Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 11/23/01. The contractual start date was in September 2013. The draft report began editorial review in May 2018 and was accepted for publication in December 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Stuart A Taylor reports personal fees from Robarts Clinical Trials Inc. (London, ON, Canada) outside the submitted work. Simon Travis reports receiving fees for consultancy work and/or speaking engagements from the following: AbbVie Inc. (Chicago, IL, USA), Centocor Inc. (Horsham, PA, USA), Schering-Plough (Kenilworth, NJ, USA), Bristol-Myers Squibb (New York, NY, USA), Chemocentryx Inc. (Mountain View, CA, USA), Cosmo Pharmaceuticals (Dublin, Ireland), Elan Pharma Inc. (Dublin, Ireland), Genentech Inc. (San Francisco, CA, USA), Giuliani SpA (Milan, Italy), Merck & Co. Inc. (Kenilworth, NJ, USA), Takeda UK Ltd (Woodburn Green, Buckinghamshire, UK), Otsuka Pharmaceuticals (Tokyo, Japan), PDL BioPharma (Nevada, NV, USA), Pfizer Inc. (San Francisco, CA, USA), Shire Pharmaceuticals UK (St Helier, Jersey), Glenmark Pharmaceuticals (Maharashtra, India), Synthon Biopharmaceuticals (Nijmegen, the Netherlands), NPS Pharmaceuticals (Bedminster, NJ, USA), Eli Lilly and Company (Indiana, IN, USA), Warner Chilcott Ltd, Proximagen Group Ltd (London, UK), VHsquared Ltd (Cambridge, UK), Topivert Pharma Ltd (London, UK), Ferring Pharmaceuticals (Saint-Prex, Switzerland), Celgene Corporation (Summit, NJ, USA), GlaxoSmithKline plc (Brentford, UK), Amgen Inc. (Thousand Oaks, CA, USA), Biogen Inc. (Cambridge, MA, USA), Enterome SA (Paris, France), Immunocore Ltd (Oxford, UK), Immunometabolism/Third Rock Ventures (Boston, MA, USA), Bioclinica Inc. (Newtown, PA, USA), Boehringer Ingelheim GmBH (Ingelheim am Rhein, Germany), Gilead Sciences Inc. (Foster City, CA, USA), Grunenthal Ltd (Aachen, Germany), Janssen Pharmaceutica (Beerse, Belgium), Novartis AG (Basel, Switzerland), Receptos Inc. (San Diego, CA, USA), Pharm-Olam International UK Ltd (Bracknell, UK), Sigmoid Pharma (Dublin, Ireland), Theravance Biopharma Inc. (Dublin, Ireland), Given Imaging Ltd (Yokneam Illit, Israel), UCB Pharma SA (Brussels, Belgium), Tillotts Pharma AG (Rheinfelden, Switzerland), Sanofi Aventis SA (Paris, France), Vifor Pharma (St Gallen, Switzerland), Abbott Laboratories Ltd (Chicago, IL, USA) and Procter and Gamble Ltd (Cincinnati, OH, USA). Simon Travis reports directorships of charities IBD2020 (Barnet, UK; UK 09762150), Cure Crohn’s Colitis (Sydney, Australia; ABN 85 154 588 717) and the Truelove Foundation (London, UK; UK 11056711). Simon Travis also reports receiving fees from the following for expert testimony work and/or royalties: Santarus Inc. (San Diego, CA, USA), Cosmo Technologies Ltd (Dublin, Ireland), Tillotts Pharma AG, Wiley-Blackwell Inc. (Hoboken, NJ, USA), Elsevier Ltd (Amsterdam, the Netherlands) and Oxford University Press (Oxford, UK). Simon Travis has received research grants from the following: AbbVie Inc., the International Organization for the Study of Inflammatory Bowel Disease, Eli Lilly and Company, UCB Inc. (Brussels, Belgium), Vifor Pharma, Norman Collisson Foundation (Bicester, UK), Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Schering-Plough, Merck Sharpe & Dohme Corp. (Kenilworth, NJ, USA), Procter and Gamble Ltd, Warner Chilcott Ltd, Abbott Laboratories Ltd, PDL BioPharma Inc. (Incline Village, NV, USA), Takeda UK Ltd and the International Consortium for Health Care Outcomes Measurement. Ailsa Hart reports personal fees from AbbVie Inc., Atlantic Healthcare Ltd (Saffron Walden, UK), Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celltrion Inc. (Incheon, South Korea), Dr Falk Pharma UK Ltd (Bourne End, UK), Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Merck Sharpe & Dohme Corp., Napp Pharmaceuticals Ltd (Cambridge, UK), Pfizer Inc., Pharmacosmos A/S (Holbæk, Denmark), Shire Pharmaceuticals UK and Takeda UK Ltd, and non-financial support from Genentech Inc. Alastair Windsor reports personal fees from Takeda, grants from Allergan Inc. (Dublin, Ireland), personal fees from Allergan, personal fees from Cook Medical Inc. (Bloomington, IN, USA) and grants and personal fees from Bard Ltd (Crawley, UK) outside the submitted work. Andrew Plumb reports grants from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme outside the submitted work, grants from the NIHR Fellowships programme during the conduct of the study and honoraria for educational lectures delivered at events arranged by Acelity Inc. (Crawley, UK), Actavis Pharma Inc. (Parsippany-Troy Hills, NJ, USA), Dr Falk Pharma UK Ltd, Janssen-Cilag Ltd (High Wycombe, UK) and Takeda UK Ltd on the subject of inflammatory bowel disease. Ilan Jacobs reports share ownership in General Electric Company (Boston, MA, USA), which manufacturers and sells magnetic resonance imaging equipment. Charles D Murray reports personal fees from AbbVie Inc., Merck Sharpe & Dohme Corp. and Janssen Pharmaceutica outside the submitted work. Antony Higginson reports personal fees from Toshiba Corporation (Tokyo, Japan) outside the submitted work. Steve Halligan reports non-financial support from iCAD Inc. (Nashua, NH, USA) outside the submitted work, and sat on the HTA commissioning board (2008–14). Stephen Morris reports Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR) Board membership (2014–18), HSDR Evidence Synthesis Sub Board membership (2016), HTA Commissioning Board membership (2009–13) and Public Health Research Board membership (2011–17).

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Taylor et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Crohn’s disease (CD) is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) predominantly affecting the young and requiring lifelong medical and surgical therapy. Most patients are diagnosed before the age of 35 years and CD has an incidence of between 1.9 and 11.0 per 1000 person-years in western Europe. 1 According to a recent UK audit,2 IBD accounts for 0.3% of work absenteeism, costs £115M in lost productivity and accounts for 27,000 hospital admissions annually. NHS expenditure on IBD is estimated to be > £1B, with each CD patient costing, on average, £6156 per year. 3

Crohn’s disease most commonly affects the small bowel and/or colon, with a range of manifestations, from superficial bowel wall ulceration to deep penetrating disease characterised by strictures, fistulae and abscesses. A host of potentially toxic medical treatments, such as immune modulators, and targeted surgical interventions are currently used to manage patients. Diagnosis is based on a combination of clinical features, together with endoscopic, histopathological, biochemical and imaging findings. Thereafter, patient management is contingent on the extent of disease, the underlying biological activity and the presence of extraluminal complications.

Colonoscopy is fundamental to diagnosis and follow-up of CD, given its exquisite views of the bowel mucosa and ability to take biopsies for histological analysis. 4 However, colonoscopy is invasive, with a small but defined risk of serious complications, such as perforation, visualises only the bowel lumen and, at best, can interrogate only the last few centimetres of the small bowel (terminal ileum). Radiological imaging is therefore complementary for the diagnosis, staging and monitoring of CD, and can define disease presence, extent, biological activity and complications, particularly in the small bowel. 5

Radiological imaging of Crohn’s disease

Several small-bowel imaging investigations are currently utilised within the NHS, including barium small bowel follow-through (BaFT), computed tomography (CT), computed tomography enterography (CTE), ultrasonography (US) and magnetic resonance enterography (MRE). The various tests differ in their attributes. BaFT, for example, interrogates the bowel mucosa, whereas CT, US and MRE (cross-sectional imaging techniques) evaluate both the bowel wall and extraenteric tissues. An important differentiating attribute is the use or otherwise of ionising radiation. Both BaFT and CT impart a significant radiation dose, which is of concern given that CD patients are generally young and need repeat imaging over several years. A recent meta-analysis found that 11% of CD patients are exposed to potentially harmful doses of ionising radiation. 6 Furthermore, exposure to diagnostic ionising radiation is increasing, largely owing to CT,7,8 despite technological developments reducing dose exposure. 9 Conversely, neither US nor MRE impart ionising radiation and are therefore intuitively attractive modalities for imaging patients with CD. 10 Indeed, international consensus guideline committees recommend MRE and US as the imaging modalities of choice in CD. 5

Small bowel US has been established for many years11 and is potentially well suited to imaging CD; it is non-invasive, well tolerated, requires no specific patient preparation and uses standard technology widely available in the NHS. However, uptake has been somewhat hampered by perceptions of reduced accuracy, particularly in the proximal small bowel,12 and concerns about operator dependence and high levels of observer variability. 13 Furthermore, interrogation of the bowel and deeper tissues may be limited by patient obesity, obscuring bowel gas or deep pelvic location. Conversely, MRE [magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the abdomen and pelvis following ingestion of an oral contrast agent] is a more recent innovation14 and an increasingly supportive evidence base has emerged over the last 15 years. 5 MRE requires patients to ingest large volumes of oral contrast agent to distend the bowel, potentially resulting in abdominal cramps and diarrhoea, and utilises MRI technology, access to which is comparatively limited in the NHS. However, visualisation of the whole bowel is assured assuming a technically complete examination, and newer generations of radiologists are increasingly familiar with abdominal and pelvic MRI.

