Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 11/01/25. The contractual start date was in February 2013. The draft report began editorial review in February 2019 and was accepted for publication in September 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Jane Abbott, Janet Berrington, Elaine Boyle, Ursula Bowler, Jon Dorling, Nicholas Embleton, Kenny McCormick, William McGuire, Edmund Jaszczuk, Samantha Johnson, Madeleine Hurd, Oliver Hewer, Andrew King, Alison Leaf, Louise Linsell, Christopher Partlett, David Murray, Ben Stenson, Judith Rankin and Tracy Roberts report funding from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) for the trial. Jon Dorling, Janet Berrington, Elaine Boyle, Nicholas Embleton, Edmund Jaszczuk, Samantha Johnson, Andrew King, Louise Linsell, William McGuire, Christopher Partlett and Tracy Roberts report receipt of funding from NIHR, outside the submitted work. Jon Dorling reports grants from Nutrinia (Nazareth, Israel) outside the submitted work; specifically, he was funded for part of his salary to work as an expert advisor on a trial of enteral insulin. Furthermore, he was a member of the NIHR Health Technology Assessment (HTA) General Board (2017–18) and the NIHR HTA Maternity, Newborn and Child Health Panel (2013–18). Elaine Boyle reports grants from the Medical Research Council and East Midlands Specialised Commissioning Group outside the submitted work. Janet Berrington reports grants and personal fees from Danone Early Life Nutrition (Paris, France) and grants from Prolacta Biosciences US (Duarte, CA, USA) outside the submitted work. Nicholas Embleton reports grants from Prolacta Biosciences US and Danone Early Life Nutrition and personal fees from Nestlé Nutrition Institute (Vevey, Switzerland), Baxter (Deerfield, IL, USA) and Fresenius Kabi (Bad Homburg vor der Höhe, Germany) outside the submitted work. Samantha Johnson reports grants from Action Medical Research (Horsham, UK), EU Horizon 2020 (Brussels, Belguim), the Medical Research Council (London, UK), Sparks (London, UK) and the Nuffield Foundation (London, UK) outside the submitted work. William McGuire is a member of the NIHR HTA Commissioning Board (2013 to present) and the HTA and Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation Editorial Board (2012 to present). Edmund Juszczak was a member of the NIHR HTA General Board from 2016 to 2017 and the HTA funding committee (commissioning) from 2013 to 2016.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Dorling et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced and adapted from Abbott et al. 1 This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Outcomes affected by feeding strategies

In the UK, 1–2% of newborn infants are very preterm or have a very low birthweight (VLBW). Preterm birth is the major risk factor for infant mortality, with 73% of neonatal deaths in the UK occurring in infants born before 37 completed weeks of gestation. 2 As survival, especially of very preterm infants, has increased in recent years,3 the high prevalence of morbidity associated with preterm birth means that the assessment of long-term outcomes has become increasingly important. 4 Short- and long-term outcomes for preterm infants are affected by strategies that reduce infection rates, lower necrotising enterocolitis (NEC) rates, promote adequate growth and maintain access to tertiary-level facilities.

Optimising infant feeding strategies offers the potential to improve all of these outcomes. Benefits are likely to arise from both the individual and the combined effects of identifying the optimum feeding strategy, as the rates of such complications in very preterm infants are high. NEC that is severe enough to cause death or require surgery affects approximately 7.5% of infants born before 29 weeks of gestation and is the cause of death in 11% of the deaths of infants born before 32 weeks’ gestation. 5 Late-onset sepsis (LOS) affects around 25% of very preterm infants and is responsible for 10% of deaths in the same population. Long-term data following LOS or NEC suggest that these conditions almost double the risk of poor neurodevelopmental outcome. 6 Preterm infants are at significant risk of poor long-term neurodevelopmental problems: almost 12% of infants have moderate or severe disability,7 with both sepsis and NEC dramatically increasing this risk. 8–13

Nutritional support of preterm infants and speed of increasing milk feeds

Every year in the UK, around 8000 infants are born so preterm that they cannot initially be fed milk and, therefore, require intravenous nutrition. Milk feeding is gradually increased as the immature gut begins to tolerate milk and intravenous nutrition is correspondingly reduced, but there are few data determining how quickly this is best achieved. 14 One of the most serious complications of intravenous feeding is LOS, which occurs in 27% of infants born weighing < 1500 g at birth or under 29 weeks’ gestation. 14 LOS is known to cause poor long-term cognitive outcomes, liver damage and sudden death from cardiac problems resulting from misplaced catheters. 15–17 One of the most common late-onset infections is ‘catheter-related bloodstream infection’; the risk of bloodstream infection is directly related to the time the catheter is indwelling in the bloodstream. 18–20 The more rapid advancement of enteral feeds described in this study will, in principle, reduce exposure to intravenous nutrition by causing infants to reach full milk feeds (tolerating 150 ml/kg/day for 3 consecutive days) approximately 4 days earlier than the slower advancement. Reducing exposure by this amount could reduce the number of infections by between 5 and 15 cases per 250 infants, which is an absolute risk reduction of 4%. This is possibly an underestimate of the reduction, as infection risk increases with the length of time a catheter is in place. 21,22

However, faster increases in milk feed volumes may increase the likelihood of NEC that, as well as being potentially fatal, may provoke intolerance of feeds or gut dysfunction, which could result in longer times to achieve full feeds rather than shorter. Survivors of NEC also have significantly worse long-term outcomes across multiple developmental domains than those who are unaffected. 6,23 Therefore, although emerging data suggest that better health outcomes may be achieved with faster feeding increments, there are possible disadvantages of this and a randomised controlled trial (RCT) is required to support a change in clinical practice. 14

Existing evidence

Existing trial data are insufficient to determine whether or not advancing enteral feed volumes slowly (typically < 24 ml/kg/day) or more quickly (daily increments of 30–40 ml/kg) affects outcomes, including the risk of neurological impairment, LOS or NEC in very preterm or VLBW infants. 14,24–32 The Cochrane review14 included nine RCTs with a total of 949 participants (Box 1). None of the studies prior to The Speed of Increasing milk Feeds Trial (SIFT) published neurodevelopmental outcomes in early childhood and the Cochrane review authors concluded ‘that advancing enteral feed volumes at daily increments of 30 to 40 ml/kg (compared to 15 to 24 ml/kg) does not increase the risk of NEC or death in VLBW infants’. 14 They also concluded that ‘advancing the volume of enteral feeds at slow rates results in several days of delay in establishing full enteral feeds and increases the risk of invasive infection’. 14 ‘The applicability of these findings to extremely preterm, extremely low-birthweight or growth-restricted infants is limited’ due to the participants studied and ‘further randomised controlled trials in these populations may be warranted to resolve this uncertainty’. 14 SIFT provided this information by recruiting a large number of infants, including those at highest risk.

-

Typical RR 1.46, 95% CI 1.03 to 2.06; typical RD 0.07, 95% CI 0.01 to 0.13; number needed to harm 14, 95% CI 8 to 100; six trials, 553 participants.

-

Typical RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.64 to 1.62; typical RD –0.00, 95% CI –0.03 to 0.03; nine trials, 949 participants.

-

Typical RR 1.18, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.53; typical RD 0.03, 95% CI –0.02 to 0.08; eight trials, 791 participants.

CI, confidence interval; RD, risk difference; RR, risk ratio.

Objective

The study aimed to assess if faster (30 ml/kg/day) or slower (18 ml/kg/day) daily feed increments improve survival without moderate or severe disability at 24 months of age [corrected for gestational age (CGA)] and other morbidity and mortality in very preterm and/or VLBW infants.

Chapter 2 Methods

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced and adapted from Abbott et al. 1 This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Design

The SIFT was a multicentre, two-arm, non-blinded, parallel-group RCT in very preterm and/or VLBW infants in the UK and the Republic of Ireland. 1,33

Ethics approval and research governance

The SIFT protocol33 was approved by the National Research Ethics Service (NRES) Committee East Midlands – Nottingham 2 on 31 January 2013 (reference 13/EM/0030). Local approval and site-specific assessments were obtained from the NHS trusts for trial sites. The trial was registered with the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Register (https://doi.org/10.1186/ISRCTN76463425).

Patient and public involvement

The planning and delivery of the SIFT was facilitated by close engagement with infant and family representatives who were experienced in service-user representation. Bliss (www.bliss.org.uk/; accessed 29 August 2019), the UK national charity for ‘babies born premature or sick’, was the most heavily involved charity. Parents of children who had received neonatal intensive care contributed directly and via Bliss to both the development of trial materials [e.g. parent information leaflets (PILs) and consent forms] and training research staff (e.g. in simulated ‘consent-seeking’ sessions). INVOLVE good practice guidelines were followed to ensure service-user leadership in the trial delivery and dissemination of the findings. INVOLVE is a national advisory group established and funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) to support active public involvement in NHS, public health and social care research (www.invo.org.uk/about-involve/; accessed 9 December 2019).

Participants

Inclusion criteria

-

Gestational age at birth of < 32 weeks and/or birthweight of < 1500 g.

-

Receiving ≤ 30 ml/kg/day of milk at randomisation.

-

Written informed parental consent.

Exclusion criteria

-

Severe congenital anomaly.

-

No realistic prospect of survival.

-

Unlikely to be traceable for follow-up at 24 months of age (e.g. infants of non-UK residents).

Setting

The setting was neonatal units caring for very preterm infants in the UK and the Republic of Ireland:

-

Recruiting sites – parental consent was obtained, infants were enrolled by randomisation and participation in the trial was commenced (n = 55; see Appendix 1).

