Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 12/167/135. The contractual start date was in October 2014. The draft report began editorial review in April 2018 and was accepted for publication in September 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Peter Hajek received research funding from, and provided consultancy to, manufacturers of stop smoking medications (Pfizer Inc., New York City, NY, USA). Hayden J McRobbie received a grant from the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment programme; he also received honoraria for speaking at smoking cessation meetings and attended advisory board meetings organised by Pfizer Inc. and Johnson & Johnson (New Brunswick, NJ, USA). Dunja Przulj received a research grant from Pfizer Inc. Maciej Goniewicz provided consultancy to Johnson & Johnson. Lynne Dawkins reports personal fees from attorneys at law outside the submitted work. Jinshuo Li reports grants from the National Coordinating Centre for Health Technology Assessment (NCCHTA) during the conduct of the study.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Hajek et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

E-cigarettes are a popular option for smokers seeking to limit the health risks of smoking. 1 E-cigarettes are unlikely to be harmless, but the risk of their use has been estimated to be < 5% of the risks of smoking. 2,3 No health risks were identified over some 18 months of use,4 and there is some evidence that smokers who successfully switch to vaping reduce their nicotine dependence and often stop vaping as well. For example, in the UK, there are currently some 1.5 million ex-smokers who have stopped smoking with the help of e-cigarettes, of whom some 700,000 have stopped vaping as well. 5

Current smoking cessation treatments provide a combination of behavioural support and medications that target cigarette withdrawal discomfort,6 but sensorimotor factors that accompany smoking and that are likely to be reinforcing for smokers are not well addressed. 7 E-cigarettes pose a promise to fill this gap, and some UK Stop Smoking Services (SSSs) are now including e-cigarettes in their routine work. However, data on e-cigarette efficacy in this context are limited. Information is needed on whether or not e-cigarettes can match or even surpass the efficacy of other evidence-based treatments that are currently used. The question is particularly important because e-cigarettes are much less expensive than stop smoking medications and smokers are purchasing e-cigarettes themselves, which means that their use represents no cost to health-care systems. In addition, they hold a greater appeal to smokers and are used more widely than licensed stop smoking medication,8 which suggests that they could potentially have a bigger population impact.

Only three randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have evaluated the efficacy of e-cigarettes when offered proactively by health professionals as a stop smoking treatment. A Cochrane meta-analysis4 of two trials that provided long-term outcomes9,10 (both trials used early e-cigarette models with poor nicotine delivery) found evidence that e-cigarettes containing nicotine are more likely to help smokers quit than placebo e-cigarettes with one trial showing the same (low) effect for e-cigarettes and for nicotine patches. 9 The third trial11 had only a 2-month outcome and so was not included in the meta-analysis, but it showed a significant effect of a more advanced (second-generation) e-cigarette product. Another trial12 was published in 2018, but its rationale was unclear and is difficult to interpret. Participants had access to cartridge-based e-cigarettes in both trial arms, but one arm was also given stop smoking medications. In addition, treatments were offered to people who did not ask to be treated and, to be classified as an abstainer, participants had to undergo repeated blood sampling. ‘Abstinence rates’ were thus extremely low (1% in the arm allocated e-cigarettes only and 0.5% in the arm allocated medication plus e-cigarettes). The trial12 also evaluated incentives. Paying abstainers US$600 to attend the blood sampling increased ‘abstinence rates’ only to 2.9%. 12

The present trial was set up to evaluate the efficacy of a refillable e-cigarettes compared with the efficacy of nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) products as currently used routinely by SSSs, when accompanied by weekly behavioural support (as provided routinely by the services). In routine use, NRTs are included as a single product of the patient’s choice, selected from among a number of available options, or in combinations, depending on a patient’s preferences.

Chapter 2 Methods

Some parts of this chapter are from The New England Journal of Medicine, Hajek P, et al. 13 A randomized trial of e-cigarettes versus nicotine-replacement therapy, Vol. 380, pp. 629–37. Copyright © 2019 Massachusetts Medical Society. Reprinted with permission.

Overview of trial design

This was a pragmatic RCT conducted between 2015 and 2018 in three sites in England that provide local SSSs. Eligible smokers seeking help to quit were randomised (1 : 1) to receive a NRT of their choice (a single NRT product or product combinations) plus usual care (weekly behavioural support provided by the SSS) or e-cigarettes plus usual care. Participants attended weekly sessions at their SSS, as per standard practice, and were followed up by telephone at 6 and 12 months. Participants reporting abstinence or at least a 50% reduction in smoking at 12 months were invited to attend for carbon monoxide (CO) validation.

Changes to the trial design

There was a change of chief investigator from Professor McRobbie to Professor Hajek (who was a co-investigator) because Professor McRobbie moved to New Zealand. A new advertising strategy (i.e. leaflets distributed to local households) was added. These and other minor changes are shown in Table 32 in Appendix 1.

Participants

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Participants were included if they were aged ≥ 18 years, were current smokers who wanted to quit smoking and were able to read/write/understand English. Participants were excluded if they were pregnant or breastfeeding, had a strong preference for or against using NRT or e-cigarettes in their quit attempt, were currently enrolled in other interventional research or were currently using NRT or e-cigarettes.

Recruitment

Between May 2015 and January 2017, 886 participants were recruited. SSSs included information about the study in their advertising (typically posters, leaflets, digital media, local papers, through general practices, mail-outs to previous attenders and in local radio/newspaper interviews). Leaflets advertising the trial were also delivered to local households. An example of the advertisements can be seen in the study documentation at www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/12167135/#/ (accessed 18 February 2019).

Advertisements directed participants to contact the local trial team, which provided further information about the trial, assessed eligibility and invited potential participants to a screening session at their local SSS.

Setting

Recruitment and delivery of the interventions took place at the Health and Lifestyle Research Unit at Queen Mary University of London (QMUL), which is commissioned to deliver the SSS for the local boroughs of Tower Hamlets and the City of London, and the Leicester and East Sussex SSSs. Follow-up calls were carried out by researchers at the Health and Lifestyle Research Unit.

Trial procedures

Informed consent procedures

Following initial confirmation of eligibility by telephone/e-mail, participants were invited to attend a screening (baseline) session at their local SSS. Potential participants were provided with written information, along with the standard SSS client registration form, prior to their screening session. Participants were given sufficient time to read the written information and to consider whether or not they wanted to participate.

At the screening (baseline) session, trial details were discussed and eligibility was reconfirmed. Those who were interested and eligible gave informed consent obtained by members of staff trained in good clinical practice.

Interventions

Identical multisession behavioural support was provided to both trial arms. The exact procedures differed slightly between trial sites, but they followed the same treatment approach (withdrawal-oriented therapy14) that involves face-to-face support sessions with CO monitoring, which usually begins 1 or 2 weeks prior to the target quit date (TQD). Clients attended sessions weekly, typically for 4 weeks post TQD. Trial data were collected face to face at the baseline session, at TQD and for the first 4 weeks post TQD.

All participants were telephoned at 26 and 52 weeks post TQD to obtain smoking status and assess e-cigarettes/NRT/other product use and adverse reactions (ARs); at 52 weeks, those reporting abstinence or smoking reduction of 50% or more were invited back to the service that they had attended to give a CO reading.

Participants received £20 compensation for their time and travel at the 52-week visit. No other compensation was provided at any time during the trial.

As per usual-care protocol, participants who missed appointments or who were not contactable at follow-up were contacted by other means to check on their progress (i.e. text, telephone, e-mail, letter). When there was no response, up to six attempts at contact were made at 4 weeks, up to five attempts at 6 months and up to eight attempts at 1 year.

Nicotine replacement therapy arm

Participants were advised about the NRT products available at the baseline session. They chose their preferred NRT, as per usual practice, and were also provided with an option to use NRT combinations (normally the patch and one of the oral products) as per usual practice. The supply of NRT differed slightly between the different trial sites. A letter of recommendation (LOR) to supply NRT was issued on a fortnightly basis for up to 12 weeks at the London SSS, which service users exchange at a pharmacy in return for the NRT. The £8.60 prescription charge is paid by service users unless they are exempt (around 50% of SSS users are). East Sussex and Leicester service users receive direct supply of NRT free of charge, for up to 12 weeks.

To avoid a possible bias that could be generated because NRT participants had to visit their local pharmacy and potentially pay a prescription fee whereas participants randomised to e-cigarette did not, the procedure below was followed.

At sites that used LORs, all participants were given a LOR at their baseline session (as per standard practice). They were instructed to collect the NRT and bring it to their TQD session. At the TQD, those randomised to NRT kept their NRT and initiated use at the session. Participants randomised to the e-cigarette condition, swapped their NRT for an e-cigarette starter pack (see E-cigarette arm).

For sites that provided NRT directly, participants were provided with their NRT or e-cigarette during the TQD session following randomisation.

For all sites, instructions on NRT use were provided as per routine clinic support.

At the completion of the trial treatment period, participants could request further supplies of NRT in line with the SSS standard practice.

Participants in the NRT arm were free to switch to other forms of NRT; this was recorded at every contact point.

E-cigarette arm

As noted in the previous section, participants in the e-cigarette group who attended a site using LORs were given a NRT LOR at their baseline session and were asked to collect the NRT and bring it to their TQD session. Participants who were then randomised to e-cigarettes at the TQD swapped their NRT for the e-cigarette starter kit. Participants randomised to the e-cigarette arm who attended a site that did not use LORs were provided with their e-cigarette starter kit at the TQD session.

A starter pack was given to initiate e-cigarette use and demonstrate refillable e-cigarette products. Participants were expected to source their own e-liquid and were also encouraged to purchase a different device if the provided one did not suit their needs. To start the participants on using the e-cigarette, we provided a Conformité Européenne (CE)-marked refillable e-cigarette with 2 or 3 weeks’ supply (1 × 30-ml bottle) of e-liquid. The e-liquid was labelled as 18 mg/ml of nicotine, the most commonly used nicotine content at the time. 15 The e-cigarette used was ‘One Kit’, an Aspire® (Shenzhen Eigate Technology Co. Ltd, Shenzhen, China) device with a 2.1-Ω resistance atomiser coil and a 650-mAh battery, branded by the UK Ecig Store (London, UK). During the trial, the company discontinued the original One Kit, so the new ‘One Kit 2016’ device was used for 42 participants. One Kit 2016 is an Innokin® device (Innokin Technology, Shenzhen, China) with a 1.5-Ω resistance atomiser coil and a 1000-mAh battery, branded by the UK Ecig Store.

The original One Kit was purchased for the wholesale price of £5.99 with the following accessories: an atomiser five pack (£3.49), a UK adapter (£2.99) and a spare battery (£3.89). The total cost was £19.35, including the e-liquid. The One Kit 2016 was purchased for £13 with the following accessories: an atomiser five pack (£3.75), a UK adapter (£2.99) and a spare battery (£7.50). The total cost was £30.23, including the e-liquid. The e-liquid used was 30 ml of Tobacco Royale flavour, purchased from the UK Ecig Store for £2.99.

Verbal and written guidance was given about how to use the e-cigarette. Participants initiated use during the session.

Participants were instructed to obtain further supplies of e-liquid themselves and advised on how to do this via the internet or local vape shops. They were encouraged to try different strengths and flavours of e-liquids if they did not like the supplied one. Participants who did not manage to source their own supplies of e-liquid were provided with one additional supply on request (1 × 10-ml bottle), but this was not proactively offered.

The e-cigarette arm participants had to pay for e-liquid supplies once they had used their trial-allocated e-liquid or if they wanted to try other flavours, but these costs are modest and roughly balanced by the fact that some of the NRT arm participants had to pay prescription charges.

Both trial arms

To help minimise contamination, at the TQD all participants in both trial arms were asked to sign a commitment form stating that they were committed to not using the non-allocated treatment for at least 4 weeks post TQD.