Existing literature on the diagnostic accuracy of magnetic resonance enterography and ultrasonography

We searched PubMed and EMBASE for articles published between 1 January 1990 and 1 December 2017 without language restriction. We used MeSH (medical subject heading) and full-text searches for ‘Crohn’s disease’, ‘magnetic resonance imaging’, ‘ultrasound’ and ‘diagnostic accuracy’. Emphasis was placed on meta-analyses and systematic reviews using appropriate search limits. There have been several systematic reviews and meta-analyses reporting the accuracy of MRE and US for diagnosing and staging CD. 12,15–26 Many have considered MRE or US in isolation,15,17–20,22,23 whereas others have attempted to compare the two modalities (along with others, such as CT). 12,21,25,26 Some have primarily focused on assessment of disease activity,17,22,26 with most assessing diagnostic accuracy. A summary of the main meta-analyses and systematic reviews undertaken since 2010 is given in Table 1.

| Author | Year | Modalities considered | Number of included studies (participants) | Number of participants in largest contributing study (MRE or US) | Main outcome | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liu et al.23 | 2017 | CTE, MRE | 21 (913) | 72 (4 sites) | Diagnostic accuracy |

CTE: sensitivity 0.87 (95% CI 0.78 to 0.92); specificity 0.91 (95% CI 0.84 to 0.95) MRI: sensitivity 0.86 (95% CI 0.79 to 0.91); specificity 0.93 (95% CI 0.84 to 0.97) |

| Greenup et al.21 | 2016 | CTE, MRE, US | 21 (1135) | 249 (120 with CD) (1 site) | Diagnostic accuracy |

CTE: sensitivity 67–95%; specificity 70–90% MRE: sensitivity 66–100%; specificity 72–100% US: sensitivity 86–97%; specificity 83–97% |

| Choi et al.16 | 2017 | CapE, CTE, MRE, BaFT | 24 (781) | 89 (4 sites) | Diagnostic accuracy | Suspected CD:

|

| Qiu et al.24 | 2015 | CTE, MRE | 6 (290) | 73 (4 sites) | Diagnostic accuracy (active disease) |

CTE: sensitivity 85.8% (95% CI 79.2% to 90.9%); specificity 83.6% (95% CI 75.3% to 90.1%) MRE: sensitivity 87.9% (95% CI 81.8% to 92.5%); specificity 81.2% (95% CI 71.9% to 88.4%) |

| Giles et al.20 | 2013 | MRE | 11 (496) (paediatric participants only) | 87 (1 site) | Diagnostic accuracy | MRE: sensitivity (terminal ileum) 0.84 (95% CI 0.77 to 0.90); specificity 0.97 (0.91 to 0.99) |

| Dong et al.18 | 2014 | US | 15 (1558) | 249 (120 with CD) (1 site) | Diagnostic accuracy | Sensitivity 88% (95% CI 85% to 91%); specificity 97% (95% CI 96% to 98%) |

| Panés et al.12 | 2011 | CTE, MRE, US | Locating active CD:

|

296 (1 site) | Diagnostic accuracy (active disease) | Locating active CD:

|

| Ahmed et al.15 | 2016 | MRE | 19 (102) | 249 (120 with CD) (1 site) | Disease activity | Sensitivity: 88% (95% CI 86% to 91%); specificity: 88% (95% CI 84% to 91%) |

| Puylaert et al.26 | 2015 | CTE, MRE, scintigraphy, US | 19 (549) | 76 (1 site) | Disease activity | Per-participant accuracy:

|

These meta-analysis and systematic review data suggest essentially equivalent diagnostic accuracy for MRE and US in detection and staging of CD, with sensitivity and specificity generally > 80%. However, there is marked heterogeneity in the primary literature, with most contributory studies being single centre and recruiting relatively small participant numbers, typically < 50. Many studies are also retrospective and quality is generally poor. For example, in their 2017 meta-analysis, Liu et al. 23 reported that just 38% of included studies were rated as ‘good quality’ using the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies (QUADAS) tool. 27 Similarly, using the modified tool (QUADAS-2),28 Puylaert et al. 26 found that in six of their 19 included studies blinding to the reference standard was either not done or not explicitly stated. Most studies do not compare MRE and US in the same participants, which is the most effective design for diagnostic accuracy studies because, for example, it reduces bias caused by difference between participants. 29 There is also much variation in the applied standard of reference between studies, with endoscopy, surgery and imaging itself all employed. By way of example, in the largest study of US to date (296 participants),30 the standard of reference was simple barium fluoroscopic studies in > 70% of recruited participants. Similarly, in their single-centre comparative study of MRE and US in 249 participants with suspected CD (120 with a confirmed diagnosis), Castiglione et al. 31 used MRE itself as the standard of reference for small bowel Crohn’s disease (SBCD) extent in the majority of participants who did not have surgical reference standard, clearly risking incorporation bias. There is no single reference standard for defining the location, extent and activity of CD. In such circumstances, the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) acknowledges the advantages of the construct reference standard paradigm (panel diagnosis) and incorporating the concept of clinical test validation, that is, whether or not the results of an index test are meaningful in practice. 32 Very few studies have used such a consensus panel standard of reference, which considers all available clinical, endoscopic and imaging data as well as patient outcomes.

Imaging of Crohn’s disease in the NHS

According to a 2010 UK survey,33 90% of NHS radiology departments routinely perform BaFT to investigate known or suspected CD in patients, 80% perform CT, 56% perform US and 38% perform MRE. The use of MRE has certainly increased since this survey was conducted.

Across the NHS there is ad hoc provision and utilisation of newer imaging technologies in CD, with little consistency between hospitals and no coherent implementation strategy. The choice of small bowel imaging investigation currently depends largely on non-evidence-based decision-making, such as clinician personal preference, perceived costs, available infrastructure and radiological expertise.

Ultimately, the optimal imaging strategy for CD remains uncertain and single-centre data are of limited utility. Unbiased, robust data to inform the implementation strategy for newer imaging technologies are currently unavailable.

Objectives of the METRIC trial

The primary aim of the Magnetic Resonance Enterography or ulTRasound In Crohn's disease (METRIC) trial was to compare the diagnostic accuracy of MRE and US for extent of SBCD against a construct reference standard, incorporating 6 months of participant follow-up. We recruited from two cohorts of participants: newly diagnosed participants and participants with established CD clinically suspected of luminal relapse. Secondary objectives included comparative accuracy of MRE and US in grading of inflammatory activity and diagnostic accuracy in the colon, interobserver variability in interpretation of MRE and US and a cost-effectiveness analysis. The impact of an oral contrast load prior to small intestine contrast-enhanced ultrasonography (SICUS) on diagnostic accuracy compared with conventional US was investigated in a subset of participants. We also modelled the diagnostic impact of both tests on clinician decision-making, investigated the influence of MRE sequence selection on accuracy and assessed participant experience of small bowel imaging.

Chapter 2 Methods

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced or adapted from Taylor et al. 34 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Study design

The METRIC trial was a multicentre, non-randomised, single-arm, prospective cohort study comparing the diagnostic accuracy of MRE and enteric US for the presence, extent and activity of SBCD in newly diagnosed participants or participants with established disease and suspected relapse. The full protocol has been published. 34 The trial achieved NHS Research Ethics Committee approval in September 2013 (reference 13/SC/0394) and was conducted in accordance with the principles of Good Clinical Practice. The trial was supervised by University College London (UCL)’s Clinical Trials Unit, an independent Data Monitoring Committee and a Trial Steering Committee. All recruited participants gave written informed consent.

Consecutive (i.e. unselected) eligible participants underwent MRE and US in addition to standard investigations performed as part of their usual care, and their clinical course was followed for a period of 6 months. A multidisciplinary consensus panel derived the reference standard for the presence, location and biological activity of SBCD and colonic CD using all available clinical, endoscopic, imaging, biochemical and histological data over the 6-month follow-up period. A summary of participant flow in the main trial is shown in Figure 1. Agreement between radiologists’ interpretations of MRE and US was tested in a sample of participants, and the contribution of specific MRE sequences on radiologist accuracy was investigated. The influence of oral contrast type and volume on quality of bowel distension during MRE was evaluated and the effect of an oral contrast load prior to SICUS on diagnostic accuracy compared with conventional US was tested in a sample of participants. An exercise was undertaken by gastroenterologists to assess the diagnostic and therapeutic impact of MRE and US on clinical decision-making, and comparative participant experience of MRE and US was evaluated. The cost-effectiveness of MRE and US in both participant cohorts was assessed in an economic evaluation. The full study protocol can be accessed via the UCL project page [URL: www.ucl.ac.uk/cctu/research-areas/gastroenterology/metric (accessed 29 May 2019)].

FIGURE 1.

Participant flow through the main study. CRP, C-reactive protein; FC, faecal calprotectin; HBI, Harvey–Bradshaw Index. a, Already performed or pending at recruitment; b, interpreted by two independent blinded practitioners; c, required specific participant consent; d, in the absence of endoscopic visualisation; e, in the absence of existing small bowel imaging investigations or capsule endoscopy; f, for example capsule endoscopy, barium small-bowel follow-through and/or CTE, at discretion of recruitment site.

Patient and public involvement

The METRIC trial was developed in collaboration with Crohn’s and Colitis UK [URL: https://crohnsandcolitis.org.uk (accessed 29 May 2019)], which nominated a patient representative to join the trial team at the inception of the project. The patient representative helped refine the research questions, devise the protocol and successfully applied for the funding. By way of example, on their advice and guidance, we included a detailed assessment of patient priorities for imaging their disease to better understand and interpret the research findings. All patient-facing materials were designed with the patient representative (and in general were very well received by participants). The representative sat on the Trial Management Committee and Trial Steering Committee, providing guidance throughout the running of the trial and subsequent write-up, for example helping to refine recruitment strategies and advising on dissemination. This collaboration has been very productive and has now been expanded with the set-up of a patient forum to advise on current and future imaging research in CD. The forum ensures a wide representation of opinion, including age, sex and disease focus, and has been supported by Bowel & Cancer Research [URL: www.bowelcancerresearch.org (accessed 29 May 2019)] and Motilent (London, UK), which supported (in kind) meetings costs.

Recruitment sites

Participants were recruited from eight NHS hospitals in England and Scotland. A mixture of teaching and general hospitals was included. All sites were required to have an established IBD service seeing > 150 participants annually and lead radiologists had to be affiliated with the British Society of Gastrointestinal and Abdominal Radiology (BSGAR) to ensure expertise in CD imaging, including MRE and US (see Radiologist/sonographer competence and training). To meet the trial imaging blinding protocol requirements, each site had to nominate at least two radiologists/sonographers to participate in the study. Each site had a named research nurse/practitioner or researcher responsible for recruitment.

Participants

Participants were recruited to two defined cohorts:

-

those newly diagnosed with CD

-

those previously diagnosed with CD with a high suspicion of luminal relapse requiring radiological investigation.

Inclusion criteria

New diagnosis cohort

Participants were eligible for the new diagnosis cohort if either they had undergone colonoscopy or colonoscopy was planned, and they:

-

had been recently diagnosed with CD (within 3 months of recruitment) based on endoscopic, histological and radiological findings or were highly suspected of CD based on characteristic endoscopic, imaging or histological features but pending final diagnosis

-

were aged ≥ 16 years

-

were able to give fully informed consent.

