Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 10/62/03. The contractual start date was in January 2013. The draft report began editorial review in April 2018 and was accepted for publication in September 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Khalida Ismail has received honoraria for educational lectures from Sanofi SA (Paris, France), Novo Nordisk (Bagsværd, Denmark), Janssen Pharmaceutica (Beerse, Belgium) and Eli Lilly and Company (Indianapolis, IN, USA). Kirsty Winkley received consultancy fees from Merck Sharp & Dohme (Kenilworth, NJ, USA).

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Ismail et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Epidemiology of cardiovascular disease and its risk factors

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of mortality, morbidity and disability in the UK and in other developed countries. 1 However, many of the major determinants of CVD are modifiable, including tobacco smoking, a diet high in saturated fat, high low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, obesity, a sedentary lifestyle, hypertension and diabetes mellitus. 2–6 Lower educational attainment and lower socioeconomic status are associated with a greater risk of CVD, and this association is strongest for females. 7 The risk of CVD varies markedly between ethnic groups, with a higher rate of ischaemic heart disease in those of South Asian ethnicity and a higher rate of cerebrovascular disease in those of African ethnicity among those living in England and Wales. 8

Although CVD remains the most common cause of death in developed nations, mortality rates have been falling. Between 1981 and 2000, CVD mortality in the UK fell by 62% in men and 45% in women. 9 Cohort studies and prediction models suggested that a fall in the prevalence of tobacco smoking, a decline in population blood pressure levels and changes in cholesterol levels were important contributors. 9,10 Population-wide changes in modifiable risk factors, such as dietary intake, can bring about substantial benefits and further changes in blood lipids, particularly reductions in levels of non-high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol. 10 However, limited changes in physical activity (PA) and rising levels of obesity have limited the decline in CVD mortality. 10 Further efforts are therefore needed to bring about positive changes, particularly in diet, obesity and PA.

Cardiovascular risk identification

The NHS in England introduced the Health Check programme in 2009 as part of the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC)’s long-term vision for the future of public health in England. 11 In offering Health Checks to all those aged 40–74 years without a known diagnosis of CVD, the aim is to prevent heart disease, stroke, diabetes mellitus and kidney disease and to reduce health inequalities. The risk assessment includes collection of demographic data, smoking status, cholesterol level, blood pressure and diabetes mellitus status. An individualised risk management plan is given in accordance with the assessment to support lifestyle changes, such as referral to smoking cessation sessions, exercise prescriptions, lifestyle advice and signposting to local resources.

A lower-than-anticipated coverage of NHS Health Checks has been reported,12 with regional variations in attendance ranging from 27% to 52%,12 with greater uptake in patients of older age and in regions of lower deprivation. 13 Reductions in CVD risk have been reported for those attending Health Checks;14 however, a systematic review of the implementation of Health Checks found no reduction in mortality or morbidity. 15 The programme has attracted criticism owing to a lack of an up-to-date evidence base and Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) lacking the resources to implement them. 16

Several risk algorithms have been developed and validated to estimate the risk of developing CVD based on known risk factors; these risk algorithms include the Framingham Risk Score,17 the ASSIGN score,18 QRISK®19 and QRISK®220 (both QResearch, Nottingham, UK). The latter is now recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) for the identification of people at risk of CVD up to the age of 84 years in England. 21 The QRISK2 algorithm takes into account self-report ethnicity, deprivation and other relevant clinical conditions, and is updated annually to reflect changes in clinical evidence, data recording and population demographics. Once a high CVD risk is ascertained, the primary prevention of CVD is recommended via lifestyle advice and interventions.

The evidence for increasing physical activity

Physical inactivity increases mortality and the risk of diseases such as CVD and diabetes mellitus. 22 The DHSC advises adults to perform ≥ 30 minutes of at least moderate-intensity PA on ≥ 5 days per week, in ≥ 10-minute bouts, for optimum health benefits. 23 Walking is the most common form of PA in adults and is associated with reductions in CVD and all-cause mortality, and walking pace is a stronger predictor of improved outcomes than walking duration. 24 Walking is promoted as a near-perfect exercise as it has the lowest risk of harm and is now included in UK public health policy. 25,26

However, the proportion of those achieving PA recommendations is low, particularly when objective measures are used to assess PA. In England, 39% of men and 29% of women self-report achieving the recommended PA levels, but objective assessment of PA using accelerometers in a subsample of the Health Survey for England found that only 5% of men and 4% of women aged 35–64 years achieved the recommended levels. 27

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses report moderate positive short-term increases in PA following lifestyle interventions, in either a group or an individual format, but findings are limited because most studies used self-report measures. 28,29 Evidence for brief PA interventions suggests improvement in PA in the short term, but there is limited evidence for the long-term impact, cost-effectiveness and deliverability in a primary care setting. 30,31 A review of 32 trials reported that walking interventions led to improvement in a number of cardiovascular risk factors, including blood pressure and weight, but not in lipids. 32 The majority of the reviewed intervention trials recruit motivated volunteers and report low response rates, which may limit the representativeness of observed findings.

The contents of assessed interventions to promote PA differ significantly, but social support and cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) strategies, rather than health education alone, are recommended in older adults. 33 The use of pedometers as a method of self-monitoring can increase PA and improve health in the short term. 34 Compared with usual care (UC), the use of pedometers and a brief walking intervention in primary care led to improvements in 12-month PA in a sample of adults not achieving the recommended activity levels at baseline. 35 The intervention was as effective when delivered by post as when delivered by nurses in primary care, suggesting that PA can be improved in physically inactive patients with minimal resources. Details of the components used in trials of interventions to promote PA, including information on the behaviour change techniques (BCTs) used, are recommended to improve implementation and evidence syntheses. 29,36

The evidence for dietary interventions

Modest beneficial changes to dietary intake, specifically changes to fat, fibre, fruit and vegetable intake, are found following healthy diet interventions in primary care, but there is variability in intervention design and delivery as well as the methodological quality of previous studies. 37 Based on the limited evidence available, estimates of the cost-effectiveness of dietary interventions in primary care suggest that interventions need to be targeted towards the older population at greatest risk of disease to be cost-effective. 38

A systematic review of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) assessing generic dietary advice for reducing CVD risk found modest beneficial effects on mean total and LDL cholesterol levels and small reductions in blood pressure up to 12 months later, suggesting that dietary advice may contribute to an improved CVD risk profile. 39 However, the longer-term effects of dietary interventions are unknown owing to limited follow-up periods of reviewed studies. Compared with UC, dietary interventions produce modest weight losses that diminish over time. 40 Further work is needed to understand how the modest benefits of dietary interventions may be maintained.

The evidence for motivational interviewing

Motivational interviewing (MI) is a common approach to behaviour change in health care, defined as a collaborative, goal-oriented style of communication with particular emphasis on the language of change. 41 It is designed to strengthen motivation for and commitment to a specific behavioural goal by eliciting and exploring personal reasons for change within an atmosphere of acceptance and compassion. 42 The appeal of MI is that it is brief, can be delivered by a range of health-care providers, has a competency framework and can be applied to a range of health-care settings, with evidence of benefits to health outcomes when compared with other interventions. 43

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses have demonstrated significant, moderate effects of MI on diet and exercise behaviours,44 as well as on health outcomes such as reduced weight, cholesterol and blood pressure, although the number of trials is small. 45,46 However, a systematic review of MI used in lifestyle interventions for people at risk or with a diagnosis of CVD found little evidence of the benefits of MI, noting the considerable variability between interventions and the outcomes measured and that few have included a long-term follow-up to assess whether or not any observed benefits are sustained. 47 A 14-month follow-up of diabetic patients who had received a MI lifestyle intervention found no benefits in lifestyle, biomedical or psychological outcomes compared with UC. 48 A RCT with a 12-month postintervention follow-up period found that the benefits of up to five MI sessions delivered over a period of 6 months on walking and cholesterol levels were maintained in a sample of overweight or obese patients, but other CVD risk factor outcomes were not maintained. 49 Effects were stronger for those found to be at higher risk at baseline, suggesting that interventions should target high-risk patients to achieve the best results.

