Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 17/48/01. The contractual start date was in August 2017. The draft report began editorial review in October 2018 and was accepted for publication in June 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Stevenson et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (CJD) is a progressive, fatal disease affecting the brain. CJD is caused by an abnormal transmissible protein called a prion. Once CJD is transmitted, the concentration of CJD prions varies throughout the body, but reaches high levels in the brain and posterior eye, resulting in neurological symptoms including rapidly progressive dementia, extrapyramidal signs and visual symptoms. Most people with clinically diagnosed CJD will die within 1 year of the symptoms appearing.

Four classifications of CJD exist: sporadic CJD (sCJD), variant CJD (vCJD), genetic CJD (gCJD) and iatrogenic CJD (iCJD). Referrals of suspected CJD and values for death definitely related (with neuropathological confirmation) or probably related (without neuropathological confirmation) to CJD are recorded by the National CJD Research and Surveillance Unit (NCJDRSU) in Edinburgh. 1 This source estimates that since 1990 there have been 3746 referrals for investigation and 2370 deaths from definite or probable CJD (as of 8 January 2018).

Sporadic CJD has historically been the most common type of CJD, accounting for around 85% of CJD cases. The cause of sCJD is thought to be the spontaneous generation of an abnormal isoform of prion protein (PrP). sCJD generally occurs later in life (in those with a mean age of 67 years) and has a short survival post diagnosis of around 4 months. 2 Although there is evidence of a genetic predisposition to sCJD, the precise cause of the disorder is unknown.

Genetic CJD, also known as familial or inherited CJD, is associated with a pathogenic mutation in the prion protein gene (PRNP) and includes conditions known as fatal familial insomnia (FFI) and Gerstmann–Schäussler–Scheinker (GSS) syndrome. Overall, gCJD accounts for between 5% and 15% of CJD cases or approximately 10 CJD deaths in the UK, per year.

Variant CJD was observed following the exposure of the UK population during the late 1980s and early 1990s to bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), which was presumed to be transmitted to humans by eating food contaminated with the brain, spinal cord or digestive tract of infected carcasses. The vCJD epidemic peaked in 2000 with 28 deaths and has since declined, with only two ‘definite or probable’ vCJD deaths reported since 2012. The majority of cases have occurred in a younger population compared with that observed in sCJD, with a mean age of 26 years. The median disease duration post diagnosis is longer in vCJD (14 months) than that observed in sCJD. All people who have contracted clinically observed vCJD have died.

Incidences of iCJD, which is the transmission of prion disease through medical procedures or equipment, have been recorded for procedures such as dura mater grafts, electroencephalography (EEG) needles and neurosurgery, and from receipt of corneal grafts, growth hormones, gonadotrophin or packed red blood cells. 3

The current decision problem focuses on the risk of transmission of CJD (of all forms) via surgical instruments. Prions are unlikely to be completely deactivated on surgical instruments by conventional hospital cleansing and sterilisation techniques4 and, therefore, patients may be infected iatrogenically with CJD by surgical instruments resulting in a surgically transmitted CJD (stCJD) case. Iatrogenic transmission can occur when surgical instruments, endoscopes or laryngoscopes are used during high-risk neurosurgical procedures in patients who have asymptomatic CJD but who are infectious because neural tissue in particular has a high infectious load. 5 Four cases of iCJD transmitted via neurosurgery were observed between 1952 and 1974 from three sporadic index cases of CJD. 6 Stringent public health requirements are in place to limit the risk of iCJD being spread from people with an increased risk of developing CJD, or with CJD, or for whom a diagnosis of CJD is being considered or cannot be excluded.

Immediately following the recognition of vCJD, as a consequence of the BSE outbreak, the potential scale of the number of infections was uncertain; estimations incorporated potential subclinical vCJD infections identified from a histopathological survey of lymphoreticular tissue to be 237 per million [95% confidence interval (CI) 49 to 692 per million]. 7–9 Surgical transmission of CJD in this scenario was considered to pose a potential risk to public health by virtue of a self-sustaining iatrogenic epidemic. Therefore, in 2005 the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) commissioned the School of Health and Related Research (ScHARR) at the University of Sheffield to conduct a systematic review and perform cost-effectiveness modelling of evidence on patient safety and reduction of risks of transmission of CJD. 10 This evidence, together with data collected from experts, was used to populate a mathematical model assessing the cost-effectiveness of single-use surgical instruments. 11,12 The outputs from the model and a separate risk assessment conducted by the Department of Health Economics, Statistics and Operational Research Division13 were used to inform the NICE Interventional Procedures Guidance 196 (IPG196) Patient Safety and Reduction of Risk of Transmission of Creutzfeldt–Jakob Disease (CJD) Via Interventional Procedures. 14 The existing guidance includes recommendations on decontamination methods and guidance for set-keeping to ensure that instruments in contact with potentially high-risk tissues do not move from one set to another. Furthermore, supplementary instruments (SIs) used during high-risk procedures were recommended to either be single-use or to remain with the set with which they were introduced. An age split was also recommended with separate instruments used for people born before 1997 (and at risk of dietary exposure to BSE) and those born after 1996 (who were believed, at the time of writing IPG196, to be not infected with vCJD). High-risk procedures are regarded as intradural neurosurgical operations on the brain (excluding operations on the spine and peripheral nerves), neuroendoscopy, and posterior eye procedures that involve the retina or optic nerve. 14 Although the cost-effectiveness analysis indicated that the introduction of single-use instruments for all high-risk procedures was not cost-effective, there was great uncertainty in these results and a recommendation was made by the study authors that policy might need to be revised if new relevant data become available.

An epidemic of CJD has not occurred since the publication of IPG196 and no conclusive evidence of transmission by surgery has transpired to date. However, a number of developments have occurred since 2006 that include:

-

a finding of abnormal prion accumulation in the appendixes of low-risk cohorts (i.e. those born after 1996)15,16

-

continued evolution of high quality and less expensive single-use instruments

-

anecdotal reports of difficulties implementing the recommendation from IPG196 related to keeping instruments in their original sets across a number of units

-

anecdotal reports of problems in maintaining quarantined instruments for patients born after 1996.

A recent study has also implicated neurosurgery as a possible iatrogenic source for amyloid beta accumulation in the brain, a peptide that is associated with Alzheimer’s disease. 17 This finding underlines the potential risk associated with high-risk procedures and the importance of assessing evidence relevant to decontamination or disposal of neurosurgical equipment.

Purpose of the research

The objective of the current research is to update selected evidence from the research project conducted in 2005 (project number IP1553)18,19 that informed NICE guidance IPG19611 for the NICE Interventional Procedures (IPs) committee to review the decision problem in 2018. The aim is to review the evidence base for the current risk of transmission of CJD (any form) related to surgery in order to provide up-to-date relevant evidence to NICE, and to inform the cost-effectiveness of potential management strategies.

Research objectives

-

To perform updates of the systematic reviews completed in 2005 on the clinical evidence on patient safety and risks of transmission of CJD via surgery.

-

To update the economic model and, where necessary, seek new input from expert elicitation to make the model relevant for the decision problem today.

-

To undertake modelling to estimate the cost-effectiveness of strategies to reduce the risk of transmission of CJD via surgical procedures.

Chapter 2 Clinical evidence

Methods for systematic reviews

The protocol for this project was developed in consultation with the NICE Interventional Procedures Advisory Committee and was registered on the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) systematic review database (PROSPERO registration number CRD42017071807). The project aimed first to update the evidence for the following eight research questions:

-

What is the incidence of CJD and what is the prevalence of CJD-related prions in humans in the UK?

-

What is the risk of secondary transmission of CJD by surgical procedure?

-

What are the incubation periods of acquired transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs)?

-

What is the infectivity of CJD?

-

What is the evidence on the efficacy of decontamination techniques for instruments infected with prions?

-

What is the evidence that instruments used for high-risk procedures remain in their original sets?

-

What is the evidence for complication rates of single-use compared with reusable instruments for high-risk procedures?

-

What is the evidence for likelihood of future surgery for a patient undergoing high-risk procedures?

Eight systematic reviews have been completed to address these research questions. These reviews adhered to best practice systematic review methodology in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 200920 standards.

Eligibility criteria

The inclusion and exclusion criteria differ for each review question. These are broadly summarised in Table 1.

| Review question | Eligibility criteria for inclusion into the review |

|---|---|

| What is the incidence of CJD and what is the prevalence of CJD-related prions in humans in the UK? |

|

| What is the risk of secondary transmission of CJD by surgical procedure? |

|

| What are the incubation periods of acquired TSEs? |

|

| What is the infectivity of CJD? |

|

| What is the evidence on the efficacy of decontamination techniques for instruments infected with CJD/TSE/prions? |

|

| What is the evidence that instruments used for high-risk procedures remain in their original sets? |

|

| What is the evidence for complication rates of single-use compared with reusable instruments for high-risk procedures? |

|

| What is the evidence for risk of future surgery for a patient undergoing high-risk procedures? |

|

Search strategy

Literature searches were conducted to retrieve relevant evidence. Electronic databases were searched on 14 August 2017:

-

MEDLINE Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations – via Ovid® (Wolters Kluwer, Alphen aan den Rijn, the Netherlands), 1946 to 2017

-

EMBASE – via Ovid, 1974 to 2017

-

Science Citation Index and Conference Proceedings Citation Index– Web of Science™ (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA), 1990 to 2017.

A date restriction from 2005 to 2017 was applied for the first seven review questions. For the final review question regarding the risk of future surgery in patients who have had high-risk procedures, because no relevant evidence was found in the previous review, the search strategy was revised and searches were performed from database inception to 2017. No language or study design limits were applied to the searches. The search strategies are presented in Appendix 1.

Members of the NICE IP’s committee were consulted as content experts for potentially relevant papers for all review questions. Papers recommended by experts were subject to bibliography checking.

The searches combined terms that would be relevant for more than one review question. Therefore, five targeted literature searches, instead of eight, for all review questions were conducted, which combined terms for:

-

Searches for the UK incidence and prevalence of CJD and the incubation period of acquired human TSEs.

Electronic literature searches were performed to identify relevant articles. Terms for ‘incidence and prevalence’ or ‘incubation’ (see Appendix 1, search strategy lines 10–15) were combined with ‘CJD’ population terms (see Appendix 1, search strategy lines 1–9). The terms applied were identical to those used in appendices 1 and 3 in the original systematic review. 10

-

Searches for the secondary transmission of CJD by invasive diagnostic or surgical procedures; infectious mass required to transmit CJD; and the decontamination of surgical, anaesthetic and diagnostic instruments, scopes and implantable devices.

Electronic literature searches were performed to identify relevant articles. Terms for ‘transmission’ and ‘transfer’ (see Appendix 1, search strategy line 27) and ‘instrument decontamination’ (see Appendix 1, search strategy lines 28–33) were combined with ‘CJD’ population terms in humans or non-human mammals (see Appendix 1, search strategy lines 18–25).

-

Searches for the extent to which surgical instruments remain in their original sets following use and decontamination.

Electronic literature searches were performed to identify articles that report on the extent to which surgical instruments remain in their original sets following use and decontamination. Terms for ‘instrument decontamination’ (see Appendix 1, search strategy lines 36–41) were combined with ‘high-risk surgical procedures’ (see Appendix 1, search strategy lines 42–56). A list of high-risk surgical procedures were taken from appendix C of NICE IPG196. 14

-

Searches for the complication rates associated with the use of single-use versus reusable anaesthetic, diagnostic or surgical instruments.

Electronic literature searches were performed to identify articles that report on complication rates associated with the use of single-use versus reusable anaesthetic, diagnostic or surgical instruments. Terms for ‘disposable’ or single-use’ instruments (see Appendix 1, search strategy lines 60–63), including specifically named instruments recommended at the NICE committee meeting in June 2017 (see Appendix 1, search strategy line 63), were combined with ‘high-risk surgical procedures’ (see Appendix 1, search strategy lines 65–79) or ‘complications’ (see Appendix 1, search strategy lines 81–84).

-

Searches for the risk of future surgery following surgery.

