Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 14/140/84. The contractual start date was in December 2015. The draft report began editorial review in August 2018 and was accepted for publication in June 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Timothy Iveson reports honoraria from Amgen Inc. (Thousand Oaks, CA, USA), Bayer AG (Leverkusen, Germany), Bristol-Myers Squibb (New York, NY, USA), Celgene Corporation (Summit, NJ, USA), Pierre-Fabre (Paris, France), Roche (Roche Holding AG, Basel, Switzerland) and Servier (Laboratories Servier, Suresnes, France). Kathleen A Boyd reports grants from the Medical Research Council during the conduct of the study. Mark P Saunders reports personal fees from Servier, Amgen, Merck (Merck and Co., Kenilworth, New Jersey, USA), Eisai (Eisai Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) and Roche outside the submitted work. Jim Cassidy reports grants from the Medical Research Council during the conduct of the study and is currently an employee of Celgene Corporation. Josep Tabernero reports personal fees from Array Biopharma (Boulder, CO, USA), AstraZeneca (Cambridge, UK), Bayer AG (Leverkusen, Germany), BeiGene (Beijing, China), Boehringer Ingelheim (Ingelheim am Rhein, Germany), Chugai (Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Tokyo, Japan), Genentech, Inc. (South San Francisco, CA, USA), Genmab A/S (Copenhagen, Denmark), Halozyme (Halozyme Therapeutics, San Diego, CA, USA), Imugene Limited (Sydney, NSW, Australia), Inflection Biosciences Limited (Blackrock, Dublin), Ipsen (Paris, France), Kura Oncology (San Diego, CA, USA), Eli Lilly and Company (Indianapolis, IN, USA), Merck, Menarini (The Menarini Group, Florence, Italy), Merck Serono (Rockland, MA, USA), Merrimack Pharmaceuticals (MA, USA), Merus (Utrecht, the Netherlands), Molecular Partners (Molecular Partners AG, Zurich, Switzerland), Novartis (Novartis International AG, Basel, Switzerland), Peptomyc, Pfizer Inc. (New York, NY, USA), Pharmacyclics (Pharmacyclics LLC, Sunnyvale, CA, USA), ProteoDesign SL (Barcelona, Spain), Rafael Pharmaceuticals (Stony Brook, NY, USA), F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, Sanofi (Sanofi S. A., Paris, France), Seattle Genetics (Bothwell, WA, USA), Servier, Symphogen (Symphogen A/S, Ballerup, Denmark), Taiho Pharmaceutical (Tokyo, Japan), VCN Biosciences (Barcelona, Spain), Biocartis (Biocartis Group, Mechelen, Belgium), Foundation Medicine (Cambridge, MA, USA), HalioDX (Marseille, France), SAS Pharmaceuticals (Delhi, India) and Roche Diagnostics outside the submitted work. Bengt Glimelius reports support from PledPharma AB for being on advisory boards. Sherif Raouf reports grants, personal fees and non-financial support from Roche, grants and personal fees from Amgen, and grants and personal fees from Merck outside the submitted work. David Farrugia reports that he received honoraria for speaking in educational events and support for meeting attendance from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, Ipsen, Amgen, AstraZeneca and Merck. David Cunningham reports grants from 4SC (4SC AG, Planegg, Germany), AstraZeneca, Bayer, Amgen, Celgene, Clovis Oncology (Boulder, CO, USA), Eli Lilly and Company, Janssen Pharmaceuticals (Beerse, Belgium), MedImmune (Gaithersburg, MD, USA), Merck, Merrimack and Sanofi, outside the submitted work. Tamish Hickish reports grants from Pfizer, Roche, Pierre Fabre (Paris, France) and personal fees from Eli Lilly and Company during the conduct of the study. John Bridgewater reports funding from the University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust/University College London Biomedical Research Centre. David Cunningham reports funding from the National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centres at the Royal Marsden.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Iveson et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Colorectal cancer is a common malignancy, with 1,360,000 cases annually, leading to 694,000 deaths each year. Colorectal cancer accounts for 12% of all new cancer cases each year in the UK, with approximately 41,265 cases estimated in 2014. 1 The initial treatment for patients presenting with colorectal cancer is usually surgical resection, which is potentially curative; however, 40–50% of patients subsequently relapse and die as a result of the disease becoming metastatic. 2 Postoperative adjuvant fluoropyrimidine-based chemotherapy was first shown to reduce the recurrence of colon cancer in 1990. 3 Initially, adjuvant treatment was given for 12 months, but a randomised study suggested equivalence for 6 months of treatment,4 which is now accepted as the standard duration for adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with high-risk stage II or stage III colorectal cancer. 5

High-risk stage II is defined as having one of the following risk features: T4 disease, tumour obstruction and/or perforation, < 10 lymph nodes harvested, poorly differentiated histology, perineural invasion or extramural venous/lymphatic vascular invasion.

The addition of oxaliplatin to a fluoropyrimidine-based regimen has been shown to improve 3-year disease-free survival (DFS) in patients with colorectal cancer. 6–8 The benefit seen in the MOSAIC6 and NSABP C-077 studies was similar, despite the total oxaliplatin doses being different (1020 mg/m2 and 765 mg/m2, respectively). 6,7 These studies led to the adoption of oxaliplatin and fluoropyrimidine chemotherapy as the adjuvant treatment of choice for most patients with stage III disease who were aged < 70 years. 5,9 However, the administration of oxaliplatin with the fluoropyrimidine backbone results in additional toxicity, with increased neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, diarrhoea, nausea and vomiting. 6,7 There is also increased peripheral neuropathy, which is cumulative, dose-dependent and often irreversible, persisting long term despite the treatment of colorectal cancer having been curative. Neurotoxicity was measured using the National Cancer Institute (NCI) common terminology criteria for adverse events (CTCAE) (version 1) in MOSAIC study,6 and the NCI-Sanofi Neurosensory score in the NSABP C-07 study. 7 In the MOSAIC trial, 12.4% of patients experienced grade 3 sensory neuropathy, with 0.5% having residual problems at 18 months;6 in the NSABP C-07 trial, 8.4% of patients had grade 3 or 4 neuropathy at the end of treatment, with 10% reporting some residual neuropathy beyond 2 years. 10

As the toxicity of oxaliplatin and fluoropyrimidine regimens is cumulative, a reduction in the duration of adjuvant treatment could potentially ameliorate such effects;11 however, whether or not short-duration adjuvant treatment could compromise efficacy is widely debated. Data for one study12 are available in the literature, comparing 3 months with 6 months of adjuvant treatment with a fluoropyrimidine-based chemotherapy regimen; however, the study was conducted before the introduction of oxaliplatin-combination adjuvant treatment. Although the study was somewhat underpowered, reducing treatment duration did not appear to affect patient outcomes and was associated with reduced toxicity and improved health-related quality of life (HRQoL).

The cost of treatment for colorectal cancer in the first year after diagnosis is considerably higher than that of treating other common cancers and was estimated to cost the English health-care system £542M in 2010. 13 Three-month duration adjuvant chemotherapy for patients with colorectal cancer could be anticipated to be more cost-effective than the current standard 6-month duration, provided that efficacy is maintained. Benefits might be associated not only with lower treatment costs but also with reduced expenditure to manage problematic side effects and improvements in HRQoL.

The Short Course Oncology Therapy (SCOT) study was designed to compare 3-month and 6-month oxaliplatin-based adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with colorectal cancer in terms of efficacy, toxicity, HRQoL and economic aspects. At the time of starting this study, no published data were available on the effectiveness of short-duration treatment with adjuvant oxaliplatin and fluoropyrimidine regimens in patients with colorectal cancer. The main objective of the study was to identify whether or not 3-month adjuvant chemotherapy was inferior to 6-month treatment in terms of DFS rate. The trial also aimed to compare overall survival, toxicity and HRQoL in patients between the two treatment groups and to assess the cost-effectiveness of the two regimens. The SCOT study was designed as an international, stand-alone study of adjuvant oxaliplatin and fluoropyrimidine treatment conducted in patients with high-risk stage II or stage III colon or rectal cancers. Although stand-alone, the SCOT study was conducted in parallel with the International Duration Evaluation of Adjuvant chemotherapy (IDEA) collaborative initiative, which aimed to consolidate results from numerous worldwide trials that were attempting to clarify the importance of adjuvant treatment duration for colon cancer patients. The IDEA initiative was restricted to treatment of patients with stage III colon cancer; therefore, it was prospectively planned that patient data from the SCOT study would be pooled with those from six other studies (TOSCA, IDEA France, CALGB/SWOG 80702, ACHIEVE and HORG). 14

Chapter 2 Methods

Study design

The SCOT study was an international, randomised (1 : 1), open-label (non-blinded), non-inferiority, Phase III, parallel-group trial comparing 6 months with 3 months of oxaliplatin plus fluoropyrimidine adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with high-risk stage II or stage III colorectal cancer.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines;15 all aspects of the study received ethics approval from the ethics services in the participating countries. All participants provided written informed consent before enrolment.

Study participants

Parts of this section are taken from Iveson et al. 16 © The Author(s). Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an Open Access article under the CC BY 4.0 license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Patients were recruited from 244 oncology clinics from six countries (the UK, Denmark, Spain, Sweden, Australia and New Zealand).

Eligible patients were adults aged ≥ 18 years who had undergone curative resection for high-risk stage II (having one or more of the following risk features: T4 disease, tumour obstruction and/or perforation of the primary tumour, < 10 lymph nodes harvested, poorly differentiated histology, perineural invasion or extramural venous/lymphatic vascular invasion) or stage III adenocarcinoma of the colon or rectum.

Patients were enrolled within 11 weeks of surgery and started treatment in their allocated treatment group within 2 weeks of randomisation. Other eligibility inclusion requirements included having a World Health Organization performance status of 0 or 1, having adequate organ function and having a life expectancy of > 5 years with reference to non-cancer-related disease, accepting that they may die earlier due to colorectal cancer. Patients were to have a normal computed tomography scan of the chest, abdomen and pelvis prior to study enrolment and a carcinoembryonic antigen level of < 1.2 times the local upper limit of normal (ULN) in the week prior to randomisation. Rectal cancer patients were to have undergone total mesorectal excision with negative resection margins (> 1 mm clearance).

Exclusion criteria included undergoing chemotherapy (except chemotherapy administered with curative intent that had been completed > 5 years previously with no residual complications); having undergone previous long-course chemoradiotherapy (preoperative short-course radiotherapy was allowed); having moderate or severe renal impairment (creatinine clearance rate of < 30 ml/minute using the Cockcroft–Gault equation); having a haemoglobin concentration of < 9 g/dl, an absolute neutrophil count of < 1.5 × 109 per litre, a platelet count of < 100 × 109 per litre, and aspartate aminotransferase or alanine aminotransferase levels of > 2.5 × ULN; having clinically significant cardiovascular disease; being pregnant or lactating; being of childbearing potential and not using or being unwilling to use medically approved contraception (postmenopausal women were to have been amenorrhoeic for ≥ 12 months to be considered of non-childbearing potential); having previous malignancy other than adequately treated in situ carcinoma of the uterine cervix or basal or squamous cell carcinoma of the skin (unless there was a disease-free interval of ≥ 5 years); and having known or suspected dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase deficiency.

Public/patient involvement

The original SCOT study protocol was formally reviewed by consumers as part of the internal review and approval processes at the Glasgow Clinical Trials Unit. Patients were involved informally in the original concept of the trial, and they thought that whether or not shorter chemotherapy could reap the same benefit as longer chemotherapy was an exceptionally important question to define.

Patients at the clinics of the lead investigators were also asked about a proposal to extend study follow-up to increase the number of DFS events for analysis (application to the NIHR programme in 2014). As they felt that the question was exceptionally important, the view was that every effort should be made to extend the study to ensure that a thorough and accurate answer could be obtained for both patients with low-risk and patients with high-risk disease. The proposal to extend the study was also formally discussed and supported both by the main National Cancer Research Institute Colorectal Clinical Studies group and at the meeting of the Adjuvant and Advanced Disease subgroups. The public/patient representative at these meetings was fully supportive.

Study interventions

Parts of this section are taken from Iveson et al. 16 © The Author(s). Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an Open Access article under the CC BY 4.0 license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

The adjuvant treatment regimen used was oxaliplatin with 5-fluorouracil (5FU) or oxaliplatin with capecitabine. Participating sites were able to select which treatment combination they wanted to use on an individual-patient basis, reflecting the choice of the patient and/or physician.

Oxaliplatin and 5-fluorouracil

For patients receiving oxaliplatin and 5FU, treatment was given every 2 weeks, the intention being to deliver six cycles to patients assigned 3 months of therapy and 12 cycles to patients assigned 6 months of therapy. On the first day of each cycle, 85 mg/m2 of intravenous (i.v.) oxaliplatin was given over 2 hours, concurrently with 175 mg of L-folinic acid or 350 mg of folinic acid (also known as leucovorin). This was followed by a 400 mg/m2 5FU i.v. bolus injection administered over 5 minutes, and then a continuous i.v. infusion of 2400 mg/m2 of 5FU over 46 hours. At the investigator’s discretion, patients who were aged > 70 years could start both 5FU infusions at 75% of the specified starting dose, if clinically indicated.

If a grade 1 adverse event (AE) occurred as a result of chemotherapy, treatment was to be continued at the full dose. For treatment-related AEs of grade ≥ 2, treatment was to be withheld until recovery to grade 1 and then restarted. If more than one delay or a delay of ≥ 2 weeks occurred, doses of oxaliplatin and infused 5FU were to be kept the same but the bolus 5FU dose was to be omitted; if further delays occurred as a result of myelotoxicity, the oxaliplatin and infusional 5FU doses were to be reduced by 25%. In addition, if after the first cycle the neutrophil count was < 1.0 × 109 cells/l, the bolus 5FU dose was to be omitted and the oxaliplatin and infused 5FU doses were to be reduced by 25%. Wherever possible, the oxaliplatin dose was to be reduced rather than discontinued; if oxaliplatin dosing had to be discontinued, 5FU was to be continued where possible.

Oxaliplatin and capecitabine

For patients receiving oxaliplatin and capecitabine, treatment was given every 3 weeks, the intention being to deliver four cycles to patients assigned 3 months of therapy and eight cycles to patients assigned 6 months of therapy. On the first day of each cycle, 130 mg/m2 of i.v. oxaliplatin was given over 2 hours. Oral capecitabine 1000 mg/m2 was taken twice per day for the first 14 days of each cycle. Patients with a creatinine clearance rate of 30–50 ml/minute were to start capecitabine treatment at 75% of the specified dose. Patients aged > 70 years could be considered for treatment with capecitabine at 75% of the full dose, with the decision to reduce dose being made at the discretion of the investigator depending on the fitness of the individual patient. If the investigator considered that any patient required dose reduction because of any other comorbidity, the patient could receive a minimum starting dose of oral capecitabine of 800 mg/m2 twice per day.

If a grade 1 AE occurred as a result of chemotherapy, treatment was to be continued at the full dose. For treatment-related AEs of grade ≥ 2, treatment was to be withheld until recovery to grade 1 and then restarted. For AEs related to oxaliplatin and capecitabine, if more than one delay or a delay of ≥ 2 weeks occurred, capecitabine and oxaliplatin doses were to be reduced by 25%; if further delays occurred as a result of myelotoxicity, further dose reductions were allowed at the investigator’s discretion.

Objectives

The objective of the SCOT study was to assess the efficacy of 3-month versus 6-month adjuvant chemotherapy for colorectal cancer and to compare the associated toxicity and HRQoL. The study also provided data for an economic analysis of the cost-effectiveness of the two regimens. The primary end point of the study was DFS, the null hypothesis being that 3-month chemotherapy is inferior to 6-month chemotherapy with a hazard ratio (HR) of > 1.13. Secondary end points were overall survival, safety, HRQoL and cost-effectiveness parameters.

The aim of the economic evaluation was to explore the cost-effectiveness of 3-month versus 6-month adjuvant chemotherapy [in terms of incremental cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gains and net monetary benefit (NMB)], using trial data on treatment and hospitalisations costs, HRQoL and survival outcomes within the timeframe of the SCOT clinical trial.

Outcomes

Parts of this section are taken from Iveson et al. 16 © The Author(s). Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an Open Access article under the CC BY 4.0 license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Disease-free survival was defined as the time from randomisation (or from trial registration for those randomised after 3 months of therapy) to relapse, development of a new colorectal cancer, or death from any cause. Overall survival was defined as the time from randomisation (or registration for those randomised at 3 months) to death from any cause. Toxicity was assessed by the investigators after each cycle of chemotherapy with AEs graded using NCI CTCAE version 3.

Patients were followed up for a minimum of 3 years to a maximum of 8 years, with full blood count, urea and electrolyte levels, liver function and carcinoembryonic antigen all being tested at 9, 12, 18, 24 and 36 months, and then annually. Computed tomography of the chest, abdomen and pelvis was conducted at 6, 12, 18, 24 and 36 months.

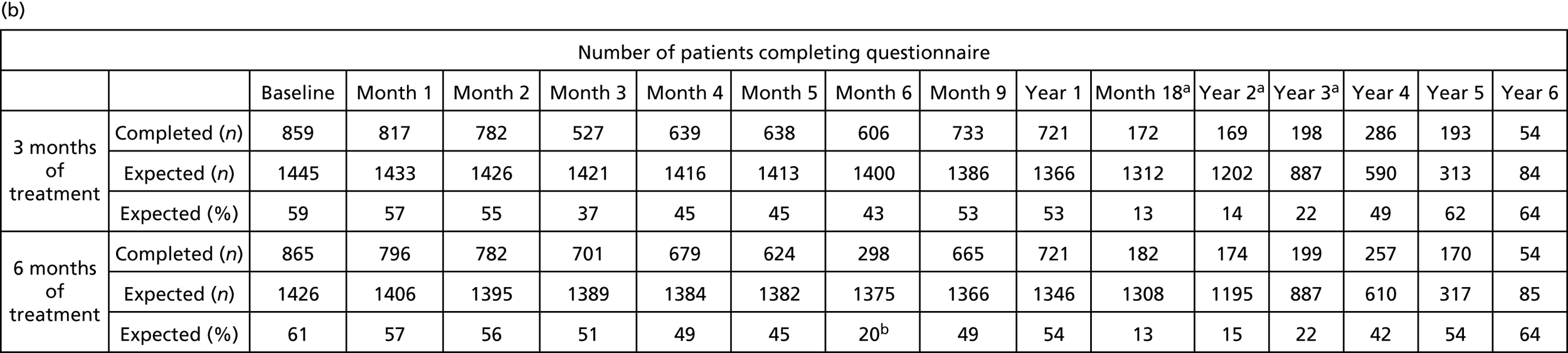

Health-related quality of life was assessed using the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) questionnaires QLQ-C3017 and QLQ-CR29,18 and using the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, three-level version (EQ-5D-3L) (with both the visual analogue scale and the health index),19 with UK value sets. 20 Neuropathy was assessed using the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy/Gynecologic Oncology Group–Neurotoxicity (FACT/GOG-Ntx4) questionnaire. 21 Questionnaires were administered at baseline and before each treatment cycle. Additionally, HRQoL was assessed each month in the first 3 months after treatment for the 3-month treatment group. Subsequent assessments were conducted at 9 and 12 months for the EORTC questionnaires; 9, 12, 18 and 24 months and then annually for the EQ-5D-3L; and up to 12 months for the FACT/GOG-Ntx4.

Sample size

Parts of this section are taken from Iveson et al. 16 © The Author(s). Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an Open Access article under the CC BY 4.0 license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

In the previous MOSAIC trial, 3-year DFS in the oxaliplatin and 5FU treatment group was 78% compared with 73% for 5FU plus leucovorin. 6 To be able to conclude that the 3-month treatment group in the SCOT study was non-inferior, it was assumed that at least half of this benefit should be retained.

