Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 13/14/01. The contractual start date was in September 2014. The draft report began editorial review in October 2017 and was accepted for publication in March 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Shirley A Thomas and Avril ER Drummond report grants from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) and the Stroke Association outside the submitted work. Rebecca L Palmer is an author of the Consent Support Tool, which was piloted in the work and is discussed in the report. Roshan das Nair is a member of the NIHR Health Services and Delivery Research Board. Nicholas R Latimer is supported by the NIHR (NIHR Post Doctoral Fellowship PDF-2015-08-022). Stephen J Walters is a member of the NIHR Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Clinical Trials Board and the NIHR HTA Funding Boards Policy Group; he also reports grants from the NIHR HTA programme during the conduct of the study, personal fees from royalties, research grants from the NIHR and the Medical Research Council, personal fees from external examining fees and book royalties outside the submitted work. Cindy L Cooper is a member of the NIHR Clinical Trials Unit Standing Advisory Committee.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Thomas et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Post-stroke depression

Stroke

Stroke is a condition in which interruption of the blood supply to the brain causes brain damage. This leads to the impairment of motor, sensory and cognitive abilities. Cognitive impairments include disorders of communication, such as aphasia, and problems with attention, memory, visuospatial abilities and executive function. These cognitive impairments have a negative effect on recovery and long-term outcomes. 1–3

Depression after stroke

Many stroke patients experience emotional consequences, including depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress, anger, apathy and frustration. Depression is the most commonly investigated emotional consequence of stroke. 4,5

Several recent reviews5–8 have reported that about one-third of stroke patients have depression at any time point. Two of these reviews1,2 included a meta-analysis. Ayerbe et al. 1 analysed data from 43 studies published between 1983 and 2011. They reported an average prevalence of depression among stroke survivors of 29% [95% confidence interval (CI) 25% to 32%] of stroke survivors with depression, with a prevalence of 28% (95% CI 23% to 34%) within 1 month of stroke, 31% (95% CI 24% to 39%) at 1–6 months, 33% (95% CI 23% to 43%) at 6 months to 1 year and 25% (95% CI 19% to 32%) at > 1 year. Hackett and Pickles2 conducted a similar review and identified 61 studies. They obtained a pooled prevalence of depression among stroke survivors 31% (95% CI 28% to 35%) at any time, up to 5 years after stroke. Hackett et al. 3 also highlighted that this figure was not significantly different from the proportion in their earlier review (33%, 95% CI 29% to 36%; difference of 2%, 95% CI < 1% to 3%), suggesting that the management of the problem had not substantially improved over the previous 10 years.

Factors associated with depression after stroke

Effective treatment of depression is important because depression is associated with worse rehabilitation outcomes4–7 and increased disability. 1 Stroke survivors who are depressed may engage less in rehabilitation, which, in turn, can lead to decreased functional recovery. 4 Depression is also associated with increased mortality. 1,8,9 Not only does depression affect stroke survivors themselves but it also has an effect on their carers. 10 It has cost implications for the NHS because it is associated with increased health-care utilisation. 9

Most studies have assessed depression and its potential outcomes at the same time point, making it unclear whether depression is a cause or consequence of the outcome variable. Ayerbe et al. 1 reviewed only those studies in which depression was assessed at an earlier time point than the outcome and found that disability, lower quality of life (QoL) and mortality may be outcomes of depression in stroke survivors. In a more recent review, Towfighi et al. 11 concluded that the most consistent predictors of post-stroke depression are physical disability, stroke severity, history of depression and cognitive impairment. They also reported that post-stroke depression is associated with higher rates of health-care use after stroke. Therefore, in addition to improving mood, effective treatment of post-stroke depression is important as this has the potential to improve functional outcomes and QoL and reduce health-care costs.

Many studies of depression after stroke are based on clinical interviews or questionnaires to assess depression but these may not be appropriate for those with communication problems. About one-third of stroke survivors have aphasia,12,13 which may affect all communication modalities, namely speaking, understanding, reading and writing. Studies that have used measures of depression appropriate for those with communication problems have reported that stroke survivors with aphasia may be particularly susceptible to post-stroke depression. 14,15

Current service provision

Psychological treatments for depression after stroke

Previous research16 indicates that a high proportion of depressed stroke patients are likely to be taking antidepressants and so suggests that antidepressants have not resolved the mood problem. Previous research also suggests that few stroke survivors receive ongoing psychological treatment. 17 The Communication and Low Mood (CALM) trial of behavioural activation (BA) for low mood in people with aphasia17 found that, at 3-month follow-up, only 14% of participants who had been identified as having low mood after stroke had received mental health treatment in the past 3 months (from a mental health nurse, counsellor, psychologist, or psychiatrist). Although Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) has extended its remit to include people with physical health problems,18,19 the current uptake by stroke survivors is unknown.

Among the several psychological approaches to the treatment of depression, cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) is the most widely used psychological treatment for depression in clinical practice20 and may be appropriate for those with stroke. 21,22 There is evidence from single case design studies that some patients with post-stroke depression improve following CBT. 23,24 However, a randomised controlled trial25 (RCT) of CBT for post-stroke depression found no significant difference between those participants who received CBT, an attention placebo or usual care. One of the possible reasons for the lack of efficacy was that psychological treatments need to be tailored for people with aphasia and cognitive impairment. 22,25 A systematic review26 of the modifications to CBT that were required for people with cognitive impairments caused by acquired brain injury reported promoting an understanding of how specific changes to cognition, affect and behaviour occur as a result of brain injury and the use of memory aids. 27 However, a randomised trial of augmented CBT, in which CBT was adapted to suit those with stroke, also found no evidence of benefit in comparison with a cognitive training control group. In addition, a trial28 of CBT at different time points after stroke found no overall effect of CBT in comparison with usual care, although there was some evidence that CBT improved mood in those who were recruited > 9 months after stroke. Therefore, there is currently little evidence to support the provision of CBT after stroke.

Effectiveness of psychological interventions for depression after stroke

Other psychological interventions that may be appropriate for those with depression after stroke include counselling, motivational interviewing and problem-solving training. Some of these have been provided early after stroke in an attempt to prevent the development of depression,29–35 whereas others have been provided later to those who have developed depression. 36,37

There is currently limited evidence for the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of these psychological therapies for treating post-stroke depression. 38 Towfighi et al. 11 identified seven trials (n = 775 participants) of psychological interventions for depression after stroke and concluded that these trials suggest that brief psychosocial interventions may be useful and effective in the treatment of post-stroke depression. Two of these trials36,37 evaluated a brief psychosocial behavioural intervention, but details of the content of the intervention are limited. Motivational interviewing31,35 has also been shown to reduce post-stroke depression but studies recruited participants early after stroke and excluded those with severe communication or cognitive problems, so these findings may not be applicable to the broad range of stroke survivors with post-stroke depression.

Behavioural activation

A psychological intervention that may be suitable for stroke survivors is BA therapy. BA is based on the behavioural model of depression, in which depression is believed to result from a lack of response-contingent positive reinforcement. 39 Positive reinforcement is dependent on the person’s actions,40 and reduction in activity can lead to loss of reinforcement. Low positive reinforcement can arise from several sources: a deficiency in the individual’s skills (e.g. lack of social skills), limited availability of potential reinforcers in the environment and a decreased ability to enjoy pleasant events. The individual may engage in few activities that generate reinforcement. These antecedents contribute to a low rate of positive reinforcement, and so there are reduced feelings of mastery and esteem in success, which can lead to feelings of depression. As individuals become depressed they reduce participation in activities and hobbies, decreasing the level of reinforcement further and so leading to a vicious cycle. 41 It is proposed that depression is, therefore, maintained by a cycle of depressed mood, decreased activity and avoidance. 42

A stroke can result in a loss or restriction of rewarding activities and interactions (such as everyday activities, hobbies and social interactions) and this loss may lead to depression. The symptoms of depression (such as reduced motivation and lack of energy), in addition to the consequences of stroke, can mean that some behaviours or activities become more difficult and lose the positive reinforcement that they used to provide. BA aims to increase activity level, particularly the frequency of valued activities, and decrease avoidance behaviours in order to improve mood. In addition to its focus on reduced positive reinforcement leading to depression, BA is also concerned with addressing avoidance behaviours that contribute to depression. Depressed people may use avoidance as a coping strategy. 43 For example, someone who feels low in mood may withdraw from social contacts because they find this activity challenging and causing them discomfort. Avoiding this activity provides short-term relief and is negatively reinforced, thereby increasing the likelihood that they will repeat this avoidance again in the future.

Behavioural activation is effective at treating depression in adults in primary-care settings44–46 and in older adults. 47 It has been found to have comparable effectiveness to CBT in treating depression. 48 In a randomised controlled non-inferiority trial, Richards et al. 49 found that BA had comparable effects to CBT for people with depression in primary care and could be delivered by mental health workers with less intensive and less costly training than that required to deliver CBT and was, thus, also more cost-effective.

Behavioural activation is considered a straightforward approach and, as such, is suitable for those with reduced cognitive or communication ability. Stroke patients have cognitive impairment and some have communication problems, which makes BA an appropriate treatment. A multicentre RCT, the CALM trial,17 evaluated BA delivered by an assistant psychologist (AP) for treating low mood in stroke patients with aphasia. This trial17 found that mood was significantly better at 6-month follow-up in those who received BA than in those who received usual clinical care. In addition, reduced resource use suggested potential cost-effectiveness. 50

The transferability of BA to hard-to-reach populations, such as those with aphasia and severe cognitive problems,51–54 adds to its potential as a psychological intervention for depression after stroke. Given that the CALM trial17 demonstrated that it was possible to deliver BA to stroke survivors with aphasia and that studies of BA in people with dementia indicate that it is suitable for those with cognitive impairment,54 there is significant potential for using BA for treating depression in stroke survivors with mild to moderate communication and cognitive impairment.

Rationale and objectives

The Behavioural Activation Therapy for Depression after Stroke (BEADS) trial was designed and conducted in response to a commissioned call from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme to answer the research question ‘How feasible is a study to investigate the clinical and cost-effectiveness of a psychological intervention for people with post-stroke depression?’.

The BEADS trial was a multicentre trial designed to test the feasibility and clinical outcomes of BA for treating post-stroke depression, as well as its acceptability to patients, carers and therapists. We also collected data on the feasibility of delivering the BA intervention in the NHS as part of routine clinical practice. This feasibility work was essential in informing a proposal for a definitive (Phase III) multicentre RCT evaluating the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of BA for treating post-stroke depression. However, as a feasibility study, the BEADS trial was not powered to explore any factors that may modify the effects of treatment.

Primary objective

The primary objective was to determine the feasibility of proceeding to a definitive trial.

Secondary objective

The secondary objective was to determine the feasibility of delivering BA to people with post-stroke depression.

Chapter 2 Methods

The feasibility trial

This feasibility trial is reported in accordance with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement55 and the pilot and feasibility trials extension. 56 The full protocol has been published. 57

Trial design

This study used a parallel-group, feasibility, multicentre RCT design with nested qualitative research and economic evaluation to compare BA therapy with usual stroke care for patients with post-stroke depression. Participants were allocated to BA or usual stroke care at a ratio of 1 : 1.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was granted on 29 January 2015 by the National Research Ethics Service (NRES) Committee East Midlands – Leicester (reference number 15/EM/0014).

Important changes to the methods after feasibility trial commencement

Changes made to the essential documentation during the trial and following ethics approval on 29 January 2015 can be found in Appendix 1.

Early in the recruitment phase substantial amendment 2 [Protocol v2.1, Research Ethics Committee (REC) approved 8 July 2015] provided additional options in the recruitment process. This allowed the therapists to contact patients directly by telephone following initial consent to be contacted. This streamlined the recruitment process by providing the opportunity for the therapist to explain more about the research and arrange a home visit to complete screening measures. This amendment also broadened the recruitment routes to include potential participants on acute outpatient caseloads.

In substantial amendment 3 (Protocol v2.2, REC approved 7 September 2015), an additional exclusion criterion were added to exclude patients who were currently receiving psychological intervention. Five out of the 49 participants were recruited prior to this exclusion criterion being added. Furthermore, it was specified that participants in the intervention group could be withdrawn from the intervention if it was subsequently agreed that the patient needed immediate clinical psychology input. This amendment also clarified that participation in the study would not compromise access to other services (i.e. psychological input) that were part of usual care.

Minor amendments were also made including changes in study personnel and contact details. In addition, another secondary end point was added to estimate the sample size for a definitive trial and clarification that two or fewer missing items within the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)58 could be imputed if required.

Participants and eligibility criteria

Recruitment of participants

Participants were identified from hospital and community stroke databases at three stroke services, as well as the corresponding acute hospital stroke wards, and from voluntary support groups. Participants were approached by letter or by clinicians in community and acute stroke teams, or by voluntary group leaders. Self-referrals were facilitated by advertising the study in newsletters of relevant charities and societies. Posters were displayed in local voluntary sector groups, libraries and local community centres so that potential participants unknown to local hospital and community stroke teams could self-present to the local research team. The methods of identifying potential participants were kept broad to allow assessment of the optimum recruitment strategy for the definitive study. This also enabled recruitment of a representative cross-section of the population.

Participants were recruited from three centres (see Settings and locations where the data were collected). The process for recruitment varied depending on where the participant was recruited from.

Hospital stroke database and community stroke team database

At each site, the clinical teams sent invitation letters to those on the hospital or community stroke databases of discharged patients. Patients were sent a postal pack containing a covering letter, a participant information sheet, a reply slip, the PHQ-9, the Visual Analogue Mood Scales (VAMS) ‘Sad’ item and a prepaid envelope. Patients who were interested in taking part returned the reply slip and completed PHQ-9 and VAMS ‘Sad’ item to the therapist. Return of completed questionnaires was taken as implied consent to be contacted by the therapist (i.e. for potential recruitment into the trial). Those patients who did not reply were contacted by telephone by the clinical team to remind them about the study. The PHQ-9 and VAMS ‘Sad’ item were used to assess whether or not participants met the inclusion criterion of having depression. Participants who returned the reply slip with the completed PHQ-9 and VAMS ‘Sad’ item were contacted by the therapist if they were identified as depressed (scoring ≥ 10 points on PHQ-9 or ≥ 50 points on the VAMS ‘Sad’ item). Those who were identified as not being depressed (i.e. scores of < 10 points on the PHQ-9 or < 50 points on the VAMS ‘Sad’ item) were thanked for their interest and informed that they were not eligible.

Therapists contacted patients who were classified as depressed to arrange a visit. The purpose of the visit was to check that the participant met the remainder of the inclusion criteria, to explain the study and to formally invite eligible patients to take part, obtain signed consent and complete baseline assessments. If a patient returned the reply slip to express interest in the study but did not return the completed PHQ-9 and VAMS ‘Sad’ item, the therapist offered to visit and support the patient to complete these assessments.

Patients currently on acute hospital stroke wards

At each site, research nurses visited hospital stroke wards to provide information about the research to potential participants and seek their permission to be contacted by the research team and, therefore, permission for their contact details to be passed on to the research team. A screening form was used to collect key demographic and contact information from all consented participants, who were then contacted by the local therapist 3 months from the date of consent to be contacted. Before making contact, the local research nurse or general practitioner (GP) was contacted to check whether or not the patient was still alive.

Patients were then contacted by telephone to tell them more about the research and arrange a home visit, during which they completed the PHQ-9 and VAMS ‘Sad’ item. Those patients who were identified as not being depressed were thanked for their interest and were informed that they were not eligible. For patients who were classified as depressed, the therapist either (1) arranged a subsequent home visit or (2) continued with recruitment as per the steps in Hospital stroke database and community stroke team database. Alternatively, instead of a home visit or telephone call, the patient could be sent a pack containing a covering letter, a participant information sheet, a reply slip, the PHQ-9, the VAMS ‘Sad’ item and a prepaid envelope addressed to the therapist for that site. The same steps outlined in Hospital stroke database and community stroke team database were then followed.

