Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 09/144/50. The contractual start date was in January 2012. The draft report began editorial review in April 2018 and was accepted for publication in February 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Michael King is a member of the Clinical Trial Units funded by the National Institute for Health Research and the Rapid Trials and Add-on Studies Board. Rumana Z Omar is a member of the Health Technology Assessment General Board. John Strang reports grants from Camurus (Lund, Sweden), Martindale Pharma (now Ethypharm UK, Woodburn Green, UK), Mundipharma (Mundipharma International Limited, Cambridge, UK) and Braeburn Pharma (Braeburn Inc., Plymouth Meeting, PA, USA), and other from Martindale Pharma and Braeburn Pharma outside the submitted work. In addition, John Strang has a patent Euro-Celtique SA issued and a patent pending with King’s College London.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Johnson et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Cannabis is the most commonly used drug among people with psychosis, with rates of current use around the time of the onset of psychosis regularly recorded as between 34% and 50%,1–5 which are well above the use patterns in non-psychotic populations of the same age. Continued use following the onset of psychosis is associated with poorer individual outcomes and greater societal burdens. Hazards include delays in remission, suicidal behaviour, violence and homelessness. 1,5–11 In longitudinal studies in first-episode psychosis, cannabis use is associated with substantially higher relapse rates. 9 An Australian study reported a 51% relapse rate over 15 months’ follow-up among substance users (mostly of cannabis) compared with a 17% relapse rate among non-users;12 this was accompanied by a threefold difference in inpatient admission rates. Similarly, a Dutch study reported a 42% relapse rate among persistent cannabis users compared with a 17% relapse rate among those who had never used cannabis or stopped around the time of first onset. 6 A dose–response relationship between the severity of cannabis misuse and the time to relapse was also reported in this study. 6 The type of cannabis used may also be important. In a study of 410 first-episode psychosis patients in south London, users of skunk, a particularly potent form of cannabis, were approximately three times more likely to experience a future psychotic episode than non-users, with daily skunk use associated with a more than fivefold increase in risk. 13

There are substantial consequences for service use and costs, as well as for clinical course. Studies of comorbid substance misuse among people with established psychosis indicate that people who persist in problematic drug use are heavy users of acute mental health services, are more likely to engage in acts of violence than others with psychotic illness and are less likely to work, sometimes using disability benefits to sustain drug use. 5,12,14–16

Thus, if a reduction in cannabis use can be achieved very early in the course of a psychotic illness, this has the potential to improve the illness course, life chances and social recovery of young people who develop psychosis and to reduce the burden on carers, mental health services, criminal justice and welfare services and wider society over many years. This is the overall aim of the current study. Systematic reviews have found that the evidence on effective interventions for comorbid substance misuse in established psychosis is very limited, with interventions tending to have little effect. 17–19 Despite a promising pilot study,20 a large Medical Research Council-funded trial, the MIDAS (Motivational Interventions for Drugs & Alcohol misuse in Schizophrenia) study, showed no effect on primary or secondary outcomes from a relatively lengthy intervention (29 sessions over 9 months) consisting of motivational interviewing (MI) and cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT). The difficulties of intervening effectively in established psychosis suggest that it may be fruitful to target an earlier stage of illness when, according to several recent studies, patterns of use are in a state of substantial flux. 21,22 Many people are ambivalent about persisting with cannabis use and have substantial motivation for change, although some who initially abstain soon return to use. 23 This contrasts with the very limited motivation for change found in established psychosis,24 so that early psychosis may well be a stage at which achieving change with a relatively brief intervention is more feasible. However, in a similar study25 to the MIDAS trial, a MI and CBT intervention was trialled for cannabis with Early Intervention in Psychosis (EIP) service users, also over 9 months (24 sessions), and again found no benefit of the intervention compared with treatment as usual (TAU).

The very limited benefits achieved from psychological interventions such as MI and CBT in comorbid substance misuse in psychosis have made us look elsewhere for an effective intervention. Contingency management (CM) is an approach that involves offering rewards contingent on engagement in substance use treatment and on evidence of abstinence. CM has now accumulated a robust evidence base in a variety of contexts, including smoking cessation,26,27 heavy drinking28 and drug misuse29–35 and, in a fairly recent trial of a 12-week CM intervention, it was found to be clinically effective and cost-effective in reducing stimulant misuse in a cohort of patients with severe mental illness. 36 Furthermore, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has recommended that it be adopted in the UK. 37 However, with the exception of a small number of recent evaluative studies in Europe,38 the evidence base is drawn almost entirely from the USA. There is relatively little UK experience of using CM, with only a few evaluations of CM reported. Recent examples include the CONMAN trial, which provided an evidence base for CM in uptake of hepatitis B vaccines among opiate users,39 and the FIAT trial, which found incentives to be effective in reinforcing adherence to antipsychotic medication. 40 The NICE review of psychosocial interventions37 identified 14 trials of CM (all from the USA) that met the criteria for inclusion, which included cannabis use. A consistent finding of a benefit from CM was reported, with most studies using abstinence at 12 weeks as their outcome measure. Just one North American CM study has so far been reported among people with comorbid substance misuse and psychosis. 41 The substances included were cocaine, heroin and cannabis. This was unusual among treatment studies in this population in finding a positive effect. Bellack et al. 41 reported that CM, combined with a psychological intervention, resulted in more drug-free urines than an enhanced TAU intervention (Supportive Treatment for Addiction Recovery) and resulted in reduced hospitalisation and a better quality of life. However, only a small proportion of participants abused cannabis (7%), with 93% abusing cocaine or heroin. Sigmon et al. 42,43 performed two small feasibility studies using a within-subjects reversal design that also reported a beneficial effect from the intervention. We have found no other evidence of CM studies for cannabis use in a population with psychosis.

In the present study, we investigated the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of CM for reducing cannabis use among EIP service users. This was evaluated in terms of clinical service use, presence of psychotic symptoms, cannabis use and health economic measures. The primary outcome was whether or not CM improves time to relapse, measured as admission to acute mental health services, compared with recommended standard care. Our overall objectives were as follows:

-

To conduct an internal pilot study of a specific intervention based on CM for cannabis use in early psychosis, acquiring evidence regarding rates of recruitment and follow-up, as well as feasibility and acceptability of the intervention in an Early Intervention Service context.

-

If pilot trial criteria for recruitment and retention were met, to proceed with a full multicentre pragmatic randomised controlled trial (RCT), testing whether or not the intervention results in an increase in time to relapse compared with a control arm. Both the CM arm and the control arm were to receive an optimised form of EIP TAU for cannabis, involving delivery by care co-ordinators of a standardised psychoeducation package.

-

To test whether or not the intervention results in an increase in the time to relapse, a decrease in cannabis use, a decrease in positive psychotic symptoms, and an increase in participation in work or education when compared with the control arm.

-

To assess the cost-effectiveness of the intervention from a NHS perspective.

Chapter 2 Methods

Overall design

The CIRCLE (Contingency Intervention for Reduction of Cannabis in Early Psychosis) trial was a rater-blind, multicentre RCT with two arms. The CM arm received a 12-week CM intervention, as well as a manualised psychoeducation intervention delivered by clinical staff, which represents an optimised version of TAU offered by EIPs in the management of cannabis misuse. The control arm received TAU only. Assessments were performed at the time of consent, at 12 weeks following trial inclusion (at the end of the intervention period) and at 18 months following trial inclusion. The primary outcome was time to relapse, operationalised as an admission to an acute mental health service. A Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT) diagram for the trial is shown in Table 1. An initial internal pilot was successfully completed to demonstrate the feasibility of recruitment and of delivering the interventions. Subsequently, the main phase of the trial was approved and received ethics approval in amendment version 4 (approved on 23 July 2013).

| Time point | Enrolment | Allocation | Study period | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post allocation | Close-out | |||||||

| –t 1 | 0 | Week 1 | Week 2 | Week 3 | Week... | Week 12 | 18 months | |

| Enrolment | ||||||||

| Screened for eligibility | ✗ | |||||||

| Informed consent | ✗ | |||||||

| Allocation | ✗ | |||||||

| Interventions | ||||||||

| CM – CM arm only | ↔ | |||||||

| OTAU – CM and control arms | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| Assessments | ||||||||

| Demographics | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| EQ-5D | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| PANSS | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| SF-12 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| SCID (Part E) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| CSRI | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| TLFB | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| Urinalysis for cannabis (not part of CM intervention) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| Acute admissions data recorded from patient notes | ✗ | |||||||

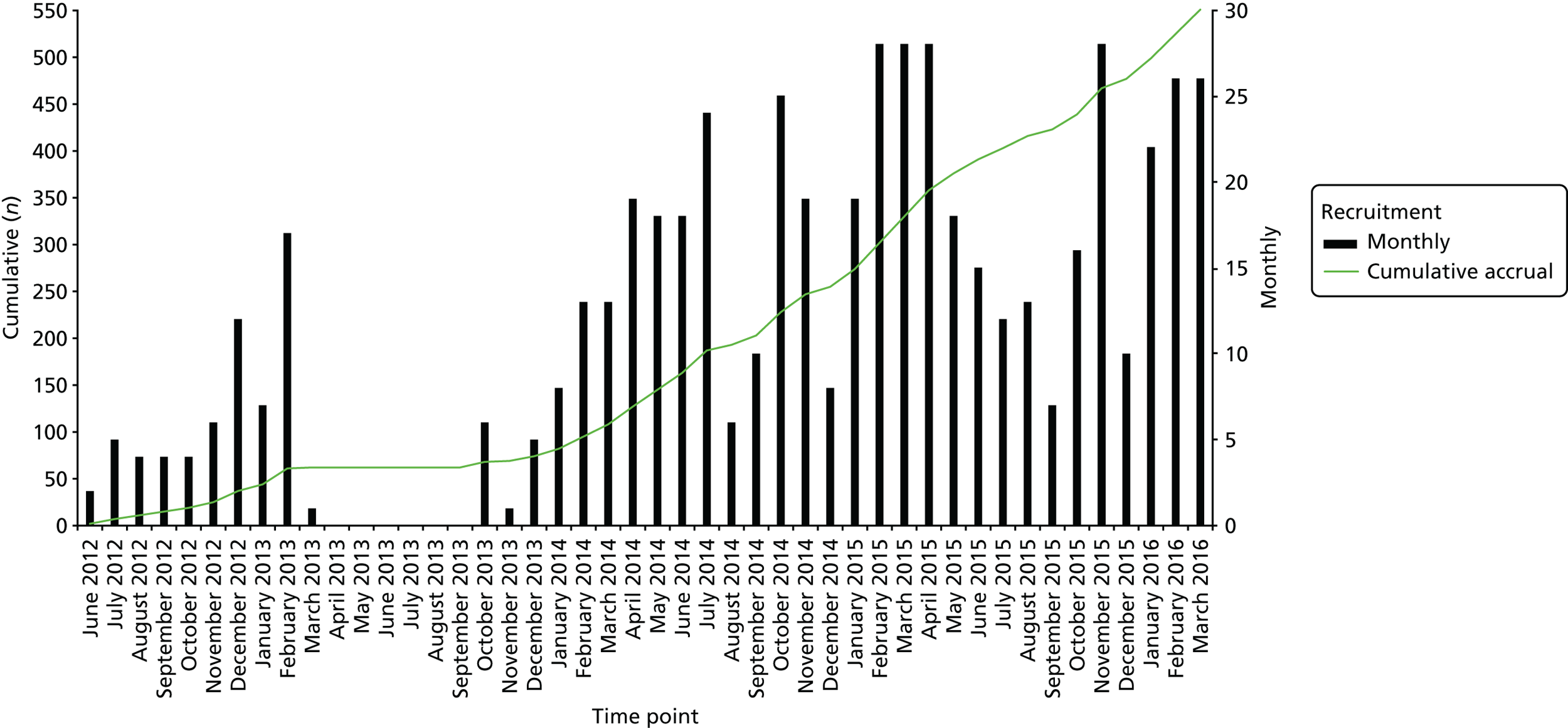

Setting

Participants were recruited to the trial via EIP services throughout the Midlands and the south-east of England. Sites were added to the trial until the recruitment target (n = 544) was achieved. A total of 70 teams from 23 NHS trusts took part in the trial, representing a range of geographical and demographic characteristics. Willingness to participate and proximity to trial centres drove site selection, with almost all sites that were approached agreeing to participate.

Participants

The following inclusion and exclusion criteria were used to identify participants.

Inclusion criteria

The cohort was EIP service users with recent cannabis use. Recent cannabis use was operationalised as having used cannabis at least once during 12 of the previous 24 weeks. Additional eligibility criteria included (1) being aged 18–36 years, (2) having stable accommodation (i.e. not street homeless or roofless), (3) speaking enough English to be able to understand fully and answer the assessment instruments and (4) being able to give informed consent to participate in the trial.

Early Intervention in Psychosis teams have been set up across England following the 2000 NHS Plan. 45 Standard criteria for EIP include developing symptoms of psychotic illness for the first time, with positive psychotic symptoms persisting for at least 1 week and being accompanied by evidence of significant risk and/or functional decline. Service users are typically discharged after 3 years on the caseload of an EIP team. At the start of the pilot study, EIP service users needed to be recruited within the first 2 years of entry to the EIP service. This was changed with substantial amendment 2 (dated 15 June 2012, approved on 5 July 2012) and in protocol version 3 (dated 15 December 2012) to include all EIP service users. This was very early on in the pilot phase of the trial and was an expansion of the eligibility criteria, and so all participants who were already recruited were still eligible for the trial. Second, following the pilot, the eligibility criteria were changed to explicitly exclude patients who required to receive drug testing as part of a community treatment order or probation. This was because of such conditions potentially biasing the results of the intervention or interfering with the way the intervention was delivered. In fact, we had not recruited such participants during the pilot study and, therefore, this change should not affect the trial results. This change was approved in substantial amendment 4 (dated 23 July 2013) and is contained in protocol version 5, dated 17 June 2013.

Exclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria included (1) those who failed EIP service inclusion criteria, (2) those currently engaged in treatment for cannabis use with another agency, (3) those currently compulsorily detained in hospital or prison and (4) those on probation or a community treatment order requiring drug testing for cannabis.

Measures and research data collection

Trial assessors

The trial research workers performed assessments of outcome. Primary outcome assessors were blinded to randomised allocation. Secondary outcome assessors were blinded at the 18-month assessment interview. Research staff were trained in the use of all measures by members of the CIRCLE trial team. Joint ratings with one another and with senior members of the team supervising them were used to establish reliability.

Obtaining informed consent

In the first instance, an EIP staff member obtained agreement from service users to be contacted by a member of the CIRCLE trial research team. If agreement was obtained, a researcher then met with the service user to provide a participant information sheet that was written in plain English and explained all aspects of the trial. The researcher also explained verbally all benefits of the trial and known risks, and service users’ understanding was checked. If the service user was happy to discuss such details with the researcher, eligibility for the trial was also considered. However, eligibility was confirmed for all service users at the baseline interview assessment following consent. The service user was then given at least 48 hours to consider participation prior to consent being taken. Once consent had been obtained, the baseline interview assessment was performed.

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was time to relapse. Admission to a psychiatric hospital, crisis resolution team or crisis house, or other acute mental health service intended as an equivalent to hospital was used as a proxy marker of relapse. The primary outcome was assessed at 18-month follow-up based on the electronic patient records. The dates of admission were recorded and participants were followed up until the end of the 18-month trial period unless they were lost to follow-up.

Assessment interviews

Participants received three assessment interviews: at the time of consent, at 12 weeks following consent and at 18 months following consent (a time at which a significant proportion of young persons with psychosis will have relapsed if they are going to do so). 46,47 Participants were given a £20 voucher to thank them for their time at the baseline assessment, and at the follow-up assessment participants received an extra £10 for the provision of a urine sample. At 18 months, the primary outcome data and some secondary outcome data were collected from electronic patient records.

Outcome measures at interview

At all assessment interviews, data were collected on the following measures:

-

Demographic and social information –

-

Demographic information included age, sex, ethnicity, education, living arrangements, employment and any state benefits currently being received. Details of the most recent diagnosis recorded in a participant’s patient records were also documented.

-

-

Cannabis use –

-

The timeline followback (TLFB)48 method was used to record self-reported cannabis use over the previous 6 months at baseline and 18 months, and for the previous 3 months at the 3-month follow-up assessment interview. The TLFB method is a retrospective, calendar-based measure of daily substance use, with good test–retest reliability demonstrated for cannabis. 49 This was used to establish eligibility in terms of cannabis use and extent of recent use.

-

The Structured Clinical Interview for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, (SCID), part E, was used to evaluate a participant’s history of alcohol and substance misuse disorders.

-

Specimens for urinalysis were obtained, with the threshold set at a level for detecting cannabis use in the previous 28 days (i.e. 50 ng/ml of cannabis metabolites).

-

-

Psychotic symptoms –

-

Service use and health economic analysis –

-

The Client Service Receipt Inventory (CSRI) developed originally by Beecham and Knapp52 was used to record clinical service use, medication use, receipt of state welfare and use of other state-funded services, including criminal justice services. Data were collected for the previous 6 months at baseline and 18 months, and for the preceding 3 months at the 3-month follow-up assessment interview. At 18 months, to minimise loss to follow-up, data were collected from patient records for a subset of the resources deemed most likely to contribute to higher costs and that could feasibly be collected. This was performed at the same time as data collection for the primary outcome.

-

The Short Form questionnaire-12 items (SF-12)53 and the EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D)54 are the widely used measures of health status with good psychometric properties55,56 that were used to derive quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs).

-

Details of a participant’s referral to the EIP service, history of admission to acute mental health services and time spent on a community treatment order were recorded on the demographics form.

-

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes included between-group differences at follow-up for:

-

positive symptom severity, measured by the total score on the PANSS50

-

social functioning, based on self-reports of engagement in work or study

-

number of days of cannabis use in the previous 12 weeks (for 12-week follow-up) or 6 months (for 18-month follow-up) based on the TLFB method

-

proportion of cannabis-free urines

-

number of admissions over 18 months’ follow-up

-

QALYs (SF-12 and EQ-5D)57 and service use (CSRI) were used in the cost-effectiveness analyses, as described in Health economic analyses. Service-utilisation data were augmented when possible from participants’ medical records at 18 months.

Trial processes and interventions

Group allocation

Following pre-trial assessments, consenting clients were randomised to a group with a 1 : 1 ratio, stratified on severity of cannabis use (1–3 uses per week, > 3 uses per week). A remote, impartial randomisation service managed the allocation to groups co-ordinated by Priment Clinical Trials Unit based at University College London.

Interventions

The optimised treatment-as-usual (OTAU) package was the context in which we assessed the impact of the CM intervention. The CM intervention involved the offer of voucher rewards for cannabis-free urines over 12 weeks to recent cannabis users with early psychosis. We first describe OTAU, which was delivered to both the CM arm and the control arm, and then the CM intervention to be received by the CM arm only.

Optimised treatment as usual (psychoeducation package)

Our accounts of the interventions include text reproduced from Johnson et al. 44 This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

To be confident that we measured the effects of CM, a psychoeducation intervention was delivered to both the CM arm and the control arm with the aim of achieving currently agreed good practice across both the CM arm and the control arm. Guidelines on EIP care recommends that psychoeducation interventions for cannabis should be an important component of routine care, but consultations with EIP managers and staff suggest that this is not often realised in practice, and we did not find routinely used resources for delivering such interventions. Our aim was to create a standardised version of good-quality psychoeducation to be delivered by staff working in EIP teams who were recruiting to the trial. A training manual for delivering the package, and supporting materials, were provided by the research team to clinicians delivering TAU. The intervention was designed to be sufficiently highly structured for staff without high-level clinical qualifications, such as support workers or assistant psychologists, to be able to deliver it competently following brief training.

The TAU was designed to be an individually tailored psychoeducation approach to cannabis use for generic EIP clinicians, which applies general psychoeducation approaches used in first-episode psychosis. 58 The psychoeducation package was developed by the research team through an iterative process, with frequent input from service users. It drew on the psychoeducation package offered in the control arm of a previous Melbourne pilot study of psychological intervention for cannabis use, the Cannabis and Psychosis trial;59 however, it was a novel package developed for this trial. The package comprised six modules that were delivered via a standard personal computer or laptop. Full delivery of all six modules was intended to take approximately 3 hours, normally offered over six regularly programmed sessions of 30 minutes’ duration. The package included a Portable Document Format (PDF) package for clinicians to work through with their clients, which presents information regarding the effects of cannabis, and motivational materials and strategies for harm reduction or for abstaining from cannabis. The package also included video materials, short quizzes, audio files and further information and written records of the modules for the service user to keep. The primary goal of the materials was to deliver information to meet psychoeducation goals, not to act as a psychological intervention. The clinician’s main aim was harm minimisation, with an acknowledgement that, in a young person with psychosis, cannabis abstinence may be required to ensure that no harm is done. The content was based on MI principles, relapse prevention and harm reduction strategies.

The psychoeducation package presented current information on the potential advantages and disadvantages of cannabis use and of cannabis abstinence. To help the participant to make an informed decision about continued use, EIP staff discussed the positives and negatives of cannabis use by exploring its impact on seven areas: family, finance, activity/engagement in work or education, mental health, physical health, legality and social group/friendships. Finally, staff discussed setting goals regarding the young person’s future use of cannabis in the context of harm minimisation, as well as strategies for achieving their goals and avoiding relapse into patterns of cannabis use that compromise those goals.

Contingency management

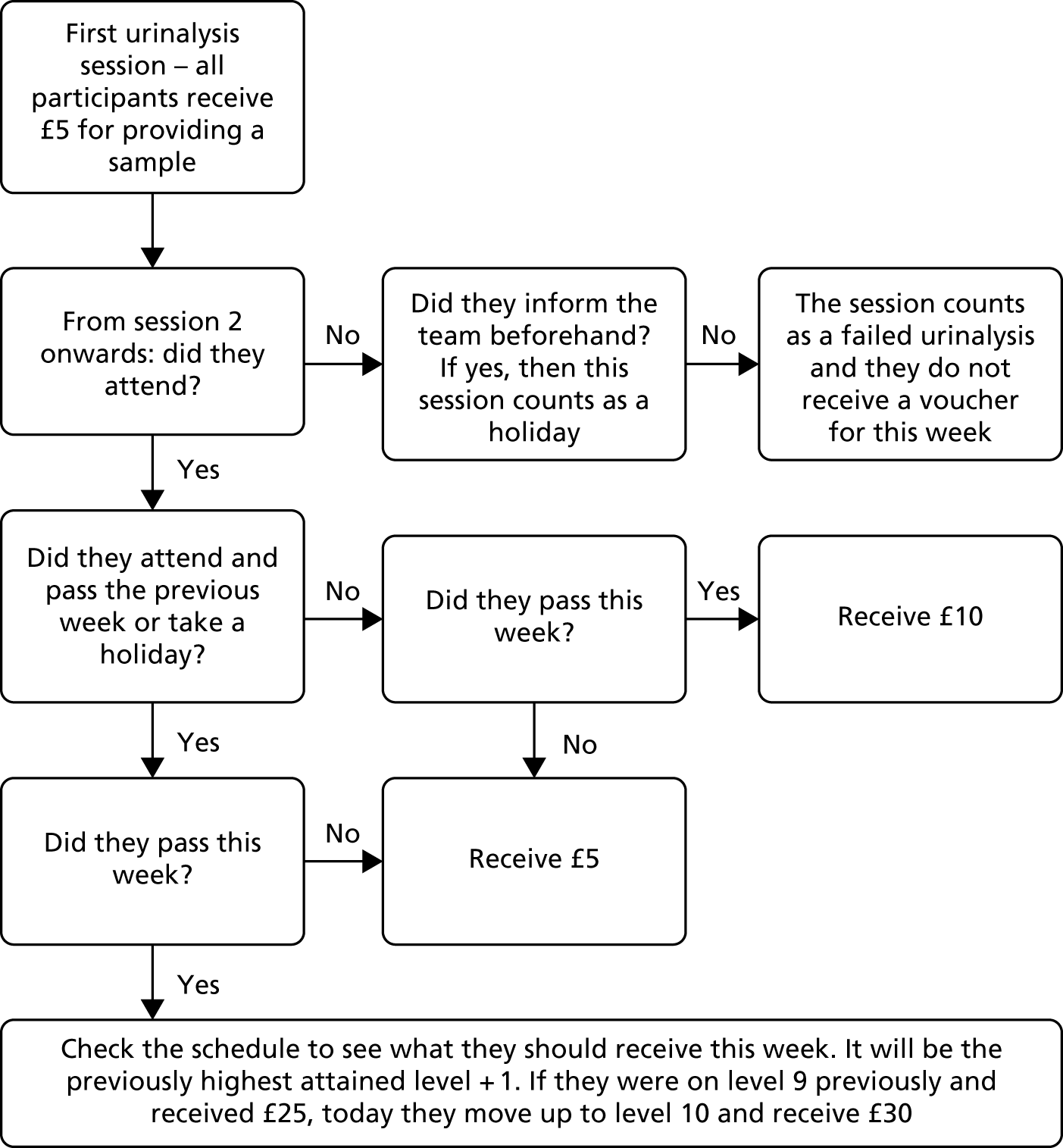

The CM intervention offered financial incentives contingent on urinalysis results indicating cannabis abstinence. The intervention voucher schedule and rules were adapted from Budney et al. ,60,61 who offered a voucher-based CM intervention for the treatment of cannabis dependence in the general population. The intervention comprised 12 once-weekly urinalysis sessions and was delivered by clinicians supported by the CIRCLE trial research team. At each session, the participant was required to provide a urine sample.

