Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 15/10/11. The contractual start date was in December 2016. The draft report began editorial review in April 2019 and was accepted for publication in August 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Joanna Coast reports grants from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme during the conduct of the study; and she led the development of the ICECAP (ICEpop CAPability) instruments. Claire Goodman is a NIHR Senior Investigator. Ben Hardwick reports grants from the NIHR HTA programme during the conduct of the study. Catherine Walshe reports that she was a member of the NIHR Health Services and Delivery Research programme Researcher Led Committee during the conduct of the study.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Froggatt et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Scientific background

Dementia is a life-limiting condition, and survival time from diagnosis decreases with age, from 6.7 to 1.9 years. 1 In advanced dementia, an individual is fully dependent on others for care; they can be chair- or bedbound, doubly incontinent and no longer able to communicate verbally [assessed as having a Functional Assessment Staging Test (FAST) score of 6 or 7]. 2 For many people with advanced dementia, a move to a care home is required because they can no longer live independently at home. 3 ‘Care home’ is a generic term that refers to:

A collective institutional setting where care is provided for older people who live there, 24 hours a day, seven days a week, for an undefined period of time. The care provided includes on site provision of personal assistance with activities of daily living. Nursing and medical care may be provided on-site or by nursing and medical professionals working from an organisation external to the setting.

Froggatt and Reitinger, p. 14. 4

Nursing homes are care homes that employ on-site nurses who are present 24 hours per day, 7 days per week for people with higher levels of dependency and health-care needs. At least two-thirds of people in care homes are estimated to have dementia5 and will therefore die with, if not of, dementia. 6 In England and Wales, approximately 18% of the population die in care homes. 7 In an ageing population, the numbers of people with advanced dementia who require palliative and end-of-life care in care homes will rise. 8

Dying with advanced dementia is often prolonged and distressing, with poor quality of life and death reported,9,10 through either under- or overtreatment. 11–13 People dying with advanced dementia suffer symptoms such as pain, which leads to distressing behaviours such as agitation and sleep disturbance. 14 Evidence suggests that there is also a negative impact on carers who witness dying when there is pain, agitation and distress. 15 There is therefore a need for appropriate care that will ensure a good quality of life and a good quality of dying. 13,16

Health-care practitioners can struggle to provide appropriate care for people with advanced dementia. 17 Palliative and end-of-life care seeks to address the needs of people whose disease is not responsive to curative treatment by providing active care and treatment that addresses all physical, psychological, spiritual and social domains. 18 Challenges in providing appropriate palliative and end-of-life care for people with dementia are recognised19 and interventions to support good practice are being sought.

One intervention for those with advanced dementia that is gaining increasing currency with practitioners, but without good evidence of effect, is Namaste Care. 20 Namaste Care is a non-pharmacological, complex intervention to improve the quality of life and care at the end of life that is designed to ameliorate challenging symptoms such as agitation, pain, distress and sleep disturbance. It is proposed that this intervention, delivered by nurses and care assistants, could, if successful, enable the skilled and confident delivery of care known to improve both quality of care and quality of dying. 20 Small-scale studies have demonstrated this intervention’s potential to reduce pain, urinary tract infections and distress, improve sleep and reduce agitation. 21–25

A future full trial is urgently required to determine the efficacy of an intervention already spreading across end-of-life and nursing home care settings to ensure that only appropriate cost-effective and clinically effective technology that can be practically delivered is adopted.

Explanation of rationale

Namaste Care is based on the premise that people with advanced dementia have the right to be cared for as human beings with full moral worth23–25 and draws on principles of person-centred care. 26 There is little strong evidence for Namaste Care as a multicomponent intervention, but some disparate evidence suggests that it leads to a reduction in the severity of physical and behavioural symptoms, and changes in social interaction, agitation and delirium. 22,27,28 Wider benefits to the health economy are suggested with respect to the reduced use of psychotropic medication. 27 Family and staff report increased satisfaction with care following delivery of Namaste Care. 29

Understanding the effect (including cost-effectiveness) of Namaste Care and how best to organise care to achieve this effect will enable clear decision-making about health-care practice for those with advanced dementia, and whether or not and how to change the focus of care for those with advanced dementia nearing the end of life. This research will provide a clear specification for the delivery of Namaste Care that will feed forwards into health-care decision-making.

This trial is also part of a cohort of larger clinical studies being undertaken internationally (Canada30 and the Netherlands31) to develop a robust comparable evidence base for the efficacy of the intervention.

Study overall aim

The aim of the study is to undertake robust, evidence-based development of the Namaste Care intervention followed by a feasibility trial to determine the parameters of a full trial of Namaste Care in nursing home settings.

Research question

What is the feasibility of conducting a cluster randomised controlled trial in a nursing home context to understand the impact on quality of life, and quality of dying, of the Namaste Care intervention for people with advanced dementia, when compared with usual end-of-life care?

Aim

The main aim of the feasibility trial was to ascertain the feasibility of conducting a full trial of the Namaste Care intervention.

Objectives

The feasibility aims of the research design and data collection processes to enable the design of a full trial to determine the efficacy of Namaste Care were to:

-

understand how best to sample and recruit nursing homes into a cluster randomised controlled trial of Namaste Care

-

establish recruitment, retention and attrition rates at the level of the nursing home and of the individual resident, informal carer and nursing home staff

-

determine the most appropriate selection, timing and administration of primary and secondary outcome measures for a full cluster randomised controlled trial of Namaste Care against criteria of bias minimisation, burden and acceptability

-

assess the acceptability (to staff and family), fidelity and sustainability of the Namaste Care intervention

-

establish the willingness of a large number of nursing homes, representing the range of nursing homes with respect to provider type, size and resident care needs, to participate in a full trial.

Chapter 2 Realist review of Namaste Care and other multisensory interventions

This chapter includes text from the paper by Bunn et al. 32 This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

We conducted a stakeholder-driven realist review. It was conducted and reported in accordance with the Realist and Meta-narrative Evidence Syntheses: Evolving Standards (RAMESES). 33 This review is registered as PROSPERO CRD42016047512. The aim of the review was to develop a theory-driven explanation of how the Namaste Care intervention might work, and in what circumstances, to inform the development of the Namaste Care intervention.

Rationale for using a realist approach

Realist review is a systematic, theory-driven approach that aims to make explicit the underlying processes, structures or reasoning (mechanisms) of how and why complex interventions work (or do not) in particular settings or contexts. 34,35 Namaste Care is a complex multicomponent intervention dependent on the behaviours and choices of those delivering and receiving the care. The purpose of this review was to develop an explanatory account or programme theory about Namaste Care and how it might work for people with advanced dementia living in long-term care settings, such as nursing homes. We knew when starting the review that most of the literature on Namaste Care was descriptive and experiential. However, in a realist approach the unit of analysis is the programme theory or underpinning mechanism of action, rather than the intervention. 34 This allowed us to draw on a broader range of literature rather than literature focusing solely on Namaste Care.

Programme theory comprises configurations of context (the background conditions/circumstances in which interventions are delivered and in which mechanisms are triggered), mechanism (the responses or changes that are brought about through a programme within a particular context) and outcomes. The development of these context–mechanism–outcome (CMO) configurations is iterative, involving data collection, theorising and stakeholder engagement. Stakeholders with direct experience of providing end-of-life care to people with dementia in care home settings were involved in defining the scope of the review and, later, in validating the programme theory. 33,34

Methods

Phase 1: defining the scope of the realist review – concept-mining and theory development

In phase 1, we searched the literature and consulted with stakeholders to develop provisional programme theories about how Namaste Care might work. To identify relevant literature, we searched PubMed and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) for all available literature describing the implementation or use of Namaste Care, conducted forwards and backwards citation tracking and hand-searched a book by Joyce Simard, the originator of Namaste Care. 20 We searched for research studies of any design and descriptive items in non-academic journals.

In conjunction with scoping the literature, we conducted face-to-face or telephone interviews with 11 participants involved in delivering Namaste Care, training of care home staff in Namaste Care, and for research within dementia and/or palliative and end-of-life care. Participants were based in the UK, the Netherlands and the USA. Participants were recruited for their known expertise and through snowball sampling. Interviews were conducted either face to face or by telephone or Skype™ (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) video call. Participants were given a copy of the study information sheet, which provided contact details of the research team, and a consent form that they were asked to read and sign. Interviews were conducted using realist principles36 and were guided by a topic guide. The interview schedules were designed to explore participants’ experiences of Namaste Care for people living with dementia and their views on what they considered to be the essential components of the intervention, and how and on what outcomes the intervention was thought to work. Research Ethics Committee approval was obtained from Lancaster University (reference number 17/wa/0378).

Findings from the literature and interviews were used to develop a preliminary theory in the form of 13 explanatory ‘if–then’ statements. 32 ‘If–then’ statements are the identification of an intervention/activity linked to outcome(s). They contain references to contexts and mechanisms, although these may not be very explicit at this stage. 37 Following this, we held a workshop to review and refine the theory. Participants for the workshop were recruited based on their expertise in Namaste Care and/or in dementia or end-of-life care. The workshop included seven external participants (three of whom had participated in interviews) and six members of the study team (one of whom was a participant and public involvement lead). At the workshop, members of the project team presented the preliminary findings from the scoping, the outcomes identified from the literature and the if–then statements. We adapted nominal group technique to facilitate the discussion of the if–then statements. The purpose was to understand what participants thought was needed for Namaste Care to work, how they thought Namaste Care changed the behaviour of residents and staff, and why/how it worked. Nominal group technique is a process that promotes the generation of ideas to develop a set of priorities and enables the participation of all group members. 38 Participants’ comments were recorded, and statements were ranked by participants in order of importance.

