Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 11/112/01. The contractual start date was in November 2013. The draft report began editorial review in June 2018 and was accepted for publication in January 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Sarah Hewlett’s institution received a grant from Novartis International AG (Basel, Switzerland) after the trial ended, to train rheumatology teams in fatigue management. Ernest Choy’s institution received grants from the Medical Research Council (London, UK) and Versus Arthritis (formerly Arthritis Research UK) (Chesterfield, UK). In addition, Ernest Choy has received grants/consultancy or speaker’s fees from AbbVie Inc. (North Chicago, IL, USA), Bristol-Myers Squibb (New York, NY, USA), Chugai Pharmaceutical Co. (Tokyo, Japan), Eli Lilly and Company (Indianapolis, IN, USA), Janssen: Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson (Beerse, Belgium), Novartis International AG, ObsEva SA (Geneva, Switzerland), Pfizer Inc. (New York, NY, USA), Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (Tarrytown, NY, USA), F. Hoffmann-La Roche AG (Basel, Switzerland), R-Pharm JSC (Moscow, Russia), Sanofi SA (Paris, France), SynAct Pharma (Lund, Sweden), Tonix Pharmaceuticals (New York, NY, USA) and UCB Pharma Ltd (Slough, UK). William Hollingworth is a member of the Health Technology Assessment Clinical Trial Board (2016–present).

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Hewlett et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Scientific background

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) affects approximately 0.5 million people in the UK,1 with widespread synovitis leading to joint pain and stiffness in repeated flares of inflammatory activity. Over time this inflammatory activity can result in multiple joint damage and disability, with major impacts on quality of life, including social and work life. 2 Initiation of very early pharmacological treatment (treat to target) aims to switch off these inflammatory processes and is combined with multidisciplinary interventions by secondary care rheumatology teams to support self-management of symptoms and lifestyle. 3,4

In the past decade, consultation with people with RA regarding their treatment priorities has highlighted the importance of fatigue as a symptom. 5 For many people with RA, fatigue is present on most days and can be as extreme as that seen in chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS), and as severe as their RA pain. 6,7 Qualitative research shows that people find RA fatigue to be not only a physical experience, but also to have emotional and cognitive elements that can have an impact on their work, family roles and relationships. 8,9 Quality of life is reduced by fatigue,10 which patients report as being as difficult as pain to manage. However, fatigue is often ignored by the rheumatology team,9,11 despite being one of patients’ top priorities. 5 People with RA consider fatigue to be a major feature in work loss,12 which affects two-thirds of working people with RA. In addition, approximately one-fifth of people with RA become work-disabled within 5 years, resulting in an annual UK work production loss from RA of around £2 billion. 13,14 These findings led to international consensus that the effect of interventions on RA fatigue should now be reported in all RA clinical trials alongside the traditional core set. 15

Inflammation as a possible mechanism for rheumatoid arthritis fatigue

If the inflammatory processes of RA are the major driver of RA fatigue, either directly or through the effects of inflammation on pain and function, then pharmacological interventions for RA inflammation should also significantly improve fatigue. However, systematic review shows that biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (bDMARDs) to control RA inflammation yield only a small to moderate improvement in RA fatigue (32 studies involving 14,628 patients), although the quality of the studies was variable. 16 Inflammatory activity, not fatigue, is the indication for initiating or changing bDMARD therapy; therefore, these studies did not recruit patients specifically with fatigue. 16 The findings are supported by other studies that show that RA fatigue continues to be problematic even for those patients who achieve disease (i.e. inflammatory) remission. 17 Therefore, it is unlikely that inflammation alone is the single driver for RA fatigue.

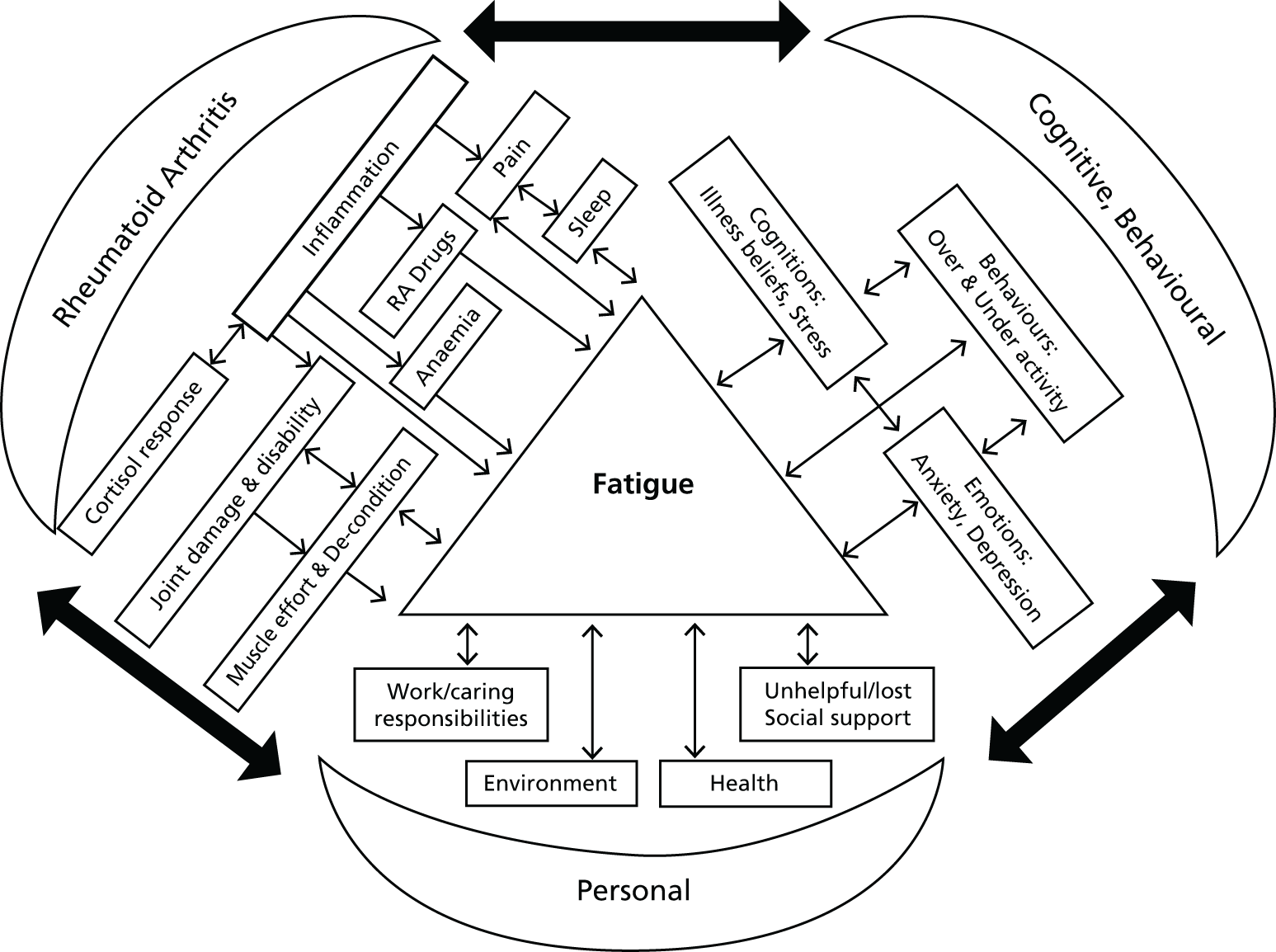

Multicausal pathways as a likely mechanism for rheumatoid arthritis fatigue

A systematic review of causal studies relating to RA fatigue could not draw conclusions as a result of the quality of the evidence, which was largely cross-sectional or longitudinal studies that rarely controlled for baseline fatigue. 18 Therefore, with insufficient studies, and often conflicting results on any single causal mechanism for fatigue (e.g. inflammation, disability, depression),18 it is postulated that, conceptually, RA fatigue is likely to have complex and multicausal pathways (see Appendix 1). 19 These pathways are categorised as potentially involving interactions between or within three elements: (1) disease processes (RA elements); (2) thoughts, feelings and behaviours (cognitive/behavioural elements); and (3) life issues (personal elements). 19 Pathways will vary between patients and potentially even within patients for individual fatigue episodes. For example, on one occasion fatigue may be driven by inflammation causing pain and disrupting sleep, interacting with heavy work responsibilities that lead to overactivity (keeping going until exhausted); however, on another occasion fatigue may be driven by low mood, leading to behavioural withdrawal (deactivation) and subsequent deconditioning. In this conceptual model, self-management strategies appear crucial in managing fatigue impact.

Physical exercise interventions

Physical exercise interventions might address muscle or respiratory deconditioning from inactivity that cause fatigue. A systematic review of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of non-pharmacological interventions reporting RA fatigue identified six physical exercise interventions (five RCTs involving 371 patients), including pool therapy, yoga, t’ai chi, low-impact aerobics, strength training and stationary cycling. 20 Meta-analysis showed a small effect on fatigue severity. However, none of these studies had fatigue as a primary outcome, fatigue was not an inclusion criterion and studies were not powered to detect fatigue change.

Psychosocial interventions and underpinning theory

A broader approach of psychosocial interventions for helping people manage their fatigue may address multiple elements in the conceptual model simultaneously. 19 Educational interventions may provide the information people need to identify and change behaviours that might be stopping their management of fatigue [e.g. introducing ideas of breaking up periods of activity with rest (pacing)]. Interventions that also address thoughts or feelings related to fatigue and its management might lead to more beneficial coping strategies by looking at ways of managing stress, low mood and priorities for a work–life balance.