Electronic literature searches were performed to identify articles that report on the risk of future surgery following surgery. Terms for ‘reoperation’ or ‘repeat surgery’ were combined (see Appendix 1, search strategy lines 88–90) with ‘high-risk surgical procedures’ (see Appendix 1, search strategy lines 92–106). As the review question was reconceptualised to be more sensitive to potentially relevant studies than the previous review undertaken in 2006, no date restrictions were applied.

Cost-effectiveness searches

A literature search was undertaken to identify evidence relevant to the cost-effectiveness model such as relevant economic evaluations in CJD.

Four electronic databases were searched on 7 June 2017 from 2004 to present:

-

MEDLINE, MEDLINE Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations – via Ovid, 1946 to 2017

-

EMBASE – via Ovid, 1974 to 2017

-

The Cochrane Library (Wiley Online Library) Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 1996 to 2017; Health Technology Assessment Database, 1995 to 2016; NHS Economic Evaluation Database, 1995 to 2015

-

Science Citation Index and Conference Proceedings Citation Index – Web of Science, 1990 to 2017.

The search strategy comprised Medical Subject Headings or Emtree thesaurus terms and free-text synonyms for ‘CJD’. Searches were translated across databases and were not limited by language. The search strategies are presented in Appendix 2. Search filters designed to identify economic evaluations were used on MEDLINE and EMBASE.

Study selection

Results from the electronic bibliographic searches were imported into reference management software, EndNote Version 8 [Clarivate Analytics (formerly Thomson Reuters), Philadelphia, PA, USA], and duplicates were removed. Titles and abstracts of retrieved records were examined by one reviewer (LU) and irrelevant citations were excluded. A proportion (10%) of randomly selected excluded citations were double-checked by a second reviewer (CC) and any disagreements were resolved by discussion between the reviewers. Consultation with the third designated team member (MS) was not required for any citation. At the full-paper stage, all citations excluded from a particular review question by the reviewer were double-checked by the second reviewer. Lists of these citations, with the principal reason for exclusion, are reported for each review in Appendix 3. Data identified from countries outside the UK were incorporated if deemed relevant.

Literature identified within the cost-effectiveness review was processed in a similar manner. Titles and abstracts of retrieved records were examined by one reviewer (MS) and irrelevant citations were excluded. A proportion (10%) of randomly selected excluded citations were double-checked by a second reviewer (LU). All full-text articles were independently assessed for inclusion by two reviewers (MS, and LU). No disagreements were required to be resolved through discussion or with involvement of the third designated team member (CC).

Data extraction

Bespoke data extraction forms were developed for each review question in Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) to record relevant outcome data for the review question in hand. All data were extracted by one systematic reviewer (LU for reviews 1, 2 and 4; CC for reviews 3, 5, 6, 7 and 8) and independently checked by a second reviewer (LU for reviews 3, 5, 6, 7 and 8; CC for reviews 1, 2 and 4). Any disagreements were resolved by discussion and consensus or by consulting with a third member of the project team (MS).

Quality assessment

Formal quality assessment using standard checklists, such as the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool, was considered for these systematic reviews. The value of conducting quality assessment is to assess how a study has been conducted in order to balance the numerical findings (or the statistical strength of effects) against the methodological quality. There are a range of quality assessment tools available depending on the study type included; quality assessment is not only amenable to a review of RCTs. However, none of the review questions sought data that were estimating treatment effects; therefore, the typical domains of quality assessment, such as randomisation, performance bias, detection bias and attrition bias, are less relevant. Furthermore, in many cases, the included ‘studies’ in this review were not amenable to quality assessment because (1) they are surveillance reports, thereby not constituting the traditional definition of a study or (2) they are laboratory studies using highly specific scientific methods that are not amenable to the quality assessment for clinical trials. As these included studies were mainly observational in nature, the data of interest were less vulnerable to author conflicts of interest or systematic bias. Assessment of study heterogeneity is most important when performing formal synthesis to estimate treatment effects, which is not the objective of this review. Indeed, limitations to review inclusion criteria based on study design, scientific discipline, setting or context would potentially have restricted the external validity of the review. Therefore, no formal quality assessment has been undertaken and the protocol for the systematic review, registered on the PROSPERO database (CRD42017071807), was updated accordingly. 21 The purpose of the reviews was primarily to describe the relevant literature rather than to aggregate data or rank individual studies.

Data analysis/synthesis

Data were tabulated, synthesised and discussed narratively for each review question. Meta-analyses were planned to be conducted by an experienced statistician using appropriate software, and heterogeneity was to be explored using meta-regression where comparable data were available. However, no suitable data were identified for formal aggregation using meta-analysis.

Meta-biases and assessment of external validity

Owing to the complex nature of the clinical topic, the number of review questions and the diverse information required to inform the economic model, the systematic reviews were methodologically challenging. To obtain high-quality, trustworthy data and to maintain the external validity of the reviews, the inclusion criteria were kept broad until full text retrieval. After discussion within the project team and with the NICE committee experts, a decision was made to take a broad approach during the assessment of study relevance, rather than applying stringent inclusion criteria.

The risk of this approach was that the evidence generated from the reviews was less amenable to replication. However, the purpose the clinical reviews was to inform commissioners about potential risks of CJD transmission via surgery rather than estimating treatment effect. Therefore, a more inclusive methodological approach by the evidence review group in this complex clinical topic was deemed justifiable.

Literature search results

The literature searches of bibliographic databases were performed on 14 August 2017 and yielded 8466 citations. During the screening process, a citation of potential relevance to review question 2 was identified that had not been picked up by the literature searches. Therefore, the information specialist in consultation with the project team revised the search terms for review 2 to perform an additional search on 2 October 2017, resulting in a further 310 citations. A total of 41 further citations were obtained and assessed for eligibility either from recommendations from NICE’s committee members (n = 16) or through checking the reference lists of relevant citations (n = 25). After duplicates were removed, the 8549 titles and abstracts were reviewed by one reviewer (LU). In total, 10% of excluded citations were independently assessed by a second reviewer (CC) with very good agreement (κ = 0.98). Any disagreements were carried forward for further discussion but none was ultimately deemed eligible for full text inspection by either reviewer (see Appendix 3 for the table of excluded studies). A PRISMA flow diagram illustrating the process of identifying citations through to final study selection for each review question is shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

The PRISMA flow diagram of studies included in systematic reviews.

The incidence of Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease and the prevalence of Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease-related prions in humans in the UK

The purpose of this review was to identify published and unpublished evidence for:

-

the incidence of CJD (sporadic, genetic, variant and iatrogenic)

-

the prevalence of CJD-related prions in humans in the UK.

The NCJDRSU provides the most comprehensive and regularly updated figures for the UK. Globally, figures are gathered by the CJD International Surveillance Network (EuroCJD);22 however, this source was last updated in May 2015 and is therefore less up to date than the NCJDRSU. The literature searches were also used to retrieve the most recent or complete figures, incidence trends or studies regarding subclinical prevalence of CJD prions in tissue. A total of 69 published citations were identified as being relevant to the incidence of clinical CJD or the prevalence of subclinical CJD around the world.

The incidence of Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease

The global incidence of CJD is typically reported to be around 1 to 2 cases per million per year,22 based on surveillance studies published around the world from 2005 (Table 2). Higher incidence rates may be more likely to occur in areas with access to established surveillance units for referring suspected cases of prion disease. In the UK since 1990, the NCJDRSU has been mandated to actively monitor and identify all CJD cases. By contrast, a paper by Jeon et al. 28 described that CJD surveillance did not begin in Korea until 2001, and iCJD was not studied in Korea prior to 2011. This indicates geographical variation in how CJD may have been detected and reported in time globally.

| Country | Time period of estimation | CJD incidence or mortality rate per million | CJD types included | Study author/source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | 1993–2017 | 1.49 | Sporadic | EuroCJD22 |

| Australia | 1993–2016 | 1.20 | Sporadic | EuroCJD22 |

| Belgium | 1997–2017 | 1.19 | Sporadic | EuroCJD22 |

| Canada | 1994–2017 | 1.03 | Sporadic | EuroCJD22 |

| Czech Republic | 2000–17 | 1.16 | Sporadic | EuroCJD22 |

| Denmark | 1993–2017 | 1.45 | Sporadic | EuroCJD22 |

| Estonia | 2004–17 | 0.32 | Sporadic | EuroCJD22 |

| France | 1993–2017 | 1.53 | Sporadic | EuroCJD22 |

| Germany | 1993–2017 | 1.36 | Sporadic | EuroCJD22 |

| Hungary | 1997–2017 | 1.07 | Sporadic | EuroCJD22 |

| Italy | 1993–2017 | 1.44 | Sporadic | EuroCJD22 |

| Netherlands | 1993–2017 | 1.21 | Sporadic | EuroCJD22 |

| Norway | 1995–2017 | 0.96 | Sporadic | EuroCJD22 |

| Slovakia | 1993–2017 | 0.85 | Sporadic | EuroCJD22 |

| Slovenia | 1993–2017 | 1.38 | Sporadic | EuroCJD22 |

| Spain | 1993–2017 | 1.30 | Sporadic | EuroCJD22 |

| UK | 1993–2017 | 1.19 | Sporadic | NCJDRSU 20161 |

| USA | 2016 | 1.22 | Excludes vCJD | US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention23 |

| Japan | 1999–2015 | 1.3 | All types | Yamada et al.24 |

| Australia | 1993–2014 | 1.2 | All types | Klug et al.25 |

| Finland | 1997–2013 | 1.45 | Sporadic | EuroCJD22 |

| Cyprus | 1995–2013 | 0.70 | Sporadic | EuroCJD22 |

| Germany | 1993–2013 | 1.33 | Excludes vCJD | EuroCJD22 |

| Holland | 1993–2013 | 1.21 | Excludes vCJD | EuroCJD22 |

| Hungary | 1997–2013 | 1.65 | Excludes vCJD | EuroCJD22 |

| Sweden | 1997–2013 | 1.44 | Excludes vCJD | EuroCJD22 |

| Switzerland | 1993–2013 | 1.72 | Sporadic | EuroCJD22 |

| Argentina | 2008 | 0.85 | All types | Begué et al.26 |

| Greece | 1997–2008 | 0.62 | Sporadic | EuroCJD22 |

| Taiwan | 1998–2007 | 0.55 | Sporadic | Lu et al.27 |

A study by Gao et al. 29 does not report an incidence rate per million for CJD in China, but does report that during the period from 2006 to 2010, 261 patients were diagnosed with sCJD and 23 patients were diagnosed with genetic human prion diseases out of a group of 624 suspected patients who were referred to China CJD surveillance. 29

Increase in the UK sporadic Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease incidence over time

Between 1990 and 2017, the NCJDRSU recorded figures of iCJD [from receipt of human gonadotrophin (hGN), human-derived growth hormone or dura mater) and vCJD, which were relatively low compared with sCJD. Figure 2 plots the number of deaths in the UK that have been attributed to definite or probable CJD between 1996 and 2017 (as of 2 May 2018) as reported by the NCJDRSU. An increase in sCJD cases is noted over the 27-year period, whereas iatrogenic, genetic and variant forms remain rare.

FIGURE 2.

Deaths attributed to definite or probable CJD in the UK, using data from the NCJDRSU, between 1996 and 2017. 30

Possible reasons for the increase in the detection of sCJD cases in the UK are speculated to include:

-

improved case ascertainment because of clinician awareness and/or improvements in diagnostic testing

-

population increases

-

an ageing population

-

changes to the sporadic case definition to include cerebrospinal fluid and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) diagnostic tests.

An upwards trajectory of CJD cases may be attributable to the way that data are collected for the surveillance of CJD. Case ascertainment is likely to improve in areas where CJD surveillance is strong, where there is greater awareness among health-care professionals of CJD and where there are more neurologists who are able to diagnose CJD. As the national surveillance programme for CJD has been operating since May 1990, and is a prospective surveillance programme, there are likely to be improvements over time with respect to how this rare condition is detected, referred, investigated and reported when compared with retrospective surveillance studies. Moreover, owing to the potential for iatrogenic transmission, there has been a focused collaborative effort to examine the evidence of transmission through different exposures by examining the links to confirmed CJD cases through retrospective ‘lookback’ studies. 31

The gradual increase in sCJD but not gCJD, adds support to the ‘ageing population’ theory over merely population increase and improved case ascertainment.

