Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 15/10/17. The contractual start date was in January 2017. The draft report began editorial review in October 2018 and was accepted for publication in March 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Irene Higginson reports involvement in the following National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) funding boards: Health Services and Delivery Research Commissioning Board (2009–15), Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Efficient Study Designs (2015–16), HTA End of Life Care and Add on Studies (2015–16) and Service Delivery and Organisation Studies Panel (2009–12). Wei Gao reports involvement in the NIHR HTA End of Life Care and Add on Studies Board (2015–16).

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Koffman et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 The management of clinical uncertainty in hospital settings

Parts of this report have been reproduced/adapted from Koffman et al. 1 The Authors 2019. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Summary of the Health Technology Assessment brief

In 2015, the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment programme published a commissioning brief with a focus on clinical and applied health research into end-of-life care. Interventions for patients in the last 30 days of life were of particular interest. Applicants were asked to consider (1) the use of technologies or interventions that enable and support informed decision-making and choice during the process of end-of-life care, (2) the use of technologies or interventions that enable and support a patient’s ability to die at home if they wish and (3) interventions to support patients, carers and health-care professionals (HCPs) to enable the development of knowledge, skills and confidence in care delivery. This report contains the research conducted in response to this brief (URL: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/151017/#/; accessed 8 February 2019).

Summary of current evidence and policy context

Background rationale

The magnitude of dying in hospital settings

Every year, more than 500,000 people die in the UK,2 and this number is rising. 3 Of these deaths, more than half occur in hospital. 4 However, 69.2% (range 51–84%) of patients and their families would prefer to die at home. 5 Most deaths are anticipated, with up to 75% of all deaths expected, so there is time for discharge to home or more familiar and preferred surroundings. Major reasons for hospital death are poor communication about declining health between patients and HCPs6 and poor identification and management of patients whose situations are ‘clinically uncertain’. 7

Clinical uncertainty in hospital settings

Clinical uncertainty is not a simple concept and a situation of uncertainty usually results from several inter-related factors. Mishel8 was one of the first to develop an overarching theory of uncertainty in an illness, and aimed to explain the underlying processes governing patients’ experiences of uncertainty. Specifically, four concepts contribute to an uncertain state: complexity, unpredictability, ambiguity and lack of information. 8–10 McCormick11 further developed these ideas and described situations of uncertainty in terms of the probability of events occurring, the temporality of events and individuals’ perceptions of their situation.

If clinical uncertainty is not explicitly addressed, there are worse psychological outcomes for patients. 12,13 Evidence suggests that, in the last 30 days of life, the combination of deteriorating health and clinical uncertainty are highly distressing for patients in a hospital and their families. 14,15 This distress is amplified when discussions about their situation and preferences for care and location of death are absent; 67–80% of people want to be informed about poor prognosis. 16 However, research shows that discussions about prognosis rarely occur,17 increasing the likelihood of hospital deaths, but also leading to poor satisfaction, mistrust and loss of confidence in HCPs. 18–21 Indeed, complaints about care at the end of life in hospital settings are frequent. 22

Clinical uncertainty also affects clinicians’ confidence and their practice. Clinicians frequently struggle with uncertainty, which can result in overtreatment or overinvestigation,23 increased costs13 and lack of communication with patients about their future. 24,25 Furthermore, clinicians often feel inappropriately trained to deal with uncertainty; only 4 out of 21 UK postgraduate medical training curricula contain detailed recommendations and curriculum goals relevant to dealing with uncertainty. However, when situations of uncertainty are acknowledged and managed alongside high-quality care, particularly at the end of life, collaborative decision-making is possible. 26 This empowers patients and their carers,27–29 and in turn leads to improved outcomes and increased satisfaction with care. 30,31

The potential for better care

Poor hospital care and inadequate communication, which include patient safety and adverse events, have received increasing attention, particularly regarding the frail elderly and the dying. The Francis Report,32 the independent review of the Liverpool Care Pathway for the Dying Patient33 and the Parliamentary and Health Services Ombudsman’s report34 into complaints about end-of-life care all highlight the devastating effect poor communication and lack of honesty can have on patients and their families towards the end of life. Research has also demonstrated that the costs of patient care in the last year of life are high. 35 Yet when specialist palliative care services are available in hospital and community settings, health service costs can be reduced and patient- and family-centred outcomes improved. 36–38

In 2010, a London hospital identified inconsistencies in the quality of care for patients whose situations were clinically uncertain, for those who were deteriorating and especially for those at the end of life. 34 Issues included inadequate decision-making and poor engagement with patients and carers. A potential solution to caring and supporting patients and their relatives in this situation, developed under the umbrella of a bundle (Box 1 explains the concept of a ‘care bundle’), is referred to as the ‘AMBER care bundle’, where AMBER stands for Assessment; Management; Best practice; Engagement; Recovery uncertain.

The US Institute for Healthcare Improvement describes care bundles as a set of evidence-based interventions for patients that when implemented in combination are aimed at resulting in outcomes that are superior to when delivered alone. 39 They typically consist of a small number of interventions (normally 4–5), which, when implemented together, are associated with improvements in clinical outcomes. 40 The concept of the care bundle approach was originally developed in the USA in intensive care units to achieve the highest levels of reliability in critical care processes that would result in improved outcomes, while at the same time introducing concepts of enhanced teamwork and communication. Since that time, the development and use of care bundles within health care have continued to rapidly evolve both inside and outside the critical care setting.

The AMBER care bundle follows an algorithmic approach to encourage clinical teams to develop and document a clear medical plan, considering anticipated outcomes and resuscitation and escalation status, and to revisit the plan daily. The AMBER care bundle encourages staff, patients, and families to continue with treatment in the hope of a recovery, while talking openly about preferences and priorities should the worst happen. The bundle is modelled on previous empirical work that includes a literature review and examination of clinical records to determine need. 34 However, this bundle was developed to address an identified gap in clinical practice, hence it does not have theoretical underpinnings. Once staff have identified patients who are deteriorating, whose situations are clinically uncertain, with limited reversibility and who are at risk of dying during their current episode of care despite treatment, the multidisciplinary team (MDT) is expected to complete the four tasks within the care bundle. This involves asking:

-

Has a medical plan been documented in the patient records that includes current key issues, anticipated outcomes and their resuscitation status?

-

Has an escalation/de-escalation decision been documented (ward only, high dependency, intensive care)?

-

Has the medical plan been discussed and agreed with nursing staff?

-

Has a patient/carer discussion, or meeting, been held and clearly documented?

With this information, HCPs consider whether or not the patient is still suitable for the intervention, if there had been any medical changes, and if they need to speak with the patient and their relatives daily.

The patient/carer discussion of the AMBER care bundle includes:

-

talking to the patient and family to let them know that the clinical team has concerns about their condition, and to establish their preferences and wishes

-

deciding together how the patient will be cared for should their condition change (i.e. worsen).

The intended benefits of the AMBER care bundle include:

-

increased and improved communication

-

enabling/supporting informed and shared decision-making and choice during end-of-life care

-

improved patient-/family-centred quality of life by reducing anxiety

-

enabling home death if preferred

-

supporting HCPs to develop knowledge, skills and confidence in end-of-life care delivery

-

reducing unnecessary hospital admissions while improving cost-effectiveness (reducing length of hospital stays) and making more efficient use of health services.

The AMBER care bundle is a complex intervention in that it:

-

Comprises multiple components and layers (identification, current and future care planning including escalation and de-escalation decisions, communication delivery, assessment of patient preferences and systematic follow-up, acknowledging dynamic wishes and physical conditions).

-

Aims to change behaviours of health-/social-care professionals delivering the intervention by enhancing recognition of clinical uncertainty in clinical outcomes, patients in the last months of life and management of care expectations.

