Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 11/136/52. The contractual start date was in March 2015. The draft report began editorial review in October 2018 and was accepted for publication in May 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Catherine Hewitt is a member of the Health Technology Assessment Commissioning Board. Suzy Ker reports personal fees from the NHS outside the submitted work.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Peckham et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Some of the information in this chapter is reported in Peckham et al. 1 This contains information licensed under the Non-Commercial Government Licence v2.0.

Smoking and severe mental ill health

People with severe mental ill health (SMI), such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, are more likely to smoke and to smoke more heavily than those without SMI. 2,3 Estimates of the percentage of people with SMI who smoke vary depending on the setting, with up to 70% of inpatients smoking. 4 The presence of mental ill health is associated with an elevated risk of smoking by a factor of odds ratio (OR) 2.2 [95% confidence interval (CI) 1.7 to 2.8]. 2 Smokers with SMI are more nicotine dependent, more likely to become medically ill with smoking-related diseases and less likely to access help in quitting than the general population. 5 People with SMI tend to:

-

begin smoking at a higher rate before diagnosis or treatment for SMI than smokers without SMI6,7

-

smoke each cigarette more intensely, extracting more nicotine per cigarette. 8

People with SMI are also more likely to be unemployed than the general population. Smoking is known to be part of the ‘culture’ of mental health services, among both staff and patients. In addition, people with SMI often lack self-esteem and see the future as ‘bleak’; as a consequence, they may not be motivated to look after their physical health. 9 Many people with SMI are also misinformed about the risks and benefits of smoking versus nicotine dependence treatment. 10 They often fear and overestimate the medical risks of nicotine replacement therapy (NRT). 11 Many believe that smoking relieves depression and anxiety12 (nicotine increases anxiety13).

Smoking contributes to the poor physical health of those with SMI. In the UK, the standardised mortality rate for all causes of death for people with schizophrenia was 289 (95% CI 247 to 337), amounting to a threefold increase in mortality compared with the population of England and Wales. 14 Although people with SMI are more likely to smoke than the general population, there is evidence that general practitioners (GPs) are less likely to intervene with smokers who have a mental disorder than those who do not have a mental disorder. 5 Although the number of people in the general population who smoke has declined over the last 20 years, the number of people with SMI who smoke has not seen a similar decline. 3 The smoking rate among people with SMI in England is 40.5%,15 which is more than double that of the general population. 16 Smoking rates in people with SMI vary across settings, with up to 70% of people in psychiatric units smoking. 4

It is within this context that a number of policy initiatives have emerged that emphasise improving the physical care of those with SMI, including taking initiatives to facilitate smoking cessation and the promotion of smoke-free environments in secondary care services. 2,17,18

Existing knowledge

Smokers most commonly cite ‘stress relief and enjoyment’ as their main ‘reason’ for smoking,19 although the major cause is nicotine dependence. Nicotine acts in the midbrain, creating impulses to smoke in the face of stimuli associated with smoking20 and producing what may be thought of as a kind of ‘nicotine hunger’ (a feeling of needing to smoke) when blood nicotine concentrations are depleted. Smokers also experience nicotine withdrawal symptoms, such as unpleasant mood swings and physical symptoms, that occur on abstinence and are relieved by smoking. 21 Nicotine dependence is the main reason that most unassisted quit attempts fail within a week. 22 Cochrane systematic reviews23–30 and guidance from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)31 highlight the following smoking cessation interventions (including medications used as smoking cessation aids) that help smokers reduce their tobacco intake and quit smoking.

Nicotine replacement therapy

At the time of the trial, there were seven different available forms of administering NRT for use as smoking cessation aids. These were the nicotine patch, gum, lozenge, inhaler, spray (oral or nasal) and sublingual tablet (microtab). These provide a ‘clean’ alternative source of nicotine without the other 4000 toxic chemicals found in cigarette smoke. All deliver a lower dose of nicotine than the dose that would be received through smoking, with the only difference being the differing absorption rates owing to different methods of delivery. Nicotine replacement products can be used singly or in combination, for example a patch combined with a product that delivers nicotine faster, such as the nasal spray. A meta-analysis of > 100 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) shows that any form of NRT is effective in terms of smoking cessation (risk ratio 1.55, 95% CI 1.49 to 1.61). 32 For those who are not ready to stop smoking but are interested in cutting down, NRT prescription has been shown to reduce smoking and to facilitate quit rates later on (reduce to stop, or cut down to quit). 33

Antidepressants and nicotine receptor agonists

Two non-nicotine pharmacotherapies have been licensed as smoking cessation aids. These are varenicline [Chantix® (USA) and Champix® (the European Union and other countries); Pfizer Inc., New York, NY, USA], a nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, and bupropion (Zyban®; GlaxoSmithKline plc, Brentford UK), a noradenaline and dopamine reuptake inhibitor, which was first introduced as an atypical antidepressant. Varenicline is almost certainly the most effective treatment to date (OR for 12-month continuous abstinence for varenicline vs. placebo 3.22, 95% CI 2.43 to 4.27). It is more efficacious than bupropion (OR for varenicline vs. bupropion 1.66, 95% CI 1.28 to 2.16). 29 However, its use in people with SMI may be limited by case reports of depression or mental health worsening in populations with a previous history of mental health difficulties. Yet, a recent systematic review found there to be no increase in adverse effects in people with SMI taking varenicline compared with those without SMI,34 and a recent trial among people with a range of mental health problems showed varenicline as being effective and having a good safety profile. 35 Therefore, these fears appear to be unfounded.

Behavioural support

Advice, discussion and encouragement can be delivered via a range of means: individually or in a group, in an open (rolling) or closed group, face to face or over the telephone or internet. Meta-analyses of trials of multisession ‘intensive behavioural support versus brief advice’ found ORs of 1.56 (95% CI 1.32 to 1.84) for individual support and 2.04 (95% CI 1.60 to 2.60) for group support. 25,26 Regular support over the telephone is also effective. A meta-analysis of 10 trials of telephone support for people stopping smoking gave an OR of 1.64 (95% CI 1.41 to 1.92). 28 There is some evidence to suggest that group support may be more effective in general than one-to-one support36 and that it should involve multiple sessions. 36

The accumulated evidence for the use of current smoking cessation interventions has been distilled into clear recommendations for health professionals31 and a manual for those designing and delivering smoking cessation services. 37 In addition, guidance has been issued by NICE to guide the use of smoking cessation interventions for those with SMI. 38

Evidence on the effectiveness of smoking cessation strategies in SMI comes from a systematic review of randomised trials by Banham and Gilbody,39 which was updated in 2017. 40 These reviews draw on the results of 26 RCTs of smoking cessation interventions among those with SMI and show that combinations of behavioural support and pharmacotherapy (NRT and bupropion) are effective in facilitating smoking cessation. The evidence is strongest from varenicline, through the use of which the odds of quitting were improved fourfold (five trials; risk ratio 4.13, 95% CI 1.36 to 12.53).

Rationale for the SCIMITAR+ trial

Despite the higher prevalence of smoking, a substantial proportion of people with SMI express a desire to quit, but they expect to find it harder than those in the general population. 41 The introduction in 2004 of a new General Medical Services (GMS) contract42 created a policy impetus to improve the quality of primary care in priority areas. In terms of mental health, the new GMS contract specified that primary care is responsible for the provision of physical health care. Importantly, for smoking cessation initiatives, it ‘incentivised’ GPs to (1) produce a register of people with severe long-term mental health [Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) indicator MH8 – the SMI register] and (2) ensure that at least 90% of SMI patients have had a review that includes smoking status recorded within the previous 15 months (QOF indicator MH9 – SMI health check). This check included patients seen in primary care, secondary care and under shared care arrangements. Though this GMS target has now been withdrawn, this was an incentive at the time of conception of the SCIMITAR+ (smoking cessation intervention for severe mental ill health) trial.

In addition, for those who are admitted to hospital (including inpatient psychiatric units), the introduction of smoke-free policies provides an opportunity to address smoking (Public Health Guidance 4817). The admission of an individual to hospital, while being stressful and occurring at a time of personal crisis, also provides a unique opportunity to provide general health advice and to engage individuals in interventions targeted at smoking reduction and cessation.

Recent guidance issued by NICE17 offers clear statements of purpose to make secondary care services (including mental health services) entirely smoke free and to promote a smoke-free culture among staff and users of the services. Mental health services are highlighted as an area of priority and an unmet need in relation to smoking cessation, and there is clear guidance that services should be developed and implemented as a matter of some priority.

In 2009, the SCIMITAR pilot trial was devised to test whether or not a bespoke smoking cessation (BSC) intervention tailored to the needs of people with SMI would be acceptable to people with SMI. 43 In addition, it tested whether or not it was feasible to recruit and retain participants in a RCT to test this intervention. Recruitment to the pilot trial took place between May 2011 and May 2012. Results from the SCIMITAR pilot trial indicated that the intervention was acceptable to participants and that it was possible to recruit and retain participants in such a trial. 43 Although the trial was not powered to detect a difference between the bespoke intervention and usual care, the results indicated that there was a potential but non-statistically significant benefit of the bespoke intervention over usual care in terms of the proportion of self-reported quitters [12/33 (36%) vs. 8/35 (23%) adjusted OR 2.9, 95% CI 0.8 to 10.5]. Following this, the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment programme commissioned a fully powered RCT (SCIMITAR+) to explore the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the SCIMITAR BSC intervention.

Research objectives44

-

To establish the clinical effectiveness of a BSC intervention compared with usual care for people with SMI.

-

To establish the cost-effectiveness of a BSC intervention for people with SMI.

Chapter 2 Methods

Some of the information in this chapter is reported in Peckham et al. 1 This contains information licensed under the Non-Commercial Government Licence v2.0.

Study design

This study was a pragmatic, two-arm, parallel-group RCT. The setting was in primary care and specialist mental health services within secondary care. Given that patients with SMI are a ‘hard-to-reach population’, a range of complementary strategies were used to try to identify and recruit eligible participants. A two-stage recruitment process was employed to check for eligibility, to check understanding of the study and to obtain consent. Participants were individually randomised to receive usual care or usual care plus a BSC service. Participants were followed up over the course of 12 months, with data collected at 6 and 12 months post randomisation. 44

Approvals obtained

Ethics approval was sought and granted on 15 March 2015 by Leeds East Research Ethic Committee (reference number 15/YH/0051). Approval was also obtained from the relevant research and development departments (see Appendix 1).

Trial sites

The study was conducted in 22 sites in England. Sites recruited throughout the duration of the study.

Participant eligibility

Inclusion criteria

To be eligible for inclusion in this study, participants needed to meet the following inclusion criteria:

-

aged ≥ 18 years

-

have SMI

-

be a smoker who expresses an interest in wanting to cut down on smoking (though not necessarily quitting)

-

smoke at least five cigarettes per day.

