations. In the first 6 months following randomisation, five fractures were reported by PDSAFE participants and nine by control group participants; during the period 6–12 months post randomisation, PDSAFE participants reported seven fractures and control group participants reported three fractures.

Chapter 5 Qualitative process evaluation: part 1

The next two chapters describe the two-stage qualitative process evaluation. This chapter explores the expectations and experiences of participants in the PDSAFE intervention in a longitudinal qualitative study.

Aims

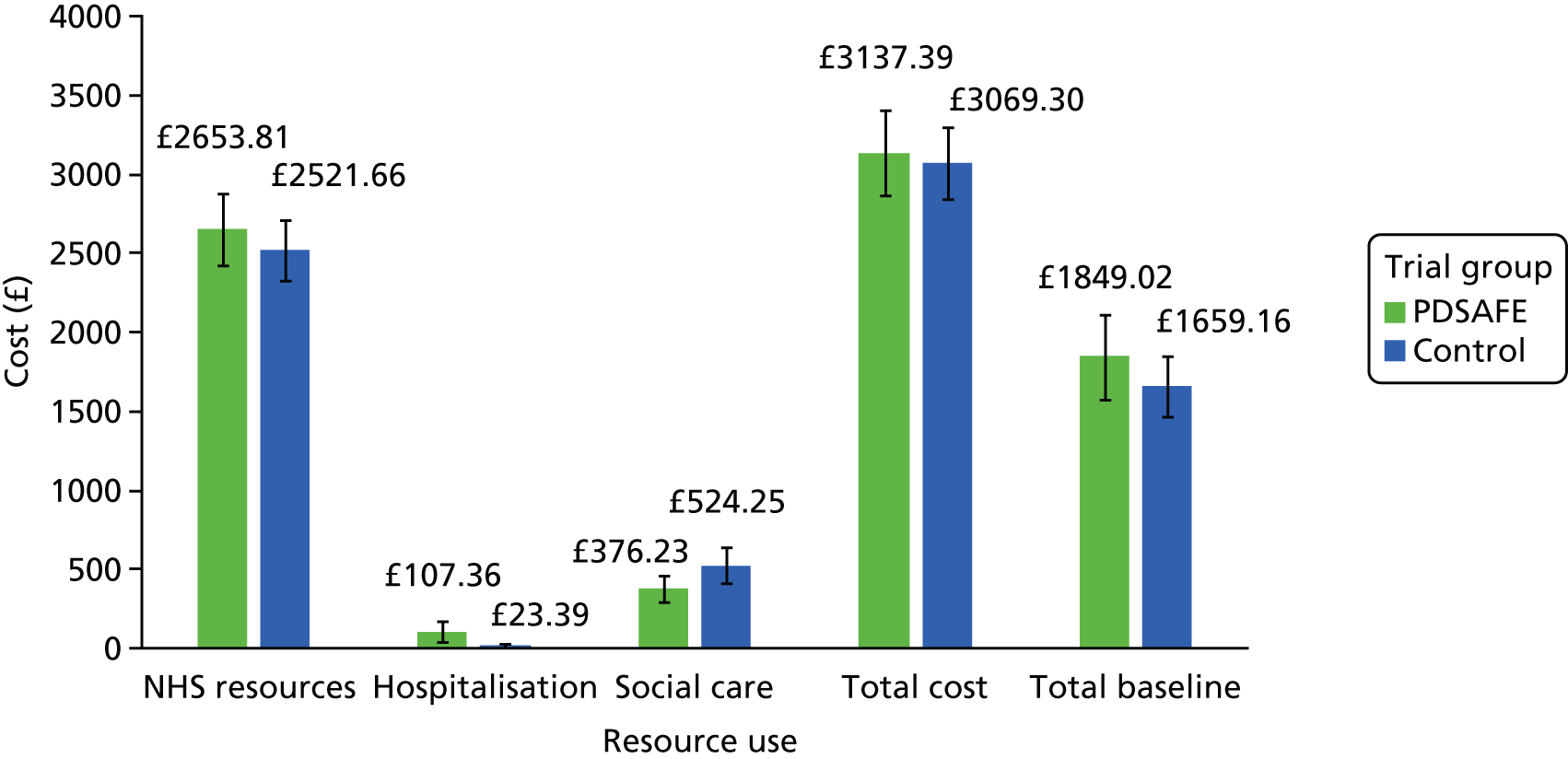

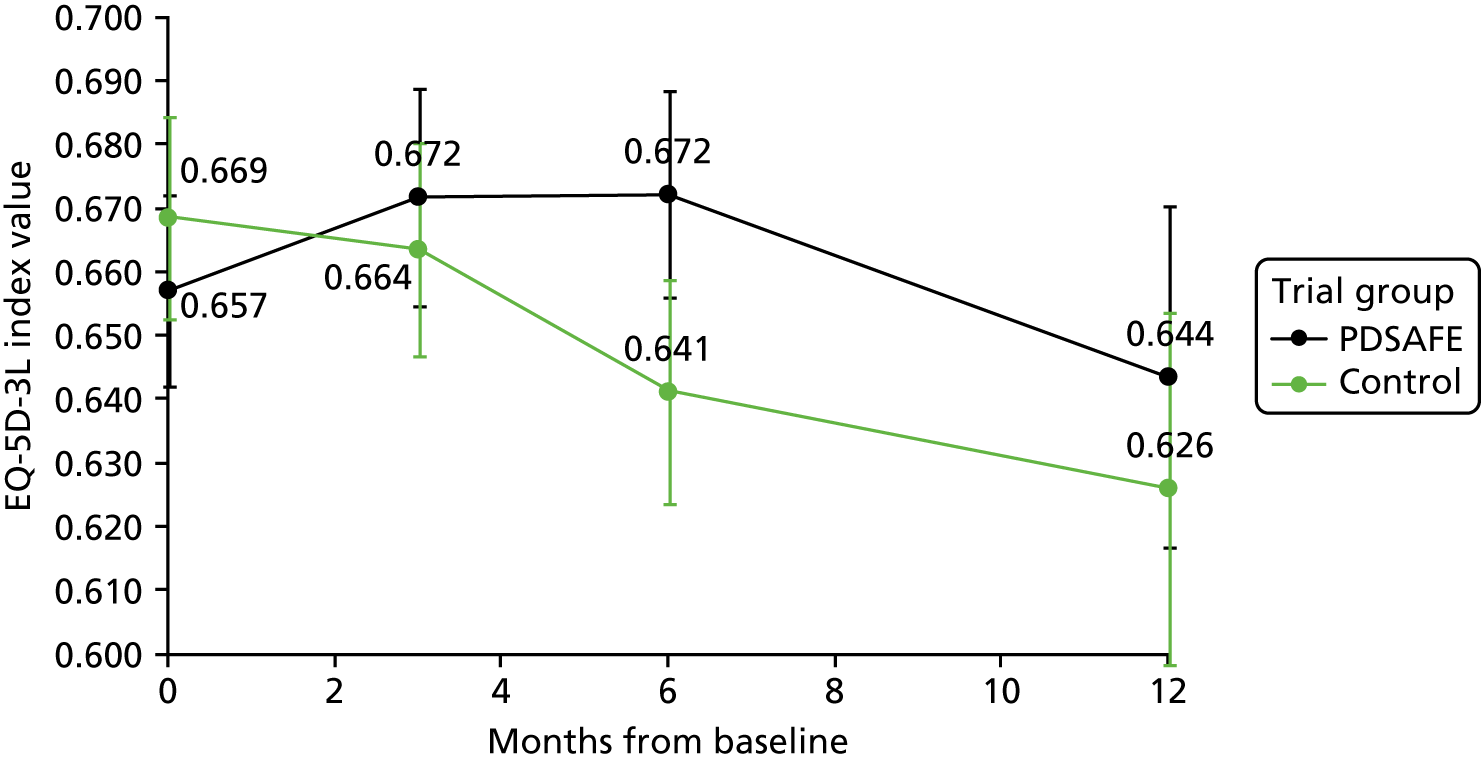

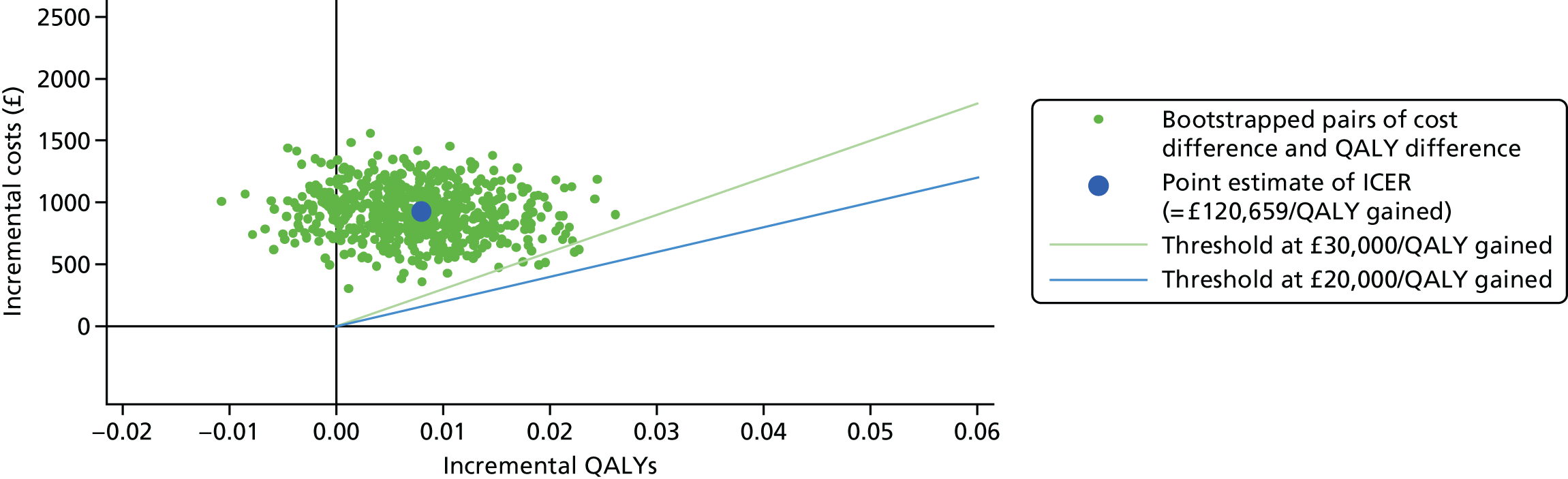

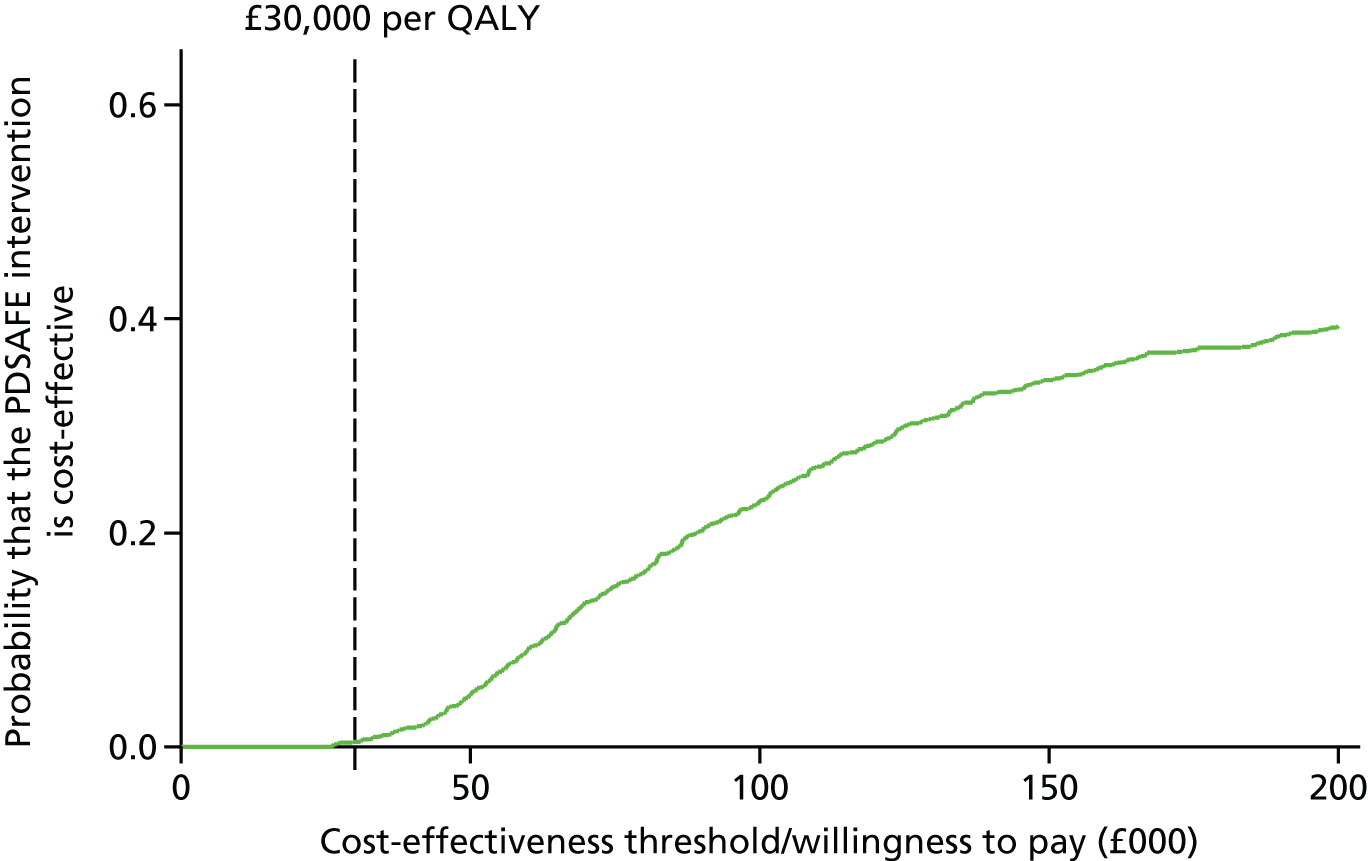

-