Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned and funded by the HTA programme on behalf of NICE as project number 16/51/20. The protocol was agreed in January 2017. The assessment report began editorial review in August 2017 and was accepted for publication in November 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Fleeman et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Thyroid cancer: overview

Thyroid cancer is a rare cancer, representing only 1% of all malignancies in England and Wales. 1 It is caused by the growth of abnormal cells in the thyroid gland. This is a small gland at the base of the neck that secretes three hormones: triiodothyronine (T3), thyroxine (T4) and calcitonin. T3 and T4 control the rate of metabolism in the body, and calcitonin works with the parathyroid hormone to control the amount of calcium in the blood. 2 Thyroid cancer is usually asymptomatic and is often discovered incidentally via imaging studies [e.g. sonograms, computerised tomography (CT) scans and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)] that are carried out for another reason, or when patients present with a large palpable nodule in the neck. 3 The actual diagnosis of thyroid cancer is usually made using ultrasonography and biopsy (typically, a fine-needle aspiration). 4

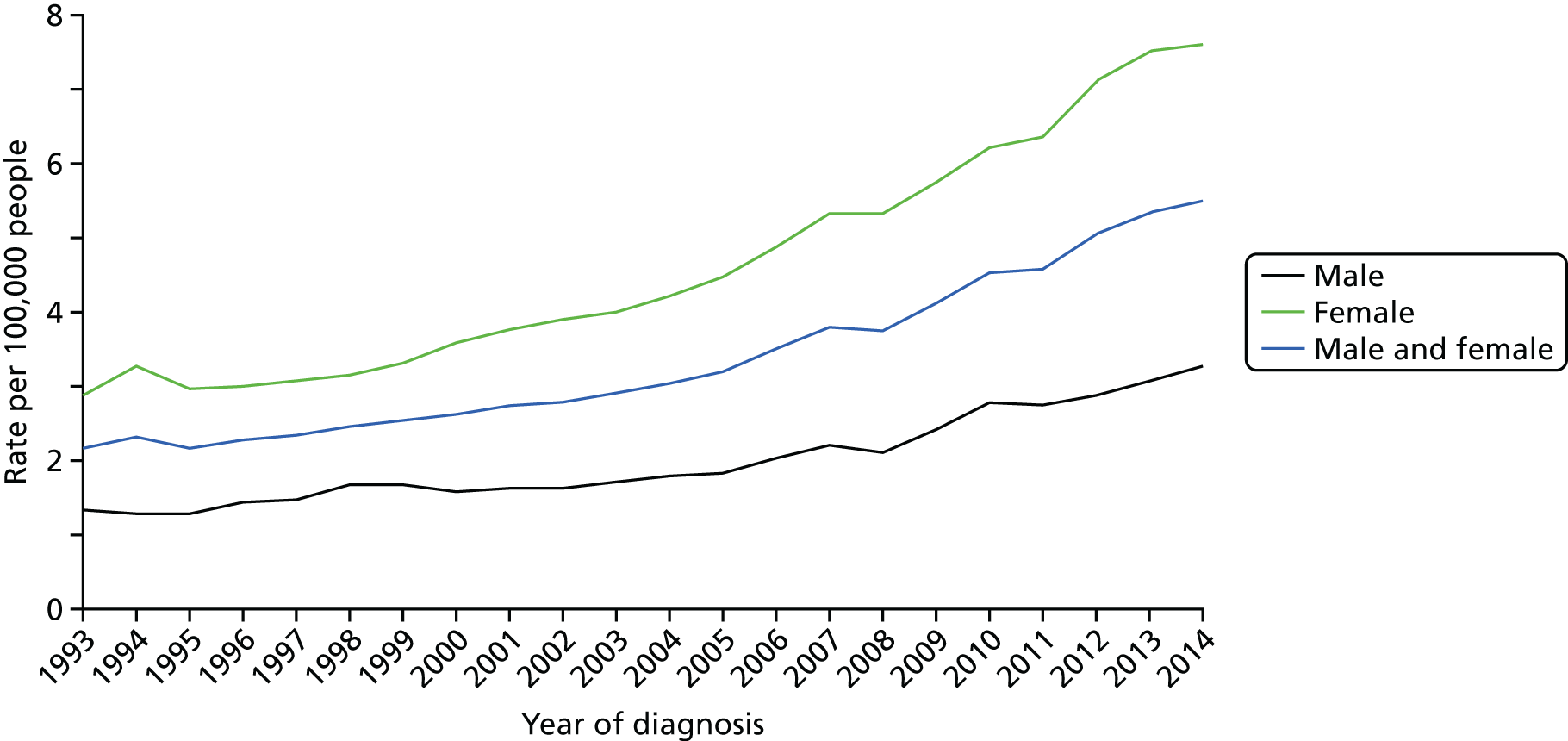

The incidence of thyroid cancer is increasing worldwide. 4–10 In the UK, between the period 2003–5 and the period 2012–14, thyroid cancer incidence rates increased by 74% (Figure 1). 1 In 2014, there were 3404 patients diagnosed with thyroid cancer in the UK, 2941 in England and 123 in Wales. 1 The reasons for the increase in incidence are unknown, but are thought to be, at least in part, attributable to improved diagnostic and detection techniques. 11

FIGURE 1.

Average number of new cases per year per 100,000 people in the UK. Based on a graphic created by Cancer Research UK. 1

The incidence of thyroid cancer is 2.5 times greater in women than in men. 1 The reasons for this disparity are unclear. 12 Thyroid cancer incidence is strongly related to age, with the highest incidence rates being in older males, and the highest incidence rates among females being in younger and middle-aged women (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Age-specific incidence rates per 100,000 people in the UK. Based on a graphic created by Cancer Research UK. 1

In the UK, thyroid cancer accounts for < 1% of male cancer deaths and < 1% of female cancer deaths. 13 The mortality rate in the UK is reported to be < 1 death per 100,000 people. 13 In 2014, there were 376 thyroid cancer deaths in the UK, 154 (41%) in males and 222 (59%) in females, giving a male-to-female ratio of around 7 : 10. In England and Wales, there were 331 thyroid cancer deaths: 137 in males and 194 in females. 13

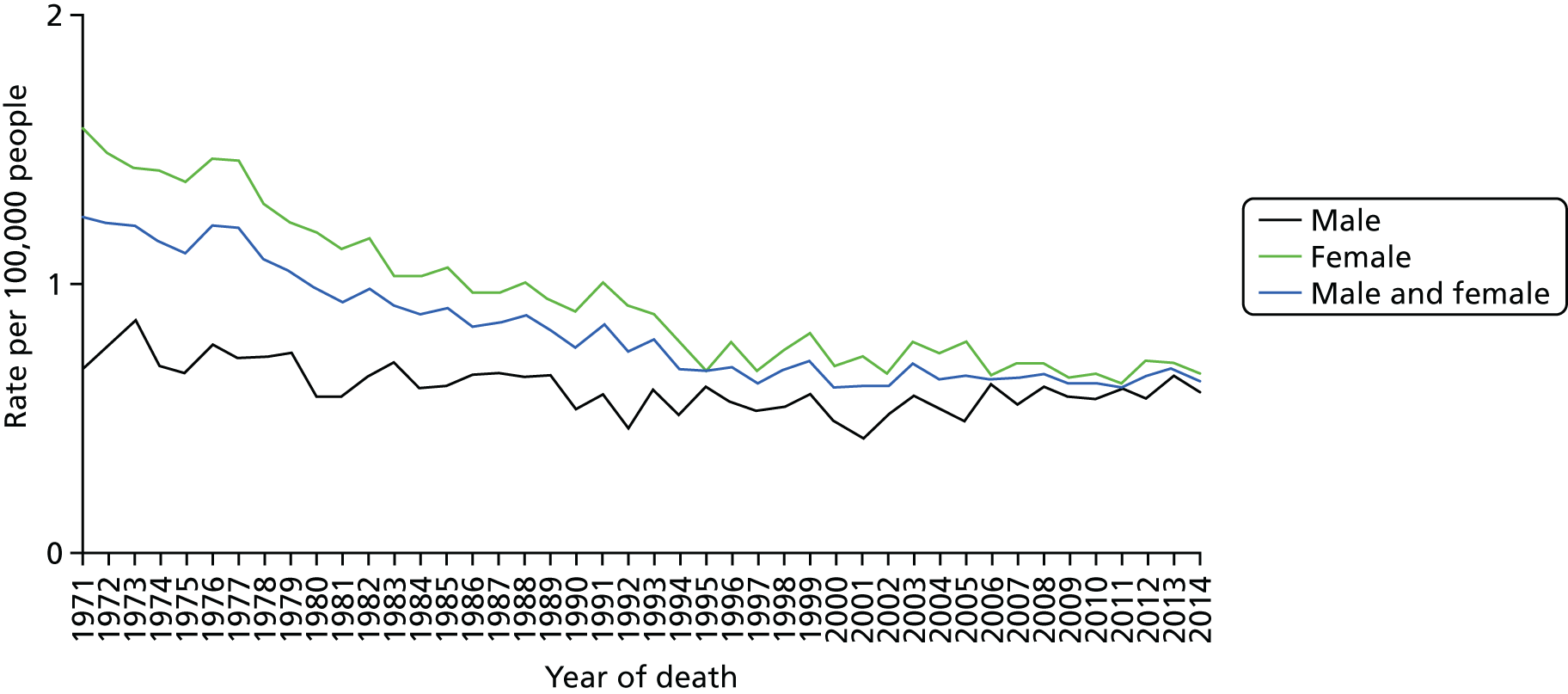

Although the incidence of thyroid cancer in the UK increased between the period 2003–5 and the period 2012–14, overall mortality rates remained stable during this time (Figure 3);13 however, between 1970 and 2014, thyroid cancer mortality rates decreased by 46% in the UK, the decrease being more marked in females (54%) than in males (24%). 13 Mortality rates for thyroid cancer are projected to rise in the future: in the UK, it is expected that between 2014 and 2035 mortality will increase by 7%; however, the overall rate is expected to remain relatively low at 1 death per 100,000 people. 13

FIGURE 3.

European age-standardised thyroid cancer mortality rates in the UK: 1971–2014. Based on a graphic created by Cancer Research UK. 13

Differentiated thyroid cancer

The most common form of thyroid cancer is differentiated thyroid cancer (DTC); DTC is reported to account for approximately 94% of thyroid carcinomas. 14,15 Less common types of thyroid cancer include medullary carcinoma and anaplastic carcinoma; these have been reported to account for approximately 4% and approximately 2% of all thyroid carcinomas, respectively. 15

Differentiated thyroid cancer is a specific type of thyroid cancer made up of different subtypes including papillary carcinoma (PTC), follicular carcinoma (FTC) and Hürthle cell carcinoma. PTC is the most common type of DTC, accounting for approximately 83%15 to 86%16 of all cases; FTC accounts for approximately 10%16 to 13%,15 and Hürthle cell carcinoma accounts for approximately 3%15 to 4%. 16 Hürthle cell carcinomas are usually grouped with FTCs because they present and behave similarly. 17

The median age for all patients with DTC is reported to be 45 years;18 however, estimates of the median age at onset for the subtypes of DTC have been reported to vary:

-

Papillary carcinoma often affects people aged < 40 years,17 but it is also reported that the median age of patients with PTC is 45 years. 19

-

The peak age for the onset of FTC has been stated to be between 40 and 60 years,20 but, again, the median age has been reported to be approximately 45 years. 21

-

The median age of patients with Hürthle cell carcinoma has been reported to be 55 years. 21

In general, the prognosis for patients with DTC is relatively good. The overall 10-year survival rate for middle-aged adults is reported to be 80–90%. 4 It has also been reported that > 85% of patients with DTC have a ‘normal’ life expectancy;22 however, the prognosis generally gets worse with increasing age at the time of diagnosis, particularly for patients aged ≥ 45 years. 4 In addition, young children (aged < 10 years) are at higher risk of recurrence than older children. 4 Prognosis may also be affected by DTC subtype (histology). An analysis of US National Cancer Database data on 41,375 patients with DTC who were treated between 1985 and 199515 has shown that the 10-year relative survival for patients with PTC is 93%, whereas for patients with FTC it is 85%, and for patients with Hürthle cell carcinoma it is 76%.