There is no agreed definition of SMI, so we adopted a pragmatic definition, that is, a documented diagnosis of schizophrenia or delusional/psychotic illness [International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition (ICD-10),45 F20.X and F22.X or Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)46 equivalent] or bipolar disorder (ICD F31.X or DSM equivalent). This SMI-inclusive diagnosis needed to have been made by specialist psychiatric services and to have been documented in either GP notes or psychiatric notes.

Exclusion criteria

People were ineligible if they met the following criteria:

-

currently pregnant or breastfeeding

-

with comorbid drug or alcohol problems (as ascertained by the GP or mental health worker)

-

non-English speakers

-

lacking capacity to participate in the trial (guided by the 2005 Mental Capacity Act 7147)

-

currently receiving advice from a smoking cessation advisor.

People with SMI who smoke while concurrently abusing substances may require additional medication or specialist advice, which was beyond the brief of the mental health smoking cessation practitioner (MH-SCP) and this trial. Similarly, smoking cessation in pregnancy also requires specialist knowledge. It was planned that any participant who became pregnant during the course of the trial would be fully withdrawn from the study and referred to local smoking cessation services specific to pregnancy.

Identifying participants

We used five methods to recruit participants.

Direct general practitioner referral or referral following database screening

General practitioners are encouraged to offer opportunistic advice and information about smoking cessation services to all people who smoke whenever they consult in primary care. GPs taking part in this study were provided with patient study information packs to give to people with SMI who were receptive to participating in the trial. GPs then completed and faxed a referral form and the person’s ‘consent to be contacted’ form to the SCIMITAR+ researchers who approached the person for recruitment.

The GP practices were also asked to consult their patient databases and SMI register, if available, to screen for potentially eligible participants. Information packs were sent from the GP practice, inviting people willing to take part in the study to return a completed ‘consent to be contacted’ form to the SCIMITAR+ researchers, who then approached them to ascertain eligibility and recruitment.

Primary care referral following annual health check

At the time of the trial, the annual primary care health check for people with SMI (MH9) represented an opportunity to address smoking behaviour and to offer enhanced smoking cessation services within the context of a trial. Health checks are generally conducted by practice nurses, and we encouraged all primary care staff to make SMI smokers aware of the trial when they received their annual primary care health check. Information packs were given to interested and potentially eligible people during their health check. Similar to GP referrals, practice nurses were instructed to complete referral forms and to fax the persons’ completed ‘consent to be contacted’ form to the SCIMITAR+ researchers, who then approached them for eligibility and recruitment.

Community mental health teams

Study researchers worked with care co-ordinators and members of the community mental health team (CMHT) to screen their caseloads for potentially eligible participants who matched the inclusion criteria. People identified as potentially suitable for the SCIMITAR+ trial were either provided with a copy of the information pack by their care co-ordinator or other mental health professional or sent an information pack in the post. The information pack contained a ‘consent to be contacted’ form for potential participants to return to the SCIMITAR+ researchers, giving permission for the researcher to contact them by telephone or letter or in person to discuss the trial further.

Service user groups44

Service user groups were provided with information about the study along with copies of a SCIMITAR+ flyer. Interested service users could then contact the mental health professional named on the flyer or their care co-ordinator. Alternatively, the staff member at the service user group could contact the service user’s care co-ordinator on their behalf.

Lifestyle Health and Wellbeing Survey

The Lifestyle Health and Wellbeing Cohort is a prospective study that forms a platform for interventional studies (‘Trials within cohorts’), co-ordinated by the University of York, recruiting adults with SMI aged ≥ 18 years from primary and secondary care. Participants in the Lifestyle Health and Wellbeing Survey complete a series of questions about their health and well-being, including questions about their smoking status. Cohort participants who reported smoking and were potentially interested in cutting down on or quitting smoking were invited to take part in the SCIMITAR+ trial.

Screening for eligibility

After receiving an information pack and once a person gave consent to be contacted (either verbally to the recruiting clinician or in writing to the SCIMTAR+ researchers), a SCIMITAR+ researcher approached them by telephone, face to face or by e-mail, depending on the person’s preference. After briefly explaining the trial, the researcher checked the person’s eligibility by asking about their smoking habits, specifically (1) whether or not they smoke; (2) if so, how much they smoke (they needed to smoke at least five cigarettes per day to be eligible); (3) if they would consider quitting or cutting down, with a view to quitting within the next 6 months; and (4) whether or not they were currently receiving advice from a smoking cessation advisor. These questions ensured that the person currently smoked but was contemplating quitting. The researcher also asked screening questions about pregnancy and breastfeeding, and drug and alcohol usage, which led to exclusion if present. The researcher then arranged a meeting at a mutually convenient time and venue.

Consenting participants

When a potential participant met with the SCIMITAR+ researcher, they were given the opportunity to clarify any points they did not understand and to ask any questions. A full explanation of the trial was given by the SCIMITAR+ researcher. It was emphasised that they may withdraw their consent to participate at any time without loss of treatment options that would otherwise be available to them. They were also informed that, by consenting, they agreed to their GP being informed of their participation in the trial. Written informed consent was then obtained, with both the participant and the researcher signing and dating the consent forms prior to collecting baseline data (see Appendix 2 for participant information sheets and consent forms).

Baseline assessment

Once a participant had consented to take part in the trial, they completed the baseline questionnaires. Height and weight measurements were completed to calculate the participant’s body mass index (BMI) and an exhaled breath carbon monoxide (CO) reading was taken. These made up the baseline data set. The participant was randomised on completion of this data set.

Randomisation

Eligible, consenting individuals were randomised 1 : 1 to either the BSC service or usual care. The researcher contacted a secure telephone randomisation service run by the York Trials Unit. Simple randomisation was used, following a computer-generated number sequence devised by an independent data manager otherwise not involved in the conduct of the trial. Once given the details of the participant’s allocation, the researcher immediately informed the participant of their allocation and what would happen next. If allocated to the BSC arm, researchers at the University of York then contacted the MH-SCP in the participant’s area and organised for them to contact the participant to arrange a mutually convenient time to meet. A letter was sent to the GP and mental health specialist for the participant’s records and to advise them on subsequent smoking cessation management. Owing to the nature of the intervention, it was not possible to blind participants, GPs, researchers or the MH-SCPs to the treatment allocation.

Ineligible and non-consenting individuals

All ineligible and non-consenting persons were referred back to their GP/mental health service.

Sample size

Results from the SCIMITAR pilot trial were used to inform the sample size calculation for this trial. In the pilot trial, a quit rate of 23% was observed at 12 months in the usual-care arm and a quit rate of 36% was observed in the BSC arm. 43 The SCIMITAR+ trial was powered at 80% to detect a relative risk increase in quitting of 1.7, assuming a control quit rate of 20% (an increase to a quit rate of 34% in the intervention group), equal randomisation and a two-sided alpha of 0.05. Allowing for a 20% loss to follow-up at 12 months required a total sample size of at least 393 to be recruited and randomised. We therefore proposed to recruit 400 participants in total to ensure sufficient power according to the preceding statistical assumptions.

Description of interventions

Trial intervention

Participants in the intervention group were allocated to receive a BSC intervention designed specifically to help people with SMI stop smoking. This intervention was delivered by a mental health professional (care co-ordinator, support worker, mental health nurse) trained in smoking cessation interventions. The training took place over 2 days and was provided by trained smoking cessation advisors. The BSC intervention consisted of up to 12 one-to-one face-to-face meetings between the participant and the MH-SCP, who worked in conjunction with the participant and their GP or mental health specialist to ensure that the participant received smoking cessation medication and medication monitoring. The initial meeting generally took 1 hour, with subsequent meetings lasting 30 minutes. Meetings were initially weekly; however, towards the end of the programme the participant had the choice of meeting fortnightly if preferred. Pharmacotherapies were provided for as long as was deemed necessary, in line with NICE guidance,17 and were determined by the GP without the influence of the SCIMITAR+ trial team. In line with NICE recommendations, MH-SCPs offered advice on the range of treatment options available to people in the NHS (including medication, behavioural support and follow-up). 31 It was not the remit of the trial to assess specific smoking cessation pharmacotherapies or treatments per se, although data on frequency of their use were collected. The intervention was based on that used by the National Centre for Smoking Cessation and Training (NCSCT), but the following specific modifications were applied to tailor the intervention to people with SMI: (1) recognising the need for several assessment sessions prior to setting a ‘quit date’; (2) recognising the purpose of smoking in the context of their mental illness, such as the use of smoking to relieve side effects from antipsychotic medication (and how this will be managed during a cessation attempt); (3) recognising the need to involve other members of the multidisciplinary team in planning a successful quit attempt for those with complex care needs and multiagency programmes of care; (4) arranging meetings so that they take place in a mutually agreeable location, often in the participant’s home rather than in the GP surgery or on NHS trust premises; (5) providing additional face-to-face support following an unsuccessful quit attempt or relapse; and (6) informing the GP and psychiatrist of a successful quit attempt so that they can review antipsychotic medication doses in line with changes in metabolism. Participants were encouraged to (1) reduce smoking to quit, (2) set their own quit dates and (3) make several attempts to quit if their initial attempt failed. All participants remained under the care of their GP and continued to receive their usual NHS treatment.

A detailed description of the development and content of the smoking cessation intervention is given in the report of the SCIMITAR pilot trial. 1

Control intervention

This was a ‘usual-care’ control group, whereby participants were encouraged to consult with their GP or local NHS quit smoking services. GPs were given advice to follow current NICE guidelines for smoking cessation, without the additional support of a bespoke MH-SCP. Usual care could include pharmacotherapies to aid smoking cessation (NRTs, bupropion or varenicline either separately or in combination), access to self-help materials and referral to local NHS stop smoking clinics (which would not be specifically tailored to the needs of those with SMI). Participants were encouraged to reduce smoking to quit and set their own quit dates; however, they were managed solely by their own GP or mental health specialist and, crucially, did not receive regular visits from a MH-SCP. Details of NRT that control participants received were gathered by accessing participants’ GP notes, and details of any smoking cessation management were requested from participants in the follow-up questionnaires.

Smoking cessation medication provision

Clear guidance on the prescription of anti-smoking medications in the presence of SMI (including safety considerations) has been published and was made available to all GPs to help inform their prescribing decisions (for both control and intervention participants). 48 A key feature of the SCIMITAR+ trial was to ensure that GPs manage anti-smoking medications within this framework and in accordance with their prior knowledge of the patient and their concomitant use of medication. This was carried out with the aim of replicating ‘real-life practice’ of the use of anti-smoking medications in primary care. The medication profile of the individual participants was reviewed by their GP or mental health specialist to assess any potential safety issues (in line with the latest practice guidance on the provision of smoking cessation interventions in the NHS2). An important aspect of the design of this study was that the SCIMITAR+ team had no direct influence over prescribing decisions by GPs, as this was not a drug trial or an investigation of a medicinal product(s).

Follow-up

Participants were followed up 6 months and 12 months after randomisation.

All assessments were carried out face to face where possible and, where not possible, a systematic approach was used to explore other avenues to collect self-report data; the participant was offered the option of completing the questionnaires over the telephone or having the questionnaires sent by post for them to complete and return. If it was not possible to make contact with the participant, a family member or friend, designated by the participant at their baseline interview, was contacted to verify the participant’s current smoking status.