After the workshop, members of the project team who had attended the workshop reviewed the if–then statements, and the rankings, and grouped them into three categories:

-

how Namaste Care is introduced to the care home, including the structure of the intervention, frequency and resources

-

characteristics/approach of the care home staff and characteristics of the Namaste Care programme, for example staff providing person-centred care and engaging in biography work with residents

-

how Namaste Care is delivered, including meaningful activities involving all five senses and adaptation of activities to individual circumstances and preferences.

These categories became the basis for the three preliminary CMOs32 that were taken forward for testing in phase 2.

Phase 2: retrieval, review and synthesis

Inclusion criteria and study identification

In phase 2, we undertook systematic searches to identify sufficient evidence to test and develop the three CMOs identified in phase 1. 39 As the literature on Namaste Care is limited, we widened the searches to include studies that drew on similar principles or approaches to Namaste Care. The rationale for this was that these offered opportunities for transferable learning and allowed us to test aspects of our programme theory, such as the mechanisms of action.

The inclusion criteria for studies were as follows:

-

All or some participants with advanced dementia. This included studies in which the definition of ‘advanced dementia’ was based on the authors’ reports and studies that provided more formal definitions or used measures such as the Mini Mental State Examination.

-

People living in a long-term care institution (e.g. a care home or a nursing home).

-

Interventions that drew on similar principles to Namaste Care or included components of Namaste Care (e.g. music therapy, massage, aromatherapy) and that offered opportunities for transferable learning. This included group-based or one-to-one interventions. Interventions could be delivered by care home staff or by external facilitators.

-

Published and unpublished studies of any design.

The searches focused on papers published in the last 10 years to reflect the rapid expansion of work and interest in the research area. We searched PubMed, Scopus and CINAHL and undertook lateral searching such as forwards and backwards citation tracking.

Search terms and dates are given in Box 1.

Run 24 April 2017, focused on elements of Namaste Care intervention such as massage, music, sensory stimulation) sensory[Title/Abstract] OR touch[Title/Abstract] OR senses[Title/Abstract] OR massage[Title/Abstract] OR namaste[Title/Abstract] OR music[Title/Abstract] OR smell[Title/Abstract] OR aroma[Title/Abstract]) OR (‘massage therapy’) OR (‘sensory stimulation’) OR (‘music therapy’) OR (‘therapeutic touch’)) AND ((‘dementia’) OR (‘alzheimers’) OR (‘end of life’) OR (‘palliative’) OR (‘coma’)) Filters: published in the last 10 years; Humans

PubMed search 2Run 26 April 2017, terms relating to person-centred care) ((‘person centred care’) OR (‘person centred care’[Title/Abstract]) OR (person centred care) OR ((‘biography’) OR (biography[Title/Abstract] OR biographical[Title/Abstract]))) AND ((‘residential care’) OR (‘nursing home’) OR (‘care home’) OR (‘residential home’))

Selection and appraisal of documents

Results of the searches were imported into bibliographic software. Two researchers independently screened the title and abstract of records and the full text of articles that appeared to be relevant. Papers were assessed for inclusion on the basis of whether or not they were considered ‘good enough and relevant enough’. 40,41 This was an ongoing process that involved discussion between research team members. ‘Good enough’ was based on the reviewers’ assessment of whether or not the research was of a sufficient standard based on the detail provided, the articulation of how the intervention worked and if the claims made were considered credible. Papers were judged to be relevant if it was felt that the authors provided sufficient information and/or theoretical discussion to contribute to the programme theories being tested. For example, although many studies were not focused on Namaste Care, they could still be included if they were felt to share an underpinning mechanism of action. 34 Studies that were poorly conducted could still be included if the relevance was high, for example if they contributed to our understanding about how a programme was thought to work. We tested for conceptual saturation through regular discussion among team members involved in data extraction. 42 For example, multiple studies drew on theories of biography and person-centred care as a rationale for the intervention and to explain how they worked.

Data extraction and synthesis

In the first stage of the review, we extracted information on how Namaste Care was interpreted and delivered, including the core components, and reported outcomes. In stage 2, we extracted information on study focus, participants, setting and intervention (including method of delivery and duration), how outcomes were measured and reported, and how underlying assumptions about the intervention were articulated. In a realist review, data are not restricted to outcomes measured or results reported but also include author explanations. For example, discussions can provide a rich source of ‘data’ that helps explain how an intervention was thought to work (or why it did not). Data were extracted into a Microsoft Access (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) database and the ‘query’ feature was used to create tables enabling the identification of recurrent patterns of contexts and outcomes in the data and the possible mechanisms by which these occurred. 43 In addition, we created data tables to map the most commonly reported outcomes (e.g. agitation) against data on context, mechanisms and our programme theory.

Testing and refining programme theory

To enhance the trustworthiness of our programme theory, we discussed the CMOs at a second project team workshop (n = 7) and undertook a second round of stakeholder consultation. This consultation involved discussing the CMOs and it was conducted via telephone interviews (n = 1), face to face (n = 2) and by e-mail (n = 1). In addition, findings from the review were presented to, and discussed with, a group of end-of-life care specialists (n = 40) at a community of practice meeting organised by specialist end-of-life and dementia care organisations. Many of those attending had direct experience of Namaste Care. Stakeholders were from similar groups as in phase 1 (two people took part in both sets of consultations).

Results

Description of included evidence

Phase 1

In phase 1 we found 25 papers relating to Namaste Care, 18 of which provided sufficient information for theory development. The majority were descriptive accounts of Namaste Care rather than research studies. Of the seven research studies, three included some before-and-after data,22,44,45 three were qualitative46–48 and one (reported in three papers)27,29,49 used an action research approach. Only five studies21,22,27,44,45 presented data on resident outcomes. The seven research studies and one further Namaste Care study identified during the phase 1 searches50 were taken forward for inclusion in phase 2.

The core elements of Namaste Care, derived from the literature and stakeholder accounts, are:

-

the environment (e.g. calm, warm, scented, music, group setting, gentle lighting)

-

time (done every day, performed slowly, dedicated time for each person)

-

use of loving touch, which might include massage, hair care, skin care, tactile items

-

provision of food and drink

-

pain assessment.

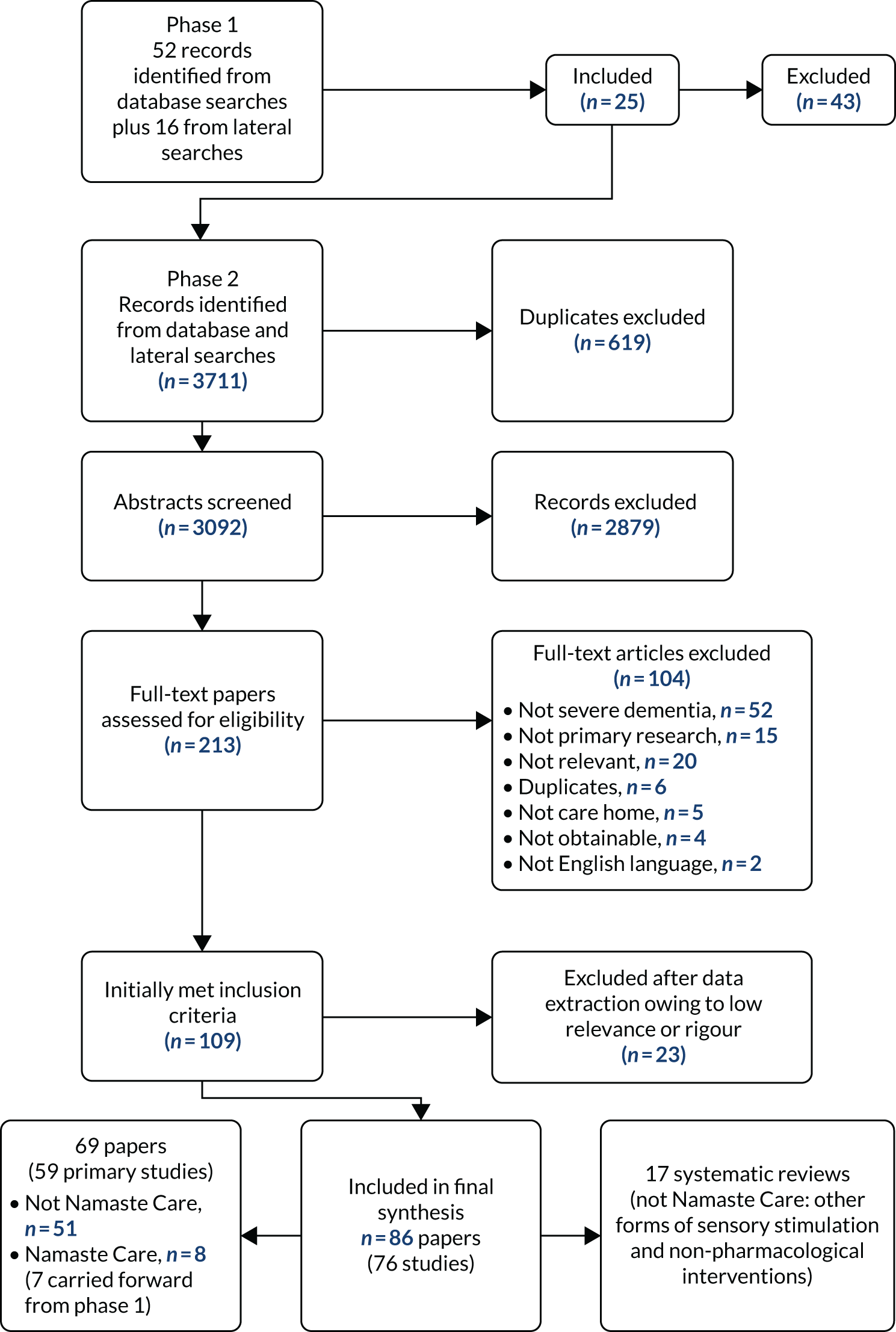

In phase 2 we included 86 papers. The selection process for studies is summarised in Figure 1. Further details of the Namaste Care studies are listed in additional file 3 of Bunn et al. 32

FIGURE 1.