Measurements

Measurements were collected as follows:

-

participant demographics, smoking history and previous/current medical conditions

-

Fagerström Test for Cigarette Dependence (FTCD) score16

-

score on the Mood and Physical Symptoms Scale, which measures severity of urges to smoke and other tobacco withdrawal symptoms17

-

self-reported smoking status

-

end-expired CO reading, collected using a CO monitor [a reading of < 8 parts per million (p.p.m.) was used as a cut-off point for validating self-reported abstinence]

-

an ARs checklist (see Adverse reactions)

-

e-cigarette/NRT use and ratings of helpfulness in refraining from smoking cigarettes (from 1 = not at all helpful to 5 = extremely helpful) and satisfaction and how good it tasted in comparison with usual cigarettes (much less than normal cigarettes = 1, a little less = 2, the same = 3, a little more = 4, much more than normal cigarettes = 5)

-

in the case of participants who stopped using e-cigarettes/NRT or who switched to a different type of e-cigarette/NRT, reasons for doing so

-

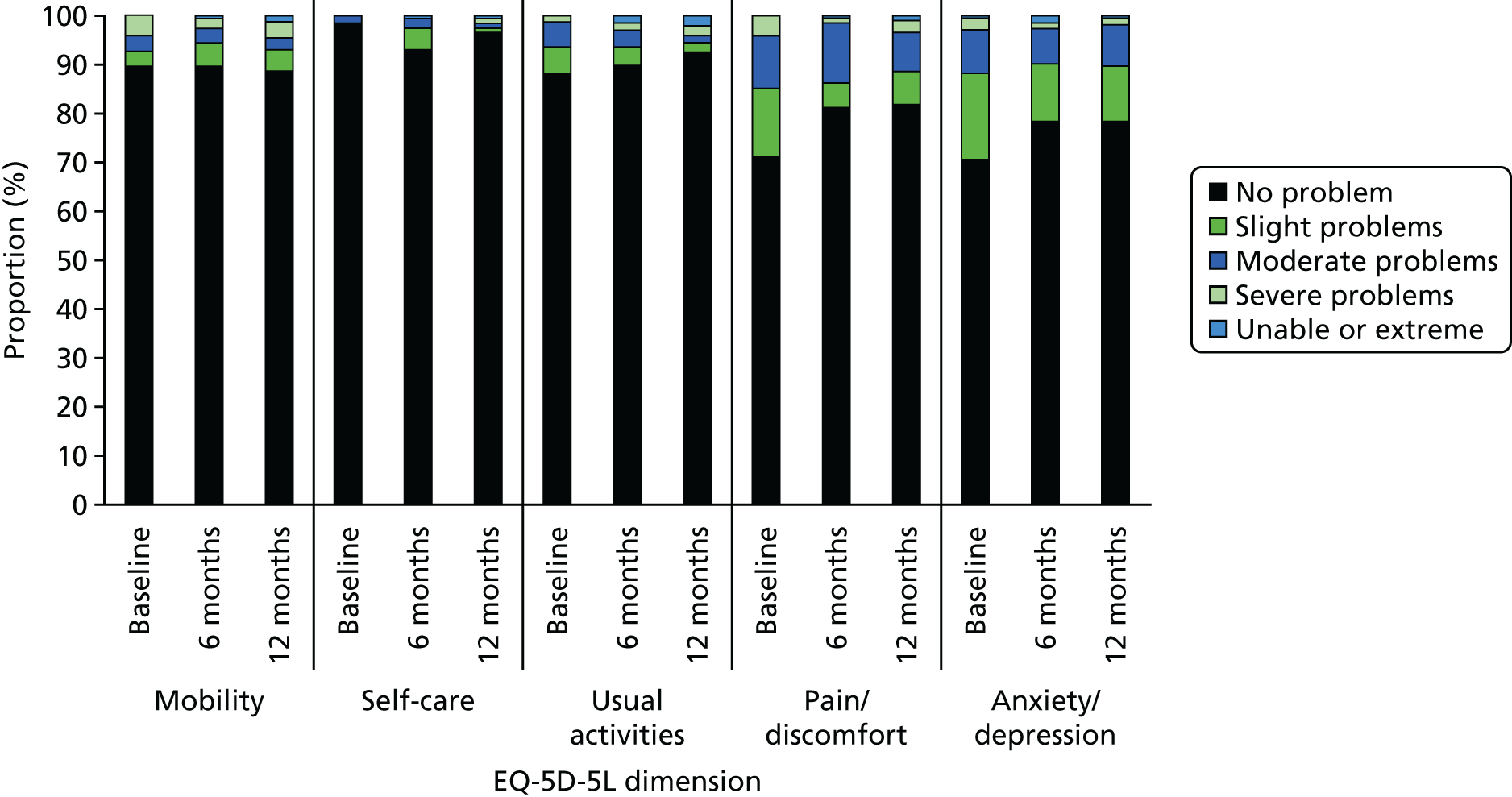

additional economic evaluation measures: EuroQoL-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L), score at baseline and at 6 and 12 months;18 smoking cessation service and health service use at baseline and during the preceding period at 6 and 12 months.

Adverse reactions

With the agreement of the trial sponsor and Research Ethics Committee (REC), data on adverse events (AEs) were not collected, as the safety profiles of NRT are well established and a number of studies4,19 have now identified the likely ARs to e-cigarettes. Instead, an ARs checklist was used (Table 1 shows the schedule of collection of measurements), which asked whether or not any ARs had been experienced since the last contact. Those reporting ARs were asked whether the AR had stopped them from doing things they would usually do, as an indication of severity. The following were evaluated at each session: nausea, throat/mouth irritation, sleep disturbances, dizziness, headache and four indicators of respiratory health: shortness of breath, cough, wheezing and phlegm.

| Measures/procedures | Trial session | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | TQD | TQD + 1 week | TQD + 2 weeks | TQD + 3 weeks | TQD + 4 weeks | TQD + 26 weeks | TQD + 52 weeks | |

| Informed consent | ✓ | |||||||

| Baseline questionnaire | ✓ | |||||||

| Current illness | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Current medication | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Randomisation | ✓ | |||||||

| Commitment form | ✓ | |||||||

| CO reading | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ (if abstinent or there was a 50% reduction) | |

| MPSS | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Smoking status/CPD | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| ARs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| E-cigarette/NRT ratings | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| E-cigarette/NRT use and helpfulness | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| E-cigarette dispensed, demonstration on first use | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| NRTa dispensed, demonstration on first use | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| EQ-5D-5L questionnaire | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Smoking cessation service and health service use | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

Serious adverse events (SAEs), including death, overnight hospitalisation and permanent disability, were also recorded.

Data management

Data collection and entry

A web-based application, using an Oracle 11g database, was used to collect data. This was set up and hosted by the Barts Clinical Trials Unit (CTU). The electronic data capture forms were web based and built using Java (Oracle Corporation, Redwood Shores, CA, USA) with data validation in JavaScript (Java framework Struts 2) (Netscape Communications Corporation, Dulles, VA, USA; Mozilla Foundation, Mountain View, CA, USA; Ecma International, Geneva, Switzerland). When the web-based application was unavailable, data were collected on paper case report forms (CRFs) and questionnaires and then entered into the database at the earliest opportunity. All data were kept in accordance with good clinical practice and data protection requirements.

Data quality

The co-ordinating site checked electronic CRFs on a weekly basis for anomalies and raised and resolved queries with the researcher/advisor concerned. Once recruitment and follow-up were complete, the trial team cleaned the data.

A sample of paper CRFs/questionnaires were also checked. Ten per cent were randomly selected for comparison between written and database entries. The predetermined quality target of ≤ 2% discrepancies was met.

Sample size

At the time the trial protocol [available at www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/12167135/#/ (accessed 23 April 2019)] was drawn up, the 12-month validated abstinence rate (i.e. the primary outcome) associated with usual care in our setting was 14%. 20 The projection of a feasible rate with the e-cigarettes was based on the research team’s work and two published studies. The research team’s work suggested that e-cigarettes deliver nicotine quickly, with time to the maximum concentration occurring within 5 minutes. 21 This is similar to nicotine nasal spray. In a comparative study of nicotine nasal spray plus patch versus patch alone, 1-year abstinence rates were 27% versus 11%, respectively [risk ratio (RR) 2.45]. 22 In a 2014 cohort study23 in Italy, a second-generation e-cigarette achieved 36% CO-validated abstinence at 6 months. Assuming 25% relapse between 6 and 12 months,24 this would translate to a 1-year abstinence rate of 27%. Relative to the assumed usual care rate, this would give a RR of 1.9. However, quit rates in countries with little tradition of stop smoking treatments tend to be much higher than in the UK. The research team wanted to detect a RR of 1.7 (e-cigarette rate = 24%) with 0.95 power, but also have reasonable power (e.g. 0.75) if the RR should be as low as 1.5 (e-cigarette rate = 21%). This figure still represents a clinically significant difference. To achieve these levels of power (two-sided alpha = 0.05, continuity correction), a total of 886 participants (443 in each group) was required.

It is noted in the statistical analysis plan that, since the trial protocol was written, a new evaluation of the UK SSSs has been published. 25 The validated 1-year quit rate has declined to 8%. This figure is derived from quit rates in general practice and pharmacy services of 5% and in specialist support services of 10% for individual and 12% for group support. The decline is probably a result of a ‘hardening’ of treatment population, namely the services see an increasing number of reattenders, people with serious health issues, etc. Using a quit rate of 10% in the usual-care arm, which provides multicontact support, and 17% in the e-cigarette arm (RR 1.70), the trial sample size still provides at least 85% power to detect such a difference with a two-tail test of proportions.

Assuming that the true percentage in both arms is 10%, the 95% confidence interval (CI) for the difference in proportions will have a width of ± 4% around the observed difference.

Randomisation

Randomisation (1 : 1 in permuted blocks of 20) was undertaken using a web-based application, set up by the Barts CTU, and was stratified by trial site. Participants who were eligible and consented to take part were randomly allocated to the NRT arm or the e-cigarette arm on the TQD session by researchers/stop smoking advisors. The TQD was used as the point of randomisation to minimise any differential drop-out. The staff randomising the participant accessed the web-based application when the participant was with them, entering their participant identification number, date of birth and initials into the program. There were no stratification factors. The allocation was immediately provided by the program. In the event of the site having no web access, staff were able to fax/e-mail the relevant CRFs to the CTU for a telephone randomisation to take place during standard working hours.

Treatment blinding

Participants could not be blinded to the intervention they were receiving, and trial staff could not be blinded when providing the interventions and collecting data.

Unblinded data were seen and analysed by the trial statistician for the purposes of the Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC) meetings. All other trial staff who had access to outcome data remained blinded until prespecified data analyses were complete. Prespecified data analyses were conducted blind to treatment allocation.

Statistical methods

Changes from planned analysis

There were no changes from the planned analysis, from either the trial protocol or the statistical analysis plan. See the project web page for the statistical analysis plan [www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/12167135/#/ (accessed 18 February 2019)].

General analysis principles

The main analysis for each outcome used intention-to-treat principles, meaning that all participants with a recorded outcome were included in the analysis and were analysed according to the treatment group to which they were randomised. More information on which participants were included in each analysis is available in Withdrawn participants.

In all analyses for all outcomes, the following are presented:

-

the number of participants included in the analysis, by treatment group (for the primary outcome data, this will be all randomised participants; see the next section)

-

a summary measure of the outcome by treatment group, for example mean [standard deviation (SD)] for continuous outcomes and number (%) for binary outcomes

-

treatment effect (risk ratio of abstinence for e-cigarettes relative to NRT), with 95% CI

-

two-sided p-values (the significance level was set at 5%).

Missing data

To deal with incomplete data (i.e. when patients had missing data at one of the follow-up time points), the research team:

-

attempted to follow up all randomised patients, even if they had discontinued participation

-

included participants lost to follow-up (i.e. missing cases) or not providing biochemical validation as non-abstainers

-

carried out sensitivity analyses using multiple imputations via chained equation and excluding cases with missing outcomes.

Withdrawn participants

Participants requesting no further follow-up were included in the analysis, as per intention to treat (such participants were counted as smokers for the time points after withdrawal, as per the Russell Standard26).

Participants who died were excluded from the sample, as per the Russell Standard.

Participants who moved to an untraceable address and whose telephone number(s) and e-mail address were no longer in use were excluded from the sample from the point that notification was received that they were no longer living at the address and their telephone number(s)/e-mail address were no longer in use, as per the Russell Standard. They were included in the sample analysis up until this point and coded as relapsed after that point.

Chapter 3 Outcomes

Some parts of this chapter are from The New England Journal of Medicine, Hajek P, et al. 13 A randomized trial of e-cigarettes versus nicotine-replacement therapy, Vol. 380, pp. 629–37. Copyright © 2019 Massachusetts Medical Society. Reprinted with permission.

Primary outcome

Sustained abstinence at 52 weeks was calculated as per the Russell Standard26 (i.e. a self-report of smoking no more than five cigarettes since 2 weeks post TQD), validated by a CO reading of < 8 p.p.m. at the 52-week follow-up. (CO in expired breath is a commonly used biochemical validation tool that is particularly useful when people continue to use nicotine because methods based on the detection of nicotine metabolites are not appropriate in such cases. The CO assay detects only smoking over the previous ≈24 hours, but trial participants do not usually know of the assay’s half-life, and dependent smokers typically smoke daily.)

If outcome data at previous follow-up points were missing but no data were available to contradict claims of sustained abstinence, the participants who reported smoking no more than five cigarettes in total since 2 weeks post TQD at the 52-week follow-up and whose self-report was validated by a CO reading of < 8 p.p.m. were classed as meeting the primary outcome definition.

In the primary analysis, all participants were included in the arm to which they were randomised, but sensitivity analyses were conducted that took into account use of non-allocated products.

Sensitivity analyses for primary outcome

The following sensitivity analyses of the primary outcome were conducted:

-

including only participants who attended at least one treatment session, namely only those who engaged in treatment

-

excluding participants who used the unassigned trial product for 5 consecutive days or more

-

using multiple imputation of smoking status in participants with missing follow-up data by chained equations.

At the request of the chairperson of the Trial Steering Committee (TSC), an analysis limited to participants who completed the 12-month follow-up is also included. (This is normally not done in this field, as it increases quit rates and can obscure treatment effects; treatment failures are more likely to drop out, and so missingness is not random.)

Secondary outcomes

We examined the differences between study arms in the proportions of participants with 6- to 12-month sustained abstinence, abstinence at 4 and 26 weeks, and sustained reduction of 50% or greater in baseline cigarette consumption and CO levels at 52 weeks, using binomial regression.

At each time point, seven-day abstinence rates were also calculated. This measure is less informative because 7 days of not smoking does not convey much health benefit and, compared with sustained abstinence, is a weak predictor of smoking status in future. Seven-day abstinence is also influenced by other, more recently occurring factors, so is likely to diminish the effects of a treatment delivered 1 year ago. However, it is still used in less rigorous studies and so it was included to allow across-trial comparisons.