Outcomes

Primary outcomes

The primary outcome was self-reported abstinence from smoking at 12 months post randomisation, defined as answering ‘not even a puff’ to the question ‘have you smoked in the last week?’, validated by CO breath measure, with abstinence defined as a CO measurement of < 10 parts per million (p.p.m.).

Secondary outcomes

-

Self-reported smoking cessation.

-

Number of cigarettes smoked per day (self-report).

-

Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND). 49

-

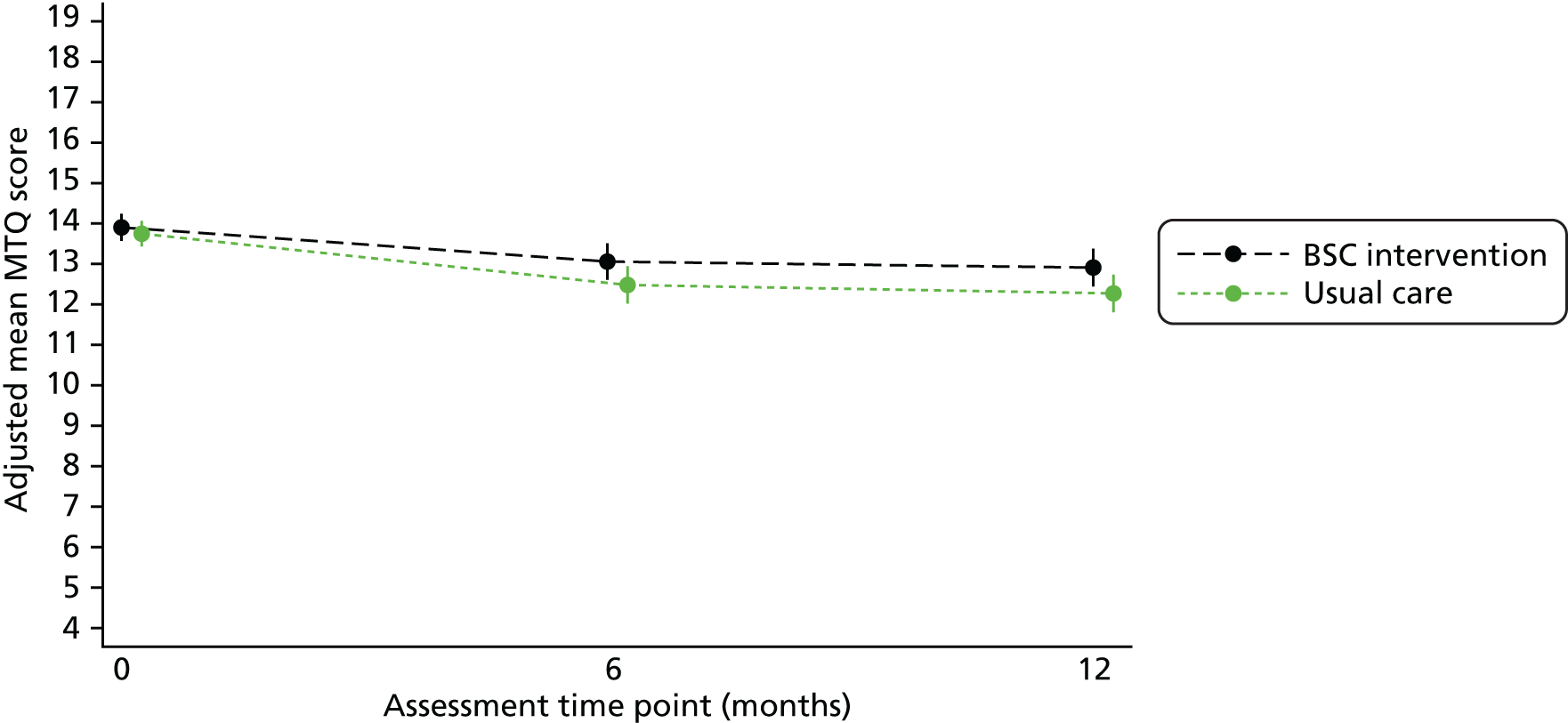

Motivation to Quit questionnaire (MTQ). 50

-

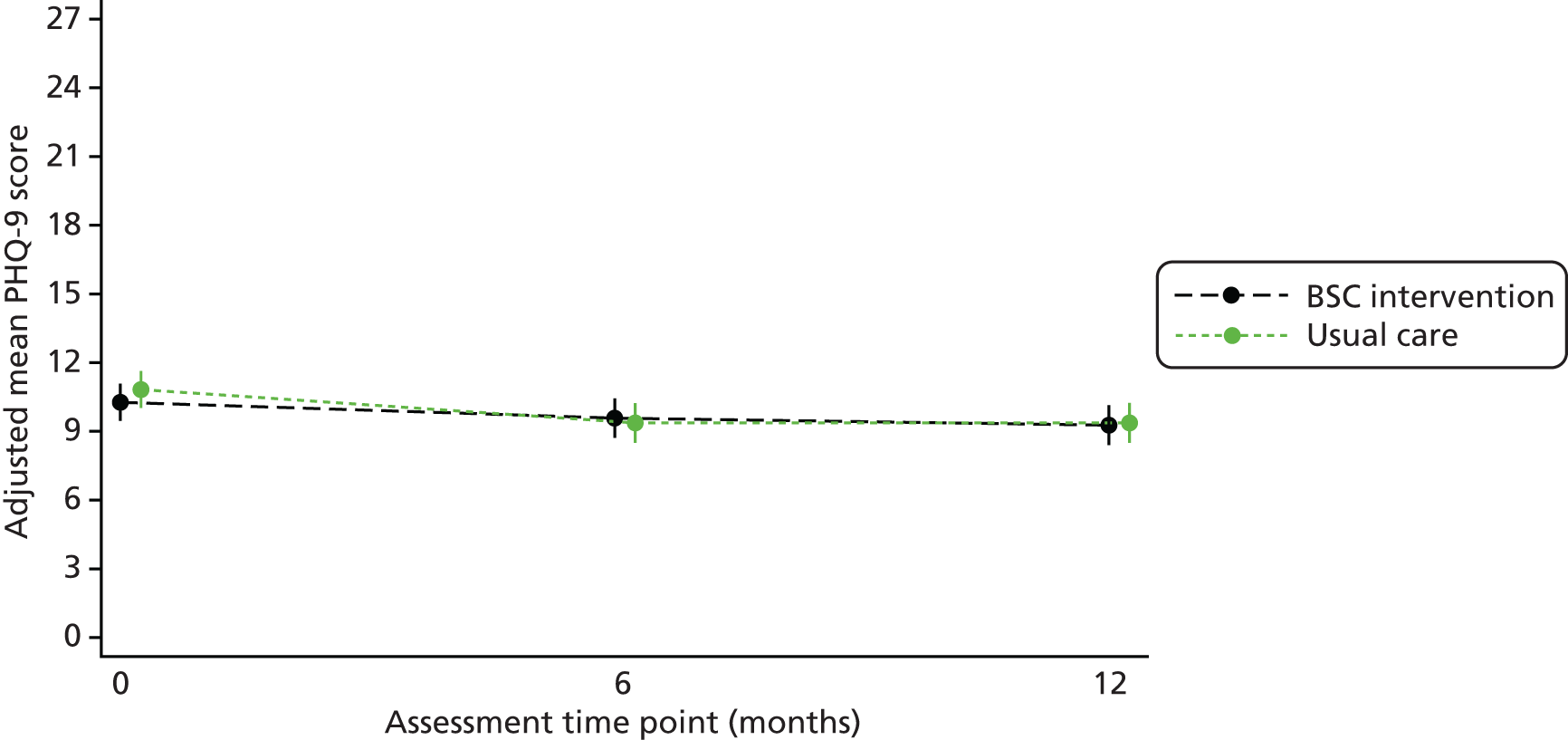

Patient Health Questionnaire-9 items (PHQ-9). 51

-

Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 items (GAD-7). 52

-

Health-related quality of life [Short Form questionnaire-12 items (SF-12) version 1 was used, as this was used in the pilot trial]. 53

-

EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L). 54

-

BMI.

-

Health service use collected via a bespoke questionnaire.

Table 1 gives details of the measures collected and the time points at which they were collected.

| Assessment | Time point | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 6 months post randomisation | 12 months post randomisation | |

| Eligibility and consent | |||

| Eligibility | ✗ | ||

| Consent | ✗ | ||

| Background and follow-up | |||

| Personal details, general health | ✗ | ||

| BMI | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Mental health details | |||

| Mental health history | ✗ | ||

| Current mental health status | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Current medications | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Referrals to mental health services | ✗ | ✗ | |

| Admissions to hospital related to mental health | ✗ | ✗ | |

| Smoking details | |||

| Smoking history | ✗ | ||

| Current smoking status | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Use of electronic cigarettes | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Use of smoking cessation services | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| CO measurement | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Adverse event reporting | Ongoing collection | ||

| Questionnaires | |||

| FTND | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| MTQ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| PHQ-9 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| GAD-7 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Health-related quality of life (SF-12) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Health-state utility (EQ-5D-5L) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Health economics/service utilisation questionnaire | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

Withdrawal

A study participant could be withdrawn from the trial by their GP, mental health specialist or smoking cessation practitioner, or may choose to do so themselves, at any time. If the withdrawal was due to an adverse event, procedures followed a trial-specific standard operating procedure (SOP) for adverse events (see Appendix 3).

Where possible, data were collected on the nature of the withdrawal. Reasons for a practitioner to withdraw a participant included pregnancy, admission to hospital for reasons unrelated to the trial and, inability to attend treatment or assessment sessions. Relapse to resuming smoking was not a reason to withdraw a participant, as they could resume treatment and make several attempts to quit smoking.

Participants were given a choice of (1) withdrawal from treatment only (participants were still followed up at 6 and 12 months), (2) withdrawal from follow-up or (3) complete withdrawal from the study, including follow-up and medication data collection. Withdrawal from the study did not affect the participants’ treatment or access to NHS services.

Any data collected from the participant prior to withdrawal were still included in the final analysis of the data.

Participant concordance

Mental health smoking cessation practitioners were asked to complete a treatment log that recorded all participants’ contacts (face-to-face meetings, telephone calls and joint appointments with MH-SCPs and GPs) to judge the degree to which the intervention, as designed on a session-by-session basis, was actually delivered in practice by MH-SCPs.

At each meeting, MH-SCPs would take a CO measurement from the participant. Measurements of ≥ 10 p.p.m. indicated that the participant had not ceased smoking. If the participant claimed to have stopped but their CO readings were ≥ 10 p.p.m., they were probed about when they last smoked and whether or not they had had any minor relapses during their quit attempt.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were conducted following the principles of intention to treat, including all randomised participants in the groups to which they were randomised, where data were available. Analyses were conducted in Stata® version 15 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). All statistical tests were two-sided at the 5% significance level.

