Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 14/42/01. The contractual start date was in February 2016. The draft report began editorial review in February 2019 and was accepted for publication in May 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

James Prentis has received personal fees from Pharmacosmos A/S (Holbaek, Denmark) outside the submitted work. Elaine McColl was a member of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Journals Library Editorial Group from 2013 to 2016 and was a member of the NIHR Clinical Trials Unit Standing Advisory Committee until 2016. Denise Howel was a member of the NIHR Health Services and Delivery Research Healthcare Delivery Research Commissioning Board from January 2012 until May 2016 and was a member of the NIHR Programme Grants for Applied Research subpanel from February 2017. Eileen Kaner was a panel member of the NIHR Public Health Research Research Funding Board until October 2016.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Snowden et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Reproduced with permission from Snowden et al. 1 This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Structure of this report

This report documents a feasibility study and pilot randomised controlled trial (RCT) of brief behavioural interventions (BBIs) to reduce alcohol consumption before elective orthopaedic surgery.

Chapter 1 describes the context of the issue, considering postoperative complications and the role of the preoperative assessment clinic (PAC) in identifying and addressing surgical risk in the context of reducing postoperative complications. This is followed by a review of the literature regarding brief interventions (BIs) and alcohol-focused interventions in the perioperative period.

Chapter 2 details the development of the intervention, the intervention training package and research conducted to characterise the comparator condition of ‘treatment as usual’ (TAU).

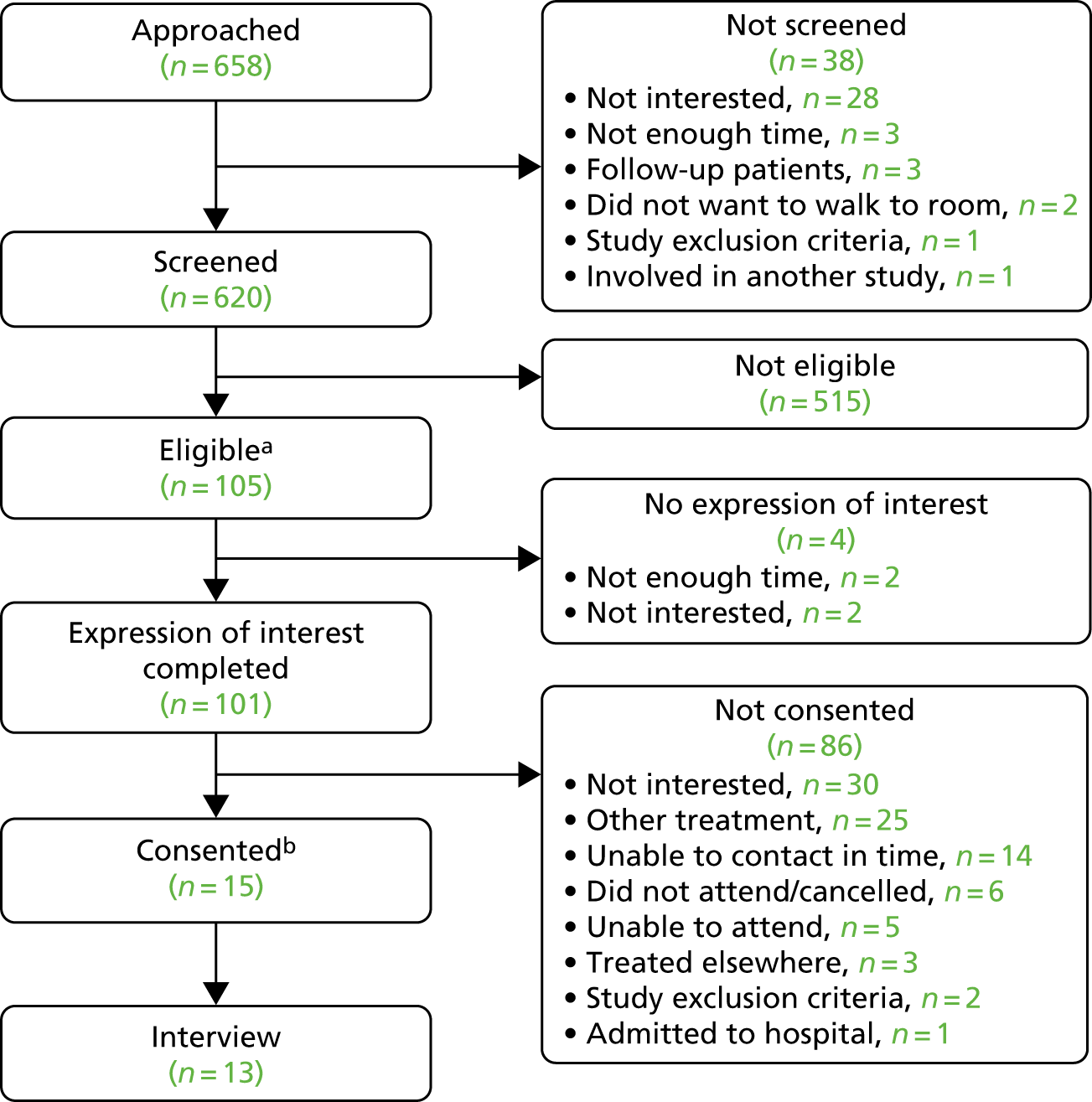

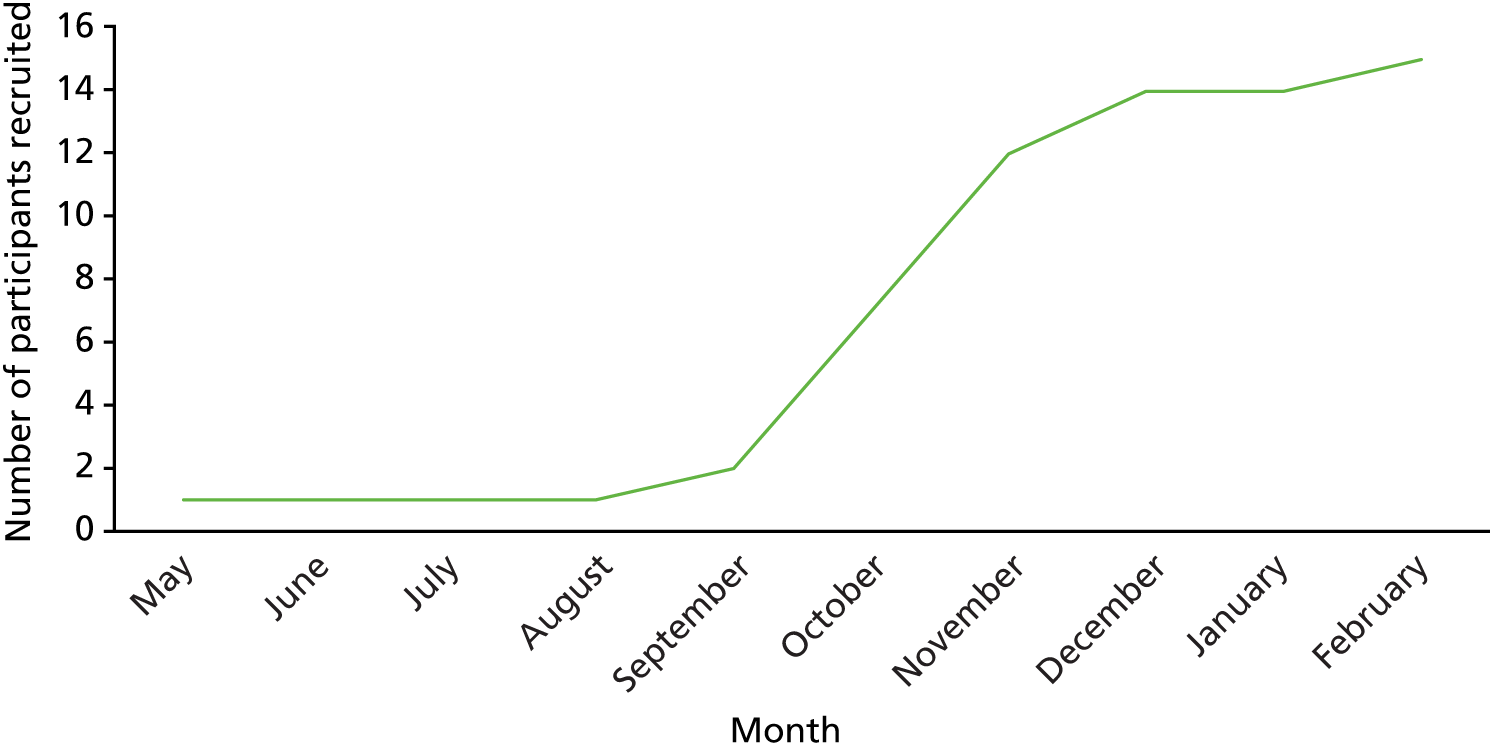

Chapter 3 presents the methods and results from the feasibility study, including qualitative interviews with health-care professionals (HCPs) and patient participants.