The time to relapse was examined using a Cox analysis.

Table 2 shows the definitions used for secondary outcomes.

| Outcome | Definition |

|---|---|

| CO-validated sustained abstinence between 26 and 52 weeks post TQD | Reporting no more than five cigarettes smoked between weeks 26 and 52, accompanied by a CO reading of < 8 p.p.m. at week 52 |

| For all outcomes, if data from previous follow-ups were missing but no data contradicted the outcome as measured at the given point, this was accepted | |

| CO-validated sustained abstinence at 4 weeks post TQD | Reporting not a single puff in the previous 2 weeks at Q + 4 follow-up, accompanied by a CO reading of < 8 p.p.m. at Q + 4 |

| Sustained abstinence at 26 weeks post TQD | Reporting no more than five cigarettes smoked since 2 weeks post TQD at Q + 24 |

| 7-day point prevalence at 4 weeks post TQD | Reporting not a single puff in the previous 7 days |

| 7-day point prevalence at 26 weeks post TQD | Reporting not a single puff in the previous 7 days |

| 7-day point prevalence at 52 weeks post TQD | Reporting not a single puff in the previous 7 days |

| Smoking reduction in participants who did not achieve abstinence at 52 weeks | Self-reported daily cigarette consumption at Q + 52 reduced by at least 50% from baseline consumption, accompanied by a CO reading at Q + 52 reduced by at least 50% from that at baseline. Participants with missing data were classified as non-reducers |

Each outcome was adjusted for baseline covariates selected using a stepwise regression approach so that only significant covariates (p = 0.1) were included in the final model.

Tobacco withdrawal symptoms at 1 and 4 weeks

Between-group differences in urges to smoke and changes (from baseline) in tobacco withdrawal symptoms were examined using t-tests in both the whole sample and the abstainers-only sample.

Treatment ratings (satisfaction, taste, helpfulness, reasons for stopping product use)

Differences in mean ratings of satisfaction, taste of the product, product helpfulness and reasons for stopping product use were examined between groups using t-tests at 1 and 4 weeks post TQD. Adjustments for normal distribution were applied when needed and non-parametric tests were used where necessary. When two NRT products were used and rated, the average rating of the two was taken.

Adverse reactions

The chi-squared test was used to compare, between arms, the frequency of participants who reported each AR (sleep disturbance, nausea or throat/mouth irritation) on at least one occasion. The Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) coding system was used.

Changes in respiratory symptoms

Using logistic regression, we compared changes in cough, wheezing, phlegm production and shortness of breath from baseline to 52 weeks in the two arms. Symptoms at 52 weeks were regressed onto trial arm with adjustment for baseline score and study site.

The details of the cost-effectiveness analysis methods are included in the cost-effectiveness section.

Statistical software

All analyses were carried out using Stata® software, version 15 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Patient and public involvement

Two members of the public served on the TSC. Along with two others, they also contributed to a patient and public involvement (PPI) panel, which convened throughout the trial. Three members of the panel were current e-cigarette users. When PPI members were not available for the meetings/teleconferences, they were contacted by e-mail for their feedback.

Trial committees

The DMEC and the TSC convened every 6–12 months. The Trial Management Group also met regularly throughout the study. Appendix 1, Table 33, shows the members of the trial committees.

The chief investigator, study manager and a minute-taker (who was a member of the trial team) also attended the TSC and DMEC meetings. The trial statistician (originally Mr John Stapleton, followed by Dr Irene Kaimi) also attended the DMEC meetings.

Quality control and quality assurance

A risk assessment was carried out in conjunction with the trial sponsor and Barts CTU, which was used as a basis for the trial monitoring plan. During the recruitment phase, a monitor from the co-ordinating site carried out 6-monthly monitoring visits at each of the sites. The Barts CTU was responsible for oversight of the monitoring process and overall audit of the trial.

Approvals

The trial was sponsored by the QMUL Joint Management Research Office. Ethics approval was obtained from the National Research Ethics Service Committee London – Camden and Islington REC on 19 December 2014 (reference number14/LO/2235).

The results and the discussion of the Trial of E-Cigarettes (TEC) are presented in Chapter 4. The methods and results of the economical evaluation are presented in Chapter 5.

Chapter 4 The TEC trial

Some parts of this chapter are from The New England Journal of Medicine, Hajek P, et al. 13 A randomized trial of e-cigarettes versus nicotine-replacement therapy, Vol. 380, pp. 629–37. Copyright © 2019 Massachusetts Medical Society. Reprinted with permission.

Results

The methods and results of the economical evaluation are presented after the main trial section.

Participant flow

Figure 1 shows the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram.

FIGURE 1.

The CONSORT flow diagram. From Hajek P, et al. 13 A randomized trial of e-cigarettes versus nicotine-replacement therapy. The New England Journal of Medicine Vol. 380, pp. 629–37. Copyright © 2019 Massachusetts Medical Society. Reprinted with permission.

The follow-up rates at 12 months were 81% in the e-cigarette arm and 77% in the NRT arm [χ2(1) = 2.1; p = 0.09].

Sample characteristics

Participant characteristics are shown in Table 3.

| Characteristic | Trial arm | Total (N = 884) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| E-cigarette (N = 438) | NRT (N = 446) | ||

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 41 (33–53) | 41 (33–51) | 41 (33–52) |

| Female, n (%) | 211 (48.2) | 213 (47.8) | 424 (48.0) |

| Marital status, n (%) | |||

| Single | 224 (51.1) | 249 (55.8) | 473 (53.5) |

| Separated or divorced | 89 (20.1) | 86 (19.3) | 174 (19.6) |

| Married | 116 (26.5) | 105 (23.5) | 221 (24.9) |

| Widowed | 10 (2.3) | 6 (1.4) | 16 (1.8) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| White British | 322 (73.5) | 311 (69.7) | 633 (71.6) |

| White other | 35 (8.0) | 41 (9.2) | 76 (8.6) |

| Black | 15 (3.4) | 15 (3.4) | 30 (3.4) |

| Asian | 29 (6.6) | 37 (8.3) | 66 (7.5) |

| Mixed | 22 (5.0) | 28 (6.3) | 50 (5.7) |

| Other | 9 (2.1) | 9 (2.0) | 18 (2.0) |

| Missing | 6 (1.4) | 5 (1.1) | 11 (1.2) |

| Educational qualification, n (%) | |||

| Primary school | 19 (4.3) | 22 (4.9) | 41 (4.6) |

| Secondary school | 141 (32.2) | 130 (29.2) | 271 (30.7) |

| Further education/diploma | 117 (26.7) | 127 (28.5) | 244 (27.6) |

| Higher education | 161 (36.7) | 167 (37.5) | 328 (37.1) |

| Employment status, n (%) | |||

| In paid employment | 299 (68.3) | 316 (70.9) | 615 (69.6) |

| Receives free prescriptions, n (%) | 181 (41.3) | 179 (40.1) | 360 (40.7) |

| Smoking and quitting history | |||

| Cigarettes smoked per day, median (IQR) | 15 (10–20) | 15 (10–20) | 15 (10–20) |

| Baseline CO, median (IQR) | 20 (13–27) | 21 (13–28) | 20 (13–28) |

| FTCD, mean (SD) | 4.5 (2.5) | 4.6 (2.4) | 4.6 (2.4) |

| Previous use of stop smoking products, n (%) | |||

| NRT | 328 (74.9) | 334 (74.9) | 662 (74.9) |

| Varenicline (Champix®; Pfizer Inc., New York City, NY, USA) | 149 (34.1) | 151 (33.8) | 300 (33.9) |

| Bupropion (Zyban®; GlaxoSmithKline plc, Brentford, UK) | 34 (7.8) | 35 (7.9) | 69 (7.8) |

| E-cigarettes | 186 (42.5) | 181 (40.6) | 367 (41.5) |

| Never tried NRT, varenicline or bupropion | 84 (19.2) | 92 (20.6) | 176 (19.9) |

| Age (years) initiated smoking, median (IQR) | 16 (14–18) | 16 (14–18) | 16 (14–18) |

| Spouse/partner smokes, n (%) | 167 (38.1) | 178 (39.1) | 345 (39.1) |

| Study site, n (%) | |||

| London | 289 (66.0) | 295 (66.2) | 584 (66.1) |

| Leicester | 92 (21.0) | 96 (21.5) | 188 (21.3) |

| East Sussex | 57 (13.0) | 55 (12.3) | 112 (12.7) |

The sample comprised mostly middle-aged smokers who started to smoke at a median age of 16 years and tried various smoking cessation aids before joining the trial.

Abstinence rates

Table 4 shows abstinence rates in the two trial arms at different time points. Abstinence rates were consistently higher with e-cigarettes than with NRT for both primary and secondary outcomes. There were no significant differences between quit rates across the trial sites [e.g. χ2(2) = 4.2; p = 0.12 for the primary outcome].

| Outcome | Trial arm, n (%) | Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E-cigarette (N = 438) | NRT (N = 446) | Relative risk (95% CI)a | p-value | Relative risk (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Primary outcome | ||||||

| 52-week abstinence | 79 (18.0) | 44 (9.9) | 1.83 (1.30 to 2.58) | 0.001 | 1.75 (1.24 to 2.46)b | 0.001 |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||||

| Abstinence between 26 and 52 weeks | 93 (21.2) | 53 (11.9) | 1.79 (1.32 to 2.44) | < 0.001 | 1.82 (1.34 to 2.47)c | < 0.001 |

| 4 weeks post TQD | 192 (43.8) | 134 (30.0) | 1.45 (1.22 to 1.74) | < 0.001 | 1.43 (1.20 to 1.71)d | < 0.001 |

| 26 weeks post TQD | 155 (35.4) | 112 (25.1) | 1.40 (1.14 to 1.72) | 0.001 | 1.36 (1.15 to 1.67)b | 0.003 |

| CO-validatede reduction ≥ 50% in non-abstainers at 24–52 weeks; n/N (%) | 44/345 (12.8) | 29/393 (7.4) | 1.75 (1.12 to 2.72) | 0.01 | 1.73 (1.11 to 2.69) | 0.02 |

Sensitivity analyses for the primary outcome

Regarding the primary outcome, sustained 1-year abstinence rates were 18.0% and 9.9% in the e-cigarette and NRT arms, respectively (RR 1.83, 95% CI 1.30 to 2.58; p = 0.001) (see Table 4). The results of the four sensitivity analyses of the primary outcome tallied with the main analysis, indicating greater abstinence in the e-cigarette arm than in the NRT arm (RR 1.75 to RR = 1.85; p < 0.001) (Table 5). The absolute risk difference for the primary outcome was 8.1% (95% CI 3.6% to 12.7%), with a number needed to treat of 12.

| Sensitivity analysesa | RR | p-value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participants who attended ≥ 1 treatment session (e-cigarette arm, n = 411; NRT arm, n = 418) | 1.79 | 0.001 | 1.27 to 2.52 |

| Participants using non-allocated product for ≥ 5 days excluded (e-cigarette arm, n = 411; NRT arm, n = 345) | 1.84 | 0.001 | 1.27 to 2.66 |

| Participants with missing outcome at 52 weeks excluded (e-cigarette arm, n = 356; NRT arm, n = 342) | 1.75 | 0.001 | 1.25 to 1.45 |

| Multiple imputation of missing information by chained equations (e-cigarette arm, n = 438; NRT arm, n = 446) | 1.85 | < 0.001 | 1.32 to 2.60 |

Among the e-cigarette arm abstainers, two (3%) were using non-allocated NRT at 12 months, whereas, in the NRT arm, nine (20%) were using non-allocated e-cigarettes. An additional sensitivity analysis that was not prespecified, in which the abstainers using non-allocated products were removed from the sample, was carried out. This per-protocol analysis resulted in a 52-week abstinence rate in the e-cigarette and NRT arms of 17.7% and 8.0%, respectively (RR 2.21, 95% CI 1.52 to 3.22; p < .001).

Table 4 also shows the secondary abstinence outcomes. Abstinence rates were consistently higher in the e-cigarette arm, including 7-day point prevalence abstinence rates (Table 6).

| 7-day smoking abstinence at each follow-up | Trial arm, n (%) | Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E-cigarette (N = 446) | NRT (N = 438) | Relative risk (95% CI) | p-value | Relative risk (95% CI) | p-value | |

| 4 weeks post TQD | 195 (44.4) | 136 (30.4) | 1.46 (1.23 to 1.74) | < 0.001 | 1.43 (1.20 to 1.70)a | < 0.001 |

| 26 weeks post TQD | 158 (36.0) | 115 (25.7) | 1.39 (1.14 to 1.70) | 0.001 | 1.36 (1.12 to 1.66)b | 0.002 |

| 1 year post TQD | 146 (33.3) | 98 (21.9) | 1.52 (1.23 to 1.90) | < 0.001 | 1.52 (1.22 to 1.89)c | < 0.001 |

Among participants who did not achieve full abstinence, more participants in the e-cigarette arm than in the NRT arm achieved a validated reduction of smoking of ≥ 50% (see Table 6).

Time to relapse was not significantly different in the two trial arms (HR 1.14, 95% CI 0.96 to 1.34; p = 0.12). The relapse rates at 1 year among 4-week abstainers did not differ between the two trial arms (RR 1.27, 95% CI 0.93 to 1.73; p = 0.14).

Figure 2 shows the time to relapse in the two conditions.

