Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 11/15/13. The contractual start date was in September 2013. The draft report began editorial review in March 2018 and was accepted for publication in February 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Claire A Surr was previously employed by the University of Bradford, which owns the intellectual property (IP) rights to the Dementia Care Mapping™ (DCM) intervention tested in this trial. In this role, she held responsibility for DCM training and method development. She was a technical author on the British Standards Institute’s PAS 800 guide on implementing DCM in health and social care provider organisations. She declares personal fees from Hawker Publications Ltd (London, UK) outside the submitted work. Clive Ballard reports grants and personal fees from Acadia Pharmaceuticals (San Diego, CA, USA) and Lundbeck Ltd (Copenhagen, Denmark), personal fees from Hoffman-La Roche Ltd (Basel, Switzerland), Otsuka Pharmaceutical (Tokyo, Japan), Novartis International AG (Basel, Switzerland), Eli Lilly and Company (Indianapolis, IN, USA) and Pfizer Inc. (New York, NY, USA) outside the submitted work. Murna Downs works at the University of Bradford, which holds the IP rights for DCM and runs courses for practitioners and professionals who wish to learn how to use the method. David Meads was a member of the NIHR Health Technology Assessment Elective and Emergency Specialist Care methods panel from February 2013 to June 2017. Louise Robinson was a member of the NIHR Primary Care Themed Call Board until 18 February 2014.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Surr et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Scientific background

Of those living with dementia in the UK, 38% reside in a care home,1 and at least 80% of people living in care homes have dementia. 2 In 2017, over 16,000 care homes were registered in England, around 11,900 residential homes and 4500 nursing homes,3 the majority of which provide care for older people. Concerns have consistently been raised about care home quality. 4,5 Improvement in care quality and in staff knowledge and skills has been a consistent UK government research and practice development priority for nearly a decade. 6–9 Poor-quality care is associated with poor outcomes for people with dementia, including an increase in behaviours that staff may find challenging to support (BSC). 10,11 Developing an informed and effective care home workforce is a strategic component of improving care quality;6,12 however, there remains limited robust evidence regarding effective evidence-based staff training and practice development interventions for care homes providing care for people with dementia. 13,14 Furthermore, it is often difficult to achieve widespread implementation into real-world practice of evidence-based training interventions developed in the context of research. 14,15

Dementia Care Mapping™ (DCM)16,17 is a whole-home, practice development intervention that has been widely used in health and social care settings, nationally18 and internationally,19 to support the embedding of person-centred care in practice. There is good evidence of its use in practice settings as a quality audit and improvement tool. 20–29 This trial was designed to provide robust evidence on the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of DCM as an intervention to support care homes in sustainably transferring the learning gained from person-centred care training (PCCT) into care practice. The trial aimed to determine whether or not DCM could provide a solution for achieving widespread implementation of an approach to training and practice development that is practical for use in routine health and social care.

Behaviours that staff may find challenging to support

The behaviours that may be expressed by people with dementia in care home settings, such as agitation, aggression, restlessness, hallucinations, delusions, depression, anxiety and apathy, may be considered by staff as challenging to support. 30 These BSC are also known as ‘neuropsychiatric’ symptoms or ‘behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia’ (BPSD). We have chosen to use the term BSC rather than BPSD, as the former reflects a more person-centred terminology that better emphasises the biopsychosocial causes of such behaviours. It also represents the terminology used by relatives and staff in care home settings. Up to 90% of people living with dementia experience one or more of these behaviours during the course of their condition30 and BSC are reported in up to 79% of care home residents at any one time. 31 BSC also cause distress to the people with dementia experiencing them,32 are associated with reduced quality of life33,34 and have a negative impact on the well-being of other residents. 35 BSC also have significant associated costs,36,37 including increased risk of hospitalisation,38,39 higher accident and emergency use37 and the production of excess disability, whereby the functional abilities of people decline more quickly than is otherwise expected. 37 Therefore, reducing BSC has the potential to improve the quality of life of people with dementia living in care homes and to reduce the costs of providing care to this group.

Agitation is the most common,31,40 the most distressing to the person with dementia32 and the most difficult to manage41 of all BSC in care home settings. Agitation includes aggressive behaviours, physically non-aggressive behaviours and verbal agitation,42 including pacing, spitting, verbal aggression, constant requests for attention, hitting, kicking, pushing, throwing things, screaming, biting, scratching, intentional falling, hurting oneself and/or others, making sexual advances and restlessness. 43 The presence of these behaviours puts the person who is agitated at risk of triggering aggressive responses from other residents44 and causes distress for other residents, the person’s family and staff. Rates of > 60% are reported of nursing-home residents with dementia displaying agitation,45,46 making it an extremely common BSC and potentially harmful for the people experiencing it, other residents and staff.

The presence of agitation is reported as highly challenging compared with other BSC in terms of clinical management. 41 Agitation places an increased burden on care staff,47,48 who feel less confident in dealing with situations in which residents are agitated than in their management of other BSC. 49 There is an association between a person with dementia experiencing agitation and fewer visits from relatives, experiencing social isolation48 and poorer quality of life. 33 The frequency of agitated behaviours, the difficulties staff have in managing these behaviours and the potential risks they pose to the person, other residents and staff mean that drug treatments such as antipsychotics and other psychotropic medications are frequently prescribed as a first-line management approach. However, antipsychotics are linked to stroke and excess deaths,50 which means that their reduced use is an ongoing priority. 4,9 There is a concern that the mandated reduction in antipsychotic prescribing may in turn lead to the prescription of other psychotropic drugs as an alternative,51,52 despite a lack of evidence of their efficacy. Investigating psychosocial approaches to reducing the incidence of agitation and supporting staff with BSC management is therefore a research priority. 5

Agitation and other BSC are not an inevitable consequence of dementia. Agitation is often exacerbated by poor care practices and a poor surrounding environment of the person with dementia,53 as well as by poorly managed physical health and pain. 41,54 Such behaviours often reflect an expression of unmet needs by a person with dementia in response to staff members’ inadequate understanding of a person’s needs or poor-quality care. 4,54,55 This is often related to a lack of stimulation of and engagement with the person with dementia. 56 For example, Brodaty et al. 57 found significant variability between care homes in terms of the proportions of residents within each setting who displayed BSC, indicating a care home-level effect that may include both admissions criteria and care practices. Likewise, Weber et al. 58 reported a significant reduction in BSC when people with dementia attended a therapeutic day hospital programme compared with when they were at home, again indicating the impact of the psychosocial environment. The presence of agitation within individuals with dementia in care home settings is, therefore, likely to be associated with organisational aspects of care and the care culture. 54 Therefore, the use of psychosocial interventions that address the quality of care practice4,59–61 are recommended, with agitation being a key treatment target area for people with dementia in care homes. 62

Person-centred care

Person-centred care is an effective psychosocial approach in dementia care63 that is considered a best-practice approach to reducing agitation and other BSC. 59 Person-centred care means providing a supportive social environment within a care setting in which people with dementia are valued and treated as individuals and staff are encouraged to see the world from their perspective. 59,64 Person-centred care, therefore, involves evaluating and responding to the unique needs of each person with dementia and offering an individualised approach. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and Social Care Institute for Excellence (SCIE) dementia guideline59 recommends individualised, holistic or person-centred assessment and care planning, with regular review and individually tailored and monitored psychosocial interventions for BSC. The delivery of care that is person centred is associated with a reduction in agitated behaviours,65 and in BSC more generally,61 and with reduced use of antipsychotics. 63,66,67 Bird et al. 68 found that multifaceted, individualised interventions lead to significant reductions in BSC. Therefore, the most useful interventions to effect change identify individual causes of BSC and suggest appropriate person-centred solutions. 68–70 This approach is reliant on staff having the required knowledge, skills and confidence to deliver person-centred care. The provision of person-centred support is an element of the common induction standards71 for all social care workers in England. The provision of at least basic training to staff on person-centred care is expected within all care homes in England59 and is a regulatory requirement. 72 Currently, there are no widely implemented quality criteria for PCCT and the content, approaches, quality and efficacy of PCCT vary considerably across the sector. 73 Effective PCCT can produce immediate practice benefits;65,67 however, owing to the variability of the amount, content and quality of PCCT that staff receive across the sector, the knowledge, skills and staff confidence levels in relation to delivery of person-centred care remain a concern. 49,74 Research indicates that standardising PCCT is unlikely to address these issues14 and, therefore, evidence-based approaches to help staff sustainably embed PCCT into practice are required. 15

Although effective PCCT can produce immediate practice benefits, evidence suggests that PCCT alone might not sustain change over time13,65,67,75 and that PCCT needs to be accompanied by an additional intervention to support ongoing change. 66,76 For example, Fossey et al. 66 employed PCCT alongside a comprehensive 10-month focused intervention for training staff (FITS), including ongoing staff training and support. At post test, antipsychotic medication use had decreased by > 40% in the intervention group. Chenoweth et al. 63 provided PCCT to two staff members who then disseminated person-centred care practice across the site. Researchers provided additional individualised care planning and ongoing telephone support during a 4-month intervention period. Ten months after randomisation, agitation levels were significantly lower than in the usual-care control sites. A limitation of both of these studies is that it is unclear whether PCCT, additional support or both caused the effect. Evidence of the efficacy of PCCT after a longer follow-up period is limited;13 however, Moniz-Cook et al. 67 found that the benefits of PCCT alone were not sustained after 1 year. The PCCT programmes evaluated thus far indicate that embedding additional support into the training intervention is required to produce sustained benefits. 15,77,78 Implementing evidence-based health-care interventions in real-world practice is a recognised challenge, with barriers to implementation of research-designed interventions reported across all areas of practice. 79–81 Current successful interventions that combine staff training with ongoing support, such as the FITS,66 are resource intensive, requiring regular ongoing input from a specialist practitioner, and it has not yet been possible to implement them widely in everyday practice. 82 Interventions are required that provide staff with knowledge to support BSC management and that are cost-effective and feasible to implement. Any such intervention will need to accommodate the varying amounts, content and quality of PCCT that is a feature of the sector. DCM is an intervention that may address this issue.