The size and spread of the tumour affect prognosis. Studies cited by the British Thyroid Association (BTA)4 are reported to show that the risk of recurrence and mortality correlates with the size of the primary tumour. Extrathyroidal invasion, lymph node metastases and distant metastases are also reported to be important prognostic factors. 4

First-line treatment options for patients with differentiated thyroid cancer

There are currently no National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines and no NICE guidance for treating patients with DTC or any other type of thyroid cancer. Other clinical guidelines do present some recommendations. In chronological order from date of publication, relevant clinical guidelines include the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) guidelines (2012),23 BTA guidelines (2014),4 American Thyroid Association guidelines (2015)24 and National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines (2017). 25

Owing to the indolent course of the disease, many patients with DTC, even if they have metastatic disease, do not require therapy for several years after diagnosis. 26 Treatments for DTC depend on factors including age, extent of disease, and histology, but usually involve surgery to remove all or part of the thyroid gland (thyroidectomy) followed by lifelong thyroxine for thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) suppression from the low–normal to fully suppressed range dependent on risk factors. 4,23–25

Treatment options for patients with differentiated thyroid cancer that has progressed following surgery

Following initial surgery, it is estimated that between 5% and 20% of patients with DTC develop local or regional recurrences (approximately two-thirds of these involve cervical lymph nodes27) and between 10% and 15% of patients with DTC develop distant metastases. 4,24 The most common sites for metastases are reported to be the lungs (50%), bones (25%), lungs and bones (20%) or other (5%). 24 It has been noted that the presence of bone metastases has been associated with a worse prognosis than metastases in other sites. 23

The sites that DTC is most likely to spread to vary by histology. For patients aged > 40 years, it has been reported that 10% of patients with PTC, 25% of patients with FTC and 35% of patients with Hürthle cell carcinoma develop distant metastases. 28,29 PTC tends to spread to lymph nodes in the neck, whereas FTC usually spreads to the bones or lungs. 17 Hürthle cell carcinoma is more likely than FTC to spread to lymph nodes in the neck. 30

A radioactive iodine uptake test is commonly used to determine whether or not DTC has spread. The test involves a patient being given a liquid or capsule containing radioactive iodine (iodine-123) to swallow. Two separate uptake measurements are then commonly obtained at different time points within a 24-hour period. The patient is then scanned to see how much of this radioactive iodine has been absorbed by the thyroid (radioactive uptake). Positive results (evidence of iodine-123 uptake) denote the presence of disease, whereas negative results (no radioactive uptake) denote the absence of disease.

It is recommended in clinical guidelines4,23–25 that patients with DTC and evidence of radioactive iodine uptake should undergo treatment with radioactive iodine (also known as radioactive iodine ablation) to treat residual, recurrent or metastatic disease. Patients are typically tested 1–2 months after surgery. Radioactive iodine treatment has been used for > 60 years. It is administered in hospital (during an inpatient stay) and can be given to patients on more than one occasion, as necessary. 4

Like the radioactive iodine uptake test used to diagnose DTC, radioactive iodine treatment involves swallowing radioactive iodine in either liquid or capsule form; however, the radioactive iodine is a different form (iodine-131) to that used for scans (iodine-123): the purpose of radioactive iodine treatment is to destroy cancerous cells. Thus, patients with iodine-131 uptake are responsive to treatment, which can be confirmed by imaging studies.

Approximately 33% of patients with advanced disease can be cured and many others achieve long-term disease stabilisation. 31 From published French registry data,32 the 10-year survival rate for patients with distant metastases who successfully responded to treatment with radioactive iodine is 92%. 32

Radioactive iodine-refractory differentiated thyroid cancer

Although for many patients radioactive iodine is an effective treatment, some patients become resistant to the treatment (decreased or no radioactive iodine uptake) or are unable to safely tolerate additional doses. These patients are considered to have radioactive iodine-refractory DTC (RR-DTC) and are the focus of this multiple technology appraisal (MTA).

Although clinical criteria and algorithms have been developed and reported in clinical guidelines,4,23–25 there is no agreed precise definition of RR-DTC;33 however, a review of the literature published in February 201731 highlights key features that can be considered in defining RR-DTC:

-

Metastatic disease that does not take up radioactive iodine at the time of the first radioactive iodine treatment.

-

Ability to take up radioactive iodine has been lost after previous evidence of uptake of radioactive iodine.

-

Radioactive iodine uptake is retained in some lesions but not in others.

-

Metastatic disease that progresses despite substantial uptake of radioactive iodine.

-

Absence of complete response to treatment after > 600 mCi of cumulative activity of radioactive iodine.

-

Evidence of high uptake of fludeoxyglucose (FDG) 18F on positron emission tomography or CT scan; however, importantly, the authors of this review31 state that this reason alone should not be used to abandon radioactive iodine treatment.

Before deciding whether or not a patient’s disease can be described as being RR-DTC, it is important to determine that decreased radioactive iodine uptake is not due to iodine contamination or insufficient TSH. 34

Radioactive iodine-refractory DTC is a life-threatening form of thyroid cancer with a tendency to progress and metastasise. 14 From published French registry data,32 the 10-year survival rate and median overall survival (OS) for patients with distant metastases who failed to respond to treatment (no iodine-131 uptake) was 10% and 3 years, respectively. For those who appear to respond to radioactive iodine treatment (iodine-131 uptake) but who did not then attain negative imaging studies, the 10-year survival and median OS was 29% and 6 years, respectively. A separate analysis of patients with lung and/or bone metastases35 found that 10-year survival and median OS for those who did not have a complete response to treatment with radioactive iodine was 14% and 5 years, respectively. Data from Canada5 have suggested that the median OS for patients with RR-DTC may be between 2.5 and 3.5 years.

The proportion of patients whose disease becomes refractory to treatment with radioactive iodine is relatively small, and so RR-DTC is described as an ultra-orphan condition. 7,8 Estimates of the proportion of patients who become refractory vary but commonly lie within the range of 5–15%. 7,8,14,16,32,35–37

As with early-stage DTC, many patients with RR-DTC are initially asymptomatic. As highlighted in a literature review published by Schmidt et al.,31 even patients with distant metastases may have a disease that does not progress for many years; however, as noted by Thyroid Cancer Canada,5 the cancer continues to progress with no obvious symptoms.

For patients with rapidly progressing disease, which is characterised by symptomatic disease, the symptoms of RR-DTC can be severe, profoundly debilitating and result in patients becoming increasingly dependent on carers. 8 Clinical advice to the Assessment Group (AG) is that the percentage of patients with RR-DTC with rapidly progressing disease is likely to be approximately 25% to 30%. As a result of their symptoms, patients with clinically significant progressive RR-DTC may suffer a poor quality of life and the psychological impact of the disease can also be substantial, resulting in low mood and fatigue. 38 It has also been stated that patients with RR-DTC often experience multiple complications. 39

Treatment options for patients with radioactive iodine-refractory differentiated thyroid cancer

Radioactive iodine-refractory DTC is typically asymptomatic, but symptoms start to occur as the disease progresses. Symptoms associated with lymph nodes of the neck include difficulty swallowing and/or breathing, pain or sensitivity in the front of the neck or throat, hoarseness or other voice changes, and swelling of the lymph nodes in the neck. 4 Symptoms associated with lung metastases also include swallowing and breathing difficulties. 26 Pain often presents as the principal symptom of metastatic bone involvement. 29,40 Fractures and spinal cord compression are also associated with bone metastases.

Because many treatments, particularly systemic treatments, can have severe side effects and impact significantly on health-related quality of life (HRQoL), clinical advice to the AG is that best supportive care (BSC) tends to be the preferred treatment option, at least until symptoms occur. BSC typically entails TSH suppression therapy and imaging every 3 to 12 months. Palliative radiotherapy and symptom relief are also offered when necessary.

Patients experiencing RR-DTC symptoms and/or patients with rapidly progressing disease are those in need of systemic treatment,31 as reflected in clinical guidelines. 4,23–25 The aim of systemic treatment for patients with rapidly progressing and/or symptomatic RR-DTC is to gain local disease control in the neck and manage systemic disease. 41 Another important objective of treatment is to prolong survival;27 however, treatment options for patients with RR-DTC are limited. Within the ESMO guidelines published in 2012,23 it is stated that chemotherapy should not be given to patients with RR-DTC as it is associated with significant toxicity with no proven evidence of effectiveness. The authors of these guidelines stated that surgical resection and external beam radiotherapy represented the only therapeutic options and they strongly encouraged enrolment of patients in experimental trials with targeted therapy. Similarly, the authors of the guidelines published by the BTA in 20144 only recommended chemotherapy for patients with rapidly progressive, symptomatic RR-DTC who have good performance status (PS), and only when access to targeted therapies in clinical trials is unavailable or when targeted therapies have proved unsuccessful. The authors of the more recent US guidelines published by the American Thyroid Association24 and NCCN25 recommend that patients with RR-DTC should usually avoid treatment with chemotherapy. Clinical advice received by the AG is that chemotherapy is rarely used to treat RR-DTC in UK NHS practice.

Targeted therapies were not widely available and were only the subject of clinical trials between 2012 and 2014, when the ESMO guidelines23 and the BTA guidelines4 were published. The authors of the BTA guidelines4 considered the most promising targeted therapies at that time to be lenvatinib and sorafenib. 4 By 2017, the authors of the NCCN guidelines25 recommended lenvatinib or sorafenib as the treatment of choice for patients with progressive and/or symptomatic disease; lenvatinib is stated to be the ‘preferred’ option based on a response rate of 65% for lenvatinib, compared with 12% for sorafenib, although these agents have not been directly compared. However, the authors state that the decision should be based on the individual patient, taking into account the likelihood of response and comorbidities. 25 In cases in which lenvatinib or sorafenib are not available or not appropriate, drugs not regulated by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) but used in the context of clinical trials are also recommended by the authors of the NCCN guidelines. 25

Description of technology under assessment

The two interventions under consideration in this MTA are lenvatinib (Lenvima), manufactured by Eisai Ltd, and sorafenib (Nexavar), manufactured by Bayer HealthCare. Both are a type of tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) known as a multikinase inhibitor (MKI).

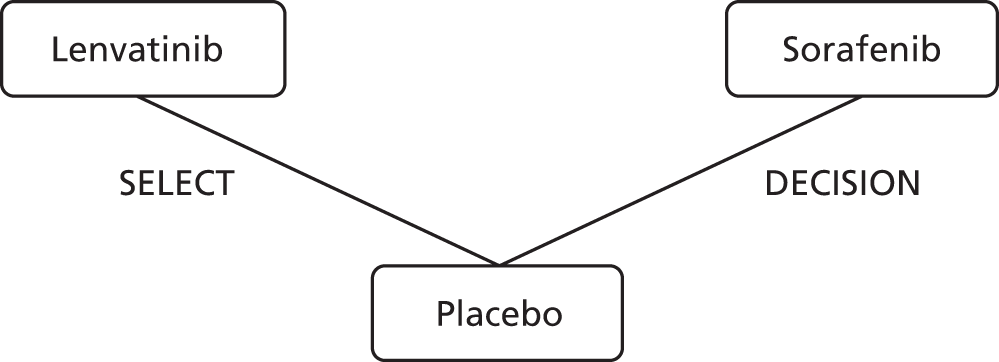

A brief comparison of the key features of the two interventions is given in Table 1. The AG notes that lenvatinib and sorafenib appear to have slightly different mechanisms of action. 42 Both drugs have been approved for treating RR-DTC in the USA43,44 and Europe,49,50 with sorafenib being the first of the two agents to be approved in both jurisdictions. In the USA and Europe, the marketing indications for both lenvatinib and sorafenib are for identical patient populations. Approval in the USA and Europe was based largely on evidence from two Phase III randomised controlled trials (RCTs): SELECT,51 in which lenvatinib was compared with placebo, and DECISION (StuDy of sorafEnib in loCally advanced or metastatIc patientS with radioactive Iodine-refractory thyrOid caNcer),52 in which sorafenib was compared with placebo.

| Feature | Lenvatinib | Sorafenib |

|---|---|---|

| Brand name | Lenvima | Nexavar |

| Manufacturer | Eisai Ltd | Bayer HealthCare |

| Class of drug | Oral MKI | Oral MKI |

| Mechanism of action | Targets VEGFR1, VEGFR2, VEGFR3, FGFR1, FGFR2, FGFR3, FGFR4, PDGFR alpha, PDGFR beta, RET and KIT42 | Targets BRAF, RET, VEGFR2 and VEGFR342 |

| US marketing indication | For the treatment of locally recurrent or metastatic, progressive, RR-DTC (15 February 2015)43 | For the treatment of locally recurrent or metastatic, progressive, differentiated thyroid carcinoma refractory to radioactive iodine treatment (22 November 2013)44 |

| European Union marketing indication | For the treatment of adult patients with progressive, locally advanced or metastatic, differentiated (papillary/follicular/Hürthle cell) thyroid carcinoma, refractory to radioactive iodine (28 May 2015)45 |

For the treatment of patients with progressive, locally advanced or metastatic, differentiated (papillary/follicular/Hürthle cell) thyroid carcinoma, refractory to radioactive iodine (25 January 2015)46 In addition to RR-DTC, sorafenib is also indicated for treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma and the treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma46 |

| Dose information for treating RR-DTC |

24 mg (two 10-mg capsules and one 4-mg capsule) once daily AEs can be managed through dose reduction and treatment is continued until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity45 |

400 mg (two 200-mg tablets) twice daily, taken without food or with a low-fat meal AEs can be managed through dose reduction and treatment is continued until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity46 |

| Important identified risks |

Important risks highlighted by the EMA27 include hypertension, proteinuria, renal failure or impairment, hypokalaemia, cardiac failure, posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome, hepatotoxicity, haemorrhagic events, arterial thromboembolic events, QTc prolongation and hypocalcaemia Further information, including how to manage some of the risks (e.g. the use of hypertensives for hypertension) is provided in the SmPC46 |

Important risks highlighted by the EMA26 include severe skin AEs; hand–foot syndrome; hypertension; posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome; haemorrhage including lung haemorrhage, gastrointestinal haemorrhage and cerebral haemorrhage; arterial thrombosis (myocardial infarction); congestive heart failure; squamous cell cancer of the skin; gastrointestinal perforation; symptomatic pancreatitis and increases in lipase and amylase; hypophosphataemia; renal dysfunction; interstitial lung disease-like events; and drug-induced hepatitis Further information, including how to manage some of the risks (e.g. the use of topical therapies, temporary treatment interruption and/or dose modification or treatment discontinuation for hand–foot syndrome) is provided in the SmPC46 |

| List price per pack | £1437.00 for a pack of 30 4-mg capsules and £1437.00 for a pack of 30 10-mg capsules8 | £3576.56 for a pack of 112 200-mg tablets47 |

| Cost per yeara | £52,30738 | £38,74648 |

Approval for use in NHS Scotland was granted to sorafenib in June 201548 and to lenvatinib in September 2016. 38 Both approvals are for the treatment of patients with progressive, locally advanced or metastatic RR-DTC. In NHS Scotland, the use of both lenvatinib and sorafenib is contingent on the continuing availability of Patient Access Scheme (PAS) prices that have been assessed by the PAS Assessment Group.