FIGURE 2.

Time to relapse.

Attendance and adherence

Table 7 shows session attendance and adherence to each treatment and length of NRT/e-cigarette use. Adherence to e-cigarettes was greater from early on, with many more participants still using e-cigarettes at 6 and 12 months, while only a few still used NRT.

| Measure of adherence | Trial arm | p-value | χ2, Z | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E-cigarette (N = 438) | NRT (N = 446) | |||

| Number of contacts completed,a median (IQR) | 5 (4–5) | 5 (4–5) | ||

| Maximum sessions completed, n (%) | ||||

| 1 | 8 (1.8) | 10 (2.2) | χ2(4) = 8.8; p = 0.07 | |

| 2 | 25 (5.7) | 40 (9.0) | ||

| 3 | 38 (8.7) | 45 (10.1) | ||

| 4 | 86 (19.6) | 106 (23.8) | ||

| 5 | 281 (64.2) | 245 (54.9) | ||

| Use of allocated products over the initial 4 weeksb | ||||

| On how many days used (0–28), median (IQR) | 28 (25–28) | 24 (19–27) | < 0.001 | Z = 11.6 |

| n (%) using daily over the full 4 weeks | 232 (53.0) | 46 (10.3) | < 0.001 | χ2(1) = 186.5 |

| Days used in past week, median (IQR) (the results were similar for weeks 1–4) | 7 (7–7) | 6.5 (3.5–7) | < 0.001 | Z = 8.1–9.1 |

| Use of allocated products at 26 weeks | ||||

| n (%) using at 26 weeks | 180 (41.1) | 33 (7.4) | < 0.001 | χ2(1) = 137.2 |

| Use of allocated products at 52 weeks | ||||

| n (%) using at 52 weeks | 173 (39.5) | 19 (4.3) | < 0.001 | χ2(1) = 161.4 |

Of the 19 participants in the NRT arm using NRT at 12 months, four were using NRT combinations. Products used were patches (n = 7), chewing gum (n = 6), mouth spray (n = 5), inhalator (n = 2), mouth strips, microtabs and lozenge (n = 1 each). Of the 173 participants in the e-cigarette arm using e-cigarettes at 12 months, 168 (97%) used refillable products.

Table 8 shows reasons for discontinuing product use. Participants in the NRT arm were more likely to dislike the taste, have ARs and find the product not satisfying.

| Reason | Trial arm, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| E-cigarette (N = 88) | NRT (N = 166) | |

| Cost | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Did not like the taste | 4 (4.6) | 19 (11.5) |

| AR | 7 (8.0) | 25 (15.1) |

| Not satisfying | 4 (4.6) | 16 (10.0) |

| Difficult to use | 2 (2.3) | 1 (0.6) |

| Embarrassing to use | 0 (0) | 1 (0.6) |

| Difficult to obtain them | 0 (0) | 1 (0.6) |

| Smoking normal cigarettes now | 8 (9.1) | 17 (10.2) |

| To quit nicotine | 0 (0) | 6 (3.6) |

| Other | 63 (71.6) | 80 (48.2) |

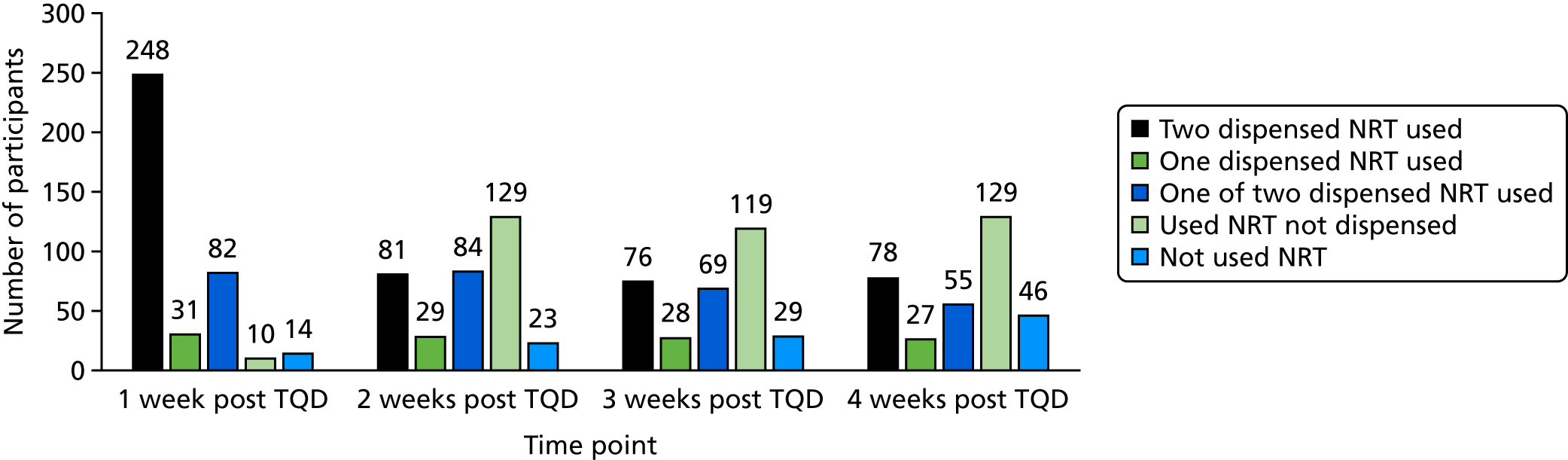

Overall, there were more participants assigned to NRT who used e-cigarettes than participants assigned to e-cigarettes who used NRT. The initial cross-contamination levels were low. A 15% level of cross-contamination in the first 4 weeks post TQD was predefined as being acceptable; the reported level was < 3%. Cross-contamination was defined as non-allocated product use on at least 5 consecutive days.

However, later in the trial, more people from the NRT arm were using e-cigarettes than the other way round. Participants who switched from NRT to e-cigarettes also used the non-allocated product for longer than those who switched from e-cigarettes to NRT. Similar very low proportions of participants in both trial arms used other stop smoking medications during the first 4 weeks (Table 9).

| Non-allocated product use | Trial arm | p-value | t-value/χ2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E-cigarette (N = 438) | NRT (N = 446) | |||

| Non-allocated product use within the first 4 weeks | ||||

| Used for ≥ 5 consecutive days, n (%) | 3 (0.7) | 11 (2.5) | 0.06 | Fisher’s exact test |

| Non-allocated product use at 6 months (excludes first 4 weeks) | ||||

| Used for ≥ 5 consecutive days since 4 weeks, n (%) | 16 (3.6) | 57 (12.8) | < 0.001 | χ2(1) = 24.3 |

| Duration (in weeks) of non-allocated product use since previous assessment (0–20), median (IQR) | 3 (1–9) | 8 (1–20) | 0.2 | Z = –1.2 |

| Non-allocated product use at 12 months (excludes first 4 weeks) | ||||

| Used for ≥ 5 consecutive days since 26 weeks, n (%) | 14 (3.2) | 77 (17.3) | < 0.001 | χ2(1) = 47.4 |

| Duration (in weeks) of non-allocated product use since previous assessment (0–24), median (IQR) | 6.5 (0–12) | 20 (6–24) | 0.002 | Z = –3.1 |