-

Continuing care sites – clinicians continued to administer the intervention and collect data if a participant was transferred from a recruiting or another continuing care site (n = 78; see Appendix 2).

Infants were able to participate in other clinical trials at the same time as taking part in the SIFT, depending on the nature of the interventions in the other trials. The Enteral Lactoferrin In Neonates (ELFIN) trial was designed alongside the SIFT to allow enrolment of infants into both trials. 1,34 The SIFT and the ELFIN trial shared some procedures including some joint data collection forms and other documents. Other trials running concurrently were discussed by the chief investigators or their delegated representative, who agreed whether or not joint recruitment was appropriate.

Screening and eligibility assessment

The local health-care team identified potential participants who met the eligibility criteria. Exclusion criteria were defined and assessed by clinicians. Assessment of eligibility was accepted to be within the scope of competency of appropriately trained and experienced neonatal nurses, as no specific medical assessments were required. Competency was formally delegated by the principal investigator (PI) on the delegation log.

Informed consent and recruitment

Parents of potential participants were approached only after receiving a PIL, which gave a full verbal and written explanation of the trial. Parents who did not speak English were approached only if an adult interpreter was available and if they were likely to be resident in the UK or the Republic of Ireland for at least 2 years.

The consent-seeking process included informing parents of the possible benefits and risks as a staged process. 35 If the anticipated infant was likely to be eligible to participate in the trial, preliminary verbal information and the PIL were offered prior to birth and this was followed up after birth. For infants who were not identified antenatally or if other issues took precedence, information was provided after birth.

Written informed parental consent was obtained by means of a dated parental signature and the signature of the person who obtained the informed consent; this was the PI or the health-care professional with delegated authority. The parents were given a copy of the signed informed consent form. A copy was retained both in the infant’s medical notes and in the site file by the PI and the original copy was posted to the trials unit co-ordinating centre.

No financial or material incentive or compensation was given to the participants or parents to take part. It was highlighted to parents that they were free to withdraw their infant from the trial at any time without the need to provide an explanation or reason. The PIL explained that such a decision would not affect any aspect of clinical care.

The trial entry form was completed after informed consent was received. Information on the form was then entered in the randomisation website hosted by the National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit (NPEU) Clinical Trial Unit (CTU) (https://rct.npeu.ox.ac.uk/; accessed 30 May 2015). Randomisation took place when the clinicians were ready to increase the feeds to > 30 ml/kg/day. Infants were considered to have been enrolled once they were allocated a study number and one of the two rates of feeding increment.

Interventions

Trial participants were allocated randomly to receive daily increments in milk feed volume of either 30 ml/kg or 18 ml/kg.

All other aspects of feeding and care followed routine clinical practice in the individual units, including the capacity to stop or alter the rate of the increase in feeds if clinically indicated.

Randomisation

Randomisation was performed by computer through a secure website hosted by the NPEU CTU, University of Oxford. A minimisation algorithm was used to balance prognostic factors: hospital, multiple birth, gestational age ranges and birthweight of < 10th centile for gestational age. The algorithm included a random component that minimises with 80% probability of reducing predictability. Multiple births were allocated to the same feeding increment rate.

Allocation concealment and blinding

The allocation sequence was concealed from those who were assigning participants by the web-based randomisation. It was not possible to safely and completely blind caregivers and parents to the feed rate. This was because nurses, doctors and parents indicated the need to know how much milk was being given as part of feeding practice and care-giving. Blinded end-point reviewers were not aware of the allocation for any participant when reviewing the outcome data.

Primary and secondary outcomes

The primary outcome was survival without moderate or severe neurodevelopmental disability at 24 months of age CGA. Moderate or severe neurodevelopmental disability was defined as any of:

-

moderate or severe visual impairment (i.e. reduced vision uncorrected with aids, blind in one eye with good vision in the contralateral eye or blind/perceives light only)

-

moderate or severe hearing impairment (i.e. hearing loss corrected with hearing aids, some hearing loss but not corrected by hearing aids, or deaf)

-

moderate or severe gross motor impairment (i.e. unable to walk or sit independently)

-

moderate or severe cognitive impairment, assessed using the Parent Report of Children’s Abilities – Revised (PARCA-R).

A total PARCA-R score of < 44 was used to identify children with moderate or severe cognitive impairment. 38 The definition is summarised in Box 2.

Secondary outcomes included:

-

mortality

-

moderate or severe neurodevelopmental disability at 24 months CGA

-

death before discharge home

-

microbiologically confirmed (Box 3) or clinically suspected late-onset invasive sepsis (Box 4) from trial entry to discharge home

-

NEC (Bell’s stage 2 or 3) from trial entry to discharge home40–42

-

time taken to reach full milk feeds (tolerating 150 ml/kg/day for 3 consecutive days)

-

growth (change in weight and head circumference z-score for gestational age) from birth to discharge home

-

duration of parenteral feeding

-

duration of time in intensive care

-

duration of hospital stay to discharge home

-

diagnosis of cerebral palsy by a doctor or other health professional

-

the individual components of the definition of moderate or severe neurodevelopmental disability.

Diagnoses of moderate or severe neurodevelopmental disability, LOS and NEC were confirmed by the blinded end-point review committee (BERC) using standard definitions (see Appendix 3 and the published protocol1,33). All of the data collection forms were assessed independently by pairs of clinicians who were unaware of allocation. We noted that owing to ‘rounding’ of the feed rate to the nearest 0.5 ml or to small changes in a daily weight in the clinical setting, some infants on ‘full feeds’ received only 146–149 ml/kg/day. We therefore considered an infant to be on full feeds if ≥ 145 ml/kg/day was tolerated for 3 consecutive days. Infants who did not meet these criteria were reviewed by the BERC to determine if a sustained level of feeding at a level below this had been achieved before discharge. Examples of this included feeds being stopped during transfer or for a procedure, use of higher-calorie formula or fluid restriction after 150 ml/kg/day had been reached.

For live infants, a parent-report questionnaire was used to assess sensory and gross motor impairment and standardised measures were used to assess cognitive function in order to identify children with:

-

Moderate/severe visual impairment (reduced vision uncorrected with aids, blind in one eye with good vision in the contralateral eye or blind/perceives light only).

-

Moderate/severe hearing impairment (hearing loss corrected with aids, some hearing loss but not corrected by aids, or deaf).

-

Moderate/severe gross motor impairment (unable to walk or sit independently).

-

Moderate/severe cognitive impairment assessed using the PARCA-R. Total PARCA-R scores of < 44 were used to identify children with moderate/severe cognitive impairment. 36,37

A child who has any one or more of these impairments will be classified as having a moderate/severe disability.

Definitions for motor and sensory impairments described above are as defined in the report published by, and reproduced with permission from, the British Association of Perinatal Medicine in 2008. 38

Microbiological culture of potentially pathogenic bacteria (including coagulase-negative staphylococci species, but excluding probable skin contaminants such as diphtheroids, micrococci, propionibacteria, or a mixed flora) or fungi from blood or cerebrospinal fluid sampled aseptically more than 72 h after birth, and treatment, or clinician intention to treat, for 5 days or more with intravenous antibiotics (excluding antimicrobial prophylaxis) after investigation was done. If the infant died or was discharged or transferred before the completion of 5 days of antibiotics, this condition would still be met if the intention was to treat for at least 5 days.

Reproduced from The ELFIN Trial Investigators Group. 39 (© The authors. Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an Open Access article under the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license. See https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.)

Absence of positive microbiological culture, or culture of a mixed microbial flora or of probable skin contaminants (ie,diphtheroids, micrococci, propionibacteria) only, and treatment or clinician intention to treat for 5 days or more with intravenous antibiotics (excluding antimicrobial prophylaxis) after the investigation was undertaken for an infant who presents at least 3 of the following clinical or laboratory features of invasive infection:

-

increase in oxygen requirement or ventilatory support

-

increase in frequency of episodes of bradycardia or apnoea

-

temperature instability

-

ileus or enteral feeds intolerance or abdominal distension

-

reduced urine output to less than 1 mL/kg per h

-

impaired peripheral perfusion (capillary refill time longer than 3 seconds, skin mottling or core-peripheral temperature gap greater than 2°C)

-

hypotension (clinician-defined as needing volume or inotrope support)

-

irritability, lethargy, or hypotonia (clinician-defined))

-

increase in serum C-reactive protein concentrations to more than 15 mg/L or in procalcitonin concentrations to 2 ng/mL or more

-

white blood cells count smaller than 4×109/L or greater than 20×109/L

-

platelet count less than 100×109/L

-

glucose intolerance (blood glucose smaller than 40 mg/dL or greater than 180 mg/dL)

-

metabolic acidosis (base excess less than –10 mmol/L or lactate concentration greater than 2 mmol/L).

Reproduced from The ELFIN Trial Investigators Group. 39 (© The authors. Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an Open Access article under the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license. See https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.)

Sample size

It was estimated that 80% of infants would survive to 24 months of age and 11% of survivors would have moderate or severe neurodevelopmental disability. 7 It was expected that the proportion with the primary outcome would be 71% in the comparator (slower increment) group. With a total sample size of 2500 and allowing for a questionnaire response rate of 80%, there would be 90% power to detect an absolute difference of 6.3% with a two-sided 5% significance level. Similarly, a sample size of 2500 infants would have 90% power to detect an absolute difference of 5.4% (from 25.0% in the comparator group) in the incidence of LOS43 and an absolute difference of 3.5% (from 6.0% in comparator group) in the incidence of NEC (Bell’s stage 2 or 3). 40–42

Subsequently, an inflation factor of 1.12 was applied to the sample size to allow for multiple births as they received the same allocation and would probably have correlated outcomes. This adjustment assumed the proportion of multiple births to be 25% and an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.9 for the primary outcome at 24 months CGA, based on a previous study. 44 The total target sample size was therefore increased to 2800.