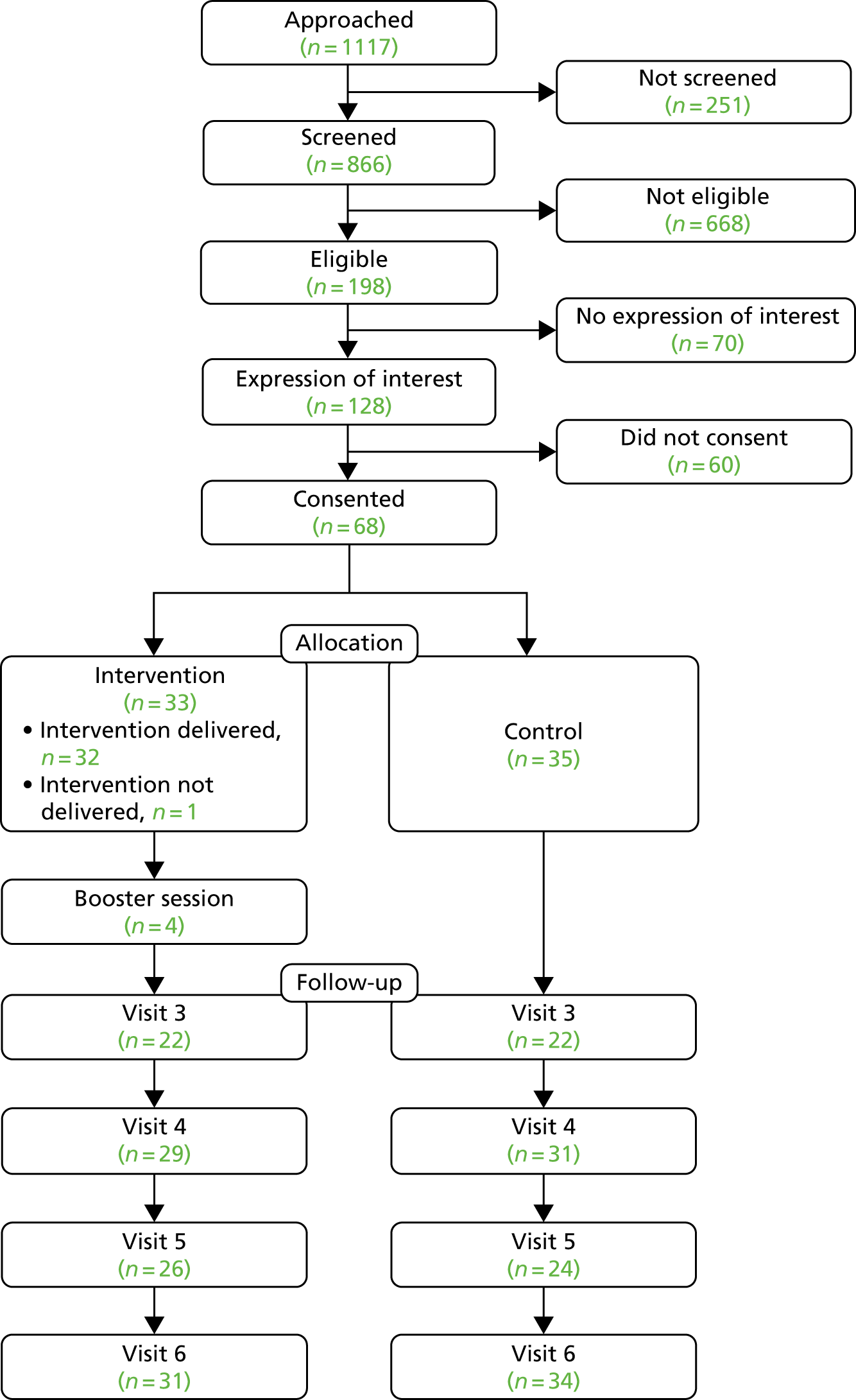

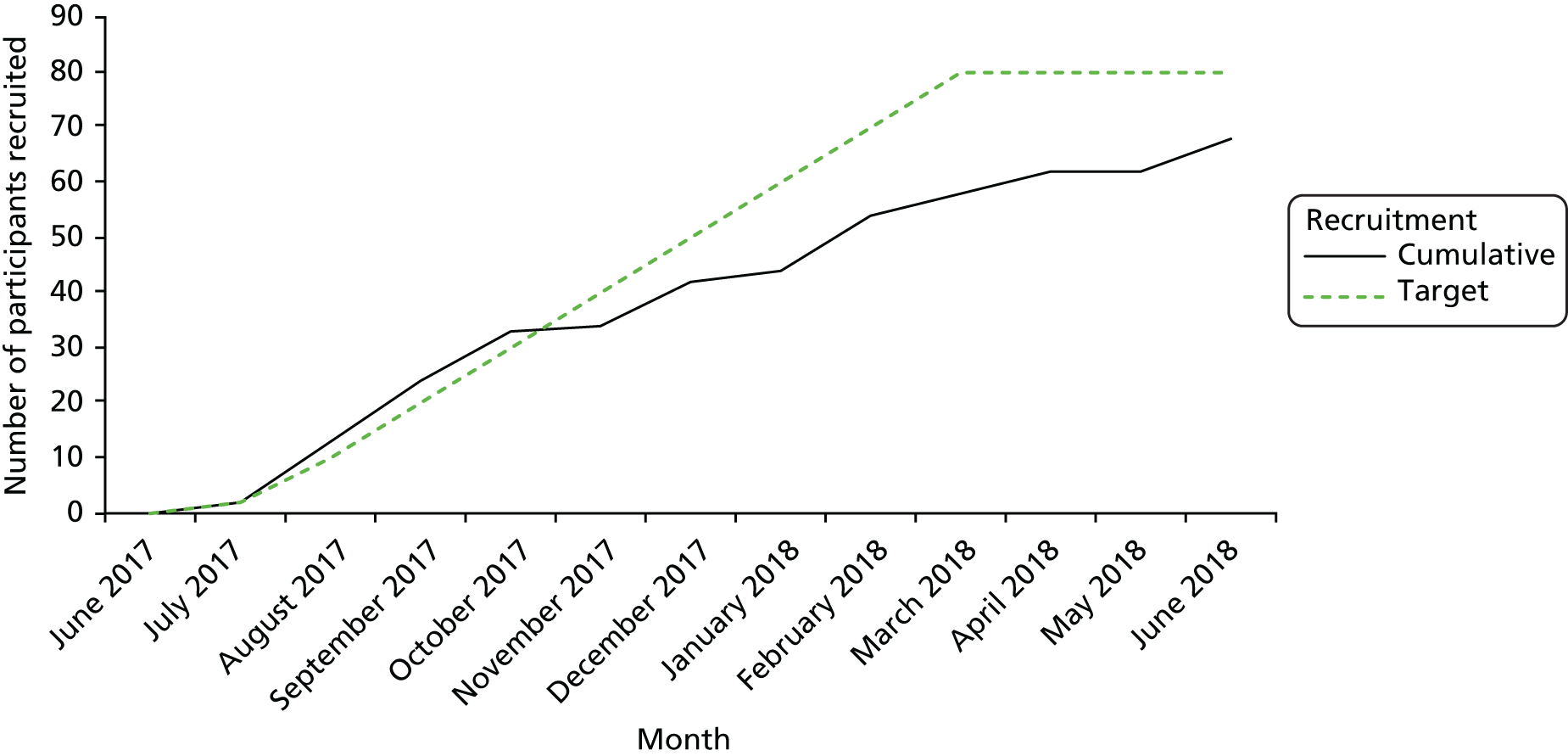

Chapter 4 describes the methods and results of the pilot RCT, including rates of recruitment and retention of patient participants, rates of completion of outcome measures and qualitative work exploring the acceptability of processes to both patient and HCP participants.

The key findings of the project are summarised and discussed in Chapter 5, with conclusions and recommendations for future research presented in Chapter 6.

Background

Perioperative morbidity and mortality after elective surgery is an important public health issue. 2 Although surgical mortality is reducing worldwide,3,4 even at the lowest mortality rate estimation of 1.1%, the volume of surgery being performed means that approximately 85,000 patients per year will not survive to 30 days following surgery. By contrast, postoperative morbidity or ill health is more common than mortality and remains at a relatively consistent level across sites and over time. 3 This clinical paradox has led to the accepted concept of ‘failure to rescue’, whereby the failure to identify and treat complications at an early stage following surgery leads to early mortality. 3,5

Although overall mortality rates remain important in a global sense,2 there has been a shift of focus to the reduction of morbidity after both high- and low-risk surgeries. 5 Postoperative complications have profound implications in terms of both patient well-being4 and utilisation of health-care resource increasing the costs of surgery two- to threefold. 2,6,7

The spectrum of alcohol use from abstinence to dependence is broad and can be subdivided in a number of ways. The research and clinical literature has, and still does, employ a variety of terms, often interchangeably, to describe different patterns of drinking. Many of these terms are included in the Glossary. Terms of specific interest to this work are described here. In the UK, ‘lower-risk’ drinking is considered to be the consumption of ≤ 14 units of alcohol per week (1 unit is 8 g of alcohol), with additional guidelines specifying that drinks should be spread evenly over ≥ 3 days and that ‘binge drinking’ (i.e. the consumption of ≥ 6 units on a single occasion) should be avoided. Any drinking above this level can be considered to increase the risk of experiencing alcohol-related harm. The term ‘increased risk’ drinking has replaced the term ‘hazardous drinking’ and is used to describe patterns of alcohol consumption that exceed the lower-risk drinking guidelines and are associated with an increased risk of experiencing harm as a result of alcohol consumption, although actual harm may not yet have occurred. Regular consumption in the range of 15–35 units per week for women and 15–50 units per week for men would usually fall into this category. 8 Higher-risk drinking, previously ‘harmful drinking’, is a pattern of alcohol consumption that results in harm to physical or mental health, with regular consumption in excess of 35 units per week for women and of 50 units per week for men. 8