| Other non-study stop smoking medication use (including single use) | ||||

| Varenicline, n (%) | 15 (3.4) | 13 (2.9) | 0.7 | |

| Bupropion, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | N/A | |

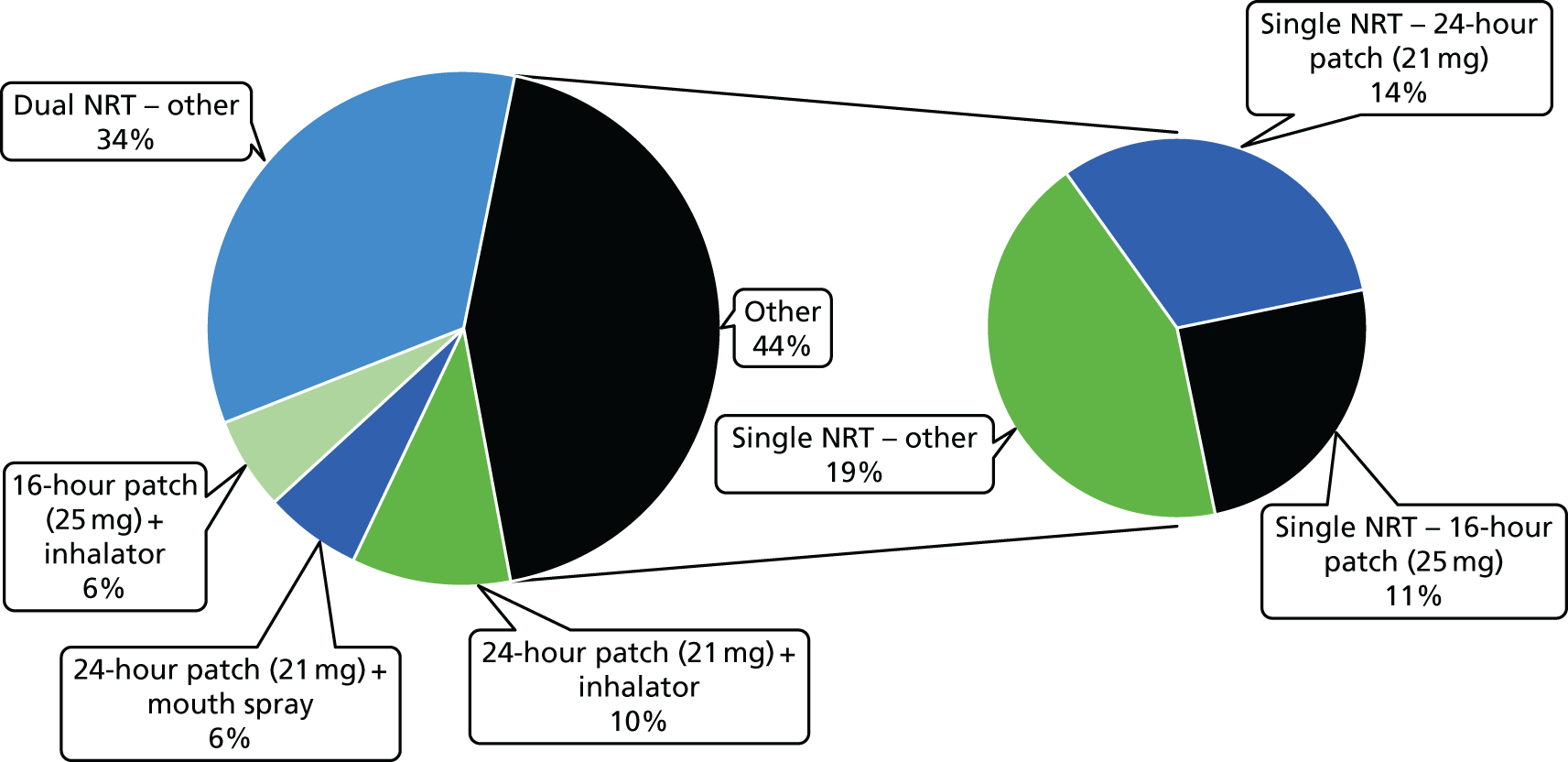

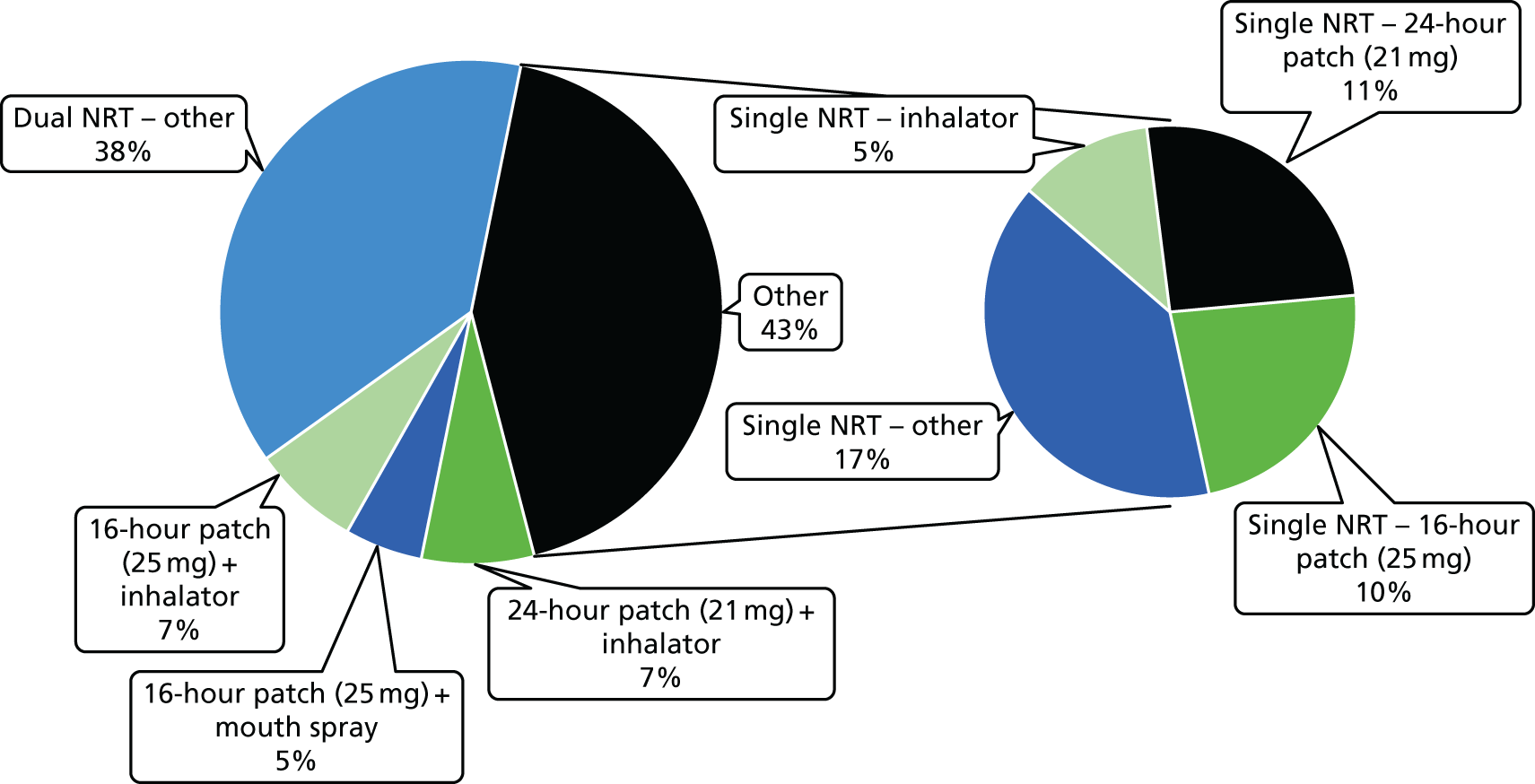

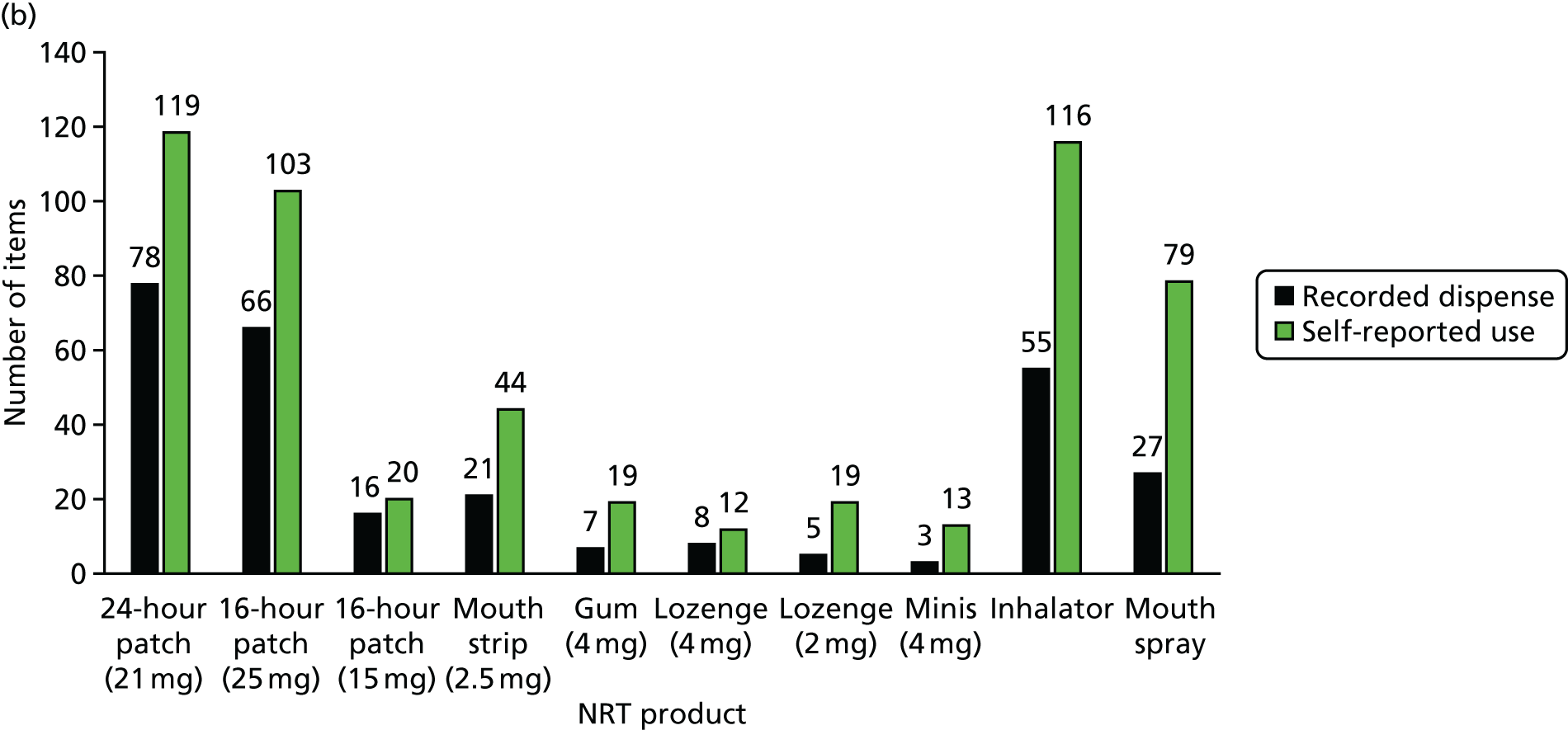

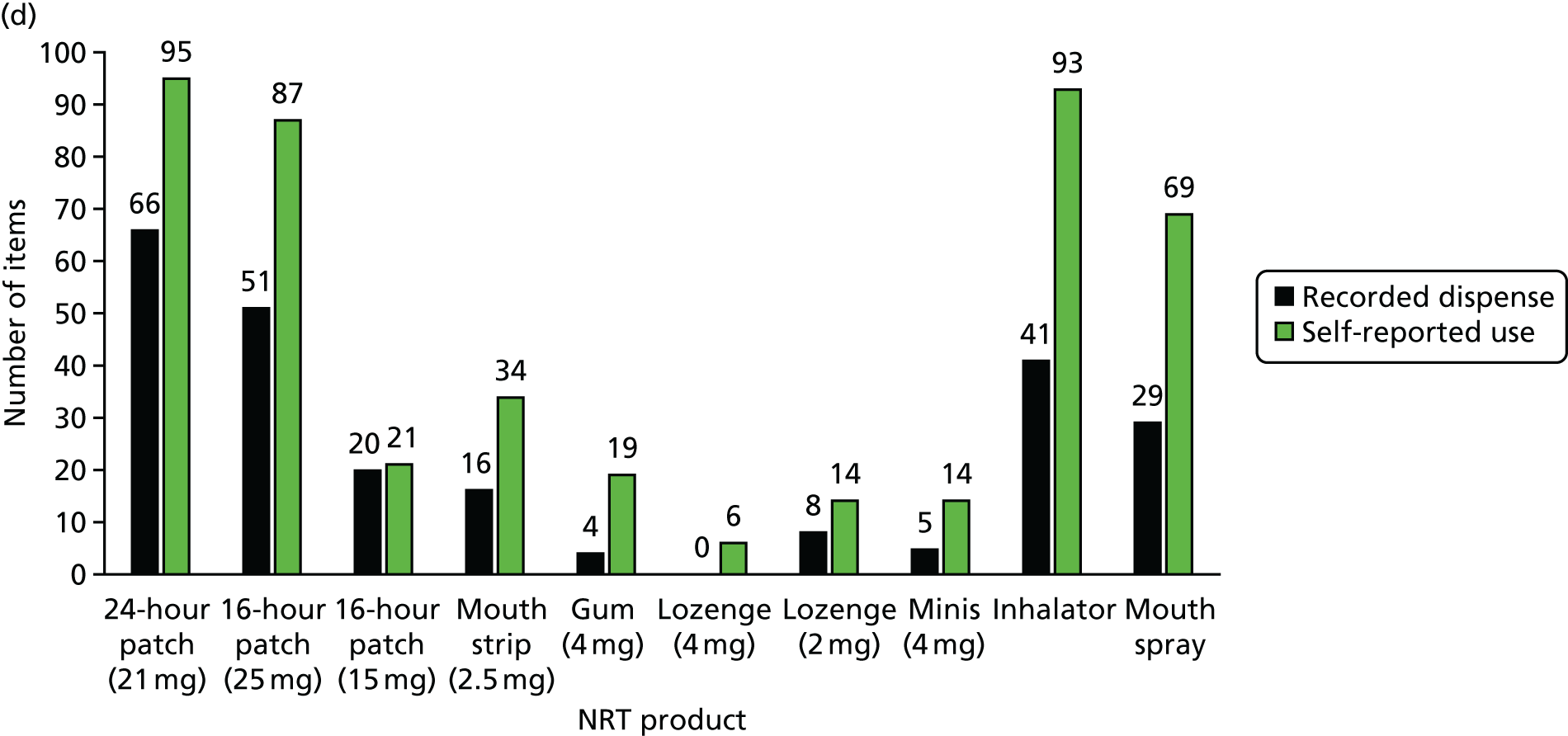

Table 10 shows the NRT products selected initially by the participants in the NRT arm.

| NRT products used | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Type of NRT selected initially | N = 442a,b |

| 24-hour patch (21 mg) | 190 (43) |

| 24-hour patch (14 mg) | 4 (1) |

| 16-hour patch (25 mg) | 149 (34) |

| 16-hour patch (15 mg) | 29 (7) |

| 16-hour patch (10 mg) | 1 (0.2) |

| Microtab (2 mg) | 0 |

| Mouth strips (2.5 mg) | 68 (15) |

| Gum (4 mg) | 25 (6) |

| Gum (2 mg) | 8 (2) |

| Lozenge (4 mg) | 20 (5) |

| Lozenge (2 mg) | 17 (4) |

| Nasal spray | 2 (0.5) |

| Minis (4 mg) | 33 (8) |

| Minis (1.5 mg) | 2 (0.5) |

| Inhalator | 163 (37) |

| Mouth spray | 124 (28) |

| Selecting two NRT products | 393 (88) |

| Switched to different NRT product in first 4 weeks | 260 (59) |

The majority of participants (88.1%) received two NRT products. The nicotine patch was by far the most popular, followed by the nicotine inhalator and nicotine mouth spray. Switching to different NRT products during the first 4 weeks of treatment was fairly common (see Table 10).

Table 11 shows the e-cigarette products used by participants in the e-cigarette arm. Most of those who used e-cigarettes began purchasing e-liquid themselves from early on; very few requested e-liquid supply beyond the first bottle. Hardly any participants (< 1%) switched to a cartridge e-cigarette. The nicotine strength of the e-liquid declined over time. Flavour choices varied with time; fruit and tobacco flavours were most popular, with mint and chocolate/candy flavours following (Table 12).

| E-cigarette products used | |

|---|---|

| E-cigarette arm participants using refillable e-cigarettes, n (%) | |

| 1 week post TQD (N = 384)a | 383 (99.7) |

| 4 weeks post TQD (N = 343)a | 343 (100) |

| 26 weeks post TQD (N = 270)a | 265 (98.2) |

| 52 weeks post TQD (N = 235)a | 227 (96.6) |

| E-liquid nicotine strength in mg/ml, median (IQR) | |

| 4 weeks post TQD (N = 340) | 18 (16–18) |

| 26 weeks post TQD (N = 267) | 12 (6–18) |

| 52 weeks post TQD (N = 232) | 11 (5–18) |

| Requested further e-liquid supply at 2 weeks post TQD, n (% of full sample) | 30 (7) |

| Flavoura | Week, n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (N = 155) | 4 (N = 156) | 26 (N = 516) | 52 (N = 511) | |

| Tobacco | 15 (10) | 44 (28) | 163 (32) | 127 (25) |

| Fruit | 70 (45) | 51 (33) | 150 (30) | 169 (33) |

| Menthol/mint | 31 (20) | 20 (13) | 75 (15) | 81 (16) |

| Tobacco menthol | 5 (3.2) | 7 (4.5) | 13 (2.5) | 12 (2.3) |

| Vanilla | 5 (3.2) | 1 (0.6) | 11 (2.1) | 14 (2.7) |

| Chocolate, dessert, candy or sweet | 17 (11) | 18 (12) | 62 (12) | 72 (14) |

| No flavour | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.4) |

| Coffee | 2 (1.3) | 1 (0.6) | 6 (1.2) | 8 (1.6) |

| Alcoholic drink | 2 (1.3) | 2 (1.3) | 7 (1.4) | 3 (0.6) |

| Energy or soft drink | 6 (3.9) | 10 (6.4) | 17 (3.3) | 13 (2.5) |

| Other | 2 (1.3) | 2 (1.3) | 12 (2.3) | 10 (2.0) |

Table 13 compares ratings of NRT and e-cigarettes in terms of perceived helpfulness in stopping smoking, and in terms of taste and satisfaction compared with conventional cigarettes. Only cases with complete data across measures are included. E-cigarettes received significantly better ratings for all three variables at both time points. Both products were perceived as less satisfying compared with cigarettes, but e-cigarettes provided higher satisfaction than NRT (see Table 13).