Sorafenib has been available in England, since July 2016, via the Cancer Drugs Fund (CDF). It is currently funded for all patients with RR-DTC for whom the treating specialist has established that treatment with sorafenib may be beneficial. According to Bayer HealthCare, based on its analysis of notification data from July 2013 to June 2016, sorafenib has become the standard of care for patients for whom systemic treatment is appropriate. 7 Lenvatinib is not currently available to patients treated in the English or Welsh NHS.

Eisai Ltd8 has estimated the incidence of patients in England and Wales with RR-DTC who are potentially eligible for treatment with lenvatinib or sorafenib to be approximately 280 each year. Bayer HealthCare7 has estimated the incidence to be approximately 225 patients per year. The AG notes that the estimates given by the companies differ in how they are calculated. The estimates provided by the companies are reflective of the population defined by the agreed final scope of this appraisal; however, neither estimate appears to account for the fact that lenvatinib and sorafenib are likely to only be preferred for patients with symptomatic and/or rapidly progressing disease. Clinical advice to the AG is that there are no generally agreed definitions of ‘symptomatic’ or ‘rapidly progressive disease’ and that, in clinical practice, definition of a patient’s disease status depends on individual patient characteristics. Therefore, it is difficult to further segment the population.

Chapter 2 Definition of the decision problem

Decision problem addressed by the Assessment Group

The decision problem for this appraisal, as described in the final scope issued by NICE,53 is summarised in Table 2.

| Parameter | In the NICE scope53 | Addressed by the AG |

|---|---|---|

| Interventions |

Lenvatinib Sorafenib |

As per scope |

| Population | Adults with progressive, locally advanced or metastatic, differentiated thyroid carcinoma refractory to radioactive iodine | As per scope |

| Comparators |

The interventions listed above will be compared with each other BSC |

Explore the feasibility of comparing lenvatinib with sorafenib Comparisons of interventions with BSC |

| Outcomes | The outcome measures to be considered include:

|

As per scope |

| Economic analysis |

The reference case stipulates that the cost-effectiveness of treatments should be expressed in terms of incremental cost per quality-adjusted life-year The reference case stipulates that the time horizon for estimating clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness should be sufficiently long to reflect any differences in costs or outcomes between the technologies being compared Costs will be considered from a NHS and Personal Social Services perspective |

As per scope |

| Other considerations |

If the evidence allows, consideration will be given to subgroups based on previous treatment with TKIs Guidance will only be issued in accordance with the marketing authorisation. When the wording of the therapeutic indication does not include specific treatment combinations, guidance will be issued only in the context of the evidence that has underpinned the marketing authorisation granted by the regulator |

As per scope |

The overall aims and objectives of the assessment

The aim of this research was to assess the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of lenvatinib versus sorafenib, within their respective EU marketing authorisations,45,46 for the treatment of patients with RR-DTC. The research objectives are given below:

-

To carry out systematic reviews to compare the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of –

-

treatment with lenvatinib with treatment with sorafenib for RR-DTC

-

treatment with lenvatinib with BSC for RR-DTC

-

treatment with sorafenib with BSC for RR-DTC.

-

-

To develop an economic model to compare the cost-effectiveness of –

-

treatment with lenvatinib with treatment with sorafenib for RR-DTC

-

treatment with lenvatinib with BSC for RR-DTC

-

treatment with sorafenib with BSC for RR-DTC.

-

Chapter 3 Methods for reviewing clinical effectiveness literature

Search strategy

The AG identified clinical studies and systematic reviews by searching EMBASE, MEDLINE, PubMed and The Cochrane Library from 1999 onwards. All databases were searched on 10 January 2017. Based on the fact that the FDA approved sorafenib for its first indication in 2005, and lenvatinib in 2015, the AG considered that this date span would allow all relevant clinical evidence to be identified. Searches were restricted to publications in English language. The AG did not use any other search filters. The search strategies used by the AG are provided in Appendix 1. In addition to the electronic database searches, information on studies in progress was sought (on 16 May 2017) by searching the ClinicalTrials.gov website, the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform and the European Union Clinical Trials Register. The references in the systematic reviews included in the AG’s review of systematic reviews, and those listed in the submissions from professional stakeholders that were submitted to NICE, as part of the NICE MTA process, were cross-checked to identify any relevant studies not retrieved from the electronic database searches. Literature search results were uploaded to and managed using EndNote X7.4 [Clarivate Analytics (formerly Thomson Reuters), Philadelphia, PA, USA] software.

Study selection

The eligibility criteria listed in Table 3 were used to identify studies for inclusion in the AG’s literature review.

| Criteria | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Patient population | Adults with progressive, locally advanced or metastatic, differentiated thyroid carcinoma refractory to radioactive iodine | Patients with other types of thyroid cancer or diseases |

| Interventions | Lenvatinib or sorafenib monotherapy (or in combination with BSC) | Lenvatinib or sorafenib in combination with other agents |

| Comparators | Lenvatinib or sorafenib monotherapy (or in combination with BSC), BSC and placebo | A comparator other than lenvatinib, sorafenib, BSC and placebo |

| Outcomes | The outcome measures to be considered include OS, progression-free survival, response rate, adverse effects of treatment and HRQoL | No study was excluded based on outcomes |

| Study design | RCTs, systematic reviews and prospective observational studies | Retrospective cohort studies, case series, case reports, comments, letters, editorials, in vitro, animal and genetic or histochemical studies |

| Restrictions | English language only | Non-English-language studies |

Two reviewers (JH and RH) independently screened all titles and abstracts that were identified in the initial searches (screening stage 1). Based on the titles and abstracts, full-text papers that appeared to be relevant were obtained and assessed for inclusion by the same two reviewers in accordance with the AG’s eligibility criteria (screening stage 2). When necessary, discrepancies were resolved by consultation with a third reviewer (NF). At both stages of screening, studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded, and, at screening stage 2, the reasons for excluding studies were noted.

The eligibility criteria in Table 3 differ slightly from those specified in the AG’s systematic review protocol. 55 The AG, responding to a suggestion from NICE in relation to the final protocol,55 agreed to include evidence from prospective observational studies that had been submitted to the European Medicines Agency (EMA); however, as only reviewing studies included in the EMA submissions26,27 would have introduced selection bias, the AG included all prospective observational studies of patients with RR-DTC identified by its searches.

Data extraction and quality assessment strategy

Data relating to RCT study characteristics and outcomes were extracted by one reviewer (NF) and independently checked for accuracy by a second reviewer (YD). Data relating to study characteristics and outcomes of systematic reviews and observational studies were extracted by one reviewer (JH or NF) and independently checked for accuracy by a second reviewer (JG). In all cases, a consensus was reached. Study data reported in multiple publications were extracted and reported as a single study. Data were extracted into tables in Microsoft Word (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA).

As specified in the AG’s systematic review protocol,55 the quality of included RCTs and systematic reviews was assessed according to the criteria set out in the Centre for Review and Dissemination’s guidance56 for undertaking reviews in health care. The quality of the included RCTs was assessed by one reviewer (YD) and independently checked for agreement by a second reviewer (NF). In all cases, a consensus was reached. The quality of the included systematic reviews was assessed by one reviewer (JG) and independently checked for agreement by a second reviewer (YD). When necessary, discrepancies were resolved by consultation with a third reviewer (MR).

Methods of analysis/synthesis

The AG’s data extraction and quality assessment results are presented in structured tables and as a narrative summary. Data from RCTs are considered to provide primary clinical effectiveness evidence, with data from systematic reviews and observational studies considered to provide supporting evidence.

As the available evidence did not include two or more RCTs comparing the same intervention, the AG was not able to conduct a meta-analysis of RCT data.

The AG assessed the feasibility of conducting an indirect comparison of effectiveness data (including a comparison to assess effectiveness according to previous treatment with TKIs) by evaluating the clinical and methodological heterogeneity of the included RCTs. Heterogeneity was assessed by comparing (1) trial characteristics, (2) participant characteristics, (3) outcome data and (4) study quality.

Chapter 4 Findings from the systematic review of clinical effectiveness literature

Quantity and quality of research available

Included studies

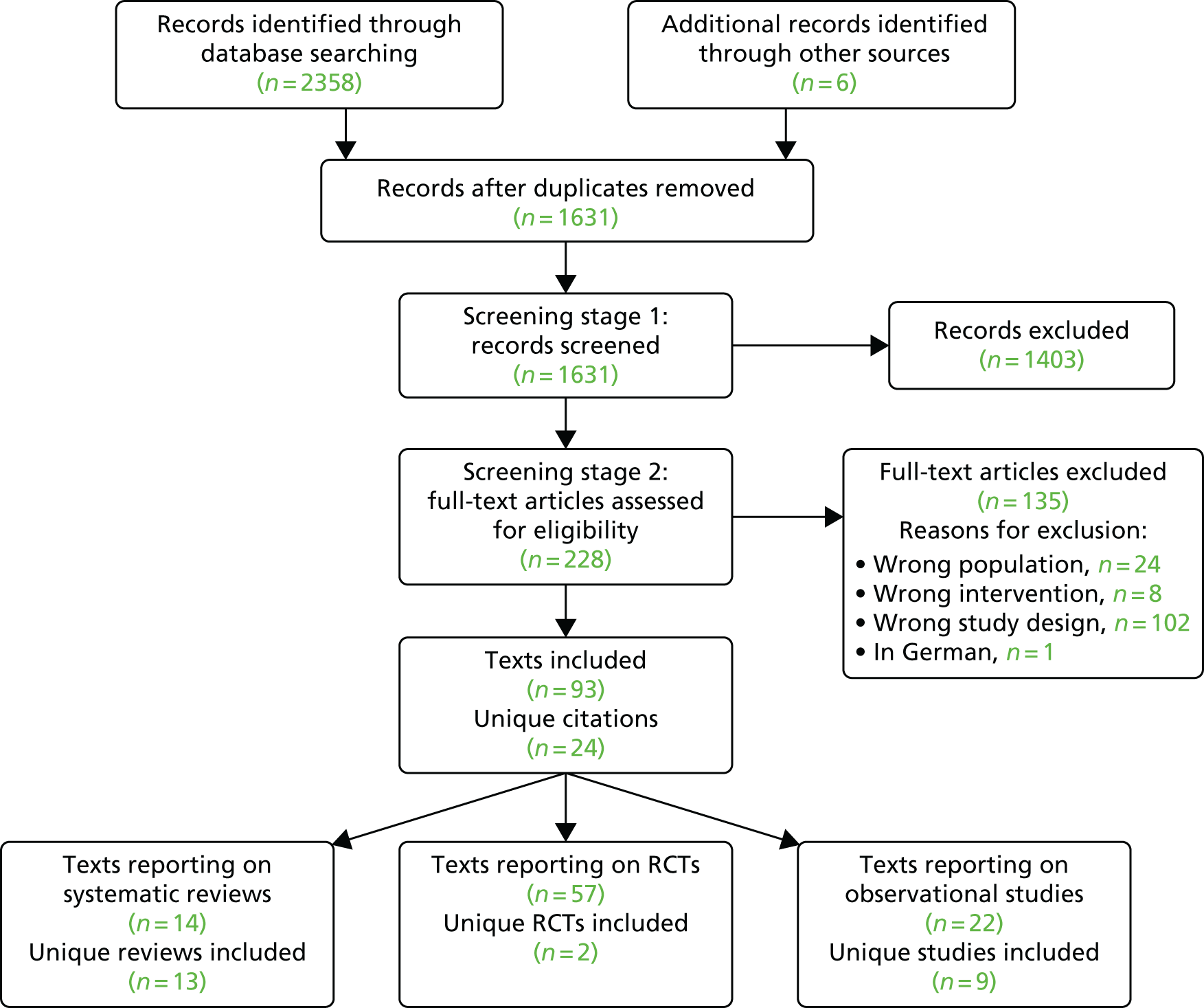

The process of study selection is shown in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram in Figure 4. The electronic searches yielded 2358 papers, and six additional references5–8,57,58 were identified through other sources. In total, the AG included 93 papers5–8,33,51,52,57–142 reporting on 24 separate studies and reviews: two unique RCTs,51,52 13 unique systematic reviews5–8,33,57,61,93,97,104,127,138,141 and nine unique prospective observational studies. 59,77,78,81,88,101,103,126,135

FIGURE 4.