Rationale for cognitive–behavioural therapy for fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis

Cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) aims to help people work out for themselves the links between their thoughts (cognitions) and feelings and how these may be driving their actions (behaviours), and addresses these underpinning cognitions as a way of prompting behaviour changes. 21 For example, a belief that it is one’s role to do the household chores may prevent someone asking family members to help, which, combined with feeling shame or guilt if chores are left undone, may drive persistence in undertaking chores. This excessive activity leads to episodes of overwhelming fatigue and enforced rest (so-called ‘crashes’), commonly called the ‘boom-and-bust’ cycle. Addressing these previously unchallenged beliefs about what family members would think about a request for help, and whether or not leaving some chores undone would be a catastrophe, might prompt behaviour changes that result in less fatigue. The lack of an existing clear approach to self-management of fatigue from RA professionals may contribute to a sense of powerlessness and passivity among people with RA fatigue who feel their lives are controlled by its perceived unpredictability. CBT provides a framework through which a person can better understand those components of fatigue experiences that are controllable, and, through this, make a shift in core beliefs towards taking control rather than being passive. On the basis of such a shift a person could become progressively less passive and more self-confident through better self-management of activity and fatigue symptoms so that the impact of fatigue is reduced.

A systematic review of group education programmes for general self-management in musculoskeletal conditions found that a CBT approach is more likely to lead to people making behaviour changes than information alone,22 and CBT has been shown to be effective for fatigue in CFS and multiple sclerosis. 23,24 Problem-solving and goal-setting as routes to enhancing self-efficacy (see Underpinning theory: self-efficacy and social cognitive theory) are the core self-management skills that patients learn in CBT.

Underpinning theory: self-efficacy and social cognitive theory

Managing daily life with RA in order to minimise fatigue requires changing behaviours that might have been contributing to fatigue onset, perpetuating it, or limiting its management. Changing habitual behaviours can be hard, and self-efficacy is the belief or confidence that one can successfully execute an action or master a situation and is a strong predictor of behaviour change and persistence in the face of difficulty. 25 Self-efficacy is cultivated through reinterpretation of symptoms (understanding that fatigue has many causes that could be tackled), mastering the new behaviours (through progressive goal-setting), and by modelling and social persuasion (from seeing the successful changes and adaptions of other RA patients). 26 Therefore, learning about fatigue management as part of a group can enhance these self-efficacy processes because other patients in similar situations act as role models: validating the complexity of fatigue and demonstrating more effective ways of mastering it through the efforts they make as fellow participants on the programme [social cognitive theory (SCT)]. 25,26 It has been demonstrated that interventions based on SCT and/or CBT enhance self-efficacy and produce better patient outcomes than simply providing self-management information. 22,27 Learning with others in similar circumstances may be particularly helpful for validating invisible symptoms, such as fatigue.

Evidence for psychosocial interventions on rheumatoid arthritis fatigue

Three RCTs trialled one-to-one CBT, a group programme (based on SCT) and a group CBT programme (SCT/CBT) over 11, 16 and 22 hours, respectively, and reported improved fatigue in RA patients. 28–30 However, interventions were not primarily aimed at improving fatigue severity; thus, patients were not recruited because of fatigue, nor were studies powered to detect fatigue change. Furthermore, participation in the studies was restricted (e.g. to those with early disease, mild disability or psychological distress or who have a partner). However, RA fatigue occurs in the majority of patients;6,7 therefore, self-management interventions should be tested across a wide RA population. Therefore, the original 18-week RCT was conducted to test a fatigue self-management programme in a broad RA population (fatigue score of ≥ 6/10), using group CBT (13 hours SCT/CBT), led by a clinical psychologist and specialist pain management occupational therapist (OT), compared with groups receiving fatigue self-management information alone (n = 127). 31 The group CBT intervention improved fatigue impact (effect size 0.77) alongside fatigue severity and coping with fatigue, as well as disability, sleep and mood (depression, helplessness, self-efficacy). In the qualitative evaluation undertaken through participant interviews, patients spontaneously raised the significance of key elements of the CBT used by the clinical psychologist (working links out for themselves, goal-setting, activity diaries), and SCT components (the value of being in a group). 32

A systematic review identified 15 psychosocial interventions reporting RA fatigue, including the previous study (13 RCTs involving 1556 patients). 20 Interventions included expressive writing, CBT, mindfulness, lifestyle management, self-management, energy conservation and group education, and showed an overall small benefit on RA fatigue severity. The overall quality of trials was rated as being low, largely accounted for by small patient numbers and the difficulty of blinding participants in interventions that require engagement for behaviour change. Within the systematic review, the RCTs detailed above, which were the only interventions in which improving fatigue was an aim or inclusion criterion,28,30,31 had stronger methodological qualities and stronger effects on fatigue.

Rationale for programme delivery by rheumatology clinical teams

The fatigue self-management programme using CBT and SCT was delivered by a CBT-trained clinical psychologist. 31 However, only 8% of rheumatology units have a clinical psychologist on their team;33 therefore, implementation in routine NHS care is currently difficult. Enabling people with long-term conditions to self-manage is a key government target,34 and RA-specific guidelines by rheumatology professional bodies and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)3,4,35 highlight the need to address self-management, including fatigue. Given the success of psychological therapies but the shortage of clinical psychologists, Improving Access to Psychological Therapies is also a government health policy. 36 This is being achieved through manualisation of psychological interventions and training non-clinical assistants to deliver them, often by telephone and under the supervision of a psychologist, adhering closely to the intervention stipulated and referring those cases that are not straightforward to the psychologist. It might be that RA fatigue self-management programmes do not need to be delivered by trained CBT psychologists, but could be delivered by, for example, Improving Access to Psychological Therapies practitioners guided by a manual. However, in people with RA fatigue, thoughts, feelings and behaviours will also interact with their need to manage a complex, lifelong and fluctuating chronic physical illness that in itself requires managing the interactions between pain, inflamed joints, disrupted sleep, multiple medications and their accumulative effects on overall well-being. Therefore, in order to address these issues, psychological therapies need to be provided by clinicians who understand the multiple interactions between fatigue and the patient’s wider self-management of fluctuating RA symptoms. The multidisciplinary team, particularly rheumatology nurse specialists (RNSs) and OTs, routinely support RA patients in self-management and understand these interactions; therefore, with appropriate training and support RNSs and OTs are ideally placed to deliver a group fatigue intervention using cognitive–behavioural (CB) approaches, thus embedding fatigue management within usual care.

Development of the RAFT programme intervention for delivery by clinical teams

The original group CBT fatigue intervention delivered by a clinical psychologist and specialist OT to people with RA31 was developed from clinical experience of chronic pain and CFS self-management programmes, using the Medical Research Council’s framework for complex interventions. 37 The intervention was grounded in qualitative data about RA patients’ experiences of fatigue9 and clinical RA experience. The intervention comprised six 2-hour sessions, running once per week (weeks 1–6), and a 1-hour consolidation session (week 14), and was delivered to groups of approximately 5–7 patients. For delivery by clinical teams, a tutor manual was produced, and the intervention given the acronym RAFT (Reducing Arthritis Fatigue by clinical Teams using CB approaches).

The RAFT programme delivery: cognitive–behavioural and social cognitive theory approaches

The CB approach used was one of reflective discovery through Socratic questioning, in which tutors ask simple questions to enable patients to identify the links between their thoughts, feelings, behaviours and symptoms (i.e. fatigue). 21 This was in contrast to the more didactic information- or advice-giving by the tutors, in which the patients were passive recipients of information. Self-monitoring (daily activity/rest charts) and goal-setting are the most effective tools in bringing about behavioural change,38 and the use of metaphors helps turn abstract or difficult therapeutic concepts into a form that can be more easily understood and remembered. 39 The value of group CB programmes is that fellow patients are a credible source to legitimise or validate invisible symptoms, such as fatigue, and provide role models and peer support in the goal-setting and problem-solving processes. 25

The RAFT programme content

The RAFT programme addresses the potential interactive drivers of fatigue (see Appendix 1)19 and its management, with the tutors facilitating topic discussions for the first hour, then splitting after a short tea break into two groups for detailed goal-setting. Topics, goal-setting and homework build on earlier sessions over the weeks (see Appendix 2). 40 The group initially validates this invisible symptom of fatigue and the problem of managing it, then explores pacing and how underpinning thoughts drive boom-and-bust cycles (week 1). Between sessions patients are asked to monitor their patterns of activity, rest and fatigue crashes by colouring in an hourly chart. In week 2, things that energise or drain are the topic, and personal priorities to improve overall life balance then feed into goal-setting, when each participant’s daily activity chart is discussed to elucidate behaviour patterns and their consequences (fatigue). These charts are the focus of the small group discussions each week and give a visual overview of a changing balance of rest, activity, sleep and relaxation/energisers and, hopefully, fewer fatigue crashes because of improvements in pacing as the programme progresses. Subsequent topics are sleep (week 3), with its links to stress (week 4), and the struggle to communicate what can and cannot be done because of fatigue (week 5). Week 6 looks at dealing with setbacks (using a metaphor of ‘falling into the pit’ that is fatigue), and reviews the skills introduced in weeks 1–5. The consolidation session (week 14) helps participants reflect on their progress in acceptance and self-management of fatigue (using the metaphor of leaving the ‘isolation of a desert island’ that is fatigue), and finishes with longer-term goals.

The RAFT programme training and materials for tutors

The RAFT programme was manualised for the tutors, including a detailed guide for each session, sample texts, diagrams and patient handouts (these were piloted and refined). 41 The RAFT programme was co-facilitated by a pair of tutors, who were clinical rheumatology nurses and/or OTs. A 4-day training programme was delivered to all the RAFT programme tutors together, covering RA fatigue and the conceptual model, information on CB principles, Socratic questioning (used to help patients identify thoughts that drive behaviours), self-efficacy, goal-setting and group management, and each RAFT programme session was discussed and demonstrated or rehearsed. To complete their training, tutor pairs delivered a practice programme to patients and were observed and given feedback by a trainer (a clinical psychologist, specialist OT or a rheumatology nurse specialising in fatigue: NA, BK and SH). As tutors were experienced rheumatology clinicians, little clinical supervision was required; thus, one session in each of programmes 2 and 4 was supervised by a trainer.

