Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 11/36/33. The contractual start date was in March 2013. The draft report began editorial review in December 2017 and was accepted for publication in July 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Christopher McCabe has received grant funding from the University of Alberta and Alberta Innovates Health Solutions (Edmonton, AB, Canada). Julia Brown is Deputy Director of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Clinical Evaluation and Trials Board and has received grant funding for the following studies: the NIHR eRAPID Programme Grants for Applied Research (PGfAR) trial, the NIHR Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation (EME) GLiSten trial, the NIHR HTA LAVA trial (liver resection surgery versus thermal ablation for colorectal liver metastases), the NIHR EME IntAct (Intraoperative flourescence angiography to prevent Anastomotic leak in rectal cancer surgery), NIHR Research for Patient Benefit LACE (Life After Cancer Epidemiology) trial, the NIHR EME ROLARR (RObotic vs. LAparoscopic Resection for Rectal cancer) trial, the NIHR HTA SaFarI (Sacral nerve stimulation versus the FENIX TM magnetic sphincter augmentation for faecal incontinence: a Randomised Investigation and the NIHR StamINA Programme Development Grant trial. Claire Hulme and E Andrea Nelson have been members of the NIHR HTA Commissioning Board and E Andrea Nelson has received funding for the NIHR HTA CODIFI (Concordance in Diabetic Foot Ulcer Infection) study. Elizabeth McGinnis has received funding for NIHR Health Service and Delivery Research (HSDR) Information Systems, Monitoring and Managing from Ward to Board and the NIHR PGfAR SWHSI (Surgical Wounds Healing by Secondary Intention) trial. Isabelle L Smith and Susanne Coleman have received a NIHR personal fellowship. Benjamin Thorpe has received a NIHR research methods fellowship. Delia Muir has received a Wellcome Trust Engagement Fellowship. Rachael Gilberts has received funding for the NIHR HTA ALPHA (ALitretinoin versus PUVA in severe chronic HAnd eczema) and MIDFUT (Multiple Interventions for Diabetic Foot Ulcer Treatment) trials. Nikki Stubbs has received funding for NIHR PGfAR SWHSI and NIHR HTA AMBER (Abdominal Massage for Bowel Dysfunction Effectiveness Research) trial. Jane Nixon has received funding for NIHR HTA MIDFUT, CODIFI and ALPHA. Sarah Brown has received funding for NIHR HTA ALPHA, MIDFUT, FORVAD (Clinical and cost-effectiveness of posterior cervical FORaminotomy Versus Anterior cervical Discectomy in the treatment of cervical brachialgia: a multicentre, Phase III, randomised controlled trial), the NIHR PGfAR PROMPT (early detection to improve outcome in patients with undiagnosed psoriatic arthritis), ARUK (Arthritis Research UK) SALRISE (SALivary electro-stimulation for the treatment of dry mouth in patients with Sjögren’s syndrome: a multicentRe randomISEd sham-controlled double-blind study).

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Nixon et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Pressure ulcers (PUs) are a major burden on patients, carers and the health-care system,1,2 affecting approximately one in seven hospitals and 1 in 20 community patients. 3–6 PUs greatly affect patients and their carers with physical, social and psychological factors. Distressing symptoms including pain, exudate and odour, increased care burden, prolonged rehabilitation, requirement for bed rest, hospitalisation and, for those who work, sickness absences are often reported. 1 They are a cross-specialty problem, a complication of serious acute or chronic illness in patient populations characterised by high levels of comorbidity and mortality. 7

A PU is described as ‘localized injury to the skin and/or underlying tissue usually over a bony prominence, as a result of pressure, or pressure in combination with shear’8 (reproduced with permission from the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel, the European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel and the Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance). The primary cause of a PU is mechanical load in the form of pressure, or pressure and shear, applied to soft tissues, generally over a bony prominence. The magnitude or duration of the mechanical load is such that it causes cell deformation leading to cell membrane rupture and/or impairment of the blood supply and tissue ischaemia, resulting in tissue damage. 9,10

Classification

Pressure ulcers range in severity from intact skin with non-blanchable erythema to severe ulcers involving fat, muscle and bone. Various classification systems have been developed8,11,12 using terms such as ‘grade’, ‘stage’ and ‘category’. The most widely used international classifications use a numerical scale of 1–4 to indicate increasing severity of skin and underlying soft tissue/bone involvement, with additional descriptors including ‘unstageable’ and ‘deep tissue injury’ for which a 1–4 classification cannot be determined from clinical examination. 8,12

More recently, Australian and US groups have advocated that the term ‘pressure injury’ be adopted to replace the term ‘pressure ulcer’. 13,14 The European position15 and a NHS Improvement Definitions Task and Finish Group16 both recommend that the term ‘pressure ulcer’ is retained so that the UK is aligned with the most up-to-date International Classification of Diseases, 11th Revision. 17

For the purposes of this report, the term ‘pressure ulcer’ and its abbreviation ‘PU’ will be used.

Risk factors

A systematic review on PU risk factors identified the risk factor domains emerging most frequently in multivariable modelling of independent predictors of PU development as mobility/activity, perfusion (including diabetes) and skin/PU status. 18 Moisture, age, haematological measures, nutrition and general health status are also important, but emerge inconsistently in multivariable modelling. The importance of body temperature and immunity require further confirmatory research and there is no clear evidence that race and gender are important to PU development. 18 The risk factor systematic review informed the development of a PU conceptual framework that maps the potential relationships between the key ‘direct causal factors’ (immobility/inactivity, perfusion and skin status) and the large number of other ‘indirect causal factors’ (e.g. moisture, age, nutrition, acute illness). 9

Importance

Over the past three decades, government health departments, national guideline agencies, commissioners and funders of health care have promoted policies, incentives and guidelines that focus on the prevention of PUs. 5,12,19–22 This reflects the high personal costs incurred by patients1,23 and the high financial costs incurred by health-care funders and providers in the treatment of PUs due to increased length of hospital stay, hospital admission, community nursing, treatments (reconstruction surgery/mattresses/dressings/technical therapies) and complications (serious infection). 24,25 Litigation is also a burden on health-care providers and is predicted to increase because of general societal trends and, in some cases (e.g. the UK), changes in the national policies that have led to investigation by government agencies of severe PUs to detect institutional and professional neglect of vulnerable adults. 21,22

Interventions for pressure ulcer prevention

In all national and international guidelines, there are three main components of PU prevention practice, including:

-

formal risk assessment to identify ‘at risk’ patients and target preventative interventions

-

minimising both the intensity and the duration of exposure to mechanical loads on vulnerable skin sites not adapted to loading8,12 through –

-

minimising exposure to localised pressure through use of pressure-redistributing mattresses/cushions

-

intermittent pressure relief26 through major or minor repositioning of patients and/or mattresses and cushions that alternate temporarily to relieve pressure

-

complete pressure relief through continuous offloading of a specific skin site12 achieved by positioning patients or providing a heel offloading device so that a specific skin site (i.e. a skin site with an existing PU or adverse skin status) is completely offloaded at all times.

-

-

optimising skin condition through cleansing, drying and minimising exposure to moisture. 12

In this randomised controlled trial (RCT), the focus was on the effectiveness of two interventions: one minimising the intensity of pressure and one minimising both the intensity and the duration of pressure.

Pressure ulcer prevention mattresses

Pressure-relieving mattresses either distribute a patient’s weight over a larger contact area, providing ‘constant low pressure’ to reduce pressure intensity, or mechanically distribute a patient’s weight over a large contact area AND vary the pressure beneath the patient in order to reduce both the intensity and the duration of pressure [alternating pressure mattresses (APMs)]. 27 There are a range of ‘constant low pressure’ mattresses that are classified as ‘low technology’ [e.g. high-specification foam, gel, water] and ‘high technology’ [e.g. electrically powered air and air-fluidised (bead) beds]. All the alternating pressure mattresses are electrically powered and are classified as high technology. 27 Unit costs vary considerably; mattresses used frequently in the UK can be as little as £80–35228 for a low-technology high-specification foam mattress or as much as £500–4000 for a high-technology alternating pressure mattress. 28 In this study, these two main mattress types, utilised within the NHS, were compared, namely (1) high-technology APMs and (2) HSFMs, which are low-technology support surfaces. 27

Table 1 illustrates different types of mattresses and their classifications as ‘low technology’ and ‘high technology’, as adapted from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines12 and Cochrane systematic review. 27 Only HSFMs and APMs were used in this study.

| Mattress type | Technology |

|---|---|

| Static overlay | Low |

| HSFM | Low |

| Static air filled | Low |

| Gel filled | Low |

| Alternating pressure | High |

| Hybrid foam/alternating pressure | High |

| Low air loss | High |

| Hybrid alternating pressure/low air loss | High |

| Specialised | High |

| Hybrid alternating top layer and air-filled static | High |

Mattress intervention effectiveness

Overall in this field, the quality of trials is poor [small underpowered studies without allocation concealment, intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis or a priori sample size estimate]. 27,29 NICE guidelines12 and systematic review evidence27 highlight the fact that NHS resource availability is not based on robust health economic evaluations.

The fifth version of the Cochrane systematic review of support surfaces for PU prevention27 was published in 2015. The review included 59 RCTs, of which 11 compared the effectiveness of APMs with a range of low-technology (including high-specification foam, gel, silicone, water, static air) and high-technology constant low-pressure mattresses (low air loss). Most trials showed no evidence of a difference between treatment groups, although some were too small and underpowered to detect clinically important differences. Pooling of data in a meta-analysis of 10 trials of APMs versus various constant low-pressure mattresses showed no evidence of a difference in effectiveness for PU prevention.

Of the 11 RCTs, only one study compared APMs with a HSFM (viscoelastic)30 as part of a 2 × 2 factorial design incorporating two methods of risk assessment (Braden Scale31 score vs. observation of category 1) and two mattress/repositioning interventions (APM overlay vs. HSFM with turning every 4 hours). The study took place in a single centre and recruited patients from surgery, internal medicine and elderly care. Patients aged ≥ 18 years, with an expected length of stay of > 3 days were recruited and randomised to be ‘risk assessed’ using either the Braden Scale31 or observation of a category 1 skin area. Those identified as being at risk of developing a PU then had a second-level randomisation, with allocation to an APM or HSFM with turning every 4 hours. A total of 447 patients had the second-level randomisation and the incidence of PUs (of category ≥ 2) was 15.3% (34/222) in the APM arm and 15.6% (35/225) in the HSFM plus repositioning arm. Outcome data were recorded by ward staff. There were more heel ulcers reported in the HSFM arm, but more severe ulcers developed in the APM arm. An adjusted analysis incorporating risk assessment was not reported. Results are confounded by the inclusion in the HSFM arm of turning every 4 hours, and the potential for contamination between methods of risk assessment was not explored (including impact on outcome assessment, i.e. staff in the category 1 risk assessment arm were already alert to pressure damage); a major limitation is that outcome data were recorded by ward staff.

The review concluded that the relative merits of APMs and constant low-pressure mattresses are unclear. The review recommended the evaluation of APMs compared with constant low-pressure mattresses (such as HSFMs) because of their widespread use. 27 Similarly, NICE guidelines12 research recommendations acknowledge the limited evidence of effectiveness of pressure-redistributing devices and recommend further research. They particularly note the variation in cost of APMs compared with HSFMs.

The patient perspective

Although NICE guidelines12 are underpinned by the principle that all health-care professionals should deliver patient-centred care, it is exceptional to find a RCT with a patient-centred outcome such as acceptability, comfort or quality of life (QoL). Only four out of 59 RCTs included in the Cochrane review27 report patient comfort or acceptability of the mattress as an outcome and none report a patient’s QoL.

There is evidence from qualitative studies exploring the lived experience of patients with PUs23,32 and secondary end-point data in Pressure RElieving Support SUrfaces: a Randomised Evaluation (PRESSURE) 133 that some patients do not like APMs; a network meta-analysis34 reported that APMs had the lowest probability of being the most comfortable compared with other mattress types. Alternating pressure mattresses comprise large air-filled pockets that inflate and deflate in cycles. The alternating sensation is disliked by some patients and can cause feelings of nausea and affect sleep. In addition, on patient movement, the air-filled pockets are compressed and patients find it difficult to mobilise in bed and also report feeling unstable at the mattress edge, when they are getting in and out of bed, or feeling like they will be ‘rolled out of bed’, creating an unsafe feeling. 23,32,33 Other issues include noise from the pump, technical failure and attendant alarms. This was further supported by members of the Pressure Ulcer Research Service User Network (PURSUN),35 which supports research prioritisation and informs grant development, project delivery and data interpretation. Some members of the group feel strongly that APMs can be uncomfortable and debilitating, restrict movement and independence, exacerbate existing balance/mobility problems and leave patients in need of extra care (i.e. help in repositioning).

Practice guidelines

Previous NICE guidance26 stated that:

. . . decisions about which pressure-relieving device to use should be based on cost considerations and an overall assessment of the individual. Holistic assessment should include all of the following: identified levels of risk, skin assessment, comfort, general health state, lifestyle and abilities, critical care needs and acceptability of the proposed pressure-relieving equipment to the patient and/or carer.

It is not clear what ‘cost considerations’ means, but, in practice, decisions are generally made on unit costs and not cost-effectiveness, this being challenged following publication of PRESSURE 1,33 in which it was demonstrated that, despite no clinical difference between mattresses, there was a 64% probability that the more expensive APM replacement (unit cost ≈£4000) was more cost-effective than the cheaper APM overlay (unit cost ≈£1000).