Increase in sporadic Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease incidence globally

Reports of increased rates of sCJD were noted from other countries. In Finland, an increased incidence of sCJD was noted between 1974 and 1989 of 0.6 per million to 1.36–1.44 per million in 2007–13, as reported in an abstract by Isotalo et al. 32 An abstract by Chen33 reports that sCJD incidence rates in Taiwan doubled between 2008 and 2015. They also report that age at onset became younger. Chen33 speculates that the reasons for the increase in CJD cases include physician’s sensitivity in recognising CJD; improved reporting systems; concerns around vCJD, and high media coverage. A published study34 from Belgium noted a relevant trend of significantly increased age-specific incidence of sCJD patients between the age of 70 and 90 years in the period 2002–04 compared with 1998–2001, using retrospectively obtained data (1990–1997; p < 0.01). The authors conducted a clinical and biochemical analysis to investigate this increase, but could not identify any reason other than an increased vigilance for the diagnosis. Similarly, in Japan, Ae et al. 35 report in a study abstract that the annual incidence of human prion diseases has increased since 1999, particularly so in older patients (aged ≥ 70 years), with cases of rapidly developing dementia increasingly being identified by domestic physicians.

One study from Slovenia reported an apparent fluctuation of sCJD cases in 2015, with seven definite and two probable sCJD cases resulting in an incidence of 4.36 per million for the country that year. 36

Autopsy and biopsy in Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease

In the UK, confirmation of CJD from neuropathological (via autopsy or brain biopsy), immunocytochemical or biochemical examination is required for obtaining a definitive sCJD diagnosis. For vCJD, confirmation must be from neuropathology. 1 Despite the observed increase in sCJD cases over the last twenty years, autopsy is not performed routinely on sCJD cases. In the UK, almost 50% of all cases referred to the NCJDRSU undergo autopsy. 2 The most recent case of vCJD appeared in its clinical presentation and neuroimaging to be sCJD, but as the age of the patient was atypically young (aged 36 years), a pathological examination after death in February 2016 confirmed it to be vCJD despite the absence of clinical epidemiologic diagnostic criteria for probable or possible vCJD. 37 On the basis of this recent vCJD case, pathological examination of every sCJD case would be required to know the true figures of autopsy-proven sCJD and vCJD. Given this, an alternative explanation for the increasing number of sCJD cases over the last 20 years could be attributable to an altered incubation and clinical presentation of acquired CJD (variant or iatrogenic CJD) that mimics sCJD or another neurological condition. Indeed, surgery has been posited as a risk factor the transmission of sCJD by a number of epidemiological studies; a retrospective study by Urwin et al. ,38 described as ongoing, is seeking to investigate this risk factor further by reviewing UK sCJD cases.

Cursory analysis of published literature from studies on CJD around the world generates potential reasons for why autopsy is not always routinely completed in sCJD patients. Brain biopsy and autopsy of suspected CJD cases carry the risk of iatrogenic transmission to medical or pathology staff, meaning that there is an extra burden of duty to ensure that stringent infection control protocols are followed. Protocols for instrument decontamination are required for brain biopsy. For example, Shi et al. 39 state that although an intracranial biopsy procedure is invasive and carries risk of cerebral infection or hematoma, it is generally a safe and well-tolerated procedure; however, special precautions to prevent the spread of prions must be taken. Medical instruments and equipment supplies must be either destroyed by incineration or autoclaved and sterilised. Similarly, Baig and Phillips. 40 state that getting a biopsy in a timely manner is often not possible given the costly and aggressive nature of the diagnostic test and that the rigorous decontamination and sterilisation techniques for handling tissue at biopsy may make it impractical in a community setting.

Ethnic and geographical differences

Variations in CJD incidence according to ethnicity by Maddox et al. 41 and Holman et al. 42 were noted in the literature. In the USA, the age-adjusted CJD incidence for white people was reported as being 2.7 times higher than that for black people (1.04 and 0.40 per million, respectively). Similarly, the estimated incidence of CJD (0.7 per million) among Asians and Pacific Islanders in the USA between 2003 and 2009 was reported by Maddox et al. 43 as being significantly lower than that for white people (p < 0.001).

Nakatani et al. 44 noted that the occurrence of sCJD appeared to have regional variations in Japan, suggesting that the existence of genetic or region-specific factors may affect the incidence of the disease, such as hereditary background or other local factors. In this study, geographical clusters of sCJD were scattered in the western half of Japan. However, no direct evidence to support theories about the causative factors underlying this trend are presented and, therefore, this particular phenomenon remains to be explored. Klug et al. 45 conducted a spatial and epidemiological analysis of sCJD case-clusters in Australia. The authors concluded that the observed increase of sCJD cases in a geographic area is more likely to be related to better awareness of the disease by local neurologists rather than to an increase in risk factors.

Genetic forms of CJD are most often associated with a mutation at codon 200. 46 Mitrova et al. 47 report that although gCJD represents approximately 10–15% of all CJD patients in the majority of countries, in Slovakia the rate of gCJD has been higher than 65% since 1975 owing to an accumulation of gCJD incidence in two clusters in central Slovakia. The authors state that all but one of the 202 patients who had gCJD in Slovakia carried the mutation form E200K and highlight that asymptomatic carriers of this gene could contribute to iatrogenic transmission of CJD. A voluntary genetic testing study conducted by the authors showed positivity for the E200K mutation in 9 out of 2662 subjects who were unrelated to the gCJD cases both inside and outside the focal cluster. This finding indicates an unusual phenomenon of an increased prevalence of the E200K mutation linked to gCJD in the Slovak region. A study by Ladogana et al. 48 reported similar prevalence of sCJD across the UK, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands and Slovakia, but also reported an excess of genetic cases in Italy and Slovakia.

Geographical differences in CJD incidence are likely to be influenced by ascertainment bias in countries where access to health care is free and, moreover, when active national CJD surveillance is in place.

Diagnosis of Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease

Global differences in the culture of pursuing autopsy to confirm CJD diagnosis and subtype are likely to exist depending on national CJD surveillance protocols. For example, Tuskan–Mohar et al. 49 report that post-mortem examination was not performed in any of the five cases of CJD occurring in Croatia between 2001 and 2011 owing to patient families’ refusal of the procedure. More generally, Kosier50 state anecdotally in a US case report that the diagnosis of CJD is often delayed because of clinician bias towards more obvious possible medical or psychiatric causes. Litzroth et al. 51 highlight that in Belgium, between 1998 and 2012, on average 60% of hospitalised patients who died with suspected CJD were captured by the surveillance system. The authors also report that 11% of surveyed neurologists would not refer suspect vCJD cases for autopsy, nor contact a reference centre for diagnostic support and that 61% of surveyed neurologists were not familiar with the surveillance system.

Two studies from Ireland describe a relatively sensitive surveillance system for CJD detection but less accuracy in obtaining a final confirmatory CJD diagnosis. From a review of 21 referrals to the National CJD Centre in Ireland, Brett et al. 52 found that only five referrals were positive for CJD, with 12 being referred as part of their differential diagnosis. Brett et al. 52 cautioned that, more often than not, the clinical suspicion of CJD was not borne from the final neuropathological diagnosis and that failure by clinicians to adhere to the recommended CJD investigation algorithm impacts adversely on the neuropathology workload and causes unnecessary concern among operating theatre, laboratory and nursing personnel. Loftus et al. 53 also raised the issue that the terms ‘probable CJD’ and ‘definite CJD’ might be used indiscriminately. They highlight from an analysis of 100 cases of CJD in Ireland, that approximately half of cases (50/96 referrals) were confirmed as definite CJD via tissue samples through biopsy or autopsy. 53 The authors proposed an algorithm for CJD referrals to reduce infection control and diagnostic difficulties encountered in CJD surveillance.

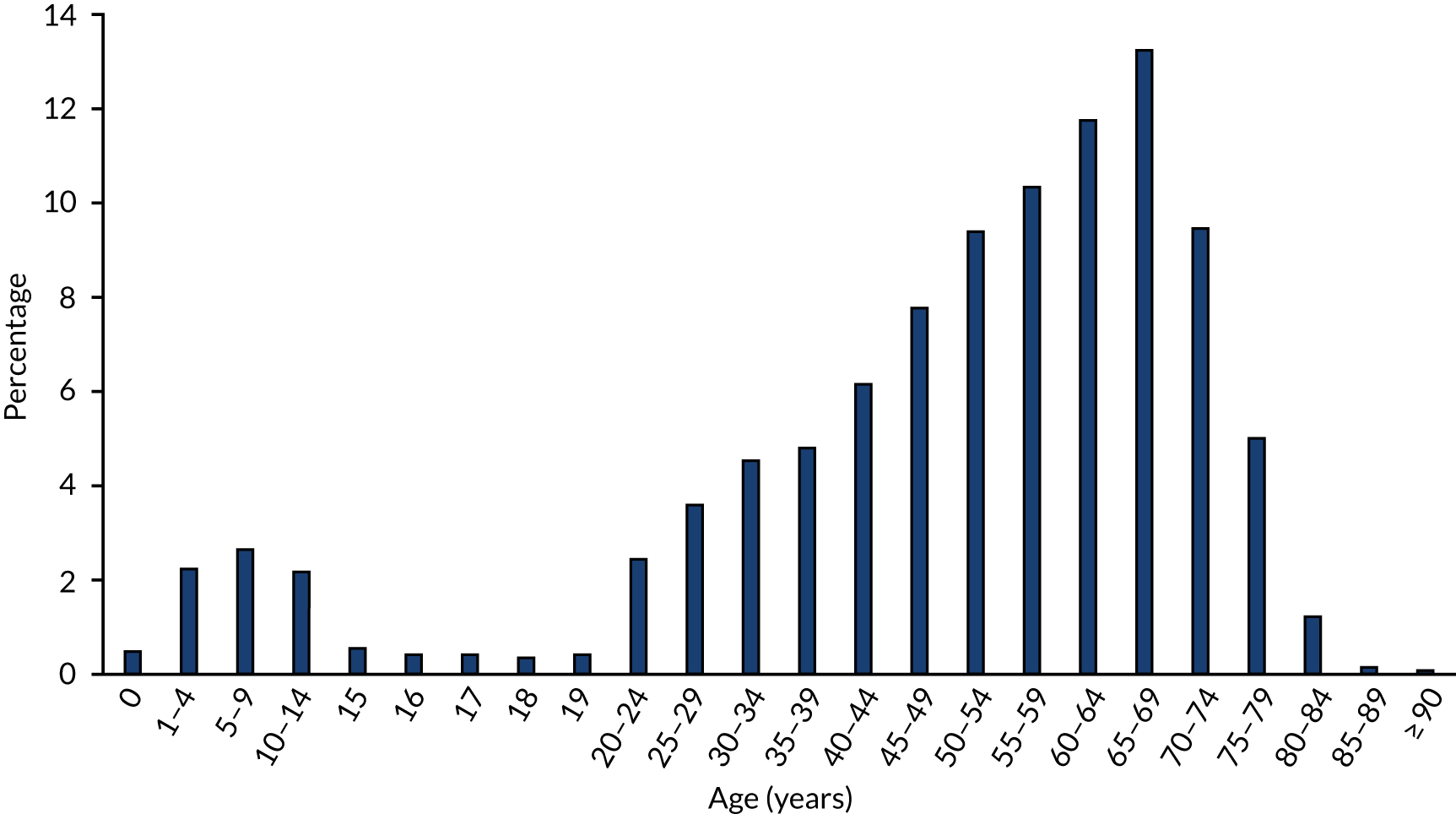

Despite the fact that sCJD is a condition known to affect older people, its detection may have improved in the last 6 years. Figure 3 is taken from the 25th Annual Report of the NCJDRSU2 and shows a steep increase in the detection of CJD mortality in the UK,2 particularly in the age category of 65–69 years. However, incidence using age-adjusted data of CJD-related deaths per million will be influenced by the assumed population in each band. The mortality rates for 1995–2004 use the same census data as those for 2005–9. However, if there are proportionately more older people in the more recent age band, the incidence will be inflated.

