Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 12/194/01. The contractual start date was in June 2014. The draft report began editorial review in June 2018 and was accepted for publication in February 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Crispin Day is the lead developer of two parenting programmes used in this report: Helping Families Programme (HFP) and Empowering Parents Empowering Communities. Mike J Crawford has previously received research grant funding from the National Institute for Health Research. Lucy Harris is a co-developer of the Helping Families Programme. Mary McMurran was an author of the Psychoeducation plus Problems Solving (PEPS) intervention for adults with personality disorder. PEPS helped to inform the modified HFP. Paul Moran reports personal fees from a talk given at the fourth Bergen International Conference on Forensic Psychiatry, 2016, outside the submitted work. He led the development of the Standardised Assessment of Personality – Abbreviated Scale (SAPAS), the personality disorder screen used in this study.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Day et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Child mental health and parenting

There are 10.5 million children in the UK, approximately 1 million of whom experience significant emotional and behavioural disorders that interfere with their developmental progress, family life and school achievement, and increase their long-term risks of poor adult mental health, unemployment and offending. 1–5

Understanding of early life and parenthood has grown rapidly, resulting in a better, albeit imperfect, understanding of the ways in which a range of biological and environmental factors combine to influence physical, psychological and social development throughout childhood. 6–8

The most influential factors are typically located within the individual child and are the characteristics of their immediate parenting and care environment. 9 Children’s parenting environment is, in turn, influenced by the characteristics and life circumstances of each family, such as their health, mental health, life events, developmental history and social support, as well as broader social and economic conditions, such as employment, education and housing. 7

Affectionate, responsive, authoritative parenting has been consistently linked to better child outcomes. Parents are more developmentally effective when they use open, participative communication; have a sensitive and involved understanding of their child’s individual and personal needs; maintain household and relationship consistency; have routines and structure; and use flexible, problem-centred coping styles to manage parenting and its demands. 10

Effective parenting intervention as a means to improve child developmental outcomes is a significant policy and service priority in England. 11–13 Implementation to date has mainly focused on the provision of existing evidence-based programmes to generalised populations rather than to parents and children with multiple and specific mental health risks and needs. This is mainly because the evidence for specialised parenting programmes has been underdeveloped.

This research focused on the development of a specialised parenting programme for parents with severe personality difficulties who have children with emotional and behavioural problems.

Severe parent personality difficulties and disorders

The likelihood of severe and persistent child mental health problems increases when a parent is affected by significant personality difficulties, characterised by problematic interpersonal relationships, emotional arousal and regulation, impulse control, ways of perceiving and thinking, and style of relating to others and social functioning. 14,15

Personality difficulties are dimensional by nature and increasing severity is associated with greater impairment and poorer outcomes. 16,17 Severe personality difficulties include the diagnosis of personality disorders. These are common, long-term mental disorders that are characterised by significant impairments in self and interpersonal functioning that do not reflect an individual’s developmental stage, sociocultural environment, the physiological effects of a substance or a general medical condition. 18

Such difficulties are relatively stable over time: enduring, pervasive and clearly maladaptive to a broad range of personal and social situations. Difficulties are likely to emerge during childhood and persist into adulthood. They are associated with considerable personal distress and adverse life outcomes, including poorer physical and mental health, reduced life expectancy, social isolation, unemployment, intimate partner violence and exposure to substance misuse. 19,20

There are numerous biological, psychological and social risk factors that vary according to personality disorder type, the individual affected, and their past and current circumstances. Overall, findings show that genetic disposition and life experiences play a key role in the development of personality disorders. 6 Exposure to early childhood adversities, including emotional neglect, family chaos, family conflict and parental mental health difficulties, as well as specific trauma and abuse, has persistently been associated with the subsequent development of severe interpersonal difficulties and personality disorders. 6,20–23

In the UK, > 4% of the general population meet the diagnostic criteria for a personality disorder. Among users of mental health services, the prevalence of personality disorders has been estimated to be as high as 40% and, of this population, about 25% are parents. 24–26

Personality disorders, parenting and child outcomes

The inter-related mental health needs of children and their parents, and the associations between family functioning and wider disadvantage, have been highlighted in recent policy and practice recommendations. 13,27–29

Personality disorders, particularly borderline personality disorder, are associated with an extensive range of difficulties that may impair parenting. They can affect parents’ capacity to offer the stable, responsive care and nurture required for healthy child development. 30 They may result in more frequent insensitive, intrusive and overprotective interactions with children, and greater difficulties in reading children’s feelings. 31–37 Family environments are more frequently characterised by higher levels of hostility and less cohesion, as well as more inconsistent and unpredictable family routines and organisation. 38–40 The parents affected may feel more stressed in their parenting role, less competent and less satisfied. 31,32,39,40

As a consequence, children affected are at greater risk of enduring mental health problems, child maltreatment and abuse. Offspring are more likely to experience a range of negative emotional, social, behavioural and cognitive outcomes from infancy onwards, including parent–child relationship difficulties, disrupted attachment styles, poorer theory of mind, difficulties in labelling and understanding the causes of common emotions, depression, behaviour problems and attention deficit disorder. 40–49

Parenting a child with significant emotional and behavioural difficulties is stressful in itself and it may worsen a vulnerable parent’s own mental health. 49

Psychoeducational parent training programmes

Psychoeducation is an evidence-based psychotherapeutic modality used across a wide range of health conditions, including child emotional and behavioural disorders and adult personality disorders. 5,50,51 The strongest effects for psychoeducational parenting programmes are obtained for disruptive child behaviour problems. 51,52 Psychoeducational approaches are also available for children with anxiety and other internalising difficulties, but the evidence base is more limited. 53

Parenting programmes are usually delivered in individual or multifamily group formats. They generally aim to increase parental knowledge and insight about the nature, cause and management of their child’s difficulties, improve parents’ use of effective parenting strategies and mobilise their coping resources in order to improve parenting, child and parent outcomes.

Typically, psychoeducational parenting programmes use structured, manualised approaches with clearly specified content and methods. Parenting programmes are usually attended by parents only, though some include children and/or teachers. Standard parenting programmes are typically delivered over 8–12 weekly sessions, each lasting 1–2 hours.

Content is usually derived from social learning, relationship and communication theories. Methods include group discussion, skills rehearsal, role play and video modelling of effective parent–child communication, interaction and relationship methods, together with the use of positive parenting and discipline strategies.

Typically, there is little adaptation and tailoring for parents affected by mental health difficulties. As a consequence, standard parenting programmes may achieve lower engagement, lower completion rates and poorer outcomes for families with co-occurring child and parental psychopathology than for parents without co-occurring difficulties. 54

Specialised parenting programmes have been developed for families with more complex difficulties, such as parents experiencing drug misuse, young mothers, and parents whose children have been excluded from primary school. 55–57 Delivered over a longer period, specialised programmes are more likely to use an individual, personalised format, consisting of multiple components that address the inter-relationship between adult psychosocial difficulties, parenting and the children’s developmental needs.

The NHS and other costs of child mental health problems and adult personality disorders

The strongest evidence for the cost-effectiveness of child mental health interventions relates to parenting programmes for severe child disruptive behaviour. 11,58 These interventions cost approximately £1200 per parent participant, producing potential societal savings of approximately £16,500 per family over a 25-year period. 59 Potentially higher savings over the longer term of approximately £5B may accrue through parenting interventions for families at high risk of multiple, adverse mental health and social outcomes. 60

The annual direct treatment costs in the UK for adults with personality disorders exceed £70M, with wider societal costs estimated at £8B per year in England. 61 This reflects the considerable demands placed on a range of services, including emergency departments, social services and the criminal justice system.