| Rating | Trial arm, mean (SD) | t-value; p-value | Mean difference (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E-cigarette (n = 324)a | NRTb (n = 228)a | |||

| Helpfulnessc | ||||

| 1 week post TQD | 4.3 (0.9) | 3.6 (0.9) | 8.4; < 0.001 | 0.7 (0.5 to 0.9) |

| 4 weeks post TQD | 4.3 (0.9) | 3.7 (0.9) | 7.0; < 0.001 | 0.6 (0.4 to 0.7) |

| Tasted | ||||

| 1 week post TQD | 3.0 (1.4) | 2.7 (1.6) | 2.5; 0.015 | 0.3 (0.1 to.06) |

| 4 weeks post TQD | 3.5 (1.3) | 3.1 (1.5) | 3.3; 0.001 | 0.4 (0.2 to 0.6) |

| Satisfactiond | ||||

| 1 week post TQD | 2.4 (1.0) | 2.0 (1.2) | 4.3; < 0.001 | 0.4 (0.2 to 0.6) |

| 4 weeks post TQD | 2.7 (1.1) | 2.3 (1.2) | 4.7; < 0.001 | 0.5 (0.3 to 0.6) |

Urges to smoke

Table 14 shows urges to smoke in participants abstaining from smoking at 1 and 4 weeks post TQD in the two trial arms. Participants in the e-cigarette arm experienced lower frequency of urges to smoke and reduced strength of urges than participants in the NRT arm.

| Urge to smoke | Trial arm at 1 week, mean (SD) | t-test; p-value | Trial arm at 4 weeks, mean (SD) | t-test; p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E-cigarette (n = 158) | NRT (n = 131) | E-cigarette (n = 186) | NRT (n = 132) | |||

| Frequency | 2.5 (1.1) | 2.8 (0.9) | –3.1; 0.002 | 1.9 (0.9) | 2.2 (0.8) | –3.3; 0.001 |

| Strength | 2.7 (1.1) | 3.2 (1.0) | –3.6; 0.0004 | 2.1 (1.1) | 2.4 (1.0) | –2.6; 0.001 |

| Composite urge score | 2.6 (1.0) | 3.0 (0.9) | –3.6; 0.0003 | 2.0 (1.0) | 2.3 (0.9) | –3.1; 0.003 |

Among all participants, the level of urges to smoke is higher, but the difference between the two trial arms is similar, with the e-cigarette arm reporting lower frequency of urges to smoke and reduced urge intensity than the NRT arm (Table 15).

| Urge to smoke | Trial arm at 1 week, mean (SD) | t-test; p-value | Trial arm at 4 weeks, mean (SD) | t-test; p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E-cigarette (n = 389) | NRT (n = 383) | E-cigarette (n = 365) | NRT (n = 334) | |||

| Frequency | 2.8 (0.05) | 3.1 (0.05) | –3.8; 0.0002 | 2.3 (0.06) | 2.7 (0.06) | –4.1; < 0.001 |

| Strength | 3.1 (0.06) | 3.3 (0.05) | –3.8; 0.0002 | 2.6 (0.06) | 2.9 (0.06) | –3.6; 0.0004 |

| Composite urge score | 2.9 (0.05) | 3.2 (0.05) | –4.2; < 0.001 | 2.4 (0.05) | 2.8 (0.06) | –4.1; 0.0001 |

Withdrawal symptoms

Regarding other withdrawal symptoms, abstainers in the e-cigarette arm suffered less restlessness, irritability and inability to concentrate during the first week of abstinence. By week 4, abstainers in both trial arms suffered little discomfort and the differences were no longer significant (Table 16). Among all participants, irritability, restlessness, hunger, poor concentration and the composite withdrawal score were all less severe in the e-cigarette arm than in the NRT arm during the first week of abstinence, with only the difference in hunger and the composite withdrawal score persisting at week 4 (Table 17).

| Withdrawal symptom | Trial arm, mean (SD) | t-value; p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| E-cigarette (n = 158) | NRT (n = 131) | ||

| 1 week post TQD | |||

| Depressed | 0.05 (0.7) | 0.08 (.8) | –0.3; 0.77 |

| Irritable | 0.27 (1.2) | 0.78 (0.12) | –3.4; 0.001 |

| Restless | 0.13 (1.1) | 0.43 (1.5) | –2.0; 0.05 |

| Hungry | 0.33 (1.1) | 0.59 (1.3) | –1.9; 0.06 |

| Poor concentration | –0.06 (0.8) | 0.25 (1.2) | –2.6; 0.009 |

| Composite score | 0.14 (0.58) | 0.43 (0.75) | –3.6; 0.001 |

| 4 weeks post TQD | (n = 191) | (n = 134) | |

| Depressed | –0.02 (0.8) | –0.04 (0.9) | –0.2; 0.86 |

| Irritable | –0.01 (0.1) | 0.20 (1.1) | –1.7; 0.09 |

| Restless | –0.13 (1.1) | –0.08 (1.3) | –0.3; 0.74 |

| Hungry | 0.19 (1.2) | 0.31 (1.4) | –0.8; 0.43 |

| Poor concentration | –0.15 (0.9) | –0.04 (1.0) | –1.0; 0.30 |

| Composite score | –0.01 (0.6) | 0.08 (0.8) | –1.3; 0.20 |

| Withdrawal symptom | Trial arm, mean (SD) | t-value; p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| E-cigarette (n = 389) | NRT (n = 383) | ||

| 1 week post TQD | |||

| Depressed | 0.1 (0.1) | 0.1 (0.1) | –1.0; 0.30 |

| Irritable | 0.4 (0.1) | 0.6 (0.1) | –2.7; 0.008 |

| Restless | 0.1 (0.1) | 0.4 (0.1) | –2.8; 0.006 |

| Hungry | 0.3 (0.1) | 0.5 (0.1) | –2.6; 0.01 |

| Poor concentration | 0.1 (.01) | 0.2 (0.1) | –2.9; 0.004 |

| Composite score | 0.2 (0.1) | 0.4 (0.1) | –4.1; 0.0001 |

| 4 weeks post TQD | (n = 364) | (n = 334) | |

| Depressed | 0.12 (0.1) | 0.13 (0.1) | –0.2; 0.87 |

| Irritable | 0.11 (0.1) | 0.24 (0.1) | –1.5; 0.13 |

| Restless | –0.02 (0.1) | 0.04 (0.1) | –0.7; 0.51 |

| Hungry | 0.10 (0.1) | 0.39 (0.1) | –2.9; 0.004 |

| Poor concentration | –0.04 (0.1) | 0.06 (0.1) | –1.3; 0.18 |

| Composite score | 0.1 (0.04) | 0.2 (0.04) | –2.2; 0.03 |

Product safety

Safety of the trial products was evaluated in three ways: SAEs were recorded, data were collected on elicited ARs, and changes in respiratory symptoms over the duration of 1 year were monitored.

Two participants died in the follow-up period, one in each trial arm. The cause of death of the NRT participant was traumatic neck injury and that of the e-cigarette participant was ischaemic heart disease. There were 27 SAEs reported in the e-cigarette arm and 22 in the NRT arm (see Appendix 1, Table 34). None of the SAEs were classed as related to study product use. There were six pulmonary events: five in the e-cigarette arm and one in the NRT arm (not counting a hospitalisation concerning a lung mass in the NRT arm). The two participants who were hospitalised with pneumonia were both smoking at the time (one was also vaping). The participant in the e-cigarette arm who was hospitalised with asthma had recently stopped vaping and relapsed to smoking. One of the participants with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) exacerbation was smoking and vaping at the time; e-cigarette use was not ascertained in the remaining case.

Adverse reactions

Table 18 shows the incidence of elicited ARs in the two trial arms that were reported at least once. NRT caused more nausea, whereas e-cigarettes caused more throat/mouth irritation.

| AR | Trial arm, n (%) | Relative risk (95% CI)b | |

|---|---|---|---|

| E-cigarette (N = 438) | NRT (N = 446) | ||

| Nausea | 137 (31) | 169 (38) | 0.83 (0.69 to 0.99) |

| Sleep disturbances | 279 (64) | 303 (68) | 0.94 (0.986 to 1.04) |

| Throat/mouth irritationa | 286 (65) | 221 (51) | 1.27 (1.13 to 1.43) |

All three reactions (nausea, sleep disturbance and throat/mouth irritation) were mostly mild. Table 19 shows the proportion of participants who rated these reactions as severe. The two trial arms did not differ in this respect.

| AR | Trial arm, n (%) | Relative risk (95% CI)a | |

|---|---|---|---|

| E-cigarette (N = 438) | NRT (N = 446) | ||

| Nausea | 29 (6.6) | 29 (6.5) | 1.02 (0.62 to 1.67) |

| Sleep disturbances | 57 (13) | 58 (13) | 1.0 (0.71 to 1.4) |

| Throat/mouth irritationb | 26 (5.9) | 17 (3.8) | 1.51 (0.84 to 2.74) |

Table 20 compares the two trial arms in terms of self-reported respiratory symptoms among participants who provided relevant data. The p-value and odds ratio relate to the occurrence of respiratory symptoms at 12 months, adjusted for the baseline symptoms occurrence and trial centre. Significantly more participants in the e-cigarette arm than in the NRT arm stopped coughing and producing phlegm.

| Respiratory symptom | Trial arm, n (%) | p-value | Relative riska (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E-cigarette (N = 315) | NRT (N = 279) | |||||

| Baseline | 12 months | Baseline | 12 months | |||

| Shortness of breath | 120 (38.1) | 66 (21.0) | 92 (33.0) | 64 (22.9) | 0.25 | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.1) |

| Wheezing | 102 (32.4) | 74 (23.5) | 86 (30.8) | 59 (21.2) | 0.73 | 1.1 (0.8 to 1.4) |

| Cough | 173 (54.9) | 97 (30.8) | 144 (51.6) | 111 (39.8) | 0.004 | 0.8 (0.6 to 0.9) |

| Phlegm | 137 (43.5) | 79 (25.1) | 121 (43.4) | 103 (36.9) | 0.002 | 0.7 (0.6 to 0.9) |

To determine whether or not the better cough and phlegm outcomes in the e-cigarette arm participants were a result of their higher quit rate, a non-planned exploratory analysis controlling for 1-year abstinence status was run. This did not alter the results (RR = 0.8, 95% CI 0.6 to 0.9, p = 0.008, for cough; and RR = 0.7, 95% CI 0.6 to 0.9, p = 0.004, for phlegm).

Discussion

Clear differences between the quit rates in the two trial arms emerged early on, with the participants in the e-cigarette arm having significantly higher validated quit rates at all time points. Sustained biochemically validated 1-year quit rate with NRT products of patient choice, including NRT combinations and an opportunity to vary products, was 9.9%, tallying closely with success rates reported previously for the UK SSSs 1-year validated outcome. 25 In the e-cigarette arm, the quit rate was 18.0%. Participants in the e-cigarette arm showed significantly better adherence and experienced fewer urges to smoke, and reduced strength of urges, throughout the initial 4 weeks of their quit attempt than those in the NRT arm. Participants assigned to e-cigarettes reported significantly less coughing and phlegm at 1 year than those assigned to NRT.

In the following sections, key aspects of the trial and of its findings are discussed.

Sample representativeness

The trial sample comprised participants who are typical of clientele of UK SSSs: middle-aged smokers unable to quit smoking unaided, including some 40% in receipt of free prescriptions (a marker of illness or social disadvantage), with high baseline CO readings, who have tried a range of stop smoking aids before. The findings are likely to be valid for clinical samples but may not be generalisable to smokers who are less dependent or who try e-cigarettes for reasons other than quitting smoking.

Representativeness of the two interventions

In this pragmatic trial, e-cigarettes were used as they could be used in routine SSS practice, namely smokers were provided with a starter kit and advised to purchase e-liquids with a flavour and nicotine strength that they found helpful. They were also encouraged to buy a different e-cigarette model if needed. A range of e-cigarette products and e-liquids are available for smokers with different needs and the practise utilises the opportunity this provides. Participants who found e-cigarettes helpful had no problem with purchasing their own supplies. In fact, by the end of the first 2 weeks of treatment, when trial e-liquid was still available, most were already using e-liquids that they had purchased themselves. This approach makes it probable that the results can be achieved in any setting that can replicate the trial conditions, but it also means that the trial results may not be replicated if just one type of e-cigarette is provided to all participants, especially if this is a weak cartridge-based product.

Nicotine replacement therapy was provided under generous conditions that are probably optimal for treatment efficacy. The medication was provided free of charge, apart from the prescription charge applicable at one trial site. Participants were encouraged to select from among the full range of NRT preparations products that best fit their needs; most participants (88%) were provided with two forms of NRT, usually a patch plus a fast-acting NRT formulation, and more than one-third of participants experimented with different NRT products during the initial treatment period. NRT use was also supervised by SSS clinicians trained in guiding clients and optimising NRT use.

Caution was taken to avoid possible bias related to product cost and effort needed to obtain it. At the SSSs that provide NRT on LOR, participants in both groups had to collect NRT from a pharmacy, and the e-cigarette group exchanged this for an e-cigarette at randomisation. Reassuringly, no participant listed cost as the reason for discontinuing product use.