Suspected relapse cohort

Participants were eligible for the suspected relapse cohort if they:

-

had a known diagnosis of CD with a high clinical suspicion of luminal relapse indicating radiological investigation

-

were aged ≥ 16 years

-

were able to give fully informed consent.

A high clinical suspicion of luminal relapse was defined as objective markers of inflammatory activity [a C-reactive protein (CRP) level of > 8 mg/l or a faecal calprotectin (FC) level of > 100 µg/g] or symptoms suggestive of luminal stenosis (including obstructive symptoms such as colicky abdominal pain and vomiting) or abnormal endoscopy suggesting relapse. A CRP level of > 8 mg/l (rather than > 5 mg/l) was selected to increase specificity for participants with true relapse.

Exclusion criteria

Participants were not eligible for recruitment to either study cohort if they:

-

had any psychiatric or other disorder likely to affect informed consent

-

had evidence of severe or uncontrolled systemic disease that at the principal investigator’s discretion rendered the individual unsuitable for participation

-

were pregnant

-

had contraindications to MRE (e.g. allergy to all suitable contrast agents, cardiac pacemaker, severe claustrophobia, an inability to lie flat).

Participants were not eligible for recruitment to the new diagnosis cohort if they:

-

had a final diagnosis other than CD

-

underwent surgical resection prior to a pending colonoscopy.

Test methods

Recruited participants to both study cohorts underwent MRE and US.

Magnetic resonance enterography

Technical parameters

Magnetic resonance enterography was performed by the usual clinical radiographer team at each recruitment site. To improve generalisability of results, the MRI platform (i.e. manufacturer and tesla (T) strength) utilised was allocated by the lead site radiologist according to availability and their usual practice. Exact imaging parameters varied according to MRI platform but a minimum data set of sequences was acquired, including T2-weighted images with and without fat saturation, steady-state free precession gradient echo images, diffusion-weighted images and T1-weighted images after intravenous gadolinium injection, as defined by the study investigators (see Appendix 1, Table 40). The choice of oral contrast prior to MRE was also at the discretion of the recruitment site and in accordance with their usual practice (see Appendix 2, Table 41). Where possible, radiographers recorded the volume of oral contrast ingested by participants and the time taken for ingestion prior to MRE.

In some participants, MRE had been performed as part of usual clinical care prior to recruitment. If it had been performed within the preceding 4 weeks and according to the minimum data set of sequences, it was deemed sufficient for the purposes of the study and not repeated (see Trial blinding).

Ultrasonography

Technical parameters

Ultrasonography was performed by local site radiologists or sonographers (see Radiologist/sonographer competence and training) using standard US platforms at recruitment sites. Participants were nil by mouth for 4 hours and no oral contrast was administered prior to US, although ingestion of two cups of water by participants just prior to the scan was permissible to improve visualisation of the duodenum. A sample of the participants were recruited to a substudy of SICUS and underwent an additional US after ingesting oral contrast medium (see Chapter 4). The colon and small bowel were systematically interrogated using both curvilinear and high-resolution linear probes (minimum 5 MHz frequency). Colour Doppler was routinely applied (with typical flow settings 6–9 m/second) but intravenous US contrast agents were not administered. US performed as part of usual clinical care prior to recruitment was repeated for the purposes of the study if appropriate blinding of the operator could not be assured (see Trial blinding).

Quality assurance

All sites sent in MRE and US images to the lead site [University College Hospital (UCLH)] for secure upload and storage. Compliance with the minimal protocol data set was confirmed but formal quality assurance was not undertaken given that all sites were experienced in both MRE and US techniques.

Clinical investigations

Colonoscopy

Participants recruited to the new diagnosis cohort either had undergone colonoscopy or had colonoscopy planned as part of usual clinical care at recruitment. Participants recruited to the suspected relapse cohort underwent colonoscopy only if deemed necessary as part of their routine clinical care, irrespective of study recruitment. Colonoscopy was performed and reported by local gastroenterologists as per usual clinical practice.

Additional small bowel imaging

All participants recruited to the trial underwent MRE and US. However, in addition, some participants underwent additional small bowel imaging, for example CTE or BaFT, either prior to or after recruitment as part of their usual clinical care. All additional small bowel imaging tests were performed and reported by local radiologists as per their standard clinical practice.

Radiologist/sonographer competence and training

Competence and training requirements for the study were defined a priori such that individuals interpreting trial imaging were representative of those individuals who report small bowel imaging in the NHS. We specifically avoided using a small number of highly experienced subspecialty practitioners who would not be representative of the NHS radiological workforce. Across all sites, 28 practitioners interpreted the MRE and US studies (27 radiologists and one sonographer). Practitioners were selected by the sites’ lead radiologists and all met the training and experience criteria detailed below. Eight radiologists interpreted MRE only, three performed and interpreted US only and 16 performed and interpreted US and MRE. All site lead radiologists were affiliated to the BSGAR to ensure local dissemination of best practice. All reporting radiologists were post Fellowship of the Royal College of Radiologists (FRCR) and either were at consultant level and/or had ≥ 1 year of subspecialty gastrointestinal experience. All had a declared subspecialty interest in gastrointestinal radiology with previous experience of MRE and US. Specifically, radiologists interpreting MRE had a median of 10 years of experience [interquartile range (IQR) 6–11 years] and practitioners interpreting US had a median of 8 years of experience (IQR 4–11 years). The participating sonographer had undergone formal training, was already performing enteric US in clinical practice with 20 years of experience and had been deemed competent by their lead radiologist. The median number of examinations performed per month at each recruitment site (including those patients not recruited to the METRIC trial) during the conduct of the trial was 30 (range 20–50, IQR 20–45) for MRE and 25 (range 4–80, IQR 12–40) for US. The monthly range of MRE examinations across sites was 20 (Queen Alexandra Hospital, Portsmouth, and St George’s Hospital, London) to 50 (UCLH, London, and John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford). The range of monthly US examinations across sites was three (John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford) to 80 (Queen Alexandra Hospital, Portsmouth). A 2-day hands-on US training workshop was run in Portsmouth before trial commencement to standardise US technique and agree the description of enteric findings (see Reporting of trial imaging).

Study imaging interpretation and reporting

Blinding of interpreting radiologists/sonographers

Unbiased estimates of imaging test diagnostic accuracy can be achieved only if those individuals interpreting the tests are unaware of the findings of contemporaneous imaging and endoscopy. For example, a practitioner aware of endoscopically confirmed terminal ileal disease could not give an unbiased evaluation of subsequent US or MRE in the same patient. MRE and US for individual recruited participants were therefore interpreted by different practitioners blinded to all clinical information other than the cohort (suspected relapse or new diagnosis) and surgical history. Practitioners were blinded to all other current/past imaging investigations and endoscopies. Surgical history was disclosed so as not to disadvantage US (sites of surgical resection are usually indicated at the time of a clinical request for imaging). Practitioners performing US were explicitly instructed to not converse with participants about their medical history, and where possible the examination was witnessed by a research nurse. If blinding of the reporting practitioner could not be assured, for example in the case of MRE or US performed prior to study recruitment, MRE images were reanalysed by a blinded local radiologist, or a central radiologist at UCLH (if a suitable local radiologist was not available), and the US was repeated by an appropriately blinded individual (as US interpretation occurs in real time and cannot be reproduced by review of static images).

Reporting of trial imaging

The imaging appearances of CD on MRE and US are well described35 and utilised for the purposes of the study. Guidance on the criteria for disease activity was provided to practitioners based on the literature at the time of study design. 12,22 Specifically, signs of active disease on MRE included wall thickening, increased mural T2 signal, increased mesenteric T2 signal, increased enhancement (mucosal or layered), ulceration and abscess; signs of active disease on US included wall thickening, focal hyperechoic mesentery (with or without fat wrap), isolated thickened submucosal layer, poorly defined antimesenteric border, increased Doppler vascular pattern, ulceration and abscess.

Practitioners completed a case report form (CRF) recording their findings for MRE and US. Items recorded on the CRFs included the imaging platform used to acquire the images and confirmation of radiologist/sonographer blinding to other investigations. The quality of visualisation for 10 bowel segments (duodenum, jejunum, ileum, terminal ileum, caecum, ascending colon, transverse colon, descending colon, sigmoid colon and rectum) was graded as good, moderate or poor. The terminal ileum was defined as the last 10 cm of the small bowel and the jejunum was defined as the proximal bowel lying largely to the left of a diagonal line drawn from the right lower quadrant to the left lower quadrant, demonstrating a typical feathery fold pattern. Colonic segments were defined as previously described. 36 The presence of any small bowel and/or colonic CD was then recorded using six confidence levels grouped into normal (levels 1 and 2), equivocal (levels 3 and 4) and abnormal (levels 5 and 6). If disease presence was recorded as equivocal or abnormal (i.e. confidence level 3 or higher), the level of disease activity was also scored from 1 (disease definitely not active) to 6 (disease definitely active). The same grading system for disease presence and activity was then applied to each of the 10 individual bowel segments. Terminal ileal disease extending contiguously for greater than 10 cm was considered terminal ileal disease only and was not considered to be affecting both the terminal ileum segment and ileal segments separately. If a segment contained more than one site of disease (defined as > 3 cm of normal-appearing bowel between disease sites), this was recorded as a separate disease site in that segment. Similarly, if there was > 3 cm of normal-appearing bowel between terminal ileal disease and ileal disease, this was considered to be affecting both segments. In participants with prior terminal ileal resection, the neo-terminal ileum was considered to be the terminal ileum for the purposes of the trial. The presence of extraenteric complications including abscesses and fistulae were also recorded. For MRE alone, the reporting radiologist recorded if their diagnostic confidence had been influenced by diffusion-weighted images and/or contrast-enhanced images and if their diagnosis for disease presence or activity had been changed after review of these sequences (see Chapter 6).

Following completion of the CRF, radiologists/sonographers produced an unblinded standard report for the MRE and US as per usual clinical practice.

As part of an interobserver variation study, a proportion of participants underwent a second US by a separate radiologist/sonographer who completed an identical CRF (see Chapter 5).

Generation of additional small bowel imaging for discrepant magnetic resonance enterography and ultrasonography

There is no single reference standard for the presence of CD in the proximal small bowel upstream of the terminal ileum (which is usually assessed during ileocolonoscopy). In participants who had not undergone an additional small bowel imaging test [e.g. CTE, BaFT or capsule endoscopy (CapE)] as part of their usual clinical care, the only available assessment of the proximal small bowel was MRE and US, risking incorporation bias during the derivation of the reference standard. In such participants, radiologist/sonographer interpretations of MRE and US were therefore reviewed at the time of reporting to ascertain if they were discrepant for the presence of SBCD. Discrepancy was defined as (1) disease reported in the terminal ileum on only MRE or US in the absence of endoscopic visualisation of the terminal ileum and/or (2) disease reported in the small bowel upstream of the terminal ileum on only MRE or US, including additional disease sites in those patients with multifocal involvement. To avoid unnecessary additional tests, in participants with a reported single site of SBCD that differed only in segmental localisation between MRE and US (e.g. ileum vs. jejunum), the local research team reviewed the imaging and opined if the tests were probably concordant (i.e. same abnormality detected) or truly discrepant and recorded this accordingly.

