Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 07/44/03. The contractual start date was in April 2010. The draft report began editorial review in October 2018 and was accepted for publication in April 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Elaine McColl was a member of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Journals Library Editorial Group from 2013 to 2016; her employer was remunerated for her work in this regard. Luke Vale was a member of the NIHR Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Clinical Trials Board for a period of time between the years 2014 and 2018. Nicola PT Innes received a grant from The 3M Company (Maplewood, MN, USA)/ESPE to support a Clinical Fellowship in 2000; the work investigated the Hall Technique, which forms an aspect of one arm of the randomised controlled trial reported in this work. The results of the trial were reported independently.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Maguire et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Scientific background

Dental caries (decay) is the most common disease of childhood, and carries a large health and economic impact for the UK. 1–4 Treating oral disease is expensive, costing NHS England £3.4B annually. 5 Extraction of decayed primary teeth alone, carried out under general anaesthesia, costs an estimated £36M annually.

In the UK, the majority of dental care for children takes place in primary care and is carried out by general dental practitioners (GDPs) rather than by specialists. GDPs’ remuneration under the general dental service (GDS) funding system varies depending on the nation. In Scotland, a capitation and fee per item of service system operates, whereas in England and Wales, GDPs claim ‘units of dental activity’ (UDAs) to treat dental patients. Against this background, there is a long-standing debate about the best way of managing decay in children’s primary teeth.

In 2002, the results of two studies6,7 questioned the success of conventional restorative interventions [placing local anaesthesia (injections), removal of carious lesions (decay) and placement of a restoration (filling)] carried out in UK primary dental care practices in preventing pain and infection in children with decayed primary teeth. This apparent lack of effective management has caused considerable uncertainty for the dental profession and for patients and parents. There is universal agreement that guidance for the effective practice-based prevention and management of dental caries is needed, with that evidence drawn from primary dental care. This prompted the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) panel to commission the research that resulted in the Filling Children's Teeth: Indicated Or Not? (FiCTION) trial, a three-arm participant-randomised controlled trial (RCT) investigating three approaches to dental care for children with carious lesions in their primary teeth:

-

Conventional treatment with best-practice prevention (C+P) arm. Based on what has been considered standard practice for the management of carious lesions for > 50 years, this comprises the use of local anaesthetic, complete removal of carious tissue using rotary instruments and placing a restoration.

-

Biological treatment with best-practice prevention (B+P) arm. Sealing-in carious lesions is a minimally invasive approach, based on recent understanding that carious tooth tissue does not need to be completely removed to stop disease progression, and uses a variety of sealing techniques, including restorative materials or crowns, to seal the carious lesion and prevent progression.

-

Best-practice prevention alone (PA) arm. Avoiding restorative intervention, the four ‘pillars’ or components of prevention are promoted to arrest existing carious lesions and prevent any more from developing: (1) reducing frequency of sugars intake, (2) effective twice-daily brushing with fluoridated toothpaste (steps 1 and 2 involve behaviour change by the parents/guardians and children to reduce the cariogenic challenge), (3) application of topical fluoride varnishes and (4) placement of fissure sealants on first permanent molar (FPM) teeth.

Dental caries (decay) experiences of children (globally and in the UK)

Dental caries remains an important public health problem globally,8 recognised by the World Health Organization as a disease that affects 60–90% of school children and the vast majority of adults, contributing to extensive loss of natural teeth in older people. 9,10

The social gradient in health inequity means that the poorest have the worst health,11 and there is strong evidence relating oral health (especially dental caries) and socioeconomic status; children in lower socioeconomic groups are disproportionately affected by the disease, which has a linear relationship with poverty. 12 Disease levels vary starkly in the UK, with 56% of 5-year-old children in Blackburn and Darwen but only 4% of children in less deprived South Gloucester showing visible carious lesions. 13 In England, dental caries remains the primary reason for children’s admissions to hospital. 1 In 2013/14, a total of 62,747 children and young people were admitted to hospital in England, Scotland and Wales with a diagnosis of dental caries; the most common age group was 5–9 years. 1–3

Dental caries and its consequences are not limited to young children or the primary dentition. There is evidence surrounding the trajectory of disease, showing that children who experience carious lesions in their primary dentition carry a much greater burden of disease into adolescence and beyond. 14 Dental caries also affects one in three UK 12-year-olds, is positively associated with deprivation15 and is experienced by almost half of those aged 12–15 years in deprived areas. In 2013 in England, 32% of 12-year-olds experienced dental caries and required treatment, ranging from 46% of those eligible for free school meals to 30% of those ineligible. 16

Changing strategies for management of carious lesions in primary teeth

Until recently, dental caries was considered an infectious disease. As a result, treatment required removal of all bacteria, biofilm and affected tooth tissue before restoration. However, the disease is now understood to result from an ecological shift in the varying proportions of different commensal bacteria, resulting in a dysbiotic microflora in the dental biofilm. 17 Acidogenic, aciduric and cariogenic bacteria are highly competitive within the biofilm and, where there is a frequent supply of fermentable (dietary) carbohydrates, conditions develop that favour them, supporting their domination of the biofilm ecology. This ecological shift in biofilm composition leads to a concurrent shift in bacterial activity, with long periods of acidity and net mineral loss from the dental enamel and dentine resulting in the carious lesion. 18

This more recent view of the disease has allowed a rationale for the development of alternative treatments, rather than the traditional complete surgical excision (drill-and-fill) model. These alternative treatments involve controlling precipitating factors for the disease, through carbohydrate restriction (diet change to reduce sugars intake), biofilm removal (through tooth-brushing), promoting tooth tissue remineralisation (through professional- and home-applied fluoride) and biofilm sealing from substrate (using restorative techniques). 19 A resultant shift away from cariogenic- to non-cariogenic biofilm promotes remineralisation, inactivates the disease process and preserves tooth tissue. This minimal intervention dentistry approach20 follows the contemporary tenet of quaternary prevention. In addition, it avoids, or slows down, the cycle of re-restoration21 and is less invasive for patients.

The evidence for effective management of carious lesions in primary teeth

Teaching in UK dental schools has been based on guidance from the British Society of Paediatric Dentistry (BSPD). Until recently, the BSPD recommended that the optimum treatment of carious lesions in primary teeth is complete removal of the carious tissue, followed by the placement of a conventional restoration (filling) to repair lost tooth tissue. 22,23 However, these recommendations were largely based on evidence from studies conducted in either a secondary care or a specialist paediatric dental practice setting,24 rather than the primary dental care environment, where the vast majority of children are treated. More recently, the Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness Programme (SDCEP) has recognised the growing evidence for minimally invasive, biologically based approaches to carious lesion management and has developed national guidance for the management of caries in children,25 which is based on this approach.

Despite long-standing teaching in paediatric dentistry and high-quality guidance for primary dental care in the UK, the proportion of primary teeth with visible carious lesions that are restored (the Care Index) remains low. In Scotland it is 13%,26 whereas in England it is 14%. 27 The perceived ineffectiveness of the traditional ‘drill-and-fill’ methods of managing decayed primary teeth has been hypothesised as one reason why this approach is unpopular with GDPs. 28

Evidence from conventional/traditional approaches to managing carious lesions

Traditional approaches to carious lesion management involve complete carious tissue removal and placement of a restoration. However, a myriad of treatment options are available to dentists when they are deciding how to restore carious primary molars. Clinical decisions are required with respect to how much carious tooth tissue to remove, given the changing face of cariology, as well as which material to use to restore the tooth, in the light of the ongoing advances in dental materials. Restorations provided in specialist clinical environments can be effective, with studies conducted in secondary care showing high success rates for restorations in primary teeth;29,30 subsequent guidance has largely been based on this research. However, both the research quality and its generalisability to a primary dental setting is limited7,31 and a closer look at the evidence shows less clarity, because a limitation in its interpretation is the lack of an agreed core outcome set. 32,33 Cariology studies use a variety of different outcomes and different outcomes measures, making it often impossible to synthesise or directly compare materials and techniques. Few studies have measured caries-related pain and infection as an outcome when comparing different treatment approaches and fewer still have compared conventional (complete) carious lesion removal and restoration approaches with other approaches to managing carious lesions. Two RCTs have compared conventional restorative techniques with other approaches and recorded pain and/or infection as an outcome. One trial,34 a split-mouth RCT set in general dental practice, involved 18 GDPs in Scotland and compared the Hall Technique35 (a biological approach in which carious lesions are sealed in) with conventional restorations. Children, parents and dentists preferred the Hall Technique, and it outperformed the conventional restorations, with the 2-year follow-up showing that participants experienced pain and/or infection in 2% of teeth treated with the Hall Technique and in 15% of teeth treated with conventional restorations. 34 The relatively high failure rates for conventional restorations (as defined by occurrence of pain and/or infection) continued at the 5-year follow-up, with 3% failure for the Hall Technique and 17% for conventional restorations. 36 In terms of restoration longevity, the Hall Technique showed a 5% failure rate at 5 years, compared with 42% for conventional restorations. The lack of effectiveness for conventional restorations in multisurface lesions in primary teeth was replicated in a second study in Germany, in which specialists and experienced postgraduate trainees carried out treatment in a secondary care environment. 37 Conventional restorations were compared with the Hall Technique and a non-restorative cavity control (NRCC) approach (using a prevention alone approach with brushing of carious lesions to arrest them) for management of multisurface cavities [International Caries Detection and Assessment System (ICDAS) codes 3 to 5]. After 2.5 years, participants in the conventional and NRCC arms experienced pain and infection in 9% of teeth whereas participants treated with the Hall Technique experienced pain and infection in 2.5% of teeth.