The current NICE guideline12 for PU prevention utilised the evidence found in the 2011 version of the McInnes et al. 36 Cochrane review and recommended that a HSFM should be used for adults in secondary care settings or those who are assessed as being at a high risk of PUs in community and primary care environments. As this recommendation is based on trials deemed to be of low quality, NICE highlighted the following research priority:

Do pressure redistributing devices reduce the development of pressure ulcers for those who are at risk of developing a pressure ulcer?

The NICE guidelines section for PU treatment, however, do include the following caveat:

Use high-specification foam mattresses for adults with a pressure ulcer. If this is not sufficient to redistribute pressure, consider the use of a dynamic support surface.

The quality of evidence to inform this recommendation was considered to be low and none of the studies followed up patients for a sufficient time. There is no reference to the category of PU in the recommendation; however, the RCTs used to inform this included PUs of all categories.

NHS practice

Traditional hospital foam mattresses (with a marbled cover) have been superseded by HSFMs with both a ‘high-performance’ foam core and a cover designed to minimise ‘hammocking’ and build-up of moisture. There is good evidence of the benefit of HSFMs compared with traditional hospital mattresses in reducing the incidence of PUs in high-risk patient populations27 and HSFMs are in widespread use in the NHS, with many hospitals providing all patients with a HSFM as standard. Following NICE guidance,26 a HSFM is the recommended ‘minimum’ standard care for those assessed as being ‘vulnerable to PUs’.

Despite the lack of evidence of benefit, APMs are also in widespread use in the UK for at-risk patients. In two studies conducted as part of the Pressure UlceR Programme Of reSEarch (PURPOSE),37 their common use in the NHS was identified. First, the multicentre PU prevalence survey,6 involving nine hospitals across three NHS trusts and ≈3000 patients, found that ≈20% of mattresses in the adult care setting were APMs. Second, in a multicentre cohort study of 634 patients, involving high-risk patients with mobility/activity impairment and/or category 1 PUs,38 mattress allocation by ward staff to the study population was 48% HSFM and 52% APM, reflecting a lack of standardised practice.

History of this research

A Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme commissioning brief in 1998 included multicentre RCTs to compare the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of APMs with:

-

less costly alternating pressure overlays

-

low-technology constant low-pressure alternatives (such as different types of HSFM).

At that time, there was a reluctance by clinicians to randomise high-risk patients to HSFM, so the trial funded by the HTA programme, PRESSURE 1,33,37,39 dealt with only the first of the two research priorities and compared overlay and replacement APMs.

However, since then, many UK hospitals have replaced traditional hospital mattresses with HSFMs as standard for some or all clinical specialties. In addition, NICE guidance12 and the widespread use of profiling electric beds have increased clinical confidence in the use of HSFMs for high-risk patients. Furthermore, qualitative and quantitative evidence suggests that some patients do not like APMs,23,32,33 and results of the PRESSURE 1 trial33 showed a lack of difference in clinical outcomes between expensive alternating pressure replacement mattresses and cheaper alternating pressure overlay mattresses. These developments in the knowledge base and clinical experiences have challenged previously held views of clinical effectiveness based on non-randomised evaluations, which inferred the superiority of APMs and enabled trial design and delivery to address a key clinical question comparing high-technology APMs and low-technology HSFMs in the prevention of new PUs.

Summary

In the light of the priority being given to PU prevention, the high cost and lack of evidence relating to the effectiveness of mattresses in common use in the NHS, ad hoc practice in mattress allocation and the disadvantages and difficulties reported by patients in the use of APMs, we undertook a RCT to compare APMs with HSFMs in a high-risk inpatient population.

Chapter 2 Trial methods

Aims and objectives

The primary aim was to determine the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of APMs and HSFMs when used in conjunction with an electric profiling bed frame in secondary and community inpatients with evidence of acute illness, for the prevention of PUs of category ≥ 2.

Secondary aims were to assess the feasibility of using photography to quantify potential bias in the reporting of the PRESSURE 2 trial primary end point (see Chapter 5) and modify and evaluate the Pressure Ulcer Quality-of-Life (PU-QoL) instrument for use in patients at risk of PUs receiving preventative interventions (see Chapter 6).

Primary trial objective

The primary objective was to compare the time taken to develop a new PU of category ≥ 2 in participants using APM with the time taken to develop a new PU of category ≥ 2 in those using HSFM.

Secondary trial objectives (clinical)

-

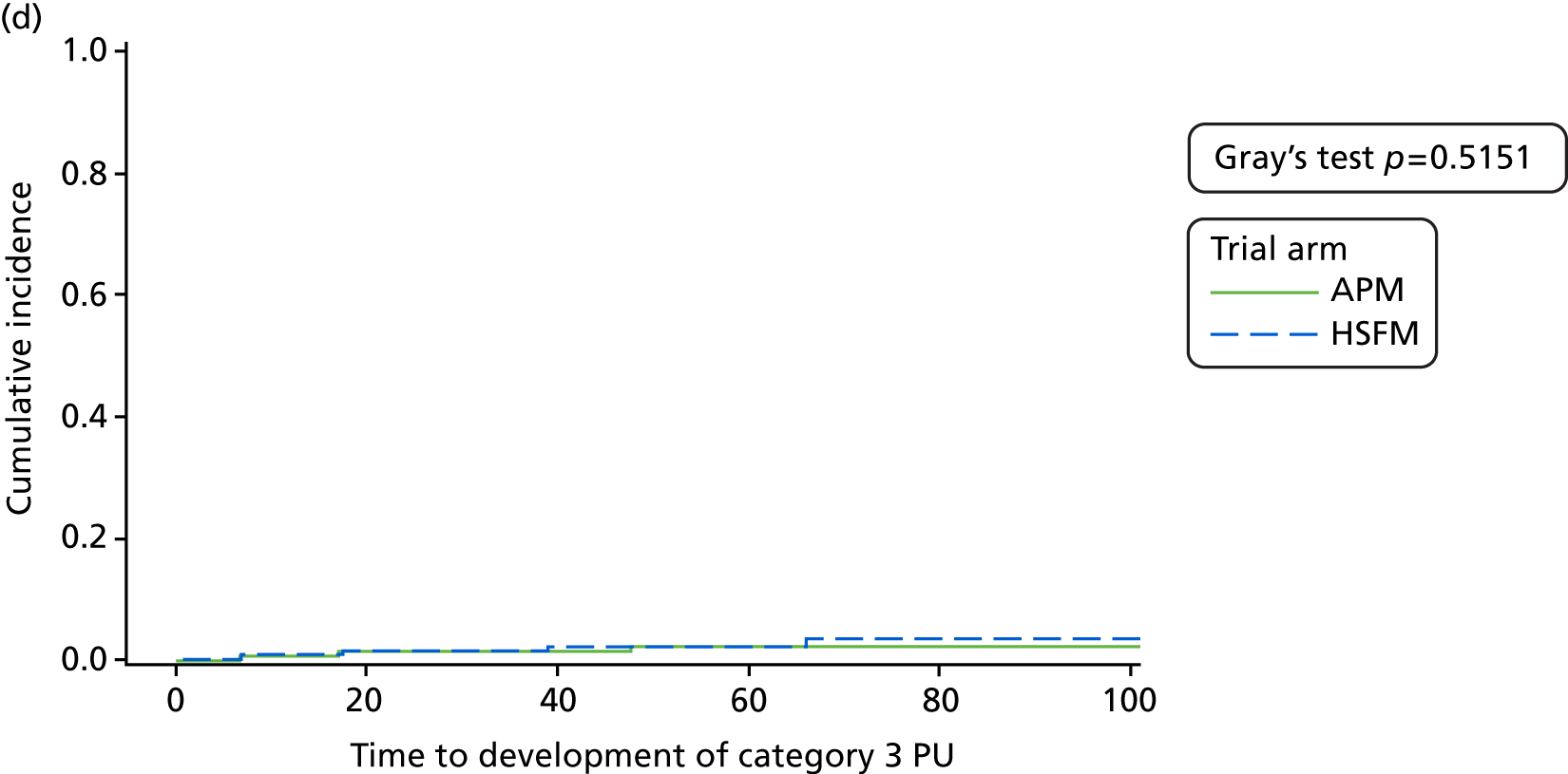

To compare the time taken to develop a new PU of category ≥ 3 between participants using APM and those using HSFM.

-

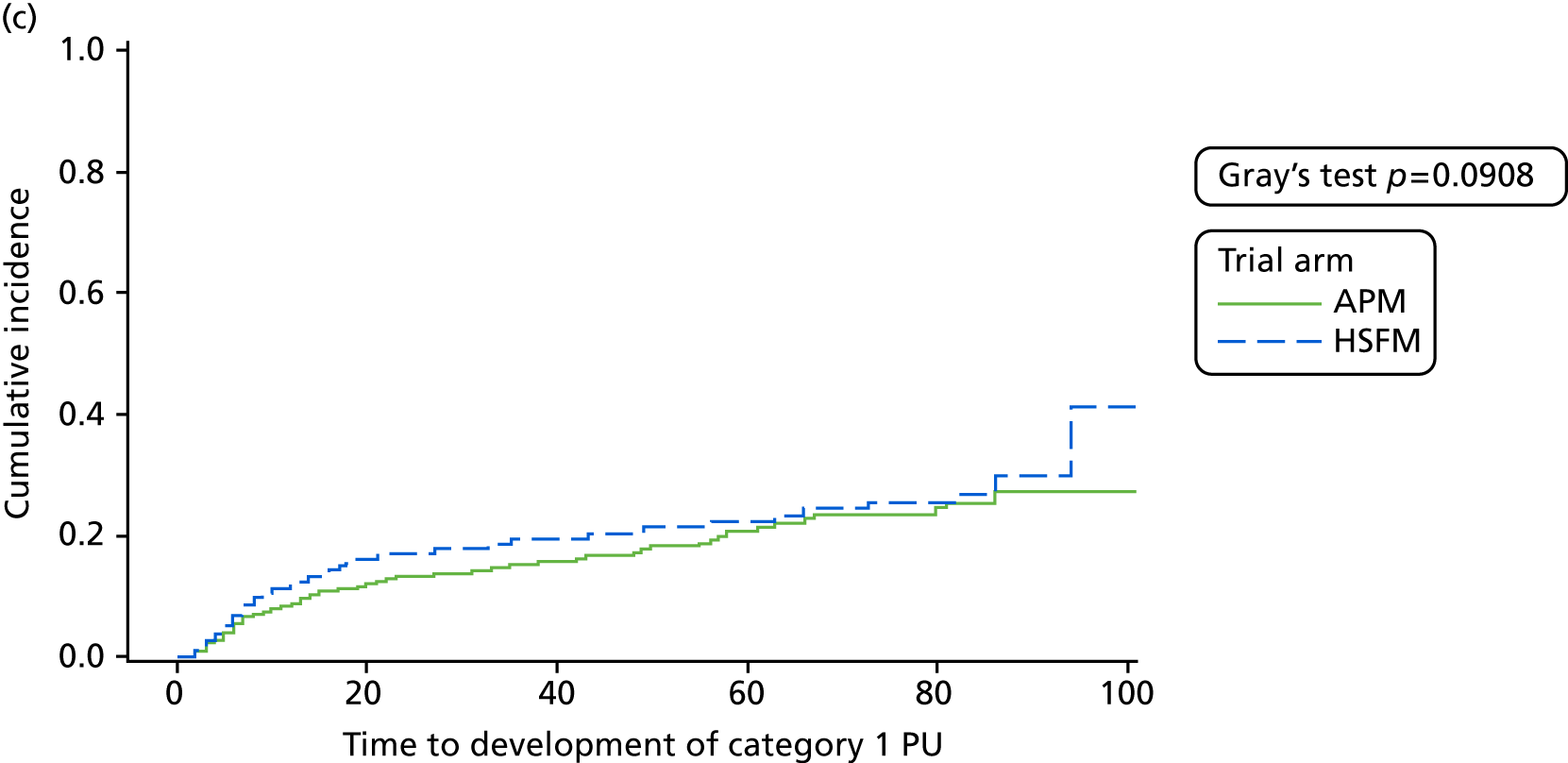

To compare the time taken to develop a new PU of category ≥ 1 between participants using APM and those using HSFM.

