Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 14/43/02. The contractual start date was in December 2015. The draft report began editorial review in June 2018 and was accepted for publication in March 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Chris Metcalfe reports grants from the UK National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme during the conduct of the study. He and Stephen Baston report grants from the NIHR HTA, Public Health Research, Health Services and Delivery Research, Programme Grants for Applied Research and Research for Patient Benefit programmes since 2009. Chris Metcalfe is also a co-director of the Bristol Randomised Trials Collaboration, a UK Clinical Research Collaboration-registered trials unit in receipt of NIHR support funding. Nicola Wiles reports grants from the University of Bristol during the conduct of the study.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Russell et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction, background and study aims

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental condition characterised by qualitative impairments in social communication and a pattern of restricted and repetitive behaviours, interests or activities. 1 Recent studies report that autism affects 1% of the UK adult population2 and 1 in 68 children in the USA. 3 Approximately 46% of autistic people have general intellectual function in the average or above range. 3 (The results of a survey of the UK autism community4 highlighted that ‘autism’, ‘on the autism spectrum’ and ‘autistic people’ are preferred terms to describe autism. From hereon in, the terms ‘autism’ and ‘autistic people’ will be used.) Autism is a lifelong condition, present from the early years, and outcomes in respect of education, employment and independent living have been shown to be relatively poor for autistic adults. 5

Mental health conditions are reported to frequently co-occur across the lifespan in autism. 6,7 Anxiety disorders and depression are the most frequently reported co-occurring conditions, with a modal rate of 40% for anxiety disorders in children,8 and rates of depression ranging from 4% to 35% across the lifespan. 9 The onset of depressive symptoms in autism appears to be early. A UK-based cohort study10 reported that autistic children and children with higher autism traits have higher depressive symptoms at the age of 10 years and that these remain elevated with an upwards trajectory until the age of 18 years. Robust epidemiological research, particularly longitudinal studies, has been lacking until relatively recently. There is increasing evidence, however, that the prevalence of depression may be significantly higher in autistic adults than in the general population. For example, a recent total population study11 of 223,842 individuals in Stockholm County, Sweden, reported that, of the 4073 who had a diagnosis of ASD, 19.8% also had a diagnosis of depression by the age of 27 years, compared with 6% of the general population sample [adjusted risk ratio 3.6, 95% confidence interval (CI) 3.4 to 3.9]. Another large, US population-based study12 including 1507 adults with a diagnosis of ASD reported a 25% prevalence of depression, representing a twofold increased risk of depression in autism.

Identification of depression in autism can be confounded by the overlap between depressive symptoms, such as social withdrawal, and core autism ‘symptoms’, for example reduced interest in or ability to socialise, which can be normative. There is also some suggestion in the literature that depression in autism may present atypically, for example as an increase in compulsive behaviour,13 providing further methodological difficulties for epidemiological research. Verbal abilities significantly influence the presentation or at least the identification of depression in this group. In addition, there is some evidence that better cognitive abilities and relatively low social impairment,14 the tendency to make social comparisons15 and a history of adverse experiences such as bullying10 may be features of autistic young people with co-occurring depression.

Measurement of depression in autism

Autism is characterised by a diverse pattern of strengths and weaknesses across multiple functional domains, including social cognitive and emotional processes. 16 Studies report high rates of alexithymia in autism,17 defined as a reduction in the ability to define and describe one’s own emotional state. The validity of self-reporting of emotional states in autism has been subject to investigation. For example, studies18,19 have investigated the validity and reliability of standardised measures of anxiety in autistic children, leading to the development of addendums to benchmark instruments or to the development of entirely new scales. In respect of the self-report and measurement of depression in adulthood, one recent study20 investigated the internal consistency and convergent and discriminant validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale21 (HADS) in a sample of 150 autistic older adolescents and adults. The authors20 reported adequate internal consistency for the depression subscale of the HADS, with a modest correlation (r = 0.56, 95% CI 0.25 to 0.77) between the HADS depression score and scores on the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 items (PHQ-9),22 a widely used self-report measure of depression. Two studies23,24 have investigated the usefulness of the Beck Depression Inventory, version 2 (BDI-II),25 in autism, reporting that it presents as an adequate screening tool for depression,23 with good internal consistency, adequate sensitivity and specificity, and good convergent validity. 24 Of note, Gotham et al. 24 reported that the cognitive symptoms of depression (e.g. negative attributions about the self) were the most frequently endorsed BDI-II items in their sample (n = 50) of autistic adolescents and adults. In the context of basic research, findings of reduced awareness of bodily sensations, such as thirst and heartbeat detection, in autistic adults,26,27 and a greater awareness of depressive cognitions over biological symptoms of depression such as reduced appetite, are unsurprising.

Treatment of depression co-occurring with autism

Depression is a debilitating mental health condition for which effective pharmacological and psychosocial treatments exist. 28,29 The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence29 (NICE) recommends a stepped-care model for the treatment of depression. Mild to moderate depression should be treated with low-intensity psychosocial interventions, psychological interventions, medication and referral for further assessment and treatment. Low-intensity interventions involve the provision evidence-based information, accessed independently or with the support of an unqualified mental health worker [guided self-help (GSH)]. Ongoing monitoring and review are also important. Low-intensity psychological interventions for depression as recommended by NICE are individual GSH interventions based on the principles of cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) to include behavioural activation and problem-solving techniques, computerised CBT or a structured group physical activity programme. 29

Cognitive–behavioural therapy is a psychological intervention integrating behavioural and cognitive theories of emotional processes to bring about change in psychological distress and associated functional impairment. CBT is traditionally an individual talking therapy, but recent decades have seen efforts to streamline its delivery and improve accessibility. Consequently, CBT interventions are now delivered in group formats, over the internet/e-mail, as part of GSH and using software. The shift in mode of delivery and reliance on a less qualified therapist or no therapist – that is, self-guided – has meant a move from individual, formulation-driven therapy to manualised, protocol-driven treatments.

Adapting cognitive–behavioural therapy for autism

Autism-specific adaptations to psychosocial interventions have been well documented. 30 Taking account of the verbal and non-verbal communication differences characteristic of autism, such as a literal interpretation of language as well as the broad pattern of executive dysfunction,31 is required for all interventions in order to make them accessible to autistic people.

Adaptations unique to CBT are outlined in the NICE clinical guidelines for adults with autism. 32 These suggest a more concrete and structured approach to treatment delivery with greater use of written and visual information; a greater emphasis on changing behaviours rather than cognitions; clarity and explanations about rules; avoiding the use of metaphors, ambiguity and hypothetical situations; involving a family member, partner, carer or professional with the person’s agreement; and facilitating engagement by offering breaks and incorporating an individual’s special interests into therapy when appropriate. Additional modifications for young people outline that psychoeducation about emotions and multiple choice worksheets for cognitive strategies can be helpful. 33

In autism research to date, there has been a greater focus on understanding and treating anxiety than on depression. 34 Adapted CBT interventions, group and individual, have been shown to be clinically effective for ameliorating anxiety in children and young people and adults. 35,36 Weston et al. 37 provide a systematic review and meta-analysis of the studies of CBT interventions for emotional disorders in autism. Small to medium effect sizes favouring CBT over control treatments were established, but the magnitude varied according to the source of outcome measurement (g = 0.24 on self-report outcomes, g = 0.66 on informant measures and g = 0.73 on clinician-rated outcomes). All treatments used in the 24 studies included in the meta-analysis were clinician led; 16 were group treatments, 15 focused on treating anxiety, two focused on treating depression and a minority (n = 4) were adult studies. Studies evaluating behavioural activation (BA) as a stand-alone treatment were excluded from the meta-analysis.

There is, then, a small literature on the usefulness of psychological interventions for depression in autism. Several studies have evaluated combined CBT protocols for anxiety and depression. These are as follows:

-

McGillivray and Evert38 conducted a quasi-experimental evaluation of group CBT versus wait list for depression and anxiety in 32 young autistic adults who scored in the clinical range on a mood or anxiety questionnaire. There was a significant effect of time but not of treatment group in terms of a reduction in scores on the depression measure. Approximately 60% in the CBT group showed a significant reduction in scores on the Depression and Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS),39 compared with 38% in the wait-list group. 38

-

Sizoo and Kuiper40 delivered two adapted psychological interventions to 59 autistic adults with clinically significant anxiety or depression scores, as measured with the HADS. The interventions comprised a 13-session adapted CBT anxiety and mood protocol and an adapted mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) treatment. 41,42 There was a significant effect of time but not of treatment group on depression and anxiety scores as measured by the HADS.

-

Spek et al. 42 randomly allocated 42 autistic adults with clinician-identified symptoms of depression, anxiety or rumination to adapted MBSR or treatment as usual (TAU). There was a significant reduction in scores on the depression (Symptom Checklist-90 depression subscale43), anxiety (Symptom Checklist-90 anxiety subscale43) and rumination measures in the MBSR group when compared with the TAU group.

Intervention studies with an exclusive focus on depression in autism are scarce. Santomauro et al. 44 conducted a feasibility crossover randomised controlled trial (RCT) of a group CBT intervention for 20 autistic adolescents with depression, defined as a BDI-II score of > 14. They found a trend towards an effect of treatment on the DASS depression subscale, but no significant effect using the BDI-II, and suggested that larger numbers of participants would be needed to gain an accurate picture of the efficacy of CBT for depression in this group.