Dementia Care Mapping™

This tool, DCM,16,17 is an established, routine care home/NHS practice development intervention that is recommended in the NICE/SCIE dementia guideline59 and is regularly used for ensuring that a systematic approach is used in the provision of individualised person-centred care. DCM is an observational tool set within a practice development cycle that is used to support the sustained implementation of PCCT in dementia care practice. 83 Following initial formal training of care staff to use the tool, its application includes five phases: briefing, observation, data analysis and reporting, feedback and action-planning. A detailed overview of the DCM intervention is provided in Chapter 2, Dementia Care Mapping™ (intervention arm). This cycle is repeated every 4–6 months to monitor and revise action plans. DCM implementation, therefore, requires no external input over the long term and is thus potentially less resource intensive and more closely aligned with real-world dementia practice than other interventions aiming to address BSC. 66

Although DCM has been used in dementia care for nearly 20 years, including in care home settings,25,84–87 and has strong face validity within the practice field,88 there is limited robust evidence of its effectiveness in relation to clinical outcomes such as the reduction of BSC. Reported benefits of DCM include the improvement of well-being in people with dementia,22,27,89 helping staff consider care delivery from the point of view of the person with dementia and the production of evidence to underpin action-planning that in turn motivates staff and increases their confidence to deliver person-centred care. 87,88

Evidence of the effects of Dementia Care Mapping™

Only six published studies have examined the benefits of using DCM for improving clinical outcomes in care homes: two pilot studies employing a pre-test/post-test design,90,91 one quasi-experimental controlled trial92 and three cluster randomised controlled trials (RCTs). 63,93,94 None of these was carried out in the UK. At the time of submission of the grant application for this trial, only the two pilot studies90,91 and one of the RCTs had been published. 63

A pilot study conducted in the Netherlands91 utilising a one-group pre-test/post-test design found that DCM, used alone, reduced verbal agitation and anxiety in people with dementia. It also improved care staff’s feelings of connection with their clients. A pre-test/post-test design pilot study90 conducted in three Australian care homes found that DCM led to improvements in the quality of staff interactions and reductions in agitation and depression, compared with three control homes. A quasi-experimental controlled trial conducted in Germany92 compared outcomes at 6 and at 16 months with baseline. Nine nursing homes units, located in nine nursing homes owned by the same group, were allocated not at random to one of three arms: a no-intervention control group (n = 3), a DCM-experienced intervention group (n = 3) and a DCM intervention group (n = 3). The DCM-experienced group had been exposed to two externally delivered DCM cycles annually over a number of years. The DCM intervention group had no previous exposure to DCM, but had expressed an interest in undertaking the method. Two staff members from both intervention groups received DCM training and were requested to implement three DCM cycles over 18 months. The control group received an intervention based on training staff about quality of life (QoL), followed by QoL assessment, using a standardised tool, of all care home residents at least every 6 months. The study found no significant difference between the two intervention groups and the control, and no difference between the two intervention groups, as regards QoL or BSC.

The first cluster RCT evaluating the efficacy of DCM was conducted in Australia63 in 15 care homes randomised equally between three arms [usual care (control), PCCT and DCM] and included 289 people with dementia (18% loss to follow-up at 10 months). The trial found that 10 months after randomisation, DCM, when used alone, was associated with significantly reduced agitation and falls in people with dementia compared with the control and PCCT groups, and with reduced staff feelings of burnout. 95 A three-arm cluster RCT93 was also conducted in 15 care homes in Norway, randomising equally between a control group, person-centred care framework implementation and DCM. The study recruited 446 people with dementia (29% loss to follow-up at 10 months). It found significant reductions in overall neuropsychiatric symptoms as measured by the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI), significant reductions in agitation and psychosis as measured by the NPI subscales and a significant improvement in QoL compared with the usual-care control. Both trials had explanatory designs involving researcher-led cycles of DCM with variable degrees of input from trained care home staff, which restricted the generalisability of the results, as the usual implementation of DCM is practitioner led. A Dutch cluster RCT conducted in 34 units across 11 care homes compared DCM with a usual-care control. 94 It recruited 434 residents (35% loss to follow-up at 12 months) and found no difference in residents’ agitation between the DCM intervention and control homes. Positive staff outcomes were found in the intervention group, including significantly fewer reported negative emotional reactions and significantly more positive reactions towards people with dementia than in the control group. The trial authors identified potential DCM intervention fidelity issues, finding less than desirable implementation in some clusters. All three RCTs were exploratory and each included only two full cycles of DCM before the final follow-up, with follow-up periods of only 10–12 months post randomisation, reducing the time for any potential change or impacts to be seen.

The results of these existing studies are mixed in terms of the reported efficacy of DCM. The studies that included researcher-led cycles of DCM (Australia and Norway) showed efficacy for some outcomes, whereas studies with cycles of DCM led by care home staff have shown no benefits of DCM (the Netherlands and Germany). A recent systematic review of DCM implementation96 found limited research in this area, with implementation found to be challenging across a number of the published studies. There was some consensus that appropriate mapper selection, preparation and ongoing support during DCM implementation, alongside effective leadership for DCM within an organisational context of commitment to the delivery of person-centred care, could support better implementation.

In summary, the limitations of the existing studies include:

-

a relatively small number of clusters (Australia and Germany) or small numbers of care homes containing multiple clusters (the Netherlands and Norway)

-

the use of DCM alone, rather than alongside PCCT in accordance with UK best-practice guidelines83 (Australia and the Netherlands), which reflects the context within each country at the time of the trial, for example in Australia, where PCCT was the exception rather than assumed good practice

-

only two full cycles of DCM before the final follow-up, which limited the potential for impacts to be seen, owing to the length of time that changes within care home practice can take to implement, and thus limited the demonstration of potential resident benefits (Australia, Norway and the Netherlands)

-

a follow-up period of no more than 12 months after randomisation, reducing the time for potential changes and impacts to be seen (Australia and Norway)

-

explanatory trial designs (Australia and Norway) involving researcher-led cycles of DCM with variable degrees of input from trained care home staff, potentially limiting staff ownership of the DCM process, the implementation of any action plans and the longer-term sustainability of DCM use; this also restricts the generalisability of the results, as the usual implementation of DCM in care practice is practitioner led

-

no formal, published process evaluation (Australia and Norway)

-

the studies were conducted in Australia, Norway, Germany and the Netherlands, where care funding, policy, context, regulations and processes are different from those of the UK.

Despite promising results on the potential efficacy of DCM in care home settings, the conduct of these trials in countries where usual-care practices, funding and systems are different from the UK and where DCM was implemented differently from its use in the UK means that their results cannot be directly transferred. A definitive RCT evaluating the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of DCM for helping staff to implement person-centred care in UK care home settings, building on this previous work, is therefore needed to inform future UK care home practice.

Rationale for the research

The knowledge intended to be gained from this trial, beyond that gained within the existing RCTs, was:

-

Previous trials used explanatory designs. By contrast, in this trial, a pragmatic trial design reflecting the conditions of DCM implementation in usual practice in UK care home settings would be used. In particular, trained care home staff, rather than researchers, led the cycles of DCM implementation. The trial design, size and statistical power allowed definitive conclusions to be drawn regarding the effectiveness of DCM as an intervention in usual practice within UK care home settings.

-

Previous RCTs had conducted only one or two DCM cycles with a follow-up period of a maximum of 12 months. In this trial, it was intended that care homes would implement three cycles of the DCM intervention with follow-up over a period of 16 months. This is beneficial because some anticipated practice changes, for example to the underlying care culture, are likely to take time to implement. In addition, given the annual staff turnover rates of around 30%97 in care homes, which may potentially lead to longer-term implementation challenges, a longer follow-up period was necessary to investigate whether or not longer-term effects and sustainability could be achieved within this context.

-

A full economic evaluation within this pragmatic trial design was included, offering a definitive position on cost-effectiveness. Only one of the previous trials conducted an economic evaluation and, given its explanatory design and conduct in a funding system different from that of the UK, the findings cannot be confidently generalised.

The design of this trial built on existing explanatory trials to offer a definitive assessment of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of DCM as a standard clinical intervention in care home settings.

Aims and objectives

The aim of the DCM Enhancing Person-centred care In Care homes (EPIC) cluster RCT was to evaluate the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of DCM implemented in addition to usual care (intervention), compared with the usual care (control) for people with dementia living in care homes in the UK.

It aimed to answer the following primary and secondary research questions.

Primary research questions

At 16 months after the randomisation of care homes, is the intervention:

-

more effective than the control in reducing agitation in residents with dementia as measured by the total Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI) score?

-

more cost-effective than the control?

Secondary research questions

Is the intervention more effective than the control at 6 and at 16 months after randomisation in:

-

reducing BSC in people with dementia over time?

-

reducing the use of antipsychotics and other psychotropic drugs in residents with dementia?

-

improving mood and QoL in residents with dementia?

-

improving care home staff well-being and role efficacy?

-

improving the quality of staff–resident interactions over time?

Other questions the trial sought to explore related to:

-

the safety profile of the intervention as assessed by the number and types of adverse events

-

any differential predictors of the effects of the intervention

-

the process, challenges, benefits and impact of implementing the intervention.

Chapter 2 Trial design and methods

Trial design

This section outlines the trial design and procedures at the commencement of trial recruitment. The original trial protocol is published elsewhere. 98 Subsequent amendments to the original trial protocol, after trial commencement, are highlighted throughout this section and then reported in detail in Summary of changes to project protocol.

This trial was a pragmatic, multicentre, cluster RCT of DCM plus usual care (intervention) versus usual care alone (control) in residential, nursing and dementia care homes across West Yorkshire, Oxfordshire and South London for people with dementia.