FIGURE 3.

Age-specific mortality rates from sCJD in the UK 1970–2016: reproduced from NCJDRSU Annual Report 2016. 2 1970–1984 mortality rates calculated using mid-1981 England and Wales population estimates based on the 1981 Census. 1985–1994 mortality rates calculated using mid-1991 UK population estimates based on the 1991 Census. 1995–2004 mortality rates calculated using mid-2001 UK population estimates based on the 2001 Census. 2005–2009 mortality rates calculated using mid-2001 UK population estimates based on the 2001 Census. 2010–2016 mortality rates calculated using mid-2011 UK population estimates based on the 2011 Census. Reproduced with permission from the National CJD Research & Surveillance Unit, University of Edinburgh. 2

Owing to the median age at onset of sCJD symptoms, it is possible that CJD and prion disease cases may be concealed among cases of more commonly encountered but similarly rapidly deteriorating neurological conditions affecting older people, such as Alzheimer’s disease. In the published literature, there are numerous reports of CJD mimicking other conditions including stroke,54,55 acute neuropathy,56 hyperparathyroidism,57 dementia,51,58–61 Lewy body dementia,51 encephalitis,51 aphasia,62 Alzheimer’s disease,51,60 psychiatric decompensation50 and movement disorder. 63 The potential for CJD cases to be misdiagnosed was first demonstrated in a study in 1995 which found from an analysis of dementia autopsies that only about 60% of prion disease cases with pathologically typical spongiform encephalopathy were identified clinically during life. 64 Therefore, the observed rates of any type of CJD could still be an underestimate of the actual rate of CJD deaths in the absence of definitive pathological examination of all cases. It is also plausible that numerous cases of CJD that occur later in life, particularly where access to clinicians with experience of diagnosing CJD is limited, may result in some cases of misclassification of CJD, despite potentially improved detection. However, given the rarity of CJD presentation worldwide and consequent clinical expertise, a degree of caution should be exercised in the interpretation of the limited available data.

Disease duration

Disease duration is regarded as the time between the onset of clinical CJD symptoms and death. sCJD is commonly reported to have a disease duration of 4–7 months;2,22,65–67 however, Nagoshi et al. 68 report that duration of disease was longer for sCJD in Japan than in Western countries. The authors state that sCJD, which represented 77.0% of cases of prion disease in their surveillance network between 1999 and 2008, had a mean disease duration of 15.7 months. This longer disease duration in Japan is more akin to the median observed in the UK for vCJD, which is 14 months from the onset of symptoms to death (NCJDRSU’s 2016 annual report2) or indeed iCJD via human growth hormone (hGH), the median of which is reported as 16 months (mean 14 months) for 22 iCJD patients. 69 Nagoshi et al. 68 also report that disease duration was longer in females (19.7 months) than males (14.5 months) for sCJD and that this tendency was also true for dura mater iCJD and types of gCJD including human GSS syndrome and FFI. Nagoshi et al. 68 also report that younger onset of disease was associated with longer disease duration for all types of CJD.

Genotype: codon 129

Methionine homozygosity at codon 129 (MM) is considered the most susceptible genotype for CJD, with sCJD and vCJD occurring mostly in individuals with the MM genotype. Both methionine (MM) and valine (VV) homozygotes at codon 129 of PRNP are at an increased risk of sCJD. 70 In the north of Europe, the MM genotype represents 38% of the general population, whereas 11% of the population have the VV genotype and 51% are heterozygotes (methionine/valine; MV) at codon 129 of PRNP. 71 An epidemiological study by Giaccone et al. 72 of the PRNP genotype of 402 consecutive sCJD cases in Italy revealed that 70.4% (n = 283) had the MM genotype, 15.4% (n = 62) were MV and 14.2% (n = 57) were VV. 72 Although the numbers of MV and VV sCJD cases appear comparable in this study, the fact that over half of the population in Europe are MV indicates that the relative incidence of sCJD in heterozygotes at codon 129 is low.

In 2006, Ironside et al. 73 re-analysed three of the appendixes identified (from the 12,674 appendix and tonsil samples analysed by Hilton et al. 7) as positive for disease-associated PrP; two of the three were found to be VV genotype, which provided the first indication that the valine homozygotes are also susceptible to vCJD infection. 73 The authors suggested that people infected with vCJD who are VV may have a prolonged incubation period with subclinical infection that could cause secondary infection via blood transfusion or surgery. Additionally, detection of subclinical prion accumulation in peripheral tissue by Gill et al. 74 from 16 positive appendix samples found that eight were MM, four were MV, and four were VV at codon 129 of PRNP, indicating that genetic susceptibility for subclinical CJD was more equally distributed in the population.

Heterozygosity at codon 129 of PRNP was generally believed to confer complete resistance to both sporadic and acquired prion diseases. 75 However, the most recent case of clinical vCJD in 2016 was heterozygous37 and an additional possible vCJD case reported by Kaski et al. 76 in 2008 was also heterozygous, but this possible vCJD case was not confirmed by autopsy. Two case reports indicate that the MV genotype is susceptible to iCJD, but the cases were subclinical. First, the case of a heterozygous 73-year-old male with haemophilia whose spleen at autopsy gave a strong positive result on repeated testing for protease-resistant prion protein (PrPres) by western blot analysis, as reported by Peden et al. 77 This patient had received over 9000 units of factor VIII concentrate prepared from plasma pools known to include donations from a vCJD-infected donor. Second, a case in 2004 of subclinical vCJD from blood transfusion, who was heterozygous at codon 129, and died from a cause unrelated to CJD78 highlights the possibility of potential transmission to this genotype. A study using mice supports the notion that transmission efficiency of vCJD is greatest in MM but indicates that all genotypes are susceptible, with the MV and VV genotypes benefiting from apparent reduced transmission efficiency and longer asymptomatic incubation periods. 79

Disease duration and genotype

Prion protein–gene data from 378 of the Japanese patients diagnosed with sCJD, reported by Nagoshi et al. ,68 showed that 364 cases (96.3%) had the MM genotype but that disease duration was longest for the 11 patients (2.9%) who were MV (mean, 32.2 months for MV vs. 16.6 months for MM and 13.2 months for VV). 68 Begué et al. 26 report data for the disease duration of sCJD from 59 definite cases in Argentina. Genotype analysis indicated that the MV genotype was associated with the longest disease duration (10.9 months), followed by the VV (5.6 months) and the MM genotypes (3.6 months). 26 Data from Rudge et al. 69 relating to CJD transmission via hGH in the UK also found that MM patients had the shortest disease duration; MM patients had a mean disease duration of 7.8 months, the VV patients 17 months and MV patients had a mean disease duration of 18.6 months (range 10–32 months). In addition, the duration of disease from first symptom was significantly longer in the MV patients (p = 0.02, two-tailed t-test). Although there were only four patients who were MM, three of these had the most rapid disease progression (p = 0.04, Mann–Whitney U-test). Yamada et al. 24 state that the majority of the general Japanese population (93%) carry the MM genotype. Considering that a large share of patients in the Argentinian sample also contained the MM genotype (n = 37, 66%), genotype data at codon 129 alone cannot account for the substantial difference in disease duration for sCJD reported between Japan and other countries.

Data from Japan,68 Argentina,26 and the UK69 therefore indicate that the MV genotype is associated with the longest disease duration compared with homozygotes. Pennington and Knight80 also reported disease duration to be significantly longer in codon 129 heterozygotes for gCJD.

Variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease

The annual number of confirmed cases of clinical vCJD has declined since 2005. As of 2016, the NCJDRSU recorded 178 cases of vCJD in the UK. 1 The most recent vCJD case occurred in an individual who was heterozygous at codon 129. 37 A further 52 cases have been reported from other countries around the world, which brings the global total of clinical vCJD cases to 231. 81 Between 2005 and 2014, 68 vCJD cases were reported from 11 countries including the UK (n = 29), France (n = 19), Spain (n = 5), Ireland (n = 3), the USA (n = 3), Holland (n = 3), Portugal (n = 2), Italy (n = 1), Canada (n = 1), Saudi Arabia (n = 1) and Taiwan (n = 1). 22 A total of 3 out of the 178 cases in the UK that occurred up to 2016 are considered to have occurred through blood transfusion. 2 A fourth case of vCJD transmission through blood transfusion was identified in the spleen of an individual (heterozygous at codon 129) who died of a non-CJD related cause. This is considered to be preclinical vCJD. 78 Three further potential, but unconfirmed, cases of CJD transmission through blood transfusion are described by Chohan et al. 82 and Davidson et al. 83 A retrospective study by Molesworth et al.,84 which was performed to identify situations where the transplantation of organs or tissues might have occurred in any of the 177 UK vCJD cases, found no evidence of transplant-associated vCJD in the UK. 84 The remaining 175 clinical vCJD cases are presumed to be related to dietary exposure to BSE. 85

Iatrogenic Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease

The most common causes of iCJD were hGH and dura mater grafts obtained from human cadavers. A review of worldwide iCJD cases published by Brown et al. 3 identified 469 cases from dura mater grafts (n = 228), surgical instruments (n = 4), EEG needles (n = 2), corneal transplants (n = 2), hGH (n = 226), hGN (n = 4) and packed red blood cells (n = 3). 3

In the UK, 85 cases of iCJD were identified between 1970 and December 2016, and are described by the NCJDRSU. 1 In total, eight cases were from dura mater grafts, 76 from hGH and one from hGN. All cases have since died, with a mean age at death for the hGH/hGN group of 35 years (range 20–51 years) and for the dura mater cases 46.5 years (range 27–78 years).

Subsequent to the three cases of blood transfusion transmitted vCJD described above, no new cases of transfusion-associated infection have been identified since 2007, based on an epidemiological analysis of CJD cases and blood transfusion recipients by Urwin et al. 86 The Urwin et al. 86 study referenced the Davidson et al. 83 paper but not the Chohan et al. 82 paper. These two papers discuss three potential, but unconfirmed, cases of CJD transmission via blood transfusion. Ward et al. 87 studied the risks in treatment for haemophilia and concluded that it is unlikely that any of the UK vCJD clinical cases to date were infected through exposure to fractionated plasma products. 87 The evidence regarding the incidence of iCJD from surgery is discussed in the review on the risk of CJD transmission via surgery.

The estimated prevalence of subclinical variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease in the UK

In vCJD, prions appear to replicate extensively within lymphoid tissue; therefore, tonsil and appendix tissues are some of the earliest sites that can be used to assess abnormal prion accumulation. Such abnormal prion accumulation prior to the onset of clinical symptoms is regarded as subclinical CJD for the purposes of risk assessment and is thought to represent a potentially background, but low, level of infection in the population. 88 Immunohistochemistry staining is regarded as highly indicative of the abnormal prion protein pattern that has been observed in cases of vCJD, but not observed in other types of CJD, and is used to estimate the approximate number of individuals who may go on to develop vCJD or be asymptomatic carriers of the disease. 89

A key study conducted by Gill et al. ,74 referred to as the ‘Appendix II’ study, examined subclinical prion accumulation in excised peripheral tissues from general population cohorts born in 1941–60 and 1961–85. 74 Detection of abnormal prion accumulation in appendix samples from these two cohorts resulted in a central estimation of 1 in 2000 for populations exposed to the BSE epidemic. The Advisory Committee on Dangerous Pathogens (ACDP) TSE subgroup produced a summary of findings16 following completion of the most recent study of stored appendixes (‘Appendix III’) and calculated a rough central prevalence estimate of asymptomatic carriers of vCJD in the UK population, previously presumed unexposed to BSE, of approximately 1 in 4200 people or 240 per million people. 15,16 This estimate is based on results of immunohistochemical (IHC) staining of appendixes from two birth cohorts, which are described in Table 3.

| Appendix III cohort | IHC stain results | Central estimate |

|---|---|---|

| Appendixes removed between 1970 and 1979 and before the BSE epidemic | Two positive samples from 14,692 appendixes | 1 in 7000 |

| Appendixes removed from patients born after 1 January 1996 and after measures to remove BSE were in place | Five positive samples from 14,824 appendixes | 1 in 3000 |

Variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease and bovine spongiform encephalopathy

The hypothesis of zoonotic transmission through dietary exposure from the BSE outbreak is largely upheld as the most plausible route of vCJD infection in humans, and transmission has been replicated in wild-type mice. 90 Moreover, a recent study by Diack et al. 91 examined two Spanish cases of vCJD: a mother and son who resided in a BSE-endemic area, who are thought to have ingested bovine brain. 91 The strain characteristics of both individuals are similar to the UK cases, implying BSE as the source of infection and supporting the hypothesis of risk via ingestion of high-titre bovine material.