Evidence from non-destructive/minimally invasive approaches to managing carious lesions

Managing carious lesions using a biological approach is based on evidence that began to emerge in the 1990s, which increasingly supports the idea that carious tissue does not need to be completely removed38 to achieve success in the management of decay. There are advantages to this minimally invasive approach: less tooth tissue is lost, there is less likelihood of irreversible damage to the dental pulp and children tolerate it more easily as there is less use of injections and rotary instruments. These biological approaches include sealing-in a carious lesion with preformed metal crowns (PMCs) using the Hall Technique and sealing in carious lesions under a fissure sealant material.

These minimally invasive strategies and their evidence are summarised in the following sections.

Selective carious lesion removal

Selective removal of carious dentine is carried out to avoid damage to the dental pulp resulting in ingress of oral bacteria and pulpal death. A Cochrane review29 compared complete with selective caries removal strategies and found that selective excavation of carious lesions (sealing some of the decay in the tooth rather than drilling it all out) was effective; in symptomless, vital, primary or permanent teeth this approach reduced the incidence of pulp exposure. Selective carious tissue removal is therefore advocated for primary teeth with the definitive restoration placed at the first visit.

Atraumatic restorative treatment

Atraumatic restorative treatment (ART) comprises removal of softened carious tooth structure with dental excavators and then placement of adhesive materials, usually glass ionomer cement (GIC), to restore cavities, pits and fissures. 39 ART is generally accepted as being less anxiety-provoking than conventional restorative techniques. 20,40,41 However, a recent Cochrane systematic review42 has cast some doubt on earlier conclusions regarding restoration longevity. The review included 11 trials on primary teeth (children aged 3–13 years) comparing ART with conventional restorations and found an odds ratio for restoration failure of 1.60 [95% confidence interval (CI) 1.13 to 2.27] for ART compared with conventional restorations over a follow-up period of 12–24 months in 643 participants. No evidence was found of a difference in cavity types, whether single or multiple surface. Only one study,43 with 40 participants, reported on pain (children aged 4–7 years) and found that children whose teeth were treated with ART reported less pain (on the Wong–Baker FACES® Pain Rating Scale44) than those treated with conventional restorations, with a mean difference of –0.65 (95% CI –1.38 to 0.07).

No carious tissue removal and no restoration (non-restorative cavity control)

This option was initially considered for lesions with no viable repair option using sealing-in methods, either because the lesion or cavity is too extensive to repair or because the child has limited ability to tolerate treatment. In these cases, tooth-brushing and remineralisation strategies remove the biofilm and arrest the decay, maintaining the tooth and avoiding an extraction. NRCC relies on frequent, effective tooth-brushing to physically debride tooth tissue and disrupt the ecology and composition of the cariogenic plaque biofilm, causing it to shift to a more balanced, non-cariogenic and healthy state. 45 The aim is to minimise the time that any substrate and cariogenic microorganisms are in contact with a susceptible tooth surface. NRCC as a carious lesion management strategy relies heavily on a child’s parents/guardians to change behaviour and adopt effective preventative strategies. Moreover, although biofilm removal with a toothbrush is theoretically possible, gaining adequate access to a lesion to scrub it effectively enough to remove the biofilm is challenging. This problem is compounded when trying to remove biofilm from dentine when it is embedded in the exposed collagen matrix. The RCT37 that found a 29% failure rate for NRCC after 2.5 years in the hands of specialists in secondary care and a prospective observational study in a community dental setting46 seem to confirm the purported difficulties found with NRCC.

No carious tissue removal and restoration with a crown using the Hall Technique

Several observational studies47,48 and RCTs with short-term follow-up49,50 support this technique but the strongest evidence comes from two RCTs with long-term follow-up (see Evidence from conventional/traditional approaches to managing carious lesions). The first RCT, by Innes et al. ,34,36 supported the use of the Hall Technique in primary dental care; however, the practitioners involved were from a single geographical area, limiting the generalisability of the findings. The second hospital-based RCT51 in Germany found lower failure rates (based on longevity of restoration and pain/infection) after 1 year with the Hall Technique (0%) than with conventional restorations (9%) or prevention alone with NRCC (8%); after 2.5 years, the respective failure rates were 7%, 33% and 29%. 37

The high success rate of the Hall Technique compared with conventional restorations is also evident in secondary care and private practice. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis52 of adhesive restorations in primary molars found that the mean survival times of restorations range from 20 to 42 months, with composite resin, compomer and resin-modified glass ionomer (RMGI) performing similarly. A Cochrane review30 that included the Hall Technique supported this, concluding that crowns placed on primary molar teeth, regardless of technique, were likely to reduce pain and infection compared with fillings and that crowns placed using the Hall Technique reduced discomfort at the time of crown fitting.

Fissure sealants applied over non-cavitated carious lesions

Fissure sealants (low viscosity, unfilled resins) successfully prevent carious lesions occurring on the occlusal (biting) surfaces of teeth. 53 They are also effective at stopping the progression of carious lesions54,55 in permanent teeth, as they prevent lesion access to the carbohydrate that is necessary for the biofilm to thrive and stay actively cariogenic. 56,57 Although the pathophysiological evidence supports the efficacy of sealing-in to slow or stop progression of carious lesions, the clinical evidence for fissure sealants shows mixed success in permanent teeth. Fissure sealant materials wear and fracture and regularly need to be replaced and, therefore, require continual observation to ensure that the seal is maintained. Similarly, for primary teeth, there is little direct evidence to inform recommendations for the size of lesion that can be sealed or the best sealant material to use. 58

Evidence from Good Practice Prevention approaches to managing caries

The four main approaches to preventing dental caries are well established and represent the four ‘pillars of prevention’. These are:

-

dietary investigation, analysis and intervention to reduce fermentable carbohydrates in the diet

-

tooth-brushing twice daily with a fluoridated toothpaste

-

fissure sealants for permanent teeth

-

topical fluoride varnish applied to primary and permanent teeth by a dental professional.

There is substantial and high-quality evidence from Cochrane reviews on the effectiveness of tooth-brushing,59 fissure sealants60 and fluoride varnish59 in preventing dental caries. However, the evidence base supporting the effectiveness of behaviour change to enact fluoride use at home (tooth-brushing with fluoride toothpaste) and of dietary change to reduce the intake of fermentable carbohydrates (primarily sugars) is more tenuous. 61

Pain and dental infection (sepsis)

Although a highly prevalent condition, the impact of childhood dental caries is often under-appreciated, as the disease itself is rarely life-threatening or overtly limiting on daily activities. However, the consequences of the disease, including pain62, interference with sleep and reduced school attendance,63 can have significant effects on children’s daily lives. In 2013, 6% of 12-year-olds and 3% of 15-year-olds reported difficulty with schoolwork because of the condition of their teeth and mouth over the previous 3 months. 16 Dental caries can also affect the general health and quality of life (QoL) of children, impairing growth and cognitive development,64 as well as interfering with nutritional status,63 and may even have an effect on attainment. 65

Estimates of pain and infection from dental caries in children are difficult to establish. However, the 2016 National Dental Inspection Programme26 epidemiological study in Scotland, in which 86% of Primary 1 children were inspected (at approximately 5 years of age), reported that 7.5% of the children examined had a dental status that required them to be issued with a letter indicating that they ‘should seek immediate dental care on account of severe decay or abscess’.

One of the difficulties with measuring pain and infection in young children is their limited ability to communicate. Young children do not find it easy to describe and report pain. 66 Cognitively, the ability to understand pain and differentiate a chronic pain from the absence of pain is a complex phenomenon. Young children who grow up with pain from an early age may not realise that this is not normal. When they do realise they have pain, it can be difficult to have them describe this precisely to help with reaching an accurate diagnosis.

Dental caries incidence

Since the turn of the millennium, it has been widely acknowledged that the commonly used threshold for the measurement of dental caries in clinical trials is no longer appropriate, because this threshold represents disease that is already well advanced (into dentine). 67,68 The National Institutes of Health (US) (NIH) Consensus Development Conference in Bethesda, MD, USA, in 200167 identified the benefits of including the recording of early dental caries in clinical trials, stating ‘There was a paradigm shift in the management of dental caries toward improved diagnosis of early non-cavitated lesions and treatment for prevention and arrest of such lesions’. In addition, the panel recommended that ‘clinical trials of established and new treatment methods . . . should conform to contemporary standards of design implementation, analysis and reporting’. Many technical adjuncts to carious lesion detection and diagnosis have become available over the years,69 but their use is not widespread in clinical dentistry and they remain, primarily, a clinical research tool.

The most widely used adjunct for carious lesion detection, which is in general use in clinical dentistry, is radiographs. The mandatory use of radiographs as part of a clinical dental research trial is universally agreed as unethical. However, they are recommended at risk-based intervals in UK guidelines. 70 Nevertheless, it is clear from the literature,71 and was highlighted in the FiCTION pilot trial and feasibility study,72,73 that radiograph use in children does not follow the expected frequency.

Child- and parent-reported outcomes: oral health-related quality of life

The value of patient-reported observations on dental treatment experiences is becoming widely accepted and patients’ perspectives are seen as valuable. Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) are now included in the vast majority of trials to evaluate changes in the impact of the condition following treatment from the patient’s perspective.