Rationale for the current research

There is increasing evidence to suggest that depression is a frequently occurring mental health problem for autistic people.

Evidence-based psychological treatment based on cognitive–behavioural theories have been successfully adapted for autistic people and shown to be clinically effective in ameliorating anxiety symptoms. The clinical effect of treatment varies according to the source of outcome measurement, but clinician and informant ratings have evidenced greater change than self-report of symptoms. Findings in the research literature hypothesise that the reported difference in noticing and reporting changes in internal states, particularly emotions, may account for this variation. There have been studies reporting adequate reliability and validity of several widely used self-report measures of depression in autistic adults.

Clinical studies suggest that CBT approaches for depression in autistic adults may well be clinically effective. However, to date, and to our knowledge, there have been no adult studies with an exclusive focus on the psychological treatment of depression using the treatments evidenced in the standard care pathway or using structured depression diagnostic protocols as part of the eligibility assessment.

Clinical trials aside, naturalistic treatment evaluations are even less well described and reported. Thus, it is not known whether or not autistic adults with mild to moderate depression routinely access CBT interventions offered in primary care or experience less favourable treatment outcomes. It is known that the materials used as part of the standard care pathway, that is low-intensity CBT for depression, routinely offered in the UK within primary care psychological services have not been specifically developed with autistic adults in mind.

To our knowledge, low-intensity psychological interventions, such as GSH, have not previously been developed for autistic people for any type of emotional problem.

The present study is a response to the themed call from the Health Technology Assessment (14/043) programme of the National Institute for Health Research in April 2014 to design a feasibility study to ‘determine whether a trial of guided self-help for people with ASD is warranted’.

Aims of the current research

-

To develop a low-intensity intervention for depression adapted for adults with ASD, based on NICE recommendations and training materials to guide therapists in supporting the intervention.

-

To investigate the feasibility and the patient and therapist acceptability of the low-intensity intervention.

-

To estimate the rates of recruitment and retention for a large-scale RCT.

-

To identify the most appropriate outcome measure for a large-scale RCT.

These aims were met by conducting a feasibility study comprising a RCT with a nested qualitative evaluation.

Chapter 2 Study methods

Feasibility study design

The study was a single-blind RCT with a nested qualitative evaluation.

Participants were randomly assigned to GSH for depression adapted for adults with autism or to TAU in a 1 : 1 ratio.

The trial was registered in the ISRCTN registry as number ISRCTN54650760.

Ethics approval was granted by Wales Research Ethics Committee (REC) 3 [Integrated Research Application System (IRAS) project ID 191558].

The study methods were prespecified in a published protocol. 45

Participants

Participants (n = 70) were recruited through two pathways in the west of England and two pathways in the north-east of England, as follows:

-

Bristol Autism Spectrum Service (BASS) provided by Avon & Wiltshire Mental Health Partnership NHS Trust (AWP)

-

‘Everyone Included’ – a research opportunity offered to all adult patients registered with AWP and consenting to be contacted about suitable research opportunities

-

an adult autism clinic in Northumberland, Tyne and Wear NHS Foundation Trust (NTW)

-

The Adult Autism Spectrum Cohort – UK [a Newcastle University-led national cohort study of adults on the autism spectrum funded by Autistica (London, UK), a UK-based charity].

Inclusion criteria

-

Was aged ≥ 18 years.

-

Had a clinical diagnosis of ASD.

-

Had current depression as measured by a PHQ-9 score of ≥ 10.

Exclusion criteria

-

Did not speak English.

-

Had literacy level such that the written materials would have been inaccessible.

-

Had risk of suicide such that a low-intensity intervention would not be in line with clinical need.

-

Had a history of psychosis.

-

Had current alcohol/substance dependence.

-

Had untreated epilepsy.

-

Had attended more than six sessions of individual CBT during the previous 6 months.

Recruitment procedures

The initial recruitment procedures differed slightly across the four pathways, as follows.

Bristol Autism Spectrum Service

Potential participants were identified by clinicians following attendance at the clinic for diagnostic assessment. Participants were considered potentially suitable if they were given a clinical diagnosis of an ASD at the end of the assessment and were identified as having low mood following a clinical interview and/or a pre-clinic screening PHQ-9 score of ≥ 10, and routine risk assessment contraindicating low-intensity intervention. Potential participants were introduced to the study by clinicians using a brief expression of interest (EOI) form. If they were interested in the study, they could return the EOI form expressing interest and requesting follow-up contact from the research team. This further introduction to the study could occur face to face in the clinic, or by postal/telephone follow-up after the clinic attendance if the clinician considered this more appropriate. Follow-up contact from the research team was ordinarily over the telephone; full information about the study was provided at this stage in the study information sheet. Standard recruitment procedures were then initiated.

Everyone Included

The Everyone Included review panel (with independent membership) approved the study for inclusion in the approach and a draft of the research opportunity letter. Potential participants were identified from an automated search of the electronic patient record system by the information analysis team in the NHS trust and based on the study inclusion/exclusion criteria. Potential participants were sent the research opportunity letter by the local NHS research and development (R&D) team and, if they made contact, were provided with a study information sheet and asked their permission for the study research team to make contact with them. No information about potential participants was sent to the study research team without permission first being gained from the potential participant. Standard recruitment procedures were then initiated.

Adult Autism Clinic in Northumberland, Tyne and Wear NHS Foundation Trust

Potential participants were identified by clinicians as those given a diagnosis of an ASD following clinic attendance and assessed as having depression sufficient to warrant signposting/referral to Increasing Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) services as per routine clinical practice. They were introduced to the study using the brief EOI form at the end of the diagnostic assessment process, ordinarily at the second assessment appointment. Potential participants interested in the study who contacted the research team were asked to complete the PHQ-9 either by post or over the telephone, and those individuals with a score of ≥ 10 were provided with the full study information sheet. Standard recruitment procedures were then implemented.

In addition, patients formerly diagnosed by the NTW Autism Diagnosis Service who had agreed to be contacted about research studies were provided with information about the project (EOI form). Potential participants who contacted the research team were provided with comprehensive information about the study and potential suitability assessed using the PHQ-9. Standard recruitment procedures were then initiated.

Adult Autism Spectrum Cohort – UK at Newcastle University

The cohort research team approved the study on application, and an introductory letter was drafted by the Newcastle University research team. Potential participants were identified from a search of the database, constrained by NTW area postcode, age, intellectual disability and history of depression, and then cross-matched with the NTW Adult Autism Clinic research register to ensure that people were not introduced to the study more than once. Potential participants were sent the introductory letter and EOI form. Those who contacted the research team were provided with comprehensive information about the study and asked for their permission to screen them for the study, including completing the PHQ-9 by post or over the telephone. Standard recruitment procedures were then initiated.

Standard recruitment procedures

The outcome of screening each potential participant using the PHQ-9 was communicated to the individual’s general practitioner (GP) with their permission.

Potential participants with a PHQ-9 score of ≥ 10 who wanted to take part in the study were invited to an eligibility assessment with the research team.

Eligibility assessment

The Clinical Interview Schedule-Revised (CIS-R)46 was administered as an automated computer questionnaire to assess the exclusion and inclusion criteria alongside the PHQ-9. It is a widely used, well-validated diagnostic instrument that generates International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10),47 psychiatric diagnoses.

Details about sociodemographic status, history of depression, current medication and current/previous psychological treatment for depression were also collected to inform the eligibility assessment in respect of the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Fully informed consent in writing was obtained from participants who had a PHQ-9 score of ≥ 10 and who were willing to take part in the study. It was established by the researcher by asking the participant to summarise their understanding of what taking part in the study would involve, asking about the voluntary nature of participation and asking the participant what they thought would happen if they no longer wanted to take part.

A statement designed to communicate a position of equipoise about the treatments was read to participants, who were then asked if they had a preference at this point for either treatment. If a preference was indicated, the reasons for this were recorded, and additional information encouraging participants to take a balanced approach towards treatment allocation was provided, aiming to minimise bias towards the outcome of randomisation.

If eligible for the study and consenting, the participant was asked to complete other quantitative measures at this appointment, which lasted 60–120 minutes.

Participants not meeting the eligibility criteria were thanked for their time and informed of the reasons. When the reason was severity of depression and/or intensity of suicidal ideation (i.e. score of 3 on item 9 of PHQ-9) such that a low-intensity intervention was not in line with current clinical need, this was explained and the information was communicated to the individual’s GP as per the study protocol.

Randomisation

Eligible, consenting participants were allocated to GSH (n = 35) or TAU (n = 35) in a 1 : 1 ratio using a remote computerised randomisation service. Randomisation was stratified by NHS regional centre (n = 2), and minimised by depression severity (mild to moderate, i.e. PHQ-9 scores of between 10 and 15, or moderate to severe, i.e. PHQ-9 scores of between 16 and 27) and antidepressant medication (currently taking or not taking). The trial manager shared the outcome of randomisation with the participants according to their communication preferences within 48 hours, and with the therapist. Follow-up measurement was conducted by researchers who were blind to treatment allocation (Figure 1 shows the timeline of events).