A taxonomy of behaviour change techniques

The limitations of current models of lifestyle interventions, particularly their short-term effects, have led to a search for more sophisticated and targeted behavioural interventions. 50 A Cochrane Database Systematic Review of multiple risk factor interventions for the primary prevention of coronary heart disease observed that techniques based on instruction and information were associated with small improvements in lipid levels and blood pressure, especially when embedded in a theoretical framework related to behaviour change. 51 A systematic review of behavioural interventions found that the techniques most effective in improving diet and PA were based on self-regulatory behaviours, such as goal-setting, self-monitoring, giving feedback, utilising social support and MI. 52 Interventions based on a psychological theory, such as the theory of planned behaviour,53 were more effective, as were those for high-risk populations. There is less evidence to support the case for any minimum threshold of intensity, mode of delivery, intervention provider and setting;50–52 therefore, further study is required to understand how the benefits of behavioural interventions on lifestyle and health outcomes can be maintained. Evaluating interventions in the context of a taxonomy of BCTs and an intervention map offers a framework that is easier to teach, test, replicate and translate. 52–54

In a pilot RCT, a group intervention developed in line with evidence of the most effective BCTs52 led to reductions in weight, when co-interventions and comorbidities were controlled for, but did not increase PA at the 12-month follow-up in people at high risk of CVD, compared with UC. 55 As this was a pilot RCT, the authors note that the intervention was acceptable to participants and that outcomes could be improved by adapting the intervention accordingly. The effects of the group-based setting were not compared with a one-to-one setting, and there is little evidence in the literature on the differences between group and individual approaches. It has been found that the benefits of group sessions outweigh individual sessions even when it is not preferred by participants,56 and that group sessions are highly valued by participants. 57 However, it is also reported that at least one individual session is critical to the success of interventions and in ameliorating disengagement in some participants. 57,58 The variability in patient samples involved in these studies, the intervention delivered and the methodology of each study limit the generalisability of the findings.

By enhancing a MI approach with effective BCTs, the modest effect sizes of each may lead to improvement in outcomes. In people with type 1 diabetes mellitus, four sessions of MI alone was not associated with improved glycaemic control, but four sessions of MI followed by eight sessions of CBT was associated with improved glycaemic control, compared with UC. 59 However, the effects were not maintained after 12 months,60 and participants stated that MI helped them to become more ready to change their behaviour but that further support was needed to implement the change. 61 The evidence for enhancing MI with CBT is not consistent, as the landmark COMBINE (Combined Pharmacotherapies and Behavioural Interventions for Alcohol Dependence) study did not demonstrate increased abstinence from alcohol in those receiving the psychological intervention. 62

The role of health trainers

The DHSC recommended the deployment of health trainers into the most deprived areas of the UK in a White Paper published in 2004. 63 A health trainer is employed by the NHS from the local community in which they serve to provide lifestyle advice to those at risk of disease, with the overall aim of the programme being to address health inequalities, an important issue within multi-ethnic and variably deprived settings. 64 The role involves identifying clients from hard-to-reach and disadvantaged groups, providing one-to-one support in identifying potential problems in lifestyles, setting goals, supporting behaviour change and reviewing client progress. 65 The health trainer programme has been found to increase uptake of NHS Health Checks, particularly in men, younger age groups and those from less affluent areas. 66

A comprehensive review of interventions delivered by lifestyle advisors found little evidence of the benefits of interventions promoting healthy diet and/or increased PA in North American trials; there was no effect on weight and little evidence of improvement in PA levels, but the intervention contents, delivery and goals varied considerably. 67 A review of the available evidence on the NHS health trainer programme thus far indicates positive outcomes and acceptability, but critics argue that the models of service provision are varied, evaluations have included no comparator group and there is a lack of evidence for the maintenance of behaviour change. 68 A health trainer programme for CVD risk reduction in patients with at least one CVD risk factor found significant reductions in CVD risk after 12 months for only those who were identified as being at high risk of CVD (a Framingham Risk Score for CVD of ≥ 20.0%) at baseline. 69 The service also led to high levels of behavioural goal achievement and small, but significant, increases in quality of life. However, as this was a service evaluation there was no comparator group and achievement of behavioural goals was self-reported and unrelated to changes in CVD risk. Further work is needed to assess the potential for health trainers to deliver complex behavioural interventions, including the employment of objective outcome measures, the assessment of maintenance of behavioural change and clinical benefits, and comparison of outcomes with a control group.

The case for an enhanced motivational interviewing intervention

At the population level, the potential benefits of reducing weight and increasing PA in those who are at risk of CVD are considerable. Modest, short-term beneficial effects of various behaviour change interventions for the primary prevention of CVD emphasise the need for more complex, targeted interventions and RCTs that assess long-term benefits. MI provides broad appeal for its collaborative patient-centred style, evidence base and deliverability, and by enhancing a MI approach with the specific BCTs that have the strongest evidence, and incorporating techniques designed to enhance maintenance, observed outcomes may be improved. The relative effectiveness of a group intervention versus an individual intervention remains uncertain, but the former offers social support and may be more cost-effective, if it is acceptable to participants. Health trainers may improve the acceptability of interventions to harder-to-reach populations and positive outcomes have been reported in health trainer programmes thus far. The investigation of the potential for a health trainer to deliver more sophisticated interventions, and for the effects to be compared with UC in a RCT setting, is yet to be undertaken.

The overall aim was to compare the effectiveness of MOVE IT (enhanced MOtiVational intErviewing InTervention), which integrates MI with CBT BCTs, in reducing weight and increasing PA in those at high risk of CVD over 24 months across three arms: (1) enhanced MI in a group format versus (2) in an individual format versus (3) UC. The primary interest was whether or not MOVE IT in a group format was more effective and cost-effective than the individual format or UC because of its potential for social support.

Chapter 2 Research objectives

The following material has been primarily reproduced from our published study protocol, Bayley et al. 70 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided he original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

The purpose of this study was to design and evaluate MOVE IT for people at high risk of CVD, to be delivered by a healthy lifestyle facilitator (HLF) employed from the local community and trained in the intervention. We opted for the job title of HLF, rather than health trainer or lifestyle advisor, as this was thought to better reflect the principles of collaborative work underpinning MI.

Primary objective

To assess whether or not MOVE IT delivered in either a (1) group or (2) individual format is more effective than UC in reducing weight (kg) and increasing PA (average number of steps per day assessed via accelerometry) 24 months later.

Secondary objectives

-

To assess whether or not group MOVE IT is more effective than the individual format in reducing weight and increasing PA 24 months later.

-

To assess whether or not MOVE IT, delivered in either (1) a group format or (2) an individual format, is more effective than UC in reducing LDL cholesterol and in reducing CVD risk score 24 months later.

-

To compare the number of fatal or non-fatal cardiovascular events, and other recorded adverse events (AEs), per treatment allocation.

-

Cost-effectiveness: to assess whether or not MOVE IT delivered in either (1) a group format or (2) an individual format is more cost-effective than UC, in terms of quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) gained over the 24-month follow-up period.

-

Process evaluation: using mixed methods, we conducted the following –

-

Mediational analysis: to examine whether or not changes in behavioural and psychological factors, such as dietary intake, health beliefs, depressive symptoms and self-efficacy, mediate the association between the intervention and outcomes.

-

Participation bias: to assess whether or not the RCT recruited those it intended, we assessed the participation bias by comparing the sociodemographic characteristics and QRISK2 scores of those who responded to the invitation to participate and those who did not.

-

Fidelity analysis: to assess whether or not MOVE IT was delivered in accordance with the manual and to compare whether or not the levels of competencies among the HLFs were associated with variations in outcomes using thematic contents analysis of sessions.

-

Participant and therapist experience: using qualitative methods, we describe the perceived expectations, benefits, strengths and limitations of the intervention from the patient and intervention provider perspective.

-

Chapter 3 Methods

The following material has been primarily reproduced from our published study protocol, Bayley et al. 70 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided he original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text. The revised protocol was published before recruitment ended. 70

Trial design

This was a three-arm parallel RCT for individuals at high risk of CVD. The three arms were (1) UC and enhanced MI in a group format, (2) UC and enhanced MI in an individual format and (3) UC. As participants in the group intervention arm, but not in the other two arms, were clustered within groups, this trial has a partially clustered (or nested) design. Interventions were delivered in 10 sessions across a period of 12 months. Participants were followed up at 12 and 24 months from baseline.

Ethics approval and research governance

The Dulwich Research Ethics Committee (REC) (reference number 12/LO/0917) granted ethics approval. The trial was registered with an International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN84864870).

Setting

The study was set in 12 South London CCGs (Bexley, Bromley, Croydon, Greenwich, Kingston, Lambeth, Lewisham, Merton, Richmond, Southwark, Sutton and Wandsworth) that are linked to each other by the South London Health Innovation and Education Cluster (SLHIEC) and inherent in this infrastructure is an efficient method for recruitment. South London has additional advantages: the population is approximately 3 million;71 nearly one-quarter of the population is African, Caribbean or South Asian; it spans the range of population densities, urbanisation and socioeconomic profiling; the development of a Health Innovation Network in South London can allow for rapid dissemination of research findings; and research resources can be shared across adjacent CCGs during periods of varying workload. General practices with list sizes of > 5000 patients were invited to take part, representing approximately 60% of all practices within the SLHIEC.