A number of screening tools have been developed to identify different patterns of alcohol use. One of the most frequently employed in health-care settings is the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT). 9,10 The AUDIT, originally developed by the World Health Organization9 and validated for use in medical settings,11 is a 10-item questionnaire that assesses alcohol consumption alongside social and health consequences of drinking behaviour and indications of possible alcohol dependence. 12 Scores range from 0 to 40 and a cut-off point of ≥ 8 has been found to have a sensitivity of 92% and a specificity of 94% for detecting increased risk or higher-risk drinking. 9

Following the development of the AUDIT, a number of shorter variants have been developed. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test Consumption (AUDIT-C) measure, which comprises the first three items of the AUDIT that focus on assessing frequency and volume of consumption as well as the frequency of high intensity or binge drinking,13 has been shown to have a similar level of accuracy,14 including validity and reliability, as the full AUDIT. 13,15 With a cut-off point of 5, this measure has been found to have a sensitivity of 74% and a specificity of 83% for detecting increased risk drinking. 16

Orthopaedic surgery and postoperative complications

Among the elective orthopaedic surgical population, average rates of mortality (0.2–0.6%)17–19 and morbidity (4–6%)17,20–22 are relatively low when compared with those for other surgical populations such as cardiac or abdominal surgery. However, orthopaedic surgery is a high-volume elective specialty,23 meaning that even low rates of mortality and morbidity can have a significant population impact. In 2017, over 100,000 primary knee replacements and 90,000 total hip replacements were performed in England and Wales. 24 The most common complications include systemic infections and cardiovascular events (e.g. pulmonary embolism), deep-vein thrombosis, wound infections, wound dehiscence, perioperative fracture and nerve injury. 17,22 In general non-cardiac surgery, any complication is associated with an average 101% increase in hospital costs. 25 In orthopaedic surgery specifically, surgical site infections are associated with, approximately, a 61% increase in costs. 26

In addition, many elective orthopaedic procedures are performed in an older population. Advancing age predisposes patients to an increased risk of acquired, multiple comorbidities, which in turn confer an increased risk of post-surgical complications. As life expectancy continues to increase, more orthopaedic procedures will be performed in older people, leading to an increase in overall surgical morbidity. 17,22,27

Any perioperative intervention that aims to reduce known preoperative risk factors that predispose patients to postoperative complications will be important in improving future postoperative outcomes.

The role of the preoperative assessment clinic

Preoperative assessment clinics aim to assess patients’ suitability for elective surgery early in the surgical pathway through the detection, optimisation and modification of coexisting conditions. Indirectly, these clinics have been shown to reduce surgical cancellations and improve day-of-surgery arrival rates. 28 Importantly, they also provide an early opportunity to identify and address modifiable risk factors associated with postoperative complications, an approach often referred to as ‘prehabilitation’. This approach has included interventions to improve nutritional status, correct diet-induced iron deficiency anaemia,29 promote smoking cessation,30 reduce anxiety,31,32 provide patients with information regarding the perioperative pathway33,34 and increase physical activity. Regarding the last, the promotion of structured exercise regimes has been shown to improve aerobic fitness35,36 and enhance functional capacity both pre- and postoperatively in total knee arthroplasty patients37 and decrease length of stay in hospital for adult surgical patients across a range of specialties. 38

Preoperative alcohol intake also represents an important target for modifiable risk factor reduction. Subsequent sections of this chapter present existing literature concerning the association of alcohol consumption and postoperative outcomes, the identification and management of alcohol consumption in the PAC and interventions that have been found to be effective in other clinical settings.

Alcohol consumption

Alcohol is a component cause of > 200 health conditions39 and has a range of negative social consequences, including familial and relationship problems,40 involvement in crime,41,42 loss of productivity and unemployment. 43,44 Alcohol consumption is a leading cause of ill health globally, accounting for an estimated 4.2% of the global burden, of disease and injury. 45 In addition, alcohol-related harm represents a large economic burden, with the combined cost of alcohol-related health harms, crime, antisocial behaviour and loss of productivity in England estimated at £21B in 2012. 46 Both volume of consumption and drinking pattern are important predictors of alcohol-related health harms. 45

With a dose–response relationship between alcohol consumption and many forms of harm, those who consume the most alcohol, including those who are alcohol dependent, undoubtedly experience the highest levels of alcohol-related harm at the individual level. However, because a far greater number of individuals drink at increased risk and higher-risk levels, it is these drinking patterns that account for the largest proportion of population-level alcohol-related harm. 47 Therefore, it is this group, who drink in excess of the lower-risk guidelines but are not alcohol dependent, who are a primary target of interventions seeking to minimise alcohol-related harm,48 a phenomenon known as the prevention paradox.

Alcohol consumption and postoperative complications

The physiological effects of alcohol (e.g. liver damage, risk of accidental injury) may directly result in a need for surgery, or may indirectly increase surgical risk. Of specific concern are systems that are inhibited by both alcohol consumption and surgery. These include the haemostatic, immune, cardiac and endocrine systems. 49 The same mechanisms by which moderate alcohol consumption can protect against the formation of blood clots50 also place those with increased levels of alcohol consumption at increased risk of prolonged bleeding during and after surgical procedures. 51 Reduced immune system function as a result of alcohol consumption is further inhibited by surgery52 and leaves the patient susceptible to both surgical site and systemic infections; subclinical cardiac insufficiency and arrhythmias53 present increased risks of cardiac complications and an altered endocrine stress response49,51 may also increase the risk of complications.

With this myriad of physiological effects of alcohol, it is not surprising that studies have identified associations between alcohol intake and perioperative complication rates across a wide range of surgical procedures (e.g. cardiac, orthopaedic and gastric). The complications most frequently associated with alcohol use are infection, sepsis, bleeding, cardiac events and deep-vein thrombosis. 51,54,55

Within this literature, a number of studies have focused on those consuming ≥ 60 g of alcohol per day and those identified as having alcohol use disorders (AUDs) or alcohol dependence. 52,56 In 1999, a review51 identified a two- to threefold increase in postoperative morbidity among individuals consuming > 60 g of alcohol per day for a minimum period of ‘several months’. However, the risk of increased postoperative complication rates may not be limited to those identified as ‘alcohol misusers’ or those with alcohol use disorder. Comparison of postoperative complication rates with scores on validated alcohol screening tools has demonstrated that the incidence of complications increases with increased screening scores among all adult drinkers. Bradley et al. 57 identified that patients with an AUDIT-C score of ≥ 5 (score range 0–12) were at increased risk of postoperative complications. Complication rates increased from 5.6% for those scoring 0–4 on AUDIT-C to 14% for those scoring 11–12 on the screening tool.

In 2013, a review conducted by Eliasen et al. 58 assessed the association between preoperative alcohol consumption and postoperative complications across a wider population of drinkers than were included in the review by Tønnesen and Kehlet. 51 They found that alcohol consumption (of 24 g per day for women and 36 g per day for men) was associated with increased rates of postoperative complications, including a 23% increased risk of wound complications, an 80% increased risk of pulmonary complications, a 24% increased risk of prolonged hospital stay and a 29% increased risk of intensive care admission. Furthermore, high, but not low to moderate (< 24 g per day for women and < 36 g per day for men), alcohol consumption was associated with increased mortality. Two similar reviews by Wåhlin and Tønnesen59 and Shabanzadeh and Sørensen60 in 2014 and 2015, respectively, concluded that the consumption of two or more standard drinks per day is enough to increase the rate of postoperative complications.

This pattern of dose-dependent association of alcohol intake with postoperative complications is also reported in orthopaedic surgical populations. Among patients undergoing total hip or knee arthroplasty, those with high levels of alcohol use showed significantly higher incidences of complications (12 out of 15 assessed),61 with an overall complication rate of 33.5% among alcohol misusers compared with 22.6% in their non-alcohol-misusing counterparts. This population was also found to have significantly longer stays in hospital. 61 Another study62 reported a 29% increase in the number of complications for every additional point on the AUDIT screening tool in patients undergoing total joint arthroplasty. This is also supported by the results of a registry-based study that considered patients who reported abstinence, low to moderate or high alcohol consumption and found a similar dose-dependent association with rates of mortality and morbidity. 63

With a strong evidence base for an association between increased alcohol consumption and increased rates of postoperative complications, it is reasonable to suggest that interventions that reduce or cease alcohol consumption in the preoperative period may result in fewer complications and better postoperative outcomes. Existing literature suggests that many of the physiological effects of increased alcohol consumption thought to explain the increased risk of postoperative complications may be improved or entirely reversed within a relatively short period of alcohol cessation (between 2 weeks and 3 months depending on the specific effect considered). 51,64,65 The effects of reduction rather than cessation of alcohol consumption are less clear.

