Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 11/58/15. The contractual start date was in July 2013. The draft report began editorial review in April 2018 and was accepted for publication in November 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Graham Burns reports personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim GmbH (Ingelheim am Rhein, Germany), Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd (Petah Tikva, Israel), Chiesi Farmaceutici SpA (Parma, Italy), Pfizer Inc. (New York City, NY, USA) and AstraZeneca plc (Cambridge, UK), and non-financial support from Chiesi and Boehringer Ingelheim, outside the submitted work. Rekha Chaudhuri reports personal fees from AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) plc (London, UK), Teva and Novartis International AG (Basel, Switzerland) for advisory board meetings, outside the submitted work. Anthony De Soyza reports grants and non-financial support from AstraZeneca and Chiesi, non-financial support from Boehringer Ingelheim, grants and personal fees from GSK, Bayer AG (Leverkusen, Germany) and Pfizer, and grants from Forest Laboratories (New York City, NY, USA)/Teva, outside the submitted work. He is also a member of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Elective and Emergency Specialist Care (EESC) Panel. Simon Gompertz reports personal fees from Pfizer and GSK, outside the submitted work. John Norrie reports grants from the NIHR HTA programme during the conduct of the study, was a member of the NIHR HTA Commissioning Board (2010–16) and is currently Deputy Chairperson of the NIHR HTA General Board (2016–present) and a NIHR Journals Library Editor (2014–present). Andrew Wilson reports grants from F. Hoffmann-La Roche (Basel, Switzerland), outside the submitted work. David Price reports grants and personal fees from Aerocrine AB (Stockholm, Sweden), AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Mylan NV (Canonsburg, PA, USA), Mundipharma International Ltd (Cambridge, UK), Napp Pharmaceuticals Ltd (Cambridge, UK), Novartis, Pfizer, Teva, Theravance Biopharma (San Francisco, CA, USA) and Zentiva Group a.s. (Prague, Czech Republic); personal fees from Almirall SA (Barcelona, Spain), Amgen Inc. (Newbury Park, CA, USA), Cipla Ltd (Mumbai, India), GSK, Kyorin Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd (Tokyo, Japan), Merck Sharp & Dohme (Kenilworth, NJ, USA), Skyepharma Production SAS (Saint-Quentin-Fallavier, France); grants from AKL Research and Development Ltd (Stevenage, UK), the British Lung Foundation, the Respiratory Effectiveness Group and the UK NHS; and non-financial support from the NIHR Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation and HTA programmes, outside the submitted work. He also reports stock/stock options from AKL Research and Development Ltd, which produces phytopharmaceuticals and owns 74% of the social enterprise Optimum Patient Care Ltd (Cambridge, UK, and Australia and Singapore) and 74% of Observational and Pragmatic Research Institute Pte Ltd (Singapore).

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Devereux et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is defined by the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) as:

a common preventable and treatable disease characterised by persistent airflow limitation that is usually progressive and associated with an enhanced chronic inflammatory response in the airways and the lungs to noxious particles or gases. Exacerbations and comorbidities contribute to the overall severity in individual patients.

People with COPD typically present with breathlessness on exertion, a productive cough and wheeze. COPD is usually diagnosed from the age of 40 years onwards and prevalence increases with age. 2 In Westernised countries, COPD is predominantly (80–90%) caused by cigarette smoking,3 but outdoor air pollution and occupational exposure to dusts, vapours and fumes can be significant contributory factors. 4,5 COPD is closely associated with social deprivation, and makes a major contribution to health inequalities in the UK. 6 The progressive airflow limitation of COPD is associated with increasing disability, work absence, long-term morbidity, common physical and psychological comorbidities and premature mortality. People with COPD are more likely to have associated comorbidities,7 including ischaemic heart disease,8 hypertension,9 heart failure,10,11 diabetes mellitus,12 osteoporosis,13 depression14 and lung cancer,15 which increase morbidity and complicate the management of COPD. 7

Acute deteriorations in symptoms, known as exacerbations, are an important clinical feature of COPD. These are usually precipitated by viral/bacterial infection and/or air pollution and are characterised by increasing breathlessness and/or cough, sputum expectoration and malaise. Many exacerbations are severe enough for patients to seek medical help, which usually takes the form of antibiotics and/or corticosteroids from their general practitioner (GP); more severe exacerbations frequently necessitate admission to hospital for more intensive treatment. Exacerbations are associated with accelerated rate of lung function decline,16 reduced physical activity,17 reduced quality of life (QoL),18 increased mortality19 and increased risk of comorbidities such as acute myocardial infarction and stroke. 20

The observational Evaluation of COPD Longitudinally to Identify Predictive Surrogate Endpoints (ECLIPSE) study of 2138 COPD patients shed light on factors that influence COPD exacerbations. 21 This study identified a frequent exacerbator (defined as two or more exacerbations in a year) phenotype that affects ≈25% of COPD patients. Patients with this phenotype have an 84% chance of at least one exacerbation in the subsequent year; moreover, this frequent exacerbator phenotype is stable for at least 3 years and can be reliably identified by patient recall. This has been supported by further work demonstrating that the strongest predictor for exacerbations is the number of exacerbations in the preceding year. 22 Frequent exacerbators account for a disproportionate amount of the annual NHS spend on COPD.

The burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on individuals and the NHS

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is a major personal and public health burden. 23,24 Data from 591 UK general practices comprising The Health Improvement Network (THIN) indicate that the prevalence of diagnosed COPD in the UK increased from ≈991,000 in 2004 to 1.2 million in 2012. 2 COPD is the fifth leading cause of death in the UK, accounting for ≈5% of all deaths (≈30,000 deaths in 2014). More than 80% of COPD patients, irrespective of disease severity, report a reduced QoL. 24–26 Comorbidities are an important feature of COPD, contributing to ill health and treatment burden. It has been estimated that, in the UK, 33% of people with COPD have hypertension, 19% have ischaemic heart disease, 18% have depression, 11% have diabetes mellitus and 6% have heart failure. 23 Over 50% of people currently diagnosed with COPD in the UK are < 65 years of age, and 24 million working days are lost each year as a result of COPD, with £3.8B per year being lost through reduced productivity. 23

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease costs the NHS > £1B per year. In 2001, average annual NHS direct costs were £819 (> £1300 in severe COPD) for each COPD patient; 60% of this was accounted for by exacerbations and 19% was due to drug costs. 27 The Hospital Episode Statistics database shows that emergency hospital admissions for exacerbations of COPD in the UK have steadily increased as a percentage of all admissions, from 0.5% in 1991 to 1% in 2000 and to 1.5% in 2008/9. 28 In 2008/9, COPD exacerbations resulted in 164,000 hospital admissions in the UK, with an average length of stay of 7.8 days, accounting for 1.3 million bed-days. 28 COPD is the second leading cause of emergency admission to hospital in the UK and is one of the most costly inpatient conditions treated by the NHS. 23,24 At least 10% of emergency admissions to hospital are as a consequence of COPD, and this proportion is even greater during winter. Approximately 25% of patients who have been diagnosed as having COPD are admitted to hospital at some point, and ≈15% of COPD patients are admitted each year. 23,24 Over 30% of patients admitted to hospital with an exacerbation of COPD are re-admitted within 30 days, and an average of 12% of COPD patients die in the year following admission to hospital. 19

Despite advances in management that have led to the current National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) COPD guidelines,24 there is still an unmet need for improved pharmacological treatment of COPD, particularly the prevention of exacerbations.

Standard chronic obstructive pulmonary disease therapy

Standard COPD therapy remains suboptimal. At the time when the Theophylline With Inhaled CorticoSteroid (TWICS) trial was conceived, most international COPD management guidelines recommended the use of inhaled corticosteroids (ICSs) – usually in combination with inhaled long-acting β2-agonists (LABAs), known as ICS/LABA – to reduce COPD exacerbation rates and to improve lung function and QoL. 1,24 Although more recent guidelines advocate the use of LABAs in combination with long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMAs), ICS/LABA and ICS/LABA/LAMA combinations remain major therapeutic options and continue to be used very widely in the treatment of COPD. 29,30 However, when compared with the marked responses observed in asthma, ICSs in COPD fail to fully suppress airway inflammation and patients continue to have exacerbations despite high ICS doses. Furthermore, little or no positive impact of ICS on mortality or disease progression is evident31,32 and concerns have been raised about long-term sequelae of high-dose ICS use in COPD. 33,34 A relative insensitivity of COPD airway inflammation to the anti-inflammatory effects of high-dose ICS has been demonstrated in induced sputum and airway biopsies of people with COPD. 35–37

In recent years, molecular mechanisms contributing to the reduced corticosteroid sensitivity of COPD have been elucidated. The chronic airway inflammation of COPD is driven by expression of multiple inflammatory genes regulated by acetylation of core histones, which open up the chromatin structure, allowing transcription factors and ribonucleic acid (RNA) polymerase II to bind to deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), enabling gene transcription and increased synthesis of inflammatory proteins. 38 In COPD, there is increased acetylation of core histones associated with the promoter regions of inflammatory genes, with the degree of acetylation being positively associated with disease severity. 39 Histone acetylation is reversed by histone deacetylase (HDAC) enzymes. Corticosteroids appear to work by reversing histone acetylation through the recruitment of a specific HDAC called HDAC2,38,40,41 thereby switching off activated inflammatory genes. In people with COPD, increased histone acetylation appears to be a consequence of markedly reduced HDAC2 activity/expression in airways, lung tissue and alveolar macrophages. 39 It has been shown that the oxidative stress of COPD activates the enzyme phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)-δ, which then phosphorylates downstream kinases, resulting in the phosphorylation and inactivation of HDAC2. 41,42 The critical role played by reduced HDAC2 in the corticosteroid resistance of COPD is demonstrated by the finding that the corticosteroid resistance of COPD bronchoalveolar macrophages is completely reversed by overexpressing HDAC2 (using a plasmid vector) to levels seen in control patients without COPD. 40

Low-dose theophylline may have synergistic anti-inflammatory effects with corticosteroids