-

Focuses on staff in primary, hospital and voluntary care, thus including different groups and organisational levels.

-

Includes several complex intended outcomes, including changes in patient involvement in decision-making around situations of clinical uncertainty. The AMBER care bundle is tailored to the individual patient’s and their family’s need and circumstances.

Why research was needed

The AMBER care bundle was identified by NHS England as one of five key enablers of Transforming End of Life Care in Acute Hospitals,41,42 and it is currently being used across a network of approximately 40 hospitals including district general hospitals (DGHs). A further rollout is planned; however, recommendation 7 from the Liverpool Care Pathway for the Dying Patient has suggested that training programmes focused on clinical uncertainty and communication with patients and their relatives must be examined. 33 It was therefore imperative that a clinical trial of the AMBER care bundle took place to accurately quantify patient, clinician and health systems benefits, and that any harms are understood and managed. 43

Now more than ever, with ageing populations and increasing numbers of people dying from cancer and non-malignant conditions,44 health-care systems should provide every patient and their family a dignified death. 45 Facing deteriorating health and uncertain recovery is distressing for patients who may be dying and their families. This is particularly due to the frequent, possibly unnecessary, hospital admissions during the last year of life:46 in England, patients currently spend an average of 29.7 days of their final 12 months in hospital. 35 This is costly for health services and for society. These concerns are endorsed by the NHS Outcomes Framework,47 which includes two outcomes to improve care for people at the end of life: (1) the proportion of patients who die in their preferred place of death (PPD) and (2) bereaved relatives’ experiences of care. Interventional research, including an evaluation of the AMBER care bundle, aimed to understand how these outcomes can be addressed with this intervention.

How the existing literature supports this study

A small but growing body of evidence sheds light on processes and outcomes associated with the AMBER care bundle. When it was introduced at a major London hospital, inpatient deaths declined (from an average of 93 to 81 per month). 34 A recent single-centre study7 identified that rather than being used as a tool to identify patients with an uncertain recovery, the AMBER care bundle was principally used when it became certain that patients would not recover. However, as this was a cross-sectional, observational trial, we were not able to observe changes over time.

We conducted the first comparative observational mixed-methods study of the AMBER care bundle and identified a mixed picture. 48 First, the AMBER care bundle was associated with increased frequency of discussions about prognosis between clinicians and patients, and higher awareness of their prognosis by patients. Second, we observed that those patients who died in locations other than hospitals had shorter lengths of stay than those who received usual care. The mean length of hospital stay for the patients supported by the bundle was 20.3 days (range 1–87 days), compared with 29.3 days (range 6–70 days) in the comparison wards. The mean length of hospital stay for all patients who were discharged and died in a place other than hospital also differed: the mean length of stay for those supported by the AMBER care bundle was 17.6 days (range 1–87 days), compared with 21.4 days (range 6–70 days) in the comparison wards. However, we identified that although the instances of communication were greater, they had lower clarity in relation to the quality of information transmitted about a patient’s condition. Moreover, relatives of patients supported by the AMBER care bundle described more unresolved concerns about caring for them at home. Although this study was informative in evaluating the AMBER care bundle, this was a quasi-experimental study. Non-random selection of comparison sites may have caused bias.

Qualitative data from the same study identified that the intervention was often used as a tool to label or categorise patients, and indirectly served a symbolic purpose in affecting behaviours of individuals and teams. Participants described the importance of training and education alongside the implementation of the intervention. However, adequate exposure to the intervention was essential in order to witness its potential added value or to embed it into practice. This was considered to be very variable. 49

Although the evidence suggests some potential benefits of the care for those supported by the AMBER care bundle, it also identifies downsides, specifically regarding information and communication. Therefore, clinical equipoise in relation to the intervention still exists. These findings pointed to a need for a robust comparative evaluation of the AMBER care bundle compared with standard care. The first step in this direction is to conduct feasibility work to optimise the intervention and to understand the most-appropriate methods to examine its potential benefits.

Feasibility trial aim and objectives

Trial aim

The aim of this exploratory, multicentre, cluster randomised controlled trial (RCT) was to optimise the design of the AMBER care bundle, and to define the outcomes, for a fully powered definitive trial of the AMBER care bundle versus standard care.

Trial objectives

-

To examine recruitment, retention and follow-up rates at both patient and cluster levels.

-

To test trial data collection measures and determine their optimum timing in a larger trial.

-

To assess the degree of contamination at a ward level due to ‘between-ward’ staff and patient movements.

-

To provide a preliminary estimate of the clinical effectiveness of the AMBER care bundle compared with standard care to inform sample size calculation for the full trial.

-

To estimate the intracluster correlation coefficient and likely cluster size.

-

To examine differences in the use of financial resources between the AMBER care bundle and standard care.

-

To examine the extent to which the AMBER care bundle requires further refinement or adaptation (e.g. referral criteria to identify which patients would benefit most) to suit local conditions.

-

To assess the acceptability of the AMBER care bundle to patients, their families and HCPs.

-

To determine the ‘active ingredients’ of the AMBER care bundle that need to be maintained to ensure fidelity of the intervention for a full trial.

-

To assess compliance with and barriers to the delivery of the AMBER care bundle.

Objectives 1 and 6–10 pertain at both individual and cluster levels. Objectives 2 and 4 pertain at the individual level. Objectives 3 and 5 pertain at the cluster level. While assessing acceptability of AMBER, we explored potential benefits and intended harms.

Patient and public involvement

We have sustained patient and public involvement (PPI) throughout all stages of the ImproveCare trial. PPI has been an integral part of all of our research processes, from inception and the development of research ideas, development of the funding application, the application to the NHS Research Ethics Service and the development of all associated documents, through to the delivery of the research project and the interpretation of the trial findings. We have engaged with our PPI members in a number of ways. One of our PPI members (SB) attended the initial Research Ethics Committee (REC) meeting with the chief investigator of the trial, helping to address the REC’s questions and also providing her experiences and highlighting the significance of the trial. We ensured that we met with our PPI members regularly and gave them opportunities to contribute throughout the trial. In close collaboration with our two PPI members (CE and SB), we benefited from their expert views to help us prioritise the research questions and ensure that the trial was undertaken in a way that was meaningful and relevant to patients whose situations are clinically uncertain and their families. We included both our PPI members as part of the Trial Steering and Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (TS DMEC), which had oversight and responsibility for the conduct of the trial. They reviewed information sheets and contributed to substantial amendments to the trial that aimed to make trial participation easier and more accessible for patients and families. We actively involved both of our PPI members in the analysis and interpretation of data from different components of this trial. For instance, our PPI members were involved in the coding of patient and relative interviews. This provided the trial team with valuable insight in understanding the data and its relevance to addressing the intervention and conduct of the trial.

Chapter 2 Design of the feasibility trial assessing the AMBER care bundle and trial processes

Research design

This trial had a parallel cluster RCT design, with a 1 : 1 allocation ratio. The design of the AMBER care bundle, and the manner in which it was implemented and then operationalised at a ward level, did not strictly follow the Medical Research Council (MRC)’s guidance on the development of complex interventions,50 the MORECare statement51 or the recent guidance on process evaluations. 52 To address this, and to inform the design of a definitive clinical trial (Figure 1), we integrated (concurrent) qualitative components of the trial. Our approach closely followed the guidance (Figure 2). 51,53

FIGURE 1.

Concurrent mixed-methods design for the feasibility cluster RCT. IPOS, Integrated Palliative care Outcome Scale.

FIGURE 2.

Conceptual framework for the evaluation of the AMBER care bundle showing which elements of the MRC’s framework have been completed (top box) and those proposed for testing in this feasibility trial (left box).