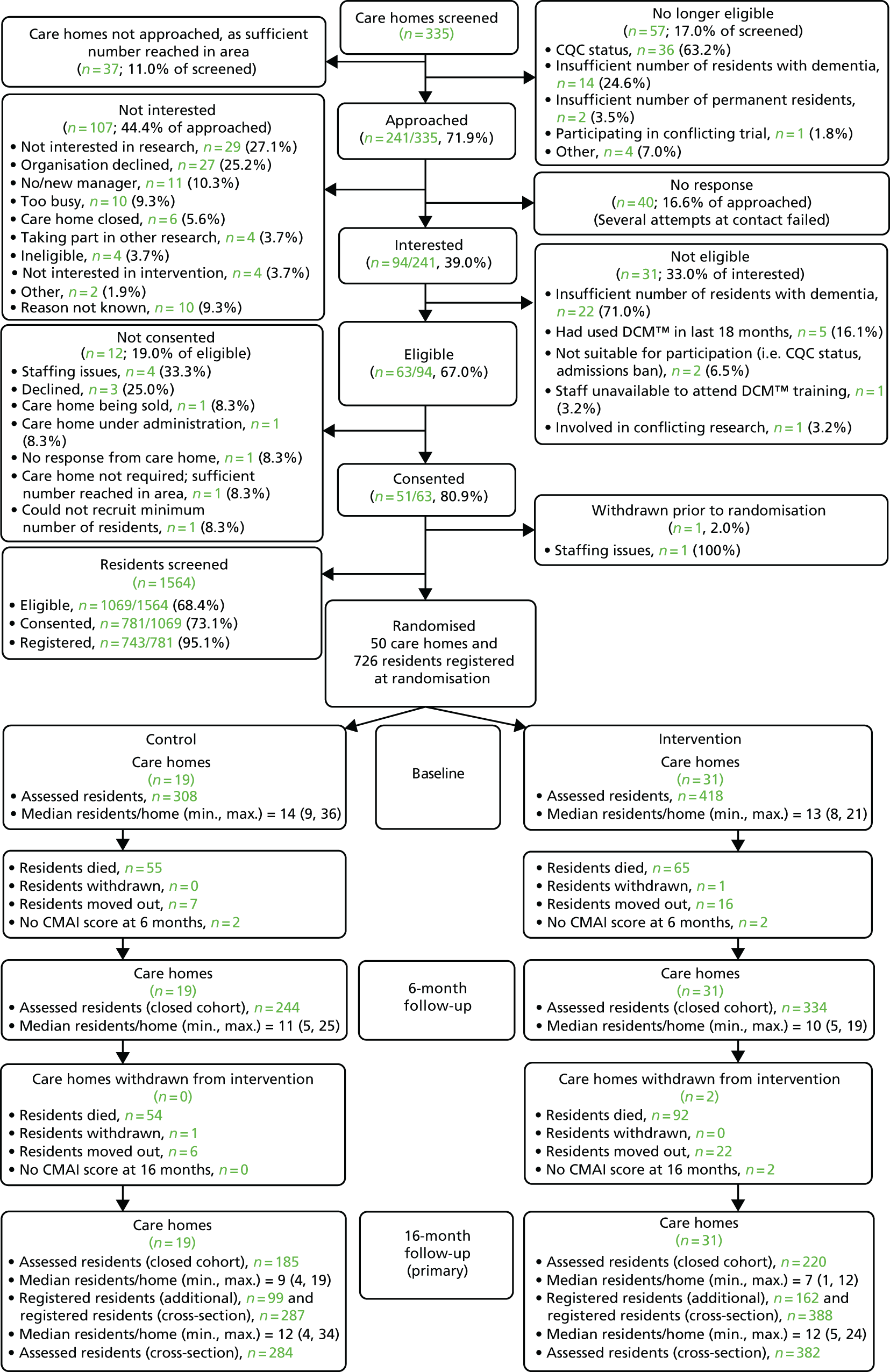

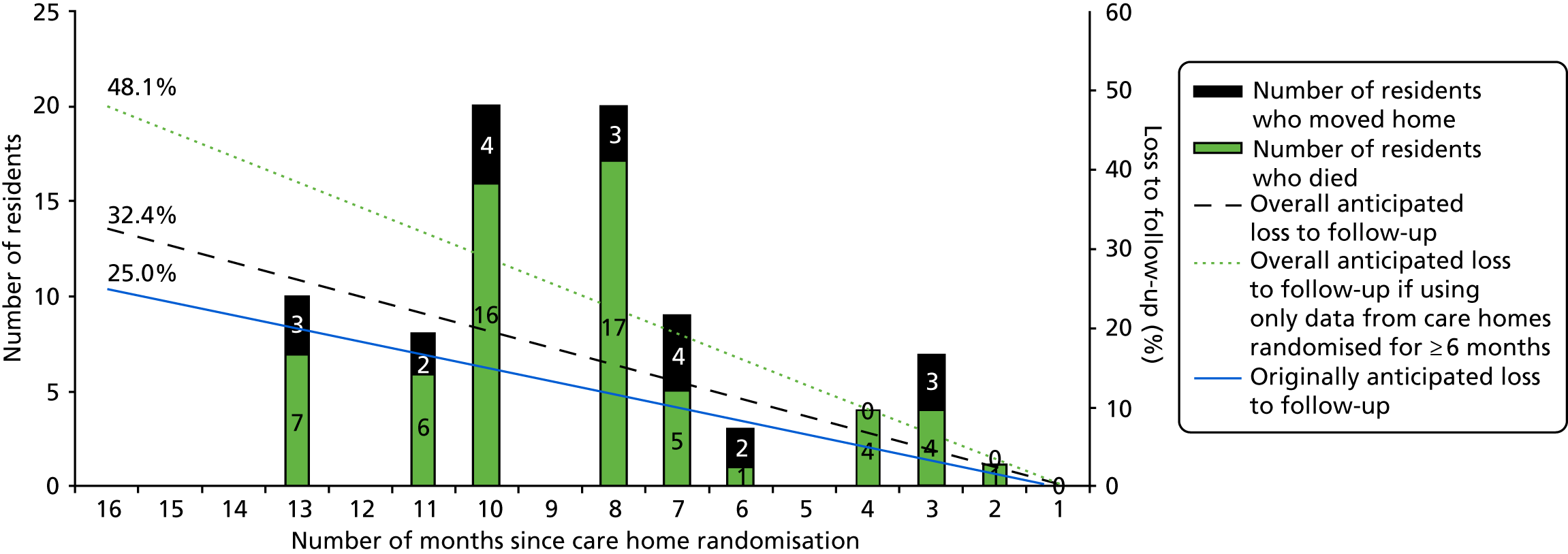

Owing to greater than expected loss to follow-up during the trial, a design change was approved to move from a closed-cohort to an open-cohort design, with additional residents recruited at the 16-month follow-up and the cross-sectional sample of residents used within the primary analysis (see Summary of changes to project protocol). The cross-sectional sample of residents was used in the primary statistical analysis (and a secondary health economic analysis), defined at baseline and at 16 months, respectively, as all residents registered at care home randomisation and at 16 months. The closed-cohort sample of residents was used in the primary health economic analysis (a supportive statistical analysis and all analyses of 6-month outcomes), defined simply as all residents registered at care home randomisation.

As the aim of DCM is to change practice across the whole care home setting and it is not possible to limit the potential effects to the care provided to only a sample of people with dementia living in the care home, a cluster design was justified. This influenced the decision to consider two important sources of clustering: cluster randomisation and DCM treatment provision, with care homes nested within treatment arms. Owing to this, we anticipated that the clustering effect would vary across arms, with a higher intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC) in the intervention arm. Therefore, an unequal allocation of care homes on a ratio of 3 : 2 to intervention and control groups, respectively, was implemented. An integral cost-effectiveness analysis and a nested qualitative process evaluation were included.

Ethics approval, research governance and study oversight

Ethics approval for the study was granted by National Research Ethics Service (NRES) Committee Yorkshire and the Humber – Bradford Leeds on 14 February 2013, Research Ethics Committee (REC) reference number: 13/YH/0016. Care home insurance and indemnity applied to trained mappers who implemented the intervention within the care home setting. Appropriate site-specific approvals were obtained from the three participating hubs: Yorkshire (Bradford Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust), Oxford (Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust) and London (Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust). The trial was registered with the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Register (ISRCTN) reference 82288852. Day-to-day management of the trial was undertaken by a Trial Management Group (TMG) comprising the co-applicants, trials researchers and staff, as well as a patient and public involvement (PPI) representative. This group met twice before the official start of the project, monthly during trial set-up and then bi-monthly or quarterly. Updates on trial progress were provided by e-mail between meetings. A Lay Advisory Group was established and contributed to TMG decisions (see Patient and public involvement).

Trial Steering Committee

The trial was overseen by a Trial Steering Committee (TSC) comprising five independent members (three academic members, one PPI representative and one care home representative). The TSC monitored trial recruitment, retention, timelines, intervention adherence, data return and quality and considered new issues. It also provided advice and approval for changes to the protocol or trial procedures. It met approximately every 6 months throughout the trial.

Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee

An independent Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC), comprising four academic members, met approximately every 6 months during the trial. It reviewed unblinded data, recruitment, retention, intervention implementation and safety by group. The DMEC also undertook an annual review of any serious adverse events (SAEs).

Participants

It was intended that 750 residents with dementia from a random sample of 50 care homes would be recruited, along with participants’ relatives and care home staff.

Care home eligibility, recruitment and consent

Care home eligibility

To be eligible for the trial, a care home was required to:

-

have a sufficient number of permanent residents with dementia [based on a formal diagnosis or Functional Assessment Staging Test of Alzheimer’s Disease (FAST) score of 4+] eligible to participate, achieving a minimum of 10 residents registered to the trial prior to care home randomisation

-

have a manager or nominated person agreeing to sign up to the trial protocol as the research lead for the duration of the project

-

have agreed to release staff for DCM training and subsequent mapping processes

-

be within the trial catchment area.

Care homes were not eligible for the trial if they:

-

were subject to Care Quality Commission (CQC) enforcement notices, admission bans or relevant moderate or major CQC compliance breaches

-

were receiving other special support for specific quality concerns, such as being currently subject to, or having pending, any serious safeguarding investigations, or receiving voluntary or compulsory admission bans or local commissioning special support, owing to quality concerns

-

had used DCM as a practice development tool within the 18 months prior to randomisation or were planning to use DCM over the course of trial involvement

-

were currently in, had recently taken part in or were planning to take part in another trial that conflicted with DCM or data collection.

If a care home was a large multisite or multifloor establishment, the one or two units with the largest percentage of residents with dementia, or in which the manager felt that DCM implementation would be most beneficial, were selected to participate as one home.

Care home recruitment

Catchment areas for each recruitment hub (Leeds Beckett University, King’s College London and Oxfordshire Health NHS Trust) were established based on postcode districts/boroughs in West Yorkshire, South London and Oxfordshire, respectively. All care homes in the catchment areas were identified and screened for initial eligibility via publicly available information (home type, number of beds and CQC status). Care homes that were deemed eligible were randomly ordered within catchment areas and divided into batches. The first batch of homes from each hub were sent the care home information sheet [see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/111513/#/ (accessed July 2019)] by post. A researcher then contacted the care homes by telephone within 1 to 3 weeks to determine their interest in taking part. If a care home expressed interest in taking part, the researcher conducted initial eligibility screening ahead of visiting to determine full eligibility and to initiate care home consent and management permissions [see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/111513/#/ (accessed July 2019)]. If the researcher was unable to make contact with the care home following several attempts, a decision was made to cease attempting to contact. Once all care homes within a batch had been contacted, or deemed uncontactable, the next batch was approached until sufficient homes were recruited.

Dementia training audit and provision of dementia awareness training

As person-centred care is considered best practice within UK care homes,59 it was expected that homes would have routinely provided staff with appropriate PCCT. 72 As the quality of PCCT is variable across the sector in the UK, to ensure that each care home met at least minimum dementia awareness training standards, a training audit was developed by the research team (its content and the minimum standards required in the trial are reported elsewhere). 99 The training audit was completed in each care home prior to baseline data collection. The researcher completed this by reviewing training records and having discussions with home managers and/or other relevant staff (e.g. the training lead). When homes fell below the minimum standard, they received a half-day dementia awareness course modified in consultation with service users from an existing resource developed by Bupa Care Services and the University of Bradford. 100 The course was delivered by an experienced trainer/mentor who coached a member of the care home staff to be able to deliver the course to additional staff. Care homes were expected to deliver the training to at least 20% of permanent direct care staff prior to baseline data collection and to complete paperwork detailing how many staff members received the training and when. Based on CQC data,101 we expected up to 20% of homes to require this dementia awareness package.

Resident eligibility, recruitment and consent

Residents were recruited to the trial at baseline, prior to care home randomisation. Additional residents were recruited 16 months after a design change to the study, owing to larger than anticipated loss to follow-up (see Design change).

Resident eligibility

At baseline, residents were eligible for the trial if they:

-

were a permanent resident in the care home and not present for receipt of respite or day care

-

had a formal diagnosis of dementia or a score of 4+ on the FAST102 (indicating mild to severe dementia) as rated by the home manager or another experienced member of staff

-

were appropriately consented (in accordance with the Mental Capacity Act 2005103 and clinical trials guidance on informed consent104,105)

-

had an allocated member of staff willing to provide proxy data

-

had sufficient proficiency in English to contribute to the data collection required for the research.

At baseline, residents were not eligible for the trial if they were:

-

known by the care home manager and/or relevant senior staff member to be terminally ill (e.g. formally admitted to an end-of-life care pathway)

-

permanently bed-bound/cared for in bed

-

currently in, had recently taken part in or were planning to take part in another trial that conflicted with DCM or with the data collected in the trial.

Resident screening

The researcher, along with the care home manager and/or a relevant member of senior staff, screened all care home residents to identify eligible people with dementia to be approached to take part in the trial. The basic demographics of all residents and their eligibility or reasons for ineligibility at screening were recorded, using only the screening number.

Resident informed consent

In accordance with the Mental Capacity Act 2005,103 all eligible residents were assumed to have capacity to consent unless assessed otherwise. The manager/senior staff member approached each eligible resident and sought their permission for the researcher to speak with them. If the resident had capacity and gave verbal consent to speak to the researcher, this was documented and the researcher approached them to discuss the study. If the resident was deemed to lack the capacity to make this decision, then the process for appointing a consultee was followed (see Consent for those without capacity).