Participants with a true SBCD discrepancy on MRE and US according to the above definitions were invited to undergo an additional small bowel investigation within 8 weeks of the initial study imaging. The choice of investigation was at the discretion of the recruitment site and could include BaFT, CTE or CapE for example. Emphasis was placed on performing a new imaging modality but a repeat MRE or unblinded US was permitted if an alternative imaging modality was deemed inappropriate by the clinical care team or participant. The additional small bowel imaging test was interpreted by a site radiologist fully unblinded to all other investigations and formed part of the later consensus panel review process for the study reference standard.

Recruitment

Suitable participants were identified by members of the local research team, who established whether or not the individual met the study entry criteria, from outpatient clinics, multidisciplinary team (MDT) meetings, inpatient wards and lists of requests for small bowel imaging and endoscopy. A screening log recorded the details of all individuals approached to take part in the study and reasons for non-participation if applicable. All individuals were handed or posted a participant information sheet detailing the study and contact details of the study team should they have any questions. The study purpose and requirements were also explained to participants face to face by an appropriately trained member of the research team. All participants gave written consent prior to participation in the main METRIC study. Participants gave additional written consent if they agreed to participate in the SICUS substudy (see Chapter 4), participate in the US interobserver substudy (see Chapter 5) or complete patient experience questionnaires (see Chapter 7). Participants retained a copy of their consent form and participant information sheet and were informed that they could withdraw from the study at any time.

Data collection and participant follow-up

Data collation was co-ordinated by the UCL Comprehensive Clinical Trails Unit (CCTU). Demographic and baseline clinical information was collected at recruitment using a specially designed CRF that recorded sex, age, family history of IBD, smoking status, current CD-related medication, previous history of bowel surgery, current symptoms and, for participants recruited to the suspected relapse cohort, time since CD diagnosis and current Montreal classification. 37 Participants were invited to supply a stool sample for measurement of FC, to supply a blood sample for CRP measurement and to complete a Harvey–Bradshaw Index (HBI) disease activity test38 at recruitment and again at 10–20 weeks, if these had not already been carried out as part of usual clinical care. The findings of endoscopies and biopsies (if performed) were recorded on CRFs, as were the findings of all contemporaneous imaging investigations (including those findings of additional small bowel imaging triggered by discrepant MRE and US reports for the presence of SBCD). Complications related to MRE or US were recorded on a specific CRF. The clinical course of participants was followed for a period of 6 months after recruitment to inform the consensus panel review process and collate data for the health economic analysis (see Chapter 10). During this time, details of any CD-related surgical interventions (including histology) were recorded on CRFs, along with additional imaging/endoscopic investigations, outpatient visits, hospital day visits, inpatient stays and details of CD medication. All CRFs were collated by local site research nurses/practitioners and sent to the CCTU by post or fax. Forms were entered onto a bespoke study database and any missing fields or apparent data inaccuracies queried with the centre to optimise data collection.

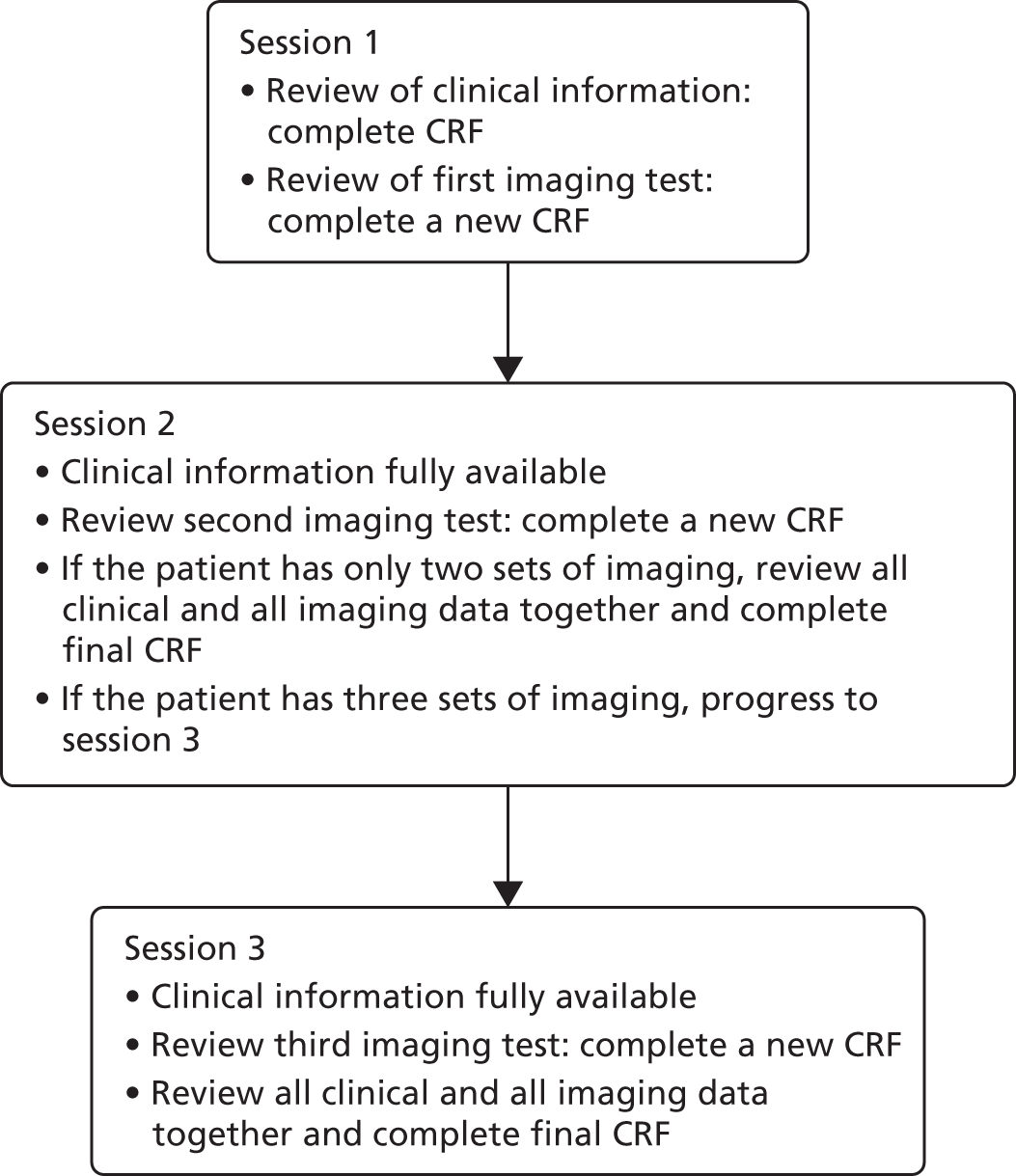

Reference standard

The METRIC trial used the construct reference standard paradigm (panel diagnosis) incorporating the concept of clinical test validation (i.e. whether or not the results of an index test are meaningful in practice). Specifically, by following the participants’ clinical course for 6 months after recruitment it was possible to assess the impact of clinical decision-making on participant outcomes based on the findings of MRE and US. For example, if biological therapy was commenced based on a MRE or US finding of active SBCD, the success or otherwise of this therapy could be ascertained using the 6-month participant outcome data, contributing to the panel decision as to the validity or otherwise of the imaging findings. Each recruitment site convened a series of consensus panels to derive the reference standard for disease presence, extent and activity at the time of consent for each participant recruited at their site. Typically, each consensus meeting considered around 10 participants in one 2- to 3-hour session and consisted of at least one gastroenterologist from the recruitment site and at least two radiologists (one internal to the site and one external, from another recruitment site), along with a member of the local research support team to aid the running of the meeting and CRF completion. A member of the Trial Management Group (TMG) attended each consensus meeting to ensure uniformity when defining disease presence, activity and extent and a histopathologist was available to the panel if required. The panel considered all available clinical information over the 6-month follow-up period, including the images and results of all small bowel investigations (including MRE, US and all generated third small bowel imaging tests), endoscopy (reports and images), surgical findings (if applicable), histopathology (surgical resection and biopsies), HBI, CRP level, FC level (and changes thereof in response to therapy), follow-up imaging and clinical course. Panels had access to all completed follow-up CRFs as well as participant clinical results, records and letters via the participant notes and/or electronic participant record. Panels also had access to the hospital picture archiving and communications system (PACS) so they could review all small bowel imaging.

For each recruited participant, the panel completed a specific consensus reference standard CRF. The imaging, endoscopic and clinical data considered by the panel were recorded, along with their interpretation of the available data for presence and activity of SBCD and colonic CD. The panel specifically recorded the findings of endoscopic and biopsy data, given its robustness as a standard of reference for the presence of colonic and terminal ileal disease. Based on all information, the panel recorded if, in their opinion, there was any small bowel or colonic CD present, and if present whether or not the disease was active. Disease could only be categorised as active if there was at least one objective marker of activity [(1) ulceration as seen at endoscopy and/or (2) measured CRP level of > 8 mg/l and/or (3) measured FC level of > 250 µg/g and/or (4) histopathological evidence of acute inflammation based on biopsy or surgery within 2 months of study imaging]. Thereafter, the presence and activity of CD in each of 10 bowel segments (duodenum, jejunum, ileum, terminal ileum, caecum, ascending colon, transverse colon, descending colon, sigmoid colon and rectum) were recorded by the panel. The original blinded study interpretations of MRE and US were reviewed by the panel and any false-negative observations for disease presence (against the consensus reference standard) were classified by the panel as radiologist perceptual error if the abnormality was visible on reviewing the imaging in retrospect, or as a technical failure of the imaging modality if it was not. The panel also documented the presence or absence of extraluminal complications including abscesses and fistulae. If consensus panels could not reach agreement on any aspect of the reference standard CRF, they were able to refer the review to another recruitment site’s consensus panel for their consideration.