Rationale for clustering

The AMBER care bundle is a complex intervention in which ward staff receive training and all patients within the wards are considered for receiving support from the intervention. It would therefore not be possible to randomise patients at the individual level within the same ward. 54 In order to prevent contamination of the control participants, which may have led to biased estimates of the intervention’s potential effect, this trial was designed to be randomised at the cluster level. Clusters, in this case, were identified as being general medical wards, and were selected from different hospitals, as randomised wards within the same hospital might have also been contaminated because of between-ward staff movements.

Components of the trial

-

The clinical trial of the patients supported by the AMBER care bundle compared with those cared for on control wards.

-

A bereavement survey of relatives/close friends of patients who fulfilled the criteria to be supported by the AMBER care bundle on intervention and control wards.

-

Qualitative interviews with patients and their relatives/close friends.

-

Non-participation observation of MDTs at the trial wards.

-

Focus groups with HCPs working on the trial wards.

-

A usual care questionnaire completed by the HCPs working on the trial wards.

-

A review of patients’ case notes and ‘heat maps’ produced at each trial ward.

Consent processes

All participants who provided written informed consent (or assent) to participate in the trial were provided with a copy of the information sheet and their signed consent (or assent) form to keep (see Appendix 2). A copy of the signed consent/assent form was filed in the participant’s medical notes, and a copy was sent to the patient’s general practitioner if they provided their general practitioner’s details. The research team retained the original signed consent form.

Research governance and ethics approval

Favourable ethics opinion was obtained from the National Research Ethics Committee – Camden and King’s Cross (REC reference 16/LO/2010) on 20 December 2016 and from the Health Research Authority (HRA) on 25 January 2017. NHS research governance approvals were obtained from each participating trial hospital. All minor and substantial amendments to trial procedures and material were reviewed and approved by the REC, HRA and local trial hospitals (referred to as trial sites).

Amendments to the protocol

Six substantial amendments were submitted during the course of the feasibility trial. The changes to the protocol and the trial procedures are outlined in this section. All amendments were approved by the REC, HRA and local trial sites (see Appendix 3 for approvals from the REC).

-

The participant information sheets and consent forms for the non-participant observation of MDT meetings were omitted from the original application and a substantial amendment was issued to ensure that these documents were reviewed and approved (REC approval date: 23 January 2017).

-

The participant information sheets for focus groups with HCPs were omitted from the original application and a substantial amendment was issued to ensure that these documents were reviewed and approved (REC approval date: 22 February 2017).

-

Following the enquiries from the Project Advisory Group (PAG) and REC regarding the ambiguity around what ‘standard care’ represented in the control arm of the trial, changes were made to the protocol that aimed to address this issue. A new study measure referred to as the ‘Standard’ or ‘Usual’ Care Questionnaire’ and the accompanying participant information sheet and consent form were developed. To understand how to characterise ‘standard care’ in the control wards, and to examine how well the AMBER care bundle was being used and adapted on the intervention wards, we also added a ‘case note review tool’ and ‘heat maps’ to the trial. Additional questions were included in topic guides for the HCP focus groups to enhance our understanding of the care provided across trial sites (REC approval date: 21 April 2017).

-

An amendment was submitted to temporarily change the chief investigator of the trial to Dr Catherine Evans from Dr Jonathan Koffman. In addition, the trial end date was extended to 31 October 2018. Owing to delays in recruitment of the nurse facilitator, general planned procedures of implementation and data collection were amended. To ensure that data from bereavement surveys were collected in time, changes were made to time points at which bereavement survey packs were sent. Finally, the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L) (reference), measure was added at other time points. Owing to these changes, trial documents and the protocol were updated (REC approval date: 24 July 2017).

-

The bereavement survey was amended to include two health economic evaluation measures and to improve the overall layout of the questionnaire (REC approval date: 1 November 2017).

-

After experiencing difficulties in recruitment at the control sites, the inclusion criteria for the trial were amended to remove the ‘Patients who were at risk of dying during their episode of care despite treatment’. Feedback from the local trial sites and the screening logs identified this criterion as challenging to interpret and implement. Furthermore, we improved the language used in the participant information sheets and letters after an incident in which a relative was distressed from a phrase used in the participant information sheet. This amendment also included an addition to conduct qualitative interviews with patients and families over the telephone, as several potential participants who were approached previously mentioned difficulties around arranging a face-to-face interview. Finally, an ‘AMBER readiness criterion’ was included to examine interventional fidelity to the AMBER care bundle at both intervention sites (REC approval date: 14 December 2017).

Data collection

The timeline for data collection for different trial components and trial sites is summarised in Figure 3. Prospective data were collected from the patients at three time points: baseline, 3–5 days and 10–15 days. After obtaining informed consent (or assent), research nurses conducted face-to-face interviews with patients (or relatives) to collect data that captured demographic and clinical circumstances. The questionnaire booklets included candidate patient outcomes using the ‘Patient/family anxiety and communication subscale’ of the Integrated Palliative care Outcome Scale (IPOS) and the ‘howRwe’ measure (see Appendix 4) and health performance status using the Australian-modified Karnofsky Performance Status scale (AKPS). Data on health resource utilisation were collected using the Client Service Receipt Inventory (CSRI). The EQ-5D-5L was used to measure health-related quality of life.

FIGURE 3.

Time frame for training on intervention wards and trial recruitment and data collection points.

Testing the candidate primary outcome measures

The first primary outcome measure we tested was the effect of being supported by the AMBER care bundle on the ‘Patient/family anxiety and communication subscale’ of IPOS. 55,56 This proposed outcome was based on the overall aim of the intervention and findings from our recent comparative observational study48 in which psychosocial issues were shown to be important patient- and family-centred concerns. The Patient/family anxiety and communication subscale incorporates items including being in receipt of information, addressing practical matters, sharing feelings with family, being at peace, and patients’ and families’ levels of anxiety and depression. A general background to the IPOS measure is presented in Box 2.

The POS was developed in the 1990s and includes domains important to patients with advanced progressive illness. 55 It consists of 10 items scored from 0 (best) to 4 (worst). It assesses physical symptoms, psychological and spiritual needs and provision of information and support. Following patient and clinician feedback, a symptom module (POS-S, adapted for specific conditions) was added. 57,58 Staff versions of POS and POS-S – important when the target population is so ill and frequently unable to complete patient-reported versions – are brief, user-friendly clinical outcome measures designed for HCPs to assess an individual’s symptoms and concerns. They typically take less than 10 minutes to complete. Both patient and staff versions of POS and POS-S have undergone extensive psychometric study. POS has validity and internal consistency in a variety of settings, including hospital inpatient care and community and outpatient services, hospice inpatient, day care and home care. 55,59 Moreover, it demonstrates construct validity and re-test reliability, and factor analysis has identified important underlying constructs relating to psychological well-being and quality of care. 56

The IPOS comprises 17 items scored from 0 (best) to 4 (worst) and assesses physical symptoms, psychological and spiritual needs, and provision of information and support. 55 The IPOS has undergone extensive validation testing including cognitive interviewing to assess acceptability and content/face validity and to identify cognitive processing issues following the model of Tourangeau. 60 Face and context validity of IPOS were refined using cognitive interviewing. 61 A recent study provides evidence that the IPOS is a robust, valid and reliable measure and would provide discrimination between relevant groups. 62 We identified among 373 participants that the IPOS can discriminate well between patients with different illness and functional characteristics. For example, in the known-group comparisons (during our testing of construct validity), the total IPOS and subscale scores discriminated well between patients who were in an unstable/deteriorating phase compared with those in a more stable phase of illness (total IPOS: F = 15.0, p < 0.001; Patient/family anxiety and communication subscale: F = 3.6, p < 0.03).

POS, Palliative care Outcome Scale; POS-S, Palliative care Outcome Scale Symptom.