-

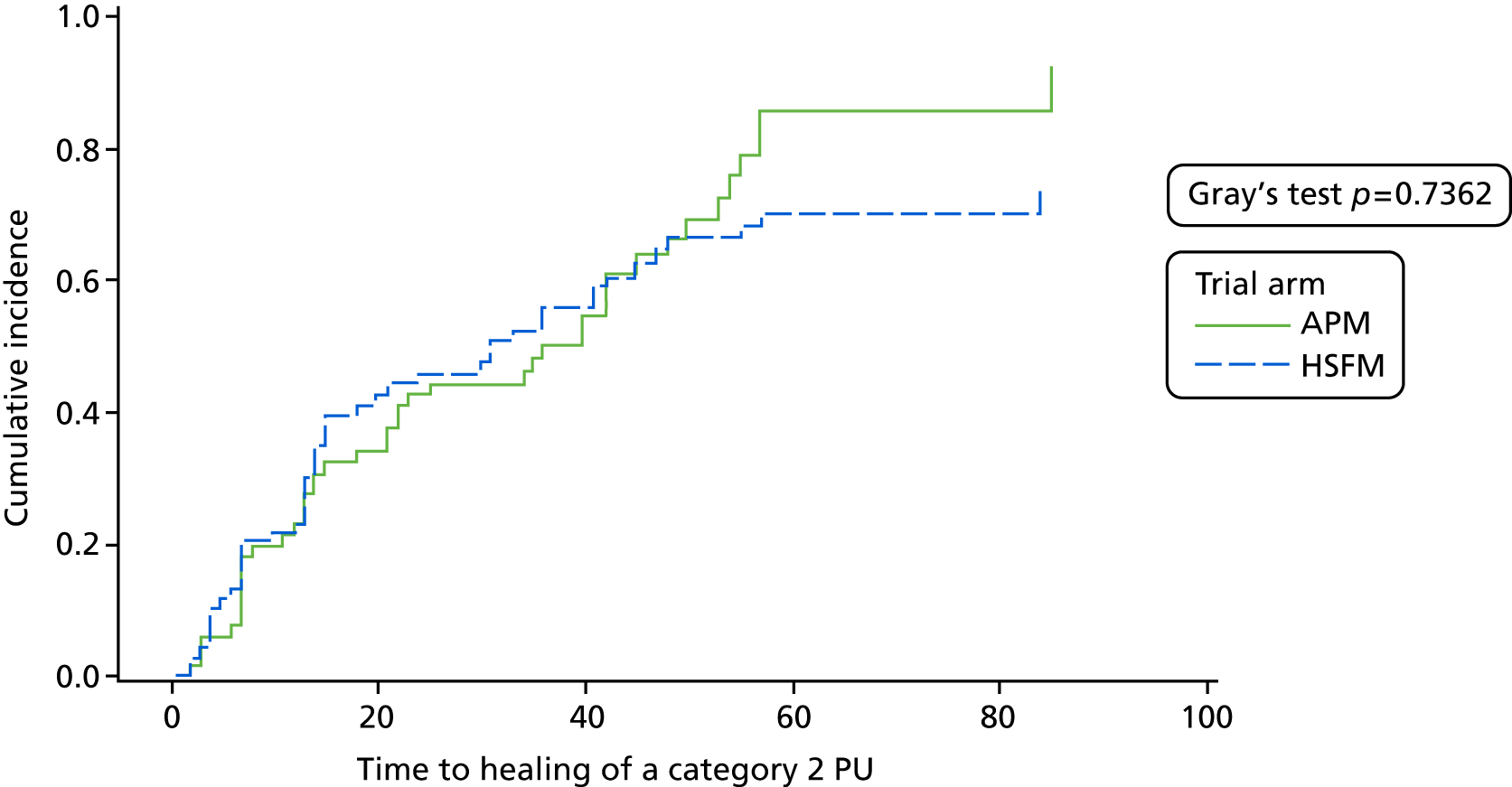

To compare the time to healing of all pre-existing category 2 PUs between participants using APM and those using HSFM.

-

To compare the incidence of mattress change between participants using APM and those using HSFM.

-

To compare safety between participants using APM and those using HSFM.

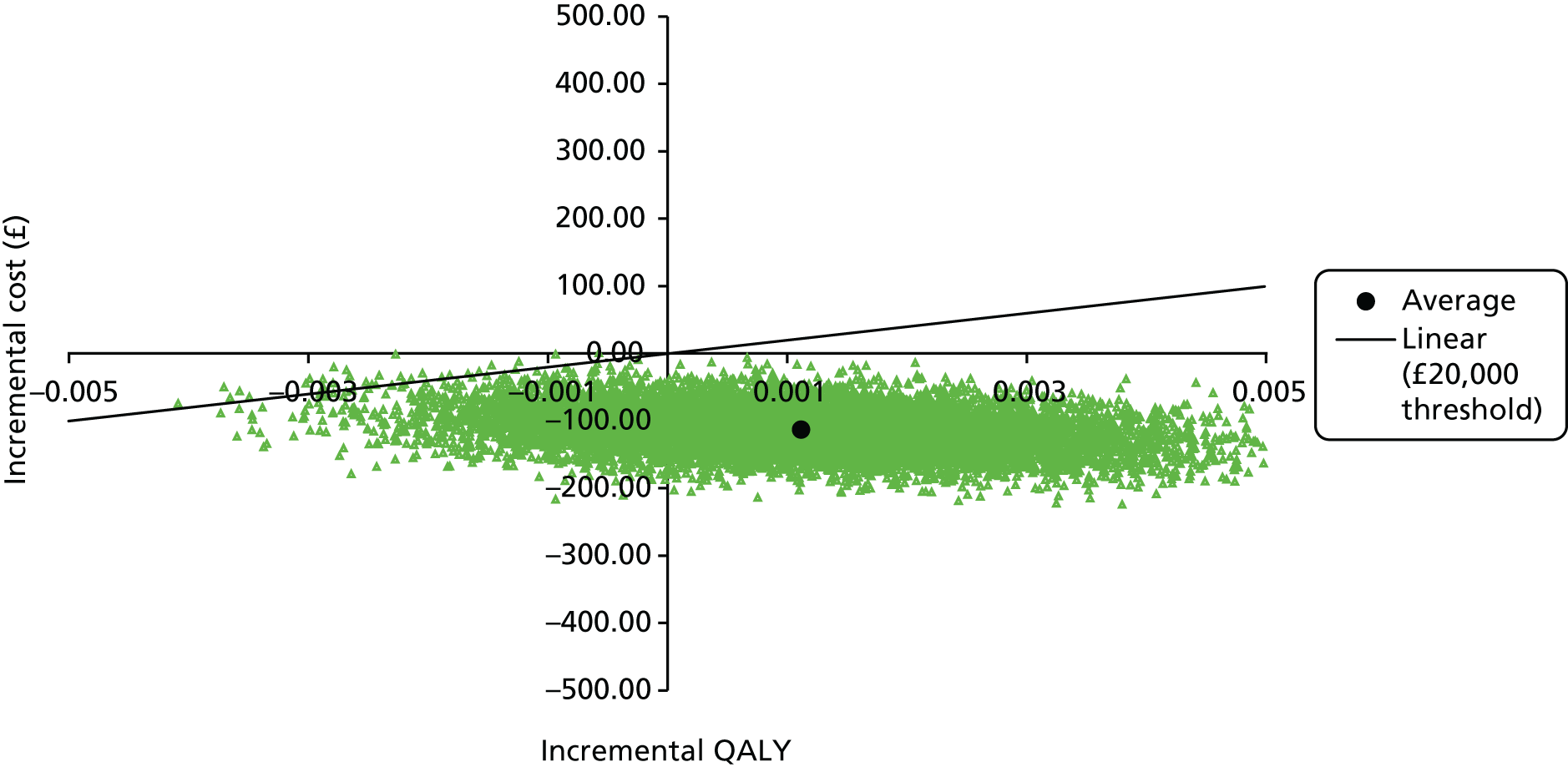

Secondary trial objectives (health economic)

-

To determine the impact of APM and HSFM on HRQoL.

-

To determine the incremental cost-effectiveness of APM compared with HSFM from the perspective of the health and social care sectors.

Photography substudy objectives

-

To assess over-reporting of category ≥ 2 PUs using photography.

-

To assess under-reporting of category ≥ 2 PUs using photography.

-

To assess consent rates for photography.

-

To assess compliance with photographs (i.e. whether or not the intended number of photographs were actually taken).

-

To assess compliance with secure transfer of photographs between the research centre and the Clinical Trials Research Unit (CTRU).

-

To assess the quality of photographs and confidence in photographic review.

Pressure Ulcer Quality of Life substudy objectives

-

To modify the PU-QoL instrument for use with patients at a high risk of PU development receiving preventative interventions – the Pressure Ulcer Quality of Life – Prevention (PU-QoL-P).

-

To undertake a comprehensive evaluation of the psychometric measurement properties of the PU-QoL-P instrument to ensure that it is acceptable, reliable, valid and responsive, and suitable for use in the UK health-care setting.

Overview of methods

This chapter outlines the main methods for the trial, including all data collection for the trial and substudy work and the analysis methods for the primary and secondary clinical results, which are detailed in Chapter 3. Analysis methods and results for the main trial health economics and QoL comparisons, the photography substudy and the PU-QoL substudy are detailed in Chapters 4, 5 and 6, respectively. The discussion in Chapter 7 draws the work together.

Trial design

The trial was a multicentre, Phase III, open, prospective, randomised, planned as a double-triangular sequential, parallel-group trial, with two planned interim analyses.

High-risk patients from secondary and community inpatient facilities with evidence of acute illness were randomised on a 1 : 1 basis to receive either APM or HSFM in conjunction with an electric profiling bed.

The intervention phase follow-up period was for a maximum of 60 days (referred to as the ‘treatment phase’) and there was a 30-day post-treatment phase follow-up (referred to as the ‘30-day final follow-up’).

The study protocol for this trial has already been published. 40 A study flow diagram/study summary can be found on page 6 of the trial protocol [see Methods on the project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/113633/#/ (accessed 20 November 2018)]. Summary details of the methods are given in the following sections.

Group sequential trial design

The group sequential design provides a formal framework and efficient design in which clinical trial data can be monitored as they accumulate, with preplanned interim analyses that can inform early stopping for superiority, inferiority or futility. PRESSURE 2 had two preplanned interim analyses and, at each interim analysis, the analysis of the primary end point (time to developing a PU of category ≥ 2) was to be conducted on both the ITT and the per-protocol populations (PPPs). The results were to be presented to the Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC), which would advise the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) if the balance of benefits and harms suggested that the trial should be stopped in accordance with planned stopping rules. 40

Ethics approval

Ethics approval for the study was given by Leeds West Research Ethics Committee [Research Ethics Committee (REC) reference number 13/YH/0066; Integrated Research Application System (IRAS) project identification: 122769]. All trial activity took place in accordance with the ethics-approved protocol, principles of Good Clinical Practice41 and the Declaration of Helsinki. 42

Eligibility and informed consent

Acute secondary and community NHS trust inpatient admissions were screened for eligibility by a clinical research nurse/registered health-care professional (CRN/P) in consultation with ward staff. Patients were eligible at any point during their inpatient stay (and irrespective of trust provider) if they fulfilled the following criteria:

-

Had evidence of acute illness through –

-

acute admission to secondary care hospital, community hospital or NHS-funded intermediate care/rehabilitation facility

-

inpatient secondary care, community hospital or NHS-funded intermediate care/rehabilitation facility with an onset of acute illness secondary to elective admission

-

recent secondary care hospital discharge to community hospital or NHS-funded intermediate care/rehabilitation facility.

-

-

Was aged ≥ 18 years.

-

Had an expected total length of stay of ≥ 5 days.

-

Was at a high risk of PU development as a result of one or more of the following:

-

Consented to participate [written, informed consent/witnessed verbal consent/consultee agreement or nearest relative/guardian/welfare attorney (in Scotland)].

-

Was expected to comply with the follow-up schedule.

-

Was on an electric profiling bed frame.

Patients were excluded if:

-

they had previously participated in the PRESSURE 2 trial

-

they had a current or previous PU of category ≥ 3

-

they had a planned admission to an intensive care unit where standard care was APM provision

-

they were unable to receive the intervention (e.g. slept at night in a chair or was unable to transfer to randomised mattress)

-

they weighed less or more than mattress weight limits (< 45 kg or > 180 kg)

-

it was ethically inappropriate to approach them.

A log was completed of all patients who were screened but not randomised, either because they were ineligible or because they declined participation. The following anonymised information was included:

-

age

-

gender

-

ethnicity

-

current mattress type

-

date screened

-

the reason why they were not eligible or declined participation

-

other reason for non-randomisation.

Potentially eligible patients were provided with a verbal explanation of the study and a patient information leaflet [see the project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/113633/#/ (accessed 20 November 2018)]. Assenting patients were formally assessed for eligibility and invited to provide informed consent. Witnessed consent process was used [see Witnessed Consent Form on the project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/113633/#/ (accessed 20 November 2018)] for those who gave consent but were physically unable to complete the written form.

A large proportion of patients suffering from or at risk of PUs have cognitive impairment affecting their understanding and/or dementia. Cognition affects compliance with repositioning and self-care. To ensure that the study population was representative of the normal NHS clinical population assessed in the course of usual care, recruitment procedures also facilitated consultee or nearest relative/guardian/welfare attorney (in Scotland) agreement [see Consultee Agreement Form on the project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/113633/#/ (accessed 20 November 2018)].

Interventions

Participants were randomised to either APM or HSFM products used by the participating centre for a maximum of 60 days. All patients were also allocated an electric profiling bed, as per standard care in the participating centres.

As this was a pragmatic trial, operational specifications for both APMs and HSFMs were defined in the PRESSURE 2 mattress specification guide (MSG) (see Appendix 1). Individual products allocated to trial participants were part of the usual-care mattress stock for each participating hospital, maximising generalisability of the trial findings.

The PRESSURE 2 MSG (see Appendix 1) provided details of foam density and cover details for HSFM and cell height (8.5 cm minimum, 29.4 cm maximum) and cycle time and frequency for APMs. Excluded mattresses, for example hybrid foam/air mattresses, were also specified. During feasibility assessment, mattresses in each centre were reviewed against the PRESSURE 2 MSG and only trusts with sufficient access to trial-eligible mattresses and electric profiling beds were able to take part in the trial. As new mattresses were marketed during the trial period, the PRESSURE 2 MSG was updated.