In week 1 of the intervention, details of the intervention were explained to the participant and they were asked to sign an ‘abstinence contract’ indicating that they understood and accepted its rules, and agreed to abide by the test results. In the first week, participants received a £5 voucher for attending and providing a urine specimen, independent of the drug test results, which provided a ‘baseline’ result. From week 2 to week 12, participants were rewarded if their urinalysis results demonstrated abstinence from cannabis use. In the pilot, the value of vouchers increased by £2 each week, contingent on consecutive negative specimens. A bonus voucher to the value of £10 was earned each time two consecutive specimens suggesting abstinence were provided. However, based on feedback from clinicians and participants gained during the qualitative substudy, changes were made to this reward schedule between the pilot and the main trial to simplify it. In the main trial, from week 2 to week 12, assuming participants provided negative samples, the voucher value rose every 2 weeks by £5. No bonus voucher was offered for passing consecutive weeks. In both the pilot and the main trial, participants who abstained from cannabis use for the full duration of the intervention earned £240 (Table 2). This change to the reward schedule made it easier for clinicians to administer and easier for clinicians and participants to understand. Removing the bonus for two consecutive clean urines made it simpler for participants and clinicians to know what reward a participant should receive for passing. In addition, the new reward schedule meant clinicians needed to stock fewer denominations of vouchers. This change to the intervention was included in the trial protocol version 5 (dated 17 June 2013), approved in substantial amendment 4 (approved 23 July 2013).

| Number of negative urines | Reward (£) |

|---|---|

| 1. Attending session | 5 |

| 2. Negative urine | 10 |

| 3. Negative urine | 10 |

| 4. Negative urine | 15 |

| 5. Negative urine | 15 |

| 6. Negative urine | 20 |

| 7. Negative urine | 20 |

| 8. Negative urine | 25 |

| 9. Negative urine | 25 |

| 10. Negative urine | 30 |

| 11. Negative urine | 30 |

| 12. Negative urine | 35 |

Failure to attend intervention sessions, specimens suggesting cannabis use or failure to submit a scheduled specimen reset the value of vouchers back to the initial £5. If the participant attended the following week and provided a negative sample, they were rewarded with £10. In the subsequent week, if the participant provided a second consecutive negative sample, the voucher values resumed from the highest previous level of reward. Vouchers were for major supermarkets, including Tesco (Welwyn Garden City, UK), Sainsbury’s (London, UK) and Asda (Leeds, UK), depending on a participant’s preference. They could be swapped in store for other shop vouchers, if preferred.

Urinalysis was performed using a small bench-top analyser (Kaiwood CHR-110; Kaiwood Technology Co. Ltd, Hsin-Shi, Taiwan) capable of providing rapid test results of drug misuse via the concentration of the drug in a urine sample. To perform the analysis, the clinician pipetted a fixed amount of urine into a buffer solution tube to give a 7 : 1 serial dilution. This allowed a standard 50 ng/ml marijuana test cassette placed in the analyser to provide a urine cannabis concentration reading of between 0 ng/ml and 350 ng/ml. Guidelines were provided to all staff delivering the intervention to allow interpretation of the test results. The guidelines set out upper and lower thresholds for urinary tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) based on recommendations from the suppliers of the urinalysis equipment, SureScreen Diagnostics (Derby, UK). Results greater than the upper threshold (350 ng/ml) clearly indicated use within the last week, and so participants with these results were not rewarded. Results below the lower threshold indicated urinary THC concentration of < 50 ng/ml, the accepted standard for detecting urinary THC; participants with these results were rewarded. Within these thresholds, urinary THC was expected to fall each week until it reached the lower THC threshold, which should be reached within 1 month. A participant with a drop in urinary THC would receive the reward. A participant with a result similar to, or higher than, the previous week would fail. A temperature strip on the side of the specimen cup allowed staff to check whether or not the sample had been tampered with.

Participants could arrange in advance to miss scheduled sessions (‘holiday week’) and still receive the reward for that week if they had a valid commitment that prevented them from attending. They could do this on a maximum of two occasions for 1 week only each time. They were still expected to show evidence of abstinence at the following session to receive a reward for the holiday week. If a participant missed the following week or provided a positive sample, no financial incentive was received for the holiday week. Holiday weeks normally needed to be arranged with the clinician performing the intervention no later than at the previous scheduled appointment. However, a dispensation of this rule was offered for unforeseeable events, such as illness, transport problems or being offered a work shift. The intervention was suspended for a maximum of 1 month if a participant relapsed or otherwise lost capacity to consent to participate. If capacity was not regained in 1 month, the intervention did not continue. If a participant failed to attend on multiple consecutive weeks or if contact was lost with the participant entirely, each missed week was counted as a failure to attend. Figure 1 is a decision flow chart for the CM intervention.

FIGURE 1.

Decision flow chart for the CM intervention.

Selection and training of staff

Clinicians delivered the CM and TAU interventions, supported by the research team. Training was given to all staff delivering the interventions by members of the research team over a period of half a day face to face, together with the provision of training material and manuals.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval for the trial was received on 16 March 2012 from the National Research Ethics Service Committee London – South East (Research Ethics Committee reference number 11/LO/1939). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants in the trial. The original consent forms are stored at the collaborating universities (University College London, King’s College London, the University of Sussex, and the University of Warwick) and copies were kept in the patients’ clinical notes. Data were also stored at the collaborating universities.

Sample size

The proposed sample size for the trial was 544 participants. This figure was based on data suggesting a usual relapse rate for cannabis users of around 50% over the trial time frame. 6,12 A 15% decrease in this relapse rate as a result of the intervention was agreed to be of substantial clinical benefit. Using a power of 90% and a significance level of 5%, a total sample size of 460 participants was estimated to be required. This sample size was based on an analysis of time to relapse and would allow detection of a 37% decrease in the hazard of relapse [hazard ratio (HR) of 0.63] in the CM arm using a Cox proportional hazards model. This sample size was calculated using Stata® version 11 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). The sample size was inflated by a factor of 1.06, assuming that each person delivering the intervention sees an average of four service user participants in the trial, and an intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.02 for clinician clustering, which gives a total sample size of 488 participants. Finally, the sample size was inflated by 10% to account for attrition for the primary outcome, giving a total sample size of 544 participants.

Statistical methods

All analyses were carried out by the treatment allocated, using all available data (complete case).

The continuous variables were summarised using mean [standard deviation (SD)] or median [interquartile range (IQR)]. Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages.

Clustering by psychoeducation clinician was accounted for in all modelling. Those participants who declined psychoeducation or for whom the psychoeducation clinician was not known were assigned to a cluster of one (i.e. just that participant). Unadjusted ICCs were calculated for all outcomes except the primary outcome because estimation of the ICC for a survival outcome is not straightforward. 62 We estimated approximate ICCs using log-transformed observed event times and also by using the censoring indicator and treating the outcome as binary. We also obtained an approximate estimate of the correlation by fitting marginal generalised estimating equation models.

Logistic regression was used to determine whether or not those who had no secondary outcome data available at 3 months, 18 months or both had different baseline characteristics to those who remained in the trial. This was repeated for each outcome to determine baseline predictors of missingness.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves by randomised groups were used to examine the primary outcome (time to relapse) descriptively. Cox proportional hazards modelling was used to compare the CM arm and the control arm, adjusting for severity of cannabis use (the stratification variable; 1–3 times per week vs. ≥ 4 times per week) at baseline and whether or not the participant was part of the pilot trial. We carried out a number of supportive analyses for the primary outcome:

-

including significant baseline predictors of missingness

-

excluding those participants who have no secondary outcome data (for 12 weeks and 18 months separately) because those who drop out or die may be different from those who remain in the trial and/or survive

-

including those in the main trial only as some minor changes were made to the protocol at the end of the pilot before the main trial commenced, which might mean that the participants behave differently to those in the pilot trial

-

controlling additionally for the number of psychoeducation sessions attended (which was offered in both arms of the trial)

-

controlling additionally for the number of admissions in the 6 months prior to baseline

-

controlling for the same factors as the primary analysis, but using centre as the clustering variable instead of therapist.

Secondary outcomes were analysed separately at 3 and 18 months. Models were adjusted for severity of cannabis use at baseline and whether or not the participant was part of the pilot trial. For the dichotomous outcomes (cannabis-positive urine, engaged in work or study), logistic regression was used. The continuous outcomes (positive and negative symptoms from PANSS), had non-normal residuals and were, therefore, log-transformed and analysed using linear regression models. For count outcomes (number of cannabis days and number of admissions over follow-up), zero inflated Poisson was applied regression as there were excess zeros in all of these outcomes, except number of cannabis days at 12 weeks which utilised Poisson regression. As with other models, these controlled for severity of cannabis use at baseline and whether or not participants were part of the pilot trial.

All secondary outcomes were also analysed after adjusting for predictors of missingness. An additional supportive analysis compared the number of admissions between trial groups. The analysis included participants who were discharged from psychiatric services within the 18-month follow-up and assumed participants did not have any admissions beyond 18 months.

Robust standard errors63 were used in all regression models to account for clustering of participants by psychoeducation clinician.

Results from all supportive and secondary analyses are presented as estimates and 95% confidence intervals (CIs), as specified in the statistical analysis plan. No p-values are presented to avoid the problem of multiple significance testing. All analyses were carried out using Stata® version 14 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Health economic analyses

The objective of the cost-effectiveness analysis was to establish the relative cost-effectiveness of CM versus OTAU at 18 months. The primary outcome was QALYs, calculated using the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, three-level version (EQ-5D-3L), health profiles combined with health-state preference values from the UK general population. The resultant mean quality-of-life utility scores of the two treatment groups were compared at 18 months using unpaired t-tests. QALYs were calculated using the area under the curve method and compared between groups, adjusting for baseline EQ-5D utility scores.

Costs were calculated based on resource use gathered from an adapted version of the CSRI. The primary analysis will take a NHS and Personal Social Services perspective.

Costs of the CM intervention and OTAU were calculated using the salaries of staff delivering the intervention, plus employer oncosts, overhead costs, the cost of providers of supervision and the cost of any equipment or consumables. A ratio of direct, face-to-face time to indirect, non-face-to-face time was applied.

Total costs at 18 months were calculated by combining resource use with unit costs at 2016 prices. Unit costs were derived from the Personal Social Services Research Unit64 and from NHS reference costs. 65 Medications were costed using NHS prescription cost analysis data. Costs and QALYs were discounted at 3.5% per year.

Costs were compared, adjusting for baseline differences. Patient-level costs and quality-of-life data were bootstrapped with replacement (n = 10,000) to populate incremental cost-effectiveness (ICER) planes, to estimate median cost-effectiveness and (pseudo) 95% CIs. The probabilities of the intervention being cost-effective at different levels of willingness to pay for health benefits were shown by generating cost-effectiveness acceptability curves. Productivity losses were calculated using a human capital approach,66 in which each day off work was valued using information on average salaries from the Office for National Statistics (2018). 67

No subgroup health economics analyses were planned. The Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) statement was completed.

Additional health economics analyses:

-

Cost-effectiveness at 3 months was reported.

-

Results from a broader perspective, including costs from criminal justice and cost of unpaid lost productivity because of illness, were reported.

-

Cost-effectiveness using alternative outcomes were reported –

-

QALYs calculated using the SF-12 data

-

time to relapse (to 18 months)

-

number of cannabis-negative urine samples

-

days of reported cannabis abstinence.

-

-

Missing data in baseline resource use, quality of life and other covariates were handled with multiple imputation using chained equations, using guidelines from Gabrio et al. 68 In line with primary outcomes analysis, the base case was a complete-case analysis.

Qualitative substudy

Following the pilot phase of the trial, a qualitative substudy was performed to inform the main trial by exploring the acceptability and feasibility of the trial design and interventions from the perspectives of both participants and clinicians. The full text of the trial design and results can be found in Appendix 3 and was included in version 1 of the trial protocol (24 October 2011). Following the main trial, further qualitative interviews were performed that were included in protocol version 7 (16 August 2016) and approved in substantial amendment 6 (approval received 22 November 2016). The results of that second qualitative data collection are still forthcoming. In the post-pilot qualitative data collection, data were collected from three groups: one-to-one interviews with 11 participants in the intervention arm, five focus groups with clinicians in EIP teams participating in the CIRCLE trial and one carer of a participant in the intervention arm. Results showed that the intervention had good acceptability among all groups, and all three groups viewed it positively. Participants described it as helpful and beneficial, and said that they would recommend it to others. Recommended changes to trial procedures that emerged from the focus groups with EIP staff included (1) simplifying the CM reward schedule; (2) adding a temperature strip to sample cups to prevent participants submitting adulterated urine samples; and (3) having a dedicated EIP team member to deliver the intervention rather than care co-ordinators, such as a support worker/assistant psychologist. As previously mentioned, these recommendations were adopted ahead of the main trial.