We included another candidate primary outcomes measure to be able to determine the measure best suited to a pragmatic trial. 53 HowRwe, a validated patient-reported experience measure,63 was used to examine changes in patients’ perceptions of their experience of health care, which are highly relevant to those whose situations are clinically uncertain and their families. A general background to the howRwe measure is presented in Box 3. This measure is considered succinct (29 words in length) and highly accessible (Flesch–Kincaid readability score of 2.2). It consists of four items: two relate to the delivery of clinical care (being treated kindly and being listened and explained to). Two further items relate to the organisation of their care, including waiting to see a HCP (time wasted) and how well organised patients perceive the ward to be. The howRwe has been successfully used across inpatient and outpatient general practice, care homes and in domiciliary care.

In England, the NHS undertakes many national surveys of patient experience. However, measures are often unwieldy and lengthy, with many being over 300 words long. The howRwe was developed as the first short generic patient experience measure for use across all health and social care sectors. 63 It comprises just 29 words and includes two items relating to clinical care (treat you kindly and listen and explain) and two items relating to the organisation of care (see you promptly and well organised) as perceived by patients. Each item has four possible responses (excellent, good, fair and poor). The summary howRwe score is calculated for individual respondents by adding the scores for each item, giving a scale with 13 possible values, from the floor, 0 (4 × poor), to the ceiling, 12 (4 × excellent). When reporting the results for a group comprising more than one respondent, mean scores are transformed arithmetically to a 0 to 100 scale, where 100 indicates that all respondents rated all items as excellent and 0 indicates that all rated all items as poor. This allows the mean item scores to be compared with the summary howRwe score on a common scale. The measure was recently trialled among 828 older patients and has undergone extensive psychometric testing64 in a variety of settings, including hospital and care homes in the community. The measure demonstrates good internal consistency, concurrent validity and discriminant and construct validity.

These two measures were reassessed at follow-up points 1 (days 3–5) and 2 (days 10–14). The success of the primary outcomes were examined based on the following criteria:65

-

appropriateness – for patients with an advanced illness (e.g. number of missing data)

-

reliability – the degree of consistency of the measure (i.e. when it gives the same repeated result under the same conditions)

-

feasibility – is the measure easy to administer to patients in an inpatient hospital setting?

Patient recruitment and consent procedures

We aimed to understand how involvement in the trial might influence participants’ situations. We used a successful strategy from a recent study examining the effectiveness of dignity therapy for people living with advanced cancer. 66 Participants in both arms were questioned at all time points to evaluate the extent to which they found participating in the process of obtaining consent and the overall research process ‘helpful’, ‘making life more meaningful’, ‘heightening their sense of purpose’, ‘lessening suffering’ and ‘increasing their will to live’. We have previously observed that self-reports of the benefits of being involved in the research process are generally more positive in the intervention group than in the control group. 67 However, qualitative accounts from participants in the control group from the previous study included statements indicating that being involved in research meant that ‘somebody cared about me’ and represented ‘an opportunity to talk to somebody about problems with a sympathetic and sensitive researcher’. 68

Participant inclusion criteria

-

Patients located on the intervention or control wards.

-

Patients who were aged ≥ 18 years.

-

Patients who were deteriorating (in accordance with the AMBER criteria).

-

Patients whose situations were clinically uncertain, with limited reversibility (in accordance with the AMBER criteria).

-

Patients who were at risk of dying during their episode of care despite treatment (in accordance with the AMBER criteria).

-

Patients who were able to provide written informed consent or for whom a personal consultee could be identified and approached to give an opinion on whether or not the patient would have wished to participate in the trial.

The bereavement survey

The objectives of the bereavement survey within this feasibility trial were to:

-

test feasibility of collecting data retrospectively

-

examine differences in the use of financial resources between the AMBER care bundle and standard care.

Participant inclusion criteria for the bereavement survey

Potential participants for the bereavement survey included the next of kin (NOK) or named relatives of deceased participants who were either (1) supported by the AMBER care bundle on intervention wards or (2) identified as fulfilling the criteria on the control wards. We identified the NOK for participants who died (1) while they were inpatients or (2) on discharge within 100 days.

Recruitment of participants for the bereavement survey

All identified NOKs were sent a letter from the research nurses at each of the participating DGHs 10–12 weeks following bereavement, with an introductory letter, the survey questionnaire and a Royal College of Psychiatrists bereavement support leaflet. Up to two reminders were sent to people who had not responded at 2 and 4 weeks after the initial posting; the second reminder included a second copy of the questionnaire. On receipt of a completed questionnaire (see Data collection for the bereavement survey), the research team recorded the date of receipt into the spreadsheet, checked completion and recorded levels of distress and grief intensity.

Data collection for the bereavement survey

We used a modified version of the QUALYCARE bereavement survey,69 which has previously been shown to be highly acceptable to participants in bereavement research. 48,70 This survey examines the last 1–2 months of the decedent’s life, including quality and consistency of information and communication with clinicians.

The survey comprises four brief and robust measurement tools previously used in cancer and end-of-life care studies. These tools collect information on health and social care services use and informal care (CSRI71,72), patient palliative outcomes in the week prior to death (IPOS55,56), health-related quality of life [EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D)73] and respondents’ bereavement outcomes (Texas Revised Inventory of Grief74). Further questions explored preferences for (and actual) place of death, relevant local issues and sociodemographic and clinical data. The format and navigation of the questionnaire have been refined according to cognitive theory literature. 75 Furthermore, the QUALYCARE questionnaire has been piloted and improved to enhance acceptability among 20 bereaved relatives recruited via the palliative medicine department of a London hospital. 70

The qualitative component

The qualitative component of this feasibility trial included interviews with patients, their relatives or close friends, non-participant observation of the MDT meetings and ward-based focus groups with HCPs. The specific objectives of these components of work were:

-

to examine the extent to which the AMBER care bundle requires further refinement or adaptation (e.g. referral criteria to identify which patients would benefit most) to suit local conditions

-

to assess the acceptability of the AMBER care bundle to patients, their families and HCPs

-

to determine the ‘active ingredients’ of the AMBER care bundle that need to be maintained to ensure fidelity of the intervention for a full trial

-

to assess compliance with and barriers to the delivery of the AMBER care bundle.

Participant inclusion criteria for the qualitative interviews

Potential participants included:

-

all patients who were recruited to the trial

-

relatives or close friends of patients who were recruited to the trial

-

patients or relatives who were able to meet face to face or have the interview over the telephone.

Exclusion criteria for the qualitative interviews

Our exclusion criteria for this component of the trial were:

-

patients who were not able to provide informed consent because of capacity-related issues

-

patients, their relatives or close friends considered by HCPs to be too unwell to be interviewed and/or too distressed to approach

-

relatives/close friends, who were not willing to provide informed consent.

Procedure for recruitment of patients and/or relatives for the qualitative interviews

The research nurses were asked to identify up to 20 patients (five per ward), and/or their relatives, who matched the inclusion criteria on intervention and control wards. Identified patients were discussed with the clinical team to see if they were suitable to be approached. Potential participants were also selected according to pre-agreed criteria (range of age groups, gender, disease type and ethnic group). If they were deemed to be appropriate, the research nurse then asked if they would like to be interviewed by the trained researcher.

Relatives were approached while they were visiting the patients and asked if they would be willing to be interviewed by the trained researcher. All participants were provided with a comprehensive participant information sheet explaining the nature of the trial and their potential involvement. This document did not allude to therapeutic promises, nor did it allude to unacceptable inducement or refer to any negative outcome of not participating. If in agreement, the researcher then contacted the potential participants, within 24 hours, to address any questions or concerns that they might have and to establish their decision to take part in the trial or not.