The researcher approached each resident who had capacity and agreed to speak to them, explaining the trial using the appropriate documentation and undertaking a further documented assessment of capacity to give informed consent. The resident was provided with the resident information sheet [see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/111513/#/ (accessed July 2019)] and, at least 24 hours later, they were given the opportunity to ask any further questions and then, for those with capacity, formal consent to participate in the trial was sought. If the resident was deemed by the researcher at any point to lack the capacity to consent, the process for appointing a consultee was followed (see Consent for those without capacity).

Consent for those with capacity

Residents who were able to give informed consent were asked to sign, or make a mark on, the trial consent form [see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/111513/#/ (accessed July 2019)]. For those who were not able to sign, a witness confirmed that informed consent had been given. Given the progressive nature of dementia, a further capacity assessment was conducted at each data collection point by the researcher to assess continued capacity. In the case of residents who lost capacity during the trial, appropriate guidance on consent in the light of changed capacity was followed,106 involving the appointment of a consultee (see Consent for those without capacity). When a resident had capacity and consented to taking part in the trial, consent to approach his or her main carer (relative/friend) was sought regarding their participation as a proxy informant.

Consent for those without capacity

When a resident was assessed and found to lack the capacity to give informed consent, a ‘Personal Consultee’ was appointed to give advice on the resident’s wishes. This was usually a relative or a close friend. When the resident had no close family or friends able or willing to act as Personal Consultee, a member of staff in the care home who knew them well but who was not actively involved in any elements of the research process (e.g. as a mapper or in giving proxy data on the resident) was appointed as a ‘Nominated Consultee’.

If the proposed Personal Consultee was present in the care home, they were approached by the researcher and given all of the appropriate documentation [see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/111513/#/ (accessed July 2019)] in person and asked for written consent to hold their personal details to enable the researcher to directly contact them thereafter. The proposed Personal Consultee was given at least 24 hours to talk to the resident and other relatives/friends about the resident’s wishes. The Personal Consultee was then asked to return the declaration form by post, within a week, expressing their advice on the resident’s wishes regarding taking part in the trial. If the Personal Consultee was not present in the care home, the documentation was sent to them by post, via the care home, on the researcher’s behalf. Details were provided on how to contact the researcher should they wish to discuss the role. For both methods of approach, if the declaration form had not been returned after 1 week, a follow-up reminder was sent by post by the researcher informing the Personal Consultee that a Nominated Consultee would be identified if no response was received within 1 week. If, after a further week, the declaration form had not been returned, the process of appointing a Nominated Consultee was followed.

A Nominated Consultee identified by the manager was approached using the appropriate documentation [see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/111513/#/ (accessed July 2019)] to discuss the potential involvement in the trial with the resident, other staff members who knew them well and any relatives/friends. The Nominated Consultee was then asked to complete the declaration form, providing advice on the resident’s wishes.

Personal and Nominated Consultees were advised that they could approach the researchers at any time to indicate if they felt that the person they were representing had changed their mind about participating in the trial and to withdraw them from participation. Given the potential frailty of those serving as Personal Consultees, a review of Personal Consultees’ capacity was undertaken by the researcher via the care home manager at 6- and 16-month follow-ups, where feasible.

Staff roles, eligibility, recruitment and consent

Staff roles

There were five staff roles within the trial, some of which were mutually exclusive (Table 1):

-

to act as a Nominated Consultee for residents (see Consent for those without capacity)

-

to provide data on standardised measures relating to their role (see Staff measures)

-

to provide proxy informant data on residents they know well (see Proxy informant eligibility, recruitment and consent)

-

to become a trained DCM mapper (see Mapper identification, eligibility and consent)

-

to participate in the trial’s process evaluation (see Process evaluation and assessment of treatment implementation).

| Staff roles | Nominated Consultee | DCM mapper | Proxy informant |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nominated Consultee | ✗ | ✗ | |

| Staff measures | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Proxy informant | ✗ | ✗ | |

| DCM mapper | ✗ | ✗ | |

| Process evaluation | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ |

Staff measures

To be eligible to complete a staff measures booklet, staff were required to be a permanent, contracted, agency or bank member of staff at the time of data collection and have sufficient proficiency in English. Consent to participate in this role was assumed through staff return of the booklet. The staff measures booklets and accompanying information sheets [see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/111513/#/ (accessed July 2019)] were distributed to all eligible staff members at each data collection visit, by either the researcher or the care home manager. Booklets were returned anonymously by the staff member either via a sealed envelope to a locked box located within the care home or posted directly to the research office in the stamped return envelope provided.

Proxy informant eligibility, recruitment and consent

To be eligible to act as a proxy informant and to provide proxy data on a resident, staff had to be a permanent or contracted member of staff who knew the resident well. Bank or agency staff were not eligible for this role. Potential proxy informants were identified by the care home manager/senior member of staff using the appropriate trial documentation [see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/111513/#/ (accessed July 2019)]. Where possible, the same proxy informant was used for each resident throughout the trial, although this was not always possible owing to staff turnover, annual leave and shift patterns.

Relative/friend eligibility, recruitment and consent

Where possible, a relative or friend who visited the care home regularly was identified for each participating resident to provide proxy data. The relative/friend proxy was identified in discussion with either the resident or the care home manager/senior member of staff. They could also act in the role of Personal Consultee. To be eligible to provide proxy data, relatives/friends were required to have visited the resident at least once per week over the previous month, be willing to provide data by either telephone or post during the data collection week and have sufficient proficiency in English to contribute to the data collection required. Relatives/friends were approached either in person by the care home manager or researcher or by post, depending on visiting patterns and times, using the appropriate trial documentation [see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/111513/#/ (accessed July 2019)].

Relative/friend recruitment took place at baseline and continued at the 6-month follow-up in some homes until December 2015, when the decision to cease further recruitment was made owing to low overall relative/friend recruitment. Data continued to be collected from consented relatives/friends throughout the trial. Their continuing eligibility for participation was reassessed at each subsequent data collection point because of changing patterns of visiting over time. When relative/friend proxies withdrew from the trial, additional participant relatives/friends were not recruited.

Registration, randomisation and blinding

Registration of residents

Residents recruited at baseline were registered with the Clinical Trials Research Unit (CTRU) at the University of Leeds following care home recruitment, training review (see Dementia training audit and provision of dementia awareness training), eligibility confirmation, obtaining informed consent and resident-level baseline data collection, but prior to care home randomisation. Following a design change (see Summary of changes to project protocol), additional residents were recruited at 16 months and were registered with the CTRU after confirmation of eligibility, informed consent and collection of their resident-level data.

Randomisation, stratification and blinding

Immediately following baseline, once all residents, staff and relatives/friends were recruited and registration was complete, care homes were randomised using the 24-hour automated randomisation system at the CTRU. Care homes fulfilling eligibility criteria were randomised on a 3 : 2 basis to either the intervention or the control group, respectively. A computer-generated minimisation programme was used,107 incorporating a random element to ensure that the arms were balanced for the following care home characteristics:

-

home/unit type (general residential/nursing or specialist dementia care)

-

size (large, ≥ 40 beds; or medium/small, < 40 beds)

-

provision of dementia awareness training by research team (yes or no)

-

recruiting hub (West Yorkshire, London or Oxford).

To maintain blinding of trial researchers collecting data within care homes, randomisation was performed by the CTRU Data Management team, who were therefore not blind to treatment allocation. Following randomisation, the CTRU informed the care home manager of the treatment allocation, by telephone call or e-mail. The intervention lead was notified of homes allocated to the intervention, so that arrangements could be confirmed for training with consented mappers and contact with the DCM expert mapper could be initiated. Researchers were not informed of treatment allocation and agreed procedures were applied to maintain blinding throughout the trial. Other CTRU staff were informed of treatment allocation only if this was required to undertake their role. All occurrences of unblinding and the reasons for and method of unblinding were recorded.

Because researchers were blinded, they were unaware of the identity of trained mappers. Therefore, a text message was sent to mappers in the intervention homes by CTRU trial management staff, ahead of data collection at 6 and at 16 months, to remind them not to provide proxy informant data if requested to do so.

Procedure

Usual care (both arms)

Usual care was defined as the care routinely delivered within the setting and was continued in all participating care homes with no restrictions imposed on current practices or on homes undertaking additional development or training. The exception was that control-arm homes were required not to implement DCM during the trial period. Details regarding any changes in usual-care practice during the course of the trial (e.g. new staff roles, change of ownership, new practice initiatives or training programmes) were documented by the researcher at follow-up visits.

To facilitate a person-centred primary care response to BSC in case care homes sought support, all general practitioners (GPs) who served each care home were provided with generic best-practice guidance about the implementation of person-centred care and managing BSC, irrespective of whether or not the residents they provided services to were participating in the trial. We did not inform individual GPs about which residents were participating in the trial.

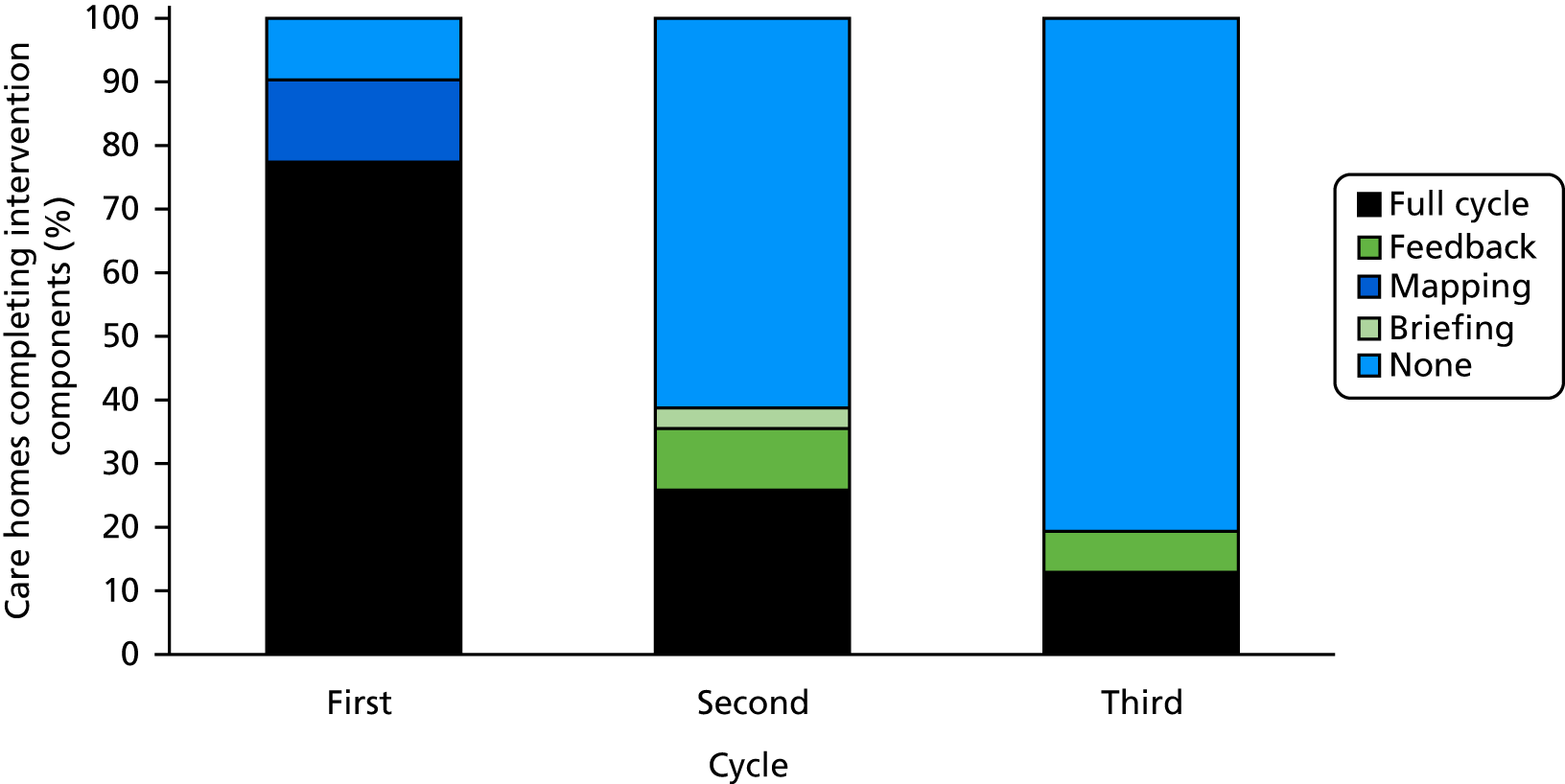

Dementia Care Mapping™ (intervention arm)