Achieving such improvements requires two key things: first, clinicians must be able to effectively identify patients at increased risk of perioperative complications as a result of alcohol consumption and, second, they must be able to provide an acceptable and effective intervention to bring about timely changes in alcohol consumption behaviour.

Preoperative alcohol screening

Although the assessment of alcohol consumption is part of standard care in preoperative assessment (PA), the use of validated screening tools is not widespread. Until recently, the more formal validated screening tools developed to assess of alcohol consumption (e.g. AUDIT, AUDIT-C), had not been employed in the preoperative setting.

Concerning the detection of alcoholism in the preoperative period, Martin et al. 66 found that routine practice identified only 16% of alcohol-dependent patients at the first visit, although this increased to 34% if the patient was seen three or more times in the preoperative period. When a screening questionnaire was used, the rates of detection on first visit were much higher (64%).

Because alcohol-dependent patients are at highest risk of intra- and postoperative complications and are at risk of the life-threatening complication of experiencing alcohol withdrawal syndrome, it is critical that they be identified and effectively manged in the preoperative period. However, they represent only a small proportion of those who may be at increased risk as a result of alcohol consumption. Kip et al. 67 considered a wider range of AUDs and compared detection rates from screening with computerised AUDIT questionnaire with those from anaesthesiologist assessment. The findings support those of Martin et al. ,66 with only 17.4% of patients who were found to be AUDIT positive (score of ≥ 8) also detected by anaesthesiologists. In addition, although anaesthesiologists were reliably able to detect patients who showed signs of dependence (25.2%), the patients with harmful (20%) or hazardous (17.2%) drinking were not detected. Furthermore, subgroup analysis found that anaesthesiologists were significantly less likely to identify AUDs in women and those aged < 50 years. 67

Among both elective and emergency orthopaedic surgical patients in Australia, 34% were identified as having hazardous drinking behaviour using the AUDIT questionnaire but only 38% of these patients reported a history of problematic alcohol consumption,68 indicating that a majority of those drinking at hazardous levels may be unaware that their drinking could represent a risk to their health.

In combination, these findings demonstrate that utilisation of validated screening tools in the preoperative period is likely to increase detection rates of AUDs across the spectrum.

Alcohol screening using validated screening tools has been shown to have good patient acceptance in both preoperative and wider health-care settings. 57,62,68–70 Indeed, the need to improve detection rates for increased risk alcohol consumption (and smoking behaviour) in hospitals has been recognised in the UK, where the Commissioning for Quality and Innovation (CQUIN) has identified these health behaviours as a priority.

The CQUIN framework aims to improve care by providing financial incentives to health-care providers in the UK who demonstrate delivery of quality and innovation in prespecified areas. The 2017–19 CQUIN targets include a goal to support people to change their behaviour in order to reduce the risk to their health from alcohol and tobacco use through identification, advice and referral to specialist services for inpatients in all acute trusts. 71 Regarding alcohol consumption, the CQUIN promotes screening with the AUDIT-C questionnaire followed by delivery of brief advice (BA) to those identified as increased risk or higher-risk drinkers and the referral of those identified as alcohol dependent. Although PA is an outpatient appointment, patients are subsequently admitted as inpatients for the surgical procedure. Thus, the PA provides an important opportunity for the CQUIN screening, intervention and referral package to be implemented earlier in the surgical pathway.

Preoperative alcohol cessation interventions

A small number of studies have considered interventions concerned with bringing about preoperative alcohol cessation among heavy drinkers with a minimum level alcohol consumption equivalent to between 4.5 and 7.5 units per day (36–60 g of alcohol) or 31.5 and 52.5 units per week (252–420 g of alcohol). The results of three RCTs (one published,64 two unpublished72,73) that targeted alcohol cessation in the preoperative period have been included in the most recent update of the Cochrane review concerning perioperative alcohol cessation interventions. 74 All three trials employed intensive interventions, including the provision of disulfiram (Antabuse® Pliva, East Hanover, NJ, USA), and aimed to achieve between 1 and 3 months of alcohol abstinence prior to surgery. Two trials also offered chlordiazepoxide hydrochloride for the treatment of withdrawal symptoms and provided motivational counselling each week, with staff available for telephone contact if required. 72,73 All three trials identified significantly higher rates of abstinence in the intervention groups than in the control. An associated finding of lower rates of postoperative complications following intervention was not statistically significant. However, when pooled data were analysed,74 there was a significant reduction in complication rates associated with reduced alcohol consumption immediately following completion of the intervention.

It is important to consider that all three of these trials were conducted in Denmark and results cannot be assumed to be generalisable to the UK setting. These trials are all concerned with individuals drinking at more than double the current UK lower-risk drinking guidelines, levels that suggest possible dependence, and thus require the provision of specialist support including pharmacotherapy. However, such intensive interventions are unlikely to be acceptable to, or appropriate for, patients drinking at increased risk levels (> 14 units per week). Because this group also confer additional risk as a result of their alcohol consumption, present for surgery in much greater numbers and are unlikely to recognise the risks associated with their own drinking behaviour, it is necessary to consider alternative, more appropriate interventions. BIs in the form of structured advice or behaviour change counselling, have been shown to be effective in bringing about reductions in alcohol consumption in other health-care settings, including primary and emergency care,75–77 and represent a potential alternative that could be employed in the PAC at relatively low cost and with minimal burden to the patient.

Brief alcohol interventions

The terms ‘brief intervention’, ‘brief behavioural intervention’ and ‘brief advice’ are often used interchangeably in the literature to describe short sessions of advice and/or behaviour change counselling that are usually delivered by a care provider. Such methods have frequently been used to address increased and higher-risk drinking behaviours. BIs usually last between 5 and 30 minutes with key intervention content including feedback on alcohol consumption often with comparison to social norms; identification of the drinker as the only one who can change their behaviour; identification of the potential harms of drinking behaviour and the potential benefits of reducing alcohol intake; advice about how to reduce alcohol consumption; and goal-setting or the development of a plan to reduce drinking. In addition to this content, the interventionist or care provider adopts a non-judgemental, empathic approach with roots in motivational enhancement therapy, which seeks to increase motivation to change and enhance self-efficacy. These core components and the associated therapeutic approach are summarised by the FRAMES (Feedback, Responsibility, Advice, Menu, Empathy, Self-efficacy) acronym. 78

Although research trials often identify decreases in alcohol consumption in both intervention and control groups (e.g. Fleming et al. 79 and Lock et al. 80), systematic reviews and meta-analyses have consistently identified positive effects of providing BI over and above changes in comparator groups. 81–83 This approach has been most frequently studied in primary care settings, where the focus is on reducing alcohol consumption in the longer term. 75,84,85 In these settings, BIs have been shown to result in an average reduction of between 20 g75 and 38 g82 of alcohol per week (2.5–5 units) compared with control groups at 6–12 months post intervention.

However, the implementation of BIs into standard practice has been limited,86 with a number of studies documenting barriers to implementation, including lack of resources, training and support. 87

There is now a small, but growing, body of evidence considering the use of BIs for alcohol consumption in other settings including general hospital wards76,88 and outpatient clinics. 89 A recent review and meta-analysis of interventions delivered to general hospital inpatients identified a significant benefit of BIs over control conditions in terms of reduction in alcohol consumption at 6 (–70 g per week) and 9 months (–183 g per week) post intervention as well as a reduction in mortality rates at 6-month (relative risk 0.42) and 1-year (relative risk 0.60) follow-up. 76 Meanwhile, it has been shown that screening and BI in outpatient clinics can reach a large number of patients90 and can result in significant reductions in alcohol consumption and in the percentage of hazardous drinkers (intervention, reduction from 60% to 27%; control, reduction from 54% to 51%). 89

With the implementation of BIs in primary care being limited, it is important to establish when and where such interventions can best be implemented in standard care. Previous research shows that patients are more accepting of health behaviour advice when it is delivered in an appropriate setting or linked to the presenting health condition. 91,92 In some settings, such as emergency care, some level of alcohol-related harm may already be present (e.g. alcohol-related injuries). On the other hand, the PAC offers an opportunity to introduce the idea of health behaviour and behaviour change before many will have incurred any significant harm but when there is a positive, salient and temporally proximal focus (i.e. elective surgery). In other words, it offers a ‘teachable moment’. The benefit of BIs targeting shorter-term changes in alcohol consumption (e.g. preoperative alcohol reduction or cessation) has not been widely studied and thus it is unclear what magnitude of effect is likely in such contexts. However, broader intervention studies predominantly show a higher level of behaviour change post intervention and at early follow-up (e.g. ≤ 3 months) than at longer-term follow-up (e.g. 12 months). 93

Further to this, the PAC patient population is both large and diverse, with most patients who receive elective surgeries being referred for at least some level of assessment. As such, the PAC offers an opportunity to screen and intervene with a large number of patients across a wide age range, many of whom may not frequently present to primary or emergency care.