Chapter 3 Results

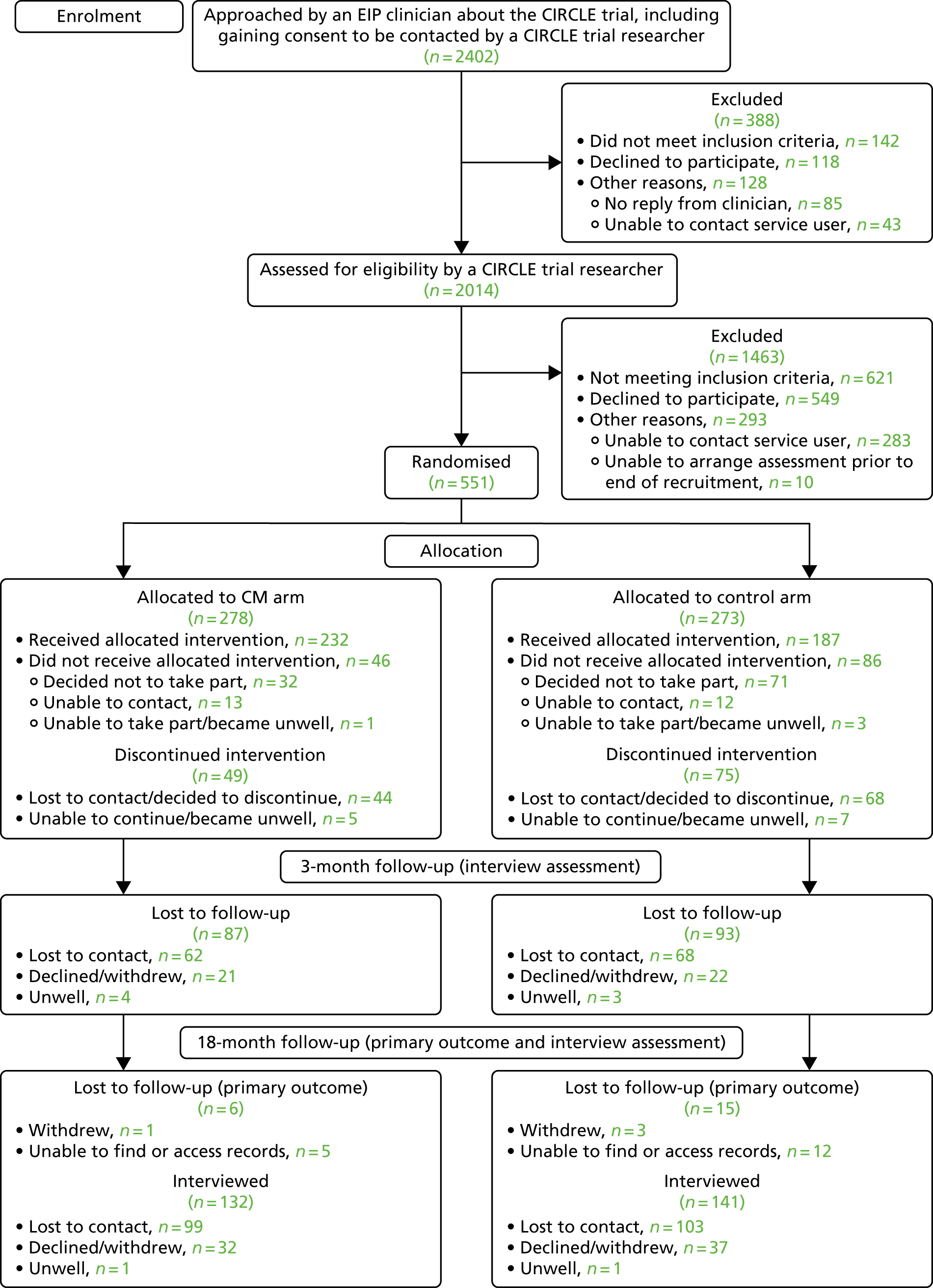

A Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT)69 flow diagram (Figure 2) shows the number of service users randomised to each arm of the trial and the numbers who have follow-up data available.

FIGURE 2.

The CONSORT flow diagram.

Demographics

The EIP clinicians reported that they had approached 2402 service users to inform them of the trial and seek consent to being contacted by a CIRCLE trial researcher. Following this, initial meetings were held with 2014 service users by the CIRCLE trial researchers, during which the trial was fully explained to potential participants. A total of 551 service users gave informed consent to participate and were then assessed and randomised into the trial.

Table 3 presents baseline characteristics of study participants. More than 85% of participants were male in both randomised arms, with a mean age of aound 25 years (SD 4 years) in both arms. More than half of participants were white and one-quarter were black. A total of 43% of each arm lived with their parents; only 5% of control and 6% of CM arm participants were married or cohabiting. Around one-third of participants were diagnosed with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder and half had other types of psychosis. In many participating services, clinicians had significant reservations about making use of schizophrenia as a diagnostic category. One-quarter of participants were engaged in ‘any work or study’ but a large majority had held open-market employment at some point, understood as work that the employee has applied for through an open job market.

| Characteristic | Randomised group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | CM | |||

| n/N or mean | % or (SD) | n/N or mean | % or (SD) | |

| Male | 240/273 | 88 | 238/278 | 86 |

| Age (years) | 25 | (4) | 24 | (4) |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| White British, European or other | 144/273 | 53 | 148/277 | 53 |

| Black Caribbean, African or British | 62/273 | 23 | 65/277 | 23 |

| Asian | 30/273 | 11 | 29/277 | 10 |

| Other | 37/273 | 14 | 35/277 | 13 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 253/273 | 93 | 259/278 | 93 |

| Married or cohabiting | 14/273 | 5 | 17/278 | 6 |

| Other | 6/273 | 2 | 2/278 | 1 |

| Educational attainment | ||||

| No qualifications | 48/273 | 18 | 43/277 | 16 |

| GCSE or equivalent | 104/273 | 38 | 133/277 | 48 |

| A level or equivalent | 67/273 | 25 | 58/277 | 21 |

| Post 18 education (including HND, trade, degree) | 54/273 | 20 | 43/277 | 16 |

| Living arrangements | ||||

| Alone | 73/273 | 27 | 73/278 | 26 |

| With parents | 117/273 | 43 | 119/278 | 43 |

| With other adults (only) | 70/273 | 26 | 69/278 | 25 |

| Other | 13/273 | 5 | 17/278 | 6 |

| Housing | ||||

| Independent permanent accommodation | 179/272 | 66 | 184/276 | 67 |

| Independent temporary accommodation | 29/272 | 11 | 27/276 | 10 |

| Supported accommodation | 44/272 | 16 | 44/276 | 16 |

| Other | 20/272 | 7 | 21/276 | 8 |

| Work or study | ||||

| Ever had open-market employment | 223/273 | 82 | 240/278 | 86 |

| Ever kept open-market employment for 1 year | 114/269 | 42 | 128/277 | 46 |

| Had open-market job since first contact with services | 67/272 | 25 | 83/278 | 30 |

| Current paid activity | 39/272 | 14 | 51/278 | 18 |

| Time since last open-market job (years), median (IQR) | 1 | (0.4–3) | 1 | (0.2–3) |

| Open-market full-time employment | 21/273 | 8 | 25/278 | 9 |

| Open-market part-time employment | 17/273 | 6 | 23/278 | 8 |

| Permitted work | 1/273 | 0.4 | 1/278 | 0.4 |

| Voluntary/unpaid work | 6/273 | 2 | 12/278 | 4 |

| Study or training | 38/273 | 14 | 30/278 | 11 |

| Full-time caring | 0/273 | 0 | 2/273 | 1 |

| Unemployed | 136/233 | 58 | 141/227 | 62 |

| Exempt because of disability | 70/271 | 26 | 65/278 | 23 |

| Any work or study | 67/273 | 25 | 73/278 | 26 |

| Benefits | ||||

| Income support | 28/272 | 10 | 30/276 | 11 |

| Incapacity benefit | 36/271 | 13 | 28/276 | 10 |

| DLA care component | 40/271 | 15 | 48/276 | 17 |

| DLA component | 14/271 | 5 | 19/276 | 7 |

| Personal independence payment | 15/270 | 6 | 18/276 | 7 |

| DLA or PIP | 60/272 | 22 | 74/276 | 27 |

| Severe disablement allowance | 3/270 | 1 | 1/275 | 0.4 |

| Council tax benefit | 22/271 | 8 | 26/276 | 9 |

| Housing benefit | 52/271 | 19 | 58/276 | 21 |

| Jobseekers’ allowance | 23/271 | 8 | 17/276 | 6 |

| Working tax credits | 4/271 | 1 | 2/276 | 1 |

| Statutory sick pay | 3/271 | 1 | 0/276 | 0 |

| Employment and support allowance | 102/272 | 38 | 125/275 | 45 |

| Other benefits | 18/271 | 7 | 11/275 | 4 |

| Diagnosis | ||||

| Schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder | 80/256 | 31 | 90/268 | 34 |

| Bipolar affective disorder | 26/256 | 10 | 19/268 | 7 |

| Depression with psychotic symptoms | 11/256 | 4 | 5/268 | 2 |

| Other psychosis | 139/256 | 54 | 154/268 | 57 |

| Alcohol abuse | 101/217 | 47 | 102/225 | 45 |

| Alcohol dependence | 67/187 | 36 | 60/189 | 32 |

| Cannabis use (previous 6 months) | ||||

| 1–3 times per week | 77/273 | 28 | 78/278 | 28 |

| > 3 times per week | 196/273 | 72 | 200/278 | 72 |

| Drugs taken (lifetime) | ||||

| Sedatives, hypnotics, anxiolytics | 39/273 | 14 | 26/277 | 9 |

| Stimulants | 69/273 | 25 | 72/277 | 26 |

| Opioids | 47/273 | 17 | 29/277 | 10 |

| Cocaine | 128/273 | 47 | 145/277 | 52 |

| Hallucinogens/PCP | 117/273 | 43 | 122/277 | 44 |

| Legal highs | 42/271 | 15 | 32/275 | 12 |

| Other | 56/273 | 21 | 40/277 | 14 |

| PANSS score, median (IQR) | ||||

| Positive symptoms | 12 | (9–17) | 13 | (9, 16) |

| Negative symptoms | 14 | (11, 19) | 14 | (10–19) |

| SF-12 score | ||||

| Physical | 52 | (10) | 52 | (10) |

| Mental | 37 | (16) | 38 | (14) |

| Number of, median (IQR) | ||||

| Days using cannabis in the previous 6 months | 108 | (67–156) | 114 | (70–162) |

| Admissions in the previous 6 months | 0 | (0–1) | 0 | (0–1) |

Most participants were using cannabis more than three times per week. The PANSS positive symptoms median scores were 12 (IQR 9–17) in the psychoeducation group and 13 (IQR 9–16) in the CM group. The PANSS negative symptoms median scores were 14 in both groups (see Table 5). The rates of alcohol misuse or dependence and of reports of using substances other than cannabis were high (e.g. 47% of the control arm and 52% of the CM arm members reported using cocaine; 36% of the control arm members and 32% of the CM arm members met the criteria for alcohol dependence).

At 3 months, demographics and outcome measures were compared alongside delivery of the intervention. At this point, among the sample participating in the interview, almost one-third of participants were engaged in work or study. A total of 72% in the psychoeducation group and 70% in the CM group had cannabis-positive urine, compared with 80% and 79% at baseline, respectively. The median PANSS positive symptom score was 11 (IQR 8–16) in the control arm and 10 (IQR 8–14) in the CM arm. For PANSS negative symptoms, the median scores were 14 (IQR 11–18) and 12 (IQR 9–17) for the psychoeducation and CM groups, respectively. The number of days using cannabis in the previous 3 months was slightly lower in the CM group than in the psychoeducation group. The median number of psychoeducation sessions attended was higher in the CM group than in the psychoeducation group [6 sessions (IQR 1–6) and 4 sessions (IQR 0–6), respectively] (Table 4). Participants in the CM and control arms attended a median of six sessions and four sessions, respectively, of the TAU psychoeducation intervention. However, 86 participants in the control arm declined the intervention or attended no sessions compared with 63 participants in the CM arm. A mean of £64 in voucher rewards was obtained in the CM treatment and the median number of CM sessions attended was 9 (IQR 3–12 sessions). A total of 46 participants declined the CM intervention, despite their initial consent to randomisation, or did not attend any sessions.

| Characteristic | Randomised group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | CM | |||

| n/N | % | n/N | % | |

| Educational attainment | ||||

| No qualifications | 28/182 | 15 | 23/189 | 12 |

| GCSE or equivalent | 63/182 | 35 | 84/189 | 44 |

| A level or equivalent | 40/182 | 22 | 38/189 | 20 |

| Post-18 education (including HND, trade, degree) | 51/182 | 28 | 44/189 | 23 |

| Living arrangements | ||||

| Alone | 60/182 | 33 | 59/189 | 31 |

| With parents | 76/182 | 42 | 79/189 | 42 |

| With other adults (only) | 39/182 | 21 | 39/189 | 21 |

| Other | 7/182 | 4 | 12/189 | 6 |

| Housing | ||||

| Independent permanent accommodation | 125/182 | 69 | 128/189 | 68 |

| Independent temporary accommodation | 15/182 | 8 | 16/189 | 8 |

| Supported accommodation | 29/182 | 16 | 27/189 | 14 |

| Other | 13/182 | 7 | 18/189 | 10 |

| Work or study | ||||

| Ever had open-market employment | 154/183 | 84 | 174/189 | 92 |

| Ever kept open-market employment for 1 year | 84/182 | 46 | 100/187 | 53 |

| Had open-market job since first contact with services | 53/183 | 29 | 73/189 | 39 |

| Current paid activity | 34/183 | 19 | 37/189 | 20 |

| Time since last open-market job (years), median (IQR) | 1.0 | (0.3–3.0) | 1.0 | (0.3–3.0) |

| Open-market full-time employment | 14/183 | 8 | 15/189 | 8 |

| Open-market part-time employment | 20/183 | 11 | 20/189 | 11 |

| Sheltered work | 0/183 | 0 | 1/189 | 0.5 |

| Permitted work | 0/183 | 0 | 2/189 | 1 |

| Voluntary/unpaid work | 5/183 | 3 | 8/189 | 4 |

| Study or training | 31/183 | 17 | 25/189 | 13 |

| Full-time caring | 0/183 | 0 | 1/189 | 0.5 |

| Unemployed | 85/149 | 57 | 90/152 | 59 |

| Exempt because of disability | 52/183 | 28 | 57/189 | 30 |

| Any work or study | 58/183 | 32 | 58/189 | 31 |

| Alcohol abuse | 71/150 | 47 | 69/162 | 43 |

| Alcohol dependence | 51/131 | 39 | 50/148 | 34 |

| Drugs taken | ||||

| Sedatives, hypnotics, anxiolytics | 23/182 | 13 | 18/188 | 10 |

| Cannabis | 181/182 | 100 | 189/189 | 100 |

| Stimulants | 39/182 | 21 | 54/188 | 29 |

| Opioids | 27/182 | 15 | 30/188 | 16 |

| Cocaine | 88/182 | 48 | 98/188 | 52 |

| Hallucinogens/PCP | 79/182 | 43 | 81/188 | 43 |

| Legal highs | 30/181 | 17 | 31/188 | 16 |

| Other | 39/182 | 21 | 42/188 | 22 |

| Cannabis-positive urine | 122/170 | 72 | 128/184 | 70 |

| PANSS score, median (IQR) | ||||

| Positive symptoms | 11 | (8–16) | 10 | (8–14) |

| Negative symptoms | 14 | (10–18) | 12 | (9–17) |

| SF-12 score, median (IQR) | ||||

| Physical | 56 | (48–60) | 55 | (47–60) |

| Mental | 40 | (27–54) | 45 | (30–55) |

| Number of, median (IQR) | ||||

| Days using cannabis in the previous 3 months | 30 | (3–84) | 26 | (1–67) |

| Psychoeducation sessions attended | 4 | (0–6) | 6 | (1–6) |

At 18 months, 33% of the psychoeducation group were engaged in work or study compared with 29% in the CM group. A total of 61% of participants in the control arm and 57% of participants in the CM arm had cannabis-positive urine. The PANSS positive and negative median score and the median number of days using cannabis in the previous 6 months were similar between arms. One-third of participants in both arms were admitted to hospital or a crisis house, were seen by a crisis resolution team or attended an acute day treatment service (Table 5).