Many PROMs have been produced to measure oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL), which was defined by Locker and Allen74 as ‘the impact of oral diseases and disorders on aspects of everyday life that a patient or person values, that are of sufficient magnitude, in terms of frequency, severity or duration to affect their experience and perception of their life overall’. Most existing measures of OHRQoL in children, including the Child Perceptions Questionnaire (CPQ), the Child – Oral Impacts on Daily Performances (C-OIDP) index and the Child – Oral Health Impact Profile (C-OHIP), are designed to cover a variety of oral conditions, such as dental caries, malocclusion and craniofacial anomalies. Although these measures have been developed for children to self-report, for young children (< 8 years of age) most studies rely on parental reports of the impact of their child’s health on their daily lives. 75

Child- and parent-reported outcomes: dental anxiety and worry

The prevalence of child dental anxiety, across Europe, ranges from 3% to 21%,76–78 with 14% of children experiencing extreme dental anxiety. 78 These findings suggest a continuum of child dental fear across populations of children, including those who attend for dental treatment. 79

The literature suggests that younger preschool children may find any form of dental intervention frightening; consequently, they may be disruptive during treatment. 80 For the younger, preschool child, it is not the actual dental intervention or seriousness of the treatment that is important, but the imaginings or fantasies stirred up by it. 81 These imaginings include feeling helpless, having to submit passively to treatment, fear of pain and being separated from their parent. Similar observations are made for children who experience dental pain and for those who suffer from high dental anxiety. 79

With psychological development, the once fearful and disruptive preschool child usually becomes able to manage dental treatment. 80 Therefore, it is important when investigating different dental treatment modalities, for preschool and primary school-aged children, to assess child dental anxiety and to examine how dental anxiety status changes with chronological age. Different dental treatment modalities may also influence children’s dental fear, and some may be more appropriate for children with dental anxiety. Therefore, it is important to assess not only dental trait anxiety (anxiety that is more stable) but also dental state anxiety (anxiety that is associated with specific situations) to assess the effect of the treatment on the dental anxiety experienced by the child patient during and after treatment.

In summary, to assess child dental anxiety in the FiCTION trial, to demonstrate how this affect changed with the experience of pain and chronological age and to identify the most appropriate treatment modality to treat carious lesions in the dentally anxious child, state measures of dental fear were chosen. The justification for choice of measures to assess child dental anxiety is described in Chapter 2, Child- and parent-reported outcomes: participant dental anxiety, worry and discomfort during dental treatment.

Economic analysis to determine the cost-effectiveness of different treatment approaches

(See Chapter 2, Cost-effectiveness of managing dental decay in primary teeth, and Chapter 4). Dental care for dental caries has high direct costs for the NHS;82 therefore, we need to ensure that health benefits are being maximised within the budget. An economic evaluation was conducted alongside the FiCTION trial to determine the cost-effectiveness of the different treatment approaches. These results can be used to facilitate efficient resource allocation for managing carious lesions in primary teeth.

Acceptability and associated experiences of the FiCTION trial arms for children, parents/guardians and dental professionals

Dental treatments vary in their degree of acceptability to patients. The more acceptable a treatment is to the patient, parent or care-deliverer, the more likely it is to be delivered and received. The value of children’s opinions on their dental treatment experiences has become more widely accepted and their perspectives are seen as credible. Although a vast body of research has compared different types of treatment to manage carious lesions, most of the research has focused on outcomes related to choice and characteristics of dental materials;33 very little research has included the preferences or perspectives of participants as outcomes.

Rationale for the FiCTION trial

As a pragmatic, parallel-group, patient-RCT in general dental practice, the aim of the FiCTION trial was to provide evidence for the most clinically effective and cost-effective approach to managing caries in children’s primary teeth in primary dental care. Such evidence would remove persistent uncertainty among dental practitioners when treating and managing carious lesions in children’s primary teeth and support dental practitioners in treatment decision-making for child patients to minimise pain and infection in primary teeth.

The implication of this research is likely to be a change in policy for service and education in the NHS and beyond.

As described earlier (see Scientific background), there is growing evidence in favour of less invasive management of dental decay, informed by the principles of minimal intervention dentistry83 and based around sealing-in carious lesions or removing biofilms and supporting remineralisation strategies with a NRCC approach. The natural separation of these interventions, therefore, into conventional management, less invasive sealing management options and non-restorative management options provided the basis for the three arms of the FiCTION RCT.

Design and key findings of the FiCTION trial pilot phase

The FiCTION trial was delivered in two phases: Phase I comprised a pilot trial, qualitative study72 and feasibility survey84 and Phase II was the FiCTION main trial. Phase II was dependent on the success and recommendations of Phase I.

As planned, purposively selected primary dental care practices in Dundee, Newcastle and Sheffield were recruited to the pilot trial. The target patient participant recruitment figure was 200 children, aged 3–7 years, with carious lesions into dentine in primary molar teeth. Once recruited, participants were randomised to a three-arm pilot trial with allocation to the caries treatment strategies described in Scientific background. Trial procedures mirrored those planned for employment in the FiCTION main trial, with the exception that follow-up was for 6 months only.

Appendix 1 presents the 26 recommendations from the pilot phase of the FiCTION trial, made to inform Phase II, the main FiCTION trial.

In summary, the experience of undertaking the FiCTION pilot trial and the feasibility study [HTA number 07/44/03, Newcastle Clinical Trials Unit (NCTU) number FS77044005] resulted in minor refinements to the design and conduct of the main trial, including changes to the presentation of parent and child information and streamlining of the recruiting process. This preparatory work enhanced our confidence in being able to recruit the target number of dental practices for the main trial, and confirmed our expectations that the time scale for recruiting the required number of participants aged 3–7 years would be challenging.

Dentists in the pilot trial were reimbursed for their time, following a detailed costing framework developed by the Primary Care Research Network (PCRN) Northern and Yorkshire; participating practices’ feedback about the process and value of the reimbursement was positive. Primary care trusts (PCTs) were also supportive of the trial and agreed that the FiCTION trial work and ‘accrual’ reimbursement would not interfere with the practice contract or UDAs (current payment system). The opportunity cost of treatment sessions forgone as a result of trial participation was not an issue for the dentists.

Chapter 2 Randomised controlled trial methods

Aims and objectives of the trial

The aim of the FiCTION trial was to compare the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of three treatment strategies for the management of dental caries in primary teeth over a period of up to 3 years (minimum 23 months) in children aged 3–7 years at the time of initiation of treatment. The three strategies compared were as follows:

-

conventional management of decay, with best-practice prevention

-

biological management of decay, with best-practice prevention

-

best-practice prevention alone.

These strategies are described in detail in Interventions.

Objectives

The objectives were to assess:

-

the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of three treatment strategies for managing dental caries in primary teeth

-

the three treatment strategies with respect to –

-

child- and parent-reported outcomes, including child OHRQoL, dental anxiety, worry and discomfort during treatment

-

acceptability and associated experiences for children, parents and members of the dental team

-

caries development and/or progression in primary and permanent teeth.

-

Summary/overview of trial design

The FiCTION trial was a multicentre, three-arm, parallel-group, participant-randomised controlled trial, with an integrated economic evaluation (see Chapter 4) and qualitative evaluation (see Chapter 5).

Trial registration and protocol availability

The FiCTION pilot trial was initially registered in the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) registry on 27 January 2009; it was extended to include the main trial on 8 May 2013. The protocol was published in BioMed Central Oral Health in 201385 and is also available on the NIHR HTA project web page [see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/074403/#/ (accessed 27 November 2019)].

Over the course of the trial, five protocol amendments were made (see Appendix 2).

Ethics and governance

The University of Dundee acted as sponsor for this trial. Favourable ethics opinion was obtained from the East of Scotland Research Ethics Committee (REC) 1 on 30 July 2012. All subsequent substantial amendments were also approved by the same REC.

All members of the trial team and practice staff had training in Good Clinical Practice (GCP), in keeping with their role in the trial. Practice staff directly involved with recruitment and consent received further training in taking informed consent in a paediatric setting.

Dental practices were required to maintain an investigator site file containing details of staff involved in the FiCTION trial, their training and their delegated roles. Dentists were named as practice leads once they satisfied the GCP/Research Governance Framework requirements.

Trial setting

The trial was conducted in primary dental care, reflecting the setting within which the vast majority of children’s dentistry is carried out. General dental practices across three of the four UK nations (Scotland, England and Wales) were grouped into five clinical centres (CCs) for management purposes:

-

Scotland, with one CC covering Tayside, Glasgow, Edinburgh and the Borders (hereafter referred to as Scotland)

-

England, with three CCs covering –

-

North East England/Cumbria (hereafter referred to as Newcastle)

-

Leeds, Sheffield, Derbyshire, Manchester and Liverpool (hereafter referred to as Leeds/Sheffield)

-

London

-

-

Wales, with one CC covering Cardiff (hereafter referred to as Wales).

To be eligible for participation in the trial, practices had to:

-

see and treat children aged 3–7 years under NHS contracts

-

see children with carious lesions in primary teeth (around one child per week was considered an appropriate frequency)

-

have the infrastructure to support the trial, preferably to include electronic patient management systems and internet access.

Practice recruitment

The initial target was to recruit 50 practices, 10 from each of the five CCs (see Sample size calculation). The selection of practices was designed to reflect the sociodemographic mix of the catchment communities. A range of strategies were used to identify and invite practices to participate. Practices from which an expression of interest in trial participation was received were visited by the research team to assess their eligibility before their inclusion was confirmed.

General strategy

The 11 practices that had participated in the FiCTION pilot trial,86 carried out in Scotland, Newcastle and Leeds/Sheffield, were invited to participate in the main trial. A further 44 practices that indicated interest in main trial participation when surveyed as part of the FiCTION feasibility study and in which at least one GDP had expressed willingness to randomise patients in that survey exercise were re-contacted and formally invited to participate by letters sent to the senior partner as well as to the GDPs working in these practices.