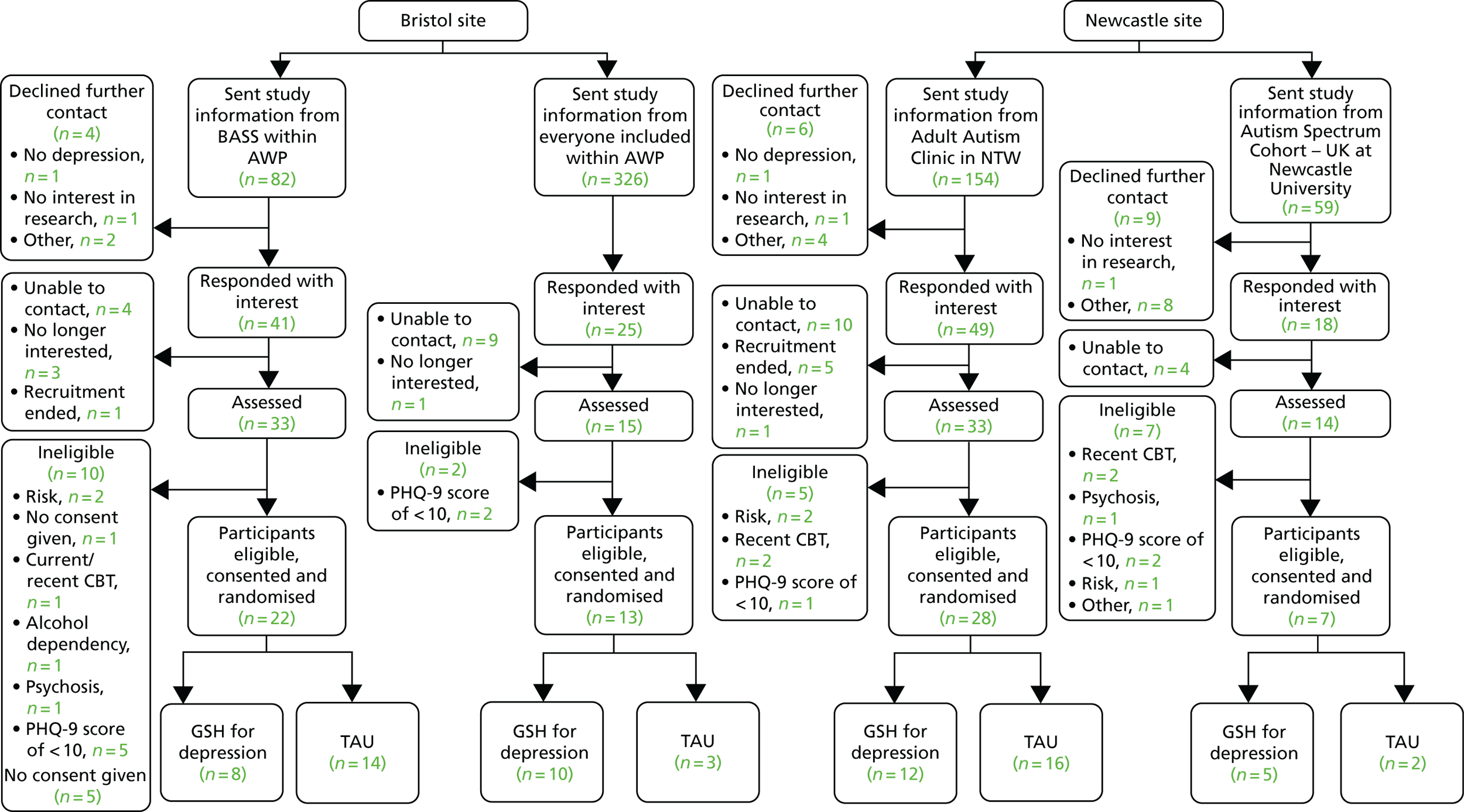

FIGURE 1.

The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram from recruitment to randomisation by site and recruitment pathway. Reproduced with permission from Russell et al. 48

Retention

To maximise retention of participants in the study, an individual protocol was developed about participants’ preferences for communication with the study team, including their preferred method of communication (e.g. e-mail, text message or telephone call), person to communicate with (e.g. self or specified other) and the number of attempts that should be made if initial communications about follow-up and appointments did not receive a response.

Interventions

Treatment as usual

Treatment as usual consisted of standard NHS care for depression as provided to the individual during the trial. This included no treatment, GP support, referral to IAPT services, referral to secondary mental health services and antidepressant medication. Participants were asked to report any treatment received at each follow-up meeting.

Guided self-help

The intervention developed in the current study adhered to the principles of a low-intensity psychological intervention for depression as outlined in NICE guidelines,29 namely 6–10 sessions of individual GSH based on the principles of CBT to include BA.

The GSH treatment developed for the study was a low-intensity intervention based on the principles of BA for depression, which was adapted for autistic people.

Rationale for guided self-help based on behavioural activation

Behavioural activation is the usual first phase of CBT for depression, ordinarily achieved through activity scheduling. BA is not simply getting people to be more active; it also aims to help people make choices about their behaviour in particular situations to better regulate their mood. People are encouraged to become more aware of the triggers for low mood and the consequences of a range of behaviours and to then use this information to adjust their activities accordingly. There is good evidence for the clinical effectiveness of BA as a treatment for depression in its own right and it is recommended as one of the low-intensity interventions in the NICE guidelines.

Behavioural activation is well suited to inform an intervention for depression in the context of autism. First, the model underpinning BA, with an emphasis on the role of the environment in precipitating and maintaining depression, has face validity. 49,50 Within the framework of BA, changes to an individual’s environment and the individual’s response to those changes can lead to depression. If the consequences of behaviours are not sufficiently rewarding, an individual will learn to do fewer of those behaviours. If a behaviour formerly had a significant role in maintaining positive mood, then doing it less creates fewer opportunities for reinforcement, which leads to further reduction, and so on. Positive reinforcement is gradually reduced and this cycle of punishing interaction, reduced frequency of behaviour and reduced reinforcement explains the persistence of depression. Many autistic people lack access to meaningful social, occupational and leisure activities and hence have fewer opportunities for positive reinforcement. There is an objective reality to the mismatch between significant parts of their social and occupational environment and their needs. The focus of BA treatment, therefore, is to help people develop a behavioural repertoire that responds more effectively to demanding environments, and, where possible, accesses rewarding experiences within them.

Second, a restricted, repetitive, stereotyped pattern of behaviour, interests and activities is one of the core characteristics of ASD. It is possible that autistic people, in addition to experiencing societal vulnerabilities in the form of lack of opportunities, are compromised in their ability to easily generate a shift in routines and behaviours towards activities and actions that may offer increased access to pleasure and a sense of achievement. This tendency towards restricted activities and interests may form part of the behavioural maintenance cycle of depression symptoms in autism. BA, with an emphasis on the active scheduling of activities, may offer precision as an intervention for depression co-occurring with autism.

Third, rigidity and perseveration in thought patterns can be part of autism, with evidence of impairments in cognitive flexibility and generativity from neuropsychological studies. 31 Cognitive interventions that target the content of thoughts and beliefs maintaining depressed mood may not be well suited to the cognitive profile of autistic people. Cognitive techniques require an individual to access and report abstract inner phenomena, for example negative automatic thoughts, and to generate and consider alternative ways of thinking about situations. These are relatively abstract activities that rely on cognitive flexibility, which may not be well suited to the cognitive strengths of autistic people.

To summarise, the principles and practice of BA may mean that it is particularly suited as a psychological treatment for depression co-occurring with autism. Lack of social opportunities and meaningful occupation may be further compounded by a pattern of restricted, repetitive behaviours and a preference for sameness. This constrains the behavioural repertoire of autistic people and can leave them unmotivated and underequipped to access positive affect, particularly through interactions with other people. The core treatment principle in BA is to increase opportunities for positive reinforcement by activating behaviour, that is, to restore mood and behaviour patterns. Furthermore, BA has previously been effectively adapted to the constraints of a low-intensity intervention.

The authors (AR, KC and SB) developed the GSH intervention. Informed by the principles of BA, session materials were developed that were designed to encourage clients to pay more attention to their physical and social environment, record their behaviours (in granular detail) across different situations and notice the feelings and body states that result from those actions. GSH is designed to promote associative learning, so that associations between behaviours and their affective consequences become more apparent to clients. The resultant learning helps them to schedule activities that are more likely to satisfy their needs and promote positive feelings, thereby increasing opportunities for positive reinforcement.

Materials were visually presented as far as possible, for example recording activities on a visual map rather than in a written diary, with any text supplemented by images. A consistent session format was used. Other autism-specific adaptations included a session on noticing positive feelings and developing a scale to do this, a structured approach to activity scheduling to scaffold the planning and organisational issues inherent in executive dysfunction and a graded approach to the introduction of new activities.