Oral theophylline has been used in the treatment of COPD for > 70 years, but usually at doses required to achieve relatively high blood concentrations (10–20 mg/l). It has been observed that the reduced HDAC2 activity of COPD can be reversed in a dose-dependent manner by low doses of theophylline; moreover, low-dose theophylline reduces corticosteroid insensitivity in COPD such that there is a marked synergistic interaction between theophylline and corticosteroids in suppressing the release of inflammatory mediators from alveolar macrophages from COPD patients. This in vitro work has shown that at (low) concentrations of 1–5 mg/l theophylline increases HDAC2 activity (sixfold) but at (high) concentrations of over ≈10 mg/l theophylline inhibits rather than stimulates HDAC2 activity. 43,44 These studies show that at concentrations of 1–5 mg/l, there is a marked synergistic effect between theophylline and corticosteroids, with theophylline inducing a 100- to 10,000-fold increase in the suppressive effect of corticosteroids on the release of pro-inflammatory mediators. Such an increase in corticosteroid potency is worthy of clinical interest, particularly if associated with reduced exacerbation rate. An explanation for the ability of low-dose (i.e. 1–5 mg/l) theophylline to increase HDAC activity has been described: it specifically inhibits the enzyme PI3K-δ with consequent restoration of HDAC2 activity to normal in COPD macrophages, rendering them steroid responsive. In mice exposed to cigarette smoke,42 steroid-resistant lung inflammation has also been found to be reduced by low-dose theophylline when given together with steroids. Similarly, rats exposed to cigarette smoke were found to have markedly decreased lung HDAC2 expression, and that reduced HDAC2 expression was correlated with increased lung destruction index. 45 The increased lung destruction index was restored to normal with ICS treatment in combination with low- (but not high-) dose theophylline. It was concluded that low-dose theophylline might provide protection from cigarette smoke damage and improve the anti-inflammatory effects of steroids by increasing HDAC2 activity.

In human peripheral blood mononuclear cells, corticosteroid insensitivity and reduced HDAC2 activity after oxidative stress have been shown to be reversed with low concentrations of theophylline. 46 In a study of human alveolar macrophages extracted from resected lung samples, the addition of hydrogen peroxide reduced HDAC expression and was associated with an increase in interleukin 8 (IL-8) and matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) release. 47 The addition of low-dose theophylline restored HDAC expression to levels above that observed with LABA, ICS and ICS/LABA.

These basic research studies suggest that low-dose (i.e. 1–5 mg/l) theophylline could increase HDAC activity and hence reduce corticosteroid resistance in COPD patients, thereby enabling ICS to switch off inflammation and potentially reduce exacerbation rates more effectively. This is supported by findings from two small randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and a population-based health administration database study. The first RCT in 35 patients with acute COPD exacerbations found that low-dose theophylline increased responsiveness to corticosteroids as measured by increased HDAC activity and further reduced concentrations of pro-inflammatory mediators in induced sputum compared with ICSs alone. 48 In the second small (n = 30) pilot RCT of COPD patients, the combination of low-dose theophylline with high-dose ICSs was associated with increased HDAC activity, improved lung function and reduced sputum inflammatory cells and mediators, whereas either drug alone was ineffective. 49 A Canadian health administration database study of 36,492 COPD patients reported that treatment with theophylline alone or in combination with ICS was more protective against exacerbations than treatment with LABA or ICS/LABA [relative risk (RR) 0.89, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.87 to 0.92]. 50

More recent studies, however, have not replicated the results of earlier studies. Fexer et al. 51 used data from a German ambulatory COPD management programme and closely matched 1496 COPD patients commenced on theophylline with 1496 COPD patients not commenced on theophylline. The use of theophylline was associated with an increased likelihood of exacerbation [hazard ratio (HR) 1.41, 95% CI 1.24 to 1.60] and hospital admission (HR 1.61, 95% CI 1.29 to 2.01). Although it was concluded that theophylline is associated with an increased incidence of exacerbations and hospitalisations, it should be noted that this study did not identify those patients on low-dose theophylline. 51 The Spanish Low-dose Theophylline as Anti-inflammatory Enhancer in Severe Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (ASSET) trial recruited patients with COPD while hospitalised for a COPD exacerbation and randomised to low-dose theophylline (100 mg twice a day) or matched placebo in addition to usual ICS/LABA treatment. 52 In total, 70 patients were randomised (theophylline, n = 36; placebo, n = 34) and 46 completed the year of treatment (theophylline, n = 23; placebo, n = 23). The addition of theophylline had no effect on the COPD exacerbation rate or plasma/sputum concentrations of HDAC and inflammatory mediators. It should be noted that the study was small and designed to detect a 50% reduction in exacerbations.

Conventionally, oral theophylline has been used as a bronchodilator in COPD; however, to achieve modest clinical effects, relatively high blood concentrations (of 10–20 mg/l) are required. The bronchodilator effect of high-dose theophylline is the consequence of inhibition of phosphodiesterase (PDE) and the consequent relaxation of airway smooth muscle. However, non-specific inhibition of PDE by theophylline is also associated with a wide range of well-recognised side effects that may occur within the conventional therapeutic range of plasma theophylline, namely nausea, gastrointestinal upset, headaches, insomnia, seizures, cardiac arrhythmias and malaise. Theophylline toxicity is dose related, and this is an issue with conventional theophylline use because the therapeutic ratio of theophylline is small and most of the beneficial bronchodilator effect occurs when near-toxic doses are given. 53 Theophylline is metabolised by cytochrome P450 mixed function oxidase; as a consequence, theophylline use is further complicated by significant drug interactions with drugs commonly prescribed to people with COPD, for example clarithromycin or ciprofloxacin. 54 The narrow therapeutic index, modest clinical effect and side effect profile of theophylline, together with drug interactions, the need for blood concentration monitoring and the availability of more effective inhaled therapies, have resulted in current COPD guidelines relegating high-dose theophylline to third-line therapy. 1

The TWICS trial was a pragmatic, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trial that was built on emerging evidence that low-dose (i.e. 1–5 mg/l) theophylline may produce a beneficial synergistic effect in COPD by increasing the corticosteroid sensitivity of the airway inflammation underlying COPD and, as a consequence, reduce the rate of COPD exacerbation when used in conjunction with ICSs.

Hypothesis

The hypothesis being tested was that the addition of low-dose theophylline to ICS therapy in COPD reduces the risk of COPD exacerbation requiring treatment with antibiotics and/or oral corticosteroids (OCSs) during the year of treatment, delivers QoL improvements and is cost-effective.

Objectives

The primary objective of the trial was to determine the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of adding low-dose theophylline to ICS therapy in patients with COPD and a history of two or more exacerbations treated with antibiotics and/or OCSs in the previous year in relation to the number of exacerbations in the 1-year treatment period requiring therapy with antibiotics and/or OCSs.

The secondary objectives were to compare the following outcomes between participants treated with low-dose theophylline and those treated with placebo:

-

hospital admissions with a primary diagnosis of exacerbation of COPD

-

total number of episodes of pneumonia

-

total number of emergency hospital admissions

-

lung function

-

all-cause and respiratory mortality

-

drug reactions and serious adverse events (SAEs)

-

health-related QoL

-

disease-specific health status

-

total ICS dose/usage

-

health-care utilisation

-

incremental cost per exacerbation avoided

-

lifetime cost-effectiveness based on extrapolation modelling

-

modelled lifetime incremental cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY).

An additional secondary objective was the time to the first exacerbation of COPD.

Outcomes

Primary outcomes

The primary outcome was the total number of exacerbations of COPD necessitating changes in management (minimum management change: use of OCSs and/or antibiotics) during the 1-year treatment period, as reported by the participant.

The primary economic outcome was cost per QALY gained during the 1-year treatment period.

Secondary outcomes

-

Total number of COPD exacerbations requiring hospital admission.

-

Total number of episodes of pneumonia.

-

Total number of emergency hospital admissions (all causes).

-

Lung function [forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), forced vital capacity (FVC)] post bronchodilator, measured using spirometry performed to American Thoracic Society (ATS)/European Respiratory Society (ERS) standards.

-

All-cause and respiratory mortality.

-

Serious adverse events and adverse reactions (ARs).

-

Total dose of ICS.

-

Utilisation of primary or secondary health care for respiratory events.

-

Disease-specific health status measured using the COPD Assessment Test (CAT) and modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) dyspnoea scale.

-

Generic health-related QoL measured using the EuroQoL-5 Dimensions, three-level version (EQ-5D-3L) index.

-

Modelled lifetime incremental cost per QALY.

An additional secondary outcome was the time to the first exacerbation of COPD.