Statistical analyses

Demographic factors, baseline clinical characteristics and outcomes were summarised with counts and percentages for categorical variables, means [standard deviations (SDs)] for normally distributed continuous variables and medians [interquartile ranges (IQRs) or simple ranges] for other continuous variables. Outcomes were analysed according to allocation, using the slower fed group as the comparator.

Risk ratios (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for the primary outcome at 24 months CGA and for the discharge outcomes of LOS and NEC, with a 99% CI used for all other dichotomous outcomes to allow for multiple comparisons. For normally distributed continuous outcomes, the mean difference (99% CI) was presented; for skewed continuous variables, the median difference (99% CI) was presented. Adjusted risk ratios were estimated using log-binomial regression, or log-Poisson regression with a robust variance estimator if the binomial model failed to converge. Linear regression was used for normally distributed continuous variables and quantile regression was used for skewed continuous variables. The primary inference was based on the analysis adjusting for the minimisation factors at randomisation. Centre was fitted as a random effect and all other factors were fitted as fixed effects. The mother’s identification was nested within centre to take account of the additional level of clustering due to multiples and siblings. This adjusts the standard error to allow for the lack of independence in trial allocation and the potential correlation in outcome.

The consistency of the effects of advancing milk feeds on the incidence of the primary outcome, LOS and NEC across specific subgroups of infants was assessed using the statistical test of interaction. Prespecified subgroup analyses included (1) week of gestation at birth, (2) birthweight of < 10th centile versus ≥ 10th centile for gestational age and (3) type of milk received during the hospital stay (i.e. breast milk only/formula only/mixed) (see Figures 3 and 4). A non-prespecified analysis assessed the effect of the speed increments on sepsis and NEC in infants with abnormal Doppler ultrasounds (see Table 4). Other deviations from the protocol included the use of quantile regression instead of Cox regression to analyse time to full feeds (as the Cox proportional hazard assumption was not satisfied) and mixed-effect log-binomial-Poisson models instead of generalised estimating equations (owing to the ease and flexibility of these methods, which were not in common use when the study was conceived). We performed a sensitivity analysis to examine the affect of missing data at 24 months on the primary outcome by considering different scenarios departing from the assumption that data were missing completely at random.

Data collection

All outcome data for this trial were routinely recorded clinical items that could be obtained from the clinical notes or local microbiology laboratory records. Information was collected using the data collection forms (see Appendix 5).

A BERC, masked to participant allocation, reviewed all case report forms (CRFs) that reported moderate or severe impairment at 24 months of age CGA, episodes of LOS, episodes of NEC or episodes of other gastrointestinal pathology. Two members who were blind to allocation independently assessed adherence to case definitions and resolved any disagreements or discrepancies by discussion or referral to a third committee member, or both. Persisting uncertainties were discussed with the site PI or research nurse or both until resolved.

We noted that owing to ‘rounding’ of the feed rate to the nearest 0.5 ml or to small changes in a daily weight in the clinical setting, some infants on ‘full feeds’ received only 146–149 ml/kg/day. We therefore considered an infant to be on full feeds if ≥ 145 ml/kg/day was tolerated for 3 consecutive days. Infants who did not meet this criterion were reviewed by the BERC to determine if a sustained level of feeding at a level below this had been achieved before discharge. Examples of this included feeds being stopped during transfer or for a procedure, use of higher-calorie formula or fluid restriction after 150 ml/kg/day had been reached.

Adverse event reporting

Adverse events were defined as serious if they:

-

resulted in death

-

were life-threatening

-

required inpatient hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation

-

resulted in persistent or significant disability/incapacity

-

were a congenital anomaly/birth defect.

The term ‘life-threatening’ refers to an event in which the participant was at risk of death at the time of the event; it does not refer to an event that hypothetically might have caused death if it were more severe. Serious adverse events (SAEs) were to be reported from randomisation to discharge home.

Expected SAEs were those that could be reasonably expected to occur in the population of eligible infants during the course of the trial or form part of the outcome data. These did not require reporting by the SIFT co-ordinating centre and referred to the following SAEs:

-

death (unless unexpected in this population)

-

NEC or focal intestinal perforation

-

microbiologically confirmed or clinically suspected late-onset invasive infection

-

bronchopulmonary dysplasia (mechanical ventilator support or supplemental oxygen at 36 weeks’ postmenstrual age)

-

intracranial abnormality (i.e. haemorrhage, parenchymal infarction or white matter damage) on cranial ultrasound scan or other imaging

-

pulmonary haemorrhage

-

patent ductus arteriosus requiring treatment (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or surgery)

-

retinopathy of prematurity.

Reporting procedures

All expected SAEs (detailed above) were recorded on a CRF and were reviewed by the Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) at regular intervals throughout the trial. Any unexpected SAEs (a SAE that was not included in the list of expected SAEs) were reported by trial sites to the SIFT co-ordinating centre as soon as possible after the event had been recognised. Information on each SAE was recorded on a SAE reporting form, which was faxed to the SIFT co-ordinating centre. Additional information received for a case (follow-up or corrections to the original case) were faxed to the SIFT co-ordinating centre on a new SAE CRF. A standard operating procedure (SOP) that outlined the reporting procedure for clinicians was provided with the SAE form and in the trial handbook. The SIFT co-ordinating centre processed and reported the events, as specified in the CTU SOPs. The chief investigator informed all of the investigators concerned of the relevant information about unexpected SAEs that could adversely affect the safety of participants. Once per year throughout the recruiting period of the trial, a safety report was submitted to the sponsor and ethics committee.

Economic analysis

A health economic analysis of the two speeds of milk feed increments was performed in this study and is described in Chapter 4.

Governance and monitoring

Structured training for site investigators, local research nurses and other clinical staff was provided during initiation meetings. Training covered areas such as seeking consent, protocol details and processes and governance requirements. These events were supported with bespoke written and online training materials that were available to all staff via the trial website (www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/sift/neonatal-staff; accessed 9 January 2020). Staff in continuing care sites were directed to online training and advised to access support from the trial team as needed.

Ongoing monitoring included review of the investigator site files that contained delegation logs, good clinical practice certificates and research curricula vitae of staff. Best-practice data management procedures and data monitoring at the study data centre and trial centres were followed to achieve quality assurance. Data management was in accordance with SOPs at the trial co-ordinating centre (NPEU CTU) and a prespecified plan. Data monitoring included review of consent forms and participant eligibility. Additional validation checks of data were carried out regularly, with data queries issued to study sites for resolution. Final data validation checks were carried out before database lock, with questions being resolved by discussion with the site PI or local research nurse where possible.

During the trial, the study statisticians produced reports for the independent Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and the independent DMC. Data quality concerns that were identified by study statisticians were reported to study data management staff and were queried when appropriate or included in future routine data validation checks, or both. Opportunities for external, independent review of summary data were provided by the DMC and the TSC meetings.

Summary of changes to the study protocol

A summary of the changes made to the original protocol is presented in Appendix 7.

Chapter 3 Results

Recruitment and retention

Patient flow, including recruitment to and retention in the trial, is detailed in Figure 1. The trial recruited infants from June 2013 to June 2015 in 55 hospitals. In total, the trial recruited 2804 infants; 1400 infants were allocated to faster daily feed increments (30 ml/kg/day) and 1404 were allocated to receive slower feed increments (18 ml/kg/day). The trial was closed on reaching the sample size. All infants received the allocated intervention, but 69 infants discontinued the intervention as a result of clinician or parental preference (see Figure 1). For 11 of these infants, parental consent was withdrawn and their data were not available for analysis, but the remainder were included in the intention-to-treat analysis. Outcome data at discharge home were not available for eight infants; their data were included in analyses except when knowledge of discharge or the date of discharge was required. In total, 68 (4.9%) infants in the faster increment group and 77 (5.5%) in the slower increment group died before 24 months CGA. Outcome data on disability at 24 months CGA were available for 1156 (87.2%) surviving infants in the faster increment group and 1169 (88.4%) in the slower increment group. The primary outcome (mortality or disability) was therefore known for 1224 (87.8%) infants in the faster increment group and 1246 (89.0%) in the slower increment group (see Figure 1 and Appendix 8).

FIGURE 1.

Flow of participants through the trial. Adapted from New England Journal of Medicine, Dorling et al. 45 Controlled trial of two incremental milk-feeding rates in preterm infants. N Engl J Med 2019;381:1434–43. Copyright © 2019 Massachusetts Medical Society.