All mattresses had to comply with The Medical Devices Regulations 2002 SI (Système International d’Unités). 43 The allocated randomised mattress was expected to be provided to the trial patient within 24 hours of randomisation.

Randomisation

Participants were randomised once eligibility was confirmed and the baseline assessments and questionnaires were completed. Participants were randomised in a 1 : 1 allocation ratio, to receive either an APM or a HSFM in conjunction with an electric profiling bed. A computer-generated minimisation program, which incorporated a random element of 0.8, was used to ensure that intervention groups were well balanced for the following factors:

-

centre

-

PU status (no PU, category 1 or 2 PU)

-

secondary care hospital, community hospital/intermediate care or rehabilitation facility

-

consent [written, witnessed verbal, or consultee or nearest relative/guardian/welfare attorney (in Scotland) agreement].

The randomisation system included an automated internal check using a patient’s NHS number to confirm that the participant had not been recruited to the trial previously.

Blinding

It was not possible to blind participants, the clinical team or the CRN/P because of the nature of the mattresses (presence/sound of a pump on the APM and different appearance of bed and sheeting on each type of mattress).

A validation substudy, using photography with blinded central review, was therefore included to assess any bias in the reporting of PUs of category ≥ 2, details of which are given in Chapter 5.

Assessments and instruments

Skin assessments

Pressure ulcer status was assessed using the international PU classification11 including categories 1–4, unstageable and suspected deep tissue injury. This classification system was chosen as it was the most frequently used system in the NHS at the start of the trial period. Additional skin status descriptors were also assessed and recorded to characterise other alterations of intact skin and skin site exclusions from the end-point derivation (Box 1), meeting practical data collection requirements for the purpose of research.

Healthy intact skin. No skin changes.

Category AAlterations to intact skin specified with subcategory code:

-

001 = blanching redness which persists

-

002 = bruising – red hue

-

003 = bruising – purple hue

-

004 = scar

-

005 = oedema

-

006 = cellulitis

-

007 = lymphoedema

-

008 = discoloration – ischaemia

-

009 = discoloration – cyanosis

-

010 = dry/flaky

-

011 = papery thin

-

012 = cracks/calloused

-

013 = spongy

-

014 = macerated

-

015 = scratches

-

016 = rash

-

017 = scab

-

018 = induration

-

019 = heat

-

999 = none of the above, please describe.

Non-blanchable erythema of intact skin. Intact skin with non-blanchable erythema of a localised area usually over a bony prominence. Discolouration of the skin, warmth, oedema, hardness or pain may also be present. Darkly pigmented skin may not have visible blanching.

Category 2Partial-thickness skin loss or blister. Partial-thickness loss of dermis presenting as a shallow open ulcer with a red-pink wound bed, without slough. May also present as an intact or open/ruptured serum or serosanguinous-filled blister.

Category 3Full-thickness skin loss. Full-thickness tissue loss. Subcutaneous fat may be visible but bone, tendon or muscle are not exposed. Some slough may be present. May include undermining and tunnelling.

Category 4Full-thickness tissue loss. Full-thickness tissue loss with exposed bone, tendon or muscle. Slough or eschar may be present. Often includes undermining or tunnelling.

Category UUnstageable. Full-thickness skin loss in which actual depth of the ulcer is completely obscured by slough (yellow, tan, grey, green or brown) and/or eschar (tan, brown or black) in the wound bed.

Category N/ANot applicable. Specify with subcategory code:

-

001 = amputation

-

002 = bandage in situ

-

003 = cast in situ

-

004 = dressing in situ

-

005 = incontinence-associated dermatitis

-

006 = other chronic wound

-

007 = device-related ulcer

-

008 = surgical wound/bruising

-

009 = traumatic wound/bruising

-

010 = dermatological skin condition (e.g. eczema)

-

011 = unable to assess

-

999 = none of the above, please describe.

Adapted from Nixon et al. 44 © The Authors, 2019. This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

In addition, photography of all category 2 PUs at first observation was undertaken (subject to consent). At each visit, all major anatomical skin areas at risk of PU development (sacrum, spine and right and left buttocks, ischial tuberosities, hips, heels, ankles and elbows) were assessed.

Risk factors (moderators)

Risk factors were recorded based on the pressure ulcer – minimum data set (PU-MDS)45 derived from a systematic review of the risk-factor literature,18 which was developed using consensus methods. The PU-MDS included descriptors for the key risk factors, namely skin status, mobility status, sensory perception, diabetes, conditions affecting macro- and microcirculatory function, nutrition and skin moisture. Data on skin status, supplementary to the minimum data set, was also recorded (see next section).

In addition, in previous exploratory work, we identified that pain was associated with the development of new PUs of category ≥ 238 and was assessed as a covariate to further explore the prognostic value of pain. Using our established method, the presence of localised skin pain on any pressure area skin site was confirmed if participants responded ‘yes’ to both the following questions:

-

At any time, do you get pain, soreness or discomfort on a pressure area? Prompt – back, bottom, hips, elbows, heels or other sites as applicable?

-

Do you think this is related to your pressure sore/lying in bed for a long time/sitting for a long time (as appropriate)?

Pressure ulcer prevention interventions (mediators) and compliance

In order to monitor selection bias at baseline and mattress compliance at follow-up, mattress type was recorded, including APM or other high-technology mattress and HSFM or other low-technology mattress (see Table 1). In addition, to characterise standard care as provided at the discretion of the attending clinical team and potential mediators, recorded PU prevention interventions included frequency of repositioning in the previous 24 hours, chair type and cushion type (when appropriate), adjuvant dressings for prevention and adjuvant prevention devices, such as heel off-loading devices, including pillows.

Quality-of-life and health resource utilisation data

The following QoL instruments were administered.

Generic quality-of-life instruments

EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version

The EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L), is a QoL measure consisting of five domains: (1) mobility, (2) self-care, (3) usual activities, (4) pain/discomfort and (5) anxiety/depression. Each of these domains has five levels: (1) no problems, (2) slight problems, (3) moderate problems, (4) severe problems and (5) extreme problems. 46

Short Form questionnaire-12 items acute

The Short Form questionnaire-12 items (SF-12) instrument was used to assess HRQoL, on the basis of evidence from a systematic review of QoL measures for chronic wounds (including PUs)47 and practical issues relating to the patient population.

Use of the Short Form questionnaire-36 items (SF-36) was considered for inclusion; however, it was decided by the project team that it was too long for use with patients with PUs (e.g. these patients are largely elderly, are highly dependent and/or have high levels of comorbidity including acute and chronic illness). Instead, the SF-12, a short version of the SF-36, was selected to reduce respondent burden. The SF-12 is a generic instrument that assesses eight QoL domains: (1) physical functioning, (2) role-physical, (3) body pain, (4) general health, (5) energy/fatigue, (6) social functioning, (7) role-emotional and (8) mental health. A physical component summary score and a mental component summary score are generated. An acute version of the SF-12 is available that incorporates a 1-week recall period, which for this condition has been found to be relevant. 48 It takes 2 minutes to administer and has been validated for researcher administration. Even though the SF-12 has not specifically been validated for use with people with PUs, it is widely used in other chronic wounds and dermatological conditions to assess changes in QoL between groups, has been used with other chronic skin wound conditions to validate their corresponding disease-specific QoL instruments and has been validated for use with elderly people. The acute SF-12 was chosen as the best available QoL instrument for the primary trial analysis at this stage.

Condition-specific instruments

Pressure Ulcer Quality of Life – Prevention

During the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) PURPOSE,37 PU-QoL, a condition-specific outcome measure, was developed for people with PUs;48 however, there is a need for a similar measure for patients at risk of PU (prevention). The PU-QoL-P was therefore developed and validated during this study. Further details can be found in Chapter 6.

Pressure Ulcer Quality of Life – Utility Index

The Pressure Ulcer Quality of Life – Utility Index (PU-QoL-UI) is a condition-specific utility measure derived from the PU-QoL instrument. 37,49 It is a researcher-administered, participant-completed questionnaire. If enrolment into the study was through consultee agreement or nearest relative/guardian/welfare attorney (in Scotland), a proxy PU-QoL-UI could be completed by the CRN/P, ideally with a carer, on behalf of the participant.

Health-care resource use

Health-care resource utilisation (e.g. diagnostic tests and medical assessments) was abstracted from health-care records (inpatient and outpatient) and a short researcher-administered questionnaire (regarding the use of community health and social care) was completed with participants.

Safety monitoring

The trial population were known to have high levels of comorbidity and mortality. Therefore, it was decided to report only events that were considered ‘related’ to the intervention.

The following adverse events (AEs) and serious adverse events (SAEs) were expected within the patient study population and were reported during the treatment and follow-up phase:

-

death (SAE)

-

hospital re-admission (SAE)

-

institutionalisation (AE)

-

device ulcers that may be considered to be related to the mattress (AE/SAE), such as plaster cast ulcers

-

falls (AE/SAE).

As these events were expected within the study population, they were subject to expedited reporting to the main REC. Further definitions of AEs and SAEs are provided in the protocol. 40

Data collection schedule

All baseline and outcome assessments were undertaken by trained CRN/Ps. Treatment phase follow-up assessments were undertaken from randomisation to the end of the treatment phase (a maximum of 60 days). A final 30-day final follow-up visit was undertaken.

Baseline

The following baseline demographic information was collected: NHS number, date of birth, gender, date of admission, type of admission, category of medical condition (e.g. medical, surgical), ethnicity, confirmation general practitioner (GP) letter sent and confirmation consultant letter sent.

The following clinical assessment information was collected: pre-randomisation mattress, skin assessment, PU category 2 photography (when present), assessment of pain on pressure area skin site, risk factors (mobility status, sensory perception, diabetes, conditions affecting macro- and microcirculatory function, nutrition, skin moisture, friction and shear), height and weight (self-reported or from records), PU prevention mattress and other interventions (mediators), and duration and size of ulcer for participants with a pre-existing category 2 PU.

The following participant questionnaires were administered: health-care resource utilisation and, at the start of the study, EQ-5D-5L, PU-QoL-UI, SF-12 and PU-QoL-P (or a proxy questionnaire pack when necessary).

The following personal data were collected (these were retained in the site file and not returned to the CTRU): name, hospital number, ward location, address and telephone number, GP name and address, and name of the hospital consultant responsible for the care of the patient.

The following randomisation information was collected: mattress allocation and date of mattress provision.

Treatment phase (maximum 60 days)

Mattress compliance and technical faults were recorded for each day (based on retrospective information from staff and participants).

A clinical assessment was conducted twice weekly to day 30, then once weekly to day 60. The clinical assessment involved skin assessment (including pain and photography of PUs of category ≥ 2 when present), PU prevention interventions (mediators), expected AEs and SAEs, unexpected and related SAEs and/or confirmation of the end of the treatment phase (patient discharged or 60 days of treatment or no longer at risk).

Participant questionnaires

The frequency of completion of the full questionnaire pack was reported by the CRN/Ps as a burden for many participants and the schedule was amended during the course of the trial. Initially, the health-care resource utilisation questionnaire, EQ-5D-5L, PU-QoL-UI, SF-12 and PU-QoL-P (or proxy questionnaire pack when necessary) were completed weekly to day 30, then fortnightly to day 60. Between April 2014 and October 2015, a revised schedule was implemented with a randomised allocation to a set of questionnaires (EQ-5D-5L/PU-QoL-UI or the SF-12/PU-QoL-P) at weeks 1 (visit 2) and 3 (visit 6) only. From November 2015 to November 2016, the PU-QoL-P questionnaire was omitted because sufficient data had been collected for conducting the analysis, and the remaining questionnaires (EQ-5D-5L, PU-QoL-UI and SF-12 or proxy questionnaire pack) were reinstated for all participants at weeks 1 and 3.

Thirty-day final follow-up

Following confirmation of the end the treatment phase (maximum 60 days), a final 30-day follow-up visit was scheduled. This was undertaken at the patient’s place of residence (i.e. hospital if an inpatient or home if discharged).

A clinical assessment that comprised skin assessment (including photography if required) was undertaken.

The following participant questionnaires were administered: health-care resource utilisation, EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D-5L), PU-QoL-UI, SF-12 and PU-QoL-P (or proxy questionnaire pack when necessary).

Trial completion

Trial completion was defined as the end of the 30-day final follow-up (i.e. 30 days after the end-of-treatment phase), withdrawal or death.

The treatment phase was defined as the time from randomisation to (whichever happened soonest):

-

discharge from an eligible inpatient facility

-

60 days from randomisation

-

no longer at a high risk.

No longer at a high risk was defined as no PU of category ≥ 1 on any skin site AND no localised skin pain on any pressure area skin site AND improved mobility and activity (Braden Scale31 activity score of 3 or 4 AND mobility score of 3 or 4). 50

End points

Primary end point

The primary end point was time to developing a new PU of category ≥ 2 from randomisation, during the (maximum) 60-day treatment phase to the 30-day final follow-up (a maximum of 90 days). The timing of the primary end point was chosen to align with requirements for the health economics analysis. Given that a PU can take between 4 and 22 weeks to completely heal depending on the category,2 and that randomised patients are discharged with an unresolved PU, the 30-day post-treatment phase follow-up assessment was included in the trial to retrieve information on treatment and utility regarding the potential long-term effect of the intervention.