Owing to the challenging nature of the patients’ clinical situations and where the potential participant was not able to meet face to face, a decision, approved by the REC, was made to conduct such interviews over the telephone. A mutually convenient time was arranged to conduct each interview. The researcher explained the trial in full again and the interview commenced after informed consent was obtained (in writing in a face-to-face interview or verbally recorded in a telephone interview). Verbal consent was documented by the researcher on the consent form for telephone interviews and signed and dated. A copy of the signed consent form was sent to the participant after the interview depending on their preference.

Data collection for the qualitative interviews with patients and relatives or close friends

The interview topic guides aimed to explore patients’ and their relatives’/close friends’ insights into the delivery of care, and their perception of involvement in critical decisions regarding their care and treatment while in hospital. Interviews were recorded on an encrypted digital voice recorder. During transcription, all potentially identifiable information was removed or anonymised. Recordings were destroyed following completion of the trial in line with King’s College London’s data-management policy.

Non-participant observation of the multidisciplinary team meetings

Informed consent was obtained prior to the meetings. However, in instances in which HCPs arrived late, informed consent was obtained at the end of the meetings. This was considered the most minimally intrusive option in the group setting, as it did not disrupt natural behaviours of HCPs already participating in the meeting.

On the intervention wards, we recorded who was present at the meetings, the frequency of the meetings, the length of meetings and type of conversations relating to patients identified as fulfilling the criteria to be supported by the AMBER care bundle. We also took note of which professions contributed to conversations, what specific actions were discussed that related to their care and how decision-making processes developed, including the management of end-of-life issues. We conducted similar observations on the two control wards with prior knowledge from the research nurses of patients who fulfilled revised criteria. Observations were written down as field notes during the meeting. All field notes that related to conversations about individual patients and their families were devoid of any identifying characteristics.

Focus groups with health-care professionals

The HCPs were invited to participate in a ward-based multiprofessional focus group to explore their views on caring for patients whose situations were clinically uncertain, views about the AMBER care bundle (if on the intervention wards) and views regarding conduct of the feasibility cluster RCT. Specifically, for the intervention wards, we wanted to understand HCPs’ insights into the ways in which the AMBER care bundle influenced communication with patients and their family members or close friends, improved HCP confidence, competence and empowerment in working with patients with advanced disease and facilitated improved team working, and to explore what changes may be required to enhance its operation. We wanted to explore their views on the acceptability of the care bundle, particularly their views on whether or not the AMBER care bundle required modification or refinement. We purposively recruited a range of HCPs with different levels of experience to share their views on caring for these patients. We worked closely with the research nurses to promote the focus groups and posted information posters in each of the wards in the weeks leading up to the focus group taking place. The focus groups were typically organised during lunch times to optimise participation and were catered with food and refreshments to offset any inconvenience staff might experience. Participants were asked to give informed consent on arrival at the focus group venue.

The ‘standard’ or ‘usual’ care questionnaire

In clinical trials, reference is often made to evaluating the outcomes of an intervention compared with standard care. 76,77 Few studies, however, explain what this type of care comprises or examine the extent to which standard care changes during the trial as a result of involvement in the trial. This methodological issue was highlighted by members of the NHS REC and by our trial statistician. We therefore developed a tool to characterise best standard care applicable for patients, and their families, whose situations are clinically uncertain, across all of the trial sites, at the following time points during the trial:

-

baseline (prior to implementation of the AMBER care bundle for the intervention wards)

-

mid patient recruitment (6 weeks after the recruitment of the first participant)

-

at the end of patient recruitment (we were mindful that some of the procedures in the ward might not change drastically throughout the trial, especially in the control sites, hence why, at the mid patient recruitment and end of patient recruitment time points, we provided respondents with the option of answering only the questions that related to when there had been a change in the procedure since the previous time point).

We collected data from the perspectives of different HCPs (a consultant, a ward manager/sister, a junior doctor/senior house officer, a health-care assistant and a staff nurse), rather than just one representative on each ward, to obtain a broader understanding of this type of care. The format, content and navigation of the ‘standard’ or ‘usual’ care questionnaire were refined based on expert opinions, including members of the PAG and senior clinical colleagues at an inner London teaching hospital. Questions addressed initial care planning and general practices, recognising dying, referral and discharge procedures. The questionnaire took 10–20 minutes to complete depending on the number of free-text data provided.

Case note reviews

The incorporation of the audit tool, which was developed by the bundle developers as part of the quality improvement process, aimed to enhance our understanding of ‘standard’ or ‘usual’ care at ward level and how this might change over time. The nurse facilitator completed the case note reviews. This audit tool is routinely used in over 30 hospitals internationally, including in England, Wales and Australia. The audit tool comprises a case note review of hospital patient records in a standardised format and a ‘heat map’ of patient mortality over a 1-year period.

The case note review was completed retrospectively and involved purposively selected 20 patients per ward, comprising 10 patients who died in the hospital and 10 patients who were discharged and died within 100 days of discharge. It was conducted for all of the trial wards and additionally for the intervention wards after the implementation of the AMBER care bundle. All identifiable patient information was removed and anonymised prior to sharing with the research team.

Trial setting

Selection of the wards

Participant recruitment and implementation of the AMBER care bundle were limited to one or two general medical wards at each hospital site. Wards with the highest number of deaths per year were considered to be suitable for this trial. Selection of the trial wards at each site was informed by ‘heat maps’ that provided contextual information at ward level on the number of deaths during admission and up to 100 days after admission across the hospital wards.

Randomisation and masking

Randomisation was at the level of the NHS trusts via an independent service at King’s Clinical Trials Unit. Four clusters were randomised at once by randomly sequencing the order of randomisation and then randomising the sites in this order into fixed blocks of two, those being the control or intervention arms. All clusters were randomised prior to collection of data at sites but after all sites had agreed to participate. Quantitative analyses masked for the group allocation were conducted. Research nurses collecting the outcome measures were not masked for the group allocation.

Trial sites

Participants were recruited from one (or two) purposefully chosen general medical ward of four DGHs in England. The trial sites were Chesterfield Royal Hospital, East Surrey Hospital, Tunbridge Wells Hospital and Northwick Park Hospital, which are major secondary care facilities typically providing an array of diagnostic and therapeutic services to local populations. There are over 250 DGHs in the UK. 78 They represent abundant settings in which to implement and test the effect of the AMBER care bundle; the findings from this feasibility trial would inform future scalability. However, DGHs are extremely busy environments in which to conduct research, with patients being rapidly assessed and transferred from medical acute admissions units to other wards within the hospital. This makes it challenging to track trial participants and obtain accurate reports of their condition or outcomes. The DGHs selected serve diverse populations including those that comprise ethnic diversity and material deprivation. The hospitals have different strengths and weaknesses in terms of their Care Quality Commission ratings (Table 1).

| Cluster | Specialties | Number of beds | End-of-life care plan | Care Quality Commission rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control arm | ||||

| One general medical ward |

|

32 |

|

Good |

| One general medical ward |

|

27 | Last days of life care agreement | Requires improvement |

| Intervention arm | ||||

| One general medical ward |

|

30 | Individualised care plan for dying patients | Good |

| Two general medical wards | Care of the elderly | 36 | End-of-life care plan | Requires improvement |

‘Standard’ or ‘usual’ care across trial sites

The standard care provided to patients who might have clinically uncertain recovery was described using the self-reported ‘standard’ or ‘usual’ care survey completed by the HCPs and the case note reviews.