If brief alcohol interventions are to be implemented in PACs, it is likely that they will be delivered by nurses rather than anaesthetists because the clinics tend to be nurse led. Although there is some evidence to suggest that physician-delivered interventions may be better received by patients,91 others have reported that nursing staff may be best placed to deliver interventions92 and that patients view interventions delivered by nursing staff as equivalent to those delivered by general practitioners (GPs). 94

Behavioural interventions in the preoperative period

To date, four trials have considered the effectiveness of behavioural interventions (including both brief and more extended interventions) targeting alcohol reduction or cessation in the preoperative period. The majority have included alcohol interventions as part of a multimodal intervention package targeting multiple health behaviours, which precludes firm decisions on the effectiveness of isolated intervention components for individual behaviours. The only trial to assess an alcohol intervention alone was reported by Shourie et al. 95 This trial commenced as a randomised trial but difficulty in recruiting patients at least 7 days before surgery led to the adoption of a non-randomised method whereby those with ≥ 7 days to surgery received the intervention and those with < 7 days to surgery were allocated to the control condition. The intervention employed was a revised version96 of the manualised BI from the ‘Drink-less’ campaign,97 which aimed to facilitate preoperative alcohol cessation. No significant intervention effect on alcohol consumption was demonstrated. This finding was attributed the intervention being delivered too close to surgery, thereby allowing too little time for either behaviour or physiological change. Three further trials used behavioural interventions targeting preoperative alcohol consumption as part of multimodal intervention packages. McHugh et al. 98 conducted a RCT with patients awaiting coronary artery bypass surgery. Patients allocated to the intervention group had their physical and mental health needs assessed and were provided with a tailored intervention package delivered in monthly health education sessions. Interventions targeted smoking, alcohol use, physical activity, diet, hypertension and hypercholesterolemia as indicated by screening and patients’ readiness to change. In addition to providing advice and information, the interventionists used a ‘pros and cons’ approach to behaviour change, goal-setting and progress monitoring. Patients in the intervention group showed greater rates of smoking cessation, physical activity and weight loss than the control group and greater improvements in blood pressure. Alcohol consumption outcome data were not published in this original study report but were included in a subsequent review,99 which identified a significant group × time interaction whereby the intervention group decreased their weekly alcohol consumption by 1.2 standard drinks per week between baseline and follow-up, whereas the control group showed an average increase of 1.3 drinks per week over the same period. With an average of > 8 months from trial entry to surgery date, patients had adequate time to implement behaviour change and observe positive health outcomes. However, the maintenance of change over an extended period, alongside the targeting of multiple health behaviours, presents its own difficulties.

Kummel et al. 100 conducted a RCT to assess the effects of guidance and counselling delivered in individual and group sessions on health behaviours in older (> 65 years) coronary artery bypass patients. Patients received one group session in the preoperative period and four sessions postoperatively. Sessions included health counselling, guidance and adjustment education, including information on risk factors for coronary heart disease, peer support and goal-setting. The primary focus of this intervention package was outcomes in the postoperative period rather than preoperative changes in health behaviour. The intervention was found to reduce alcohol consumption relative to baseline at 3-month follow-up, whereas the control group showed greater alcohol consumption at 6- and 12-month follow-up than at baseline.

The third trial101 assessing the effectiveness of a multimodal intervention package used a quasi-experimental design with patients referred for fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty. Patients were recruited over 4 months, with those undergoing surgery in the first 2 months of 2007 allocated to the control group and those receiving surgery in the next 2 months of the same year allocated to the intervention. The intervention involved completion of a preoperative risk-screening questionnaire, followed by a motivational conversation addressing identified risks with interventions for nutritional risk, physical activity, health, medication and alcohol use and/or smoking. Interventions for smoking and alcohol consumption involved the provision of information and identification of the potential benefits of stopping or abstaining in the preoperative period. Information leaflets about the identified risks were also provided. Findings showed a reduced number of ‘unplanned’ surgical pathways (including complications, readmission and mortality in the postoperative period) among intervention patients compared with controls. However, it is notable that only 4 of the 78 participants in the intervention condition were identified ‘at risk’ in terms of drinking more than the recommendations from the Danish National Board for Health (i.e. 21 units per week for men, 14 units per week for women). 101 As a result, it is not possible to conclude what, if any, benefits were gained from identifying and intervening to address risky drinking in this population.

A further trial considered preoperative alcohol consumption as part of a multimodal ‘prehabilitation’ package and planned to provide interventions for risky drinking but did not identify any patients drinking at risky levels. 102

The four studies assessing behavioural interventions for alcohol consumption in the preoperative period have been drawn together in a narrative review conducted by Fernandez et al. 99 This review identified some positive findings, with two of the trials identifying significant reductions in alcohol consumption and one identifying a significant reduction in postoperative complications. However, it also highlighted a number of methodological weaknesses of the current evidence and made multiple recommendations for future research. They pointed to difficulties in recruitment across the trials. Specifically, the studies by Shourie et al. ,95 McHugh et al. 98 and Kummel et al. 100 took between 15 months and 3.5 years to recruit 117–136 participants. These issues were further exacerbated by the fact that rates of risky drinking in participants recruited to multimodal trials were low. For example, Hansen et al. 101 identified just 4 out of 78 intervention participants as drinking above recommended guidelines and Kummel et al. 100 identified 12 out of 49 intervention patients and 21 out of 68 control patients as using alcohol at least once per week at baseline. This is in contrast to alcohol screening data, which identify 8–43% of surgical patients as screening positive for alcohol misuse,57,62–103 and rates increase to as high as 82% when considering surgeries for conditions strongly associated with alcohol use (e.g. head and neck tumour surgeries). 103 This suggests a number of possibilities: alcohol consumption levels may be much lower in certain surgical populations, those drinking at risky levels may be less likely to participate in intervention trials or alcohol consumption may be under-reported by trial participants. Fernandez et al. 99 recommend adopting clear, precise definitions of risky drinking and using unbiased screening to detect those drinking at risky levels.

Further recommendations resulting from this review99 include assessing change in alcohol use preoperatively as well as postoperatively to allow the assessment of preoperative change on postoperative outcomes; a focus on the needs of older adults because the average age of trial participants is < 50 years; using empirically supported interventions and improving the reporting of both intervention content and fidelity of delivery; delivering interventions early enough in the preoperative care pathway to allow adequate time for behaviour change and subsequent pathophysiological improvement; and careful consideration of the sample size required to ensure adequately powered evaluations.

Feasibility and acceptability of preoperative screening and alcohol intervention

There has been limited work exploring the acceptability of screening and BI methods to patients and HCPs in the context of perioperative care. Acceptability has tended to be judged on rates of uptake of screening and interventions. 57,62,68 Considering the difficulties experienced in recruiting patients to trials of preoperative alcohol interventions in previous studies, qualitative methods may provide important insight.

To the authors’ knowledge, only two studies have used qualitative methods to provide more detailed findings regarding the acceptability of perioperative alcohol intervention methods. Pedersen et al. 104 carried out qualitative interviews to assess patients’ views of the intervention materials and methods used in their trial of postoperative alcohol interventions following surgery for ankle fractures. Findings show that patients held positive views about the intervention in relation to surgery and the proposed materials. Approximately half of the patients interviewed reported that they were open to changing their drinking behaviour. The validity of these findings is restricted by the sampling technique. Specifically, patients interviewed did not receive the intervention as part of the trial but were presented with the intervention materials and asked to provide their views. Lauridsen et al. 105 interviewed 11 participants from the ongoing ‘STOP-OP’ trial of alcohol and smoking cessation interventions delivered to patients awaiting radical cystectomy. Of those interviewed, three had received an alcohol intervention alone and two had received both the smoking and the alcohol interventions. The authors reported that the interventions were well received and that patients perceived it to be a part of their treatment package rather than something separate or distinct. A number of facilitators of effective intervention were identified, including having intervention sessions scheduled alongside other appointments or delivered over the telephone, and the empathic approach of interventionists. Facilitators of alcohol and smoking cessation were also identified; these included aspects of undergoing surgery (e.g. hospital stay, nausea) that removed either the desire or the opportunity to smoke/drink, as well as a feeling of obligation to do what they could for their own health or to please family or HCPs who were ‘invested’ in the outcome of their surgery.

Despite the limited research in perioperative care, trials of BI for alcohol reduction and cessation in other contexts have assessed the acceptability of methods that may inform work in PA. Qualitative studies in other health-care settings support the findings of Pedersen et al. 104 and Lauridsen et al. ,105 with patients and staff expressing generally positive attitudes towards alcohol screening and intervention (HCPs106,107 and patients108,109). However, they have also identified a number of barriers to alcohol screening and intervention in health-care settings. These barriers include logistical issues, having the necessary alcohol knowledge and having the required training and skills. 106,110

In combination, findings from these qualitative works suggest that alcohol screening and intervention is likely to be acceptable to patients, and that surgery may increase the salience of health behaviour change and facilitate change in the short term. However, there is a need for further exploration, and overcoming or addressing logistical barriers will be important to ensure effective implementation.

Outcomes of interest for trials of preoperative alcohol interventions

With previous research having identified that alcohol consumption in the preoperative period is associated with increased risk of postoperative complications, interventions leading to alcohol reduction or cessation in the preoperative period may reduce postoperative complications and improve outcomes. Therefore, the effectiveness of a preoperative alcohol intervention would be judged initially in terms of changes in alcohol consumption behaviour and, later, by any resultant reduction in complications or improvements in outcomes. A trial of a preoperative alcohol intervention should therefore include measures of alcohol consumption, complications and condition-specific as well as general health outcomes.