The intervention followed standard procedures as set out in the DCM manual and guidance. 17,108 Two staff members from each intervention care home were trained to use DCM, followed by implementation of (ideally) three standard DCM cycles (each comprising briefing; observation; data analysis, reporting and feedback; and action-planning), in accordance with the British Standard best-practice guideline. 83 In addition, care homes were provided with fidelity guidelines, which included standardised templates for recording attendance at briefing and feedback sessions and for DCM reporting and action-planning. Other mechanisms for ensuring adherence to the intervention and for supporting mapper engagement were implemented, including support from a DCM expert mapper during cycle 1 (see Expert mapper support for cycle 1) and sending short message service (SMS) reminders to mappers ahead of each cycle.

Mapper identification, eligibility and consent

Two staff members in each home were identified by the manager as suitable to be trained in the use of DCM (mappers). To ensure timely progression from care home randomisation to DCM training, and to avoid selection bias, two mappers were identified in every consenting home at care home recruitment and their informed consent to undertake the mapper role was gained. To be eligible, staff had to be a permanent or contracted staff member, had to have the right skills and qualities as assessed by the home manager against a mapper role descriptor provided by the research team [see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/111513/#/ (accessed July 2019)], had to agree to implement DCM per protocol and had to take part in the process evaluation, if required.

Potential mappers were initially approached by the manager with reference to the written mapper role description. Once verbal consent was obtained, the researcher discussed the role and responsibilities of mappers again with reference to the role descriptor and mapper information sheet, before gaining their written informed consent [see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/111513/#/ (accessed July 2019)]. If a mapper withdrew or left the care home before the end of the trial, where feasible, another suitable member of staff was identified, consented and trained using a similar procedure, to ensure continuity of DCM implementation in the home.

Training

Following randomisation, care homes allocated to the intervention group received DCM training as soon as their mappers were able, depending in part on the course schedule.

All trial mappers attended a standard 4-day DCM training course held in Bradford or London and provided by the University of Bradford. It included an assessment of competency in the use of DCM. One additional attempt at the assessment was permitted for those attendees who failed to achieve a pass mark at the first attempt. The course trainers were informed in advance of which attendees were EPIC trial mappers. They provided data on which mappers had successfully completed and passed the course.

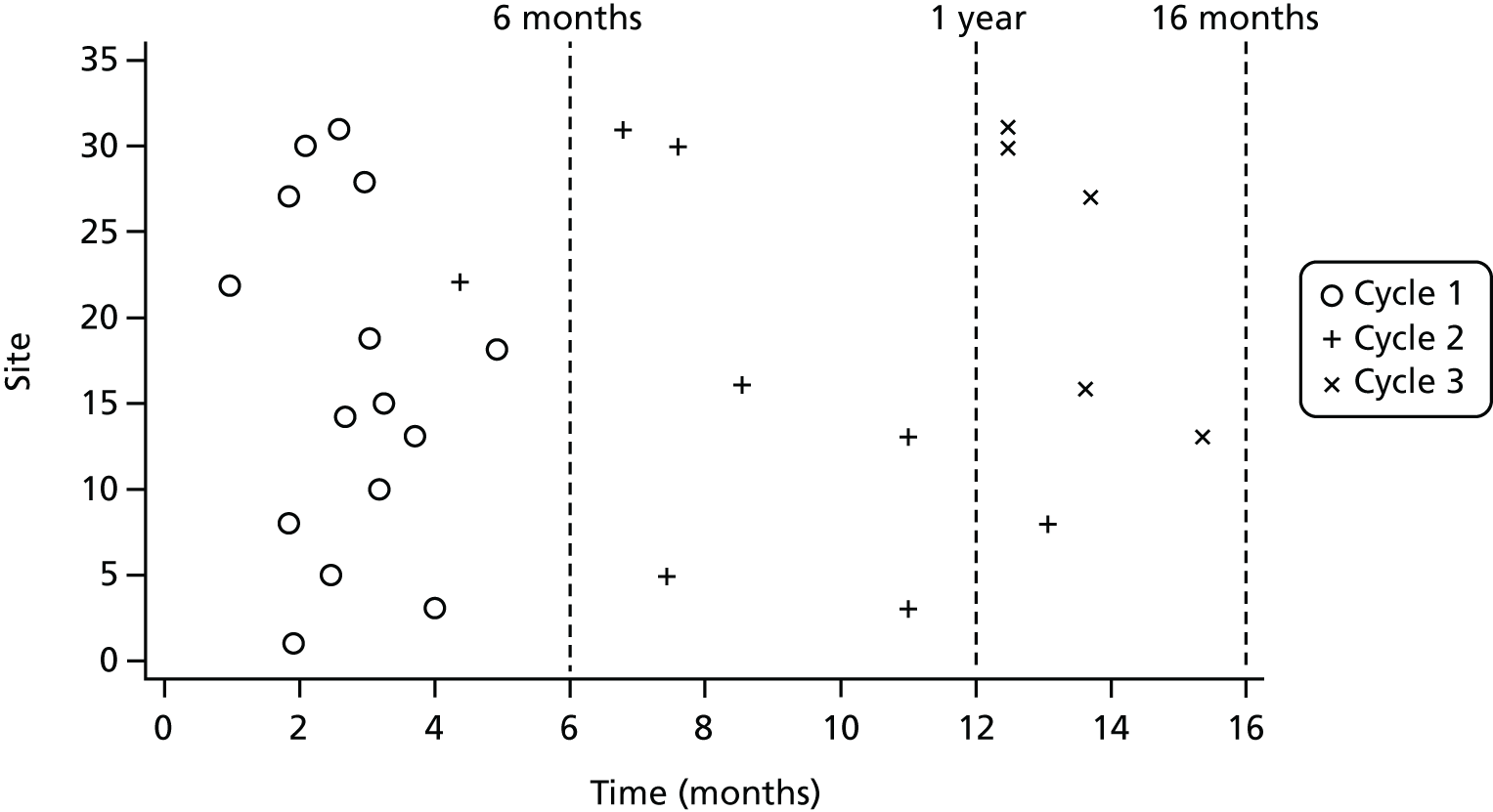

Implementation

Following completion of the formal assessed training course, implementation of DCM commenced, comprising a practice development cycle of briefing the staff team; observation over a number of hours; data analysis, reporting and feedback to the staff team; and action-planning. Re-mapping at regular intervals forms part of the standard process to monitor progress and to set new action plans. Intervention homes were scheduled to complete their first cycle 3 months after randomisation (or as soon as practicable), their second cycle at 8 months and their final cycle at 13 months. Ahead of each mapping cycle, the trial manager at the CTRU contacted mappers individually via SMS to remind them of the upcoming cycle. Paper documents were posted to them to prompt completion of the cycle.

Briefing

Mappers were asked to run at least one briefing session 1–2 weeks prior to undertaking the mapping observations. Briefing sessions informed the care home staff about DCM and the process of implementation, and provided an opportunity for staff to ask questions and for mappers to address any staff concerns.

Observation

Mappers used the standard DCM procedure. They were asked to observe as many individuals as they felt confident to, up to a total of five, for up to 6 consecutive hours on a single day if possible. Alternatively, they could observe for as long as possible on consecutive days up to a total of 6 hours. A detailed description of the DCM tool is published elsewhere83,109 and summarised here: every 5 minutes, the mapper records two pieces of information about each person they are observing, namely a behaviour category code (BCC) and a mood/engagement (ME) value. There are 23 possible BCCs for the mapper to choose from and they capture what the person with dementia is doing within that 5-minute period. The ME value encapsulates the associated mood and engagement level of the person with dementia and is chosen from a six-point scale (+5, +3, +1, –1, –3, –5). A set of rules is used to determine which BCC and ME value to choose. The mapper also records instances when a person with dementia is ‘put down’ by a care worker, known as personal detractions, and examples of excellent care, called personal enhancers. These are recorded as and when they occur. As DCM is grounded in person-centred care, for reasons of privacy and dignity, observations take place only in communal living areas, such as the lounge, the dining room and corridors. Mappers do not observe in bedrooms or bathrooms.

Data analysis, reporting and feedback

For the purposes of trial data analysis, reporting and feedback were considered as a single phase, rather than as the two separate phases of implementation described in the DCM literature. Once the data had been collected, they were analysed by the mappers and presented in a standardised report format for the purposes of feedback to the care team. In the trial, a standard template for DCM reporting was given to the mappers by the research team [see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/111513/#/ (accessed July 2019)]. DCM feedback sessions provided an opportunity for mappers to share their observations with the staff team and for collective discussion about good care practices and areas for improvement. In the trial, mappers were requested to run one or more feedback sessions with as many members of the staff team as possible within 1 month of conducting the observations.

Action-planning

Action plans of ways to improve care were then produced. As part of the feedback session, or in a subsequent meeting, staff and mappers were asked to jointly develop agreed, achievable group (care home-level) and individual resident-level action plans containing short-, medium- and longer-term goals that they wished to implement. Mappers were asked to monitor progress on these actions during the next mapping cycle.

Resident consent for mapping

Prior to mapping, residents were selected to be mapped through discussions between the care team and mappers, during the briefing session or on the day of mapping. Mappers followed DCM guidance, which states that residents may be selected for observation because they display a range of abilities or have particular care needs that staff members have difficulties meeting or understanding. Residents selected for mapping observations did not need to be consenting trial participants, as DCM was implemented as a whole-home intervention. Consent was gained verbally by the mappers, either from the resident or in discussion with their relative prior to observations taking place, in accordance with the usual consent process utilised in DCM. Any resident data collected as part of the DCM process, which was subsequently used for monitoring intervention fidelity or for any other purposes in the trial, was anonymised by the mappers before being sent to the research team.