The ‘standard’ or ‘usual’ care surveys were completed at the beginning of the data collection at each trial site by 23 HCPs who represented different seniority levels and professions working on the trial wards (Table 2). The components of care questioned in this survey did not change during the course of the trial. All sites had similar processes for clerking, referring patients to palliative care or intensive care unit (electronic referral and specific triggers) and providing emotional support to the patients and families. However, professionals had various views on who was responsible for producing a medical plan for the patients, varying from all of the MDT and the patients and families to the consultant and medical team only. Delays in recognition of patients’ clinical uncertainty and relaying of information around uncertain recovery from HCPs to patients and families were shown as the main barriers to referrals to palliative care and in escalating care at all trial sites by various HCPs. Three ward sisters [sites Int (intervention) 1, Int2 and Con (control) 2] and one health-care assistant (site Con1) stated that the principal reason for delays in referral to palliative care was the medical team’s decision to continue active treatment: ‘doctors trying to get the patient well’ (Con2001) and ‘medical team wanting to treat for another 24–48 hours’ (Int1005).

| Profession | Number of professions | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trial arm and site | ||||

| Control | Intervention | |||

| Con1 (n = 5) | Con2 (n = 5) | Int1 (n = 8a) | Int2 (n = 5) | |

| Consultant | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Ward sister/manager | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Junior doctor | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Staff nurse | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Health-care assistant | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Physician associate | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

The survey also highlighted that advance care plans (ACPs) were devised only once the patient was considered to be at the end of life: ‘when all the care has been given and the patient has not got any better’ (Int2001). After the implementation of the AMBER care bundle, HCPs at site Int1 stated ‘recognising uncertainty’, ‘deteriorating patient’, ‘clinical uncertainty’,7 ‘patient and family wishes’ and ‘frequent hospital admissions’ as reasons for devising an ACP. Within the same teams, there were disagreements around the frequency of revisiting the plans made with the patients and families. Although professionals across all sites stated that they would actively contact families and speak with the rest of the MDT as soon as possible if a patient’s health status deteriorated, HCPs within the same team were in disagreement about how often they would update the patients and families.

Survey findings showed inconsistencies in the manner in which standard care was delivered in relation to shared decision-making among HCPs and the contribution of the MDT to patients’ care and treatment plans. Although all of the survey participants were able to clearly state the systems in place at all sites, the recognition of clinical uncertainty and importance of having conversations with patients and families prior to their last days of life were considered part of the standard care provided.

Case note reviews identified that processes, documentation of plans and discussions at all trial sites were similar (Table 3). The review showed that the uncertain recovery of patients was documented in patients’ notes for the majority (> 60%) of a purposively selected sample of patients across all the trial sites. The majority of patients in the control sites had a cancer diagnosis, unlike the patients in intervention sites. In all trial sites, escalation plans were documented for 60% of participants, and ‘do not resuscitate’ orders were documented for 75% of the sample. However, the majority (> 60%) of the sample did not have an ACP documented. Besides site Con1, medical plans were discussed and agreed with the nursing staff at all other sites. Although the notes identified that discussions with patients and families took place for the majority of the sample, documentation of patients’ preferred places of care (PPCs) and PPDs and their wishes around care and treatment require improvement. With the exception of site Con2 participants, the majority of the sample received daily follow-up. However, it was not possible to examine the quality and the content of the discussions that took place.

| Descriptive variable | Trial arm and site, n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Intervention | |||

| Con1 (N = 20) | Con2 (N = 20) | Int1 (N = 20) | Int2 (N = 20) | |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 40–60 | 2 (10) | 2 (10) | 0 (0) | 3 (15) |

| 61–70 | 2 (10) | 3 (15) | 0 (0) | 6 (30) |

| 71–80 | 4 (20) | 8 (40) | 2 (10) | 6 (30) |

| 81–90 | 8 (40) | 6 (30) | 11 (55) | 5 (25) |

| ≥ 91 | 4 (20) | 1 (5) | 7 (35) | 0 (0) |

| Primary diagnosis | ||||

| Cardiology | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (20) | 0 (0) |

| Cancer | 12 (60) | 9 (45) | 2 (10) | 6 (30) |

| Acute respiratory | 5 (25) | 7 (35) | 5 (25) | 2 (10) |

| Chronic respiratory | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 10 (50) |

| Stroke | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) |

| Dementia | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (10) | 0 (0) |

| Sepsis | 2 (10) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 0 (0) |

| Frailty | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 0 (0) |

| Other | 0 (0) | 4 (20) | 5 (25) | 1 (5) |

| Uncertain recovery documented? | ||||

| Yes | 18 (90) | 15 (75) | 18 (90) | 12 (60) |

| No | 2 (10) | 5 (25) | 2 (10) | 8 (40) |

| ACP in place? | ||||

| Yes | 4a (20) | 8b (40) | 7c (35) | 2d (10) |

| No | 16 (80) | 12 (60) | 13 (65) | 18 (90) |

| Escalation plan documented? | ||||

| Yes | 15 (75) | 12 (60) | 18 (90) | 13 (65) |

| No | 5 (25) | 8 (40) | 2 (10) | 7 (35) |

| DNAR/DNACPR status | ||||

| Patient for CPR | 1 (5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (10) |

| Patient not for CPR | 16 (80) | 15 (75) | 20 (100) | 15 (75) |

| No documented decision | 3 (15) | 5 (25) | 0 (0) | 3 (15) |

| Medical plan discussed and agreed with nursing staff? | ||||

| Yes | 9 (45) | 15 (75) | 19 (95) | 16 (80) |

| No | 11 (55) | 5 (25) | 1 (5) | 4 (20) |

| Patient/family discussion? | ||||

| Yes | 19 (95) | 14 (70) | 19 (95) | 13 (65) |

| No | 1 (5) | 6 (30) | 1 (5) | 7 (35) |

| Daily follow-up? | ||||

| Yes | 19 (95) | 12 (60) | 19 (95) | 12 (60) |

| No – should have received | 1 (5) | 7 (35) | 1 (5) | 8 (40) |

| No – not needed | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Assessment of capacity? | ||||

| Yes | 11 (55) | 20 (100) | 10 (50) | 7 (35) |

| No – it was not needed | 7 (35) | 0 (0) | 9 (45) | 12 (60) |

| No – it was needed | 2 (10) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 1 (5) |

| PPC | ||||

| Person’s own home | 3 (15) | 7 (35) | 2 (10) | 10 (50) |

| Hospital | 2 (10) | 6 (30) | 2 (10) | 3 (15) |

| Care home | 0 (0) | 3 (15) | 6 (30) | 3 (15) |

| Hospice | 3 (15) | 1 (5) | 1 (5) | 1 (5) |

| Preference not documented | 11 (55) | 1 (5) | 6 (30) | 3 (15) |

| Other (including patients who were undecided) | 1 (5) | 2 (10) | 3 (15) | 0 (0) |

| PPD | ||||

| Person’s own home | 4 (20) | 3 (15) | 1 (5) | 3 (15) |

| Hospital | 2 (10) | 0 (0) | 2 (10) | 0 (0) |

| Care home | 0 (0) | 4 (20) | 1 (5) | 3 (15) |

| Hospice | 3 (15) | 1 (5) | 2 (10) | 0 (0) |

| Preference not documented | 11 (55) | 9 (45) | 3 (15) | 12 (60) |

| Other (including patients who were undecided) | 0 (0) | 3 (15) | 11 (55) | 2 (10) |

| Patient and family wishes documented | ||||

| Wishes documented | 5 (25) | 12 (60) | 16 (80) | 10 (50) |

| DNAR decision only | 4 (20) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (25) |

| No wishes documented | 9 (45) | 0 (0) | 4 (20) | 4 (20) |

| Patient offered discussion but refused | 1 (5) | 8 (40) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) |

The case note reviews were also conducted for patients who died within 100 days of discharge from hospital (see Appendix 5) and at the end of the feasibility trial on the intervention wards to identify changes from before to after implementation (see Appendix 6).

Quantitative analysis

A statistical analysis plan was developed to detail the analysis strategy and statistical considerations (missing data checks and model assumption checks). This document was approved by project statisticians and the TS DMEC. We undertook analysis in accordance with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines in collaboration with King’s Clinical Trials Unit; two statisticians (WG and RW), the chief investigator (JK) and the health economist (DY) were blind to the randomisation.