Patients currently on the active caseload of community and acute stroke teams

The BEADS trial was presented to the community and acute stroke teams at each of the study sites. The clinical care teams were asked to explain the study to potential participants at the end of therapy, outpatient appointments or between appointments by telephone. If patients were interested in taking part, the clinician asked permission for their contact details to be passed on to the research therapist. Following this, the therapist then sent a pack to the patients and followed the steps outlined in Hospital stroke database and community stroke team database or arranged a home visit and followed the steps in Patients currently on acute hospital stroke wards.

Voluntary sector (stroke and aphasia groups)

The therapists sought permission to attend stroke and aphasia groups in each site to explain the study to members. Those who were interested in taking part were invited to provide their contact details to the therapist, who then either arranged a home visit and followed the steps in Patients currently on acute hospital stroke wards or sent the patient a pack and followed the steps in Hospital stroke database and community stroke team database.

Potential participants were told that entry into the trial was entirely voluntary and that their treatment and care would not be affected by their decision. It was also explained that they could withdraw at any time, but attempts were made to avoid this happening. Participants were told that, if they withdrew, their data could not be erased and could be used in the final analyses.

Recruitment of carers and therapists

For those participants with carers, the carer was also invited to take part. Carer participants were eligible if they provided informal care to the trial participant. Family members, spouses and friends were all eligible to participate as carers. The study therapists (staff participants) were invited to take part in the qualitative interviews at the end of the study.

The presence of a carer was established by the therapist during the initial telephone call to arrange the first home visit. When the carer was present during the home visit, study therapists provided them with a copy of the participant information sheet to review and gave a verbal explanation of study participation. When appropriate and relevant, written informed consent was taken from carer participants during this first home visit. When the carer was not present during the home visit, a copy of the participant information sheet was provided for the carer and the study therapist followed this up with a telephone call to discuss the study in more depth. When the carer was interested in participating, an additional home visit was undertaken to organise written informed consent from them.

Staff participants were consented by the study therapist; research and staff participants were consented by the interviewer for the qualitative interview and by the trial manager for video recording (fidelity assessment). It was explained that participation was voluntary and that they could withdraw at any time.

At consent for recruitment into the trial, all participants opted in or opted out of receiving invitations for their treatment sessions to be video recorded as part of the fidelity assessment. Participants who declined video recording were offered the option of audio recording instead. Participants were not excluded from the study if they did not want their treatment sessions to be video or audio recorded. We documented the proportion of participants who agreed to be video (or audio) recorded.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

The criteria were designed to identify those who would be suitable for the intervention were it to be offered within clinical practice. Participants were included in the study if they:

-

had a diagnosis of stroke

-

were aged ≥ 18 years

-

were living in community settings, including home or nursing home

-

were a minimum of 3 months and a maximum of 5 years post stroke

-

were identified as depressed, defined as –

Exclusion criteria

Participants were excluded if they:

-

had a diagnosis of dementia, based on self-report or carer report, prior to their stroke

-

reported receiving medical or psychological treatment for depression at the time at which they had their stroke

-

were currently receiving a psychological intervention

-

had communication difficulties that would have an impact on their capacity to take part in the intervention, based on assessment with the Consent Support Tool60 (CST) for people with aphasia

-

had visual or hearing impairments that would have an impact on their capacity to take part in the intervention based on their therapist’s opinion at baseline assessment

-

were unable to communicate in English prior to the stroke

-

did not have mental capacity to consent to take part in the trial.

All reasons for patient exclusion were recorded.

Consent process

During training by a speech and language therapist experienced in mental capacity assessment, all recruiting researchers were taught techniques to identify whether or not a potential participant was able to understand key information provided about the project and to retain and weigh this information, as well as methods to assist participants to express their decision, adhering to the four key aspects of mental capacity outlined in the Mental Capacity Act 2005. 61

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants who were are able to give it. Those who lacked the mental capacity to provide consent were excluded from the trial. The therapists explained the details of the trial and provided a participant information sheet, ensuring that the participant had sufficient time to consider participating or not. For patients who were physically unable to sign the form (e.g. weakness in dominant hand attributable to stroke), consent could be given using a mark or line in the presence of an independent witness (who had no involvement in the trial), who would then corroborate this by signing the consent form.

A significant proportion of the stroke population have some degree of cognitive or language impairment (aphasia). The level of support required to enable a person with aphasia to provide informed consent is dependent on the severity and profile of the aphasia. In order to provide information in a format consistent with each individual’s language ability, the CST could be used. The CST provides a means of determining comprehension levels of people with aphasia, or cognitive difficulties, in order to provide information in a format that is likely to be most accessible to the person with aphasia to support their understanding. This tool also helps to identify methods that support the individual to express their decision. The therapist requested verbal consent from the potential participant to carry out part A of the CST (10 minutes). The result indicated how appropriate it was to provide the accessible information sheet. If the CST indicated that the potential participant understood fewer than two key written or spoken words in a sentence, they would be likely to find it difficult to understand all the information required to provide informed consent. These participants were thanked for their time but were not eligible for the study as, despite the intervention using techniques to support the inclusion of those people with reduced language or cognition, the intervention did rely on achieving understanding with support and actively participating in therapeutic communication.

The accessible information sheet was provided to those who understood at least two key written and spoken words. This follows standard aphasia-friendly principles, with one idea presented per page in short simple sentences in large font. Key words are in bold and each idea is represented by a pictorial image to support understanding of what the study is about. The therapists were trained to support understanding further by reading parts of the information aloud and using supportive gestures/actions (as described for information level 3 of the CST and consistent with the types of support offered in the intervention under study).

Once the potential participant was given the information and had sufficient time to ask questions and discuss with family or friends, the therapist checked that the individual had capacity to provide informed consent. This was performed by checking that they understood the information, could remember what the study was about and could clearly express their decision in the way in which they usually communicate (speaking, writing, using a communication aid). The CST provides information on ways people with aphasia might choose to express their intentions.

When the CST was not needed, owing to adequate understanding and verbal expression in conversation, the researchers were still taught to check that the trial information provided had been understood by each individual by asking yes/no questions about the content of the information and the potential consequences of their involvement to confirm the patient’s ability to weigh the information.

Participants with capacity to provide informed consent who used the accessible information provision were provided with an aphasia-friendly consent form and asked to initial all boxes before signing. When stroke symptoms prevented initialling of boxes or providing written consent, the patient could use a mark or line and a relative/friend was asked to witness the fact that the participant was consenting to the study and to sign and date the consent form to confirm this on behalf of the participant.

As participants may become distressed during the study and, therefore, may be advised to consult their GPs, consent to notify the GP was sought from all participants. Participants’ GPs were notified by letter that their patient was taking part in the research and were sent a copy of the participant information sheet for information.

Expected duration of participant participation

Study participants were expected to participate in the study for approximately 6 months.

Settings and locations where the data were collected

The University of Nottingham sponsored the trial. Co-ordination of the trial was undertaken by the Sheffield Clinical Trials Research Unit (CTRU). Participants were identified and recruited from hospital and community stroke services at Sheffield Health & Social Care NHS Foundation Trust, Derby Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and Let’s Talk Wellbeing at Nottinghamshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust. Screening and identification of potential participants was supported by Clinical Research Network (CRN) staff based at Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Derbyshire Community Health Services NHS Foundation Trust and at Sherwood Forest Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. Baseline data were collected and BA therapy was delivered by the therapists in participants’ own homes. Six-month follow-up data were collected in participants’ own homes, for those with aphasia, by blinded outcome assessors. For those without aphasia, data were collected by post unless help was requested.

Interventions

Intervention: behavioural activation therapy

Behavioural activation therapy is a structured and individualised treatment that aims to increase people’s level of activity, particularly the frequency of valued activities (pleasant or enjoyable events), and decrease avoidance behaviours, in order to improve mood. Participants randomised to receive BA were treated at their place of residence by a research therapist. The research therapists were APs at two sites and a psychological well-being practitioner (PWP) at one site. APs are psychology graduates who support the work of a clinical psychologist and work under the supervision of a clinical psychologist. Many APs aspire to train to become clinical psychologists. The level of expertise and experience of an AP can vary, but they would need to meet the person and job specification for the band at which they would be employed (NHS bands 4 or 5). PWPs have completed an accredited training course to enable them to deliver low-intensity CBT-based interventions to people with mental health conditions.

The two APs in the study were psychology graduates. They had no previous formal training in psychotherapy and had not previously worked in a stroke service. They were newly appointed to working as an AP in the stroke service at their site; their background and level of experience was comparable to the APs who delivered BA to people with aphasia in our previous CALM study. 17

Participants were offered a maximum of 15 sessions of BA over 4 months, with an expected average of 10 sessions. Therapy sessions were delivered face to face on an individual basis and lasted for about 1 hour. The intensity and duration of therapy were based on a study25 of CBT with stroke patients and were informed by the CALM study,17 in which participants received an average of nine 1-hour sessions over 3 months. Experience and criticism of the CBT trial25 was that the 3-month duration of therapy was too short. The trial62 of BA for treating depression in primary care provided 12 sessions over 3 months, but this was not in a stroke sample and patients with communication or cognitive difficulties may require a longer duration of therapy. Therefore, the duration of therapy was 4 months because the CALM study17 showed that it was difficult to complete sessions in 3 months owing to non-availability of the participants and short-term illnesses. Four months also allowed flexibility to provide therapy visits to support maintenance, as might be provided in clinical practice. However, the number of therapy sessions varied depending on the needs of the individual and their progress in therapy. The intensity of treatment was negotiated between the therapist and the participant, based on their progress in achieving their therapy goals, so as to reflect usual clinical practice.

A BA treatment manual was developed for the previous CALM trial17 based on the behavioural component of CBT for depression in stroke patients,23,25 behavioural therapy with older people41 and guidelines on conducting therapy with people who have aphasia. 21,41,51 For the BEADS trial, this therapy manual was further revised to include BA with stroke patients who do not have aphasia, and provided examples and practical guidance relevant to all stroke patients. In revising the manual from the CALM trial,17 we drew on the CBT therapy manuals of Lincoln et al. 23 and Laidlaw (Ken Laidlaw, University of Edinburgh, 2004 personal communication), BA manuals of Martell et al. ,40 Lejuez et al. 63 and Mitchell (Pamela Mitchell, University of Washington School of Nursing, 2002, personal communication), BA strategies used in low-intensity CBT64 and guidelines on adapting CBT for people with stroke. 22,51

The therapy manual contained session content for 10 sessions, using the same behavioural approaches as the CALM study. 17 Participants could receive up to 15 sessions to allow for the fact that, for some people, it may take longer to cover therapy content. Additional guidelines were provided for identifying strategies to support people with aphasia and materials were recommended to enable guidelines on conducting therapy to be followed.

Goals set during treatment to increase enjoyable activities were tailored to the individual. BA also included ‘homework’ tasks to be completed between sessions to practise exercises and increase activity levels. Behavioural treatment strategies focused on maximising mood-elevating activities. The process of BA involved identifying how the person currently spends their time, identifying activities that they enjoyed doing (this included resuming previous activities, increasing current activity levels or introducing new activities) and setting goals to increase the number of enjoyable activities.

Behavioural therapy techniques included:

-

Activity monitoring – therapists identified how participants spent their time to assess current activity level, determined what activities they enjoyed and when activities could be carried out. Participants were given an activity diary or timetable to complete as a homework task. The complexity of the diary varied depending on the cognitive and communication abilities of the patient. The activity diaries were available in a range of formats, including word cards, picture cards and photographs.

-

Activity scheduling – participants were encouraged to plan realistic activities and goals to complete each day. This was intended to increase the likelihood that activities were being carried out. The number of activities was gradually increased in order to increase the amount of positive reinforcement received. Activities were set on the basis of the abilities and goals of the individual.

-

Graded task assignment – tasks were broken down into smaller, manageable, steps to facilitate practising tasks that participants found difficult. This was intended to increase the frequency of self-reward and reduce the chances of failure and avoidance of tasks. For example, someone who wanted to go shopping, were encouraged to start by going to a familiar local shop where they knew people already; this was then extended to going to a larger shop, further away.

-

Problem solving – this included focusing on difficulties a participant may have with completing activities and using behavioural techniques (such as a graded task) for improving success at these tasks. Common problems in carrying out activities or tasks were identified and then a problem-solving approach was used to identify and practise possible solutions.

After each session, therapists completed the therapy recording form. This included the duration and location of the therapy session and whether or not there was another person present. The time taken to travel to the visit was recorded. The therapy recording form also included an estimate of how much time (in 10-minute units) had been spent on each component of therapy. The components of therapy were based on the content of BA approaches in the manual.

The therapist also completed the therapy session log. This included the planned number of treatment sessions, the number of treatment sessions completed and the reasons that sessions were missed.

Ensuring intervention fidelity

The therapists attended a 2-day workshop led by a NHS consultant clinical psychologist and the chief investigator. The workshop covered the rationale of BA therapy for treating depression, application of behavioural techniques for treating post-stroke depression and explanation of the therapy manual. The workshop included fictional case examples and role-play exercises. The workshop also included training from a speech and language therapist on communicating with stroke patients with cognitive and/or communication difficulties. Communication resources were developed during the CALM study17 (such as picture cards and activity schedules) and were provided for each of the therapists. To support between-session activities, worksheets/information-appropriate sheets were developed for varying levels of cognitive difficulties or aphasia.

It was important that the therapists delivered the intervention consistently, in accordance with the therapy manual. Weekly clinical supervision for the therapists was provided by a local clinical psychologist at each site. In addition, therapists delivering the intervention had a monthly teleconference to discuss the content of the intervention, share examples of practice and raise any difficulties with the chief investigator and NHS consultant clinical psychologist.

A sample of therapy sessions were video recorded (see Fidelity assessment for further details).

Control group: usual care

The availability of psychological support in the three sites varied. The content of usual care was decided locally by the clinical team, as per local services. In the three sites, most stroke survivors are admitted to hospital, usually to a stroke unit. On discharge, they may receive input from an early supported discharge team or from a community stroke/rehabilitation team.

Participants in the usual-care group followed the current care pathway. Participants received all other services routinely available to them as local practice but had no contact with the trial therapist. This usual-care control group provided a record of usual care to inform the design of the definitive trial.

Concomitant treatment

Those receiving medical or psychological treatment for depression at the time of stroke onset were excluded as we were interested in those who developed depression following stroke (as per exclusion criteria in Participants and eligibility criteria). Those who were currently receiving antidepressants were included so that we could record how commonly this occurs. Receipt of antidepressant medication or other psychological intervention for depression was recorded in the case report form (CRF).

Compliance

Compliance with BA was regarded as an outcome measure not a covariate and was measured by recording whether or not participants allocated to the BA intervention attended scheduled therapy sessions. The completion rates of follow-up questionnaires were also recorded.

Feasibility criterion

Primary outcome

The primary outcome measures related to the feasibility of (1) proceeding to a definitive trial and (2) delivering the BA therapy intervention with participants with post-stroke depression.

The primary end points were based on:

-

feasibility of recruitment

-

acceptability of the research procedures and measures

-

appropriateness of the baseline and outcome measures for assessing impact

-

retention of participants at outcome

-

potential value of conducting the definitive trial, based on value-of-information analysis.

Other feasibility outcomes

The secondary end points were related to the feasibility of the BA therapy intervention, based on:

-

acceptability of BA therapy to participants, carers and therapists

-

feasibility of delivering the intervention by APs or therapists under supervision of an experienced mental health practitioner

-

documentation of ‘usual care’ using a health-care resource use questionnaire

-

treatment fidelity of the BA therapy

-

feasibility of delivery of BA therapy within current services and within a definitive trial

-

estimating the sample size for a definitive trial.