Practices that formed the overall sampling frame for the feasibility study but that had not been contacted as part of that study were also invited to express an interest in the FiCTION trial (total: 632 practices across the five CCs).

Any practice responding to general advertising in the national and local dental press and expressing an interest in participating in the trial was considered in accordance with practice eligibility criteria and proximity to the CCs [Scotland (Dundee), Newcastle, Leeds/Sheffield, Wales (Cardiff) and London].

Local strategy

In addition to the general practice recruitment strategy described above, a local recruitment strategy was developed by the clinical leads at each CC in liaison with the research networks in England and Wales and the Scottish Primary Care Research Network in Scotland. This comprised e-mail and postal mailing of FiCTION trial flyers to practices and practitioners by PCRNs in England and their equivalents in Wales and Scotland. Practices wanting to express an interest in the trial were asked to contact the Dundee FiCTION trial office. Expressions of interest were followed up locally by the clinical leads with the support of their local PCRNs. Local practice recruitment meetings were held in the CCs to inform interested GDPs about the FiCTION trial and to answer any questions they may have had.

By July 2013, 56 practices had been recruited and it was recognised that additional practices would be needed to reach the target number of participants. Following consultation with the Trial Steering Committee (TSC), Independent Data Monitoring Committee (IDMC) and HTA, the target number of practices was increased to 70 and catchment areas for two of the CCs (Leeds/Sheffield and Newcastle) expanded geographically into Derbyshire/Manchester/Liverpool and Cumbria, respectively.

Practice retention

The trial manager, clinical leads and their secretaries, and the clinical researcher actively maintained regular contact with all participating practices throughout the trial. They identified practice retention or associated problems early, using the formally established communication strategy and informally through their ongoing engagement with the practice, working closely with the practitioners to troubleshoot any problems. Regular e-mail and telephone updates from clinical leads’ secretaries and the trial manager, plus quarterly newsletters from the trial core team, were issued during the trial. Active support was sought from the PCRNs, research networks and local research champions for recruitment and retention of practices.

Continuing professional development (CPD) credit for all members of each FiCTION trial practice dental team was made available for attendance at any trial training events.

The practices were remunerated with service support costs for participant screening and recruitment activities, as well as with research costs based on the additional time spent on trial-related data collection. Dental treatment was remunerated in the normal way, depending on the nation where the practice was located.

Trial participants

Child participant inclusion criteria

Children (aged 3–7 years) who:

-

were willing to be dentally examined

-

had at least one primary molar tooth with decay into dentine (i.e. carious lesion) on clinical examination

-

were known regular attendees or, if new to the practice, considered likely to return for follow-up.

Child participant exclusion criteria

-

Children aged < 3 or > 7 years.

-

Children aged 3–7 years who:

-

at the recruitment appointment, were accompanied by an adult who lacked the legal or mental capacity to give informed consent

-

at the recruitment appointment presented with either dental pain and/or dental sepsis due to caries (as diagnosed by the GDP from patient history, examination, radiographs). These participants were not enrolled into the trial at that point, but, after treatment, could be reassessed for eligibility. Discomfort or pain associated with erupting or exfoliating teeth or an incident of trauma or oral ulceration was not an exclusion criterion

-

had a medical condition requiring special considerations with their dental management, for example cardiac defects or blood dyscrasias

-

were currently involved in any other research that might have affected this trial

-

were part of a family that knew they would be moving out of the area during the 3 years following recruitment.

-

Interventions

Three multicomponent treatment strategies for managing carious lesions in the primary dentition were tested. Each patient was randomly allocated to one strategy, with the expectation that they would be managed in that arm of the trial for up to 3 years. These strategies were documented in detail in the clinical protocols used in the training of practices and were available to practices for reference thereafter.

Conventional management of carious lesions, with best-practice prevention

[This intervention will hereafter be referred to as conventional with prevention (C+P).] (See Chapter 1, Evidence from conventional/traditional approaches to managing carious lesions.) Conventional management is commonly known as the ‘drill-and-fill’ method and is the traditional approach to managing dental caries that has been taught and practised for many years. It is based on active management of carious lesions by complete removal of the carious tissue. The teeth are numbed with local anaesthesia (a dental injection), carious tissue is mechanically removed using rotary instruments (drill) or by hand excavation (using hand tools), and a restoration (filling) is placed in the tooth to fill the cavity. If the dental pulp (nerve) is exposed during carious tissue removal or there are symptoms of pulpitis, a pulpotomy (removal of some of the nerve) may be carried out, followed by provision of a metal crown (usually) or a filling. Retained roots, and teeth for which the crowns are unrestorable or the pulp chamber is open, are managed by extraction (removal) of the tooth/root following local anaesthesia.

Best-practice prevention was carried out in line with current guidelines and as per the prevention alone (PA) arm.

Biological management of carious lesions, with best-practice prevention

[This intervention will hereafter be referred to as biological with prevention (B+P).] (See Chapter 1, Evidence from non-destructive/minimally invasive approaches to managing carious lesions.) This minimally invasive approach to managing carious lesions involves sealing decay into the tooth and separating it from the oral cavity; this is achieved by application of an adhesive filling material over the caries or by covering with a metal crown. It may be clinically necessary, on occasion, to partially remove superficial carious tissue prior to the tooth being sealed. Local anaesthetic injections are rarely needed. Retained roots and teeth for which the crowns are unrestorable, or dental pulp is exposed, are managed on a tooth-by-tooth basis. In situations when a tooth has active carious lesions (decay still progressing) or when the clinician decides that the tooth is likely to give the patient pain or sepsis before it exfoliates (falls out), the caries is managed by extraction following local anaesthesia.

Best-practice prevention was carried out in line with current guidelines and as per the PA arm.

Best-practice prevention alone

[This intervention will hereafter be referred to as prevention alone (PA).] (See Chapter 1, Evidence from Good Practice Prevention approaches to managing caries.) For the PA arm, no drilling, filling or sealing of primary teeth occurred. Treatment plans for participants were based on best-practice preventative care for teeth and oral health. This involved the four component pillars of prevention, carried out according to current guidelines:25,87

-

dietary investigation, analysis and intervention to reduce fermentable carbohydrates in the diet

-

tooth-brushing twice daily with a fluoridated toothpaste, plus fluoride mouth-rinsing in children > 7 years of age

-

topical fluoride varnish applied to primary and permanent teeth by a dental professional

-

fissure sealants for permanent teeth.

Training of dentists and practice staff

Between July and October 2012, each CC hosted a practice training day to deliver clinical and trial process training (which included GCP and informed consent training) to all enrolled dentists. Whenever possible, dental therapists/hygienists/nurses and practice receptionists/managers were also trained at the practice training day. For dental team staff who could not attend a practice training day, training was delivered as part of a site initiation visit by the trial manager and clinical researcher.

Training was provided for the individual clinical procedures with which dentists were unfamiliar and was tailored as far as possible to each group of dentists. Topics included, but were not limited to, recording dental caries using ICDAS, taking radiographs in children, the Hall Technique and conventional crown provision. Additional training materials were developed for taking radiographs and for the Hall Technique;35 these materials were made available to participating dentists in their practice. Although the detection of dental sepsis (infection) is a standard part of a dental clinical examination, given its importance as one of the primary outcomes, specifically directed training was included.

Training was given during appropriate treatment planning and delivery to children according to the randomised trial arm. This comprised a didactic teaching session from members of the core team followed by practical treatment planning with cases and discussion with the local clinical lead and co-chief investigators.