As detailed in Background, the AUDIT-C and full AUDIT tools are frequently used to screen for different patterns of drinking and to assess changes in drinking behaviour.

Regarding postoperative complications, two measures are frequently used in health-care settings: the Post Operative Morbidity Survey (POMS),111 which collects data on minor complications related to postoperative pathways, and the Clavien–Dindo tool,112 which classifies the presence of more significant postoperative complications.

Specific to the disease process requiring orthopaedic surgical intervention is the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC),113 which aims to evaluate the functional ability of patients with knee and hip osteoarthritis and includes items related to pain, stiffness and physical functioning of the affected joints. In addition, broader patient-reported health outcomes may be of interest. These are frequently assessed with quality-of-life114 questionnaires, such as the EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D). 114,115

Characterising treatment as usual in preoperative assessment

In a setting where alcohol consumption is routinely assessed as part of TAU, it is important to clearly document the characteristics of TAU to allow accurate comparisons between that and any intervention delivered, and to ascertain whether or not the proposed intervention is in fact sufficiently different from TAU. A national survey116 of consultant anaesthetists involved in perioperative care found that the majority of PACs involve some form of alcohol screening, with almost half having alcohol intervention services available. However, the survey provided little detail of screening approach, or of the form and content of any interventions available. Although anaesthetists play a key role in leading PA units, the majority of PAs are conducted by nurses, who are therefore likely to be better placed to provide insight into the delivery of alcohol screening and intervention in PA.

Conclusions

Preoperative alcohol consumption is firmly associated with postoperative complications and poorer surgical outcomes and represents a modifiable risk factor suitable to be addressed using an appropriate presurgical intervention. Evidence exists to support the effectiveness of intensive interventions, combining pharmacological and behavioural aspects, in bringing about abstinence in heavy and dependent drinkers and leading to reduced rates of postoperative complications. 64,72–74 However, these methods are unlikely to be either appropriate or acceptable for the majority of increased risk drinkers, who represent a greater proportion of the surgical patient population. Although there is evidence for the effectiveness of BIs in other settings (e.g. primary care, emergency care), less is known about the use of such methods in the preoperative period. Studies employing preoperative behavioural interventions have been confounded by several methodological issues, including:

-

the use of multimodal interventions targeting a number of health behaviours98,100,101

-

poor reporting of the uptake, content and delivery98,100,101 of interventions

-

small numbers of risky drinkers in the overall trial population101

-

delivery of interventions close to the date of surgery, allowing little time for behaviour change95

-

the use of non-randomised study designs. 95

Given these limitations, drawing firm conclusions about the effectiveness of any intervention to reduce or cease alcohol consumption in the perioperative period is difficult, and further high-quality RCTs are required. In addition, with a number of the studies conducted to date having also identified issues with recruitment and having limited data regarding the acceptability of preoperative alcohol screening and intervention, it is important to explore the acceptability of proposed screening, recruitment and intervention methods with participants in order to optimise both research and intervention methods before seeking to assess effectiveness.

Aim and rationale

Summary of rationale

Brief behavioural interventions are effective in reducing alcohol consumption among increasing risk and risky drinkers and have been demonstrated to be acceptable to patients and HCPs in several clinical settings.

Upcoming major surgery provides an opportunity to deliver a BBI for reducing preoperative alcohol consumption. Reducing risky drinking preoperatively may have immediate benefits on short-term clinical outcomes after surgery. Sustained reductions in alcohol consumption are likely to support longer-term recovery, as alcohol has immunosuppressant effects. Furthermore, any such sustained changes would also decrease alcohol-related risk to future well-being in a predominantly older, orthopaedic population.

Aim

The overall aim of the project was to establish if a definitive trial of a BBI to reduce drinking prior to elective orthopaedic surgery is feasible.

Three overarching objectives reflected three sections of work, each of which had its own secondary objectives:

-

Characterise the intervention and comparator (TAU) conditions.

-

– Train HCPs to deliver structured screening and BBI to eligible patients in the PA setting.

-

– Assess fidelity of delivery of the BBI.

-

– Characterise TAU in the PAC for elective orthopaedic surgery at the three pilot RCT sites using focus groups.

-

– Characterise TAU for elective orthopaedic surgery at PACs nationally using a quantitative electronic survey.

-

-

Assess the feasibility and acceptability of consent, screening, intervention and outcome assessment procedures.

-

– Optimise the screening and behavioural intervention process in a way that nurses and patients find acceptable.

-

-

Estimate rates of eligibility, recruitment and retention in a pilot RCT.

-

– Assess completion rates for all data collection tools, including measures of alcohol consumption, quality of life and joint functionality.

-

– Establish response variability of proposed outcome measures for a definitive trial, which will include drinking status and quality of life.

-

– Estimate rates of secondary outcomes and perioperative complication rates, including bleeding and infections.

-

– Explore the acceptability of intervention and research methods with HCPs and patients through qualitative interviews.

-

Patient, public and professional involvement

There was patient, public and professional involvement at all stages of the study from inception to completion.

Prior to commencement of the study, formative work conducted at the primary site provided initial estimates of screening uptake and eligibility based on an AUDIT score of ≥ 8.

Prior to commencing the feasibility study, all patient materials were reviewed by members of a local patient and public involvement group, Voice North: (www.ncl.ac.uk/ageing/partners/internal_ageing/voice/; accessed 4 February 2019). Comments were used to inform amendments to the materials before they were submitted for relevant approvals.

Three members of this group expressed an interest in being involved in the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and attended meetings during the research programme. When these members were unable to attend meetings they were sent a copy of the meeting minutes and asked to provide comments. Further to this, a member of the research team (EL) met with lay members to discuss proposed changes between the feasibility study and the pilot RCT phase to ensure that these were considered acceptable.

During the feasibility study, anecdotal feedback from researchers and HCPs involved in the screening and recruitment of patient participants was collected. With initial rates of recruitment being lower than anticipated, this information was used to inform the amendments made to the feasibility study processes. The proposed changes were then discussed with the lay members of the TSC before being submitted for approval.

Prior to commencing the feasibility study, researchers engaged with HCPs employed in PA to inform the design of the training session. The HCPs completed questionnaires identifying their training needs and the acceptability of the proposed training methods. HCPs were also asked to complete feedback questionnaires after the group training session was delivered.

Prior to commencing the pilot RCT, HCPs involved in pre-assessment at each of the three trial sites were invited to a launch meeting, where they had the opportunity to discuss the pilot RCT and consider how the research processes would be implemented at each site. Members of the research team also met with pre-assessment leads from each site. These meetings led to the decision to allow either face-to-face screening or postal invitations followed by telephone screening to minimise the impact of extended waiting times between listing for surgery and attendance at the PAC on recruitment times. With HCPs also explaining that some patients would attend satellite hospitals for follow-up appointments, the option to conduct follow-up visits over the telephone was also included in the pilot RCT.

Chapter 2 Defining the intervention and comparator

Introduction

When considering behavioural interventions to target alcohol consumption in the preoperative setting, a key limitation of the literature is the lack of information on intervention content. 99 This prevents intervention replication117 and further exploration of what makes an intervention effective. Furthermore, fidelity of intervention delivery has not been assessed in the trials reporting on behavioural interventions in the preoperative period. 99 This makes it difficult to determine whether or not the intervention was delivered as planned and, therefore, has implications for the assessment and interpretation of intervention effectiveness. Recent reviews of alcohol interventions further highlight the importance of clear reporting of intervention content. 75,118

The field of behavioural science offers a precise and systematic approach to reporting on the content of behavioural interventions. Specifically, the Behaviour Change Technique (BCT) Taxonomy v1119 provides standardised definitions of BCTs to make reporting more consistent across disciplines, allowing comparisons of interventions to be made. Accordingly, in the current study, the behavioural intervention delivered was described in terms of behavioural components (i.e. BCTs) and fidelity of delivery was assessed in terms of whether or not specific BCTs were delivered.

Although existing screening and intervention training packages are available, these are not specific to the PA setting. For this reason, adaptations were made to an existing package to provide HCPs with the knowledge and skills they required to deliver the screening and intervention during routine clinics.

This chapter provides an overview of the development of the intervention that was then delivered during the feasibility study and pilot RCT.

Aims

-

Train HCPs to deliver structured screening and BBI to eligible patients in the PA setting.

-

Assess fidelity of delivery of the BBI.

-

Characterise TAU in the PAC for elective orthopaedic surgery at the three pilot RCT sites using focus groups.

-

Characterise TAU for elective orthopaedic surgery at PACs nationally using a quantitative electronic survey.

Optimisation of screening and behavioural intervention process

Screening tool selection

Both the AUDIT67 and the AUDIT-C62 have been used in studies in PA to report on the association of alcohol consumption with postoperative complication rates, and they have shown good patient acceptability. 57,62,68 Therefore, either or both of these tools were considered appropriate for the current study.