Aims and objectives

The objectives are reproduced from Hewlett et al. 40 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

The overall aim of this study was to test a group CB intervention for RA fatigue (the RAFT programme) that can be routinely delivered by clinical rheumatology teams across the NHS, using a manualised programme with all supporting materials, delivered by the rheumatology team after brief training and with minimal clinical supervision. 40 The objectives were to:

-

assess whether or not there is a clinically important difference in the impact of fatigue at 6 months between patients participating in a group CB self-management programme for RA fatigue, delivered by the clinical rheumatology team using a detailed manual (in addition to usual care), and patients receiving usual care alone (which includes written fatigue self-management information)

-

compare differences between trial arms for secondary outcomes of fatigue severity, coping, mood, sleep, helplessness, pain, disability, valued activities, quality of life, work, health service use, acceptability, and cost-effectiveness for the NHS, patients and society

-

evaluate and control for potential demographic, psychological and clinical predictors of fatigue change

-

evaluate persistence of effect (if any) over 2 years

-

explore whether or not clinical teams trained in CB approaches perceive any positive or negative outcomes, particularly on their wider clinical practice.

The study comprised:

-

a RCT in which the RAFT programme in addition to usual care was compared with usual care alone

-

an evaluation of the cost-effectiveness of providing the fatigue intervention

-

a nested qualitative study to explore the tutors’ (RNSs and OTs) experiences of CB approach training and any positive or negative effects on their wider clinical practice beyond the RAFT programme delivery.

As a process evaluation of the RAFT programme from the patients’ perspectives had been undertaken in the original trial with a qualitative study,32 this was not repeated. Instead, in this RCT, the process evaluation concentrated on understanding the perspectives of rheumatology clinicians who were being asked to learn new skills and deliver the RAFT programme in the nested qualitative study.

Chapter 2 Trial design and methods

Trial design

This trial evaluated the RAFT programme self-management intervention for fatigue plus usual care compared with usual care alone, through a pragmatic RCT delivered by seven hospital teams across the UK, a setting that reflected clinical practice. Clinical care, including medication change, continued as normal and without restrictions for all participants throughout the trial. In addition to clinical effectiveness (see Chapter 3), a health economic evaluation (see Chapter 4) and a qualitative evaluation of the RNS and OT tutors’ experiences (see Chapter 5) were undertaken. The protocol has been published. 40

Ethics and registration

The trial and qualitative study were approved by the East of England – Cambridgeshire and Hertfordshire Research Ethics Committee (reference number 13/EE/0310), after which each centre obtained the necessary local research and development approvals. The RCT was registered with the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number registry as ISRCTN52709998.

Participants

Inclusion criteria

In order to reflect pragmatic clinical practice, in which the majority of RA patients experience fatigue, inclusion criteria were very broad. Patients aged ≥ 18 years with confirmed RA42 were eligible if they had a fatigue severity score of ≥ 6 (out of 10) on the Bristol Rheumatoid Arthritis Fatigue Numerical Rating Scale (BRAF-NRS),43,44 which they perceived was a recurrent problem.

Exclusion criteria

Patients were excluded if they had recently changed major RA medication (within 16 weeks) or glucocorticoids (within 6 weeks), as that might influence fatigue. Patients were ineligible if they had insufficient English to participate in group discussions or lacked capacity for informed consent.

Setting

Rheumatoid arthritis is managed in secondary care; therefore, the RAFT programme was delivered by pairs of local hospital rheumatology clinicians (i.e. nurses/OTs, band 6 or 7), who understand how RA symptoms interact with fatigue in the self-management of a long-term, fluctuating condition that requires adaptation and acceptance. In order to test the generalisability of the RAFT programme, the seven participating rheumatology units encompassed a range of large and small departments, academic and non-academic, covering city and rural areas in England and Wales (Bristol, North Bristol, Cardiff, Chertsey, Poole, Torbay and Weston-super-Mare).

Recruitment procedures

Patients with RA were invited to complete the BRAF-NRS to screen for fatigue severity, either when attending clinic or by mailshot to departmental lists in the seven participating hospitals. If fatigue was scored as ≥ 6 and the patient was interested, other eligibility criteria were then checked, and an information sheet provided with a pre-paid envelope to return to the local research nurse. Each centre recruited to and delivered four consecutive RAFT programmes over 2 years. In order to randomise 5–7 patients to a RAFT programme, each centre recruited 10–14 patients and then closed that ‘cohort’. Over a 2-week period, those patients attended for informed consent and baseline assessment, and then received usual care for fatigue. When all patients had completed this, randomisation occurred and recruitment commenced for the next cohort. Delays between screening and baseline assessment were inevitable, as baseline assessments could not be performed until a centre had accrued a large enough cohort of 10–14 interested and eligible patients (which often took several months). Therefore, any changes to eligibility at baseline assessment (e.g. fatigue less severe, medication changed) were noted for potential subgroup analysis; however, the patient proceeded to randomisation, reflecting the pragmatic way in which this intervention would be delivered in practice to a population with fluctuating, recurrent fatigue and frequently changing medication regimens. Patients who were randomised to a RAFT programme but were then unable to attend the dates offered maintained their randomisation allocation and were offered the subsequent RAFT programmes being run in that centre; if they accepted then they had a new baseline assessment performed with the others in that cohort.

Interventions

The RAFT programme intervention

The RAFT programme is a CB fatigue self-management programme delivered to groups of 5–7 RA patients in six 2-hour sessions (weeks 1–6) and a 1-hour consolidation session (week 14) by a pair of local RNSs and/or OTs (see Chapter 1). Taking a pragmatic approach, if one of the tutors was unable to deliver a session, perhaps because of illness, the remaining tutor delivered the session alone. Patients were asked to attend all seven sessions if possible; however, some patients inevitably missed some sessions as RA is a fluctuating condition, in which case tutors offered to explain some of what had been missed, prior to the next session.

Fidelity to the RAFT programme during delivery

Quality and homogeneity of the RAFT programme were facilitated by standardised training and a standardised manual, with programme delivery by the same tutor pairs in each centre. However, unlike a pharmacological RCT, in a group CB intervention it is not possible to adhere to a rigid protocol in every session, as tutors must respond to the individual issues raised by patients. Therefore, fidelity evaluation was pragmatic and involved monitoring in one randomly selected session of each of the four programmes run in each centre. An independent clinical psychologist observer (Richard Cheston) used a template to record evidence of CB approaches (e.g. reflective questioning, group management, goal-setting), delivery of the RAFT programme as planned (adherence to session plans), use of the RAFT programme materials (handouts, metaphors) and any unhelpful delivery styles (e.g. didactic teaching) (see Report Supplementary Material 1). 41

Control intervention (usual care alone)

Unlike pain, RA fatigue is not routinely addressed in usual care in great detail and patients are generally given written fatigue information by the RNS. Most rheumatology units supply the free Versus Arthritis (formerly Arthritis Research UK) fatigue booklet,45 a comprehensive fatigue self-management booklet for arthritis authored by Hewlett et al. and based on their original RCT. 31 It contains information on all the topics in the RAFT programme, includes a pull-out sample activity and rest chart to complete and could be considered ‘usual care’. Usual care (i.e. provision of the Versus Arthritis fatigue booklet) was given to patients in both the control and intervention arms of the trial at the baseline visit, after consent and assessment but before randomisation. The research nurse spent approximately 5 minutes showing their patient the sections in the booklet, using a brief standardised guideline and pointing out that the booklet suggests patients might wish to request specific support from the rheumatology team to help them try the fatigue self-management activities described (generally requested via the local RNS helpline). Seeking help is thus an intended outcome of the booklet, which was captured within health-care use data collected in the trial. In order to minimise the risk of contamination between the trial arms, the helpline RNS were asked not to book in a control patient requesting fatigue support to see a clinician who was also a RAFT programme tutor if there was an alternative health professional available, and tutors recorded any control patients seen for fatigue support.

Outcomes of clinical effectiveness

Primary outcome measure (26 weeks)

As the impacts of fatigue are wide-ranging and personal to individuals’ lives, the perceived impact of fatigue was the primary outcome measure, rather than fatigue severity. 8–11 Fatigue impact was measured by a single NRS item, ‘Please circle the number that describes the effect fatigue has had on your life in the last 7 days’, with anchors of ‘No effect’ to ‘A great deal of effect’ (0–10), using the BRAF-NRS for impact (see Report Supplementary Material 2). 43,44

Secondary outcome measures (clinical)

The secondary fatigue outcomes were fatigue severity and coping (as measured using the BRAF-NRS severity, BRAF-NRS coping questionnaires) (see Report Supplementary Material 2) and a RA fatigue multidimensional questionnaire [i.e. Bristol Rheumatoid Arthritis Fatigue Multidimensional Questionnaire (BRAF-MDQ)] (see Report Supplementary Material 2), which measures overall fatigue impact and includes subscales for physical fatigue, living with fatigue, emotional fatigue and cognitive fatigue. 43,44 Each of these fatigue variables might respond differently to interventions. Other components of the RA fatigue conceptual model19 evaluated were mood [via the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)],46 pain (via the NRS), disability [via the modified Health Assessment Questionnaire (MHAQ)],47 quality of life [global arthritis impact question from the Arthritis Impact Measurement Scale (AIMS)],48 sleep quality (via a single question from the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index),49 and returning to important leisure activities previously lost to fatigue [via the discretionary activity subscale of the Valued Life Activities scale for rheumatoid arthritis (VLA)]. 50 Beyond pain, disability and fatigue, remaining items from the RA core set51 were an objective assessment of painful joints and swollen joints, an inflammatory marker (i.e. C-reactive protein) and patient global opinion of disease activity [visual analogue scale (VAS)], forming a single disease activity score [Disease Activity Score (DAS28)] through a weighted algorithm. 52 As the DAS28 requires a hospital visit to the research nurse, it was measured at weeks 0 and 26 only, and replaced at all other time points by a patient self-reported version [i.e. the simplified Patient-derived Disease Activity Score (sPDAS2)]. 53,54 Social contact questions (unvalidated) were added for weeks 52 and 104.