Clinical outcomes

Primary outcomes

The primary clinical outcome measure at 6 months was the PHQ-9. 58 For participants with moderate to severe language problems who were unable to complete the PHQ-9, the VAMS ‘Sad’ item59 was used – this is a single-item, visual analogue mood measure. The number of participants unable to complete the PHQ-9 was recorded, and the VAMS ‘Sad’ item was completed with all participants so that the relationship between the measures could be explored. This was a pragmatic approach, based on self-completion at baseline.

Secondary outcomes

The secondary clinical outcomes were the questionnaire measures used to assess the potential secondary outcomes at 6 months following BA therapy. These related to the feasibility primary end points (b) and (c). The following measures were used to assess clinical outcomes at 6 months:

-

Stroke Aphasic Depression Questionnaire – Hospital version (SADQ-H) (observer-rated depression)65

-

Nottingham Leisure Questionnaire (NLQ) (leisure activities)66

-

Nottingham Extended Activities of Daily Living (NEADL) (functional outcome)67

-

Carer Strain Index (CSI) (carer-rated level of strain)68

-

EuroQoL-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L) [health-related quality of life (HRQoL)] standard version69 and a version for people with cognitive problems70 for participants and carers

-

health-care resource use questionnaire.

Participant withdrawal

Participants had the right to withdraw from the study at any time. The reasons for leaving the study, when given, were recorded on a CRF. Participants who withdrew were still invited to complete the 6-month outcome assessments unless they had specified that they wished to have no further involvement in the trial. Individuals removed from active participation in the intervention were not replaced. Reason for withdrawal from the intervention, if known, was recorded.

Participants were withdrawn from the trial either at their own request or at the discretion of the chief investigator. The investigator could withdraw a participant in the interest of the participant (e.g. if continuation in the trial was considered to be causing undue stress) or because of a deviation from the protocol (e.g. when, following review, it transpired that a participant was incorrectly deemed eligible at the time of consent). Participants could discontinue their allocated intervention or withdraw from the study for the following reasons:

-

withdrawal of consent

-

changes to their health status preventing their continued participation

-

failure to adhere to protocol requirements.

If, during the trial, a patient allocated to the BEADS intervention subsequently required clinical psychology input (as per the protocol of the local service), the BEADS therapist (AP/PWP) discussed this with the clinical psychologist or clinical lead and the patient and all agreed what was best for the participant. If it was agreed that the patient needed immediate clinical psychology input then they were withdrawn from the BEADS intervention and they saw the clinical psychologist, or were referred to alternative provision. Therefore, the patient was withdrawn from the intervention but not the overall trial and, thus, outcome data were still collected from them. We recorded the number of participants who were withdrawn from the BEADS intervention because of a conflict in using clinical services.

Changes to trial outcomes after the trial commenced, with reasons

An additional secondary end point, to estimate the sample size for a definitive trial, was added to the protocol after the trial commenced, as an inconsistency was identified between the statistical analysis plan (SAP) and the protocol.

Sample size

As this was a feasibility study, it was not powered for efficacy and no formal interim analyses of efficacy were conducted; the sample size was adequate to estimate the uncertain critical parameters [standard deviation (SD) for continuous outcomes; consent rates, event rates and attrition rates for binary outcomes] needed to inform the design of the definitive RCT with sufficient precision. The sample size of 60 participants allowed SDs for continuous outcomes, such as the PHQ-9 and VAMS ‘Sad’ item, to be estimated to within precision of approximately ± 19% of its true value (with 95% confidence). Allowing for 15% attrition by 6 months post-randomisation follow-up, 72 participants needed to be recruited. To achieve the target sample size of 72 over the 12-month recruitment period, with three centres, we needed to randomise two participants per centre per month.

In addition to this, we estimated that we would recruit a total of 65 carers and three therapists to the study. The carer estimate was based on the CALM study,17 in which approximately 90% of people with stroke had an informal carer present who completed the study outcome assessments.

Further information on both the quantitative and the health economic analyses is provided in the SAP. This covers both the procedures for missing, unused and spurious data and definitions of populations for which data were analysed.

Explanation of any interim analyses and stopping guidelines

The overall study could have been stopped because of safety concerns or issues with study conduct at the discretion of the sponsor. There were no formal statistical criteria for stopping the trial early. Decisions to stop the trial early on grounds of safety or futility would have been made by the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) on the basis of advice from the Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC). No early stopping was planned, but the study could have been terminated early if, in the view of the TSC, no useful information was likely to be obtained by continuing. The criteria for assessing this were primarily the feasibility outcomes listed in Feasibility criterion. The TSC could also have recommended the closure of a centre but that the trial as a whole continued, on the same grounds. Unblinded adverse event (AE) data were reviewed by the DMEC, who could have recommended to the TSC that the trial was stopped if, in their opinion, there was evidence of harm in the intervention group. As this was a feasibility trial, it would not have stopped early for efficacy.

Method used to generate the random allocation sequence

Randomisation was conducted using a computer-generated list with random permuted blocks of varying sizes, created and hosted by the Sheffield CTRU in accordance with their standard operating procedures and was held on a secure server. Once a participant had consented to the study, the therapist logged into the remote, secure, internet-based randomisation system and entered basic demographic information. The allocation for that participant was then revealed to the researcher.

Type of randomisation and details of any restriction (such as blocking and block size)

Block randomisation with randomly varying block sizes of two, four and six was used so that the sequence of allocation could not be predicted. The block sizes were determined by the trial statistician and block size was not revealed to any other member of the study team. Participants were allocated to BA or usual stroke care at a ratio of 1 : 1. Randomisation was stratified by site.

Allocation concealment mechanism

Access to the allocation sequence was restricted to those with authorisation. The sequence of treatment allocations was concealed until interventions had been assigned and recruitment, data collection and analyses were complete.

Neither the participants nor the therapists were blind to which treatment the participants were receiving. The outcome assessors were blind to the treatment received and there was no requirement for them to know the treatment allocation at any stage. As a result, a procedure for breaking the code was not necessary.

Blinding

Participants were randomised at baseline (after consent and baseline assessments) in equal proportions to BA or usual stroke care. It was not pragmatically possible for the participant or therapist to be blind to the group allocation, but the researchers completing the 6-month outcome assessments were blinded and had no involvement in any other aspects of the trial. The researchers were asked to record whether or not they thought they were unblinded and were also asked to guess the group allocation. We followed guidelines71,72 to minimise unblinding during RCTs of rehabilitation.

The trial statisticians remained blind until data freeze, at which point data checks were carried out on unblinded data.

Statistical methods

As the trial was a pragmatic, parallel-group RCT, data were reported and presented in accordance with the CONSORT 2010 Statement. 55 All statistical analyses were performed in R version 3.3.1 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). 73 As a feasibility study, the main analysis was descriptive and focused on CI estimation and not formal hypothesis testing.

Analysis populations

The intention-to-treat (ITT) population includes all participants for whom consent was obtained and who were randomised to treatment, regardless of whether they received the intervention. This is the primary analysis set and end points were summarised for the ITT population unless otherwise stated.

Baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics were participants’ demographics (age, sex and ethnicity), patient- and carer-reported outcomes [PHQ-9, VAMS ‘Sad’ item, EQ-5D-5L, NEADL, NLQ, Stroke Aphasic Depression Questionnaire (SADQ), CSI and EQ-5D-5L carer], stroke history (time since last stroke, lateralisation of stroke, stroke type, side of weakness, previous stroke and depression treatment) and stroke outcomes [Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), Frenchay Aphasia Screening Test (FAST) and Modified Rankin Scale].

For continuous variables, the number of observations, mean and SD or median and interquartile range (IQR), and minimum and maximum observations were presented by treatment group and site. For categorical variables, the number and percentage of observations in each category were presented.

Imbalance between treatment arms was not tested statistically but was reported descriptively.

Feasibility outcomes

The numbers of participants screened, eligible and randomised per month per centre and overall were presented with relevant percentages. Attrition was examined by presenting the number of participants who dropped out by treatment arm, site and time since last stroke. The reasons for attrition, where given, were also presented for each participant.

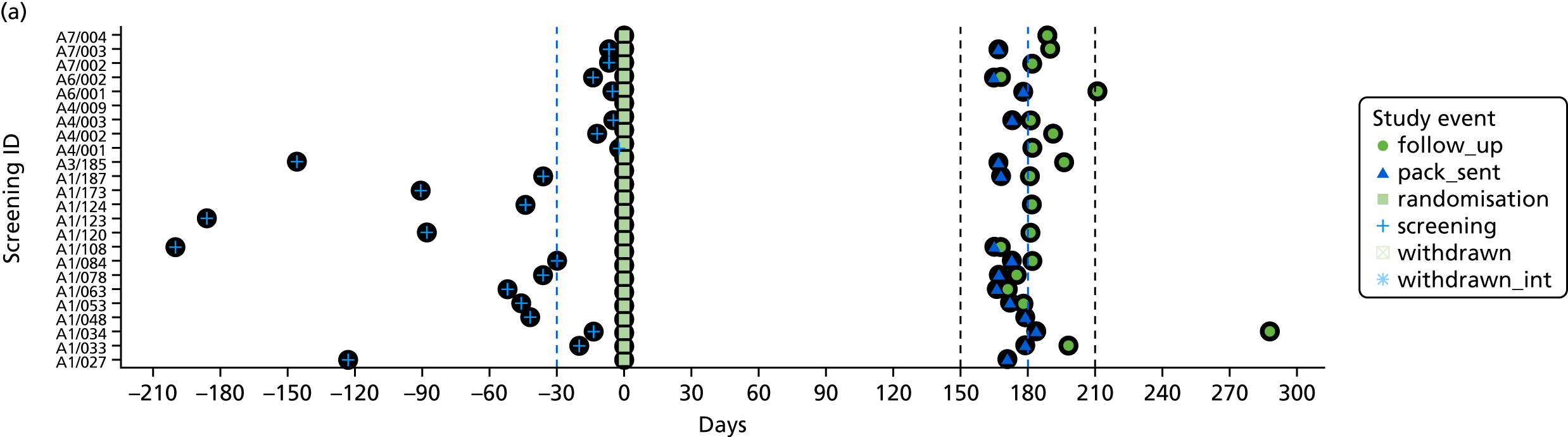

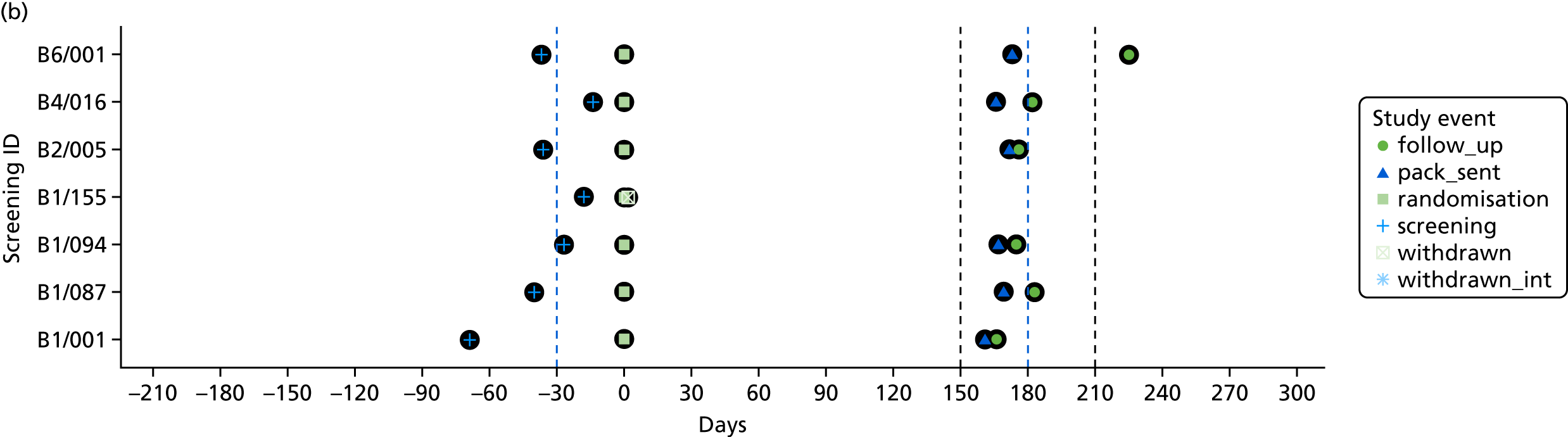

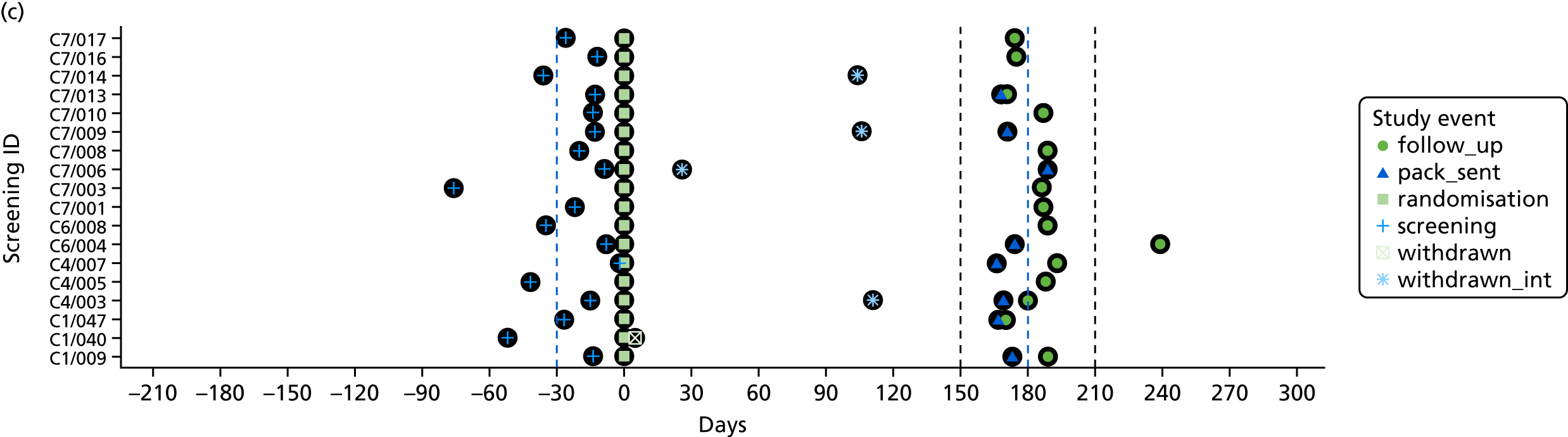

The time of key events including screening, randomisation, baseline and follow-up was plotted by participant to check that these were carried out as planned.

The number and percentage of participants randomised to the BA arm and who received at least two, five, eight and 10 therapy sessions were presented. The mean, SD, median and IQR number of planned sessions that were missed were presented.

A summary of missing patient- and carer-reported outcome measures was also presented. In addition to this, we reported the timing of the post-randomisation follow-up assessment.