Outcomes

Primary outcomes

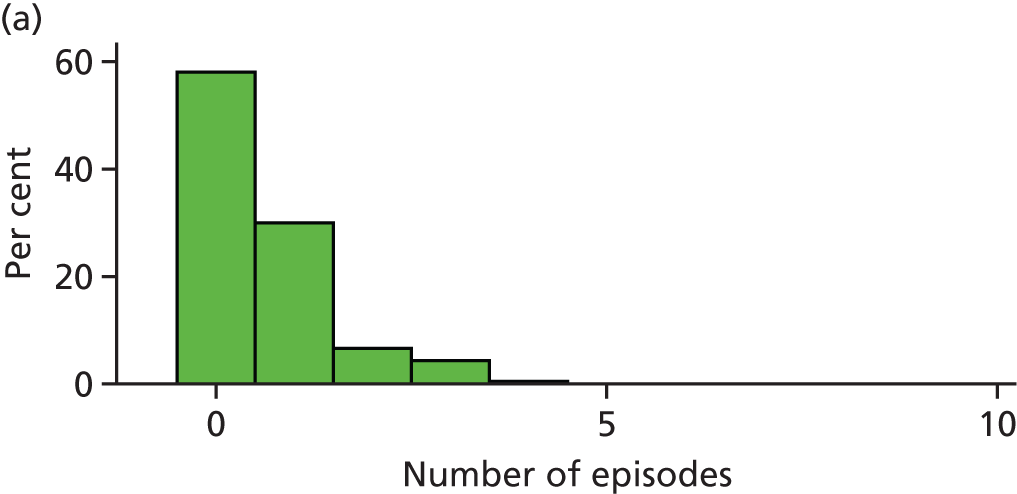

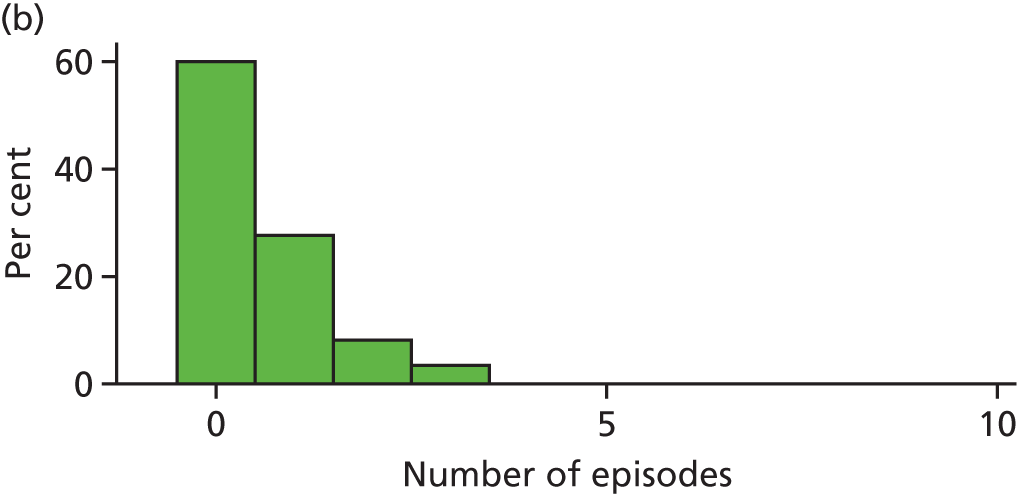

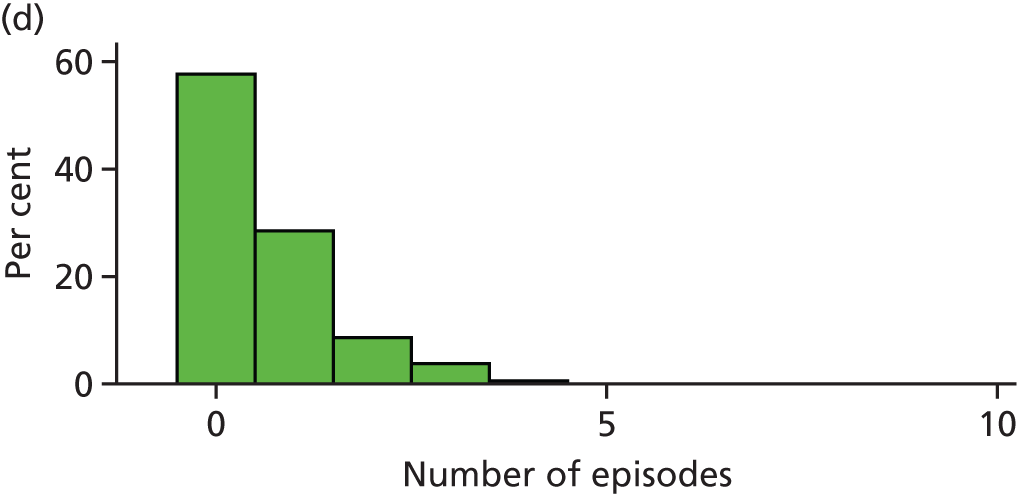

When the trial was originally designed it was powered only for a single primary outcome of incidence of dental pain and/or dental sepsis. However, as the trial progressed, it became clear that the number of episodes of dental pain and/or dental sepsis experienced by a child is a more clinically relevant outcome and, statistically, a more sensitive measure (compared with dichotomising the number of episodes into zero episodes vs. one or more episodes). Therefore, it was decided that the number of episodes of dental pain and/or dental sepsis should be a co-primary outcome.

Originally, it was planned that participants would be followed up in the study for a fixed 3-year period. However, the extension to the trial recruitment period resulted in the maximum potential follow-up ranging from 23 to 36 months; hence, the co-primary outcomes were assessed across a variable follow-up period.

Definition of the clinical effectiveness outcomes

The co-primary outcomes for clinical effectiveness were the:

-

proportion of children with at least one episode of dental pain or dental sepsis or both during the follow-up period (incidence)

-

number of episodes of dental pain or dental sepsis or both for each child during the follow-up period.

The primary outcome measure of incidence was a binary indicator of dental pain and/or dental sepsis at each treatment visit during the follow-up period (minimum of 23 months to a maximum of 36 months). Treatment visits included scheduled appointments and unscheduled/emergency appointments.

Dental pain was defined on the case report form (CRF) by a ‘yes’ response to question 7 and a ‘yes’ response to question 7a (dental caries).

Dental sepsis was defined as confirmed infection on the CRF by a ‘yes’ response to question 8.

Schedule of assessment of primary outcomes

Data for the primary outcomes of dental pain and/or dental sepsis due to caries were recorded on the CRF during or following all visits to the GDP (Table 1) [see also the project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/074403/#/ (accessed 27 November 2019)].

| Event | Type of outcome | Completed by | Scale | Where recorded | Screening visit | Baseline examination visit | Treatment visits (scheduled treatment or recall and unscheduled/emergency) | Non-attendance postal questionnaire | Final visit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment of eligibility (presence of caries, absence of dental pain and dental sepsis) | GDP | Screening log and participant’s dental record | ✗ | ||||||

| Consent/assent | GDP | Consent form | ✗ | ||||||

| Bitewing radiographs | GDP | Risk-based, in line with standard guidance – NOT a trial specific procedure | |||||||

| Caries assessment | Secondary | GDP | ICDAS | ICDAS chart | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| Pain: pre-treatment questions to GDP | Primary | GDP | CRF | ✗ | ✗ | ||||

| Sepsis: pre-treatment questions to GDP | Primary | GDP | CRF | ✗ | ✗ | ||||

| Child’s co-operation with treatment | Secondary | GDP | CRF | ✗ | ✗ | ||||

| Treatment cost data | Economic | GDP | CRF | ✗ | ✗ | ||||

| Parent-reported child dental discomfort (toothache) outside dental visits | Secondary | Parent | DDQ-8 | Parent questionnaire | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| Parent/carer proxy report of child’s OHRQoL | Secondary | Parent | P-CPQ-16 | Parent questionnaire | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Parental perception of child’s pain related to treatment | Secondary | Parent | Global rating | Parent questionnaire | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Parental perception of child’s worry pre/post treatment | Secondary | Parent | Global rating | Parent questionnaire | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Use of health services | Economic | Parent | Parent questionnaire | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| Trait dental anxiety | Secondary | Child | MCDASf | Child questionnaire | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| Child’s perception of pain related to treatment | Secondary | Child | Pictorial rating scale | Child questionnaire | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| Child’s perception of worry pre/post treatment | Secondary | Child | Pictorial rating scale | Child questionnaire | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| Treatment referrals | Economic | GDP | CRF | ||||||

| Treatment deviations | Contextual information | GDP | CRF | ||||||

Dental pain due to caries (toothache)

Assessments for dental pain were made at each visit (scheduled or emergency treatment) throughout a child’s participation in the trial using the CRF completed by dentists. To differentiate between pain originating from a decayed tooth and pain from other causes (e.g. erupting or exfoliating teeth, mouth ulcers), the dentist formed a judgement based on the patient/parent history and the clinical evidence available from examination, which was recorded on the CRF completed at each appointment.

Dental sepsis (dental infection)

Clinical visual examination for dental sepsis was specifically undertaken at every visit by the GDPs and recorded on the CRF. The clinical detection criterion for the positive recording of dental sepsis was the presence of a swelling, dental abscess or draining sinus. Clinical examination was expected to be supplemented with examination of any radiographs taken [in line with Faculty of General Dental Practice (FGDP) guidelines],70 to record radiographic signs of inter-radicular pathology. Our statistical analysis plan (SAP) indicated that, if it was found that < 80% of children had radiographs within 1 year of entry to the trial, this source of data would be considered unrepresentative and would be disregarded in the definition of dental sepsis.