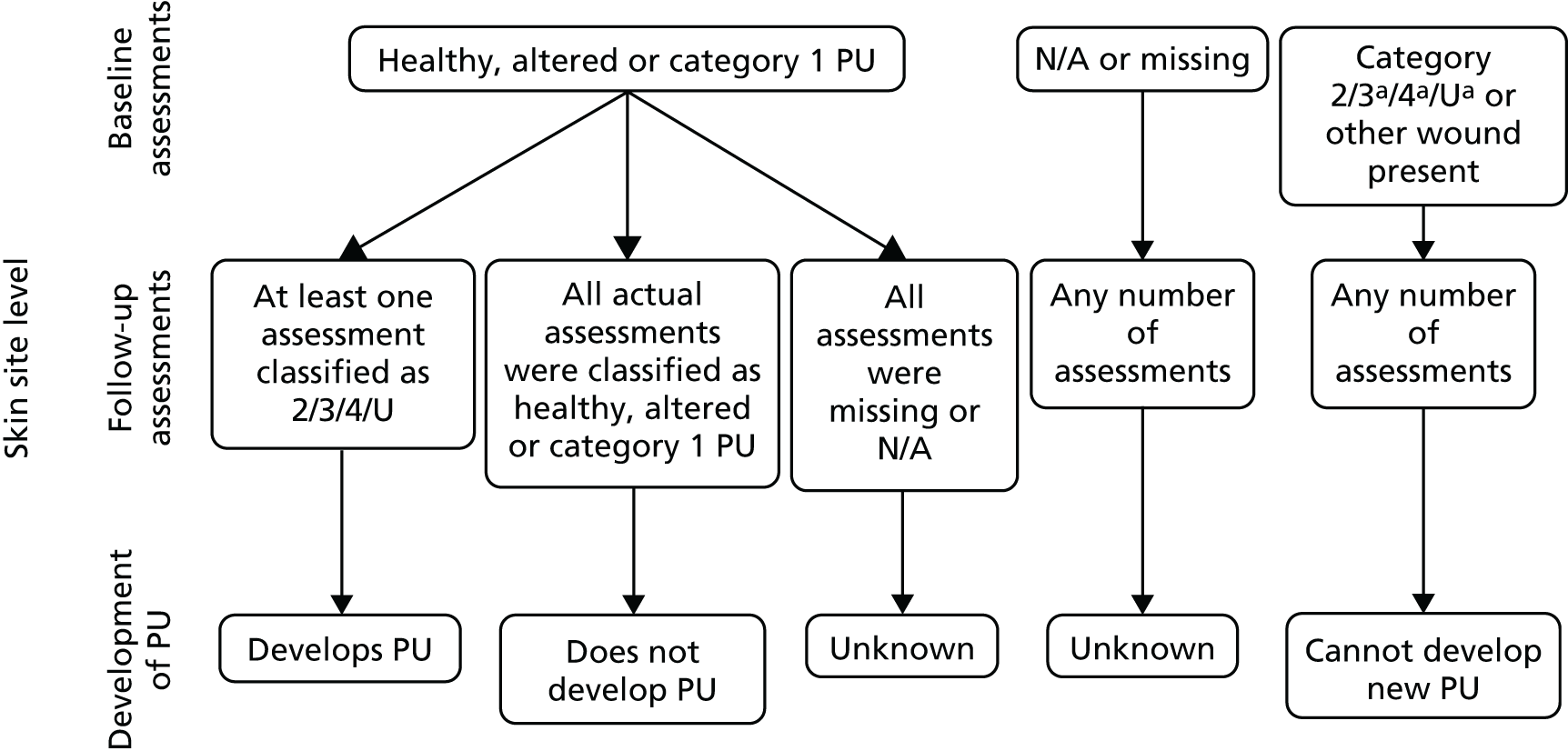

Whether or not a participant developed a new PU of category ≥ 2 was first derived on a skin site basis [see Appendix 2; see also Methods on the project web page for the statistical analysis plan (SAP) (specifically, table 2 in appendix C, and figure 2): www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/113633/#/ (accessed 20 November 2018)]. These data were then used to derive whether or not each participant developed a new PU of category ≥ 2 at any skin site and the time to development of the first new PU, competing event or censoring time [see the project web page for the SAP, section 2.3.2 time to development and censor variables: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/113633/#/ (accessed 20 November 2018)].

For participants who developed a new PU of category ≥ 2, the time to development was calculated as the duration between the date of randomisation and the date that the first new PU of category ≥ 2 was observed. Participants were categorised as a competing risk at the date they stopped the trial if they withdrew from the trial due to clinical condition or loss of capacity, or because the assessment schedule was too burdensome, or if they died; or else participants were censored at the date of their last evaluable skin assessment. Further details of the derivation of the end point and a summary of the derivation of the primary end point is provided in Appendix 2 [see also Methods on the project web page for the SAP (specifically, table 2 in appendix C and figure 2): www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/113633/#/ (accessed 20 November 2018)].

Secondary end points

-

Time to developing a new PU of category ≥ 3.

The time to development of a PU of category ≥ 3 is derived in line with the derivation of the primary end point but adjusted for the development of a more severe PU (i.e. category 3) rather than a category 2.

-

Time to developing a new PU of category ≥ 1.

The time to development of a new PU of category ≥ 1 is derived in line with the derivation of the primary end point but adjusted for the development of a less severe PU (i.e. category 1) rather than a category 2.

-

Time to healing of all pre-existing category 2 PUs.

A category 2 PU was classified as healed if the same skin site was later recorded as healthy or altered skin. Time to healing was derived as the number of days between the date of randomisation and the date all pre-existing category 2 PUs were observed to heal. Participants were categorised as a competing risk at the date they stopped the trial if they withdrew from the trial due to clinical condition or loss of capacity or because the assessment schedule was too burdensome, or they died; or else participants were censored at the date of their last evaluable skin assessment.

Trial organisational structure

The trial sponsor was the University of Leeds and responsibilities were delegated to the CTRU, as detailed in the trial contract.

Trial oversight and management was conducted by the Trial Management Group (TMG), the TSC and the DMEC. All groups met regularly throughout the trial.

Centre-level case report form (CRF) returns, data quality, screening logs, recruitment, patient disposition, protocol deviations and safety were monitored by the CTRU, TMG, TSC and DMEC. In addition, overall mattress compliance was monitored by the TSC and DMEC (with no cause for concern to prompt investigation at a centre level). Compliance with the photography and skin verification substudies and the overall event rate were monitored by the DMEC.

Public involvement methods

The CTRU hosts a network of service users, PURSUN, with personal experience of PUs and/or PU risk. The group consists of patients, carers and family members. PURSUN works to improve public involvement in PU research and raise awareness of the topic. It has an established relationship with the study team and has supported this study from conception. Public involvement activities have included the following:

-

Study design. Meetings were held with PURSUN at both the grant application and the protocol development stages. In particular, PURSUN made an important contribution to the development of the eligibility criteria (at its request, patients with existing PUs of category ≥ 3 were excluded from participation in the trial) and to the consent process for the photography substudy (as PUs commonly develop on sensitive areas of the body, such as buttocks, PURSUN advised whether or not and how the consent process should be conducted).

-

Developing participant materials.

-

Project oversight. A service user co-applicant (KW) was invited to all TMG meetings and two PURSUN members joined the TSC. Update meetings were also held with the wider network throughout the study.

-

Results interpretation. One results interpretation workshop has already been held with a small number of PURSUN members. A larger one is planned for 2019. The aim of the workshops is to discuss what the results mean for service users, and to plan a collaborative approach to dissemination and implementation.

Supporting public involvement

The Pressure Ulcer Research Service User Network is supported by a patient and public involvement (PPI) officer, who acted as the main point of contact for all service users involved in the study. Additional support and facilitation were provided by the chief investigator and trial co-ordinator. PURSUN has an established induction process whereby new members meet with the PPI officer to discuss their specific support and training needs. This same flexible approach was adopted during PRESSURE 2. Support was tailored to the needs of the individuals involved and their role in the project.

All service users involved in the study were invited to attend CTRU’s ‘Introduction to Clinical Trials’ training, a 1-day workshop open to academics, health professionals and public contributors. This training was not mandatory, but was seen as an optional development opportunity. All PURSUN members were reimbursed for their time and expenses in line with PURSUN policy and public involvement good practice guidelines. 51

Public involvement evaluation

An iterative approach to evaluation was adopted to ensure that issues could be identified and dealt with throughout the study. The service user co-applicant and TSC members were offered regular debrief meetings with the PPI officer. These meetings had the dual purpose of providing support and aiding evaluation.

Involvement activities and impact were documented via a public involvement log. The log is a shared document that can be accessed by both the PPI officer and the service user co-applicant. The log contains a series of prompt questions that encourage both documentation and reflection. The co-applicant was encouraged to document any challenges and areas in which she felt that she (or other public contributors) had made a positive impact on the study. She was also asked to think about the impact (positive or negative) that being involved in the study had on her personally.

Statistical methods

Original sample size

A maximum of 588 events (i.e. participants developing a new PU of category ≥ 2), corresponding to 2954 participants, was required for the study to have 90% power for detecting an absolute difference of 5% in the incidence of PU of category ≥ 2 between APM and HSFM, assuming an incidence rate of 18% on APM52 and 23% on HSFM [corresponding to a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.759] and a two-sided significance level of 5% and accounting for 6% loss to follow-up. 52

An incidence rate of 18% for PUs of category ≥ 2 for APMs was estimated on the ITT population for PRESSURE 1,33 the PURPOSE pain cohort study33,38 and the trial reported by Vanderwee et al. ;30 hence, the sample size estimate incorporates the effect of non-compliance. The sample size accounts for multiplicity in the interim analyses using Lan–DeMets α and β spending functions. 53

Pressure ulcer incidence rates could not be estimated accurately for the HSFM group; therefore, the maximum sample size estimate was based on the detection of the smallest relevant difference of 5% (clinical opinion). If the difference was > 5%, then the trial would have sufficient power to stop early having demonstrated superiority (or inferiority) of the APM. If the difference was < 5%, then the trial was likely to stop early for futility.

Original planned recruitment rate

It was planned to involve 10 large and 10 medium NHS trusts (comprising approximately 30 hospital sites). It was estimated that 15,000 patients would need to be screened, of whom ≈40% (6000) would be eligible and ≈50% (3000) of those eligible would consent. Accrual estimates were seven participants per month in three large trusts for 33 months, six participants per month in seven large trusts for 30 months and 3.5 participants per month in 10 medium trusts for 30 months, enabling recruitment of 3003 participants.

Revised sample size and expected accrual

The trial recruited participants at a much slower rate than originally anticipated. A recovery plan and unplanned value of information (VOI) analysis, based on the original trial assumptions, was requested by the funder; this was submitted to the funder in October 2014 and reviewed by the DMEC, which recommended trial continuation.

An unplanned interim analysis and second VOI analysis using confidential data from the trial (see Appendix 3) were requested by the funder and conducted in November/December 2015. A primary end point analysis was conducted on 909 participants. Owing to violation of the proportional hazards assumption, a piecewise Cox model was fitted to the primary end point, splitting the data into two time intervals; a sensitivity analysis was also conducted on the treatment phase (see Appendix 3). The analysis was conducted by the trial statistician, supervising statistician and health economist, and the results of these unblinded analyses were reviewed by the DMEC and remained confidential to these personnel. The hazard ratio (HR) for the treatment phase sensitivity analysis was presented to the DMEC in line with the stopping boundaries calculated for the original trial design. However, as this was an early unplanned analysis, a very low significance value was selected to minimise the impact on the overall significance level of 0.05;54 therefore, no adjustment to the p-value or width of the confidence intervals (CIs) was made at the final analysis. Following the interim analysis, the DMEC asked the team to explore alternative approaches to the piecewise Cox model in order to maximise power in the final analysis. The revised analysis plan [see the project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/113633/#/ (accessed 20 November 2018)] detailed the planned approach to include scenarios when the assumption of proportional hazards and/or independent censoring do not hold.

Following discussion between the DMEC and TSC in January 2016, the independent TSC members were informed of the overall event rate, which was much lower, at 9.9%, than the event rate of 20.5% utilised to estimate the sample size. The DMEC and TSC then asked the TMG, who were blinded to the overall event rate, to consider the minimum clinically relevant differences on varying centred event rates including 15%, 10% and 5% to help inform the DMEC and TSC’s recommendations to the funder on the continuation of the trial. A relative difference of 25% centred on an overall event rate of 15%, corresponding to an absolute difference of 3.75%, was considered to be clinically meaningful and the preferred minimum clinically relevant difference. For an overall event rate of 10%, a relative difference of 33.3%, corresponding to an absolute difference of 3.3%, was considered to be clinically meaningful and the preferred minimum clinically relevant difference. In the third scenario, a relative difference of 50.0% centred on an overall event rate of 5%, corresponding to an absolute difference of 2.5%, was considered to be clinically meaningful and the preferred minimum clinically relevant difference. In all of these cases, a costed extension would have been required to power the study based on these differences. The TMG also noted that relative differences of 33.3%, 40% and 60% centred on event rates of 15%, 10% and 5%, corresponding to absolute differences of 5%, 4% and 3%, respectively, were considered important to detect. In addition, having sufficient precision in the estimate of the treatment effect to conclude futility was also considered important by the TMG.