Demographic and other baseline characteristics

The baseline characteristics and demographic features of the participating infants were well balanced between the two feeding increment groups (Table 1). The median gestational age was 29 weeks in both groups (36% at < 28 weeks). The mean birthweight was 1144 g in the faster increment group and 1142 g in the slower increment group. Overall, 60% of infants were born via caesarean section; 24% of infants were born following rupture of maternal amniotic membranes for > 24 hours; and 16% of infants had evidence of absent or reversed end diastolic flow in the fetal umbilical arteries. The allocation groups were well balanced in individual recruiting sites, as per the minimisation algorithm (see Appendix 9).

| Characteristic | Faster feed increment group (30 ml/kg/day) (N = 1394) | Slower feed increment group (18 ml/kg/day) (N = 1399) |

|---|---|---|

| Number of centres,a n | 55 | 54 |

| Male sex, n/N (%) | 739/1394 (53.0) | 726/1398 (51.9) |

| Missing, n | 0 | 1 |

| Infant age at randomisation (days) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 4 (3–6) | 4 (3–6) |

| Birthweight of < 10th centile for gestational agea | ||

| Total, n/N (%) | 295/1394 (21.2) | 291/1398 (20.8) |

| Missing, n | 0 | 1 |

| Gestation at delivery (completed weeks),a n/N (%) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 29 (27–30) | 29 (27–30) |

| 23+0 to 23+6 | 30/1394 (2.2) | 31/1399 (2.2) |

| 24+0 to 24+6 | 72/1394 (5.2) | 69/1399 (4.9) |

| 25+0 to 25+6 | 103/1394 (7.4) | 101/1399 (7.2) |

| 26+0 to 27+6 | 291/1394 (20.9) | 297/1399 (21.2) |

| 28+0 to 29+6 | 377/1394 (27.0) | 383/1399 (27.4) |

| 30+0 to 31+6 | 432/1394 (31.0) | 432/1399 (30.9) |

| 32+0 to 36+6 | 88/1394 (6.3) | 86/1399 (6.1) |

| ≥ 37 +0 | 1/1394 (0.1) | 0/1399 (0.0) |

| Birthweight (g), n/N (%) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 1144.2 (339.3) | 1142.3 (328.9) |

| < 500 | 10/1394 (0.7) | 7/1399 (0.5) |

| 500 to 749 | 178/1394 (12.8) | 164/1399 (11.7) |

| 750 to 999 | 316/1394 (22.7) | 345/1399 (24.7) |

| 1000 to 1249 | 348/1394 (25.0) | 349/1399 (24.9) |

| 1250 to 1499 | 313/1394 (22.5) | 328/1399 (23.4) |

| ≥ 1500 | 229/1394 (16.4) | 206/1399 (14.7) |

| Infant heart rate > 100 beats per minute at 5 minutes | ||

| Total, n/N (%) | 1263/1374 (91.9) | 1265/1381 (91.6) |

| Missing, n | 20 | 18 |

| Infant temperature on admission (°C) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 36.8 (0.7) | 36.8 (0.8) |

| Missing, n | 8 | 8 |

| Infant worst base excess within the first 24 hours of birth (mEq/l) | ||

| Mean (SD) | –6.1 (4.0) | –6.1 (3.9) |

| Missing, n | 29 | 26 |

| Infant ventilated via endotracheal tube at randomisation | ||

| Total, n/N (%) | 316/1392 (22.7) | 293/1397 (21.0) |

| Missing, n | 2 | 2 |

| Infant had absent or reversed end diastolic flow | ||

| Total, n/N (%) | 209/1372 (15.2) | 226/1380 (16.4) |

| Missing, n | 22 | 19 |

| Time from trial entry to first feed (days) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–1) |

| Missing, n | 5 | 4 |

| Mother’s age at randomisation (years) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 30.5 (6.2) | 30.7 (6.2) |

| Missing, n | 0 | 1 |

| Multiple pregnancy | ||

| Multiple pregnancy,a,b n/N (%) | 412/1394 (29.6) | 411/1399 (29.4) |

| Singlesc | 3 | 5 |

| Twinsd | 358 | 359 |

| Tripletse | 51 | 47 |

| Caesarean section delivery | ||

| Total, n/N (%) | 841/1393 (60.4) | 847/1399 (60.5) |

| Missing, n | 1 | 0 |

| Membranes ruptured before labour | ||

| Total, n/N (%) | 496/1373 (36.1) | 486/1380 (35.2) |

| Missing, n | 21 | 19 |

| Membranes ruptured > 24 hours before delivery | ||

| Total, n/N (%) | 323/1377 (23.5) | 338/1380 (24.5) |

| Missing, n | 17 | 19 |

Adherence

All of the infants received the allocated intervention but 69 infants discontinued the intervention: 66 from clinician or parental preference and three from transfer to a non-participating hospital (see Figure 1). For 11 of these 66 infants, parental consent was withdrawn and their data were not available for analysis. The remainder were included in intention-to-treat analyses. Outcome data at discharge home were not available for eight infants; their data were included in analyses except when knowledge of discharge or the date of discharge was required. In total, 68 (4.9%) infants in the faster increment group and 77 (5.5%) in the slower increment group died before 24 months CGA. Primary outcome classification at 24 months CGA was possible in 1224 (87.8%) infants in the faster increment group and 1246 (89.0%) in the slower increment group.

Outcomes

The estimates of effect for the primary and secondary outcomes are presented in Table 2 for outcomes at 24 months of age CGA and Table 3 for outcomes at hospital discharge.

| Outcome at 24 months of age CGA | Faster feed increment group (30 ml/kg/day) (N = 1394) | Slower feed increment group (18 ml/kg/day) (N = 1399) | Unadjusted effect measure (CI)a,b | Adjusted effect measure (CI)a,b,c | p-valued |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome | |||||

| Survival without moderate or severe disability,e n/N (%) | 802/1224 (65.5) | 848/1246 (68.1) | 0.96 (0.91 to 1.02) | 0.96 (0.92 to 1.01) | 0.16 |

| Missing, n | 170 | 153 | |||

| Survival, n/N (%) | 1326/1394 (95.1) | 1322/1399 (94.5) | 1.01 (0.99 to 1.02) | 1.01 (0.99 to 1.03) | 0.55 |

| Missing, n | 0 | 0 | |||

| Moderate or severe disability, n/N (%) | 354/1156 (30.6) | 321/1169 (27.5) | 1.12 (0.98 to 1.28) | 1.10 (0.97 to 1.25) | 0.12 |

| Missing, n | 238 | 230 | |||

| Secondary outcome | |||||

| Moderate or severe visual impairment, n/N (%) | 21/1156 (1.8) | 16/1171 (1.4) | 1.33 (0.57 to 3.10) | 1.28 (0.43 to 3.83) | 0.57 |

| Missing, n | 238 | 228 | |||

| Moderate or severe hearing impairment, n/N (%) | 58/1143 (5.1) | 41/1172 (3.5) | 1.45 (0.86 to 2.46) | 1.43 (0.79 to 2.57) | 0.12 |

| Missing, n | 251 | 227 | |||

| Moderate or severe motor impairment, n/N (%) | 87/1164 (7.5) | 59/1177 (5.0) | 1.49 (0.96 to 2.32) | 1.48 (1.02 to 2.14) | 0.007 |

| Missing, n | 230 | 222 | |||

| Moderate or severe cognitive impairment, n/N (%) | 307/1156 (26.6) | 289/1170 (24.7) | 1.08 (0.89 to 1.30) | 1.06 (0.89 to 1.27) | 0.39 |

| Missing, n | 238 | 229 | |||

| PARCA-R | |||||

| Composite score | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 72.5 (38.3) | 73.9 (37.8) | –1.46 (–6.31 to 3.39) | –0.62 (–4.82 to 3.59) | 0.71 |

| Median (IQR) | 69 (40–100) | 70 (43–101) | |||

| Missing, n | 419 | 392 | |||

| Non-verbal cognition scale score | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 25.1 (6.2) | 25.5 (5.7) | –0.45 (–1.18 to 0.29) | –0.36 (–1.01 to 0.29) | 0.15 |

| Median (IQR) | 27 (23–29) | 27 (23–29) | |||

| Missing, n | 414 | 390 | |||

| Vocabulary subscale score | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 39.3 (29.7) | 40.3 (30.1) | –0.99 (–4.81 to 2.83) | –0.37 (–3.71 to 2.97) | 0.78 |

| Median (IQR) | 34 (13–60) | 35 (14–62) | |||

| Missing, n | 412 | 383 | |||

| Sentence complexity subscale score | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 7.9 (5.7) | 7.9 (5.4) | –0.09 (–0.79 to 0.61) | –0.05 (–0.73 to 0.64) | 0.86 |

| Median (IQR) | 7 (3–12) | 8 (4–11) | |||

| Missing, n | 405 | 379 | |||

| Diagnosis of cerebral palsy by a doctor or other health professional | |||||

| Total, n/N (%) | 58/1084 (5.4) | 35/1099 (3.2) | 1.68 (0.97 to 2.91) | 1.66 (0.97 to 2.84) | 0.015 |

| Missing, n | 310 | 300 | |||

| Outcome from trial entry to discharge home | Faster feed increment group (30 ml/kg/day) (N = 1394) | Slower feed increment group (18 ml/kg/day) (N = 1399) | Unadjusted effect measure (CI)a,b | Adjusted effect measure (CI)a,b,c | p-valued |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary discharge outcome | |||||

| Microbiologically confirmed or clinically suspected LOS, n/N (%) | 414/1389 (29.8) | 434/1397 (31.1) | 0.96 (0.85 to 1.08) | 0.96 (0.86 to 1.07) | 0.43 |

| Missing, n | 5 | 2 | |||

| NEC (Bell’s stage 2 or 3), n/N (%) | 70/1394 (5.0) | 78/1399 (5.6) | 0.90 (0.66 to 1.24) | 0.88 (0.68 to 1.16) | 0.37 |

| Missing, n | 0 | 0 | |||

| Secondary outcome | |||||

| Death before discharge, n/N (%) | 60/1392 (4.3) | 65/1393 (4.7) | 0.92 (0.59 to 1.45) | 0.91 (0.55 to 1.53) | 0.65 |

| Missing, n | 2 | 6 | |||

| Time taken to reach full milk feeds (days) (145 ml/kg/day for 3 consecutive days), median (IQR) and median difference (99% CI) | 7 (7–10) | 10 (9–13) | –3.0 (–3.3 to –2.7) | –2.7 (–3.1 to –2.4) | < 0.001 |