The PRISMA flow diagram: studies included in AG’s systematic review. Reproduced with permission from Fleeman et al. 54 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Excluded studies

A full list of studies excluded at stage 2 with reasons for exclusion is presented in Appendix 2, Table 32.

Evidence from randomised controlled trials

Only two RCTs were identified as relevant for inclusion in the AG’s systematic review: SELECT and DECISION. Except when stated otherwise, all information about these two trials has been extracted from the two key trial publications. 51,52

Trial characteristics

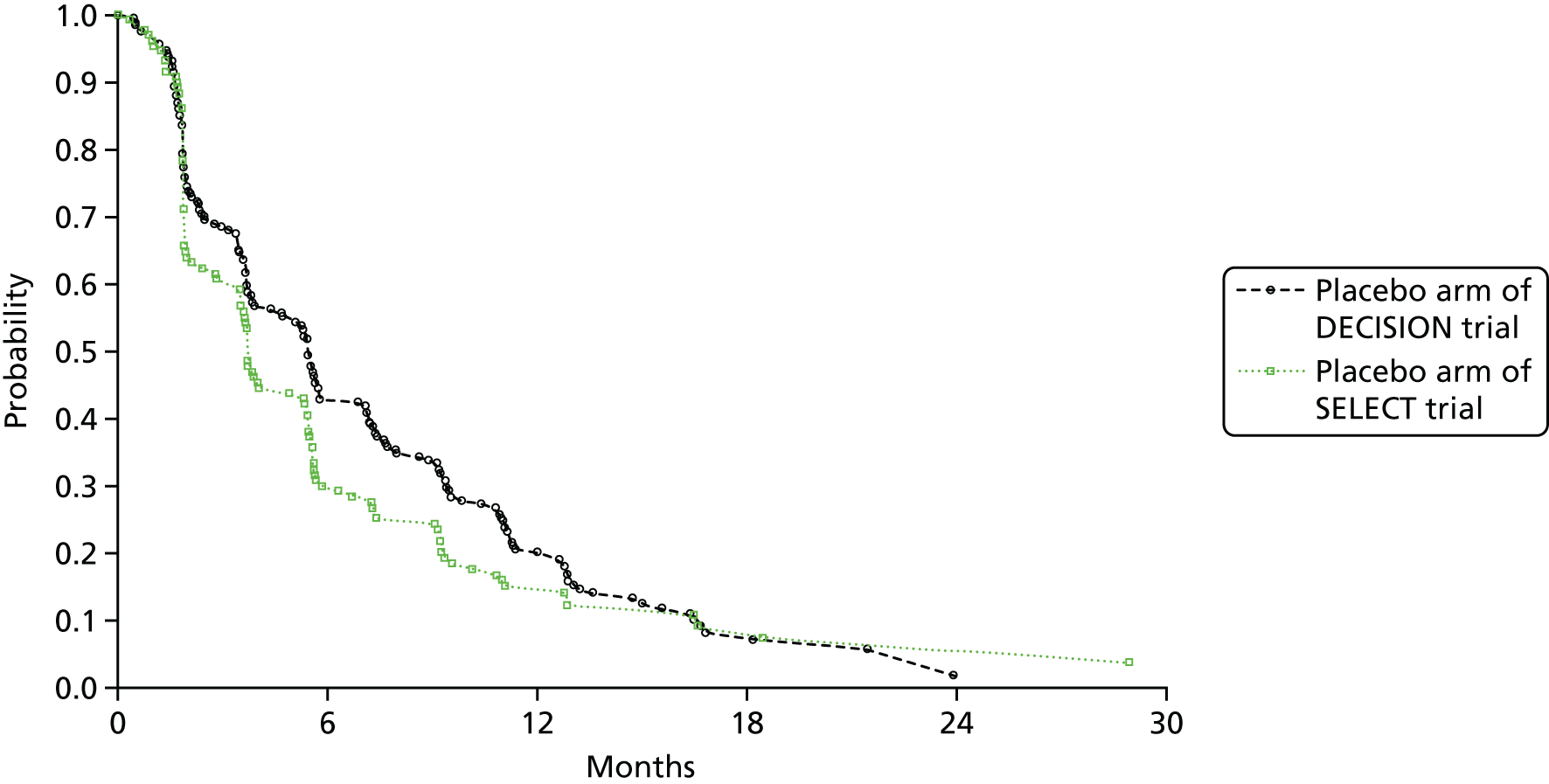

A summary of the characteristics of the two included trials is provided in Table 4. Both trials were Phase III, multicentre, double-blind RCTs designed to compare the intervention of interest (lenvatinib or sorafenib) with placebo. Subjects were randomised in a ratio of 2 : 1 to the intervention and comparator arms of SELECT, whereas they were randomised in a ratio of 1 : 1 in DECISION. In both trials, the primary outcome was progression-free survival (PFS) assessed by blinded independent review. Both trials also reported investigator-assessed PFS. Unless otherwise specified, in the remainder of this AG report on clinical effectiveness, PFS refers to PFS assessed by blinded independent review.

| Parameter | Study | |

|---|---|---|

| SELECT | DECISION | |

| Primary reference | Schlumberger et al. 201551 | Brose et al. 201452 |

| Number of centres | 117 | 81 |

| Stratification factors | Subjects were stratified by age (≤ 65 years or > 65 years), geographical region (Europe, North America or other) and receipt or non-receipt of prior VEGFR-targeted therapy (0 or 1) | Subjects were stratified by age (< 60 years or ≥ 60 years) and geographical region (North America, Europe or Asia) |

| Country | Centres were distributed as follows: Europe, 60 (51.3%); North America, 31 (26.5%); Asia Pacific, 13 (11.1%); Japan, 6 (5.1%); and Latin America, 7 (6.0%) | 18 countries from Europe (59.7%) (Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, Poland, Russia, Spain, Sweden, the Netherlands and the UK), the USA (17.3%) and Asia (23%) (China, Japan, South Korea and Saudi Arabia) |

| Recruitment period | 5 August 2011 to 4 October 2012 | 5 November 2009 to 29 August 2012 |

| Participants (n) | 612 assessed, 392 randomised | 556 enrolled, 419 randomised |

| Intervention dose and schedule | Lenvatinib 24 mg (two 10-mg capsules and one 4-mg capsule) continuous once daily (n = 261) | Sorafenib 400 mg (two 200-mg tablets) twice daily for a total daily dose of 800 mg (n = 207) |

| Comparator arm (n) | Placebo: 131 | Placebo: 210 |

| Primary outcome | PFS, assessed every 8 weeksa and determined by blinded independent imaging review conducted by the imaging core laboratory using RECIST 1.1 | PFS, assessed every 8 weeks by central independent blinded review using RECIST 1.0 |

| Relevant secondary outcomes |

|

|

| Primary analysis | ≥ 214 progression events or deaths | ≈267 progression events |

| Data cut-off points | November 2013, June 2014 and August 2015 | August 2012, May 2013 and July 2015 |

Analysis of clinical efficacy

All efficacy outcomes from both trials, including tumour response evaluations in SELECT, were undertaken using data from the intention-to-treat (ITT) population. Tumour response evaluations in DECISION were undertaken using data from the per-protocol population (i.e. randomised patients who were evaluable for tumour response with imaging data, had received the intervention or placebo as allocated and had no major protocol deviations).

Analysis of safety

Safety analyses for both trials were undertaken using data from the population of patients who were randomised and received at least one dose of study drug and had at least one post-baseline safety evaluation. In SELECT, the numbers of patients included in the ITT and safety populations were identical.

Patients eligible for inclusion

A summary of the criteria describing patient eligibility for entry into SELECT and DECISION is presented in Appendix 3, Table 33. Both trials only included patients with RR-DTC and who had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) PS of 0–2. As highlighted in Chapter 1, Radioactive iodine-refractory differentiated thyroid cancer, there is no universally agreed definition of RR-DTC. The definitions used to define RR-DTC in the two trials were broadly similar (see Appendix 3, Table 34, for definitions employed by the trials for RR-DTC).

The main difference in trial eligibility was that SELECT permitted the enrolment of patients who had been previously treated with a vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR)-targeted therapy (including sorafenib) and DECISION did not. Age, region and VEGFR-targeted therapy were stratification factors in SELECT, whereas age and region were stratification factors in DECISION.

Dose modifications/interruptions and concomitant therapy

In both trials, the starting dose for treatment with lenvatinib or sorafenib was the licensed dose (24 mg and 800 mg, respectively). Both trials permitted dose modifications or interruptions. The criteria were not stated in the protocol for SELECT but the summary of product characteristics (SmPC)45 includes a dose/toxicity management plan for lenvatinib. For DECISION, Brose et al. 72 stated that dose modifications or interruptions were allowed, based on specific criteria, for grade 2 to grade 3 hand–foot syndrome and other adverse events (AEs).

A summary of the concomitant therapies permitted and prohibited in each trial is presented in Appendix 3, Table 35. Although neither trial describes BSC for patients in either arm, permitted concomitant therapies could be considered to be BSC and were available to patients in both arms of both trials. The main difference between the two trials is that palliative radiotherapy, which is commonly available as part of BSC in UK NHS clinical practice, was not permitted in either arm of SELECT.

Subgroup analyses

In SELECT, subgroup analyses were prespecified for patients previously treated with a VEGFR-targeted therapy and for those who were not. Both trials also included prespecified subgroup analyses for age, region, sex and histology. Subgroup analyses were prespecified for PFS, OS and objective tumour response rate (ORR) in SELECT but only for PFS in DECISION. Other prespecified subgroup analyses in SELECT were for race and for patients whose TSH level was highest prior to progression. Other prespecified subgroup analyses in DECISION included site of metastasis, FDG take-up, prior radioactive iodine cumulative dosing, tumour burden as measured by number of target or non-target lesions and as measured by the sum of target diameters. Many other post hoc subgroup analyses were also conducted for both trials (see Appendix 3, Table 37).

Follow-up, dose intensity and treatment crossover and other subsequent therapy received

At the time of the primary data cut-off points for both trials, OS data were immature. Therefore, for both trials, OS was updated at two subsequent data cut-off points. The median duration of follow-up at each data cut-off point was approximately 17 months at the first data cut-off point in both trials and there were approximately 20 months of additional follow-up in both trials by the final data cut-off point (see Appendix 3, Table 36).

Patients were eligible to receive treatment (intervention or placebo) in both trials until disease progression. An important feature of both trials is that, on disease progression, patients were unblinded and permitted to cross over from the placebo arm to the active treatment arm. In both trials, patients who crossed over were entered into an open-label extension phase of the same trial. In DECISION, patients who had progressed on sorafenib were also eligible to enter the open-label extension phase of the trial and receive further sorafenib until further disease progression. However, patients who progressed on lenvatinib in SELECT were not permitted to receive additional lenvatinib in the open-label extension phase. Information on treatment crossover and subsequent treatment received is reported in Table 5; it is evident that the majority of patients in both placebo arms, and particularly in the placebo arm of SELECT, crossed over to receive lenvatinib or sorafenib.

| Characteristic | Study, n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SELECT | DECISION | |||

| Lenvatinib (N = 261) | Placebo (N = 131) | Sorafenib (N = 207) | Placebo (N = 210) | |

| Patients who crossed over: first data cut-off point | N/A | 109 (83.2) | 55 (26.6)a | 150 (71.4) |

| Patients who crossed over: second data cut-off point | N/A | 115 (87.8) | NR | 157 (74.8) |

| Patients who crossed over: third data cut-off point | N/A | 115 (87.8) | NR | 158 (75.0) |

In addition, some patients received subsequent anti-cancer treatments, not part of the trial protocols, on disease progression (see Appendix 3, Table 39). In SELECT, at the first data cut-off point (November 2013), 15.7% of patients randomised to lenvatinib and 12.2% of patients randomised to placebo received subsequent treatment. In DECISION, at the first data cut-off point (August 2012), 20.3% of patients randomised to sorafenib and 8.6% of patients randomised to placebo received subsequent treatments. For the most part, subsequent treatment in both trials comprised antineoplastic and immunomodulating agents. The specific antineoplastic and immunomodulating agents were reported only for SELECT, as data were not collected on the specific agents used during the trial follow-up for DECISION. Most commonly, patients received pazopanib (Votrient®, Novartis) (17.1% and 18.8% of patients who received subsequent therapy in the lenvatinib and placebo arms, respectively) and/or sorafenib (14.6% and 12.5% of patients who received subsequent therapy in the lenvatinib and placebo arms, respectively).

Methods used for adjusting for treatment crossover

As patients in both trials were permitted to cross over to receive the intervention drug on disease progression, the OS results are likely to be confounded. The authors of the SELECT publication51 employed the rank-preserving structural failure time model (RPSFTM) to adjust the OS results for patient crossover. The OS results from DECISION have been adjusted using both the RPSFTM and the iterative parameter estimation (IPE). The unadjusted and adjusted OS analyses have been reported in conference abstracts for SELECT,87 DECISION58,68,110 and in the company submissions. 7,8

As patients were not censored when they received postprogression treatments, the RPSFTM and IPE methods implicitly included all subsequent therapies as an inherent part of the intervention/control treatment effect. In other words, it is assumed that the subsequent therapy administered to patients in each arm of the trial is reflective of the subsequent therapy that would have been offered to patients receiving the same treatment in clinical practice.