Chapter 2 Methods/design

Trial design

The trial protocol has been published in an open-access journal. 55

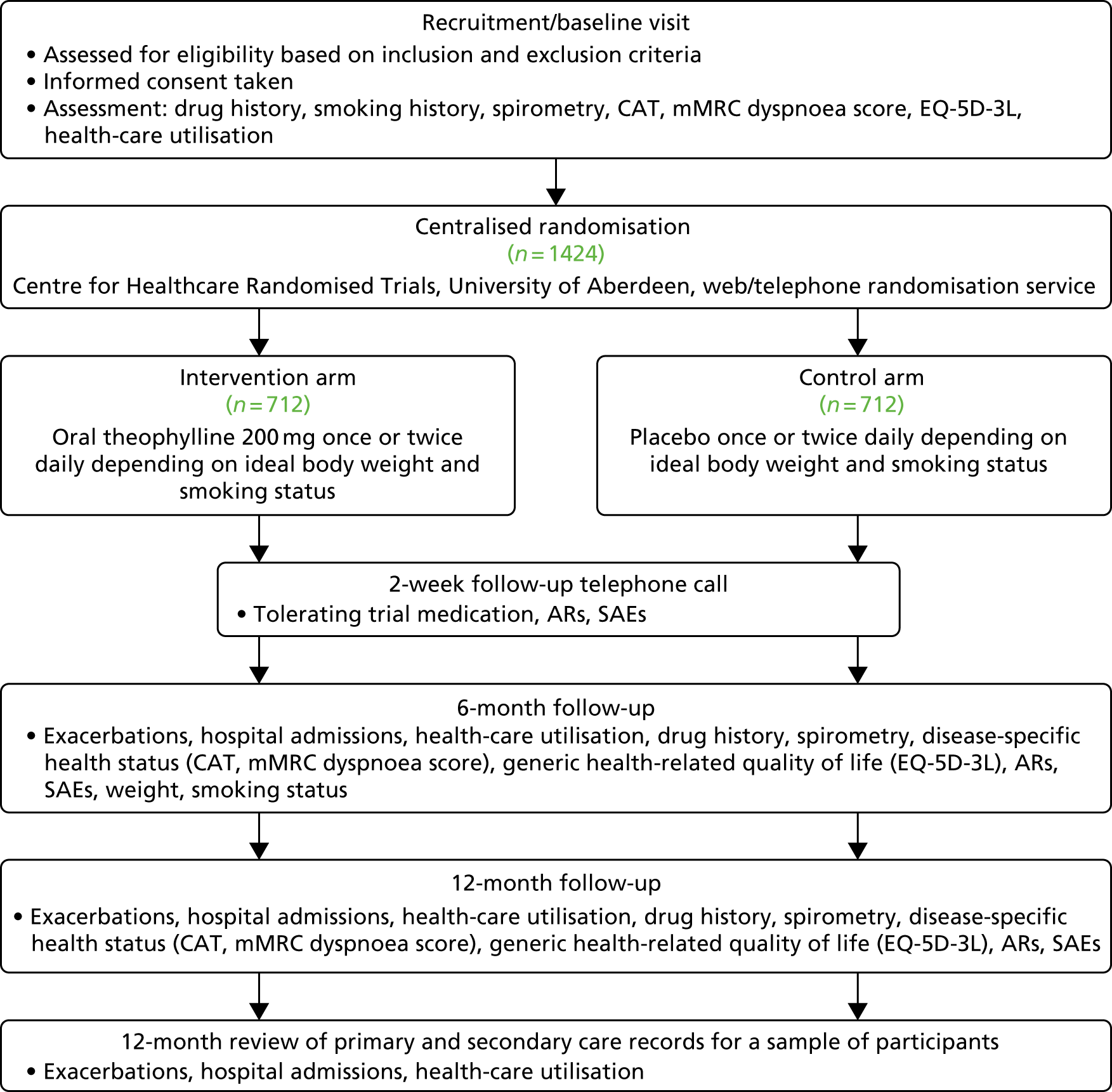

The TWICS trial was a pragmatic, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, parallel-arm, UK multicentre clinical trial that compared the addition of low-dose theophylline or placebo for 52 weeks with current COPD therapy that included ICSs in patients with COPD who had experienced two or more exacerbations of COPD in the previous year treated with OCSs and/or antibiotics. The aim was to recruit 1424 participants, with at least 50% recruited in primary care. The trial was approved by Scotland A Research Ethics Committee (REC) (reference number 13/SS/0081) and the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) (EudraCT 2013-001490-25, Clinical Trial Authorisation 21583/0218/001). All participants provided written informed consent, which included consent to inform a participant’s GP of involvement in the trial and consent to pass on a participant’s name and address to a third-party distributer that delivered the trial drug to participants’ homes. Figure 1 provides a schematic representation of the trial design and schedule. Face-to-face trial assessments were carried out at recruitment/baseline and at 6 and 12 months, as shown in Figure 2.

FIGURE 1.

Trial design.

FIGURE 2.

Flow diagram of trial schedule.

The trial was registered on 19 September 2013 as ISRCTN27066620.

Participants

Inclusion criteria

The participants in the TWICS trial were people with COPD who were likely to experience an exacerbation during the 52-week treatment period as evidenced by two or more exacerbations of COPD in the previous year treated with OCSs or antibiotics. Participants had to meet all of the following inclusion criteria, which are typical of studies of people with COPD with exacerbations as the primary end point:

-

aged ≥ 40 years

-

a smoking history of ≥ 10 pack-years

-

an established predominant respiratory diagnosis of COPD (GOLD/NICE guideline definition: post bronchodilator FEV1/FVC of < 0.7)1,2

-

current use of ICS therapy at the baseline/recruitment visit

-

a history of at least two exacerbations requiring treatment with antibiotics and/or OCS use in the previous year, based on patient report

-

clinically stable with no COPD exacerbation for at least the previous 4 weeks

-

able to swallow trial medication

-

able and willing to give informed consent to participate

-

able and willing to participate in the trial procedures, undergo spirometric assessment and complete the trial questionnaire.

Potential participants with COPD who did not fulfil the lung function criterion of FEV1/FVC of < 0.7 at the recruitment/baseline visit were asked to complete a slow vital capacity (SVC) manoeuvre, and FEV1/SVC of < 0.7 was accepted as evidence of airflow obstruction. Historical evidence of FEV1/FVC of < 0.7 was deemed acceptable for those participants who did not achieve FEV1/FVC of < 0.7 or FEV1/SVC of < 0.7 or who were unable to complete spirometry at the recruitment/baseline assessment. Eligibility for inclusion was confirmed by a medically qualified person.

Exclusion criteria

The exclusion criteria for the TWICS trial were typical of studies of people with COPD but also included criteria specific for theophylline, notably concomitant treatment with drugs that were likely to increase plasma theophylline concentration above the low-dose range of 1–5 mg/l. Potential participants were excluded if they fulfilled any of the following criteria:

-

severe or unstable ischaemic heart disease

-

a predominant respiratory disease other than COPD

-

any other significant disease/disorder that, in the investigator’s opinion, put the patient at risk because of trial participation, or might influence the results of the trial or the patient’s ability to participate in the trial

-

previous allocation of a randomisation code in the trial or current participation in another interventional study [Clinical Trial of an Investigational Medicinal Product (CTIMP) or non-CTIMP]

-

women who were pregnant or breastfeeding, or were planning a pregnancy during the trial period

-

current medication includes theophylline

-

known or suspected intolerance to theophylline

-

current use of drugs known to interact with theophylline and/or increase plasma theophylline54 –

-

antimicrobials: aciclovir, clarithromycin, ciprofloxacin, erythromycin, fluconazole, ketoconazole, levofloxacin and norfloxacin

-

cardiovascular drugs: diltiazem, mexiletine, pentoxifylline and verapamil

-

neurological drugs: bupropion, disulfiram, fluvoxamine and lithium

-

hormonal drugs: medroxyprogesterone and oestrogens

-

immunological drugs: methotrexate, peginterferon alpha and tacrolimus

-

miscellaneous: cimetidine, deferasirox, febuxostat, roflumilast and thiabendazole.

-

Patients with COPD as a consequence of alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency were excluded; however, short- or long-term use of azithromycin56 or use of topical oestrogens or aciclovir were not exclusion criteria.

Identification

Potential participants were recruited from both primary and secondary care sites across the UK. To ensure generalisability, the intention was that the majority of participants (> 50%) would be recruited from primary care. Recruitment strategies differed between centres depending on local geographic and NHS organisational factors.

Primary care and other community-based services

In England, recruitment from general practices was conducted in conjunction with the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Clinical Research Network (CRN) at the national and local levels. Practices could participate as independent research sites or as participant identification centres (PICs) for secondary care or other primary care research sites.

In general practices, the local CRN/collaborating recruitment site/trial office liaised directly with practice staff who performed database searches (based on search criteria including the use of inhaled preparations containing corticosteroids, a record of one exacerbation treated with OCSs in the previous year and the use of interacting medications) to identify potential participants. Potentially suitable patients were sent an invitation letter and a participant information leaflet (PIL). For general practices acting as independent research sites, interested potential participants were invited to contact the practice-based trial team for more information and to arrange a recruitment visit. For general practices acting as PICs, interested potential participants were invited to contact the local trial team at the associated secondary or primary care research site for more information and to arrange a recruitment visit. All invitation material, consent forms, trial case report forms and participant-completed questionnaires can be found on the project web page at www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/115815/#/ (accessed 23 April 2019).

In Scotland, the Scottish Primary Care Research Network mirrored the role undertaken by the English CRN by identifying potential participants in primary care, with interested patients being invited to make contact with a local trial team based in secondary care.

Potential participants were also identified from other community COPD services, such as pulmonary rehabilitation, COPD community matrons, smoking cessation services and integrated/intermediate care services for patients with COPD. Potentially suitable participants identified by these services were sent an invitation letter and a PIL, and if interested, participants were asked to contact the local trial team (usually in secondary care) for more information and to arrange a recruitment visit.

Secondary care

Potential participants were also identified from patients attending (or who had previously attended) respiratory outpatient appointments or who had been inpatients at the hospitals of the individual recruiting centres. Potentially suitable patients were sent an invitation letter and a PIL from a member of their hospital care team (usually their consultant). Interested patients were invited to contact the local hospital-based trial team for more information and to arrange a recruitment visit.

Recruitment/baseline visit

At the recruitment visit, a participant’s eligibility was confirmed by a medically qualified doctor and fully informed consent was recorded in writing. Baseline data (see Data collection) were also collected.

Randomisation/treatment allocation

Participants were randomised, usually by a research nurse, using a computerised randomisation system available as both an interactive voice response telephone system and an internet-based application; the internet application was used for all randomisations within the trial. The randomisation service was created and administered by the Centre for Healthcare Randomised Trials (CHaRT) in the University of Aberdeen. Consenting participants were stratified by trial centre (for participants recruited in secondary care) or area (for participants recruited in primary care) and by where the participant had been identified (primary or secondary care) and then randomised with equal probability to the intervention (low-dose theophylline) and control (placebo) arms.

The random allocation sequence for the TWICS trial was generated using permuted blocks. This provided randomly generated blocks of entries of varying sizes permuted for each combination of trial centre/area and where the participant had been identified (primary or secondary care). Each entry was assigned a treatment according to a randomly generated sequence utilising block sizes of two or four. Each treatment option was assigned an equal number of times within each block, ensuring that the total number of entries assigned to each treatment remained balanced. The sequence of blocks was also random, so it was not possible for anyone to determine the next treatment to be allocated based on previous allocations made during the randomisation process.