Recruitment and retention

The flow of participants through the trial is described in Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagrams (see Figures 3–5), two of which describe recruitment up to randomisation (one for primary care and one for secondary care) and one of which presents the flow of participants from randomisation to analysis. The response rates, time to return and mode of completion of the 6- and 12-month participant questionnaires are summarised by treatment group.

Baseline data

Baseline data are summarised by treatment group, using mean standard deviation (SD), median and range for continuous data, and count and percentage for categorical variables. No formal statistical comparisons between the two groups were undertaken on baseline data.

Data manipulations and questionnaire scoring

Number of cigarettes smoked

Participants were asked how many cigarettes they normally smoked per day and how much tobacco they used per day. It was assumed that 0.5 g of tobacco equates to one cigarette. 55

Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence

The FTND is a 6-item questionnaire. 49 Item scores are added together to give a total score between 1 and 10: a score of 1–2 indicates low dependence, 3–4 indicates low to moderate dependence, 5–7 indicates moderate dependence and 8–10 indicates high dependence.

Motivation to Quit questionnaire

The MTQ is a 4-item questionnaire scored from 4 to 19, by adding together the responses to each item, with higher scores indicating a greater motivation to stop smoking. 50

Patient Health Questionnaire-9 items

The PHQ-9 is a 9-item instrument. It asks the subject to indicate how often in the last 2 weeks they have been bothered by nine problems, which are each scored on the scale of 0 = not at all, 1 = several days, 2 = more than half the days, and 3 = nearly every day. 51 A total score is obtained from adding together the nine item scores. Scores can be categorised as follows: 0–4 indicates minimal depression, 5–9 indicates mild depression, 10–14 indicates moderate depression, 15–19 indicates moderately severe depression and 20–27 indicates severe depression. If one or two values are missing from the score, then they can be substituted with the average score of the non-missing items (scored pro rata and total score rounded to nearest integer). Questionnaires with more than two missing values are disregarded.

Generalised Anxiety Disorder Assessment-7 items

The GAD-7 is a 7-item instrument. 52 For each item, scores of 0, 1, 2 and 3 are given to the possible responses of ‘not at all’, ‘several days’, ‘more than half the days’ and ‘nearly every day’, respectively. The GAD-7 total score ranges from 0 to 21. Scores of 5, 10 and 15 represent cut-off points for mild, moderate and severe anxiety, respectively. If one or two values are missing from the score, then they can be substituted with the average score of the non-missing items (scored pro rata and total score rounded to nearest integer). Questionnaires with more than two missing values are disregarded.

Short Form questionnaire-12 items (version 1)

The SF-12 consists of two subscales – a physical component and a mental component – both of which are scored within the range of 0–100, with 0 indicating the lowest level of health and 100 indicating the highest level of health measured by the scale. Scoring was conducted in accordance with the SF-12 scoring manual. 53

Body mass index

A participant’s weight was measured in kilograms at each follow-up visit and their height was measured in metres at the baseline visit. BMI was calculated by dividing weight by height squared and is expressed in the units kg/m2.

Primary analysis

The primary outcome of CO-verified smoking cessation at 12 months was intended to be analysed via a mixed-effect logistic regression model to compare the BSC service intervention with usual care. The model was to include CO-verified smoking status at 6 and 12 months (repeated measures within participants) and be adjusted for baseline smoking severity (self-reported number of cigarettes smoked per day), time, treatment group and a treatment group-by-time interaction, with site as a random effect. Participants nested within site were also to be treated as a random effect to account for the repeated measures within the subjects. However, this model failed to converge. Therefore, separate multilevel logistic regression models were run to compare the outcomes at 6 and 12 months, that is, two models, instead of one model that incorporates the repeated measurements. The two models were each adjusted for baseline smoking severity, with site as a random effect. The OR, corresponding two-sided 95% CI and p-value for the treatment effect at 6 and 12 months are presented. The treatment effect at 12 months serves as the primary end point, and the effect at 6 months serves as a secondary end point. Participants were analysed according to their original random group allocation and were included in the models if they provided a CO reading and a response to the self-reported question relating to amount smoked in the previous week at that particular time point.

Sensitivity analyses

Unadjusted odds ratio

The unadjusted, marginal OR for smoking status at 6 and 12 months is presented for comparability.

Post hoc generalised estimating equations analysis

Given that the prespecified repeated measures mixed logistic regression model did not converge, post hoc sensitivity analyses were conducted using generalised estimating equation (GEE) techniques. This allowed for the repeated measures within participants to be accounted for, but the multilevel nature of the data (i.e. participants within site) cannot be controlled in the same way that including a random effect for site in the mixed logistic regression can be. Two GEE models were run: (1) one controlling for baseline smoking severity, and including an interaction between allocation and time, and (2) one controlling for both baseline smoking severity and site as covariates, and including an interaction between allocation and time. Both specified a binomial family and logit link, with an exchangeable correlation structure.

Accounting for missing carbon monoxide-verified smoking status

Self-reported smoking status was considered when CO-verified smoking status was missing. Further sensitivity analyses were conducted treating participants who still had missing outcome data in the following two ways: one treated participants with missing data as smokers under a worst case scenario, and the other used multiple imputation techniques. Twenty imputations were generated by multiple imputation using chained equations with a burn-in of 10. To avoid bias, the imputation model used all variables that were included in the analysis models (baseline smoking severity, CO-verified smoking status at 6 and 12 months, site and allocation). 56

Secondary analyses

All data collected at 6 and 12 months are summarised descriptively by treatment group, including an investigation into the number of missing data.

Self-reported smoking cessation

The primary analysis was repeated using self-reported smoking status at 6 and 12 months as the outcome (cessation defined as answering ‘not even a puff’ to the question ‘have you smoked in the last week?’).

Number of cigarettes smoked per day

The number of cigarettes smoked per day, as reported as part of the FTND, at 6 and 12 months was compared between the two groups using a mixed-effect negative binomial regression model, adjusting for the same covariates as the primary analysis and the repeated measures within participants. Incidence rate ratios and their associated 95% CIs and p-values are provided.

Continuous secondary outcomes: Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence, Motivation to Quit questionnaire, Patient Health Questionnaire-9 items, Generalised Anxiety Disorder Assessment-7 items, Short Form questionnaire-12 items and body mass index

The FTND, MTQ, PHQ-9, GAD-7, SF-12 physical component and SF-12 mental component scores and BMI were all analysed in the same way. Scores were compared between treatment groups using a covariance pattern linear mixed model. The outcome modelled was the total score at 6 and 12 months. Each model included baseline score, baseline smoking severity, treatment group, time and a treatment group-by-time interaction term as fixed effects, and site as a random effect.

Different covariance structures for the repeated measurements that are available as part of Stata were explored and the most appropriate pattern was used for the final model, based on the one that produced the smallest Akaike information criterion (AIC). Model assumptions were checked via a Q–Q plot to assess the normality of the standardised residuals and a scatterplot of the residuals against fitted values.

Predicted means for each group and the adjusted mean difference (with 95% CI and p-value) between treatment groups at 6 and 12 months are given.

Other outcomes

Self-reported number of attempts to quit, periods of cessation and e-cigarette use will be summarised descriptively by treatment group and time point.

Compliance with the intervention

Treatment session data are summarised for participants in the intervention group, including the number of sessions attended, and the duration and location (e.g. participant’s home) of the sessions. A complier-average causal effect (CACE) analysis for the primary outcome (CO-verified smoking status at 12 months post randomisation) was conducted to obtain an unbiased estimate of the intervention effectiveness in the presence of full compliance. A two-stage least squares instrumental variable approach, with randomised group as the instrumental variable, was used. We defined compliance with the intervention for those allocated to BSC as the number of sessions attended.

Health economic analysis

The health economic analysis for the SCIMITAR+ trial assessed the cost-effectiveness of supplementing usual care with BSC, compared with usual care alone, within the trial. Although the impact of smoking cessation is likely to be observed in the long term, the within-trial evaluation could provide a relatively realistic estimate of intervention costs, necessary parameter inputs for model projection and potentially some insights into the difference in change, in the case of lacking in capacity of a long-term follow-up. The economic evaluation took the form of an incremental cost-effectiveness analysis from a NHS and Personal Social Services perspective, as recommended by NICE guidance. 57

The costs of BSC and usual care were identified, measured and valued. Costs and outcomes were collected at participant level and based on the trial population. Health outcomes were measured using quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs), as per NICE guidance. 57 QALYs were constructed from the EQ-5D-5L,54 which was collected at baseline and during follow-up.

Costs

The total costs encompassed intervention costs and health-care and social services use costs. A wider range of societal costs were collected but analysed separately.

Intervention costs

The intervention costs were identified by two stages corresponding to the timeline of the trial, which were the pre-intervention stage and the intervention stage.

Training and supervision

The pre-intervention stage is the training period for MH-SCPs. To deliver the intervention, four members of the SCIMITAR+ team attended a 2-day training session delivered by the NCSCT, and then acted as trainers for all MH-SCPs. The MH-SCPs received a 2-day training session, in line with that provided by the NCSCT, with specific adaptations for people with SMI. This was delivered by the four trained members of the SCIMITAR+ team, two at a time. The cost of the initial training from the NCSCT was estimated using the invoice. The opportunity cost of time spent on the initial training by our research team and the cost of delivering the training for MH-SCPs were costed at NHS band 6 instead of researchers’ wages to reflect the costs to the NHS. The opportunity costs of time spent on these training sessions by the MH-SCPs were also estimated for 2 working days for NHS band 4 staff. A full day was considered 7.5 working hours. The staff cost included salary oncosts, overheads and capital.

Each practitioner was given a 43-page SCIMITAR+ Standard Treatment Protocol and a 51-page NCSCT Standard Treatment Programme. These were printed in-house at £0.02 per page.

After training, all MH-SCPs received regular supervision, which was delivered by the trainer of the additional training. Supervision time was recorded by the supervisor and allocated to each participant in the BSC group.

Intervention delivery

The intervention stage is the period during which the intervention/control treatment was delivered. Costs were estimated for both the BSC group and the usual-care group accordingly.

For the intervention group, costs included costs of BSC and usual GP care. BSC was costed based on the working time and caseload of MH-SCPs, including travel time to the prearranged location for the appointment. These sessions were recorded in treatment logs by MH-SCPs. Each practitioner was equipped with a CO monitor, which cost £120 and had a life span of 5 years. The depreciation value of the CO monitor in the first year was calculated using double-declining balance to estimate the cost of the CO monitor during the trial period.

Usual GP care included participants’ contact with usual-care practitioners [e.g. GPs, pharmacists, stop smoking services (SSSs), etc.] for smoking cessation and prescriptions of pharmacotherapies for smoking cessation. Usual-care contact was collected through self-reported questionnaires, and prescriptions were extracted from their medical records. The overall cost of contact with practitioners was then calculated by multiplying the number of contact sessions by their national average unit costs (see Table 2). The prescriptions were matched by their generic names, dosage and form to the Prescription Cost Analysis – England,58 and their costs were calculated by multiplying the weighted average net ingredient cost (NIC) per unit by the recorded quantities used within the trial period. In the case of missing values on dosage or form, a weighted average matching available information was used for estimation. Some medications were recorded by prescription instead of quantity; these were consequently estimated based on the weighted average NIC per prescription item.