Two autistic adults provided feedback and advice about the design of the materials during the development phase. This included commenting on the accessibility and content of the written text, suitability of the accompanying visual images, visual layout and format of the session materials, amount of material to be covered each session and homework tasks. The volunteers responded to a request through a service network newsletter for help with the development of the intervention. A number of people responded, and this was followed up by a telephone call from the researchers. A number of the responders were on current waiting lists for mental health treatment and it was agreed that the research study may not be able to offer sufficient support to facilitate their participation in the research at that point. The two volunteers in a position to help had attended psychological therapy in the past, and one had specifically received CBT for depression. Both reported that mental health difficulties were not currently having an impact on their social and occupational function. The volunteers attended up to three individual meetings with a member of the research team and were reimbursed for their time in accordance with the INVOLVE guidelines. 51 The first iteration of the session materials was available and the meeting was used to review the materials and discuss the feedback and suggested changes. This was an open process without an a priori agenda for feedback. The volunteers were able to comment on any aspects of the GSH that they considered important. For example, the materials for the planning session included a short form with questions and prompts to enable the coach to learn about the individual’s autism. One volunteer commented that this was a good idea, but that the examples and prompts could be improved. They made specific suggestions about changes to improve the content, which were included. One of the volunteers had a background in graphic design and was able to make specific recommendations about the visual layout and format of the materials. The two volunteers brought different skill sets and experiences to the task. One volunteer’s recent experience of accessing CBT was invaluable when considering the content of the intervention, for example the suitability of the proposed ‘homework’ tasks. This volunteer was able to reflect on what had made between-session tasks difficult in their experience, primarily the lack of specificity. This discussion enabled the researcher to make specific suggestions about the structure of the homework tasks and to gain feedback from the volunteer. The creative background and visual sensitivity of the other volunteer was extremely helpful in ensuring that the materials ‘looked’ right.

The GSH intervention comprised materials for nine individual sessions to be held weekly and facilitated by a coach. A short manual was developed for the coaches to accompany the session materials.

The first session was a ‘planning’ session, the aim of which was to orient the participant to the purpose of GSH and the role of the coach, and to orient the coach to the individual’s unique needs as an autistic adult. Individual goals for treatment were developed during this session. In sessions 2–5 the primary aim was learning about the links between situations, behaviour and feelings. Sessions 6–9 focused on scheduling activities that were in line with treatment goals and would bring about opportunities for increased positive mood. To encourage the scheduling of a broader repertoire of activities, Maslow’s hierarchy of needs52 was presented in session 6 as a framework for thinking further about activity scheduling. People were encouraged to notice and record activities in their diary map according to the different levels of need, for example physiological need, social need and self-esteem, as well as in respect of positive feelings.

The duration of sessions was 30–45 minutes, with the exception of the planning session, which was longer. This could last up to 90 minutes to facilitate engagement.

Participants who attended five or more sessions were considered to have received a minimally clinically effective dose of treatment.

The intervention was delivered face to face, with the later sessions (6–9) amenable to delivery over the telephone if preferred. In exceptional circumstances, for example if the individual was completely unable to access the treatment face to face, the treatment was offered over Skype™ (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA).

The coach in GSH was a graduate-level psychologist who had foundation knowledge of CBT but not necessarily any experience of delivering low-intensity interventions and ordinarily did not have the knowledge and skills to deliver individual, formulation-driven (i.e. high-intensity) CBT. Coaches were usually assistant psychologists (n = 4), although a small number of patients were treated by clinical psychologists in training (n = 3).

Coaches received 15 hours of training in the intervention and in working with autistic people. They received 1 hour minimum of clinical supervision on a weekly basis from the clinical psychologists who developed the intervention (AR, SB and KC). Supervision was face to face or remote (over the telephone/Skype) and was delivered on an individual or a group basis.

Outcome measures, namely the PHQ-9, Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7), an abbreviated Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) and visual analogue rating of activity engagement, were completed at the start of each session to simulate standard practice in low-intensity interventions.

As this was a feasibility study, the session content and duration were recorded by the coaches at the end of each session.

Outcome measurement

Follow-up assessments were conducted 10, 16 and 24 weeks post randomisation by researchers blind to treatment allocation (Table 1). The feasibility of delivering the intervention over 10 weeks was also evaluated. Thus, it was not clear a priori if 10 or 16 weeks post randomisation would be the most clinically effective point of outcome measurement (i.e. whether the majority of participants were unable to complete the intervention within 10 weeks).

| Measure | Baseline | GSH group each session | 10 weeks (end of intervention) | 16 weeks | 24 weeks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ✓ | ||||

| PHQ-9 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| CIS-R | ✓ | ||||

| BDI-II | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| SIGH-D | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| GAD-7 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| OCI-R | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| PANAS | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| SF-12 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| EQ-5D-5L | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Participant Global Rating of Change | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| RBQ-2A | ✓ | ||||

| RRQ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Economic evaluation | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

The findings of previous research have suggested that self-report measures may not be the optimal method to capture change. Furthermore, the psychometric properties of just one self-report measure of depression (BDI-II) had been investigated in autistic adults at the time of the design of the study. Therefore, a suite of measures of depression symptoms was included. An aim of the study was to identify the most appropriate outcome measure for a large-scale RCT, and so it was not possible to specify the primary outcome measure of depression a priori.

Measures could be completed electronically using a tablet or could be made available for paper-and-pen completion. The majority of participants completed the measures electronically. This could be done remotely or face to face in clinic as the participant preferred. The majority of participants in the Avon and Wiltshire region preferred to complete the measures remotely, whereas the majority in the north-east preferred to attend an outcome appointment in person.

The duration of measurement varied, with eligibility and baseline assessment appointments lasting up to 90 minutes and outcome measurement taking approximately 60 minutes.

Depression measures

Patient Health Questionnaire-9 items

The PHQ-922 is a nine-item self-report measure of depression that is commonly used in primary care settings. The PHQ-9 has been found to be reliable (Cronbach’s α = 0.84–0.93), valid and sensitive to change in the general population. 53 To the authors’ knowledge, the psychometric properties of the scale have not been investigated in the autistic population.

Beck Depression Inventory-II

The BDI-II25 is a widely used 21-item self-report measure of depression. The BDI-II has been found to be reliable (Cronbach’s α = 0.92) for outpatients. 25 A validation study24 of 50 young people with ASD reported good internal consistency on the BDI-II (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.90).

GRID-Hamilton Depression Rating Scale

The GRID-HAMD54 is a version of the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D). 55 It is a 17-item clinician-administered interview that has been found to be reliable and valid in the general population but, to our knowledge, has not been investigated in the autistic population. 54 GRID-HAMD interviews were audio-recorded, with participant consent, for the purposes of inter-rater reliability. The first six HAM-D interviews by each interviewer were subject to a second independent rating, excluding items 8 and 9 (i.e. observation of psychomotor retardation and agitation), which need to be assessed face to face, to establish the reliability of each assessor. To establish reliability across the study, a random sample (20%) of GRID-HAMD recordings were independently rated.

Participant Global Rating of Change

Participants were asked to rate whether their depression was better, worse or much the same on a 5-point scale at the 16- and 24-week follow-ups.

Other measures

Other measures included measures of anxiety and obsessive–compulsive symptoms to account for the potential impact the high rates of co-occurring anxiety problems in autism might have on the feasibility of the intervention delivery and outcome. They also included a positive and negative affect rating scale as the intervention was designed to promote positive feelings, a set of functional outcome measures and questions about health and social care service use.

Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7

The GAD-756 is a seven-item self-report measure of anxiety. The scale has been found to be reliable and valid in the typically developing population56 (Cronbach’s α = 0.92). However, its psychometric properties for use with autistic individuals are not known.

Obsessive–Compulsive Inventory-Revised

The Obsessive–Compulsive Inventory-Revised (OCI-R)57 is an 18-item self-report measure of the symptoms of obsessive–compulsive disorder, with items such as ‘I feel I have to repeat certain numbers’ scored on a five-point Likert scale (0–4), indicating increasing frequency. The scale has been found to be reliable and valid. 57 The OCI-R was found to have good psychometric properties in a sample of 225 autistic people. 58

Positive and Negative Affect Schedule

The PANAS59 is a 20-item self-report scale of positive and negative affect. The scale has been found to be reliable, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.89 for the positive affect scale and of 0.85 for the negative affect scale, but it has not been used with autistic individuals. 59

Work and Social Adjustment Scale

The Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS)60 is a five-item self-report measure of impaired functioning that has been found to be reliable (Cronbach’s α = 0.7–0.94) and valid in typically developing individuals. It has been used with autism populations, but its psychometric properties have not been assessed.

EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version

The EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L)61 is a five-item self-report measure of health, with items measured on a 5-point Likert scale (1 to 5) indicating severity. It has been found to be reliable and valid in the typically developing population. 62

Short Form questionnaire-12 items

The Short Form questionnaire-12 items (SF-12)63 is a 12-item self-report measure of physical and mental health. It has been found to be a reliable and valid measure among people with severe mental health problems, but psychometric properties for autistic populations are not available. 64

Adult Repetitive Behaviour Questionnaire-2

The Adult Repetitive Behaviour Questionnaire-2 (RBQ-2A)65 is a 20-item self-report measure of repetitive behaviours. It has been found to have good internal consistency, with Cronbach alphas of between 0.73 and 0.83, and autistic people score significantly higher on the measure than typically developing individuals, suggesting that it is a valid measure of autism-specific repetitive behaviours.

Rumination–Reflection Questionnaire

The Rumination–Reflection Questionnaire (RRQ)66 is a 12-item self-report questionnaire comprising two subscales: rumination and reflection. The measure has good psychometric properties; the rumination scale has a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.90, and the reflection scale has a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.91.

Economic evaluation

We aimed to assess the feasibility of collecting data on statutory health and voluntary service use. This was assessed with a questionnaire collecting information on the use of other primary and community care services (NHS Direct, attendances at walk-in centres, use of community health-care services); secondary care related to mental health (number of outpatient visits, type of clinic and reason for visit, inpatient stays, length of stay and reason for stay); use of social services and disability payments received; personal costs related to mental health (expenditure on over-the-counter medication, expenditure on prescriptions, travel costs associated with health-care visits, loss of earnings, out-of-pocket expenditure on other services, e.g. private counselling or complementary or alternative therapies, child care and domestic help); time off work; and unpaid activities. We also accessed GP records to obtain information on the number of primary care consultations, by type (e.g. face to face, telephone), who was seen and prescribed medication.