Following discussion of the minimum clinically relevant differences with the TMG, DMEC and TSC supported a 6-month recruitment extension (requiring no additional HTA funding) request, which was submitted in June 2016, to continue recruitment until the end of November 2016, by which time approximately 1996 participants were expected to be recruited, allowing a difference of 4% to be detected with at least 80% power, assuming an overall event rate of 10%.

A request for additional funding to continue recruitment for 14 months beyond the original planned recruitment end date to achieve a sample size of 2728 participants to detect the minimum clinically relevant difference between mattresses of 3.3% with 80% power, together with a clinically meaningful improvement in precision of a further 3% under the assumption of no difference, was also supported by the TSC and DMEC.

The funder did not support additional funding to achieve the higher sample size, but did approve the 6-month extension request and accruals were maximised by continued recruitment until the end of the extension period, which was 30 November 2016.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using SAS® software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

A SAP was approved prior to the relevant analysis being conducted [see Methods on the project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/113633/#/ (accessed 20 November 2018)].

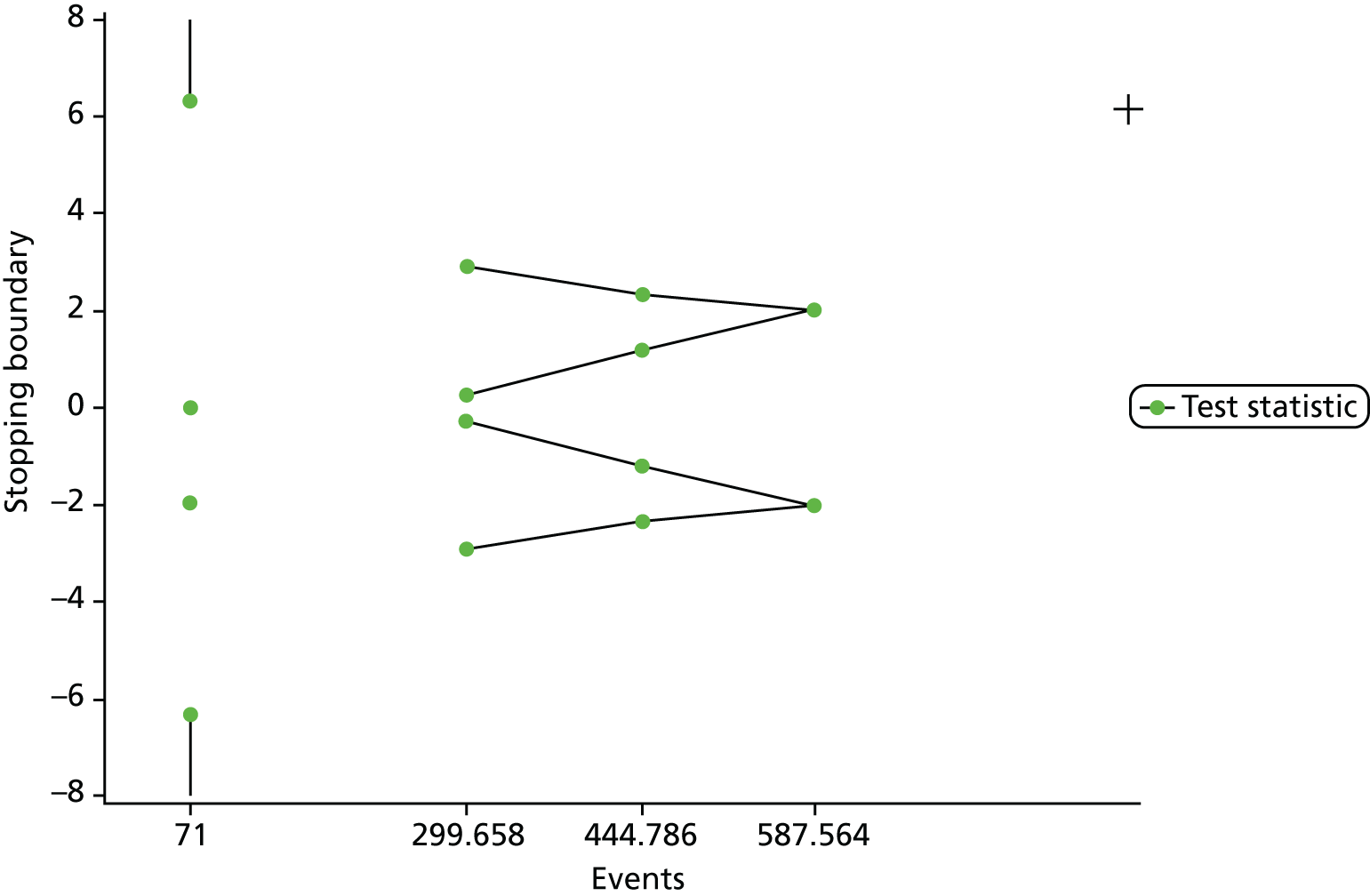

Reflecting the double-triangular sequential design, a maximum of three analyses were originally planned with unequally spaced reviews at event-driven coherent cut-off points, as specified below.

Interim analysis 1 was to be conducted after 300 events, corresponding to the earliest time point for stopping the trial by demonstrating overwhelming evidence of efficacy or futility. This would have also corresponded to the minimum number of events required for conducting the economic evaluation. The futility boundaries were constructed as non-binding in order for the DMEC to over-rule a decision of stopping early for futility in the event that a futility boundary is crossed.

Interim analysis 2 was to be conducted after 445 events, corresponding to the number of expected events required for trial termination under futility (with 434 corresponding to the number of events required for demonstrating superiority or inferiority of APM to HSFM).

The final analysis was to be conducted after 588 events had occurred.

In addition, in the event of an early stopping signal for futility, an assessment of the value of continuing with the trial from the NHS decision-making perspective, via an expected value of sample information (EVSI) analysis, was also planned, to inform the deliberations of the DMEC.

Following the unplanned interim analysis and the extension to recruitment, only the final analysis was conducted.

Patient populations

All participants recruited to the trial were included in the analysis using ITT and analysed in accordance with the randomised allocation and actual stratification factors.

A PPP analysis was also undertaken by allocated mattress; all major protocol violators and participants who did not receive their randomised mattress within 2 days of randomisation or who spent < 60% of their follow-up time on their randomised mattress were excluded (see Methods on the project web page for further details of exclusions: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/113633/#/ (accessed 20 November 2018)].

The safety population included all participants who were recruited to the trial.

The population used to calculate the time to healing of category 2 PUs included all participants with at least one pre-existing category 2 PU at the baseline assessment.

Missing data

Missing categorical data at baseline were included in the analysis models as a specific category. Any missing dates in the end-point derivation were imputed based on visit dates before and after, and in accordance with the visit schedule.

Final analysis

Primary end point

The primary end-point analysis was the time taken to develop a new PU of category ≥ 2 from randomisation to 30-day final follow-up.

A Fine and Gray55 model was fitted to the primary end point, with adjustment for the following minimisation factors: health-care setting, PU status, consent and covariates (i.e. presence of pain on a healthy, altered or category 1 PU skin site and the presence of conditions affecting peripheral circulation). A likelihood ratio test was used to assess the effect of adding mattress group to this model. The HR was calculated for the mattress group effect, and is presented with the corresponding CIs and p-value in Chapter 3. The cumulative incidence of developing a PU of category ≥ 2 by 30-day final follow-up in each group is also presented.

The median time to event is presented for those participants developing a PU of category ≥ 2 by mattress group and overall.

The Fine and Gray55 model was used rather than the Cox proportional hazards model in order to account for competing risks. That is, participants who do not develop a PU of category ≥ 2 during the treatment phase or by 30-day final follow-up were categorised as a competing risk at the date they stopped the trial if they withdrew from the trial due to poorly clinical condition or loss of capacity, or because the assessment schedule was too burdensome. Death was also considered a competing risk at the date of death. Other participants who did not develop a PU of category ≥ 2 during the treatment phase or by 30-day final follow-up were censored at the date of their last evaluable skin assessment. Centre was intended to be fitted as a random effect; however, this was not possible with the Fine and Gray55 model in SAS version 9.4.

Sensitivity analysis

A sensitivity analysis was conducted for the time taken to develop a PU of category ≥ 2 during the treatment phase.

This sensitivity analysis for the end point of time to developing a PU of category ≥ 2 during the treatment phase was specified in version 1.0 of the SAP finalised prior to the unplanned interim analysis being conducted. The end point of time to developing a PU of category ≥ 2 during the treatment phase was analysed using the Fine and Gray55 model, in line with the primary analysis.