Qualitative evidence92 has identified time and burden of new processes as key barriers to the implementation of alcohol screening and BI, and findings from alcohol screening studies conducted in PA have reported that the majority of patients drink at ‘safe’ or ‘sensible’ drinking levels. 62,103 Therefore, it is appropriate to use a short initial screen (AUDIT-C) to identify potentially eligible patients, with the longer full AUDIT being used to inform intervention delivery and, potentially, the tailoring of intervention content.

Optimisation of the intervention tools

It is appropriate to adopt and adapt an intervention package that has demonstrated effectiveness in other health-care settings. 75 The ‘How much is too much? Simple Structured Advice’ and the ‘How much is too much? Extended Brief Intervention’ tools, originally developed by the World Health Organization for use in a collaborative study on alcohol screening and BI,120 later revised for use in the UK as part of the Drink-Less Brief Intervention programme121 and subsequently updated and utilised in the Screening and Intervention Programme for Sensible Drinking (SIPS),84 were adopted to guide the BBI. In addition, the Department of Health and Social Care’s ‘How much is too much?’ booklet122 was used as a leaflet for patients to motivate and facilitate behaviour change after the session.

The most recent iteration of these intervention materials was reviewed by three members of the project team (EL, LA and CH) and revised in accordance with developments in alcohol intervention research and to maximise integration and acceptance among the orthopaedic surgical population and in the preoperative setting. The following amendments were made:

-

The term ‘unit’ was replaced with ‘standard drink’ (standard drink = 1 unit = 8 g of pure alcohol) in accordance with current research and international agreement.

-

Additional drink icons were included to indicate the alcohol content of standard drinks.

-

The terms sensible, hazardous and harmful drinking were replaced with low, increased and high risk, respectively, to reflect the updated Department of Health and Social Care terminology.

-

The graphic displaying normative drinking data was amended to show risk categories in place of alcohol disorders.

-

Information relating to the common effects of alcohol use and the benefits of ‘cutting down’ was tailored to fit the pre-surgical population by including additional information about the relationship between alcohol use and immune function, recovery time and postoperative complications.

-

The category of ‘sensible drinking’ was amended to include one single recommendation for both male and female drinkers, in line with updated guidelines.

-

Information on avoiding alcohol when pregnant was removed as patients who were pregnant would not undergo this type of elective surgical procedure.

-

Information about risks relating to alcohol consumption and the potential benefits of reducing drinking was reordered so that the items most relevant to surgery appeared first (e.g. risk of complications, potential for weight loss), followed by those most relevant to older patient populations.

The revised intervention materials were then circulated to members of the patient and public involvement group Voice North for their consideration and feedback. Comments on the patient booklet were reviewed, summarised and responded to. Changes made were as follows:

-

Addition of ‘when you get bad news’ to the list of examples of difficult times.

-

Replacement of the previous logo with a project-specific logo.

-

Specification that goal-setting and behavioural monitoring would work only if individuals were honest about their consumption.

-

Clarification that the amount of alcohol in a drink depends on the size and strength of the drink.

-

Rewording of the definition of a small glass of wine from ‘8–10% alcohol by volume in a 125 ml glass’ to ‘a 125 ml glass of wine (8–10% alcohol by volume)’.

No comments on the simple structured advice or extended BI tools were received, so no further amendments were made to these. For the purposes of this study, and to avoid confusion with previous iterations, the tools were renamed as follows:

-

BA tool – formerly the ‘How much is too much? Simple Structured Advice’ tool

-

BI tool – formerly the ‘How much is too much? Extended Brief Intervention’ tool

-

patient leaflet – formerly the Department of Health and Social Care’s ‘How much is too much?’ booklet.

Once changes had been made in response to comments, the content of the intervention tools was coded in terms of BCTs (see Appendix 1).

Description of intervention delivery

The AUDIT-C, with a cut-off point of 5, was employed as an initial screen to identify potentially eligible patients. After patients provided informed consent to participate, the full AUDIT, with a cut-off point of 8, was used to assess baseline alcohol use and identify those eligible to receive the intervention. The intervention was designed to be delivered in up to two sessions, the first to be delivered face to face in the PAC. The second, an optional booster, could be delivered either over the telephone or face to face in the PAC (as per patient preference) approximately 1 week before surgery. The screening and intervention tools were used to guide the content of the sessions, and HCPs were also trained in the use of brief motivational techniques to enhance motivation to change, which helped guide the style of delivery.

The first session lasted up to 30 minutes and was delivered following completion of the full AUDIT questionnaire. The outcome of AUDIT was used to provide patients with their screening score and feedback in relation to this (i.e. whether this related to low- or high-risk drinking behaviour). This was followed by 5 minutes of structured BA using the BA tool. The BA delivered was designed to be tailored to individual patients. As such, patients were asked about existing knowledge of alcohol consumption and its effects to avoid the delivery of information that might not be relevant or appropriate. BA could include information about the lower-risk drinking guidelines, explanation of the term ‘standard drink’, normative comparison of drinking behaviour, feedback on risk including risk of postoperative complication, the potential benefits of reducing alcohol consumption and strategies that could be used to reduce drinking (e.g. goal-setting). This component of the intervention targeted motivation by providing information to increase intention to make behavioural changes. The remainder of the intervention session (15–20 minutes) involved the delivery of a behaviour change intervention that aimed to target volition (i.e. enactment of behaviour change). This component of the intervention could cover assessment of motivation and confidence to change drinking behaviour; identification of the pros and cons of changing drinking behaviour; goal-setting, problem-solving and action planning; and identification of sources of social support. Patient participants were given copies of the BA and BI tools, as well as a copy of the patient leaflet.

As a follow-up to the intervention described above, patients were offered an optional booster session. Patient participants either consented or declined to be contacted about the booster session during initial informed consent. Those who consented were contacted approximately 1 week before surgery, when their interest in the booster session was confirmed and a suitable date and time to receive the booster session was arranged. The session could be delivered over the telephone or face to face in the PAC as per patient preference. The booster session commenced with patients completing the full AUDIT questionnaire to facilitate a review of their progress since delivery of the initial intervention. For patients who had previously set goals, these could be reviewed and revised if necessary. For those who had not yet set goals or made action plans, this session provided an opportunity to do so. The session aimed to prompt behaviour change maintenance for those who had made changes and increase self-efficacy with a view to making changes for those who had not.

The finalised BBI is summarised in Table 1.

| Item | Details |

|---|---|

| Name | Preoperative Behavioural Intervention to Reduce Drinking before elective orthopaedic Surgery (Preop BIRDS) |

| Why? | Preoperative alcohol consumption is related to increased risk of postoperative complications. The aim of the intervention is to support patients to reduce or cease alcohol consumption prior to elective orthopaedic surgery |

| What? |

Materials: HCPs are trained to screen for increased risk alcohol consumption and to deliver the following behavioural intervention materials – BA tool, BI tool, patient leaflet Training also covers use of brief motivational techniques to increase motivation for change. Training of HCPs is supported by a training manual Procedures: the intervention is delivered over two sessions (the second is optional). The first session involves provision of 5 minutes of structured advice that aims to increase motivation via use of a ‘BA sheet’. This is followed by delivery of a behaviour change intervention lasting 15–25 minutes using the BI sheet. This intervention targets volitional aspects of behaviour change. The aim of the second optional booster session is to review and/or revise behavioural goals, provide feedback on performance and discuss self-monitoring to increase self-efficacy. This session is also designed to allow those individuals who have shown an initial intention to make changes, but who have not formally set behavioural goal(s) and made plans, to do so if desired |

| Who provided? | HCPs employed in the PACs who received training in the delivery of screening and BBI |

| How? | The initial intervention session is delivered face to face during routine clinics. The second session, an optional booster, is delivered either face to face in clinic or over the telephone, depending on patient preference. All intervention sessions are delivered one to one |

| Where? | Intervention sessions are delivered during routine PACs. Where the patient opts to receive a booster session over the telephone, the HCP delivering the session calls from the PAC |

| When and how much? | The first session involving delivery of BA and BBI lasts approximately 30 minutes and is delivered during routine PACs once all clinical procedures have been completed. The second optional ‘booster’ session lasts approximately 20 minutes and is delivered around 1 week before surgery |

| Tailoring | Intervention materials incorporate specific BCTs that target intention formation and enactment of behaviour change (e.g. information on health consequences, social support, goal-setting behaviour, problem-solving, restructuring the physical environment). HCPs are trained to use these techniques to tailor the intervention to the needs and preferences of individual patients, for example providing information relevant to and requested by the patient and supporting them to set meaningful and realistic goals that fit in with their own specific circumstances. Brief motivational techniques are used by HCPs allow them to determine level of motivation to change and tailor the intervention to target motivation or volition at the appropriate times |

| How well? | Consultations with participating patients are audio-recorded to allow an assessment of skill acquisition and fidelity of delivery of the intervention post training. The aim is to improve fidelity of delivery by providing feedback to HCPs including aspects of intervention delivery that went well and where they could improve. A member of the research team provided feedback to each HCP following delivery of intervention sessions 2 and 4 |

Training development

The HCPs employed in PA at the primary site were involved in the development of the training to make sure it met their needs. The training was developed in accordance with the Behaviour Change Wheel123 and the various components were selected based on a needs assessment using the Capability, Opportunity and Motivation to perform a particular Behaviour (COM-B)124 and Theoretical Domains Framework. 125 The BCT Taxonomy version 1119 was then used to help select BCTs to help operationalise the theory within the training.