Secondary outcome measures (processes)

To understand what key processes may relate to behavioural change, helplessness [via the Arthritis Helplessness Index (AHI)]55 and self-efficacy [via the Rheumatoid Arthritis Self-Efficacy (RASE) scale]56 were measured. The RASE scale contains questions on self-efficacy beliefs for managing RA covered in both the RAFT programme and the usual-care Versus Arthritis fatigue booklet. 45

Secondary outcome measures (acceptability and feasibility)

Acceptability of the RAFT programme and the usual-care booklet45 was assessed at week 26 by patient satisfaction and the likelihood that patients would recommend the programme or booklet to others, and by programme attendance. Feasibility of delivery in the NHS was captured through monitoring of programme scheduling and delivery, and the tutor qualitative evaluation.

Follow-up time points, data collection and management

Baseline assessments (and usual care) for each cohort were conducted over a 2-week period. The cohort was then randomised, and those patients randomised to the RAFT programme commenced their local programme within a few weeks. To standardise data collection across all cohorts and centres, the date of each cohort’s first RAFT programme session was designated as week 1 for both trial arms. Outcomes were then measured at weeks 6 (end of the RAFT programme), 26 (primary end point), 52, 78 and 104, apart from DAS28 and social contact as described in Secondary outcome measures (clinical). Only fatigue data were collected at weeks 10 and 18 (via the BRAF-NRS for impact, severity and coping and BRAF-MDQ),43,44 to capture outcomes 4 weeks before and after the week 14 consolidation session. Data were collected primarily by patient self-report questionnaire, except for objective measures of disease activity, which were evaluated by the local research nurse (after standardised training) at weeks 0 and 26. Patients completed their self-report questionnaire pack during those visits, but at all other time points questionnaire packs were posted to patients from the central trial team in Bristol, with pre-paid envelopes. In order to maximise data returns, the trial co-ordinator or trial administrator (ZP and CA), with ethics approval, telephoned each patient at each assessment point to collect the primary outcome (i.e. the BRAF-NRS impact) and inform the patient that the questionnaire pack was being posted (participants were contacted once more if packs were not returned within 2 weeks). Data were returned direct to the managing centre (University of the West of England, Bristol, UK) and entered onto an Microsoft Access® database (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) that was created by the Bristol Randomised Trials Collaboration (BRTC) unit. Data entry was then checked by a second researcher against the original questionnaires (100% of entries were checked) (Table 1).

| Assessment | Measure | Score range | Week | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 6 | 10 | 18 | 26 | 52 | 78 | 104 | |||

| Nurse led | ||||||||||

| Demographic data | n/a | ✓ | ||||||||

| Disease activity | DAS2852 | 0.96+a | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Primary outcome | ||||||||||

| By telephone | BRAF-NRS43,44 | 0–10 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Questionnaire (self-reported) | ||||||||||

| Fatigue severity | BRAF-NRS43,44 | 0–10 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Fatigue coping | BRAF-NRS43,44 | 0–10b | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Fatigue overall impact | BRAF-MDQ43,44 | 0–70 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Physical fatigue | BRAF-MDQ43,44 | 0–22 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Emotional fatigue | BRAF-MDQ43,44 | 0–12 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Cognitive fatigue | BRAF-MDQ43,44 | 0–15 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Living with fatigue | BRAF-MDQ43,44 | 0–21 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Pain | NRS | 0–10 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Disability | MHAQ47 | 0–3 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Quality of life | AIMS VAS48 | 0–100 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Disease activity | sPDAS253,54 | 2.4–7.9 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Anxiety | HADS46 | 0–21 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Depression | HADS46 | 0–21 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Sleep quality | Pittsburgh item49 | 1–4 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Valued life activities | VLA50 | 0–3 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Helplessness | AHI55 | 5–30 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Self-efficacy | RASE56 | 28–140b | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Satisfaction and acceptability | ✓ | |||||||||

| Social contact | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

Protocol amendments during the trial

Prior to the first baseline assessment, the global impact of arthritis question48 was added (amendment 1, January 2014). Amendment 2 (February 2015) comprised the addition of the social contact questions (at weeks 52 and 104), following reflection by the Study Management Group that the RAFT programme promotes resisting the desire to isolate oneself. In addition, the qualitative evaluation of tutor experiences through focus groups was expanded to offer one-to-one interviews in order to allow easier discussion of individual opinions. Amendment 3 (September 2015) allowed for the possibility of an additional RAFT programme to run in the case of low levels of recruitment or high levels of attrition (but this was not needed).

Sample size

The sample size calculation has previously been published. 40 In the original trial of CBT delivered by a clinical psychologist, the baseline-adjusted difference in fatigue impact between trial arms was 1.95 units on a VAS (0–10) [95% confidence interval (CI) −2.99 to −0.90 units; p < 0.001], giving an effect size of 0.77. 31 As the RAFT programme is delivered by clinical teams using CB approaches rather than by a CB therapist, the RCT reported here was powered to be able to demonstrate 75% of that (1.46 units, effect size 0.54). For a two-sided significance of 0.05 and a power of 90%, 73 patients per trial arm were required. The study was interested in the average effect across all centres; therefore, no loss of power from randomising patients by centre was considered. 57,58 In the RAFT programme arm there was potential for clustering effects from the seven centres (including the one tutor pair per centre), and from the CB group within centres. In the original RCT, the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) for the CBT group and the primary outcome was < 0.00001, with no data for centre/tutor effects as it was a single-centre study. 31 In the present RCT, an overall ICC value of 0.01 was employed for groups clustered within and between centres, and was used for estimating a design effect,59 increasing the sample size to 75 per trial arm.

In the original RCT,31 most attrition was not from the intervention but from loss to questionnaire completion; therefore, to maximise data returns in this RCT the primary outcome was collected by telephone by the central RAFT programme team as described above, and patients who wished to withdraw were asked if they might continue providing a fatigue impact NRS by telephone (ethics approval given). It was intended to achieve 80% of primary outcome data at week 26, but longer-term attrition was unknown. Therefore, we assumed 50% retention and thus capacity was planned to recruit up to 150 patients per trial arm. A pragmatic approach took account of the need to form viable RAFT programme groups and natural variations in group size; therefore, a target of seven centres each running four RAFT programmes, with an average of six participants per RAFT programme group and six participants randomised to usual care (n = 336), provided contingency for smaller groups.

Minimising attrition

In order to reduce attrition prior to starting a RAFT programme, patients were consented and randomised as close to the dates of the CB programmes as possible and the local research nurse kept patients informed of the potential programme dates. Three-quarters of participants in the original RCT attended most of their seven CBT sessions, suggesting that the RAFT programme would be acceptable. 31 In this RCT a 2-year follow-up potentially risked significant loss to questionnaire completion over time; therefore, to maximise questionnaire returns, the primary outcome data (i.e. fatigue impact NRS scores) were collected by the central trial team by telephone each time (see Follow-up time points, data collection and management). To enhance feelings of community, engagement and responsibility, all RAFT programme study materials included the study logo; questionnaire packs were accompanied by a short newsletter highlighting overall questionnaire return rates, and thank-you notelets were sent at major time points.

Randomisation, concealment and blinding

After consent at the baseline visit, the local research nurse allocated each patient the next consecutive study identification number; as patients chose from several available baseline visit dates and times, this allocation was unlikely to be influenced by the research nurse. When a centre had finished all baseline visits for that cohort (10–14 participants, assessed over a 2-week period), the research nurse sent the unique study numbers to the trial co-ordinator in Bristol, which requested that the BRTC unit conduct the randomisation for that centre’s cohort (concealed from the RAFT programme study team and the research nurse). Computer-generated randomisation (using a specially created Access database) was performed for each cohort (1, 2, 3 and 4) in each centre (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7) consecutively over 2 years as each cohort was finalised and all its participants had attended for consent, baseline assessment and delivery of usual care. Allocation was 1 : 1 within cohorts but, in the event of an odd number, the RAFT programme trial arm received the extra patient on the grounds that risk of attrition was likely to be higher in that arm. The BRTC unit informed the trial co-ordinator of the arm allocations, and the trial co-ordinator informed the local research nurse, who subsequently telephoned each consented patient using a brief, standardised guideline to ensure that no suggestion other than equipoise between the arms was communicated. Those randomised to the RAFT programme trial arm had the dates, times and venue confirmed. Blinding of clinicians delivering the RAFT programme was not possible, nor could patients be blind because of the need to engage them in making behavioural and cognitive changes and attend or not attend the RAFT programme sessions. However, most outcome measures used were validated tools and analysis was performed blind to allocation.

Overview of evaluation methods

Clinical and health economic analysis followed the predefined statistical and health economics analysis plan (SAP) [see URL: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/1111201/#/documentation (accessed 12 April 2019)], which was agreed in discussion with the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and Data Management and Ethics Committee (DMEC). Detailed methods and results are presented separately for the clinical, health economic and qualitative evaluations (see Chapters 3–5).