Potentially improved treatments that lead to even small reductions in personality-related problems and child behaviour problems could lead to substantial savings in personal and service costs.

Current clinical and service challenges for coexisting parent and child mental health problems

Despite the high risk of poor child, parent and family outcomes across a range of domains, and the associated high service, social and economic costs, the treatment of coexistent child and parent mental health difficulties currently poses a serious challenge to mental health services. Despite policy initiatives advocating integration and care co-ordination, much current mental health provision offers fragmented care that focuses on the needs of either the adult or the child. 62

Many parents with severe personality difficulties may be reluctant to disclose these problems to practitioners, owing to the stigma associated with personality disorder diagnosis and a fear of safeguarding procedures. 63 Parents diagnosed with a personality disorder may be especially aware of enduring negative attitudes among some clinical staff. 64–67

As a consequence, the presence of severe personality difficulties may be under-recognised and their consequent effects on parenting may remain unaddressed, which may lead to an escalation in difficulties, resulting in a mental health crisis and a child protection intervention. 41

Development and evaluation of a specialised psychoeducational parenting intervention

At the time of commission, no evidence-based parenting programme existed that was specifically designed to meet the needs of parents affected by personality disorders. 68

Complex intervention

A specialised parenting programme of this type was likely to be complex to develop and deliver for the following reasons.

-

The specialised parenting programme would need to concurrently address multimorbidity across parenting, child and parent outcomes.

-

Target parents are affected by a mental health condition associated with a known stigma.

-

Parents affected by severe personality difficulties, including personality disorders, are more likely to find programme engagement and participation problematic.

-

There is a recognised gap in routine parenting programme provision for the target population.

-

The specialised parenting programme would be likely to consist of several interacting components delivered over multiple contacts and would be likely to require tailoring and personalisation.

-

Programme delivery would be likely to require highly specialist skills and knowledge.

Manualisation

Programme manualisation increases the likelihood of reliable implementation with fidelity and consistent replication across individuals and over time. 69 Manualisation is particularly important for the proposed intervention given the complexity of the target population and the intervention content.

Manualisation required the specification of the rationale, theory and goals of the parenting programme, as well as a description of the intervention materials, methods and procedures, mode and location of delivery, practitioner characteristics, therapist training and implementation requirements.

Phased development

A phased and iterative approach to the systematic design and evaluation of this type of complex and specialised parenting intervention was recommended to include the following. 69,70

-

Use of best available theory and evidence from existing manualised interventions and systematic reviews to establish a differentiated conceptual model of parenting for adults affected by severe personality difficulties.

-

Production of the novel intervention manual with content and methods that have the potential to improve parenting, parent, child and family functioning while attending to safeguarding needs.

-

Feasibility and pilot testing to examine key uncertainties and generate quantitative and qualitative evidence about:

-

Manual content and intervention methods including acceptability, compliance, intervention intensity, tailoring and personalisation, fidelity methods and adherence.

-

Research design and methods, including comparison conditions, primary and secondary outcomes, measurement, recruitment, retention, and effect size (ES) estimates.

-

Intervention implementation, subjective participant experience and relevant contextual factors.

-

-

Evidence synthesis from feasibility and pilot testing to inform subsequent research, potentially including a large-scale definitive trial, and improvements to the routine care and treatment of the target population and other high-risk, underserved parent and child populations.

In practice, these tasks are typically non-linear and iterative because evidence and experience from multiple sources is acquired and assimilated. 71–73 These tasks often require synthesis of evidence from rapid reviews and in-depth service user and clinician consultations. The rationale, aims and objectives of pilot and feasibility randomised trials are distinct and differ from those of other randomised trials. 71

Decision-making regarding the transition from a feasibility to a definitive trial can be a complex process. 73 It requires the systematic and transparent identification and realistic appraisal of evidence that:

-

supports preliminary design and evaluation decisions

-

identifies problems that may undermine the acceptability and delivery of the proposed trial intervention and the conduct of the evaluation

-

identifies potential solutions to the intervention and research design difficulties

-

informs the viability of the best available future options, including recommendations for the design of a full-scale, definitive evaluation.

Conclusion

This research programme aimed to advance scientific and clinical knowledge for a population of parents and children whose needs are not currently well met by existing services and where specialised early intervention is strongly indicated but rarely tested. Its phased, iterative approach was intended to generate knowledge about the design, delivery and initial evaluation of a complex psychoeducational parenting programme for parents who are often marginalised by conventional parenting programmes. The immediate patient and NHS benefits were intended to be improved child and parental mental health, with a longer-term potential to reduce the entrenched burden of psychosocial adversity and intergenerational transmission of mental disorders within families.

Chapter 2 The development, feasibility testing and evaluation of a new psychoeducational parenting programme: Helping Families Programme

Context

In 2013, the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme announced a commissioned call for a research programme to develop and evaluate psychoeducational support for parents affected by personality disorders who have children with severe emotional and behavioural problems and were attending or being considered for referral to child and adolescent mental health services. Applicants were advised to define exact parent inclusion criteria. A study design was advised that (1) incorporated feasibility work to develop and manualise the process for identifying and selecting parental caregivers with personality disorders and to develop the therapeutic intervention, leading to (2) a small pilot randomised controlled trial (RCT) to test the feasibility of a trial. The comparator was expected to be usual care. Consideration was to be given to any existing mental health care that parents were receiving and the logistics of linking it to child and adult services.

Key research outcomes and outputs of the research programme were envisaged to be (1) the development and manualisation of a process for identifying and treating parental caregivers who would be eligible for the intervention, including acceptability of selection and randomisation; (2) the development of an intervention tailored to parents with personality disorders or the manualisation of an existing intervention; (3) the pre/post measurement of appropriate child and parent outcomes; and (4) an estimation of the parameters for a substantive study. 74 The ethics considerations of diagnosing personality disorders in people who may not have sought a diagnosis were also to be explored.

Research programme design

A pragmatic, mixed-methods research programme was planned to address these HTA requirements that involved three inter-related phases. 74

-

Phase 1: intervention and research evaluation development – to produce a draft manualised psychoeducational intervention and screening process for parents with personality disorders who have children with emotional or behavioural disorders.

-

Phase 2: pre-trial feasibility testing – to assess the acceptability to clinicians and service users of the proposed psychoeducational parenting programme and screening manual, the viability of their implementation and a description of usual care.

-

Phase 3: feasibility RCT and process evaluation – to generate quantitative and qualitative evidence about intervention implementation, research design and methods, and ES estimates to inform recommendations about a subsequent research evaluation. 5

The phased design was intended to produce research findings that would be concurrently and sequentially combined to inform the development and refinement of the new health technology and its evaluation. 74 Each phase involved staff and service users of child and adult services across two NHS mental health trusts in order to gain a better understanding of the intervention and evaluation methods across varied service circumstances.

Research programme plan and milestones

The programme plan involved three phases, as follows. 74

-

Phase 1: intervention and research evaluation development (months 1–9), including –

-

project set-up; distillation of intervention components

-

conduct of parent and clinician consultation groups; production of draft psychoeducational parenting intervention and screening manuals

-

completion of the phase 2 research protocol, ethics and service approvals.