Expert mapper support for cycle 1

This pragmatic trial aimed to ensure that DCM implementation reflected what is possible in a typical UK care home, maximising relevance to practice. However, the first cycle of mapping was supported by an expert in the use of DCM (a DCM expert mapper), who was assigned by the research team. This is not standard practice, as trained mappers would usually engage in DCM without further support following training completion. However, it was implemented in the trial to support implementation fidelity across clusters (see Process evaluation and assessment of treatment implementation), provide coaching for care home mappers, encourage implementation and support establishment of inter-rater reliability of DCM coding between trained mappers in each care home. The DCM expert mapper worked alongside the mappers during their first DCM cycle, spending 3 days in the care home supporting the establishment of inter-rater reliability on DCM coding frames, briefing, mapping observations and delivery of the feedback and action-planning session. Two additional days of desk-based support were provided on the preparation of briefing documentation, the feedback report and action plans. Telephone and e-mail support for DCM implementation from the DCM intervention lead was available to all intervention homes thereafter, if required.

Outcomes

Primary end point

The primary end point was agitation at 16 months following randomisation, measured by the CMAI, as rated by staff proxy. The Pittsburgh Agitation Scale (PAS) and a modified observational CMAI (CMAI-O), rated by independent researchers, provided a means of assessing concurrent validity, addressing the issue of potential detection bias owing to the inability to blind staff to intervention allocation status.

Health economic end points

The primary health economic end point was cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) at 16 months. A secondary end point was cost per unit of improvement in CMAI score at 16 months. Both of these adopted the health and personal social service provider perspective.

Secondary end points

Secondary end points relating to residents were:

-

BSC (NPI)

-

mood (NPI)

-

QoL [Quality of Life in Late-Stage Dementia (QUALID) scale, Quality of Life in Alzheimer’s Disease (QOL-AD) measure, Dementia Quality of Life (DEMQOL) measure and EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L)]

-

prescribed medication

-

safety (SAEs and safeguarding).

Secondary end points relating to staff were:

-

the Sense of Competence in Dementia Care Staff (SCIDS) scale.

Secondary end points relating to homes were:

-

the Quality of Interactions Schedule (QUIS).

Furthermore, intervention fidelity was assessed. All other data are potential mediators or moderators of the treatment effect. Measures, collection time points and methods of completion are summarised in Table 2.

| Assessment | Method of completion (completed with/on) | Purpose | Level | Timeline | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screening | Baseline | 6 months | 16 months | ||||

| Resident demographics | Researcher assessment (CM, CR) | Individual | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| CMAI | Researcher interview (SP) | Primary end point | Individual | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| CMAI-O | Independent researcher observations (R) | Independent assessment of concurrent validity of CMAI for detection of potential bias | Individual | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| PAS | Independent researcher observations (R) | Independent assessment of concurrent validity of CMAI for detection of potential bias | Individual | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| NPI – nursing home version | Researcher interview (SP) | Secondary end point | Individual | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| DEMQOL measure – proxy version | Researcher interview (SP, RF) | Health economics end point | Individual | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| EQ-5D-5L/EQ-5D-5L – proxy version | Researcher interview (R, RF, SP) | Health economics end point | Individual | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| QUALID scale | Researcher interview (SP, RF) | Secondary end point | Individual | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| QOL-AD measure (care home) | Researcher interview (R) | Secondary end point | Individual | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| Health-care resource use | Researcher assessment (CR) | Health economics end point | Individual | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| Prescription medications | Researcher assessment (CR) | Secondary end point | Individual | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| Resident comorbidities | Researcher assessment (CR) | Individual | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Clinical Dementia Rating scale | Researcher interview (SP) | Process measure | Individual | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| FAST | Researcher interview (SP) | Individual | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| General Health Questionnaire – 12 itemsa | Self-completed (S) | Secondary end point | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| SCIDS scale | Self-completed (S) | Secondary end point | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| QUIS | Researcher observations (R, S) | Process measure | Cluster | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| Care home demographics | Researcher interview (CM) | Cluster | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Environmental Audit Tool | Researcher observations (CH) | Process measure | Cluster | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| Group Living Home Characteristics questionnaire | Researcher assessment (CH) | Secondary end point | Cluster | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| Assessment of Dementia Awareness and Person-Centred Care Training audit | Researcher assessment (CM, CR) | Pre-baseline benchmarking for provision of additional person-centred dementia awareness training and usual-care monitoring | Cluster | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| Safety reporting | Researcher assessment (CM) | Safety | Monthly following randomisation | ||||

| Reporting unexpected SAEs | Researcher assessment (CM) | Safety | As highlighted | ||||

To ensure that a consistent data set was available for each resident at each time point, the main informant for the primary outcome and for proxy-completed secondary outcomes was a staff proxy informant. These data were supplemented, where possible, by information provided by the resident (when able) and by their relative/friend (when available).

Resident measures

Primary outcome measure: Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory42,43

The CMAI measures 29 agitated or aggressive behaviours. 110 The frequency of each symptom is rated on a seven-point scale (1–7) ranging from ‘never’ to ‘several times an hour’, based on observations over the previous 2 weeks. A total score is obtained by summing the individual frequency scores, yielding a total score ranging from 29 to 203. The CMAI has good psychometric properties111 when used in a care home setting. Data from previous similar studies provide an expected points change to inform the sample size calculation. The CMAI was completed via researcher interview with the staff proxy informant, in accordance with the CMAI manual. 43

As blinding staff to intervention allocation was not possible, two independent observational measures of agitation were collected to assess potential bias in completion of the CMAI by staff proxy informants [see Agitation measures (supportive outcomes)]. Observation scales have been shown to have good convergence with informant measures of agitation. 112 Observations were completed by an independent blinded researcher who was not involved in any other data collection in the care home.

Agitation measures (supportive outcomes)

Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory – Observational113

The CMAI-O was developed by the trial team, with the permission of the CMAI’s author, to provide an observational measure of agitation. It is rated on a four-point scale (1–4) ranging from ‘never’ to ‘several times an hour’, based on observations over 1 day. The CMAI-O data collection was completed on participating trial residents in communal areas between approximately 10.00–12.00 and 14.00–17.00 (dependent on meal times in each care home). A copy is available from the authors on request.

Pittsburgh Agitation Scale114

The PAS is an established observational rating of agitation. The scale has good reported reliability and validity. 114 Observations are conducted for between 1 and 8 hours. PAS data were collected on participating trial residents in communal areas between 10.00 and 12.00 and between 14.00 and 17.00.

Neuropsychiatric Inventory – nursing home version115

The Neuropsychiatric Inventory – nursing home version (NPI-NH) records a broader range of BSC including delusions, hallucinations, agitation/aggression, depression/dysphoria, anxiety, elation/euphoria, apathy/indifference, disinhibition, irritability/lability, aberrant motor behaviour, sleep and night-time behaviour disorders and appetite/eating disorders. The NPI-NH is a 12-item version designed for use with nursing-home/care home populations and has good reported reliability and validity. 115

Quality of life

Dementia Quality of Life measure proxy version116

The DEMQOL measure proxy version (DEMQOL-proxy) is a QoL questionnaire designed specifically for use in people with dementia. It has 32 items covering mood, behavioural symptoms, cognition and memory, physical and social functioning, and general health. It is administered by interview with a carer (formal or family) of the person with dementia. The DEMQOL-proxy has acceptable psychometric properties for measuring QoL in dementia117 and is modelled to enable the derivation of preference-based indices (utility values), with the latter employed in the secondary cost–utility analyses. 118

EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version – self-report and proxy versions119

The EQ-5D-5L is an accepted standardised, five-item measure of health outcomes that provides a single index value for health status120 covering usual activities, self-care, mobility, pain and anxiety/depression, each with five response options (no problems, slight problems, moderate problems, severe problems and unable to do the task). Both the self-report and the proxy versions were used in the trial.

Quality of Life in Late Stage Dementia121

The QUALID scale is an 11-item scale that rates the presence and frequency of QoL indicators over the previous 7 days using proxy report. It is a reliable and valid scale for rating QoL in people with moderate to severe dementia and has good internal consistency, test–retest reliability and inter-rater reliability. 121

Quality of Life in Alzheimer’s Disease (care home)122

The QOL-AD measure is a 13-item self-report measure of QoL with good reported internal reliability, test–retest reliability and convergent validity. 122 It is reported to be reliable in use with people with mild to severe dementia. 123–125 The adapted version of the QOL-AD measure126 is a 15-item questionnaire developed for use in care homes and it uses simple language and a four-response answer that is consistent across all questions (poor, fair, good or excellent). It includes minor changes to the standard QOL-AD measure to ensure relevance to those living in long-term care (e.g. an amendment of the wording of existing items, the removal of questions on management of money and marriage status, and the addition of questions relating to relationships with staff, one’s ability to take care of oneself, one’s ability to live with others and one’s ability to make choices). It has good reported internal consistency. 126

Demographics, health and health-care resource use

Resident demographics

Standardised demographic information (sex, date of birth, etc.) was collected by the researcher via interview with the care home manager or other senior member of staff and a review of the resident’s care records.

Health-care resource use

This measure was adapted from one developed for a care home feasibility trial. 127 The measure captured the use of primary and secondary care, including hospital-based care [e.g. hospital and accident and emergency (A&E) visits and stays], community-based care (e.g. GP visits and contact with other health-care professionals such as physiotherapists and psychiatrists) and other costs (e.g. adapted beds and other aids) incurred during the previous 3 months.

Prescription medications

The prescription of medications within categories of interest (e.g. antipsychotic, benzodiazepine, non-benzodiazepine anxiolytic, non-benzodiazepine antipsychotic, memantine, antidepressant, cholinesterase inhibitor, anticonvulsant, mood stabiliser and pain relief), and the administration of these if prescribed on an as required (PRN) basis, was recorded on a standardised case report form (CRF). This was completed by the researcher through a review of residents’ medication records for the previous month.

Resident comorbidities

These were collected by the researcher using a standardised CRF through a review of residents’ care records.

Dementia severity

Clinical Dementia Rating scale128

The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) scale is a well-utilised, standardised scale for rating the severity of dementia, ranging from no cognitive impairment to severe or advanced dementia. 129 Impairment on six cognitive categories is rated and an algorithm is used to calculate the overall severity rating. Severity is rated by a trained assessor via informal interview/conversation with the person, or with a proxy who knows the person well. In this study, the CDR scale was completed by the researcher through interview with a staff proxy who knew the resident well.

Functional Assessment Staging Test102

The FAST is a scale designed to record the functional severity of dementia. Scores range from 1 (no dementia) to 7 (severe dementia) with levels 6 and 7 each having five sublevels. It is designed for use particularly in more moderate to severe dementia. It is completed by proxy report from a caregiver. 102

Staff measures

Staff work stress

General Health Questionnaire – 12 items130

The General Health Questionnaire – 12 items (GHQ-12) is a measure of stress/psychological well-being used in the general population. It has good reported psychometric properties. 131 It contains 12 items related to mental health, each scored on a four-point scale of the frequency of symptoms or behaviours (‘less than usual’ to ‘much more than usual’). Owing to poor return rates, the collection of GHQ-12 data ceased during the trial (see Summary of changes to project protocol for further details).