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow chart detailing the selection of studies for the review.

With respect to research design, the 86 papers reported:

-

59 papers reporting 51 primary studies (not Namaste Care)69–129

-

10 papers reporting 8 Namaste Care studies. 22,27,29,44–48,50,130

The designs of the 59 primary studies were:

-

24 randomised controlled trials (reported in 26 papers75–77,82,83,87,95,96,98–102,105,107–115,117,119,123,128,129)

-

four observational studies (reported in 10 papers69–74,84,86,116,126)

-

one action research study (reported in three papers27,29,130).

The remaining six studies78,80,92,104,109,127 used a variety of study designs, including retrospective and crossover.

Studies were conducted in a variety of countries including the USA (n = 1720,46,69–74,79,85,87,92,93,101,116,125,126), the UK (n = 1429,44,45,48,50,75–78,89,97,102,103,113), Australia (n = 947,88,99,100,104,114,121,127), Japan (n = 583,95,110,111,120), Spain (n = 396,109,112), Sweden (n = 384,86,106) and Taiwan (n = 3115,118,119). There were two studies in Canada,98,122 Portugal,80,81 Norway90,94 and Italy107,131 and one study in each of the Netherlands,123 France,105 Belgium124 and Ireland. 117 Studies were generally small, with 33 having < 50 participants.

Details of the interventions and how they were delivered

Studies covered a range of sensory and multisensory interventions (Table 1), with multisensory interventions and music therapy being the most common interventions included. Interventions were most commonly delivered by researchers or by outside facilitators such as music therapists. Care home staff were involved in delivering the intervention in only 1381,84,86,103,104,106,111,113,114,117,118,125,127 out of the 59 non-Namaste Care primary studies. Among Namaste Care studies, the programme was delivered by care home staff in six,44–47,50 by Namaste Care workers in two22,27 and by activity co-ordinators in one. 48

| Category | Primary studies (n) | Reviews (n) |

|---|---|---|

| Namaste Care | 822,27,44–48,50 | 0 |

| Multisensory | 2150,69–71,73,75,76,78–81,92–94,96,98,101,112,117,124–127 | 0 |

| Music | 1861,72,77,79,84,86,91,104,105,110,115,118,119,121,123,126,131 | 653,54,58,61,63,64 |

| Touch/massage | 1082,87,93,95,99,100,106,109,120,126 | 164 |

| Aromatherapy | 582,83,102,111,113 | 252,62 |

| Environment | 770,74,85,90,92,98,116 | 256,132 |

| Other (e.g. person-centred care, use of biography) | 644,59,89,103,114,122 | 555,57,59,60,68 |

The longest and most frequent sessions were reported in the Namaste Care studies, with several22,27,44 reporting that Namaste Care was delivered for 4 hours, 7 days per week.

Programme theory

Our review resulted in three CMO configurations that together provide an account of how and why Namaste Care might work for people with advanced dementia. These are presented in Figure 2 and described in the text below. Interventions were delivered by a variety of different occupational groups; we use the term ‘provider’ to encompass all of these.

FIGURE 2.

Summary of the programme theory.

Context–mechanism–outcome 1: Namaste Care provides structured access to social and physical stimulation

The programme theory is that care home interventions (e.g. Namaste Care) that provide regular and structured access to social and physical stimulation for residents with advanced dementia (C) give staff permission to engage with residents outside task-based care, and trigger responses such as familiarity, reassurance and trust in residents (M), creating a positive impact on resident behaviour and mood (O).

The evidence suggests that one of the most important aspects of programmes is how they enable meaningful relationships to form between providers and residents who are no longer able to communicate easily with speech and have other symptoms consistent with advanced dementia, for example by having the same person provide each session, by incorporating one-to-one interaction into an activity and by providers having the skills to work with people with advanced dementia. 50,64,77,84,92,96,106,121,123,131 By contrast, interventions involving providers who are unfamiliar to residents and/or do not have the appropriate skills99,100 or are unable to engage socially with people with dementia may be less effective. 127 Stakeholders at the workshop suggested that having the same person deliver Namaste Care was not always practical and that rather the aim should be to achieve a consistent approach and attitude towards programme delivery:

What they felt positive about was that they’d managed to create and access what they called a special atmosphere, an environment to practise Namaste Care.

Nam06

Social stimulation appears to be a particularly key component of interventions. In a series of studies, Cohen-Mansfield and colleagues69–74,116,126 evaluated a variety of stimuli for people with dementia living in care homes. They found that social stimulation, especially when it involved one-to-one interaction and the active participation of the resident, had the most dramatic effect on engagement and attention. 73 The importance of one-to-one attention and social stimulation was also highlighted in other studies96,105,113,123 and by stakeholders:

I think when Namaste [Care] really works is when you can create a space where people who are withdrawn can actually come out of that shell and can connect and make eye contact and maybe start to try and talk again.

Nam03

I think most of us are sort of social people, we don’t spend 24 hours a day in a room . . . by bringing them out into a shared space they’re in a room that’s set up for that, they’ve got people around them, and I think the staff there do have good connections with their residents.

Nam04

In Namaste Care, physical stimulation is provided through both the components of the intervention and the environment in which the programme is delivered. For example, scents and soft music were felt to be calming and soothing for residents. 22,27,46 Stakeholders supported this, suggesting that the right space could help overstimulated residents relax and that benefits were also seen outside the Namaste Care space:

We’ve had a lot of residents upstairs that are quite vocal and can be slightly aggressive during personal care and then that’s kind of improved over time with the Namaste and the whole calming atmosphere they’re not shouting out as much.

Nam02

Although some non-Namaste Care studies referred to the importance of environment (e.g. having a private space or a quiet room), in many studies the space was not described. However, studies92,97 did identify practical as well as therapeutic benefits to having a designated space, suggesting that sessions were less likely to be cancelled because of competing priorities and that activities could take place as and when needed by the residents. However, although space might be an important context, it is unlikely to trigger staff engagement without additional resources such as the allocation of time and management support. A study127 evaluating the use of a sensory room for people with dementia (Snoezelen®; www.snoezelen.info) found that staff missed sessions because they did not see them as a priority. Stakeholders suggested that for Namaste Care to be achievable and adopted as a core part of the work of the care home, it was important that staff were given permission, through the appropriate allocation of time and resources, to engage with it:

I think that’s a really big thing that Namaste adds is that there’s like structured time to really pay attention to the residents and yeah, and give them that extra time, and also the opportunity to make contact with the residents.

Nam09

I think it encourages them to work together and it encourages them and gives them permission to find space for their residents . . . and the fact that everybody’s doing it makes it acceptable within the care home, it’s not like somebody’s taken an hour out of their day to try and spend time with a resident and everybody else is saying you should be working, everybody’s doing a similar thing.

Nam04

The originator of Namaste Care suggests that it should be delivered twice per day, 7 days per week. 20 Three non-randomised studies22,27,44 reported that Namaste Care was delivered in this way, and this was endorsed by some stakeholders who saw it as important in normalising the approach within the day-to-day work of the care home:

When you see proper results is when it’s a programme, when it happens 7 days a week and before and after lunch and that involves a huge change in the culture of the care home.

Nam03

However, some stakeholders suggested that this intensity was unlikely to be feasible in most care homes in the UK. From the non-Namaste Care studies we found little empirical evidence on the optimal ‘dose’ of sensory interventions such as Namaste Care, although a meta-analysis53 of music therapy found that sessions provided twice per week had a more statistically significant impact on disruptive behaviours, anxiety and mood than weekly sessions.

There was little evidence on the benefits of group versus one-to-one delivery. A meta-analysis53 of music therapy for people with dementia found that group therapy had more positive effects on disruptive behaviours and anxiety than individual therapy. However, this analysis did not distinguish between those with and those without severe dementia. One randomised controlled trial115 found that group music therapy was more effective for residents with mild and moderate dementia than for those with severe dementia, and another123 suggested that it was more difficult to achieve therapeutic goals if the ratio of participants to therapist was too high (e.g. five residents to one therapist).

Context–mechanism–outcome 2: equipping staff to cope effectively with complex behaviours and variable responses

Programme theory: interventions that include a ‘toolkit’ of multisensory activities equip staff to work effectively with residents with complex behaviours and variable responses, leading to improvements in resident outcomes (e.g. reduced agitation) through triggering responses such as engagement and connection between residents and carers.