| Missing, n | 72 | 102 | |||

| Weight SD score at discharge home,d mean (SD) and mean difference (99% CI) | –1.5 (1.1) | –1.5 (1.1) | –0.04 (–0.15 to 0.08) | –0.02 (–0.11 to 0.08) | 0.67 |

| Missing, n | 75 | 77 | |||

| Head circumference SD score at discharge home,d mean (SD) and mean difference (99% CI) | –0.8 (1.5) | –0.7 (1.7) | –0.09 (–0.27 to 0.09) | –0.07 (–0.24 to 0.10) | 0.31 |

| Missing, n | 258 | 228 | |||

| Duration of parenteral feeding (days) from trial entry to discharge home, median (IQR) and median difference (99% CI) | 9 (7–14) | 11 (9–16) | –2.0 (–2.4 to –1.6) | –2.2 (–2.7 to –1.6) | < 0.001 |

| Length of time in intensive care (days) from trial entry to discharge home, median (IQR) and median difference (99% CI) | 7 (4–21) | 8 (4–21) | –1.0 (–2.6 to 0.6) | –0.4 (–1.5 to 0.6) | 0.30 |

| Length of hospital stay (days) from trial entry to discharge home,e median (IQR) and median difference (99% CI) | 54 (37–81) | 55 (38–78) | –1.0 (–5.2 to 3.2) | 0.1 (–1.9 to 2.0) | 0.94 |

| Missing, n | 62 | 71 | |||

Primary outcome

Data were available for 2470 infants (88%) at 24 months of age CGA. In the faster increment group, 802 out of 1224 (65.5%) infants survived to 24 months of age CGA without moderate or severe disability, compared with 848 out of 1246 (68.1%) infants in the slower increment group [adjusted risk ratio (ARR) 0.96, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.01]. There were also no significant differences in the separate components of the composite outcome, with survival occurring in 1326 out of 1394 (95.1%) infants in the faster increment group and 1322 out of 1399 (94.5%) infants in the slower increment group, and moderate or severe disability in 354 out of 1156 (30.6%) infants in the faster increment group and 321 out of 1169 (27.5%) infants in the slower increment group.

Secondary outcomes at 24 months of age corrected for gestational age

For one of the components of the definition of moderate or severe neurodevelopmental disability at 24 months CGA, there was evidence of a significant difference between groups after adjustment for the factors used in the minimisation algorithm. Moderate or severe motor impairment occurred in 87 out of 1164 (7.5%) infants in the faster increment group and 59 out of 1177 (5.0%) infants in the slower increment group (ARR 1.48, 99% CI 1.02 to 2.14; p = 0.007) (see Table 2).

There was, however, no evidence of a significant difference between groups in the other three components of the disability definition (moderate or severe visual, hearing or cognitive impairment). However, numerically more adverse outcomes were seen in the faster increment group for each of these components; this was also the case for the diagnosis of cerebral palsy by a doctor or other health professional, which occurred in 5.4% of the faster increment group and 3.2% of the slower increment group (ARR 1.66, 99% CI 0.97 to 2.84; p = 0.015).

Other secondary outcomes

In total, 414 out of 1389 (29.8%) infants in the faster increment group had microbiologically confirmed or clinically suspected LOS, compared with 434 out of 1397 (31.1%) infants in the slower increment group (ARR 0.96, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.07; p = 0.43). Bell’s stage 2 or 3 NEC occurred in 70 out of 1394 (5.0%) infants in the faster increment group and 78 out of 1399 (5.6%) infants in the slower increment group (ARR 0.88, 95% CI 0.68 to 1.16; p = 0.37) (see Table 3).

The faster increment group reached full milk feeds significantly sooner: median 7 days from trial entry (IQR 7–10 days), compared with 10 days (IQR 9–13 days) in the slower increment group (adjusted median difference –2.7 days, 99% CI –3.1 to –2.4 days; p < 0.001). Significantly fewer days of parenteral nutrition from trial entry were seen in the faster increment group: 9 days (IQR 7–14 days), compared with 11 days (IQR 9–16 days) in the slower increment group (adjusted median difference –2.2 days, 99% CI –2.7 to –1.6 days; p < 0.001).

There was no evidence of between-group differences for (1) death during hospitalisation, (2) weight and head circumference SD scores at discharge home, (3) duration of time in intensive care from trial entry or (4) duration of hospital stay from trial entry (see Table 2).

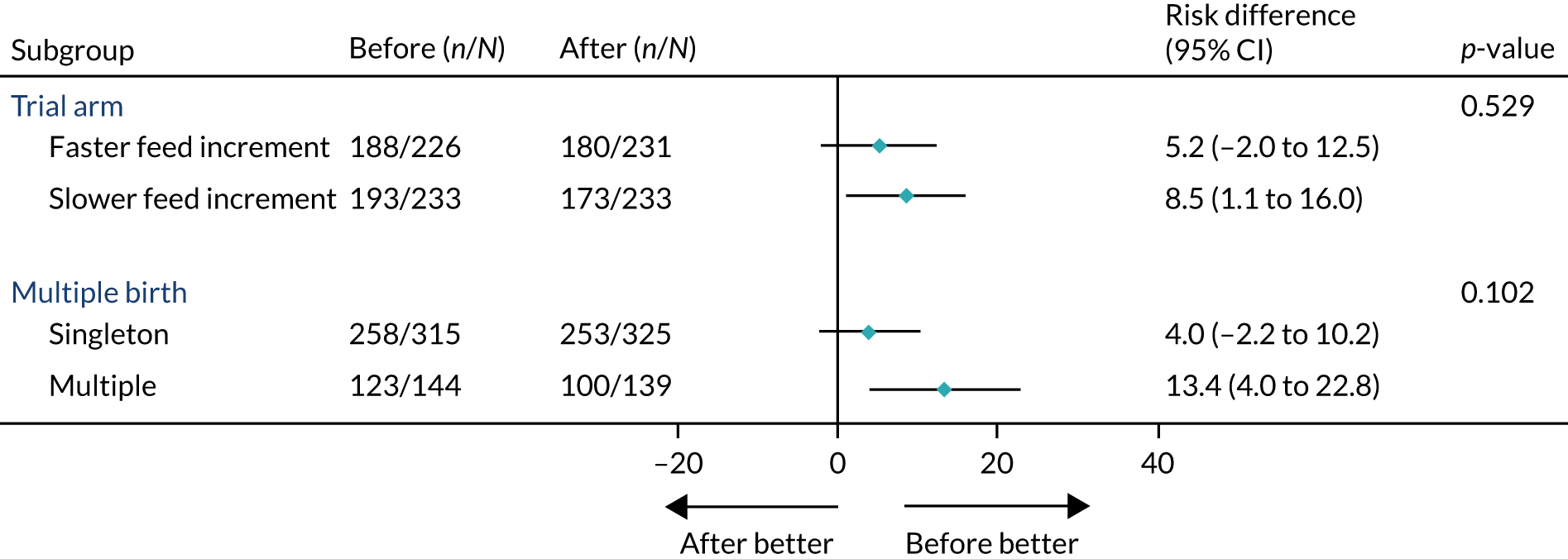

Subgroup analyses

A subgroup analysis showed a significant interaction (p = 0.045) with the primary outcome for the type of enteral milk received: human, formula or both (Figure 2). No significant interaction was seen with the primary outcome for completed weeks of gestation at birth (p = 0.076) or birthweight < 10th centile or ≥ 10th centile for gestational age (p = 0.18). A post hoc analysis was also undertaken to assess the interaction of the presence of absent or reversed antenatal umbilical Doppler studies with the two incremental feed rates (see Tables 4 and 5).

FIGURE 2.

Subgroup analyses for survival without moderate or severe disability to 24 months of age CGA. n/N refers to the number of infants with the primary outcome/number of infants in that category. a, The primary outcome was survival without moderate or severe neurodevelopmental disability (CGA). p-values for interaction were adjusted for minimisation factors: collaborating hospital, single or multiple birth, gestational age at birth, and whether or not the birthweight was below the 10th percentile for gestational age, when technically possible. p-values and CIs were not adjusted for multiple comparisons and should not be used to infer definitive treatment effects. Adapted from New England Journal of Medicine, Dorling et al. 45 Controlled trial of two incremental milk-feeding rates in preterm infants. N Engl J Med 2019;381:1434–43. Copyright © 2019 Massachusetts Medical Society.

The subgroup analyses did not show any significant interactions with NEC (Figure 3) for:

-

completed weeks of gestation at birth (p = 0.63)

-

birthweight < 10th centile or ≥ 10th centile for gestational age (p = 0.25)

-

the type of enteral milk received (human, formula or both) (p = 0.53)

-

the presence of absent or reversed antenatal umbilical Doppler studies (p = 0.09). This was a post hoc analysis.

FIGURE 3.

Subgroup analyses for NEC from trial entry to discharge from hospital. a, n/N refers to the number of infants with one or more episodes of NEC from trial entry to hospital discharge/number of infants in that category. b, Combined with the 30+0 to 31+6 weeks’ category for calculation of RR. c, Combined with mixed category for calculation of RR. ARRs (faster/slower) and p-values for an interaction between allocation and category are shown. Adapted from New England Journal of Medicine, Dorling et al. 45 Controlled trial of two incremental milk-feeding rates in preterm infants. N Engl J Med 2019;381:1434–43. Copyright © 2019 Massachusetts Medical Society.

The subgroup analyses did not show any significant interactions with confirmed or suspected LOS (Figure 4) for:

-

completed weeks of gestation at birth (p = 0.07)

-

birthweight < 10th centile or ≥ 10th centile for gestational age (p = 0.51)

-

type of enteral milk received (human, formula or both) (p = 0.56)

-

presence of absent or reversed antenatal umbilical Doppler studies (p = 0.16). This was a post hoc analysis.