Sample size

This feasibility study was not powered to detect important clinical differences between GSH and TAU. We collected data on outcomes that were used to inform a future large-scale trial. Recruiting a sample of 70 participants, 35 in each group, will inform decision-making about the practical issues of conducting such a trial and will be used to estimate the standard of the continuous depression outcome with reasonable precision. 67 Such a number would provide estimates of the completion rates of the intervention and retention rates that would assist in planning the recruitment for a future RCT. For example, if 80% of those randomised to GSH received the intervention, the 95% CI would be 63% to 92%. Similarly, if 85% of those randomised were followed up at 10 weeks, the 95% CI for the retention rate would be 75% to 93%.

Qualitative study

A nested qualitative study (see Chapter 4) was designed to investigate the feasibility and patient and therapist acceptability of the intervention. The methods and results are fully described in Chapter 4.

Data monitoring and oversight

An adverse event standard operating procedure (SOP) (see Appendix 3) was developed for the study in line with Good Clinical Practice guidelines,68 and this was followed by all members of the research team. Adverse events are defined as significant negative episodes or deterioration in a participant’s condition during a trial. Adverse events were reported by research assistants and coaches to clinically qualified trial staff, who ascertained whether or not these were linked to participation in the trial. A record was kept of adverse events during the trial. Any serious adverse events of an unexpected and related nature would have been reported to the main REC, the study sponsor and Trial Steering Committee (TSC), but this did not happen during the trial.

A risk management SOP was also developed for the trial and followed by all members of staff working on the study. As this was a depression-focused study, participants’ suicide risk was monitored using the suicidality items on the PHQ-9 and BDI-II, and participant responses to the suicidality item of the HAM-D. If the participant stated that they had experienced suicidal/self-harming thoughts every day in the last week (PHQ-9) or that they would like to kill themselves, or would kill themselves if they had the chance (BDI-II), then a letter was sent to their GP highlighting the individual’s risk. If the individual was considered to be high risk, a qualified clinician could follow up further by offering information to the participant about local crisis teams, and calling their GP to ensure that the information was shared in a timely manner.

A Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC) and the TSC provided independent oversight of the study, meeting at 6-monthly intervals. Adverse events and risk information was shared with the committees, who had the option of terminating the trial prematurely if they felt this to be warranted.

Patient and public involvement

Two autistic adults were involved in the design and format of the GSH materials.

A consultation group of autistic adults provided feedback on the final version of the study information sheets and the initial GSH session.

An autistic researcher was a member of the TSC.

The study was presented to an NHS clinician network during the development phase to obtain feedback about the planned research.

The study was presented to a service user group in one of the regional sites (Bristol) to raise awareness of the research and to consult about the research plans.

Summary of changes to the project protocol

All changes were approved following the submission of amendments to the REC:

-

Additional measures, the Adult Repetitive Behaviour Questionnaire and the Rumination subscale of the RRQ, were included in the protocol to characterise the participants in respect of autism and depression characteristics. 65,66 The Participant Global Rating of Change was introduced at 16 and 24 weeks to gain patient-centred views about improvement in depression to supplement standardised symptom measures.

-

When the study opened to recruitment, consultation with the clinical services indicated that the recruitment pathways as specified in the protocol (v1.1) did not enable them to invite all potentially eligible participants to find out about the study. For example, in the BASS, not all participants completed the PHQ-9 prior to clinic attendance. Hence, the protocol was amended on the guidance of clinicians in both clinics to improve access to the study for potentially eligible participants.

Outcomes of feasibility study

A statistical analysis plan (SAP) was written and agreed by the DMEC and TSC before any analysis was carried out. As this was a feasibility study, no formal sample size was defined and, therefore, the study was not powered to show any differences between treatment groups. All analyses were prespecified in keeping with the outcomes of this feasibility study.

These outcomes were:

-

an estimation of the rate of recruitment for a large-scale RCT

-

an estimation of the retention rates to inform the RCT

-

the proportion of adults with ASD consenting to the study

-

the proportion completing the baseline assessment and entering the randomised phase

-

for those in the intervention group, the number of GSH sessions attended and the proportion completing five or more sessions

-

the proportion completing follow-up assessments at 10, 16 and 24 weeks post randomisation.

Inter-rater reliability of the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale

The HAM-D is an observer-rated instrument, with seven assessors interviewing participants. During the study, it was important to establish inter-rater reliability by using two assessors to re-rate these interviews. It was also important for subsequent analyses to compare the sensitivity to change of the two self-reported depression measures (BDI-II and PHQ-9), with which the HAM-D was to be used as the gold-standard measure for comparison.

We assessed inter-rater reliability early in the study (June 2017); a second assessor independently rated the audio-recordings of the first six interviews completed by the initial assessor in Newcastle and the first eight interviews completed by the initial assessor in Bristol. Agreement between assessors by HAM-D item (excluding the two items that required direct observation, i.e. psychomotor agitation and psychomotor retardation) was calculated as a percentage of total number of agreements on ratings of individual items.

By the end of the study, the first eight HAM-D assessments for each of the seven assessors (three in Bristol and four in Newcastle) had been double rated and the inter-rater reliability of the HAM-D was assessed. As most of the second ratings were conducted by listening to an audio-recording of the interview with the participant, the two items of the HAM-D that require direct observation (psychomotor agitation and psychomotor retardation) were not included in the total score. Therefore, the HAM-D scores being compared were the total of 15 items in the HAM-D without prorating due to the established variability across individual items. 69 Cohen’s kappa was calculated for every pair of assessors. Agreement was defined as both of the assessors’ total score falling within the same three-point range of HAM-D scores, which has been suggested to be clinically relevant. 28 A value of Cohen’s kappa of ≥ 0.8 was prespecified as acceptable.

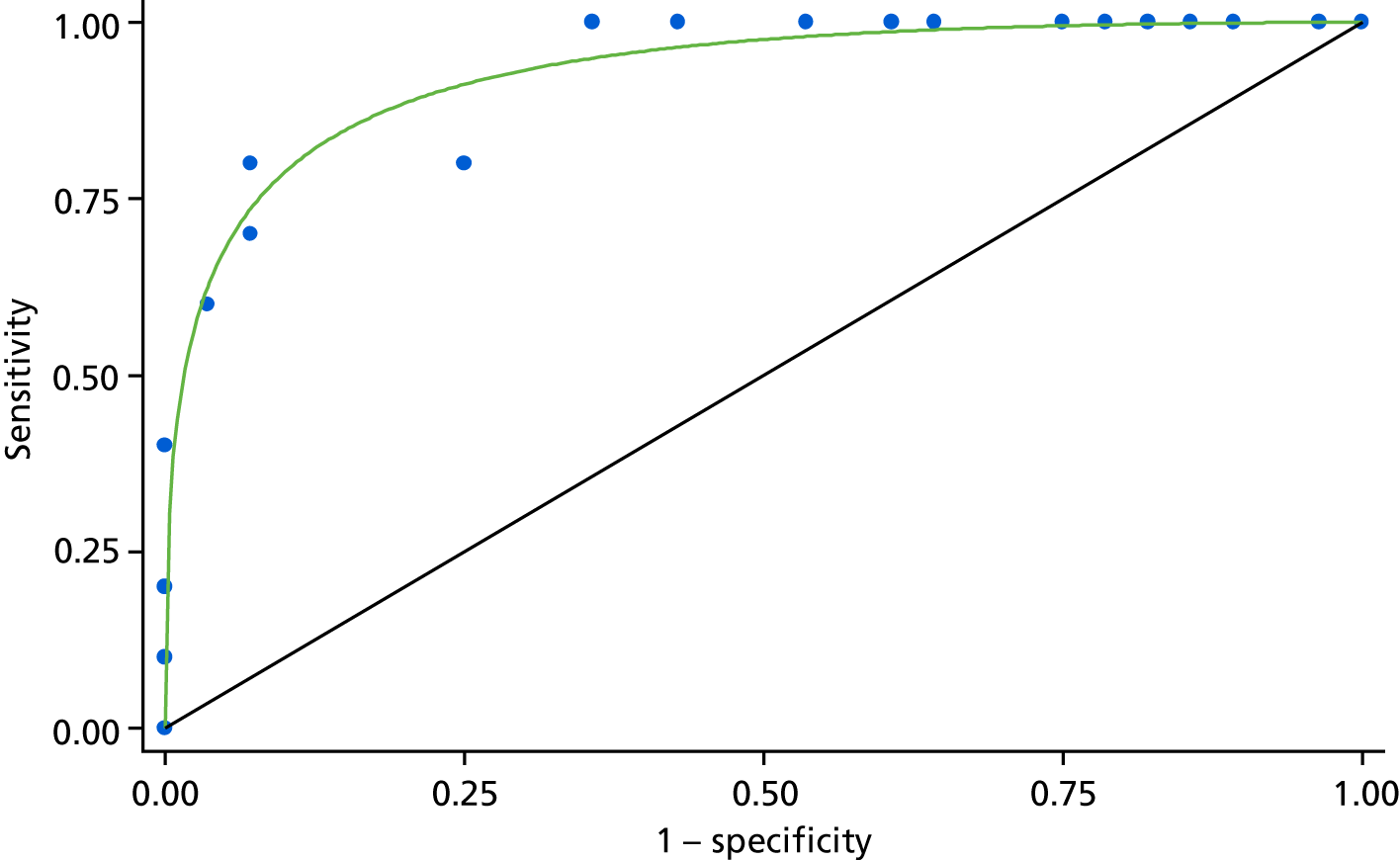

Sensitivity to change of depression outcome measures

We explored the sensitivity to change of the two self-reported measures of depression (PHQ-9 and BDI-II) in comparison with the observer-rated HAM-D (clinician-administered interview) to identify the most appropriate outcome measure(s) for the main trial. We also identified the time point that would be used to measure the primary outcome in the main trial (based on the time point at which most participants had completed the intervention).