-

-

Phase 2: pre-trial feasibility work (months 10–18), including –

-

selection and training of the research therapists for the new psychoeducational parenting intervention

-

completion of the planned pre-trial case series

-

revision of the psychoeducational parenting intervention and screening manuals; completion of the phase 3 research protocol, ethics and service approvals.

-

-

Phase 3: randomised feasibility trial and process evaluation (months 19–37), including –

-

completion of the planned randomised feasibility trial and process evaluation

-

undertaking of the follow-up evaluation

-

completion of the analysis and write-up.

-

Delays in phase 2 ethics approval, case series and trial recruitment required an 8-month no-cost extension to the original timetable.

Existing manualised interventions

The research programme used two existing manualised interventions as the basis for the development of the new psychoeducational parenting programme. These existing interventions were the Helping Families Programme (HFP) and Psycho-Education with Problem-Solving (PEPS).

Helping Families Programme

The HFP had previously shown promise as a specialised psychoeducational programme for parents with complex psychosocial needs, including parents with school-excluded children and children subject to safeguarding. 55,75–78 The programme had been field tested in several NHS Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) and local authority children’s social care services.

The HFP’s manualised methods combined parenting psychoeducation with cognitive, behavioural and interpersonal strategies intended to:5

-

improve parent–child relationships and interpersonal conflicts

-

promote effective parenting and parental coping with daily stress

-

implement effective parent mood regulation strategies and promote parental warmth and consistency

-

minimise parental harm from substance misuse

-

build family social support.

The intervention had three main therapeutic components:

-

Collaborative relationships – this focused on promoting parent engagement, shared ecological assessment and the development of personalised action plans using methods derived from the evidence-based Family Partnership Model. 79

-

Parenting groundwork – this focused on intervention to improve parent characteristics that may interfere with parenting capacity such as emotional dysregulation, interpersonal hostility, and erratic and inconsistent behavioural patterns.

-

Parenting strategies – this focused on helping parents to use more effective, consistent and safer parenting behaviours, improve communication skills and parent–child interaction methods and optimise emotional nurture.

Results from real-world cohort studies demonstrated good service user acceptability and effects on a range of child and parent outcomes. 75–78

The HFP’s flexible, modular structure and goal-directed approach had strong potential to form the basis of the new, specialised psychoeducational intervention. Modification to the HFP’s existing theory, methods and content was potentially required to achieve closer alignment with the specific needs of the target population.

Psychoeducation with problem solving

Drawing on existing examples of manualised psychoeducational interventions within the field of personality disorders, PEPS was a feasible candidate intervention to provide psychoeducational content specifically designed for the target population. 80–83

Developed for adults with personality disorders, PEPS used structured clinical assessment and psychoeducational methods to explore the meaning of personality disorder diagnosis and linked this to personal difficulties in social functioning and relationships. In common with the HFP, personal goals were then formulated and addressed using focused problem-solving methods. In recognition that people with personality disorders often have difficulties maintaining participation in treatment,84 PEPS also used well-defined theory and methods to optimise participant motivation and therapeutic rapport. 85,86 Although a Phase III clinical trial of PEPS did not show evidence of improved mental health or social functioning, many recipients valued the information that they received about their condition, and uptake of the psychoeducational component of the intervention was high. 87

Research locations

Two NHS trusts participated in the research programme, South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust (SLAM) and Central and North-West London NHS Foundation Trust (CNWL), which were site 1 and site 2, respectively. These sites were selected because both NHS trusts serve large and diverse populations with high rates of adult and child mental health problems. Additional fieldwork was undertaken with coterminous local authority children’s social services.

South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust (site 1)

With a total catchment population of approximately 1.2 million people, SLAM provides mental health services to four London boroughs (Southwark, Lambeth, Lewisham and Croydon) together with several regional and national specialist services.

At the time of the research, adult mental health services were configured into clinical academic groups (CAGs) centred on distinct disorder clusters. The mood, anxiety and personality (MAP) CAG included eight community teams offering assessment and case management for adults aged 18–65 years with a range of emotional and personality problems. The MAP CAG had a further three specialist outpatient services offering a range of individual and group therapies and a service-user-led support network.

The CAMHS CAG had four borough community services that worked with children and adolescents aged 0–18 years, experiencing a range of emotional, behavioural, neurodevelopmental and other disorders. Additional specialist regional and national teams provided assessment and treatment centred on specific treatment modalities and clinical criteria.

Central and North-West London NHS Foundation Trust (site 2)

Central and North-West London NHS Foundation Trust provides services to a catchment area of 1.45 million people across five London boroughs (Brent, Harrow, Hillingdon, Kensington and Chelsea, and Westminster) and Milton Keynes. At the time of the research, adults with personality disorders primarily received care from seven community recovery teams. A specialist personality disorder service provided an 18-month group-based treatment programme for adult service users from Kensington and Chelsea and Westminster.

Community CAMHS teams were located in each of the CNWL boroughs and Milton Keynes, providing multidisciplinary assessment and treatment to children and adolescents aged 0–18 years. In addition, a specialist parental mental health service was operated jointly by the trust and the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children in the Royal London Borough of Kensington and Chelsea.

Research population

The target population was parents and their children who had coexisting mental health difficulties. Initially, parent caregivers were required to fulfil diagnostic criteria for one or more personality disorders. Based on feasibility evidence acquired during the research, this criterion was subsequently redefined to include parents with severe personality difficulties, including personality disorders. Index children had severe emotional and behavioural problems and were either attending or being considered for referral to routine CAMHS.

In advance of the research programme, examination of SLAM MAP CAG electronic patient records identified 556 adults (16.0%) with a diagnosis of personality disorder and a further 900 recorded personality disorder cases in CNWL. Case audit data indicated that approximately one-quarter of service users in CNWL’s specialist personality disorder service were parents with dependent children. Although no specific routine monitoring data were available from either trust, extrapolated estimates suggested that approximately 350 service users across both trusts were parents with a recorded diagnosis of personality disorder, only a minority of whom may have been receiving parenting interventions. 85

A large proportion of these parents would be expected to have children with mental health problems. Precise figures were unavailable, but the rates of mental disorders in offspring of parents with Axis I diagnoses are in the region of 30–50% and may be even higher where a parent has a personality disorder. 88–90

Examination of SLAM CAMHS CAG electronic patient records identified 1650 (24%) service users for whom parental mental health needs had been recorded in brief risk screens. It was estimated that around 40% may have been parents whose difficulties would meet the criteria for a personality disorder. Half of the identified children were likely to have been referred for significant emotional and behavioural difficulties. Similar rates were expected to apply to the CNWL CAMHS service user population of 4200. Across the two participating trusts, these estimates suggested a combined eligible CAMHS population of approximately 500 families where a parent may be affected by a personality disorder and the child may have emotional and behavioural difficulties.

Governance

The research team included established expert researchers, clinicians and a service user consultant with specialist experience of people affected by personality disorders. 5,74

The chief investigator (CD) had overall managerial responsibility for the research programme. He was accountable for project objectives and milestones and ensured that the research was run in accordance with agreed procedures and protocols. An operational research team, directed by Crispin Day and consisting over time of Lucy Harris, Daniel Michelson, Paul Ramchandani and Jackie Briskman, was responsible for the day-to-day co-ordination of research activity across the two NHS trusts, the supervision of research workers and the clinical supervision of research therapists (LH).