The SCOT study was designed as a randomised (1 : 1) non-inferiority trial aiming to reliably determine whether or not there was < 2.5% decrease in the 3-year DFS for patients in the 3-month treatment group (from 78% in the 6-month treatment group), which corresponds to excluding a HR of > 1.13 with 90% power at the 2.5%, one-sided level of significance. Assuming that the study would recruit over a period of 5 years with a subsequent minimum follow-up of 2 years, this design required 8600 patients to undergo randomisation and 2750 events (relapses, deaths or new colorectal cancers) to be observed; to allow for loss to follow-up, the recruitment target was 9500 patients.

From the outset, it was recognised that detecting meaningful differences based on safety and HRQoL data would not require information from all of the 9500 planned patients. For safety outcomes, 700 patients (350 in each group) were deemed sufficient to detect (80% power and a 2-sided significance level of 5%) a halving in the proportion of patients with grade 3 or 4 toxic effects from 12% to 6% (12% being the rate at which grade 3 or 4 paraesthesia, the most common non-haematological grade 3 or 4 toxic effect, occurred in the oxaliplatin treatment group in the MOSAIC trial). 6 This sample size would allow small changes in global HRQoL to be detected (assuming a difference of magnitude of 7.5322 and a standard deviation of 23.4)17 with 95% power at the 1% significance level. This more stringent level of significance was used to allow for multiple testing across various health-related quality-of-life scales. It should be noted that the power and sample size calculations for safety and health-related quality-of-life outcomes are based on a superiority comparisons, not on non-equivalence.

All sample size calculations were made in EAST 5.3.0.0 (Cytel Corporation, Cambridge, MA, USA).

Information on toxicity and health-related quality-of-life end points was collected from recruited patients until the number required was exceeded and the decision to stop was endorsed by the independent data monitoring committee (DMC) and trial steering committee. An administrative delay in notifying sites about the end of collection of detailed toxicity information resulted in data being collected from 868 patients. The DMC had access to summary plots of EORTC HRQoL data, EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) health status data and FACT/GOG-Ntx4 neuropathy data. In May 2010 (based on interim data from 1047 randomised patients), the committee recommended that the collection of HRQoL data and FACT/GOG-Ntx4 data should be continued because they were concerned that the number of missing data might undermine comparison at later time points. They also recommended that collection of FACT/GOG-Ntx4 data should be extended beyond 12 months for new patients and, where possible, for patients already participating in the study. In November 2010, the DMC recommended that the collection of these data should stop once 1800 patients had been recruited; delays in the amendment of the protocol led to patient recruitment beyond this recommendation. These extensions to data collection were made to compensate for missing data and were not based on formal power calculations.

Randomisation

The adjuvant treatment (oxaliplatin and 5FU or oxaliplatin and capecitabine) that was administered was selected on an individual-patient basis and was not randomised. Patients were randomised (1 : 1) centrally to receive either 3 months or 6 months of treatment using a minimisation algorithm incorporating a random component (80% probability of allocation to the ‘minimum’ group; 1 : 1 randomisation if no preferred group). Minimisation factors were study centre, treatment regimen, sex, disease site (colon or rectum), N stage (X, 0, 1 or 2), T stage (X, 0, 1, 2, 3 or 4) and capecitabine starting dose (from February 2010 for those receiving oxaliplatin and capecitabine). Centralised randomisation was conducted by the Cancer Research UK Clinical Trials Unit (Glasgow, UK). The computerised randomisation system allocated every patient a unique identification number and determined their treatment duration.

Initially, some participating centres were randomly allocated such that patients would be registered in the study prior to starting treatment but then be randomised after completing the first 3 months of treatment (delayed randomisation) to either receive a further 3 months of treatment or stop treatment. The remaining centres randomised patients to 3 months or 6 months of treatment prior to starting treatment. This delayed randomisation approach was discontinued because of a poorer randomisation rate [median 4.09, interquartile range (IQR) 1.29–7.09; n = 41, patients/centre/year] than in centres that randomised patients before the start of treatment (median 5.21, IQR 3.56–11.55; n = 36). 24

The study was open-label for patients, clinicians, and those conducting data analysis.

Statistical analyses

Parts of this section are taken from Iveson et al. 16 © The Author(s). Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an Open Access article under the CC BY 4.0 license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Efficacy and safety analyses

The efficacy analyses of DFS and overall survival included, as far as possible, all randomly assigned patients [the intention-to-treat (ITT) population] and were plotted using Kaplan–Meier techniques. Analysis of treatment delivery and safety was based on patients who started the study treatment. The analysis time was prespecified in the study protocol. Statistical analyses used SPSS version 22 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) and R version 3.1.2 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). The data cut-off point for this analysis was 1 December 2016.

Comparison of disease-free and overall survival between treatment groups was based on a Cox regression model incorporating minimisation factors as covariates; this approach was also used to derive the HR and associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The p-value for testing the null hypothesis, that the HR comparing 3 months with 6 months of adjuvant treatment was ≥ 1.13, was derived from this model by comparing the log-likelihood of the fitted model with the log-likelihood of a model where the HR between groups was set to 1.13 using a likelihood-ratio test. The proportional hazards assumption implicit in these analyses was examined graphically using a log-minus log plot of survival function against log time and using a test of the interaction between treatment group and time (logged) obtained from a Cox model incorporating an appropriate time-varying covariate.

The components of the forest plot (estimated hazard for the comparison between groups and associated 95% CI) were derived from a Cox model that included separate terms for the effect of duration in each category of the relevant stratification factor or other factors being examined. The p-value for heterogeneity was derived from comparison of the log-likelihoods of a model with separate terms for the effect of duration in each category compared with the model with a single overall term. The aim of this analysis was to establish whether or not the impact of treatment duration varied across important patient subgroups.

Multiple imputation analysis25 was used to fill in missing data for questionnaires in the HRQoL and neuropathy scales. Five multiple imputation sets were produced for each HRQoL or neuropathy scale and the area under the curve (AUC)26 was calculated with imputed data, as prespecified in the statistical analysis plan. The AUC was then adjusted by dividing by the follow-up period and subtracting the baseline value for each patient to produce a standardised-adjusted AUC. The standardised-adjusted AUC was calculated for the five imputed data sets and compared between the randomised treatment groups via a generalised linear model (with treatment group as an independent factor and study minimisation factors as covariates). The test statistics associated with treatment group from each of the five imputations were finally combined to provide an overall p-value that took into account the extent of missing data. To allow for the number of scales being examined, an adjustment for multiple comparisons (separately for the EORTC and the EQ-5D questionnaires) was made using the sharpened Hochberg procedure;27 the p-value threshold for statistical significance was 5% after adjustment. Comparison of these scales at individual time points also made use of multiple imputation and generalised linear models.

The Mann–Whitney U-test was used to compare ordered categorical variables for toxicity grade. Fisher’s exact test was used to compare the incidence of grade 3–5 toxicity and logistic regression was used to estimate the odds ratio and associated CI for the incidence of grade 3–5 toxicity.

Study data were reviewed by the DMC approximately once a year to assess safety and efficacy issues from an ethics viewpoint. Conditional power methods28 were used to aid the committee in reaching decisions about study continuation, but no formal stopping rules were set. The conditional power for DFS was presented at the fifth (June 2012), sixth (January 2013) and seventh (October 2013) meetings of the DMC; the DMC requested the analysis because of apparent differences in DFS curves. The results were discussed by the DMC in the context of the limited follow-up of patients and available survival data. The DMC concluded that no action was required.

Changes to the study protocol

The approach of randomising patients to a treatment group was changed after the trial had been running for 1 year; after this time all patients were randomised as they started adjuvant therapy (rather than some being randomised after 3 months of adjuvant chemotherapy), as this approach proved to have a higher randomisation rate and a lower dropout rate.

From March 2012, the requirement for the neuropathy questionnaire to be completed was extended to follow-up visits at 18 and 24 months; from December 2012 the neuropathy questionnaire was to be completed at follow-up visits to a maximum of 8 years. These extensions to data collection were made to compensate for missing data and to monitor long-term change in neuropathy.

The planned duration of patient follow-up for the primary analysis was extended so that (1) patients with stage III disease were to be followed up until the end November 2014 or for a minimum of 3 years (if they did not have ≥ 3 years of follow-up at the end of November 2014) and (2) all patients with stage II disease were to be followed up until the end of November 2016. Follow-up was extended to increase the number of events for the primary study analysis.

Chapter 3 Results

Participant recruitment and flow

The data cut-off point for the analyses presented here was 1 December 2016, at which time patients in both treatment groups had undergone median follow-up of 37 months (IQR 36–49 months, as calculated using the reverse Kaplan–Meier approach). A total of 88% of patients were followed up for a minimum of 3 years, which allowed for a 2-month window around the follow-up time. A total of 787 patients had died by the time of analysis. Study patients are still undergoing follow-up to support further DFS and overall survival analyses.

A total of 6088 patients were randomised to the trial between 27 March 2008 and 29 November 2013 from 244 centres: 5244 patients were randomised at 164 study centres in the UK, 311 patients at 10 centres in Denmark, 237 patients at 19 centres in Spain, 197 patients at 32 centres in Australia, 83 patients at 14 centres in Sweden, and 16 patients at five centres in New Zealand. The study did not meet its target of 9500 patients as a result of slow recruitment; despite extending the planned enrolment period by 6 months, the target was not reached and recruitment was stopped to allow adequate follow-up of ongoing randomised patients within the budget for the trial. This allowed the minimum follow-up period to be extended to 3 years. A total of 1482 DFS events were observed, which gave the study 66% power rather than the planned 90% power for rejecting the null hypothesis.

A total of 6065 patients were included in the ITT analysis population, 6022 of whom started study treatment. Treatment safety/toxicity was assessed after each chemotherapy cycle for 868 patients. HRQoL was assessed using EORTC QLQ-C30 and CR29 (n = 1829) and EQ-5D-3L (n = 1828) and neuropathy were assessed using FACT/GOG-Ntx4 (n = 2871).

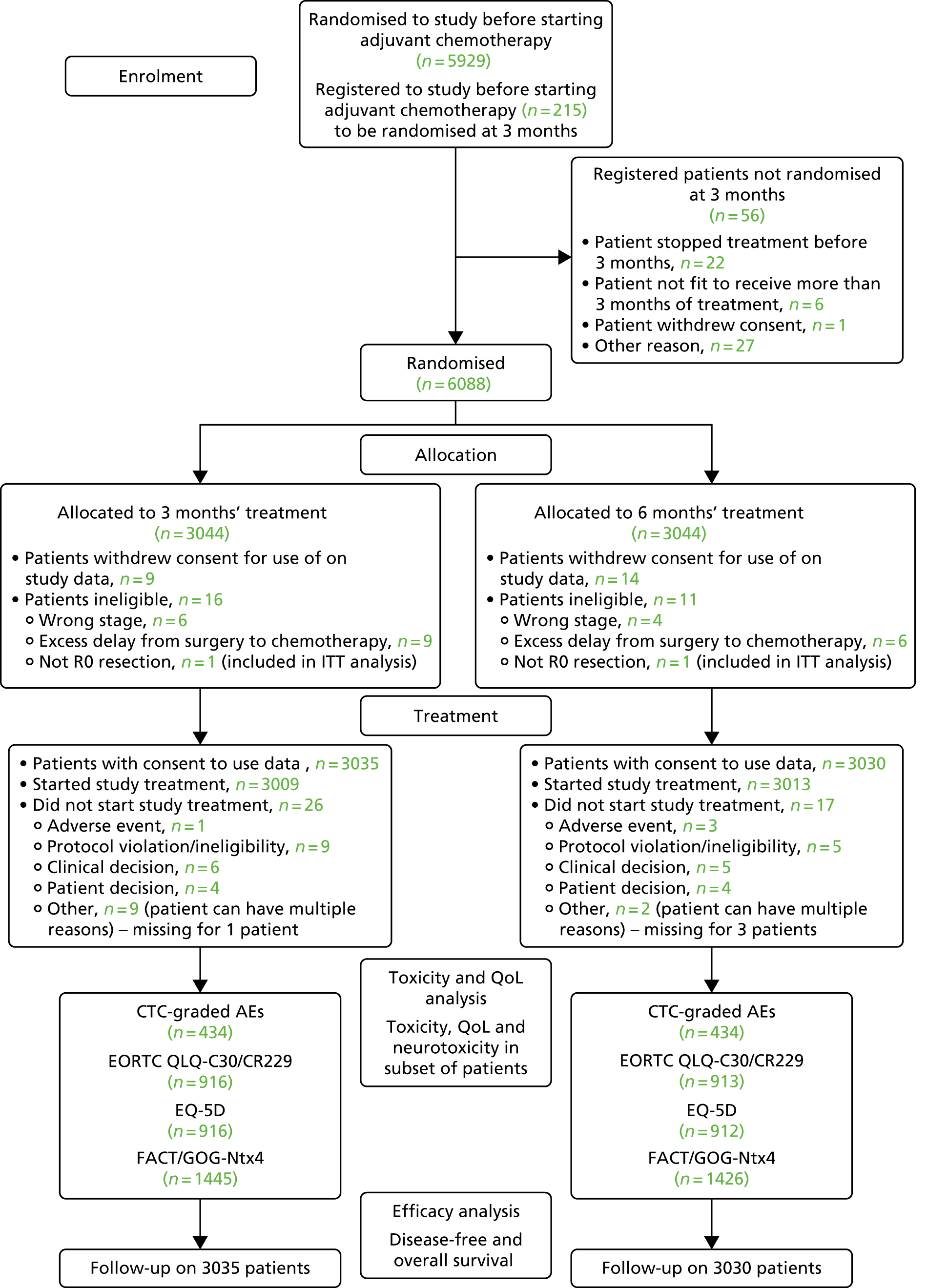

The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram (Figure 1) shows patients who entered and progressed through the trial and provided data for the different assessment parameters. Of the 6088 patients entering the trial, 3044 were randomised into each treatment group (3-month and 6-month duration). Of these 3044 patients, 3035 (99.7% of 3044 randomised to this group) in the 3-month treatment group were included in the ITT analyses, with 3009 patients receiving the study drug, and 3030 (99.5% of 3044 randomised to this group) in the 6-month treatment group were included in the ITT analyses, with 3013 patients receiving the study drug. The reasons patients were not included in the ITT analysis and did not start study treatment are also detailed in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

The CONSORT flow diagram of patient progression through the SCOT trial. Reproduced from Iveson et al. 16 © The Author(s). Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an Open Access article under the CC BY 4.0 license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Baseline data

Baseline data (recorded at the time of randomisation) identified approximately 60% of patients as male and 40% as female, with the median age being 65 years. Most patients (> 80%) had a diagnosis of colon cancer and approximately 80% had stage III disease. For about 67% of patients, the planned treatment was oxaliplatin and capecitabine, with the remaining 33% planned to receive oxaliplatin and 5FU. Baseline characteristics were comparable for the 3-month and 6-month treatment groups for the overall patient population (Table 1) and for the other analysis sets considering toxicity and HRQoL (see Appendix 1).

| Characteristic | Randomised treatment group | |

|---|---|---|

| 3 months of treatment (N = 3044) | 6 months of treatment (N = 3044) | |

| Gender, n (%) | ||

| Female | 1201 (39.5) | 1200 (39.4) |

| Male | 1843 (60.5) | 1844 (60.6) |

| Total | 3044 (100.0) | 3044 (100.0) |

| Age (years) | ||

| Median | 65 | 65 |

| IQR | 58–70 | 58–70 |

| Range | 23–84 | 20–85 |

| Total | 3044 | 3044 |

| Performance status at randomisation, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 2190 (71.9) | 2144 (70.4) |

| 1 | 854 (28.1) | 900 (29.6) |

| Total | 3044 (100.0) | 3044 (100.0) |

| Disease site, n (%) | ||

| Colon | 2492 (81.9) | 2495 (82.0) |

| Rectum | 552 (18.1) | 549 (18.0) |

| Total | 3044 (100.0) | 3044 (100.0) |

| T stage, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 1 (0.0) | 3 (0.1) |

| 1 | 92 (3.0) | 95 (3.1) |

| 2 | 284 (9.3) | 283 (9.3) |

| 3 | 1749 (57.5) | 1748 (57.4) |

| 4 | 917 (30.1) | 915 (30.1) |

| X | 1(0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Total | 3044 (100.0) | 3044 (100.0) |

| N stage, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 559 (18.4) | 557 (18.3) |

| 1 | 1731 (56.9) | 1732 (56.9) |

| 2 | 754 (24.8) | 755 (24.8) |

| Total | 3044 (100.0) | 3044 (100.0) |

| Planned treatment, n (%) | ||

| FOLFOX | 993 (32.6) | 988 (32.5) |

| CAPOX | 2051 (67.4) | 2056 (67.5) |

| Total | 3044 (100.0) | 3044 (100.0) |

| If CAPOX planned, starting dose of capecitabine, n (%) | ||

| 750 mg/m2 | 348 (19.5) | 349 (19.4) |

| 800 mg/m2 | 72 (4.0) | 78 (4.3) |

| 1000 mg/m2 | 1369 (76.5) | 1370 (76.2) |

| Total | 1789 (100.0) | 1797 (100.0) |

| High-risk stage II, n (%) | ||

| No | 2493 (81.9) | 2499 (82.1) |

| Yes | 551 (18.1) | 545 (17.9) |

| Total | 3044 (100.0) | 3044 (100.0) |

| Randomisation time point, n (%) | ||

| Baseline | 2964 (97.4) | 2965 (97.4) |

| 3 months | 80 (2.6) | 79 (2.6) |

| Total | 3044 (100.0) | 3044 (100.0) |

Exposure to study medication

The duration of adjuvant chemotherapy, based on the number of treatment cycles delivered, is presented in Table 2; for the purpose of this analysis, one cycle of oxaliplatin and 5FU equated to 2 weeks of treatment and one cycle of oxaliplatin and capecitabine equated to 3 weeks of treatment. Overall, 83.3% of patients randomised to the 3-month treatment group received 3 months of treatment: the frequency was slightly higher for those receiving oxaliplatin and 5FU (86.2% of patients vs. 81.9% of those receiving oxaliplatin and capecitabine). Overall, 58.8% of those randomised to the 6-month treatment group received 6 months of treatment, with the proportion being similar for those receiving oxaliplatin and 5FU (59.5%) and for those receiving oxaliplatin and capecitabine (58.5%); 6.9% of patients randomised to 6 months of treatment stopped treatment at 3 months. A total of 13.8% of patients stopped treatment before 3 months, with the proportion being similar for those randomised to receive 3 months of treatment (14.1%) and for those randomised to receive 6 months of treatment (13.8%).

| Treatment | Duration of treatment (based on the number of cycles) (weeks) | 3-month treatment (N = 3044), n (%) | 6-month treatment (N = 3044), n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| FOLFOX | < 12 | 116 (11.8) | 107 (10.9) |

| 12 | 845 (86.2) | 55 (5.6) | |

| > 12, ≤ 16 | 18 (1.8) | 64 (6.5) | |

| > 16, ≤ 20 | 0 (0.0) | 88 (8.9) | |

| > 20, ≤ 24 | 1 (0.1) | 74 (7.5) | |

| 24 | 0 (0.0) | 586 (59.5) | |

| > 24 | 0 (0.0) | 11 (1.1) | |

| Total | 980 (100.0) | 985 (100.0) | |

| CAPOX | < 12 | 310 (15.2) | 310 (15.3) |

| 12 | 1675 (81.9) | 154 (7.6) | |

| > 12, ≤ 16 | 59 (2.9) | 75 (3.7) | |

| > 16, ≤ 20 | 0 (0.0) | 124 (6.1) | |

| > 20, ≤ 24 | 0 (0.0) | 141 (7.0) | |

| 24 | 0 (0.0) | 1187 (58.5) | |

| > 24 | 0 (0.0) | 37 (1.8) | |

| Total | 2044 (100.0) | 2028 (100.0) | |

| All patients | < 12 | 426 (14.1) | 417 (13.8) |

| 12 | 2520 (83.3) | 209 (6.9) | |

| > 12, ≤ 16 | 77 (2.5) | 139 (4.6) | |

| > 16, ≤ 20 | 0 (0.0) | 212 (7.0) | |

| > 20, ≤ 24 | 1 (0.0) | 215 (7.1) | |

| 24 | 0 (0.0) | 1773 (58.8) | |

| > 24 | 0 (0.0) | 48 (1.6) | |

| Total | 3024a (100.0) | 3013b (100.0) |

The overall median treatment duration based on actual start and end dates was 11.3 weeks (IQR 10.1–12.6 weeks) for the 3-month treatment group and 23.1 weeks (IQR 17.0–25.3 weeks) for the 6-month treatment group. A higher proportion of patients receiving oxaliplatin and 5FU had at least one delayed cycle in both the 3-month (65.0% vs. 45.2% with oxaliplatin and capecitabine) and the 6-month (83.0% vs. 66.3%) treatment groups.