FIGURE 4.

Subgroup analyses for confirmed or suspected LOS from trial entry to discharge from hospital. a, n/N refers to the number of infants with one or more episodes of LOS from trial entry to hospital discharge/number of infants in that category. Adapted from New England Journal of Medicine, Dorling et al. 45 Controlled trial of two incremental milk-feeding rates in preterm infants. N Engl J Med 2019;381:1434–43. Copyright © 2019 Massachusetts Medical Society.

Adjusted risk ratios (faster/slower) and p-values for an interaction between allocation and presence of absent or reversed antenatal umbilical Doppler studies are shown in Tables 4 and 5.

| Necrotising enterocolitis | Faster feed increment group (30 ml/kg/day) (N = 1394) | Slower feed increment group (18 ml/kg/day) (N = 1399) | Adjusted relative risk (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absent or reversed end diastolic flow in the umbilical arteries identified, n/N (%) | |||

| No | 62/1163 (5.3) | 62/1154 (5.4) | 1.00 (0.73 to 1.35) |

| Yes | 8/209 (3.8) | 16/226 (7.1) | 0.49 (0.23 to 1.06) |

| Unknown | 22 | 19 | |

| Late-onset sepsis | Faster feed increment group (30 ml/kg/day) (N = 1394) | Slower feed increment group (18 ml/kg/day) (N = 1399) | Adjusted relative risk (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absent or reversed end diastolic flow in the umbilical arteries identified, n/N (%) | |||

| No | 337/1159 (29.1) | 361/1152 (31.3) | 0.94 (0.84 to 1.05) |

| Yes | 69/208 (33.2) | 66/226 (29.2) | 1.10 (0.89 to 1.36) |

| Unknown | 27 | 1 | |

Safety and adverse events

Sixty-two SAEs were reported, including follow-up reports, relating to 52 separate incidents. Of these 52 events, 34 were not related or relevant to the trial. Fourteen were deemed ‘possibly’ related, but were listed in the protocol as expected SAEs. 33

Four SAEs were deemed ‘possibly’ trial related and were not on the list of expected SAEs. All were reported to the Research Ethics Committee (REC), the DMC and the TSC in previous communications. These four SAEs were two cases of intracardiac thrombosis, one case of prolonged conjugated jaundice and one case of dehydration when a central venous line extravasated. Table 6 summarises the reported adverse events (definitions of adverse reactions and events are presented in Appendix 6).

| Group | Age at SAE (days) | Brief description of event | Severity | Related to trial |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Faster increment group (30 ml/kg/day) (n = 1394) | 55 | Intracardiac thrombus, superior vena cava occluded; deteriorating renal function | Moderate | Possibly |

| 52 | Infant developed prolonged conjugated jaundice | Moderate | Possibly | |

| Slower increment group (18 ml/kg/day) (n = 1399) | 36 | Intracardiac thrombus | Moderate | Possibly |

| 9 | Central venous line extravasated, dehydration and lack of fluids | Mild | Possibly |

Chapter 4 Economic evaluation

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced and adapted from Tahir et al. 47 This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to copy, redistribute, remix, transform and build upon this work for any purpose, provided the original work is properly cited, a link to the licence is given, and indication of whether changes were made. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Introduction

This chapter reports the economic evaluation conducted as part of SIFT. The objective of the economic evaluation was to compare the relative cost-effectiveness of two rates of enteral feed advancement, faster feed increments (30 ml/kg/day) with slower feed increments (18 ml/kg/day), on the principal outcome of survival without moderate or severe disability at 24 months of age CGA.

Methods

A within-trial cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) was performed from the perspective of the NHS and Personal Social Services (PSS) in line with recommended practice. 48 The CEA results are expressed in terms of additional cost per survivor without disability at 24 months of age CGA.

Outcomes

The primary outcome of the CEA was disability-free survival at 24 months of age CGA. Secondary outcomes of the trial included microbiologically confirmed or clinically suspected LOS and NEC. These secondary clinical outcomes are presented here as part of a cost–consequence analysis (CCA). All statistical analyses were conducted in Stata® version 15 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Data

Resource use and costs

Under the NHS and PSS perspective, only the direct costs to the health service provider incurred within the time horizon of the trial were included. Costs incurred during the initial hospital stay and interactions associated with the health service from discharge home to 24 months of age (CGA) were also included. Resource use data were collected prospectively from centres participating in the trial. All centres completed a total of eight different data collection forms that included specific items measuring health-care use. Where SAEs were reported, the associated resource use was collected on an additional form by the relevant participating centres. For instance, the severity of the event and any subsequent additional hospitalisation were recorded, as well as the use of concomitant medication. Health service use until 24 months of age (CGA) was measured through a parent questionnaire (URL: www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/downloads/files/sift/SIFT%202%20Year%20Form%20-%20V2_21%20Sept%202015.pdf; accessed 7 March 2019), which included health-care-related resource use items such as use of primary care services and hospital readmissions.

We also measured out-of-pocket costs to families during the 2-year follow-up period to capture the broader costs that were associated with each trial group, which had the purpose of presenting an additional analysis from a wider perspective. The parent questionnaire included specific items measuring personal financial costs, such as purchasing special equipment, home changes and the travel costs resulting from hospital or outpatient visits. Indirect non-medical costs, referring to income or productivity loss, were also collected. These included both paid and unpaid time off work as a result of the infant’s health. 7 This was valued by multiplying the gross wage rate with the time lost (measured in days) as a result of the infant’s health.

Valuation of resource use

‘Top-down’ methods of costing were used to value resource use. Aggregate cost data were taken from standard published sources to assign costs to resource use variables such as inpatient days. Relevant unit costs were obtained from several sources, but predominantly NHS Reference Costs 2017/1849 and the most recently published Unit Costs of Health and Social Care. 50 Medication prices were extracted from the British National Formulary (BNF)51 and some unit costs were also extracted from existing literature in this area. 52,53 Unit costs were then combined with resource volumes in order to calculate the costs of health service use for each feeding allocation. Table 7 presents the relevant items of resource use, their associated unit costs and the source from which these costs were obtained. All costs were expressed in Great British pounds (GBP) and in 2016–17 prices. Costs were inflated where necessary, using the Hospital and Community Health Services Pay and Prices Index. 50

| Resource use items | Unit cost (£)a | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Intervention | ||

| Cost per day on parenteral nutrition | 45.00 | Walter et al.55 |

| Intensive care: cost per day in intensive care differentiated by level of care required | ||

| Level 1: intensive care | 1295.00 | NHS Reference Costs 2017/18 49 |

| Level 2: high-dependency care | 1032.00 | |

| Level 3: special care | 510.00 | |

| Initial hospital stay | ||

| Cost per pulmonary haemorrhage | 1485.00 | NHS Reference Costs 2017/18 49 |

| Cost per intraventricular haemorrhage by severity | ||

| Grade 1 IVH/germinal matrix haemorrhage | 862.00 | NHS Reference Costs 2017/18 49 |

| Grade 2 IVH | 1472.00 | NHS Reference Costs 2017/18 49 |

| Grade 3/4 IVH | 1519.00 | NHS Reference Costs 2017/18 49 |

| Course of shunts for hydrocephalus | 2608.00 | NHS Reference Costs 2017/18 49 |

| Bronchopulmonary dysplasias | 5954.00 | NHS Reference Costs 2017/18 49 |

| Periventricular leukomalacias | 1341.00 | NHS Reference Costs 2017/18 49 |

| Retinopathy treated medically or surgically | 1603.00 | NHS Reference Costs 2017/18 49 |

| Patent ductus arteriosus treated with NSAID | 1152.00 | BNFC56 |

| Surgeries due to gut signs | 6629.00 | NHS Reference Costs 2017/18 49 |

| Cost of antibiotic medication per day | 3.00 | BNFC56 |

| Cost of antifungal treatment per day | 1.06 | BNFC56 |

| Cost per ml of preterm milk formula | 0.02 | Ganapathy et al.52 |

| Cost per packet of breast milk fortifier | 0.93 | Ganapathy et al.52 |

| Cost per litre of donor breast milk | 335.00 | Renfrew et al.53 |

| Cost per 200 ml of term formula milk | 2.00 | Renfrew et al.53 |

| Resource use during 2-year follow-up | ||

| Cost per outpatient day | 199.00 | NHS Reference Costs 2017/18 49 |

| Cost per inpatient day | 635.00 | NHS Reference Costs 2017/18 49 |

| Cost per operation | 2247.00 | NHS Reference Costs 2017/18 49 |

| Cost per general practitioner visit | 33.00 | PSSRU50 |

| Cost per health visitor visit | 75.00 | PSSRU50 |

| Cost per community nurse visit | 36.00 | PSSRU50 |

| Cost per home visitor/volunteer visit | 19.00 | PSSRU50 |

| Cost per community paediatrician visit | 407.00 | NHS Reference Costs 2017/18 49 |

| Cost per physiotherapist visit | 95.00 | NHS Reference Costs 2017/18 49 |

| Cost per social worker visit | 39.00 | PSSRU50 |

| Cost per speech and language therapist visit | 95.00 | NHS Reference Costs 2017/18 49 |

| Cost per dietitian visit | 85.00 | NHS Reference Costs 2017/18 49 |

| Cost per other health-care professional visit | 135.00 | NHS Reference Costs 2017/18 49 |

Economic analysis

A CCA was conducted as a preliminary measure to compare the disaggregated costs with the outcomes for both feeding increments. CCA is a form of economic evaluation where disaggregated costs and outcomes (consequences) are presented in their natural units. 57 To calculate costs, the quantity of resource use per infant was multiplied by unit costs. Mean costs per infant were estimated and the mean cost differences between the two feeding allocations were calculated. To address the skewness often present in cost data, a bootstrapping approach58 was carried out to calculate CIs around the mean costs. If the CIs of the difference in mean resource use and the costs between groups do not cross zero, this indicates a significant difference. In bootstrapping, repeated random samples of the same size as the original sample are drawn with replacement from the data. 58 The statistic of interest (mean) is calculated from each resample and these bootstrap estimates of the original statistic are then used to build up an empirical distribution for the statistic. 58

The primary base-case economic analysis took the form of a CEA from the perspective of the NHS and PSS. A CEA is a method for assessing the gains in health relative to the costs of different health interventions. 59 In the current study, health consequences are measured as a clinical outcome rather than in the form of health-related utilities, such as quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs). An incremental analysis was conducted, comparing incremental (additional) costs with the outcomes between the two feeding allocations. Costs and clinical outcomes associated with each feeding allocation were combined by calculating incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs). An ICER is expressed as the incremental cost (£) per incremental gain in a natural unit. 60 Cost data were discounted at 3.5% but discounting is not applied to outcomes in natural units; thus, outcomes were not discounted. Cost-effectiveness was based on the principal outcome of additional cost per survival without moderate to severe disability at 24 months of age CGA and from the perspective of the NHS and PSS.