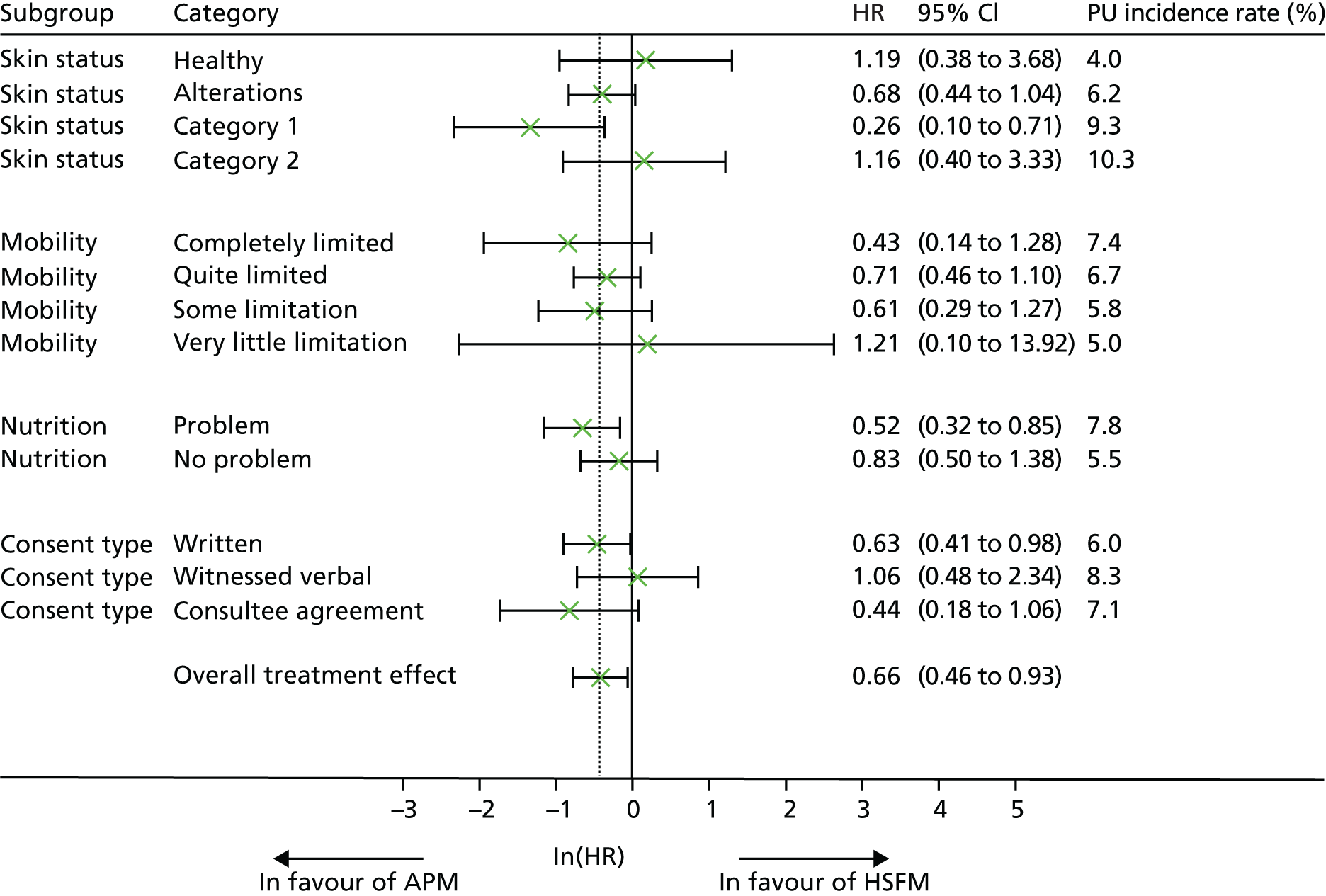

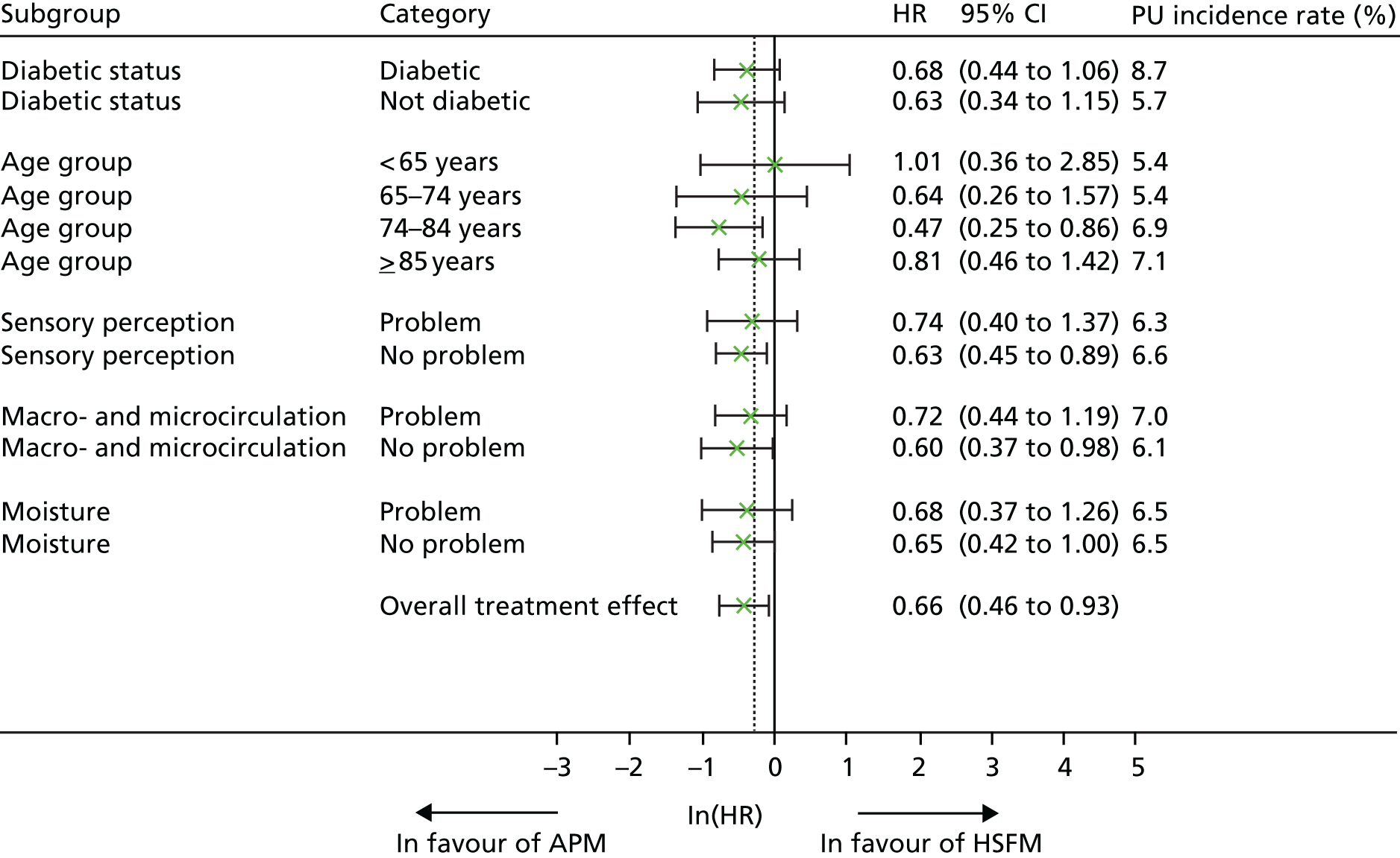

Moderator analysis

Potential predictors of response (time to developing a PU of category ≥ 2) were explored using baseline measurements: pre-existing PUs, category A skin status, diabetes, age, mobility, sensory perception, macro- and microcirculatory function, nutritional status, skin moisture, presence of pain at pressure area skin site and consent type by assessing potential predictor by mattress group interactions in the primary model.

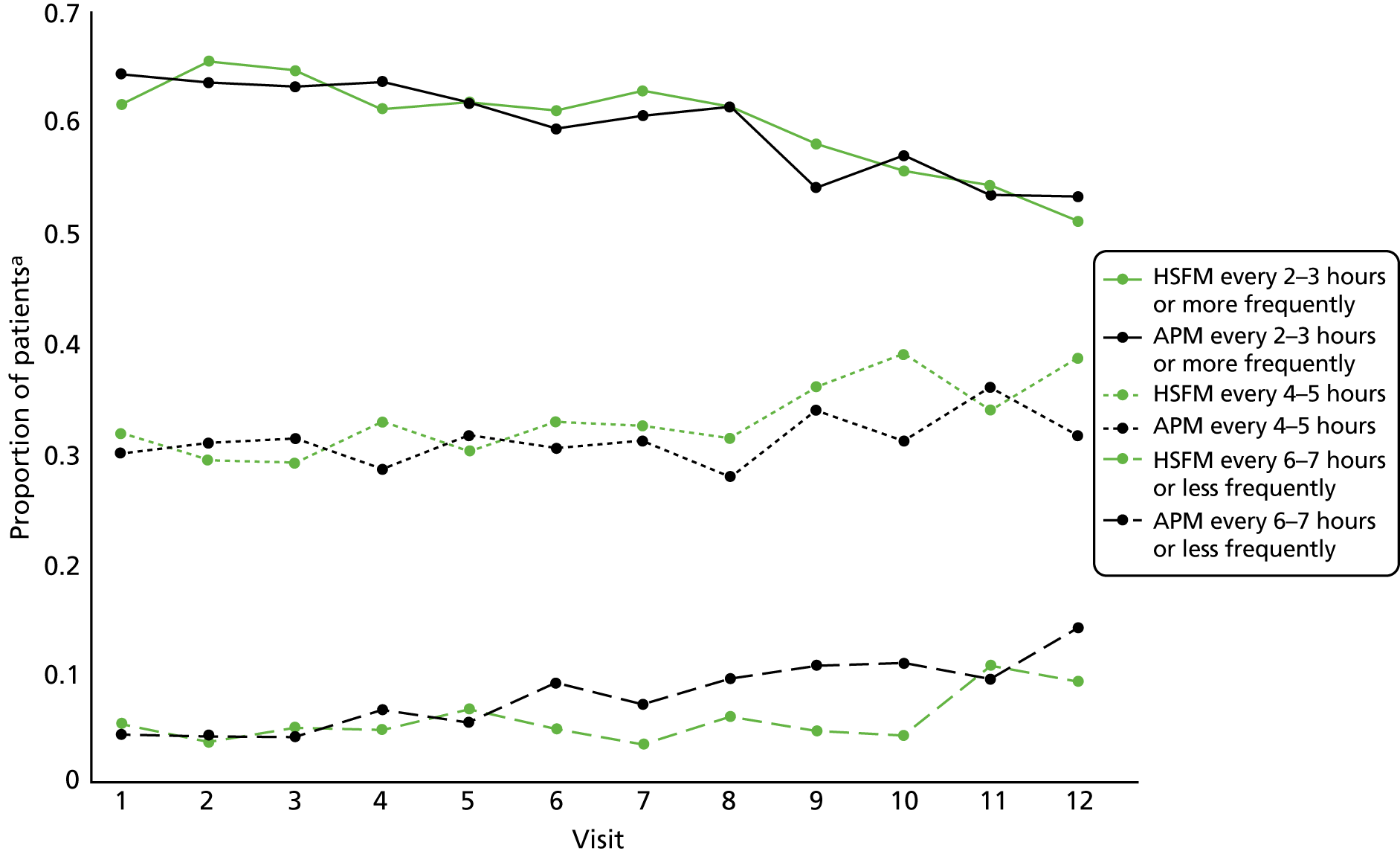

Mediator analysis

An analysis using the Baron and Kenny56 method was planned, with the goal of identifying potential mediators such as time on the allocated mattress, patient repositioning, cushions, heel protectors and protective dressings. However, applications of the Baron and Kenny56 method to time-to-event analyses have been strongly criticised and are known to give biased results. 57 Alternative methods have been developed58,59 but do not apply directly to analyses with competing risks. These methods would have required us to assume that competing risks could be treated as uninformative censoring. This assumption was not considered reasonable, and therefore no mediator analyses were performed. However, a descriptive summary of the potential mediator, repositioning, is presented over time by mattress group. Further investigative work is planned for the other mediators, including investigating the quality of the data and how practice changes over time.

Secondary end point analysis

The secondary end points of time to developing a PU of category ≥ 1 and time to developing a PU of category ≥ 3 to 30-day final follow-up were analysed using the Fine and Gray55 model in line with the primary analysis. To note, for the analysis of time to developing a PU of category ≥ 1, the covariate for the presence of pain excluded pre-existing category 1 PUs and was an indicator variable to denote whether or not there was pain at healthy or altered skin sites only.

For time to healing of a pre-existing PU of category 2, a Fine and Gray55 model was fitted to the outcome time to healing of all pre-existing category 2 PUs to 30-day final follow-up. The following covariates were considered for inclusion in the model: health-care setting, consent type, the presence of a condition affecting peripheral circulation and mattress group.

For all models, the adequacy of the proportional hazards assumption was explored through examination of the Schoenfeld residuals and ln (cumulative hazard) over time, and via a formal test for interaction of mattress and ln (time). 60

Mattress compliance

Descriptive statistics on the time to receiving allocated mattress, reasons for not receiving mattress on the day of randomisation, reason for first mattress change from randomised mattress, and time spent on the randomised mattress during the treatment phase are presented by mattress group. In addition, the mattress in use at the time of screening for patients who were ineligible because either the patient or the staff were unwilling to change the mattress is presented in Appendix 4, Table 69.

Safety

Expected AEs and SAEs and related unexpected serious adverse events (RU SAEs) are summarised by allocated mattress and mattress at the time of the AE/SAE.

Summary of main changes to the protocol

Throughout the trial, five substantial amendments to the protocol were submitted and approved by the REC. The important changes from a patient perspective were the collection of the QoL information and questionnaires as described in Data collection schedule. Prior to starting recruitment (August 2013), modifications to the eligibility criteria, collection of the NHS number and collection of PU-QoL-UI at baseline were added. Two additional objectives were added in an amendment approved in September 2013, to improve the analysis. These were to compare the:

-

incidence of mattress change between patients using APM and those using HSFM

-

safety between patients using APM and those using HSFM.

When and who performs the photography substudy data collection were also clarified. In February 2014, the amendment provided details of the EQ-5D-5L, PU-QoL-UI, SF-12, health resource use survey (1-week recall) and PU-QoL-P questionnaires and specified when they would be administered. In April 2014, an urgent safety measure led to the changes in questionnaire administration, Scottish centres were added, which required additional documents to comply with legislation for consenting participants who lacked capacity. The last substantial amendment, implemented in November 2015, made further changes to the frequency of questionnaire administration and incorporated other health-care professionals as well as nurses to collect data.

Chapter 3 Clinical results

This chapter presents the findings of the analysis for the clinical outcomes.

Participant flow

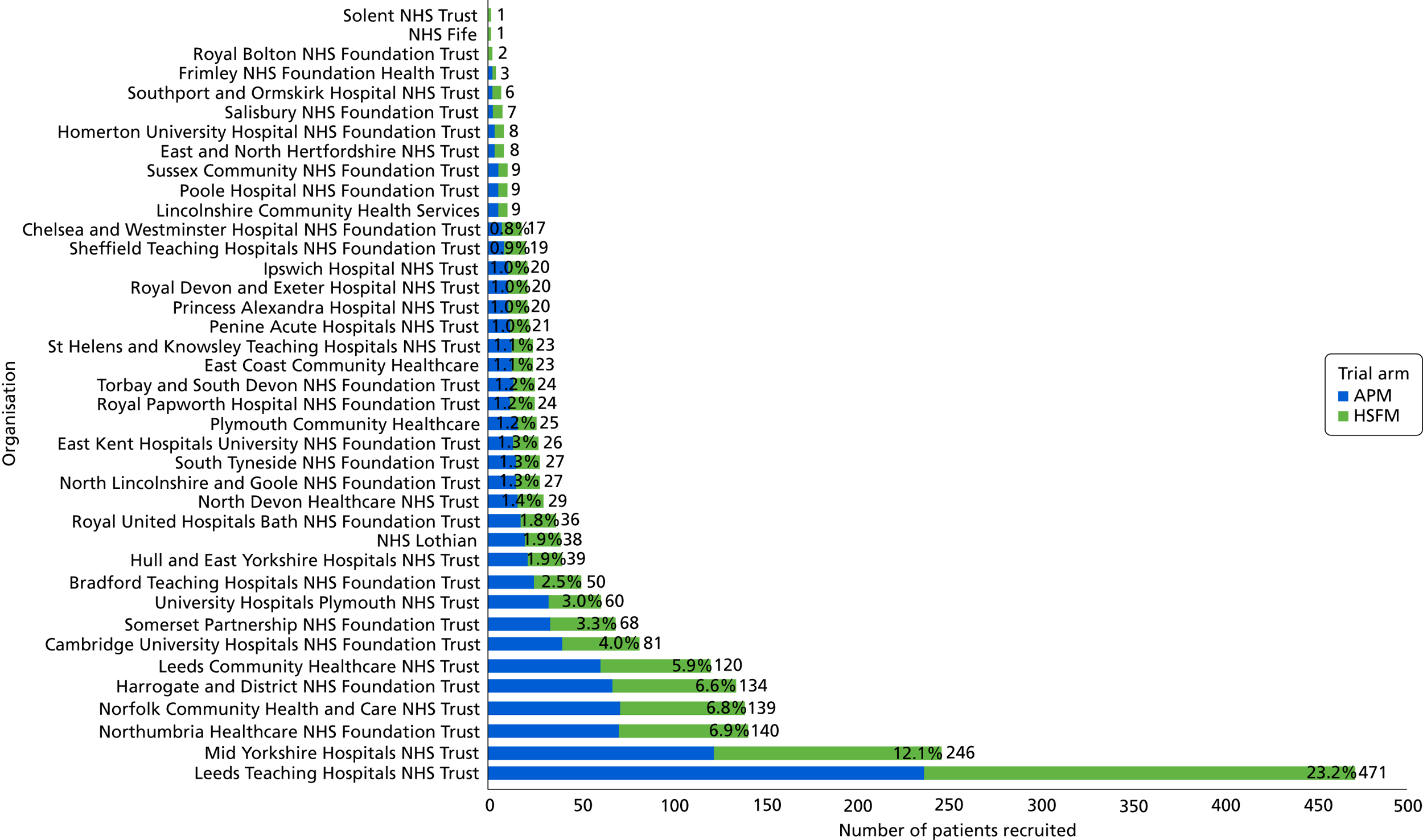

In total, 15,277 patients were assessed for study eligibility and 2030 randomisations took place between August 2013 and 30 November 2016. There were 41 NHS trusts/health boards comprising 47 centres that opened (i.e. met all local regulatory requirements), of which 39 NHS trusts/health boards and 42 centres recruited participants. Of the recruiting trusts/health boards, the numbers of participants randomised by each trust ranged from 1 to 471, with a median of 24 (Figure 1). The mean recruitment per trust was 1.6 participants per month. The recruiting centres/trusts comprised 25 teaching hospitals (21 acute NHS trusts and two health boards), 13 general hospitals (11 acute) and nine community hospitals (in nine community care NHS trusts). Others were combined acute and community trusts.