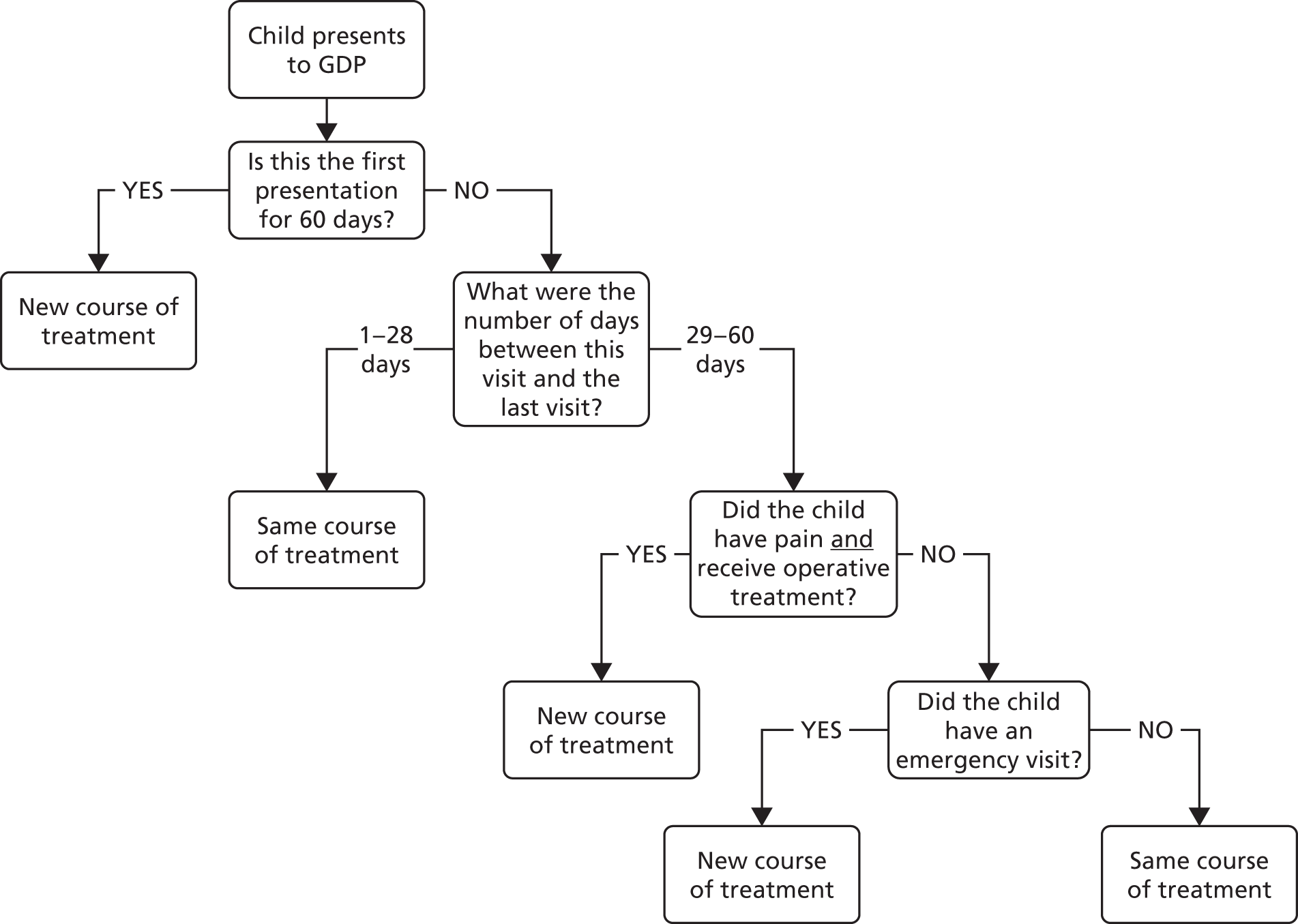

Definition of an episode

Reproduced from Innes NP, Clarkson JE, Douglas GVA, Ryan V, Wilson N, Homer T, et al. , Journal of Dental Research, 99(1), pp. 36–43, copyright © 2020 by International & American Associations for Dental Research 2019. Reprinted by Permission of SAGE Publications, Inc. 88

Several treatment visits (i.e. a course of treatment) can be associated with the same ‘episode’ of dental pain and/or dental sepsis. Therefore, we needed a definition of an ‘episode’ of dental pain and/or dental sepsis due to caries; this definition was operationalised on a tooth-by-tooth basis using CRF data, according to the following algorithm:

-

Let Y (yes) = the presence of dental pain and/or dental sepsis at a single treatment visit (as defined above); N (no) otherwise.

-

Let YY = the presence of dental pain and/or dental sepsis at consecutive treatment visits (i.e. on consecutive CRFs).

-

Y on one or more teeth at a single treatment visit = an episode.

-

Any number of consecutive ‘yeses’ on the same tooth, regardless of timeframe = a single episode (e.g. YYYYY over 5 months).

-

YY on different teeth (regardless of timeframe) = two separate episodes.

-

YNY on the same tooth = two separate episodes (regardless of the timeframe).

Although episodes were defined on a tooth-by-tooth basis, for a given child, if there were two (or more) teeth with dental pain and/or dental sepsis at the same visit, this was recorded as one episode at that visit for that child. For example, if a particular tooth had dental pain and/or dental sepsis at two consecutive visits and at the second visit a different tooth also had dental pain and/or dental sepsis this would be counted as one episode.

It was assumed that those who did not return for regular appointments during their follow-up did not experience dental pain and/or dental sepsis.

Secondary outcomes

See the project web page [www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/074403/#/ (accessed 27 November 2019)] for the SAP and study documentation, patient information sheet and questionnaires, for additional detail on the secondary outcome measures used.

Incidence of dental caries in primary and permanent teeth

A systematic review of clinical caries detection systems revealed a vast selection of scales with many inconsistencies in how the caries process was measured. 89 This review and the NIH consensus statement67 led to the development of an evidence-based and histologically validated system for staging dental caries, known as the ICDAS system. 90 This system is widely used in clinical research as a reference standard for measuring caries prevalence and incidence that all clinicians can use ethically, without harm and irrespective of the equipment they have. These features, along with the reported acceptable validity and reliability of ICDAS in primary teeth91 and the permanent dentition,92 make it an appropriate tool for dental caries measurement. Because, at a population level, nearly all caries experience in the permanent teeth of children in this age group are accounted for in the FPM teeth, the analysis of caries in permanent teeth focuses on these teeth alone.

Detailed measurements of caries experience were recorded at baseline and final assessment by the GDPs using the CRF and ICDAS charting. The dentists measured both early and more advanced stages of dental caries. The primary requirement for the examination was clean, dry teeth. All surfaces of all teeth were examined and the status of each was recorded in terms of caries and restorations. In the event of enough data (at least 80% of children with a radiograph taken within 1 year of entry to the trial) being available to provide a valid measure in this population, it was planned that bitewing radiographs, taken in line with FGDP guidelines (with blinded, independent assessment), would be used as an independent measure of dental caries. However, as the guidance for frequency of bitewing radiographs is based on caries risk assessment, and as some children may have moved out of the high-risk group during the course of the trial, it was anticipated that the frequency of bitewing radiographs taken for some children might reduce over the period of the trial. In addition, some children might have been unco-operative with this type of assessment, in view of their young age.

As the SAP [see the project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/074403/#/ (accessed 27 November 2019)] describes, an incident of caries was defined in terms of the observations made on the ICDAS charts scored at baseline and at the final visit. As observations on surfaces of the same tooth and between adjacent surfaces of different teeth were likely to be correlated, a single whole-mouth Caries Assessment Score for each child was derived and a computer program written to define for each child whether or not there had been disease development/progression from baseline to the final visit in teeth that were ‘sound/reversible’ at baseline, that is caries-free or with non-cavitated enamel caries [see appendix 1 in the SAP, as found on the project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/074403/#/ (accessed 27 November 2019)]. Primary and permanent teeth were analysed separately.

Child- and parent-reported outcomes: participant oral health-related quality of life

Our chosen measure of OHRQoL was the Parental–Caregivers Perceptions Questionnaire (P-CPQ). The P-CPQ, in its original 31-item version,93 was found to be reliable and valid for use in the UK. 94 More recently, a modified 16-item short form, Parental–Caregivers Perceptions Questionnaire-16 items (P-CPQ-16), has been developed and validated;95,96 to minimise respondent burden, this shortened version was selected for use in the trial [see the project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/074403/#/ (accessed 22 February 2019)]. The questionnaire includes four domains: oral symptoms, functional limitations, emotional well-being and social well-being. Parents are asked to indicate, using a six-point Likert scale (‘never’ = 0, ‘once or twice’ = 1, ‘sometimes’ = 2, ‘often’ = 3, ‘every day or almost every day’ = 4, and ‘do not know’ = 7), the frequency with which the events affected their children in the previous 3 months. The P-CPQ-16 also includes two global ratings: the parent’s ratings of the child’s oral health and their rating of the extent to which the oral/orofacial condition affects his/her life overall;97,98 these are rated on five-point response scales ranging from ‘excellent’ to ‘poor’ for the former and from ‘not at all’ to ‘very much’ for the latter.

Parents were asked to complete the P-CPQ-16 at the baseline or the final visit; if the final visit was not attended, parents were sent a non-attendance questionnaire [see Table 1 and the project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/074403/#/ (accessed 27 November 2019)]. A score for each visit was calculated, ranging from 0 to 64 (a lower score represents better OHRQoL). The global ratings are not included in the calculation of the scores.

Child- and parent-reported outcomes: participant dental anxiety, worry and discomfort during dental treatment

In measuring participant dental anxiety, we distinguished between underlying trait anxiety and treatment-related state anxiety. As with the assessment of OHRQoL, the challenges of child self-report and the need for parental proxy report for some constructs was recognised. The choice of measures was informed by a published systematic review of measures of child dental anxiety by Porritt et al. 99

The chosen measure of trait anxiety was a six-item version of the Modified Child Dental Anxiety Scale (faces) (MCDASf). As the last two questions of the standard MCDASf ask about conscious sedation and dental general anaesthesia, neither of which was relevant to FiCTION trial patients, these were omitted, as recommended by SDCEP. 100 The Modified Child Dental Anxiety Scale (MCDAS)101 aims to assess dental anxiety in children and has been shown to be an acceptable measure of child dental anxiety in children aged 8–15-years, exhibiting good internal consistency and validity. 101,102 The MCDASf is a modified version for younger children and has also been tested for criterion and construct validity and test–retest assessment reliability. 103 The response format for each of the six items is in the form of five faces showing different expressions, from ‘relaxed/not worried’ to ‘very worried’. Howard and Freeman103 concluded that the MCDASf can be used with confidence to assess dental anxiety in children, although they indicated that it has not been formally validated in those aged < 8 years. The MCDASf was completed by the child before treatment at baseline and at every visit to provide information on his or her anxiety at each dental encounter throughout the trial. The total score for each assessment was calculated, ranging from 6 to 30, with lower scores indicating less dental trait anxiety.