The use of ‘loving touch’ is perceived to be key to Namaste Care, with touch thought to evoke an emotional response that leads to physical engagement. 47 We found some evidence to suggest that touch (such as hand massage) can have a calming effect,95 reduce behavioural symptoms,69,120 improve sleep87 and increase engagement. 93 Hand massage may be more effective than simulated social intervention (e.g. holding a doll) because the intervention combines one-to-one social interaction with sensory stimulation. 116

Stakeholders also reported that Namaste Care had a positive impact on relationships and resident behaviour:

Our residents are calmer and eating more, we’ve got residents talking that never used to talk, we’ve got really anxious residents that would be constantly calling for somebody that will actually sit in there for an hour and not call out once . . .

Nam01

Music also appears to trigger emotional responses in people with advanced dementia. There is evidence that receptivity to music can remain until the late stages of dementia. 58 Primary studies73,86,97,107 and reviews53,58 reported that music therapy improved communication and connection, increased engagement and reduced agitation. 84,86,97,131

There is some evidence to suggest that the most effective interventions are those that equip care staff to cope effectively with the complexity of caring for people with advanced dementia. A systematic review64 of interventions to reduce agitation in people with dementia found that the complexity of behaviour associated with dementia required a multifaceted response that could be tailored to the needs of individuals. Stimulating a range of senses may be particularly important for people no longer able to verbalise,50 and as cognitive function deteriorates people with dementia can become very sensitive to sensory experiences. 78,81 Stakeholders talked about the impact of Namaste Care on care home staff and the way in which the staff perceived people with advanced dementia:

I think watching staff I think what you see is that they realise that this person that may be end of life, they may have really quite advanced dementia but we’re still reaching them . . . they’re still living, they’ve still got all the things that we have, we just need to find it in a different way and I think that changed people’s perceptions.

Nam01

The multisensory nature of an intervention such as Namaste Care means that staff have a range of activities to draw on, giving residents a choice of what is delivered and access to different stimulation (touch, auditory, olfactory and visual). 50,64,75,78,79 The assumption from this evidence is that it is the combined effect of being able to use a range of activities that triggers staff capacity and ability to respond to residents’ symptoms and behaviours, and not individual activities.

Context–mechanism–outcome 3: providing a framework for person-centred care

Programme theory: multisensory interventions that focus attention on residents’ individual biographies and that attempt to connect with residents’ reality make staff more responsive to residents’ needs and lead to improvements in resident outcomes (such as increased responsiveness).

Many studies20,60,61,64,100 suggested that, because people respond differently to the same stimuli, interventions need to be tailored to the needs of the individual. Aspects of interventions that needed to be tailored included the environment,133 the music played,84,110,115,119 the aromas used,82,83,111,124 the way someone was touched99,100,106,113 and how someone was spoken to. 93,121 It was also seen as important to consider people’s known habits and preferences, the stage of dementia that people presented with and whether or not their current preferences may be different from their previous habits. 93,97 How this might work in practice, where the intervention creates a heightened awareness of the individual’s preferences, is illustrated in this quotation from a stakeholder:

While you’re doing it and while you’re observing it you notice things that actually that might not work so well for that person . . . so it’s about thinking about your residents and how they’re changing and what we need to do to keep people involved.

Nam01

Using past and current preferences to tailor interventions was reported to reduce agitation64,69,114 and increase alertness or engagement. 72 There was also evidence (although this was largely qualitative or anecdotal) that personalised interventions made staff notice more about residents and their abilities,27,29,50,93 leading to improved communication between staff and residents,61,68,77,84,127 the development of trusting relationships between residents and caregivers89,92,106 and a shift towards a more person-centred culture of care:29,46

You’ve got to have fundamentally good nursing care and the staff need to have good dementia care training as well . . . but what I think Namaste [Care] does is to make it real for them, you know, it makes the person-centred care real for them and it then feeds into the basic care that they’re giving.

Nam03

In our original programme theory, we hypothesised that Namaste Care would have benefits for family members, either through better connection with their family member with dementia or through improved communication with staff. Few studies measured outcomes for family members, although there was some anecdotal and qualitative evidence that Namaste Care improved connections between family members and residents44,48,50,85,93,94 and between relatives and care home staff,44,46,50 for example as described by this stakeholder:

Very often I think relatives don’t see the positive relationship that carers have because when you’re visiting somebody the staff step back, it’s a visit and they just turn up and say, we need to change your mum or it’s lunchtime, will you feed her or shall I or it’s time we changed her for bed or whatever and so it’s very tasky but in Namaste the family actually see the efforts to get somebody to respond and the positive stuff.

Nam03

Conclusions

This realist review provided a coherent account of how Namaste Care, and other multisensory interventions, might work. The evidence on Namaste Care is currently limited, but we drew on a wider literature to test the evidence from a range of studies looking at sensory stimulation and implementation in care homes. The findings from the review were used to develop the Namaste Care intervention delivered in phase 2 and described in Chapter 3. The review also provides practitioners and researchers with a framework to judge the feasibility and likely success of Namaste Care in long-term settings. The proposed theoretical account of what works, why and in what circumstances is not final. As further relevant evidence emerges, it will be refined, challenged and developed further. Nevertheless, it is reasonable to conclude that the key mechanisms that Namaste Care triggers for residents are feelings of familiarity, reassurance, engagement and connection, and that for staff it gives them permission and awareness to engage with residents in a more person-centred way.

Chapter 3 Design and methods: intervention development, cluster randomised controlled trial and process evaluation

The Namaste trial is a cluster randomised controlled trial undertaken to establish if it is feasible to undertake such a trial in nursing homes and if it is possible for the intervention to be implemented as prescribed. The trial protocol134 was reviewed and published in BMJ Open in 2018.

Study design

This was a cluster randomised controlled trial with a non-blinded outcome assessment. The eight clusters were randomised 3 : 1 to the intervention or usual care arm. A cluster trial was chosen, with the nursing home defined as a cluster. This ensured that there was no contamination between the comparator with the test intervention. A qualitative process evaluation and economic analysis ran alongside the trial element of the study, preceded by a process to develop the Namaste Care intervention.

Study setting

The trial was conducted in eight nursing homes, where on-site nursing was available 24 hours per day. This setting was chosen rather than all care homes because it was necessary to have nursing oversight of the intervention delivery and components of it, for example comfort assessment.

Nursing home eligibility

The inclusion criteria were specified in the protocol. 134 The main criteria for participation were that the facility had more than 30 beds (to ensure that there were enough residents for inclusion in the study) and that it was currently engaged with palliative care delivery, as evidenced by involvement in established palliative care programmes. The facility also needed to be able to identify a space that could be dedicated to deliver the intervention. Facilities were not recruited if they had a Care Quality Commission (CQC) rating of ‘needs improvement’ or ‘inadequate’. They were excluded on these grounds because sites addressing quality issues would not necessarily be in a position to engage in research and the change that this requires.

Participants: eligibility criteria

The specific inclusion and exclusion criteria for residents, informal carers and nursing home staff are presented in the protocol. 134

People with dementia

Residents were included in the trial if they lived permanently in the nursing home (and were not present to receive respite or day care). The intervention addresses the needs of people with advanced dementia, so participants needed to have had a formal assessment of advanced dementia based on having a FAST score of 6 or 7. 2 A FAST score of 6 or 7 indicates a need for assistance with personal care and urinary and faecal incontinence, and a higher score reflects reduced mobility and a reduced ability to speak. This was assessed by the nursing home manager or another experienced member of staff. However, residents who were bedbound and unable to leave their room to join the group were not eligible to participate. All participants lacked mental capacity (as assessed and documented with the capacity assessment process in use within each site). As the study relied on proxy data collection, each resident needed to have a key worker member of staff available who was willing to provide proxy outcome data.

Informal carers

Informal carer participants were recruited if they were > 18 years, and self-identified as the relative or friend who acted as an informal carer for a participant included in the study. The informal carer could be, but was not necessarily, the person acting as personal consultee.

Nursing home staff

All nursing home staff, including managers, nurses, care assistants and activity co-ordinators, who were paid to provide care were eligible to participate.

Recruitment

Nursing homes

Recruitment of the cluster nursing homes was undertaken between August 2017 and November 2017. Commitment to participation from one small provider chain prior to the award of funding led to two nursing homes from this group participating. A wider search for participating nursing homes was undertaken using CQC databases and local ENRICH (Enabling Research in Care Homes) network contacts.

People with dementia

Senior staff in the nursing home were asked to identify residents who met the inclusion criteria. As all participants lacked mental capacity, the process of recruitment and consent involved personal consultees or, if no personal consultee was available or responded, a nominated consultee was identified.

Informal carers

Eligible informal carers of residents participating in the trial were identified by the nursing home manager or a senior staff member. This person was not necessarily the informal carer who had acted as a personal consultee for the resident.

Nursing home staff

Information about the study was distributed to all nursing home staff in information packs and at staff meetings.

Data collection

Data collection was undertaken at baseline and at 2 weeks, 4 weeks and monthly until 24 weeks (and post bereavement, if appropriate) using five methods: questionnaires, observation, interviews (individual and group), completion of a session activity log and use of an ActiGraph device (Activinsights Ltd, Kimbolton, UK).

Person with dementia measures

Demographic and clinical characteristics

For residents, data on their age, sex, ethnicity, existing medical conditions and stage of dementia (assessed using the FAST2) were collected at baseline.