The Appendix III study75,76 highlights that abnormally stained appendixes associated with vCJD prion accumulation have been confirmed in cohorts of people who were not considered to have had significant exposure to BSE because they were either from appendixes removed before the BSE epidemic in the UK (prior to 1980) or from appendixes from patients born after food safety measures to limit BSE were implemented (after 1996). The presence of seven positive samples in these cohorts could suggest that there is low background prevalence of abnormal prion protein staining in human lymphoid tissue that may not represent subclinical vCJD or be related to the BSE outbreak, and may be unlikely to progress to vCJD. Another possible interpretation is that the duration of the BSE epidemic and subsequent ingestion by humans through the food chain was longer than the presumed duration of human exposure to the BSE epidemic (between 1980 and1996). Moreover, planned statistical analysis, as described by Gill et al. ,74 found no difference between the prevalence observed in the cohort considered to be most at risk of the BSE epidemic (people born 1961–85) and an older cohort (born 1941–60).

These two possible explanations are considered by the ACDP TSE subgroup as not necessarily being mutually exclusive nor fully satisfactory.

Previous estimates of prevalence of abnormal prion in humans

Primary studies (published after 2005) that provide estimates for subclinical CJD in the general population based on analysis of peripheral tissue are described in Table 4. Central estimates range between 0 and 493 per million people in the population. Studies providing evidence of the prevalence of vCJD prions in lymphoid tissues published prior to 2005 are described in a review published by Olsen et al. 94 This review includes the cross-sectional study by Hilton et al. 7 that estimated the prevalence in the sample population to be 120 per million from 11,228 appendixes.

| Study (first author and year of publication) | Design | Number of samples | Predicted/estimated prevalence | Description of estimation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gill et al. (2013)74 | UK histological analysis of appendix samples from the 1941–60 and 1961–85 birth cohorts | 32,441 |

|

|

| de Marco (2010)92 | Two estimations based on UK tonsil tissue samples from the 1961–85 birth cohort | 10,075 |

|

|

| Clewley (2009)93 | UK estimation combining tonsil tissue samples | 63,007 (32,661 from the 1961–95 cohorts) |

|

|

Obtaining definitive prevalence estimations

Subclinical vCJD can be detected through typical PrP staining in lymphoid tissue or through observation of the presence of florid plaques in the brain at autopsy; however, systematic lymphoid or neuropathological examination is not performed routinely in post-mortems. To collect a truly accurate picture of the prevalence of CJD through abnormal prion protein in humans, the UK Health Protection Agency proposed the creation of a post-mortem tissue archive. 95 The study required tissue from a large number of post-mortems and the participation of coroners in England and Wales. However, the Coroners’ Society of England and Wales (CSEW) declined to participate in the study, citing various issues including its putative legality, cost and feasibility. 96 The CSEW concluded that to participate in the study would ‘adversely affect the independence of the coronial service and would further erode public confidence’. 97 McGowan and Viens95 describe that as death investigation systems with substantial independence are not directly answerable to central government, they cannot be instructed to participate in any disease surveillance programme, regardless of how crucial it is to the protection of human health and safety.

Discussion of the incidence and prevalence of Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease

The incidence of CJD is relatively stable around the world (between 1 and 2 cases per million people) but age-adjusted detection of sCJD is increasing in the UK as well as in other countries. Reasons posited for this increase include improved case ascertainment and an ageing population. The estimated prevalence of subclinical vCJD from lymphoid tissues of people in the UK who were exposed to the BSE epidemic was 1 in 2000 people and the estimated prevalence of CJD-related prions in lymphoid tissues in the UK population who are not thought to be exposed to the BSE epidemic was 1 in 4200 people. This suggests a potentially constant underlying rate of abnormal prion accumulation in lymphoreticular tissue in the UK population, which may or may not represent disease that will progress to clinical CJD. Estimations of prevalence are currently limited to retrospective cohort studies of anonymised tonsil or appendix samples.

The risk of Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease transmission via surgery

The literature searches retrieved no further published papers from the period 2005 to 2017 reporting confirmed cases of stCJD, further to the four neurosurgical cases which occurred between 1952 and 1974. 3 These four historical cases (three in the UK and one in France) are distinct from the known dura mater and hGH iCJD cohorts, and occurred prior to the vCJD epidemic that began in the late 1980s. The four historical surgical cases, therefore, represent a small proportion of the known iCJD cases (469 iCJD cases according to Brown et al. 3) and occurred when methods for cleaning surgical instruments were not adequate assuming current decontamination standards. Consequently, the risk of CJD transmission via surgery according to recent direct evidence appears to be low. However, the long asymptomatic incubation periods noted in some cases of CJD, the difficulties of eradicating prions from neurosurgical instruments (especially once adhered to dry instruments), the high levels of infectivity of CJD in the brain and a presumed subclinical underlying prevalence (albeit low) in the general population mean that there is a margin of uncertainty around detecting and quantifying the risk of CJD transmission via surgery.

Observational studies implicating surgery in Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease

Despite the absence of studies providing direct evidence of further cases of stCJD, a number of papers were identified which allude to a potential relationship between CJD cases and prior surgery. Papers that investigate but do not provide evidence of a direct link to surgery are listed in Table 5.

| Study (first author and year(s) of publication) | Design | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Kobayashi (2015 and 2016)98–100 | Two historical sCJD cases with neuropathological and biochemical features of plaque-type dura mater-acquired-CJD. The authors posit that these cases (a neurosurgeon and a patient with a medical history of neurosurgery without dura mater grafting) represent iCJD through cross-contamination from neurosurgical instruments or through occupational exposure as a neurosurgeon | Two published papers and a conference abstract |

| Gnanajothy (2013)101 | Case report of 64-year-old man diagnosed with CJD (type of CJD not reported) 3 months after cataract surgery. The authors discuss the possibility that the visual symptoms that prompted the surgery might have represented onset of the disease rather than it being the case that the procedure itself transmitted the disease (i.e. the patient already had CJD) | Published paper |

| Tuck (2013)102 | Case report of sCJD that was posited to be iCJD via surgery because of the patient’s young age. At 33 years of age, the patient experienced progressive deficits over 3 months. Review of medical history revealed that a ventriculoperitoneal shunt was placed at 11 years of age for hydrocephalus. Autopsy results were consistent with sCJD | Conference abstract |

| Moreno (2013)103 | A surveillance study in Meixoeiro Hospital (Spain) reported 12 cases of CJD (10 sCJD and 2 gCJD) from 1997 to 2010, which represented a high average yearly rate of 4.6 per million people (3.8 for sCJD and 0.8 for gCJD). According to the Poisson distribution for the 12 cases (with an expected annual incidence of 1.5 cases per million people), only 3.9 cases would have been expected over a 14-year period. A total of 8 out of 12 CJD cases had undergone at least one surgical or invasive medical procedure | Published paper |

| Puopolo (2011)104 | A case–control study found that ‘history of surgery’ was more frequent in sCJD cases (n = 13, 2%; neurosurgery, n = 12; cornea transplantation, n = 1) vs. no-CJD cases (n = 5, 1%; neurosurgery n = 5) and none in genetic TSE patients. A crude OR of 1.57 (95% CI 1.14 to 2.16) was reported. Results did not reach statistical significance when adjusted for a 10-year time lag | Published paper (included in de Pedro-Cuesta et al.112) |

|

de Pedro-Cuesta (2011)105 Mahillo-Fernandez (2008)106 |

A case–control study of sCJD to look for risk factors from 167 sCJD cases in Denmark and Sweden. Surgery for ‘lower risk procedures’ (i.e. surgery to veins, peritoneal cavity and lymph nodes) compared with high-risk procedures (i.e. surgery to brain, spinal cord, retina and optic nerve) carried out > 20 years before disease onset was associated with an increased risk of sCJD (OR 2.81, 95% CI 1.62 to 4.88). When tissues or structures were reclassified by hypothetical transmission risk at a latency of ≥ 1 year, surgery to the retina and optic nerve were the most strongly associated risk factors (OR 5.53, 95% CI 1.08 to 28.0) | Two published papers (included in de Pedro-Cuesta et al.112) |

| Hamaguchi (2009)107,108 | A case–control study in Japan with 753 sCJD patients and 210 controls. Surgery was not a risk factor for sCJD prior to disease onset. However, 4.5% of sCJD patients underwent surgery after onset of sCJD, including neurosurgery in 0.8% and ophthalmic surgery in 1.9% of patients. Among the neurosurgery cases, the symptoms of sCJD were misdiagnosed as those of other neurological diseases, and the surgeries were performed near disease onset. The authors concluded that, despite absence of empirical evidence of transmission via surgery, the risk of contracting CJD via surgery is still present because patients are operated on after disease onset | Two published papers (included in de Pedro-Cuesta et al.112) |

| Ruegger (2009)109 | A case–control study in Switzerland found that 69 sCJD patients, compared with 224 controls, were more likely (p < 0.05) to have travelled abroad, worked at an animal laboratory, undergone invasive dental treatment, had orthopaedic surgery, had ophthalmologic surgery after 1980, attended regular GP visits, taken medication regularly, and consumed kidney. No differences between patients and controls were found for residency, family history, and exposure to environmental and other dietary factors. Other types of surgery were not found to be a possible factor. Previous under-reporting/misdiagnosis was proposed as the most likely explanation for the increased annual mortality | Published paper (included in de Pedro-Cuesta et al.112) |

| Ward (2006)110 | Case–control study of 136 vCJD patients and 922 controls. Investigation of risk factors in the UK identified dietary exposure to contaminated beef products as the main route of infection of vCJD with no convincing evidence of increased risk through medical, surgical, or occupational exposure or exposure to animals | Published paper (included in de Pedro-Cuesta et al.112) |

| Ward (2008)111 | A case–control study in the UK of 431 sCJD patients and 454 controls, found increased risk was not associated with surgical categories chosen a priori but appeared most marked for ‘other surgery’, especially the three subcategories: (1) skin stitches, (2) nose/throat operations and (3) removal of growths/cysts/moles. No convincing evidence was found of links between cases undergoing neurosurgery or gynaecological surgery | Published paper (included in de Pedro-Cuesta et al.112) |

Issues of reliability and validity in case–control studies

Because sCJD is idiopathic, its aetiological basis is presumed to be spontaneous but this is not known with any certainty. 89 Therefore, case–control studies are a frequently encountered design in estimating possible and plausible risk factors for sCJD. de Pedro-Cuesta et al. 112 caution about the potential biases in these study designs in an assessment of 18 case–control studies of CJD. From a combined analysis of studies, the authors found that history of surgery or blood transfusion was associated with a risk of sCJD in some, but not all, recent studies using a 10-year or longer lag time, when controls were longitudinally sampled. Furthermore, they found that none of surgical history, blood transfusion, dental treatments or endoscopic examinations was linked to vCJD. However, the authors highlight that the validity of the findings in these case–control studies may be undermined by (1) the selection of control cases; (2) exposure assessment in lifetime periods of different durations; (3) disregarding ‘at-risk’ periods for exposure in the controls, or asymmetry between the case and control data; and (4) confounding by concomitant blood transfusion at the time of surgery. They also postulate that surgery at early clinical onset might be over-represented among cases.

As a retrospective study design, case–control studies are prone to bias. The source of cases and the selection of control (matched or unmatched) cannot be performed blindly or impartially; therefore, there is a high risk of selection bias on the researcher’s part. Owing to long incubation periods and the reliance on family members’ reports of medical histories, there is also substantial likelihood of recall bias. Case–control designs are also less useful when the study exposures are rare, as in the case of surgery or blood transfusion. Therefore, the utility of these studies in attempting to fairly estimate risk factors is limited. However, as CJD is rare, fatal and has a potentially long latency period, there are few plausible alternative study designs to establish potential lifetime risk factors in humans. Therefore, the use of community controls and ascertainment of surgical exposures through the use of medical records in case–control designs is currently the most feasible approach for identifying the potential association between surgery and CJD at a population level.