Health-care and social services costs

Health-care and social service resources utilised by participants outside the trial were measured by an adapted Health Economic/Service Utilisation Questionnaire. These included mainly secondary care and community-based services.

This questionnaire was part of the questionnaire for baseline, 6- and 12-month follow-up and collected the quantity of resources utilised by participants, covering the usage in the 6 months before each time point. After the physical unit of resources was identified by the questionnaire, their quantities were multiplied by their national average unit costs extracted from Unit Costs of Health and Social Care 2017,59 NHS Reference Costs 2016–1760 or inflated from Unit Costs of Health and Social Care 201561 if recent data were unavailable (Table 2).

| Service items/products | Unit cost (2016/17) | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Usual GP care for smoking cessation | ||

| Cessation consultation with GP | £40/session | 61 |

| Cessation consultation with pharmacist | £7/session | 61 |

| SSS | £19/session | 61,62 |

| SSS helpline | £7/call | 61,63 |

| Health care and social services | ||

| A&E department | £175/attendance | 60 |

| Hospital admission | £604/night; £1938/FCE | 60 |

| Hospital outpatient appointment | £138/attendance | 60 |

| Day case/procedure | £736/episode | 60 |

| Emergency ambulance | £99/use | 60 |

| GP home visit | £56/9.22-minute consultation plus 12 minutes of travel | 59,61 |

| GP surgery | £31/9.22-minute consultation | 59 |

| GP telephone | £15/call | 59 |

| Practice nurse | £9/15.5-minute consultation | 59,61 |

| District nurse | £36/contact | 60 |

| Community psychiatric nurse | £61/contact | 60 |

| Health visitor | £64/contact | 60 |

| Clinical psychologist | £40/45-minute session | 59 |

| NHS counsellor | £39/55-minute session | 59 |

| NHS dentist | £138/contact | 60 |

| Podiatrist | £44/contact | 60 |

| Occupational therapist | £77/contact | 60 |

| Physiotherapist | £53/contact | 60 |

| CBT | £100/session | 59 |

| MBCT | £15/session | 59 |

| Crisis team | £192/team contact | 59 |

| CMHT | £197/contact | 59 |

| Day care service | £92/patient day | 60 |

| Social worker | £30/30-minute visit | 59 |

| Family support worker | £27/30-minute visit | 59 |

| Drug/alcohol support worker | £118/contact | 60 |

| NRT products | ||

| Nasal spray | £23/bottle | Estimated market price |

| Microtab | £16/pack | Estimated market price |

| Patch | £13/7-piece pack | Estimated market price |

| Gum | £13/96-piece pack | Estimated market price |

| Lozenge | £13/96-piece pack | Estimated market price |

| Mouth spray | £19/bottle | Estimated market price |

| Inhalator | £21/20 cartridges | Estimated market price |

All costs were presented in 2016/17 Great British pounds. Discounting was not required in this study, as the evaluation was conducted within a 12-month time frame.

The use of antipsychotics was extracted from participants’ medical notes. As with prescription of pharmacotherapies, they were matched by their generic names, dosage and form to the Prescription Cost Analysis – England. 58

The costs of health-care and social services use in the 6 months before baseline were used as one of the baseline covariates for costs.

Wider societal costs

Costs incurred outside the NHS perspective were collected in the questionnaire by self-report and added to the base-case analysis to present a separate analysis from a societal perspective. These included out-of-pocket purchases of NRT products and e-cigarettes, and travel costs for the participants to attend the smoking cessation appointments. As the market pricing of NRT products is highly complicated because of deals, bundles or packaging, a set of estimated market prices was summarised, based on prices from big supermarkets and pharmacies, such as Sainsbury’s (www.sainsburys.co.uk), Morrison’s (www.groceries.morrisons.com), Boots (www.boots.com) and Lloyds Pharmacy (www.lloydspharmacy.com). It was further simplified by using only one package size for patch, gum, lozenge and inhalator, as they were available in various package sizes (see Table 2).

Health-related quality of life

The EQ-5D-5L was used to measure health-related quality of life in both the BSC group and the usual-care group. The instrument was used at baseline and at 6- and 12-month follow-up. An index score was calculated using the mapping function developed by van Hout et al. 64 The index score ranges from –0.594 to 1, with higher scores indicating better health-related quality of life. QALYs were then derived from EQ-5D-5L index score at three time points by calculating the area under the curve. 65 The accompanied visual analogue scale (VAS) was also reported, ranging from 0 to 100, with higher numbers indicating better health-related quality of life.

After the original plan was finalised, a EQ-5D-5L value set for England was released by the Office of Health Economics. 66 Following that development, NICE released a position statement in August 2017 stating that, for the data gathered using EQ-5D-5L, the mapping function approach is still the preferred method for reference case analysis and the five-level version valuation set is not recommended for use at this time. 67 The updated statement in November 2018 retained this position. 68 Therefore, we maintained the original plan and disregarded the available five-level version valuation set for England.

Missing data

For the baseline covariates, little to no missing data were expected. These missing values were imputed by the mean of the parameter in the whole sample because these were information collected before the intervention began and the randomisation functioned to balance the parameters between two arms.

Methods for dealing with missing data on the primary outcome (CO-verified smoking cessation) followed the approach used in the previous statistical analysis. The missing data on costs and quality-of-life elements at follow-ups were imputed using multiple imputation. A chained equation model was developed, and predictive mean matching was used as the main imputation method for continuous variables, using 10 nearest neighbours to the prediction as a set from which to draw. All missing data were imputed separately by trial group. The imputation was performed on the aggregated level estimate, that is, EQ-5D-5L utility value converted from data provided by participants. As a rule of thumb, the number of imputations was set to the highest percentage of all missing values. 69

Analysis

Primary analysis

The primary health economic analysis was conducted on an intention-to-treat basis, including all randomised participants in the groups to which they were randomised. The CO-verified smoking cessation rate at 12 months was calculated for both groups in the statistical analysis. Intervention cost per CO-verified quitter at 12 months and incremental intervention cost per additional quitter was reported to provide a comparison with the SSS statistics.

Intervention costs and wider health-care and social services costs were used to calculate total cost per participant. The EQ-5D-5L was used to calculate QALYs per participant. An incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) was calculated and compared with the willingness-to-pay (WTP) threshold recommended by NICE (£20,000–30,000). 57

Sensitivity analysis

Uncertainty around the ICER was quantified using a non-parametric bootstrap technique whereby 5000 samples were generated by resampling. Confidence intervals around the ICER were estimated and plotted on a cost-effectiveness plane to illustrate the overall uncertainty of both costs and QALYs. Cost-effectiveness acceptability curves were constructed from the bootstrapped samples by converting ICER to net monetary benefit. 70

A complete-case analysis was also carried out to assess the uncertainty due to missing data.

Secondary analysis

Several exploratory analyses were also conducted in addition to the reference case analysis recommended by the NICE guidance. 57

Wider societal costs were summarised and presented as a separate analysis to provide an estimate of costs outside the NHS. Using the information on the number of cigarettes smoked per day, an estimate of money spent on cigarettes was calculated to demonstrate the monetary impact on the financial condition of the participants. Previous evidence suggested that smokers with SMI might require a lower dosage of antipsychotics to achieve the same effect if they stop smoking. 2 Therefore, a comparison of the costs of antipsychotics between two halves of the trial period by participants’ smoking status among this sample was conducted.

Adverse events

A trial-specific procedure for detecting and reporting adverse events was implemented.

An adverse event was defined as any unexpected effect or untoward clinical event affecting the participant. Standard criteria for serious adverse events (SAEs) were used.

The participant’s MH-SCP, GP or mental health specialist was requested to inform the research team of any SAEs or non-SAEs. In addition, when participants indicated hospital attendance or use of emergency services either during a visit or in questionnaire responses, this was followed up by the research team as required.

All adverse events and SAEs were independently reviewed by a clinician and were routinely reported to the Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee and the Independent Trial Steering Committee (TSC).

Adverse event data are summarised descriptively by treatment group.

Suicide and self-harm risk protocol

A protocol for identifying and reporting potential suicide risk was implemented (see Appendix 3 for protocol). Item 9 on the PHQ-9, which asks if the participant has had ‘thoughts that you would be better off dead or of hurting yourself in some way’, was used to identify any suicide risk.

If the participant indicated a response of 3 (i.e. nearly every day) for this item at baseline or at any of the follow-up interviews, then the suicide protocol was implemented and the participant was asked if they had talked to their GP, psychiatrist or care co-ordinator/community psychiatric nurse (CPN) about these feelings. If they had not, consent was sought to contact the participant’s GP to inform them of the situation. If the participant refused, the relevant designated psychiatrist/health professional was contacted. If the health professional agreed, the participant’s GP or psychiatrist was contacted immediately. A Suicidal Intent Form was completed and, when applicable, a Suicidal Intent Form: Psychiatrist/Health Professional was also completed. These forms were stored with the participant’s trial records.

Patient and public involvement in research

The SCIMITAR+ trial benefited from the involvement of users of mental health services and carers of people with SMI throughout the research period. Our TSC included representation from carers and service users. Our protocol and study materials were scrutinised and supported by users and carers in the north-west of England.

We invited service users from a patient and public involvement (PPI) group based in the north-west to be involved in the study. One of the collaborators works at the University of Manchester, the institution that organised the PPI group. From this group, service users provided input on the recruitment materials. Service users from this group were also invited to sit on the TSC; we had two service users sit on the TSC and provide input into the running of the trial. We also had the benefit of a carer who sat on the TSC in the pilot trial and continued to sit on the TSC in the main trial.

A service user and carer were invited to attend one of our yearly SCIMITAR+ meetings, which we held for all the organisations taking part in the study. They gave a presentation on smoking and giving up smoking and provided useful input into the study. They continue to remain involved and provide advice on our work. We are seeking advice from service users regarding the dissemination of the SCIMITAR+ trial and have recently formed a PPI group at the University of York for service users with SMI. We will be asking this group to provide input into our dissemination plan.

Chapter 3 Changes to the protocol

The current version of the protocol is version 2.5.

Recruitment from service user groups

After the trial had been recruiting for 3 months, recruitment from service user groups was added as an additional recruitment method. This involved providing service user groups with information about the SCIMITAR+ trial, along with copies of the flyer. Interested service users could then contact the mental health professional named on the flyer or their care co-ordinator, or, if the service user preferred, the staff member at the service user group could contact the service users’ care co-ordinator on their behalf.

This recruitment method was added to broaden the range of recruitment methods and therefore broaden the range of participants invited to take part in the SCIMITAR+ trial. This method also had the potential to offer service users who may not routinely be attending a clinic, and therefore not approached by a clinician, the opportunity to take part in the study.