The HCPs were asked to complete an adapted version of the COM–B self-evaluation questionnaire (see Appendix 2) containing 19 items designed to assess existing levels of COM–B, in this case to deliver alcohol screening and behavioural intervention to patients. They were asked to assess what they felt needed to change for that behaviour to occur. Tick boxes were provided for each question, with free-text boxes to collect additional information and context. Twelve HCPs completed and returned questionnaires (see Appendix 3 for a summary of responses). Assessment of questionnaire responses identified that HCPs required support to increase all three domains (capability, opportunity, motivation). Having an understanding of why alcohol reduction or cessation was important in the preoperative period was seen as key to enhancing HCPs’ motivation to deliver a screening and behavioural intervention, while also providing them with the capability to motivate patients to change their behaviour.

To enhance capability, HCPs reported that they needed training in the BBI and that this should include a clear plan of how to deliver it. In addition, HCPs requested supporting materials to facilitate intervention delivery that would include visual aids to help communicate information. The need for adequate ‘protected’ time in their appointment schedule to facilitate delivery was emphasised, as was knowing that all colleagues would work together to facilitate delivery of the intervention.

The TDF125 was used to identify potential candidate techniques to address HCPs’ training needs. The provision of education, training and modelling, along with the use of persuasion, incentivisation, and enablement, was identified as a potential component of the training package. To determine the acceptability of these methods to HCPs, the lead nurse from the primary site completed an amended version of the APEASE questionnaire (see Appendix 4), which assessed the anticipated affordability, practicability, effectiveness, acceptability, safety and equity of these techniques. All suggested techniques were found to be acceptable.

These techniques were subsequently used to guide the selection of training content in terms of BCTs. 119 A draft training strategy describing how these BCTs would be delivered was developed and then expanded into a 2-hour face-to-face group training session with a supporting manual.

Training content

The group training sessions included the following components: education about alcohol consumption (i.e. recommended limits and accepted terms and definitions) and surgical outcomes; the potential benefits of delivering a BI for alcohol reduction/cessation during PAs (BCT – education about health consequences, information about social and environmental consequences, credible source); instructions on how to perform alcohol screening and intervention with demonstration videos (BCT – instructions on how to perform the behaviour, demonstration of behaviour); role-play activities to practice intervention delivery (BCT – behavioural practice/rehearsal, feedback on behaviour); brainstorming of potential barriers to delivery and formation of plans to address these (BCT – problem-solving); and a quiz and prize to test nurses’ knowledge (BCT – material incentives). To allow tailoring of the intervention to the needs and preferences of individual patients, HCPs were trained to identify and use the BCTs embedded in the intervention tools, for example providing information relevant to and requested by the patient and supporting them to set meaningful and realistic goals. In addition, the training covered the use of brief motivational techniques to allow HCPs to determine the level of motivation to change and tailor the intervention to target motivation or volition at the appropriate times.

Training delivery

During the feasibility study, the training was delivered as a group session led by three psychologists (EL, LA and Sebastian Potthoff), each of whom covered different aspects of the training based on their own areas of expertise and experience. Microsoft PowerPoint® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) slides and video recordings of intervention delivery were used as visual aids during the training sessions. A training manual was also given to each staff member who attended the session alongside a copy of the screening and behavioural intervention tools.

When new staff members joined the study, additional training sessions were delivered by one of the psychologists (EL).

Evaluation of the training

The HCPs were asked to complete an evaluation form (see Appendix 5) on completion of the training. This asked them to indicate how strongly they agreed or disagreed with 15 statements relating to the delivery and content of the training as well as knowledge and skills gained. Responses were on a scale from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree). Five of the 10 HCPs who attended completed the evaluation form. Feedback indicated that the training was enjoyable and well structured and that the content was appropriate, with adequate time allocated for questions and discussion. Although the training was considered beneficial for the delivery of screening and behavioural intervention during the study, it was not rated as beneficial for clinical practice more generally.

Fidelity of delivery: feasibility study

Fidelity of delivery was assessed during the feasibility study; the findings were used to document whether or not interventions were being delivered as intended and to inform further refinement of the intervention and training package. To facilitate skill acquisition and support effective delivery of interventions by HCPs, written feedback was provided on the initial intervention sessions delivered by each HCP. During the feasibility study, feedback was provided on sessions 1 and 4. However, following feedback from HCPs, this was amended to sessions 2 and 4 for the pilot RCT.

All intervention sessions were audio-recorded when the patient had provided consent for this. Recordings were transcribed verbatim and anonymised. Transcripts were read and independently coded by two members of the research team (EL and LA). Where applicable, feedback on skill acquisition and fidelity of delivery was constructed by the same two researchers (EL and LA). When fidelity of delivery was > 80%, written feedback was provided to the HCP. When fidelity of delivery was < 80%, the research associate (EL) contacted the HCP to arrange an additional, one-to-one, face-to-face feedback and training session, lasting up to 1 hour, to focus on components of the intervention that had been omitted when it might have been appropriate to deliver them.

When patient participants in sessions 1 and/or 4 did not consent to audio-recording, fidelity of delivery assessments were conducted and feedback was provided for the next recorded session.

Fidelity of delivery was assessed using a standardised checklist of 18 BCTs (those present in the intervention materials; see Appendix 1). As interventions were designed to be tailored, coders first rated which BCTs and counselling techniques were delivered before assessing whether or not they had been delivered appropriately (i.e. were BCTs delivered that best met the needs of the patient). This was to determine whether or not any BCTs had been delivered simply because they formed part of the intervention.

Of the 10 HCPs who consented to take part in the study, four went on to deliver intervention sessions. Staff allocation to each intervention varied based on shift patterns and availability. A total of nine initial intervention sessions were delivered during the study, with seven of these audio-recorded and assessed for fidelity of delivery.

All intervention sessions included delivery of BA, BI and the patient leaflet. Delivery of 9 of the 18 possible BCTs was coded as occurring. Specific content varied between sessions indicating tailoring of interventions. The most consistently delivered BCTs were information about health consequences (5.1), goal-setting behaviour (1.1), social support (unspecified) (3.1) and pros and cons (9.2).

Fidelity of delivery was low, with 20–50% (mean = 40%) of BCTs considered to be appropriate being successfully delivered. However, there were clear indications of attempts to deliver additional BCTs but, as delivery did not fully meet the definitions in the BCT Taxonomy v1, these were not coded.

Optimisation of the training package

Intervention and interview transcripts generated during the feasibility study were reviewed by three members of the project team in (EL, LA and CH) to identify barriers to effective intervention delivery and to inform revision of the training, screening and intervention package ahead of delivery during the pilot RCT. Barriers identified and addressed are detailed in Table 2.

| Barrier | Explanation | Addressed |

|---|---|---|

| Time lag between training and intervention | A substantial period of time elapsed between training and commencement of intervention delivery | Training in the pilot RCT phase to be delivered as close as possible to the commencement of screening and recruitment without risking delays to the project |

| Infrequent intervention delivery | With only a small number of patient participants recruited in the feasibility trial and consent rates fluctuating, intervention delivery occurred infrequently over a fairly extended period | The pilot RCT to include a greater number of patients and resolution of issues with recruitment during feasibility trial, which should lead to more consistent recruitment rates in the pilot RCT |

| Adequate time to deliver intervention | HCPs felt that they sometimes had to ‘make time’ to deliver the intervention and could be pressured if the clinic was not running to time or if other patients arrived either late or early for their appointments | Extended appointments to be arranged for research participants, with the participant attending ahead of their PA appointment to complete consent and randomisation processes and additional time for intervention delivery allocated. Each site in the pilot RCT to have a HCA available to aid facilitation of the intervention sessions |

| Identifying level of motivation | HCPs were not always able to identify how motivated patients were to change | Instruction on how to use the questions exploring motivation to change and confidence in changing behaviour, which appear in the BI tool, to identify how motivated patients are to change their behaviour. During training, explicitly identify skills HCPs already use that will help them to identify level of motivation, specifically ‘listen, ask, think’ |

| Tailoring intervention content to level of motivation | HCPs were aware that they should tailor the interventions but intervention transcripts showed they were not always successful in tailoring content to level of motivation | Additional educational aspect in the training to explain intervention aspects relevant to motivating patients or targeting volition. Addressed in expanded ‘action-planning’ section of the training |

| Tailoring screening and interventions to address screening reactivity | HCPs were not clear about how to tailor intervention sessions or how best to complete AUDIT questionnaires when patient participants had changed their drinking between initial screening and intervention delivery | Be explicit in training that initial AUDIT is concerned with drinking over the past 6 months. Include time scale for each AUDIT questionnaire on the questionnaire. Address this in the training session along with tailoring of the intervention to level of motivation |

| Delivery of BCTs attempted but not successful | BCTs ‘social support’, ‘goal-setting’ and ‘problem-solving’ were frequently attempted but not successfully delivered during interventions | Additional instruction provided on delivery of these BCTs. These examples were targeted in expanded coping planning section of the training |