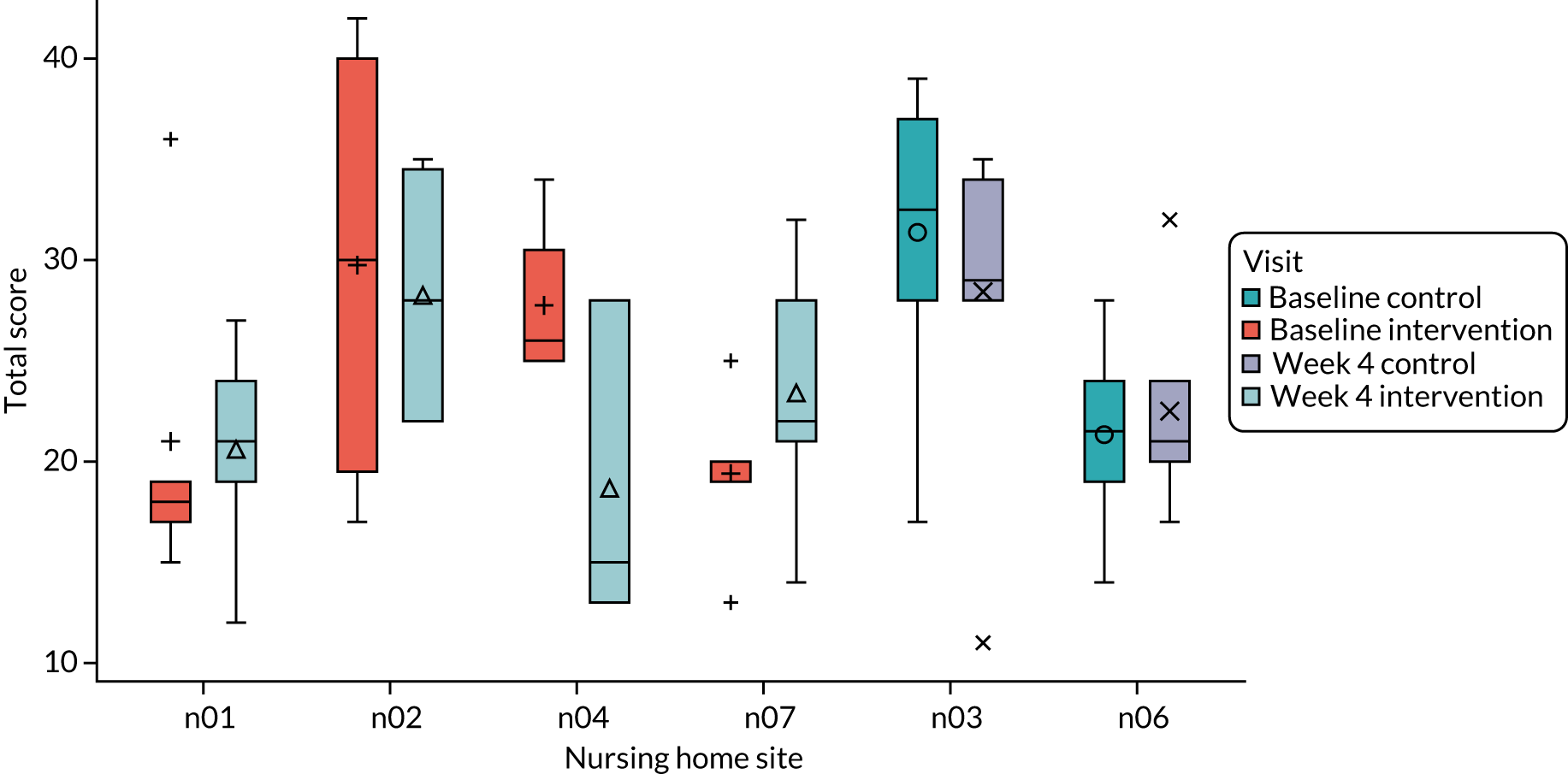

Potential outcomes for main trial

We considered two contender primary outcomes: (1) quality of dying (dementia) [using the Comfort Assessment in Dying – End of Life Care in Dementia (CAD-EOLD)]16,135 and (2) quality of life [using the Quality of Life in Late Stage Dementia (QUALID)]136 (Table 2). For people with advanced dementia living in nursing homes, both quality of life and quality of dying are important outcomes. It is also not always clear which is the most appropriate outcome to measure for people living and dying with advanced dementia. Although this was designed as an end-of-life study, it was not clear if the population with advanced dementia who were eligible to receive the Namaste Care intervention would die during the study. Consequently, one of the feasibility aims was to see whether or not an outcome measure about quality of dying would be appropriate for a full trial.

| Outcome measures or rationale for data collection | Time point of data collection | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline of the individual resident taking part in the study | 2 weeks (after the individual resident has the first Namaste Care session) | 4 weeks (after the individual resident has the first Namaste Care session) | Every 4 weeks up to 24 weeks (after the individual resident has the first Namaste Care session) | 24 weeks (after the individual resident has the first Namaste Care session) or following death | |

| Resident demographicsa | ✗ | ||||

| Quality of dying (dementia) (CAD-EOLD)a | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Quality of life of the person with dementia (QUALID)a | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| NPI-Qa | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Pain (PAIN-AD)a | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| EQ-5D-5La | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| ICECAP-SCMa | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| ICECAP-Oa | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| CMAIa | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Sleep/activity (actigraphy) | Ongoing for 28 days | ||||

| Think-aloud tools (ICECAP-O and ICECAP-SCM)b | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| Resource use (primary and secondary care)c | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

We chose 4 weeks as a primary end point because we wanted to include as many participants as possible in the analysis and recognised that, in this frail and ill participant group, intervention effects needed to be rapid to be meaningful. Attrition due to death is a limiting factor in the successful completion of studies that involve participants with advanced disease. 137 Hence, using early end points is recommended. 138 In previous work evaluating Namaste Care, early deaths (< 2 months) were not uncommon. 139 Benefits from the intervention have been reported within days,139 so by recording an early assessment at 2 weeks and 4 weeks some record of temporal change was made. Missing data and attrition were also likely to be an issue and so having an early measure of 2 weeks could be used to impute missing data.

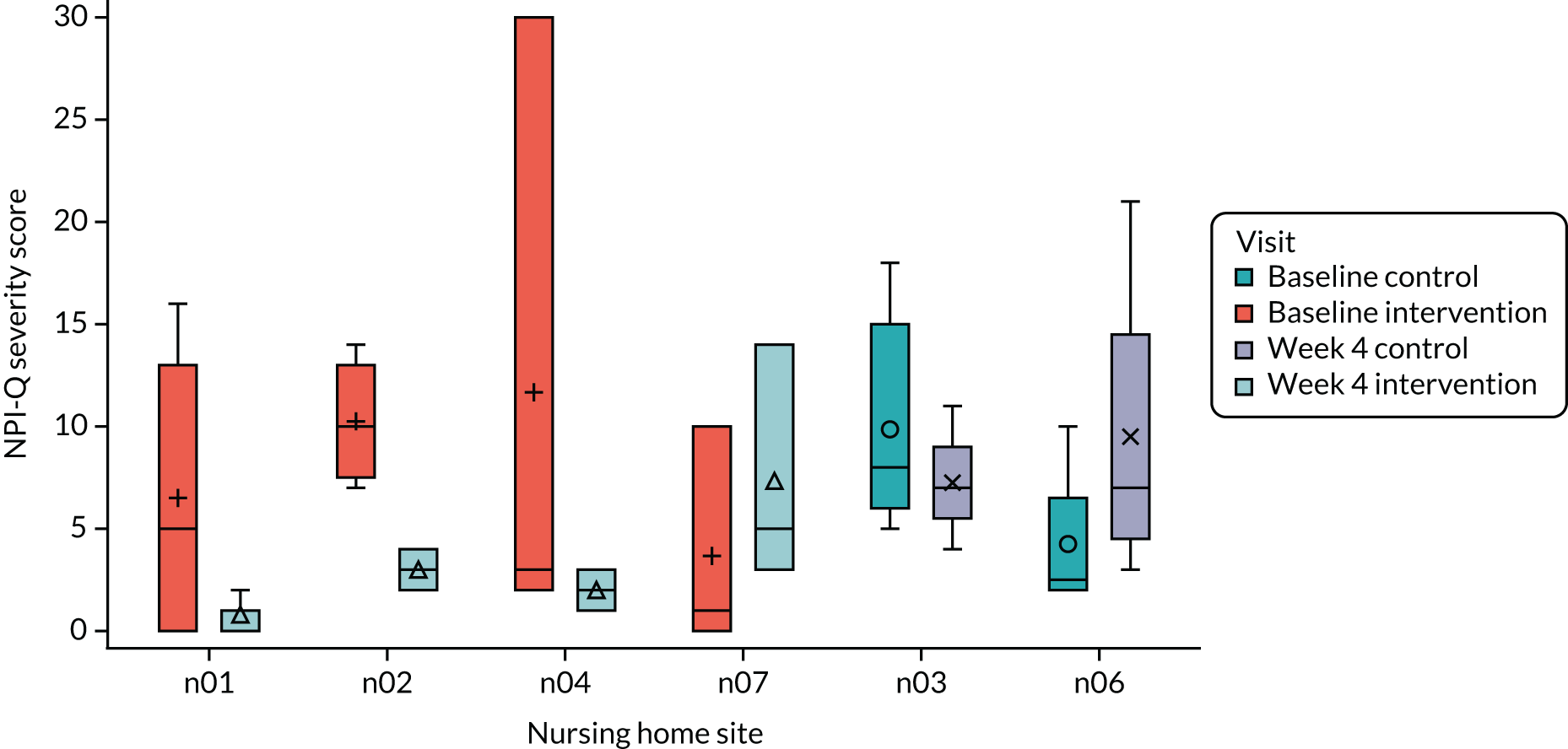

Secondary outcome measures

A number of secondary outcome measures were also included, chosen because of their potential to measures changes in outcomes that reflect different dimensions of the Namaste Care intervention (see Table 2).