Study management

The project was managed and co-ordinated centrally in Bristol by the chief investigator (SH), trial co-ordinator (ZP) and trial administrator (CA), with all outcome assessments (apart from baseline and week 26) being sent out by, and returned to, the central study team, thereby enabling careful monitoring of timelines and returns. Each centre employed a research nurse to manage local recruitment, cohort building and closure, visits for consent and baseline assessment, and week 26 assessment. The trial co-ordinator maintained the overall site documentation and a local study file for each site and liaised with all sites and with the BRTC randomisation service. The central co-ordinating team (i.e. SH, ZP and CA) held weekly meetings to set up the trial, with other key trial staff, co-applicants and patient partners attending as appropriate. Monthly Trial Management Group meetings of the researcher co-applicants were held and the wider group of rheumatologist co-applicants (local principal investigators) attended when appropriate. The independent TSC and DMEC convened at key time points to support the trial development and review progress. All meetings were reduced in frequency once the trial was established, but resumed more frequently during database closure, data analysis and interpretation. The RCT was sponsored by the University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust.

Patient and public involvement

Patient involvement occurred throughout the project and was provided by two patients who had participated in the original trial (Clive Rooke and Frances Robinson). 31 The aim of a joint enterprise with patient partners was for them to bring experiential knowledge of RA fatigue and receiving the original CBT intervention from a psychologist. The patient partners advised on outcomes to be evaluated, questionnaire pack design, recruitment processes and all trial patient materials. The patient partners suggested improvements to the patient handouts used in the RAFT programme and advised that the relaxation CD be re-recorded to improve sound quality. The patient partners attended the tutor training days to talk with the tutors and the principal investigators about their experience of fatigue. Continued involvement (by Clive Rooke) included advising on the formatting of the tutor manual, attendance at major project review meetings and analysis of the qualitative data.

Chapter 3 Clinical evaluation: analysis methods and results

Statistical analysis methods

The analysis and reporting of this trial was undertaken in accordance with Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines. 60 All statistical analyses were undertaken using Stata version 14.1.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA), following a predefined SAP [see URL: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/1111201/#/documentation (accessed 12 April 2019)], which was agreed with the TSC and the DMEC. The primary comparative analyses between randomised trial arms were conducted on an intention-to-treat (ITT) basis without imputation of missing data.

Preliminary analyses (baseline comparability)

Descriptive statistics of key clinical and sociodemographic characteristics were used to compare randomisation trial arms at baseline and to inform any additional adjustment of the primary and secondary analyses when appropriate.

Primary analysis

The primary analysis used linear regression to compare BRAF-NRS impact score at 26 weeks (the primary outcome) between trial arms as randomised and adjusted for baseline values of the outcome and recruitment centre (stratification variable). The result of the linear regression model is presented as an adjusted difference in means between the RAFT programme and control arms, alongside the associated 95% CI and p-value for the comparison. A standardised effect size for the primary outcome was also calculated as the adjusted difference in mean divided by the pooled baseline standard deviation (SD).

Secondary analyses

Primary outcome measure

Secondary analyses of the primary outcome included additional adjustment of the primary analysis for any prognostic variables demonstrating a marked imbalance at baseline (ascertained using descriptive statistics). There was a gap in time between eligibility screening and baseline measurement. Owing to this time gap, some individuals who had a BRAF-NRS severity score of ≥ 6 points (out of 10 points) at screening (an eligibility criterion) subsequently had a lower BRAF-NRS severity score of < 6 points at the time of randomisation. For this reason, the primary analysis was repeated and restricted to those individuals who had a BRAF-NRS severity score of ≥ 6 points at randomisation (analysis not prespecified).

A repeated measures mixed-effects model was used to examine the effect of the intervention over time by including up to four follow-up BRAF-NRS impact scores (at weeks 26, 52, 78 and 104), adjusted for baseline values of the outcome and for recruitment centre. This analysis provided an estimate of the average effect size over the duration of follow-up. A potential convergence or divergence between trial arms was investigated by repeating the analysis with the inclusion of a time-by-treatment group interaction term. The repeated measures analysis was repeated on those individuals with a BRAF-NRS severity score of ≥ 6 points at randomisation.

Secondary outcome measures

The effect of the intervention on the secondary outcomes collected at 26 weeks was also examined using appropriate regression models adjusted for baseline values of the outcome being investigated and for recruitment centre. The secondary outcomes were also subject to repeated measures analysis using data collected at the 26-, 52-, 78- and 104-week follow-ups.

A potential difference between trial arms in the changes in major RA medications that might influence the primary outcome was investigated using a chi-squared test. A change in major RA medications was defined as stopping, starting or changing the dose of one or more disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), bDMARDs or glucocorticoid medications during a single time period. Acceptability of the RAFT programme or the usual-care booklet to patients was measured by the RAFT programme attendance rates, satisfaction and recommendation to others, and is summarised using descriptive statistics.

Potential clustering effects

Owing to the hierarchical nature of the data (i.e. participants nested within centres and then within cohorts), there is potential for clustering effects in the trial. To investigate this, a linear mixed-effects model, which included centre and cohort as cluster-level variables, was compared with the linear regression primary analysis model by means of the likelihood ratio test.

Missing data

The sensitivity of the primary analysis to the impact of missing data was examined. The method of multiple imputation by chained equations using predictive mean matching was used to impute missing data. The imputation model included all variables that were part of the ITT primary analysis, variables identified from the previous trial as being related to fatigue impact (fatigue severity, pain and both self-reported and nurse-rated disease activity), and baseline variables that were associated with missingness of the primary outcome. In total, 20 imputed data sets were generated and combined using Rubin’s rules. The primary analysis model was then repeated using the imputed data.

Treatment efficacy

Complier-average causal effect (CACE) analysis was used to investigate the efficacy of the RAFT programme intervention in reducing fatigue impact at 26 weeks. The CACE methodology compares outcomes among those who ‘complied’ with the intervention and a comparable group of ‘would be compliers’ in the control arm. 61 (The word ’compliance’ is used here as a statistical term; clinically the word adherence is used to describe active rather than passive decisions to participate.) CACE analysis provides an estimate of the efficacy of the intervention for comparison with the ITT estimate of the offer of the intervention, while respecting randomisation and avoiding biases inherent to crude per-protocol analyses, in which only individuals in the RAFT programme arm are included. In this trial ‘compliance’ was defined as attending at least two sessions of the RAFT programme (session 1 plus any other session). However, those individuals randomised to the RAFT programme intervention arm but who did not attend (i.e. withdrew and did not attend the first RAFT programme session) had no follow-up data collected. This is problematic as it meant that outcome information was not available for a group of individuals who would be considered ‘non-compliant’ and have contributed information to the CACE analysis. It also potentially violated the exclusion restriction assumption: if individuals in the RAFT programme intervention arm were considered participants only if they attended the first CB session (which might then have an impact on their outcome), then the offer of the intervention does affect outcome. To address this issue, the two stages of the two-stage least squares (2SLS) CACE estimation were carried out separately to allow for loss to follow-up that was dependent on compliance. The first-stage regression uses all individuals randomised to predict compliance. The second stage involved only those with non-missing outcomes, but modelled these using the predicted values of compliance obtained from the ‘complete’ first stage.

Interpretation of findings

When designing the trial it was stated that the traditional effect size of > 0.5 would be considered to reflect a clinically meaningful effect. 40 During the discussions to interpret the findings, the Trial Management Group, with input from the TSC statistician, discussed the issue of effect sizes in terms of their clinical importance. Over the years, concerns have been raised in the literature as to whether only an effect size ≥ 0.5 must be considered clinically meaningful, or if smaller effect sizes might be considered by patients to have had an effect. For example, Sloan et al. 62 argue that this cut-off point is only a broad guideline and that clinical meaningfulness must be related to each specific health issue under investigation (i.e. it would be different for different patient outcomes). They recommend that, if supported by additional data related to that specific health issue, ‘small’ effect sizes of 0.2 can also be considered clinically meaningful. Although there are no data on clinically meaningful change in RA fatigue impact, Khanna et al. 63 demonstrated that patients reported that they experienced a noticeable improvement in RA fatigue severity at effect sizes 0.27 to 0.39. It was therefore decided to take a broader view when interpreting the findings and also to consider additional data to inform consideration of clinically meaningful change and effect sizes (a departure from the protocol).

Subgroup and exploratory analyses

Number of sessions attended

It was hypothesised a priori that those individuals attending a greater number of the RAFT programme sessions would show a greater improvement than those who attended fewer sessions. The theoretical justification was that greater exposure to the RAFT programme intervention should improve self-management skills. A structural mean model 2SLS instrumental variable approach, which respects randomisation,64 was used to investigate the impact of number of sessions of the RAFT programme attended on BRAF-NRS impact score. As with the treatment efficacy CACE analysis, the non-follow-up of those individuals randomised to the RAFT programme intervention arm but who did not attend the first session of the RAFT programme is problematic. The same approach (i.e. a separate two-stage approach) was used to address this issue. A further assumption of this model was that of a linear relationship between session attendance and BRAF-NRS impact score, that is, that the impact of an increase in attendance of one session was the same across all the different sessions (i.e. all sessions had a similar effect on patient outcome).

Consolidation session (week 14)

The RAFT programme intervention was delivered in seven sessions: sessions 1–6 delivered weekly over weeks 1–6, followed by session 7 at week 14 to consolidate skills and behaviours. Separate linear regression models were used to examine the effect of the RAFT programme on BRAF-NRS impact score at 6 weeks (immediately after the final RAFT programme session), at 10 weeks (4 weeks before the consolidation session) and at the 18-week follow-up (4 weeks after the consolidation session).

Predictors of fatigue impact change

Certain clinical and demographic characteristics were examined as potential predictors of fatigue impact change. All of these variables of interest were first added as covariates to the primary analysis model and then removed from the model one by one in a process of stepwise deletion until only covariates with a p-value of < 0.05 were retained (i.e. the covariate with the highest p-value from the initial model was removed, the model was then repeated without this covariate and the variable with the highest p-value in this second model was then removed, etc.). The starting model comprised the primary analysis model additionally adjusted for baseline pain (i.e. NRS score), disease activity (i.e. DAS28 score), BRAF-NRS coping score, age, comorbidity, work status, disease duration and sex.