Recruitment from the Lifestyle Health and Wellbeing Survey

Using the Lifestyle Health and Wellbeing Survey to recruit was added as a recruitment option after the trial had been recruiting for 8 months. The survey is a questionnaire-based prospective study involving adults aged ≥ 18 years with SMI. Participants in the survey complete a series of questions about their health and well-being, including questions about their smoking. Participants in the survey who consented to being contacted by the research team and who smoked and were potentially interested in cutting down on or quitting smoking were invited to take part in the SCIMITAR+ trial.

The use of the Lifestyle Health and Wellbeing Survey was included to broaden the range of recruitment options and to offer people who may not have been invited by their mental health team or GP to take part in the SCIMITAR+ trial the opportunity to do so. During the course of the SCIMITAR+ trial, we noticed that some clinicians were gatekeeping: instead of checking whether or not a person wanted to do something about their smoking, they were stating that the person did not want to stop smoking. In the survey, each person was asked whether or not they wanted to do something about their smoking, thus removing the possibility of an incorrect assumption being made.

Chapter 4 Results

Recruitment

Recruitment started in October 2015 and ended in December 2016. Over the course of the trial, 40 GP surgeries mailed out recruitment packs, and 21 mental health trusts were enlisted to recruit participants.

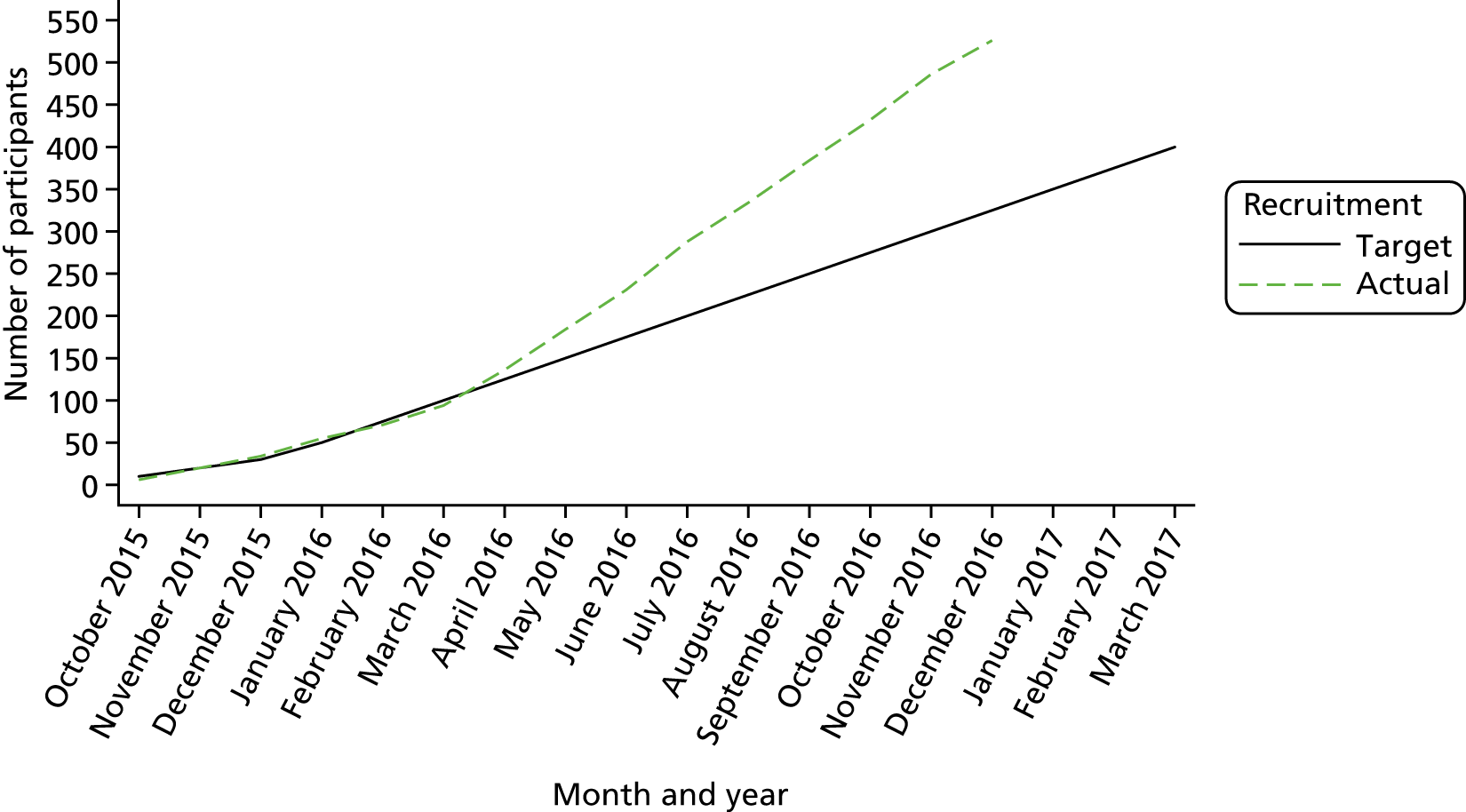

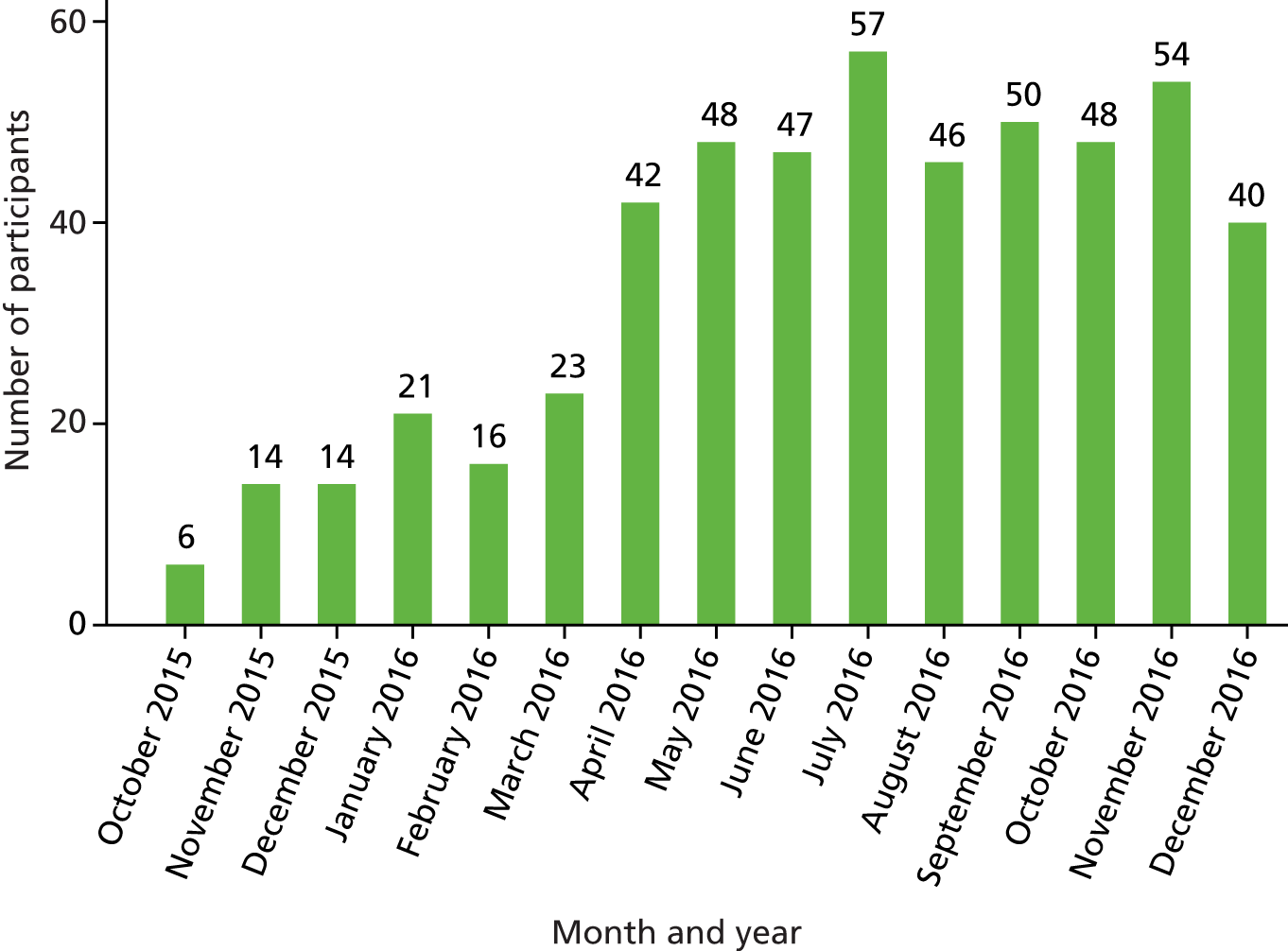

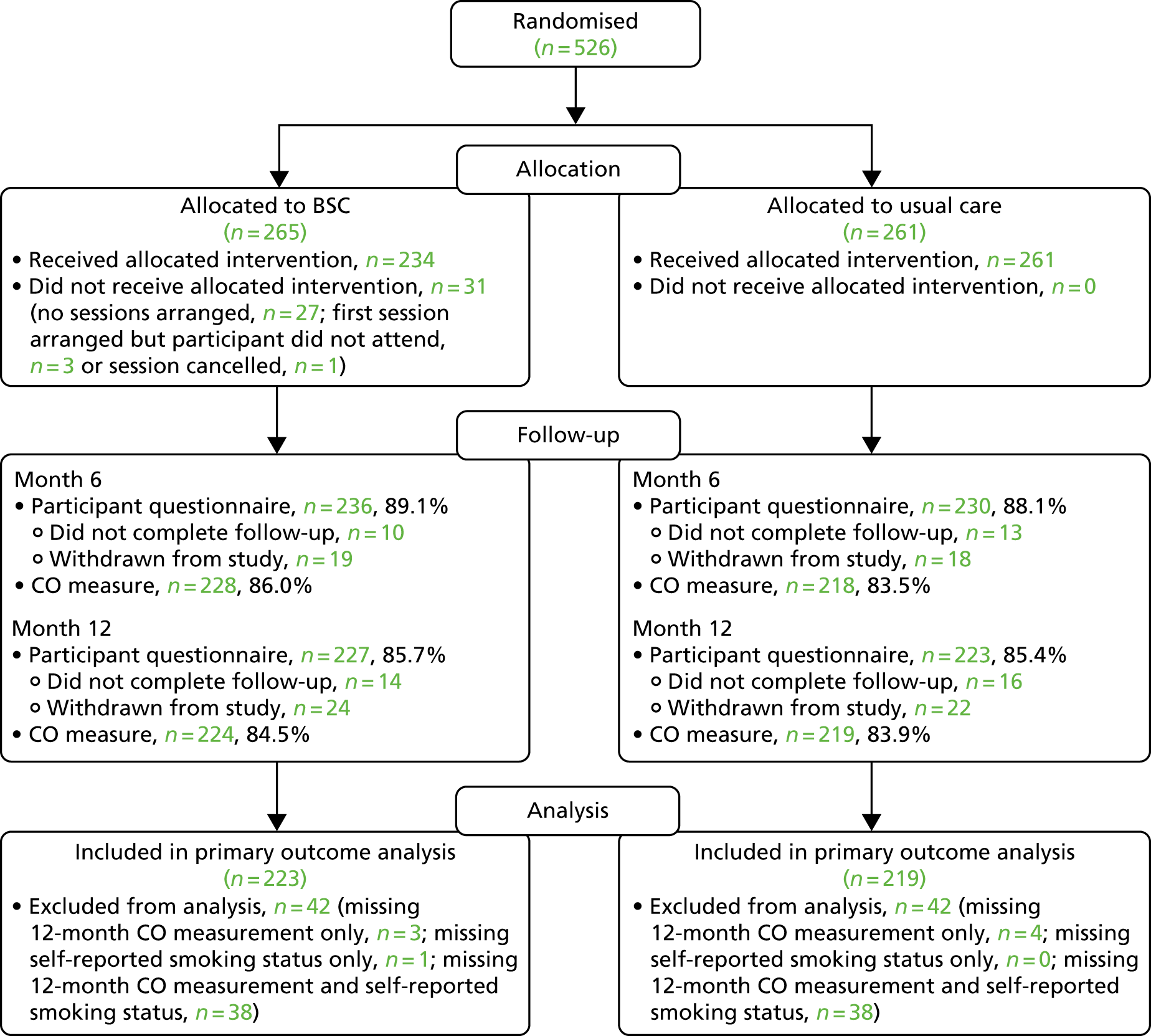

A total of 526 participants were recruited to the trial. The target and actual rates of recruitment are shown in Figure 1, and monthly recruitment figures are shown in Figure 2. Recruitment took place at 21 mental health trusts and 16 GP surgery sites (one GP site was a standalone site and the other GP sites were acting as participant identification centres for the mental health trusts), although eligible and randomised participants were primarily identified from mental health trusts. Table 3 shows the recruitment broken down by method. Mental health trusts recruited between four and 52 participants per trust, and GP surgeries recruited between one and five participants. Participant flow through the trial is shown in CONSORT flow diagrams in Figures 3–5. Of the 526 participants, 265 were randomised to the BSC group and 261 were randomised to the usual-care group.

FIGURE 1.

The SCIMITAR+ target and actual recruitment rates.

FIGURE 2.

Monthly recruitment into the SCIMITAR+ trial.

| Recruitment method | Number recruited (N = 526), n (%) |

|---|---|

| CMHT direct referral | 377 (72) |

| Psychiatrist direct referral | 40 (8) |

| CMHT database screen | 37 (7) |

| CMHT/psychiatrist unknown | 28 (5) |

| GP database screen | 22 (4) |

| Recruitment from Lifestyle Health and Wellbeing Survey | 13 (2) |

| GP direct referral | 1 (0.2) |

| GP unknown | 1 (0.2) |

| Service user group | 1 (0.2) |

| Unknown | 6 (1) |

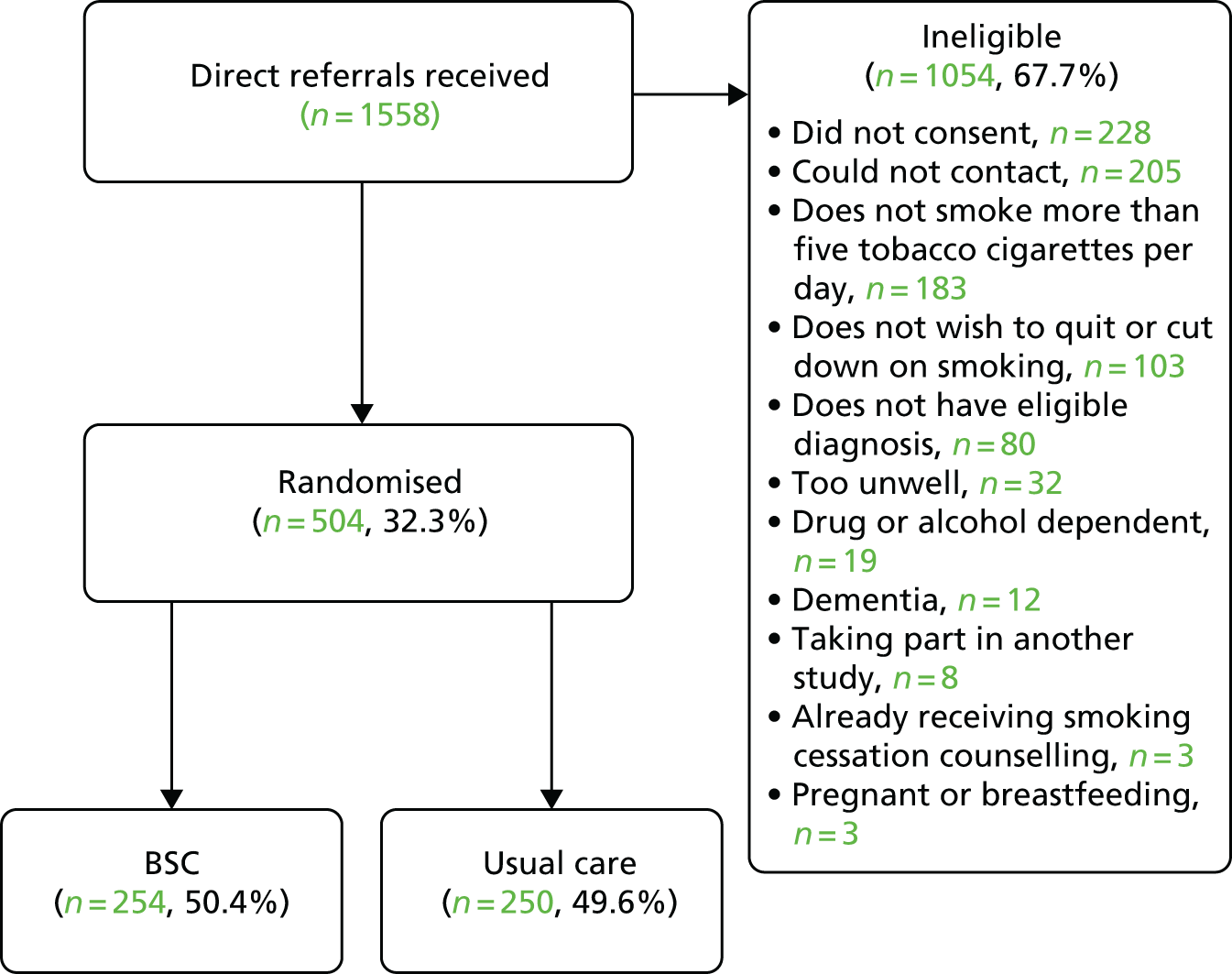

FIGURE 3.

Primary care CONSORT flow diagram up to randomisation.

FIGURE 4.

Secondary care CONSORT flow diagram up to randomisation.

FIGURE 5.

The CONSORT flow diagram showing participant flow through the trial, from randomisation.

Primary care

A total of 1162 participants were identified as potentially eligible from GP practice lists and were sent a recruitment pack, of which 48 (4.1%) returned a ‘consent to contact’ form. Twenty-six of these were ineligible and the remaining 22 were randomised, 11 to each trial arm. The randomisation rate for the GP mailout was 1.9%.