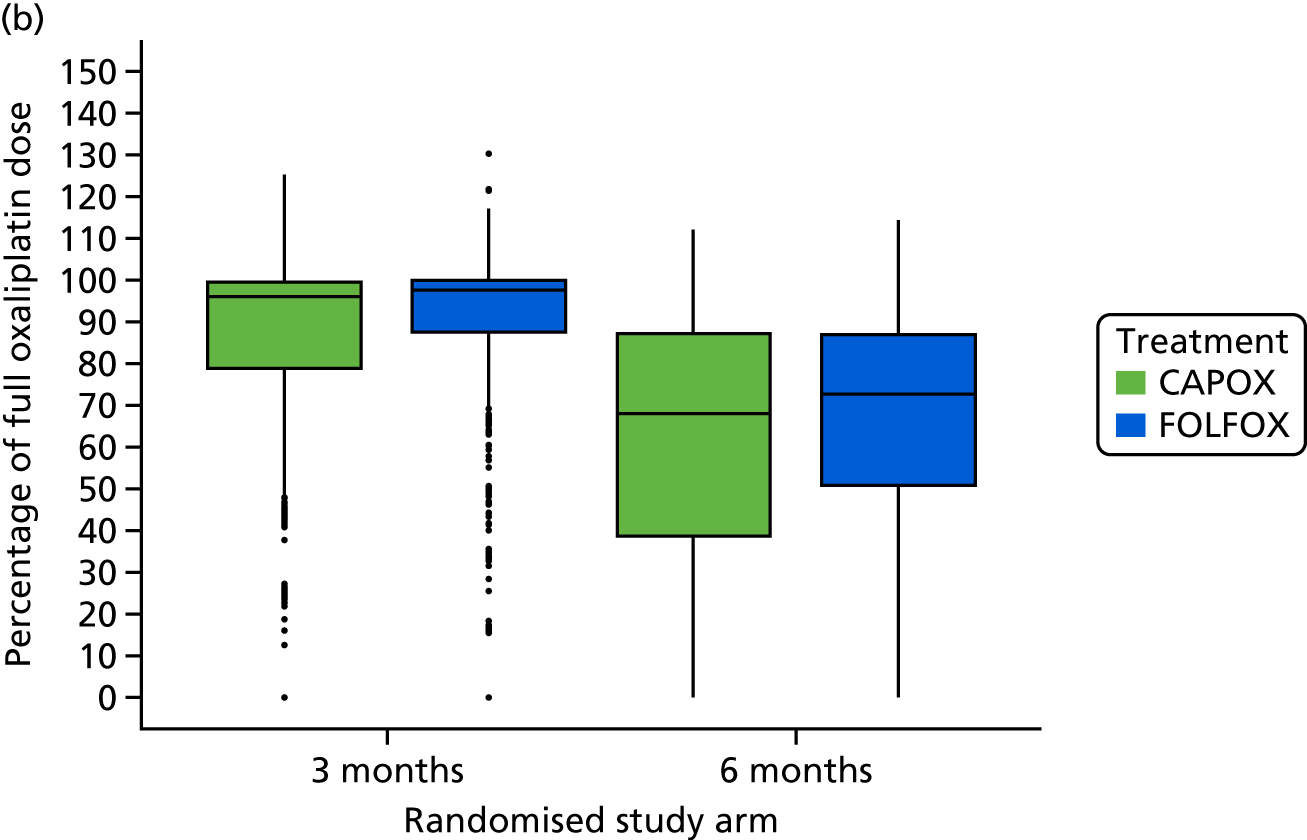

The median percentage of the full fluoropyrimidine dose delivered was 95.3% (IQR 83.1–99.8%) in the 3-month and 83.2% (IQR 56.7–95.7%) in the 6-month treatment groups. The median percentage of the full oxaliplatin dose delivered was 96.6% (IQR 82.3% to 99.7%) in the 3-month and 70.2% (IQR 44.3% to 87.1%) in the 6-month treatment groups. These values were similar irrespective of the fluoropyrimidine backbone (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Treatment delivery by treatment group and adjuvant regimen. (a) Treatment duration; (b) percentage of intended oxaliplatin dose; and (c) percentage of intended 5FU/capecitabine dose. Boxes show median and IQR; whiskers show range; dots represent outliers. FOLFOX, oxaliplatin and 5FU. Adapted from Iveson et al. 16 © The Author(s). Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an Open Access article under the CC BY 4.0 license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

A total of 788 patients (26.2%) underwent 5FU or capecitabine dose reduction in the 3-month treatment group compared with 1286 patients (42.7%) in the 6-month treatment group; 906 patients (30.1%) underwent oxaliplatin dose reduction in the 3-month treatment group compared with 1869 patients (62.0%) in the 6-month treatment group.

As patients receiving oxaliplatin and 5FU require insertion of a line, this could potentially delay the start of their treatment. However, the difference in mean time from surgery to the start of adjuvant chemotherapy was negligible when comparing patients treated with oxaliplatin and 5FU [mean 58 days, standard deviation (SD) 16 days)] and those treated with oxaliplatin and capecitabine (mean 56 days, SD 14 days).

Comparison of efficacy for 3-month versus 6-month adjuvant chemotherapy

Disease-free survival

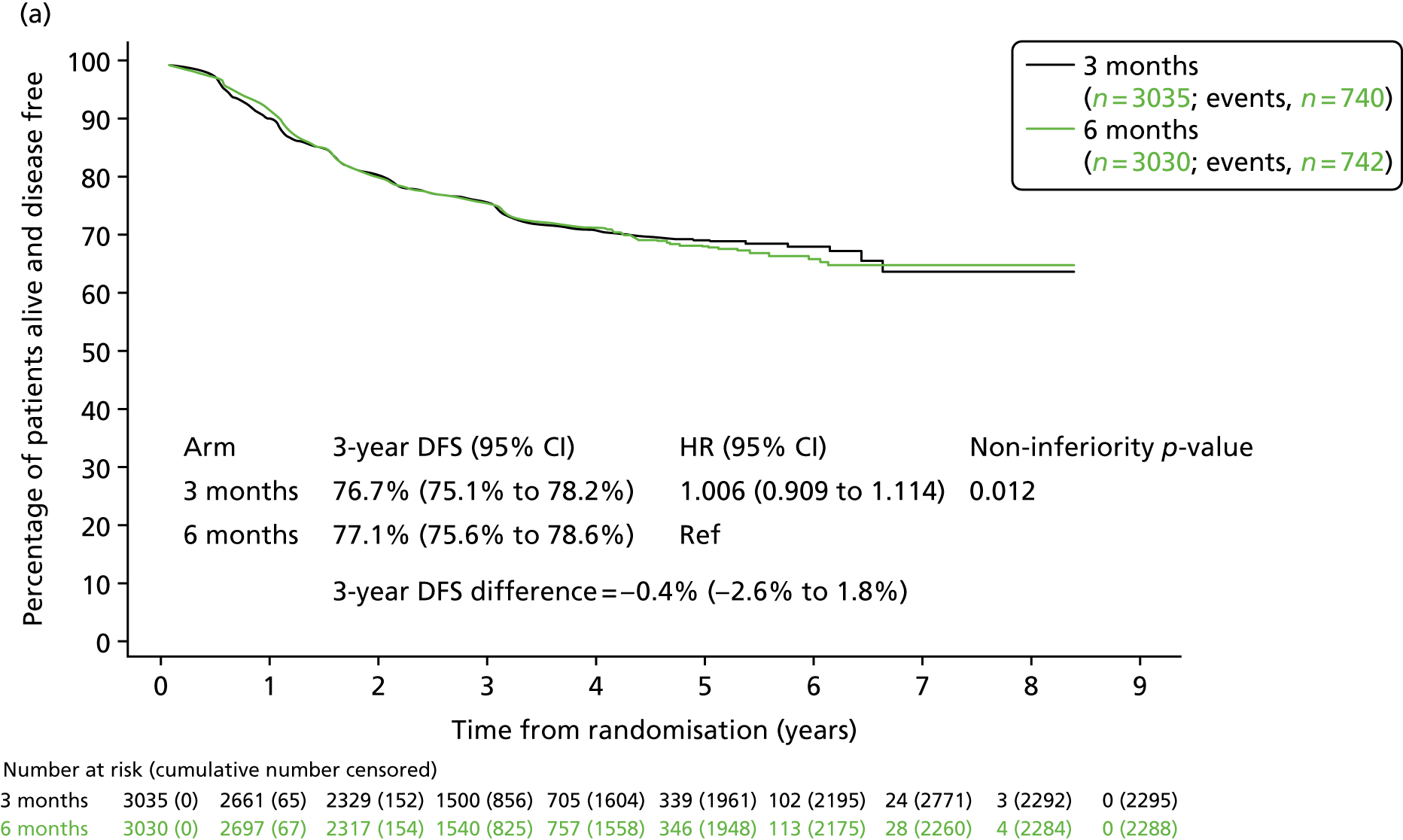

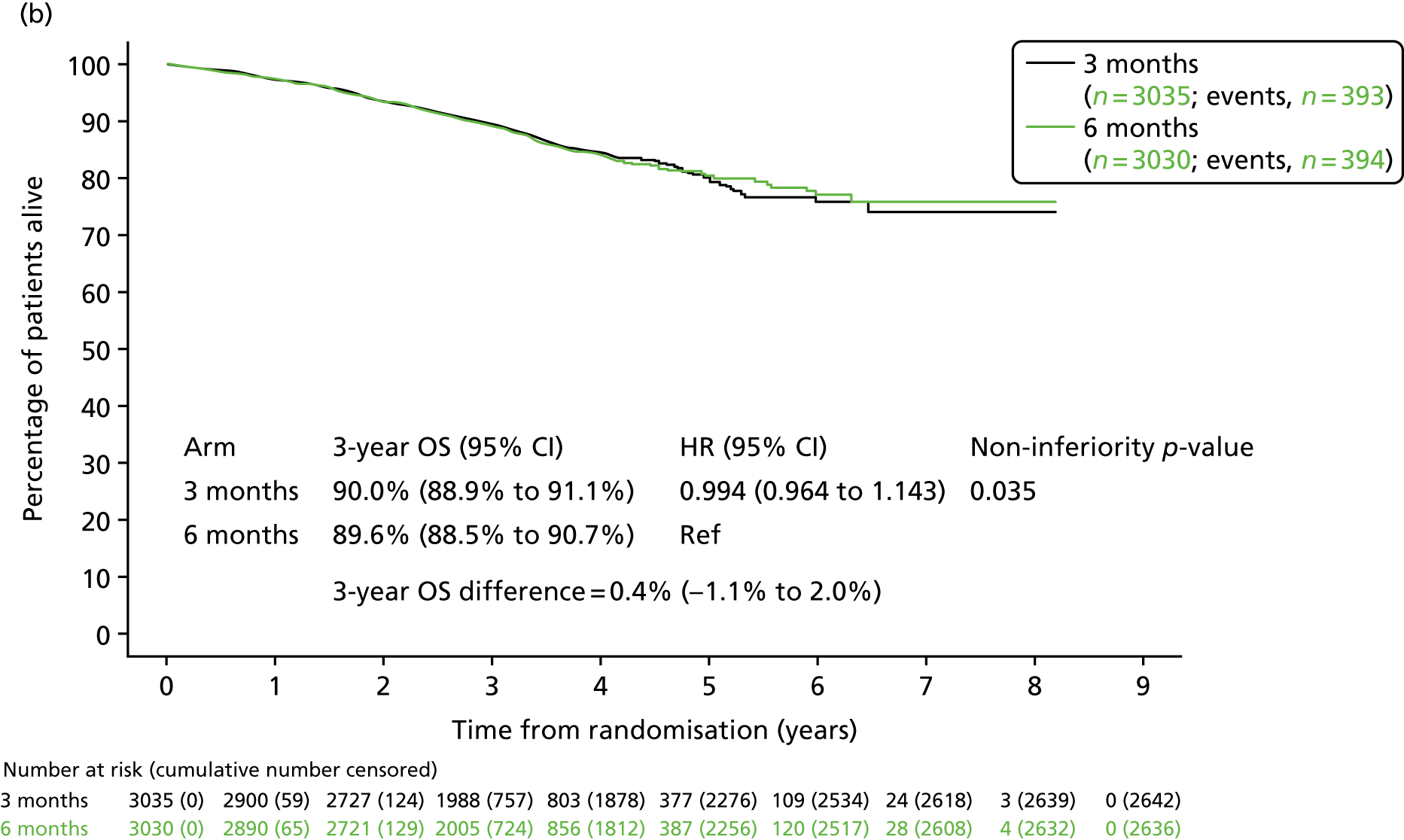

By the time of analysis there had been 1482 DFS events (740 in the 3-month treatment group and 742 in the 6-month treatment group). In the 3-month treatment group, 658 patients (21.7%) experienced disease recurrence, 71 patients (2.1%) died without disease recurrence or a new primary colorectal lesion, and 11 patients (0.4%) had a new primary colorectal cancer lesion; in the 6-month treatment group, 654 patients (21.6%) experienced disease recurrence, 76 patients (2.6%) died without disease recurrence or new primary colorectal lesion, and 12 patients (0.4%) had a new primary colorectal cancer lesion. The 3-year DFS rate in the 3-month treatment group was 76.7% [standard error (SE) 0.8%] and in the 6-month treatment group was 77.1% (SE 0.8%); this equated to a HR of 1.006 [95% CI 0.909 to 1.114; p-value for non-inferiority (pNI) = 0.012] and therefore met the criteria confirming non-inferiority for 3-month compared with 6-month adjuvant chemotherapy (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

(a) Disease-free survival and (b) overall survival, by treatment group. Adapted from Iveson et al. 16 © The Author(s). Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an Open Access article under the CC BY 4.0 license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Sensitivity analysis considered the difference between treatment groups based on the actual duration of treatment (Figure 4). For eligible patient who received 3 months (2513 patients; see Table 2) or 6 months (1771 patients; see Table 2) of adjuvant chemotherapy, the observed HR was 1.158 (95% CI 1.018, 1.317; p = 0.641) with non-inferiority not confirmed in any of these smaller, non-ITT populations.

FIGURE 4.

Plot of 3-month/6-month HR by actual treatment duration (analysis according to duration restricted to eligible patients who started treatment) with associated non-inferiority p-values. Reproduced from Iveson et al. 16 © The Author(s). Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an Open Access article under the CC BY 4.0 license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