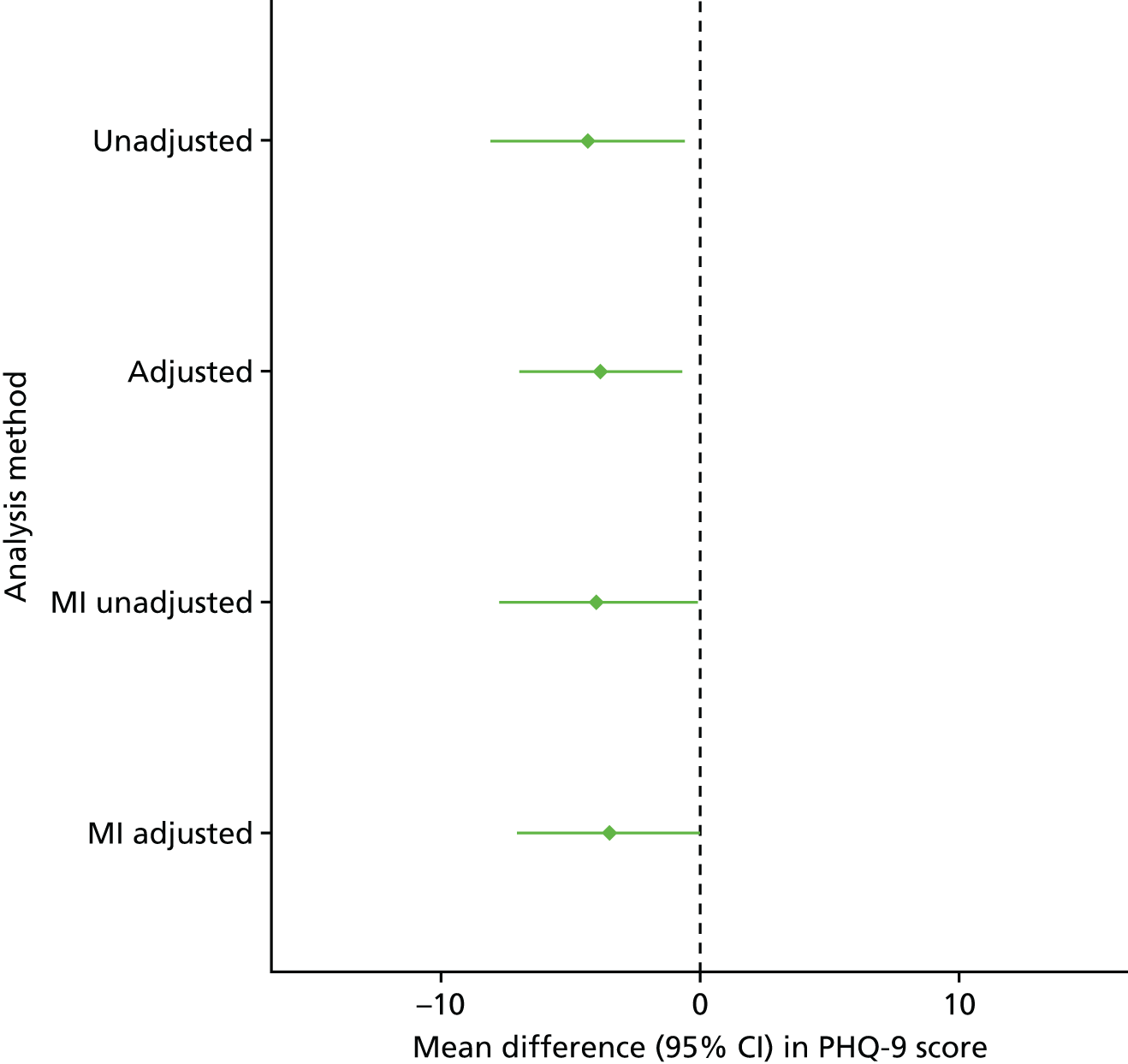

As part of the feasibility analysis, the effect size for the 6-month PHQ-9 outcome (the probable primary end point for the definitive study), that is the difference in mean scores between the BA and control groups, was estimated, along with its associated 95% CI estimate,74 using a mixed-effects model; site was included as a random effect and baseline PHQ-9 as a covariate to check that the likely effect was within a clinically relevant range as confirmation that it was worth progressing with the definitive trial.

The following sensitivity analyses were presented alongside the ITT analysis:

-

multiple imputation of missing primary outcome data

-

unadjusted analysis.

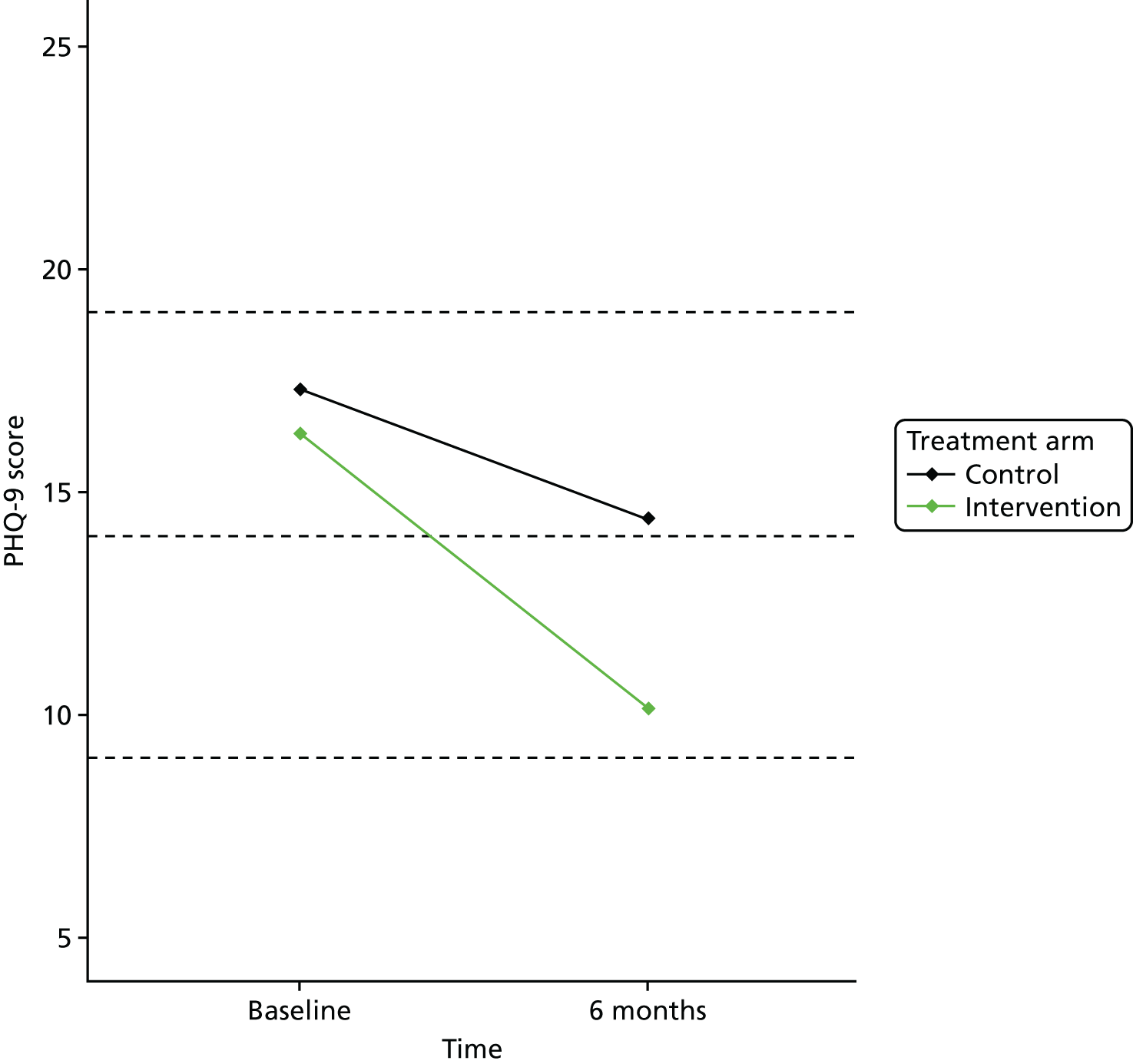

Although this was not prespecified, to examine the effect of the treatment, we also examined the change in PHQ-9 depression categories (Table 1).

| PHQ-9 score (points) | Depression category |

|---|---|

| 0–4 | Minimal depression |

| 5–9 | Mild depression |

| 10–14 | Moderate depression |

| 15–19 | Moderately severe depression |

| 20–27 | Severe depression |

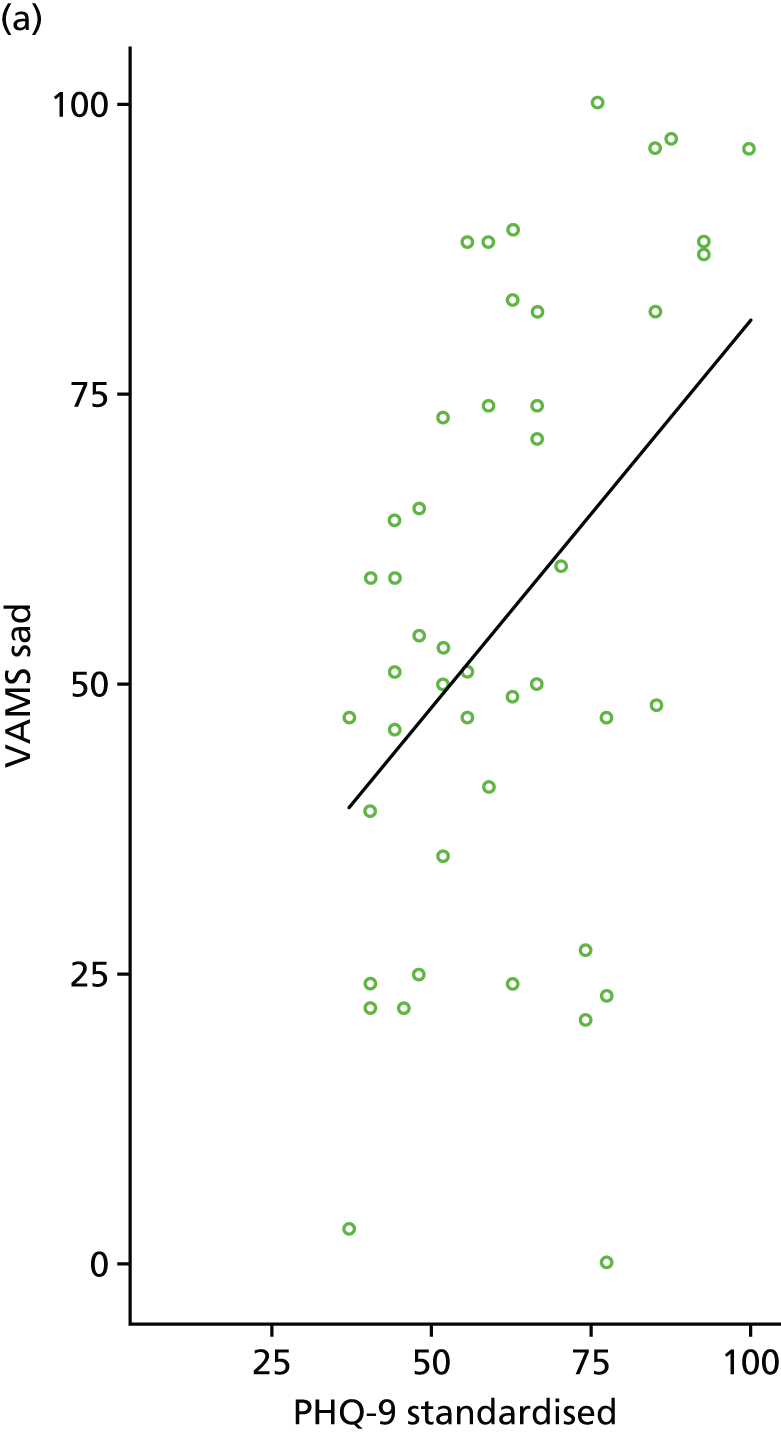

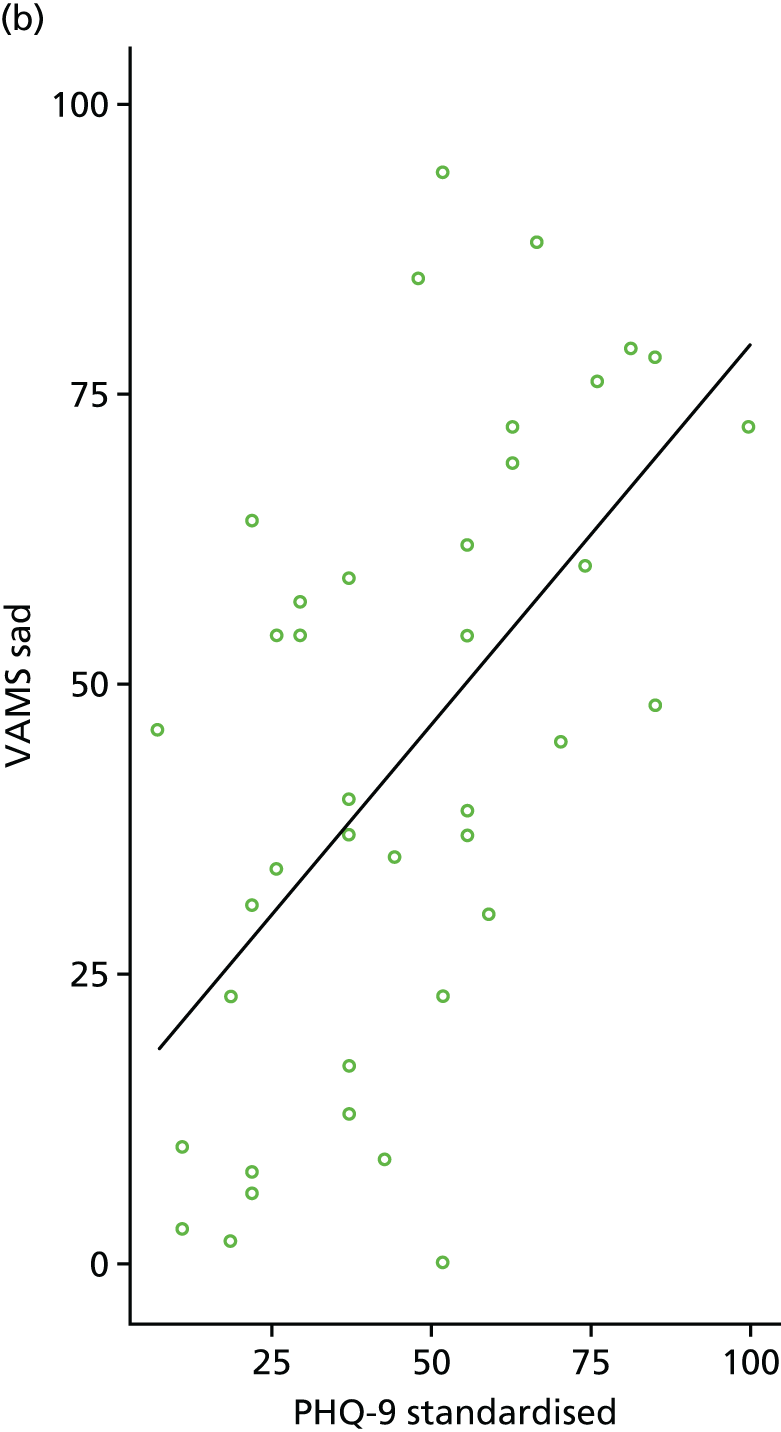

Individual PHQ-9 score and depression category at baseline and follow-up were plotted by treatment arm. To assess the level of agreement between PHQ-9 and VAMS ‘Sad’ item, scatterplots were generated using baseline and 6-month follow-up data. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was also calculated using baseline and 6-month follow-up data.

Sample size calculations for a definitive trial

We calculated a sample size for a definitive trial comparing BA with usual care in participants with post-stroke depression. The primary end point used was PHQ-9 at 6 months post randomisation. The sample size was based on a range of differences in PHQ-9 of between 3 and 5 points75 and a range of conservative estimates of SD of 7–11 points, giving a range of standardised effect sizes between 0.27 and 0.71, allowing us to determine the most appropriate option. Feasibility data were used to calculate the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) in the intervention arm based on clustering by site. Furthermore, the feasibility trial attrition rate was used to adjust the final sample size calculation.