Eligibility criteria

The following eligibility criteria were used by general practitioners (GPs) during the initial search for eligible patients. In addition, exclusions were made following patient response to the invitation when the research assistant found that the patient did not meet the following criteria. When in any doubt, the opinion and approval of the patient’s GP was sought.

The inclusion criteria were:

-

being aged ≥ 40 years and ≤ 74 years

-

having a CVD risk score of ≥ 20.0%, calculated using QRISK2, a validated predictive tool for identifying the percentage risk of having a fatal or non-fatal cardiovascular event in the next 10 years72

-

being fluent in conversational English

-

being permanently resident and planning to stay in the UK at least three-quarters of a year.

The exclusion criteria were:

-

having established CVD (including congenital heart disease, angina, myocardial infarction, coronary revascularisation procedures, peripheral artery disease, coronary artery bypass graft or angioplasty)

-

having a pacemaker

-

being on a register for diabetes mellitus, kidney disease, atrial fibrillation or stroke (either ischaemic or haemorrhagic, including transient ischaemic attacks)

-

having chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

-

having a disabling neurological disorder

-

having a severe mental illness such as psychosis, a learning disability, dementia or cognitive impairment

-

being registered blind

-

being housebound or resident in a nursing home

-

being unable to move about independently or not being ambulatory

-

having more than three falls in the previous year

-

being pregnant

-

having advanced cancer

-

being morbidly obese [body mass index (BMI) of > 50 kg/m2]

-

currently participating in a weight-loss programme

-

living in the same household as another participant who was already randomised.

Sample size

The power calculation of our main outcome variables is based on the findings of previous research. 34,73 We selected a very conservative effect size of 0.25, expressed as the difference in units of pooled standard deviations (SDs), which translates to an ability to detect differences between two arms of 675 steps per day, 1.25 kg of weight and total cholesterol of 0.25 mmol/l. Our study was powered to detect changes that may be modest at the individual level but that would have an important impact if occurring at the population level. 74

We took into account clustering effect within the group intervention [intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.05] by calculating the optimal sample size in presence of differential clustering effects. 75 A sample size of 1420 participants in total was needed to detect these differences in our primary hypotheses, and a two-tailed alpha of 0.025 was used to take account of multiple comparisons for ‘individual versus UC’, ‘group versus UC’ and ‘group versus individual’. Assuming an approximate 17% loss to follow-up, a total sample size of 1704 was calculated.

Recruitment

Invitation procedure

Participating general practices screened primary care databases for eligible patients using either EMIS (EMIS Health, Leeds, UK) or Vision (In Practice Systems, London, UK) medical records systems, two of the clinical software programmes most commonly used in UK primary care. Patients who met the eligibility criteria were invited to participate via a standardised letter from their general practice, which was posted along with a participant information sheet. A prepaid return envelope was included for the return of a reply slip, for the patient to express interest to take part, to the main study centre. After the patient had given permission to be contacted, a research assistant made telephone contact with the patient to confirm that they met all eligibility criteria and to schedule a first appointment.

Consenting participants

As participants attended a first appointment with the research assistant, they were asked to read and complete a consent form. Participants were given the opportunity to ask any questions regarding the study or the consent statements.

Calculation of cardiovascular disease risk score

Once consented, data collection began with CVD risk screening; a summary is given in Table 1. High CVD risk was calculated using QRISK2, a validated predictive tool for identifying those at a ≥ 20.0% chance of having a fatal or non-fatal cardiovascular event over the next 10 years. 72 The measures required for the calculation of QRISK2 score are:

-

Age (years).

-

Sex.

-

Self-report ethnicity.

-

Postcode.

-

Smoking status – current (if current, how many cigarettes or equivalent per day), ex-smoker or non-smoker. We also collected the number of years smoking for current and ex-smokers.

-

Diabetes mellitus status (none, type 1 or type 2).

-

Rheumatoid arthritis status.

-

Chronic kidney disease status.

-

Atrial fibrillation status.

-

Hypertensive treatment status.

-

Family history of CVD (a first-degree relative diagnosed with angina or heart attack when < 60 years of age).

-

Height (cm) and weight (kg) were taken for a calculation of BMI (kg/m2).

-

Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) – the third of three measurements taken.

-

The ratio of HDL cholesterol (mmol/l) to total cholesterol (mmol/l).

| Data collection | Time point | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CVD risk screening | Baseline | Post baseline and pre randomisation | 12 months | Post 12 monthsa | 24 months | Post 24 monthsa | |

| Eligibility form | ✓ | ||||||

| Consent form | ✓ | ||||||

| Sociodemographic characteristics | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Changes to sociodemographic characteristics | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| 7-day accelerometer data returned | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Biomedical data | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Blood results analysed | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Record of past interventions | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| AUDIT | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Smoking status | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| PHQ-9 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| GPPAQ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| IPAQ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| BIPQ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Self-efficacy scale | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| EQ-5D | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| 24-hour dietary recall | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| CSRI | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Medication data | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| AE questionnaire | ✓ | ||||||

| Participant feedback questionnaire | ✓ | ||||||

Postcode data were collected for the calculation of Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) 2010 scores76 (based on lower-layer super output area). 77 The IMD incorporates seven domains: income deprivation, employment deprivation, health deprivation and disability, education deprivation, crime, barriers to housing and services and living environment.

Levels of LDL cholesterol (mmol/l), triglycerides (mmol/l), plasma glucose (mmol/l) and glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) (mmol/mol) were also taken at this time point, and patients with a HbA1c level of > 47 mmol/mol were subsequently excluded.

Baseline measures

If QRISK2 score was calculated as ≥ 20.0%, participants were subsequently invited to a second appointment for the collection of the following data prior to randomisation.

Sociodemographic data

These were age, sex, self-report ethnicity and family history of CVD collected for the QRISK2 calculation, occupational status, educational attainment, marital status, literacy [using the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM)78] and place of residence.

Biomedical data

These were weight, height, BMI, blood pressure, plasma glucose level, lipids and HbA1c level, which were collected for the QRISK2 calculation. Data collection included a full-body composition analysis and measurement of waist, hip and arm circumferences.

Weight and body composition were measured in light clothing without shoes on the Class 3 Tanita® SC-240 digital scale (Tanita, Amsterdam, the Netherlands) to 0.1 units for weight (kg), fat range (%), fat mass (kg), fat-free mass (kg), body water (kg), muscle mass (kg), bone mass (kg) and to the nearest 1 unit for visceral fat (level) and impedance (ohm) and basal metabolic rate (kcal). Height was measured to 0.1 cm using stadiometers with the supported stretch stature method and weight and height measurements were used to calculate BMI (kg/m2).

Waist circumference (cm) was measured horizontally halfway between the lowest rib and the upper prominence of the pelvis using a non-extensible steel tape against the bare abdomen. Hip circumference (cm) was measured at the widest part of the hip. Arm circumference (cm) was taken from the mid-upper arm, at the midpoint between the top of the shoulder and the point of the elbow. Two measurements were taken for each circumference, with a third taken if the first two measurements differed by > 0.5 cm.

Blood pressure (mmHg/mmHg) and resting heart rate (beats per minute) were measured with digital Omron blood pressure monitors [Omron Healthcare (UK) Ltd, Milton Keynes, UK) using standardised procedures of three readings taken 1 minute apart while seated.

Lifestyle data

These were smoking status collected for QRISK2 calculation, PA, alcohol intake and dietary intake.

Physical activity was measured objectively using the ActiGraph GT3X accelerometer (ActiGraph, Pensacola, FL, USA), a validated tri-axial movement sensor that also records step count. 79 The research assistant explained to the participant how to wear the accelerometer: on a belt over the hip for 7 days, from waking in the morning until going to bed at night and removing only for bathing. Participants were asked to keep a log of activities, including sedentary activity, to assist with the qualitative interpretation of the data. The output from the accelerometer includes number of steps taken and time spent doing PA using standard cut-off points for sedentary activity and light, moderate, vigorous and very vigorous PA. The research assistant ensured that, on the participant returning the accelerometer, it had been worn for ≥ 540 minutes on each of ≥ 5 days, and, if not, the participant was asked to wear the accelerometer for another 7 days. Step count per day and a measurement of PA at an at least moderate level [moderate to vigorous PA (MVPA)] in > 10-minute bouts were extracted from the collected data. Standardised vertical axis cut-off points for PA were used to classify sedentary (0–99 counts per minute), light (100–1951 counts per minute), moderate (1952–5724 counts per minute), vigorous (5725–9498 counts per minute) and very vigorous (≥ 9499 counts per minute) activity, with MVPA equating to ≥ 1952 counts per minute. 80 Self-report PA was also measured using the General Practice Physical Activity Questionnaire and the International Physical Activity Questionnaire81 at both the baseline appointment and after 1 week of accelerometer wear.