The measurement of dental state anxiety, to assess how the child responded to the particular treatment provided, was an important dimension of this trial. As with the MCDASf, it was necessary to choose an instrument appropriate to the age and cognitive abilities of the child participants. Visual analogue and pictorial scales are known to be useful in assessing single item constructs such as pre- and post-operative child dental anxiety (‘worry’). Although difficulties are noted with regard to the consistency of overall test–retest reliability, the reliability is noted to improve in the middle and the extremes of the scale. 104 Therefore, we judged that a pictorial scale using faces as the descriptors105 would be an appropriate means of assessing child dental state anxiety. Accordingly, at the start of each treatment visit the child completed a faces-based pictorial scale, scored 1 to 3, where 1 was ‘not at all worried’ and 3 was ‘very worried’, to report on their level of worry prior to arriving at the dentist’s for their visit (anticipatory anxiety). The child subsequently completed a second pictorial scale with the response options and scoring system at the end of each treatment visit to report on treatment-related dental state anxiety.

Although accounts of the use and psychometric properties of parent-proxy measures of children’s state anxiety are equivocal,104,106,107 such assessments have been shown to be valuable when assessing anxiety in younger children. 104,108 Therefore, in parallel with the child self-reports of anticipatory and treatment-related anxiety, parents were asked to make assessments of their child’s worry levels prior to arrival at the dentist’s for their visit and following treatment; these assessments were recorded using a single categorical global worry question for each time point, scored 1 to 5, where 1 was ‘not at all worried’ and 5 was ‘very worried’.

Discomfort during dental treatment was assessed by the child in relation to their treatment experience at the end of each visit using a global question on hurt, with a face format pictorial scale, scored 1 to 3, where 1 was ‘not at all hurt’ and 3 was ‘hurt a lot’. In addition, parents were asked to report on their perceptions of their child’s levels of pain regarding that particular visit to the dentist using a global question on pain due to treatment, scored 1 to 5, where 1 was ‘not at all painful’ and 5 was ‘very painful’.

Dentists also estimated child discomfort at every visit using a global discomfort question scored 1 to 5, where 1 was ‘no apparent discomfort’ and 5 was ‘significant and unacceptable’ discomfort, with these ratings being reported via the CRF.

There was no specific validation of any of the above pictorial or global rating scales.

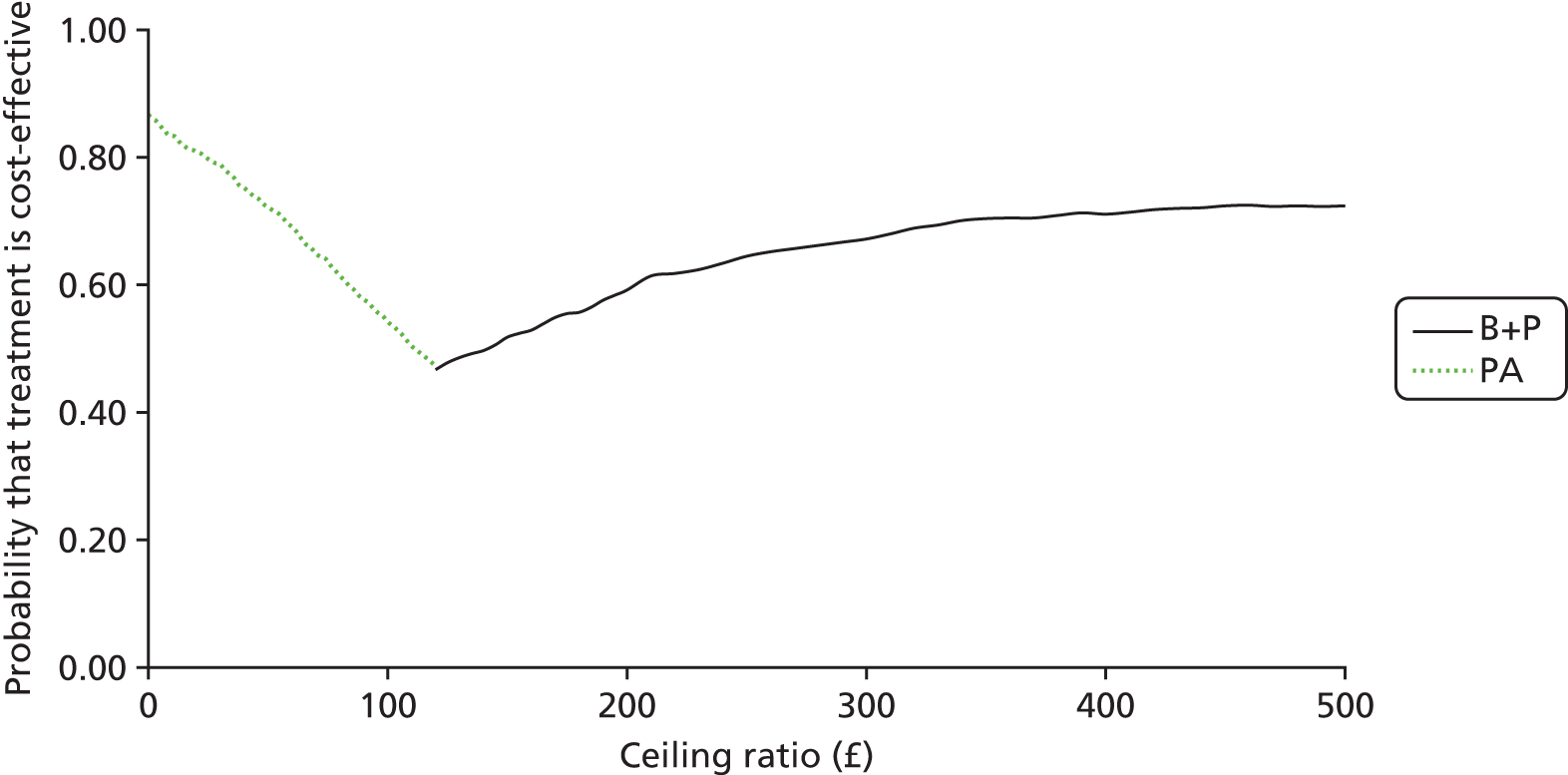

Cost-effectiveness of managing dental decay in primary teeth

(See Chapter 4.) The objective of the economics analysis in the FiCTION trial was to determine the relative cost-effectiveness of alternative ways of managing dental decay in primary teeth. The primary (base-case) analysis focused on estimating the cost of the three treatment strategies based on the resources (staff time, consumable materials and reusable materials) used to provide care at each visit. The differences in costs between different treatments were equated to the differences in effectiveness measured in terms of dental pain and/or dental sepsis. Sensitivity analyses determined the effect on results when costs were based on current charges to the NHS. Finally, a wider societal perspective was adopted to account for parental costs. The inclusion of a thorough economic evaluation as part of the FiCTION trial was crucial to help address uncertainties surrounding the effectiveness and efficiency of each treatment strategy.

Acceptability and associated experiences of treatment strategy for children and parents/carers and dental professionals

(See Chapter 5.) Given the difficulty in measuring children’s attitudes towards treatment strategies, identified in the pilot trial, the acceptability of the three treatment strategies was explored using a child-centred approach with qualitative methods, and specifically with child participatory activities, to allow children rather than adults to shape the data collection process. 109 Separate ethics approval was sought for this study.

Dentist-reported child behaviour and compliance was measured at each appointment using a behaviour score of 1 to 4, where 1 was ‘The child refused the treatment: . . . It was very difficult to make any progress’ and 4 was ‘Child was completely co-operative’, recorded on the CRF.

The dental professionals’ experiences of the three treatment strategies was explored qualitatively through interviews and focus groups. Topic guides were derived from qualitative information collected during the FiCTION pilot trial.

Safety (harms)

The three interventions tested in this trial are all in common use in general dental practice and were considered to be of relatively low risk. Expected adverse events (AEs) are summarised in Appendix 3.

Because of the type of trial, non-serious AEs were not captured. However, the practice lead was required to report all serious adverse events (SAEs) to NCTU via a secure fax line within 24 hours of the practice learning of an occurrence.

A SAE is defined as any untoward and unexpected medical occurrence or effect that:

-

results in death

-

is life-threatening (refers to an event in which the subject was at risk of death at the time of the event; it does not refer to an event that hypothetically might have caused death if it were more severe)

-

requires hospitalisation (for > 24 hours), or prolongation of the participant’s existing hospitalisation

-

results in persistent or significant disability or incapacity

-

is a congenital anomaly or birth defect.

Dental practice staff were reminded that clinical judgement should be exercised in deciding whether or not an AE was serious in other situations. Important AEs that were not immediately life-threatening or did not result in death or hospitalisation but might jeopardise the subject or require intervention to prevent one of the other outcomes listed in the definition above were also considered to be serious.

Hospitalisations for elective treatment of a pre-existing condition did not require reporting as SAEs. Unrelated hospitalisations were to be elicited at the post-treatment follow-up appointment, scheduled subsequent appointments and all unscheduled/emergency appointments.

All SAEs that, in the opinion of a co-chief investigator, were ‘related’ (i.e. resulted from the administration of any of the research procedures) and ‘unexpected’ (see Appendix 3) were reported to the REC.

Sample size calculation

At the planning stage, the proposed primary outcome was the proportion of children reporting either dental pain and/or dental sepsis during 3 years of follow-up. Based on evidence from previous studies on similar populations receiving no fillings,6,7 conventional fillings and the Hall Technique,34 sepsis rates of 20%, 10% and 3% were expected in the PA, C+P and B+P arms, respectively. Using the ‘sampsi’ procedure (a sample size calculation based on a two-sample test of proportions assuming a normal approximation and incorporating a continuity correction) in Stata® version 9 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA), and assuming a significance level of 2.5% (to allow for the multiple testing involved in a three-arm trial), the required sample size was calculated as:

-

two groups of 334 children to detect a difference in rates of between 20% and 10%, with 90% power, for PA versus C+P

-

two groups of 334 children to detect a difference in rates of between 3% and 10%, with 90% power, for B+P versus C+P.