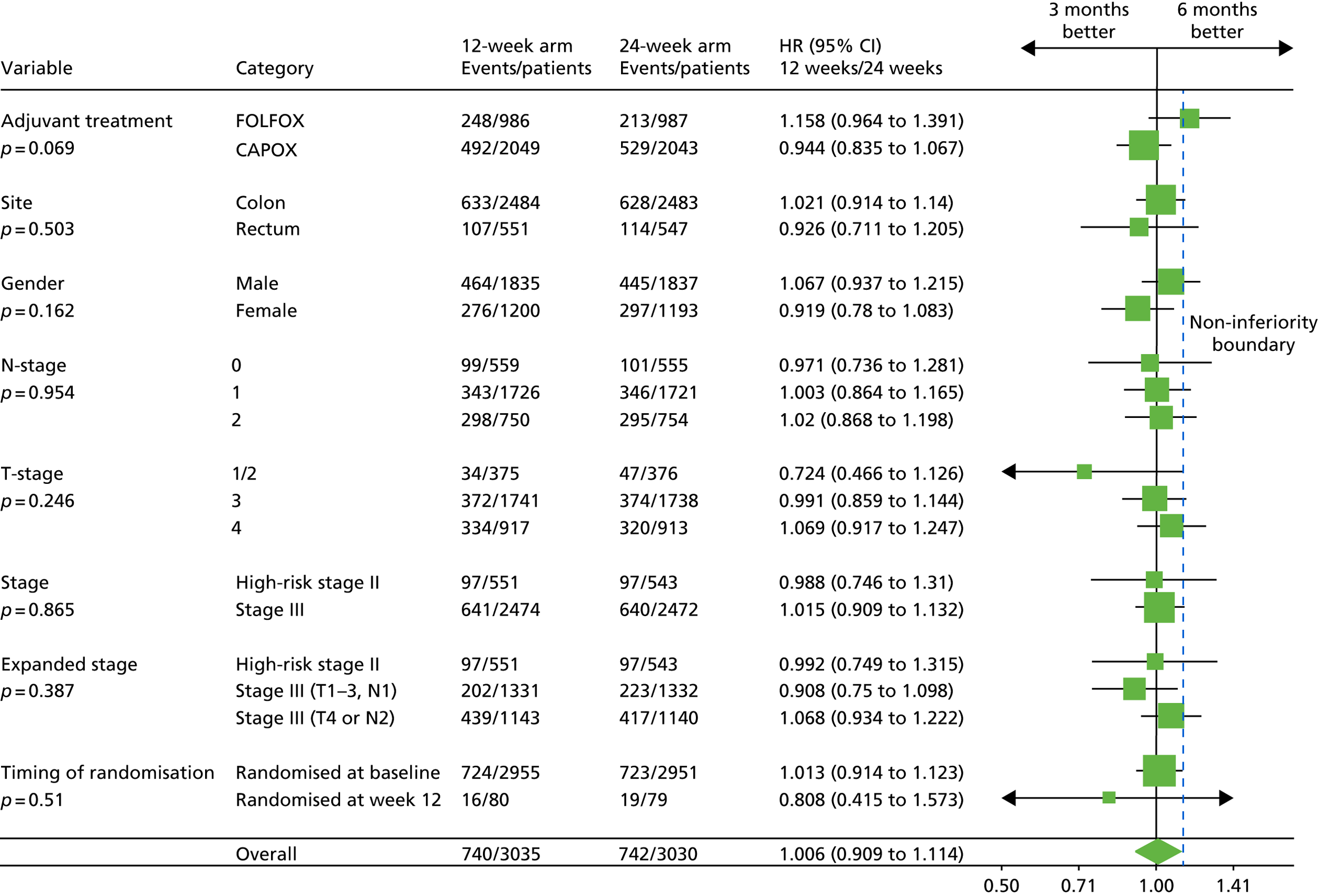

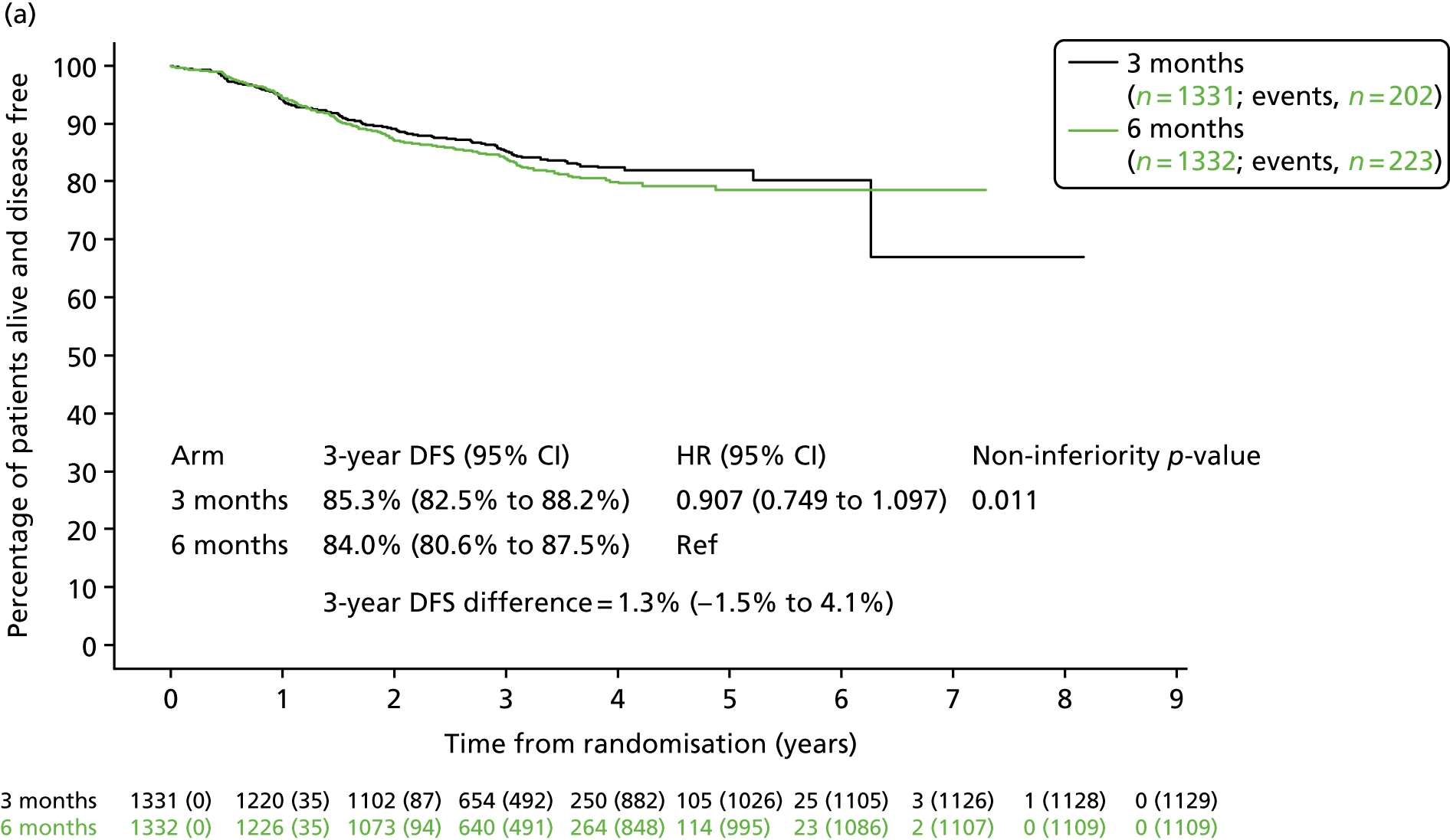

Heterogeneity of the 3-month versus 6-month effect was assessed for the stratification factors used for randomisation and for the randomisation time-point. The resulting HRs, 95% CIs and p-values testing the heterogeneity of the treatment-duration effect for these subgroups are presented in Figure 5. The adjuvant treatment regimen selected at randomisation was associated with a trend towards heterogeneity in effect (p = 0.069).

FIGURE 5.

Disease-free survival and heterogeneity in subgroups by minimisation variables. Categories are listed as recorded at randomisation; 10 patients in the 3-month treatment group and 15 patients in the 6-month treatment group could not be allocated to high-risk stage II or stage III based on T/N data recorded at randomisation. CAPOX, oxaliplatin and capecitabine; FOLFOX, oxaliplatin and 5FU. Adapted from Iveson et al. 16 © The Author(s). Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an Open Access article under the CC BY 4.0 license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

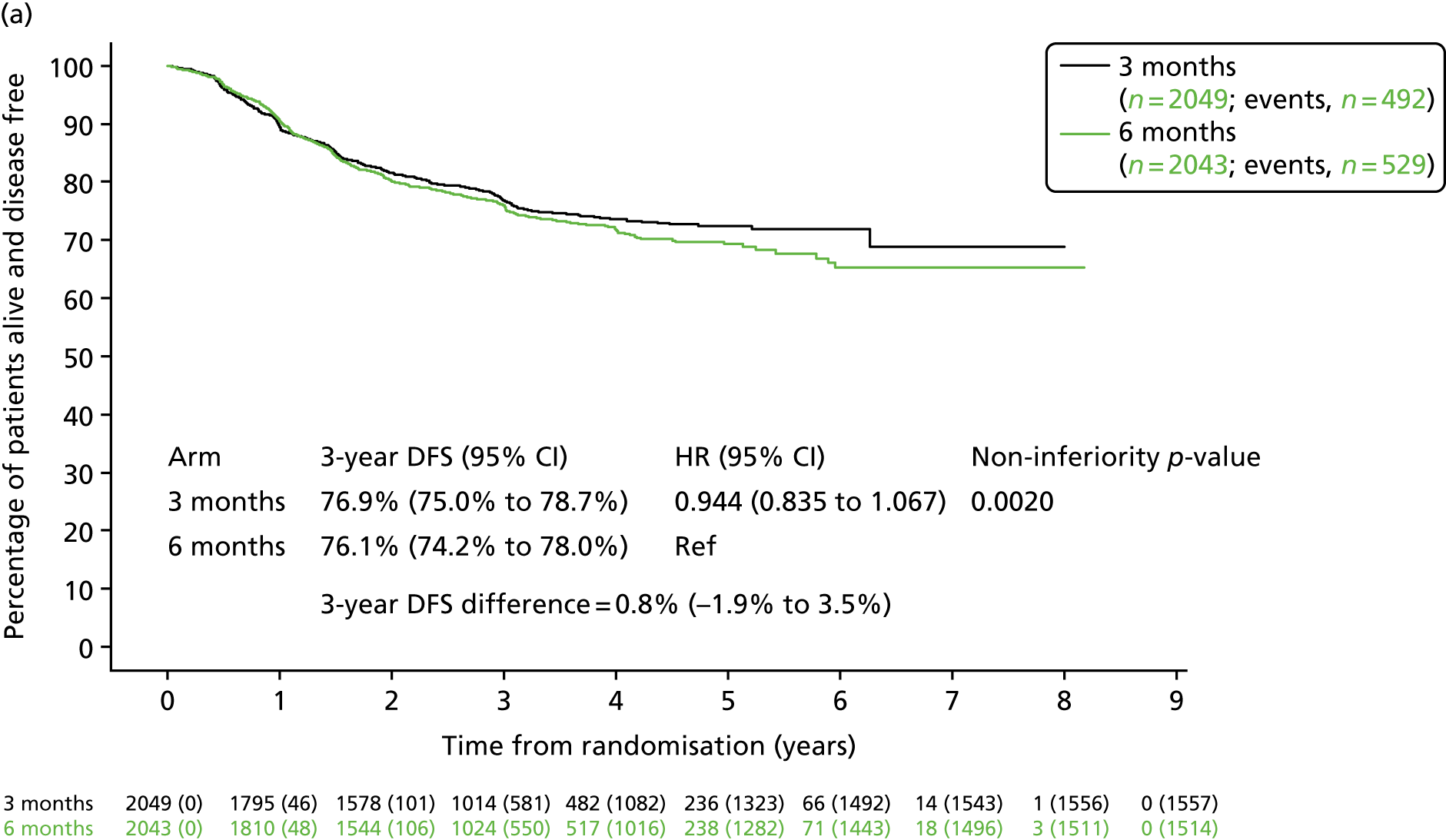

Further (post hoc) analysis of DFS for patients receiving 3-month or 6-month duration adjuvant chemotherapy was conducted separately for patients who received oxaliplatin and 5FU and for patients who received oxaliplatin and capecitabine (Figure 6). For patients receiving oxaliplatin and capecitabine, the 3-year DFS rate for the 3-month treatment group was 76.9% (SE 1.0%) and for the 6-month treatment group was 76.1% (SE 1.0%), resulting in a HR of 0.944 (95% CI 0.835 to 1.067; pNI = 0.002), which met the criteria for non-inferiority. However, for patients receiving oxaliplatin and 5FU, the 3-year DFS for the 3-month treatment group was 76.3% (SE 1.4%) and for the 6-month treatment group was 79.2% (SE 1.3%), resulting in a HR of 1.158 (95% CI 0.964 to 1.391; pNI = 0.591), which did not meet the non-inferiority criteria.

FIGURE 6.

Disease-free survival by treatment group and adjuvant chemotherapy regimen. (a) CAPOX; and (b) FOLFOX. CAPOX, oxaliplatin and capecitabine; FOLFOX, oxaliplatin and 5FU. Adapted with minor corrections from Iveson et al. 16 © The Author(s). Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an Open Access article under the CC BY 4.0 license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

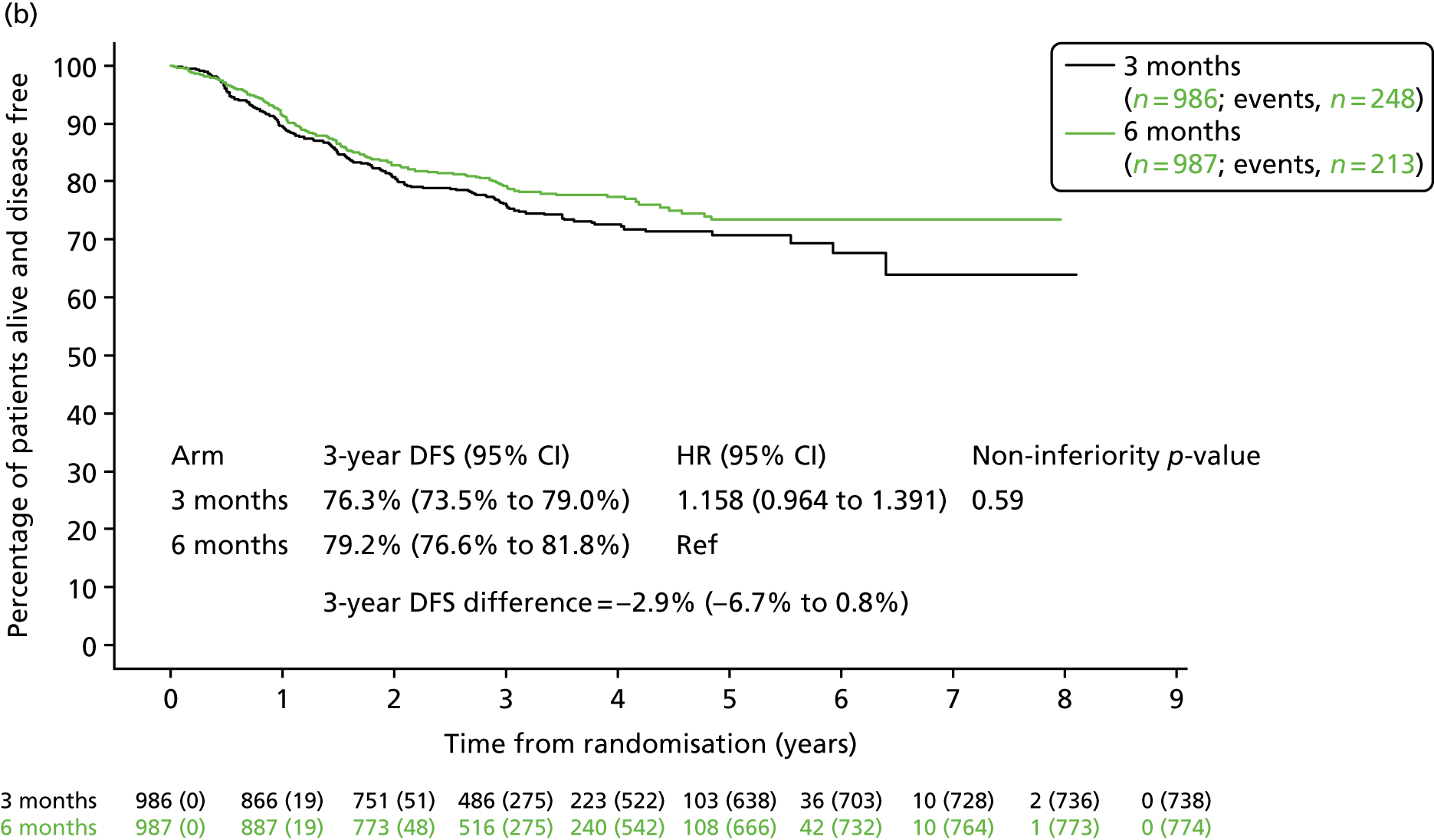

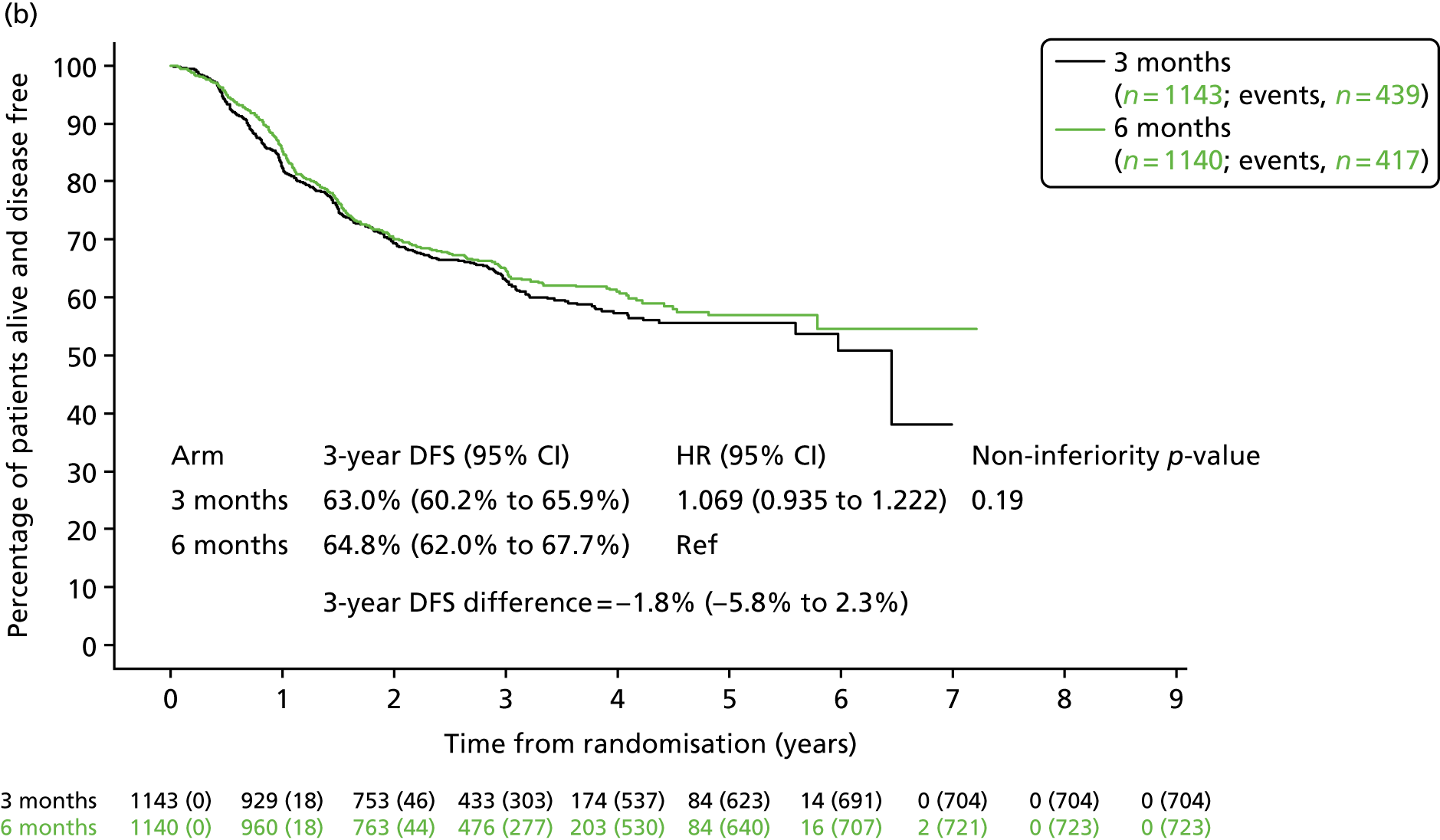

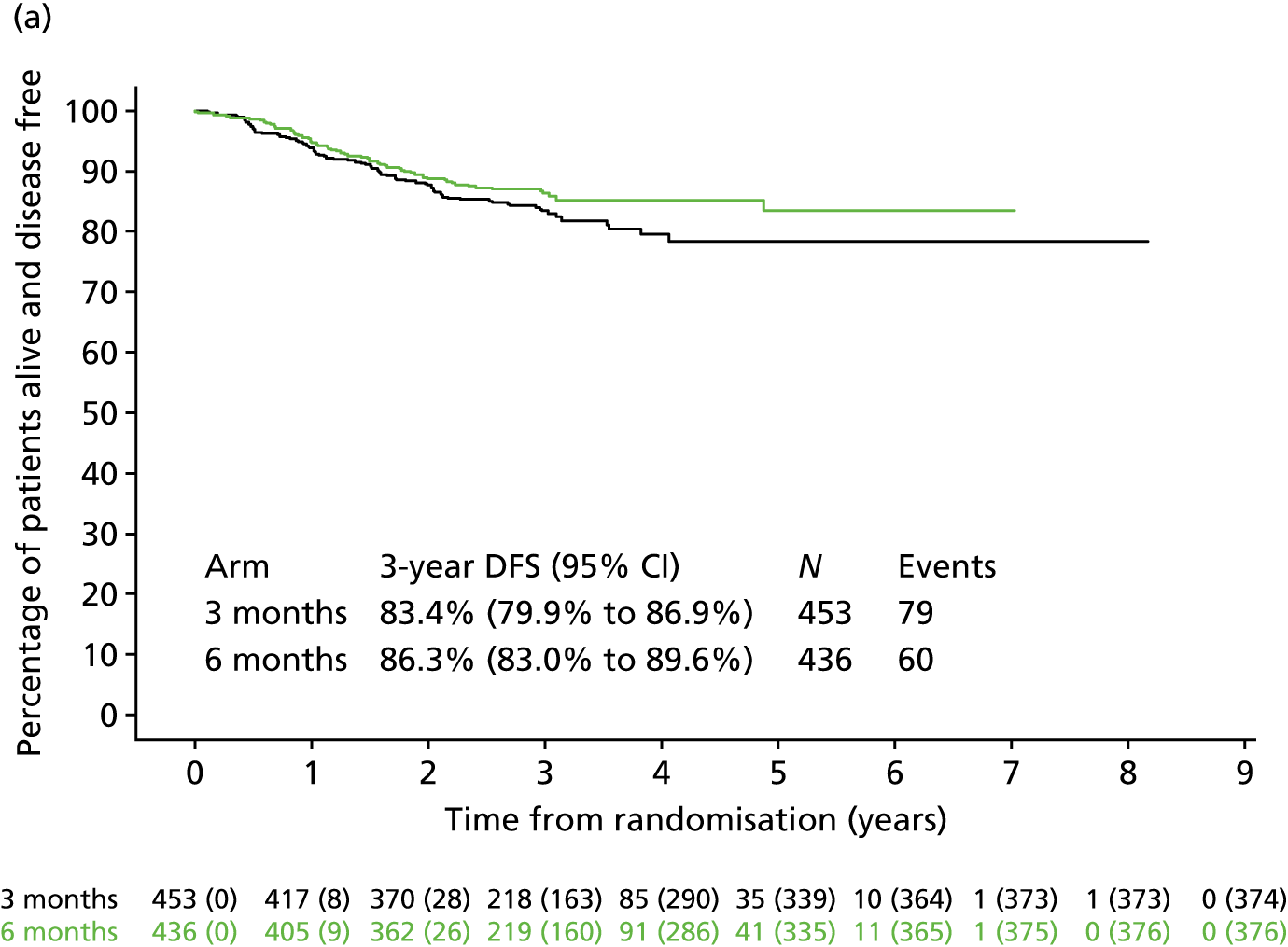

Previous clinical trials in patients with colorectal cancer have shown a marked difference in the risk of relapse between patients with T1–3, N1 disease and those with T4 or N2 disease. 29 Post hoc analyses were therefore conducted to assess whether or not disease stage affected DFS rate for patients with differing adjuvant treatment durations. Kaplan–Meier curves (Figure 7) showed that 3-year DFS for patients with T1–3, N1 primary disease in the 3-month treatment group reached 85.3% (SE 1.0%) and for the 6-month treatment group reached 84.0% (SE 1.0%), giving a HR of 0.907 (95% CI 0.749 to 1.097; pNI = 0.011). For patients with T1–3, N1 disease non-inferiority was, therefore, demonstrated when comparing 3-month with 6-month chemotherapy. For stage III colorectal cancer patients with T4 and/or N2 pathology, 3-year DFS for the 3-month treatment group was 63.0% (SE 1.5%) and for the 6-month treatment group was 64.8% (SE 1.4%), giving a HR of 1.069 (95% CI 0.935 to 1.222; pNI = 0.19), which did not meet the non-inferiority criteria.