It was possible to randomise a participant only if the relevant eligibility criteria had been met. In addition to trial centre/area and where the participant had been identified (primary or secondary care), sex, height, weight, smoking status (and, for smokers, number of cigarettes per day) and date of birth were captured during the randomisation process to calculate the correct dosage of trial medication for that participant and assign an appropriate drug pack.

With this information captured, the randomisation process assigned a trial number (i.e. a participant identification), allocated a treatment and assigned a drug pack. The user/caller was notified of the trial number and drug pack either on screen or during the randomisation telephone call. The allocated treatment remained blinded throughout, with neither the user/caller nor the participant (or anyone involved in the participant’s care or the assessment of outcomes) made aware of the allocation. All of the data captured or assigned were saved to a secure database.

The random permuted blocks that defined how treatments were allocated to participants were created by the CHaRT programming team during the system development process. The system built to utilise these permuted blocks was tested by a run of simulated randomisations that allowed the outcomes to be cross-checked and validated. Before the randomisation system went ‘live’, enough blocks were created to ensure that entries existed for the maximum expected number of participants across the maximum expected number of trial centres/areas. However, the randomisation system was flexible enough to allow the option to add further permuted blocks to the list if more were required during the lifetime of the trial. In such circumstances, randomly generated sequences in blocks of two and four continued to be utilised.

Intervention

The active intervention was 200-mg tablets of Uniphyllin modified release (MR) taken once or twice a day for 52 weeks. The placebo was manufactured to be visually identical, and was also taken once or twice a day for 52 weeks. The packaging and labelling of active and placebo interventions were identical. The intervention was for 52 weeks of therapy. The 200-mg tablets of Uniphyllin MR and placebo were supplied by Napp Pharmaceuticals Ltd (Cambridge, UK). Napp Pharmaceuticals Ltd is the holder of the marketing authorisation for 200-mg tablets of Uniphyllin MR (marketing authorisation number: PL 16950/0066–0068). Uniphyllin Continus 200 mg, 300 mg and 400 mg is licensed for the treatment and prophylaxis of bronchospasm associated with COPD, asthma and chronic bronchitis; consequently, theophylline was administered within licensed indication. 54 Placebo tablets were manufactured by Mundipharma Research Ltd (Cambridge, UK).

Dosage

The pre-clinical studies outlined in Chapter 1 demonstrate the critical importance of plasma theophylline concentration, with plasma concentrations of 1–5 mg/l having the maximal effect in reducing corticosteroid insensitivity, whereas at concentrations of > 10 mg/l theophylline is inhibitory, augmenting corticosteroid insensitivity. Theophylline dosing in the TWICS trial was based on pharmacokinetic modelling57–66 of theophylline, incorporating the major determinants of theophylline steady-state concentration (Css) [i.e. weight, smoking status and clearance of theophylline (i.e. low, normal, high)], and was designed to achieve a Css plasma theophylline of 1–5 mg/l, and to certainly be < 10 mg/l (> 10 mg is the concentration associated with high-dose theophylline, possible side effects and augmentation of corticosteroid insensitivity). For full details, see Appendix 1.

The dosing of both the interventional arm (200-mg tablets of Uniphyllin MR) and the control arm (placebo tablets) was determined by a participant’s ideal body weight (IBW) and self-reported smoking status:

-

A dose of 200 mg of theophylline MR (one tablet) once daily (or one placebo once daily) was taken by participants who did not smoke, or participants who smoked but had an IBW of ≤ 60 kg.

-

A dose of 200 mg of theophylline MR (one tablet) twice daily (or one placebo twice daily) was taken by participants who smoked and had an IBW of > 60 kg.

Ideal body weight was used unless a participant’s actual weight was lower than the ideal body weight; in such cases, actual body weight was used to determine dose.

Ideal body weight was calculated using the following standard equations:67

For the calculation of dose, to be classed as a ‘non-smoker’ at recruitment, a participant must have abstained from smoking for ≥ 12 weeks. Participants who had given up smoking recently (< 12 weeks ago) were classed as smokers.

Protocol-defined changes in dose during the treatment period

Table 1 summarises changes in dose during the treatment period based on changes in smoking status or weight.

| Characteristics at baseline | Initial dose | Changes to smoking during follow-up | Changes to weight during follow-up | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IBW (kg) | ABW (kg) | Smoking status | Change to smoking status | Dose change | Change to weight | Dose change | |

| > 60 | > 60 | Smoker | bd | Stop smoking | Reduce to od | Lose; ABW now ≤ 60 kg | Reduce to od |

| > 60 | ≤ 60 | Smoker | od | Stop smoking | No change | Gain; ABW now > 60 kg | Increase to bd |

| ≤ 60 | > 60 | Smoker | od | Stop smoking | No change | Lose; ABW now ≤ 60 kg | No change |

| Gain | No change | ||||||

| ≤ 60 | ≤ 60 | Smoker | od | Stop smoking | No change | Gain | No change |

| > 60 | > 60 | Non-smoker | od | Start smoking | Increase to bd | Lose; ABW now ≤ 60 kg | No change |

| Gain | No change | ||||||

| > 60 | ≤ 60 | Non-smoker | od | Start smoking | No change | Gain | No change |

| ≤ 60 | > 60 | Non-smoker | od | Start smoking | No change | Lose; ABW now ≤ 60 kg | No change |

| Gain | No change | ||||||

| < 60 | ≤ 60 | Non-smoker | od | Start smoking | No change | Gain | No change |

Changes in smoking status

Changes in smoking status are known to influence the pharmacokinetics of theophylline (smokers clear the drug more rapidly). Self-reported smoking status was checked at every contact and participants were advised, in writing and verbally, to contact their trial team if their smoking status changed during the treatment period. Participants who stopped smoking during the treatment period were reclassified as ‘non-smokers’ if they abstained from smoking for ≥ 12 weeks. Smoking participants whose IBW (and actual body weight) was > 60 kg and who stopped smoking had their dose reduced to 200 mg once daily (od) (one tablet once a day); those with an IBW of ≤ 60 kg maintained their 200 mg od dose. Participants who started smoking during the treatment period were reclassified as ‘smokers’ when they had smoked for ≥ 12 weeks. Non-smoking participants whose IBW (and actual body weight) was > 60 kg and who started smoking had their dose increased to 200 mg twice a day (bd) (one tablet twice a day).

Changes in weight

Changes in weight are known to influence the pharmacokinetics of theophylline. Participants who smoked and had an IBW of > 60 kg but an actual body weight of ≤ 60 kg had their dose reduced to 200 mg od. Participants who smoked and had an IBW of > 60 kg but whose actual body weight increased to > 60 kg had their dose increased to 200 mg bd.

Changes in concomitant medication

When informed of their patient’s participation in the trial, GPs were advised to manage their patient for exacerbations as per normal clinical practice but to assume that the participant was taking low-dose theophylline. GPs were advised to avoid, whenever possible, prescribing drugs that were likely to increase plasma theophylline concentrations; they were provided with a list of such drugs. In the event that drugs known to increase theophylline concentration had to be prescribed for ≤ 3 weeks, GPs/participants were asked to suspend the trial medication and recommence it after the course of the interacting drug had been completed, for example prescription of clarithromycin for an exacerbation of COPD. If the interacting drug was to be prescribed for > 3 weeks, GPs/participants were asked to discontinue the trial medication but remain in the trial, and were followed up in accordance with the trial protocol.

Participants were asked to carry a trial card and to show this to anyone prescribing medication for them. This advised the prescriber to assume that the participant was taking low-dose theophylline and included a link to the list of drugs that may increase plasma theophylline concentrations.

Theophylline in the form of intravenous aminophylline is sometimes used in the treatment of severe acute exacerbations of COPD in the hospital setting. It was anticipated that, during the trial, some participants would be hospitalised with life-threatening exacerbations of COPD and that the treating physician may wish to use intravenous aminophylline. The commonly used clinical protocol for intravenous aminophylline was established during the era of high-dose oral theophylline, when patients would be prescribed oral theophylline aiming for a plasma concentration of 10–20 mg/l and a loading dose of aminophylline would raise plasma theophylline concentrations to toxic concentrations (i.e. > 20 mg/l). For a patient not established on oral theophylline, the intravenous protocol comprises a bolus of intravenous aminophylline (usually 250 mg, or 5 mg/kg) followed by a maintenance dose (0.5 mg/kg/hour). For a patient established on oral theophylline, the bolus dose is omitted (because of concerns regarding toxicity) and a maintenance infusion (0.5 mg/kg/hour) is commenced. In the era of high-dose theophylline, it was critical to establish if a patient was taking oral theophylline before a physician started a patient on intravenous aminophylline.

Pharmacokinetic modelling of the low-dose theophylline dosing regimen demonstrated that a 250-mg (or 5 mg/kg if a participant’s weight was < 50 kg) loading dose of aminophylline could be administered to trial participants and their plasma theophylline would remain within the therapeutic high-dose bronchodilating concentration of 10–20 mg/l (see Appendix 1). As per guideline recommendations for plasma theophylline monitoring,24 we advised that plasma theophylline be measured 24 hours after commencing intravenous aminophylline (allocation status would not be discernible from such a concentration). The trial drug was discontinued during intravenous aminophylline therapy, but restarted after discontinuation of intravenous aminophylline therapy.

The advice regarding use of intravenous aminophylline was summarised on a participant’s trial card. In reality, no treating physician contacted the trial team with concerns about intravenous aminophylline.

Supply of trial medication

Each participant received their first bottle of 4 weeks of trial medication (or placebo) from a participating clinical trials pharmacy. For secondary care sites, this was usually the clinical trials pharmacy based at that secondary care site. For participants recruited in primary care study sites, the first bottle of medication was dispensed from the clinical trials pharmacy in NHS Grampian and couriered to a participant’s address.

Each participant also received two further supplies of six bottles (each bottle being a 4-week supply). These supplies were dispatched to participants by a third party (AndersonBrecon, Hereford, UK) and delivered to participants’ addresses via a courier. These shipments were made around weeks 3 and 27 to enable continuity of supply. Receipt of trial medication to a participant’s home address was confirmed by signature on receipt.