Alcohol intake was measured using the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT),82 which has a range of scores values from 0 to 40. Participants were categorised as abstainers (score 0), low-risk drinkers (score 1–7) or possibly harmful drinkers (score ≥ 8).

Dietary intake was assessed using a standardised multiple-pass 24-hour dietary recall, which provides a more objective and reliable measure of change in intervention studies, at both the baseline appointment with the research assistant and independently after 1 week of accelerometer wear. Research assistants were trained to follow a standardised protocol and ask neutral probing questions to encourage recall of food items, and were taught about different methods of food preparations and brands in different cultures. Portion size was assessed using food photographs to estimate daily calorie intake. 83,84 Dietplan7 software (Forestfield Software Ltd, Horsham, UK) was used for coding the 24-hour recall diaries and deriving nutrient intake. For food not listed in the software’s database, we created new food codes and inputted the available nutritional information. If nutritional information was unavailable for an unlisted type of food, we selected the most similar type of food already in the database.

Psychological data

These included depressive symptoms, health beliefs and health state. Depressive symptoms were collected using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 items (PHQ-9),85 as depression is associated with worse outcomes in CVD. 86 Each of the nine items are scored from 0 to 3 depending on frequency of occurrence of symptoms, for a score in the range of 0–27. One or two missing items can be substituted with the average score of non-missing items. When there are more than two missing values, the questionnaire is not scored. The questionnaire is followed by a functioning question, and the questionnaire results are provided to the patient’s GP.

The Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire was adapted to be used for ‘high risk of CVD’ rather than for an illness. 87 The questionnaire asks the participant to rate their beliefs of the causes of their high risk of CVD and how being at high risk affects them. A total score is calculated by summing together all items, with items 3, 4 and 7 reverse-scored, a higher score reflecting a more serious view of the high risk of CVD.

We also used a validated self-efficacy questionnaire for exercise,88 and adapted this to assess self-efficacy in keeping to a healthy diet as well as psychological processes we were seeking to change through the intervention. Average scores for both exercise and diet self-efficacy were calculated by summing together the score of each answered item and dividing by the number of items answered.

The EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) was used to measure the health state of the participant on the dimensions of mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain or discomfort and anxiety or depression using three levels: no problems, some problems or extreme problems. 89 Participants are asked to rate their current health state within the 0–100 range.

Health-care usage data

Health-care usage was assessed using the Client Service Receipt Inventory (CSRI),90 which included usage of hospital services, community-based services and support received from friends or relatives for any health reasons for the 12-month period leading up to the appointment. Data on current prescription medication were also collected from medical records.

Randomisation and allocation concealment

Simple randomisation was used, with general practice included as a random factor in the model and emphasis being on more practices and fewer patients per practice. Randomisation of participants was conducted by the data manager from an independent clinical trials unit (King’s College London) using computer-generated randomisation blocks with block sizes of 10. In each block, 10 participants were randomised to the group intervention arm, the individual intervention arm or the UC arm in a 4 : 3 : 3 ratio. The unequal allocation ratio ensured that the group intervention arm had approximately 33% more participants, allowing the group sessions to run with enough participants.

As this is a complex psychological intervention, it was not possible to conceal the allocation to the participants or the HLFs post randomisation. Research assistants, statisticians and technicians were blind to the allocation. Participants were reminded in advance of and during the follow-up appointments not to reveal their allocation.

Outcome measures

At the 12- and 24-month follow-up assessments, participants were asked if there had been any change to their sociodemographic status, such as accommodation, relationship status and educational attainment. AE and participant feedback questionnaires were administered. All other baseline measures were repeated at the 12- and 24-month follow-ups (see Table 1).

Trial arms and intervention details

Arm 1: usual care and enhanced motivational interviewing in a group format

Theoretical framework

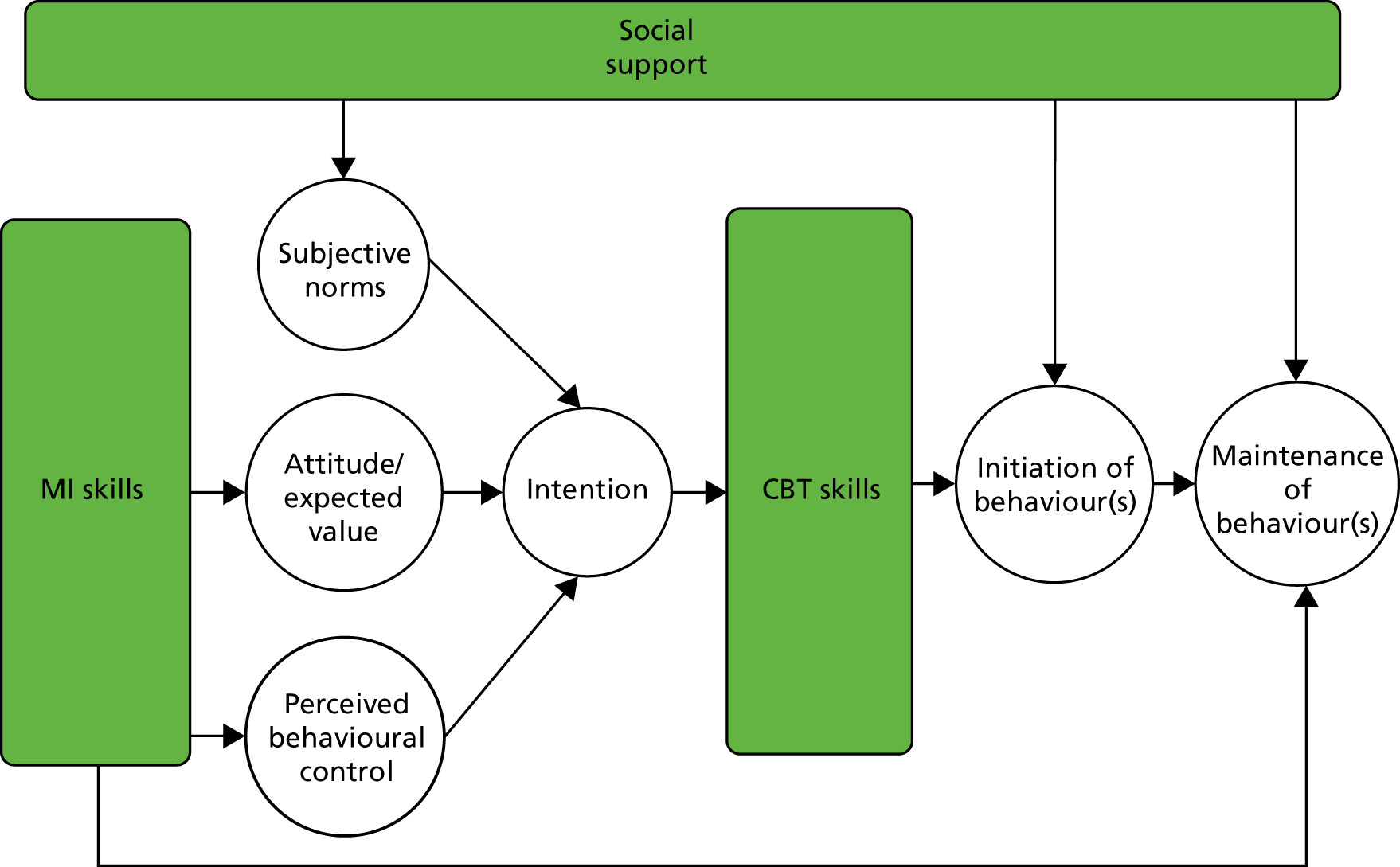

The intervention is based on the theory of planned behaviour for initiation of behaviour change: to change behaviour, people need to form an intention. 53 Intention formation is influenced by three constructs: (1) expected value or positive attitude (people see the value in making the change), (2) subjective norm (significant others and peers also value the change) and (3) self-efficacy (people believe that they are capable of making the change).

Our intervention taps into all three constructs using principles and techniques from MI,41 CBT91 and social cognitive theory92 (Figure 1). MI is used to support participants in forming healthy intentions. MI is a collaborative conversation style for strengthening a person’s own motivation for, belief in and commitment to change. Hobbis and Sutton91 highlight the gap between translating intention into action and illustrate how CBT can be applied to bridge this gap. For this intervention, techniques from CBT are used to support the transition from intention to action, and action to maintenance. 93 Identifying and challenging unhelpful thoughts or thinking styles can promote more positive emotions and behaviours, for example ‘When I get breathless after some exercise (bodily sensation), this means that I am going to damage my heart (incorrect cognition)’ or ‘I have eaten one doughnut (behaviour), I might as well eat the whole bag (all or nothing cognition)’.