A project management group (PMG), chaired by Crispin Day and consisting of all co-applicants, met quarterly to oversee the research, monitor project achievements, review generated findings and formulate actions required to address significant issues related to project progress. A manualisation working group (MWG), including lead developers of the HFP (CD, LH) and PEPS (MM), led the development of the new psychoeducational parenting programme and the synthesis of findings across phases 1 and 2.

Trial Steering Committee

The chief investigator reported to an independent Trial Steering Committee (TSC), which ensured the scientific integrity of the trial. The TSC, convened in June 2014, was chaired by Professor Peter Fonagy, head of the division of psychology and language sciences at University College London and chief executive of the Anna Freud National Centre for Children and Families. Members of the TSC included independent senior clinicians and academics with expertise in trials and/or families with complex interpersonal needs, together with the chief investigator and the research programme’s service user lead. The TSC met formally every 6 months to monitor and review progress.

The TSC reviewed and approved research protocols and research ethics applications for each research phase. It reviewed and supported the approved phases 2 and 3 no-cost extensions.

Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee

The Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC) monitored the research programme’s safety and efficacy data. The DMEC was established in parallel with the TSC and met on an annual basis. The chair was Professor Philip Graham, Emeritus Professor of Child Psychiatry at the University College London Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health, London. Other members were experts in the assessment and treatment of personality disorders and quantitative statistics. The TSC would liaise with the DMEC should safety, ethics or efficacy issues emerge that had implications for continuing, modifying or stopping the trial. The DMEC reviewed and approved research protocols and research ethics applications for each phase of the research programme.

Independent ethics review

Professor Richard Ashcroft (Professor of Bioethics, Queen Mary University of London) independently reviewed the ethics dimensions of the original research proposal and the iterative development of the new psychoeducational parenting programme.

Patient and public involvement

The research programme’s service user expert from 2014 to 2017 was Lou Morgan, executive director of Emergence (Emergence Plus CIC, London, UK), a service user-led organisation supporting people affected by personality disorder. As chairperson of the Service User Advisory Panel (SUAP), she led service user involvement in the design, management and governance of the research programme. She sat on the PMG and the TSC. Following the administrative closure of Emergence in 2017, Lisa Foote was appointed to lead the programme’s service user involvement on behalf of the McPin Foundation (The McPin Foundation, London, UK), which exists to transform mental health research by putting the lived experiences of people affected by mental health problems at the heart of research methods and the research agenda.

The SUAPs were convened during phases 1 and 2 to ensure that research design, conduct and dissemination accurately reflected the priorities and experiences of families affected by coexisting child and parental mental health difficulties. The initial intention was to convene both parent and youth advisory panels. Only the former was formally convened, as parent users were the sole focus and target of the proposed psychoeducational parenting programme and research participation.

The parent service user advisory panel comprised parents with relevant lived experience. It provided feedback and constructive review across each research phase, including draft psychoeducational content and methods, research design and methods, review of generated findings, design of participant information resources and dissemination of materials. Practical support, expenses and access to relevant training were provided in accordance with good practice guidelines from INVOLVE. 91

Before taking over service user leadership, an experienced service user researcher (LF) was involved in the design, facilitation and analysis of phase 1 focus groups, phase 2 design, data collection and analysis, phase 3 analysis and validation. Service user leads were involved in the dissemination of programme findings across each research phase.

Conclusion

A pragmatic, mixed-methods research programme was planned to develop and evaluate a new specialised psychoeducational parenting programme for parents affected by a personality disorder and their children with severe emotional and behavioural problems.

The iterative design was intended to produce a more precise theoretical model to describe the inter-relationship between parental personality difficulties, parenting, child development and environmental contexts. Based on the integration of two existing interventions, the new psychoeducational parenting programme, if practical and acceptable, had the potential to have an impact on the immediate and longer-term effects of personality disorders on parenting, family function, child development and associated societal costs. The planned mixed-methods evaluation aimed to examine the feasibility of research design and procedures used to evaluate the acceptability, the impact and the health economics of the new intervention.

Chapter 3 Phase 1: intervention and research evaluation development

Phase 1 aim and objectives

The main aim was to develop the new manualised psychoeducational parenting intervention and the related screening and evaluation methods. 74 The phase 1 objectives were to:

-

produce a modified version of the HFP, the Helping Families Programme-Modified (HFP-M), incorporating content from PEPS

-

produce draft screening methods for the identification and recruitment of eligible parents from the target population

-

distil, synthesise and incorporate findings from a scoping review of relevant research and consultation groups with service users and clinicians into the production of the modified HFP manual and screening process.

Phase 1 design

Phase 1 involved four concurrent and inter-related activities:

-

iterative production of the modified HFP manual and associated screening and evaluation methods

-

a rapid scoping review of relevant evidence

-

consultation with services users from the target population

-

consultation with clinicians working in mental health and children’s social care services.

Development of the Helping Families Programme-Modified manual

The MWG used the template for the intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist to guide the synthesis of the content and methods from the two existing intervention manuals to produce the modified HFP manual and concurrent evaluation methods. 69 The TIDieR checklist consists of the following nine areas:

-

characteristics of the target population, including the intended HFP-M recipients, current patterns of service use, and eligibility criteria for research evaluation

-

conceptual model and intervention rationale, including concepts and theories underpinning the HFP-M intervention, its aims and its purpose

-

intervention organisation and delivery, including the HFP-M therapist characteristics, training and supervision, and service structures that are required to deliver the intervention

-

service and keyworker engagement and social marketing, including methods to optimise routine service and keyworker interest and enthusiasm for the HFP-M and its research evaluation, intended service user and service benefits, and management of potential barriers

-

identification of intervention recipients and research participants, including feasible, accurate identification of target service users, and related clinical and research processes

-

engagement of service users in the HFP-M and its research evaluation, including effective ways of describing the HFP-M and its evaluation so that services users can make informed choices about participation

-

case co-ordination and integration with usual care, including the use of the HFP-M to augment or replace routine clinical practice and related case co-ordination

-

intervention format, including optimal structure, frequency and duration of the HFP-M intervention sessions, materials, and intersession activities

-

intervention content, including the HFP-M psychoeducational topics, methods to optimise recipient engagement, content and delivery, personalisation and fidelity monitoring.

Rapid scoping review of relevant research

Design

Scoping reviews are appropriate when the topic of interest is complex and comprehensive reviews are unavailable. 92,93 The methodology provided a feasible mechanism to summarise and distribute relevant research findings to the MWG. Scoping reviews are typically based on broadly defined research questions, eligibility criteria and quality criteria.

The purpose was to rapidly identify and distil research findings to inform the MWG’s use of the predefined features of the TIDieR checklist to inform manual development and research design. 69 The primary research question for the rapid evidence review was:

What is known from the existing literature about (a) the rationale, engagement and participation in interventions designed for parents affected by personality disorders who have children with mental health problems, and (b) the identification, screening and recruitment of such parents to research studies?