| Characteristic | Randomised group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | CM | |||

| n/N | % | n/N | % | |

| Educational attainment | ||||

| No qualifications | 21/134 | 16 | 22/143 | 15 |

| GCSE or equivalent | 41/134 | 31 | 57/143 | 40 |

| A level or equivalent | 33/134 | 25 | 31/143 | 22 |

| Post-18 education (including HND, trade, degree) | 39/134 | 29 | 33/143 | 23 |

| Living arrangements | ||||

| Alone | 49/134 | 37 | 50/143 | 35 |

| With parents | 57/134 | 43 | 55/143 | 38 |

| With other adults (only) | 21/134 | 16 | 25/143 | 17 |

| Other | 7/134 | 5 | 13/143 | 9 |

| Housing | ||||

| Independent permanent accommodation | 87/133 | 65 | 98/144 | 68 |

| Independent temporary accommodation | 13/133 | 10 | 11/144 | 8 |

| Supported accommodation | 21/133 | 16 | 24/144 | 17 |

| Other | 12/133 | 9 | 11/144 | 8 |

| Work or study | ||||

| Ever had open-market employment | 117/135 | 87 | 135/145 | 93 |

| Ever kept open-market employment for 1 year | 69/132 | 52 | 84/145 | 58 |

| Had open-market job since first contact with services | 54/135 | 40 | 63/144 | 44 |

| Current paid activity | 33/135 | 24 | 31/145 | 21 |

| Time since last open-market job (years) | 2.0 | (0.0–4.0) | 2.0 | (0.3–4.0) |

| Open-market full-time employment | 16/135 | 12 | 18/145 | 12 |

| Open-market part-time employment | 16/135 | 12 | 10/145 | 7 |

| Permitted work | 0/135 | 0 | 2/135 | 1 |

| Voluntary/unpaid work | 9/135 | 7 | 9/145 | 6 |

| Study or training | 21/135 | 16 | 16/145 | 11 |

| Full-time caring | 0/135 | 0 | 1/145 | 1 |

| Unemployed | 71/102 | 70 | 68/114 | 60 |

| Exempt because of disability | 33/135 | 24 | 55/145 | 38 |

| Any work or study | 45/135 | 33 | 42/145 | 29 |

| Alcohol abuse | 56/104 | 54 | 62/116 | 53 |

| Alcohol dependence | 41/84 | 49 | 42/81 | 52 |

| Drugs taken (lifetime) | ||||

| Sedatives, hypnotics, anxiolytics | 20/133 | 15 | 13/142 | 9 |

| Cannabis | 133/133 | 100 | 142/142 | 100 |

| Stimulants | 34/133 | 26 | 39/142 | 27 |

| Opioids | 22/133 | 17 | 23/142 | 16 |

| Cocaine | 64/133 | 48 | 77/142 | 54 |

| Hallucinogens/PCP | 59/133 | 44 | 69/142 | 49 |

| Legal highs | 10/130 | 8 | 12/141 | 9 |

| Other | 34/133 | 26 | 30/142 | 21 |

| Cannabis-positive urine | 76/124 | 61 | 77/136 | 57 |

| PANSS score, median (IQR) | ||||

| Positive symptoms | 10 | (8–15) | 11 | (8–13) |

| Negative symptoms | 12 | (8–17) | 12 | (9–17) |

| SF-12 score, median (IQR) | ||||

| Physical | 55 | (47–60) | 55 | (48–59) |

| Mental | 42 | (31–55) | 43 | (30–55) |

| Drug use and admission to acute mental health service | ||||

| Number of days using cannabis in the previous 6 months | 26 | (1–142) | 26 | (0–118) |

| Admitted to a crisis house, seen by crisis resolution team, or attended an acute day treatment service | 85/259 | 33 | 90/272 | 33 |

| Number of admissions during 18-month follow-up, median (IQR) | 0 | (0–1) | 0 | (0–1) |

Associations with missing data

Tables related to missing data are in Appendix 1. The employment status of participants appeared to be associated with missing data on secondary outcomes. For example, participants seemed more likely to be missing data for all 3-month secondary outcomes if they were unemployed (see Table 9) [odds ratio (OR) 1.78, 95% CI 1.06 to 2.99]; however, they seemed less likely to have 3-month data missing if they were exempt from work because of disability (OR 0.51, 95% CI 0.29 to 0.90) (see Table 4). Participants appeared to be less likely to have all 18 secondary outcomes missing if they did some voluntary work at baseline (OR 0.39, 95% CI 0.15 to 0.99) (see Table 10). Participants were more likely to have 3- and 18-month data missing if they had an open-market job since contact with services, had current paid activity at baseline or were employed part time at baseline (see Appendix 1, Table 14).

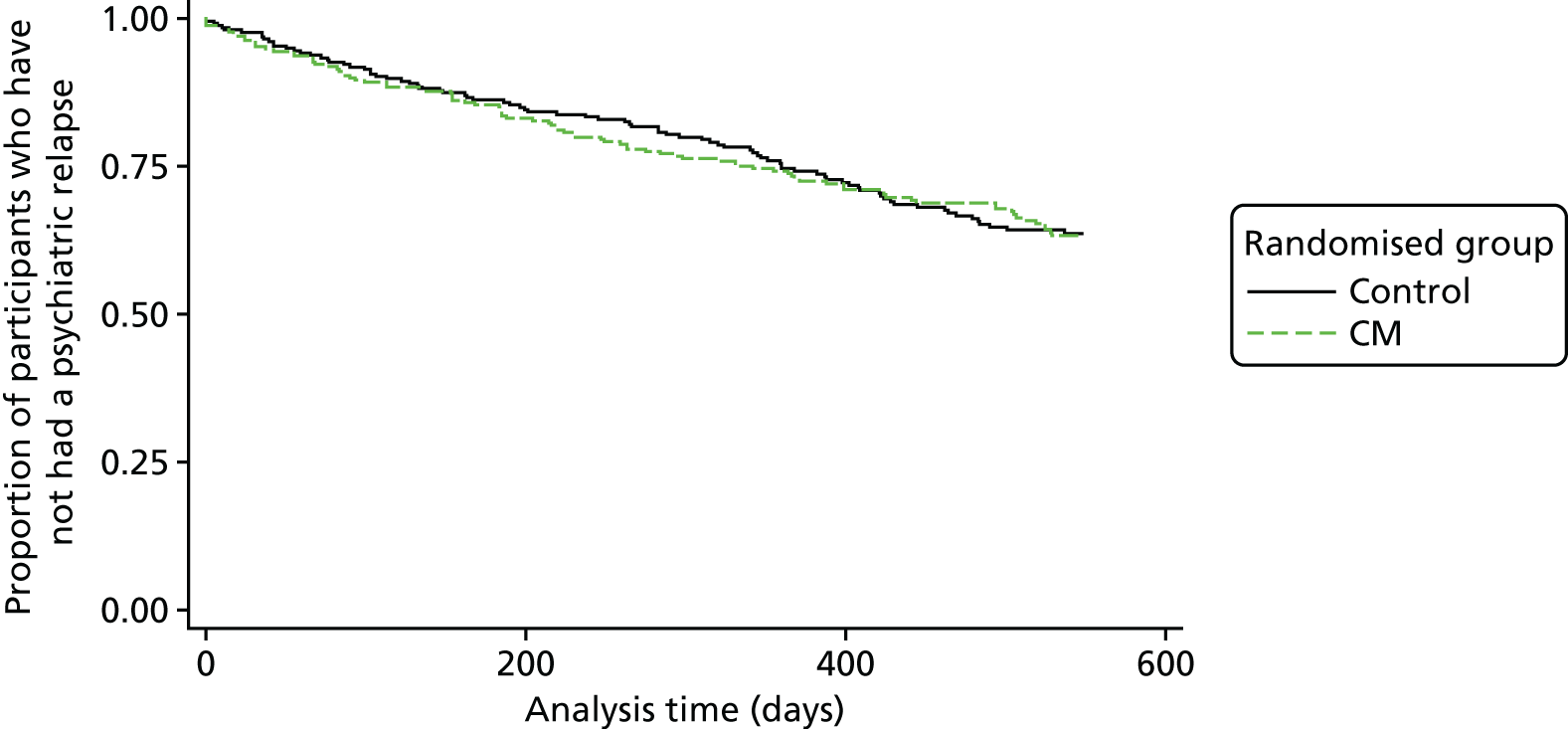

Outcomes

There was no significant difference in time to admission between the randomised groups (HR 1.03, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.40) (Figure 3). Results from the supportive analyses were similar (see Table 4). The odds of at least one admission over 18 months’ follow-up are slightly higher for the CM group than for the psychoeducation group (OR 1.02, 95% CI 0.70 to 1.48), but approximately 33% of participants in both groups were admitted. The ICC estimates obtained from using the log-transformed event times using the analysis-of-variance approach and the marginal models were similar and produced an ICC estimate of 0.01 after adjusting for randomisation group, severity of cannabis use (the stratification variable) at baseline and whether or not the participant was part of the pilot trial. The binary outcome analysis produced a near-zero estimate of the between-cluster variance. In addition, we fitted the primary analysis model without robust standard errors. The estimates of the standard errors and p-values for the covariates were similar to those obtained when robust standard errors were used, suggesting that the ICC is small and consistent with the estimates of 0.01.

FIGURE 3.

Kaplan–Meier survival curve by randomised group for the primary outcome, time to relapse.

Those in the CM arm who had a full 18 months’ follow-up had a slightly higher rate ratio for number of admissions than the controls [incidence rate ratio (IRR) 1.08, 95% CI 0.75 to 1.54]; this changed little when assuming that those who were discharged from services had no admissions during follow-up or when including predictors of missingness. Those randomised to CM had slightly lower odds of cannabis-positive urine at 3 months and 18 months than those randomised to OTAU (OR 0.86, 95% CI 0.56 to 1.34; and OR 0.84, 95% CI 0.49 to 1.41, respectively). However, those in the CM arm also had lower odds of paid work or study at both 3 months and 18 months. For the log-transformed PANSS positive outcome at 3 months, the CM score is, on average, 7% lower than that of the psychoeducation group (95% CI –14% to 0%). Results for the log-transformed PANSS negative score at 3 months are similar. Illicit substance use other than cannabis was very low at both follow-ups [3-month median days of use = 0 (IQR 0–1), in both groups, 18-month median days of use = 0 in both groups (IQR 0–2 in control; IQR 0–1 in experimental)]. On average, the number of alcohol-using days was 4 (control IQR 0–12 days; experimental IQR 0–15 days) in both groups at 3 months, and 6 days (IQR 0–24 days) in both groups at 18 months.

Mean quality-of-life utility scores of the two treatment groups were compared at 18 months using unpaired t-tests. No significant difference was observed between the two groups using EQ-5D utility scores (95% CI –0.02 to –0.078; p = 0.25). The result was the same when using SF-12 utility scores (95% CI –0.022 to –0.037; p = 0.6).