Outcomes

A summary of the primary and secondary outcomes is shown in Appendix 3, Table 42. The primary outcome for the main study was the difference in per-participant sensitivity between MRE and US for the correct identification and localisation of SBCD, irrespective of activity, against the consensus reference standard. For location matching, the small bowel was divided into duodenum, jejunum, ileum and terminal ileum (see Reporting of trial imaging). Given the potential clinical impact of underdiagnosed SBCD (e.g. primary surgery for isolated terminal ileal disease vs. medical management for more diffuse disease), to be a true positive for the primary outcome the index test had to correctly locate both the presence and segmental location of the disease. A summary of the criteria for agreement with the reference standard for disease extent is given in Appendix 4, Table 43. Disease reported as equivocal was treated as positive for disease presence given the potential clinical implications of an equivocal result on patient management and the need for further investigations. A sensitivity analysis treating equivocal results as negative for disease presence was also performed.

Secondary outcome measures were the difference in per-participant specificity of MRE and US for the correct identification and localisation of SBCD irrespective of activity and the per-participant sensitivity and specificity for identification of colonic CD presence and extent. Additional secondary outcome measures were per-participant sensitivity and specificity for the presence of active SBCD and colonic CD against the consensus reference standard. The secondary analyses were repeated for the terminal ileum and colonic segments in participants with an available colonoscopic reference standard, given its robustness in CD identification and activity assessment.

The primary and secondary analyses were performed for both cohorts combined and then separately for the new diagnosis and suspected relapse cohorts.

Additional secondary outcomes pertaining to the comparative impact of MRE and US on clinician diagnostic confidence and management, the lifetime incremental cost and cost-effectiveness of assessment using MRE or US, diagnostic accuracy of SICUS compared with conventional US, comparative participant experience of MRE and US, diagnostic impact of novel MRE sequences and interobserver variation in the evaluation of MRE and US data sets are described in the relevant chapters (see Chapters 4–10).

Sample size

Primary outcome

The sample size calculation was based on the primary outcome stipulated by the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) commissioning brief: diagnostic accuracy for SBCD extent. There are two aspects of correctly assigning disease extent: correctly detecting the presence of disease and correctly assigning its segmental location. Study power was thus based on a two-faceted compound accuracy measure (disease presence and disease location). Based on the available literature at the time of study design (see Report Supplementary Material 1), it was assumed that MRE had 93% sensitivity for disease presence and 90% sensitivity for disease location, resulting in an overall compound accuracy for disease extent of 83% (93% × 90%). The corresponding assumed values for US were 88%, 83% and 73%, resulting in a 10% difference in overall compound accuracy for disease extent between MRE and US (83% vs. 73%). Assuming moderate correlation between the two imaging tests (68% positive test result on both MRE and US), a total of 210 participants with SBCD were required to detect a 10% superiority of MRE over US at 90% power (type II error). 39 Assuming a SBCD prevalence of 70%, a cohort of 301 participants was required, and assuming 10% loss to follow-up/non-CD final diagnosis, a total cohort of 334 participants (167 new diagnosis participants and 167 suspected relapse participants) was required. A sample size of 156 participants was sufficient to detect a 13% difference in sensitivity for the primary outcome between MRE and US at 80% power.

Secondary outcomes

Study power for correct per-participant identification of disease activity assumed sensitivities of 88% and 78% for MRE and US, respectively (see Report Supplementary Material 1). A total of 204 participants with active disease gave 80% power to detect a 10% difference in correct per-participant disease activity classification. Assuming a SBCD prevalence of 70% and 10% loss to follow-up, a cohort of 324 participants was required. Sensitivity for correct per-participant identification of active disease in the terminal ileum against a colonoscopic reference standard assumed that 200 participants would have colonoscopic data available (all the new diagnosis cohort and one-third of the suspected relapse cohort). Assuming sensitivities for segmental disease activity of 75% and 60% for MRE and US, respectively, and 70% prevalence of SBCD, 195 participants was sufficient to detect a 15% difference in sensitivity.

Analysis

Disease reported as equivocal was treated as positive in the analysis. The primary outcome was calculated per participant. Secondary outcomes for bowel segments were based on all segments, excluding those segments resected at baseline (for terminal ileal resections, the neo-terminal ileum was considered to be the terminal ileum).

Direct comparison of sensitivity and specificity differences between MRE and US were calculated using bivariate multilevel participant-specific (conditional) random-effects models, from paired data using meqrlogit in Stata® 14.2 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). When models did not converge owing to small numbers of participants, McNemar’s comparison of paired proportions was used to obtain univariable estimates, and exact 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. Analysis by colonic segment used a population-averaged random-effects model (using logit including robust standard errors). Statistical significance was based on 95% CIs. There were no missing data for per-participant diagnosis of disease presence or disease extent.

Chapter 3 Results

This chapter contains material that is reproduced from Taylor et al. 40 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Participants

Recruitment began in December 2013 and was completed in September 2016. Overall, 518 participants were assessed for eligibility, of whom 183 were excluded, predominantly because they did not meet the inclusion criteria or declined participation (Table 2).

| Reason for exclusion | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Non-CD diagnosis | 22 (12) |

| Not able to give informed consent | 7 (4) |

| Declined participation | 58 (32) |

| No response to invitation to participate | 28 (15) |

| Contraindication to MRI | 8 (4) |

| Newly diagnosed > 3 months previously | 2 (1) |

| Unable to complete MRE and/or US in timely fashion | 20 (11) |

| Aged < 16 years | 2 (1) |

| Previous recruitment or declined approach | 5 (3) |

| CRP level not raised (suspected relapse cohort) | 13 (7) |

| Moved/lived far way | 4 (2) |

| Proceeded straight to surgery prior to colonoscopy (new diagnosis cohort) | 4 (2) |

| Unknown | 10 (6) |

| Total | 183 |

Of the 335 participants who entered the trial, 51 were subsequently excluded (Table 3). The most frequent reason was an ultimate diagnosis other than CD (31 participants).

| Reason for withdrawal | Cohort, n (%) | Total, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| New diagnosis | Suspected relapse | ||

| Participant withdrew consent | 0 (0) | 3 (18) | 3 (6) |

| Final diagnosis other than CD | 25 (73) | 6 (35) | 31 (60) |

| Participant did not undergo MRE | 0 (0) | 5 (29) | 5 (10) |

| Participant did not undergo US | 2 (6) | 1 (6) | 3 (6) |

| Participant did not undergo MRE or US | 2 (6) | 0 (0) | 2 (4) |

| Lost to follow-up | 2 (6) | 0 (0) | 2 (4) |

| Underwent surgery without colonoscopy | 2 (6) | 0 (0) | 2 (4) |

| No longer wished to participate at follow-up | 1 (3) | 2 (12) | 3 (6) |

| Total | 34 | 17 | 51 |

The final cohort was 284 participants (133 and 151 in new diagnosis and suspected relapse cohorts, respectively) (Figure 2). Appendix 5, Table 44, shows the recruitment and withdrawal numbers for each of the eight recruitment sites. Figure 2 is the patient flow diagram.

FIGURE 2.

Participant flow diagram. Reproduced from Taylor et al. 40 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Baseline participant characteristics

The demographic data of the final study cohort are shown in Table 4. There were marginally more men in the new diagnosis cohort and more women in the suspected relapse cohort. Overall, 154 (54%) participants were female. In the suspected relapse cohort, 101 (67%) participants had had CD for ≥ 6 years and 53 (35%) and 14 (9%) had a stricturing or penetrating disease phenotype, respectively.

| Variable | Cohort, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| New diagnosis (N = 133) | Suspected relapse (N = 151) | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 69 (52) | 61 (40) |

| Female | 64 (48) | 90 (60) |

| Age (years) | ||

| 16–25 | 49 (36) | 46 (30) |

| 26–35 | 32 (24) | 36 (24) |

| 36–45 | 18 (14) | 28 (19) |

| > 45 | 34 (26) | 41 (27) |

| Disease duration | ||

| < 1 year | N/A | 5 (3) |

| 1–5 years | N//A | 45 (30) |

| 6–10 years | N/A | 39 (26) |

| > 10 years | N/A | 62 (41) |

| Disease location (Montreal classification)a | ||

| L1 | N/A | 56 (37) |

| L2 | N/A | 17 (11) |

| L3 | N/A | 74 (49) |

| L4 | N/A | 4 (3) |

| Disease behaviour (Montreal classification)a | ||

| B1 | N/A | 80 (53) |

| B1p | N/A | 4 (3) |

| B2 | N/A | 52 (34) |

| B2p | N/A | 1 (1) |

| B3 | N//A | 12 (8) |

| B3p | N/A | 2 (1) |

| Medicationb | ||

| None | 62 (47) | 32 (21) |

| 5-ASA | 21 (16) | 26 (17) |

| Steroids | 48 (36) | 28 (19) |

| Immunomodulators | 16 (12) | 75 (50) |

| Anti-TNF therapy | 5 (4) | 42 (28) |

| Previous enteric resection | 1 (1)c | 72 (48) |

Participants had a range of presenting symptoms, notably abdominal pain and diarrhoea (see Appendix 6, Table 45). In general, symptoms were similar between the two cohorts, although the proportion of participants reporting bloody diarrhoea was higher in those participants newly diagnosed, and a greater proportion of those participants with relapse reported obstructive symptoms. There were no reported major adverse events following MRE or US.