The RPSFTM and IPE methods also both rely critically on the ‘common treatment effect’ assumption, that is, the effect of receiving the experimental treatment is the same when received on diagnosis (i.e. in patients initially randomised to the experimental arm) as it is in treatment switchers (i.e. patients from the control arm who switch to receive the experimental treatment). In practice, it is unlikely that the ‘common treatment effect’ assumption will ever be completely true; however, it is appropriate to use RPSFTM/IPE methods if the assumption is likely to be approximately true. 143 Clinical advice to the AG was that for both SELECT and DECISION it is reasonable to assume that patients who switched from the placebo arm to receive the experimental treatment (i.e. lenvatinib/sorafenib) would experience the same treatment effect as patients who were originally randomised to the experimental arm.

In addition to the assumptions that are common to both the RPSFTM and the IPE methods, the IPE method also assumes that survival times follow a parametric distribution. To implement this method, a suitable parametric model must be identified, which can be problematic. The AG has been unable to identify information on how the IPE analysis was carried out using data from DECISION, including details of the parametric model chosen, and so is not able to comment on the suitability of this method.

Generally, the key assumption of a ‘common treatment effect’ that underpins RPSFTM appears to be valid, and because a large number of placebo patients crossed over to active treatment in both trials, the AG is of the opinion that RPSFTM is the most suitable method for adjusting for treatment switching in SELECT and DECISION. However, a caveat to the use of the RPSFTM-adjusted OS results for both trials is that differences in poststudy (postprogression) anti-cancer treatments administered to patients in each treatment arm are not accounted for in this analysis.

Participant characteristics

Overall, the baseline characteristics of patients included in SELECT and in DECISION were balanced between treatment arms (Table 6). Nevertheless, there are a few notable differences between the treatment arms and also across the trials.

| Characteristic | Study | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SELECT | DECISION | |||

| Lenvatinib (N = 261) | Placebo (N = 131) | Sorafenib (N = 207) | Placebo (N = 210) | |

| Age (years), median (minimum to maximum) | 64 (27 to 89) | 61 (21 to 81) | 63 (24 to 82) | 63 (30 to 87) |

| Male, n (%) | 125 (47.9) | 75 (57.3) | 104 (50.2) | 95 (45.2) |

| Race, n (%) | ||||

| White | 208 (79.7) | 103 (78.6) | 123 (59.4) | 128 (61.0) |

| Black of African American | 4 (1.5) | 4 (3.1) | 6 (2.9) | 5 (2.4) |

| Asian | 46 (17.6) | 24 (18.1) | 47 (22.7) | 52 (24.8) |

| Other | 3 (1.2) | 0 | 2 (1.0) | 2 (1.0) |

| Missing or uncodeable | 29 (14.0) | 23 (11.0) | ||

| Region, n (%) | ||||

| Europe | 131 (50.2) | 64 (48.9) | 124 (59.9) | 125 (59.5) |

| North America | 77 (29.5) | 39 (29.8) | 36 (17.4) | 36 (17.1) |

| Other | 53 (20.3) | 28 (21.4) | 47 (22.7) | 49 (23.3) |

| Time from diagnosis of DTC to randomisation (months), median (range) | 66 (0.4–573.6) | 73.9 (6.0–484.8) | 66.2 (3.9–362.4) | 66.9 (6.6–401.8) |

| ECOG PS, n (%) | ||||

| 0 | 144 (55.2) | 68 (51.9) | 130 (62.8) | 129 (61.4) |

| 1 | 104 (39.8) | 61 (46.6) | 69 (33.3) | 74 (35.2) |

| 2 | 12 (4.6) | 2 (1.5) | 7 (3.4) | 6 (2.9) |

| 3 | 1 (0.4) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Not available | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) |

| Histology, n (%) | ||||

| Papillary | 132 (50.6) | 68 (51.9) | 118 (57.0) | 119 (56.7) |

| Poorly differentiated | 28 (10.7) | 19 (14.5) | 24 (11.6) | 16 (7.6) |

| Follicular, not Hürthle cell | 53 (20.3) | 22 (16.8) | 13 (6.3) | 19 (9.0) |

| Hürthle cell | 48 (18.4) | 22 (16.8) | 37 (17.9) | 37 (17.6) |

| Other | 0 | 0 | 2 (1.0) | 5 (2.4) |

| Missing or non-diagnosed | 0 | 0 | 13 (6.3) | 14 (6.7) |

| Metastases, n (%) | ||||

| Locally advanced | 4 (1.5) | 0 | 7 (3.4) | 8 (3.8) |

| Distant | 257 (98.5) | 131 (100) | 200 (96.6) | 202 (96.2) |

| Metastases site, n (%) | ||||

| Lung | 226 (86.6) | 124 (94.7) | 178 (86.0) | 181 (86.2) |

| Lymph node | 138 (52.9) | 64 (48.9) | 113 (54.6) | 101 (48.1) |

| Bone | 104 (39.8) | 48 (36.6) | 57 (27.5) | 56 (26.7) |

| Pleura | 46 (17.0) | 18 (13.7) | 40 (19.3) | 24 (11.4) |

| Head and neck | NR | NR | 33 (15.9) | 34 (16.2) |

| Liver | 43 (16.5) | 28 (21.4) | 28 (13.5) | 30 (14.3) |

| Thyroid surgery, n (%) | 261 (100) | 131 (100) | 207 (100) | 208 (99.0) |

| Median cumulative radioiodine activity (mCi) | 350 | 400 | 376 | |

| Target tumour size, n (%) | ||||

| < 35 | 65 (24.9) | 28 (21.4) | 44 (21.3) | 51 (24.3) |

| 36–60 | 72 (27.6) | 32 (24.4) | 34 (16.4) | 48 (22.9) |

| 61–92 | 63 (24.1) | 34 (26.0) | 51 (24.6) | 34 (16.2) |

| > 92 | 61 (23.4) | 37 (28.2) | 78 (37.7) | 77 (36.7) |

| Prior VEGFR-targeted therapy, n (%) | 66 (25.3) | 27 (20.6) | 0 | 0 |

In SELECT, there was a lower proportion of males in the lenvatinib arm (47.9%) than in the placebo arm (57.3%). The median time from diagnosis of DTC to randomisation was shorter in the lenvatinib arm than in the placebo arm (66.0 vs. 73.9 months). Compared with the placebo arm, a smaller proportion of patients in the lenvatinib arm had metastases in the lung [86.6% (lenvatinib) vs. 94.7% (placebo)] or liver [16.5% (lenvatinib) vs. 21.4% (placebo)].

In DECISION, a higher proportion of patients in the sorafenib arm had metastases in the lymph node (54.6%) or pleura (19.3%) than in the placebo arm (48.1% and 11.4%, respectively). There was a higher proportion of males in the sorafenib arm (50.2%) than in the placebo arm (45.2%).

As previously highlighted, patients in SELECT could have been previously treated with a VEGFR-targeted therapy (including sorafenib) prior to trial entry whereas patients in DECISION could not. Approximately one-quarter (23.7%) of patients in SELECT had received prior treatment with a VEGFR-targeted therapy. In the lenvatinib arm, of 66 patients previously treated with a VEGFR-targeted therapy, 51 patients (77.2%) were treated with sorafenib. In the placebo arm, of 27 patients previously treated with a VEGFR-targeted therapy, 21 patients (77.8%) were treated with sorafenib. Other VEGFR-targeted therapies used prior to trial entry in SELECT included sunitinib (Sutent®, Pfizer) and pazopanib. The median duration of any prior therapy was ≈11 months in both arms.

A higher proportion of enrolled patients were from North America in SELECT than in DECISION (29.6% vs. 17.3%, respectively) and a lower proportion of patients were from Europe in SELECT than in DECISION (49.7% vs. 59.7%, respectively). A greater proportion of patients were white in SELECT (79.3%) than in DECISION (60.2%). A higher proportion of patients had bone metastases in SELECT than in DECISION (38.8% vs. 27.1%, respectively).

Comparison of assessments of risk of bias

A summary of the risk-of-bias assessments for both trials is reproduced in Appendix 3, Table 48. Overall, the AG considered the risk of bias to be low in both trials.