FIGURE 1.

Recruitment by organisation.

A Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram of trial progress is presented in Figure 2. Of the 15,277 patients screened, 877 (5.7%) were not assessed for eligibility; the main reasons for this included ethically inappropriate to approach (n = 482, 55.0%), discharged (n = 157, 17.9%) or missed by the research team (n = 68, 7.8%). Of the 14,400 patients assessed for eligibility, 9323 (64.7%) were ineligible, with the main reasons including not at a high risk of PU development (n = 2180, 23.4%), length of stay expected to be < 5 days (n = 1640, 17.6%), patient (n = 938, 10.1%) or staff (n = 1116, 12.0%) unwilling to change mattress and patient too unwell to change mattress (n = 709, 7.6%). Of the 5077 eligible patients, 2068 (40.7%) consented and 2030 (40.0%) were randomised.

FIGURE 2.

The CONSORT flow diagram. ICU, intensive care unit; TVTM, tissue viability team member. Adapted from Nixon et al. 44 © The Authors, 2019. This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

The screened population and randomised populations were similar in respect of age, gender and ethnicity (see Appendix 4) with the exception of mattress type at screening. In terms of mattress type, in the screened population, 50% (n = 7640) had been allocated an APM or another high-technology device and 48.8% (n = 7462) had been allocated a HSFM or other low-technology mattress by ward staff, whereas in the randomised population a lower proportion of patients (n = 868, 42.2%) were allocated to APM or another high-technology device than to HSFM or another low-technology device by ward staff (n = 1149, 56.6%) (see Appendix 4, Table 68).

In addition, of the 1116 patients for whom staff were unwilling to change mattress, 78.9% (n = 881) were on APMs or other high-technology mattresses and 20.8% (n = 232) were on HSFM or other low-technology mattresses (see Figure 2). This contrasts with the 938 patients who were unwilling to change mattress, of whom 52.0% (n = 488) were on APMs or other high-technology mattress and 47.7% (n = 447) were on HSFM or other low-technology mattress (see Figure 2).

Of those patients randomised, 1017 (50.1%) were allocated to APM and 1013 (49.9%) to HSFM, with 81.5% of participants in each group receiving the allocated mattress within 48 hours. A total of 119 participants were withdrawn [62 (6.1%) of those were allocated to APM and 57 (5.6%) to HSFM] and 166 patients died between randomisation and withdrawal or the 30-day final follow-up period [82 (8.1%) of those were allocated to APM and 84 (8.3%) were allocated to HSFM]. One patient was inadvertently randomised twice and was withdrawn from trial participation as soon as this was identified. Data arising from the second randomisation were excluded from the analysis population; therefore, the analysis population comprises a total of 2029 participants (see Figure 2).

Baseline characteristics

Patient characteristics were balanced across the mattress groups and are detailed in Tables 2–6. In summary, the study population comprised largely elderly patients (median age 81 years, range 21–105 years); 55.2% (n = 1119) were female and 98.2% (n = 1992) were of white ethnicity. Participants were inpatients for a median of 7 days (range 0–388 days) prior to randomisation.

Participants were inpatients on medical (64.6%, n = 1310), orthopaedics and trauma (22.3%, n = 453), surgical (7.6%, n = 155) and other wards (5.2%, n = 106), including oncology, critical care, neurosciences, renal, gastroenterology and spinal injuries unit (Table 2). Participants were inpatients in secondary care hospitals (69.7%, n = 1414), community hospitals (18.7%, n = 379) and intermediate care/rehabilitation facilities (11.5%, n = 234).

| Attribute | Trial arm | Overall (N = 2029) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| APM (N = 1016) | HSFM (N = 1013) | ||

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Male | 462 (45.5) | 445 (43.9) | 907 (44.7) |

| Female | 553 (54.4) | 566 (55.9) | 1119 (55.2) |

| Missing | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.2) | 3 (0.1) |

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 77.8 (13.42) | 78.2 (12.87) | 78.0 (13.1) |

| Median (range) | 81 (21.1–105) | 81 (21.9–101) | 81 (21–105) |

| IQR | (71.3–87.0) | (71.9–87.2) | (71.6–87.1) |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| White | 1000 (98.4) | 992 (97.9) | 1992 (98.2) |

| Mixed race | 3 (0.3) | 3 (0.3) | 6 (0.3) |

| Non-white | 12 (1.2) | 16 (1.6) | 28 (1.4) |

| Missing | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.2) | 3 (0.1) |

| Medical specialty, n (%) | |||

| Medical | 641 (63.1) | 669 (66.1) | 1310 (64.6) |

| Surgical | 83 (8.2) | 72 (7.1) | 155 (7.6) |

| Orthopaedics and trauma | 233 (22.9) | 220 (21.7) | 453 (22.3) |

| Oncology | 21 (2.1) | 16 (1.6) | 37 (1.8) |

| Critical care | 10 (1.0) | 6 (0.6) | 16 (0.8) |

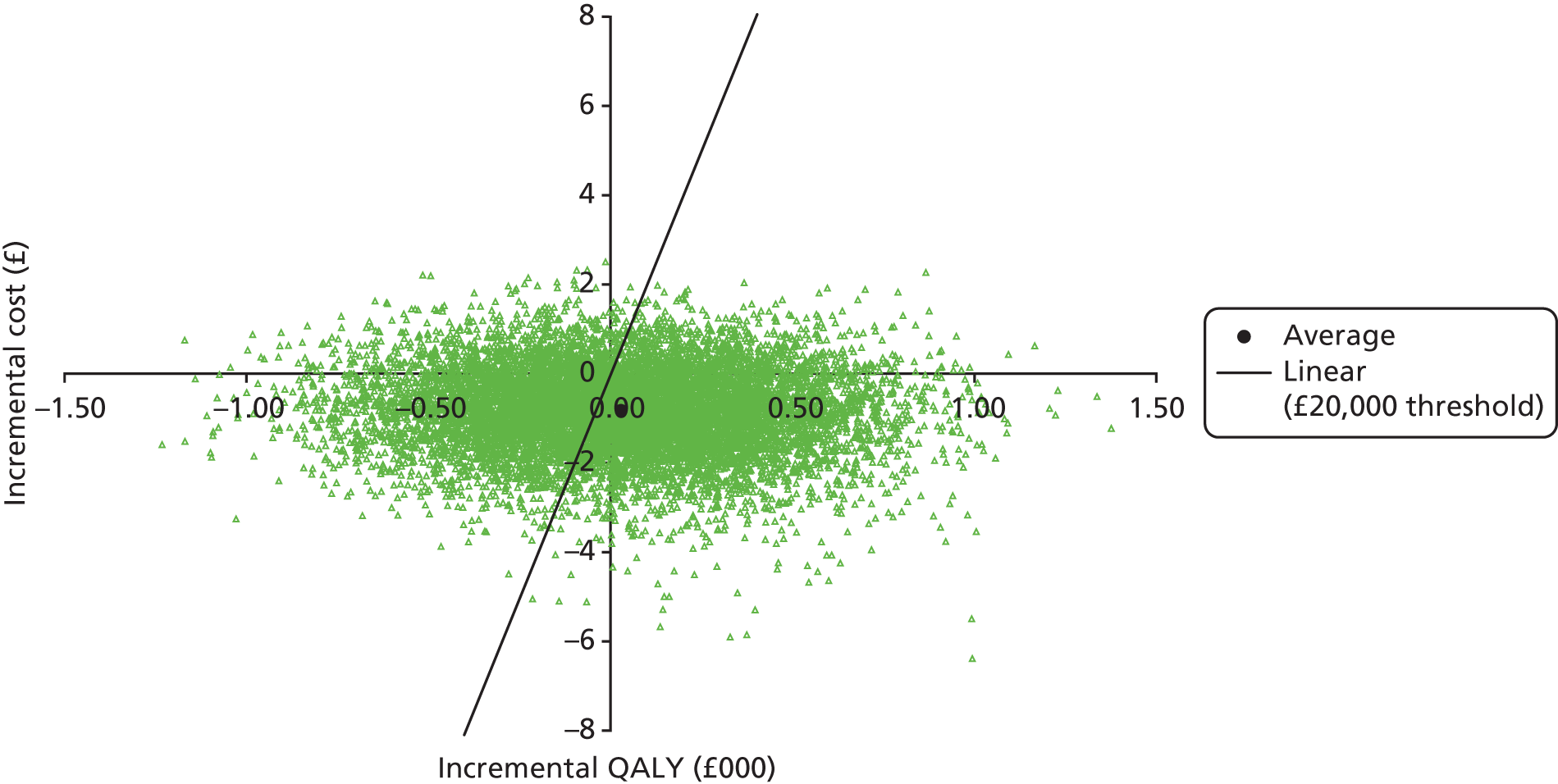

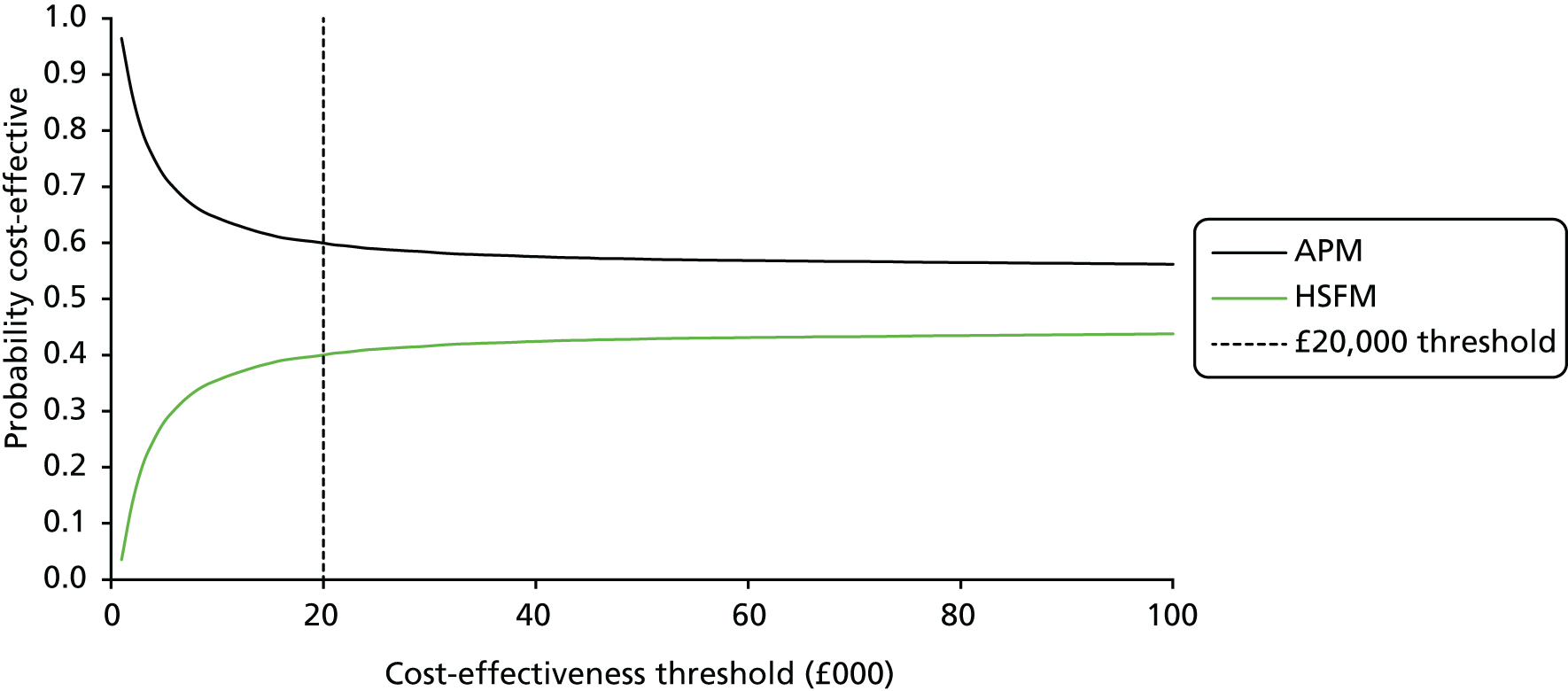

| Neurosciences | 17 (1.7) | 15 (1.5) | 32 (1.6) |