Consensus reference standard

The available small bowel imaging tests (including third tests generated by a discrepancy for SBCD presence or location between MRE and US), CRP and FC levels, HBI and surgical resection specimens available to the consensus panels are shown in Table 5. A total of 10 (8%) new diagnosis participants did not undergo full colonoscopy despite this being planned at recruitment. Of these, five underwent flexible sigmoidoscopy instead, and the remaining either declined or had a change in their clinical investigational plan. Colonoscopy data were available for 66 (44%) of the suspected relapse cohort participants. There was a range of small bowel imaging tests available over and above MRE and US, including CapE, BaFT and CTE.

| Variable | Cohort, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| New diagnosis (N = 133) | Suspected relapse (N = 151) | |

| MRE | 133 (100) | 151 (100) |

| US | 133 (100) | 151 (100) |

| Colonoscopy | 123 (92) | 66 (44)a |

| Gastroscopy | 11 (8) | 6 (4) |

| Sigmoidoscopy | 5 (4) | 12 (8) |

| CapE | 10 (8) | 8 (5) |

| CTE | 4 (3) | 9 (6) |

| CT abdomen and/or pelvis | 21 (16) | 13 (9) |

| MR enteroclysis | 4 (3) | 6 (4) |

| MRI abdomen and/or pelvis | 5 (4) | 8 (5) |

| BaFT | 8 (6) | 19 (13) |

| Barium enteroclysis | 3 (2) | 7 (5) |

| Hydrosonography | 28 (21) | 37 (25) |

| White cell scan | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| CRP level | ||

| Baseline | 127 (95) | 145 (96) |

| 10–20 weeks | 108 (81) | 120 (79) |

| HBI | ||

| Baseline | 124 (93) | 142 (94) |

| 10–20 weeks | 71 (53) | 77 (51) |

| FC level | ||

| Baseline | 87 (65) | 89 (59) |

| 10–20 weeks | 53 (40) | 65 (43) |

| Surgical resection | ||

| Before recruitment | 1 (1) | 72 (48) |

| During trial follow-up | 1 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Other | 8 (6) | 20 (13) |

Based on the consensus reference standard, 233 (82%) participants had SBCD (meeting the requirements of the sample size calculation), which was active in 209 (89%) (Table 6). A total of 129 (45%) participants had colonic CD, which was active in 126 (98%). Participants often fulfilled more than one criterion for active disease (raised CRP/FC levels, ulceration at endoscopy, histopathological evidence of inflammation) (see Table 6). The prevalence of SBCD was similar between the new diagnosis and suspected relapse cohorts, although colonic CD tended to be more prevalent in the former. The prevalence of activity was high when disease was present and was also similar between the two cohorts.

| Variable | Cohort | |

|---|---|---|

| New diagnosis (N = 133) | Suspected relapse (N = 151) | |

| Disease presence | ||

| SBCD present, n (%) | 111 (83) | 122 (81) |

| Colonic CD present, n (%) | 77 (58) | 52 (34) |

| Both SBCD and colonic CD present, n (%) | 55 (41) | 37 (25) |

| Total number of participants with disease present, n (%) | 133 (100) | 137 (91) |

| Average number of involved small bowel segments [median (IQR), maximum] | 1 (1–1), 4 | 1 (1–1), 3 |

| Average number of involved colonic segments [median (IQR), maximum] | 1 (0–3), 6 | 0 (0–1), 6 |

| Disease activity, n (%) | ||

| Small bowel active disease | 104 (94) | 105 (86) |

| Colonic active disease | 76 (99) | 50 (96) |

| Total number of participants with active diseasea | 130 (98) | 121 (88) |

| Criteria for activity, n (%) | ||

| Ulceration at endoscopy | 71 (55) | 26 (21) |

| CRP level of > 8 mg/l | 47 (36) | 57 (47) |

| FC level of > 250 µg/g | 41 (32) | 43 (36) |

| Histological evidence of activity | 100 (77) | 36 (30) |

The presence and activity of SBCD and colonic CD according to individual bowel segments is shown in Appendix 7, Table 46. The prevalence of individual small bowel segmental disease was similar between the new diagnosis and suspected relapse cohorts, although segmental colonic CD was more prevalent in the former.

A total of 21 participants had enteric fistulae and seven participants had an intra-abdominal abscess. Specifically, three (2%) and four (3%) participants had an abscess in the new diagnosis cohort and in the suspected relapse cohort, respectively. A total of 10 (8%) and 11 (7%) participants had a fistula in the new diagnosis cohort and in the suspected relapse cohort, respectively.

There were 61 bowel segments considered to have a stenosis causing obstruction: 18 in the new diagnosis cohort and 43 in the suspected relapse cohort.

The practitioners’ opinion on the quality of segmental visualisation for both MRE and US according to the participant cohort is shown in Appendix 8, Tables 47 and 48. In general, visualisation of ileal and terminal ileal segments was rated as at least moderate in > 90% of participants on both MRE and US, with no major difference between cohorts. Visualisation of the duodenum was rated as poor in 15 out of 133 (11%) new diagnosis participants and 18 out 151 (12%) suspected relapse participants on MRE, and in 23 out of 133 (17%) new diagnosis participants and 27 out of 151 (18%) suspected relapse participants for US. Jejunal visualisation tended to be better on US, for example rated as poor in 23 out of 151 (15%) suspected relapse participants on MRE compared with 8 out of 151 (5%) on US. Colonic visualisation was inferior to that of the small bowel on both MRE and US but better on US than MRE for five out of six segments. For example, visualisation of the descending colon was rated as good in 58 out of 133 (44%) new diagnosis participants using MRE compared with 92 out of 133 (69%) new diagnosis participants on US. The only exception was the rectum, where visualisation was rated as poor in 74 out of 133 (56%) new diagnosis participants on US compared with 40 out of 133 (30%) new diagnosis participants on MRE.

Test results and outcomes

Identification and localisation of small bowel and colonic Crohn’s disease against the consensus reference standard

In total, 53 participants (24 new diagnosis and 29 suspected relapse participants) were discrepant for SBCD presence or location between MRE and US, of whom 48 had an additional small bowel imaging test available to the consensus panel. Of these, 17 (71%) new diagnosis participants and 17 (59%) suspected relapse participants were discrepant for the presence of terminal ileal disease. The full range of imaging and endoscopic data available to the consensus panels for these participants is shown in Appendix 9, Table 49.

Appendix 10, Table 50, provides the raw data for the primary outcome and main secondary outcome.

Primary outcome

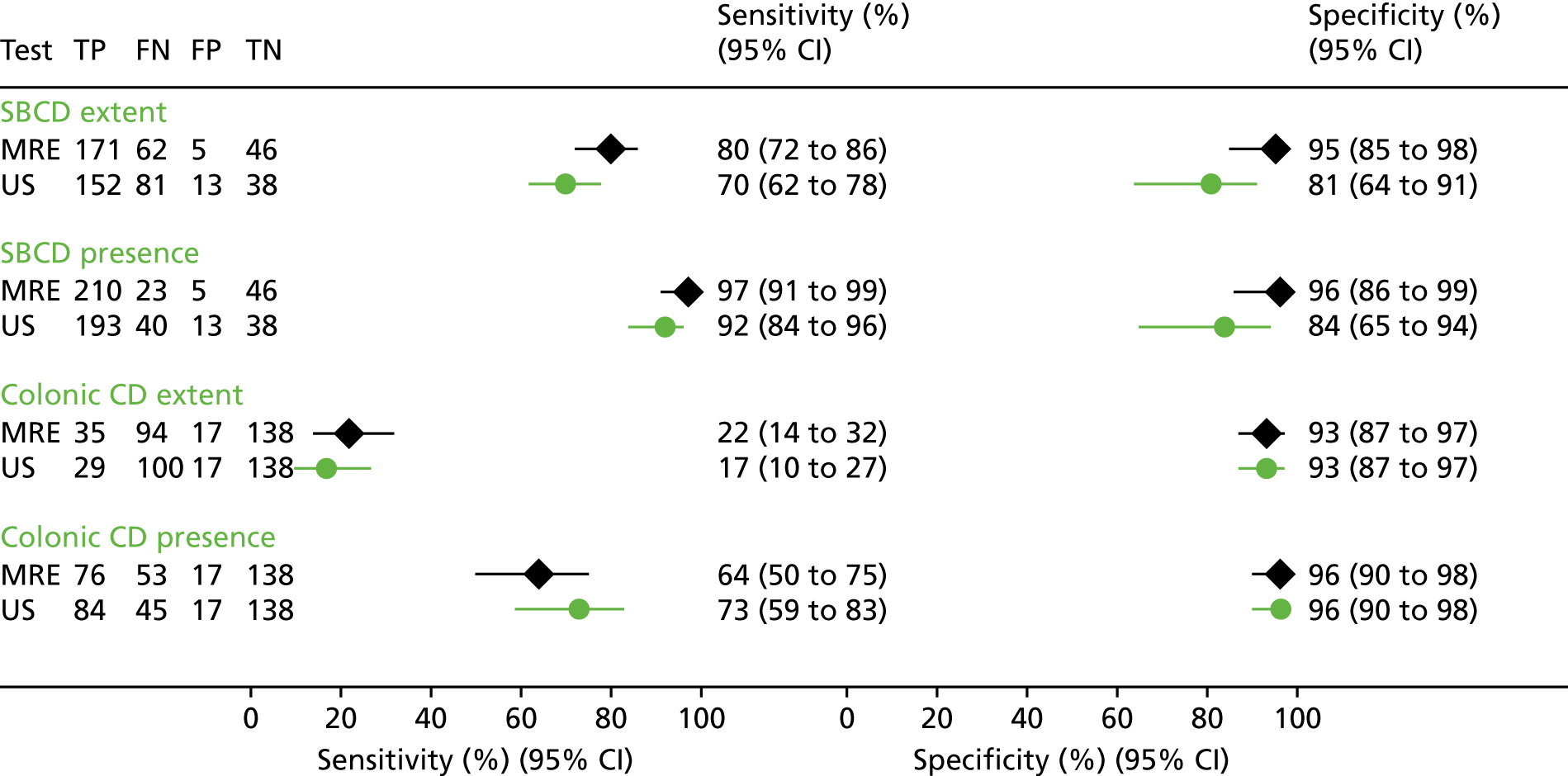

For SBCD extent, MRE sensitivity (i.e. presence and correct segmental location) was 80% (95% CI 72% to 86%), compared with 70% (95% CI 62% to 78%) for US, a difference of 10% (95% CI 1% to 18%), which was statistically significant (p = 0.027) (Table 7 and Figure 3).

| Variable | Disease-positive participants (n)a | Sensitivity, % (95% CI; p-value) | Disease-negative participants (n)a | Specificity, % (95% CI; p-value) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MRE | US | Difference | MRE | US | Difference | |||

| SBCD | ||||||||

| Extentb | 233 | 80 (72 to 86) | 70 (62 to 78) | 10 (1 to 18; 0.027) | 51 | 95 (85 to 98) | 81 (64 to 91) | 14 (1 to 27; 0.039) |

| Presence | 233 | 97 (91 to 99) | 92 (84 to 96) | 5 (1 to 9; 0.025) | 51 | 96 (86 to 99) | 84 (65 to 94) | 12 (0 to 25; 0.054) |

| Colonic CD | ||||||||

| Extentb | 129 | 22 (14 to 32) | 17 (10 to 27) | 5 (–5 to 15; 0.332) | 155 | 93 (87 to 97) | 93 (87 to 97) | 0 (–5 to 5; 1.000) |

| Presence | 129 | 64 (50 to 75) | 73 (59 to 83) | –9 (–23 to 5; 0.202) | 155 | 96 (90 to 98) | 96 (90 to 98) | 0 (–3 to 3; 1.000) |

| SBCD and colonic CD | ||||||||

| Etentb | 270 | 45 (36 to 54) | 29 (21 to 38) | 16 (6 to 25; 0.002) | 14 | 80 (42 to 96) | 61 (23 to 89) | 19 (–20 to 59; 0.337) |

| Presencec | 270 | 78 (70 to 85) | 71 (62 to 79) | 7 (–2 to 15; 0.117) | 14 | 80 (42 to 96) | 61 (23 to 89) | 19 (–20 to 59; 0.335) |

FIGURE 3.