FIGURE 1.

Theoretical framework and intervention map. White background indicates psychological process; green background indicates behaviour change technique.

Social cognitive theory emphasises the importance of significant others in shaping people’s behaviours. The theory of planned behaviour also highlights this aspect through the ‘subjective norm’ construct. In our intervention, social networks from the participants’ own lives and/or group members (in the group intervention arm) were actively utilised to provide practical and emotional support and opportunities for modelling health behaviours during all phases of the intervention.

Intervention development

We conducted a scoping study to identify manuals published in English in the previous 5 years to improve diet and/or PA in the peer-reviewed and grey literature. The aim was to map the quality, contents and cultural diversity of these manuals to inform the content of our intervention. The clinical psychologist (CP) devised the intervention based on this synthesis and on our expertise in developing lifestyle interventions. We used an iterative process to draft the manual and refine it over 2–3 cycles. There are two manualised outputs from the trial:

-

An intervention curriculum. This provides an outline of each intervention session, including key learning points, interactive activities and action planning.

-

A participant workbook. This includes key learning points from each session, action planning worksheets, case studies and a self-monitoring diary for each participant.

The participants also received a pedometer, with guidance on how to use it effectively, and access to online, DVD (digital versatile disc) and paper resources on CVD risk.

The programme consisted of 10 sessions, plus an introductory telephone session, spread over 12 months. The outline of each session is given in Table 2. Each participant allocated to a treatment arm had a ‘session 0’ telephone call as an introduction to the intervention, to receive their intervention packs and to become familiar with the HLF. The intensive phase consisted of six weekly sessions at the beginning of the first quarter. The first three sessions focused on PA and the second three sessions focused on diet. The maintenance phase consisted of four sessions delivered at 3, 6, 9 and 12 months after intervention commencement.

| Session (time from intervention commencement) | Content |

|---|---|

| Intensive phase | |

| Session 0 |

Focus: introduce the intervention Examples of delivery: structure of the programme, ice breaker, rapport building with HLF, give out pedometers and baseline measures |

| Session 1: PA (week 1) |

Focus: increasing routine activity Examples of delivery: elicit views regarding walking more and sitting less and instruction on use of pedometer. Support individual goal-setting |

| Session 2: PA (week 2) |

Focus: increasing non-routine activity Examples of delivery: elicit views on recommended activity levels and reflect on previously enjoyed exercise and its benefits. Provide information/demonstration/leaflets regarding local exercise options. Support individual goal-setting |

| Session 3: PA (week 3) |

Focus: to maintain PA changes Examples of delivery: elicit views regarding lapse vs. relapse using case studies. Discuss lapse triggers and strategies to manage them. Support individual relapse-prevention plans (including implementation intentions) |

| Session 4: diet (week 4) |

Focus: increasing health food choices Examples of delivery: elicit views on healthy eating principles. Interactive games regarding healthy snacks. Support individual goal-setting |

| Session 5: diet (week 5) |

Focus: decreasing unhealthy food choices Examples of delivery: elicit views on foods to avoid in excess. Interactive games regarding food labelling and high-fat and high-salt foods. Support individual goal-setting |

| Session 6: diet (week 6) |

Focus: to maintain dietary changes Examples of delivery: elicit views regarding lapse vs. relapse using case studies. Discuss lapse triggers and strategies to manage them. Support individual relapse-prevention plans (including implementation intentions) |

| Maintenance phase | |

| Session 7 (3 months) |

Focus: review progress and problem-solve setbacks Examples of delivery: highlight positive changes in review session, discuss setbacks and potential ways forward. Support individual relapse-prevention plans |

| Session 8 (6 months) |

Focus: review progress and problem-solve setbacks Examples of delivery: highlight positive changes in review session, discuss setbacks and potential ways forward. Support individual relapse-prevention plans |

| Session 9 (9 months) |

Focus: review progress and problem-solve setbacks Examples of delivery: highlight positive changes in review session, discuss setbacks and potential ways forward. Support individual relapse-prevention plans |

| Session 10 (12 months) |

Focus: review progress and problem-solve setbacks Examples of delivery: highlight positive changes in review session, discuss setbacks and potential ways forward. Support individual relapse-prevention plans |

Those randomised to the group intervention arm were encouraged to use peer learning and the peer support environment to facilitate change during both the intensive phase and the maintenance phase. Each group had a maximum of 11 participants and sessions lasted for 120 minutes. The intervention was delivered in local venues, such as community halls and health centres. Between sessions and during follow-up, participants were encouraged to communicate with each other and the HLF. Novel methods and teaching aids were used to supplement the delivery of BCTs, such as visual aids (food labels)/cue cards, exercise demonstrations, video/audio material of patient testimonials, activity-based learning around meal planning, and text/e-mail reminders. HLFs were expected to offer sessions between 08.00 and 21.00, enabling flexibility for participants in full-time work or with carer roles. Cultural and religious awareness was built in to the intervention.

For ease of translation, the key components of the programme have been defined in accordance with Abraham and Michie’s BCT taxonomy:54

-

provide information on consequences

-

prompt intention formation

-

prompt barrier identification

-

prompt specific goal-setting

-

prompt review of behavioural goals

-

prompt self-monitoring of behaviour

-

teach to use prompts or cues

-

agree on behavioural contract

-

use follow-up prompts

-

plan social support or social change

-

relapse prevention

-

MI.

Training the healthy lifestyle facilitators

The HLFs were employed at NHS band 3 level by King’s College Hospital and seconded as appropriate to the CCG. The training programme lasted for 8 weeks and involved a standardised package of training materials. The teaching was a combination of didactic learning, role playing and feedback, group exercises, reading and case study discussion. The HLFs used rating scales for self-monitoring of skill progression during role playing.

Each HLF’s competency was assessed at the end of training via a knowledge test and through observing delivery of two sessions (one intensive, one maintenance). Four domains were assessed: MI, BCTs, group skills and time management, utilising relevant coding frameworks (see Appendix 1). The competency thresholds were adapted for the study,94–96 requiring each HLF to demonstrate ‘moderate proficiency’ in each of the domains before delivering the intervention, meaning that they delivered 70% of BCTs, were 90% MI-adherent and scored in the moderate range in at least two of the other Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity (MITI)97 categories, in at least three of the group skills categories and in time management. HLFs that were not competent on initial assessment received further training and reassessment to reach the required competency level.

Healthy lifestyle facilitator competency was monitored throughout the intervention by the CP, who facilitated fortnightly group supervision and weekly e-mail supervision (based on the HLFs completing reflective practice logs). The CP also conducted quality assurance of the intervention administration by regularly reviewing audiotaped sessions (one individual session per month and two group sessions every 8 months) and providing feedback, as needed.

Arm 2: usual care and enhanced motivational interviewing in an individual format

This had the same components as the group intervention arm but was delivered individually (i.e. one to one). There was no opportunity/expectation/guidance for participants to form groups with each other between sessions. The number, content and spread of sessions was the same and sessions lasted for 40 minutes; we reduced the duration of each session to approximately control for attention in the two treatment arms.

Arm 3: usual care only

General practitioners participating in the study were expected to follow their local Health Check pathway for those patients who had a CVD risk score of ≥ 20.0%.

Clinical effectiveness

Primary outcomes

The primary outcomes were change in weight (kg) and PA (average number of steps per day) between arms.

Secondary outcomes

Changes in LDL cholesterol and CVD risk score were assessed. The QRISK2 measurement of CVD risk is sensitive to changes in weight, cholesterol level, blood pressure, HbA1c level and smoking status. The number of fatal and non-fatal CVD events and hospital admissions were recorded using an AE questionnaire and by recording hospital services usage using the CSRI. Changes in dietary habits were measured via analysis of dietary recall data. Health beliefs and depression at 12 and 24 months were assessed as measures of mediating processes.

Cost-effectiveness

The main perspective for the economic evaluation is that of the health-care system. The EuroQol-5 Dimensions, three-level version (EQ-5D-3L) is used to generate QALYs for use in economic analyses. 98 Intervention costs were calculated taking into account staff time for delivering the sessions and the unit costs include elements for overheads and oncosts and account for the ratio of direct-to-indirect contact time. We assumed that the clinician would be grade 3 and that the unit cost per hour was £32.40. For the group intervention, the costs are apportioned over the number of attendees, which averaged 5.5. Other service use was measured at baseline, 12 months and 24 months using the CSRI. EQ-5D instruments were developed in the 1980s and have been subsequently adapted for use in around 500 studies. Service costs were calculated by combining service use data with information on unit costs. 99,100 We had originally planned to explore the cost of lost employment. However, these data were not adequately recorded and so this was omitted.