Risk of Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease through occupational exposure for health-care professionals

In 2009, the Spanish CJD registry was notified of a case of sCJD in an experienced general pathologist/neuropathologist, which prompted investigation into the possible risks to health-care professionals in contact with CJD patients. 113 As a result, Alcade-Cabero et al. 113 reported the data requested from the EuroCJD surveillance network, which documented 65 physicians or dentists (including two pathologists) and 137 health-care workers from 8321 registered sCJD cases from 21 countries. Control data, which used ‘non-cases’ from five countries, recorded 15 physicians and 68 other health-care professionals among 2968 controls or non-cases, and suggested that there was no relative excess of sCJD among health-care professionals. The study authors also performed a literature review examining reports (n = 12) pertaining to 66 health-care professionals with sCJD, and analytical studies on health-related occupations and sCJD (n = 5). From a range of occupations, only people working at physicians’ offices were found to be at a statistically significant risk of sCJD [odds ratio (OR 4.6, 95% CI 1.2 to 17.6)]. The authors concluded that a wide spectrum of medical specialties and health-care professions are represented in sCJD cases and that there is no evidence of an increased occupational risk for health-care professionals. The authors do caution that there may be a specific risk in some professions associated with direct contact with high human-infectivity tissue. The NCJDRSU continue to monitor occupational exposure to CJD in health-care professionals.

Risk of Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease in surgery and age

de Pedro-Cuesta et al. 114 performed a retrospective analysis of 167 cases of sCJD between 1987 and 2003. From a study of 167 probable or definite CJD cases and 835 matched controls, the authors suggest that a younger age at first surgery may increase the risks of acquiring sCJD: patients aged < 30 years (OR 12.80, 95% CI 2.56 to 64.00), patients aged 30–39 years (OR 3.04, 95% CI 1.26 to 7.33) and patients aged ≥ 40 years (OR 1.75, 95% CI 0.89 to 3.45), for anatomically classified surgical procedures. As highlighted by the same authors in a different study,112 caution should be urged when interpreting conclusions from analyses on indirect evidence in retrospective samples. Additionally, the ≥ 40-year age group contains those who are elderly and may die before clinical symptoms appear or may remain undiagnosed.

Risk of iCJD transmission through surgery can potentially occur when patients are unwittingly treated in hospital at the time of symptom onset. Cruz et al. 115 used a cross-sectional design to study surgical procedures in sCJD patients and controls to estimate subclinical and clinical risks to future surgery. The authors posit that patients with sCJD in the clinical stage undergo a considerably higher frequency of surgical procedures than non-CJD patients, including neurosurgery. The authors argue that identification of such potentially higher-risk events, where surgery is undertaken in infectious patients around the onset of clinical symptoms, but prior to CJD diagnosis, might well constitute a priority in clinical settings. A conference abstract by Kobayashi116 reinforces this concern by providing data from the Japanese CJD Surveillance registry. From an analysis of 760 CJD patients, Kobayashi116 identify that six patients had undergone neurosurgery after the onset but before the diagnosis of CJD during the period from 1999 to 2008. 116

Cases of suspected but unconfirmed Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease transmission via neurosurgery

Patients may be identified as being ‘at increased risk’ of CJD if they have had surgery using instruments that had been used on someone who went on to develop CJD or someone who was ‘at increased risk’ of CJD. 117 A study by Hall et al. 118 reports that 154 patients in the UK are considered to be ‘at increased risk’ of various forms of CJD following neurosurgery. This paper reports that of these 154 patients, only 129 have been informed that they are at an increased risk of CJD, either because of deaths before notification or because a local decision was taken not to inform the individual. Although no incidence of CJD has been reported within these 154 patients, the authors highlight that ‘at-increased-risk’ patients often have a relatively short life expectancy because of their medical conditions. Diagnosing asymptomatic infection requires testing specific tissues that are most readily available at post-mortem. Few post-mortems have been conducted when at-increased-risk individuals have died; therefore, some asymptomatic infections may have been missed.

Two published papers119,120 from the USA report instances in which potential iCJD exposure via neurosurgery was investigated in hospitals; however, no confirmed cases of transmission were subsequently identified.

Risks in surgery other than neurosurgery

Prospective risks from surgery

A study by Baig and Phillips40 describes a case report of a male patient (aged 66 years) who had surgical fixation of a hip fracture, most probably around the onset of CJD symptoms; therefore, given the lack of symptoms, the standard sterilisation method was appropriately used. The authors highlight that this standard decontamination method is typically not adequate for the eradication of the CJD prion protein, thus presenting a theoretical risk of prion protein transmission through surgical equipment. The focus of this paper is not on the implication that the patient contracted iCJD via surgical transmission but instead highlights a circumstance where subsequent iatrogenic transmission may have occurred because of a lack of high-risk decontamination procedures. However, surgery of low infective tissues in individuals diagnosed with CJD is noted to be common and,110,111 therefore, surgery that did not involve high (or medium) infectivity tissues would not be regarded as a risk of iatrogenic transmission.

A recent study by Orrú et al. 121 found infectivity in the skin of sCJD patients, albeit at prion levels 1000–100,000 times lower than that in the brain and detectable only by an extremely sensitive assay. 121,122 However, a study using humanised transgenic mouse models demonstrated that the skin prions were infectious. The study authors argue that extra precautions should be taken during non-neurosurgeries in sCJD patients, particularly when instruments will be re-used, because infectivity through skin was previously unknown.

A study by Notari et al. 123 found from a neuropathological examination of a vCJD case in the USA that as well as detection of PrPres in the brain, lymphoreticular system, pituitary and adrenal glands, and gastrointestinal tract, PrPres was also detected in the dura mater, liver, pancreas, kidney, ovary, uterus and skin. 123 The authors concluded that the number of organs affected in vCJD is greater than previously realised, and this further underscores the risk of iatrogenic transmission in vCJD.

Risks in eye surgery

Davanipour et al. 124 postulate that ocular tonometry is a risk factor for contracting sCJD from a case–control study conducted across 11 states in the USA. Contact tonometry is used by ophthalmologists to diagnose glaucoma. The authors conclude that disposable covers or non-contact tonometry should be used in the absence of adequate decontamination processes. 124

Tullo et al. 125 document that there were three recipients of either cornea or sclera from a woman who died of biopsy-proven carcinoma of the bronchus in 1997, but was later neuropathologically identified as having sCJD. 125 At the time of publication, two recipients remained symptom-free of CJD, whereas one patient had died, aged 92 years (7 years after surgery), showing some signs of dementia that were not considered indicative of iCJD.

Jirsova et al. 126 conducted an analysis of brain tissue samples from the frontal lobe of 1142 eye donors obtained from three tissue banks in the Czech Republic. As no pathogenic prions were found, the authors presume a very low risk of transmission of CJD through corneal graft transplantation. However, the authors’ conclusion can be regarded as a logical fallacy, denying the antecedent, because in the absence of sCJD cases in the analysis it is not possible to conclude on the risk of CJD transmission via surgery in corneal graft transplantation. Additionally, Maddox et al. 127 used data from corneal transplantation and CJD deaths from 1990 to 2006 in a statistical analysis, to suggest that a case of coincidental sCJD will occur among the population of corneal transplant recipients approximately every 1.5 years. 127