Effect of e-cigarettes on smoking cessation

The only previous trial9 reported a small, non-significant, advantage of e-cigarettes over patches (7.3% vs. 5.8% quit rates at 6 months). However, it used an early unreliable Cig-A-Like e-cigarette (Elusion™, Auckland, New Zealand) with very low nicotine delivery (maximum concentration of 3 ng/ml, compared with 18 ng/ml from cigarettes and 10 ng/ml from refillable e-cigarettes using 20 mg/ml e-liquid)27 and the products were provided with no face-to-face support, which explains the low quit rates. In this trial, e-cigarettes were significantly more effective than NRT at all time points, despite the fact that the number of participants in the NRT arm who also used e-cigarettes was more than three times the number in the e-cigarette arm who used NRT as well. Such ‘contamination’ could not exert much influence on the primary outcome of abstinence from the third week of treatment onwards; at 3 weeks contamination was low, but those who abstained for longer periods included abstainers in the NRT arm who quit with the help of e-cigarettes, making the results conservative.

Product use at 1 year

Most abstainers in the e-cigarette arm (80%) were still vaping at 1 year, whereas only 9% of NRT arm abstainers were still using NRT. Ongoing use of nicotine-containing products could be seen in both a positive and negative light. Product use may assist with maintaining smoking abstinence and preventing relapse, ameliorate the weight gain that typically follows nicotine withdrawal and provide some continuation of the positive subjective effects that smokers used to get from smoking. However, it can be also a cause for concern if overcoming nicotine addiction is seen as an important aim in itself, even if ongoing nicotine use carries negligible health risks, or if ongoing vaping poses clear health risks.

Regarding continuous nicotine use, when NRT was first introduced, the view that combating nicotine use is the main purpose of stop smoking interventions led to claims that someone who stopped smoking successfully but still uses NRT should not be counted as a treatment success. However, the motivation for helping smokers quit is to help them to avoid the health risks of smoking, and, once this rationale became widely accepted, such concerns largely disappeared. The SSS sees its aim as helping smokers avoid smoking-related disease and death, and there are no concerns about long-term use of NRT, especially as such use prevents relapse in ex-smokers with high tobacco dependence and other negative prognostic signs. 28 However, the concerns about ongoing nicotine use are likely to re-emerge as smokers switch to vaping. For those who are concerned about nicotine use per se, some reassurance is provided by data showing that vapers show lower dependence on e-cigarettes than on cigarettes,29,30 and smokers who successfully stop smoking with the help of e-cigarettes tend to eventually stop vaping as well. 10 It is currently estimated that the health risks of long-term vaping are unlikely to exceed 5% of the risks of smoking. 2 Some risks may yet emerge and ongoing monitoring is needed, but no health risks from e-cigarettes used for up to 1.5 years have been identified to date, and biomarkers of risk that have been examined so far show that long-term vapers do not differ from long-term NRT users (and probably also from non-smokers). 31

Product adherence and attractiveness

Among participants who engaged with treatment, adherence was initially high in both trial arms. The difference in adherence to the two products increased markedly over time, with participants being much more likely to continue with e-cigarette use than with NRT use at later follow-ups. This could be related to the fact that NRTs are presented as a medicinal product with an expectation of time-limited use, whereas e-cigarettes are a consumer product that is more easily accessible and not linked to expectations of short-term use only. However, satisfaction with the product may have been the most important factor as suggested by other data on product differences. Unsatisfactory taste, lack of satisfaction and ARs were the main reasons for stopping NRT use and were more frequent in the NRT trial arm than in the e-cigarette trial arm. E-cigarettes were also rated as significantly more helpful, more similar to cigarettes in taste and more satisfying than NRT.

It is possible that, apart from better sensory effects, e-cigarettes were also providing better tailored nicotine replacement than NRT. Allowing participants to select their own e-liquid could have provided better dose tailoring than NRT products allow. It is paradoxical that smokers can select their nicotine levels freely while they smoke, but once they enter NRT treatment this autonomy is removed and nicotine dosing is placed in the hands of those who treat them. In addition, NRT products are formulated to provide very low nicotine doses, far below what smokers normally obtain from their cigarettes. Using NRT combinations could ameliorate this problem, but the short-acting products added to patches are typically used only opportunistically. Future studies should collect cotinine samples to allow comparisons of the actual nicotine intake.

E-cigarette and nicotine replacement therapy products used

The starter pack consisted of a refillable (tank) e-cigarette. Very few users switched to cartridge-based products. This corresponds to data showing that e-cigarette users prefer refillable e-cigarettes5 and that these provide higher nicotine levels,32 better relief from craving and higher satisfaction33 than Cig-A-Like products. Vapers tried a wide range of e-liquid flavours. Fruit flavours were the most popular, with tobacco flavour also popular at 6 months but less so at 1 year. Sweet flavours (chocolate, candy) and menthol increased in popularity over time. This corresponds with data showing that fruit flavours are the most popular, with many smokers also liking candy flavours. 5 NRT product choices were similar to those observed across SSSs. 34 The patch was by far the most popular choice, followed by the inhalator and mouth spray.

Effects of the two treatments on withdrawal symptoms

Participants using e-cigarettes reported significantly lower intensity and frequency of urges to smoke than participants using NRT throughout the initial treatment period. All existing stop smoking medications are assumed to exert their main therapeutic effect via craving reduction, and this is likely to be the case with e-cigarettes too. Most other tobacco withdrawal symptoms were also lower in the e-cigarette arm than in the NRT arm during the first week of abstinence, although this effect subsided by 4 weeks, when most withdrawal symptoms in continued abstainers reduced to almost zero.

Product safety

There was one death in each trial arm. A difference in frequency of acute pulmonary events was noted (five in the e-cigarette arm vs. one in the NRT arm, or two if counting a lung mass in the NRT arm). Two of the e-cigarette-arm participants with pulmonary SAEs were not vaping at the time, two were vaping and smoking, and the vaping status of one is not known. The difference is likely to be due to chance; however, the study design did not set out to examine e-cigarette safety. Future study designs should include more reliable evaluation of any possible pulmonary risks of vaping.

Sleep disturbance was monitored, as this is considered to be an AE that is commonly associated with the use of NRT patches, but sleep disturbance was equally common in both trial arms. As expected, throat/mouth irritation was more frequently noted by e-cigarette users and nausea was reported more frequently by NRT users, but both effects were mostly mild. The two groups did not differ in the incidence of severe reactions.

Contrary to general expectations, e-cigarette use seemed to have a significantly positive impact on elicited respiratory symptoms. Previous findings on this have been contradictory. Studies of cells and animals have suggested that vaping may result in respiratory infections;35,36 however, a large internet survey of vapers found that the switch from smoking to vaping was accompanied by reduction in respiratory infections. 37 It was proposed that this could be because of the antibacterial properties of propylene glycol, which is usually one of the constituents of e-liquid. Respiratory symptoms were monitored to see if vaping has any negative or positive effects. Changes in wheezing and shortness of breath did not differ between the two arms, but there was a significant difference in two other symptoms that are more closely linked to respiratory infections: cough and generating phlegm. There was improvement in both study arms compared to baseline, but the improvement in the e-cigarette arm was significantly larger. Importantly, the effects were not due to the higher quit rate in the e-cigarette arm, and so they support the hypothesis suggested by previous observations that vaping provides protection against respiratory tract infections. Future studies should include objective measures of lung health and respiratory symptoms.