FIGURE 7.

Disease-free survival by treatment group and disease stage. (a) T1–3 or N1; and (b) T4 or N2. Adapted with minor corrections from Iveson et al. 16 © The Author(s). Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an Open Access article under the CC BY 4.0 license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

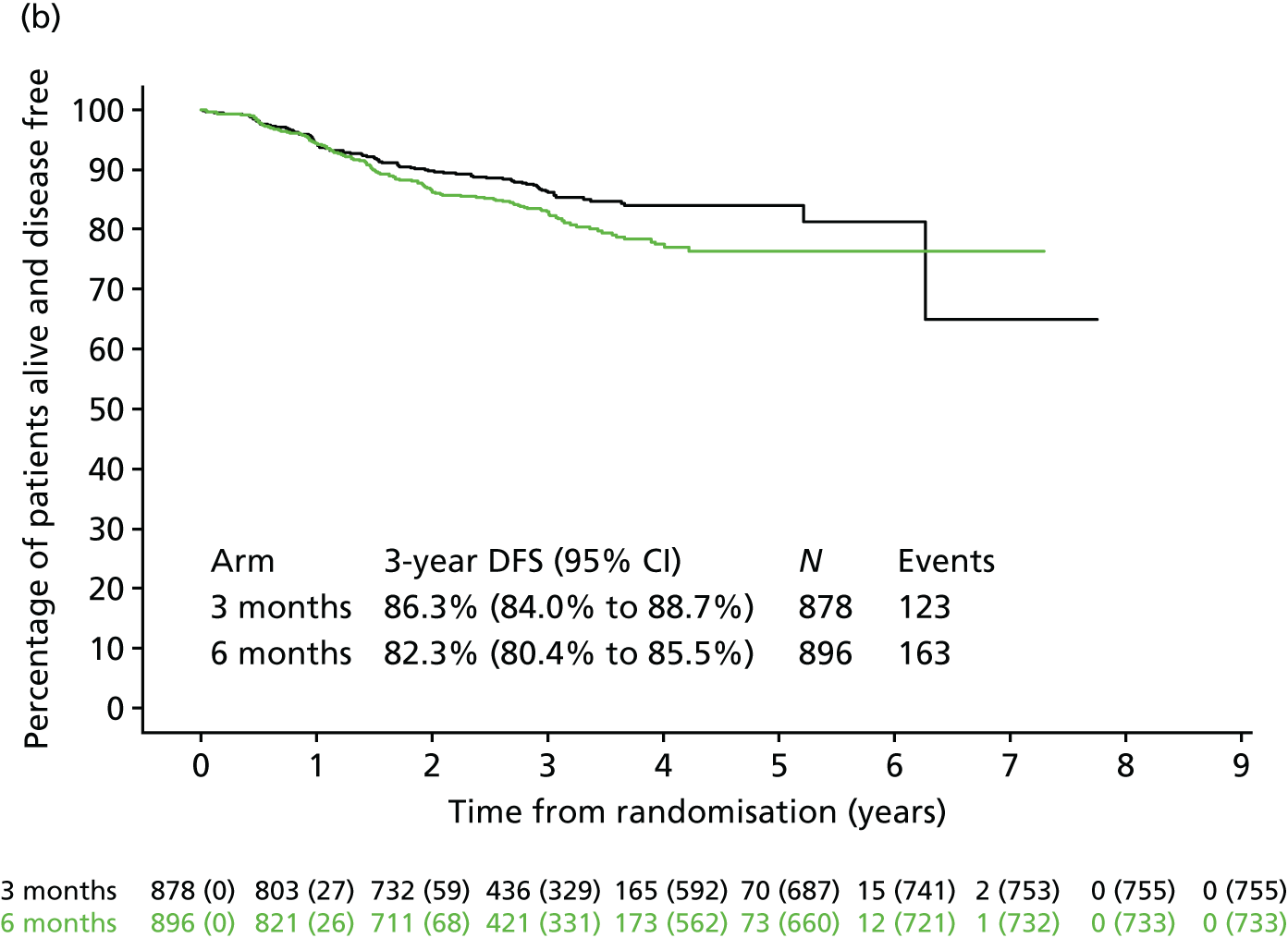

Analysis of these prognostic groups according to the chemotherapy regimen they received (Figure 8) showed that Kaplan–Meier DFS curves suggest that 3 months of treatment with oxaliplatin and oxaliplatin (CAPOX) may be adequate both for T1–3, N1 and for T4 and/or N2 patients (most reliably for T1–3, N1), but this is not as clear for oxaliplatin and 5FU (FOLFOX), particularly for T4 and/or N2.

FIGURE 8.

Disease-free survival by treatment group, disease stage, and adjuvant chemotherapy regimen. (a) Low-risk stage III (T1–3, N1)/FOLFOX; (b) low-risk stage III (T1–3, N1)/CAPOX; (c) high-risk stage III (T4 or N2)/FOLFOX; and (d) high-risk stage III (T4 or N2)/CAPOX. CAPOX, oxaliplatin and capecitabine; FOLFOX, oxaliplatin and 5FU. Adapted from Iveson et al. 16 © The Author(s). Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an Open Access article under the CC BY 4.0 license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Note that although curves in some of the subgroups in Figures 7 and 8 cross, there is no suggestion in any case that the proportional-hazards assumption is violated (minimum p-value testing for non-proportionality, p = 0.226).

Overall survival

By the time of analysis, 787 participants in the 3-month treatment group had died [393 (12.9% of 3035 in the efficacy analysis) and 394 participants in the 6-month treatment group had died (13.0% of the 3030 in the efficacy analysis). The 3-year overall survival rate for the 3-month treatment group was 90.0% (SE 0.6%) and for the 6-month treatment group was 89.6% (SE 0.6%), equating to a HR of 0.994 (95% CI 0.964 to 1.143; pNI = 0.035; see Figure 3b). Sixteen deaths in each treatment group were considered related to study medication.

Safety

The occurrence of AEs was analysed for a total of 868 patients, comprising 434 patients in each treatment group. Table 3 shows the maximum NCI CTCAE grade recorded per patient for AEs with an incidence of ≥ 10% in either treatment group. Most of these events (alopecia, anaemia, anorexia, diarrhoea, fatigue, hand–foot syndrome, mucositis, sensory neuropathy, neutropenia, pain, rash, altered taste, thrombocytopenia and watery eye) showed a statistically significant increase in grade for the 6-month treatment group compared with the 3-month treatment group.

| Adverse event | Randomised treatment group, n (%) | p-value (comparison of ordered categories) | p-value (comparison of percentage of grade 3/4/5 adverse events) | Odds ratio for incidence of grade 3/4/5 toxicities (6 months/3 months) from logistic regression (CI) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 months of treatment (N = 434) | 6 months of treatment (N = 434) | |||||||||||||

| 0 | 1–2 | 3 | 4 | Missing | 0 | 1–2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Missing | ||||

| Alopecia | 345 (83.3) | 69 (16.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 20 (–) | 309 (76.1) | 97 (23.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 28 (–) | 0.0094 | – | Not estimable |

| Anaemia | 270 (64.7) | 143 (34.3) | 2 (0.5) | 2 (0.5) | 17 (–) | 212 (52.2) | 190 (46.8) | 3 (0.7) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 28 (–) | 0.00013 | 1.00 | 1.027 (0.255–0.4.136) |

| Anorexia | 312 (75.9) | 92 (22.4) | 7 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) | 23 (–) | 262 (64.7) | 140 (34.6) | 3 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 29 (–) | 0.00043 | 0.34 | 0.431 (0.111–1.677) |

| Constipation | 289 (69.8) | 122 (29.5) | 2 (0.5) | 1 (0.2) | 20 (–) | 268 (66.0) | 135 (33.3) | 3 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 28 (–) | 0.28 | 1.00 | 1.010 (0.205–5.083) |

| Diarrhoea | 128 (30.7) | 243 (58.3) | 44 (10.6) | 2 (0.5) | 17 (–) | 99 (24.4) | 241 (59.4) | 63 (15.5) | 2 (0.5) | 1 (0.2) | 28 (–) | 0.0079 | 0.033 | 1.566 (1.045–2.345) |

| Fatigue | 58 (14.0) | 320 (77.1) | 35 (8.4) | 2 (0.5) | 19 (–) | 41 (10.1) | 333 (82.0) | 32 (7.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 28 (–) | 0.022 | 0.62 | 0.874 (0.533–1.433) |

| Hand–foot syndrome | 277 (66.9) | 129 (31.2) | 8 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) | 20 (–) | 218 (53.7) | 169 (41.6) | 18 (4.4) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 28 (–) | <0.0001 | 0.031 | 2.492 (1.078–5.758) |

| Mucositis (clinical exam) | 355 (86.0) | 56 (13.6) | 2 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 21 (–) | 320 (79.0) | 83 (20.5) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 29 (–) | 0.013 | 1.00 | 1.020 (0.143–7.275) |

| Mucositis (functional/symptomatic) | 283 (68.4) | 127 (30.7) | 4 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 20 (–) | 242 (59.6) | 159 (39.2) | 4 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 28 (–) | 0.0066 | 0.75 | 1.278 (0.341–4.794) |

| Nausea | 147 (35.3) | 249 (59.9) | 20 (4.8) | 0 (0.0) | 18 (–) | 120 (29.6) | 277 (68.2) | 9 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 28 (–) | 0.26 | 0.057 | 0.449 (0.202–0.998) |

| Neuropathy: sensory | 37 (8.8) | 365 (86.9) | 18 (4.3) | 0 (0.0) | 14 (–) | 28 (6.8) | 314 (76.8) | 65 (15.9) | 2 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 25 (–) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 4.375 (2.550–7.508) |

| Neutropenia | 287 (69.0) | 90 (21.6) | 23 (5.5) | 16 (3.8) | 18 (–) | 221 (54.4) | 127 (31.3) | 43 (10.6) | 14 (3.4) | 1 (0.2) | 28 (–) | <0.0001 | 0.031 | 1.611 (1.046–2.480) |

| Pain: other (specify) | 311 (74.0) | 99 (23.6) | 10 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | 14 (–) | 278 (68.0) | 107 (26.2) | 24 (5.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 25 (–) | 0.026 | 0.014 | 2.556 (1.206–5.415) |

| Rash | 359 (86.9) | 52 (12.6) | 2 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 21 (–) | 320 (79.0) | 84 (20.7) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 29 (–) | 0.00061 | 1.00 | 0.509 (0.046–5.632) |

| Taste alteration | 231 (56.1) | 180 (43.7) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 22 (–) | 179 (44.4) | 222 (55.1) | 2 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 31 (–) | 0.0021 | 0.57 | 2.050 (0.185–22.696) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 290 (69.7) | 117 (28.1) | 5 (1.2) | 4 (1.0) | 18 (–) | 253 (62.3) | 145 (35.7) | 5 (1.2) | 2 (0.5) | 1 (0.2) | 28 (–) | 0.020 | 1.00 | 0.909 (0.347–2.380) |

| Vomiting | 304 (73.1) | 98 (23.6) | 14 (3.4) | 0 (0.0) | 18 (–) | 270 (66.5) | 126 (31.0) | 10 (2.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 28 (–) | 0.056 | 0.54 | 0.725 (0.318–1.652) |

| Watery eye | 339 (82.7) | 71 (17.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 24 (–) | 310 (76.7) | 92 (22.8) | 2 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 30 (–) | 0.028 | 0.25 | Not estimable |

The overall frequency of grade ≥ 3 toxicity was 59.4% for 6-month duration adjuvant chemotherapy and 35.7% for 3-month adjuvant chemotherapy (p < 0.001). Sensory neuropathy, diarrhoea, neutropenia, fatigue, pain, nausea and hand–foot syndrome were the most common grade ≥ 3 AEs reported. The difference in frequency between treatment groups was statistically significant for diarrhoea (p = 0.033), neutropenia (p = 0.023), pain (p = 0.014), hand–foot syndrome (p = 0.031) and sensory neuropathy (p < 0.001). The AE for which there was the most marked increase in the proportion of patients with grade ≥ 3 with 6-month adjuvant chemotherapy was sensory neuropathy (16.4% vs. 4.3% with 3-month treatment).

The proportion of those with febrile neutropenia was 1.6% of patients for the 3-month treatment group and 1.2% for the 6-month treatment group. Figure 9 shows that diarrhoea and hand–foot syndrome were more common in patients receiving oxaliplatin and capecitabine and that neutropenia was more common in those receiving oxaliplatin and 5FU.

FIGURE 9.

Frequency of patients with selected grade ≥ 3 toxicities, by treatment group and treatment regimen. (a) CAPOX 3 months; (b) CAPOX 6 months; (c) FOLFOX 3 months; and (d) FOLFOX 3 months. CAPOX, oxaliplatin and capecitabine; FOLFOX, oxaliplatin and 5FU.

A total of 244 patients in the 3-month treatment group and 576 patients in the 6-month treatment group cited AEs as the reason for stopping treatment early. The most frequently cited AEs leading to treatment discontinuation were diarrhoea (n = 90 patients) for the 3-month treatment group, and diarrhoea (n = 150 patients) and peripheral neuropathy (n = 156 patients) for the 6-month treatment group.

Serious adverse reactions were reported for 421 patients in the 3-month treatment group and for 511 patients in the 6-month treatment group. Gastrointestinal SAEs were most common and occurred in similar proportions of patients in both groups. Thirty-two patients died owing to events attributed to treatment toxicity, with the events distributed equally between the groups (16 patients died in each group); 27 of these deaths occurred during the first 3 months of treatment. A total of 21 patients of the 4108 who received oxaliplatin and capecitabine (0.51%) and 11 patients of the 1980 who received oxaliplatin and 5FU (0.56%) were reported to have died from toxicity.

Peripheral neuropathy was also assessed using a patient-reported outcome (PRO) FACT/GOG-Ntx4 questionnaire. Data were available for 2871 patients who were assessed for up to 7 years. The mean FACT/GOG-Ntx4 questionnaire neuropathy scores for patients receiving 3-month and 6-month adjuvant chemotherapy are shown in Figure 10. The neurotoxicity standardised-adjusted AUC differed markedly between the groups (p < 0.001), with a higher rate of neuropathy for the 6-month treatment group being clearly apparent from 4 months and persisting to ≥ 5 years (p < 0.001). Peak neuropathy occurred at 6 months for the 3-month treatment group and at 9 months for the 6-month treatment group.

FIGURE 10.

Peripheral neuropathy score, by treatment group. Data beyond year 6 were omitted because of small numbers. Error bars show 95% CIs. a, Low completion rate at these time points reflect the fact that neurotoxicity data were initially collected only up to 12 months; b, low return rate because patients were assessed at the start of the last cycle rather than at 6 months. Adapted from Iveson et al. 16 © The Author(s). Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an Open Access article under the CC BY 4.0 license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Health-related quality of life

A total of 1829 patients provided data on the EORTC questionnaires. Global health status and all functional and symptom scales of the EORTC QLQ-C30 showed statistically significant differences in terms of standardised-adjusted AUC, indicating better functioning and fewer side effects in patients receiving 3-month adjuvant chemotherapy. Scores for the two groups mirrored each other over the first 3 months of treatment but subsequently improved from months 4 to 6 for patients in the 3-month treatment group, indicative of functional improvement and decreased side effects in those who stopped treatment at 3 months (Figure 11). For the EORTC QLQ-CR29, statistically significant differences were apparent for body image (p = 0.037), dry mouth (p < 0.0001), hair loss (p = 0.035) and taste (p < 0.0001) scales. The magnitudes of the mean differences in functional and global health status scales between treatment groups were indicative of ‘moderate’ differences for global health status, role functioning, and social function and ‘a little’ difference for physical, emotional and cognitive functions. 22

FIGURE 11.