Process evaluation

The overall aim of the qualitative analysis is to identify and describe factors and processes that affect the delivery, receipt and outcome of the study to aid interpretation and translation of the observed findings. Process data are analysed before outcome data wherever possible to reduce bias in interpretation. The main themes are described in the following sections.

Participation bias

The extent to which the intervention reached out to eligible participants is assessed by (1) the makeup of general practices that agreed and declined to participate, (2) participation biases and (3) attrition biases. We also invited participants who did not complete the intervention to attend a focus group to give feedback on the programme.

Fidelity analysis

We measured adherence and competence of the trained HLF team in delivering the manualised intervention. See Chapter 8 for a full description.

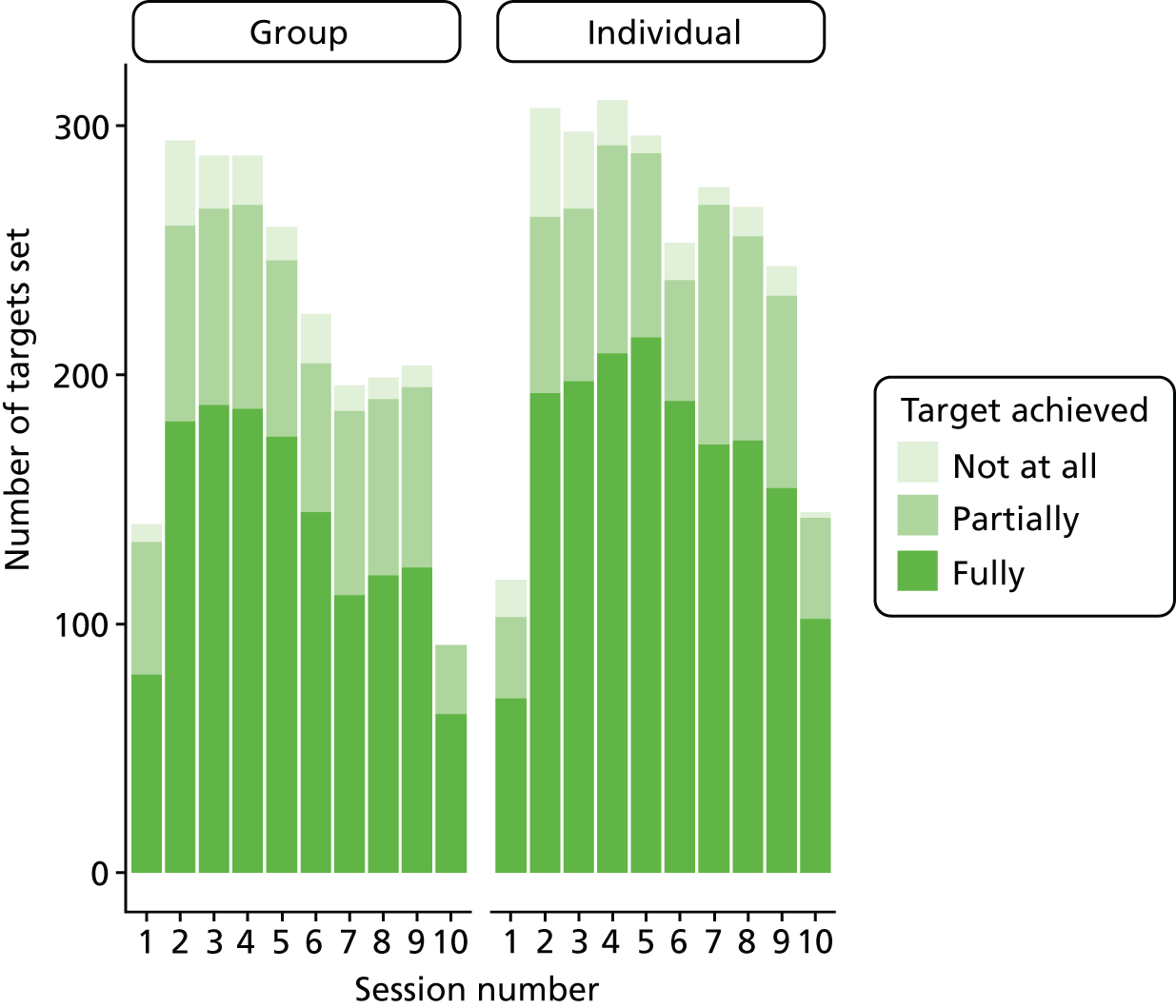

Processes of change

The HLFs would record if targets were met (not at all, partially or fully) at the beginning of each session as a measure of participant adherence to the intervention. Supervision and interviews with the HLFs were used to assess which BCTs were popular, why and for which lifestyle behaviour. We administered a process questionnaire at the end of the study that required all randomised participants to discuss, in open-ended and standardised structured questions, which techniques they had found most useful, their appraisal of the techniques and their level of satisfaction with the interventions of their allocated arms. We included the UC arm to assess the similarity and differences with the intervention arms as there may have been some overlap. In addition to the questionnaire, we conducted focus groups with a small number of participants to elicit more detailed feedback (see Chapter 4).

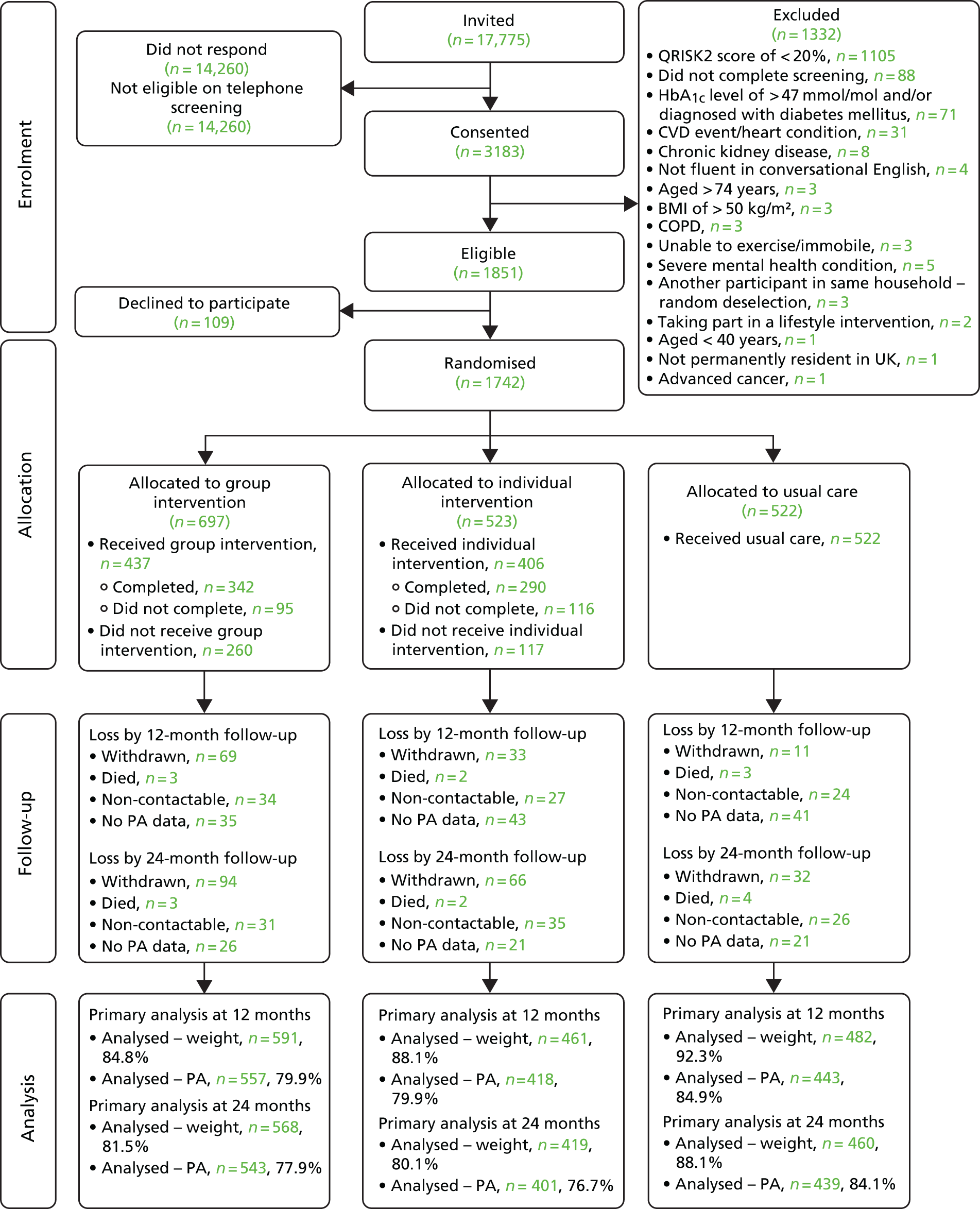

Statistical analysis

Analysis and reporting is aligned with Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines,101 with primary analyses being on an intention-to-treat (ITT) basis. A description of the sample will be presented using mean (SD) or count (percentage). The baseline characteristics of those who withdrew and those who did not complete the intervention are compared with those of participants who completed follow-up. Descriptive data also include maximum values, minimum values, medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) when appropriate. Significance is reported to a two-tailed alpha level of 0.05 as appropriate for comparisons.