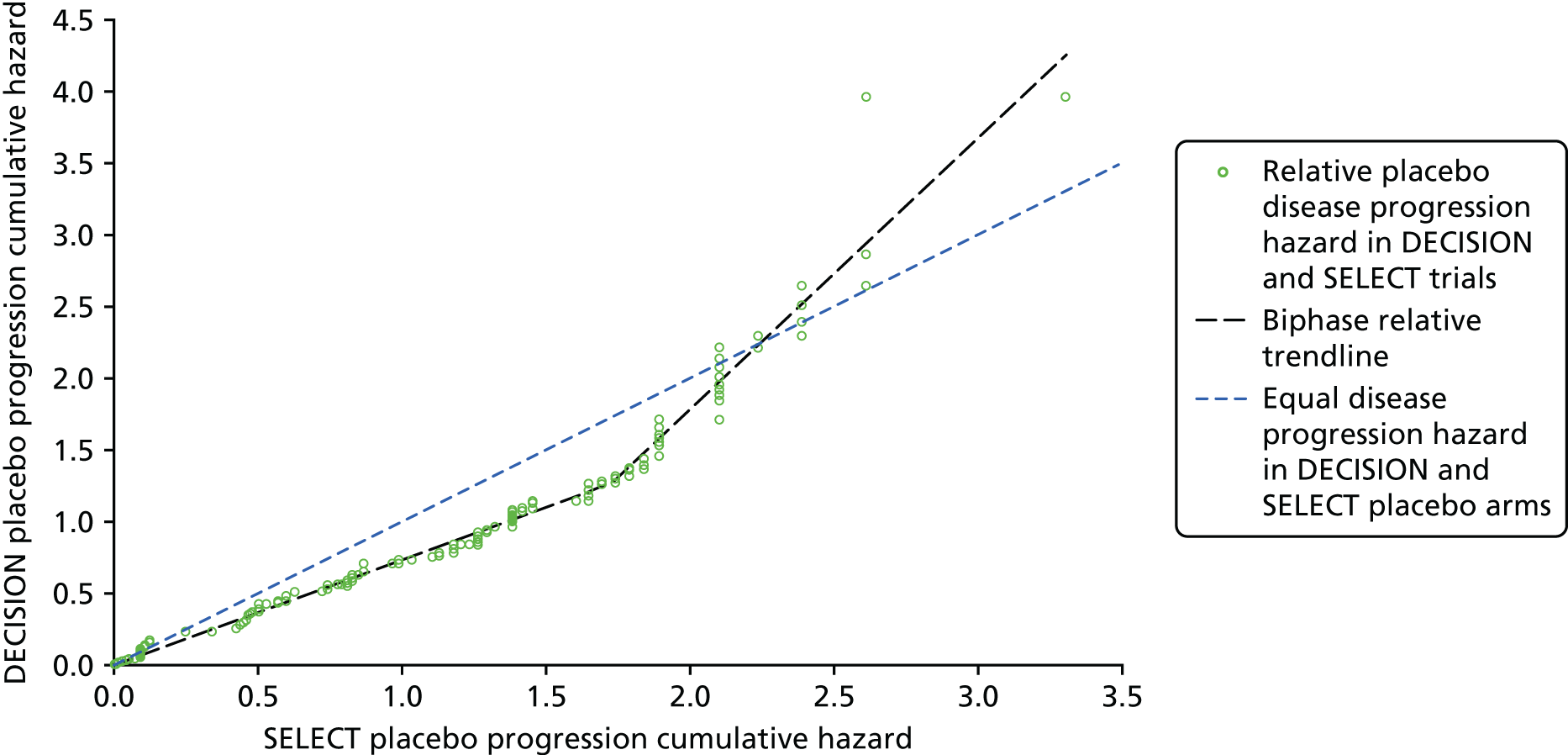

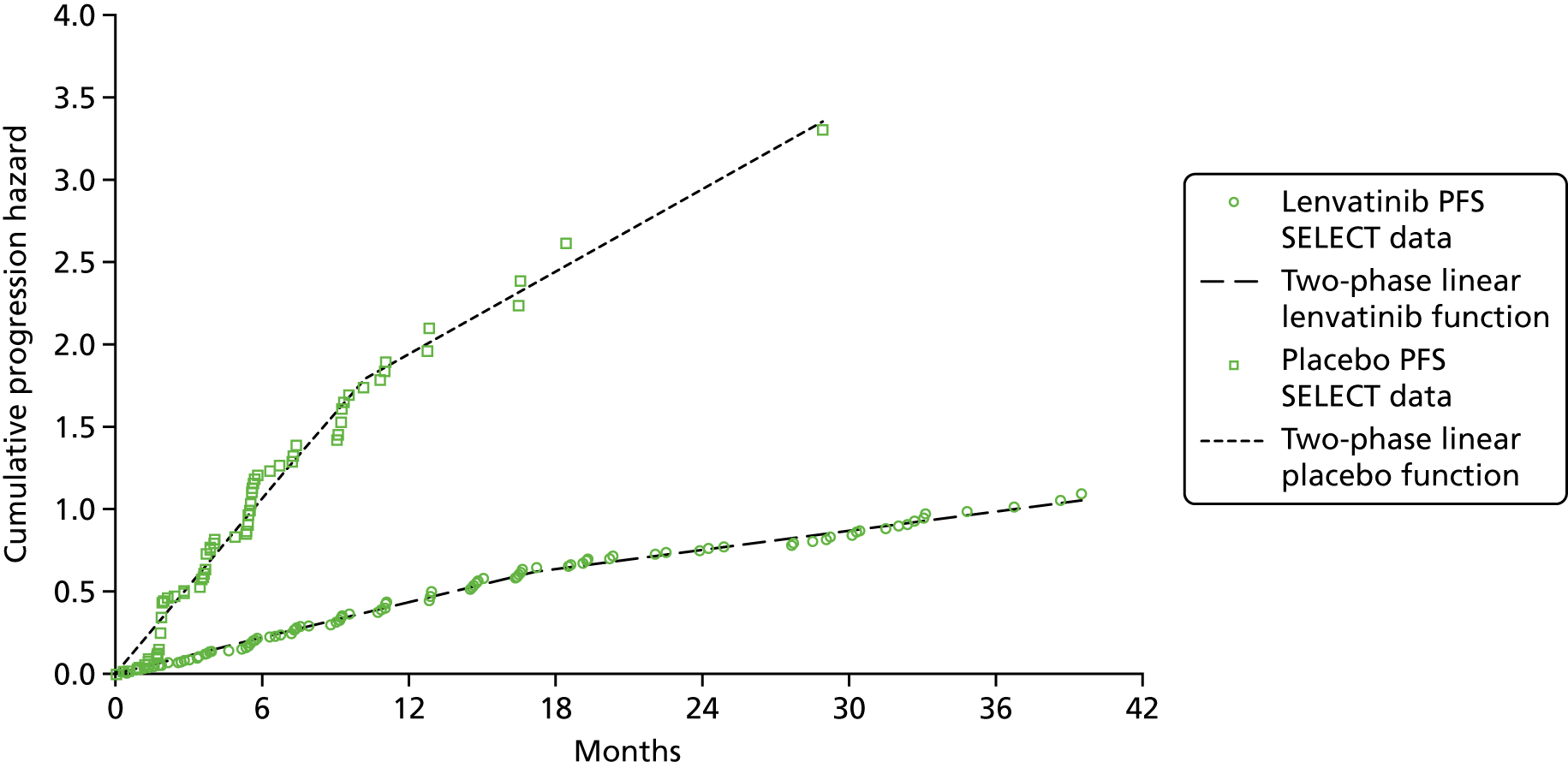

Consideration of proportional hazards assumption

Cox proportional hazards (PHs) modelling was used to generate PFS, unadjusted OS and adjusted OS hazard ratios (HRs) from data collected during SELECT and DECISION. The validity of this method relies on the event hazards associated with the intervention and comparator data being proportional over time within each trial. The AG assessed the validity of the PH assumption for all analyses, when possible, provided in the submissions from Eisai Ltd8 and Bayer HealthCare7 that included a HR result (see Appendix 6 for methods and results). The AG concluded that the PH assumption was not valid for PFS, unadjusted OS or RPSFTM-adjusted OS in SELECT or for PFS or RPSFTM-adjusted OS in DECISION. This means that the majority of the survival HRs generated using data from SELECT and DECISION and, consequently, statements about the statistical significance of results should be interpreted with caution.

Overall survival

A summary of the unadjusted and adjusted OS findings from the most recent data cut-off points from both trials is presented in Table 7. The findings for all data cut-off points are summarised in Appendix 3, Table 38.

| Outcome | Study | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SELECT | DECISION | |||

| Lenvatinib (N = 261) | Placebo (N = 131) | Sorafenib (N = 207) | Placebo (N = 210) | |

| Data cut-off pointa | Third data cut-off point (August 2015) | Third data cut-off point (July 2015) | ||

| Deaths, n (%) | 121 (46.4) | 70 (53.4) | 103 (49.8) | 109 (51.9) |

| OS (months), median (95% CI) | 41.6 (31.2 to NE) | 34.5 (21.7 to NE) | 39.4 (32.7 to 51.4) | 42.8 (34.7 to 52.6) |

| Unadjusted HR (95% CI); p-value | 0.84 (0.62 to 1.13); nominal p = 0.2475 | 0.92 (0.71 to 1.21); one-sided p = 0.28 | ||

| RPSFTM-adjusted HR (95% CI); p-value, cox method | NR | 0.77 (0.58 to 1.02); NR | ||

| RPSFTM-adjusted HR (95% CI); p-value, bootstrapping method | 0.54; nominal p = 0.0025 (0.36 to 0.80) | 0.77 (0.42 to 1.79); NR | ||

| IPE-adjusted HR (95% CI); p-value, cox method | N/A | 0.80 (0.61 to 1.05); NR | ||

| IPE-adjusted HR (95% CI); p-value, bootstrapping method | N/A | 0.80 (0.48 to 1.71); NR | ||

In both trials, there was no statistically significant difference in unadjusted OS between trial arms. However, when RPSFTM was used, patients in the lenvatinib arm had a statistically significant improvement in OS when compared with patients in the placebo arm in SELECT. The difference in OS between sorafenib and placebo was not reported to be statistically significant when using either the RPSFTM or IPE method in DECISION.

Progression-free survival

In both trials, the primary outcome was PFS by blinded independent review. The findings for PFS reported in SELECT and DECISION are summarised for the first data cut-off points (November 2013 and August 2012, respectively) in Table 8 because this was the only data cut-off point for which PFS results had been published for both trials.

| Outcome | Study | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SELECT | DECISION | |||

| Lenvatinib (N = 261) | Placebo (N = 131) | Sorafenib (N = 207) | Placebo (N = 210) | |

| First data cut-off point (November 2013) | First data cut-off point (August 2012) | |||

| PFS by blinded independent review | ||||

| Events, n (%) | 93 (35.6) | 109 (83.2) | 113 (54.6) | 137 (65.2) |

| Died before progression, n (%) | 14 (5.4) | 4 (3.1) | NR | NR |

| PFS (months), median (95% CI) | 18.3 (15.1 to NE) | 3.6 (2.2 to 3.7) | 10.8 (NR) | 5.8 (NR) |

| Stratified HR (95% CI);a p-value | 0.21 (0.14 to 0.31); < 0.001 | 0.59 (0.45 to 0.76); < 0.0001 | ||

| Investigator-assessed PFS | ||||

| Events, n (%) | 91 (34.9) | 104 (79.4) | 140 (67.6) | 184 (87.6) |

| Died before progression, n (%) | 16 (6.1) | 6 (4.6) | NR | NR |

| PFS (months), median (95% CI) | 16.6 (4.8 to NE) | 3.7 (3.5 to NE) | 10.8 (NR) | 5.4 (NR) |

| Stratified HR (95% CI);a p-value | 0.24 (0.16 to 0.35); < 0.001 | 0.49 (0.39 to 0.61); < 0.0001 | ||

In SELECT, there was a median improvement in PFS (blinded independent review) of 14.7 months with lenvatinib when compared with placebo. In DECISION, there was a 5-month median improvement in PFS (blinded independent review) with sorafenib when compared with placebo. The differences in median PFS assessed by investigators were marginally decreased in SELECT (12.9 months) and marginally increased in DECISION (5.4 months). However, the HRs in both trials were similar to those from the assessments by blinded independent review.

The SELECT trial is the only trial that also reports PFS for another data cut-off point. 85,86 This was available for investigator-assessed PFS at the third data cut-off point (August 2015). Compared with the first data cut-off point, median PFS was reported to be slightly higher in the lenvatinib arm at the third data cut-off point (19.4 months), but the median PFS remained the same in the placebo arm (3.7 months), a difference of 15.7 months. However, for both data cut-off points, the HR between arms was identical (0.24) and reported to be statistically significant (p < 0.001).

The findings for all data cut-off points are summarised in Appendix 3, Table 41.

Objective tumour response

The findings for objective tumour response are reported in Appendix 3, Table 42. In both trials, the tumour response assessment was conducted by blinded independent review at the first data cut-off point and favoured patients in the intervention arms compared with patients in the placebo arms. It is noticeable that the difference in ORR between the intervention and placebo arms was much greater for patients treated with lenvatinib in SELECT (63.2%) than for those treated with sorafenib in DECISION (11.7%). This is attributable to the much higher proportion of patients who were treated with lenvatinib and had a partial response in SELECT than the proportion of patients treated with sorafenib in DECISION. Complete responses were only reported for patients treated with lenvatinib, albeit there were very few patients (1.5%). ORR was statistically significantly improved in both trials for patients treated with either lenvatinib or sorafenib when compared with placebo.

The objective tumour response evaluations for SELECT were conducted using an ITT analysis. In DECISION, patients for whom it was not possible to evaluate a tumour response were excluded from the analysis (as per the requirements of a per-protocol analysis). If all patients are included in the evaluations using ORR data from DECISION, the ORR is marginally decreased in both arms: 11.6% for sorafenib and 0.5% for placebo.

Time to response was reported only for SELECT. The median time to response was 2.0 months for patients treated with lenvatinib compared with 5.6 months for patients in the placebo arm. The median duration of response was not estimable for patients in SELECT; however, for those treated with lenvatinib, the restricted mean was 17.34 months. Time to response was not reported in DECISION, but the median duration of response was 10.2 months for patients treated with sorafenib.

Both trials also assessed disease control rates (complete response + partial response + stable disease), and SELECT reported clinical benefit rate (complete response + partial response + durable stable disease). In each trial, the findings were statistically significantly in favour of lenvatinib or sorafenib compared with placebo. However, comparisons between trials cannot be easily made as the definition of disease control rate differed across trials because of differences in the length of stable disease required for control. SELECT required a stable disease of ≥ 7 weeks whereas DECISION required a length of ≥ 4 weeks; however, both trials did report the proportion of patients with stable disease of ≥ 6 months. This was similar in the placebo arms of both trials (SELECT, 29.8%; DECISION, 33.2%), whereas in the intervention arms, it was 15.3% for patients treated with lenvatinib and 41.8% for patients treated with sorafenib. Therefore, a clinical benefit at 6 months was reported by 79.5% of patients treated with lenvatinib compared with 31.3% of patients who received the placebo in SELECT, and 54.0% patients treated with sorafenib compared with 33.7% who received the placebo in DECISION. In the submission from Bayer HealthCare,7 it is noted that most sorafenib-treated patients (77%) experienced target lesion tumour shrinkage (compared with 28% of patients in the placebo arm).

Safety findings

Safety data from SELECT and DECISION were reported for the first data cut-off point (November 2013 and August 2012, respectively). For the individual types of AEs experienced by patients, the published paper for SELECT presented data for treatment-related AEs whereas the published paper for DECISION presented data for any treatment-emergent AEs. Therefore, data for specific types of treatment-emergent AEs were extracted from the pharmaceutical company submission (Eisai Ltd8) for SELECT.

All-grade and grade ≥ 3 adverse events

Nearly all of the patients who received lenvatinib or sorafenib reported an AE, and ≈90% of patients who received placebo reported an AE. AEs that were reported by ≥ 30% of patients and grade ≥ 3 AEs that were reported by ≥ 1.5% of patients in any of the arms are summarised in Appendix 3, Tables 44 and 45. All types of AEs were more common in patients treated with lenvatinib or sorafenib than in patients in the placebo arms of both trials. Hand–foot syndrome was reported by approximately three-quarters of patients in DECISION. Approximately two-thirds of patients reported all-grade hypertension or diarrhoea when treated with lenvatinib in SELECT, similar to the proportion treated with sorafenib reporting all-grade diarrhoea or alopecia in DECISION. Weight loss was reported by approximately half of all patients treated with either lenvatinib or sorafenib. By far the most common grade ≥ 3 AEs for patients treated with lenvatinib and sorafenib were hypertension (> 40%) and hand–foot syndrome (> 20%), respectively.

Serious adverse events (including fatal adverse events)

Serious adverse events (SAEs) reported in SELECT and DECISION are summarised in Appendix 3, Table 45. In SELECT, approximately half of the patients in the lenvatinib arm reported a SAE. Just over one-third of patients reported a SAE in the sorafenib arm of DECISION. Approximately one-quarter of patients in the placebo arms of both trials reported a SAE. The only SAE reported by ≥ 2% of patients in both trials was dyspnoea, which was at least as common for patients who received placebo as for those who received lenvatinib or sorafenib. The most common SAEs (reported by ≥ 3% of patients) reported for patients treated with lenvatinib in SELECT were pneumonia and hypertension. The most common SAEs (reported by ≥ 3% of patients) reported by patients treated with sorafenib in DECISION were secondary malignancy and pleural effusion.

Deaths from AEs were reported for 7.7% of patients treated with lenvatinib and 4.6% of patients in the placebo arm in SELECT. Fatal AEs in DECISION were reported for 5.8% of patients treated with sorafenib and 2.9% of patients in the placebo arm.

Treatment-related adverse events

A summary of treatment-related AEs is presented in Appendix 3, Table 46. A very high proportion of all-grade AEs (≥ 96%) were considered to be related to treatment with lenvatinib or sorafenib. The proportion of all-grade AEs considered to be treatment related was high (> 50%) in the placebo arms of both trials.

In SELECT, the causes of death considered to be treatment related in the lenvatinib arm were one case each of pulmonary embolism, haemorrhagic stroke and general deterioration of physical health; three cases were reported as deaths or sudden deaths (not otherwise specified). DECISION was the only trial in which a patient in the placebo arm was considered to have died because of a treatment-related AE. The cause of death for this patient was subdural haematoma. The cause of death for a patient in the sorafenib arm that was considered to be treatment related was myocardial infarction.