Clinical outcomes

Primary outcomes

The primary clinical outcome measure at 6 months was the PHQ-9. 58 We planned that those participants with moderate to severe language problems who were unable to complete the PHQ-9 would instead complete the VAMS ‘Sad’ item59 – this was a single-item, visual analogue mood measure. However, we did not have any participants with moderate to severe language problems who did not complete the PHQ-9. A comparison of PHQ-9 to VAMS ‘Sad’ item was carried out as described above to inform a potential definitive trial.

To assess the quality of the primary outcome, the follow-up window, defined as the period between screening and 6-month follow-up assessment, was calculated for each participant. A mean and SD of follow-up time in days were calculated. Timing of key events (screening, consent, randomisation, withdrawal and follow-up) were plotted with number of days on the x-axis and screening number on the y-axis.

The secondary outcomes at 6 months post randomisation were analysed using a multiple linear regression model on the ITT population adjusting for baseline measure and centre to examine the difference between treatment arms. Mean differences and their 95% CIs were presented.

Missing spurious and unused data

The numbers of missing scores for each of the primary and secondary outcomes at baseline and 6 months post randomisation were presented by treatment arm. Furthermore, the number and percentage of missing items were presented for each of these questionnaires.

Multiple imputation was carried out using the Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations ‘mice’ package in R statistical software. 76 Missing 6-month post-randomisation PHQ-9 scores were imputed using chained equations and 30 multiply imputed data sets. The multiple imputation model included sex, age, treatment group, PHQ-9 score at baseline and/or 6 months, EQ-5D-5L at baseline and 6 months and SADQ at baseline and 6 months as predictors.

Safety outcomes

The number of AEs and serious adverse events (SAEs) was recorded and presented by treatment arm. These events were further categorised by the type of AE (fall, worsening health, etc.) and whether or not they resulted in a hospital stay.

Patient and public involvement

The BEADS trial received input from the patient and public involvement (PPI) group (including one patient with significant aphasia) on aspects of the design and methods development as well as study oversight. Two patients and one carer attended five scheduled meetings to discuss feedback on how the study was being conducted, including ideas about recruitment, study documents, ensuring the well-being of the patients and carers, and supporting the therapists. The meetings were attended by the PPI group members, the trial manager and the chief investigator. Meetings took place prior to receiving ethics approval when study materials were being developed, during recruitment and intervention delivery, and after the study to discuss the study results. The meetings each had an agenda that was agreed by the group. A summary of the discussions was written up by the trial manager and chief investigator and was circulated to the group for them to add any points and to ensure that it was an accurate summary of the meeting. Suggestions were put into practice with the creation of a short study summary card and a spiral-bound version of the aphasia-friendly participant information sheet. At the suggestion of the patient and carer representatives, the therapists were invited to join the PPI meetings. In these meetings, the PPI group members were able to ask the therapists questions and give suggestions. PPI group members asked the therapists if they found their job difficult and whether or not there were any challenges with delivering the intervention. The therapists explained that they were well supported and that they enjoyed their role. The PPI group members felt that this was crucial to the success of the study. Another question asked by the PPI group was whether the therapists felt that having the carer being present during therapy was helpful or not. The therapists explained that the carer provided support to the patient. One of the therapists said that they made sure they addressed any discussion or questions to the participant directly, so that they could choose when they wanted their carer to answer on their behalf.

Fidelity assessment

To ensure the fidelity of the intervention, the content of treatment was described and analysed against the manual.

Therapy sessions were video recorded to ensure that the treatment was being delivered in accordance with the manual and to be potentially used for future training. The plan was to select participants and sessions iteratively, using purposive sampling to represent the range of severity of depression (mild, moderate, severe from baseline scores) and across the phases of therapy (beginning, middle and end). We planned to video record up to 24 therapy sessions (based on recruiting the target sample size). It was anticipated that more sessions would be recorded in the middle phase of therapy because this covered more of the therapy sessions and is when the majority of the BA intervention occurs.

The video recordings were transferred to a secure encrypted device, deleted from the video recorder prior to transportation and stored in a secure area on the University of Nottingham server.

Practices for video recording drew on guidance on minimising intrusiveness of the recording. 77,78 Coding of video recordings was carried out by an independent researcher using a time sampling procedure. Recordings were made on the minute, every minute, throughout the recording. On each observation, the activity of the therapist and participants was given the appropriate activity code.

The assessors analysing the video recordings applied a customised therapy record form designed to capture a variety of key elements spanning all aspects of the intervention. The recordings included activities that were expected in all sessions and those that were session specific. They also included content derived from the treatment manual and other content. The other content included activities that were likely to occur but were not specified in the manual, such as social chat and making travel arrangements. A sample of recordings was checked by another observer and discrepancies were resolved by discussion.

The video-recording categories are shown in Appendix 2.

Data from coding sheets were entered into Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS) version 22 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) for analysis.

Health economic methods

Background

The health economic analysis had two key components that related to the primary end points of the trial:

-

assessing the feasibility of collecting data that may be used in a health economic analysis

-

conducting an economic evaluation and a value-of-information analysis in order to provide information on the potential value of conducting the definitive trial.

Overview

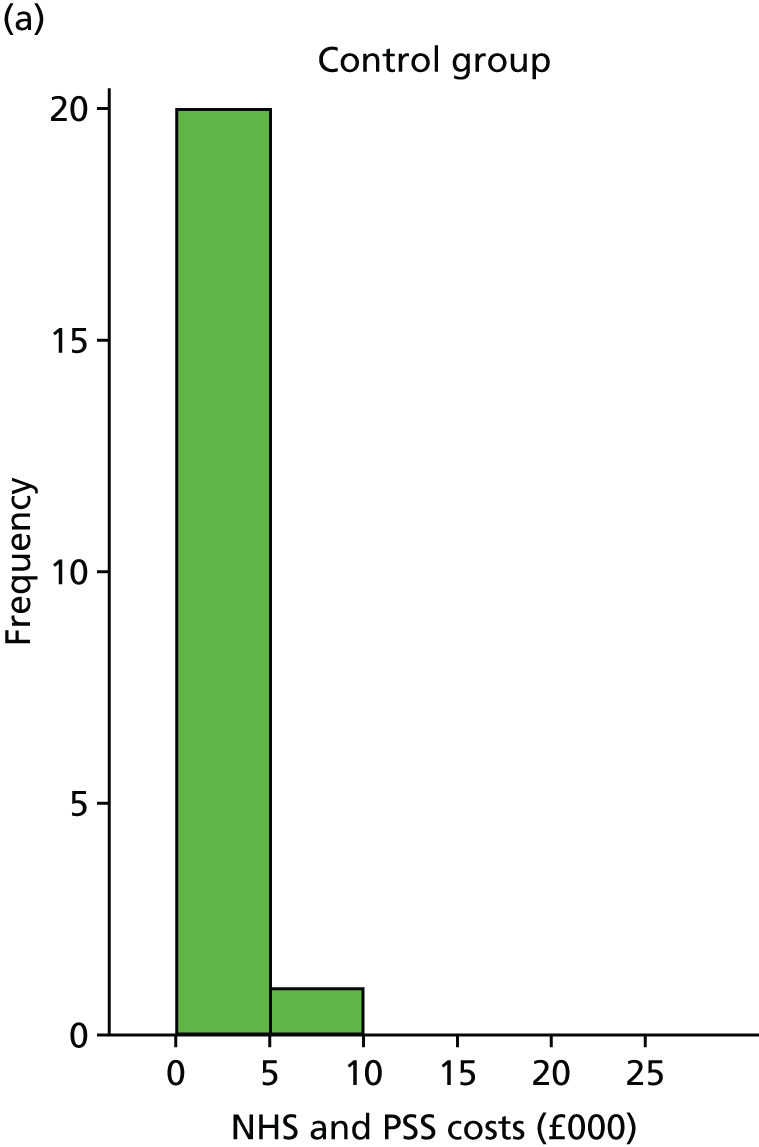

For the feasibility analysis, the number of participants who had complete data for each of the key measures is reported for each time point by treatment group and overall. For patient and carer questionnaires, the item response rate at each visit (baseline and 6 months) is reported. Response rate was measured as a fraction of the total number of items. This provides an analysis of the feasibility of collecting data required to complete a health economic analysis. For the health economics analysis, the data of most relevance are those from the:

-

EQ-5D-5L – standard version (completed by participants who are able)

-

EQ-5D-5L – aphasia-accessible version (completed by all participants)

-

EQ-5D-5L – completed by the carers of participants for themselves

-

EQ-5D-5L – completed by the carers of participants on behalf of the participant

-

resource use questionnaire.