The sample size was then increased by an inflation factor of 1.09 (giving 365 children per arm at end of follow-up) to allow for adjustment of estimates of effect size, taking into account variation between randomisation strata (dental practices).

Based on previous experience (Jan E Clarkson, University of Dundee, 1 July 2010, personal communication) of conducting RCTs in primary dental care, the sample size was further inflated to allow for a loss to follow-up of 25% over 3 years, requiring 487 children to be consented and randomised to each intervention arm (a target sample size of 1460 in total). In the pilot trial, participants were followed up for only 6 months, rather than the 3 years proposed for the main trial. Therefore, although follow-up in the pilot was complete, no adjustment was made to the assumed rate of loss to follow-up (25%) for the full trial.

The original aim, therefore, was to invite 18,717 children to attend for screening, of whom 12,166 (65%) were expected to actually attend and agree to be screened for the trial. Based on findings from the pilot trial, it was initially assumed that 1825 (15%) of those screened would be eligible and 1460 (80%) of those eligible would consent to be randomised.

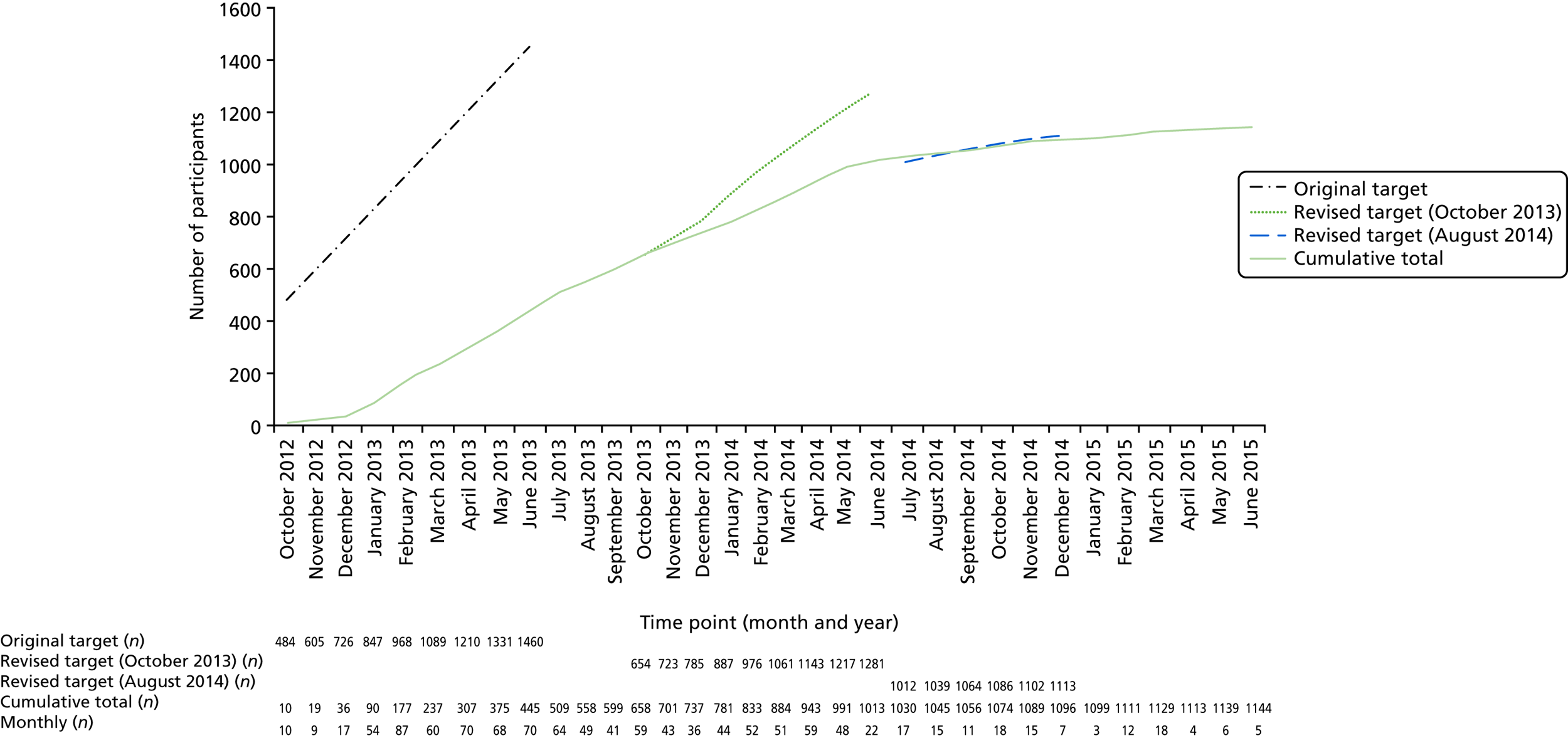

However, as the main trial progressed, the rates of participant identification, recruitment and consent proved lower than anticipated from experience in the pilot trial, amounting to 994 accruals by the end of June 2014. Therefore, a contract variation request was submitted to the HTA programme in August 2014 explaining that, based on the recruitment trajectory at the time, and with recruitment anticipated to continue until 31 December 2014 and follow-up until 30 June 2016, the trial would recruit only 1113 children. This would correspond to an effective sample size (after allowing for 25% loss to follow-up) of three groups of 278 children with a mean length of follow-up of 24.6 months. Assuming a linear incidence of dental pain and/or dental sepsis over the follow-up period, this would result in only 61% power to detect a difference between the arms for the primary outcome, dental pain and/or dental sepsis, assuming a type 1 error rate of 2.5%. In August 2014, it was therefore agreed by the NIHR HTA programme that there should be a 12-month extension to the trial, with the end of recruitment, end of follow-up and end of trial set at 31 December 2014, 30 June 2017 and 31 December 2017, respectively. No new practices would be recruited and those children recruited after June 2014 would not have the full 3 years of follow-up.

Allowing for 25% loss to follow-up, the effective sample size under this scenario would be three groups of 278 children followed up for, on average, 35.5 months. Assuming a linear incidence of dental pain and/or dental sepsis over the period of follow-up, this would result in 82.0% power (77.4% power if an adjustment for strata was necessary) to detect the hypothesised effect sizes (19.72% vs. 9.86% for PA vs. C+P and 2.96% vs. 9.86% for B+P vs. C+P), assuming a type 1 error rate of 2.5%.

It was subsequently (November 2014) agreed with the NIHR HTA programme that, owing to the already variable follow-up and in order to maximise the chances of reaching the desired power, recruitment could continue until 30 June 2015 (with follow-up still finishing on 30 June 2017) and that new sites could be added to facilitate this recruitment on the understanding that any additional costs would be absorbed by the existing budget.

Participant timeline: screening, recruitment, consent, retention, withdrawal and visit schedule

The flow diagram of the FiCTION trial is shown in Figure 1. The participant identification and recruitment strategy were informed by the experiences in the pilot trial. 86

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of the FiCTION trial.

Identification and screening of participants

Potential trial participants were children aged 3–7 years who were identified from participating dental practices, which invited the potential participants to participate through two routes:

-

Simple searches of practice databases to identify potentially eligible children, using a date of birth query. Potentially eligible children due for a recall visit were invited to participate by letter of invitation from the child’s GDP. This letter, together with information sheets for parents and the child (the child’s version was pictorial and age-appropriate), was sent with their dental appointment card at least 1 week ahead of the scheduled recall visit.

-

Parents of children presenting opportunistically, and identified as being potentially eligible for participation, were invited to participate at the time of presentation. Unless they declined immediately these parents were given the invitation letter and the parent and child information sheets, and time (a minimum of 24 hours) was allowed to consider participation in the trial before consent was sought.

Potential participants identified through both routes had a routine screening examination (‘check-up’) to confirm eligibility. This screening consisted of standard dental recall clinical investigations (including medical and dental history taking, questioning regarding oral pain since last visit and current oral pain, clinical examination of the soft tissues and teeth, and radiographs in line with national guidance). This allowed the identification of children with dental caries and the exclusion of children with current dental pain or dental sepsis due to caries, as well as medically compromised children.

For those children without evidence of caries into dentine or where dental pain due to caries and/or dental sepsis were present at the screening visit, the GDP explained why it was not possible to take part in the FiCTION trial at that time and, if relevant, treated the carious lesion(s) and related pain and/or sepsis. The family was informed that if the child re-presented with dental caries but without pain or sepsis, he or she could then be considered for the FiCTION trial. If a child was caries-free at screening but subsequently presented to the practice with caries during the recruitment phase of the trial, he or she could be invited to join the trial.

Recruitment and consent

Post screening, if there was evidence of dental caries and absence of both dental pain due to caries and dental sepsis, a FiCTION trial-trained dentist in the practice discussed the trial with the parent and child, supplementing the written trial information, and answered any questions they may have had. If the parent and child were willing to participate, and once eligibility had been confirmed, parental written informed consent, and oral or written assent from the child, were obtained by the FiCTION trial-trained dentist prior to any trial-specific procedures being carried out.

The child was then given a subsequent treatment appointment. It was intended that randomisation to a treatment arm should be carried out via the NCTU secure web-based randomisation service before the child returned for the subsequent visit, at which time the child and parent would be informed of the treatment arm to which the child had been allocated. A detailed ICDAS dental chart was completed at the initial treatment visit. Treatment was commenced as per the child’s randomised arm and clinical protocol. Families were also presented with a letter to give to their general medical practitioner to inform them of the child’s involvement in the trial.

For those children for whom consent was not given for participation in the trial, the dentist carried out the child’s normal dental care.

Participant management and visit schedule