Secondary care

The number of direct referrals received was 1558. Two-thirds of these were ineligible, non-consenting and/or could not be contacted (n = 1054, 67.7%) and the remaining 504 were randomised, 254 to the BSC group and 250 to the usual-care group. The randomisation rate for direct referrals was 32.3%.

Taking part in another study was not one of the exclusion criteria for the SCIMITAR+ trial; however, some people were taking part in a study that precluded participants from taking part in other research studies.

Baseline data

The baseline characteristics of participants are summarised in the following tables, and the treatment groups appear well balanced across baseline data. Table 4 summarises the sociodemographic and employment data for the participants. Overall, 58.7% of the participants were male, 41.1% were female and one participant identified as transgender (0.2%). The mean age of participants was 46 years, with a range from 19 to 72 years. The vast majority of participants were white (89.7%). Over two-thirds of the participants were unemployed but not seeking work owing to ill health (67.7%).

| Characteristic | BSC (N = 265) | Usual care (N = 261) | Overall (N = 526) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex/gender, n (%) | |||

| Male | 159 (60.0) | 150 (57.5) | 309 (58.7) |

| Female | 105 (39.6) | 111 (42.5) | 216 (41.1) |

| Transgender | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) |

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 46.5 (12.5) | 45.5 (11.7) | 46.0 (12.1) |

| Median (min., max.) | 47 (19, 72) | 46 (19, 71) | 47 (19, 72) |

| Missing, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| White | 241 (90.9) | 231 (88.5) | 472 (89.7) |

| Mixed | 9 (3.4) | 10 (3.8) | 19 (3.6) |

| Asian | 5 (1.9) | 11 (4.2) | 16 (3.0) |

| Black | 9 (3.4) | 7 (2.7) | 16 (3.0) |

| Chinese | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | 2 (0.4) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.2) |

| Highest educational qualification, n (%) | |||

| None | 42 (15.8) | 41 (15.7) | 83 (15.8) |

| GCSE/O level | 74 (27.9) | 91 (34.9) | 165 (31.4) |

| GCE A/AS level or Scottish Higher | 20 (7.5) | 23 (8.8) | 43 (8.2) |

| NVQ/SVQ levels 1–3 | 39 (14.7) | 21 (8.0) | 60 (11.4) |

| GNVQ (Advanced) | 2 (0.8) | 7 (2.7) | 9 (1.7) |

| BTEC certificate | 4 (1.5) | 2 (0.8) | 6 (1.1) |

| BTEC diploma | 7 (2.6) | 11 (4.2) | 18 (3.4) |

| National Certificate or Diploma | 7 (2.6) | 5 (1.9) | 12 (2.3) |

| Qualified teacher status | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.2) |

| Higher education diploma | 5 (1.9) | 7 (2.7) | 12 (2.3) |

| Degree (first degree/ordinary degree) | 24 (9.1) | 13 (5.0) | 37 (7.0) |

| Postgraduate certificate | 2 (0.8) | 2 (0.8) | 4 (0.8) |

| Postgraduate diploma | 2 (0.8) | 1 (0.4) | 3 (0.6) |

| Master’s degree | 4 (1.5) | 6 (2.3) | 10 (1.9) |

| PhD | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) |

| Other | 30 (11.3) | 25 (9.6) | 55 (10.5) |

| Missing | 2 (0.8) | 5 (1.9) | 7 (1.3) |

| Employment, n (%) | |||

| Employed full time | 3 (1.1) | 16 (6.1) | 19 (3.6) |

| Employed part time | 9 (3.4) | 11 (4.2) | 20 (3.8) |

| Self-employed | 2 (0.8) | 2 (0.8) | 4 (0.8) |

| Retired | 19 (7.2) | 16 (6.1) | 35 (6.7) |

| Looking after family or home | 4 (1.5) | 3 (1.1) | 7 (1.3) |

| Student | 5 (1.9) | 5 (1.9) | 10 (1.9) |

| Voluntary worker | 11 (4.2) | 18 (6.9) | 29 (5.5) |

| Not employed but seeking work | 16 (6.0) | 15 (5.7) | 31 (5.9) |

| Not employed but not seeking work because of ill health | 185 (69.8) | 171 (65.5) | 356 (67.7) |