Method

PsycINFO and PubMed were searched from September 2014 to December 2014, using the terms [parenting OR personality disorder] AND [screening OR intervention OR treatment]. Manual searches were completed of all relevant narrative and systematic reviews and individual studies. Further papers were identified by co-applicants, professional networks and relevant user organisations. Initial searches identified 2427 potentially relevant papers. Articles from the searches were screened using titles and abstracts, with studies not meeting the following inclusion criteria discarded:

-

studies reported findings in one or more of the predefined features areas of the MWG TIDieR checklist

-

participant parents were aged ≥ 18 years with a personality disorder and/or children with mental health disorders

-

articles were published in English.

Full articles were obtained for 80 studies that met the selection criteria, nine of which were discarded as they did not represent a ‘best fit’ with the research question. Data were extracted by two researchers based on the topic areas of the MWG TIDieR checklist (DM and Ruth Wilson).

Results

Characteristics of the target population

As outlined in Chapter 1, personality disorders are associated with substantial behavioural, emotional, social and cognitive impairments of parenting. They are also associated with significant personal, social and economic adversity, both current and past, that is likely to undermine parental competence and parenting capacity. 6,20–23 Parents affected by personality disorders are more frequently exposed to negative life events. 96

People affected by personality disorders more frequently experience feelings of alienation from services, which leads to disengagement and being more likely to be subject to negative staff attitudes and behaviours. 97–99 As a result of interpersonal difficulties, poor impulse control, instability, relationship conflict and multiple life problems, people affected with personality disorders may feel antagonistic, avoidant and reluctant to engage with services. They may attribute their difficulties to factors that are outside their control, and have low self-belief and efficacy as well as having few reliable social and family resources.

Helping Families Programme conceptual model and intervention rationale

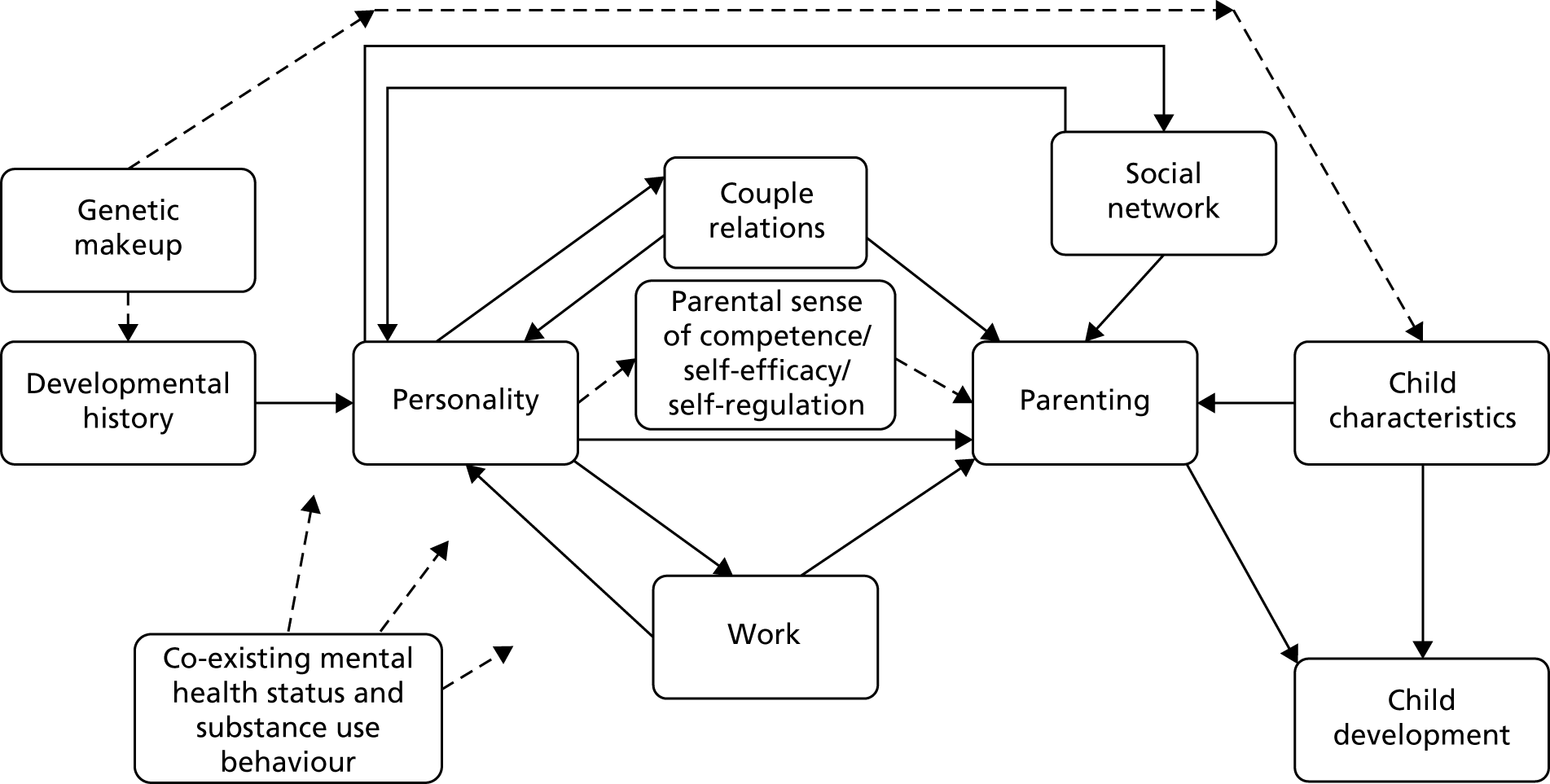

The Multiple Determinants of Parenting (MDP) conceptual model100 is a well-established framework that specifies how the interaction between child characteristics and parenting is influenced by the multiple impacts of parents’ personality, couple relations, family and social networks and work experiences (Figure 1). According to the model, parents’ own proximal and distal developmental history shapes their personality including behaviour, cognition, attitudes, values, emotional regulation and coping. The MDP model illustrates the central role that parenting has in influencing child outcomes as well as its role in mediating the effects of other parent factors that influence child outcomes.

FIGURE 1.

Modified multiple determinants of parenting model.

Additional factors, identified since the initial development of the MDP conceptual model, that may have particular salience for parents with severe personality difficulties include the impact and transmission of heritable characteristics and the multiple impacts across the MDP model of coexisting mental health and substance use problems.

The MDP model offered a useful conceptual framework to underpin the HFP-M because:

-

The genetic transmission of some personality disorder characteristics may increase children’s inherent vulnerability to developing prodromal personality difficulties and other mental health problems. 101

-

The persistent, pervasive and problematic interpersonal difficulties associated with personality disorders are likely to have a direct effect on the child’s parenting environment. 14,16,20,30

-

Parents affected by a personality disorder are at increased risk of parenting behaviours, emotional regulation, interactions and relationships, and cognition, that have a detrimental impact on child outcomes. These include harsh, neglectful and abusive parenting practices; emotional hostility and intrusiveness; critical, dismissive and intrusive interaction; inconsistent and unpredictable parental routines, responses and reactions; over-involvement and protectiveness; and difficulties in accurately identifying and responding sensitively to children’s emotional and developmental needs. 31–49

-

Parents affected by severe personality difficulties may be aware of normative, positive parenting but their efforts may be undermined by their personality and interpersonal functioning. 49

-

Parents affected by personality disorders are at an increased risk of coexisting mental health conditions, particularly depression and substance misuse. 17,19,24–26

-

Parents themselves may have developmental histories characterised by poor attachment, neglect and life crises. 6,21,23

-

Personality disorders are associated with personal, social and economic adversity including interpersonal conflict, intimate partner and other violence, lone parenthood, social isolation, worklessness and insecure employment. 24,93,102

Organisation and intervention delivery

The organised provision of parenting interventions is heterogeneous and it occurs across multiple types of services. 103 Parents often value community-based provision. Practitioner qualification level and type varies considerably across delivery. Practitioner skill level may improve parent initial engagement, continuing intervention participation and outcome. 104

Challenges for staff working with service users affected by personality disorders are well documented. 105 Regular supervision for staff is an integral part of specialist therapies designed for service users affected by personality disorders. 106,107

Although implementation is inconsistent, family-focused approaches in adult mental health services are advocated to improve the engagement of hard-to-reach parents and families. 28 CAMHS tend to focus on the needs of children and do not frequently integrate the treatment of parental mental health difficulties into routine provision.