Sensitivity and specificity of MRE and US for SBCD and colonic CD extent and presence against the consensus reference standard. Sensitivity, specificity and 95% CIs are analysed to compare test accuracy within individual participants using bivariate multilevel participant-specific (conditional) random-effects modelling. FN, false negative; FP, false positive; TN, true negative; TP, true positive. Reproduced from Taylor et al. 40 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Secondary outcomes

Magnetic resonance enterography specificity for SBCD extent was also significantly greater than that of US [95% (95% CI 85% to 98%) vs. 81% (95% CI 64% to 91%), respectively, a difference of 14% (95% CI 1% to 27%)].

The potential impact of staging SBCD extent with either MRE or US in a theoretical 1000-participant cohort is shown in Figure 4.

FIGURE 4.

Potential impact of staging SBCD extent with either MRE or US in a theoretical 1000-participant cohort. Numbers of hypothetical participants are calculated from sensitivity and specificity results comparing test accuracy within individual participants.

Regardless of location, sensitivity of MRE for SBCD presence was 97% (95% CI 91% to 99%), significantly greater than that of US [92% (95% CI 84% to 96%)] [a difference of 5% (95% CI 1% to 9%)]. MRE and US specificity for SBCD presence was 96% (95% CI 86% to 99%) and 84% (95% CI 65% to 94%), respectively: a difference of 12% (95% CI 0% to 25%). The potential impact of staging SBCD presence with either MRE or US in a theoretical 1000-participant cohort is shown in Appendix 11, Figure 11.

There were no significant differences in sensitivity or specificity between MRE and US for colonic CD extent or presence (see Table 7), although for both tests sensitivities were considerably less than for SBCD. MRE was 64% (95% CI 50% to 75%) sensitive for colonic CD presence but just 22% (14% to 32%) sensitive for extent (which required correct identification of involved colonic segments); the corresponding figures for US were 73% (59% to 83%) and 17% (10% to 27%).

The sensitivity and specificity for individual small bowel and colonic segments is given in Table 8. Although the study was not powered to detect differences on a segmental level, MRE was significantly more sensitive than US for ileal disease [84% (95% CI 67% to 93%) vs. 56% (95% CI 38 to 73), respectively]. Sensitivity for the eight diseased duodenal segments was low, at 25% (95% CI 7% to 59%), for both MRE and US. Sensitivity for jejunal disease was 71% (95% CI 38% to 91%) for MRE and 63% (95% CI 32% to 86%) for US. For five out of six colonic segments, sensitivity was ≈40–50% for both tests. However, sensitivity for rectal disease was significantly lower for US [22% (95% CI 13% to 35%)] than for MRE [44% (95% CI 32% to 58%)], with a difference of 22% (95% CI 9% to 35%).

| Variable | Disease-positive segments (n)a | Sensitivity, % (95% CI; p-value) | Disease-negative segments (n)a | Specificity, % (95% CI; p-value) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MRE | US | Difference | MRE | US | Difference | |||

| Small bowel segments | ||||||||

| Duodenumb | 8 | 25 (7 to 59) | 25 (7 to 59) | 0 (–13 to 13; 1.000) | 276 | 100 (99 to 100) | 99 (97 to 100) | 1 (0 to 3; 0.250) |

| Jejunum | 13 | 71 (38 to 91) | 63 (32 to 86) | 8 (–29 to 46; 0.664) | 271 | 99 (93 to 100) | 99 (94 to 100) | 0 (–2 to 1; 0.741) |

| Ileum | 38 | 84 (67 to 93) | 56 (38 to 73) | 28 (8 to 49; 0.008) | 246 | 93 (87 to 97) | 93 (87 to 96) | 0 (–4 to 4; 0.871) |

| Terminal ileum | 217 | 96 (91 to 99) | 92 (84 to 96) | 4 (0 to 8; 0.051) | 67 | 97 (90 to 99) | 93 (81 to 98) | 4 (–2 to 10; 0.197) |

| Colonic segmentsc | ||||||||

| Caecum | 78 | 46 (35 to 57) | 46 (35 to 57) | 0 (–12 to 12; 1.000) | 147 | 96 (92 to 99) | 90 (85 to 94) | 6 (0 to 12; 0.036) |

| Ascending | 67 | 49 (38 to 61) | 49 (38 to 61) | 0 (–10 to 10; 1.000) | 200 | 96 (93 to 98) | 92 (88 to 95) | 4 (0 to 8; 0.058) |

| Transverse | 61 | 46 (34 to 58) | 44 (32 to 57) | 2 (–12 to 15; 0.809) | 218 | 97 (93 to 98) | 95 (91 to 97) | 2 (–1 to 5; 0.130) |

| Descending | 59 | 53 (40 to 65) | 41 (29 to 54) | 12 (–1 to 24; 0.063) | 221 | 98 (95 to 99) | 95 (91 to 97) | 3 (0 to 6; 0.033) |

| Sigmoid | 76 | 46 (35 to 57) | 43 (33 to 55) | 3 (–11 to 16; 0.695) | 203 | 96 (92 to 98) | 93 (89 to 96) | 3 (–1 to 7; 0.179) |

| Rectum | 54 | 44 (32 to 58) | 22 (13 to 35) | 22 (9 to 35; 0.001) | 228 | 97 (94 to 99) | 93 (89 to 96) | 4 (0 to 7; 0.072) |

The sensitivity and specificity of MRE and US for SBCD and colonic CD presence and extent according to the participant cohort is shown in Table 9. Sensitivities of both tests for SBCD presence and extent in the new diagnosis and suspected relapse participant cohorts were very similar to those sensitivities estimated across all participants (see Table 7), although differences were not statistically significant (the study was not powered to detect differences in the cohorts).

| Variable | New diagnosis (N = 133) | Suspected relapse (N = 151) | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease-positive participants (n)a | Disease-negative participants (n)a | Sensitivity, % (95% CI; p-value) | Specificity, % (95% CI; p-value) | Disease-positive participants (n)a | Disease-negative participants (n)a | Sensitivity, % (95% CI; p-value) | Specificity, % (95% CI; p-value) | |||||||||

| MRE | US | Difference | MRE | US | Difference | MRE | US | Difference | MRE | US | Difference | |||||

| SBCD | ||||||||||||||||

| Extentb | 111 | 22 | 77 (66 to 86) | 66 (54 to 77) | 11 (–2 to 24; 0.099) | 98 (82 to 100) | 88 (64 to 97) | 10 (–5 to 24; 0.195) | 122 | 29 | 82 (72 to 89) | 74 (62 to 83) | 8 (–3 to 19; 0.141) | 92 (74 to 98) | 75 (50 to 90) | 17 (–3 to 37; 0.099) |

| Presence | 111 | 22 | 96 (89 to 99) | 92 (82 to 96) | 4 (–1 to 10; 0.148) | 99 (84 to 100) | 91 (65 to 98) | 8 (–5 to 21; 0.238) | 122 | 29 | 97 (91 to 99) | 92 (82 to 96) | 5 (0 to 11; 0.063) | 94 (76 to 99) | 78 (50 to 92) | 16 (–4 to 36; 0.111) |

| Colonic CD | ||||||||||||||||

| Extentb | 77 | 56 | 17 (9 to 30) | 9 (4 to 19) | 8 (–2 to 19; 0.115) | 93 (82 to 98) | 92 (80 to 97) | 1 (–7 to 10; 0.752) | 52 | 99 | 31 (17 to 48) | 33 (19 to 51) | –2 (–22 to 17; 0.817) | 93 (85 to 97) | 94 (86 to 97) | –1 (–7 to 5; 0.804) |

| Presence | 77 | 56 | 47 (31 to 64) | 67 (49 to 81) | –20 (–39 to –1; 0.043) | 96 (86 to 99) | 95 (84 to 98) | 1 (–5 to 7; 0.738) | 52 | 99 | 84 (67 to 94) | 80 (61 to 91) | 4 (–11 to 20; 0.589) | 96 (88 to 98) | 95 (89 to 99) | –1 (–5 to 4; 0.791) |

| SBCD and colonic CD | ||||||||||||||||

| Extentb | 133 | 0 | 33 (22 to 46) | 20 (12 to 30) | 13 (1 to 26; 0.029) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 137 | 14 | 56 (43 to 68) | 40 (28 to 52) | 16 (2 to 31; 0.027) | 80 (42 to 96) | 61 (24 to 88) | 19 (–20 to 59; 0.339) |

| Presencec | 133 | 0 | 65 (52 to 76) | 66 (53 to 77) | –1 (–15 to 13; 0.877) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 137 | 14 | 88 (79 to 93) | 76 (64 to 85) | 12 (2 to 22; 0.018) | 80 (42 to 96) | 61 (23 to 89) | 19 (–20 to 59; 0.336) |

However, US had significantly greater sensitivity for colonic CD presence than MRE in the new diagnosis cohort [67% (95% CI 49% to 81%) vs. 47% (95% CI 31% to 64%), respectively: a difference 20% (95% CI 1% to 39%)]. For both MRE and US, sensitivity for colonic CD presence was higher in the suspected relapse participant cohort, although the estimated sensitivity for colonic CD extent was poor for both: MRE had 17% (95% CI 9% to 30%) sensitivity for colonic CD extent in the new diagnosis cohort and 31% (95% CI 17% to 48%) sensitivity in the suspected relapse cohort. The corresponding figures for US were 9% (95% CI 4% to 19%) and 33% (95% CI 19% to 51%), respectively.

The sensitivity and specificity for individual small bowel and colonic segments according to participant cohort is given in Appendix 12, Table 51. In general, sensitivities of both tests for small bowel segmental disease presence in the new diagnosis and suspected relapse cohorts were very similar to those sensitivities estimated across all participants, although we note that the study was not powered to detect differences in the cohorts (see Table 8). MRE had 100% (95% CI 61% to 100%) sensitivity for jejunal disease in the suspected relapse cohort, compared with 43% (95% CI 16% to 75%) in the new diagnosis cohort, although there were only six and seven positive segments in each cohort, respectively. Sensitivity for colonic segmental disease was higher in the suspected relapse cohort than in the new diagnosis cohort for both MRE and US, consistent with the findings across all participants (see Tables 7 and 8).