Data collection

Baseline, outcome and safety data were collected by face-to-face assessments conducted at recruitment/baseline (week 0), 6 months (week 26) and 12 months (week 52). Participants were telephoned 2 weeks after starting the trial medication to ensure that they were tolerating the medication. The schedule for data collection in the trial is outlined in Table 2. If a participant was unable to attend a scheduled follow-up assessment visit because of an acute illness, for example exacerbation of COPD, or other reasons, the visit was postponed and the participant was assessed within 4 weeks of the scheduled assessment visit. Participants unable to attend a face-to-face assessment at 6 and 12 months were followed up by telephone or home visit, or were sent the questionnaires to complete at home.

| Assessment | Time point | Post-study GP records | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recruitment | 2 weeks (telephone) | Month 6 (face to face) | Month 12 (face to face) | ||

| Assessment of eligibility criteria | ✓ | ||||

| Written informed consent | ✓ | ||||

| Demographic data; contact details | ✓ | ||||

| Clinical history | ✓ | ||||

| Drug history | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Smoking status | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Height | ✓ | ||||

| Weight | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Total number of COPD exacerbations requiring OCSs/antibiotics | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Hospital admissions | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Health-related quality of life | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Disease-related health status (CAT, mMRC dyspnoea, HARQ) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Post-bronchodilator lung function | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| AEs/drug reactions | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Health-care utilisation | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Patient compliance | ✓ | ✓ | |||

The following data were collected.

Demographic and clinical data

Demographic, contact, clinical history and, if necessary, clinical examination data were captured at the recruitment visit.

Drug history

Regular use of prescription drugs was recorded at recruitment and at the 6- and 12-month assessments. ICS use was checked at recruitment and at 6 and 12 months. Many participants brought their repeat prescription list with them to the assessments. Participants were asked how many times a day they used their ICS preparation and the dose.

Smoking history

Smoking history (i.e. age commenced, age ceased and average number of cigarettes smoked per day) and current smoking status were recorded at recruitment, and pack-year consumption was computed. At the 6- and 12-month assessments, current smoking status was recorded.

Height and weight

Height was measured using clinic stadiometers at baseline. Weight was assessed using clinic scales at recruitment and at the 6- and 12-month assessments.

Number of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations

The primary outcome measure of the total number of COPD exacerbations requiring antibiotics/OCSs while on trial medication was ascertained at the 6- and 12-month assessments. Participants were encouraged to record any exacerbations in a space provided on the outer packaging (carton) used to ship medication or on the participant follow-up card, and to bring this to their follow-up assessments. If follow-up at 12 months could not be completed, GPs were contacted and asked to provide information on the number of exacerbations experienced by the participant in the treatment period, and whether or not these resulted in hospital admission.

The ATS/ERS guideline definition of COPD exacerbation was used: a worsening of a patient’s dyspnoea, cough or sputum beyond day-to-day variability sufficient to warrant a change in management. 55,68 The minimum management change was treatment with antibiotics or OCSs. A minimum of 2 weeks between consecutive hospitalisations or the start of a new therapy was necessary to consider events as separate. A modified ATS/ERS operational classification of exacerbation severity was used for each exacerbation:68

-

level I – increased use of a short-acting β2 agonist (SABA) (mild)

-

level II – use of OCSs or antibiotics (moderate)

-

level III – care by services to prevent hospitalisation (moderate)

-

level IV – admitted to hospital (severe).

An exercise to validate patient-reported exacerbations was carried out (see Appendix 2).

Hospital admissions

The number of unscheduled hospital admissions while on trial medication was ascertained at the 6- and 12-month assessments. Emergency admissions consequent on COPD were also identified. Participants were encouraged to record any hospital admissions in the space provided on the outer packaging (carton) used to ship medication or on the participant follow-up card, and to bring this to their follow-up assessments. If follow-up at 12 months could not be completed, participants’ GP or hospital records were checked to ascertain the number of hospital admissions during the treatment period.

Health-related quality of life

Health-related quality-of-life data were captured at recruitment and at the 6- and 12-month assessments by questionnaire using the EQ-5D-3L index,69,70 which has been used widely in studies of COPD. The completed instrument can be translated into quality-of-life utilities suitable for calculation of QALYs through the published UK tariffs. 71

Disease-related health status

Disease-related health status was ascertained at recruitment and at the 6- and 12-month assessments by participant completion of the CAT. 71–74 CAT is an eight-item unidimensional measure of the impact of COPD on a patient’s health. CAT has a scoring interval of 0–40, with 0–5 being the norm for healthy non-smokers and > 30 being indicative of a very high impact of COPD on quality of life. 72 CAT is reliable and responsive, correlates very closely with the St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire and is preferred because it provides a more comprehensive assessment of the symptomatic impact of COPD and is shorter and, thus, easier to complete. 72–74

Participants were also asked to grade their breathlessness using the mMRC dyspnoea scale at recruitment and at the 6- and 12-month assessments. 75 The mMRC dyspnoea scale has been in use for many years to grade the effect of breathlessness on daily activities. The mMRC dyspnoea scale is a single question that assesses breathlessness related to activities; the scoring interval is 0–4, with 0 being ‘not troubled by breathlessness except on strenuous exercise’ and 4 being ‘too breathless to leave the house, or breathless when dressing or undressing’. The mMRC score has been validated against walking test performance and other metrics of COPD health status, for example the St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire. 76

In self-selected recruitment centres, the Hull Airway Reflux Questionnaire (HARQ) was completed by participants at recruitment and at 6 and 12 months. HARQ was used to assess symptoms not elucidated by CAT or the mMRC dyspnoea scale. HARQ is a validated, self-administered questionnaire that is responsive to treatment effects. 77

Post-bronchodilator lung function

Lung function was measured at recruitment and at 6 and 12 months using spirometry performed to ATS/ERS standards. 78 Spirometry is a routine part of the clinical assessment of people with COPD. Post-bronchodilator (LABA within 8 hours, SABA within 2 hours) FEV1 and FVC were measured. If necessary, lung function was measured 15 minutes after administration of a participant’s own SABA. The European Coal and Steel Community predictive equations were used to compute predicted values for FEV1 and FVC. 79 When spirometry was contraindicated, or participants were not able to complete spirometry, it was omitted.

Health-care utilisation

Health-care utilisation during the previous 6 months was ascertained at recruitment and at the 6- and 12-month assessments using a modified version of the Client Service Receipt Inventory (CSRI). 80 CSRI is a research questionnaire for retrospectively collecting cost-related information about a participant’s use of health and social care services.

Adverse reactions and serious adverse events

This trial complied with the UK NHS Health Research Authority guidelines for reporting adverse events (AEs). 81 ARs and SAEs occurring during the 12-month follow-up period were ascertained at the 2-week telephone call and at the 6- and 12-month assessments. Participants were notified of recognised ARs and encouraged to contact their local trial centre if they experienced these.

Hospitalisations for treatment planned prior to randomisation and hospitalisations for elective treatment of pre-existing conditions were not considered, recorded or reported as SAEs. Complications occurring during such hospitalisation were also not considered, recorded or reported as SAEs, unless there was a possibility that the complication arose because of the trial medication (i.e. a possible AR). Exacerbations of COPD, pneumonia or hospital admissions as a consequence of exacerbations of COPD or pneumonia were not considered, recorded or reported as AEs or SAEs because they were primary and secondary outcomes for the trial.

Serious adverse events were assessed as to whether or not the SAE was likely to be related to the treatment using the following definitions:

-

unrelated – when an event is not considered to be related to the trial drug

-

possibly – although a relationship to the trial drug cannot be completely ruled out, the nature of the event, the underlying disease, concomitant medication or temporal relationship make other explanations possible

-

probably – the temporal relationship and absence of a more likely explanation suggest that the event could be related to the trial drug

-

definitely – the known effects of the trial drug or its therapeutic class, or based on challenge testing, suggest that the trial drug is the most likely cause.

The reference safety information used to assess whether or not the event was expected was section 4.8 of the Summary of Product Characteristics for theophylline. 54

Compliance

Compliance/adherence and persistence with trial medication were assessed at the 6- and 12-month assessments. Participants were asked to return empty drug bottles and unused medication; compliance was calculated by pill counting. 82 Participants were deemed to be compliant if they had taken ≥ 70% of the expected doses.

Participant withdrawal

Participants who withdrew from treatment (e.g. because of unacceptable side effects, or because they were prescribed a contraindicated medicine for > 3 weeks) but who agreed to remain in the trial for follow-up were followed up at 6 and 12 months. Those who did not want to attend for clinical follow-up at 6 and 12 months could be followed up by telephone or home visit, or could opt to receive questionnaires at home. Participants who wanted to withdraw from trial follow-up could continue to contribute follow-up data by agreeing to have data extracted from their primary and secondary care medical records.