The cost-effectiveness estimates are presented on a cost-effectiveness plane, to illustrate the incremental cost and effect of the intervention (faster feed increments). The cost-effectiveness plane has four quadrants, each with a different implication for the decision of implementing the intervention. 61 This was used to determine the relative position of the results. For example, faster feed increments might be said to ‘dominate’ slower feed increments if its position on the plane showed that the cost of the intervention was lower and the effectiveness in achieving the outcome was greater, when compared with slower feed increments. In other words, if faster feed increments were cheaper and more effective than slower feed increments, faster feed increments would be said to dominate.

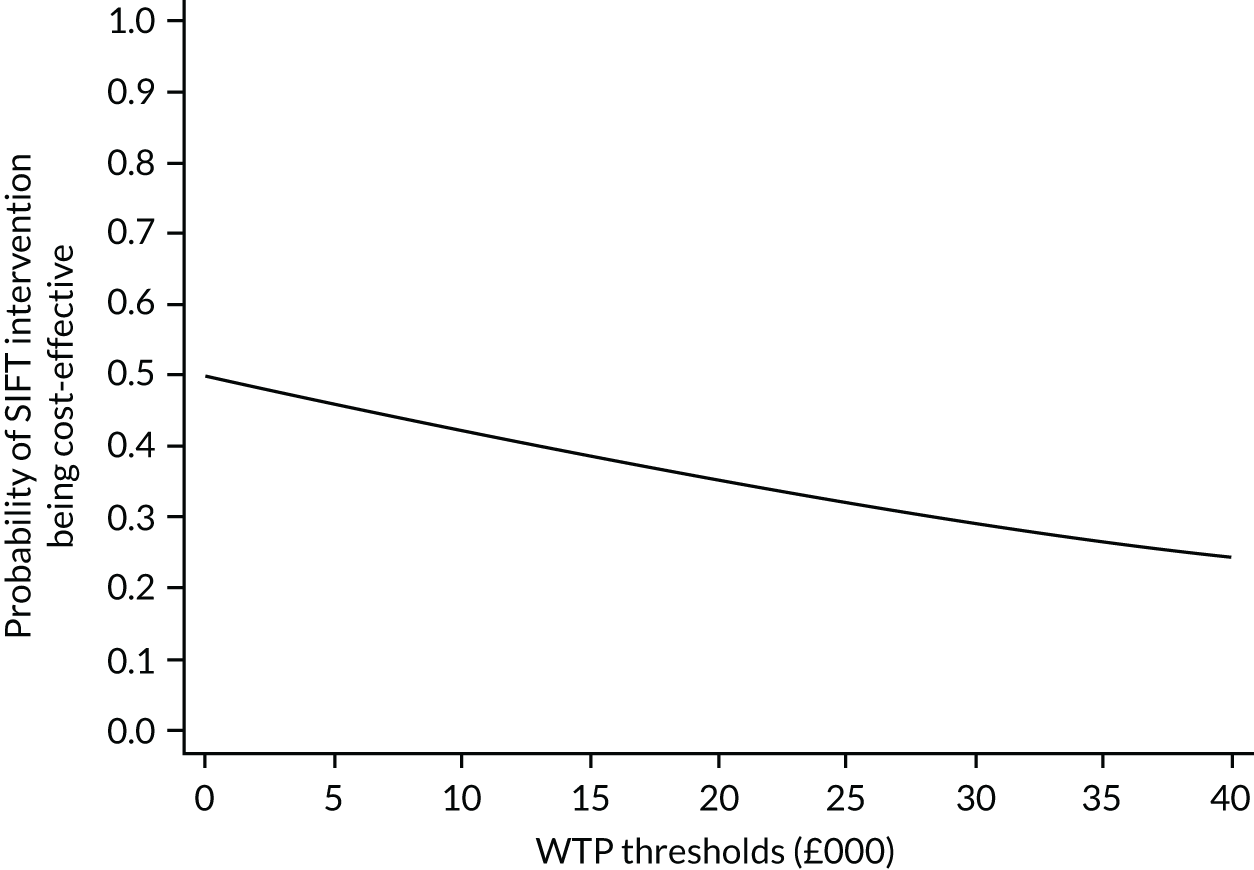

Sensitivity analysis

Statistical uncertainty around the difference in ICERs was estimated by 5000 bootstrap replications, represented as scatter points on the cost-effectiveness plane. Results were presented using cost-effectiveness acceptability curves (CEACs) to reflect sampling variation and uncertainties in the cost-effectiveness value where appropriate. A CEAC shows the probability that an intervention (e.g. faster feed increments) is cost-effective compared with the alternative (e.g. slower feed increments) given the observed data, for a range of maximum monetary values (thresholds) that decision-makers might be willing to pay for a particular unit change in outcome. 61 Unlike economic evaluations, in which outcomes are expressed in QALYs, there is no set monetary threshold here for the primary outcome. Therefore, we examined cost-effectiveness at a range of monetary willingness-to-pay (WTP) thresholds (£0 to £40,000 per additional prematurity-adjusted survivor without disability at 24 months).

To explore the cost of missing resource use data for those infants who did not complete follow-up (15.4%), multiple imputation was performed. Multiple imputation replaces each missing observation with a set of plausible imputed (predicted) values, drawn from the posterior predictive distribution of the missing data given the observed data. 62 Because the missing values are replaced with predicted values, calculated in this way, this method is more favourable than simpler methods, such as replacing missing values with the means of all available values. Costs were imputed at the total cost level and the imputation model used 500 imputations.

Results

Participants

In total, 2804 infants were recruited into the trial, of whom 1400 were randomised to faster feed increments and 1404 were randomised to slower feed increments. Consent was withdrawn for six infants in the faster increment group and for five infants in the slower increment group. A total of 129 deaths occurred before discharge home during infants’ initial hospital stay. Of these deaths, 62 occurred in the faster increment group and the remaining 67 were in the slower increment group.

Follow-up rates at 24 months CGA in survivors were 84.3% (1175 infants) and 85.0% (1189 infants) in the faster increment group and slower increment group, respectively.

Resource use

Average volumes of resource use per infant during the initial hospital stay and the 2-year follow-up are presented in Table 8. On average, infants receiving slower feed increments spent more days in intensive care and in hospital. There was very little variation in resource use during the initial hospital stay across a number of variables, including number of surgeries owing to gut signs or intracranial abnormalities.

| Resource items | Faster feed increment group (N = 1394), mean (SD) | Slower feed increment group (N = 1399), mean (SD) | Bootstrap difference, adjusted mean difference (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Days receiving faster or slower feed increments | 13.24 (16.22) | 15.04 (14.31) | –1.80 (–2.87 to –0.55)a |

| Days in intensive care | |||

| Level 1: intensive care | 15.06 (18.43) | 14.72 (17.48) | 0.34 (–0.96 to 1.71) |

| Level 2: high-dependency care | 20.71 (24.79) | 21.12 (19.65) | –0.41 (–1.96 to 1.51) |

| Level 3: special care | 30.13 (15.28) | 29.60 (15.05) | 0.53 (–0.58 to 1.68) |

| Initial hospital stay | |||

| Days in hospital | 91.00 (94.77) | 94.44 (103.76) | –3.25 (–11.07 to 3.30) |

| Grade 1 IVH/germinal matrix haemorrhage, proportion of daysa | 0.15 (0.38) | 0.16 (0.44) | –0.01 (–0.04 to 0.02) |

| Grade 2 IVH, proportion of days | 0.10 (0.36) | 0.09 (0.34) | 0.006 (–0.02 to 0.03) |

| Grade 3 IVH, proportion of days | 0.04 (0.25) | 0.03 (0.25) | 0.007 (–0.01 to 0.02) |

| Grade 4 IVH, proportion of days | 0.04 (0.24) | 0.03 (0.25) | 0.007 (–0.02 to 0.02) |

| Shunts for hydrocephalus, proportion of days | 0.01 (0.13) | 0.01 (0.18) | –0.002 (–0.02 to 0.009) |

| Bronchopulmonary dysplasias, proportion of days | 0.32 (0.89) | 0.31 (0.90) | 0.01 (–0.04 to 0.06) |