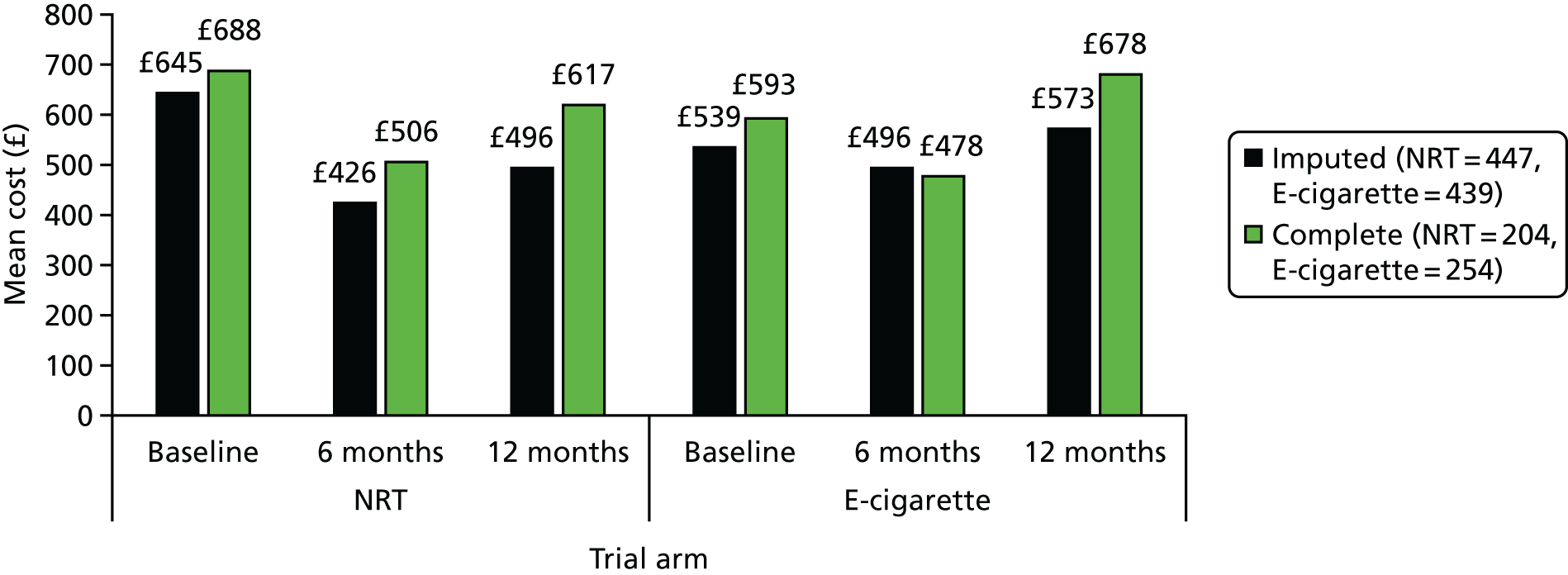

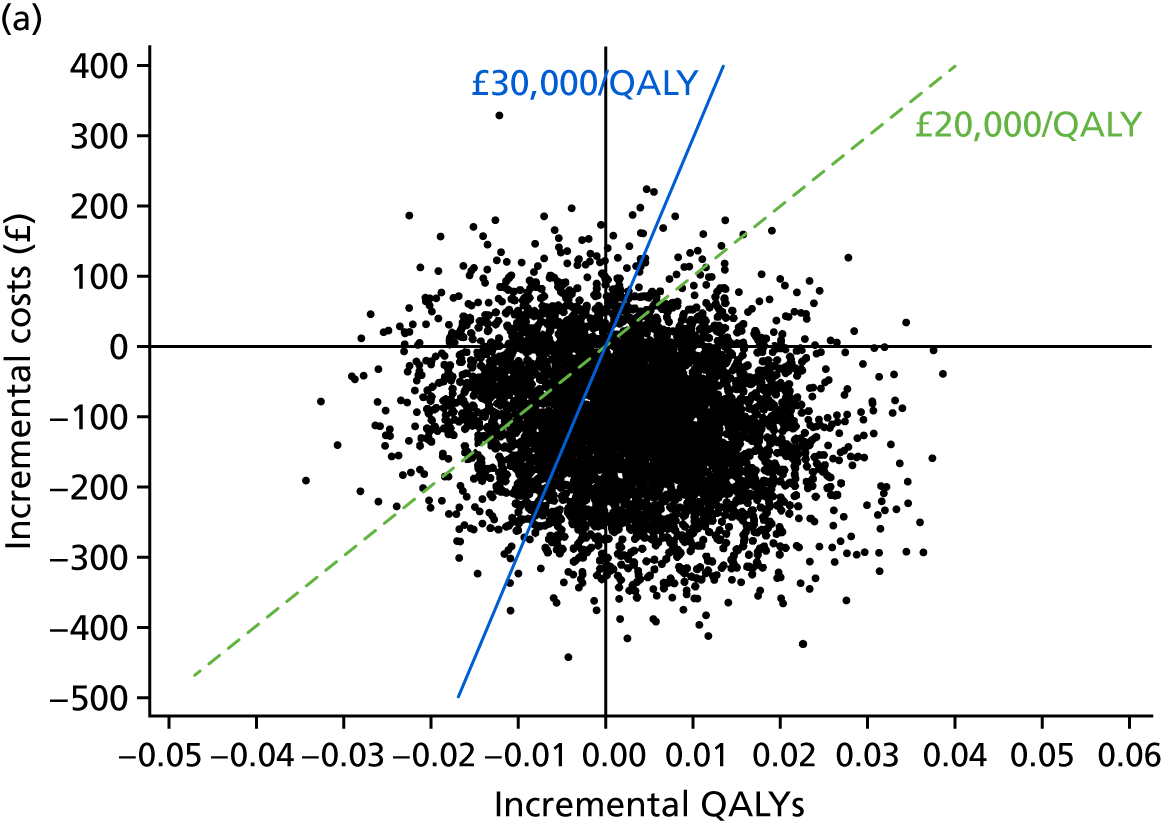

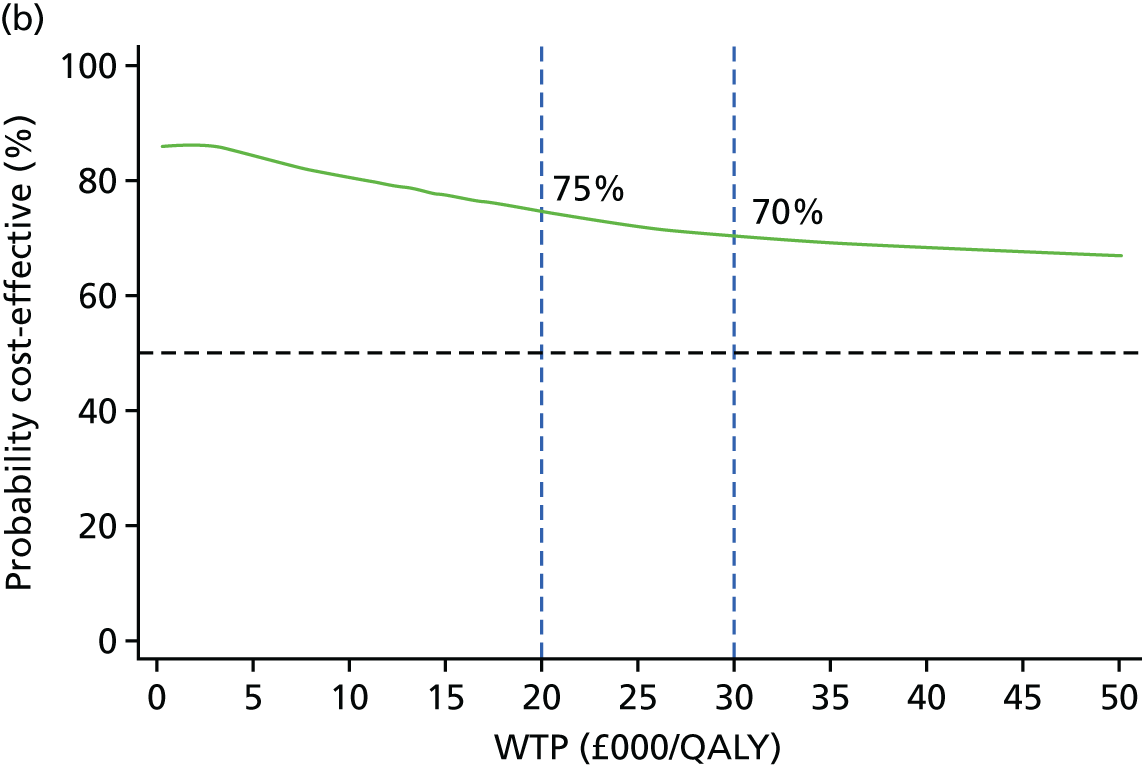

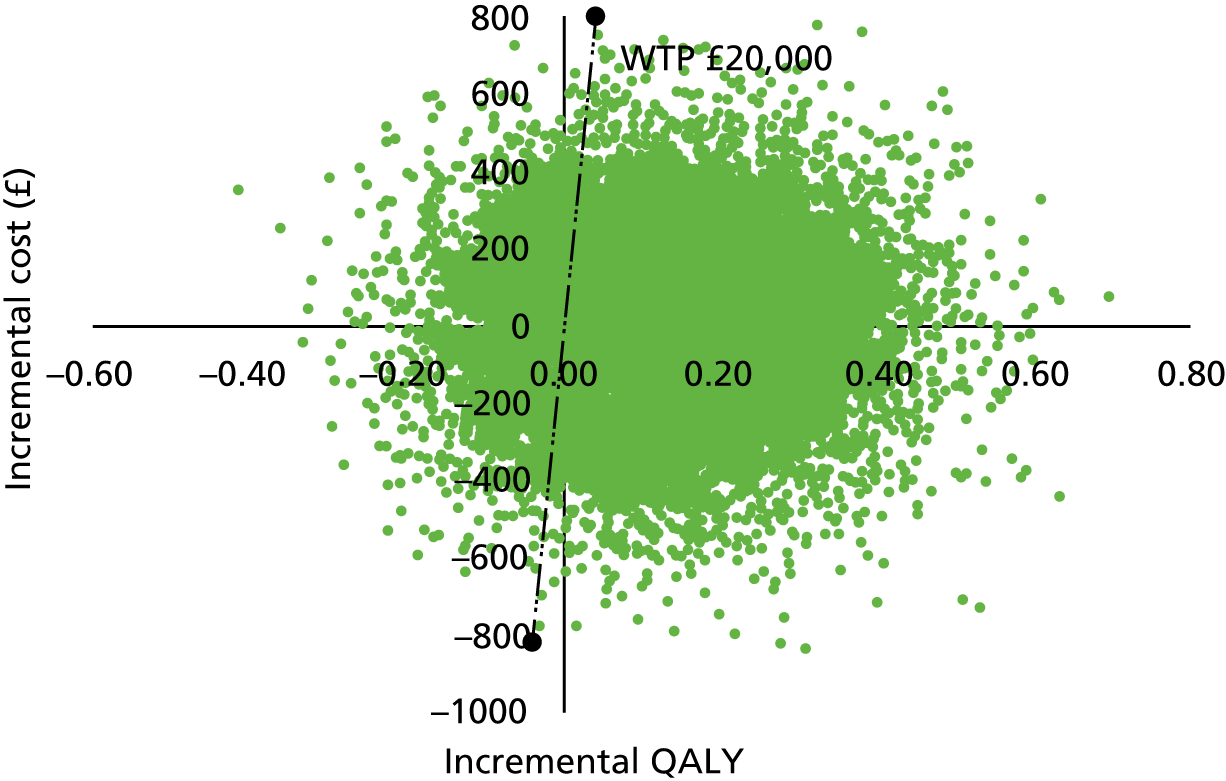

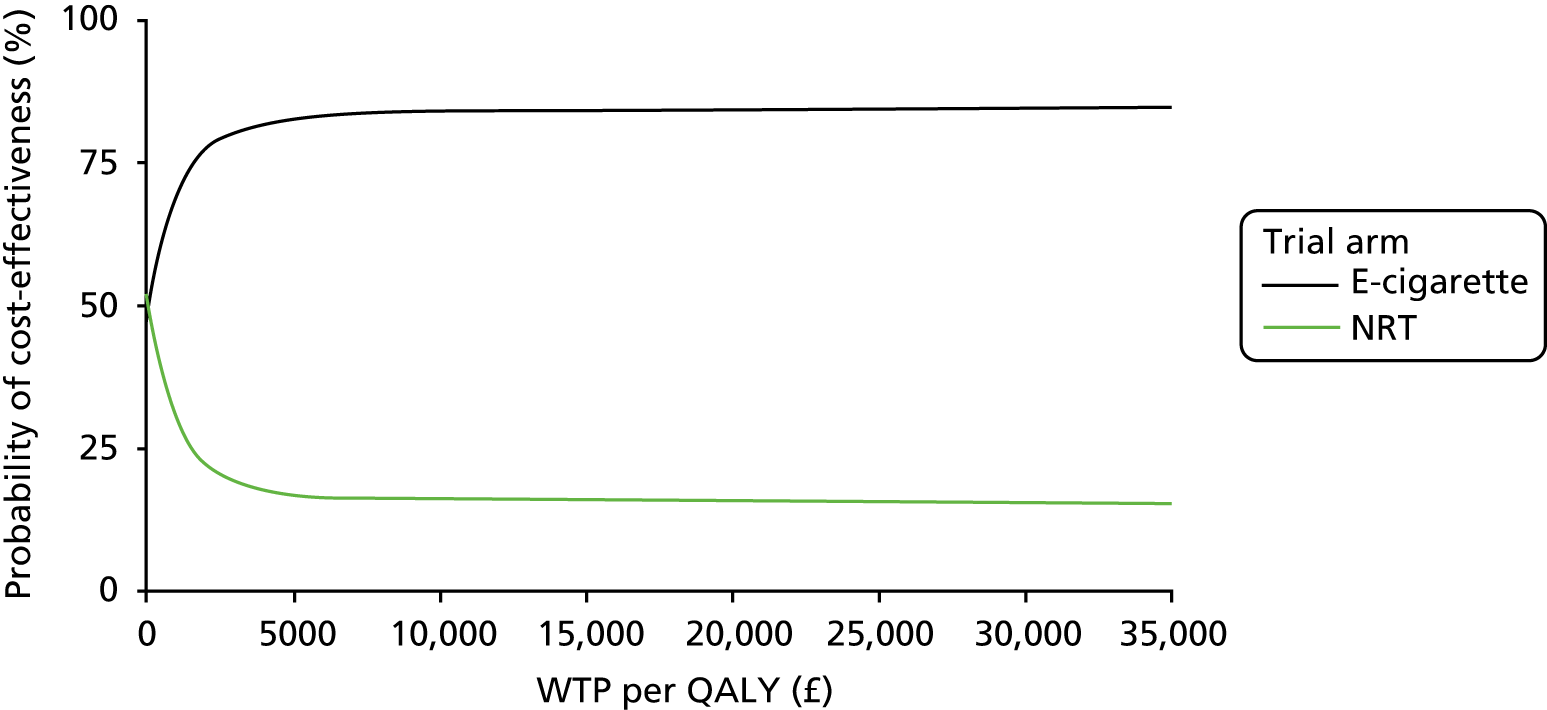

Economic analysis

The full economic analysis is presented in Chapter 5, but, in summary, compared with NRT intervention, e-cigarette intervention was less costly and generated higher quit rates; therefore, it was also more cost-effective. There was an indication that the e-cigarette arm achieved a higher quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gain than the NRT arm during the 12-month period, but the difference was not significant. The e-cigarette intervention did not appear to lead to an increase in spending on cessation aids on the smokers’ part while reducing the costs to the smoking cessation services.

Trial limitations

One obvious limitation of open-label trials is the possible effect of expectations. There is no evidence that expectations can boost long-term abstinence rates, but it is likely that they can lower the quit rate in the condition that is seen as inferior, for example if therapists communicate low expectations and/or patients think that they have received the short straw they may drop out of treatment or not put as much effort into quitting. This trial was presented as testing whether or not e-cigarettes are as effective as NRT to avoid creating expectations of its superiority. It was also possible to check whether or not a depressed quitting in the NRT condition contributed to the trial results. A study25 of the long-term quit rates among a group of SSSs with above average early outcomes, using the same outcome criteria as this trial, showed an overall validated 1-year quit rate of 8%. Clients receiving identical individual treatment as used in this trial, provided by specialist advisors, had a quit rate of 10%. However, 46% were treated with varenicline, which was associated with significantly higher abstinence than NRT (12% vs. 7%, respectively). A large RCT38 has recently confirmed the superiority of varenicline over other medications. Thus, it is reassuring that the NRT-arm quit rate (10%) was commensurate with or superior to the standard outcome in this treatment setting.

We tried to make treatment access similar in the two trial arms, but all e-cigarette users had to pay for their supplies, whereas only about half of NRT users had to pay prescription charges. However, this is unlikely to play a major role, as cost was not listed among the important reasons for discontinuing product use by either trial arm.

The 79% follow-up rate at 1 year was comparable with the 78% follow-up rate achieved in another recent NIHR-funded trial in the same setting and population,39 79% achieved in SSS service evaluation25 and 75% in an earlier trial that also took place within SSSs. 40 The follow-up rate was somewhat lower in the NRT arm (77% for NRT vs. 81% for e-cigarettes), which probably reflects the fact that unsuccessful quitters are more likely to drop out. Delivering higher rates of follow-up in this population is difficult. Smokers receiving face-to-face support usually feel embarrassed if they do not succeed, and avoid further contact. However, incomplete data are another trial limitation.

Participants’ weight was not monitored, nor were participants asked about weight changes that they experienced. As evidence is emerging that e-cigarette use may ameliorate post-cessation weight gain, future studies should include such monitoring.

As discussed in Sample representativeness, the trial sample comprised dependent smokers seeking treatment, and they received instructions, support and monitoring of their progress. The results may not be generalisable to other types of smokers and other settings. The trial did not evaluate any one particular e-cigarette product, but the choice of e-cigarette devices and e-liquids that smokers can access currently in the UK. Practically all e-cigarette arm participants used refillable e-cigarettes. The results may not apply to the now largely obsolete Cig-A-Like e-cigarette (now produced almost exclusively by the tobacco industry) or to settings and countries that only allow one particular e-cigarette product.

Implications for health care

Stop Smoking Services have become more receptive to e-cigarettes over the past few years and most now condone or encourage e-cigarette use, but only a few provide e-cigarette starter packs. The reluctance to do so is understandable, because evidence of the comparative efficacy of e-cigarettes is limited to one trial9 showing that early e-cigarettes matched NRT patches when used with minimal support. The results of the current trial are likely to change the current practice. The trial provides evidence that e-cigarettes not only match but surpass the efficacy of NRT, even when combination NRT is provided alongside expert advice and supervision.

The adoption of e-cigarettes by SSSs could generate several benefits. It is likely that e-cigarettes as a smoking cessation tool are more effective if accompanied by support and monitoring, as has been shown for NRT. 41 If smokers switching to e-cigarettes do so with SSS support, they are likely to improve their chance of successfully stopping smoking. The offer of e-cigarette starter packs could be particularly attractive to disadvantaged smokers, thus improving the service reach in areas where it is most needed. Offering e-cigarettes as one of the treatment options would also make the services more economical. The full course of a single NRT product is typically > £100 and combinations of two NRT products, widely used by SSSs, cost even more. The more advanced starter pack used in this trial cost £30. If SSSs start to provide e-cigarettes, this may also counteract some of the antivaping reporting in UK tabloids and contribute to dispelling the worrying increase among smokers of a belief that e-cigarettes are as dangerous as cigarettes. 2