| Not employed but not seeking work for some other reason | 8 (3.0) | 4 (1.5) | 12 (2.3) |

| Other | 3 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.6) |

| Marital status, n (%) | |||

| Single | 177 (66.8) | 171 (65.5) | 348 (66.2) |

| Married | 32 (12.1) | 26 (10.0) | 58 (11.0) |

| Living with a partner/co-habiting | 13 (4.9) | 16 (6.1) | 29 (5.5) |

| Divorced/separated | 33 (12.5) | 46 (17.6) | 79 (15.0) |

| Widowed | 10 (3.8) | 2 (0.8) | 12 (2.3) |

| Accommodation, n (%) | |||

| Detached house | 10 (3.8) | 18 (6.9) | 28 (5.3) |

| Semidetached house | 40 (15.1) | 48 (18.4) | 88 (16.7) |

| Terraced house | 45 (17.0) | 32 (12.3) | 77 (14.6) |

| Flat | 123 (46.4) | 113 (43.3) | 236 (44.9) |

| Bedsit/studio | 6 (2.3) | 11 (4.2) | 17 (3.2) |

| Communal establishment | 36 (13.6) | 35 (13.4) | 71 (13.5) |

| Caravan/other mobile shelter | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) |

| No fixed abode | 2 (0.8) | 2 (0.8) | 4 (0.8) |

| Missing | 2 (0.8) | 2 (0.8) | 4 (0.8) |

Table 5 presents data on the general health of the participants at baseline. Most participants reported at least moderate health in the last year (65.4%), despite most participants reporting that they experienced at least one of the listed medical conditions (85.6%). The majority of participants (83.5%) felt that smoking had negatively affected their health, and 70.9% reported that they had been advised to stop smoking by their GP. The mean BMI of participants was 29.9 kg/m2 (range 16.6–59.8 kg/m2), which falls in the overweight range.

| Characteristic | BSC (N = 265) | Usual care (N = 261) | Overall (N = 526) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Health over the past year, n (%) | |||

| Excellent | 14 (5.3) | 1 (0.4) | 15 (2.9) |

| Good | 50 (18.9) | 62 (23.8) | 112 (21.3) |

| Moderate | 101 (38.1) | 116 (44.4) | 217 (41.3) |

| Poor | 77 (29.1) | 62 (23.8) | 139 (26.4) |

| Very poor | 23 (8.7) | 18 (6.9) | 41 (7.8) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.8) | 2 (0.4) |

| Feel smoking has negatively affected health, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 220 (83.0) | 219 (83.9) | 439 (83.5) |

| No | 45 (17.0) | 42 (16.1) | 87 (16.5) |

| GP or doctor gave advice on quitting smoking, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 192 (72.5) | 181 (69.3) | 373 (70.9) |

| No | 73 (27.5) | 80 (30.7) | 153 (29.1) |

| Health problems, n (%) | |||

| Asthma | 89 (33.6) | 82 (31.4) | 171 (32.5) |

| Chronic bronchitis | 29 (10.9) | 34 (13.0) | 63 (12.0) |

| Other chest trouble | 83 (31.3) | 106 (40.6) | 189 (35.9) |

| Diabetes | 39 (14.7) | 38 (14.6) | 77 (14.6) |

| Stomach/digestive disorder | 67 (25.3) | 87 (33.3) | 154 (29.3) |

| Haemorrhoids (piles) | 44 (16.6) | 48 (18.4) | 92 (17.5) |

| Liver trouble | 19 (7.2) | 19 (7.3) | 38 (7.2) |

| Rheumatic disorder or arthritis | 43 (16.2) | 56 (21.5) | 99 (18.8) |

| Lung cancer | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.2) |

| Other cancer | 9 (3.4) | 9 (3.4) | 18 (3.4) |

| Varicose veins | 26 (9.8) | 25 (9.6) | 51 (9.7) |

| Stroke | 12 (4.5) | 11 (4.2) | 23 (4.4) |

| Migraine | 79 (29.8) | 71 (27.2) | 150 (28.5) |

| Back trouble | 116 (43.8) | 122 (46.7) | 238 (45.2) |

| Epilepsy | 17 (6.4) | 11 (4.2) | 28 (5.3) |

| ME or chronic fatigue | 18 (6.8) | 26 (10.0) | 44 (8.4) |

| High blood pressure | 56 (21.1) | 62 (23.8) | 118 (22.4) |

| Healthy life, n (%) | |||

| A very healthy life | 17 (6.4) | 11 (4.2) | 28 (5.3) |

| A fairly healthy life | 118 (44.5) | 114 (43.7) | 232 (44.1) |

| A not very healthy life | 94 (35.5) | 101 (38.7) | 195 (37.1) |

| An unhealthy life | 36 (13.6) | 32 (12.3) | 68 (12.9) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 3 (1.1) | 3 (0.6) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 30.2 (7.1) | 29.7 (6.3) | 29.9 (6.7) |

| Median (min., max.) | 29.0 (16.6, 59.8) | 29.4 (16.9, 48.4) | 29.3 (16.6, 59.8) |

| Missing, n (%) | 2 (0.8) | 3 (1.1) | 5 (1.0) |

| Eat five portions of fruit and vegetables a day, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 113 (42.6) | 106 (40.6) | 219 (41.6) |

| No | 152 (57.4) | 152 (58.2) | 304 (57.8) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 3 (1.1) | 3 (0.6) |

| Exercise for 20 minutes or more, n (%) | |||

| Daily | 92 (34.7) | 89 (34.1) | 181 (34.4) |

| Weekly | 72 (27.2) | 68 (26.1) | 140 (26.6) |

| Monthly | 9 (3.4) | 7 (2.7) | 16 (3.0) |

| Seldom | 33 (12.5) | 43 (16.5) | 76 (14.4) |

| Never | 59 (22.3) | 51 (19.5) | 110 (20.9) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 3 (1.1) | 3 (0.6) |

| Drink alcohol, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 141 (53.2) | 140 (53.6) | 281 (53.4) |

| No | 122 (46.0) | 121 (46.4) | 243 (46.2) |

| Missing | 2 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.4) |

| If yes, units in last week | n = 141 | n = 140 | n = 281 |

| Mean (SD) | 10.1 (15.8) | 8.8 (16.0) | 9.5 (15.9) |

| Median (min., max.) | 4 (0, 84) | 4 (0, 140) | 4 (0, 140) |

| Missing, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

Table 6 summarises baseline mental health status. The most common severe mental health problems were schizophrenia or other psychotic illness (n = 342, 65.0%), bipolar disorder (n = 115, 21.9%) and schizoaffective disorder (n = 66, 12.5%). Nearly two-thirds of the participants had a care programme approach (CPA) co-ordinator (64.4%) and/or a CPN (64.6%), and 83.3% were under the care of a CMHT. On average, participants were aged 26 years when they were first diagnosed with their mental health problem and had required psychiatric treatment in hospital an average of 2.8 times (range 0–100 times) in the last 10 years. Most (64.3%) participants described their condition as ‘stable’, but 13.7% described their condition as ‘unstable’ (although each participant had been judged to be stable from the point of view of their condition by either their GP or a responsible mental health professional), and 22.0% either were unsure or did not respond to this question.

| Characteristic | BSC (N = 265) | Usual care (N = 261) | Overall (N = 526) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at first diagnosis (years) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 26.1 (10.3) | 26.4 (10.5) | 26.3 (10.4) |

| Median (min., max.) | 24 (2, 60) | 25 (0, 59) | 24 (2, 60) |

| Missing, n (%) | 4 (1.5) | 7 (2.7) | 11 (2.1) |

| Most recent diagnosis, n (%) | |||

| Bipolar disorder | 59 (22.3) | 56 (21.5) | 115 (21.9) |

| Schizoaffective disorder | 25 (9.4) | 41 (15.7) | 66 (12.5) |

| Schizophrenia | 138 (52.1) | 125 (47.9) | 263 (50.0) |

| Other psychotic disorder | 41 (15.5) | 39 (14.9) | 80 (15.2) |

| Missing | 2 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.4) |

| Type of professional seen by participant, n (%) | |||

| CPA co-ordinator | 166 (62.6) | 173 (66.3) | 339 (64.4) |

| CPN | 171 (64.5) | 169 (64.8) | 340 (64.6) |

| CMHT | 217 (81.9) | 221 (84.7) | 438 (83.3) |

| Time since last health check (months) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 5.4 (11.9) | 4.4 (6.7) | 4.9 (9.6) |

| Median (min., max.) | 1.9 (0.1, 116.5) | 2.1 (0.1, 63.0) | 2.0 (0.1, 116.5) |

| Missing, n (%) | 102 (38.5) | 94 (36.0) | 196 (37.3) |

| Number of times needed psychiatric treatment in hospital in last 10 years | |||

| Mean (SD) | 2.9 (6.9) | 2.7 (4.7) | 2.8 (5.9) |

| Median (min., max.) | 1 (0, 100) | 1 (0, 50) | 1 (0, 100) |

| Missing, n (%) | 4 (1.5) | 6 (2.3) | 10 (1.9) |

| Would you describe your condition as . . . , n (%) | |||

| Stable | 172 (64.9) | 166 (63.6) | 338 (64.3) |

| Unstable | 40 (15.1) | 32 (12.3) | 72 (13.7) |

| Unsure | 53 (20.0) | 62 (23.8) | 115 (21.9) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.2) |

Participants reported that they started smoking, on average, at the age of 16 years (range 5–50 years) and had been smoking for a mean of 29.9 (SD 12.9) years (Table 7). The most common form of tobacco used was factory-made cigarettes, reportedly used by 63.3% of participants, followed by hand-rolled cigarettes (58.7%). The mean number of cigarettes smoked per day was 24.9 (range 3–100 cigarettes) (although all participants reported smoking at least five cigarettes per day when the eligibility check was carried out, one participant stated that they smoked three cigarettes per day in the self-complete smoking questionnaire). The median number of attempts to quit ever was 3, with a range of 0–200. The median duration of longest quit attempt reported was 40 days, with a range of 0 days to 188 months. The most common self-reported previous strategies used to stop smoking were ‘cold turkey’ (55.3%) followed by NRTs (20.3%).

| Characteristic | BSC (N = 265) | Usual care (N = 261) | Overall (N = 526) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age started smoking (years) | |||