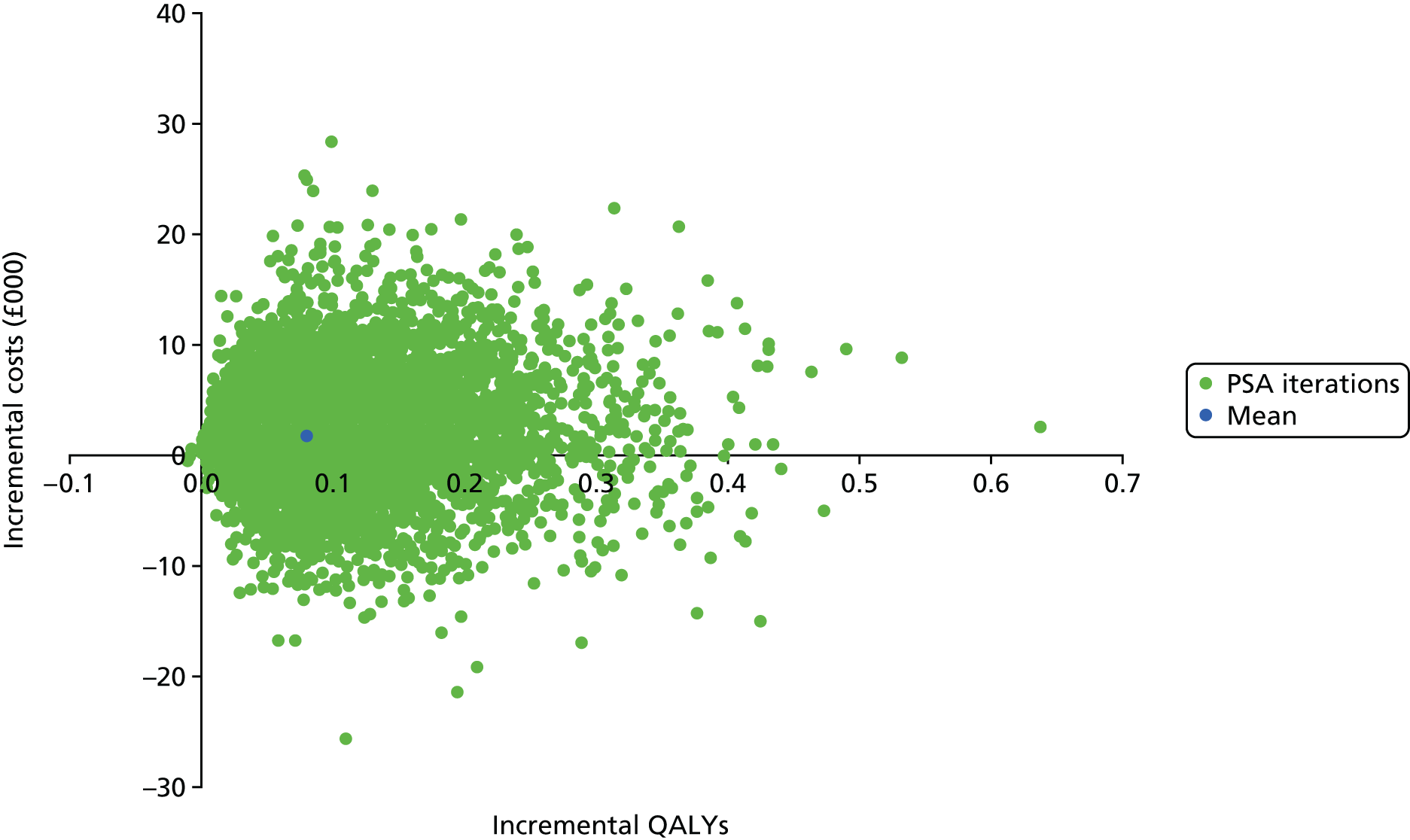

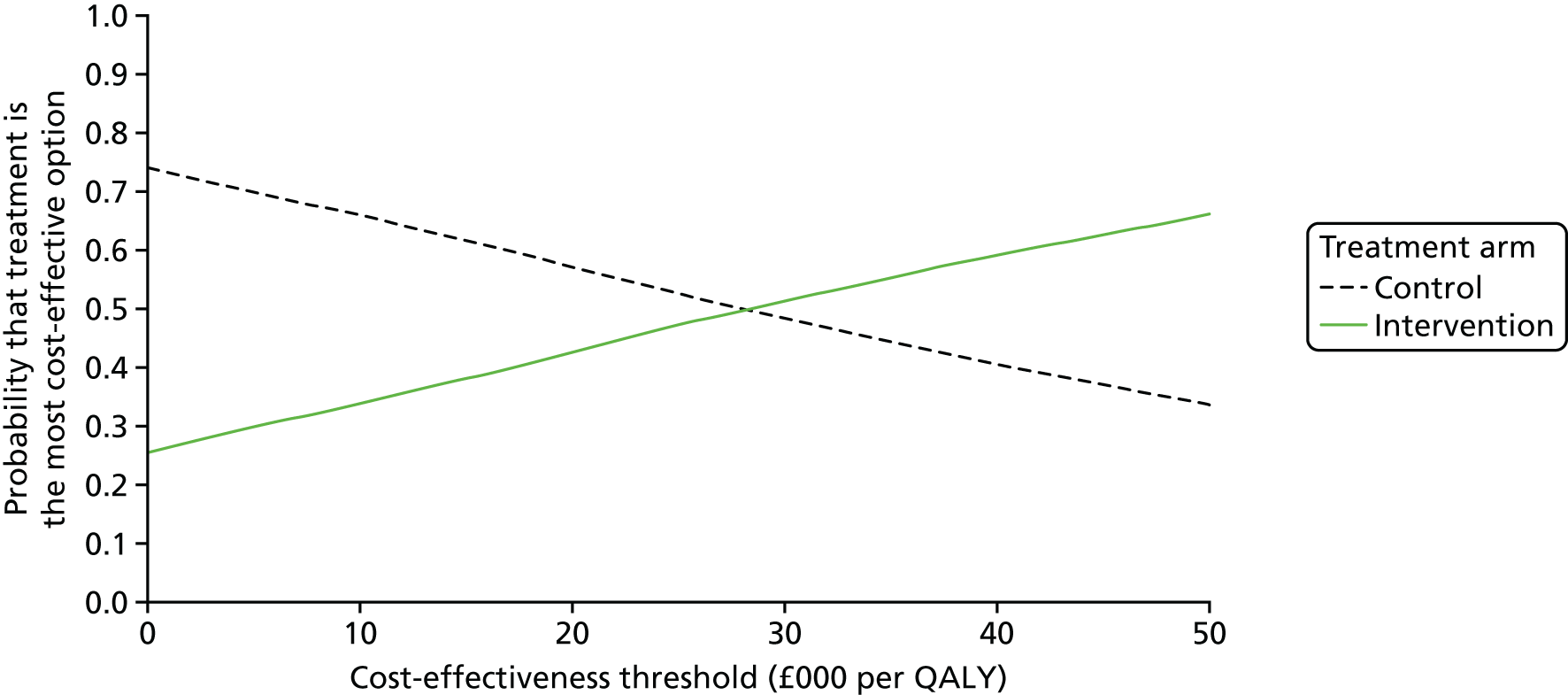

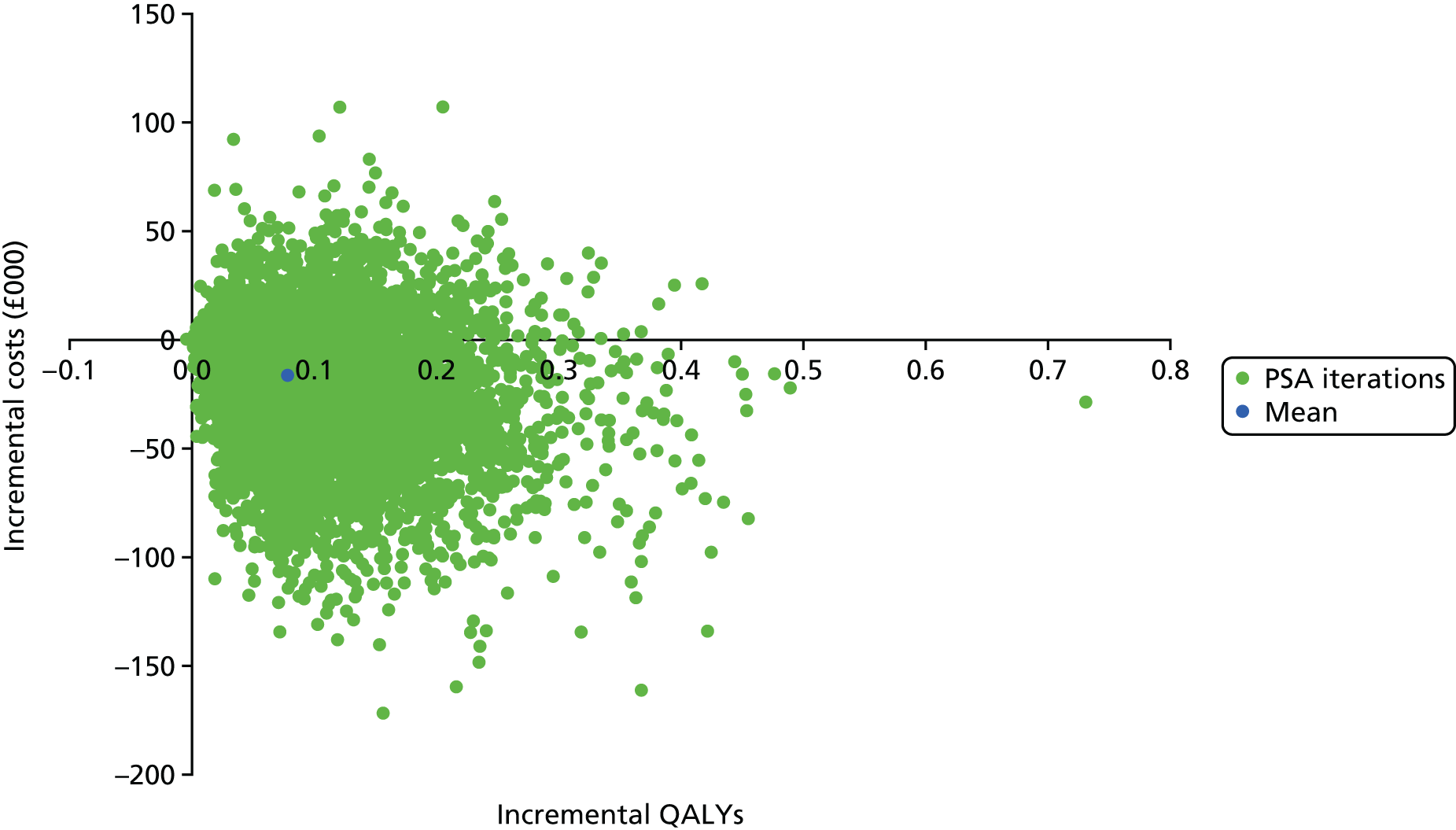

For the economic evaluation, a series of cost-effectiveness analyses were conducted:

-

within-trial analysis from a NHS and Personal Social Services (PSS) perspective

-

within-trial analysis from a societal perspective

-

model-based analysis from a NHS and PSS perspective

-

model-based analysis from a societal perspective.

Owing to the importance of carers for people with post-stroke depression, it was important to include analyses undertaken with a societal perspective to supplement the NHS and PSS analyses.

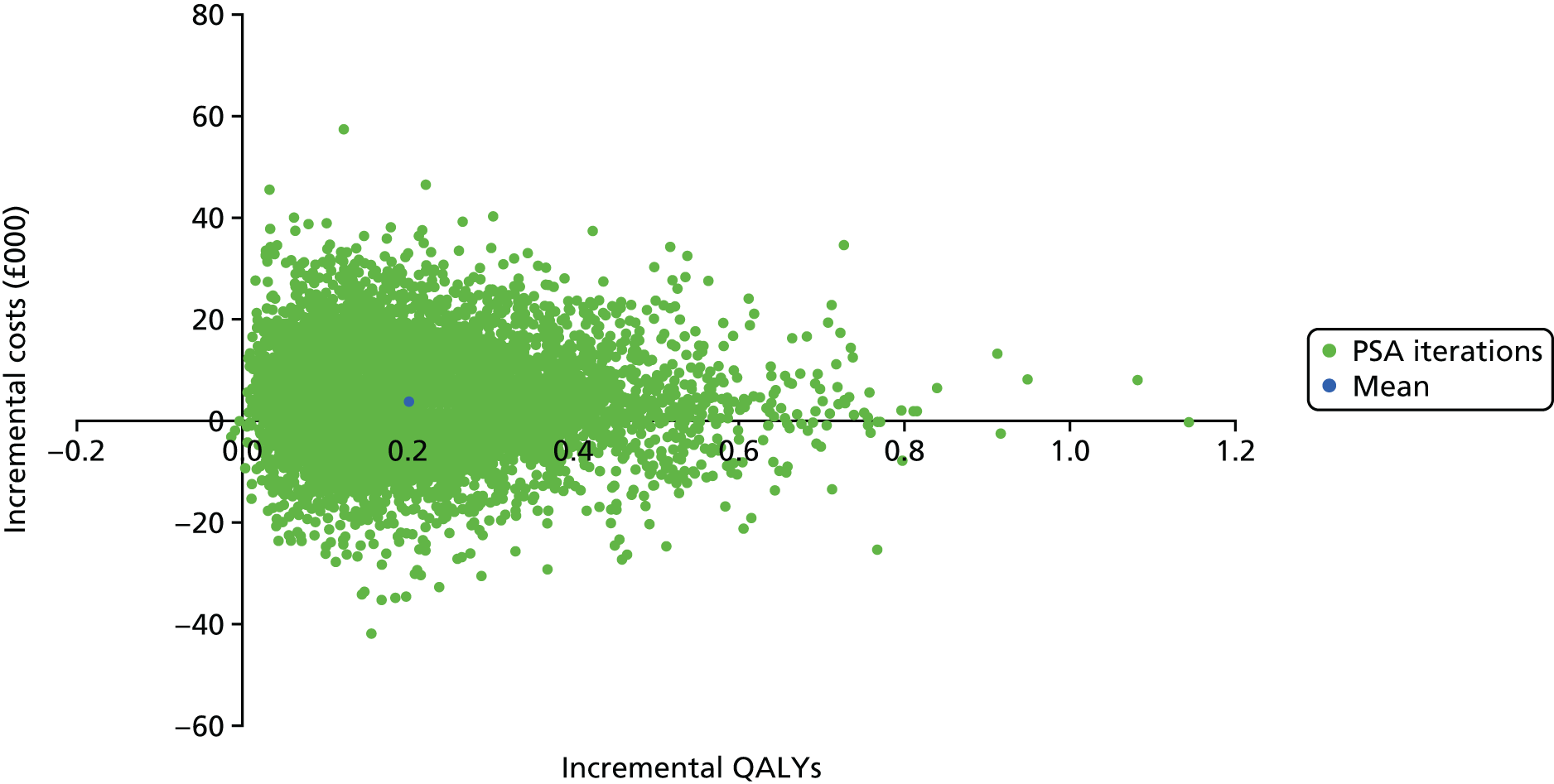

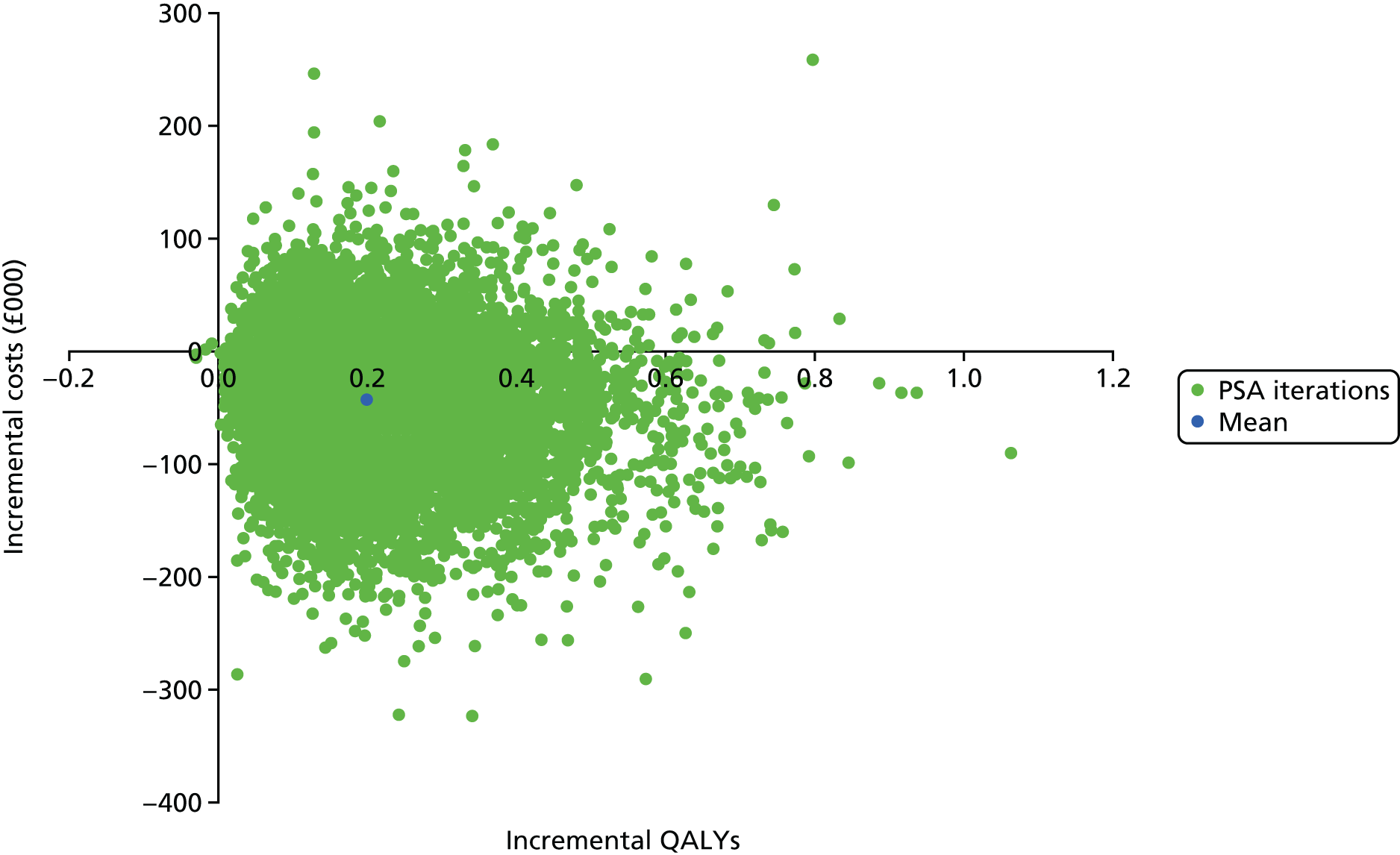

The within-trial analyses were undertaken both with and without multiple imputation, which was used to estimate values for missing data. Patient-level costs and outcomes were assessed over the full length of the feasibility study and this was supplemented with the construction of a simple economic model to examine the longer-term cost-effectiveness of treatment and priorities for future research. Costs and utilities were estimated for individual patients using data collected at baseline and follow-up, based on responses to EQ-5D-5L and resource use questionnaires, combined with standard cost and valuation sources. 79,80 Differences between costs and quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) in the two groups were described and the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) was calculated.

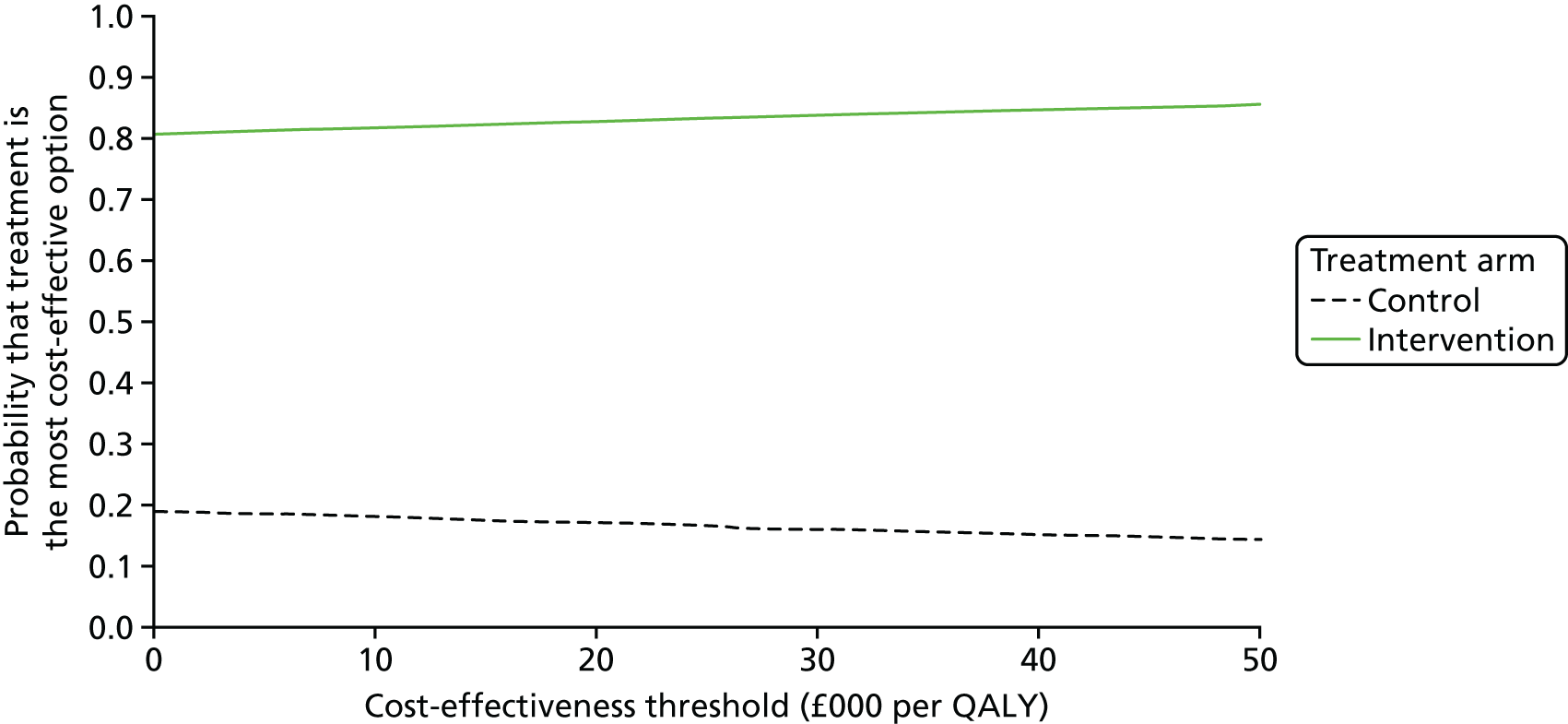

The main aim of the BEADS trial was to assess the feasibility of conducting a future definitive RCT to investigate the clinical and cost-effectiveness of BA therapy for people with post-stroke depression. Therefore, our analysis cannot provide conclusive cost-effectiveness results. However, early cost-effectiveness modelling remains of value because it provides insight into the likely cost-effectiveness of the intervention and demonstrates the value of pursuing further research, particularly when value-of-information analyses are included. 81,82 The value-of-information framework allows the maximum value of further research to be estimated, taking into account the uncertainty in the parameters included in the economic model. 83,84 We estimated the expected value of perfect information (EVPI), representing the maximum value of further research on all uncertain parameters in the economic model, and also estimated the expected value of perfect partial information (EVPPI), representing the maximum value of obtaining more information on each specific parameter (or group of parameters) included in the model.