Job or role efficacy

Sense of Competence in Dementia Care Staff scale132

The SCIDS scale is a user-friendly, self-complete, 17-item scale measuring staff members’ competence in caring for people with dementia across four subscales (professionalism, building relationships, care challenges and sustaining personhood). Each item is rated on a four-point scale of confidence (‘not at all’ to ‘very much’). It has acceptable internal consistency and test–retest reliability. 132

Organisational measures

Care quality

Quality of Interactions Schedule133

The QUIS is an observational measure of the quality and quantity of staff interactions with residents during care delivery, at the care home level. It records five types of interactions (positive social, positive care, neutral, negative protective and negative restrictive) and has reported adequate inter-rater reliability and sensitivity. 134 The QUIS was completed via researcher observation, using a time-sampling technique in each setting. In accordance with QUIS guidelines,133,135 observations of interactions at 5-minute intervals were conducted in communal areas in the care home and recorded, then summarised into 15-minute intervals. One-hour observations were completed at two time points (a.m. and p.m.) over 2 days within the same week (7-day period) in line with care home activities (e.g. morning coffee break) in the most populated communal area in the home. For the purposes of analysis in this trial, the proportion of interactions that were positive (positive social and positive care) was used.

Care home environment and characteristics

Care home demographics questionnaire

This questionnaire, designed by the study team, collected organisational data regarding each care home (size, type, ownership, geography, staff turnover, staff ratios, resident demographics, etc.) and its manager (qualifications, length of time in post, leadership style, etc.).

Environmental Audit Tool136

The Environmental Audit Tool (EAT) is an instrument with reported adequate reliability and validity used to differentiate between the quality of the physical environment in various types of dementia care facilities. 136 It was completed by the researcher with the assistance of a staff member if required.

Group Living Home Characteristics questionnaire137

The Group Living Home Characteristics (GLHC) questionnaire is a measure of the style of care being delivered in the care home. It examines how ‘home-like’ care delivered is. It includes four subscales (physical environment, residents, relatives/other visitors and staff), each containing at least three related statements answered according to a five-point scale (‘never’ to ‘always’). It was completed by the researcher.

Assessment of Dementia Awareness and Person-Centred Care Training audit99

For information on the Assessment of Dementia Awareness and Person-Centred Care Training (ADAPT) audit, see Dementia training audit and provision of dementia awareness training.

Safety reporting and reported unexpected serious adverse events

For information, see Resident safety.

Sample size

The sample size was calculated to detect a moderate standardised effect size of 0.4 on the primary outcome: the between-group difference in mean CMAI scores at 16 months. We assumed that the standard deviation (SD) would be similar to that observed in a recently completed trial in UK care homes (7.5 points). 66 The moderate effect size translated into a minimum difference of 3 points. If greater variation in CMAI scores was observed (SDs ranging from 15 to 20 points as reported by Zuidema et al. 138) then, for the same effect size, a difference of 6 to 8 points could be detected, respectively. A difference of 8 points on the CMAI score is seen as indicative of real behavioural change. 138 Fifty care homes, each recruiting 15 participants, provide 90% power at a 5% significance level to detect a clinically important difference of 3 points (SD 7.5 points), assuming 25% loss to follow-up (as seen in Chenoweth et al. 63) and an inflation factor of 2.0 (i.e. a cluster size of 11 participants available for analysis after loss to follow-up and an ICC no greater than 0.166).

As provision of care is a further source of clustering and because the ICC was anticipated to be higher in the intervention arm (based on clinical opinion), an allocation ratio of 3 : 2 was used, resulting in there being 30 (450) and 20 (300) care homes (residents) in the intervention and control arms, respectively, namely 50 (750) care homes (residents) overall.

During the trial, the TMG, DMEC and TSC monitored loss to follow-up. This was higher than the anticipated maximum of 25%, mainly owing to death rates. To maintain a statistical power close to 90% and to preserve our ability to detect an effect size of 0.4 SDs, to maintain validity and to increase the generalisability of the trial, we recruited additional, newly eligible, consenting residents from the randomised care homes 16 months after randomisation and performed a cross-sectional analysis of the data (see Summary of changes to project protocol).