The EORTC global health status, by treatment group. a, Low return rate as patients were assessed at the start of the last cycle rather than at 6 months. Reproduced from Iveson et al. 16 © The Author(s). Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an Open Access article under the CC BY 4.0 license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

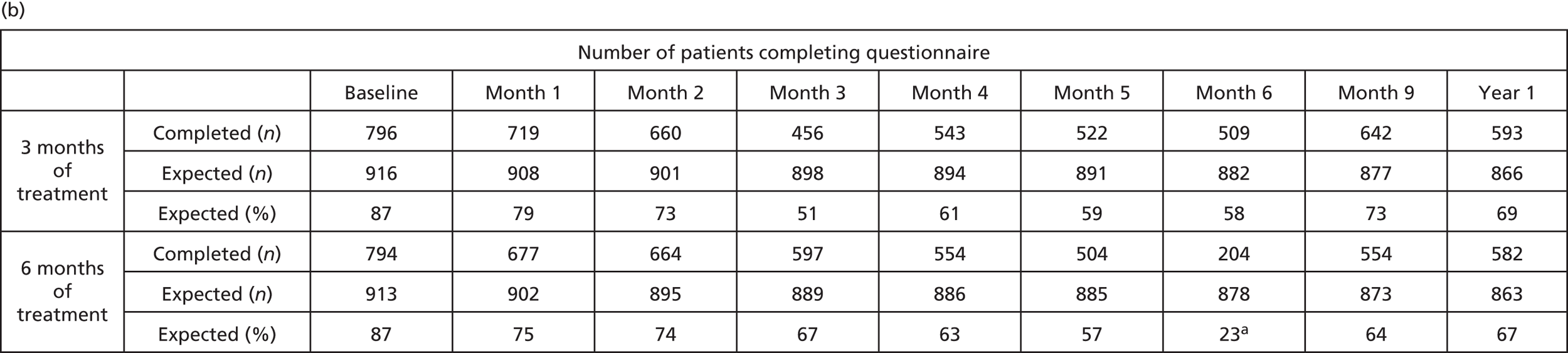

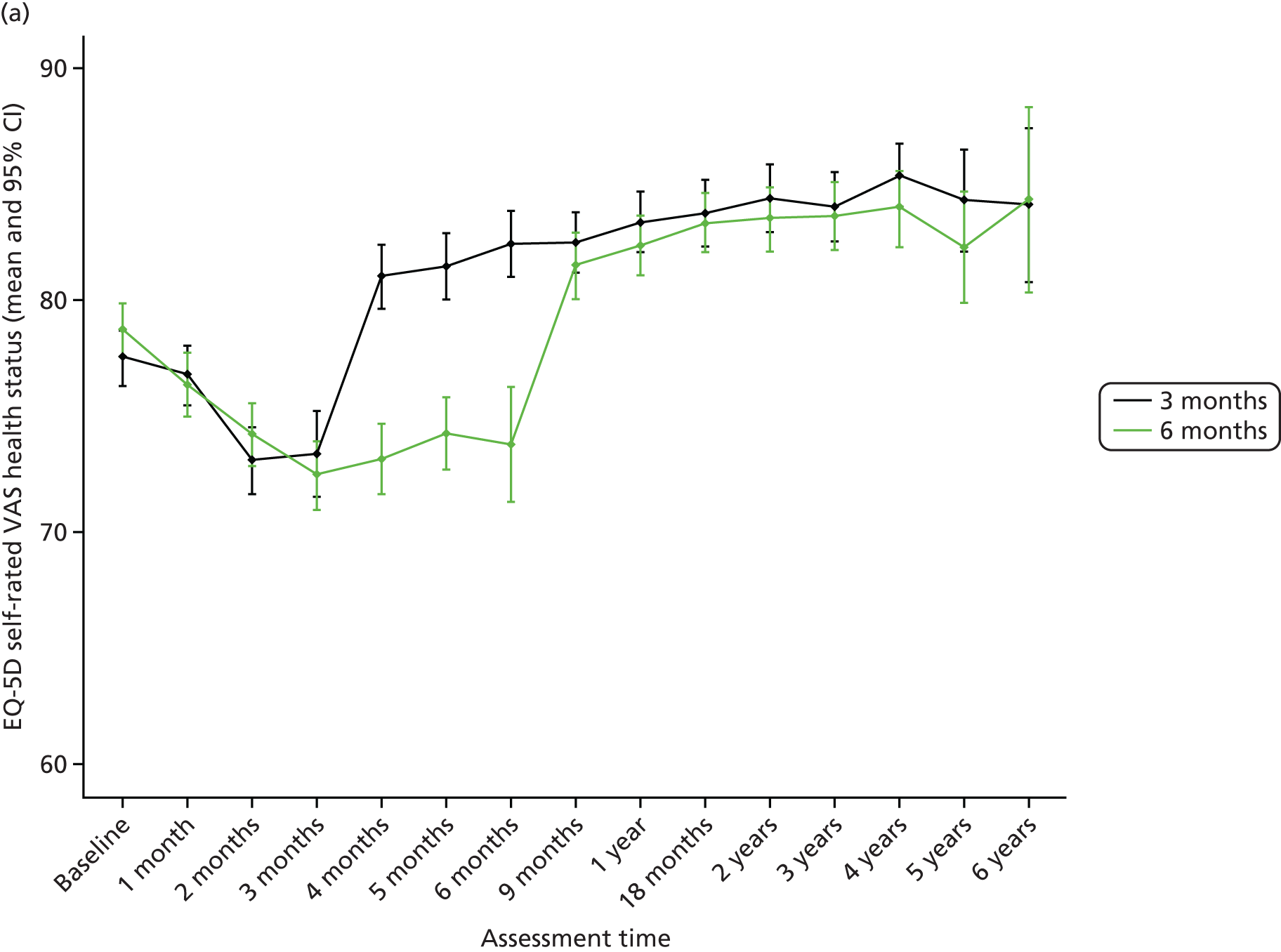

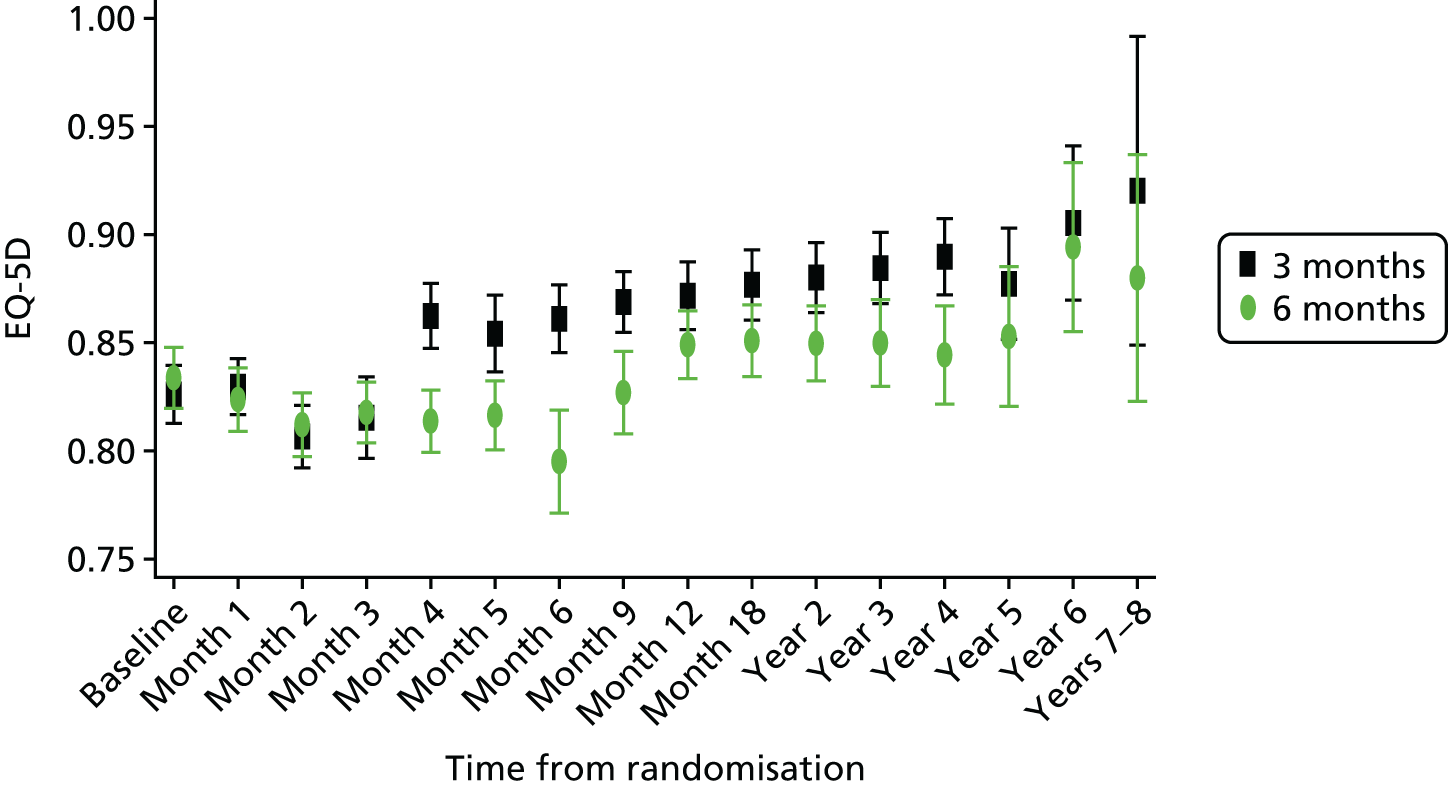

A total of 1828 patients provided data on the EQ-5D. Statistically significant differences in standardised-adjusted AUC were seen for both the EQ-5D self-rated visual analogue scale (p = 0.00081) and the EQ-5D-3L health index (p = 0.00081). Differences between the two treatment groups were apparent from months 4 to 6 (Figure 12), consistent with the time when those in the 6-month treatment group were still receiving treatment but those in the 3-month treatment group had finished. From 9 months to the 7-year follow-up, there were no clinically relevant differences23 between the treatment groups.

FIGURE 12.

The EQ-5D self-rated visual analogue scale, by treatment group. Data beyond year 6 were omitted because of small numbers. a, Low return rate as patients were assessed at the start of the last cycle rather than at 6 months. VAS, visual analogue scale. Reproduced from Iveson et al. 16 © The Author(s). Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an Open Access article under the CC BY 4.0 license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Given the notable number of missing data for HRQoL assessments (FACT/GOG-Ntx4, EORTC and EQ-5D), the reasons for missing questionnaires were analysed and are presented in Appendix 2. Missing questionnaire data were generally related to various errors. Patients who did complete questionnaires were shown to be representative of the overall study population, with no indication that missing data were associated with any particular baseline characteristic. Sensitivity analyses comparing the primary results with those based on just observed data or using data imputed only for patients who completed baseline questionnaires showed similar results.

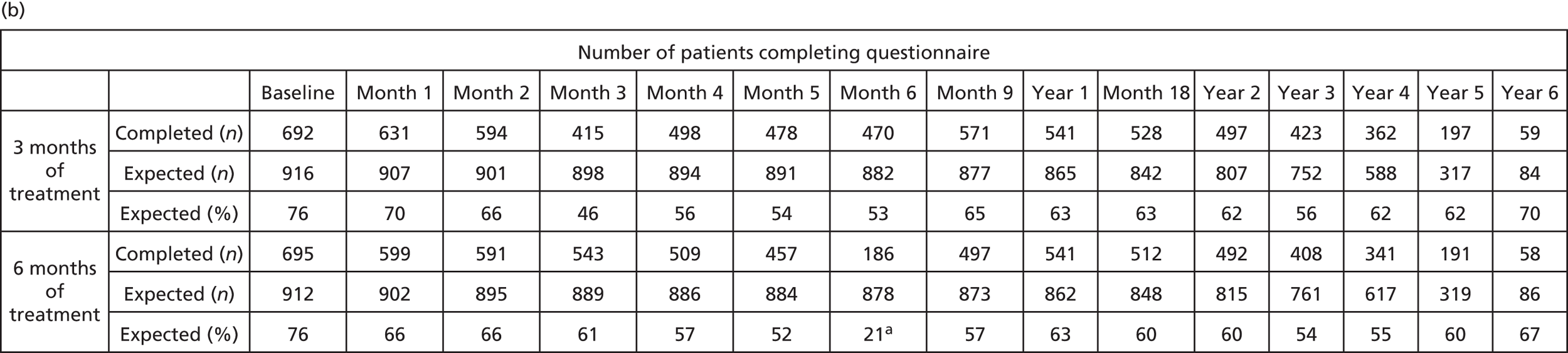

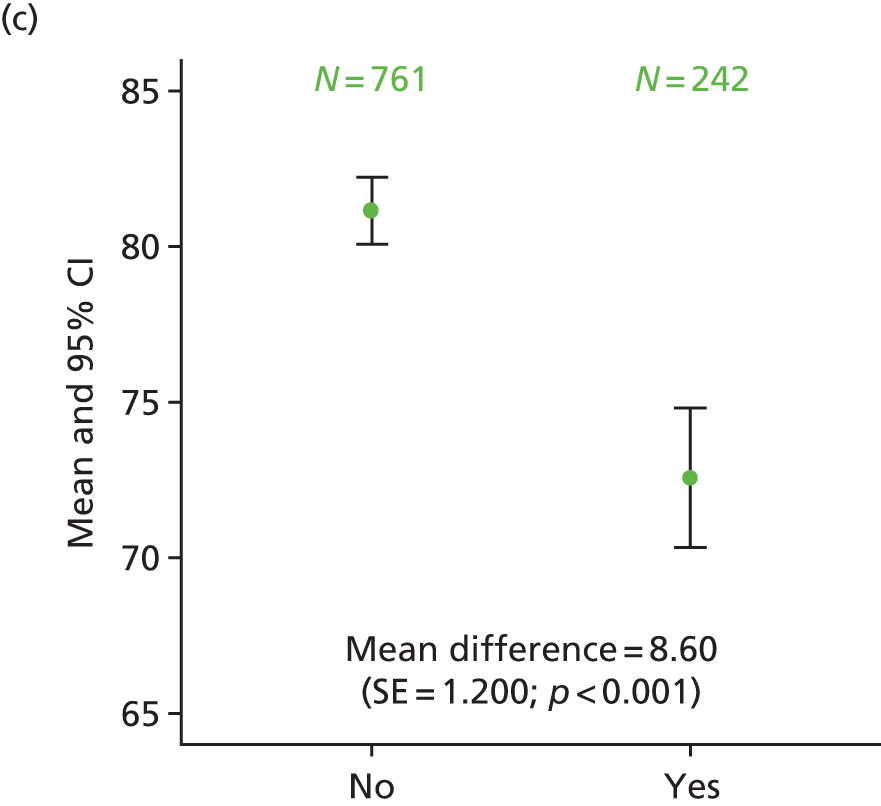

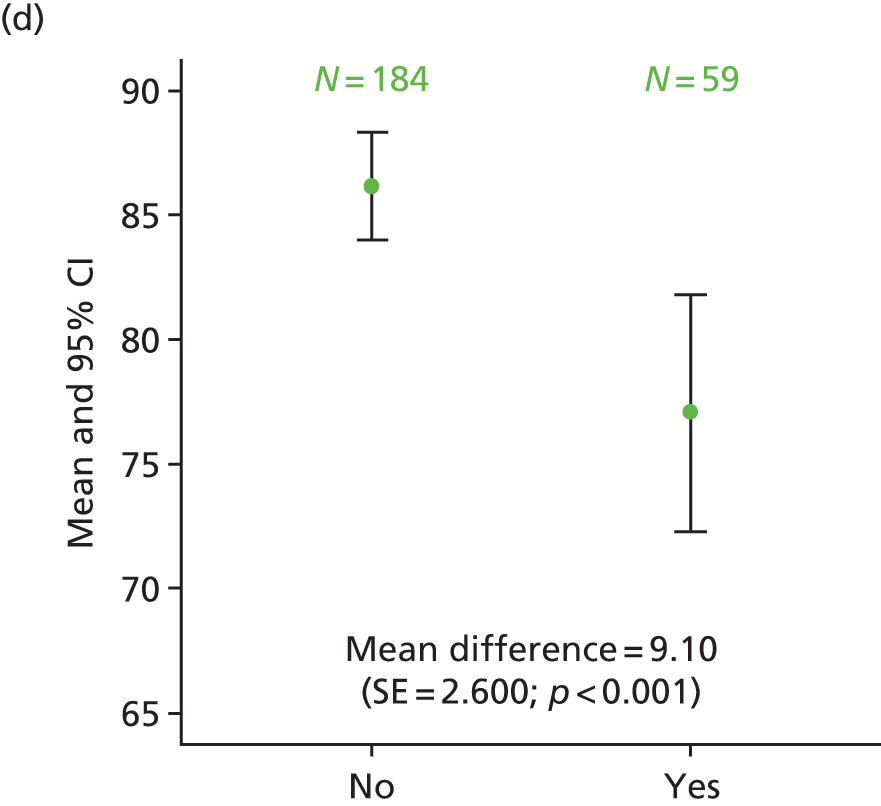

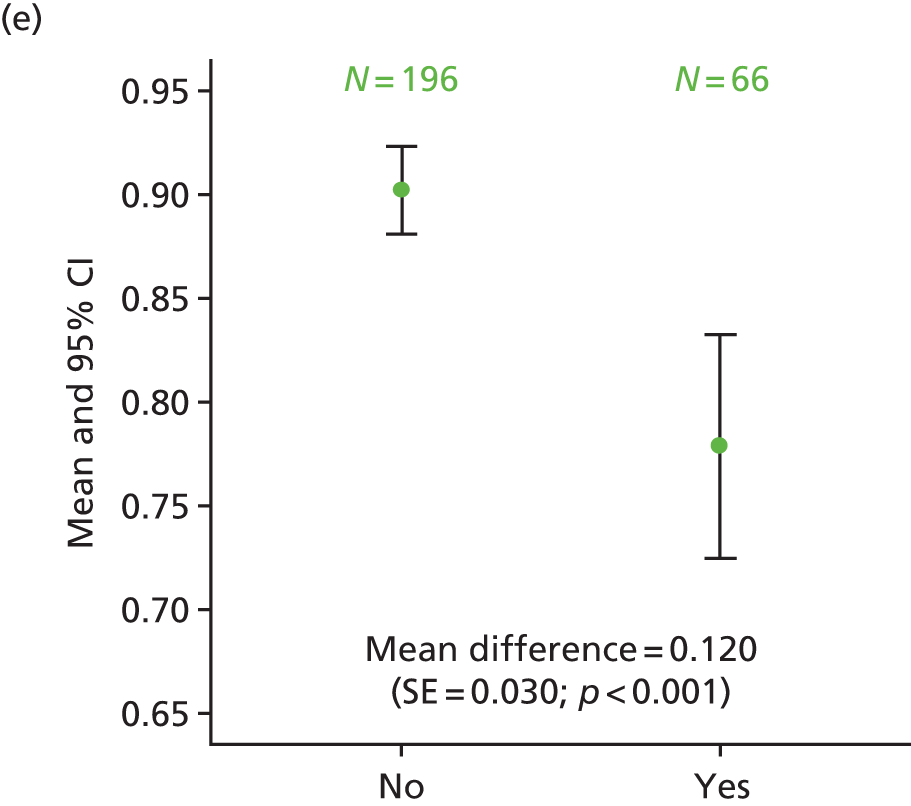

Exploratory analysis considered differences in HRQoL scales when comparing patients with ‘quite a bit’/‘very much’ numbness or tingling or discomfort in hands or feet on the FACT/GOG-Ntx4 toxicity questionnaire with those who rated these symptoms as ‘somewhat’/‘a little bit’/‘not at all’. The proportion of patients recording neuropathy symptoms as being present ‘quite a bit’ or ‘very much’ was higher for patients in the 6-month treatment group at 1 year (34% vs. 14% of patients in the 3-month treatment group), 3 years (32% vs. 17%) and 5 years (29% vs. 16%). This analysis consistently demonstrated statistically significantly poorer HRQoL across the different scales for patients who had ‘quite a bit’ or ‘very much’ recorded for neuropathy symptoms, at all time points (p < 0.001; Figure 13).

FIGURE 13.

Differences in HRQoL assessments based on the degree of numbness/tingling/discomfort in hands or feet. (a) EQ-5D visual analogue scale 1 year; (b) EQ-5D-3L health index 1 year; (c) EORTC global quality of life 1 year; (d) EQ-5D visual analogue scale 3 years; (e) EQ-5D-3L health index 3 years; (f) EQ-5D visual analogue scale 5 years; and (g) EQ-5D-3L health index 5 years. No/yes on all the x-axes refers to whether or not the patient experienced ‘quite a bit/very much numbness or tingling or discomfort in hands or feet’ on the FACT/GOG-Ntx4 toxicity score. Adapted from Iveson et al. 16 © The Author(s). Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an Open Access article under the CC BY 4.0 license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Chapter 4 Economic analyses

Methodology

The economic analysis was undertaken from the perspective of the UK NHS and Personal Social Services for the 2016 base year, adhering to good practice guidelines. 30,31 A within-trial analysis utilised the individual patient-level data on resource use, HRQoL (EQ-5D-3L) and survival.