Sample size

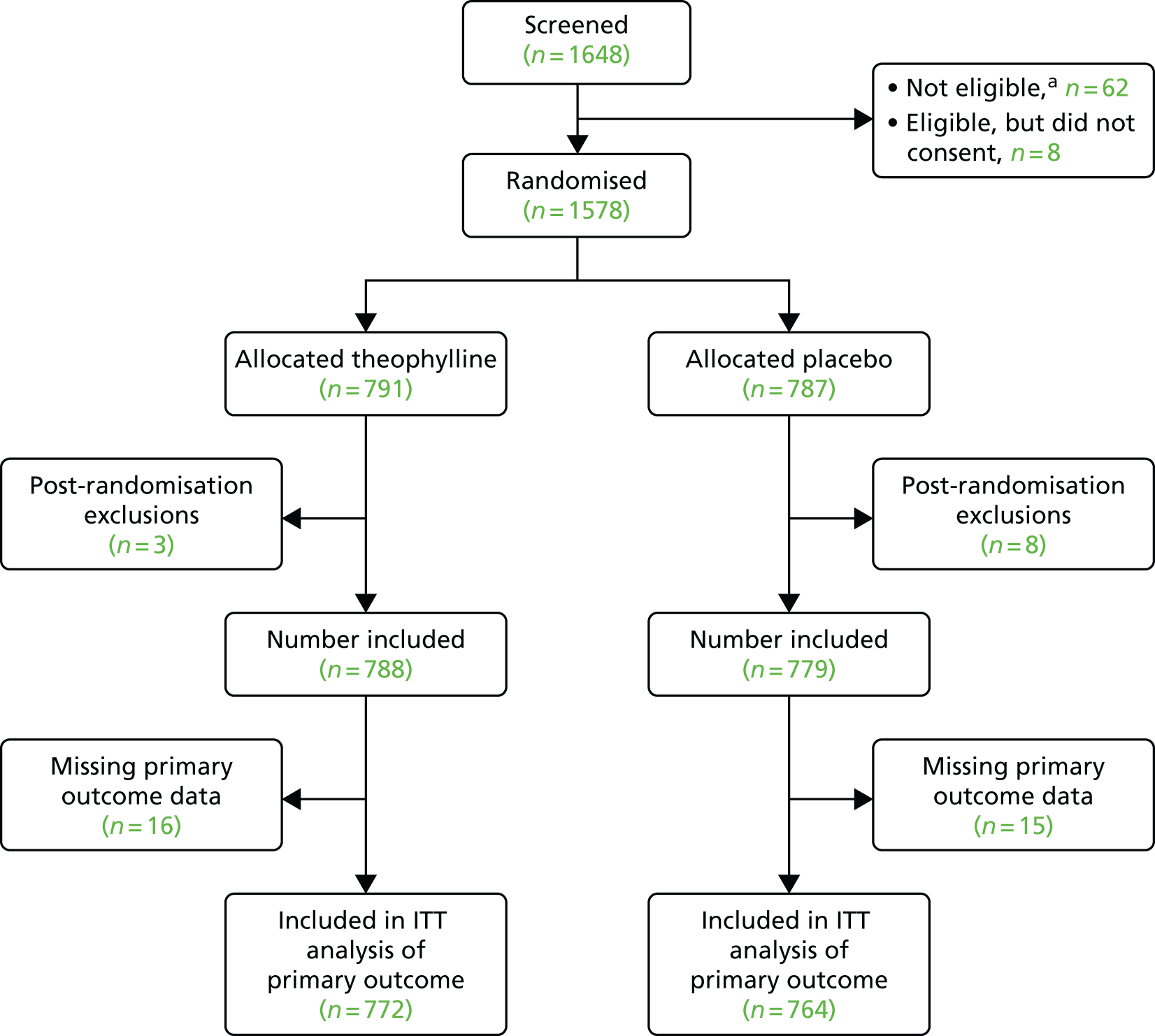

The sample size of 1424 was estimated on the basis of the ECLIPSE study reporting the frequency of COPD exacerbations in 2138 patients. 21 For patients identical to the target population (who in a 1-year period have had at least two self-reported COPD exacerbations requiring antibiotics or OCSs), the mean number of COPD exacerbations within 1 year was 2.22 (SD 1.86). 21 Given a similar rate in the placebo arm, 669 participants were needed in each arm of the trial to detect a clinically important reduction in COPD exacerbations of 15% (i.e. from a mean of 2.22 to 1.89) with 90% power at the two-sided 5% significance level. Allowing for 6% loss to follow-up,83 this was inflated to 712 participants in each trial arm, giving 1424 in total.

The sample size of 1424 included a 6% loss to follow-up based on a Cochrane Review of oral theophylline in COPD. 83 During the present trial, a higher proportion of participants than expected ceased their trial medication (although most were not lost to follow-up). With the appropriate REC and regulatory approvals, recruitment continued beyond 1424 in the time available, with the total number recruited being 1578 to counteract this loss of person-years on medication. Recruitment ended in August 2016.

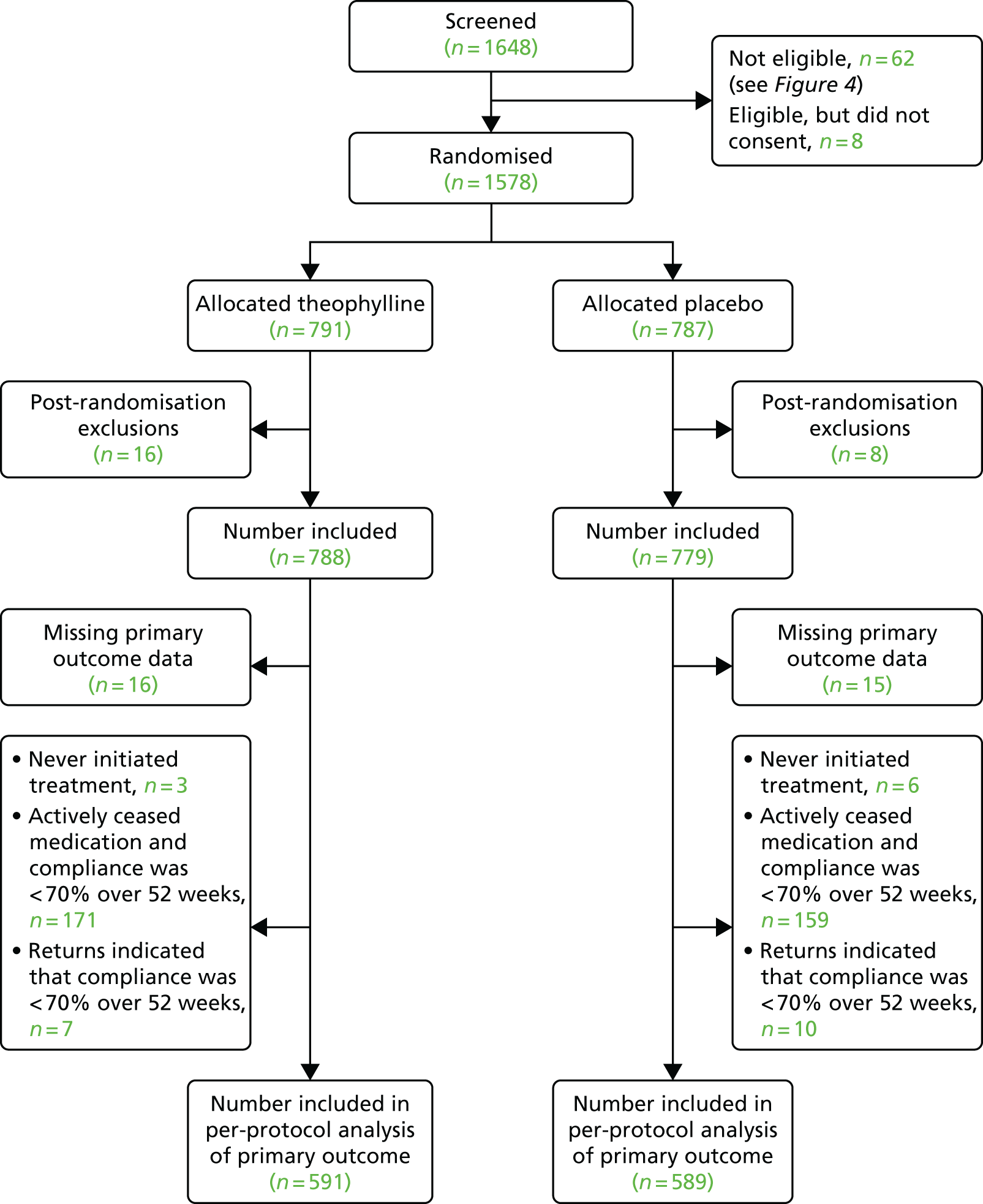

Statistical analysis

All analyses were prespecified in the statistical analysis plan, which was approved by both the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and the Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) in advance of analysis. The statistical analysis plan can be found on the project web page at www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/115815/#/ (accessed 23 April 2019). Unless prespecified, a 5% two-sided significance level was used to denote statistical significance throughout and estimates are presented alongside their 95% CIs. No adjustments were made for multiple testing. All analyses were conducted in accordance with the intention-to-treat (ITT) principle, with a per-protocol analysis performed as a sensitivity analysis. The per-protocol analysis excluded participants who were not compliant, with compliance being defined as taking ≥ 70% of their expected doses of trial medication. All analyses were undertaken in Stata® version 14 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Categorical variables are described with number and percentage in each category. Continuous variables are described with mean and SD if normally distributed and median and interquartile range (IQR) if skewed. The number of missing data is reported for each variable.

Primary outcome

The primary outcome (i.e. the number of COPD exacerbations requiring antibiotics and/or OCSs in the 12-month treatment period following randomisation) was compared between randomised groups using a generalised linear model (GLM) with log-link function, overdispersion parameter and length of time in trial as an offset. The estimated treatment effect is presented as unadjusted rate ratio followed by adjusted rate ratio for a set of prespecified baseline variables. The adjustment variables were centre (as a random effect), where the participant was identified (primary or secondary care), age (in years) centred on the mean, sex (male/female), smoking in pack-years, FEV1% predicted, number of COPD exacerbations in the previous year, treatment with LAMA/LABA or a combination, and treatment with long-term antibiotics. Participants who did not provide a full 12 months of follow-up information were included to the point at which they were lost to follow-up, with their time in the trial utilised in the offset variable.

Secondary outcomes

The total number of COPD exacerbations requiring hospital admission and the total number of emergency admissions (all causes) were analysed in the same way as the primary outcome. Occurrence of pneumonia during follow-up was analysed with a mixed-effects logit model. QoL measures (i.e. CAT, EQ-5D-3L, HARQ) and lung function (i.e. FEV1 and FVC) measured at baseline and at the 6- and 12-month follow-ups were compared between groups using a mixed-effects model unadjusted and adjusted for the same prespecified covariate set as described for the primary outcome. Fixed effects included visit number and treatment, with participant and participant–visit interaction fitted as random effects. A treatment–visit interaction was included to assess the differential treatment effect on rate of change in outcome. An autoregressive [AR(1)] correlation structure was used throughout. All participants in the ITT population were included in the analysis and missing outcome data were assumed to be missing at random. Breathlessness as measured by the mMRC dyspnoea scale was analysed using a mixed-effects GLM using a logit link function. All-cause mortality rate and COPD-related mortality and time to first exacerbation were compared between randomised groups using Kaplan–Meier survival curves and Cox regression for adjustment. Total dose of ICS at the end of follow-up and change in total daily dose from baseline were calculated and compared between randomised groups using an independent-samples t-test and linear regression for adjustment. The proportion of participants changing medication during the follow-up period was compared using a chi-squared test.