The differences in treatment effect between the three arms at 12 and 24 months of this partially nested design are analysed using mixed-effects models, with pre-randomisation values as a covariate. 102 In the linear mixed model, ‘treatment arm’, ‘time’ (as a categorical variable with two levels: 12 and 24 months), the ‘interaction between treatment group and time’, ‘borough’, ‘ethnicity’ and the ‘baseline values’ of the outcome variable are the fixed part of the model. The random parts of the models are ‘general practice’ (participants are nested in practices) and ‘therapy group’. The design of the study is complex because we have a partially clustered cross-classified design. In the previous version of the analysis plan, we planned to account for the partially nested design of ‘therapy group’ in an approach that matches the non-parallel data structure. 103 However, preliminary analyses with blinded data revealed that this complex model of a partially nested, cross-classified design did not converge. Thus, in agreement with the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC) (on 6 July 2017), we decided to drop the random effect for therapist from the primary analyses. We are aware that we may underestimate standard errors of treatment effects; however, health intervention therapist effects in similar studies [e.g. the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR)-funded IMPACT104 and Diabetes-6105 RCTs] ranged between negligible and small (ICC range 0 to 0.02).

The dependency of the repeated observations of the same participants at 12 and 24 months and the covariance between the residuals within the lowest-level group ‘patients’ are correlated by using an unstructured covariance pattern model. For the final model, the group difference estimates and associated confidence intervals (CIs) are reported for 12 (for secondary analyses) and 24 months after randomisation.

In a sensitivity analysis, the random effect of borough was replaced by a partially nested random effect for therapist group, as described previously, and results compared.

The described analysis approach provides valid inferences under the assumption that the missing data mechanism can be ignored (missing at random). Sensitivity of results to missing data was further assessed by including covariates predictive of missingness in the analyses model.

The significance level was 2.5% (two-sided) for the two main comparisons of (1) group format versus UC and (2) individual format versus UC. The (secondary) comparison (group format vs. individual format) was assessed on a 5% significance level as our research hypotheses is a null hypothesis of no difference.

The large sample size should have ensured that all possible confounding variables are equally distributed between treatment arms. However, in the sensitivity analysis, we extended the model of the primary analysis by including baseline variables with substantial imbalance, thought to be important in determining outcome. The potential baseline variables were age, sex, IMD, education, marital status and smoking status.

The following further sensitivity analyses were conducted and, for all analyses, changes in predicted treatment outcome differences are presented in the analysis plan – available on the project webpage [see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/106203/#/ (accessed 29 April 2019)].

Sensitivity analysis adjusting for delay in intervention start

Participants allocated to the intervention arms began intervention sessions at different time points relative to randomisation. Therefore, we conducted a sensitivity analysis to include time between randomisation and session 0 of the intervention in the model.

Sensitivity analysis adjusting for unblinding of research assistants at follow-up

Every effort was made to avoid participants revealing their treatment allocation to the research assistant at follow-up. Research assistants recorded whether or not they were unblinded to treatment allocation at either the 12- or the 24-month follow-up. We conducted a sensitivity analysis to include unblinding (yes/no) at follow-up time into the model.

Sensitivity analysis adjusting for insufficient accelerometer wear at baseline

We conducted a sensitivity analysis to include the number of valid days (≥ 540 minutes) of accelerometer wear at baseline in the model.

Sensitivity analysis adjusting for insufficient accelerometer wear at follow-up

We conducted a sensitivity analysis to include the number of valid days (≥ 540 minutes) of accelerometer wear at 12 and 24 months in the model.

Sensitivity analysis adjusting for the recruitment of participants with a body mass index of < 25 kg/m2

Although BMI was not included in the eligibility criteria, an aim of the study was to assess reduction in weight, which would be inappropriate for participants who were of healthy weight or underweight at baseline. We conducted a sensitivity analysis to include a BMI of < 25 kg/m2 (yes/no) at baseline in the model.

Sensitivity analysis adjusting for the recruitment of participants with a QRISK2 score of < 20.0%

We conducted a sensitivity analysis to include a QRISK2 score of ≥ 20.0% (yes/no) at baseline in the model.

Dietary intake analysis

When available, the dietary recall diary from the appointment (or, if missing, the later diary) was used. Owing to resource constraints, we a priori elected to analyse a random sample of 602 participants who had a recall diary available for each time point (baseline and 12- and 24-month follow-ups). The random selection of the 602 participants approximately followed the treatment allocation ratio used for the study (4 : 3 : 3). Thus, the arm sizes for the group, individual and UC arms were 240, 180 and 182, respectively.

Food quantities and nutrient intake were checked for outliers, indicating possible data entry errors. Eight nutrients (water, protein, fat, carbohydrates, total sugar, fibre, saturated fat and sodium) and total energy intake (kcal) were selected as variables of interest. These variables were selected based on their relevance to the intervention (i.e. its emphasis on reducing fat/sugar/salt intake and increasing water/fibre intake).

Dietary intake data are summarised at each time point using means (SDs). A linear mixed-effects model, accounting for the partially nested design, tested if there were any effects of treatment arm and time or their interaction on nutrient intake. The model controlled for participant age, sex, ethnicity, IMD 2010 baseline score76 and if the day recalled was Saturday/Sunday (binary yes/no variable).

A series of mediation analyses were conducted to test if dietary intake measured at the 12-month follow-up mediated the effect of the intervention on the primary outcomes (weight and PA) or QRISK2 score at the 24-month follow-up. Owing to the limitations of the software used – R version 3.4.2 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) and the mediation package [URL: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/mediation/mediation.pdf (accessed 29 April 2019)] – each mediation analysis was constrained to testing differences between two of the treatment arms. Thus, a total of 81 mediation analyses were run [three outcomes × nine diet variables × three treatment arm comparisons (UC vs. group, UC vs. individual, group vs. individual)]. The mediation models controlled for participant age, sex, ethnicity, IMD 2010 baseline score,76 if the day recalled was Saturday/Sunday (binary yes/no variable), baseline diet and baseline value for the respective outcome.

Although many statistical tests were carried out for the dietary intake analysis, these tests were largely exploratory. Therefore, a two-tailed alpha level of 0.01 was used to determine statistical significance. For the linear mixed-effects models, the fixed-effect estimates for the effects of time and treatment arm and their interaction were bootstrapped with 1000 replicates and their 95% CIs calculated.

Cost-effectiveness analysis

Health-care costs are compared between the two treatment arms and UC. Given that the data are likely to be skewed, we use bootstrapping methods to estimate 95% CIs around the mean cost differences. QALYs are calculated from the EQ-5D-3L administered at baseline, 12 months and 24 months. Area under the curve methods allow us to calculate the QALY gain over the entire follow-up period and QALY differences are analysed controlling for baseline EQ-5D-3L score in a regression model. If costs were higher for one arm than for another and QALY gains are greater, we then constructed an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) to show the cost per extra QALY gained. There will be uncertainty around cost and QALY estimates and this is explored using cost-effectiveness planes generated from 1000 bootstrapped resamples of the data for each of the comparisons. Bootstrapping was carried out using the bsample routine in Stata® Version 15 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA), with the strata option used so resampling was by arm. Separate regressions of costs and QALYs were performed on each bootstrapped sample and results retrieved and plotted on the plane. Finally, we generated cost-effectiveness acceptability curves, using the net-benefit approach and bootstrapping, to indicate the probability that any of the three approaches is the most cost-effective for different values placed on a QALY gain. The range of values used is £0 to £100,000. This includes the threshold that is used by the NICE: £20,000–30,000. Sensitivity analyses are carried out around key costs, particularly those for the interventions themselves. We did not impute for missing values and a complete-case analysis was instead conducted.

Ethics issues

The trial was reviewed by the Dulwich REC and has been approved (reference 12/LO/0917). The TSC provided overall trial supervision, supported by the DMEC. The main ethics consideration was to ensure that the risk of harm to participants was minimised and that they were fully informed of any risks. We considered literacy and cultural sensitivities in obtaining informed consent. Other ethics considerations were in ensuring that recruitment and informed consent were handled in such a way that potential participants were not put under pressure to take part and that confidentiality was preserved. All participant data are stored using a unique study identifier and electronic data are password protected.