Resource use

Service use is detailed in Table 6. Note that service use for inpatient activity is reported for the full trial period, whereas other types of service use does not cover the period from 3 to 12 months post randomisation.

| Service | Randomised group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental | Control | |||||

| Mean | SD | % | Mean | SD | % | |

| Service use over the trial period (18 months) | ||||||

| Inpatient stays (bed-days) | 89.4 | 92.9 | 24.1 | 90.9 | 97.2 | 24.2 |

| Service use from 0–3 and 12–18 months (contacts) | ||||||

| EIP team member | 11.7 | 9.6 | 68.7 | 11.1 | 8.4 | 68.9 |

| GP | 3.1 | 2.4 | 51.1 | 2.9 | 2.1 | 44.7 |

| Psychiatrist | 3.2 | 2.8 | 54.3 | 3.2 | 3 | 53.1 |

| Psychologist | 5 | 5 | 22.7 | 5.6 | 5.8 | 20.9 |

| Home treatment/crisis team member | 10.7 | 14.5 | 9.0 | 12.8 | 22.6 | 10.3 |

| Mental health nurse | 9.1 | 13.8 | 15.1 | 7 | 7.3 | 13.9 |

| Adult education class | 5.4 | 4.9 | 2.5 | 9 | 8.5 | 3.7 |

| Assertive outreach team member | 8.4 | 11.2 | 1.8 | 9 | 7 | 1.1 |

| Class/group at a leisure centre | 14.6 | 21.9 | 4.0 | 25.2 | 38.7 | 4.4 |

| Community mental health centre | 8.8 | 6.4 | 4.3 | 7.6 | 8.1 | 2.6 |

| Day care centre/day hospital | 5.2 | 3.8 | 1.4 | 27 | 9.9 | 0.7 |

| Drop-in centre | 16.5 | 21.2 | 1.4 | 10.8 | 16 | 4.8 |

| Drug/alcohol service | 16 | 26.9 | 4.0 | 6 | 7.6 | 4.8 |

| Drug and alcohol advisor | 5.5 | 9.2 | 9.4 | 7.9 | 17.2 | 10.6 |

| Occupational therapist | 2.1 | 1.5 | 6.1 | 3.7 | 4.5 | 7.0 |

| Other counsellor/therapist | 7.6 | 7.4 | 4.0 | 7.6 | 7.2 | 5.1 |

| Other doctor | 2.1 | 2.4 | 7.6 | 3.7 | 4 | 8.1 |

| Self-help/support group | 6.8 | 9.3 | 7.2 | 6.5 | 7.7 | 5.1 |

| Social worker | 10.4 | 17.8 | 7.9 | 7.5 | 8.1 | 10.3 |

Use of some services, such as assertive outreach, day care centres/day hospitals, community mental health centres, adult education classes, drop-in centres and classes at leisure centres, was low, being accessed by < 5% of the sample.

Reported use of EIP services was high, with 69% of the sample having a mean of 11 (SD 9) contacts. Use of psychiatrists (54% of the sample) and general practitioners (GPs) (48%) was also high. Over one-fifth of patients reported seeing a psychologist, whereas 15% of patients were seen by a mental health nurse. Around 10% of patients were seen by home treatment or crisis team members. Inpatient use was high among the one-quarter of patients who were admitted, with an average of 90 (SD 95) bed-days over the 18-month period from randomisation.

A small proportion of participants were on a community treatment order at baseline [4.0% (22/551)] and at 18 months [2.7% (14/512)]. Of the 71 people in education at baseline, 50.7% took any days off as a consequence of health problems for a mean of 30 (median 10) days. At 18 months, 29 people were in education, with 31.0% taking any days off as a consequence of health problems for a mean of 6 (median 2) days. A total of 76% of participants claimed at least one benefit in the baseline period, compared with 83% over the follow-up period.

A total of 16% of participants had been in employment in the previous 6 months at baseline, compared with 23% from 12 to 18 months. Of those, the percentage of participants having any days off work as a consequence of health problems fell in both arms, from 55% to 41% (CM) and from 72% to 55% (OTAU).

A total of 10% of participants met with a drug and alcohol advisor at least once, averaging seven contacts (median 14); 4% of participants interacted with drug and alcohol service groups an average of 11 times (median 19).

Total cost

The mean cost of the CM intervention was £295.51 per patient (range £0–602) with a median of five psychoeducation sessions attended and a median of eight urinalysis tests conducted for cannabis. Mean rewards for cannabis abstinence were £68 per patient. The mean cost of the OTAU intervention was £140.33 per patient (range £0–307), with a median of four psychoeducation sessions attended.

Table 7 shows total costs per patient by each period of the trial. Although reported service use notes a gap from 3 to12 months post randomisation, this table imputes those missing costs from the costs of the other period. The imputed portion of the costs for this period represents less than one-quarter of the overall costs in the period.

| Outcome | Estimate | 95% CI | ICC | ICC 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time to relapse controlling for level of cannabis use and if in the pilot study (HR) – primary outcome, primary analysis | 1.03a | 0.76 to 1.40 | ||

| Time to relapse controlling for level of cannabis use, if in the pilot study and predictors of missingness (HR) | 1.02 | 0.75 to 1.40 | ||

| Time to relapse controlling for level of cannabis use, if in the pilot study, excluding those who did not have any other data at 12 weeks (HR) | 0.83 | 0.55 to 1.26 | ||

| Time to relapse controlling for level of cannabis use, if in the pilot study, excluding those who did not have any other data at 18 months (HR) | 1.04 | 0.66 to 1.63 | ||

| Time to relapse controlling for level of cannabis use, including only those in the main trial (HR) | 0.94 | 0.67 to 1.31 | ||

| Time to relapse controlling for level of cannabis use, if in the pilot study and number of psychoeducation sessions attended (HR) | 1.14 | 0.81 to 1.61 | ||

| Time to relapse controlling for level of cannabis use, if in the pilot study and number of admissions in the 6 months before baseline as a continuous (HR) | 1.07 | 0.79 to 1.47 | ||

| Time to relapse controlling for level of cannabis use, if in the pilot study and at least one admission in the 6 months before baseline (HR) | 1.04 | 0.77 to 1.41 | ||

| Time to relapse controlling for level of cannabis use and if in the pilot study using the trust as the clustering variable (HR) | 1.03 | 0.79 to 1.35 | ||

| Cannabis-positive urine sample at 12 weeks (OR) | 0.86 | 0.56 to 1.34 | 0.00 | 0.00 to 0.11 |

| Cannabis-positive urine sample at 12 weeks controlling for predictors of missingness (OR) | 0.85 | 0.55 to 1.32 | ||

| Cannabis-positive urine sample at 18 months (OR) | 0.84 | 0.49 to 1.41 | 0.00 | 0.00 to 0.15 |

| Cannabis-positive urine sample at 18 months controlling for predictors of missingness (OR) | 0.85 | 0.50 to 1.43 | ||

| Log-positive symptoms on the PANSS at 12 weeks (coefficient) | –0.07 | –0.14 to –0.00 | 0.06 | 0.00 to 0.17 |

| Log-positive symptoms on the PANSS at 12 weeks controlling for predictors of missingness (coefficient) | –0.07 | –0.14 to –0.00 | ||

| Log-positive symptoms on the PANSS at 18 months (coefficient) | –0.04 | –0.13 to 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.00 to 0.20 |

| Log-positive symptoms on the PANSS at 18 months controlling for predictors of missingness (coefficient) | –0.04 | –0.13 to 0.04 | ||

| Log-negative symptoms on the PANSS at 12 weeks (coefficient) | –0.08 | –0.16 to 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 to 0.11 |

| Log-negative symptoms on the PANSS at 12 weeks controlling for predictors of missingness (coefficient) | –0.08 | –0.16 to 0.00 | ||

| Log-negative symptoms on the PANSS at 18 months (coefficient) | 0.01 | –0.08 to 0.11 | 0.19 | 0.03 to 0.34 |

| Log-negative symptoms on the PANSS at 18 months controlling for predictors of missingness (coefficient) | 0.01 | –0.08 to 0.11 | ||

| Paid work or study at 12 weeks (OR) | 0.95 | 0.62 to 1.46 | 0.00 | 0.00 to 0.11 |

| Paid work or study at 12 weeks controlling for predictors of missingness (OR) | 0.94 | 0.60 to 1.47 | ||

| Paid work or study at 18 months (OR) | 0.82 | 0.50 to 1.35 | 0.14 | 0.00 to 0.30 |

| Paid work or study at 18 months controlling for predictors of missingness (OR) | 0.82 | 0.50 to 1.35 | ||

| Number of days that cannabis was used in the previous 12 weeks (12-week follow-up) (IRR) | 0.89 | 0.75 to 1.04 | 0.07 | 0.00 to 0.19 |

| Number of days that cannabis was used in the previous 12 weeks (12-week follow-up) controlling for predictors of missingness (IRR) | 0.88 | 0.75 to 1.04 | ||

| Number of days that cannabis was used in the previous 6 months (18-month follow-up) (IRR) | 1.09 | 0.88 to 1.36 | 0.00 | 0.00 to 0.14 |

| Number of days that cannabis was used in the previous 6 months (18-month follow-up) controlling for predictors of missingness (IRR) | 1.08 | 0.87 to 1.33 | ||

| Number of admissions over 18 months’ follow-up for those with full follow-up or those who died (IRR) | 1.08 | 0.75 to 1.54 | 0.29 | 0.16 to 0.43 |

| Number of admissions over 18 months’ follow-up for those with full follow-up or those who died controlling for predictors of missingness (IRR) | 1.09 | 0.76 to 1.55 | ||

| Number of admissions over 18 months’ follow-up for those with full follow-up, those who died and those who were discharged before the end of follow-up, assuming discharged people did not have any admissions during follow-up | 1.06 | 0.75 to 1.48 | ||

| At least one admission over 18 months’ follow-up (OR) | 1.02 | 0.70 to 1.48 | 0.02 | 0.00 to 0.13 |

| At least one admission over 18 months’ follow-up controlling for predictors of missingness (OR) | 1.01 | 0.69 to 1.48 |

Economic evaluation

In analyses adjusted for baseline cost, the adjusted mean difference between the two arms was –£4277 (95% CI –£12,662 to £4107; p = 0.32). The null hypothesis of no difference in costs between the two treatment groups cannot be rejected. These results remained the same when the period of 3 to 12 months (including some imputed costs) was excluded, or regardless of the time period tested, as Table 8 shows.

| Cost | Randomised group | Adjusted mean difference | 95% CI | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental | Control | ||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||||

| Intervention costs only (n = 533) | 296 | 186 | 140 | 117 | – | – | – |

| Baseline period (6 months) (n = 550) | 2586 | 7345 | 2123 | 4942 | – | – | – |

| Intervention period (3 months) (n = 371) | 2305 | 6826 | 2715 | 8962 | –693 | –2124 to 738 | 0.34 |

| 3–12 months (n = 551) | 8591 | 19,944 | 8902 | 22,282 | –677 | –4140 to 2785 | 0.70 |

| 12–18 months (n = 278) | 4221 | 9325 | 5683 | 11,772 | –1596 | –4103 to 911 | 0.21 |

| Total cost (n = 236) | 14,790 | 33,767 | 17,705 | 35,898 | –4475 | –12,894 to 3945 | 0.30 |

Table 9 shows that costs for inpatient stays were lower for the CM arm (£10,342 vs. £13,247) than the OTAU arm, with large SDs (£34,029 and £35,747, respectively), whereas costs for other items were broadly similar. In the broader perspective, reported benefits received were the largest additional cost.

| Cost item | Randomised group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental | Control | |||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Costs over the 18-month follow-up period | ||||

| Inpatient stays | 10,342 | 34,029 | 13,247 | 35,747 |

| Costs over the 0- to 3-month and 12- to 18-month follow-up periods | ||||

| EIP team member | 302 | 256 | 303 | 229 |

| GP | 127 | 138 | 134 | 166 |

| Psychiatrist | 404 | 462 | 479 | 522 |

| Psychologist | 416 | 810 | 445 | 894 |

| Home treatment/crisis team member | 47 | 220 | 21 | 60 |

| Mental health nurse | 130 | 438 | 129 | 344 |

| Adult education class | 4 | 39 | 18 | 83 |

| Assertive outreach team member | 4 | 29 | 5 | 33 |

| Class/group at a leisure centre | 10 | 65 | 33 | 225 |

| Community mental health centre | 79 | 469 | 40 | 250 |

| Day care centre/day hospital | 4 | 41 | 3 | 29 |

| Drop-in centre | 12 | 88 | 33 | 246 |

| Drug/alcohol service | 163 | 1221 | 23 | 144 |

| Drug and alcohol advisor | 291 | 2090 | 116 | 423 |

| Medication | 308 | 644 | 288 | 601 |

| Occupational therapist | 37 | 148 | 62 | 250 |

| Other counsellor/therapist | 53 | 347 | 156 | 694 |

| Other doctor | 26 | 90 | 75 | 413 |

| Self-help/support group | 16 | 89 | 9 | 50 |

| Social worker | 44 | 316 | 58 | 193 |

| Broader perspective costs over the 0- to 3-month and 12- to 18-month follow-up periods | ||||