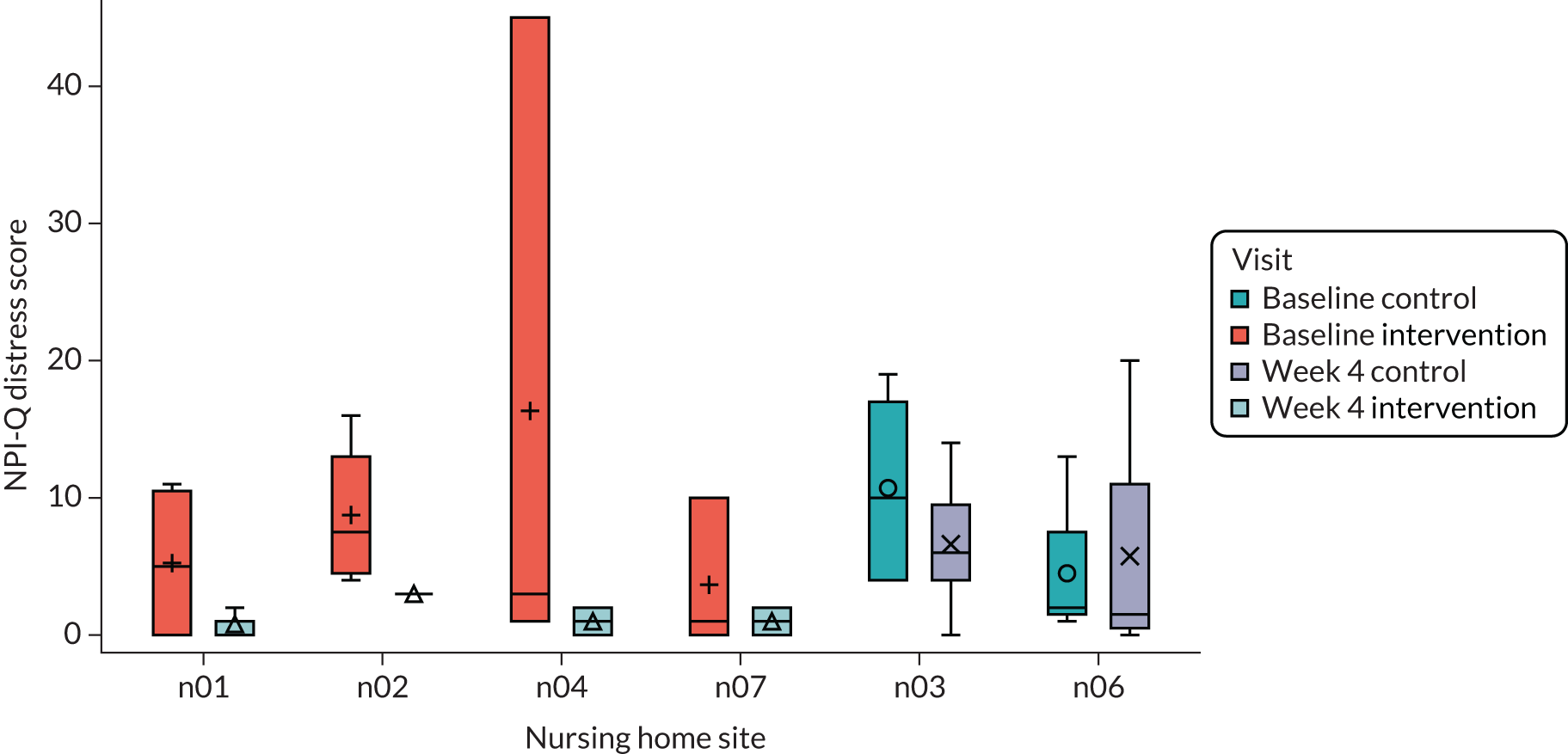

Resident measures

Secondary outcome measures for residents included physical and psychological symptoms [using the Neuropsychiatric Inventory – Questionnaire (NPI-Q)],140,141 pain [using the Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia (PAIN-AD)]142 and agitation [using the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI)]143 (see Table 2). Sleep and activity were measured using actigraphy, which we hoped offered an objective way to assess outcomes that would support the proxy reporting used for the other measures. Residents wore an ActiGraph device for 28 days to measure their sleep levels and patterns and activity.

Informal carer measures

Informal carer measures were used to collect proxy data about residents’ sociodemographic characteristics and satisfaction with care [Satisfaction With Care – End of Life in Dementia (SWC-EOLD)] (Table 3), as well as economic data, including quality of life (see Chapter 6).

| Outcome measures or rationale for data collection | Time point of data collection | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline of the individual resident taking part in the study | 2 weeks | 4 weeks | 24 weeks or following death | |

| Informal carer demographics | ✗ | |||

| SWC-EOLD | ✗ | ✗ | At least 8 weeks after death | |

| ICECAP-CPM | At least 8 weeks after death | |||

| EQ-5D-5L | ✗ | At least 8 weeks after death | ||

| Think-aloud tool (ICECAP-CPM) | At least 8 weeks after death | |||

| Resource use information (Client Service Receipt Inventory) | ✗ | |||

Nursing home staff measures

Nursing home staff completed a form that recorded their sociodemographic details and work characteristics.

Nursing home organisational measures

Organisational measures were collected to provide contextual data for the findings with respect to retention and the impact on staff. This included person-centredness [the Person-Centred Care Assessment Tool (P-CAT)144] and organisational readiness for change (Alberta Context Tool145). Nursing home staff measures and nursing home organisational measures were collected from all staff on duty on the day of the baseline visit.

Intervention

The intervention is a programme of care (Namaste Care) delivered in the intervention care homes by care staff working in the facility. It requires implementation at the organisational (cluster) level and also with individual residents (participants). The following description uses the TIDieR (Template for Intervention Description and Replication) guidelines for intervention description (items 1–9). 146

Namaste Care seeks to give comfort and pleasure to people with advanced dementia through engagement, meaningful and creative activities as well as sensory stimulation to reflect the resident’s ‘life story’. 20 Core elements of the intervention were considered to be that:

-

The Namaste Care sessions should be undertaken within a designated space in the nursing home. This space could be in a room that is used for other purposes (e.g. a dining room), but at specified times it is to be used only for the Namaste Care session.

-

The environment of the designated space must be made ‘special’. It should enable a feeling of calm (i.e. welcoming and homely, with natural or slightly dimmed lighting, perhaps attractive scents, such as lavender from an aromatherapy diffuser, and with soft music playing).

-

The Namaste Care sessions should be undertaken in a group setting.

-

Food snacks and drinks should be offered to the residents throughout the session.

-

A minimum of two nursing home staff members or volunteers should be present to run the Namaste Care sessions.

-

The duration and frequency of Namaste Care delivery as proposed by its originator (2 hours per day, twice per day, 7 days per week) was promoted, but flexibility in this was allowed as part of the feasibility objectives. 20

Namaste Care champions were appointed in each nursing care home in the intervention arm. At least two care staff (registered nurses, care assistants or activity co-ordinators) attended a 1-day workshop about Namaste Care, led by an experienced external facilitator. A follow-up training session was held at each nursing care home to train more staff and provide advice on preparing the Namaste Care space. Nursing homes were given a copy of the Namaste Care guide developed by the research team.

Intervention development and refinement

Developing, refining and clearly specifying the Namaste Care intervention to ensure that it was suitable to use in the feasibility trial was essential for a number of reasons, including training, understanding fidelity, ascribing outcomes to the intervention if a full trial was deemed feasible, and appropriate implementation. 146 Following the realist review of the literature (see Chapter 2), the components of the intervention were mapped onto the identified components (Table 4).

| Key element | Present in revised Namaste Care intervention specification |

|---|---|

| Importance of activities that enabled development of moments of connection for people with advanced dementia |

Principle outlined in Namaste Guide Multisensory activities outlined to address taste, smell, sound, sight and touch Relational care and working with family and friends present in guide |

| CMO1: providing structured access to social and physical stimulation |

Identified space Regular sessions once or twice per day up to 7 days per week Multisensory activities provided |

| CMO2: equipping care home staff to cope effectively with complex behaviours and variable responses |

Training – off-site and on-site Comfort assessment present in training and guide |

| CMO3: providing a framework for person-centred care |

Family conference to explore individual life story and preferences Identification of person-centred interests and activities |

Four iterative stages of intervention refinement were then followed, incorporating co-design of the intervention description with nursing care home staff and family carers. First, existing materials used to support Namaste Care were gathered and, together with the review results, a draft intervention description and guide were collated. Second, these materials were explored with nursing care home staff new to Namaste Care, but outside the trial homes. Third, modified nominal group techniques were used with nursing care home staff, volunteers and family carers with experience of Namaste Care in practice to refine, prioritise and re-present the information in a format suitable to be used with nursing care home staff. Fourth, our public involvement panel were involved (see Chapter 7) in final refinement of the materials.

This stage of the study was conducted with the approval of Lancaster University Faculty of Health and Medicine Research Ethics Committee (17 November 2016/FHMREC16028), and written consent was obtained from all participants.