Service attendance may be affected by service users’ greater exposure to adverse life events and their response to them. 96

Routine service and clinician engagement and social marketing

Personality disorders are associated with known stigma, pejorative clinician beliefs and an expectancy to receive negative treatment. Adult mental health practitioners have concerns that discussing children’s difficulties with parent service users may detrimentally affect their mental health and may lead to increased service use. 108 Conversely, clinicians are also concerned that discussion of parenting may discomfort parents and lead to therapeutic disengagement. 109

Clinicians expressed reservations about the intervention effectiveness for this target population and were concerned about additional burdens of case management that may result from multiple service involvement. 110

Identification of potential intervention recipients and research participants

Accurate identification of parental mental health difficulties within child mental health care and the identification of child emotional and behavioural problems within adult mental health services varies considerably. It may depend on individual clinician characteristics, such as perceived role, confidence and competence rather than operational procedures. 108,109,111

Practitioner concerns about diagnosing personality disorders are well documented. 110 Many adult mental health staff members have not undertaken training in child development and the assessment and treatment of child mental health difficulties.

Well-established, psychometrically robust screening instruments are available to identify personality disorders and child mental health disorders. For example, the Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV), Axis II Disorders (SCID-II) is a gold standard tool for the diagnosis of personality disorders. 112 Inter-rater reliability scores for the SCID-II are excellent,113 with no significant differences between experienced and recently trained interviewers. 114 The Standardised Assessment of Personality – Abbreviated Scale (SAPAS) is a very brief interviewer-administered, structured screening tool designed to identify individuals with a potential personality disorder. 115 It does not screen for specific subtypes of personality disorders; rather, increasing scores indicate increasing likelihood that an individual has any personality disorder.

Candidate screening tools for child mental disorders include the Development and Well-Being Assessment (DAWBA), intended for children aged 5–16 years. The Pre-School Age Psychiatric Assessment (PAPA) can be used for children aged 3–4 years. Both are well-validated standardised tools completed by interview or computer for assessing child emotional and behavioural disorders. 116,117 The DAWBA covers common emotional, behavioural and hyperactivity disorders without neglecting less, but sometimes more severe, disorders. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) is a brief behavioural screening questionnaire for 3- to 16-year-olds that is used extensively to identify common mental health problems. 118 The 25 items are divided between five scales that measure emotional, conduct, hyperactivity/inattention and peer relationship problems together with prosocial behaviour.

Engagement of service users and their interest in Helping Families Programme-Modified and its research evaluation

Time demands, flexibility and scheduling concerns are a significant barrier to participation in parenting programmes. 119 Parent and children involvement in concurrent intensive mental health, health, social care and education appointments may hinder participation.

Treatment trial participants have expressed concerns about (1) the burden of assessments and research procedures, (2) participation in interventions with unproven effects and (3) poor quality of information about potential risks and benefits. 120

Some parent service users may be reluctant to be open about difficulties, owing to fears about involvement of child protection services. 104

Case co-ordination and integration of Helping Families Programme-Modified with treatment as usual

A large-scale systematic review of trial data suggested that treatment as usual was often poorly defined and highly variable for service users affected by personality disorders. 119 Evidence from RCTs showed that better planned and organised non-specialist treatments may be comparable in effect to specialist treatments for people with borderline personality disorder. 121–125 Effective components may include experienced therapists, supportive therapeutic process, life problem focus, non-intensive format and case management integration.

Consistent with good standards of clinical practice, evidence suggests that research clinicians should retain ongoing contact with referring practitioners. Evidence from research trials showed that changes in participant functioning are important to communicate to routine services and failure to do so may have negative consequences for care co-ordination. 120

Intervention format

Session number and frequency of parenting programmes vary. Commonly, between 8 and 12 sessions and up to 16 weekly sessions can be provided. 51,54 Individualised programme formats are often superior for families with complex psychosocial needs. 51

Barriers to parenting programme participation include location accessibility, parent treatment expectancies and intervention burden. 126 Some parents are discouraged by longer programmes, whereas others are willing to engage in longer programmes when there is a known benefit. 127,128

For either format, structured, focused, meaningful content including practical activities and written information will probably increase parent engagement. 129 The volume of intersession activity undertaken by participants of parenting programmes does not appear to predict larger ESs for child outcomes and parenting skills. 130 Parents’ actual use of positive parenting techniques with their child has been found to predict larger ESs for child behavioural problems and parenting skills. 130

Evidence-based interventions for personality disorders tend to be delivered over extended time periods. 131

Intervention content

Parenting programmes are usually designed according to children’s developmental stages, with parenting content tailored accordingly. Programmes addressing wide developmental ranges are uncommon. Significant reductions in child behavioural difficulties have been widely demonstrated in studies involving parents of children aged 3–11 years. 51,132 Though feasible for parents with adolescents, the evidence base is small and further outcome research is required. 133,134

Much psychosocial treatment evidence for personality disorders is based on interventions for people affected by borderline personality disorder. Intervention characteristics associated with increased effectiveness include structured, goal-orientated methods; information provision and psychoeducational content; focus on managing current life situations; active, responsive and validating therapeutic experiences; active service user participation and agency; and limited therapeutic intensity and therapist consistency. 106,135,136

As described above, parents affected by personality disorders may have impairments across a range of parenting functions. Established parenting programmes typically have a narrow focus on parenting skills, parent–child interaction and communication. 51,137,138 There is generally less focus on therapeutic process, parent engagement and personalisation in many group format programmes. Larger ESs are associated with positive parent–child interactions, developing parent emotional communication skills, learning consistent parental responding, and learning ‘time out’ as a disciplinary skill. 130

Personalising intervention content to individual characteristics is recommended for programmes aimed at families with complex psychosocial needs. 54,55 For example, specialised programmes for depressed parents that include topics to address parental mental health have been found to be effective in modestly improving child outcomes. 54

Intervention fidelity procedures improve the accurate interpretation of manual content and may reduce the influence of possible confounders. 139 Key fidelity components include manualised intervention format, methods and content; intervention training; monitoring intervention delivery; and monitoring of intervention receipt. 140

Consultation with service users

Design

The purpose was to obtain advice and guidance from service users with relevant lived experience about (1) scoping review evidence, (2) key characteristics of the proposed parenting intervention and screening methods, and (3) the contents and methods of the draft HFP-M and screening manual. 74 Two initial consultation groups were held between September 2014 and October 2014, with a follow-up group to verify findings. A small group discussion format was used as the most effective way to generate ideas and encourage service users to share experiences and opinions.