Sensitivity analyses

To assess the impact of death on the treatment effect for the primary outcome, the total number of exacerbations and the number of exacerbations requiring hospital admission, we undertook a sensitivity analysis excluding those participants who died during the trial period. A sensitivity analysis for QoL and lung function was also undertaken by repeating the mixed-effects models on only those participants who survived until the 12-month follow-up.

Prespecified subgroup analysis

The analysis for the primary outcome was repeated for a number of subgroups. The subgroups were age (< 60, 60–69, ≥ 70 years), sex, body mass index (BMI) (< 18.5, ≥ 18.5–< 25, ≥ 25 kg/m2), smoking status at recruitment (ex-/current smoker), baseline treatment for COPD [triple therapy (ICS/LAMA/LABA), double therapy (ICS/LAMA or ICS/LABA) or single therapy (ICS only)], GOLD stage (I or II, III, IV), number of exacerbations in the 12 months prior to recruitment (2, 3 or 4, ≥ 5), taking OCSs at recruitment (yes/no) and dose of inhaled ICS at recruitment (1600 or ≥ 1600 µg per day of beclomethasone equivalents). A subgroup analysis was undertaken by the addition of a treatment–covariate interaction term and using the ‘lincom’ command in Stata to obtain group-specific estimates. We report observed mean (SD) exacerbations in each subgroup by treatment group, the treatment effect [incidence rate ratio (IRR) and 99% CIs] along with the p-value for the interaction term. We used 99% CIs because of the exploratory nature of the subgroup analysis.

Health economics

Resource use

Health-care resource utilisation during the previous 6 months was collected at the 6- and 12-month assessments using a modified version of the CSRI. 84 The CSRI is a research questionnaire for retrospectively collecting cost-related information about a participant’s use of health and social care services. The main resources whose use was collected during the follow-up period were as follows:

-

theophylline intervention

-

costs of exacerbation treatment; this was broken down into two groups of costs – (1) the location of the treatment, ‘home’, ‘care by services to prevent hospitalisation’ and ‘admitted to hospital’ and (2) the treatment cost of the exacerbations, including medication

-

cost of COPD maintenance medications

-

other health service use (including inpatient, outpatient and primary care use); none of these included exacerbation costs

-

non-COPD emergency hospital admissions

-

regular medication.

Baseline resource use was collected for current use of COPD maintenance treatment and regular medication. For calculating baseline resource use and costs, we have assumed use to be for the 6 months prior to baseline. The number of exacerbations needing treatment in the previous 12 months and the number of exacerbations resulting in hospitalisation in the previous 12 months were also collected.

Unit costs

All resource use was valued in Great British pounds (GBP) and indexed to 2016, using the Health Service Cost Index85 to adjust if necessary.

-

Medication costs were obtained from the British National Formulary (BNF). 86

-

For exacerbations, non-COPD emergency admissions, inpatient stays, outpatient attendances and primary care, costs were obtained from NHS Reference Costs 2015 to 2016,87 Information Services Division (ISD),88 Personal Social Services Research Unit (PSSRU),85 the BNF86 and papers by Oostenbrink et al. 89 and Scott et al. 90

The total cost per participant was calculated by assigning unit costs to resource use for each participant. Total mean costs were calculated using a GLM with a gamma family and clustering for centre number. After multiple imputation, total costs were adjusted for baseline characteristics using standard regression methods, to account for any differences in cost-related variables at baseline. 91

Unit costs and their sources are presented in Table 3.

| Resource | Unit | Unit cost (£) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | |||

| Theophylline | 200 mg od | 0.05 | BNF86 |

| 200 mg bd | 0.11 | BNF86 | |

| Exacerbation treatment | |||

| Oxygen | Per day | 19 | Oostenbrink et al.89 |

| Medication | Daily dose | Various | BNF86 |

| Inpatient costs | |||

| Ward stay (elective) | Bed-day | 362 | NHS Reference Costs 2015 to 2016 (elective excess bed-day unit cost)87 |

| Ward stay (non-elective) | Bed-day | 298 | NHS Reference Costs 2015 to 2016 (non-elective excess bed-day unit cost)87 |

| COPD-related ward stay | Bed-day | 262 | NHS Reference Costs 2015 to 2016 (weighted average of COPD hospital stays DZ65)87 |

| Long stay on ward | Day | 133 | PSSRU (not-for-profit care home fee: mean £931 per week)85 |

| Outpatient costs | |||

| Day case | Day | 521 | ISD costs book (day cases, all specialties)88 |

| Outpatient appointment | Appointment | 177 | NHS Reference Costs 2015 to 2016 (total outpatient attendances unit cost)87 |

| Primary care costs | |||

| Emergency GP visit | Per contact | 86 | Based on Scott et al.90 for out-of-hours home visit |

| Routine GP visit | Per contact | 31 | PSSRU (including direct care staff costs, without qualifications, 9.22 minutes)85 |

| Community/district nurse | Per contact | 38 | NHS Reference Costs 2015 to 2016 (Community Health Services – N02AF – district nurse)87 |

| Hospital at home team | Per contact | 84 | NHS Reference Costs 2015 to 2016 (Community Health Services – N08AF – specialist nursing asthma and respiratory nursing liaison)87 |

| GP telephone | Per contact | 23.43 | PSSRU (including direct care staff costs, without qualification costs, 7.1 minutes)85 |

| GP home visit | Per contact | 77.22 | PSSRU (including direct care staff costs, without qualification costs, 11.4 minutes visit plus 12 minutes of travelling time)85 |

| Blood test | Per contact | 14.42 | ISD costs book88 (laboratory services, haematology plus practice nurse appointment, PSSRU 201685) |

| Dental service | Per contact | 77 | NHS Reference Costs 2015 to 2016 (general dental service attendance)87 |

| Hearing aid clinic | Per contact | 53 | NHS Reference Costs 2015 to 2016 (audiology)87 |

| Occupational therapist | Per contact | 79 | NHS Reference Costs 2015 to 2016 (occupational therapist)87 |

| Diabetic nurse | Per contact | 71 | NHS Reference Costs 2015 to 2016 (specialist nursing, diabetic)87 |

| Cardiac nurse | Per contact | 81 | NHS Reference Costs 2015 to 2016 (specialist nursing, cardiac)87 |

| Long-term condition nurse/community matron | Per contact | 89 | NHS Reference Costs 2015 to 2016 (active case management)87 |

| Paramedic | Per contact | 181 | NHS Reference Costs 2015 to 2016 (ambulance, see, treat, refer)87 |

| Chiropodist/community clinic/endoscopy | Per contact | 60 | NHS Reference Costs 2015 to 2016 (mean of community health services, no separate chiropodist or community clinic cost)87 |

| Physiotherapist | Per contact | 49 | NHS Reference Costs 2015 to 2016 (physiotherapist)87 |

| Podiatrist | Per contact | 40 | NHS Reference Costs 2015 to 2016 (podiatrist)87 |

| Practice nurse | Per contact | 9.42 | PSSRU (practice nurse, 15.5 minutes per contact)85 |

| Speech therapist | Per contact | 88 | NHS Reference Costs 2015 to 2016 (speech and language therapist)87 |

| Nurse telephone call | Per contact | 6.10 | PSSRU (nurse-led triage)85 |

| Treatment room nurse | Per contact | 27 | NHS Reference Costs 2015 to 2016 (specialist nursing, treatment room)87 |

| Urine sample/sputum test | Per contact | 10.28 | ISD costs book88 (clinical chemistry, plus practice nurse appointment, PSSRU85) |

| Dietitian | Per contact | 81 | NHS Reference Costs 2015 to 2016 (dietitian)87 |

| Influenza vaccination | Per contact | 14.67 | BNF86 plus practice nurse appointment, PSSRU 201685 |

| Early support discharge | Per contact | 124 | NHS Reference Costs 2015 to 2016 (crisis response and early discharge services)87 |

| Diagnostic imaging | Per contact | 37.3 | NHS Reference Costs 2015 to 2016 (total outpatient attendances, diagnostic imaging)87 |

| Optometry | Per contact | 79.19 | NHS Reference Costs 2015 to 2016 (total outpatient attendances, optometry)87 |

| Health-care assistant | Per contact | 6.20 | PSSRU 2016 (band 3 nurse, 15.5 minutes)85 |

| Talking matters | Per contact | 24.06 | PSSRU 2009/10 (counselling services in primary care, telephone consultation 29.7 minutes)92 |

| Community psychiatric nurse/stroke nurse | Per contact | 77 | NHS Reference Costs 2015 to 2016 (other specialist nursing)87 |

| Counselling | Per contact | 78.27 | PSSRU 2009/10 (counselling services in primary care, consultation 96.6 minutes)92 |

| Breast care nurse | Per contact | 59 | NHS Reference Costs 2015 to 2016 (beast care nursing)87 |

| Community mental health team | Per contact | 121 | NHS Reference Costs 2015 to 2016 (other mental health specialist team)87 |

| Pulmonary rehabilitation | Per contact | 78 | NHS Reference Costs 2015 to 2016 (other single condition community rehabilitation teams)87 |

| Emergency costs | |||

| Ambulance | Per attendance | 236 | NHS Reference Costs 2015 to 2016 (see, treat convey)87 |

| Accident and emergency attendance | Per attendance | 138 | NHS Reference Costs 2015 to 2016 (emergency medicine average unit cost)87 |

Health outcomes

The economic outcome used was the QALY, a combination of quality and quantity of life. The QoL measure was generated using completed EQ-5D-3L questionnaires. Participants completed the questionnaire at baseline and at 6 months and 12 months.