For each of the self-reported depression outcome measures (PHQ-9 and BDI-II), we examined:

-

acceptability (proportion of individuals providing sufficient data)

-

agreement between continuous scores using the intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC) from a two-way mixed effect, repeated measures analysis of variance model (observations are random, outcome measure instrument is fixed)

-

Bland–Altman plots

-

sensitivity to change (defined as a binary outcome of at least 50% improvement in symptoms on HAM-D at the time measuring the primary outcome compared with baseline) using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analyses separately for each measure.

We also compared the continuous scores on the depression outcome measures only (HAM-D, PHQ-9, BDI-II) between the groups.

Economic evaluation

The focus of this feasibility study was piloting the methods of economic data collection rather than comparing costs. Participants were asked to report details of their use of health services and voluntary services during the trial as part of the follow-up questionnaires at 10, 16 and 24 weeks. Data collected included medication use, use of primary care and secondary care [including outpatient appointments, inpatient stays and attendances at accident and emergency (A&E) for their mental health] and the use of autism support services. Participants were asked to recall their use of these services during the interval since the last contact (e.g. baseline to 10 weeks, 10–16 weeks and 16–24 weeks). In addition, data on medication and use of primary and secondary care services were collected from electronic medical records (EMRs) at the end of the study to inform the decision regarding the source of data for a larger-scale trial. These included data from 2 months before the participant entered the study until the date the participant ended the study, namely 24 weeks after randomisation.

The data on health and voluntary service use were described, using appropriate statistics, to inform which economic data were to be collected in the main trial. These included examining completeness of data; determining which source of data should be used in the main trial (when information from both self-report and medical records is available – antidepressant medication use, use of primary care services and NHS outpatient or community mental health team clinics for mental health problems); identifying any redundant questions; and identifying any additional questions required to enable costing in the main trial.

To analyse the self-reported data over the whole study period, each participant was recorded as using each health-care or voluntary service (outcome) if they had done so at least once over the three assessment points detailed above, even if they additionally recorded a negative or missing response at another assessment point. If a participant responded ‘no’ at all assessment points, or ‘no’ at some assessments and missing at others, they were recorded as not having that outcome.

Concordance between self-reported data and the EMR data was defined as the outcome being recorded as both yes (or both no) in the self-reported data and the EMR data, and data were regarded as missing if that outcome was not recorded. These analyses were possible only for the outcomes of antidepressant medication use, use of primary care services and NHS outpatient or community mental health team clinics for mental health problems.

Post hoc analysis

During the study an amendment was made to collect a Participant Global Rating of Change in depression (May 2017). This question was asked at the 16- and 24-week follow-up to find out how the participant felt their depression was compared with baseline (i.e. 16 or 24 weeks earlier).

Chapter 3 Results

Recruitment

The planned start of recruitment to the study was delayed by 5 months owing to time gaining ethics approval. Recruitment was conducted over 12 months (6 October 2016 to 30 September 2017) and by the end of recruitment 70 participants had consented and been randomised to treatment as per protocol. The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagrams for the 70 participants are shown in Figures 1 and 2. 70 First, participant recruitment into the study is shown by regional centre, Bristol or Newcastle, with the two recruitment pathways within each centre – an NHS clinic and research opportunity or research register – depicted to the point of randomisation, that is, four pathways (see Figure 1). Participant flow through the study beyond randomisation is shown by regional centre only (Bristol or Newcastle) in Figure 2.

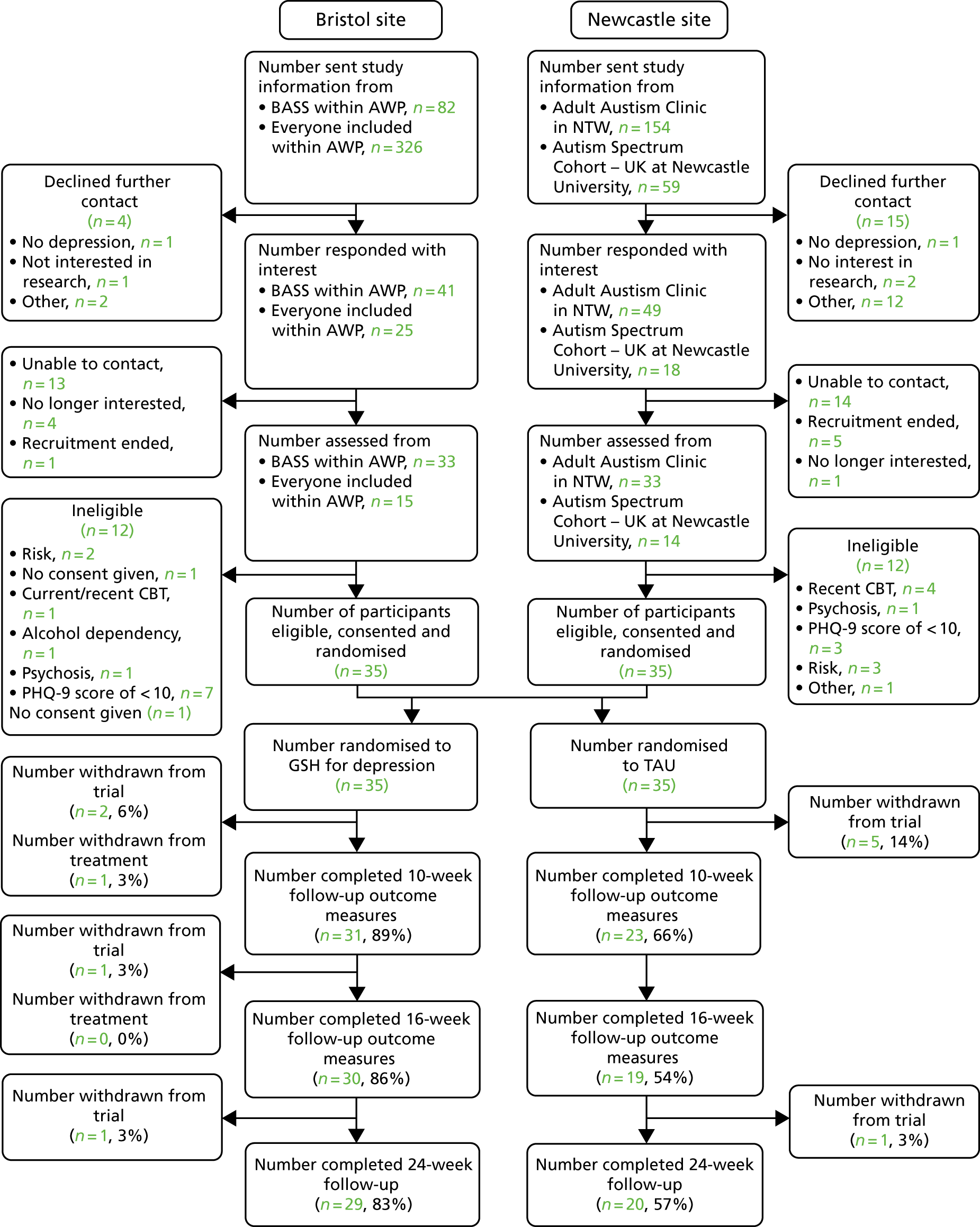

FIGURE 2.

The CONSORT flow diagram from recruitment onwards by site. Reproduced with permission from Russell et al. 48

The overall rate of recruitment into the study was 3.2 patients per month [standard deviation (SD) 1.7 patients per month] over 12 months, with 3.2 patients per month (SD 1.3 patients per month) in Bristol and 3.2 patients per month (SD 2.1 patients per month) in Newcastle. However, as there was variability in recruitment procedures and timings across the four recruitment pathways, examining the mean rate of recruitment by region is perhaps less meaningful than considering recruitment by type or by clinic referral versus research register, as well as by regional centre.

In the BASS, 27% (22/82) of adults who were sent study information and were eligible for the study consented to be randomised. The corresponding figure was 18% (28/154) in the Newcastle Adult Autism Clinic. The Newcastle Adult Autism Clinic was able to contact a relatively large retrospective list of previous clinic attendees who had agreed to be contacted about future research.

Rates of randomisation through the NHS Adult Autism Clinics were relatively consistent during the recruitment period. In the BASS, an average of 1.8 participants were randomised each month. In the Newcastle Adult Autism Clinic, an average of 2.33 participants were randomised each month.