In general, regular PA is associated with improved health outcomes and this outweighs the risk of sedentary lifestyles. However, sudden increases in vigorous PA for otherwise sedentary individuals is associated with a higher risk of myocardial infarction and of musculoskeletal injuries, which may be pertinent as we were intervening in a group that is at high risk of CVD. However, one of the components of BCTs is to deliver the message that PA should be increased in a graded manner rather than suddenly. The intervention discouraged excessive and/or sudden changes to lifestyles. Weight loss could worsen frailty by accelerating the usual age-related loss of muscle that leads to sarcopenia, but combining weight loss with increased PA can actually ameliorate frailty. 106 Importantly, our intervention is based on healthier diets and gradual and sustainable weight loss as opposed to commercial weight-loss programmes. We considered risks to be small and minimal owing to the exclusion of patients with existing CVD and the use of GP advice when CVD events occurred during participation.

Adverse events

An AE, which may be classed as serious, was defined as any untoward occurrence during the study that should be reported to the REC and TSC within an agreed time frame. A suspected unexpected serious AE was defined as an untoward occurrence that is related to the intervention and is unexpected. Participants had the opportunity to report AEs at 12-month and 24-month study appointments with the research assistant as an AE questionnaire was administered, and participants receiving the intervention were able to report at any time during the intervention period to the HLF. All serious AEs and laboratory values were reviewed by the principal investigator (PI) and a co-investigator, and the PI was responsible for determining causality and reporting any AE related to the study to the REC using the National Research Ethics Service guidance.

The AE questionnaire included asking specifically about physical injuries, which were coded as one of the following types of injury: (1) dislocation, (2) fracture, (3) sprain/strain, (4) other injury to a muscle/tendon or (5) other. Details were also collected of how the injury occurred (context, e.g. if the participant fell) and whether or not any treatment was administered. Cardiovascular events were similarly coded, with the following categories used: (1) angina, (2) atrial fibrillation, (3) coronary heart disease, (4) coronary bypass, (5) myocardial infarction, (6) stroke or transient ischaemic attack, or (7) other. Details were also added and verified by checking the participant’s medical records, as necessary.

Obtaining informed consent

General practice staff conducted the searches using our guidance and invited potential participants to give permission for research assistants to contact them. Research assistants invited potential participants to meet them in the general practice, and they were given verbal and written information about the study and at least 1 week to think about participating. We invited patients who were eligible but declined participation to give informed consent for the collection of baseline data to assess the generalisability of our findings.

Withdrawal and stopping rules

Participants were free to withdraw from the study at any time. If the participant withdrew from the intervention, they were asked if they were happy to attend follow-up study appointments and for further data to be collected. If they withdrew from the study without consent to follow-up, no further data were collected.

There were no formal stopping rules. This is because the intervention did not ask participants to do anything more than follow usual GP advice regarding diet and PA. However, the PI evaluated the causality of any AE and advised withdrawal if necessary.

Time period for retention of trial documentation

Copies of patient consent forms were kept for 12 months after the study ended. Personal data that are identifiable by patient name or address will be destroyed 3 years after the study ended. Other trial records will be archived for 7 years after the trial ended before being destroyed.

Patient and public involvement

Before the trial began, we held a focus group with 10 patients from a general practice in Peckham, London. All patients were of African, Caribbean or South Asian ethnicity, first generation migrants and at high risk of CVD, and were distributed equally between sexes. The group understood the rationale of the MOVE IT trial. They recognised that daily stressors affect lifestyle choices and welcomed the chance to talk about this and think differently. The preference was for interventions in an individual format, but they could see the potential benefits of learning from others in a group. Flexible appointment times were stressed as being important, so that the intervention could fit around other activities. The patients felt that it was necessary to provide more information about individual health status rather than just telling patients that they are at high risk of heart disease. They also gave tips on how to recruit; they thought that by getting some patients on board, these patients could network in the local community. These comments were incorporated into the intervention.

We invited this group of patients to form a patient and public involvement (PPI) group to help with the development of study documentation, including the patient information sheet and consent form. A PPI group of five patients was formed, and two members remained involved until the end of the trial. Their role during recruitment involved advertising the trial to both general practices and potential participants, advising on the development of poster and leaflet campaigns to increase public awareness and actively recruiting general practice sites across four of the CCGs. As part of the process evaluation, we sought PPI in the development of topic guides to be used in focus groups to gain feedback from participants who attended the intervention.

Throughout the trial, the trial team updated PPI members with progress and welcomed feedback. The PPI members attended all TSC meetings throughout the trial to gain more detailed feedback and discuss points of interest with the trial manager, PI and co-investigators.

Chapter 4 Protocol changes

It was necessary to make amendments to the original protocol for a number of unforeseen reasons and to enable improvement in our study methodology and the collected data.

Low uptake of NHS Health Checks

In parallel to setting up MOVE IT, there were increasing numbers of reports and concerns that there was a lower-than-anticipated uptake of NHS Health Checks,12 with regional variations in attendance ranging from 27% to 52% and greater uptake among older patients and in regions of lower deprivation. 13 We also observed this when we started recruiting and that this was delaying the project.

It was necessary to amend the protocol to detail that the researcher would repeat all CVD risk algorithm measures at screening. General practice searches for eligible participants could therefore not rely on recent Health Check data but instead on estimates of CVD risk using outdated data or inaccurate substitutions for missing data.

This change to the protocol led to the exclusion of a large number of patients whose medical record data suggested that they were at a ≥ 20.0% QRISK2 score but on screening were found to have a score of < 20.0% (see Chapter 5). Consequently, more resources were required to complete recruitment to target (substantial amendment; approved in July 2013).

Change to recruitment and study time frame

As research assistants were screening a larger proportion of ineligible patients who could not be randomised, the recruitment period had to be extended from 12 months to 21 months to allow the target sample size to be reached. This required an increase in funding to support a greater number of research assistants and for a longer period of time to support the recruitment procedures at a greater number of research sites. As a result, the end-of-study follow-ups were also extended by a further 9 months (minor amendment; approved on 16 March 2015).

Research sites

We initially invited general practice sites with list sizes of > 8000 patients. We extended invitations to smaller practices with > 5000 patients, as we required an increase in the number of sites owing to the high number of responses from ineligible patients (substantial amendment; approved in July 2013).

Randomisation

Randomisation was not stratified by general practice and ethnicity as planned, as the numbers of patients in many practices are not large enough to stratify by both factors. Simple randomisation was agreed to be the best method, with surgery included as a random factor in the model, and emphasis being on more practices and fewer patients per practice (substantial amendment; approved in July 2013).

Research measures

Three blood pressure measures were taken. The third, rather than the mean, systolic blood pressure is used in the QRISK2 algorithm and will be reported in this final report (substantial amendment; approved on 9 June 2015).

Intervention details

The proposed health trainer job title was changed to HLF to better incorporate the MI aspect of the intervention whereby the participant was ‘facilitated’ rather than ‘trained’ to make healthy lifestyle changes.

We revised the definition and description of MI to that used in the third edition of the MI textbook. 42 The intervention was updated to include a session 0, which was an introductory session via telephone. The length of group intervention sessions was increased to 120 minutes, rather than 90 minutes, to better match for attention with the individual intervention sessions (substantial amendment; approved in July 2013).

Further to the above changes, we changed the protocol to state that participants would be seen for intervention sessions within 6 months from randomisation, as this time period was not initially stated and the start of intervention sessions was presumed to be immediate. The time period varied greatly owing to (1) large numbers of participants randomised and waiting to be seen, as a result of the accelerated recruitment rate to meet the target, and (2) HLF staff turnover and the subsequent recruitment and training of new staff members, which created delays. When this time period was exceeded, we made every effort to still engage participants in the intervention and continued to follow-up for the ITT analysis (substantial amendment; approved on 9 June 2015).

Additional consent procedures

Participants were given the opportunity to consent to the following additional items post randomisation:

-

Once participants had completed all research measures, they were asked if we could link their data to other collaborating research studies in which they also participated (substantial amendment; approved on 21 September 2015).

-

We requested access to Hospital Episodes Statistics data,107 information on all hospital appointments for up to a 6-year period beginning 12 months before participating in the study. However, as this was requested after participants completed the study, we did not gain consent from all participants for this and thus did not seek the Hospital Episodes Statistics data and used only CSRI information on hospital services usage (substantial amendment; approved on 21 September 2015). We requested that participants provided consent to these points remotely, via a letter to and a telephone call with the participant, to avoid unnecessary appointment scheduling (minor amendment; approved on 13 January 2016).

-

A small number of participants who received the intervention (group or individual) were randomly selected to be invited to a focus group to provide feedback. They were asked to provide written informed consent to take part in an audiotaped focus group (substantial amendment; approved on 7 March 2016).

-