Self-efficacy

The RASE scale has 28 items that ask about beliefs regarding self-management tasks, many of which are discussed during the RAFT programme. To examine the impact of the RAFT programme intervention on particular components of self-efficacy, the change in RASE scale item scores from 0 to 26 weeks in the control and the RAFT programme intervention trial arms was compared using t-tests.

Tutor delivery over time

It was hypothesised that the size of the effect of the RAFT programme intervention may differ between cohorts as tutors within each centre may have improved in their delivery of the intervention over time. To explore this, the mean change in fatigue, impact from 0 to 26 weeks, is presented by intervention arm and cohort. The difference in mean change (between trial interventions) by cohort is also presented (this was not in the SAP but was prespecified before any analysis commenced).

Social contact

Group work may enhance the seeking of social support (see Chapter 2, Protocol amendments during the trial). The social contact data are analysed using simple percentages.

Results

The key clinical findings from the RAFT programme trial presented here have been previously published. 65

Participant flow

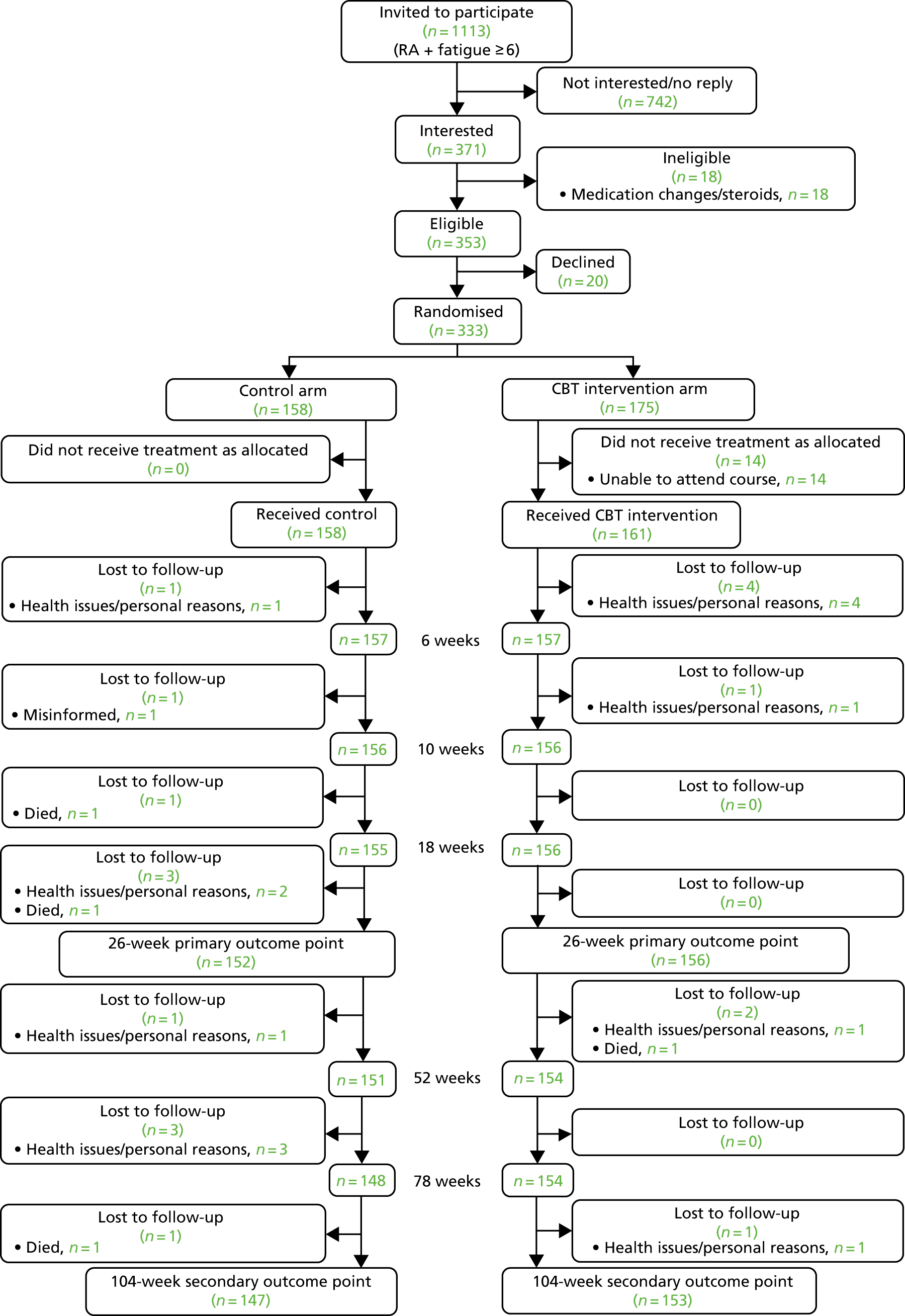

Recruitment commenced in December 2013, with the first patient consent received in February 2014 and the last in October 2015, and the trial completed as planned with the final follow-up questionnaires returned in January 2018. The flow of eligible patients with RA and a fatigue severity score of ≥ 6 points from invitation to participation through to week 104 is detailed in Figure 1. Over the 2 years a total of 333 patients were randomised, comprising four consecutive cohorts in each of the seven centres (see Chapter 2, Recruitment procedures), with similar numbers across centres (see Appendix 3). All patients accepted their randomised allocation.

FIGURE 1.

Participant flow chart. Reproduced from Hewlett et al. 65 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

After consent and baseline assessment, all patients received usual care before randomisation, i.e. the Versus Arthritis fatigue booklet. 45 Of the 175 patients randomised to additionally receive the RAFT programme, 14 did not receive the intervention because of an inability to find suitable programme dates. Of the 161 patients who received the RAFT programme, five patients withdrew for personal/health reasons (four patients during programme delivery, having received up to three of the seven sessions, and one patient withdrew before the week 10 assessment). Therefore, 156 of the 175 RAFT programme patients provided primary outcome data at week 26, and 153 patients provided data at week 104 (89.9% and 87.4% of those patients randomised, respectively). Of the 158 patients randomised to usual care only, six patients withdrew before week 26, leaving 152 patients providing primary outcome data at week 26 and 147 patients providing data at week 104 (96% and 93.0%, respectively).

Follow-up data completion

The majority of patients provided primary outcome fatigue impact data (BRAF-NRS impact data were collected by telephone), with 308 and 296 patients completing BRAF-NRS impact at weeks 26 and 104, respectively (see Appendix 4). Therefore, the 50% attrition allowed for at 2 years did not materialise and the follow-up numbers exceeded the required total sample size of 150. Secondary outcome data questionnaire packs were returned by > 88% of patients at 26 weeks and 78% of patients at 104 weeks (lowest completion rate was 72% for sleep quality at week 78, see Appendix 4). Six patients who were randomised to a RAFT programme but could not attend their planned programme dates attended a later programme, when a fresh baseline assessment was made. However, at the end of RAFT programme delivery in the seven centres, 14 patients randomised to the RAFT programme had been unable to attend any local programme dates and the 26-week primary outcome data were not obtained from them.

The RAFT programme delivery and tutor adherence

All seven rheumatology centres were able to provide at least two clinicians for training and, of those 15 who were trained, 14 went on to deliver the RAFT programme. One tutor pair comprised OTs, two tutor pairs were nurses and four pairs were mixed nurse and OT. They had a mean of 5.3 years’ rheumatology experience (range 0–17 years) and had been qualified for a mean of 18 years (range 6–30 years) and 10 had some experience of running patient groups, of whom four also reported some prior relevant knowledge such as goal-setting or CBT (data not detailed to preserve anonymity).

All seven hospitals were able to deliver all four 14-week RAFT programmes as planned and on time, indicating feasibility to deliver in the NHS, which is explored further in the qualitative evaluation (see Chapter 5). Tutor pairs remained unchanged throughout the RAFT programmes, apart from one centre where tutor absence for two programmes was covered by the remaining tutor co-delivering one programme with a trainer and one with a locum tutor who had observed the previous programme. There were 196 RAFT sessions (28 programmes comprising seven sessions), of which seven (3.6%) were delivered by a single tutor due to absence. Independent monitoring for tutor adherence (fidelity) to the RAFT programme delivery and CB principles was carried out as planned and no remedial teaching was deemed necessary.

The RAFT programme attendance

At randomisation, the RAFT programme group sizes averaged six patients (with a range of five to eight patients). The RAFT programme patients attended a mean of 5.85 of their 7 RAFT programme sessions (SD 1.63 sessions). Most of the 156 patients had high attendance rates, with 87.2% (n = 136) attending 5–7 sessions (Table 2).

| Total number of sessions attended | Patients (N = 156), n (%) |

|---|---|

| 1 | 7 (4.5) |

| 2 | 6 (3.8) |

| 3 | 4 (2.6) |

| 4 | 3 (2.0) |

| 5 | 20 (12.8) |

| 6 | 42 (26.9) |

| 7 | 74 (47.4) |

All 156 RAFT programme patients attended their first session and each of the subsequent sessions (i.e. sessions 2–7) was attended by ≥ 75% of the randomised patients (Table 3).

| Individual session | Patients (N = 156), n (%) |

|---|---|

| 1 | 156 (100) |

| 2 | 137 (87.8) |

| 3 | 129 (82.7) |

| 4 | 125 (80.1) |

| 5 | 129 (82.7) |

| 6 | 119 (76.3) |

| 7 | 118 (75.6) |

Adverse events

No related serious adverse events were reported by tutors.