Method

Participants

Participants were parents with relevant lived experience of personality and child mental health disorders attending the mental health services of SLAM and CNWL. Recruitment used the pre-existing networks of the study investigators and collaborating services using word of mouth, clinician recommendation, posters and leaflets. A total of eight service users, seven females and one male, participated. Participants received an explanation of the aims and purpose of the consultation group prior to attendance and gave written consent for participation and recording.

Format and procedure

Consultation groups were held in service settings familiar to the participants. Each group lasted 60–90 minutes. Moderators sought to create a welcoming and informal atmosphere. Refreshments were available throughout the sessions.

A semistructured format moderated by a service user researcher and a clinical researcher was used to guide participants through an open-ended discussion of the following topics:

-

rationale, aims, structure and content of the proposed programme

-

methods for introducing the research programme to potential participant parents

-

screening and consent methods

-

compatibility of parent programme participation alongside other care.

Moderators presented information accompanied by written handouts and PowerPoint® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) slides. Open, exploratory prompts were used to encourage discussion, elicit and clarify service users’ ideas, and develop researcher understanding. Generated findings from the first consultation group were shared with the subsequent group to stimulate and enrich discussion. Groups ended with a summary of the research team’s next steps and a debrief about the participants’ experience.

Analysis

Each consultation group was recorded and transcribed verbatim. Group moderators initially read transcripts together with contemporaneous notes in order to identify generated themes, key recommendations and advice offered by the service user participants. Researchers identified areas of consensus in participant opinions as well as variations.

Service user views were organised in relation to the nine predefined features of the MWG TIDieR checklist. 69 The MWG were responsible for distilling and synthesising findings in conjunction with those from the scoping review and clinician consultation.

Findings

Characteristics of the target population and conceptual model

Participants described their lived experience of stigma associated with the term ‘personality disorder’, which most felt would potentially affect engagement in the intervention and research evaluation. There were also some concerns expressed about the development of a ‘special programme for [parents affected by] personality disorder’ [service user (SU) 1] and the potential for activating ‘blame and guilt’ (SU 2) in parents.

Service users raised doubts about whether or not children needed to be already involved with CAMHS in order for their parent to be eligible for the intervention.

Organisation and intervention delivery

Participants highlighted that clinicians delivering the proposed intervention should have a good understanding of personality disorders, their individual effects and the potential personal impact of the proposed psychoeducational programme, for example, ‘. . . they have to have a good understanding of borderline because it is so easy to trigger somebody’ (SU 2).

Service users typically underlined the importance of offering the programme within the context of a ‘trusting therapeutic relationship’ (SU 4) because of the guilt experienced by many parents affected by personality disorders.

Participants gave support to the structural location of the proposed intervention in both child and adult mental health services. Participants expressed some concern about locating it in children’s social care provision.

Routine service and clinician engagement and social marketing

Participants suggested that clinicians should understand the importance of improving support for parents affected by personality disorders but they did not make any specific recommendations about the optimal ways of engaging mental health staff in the research evaluation.

Identification of potential intervention recipients and research participants

Service users questioned the value of relying on clinicians’ judgement in the identification of potentially eligible parents. Some suggested that practitioners may not be knowledgeable about the parenting difficulties experienced by service users.

Participants did not provide feedback on the examples of screening tools shared by the group leaders. These included the Structured Clinical Interviews for DSM-IV Axis II Disorders (SCID-II), the SAPAS, the DAWBA and the SDQ. However, they raised a broader concern that parents ‘wouldn’t necessarily give all their information at once’ (SU 3), suggesting that the accuracy in referral and screening processes may vary accordingly.

Participants felt that identification, engagement and access to the intervention would be easier when a parent was already ‘in the system’ (SU 3) as an identified service user.

Engagement of service users and their interest in the Helping Families Programme-Modified and its research evaluation

Service users felt that the primary motivation for parents to participate in the intervention was to help and support their children. Engagement was likely to be affected by parents’ level of awareness of the impact of their own mental health difficulties on their parenting and on the outcomes of their child. Parent engagement may be greater when it is focused on ‘what you can do, rather than what you haven’t done’ (SU 7) as a parent.

Participants felt that parents would be highly sensitive to clinicians’ use of ‘judgemental’ (SU 8) language. They recommended that the offer to participate in research should be introduced by a practitioner whom the parent trusted. Participants advocated a ‘softly, softly’ (SU 1) approach that avoided activating parents’ underlying guilt. Service users expressed concerns about the involvement of children’s social services ‘at any stage’ (SU 7).

Participants promoted the importance of clear, non-patronising, plain English explanations of the intervention and research that were tailored to the needs of the individual and their circumstances with ‘no therapy speak or ‘psychobabble’ (SU 1).

Case co-ordination and integration of Helping Families Programme-Modified with usual care

Participants held differing views about participation in the proposed intervention alongside attending existing treatment services. Some service users felt that it could be ‘overwhelming and confusing’ (SU 3), whereas others felt that it should be determined by the needs and the resilience of the individual service user, and the frequency of attendance and the emotional intensity of other interventions. For example, some day care services for people affected by personality disorders require multiple attendances each week and can be ‘emotionally demanding’ (SU 8). However, ‘just seeing a psychologist for an hour a week as well as taking part in a parenting programme was more manageable’ (SU 7). Consultees felt that parents of younger children and those with other carer responsibilities may find it difficult to consistently attend appointments outside their home.

Service users advocated the inclusion of crisis plans in case co-ordination so that programme participants would know whom to contact between appointments and in the event of emergencies.

Service users were uncertain about what constituted treatment as usual for parents affected by personality disorders, with one commenting that ‘there isn’t a lot of support out there for me yet’ (SU 6).

Intervention format

Service users advocated a flexible approach to programme delivery and duration that was tailored to individual needs. For example, additional sessions may be required to take account of some parents ‘going at a slower pace, depending on how they have received the therapy’ (SU 1). Programme delivery would also need to be adjusted to account for parents’ other commitments, such as school holidays and other medical and school appointments. The option of receiving ongoing telephone support as part of the psychoeducational programme was considered useful.

Participants recommended several strategies for retaining parents’ participation in the proposed programme. These included therapists ‘having a very good understanding of the issues that affect people with personality disorder’ (SU 2), building ‘effective partnerships with parents’ (SU 7), reflecting on ‘parents’ past achievements’ (SU 4), ‘working at the parent’s pace’ (SU 1), ‘having a very good understanding of the parent’s issues in order to be realistic and use incremental goal-setting’ (SU 1) and ‘encouraging and being patient in supporting the parent in their goals’ (SU 2). Service users also recommended that intervention participants should be able to change therapists, if necessary.

Intervention content

Participants considered that a parenting programme based on a psychoeducational approach would be welcomed and would be likely to increase participants’ self-awareness, reflection and skills acquisition, particularly when tailored to an individual's needs and experiences associated with the personality disorder. Given the anticipated complexity of participants’ lives, service users felt that programme delivery would inevitably require ‘a balance between a “therapeutic element” and directing service users back to the parenting’ (SU 3).

An overly didactic, expert approach that relied on instructing parents what to do risked alienating parents and inducing negative reactions. For example, one parent said ‘I already feel guilty because I do know the list of strategies, I do know I am meant to be ignoring, rewarding, doing this doing that, but because of where I am in my depression or where I am with my disorder it means I can’t always draw upon those skills. It feels even worse. So, I don’t know how you solve that, but I just think “no”, I don’t want another list. Sorry.’ (SU 3).