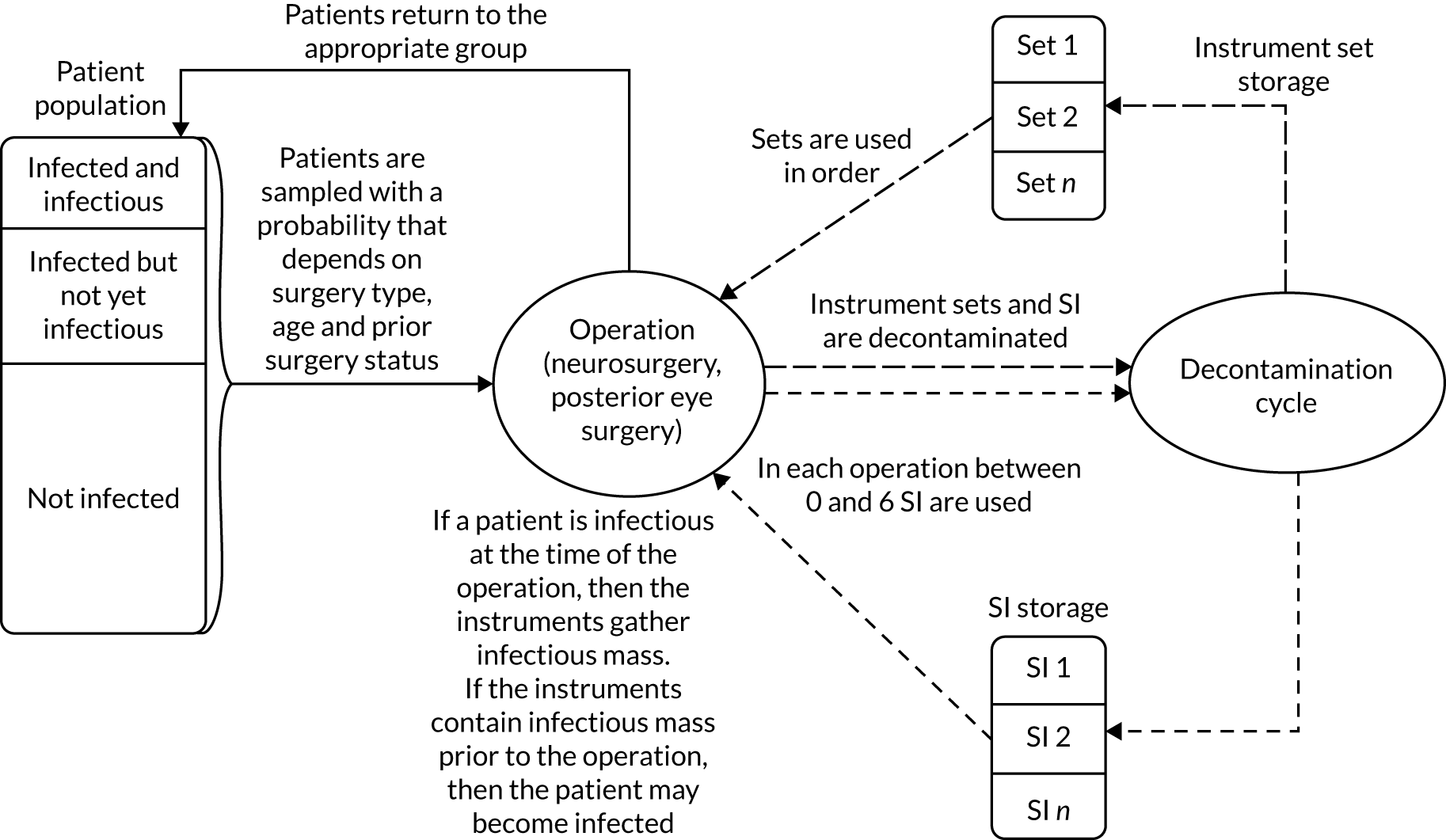

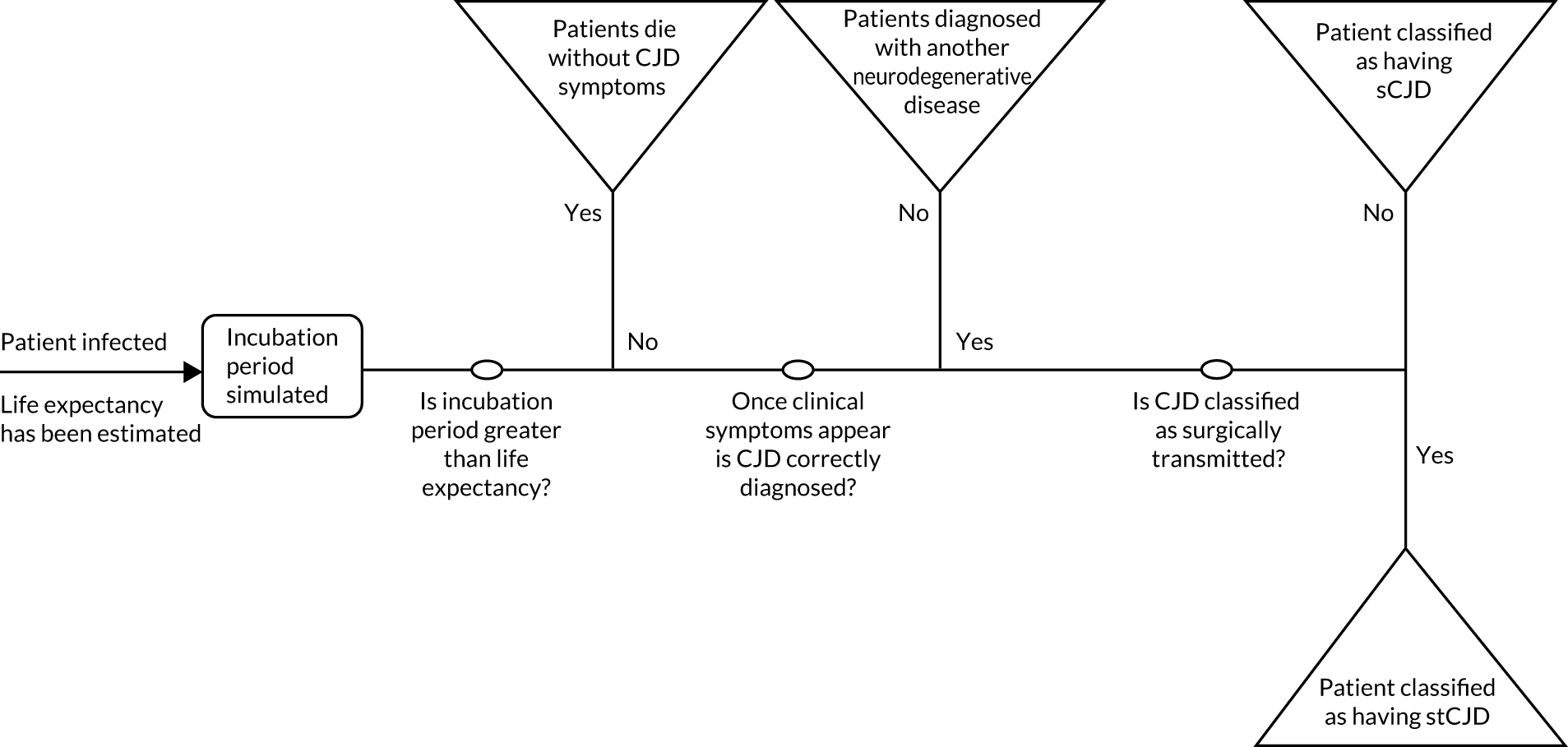

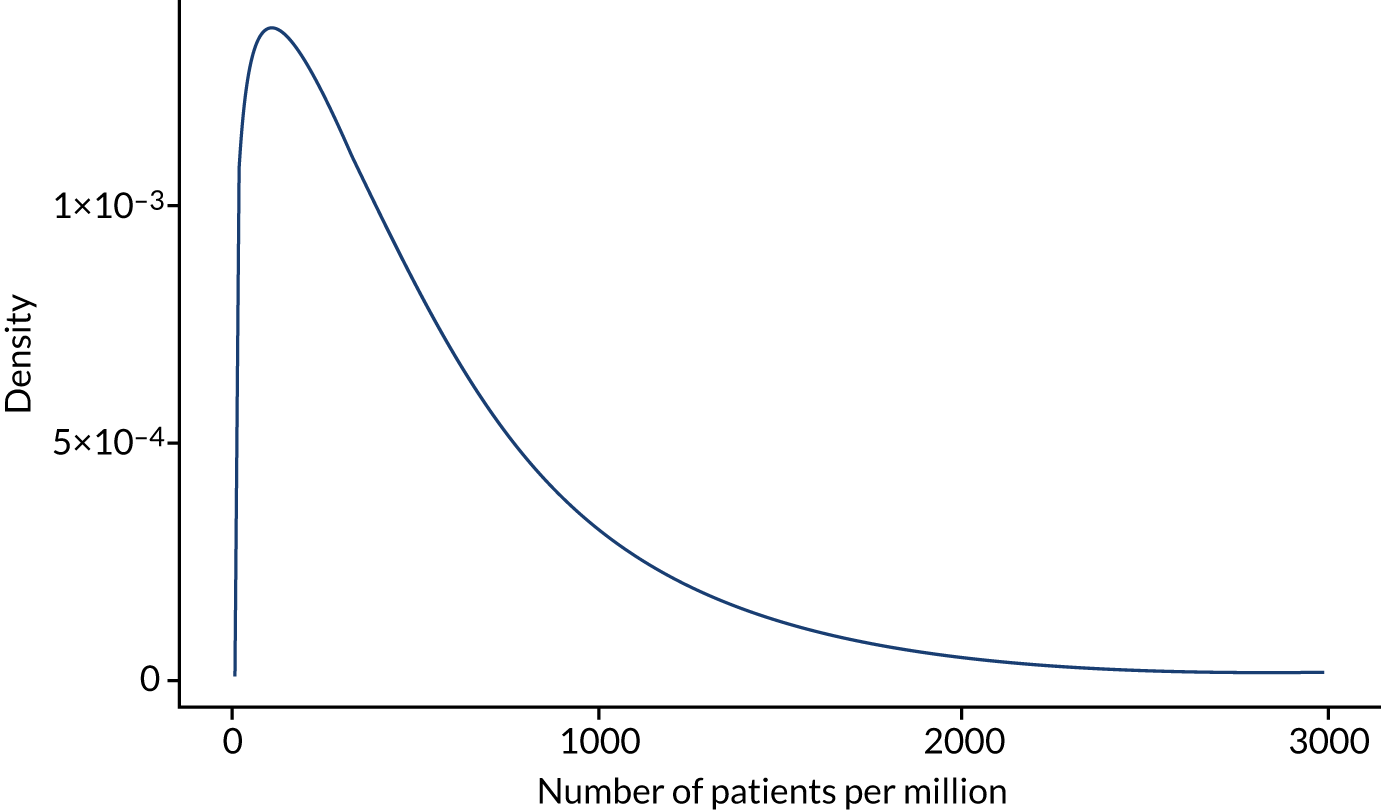

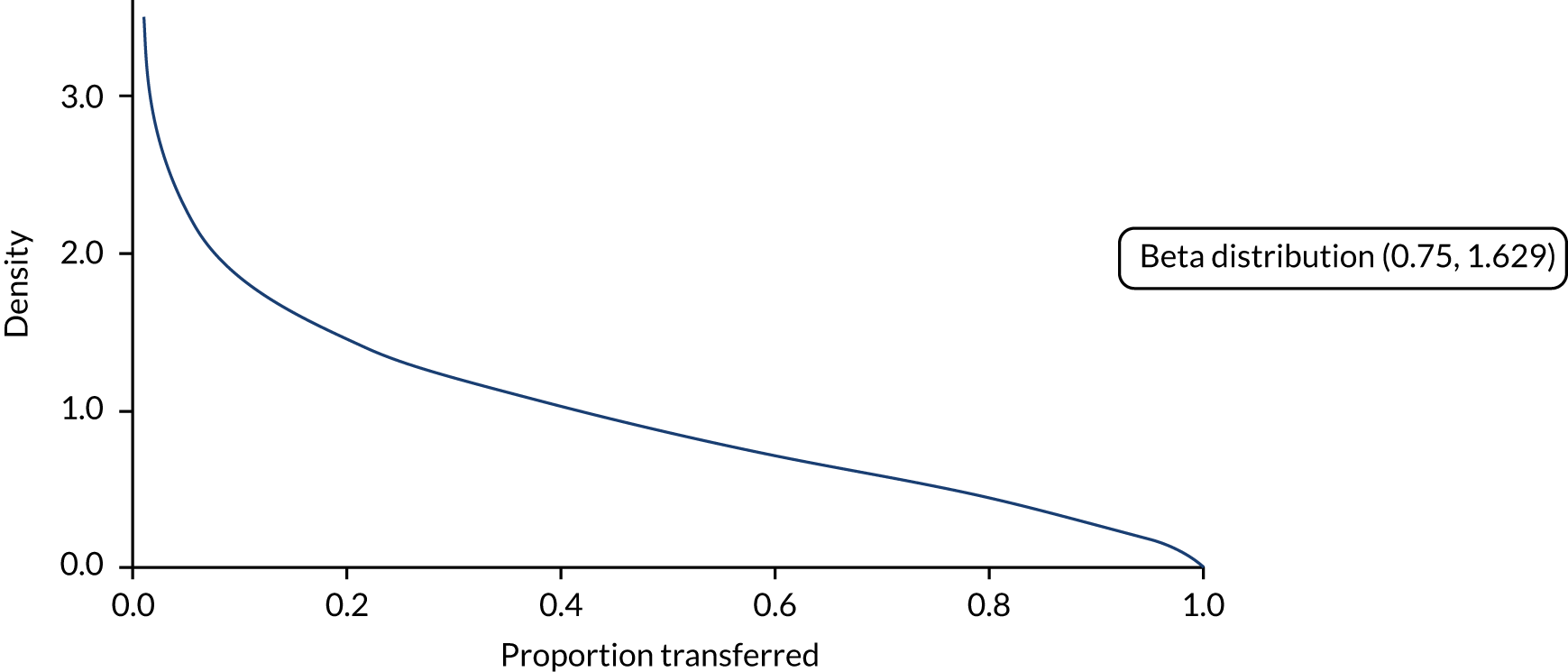