These stages are briefly described:

-

Approaches were made to 69 organisations (2 NHS trusts, 11 hospices, 56 nursing/care homes) known to already use Namaste Care in practice. Materials received from three organisations, together with the Namaste Care book,147 were used in the preparation of a draft intervention and implementation description and guide, prioritised using findings from the realist review. The design of written materials was guided by best evidence on writing manuals and guidelines. 148–154

-

Nursing and support staff (n = 3) from two nursing care homes that had not used Namaste Care participated in a 2-hour workshop to discuss the emergent intervention guide. They amended the wording to suit a UK situation, and advised on the addition of colour-coding and infographics to aid use of the guide in practice.

-

Two consensus workshops were held with those who had experience of Namaste Care in practice in nursing care home settings (n = 17 staff, volunteers, family carers). We used modified nominal group methods including exposure to stimulus materials (realist review and emergent guide from stages 1 and 2) and silent generation of ideas, and then held a round-robin and group discussion to clarify and rank elements of the intervention. 155–158 This resulted in the addition of a section to the guide, further shortening of the guide booklet and better specification of some elements, such as intervention timing, frequency, focus and staffing. Participants also helped identify potential adverse events that may be associated with the intervention.

-

Finally, the materials were presented to the study public involvement panel, who clarified wording and recommended changes to the colours of the infographics to enhance their readability.

These changes are summarised in Table 5. The final study guide and infographics used to support the study are in Report Supplementary Material 1. 159

| Stage | Content | Presentation |

|---|---|---|

| 2: workshop (no experience of Namaste Care) |

Need for a brief overview document Materials for family members Use of graphics (infographics and images) Colour-coding of sections Wording anglicised |

|

| 3: consensus workshops (experience of Namaste Care) |

Further section, ‘preparing people and organisations for Namaste Care’, added Further detail provided on intervention timing, frequency, focus and staffing requirements Relational and philosophical aspects of the intervention emphasised Identification of potential adverse events incorporated |

Renaming the materials as a ‘guide’ rather than a ‘manual’ Guide shortened to 16 pages Guide materials to be used as basis of formal training |

| 4: PPI consultation |

Clarification of wording Recommended changes to the colours of the infographics to enhance readability |

Usual care

Usual care is the term used to describe the control arm of this trial. This is the usual care provided in a nursing home for people with dementia that addresses the key components of good palliative care practice. The study team provided no further education, training or support on care to the nursing homes in the control arm of the trial.

Outcomes for a full trial

To decide whether or not a full trial would be feasible, a number of criteria were identified before the start of the study (Table 6).

| Indicator | Data source | Achieved if |

|---|---|---|

| Recruitment rate | Researcher records | Six residents per care home recruited |

| Attrition rate | Researcher records | No more than two residents per care home cease receiving the intervention because of practical or preference issues |

| Number of Namaste Care sessions delivered by nursing home staff in 1 week | Nursing home staff completed Namaste Care pro forma | At least 7/14 sessions held per week (50% per week) |

| Average length of Namaste Care session | Nursing home staff completed Namaste Care pro forma | Average length is 1.5 hours |

| Potential primary outcome data completion | Complete CAD-EOLD and QUALID questionnaires | 80% of residents participating in the study have CAD-EOLD and QUALID questionnaires completed for them |

| Namaste Care intervention acceptability to staff and family |

Interviews (family) Focus group (staff) Nursing home staff completed Namaste Care pro forma |

Intervention described as acceptable in terms of components of care provided, timing and frequency of delivery |

| Namaste Care intervention suitable for UK nursing home environments |

Interviews (family) Focus group (staff) Observation of care delivery |

Intervention described as being suitable for this context |

| Identification of a sufficient pool of nursing homes that reflect nursing home diversity and that would be willing to participate in a full trial | ENRICH network data; CQC database | Identified a pool of nursing homes willing to participate in a future trial that exceeds the proposed sample required for a future trial |

Process evaluation

A robust process evaluation was undertaken to ensure the capture of data that directly addressed the feasibility objectives and addressed the acceptability, fidelity and sustainability of the intervention. This evaluation identified factors that influenced the implementation of the Namaste Care intervention in the context of a cluster randomised controlled trial to enable a full trial to be planned. In designing the process evaluation, we drew from a framework for designing process evaluations for cluster controlled randomised trials of complex interventions,160 and descriptors of components of process evaluations. 161 The process evaluation also provided key information to add to the programme theory developed in phase 1 in relation to how and why Namaste Care might work as a complex intervention. 162

The process evaluation involved interviews, observation of the Namaste Care intervention being delivered by care staff and the completion of activity logs. At the start of the study, individual semistructured interviews were conducted with managers. At the end of the study, individual interviews were conducted with informal carers and focus groups were held with care home staff. We assessed perceptions of Namaste Care or usual care, and the fidelity, acceptability and appropriateness of Namaste Care or of usual care. We also assessed the fidelity, acceptability and appropriateness of Namaste Care (intervention arm) or assessed the activities used in usual care (control arm) through observation in each site at 2, 4 and 24 weeks. We also asked staff to complete an activity log for each Namaste session.

Informal carer interviews

Interviews with informal carers were undertaken to assess the informal carers’ perceptions of Namaste Care (intervention arm) or informal carers’ perceptions of the activities offered in usual care (control arm). Interviews were conducted approximately 16–24 weeks after the first resident was recruited at the nursing home. The informal carer could also be interviewed if their relative died, but to reduce distress this would be at least 8 weeks after the resident’s death, as specified in the ethics application.

Manager interviews

The managers of all eight intervention and control nursing homes were invited to take part in an interview before the first resident was recruited in their nursing home. The aim was to explore their organisation’s readiness for change and the context of care. Demographic contextual data about each nursing home were also collected.

All eight managers agreed to take part in an interview, and the interviews took place in the study nursing homes. The interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed; the length of the interviews ranged from 15 to 40 minutes. The topics included in the intervention arm interview were based on the criteria for readiness for change identified by Goodman et al. 163 that addressed aspects of the care home’s readiness to take on new interventions and the fit between current care approaches and Namaste Care. The interview in the control arm covered the same topics but questions were asked in a more general way without reference to Namaste Care.

Nursing home staff interviews

Group interviews were held in each participating nursing home at the end of the study to assess staff members’ perceptions of Namaste Care (intervention arm) or perceptions of the usual care activities (control arm).

Structured observation

To assess the fidelity, acceptability and appropriateness of Namaste Care, observation of the Namaste Care sessions was undertaken at 2, 4 and 24 weeks after the first resident was recruited in the intervention homes. Observation was conducted in the control homes at 2 and 4 weeks to assess the delivery of ‘usual’ care. In control homes, the researcher observed the residents in communal spaces where ‘usual’ care activities were taking place. A structured schedule that reflected the core components of the intervention was used in both control and intervention homes, as were field notes. Observation was undertaken for up to 20 minutes at the beginning, middle and end of the sessions, and audio-recordings were made to ensure that all verbal data were captured.

Session activity log

An activity log was completed by the staff delivering the Namaste Care session at each session to assess the fidelity and appropriateness of the Namaste Care (intervention arm only).

Health economic analysis

Economic assessments combined qualitative assessments of feasibility of use for the outcome measures gained through the use of think-aloud techniques and more quantitative assessments of agreement between proxies, and assessments of construct validity for the measures164 (see Chapter 6 for further detail).

Adverse events

During the study there was a relatively high risk of death and hospitalisation and an expectation of progression of disease for participants. These were not anticipated to be related to the receipt of the intervention. These types of events were not treated as adverse events or serious adverse events as they were not unexpected in this resident population. These were to be reported only if concern was raised by anyone associated with the study that death, hospitalisation or any other medical occurrence were directly related to study participation.

As this was a feasibility study, any events reported to any personnel involved in the trial (including health professionals, informal carers or research team members) that were considered adverse events were noted on a trial event recording form, which was completed by or returned to the trial manager and/or chief investigator. The trial manager or chief investigator would investigate the event with the person who reported it, and other involved individuals, and then take appropriate action following standard operating procedures aligned with the clinical trials unit policies.

Quantitative analysis

As this was a feasibility trial, the main purpose was to undertake a descriptive statistical analysis based on the full trial indicators to see if it would be feasible to undertake a full trial. The analysis was not undertaken to determine the effect of the intervention. Analysis of the outcome data focused on recruitment, response and completion rates, and missing data. Reasons for non-consent and missing outcome data were reported. Primary and secondary outcomes at baseline and follow-up were summarised using descriptive statistics [mean, standard deviation (SD), interquartile range]. Intracluster correlation coefficients (ICCs) were calculated for a definitive trial design.