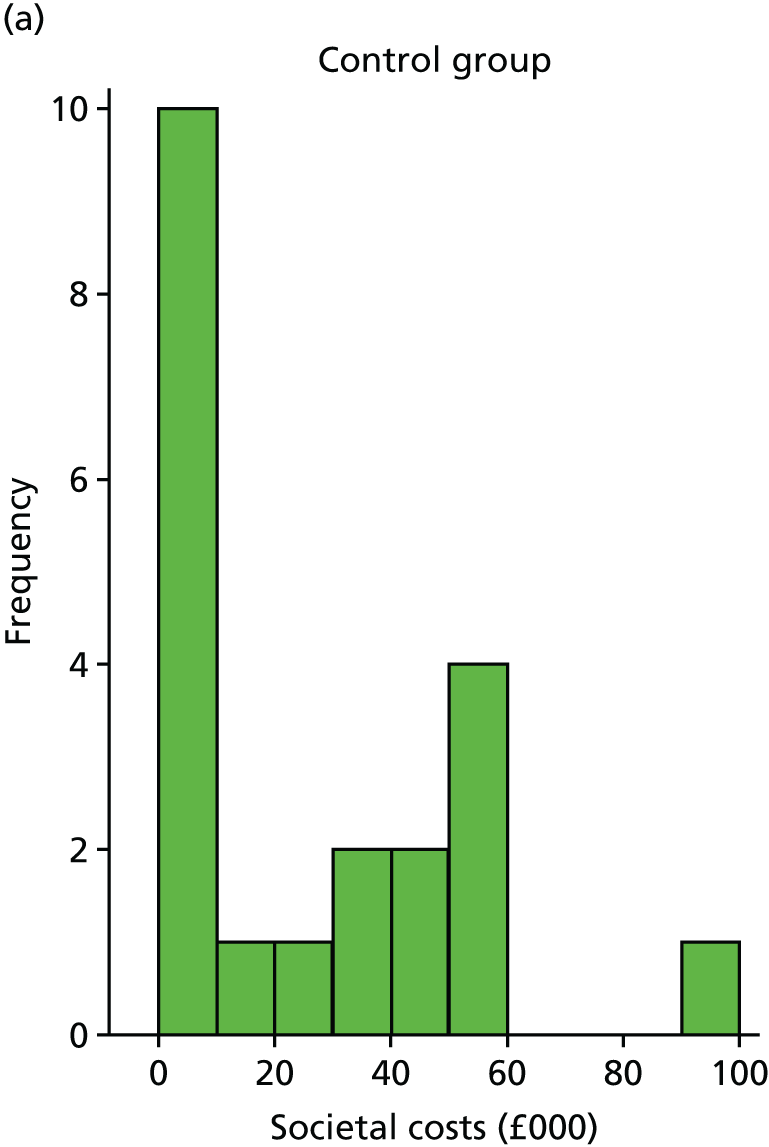

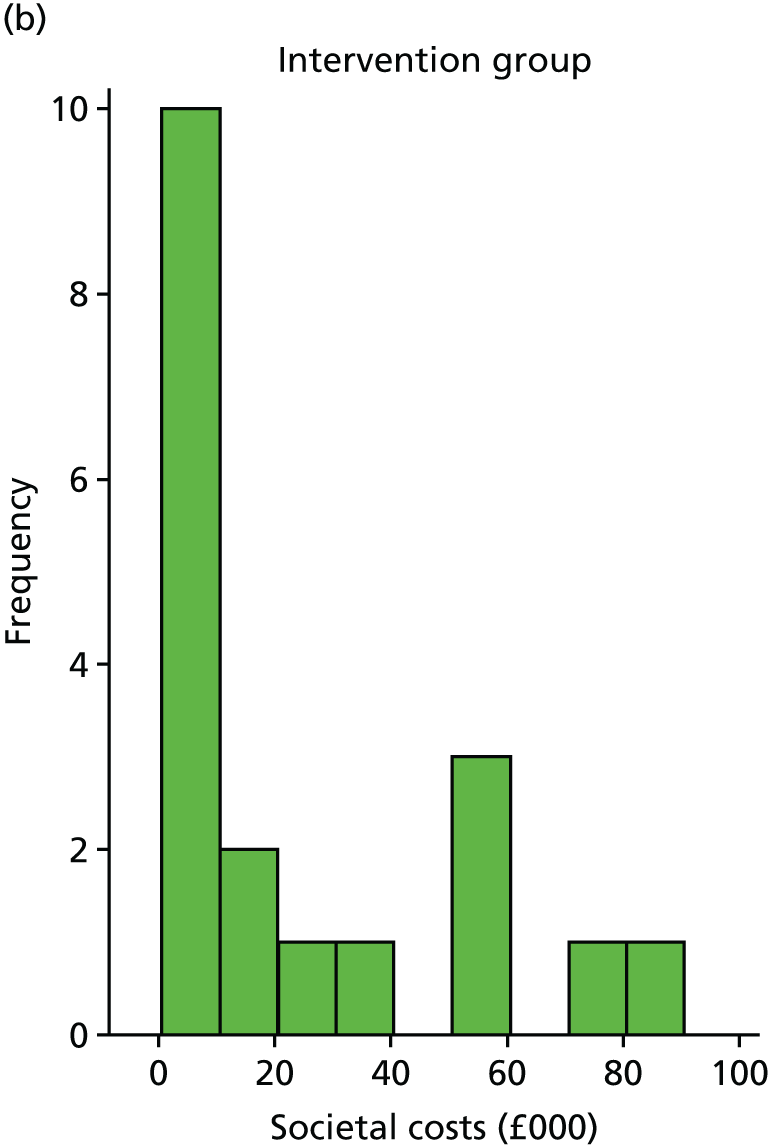

Resource use

Costs were estimated for each participant, including intervention costs (based on staff time and number of sessions) and health-care resource use. Questionnaires were tested as a method for collecting resource use data. The resource use questionnaire included questions about a participant’s use of health services over the previous 3 months, representing the final 3 months of the follow-up period. As data were required for the entire 6-month follow-up period, we assumed that costs for the first 3 months were the same as for the final 3 months. In the questionnaire, resources were split by services, such as inpatient, outpatient, primary care and community services, and, where necessary, included average appointment length. Participants were also asked to record dosages of medication relating to depression, and information about carer time and employment. This information was used to calculate total medical costs and societal costs.

Unit costs

Resource use data were combined with unit cost data from the latest versions of the Personal Social Services Research Unit (PSSRU) unit cost publication,85 NHS reference costs79 and the British National Formulary86 in order to calculate costs for inclusion in the economic analysis. When appropriate values were not available from the latest version of the PSSRU unit costs publication, earlier versions were consulted87–89 and prices were inflated using the hospital and community health services index. 85

The unit costs used to estimate the costs associated with the resource use observed in the trial are presented in Appendix 3.

Outcomes

Participants who did not have moderate or severe language problems were asked to complete the standard version of the EQ-5D-5L as well as an amended (and as yet unvalidated) accessible version (based on pictures). 57 Participants who had moderate to severe language problems were asked to complete the accessible version of the EQ-5D-5L. In addition, for participants who had carers, the carer was asked to complete a standard EQ-5D-5L by proxy. This allowed us to test alternative methods for collecting data from which to calculate QALYs.

Analysis

Within-trial analysis

Utility scores, based on EQ-5D-5L responses, were calculated for participants at baseline and follow-up. Differences in costs and QALYs between the two groups were estimated over the 6-month trial period using seemingly unrelated regression (SUR). SUR allows for correlation between costs and utility data. 90–92 The SUR model was specified to adjust for baseline EQ-5D-5L as suggested by Manca et al. 93 and also adjusted for baseline (pre-randomisation) costs. The regression was run for participants with no missing data (complete cases) and also for all participants including imputed values for costs and utilities.

For missing EQ-5D-5L data, multiple imputation was used as described in Analysis populations. Predictive mean matching was used to impute the missing data for costs using a chained regression. 94 Thirty imputations were generated for each missing value and the mean of these was used in the final imputed data set analysis. Differences between costs and QALYs were summarised using the ICER and CIs were algebraically determined by using the variance–covariance matrix.

A supplementary societal perspective analysis involved costing carer time associated with each participant (collected using the resource use questionnaire) using the human capital approach. 95 The resource use questionnaire also collected data on employment changes and private care costs, which were incorporated in the societal analysis.

Model-based analysis

The trial-based analysis was supplemented with an analysis using a simple decision-analytic model, used to estimate the cost-effectiveness of the intervention over the lifetime of participants. This was populated using the trial data combined with unit costs and mortality rates as well as assumptions regarding the maintenance of the treatment effect over time. The base-case analysis was undertaken from a NHS and PSS perspective, but a supplementary societal analysis was also undertaken.

The structure of the model (Figure 1) was based on that used to estimate the cost-effectiveness of computerised aphasia treatment compared with usual stimulation in the CACTUS study. 70 A simple three-state Markov model was used to extrapolate the data from the trial to a simulated cohort over a lifetime horizon. Participants entered the model in the no response state. Each month, they could remain in this state or transition to the good response state or death. Once in the good response state, participants could remain in this state or move back to the no response state or to death.

FIGURE 1.

Markov model.

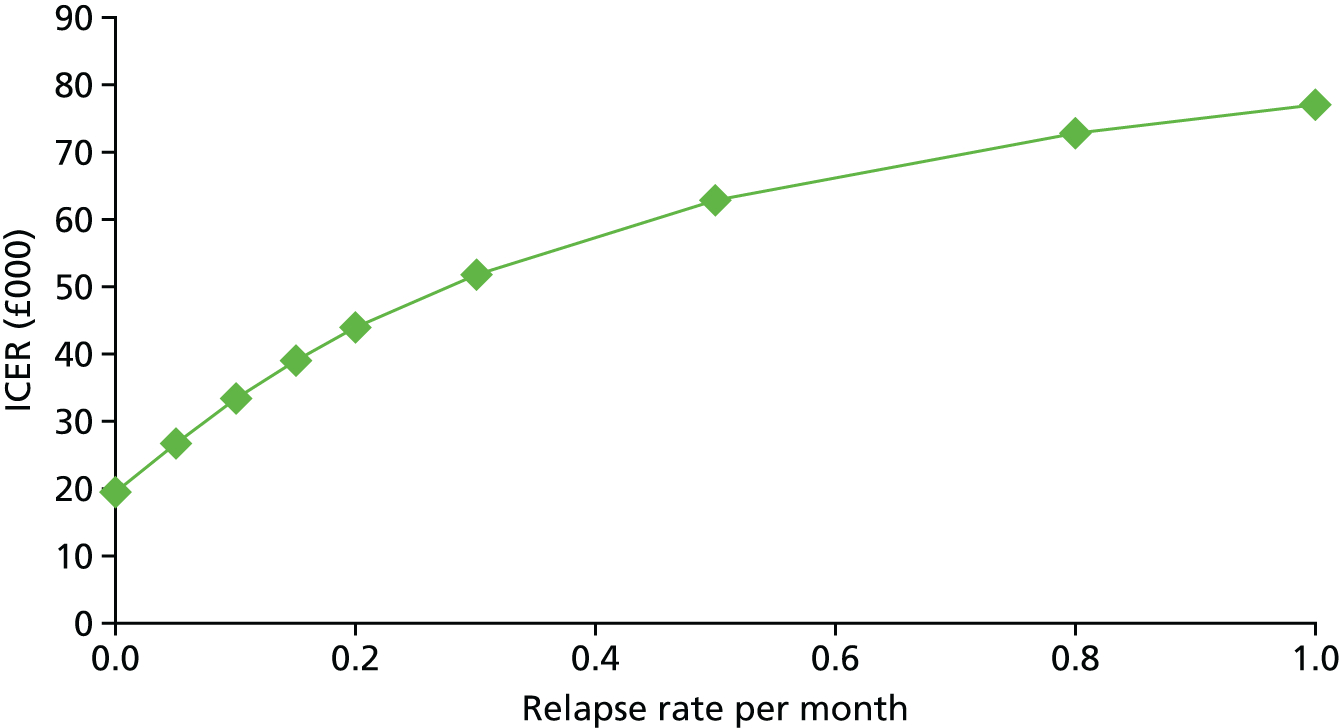

Transition probabilities were primarily based on the trial data. The primary clinical outcome measure was the PHQ-9; therefore, we based our definition of ‘good response’ on PHQ-9 scores. Specifically, participants moved from the ‘no response’ state to the ‘good response’ state if they achieved a 4.78-point decrease in PHQ-9 score from baseline to follow-up. This definition of a response was chosen based on the minimum important clinical difference of PHQ-9 reported by Löwe et al. 75 In the model, we assumed that the intervention would be given over 4 months, as in the trial, and a response (if achieved) would occur after 3 months. As the trial had only one follow-up time point, it was not possible to estimate a relapse rate for a good response. Hence, in the base case, it was assumed that the relapse rate was zero. A sensitivity analysis was carried out to estimate the effect on cost-effectiveness of changing the relapse rate; in this analysis, it was assumed that participants in the ‘good response’ state could move back to the ‘no response’ state after 6 months.

Transitions from the ‘no response’ and ‘good response’ states to death were based on evidence on long-term survival following stroke,96 combined with background mortality rates from the Office for National Statistics,97 reflecting the approach taken in a previous economic evaluation of an intervention for people with aphasia. 70 The same mortality rate was used for the ‘no response’ and ‘good response’ states.

The HRQoL utility scores applied to each health state were reduced over time on the basis of multipliers estimated by Ara and Brazier. 98 QALYs were estimated for each cycle of the model by combining utility scores with life-years, allowing the total QALYs associated with each treatment strategy to be calculated. Costs and QALYs were discounted at a rate of 3.5% each year, in line with recommendations made by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). 99

Distributions were placed around each of the uncertain parameters included in the model for use in probabilistic sensitivity analysis (PSA), which allowed the estimation of cost-effectiveness acceptability curves (CEACs) and a value-of-information analysis. Gamma distributions were used for costs, log-normal distributions for utilities, and beta distributions for probabilities, with dispersions based on numbers observed in the trial. The PSA was supplemented with deterministic scenario analysis on the relapse rate as this was not observed directly in the trial.

The EVPI and EVPPI analyses were undertaken assuming a cost-effectiveness threshold of £20,000 per QALY gained (based on NICE decision rules99) over a 10-year period (assuming that it might take 10 years before a new treatment for these patients is developed), using a 3.5% discount rate. The Sheffield Accelerated Value of Information tool100 was used to estimate the EVPI and EVPPI.