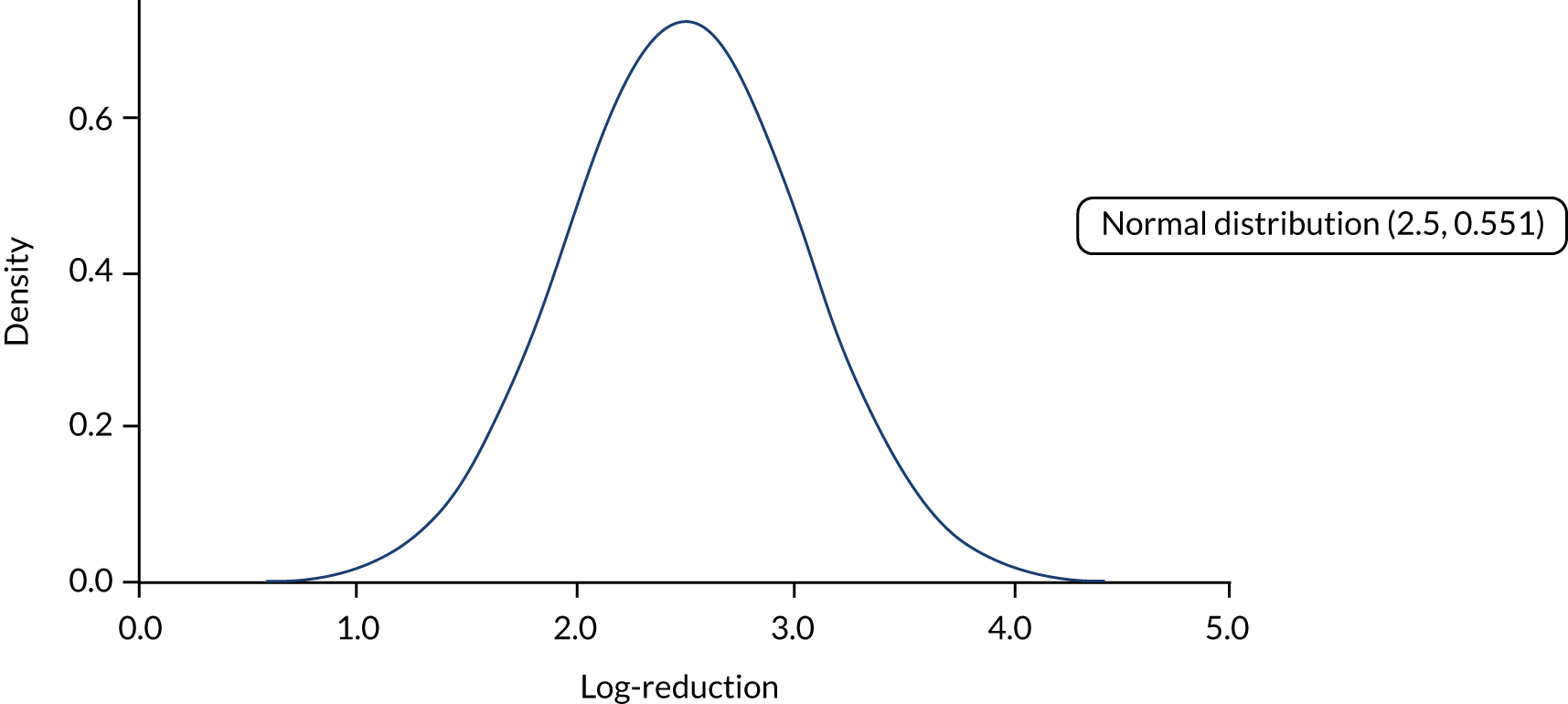

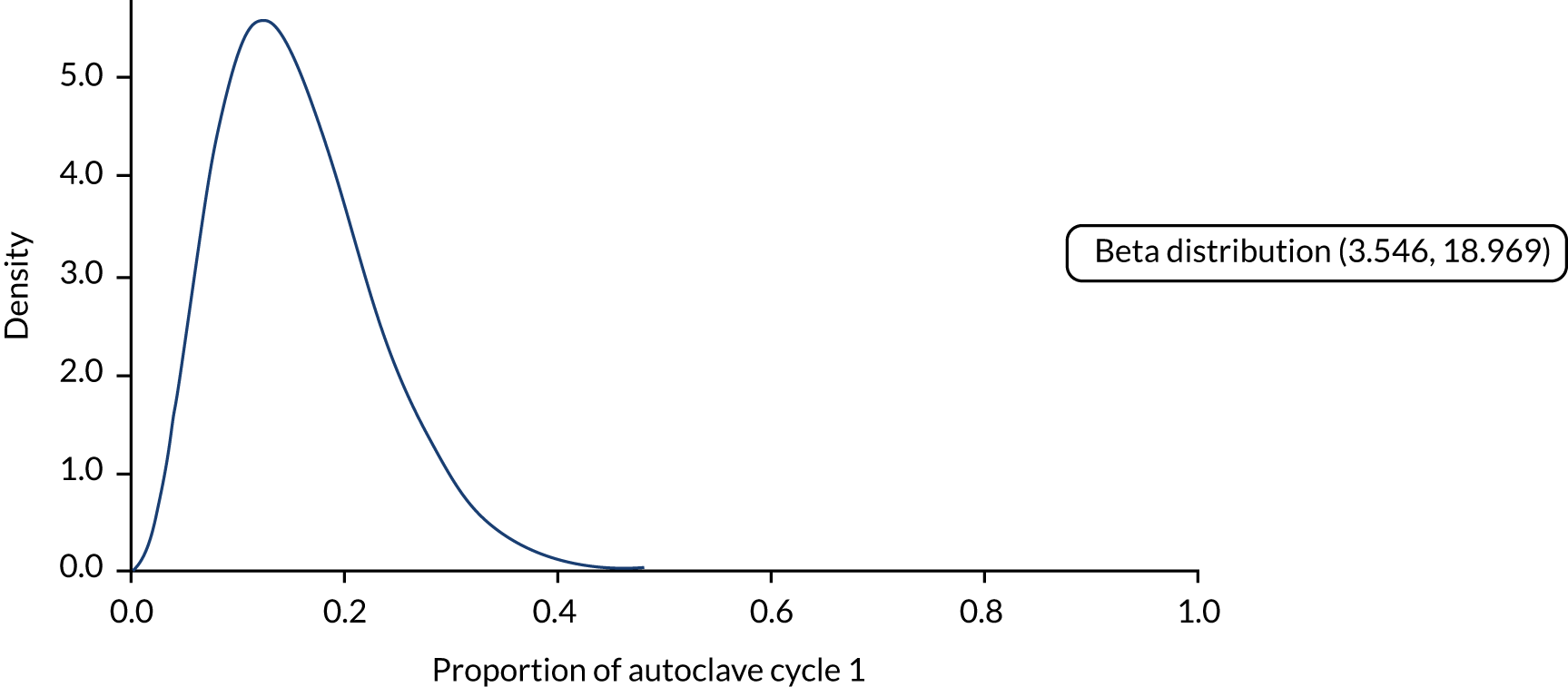

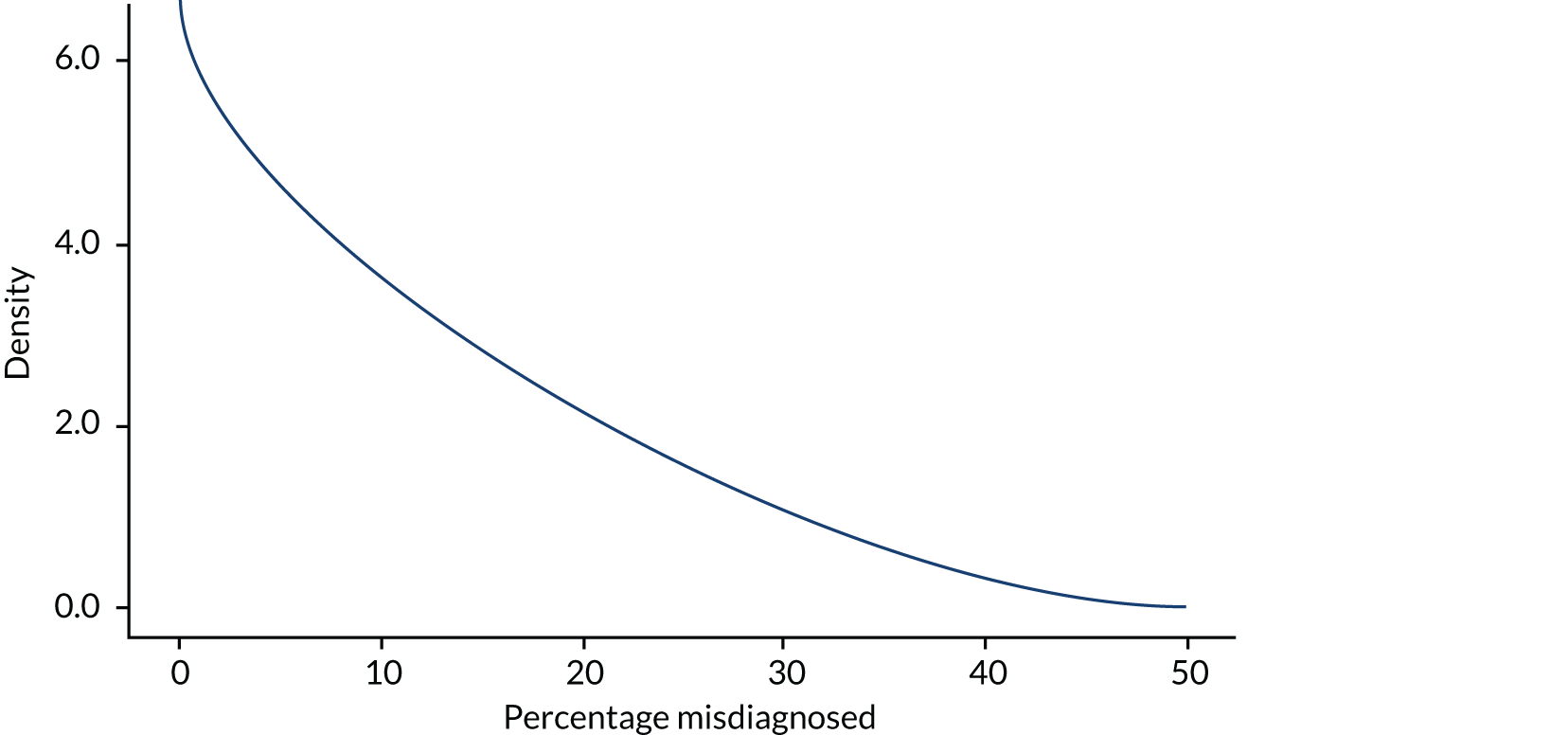

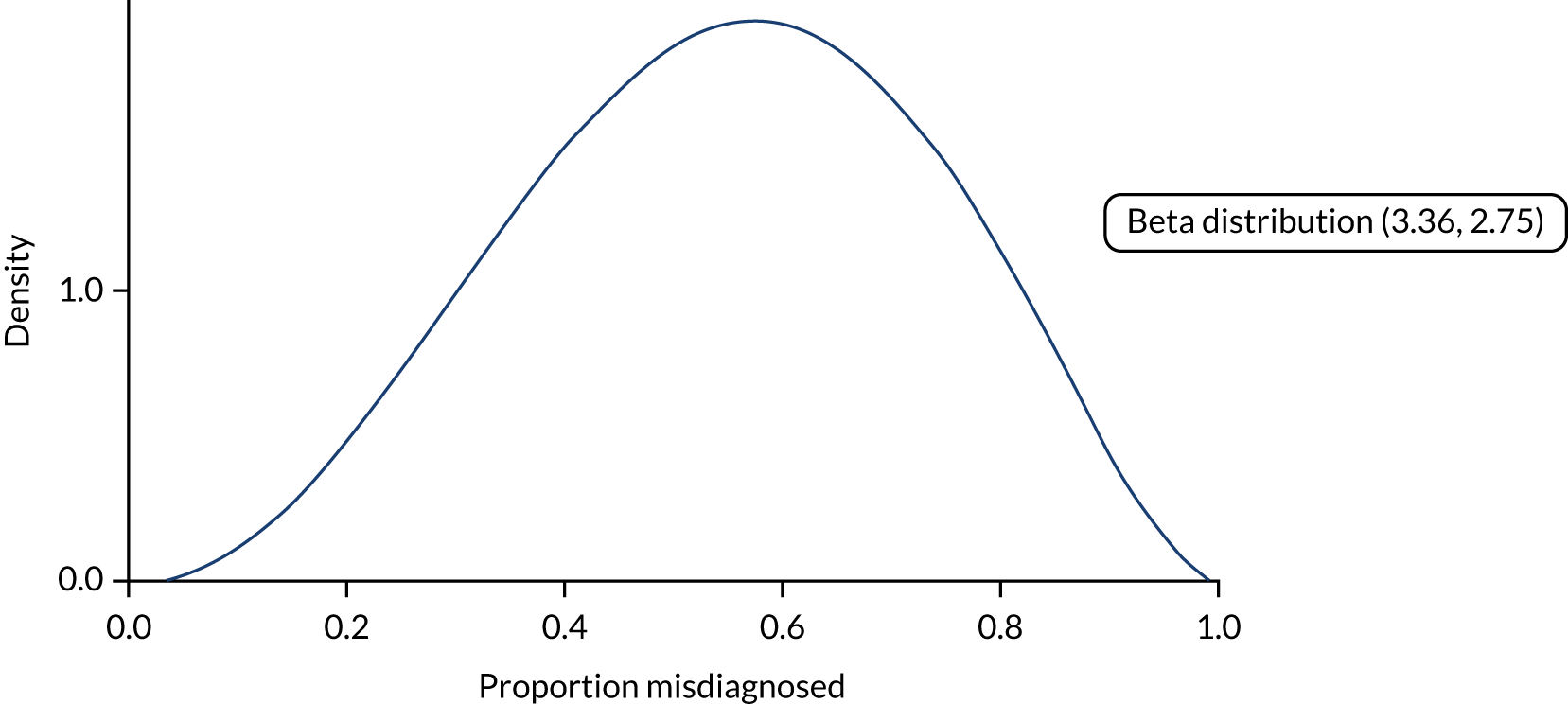

Risks in dentistry