The sleep/activity data from the ActiGraph device were an important element of this study. The search for an objective measure that provides clinically meaningful data for this population, among whom there is heavy reliance on proxy data, is ongoing. The acceptability of the ActiGraph device was a key question, but also of importance was the nature of the data and how they shaped the analysis of the different variables (Table 7) such as sleep–wake ratios, total sleep time, sleep efficiency, wake after sleep onset and total activity, alongside rhythm fragmentation and synchronisation.

| Term | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Sleep–wake ratio | Ratio of total sleep time to time awake |

| Total sleep time | Refers to total time of periods of inactivity (inferred to be sleep) within the sleep period time |

| Sleep efficiency | Ratio of total sleep time to time in bed |

| Wake after sleep onset | Periods of wakefulness occurring after defined sleep onset |

| Rhythm fragmentation; intradaily variability | Frequency and extent of transitions between periods of rest and activity on an hourly basis. Quantifies how fragmented the rhythm is relative to its 24-hour amplitude; more frequent alterations between an active and an inactive state lead to a higher intradaily variability |

| Rhythm synchronisation; interdaily stability | Quantifies the rhythm’s synchronisation, the stability of the rhythm or the extent to which the profiles of individual days resemble each other |

A participant’s rhythm fragmentation and synchronisation were estimated using intradaily variability and interdaily stability. Intradaily variability quantifies the frequency and extent of transitions between periods of rest and activity on an hourly basis. Interdaily stability quantifies the extent to which the rhythms synchronise to Zeitgeber’s 24-hour day–night cycle. 165,166

Qualitative analysis

Interviews

All interviews (manager, informal carer, nursing home staff) were recorded, transcribed and anonymised. Framework analysis was used to analyse the transcripts,167,168 aided by using the qualitative analysis package NVivo 11 (QSR International, Warrington, UK).

Observation analysis and session activity log analysis

Definitions were developed for the core components of the Namaste Care session to ensure that researchers applied the level of agreement scores consistently during analysis. The data from the observation forms and recordings were compared with those from the relevant Namaste Care activity logs to analyse the extent of agreement between the different types of data. This comparison was initially carried out independently by two researchers and then cross-checked to ensure that definitions had been applied consistently across all of the nursing homes. Any discrepancies were discussed and advice sought, as appropriate, from a senior researcher in order to reach agreement.

Sample size

The sample size of eight nursing homes (six intervention and two control) with eight residents per cluster was selected as it offered a reasonable test of the intervention to assess the feasibility objectives. The numbers of residents in feasibility studies have ranged from 2128 to 6169 to 14. 170

Randomisation

The eight nursing homes were randomised to either the intervention arm or the control arm by assigning an ID to each nursing home and then randomly selecting each ID. The random allocation was carried out by a statistician who was employed by the Clinical Trials Research Centre at the University of Liverpool and not otherwise involved in the trial. A one-off computer generated randomisation procedure was used.

Blinding

The nature of the intervention and its delivery meant that it was not possible to blind nursing homes or staff to the allocation status. When possible, to minimise potential for bias, staff involved in the delivery of the Namaste Care intervention were not involved in completing the outcome measures. However, in practice the staff available on the day of data collection were, at times, the staff who had delivered Namaste Care sessions. It was also not possible to blind researchers to the allocation of nursing homes, as the intervention required changes to the nursing home environment that were visible to any researcher visiting the facility. Statisticians carrying out the analysis were blinded as to which data were from control sites and which were from intervention sites.

Ethics

The trial was approved by the Wales Research Ethics Committee 5 Bangor Research Ethics Committee (reference number 17/WA/0378) on 22 November 2017.

Changes to the protocol

Over the course of the whole trial, one amendment was submitted to the research ethics committee (22 February 2018; approval received 6 March 2018). Amendments consisted of changes to clarify the process of staff recruitment, information on how the think-aloud interviews would be conducted and a new format for questionnaire presentation.

Chapter 4 Results of cluster randomised controlled trial

The primary objective of this feasibility study is to ascertain the feasibility of conducting a full trial of the Namaste Care intervention. The feasibility aims of the research design and data collection processes to enable the design of a full trial to determine the efficacy of Namaste Care are:

-

to understand how best to sample and recruit nursing homes into a cluster randomised controlled trial of Namaste Care

-

to establish recruitment, retention and attrition rates at the level of the nursing home and individual resident, informal carer and nursing home staff

-

to determine the most appropriate selection, timing and administration of primary and secondary outcome measures for a full cluster randomised controlled trial of Namaste Care against criteria of bias minimisation, burden and acceptability

-

to assess the acceptability, fidelity and sustainability of the Namaste Care intervention

-

to establish the willingness of a large number of nursing homes representing the range of nursing homes, with respect to provider type, size and resident care needs, to participate in a full trial.

Sampling and recruitment of nursing homes

The recruitment of the nursing homes used the inclusion criteria outlined in Chapter 3.

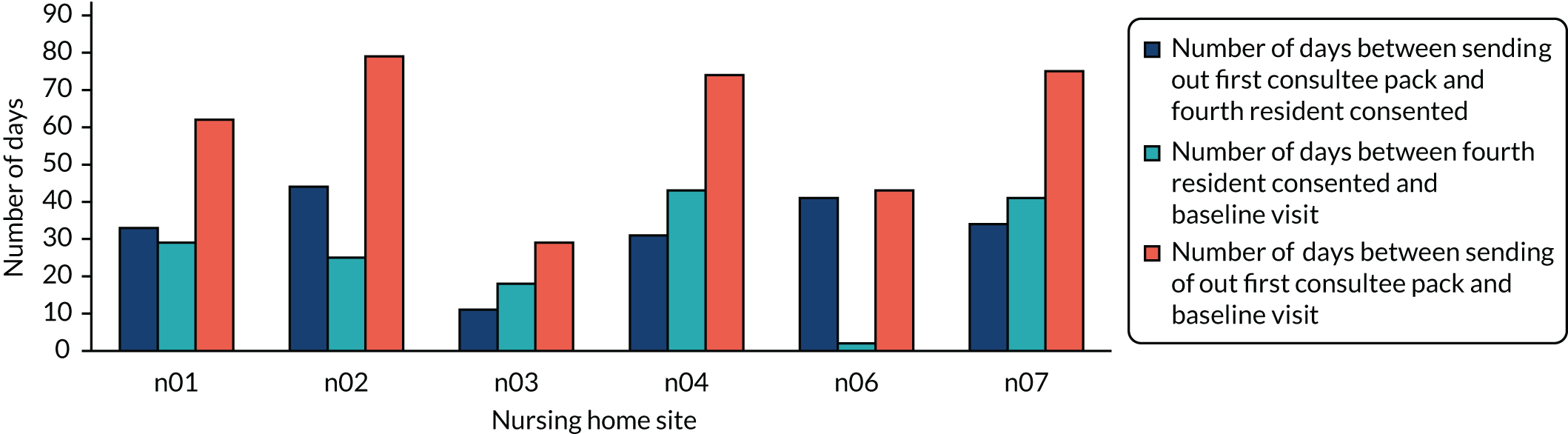

Thirty-six facilities were approached in the north-west of England (Figure 3); nine were recruited, and eight consented to be included in the trial. During the funding application process, a regional not-for-profit provider committed to be involved in the study and provide nursing home sites for the study. However, the senior management commitment did not result in nursing homes meeting the inclusion criteria, and only two facilities participated. Engagement with ENRICH and the Clinical Research Network was key to identifying nursing homes that met the inclusion criteria and were interested in participating in a research study. A major reason why nursing homes did not participate was the difficulty of speaking to a manager about the study.

FIGURE 3.

The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram: summary of recruitment and follow-up.

The time taken to recruit eight nursing homes was 41 weeks, from initial contacts in August 2017 to the first baseline visit in May 2018. The average number of days from first contact to the baseline visit across the eight sites was 241 days (34 weeks), with a range of 193–255 days (Table 8). The varying lengths of time required for recruitment reflected differences in how long it took for the clinical trial agreement to be signed by the nursing home managers. Randomisation could not occur until all of the eight nursing homes had signed the agreement, thereby delaying study commencement. Delay in managers signing the form resulted from their unfamiliarity with that type of documentation, which is widely used in the NHS. This lack of knowledge needs to be taken account of by the research team as they support managers to participate.

| Length of time for nursing home recruitment | Nursing home | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n01 | n02 | n03 | n04 | n05 | n06 | n07 | n08 | Mean | |

| Number of days between initial contact and contract being sent out | 96 | 104 | 97 | 22 | 99 | 44 | 27 | 21 | 63 |

| Number of days between contract being sent out and signed by the nursing home manager | 27 | 5 | 22 | 51 | 7 | 26 | 20 | 7 | 21 |

| Number of days between contract being signed and randomisation | 34 | 56 | 39 | 10 | 54 | 35 | 41 | 48 | 40 |

| Number of days between randomisation and baseline visit | 114 | 120 | 98 | 113 | w | 137 | 105 | w | 115 |

| Total number of days from initial contact to baseline visit | 271 | 285 | 256 | 196 | N/A | 242 | 193 | N/A | 241 |

Telephone and face-to-face support was required by the study team to facilitate the signing of the clinical trial agreement between the university and the individual nursing homes.

Learning for a future trial

-

Ensure that enough time is required for the necessary agreements to be in place so that randomisation can occur promptly and this should be factored into study planning.

-

The study design should allow the study to commence as nursing homes consent, rather than waiting for all sites to be ready (randomisation in blocks of four nursing homes).

-

Research support is required for nursing home managers agreeing to participate to facilitate contracting and governance.

Recruitment, retention and attrition of participants

Cluster: nursing home

Six out of the eight clusters (nursing homes) (four in the intervention group and two in the control group) remained in the study for full analysis. The withdrawal of two nursing homes after randomisation and before the start of resident recruitment was a result of staffing issues (the resignation of a manager) and start delays (that led a manager to decide that the intervention would not work for the residents in that care home). Once the trial had commenced, no nursing homes withdrew.

Learning for a future trial

Once nursing homes consented and the study commenced, retention was excellent, but there is a need to shorten the period between engaging with nursing homes and starting the study.

Nursing homes