All percentages, means, medians, ranges, standard deviations (SDs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were rounded up to one decimal point. No tests of significance were conducted as this was a feasibility trial with no aim to test the effectiveness of AMBER compared with standard care. However, 95% CIs were provided to indicate the precision of the estimates from the preliminary trial.

Data entry

All data were entered into predesigned EpiData (EpiData Association, Odense, Denmark) databases. Ten per cent of the data were double-entered and cross-checks were conducted. No discordance was detected for the primary outcome measures (100% match for IPOS patient/family anxiety and communication subscale and howRwe), with very high accuracy for the rest of the questionnaires.

Sample size for the feasibility cluster randomised controlled trial

A formal power calculation was not appropriate because effectiveness was not being evaluated. Any investigations of changes in trial parameters were exploratory only. Based on the information about number of deaths and prior studies, we aimed to recruit 40 patients per trial arm to meet our feasibility objectives.

Economic evaluation

The data analysis in the economic evaluation examined resource implications from both (1) a health/social care perspective and (2) a societal perspective. We made preliminary cost-effectiveness calculations (e.g. combining CSRI data on costs and EQ-5D score). Economic evaluation is an emergent area in palliative care and uncertainty surrounds best practice. 72 The feasibility trial tested procedures to inform the economic evaluation in the full cluster RCT protocol.

Qualitative data analysis

The qualitative data analysis approach was informed by the Framework approach to inductively code and organise the data and identify emerging themes from the interviews. 79 The Framework approach involves a five-stage matrix-based approach comprising:

-

Familiarisation. We immersed ourselves in the raw data from the interviews by listening in detail to audio-recordings, reading and rereading transcripts and also studying field notes to list key ideas and recurrent themes.

-

Identifying a thematic framework. We developed a thematic framework to identify all of the key issues, concepts and themes so the data could be examined. This was carried out by drawing on a priori issues and questions derived from the aims and objectives of the trial as well as issues raised by the participants themselves. The end product of this stage comprised a detailed ‘index’ of the data so we could ‘label’ the data into manageable chunks for subsequent retrieval and exploration.

-

Indexing. We applied our thematic framework to all the data in textual form by annotating the transcripts with codes from the index, supported by short text descriptors to elaborate the index heading. We made use of NVivo 11 data analysis software (QSR International, Warrington, UK) to facilitate this process.

-

Charting. We rearranged the data according to the part of the thematic framework to which they related, and formed charts. The charting process involved a considerable amount of abstraction and synthesis.

-

Mapping and interpretation. Finally, we made use of the charts to define concepts, map the range and nature of phenomena, create typologies and find associations between themes with a view to providing explanations for the findings.

We addressed issues of rigour and trustworthiness in the analysis. We (JK, EY and HJ – blinded to intervention allocation) randomly selected interview transcripts to review the application of the thematic framework, the coding and the completeness of the framework. When coding differed or areas of the framework were inconsistent, these issues were reconsidered in detail until a consensus was achieved. 80 During this process, we took care to examine what appeared to be more unusual or non-confirmatory views and considered what the data told us about their causes to avoid making unwarranted claims about patterns and regularities in the data. 80 Excerpts from the interview transcripts are presented to illustrate themes representing a range of views rather than being reliant on selected individuals. All quotations from participants (patients, relatives and HCPs, and their specific trial sites) have been anonymised to preserve confidentiality.

Mixed methods: triangulation of data

The aim of the data integration was to examine different aspects of the AMBER care bundle experience and participation in the research trial. Data were integrated using a method of data ‘triangulation’, which combines data sources from more than one source (quantitative and qualitative) to address the same phenomenon. 81,82

The process of triangulating findings from the different methodological approaches took place at the interpretation stage of a feasibility trial after all data sets have been analysed separately. Specifically, we listed the findings from each component of a trial and then considered where findings from each approach agree (convergence), offer complementary information on the same issue (complementarity) or appear to contradict each other (discrepancy or dissonance). We looked for instances of convergence but also for disagreements between findings from different approaches. We believe that disagreement is not a sign that something necessarily went wrong with our feasibility trial. Indeed, instances of ‘intermethod discrepancy’ may lead to a better understanding of how the intervention operates, its effects and where it can be improved. We also looked for instances of silence – where a theme or finding arises from one data set but not from others. Silence might be expected because of the strengths of different methods to examine different aspects of the bundle.

Implementation of the AMBER care bundle

The process of implementing the AMBER care bundle comprised three stages:

-

Findings from the ‘heat maps’ were shared with the hospital staff to inform them about the suitability of the wards for the AMBER care bundle and enabled them to use the data for their own quality assessment. Heat maps did not include any identifiable patient-related information.

-

A baseline review of patients’ clinical case notes was conducted on each of the selected wards prior to the AMBER care bundle implementation. The case notes were scrutinised to –

-

identify patients who would be suitable to be supported by the intervention

-

check if a documented plan for their care was in place

-

identify if there was evidence of an escalation plan and if the medical plan had been agreed with nursing staff

-

identify if there was evidence that a conversation had taken place with the patient and their relatives regarding their uncertain clinical situation and care preferences

-

identify if there was evidence that capacity and or best interests assessments had been appropriately addressed

-

identify, for patients discharged from hospital, any non-elective readmissions in the last 100 days, and the outcome (died or discharged).

-

-

Once a suitable ward had been identified, the nurse facilitator engaged in four steps to introduce and implement the AMBER care bundle on each ward. This involved –

-

familiarisation with the ward

-

introducing the intervention to HCPs and training them on its use

-

supporting HCPs in the practice of using the AMBER care bundle (role modelling and developing relevant communication skills)

-

observing how HCPs used the AMBER care bundle

-

exit plans and completion of a follow-up case note review.

-

The criteria to determine if the ward was perceived to be ready to support suitable patients and their families with the AMBER care bundle included fulfilling the criteria described in Table 4.

| Aspect of training | Baseline criteria |

|---|---|

| Education inputs completed/clinical processes adjusted as planned |

|

| Patients supported by the AMBER care bundle – open communication (observe in practice/notes) – patient/family awareness/feel supported (ad hoc feedback) |

|

| Senior staff (medical, nursing, allied health professionals, critical care outreach) able to identify patients (observe white board rounds without needing to prompt, different HCPs raise the concern) – effective MDT working and ability to work across hierarchies around clinical uncertainty of recovery | At MDT meetings and ward rounds, staff are able to identify patients who meet the AMBER care bundle criteria without prompts from the nurse facilitator. When asked if there are any patients they think may have an uncertain recovery and meet the AMBER care bundle criteria, junior and non-medical members of the team as well as medical colleagues are able to highlight potential patients for discussion with the wider team. They may use different terminology but allude to a clinical uncertainty of recovery – the patient may or may not recover |

| Staff able to describe the AMBER care bundle well (five staff at random) – includes relevant teams working with the ward |

When asked about their understanding of the intervention, staff are aware that it is used to support very unwell patients who may or may not be approaching the end of life and patients who have clinical uncertainty, and that the aim is to have a clear plan (medical/escalation/resuscitation) and involve patients/families in discussions regarding care and preferences NB flexibility is required here – staff may not all use the same terminology depending on their individual experience, but an awareness of the principles is the important factor |

| Awareness of the plan for patients receiving care supported with the AMBER care bundle (MDT aware, observation on handover) – what is important to the patient and escalation plan? | At handover and when asked, senior staff demonstrate an awareness of the patient’s current medical, escalation and resuscitation plan. They are aware of the patient’s/family’s wishes/preferences (e.g. PPC, who they want to care for them) |

| Good documentation and adherence to standards processes. Good communication on discharge and handover to general practitioner and community teams (notes) |

|

Prior to start of the data collection at sites Int1 and Int2, the following were achieved in terms of implementation of the AMBER care bundle:

-

More than 90% of the nursing, medical and therapy staff, the discharge planning teams, ward clerks, the palliative care teams and the respiratory teams were trained; critical care outreach teams were briefed; education inputs were completed; and clinical processes were adjusted to accommodate use of the AMBER care bundle.