Preliminary analyses (baseline comparability)

The 25 patients who did not complete to 26 weeks were very similar to the 308 patients who did complete to this primary end point in terms of baseline demographic data (age, sex, disease duration, comorbidity), and fatigue severity (entry criterion) and impact (primary outcome) (see Appendix 5). They had similar clinical status to those who completed the study (see Appendix 6).

Baseline demographic data were similar between trial arms, with the majority of patients being female, as reflects the RA population (Table 4). The patients were aged > 60 years, on average, with a wide range of disease duration. The majority of patients were of moderate to high socioeconomic status and white, and a small proportion had previously attended a general rheumatology self-management programme many years earlier.

| Demographic variable | Trial arm, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Control (N = 152) | RAFT (N = 156) | |

| Female | 121 (79.6) | 125 (80.1) |

| Age (years)a | 61.8 (54.4, 69.6) | 63.7 (54.2, 69.9) |

| Disease duration (years)a | 10 (3, 20) | 10 (5, 19) |

| Socioeconomic status: Englandb | ||

| Deprived | 28 (21.1) | 23 (17.2) |

| Moderate | 60 (45.1) | 65 (48.5) |

| Affluent | 45 (33.8) | 46 (34.3) |

| Socioeconomic status: Walesb | ||

| Deprived | 7 (41.2) | 7 (35.0) |

| Moderate | 3 (17.7) | 5 (25.0) |

| Affluent | 7 (41.2) | 8 (45.0) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| White | 147 (98.0) | 151 (96.8) |

| Asian/Asian British/other | 3 (2.0) | 5 (3.1) |

| Other self-management programmes | 21 (14.0) | 16 (10.3) |

| Years since previous programmea | 8 (5, 11) | 5 (3, 10) |

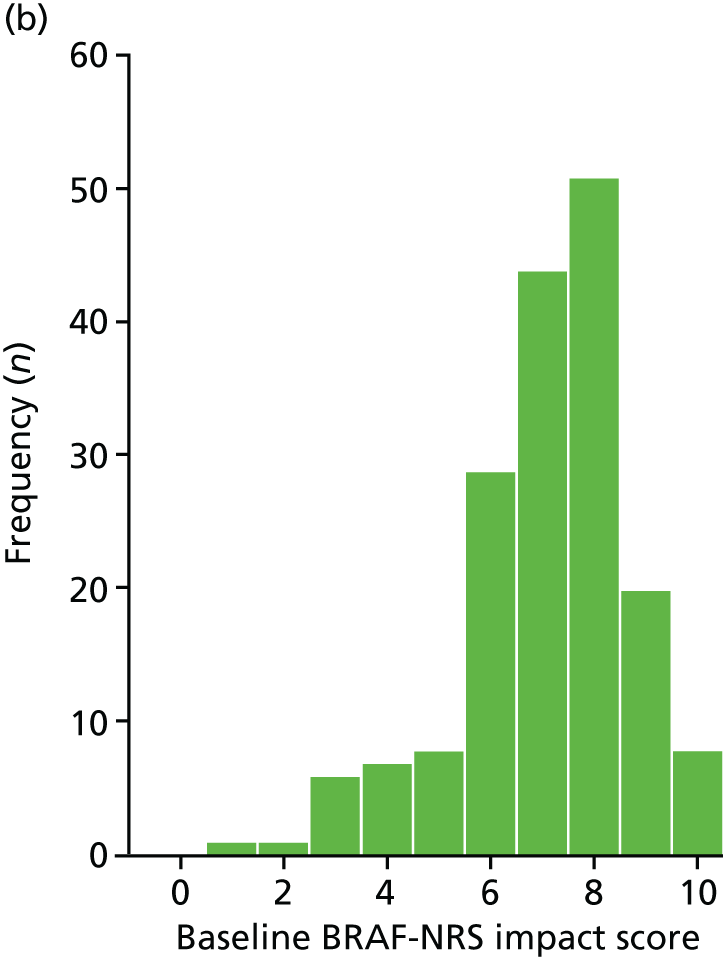

Baseline clinical data were similar between arms and were therefore well balanced (Table 5). On average, patients had high fatigue impact scores (i.e. a BRAF-NRS impact score of > 7/10), which were slightly higher than fatigue severity scores, and had a low perceived ability to cope with fatigue (measured via the BRAF-NRS coping questionnaire). The participants had relatively high levels of disease activity (inflammation) with DAS28 scores of > 4.2 (> 5.1 is the eligibility criterion for starting bDMARDs). On average, participants had moderate pain, low disability and moderate self-efficacy and helplessness at baseline. The distribution of the primary outcome, fatigue impact, is shown in Figure 2.

| Clinical variable | Trial arm | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (N = 158) | RAFT (N = 175) | |||

| n (%)a | Mean (SD) | n (%)a | Mean (SD) | |

| Fatigue | ||||

| BRAF-NRS impact (0–10) | 152 (96.2) | 7.23 (1.6) | 156 (89.1) | 7.10 (1.7) |

| BRAF-NRS severity (0–10) | 142 (89.9) | 6.85 (1.57) | 152 (86.9) | 6.89 (1.57) |

| BRAF-NRS coping (0–10)b | 142 (89.9) | 4.84 (2.09) | 152 (86.9) | 5.16 (2.08) |

| BRAF-MDQ overall impact (0–70) | 142 (89.9) | 40.39 (12.99) | 152 (86.9) | 40.42 (12.70) |

| BRAF-MDQ physical (0–22) | 142 (89.9) | 16.19 (3.21) | 152 (86.9) | 16.12 (3.39) |

| BRAF-MDQ emotional (0–12) | 142 (89.9) | 6.71 (3.31) | 152 (86.9) | 6.55 (3.18) |

| BRAF-MDQ cognitive (0–15) | 142 (89.9) | 7.58 (4.04) | 152 (86.9) | 7.54 (4.00) |

| BRAF-MDQ living (0–21) | 142 (89.9) | 9.90 (5.18) | 152 (86.9) | 10.21 (5.05) |

| Pain: NRS (0–10) | 142 (89.9) | 5.57 (2.10) | 152 (86.9) | 5.70 (2.12) |

| Disability: MHAQ (0–3) | 142 (89.9) | 0.76 (0.51) | 151 (86.3) | 0.75 (0.53) |

| Quality of life: AIMS VAS (0–100) | 141 (89.2) | 49.89 (20.44) | 152 (86.9) | 49.16 (22.27) |

| Disease activity | ||||

| Assessed: DAS28 (0.96+) | 145 (91.8) | 4.23 (1.11) | 147 (84.0) | 4.22 (1.30) |

| Self-reported: sPDAS2 (2.4–7.9) | 142 (89.9) | 4.36 (0.99) | 151 (86.3) | 4.44 (1.06) |

| Anxiety: HADS (0–21) | 142 (89.9) | 8.01 (4.45) | 151 (86.3) | 7.29 (4.08) |

| Depression: HADS (0–21) | 142 (89.9) | 6.79 (3.94) | 151 (86.3) | 7.18 (3.59) |

| Valued life activities: VLA (0–3) | 142 (89.9) | 1.08 (0.60) | 151 (86.3) | 1.16 (0.61) |

| Helplessness: AHI (5–30) | 142 (89.9) | 18.98 (4.74) | 152 (86.9) | 19.03 (4.67) |

| Self-efficacy: RASE scale (28–140)b | 142 (89.9) | 104.38 (11.34) | 151 (86.3) | 102.49 (11.51) |

| Sleep quality | 142 (89.9) | 149 (85.1) | ||

| Very goodc | 5 (3.5%) | 9 (6.0%) | ||

| Fairly goodc | 58 (40.9%) | 48 (32.2%) | ||

| Fairly badc | 51 (35.9%) | 56 (37.6%) | ||

| Very badc | 28 (19.7%) | 36 (24.2%) | ||

FIGURE 2.

Distribution of baseline BRAF-NRS impact scores, by trial arm. (a) Control; and (b) the RAFT programme.

Participants had eligible fatigue scores at screening (i.e. a BRAF-NRS severity score of ≥ 6/10), but often had to wait for a sufficient number of participants to be recruited in order to close their cohort ready for consent, baseline assessment and randomisation. At the later baseline assessment, the fatigue severity scores of 23 out of 152 control patients and 23 out of 156 RAFT programme patients had fallen below the inclusion criterion (15.1% and 14.6%, respectively); however, as this was a pragmatic trial aiming to reflect how the RAFT programme would be delivered in clinical practice, the participants proceeded to randomisation.

Primary analysis

There was no difference between the trial arms for fatigue impact at baseline and both arms had improved fatigue impact at week 26 (Table 6). Patients in the control arm improved by a mean of –0.88 (SD 2.4, Wilcoxon signed-rank test statistic –3.560; p < 0.001), and those in the RAFT programme improved by a mean of –1.36 (SD 2.7, Wilcoxon signed-rank test statistic –5.666; p < 0.001).

| Primary outcome | Trial arm | Adjustedb mean difference (95% CI) | p-value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | RAFT | |||||||

| n (%)a | Week, mean (SD) | n (%)a | Week, mean (SD) | |||||

| 0 | 26 | 0 | 26 | |||||

| BRAF-NRS impact score | 152 (96.2) | 7.23 (1.6) | 6.36 (2.42) | 156 (89.1) | 7.10 (1.7) | 5.74 (2.41) | –0.59 (–1.11 to –0.06) | 0.03 |

The primary outcome was the BRAF-NRS impact score at 26 weeks (ranging from 0 to 10, with the lower score representing the better outcome). Linear regression was used to investigate the impact of the intervention on the primary outcome, adjusted only for baseline score and centre as other factors were similar between trial arms (see Table 5). Individuals in the RAFT programme had a BRAF-NRS impact score at 26 weeks that was, on average, –0.59 units lower (better) than that of those in the usual-care arm, with a 95% CI ranging from a 1.11 to a 0.06 reduction in fatigue impact (p = 0.03). The adjusted mean difference between arms equated to a standardised effect size of 0.36.