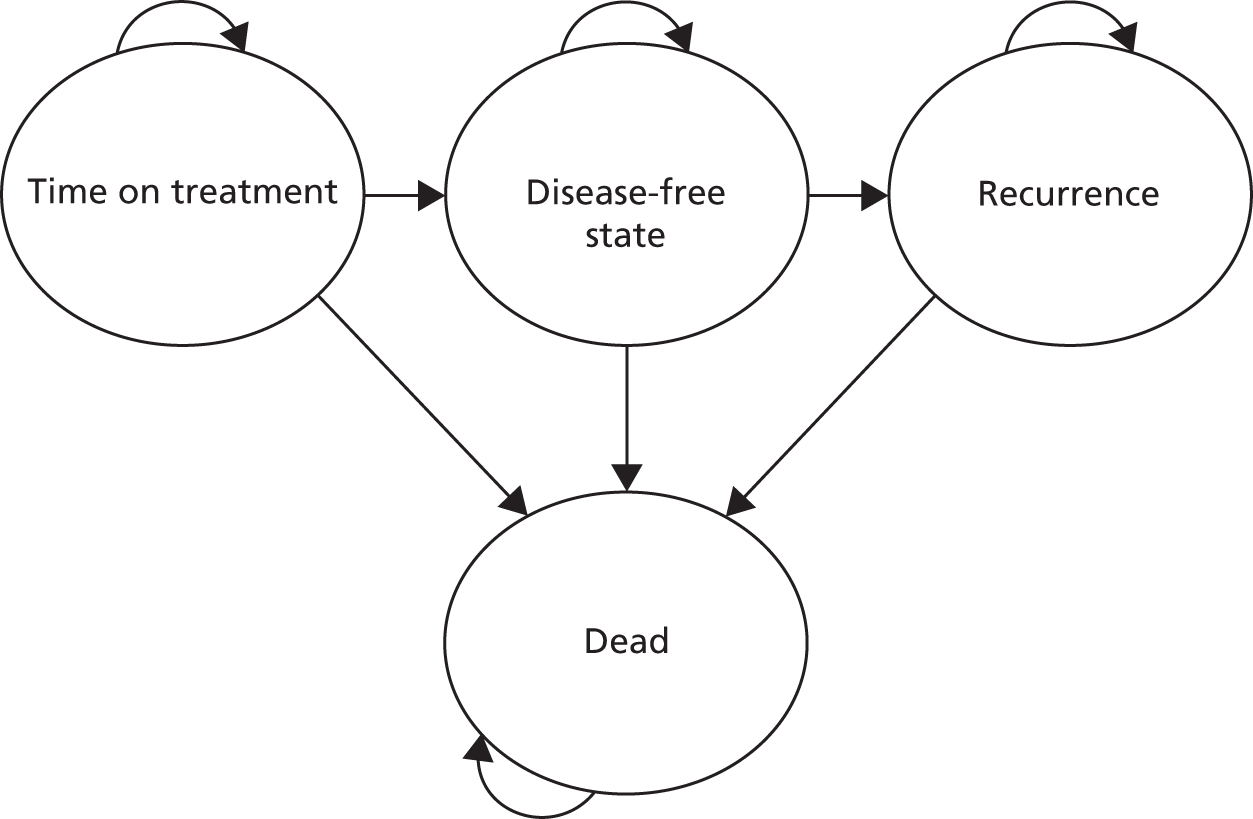

Outcome data

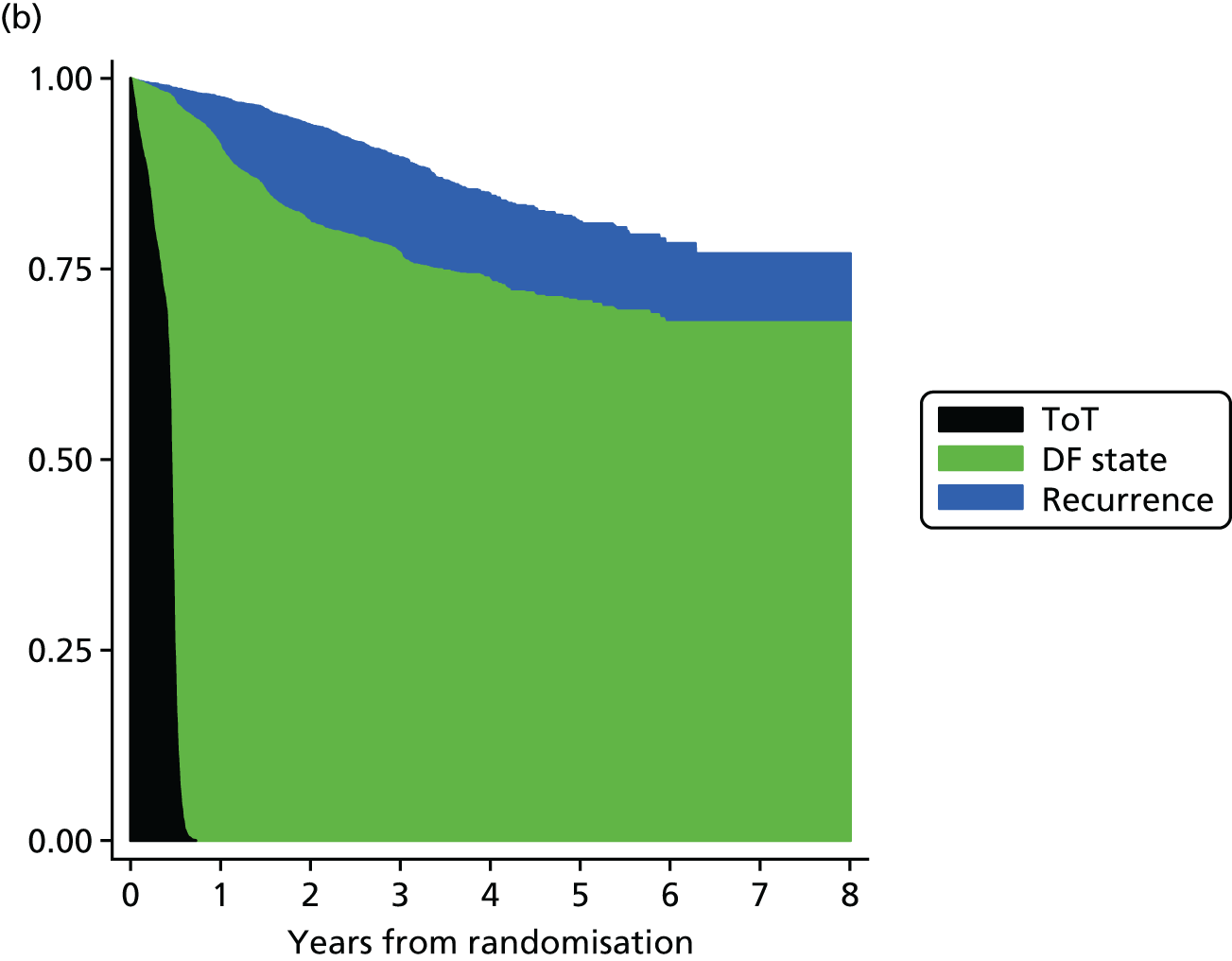

The effectiveness measure for the economic analysis was the discounted QALY gain per patient; QALYs were calculated using quality-adjusted survival analysis. 32 Overall survival data from the SCOT study were partitioned into three health states: time on treatment (ToT), disease-free state post treatment and recurrence (Figure 14). The model begins with patients who have undergone surgery and are now assumed to be disease-free, who begin treatment with chemotherapy (ToT state). After completing treatment, patients move into the disease-free state and remain here until they experience a recurrence or die. Patients who experience a recurrence remain in the recurrence state until they die.

FIGURE 14.

Partitioned survival model.

Kaplan–Meier survival estimates were used for computation of quality-adjusted survival time in each health state over the 8-year within-trial period. A separate model estimated HRQoL for each health state.

The EQ-5D-3L data were collected for a subsample of 1832 patients (about 30% of the study sample) at baseline and all follow-up times and combined with the UK EQ-5D-3L health-utility scores20 to calculate utilities. Table 4 details the characteristics of patients by EQ-5D subsample in comparison with the whole study sample. An interim analysis33 of the SCOT study EQ-5D and AE data showed that adequate data were collected from the first 1832 patients in the SCOT study; therefore, discontinuation of the EQ-5D was recommended for new study recruits beyond that point. To control for plausible differences between the EQ-5D and total study populations, the HRQoL model included co-variables such as planned treatment, high-risk disease, gender, age and ethnicity. The model predicts health utilities for the average characteristics of the patients in each health state.

| Characteristic | Total (N = 6065) | Non-EQ-5D (N = 4308) | EQ-5D (N = 1757) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Planned treatment (%) | ||||

| Oxaliplatin and capecitabine | 67.5 | 67.5 | 67.5 | |

| Oxaliplatin and 5FU | 32.5 | 32.5 | 32.5 | 0.99 |

| Gender (%) and age (mean) | ||||

| Female | 39.46 | 39.65 | 38.99 | |

| Male | 60.54 | 60.35 | 61.01 | 0.633 |

| Age | 63.43 | 63.35 | 63.62 | 0.3094 |

| Disease risk (%) | ||||

| High | 53.19 | 54.32 | 50.43 | |

| Low | 46.81 | 45.68 | 49.57 | 0.006 |

| Ethnicity (%) | ||||

| White/Caucasian | 94.02 | 82.61 | 77.95 | |

| African/Caribbean | 1.37 | 1.09 | 0.97 | |

| South Asian | 1.42 | 1.02 | 0.86 | |

| Chinese | 0.4 | 0.25 | 0.19 | |

| Other | 2.79 | 15.04 | 20.03 | < 0.001 |

A linear regression with SEs clustered at the individual level estimated the HRQoL, including the following independent variables: health state, treatment group and individual characteristics. Time in the health states – ToT, disease-free state and recurrence – was computed by integration of the Kaplan–Meier curves and then adjusted by HRQoL using the method of integrated quality-survival product to compute QALYs. This approach to quality-adjusted survival analysis avoids problems with informative censoring in survival analysis based on individual QALYs as an end point. 34

Cost data

The main cost categories were chemotherapy treatment and hospitalisation. Costs associated with patient treatment were calculated by measuring and valuing resources used by trial participants during the treatment and follow-up periods. Patient-level resource-use data were collected for adjuvant chemotherapy dose/duration and hospitalisation during treatment and follow-up for the whole study sample. Costs were valued in 2016 Great British pounds. The oxaliplatin, capecitabine and 5FU doses administered were recorded, and the numbers of each were combined with their unit costs; the cost per mg of each drug was obtained from the British National Formulary 73, where the lowest price per unit available was used. 35 Hospitalisation costs incurred by patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy and being treated for adverse reactions were recorded. Hospitalisation resource use data included overnight stays in an intensive care unit, a high-dependency unit and general medicine wards,36 and inpatient chemotherapy administration as well as day cases and outpatient cases. Primary care costs (general practitioner visits) were less relevant to this context and were therefore excluded. Direct and non-direct costs for each hospitalisation were obtained from the Information Services Division of NHS Scotland. 37 Direct costs were attributed to medical, nursing, health professional, pharmacy, theatre, laboratory and other costs. For inpatient and day cases occurring within the treatment period, the pharmacy cost was subtracted to avoid double-counting chemotherapy medication. The cost of treating AEs was assumed to be included in hospitalisation costs for patients attending hospital for night or day cases or during outpatient visits.

Given that the follow-up period differed among patients, the total cost per patient was estimated as the Kaplan–Meier survival analysis;38 this allowed the average total cost to be estimated as the sum of the average cost for each period multiplied by the probability of surviving at the beginning of the period.

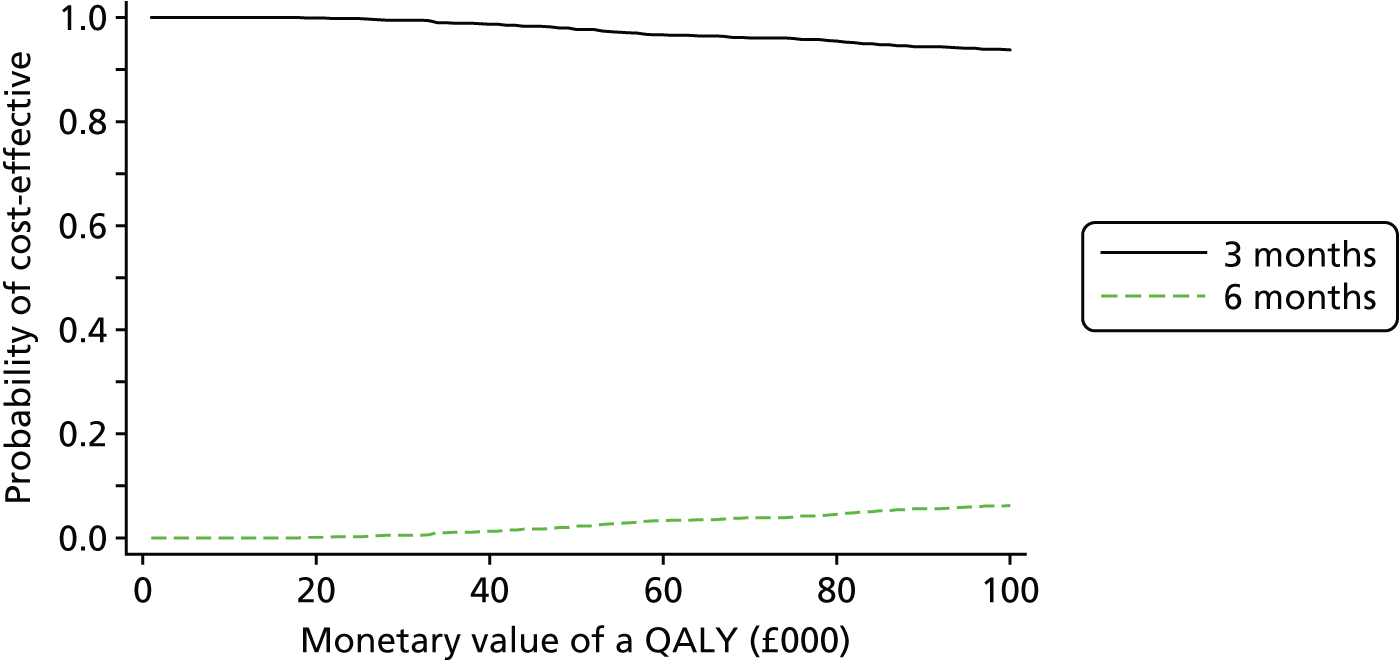

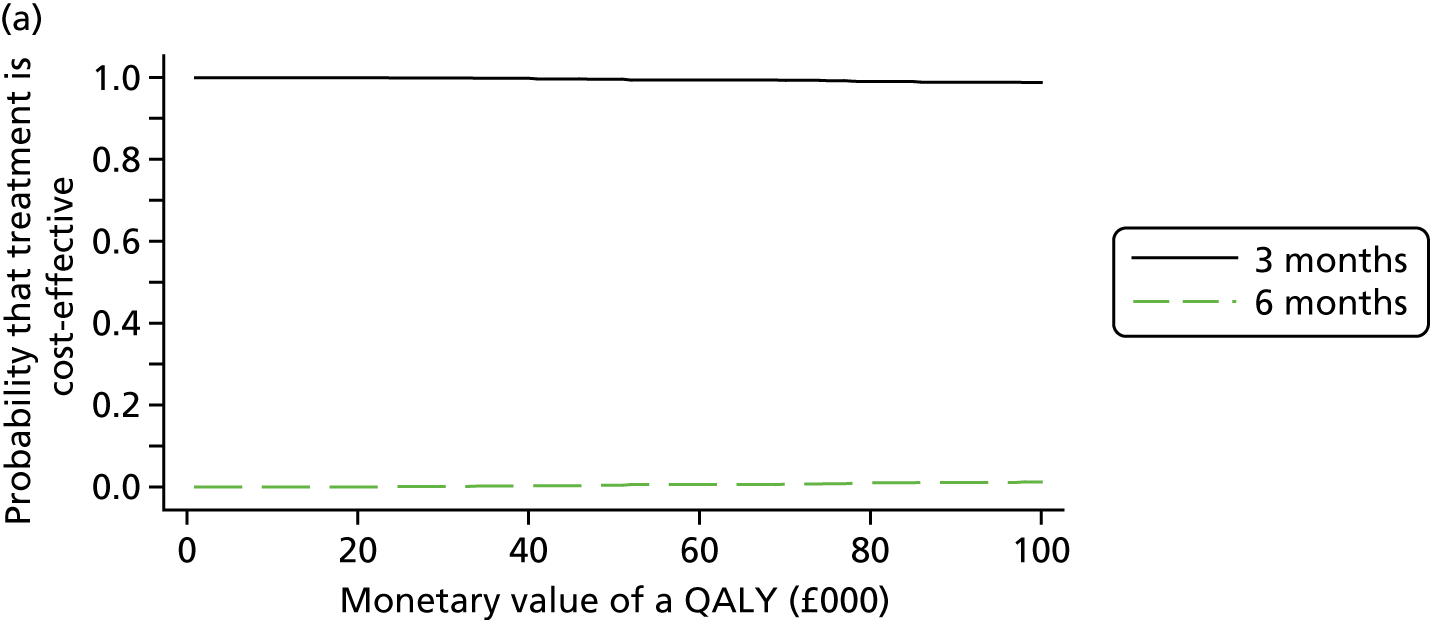

Cost-effectiveness

The cost and QALY outcomes for each treatment group were estimated and combined with the upper UK decision threshold for cost-effectiveness of £30,000 per QALY30 to report outcomes in terms of NMB according to good reporting practice guidance. 39 The incremental NMB is the difference between the NMB of the two groups.