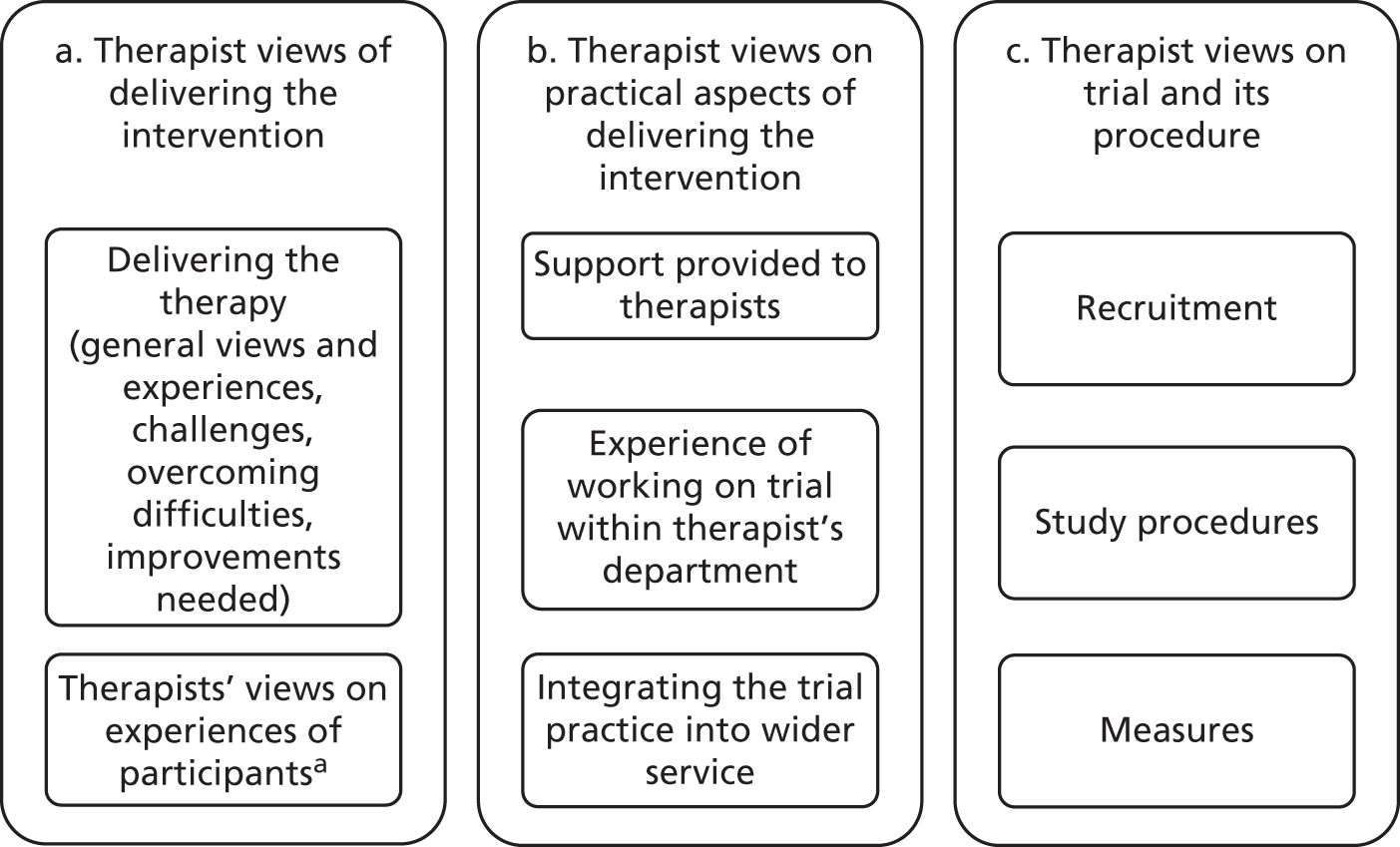

The qualitative research

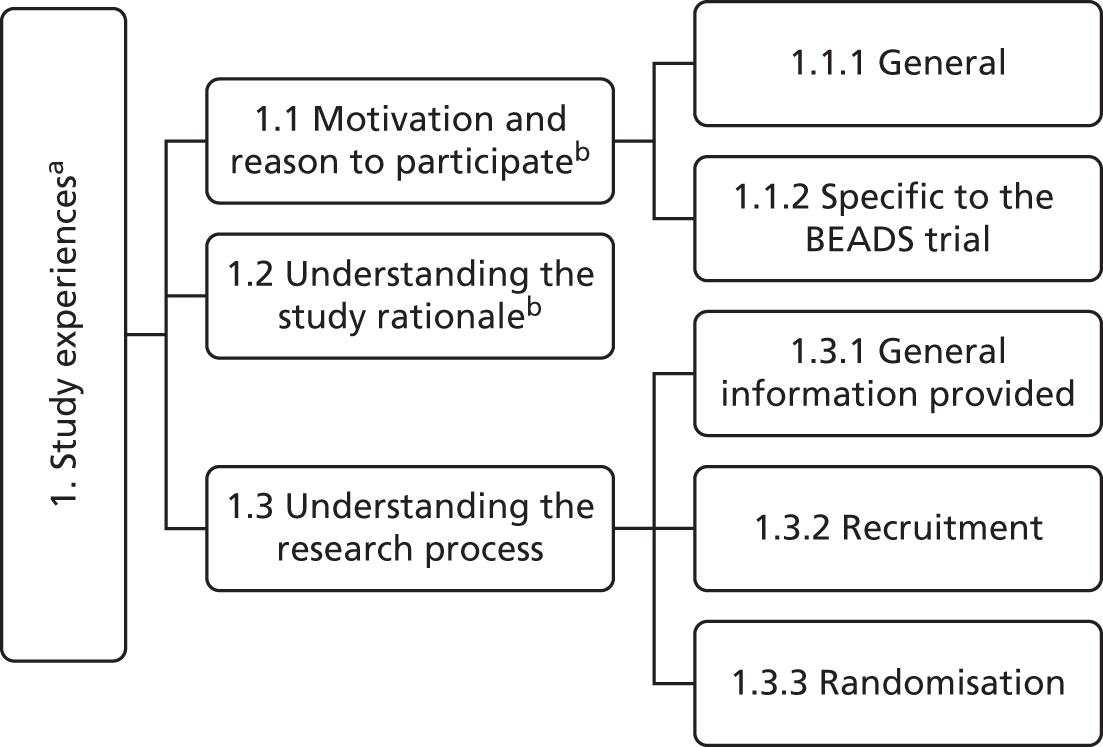

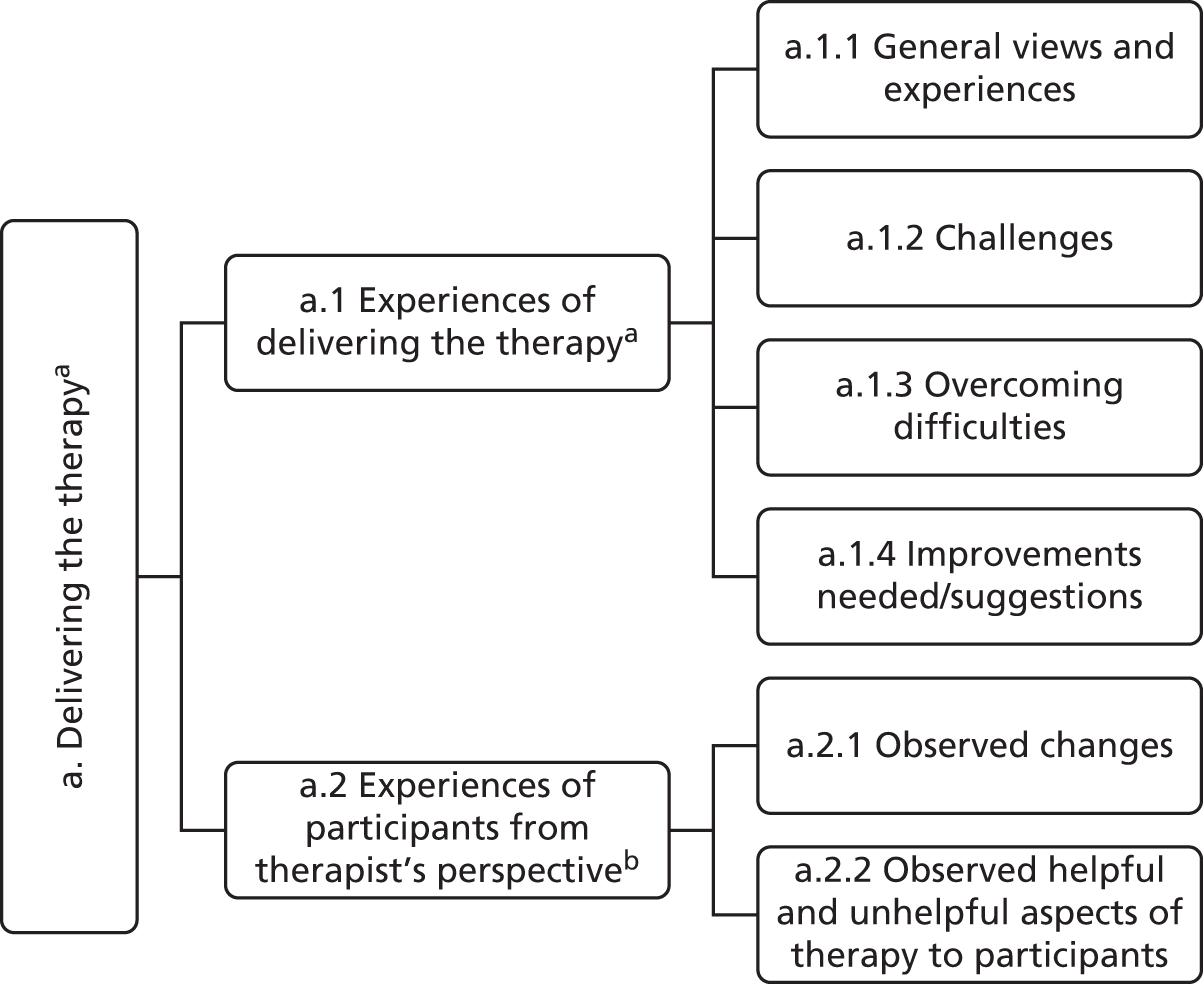

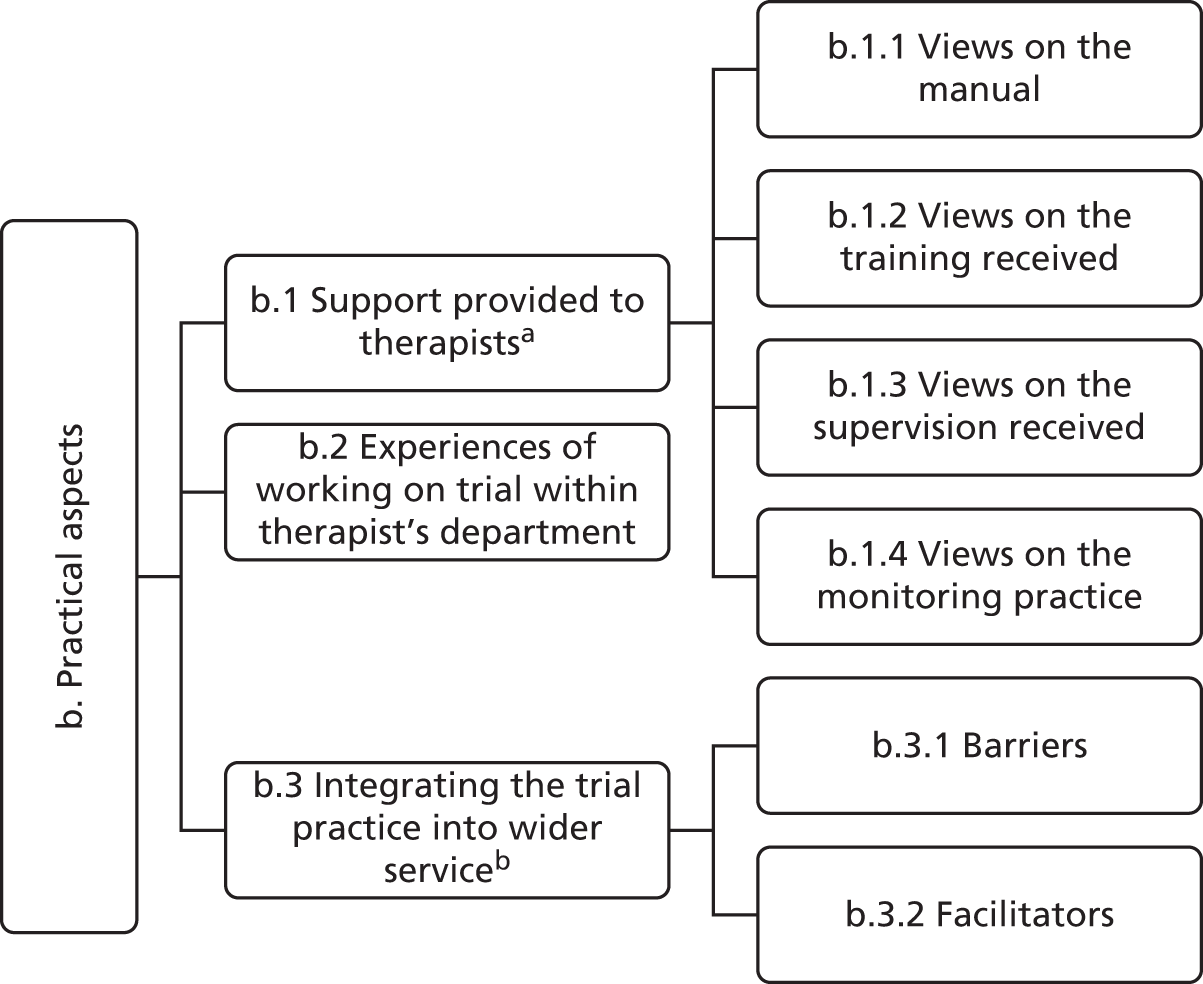

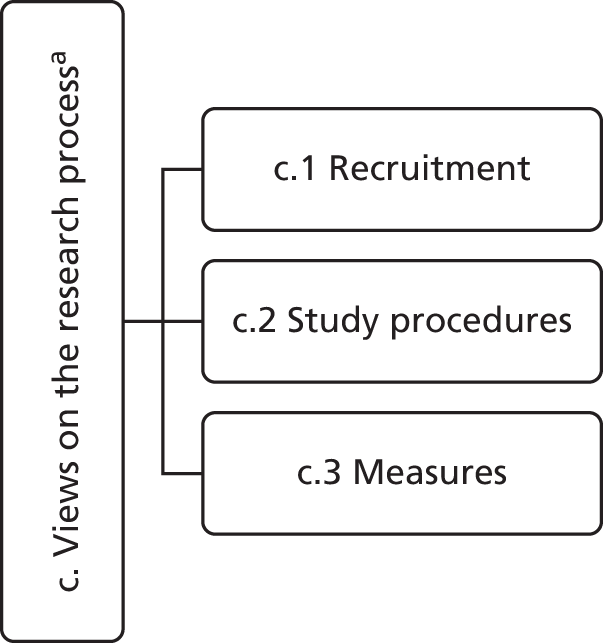

A series of qualitative interviews with a sample of participants and carers (from both the intervention and the control arms of the study), as well as all three therapists, were completed by an independent researcher to provide a description of the acceptability of the design and procedures used in the trial and the BA intervention. We interviewed 16 participants and 10 carers. The participant and carer interviews were completed in the interviewees’ homes (or an agreed convenient, private location) and the therapist interviews were completed in private locations, as agreed with the researcher. Participants and carers were interviewed after 6-month outcome assessments had been completed. Therapists were interviewed after they had completed all therapy sessions for the study. The interviews took between 10 and 55 minutes. All participants were provided with information concerning the purpose of the study, issues relating to confidentiality and anonymity of the data, and their rights as a participant. All participants provided informed consent to participate in the interview, which was also audio recorded on an encrypted digital recorder and transferred to a secure area on the University of Nottingham server. The researcher transcribed all of the interviews; the transcripts did not include any personal identifiers and the recordings were deleted on completion of the transcription.

Interviewer characteristics