Research recruitment pathways – as described in Chapter 2 – different procedures for screening and inviting participants to find out about the study were followed, according to the local study protocols. There were also differences in timing. For the ‘Everyone Included’ pathway in the Bristol site, screening and contacting potentially eligible participants happened at regular intervals and at least one participant was randomised to the study each month, with an average of 1.08 participants per month. The Adult Autism Spectrum Cohort – UK study at Newcastle University was not active as a recruitment pathway at the start of the study, and participants from this pathway were contacted only during the final 6 months of recruitment (March–October 2017). An average of 1.16 participants were recruited each month during the 6-month period when this pathway was in operation.

In total, 40% (10/25) of adults who were interested in the study and assessed, but who were not eligible, had a PHQ-9 score of > 10; 20% (5/25) were not eligible owing to their risk of suicide; the remaining 40% (10/25) were not eligible owing to psychosis (n = 2), current/recent CBT (n = 5) or alcohol dependency (n = 1), or because they could not give informed consent owing to high levels of distress (n = 1) or for some ‘other’ reason (i.e. ineligible as outside the postcode area) (n = 1).

Participants characteristics

Most participants in the trial were male (n = 51/69, 74%) and the mean age of participants was 38 years (SD 13.2 years; n = 57) (figures by treatment group are shown in Table 2). A significant proportion of the participants (n = 21/62, 32%) were employed in either full -or part-time work. Thirty-two per cent (n = 21/65) were educated to at least A level or equivalent. The majority were currently living in owner-occupied properties (38%, n = 25/65), and 56% (n = 35/63) were cohabiting, which included living with family members. Thirty-three per cent (n = 21/64) had moderate financial stress described as low or no wage, benefits as income, a debt management plan or housing status at risk.

| Variable | TAU (N = 35 randomised) | GSH (N = 35 randomised) |

|---|---|---|

| Stratification variable: centre, N completed (%) | ||

| Bristol | 17 (49) | 18 (51) |

| Newcastle | 18 (51) | 17 (49) |

| Minimisation variable: antidepressant medication, N completed (%) | ||

| Currently taking | 18 (51) | 20 (57) |

| Not taking | 17 (49) | 15 (43) |

| Minimisation variable: PHQ-9 score, n/N completed (%) | ||

| Mild to moderate (scores between 10 and 15) [N completed (%)] | 19 (54) | 19 (54) |

| Moderate to severe (scores between 16 and 27) [N completed (%)] | 16 (46) | 16 (46) |

| Gender: male | 27/35 (77) | 24/34 (71) |

| Age (years), mean (SD), n | 40.2 (12.6), 28 | 35.3 (13.6), 29 |

| Ethnicity: white | 33/35 (94) | 33/34 (97) |

| Accommodation type: owner-occupied | 11/31 (35) | 14/34 (41) |

| Residential status: primary tenant/leaseholder | 17/30 (57) | 11/33 (33) |

| Education: GCSE or above | 28/31 (90) | 33/34 (97) |

| Employment status: paid or voluntary employment or training (full- or part-time) | 17/32 (53) | 15/33 (45) |

| Financial support/stress: moderate/significant financial stressa | 17/31 (55) | 11/33 (33) |

| Relationship status: single | 23/31 (74) | 19/34 (56) |

| Currently taking other medication for mental health | 5/28 (18) | 7/32 (22) |

| Experience of psychological/talking therapy: at least one experiencea | 21/29 (72) | 20/29 (69) |

| Current alcohol or substance dependency: no | 28/29 (97) | 30/30 (100) |

| PHQ-9 score, mean (SD), n | 16.5 (4.8), 35 | 15.0 (3.2), 35 |

| BDI-II score, mean (SD), n | 32.0 (11.5), 31 | 29.9 (8.8), 33 |

| HAM-D score, mean (SD), n | 17.6 (6.9), 29 | 17.4 (5.6), 34 |

| CIS-R score, mean (SD), n | 29.4 (11.0), 35 | 30.5 (8.6), 34 |

| Depression duration, n/N completed (%) | ||

| < 2 weeks | 1/24 (4) | 0/28 (0) |

| Between 2 weeks and 6 months | 5/24 (21) | 3/28 (11) |

| Between 6 months and 1 year | 3/24 (13) | 1/28 (4) |

| Between 1 and 2 years | 0/24 (0) | 4/28 (14) |

| ≥ 2 years | 15/24 (63) | 20/28 (71) |

| CIS-R categories (ICD-10), n/N completed (%) | ||

| Primary diagnosis | ||

| No diagnosis identified | 2/35 (6) | 1/34 (3) |

| Generalised anxiety disorder – mild | 0/35 (0) | 1/34 (3) |

| Mixed anxiety and depressive disorder | 1/35 (3) | 1/34 (3) |

| Specific (isolated) phobia | 2/35 (6) | 0/34 (0) |

| Agoraphobia | 1/35 (3) | 0/34 (0) |

| Generalised anxiety disorder | 4/35 (11) | 4/34 (12) |

| Panic disorder | 2/35 (6) | 1/34 (3) |

| Mild depressive episode | 5/35 (14) | 6/34 (18) |

| Moderate depressive episode | 13/35 (37) | 16/34 (47) |

| Severe depressive episode | 5/35 (14) | 4/34 (12) |

| Secondary diagnosis | ||

| No diagnosis identified | 3/35 (9) | 1/34 (3) |

| Mixed anxiety and depressive disorder (mild) | 2/35 (6) | 2/34 (6) |

| Mixed anxiety and depressive disorder | 12/35 (34) | 7/34 (21) |

| Specific (isolated) phobia | 1/35 (3) | 2/34 (6) |

| Social phobia | 2/35 (6) | 5/34 (15) |

| Agoraphobia | 1/35 (3) | 1/34 (3) |

| Generalised anxiety disorder | 12/35 (34) | 12/34 (35) |

| Panic disorder | 2/35 (6) | 4/34 (12) |

| PANAS positive score, mean (SD), n | 19.2 (6.7), 31 | 22.2 (7.2), 33 |

| PANAS negative score, mean (SD), n | 28.2 (8.2), 31 | 29.9 (7.7), 34 |

| GAD-7 score, mean (SD), n | 12.9 (4.4), 32 | 12.4 (4.5), 34 |

| OCI-R score, mean (SD), n | 31.2 (15.4), 29 | 29.0 (13.7), 34 |

| WSAS score, mean (SD), n | 25.8 (8.9), 32 | 24.8 (7.8), 33 |

| SF-12 normalised physical function score, mean (SD), n | 43.4 (11.3), 30 | 41.8 (9.0), 32 |

| SF-12 normalised mental health score, mean (SD), n | 29.6 (10.0), 30 | 30.5 (7.0), 32 |

| EQ-5D-5L score, mean (SD), n | 0.605 (0.210), 31 | 0.621 (0.214), 33 |

| RBQ-2A score, mean (SD), n | 2.5 (0.5), 32 | 2.4 (0.5), 34 |

| RRQ rumination score, mean (SD), n | 4.1 (0.5), 30 | 4.1 (0.5), 33 |

At baseline, the mean PHQ-9 score was 15.8 (SD 4.1), with 55% of participants (n = 38/69) meeting ICD-10 criteria for a primary diagnosis of a moderate or severe depressive episode, and 24% (n = 15/62) having a primary diagnosis of an anxiety disorder according to the CIS-R (GAD-7, phobia or panic). Sixty-seven per cent (n = 35/52) had been depressed for ≥ 2 years. Fifty-four per cent of participants (n = 36/66) were taking antidepressant medication at baseline.

The numbers of participants in the two randomised groups (GSH and TAU) at baseline (see Table 2) were balanced in terms of the two minimisation variables (antidepressant medication and PHQ-9 score categories). Because the sample size was small (35 participants in each group), it was not unexpected that there would be some imbalance in characteristics between the groups by chance. The randomised groups had slight differences (> 5 points or > 5% as applicable; not prespecified in the SAP) in a number of variables measured at baseline. Those randomised to receive TAU were slightly older and were more likely to be male, in paid/voluntary employment and single than those randomised to GSH. The GSH group included more owner-occupiers and had a higher level of educational attainment [General Certificates of Secondary Education (GCSEs) or above]. The two groups were similar in terms of the percentage of participants taking medication for mental health, and having at least one experience of psychological/talking therapy.

Scores on the three depression measures (PHQ-9, BDI-II and HAM-D) were similar between the two groups at baseline. Most participants had a primary ICD-10 diagnosis of moderate or severe depression based on the CIS-R, although this was slightly unbalanced between the groups (TAU, 51%; GSH, 59%). The PANAS positive scores, PANAS negative scores, GAD-7 scores, OCI-R scores, WSAS scores, SF-12 normalised physical function scores, SF-12 normalised mental health scores, EQ-5D-5L scores, RBQ-2A score and RRQ rumination scores were also similar between the groups at baseline.

Participant retention

Seventeen per cent (6/35) of participants allocated to TAU and 11% (4/35) of participants allocated to GSH withdrew from the trial (Figure 2).