Analyses were performed using Stata 14.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) to compare mean cost and mean QALY differences between the treatment groups (3-month vs. 6-month treatment) and the NMB was reported in line with recent reporting guidelines39 and the UK reference case. 30 Discounting of costs and QALY outcomes beyond 1 year was applied at a rate of 3.5%. 30

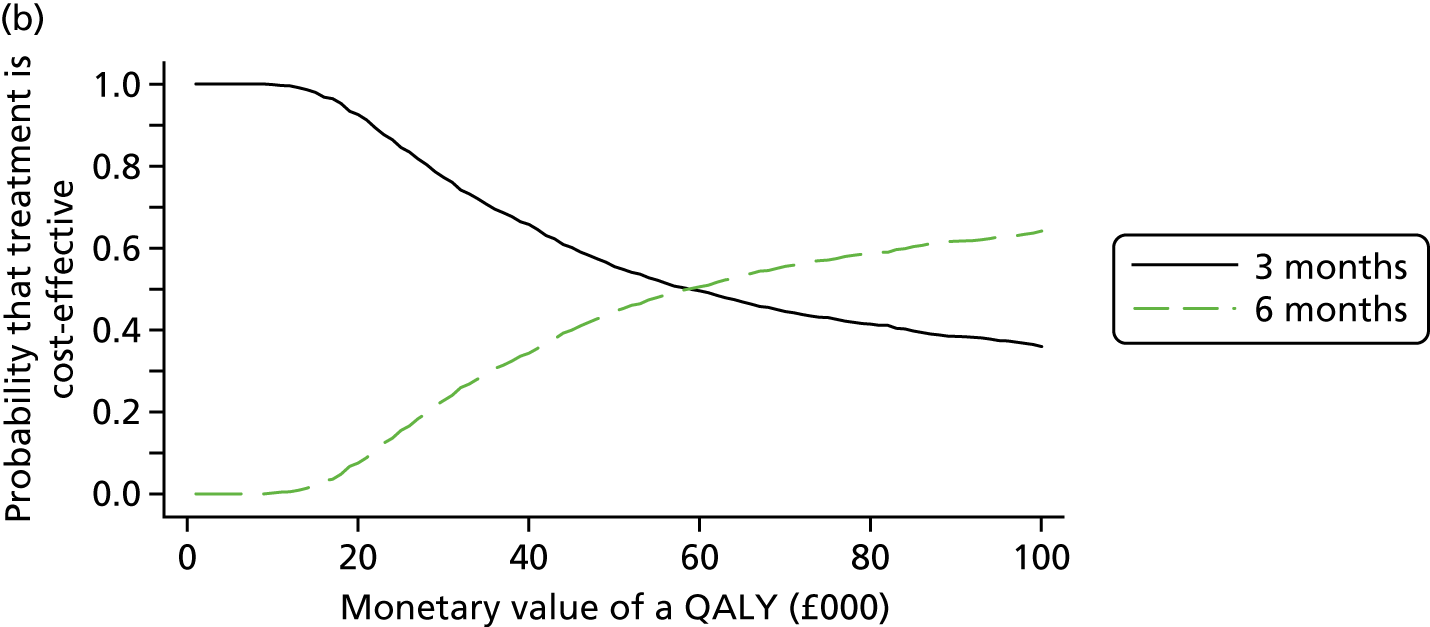

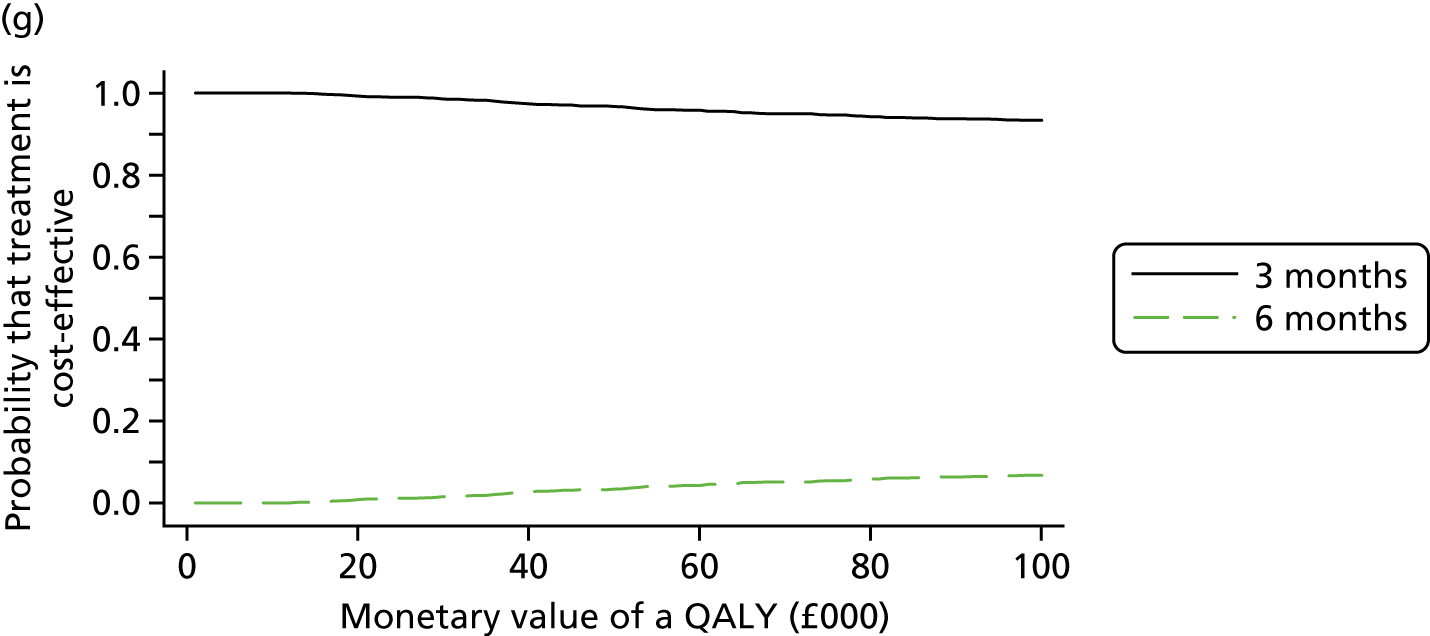

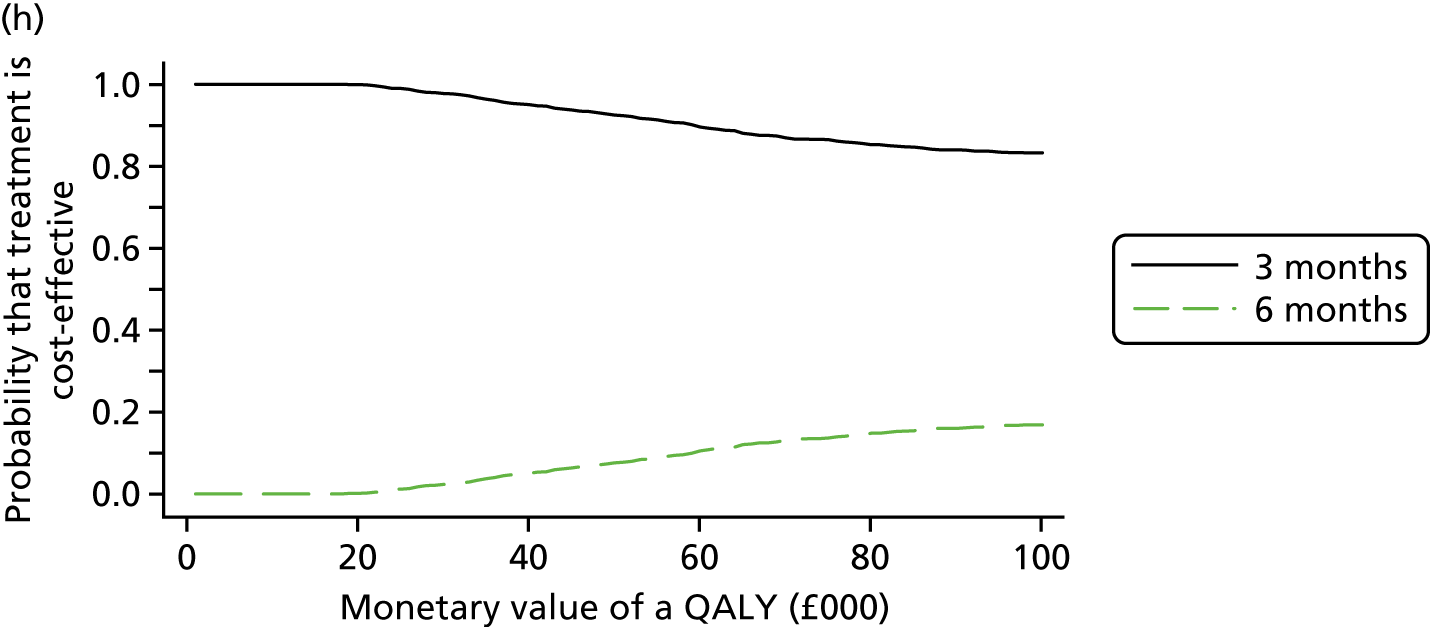

Bootstrapping (1000 iterations)40 was used to account for uncertainty around the difference in costs and QALYs and to assess how this uncertainty affects the cost-effectiveness outcome. Uncertainty was reported through CIs and the computation of cost-effectiveness acceptability probabilities was estimated as a function of the threshold for the monetary value of a QALY. 41 Subgroup analyses were undertaken, in line with the main trial analyses, to consider cost-effectiveness of the two treatment duration strategies according to planned treatment regimen (oxaliplatin and 5FU or oxaliplatin and capecitabine), disease risk (high or low), gender and age.

Results

Cost-effectiveness analyses were conducted on information provided by the 6065 patients who consented to their data being used (see Figure 1).

Effectiveness

Kaplan–Meier estimates up to 8 years after randomisation were used to determine how overall survival time would be split into the three health states – ToT, disease-free and recurrence – for the two treatment groups, as shown in Table 5. As would be expected, ToT was significantly higher for patients in the 6-month treatment group, whereas disease-free was just outside the 5% statistical-significance level but favoured the 3-month treatment group. No difference was seen between the groups for time in recurrence or overall survival. Figure 15 shows the time of overall survival partitioned into ToT, disease-free state and recurrence state for the two treatment groups, as generated using Kaplan–Meier estimates.

| Survival analysis (restricted mean survival) | 3-month treatment, mean (n = 3035 patients) | 6-month treatment, mean (n = 3030 patients) | Incremental difference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | p-value | |||

| Time-on-treatmenta | 0.21 | 0.39 | –0.18 | 0.000 |

| Disease-free | 5.93 | 5.74 | 0.19 | 0.053 |

| Recurrence | 0.73 | 0.77 | –0.041 | 0.605 |

| Total (overall survival) | 6.87 | 6.90 | –0.032 | 10.695 |

FIGURE 15.

Overall survival partitioned into ToT, disease-free state after treatment, and recurrence, Kaplan–Meier estimates over 8 years, by treatment group at (a) 3 months and (b) 6 months. DF, disease free.

Kaplan–Meier estimates of how overall survival time would be split into the three health states – ToT, disease-free and recurrence – for the two treatment groups, by subgroup, are shown in Table 6.

| Health state | 3-month treatment, mean | 6-month treatment, mean | Incremental difference, mean (p-value) | 3-month treatment, mean | 6-month treatment, mean | Incremental difference, mean (p-value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| By planned treatment | ||||||

| Oxaliplatin and 5FU (N = 1971) | Oxaliplatin and capecitabine (N = 4094) | |||||

| Patients (n) | 984 | 987 | 2051 | 2043 | ||

| Recurrence | 0.78 | 0.67 | 0.11 (0.336) | 0.71 | 0.82 | –0.10 (0.336) |

| Disease-free | 5.81 | 5.96 | –0.14 (0.360) | 5.98 | 5.63 | 0.35 (0.004) |

| ToT | 0.22 | 0.42 | 0.20 (< 0.001) | 0.20 | 0.37 | –0.17 (< 0.001) |

| Total (overall survival) | 6.82 | 7.05 | –0.22 (0.128) | 6.90 | 6.83 | 0.071 (0.508) |

| By risk | ||||||

| High risk (N = 2839) | Low risk (N = 3226) | |||||

| Patients (n) | 1424 | 1415 | 1611 | 1615 | ||

| Recurrence | 0.95 | 0.86 | 0.08 (0.434) | 0.55 | 0.71 | –0.16 (0.158) |

| Disease-free | 5.14 | 5.10 | 0.04 (0.739) | 6.62 | 6.30 | 0.32 (0.016) |

| ToT | 0.21 | 0.40 | –0.18 (< 0.001) | 0.21 | 0.39 | –0.18 (< 0.001) |

| Total (overall survival) | 6.31 | 6.36 | –0.048 (0.736) | 7.39 | 7.42 | –0.023 (0.806) |

| By gender | ||||||

| Female (N = 2393) | Male (N = 3672) | |||||

| Patients (n) | 1199 | 1194 | 1836 | 1836 | ||

| Recurrence | 0.60 | 0.67 | –0.07 (0.576) | 0.82 | 0.84 | –0.02 (0.817) |

| Disease-free | 6.10 | 5.73 | 0.37 (0.006) | 5.80 | 5.74 | 0.053 (0.690) |

| ToT | 0.21 | 0.38 | –0.16 (< 0.001) | 0.21 | 0.40 | –0.19 (< 0.001) |

| Total (overall survival) | 6.92 | 6.78 | 0.14 (0.279) | 6.82 | 6.98 | –0.16 (0.195) |

| By age | ||||||

| ≥ 65 years (N = 3065) | < 65 years (N = 3000) | |||||

| Patients (n) | 1525 | 1540 | 1510 | 1490 | ||

| Recurrence | 0.80 | 0.65 | 0.15 (0.287) | 0.69 | 0.89 | –0.20 (0.042) |

| Disease-free | 5.72 | 5.69 | 0.03 (0.838) | 6.10 | 5.78 | 0.31 (0.013) |

| ToT | 0.21 | 0.38 | –0.16 (< 0.001) | 0.21 | 0.41 | –0.20 (< 0.001) |

| Total (overall survival) | 6.73 | 6.72 | 0.02 (0.900) | 7.01 | 7.09 | –0.077 (0.518) |

Table 7 shows the results of the utility model for non-missing observations. The effect of recurrence and ToT was captured by assigning a value of 1 to the EQ-5D responses occurring in those health states. ToT and recurrence have a significant negative effect on utility, as would be expected; however, the 3-month treatment group was estimated to have higher HRQoL (p < 0.05) even after controlling for recurrence and ToT. These results are consistent with the higher incidence of AEs in the 6-month than in the 3-month treatment group. Patient characteristics were included in the model to adjust health utilities to the average values for the whole SCOT study sample, with and without the EQ-5D data. A statistically significant positive effect on HRQoL was associated with the variables male and age, with a negative effect seen for African/Caribbean and South Asian patients compared with white/Caucasian patients. Planned treatment and disease risk did not have a significant effect.

| Variable | Coefficient | Standard error |

|---|---|---|

| Number of patientsa (n) | 1757 | |

| Number of observations (n) | 16,091 | |

| Health states (reference: disease-free) | ||

| ToT | –0.0394d | 0.00408 |

| Recurrence | –0.0578d | 0.0139 |

| Treatment group: 6 months | –0.0154b | 0.00730 |

| Other characteristics | ||

| Oxaliplatin and capecitabine | 0.00402 | 0.00783 |

| High risk | –0.00911 | 0.00724 |

| Male | 0.0159b | 0.00733 |

| Age | 0.00162d | 0.000429 |

| Ethnicity (reference: white/Caucasian) | ||

| African/Caribbean | –0.0810b | 0.0385 |

| South Asian | –0.145c | 0.0536 |

| Chinese | –0.0447 | 0.0772 |

| Other | 0.0178 | 0.0217 |

| Constant | 0.866d | 0.00944 |

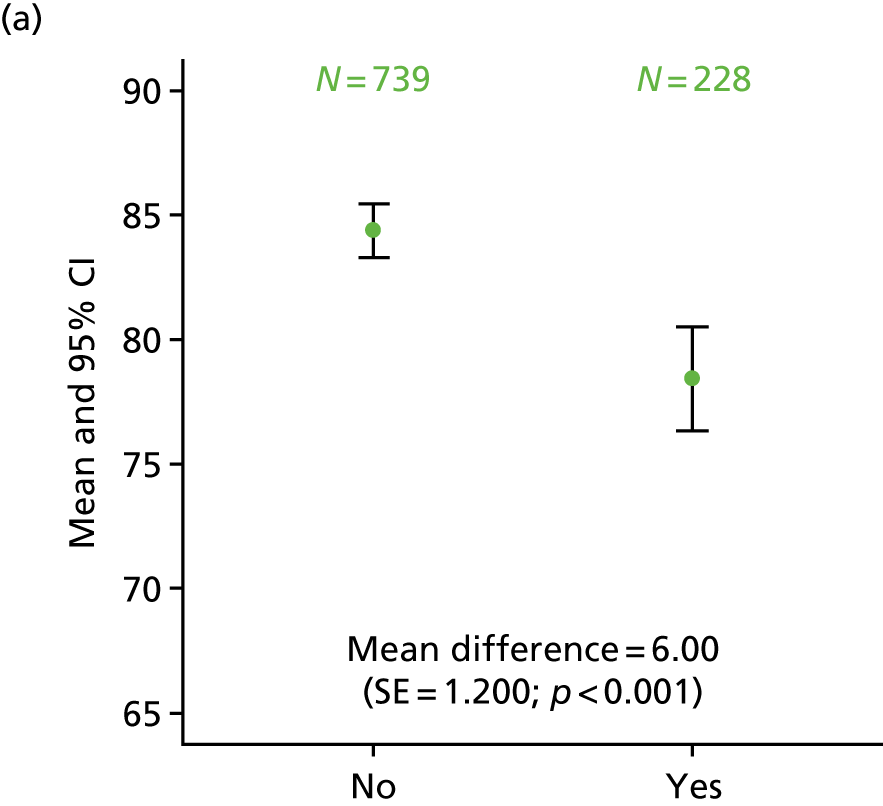

The results of the model follow the pattern of the evolution of EQ-5D scores over time as shown in Figure 16. After baseline, HRQoL decreased for both groups to 3 months; at this point, health utilities for those in the 3-month treatment group increased as they completed treatment, whereas lower HRQoL persisted for patients receiving 6 months of adjuvant chemotherapy. Changes in HRQoL were primarily related to ToT, although Figure 16 illustrates that some difference in HRQoL was evident between the two groups beyond 6 months (completion of adjuvant chemotherapy).

FIGURE 16.

Evolution of EQ-5D utilities over time, by treatment group. Presented as means and 95% CIs.

Costs

The unit costs for treatment and hospitalisation are detailed in Table 8, and Table 9 provides a detailed unit cost breakdown for each of the hospitalisation cost categories. Tables 10 and 11 detail resource use for chemotherapy and hospitalisations, respectively, for each group of the intervention and by planned treatment regimen.

| Adjuvant chemotherapy drug | Description | Cost (£) | Unit cost (£/mg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxaliplatin | 200 mg/40 ml concentrate of oxaliplatin for solution for infusion vials | 595.65 | 2.98 |

| Capecitabine | 500-mg tablets of capecitabine, 120 tablets | 146.00 | 2.43 × 10–3 |

| 5FU (bolus) | 500 mg/20 ml solution of 5FU for injection vials, 10 vials | 64.00 | 1.28 × 10–2 |

| 5FU (infusion) | 2.5 g/100 ml solution of 5FU for infusion vials | 32.00 | 1.28 × 10–2 |

| Hospitalisation type | Description | Unit cost (£/night or case) | |

| Intensive care unit | Night in intensive care unit | 2190.35 | |

| High-dependency unit | Night in intensive care unit | 937.87 | |

| General medicine | Night in general medicine unit | 476.73 | |

| Inpatient (clinical oncology) | Night in clinical oncology unit, as inpatient | 896.88 | |

| Day case (clinical oncology) | Day case at clinical oncology | 813.22 | |

| Outpatient (clinical oncology) | Outpatient attendance for clinical oncology | 251.77 | |

| Hospitalisations | Cost per night or case (£) | Total cost (£) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medical | Nursing | Allied health professional | Pharmacy | Theatre | Laboratory | Other | Non-direct costs | ||

| Intensive care unita | 284.24 | 1029.79 | 36.63 | 263.48 | 9.83 | 76.44 | 22.35 | 467.59 | 2190.35 |

| High-dependency unita | 125.74 | 423.47 | 13.82 | 87.07 | 41.43 | 6.40 | 239.95 | 937.87 | |

| General medicinea | 73.12 | 161.03 | 16.60 | 47.80 | 3.77 | 25.77 | 5.81 | 142.82 | 476.73 |

| Inpatient (clinical oncology)a | 103.47 | 198.66 | 74.87 | 157.15 | 30.71 | 38.25 | 293.77 | 896.88 | |

| Day case (clinical oncology)b | 147.27 | 77.37 | 51.67 | 281.32 | 17.41 | 24.84 | 213.34 | 813.22 | |

| Outpatient (clinical oncology)c | – | – | – | – | – | – | 192.40 | 59.37 | 251.77 |

| Drug | All patients (N = 6065) | Oxaliplatin and 5FU (N = 1971) | Oxaliplatin and capecitabine (N = 4094) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3-month treatment, mean | 6-month treatment, mean | Incremental difference: 3-month vs. 6-month; p-value | 3-month treatment | 6-month treatment | Incremental difference: 3-month vs. 6-month; p-value | 3-month treatment | 6-month treatment | Incremental difference: 3-month vs. 6-month; p-value | |