Secondary analysis

Primary outcome measure

Analysis adjusting for variables imbalanced at baseline was not required as no variables were imbalanced.

Baseline eligibility and 26-week outcome

The primary analysis was repeated excluding those individuals who had fallen below the eligibility criterion of BRAF-NRS severity of ≥ 6.0 points between screening and baseline (n/N = 3/152 control patients and n/N = 23/156 RAFT programme patients). For baseline-eligible patients, the fatigue impact score at 26 weeks was lower in the RAFT programme than in the control arm, with an adjusted mean difference between arms in fatigue impact of –0.82, a slightly larger effect than observed in the primary complete-case (screening-eligible) analysis (Table 7).

| Eligibility | n | BRAF-NRS impact score, adjusted mean differencea (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Screening-eligible patients | 308 | –0.59 (–1.11 to –0.06) | 0.03 |

| Baseline-eligible patients | 262 | –0.82 (–1.40 to –0.24) | 0.01 |

Primary outcome at 26–104 weeks

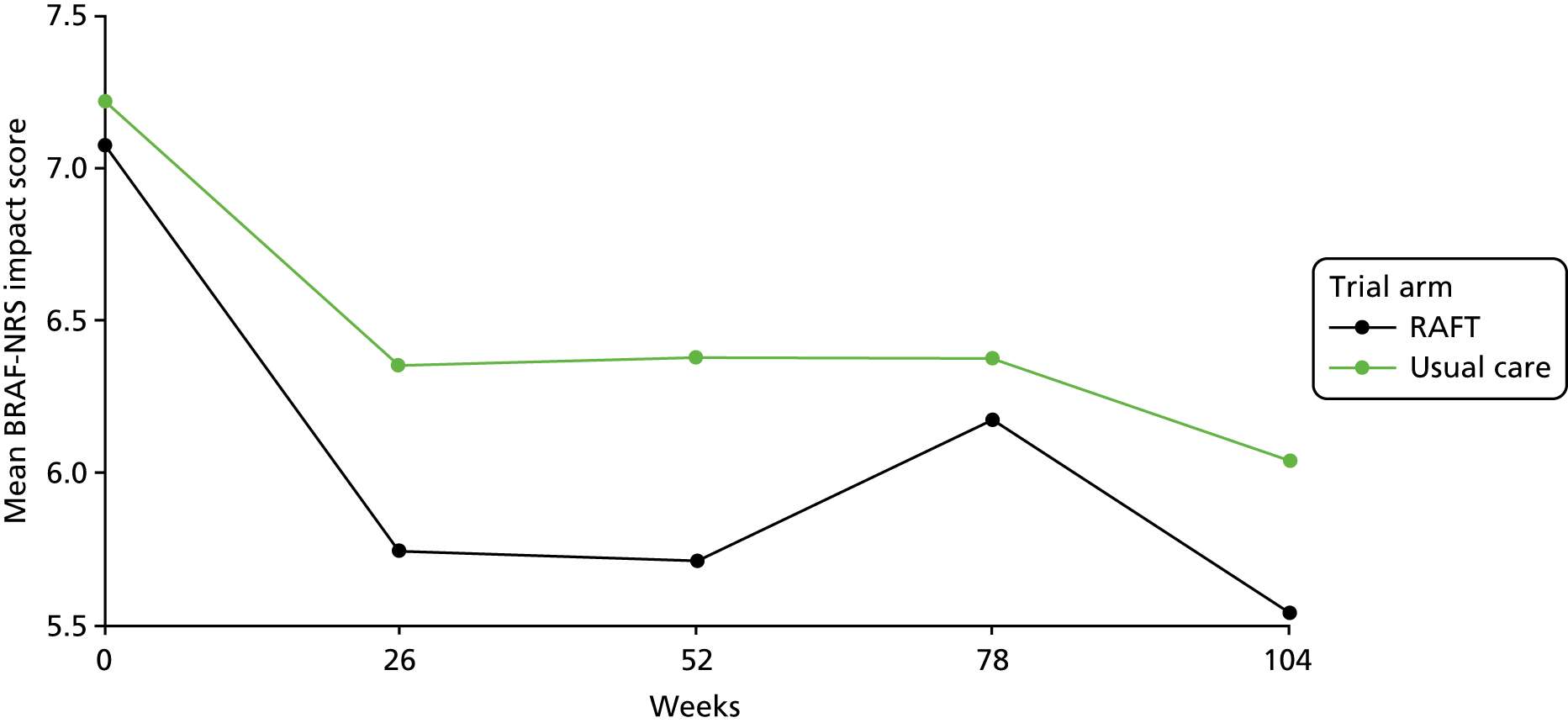

The BRAF-NRS impact score differed between trial arms over weeks 0–104 (Figure 3). Based on repeated measures analysis and using data from the 26-, 52-, 78- and 104-week follow-up time points, the group receiving the RAFT programme intervention had a BRAF-NRS impact score that was, on average, 0.49 units lower (i.e. better) than in the control arm over the 2 years, on a scale of 0–10 (adjusted mean difference –0.49) (Table 8).

FIGURE 3.

The BRAF-NRS impact scores over weeks 0–104, by trial arm. Reproduced from Hewlett et al. 65 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

| Trial arm | Time point | Repeated measures (N = 308) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 26 weeks (N = 308) | 52 weeks (N = 305) | 78 weeks (N = 300) | 104 weeks (N = 296) | |||||||

| n | BRAF-NRS impact score, mean (SD) | n | BRAF-NRS impact score, mean (SD) | n | BRAF-NRS impact score, mean (SD) | n | BRAF-NRS impact score, mean (SD) | Adjusted mean differencea (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Control | 152 | 6.36 (2.42) | 151 | 6.38 (2.19) | 146 | 6.38 (2.23) | 145 | 6.05 (2.14) | –0.49 (–0.83 to –0.14) | 0.01 |

| RAFT | 156 | 5.74 (2.41) | 154 | 5.72 (2.23) | 154 | 6.17 (2.24) | 151 | 5.54 (2.28) | ||

When a treatment arm-by-time interaction term was added to the model there was no evidence that the difference between the RAFT programme and the control arm varied over time (interaction between treatment and time, p = 0.52). The estimated treatment effects at each of the follow-up time points were similar and in favour of the RAFT programme, with the exception of that at the 78-week follow-up time point, which was non-significant (see Appendix 7).

Baseline eligibility and 2-year follow-up

The repeated measures analysis was repeated excluding those individuals who had fallen below the eligibility criterion of a BRAF-NRS severity score ≥ 6.0 between screening and baseline (n/N = 23/152 control patients and n/N = 23/156 RAFT programme patients). For baseline-eligible patients, the RAFT programme patients had a BRAF-NRS impact score that was, on average, 0.58 lower (i.e. better) than those in the control arm over the 2 years (adjusted mean difference –0.58) (Table 9). This represents a slightly larger treatment effect than observed when analysing all screening-eligible participants.

| Eligibility | n | BRAF-NRS impact score, adjusted mean differencea (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Screening-eligible participants | 308 | –0.49 (–0.83 to –0.14) | 0.01 |

| Baseline-eligible participants | 262 | –0.58 (–0.95 to –0.22) | 0.002 |

Secondary outcome measures

Secondary outcomes at 26 weeks

Both trial arms appeared to demonstrate improvement in some secondary outcomes at 26 weeks, particularly overall fatigue impact score (BRAF-MDQ overall) and its fatigue subscales, self-efficacy (RASE scale score) and sleep (see Appendix 8). There appeared to be little change in disease activity measures (DAS28 and sPDAS2), pain, disability or mood.

After adjusting for baseline scores and centre, there was evidence of a difference between arms in overall fatigue impact score (BRAF-MDQ overall), and the subscales emotional fatigue and living with fatigue, as well as the process measure of self-efficacy for managing RA (i.e. RASE scale score), with the adjusted mean differences in favour of the RAFT programme intervention (Table 10). Standardised effect sizes calculated for these variables ranged from 0.23 to 0.28. There was no evidence of a difference between the trial arms for any other secondary outcome, including fatigue severity. Over the 26 weeks, 20 out of 141 control patients reported seeking extra appointments for fatigue help, compared with 8 out of 152 RAFT programme patients (14.2% vs. 5.2%; p < 0.01).

| Clinical outcome | Trial arm | Adjusted mean differenceb (95% CI) | p-value | Effect size | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | RAFT | ||||||

| n (%)a | Mean (SD) | n (%)a | Mean (SD) | ||||

| Fatigue | |||||||

| BRAF-NRS severity (0–10) | 142 (89.9) | 6.13 (2.30) | 152 (86.9) | 5.91 (2.22) | –0.24 (–0.75 to 0.27) | 0.35 | |

| BRAF-NRS coping (0–10)c | 142 (89.9) | 5.32 (2.42) | 152 (86.9) | 5.25 (2.33) | –0.15 (–0.69 to 0.39) | 0.58 | |

| BRAF-MDQ overall impact (0–70) | 142 (89.9) | 34.74 (16.41) | 152 (86.9) | 31.51 (16.02) | –3.42 (–6.44 to –0.39) | 0.03 | 0.27 |

| BRAF-MDQ physical (0–22) | 142 (89.9) | 14.40 (5.23) | 152 (86.9) | 13.72 (4.91) | –0.68 (–1.78 to 0.42) | 0.23 | |

| BRAF-MDQ emotional (0–12) | 142 (89.9) | 5.36 (3.79) | 152 (86.9) | 4.37 (3.51) | –0.91 (–1.58 to –0.23) | 0.01 | 0.28 |