Patient-reported health-related QoL obtained from EQ-5D-3L questionnaires was valued in terms of utilities (on a scale from –0.59 to 1, where 1 is full health) using a standard UK value set,71 which were converted into QALYs using standard area under the curve methods; patient utility measurements from each follow-up point were weighted by the time interval between follow-up points. Discrete changes in utility values between follow-up time points were assumed to be linear. After multiple imputation, QALYs were adjusted for baseline characteristics using standard regression methods.

Analysis

The total cost per participant in each intervention was summed and divided by the number of participants in each arm to calculate the total mean cost per participant in each arm, along with the difference in means and a 95% CI.

The mean number of QALYs per participant for each intervention was calculated by summing all participants’ QALYs and dividing by the number of participants in that intervention arm. The differences in the means were also calculated, along with a 95% CI.

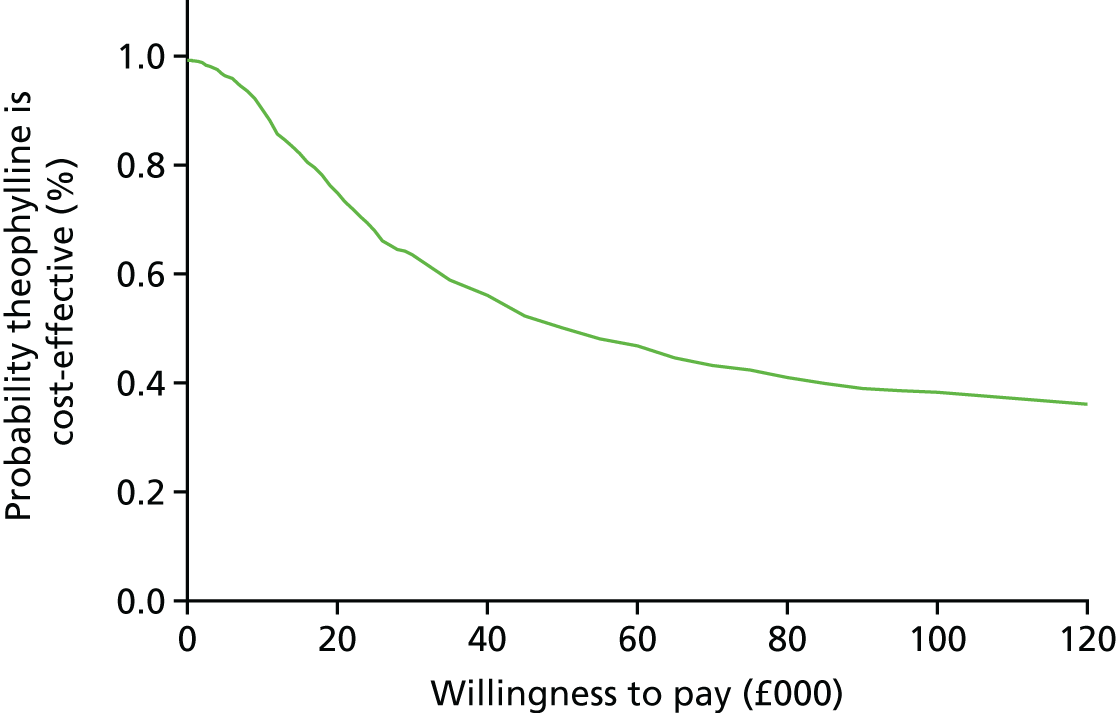

The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) was calculated by dividing the difference in mean costs by the difference in mean QALYs. The NICE threshold of £20,000 to £30,000 per QALY was used when judging whether or not the intervention was cost-effective. 93

Withdrawn participants were included in the analysis; the total time they spent in the trial was used to adjust total costs and QALYs using regression methods.

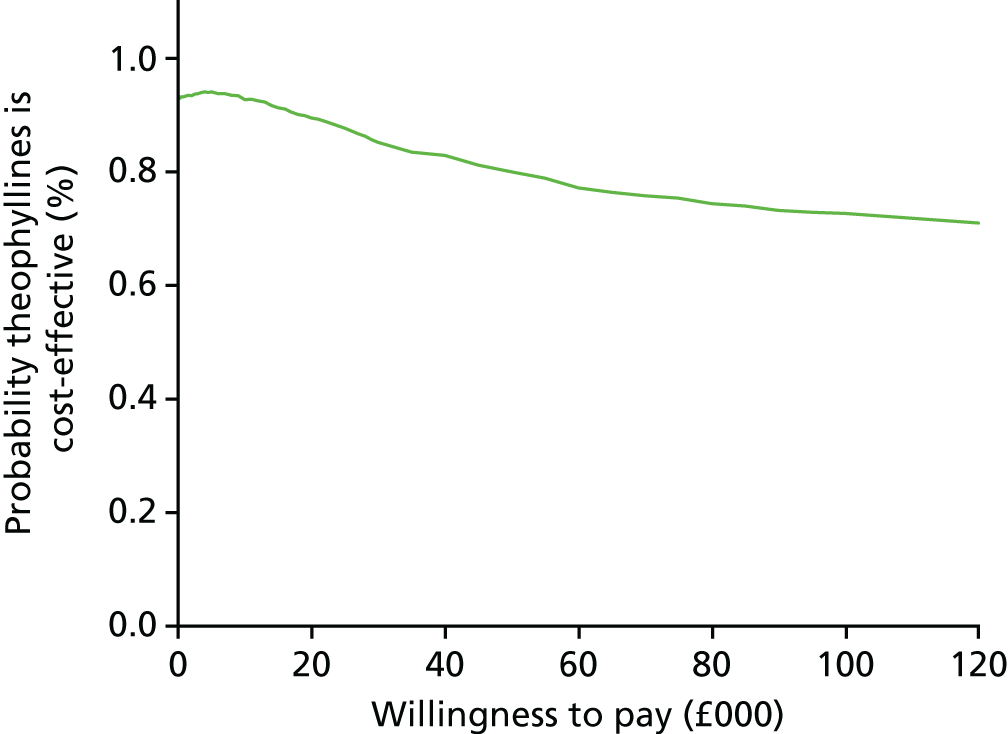

To explore the uncertainty around the cost and QALY differences and the resulting ICER, a non-parametric bootstrapping technique was employed with 1000 iterations. The results are presented (see Figures 7–10) using a cost-effectiveness plane, showing all 1000 incremental cost-effectiveness pairs, and a cost-effectiveness acceptability curve.

The analysis was carried out using Stata version 14.

Missing data

There was a small amount of multivariate missingness in collected resource data.

Resource use data were not available for some exacerbations because this was not reported by participants or because only limited data were available from GP or hospital records. Missing resource use data on exacerbations were dealt with as follows:

-

For exacerbations with missing length of exacerbation data, the length was assumed to be the mean length of exacerbation specific to that treatment arm.

-

For exacerbations missing a marker to indicate the location of treatment, this was assumed to be at home, as most locations of treatments were at home (> 80%).

-

For exacerbations treated in hospital, missing lengths of stay were assumed to be the length of exacerbation.

-

For exacerbations missing treatment costs, a mean cost of treatment, specific to that treatment arm, was assumed.

At a resource use level, there were small numbers of missing data, which were dealt with as follows:

-

If the length of stay data were missing for emergency hospital admissions, these were imputed using the mean length of stay specific to that treatment arm.

-

If participants had no observations completed to indicate the duration of a COPD maintenance treatment, it was assumed that the treatment duration was the 6 months prior to the date on which the information about the COPD maintenance treatment was collected.

-

If a participant indicated that they had received a COPD maintenance treatment but no medication details were available, a mean cost, specific to that treatment arm, was imputed for that specific maintenance medication.

-

If resource use data were missing for inpatient, outpatient and primary care service use, the participant was assumed not to have used the resource in question.

Complete cases were analysed initially and multiple imputation was used to explore the effect of missing data on the analysis.

The multiple imputation technique used was multiple imputation by chained equations. Multiple imputation assumes that data are missing at random; missing data may depend on observed data.

Assumptions

The following assumptions were made in the health economics analysis: a complete case is defined as a case with data covering resource use for the 12-month follow-up period. In a small number of participants, there was no 6-month data collection; however, the 12-month data collection covered resource use for the whole of the 12-month follow-up period.

Patient and public involvement

A person with COPD was an independent voting member of the TSC. Initially, this was a patient from the Aberdeen Chest Clinic who was nominated by Chest Heart & Stroke Scotland (CHSS) as part of its Voices Scotland initiative. In 2015, this person had to resign from the TSC because of ill health and was replaced by another patient, who is living with COPD, from the Aberdeen Chest Clinic.

Early versions of the trial protocol and PILs were reviewed by a representative from the British Lung Foundation–North Region and by a person who lives with COPD and attends the chest clinic at the Freeman Hospital, Newcastle. They both attended the trial initiation meeting, purposely held in Newcastle in February 2013, and contributed suggestions and changes to the final trial design that were reflected in the protocol and PIL.

The TWICS trial was publicised in 2014 by a press release that included supportive quotations from the British Lung Foundation and CHSS. This publicity resulted in members of the public with COPD volunteering to participate; with their permission, their details were passed on to their local TWICS trial site.

We anticipate that the patient and public involvement (PPI) member of the TSC will comment on the results letter to be sent to trial participants. It is also anticipated that the publication of the trial results will be co-ordinated with press releases from the participating academic/NHS institutions, the British Lung Foundation and CHSS. Members of the trial team will be participating in local public engagement with research activities.

Protocol amendments

There were seven protocol amendments, which are summarised in Table 4.

| Version number, date | Summary of amendments |

|---|---|

| Version 2, 20 June 2013 | Version initially approved by the REC |

| Version 3, 5 August 2013 | To incorporate clarification of the definition of smoker and non-smoker as required by the MHRA |

| Version 4, 5 February 2014 |

|

| Version 5, 2 July 2014 |

|

| Version 6, 4 August 2014 |

|

| Version 7, 11 August 2015 |

|

| Version 8, 19 May 2016 | To amend the protocol to allow for over-recruitment |

| Version 9, 14 April 2017 |

|

Trial oversight

A TSC, with independent members, including PPI members, oversaw the conduct and progress of the trial. An independent DMC oversaw the safety of participants in the trial.

Breaches