| Court attendance | 81 | 293 | 159 | 581 |

| Police | 48 | 152 | 60 | 235 |

| Police cell | 20 | 75 | 31 | 89 |

| Prison | 53 | 559 | 137 | 977 |

| Probation officer | 10 | 60 | 4 | 20 |

| Solicitor | 4 | 18 | 25 | 92 |

| Benefits | 3609 | 2393 | 3294 | 2298 |

| Productivity losses | 219 | 1054 | 171 | 621 |

Outcomes

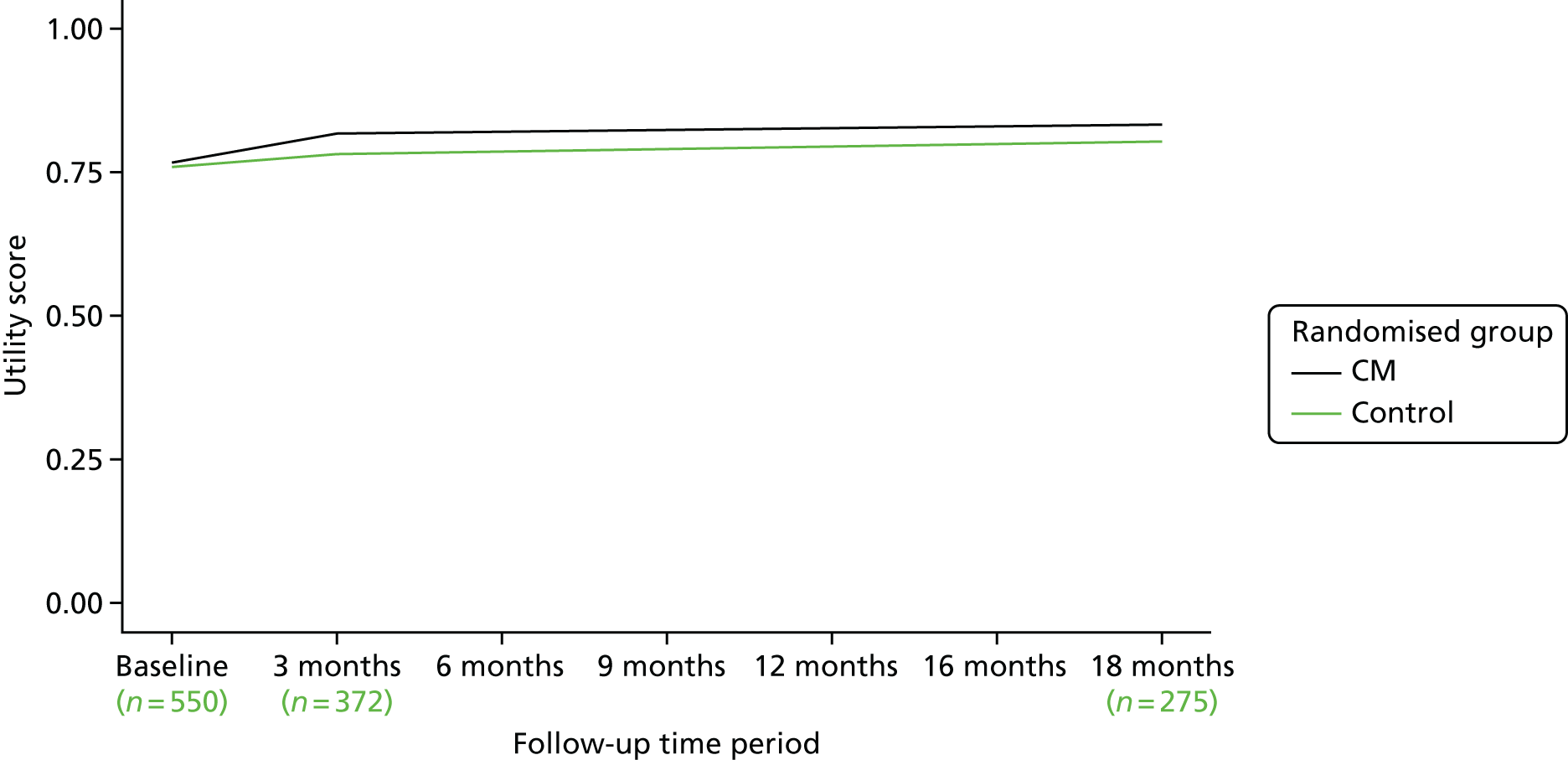

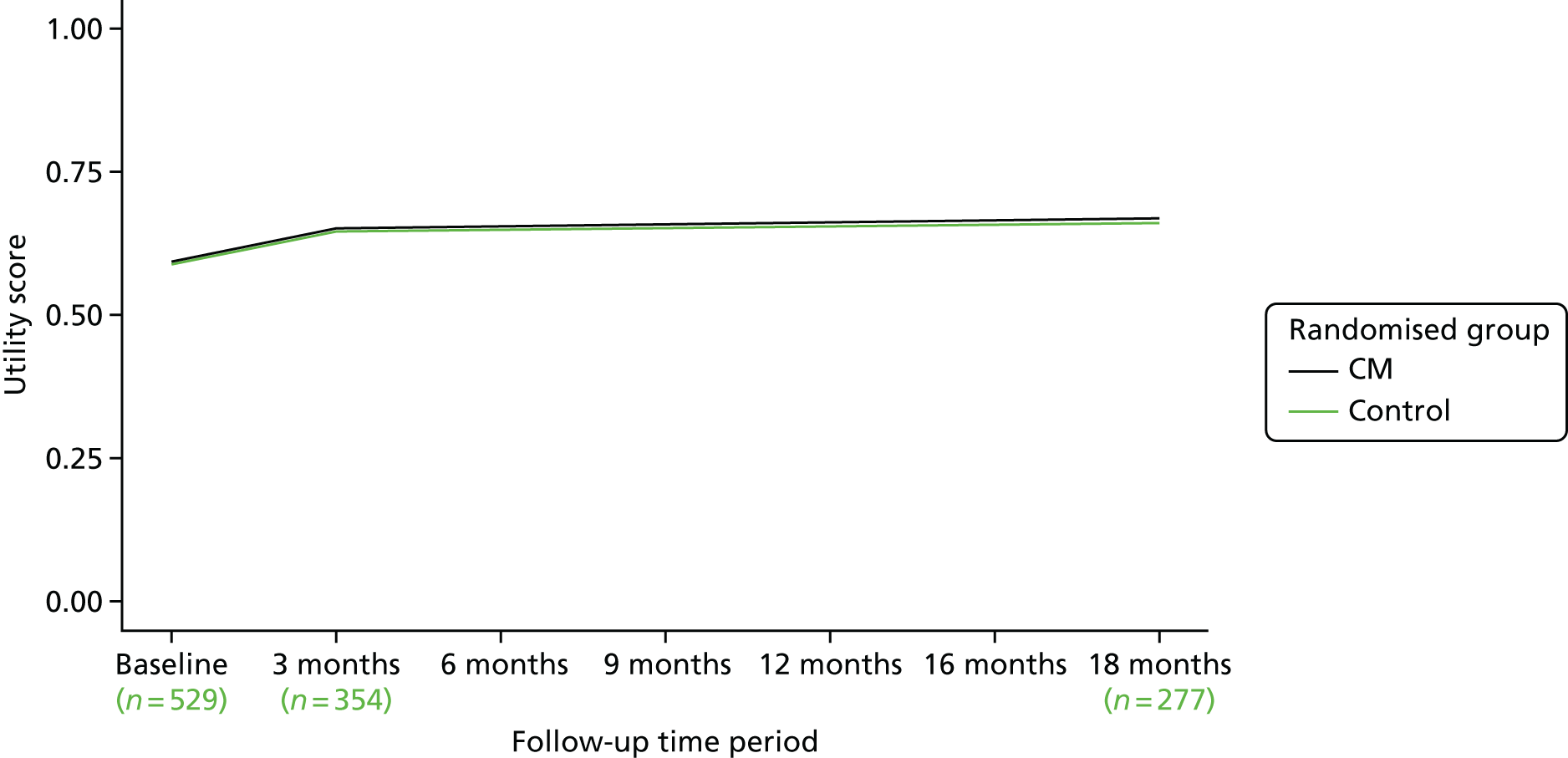

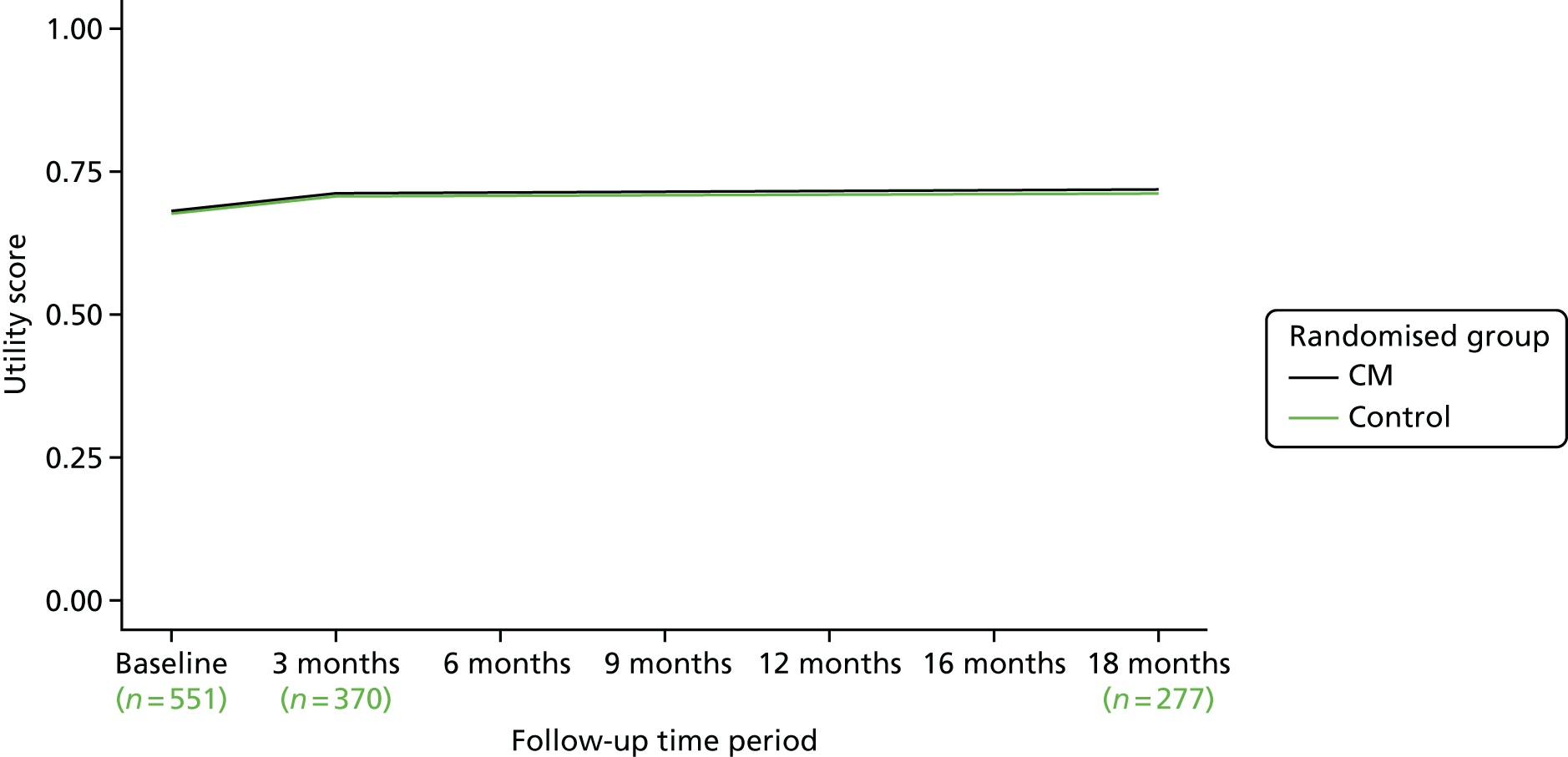

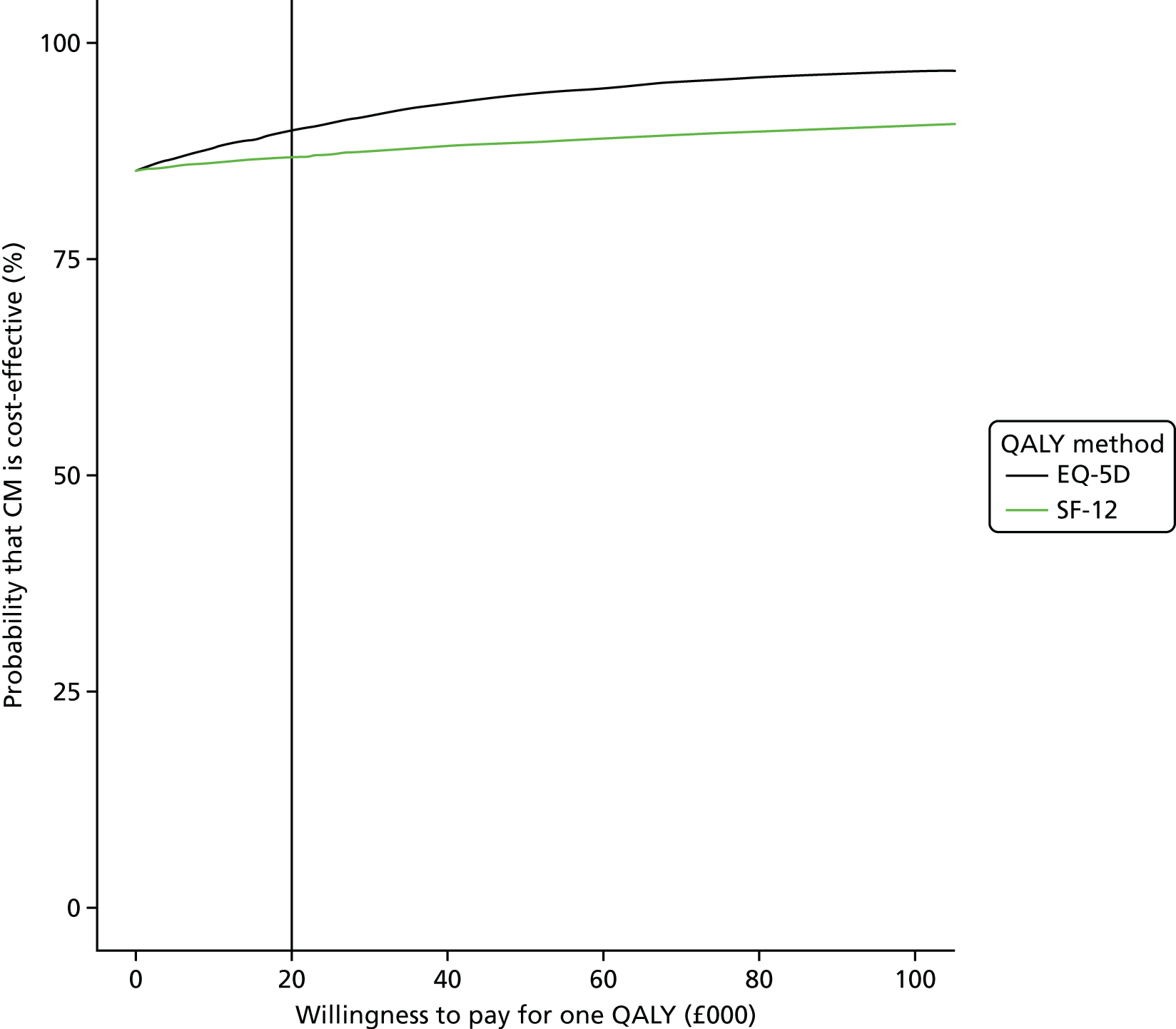

The EQ-5D tariff over the 18-month follow-up period is detailed in Table 10 and shown graphically in Figure 4. Utility scores are similar between groups over the follow-up period, with the CM arm having a modestly higher mean raw tariff score at baseline (CM, 0.77; OTAU, 0.76) and all the way through to 18 months (CM, 0.83; OTAU, 0.80). When QALYs are calculated, the mean for the CM arm was higher (CM, 1.21; OTAU, 1.15), but this difference was not significant when adjusting for baseline EQ-5D score (adjusted mean difference 0.053, 95% CI –0.0069 to 0.11; p = 0.083). These differences were smaller when looking at other quality-of-life measures. Figure 4 shows the EQ-5D-3L utility scores over time. Figure 5 shows reported EQ-5D visual analogue scale (VAS) scores over time. The adjusted mean difference for the EQ-5D VAS was 1.2 (95% CI –3.0 to 5.3; p = 0.58). Figure 6 shows SF-6D (Short Form questionnaire-6 Dimensions) utility scores, also showing little difference. Again, the adjusted mean difference had a positive sign (0.015), and again this difference was not significantly different from zero (95% CI –0.018 to 0.048; p = 0.37).

| Quality-of-life measure | Randomised group | Adjusted mean difference | 95% CI | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental | Control | ||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||||

| EQ-5D-3L tariff | |||||||

| Baseline (n = 548) | 0.77 | 0.26 | 0.76 | 0.25 | – | – | – |

| 3 months (n = 372) | 0.82 | 0.24 | 0.78 | 0.26 | – | – | – |

| 18 months (n = 275) | 0.83 | 0.18 | 0.8 | 0.23 | – | – | – |

| QALYs – EQ-5D-3L | |||||||

| 3 months (n = 371) | 0.18 | 0.05 | 0.18 | 0.05 | 0.0046 | –0.01072 to 0.01 | 0.09 |