Identification and localisation of small bowel Crohn’s disease and colonic Crohn’s disease against an ileocolonoscopic reference

Colonoscopy data were available for 186 participants (123 in the new diagnosis cohort and 63 in the suspected relapse cohort). The sensitivity and specificity of MRE and US for terminal ileal and colonic segmental disease against an ileocolonoscopic standard of reference is shown in Table 10. 40 MRE had a sensitivity of 97% (95% CI 91% to 99%) for terminal ileal disease presence, compared with a sensitivity of 91% (95% CI 79% to 97%) for US: a difference of 6% (95% CI –1% to 12%), which is similar to the 5% sensitivity difference between the tests for the presence of SBCD against the consensus reference standard (see Table 7). However, specificity was low, at 41% (95% CI 21% to 64%) for MRE and 33% (95% CI 15% to 57%) for US. Sensitivity for colonic CD presence was modest for both MRE and US [41% (95% CI 26% to 58%) and 49% (95% CI 33% to 65%)] and somewhat lower than the consensus reference standard, which included the 98 participants without ileocolonoscopy. The differences between MRE and US were not statistically significant (the study was not powered to detect differences based on a colonoscopic standard of reference alone).

| Variable | Disease-positive participants (n)a | Sensitivity, % (95% CI; p-value) | Disease-negative participants (n)a | Specificity, % (95% CI; p-value) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MRE | US | Difference | MRE | US | Difference | |||

| Colonic CD | ||||||||

| Extentb | 109 | 3 (1 to 11) | 2 (0 to 8) | 1 (–2 to 4; 0.429) | 77 | 94 (81 to 98) | 89 (73 to 96) | 5 (–3 to 14; 0.240) |

| Presence | 109 | 41 (26 to 58) | 49 (33 to 65) | –8 (–26 to 9; 0.368) | 77 | 95 (85 to 98) | 90 (76 to 96) | 5 (–3 to 13; 0.233) |

| Disease-positive segments (n)a | Sensitivity, % (95% CI; p-value) | Disease-negative segments (n)a | Specificity, % (95% CI; p-value) | |||||

| MRE | US | Difference | MRE | US | Difference | |||

| Small bowel segments | ||||||||

| Terminal ileum | 105 | 97 (91 to 99) | 91 (79 to 97) | 6 (–1 to 12; 0.091) | 81 | 41 (21 to 64) | 33 (15 to 57) | 8 (–14 to 30; 0.474) |

| Colonic segmentsc | ||||||||

| Caecum | 73 | 22 (14 to 33) | 25 (16 to 36) | –3 (–14 to 9; 0.638) | 101 | 72 (63 to 80) | 65 (56 to 74) | 7 (0 to 13; 0.043) |

| Ascending | 62 | 26 (16 to 38) | 23 (14 to 35) | 3 (–6 to 12; 0.479) | 121 | 88 (80 to 92) | 81 (73 to 87) | 7 (0 to 13; 0.043) |

| Transverse | 54 | 24 (15 to 37) | 24 (15 to 37) | 0 (–9 to 9; 1.000) | 132 | 92 (86 to 96) | 90 (84 to 94) | 2 (–2 to 6; 0.256) |

| Descending | 58 | 27 (18 to 40) | 24 (15 to 37) | 3 (–6 to 13; 0.479) | 128 | 95 (90 to 98) | 93 (87 to 96) | 2 (–1 to 6; 0.178) |

| Sigmoid | 74 | 24 (16 to 35) | 28 (19 to 40) | –4 (–17 to 9; 0.532) | 111 | 94 (87 to 97) | 94 (87 to 97) | 0 (–6 to 6; 1.000) |

| Rectum | 61 | 26 (17 to 39) | 13 (7 to 24) | 13 (2 to 25; 0.027) | 125 | 97 (92 to 99) | 94 (88 to 97) | 3 (–2 to 8; 0.204) |

The sensitivity and specificity of MRE and US for terminal ileal and colonic segmental disease against an ileocolonoscopic standard of reference according to the participant cohort is show in Appendix 13, Table 52.

Extraenteric complications

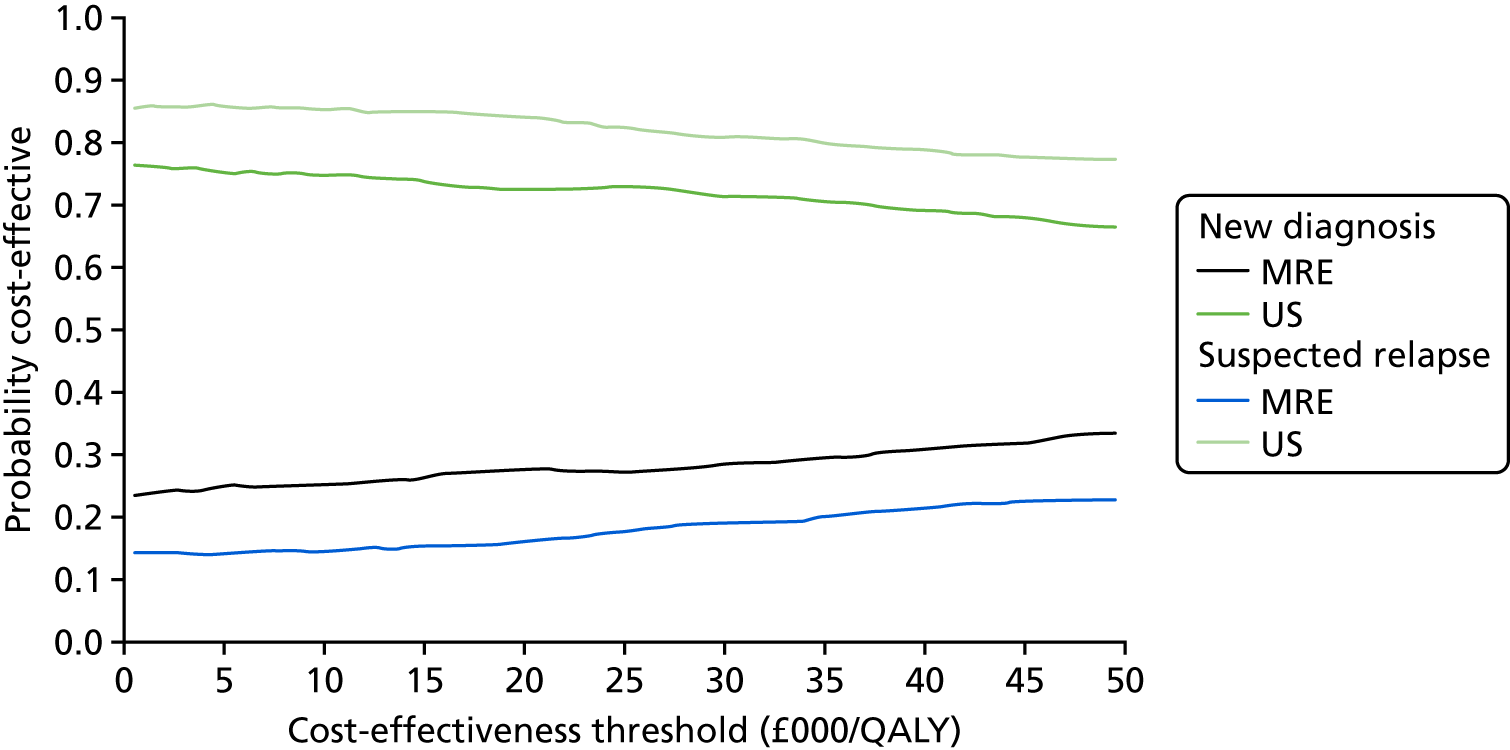

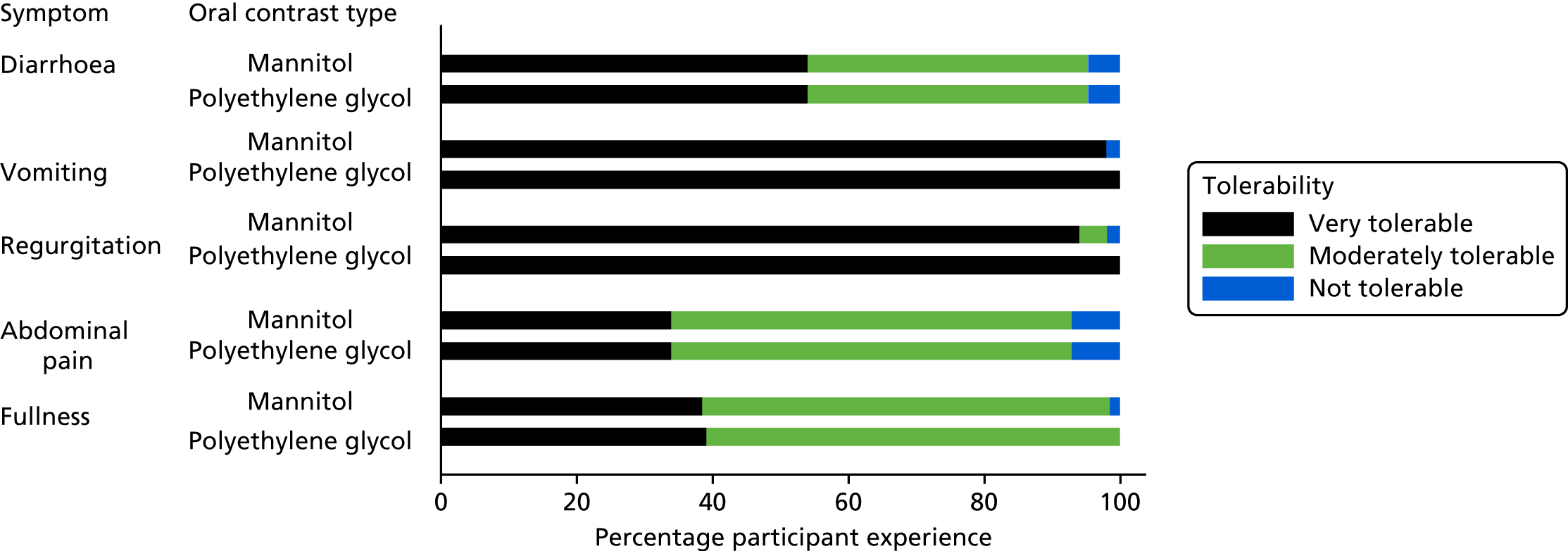

Magnetic resonance enterography detected five out of seven (71%) abscesses and 18 out of 21 (86%) participants with enteric fistulae, compared with three out of seven (43%) and 11 out of 21 (52%) for US, respectively. Of the 61 participants with a stenosis considered to be causing obstruction by the consensus reference standard, MRE detected 33 (54%) and US detected 20 (33%) of these. There were 52 false-positive segments for stenosis on MRE and 45 for US.