Follow-up rates at 10, 16 and 24 weeks differed between the groups, with the GSH group having higher rates of follow-up than the TAU group (see Figure 2; Table 3). The largest difference in follow-up rates was at 16 weeks (86% for GSH compared with 54% for TAU).

| Follow-up time point | Overall, % (95% CI), n | TAU, % (95% CI), n | GSH, % (95% CI), n |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 weeks | 77 (66 to 86), 54 | 66 (48 to 80), 23 | 89 (73 to 96), 31 |

| 16 weeks | 70 (58 to 80), 49 | 54 (38 to 70), 19 | 86 (70 to 94), 30 |

| 24 weeks | 70 (58 to 80), 49 | 57 (40 to 73), 20 | 83 (66 to 92), 29 |

Outcome measures

On the PHQ-9, BDI-II, HAM-D, CIS-R, OCI-R, PANAS negative, GAD-7, WSAS, RBQ-2A and RRQ measures, a lower score is a more positive outcome. On the PANAS positive, SF-12 and EQ-5D-5L utility measures, a higher score is a more positive outcome.

Ten weeks

The mean scores on most of the outcome measures (PHQ-9, BDI-II, OCI-R, PANAS negative, GAD-7) were higher (worse outcome) or lower (PANAS positive, SF-12 physical function; worse outcome) for those in the TAU group than for those in the GSH group (Table 4). Across most measures, around 15% more participants responded in the GSH group than in the TAU group. The mean scores on the HAM-D, EQ-5D-5L and RRQ measures showed little difference between the groups.

| Outcome measure completed at 10 weeks post randomisation | TAU,a mean (SD), N completed | GSH,b mean (SD), N completed |

|---|---|---|

| PHQ-9 score | 14.1 (6.5), 23 | 11.0 (5.3), 31 |

| BDI-II score | 28.2 (11.8), 23 | 23.2 (11.4), 31 |

| HAM-D score | 13.2 (6.0), 17 | 13.6 (5.7), 27 |

| OCI-R score | 27.3 (18.3), 20 | 23.0 (13.9), 29 |

| PANAS: positive score | 19.6 (6.7), 23 | 22.5 (8.4), 31 |

| PANAS: negative score | 28.0 (7.2), 23 | 24.6 (7.7), 31 |

| GAD-7 score | 11.8 (5.4), 23 | 8.8 (5.3), 31 |

| WSAS score | 22.5 (9.7), 22 | 24.1 (9.2), 29 |

| SF-12 normalised physical function score | 45.2 (11.0), 22 | 42.4 (9.4), 28 |

| SF-12 normalised mental health score | 29.7 (12.4), 22 | 31.6 (9.2), 28 |

| EQ-5D-5L score | 0.590 (0.215), 22 | 0.606 (0.202), 29 |

| RRQ rumination score | 3.9 (0.8), 23 | 4.1 (0.6), 29 |

Sixteen weeks

By 16 weeks post randomisation, the mean scores for several outcome measures (PHQ-9, BDI-II, OCI-R, HAM-D, PANAS negative and GAD-7) in the GSH treatment group had further decreased (lower score, better outcome) or had increased (SF-12 physical function; higher score, better outcome) compared with scores at 10 weeks (Table 5). The mean scores of the outcome measures in the TAU group had also changed (compared with scores at 10 weeks), but not by as much, and the score changes were more variable and not consistently in the same direction. Differences between the group mean scores on HAM-D and quality of life (as measured with the EQ-5D-5L) presented as slightly larger at 16 weeks than at 10 weeks. The trend of increases in scores from baseline continued, with both groups showing better outcomes across all measures, except SF-12 normalised physical function for those in the GSH treatment group. There was, however, a large difference between the groups in the proportion of participants who were followed up and completed the measures (22% more participants were followed up in the GSH group); therefore, the findings should be interpreted with caution given the potential for bias.

| Outcome measure completed at 16 weeks post randomisation | TAU,a mean (SD), n completed | GSH,b mean (SD), n completed |

|---|---|---|

| PHQ-9 score | 12.9 (6.6), 17 | 9.4 (5.9), 28 |

| BDI-II score | 27.6 (13.6), 16 | 18.7 (10.3), 28 |

| HAM-D score | 14.5 (7.3), 18 | 10.5 (6.2), 29 |

| OCI-R score | 23.3 (16.4), 17 | 20.0 (12.0), 28 |

| PANAS: positive score | 20.5 (7.9), 17 | 25.0 (9.5), 27 |

| PANAS: negative score | 26.5 (8.6), 17 | 21.9 (7.2), 27 |

| GAD-7 score | 10.6 (5.7), 17 | 8.3 (4.5), 28 |

| WSAS score | 23.5 (9.9), 17 | 18.0 (9.8), 27 |

| SF-12 normalised physical function score | 42.8 (11.8), 16 | 41.5 (9.0), 27 |

| SF-12 normalised mental health score | 30.5 (11.7), 16 | 35.6 (10.0), 27 |

| EQ-5D-5L score | 0.660 (0.189), 16 | 0.691 (0.236), 28 |

Twenty-four weeks

By 24 weeks (Table 6) the mean scores for several outcome measures (PHQ-9, BDI-II, HAM-D, OCI-R, PANAS negative, GAD-7, WSAS) had increased (higher score, worse outcome) or decreased (SF-12 physical function; lower score, worse outcome) in both groups compared with 16 weeks. SF-12 physical function and quality of life (EQ-5D-5L) had increased (higher score, better outcome) in the GSH group. The trend from baseline continued, with both groups showing better outcomes across all measures, except for the PANAS positive score for those in the TAU treatment group and the SF-12 normalised mental health for those in the GSH treatment group. However, as previously, these findings should be interpreted with caution given the large differences in the proportion of participants who completed the measures between the groups, with 18% more participants in the GSH group than in the TAU group.

| Outcome measure completed at 24 weeks post randomisation | TAU,a mean (SD), n completed | GSH,b mean (SD), n completed |

|---|---|---|

| PHQ-9 score | 15.2 (6.4), 20 | 10.1 (6.1), 28 |

| BDI-II score | 29.6 (13.7), 20 | 20.3 (11.8), 28 |

| HAM-D score | 14.5 (8.0), 18 | 12.3 (7.1), 26 |

| OCI-R score | 25.7 (16.5), 17 | 22.1 (13.7), 27 |

| PANAS: positive score | 17.9 (5.4), 19 | 22.9 (9.1), 27 |

| PANAS: negative score | 26.6 (8.8), 18 | 24.3 (8.0), 28 |

| GAD-7 score | 12.3 (5.5), 20 | 8.5 (5.0), 28 |

| WSAS score | 24.6 (7.8), 20 | 19.2 (6.9), 28 |

| SF-12 normalised physical function score | 37.8 (14.3), 17 | 44.3 (9.8), 26 |

| SF-12 normalised mental health score | 28.9 (10.4), 17 | 33.2 (10.5), 26 |

| EQ-5D-5L score | 0.535 (0.223), 20 | 0.713 (0.185), 27 |

Adherence to guided self-help treatment

Eleven per cent (4/35) of participants in the GSH group withdrew from treatment (Figure 2). Of these, two participants did not receive any GSH treatment sessions and withdrew from trial, one participant attended two GSH sessions and withdrew from the trial and one participant withdrew after attending five GSH sessions but did not withdraw from the trial.

Ninety-one per cent (32/35) of participants received at least one session of GSH (Table 7). Of those who did not receive any GSH treatment sessions, two participants withdrew from the trial before they started treatment and one participant became too unwell to begin the treatment after randomisation but did not formally withdraw.

| Treatment information | GSHa n/N (%) |

|---|---|

| Treatment started | |

| ≤ 2 weeks after randomisation | 20/32 (63) |

| > 2 weeks after randomisation | 12/32 (38) |

| Total number of sessions attended | |

| 0 | 3/35 (9) |

| 1 | 0/35 (0) |

| 2 | 1/35 (3) |

| 3 | 0/35 (0) |

| 4 | 1/35 (3) |

| 5 | 1/35 (3) |

| 6 | 1/35 (3) |

| 7 | 0/35 (0) |

| 8 | 3/35 (9) |

| 9 | 25/35 (71) |

| Number completing five or more sessions | 30/35 (86) |

| Mean number of treatment sessions (SD), n | 7.6 (2.9), 35 |

| Number completing treatment: | |

| By 10 weeks | 10/32 (31) |

| By 16 weeks | 23/32 (72) |

| By 24 weeks | 27/32 (84) |

| Did not complete treatment | 5/32 (16) |

| Treatment conducted | |

| Face to face | 29/32 (91) |

| Skype | 3/32 (9) |

Sixty-three per cent (20/32) of participants started GSH treatment within 2 weeks of randomisation (see Table 7). The mean number of treatment sessions was 8.3 (SD 1.7 sessions, n = 32) and 94% (30/32) completed five or more sessions (prespecified as an adequate ‘dose’ of treatment). Seventy-two per cent (23/32) had completed treatment by 16 weeks. Ninety-one per cent (29/32) of participants had their treatment sessions conducted face to face; however, some participants could not attend face-to-face sessions (work/childcare commitments, n = 1; unable to leave the house, n = 2) and were offered treatment via Skype (9%, 3/32).

Treatment as usual

Of those in the TAU group who completed the use of services section of the follow-up questionnaire at 24 weeks, 15 had been prescribed antidepressant medication, nine had received primary care mental health support and one had received mental health support from secondary care services.

Candidate primary depression outcome(s) for main trial

As 72% of participants completed the GSH treatment by 16 weeks, the acceptability of the three outcome depression measures (PHQ-9, BDI-II and HAM-D) was assessed at this time point. A comparison was also carried out in respect of the sensitivity to change of the self-report measures of depression (PHQ-9 and BDI-II) with that of the observer-rated HAM-D.

Acceptability