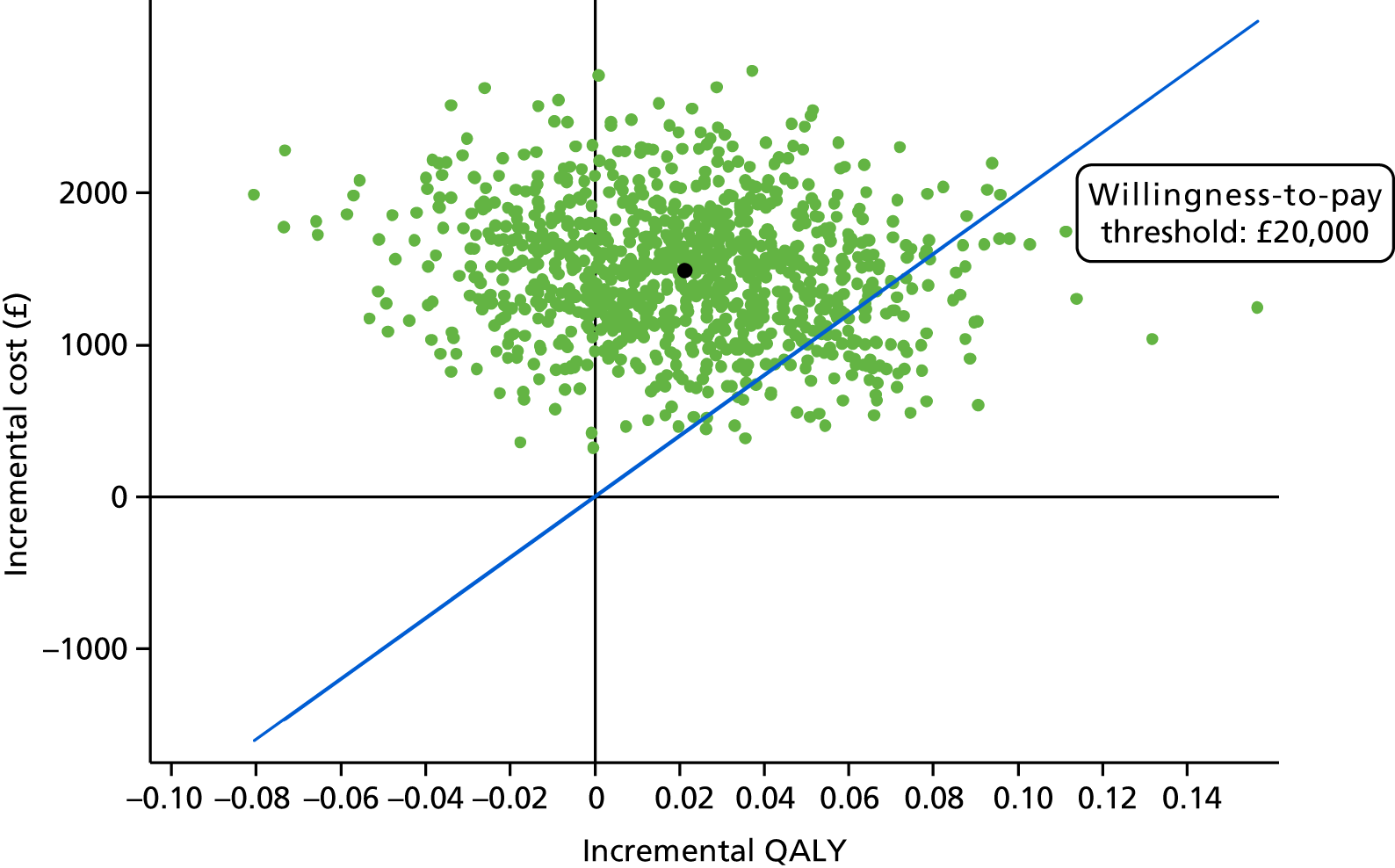

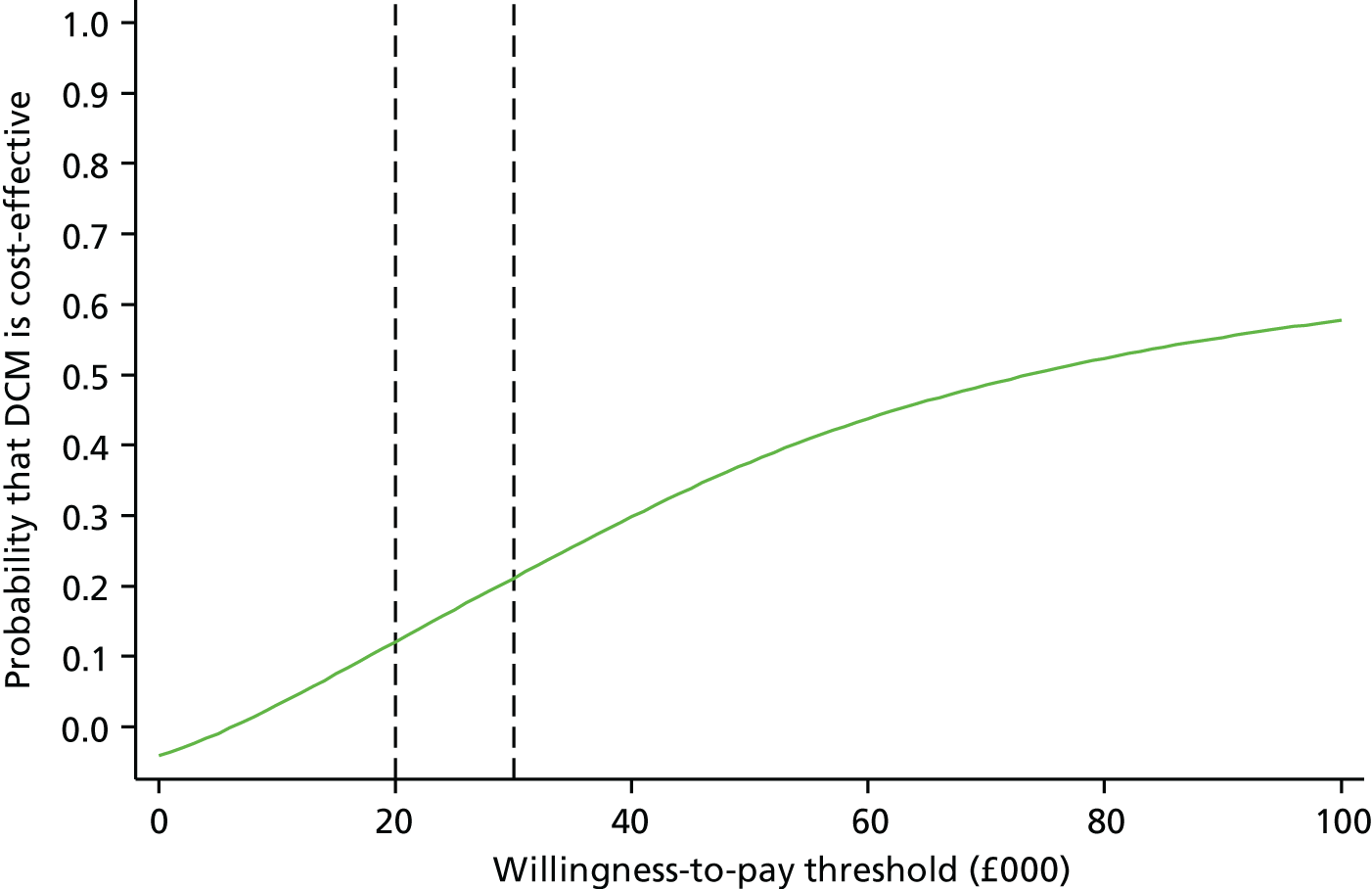

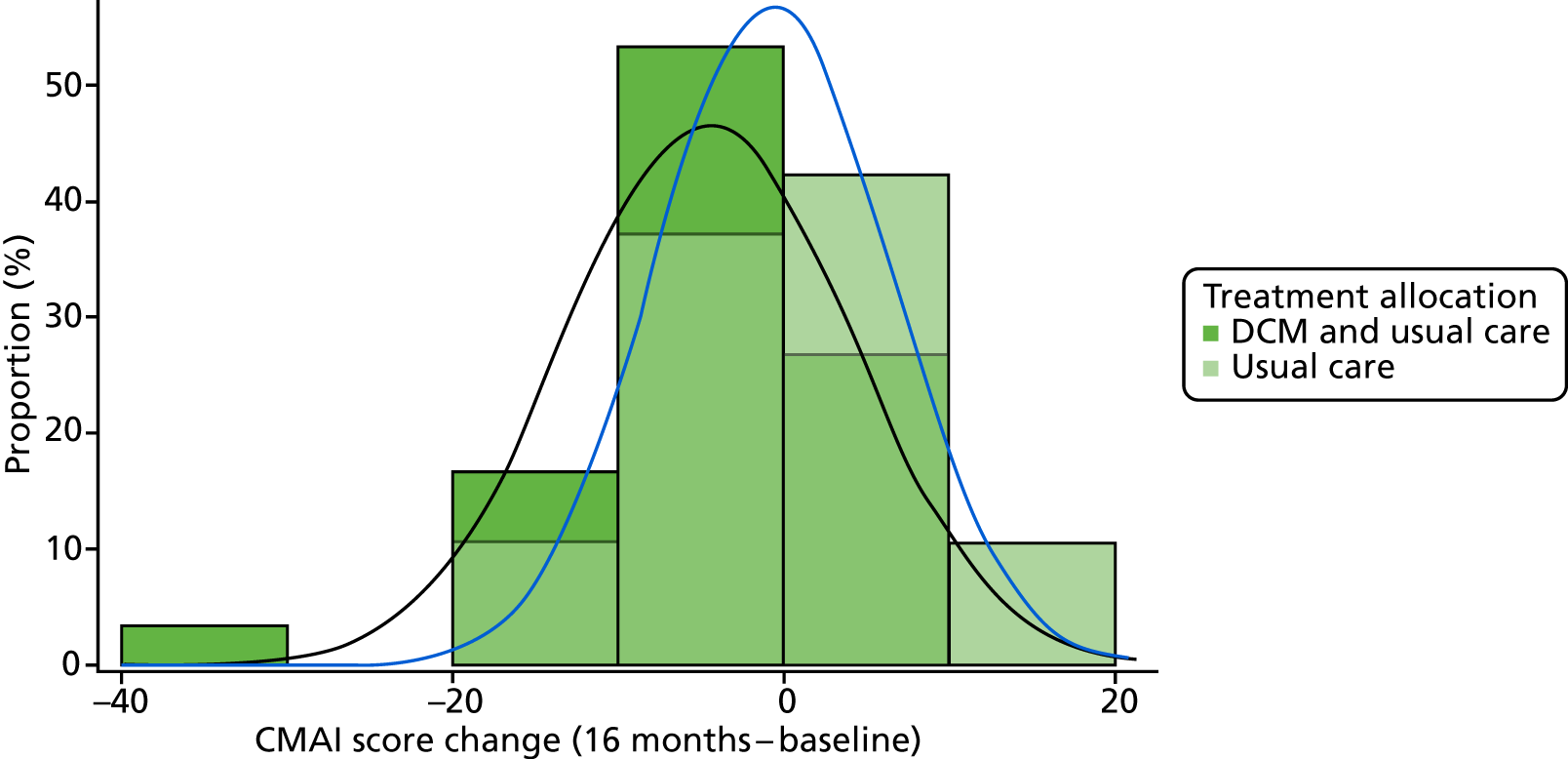

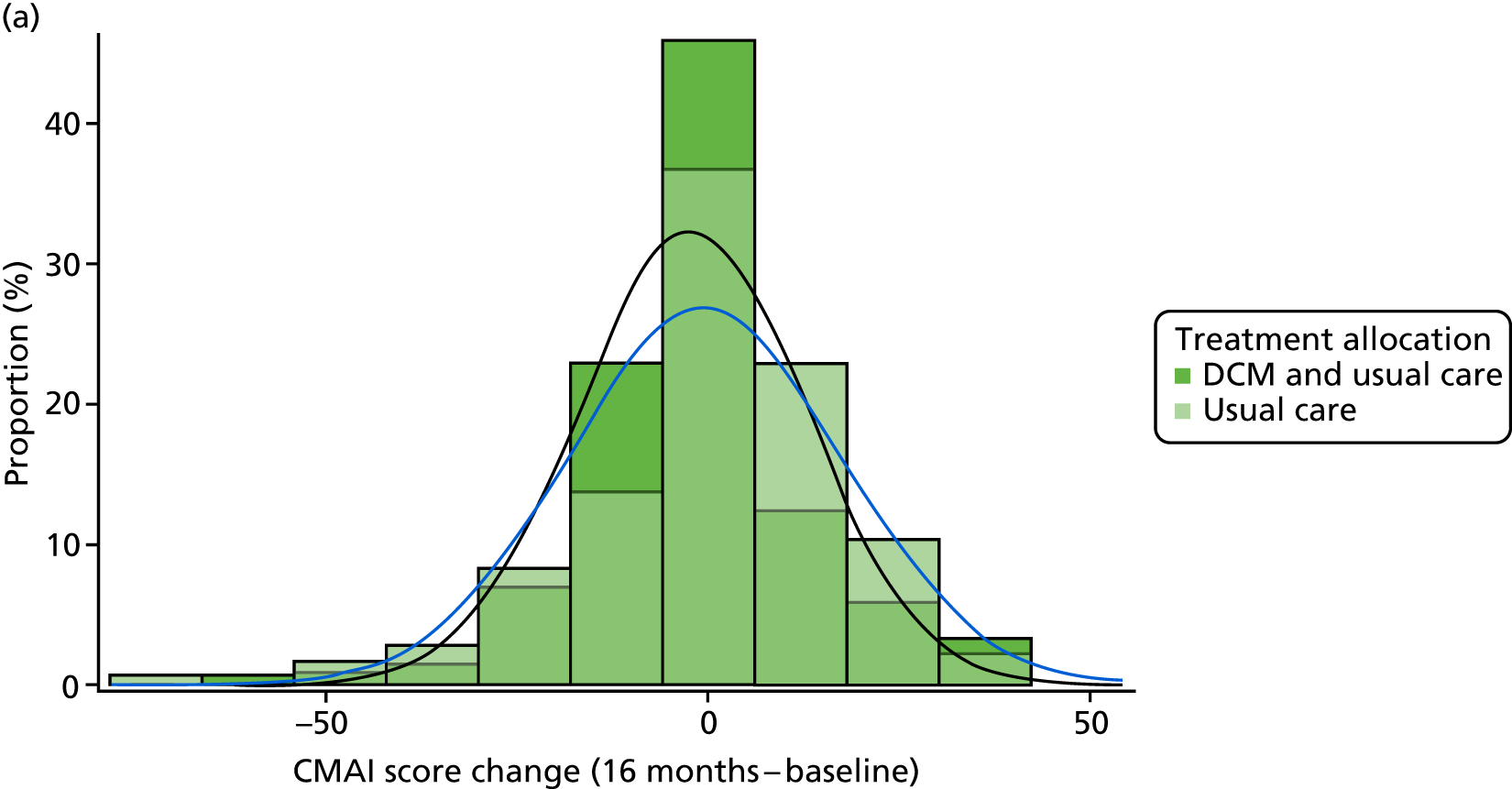

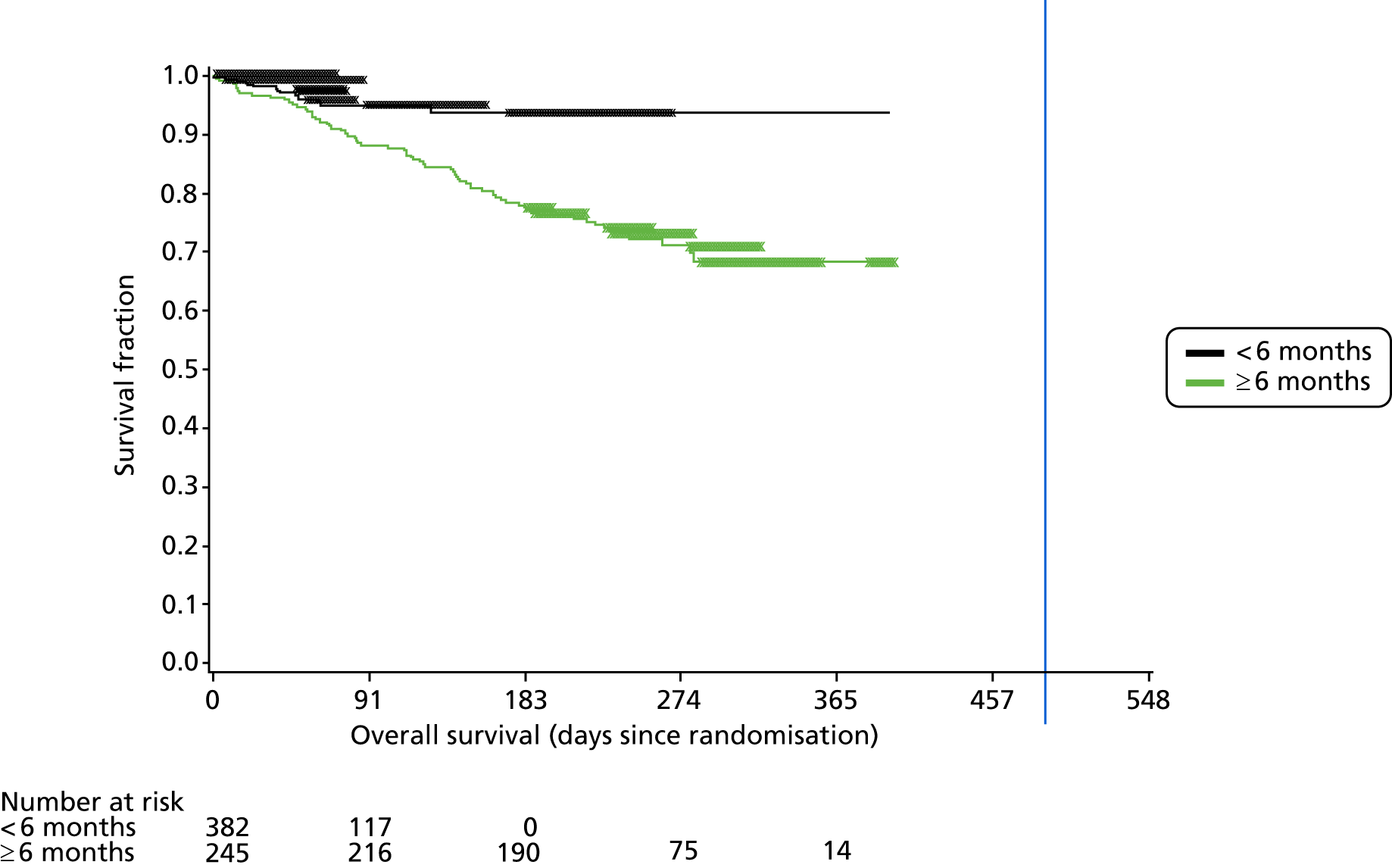

Statistical and health economic methods