| 18 months (n = 236) | 1.2 | 0.26 | 1.2 | 0.31 | 0.053 | –0.1169 to 0.11 | 0.083 |

| EQ-5D VAS | |||||||

| Baseline (n = 528) | 59 | 19 | 59 | 21 | – | – | – |

| 3 months (n = 354) | 65 | 20 | 65 | 19 | 0.32 | –3.4 to 4.0 | 0.87 |

| 18 months (n = 277) | 67 | 17 | 66 | 19 | 1.2 | –3.0 to 5.3 | 0.58 |

| SF-12 tariff | |||||||

| Baseline (n = 549) | 0.68 | 0.12 | 0.68 | 0.13 | – | – | – |

| 3 months (n = 370) | 0.71 | 0.14 | 0.71 | 0.14 | – | – | – |

| 18 months (n = 277) | 0.72 | 0.12 | 0.71 | 0.13 | – | – | – |

| QALYs – SF-12 | |||||||

| 3 months (n = 370) | 0.16 | 0.025 | 0.16 | 0.026 | 0.00051 | –0.0023 to 0.0034 | 0.72 |

| 18 months (n = 235) | 1 | 0.15 | 1 | 0.16 | 0.015 | –0.018 to 0.048 | 0.37 |

FIGURE 4.

The EQ-5D-3L utility scores by randomised group over time.

FIGURE 5.

The EQ-5D VAS utility scores over time.

FIGURE 6.

The SF-6D utility scores over time.

Cost-effectiveness analysis

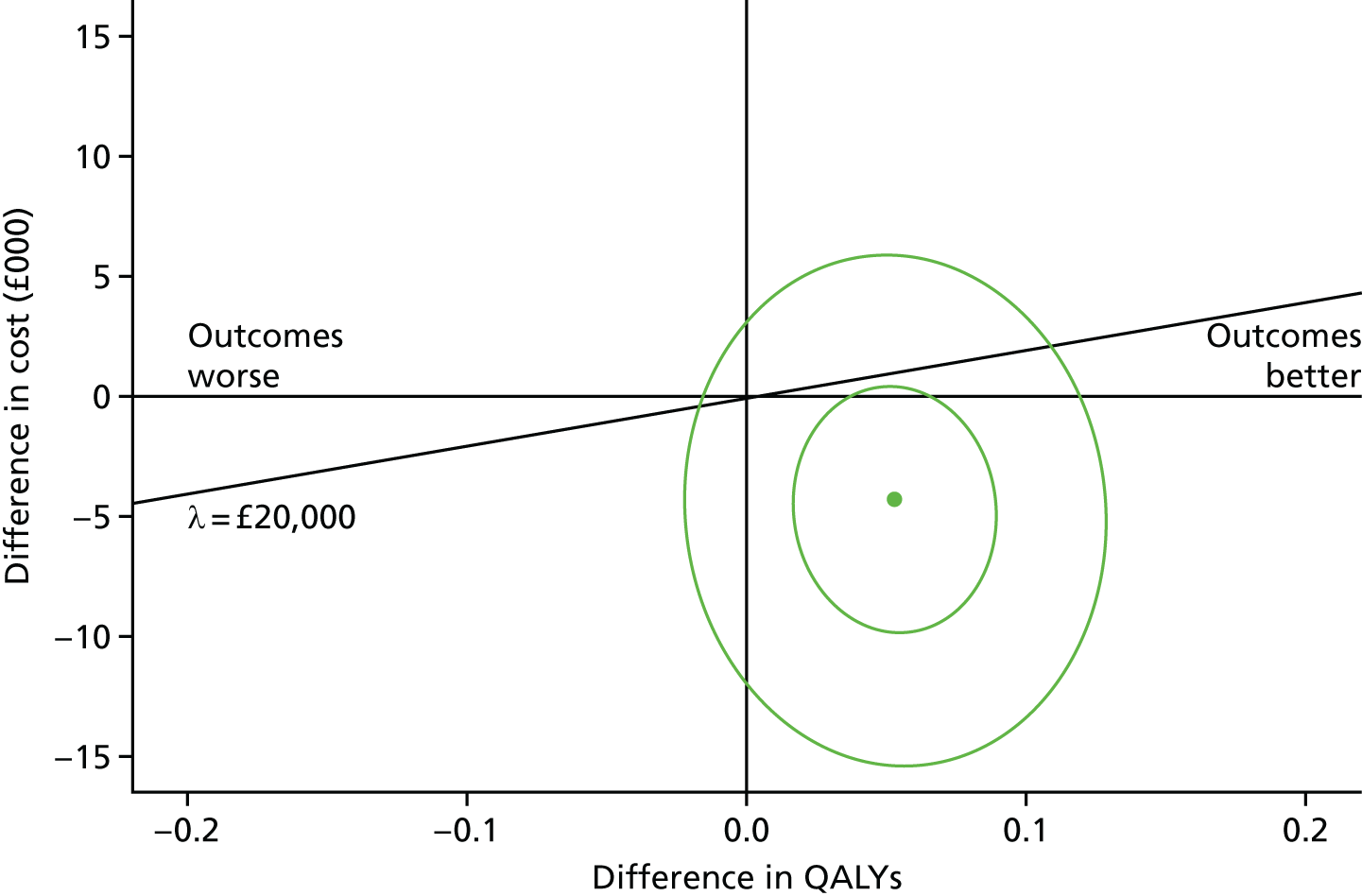

Figure 7 shows the cost-effectiveness plane showing bootstrap cost and QALY (EQ-5D) pairs at the 18-month follow-up. There are 10,000 bootstrapped samples shown, with 50% and 95% confidence ellipses surrounding the bootstrapped pairs. The central dot shows the adjusted mean cost difference of –£4277 and the adjusted mean QALY difference of 0.053. This represents an ICER of –£80,772. The bootstrapped replications of costs and outcomes fall with the majority in the south-east quadrant (81.8%), with very few in the north-west (0.6%), and more in the north-east (14.1%) than in the south-west quadrant (3.5%).

FIGURE 7.

The EQ-5D-3L cost-effectiveness plane.

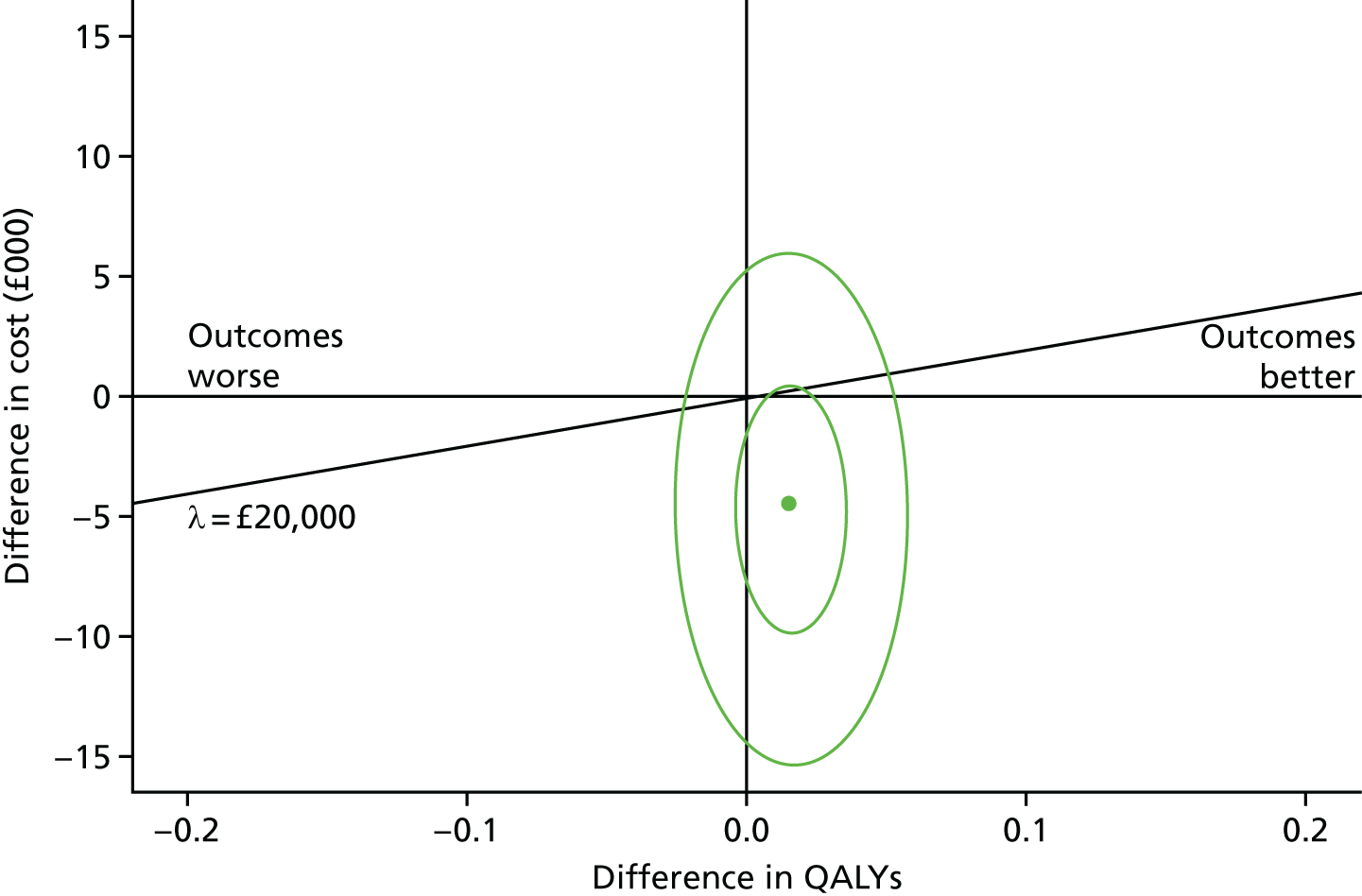

When this is compared with a cost-effectiveness plane using QALYs generated by the SF-6D (Figure 8), we see less variation in QALY differences, with fewer, but still a majority of, replications to the east of the plot. The relevant mean QALY difference with the SF-6D is 0.015, and the ICER is –£284,937. Both plots suggest that CM may be a cost-effective alternative to OTAU. This is also shown in Figure 9.

FIGURE 8.

The SF-6D cost-effectiveness plane.