-

HCPs were able to discuss ‘clinical uncertainty’ and care preferences with patients and families supported by the AMBER care bundle and provide appropriate support (observed by the nurse facilitator).

-

HCPs were able to identify patients eligible for the intervention without prompting in MDT meetings, including senior medical, junior medical and non-medical staff (observed by the nurse facilitator).

-

Five randomly selected HCPs at each intervention site were able to correctly describe the AMBER care bundle, as per the inclusion criteria, to the nurse facilitator.

-

Senior HCPs discussed what they considered to be important to patients, and their escalation plans when present, at handover meetings (observed by the nurse facilitator).

-

Four main components of the AMBER care bundle were completed in more than 80% of patients’ clinical notes; discharge letters regularly contained information as per the AMBER care bundle inclusion criteria (observed by the nurse facilitator).

Recruitment of the nurse facilitator

The trial successfully recruited a palliative care clinical nurse specialist (CNS) (NHS nursing band 8a) who possessed extensive experience in implementing the AMBER care bundle across all the wards at another NHS trust, with an excellent understanding of the AMBER care bundle, end-of-life care, service and quality improvement, demonstrable knowledge and skills in advanced communication, interpersonal and leadership qualities, an excellent understanding of the NHS infrastructure and a proven ability to think and plan strategically.

Chapter 3 Findings from the feasibility cluster randomised controlled trial of the AMBER care bundle

Findings in relation to each trial objective are presented in this chapter.

Screening processes and initial approach

The screening process varied across the four trial sites. Screening, providing information about the trial, consenting and administration of the questionnaire booklets were completed by the research nurses at all sites. The central research team was updated on a weekly basis.

At site Con1, research nurses screened all of the patients on the trial ward at the beginning of the week and then checked on a daily basis for recently admitted patients who may meet the trial inclusion criteria. They then discussed these patients with clinicians and jointly agreed on each patient’s eligibility status. At site Con2, research nurses screened the patients on a weekly basis. However, the identification of eligible patients and introducing the trial to potential participants were generally completed by the principal investigator and his medical colleagues. At sites Int1 and Int2, research nurses made use of the hospital ward white boards to identify patients who were supported by the AMBER care bundle.

Participant flow

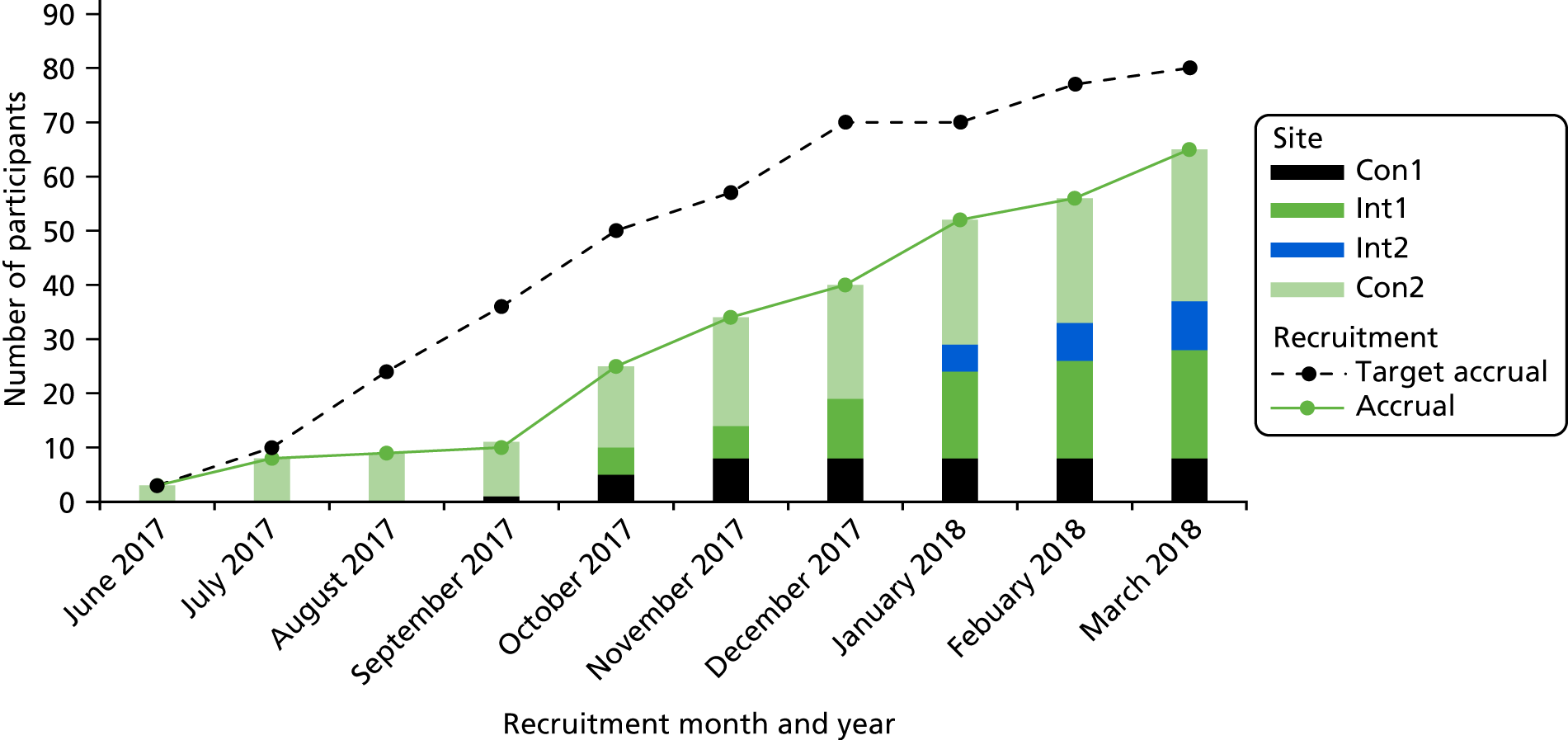

Figure 4 is the CONSORT flow diagram of participant recruitment from screening to baseline to time point 1 (3–5 days), time point 2 (10–15 days) and thenceforth to analysis. In total, 65 patients were recruited to the trial: 29 participants in the intervention arm and 36 participants in the control arm were consented and had completed baseline measures. We aimed to recruit a minimum of 80 participants, and were able to successfully recruit 81.3% of this target. As the AMBER care bundle is an intervention that does not require active participation of the patients or relatives, the intervention completion is not applicable, hence it is not included in the CONSORT flow diagram. We had planned for recruitment to take > 3 months at each of the trial sites, with an average of seven participants consented per month. However, we extended the recruitment period, as the recruitment rate was slower than expected. Figure 5 presents the monthly cumulative recruitment figures for each site (bars), the accrual rate (green line) and target accrual rate (dashed line) over the 9-month data collection period. It should be noted that trial sites opened to recruitment at different time points. Comparing the gradients of the targeted and achieved accrual, the recruitment kept up with the planned rate once the initial delays and issues around understanding the trial were overcome.

FIGURE 4.

The CONSORT flow diagram. Reproduced from Koffman et al. 1 ©The Authors 2019. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated. This figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

FIGURE 5.

Monthly recruitment rate by site.

Recruitment, retention and follow-up rates

The feasibility of the recruitment strategy was examined by summarising the screening, eligibility, approach and consent processes, reasons for non-participation and the numbers of participants involved at each stage.