Timing of adverse events

In both trials, there have been subsequent analyses of the timing of AE occurrences in the treatment cycle reported. For SELECT, Haddad et al. 91 reported the incidence and timing of five AEs: proteinuria, diarrhoea, fatigue/asthenia/malaise, rash and hand–foot syndrome. Hypertension was a notable AE omitted from the analysis. For DECISION, detailed analysis of the AE occurrence patterns in patients is published in a peer-reviewed paper by Worden et al. 139 Findings from the two trials cannot be easily compared because Haddad et al. 91 reported their findings as median time to first onset and median time to last resolution, whereas Worden et al. 139 reported the proportion of AEs occurring during each cycle. The AEs reported included hand–foot syndrome, rash/desquamation, diarrhoea, fatigue, hypertension, weight loss, increased TSH levels and hypocalcaemia. Increased TSH levels were described as a ‘study-specific’ AE, with a maximum severity of grade 1; this AE was reported by 69 patients (33.3%) treated with sorafenib. 139

In SELECT, Haddad et al. 91 found that generally AEs for patients treated with lenvatinib occurred early in the treatment process and were resolved. Median time to onset for patients treated with lenvatinib ranged from 3.0 weeks with fatigue/asthenia/malaise to 12.1 weeks with diarrhoea. With regard to resolution, this ranged from a median of 5.9 weeks with rash to a median of 20.0 weeks with hand–foot syndrome.

In DECISION, Worden et al. 139 found that in patients treated with sorafenib, the incidence of AEs was usually highest in the first cycle or the first two cycles. Severity tended to diminish with each cycle (over the first nine cycles). The prevalence of AEs (defined as the number of patients with a new or continuing AE during a treatment cycle) tended to remain stable. Diarrhoea and TSH were notable exceptions in that prevalence steadily increased over the first five or six cycles, at which point the prevalence peaked. Only weight loss, which was primarily grade 1 or grade 2 and highest in the first four cycles, tended to increase in severity over time (from grade 1 to grade 2: a greater proportion of patients experienced grade 2 toxicity in cycle 9 compared with cycles 1 and 2). The authors noted that in general, AEs with sorafenib were manageable over time following dose modification and/or concomitant medications, such as antidiarrhoeals, antihypertensives or dermatological preparations.

Dose modifications

Dose modifications as a result of AEs were more common for patients treated with lenvatinib and sorafenib than for those who received placebo (Table 9). It is of note that the incidence of dose interruptions with lenvatinib in SELECT was higher than with sorafenib in DECISION. The incidence of dose interruptions and dose reductions were lower in the placebo arm of SELECT than in the placebo arm of DECISION.

| Outcome | Study, n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SELECT | DECISION | |||

| Lenvatinib (N = 261) | Placebo (N = 131) | Sorafenib (N = 207) | Placebo (N = 209) | |

| Dose interruptions because of an AE | 215 (82.4) | 24 (18.3) | 137 (66.2) | 54 (25.8) |

| Dose reductions because of an AE | 177 (67.8) | 6 (4.6) | 133 (64.3) | 19 (9.1) |

| Discontinued treatment because of an AE | 43 (16.5) | 6 (4.6) | 39 (18.8) | 8 (3.8) |

It is reported that, in SELECT, the most common AEs developing during treatment that led to a dose interruption or reduction among patients receiving lenvatinib were diarrhoea (22.6%), hypertension (19.9%), proteinuria (18.8%) and decreased appetite (18.0%). It is also noted that four patients in the lenvatinib arm (1.5%) required dose adjustments owing to hypocalcaemia. In the submission from Eisai Ltd,8 it is further noted that 1.1% of patients discontinued treatment because of hypertension and 1.1% of patients discontinued because of asthenia. In DECISION, it is reported that hand–foot syndrome was the most common reason for sorafenib dose interruptions (26.6%), reductions (33.8%) and withdrawals (5.3%).

Health-related quality-of-life findings

It was reported in the European Public Assessment Report (EPAR)27 that, although HRQoL data were not collected in the randomised part of SELECT,51 HRQoL would be assessed in 30 patients who participated in the open-label extension phase of the trial. The AG is unaware of whether or not these findings have been published.

For DECISION, HRQoL was reported in a conference abstract by Schlumberger et al. 120 More detailed HRQoL results were also reported in the submission from Bayer HealthCare. 7 Cancer-specific HRQoL was measured using the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – General (FACT-G) questionnaire144 and general health status was measured using the generic EuroQol-5 Dimensions, three-level version (EQ-5D-3L) and the EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) visual analogue scale (VAS). 145 The FACT-G questionnaire is a validated 27-item questionnaire designed to assess the following dimensions in cancer patients: physical well-being, social/family well-being, emotional well-being and functional well-being. The FACT-G total score ranges from 0 to 108 points, with higher scores representing a better HRQoL. Similarly, the EQ-5D is a validated instrument in which higher scores represent better health status.

All questionnaires were self-administered at baseline and day 1 of every 28-day cycle. The overall questionnaire completion rate during the trial was reported by the authors to be 96%. 120 However, the actual number of patients completing the questionnaires reduces with each cycle because only patients with progression-free disease were asked to complete the questionnaires. Thus, for example, as shown in the submission from Bayer HealthCare7 by the response to one of the physical well-being questions, by cycle 13 the number of patients who responded was 87: 40.1% of all patients enrolled into the trial.

Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – General

Minimally important differences in the FACT-G total score (i.e. a difference considered to be clinically meaningful) have been reported to range between 3 and 7 points. 144 At baseline, it was reported7,120 that FACT-G scores were comparable to a normative adult cancer population, the mean scores being 81 points [standard deviation (SD) 15 points] in the sorafenib arm and 82 points (SD 14 points) in the placebo arm. However, at the first assessment (cycle 2, day 1), the score for the sorafenib arm had fallen to 76 points (SD 15 points), whereas the score in the placebo arm remained very similar to baseline. The authors of the conference abstract120 reported that the scores in the sorafenib arm thereafter remained similar to the scores at the first assessment, whereas the scores remained similar to the baseline scores in the placebo arm. A mixed linear model estimated that, compared with placebo, the FACT-G score was 3.45 points lower in the sorafenib arm (p = 0.0006), representing a clinically meaningful difference between arms in favour of the placebo arm. The authors attributed the diminished HRQoL score to AEs. Indeed, the submission from Bayer HealthCare7 noted that in response to the FACT-G physical well-being domain question ‘I am bothered by side effects’, the proportion of patients in the sorafenib arm who replied ‘quite a bit’ or ‘very much’ increased from 1.5% at cycle 1 to 29.6% at cycle 2. However, this proportion gradually diminished over time: it was 16.8% by cycle 6 and 8.0% by cycle 13.

EuroQol-5 Dimensions index and visual analogue scale

For UK utility scores, a change of 0.10 points on the EQ-5D index has been reported by Pickard et al. 146 to be clinically meaningful for all cancers (using ECOG PS as the anchor). Similarly, the same study reported a change of at ≥ 7 points on the VAS to be clinically meaningful. 146 It was reported in DECISION7,120 that the patterns for EQ-5D index and VAS were similar to that of the FACT-G; after the first assessment, the scores in the sorafenib arm were lower than the scores in the placebo arm. Although the between-arm differences were statistically significant (p < 0.0001 for both EQ-5D index and VAS), the treatment effects (–0.07 and –6.75, respectively) were of a small magnitude and did not reach the threshold for a clinically meaningful difference. It is reported in the submission from Bayer HealthCare7 that dimensions in the EQ-5D index that are sensitive to AEs include mobility, usual activities and pain/discomfort.

Subgroup analyses from randomised controlled trials

Only subgroup analyses considered by the AG to be of direct relevance to the decision problem have been reported in the remainder of this report. The AG considered the following subgroup analyses to be relevant (with rationale given):

-

patients previously treated and not previously treated with TKIs (prespecified subgroup in the NICE scope53 and AG decision problem)

-

patients with and without symptomatic disease at baseline (as highlighted in Chapter 1, Treatment options for patients with radioactive iodine-refractory differentiated thyroid cancer, systemic treatment is recommended for patients who have symptomatic disease)

-

analyses of subgroups that were prespecified in the trials and in which there appeared to be differences in baseline characteristics within or across trials (as differences in baseline characteristics may influence results).

As previously highlighted, the AG concluded that the assumption of PH does not hold in any of the analyses that it was able to check other than unadjusted OS in DECISION. This means that the majority of the survival HRs generated using data from SELECT and DECISION and, consequently, statements about the statistical significance of results should be interpreted with caution.

Patients previously treated and patients not previously treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors

Subgroup analyses have been reported for patients previously treated with a TKI (e.g. VEGFR-targeted therapy) in SELECT but only for PFS and ORR. 51,105,106 No patients in DECISION had received prior treatment with a TKI.

Results from subgroup analyses using data from SELECT51,105,106 showed that PFS was statistically significantly longer for patients treated with lenvatinib compared with placebo for patients previously treated with VEGFR-targeted therapy (including sorafenib) (Table 10). For patients who were VEGFR-targeted therapy naive, PFS was also statistically significantly longer for patients treated with lenvatinib compared with placebo.

| Outcome | Treatment with VEGFR-targeted therapy | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prior treatment | No prior treatment | |||

| Lenvatinib (N = 66) | Placebo (N = 27) | Lenvatinib (N = 195) | Placebo (N = 104) | |

| Events, n (%) | 31 (47.0) | 25 (92.6) | 76 (39.0) | 88 (84.6) |

| Median PFS (months) | 15.1 | 3.6 | 18.7 | 3.6 |

| HR (95% CI) | 0.22 (0.12 to 0.41) | 0.20 (0.14 to 0.27) | ||

Compared with patients in the placebo arm, ORR was statistically significantly improved for patients treated with lenvatinib whether or not they had been previously treated with a VEGFR-targeted therapy (see Appendix 3, Table 47). 51,105,106 In both subgroups, ORRs were similar to the ORRs observed in the overall trial population (lenvatinib 64.8% and placebo 1.5%).

Newbold et al. 105,106 reported that any all-grade and grade ≥ 3 AEs were similar in the two subgroups of patients receiving lenvatinib (prior VEGFR-targeted therapy 100.0% and 87.9%, respectively; no prior VEGFR-targeted therapy 99.5% and 86.7%, respectively). However, SAEs were more common in the lenvatinib arm among patients who had received prior VEGFR-targeted therapy (60.6%) than among those who had not (50.8%). For patients in the placebo arm, the opposite was the case, with SAEs being less common among patients who had received prior VEGFR-targeted therapy (18.5%) than among those who had not (25.0%).

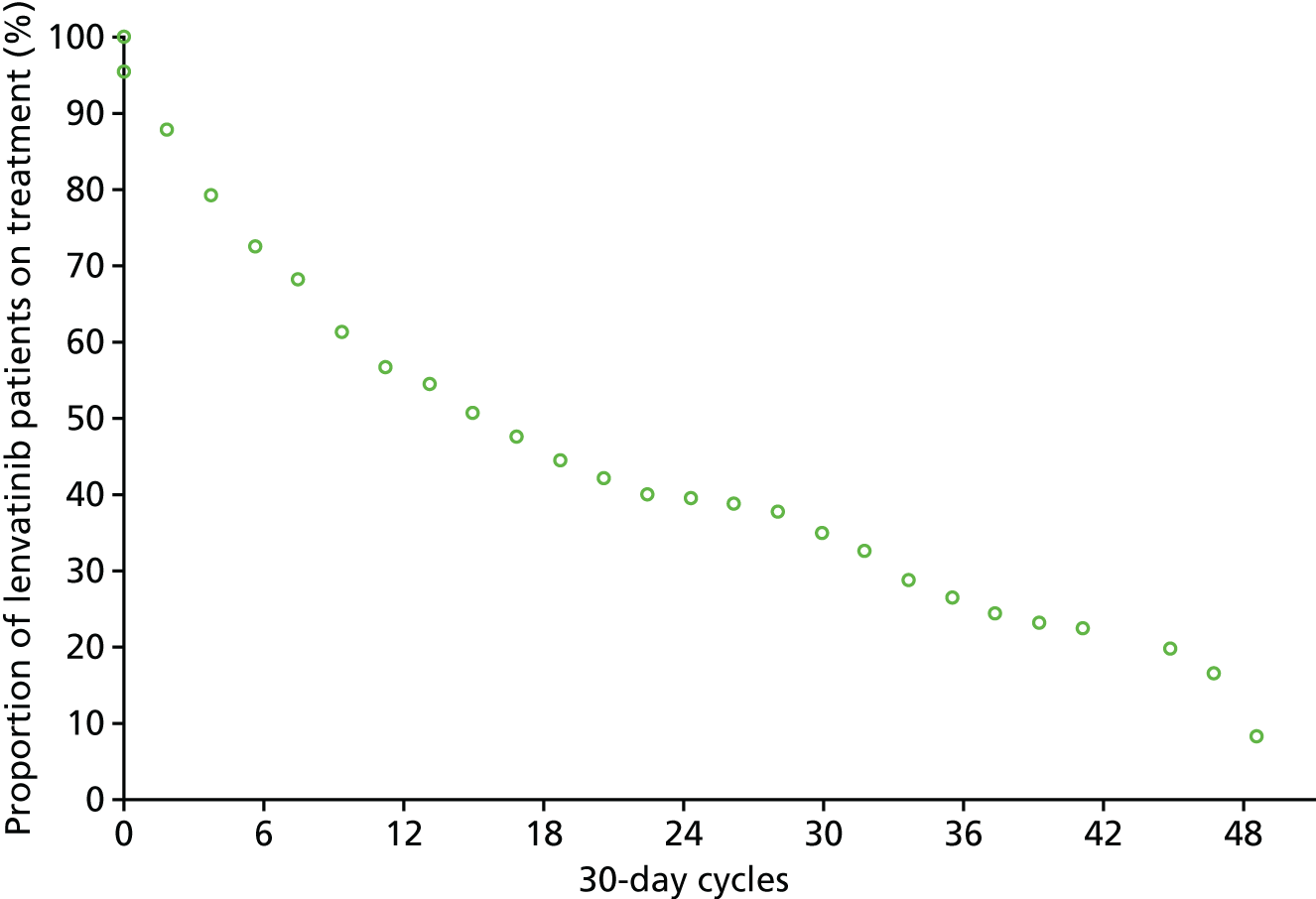

Patients who had not received prior VEGFR-targeted therapy were treated with more cycles of lenvatinib (median 16 cycles) than those who had received prior VEGFR-targeted therapy (median 12.5 cycles). The proportion of patients who had at least one lenvatinib dose reduction was also similar between subgroups (prior VEGFR-targeted therapy 81.8% and no VEGFR-targeted therapy 86.7%). Patients with no prior VEGFR-targeted therapy had an earlier median time to first dose reduction (8.9 weeks) than patients with prior VEGFR-targeted therapy (14.8 weeks). Patients with no prior VEGFR-targeted therapy also had a lower median daily dose of lenvatinib than those with prior VEGFR-targeted therapy (16.1 vs. 20.1 mg, respectively).