A more collaborative approach based on shared understanding, respect and problem-solving was considered to be a more effective way of engaging parents. Participants felt that therapists should show flexibility in relation to the specific parenting strategies contained in the programme content. These should be tailored to individual parents’ knowledge, experience and circumstances, taking into account ‘what has and hasn’t worked in the past’ (SU 1).

Participants advocated the inclusion of programme content that focused on managing crises, for example the HFP-M Firefighting module. However, participants did recognise the challenges of using such methods when ‘a parent is stuck in a crisis’ (SU 2).

Descriptions of the methods, contents and materials of the HFP Parenting Groundwork and Parenting Strategies content received positive support, particularly topics which focused on forming a positive relationship with your child, understanding a child’s perspective, having fun with your child, boundaries, and learning how to play with your child.

Service users felt that care should reflect and be tailored to the needs of the individual. They did not make explicit recommendations about the best ways that clinicians could maintain the fidelity of specific intervention methods.

Consultation with service clinicians and managers

Design

The purpose was to obtain advice and guidance on key characteristics of the proposed parenting intervention and screening methods from clinicians and service managers working in relevant adult and child mental health services. 74 Two initial consultation groups were held between September 2014 and October 2014, with a follow-up group to share findings using a similar format and methods to those described above.

Method

Participants

Participants were all clinicians and managers working in mental health services across the two sites. Twenty-six participants were recruited through existing service networks using word of mouth, peer recommendations and e-mail invitations to team leaders. Participants received an explanation of the aims of the consultation and gave written consent for participation and audio-recording.

Format and procedure

The consultation groups were held in routine service settings. The sessions lasted between 60 and 90 minutes. Refreshments were available throughout the sessions. Each group used a semistructured format moderated by researchers (DM and Ruth Wilson) covering the same topics as the service user consultation groups. After creating a welcoming and informal atmosphere, moderators led participants through an open-ended discussion of key topics derived from the TIDieR checklist. Moderators presented information accompanied by handouts and PowerPoint slides. The groups ended with a summary of the research team’s next steps and a debrief about the participants’ experience of the consultation group.

Analysis

The same procedures as the service user consultation groups were used to identify key themes, recommendations and advice offered by service consultees, which were then categorised into the nine predefined features of the MWG checklist. The MWG synthesised these findings with other phase 1 findings.

Findings

Characteristics of the target population and conceptual model

Participants considered that research therapists’ management of the interpersonal challenges involved in working with the target population ‘would be key’ (SLAM group 1) to the success of their implementation of the proposed programme.

Supervision was considered to be a crucial support component for the research therapists.

Organisation and intervention delivery

Some staff expressed concerns about ‘helicoptering’ (CNWL group 1) specialist research therapists into routine services to deliver the intervention, as opposed to the provision of the intervention by routine staff. Staff were concerned that poorly co-ordinated care may hinder the transition when involvement in the proposed programme ended and that it may also disrupt existing ‘support networks’ (CNWL group 1).

Staff expressed concerns about ‘bridging the gap’ (CNWL group 1) that often exists between adult and child mental health services. Staff considered that there was equal value in siting the proposed intervention in both child and adult mental health services. Some staff advocated the creation of parental mental health services with a crossover between current adult and child services.

Routine service and clinician engagement and social marketing

Staff felt that ‘there is a need for this intervention’ (SLAM group 2) and could readily identify service users who would meet programme criteria and who would potentially benefit from the intervention. Introductory discussions about the proposed programme would depend on a service clinician’s confidence to talk about children’s difficulties as well as the parents’ own personal difficulties. Competence and confidence to do this varied between practitioners.

Staff recommended the use of individual clinical judgement in raising the programme with parents. They also recommended training sessions on introducing the programme and research evaluation as well as printed information to support initial discussions, including the potential benefits and challenges of participation.

Staff were unsure about how the proposed programme would complement other existing interventions available for the target population. Staff expressed concern about the potentially ‘destabilising effects that may occur’ (SLAM group 1) with parents’ programme participation and the risks that routine service clinicians could be ‘picking up the pieces’ (SLAM group 1).

Identification of potential intervention recipients and research participants

Staff were concerned that the existing structure of services and patient information systems would make it difficult for practitioners to identify eligible families. Child mental health staff were not routinely aware of all parents’ mental health status and service use. Adult mental health staff who were involved would not routinely have information about child mental health status but felt that they would have sufficient information to make recommended referrals. Some existing procedures, such as completion of the SLAM Child Risk Screen, would support initial identification. Identification of potentially eligible families would probably rely on the examination of individual caseloads.

Brief training in identification of eligible families was recommended, as well as further training for adult mental health staff in child and adolescent mental health. Some staff welcomed the use of tools to aid identification of eligible parents, whereas others felt that they could rely on their professional judgement. Positive feedback was given about the SAPAS as a screening tool.

Owing to the difficulties in accessing care, some staff raised concerns about eligibility criteria that required referral and/or attendance at CAMHS.

Engagement of service users and their interest in the Helping Families Programme-Modified and its research evaluation

Participants emphasised the importance of personalised discussions between service clinicians and eligible parents. Clinicians were concerned that parents may be ‘defensive’ (SLAM group 2) about discussing the impact of their own difficulties on their children. They were also concerned about the subsequent adverse effect on their relationships with referred service users. Most of the staff did not want to use a specific script for introducing the research programme but they wanted information sheets and guides that included suggested words and phrasing.

Although introducing the research programme would be easier for parents with existing personality disorder diagnoses, staff raised concerns about whether or not a diagnosis of personality disorder was necessary for inclusion in the programme, particularly given the associated stigma. Concerns were expressed about parents’ ability to distinguish between ‘a research and a clinical diagnosis’ (SLAM group 1) of a personality disorder, the risk of false positives, and the treatment options available for parents identified through the screening process as meeting the criteria for a research diagnosis. This was of particular concern for parent service users without an established personality disorder diagnosis who might be referred from CAMHS and subsequently allocated to a treatment-as-usual condition.

Case co-ordination and integration of Helping Families Programme-Modified with usual care

Staff explained that treatment as usual varied considerably both between and within adult and child mental health services. Staff expressed mixed views about the involvement of programme participants in other intensive interventions. They felt that the programme complemented many other available treatments, although some members of staff were concerned that participation in concurrent treatments may be ‘too much’ (SLAM group 2) and that families may become ‘overloaded’ (CNWL group 1).

Views on case co-ordination for parents involved in the proposed programme varied. Staff advocated an active role for keyworkers to introduce the research therapist to eligible parents. Some staff were concerned that eligible parents may be discharged from routine services once accepted on the research programme. Staff saw the potential for integrating the proposed programme into service user care plans and for it to become part of existing clinical pathways.

Intervention format

Some staff were uncertain about the duration of the proposed programme on the basis that interventions with service users affected by personality disorders may often be of considerable duration. They also thought that considerable time may be required to build effective therapeutic relationships.

Most of the staff advocated delivery of the programme in individual, rather than group, format. They felt that this would increase engagement and personalisation and promote change. Some staff suggested that home-based interventions may be subject to more threats to fidelity that clinic-based treatments.

Intervention content