| Periventricular leukomalacias, proportion of days | 0.03 (0.27) | 0.02 (0.20) | 0.009 (–0.006 to 0.02) |

| Retinopathies treated medically or surgically, proportion of days | 0.07 (0.36) | 0.06 (0.32) | 0.02 (–0.002 to 0.04) |

| PDA treated with NSAID or surgery, proportion of days | 0.16 (0.49) | 0.17 (0.47) | –0.001 (–0.03 to 0.03) |

| Surgeries as a result of gut signs, proportion of days | 0.04 (0.25) | 0.04 (0.23) | 0.001 (–0.02 to 0.02) |

| Days on antibiotic medication | 5.60 (11.13) | 5.55 (10.85) | 0.05 (–0.70 to 0.10) |

| Days treated with antifungals | 1.20 (5.90) | 1.59 (7.52) | –0.39 (–0.86 to 0.10) |

| Days receiving preterm milk formula | 1.74 (3.93) | 1.88 (4.14) | –0.14 (–0.44 to 0.15) |

| Days receiving breast milk fortifier | 0.86 (2.47) | 0.83 (2.45) | 0.02 (–0.19 to 0.20) |

| Days receiving donated breast milk | 1.35 (3.34) | 1.43 (3.67) | –0.12 (–0.41 to 0.11) |

| Days receiving term formula milk | 0.24 (1.35) | 0.24 (1.57) | –0.001 (–0.11 to 0.11) |

| Resource use during 2-year follow-up | |||

| Readmissions, proportion of days | 0.34 (0.48) | 0.34 (0.48) | –0.006 (–0.04 to 0.03) |

| Operations, proportion of days | 1.47 (15.71) | 1.46 (0.36) | 0.02 (–0.99 to 1.10) |

| Days as an inpatient, proportion of days | 3.23 (17.33) | 2.82 (11.84) | 0.41 (–0.60 to 1.73) |

| Routine hospital follow-up visits as a day patient, proportion of days | 3.08 (6.82) | 3.17 (6.78) | –0.1 (–0.59 to 0.41) |

| Other hospital outpatient visits as a day patient, proportion of days | 0.39 (0.49) | 0.37 (0.49) | 0.02 (–0.02 to 0.06) |

| Paediatrician visits as a day patient, proportion of days | 1.55 (3.96) | 1.58 (3.57) | –0.03 (–0.29 to 0.26) |

| Number of general practitioner visits | 2.68 (6.06) | 2.42 (5.60) | 0.26 (–0.17 to 0.70) |

| Number of health visitor appointments | 2.05 (6.27) | 1.88 (5.86) | 0.17 (–0.26 to 0.61) |

| Number of community nurse visits | 2.25 (21.38) | 1.28 (6.40) | 0.97 (0.10 to 2.36)a |

| Number of home visitor/volunteer visits | 0.05 (0.21) | 0.04 (0.20) | 0.004 (–0.01 to 0.02) |

| Number of community paediatrician visits | 0.27 (1.46) | 0.29 (1.75) | –0.01 (–0.14 to 0.11) |

| Number of physiotherapist visits | 2.03 (8.00) | 1.93 (8.21) | 0.1 (–0.48 to 0.71) |

| Number of social worker visits | 0.22 (2.02) | 0.19 (2.46) | 0.03 (–0.14 to 0.19) |

| Number of speech and language therapist visits | 0.54 (2.70) | 0.53 (2.87) | 0.006 (–0.21 to 0.20) |

| Number of dietitian visits | 0.68 (3.47) | 0.73 (3.16) | –0.05 (–0.27 to 0.21) |

For the follow-up data, there was very little variation in mean resource use between groups. Infants who had received faster feed increments reported a slightly higher number of days as inpatients, community nurse visits, physiotherapist visits and health visitor visits than the slower feed increment group did.

Costs

Mean resource use was combined with unit costs (see Table 7) to derive the health service costs accruing from each feeding strategy (Table 9). Average costs of the initial hospital stay did not differ very much between the two groups; this is not surprising given that mean resource use was very similar between groups. Mean costs throughout the 2-year follow-up are also presented in Table 9. The most sizeable cost difference was in the cost of inpatient stays; this cost £267 more in the faster increment group. Throughout the follow-up period, health service costs were generally slightly higher for the faster increment group, particularly for primary care services, such as general practitioner, health visitor and community nurse visits.

| Resource items | Faster feed increment group (n = 1394), mean (SD) | Slower feed increment group (n = 1399), mean (SD) | Bootstrap difference, adjusted mean difference (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Days receiving faster or slower feeds | 597 (731) | 678 (645) | –80 (–126 to –30) |

| Days in intensive care | |||

| Level 1: intensive care | 19,506 (23,863) | 19,063 (22,631) | 443 (–1272 to 2277) |

| Level 2: high-dependency care | 21,378 (25,578) | 21,798 (20,280) | –420 (–2016 to 1566) |

| Level 3: special care | 15,375 (7793) | 15,102 (7676) | 273 (–315 to 887) |

| Initial hospital stay | |||

| Grade 1 IVH/germinal matrix haemorrhage, proportion of days | 127 (331) | 134 (381) | –11 (–38 to 15) |

| Grade 2 IVH, proportion of days | 143 (532) | 136 (494) | 7 (–28 to 46) |

| Grade 3 IVH, proportion of days | 60 (378) | 50 (381) | 10 (–19 to 40) |

| Grade 4 IVH, proportion of days | 54 (364) | 51 (366) | 4 (–23 to 30) |

| Shunts for hydrocephalus, proportion of days | 24 (348) | 28 (477) | –4 (–40 to 24) |

| Bronchopulmonary dysplasias, proportion of days | 2475 (3970) | 2392 (4112) | 83 (–214 to 362) |

| Periventricular leukomalacias, proportion of days | 48 (305) | 36 (240) | 12 (–7 to 32) |

| Retinopathies treated medically or surgically, proportion of days | 137 (499) | 103 (453) | 35 (–1 to 70) |

| PDA treated with NSAID or surgery, proportion of days | 202 (509) | 202 (537) | 0.58 (–37 to 43) |

| Surgeries as a result of gut signs, proportion of days | 237 (1567) | 231 (1536) | 5 (–116 to 114) |

| Days on antibiotic medication | 16 (33) | 16 (32) | 0.16 (–2 to 3) |

| Antifungals | 1 (6) | 2 (8) | –0.41 (–0.89 to 0.14) |

| Preterm milk formula | 0.04 (0.08) | 0.04 (0.09) | –0.003 (–0.009 to 0.004) |

| Breast milk fortifier | 0.79 (2) | 0.78 (2) | 0.02 (–0.17 to 0.20) |

| Donated breast milk | 438 (1120) | 480 (1232) | –41 (–127 to 51) |

| Term formula milk | 0.37 (2) | 0.37 (2) | –0.001 (–0.19 to 0.15) |

| Resource use during 2-year follow-up | |||

| Number of operations | 3316 (35,294) | 3273 (29,567) | 42 (–2259 to 2612) |

| Number of inpatient stays | 2150 (11,057) | 1883 (7577) | 267 (–326 to 1076) |

| Number of outpatient visits | 1067 (1971) | 1082 (1827) | –18 (–162 to 112) |

| Number of general practitioner visits | 88 (200) | 80 (185) | 9 (–6 to 24) |

| Number of health visitor appointments | 154 (471) | 141 (440) | 13 (–23 to 45) |

| Number of community nurse visits | 81 (770) | 46 (230) | 35 (5 to 94) |

| Number of home visitor/volunteer visits | 0.86 (4) | 0.77 (4) | 0.09 (–0.20 to 0.40) |

| Number of community paediatrician visits | 112 (596) | 117 (712) | –6 (–59 to 39) |

| Number of physiotherapist visits | 193 (760) | 183 (780) | 9 (–55 to 61) |

| Number of social worker visits | 9 (79) | 8 (96) | 1 (–6 to 7) |

| Number of speech and language therapist visits | 51 (257) | 50 (273) | 0.59 (–19 to 18) |

| Number of dietitian visits | 58 (295) | 62 (269) | –4 (–23 to 19) |

Mean total costs for each group are presented in Table 10. Faster feed increments cost approximately £1043 less per infant than slower feed increments during infants’ initial hospital stay; however, within the 2-year follow-up the faster increment group was more costly by approximately £349 per infant. Overall, the intervention of faster feed increments was less costly.

| Cost category | Faster increments (n = 1224) | Slower increments (n = 1246) | Bootstrap mean difference (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total cost | Mean | SD | Total cost | Mean | SD | ||

| Costs of initial hospital care | 124,386,552 | 101,623a | 80,759 | 126,923,790 | 101,865 | 80,498 | –242 (–6307 to 6251) |

| Costs from initial discharge from hospital up to 24 months corrected age | 10,151,856 | 8,294 | 49,585 | 9,698,864 | 7,784 | 38,473 | 510 (–2864 to 4508) |

| Total costs of health service use after initial discharge from hospital and up to 24 months corrected age CGA | 134,538,408 | 109,917 | 98,040 | 136,623,900 | 109,650 | 94,788 | 267 (–6928 to 8117) |

Mean total costs

Mean total costs are detailed in Table 10.

Cost–consequence analysis

The disaggregated CCA results (Table 11) show that the faster feed increment (the intervention) was slightly more costly and also less effective in terms of achieving the primary outcome of survival without moderate or severe neurodevelopmental disability at 24 months of age CGA.

| Costs/consequences | Faster feed group (N = 1224) | Slower feed group (N = 1246) |

|---|---|---|

| Total costs of health service use for 2 years | £134,538,408 | £136,623,900 |

| Costs of initial hospital care | £124,386,552 | £126,923,790 |