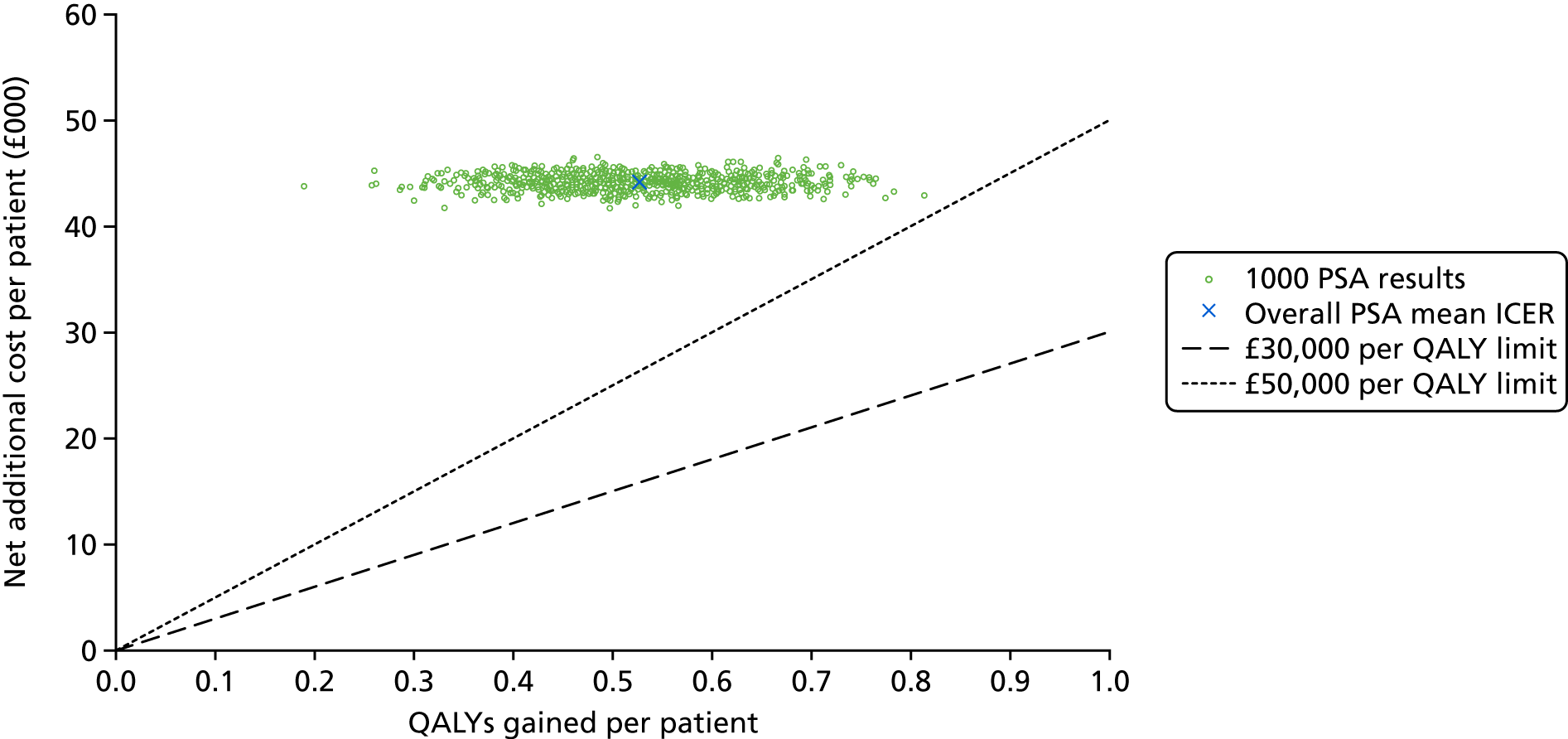

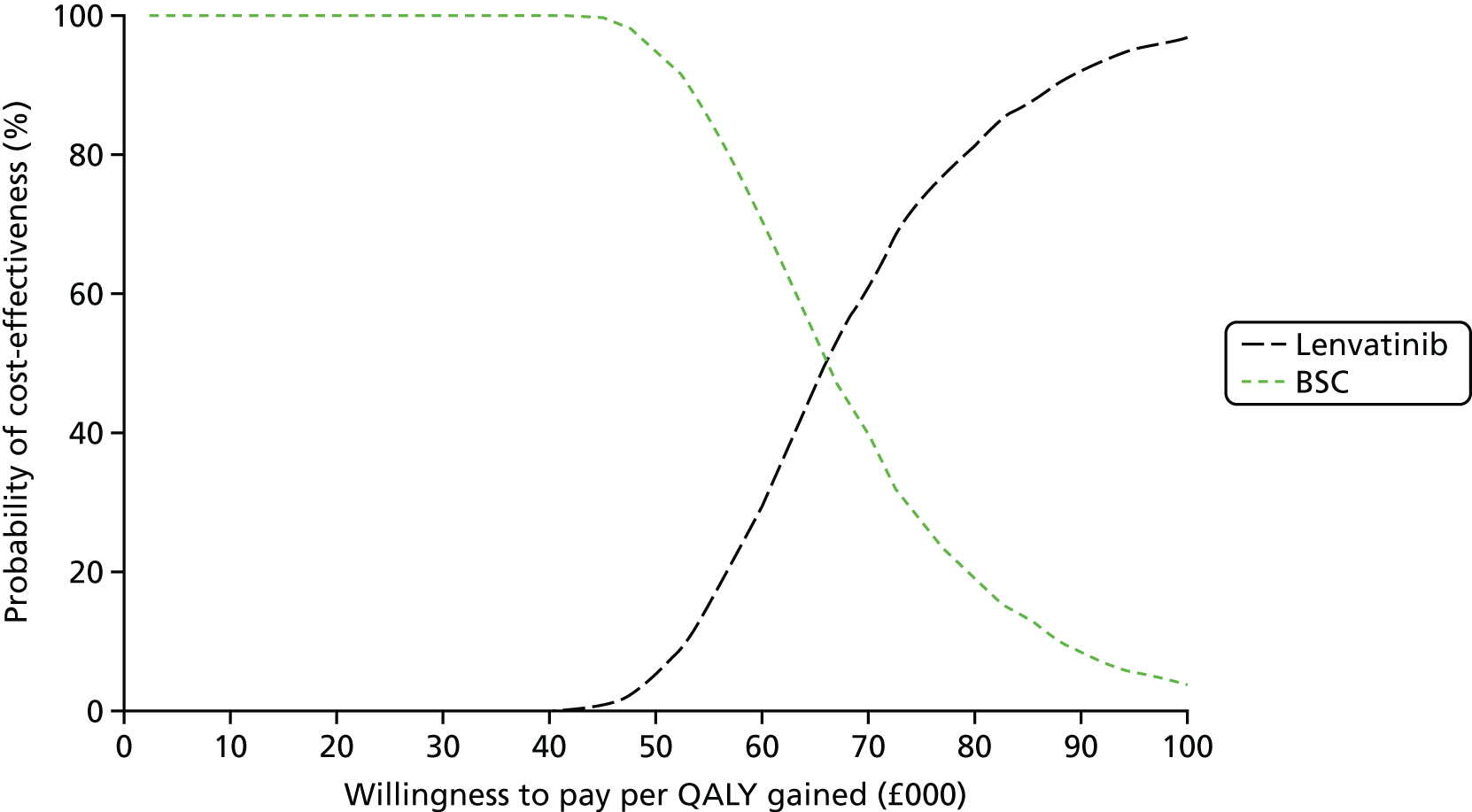

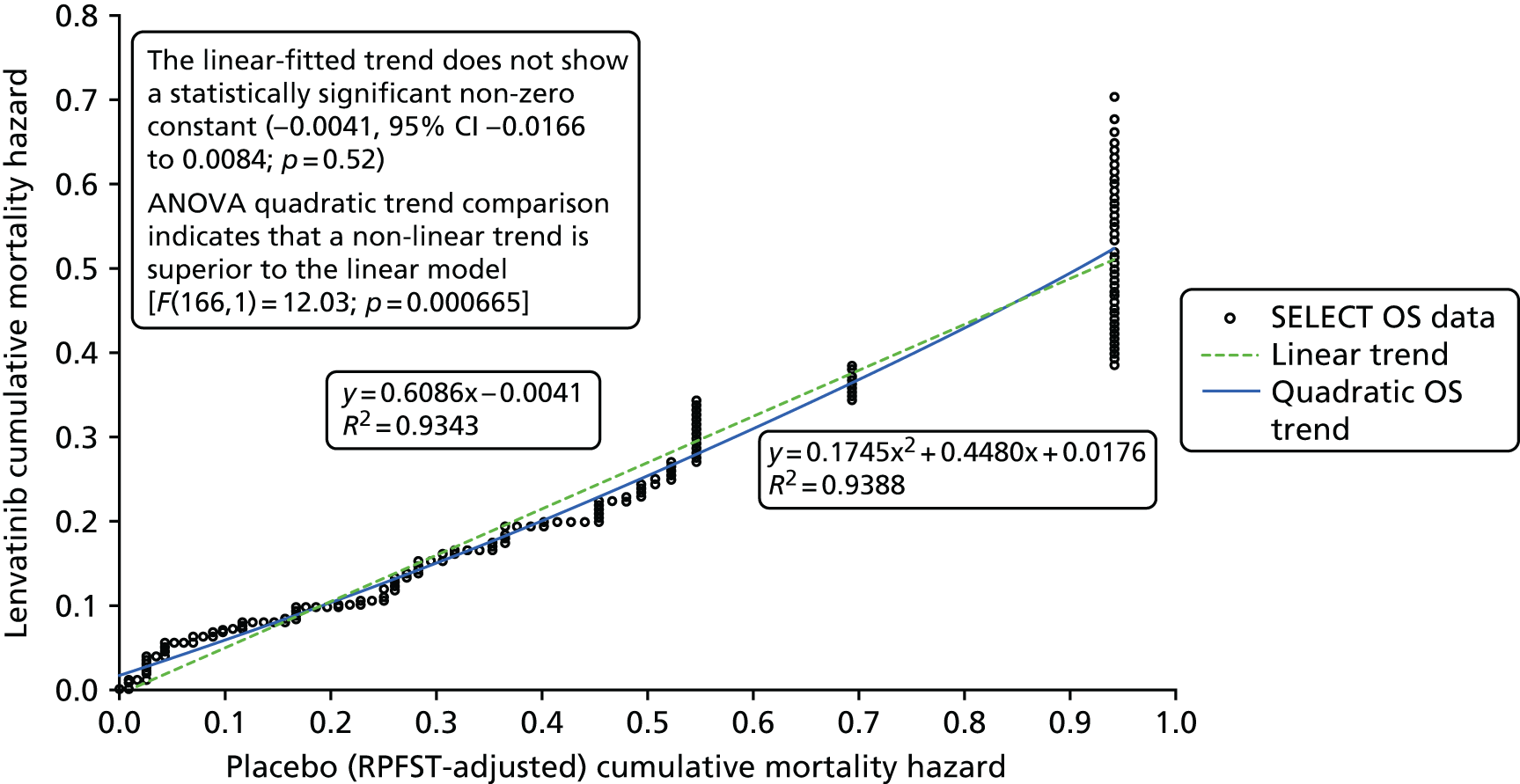

Patients with and without symptomatic disease at baseline